Имболк – ночь с 1 на 2 февраля

Прежде чем мы приступим, я хочу напомнить, что у нас тут 2023 год, города и прочие радости цивилизации. Поэтому мы, конечно, стараемся по традициям, но делаем поправку на современность. Например, на Имболк рекомендуется использовать только парное молоко. У вас у всех корова в хлеву у дома стоит? Или ягнята народились? Ну вот и у меня нет. Поэтому давайте творчески.

Имболк – первый праздник Колеса года в новом календарном году. Просыпается первая стихия – Воздух, темное время начинает потихоньку уходить, просыпается богиня Бригита и природа вместе с ней. Просыпаются духи природы, пришло время наладить контакт с домовым и разными сущностями.

В это время в местах распространения кельтских традиций начинали рождаться первые ягнята, овцы давали молоко. Поэтому символ праздника именно молоко, и оно является символом плодородия в этот день. Имболк и переводится как «молоко».

Важно! Плодородие на Имболк не равно сбору урожая, то есть итогу определенного процесса. На самом деле речь идет о великой жизненной и творческой силе, проявляющейся и в весеннем возрождении природы, и в ее дальнейшем процветании, и во всех аспектах творения человека, понимаемом как сотворчество силам природы и богам.

И хотя февраль – это все еще зима, но весна уже начинает вступать в свои права, и Богиня, закутанная в мантии старухи, вот-вот превратится в юную невесту и пробудит природу.

Имболк – это время очищения и надежды, время огней, костров и свечей. Считается, что тысяча зажженных свечей даст Солнечному Мальчику необходимую силу, чтобы вырасти большим и сияющим. Напоминаю, что Бог-Солнце родился на Йоль. Давайте поможем Солнцу вырасти, я уже свечей заготовила)

Что дает нам Воздух?

Воздух – это сила слова, идеи, информация. Именно на Имболк планируют предстоящий год и запрашивают необходимую информацию. Как вы все знаете, в современном мире кто владеет правильной информацией, тот и на коне. Применять, правда, ее еще надо уметь.

Кто такая Бригита, которой кельты посвящали этот праздник?

Бригита – кельтская богиня плодородия, кузнечного дела, ремесел и поэзии, целительства. В нашем мире кузнечное дело, прямо скажем, не сильно актуально, поэтому посмотрим в суть. Бригитта – богиня творчества, вдохновения, раскрытия таланта, слов, поэзии и целительства.

Бригита принадлежит к трёхликим божествам. Но она не похожа, например, на Норн, которые отражают периоды жизни человека. Она воплощает в себе разные сферы деятельности и ремёсла.

Первый огонь богини помогает талантливым людям создавать произведения искусства, получать вдохновение и постигать новые вершины в своём мастерстве.

Вторым огнём Бригиты называли пламя сердца, то состояние, благодаря которому человек не охладевает ко всему происходящему в мире, не становится равнодушным. Покровительством всегда пользовались целители и жрецы, дававшие благословение. Такой огонь не позволяет человеку оставить без помощи того, кто в ней нуждается.

Третий огонь Бригиты — это вдохновение в чистом виде, что позволяет творцу парить в мечтах, забывая о бренном, и создавать великолепные песни и стихи, вдохновляющие народ. Особым её покровительством пользовались бродячие поэты и музыканты.

Как многие верховные женские божества других народов, у кельтов Бригита связывалась и с силами плодородия. Считалось, что она по весне бросает свой зелёный плащ на землю, заставляя оживать растения и придавая силы побегам.

Алтарь

На алтарь надо обязательно поставить птиц – символ Воздуха и спутников Бригитты. Украсьте алтарь снежинками, свечами, ледяными чашами, хрустальным бокалом со снегом, подснежниками, горным хрусталем, травами Имболка. Свечи натрите аромамаслами. Можно сделать композицию из перьев.

Живые подснежники раздобыть проблематично, поэтому можно подойти творчески и нарисовать картину или поставить готовый постер какой-то, слепить из полимерной глины или пластилина, сделать из бумаги. Проявите максимум творчества, ведь Бригита его покровительница. Тоже самое с птицами и другими украшениями.

Можно поставить любые белые или желтые цветы, или купить крокусы в магазине. Сейчас уже продаются. Или первые нарциссы.

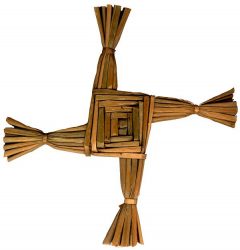

Крест Бригиты – основной символ праздника.

Крест символизирует собой древний кельтский солярный символ, то есть Солнце по-простому. По идее делать его нужно из кукурузы или пшеницы, которая была заготовлена на Ламмас. Но и из обычной веревки тоже подойдет. Выглядит сложно на первый взгляд, но делается легко. Обязательно поместите его на алтарь. А также используйте в ритуалах.

А вот такой потрясающий декор можно сделать и на алтарь, и для украшения

РИТУАЛЫ НА ИМБОЛК

🕊🕊🕊Птица-вестник

Сделайте из бумаги самую простую птичку-оригами, положите в круг из восьми свечей и зажгите их, приговаривая:

Освети моему творению путь, о свеча жизни и смерти.

Когда все свечи будут зажжены, скажите:

Птица-вестник, бумажные крылья,

Глаза твои видят от зари до зари.

Уши твои слышат шепот и тайны.

Расскажи нам, покажи все,

Служи в час нужды мне, помоги,

Волей сил богов ты оживи.

Да будет так!

Теперь спрячьте птичку в укромное место. Когда захотите узнать какую-то информацию, возьмите ее в руки и закройте глаза. Первые пришедшие мысли и образы и будут ответом.

Заморозим беду

Напишите на листке бумаги вашу проблему. Затем положите бумагу в бутылочку с водой, отнесите ее в безлюдное место и положите в снег со словами:

Бури, морозы и снега,

Услышьте вы меня.

Заморозьте мои печали,

Охладите сердце,

Унесите их в далекие края,

В ваши края,

В забвения страну.

Да будет так!

Возвращайтесь домой.

Корм для птиц

Выйдите на открытое место с мешочком корма (пакетик тоже сгодится), можно пойти в лес или парк. Нашепчите на мешочек всякие добрые пожелания: здоровья, счастья, богатства и т. д. Рассыпьте семена, приговаривая:

Птички, птички, соберитесь,

Моими пожеланиями поделитесь.

Занесите их в разные края,

Пусть растут желания.

Зимние, весенние, летние, осенние,

Птицы небесные красивые,

Летите, летите вы ко мне.

Когда птицы прилетят и все съедят, поблагодарите их и идите домой, ни с кем не разговаривая по дороге.

Девятнадцать Свечей Бригит

Подготовьте 19 белых тонких восковых свечей. Нет белых, ставьте любые светлые или неокрашенные. Положите на алтарь Крест Бригит собственного изготовления. Ставьте по одной зажженой свече около кресте, произнося следующие слова:

«Первая свеча — рождение солнца,

Вторая свеча — пламя, что никогда не гаснет,

Третья — создание огня, дающее свет и тепло,

Четвертая — символ возрождения Бога,

Пятая — жизнь новой весны,

Шестая — символ чистоты,

Седьмая — символ обновления,

Седьмая — во имя любви,

Восьмая — во имя равновесия,

Девятая — дыхание новой жизни,

Десятая — связь с истиной,

Одиннадцатая — в честь Невесты,

Двенадцатая — в честь моего Пути,

Тринадцатая — в честь искусств,

Четырнадцатая — дань мудрости,

Пятнадцатая — в честь Имболка,

Шестнадцатая — во имя силы,

Семнадцатая — во имя земли,

Восемнадцатая — в честь Бригиты,

И последняя свеча — первая свеча, рождение солнца,

Огонь, что никогда не гаснет.»

Если место позволяет, то можно сделать круг из свечей. Если нет, то как-нибудь расставьте, чтобы вам нравилась композиция. Свечи должны догореть, поэтому берите на минимальное время горения из тех, что у вас есть. Крест на праздник оставьте на алтаре, а потом повесьте куда-то в качестве оберега.

Источник фото: RG.ru

Второго февраля язычники отмечают праздник огня — Имболк. Также в народе торжество называли Днем факелов и огней. В этот день, как и по другим праздникам Колеса Года, люди строили планы на весь следующий год.

- Что значит языческий праздник Имболк

- Традиции и обряды праздника

Что значит языческий праздник Имболк

Имболк — яркий праздник, но некоторые тонкости этого мероприятия могут показаться непонятными для христиан. Наши предки считали данное торжеством началом наиболее сложного цикла в году. Зима не отступает, а напоследок старается «попрощаться» особенно сильными морозами. Запасы пищи уже ограничены и нет того изобилия, с которым люди заканчивали осень. Тем не менее приходится как-то жить вплоть до весны. И провизия появится не сразу — новый урожай ожидали лишь к началу осени. Все это время следовало употреблять немало пищи, чтобы в хорошем состоянии подойти к полевым работам.

Чтобы год был удачным, на вечер Имболка принято было зажигать множество огней. Буквально весь дом должен был светиться и наполниться огнем, чтобы каждый из домочадцев вспомнил о весеннем тепле и с большим рвением ждал марта и апреля. Даже при низких температурах огонь способен рассказать нам о простых вещах. Любая проблема, которая встречается в нашей жизни, рано или поздно заканчивается. Природа, как и человек, подвержена изменениям. По этой причине, какими бы ни были мороз и снег, они вскоре пройдут, и земля подарит нам новые возможности.

В некоторых случаях мы приходим в замешательство, предполагая, что проблемы будут длиться вечно. И человеческие трудности сопоставимы с погодной ситуацией, где зима продолжает бороться за право руководить планетой. Тем не менее, все разрушительное и неконструктивное рано или поздно умирает. Оно сыграло свою роль в нашей жизни и теперь важно отпустить сложности восвояси. Важно, даже пребывая в постоянном стрессе и дисгармонии, «видеть свет в конце тоннеля» и постоянно туда стремиться. Иногда выход из ситуации находится не потому, что мы делаем все возможное для этого, а просто потому, что любой период заканчивается и Вселенная помогает решить проблему.

Традиции Имболка говорят о важности целомудренно воспринимать любую проблему и счастье. В любой из этих моментов нужно вспоминать, что он рано или поздно закончится. И это вызывает печаль. Может закончиться позитивный или отрицательный момент. Благодаря языческому празднику мы напоминаем себе о неизбежном завершении всего. Не так важно, какие чувства мы при этом испытываем. Важно принять это и лишь мудрость способна понять реалии непростой жизни.

Что означает название праздника?

Имболк имеет много разных словоформ, среди которых Оймелк, Имолаг, Имэлк и другие. Суть его заключается в переходном периоде между концом зимы и началом весны. У кельтов торжество называли Днем молока:

- принято считать, что название праздника взято с гэльского языка и переводится как «овечье молоко»;

- в древнеирландском языке mblec также обозначает молоко, тогда как приставка «imb» обозначает ливень.

Традиции и обряды праздника

Праздник кельтов плохо изучен историками, поэтому принято связывать его с самыми разными традициями:

- Имболк считается днем очищения, поэтому язычники массово омывались и купали своих домашних животных. Всей семьей они убирали в домах, старались вымыть каждую щель. Следовало провести как внешнее, так и внутреннее очищение. В первую очередь избавлялись от негативных мыслей. Не принято было спать вовсе без света — оставляли хотя бы одну свечу, ведь огонь — неразрывный символ праздника. Причиной тому богиня Брагита, которая наполняла мир светом;

- это явно не лучший день для пива, интима или рукоделия;

- люди отказывались от поездок в соседние деревни, лучше было отметить его в кругу семьи;

- Имболк — идеальное время для предсказания будущего. Угадывали не только ближайшую погоду, но также имя жениха, дату свадьбы, урожайность и другие сведения;

- перед домом накануне праздника выкапывали небольшую ямку, куда наливалось молоко;

- иногда приносили домашних животных в жертву, после чего их закапывали неподалеку от реки или озера.

- в ночь между первым и вторым января на маслобойке оставляли кусок хлеба с намазанным маслом, что считалось жертвой богине Бригите;

- принято было готовить венки и вешать их на кухне;

- какую-нибудь вкусную еду нужно было вынести за порог дома. Говорили, что в любой момент мимо проходящая Бригита может захотеть перекусить;

- на пороге дома оставляли шелковую ленту, при помощи которой получали благословление Бригиты. Затем этой тканью залечивали болезни и использовали в качестве оберега;

- прежде чем весной сажать семена, их благословляли в этот праздник;

- принято было в этот день украшать дом свечами и лентами, а на столе обязательно должен был стоять кувшин с талой водой;

- на Имболк употребляли, в основном, молочные блюда. Но в рационе могли присутствовать и мясные блюда. Особенно пользовались популярностью специи, лук, изюм и чеснок. Пили не только молоко, а также каши и напитки на молочной основе. Не принято было лишь употреблять в пищу кисломолочные продукты. Допускались пряные вина, глинтвейн, чай на молоке, а также орехи и сухофрукты.

Имболк – старинный кельтский праздник. С древнеирландского «Imbolc» переводится «в молоке». В разных источниках название интерпретируется, как «во чреве матери», «овечье молоко» и «очищающий ливень».

Имболк представляет вариации одного события – приход весны, что еще скрывается покровом лютой зимы. У разных религий это Сретенье, Громница, Оймелк, Праздник Пана, Факелов, Луперкалия, День Бригитты, Фестиваль Подснежников, День Сурка и японский Сэцубун. Поэтому отмечают его и ведьмы, колдуны или последователи традиций Викки, Нью-Эйдж и не подозревающие истинной сути обычные жители разных стран.

Когда празднуют

Имболк приходит через равные промежутки времени после Йоля и перед Остарой. С него начинается цикл из восьми праздников текущего года. Астрономически в этот период Солнце проходит с 10 по 15 градус созвездия Водолея, что соответствует календарным датам с 29 января по 4 февраля.

Виккиане традиционно празднуют Имболк 1–2 февраля – в серединной точке между зимним солнцестоянием и весенним равноденствием. В это время, когда режим зимней спячки сменяется пробуждением природы.

Imbolc соответствует первому саббату из второго Магического креста. Посвящается он богине Бригите, которая на Самайн принесла себя в жертву ради рождения бога. Имболк – момент выздоровления богини, и это не просто очередной точкой Силы, но момент очищения перед обновлением.

Древние кельты считали ночные часы важнее дневных. Да и отсчет времени вели не с полуночи, как сегодня, а с полудня. Потому нет ничего удивительного в том, что празднование Имболка начинается с вечера 1 февраля. Сопряженное с огненными шоу, шабашами, пиршествами, личными и коллективными ритуалами торжество длится всю ночь и весь следующий день.

Легенды о богине Бригит

Праздник посвящается триединой богине Бригит, о коей люди сложили немало легенд. Согласно одной, она родилась с пламенем на голове. Этот огонь не обжигает и не карает, он приносит облегчение, дарит надежду, исцеление, очищает душу, помогает человеку раскрыть собственные таланты, обрести мудрость и вдохновение. Бригита считается покровительницей кузнечного ремесла, врачевания, семейного очага, поэзии, материнства, дома.

Согласно христианским мифам, Святая принимала роды у самой Девы Марии. Другая легенда рассказывает, что она основала аббатство Cill Dara на месте древнего друидского святилища. До ХVI века в в нем постоянно поддерживался живой огонь. Но потом аббатство закрыли. В 1993 году благодаря сестринству Brigidine Sisters огонь зажгли вновь.

В викканской традиции это Бригита родила бога и к Имболку оправилась от родов, но продолжает кормить грудью. Растить, воспитывать юного бога помогают домашние духи. Дитя набирает силы, а вместе с ним становится сильнее и могущественнее мать. Легенда описывает рождение нового Солнца, что с каждым днем все сильнее согревает землю и пробуждает к новой жизни.

Имблок — праздник Огня

Как и другие праздники, Колеса года Имболк связывают огнем. Но костры Самайна считаются погребальными, на Белтейн разжигают пламя страсти, а йольские фонари символизируют огонек надежды, а свечи Имболка дают очищение и возрождение. На смену cтарухе в черном приходит невеста в белоснежном одеянии. Чтобы указать деве путь из тьмы, и зажигаются огни.

В эту ночь на улице разводят костры, устраивают факельные шествия, фестивали огня. В доме после заката устанавливают на подоконниках свечи, где они горят до рассвета. Для этих целей используют и керосиновые лампы с красными стеклами.

Имблок – не праздник одного дня. Он открывает целую неделю, что используют для накопления силы и раскрытия внутреннего потенциала. На него заранее приобретают семь свечей всех цветов радуги и зажигают по одной каждый вечер.

Что делают на Имболк

Ввиду пробуждения природы Имболк считается первым в году праздником плодородия. Это время для ритуалов на обильный урожай, прибыль, приобретение. В ночь с 1 на 2 февраля хорошо раскачиваются застойные ситуации в делах, бизнесе, любви.

В начале февраля просыпаются духи природы, пришло время наладить контакт с домовым и разными сущностями, проводить магические обряды на погосте, обращаться к кладбищенским духам и хозяйке кладбища – одной из ипостасей Бригит.

На конец января – начало февраля приходится отел домашнего скота, потому Имболк считается праздником молока. Оно хорошее подспорье, когда в погребах иссякают запасы летнего урожая. По этой причине во многих ритуалах используется молоко, а на стол подаются приготовленные из этого продукта блюда.

На Имблок нельзя работать, заниматься рукоделием, сексом, пить спиртное. Посещают престарелых родственников, помогают с уборкой и готовкой. Обязательно окропить водой (талой) всех домочадцев, включая домашних питомцев, чтобы обеспечить им защиту и благополучие.

Вариации праздника у других народов

Праздник, что посвящается первым проблескам весны, присутствует в культурах разных народов. Древние римляне проводили церемонию Луперкалии, ныне она нашла отражение в Дне святого Валентина.

Славянские народы отмечали Громницу, или День медведя. Если 1–2 февраля медведи просыпались и выходили из берлоги, то зиме пришел конец. Эта традиция, но в измененном виде соблюдается и сегодня. В Америке и Канаде наблюдают за поведением сурков, в Греции – ежей, в Германии – барсуков. А символ Имблока – выбирающаяся, чтобы оценить погоду, из норы змея.

Третьего февраля в Японии отмечается Сэцубун, что в переводе означает «разделение сезонов». Японцы в этот день прогоняют нечисть. Нашел праздник Имболк отражение и в Христианстве. Встречу зимы с весной именуют Сретенье Господне. Еще один современный праздник, что имеет сходство с празднованием Имболка, – Масленица.

Символика

Алтарь

В Имболк обряды и ритуалы проводятся в специальном месте, на алтаре. Его украшают покрывалом, что сочетает белый и красный/желтый цвета. Первый символизирует снежный покров, второй – кровь/восходящее солнце. На покрытый алтарь ставят любые растения, что ассоциируются с ростом (горшок с луковицей цветка), графин или чашу со снегом или талой водой.

Что еще устанавливают на алтаре:

- миниатюрную наковальню, молот;

- крест Бригиты, хлебных куколок;

- статую богини;

- целебные травы;

- выпечку, что приготовлена на молоке;

- стихи собственного или чужого сочинения;

- свечи, котел с огнем;

- любой кельтский декор.

Свечи – оранжевого цвета, подойдут красные, желтые или белые – натирают маслом муската, корицы, ладана, розмарина. Дом или одну комнату декорируют лентами, цветами белого, желтого, оранжевого оттенков. Одеваются в свободную светлую или белую одежду. Волосы украшают красными, оранжевыми лентами.

Крест Бригиды, хлебные куколки и кельтские узлы

Любые амулеты выполняются самостоятельно 1 февраля. Недопустимо прерывать работу. Крест Бригиды считается солярным символом не только потому, что его лучи смещаются от центра. Бригида непросто покровительница домашнего очага. Ее свзывают с возрождением природы, весной, Солнцем, теплом.

Имблок в Колесе года располагается напротив праздника урожая Лугнасада, поэтому подходящий материал для оберега – пшеничные колоски или солома. Для связки используют льняные нитки или тонкие ленты. Из колосков делают хлебных куколок. Все освящают на Имблока. Тогда весь год они будут защищать от:

- любых природных катаклизмов;

- буйства домашних духов;

- проникновения извне темных сил;

- неупокоенных душ;

- негативно настроенных людей.

В этот день занимаются и плетением кельтских узлов для амулетов и талисманов. Дело это непростое и кропотливое, потренируйтесь заранее, чтобы в день Х не возникло трудностей. Любые заминки при изготовлении магических артефактов сказываются на их силе.

Обряды в Имболк

На Имболк пробуждается и природа, и все энергии материального мира. Энергия праздника богини Бригиты восстанавливает и очищает загрязненное пространство, влияет на смягчение людских сердец. Чтобы впустить таковую в собственный дом, тело душу, очиститесь от негатива, что накопился за год.

Очищение дома

Перед праздником обязательно делают генеральную уборку, выносят то ненужное, что есть в доме. После исполняют ритуал. Понадобится:

- вода;

- морская соль;

- пучок шалфея:

- масло ладана, розмарина;

- голубая свеча.

Для очистительного обряда смешивают воду и соль в емкости и зажигают свечу. Проходятся по всем комнатам (по часовой стрелке) и смачивают пучок травы в соленой жидкости окропляют поверхности со словами:

«С очищающей силой воды, с чистым дыханием воздуха, со страстным жаром огня, с заземляющей энергией земли я очищаю это пространство».

После слегка смазывают маслом подоконники и двери или рисуют защитные символы. Процесс сопровождается заклинанием:

«Пусть Богиня благословит этот дом, сделав его священным и чистым, чтобы только любовь и радость могли войти через эту дверь/окно».

Ритуал очищения тела

Обязательно совершить ритуальное омовение. Ванную комнату украсьте декоративными или живыми цветами, зажгите белые и зеленые свечи, аромалампу с можжевельником. Когда принимаете ванну, расслабьтесь и сконцентрируйтесь на будущих изменениях природы. Мылом возьмите зеленого цвета, а вытирайтесь белоснежным полотенцем.

Время духовного очищения

Это пора, чтобы пересмотреть все планы, выкинуть из головы несущественные желания, задать четкое направление на будущее. В этом поможет специальный ритуал. Понадобится желтая свеча, белые, розовые или желтые цветы, лист бумаги, ручка. И действуйте по пунктам:

- Сделайте магический круг и призовите Бригиту.

- Выскажите вслух намерение – осознайте истинные цели и желания.

- Зажгите свечу, сядьте и глядите на нее.

- Призовите Бригиту, предложить дары, попросите помощи.

- Сконцентрируйтесь на пламени и руках одновременно, перейдите в измененное состояние.

- Закройте глаза и мысленно войдите в пламя свечи.

- Опять призовите богиню в помощь.

- Обратитесь к собственной душе, выскажите одно желание или цель.

- Дождитесь ответа (мысль, визуальный образ, приятные или неприятные ощущения). Запрещается анализировать, критиковать, приводить разумные доводы. Нужна полная отстраненность и отключение ума.

Все важные цели и желания запишите заранее на листке. - Поблагодарите душу, вернитесь к реальности.

- Обратитесь к богине, чтобы благословила намерения на быструю и благополучную реализацию.

- Поблагодарите за содействие и закройте круг.

Молитва про хранение пламени

Есть немало заговоров, что лучше оказывают действие в Имблок. Прочитайте молитву Бригид:

«Могучая Бригид, хранительница пламени, пылающая в темноте зимы. О богиня, мы чтим тебя, несущую свет, целительный и возвышенный. Благослови же нас ныне, Мать очага, дабы мы были столь же плодородны, как и сама почва, и наша жизнь стала изобильна и плодородна».

Ритуалы на Имболк со свечами

«Благословенно будь, создание Огня!

Яркое пламя, греющее, а не сжигающее,

Символ Света, а не Всесожжения,

Яркий свет в темноте магической ночи.

Во имя Бога и Богини,

Да будет так».

После возьмите свечи и по одной ставить на алтарь, каждую сопровождайте собственным заклинанием:

«Первая свеча — рождение солнца;

Вторая — пламя, что не погаснет;

Третья — создание огня, что дает свет и тепло;

Четвертая — символ возрождения Бога;

Пятая — жизнь новой весны;

Шестая — символ чистоты;

Седьмая — обновление;

Седьмая — во имя любви;

Восьмая — во имя равновесия;

Девятая — дыхание новой жизни;

Десятая — связь с истиной;

Одиннадцатая — в честь Невесты;

Двенадцатая — в честь моего пути;

Тринадцатая — в честь искусств;

Четырнадцатая — дань мудрости;

Пятнадцатая — в честь Имболка;

Шестнадцатая — во имя силы;

Семнадцатая — во имя земли;

Восемнадцатая — Бригите;

И последняя свеча — первая свеча, рождение солнца;

Огонь, что никогда не гаснет.»

Для другого свечного ритуала понадобится наполовину наполненная талой водой стеклянная ваза. Полчашки молока или сливок. Молочные продукты используют не магазинные, а домашние. Емкость с водой поставьте перед собой (на алтарь или стол), чашку с молоком – сбоку. Зажгите свечу (белого или желтого цвета).

Глядите на воду и сформируйте желание, визуализируйте его, наполните силой. Влейте в воду молоко и спокойно посидите. После выйдите на улицу, отпустите намерение и вылейте содержимое чаши на землю. Обязательно обратитесь к Мирозданию, чтобы оно посодействовало в исполнении то, что пожелали.

Вернитесь в дом. Потушите свечу и обязательно «заземлитесь» (поешьте, сделайте пару физических упражнений или другое).

Праздничный стол

Традиционная пища на Имблок – блюда на основе молока. Это не значит, есть одну молочную кашу. К столу подают любые блюда, напитки и десерты, в состав коих входит хоть капля молока. А кисломолочные продукты, как и алкоголь, под строгим запретом.

На праздник готовятся и мясные кушанья, но с большим количеством моркови, лука и чеснока, щедро сдобренные перцем и карри. Обязательно подаются сухофрукты и орехи. Испеките настоящий волшебный пирог. Из продуктов понадобится:

- мука – 300 г;

- яйца – 2 шт.;

- сливочное масло – 125 г;

- молоко – 4 ст. л.;

- сахар – 175 г;

- соль – щепотка;

- разрыхлитель – 1 ч. л.;

- семена тмина – 25 г.

Во время приготовления читайте заговор:

«Непрерывное движение, пусть все вещи текут, как круги магии, пусть сила растет, элементы смешиваются. Примите мою мольбу. Как я хочу, чтобы так оно и было.»

Готовится следующим образом:

- Просейте в миску (можно, магический котел) муку с разрыхлителем и солью. В этот момент думайте о семье, друзьях или личных желаниях.

- В отдельной посуде взбейте яйца – визуализируйте, как они пропитываются светом, энергией, вдохновением.

- Смешайте семена тмина и сахар. Влейте в массу яичную смесь и перемешайте. Замешивайте строго деревянной ложкой или лопаткой.

- Потихоньку подливайте молоко.

- Смажьте маслом форму, вылейте в нее тесто и отправьте в духовку на час-полтора, запекается при температуре 180–190°.

Когда волшебный пирог станет золотисто-коричневым, вынимайте из духовки и остудите. А подается десерт с магической начинкой с пряным молочным напитком: прогрейте молоко, добавьте мед и ванильный сахар. Перемешайте и разлейте в чашки. Сверху присыпьте корицей.

Мир дарит увлеченному магией человеку множество возможностей для жизненного благополучия и развития творческого потенциала. Упускать таковые, значит, ограничивать собственную жизнь и саму свою сущность. Первый солнечный праздник используйте в полной мере. Трепетная Невеста, опытная Мать и мудрая Старуха – триединая богиня Бригит – никому не откажет в помощи.

Вконтакте

Одноклассники

Содержание:

Красивая легенда праздника Колеса Года

Символы праздника Имболк в Колесе года

Обряды и традиции на праздник Имболк у славян

Особенности празднования Имболка 2023 у славян

В эти дни отмечают еще один праздник Колеса года — Имболк или «Пробуждение» (у славян). В календаре язычников он стоит между зимним солнцестоянием (Йоль) и весенним равноденствием, а его празднование проходит с 1 на 2 февраля. Эта мистическая ночь окутана невероятными ритуалами, обрядами и традициями, поэтому славяне называют Имболк романтично «Громница».

Праздник Имболк в Колесе года знаменует прохождение суровых зим

Магия Имболка поможет реализовать свое творческое начало…

Красивая легенда праздника Колеса Года

Праздник Имболк с магическими ритуалами ассоциируется у ирландцев, как и у славян, с началом нового жизненного цикла. Именно сейчас у овец появляется молоко, а на земле прорастают первые семена. Имболк в Колесе года описывает романтичную легенду про богиню Бригитту или «Мать Хлеба». Состарившись, она приносит себя в жертву на великий Самайн, погружаясь в сон смерти, а ее дух обнимает яблоневые сады волшебного острова Авалон. Праздник Имболк в феврале 2023 знаменует пробуждение Бригитты в образе юной, ранимой девочки. Но ее окончательное возвращение к людям случится чуть-чуть позже, на Остару.

Бригитта — вот она богиня, в образе юной девушки…

У Имболка много имен: Громница, праздник Богородицы, фестиваль подснежников

Символы праздника Имболк в Колесе года

Праздник факелов и огней зажигает новые старты, пройдя все ритуалы празднования. Колесо года непрерывно крутится, догоняя праздник Имболк или Пробуждение, Громницу (у славян). Как и в Белтейн, в праздник Имболк нужно зажигать лампы в доме, чтобы прогнать сущностей. В одежде из палитры цветов лучше отдать предпочтение белому, желтому, бледно-розовом, светло-зеленому, лавандовому оттенкам.

Праздник обрастает красивыми легендами и чудесными традициями

Пора запастись на Имболк оккультными символами

Считается, что удачу и прибыль в этот день приносят цветы в горшке. Обзавестись лучше вечнозелеными растениями, ветками ивы, клевером, розмарином, листьями черники, фиалками. С ними связано огромное количество ритуалов на праздник Имболк. Имболк ассоциируется с рогатым быком, который в праздник Колеса года набирает силу. Никакой говядины на столе!

Чем больше горшечных растений в доме на Имболк, тем быстрее сбудутся заветные желания!

Обряды и традиции на праздник Имболк у славян

Накануне «Пробуждения» или Громницы, необходимо вымывать полы в доме, смахивать паутину и пыль, принять ванну, переодеться в чистое белье. Многие ритуалы на праздник Имболк славяне связывают со святой водой небес. Если накануне пройдет ливень, то воду обязательно нужно собрать для омовения.

Ливень, град или снег в ночь на 2 февраля считаются благословенными

Накануне праздника Имболка, одной из важных спиц Колеса Года, перебирают запасы еды, заменяют веники на новые. Во время праздника приветствуется сдержанность. По традиции на Имболк женщины смело увиливают от работы и даже любимого рукоделия. В современном мире позвольте себе spa, ванну, ароматерапию, медитацию, занятия йогой…

Время отдохнуть!

Праздник Имболк и ритуалы за столом

Соблюдая ритуалы и традиции Имболка, на стол выставляют тарелку с блинами и оладьями, символизирующими солнце, блюдо с сухофруктами, семенами и орехами, не хмельные горячие напитки, чай на молоке. А еще, оказывается, в древние времена на Имболк проводились состязания бардов, ведь Бригитта — покровительница поэзии. Колесо года набирается лирики и очарования в праздник Имболк!

Почти все обряды Имболка связаны с очищением, физическим и духовным!

В праздничную ночь Имболка обязательно печется хлеб и взбивается свежее масло, а на столы подается кувшин молока, рассыпчатое масляное печенье, молочные каши, сырные тарелки. Молоко с хлебом считается угощением для Бригитты, поэтому щедрые хозяева ставят в праздник Имболк у порога миску с молоком.

Воздержитесь от говядины в праздничный вечер. Только хлеб, молоко и молодые сыры!

Ритуал с Крестом на Имболк: славяне научат!

Славянам близок символ креста, а вот в горной Шотландии, где до сих пор хранятся языческие обычаи, с XIX в. плетут из колосьев от последнего снопа оригинальную «куклу» Brideog, из стеблей камыша, соломы — «крест святой Бригитты». На Имболок Колеса года почитают обеих богинь: «галльскую Минерву» (римские обычаи, ритуалы) и святую Бригитту, обученную с юности целительству (славяне). Такую куколку укладывают на чистую постель, а рядом ставят кувшин с молоком. Он служит оберегом после зимнего смертного сна богини, источником новых сил Колеса Года.

Такой крест вешали на дверях домов, как символ мира и доброй воли

Техника плетения креста на Имболк довольно простая

Молоко — как главная тема праздника

Основной символ на праздник Имболк — молоко. Напиток пьют, выливают на плодородную землю, в водоемы, а также обрызгивают постель и пороги в доме. Чтобы отпраздновать Имболк в соответствии с традициями Колеса Года… налей себе чашечку молока или кофе, но со сливками. А еще разрешаются глинтвейн, пряные вина, травяные чаи. Любимому можно намекнуть на оригинальный подарок — парфюм со сладким ароматом сгущенного молока, ванильной пенки, соленого масла на французской греночке.

Молоко станет важным напитком в Имболк!

Особенности празднования Имболка 2023 у славян

Имболк или «праздник огней» у славян всегда приходит с наступлением сумерек, поэтому осветить свой дом как можно ярче — задача №1. Свет и свечи не тушат до первых лучей солнца, очищая все вокруг от тьмы, особенно душу.

…и пусть горит до восхода солнца!

Славяне прозвали праздник Громницей, днем огня, исцеления души и тела. Славяне в Громницу проводят обряды и ритуалы окуривания людей и животных специальными лечебными травами. Раньше они выпекали хлеб, а его кусочки надевали на рога волам, избегая болезней. В Европе ритуалы праздника Имболк связывают с ведьмами: чтобы ветра «волчьего месяца» не приносили бурь, вдоль побережья сжигали веники и метлы. Тогда колдуньи не могли больше ворожить с природой, насылая грозы и метели.

Чем полезным заняться в Имболк? Ну, конечно, ворожить и гадать!

Предвкушение весны тем слаще, чем сильнее ее ждешь!

Для колдунов и шаманов праздник Имболк — это время великой инициации Колеса Года. Молодые волшебники 1-2 февраля проходят особые ритуалы посвящений, сквозь молоко и огонь. В благословенный день Колеса года рекомендуется проводить:

- весеннее очищение

- любые магические ритуалы (гадание на суженого)

- ритуалы для возвращения уверенности, сил

- церемониальные ритуалы с символами Имболка — льдом, семенами, ранней первыми проростками или цветами

- сжигание черной, белой, рыжей свечи как в стародавних обрядах славян.

Имболк еще — это «праздник свечей» и традиционные шабаши!

Название праздника, кстати, связывают с кельтским словом Oimealg — «овечье молоко»

Помни, что энергия праздника Имболк восстанавливает все слабое, бессильное или загрязненное (землю, тело, душу). Отбрось в Имболк грустные мысли, согрей вино, добавив в него сушеные ягоды облепихи и брусники, задобри домовых и богов прямо сейчас! В Колесе года — это один из тех самых домашних, камерных праздников, который требует от тебя лишь атмосферу уюта и запах топленого молока…

В современном мире Имболк — это лучшее время для планирования и новых начинаний

Богиня Бригитта покровительствует семейным ценностям и благополучию…

…пока овечки дают первое молоко

| Imbolc / St Brigid’s Day | |

|---|---|

Brigid’s cross |

|

| Also called | Lá Fhéile Bríde (Irish) Là Fhèill Brìghde (Scottish Gaelic) Laa’l Breeshey (Manx) |

| Observed by | Historically: Gaels Today: Irish people, Scottish people, Manx people, Modern Pagans |

| Type | Cultural, Christian (Roman Catholic, Anglican), Pagan (Celtic neopaganism, Wicca) |

| Significance | beginning of spring, feast day of Saint Brigid |

| Celebrations | feasting, making Brigid’s crosses and Brídeógs, visiting holy wells, divination, spring cleaning |

| Date | 1 February (or 1 August for some Neopagans in the S. Hemisphere) |

| Related to | Gŵyl Fair y Canhwyllau, Candlemas, Groundhog Day |

Imbolc or Imbolg (Irish pronunciation: [ɪˈmˠɔlˠɡ]), also called Saint Brigid’s Day (Irish: Lá Fhéile Bríde; Scottish Gaelic: Là Fhèill Brìghde; Manx: Laa’l Breeshey), is a Gaelic traditional festival. It marks the beginning of spring, and for Christians it is the feast day of Saint Brigid, Ireland’s patroness saint. It is held on 1 February, which is about halfway between the winter solstice and the spring equinox.[1][2] Historically, its traditions were widely observed throughout Ireland, Scotland and the Isle of Man. Imbolc is one of the four Gaelic seasonal festivals, along with: Bealtaine, Lughnasadh and Samhain.[3]

Imbolc is mentioned in early Irish literature, and some evidence suggests it was also an important date in ancient times. It is believed that Imbolc was originally a pagan festival associated with the lambing season and the goddess Brigid. Historians suggest that the saint and her feast day are Christianizations of these.[4] The customs of St Brigid’s Day did not begin to be recorded in detail until the early modern era. In recent centuries, its traditions have included weaving Brigid’s crosses, which are hung over doors and windows for protection against fire, illness and evil spirits. People also made a doll of Brigid (a Brídeóg), which was paraded from house-to-house by girls, sometimes accompanied by ‘strawboys’. Brigid was said to visit one’s home on St Brigid’s Eve. To receive her blessings, people would make a bed for Brigid, leave her food and drink, and set items of clothing outside for her to bless. Holy wells would be visited, a special meal would be had, and it was traditionally a time for weather divination.

Although many of its traditions died out in the 20th century, it is still observed by some Christians as a religious holiday and by some non-Christians as a cultural one, and its customs have been revived in some places. Since the latter 20th century, Celtic neopagans and Wiccans have observed Imbolc as a religious holiday.[1][2] From 2023, «Imbolc/St Brigid’s Day» will be a yearly public holiday in the Republic of Ireland.[5]

Origins and etymology[edit]

Historians such as historian Ronald Hutton argue that the festival must have pre-Christian origins.[6] Some scholars argue that the date of Imbolc was significant in Ireland since the Neolithic period.[7] A few passage tombs in Ireland are aligned with the sunrise around the times of Imbolc and Samhain. This includes the Mound of the Hostages on the Hill of Tara,[8][9] and Cairn L at Slieve na Calliagh.[10] Frank Prendergast argues that this alignment is so rare that it is rather a product of chance.[11]

The etymology of Imbolc or Imbolg is unclear. The most common explanation is that it comes from the Old Irish i mbolc (Modern Irish: i mbolg), meaning ‘in the belly’, and refers to the pregnancy of ewes at this time of year.[12] Joseph Vendryes linked it to the Old Irish verb folcaim, ‘to wash/cleanse oneself’. He suggested that it referred to a ritual cleansing, similar to the ancient Roman festival Februa or Lupercalia, which took place at the same time of year.[13][14] Eric P. Hamp derives it from a Proto-Indo-European root meaning both ‘milk’ and ‘cleansing’.[15] Professor Alan Ward derives it from the Proto-Celtic *embibolgon, ‘budding’.[16] The early 10th century Cormac’s Glossary has an entry for Oímelc, calling it the beginning of spring and deriving it from oí-melg (‘ewe milk’), explaining it as «the time that sheep’s milk comes».[17] However, linguists believe this is the writer’s own respelling of the word to give it an understandable etymology.[18]

The Táin Bó Cúailnge (‘Cattle Raid of Cooley’) indicates that Imbolc (spelt imolg) is three months after the 1 November festival of Samhain.[19] Imbolc is mentioned in another Old Irish poem about the Táin in the Metrical Dindshenchas: «iar n-imbulc, ba garb a ngeilt«, which Edward Gwynn translates «after Candlemas, rough was their herding».[15] Candlemas is the Christian holy day which falls on 2 February and is known in Irish as Lá Fhéile Muire na gCoinneal, ‘feast day of Mary of the Candles’.[20]

Hutton writes that Imbolc must have been «important enough for its date to be dedicated subsequently to Brigid … the Mother Saint of Ireland».[6] Cogitosus, writing in the late 7th century, first mentions a feast day of Saint Brigid being observed in Kildare on 1 February.[21] Brigid is said to have lived in the 6th century and founded the important monastery of Kildare. She became the focus of a major cult. However, there are few historical facts about her, and her early hagiographies «are mainly anecdotes and miracle stories, some of which are deeply rooted in Irish pagan folklore».[22] It is suggested that Saint Brigid is based on Brigid, a Gaelic goddess.[23] Like the saint, the goddess is associated with wisdom, poetry, healing, protection, blacksmithing and domesticated animals, according to Cormac’s Glossary and Lebor Gabála Érenn.[21][24] It is suggested that the festival, which celebrates the onset of spring, is linked with Brigid in her role as a fertility goddess.[25] According to Hutton, it could be that the goddess Brigid was already linked to Imbolc and this was continued by making it the saint’s feast day. Or it could be that Imbolc’s association with milk drew the saint to it, because of a legend that she had been the wet-nurse of Christ.[6]

Historic customs[edit]

The festival of Imbolc is mentioned in several early Irish manuscripts, but they say very little about its original rites and customs.[6] Imbolc was one of four main seasonal festivals in Gaelic Ireland, along with Beltane (1 May), Lughnasadh (1 August) and Samhain (1 November). The tale Tochmarc Emire, which survives in a 10th-century version, names Imbolc as one of the four Gaelic seasonal festivals, and says it is «when the ewes are milked at spring’s beginning».[6][26] This linking of Imbolc with the arrival of lambs and sheep’s milk probably reflected farming customs that ensured lambs were born before calves. In late winter/early spring, sheep could survive better than cows on the meager vegetation, and farmers sought to resume milking as soon as possible due to their dwindling stores.[13] The Hibernica Minora includes an Old Irish poem about the four seasonal festivals. Translated by Kuno Meyer (1894), it says «Tasting of each food according to order, this is what is proper at Imbolc: washing the hands, the feet, the head». This suggests ritual cleansing.[13] It has been suggested that originally the timing of the festival was more fluid and associated with the onset of the lambing season[25] (which could vary by as much as two weeks before or after 1 February),[12] the beginning of preparations for the spring sowing,[27] and the blooming of blackthorn.[28]

Prominent folklorist Seán Ó Súilleabháin wrote: «The main significance of the Feast of St. Brigid would seem to be that it was a Christianisation of one of the focal points of the agricultural year in Ireland, the starting point of preparations for the spring sowing. Every manifestation of the cult of the saint (or of the deity she replaced) is bound up in some way with food production».[27]

From the 18th century to the mid 20th century, many accounts of St Brigid’s Day were recorded by folklorists and other writers. They tell us how it was celebrated then, and shed light on how it may have been celebrated in the past.[2][29]

Brigid’s crosses[edit]

In Ireland, Brigid’s crosses (pictured) are traditionally made on St Brigid’s Day. A Brigid’s cross usually consists of rushes woven into a four-armed equilateral cross, although there were also three-armed crosses.[30][31] They are traditionally hung over doors, windows and stables to welcome Brigid and for protection against fire, lightning, illness and evil spirits.[32] The crosses are generally left there until the next St Brigid’s Day.[6] In western Connacht, people made a Crios Bríde (Bríd‘s girdle); a great ring of rushes with a cross woven in the middle. Young boys would carry it around the village, inviting people to step through it and so be blessed.[6]

Welcoming Brigid[edit]

On St Brigid’s Eve, Brigid was said to visit virtuous households and bless the inhabitants.[6] As Brigid represented the light half of the year, and the power that will bring people from the dark season of winter into spring, her presence was very important at this time of year.[33][34]

Before going to bed, people would leave items of clothing or strips of cloth outside for Brigid to bless.[6] The next morning, they would be brought inside, and believed to now have powers of healing and protection.[33][34]

Brigid would be symbolically invited into the house and a bed would often be made for her. In the north of Ireland, a family member, representing Brigid, would circle the home three times carrying rushes. They would then knock on the door three times, asking to be let in. On the third attempt they are welcomed in, a meal is had, and the rushes are then made into crosses or a bed for Brigid.[35] In 18th century Mann, the custom was to stand at the door with a bundle of rushes and say «Brede, Brede, come to my house tonight. Open the door for Brede and let Brede come in». Similarly, in County Donegal, the family member who was sent to fetch the rushes knelt on the front step and repeated three times, «Go on your knees, open your eyes, and let in St Brigid». Those inside the house answered three times «She’s welcome».[36] The rushes were then strewn on the floor as a carpet or bed for Brigid. In the 19th century, some old Manx women would make a bed for Brigid in the barn with food, ale, and a candle on a table.[6] The custom of making Brigid’s bed was particularly common in the Hebrides of Scotland, where it was recorded as far back as the 17th century. A bed of hay or a basket-like cradle would be made for Brigid and someone would then call out three times: «a Bhríd, a Bhríd, thig a stigh as gabh do leabaidh» («Bríd Bríd, come in; thy bed is ready»).[6] A corn dolly called the dealbh Bríde (icon of Brigid) would be laid in the bed and a white wand, usually made of birch, would be laid beside it.[6] It represented the wand that Brigid was said to use to make the vegetation start growing again.[37] Women in some parts of the Hebrides would also dance while holding a large cloth and calling out «Bridean, Bridean, thig an nall ‘s dean do leabaidh» («Bríd, Bríd, come over and make your bed»).[6]

Ashes from the fire would be raked smooth and, in the morning, they would look for some kind of mark on the ashes as a sign that Brigid had visited.[6][38] If there was no mark, they believed bad fortune would come unless they buried a cockerel at the meeting of three streams as an offering and burned incense on their fire that night.[6]

Brigid’s procession[edit]

In Ireland and Scotland, a representation of Brigid would be paraded around the community by girls and young women. Usually, it was a doll-like figure known as a Brídeóg (also called a ‘Breedhoge’ or ‘Biddy’). It would be made from rushes or reeds and clad in bits of cloth, flowers, or shells.[6][38] In the Hebrides of Scotland, a bright shell or crystal called the reul-iuil Bríde (guiding star of Brigid) was set on its chest. The girls would carry it in procession while singing a hymn to Brigid. All wore white with their hair unbound as a symbol of purity and youth. They visited every house in the area, where they received either food or more decoration for the Brídeóg. Afterward, they feasted in a house with the Brídeóg set in a place of honour, and put it to bed with lullabies. When the meal was done, the local young men humbly asked for admission, made obeisance to the Brídeóg, and joined the girls in dancing and merrymaking.[6] In many places, only unwed girls could carry the Brídeóg, but in some both boys and girls carried it.[39]

In some areas, rather than carrying a Brídeóg, a girl took on the role of Brigid. Escorted by other girls, she went house-to-house wearing ‘Brigid’s crown’ and carrying ‘Brigid’s shield’ and ‘Brigid’s cross’, all of which were made from rushes.[32] The procession in some places included ‘strawboys’, who wore conical straw hats, masks and played folk music; much like the wrenboys.[32] Up until the mid-20th century, children in Ireland still went house-to-house asking for pennies for «poor Biddy», or money for the poor. In County Kerry, men in white robes went from house to house singing.[40]

Weather divination[edit]

The festival was traditionally a time of weather divination, and the old tradition of watching to see if serpents or badgers came from their winter dens may be a forerunner of the North American Groundhog Day. A Scottish Gaelic proverb about the day is:

|

Thig an nathair as an toll |

The serpent will come from the hole |

Imbolc was believed to be when the Cailleach—the divine hag of Gaelic tradition—gathers her firewood for the rest of the winter. Legend has it that if she wishes to make the winter last a good while longer, she will make sure the weather on Imbolc is bright and sunny, so she can gather plenty of firewood. Therefore, people would be relieved if Imbolc is a day of foul weather, as it means the Cailleach is asleep and winter is almost over.[42] At Imbolc on the Isle of Man, where she is known as Caillagh ny Groamagh, the Cailleach is said to take the form of a gigantic bird carrying sticks in her beak.[42]

Other customs[edit]

Families would have a special meal or supper on St Brigid’s Eve to mark the last night of winter.[6] This typically included food such as colcannon, sowans, dumplings, barmbrack or bannocks.[43] Often, some of the food and drink would be set aside for Brigid.[6]

In Ireland, a spring cleaning was customary around the time of St Brigid’s Day.[43]

People traditionally visit holy wells and pray for health while walking ‘sunwise’ around the well. They might then leave offerings, typically coins or strips of cloth/ribbon (see clootie well). Historically, water from the well was used to bless the home, family members, livestock, and fields.[43][44]

Donald Alexander Mackenzie also recorded in the 19th century that offerings were made «to earth and sea». The offering could be milk poured into the ground or porridge poured into the water, as a libation.[45]

In County Kilkenny, graves were decorated with box and laurel flowers (or any other flowers that could be found at that time). A Branch of Virginity was decorated with white ribbons and placed on the grave of a recently deceased maiden.[46]

Today[edit]

People making Brigid’s crosses at St Brigid’s Well near Liscannor.

Today, St Brigid’s Day and Imbolc is observed by Christians and non-Christians. Some people still make Brigid’s crosses and Brídeogs or visit holy wells dedicated to St Brigid on 1 February.[47] Brigid’s Day parades have been revived in the town of Killorglin, County Kerry, which holds a yearly «Biddy’s Day Festival». Men and women wearing elaborate straw hats and masks visit public houses carrying a Brídeóg to ward off evil spirits and bring good luck for the coming year. There are folk music sessions, historical talks, film screenings, drama productions and cross-weaving workshops. The main event is a torchlight parade of ‘Biddy groups’ through the town.[48][49] Since 2009 a yearly «Brigid of Faughart Festival» is held in County Louth. This celebrates Brigid as both saint and goddess, and includes the long-standing pilgrimage to Faughart as well as music, poetry and lectures.[50]

The «Imbolc International Music Festival» of folk music is held in Derry at this time of year.[51] In England, the village of Marsden, West Yorkshire holds a biennial «Imbolc Fire Festival» which includes a lantern procession, fire performers, music, fireworks, and a symbolic battle between giant characters representing the Green Man and Jack Frost.[52]

More recently, Irish embassies have hosted yearly events on St Brigid’s Day to celebrate famous women of the Irish diaspora and showcase the work of Irish female emigrants in the arts.[53] In 2022, Dublin hosted its first «Brigit Festival», celebrating «the contributions of Irish women» past and present through exhibitions, tours, lectures, films and a concert.[54]

From 2023, «Imbolc/St Brigid’s Day» will be a yearly public holiday in the Republic of Ireland, to mark both the saint’s feast day and the seasonal festival.[5] A government statement noted that it will be the first Irish public holiday named after a woman, and «means that all four of the traditional Celtic seasonal festival will now be public holidays».[5]

Neopaganism[edit]

Imbolc or Imbolc-based festivals are held by some Neopagans. As there are many kinds of Neopaganism, their Imbolc celebrations can be very different despite the shared name. Some try to emulate the historic festival as much as possible. Other Neopagans base their celebrations on many sources, with historic accounts of Imbolc being only one of them.[55][56]

Neopagans usually celebrate Imbolc on 1 February in the Northern Hemisphere and 1 August in the Southern Hemisphere.[57][58][59][60] Some Neopagans celebrate it at the astronomical midpoint between the winter solstice and spring equinox (or the full moon nearest this point). In the Northern Hemisphere, this is usually on 3 or 4 February.[61] Other Neopagans celebrate Imbolc when the primroses, dandelions, and other spring flowers emerge.[62]

Celtic Reconstructionist[edit]

Celtic Reconstructionists strive to reconstruct ancient Celtic religion. Their religious practices are based on research and historical accounts,[63][64] but may be modified slightly to suit modern life. They avoid syncretism (i.e. combining practises from different cultures). They usually celebrate the festival when the first stirrings of spring are felt, or on the full moon nearest this. Many use traditional songs and rites from sources such as The Silver Bough and The Carmina Gadelica. It is a time of honouring the goddess Brigid, and many of her dedicants choose this time of year for rituals to her.[63][64]

Wicca and Neo-Druidry[edit]

Wiccans and Neo-Druids celebrate Imbolc as one of the eight Sabbats in their Wheel of the Year, following Midwinter and preceding Ostara. In Wicca, Imbolc is commonly associated with the goddess Brigid and as such, it is sometimes seen as a «women’s holiday» with specific rites only for female members of a coven.[65] Among Dianic Wiccans, Imbolc is the traditional time for initiations.[66]

See also[edit]

- Candlemas

- Faoilleach

- Irish calendar

- Quarter days

- Vasant Panchami

- Wheel of the Year (Cross-Quarter days)

References[edit]

- ^ a b Danaher, Kevin (1972) The Year in Ireland: Irish Calendar Customs Dublin, Mercier. ISBN 978-1-85635-093-8 p. 38

- ^ a b c McNeill, F. Marian (1959, 1961) The Silver Bough, Vol. 1–4. William MacLellan, Glasgow; Vol. 2, pp. 11–42

- ^ Cunliffe, Barry (1997). The Ancient Celts. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Page 188-190.

- ^ Berger, Pamela (1985). The Goddess Obscured: Transformation of the Grain Protectress from Goddess to Saint. Boston: Beacon Press. pp. 70–73. ISBN 978-0-8070-6723-9.

- ^ a b c «Government agrees Covid Recognition Payment and New Public Holiday». Gov.ie. Department of the Taoiseach. Retrieved 20 January 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Hutton, Ronald (1996). Stations of the Sun: A History of the Ritual Year in Britain. Oxford University Press. pp. 134–138. ISBN 978-0-19-820570-8.

- ^ «Imbolc». Newgrange UNESCO World Heritage website. Retrieved 1 June 2011.

- ^ Hill of Tara «…the chamber is illuminated on the mornings around Samhain (early November) and Imbolc (early February).» accessed 1 February 2022, www.boynevalleytours.com

- ^ Murphy, Anthony. «Mythical Ireland – Ancient Sites – The Hill of Tara – Teamhair». Mythical Ireland – New light on the ancient past. Retrieved 15 January 2018.

- ^ Brennan, Martin. The Stones of Time: Calendars, Sundials, and Stone Chambers of Ancient Ireland. Inner Traditions, 1994. pp. 110–11

- ^ Prendergast, Frank (2021). Gunzburg, Darrelyn (ed.). The Archaeology of Height: Cultural Meaning in the Relativity of Irish Megalithic Tomb Siting. London, New York, Oxford, New Delhi, Sydne: Bloomsbury Academic. pp. 13–42.

- ^ a b Chadwick, Nora K. (1970). The Celts. Harmondsworth: Penguin. p. 181. ISBN 978-0-14-021211-2.

- ^ a b c Patterson, Nerys. Cattle Lords and Clansmen: The Social Structure of Early Ireland. University of Notre Dame Press, 1994. p.129

- ^ Wright, Brian. Brigid: Goddess, Druidess and Saint. The History Press, 2011. p. 83

- ^ a b Hamp, Eric (1979–1980). «Imbolc, Óimelc». Studia Celtica (14/15): 106–113.

- ^ Ward, Alan (2011). The Myths of the Gods: Structures in Irish Mythology. p. 15. Archived from the original on 30 January 2017 – via CreateSpace.

- ^ Meyer, Kuno, Sanas Cormaic: an Old-Irish Glossary compiled by Cormac úa Cuilennáin, King-Bishop of Cashel in the ninth century (1912).

- ^ Kelly, Fergus. Early Irish Farming: A Study Based Mainly on the Law-texts of the 7th and 8th centuries AD. School of Celtic Studies, Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 1997. p.460

- ^ Ó Cathasaigh, Tomás (1993). «Mythology in Táin Bó Cúailnge», in Studien zur Táin Bó Cúailnge, p.123

- ^ MacKillop, James (1998). Dictionary of Celtic mythology. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 270. ISBN 978-0-19-280120-3.

- ^ a b Ó hÓgáin, Dáithí. Myth, Legend & Romance: An encyclopedia of the Irish folk tradition. Prentice-Hall Press, 1991. pp.60–61

- ^ Farmer, David. The Oxford Dictionary of Saints (Fifth Edition, Revised). Oxford University Press, 2011. p.66

- ^ MacKillop, James (1998). Dictionary of Celtic mythology. Oxford University Press. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-19-280120-3.

- ^ Wright, Brian. Brigid: Goddess, Druidess and Saint. The History Press, 2011. pp.26–27

- ^ a b Koch, John T. Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. 2006. p. 287.

- ^ «The Wooing of Emer by Cú Chulainn». Corpus of Electronic Texts Edition.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b Danaher (1972), The Year in Ireland, p.13

- ^ Aveni, Anthony F. (2004). The Book of the Year: A Brief History of Our Seasonal Holidays. Oxford University Press, USA. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-19-517154-9.

- ^ Danaher, Kevin (1972) The Year in Ireland: Irish Calendar Customs Dublin, Mercier. ISBN 978-1-85635-093-8 pp. 200–229

- ^ Ó Duinn, Seán (2005). The Rites of Brigid: Goddess and Saint. Dublin: Columba Press. p. 121. ISBN 978-1-85607-483-4.

- ^ Evans, Emyr Estyn. Irish Folk Ways, 1957. p. 268

- ^ a b c Danaher, The Year in Ireland, pp.22–25

- ^ a b McNeill, F. Marian (1959) The Silver Bough, Vol. 1,2,4. William MacLellan, Glasgow

- ^ a b «Carmina Gadelica Vol. 1: II. Aimsire: Seasons: 70 (notes). Genealogy of Bride. Sloinntireachd Bhride». Sacred-texts.com. Retrieved 15 January 2018.

- ^ Danaher, The Year in Ireland, pp. 20–21, 97–98

- ^ «Ray (2) | The Schools’ Collection». dúchas.ie. Retrieved 13 February 2022.

- ^ Carmichael, Carmina Gadelica, p. 582

- ^ a b Monaghan, Patricia. The Encyclopedia of Celtic Mythology and Folklore. Infobase Publishing, 2004. p. 256.

- ^ Monaghan, p. 58.

- ^ Monaghan, p. 44.

- ^ Carmichael, Alexander (1900) Carmina Gadelica: Hymns and Incantations, Ortha Nan Gaidheal, Volume I, p. 169 The Sacred Texts Archive

- ^ a b Briggs, Katharine (1976) An Encyclopedia of Fairies. New York, Pantheon Books., pp. 57–60

- ^ a b c Danaher, The Year in Ireland, p. 15.

- ^ Monaghan, p. 41.

- ^ Mackenzie, Donald. Wonder Tales from Scottish Myth and Legend (1917). p. 19.

- ^ «Scoil na mBráthar, Calainn | The Schools’ Collection». dúchas.ie. Retrieved 13 February 2022.

- ^ Monaghan, p. 60.

- ^ «Biddy spirit alive and well in Kerry». The Kerryman. 27 January 2018.

- ^ «Three years on, Biddy’s Day Festival still going from strength to strength». The Kerryman. 2 February 2019.

- ^ «Events planned for Brigid of Faughart Festival». Irish Independent. 24 January 2022.

- ^ «Music returns to Derry air with the Imbolc International Music Festival». The Irish News. 7 January 2022.

- ^ «Everything you need to know about Marsden’s Imbolc Fire Festival». Huddersfield Daily Examiner. 23 January 2018.

- ^ «St Brigid’s Day: Irish women to be celebrated around the world». The Irish Times. 31 January 2019.

- ^ «Dublin to host St Brigid’s Day events, celebrating the original Brigit». The Irish Times. 30 January 2022.

- ^ Adler, Margot (1979) Drawing Down the Moon: Witches, Druids, Goddess-Worshippers, and Other Pagans in America Today. Boston, Beacon Press ISBN 978-0-8070-3237-4. p. 3

- ^ McColman, Carl (2003) Complete Idiot’s Guide to Celtic Wisdom. Alpha Press ISBN 978-0-02-864417-2. p. 51

- ^ Drury, Nevill (2009). «The Modern Magical Revival: Esbats and Sabbats». In Pizza, Murphy; Lewis, James R (eds.). Handbook of Contemporary Paganism. Leiden, Netherlands: Brill Publishers. pp. 63–67. ISBN 978-90-04-16373-7.

- ^ Hume, Lynne (1997). Witchcraft and Paganism in Australia. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press. ISBN 978-0-522-84782-6.

- ^ Vos, Donna (2002). Dancing Under an African Moon: Paganism and Wicca in South Africa. Cape Town: Zebra Press. pp. 79–86. ISBN 978-1-86872-653-0.

- ^ Bodsworth, Roxanne T (2003). Sunwyse: Celebrating the Sacred Wheel of the Year in Australia. Victoria, Australia: Hihorse Publishing. ISBN 978-0-909223-03-8.

- ^ «archaeoastronomy.com explains the reason we have seasons». Archaeoastronomy.com. Retrieved 15 January 2018.

- ^ Bonewits, Isaac (2006) Bonewits’s Essential Guide to Druidism. New York, Kensington Publishing Group ISBN 978-0-8065-2710-9. pp. 184–5

- ^ a b McColman, Carl (2003) p. 12

- ^ a b Bonewits (2006) pp. 130–7

- ^ Gallagher, Ann-Marie (2005). The Wicca Bible: The Definitive Guide to Magic and the Craft. London: Godsfield Press. Page 63.

- ^ Budapest, Zsuzsanna (1980) The Holy Book of Women’s Mysteries ISBN 978-0-914728-67-2

Further reading[edit]

- Carmichael, Alexander (1992) Carmina Gadelica: Hymns and Incantations (with illustrative notes onwards, rites, and customs dying and obsolete/ orally collected in the Highlands and Islands of Scotland) Hudson, NY, Lindisfarne Press, ISBN 978-0-940262-50-8

- Chadwick, Nora (1970) The Celts London, Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-021211-2

- Danaher, Kevin (1972) The Year in Ireland. Dublin, Mercier. ISBN 978-1-85635-093-8

- McNeill, F. Marian (1959) The Silver Bough, Vol. 1–4. William MacLellan, Glasgow

- Ó Catháin, Séamas (1995) Festival of Brigit

Look up Imbolc in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

| Imbolc / St Brigid’s Day | |

|---|---|

Brigid’s cross |

|

| Also called | Lá Fhéile Bríde (Irish) Là Fhèill Brìghde (Scottish Gaelic) Laa’l Breeshey (Manx) |

| Observed by | Historically: Gaels Today: Irish people, Scottish people, Manx people, Modern Pagans |

| Type | Cultural, Christian (Roman Catholic, Anglican), Pagan (Celtic neopaganism, Wicca) |

| Significance | beginning of spring, feast day of Saint Brigid |

| Celebrations | feasting, making Brigid’s crosses and Brídeógs, visiting holy wells, divination, spring cleaning |

| Date | 1 February (or 1 August for some Neopagans in the S. Hemisphere) |

| Related to | Gŵyl Fair y Canhwyllau, Candlemas, Groundhog Day |

Imbolc or Imbolg (Irish pronunciation: [ɪˈmˠɔlˠɡ]), also called Saint Brigid’s Day (Irish: Lá Fhéile Bríde; Scottish Gaelic: Là Fhèill Brìghde; Manx: Laa’l Breeshey), is a Gaelic traditional festival. It marks the beginning of spring, and for Christians it is the feast day of Saint Brigid, Ireland’s patroness saint. It is held on 1 February, which is about halfway between the winter solstice and the spring equinox.[1][2] Historically, its traditions were widely observed throughout Ireland, Scotland and the Isle of Man. Imbolc is one of the four Gaelic seasonal festivals, along with: Bealtaine, Lughnasadh and Samhain.[3]

Imbolc is mentioned in early Irish literature, and some evidence suggests it was also an important date in ancient times. It is believed that Imbolc was originally a pagan festival associated with the lambing season and the goddess Brigid. Historians suggest that the saint and her feast day are Christianizations of these.[4] The customs of St Brigid’s Day did not begin to be recorded in detail until the early modern era. In recent centuries, its traditions have included weaving Brigid’s crosses, which are hung over doors and windows for protection against fire, illness and evil spirits. People also made a doll of Brigid (a Brídeóg), which was paraded from house-to-house by girls, sometimes accompanied by ‘strawboys’. Brigid was said to visit one’s home on St Brigid’s Eve. To receive her blessings, people would make a bed for Brigid, leave her food and drink, and set items of clothing outside for her to bless. Holy wells would be visited, a special meal would be had, and it was traditionally a time for weather divination.

Although many of its traditions died out in the 20th century, it is still observed by some Christians as a religious holiday and by some non-Christians as a cultural one, and its customs have been revived in some places. Since the latter 20th century, Celtic neopagans and Wiccans have observed Imbolc as a religious holiday.[1][2] From 2023, «Imbolc/St Brigid’s Day» will be a yearly public holiday in the Republic of Ireland.[5]

Origins and etymology[edit]

Historians such as historian Ronald Hutton argue that the festival must have pre-Christian origins.[6] Some scholars argue that the date of Imbolc was significant in Ireland since the Neolithic period.[7] A few passage tombs in Ireland are aligned with the sunrise around the times of Imbolc and Samhain. This includes the Mound of the Hostages on the Hill of Tara,[8][9] and Cairn L at Slieve na Calliagh.[10] Frank Prendergast argues that this alignment is so rare that it is rather a product of chance.[11]

The etymology of Imbolc or Imbolg is unclear. The most common explanation is that it comes from the Old Irish i mbolc (Modern Irish: i mbolg), meaning ‘in the belly’, and refers to the pregnancy of ewes at this time of year.[12] Joseph Vendryes linked it to the Old Irish verb folcaim, ‘to wash/cleanse oneself’. He suggested that it referred to a ritual cleansing, similar to the ancient Roman festival Februa or Lupercalia, which took place at the same time of year.[13][14] Eric P. Hamp derives it from a Proto-Indo-European root meaning both ‘milk’ and ‘cleansing’.[15] Professor Alan Ward derives it from the Proto-Celtic *embibolgon, ‘budding’.[16] The early 10th century Cormac’s Glossary has an entry for Oímelc, calling it the beginning of spring and deriving it from oí-melg (‘ewe milk’), explaining it as «the time that sheep’s milk comes».[17] However, linguists believe this is the writer’s own respelling of the word to give it an understandable etymology.[18]

The Táin Bó Cúailnge (‘Cattle Raid of Cooley’) indicates that Imbolc (spelt imolg) is three months after the 1 November festival of Samhain.[19] Imbolc is mentioned in another Old Irish poem about the Táin in the Metrical Dindshenchas: «iar n-imbulc, ba garb a ngeilt«, which Edward Gwynn translates «after Candlemas, rough was their herding».[15] Candlemas is the Christian holy day which falls on 2 February and is known in Irish as Lá Fhéile Muire na gCoinneal, ‘feast day of Mary of the Candles’.[20]

Hutton writes that Imbolc must have been «important enough for its date to be dedicated subsequently to Brigid … the Mother Saint of Ireland».[6] Cogitosus, writing in the late 7th century, first mentions a feast day of Saint Brigid being observed in Kildare on 1 February.[21] Brigid is said to have lived in the 6th century and founded the important monastery of Kildare. She became the focus of a major cult. However, there are few historical facts about her, and her early hagiographies «are mainly anecdotes and miracle stories, some of which are deeply rooted in Irish pagan folklore».[22] It is suggested that Saint Brigid is based on Brigid, a Gaelic goddess.[23] Like the saint, the goddess is associated with wisdom, poetry, healing, protection, blacksmithing and domesticated animals, according to Cormac’s Glossary and Lebor Gabála Érenn.[21][24] It is suggested that the festival, which celebrates the onset of spring, is linked with Brigid in her role as a fertility goddess.[25] According to Hutton, it could be that the goddess Brigid was already linked to Imbolc and this was continued by making it the saint’s feast day. Or it could be that Imbolc’s association with milk drew the saint to it, because of a legend that she had been the wet-nurse of Christ.[6]

Historic customs[edit]

The festival of Imbolc is mentioned in several early Irish manuscripts, but they say very little about its original rites and customs.[6] Imbolc was one of four main seasonal festivals in Gaelic Ireland, along with Beltane (1 May), Lughnasadh (1 August) and Samhain (1 November). The tale Tochmarc Emire, which survives in a 10th-century version, names Imbolc as one of the four Gaelic seasonal festivals, and says it is «when the ewes are milked at spring’s beginning».[6][26] This linking of Imbolc with the arrival of lambs and sheep’s milk probably reflected farming customs that ensured lambs were born before calves. In late winter/early spring, sheep could survive better than cows on the meager vegetation, and farmers sought to resume milking as soon as possible due to their dwindling stores.[13] The Hibernica Minora includes an Old Irish poem about the four seasonal festivals. Translated by Kuno Meyer (1894), it says «Tasting of each food according to order, this is what is proper at Imbolc: washing the hands, the feet, the head». This suggests ritual cleansing.[13] It has been suggested that originally the timing of the festival was more fluid and associated with the onset of the lambing season[25] (which could vary by as much as two weeks before or after 1 February),[12] the beginning of preparations for the spring sowing,[27] and the blooming of blackthorn.[28]

Prominent folklorist Seán Ó Súilleabháin wrote: «The main significance of the Feast of St. Brigid would seem to be that it was a Christianisation of one of the focal points of the agricultural year in Ireland, the starting point of preparations for the spring sowing. Every manifestation of the cult of the saint (or of the deity she replaced) is bound up in some way with food production».[27]

From the 18th century to the mid 20th century, many accounts of St Brigid’s Day were recorded by folklorists and other writers. They tell us how it was celebrated then, and shed light on how it may have been celebrated in the past.[2][29]

Brigid’s crosses[edit]

In Ireland, Brigid’s crosses (pictured) are traditionally made on St Brigid’s Day. A Brigid’s cross usually consists of rushes woven into a four-armed equilateral cross, although there were also three-armed crosses.[30][31] They are traditionally hung over doors, windows and stables to welcome Brigid and for protection against fire, lightning, illness and evil spirits.[32] The crosses are generally left there until the next St Brigid’s Day.[6] In western Connacht, people made a Crios Bríde (Bríd‘s girdle); a great ring of rushes with a cross woven in the middle. Young boys would carry it around the village, inviting people to step through it and so be blessed.[6]

Welcoming Brigid[edit]

On St Brigid’s Eve, Brigid was said to visit virtuous households and bless the inhabitants.[6] As Brigid represented the light half of the year, and the power that will bring people from the dark season of winter into spring, her presence was very important at this time of year.[33][34]

Before going to bed, people would leave items of clothing or strips of cloth outside for Brigid to bless.[6] The next morning, they would be brought inside, and believed to now have powers of healing and protection.[33][34]

Brigid would be symbolically invited into the house and a bed would often be made for her. In the north of Ireland, a family member, representing Brigid, would circle the home three times carrying rushes. They would then knock on the door three times, asking to be let in. On the third attempt they are welcomed in, a meal is had, and the rushes are then made into crosses or a bed for Brigid.[35] In 18th century Mann, the custom was to stand at the door with a bundle of rushes and say «Brede, Brede, come to my house tonight. Open the door for Brede and let Brede come in». Similarly, in County Donegal, the family member who was sent to fetch the rushes knelt on the front step and repeated three times, «Go on your knees, open your eyes, and let in St Brigid». Those inside the house answered three times «She’s welcome».[36] The rushes were then strewn on the floor as a carpet or bed for Brigid. In the 19th century, some old Manx women would make a bed for Brigid in the barn with food, ale, and a candle on a table.[6] The custom of making Brigid’s bed was particularly common in the Hebrides of Scotland, where it was recorded as far back as the 17th century. A bed of hay or a basket-like cradle would be made for Brigid and someone would then call out three times: «a Bhríd, a Bhríd, thig a stigh as gabh do leabaidh» («Bríd Bríd, come in; thy bed is ready»).[6] A corn dolly called the dealbh Bríde (icon of Brigid) would be laid in the bed and a white wand, usually made of birch, would be laid beside it.[6] It represented the wand that Brigid was said to use to make the vegetation start growing again.[37] Women in some parts of the Hebrides would also dance while holding a large cloth and calling out «Bridean, Bridean, thig an nall ‘s dean do leabaidh» («Bríd, Bríd, come over and make your bed»).[6]

Ashes from the fire would be raked smooth and, in the morning, they would look for some kind of mark on the ashes as a sign that Brigid had visited.[6][38] If there was no mark, they believed bad fortune would come unless they buried a cockerel at the meeting of three streams as an offering and burned incense on their fire that night.[6]

Brigid’s procession[edit]

In Ireland and Scotland, a representation of Brigid would be paraded around the community by girls and young women. Usually, it was a doll-like figure known as a Brídeóg (also called a ‘Breedhoge’ or ‘Biddy’). It would be made from rushes or reeds and clad in bits of cloth, flowers, or shells.[6][38] In the Hebrides of Scotland, a bright shell or crystal called the reul-iuil Bríde (guiding star of Brigid) was set on its chest. The girls would carry it in procession while singing a hymn to Brigid. All wore white with their hair unbound as a symbol of purity and youth. They visited every house in the area, where they received either food or more decoration for the Brídeóg. Afterward, they feasted in a house with the Brídeóg set in a place of honour, and put it to bed with lullabies. When the meal was done, the local young men humbly asked for admission, made obeisance to the Brídeóg, and joined the girls in dancing and merrymaking.[6] In many places, only unwed girls could carry the Brídeóg, but in some both boys and girls carried it.[39]

In some areas, rather than carrying a Brídeóg, a girl took on the role of Brigid. Escorted by other girls, she went house-to-house wearing ‘Brigid’s crown’ and carrying ‘Brigid’s shield’ and ‘Brigid’s cross’, all of which were made from rushes.[32] The procession in some places included ‘strawboys’, who wore conical straw hats, masks and played folk music; much like the wrenboys.[32] Up until the mid-20th century, children in Ireland still went house-to-house asking for pennies for «poor Biddy», or money for the poor. In County Kerry, men in white robes went from house to house singing.[40]

Weather divination[edit]

The festival was traditionally a time of weather divination, and the old tradition of watching to see if serpents or badgers came from their winter dens may be a forerunner of the North American Groundhog Day. A Scottish Gaelic proverb about the day is:

|

Thig an nathair as an toll |

The serpent will come from the hole |

Imbolc was believed to be when the Cailleach—the divine hag of Gaelic tradition—gathers her firewood for the rest of the winter. Legend has it that if she wishes to make the winter last a good while longer, she will make sure the weather on Imbolc is bright and sunny, so she can gather plenty of firewood. Therefore, people would be relieved if Imbolc is a day of foul weather, as it means the Cailleach is asleep and winter is almost over.[42] At Imbolc on the Isle of Man, where she is known as Caillagh ny Groamagh, the Cailleach is said to take the form of a gigantic bird carrying sticks in her beak.[42]

Other customs[edit]

Families would have a special meal or supper on St Brigid’s Eve to mark the last night of winter.[6] This typically included food such as colcannon, sowans, dumplings, barmbrack or bannocks.[43] Often, some of the food and drink would be set aside for Brigid.[6]

In Ireland, a spring cleaning was customary around the time of St Brigid’s Day.[43]

People traditionally visit holy wells and pray for health while walking ‘sunwise’ around the well. They might then leave offerings, typically coins or strips of cloth/ribbon (see clootie well). Historically, water from the well was used to bless the home, family members, livestock, and fields.[43][44]

Donald Alexander Mackenzie also recorded in the 19th century that offerings were made «to earth and sea». The offering could be milk poured into the ground or porridge poured into the water, as a libation.[45]

In County Kilkenny, graves were decorated with box and laurel flowers (or any other flowers that could be found at that time). A Branch of Virginity was decorated with white ribbons and placed on the grave of a recently deceased maiden.[46]

Today[edit]

People making Brigid’s crosses at St Brigid’s Well near Liscannor.