День святого Патрика: что это за праздник и как правильно его отмечать

Почему национальный ирландский праздник вдруг стали отмечать в России

17 марта 2022, 06:51, Оксана Михайлова

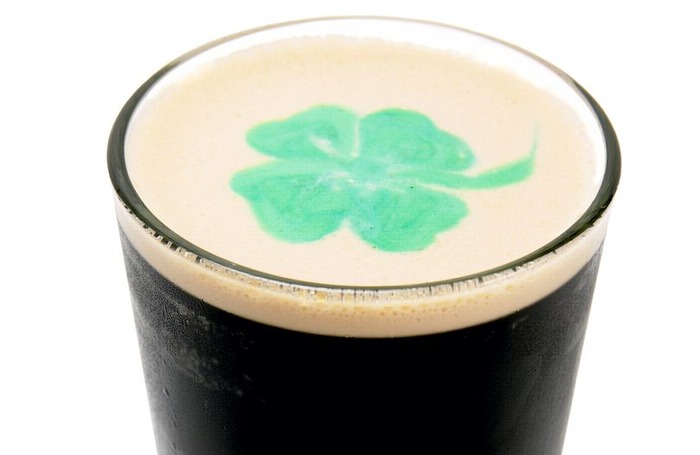

День святого Патрика / Фото: Jill Wellington с сайта Pixabay

День Святого Патрика — ирландский праздник. Пышно отмечают его 17 марта, но торжества продолжаются целых пять дней. В 1762 году символами этого дня стали трилистник и зелёный цвет, а с 1980-х ещё и пиво — много пива, которое буквально рекой льётся во всех барах и ресторанах. Читайте об этом празднике на amic.ru.

-

Кто такой святой Патрик?

Подробностей жития этого человека крайне мало. Точно неизвестно, когда он родился и умер (предположительно, 17 марта в V веке). Место похорон святого, по преданию, должны были определить быки, запряжённые в повозку с его телом. Где они остановились, там святого и закопали. Вот только где точно — никому неизвестно.Святому приписывают распространение христианства в Ирландии. Есть информация, что ему был пожалован епископский сан, а миссионерской деятельностью он занялся уже будучи епископом.

А вот Патрик — это прозвище. Так святого назвали пираты, что выкрали его и продали в рабство. Звали же Патрика то ли Майгон, то ли Майвин. Как точно — история умалчивает.

Святой считается покровителем Ирландии. В этой стране день его памяти — государственный праздник.

-

Как ирландский христианский праздник стал практически международным?

В Ирландии его отмечают с VII века. Чуть позже интерес к этому празднику стал появляться и в других странах — преимущественно в тех, где есть ирландская диаспора. Сначала это был североамериканский континент. Прибывшие туда ирландские иммигранты привезли и свои традиции. Активная же пропаганда началась не так давно — в 90-х годах XX века. Первый крупный фестиваль, приуроченный к этому празднику и проведённый за пределами Ирландии, прошёл в 1996 году. -

Почему цвет праздника зелёный?

Потому что это национальный цвет Ирландии. Зелёный флаг использовался и повстанцами в 1641 году, и членами общества объединённых ирландцев, которые боролись за независимость от Англии в 1790 году. В современном мире на Патрика едят, веселятся, одеваются в зелёное, пьют зелёное пиво. Одним словом, встречают весну во всеоружии, ведь этот цвет для многих — ещё и символ весны и пробуждения природы. -

Как праздник проник в Россию?

Произошло это в 1992-м. Летом же 1991 года в столице России открылся Ирландский торговый дом на Арбате. Ну а раз открылся, почему бы не понести ирландскую культуру в российские массы.Так, в 1992 году в Москве состоялся первый в РФ фестиваль святого Патрика. Действо происходило напротив Ирландского торгового дома и в мельчайших деталях имитировало проведение праздника в Ирландии.

Жителям столицы тот день запомнился обилием зелёного цвета, трилистниками, закреплёнными на одежде участников, и ирландскими музыкой и танцами. А ещё лепреконами. Правда, они не имеют никакой связи с христианским праздником — это языческие персонажи. Лепреконы — волшебные существа, и якобы если поймать хотя бы одного, он исполнит самые сокровенные желания. В общем, праздник понравился, а потому потихоньку закрепился и стал отмечаться и в других российских городах.

-

Почему на христианский праздник пьют пиво?

Эта традиция возникла в 80-х годах XX века. До этого все ирландские пабы 17 марта закрывались. Католикам же позволялись некоторые послабления в меню, которое по церковным канонам должно было быть постным — ведь День святого Патрика почти всегда приходится на Великий пост. 17 марта ирландцам разрешалось есть мясную пищу — традиционную капусту с беконом.Пивная же традиция появилась по воле одной из крупнейших торговых марок пива, которая провела широкомасштабную рекламную кампанию своей продукции, где утверждала, что на День святого Патрика не грех выпить. С христианскими традициями такие алкогольные возлияния не имеют ничего общего.

-

Когда Православная церковь включила Патрика в список своих святых?

Произошло это 9 марта 2017 года на заседании Священного Синода. Так в православном календаре появились ещё 15 памятных дат, среди которых и День святого Патрика. Кстати, в православии его вспоминают не 17, а 30 марта. -

Как за границей отмечают День святого Патрика?

17 марта тесно переплетаются языческие и христианские традиции. Кто-то по старинке мечтает найти лепрекона и разбогатеть. Кто-то обязательно выпивает «чарку Патрика» — рюмку виски, куда предварительно положили листок клевера. В народе об этом действе так и говорят — «осушим трилистник».В то же время многие верующие отправляются в чистилище святого Патрика — это место популярно у паломников с XIII века, здесь люди обретают покаяние и исцеляются духовно, или на гору Croagh Patrick — считается, что именно тут святой низверг змей в океан (под змеями понимают языческих богов, потому что рептилий в этой местности никогда не было).

| Saint Patrick’s Day | |

|---|---|

Saint Patrick depicted in a stained-glass window at Saint Benin’s Church, Ireland |

|

| Official name | Saint Patrick’s Day |

| Also called |

|

| Observed by |

|

| Type | Ethnic, national, Christian |

| Significance | Feast day of Saint Patrick, commemoration of the arrival of Christianity in Ireland[5][6] |

| Celebrations |

|

| Observances | Christian processions; attending Mass or service |

| Date | 17 March |

| Next time | 17 March 2023 |

| Frequency | Annual |

Saint Patrick’s Day, or the Feast of Saint Patrick (Irish: Lá Fhéile Pádraig, lit. ‘the Day of the Festival of Patrick’), is a cultural and religious celebration held on 17 March, the traditional death date of Saint Patrick (c. 385 – c. 461), the foremost patron saint of Ireland.

Saint Patrick’s Day was made an official Christian feast day in the early 17th century and is observed by the Catholic Church, the Anglican Communion (especially the Church of Ireland),[7] the Eastern Orthodox Church, and the Lutheran Church. The day commemorates Saint Patrick and the arrival of Christianity in Ireland, and celebrates the heritage and culture of the Irish in general.[5][8] Celebrations generally involve public parades and festivals, céilithe, and the wearing of green attire or shamrocks.[9] Christians who belong to liturgical denominations also attend church services[8][10] and historically the Lenten restrictions on eating and drinking alcohol were lifted for the day, which has encouraged and propagated the holiday’s tradition of alcohol consumption.[8][9][11][12]

Saint Patrick’s Day is a public holiday in the Republic of Ireland,[13] Northern Ireland,[14] the Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador (for provincial government employees), and the British Overseas Territory of Montserrat. It is also widely celebrated in the United Kingdom,[15] Canada, United States, Argentina, Australia and New Zealand, especially amongst Irish diaspora. Saint Patrick’s Day is celebrated in more countries than any other national festival.[16] Modern celebrations have been greatly influenced by those of the Irish diaspora, particularly those that developed in North America. However, there has been criticism of Saint Patrick’s Day celebrations for having become too commercialised and for fostering negative stereotypes of the Irish people.[17]

Saint Patrick[edit]

Saint Patrick was a 5th-century Romano-British Christian missionary and Bishop in Ireland. Much of what is known about Saint Patrick comes from the Declaration, which was allegedly written by Patrick himself. It is believed that he was born in Roman Britain in the fourth century, into a wealthy Romano-British family. His father was a deacon and his grandfather was a priest in the Christian church. According to the Declaration, at the age of sixteen, he was kidnapped by Irish raiders and taken as a slave to Gaelic Ireland.[18] It says that he spent six years there working as a shepherd and that during this time he found God. The Declaration says that God told Patrick to flee to the coast, where a ship would be waiting to take him home. After making his way home, Patrick went on to become a priest.[19]

According to tradition, Patrick returned to Ireland to convert the pagan Irish to Christianity. The Declaration says that he spent many years evangelising in the northern half of Ireland and converted thousands.

Patrick’s efforts were eventually turned into an allegory in which he drove «snakes» out of Ireland, despite the fact that snakes were not known to inhabit the region.[20]

Tradition holds that he died on 17 March and was buried at Downpatrick. Over the following centuries, many legends grew up around Patrick and he became Ireland’s foremost saint.

Celebration and traditions[edit]

According to legend, Saint Patrick used the three-leaved shamrock to explain the Holy Trinity to Irish pagans.

Today’s Saint Patrick’s Day celebrations have been greatly influenced by those that developed among the Irish diaspora, especially in North America. Until the late 20th century, Saint Patrick’s Day was often a bigger celebration among the diaspora than it was in Ireland.[16]

Celebrations generally involve public parades and festivals, Irish traditional music sessions (céilithe), and the wearing of green attire or shamrocks.[9] There are also formal gatherings such as banquets and dances, although these were more common in the past. Saint Patrick’s Day parades began in North America in the 18th century but did not spread to Ireland until the 20th century.[21] The participants generally include marching bands, the military, fire brigades, cultural organisations, charitable organisations, voluntary associations, youth groups, fraternities, and so on. However, over time, many of the parades have become more akin to a carnival. More effort is made to use the Irish language, especially in Ireland, where 1 March to St Patrick’s Day on 17 March is Seachtain na Gaeilge («Irish language week»).[22]

Since 2010, famous landmarks have been lit up in green on Saint Patrick’s Day as part of Tourism Ireland’s «Global Greening Initiative» or «Going Green for St Patrick’s Day».[23][24] The Sydney Opera House and the Sky Tower in Auckland were the first landmarks to participate and since then over 300 landmarks in fifty countries across the globe have gone green for Saint Patricks day.[25][26]

Christians may also attend church services,[8][10] and the Lenten restrictions on eating and drinking alcohol are lifted for the day. Perhaps because of this, drinking alcohol – particularly Irish whiskey, beer, or cider – has become an integral part of the celebrations.[8][9][11][12] The Saint Patrick’s Day custom of «drowning the shamrock» or «wetting the shamrock» was historically popular. At the end of the celebrations, especially in Ireland, a shamrock is put into the bottom of a cup, which is then filled with whiskey, beer, or cider. It is then drunk as a toast to Saint Patrick, Ireland, or those present. The shamrock would either be swallowed with the drink or taken out and tossed over the shoulder for good luck. [27][28][29]

Irish Government Ministers travel abroad on official visits to various countries around the globe to celebrate Saint Patrick’s Day and promote Ireland.[30][31] The most prominent of these is the visit of the Irish Taoiseach (Irish Prime Minister) with the U.S. President which happens on or around Saint Patrick’s Day.[32][33] Traditionally the Taoiseach presents the U.S. President a Waterford Crystal bowl filled with shamrocks.[34] This tradition began when in 1952, Irish Ambassador to the U.S. John Hearne sent a box of shamrocks to President Harry S. Truman. From then on it became an annual tradition of the Irish ambassador to the U.S. to present the Saint Patrick’s Day shamrock to an official in the U.S. President’s administration, although on some occasions the shamrock presentation was made by the Irish Taoiseach or Irish President to the U.S. President personally in Washington, such as when President Dwight D. Eisenhower met Taoiseach John A. Costello in 1956 and President Seán T. O’Kelly in 1959 or when President Ronald Reagan met Taoiseach Garret FitzGerald in 1986 and Taoiseach Charles Haughey in 1987.[32][34] However it was only after the meeting between Taoiseach Albert Reynolds and President Bill Clinton in 1994 that the presenting of the shamrock ceremony became an annual event for the leaders of both countries for Saint Patrick’s Day.[32][35] The presenting of the Shamrock ceremony was cancelled in 2020 due to the severity of the COVID-19 pandemic.[36][37]

Wearing green[edit]

A St Patrick’s Day greeting card from 1907

On Saint Patrick’s Day, it is customary to wear shamrocks, green clothing or green accessories. Saint Patrick is said to have used the shamrock, a three-leaved plant, to explain the Holy Trinity to the pagan Irish.[38][39] This story first appears in writing in 1726, though it may be older. In pagan Ireland, three was a significant number and the Irish had many triple deities, which may have aided St Patrick in his evangelisation efforts.[40][41] Roger Homan writes, «We can perhaps see St Patrick drawing upon the visual concept of the triskele when he uses the shamrock to explain the Trinity».[42] Patricia Monaghan says there is no evidence the shamrock was sacred to the pagan Irish.[40] Jack Santino speculates that it may have represented the regenerative powers of nature, and was recast in a Christian context—icons of St Patrick often depict the saint «with a cross in one hand and a sprig of shamrocks in the other».[43]

The first association of the colour green with Ireland is from a legend in the 11th century Lebor Gabála Érenn (The Book of the Taking of Ireland). It tells of Goídel Glas (Goídel the green), the eponymous ancestor of the Gaels and creator of the Goidelic languages (Irish, Scottish Gaelic, Manx).[44][45] Goídel is bitten by a venomous snake but saved from death by Moses placing his staff on the snakebite, leaving him with a green mark. His descendants settle in Ireland, a land free of snakes.[46] One of these, Íth, climbs the Tower of Hercules and is so captivated by the sight of a beautiful green island in the distance that he must set sail immediately.[44][45][46]

The colour green was further associated with Ireland from the 1640s, when the green harp flag was used by the Irish Catholic Confederation. Later, James Connolly described this flag as representing «the sacred emblem of Ireland’s unconquered soul».[47] Green ribbons and shamrocks have been worn on St Patrick’s Day since at least the 1680s.[48] Since then, the colour green and its association with St Patrick’s Day have grown.[49] The Friendly Brothers of St Patrick, an Irish fraternity founded in about 1750,[50] adopted green as its colour.[51] The Order of St Patrick, an Anglo-Irish chivalric order founded in 1783, instead adopted blue as its colour, which led to blue being associated with St Patrick. In the 1790s, the colour green was adopted by the United Irishmen. This was a republican organisation—led mostly by Protestants but with many Catholic members—who launched a rebellion in 1798 against British rule. Ireland was first called «the Emerald Isle» in «When Erin First Rose» (1795), a poem by a co-founder of the United Irishmen, William Drennan, which stresses the historical importance of green to the Irish.[52][53][54][55] The phrase «wearing of the green» comes from a song of the same name about United Irishmen being persecuted for wearing green. The flags of the 1916 Easter Rising featured green, such as the Starry Plough banner and the Proclamation Flag of the Irish Republic. When the Irish Free State was founded in 1922, the government ordered all post boxes be painted green, under the slogan «green paint for a green people»;[56][57] in 1924, the government introduced a green Irish passport.[58][59][60]

The wearing of the ‘St Patrick’s Day Cross’ was also a popular custom in Ireland until the early 20th century. These were a Celtic Christian cross made of paper that was «covered with silk or ribbon of different colours, and a bunch or rosette of green silk in the centre».[61]

Ireland[edit]

A St Patrick’s Day parade in Dublin

Saint Patrick’s feast day, as a kind of national day, was already being celebrated by the Irish in Europe in the ninth and tenth centuries. In later times, he became more and more widely seen as the patron of Ireland.[62] Saint Patrick’s feast day was finally placed on the universal liturgical calendar in the Catholic Church due to the influence of Waterford-born Franciscan scholar Luke Wadding[63] in the early 1600s. Saint Patrick’s Day thus became a holy day of obligation for Roman Catholics in Ireland. It is also a feast day in the Church of Ireland, which is part of the worldwide Anglican Communion. The church calendar avoids the observance of saints’ feasts during certain solemnities, moving the saint’s day to a time outside those periods. St Patrick’s Day is occasionally affected by this requirement, when 17 March falls during Holy Week. This happened in 1940, when Saint Patrick’s Day was observed on 3 April to avoid it coinciding with Palm Sunday, and again in 2008, where it was officially observed on 15 March.[64] St Patrick’s Day will not fall within Holy Week again until 2160.[65][66] However, the popular festivities may still be held on 17 March or on a weekend near to the feast day.[67]

In 1903, St Patrick’s Day became an official public holiday in Ireland. This was thanks to the Bank Holiday (Ireland) Act 1903, an act of the United Kingdom Parliament introduced by Irish Member of Parliament James O’Mara.[68]

The first St Patrick’s Day parade in Ireland was held in Waterford in 1903. The week of St Patrick’s Day 1903 had been declared Irish Language Week by the Gaelic League and in Waterford they opted to have a procession on Sunday 15 March. The procession comprised the Mayor and members of Waterford Corporation, the Trades Hall, the various trade unions and bands who included the ‘Barrack St Band’ and the ‘Thomas Francis Meagher Band’.[69] The parade began at the premises of the Gaelic League in George’s St and finished in the Peoples Park, where the public were addressed by the Mayor and other dignitaries.[70][71] On Tuesday 17 March, most Waterford businesses—including public houses—were closed and marching bands paraded as they had two days previously.[72] The Waterford Trades Hall had been emphatic that the National Holiday be observed.[70]

On St Patrick’s Day 1916, the Irish Volunteers—an Irish nationalist paramilitary organisation—held parades throughout Ireland. The authorities recorded 38 St Patrick’s Day parades, involving 6,000 marchers, almost half of whom were said to be armed.[73] The following month, the Irish Volunteers launched the Easter Rising against British rule. This marked the beginning of the Irish revolutionary period and led to the Irish War of Independence and Civil War. During this time, St Patrick’s Day celebrations in Ireland were muted, although the day was sometimes chosen to hold large political rallies.[74] The celebrations remained low-key after the creation of the Irish Free State; the only state-organized observance was a military procession and trooping of the colours, and an Irish-language mass attended by government ministers.[75] In 1927, the Irish Free State government banned the selling of alcohol on St Patrick’s Day, although it remained legal in Northern Ireland. The ban was not repealed until 1961.[76]

The first official, state-sponsored St Patrick’s Day parade in Dublin took place in 1931.[77] On three occasions, parades across the Republic of Ireland have been cancelled from taking place on St Patrick’s Day, with all years involving health and safety reasons.[78][79] In 2001, as a precaution to the foot-and-mouth outbreak, St Patrick’s Day celebrations were postponed to May[80][81][82] and in 2020 and 2021, as a consequence to the severity of the COVID-19 pandemic, the St Patrick’s Day Parade was cancelled outright.[83][84][85][86] Organisers of the St Patrick’s Day Festival 2021 will instead host virtual events around Ireland on their SPF TV online channel.[87][88][89]

In Northern Ireland, the celebration of St Patrick’s Day was affected by sectarian divisions.[90] A majority of the population were Protestant Ulster unionists who saw themselves as British, while a substantial minority were Catholic Irish nationalists who saw themselves as Irish. Although it was a public holiday, Northern Ireland’s unionist government did not officially observe St Patrick’s Day.[90] During the conflict known as the Troubles (late 1960s–late 1990s), public St Patrick’s Day celebrations were rare and tended to be associated with the Catholic community.[90] In 1976, loyalists detonated a car bomb outside a pub crowded with Catholics celebrating St Patrick’s Day in Dungannon; four civilians were killed and many injured. However, some Protestant unionists attempted to ‘re-claim’ the festival, and in 1985 the Orange Order held its own St Patrick’s Day parade.[90] Since the end of the conflict in 1998 there have been cross-community St Patrick’s Day parades in towns throughout Northern Ireland, which have attracted thousands of spectators.[90]

In the mid-1990s the government of the Republic of Ireland began a campaign to use St Patrick’s Day to showcase Ireland and its culture.[91] The government set up a group called St Patrick’s Festival, with the aims:

- To offer a national festival that ranks amongst all of the greatest celebrations in the world

- To create energy and excitement throughout Ireland via innovation, creativity, grassroots involvement, and marketing activity

- To provide the opportunity and motivation for people of Irish descent (and those who sometimes wish they were Irish) to attend and join in the imaginative and expressive celebrations

- To project, internationally, an accurate image of Ireland as a creative, professional and sophisticated country with wide appeal.[92]

The first St Patrick’s Festival was held on 17 March 1996. In 1997, it became a three-day event, and by 2000 it was a four-day event. By 2006, the festival was five days long; more than 675,000 people attended the 2009 parade. Overall 2009’s five-day festival saw almost 1 million visitors, who took part in festivities that included concerts, outdoor theatre performances, and fireworks.[93] The Skyfest which ran from 2006 to 2012 formed the centrepiece of the St Patrick’s festival.[94][95]

The topic of the 2004 St Patrick’s Symposium was «Talking Irish», during which the nature of Irish identity, economic success, and the future were discussed. Since 1996, there has been a greater emphasis on celebrating and projecting a fluid and inclusive notion of «Irishness» rather than an identity based around traditional religious or ethnic allegiance. The week around St Patrick’s Day usually involves Irish language speakers using more Irish during Seachtain na Gaeilge («Irish Language Week»).[96]

Christian leaders in Ireland have expressed concern about the secularisation of St Patrick’s Day. In The Word magazine’s March 2007 issue, Fr Vincent Twomey wrote, «It is time to reclaim St Patrick’s Day as a church festival». He questioned the need for «mindless alcohol-fuelled revelry» and concluded that «it is time to bring the piety and the fun together».[97]

The biggest celebrations outside the cities are in Downpatrick, County Down, where Saint Patrick is said to be buried. The shortest St. Patrick’s Day parade in the world formerly took place in Dripsey, County Cork. The parade lasted just 23.4 metres and traveled between the village’s two pubs. The annual event began in 1999, but ceased after five years when one of the two pubs closed.[98]

Celebrations elsewhere[edit]

Europe[edit]

England[edit]

In England, the British Royals traditionally present bowls of shamrock to members of the Irish Guards, a regiment in the British Army, following Queen Alexandra introducing the tradition in 1901.[99][100] Since 2012 the Duchess of Cambridge has presented the bowls of shamrock to the Irish Guards. While female royals are often tasked with presenting the bowls of shamrock, male royals have also undertaken the role, such as King George VI in 1950 to mark the 50th anniversary of the formation of the Irish Guards, and in 2016 the Duke of Cambridge in place of his wife.[101][102] Fresh Shamrocks are presented to the Irish Guards, regardless of where they are stationed, and are flown in from Ireland.[103]

While some Saint Patrick’s Day celebrations could be conducted openly in Britain pre 1960s, this would change following the commencement by the IRA’s bombing campaign on mainland Britain and as a consequence this resulted in a suspicion of all things Irish and those who supported them which led to people of Irish descent wearing a sprig of shamrock on Saint Patrick’s day in private or attending specific events.[104] Today after many years following the Good Friday Agreement, people of Irish descent openly wear a sprig of shamrock to celebrate their Irishness.[104]

Christian denominations in Great Britain observing his feast day include The Church of England and the Roman Catholic Church.[105]

Birmingham holds the largest Saint Patrick’s Day parade in Britain with a city centre parade[106] over a two-mile (3 km) route through the city centre. The organisers describe it as the third biggest parade in the world after Dublin and New York.[107]

London, since 2002, has had an annual Saint Patrick’s Day parade which takes place on weekends around the 17th, usually in Trafalgar Square. In 2008 the water in the Trafalgar Square fountains was dyed green. In 2020 the Parade was cancelled due to the COVID-19 pandemic.[citation needed]

Liverpool has the highest proportion of residents with Irish ancestry of any English city.[108] This has led to a long-standing celebration on St Patrick’s Day in terms of music, cultural events and the parade.[citation needed]

Manchester hosts a two-week Irish festival in the weeks prior to Saint Patrick’s Day. The festival includes an Irish Market based at the city’s town hall which flies the Irish tricolour opposite the Union Flag, a large parade as well as a large number of cultural and learning events throughout the two-week period.[109]

Malta[edit]

The first Saint Patrick’s Day celebrations in Malta took place in the early 20th century by soldiers of the Royal Dublin Fusiliers who were stationed in Floriana. Celebrations were held in the Balzunetta area of the town, which contained a number of bars and was located close to the barracks. The Irish diaspora in Malta continued to celebrate the feast annually.[110]

Today, Saint Patrick’s Day is mainly celebrated in Spinola Bay and Paceville areas of St Julian’s,[111] although other celebrations still occur at Floriana[110] and other locations.[112][113] Thousands of Maltese attend the celebrations, «which are more associated with drinking beer than traditional Irish culture.»[114][115]

Norway[edit]

Norway has had a St. Patrick’s Day parade in Oslo since 2000, first organized by Irish expatriates living in Norway, and partially coordinated with the Irish embassy in Oslo.[116]

Russia[edit]

Moscow hosts an annual Saint Patrick’s Day festival.

The first Saint Patrick’s Day parade in Russia took place in 1992.[117] Since 1999, there has been a yearly «Saint Patrick’s Day» festival in Moscow and other Russian cities.[118] The official part of the Moscow parade is a military-style parade and is held in collaboration with the Moscow government and the Irish embassy in Moscow. The unofficial parade is held by volunteers and resembles a carnival. In 2014, Moscow Irish Week was celebrated from 12 to 23 March, which includes Saint Patrick’s Day on 17 March. Over 70 events celebrating Irish culture in Moscow, St Petersburg, Yekaterinburg, Voronezh, and Volgograd were sponsored by the Irish Embassy, the Moscow City Government, and other organisations.[119]

In 2017, the Russian Orthodox Church added the feast day of Saint Patrick to its liturgical calendar, to be celebrated on 30 March [O.S. 17 March].[120]

Bosnia and Herzegovina[edit]

Sarajevo, the capital city of Bosnia and Herzegovina has a large Irish expatriate community.[121][122] The community established the Sarajevo Irish Festival in 2015, which is held for three days around and including Saint Patrick’s Day. The festival organizes an annual a parade, hosts Irish theatre companies, screens Irish films and organizes concerts of Irish folk musicians. The festival has hosted numerous Irish artists, filmmakers, theatre directors and musicians such as Conor Horgan, Ailis Ni Riain, Dermot Dunne, Mick Moloney, Chloë Agnew and others.[123][124][125]

Scotland[edit]

The Scottish town of Coatbridge, where the majority of the town’s population are of Irish descent,[126][127] also has a Saint Patrick’s Day Festival which includes celebrations and parades in the town centre.[127][128]

Glasgow has a considerably large Irish population; due, for the most part, to the Irish immigration during the 19th century. This immigration was the main cause in raising the population of Glasgow by over 100,000 people.[129] Due to this large Irish population, there are many Irish-themed pubs and Irish interest groups who hold yearly celebrations on Saint Patrick’s day in Glasgow. Glasgow has held a yearly Saint Patrick’s Day parade and festival since 2007.[130]

Switzerland[edit]

While Saint Patrick’s Day in Switzerland is commonly celebrated on 17 March with festivities similar to those in neighbouring central European countries, it is not unusual for Swiss students to organise celebrations in their own living spaces on Saint Patrick’s Eve. Most popular are usually those in Zurich’s Kreis 4. Traditionally, guests also contribute with beverages and dress in green.[131]

Lithuania[edit]

Although it is not a national holiday in Lithuania, the Vilnia River is dyed green every year on the Saint Patrick’s Day in the capital Vilnius.[132]

Americas[edit]

Canada[edit]

Montreal hosts one of the longest-running and largest Saint Patrick’s Day parades in North America

One of the longest-running and largest Saint Patrick’s Day (French: le jour de la Saint-Patrick) parades in North America occurs each year in Montreal,[133] whose city flag includes a shamrock in its lower-right quadrant. The yearly celebration has been organised by the United Irish Societies of Montreal since 1929. The parade has been held yearly without interruption since 1824. St Patrick’s Day itself, however, has been celebrated in Montreal since as far back as 1759 by Irish soldiers in the Montreal Garrison following the British conquest of New France.

In Saint John, New Brunswick Saint Patrick’s Day is celebrated as a week-long celebration. Shortly after the JP Collins Celtic Festival is an Irish festival celebrating Saint John’s Irish heritage. The festival is named for a young Irish doctor James Patrick Collins who worked on Partridge Island (Saint John County) quarantine station tending to sick Irish immigrants before he died there himself.

In Manitoba, the Irish Association of Manitoba runs a yearly three-day festival of music and culture based around St Patrick’s Day.[134]

In 2004, the CelticFest Vancouver Society organised its first yearly festival in downtown Vancouver to celebrate the Celtic Nations and their cultures. This event, which includes a parade, occurs each year during the weekend nearest St Patrick’s Day.[135]

In Quebec City, there was a parade from 1837 to 1926. The Quebec City St-Patrick Parade returned in 2010 after more than 84 years. For the occasion, a portion of the New York Police Department Pipes and Drums were present as special guests.

There has been a parade held in Toronto since at least 1863.[136]

The Toronto Maple Leafs hockey team was known as the Toronto St. Patricks from 1919 to 1927, and wore green jerseys. In 1999, when the Maple Leafs played on St Patrick’s Day, they wore green St Patrick’s retro uniforms.[citation needed]

Some groups, notably Guinness, have lobbied to make Saint Patrick’s Day a national holiday.[137]

In March 2009, the Calgary Tower changed its top exterior lights to new green CFL bulbs just in time for St Patrick’s Day. Part of an environmental non-profit organisation’s campaign (Project Porchlight), the green represented environmental concerns. Approximately 210 lights were changed in time for Saint Patrick’s Day, and resembled a Leprechaun’s hat. After a week, white CFLs took their place. The change was estimated to save the Calgary Tower some $12,000 and reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 104 tonnes.[138]

United States[edit]

Saint Patrick’s Day, while not a legal holiday in the United States, is nonetheless widely recognised and observed throughout the country as a celebration of Irish and Irish-American culture. Celebrations include prominent displays of the colour green, religious observances, numerous parades, and copious consumption of alcohol.[11] The holiday has been celebrated in what is now the U.S since 1601.[140]

In 2020, for the first time in over 250 years, the parade in New York City, the largest in the world, was postponed due to concerns about the COVID-19 pandemic.[141]

Mexico[edit]

The Saint Patrick’s Battalion is honored in Mexico on Saint Patrick’s Day.[142]

Argentina[edit]

In Buenos Aires, a party is held in the downtown street of Reconquista, where there are several Irish pubs;[143][144] in 2006, there were 50,000 people in this street and the pubs nearby.[145] Neither the Catholic Church nor the Irish community, the fifth largest in the world outside Ireland,[146] take part in the organisation of the parties.

Montserrat[edit]

The island of Montserrat is known as the «Emerald Island of the Caribbean» because of its founding by Irish refugees from Saint Kitts and Nevis. Montserrat is one of three places where Saint Patrick’s Day is a public holiday, along with Ireland and the Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador. The holiday in Montserrat also commemorates a failed slave uprising that occurred on 17 March 1768.[147]

Oceania[edit]

Australia[edit]

St Patrick’s Day is not a national holiday in Australia, although it is celebrated each year across the country’s states and territories.[148][149][150] Festivals and parades are often held on weekends around 17 March in cities such as Sydney,[151] Brisbane,[152] Adelaide,[153] and Melbourne.[154] On occasion, festivals and parades are cancelled. For instance, Melbourne’s 2006 and 2007 St Patrick’s Day festivals and parades were cancelled due to sporting events (Commonwealth Games and Australian Grand Prix) being booked on and around the planned St Patrick’s Day festivals and parades in the city.[155] In Sydney the parade and family day was cancelled in 2016 due to financial problems.[156][157] However, Brisbane’s St Patrick’s Day parade, which was cancelled at the outbreak of World War II and wasn’t revived until 1990,[158] was not called off in 2020 as precaution for the COVID-19 pandemic, in contrast to many other St Patrick’s Day parades around the world.[159]

The first mention of St Patrick’s Day being celebrated in Australia was in 1795, when Irish convicts and administrators, Catholic and Protestant, in the penal colony came together to celebrate the day as a national holiday, despite a ban against assemblies being in place at the time.[160] This unified day of Irish nationalist observance would soon dissipate over time, with celebrations on St Patrick’s Day becoming divisive between religions and social classes, representative more of Australianness than of Irishness and held intermittingly throughout the years.[160][161][162] Historian Patrick O’Farrell credits the 1916 Easter Rising in Dublin and Archbishop Daniel Mannix of Melbourne for re-igniting St Patrick’s Day celebrations in Australia and reviving the sense of Irishness amongst those with Irish heritage.[160] The organisers of the St Patrick’s festivities in the past were, more often than not, the Catholic clergy[163] which often courted controversy.[164][165] Bishop Patrick Phelan of Sale described in 1921 how the authorities in Victoria had ordered that a Union Jack be flown at the front of the St Patrick’s Day parade and following the refusal by Irishmen and Irish-Australians to do so, the authorities paid for an individual to carry the flag at the head of the parade.[166][167] This individual was later assaulted by two men who were later fined in court.[168][169]

New Zealand[edit]

From 1878 to 1955, St Patrick’s Day was recognised as a public holiday in New Zealand, together with St George’s Day (England) and St Andrew’s Day (Scotland).[170][171][172] Auckland attracted many Irish migrants in the 1850s and 1860s, and it was here where some of the earliest St Patrick’s Day celebrations took place, which often entailed the hosting of community picnics.[173] However, this rapidly evolved from the late 1860s onwards to include holding parades with pipe bands and marching children wearing green, sporting events, concerts, balls and other social events, where people displayed their Irishness with pride.[173] While St Patrick’s Day is no longer recognised as a public holiday, it continues to be celebrated across New Zealand with festivals and parades at weekends on or around 17 March.[174][175]

Asia[edit]

Saint Patrick’s parades are now held in many locations across Japan.[176] The first parade, in Tokyo, was organised by The Irish Network Japan (INJ) in 1992.

The Irish Association of Korea has celebrated Saint Patrick’s Day since 1976 in Seoul, the capital city of South Korea. The place of the parade and festival has been moved from Itaewon and Daehangno to Cheonggyecheon.[177]

In Malaysia, the St Patrick’s Society of Selangor, founded in 1925, organises a yearly St Patrick’s Ball, described as the biggest Saint Patrick’s Day celebration in Asia. Guinness Anchor Berhad also organises 36 parties across the country in places like the Klang Valley, Penang, Johor Bahru, Malacca, Ipoh, Kuantan, Kota Kinabalu, Miri and Kuching.

International Space Station[edit]

Astronauts on board the International Space Station have celebrated the festival in different ways. Irish-American Catherine Coleman played a hundred-year-old flute belonging to Matt Molloy and a tin whistle belonging to Paddy Moloney, both members of the Irish music group The Chieftains, while floating weightless in the space station on Saint Patrick’s Day in 2011.[178][179][180] Her performance was later included in a track called «The Chieftains in Orbit» on the group’s 2012 album, Voice of Ages.[181]

Chris Hadfield took photographs of Ireland from Earth orbit, and a picture of himself wearing green clothing in the space station, and posted them online on Saint Patrick’s Day in 2013. He also posted online a recording of himself singing «Danny Boy» in space.[182][183]

Criticism[edit]

Saint Patrick’s Day celebrations have been criticised, particularly for their association with public drunkenness and disorderly conduct. Some argue that the festivities have become too commercialised and tacky,[184][185] and have strayed from their original purpose of honouring St Patrick and Irish heritage.[186][187][184] Irish American journalist Niall O’Dowd has criticised attempts to recast Saint Patrick’s Day as a celebration of multiculturalism rather than a celebration of Irishness.[188]

Man in a leprechaun outfit on Saint Patrick’s Day

Saint Patrick’s Day celebrations have also been criticised for fostering demeaning stereotypes of Ireland and Irish people.[184] An example is the wearing of ‘leprechaun outfits’,[189] which are based on derogatory 19th century caricatures of the Irish.[190] In the run up to St Patrick’s Day 2014, the Ancient Order of Hibernians successfully campaigned to stop major American retailers from selling novelty merchandise that promoted negative Irish stereotypes.[191]

Some[who?] have described Saint Patrick’s Day celebrations outside Ireland as displays of «Plastic Paddyness»; where foreigners appropriate and misrepresent Irish culture, claim Irish identity, and enact Irish stereotypes.[192]

LGBT groups in the US were long banned from marching in Saint Patrick’s Day parades in New York City and Boston, resulting in the landmark Supreme Court decision of Hurley v. Irish-American Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual Group of Boston. In New York City, the ban was lifted in 2014,[193] but LGBT groups still find that barriers to participation exist.[194] In Boston, the ban on LGBT group participation was lifted in 2015.[195]

Sports events[edit]

- Traditionally the All-Ireland Senior Club Football Championship and All-Ireland Senior Club Hurling Championship were held on Saint Patrick’s Day in Croke Park, Dublin, but since 2020 these now take place in January. The Interprovincial Championship was previously held on 17 March but this was switched to games being played in Autumn.

- The Leinster Schools Rugby Senior Cup, Munster Schools Rugby Senior Cup and Ulster Schools Senior Cup are held on Saint Patrick’s Day. The Connacht Schools Rugby Senior Cup is held on the weekend before Saint Patrick’s Day.

- Horse racing at the Cheltenham Festival attracts large numbers of Irish people, both residents of Britain and many who travel from Ireland, and usually coincides with Saint Patrick’s Day.[196]

- The Six Nations Championship is an annual international rugby Union tournament competed by England, France, Ireland, Italy, Scotland, and Wales and reaches its climax on or around Saint Patrick’s Day.[197][198] On St Patrick’s Day 2018, Ireland defeated England 24–15 at Twickenham, London to claim the third Grand Slam in their history.[199][200]

- The Saint Patrick’s Day Test is an international rugby league tournament that is played between the US and Ireland. The competition was first started in 1995 and continued in 1996, 2000, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2011, and 2012. Ireland won the first two tests as well as the one in 2011, with the US winning the remaining 5. The game is usually held on or around 17 March to coincide with Saint Patrick’s Day.[201]

- The major professional sports leagues of the United States and Canada that play during March often wear special third jerseys to acknowledge the holiday. Examples include the Buffalo Sabres (who have worn special Irish-themed practice jerseys), Toronto Maple Leafs (who wear Toronto St. Patricks throwbacks), New York Knicks, Toronto Raptors, and most Major League Baseball teams. The New Jersey Devils have worn their green-and-red throwback jerseys on or around Saint Patrick’s Day in recent years.[202]

See also[edit]

- Gaelic calendar, also known as Irish calendar

- «It’s a Great Day for the Irish»

- Order of St. Patrick

- Saint Patrick’s Breastplate

- St. Patrick’s Day Snowstorm of 1892

- Saint Urho

References[edit]

- ^ Doug Bolton (16 March 2016). «One Irish creative agency is leading the charge against ‘St. Patty’s Day’«. The Independent. Archived from the original on 12 March 2018. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

That’s the thinking behind the No More Patty Google Chrome extension, created by Dublin-based creative agency in the Company of Huskies. The extension can be installed in a few clicks, and automatically replaces every online mention of the «very wrong» ‘Patty’ with the «absolutely right» ‘Paddy’.

- ^ Aric Jenkins (15 March 2017). «Why Some Irish People Don’t Want You to Call It St. Patty’s Day». Time. Archived from the original on 10 May 2019. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- ^ «Is It «St. Patrick’s Day» Or «St. Patricks Day»?». dictionary.com. 17 March 2021. Archived from the original on 18 March 2020. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- ^ Jordan Valinsky. (17 March 2014). «Dublin Airport would like to remind you it’s St. Paddy’s Day, not St. Patty’s Day». The Week. Archived from the original on 28 March 2020. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- ^ a b Ritschel, Chelsea; Michallon, Clémence (17 March 2022). «What is the meaning behind St Patrick’s Day?». The Independent. Retrieved 17 March 2022.

The day of celebration, which marks the day of St Patrick’s death, was originally a religious holiday meant to celebrate the arrival of Christianity in Ireland, and made official by the Catholic Church in the early 17th century. Observed by the Catholic Church, the Anglican Communion, the Eastern Orthodox Church, and the Lutheran Church, the day was typically observed with services, feasts and alcohol.

- ^ Ariel, Shlomo (17 April 2018). Multi-Dimensional Therapy with Families, Children and Adults: The Diamond Model. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-351-58794-5.

In many culture, identity perception is supported by constitutive myths, traditions and rituals (e.g. the Jewish Passover, the myth of the foundation of Rome [the tale of Romulus and Remus] and St. Patrick’s Day, which commemorates the arrival of Christianity to Ireland and celebrates the heritage and culture of the Irish in general).

- ^ «St Patrick’s Day celebrations». Church of Ireland. The Irish Times. 12 March 2011. Archived from the original on 15 May 2011. Retrieved 17 March 2013 – via ireland.anglican.org.

- ^ a b c d e Willard Burgess Moore (1989). Circles of Tradition: Folk Arts in Minnesota. Minnesota Historical Society Press. p. 52. ISBN 9780873512398. Retrieved 13 November 2010.

In nineteenth-century America it became a celebration of Irishness, more than a religious occasion, though attending Mass continues as an essential part of the day.

- ^ a b c d Willard Burgess Moore (1989). Circles of Tradition: Folk Arts in Minnesota. Minnesota Historical Society Press. p. 52. ISBN 9780873512398. Retrieved 13 November 2010.

The religious occasion did involve the wearing of shamrocks, an Irish symbol of the Holy Trinity, and the lifting of Lenten restrictions on drinking.

- ^ a b Edna Barth (2001). Shamrocks, Harps, and Shillelaghs: The Story of the St. Patrick’s Day Symbols. Sandpiper. p. 7. ISBN 0618096515. Archived from the original on 21 November 2015. Retrieved 13 November 2010.

For most Irish-Americans, this holiday (from holy day) is partially religious but overwhelmingly festive. For most Irish people in Ireland the day has little to do with religion at all and St. Patrick’s Day church services are followed by parades and parties, the latter being the best attended. The festivities are marked by Irish music, songs, and dances.

- ^ a b c John Nagle (2009). Multiculturalism’s Double-Bind. Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-0-754-67607-2. Archived from the original on 19 August 2020. Retrieved 13 November 2010.

Like many other forms of carnival, St. Patrick’s Day is a feast day, a break from Lent in which adherents are allowed to temporarily abandon rigorous fasting by indulging the forbidden. Since alcohol is often proscribed during Lent the copious consumption of alcohol is seen as an integral part of St. Patrick’s day.

- ^ a b James Terence Fisher (30 November 2007). Communion of Immigrants: A History of Catholics in America. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199842254. Archived from the original on 6 October 2015. Retrieved 13 November 2010.

The 40-day period (not counting Sundays) prior to Easter is known as Lent, a time of prayer and fasting. Pastors of Irish- American parishes often supplied «dispensations» for St. Patrick s Day, enabling parishioners to forego Lenten sacrifices in order to celebrate the feast of their patron saint.

- ^ «Public holidays in Ireland». Citizens Information Board. Archived from the original on 17 November 2010. Retrieved 13 November 2010.

- ^ «Bank holidays». NI Direct. Archived from the original on 22 November 2010. Retrieved 13 November 2010.

- ^ Ritschel, Chelsea (17 March 2019). «St Patrick’s Day 2019: When is it and where can I celebrate?». The Independent. Archived from the original on 23 April 2019. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- ^ a b Cronin & Adair (2002), p. 242[1]

- ^ Varin, Andra. «The Americanization of St. Patrick’s Day». ABC News. Archived from the original on 17 April 2020. Retrieved 17 March 2020.

- ^ «Confession of St. Patrick». Christian Classics Ethereal Library at Calvin College. Archived from the original on 16 December 2009. Retrieved 10 March 2010.

- ^ Bridgwater, William; Kurtz, Seymour, eds. (1963). «Saint Patrick». The Columbia Encyclopedia (3rd ed.). New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 1611–12.

- ^ Owen, James (15 March 2014). «Did St. Patrick Really Drive Snakes Out of Ireland?». National Geographic. Archived from the original on 18 March 2021. Retrieved 18 March 2021.

- ^ Cronin & Adair (2002), p. xxiii.

- ^ «Seachtain na Gaeilge – 1 – 17 MARCH 2021» (in Ga). Archived from the original on 10 March 2021. Retrieved 17 March 2021.

- ^ St Patrick’s Day: Globe Goes Green. (17 March 2018). BBC News. Retrieved 8 January 2019.

- ^ The World Goes Green for St Patrick’s Day. (16 March 2018) RTE News. Retrieved 8 January 2019

- ^ Global Greening Campaign 2018. (2018) Tourism Ireland. Retrieved 8 January 2019

- ^ Ó Conghaile, Pól. (16 March 2018). Green Lights: See the Landmarks Going Green for St Patrick’s Day!. Independent.ie Retrieved 8 January 2019

- ^ Cronin & Adair (2002), p. 26.

- ^ Santino, Jack (1995). All Around the Year: Holidays and Celebrations in American Life. University of Illinois Press. p. 82.

- ^ Donal Hickey (17 March 2014). «The facts about shamrock». Irish Examiner. Archived from the original on 12 March 2016. Retrieved 11 March 2016.

- ^ How St Patrick’s Day Celebrations Went Global Archived 9 January 2019 at the Wayback Machine (9 March 2018) The Economist Retrieved 8 January 2019

- ^ Doyle, Kevin. (16 January 2018). St Patrick’s Day Exodus to See Ministers Travel to 35 Countries Archived 8 January 2019 at the Wayback Machine. Irish Independent. Retrieved 8 January 2019

- ^ a b c Collins, Stephen. (11 March 2017). A Short History of Taoisigh Visiting the White House on St Patrick’s Day Archived 11 April 2019 at the Wayback Machine. Irish Times. Retrieved 8 January 2019

- ^ St. Patrick’s Day and Irish Heritage in American History Archived 2 March 2021 at the Wayback Machine (14 March 2018). whitehouse.gov Retrieved 8 January 2019

- ^ a b Dwyer, Ryle. (2 January 2017). President Reagan’s Bowl of Shamrock and the 1,500-Year Wake Archived 10 January 2019 at the Wayback Machine. Irish Examiner. Retrieved 8 January 2019

- ^ Dwyer, Ryle. (2 January 2017). President Reagan’s Bowl of Shamrock and the 1,500-Year Wake Archived 10 January 2019 at the Wayback Machine. Irish Examiner. Retrieved 8 January 2019

- ^ O’Donovan, Brian. (12 Mar 2020). White House shamrock ceremony, New York parade cancelled. RTE News. Retrieved 12 March 2020

- ^ ITV News. (12 March 2020) White House shamrock ceremony and St Patrick’s Day parades cancelled Archived 12 March 2020 at the Wayback Machine. ITV News. Retrieved 12 March 2020

- ^ Vernon, Jennifer (15 March 2004). «St. Patrick’s Day: Fact vs. Fiction». National Geographic News. p. 2. Archived from the original on 2 December 2008. Retrieved 31 March 2009.

- ^ Newell, Jill (16 March 2000). «Holiday has history». Daily Forty-Niner. Archived from the original on 16 March 2009. Retrieved 21 March 2009.

- ^ a b Monaghan, Patricia (1 January 2009). The Encyclopedia of Celtic Mythology and Folklore. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-1-438-11037-0.

There is no evidence that the clover or wood sorrel (both of which are called shamrocks) were sacred to the Celts in any way. However, the Celts had a philosophical and cosmological vision of triplicity, with many of their divinities appearing in three. Thus when St Patrick, attempting to convert the Druids on Beltane, held up a shamrock and discoursed on the Christian Trinity, the three-in-one god, he was doing more than finding a homely symbol for a complex religious concept. He was indicating knowledge of the significance of three in the Celtic realm, a knowledge that probably made his mission far easier and more successful than if he had been unaware of that number’s meaning.

- ^ Hegarty, Neil (24 April 2012). Story of Ireland. Ebury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-448-14039-8.

In some ways, though, the Christian mission resonated: pre-Christian devotion was characterized by, for example, the worship of gods in groups of three, by sayings collected in threes (triads), and so on – from all of which the concept of the Holy Trinity was not so very far removed. Against this backdrop the myth of Patrick and his three-leafed shamrock fits quite neatly.

- ^ Homan, Roger (2006). The Art of the Sublime: Principles of Christian Art and Architecture. Ashgate Publishing. p. 37.

- ^ Santino, Jack (1995). All Around the Year: Holidays and Celebrations in American Life. University of Illinois Press. p. 80. ISBN 978-0-252-06516-3.

- ^ a b Koch, John T. (2005). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. Vol. 1 A-Celti. Oxford: ABC-Clio. ISBN 978-1-851-09440-0. Archived from the original on 19 May 2021. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- ^ a b Mackillop, James (2005). Myths and Legends of the Celts. London: Penguin Books. pp. 145–146. ISBN 978-0-141-01794-5. Archived from the original on 19 August 2020. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- ^ a b Macalister, Robert Alexander Stewart (1939). Lebor Gabála Érenn: The Book of the Taking of Ireland. Vol. 2. Dublin: Irish Texts Society by the Educational Co. of Ireland. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- ^ Phelan, Rachel, (May/June 2016). «James Connolly’s ‘Green Flag of Ireland'» Archived 11 November 2020 at the Wayback Machine History Ireland Vol. 24 Issue 3, pp. 8-9. Retrieved from History Ireland on 26 March 2018

- ^ Cronin & Adair (2002).

- ^ St. Patrick: Why Green? – video. History.com. A&E Television Networks. Archived from the original on 7 March 2010. Retrieved 17 March 2010.

- ^ Kelly, James. That Damn’d Thing Called Honour: Duelling in Ireland, 1570–1860. Cork University Press, 1995. p.65

- ^ The Fundamental Laws, Statutes and Constitutions of the Ancient Order of the Friendly Brothers of Saint Patrick. 1751.

- ^ Drennan, William. When Ireland First Rose Archived 5 February 2021 at the Wayback Machine. in Charles A. Reed (ed.) (1884) The Cabinet of Irish Literature. Volume 2. Retrieved 2 February 2021 via Library Ireland

- ^ Maye, Brian (3 February 2020). «Star of the ‘Emerald Isle’ – An Irishman’s Diary on William Drennan». The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 5 February 2021. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- ^ Langan, Sheila (13 June 2017). «How did Ireland come to be called the Emerald Isle? Ireland’s resplendent greenery played a big part, of course, in earning it the nickname the Emerald Isle but there’s more to the story». IrishCentral. Archived from the original on 8 February 2021. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- ^ «When Erin First Rose, Irish poem». web.archive.org. 16 January 2021. Retrieved 5 November 2022.

- ^ Ferguson, Stephen (2016). The Post Office in Ireland: An Illustrated History. Newbridge: Co Kildare: Irish Academic Press. p. 226. ISBN 9781911024323. Archived from the original on 19 May 2021. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- ^ Harrison, Bernice (18 March 2017). «Design Moment: Green post box, c1922: What to do with all those bloody red Brit boxes dotting the Free State? Paint ’em green». The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- ^ Fanning, Mary (12 November 1984). «Green Passport Goes Burgendy 1984: New Passports for European Member States Will Have a Common Look and Format». RTE News Archives. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- ^ The European Union Encyclopedia and Directory Archived 8 February 2021 at the Wayback Machine. (1999). 3rd Ed. p63 ISBN 9781857430561.

- ^ Resolution of the Representatives of the Governments of the Member States of the European Communities, Meeting Within the Council of 23 June 1981 Archived 15 July 2020 at the Wayback Machine. Official Journal of the European Communities. C 241. also EUR-Lex — 41981X0919 — EN Archived 1 April 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Cronin & Adair (2002), pp. 25–26[2]

- ^ Liam de Paor: St. Patrick’s World, The Christian Culture of Ireland’s Apostolic Age. Four Courts Press, Dublin, 1993

- ^ «The Catholic Encyclopedia: Luke Wadding«. Archived from the original on 17 July 2019. Retrieved 15 February 2007.

- ^ «Irish bishops move St. Patrick’s Day 2008 over conflict with Holy Week» Archived 26 April 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Catholic News

- ^ MacDonald, G. Jeffrey (6 March 2008). «St. Patrick’s Day, Catholic Church march to different drummers». USA Today. Archived from the original on 10 March 2008. Retrieved 11 March 2008.

- ^ Nevans-Pederson, Mary (13 March 2008). «No St. Pat’s Day Mass allowed in Holy Week». Dubuque Telegraph Herald. Woodward Communications, Inc. Archived from the original on 16 October 2008. Retrieved 13 March 2008.

- ^ «St. Patrick’s Day». Encyclopedia Britannica. 17 March 2021.

- ^ «James O’Mara». HumphrysFamilyTree.com. Archived from the original on 26 March 2014. Retrieved 17 March 2014.

- ^ Munster Express, 14 March 1903[full citation needed]

- ^ a b Munster Express, 21 March 1903, p.3[full citation needed]

- ^ Waterford Chronicle, 18 March 1903[full citation needed]

- ^ Waterford News, 20 March 1903[full citation needed]

- ^ Cronin & Adair (2002), p. 105.

- ^ Cronin & Adair (2002), p. 108.

- ^ Cronin & Adair (2002), p. 134.

- ^ Cronin & Adair (2002), pp. 135–136.

- ^ Armao, Frederic. «The Color Green in Ireland: Ecological Mythology and the Recycling of Identity». Environmental Issues in Political Discourse in Britain and Ireland. Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2013. p. 184

- ^ Kelly, Fiach, Wall, Martin, & Cullen, Paul (9 March 2020). Coronavirus: Three New Irish Cases Confirmed as St Patrick’s Day Parades Cancelled Archived 9 March 2020 at the Wayback Machine. The Irish Times. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- ^ The New York Times. (9 March 2020). Ireland Cancels St. Patrick’s Day Parades, Sets Aside Coronavirus Funds[permanent dead link]. The New York Times. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- ^ RTE News. (2016). St Patrick’s Day In May Archived 18 December 2019 at the Wayback Machine. RTE Archives. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- ^ CNN. (18 May 2001). Late St. Patrick’s Day for Ireland Archived 9 September 2019 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- ^ Reid, Lorna. (2 March 2001) St Patrick’s Day Parade ‘Postponed’ Archived 20 April 2020 at the Wayback Machine Irish Independent. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- ^ BBC News. (9 March 2020). Coronavirus: Irish St Patrick’s Day Parades Cancelled Archived 1 May 2020 at the Wayback Machine. BBC News. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- ^ Bain, Mark. (9 March 2020). Coronavirus: Dublin St Patrick’s Day Parade Cancelled as Belfast Council Considers Own Event. Archived 10 March 2020 at the Wayback Machine Belfast Telegraph Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- ^ RTE News. (9 March 2020). What is cancelled and what is going ahead on St Patrick’s Day? Archived 10 March 2020 at the Wayback Machine. RTE News. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- ^ O’Loughlin, Ciara. (20 January 2021). National St Patrick’s Day parade cancelled for second year in a row Archived 21 January 2021 at the Wayback Machine Irish Independent. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- ^ RTE News. (20 January 2021). St Patrick’s Festival Dublin parade cancelled for second year Archived 4 February 2021 at the Wayback Machine RTE News. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- ^ Bowers, Shauna. (20 January 2021). St Patrick’s Day parade cancelled for second year in a row due to Covid-19 Archived 23 January 2021 at the Wayback Machine The Irish Times. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- ^ BBC News (20 January 2021). Covid-19: St Patrick’s Day Dublin parade cancelled for second year Archived 26 January 2021 at the Wayback Machine. BBC News. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Cronin & Adair (2002), pp. 175–177.

- ^ «The History of the Holiday». The History Channel. A&E Television Networks. Archived from the original on 7 August 2006. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- ^ «St. Patrick’s Festival was established by the Government of Ireland in November 1995». St. Patrick’s Festival. Archived from the original on 12 March 2012. Retrieved 20 March 2012.

- ^ «St. Patrick’s Day Facts Video». History.com. A&E Television Networks. Archived from the original on 8 September 2012. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- ^ Heffernan, Breda. (13 February 2008) St Patrick’s Skyfest to Rock at Cashel Archived 8 January 2019 at the Wayback Machine. Irish Independent. Retrieved 8 January 2019

- ^ Disappointment over Skyfest Archived 8 January 2019 at the Wayback Machine (24 March 2015) Wexford People. Retrieved 8 January 2019

- ^ ««Seachtain na Gaeilge», Dublin City Council». Archived from the original on 6 August 2018. Retrieved 6 August 2018.

- ^ John Cooney (12 March 2007). «More piety, fewer pints ‘best way to celebrate’«. The Irish Independent. Archived from the original on 1 June 2021. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- ^ Jo Kerrigan (March–April 2004). «From Here to Here». Ireland of the Welcomes. Vol. 53, no. 2. Archived from the original on 21 October 2019. Retrieved 6 June 2010 – via Dripsey.

- ^ Proctor, Charlie (9 March 2018). The Duchess of Cambridge to Present Shamrocks for St. Patrick’s Day Archived 10 June 2019 at the Wayback Machine. Royal Central. Retrieved 8 January 2019

- ^ Duchess of Cambridge Presents St Patrick’s Day Shamrocks to Irish Guards Archived 14 April 2019 at the Wayback Machine. (17 March 2015) BBC News. Retrieved 8 January 2019

- ^ The Duke of Cambridge Joins the Irish Guards at the St Patrick’s Day Parade Archived 8 January 2019 at the Wayback Machine. (17 March 2016) Royal.uk. Retrieved 8 January 2019

- ^ Palmer, Richard. (17 March 2016). Prince William Handed Out Shamrocks at the St Patrick’s Day Parade as Kate Broke with Tradition Archived 14 April 2019 at the Wayback Machine. Sunday Express Retrieved 8 January 2019

- ^ Rayner, Gordon ,(17 March 2015) Duchess of Cambridge hands out St Patrick’s Day shamrocks to Irish Guards. The Telegraph. Retrieved 8 January 2019

- ^ a b Cronin, Mike; Adair, Daryl (2002). The Wearing of the Green: A History of St. Patrick’s Day. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-18004-7. Pages 180–183 Archived 12 January 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Mcbrien, Richard P. (13 October 2009). Lives of the Saints: From Mary and St. Francis of Assisi to John XXIII and Mother Teresa. HarperOne. ISBN 9780061763656. Archived from the original on 3 October 2015. Retrieved 13 November 2010.

The most famous church in the United States is dedicated to him, St. Patrick’s in New York City. St. Patrick’s Day is celebrated by people of all ethnic backgrounds by the wearing of green and parades. His feast, which is on the General Roman Calendar, has been given as March 17 in liturgical calendars and martyrologies. The Church of England, the Episcopal Church in the USA, and the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America observe his feast on this day, and he is also commemorated on the Russian Orthodox calendar.

- ^ «Brigitte Winsor: Photographs of the St Patrick’s Day Parade». Connecting Histories. 12 March 2006. Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 17 March 2010.

- ^ «St. Patrick’s Parade 2009». BBC Birmingham. 18 March 2009. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- ^ «Irish Immigration to and from Liverpool (UK)». Mersey Reporter. Archived from the original on 8 February 2013. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- ^ «Manchester Irish Festival». Archived from the original on 21 February 2016. Retrieved 17 March 2010.

- ^ a b Micallef, Roberta (18 March 2018). «St Patrick’s Day in Malta – how it started, and where it’s going». The Malta Independent. Archived from the original on 18 March 2018.

- ^ Azzopardi, Karl (17 March 2018). «Thousands take to the street of St Julian’s for St Patrick’s Day celebrations». Malta Today. Archived from the original on 17 March 2018.

- ^ «Malta celebrates St Patrick’s Day». Times of Malta. 15 March 2015. Archived from the original on 21 April 2016.

- ^ Grech Urpani, David (8 March 2018). «Finally: A Fresh Take On St. Patrick’s Day Celebrations Is Coming To Malta». Lovin Malta. Archived from the original on 16 March 2018.

- ^ Micallef, Roberta (17 March 2018). «More than 20,000 people expected to celebrate St Patrick’s Day in St Julian’s». The Malta Independent. Archived from the original on 17 March 2018.

- ^ «Thousands flock to St Julian’s to celebrate St Patrick’s feast». The Malta Independent. 17 March 2018. Archived from the original on 17 March 2018.

- ^ «Oslo Parade History». 18 March 2020. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 17 March 2021.

- ^ Москва. День Св. Патрика [Moscow. St. Patrick’s Day] (in Russian). Русское Кельтское Общество [Russian Celtic Society]. 1999–2007. Archived from the original on 17 April 2012. Retrieved 29 May 2012.

- ^ Andersen, Erin (17 March 2013). «St. Patty’s Day: Not just green beer – but some of that, too». Lincoln Journal Star. Archived from the original on 18 May 2013.

- ^ Cuddihy, Grace (18 March 2014). «Muscovites Turn Green For Irish Week». The Moscow Times. Archived from the original on 18 March 2014. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- ^ «В месяцеслов Русской Православной Церкви включены имена древних святых, подвизавшихся в западных странах» [Ancient saints who worked in Western countries have been added to the menologium of the Russian Orthodox Church]. Patriarchia.ru (in Russian). 9 March 2017. Archived from the original on 10 March 2017. Retrieved 12 March 2017.

- ^ «Sarajevo Irish Festival». Sarajevo Travel. Archived from the original on 5 April 2018. Retrieved 18 April 2018.

- ^ «Sarajevo Irish Festival». stpatricksfestival.ie. Archived from the original on 5 April 2018. Retrieved 18 April 2018.

- ^ «Pripremljen bogat program za ovogodišnji Sarajevo Irish Festival». klix.ba. Archived from the original on 25 March 2021. Retrieved 18 April 2018.

- ^ «Conor Horgan: Film o Panti Bliss je o tome kako lično jeste političko». lgbti.ba. 15 March 2017. Archived from the original on 5 April 2018. Retrieved 18 April 2018.

- ^ «Večeras otvaranje Sarajevo Irish Festivala». avaz.ba. 16 March 2016. Archived from the original on 5 April 2018. Retrieved 18 April 2018.

- ^ «Irish emigration to Scotland in the 19th and 20th centuries – Settlement of the Irish». Education Scotland. Government of Scotland. Archived from the original on 20 March 2015. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ^ a b «The Coatbridge Irish». St Patrick’s Day Festival Coatbridge. Archived from the original on 8 July 2007. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ^ «St Patrick’s Day in Coatbridge, Scotland». Coming to Scotland. 14 March 2015. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ^ Michael Moss. «Industrial Revolution: 1770s to 1830s». The Glasgow Story. Archived from the original on 22 March 2012. Retrieved 17 March 2012.

- ^ «Welcome to the Glasgow St. Patrick’s Festival 2018 Website». Glasgow’s St. Patrick’s Festival. St. Patrick’s Festival Committee. Archived from the original on 16 March 2015. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- ^ «St. Patrick’s Eve Celebrations 2012 in Zürich» (in German). Zurich Student Association. Archived from the original on 15 March 2014. Retrieved 20 February 2012.

- ^ «Švento Patriko dieną Vilnelė vėl nusidažys žaliai». madeinvilnius.lt (in Lithuanian). 13 March 2019. Archived from the original on 14 October 2019. Retrieved 14 October 2019.

- ^ «Montreal celebrates 191st St. Patrick’s Day parade Sunday». CBC News. Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. 11 March 2014. Archived from the original on 1 June 2021. Retrieved 17 March 2014.

- ^ «Coming Events». Irish Association of Manitoba. Archived from the original on 13 March 2013. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- ^ «CelticFest Vancouver». Celticfest Vancouver. Archived from the original on 1 June 2021. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- ^ Cottrell, Michael (May 1992). «St. Patrick’s Day Parades in Nineteenth-Century Toronto: A Study of Immigrant Adjustment and Elite Control». Histoire Sociale – Social History. XXV (49): 57–73. Archived from the original on 22 August 2014. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- ^ «Guinness». Proposition 3–17. Archived from the original on 23 March 2010. Retrieved 17 March 2010.

- ^ Bevan, Alexis (11 March 2009). «Calgary Tower gets full green bulb treatment». Calgary Herald. Archived from the original on 30 March 2009. Retrieved 17 March 2010.

- ^ Holmes, Evelyn (12 March 2016). «Crowds gather for St. Patrick’s Day celebrations downtown». American Broadcasting Company. Archived from the original on 13 March 2016. Retrieved 13 March 2016.

Large crowds gathered for Saturday’s St. Patrick’s Day festivities downtown. Although St. Patrick’s Day is actually on a Thursday this year, Chicago will be marking the day all weekend long. Some started the day at Mass at Old St. Patrick’s Church in the city’s West Loop neighborhood. Spectators gathered along the riverfront in the Loop for the annual dyeing of the Chicago River, which began at 9 am

- ^ «First U.S. St. Patrick’s celebration held in St. Augustine, Florida in 1600». Archived from the original on 9 November 2019. Retrieved 2 March 2020.

- ^ Stack, Liam (11 March 2020). «St. Patrick’s Day Parade Is Postponed in New York Over Coronavirus Concerns». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 12 March 2020. Retrieved 12 March 2020. «New York City’s St. Patrick’s Day Parade, the largest such celebration in the world, was postponed late Wednesday over concerns about the spread of the coronavirus»

- ^ Talley, Patricia Ann (28 February 2019). «Mexico Honors Irish Soldiers On St. Patrick’s Day-The «San Patricios»«. Imagine Mexico. Archived from the original on 3 June 2019. Retrieved 21 March 2019.

- ^ «Saint Patrick’s Day in Argentina». Sanpatricio2009.com.ar. 17 March 2009. Archived from the original on 27 July 2013. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- ^ Saint Patrick’s Day in Argentina on YouTube. Retrieved 17 March 2009.

- ^ «San Patricio convocó a una multitud». Clarin.com. 18 March 2006. Archived from the original on 25 October 2008. Retrieved 17 March 2012.

- ^ Nally, Pat (1992). «Los Irlandeses en la Argentina». Familia, Journal of the Ulster Historical Foundation. 2 (8). Archived from the original on 14 May 2016. Retrieved 6 November 2010.

- ^ Fergus, Howard A. (1996). Gallery Montserrat: some prominent people in our history. Canoe Press University of West Indies. p. 83. ISBN 976-8125-25-X. Archived from the original on 6 October 2015. Retrieved 24 December 2010.

- ^ National Museum of Australia (2020). St Patrick’s Day Archived 7 February 2021 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 2 February 2021

- ^ Irish Echo (Australia) (2019) St Patrick’s Day in Australia: Latest News Archived 21 March 2021 at the Wayback Machine. Irish Echo (Australia). Retrieved 2 February 2021

- ^ Modern Australian. (29 January 2019). The best St Patrick’s day events in Australia 2019 Archived 8 February 2021 at the Wayback Machine. Modern Australian. Retrieved 2 February 2021

- ^ Mitchell, Georgina (17 March 2018). «St Patrick’s day celebrations to turn Moore Park into the ‘green quarter’«. The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 7 February 2021. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- ^ Garcia, Jocelyn (16 March 2019). «St Patrick’s Day parade patron honoured at Brisbane festivities». Brisbane Times. Archived from the original on 7 February 2021. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- ^ Iannella, Antimo (16 March 2017). «St Patrick’s Day takes to Adelaide Oval for the first time since 1967, with celebrations at southern end of stadium». The Advertiser. Archived from the original on 10 September 2017. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- ^ Kozina, Teigan (16 March 2018). «2019 Saint Patrick’s Day 2018: Where to celebrate in Melbourne». Herald Sun. Archived from the original on 26 April 2018. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- ^ Holroyd, Jane (17 March 2006). «Irish see green over Grand Prix». The Age. Archived from the original on 6 February 2021. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- ^ Murphy, Damien (6 February 2016). «Why there will be no St Patrick’s Day Rising: Burden of debt on the centenary of the Easter Rising forces cancellation of St Patrick’s Day parade». The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 12 February 2019. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- ^ Murphy, Damien (16 March 2016). «Irish eyes not smiling: St Patrick’s Day parade cancelled in Sydney». The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 9 February 2021. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- ^ Crockford, Toby (17 March 2018). «Grand parade to be sure, when St Patrick’s Day falls on a Saturday». Brisbane Times. Archived from the original on 9 November 2020. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- ^ Layt, Stuart (10 March 2020). «Coronavirus fears won’t rain on Brisbane St Patrick’s Day parade». Brisbane Times. Archived from the original on 11 March 2020. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- ^ a b c O’Farrell, Patrick. (1995). St Patrick’s Day in Australia: The John Alexander Ferguson Lecture 1994. Journal of Royal Historical Society 81(1) 1-16.

- ^ The Sydney Morning Herald (18 March 1887). St Patrick’s Day Celebrations Archived 19 May 2021 at the Wayback Machine. The Sydney Morning Herald. New South Wales. p5. Retrieved 2 February 2021 via National Library of Australia

- ^ The Adelaide Chronicle (25 Mar 1916). St. Patrick’s Day in Adelaide Archived 19 May 2021 at the Wayback Machine. The Adelaide Chronicle Adelaide South Australia. p25. Retrieved 2 February 2021 via National Library of Australia

- ^ The Southern Cross. (20 February 1931). St. Patrick’s Day: The Adelaide Celebration: Meeting of the Committee. The Southern Cross. Adelaide South Australia. p7. Retrieved 2 February 2021 via National Library of Australia

- ^ Daley, Paul (2 April 2016). «Divided Melbourne: When Archbishop turned St Patrick’s Day into Propaganda». The Guardian. Archived from the original on 6 February 2021. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- ^ Sullivan, Tim. (2020). An Illusion of Unity: Irish Australia, the Great War and the 1920 St Patrick’s Day Parade Archived 6 February 2021 at the Wayback Machine Agora 55(1). 24–31

- ^ Fitzgerald, Ellen (21 March 2019). In the Herald : 21 March 1921: Union Jack forced on St Patrick’s Day Archived 10 February 2021 at the Wayback Machine. The Sydney Morning Herald

- ^ Warwick Daily News (21 March 1921). St Patrick’s Day: Scenes in Melbourne: Union Jack Hooted: Speech by Bishop Phelan. Warwick Daily News Queensland. p5. Retrieved 2 February 2021 via National Library of Australia

- ^ The Argus. (22 March 1921). Attack on Union Jack: St Patrick’s Day Incident: Two Men Before the Court. Archived 7 February 2021 at the Wayback Machine The Argus. Melbourne Victoria. p7. Retrieved 2 February 2021 via National Library of Australia

- ^ The Argus (31 March 1921). Attack on Union Jack: St Patrick’s Day Incident: Two Young Men Fined. The Argus. Melbourne Victoria. p7. Retrieved 2 February 2021 via National Library of Australia

- ^ Swarbrick, Nancy. (2016). Public holidays — Celebrating communities Archived 7 February 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Te Ara — the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, Retrieved 2 February 2021

- ^ Swarbrick, Nancy. (2016) Public holidays Archived 6 February 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Te Ara — the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, Retrieved 2 February 2021

- ^ Daly, Michael (20 May 2020). «How do we get public holidays? Government considering an extra long weekend». Stuff. Archived from the original on 6 February 2021. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- ^ a b Bueltmann, Tanja. (2012). Remembering the Homeland: St Patrick’s Day Celebrations in New Zealand to 1910 in Oona Frawley (ed.) (2012). Memory Ireland: Diaspora and Memory Practices Vol.2 Syracuse University Press. ISBN 9780815651710 pp101-113. Retrieved 2 February 2021

- ^ NZ Herald (17 March 2018). «St Patrick’s Day celebrations underway in Auckland». The New Zealand Herald. Archived from the original on 7 February 2021. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- ^ O’Sullivan, Aisling (16 March 2017). «Best places to celebrate St Patrick’s Day in New Zealand and around the world». Stuff. Archived from the original on 8 May 2019. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- ^ «Saint Patrick’s Day Parades & Events in Japan». Archived from the original on 8 May 2013. Retrieved 24 April 2013.

- ^ «Saint Patrick’s Day in Korea Event Page». Irish Association of Korea. Archived from the original on 14 March 2010. Retrieved 17 March 2010.

- ^ Tariq Malik (17 March 2011). «Irish Astronaut in Space Gives St. Patrick’s Day Musical Flair». Space.com. Archived from the original on 1 June 2021. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

- ^ «St. Patrick’s Day Greeting From Space». NASA TV video. 17 March 2011. Archived from the original on 1 June 2021. Retrieved 1 December 2016.

- ^ Diarmaid Fleming (15 December 2010). «Molloy’s flute to help Irish music breach the final frontier». Irish Times. Archived from the original on 1 June 2021. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- ^ Brian Boyd (10 March 2012). «Chieftains’ call-up to an army of indie admirers». Irish Times. Archived from the original on 1 June 2021. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- ^ Ronan McGreevy (17 March 2013). «Out of this world rendition of Danny Boy marks St Patrick’s Day in space». The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 17 March 2013. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

- ^ «Astronaut Chris Hadfield singing «Danny Boy» on the International Space Station». Soundcloud. 17 March 2013. Archived from the original on 18 March 2013. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

- ^ a b c Cronin & Adair (2002), p. 240.

- ^ Fionola Meredith (21 March 2013). «Time to banish perpetually offended elements in society». Belfast Telegraph. Archived from the original on 12 March 2016. Retrieved 11 March 2016.

- ^ James Flannery (17 March 2012). «St Patrick’s Day celebrates the role of all US migrants». The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 12 March 2016. Retrieved 11 March 2016.