)

День святого Мартина (англ. St. Martin’s Day), отмечаемый ежегодно 11 ноября, — большой народный праздник ряда католических стран в честь дня памяти об епископе Мартине Турском.

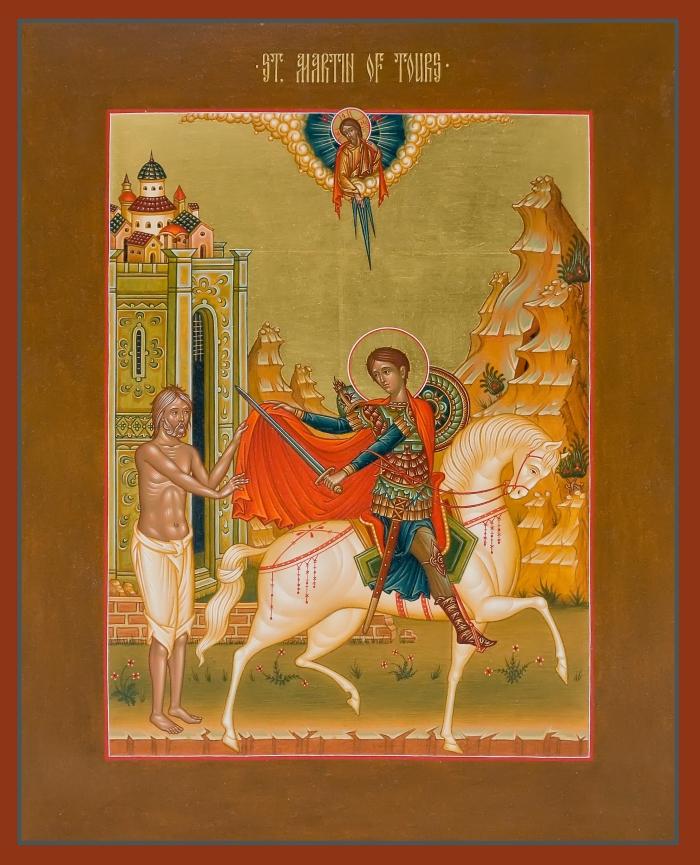

В День святого Мартина, после окончания сельских работ, прежде всего зажигались костры на каждой улице и в каждом дворе. В эти костры кидали корзины, в которых недавно лежали плоды. Через эти костры прыгали и устраивали шествия, зажигая факелы от их огня. В этих шествиях участвовали ряженые: святой Мартин на коне и Мартинов человек — мальчик, туловище и конечности которого были обернуты соломой.

Святой Мартин считается покровителем бедняков, солдат, сукноделов, домашних животных и птиц, а также альпийских пастухов. Основу легенды о святом Мартине составляет сказание о том, как однажды легион, в котором служил Мартин, приблизился к французскому городу Амис.

Была осень. В поле свистел, завывал резкий холодный ветер. Он пронизывал насквозь. Солдаты мечтали о теплом очаге и ускорили шаг. Вот они уже вошли в городские ворота. Воины не заметили сидевшего у городских ворот старого, полуобнаженного человека. От холода и голода он стучал зубами и дрожащим голосом просил о малой милостыне.

Но солдаты проходили мимо него твердыми, быстрыми шагами. Они не удостоили нищего даже взглядом. Мартин, возглавлявший свой легион, сидел на коне в богато украшенной, длинной красной накидке. Когда он увидел мерзнущего и голодного нищего, просящего милостыню, то, к удивлению солдат, остановил легион и достал меч. Солдаты не поняли в чем же дело. Что он собирается делать? Почему он достал меч? Ведь перед ним сидит беспомощный человек, нищий.

А Мартин спокойно взялся левой рукой за свою красную накидку и острым мечом отрезал ее половину, затем быстрым движением бросил кусок накидки в руки нищего. После этого он достал из сумки хлеб и отдал его нищему. Старик хотел поблагодарить Мартина, но тот уже въезжал в город Амис.

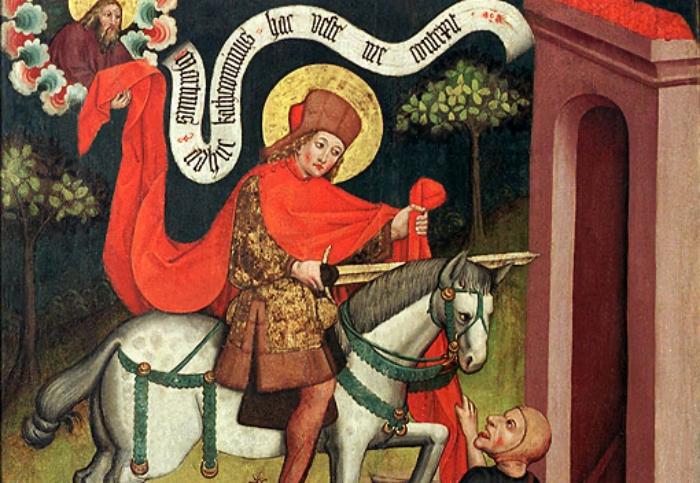

St Martin’s Day Kermis by Peeter Baltens (16th century), shows peasants celebrating by drinking the first wine of the season, and a horseman representing the saint

Saint Martin’s Day or Martinmas, sometimes historically called Old Halloween or Old Hallowmas Eve,[1][2] is the feast day of Saint Martin of Tours and is celebrated in the liturgical year on 11 November. In the Middle Ages and early modern period, it was an important festival in many parts of Europe, particularly Germanic-speaking regions. In these regions, it marked the end of the harvest season and beginning of winter.[3] and the «winter revelling season». Traditions include feasting on ‘Martinmas goose’ or ‘Martinmas beef’, drinking the first wine of the season, and mumming. In some German and Dutch-speaking towns, there are processions of children with lanterns (Laternelaufen), sometimes led by a horseman representing St Martin. The saint was also said to bestow gifts on children. In the Rhineland, it is also marked by lighting bonfires.

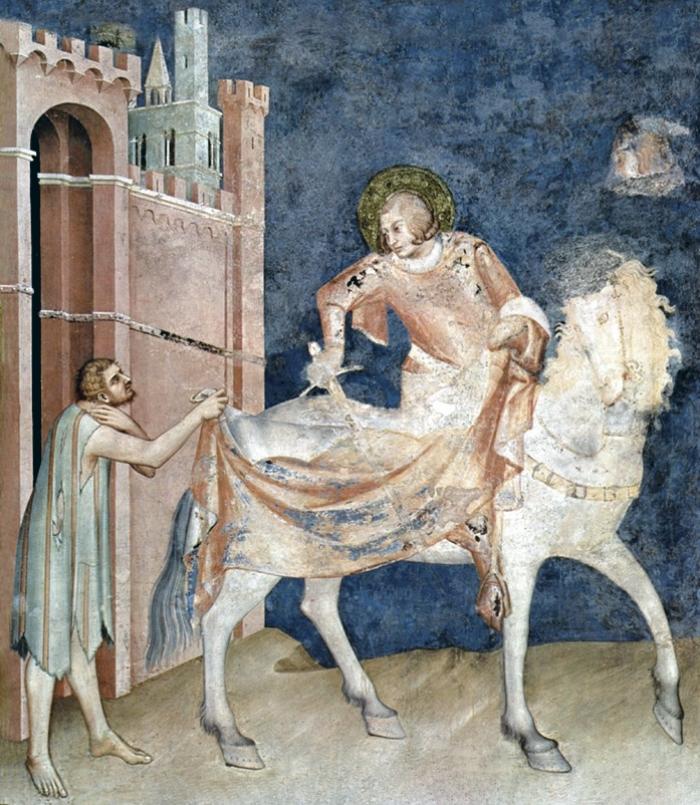

Martin of Tours (died 397) was a Roman soldier who was baptized as an adult and became a bishop in Gaul. He is best known for the tale whereby he cut his cloak in half with his sword, to give half to a beggar who was dressed in only rags in the depth of winter. That night Martin had a vision of Jesus Christ wearing the half-cloak.[4][5]

Customs[edit]

A tradition on St Martin’s Eve or Day is to share a goose for dinner.

Traditionally, in many parts of Europe, St Martin’s Day marked the end of the harvest and the beginning of winter. The feast coincides with the end of the Octave of Allhallowtide.

Feasting and drinking[edit]

Martinmas was traditionally when livestock were slaughtered for winter provision.[6] It may originally have been a time of animal sacrifice, as the Old English name for November was Blōtmōnaþ (‘sacrifice month’).[7]

Goose is eaten at Martinmas in most places. There is a legend that St Martin, when trying to avoid being ordained bishop, hid in a pen of geese whose cackling gave him away. Once a key medieval autumn feast, a custom of eating goose on the day spread to Sweden from France. It was primarily observed by the craftsmen and noblemen of the towns. In the peasant community, not everyone could afford this, so many ate duck or hen instead.[8]

In winegrowing regions of Europe, the first wine was ready around the time of Martinmas. Although there was no mention of a link between St Martin and winegrowing by Gregory of Tours or other early hagiographers, St Martin is widely credited in France with helping to spread winemaking throughout the region of Tours (Touraine) and facilitating vine-planting. The old Greek tale that Aristaeus discovered the advantage of pruning vines after watching a goat has been appropriated to St Martin.[9] He is credited with introducing the Chenin blanc grape, from which most of the white wine of western Touraine and Anjou is made.[9]

Bonfires and lanterns[edit]

Bonfires are lit on St Martin’s Eve in the Rhineland region of Germany. In the fifteenth century, these bonfires were so numerous that the festival was nicknamed Funkentag (spark day).[7] In the nineteenth century it was recorded that young people danced around the fire and leapt through the flames, and that the ashes were strewn on the fields to make them fertile.[7] Similar customs were part of the Gaelic festival Samhain (1 November).

In some German and Dutch-speaking towns, there are nighttime processions of children carrying paper lanterns or turnip lanterns and singing songs of St Martin.[7] These processions are known in German as Laternelaufen.

Gift-bringers[edit]

In parts of Flanders and the Rhineland, processions are led by a man on horseback representing St Martin, who may give out apples, nuts, cakes or other sweets for children.[7] Historically, in Ypres, children hung up stockings filled with hay on Martinmas Eve, and awoke the next morning to find gifts in them. These were said to have been left by St Martin as thanks for the fodder provided for his horse.[7]

In the Swabia and Ansbach regions of Germany, a character called Pelzmärten (‘pelt Martin’ or ‘skin Martin’) appeared at Martinmas until the 19th century. With a black face and wearing a cow bell, he ran about frightening children, and he dealt out blows as well as nuts and apples.[7]

Eve of St Martin’s Lent[edit]

In the 6th century, church councils began requiring fasting on all days, except Saturdays and Sundays, from Saint Martin’s Day to Epiphany (elsewhere, the Feast of the Three Wise Men for the stopping of the star over Bethlehem)[10] on January 6 (56 days). An addition to and an equivalent to the 40 days fasting of Lent, given its weekend breaks, this was called Quadragesima Sancti Martini (Saint Martin’s Lent, or literally «the fortieth of»).[11] This is rarely observed now. This period was shortened to begin on the Sunday before December and became the current Advent within a few centuries.[12]

Celebrations by culture[edit]

Germanic[edit]

Austrian[edit]

In Austria, St Martin’s Day is celebrated the same way as in Germany. The nights before and on the night of 11 November, children walk in processions carrying lanterns, which they made in school, and sing Martin songs.[citation needed] Martinloben is celebrated as a collective festival. Events include art exhibitions, wine tastings, and live music. Martinigansl (roasted goose) is the traditional dish of the season.[13]

Dutch and Flemish[edit]

In the Netherlands, on the evening of 11 November, children go door to door (mostly under parental supervision) with lanterns made of hollowed-out sugar beet or, more recently, paper, singing songs such as «Sinte(re) Sinte(re) Maarten», to receive sweets or fruit in return. In the past, poor people would visit farms on 11 November to get food for the winter. In the 1600s, the city of Amsterdam held boat races on the IJ, where 400 to 500 light craft, both rowing boats and sailboats, took part with a vast crowd on the banks. St Martin is the patron saint of the city of Utrecht, and St Martin’s Day is celebrated there with a big lantern parade.[citation needed]

In Flanders, the Dutch-speaking part of Belgium, St Martin’s Eve is celebrated on the evening of 10 November, mainly in West Flanders and around Ypres. Children go through the streets with paper lanterns and candles, and sing songs about St Martin. Sometimes, a man dressed as St Martin rides on a horse in front of the procession.[14] The children receive presents from either their friends or family as supposedly coming from St Martin.[citation needed] In some areas, there is a traditional goose meal.[citation needed]

In Wervik, children go from door to door, singing traditional «Séngmarténg» songs, sporting a hollow beetroot with a carved face and a candle inside called «Bolle Séngmarténg»; they gather at an evening bonfire. At the end the beetroots are thrown into the fire, and pancakes are served.[citation needed]

English[edit]

Martinmas was widely celebrated on 11 November in medieval and early modern England. In his study «Medieval English Martinmesse: The Archaeology of a Forgotten Festival», Martin Walsh describes Martinmas as a festival marking the end of the harvest season and beginning of winter.[6] He suggests it had pre-Christian roots.[6] Martinmas ushered in the «winter revelling season» and involved feasting on the meat of livestock that had been slaughtered for winter provision (especially ‘Martlemas beef’), drinking, storytelling, and mumming.[6] It was a time for saying farewell to travelling ploughmen, who shared in the feast along with the harvest-workers.[6]

According to Walsh, Martinmas eventually died out in England as a result of the English Reformation, the emergence of Guy Fawkes Night (5 November), as well as changes in farming and the Industrial Revolution.[6] Today, 11 November is Remembrance Day.

German[edit]

A widespread custom in Germany is to light bonfires, called Martinsfeuer, on St Martin’s Eve. In recent years, the processions that accompany those fires have been spread over almost a fortnight before Martinmas (Martinstag). At one time, the Rhine River valley would be lined with fires on the eve of Martinmas. In the Rhineland, Martin’s day is celebrated traditionally with a get-together during which a roasted suckling pig is shared with the neighbours.

The nights before and on the eve itself, children walk in processions called Laternelaufen, carrying lanterns, which they made in school, and sing St Martin’s songs. Usually, the walk starts at a church and goes to a public square. A man on horseback representing St Martin accompanies the children. When they reach the square, Martin’s bonfire is lit and Martin’s pretzels are distributed.[15]

In the Rhineland, the children also go from house to house with their lanterns, sing songs and get candy in return. The origin of the procession of lanterns is unclear. To some, it is a substitute for the Martinmas bonfire, which is still lit in a few cities and villages throughout Europe. It formerly symbolized the light that holiness brings to the darkness, just as St Martin brought hope to the poor through his good deeds. Even though the bonfire tradition is gradually being lost, the procession of lanterns is still practiced.[16]

A Martinsgans («St Martin’s goose»), is typically served on St Martin’s Eve following the procession of lanterns. «Martinsgans» is usually served in restaurants, roasted, with red cabbage and dumplings.[16]

The traditional sweet of Martinmas in the Rhineland is Martinshörnchen, a pastry shaped in the form of a croissant, which recalls both the hooves of St Martin’s horse and, by being the half of a pretzel, the parting of his mantle. In some areas, these pastries are instead shaped like men (Stutenkerl or Weckmänner).

St Martin’s Day is also celebrated in German Lorraine and Alsace, which border the Rhineland and are now part of France. Children receive gifts and sweets. In Alsace, in particular the Haut-Rhin mountainous region, families with young children make lanterns out of painted paper that they carry in a colourful procession up the mountain at night. Some schools organise these events, in particular schools of the Rudolf Steiner (Waldorf education) pedagogy. In these regions, the day marks the beginning of the holiday season.[citation needed] In the German speaking parts of Belgium, notably Eupen and Sankt Vith, processions similar to those in Germany take place.[citation needed]

German American[edit]

In the United States, St. Martin’s Day celebrations are uncommon, but are typically held by German American communities.[17] Many German restaurants feature a traditional menu with goose and Glühwein (a mulled red wine). St Paul, Minnesota celebrates with a traditional lantern procession around Rice Park. The evening includes German treats and traditions that highlight the season of giving.[18] In Dayton, Ohio the Dayton Liederkranz-Turner organization hosts a St Martin’s Family Celebration on the weekend before with an evening lantern parade to the singing of St Martin’s carols, followed by a bonfire.[19]

Swedish[edit]

St Martin’s Day or St Martin’s Eve (Mårtensafton) was an important medieval autumn feast in Sweden. In early November, geese are ready for slaughter, and on St Martin’s Eve it is tradition to have a roast goose dinner. The custom is particularly popular in Scania in southern Sweden, where goose farming has long been practised, but it has gradually spread northwards. A proper goose dinner also includes svartsoppa (a heavily spiced soup made from geese blood) and apple charlotte.[20]

Slavic[edit]

Croatian[edit]

In Croatia, St. Martin’s Day (Martinje, Martinovanje) marks the day when the must traditionally turns to wine. The must is usually considered impure and sinful, until it is baptised and turned into wine. The baptism is performed by someone who dresses up as a bishop and blesses the wine; this is usually done by the host. Another person is chosen as the godfather of the wine.

Czech[edit]

A Czech proverb connected with the Feast of St. Martin – Martin přijíždí na bílém koni (transl. «Martin is coming on a white horse») – signifies that the first half of November in the Czech Republic is the time when it often starts to snow. St. Martin’s Day is the traditional feast day in the run-up to Advent. Restaurants often serve roast goose as well as young wine from the recent harvest known as Svatomartinské víno, which is similar to Beaujolais nouveau as the first wine of the season. Wine shops and restaurants around Prague pour the first of the St. Martin’s wines at 11:11 a.m. Many restaurants offer special menus for the day, featuring the traditional roast goose.[21]

Polish[edit]

Procession of Saint Martin in Poznań, 2006

In Poland, 11 November is National Independence Day. St. Martin’s Day (Dzień Świętego Marcina) is celebrated mainly in the city of Poznań where its citizens buy and eat considerable amounts of croissants filled with almond paste with white poppy seeds, the Rogal świętomarciński or St. Martin’s Croissants. Legend has it that this centuries-old tradition commemorates a Poznań baker’s dream which had the saint entering the city on a white horse that lost its golden horseshoe. The next morning, the baker whipped up horseshoe-shaped croissants filled with almonds, white poppy seeds and nuts, and gave them to the poor. In recent years, competition amongst local patisseries has become fierce. The product is registered under the European Union Protected Designation of Origin and only a limited number of bakers hold an official certificate. Poznanians celebrate the festival with concerts, parades and a fireworks show on Saint Martin’s Street. Goose meat dishes are also eaten during the holiday.[22]

Slovene[edit]

The biggest event in Slovenia is the St. Martin’s Day celebration in Maribor which marks the symbolic winding up of all the wine growers’ endeavours. There is the ceremonial «christening» of the new wine, and the arrival of the Wine Queen. The square Trg Leona Štuklja is filled with musicians and stalls offering autumn produce and delicacies.[23]

Celtic[edit]

Irish[edit]

In some parts[24] of Ireland, on the eve of St. Martin’s Day (Lá Fhéile Mártain in Irish), it was tradition to sacrifice a cockerel by bleeding it. The blood was collected and sprinkled on the four corners of the house.[25][24] Also in Ireland, no wheel of any kind was to turn on St. Martin’s Day, because Martin was said by some people[24] to have been thrown into a mill stream and killed by the wheel and so it was not right to turn any kind of wheel on that day. A local legend in Co. Wexford says that putting to sea is to be avoided as St. Martin rides a white horse across Wexford Bay bringing death by drowning to any who see him.[26]

Welsh[edit]

In Welsh mythology the day is associated with the Cŵn Annwn, the spectral hounds who escort souls to the otherworld (Annwn). St Martin’s Day was one of the few nights the hounds would engage in a Wild Hunt, stalking the land for criminals and villains.[27] The supernatural character of the day in Welsh culture is evident in the number omens associated with it. Marie Trevelyan recorded that if the hooting of an owl was heard on St Martin’s Day it was seen as a bad omen for that district. If a meteor was seen, then there would be trouble for the whole nation.[28]

Latvian[edit]

Mārtiņi (Martin’s) is traditionally celebrated by Latvians on 10 November, marking the end of the preparations for winter, such as salting meat and fish, storing the harvest and making preserves. Mārtiņi also marks the beginning of masquerading and sledding, among other winter activities.

Maltese[edit]

A Maltese «Borża ta’ San Martin»

St. Martin’s Day (Jum San Martin in Maltese) is celebrated in Malta on the Sunday nearest to 11 November. Children are given a bag full of fruits and sweets associated with the feast, known by the Maltese as Il-Borża ta’ San Martin, «St. Martin’s bag». This bag may include walnuts, hazelnuts, almonds, chestnuts, dried or processed figs, seasonal fruit (like oranges, tangerines, apples and pomegranates) and «Saint Martin’s bread roll» (Maltese: Ħobża ta’ San Martin). In old days, nuts were used by the children in their games.

There is a traditional rhyme associated with this custom:

Ġewż, Lewż, Qastan, Tin

Kemm inħobbu lil San Martin.

(Walnuts, Almonds, Chestnuts, Figs

I love Saint Martin so much.)

A feast is celebrated in the village of Baħrija on the outskirts of Rabat, including a procession led by the statue of Saint Martin. There is also a fair, and a show for local animals. San Anton School, a private school on the island, organises a walk to and from a cave especially associated with Martin in remembrance of the day.

Portuguese and Galician[edit]

In Portugal, St. Martin’s Day (Dia de São Martinho) is commonly associated with the celebration of the maturation of the year’s wine, being traditionally the first day when the new wine can be tasted. It is celebrated, traditionally around a bonfire, eating the magusto, chestnuts roasted under the embers of the bonfire (sometimes dry figs and walnuts), and drinking a local light alcoholic beverage called água-pé (literally «foot water», made by adding water to the pomace left after the juice is pressed out of the grapes for wine – traditionally by stomping on them in vats with bare feet, and letting it ferment for several days), or the stronger jeropiga (a sweet liquor obtained in a very similar fashion, with aguardente added to the water). Água-pé, though no longer available for sale in supermarkets and similar outlets (it is officially banned for sale in Portugal), is still generally available in small local shops from domestic production.[citation needed]

Leite de Vasconcelos regarded the magusto as the vestige of an ancient sacrifice to honor the dead and stated that it was tradition in Barqueiros to prepare, at midnight, a table with chestnuts for the deceased family members to eat.[29] The people also mask their faces with the dark wood ashes from the bonfire.[citation needed]

A typical Portuguese saying related to Saint Martin’s Day:

É dia de São Martinho;

comem-se castanhas, prova-se o vinho.

(It is St. Martin’s Day,

we’ll eat chestnuts, we’ll taste the wine.)

This period is also quite popular because of the usual good weather period that occurs in Portugal in this time of year, called Verão de São Martinho (St. Martin’s Summer). It is frequently tied to the legend since Portuguese versions of St. Martin’s legend usually replace the snowstorm with rain (because snow is not frequent in most parts of Portugal, while rain is common at that time of the year) and have Jesus bringing the end of it, thus making the «summer» a gift from God.[citation needed]

St Martin’s Day is widely celebrated in Galicia. It is the traditional day for slaughtering fattened pigs for the winter. This tradition has given way to the popular saying «A cada cerdo le llega su San Martín from Galician A cada porquiño chégalle o seu San Martiño («Every pig gets its St Martin»). The phrase is used to indicate that wrongdoers eventually get their comeuppance.

Sicilian[edit]

In Sicily, November is the winemaking season. On the day Sicilians eat anise, hard biscuits dipped into Moscato, Malvasia or Passito. l’Estate di San Martino (Saint Martin’s Summer) is the traditional reference to a period of unseasonably warm weather in early to mid November, possibly shared with the Normans (who founded the Kingdom of Sicily) as common in at least late English folklore. The day is celebrated in a special way in a village near Messina and at a monastery dedicated to Saint Martin overlooking Palermo beyond Monreale.[30] Other places in Sicily mark the day by eating fava beans.[citation needed]

In art[edit]

Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s physically largest painting is The Wine of Saint Martin’s Day, which depicts the saint giving charity.

There is a closely similar painting by Peeter Baltens, which can be seen here.

See also[edit]

- St. Catherine’s Day

References[edit]

- ^ Bulik, Mark (1 January 2015). The Sons of Molly Maguire: The Irish Roots of America’s First Labor War. Fordham University Press. p. 43. ISBN 9780823262243.

- ^ Carlyle, Thomas (11 November 2010). The Works of Thomas Carlyle. Cambridge University Press. p. 356. ISBN 9781108022354.

- ^ George C. Homans, English Villagers of the Thirteenth Century, 2nd ed. 1991, «The Husbandman’s year» p355f.

- ^ Sulpicius Severus (397). De Vita Beati Martini Liber Unus [On the Life of St. Martin]. Retrieved 2 November 2021.

- ^ Dent, Susie (2020). Word Perfect: Etymological Entertainment For Every Day of the Year. John Murray. ISBN 978-1-5293-1150-1.

- ^ a b c d e f Walsh, Martin (2000). «Medieval English Martinmesse: The Archaeology of a Forgotten Festival». Folklore. 111 (2): 231–249. doi:10.1080/00155870020004620. S2CID 162382811.

- ^ a b c d e f g Miles, Clement A. (1912). Christmas in Ritual and Tradition. Chapter 7: All Hallow Tide to Martinmas. Reproduced by Internet Sacred Text Archive.

- ^ «St Martin’s Day – or ‘Martin Goose'» Lilja, Agneta. Sweden.se magazine-format website

- ^ a b For instance, in Hugh Johnson, Vintage: The Story of Wine 1989, p 97.

- ^ per Matthew 2:1–2:12

- ^ Philip H. Pfatteicher, Journey into the Heart of God (Oxford University Press 2013 ISBN 978-0-19999714-5)

- ^ «Saint Martin’s Lent». Encyclopædia Britannica. Britannica. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ^ «Autumn Feast of St. Martin», Austrian Tourism Board

- ^ Thomson, George William. Peeps At Many Lands: Belgium, Library of Alexandria, 1909

- ^ «St. Martin’s Day traditions honor missionary», Kaiserlautern American, 7 November 2008

- ^ a b «Celebrating St. Martin’s Day on November 11», German Missions in the United States Archived 2012-01-06 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ German traditions in the US for St. Martin’s Day

- ^ «St. Martin’s Day», St. Paul Star Tribune, November 5, 2015

- ^ «St. Martin’s Day Family Celebration». Dayton Liederkranz-Turner. Retrieved 2021-11-02.

- ^ «Mårten Gås», Sweden.SE

- ^ «St. Martin’s Day specials at Prague restaurants», Prague Post, 11 November 2011

- ^ «St. Martin’s Day Celebrations»

- ^ «St. Martin’s Day Celebrations in Maribor», Slovenian Tourist Board

- ^ a b c Marion McGarry (11 November 2020). «Why blood sacrifice rites were common in Ireland on 11 November». RTE. Retrieved 13 November 2020.

Opinion: Blood sacrifices involving pigs, sheep or geese were practiced in Ireland well into living memory on Martinmas. … the custom extended from North Connacht, down to Kerry, and across the midlands and was rarer in Ulster or on the east coast. … some say the saint met his death by being crushed between two wheels

- ^ Súilleabháin, Seán Ó (2012). Miraculous Plenty; Irish Religious Folktales and Legends. Four Courts Press. pp. 183-191 and 269. ISBN 978-0-9565628-2-1.

- ^ «A Wexford Legend — St Martin’s Eve».

- ^ Matthews, John; Matthews, Caitlín (2005). The Element Encyclopedia of Magical Creatures. HarperElement. p. 119. ISBN 978-1-4351-1086-1.

- ^ Trevelyan, Marie (1909). Folk Lore And Folk Stories Of Wales. p. 13. ISBN 9781497817180.

- ^ Leite de Vasconcelos, Opúsculos Etnologia — volumes VII, Lisboa, Imprensa Nacional, 1938

- ^ Gangi, Roberta. «The Joys of St Martin’s Summer», Best of Sicily Magazine, 2010

External links[edit]

Media related to St. Martin’s Day at Wikimedia Commons

- How to make a St. Martin’s Day lantern

- UK History of Martinmas

- St. Martin’s Day in Germany

- St. Martin of Tours

- Alice’s Medieval Feasts & Fasts

St Martin’s Day Kermis by Peeter Baltens (16th century), shows peasants celebrating by drinking the first wine of the season, and a horseman representing the saint

Saint Martin’s Day or Martinmas, sometimes historically called Old Halloween or Old Hallowmas Eve,[1][2] is the feast day of Saint Martin of Tours and is celebrated in the liturgical year on 11 November. In the Middle Ages and early modern period, it was an important festival in many parts of Europe, particularly Germanic-speaking regions. In these regions, it marked the end of the harvest season and beginning of winter.[3] and the «winter revelling season». Traditions include feasting on ‘Martinmas goose’ or ‘Martinmas beef’, drinking the first wine of the season, and mumming. In some German and Dutch-speaking towns, there are processions of children with lanterns (Laternelaufen), sometimes led by a horseman representing St Martin. The saint was also said to bestow gifts on children. In the Rhineland, it is also marked by lighting bonfires.

Martin of Tours (died 397) was a Roman soldier who was baptized as an adult and became a bishop in Gaul. He is best known for the tale whereby he cut his cloak in half with his sword, to give half to a beggar who was dressed in only rags in the depth of winter. That night Martin had a vision of Jesus Christ wearing the half-cloak.[4][5]

Customs[edit]

A tradition on St Martin’s Eve or Day is to share a goose for dinner.

Traditionally, in many parts of Europe, St Martin’s Day marked the end of the harvest and the beginning of winter. The feast coincides with the end of the Octave of Allhallowtide.

Feasting and drinking[edit]

Martinmas was traditionally when livestock were slaughtered for winter provision.[6] It may originally have been a time of animal sacrifice, as the Old English name for November was Blōtmōnaþ (‘sacrifice month’).[7]

Goose is eaten at Martinmas in most places. There is a legend that St Martin, when trying to avoid being ordained bishop, hid in a pen of geese whose cackling gave him away. Once a key medieval autumn feast, a custom of eating goose on the day spread to Sweden from France. It was primarily observed by the craftsmen and noblemen of the towns. In the peasant community, not everyone could afford this, so many ate duck or hen instead.[8]

In winegrowing regions of Europe, the first wine was ready around the time of Martinmas. Although there was no mention of a link between St Martin and winegrowing by Gregory of Tours or other early hagiographers, St Martin is widely credited in France with helping to spread winemaking throughout the region of Tours (Touraine) and facilitating vine-planting. The old Greek tale that Aristaeus discovered the advantage of pruning vines after watching a goat has been appropriated to St Martin.[9] He is credited with introducing the Chenin blanc grape, from which most of the white wine of western Touraine and Anjou is made.[9]

Bonfires and lanterns[edit]

Bonfires are lit on St Martin’s Eve in the Rhineland region of Germany. In the fifteenth century, these bonfires were so numerous that the festival was nicknamed Funkentag (spark day).[7] In the nineteenth century it was recorded that young people danced around the fire and leapt through the flames, and that the ashes were strewn on the fields to make them fertile.[7] Similar customs were part of the Gaelic festival Samhain (1 November).

In some German and Dutch-speaking towns, there are nighttime processions of children carrying paper lanterns or turnip lanterns and singing songs of St Martin.[7] These processions are known in German as Laternelaufen.

Gift-bringers[edit]

In parts of Flanders and the Rhineland, processions are led by a man on horseback representing St Martin, who may give out apples, nuts, cakes or other sweets for children.[7] Historically, in Ypres, children hung up stockings filled with hay on Martinmas Eve, and awoke the next morning to find gifts in them. These were said to have been left by St Martin as thanks for the fodder provided for his horse.[7]

In the Swabia and Ansbach regions of Germany, a character called Pelzmärten (‘pelt Martin’ or ‘skin Martin’) appeared at Martinmas until the 19th century. With a black face and wearing a cow bell, he ran about frightening children, and he dealt out blows as well as nuts and apples.[7]

Eve of St Martin’s Lent[edit]

In the 6th century, church councils began requiring fasting on all days, except Saturdays and Sundays, from Saint Martin’s Day to Epiphany (elsewhere, the Feast of the Three Wise Men for the stopping of the star over Bethlehem)[10] on January 6 (56 days). An addition to and an equivalent to the 40 days fasting of Lent, given its weekend breaks, this was called Quadragesima Sancti Martini (Saint Martin’s Lent, or literally «the fortieth of»).[11] This is rarely observed now. This period was shortened to begin on the Sunday before December and became the current Advent within a few centuries.[12]

Celebrations by culture[edit]

Germanic[edit]

Austrian[edit]

In Austria, St Martin’s Day is celebrated the same way as in Germany. The nights before and on the night of 11 November, children walk in processions carrying lanterns, which they made in school, and sing Martin songs.[citation needed] Martinloben is celebrated as a collective festival. Events include art exhibitions, wine tastings, and live music. Martinigansl (roasted goose) is the traditional dish of the season.[13]

Dutch and Flemish[edit]

In the Netherlands, on the evening of 11 November, children go door to door (mostly under parental supervision) with lanterns made of hollowed-out sugar beet or, more recently, paper, singing songs such as «Sinte(re) Sinte(re) Maarten», to receive sweets or fruit in return. In the past, poor people would visit farms on 11 November to get food for the winter. In the 1600s, the city of Amsterdam held boat races on the IJ, where 400 to 500 light craft, both rowing boats and sailboats, took part with a vast crowd on the banks. St Martin is the patron saint of the city of Utrecht, and St Martin’s Day is celebrated there with a big lantern parade.[citation needed]

In Flanders, the Dutch-speaking part of Belgium, St Martin’s Eve is celebrated on the evening of 10 November, mainly in West Flanders and around Ypres. Children go through the streets with paper lanterns and candles, and sing songs about St Martin. Sometimes, a man dressed as St Martin rides on a horse in front of the procession.[14] The children receive presents from either their friends or family as supposedly coming from St Martin.[citation needed] In some areas, there is a traditional goose meal.[citation needed]

In Wervik, children go from door to door, singing traditional «Séngmarténg» songs, sporting a hollow beetroot with a carved face and a candle inside called «Bolle Séngmarténg»; they gather at an evening bonfire. At the end the beetroots are thrown into the fire, and pancakes are served.[citation needed]

English[edit]

Martinmas was widely celebrated on 11 November in medieval and early modern England. In his study «Medieval English Martinmesse: The Archaeology of a Forgotten Festival», Martin Walsh describes Martinmas as a festival marking the end of the harvest season and beginning of winter.[6] He suggests it had pre-Christian roots.[6] Martinmas ushered in the «winter revelling season» and involved feasting on the meat of livestock that had been slaughtered for winter provision (especially ‘Martlemas beef’), drinking, storytelling, and mumming.[6] It was a time for saying farewell to travelling ploughmen, who shared in the feast along with the harvest-workers.[6]

According to Walsh, Martinmas eventually died out in England as a result of the English Reformation, the emergence of Guy Fawkes Night (5 November), as well as changes in farming and the Industrial Revolution.[6] Today, 11 November is Remembrance Day.

German[edit]

A widespread custom in Germany is to light bonfires, called Martinsfeuer, on St Martin’s Eve. In recent years, the processions that accompany those fires have been spread over almost a fortnight before Martinmas (Martinstag). At one time, the Rhine River valley would be lined with fires on the eve of Martinmas. In the Rhineland, Martin’s day is celebrated traditionally with a get-together during which a roasted suckling pig is shared with the neighbours.

The nights before and on the eve itself, children walk in processions called Laternelaufen, carrying lanterns, which they made in school, and sing St Martin’s songs. Usually, the walk starts at a church and goes to a public square. A man on horseback representing St Martin accompanies the children. When they reach the square, Martin’s bonfire is lit and Martin’s pretzels are distributed.[15]

In the Rhineland, the children also go from house to house with their lanterns, sing songs and get candy in return. The origin of the procession of lanterns is unclear. To some, it is a substitute for the Martinmas bonfire, which is still lit in a few cities and villages throughout Europe. It formerly symbolized the light that holiness brings to the darkness, just as St Martin brought hope to the poor through his good deeds. Even though the bonfire tradition is gradually being lost, the procession of lanterns is still practiced.[16]

A Martinsgans («St Martin’s goose»), is typically served on St Martin’s Eve following the procession of lanterns. «Martinsgans» is usually served in restaurants, roasted, with red cabbage and dumplings.[16]

The traditional sweet of Martinmas in the Rhineland is Martinshörnchen, a pastry shaped in the form of a croissant, which recalls both the hooves of St Martin’s horse and, by being the half of a pretzel, the parting of his mantle. In some areas, these pastries are instead shaped like men (Stutenkerl or Weckmänner).

St Martin’s Day is also celebrated in German Lorraine and Alsace, which border the Rhineland and are now part of France. Children receive gifts and sweets. In Alsace, in particular the Haut-Rhin mountainous region, families with young children make lanterns out of painted paper that they carry in a colourful procession up the mountain at night. Some schools organise these events, in particular schools of the Rudolf Steiner (Waldorf education) pedagogy. In these regions, the day marks the beginning of the holiday season.[citation needed] In the German speaking parts of Belgium, notably Eupen and Sankt Vith, processions similar to those in Germany take place.[citation needed]

German American[edit]

In the United States, St. Martin’s Day celebrations are uncommon, but are typically held by German American communities.[17] Many German restaurants feature a traditional menu with goose and Glühwein (a mulled red wine). St Paul, Minnesota celebrates with a traditional lantern procession around Rice Park. The evening includes German treats and traditions that highlight the season of giving.[18] In Dayton, Ohio the Dayton Liederkranz-Turner organization hosts a St Martin’s Family Celebration on the weekend before with an evening lantern parade to the singing of St Martin’s carols, followed by a bonfire.[19]

Swedish[edit]

St Martin’s Day or St Martin’s Eve (Mårtensafton) was an important medieval autumn feast in Sweden. In early November, geese are ready for slaughter, and on St Martin’s Eve it is tradition to have a roast goose dinner. The custom is particularly popular in Scania in southern Sweden, where goose farming has long been practised, but it has gradually spread northwards. A proper goose dinner also includes svartsoppa (a heavily spiced soup made from geese blood) and apple charlotte.[20]

Slavic[edit]

Croatian[edit]

In Croatia, St. Martin’s Day (Martinje, Martinovanje) marks the day when the must traditionally turns to wine. The must is usually considered impure and sinful, until it is baptised and turned into wine. The baptism is performed by someone who dresses up as a bishop and blesses the wine; this is usually done by the host. Another person is chosen as the godfather of the wine.

Czech[edit]

A Czech proverb connected with the Feast of St. Martin – Martin přijíždí na bílém koni (transl. «Martin is coming on a white horse») – signifies that the first half of November in the Czech Republic is the time when it often starts to snow. St. Martin’s Day is the traditional feast day in the run-up to Advent. Restaurants often serve roast goose as well as young wine from the recent harvest known as Svatomartinské víno, which is similar to Beaujolais nouveau as the first wine of the season. Wine shops and restaurants around Prague pour the first of the St. Martin’s wines at 11:11 a.m. Many restaurants offer special menus for the day, featuring the traditional roast goose.[21]

Polish[edit]

Procession of Saint Martin in Poznań, 2006

In Poland, 11 November is National Independence Day. St. Martin’s Day (Dzień Świętego Marcina) is celebrated mainly in the city of Poznań where its citizens buy and eat considerable amounts of croissants filled with almond paste with white poppy seeds, the Rogal świętomarciński or St. Martin’s Croissants. Legend has it that this centuries-old tradition commemorates a Poznań baker’s dream which had the saint entering the city on a white horse that lost its golden horseshoe. The next morning, the baker whipped up horseshoe-shaped croissants filled with almonds, white poppy seeds and nuts, and gave them to the poor. In recent years, competition amongst local patisseries has become fierce. The product is registered under the European Union Protected Designation of Origin and only a limited number of bakers hold an official certificate. Poznanians celebrate the festival with concerts, parades and a fireworks show on Saint Martin’s Street. Goose meat dishes are also eaten during the holiday.[22]

Slovene[edit]

The biggest event in Slovenia is the St. Martin’s Day celebration in Maribor which marks the symbolic winding up of all the wine growers’ endeavours. There is the ceremonial «christening» of the new wine, and the arrival of the Wine Queen. The square Trg Leona Štuklja is filled with musicians and stalls offering autumn produce and delicacies.[23]

Celtic[edit]

Irish[edit]

In some parts[24] of Ireland, on the eve of St. Martin’s Day (Lá Fhéile Mártain in Irish), it was tradition to sacrifice a cockerel by bleeding it. The blood was collected and sprinkled on the four corners of the house.[25][24] Also in Ireland, no wheel of any kind was to turn on St. Martin’s Day, because Martin was said by some people[24] to have been thrown into a mill stream and killed by the wheel and so it was not right to turn any kind of wheel on that day. A local legend in Co. Wexford says that putting to sea is to be avoided as St. Martin rides a white horse across Wexford Bay bringing death by drowning to any who see him.[26]

Welsh[edit]

In Welsh mythology the day is associated with the Cŵn Annwn, the spectral hounds who escort souls to the otherworld (Annwn). St Martin’s Day was one of the few nights the hounds would engage in a Wild Hunt, stalking the land for criminals and villains.[27] The supernatural character of the day in Welsh culture is evident in the number omens associated with it. Marie Trevelyan recorded that if the hooting of an owl was heard on St Martin’s Day it was seen as a bad omen for that district. If a meteor was seen, then there would be trouble for the whole nation.[28]

Latvian[edit]

Mārtiņi (Martin’s) is traditionally celebrated by Latvians on 10 November, marking the end of the preparations for winter, such as salting meat and fish, storing the harvest and making preserves. Mārtiņi also marks the beginning of masquerading and sledding, among other winter activities.

Maltese[edit]

A Maltese «Borża ta’ San Martin»

St. Martin’s Day (Jum San Martin in Maltese) is celebrated in Malta on the Sunday nearest to 11 November. Children are given a bag full of fruits and sweets associated with the feast, known by the Maltese as Il-Borża ta’ San Martin, «St. Martin’s bag». This bag may include walnuts, hazelnuts, almonds, chestnuts, dried or processed figs, seasonal fruit (like oranges, tangerines, apples and pomegranates) and «Saint Martin’s bread roll» (Maltese: Ħobża ta’ San Martin). In old days, nuts were used by the children in their games.

There is a traditional rhyme associated with this custom:

Ġewż, Lewż, Qastan, Tin

Kemm inħobbu lil San Martin.

(Walnuts, Almonds, Chestnuts, Figs

I love Saint Martin so much.)

A feast is celebrated in the village of Baħrija on the outskirts of Rabat, including a procession led by the statue of Saint Martin. There is also a fair, and a show for local animals. San Anton School, a private school on the island, organises a walk to and from a cave especially associated with Martin in remembrance of the day.

Portuguese and Galician[edit]

In Portugal, St. Martin’s Day (Dia de São Martinho) is commonly associated with the celebration of the maturation of the year’s wine, being traditionally the first day when the new wine can be tasted. It is celebrated, traditionally around a bonfire, eating the magusto, chestnuts roasted under the embers of the bonfire (sometimes dry figs and walnuts), and drinking a local light alcoholic beverage called água-pé (literally «foot water», made by adding water to the pomace left after the juice is pressed out of the grapes for wine – traditionally by stomping on them in vats with bare feet, and letting it ferment for several days), or the stronger jeropiga (a sweet liquor obtained in a very similar fashion, with aguardente added to the water). Água-pé, though no longer available for sale in supermarkets and similar outlets (it is officially banned for sale in Portugal), is still generally available in small local shops from domestic production.[citation needed]

Leite de Vasconcelos regarded the magusto as the vestige of an ancient sacrifice to honor the dead and stated that it was tradition in Barqueiros to prepare, at midnight, a table with chestnuts for the deceased family members to eat.[29] The people also mask their faces with the dark wood ashes from the bonfire.[citation needed]

A typical Portuguese saying related to Saint Martin’s Day:

É dia de São Martinho;

comem-se castanhas, prova-se o vinho.

(It is St. Martin’s Day,

we’ll eat chestnuts, we’ll taste the wine.)

This period is also quite popular because of the usual good weather period that occurs in Portugal in this time of year, called Verão de São Martinho (St. Martin’s Summer). It is frequently tied to the legend since Portuguese versions of St. Martin’s legend usually replace the snowstorm with rain (because snow is not frequent in most parts of Portugal, while rain is common at that time of the year) and have Jesus bringing the end of it, thus making the «summer» a gift from God.[citation needed]

St Martin’s Day is widely celebrated in Galicia. It is the traditional day for slaughtering fattened pigs for the winter. This tradition has given way to the popular saying «A cada cerdo le llega su San Martín from Galician A cada porquiño chégalle o seu San Martiño («Every pig gets its St Martin»). The phrase is used to indicate that wrongdoers eventually get their comeuppance.

Sicilian[edit]

In Sicily, November is the winemaking season. On the day Sicilians eat anise, hard biscuits dipped into Moscato, Malvasia or Passito. l’Estate di San Martino (Saint Martin’s Summer) is the traditional reference to a period of unseasonably warm weather in early to mid November, possibly shared with the Normans (who founded the Kingdom of Sicily) as common in at least late English folklore. The day is celebrated in a special way in a village near Messina and at a monastery dedicated to Saint Martin overlooking Palermo beyond Monreale.[30] Other places in Sicily mark the day by eating fava beans.[citation needed]

In art[edit]

Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s physically largest painting is The Wine of Saint Martin’s Day, which depicts the saint giving charity.

There is a closely similar painting by Peeter Baltens, which can be seen here.

See also[edit]

- St. Catherine’s Day

References[edit]

- ^ Bulik, Mark (1 January 2015). The Sons of Molly Maguire: The Irish Roots of America’s First Labor War. Fordham University Press. p. 43. ISBN 9780823262243.

- ^ Carlyle, Thomas (11 November 2010). The Works of Thomas Carlyle. Cambridge University Press. p. 356. ISBN 9781108022354.

- ^ George C. Homans, English Villagers of the Thirteenth Century, 2nd ed. 1991, «The Husbandman’s year» p355f.

- ^ Sulpicius Severus (397). De Vita Beati Martini Liber Unus [On the Life of St. Martin]. Retrieved 2 November 2021.

- ^ Dent, Susie (2020). Word Perfect: Etymological Entertainment For Every Day of the Year. John Murray. ISBN 978-1-5293-1150-1.

- ^ a b c d e f Walsh, Martin (2000). «Medieval English Martinmesse: The Archaeology of a Forgotten Festival». Folklore. 111 (2): 231–249. doi:10.1080/00155870020004620. S2CID 162382811.

- ^ a b c d e f g Miles, Clement A. (1912). Christmas in Ritual and Tradition. Chapter 7: All Hallow Tide to Martinmas. Reproduced by Internet Sacred Text Archive.

- ^ «St Martin’s Day – or ‘Martin Goose'» Lilja, Agneta. Sweden.se magazine-format website

- ^ a b For instance, in Hugh Johnson, Vintage: The Story of Wine 1989, p 97.

- ^ per Matthew 2:1–2:12

- ^ Philip H. Pfatteicher, Journey into the Heart of God (Oxford University Press 2013 ISBN 978-0-19999714-5)

- ^ «Saint Martin’s Lent». Encyclopædia Britannica. Britannica. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ^ «Autumn Feast of St. Martin», Austrian Tourism Board

- ^ Thomson, George William. Peeps At Many Lands: Belgium, Library of Alexandria, 1909

- ^ «St. Martin’s Day traditions honor missionary», Kaiserlautern American, 7 November 2008

- ^ a b «Celebrating St. Martin’s Day on November 11», German Missions in the United States Archived 2012-01-06 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ German traditions in the US for St. Martin’s Day

- ^ «St. Martin’s Day», St. Paul Star Tribune, November 5, 2015

- ^ «St. Martin’s Day Family Celebration». Dayton Liederkranz-Turner. Retrieved 2021-11-02.

- ^ «Mårten Gås», Sweden.SE

- ^ «St. Martin’s Day specials at Prague restaurants», Prague Post, 11 November 2011

- ^ «St. Martin’s Day Celebrations»

- ^ «St. Martin’s Day Celebrations in Maribor», Slovenian Tourist Board

- ^ a b c Marion McGarry (11 November 2020). «Why blood sacrifice rites were common in Ireland on 11 November». RTE. Retrieved 13 November 2020.

Opinion: Blood sacrifices involving pigs, sheep or geese were practiced in Ireland well into living memory on Martinmas. … the custom extended from North Connacht, down to Kerry, and across the midlands and was rarer in Ulster or on the east coast. … some say the saint met his death by being crushed between two wheels

- ^ Súilleabháin, Seán Ó (2012). Miraculous Plenty; Irish Religious Folktales and Legends. Four Courts Press. pp. 183-191 and 269. ISBN 978-0-9565628-2-1.

- ^ «A Wexford Legend — St Martin’s Eve».

- ^ Matthews, John; Matthews, Caitlín (2005). The Element Encyclopedia of Magical Creatures. HarperElement. p. 119. ISBN 978-1-4351-1086-1.

- ^ Trevelyan, Marie (1909). Folk Lore And Folk Stories Of Wales. p. 13. ISBN 9781497817180.

- ^ Leite de Vasconcelos, Opúsculos Etnologia — volumes VII, Lisboa, Imprensa Nacional, 1938

- ^ Gangi, Roberta. «The Joys of St Martin’s Summer», Best of Sicily Magazine, 2010

External links[edit]

Media related to St. Martin’s Day at Wikimedia Commons

- How to make a St. Martin’s Day lantern

- UK History of Martinmas

- St. Martin’s Day in Germany

- St. Martin of Tours

- Alice’s Medieval Feasts & Fasts

Оставайся на связи

Подписывайся на наш Telegram-канал и будь в курсе последних новостей и нововведений в Польше. Также делимся интересными и полезными материалами.

11 ноября вся Польша празднует День Независимости, а жители города Познань — День святого Мартина (św. Marcina), покровителя одной из главных улиц Познани. И сегодня я хочу Вас познакомить с традициями и легендами, связанными с этим святым.

Содержание

- Жизнь Святого Мартина

- История праздника

- Рогалики святого Мартина

- Заключение

Жизнь Святого Мартина

Жизнь этого Святого была тяжёлой, но в это же время и интересной. Рождён он был в семье язычников. Но уже в возрасте 10 лет присоединился к христианам, что в дальнейшем предопределило всю его жизнь. Ради того, чтобы принять крещение, Святой Мартин вступил в конфликт со своей семьёй. По этой причине крещение его прошло значительно позже. В возрасте 15 лет Святой Мартин записался в римский легион, но военную присягу принял только после совершеннолетия (по достижению 17 лет). Самое известное событие в его жизни произошло в 338 году недалеко от города Амьен. Встретив зимой полуголого нищего, Святой Мартин разорвал свой солдатский плащ и укрыл им нищего. Ночью, после этого события, он увидел во сне Христа, одетого в свой плащ. Во сне Иисус сказал своим ангелам: «Видите, как одел меня Мартин?». Уже в 339 году, после крещения Мартин задумался над правильность служения в армии. Ведь война приводит к голоду и разорению, что не свойственно христианину. Возможность уйти из легиона появилась аж в 356 году (до своего ухода он служил Юлию Цезарю). После окончания военной службы Мартин вернулся в Венгрию, к родителям, и наставил их на путь христианства. Позже он уедет во Францию, где благодаря тёплому приёму местного епископа останется в городе Пуатье. В 371 в соседнем местечке скончался епископ, и жителе этой местности очень хотели, чтобы именно Мартин возглавил церковь и принял сан епископа. А чтобы уговорить его на это, жители прибегли к небольшой хитрости: один из горожан пошёл к святому с просьбой приехать в город и исцелить его больную жену. Таким образом, он был избран путём аккламации. И 4 июля 371 г. Мартин был рукоположен в священники и рукоположен в епископы.

Служение церкви и народу длилось целых 25 лет. За это время он сумел многое изменить. Например, св. Мартин ввёл новый стиль работы: он стал жить вне собора, много времени проводил среди верующих, участвовал в синодах, посещал окрестных епископов, дружил со святыми Амвросием, Викторином и Павлином Нолийским. А в более зрелом возрасте основал монастырь, в котором очень любил останавливаться. Жил св. Мартин очень скромно, придерживался поста, каялся за грехи своих верных. Также он активно боролся с язычеством. По его указанию сносили языческие капища и идолов, вырубали священные рощи. Благодаря необычайному усердию в этом направлении вскоре из его епархии исчезли все языческие капища. В доказательство его заслуг, французы сделали св. Мартина своим покровителем.

Не раз судьба подводила святого к смерти. Однако, благодаря своей дипломатии и умению убеждать, св. Мартин договаривался с правителями о милости для себя и других. Пусть он и боролся с язычеством, но людей (язычников) он в обиду не давал. За защиту еретиков православное духовенство очень его критиковало.

Умер святой Мартин 8 ноября. Попрощаться с ним пришло около 2 тысяч монахов и монахинь а также большое количество верующих людей. Его тело было доставлено по Луаре в Тур, а похороны состоялись 11 ноября.

История праздника

День св. Мартина в давние времена означал официальный конец сельскохозяйственного года и конец осени. Считалось, что до дня Святого Мартина с поля убран весь урожай, а подвалы были полны продовольствия на зиму. В народе встречается ещё такое название этого дня как «закрома Мартина» (Marcinowe spichlerze). Также этот день был выходным для людей, работающих в сельском хозяйстве, не работали даже мельницы. 11 ноября был последним днём выпаса скота на пастбищах, закрывался сезон охоты и рыболовства.

Традиционное празднование состояло из песен и танцев, гаданий. Неотъемлемым атрибутом празднования был запечённый гусь. Было принято приносить жирных красивых гусей в костёл или монастырь, обменивать на другие продукты. В деревнях организовывали конкурс на самого жирного гуся. А всё потому, что существует легенда о том, как гусь выдал св. Мартина людям. А обстояло всё так: когда святому хотели дать епископскую хиротонию — он отказался и спрятался от папского посланника. Но его укрытие выдал гусиный гогот, за что гусей и «наказывали».

Рогалики святого Мартина

Вы спросите, как же связаны св. Мартин и Познань? Почему его так любят, да ещё и отмечают день памяти? А всё достаточно просто. Святой Мартин был частым героем ноябрьских проповедей в костёлах Познани. По легенде, во время одной из служб в 1891 году ксёндз Ян Левицкий, приходской священник прихода св. Мартина, призвал верующих поддержать нуждающихся, следуя примеру святого из Тура. В богослужении принимал участие кондитер Юзеф Мельцер, который, будучи вдохновлённым словами священника, решил испечь лакомства. Позже он продал их богатым и раздал бедным. В последующие годы к инициативе присоединились и другие кондитеры и пекари из Познани.

Ну а история рогаликов ещё интереснее и старше. Легенда гласит, что один неизвестный кондитер нашёл подкову, которую потерял конь святого. Воодушевлённый такой находкой, он испёк лакомство такой же формы, украсив его миндалём.

Существует ещё одна легенда, согласно которой рогалики были испечены в форме луны. Эта легенда связана с польским королём Яном 3 Собеским (Jan 3 Sobieski). В 1683 году король пошёл войной на Вену, захватив множество турецких знамён, на которых был изображён полумесяц.

Следующая легенда говорит о познаньском кондитере, которому приснился святой Мартин на коне. Во сне конь потерял свою подкову, которую нашёл пекарь и решил испечь пироги похожей формы.

Традицию поедания рогаликов св. Мартина 11 ноября можно сравнить с традицией поедания пончиков в жирный четверг. Что же они из себя представляют? Сдобную выпечку. А точнее, выпечку из дрожжевого теста, начинка которой состоит из белого мака, сметаны, сахара, ванилина, изюма, измельчённых фиников, а также цукатов из апельсина. Вес такого рогалика — около 250 грамм. И, конечно, каждый пекарь добавляет в рецептуру рогаликов свой секретный ингредиент, который делает выпечку неповторимой.

Во время празднования Дня Святого Мартина в Великопольском регионе съедается несколько сотен тонн рогаликов. Однако, не каждая пекарня может выпекать рогалики. За несколько дней до 11 ноября, в Великопольской ремесленной палате в Познани вручаются сертификаты для кондитерских и пекарен. Только имея такой сертификат можно выпекать рогалики св. Мартина. После вручения сертификатов, кондитеры и пекари вместе с представителями городских властей и палаты ремесленников выходят на улицы, чтобы предложить прохожим сладкое лакомство. Таким образом поддерживается традиция выпечки рогаликов.

Заключение

День Святого Мартина напоминает о таких понятиях как благотворительность и помощь слабым. Святой Мартин является патроном не только нищих и обездоленных, но и солдат, коней и зимних запасов. Единственными существами, которые могут иметь что-то против Мартина — это гуси, ибо в день св. Мартина существовала традиция запекать гуся. Помнят и чтят святого не только в Польше, но и во всей Европе, и в особенности во Франции. Этот день подарил миру надежду на доброту и наивкуснейшую выпечку.

Подписывайся на инсту

Подписывайся на наш Instagram, там еще больше интересных и полезных постов о Польше.

Святого Мартина любят и знают на территории Европы. Это один из самых известных святых Франции. Ему посвящен праздник, совпадающий у христиан и лютеран с праздником в честь сбора урожая. Этот день традиционно проводят всей семьей: на стол подают гуся, а для детей пекут сдобы. Мартин Турский покровительствует всем христианам. Праздник во имя святого ежегодно проводят осенью. Он совпадает с днем сбора урожая.

Содержание

- 1 Святой Мартин Турский, епископ

- 1.1 История жизни

- 1.2 День памяти

- 2 Праздник День святого Мартина

- 3 Праздничные традиции и обычаи

- 4 Как празднуют День святого Мартина в Германии

Святой Мартин Турский, епископ

Милостивый или Турский Мартин – это епископ Тура. Он стал одним из самых почитаемых французских святых. Мартин жил во времена существования Кандии или Лугдунской Галлии, что была частью Западной Римской империи.

Мартин стал для жителей Европы покровителем христианства. При жизни он активно насаждал традиции для монашества, но при этом сам был хорошим примером.

Турский епископ всегда мечтал стать монахом, но это удалось ему не до конца. Святой епископ был призван служить в сане, так как жители захотели видеть главой церкви только его персону. Свои мечты о монашеской жизни святой воплотил при обустройстве обители, которую выстроили рядом с местами уединения бывшего офицера Мартина.

История жизни

Мартин родился там, где сегодня расположена Венгрия. Это было местечко под названием Паннони, где были хорошо известны дела преподобного Антония Великого. С самого детства мальчик грезил о монашеской жизни. Семья мальчика была нехристианской, отец заставил его выбрать военную карьеру. Поэтому будущий святой попал на территорию Галлии, где вынужден был нести службу офицера.

Военные привыкли к жесткости, особенно, если это касается начальствующего состава. Но это утверждение не относилось к Мартину. Он относился с пониманием к каждому солдату. Однажды разорвал свой плащ военачальника и отдал раздетому мирному жителю, которого войско встретило на улице. Этот поступок привел к тому, что Мартина святого стали сравнивать с Христом.

Затем будущий святой отказался выполнять свои воинские обязанности. Мартин утверждал, что может сражаться с противником только с помощью креста, а меч берет только для преступника. Как только возможность покинуть армию появилась, Мартин это сделал. Он поспешно снял с себя все обязанности, чтобы удалиться туда, где была пустынь. Это место вблизи Пуатье было уединенным, но вскоре там разросся небольшой монастырь. По мнению автора жития святого, этот монастырь стал настоящим центром монашеской жизни. Святитель активно распространял традиции восточного монашества.

Мартин хотел простого уединения, но Господь распорядился иначе. Будущего святого вызвали в Тур, чтобы он исцелил больную. Но это была хитрость. Там Мартина провозгласили епископом. Хотя до этого он избегал даже назначения на должность простого диакона. Но милостивый так и не оставил мечты о монашестве, хотя понял, что его призвание заключается в том, чтобы помогать людям и наставлять их на истинный путь.

Первое, что сделал святитель, это образовал обитель на территории Мармутье.

Там же были установлены особые правила для монахов:

- стремление к смирению;

- терпение;

- общее имущество для всех;

- послушание наставников.

Наставник сам подавал пример. Он много молился, мало ел, носил грубую простую одежду.

Кончина Мартина датирована V веком. Там он скончался во время молитвы. Там же в храме на месте пересечения рек Вьенна и Луара жители хотели похоронить его. Но жители Тура похитили мощи и поплыли на лодках вверх по течению. Там у местного населения сохранились легенды, которые рассказывали о том, что на пути следования распускались цветы, а также пели птицы. Сегодня мощи остаются на территории Базилики города Тура, названной в честь Мартина.

День памяти

Для разных течений даты почитания отличаются. 11 ноября святого Мартина традиционно вспоминают католики и лютеране. Православные празднуют этот день 12 октября.

Ноябрь для большинства европейских стран означает окончание сезона, когда собирают урожай. При почитании Мартина традиции язычников и католиков сошлись воедино. Эти дни почитания особенно любимы детьми, так как они участвуют в настоящем торжестве и традиционно получают подарки.

Праздник День святого Мартина

Для католиков 11 ноября стало настоящим ежегодным праздником с торжественными шествиями. Известно, что основа этого дня сложилась из языческих и христианских обычаев.

Кельты праздновали Самайн, который после христианизации Европы стал днем святого Мартина. Сначала язычники отмечали пору конца урожая и начала зимних дней.

После того, как франки приняли христианство, Мартин стал покровителем всего народа. Примечательной была традиция брать плащ, который символизировал военную накидку Мартина-офицера.

Праздничные традиции и обычаи

Один из обычаев праздника – подавать печеного гуся. По легенде, однажды во время службы рядом с церковью начали кричать и бесноваться гуси. Епископ прервал службу и велел сделать из гусей жаркое. С тех пор к столу во всех домах тура стали 11 ноября подавать гусей.

Второй обычай – подача печенья из сдобного теста, которое выпекалось в форме подковы. Печенье именовали «рожками Мартина». Для рожек замешивали специальное тесто, которое должно было выстаиваться на протяжении нескольких дней. Хозяйки готовились к этому празднованию заранее: закупали продукты, мариновали гуся, замешивали тесто.

Еще одна традиция относилась к способу празднования сбора урожая. Орехи, кусочки яблок, зерно, сухарики собирали в бумажные мешочки, подвешивали к потолку и прикрепляли к ним бумажные ленты. После ежегодного обращения правителя Туры бумажные ленты поджигали, а яства сыпались на головы празднующих. Это действо символизировало сбор урожая и изобилие.

Как празднуют День святого Мартина в Германии

На территории Германии и Австрии этот праздник особенно любят. Ко дню святого Турского епископа заканчивали все сезонные работы. К этому моменту главы семейств делали запасы, продавали сырье и делили выручку, рассчитывались с наемными работниками. Пастухи били скот ветками из можжевельника, липы или березы. Затем эти ветки отдавали хозяевам, чтобы они сохранили их на зиму.

Особенность празднования на германо-австрийской территории – это наличие образа черного Мартина. Группы жителей объединялись и ходили по домам: они стучали в двери и забрасывали окна горохом и другими бобами. Чтобы подчеркнуть хулиганскую черту, жители надевали на себя черные плащи так, чтобы их невозможно было узнать.

Вечером того же дня утраивали ярмарку, где мужчины и женщины, переодетые трубодурами, ходили по улицам с бубенцами и колокольчиками.

Дети же на день святого обязательно получали выпечку, которую относили к категории обрядовой. Булочка пеклась в зависимости от региона. Например, на юге пекли сдобу с изюмом, а на востоке предпочитали булки со сливочным маслом.

Дети же ходили по лицам с репами или тыквами, которые были выдолблены изнутри. Кроме того, на дно тыквы ставили свечу. Юноши и мужчины предпочитали боле серьезные игры. Например, игра «Волк спущен». После крика, что волк спущен, на юношей набрасывались мужчины, одетые в шкуры животных. Побеждали те, кто на протяжении долгого времени уворачивались от поимки.