Ежегодно 14 июля вся Франция празднует национальный праздник Республики — День взятия Бастилии (фр. La Fête Nationale) или День 14 июля (фр. Le Quatorze Juillet), установленный еще в 1880 году.

Историческое событие, которое стало основанием для учреждения праздника, произошло во время Великой французской революции — в 1789 году восставшие парижане штурмом взяли крепость-тюрьму Бастилию — символ королевского деспотизма и освободили семерых заключенных. Это событие считается началом Великой французской революции, а также символом свержения абсолютизма.

Хотя День взятия Бастилии считается национальным праздником Франции, но отмечается он не только в этой стране, но и во всем мире. Осада и взятие Бастилии — одно из грандиозных событий в истории человечества. Оно стало символом достигнутого революционным путем политического освобождения, а само слово «Бастилия» стало нарицательным.

Торжества в этот день проходят по всей Франции. Но, пожалуй, даже встреча Нового года не сравнится с тем, что происходит в Париже 14 июля. Как известно, Великая французская революция началась с вооруженного захвата восставшими парижанами грозной и ненавистной тюрьмы-крепости Бастилии в этот день в 1789 году.

Однако, большинство ликующего народа сегодня уже не относятся к этому празднику как революционному. Им уже не важно, что и как произошло 200 с лишним лет назад. Празднуется нечто великое для каждого француза, светлое, радостное и патриотическое.

Официальная программа празднования предусматривает серию балов: балы пожарных, Большой бал, который происходит 13 июля в саду Тюильри. В сам День взятия Бастилии проходит торжественный военный парад на Елисейских полях. Парад начинается в 10 часов утра с Этуаль и двигается в сторону Лувра, принимает его президент Франции.

На площади Конкорд, напротив знаменитой Триумфальной арки, воздвигнуты специальные места для зрителей. Финалом праздника становится большой салют и фейерверк у Эйфелевой башни и на Марсовых полях. Это пиротехническое представление начинается обычно в 10 часов вечера.

Помимо официальной программы торжеств, по всему городу — в дискотеках, барах, ночных клубах, в домах и просто на улицах — проходят непрекращающиеся вечеринки. Сейчас на месте Бастилии большой транспортный круг — развязка с Колонной Бастилии в центре.

«fête nationale française» redirects here. For other French language fêtes nationales, see fête nationale.

| Bastille Day | |

|---|---|

The Patrouille de France with nine Alpha Jets over the Champs-Élysées in Paris in 2017 |

|

| Also called | French National Day (Fête nationale) The Fourteenth of July (Quatorze juillet) |

| Observed by | France |

| Type | National day |

| Significance | Commemorates the Storming of the Bastille on 14 July 1789,[1][2] and the unity of the French people at the Fête de la Fédération on 14 July 1790 |

| Celebrations | Military parades, fireworks, concerts, balls |

| Date | 14 July |

| Next time | 14 July 2023 |

| Frequency | Annual |

Bastille Day is the common name given in English-speaking countries to the national day of France, which is celebrated on 14 July each year. In French, it is formally called the Fête nationale française (French: [fɛt nasjɔnal]; «French National Celebration»); legally it is known as le 14 juillet (French: [lə katɔʁz(ə) ʒɥijɛ]; «the 14th of July»).[3]

The French National Day is the anniversary of the Storming of the Bastille on 14 July 1789,[1][2] a major event of the French Revolution,[4] as well as the Fête de la Fédération that celebrated the unity of the French people on 14 July 1790. Celebrations are held throughout France. One that has been reported as «the oldest and largest military parade in Europe»[5] is held on 14 July on the Champs-Élysées in Paris in front of the President of the Republic, along with other French officials and foreign guests.[6][7]

History[edit]

In 1789, tensions rose in France between reformist and conservative factions as the country struggled to resolve an economic crisis. In May, the Estates General legislative assembly was revived, but members of the Third Estate broke ranks, declaring themselves to be the National Assembly of the country, and on 20 June, vowed to write a constitution for the kingdom.

On 11 July Jacques Necker, the finance minister of Louis XVI, who was sympathetic to the Third Estate, was dismissed by the King, provoking an angry reaction among Parisians. Crowds formed, fearful of an attack by the royal army or by foreign regiments of mercenaries in the King’s service, and seeking to arm the general populace. Early on 14 July one crowd besieged the Hôtel des Invalides for firearms, muskets, and cannons, stored in its cellars.[8] That same day, another crowd stormed the Bastille, a fortress-prison in Paris that had historically held people jailed on the basis of lettres de cachet (literally «signet letters»), arbitrary royal indictments that could not be appealed and did not indicate the reason for the imprisonment, and was believed to hold a cache of ammunition and gunpowder. As it happened, at the time of the attack, the Bastille held only seven inmates, none of great political significance.[9]

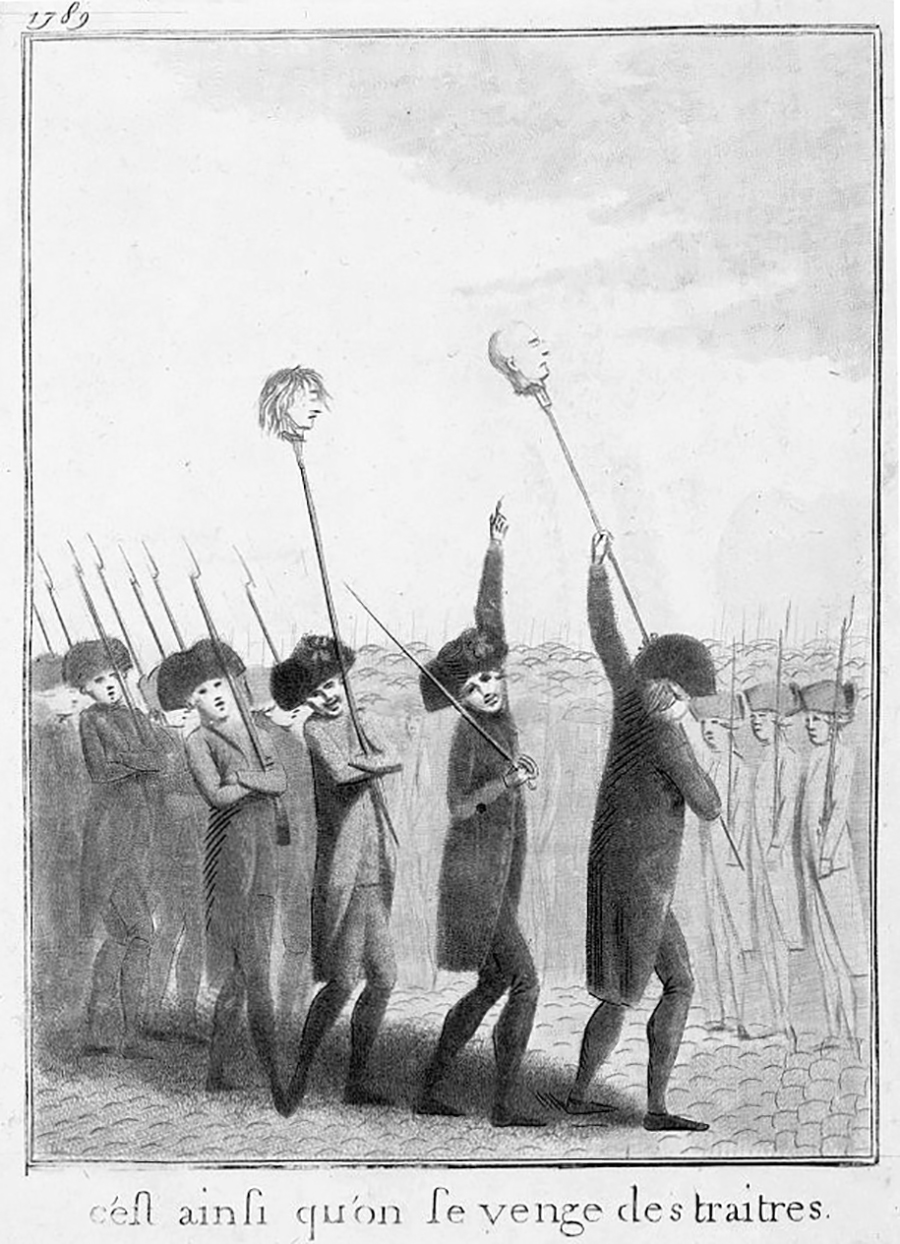

The crowd was eventually reinforced by mutinous Régiment des Gardes Françaises («French Guards»), whose usual role was to protect public buildings. They proved a fair match for the fort’s defenders, and Governor de Launay, the commander of the Bastille, capitulated and opened the gates to avoid a mutual massacre. According to the official documents, about 200 attackers and just one defender died before the capitulation. However, possibly because of a misunderstanding, fighting resumed. In this second round of fighting, de Launay and seven other defenders were killed, as was Jacques de Flesselles, the prévôt des marchands («provost of the merchants»), the elected head of the city’s guilds, who under the feudal monarchy also had the competences of a present-day mayor.[10]

Shortly after the storming of the Bastille, late in the evening of 4 August, after a very stormy session of the Assemblée constituante, feudalism was abolished. On 26 August, the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (Déclaration des Droits de l’Homme et du Citoyen) was proclaimed.[11]

Fête de la Fédération[edit]

As early as 1789, the year of the storming of the Bastille, preliminary designs for a national festival were underway. These designs were intended to strengthen the country’s national identity through the celebration of the events of 14 July 1789.[12] One of the first designs was proposed by Clément Gonchon, a French textile worker, who presented his design for a festival celebrating the anniversary of the storming of the Bastille to the French city administration and the public on 9 December 1789.[13] There were other proposals and unofficial celebrations of 14 July 1789, but the official festival sponsored by the National Assembly was called the Fête de la Fédération.[14]

The Fête de la Fédération on 14 July 1790 was a celebration of the unity of the French nation during the French Revolution. The aim of this celebration, one year after the Storming of the Bastille, was to symbolize peace. The event took place on the Champ de Mars, which was located far outside of Paris at the time. The work needed to transform the Champ de Mars into a suitable location for the celebration was not on schedule to be completed in time. On the day recalled as the Journée des brouettes («The Day of the Wheelbarrow»), thousands of Parisian citizens gathered together to finish the construction needed for the celebration.[15]

The day of the festival, the National Guard assembled and proceeded along the boulevard du Temple in the pouring rain, and were met by an estimated 260,000 Parisian citizens at the Champ de Mars.[16] A mass was celebrated by Talleyrand, bishop of Autun. The popular General Lafayette, as captain of the National Guard of Paris and a confidant of the king, took his oath to the constitution, followed by King Louis XVI. After the end of the official celebration, the day ended in a huge four-day popular feast, and people celebrated with fireworks, as well as fine wine and running nude through the streets in order to display their great freedom.[17]

Origin of the current celebration[edit]

Claude Monet, Rue Montorgueil, Paris, Festival of 30 June 1878

On 30 June 1878, a feast was officially arranged in Paris to honour the French Republic (the event was commemorated in a painting by Claude Monet).[18] On 14 July 1879, there was another feast, with a semi-official aspect. The day’s events included a reception in the Chamber of Deputies, organised and presided over by Léon Gambetta,[19] a military review at Longchamp, and a Republican Feast in the Pré Catelan.[20] All through France, Le Figaro wrote, «people feasted much to honour the storming of the Bastille».[21]

In 1880, the government of the Third Republic wanted to revive the 14 July festival. The campaign for the reinstatement of the festival was sponsored by the notable politician Léon Gambetta and scholar Henri Baudrillant.[22] On 21 May 1880, Benjamin Raspail proposed a law, signed by sixty-four members of government, to have «the Republic adopt 14 July as the day of an annual national festival». There were many disputes over which date to be remembered as the national holiday, including 4 August (the commemoration of the end of the feudal system), 5 May (when the Estates-General first assembled), 27 July (the fall of Robespierre), and 21 January (the date of Louis XVI’s execution).[23] The government decided that the date of the holiday would be 14 July, but it was still somewhat problematic. The events of 14 July 1789 were illegal under the previous government, which contradicted the Third Republic’s need to establish legal legitimacy.[24] French politicians also did not want the sole foundation of their national holiday to be rooted in a day of bloodshed and class-hatred as the day of storming the Bastille was. Instead, they based the establishment of the holiday as a dual celebration of the Fête de la Fédération, a festival celebrating the first anniversary of 14 July 1789, and the storming of the Bastille.[25] The Assembly voted in favor of the proposal on 21 May and 8 June, and the law was approved on 27 and 29 June. The law was made official on 6 July 1880.[citation needed]

In the debate leading up to the adoption of the holiday, Senator Henri Martin, who wrote the National Day law,[25] addressed the chamber on 29 June 1880:

Do not forget that behind this 14 July, where victory of the new era over the Ancien Régime was bought by fighting, do not forget that after the day of 14 July 1789, there was the day of 14 July 1790 (…) This [latter] day cannot be blamed for having shed a drop of blood, for having divided the country. It was the consecration of the unity of France (…) If some of you might have scruples against the first 14 July, they certainly hold none against the second. Whatever difference which might part us, something hovers over them, it is the great images of national unity, which we all desire, for which we would all stand, willing to die if necessary.

Bastille Day military parade[edit]

Military parade during World War I

The Bastille Day military parade is the French military parade that has been held in the morning, each year in Paris since 1880. While previously held elsewhere within or near the capital city, since 1918 it has been held on the Champs-Élysées, with the participation of the Allies as represented in the Versailles Peace Conference, and with the exception of the period of German occupation from 1940 to 1944 (when the ceremony took place in London under the command of General Charles de Gaulle); and 2020 when the COVID-19 pandemic forced its cancellation.[27] The parade passes down the Champs-Élysées from the Arc de Triomphe to the Place de la Concorde, where the President of the French Republic, his government and foreign ambassadors to France stand. This is a popular event in France, broadcast on French TV, and is the oldest and largest regular military parade in Europe.[6][7] In some years, invited detachments of foreign troops take part in the parade and foreign statesmen attend as guests[citation needed]

Smaller military parades are held in French garrison towns, including Toulon and Belfort, with local troops.[28]

-

Allied forces participate in the military parade

-

The French President traditionally welcomes honorary guests for the parade (here: Donald Trump in 2017)

-

-

Surgeon general inspector Dominique Vallet, head of the Laveran military medical school, at the ceremonies for Bastille Day in Marseille, 2012

Bastille Day celebrations in other countries[edit]

Belgium[edit]

Liège celebrates Bastille Day each year since the end of the First World War, as Liège was decorated by the Légion d’Honneur for its unexpected resistance during the Battle of Liège.[29] The city also hosts a fireworks show outside of Congress Hall. Specifically in Liège, celebrations of Bastille Day have been known to be bigger than the celebrations of the Belgian National holiday.[30] Around 35,000 people gather to celebrate Bastille Day. There is a traditional festival dance of the French consul that draws large crowds, and many unofficial events over the city celebrate the relationship between France and the city of Liège.[31]

Canada[edit]

Vancouver, British Columbia holds a celebration featuring exhibits, food and entertainment.[32] The Toronto Bastille Day festival is also celebrated in Toronto, Ontario. The festival is organized by the French community in Toronto and sponsored by the Consulate General of France. The celebration includes music, performances, sport competitions, and a French Market. At the end of the festival, there is also a traditional French bal populaire.[33]

Czech Republic[edit]

Since 2008, Prague has hosted a French market «Le marché du 14 juillet» («Fourteenth of July Market») offering traditional French food and wine as well as music. The market takes place on Kampa Island, it is usually between 11 and 14 July.[34] It acts as an event that marks the relinquish of the EU presidency from France to the Czech Republic. Traditional selections of French produce, including cheese, wine, meat, bread and pastries, are provided by the market. Throughout the event, live music is played in the evenings, with lanterns lighting up the square at night.[35]

Denmark[edit]

The amusement park Tivoli celebrates Bastille Day.[36]

Hungary[edit]

Budapest’s two-day celebration is sponsored by the Institut de France.[37] The festival is hosted along the Danube River, with streets filled with music and dancing. There are also local markets dedicated to French foods and wine, mixed with some traditional Hungarian specialties. At the end of the celebration, a fireworks show is held on the river banks.[38]

India[edit]

Bastille Day is celebrated with great festivity in Pondicherry, a former French colony, every year.[39] On the eve of Bastille Day, retired soldiers parade and celebrate the day with Indian and French National Anthems, honoring the French soldiers who were killed in the battles. Throughout the celebration, French and Indian flags fly alongside each other, projecting the mingling of cultures and heritages.[40]

Ireland[edit]

The Embassy of France in Ireland organizes several events around Dublin, Cork and Limerick for Bastille Day; including evenings of French music and tasting of French food. Many members of the French community in Ireland take part in the festivities.[41] Events in Dublin include live entertainment, speciality menus on French cuisine, and screenings of popular French films.[42]

New Zealand[edit]

The Auckland suburb of Remuera hosts an annual French-themed Bastille Day street festival.[43] Visitors enjoy mimes, dancers, music, as well as French foods and drinks. The budding relationship between the two countries, with the establishment of a Maori garden in France and exchange of their analyses of cave art, resulted in the creation of an official reception at the Residence of France. There is also an event in Wellington for the French community held at the Residence of France.[35]

South Africa[edit]

Franschhoek’s weekend festival[44] has been celebrated since 1993. (Franschhoek, or ‘French Corner,’ is situated in the Western Cape.) As South Africa’s gourmet capital, French food, wine and other entertainment is provided throughout the festival. The French Consulate in South Africa also celebrates their national holiday with a party for the French community.[35] Activities also include dressing up in different items of French clothing.[45]

French Polynesia[edit]

Following colonial rule, France annexed a large portion of what is now French Polynesia. Under French rule, Tahitians were permitted to participate in sport, singing, and dancing competitions one day a year: Bastille Day.[46] The single day of celebration evolved into the major Heiva i Tahiti festival in Papeete Tahiti, where traditional events such as canoe races, tattooing, and fire walks are held. The singing and dancing competitions continued, with music composed with traditional instruments such as a nasal flute and ukulele.[35]

United Kingdom[edit]

Within the UK, London has a large French contingent, and celebrates Bastille Day at various locations across the city including Battersea Park, Camden Town and Kentish Town.[47] Live entertainment is performed at Canary Wharf, with weeklong performances of French theatre at the Lion and Unicorn Theatre in Kentish Town. Restaurants feature cabarets and special menus across the city, and other celebrations include garden parties and sports tournaments. There is also a large event at the Bankside and Borough Market, where there is live music, street performers, and traditional French games are played.[35]

United States[edit]

The United States has over 20 cities that conduct annual celebrations of Bastille Day. The different cities celebrate with many French staples such as food, music, games, and sometimes the recreation of famous French landmarks.[48]

- Northeastern States

Baltimore, Maryland, has a large Bastille Day celebration each year at Petit Louis in the Roland Park area of Baltimore. Boston has a celebration annually, hosted by the French Cultural Center for 40 years. The street festival occurs in Boston’s Back Bay neighborhood, near the Cultural Center’s headquarters. The celebration includes francophone musical performers, dancing, and French cuisine.[49] New York City has numerous Bastille Day celebrations each July, including Bastille Day on 60th Street hosted by the French Institute Alliance Française between Fifth and Lexington Avenues on the Upper East Side of Manhattan,[50] Bastille Day on Smith Street in Brooklyn, and Bastille Day in Tribeca. There is also the annual Bastille Day Ball, taking place since 1924.[48] Philadelphia’s Bastille Day, held at Eastern State Penitentiary, involves Marie Antoinette throwing locally manufactured Tastykakes at the Parisian militia, as well as a re-enactment of the storming of the Bastille.[49] (This Philadelphia tradition ended in 2018.[51]) In Newport, Rhode Island, the annual Bastille Day celebration is organized by the local chapter of the Alliance Française. It takes place at King Park in Newport at the monument memorializing the accomplishments of the General Comte de Rochambeau whose 6,000 to 7,000 French forces landed in Newport on 11 July 1780. Their assistance in the defeat of the English in the War of Independence is well documented and is demonstrable proof of the special relationship between France and the United States.[citation needed] In Washington D.C., food, music, and auction events are sponsored by the Embassy of France. There is also a French Festival within the city, where families can meet period entertainment groups set during the time of the French Revolution. Restaurants host parties serving traditional French food.[48]

- Southern States

In Dallas, Texas, the Bastille Day celebration, «Bastille On Bishop», began in 2010 and is held annually in the Bishop Arts District of the North Oak Cliff neighborhood, southwest of downtown just across the Trinity River. Dallas’ French roots are tied to the short lived socialist Utopian community La Réunion, formed in 1855 and incorporated into the City of Dallas in 1860.[52] Miami’s celebration is organized by «French & Famous» in partnership with the French American Chamber of Commerce, the Union des Français de l’Etranger and many French brands. The event gathers over 1,000 attendees to celebrate «La Fête Nationale». The location and theme change every year. In 2017, the theme was «Guinguette Party» and attracted 1,200 francophiles at The River Yacht Club.[53] New Orleans, Louisiana, has multiple celebrations, the largest in the historic French Quarter.[54] In Austin, Texas, the Alliance Française d’Austin usually conducts a family-friendly Bastille Day party at the French Legation, the home of the French representative to the Republic of Texas from 1841 to 1845.[citation needed]

- Midwestern States

Chicago, Illinois, has hosted a variety of Bastille Day celebrations in a number of locations in the city, including Navy Pier and Oz Park. The recent incarnations have been sponsored in part by the Chicago branch of the French-American Chamber of Commerce and by the French Consulate-General in Chicago.[55] Milwaukee’s four-day street festival begins with a «Storming of the Bastille» with a 43-foot replica of the Eiffel Tower.[56] Minneapolis, Minnesota, has a celebration with wine, French food, pastries, a flea market, circus performers and bands. Also in the Twin Cities area, the local chapter of the Alliance Française has hosted an annual event for years at varying locations with a competition for the «Best Baguette of the Twin Cities.»[57][58] Montgomery, Ohio, has a celebration with wine, beer, local restaurants’ fare, pastries, games and bands.[59] St. Louis, Missouri, has annual festivals in the Soulard neighborhood, the former French village of Carondelet, Missouri, and in the Benton Park neighborhood. The Chatillon-DeMenil Mansion in the Benton Park neighborhood, holds an annual Bastille Day festival with reenactments of the beheading of Marie Antoinette and Louis XVI, traditional dancing, and artillery demonstrations. Carondelet also began hosting an annual saloon crawl to celebrate Bastille Day in 2017.[60] The Soulard neighborhood in St. Louis, Missouri celebrates its unique French heritage with special events including a parade, which honors the peasants who rejected to monarchy. The parade includes a ‘gathering of the mob,’ a walking and golf cart parade, and a mock beheading of the King and Queen.[61]

- Western States

Portland, Oregon, has celebrated Bastille Day with crowds up to 8,000, in public festivals at various public parks, since 2001. The event is coordinated by the Alliance Française of Portland.[62] Seattle’s Bastille Day celebration, held at the Seattle Center, involves performances, picnics, wine and shopping.[63] Sacramento, California, conducts annual «waiter races» in the midtown restaurant and shopping district, with a street festival.[64]

One-time celebrations[edit]

Bronze relief of a memorial dedicated to Bastille Day.

- 1979: A concert with Jean-Michel Jarre on the Place de la Concorde in Paris was the first concert to have one million attendees.[65]

- 1989: France celebrated the 200th anniversary of the French Revolution, notably with a monumental show on the Champs-Élysées in Paris, directed by French designer Jean-Paul Goude. President François Mitterrand acted as a host for invited world leaders.[66]

- 1990: A concert with Jarre was held at La Défense near Paris.[67]

- 1994: The military parade was opened by Eurocorps, a newly created European army unit including German soldiers. This was the first time German troops paraded in France since 1944, as a symbol of Franco-German reconciliation.[68]

- 1995: A concert with Jarre was held at the Eiffel Tower in Paris.[69]

- 1998: Two days after the French football team became World Cup champions, huge celebrations took place nationwide.[70]

- 2004: To commemorate the centenary of the Entente Cordiale, the British led the military parade with the Red Arrows flying overhead.[71]

- 2007: To commemorate the 50th anniversary of the Treaty of Rome, the military parade was led by troops from the 26 other EU member states, all marching at the French time.[72]

- 2014: To commemorate the 100th anniversary of the outbreak of the First World War, representatives of 80 countries who fought during this conflict were invited to the ceremony. The military parade was opened by 76 flags representing each of these countries.[73]

- 2017: To commemorate the 100th anniversary of the United States of America’s entry into the First World War, president of France Emmanuel Macron invited then-U.S. president Donald Trump to celebrate a centuries-long transatlantic tie between the two countries.[74] Trump was reported to have admired the display, and pushed for the United States to «top it» with a proposed military parade on 10 November 2018 (the eve of the Armistice Day centenary).[75][76]

Incidents during Bastille Day[edit]

- In 2002, Maxime Brunerie attempted to shoot French President Jacques Chirac during the Champs-Élysées parade.[77]

- In 2009, Paris youths set fire to more than 300 cars on Bastille Day.[78]

- In 2016, Tunisian terrorist Mohamed Lahouaiej-Bouhlel drove a truck into crowds during celebrations in the city of Nice. 86 people were killed and 434 injured along the Promenade des Anglais,[79] before the attacker was killed in a shootout with police.[80]

See also[edit]

- «Bastille Day», a song by Canadian progressive rock band Rush

- Bastille Day (1933 film), a French romantic comedy by René Clair

- Bastille Day (2016 film), a film starring Idris Elba

- Triplets of Bellville (2003 film), an animated film written and directed by Sylvain Chomet

- Bastille, a British alternative rock band named after the birthday of their frontman

- Bastille Day event

- Opération 14 juillet

- Place de la Bastille

- Public holidays in France

- Other national holidays in July:

- Canada Day in Canada

- Independence Day/Fourth of July in the United States of America

- Battle of the Boyne in Northern Ireland

- Belgian National Day

References[edit]

- ^ a b «Bastille Day – 14th July». Official Website of France. Archived from the original on 15 July 2014.

A national celebration, a re-enactment of the storming of the Bastille … Commemorating the storming of the Bastille on 14th July 1789, Bastille Day takes place on the same date each year. The main event is a grand military parade along the Champs-Élysées, attended by the President of the Republic and other political leaders. It is accompanied by fireworks and public dances in towns throughout the whole of France.

- ^ a b «La fête nationale du 14 juillet». Official Website of Elysée. 21 October 2015.

- ^ Article L. 3133-3 of French labour code on www.legifrance.gouv.fr.

- ^ «The Beginning of the French Revolution, 1789». EyeWitness to History.

Thomas Jefferson was America’s minister to France in 1789. As tensions grew and violence erupted, Jefferson traveled to Versailles and Paris to observe events first-hand. He reported his experience in a series of letters to America’s Secretary of State, John Jay. We join Jefferson’s story as tensions escalate to violence on July 12:

July 12

In the afternoon a body of about 100 German cavalry were advanced and drawn up in the Palace Louis XV. and about 300 Swiss posted at a little distance in their rear. This drew people to that spot, who naturally formed themselves in front of the troops, at first merely to look at them. But as their numbers increased their indignation arose: they retired a few steps, posted themselves on and behind large piles of loose stone collected in that Place for a bridge adjacent to it, and attacked the horse with stones. The horse charged, but the advantageous position of the people, and the showers of stones obliged them to retire, and even to quit the field altogether, leaving one of their number on the ground. The Swiss in their rear were observed never to stir. This was the signal for universal insurrection, and this body of cavalry, to avoid being massacred, retired towards Versailles.

The people now armed themselves with such weapons as they could find in Armourer’s shops and private houses, and with bludgeons, and were roaming all night through all parts of the city without any decided and practicable object.

July 13

…A Committee of magistrates and electors of the city are appointed, by their bodies, to take upon them its government.

The mob, now openly joined by the French guards, force the prisons of St. Lazare, release all the prisoners, and take a great store of corn, which they carry to the corn market. Here they get some arms, and the French guards begin to form and train them. The City committee determines to raise 48,000 Bourgeois, or rather to restrain their numbers to 48,000.’ - ^ «France commemorates WWI centenary on Bastille Day». France 24. 14 July 2014. Retrieved 13 July 2020.

- ^ a b «Champs-Élysées city visit in Paris, France – Recommended city visit of Champs-Élysées in Paris». Paris.com. Archived from the original on 7 August 2011. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- ^ a b «Celebrate Bastille Day in Paris This Year». Paris Attractions. 3 May 2011. Archived from the original on 26 March 2012. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- ^ «What Actually Happened on the Original Bastille Day».

- ^ G A Chevallaz, Histoire générale de 1789 à nos jours, p. 22, Payot, Lausanne 1974

- ^ J Isaac, L’époque révolutionnaire 1789–1851, p. 60, Hachette, Paris 1950

- ^ J Isaac, L’époque révolutionnaire 1789–1851, p. 64, Hachette, Paris 1950.

- ^ Lüsebrink, Hans-Jürgen (1997). The Bastille: A History of a Symbol of Despotism and Freedom. Duke Press University. p. 151. ISBN 9780822382751.

- ^ Lüsebrink, Hans-Jürgen; Reichardt, Rolf (1997). The Bastille: A History of a Symbol of Despotism and Freedom. Duke University Press. p. 152. ISBN 9780822382751.

- ^ Lüsebrink, Hans-Jürgen; Reichardt, Rolf (1997). The Bastille: A History of a Symbol of Despotism and Freedom. Duke University Press. p. 153. ISBN 9780822382751.

- ^ Prendergast, Christopher (2008). The Fourteenth of July. Profile Books Ltd. pp. 105–106. ISBN 9781861979391.

- ^ Prendergast, Christopher (2008). The Fourteenth of July. Profile Books Ltd. pp. 106–107. ISBN 9781861979391.

- ^ Gottschalk, Louis Reichenthal (1973). Lafayette in the French Revolution. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-30547-3.

- ^ Adamson, Natalie (15 August 2009). Painting, politics and the struggle for the École de Paris, 1944–1964. Ashgate. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-7546-5928-0. Retrieved 13 July 2011.

- ^ Nord, Philip G. (2000). Impressionists and politics: art and democracy in the nineteenth century. Psychology Press. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-415-20695-2. Retrieved 13 July 2011.

- ^ Nord, Philip G. (1995). The republican moment: struggles for democracy in nineteenth-century France. Harvard University Press. p. 205. ISBN 978-0-674-76271-8. Retrieved 13 July 2011.

- ^ «Paris Au Jour Le Jour». Le Figaro. 16 July 1879. p. 4. Retrieved 15 January 2013.

On a beaucoup banqueté avant-hier, en mémoire de la prise de la Bastille, et comme tout banquet suppose un ou plusieurs discours, on a aussi beaucoup parlé.

- ^ Prendergast, Christopher (2008). The Fourteenth of July. Profile Books Ltd. pp. 127. ISBN 9781861979391.

- ^ Prendergast, Christopher (2008). The Fourteenth of July. Profile Books Ltd. pp. 129. ISBN 9781861979391.

- ^ Prendergast, Christopher (2008). The Fourteenth of July. Profile Books Ltd. pp. 130. ISBN 9781861979391.

- ^ a b Schofield, Hugh (14 July 2013). «Bastille Day: How peace and revolution got mixed up». BBC News.

- ^ Le Quatorze Juillet at the Greeting Card Universe Blog

- ^ Défilé du 14 juillet, des origines à nos jours Archived 24 February 2011 at the Wayback Machine (14 July Parade, from its origins to the present)

- ^ «France’s National Day». shape.nato.int. Retrieved 13 October 2021.

- ^ «Travel Picks: Top 10 Bastille Day celebrations». Reuters. 13 July 2012. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- ^ «Bastille Day: world celebrations». The Telegraph. 12 July 2012. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022.

- ^ «An unusual Bastille Day: in Liège, Belgium». Eurofluence. 19 July 2014. Archived from the original on 30 October 2020. Retrieved 4 December 2018.

- ^ «Bastille Day Festival Vancouver». Bastille Day Festival Vancouver. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- ^ «Toronto Bastille Day». French Street.

- ^ «French Market at Kampa – Le marché du 14 Juillet». Prague.eu. Archived from the original on 13 July 2018. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- ^ a b c d e Trumper, David (11 July 2014). «7 places outside France where Bastille Day is celebrated». WorldFirst.

- ^ «Tivoli fejrer Bastilledag». Tivoli (in Danish). Retrieved 14 January 2022.

- ^ «Bastille Day 2007 – Budapest». Budapestresources.com. 14 July 2011. Archived from the original on 8 July 2011. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- ^ «Travel Picks: Top 10 Bastille Day celebrations». Reuters. 13 July 2012.

- ^ «Puducherry Culture». Government of Puducherry. Archived from the original on 8 May 2020. Retrieved 14 July 2014.

- ^ Miner Murray, Meghan (12 July 2019). «9 Bastille Day bashes that celebrate French culture». National Geographic.

- ^ «Bastille Day 2018». French Embassy in Ireland. Archived from the original on 13 July 2018. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- ^ «July 14th Bastille Day Celebrations in Dublin». Babylon Radio. 14 July 2016.

- ^ «Array». Remuera Business Association.

- ^ «Bastille Day Festival at Franschhoek». Franschhoek.co.za. Archived from the original on 25 July 2011. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- ^ «Bastille Day is celebrated across the world and in Franchhoek, South Africa». South African History Online. 12 November 2017.

- ^ «The Best Festival You’ve Never Heard Of: The Heiva in Tahiti». X Days in Y. 7 July 2017.

- ^ «Bastille Day London – Bastille Day Events in London, Bastille Day 2011». Viewlondon.co.uk. Archived from the original on 17 June 2011. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- ^ a b c «Where to Celebrate Bastille Day in the United States?». France-Amérique. 6 July 2017.

- ^ a b «Bastille Day: world celebrations». The Telegraph. 4 February 2016. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- ^ «Bastille Day on 60th Street, New York City, Sunday, July 15, 2012 | 12–5pm | Fifth Avenue to Lexington Avenue». Bastilledayny.com. 10 July 2011. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- ^ «Bastille Day 2018: The Farewell Tour». Eastern State Penitentiary. 7 June 2018. Retrieved 29 July 2020.

- ^ «Bastille on Bishop». Go Oak Cliff. Archived from the original on 11 November 2020. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- ^ «Le 14 juillet à Miami : Bastille Day Party de «French & Famous» !». Le Courrier de Floride (in French). 26 June 2017. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- ^ Carr, Martha (13 July 2009). «Only in New Orleans: Watch locals celebrate Bastille Day in the French Quarter». The Times-Picayune. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- ^ «Bastille Day Chicago». Consulate General of France. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- ^ «Bastille Days | Milwaukee, WI». East Town Association. 12 July 2014. Archived from the original on 26 February 2011. Retrieved 23 July 2014.

- ^ «2009 Bastille Day Celebration – Alliance Française, Minneapolis». Yelp. 11 July 2009. Retrieved 18 July 2014.

- ^ «Bastille Day celebrations, 2011». Consulat Général de France à Chicago. 14 July 2011. Archived from the original on 30 October 2013. Retrieved 18 July 2014.

- ^ «Bastille Day Celebration!». City of Montgomery, Ohio. 31 May 2018. Archived from the original on 10 April 2016. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- ^ «Bastille Day». Chatillon-DeMenil Mansion. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- ^ «Bastille Weekend 2021». Soulard Business Association. 19 July 2021. Retrieved 19 July 2021.

- ^ «Bastille Day July 14 at Jamison Square». Alliance Française de Portland. Archived from the original on 13 July 2018. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- ^ «Bastille Day celebration – Alliance Française de Seattle». Alliance Française de Seattle. Bastille Day celebration. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- ^ «Waiters’ Race & Street Festival». Sacramento Bastille Day. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- ^ Yelton, Geary (10 April 2017). «On Tour with Jean-Michel Jarre». Keyboard. Retrieved 12 July 2018.

- ^ Longworth, R.C. (15 July 1989). «French Shoot The Works With Soaring Bicentennial French». Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 12 July 2018.

- ^ «Paris La Défense – Jean-Michel Jarre | Official Site». jeanmicheljarre.com. Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- ^ Kraft, Scott (15 July 1994). «German Troops Join Bastille Day Parade in Paris». Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved 12 July 2018.

- ^ «Concert For Tolerance». Jean-Michel Jarre Official Site. Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- ^ Young, Chris (8 June 2014). «World Cup: Remembering the giddiness and glory of France ’98». The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 12 July 2018.

- ^ Broughton, Philip Delves (14 July 2004). «Best of British lead the way in parade for Bastille Day». The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 12 July 2018.

- ^ «The 14th of July : Bastille Day». French Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs. Retrieved 12 July 2018.

- ^ «Bastille Day in pictures: Soldiers from 76 countries march down Champs-Elysees». The Telegraph. 14 July 2014. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 12 July 2018.

- ^ Breeden, Aurelien (27 June 2017). «Macron Invites Trump to Paris for Bastille Day». The New York Times. Archived from the original on 1 January 2022. Retrieved 12 July 2018.

- ^ Campbell, Barbara; Chappell, Bill (16 August 2018). «No Military Parade For Trump In D.C. This Year; Pentagon Looking At Dates In 2019». NPR.org. Archived from the original on 3 July 2019. Retrieved 3 July 2019.

- ^ Juliet Eilperin, Josh Dawsey and Dan Lamothe (1 July 2019). «Trump asks for tanks, Marine One and much more for grandiose July Fourth event». The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 1 July 2019. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

Trump has been fixated since early in his term on putting on a military-heavy parade or other celebration modeled on France’s Bastille Day celebration, which he attended in Paris in 2017.

- ^ Riding, Alan (15 July 2002). «Chirac Unhurt As Man Shoots At Him in Paris». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- ^ «French youths burn 300 cars to mark Bastille Day». The Telegraph. 14 July 2009. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- ^ «Lorry attacks people on Bastile Day Celebrations». BBC News. 14 July 2016. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- ^ «Nice attack: Lorry driver confirmed as Mohamed Lahouaiej-Bouhlel». BBC News. 15 July 2016. Retrieved 17 July 2021.

External links[edit]

«fête nationale française» redirects here. For other French language fêtes nationales, see fête nationale.

| Bastille Day | |

|---|---|

The Patrouille de France with nine Alpha Jets over the Champs-Élysées in Paris in 2017 |

|

| Also called | French National Day (Fête nationale) The Fourteenth of July (Quatorze juillet) |

| Observed by | France |

| Type | National day |

| Significance | Commemorates the Storming of the Bastille on 14 July 1789,[1][2] and the unity of the French people at the Fête de la Fédération on 14 July 1790 |

| Celebrations | Military parades, fireworks, concerts, balls |

| Date | 14 July |

| Next time | 14 July 2023 |

| Frequency | Annual |

Bastille Day is the common name given in English-speaking countries to the national day of France, which is celebrated on 14 July each year. In French, it is formally called the Fête nationale française (French: [fɛt nasjɔnal]; «French National Celebration»); legally it is known as le 14 juillet (French: [lə katɔʁz(ə) ʒɥijɛ]; «the 14th of July»).[3]

The French National Day is the anniversary of the Storming of the Bastille on 14 July 1789,[1][2] a major event of the French Revolution,[4] as well as the Fête de la Fédération that celebrated the unity of the French people on 14 July 1790. Celebrations are held throughout France. One that has been reported as «the oldest and largest military parade in Europe»[5] is held on 14 July on the Champs-Élysées in Paris in front of the President of the Republic, along with other French officials and foreign guests.[6][7]

History[edit]

In 1789, tensions rose in France between reformist and conservative factions as the country struggled to resolve an economic crisis. In May, the Estates General legislative assembly was revived, but members of the Third Estate broke ranks, declaring themselves to be the National Assembly of the country, and on 20 June, vowed to write a constitution for the kingdom.

On 11 July Jacques Necker, the finance minister of Louis XVI, who was sympathetic to the Third Estate, was dismissed by the King, provoking an angry reaction among Parisians. Crowds formed, fearful of an attack by the royal army or by foreign regiments of mercenaries in the King’s service, and seeking to arm the general populace. Early on 14 July one crowd besieged the Hôtel des Invalides for firearms, muskets, and cannons, stored in its cellars.[8] That same day, another crowd stormed the Bastille, a fortress-prison in Paris that had historically held people jailed on the basis of lettres de cachet (literally «signet letters»), arbitrary royal indictments that could not be appealed and did not indicate the reason for the imprisonment, and was believed to hold a cache of ammunition and gunpowder. As it happened, at the time of the attack, the Bastille held only seven inmates, none of great political significance.[9]

The crowd was eventually reinforced by mutinous Régiment des Gardes Françaises («French Guards»), whose usual role was to protect public buildings. They proved a fair match for the fort’s defenders, and Governor de Launay, the commander of the Bastille, capitulated and opened the gates to avoid a mutual massacre. According to the official documents, about 200 attackers and just one defender died before the capitulation. However, possibly because of a misunderstanding, fighting resumed. In this second round of fighting, de Launay and seven other defenders were killed, as was Jacques de Flesselles, the prévôt des marchands («provost of the merchants»), the elected head of the city’s guilds, who under the feudal monarchy also had the competences of a present-day mayor.[10]

Shortly after the storming of the Bastille, late in the evening of 4 August, after a very stormy session of the Assemblée constituante, feudalism was abolished. On 26 August, the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (Déclaration des Droits de l’Homme et du Citoyen) was proclaimed.[11]

Fête de la Fédération[edit]

As early as 1789, the year of the storming of the Bastille, preliminary designs for a national festival were underway. These designs were intended to strengthen the country’s national identity through the celebration of the events of 14 July 1789.[12] One of the first designs was proposed by Clément Gonchon, a French textile worker, who presented his design for a festival celebrating the anniversary of the storming of the Bastille to the French city administration and the public on 9 December 1789.[13] There were other proposals and unofficial celebrations of 14 July 1789, but the official festival sponsored by the National Assembly was called the Fête de la Fédération.[14]

The Fête de la Fédération on 14 July 1790 was a celebration of the unity of the French nation during the French Revolution. The aim of this celebration, one year after the Storming of the Bastille, was to symbolize peace. The event took place on the Champ de Mars, which was located far outside of Paris at the time. The work needed to transform the Champ de Mars into a suitable location for the celebration was not on schedule to be completed in time. On the day recalled as the Journée des brouettes («The Day of the Wheelbarrow»), thousands of Parisian citizens gathered together to finish the construction needed for the celebration.[15]

The day of the festival, the National Guard assembled and proceeded along the boulevard du Temple in the pouring rain, and were met by an estimated 260,000 Parisian citizens at the Champ de Mars.[16] A mass was celebrated by Talleyrand, bishop of Autun. The popular General Lafayette, as captain of the National Guard of Paris and a confidant of the king, took his oath to the constitution, followed by King Louis XVI. After the end of the official celebration, the day ended in a huge four-day popular feast, and people celebrated with fireworks, as well as fine wine and running nude through the streets in order to display their great freedom.[17]

Origin of the current celebration[edit]

Claude Monet, Rue Montorgueil, Paris, Festival of 30 June 1878

On 30 June 1878, a feast was officially arranged in Paris to honour the French Republic (the event was commemorated in a painting by Claude Monet).[18] On 14 July 1879, there was another feast, with a semi-official aspect. The day’s events included a reception in the Chamber of Deputies, organised and presided over by Léon Gambetta,[19] a military review at Longchamp, and a Republican Feast in the Pré Catelan.[20] All through France, Le Figaro wrote, «people feasted much to honour the storming of the Bastille».[21]

In 1880, the government of the Third Republic wanted to revive the 14 July festival. The campaign for the reinstatement of the festival was sponsored by the notable politician Léon Gambetta and scholar Henri Baudrillant.[22] On 21 May 1880, Benjamin Raspail proposed a law, signed by sixty-four members of government, to have «the Republic adopt 14 July as the day of an annual national festival». There were many disputes over which date to be remembered as the national holiday, including 4 August (the commemoration of the end of the feudal system), 5 May (when the Estates-General first assembled), 27 July (the fall of Robespierre), and 21 January (the date of Louis XVI’s execution).[23] The government decided that the date of the holiday would be 14 July, but it was still somewhat problematic. The events of 14 July 1789 were illegal under the previous government, which contradicted the Third Republic’s need to establish legal legitimacy.[24] French politicians also did not want the sole foundation of their national holiday to be rooted in a day of bloodshed and class-hatred as the day of storming the Bastille was. Instead, they based the establishment of the holiday as a dual celebration of the Fête de la Fédération, a festival celebrating the first anniversary of 14 July 1789, and the storming of the Bastille.[25] The Assembly voted in favor of the proposal on 21 May and 8 June, and the law was approved on 27 and 29 June. The law was made official on 6 July 1880.[citation needed]

In the debate leading up to the adoption of the holiday, Senator Henri Martin, who wrote the National Day law,[25] addressed the chamber on 29 June 1880:

Do not forget that behind this 14 July, where victory of the new era over the Ancien Régime was bought by fighting, do not forget that after the day of 14 July 1789, there was the day of 14 July 1790 (…) This [latter] day cannot be blamed for having shed a drop of blood, for having divided the country. It was the consecration of the unity of France (…) If some of you might have scruples against the first 14 July, they certainly hold none against the second. Whatever difference which might part us, something hovers over them, it is the great images of national unity, which we all desire, for which we would all stand, willing to die if necessary.

Bastille Day military parade[edit]

Military parade during World War I

The Bastille Day military parade is the French military parade that has been held in the morning, each year in Paris since 1880. While previously held elsewhere within or near the capital city, since 1918 it has been held on the Champs-Élysées, with the participation of the Allies as represented in the Versailles Peace Conference, and with the exception of the period of German occupation from 1940 to 1944 (when the ceremony took place in London under the command of General Charles de Gaulle); and 2020 when the COVID-19 pandemic forced its cancellation.[27] The parade passes down the Champs-Élysées from the Arc de Triomphe to the Place de la Concorde, where the President of the French Republic, his government and foreign ambassadors to France stand. This is a popular event in France, broadcast on French TV, and is the oldest and largest regular military parade in Europe.[6][7] In some years, invited detachments of foreign troops take part in the parade and foreign statesmen attend as guests[citation needed]

Smaller military parades are held in French garrison towns, including Toulon and Belfort, with local troops.[28]

-

Allied forces participate in the military parade

-

The French President traditionally welcomes honorary guests for the parade (here: Donald Trump in 2017)

-

-

Surgeon general inspector Dominique Vallet, head of the Laveran military medical school, at the ceremonies for Bastille Day in Marseille, 2012

Bastille Day celebrations in other countries[edit]

Belgium[edit]

Liège celebrates Bastille Day each year since the end of the First World War, as Liège was decorated by the Légion d’Honneur for its unexpected resistance during the Battle of Liège.[29] The city also hosts a fireworks show outside of Congress Hall. Specifically in Liège, celebrations of Bastille Day have been known to be bigger than the celebrations of the Belgian National holiday.[30] Around 35,000 people gather to celebrate Bastille Day. There is a traditional festival dance of the French consul that draws large crowds, and many unofficial events over the city celebrate the relationship between France and the city of Liège.[31]

Canada[edit]

Vancouver, British Columbia holds a celebration featuring exhibits, food and entertainment.[32] The Toronto Bastille Day festival is also celebrated in Toronto, Ontario. The festival is organized by the French community in Toronto and sponsored by the Consulate General of France. The celebration includes music, performances, sport competitions, and a French Market. At the end of the festival, there is also a traditional French bal populaire.[33]

Czech Republic[edit]

Since 2008, Prague has hosted a French market «Le marché du 14 juillet» («Fourteenth of July Market») offering traditional French food and wine as well as music. The market takes place on Kampa Island, it is usually between 11 and 14 July.[34] It acts as an event that marks the relinquish of the EU presidency from France to the Czech Republic. Traditional selections of French produce, including cheese, wine, meat, bread and pastries, are provided by the market. Throughout the event, live music is played in the evenings, with lanterns lighting up the square at night.[35]

Denmark[edit]

The amusement park Tivoli celebrates Bastille Day.[36]

Hungary[edit]

Budapest’s two-day celebration is sponsored by the Institut de France.[37] The festival is hosted along the Danube River, with streets filled with music and dancing. There are also local markets dedicated to French foods and wine, mixed with some traditional Hungarian specialties. At the end of the celebration, a fireworks show is held on the river banks.[38]

India[edit]

Bastille Day is celebrated with great festivity in Pondicherry, a former French colony, every year.[39] On the eve of Bastille Day, retired soldiers parade and celebrate the day with Indian and French National Anthems, honoring the French soldiers who were killed in the battles. Throughout the celebration, French and Indian flags fly alongside each other, projecting the mingling of cultures and heritages.[40]

Ireland[edit]

The Embassy of France in Ireland organizes several events around Dublin, Cork and Limerick for Bastille Day; including evenings of French music and tasting of French food. Many members of the French community in Ireland take part in the festivities.[41] Events in Dublin include live entertainment, speciality menus on French cuisine, and screenings of popular French films.[42]

New Zealand[edit]

The Auckland suburb of Remuera hosts an annual French-themed Bastille Day street festival.[43] Visitors enjoy mimes, dancers, music, as well as French foods and drinks. The budding relationship between the two countries, with the establishment of a Maori garden in France and exchange of their analyses of cave art, resulted in the creation of an official reception at the Residence of France. There is also an event in Wellington for the French community held at the Residence of France.[35]

South Africa[edit]

Franschhoek’s weekend festival[44] has been celebrated since 1993. (Franschhoek, or ‘French Corner,’ is situated in the Western Cape.) As South Africa’s gourmet capital, French food, wine and other entertainment is provided throughout the festival. The French Consulate in South Africa also celebrates their national holiday with a party for the French community.[35] Activities also include dressing up in different items of French clothing.[45]

French Polynesia[edit]

Following colonial rule, France annexed a large portion of what is now French Polynesia. Under French rule, Tahitians were permitted to participate in sport, singing, and dancing competitions one day a year: Bastille Day.[46] The single day of celebration evolved into the major Heiva i Tahiti festival in Papeete Tahiti, where traditional events such as canoe races, tattooing, and fire walks are held. The singing and dancing competitions continued, with music composed with traditional instruments such as a nasal flute and ukulele.[35]

United Kingdom[edit]

Within the UK, London has a large French contingent, and celebrates Bastille Day at various locations across the city including Battersea Park, Camden Town and Kentish Town.[47] Live entertainment is performed at Canary Wharf, with weeklong performances of French theatre at the Lion and Unicorn Theatre in Kentish Town. Restaurants feature cabarets and special menus across the city, and other celebrations include garden parties and sports tournaments. There is also a large event at the Bankside and Borough Market, where there is live music, street performers, and traditional French games are played.[35]

United States[edit]

The United States has over 20 cities that conduct annual celebrations of Bastille Day. The different cities celebrate with many French staples such as food, music, games, and sometimes the recreation of famous French landmarks.[48]

- Northeastern States

Baltimore, Maryland, has a large Bastille Day celebration each year at Petit Louis in the Roland Park area of Baltimore. Boston has a celebration annually, hosted by the French Cultural Center for 40 years. The street festival occurs in Boston’s Back Bay neighborhood, near the Cultural Center’s headquarters. The celebration includes francophone musical performers, dancing, and French cuisine.[49] New York City has numerous Bastille Day celebrations each July, including Bastille Day on 60th Street hosted by the French Institute Alliance Française between Fifth and Lexington Avenues on the Upper East Side of Manhattan,[50] Bastille Day on Smith Street in Brooklyn, and Bastille Day in Tribeca. There is also the annual Bastille Day Ball, taking place since 1924.[48] Philadelphia’s Bastille Day, held at Eastern State Penitentiary, involves Marie Antoinette throwing locally manufactured Tastykakes at the Parisian militia, as well as a re-enactment of the storming of the Bastille.[49] (This Philadelphia tradition ended in 2018.[51]) In Newport, Rhode Island, the annual Bastille Day celebration is organized by the local chapter of the Alliance Française. It takes place at King Park in Newport at the monument memorializing the accomplishments of the General Comte de Rochambeau whose 6,000 to 7,000 French forces landed in Newport on 11 July 1780. Their assistance in the defeat of the English in the War of Independence is well documented and is demonstrable proof of the special relationship between France and the United States.[citation needed] In Washington D.C., food, music, and auction events are sponsored by the Embassy of France. There is also a French Festival within the city, where families can meet period entertainment groups set during the time of the French Revolution. Restaurants host parties serving traditional French food.[48]

- Southern States

In Dallas, Texas, the Bastille Day celebration, «Bastille On Bishop», began in 2010 and is held annually in the Bishop Arts District of the North Oak Cliff neighborhood, southwest of downtown just across the Trinity River. Dallas’ French roots are tied to the short lived socialist Utopian community La Réunion, formed in 1855 and incorporated into the City of Dallas in 1860.[52] Miami’s celebration is organized by «French & Famous» in partnership with the French American Chamber of Commerce, the Union des Français de l’Etranger and many French brands. The event gathers over 1,000 attendees to celebrate «La Fête Nationale». The location and theme change every year. In 2017, the theme was «Guinguette Party» and attracted 1,200 francophiles at The River Yacht Club.[53] New Orleans, Louisiana, has multiple celebrations, the largest in the historic French Quarter.[54] In Austin, Texas, the Alliance Française d’Austin usually conducts a family-friendly Bastille Day party at the French Legation, the home of the French representative to the Republic of Texas from 1841 to 1845.[citation needed]

- Midwestern States

Chicago, Illinois, has hosted a variety of Bastille Day celebrations in a number of locations in the city, including Navy Pier and Oz Park. The recent incarnations have been sponsored in part by the Chicago branch of the French-American Chamber of Commerce and by the French Consulate-General in Chicago.[55] Milwaukee’s four-day street festival begins with a «Storming of the Bastille» with a 43-foot replica of the Eiffel Tower.[56] Minneapolis, Minnesota, has a celebration with wine, French food, pastries, a flea market, circus performers and bands. Also in the Twin Cities area, the local chapter of the Alliance Française has hosted an annual event for years at varying locations with a competition for the «Best Baguette of the Twin Cities.»[57][58] Montgomery, Ohio, has a celebration with wine, beer, local restaurants’ fare, pastries, games and bands.[59] St. Louis, Missouri, has annual festivals in the Soulard neighborhood, the former French village of Carondelet, Missouri, and in the Benton Park neighborhood. The Chatillon-DeMenil Mansion in the Benton Park neighborhood, holds an annual Bastille Day festival with reenactments of the beheading of Marie Antoinette and Louis XVI, traditional dancing, and artillery demonstrations. Carondelet also began hosting an annual saloon crawl to celebrate Bastille Day in 2017.[60] The Soulard neighborhood in St. Louis, Missouri celebrates its unique French heritage with special events including a parade, which honors the peasants who rejected to monarchy. The parade includes a ‘gathering of the mob,’ a walking and golf cart parade, and a mock beheading of the King and Queen.[61]

- Western States

Portland, Oregon, has celebrated Bastille Day with crowds up to 8,000, in public festivals at various public parks, since 2001. The event is coordinated by the Alliance Française of Portland.[62] Seattle’s Bastille Day celebration, held at the Seattle Center, involves performances, picnics, wine and shopping.[63] Sacramento, California, conducts annual «waiter races» in the midtown restaurant and shopping district, with a street festival.[64]

One-time celebrations[edit]

Bronze relief of a memorial dedicated to Bastille Day.

- 1979: A concert with Jean-Michel Jarre on the Place de la Concorde in Paris was the first concert to have one million attendees.[65]

- 1989: France celebrated the 200th anniversary of the French Revolution, notably with a monumental show on the Champs-Élysées in Paris, directed by French designer Jean-Paul Goude. President François Mitterrand acted as a host for invited world leaders.[66]

- 1990: A concert with Jarre was held at La Défense near Paris.[67]

- 1994: The military parade was opened by Eurocorps, a newly created European army unit including German soldiers. This was the first time German troops paraded in France since 1944, as a symbol of Franco-German reconciliation.[68]

- 1995: A concert with Jarre was held at the Eiffel Tower in Paris.[69]

- 1998: Two days after the French football team became World Cup champions, huge celebrations took place nationwide.[70]

- 2004: To commemorate the centenary of the Entente Cordiale, the British led the military parade with the Red Arrows flying overhead.[71]

- 2007: To commemorate the 50th anniversary of the Treaty of Rome, the military parade was led by troops from the 26 other EU member states, all marching at the French time.[72]

- 2014: To commemorate the 100th anniversary of the outbreak of the First World War, representatives of 80 countries who fought during this conflict were invited to the ceremony. The military parade was opened by 76 flags representing each of these countries.[73]

- 2017: To commemorate the 100th anniversary of the United States of America’s entry into the First World War, president of France Emmanuel Macron invited then-U.S. president Donald Trump to celebrate a centuries-long transatlantic tie between the two countries.[74] Trump was reported to have admired the display, and pushed for the United States to «top it» with a proposed military parade on 10 November 2018 (the eve of the Armistice Day centenary).[75][76]

Incidents during Bastille Day[edit]

- In 2002, Maxime Brunerie attempted to shoot French President Jacques Chirac during the Champs-Élysées parade.[77]

- In 2009, Paris youths set fire to more than 300 cars on Bastille Day.[78]

- In 2016, Tunisian terrorist Mohamed Lahouaiej-Bouhlel drove a truck into crowds during celebrations in the city of Nice. 86 people were killed and 434 injured along the Promenade des Anglais,[79] before the attacker was killed in a shootout with police.[80]

See also[edit]

- «Bastille Day», a song by Canadian progressive rock band Rush

- Bastille Day (1933 film), a French romantic comedy by René Clair

- Bastille Day (2016 film), a film starring Idris Elba

- Triplets of Bellville (2003 film), an animated film written and directed by Sylvain Chomet

- Bastille, a British alternative rock band named after the birthday of their frontman

- Bastille Day event

- Opération 14 juillet

- Place de la Bastille

- Public holidays in France

- Other national holidays in July:

- Canada Day in Canada

- Independence Day/Fourth of July in the United States of America

- Battle of the Boyne in Northern Ireland

- Belgian National Day

References[edit]

- ^ a b «Bastille Day – 14th July». Official Website of France. Archived from the original on 15 July 2014.

A national celebration, a re-enactment of the storming of the Bastille … Commemorating the storming of the Bastille on 14th July 1789, Bastille Day takes place on the same date each year. The main event is a grand military parade along the Champs-Élysées, attended by the President of the Republic and other political leaders. It is accompanied by fireworks and public dances in towns throughout the whole of France.

- ^ a b «La fête nationale du 14 juillet». Official Website of Elysée. 21 October 2015.

- ^ Article L. 3133-3 of French labour code on www.legifrance.gouv.fr.

- ^ «The Beginning of the French Revolution, 1789». EyeWitness to History.

Thomas Jefferson was America’s minister to France in 1789. As tensions grew and violence erupted, Jefferson traveled to Versailles and Paris to observe events first-hand. He reported his experience in a series of letters to America’s Secretary of State, John Jay. We join Jefferson’s story as tensions escalate to violence on July 12:

July 12

In the afternoon a body of about 100 German cavalry were advanced and drawn up in the Palace Louis XV. and about 300 Swiss posted at a little distance in their rear. This drew people to that spot, who naturally formed themselves in front of the troops, at first merely to look at them. But as their numbers increased their indignation arose: they retired a few steps, posted themselves on and behind large piles of loose stone collected in that Place for a bridge adjacent to it, and attacked the horse with stones. The horse charged, but the advantageous position of the people, and the showers of stones obliged them to retire, and even to quit the field altogether, leaving one of their number on the ground. The Swiss in their rear were observed never to stir. This was the signal for universal insurrection, and this body of cavalry, to avoid being massacred, retired towards Versailles.

The people now armed themselves with such weapons as they could find in Armourer’s shops and private houses, and with bludgeons, and were roaming all night through all parts of the city without any decided and practicable object.

July 13

…A Committee of magistrates and electors of the city are appointed, by their bodies, to take upon them its government.

The mob, now openly joined by the French guards, force the prisons of St. Lazare, release all the prisoners, and take a great store of corn, which they carry to the corn market. Here they get some arms, and the French guards begin to form and train them. The City committee determines to raise 48,000 Bourgeois, or rather to restrain their numbers to 48,000.’ - ^ «France commemorates WWI centenary on Bastille Day». France 24. 14 July 2014. Retrieved 13 July 2020.

- ^ a b «Champs-Élysées city visit in Paris, France – Recommended city visit of Champs-Élysées in Paris». Paris.com. Archived from the original on 7 August 2011. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- ^ a b «Celebrate Bastille Day in Paris This Year». Paris Attractions. 3 May 2011. Archived from the original on 26 March 2012. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- ^ «What Actually Happened on the Original Bastille Day».

- ^ G A Chevallaz, Histoire générale de 1789 à nos jours, p. 22, Payot, Lausanne 1974

- ^ J Isaac, L’époque révolutionnaire 1789–1851, p. 60, Hachette, Paris 1950

- ^ J Isaac, L’époque révolutionnaire 1789–1851, p. 64, Hachette, Paris 1950.

- ^ Lüsebrink, Hans-Jürgen (1997). The Bastille: A History of a Symbol of Despotism and Freedom. Duke Press University. p. 151. ISBN 9780822382751.

- ^ Lüsebrink, Hans-Jürgen; Reichardt, Rolf (1997). The Bastille: A History of a Symbol of Despotism and Freedom. Duke University Press. p. 152. ISBN 9780822382751.

- ^ Lüsebrink, Hans-Jürgen; Reichardt, Rolf (1997). The Bastille: A History of a Symbol of Despotism and Freedom. Duke University Press. p. 153. ISBN 9780822382751.

- ^ Prendergast, Christopher (2008). The Fourteenth of July. Profile Books Ltd. pp. 105–106. ISBN 9781861979391.

- ^ Prendergast, Christopher (2008). The Fourteenth of July. Profile Books Ltd. pp. 106–107. ISBN 9781861979391.

- ^ Gottschalk, Louis Reichenthal (1973). Lafayette in the French Revolution. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-30547-3.

- ^ Adamson, Natalie (15 August 2009). Painting, politics and the struggle for the École de Paris, 1944–1964. Ashgate. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-7546-5928-0. Retrieved 13 July 2011.

- ^ Nord, Philip G. (2000). Impressionists and politics: art and democracy in the nineteenth century. Psychology Press. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-415-20695-2. Retrieved 13 July 2011.

- ^ Nord, Philip G. (1995). The republican moment: struggles for democracy in nineteenth-century France. Harvard University Press. p. 205. ISBN 978-0-674-76271-8. Retrieved 13 July 2011.

- ^ «Paris Au Jour Le Jour». Le Figaro. 16 July 1879. p. 4. Retrieved 15 January 2013.

On a beaucoup banqueté avant-hier, en mémoire de la prise de la Bastille, et comme tout banquet suppose un ou plusieurs discours, on a aussi beaucoup parlé.

- ^ Prendergast, Christopher (2008). The Fourteenth of July. Profile Books Ltd. pp. 127. ISBN 9781861979391.

- ^ Prendergast, Christopher (2008). The Fourteenth of July. Profile Books Ltd. pp. 129. ISBN 9781861979391.

- ^ Prendergast, Christopher (2008). The Fourteenth of July. Profile Books Ltd. pp. 130. ISBN 9781861979391.

- ^ a b Schofield, Hugh (14 July 2013). «Bastille Day: How peace and revolution got mixed up». BBC News.

- ^ Le Quatorze Juillet at the Greeting Card Universe Blog

- ^ Défilé du 14 juillet, des origines à nos jours Archived 24 February 2011 at the Wayback Machine (14 July Parade, from its origins to the present)

- ^ «France’s National Day». shape.nato.int. Retrieved 13 October 2021.

- ^ «Travel Picks: Top 10 Bastille Day celebrations». Reuters. 13 July 2012. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- ^ «Bastille Day: world celebrations». The Telegraph. 12 July 2012. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022.

- ^ «An unusual Bastille Day: in Liège, Belgium». Eurofluence. 19 July 2014. Archived from the original on 30 October 2020. Retrieved 4 December 2018.

- ^ «Bastille Day Festival Vancouver». Bastille Day Festival Vancouver. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- ^ «Toronto Bastille Day». French Street.

- ^ «French Market at Kampa – Le marché du 14 Juillet». Prague.eu. Archived from the original on 13 July 2018. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- ^ a b c d e Trumper, David (11 July 2014). «7 places outside France where Bastille Day is celebrated». WorldFirst.

- ^ «Tivoli fejrer Bastilledag». Tivoli (in Danish). Retrieved 14 January 2022.

- ^ «Bastille Day 2007 – Budapest». Budapestresources.com. 14 July 2011. Archived from the original on 8 July 2011. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- ^ «Travel Picks: Top 10 Bastille Day celebrations». Reuters. 13 July 2012.

- ^ «Puducherry Culture». Government of Puducherry. Archived from the original on 8 May 2020. Retrieved 14 July 2014.

- ^ Miner Murray, Meghan (12 July 2019). «9 Bastille Day bashes that celebrate French culture». National Geographic.

- ^ «Bastille Day 2018». French Embassy in Ireland. Archived from the original on 13 July 2018. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- ^ «July 14th Bastille Day Celebrations in Dublin». Babylon Radio. 14 July 2016.

- ^ «Array». Remuera Business Association.

- ^ «Bastille Day Festival at Franschhoek». Franschhoek.co.za. Archived from the original on 25 July 2011. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- ^ «Bastille Day is celebrated across the world and in Franchhoek, South Africa». South African History Online. 12 November 2017.

- ^ «The Best Festival You’ve Never Heard Of: The Heiva in Tahiti». X Days in Y. 7 July 2017.

- ^ «Bastille Day London – Bastille Day Events in London, Bastille Day 2011». Viewlondon.co.uk. Archived from the original on 17 June 2011. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- ^ a b c «Where to Celebrate Bastille Day in the United States?». France-Amérique. 6 July 2017.

- ^ a b «Bastille Day: world celebrations». The Telegraph. 4 February 2016. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- ^ «Bastille Day on 60th Street, New York City, Sunday, July 15, 2012 | 12–5pm | Fifth Avenue to Lexington Avenue». Bastilledayny.com. 10 July 2011. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- ^ «Bastille Day 2018: The Farewell Tour». Eastern State Penitentiary. 7 June 2018. Retrieved 29 July 2020.

- ^ «Bastille on Bishop». Go Oak Cliff. Archived from the original on 11 November 2020. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- ^ «Le 14 juillet à Miami : Bastille Day Party de «French & Famous» !». Le Courrier de Floride (in French). 26 June 2017. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- ^ Carr, Martha (13 July 2009). «Only in New Orleans: Watch locals celebrate Bastille Day in the French Quarter». The Times-Picayune. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- ^ «Bastille Day Chicago». Consulate General of France. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- ^ «Bastille Days | Milwaukee, WI». East Town Association. 12 July 2014. Archived from the original on 26 February 2011. Retrieved 23 July 2014.

- ^ «2009 Bastille Day Celebration – Alliance Française, Minneapolis». Yelp. 11 July 2009. Retrieved 18 July 2014.

- ^ «Bastille Day celebrations, 2011». Consulat Général de France à Chicago. 14 July 2011. Archived from the original on 30 October 2013. Retrieved 18 July 2014.

- ^ «Bastille Day Celebration!». City of Montgomery, Ohio. 31 May 2018. Archived from the original on 10 April 2016. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- ^ «Bastille Day». Chatillon-DeMenil Mansion. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- ^ «Bastille Weekend 2021». Soulard Business Association. 19 July 2021. Retrieved 19 July 2021.

- ^ «Bastille Day July 14 at Jamison Square». Alliance Française de Portland. Archived from the original on 13 July 2018. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- ^ «Bastille Day celebration – Alliance Française de Seattle». Alliance Française de Seattle. Bastille Day celebration. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- ^ «Waiters’ Race & Street Festival». Sacramento Bastille Day. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- ^ Yelton, Geary (10 April 2017). «On Tour with Jean-Michel Jarre». Keyboard. Retrieved 12 July 2018.

- ^ Longworth, R.C. (15 July 1989). «French Shoot The Works With Soaring Bicentennial French». Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 12 July 2018.

- ^ «Paris La Défense – Jean-Michel Jarre | Official Site». jeanmicheljarre.com. Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- ^ Kraft, Scott (15 July 1994). «German Troops Join Bastille Day Parade in Paris». Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved 12 July 2018.

- ^ «Concert For Tolerance». Jean-Michel Jarre Official Site. Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- ^ Young, Chris (8 June 2014). «World Cup: Remembering the giddiness and glory of France ’98». The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 12 July 2018.

- ^ Broughton, Philip Delves (14 July 2004). «Best of British lead the way in parade for Bastille Day». The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 12 July 2018.

- ^ «The 14th of July : Bastille Day». French Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs. Retrieved 12 July 2018.

- ^ «Bastille Day in pictures: Soldiers from 76 countries march down Champs-Elysees». The Telegraph. 14 July 2014. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 12 July 2018.

- ^ Breeden, Aurelien (27 June 2017). «Macron Invites Trump to Paris for Bastille Day». The New York Times. Archived from the original on 1 January 2022. Retrieved 12 July 2018.

- ^ Campbell, Barbara; Chappell, Bill (16 August 2018). «No Military Parade For Trump In D.C. This Year; Pentagon Looking At Dates In 2019». NPR.org. Archived from the original on 3 July 2019. Retrieved 3 July 2019.

- ^ Juliet Eilperin, Josh Dawsey and Dan Lamothe (1 July 2019). «Trump asks for tanks, Marine One and much more for grandiose July Fourth event». The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 1 July 2019. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

Trump has been fixated since early in his term on putting on a military-heavy parade or other celebration modeled on France’s Bastille Day celebration, which he attended in Paris in 2017.

- ^ Riding, Alan (15 July 2002). «Chirac Unhurt As Man Shoots At Him in Paris». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- ^ «French youths burn 300 cars to mark Bastille Day». The Telegraph. 14 July 2009. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- ^ «Lorry attacks people on Bastile Day Celebrations». BBC News. 14 July 2016. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- ^ «Nice attack: Lorry driver confirmed as Mohamed Lahouaiej-Bouhlel». BBC News. 15 July 2016. Retrieved 17 July 2021.

External links[edit]

Франция » события

В 1880 году Третья Республика подарила Франции национальный праздник 14 Июля в память о взятии крепости Бастилия, которое произошло 14 июля 1789 года.

Чем он важен для французов

С одной стороны, этот праздник напоминает французам о национальном символе – Бастилии, а с другой − о празднике Федерации, который состоялся 14 июля 1790 года – синониме национального примирения. Очень быстро национальный праздник стал народным.

История возникновения

21 мая 1880 года депутат города Парижа Бенжамин Распай предлагает законопроект о новом ежегодном национальном празднике 14 Июля. 8 июня законопроект принимается Палатой депутатов, и уже 6 июля он вступает в силу.

В это же время Министр Внутренних дел Франции назначает комиссию для подготовки программы мероприятий этого первого праздника, который, ко всему прочему, объявляется нерабочим днем.

По всей Франции за счет муниципального бюджета проводятся различные мероприятия: официальные церемонии в учебных заведениях, открытие статуй – символов Республики, раздача еды неимущим, украшение улиц флагами, смотры войск…

Предполагалось, что активное участие в празднике армии привлечет к нему и тех французов, которые были разочарованы потерей Эльзаса и Лотарингии после поражения в битве при Седане, приведшего к победе Пруссии над Францией в 1870 году и подписанию Франкфуртского соглашения 10 мая 1871 года.

Видео о параде 2019 года (продолжительность 2 часа 30 мин.)

Из-за своего светского характера праздник плохо принимается в городах, в большинстве своем настроенных консервативно. Монархисты и католики считают Революцию 1789 года драмой, а вовсе не героической эпопеей, не символом свободы и гражданской эмансипации.