Сегодня и завтра в Мексике, Гватемале, Никарагуа, Гондурасе и Сальвадоре празднуют День мертвых (или по-испански El Día de Muertos). Это крупнейший праздник, посвящённый памяти умерших. Настолько древний и значимый, что ЮНЕСКО включил его в список нематериального культурного наследия!

Если перед вами дорожки из цветов, алтари с выпечкой, фруктами и черепами, толпы людей, загримированных под скелетов – вполне вероятно, что вы попали в Мексику на День мертвых.

Мы собрали 10 самых интересных фактов об этом празднике. Для всех, кто интересуется испаноязычной культурой, к прочтению обязательно! 🌸💀

1. В отличие от Хэллоуина День мертвых отмечается два дня. 1 ноября семьи поминают души умерших детей и младенцев (исп. El Día de los Inocentes или День невинных/День ангелочков), а на следующий день, 2 ноября – взрослых (исп. Día de los Difuntos или День умерших).

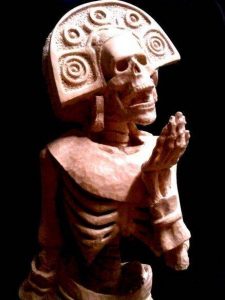

2. Празднику больше 3000 лет. Корнями он уходит в традиции ацтеков и майя, только в те времена ритуалы в память об умерших проводились летом. С приходом конкистадоров и католических праздников День мертвых сдвинулся на ноябрь, поближе к Дню всех святых и Дню всех усопших душ.

3. На самом деле это праздник жизни, а не смерти. Ацтеки верили, что смерть – вовсе не конец, а переход в другое состояние, некая трансформация. Поэтому относились к ней как к важной части жизненного цикла, а не трагическому событию.

El Día de Muertos – день, когда духи приходят в гости к живым. Так зачем их расстраивать излишней скорбью? Лучше celebrate life («праздновать жизнь»): рассказывать истории из жизни умерших родственников, вспоминать счастливые моменты и веселиться, а не горевать и плакать.

4. Поэтому День мертвых наполнен музыкой и танцами (иногда крайне необычными!) Например, La Danza de los Viejitos – танец, в котором мальчики и молодые люди одеты и загримированы под стариков. Сначала они сильно сутулятся и хромают, а затем внезапно подпрыгивают в энергичном танце. Другой танец – La Danza de los Tecuanes или танец ягуаров. В нем люди изображает сельскохозяйственных рабочих, охотящихся на ягуара. И все это в масках и карнавальных костюмах!

5. День мертвых – один из самых главных (и дорогих) праздников в Мексике: парады, украшения, разнообразные угощения. У некоторых семей в сельских районах на все эти приготовления уходит двухмесячный бюджет!

6. Обязательная часть подготовки к празднованию – генеральная уборка. Чистят и дом, и могилы – это не только дань ритуалам, а самый настоящий гражданский долг. В отличие от США большинство кладбищ в Мексике находятся в частной собственности, и жители района ухаживают за ними сами.

7. Еще одна важная часть праздника – Алтари или «подношения» (исп. ofrendas). Семьи собирают особые «композиции» для своих мертвых предков: их портреты и фото, вещи, важные для них при жизни (игрушки, книги, музыкальные инструменты и др.), любимые угощения.

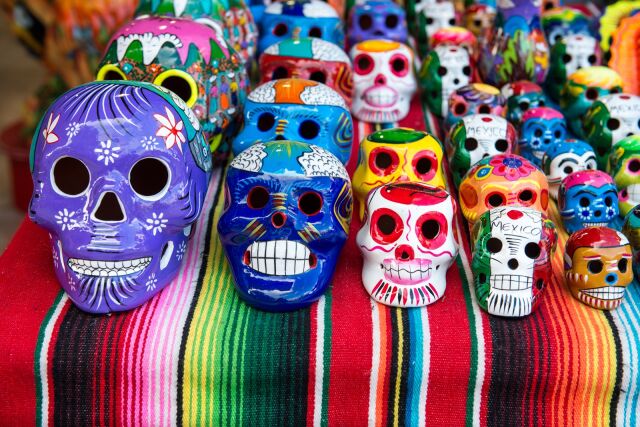

Здесь всегда присутствуют предметы, олицетворяющие четыре стихии: земля (цветы или еда), ветер (традиционные бумажные знамена), огонь (свечи) и вода. И еще сахарные черепа – без них праздник не праздник.

Алтарь – словно маяк для душ, который говорит: «мы вас помним и ждем».

8. Обычаи и традиции могут отличаться в зависимости от региона. Например, в городе Помуч на полуострове Юкатан есть необычный ритуал: вынимать кости предков из гробниц, чтобы «помыть» или протереть от пыли.

9. Проводить День мертвых на кладбище – обычное дело. По всей стране семьи устраивают там своеобразные «пикники» – с подношениями и угощениями. Обедают рядом с могилами своих родных, рассказывают истории и «празднуют жизнь»!

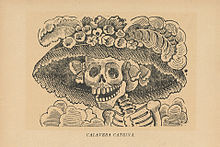

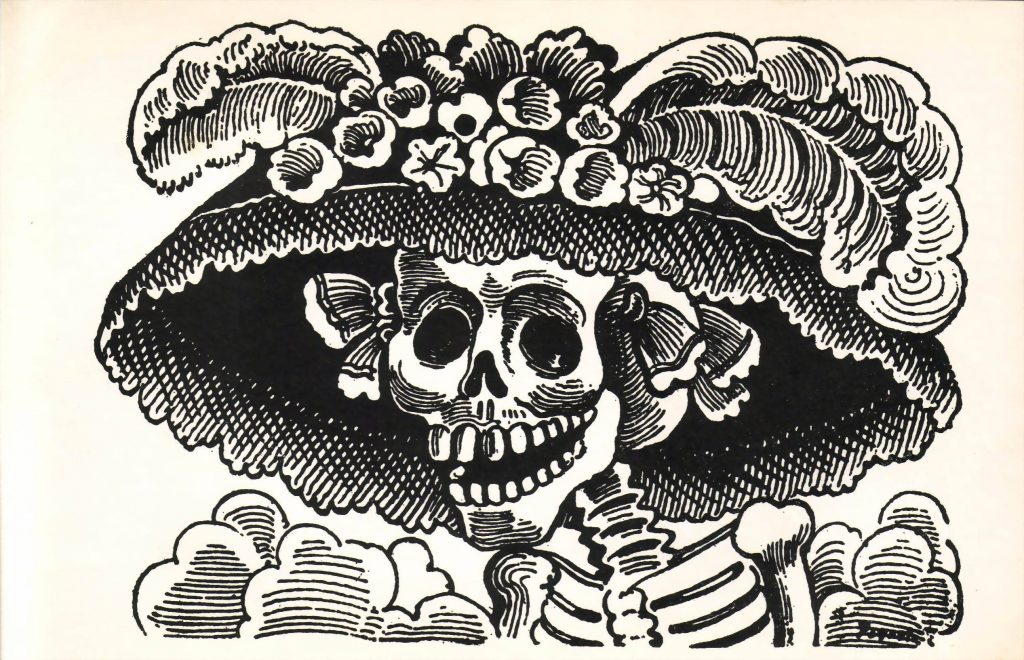

10. Скелет в большой модной шляпе и роскошном платье – еще один символ Дня мертвых. Ее зовут Ла Калавера Катрина (исп. La Catrina). Согласно городской легенде, Ла Катрина – прообраз ацтекской богини смерти Миктекачихуатль. У них обеих одна цель – почитать и защищать умерших и мирить мексиканцев со смертью.

Нынешний образ Ла Катрины создал художник Хосе Гваделупе Посада. Раньше только очень богатые люди могли позволить себе шляпы. Поэтому Посада изобразил Картину в шляпе – как символ того, что перед смертью все люди равны.

А вы празднует Хэллоуин или День мертвых? Обязательно посмотрите «Тайну Коко» или «Книгу жизни». В этих мультфильмах мексиканский праздник представлен во всей красе!

| Day of the Dead | |

|---|---|

Día de Muertos altar commemorating a deceased man in Milpa Alta, Mexico City |

|

| Observed by | Mexico, and regions with large Mexican populations |

| Type |

|

| Significance | Prayer and remembrance of friends and family members who have died |

| Celebrations | Creation of home altars to remember the dead, traditional dishes for the Day of the Dead |

| Begins | November 1 |

| Ends | November 2 |

| Date | November 2 |

| Next time | 2 November 2023 |

| Frequency | Annual |

| Related to | All Saints’ Day, All Hallows’ Eve, All Souls Day[1] |

The Day of the Dead (Spanish: Día de Muertos or Día de los Muertos)[2][3] is a holiday traditionally celebrated on November 1 and 2, though other days, such as October 31 or November 6, may be included depending on the locality.[4][5][6] It is widely observed in Mexico, where it largely developed, and is also observed in other places, especially by people of Mexican heritage. Although related to the simultaneous Christian remembrances for Hallowtide,[1] it has a much less solemn tone and is portrayed as a holiday of joyful celebration rather than mourning.[7] The multi-day holiday involves family and friends gathering to pay respects and to remember friends and family members who have died. These celebrations can take a humorous tone, as celebrants remember funny events and anecdotes about the departed.[8]

Traditions connected with the holiday include honoring the deceased using calaveras and marigold flowers known as cempazúchitl, building home altars called ofrendas with the favorite foods and beverages of the departed, and visiting graves with these items as gifts for the deceased.[9] The celebration is not solely focused on the dead, as it is also common to give gifts to friends such as candy sugar skulls, to share traditional pan de muerto with family and friends, and to write light-hearted and often irreverent verses in the form of mock epitaphs dedicated to living friends and acquaintances, a literary form known as calaveras literarias.[10]

In 2008, the tradition was inscribed in the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO.[11]

Origins, history, and similarities to other festivities

Mexican academics are divided on whether the festivity has genuine indigenous pre-Hispanic roots or whether it is a 20th-century rebranded version of a Spanish tradition developed during the presidency of Lázaro Cárdenas to encourage Mexican nationalism through an «Aztec» identity.[12][13][14] The festivity has become a national symbol in recent decades and it is taught in the nation’s school system asserting a native origin.[15] In 2008, the tradition was inscribed in the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO.[11]

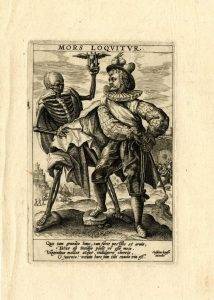

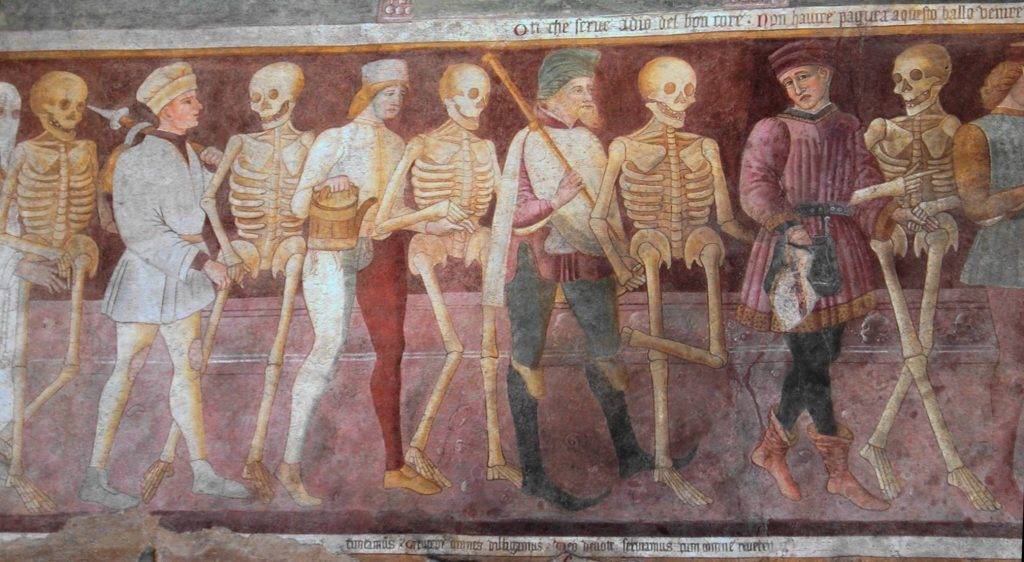

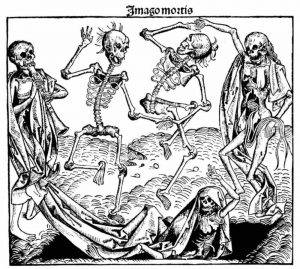

Views differ on whether the festivity has indigenous pre-Hispanic roots, whether it is a more modern adaptation of an existing European tradition, or a combination of both as a manifestation of syncretism. Similar traditions can be traced back to Medieval Europe, where celebrations like All Saints’ Day and All Souls’ Day are observed on the same days in places like Spain and Southern Europe. Critics of the native American origin claim that even though pre-Columbian Mexico had traditions that honored the dead, current depictions of the festivity have more in common with European traditions of Danse macabre and their allegories of life and death personified in the human skeleton to remind us the ephemeral nature of life.[16][12] Over the past decades, however, Mexican academia has increasingly questioned the validity of this assumption, even going as far as calling it a politically motivated fabrication. Historian Elsa Malvido, researcher for the Mexican INAH and founder of the institute’s Taller de Estudios sobre la Muerte, was the first to do so in the context of her wider research into Mexican attitudes to death and disease across the centuries. Malvido completely discards a native or even syncretic origin arguing that the tradition can be fully traced to Medieval Europe. She highlights the existence of similar traditions on the same day, not just in Spain, but in the rest of Catholic Southern Europe and Latin America such as altars for the dead, sweets in the shape of skulls and bread in the shape of bones.[16]

Agustin Sanchez Gonzalez has a similar view in his article published in the INAH’s bi-monthly journal Arqueología Mexicana. Gonzalez states that, even though the «indigenous» narrative became hegemonic, the spirit of the festivity has far more in common with European traditions of Danse macabre and their allegories of life and death personified in the human skeleton to remind us the ephemeral nature of life. He also highlights that in the 19th century press there was little mention of the Day of the Dead in the sense that we know it today. All there was were long processions to cemeteries, sometimes ending with drunkenness. Elsa Malvido also points to the recent origin of the tradition of «velar» or staying up all night with the dead. It resulted from the Reform Laws under the presidency of Benito Juarez which forced family pantheons out of Churches and into civil cemeteries, requiring rich families having servants guarding family possessions displayed at altars.[16]

The historian Ricardo Pérez Montfort has further demonstrated how the ideology known as indigenismo became more and more closely linked to post-revolutionary official projects whereas Hispanismo was identified with conservative political stances. This exclusive nationalism began to displace all other cultural perspectives to the point that in the 1930s, the Aztec god Quetzalcoatl was officially promoted by the government as a substitute for the Spanish Three Kings tradition, with a person dressed up as the deity offering gifts to poor children.[12]

In this context, the Day of the Dead began to be officially isolated from the Catholic Church by the leftist government of Lázaro Cárdenas motivated both by «indigenismo» and left-leaning anti-clericalism. Malvido herself goes as far as calling the festivity a «Cardenist invention» whereby the Catholic elements are removed and emphasis is laid on indigenous iconography, the focus on death and what Malvido considers to be the cultural invention according to which Mexicans venerate death.[14][17] Gonzalez explains that Mexican nationalism developed diverse cultural expressions with a seal of tradition but which are essentially social constructs which eventually developed ancestral tones. One of these would be the Catholic Día de Muertos which, during the 20th century, appropriated the elements of an ancient pagan rite.[12]

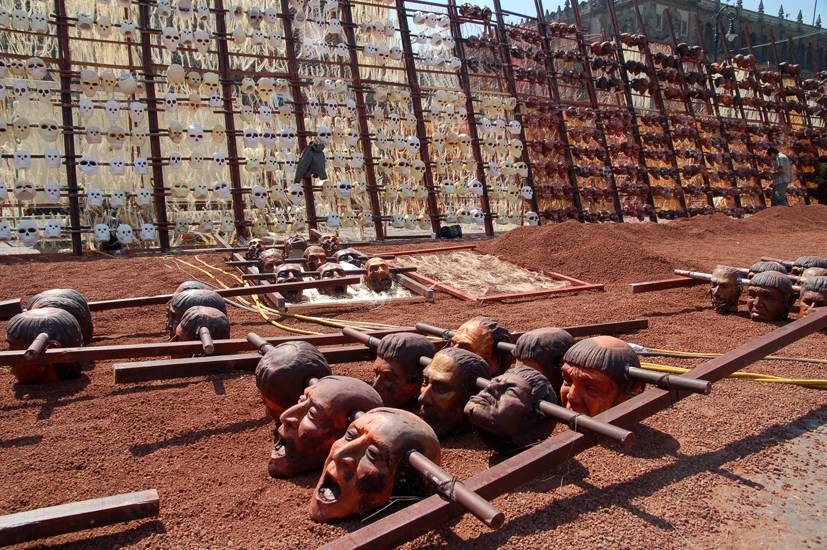

One key element of the re-developed festivity which appears during this time is La Calavera Catrina by Mexican lithographer José Guadalupe Posada. According to Gonzalez, whereas Posada is portrayed in current times as the «restorer» of Mexico’s pre-Hispanic tradition he was never interested in Native American culture or history. Posada was predominantly interested in drawing scary images which are far closer to those of the European renaissance or the horrors painted by Francisco de Goya in the Spanish war of Independence against Napoleon than the Mexica tzompantli. The recent trans-atlantic connection can also be observed in the pervasive use of couplet in allegories of death and the play Don Juan Tenorio by 19th Spanish writer José Zorrilla which is represented on this date both in Spain and in Mexico since the early 19th century due to its ghostly apparitions and cemetery scenes.[12]

Opposing views assert that despite the obvious European influence, there exists proof of pre-Columbian festivities that were very similar in spirit, with the Aztec people having at least six celebrations during the year that were very similar to Day of the Dead, the closest one being Quecholli, a celebration that honored Mixcóatl (the god of war) and was celebrated between October 20 and November 8. This celebration included elements such as the placement of altars with food (tamales) near the burying grounds of warriors to help them in their journey to the afterlife.[13] Influential Mexican poet and Nobel prize laureate Octavio Paz strongly supported the syncretic view of the Día de Muertos tradition being a continuity of ancient Aztec festivals celebrating death, as is most evident in the chapter «All Saints, Day of the Dead» of his 1950 book-length essay The Labyrinth of Solitude.[18]

Regardless of its origin, the festivity has become a national symbol in Mexico and as such is taught in the nation’s school system, typically asserting a native origin. It is also a school holiday nationwide.[15]

Observance in Mexico

Altars (ofrendas)

During Día de Muertos, the tradition is to build private altars («ofrendas») containing the favorite foods and beverages, as well as photos and memorabilia, of the departed. The intent is to encourage visits by the souls, so the souls will hear the prayers and the words of the living directed to them. These altars are often placed at home or in public spaces such as schools and libraries, but it is also common for people to go to cemeteries to place these altars next to the tombs of the departed.[8]

Mexican cempasúchil (marigold) is the traditional flower used to honor the dead.

Plans for the day are made throughout the year, including gathering the goods to be offered to the dead. During the three-day period families usually clean and decorate graves;[19] most visit the cemeteries where their loved ones are buried and decorate their graves with ofrendas (altars), which often include orange Mexican marigolds (Tagetes erecta) called cempasúchil (originally named cempōhualxōchitl, Nāhuatl for ‘twenty flowers’). In modern Mexico the marigold is sometimes called Flor de Muerto (‘Flower of Dead’). These flowers are thought to attract souls of the dead to the offerings. It is also believed the bright petals with a strong scent can guide the souls from cemeteries to their family homes.[20][21]

Toys are brought for dead children (los angelitos, or ‘the little angels’), and bottles of tequila, mezcal or pulque or jars of atole for adults. Families will also offer trinkets or the deceased’s favorite candies on the grave. Some families have ofrendas in homes, usually with foods such as candied pumpkin, pan de muerto (‘bread of dead’), and sugar skulls; and beverages such as atole. The ofrendas are left out in the homes as a welcoming gesture for the deceased.[19][21] Some people believe the spirits of the dead eat the «spiritual essence» of the ofrendas‘ food, so though the celebrators eat the food after the festivities, they believe it lacks nutritional value. Pillows and blankets are left out so the deceased can rest after their long journey. In some parts of Mexico, such as the towns of Mixquic, Pátzcuaro and Janitzio, people spend all night beside the graves of their relatives. In many places, people have picnics at the grave site, as well.

Some families build altars or small shrines in their homes;[19] these sometimes feature a Christian cross, statues or pictures of the Blessed Virgin Mary, pictures of deceased relatives and other people, scores of candles, and an ofrenda. Traditionally, families spend some time around the altar, praying and telling anecdotes about the deceased. In some locations, celebrants wear shells on their clothing, so when they dance, the noise will wake up the dead; some will also dress up as the deceased.

Food

During Day of the Dead festivities, food is both eaten by living people and given to the spirits of their departed ancestors as ofrendas (‘offerings’).[22] Tamales are one of the most common dishes prepared for this day for both purposes.[23]

Family altar for the Day of the Dead on a patio

Pan de muerto and calaveras are associated specifically with Day of the Dead. Pan de muerto is a type of sweet roll shaped like a bun, topped with sugar, and often decorated with bone-shaped pieces of the same pastry.[24] Calaveras, or sugar skulls, display colorful designs to represent the vitality and individual personality of the departed.[23]

In addition to food, drinks are also important to the tradition of Day of the Dead. Historically, the main alcoholic drink was pulque while today families will commonly drink the favorite beverage of their deceased ancestors.[23] Other drinks associated with the holiday are atole and champurrado, warm, thick, non-alcoholic masa drinks.

Agua de Jamaica (water of hibiscus) is a popular herbal tea made of the flowers and leaves of the Jamaican hibiscus plant (Hibiscus sabdariffa), known as flor de Jamaica in Mexico. It is served cold and quite sweet with a lot of ice. The ruby-red beverage is also known as hibiscus tea in English-speaking countries.[25]

In the Yucatán Peninsula, mukbil pollo (píib chicken) is traditionally prepared on October 31 or November 1, and eaten by the family throughout the following days. It is similar to a big tamale, composed of masa and pork lard, and stuffed with pork, chicken, tomato, garlic, peppers, onions, epazote, achiote, and spices. Once stuffed, the mukbil pollo is bathed in kool sauce, made with meat broth, habanero chili, and corn masa. It is then covered in banana leaves and steamed in an underground oven over the course of several hours. Once cooked, it is dug up and opened to eat.[26][27]

Calaveras

A common symbol of the holiday is the skull (in Spanish calavera), which celebrants represent in masks, called calacas (colloquial term for skeleton), and foods such as chocolate or sugar skulls, which are inscribed with the name of the recipient on the forehead. Sugar skulls can be given as gifts to both the living and the dead.[28] Other holiday foods include pan de muerto, a sweet egg bread made in various shapes from plain rounds to skulls, often decorated with white frosting to look like twisted bones.[21]

Calaverita

In some parts of the country, especially the larger cities, children in costumes roam the streets, knocking on people’s doors for a calaverita, a small gift of candies or money; they also ask passersby for it. This custom is similar to that of Halloween’s trick-or-treating in the United States, but without the component of mischief to homeowners if no treat is given.[29]

Calaveras literarias

A distinctive literary form exists within this holiday where people write short poems in traditional rhyming verse, called calaveras literarias (lit. «literary skulls»), which are mocking, light-hearted epitaphs mostly dedicated to friends, classmates, co-workers, or family members (living or dead) but also to public or historical figures, describing interesting habits and attitudes, as well as comedic or absurd anecdotes that use death-related imagery which includes but is not limited to cemeteries, skulls, or the grim reaper, all of this in situations where the dedicatee has an encounter with death itself.[30] This custom originated in the 18th or 19th century after a newspaper published a poem narrating a dream of a cemetery in the future which included the words «and all of us were dead», and then proceeding to read the tombstones. Current newspapers dedicate calaveras literarias to public figures, with cartoons of skeletons in the style of the famous calaveras of José Guadalupe Posada, a Mexican illustrator.[28] In modern Mexico, calaveras literarias are a staple of the holiday in many institutions and organizations, for example, in public schools, students are encouraged or required to write them as part of the language class.[10]

Posada created what might be his most famous print, he called the print La Calavera Catrina («The Elegant Skull») as a parody of a Mexican upper-class female. Posada’s intent with the image was to ridicule the others that would claim the culture of the Europeans over the culture of the indigenous people. The image was a skeleton with a big floppy hat decorated with two big feathers and multiple flowers on the top of the hat. Posada’s striking image of a costumed female with a skeleton face has become associated with the Day of the Dead, and Catrina figures often are a prominent part of modern Day of the Dead observances.[28]

Theatrical presentations of Don Juan Tenorio by José Zorrilla (1817–1893) are also traditional on this day.

Local traditions

The traditions and activities that take place in celebration of the Day of the Dead are not universal, often varying from town to town. For example, in the town of Pátzcuaro on the Lago de Pátzcuaro in Michoacán, the tradition is very different if the deceased is a child rather than an adult. On November 1 of the year after a child’s death, the godparents set a table in the parents’ home with sweets, fruits, pan de muerto, a cross, a rosary (used to ask the Virgin Mary to pray for them), and candles. This is meant to celebrate the child’s life, in respect and appreciation for the parents. There is also dancing with colorful costumes, often with skull-shaped masks and devil masks in the plaza or garden of the town. At midnight on November 2, the people light candles and ride winged boats called mariposas (butterflies) to Janitzio, an island in the middle of the lake where there is a cemetery, to honor and celebrate the lives of the dead there.

In contrast, the town of Ocotepec, north of Cuernavaca in the State of Morelos, opens its doors to visitors in exchange for veladoras (small wax candles) to show respect for the recently deceased. In return the visitors receive tamales and atole. This is done only by the owners of the house where someone in the household has died in the previous year. Many people of the surrounding areas arrive early to eat for free and enjoy the elaborate altars set up to receive the visitors.

Another peculiar tradition involving children is La Danza de los Viejitos (the Dance of the Old Men) where boys and young men dressed like grandfathers crouch and jump in an energetic dance.[31]

In the 2015 James Bond film Spectre, the opening sequence features a Day of the Dead parade in Mexico City. At the time, no such parade took place in Mexico City; one year later, due to the interest in the film and the government desire to promote the Mexican culture, the federal and local authorities decided to organize an actual Día de Muertos parade through Paseo de la Reforma and Centro Historico on October 29, 2016, which was attended by 250,000 people.[32][33][34] This could be seen as an example of the pizza effect. The idea of a massive celebration was also popularized in the Disney Pixar movie Coco.

Observances outside of Mexico

America

United States

Women with calaveras makeup celebrating Día de Muertos in the Mission District of San Francisco, California

In many U.S. communities with Mexican residents, Day of the Dead celebrations are very similar to those held in Mexico. In some of these communities, in states such as Texas,[35] New Mexico,[36] and Arizona,[37] the celebrations tend to be mostly traditional. The All Souls Procession has been an annual Tucson, Arizona, event since 1990. The event combines elements of traditional Day of the Dead celebrations with those of pagan harvest festivals. People wearing masks carry signs honoring the dead and an urn in which people can place slips of paper with prayers on them to be burned.[38] Likewise, Old Town San Diego, California, annually hosts a traditional two-day celebration culminating in a candlelight procession to the historic El Campo Santo Cemetery.[39]

The festival also was held annually at historic Forest Hills Cemetery in Boston’s Jamaica Plain neighborhood. Sponsored by Forest Hills Educational Trust and the folkloric performance group La Piñata, the Day of the Dead festivities celebrated the cycle of life and death. People brought offerings of flowers, photos, mementos, and food for their departed loved ones, which they placed at an elaborately and colorfully decorated altar. A program of traditional music and dance also accompanied the community event. The Jamaica Plain celebration was discontinued in 2011.[40]

The Smithsonian Institution, in collaboration with the University of Texas at El Paso and Second Life, have created a Smithsonian Latino Virtual Museum and accompanying multimedia e-book: Día de los Muertos: Day of the Dead. The project’s website contains some of the text and images which explain the origins of some of the customary core practices related to the Day of the Dead, such as the background beliefs and the offrenda (the special altar commemorating one’s deceased loved one).[41] The Made For iTunes multimedia e-book version provides additional content, such as further details; additional photo galleries; pop-up profiles of influential Latino artists and cultural figures over the decades; and video clips[42] of interviews with artists who make Día de Muertos-themed artwork, explanations and performances of Aztec and other traditional dances, an animation short that explains the customs to children, virtual poetry readings in English and Spanish.[43][44]

In 2021, the Biden-Harris administration celebrated the Día de Muertos.[45]

California

Santa Ana, California, is said to hold the «largest event in Southern California» honoring Día de Muertos, called the annual Noche de Altares, which began in 2002.[46] The celebration of the Day of the Dead in Santa Ana has grown to two large events with the creation of an event held at the Santa Ana Regional Transportation Center for the first time on November 1, 2015.[47]

In other communities, interactions between Mexican traditions and American culture are resulting in celebrations in which Mexican traditions are being extended to make artistic or sometimes political statements. For example, in Los Angeles, California, the Self Help Graphics & Art Mexican-American cultural center presents an annual Day of the Dead celebration that includes both traditional and political elements, such as altars to honor the victims of the Iraq War, highlighting the high casualty rate among Latino soldiers. An updated, intercultural version of the Day of the Dead is also evolving at Hollywood Forever Cemetery.[48] There, in a mixture of Native Californian art, Mexican traditions and Hollywood hip, conventional altars are set up side by side with altars to Jayne Mansfield and Johnny Ramone. Colorful native dancers and music intermix with performance artists, while sly pranksters play on traditional themes.

Similar traditional and intercultural updating of Mexican celebrations are held in San Francisco. For example, the Galería de la Raza, SomArts Cultural Center, Mission Cultural Center, de Young Museum and altars at Garfield Square by the Marigold Project.[49] Oakland is home to Corazon Del Pueblo in the Fruitvale district. Corazon Del Pueblo has a shop offering handcrafted Mexican gifts and a museum devoted to Day of the Dead artifacts. Also, the Fruitvale district in Oakland serves as the hub of the Día de Muertos annual festival which occurs the last weekend of October. Here, a mix of several Mexican traditions come together with traditional Aztec dancers, regional Mexican music, and other Mexican artisans to celebrate the day.[50]

Car ofrendas on display during the Oceanside, California Dia de los Muertos festival

In San Diego, California, the city that borders Mexico, the celebrations range across the entire county. All the way up at the most northern part of the county, Oceanside celebrates their annual event which includes community and family altars built around the Oceanside Civic Center and Pier View Way, as well as events at the Mission San Luis Rey de Francia. In the more central area of San Diego, City Heights celebrates through a public festival in Jeremy Henwood Memorial Park that includes at least 35 altars, lowriders, and entertainment, all for free. Down in Chula Vista, they celebrate the tradition through a movie night at Third and Davidson streets where they will be screening “Coco.” This movie night also consists of a community altar, an Altar contest, a catrin/catrina contest, as well as lots of music, food, and vendors. Overall, San Diego is booming with colorful celebrations honoring ancestors across the county.[51]

Italy

In Italy, November 2nd is All Souls’ Day and is colloquially known as Day of the Dead or «Giorno dei Morti». While many regional nuances exist, celebrations generally consist of placing flowers at cemeteries and family burial sites and speaking to deceased relatives.[52] Some traditions also include lighting a red candle or «lumino» on the window sills at sunset and laying out a table of food for deceased relatives who will come to visit. Like other Day of the Dead traditions around the world, Giorno dei Morti is a day dedicated to honoring the lives of those who have died. Additionally, it is a tradition that teaches children not to be afraid of death.

A Sicilian cannistru dei morti

In Sicily, families celebrate a long-held Day of the Dead tradition called The Festival of the Dead or «Festa dei Morti». On the eve of November 1st, La Festa di Ognissanti, or All Saints’ Day, older family members act as the «defunti», or spirits of deceased family members, who sneak into the home and hide sweets and gifts for their young descendants to awake to. On the morning of November 2nd, children begin the day by hunting to find the gifts in shoes or a special wicker basket of the dead called «cannistru dei morti» or «u cannistru», which typically consist of various sweets, small toys, boned-shaped almond flavored cookies called «ossa dei morti», sugar dolls called «pupi di zucchero», and fruit, vegetable, and ghoul shaped marzipan treats called «Frutta martorana». The pupi di zucchero, thought to be an Arabic cultural import, are often found in the shapes of folkloric characters who represent humanized versions of the souls of the dead. Eating the sugar dolls reflects the idea of the individual absorbing the dead and, in doing so, bringing the dead back to life within themselves on November 2nd. After gifts are shared and breakfast is enjoyed, the whole family will often visit the cemetery or burial site bearing flowers. They will light candles and play amongst the graves to thank the deceased for the gifts, before enjoying a hearty feast. The tradition holds that the spirits of the deceased will remain with the family to enjoy a day of feasting and merriment.[53]

Acclaimed Sicilian author Andrea Camilleri recounts his Giorno dei Morti experience as boy, as well as the negative cultural impact that WWII era American influence had on the long-held tradition.

«Every Sicilian house where there was a little boy was populated with dead familiar to him. Not ghosts with white linzòlo and with the scrunch of chains, mind you, not those that are frightening, but such and as they were seen in the photographs exhibited in the living room, worn, the occasional half smile printed on the face, the good ironed dress in a workmanlike manner, they made no difference with the living. We Nicareddri, before going to bed, put a wicker basket under the bed (the size varied according to the money there was in the family) that at night the dear dead would fill with sweets and gifts that we would find on the 2nd morning upon awakening. After a restless sleep we woke up at dawn to go hunting… Because the dead wanted to play with us, to give us fun, and therefore they didn’t put the basket back where they had found it, but went to hide it carefully, we had to look for it… The toys were tin trains, wooden toy cars, rag dolls, wooden cubes that formed landscapes… On November 2nd we returned the visit that the dead had paid us the day before: it was not a ritual, but an affectionate custom. Then, in 1943, with the American soldiers the Christmas tree arrived and slowly, year after year, the dead lost their way to the houses where they were waiting for them, happy and awake until the end, the children or the children of the children… Pity. We had lost the possibility of touching, materially, that thread that binds our personal history to that of those who had preceded us…»

— Andrea Camilleri, English translation of “The Day That The Dead Lost Their Way Home”[54]

Food plays an important part of Italy’s day of the dead tradition, with various regional treats being used as offerings to the dead on their journey to the afterlife. In Tuscany and Milan the “pane dei morti” or «bread of the dead» is said to be the characteristic offering. In northern Apulia, a wheat growing region, a sweet dish for the Day of the Dead is Colva or “Grains of the Dead”. Fave dei morti or “fava beans of the dead” are another dish for the day found widespread through Italy. Ossa dei morti, suitably elongated and frosted “bones of the dead” are sweets found in Apulia and Sicily. In Sicily, families enjoy special day of the dead cakes and cookies that are made into symbolic shapes such as skulls and finger bones. The «sweets of the dead» are a marzipan treats called frutta martorana.[55] On the night of November 1st, Sicilian parents and grandparents traditionally buy Frutta di Martorana to gift to children on November 2nd.

In addition to visiting their own family members, some people pay respects to those without a family. Some Italians take it upon themselves to adopt centuries-old unclaimed bodies and give them offerings like money or jewelry as a way to ease their pain and ask for favors.[56]

Asia and Oceania

Mexican-style Day of the Dead celebrations occur in major cities in Australia, Fiji, and Indonesia. Additionally, prominent celebrations are held in Wellington, New Zealand, complete with altars celebrating the deceased with flowers and gifts.[57]

Philippines

Due to the close cultural connections of the Philippines and Mexico, the Day of the Dead is celebrated in this Hispanic-Asian country as well. In the Philippines «Undás», «Araw ng mga Yumao» (Tagalog: «Day of those who have died»), coincides with the Roman Catholic’s celebration of All Saints’ Day and continues on to the following day: All Souls’ Day. Filipinos traditionally observe this day by visiting the family dead to clean and repair their tombs, just like in Mexico. Offerings of prayers, flowers, candles,[58] and even food, while Chinese Filipinos additionally burn joss sticks and joss paper (kim). Many also spend the day and ensuing night holding reunions at the cemetery, having feasts and merriment.

Czech Republic

As part of a promotion by the Mexican embassy in Prague, Czech Republic, since the late 20th century, some local citizens join in a Mexican-style Day of the Dead. A theater group conducts events involving candles, masks, and make-up using luminous paint in the form of sugar skulls.[59][60]

Americas

Belize

In Belize, Day of the Dead is practiced by people of the Yucatec Maya ethnicity. The celebration is known as Hanal Pixan which means ‘food for the souls’ in their language. Altars are constructed and decorated with food, drinks, candies, and candles put on them.

Bolivia

Día de las Ñatitas («Day of the Skulls») is a festival celebrated in La Paz, Bolivia, on May 5. In pre-Columbian times indigenous Andeans had a tradition of sharing a day with the bones of their ancestors on the third year after burial. Today families keep only the skulls for such rituals. Traditionally, the skulls of family members are kept at home to watch over the family and protect them during the year. On November 9, the family crowns the skulls with fresh flowers, sometimes also dressing them in various garments, and making offerings of cigarettes, coca leaves, alcohol, and various other items in thanks for the year’s protection. The skulls are also sometimes taken to the central cemetery in La Paz for a special Mass and blessing.[61][62][63]

Brazil

The Brazilian public holiday of Dia de Finados, Dia dos Mortos or Dia dos Fiéis Defuntos (Portuguese: «Day of the Dead» or «Day of the Faithful Deceased») is celebrated on November 2. Similar to other Day of the Dead celebrations, people go to cemeteries and churches with flowers and candles and offer prayers. The celebration is intended as a positive honoring of the dead. Memorializing the dead draws from indigenous and European Catholic origins.

Costa Rica

Costa Rica celebrates Día De Los Muertos on November 2. The day is also called Día de Todos Santos (All Saints Day) and Día de Todos Almas (All Souls Day). Catholic masses are celebrated and people visit their loved ones’ graves to decorate them with flowers and candles.[64]

Ecuador

In Ecuador the Day of the Dead is observed to some extent by all parts of society, though it is especially important to the indigenous Kichwa peoples, who make up an estimated quarter of the population. Indigena families gather together in the community cemetery with offerings of food for a day-long remembrance of their ancestors and lost loved ones. Ceremonial foods include colada morada, a spiced fruit porridge that derives its deep purple color from the Andean blackberry and purple maize. This is typically consumed with wawa de pan, a bread shaped like a swaddled infant, though variations include many pigs—the latter being traditional to the city of Loja. The bread, which is wheat flour-based today, but was made with masa in the pre-Columbian era, can be made savory with cheese inside or sweet with a filling of guava paste. These traditions have permeated mainstream society, as well, where food establishments add both colada morada and gaugua de pan to their menus for the season. Many non-indigenous Ecuadorians visit the graves of the deceased, cleaning and bringing flowers, or preparing the traditional foods, too.[65]

Guatemala

Guatemalan celebrations of the Day of the Dead, on November 1, are highlighted by the construction and flying of giant kites.[66] It is customary to fly kites to help the spirits find their way back to Earth. A few kites have notes for the dead attached to the strings of the kites. The kites are used as a kind of telecommunication to heaven.[28] A big event also is the consumption of fiambre, which is made only for this day during the year.[28] In addition to the traditional visits to grave sites of ancestors, the tombs and graves are decorated with flowers, candles, and food for the dead. In a few towns, Guatemalans repair and repaint the cemetery with vibrant colors to bring the cemetery to life. They fix things that have gotten damaged over the years or just simply need a touch-up, such as wooden grave cross markers. They also lay flower wreaths on the graves. Some families have picnics in the cemetery.[28]

Peru

It is common for Peruvians to visit the cemetery, play music and bring flowers to decorate the graves of dead relatives.[67]

Europe

Southern Italy and Sicily

A traditional biscotti-type cookie, ossa di morto or bones of the dead are made and placed in shoes once worn by dead relatives.[68]

See also

- Bon (festival)

- Danse Macabre

- Qingming Festival

- Literary Calaverita

- Samhain

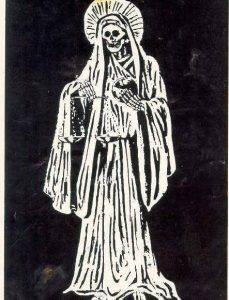

- Santa Muerte

- Skull art

- Thursday of the Dead

- Veneration of the dead

- Walpurgis Night

References

- ^ a b c Foxcroft, Nigel H. (October 28, 2019). The Kaleidoscopic Vision of Malcolm Lowry: Souls and Shamans. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 130. ISBN 978-1-4985-1658-7.

However, owing to the subjugation of the Aztec Empire by the Spanish conquistador, Hernan Coretes in 1519–1521, this festival increasingly fell under Hispanic influence. It was moved from the beginning of summer to late October—and then to early November—so that it would conicide with the Western Christian triduum (or three-day religious observance) of Allhallowtide (Hallowtide, Allsaintide, or Hallowmas). It lasts from October 31 to November 2 and comprises All Saint’s Eve (Halloween), All Saints’ Day (All Hallows’), and All Souls’ Day.

- ^ «Día de Todos los Santos, Día de los Fieles Difuntos y Día de (los) Muertos (México) se escriben con mayúscula inicial» [Día de Todos los Santos, Día de los Fieles Difuntos and Día de (los) Muertos (Mexico) are written with initial capital letter] (in Spanish). Fundéu. October 29, 2010. Retrieved November 4, 2020.

- ^ «¿’Día de Muertos’ o ‘Día de los Muertos’? El nombre usado en México para denominar a la fiesta tradicional en la que se honra a los muertos es ‘Día de Muertos’, aunque la denominación ‘Día de los Muertos’ también es gramaticalmente correcta» [‘Día de Muertos’ or ‘Día de los Muertos’? The name used in Mexico to denominate the traditional celebration in which death is honored is ‘Día de Muertos’, although the denomination ‘Día de los Muertos’ is also grammatically correct] (in Spanish). Royal Spanish Academy Official Twitter Account. November 2, 2019. Retrieved November 4, 2020.

- ^ Sacred Places of a Lifetime. National Geographic. 2008. p. 273. ISBN 978-1-4262-0336-7.

Day of the Dead celebrations take place over October 31 … November 1 (All Saints’ Day), and November 2.

- ^ Skibo, James; Skibo, James M.; Feinman, Gary (January 14, 1999). Pottery and People. University of Utah Press. p. 65. ISBN 978-0-87480-577-2.

In Yucatan, however, the Day of the Dead rituals occur on October 31, November 1, and November 6.

- ^ Arnold, Dean E. (February 7, 2018). Maya Potters’ Indigenous Knowledge: Cognition, Engagement, and Practice. University Press of Colorado. p. 206. ISBN 978-1-60732-656-4.

pottery as a distilled taskscape is best illustrated in the pottery required for Day of the Dead rituals (on October 31, November 1, and November 6), when the spirits of deceased ancestors come back to the land of the living.

- ^ Society, National Geographic (October 17, 2012). «Dia de los Muertos». National Geographic Society. Retrieved April 8, 2019.

- ^ a b Palfrey, Dale Hoyt (1995). «The Day of the Dead». Día de los Muertos Index. Access Mexico Connect. Archived from the original on November 30, 2007. Retrieved November 28, 2007.

- ^ «Dia de los Muertos». National Geographic Society. October 17, 2012. Archived from the original on November 2, 2016. Retrieved November 2, 2016.

- ^ a b Chávez, Xóchitl (October 23, 2018). «Literary Calaveras». Smithsonian Voices.

- ^ a b «Indigenous festivity dedicated to the dead». UNESCO. Archived from the original on October 11, 2014. Retrieved October 31, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e «Día de muertos, ¿tradición prehispánica o invención del siglo XX?». Relatos e Historias en México. November 2, 2020.

- ^ a b «Dos historiadoras encuentran diverso origen del Día de Muertos en México». www.opinion.com.bo.

- ^ a b ««Día de Muertos, un invento cardenista», decía Elsa Malvido». El Universal. November 3, 2017.

- ^ a b «El Día de Muertos mexicano nació como arma política o tradición prehispánica — Arte y Cultura — IntraMed». www.intramed.net.

- ^ a b c «Orígenes profundamente católicos y no prehispánicos, la fiesta de día de muertos». www.inah.gob.mx.

- ^ «09an1esp». www.jornada.com.mx.

- ^ Paz,Octavio. ‘The Labyrinth of Solitude’. N.Y.: Grove Press, 1961.

- ^ a b c Salvador, R.J. (2003). John D. Morgan and Pittu Laungani (ed.). Death and Bereavement Around the World: Death and Bereavement in the Americas. Death, Value and Meaning Series, Vol. II. Amityville, New York: Baywood Publishing Company. pp. 75–76. ISBN 978-0-89503-232-4.

- ^ «5 Facts About Día de los Muertos (The Day of the Dead)». Smithsonian Insider. October 30, 2016. Archived from the original on August 29, 2018. Retrieved August 29, 2018.

- ^ a b c Brandes, Stanley (1997). «Sugar, Colonialism, and Death: On the Origins of Mexico’s Day of the Dead». Comparative Studies in Society and History. 39 (2): 275. doi:10.1017/S0010417500020624. ISSN 0010-4175. JSTOR 179316. S2CID 145402658.

- ^ Turim, Gayle (November 2, 2012). «Day of the Dead Sweets and Treats». History Stories. History Channel. Archived from the original on June 6, 2015. Retrieved July 1, 2015.

- ^ a b c Godoy, Maria (November 2016). «Sugar Skulls, Tamales And More: Why Is That Food On The Day Of The Dead Altar?». NPR. Archived from the original on October 28, 2017. Retrieved October 25, 2017.

- ^ Castella, Krystina (October 2010). «Pan de Muerto Recipe». Epicurious. Archived from the original on July 8, 2015. Retrieved November 2, 2019.

- ^ «Jamaica iced tea». Cooking in Mexico. Archived from the original on November 4, 2011. Retrieved October 23, 2011.

- ^ Kennedy, D. (2018). Cocina esencial de México. Fondo de Cultura Económica. p. 156. ISBN 9786071656636. Retrieved June 1, 2021.

- ^ R., Muñoz. «Muc bil pollo». Diccionario enciclopédico de la Gastronomía Mexicana [Enciclopedic dictionary of Mexican Gastronomy] (in Spanish). Larousse Cocina.

- ^ a b c d e f Marchi, Regina M (2009). Day of the Dead in the USA : The Migration and Transformation of a Cultural Phenomenon. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-8135-4557-8.

- ^ «Mi Calaverita: Mexico’s Trick or Treat». Mexperience. October 31, 2020.

- ^ «These wicked Day of the Dead poems don’t spare anyone». PBS NewsHour. November 2, 2018. Retrieved May 6, 2019.

- ^ «Día de los Muertos or Day of the Dead». Archived from the original on August 29, 2018. Retrieved August 29, 2018.

- ^ «Mexico City stages first Day of the Dead parade». BBC. October 29, 2016. Archived from the original on October 30, 2016. Retrieved November 1, 2016.

- ^ «Fotogalería: Desfile por Día de Muertos reúne a 250 mil personas». Excélsior (in Spanish). October 29, 2016. Archived from the original on October 31, 2016. Retrieved November 1, 2016.

- ^ «Galerías Archivo». Televisa News. Archived from the original on November 3, 2016. Retrieved November 1, 2016.

- ^ Wise, Danno. «Port Isabel’s Day of the Dead Celebration». Texas Travel. About.com. Archived from the original on December 9, 2007. Retrieved November 28, 2007.

- ^ «Dia de los Muertos». visitalbuquerque.org. Archived from the original on November 3, 2016. Retrieved November 1, 2016.

- ^ Hedding, Judy. «Day of the Dead». Phoenix. About.com. Archived from the original on December 11, 2007. Retrieved November 28, 2007.

- ^ White, Erin (November 5, 2006). «All Souls Procession». Arizona Daily Star. Archived from the original on November 6, 2012. Retrieved November 28, 2007.

- ^ «Old Town San Diego’s Dia de los Muertos». Archived from the original on November 7, 2014. Retrieved October 19, 2014.

- ^ Oliveira, Rebeca (November 4, 2011). «Day of the Dead dies as cemetery cuts arts». Jamaica Plain Gazette. Archived from the original on October 19, 2022. Retrieved October 19, 2022.

- ^ Smithsonian Latino Virtual Museum. Día de los Muertos: Day of the Dead (Version 1.2 ed.). Archived from the original on December 22, 2014. Retrieved October 31, 2014.

- ^ «Smithsonian Latino Virtual Museum». Ustream. Archived from the original on October 31, 2014. Retrieved October 31, 2014.

- ^ Smithsonian Latino Virtual Museum. «Day of the Dead». Theater of the Dead. Archived from the original on November 12, 2014. Retrieved October 31, 2014.

- ^ Smithsonian Institution. «Smithsonian-UTEP Día de los Muertos Festival: A 2D and 3D Experience!». Smithsonian Latino Virtual Museum Press Release. Archived from the original on November 6, 2009.

- ^ @LaCasaBlanca (November 1, 2021). «Feliz Día de los Muertos de la Administración Biden-Harris. Hoy y mañana, el Presidente y la Primera Dama reconocerán el Día de los Muertos con la primera ofrenda ubicada en la Casa Blanca» (Tweet) (in Spanish). Retrieved November 4, 2021 – via Twitter.

- ^ «Less-scary holiday: Some faith groups offer alternatives to Halloween trick-or-treating». The Orange County Register. October 30, 2015. Archived from the original on October 31, 2015. Retrieved November 2, 2015.

- ^ «Viva la Vida or Noche de Altares? Santa Ana’s downtown division fuels dueling Day of the Dead events». The Orange County Register. October 30, 2015. Archived from the original on November 3, 2015. Retrieved November 2, 2015.

- ^ Quinones, Sam (October 28, 2006). «Making a night of Day of the Dead». Los Angeles Times. Retrieved November 26, 2006.

- ^ «Dia de los Muertos [Day of the Dead] – San Francisco». Archived from the original on October 17, 2014. Retrieved October 19, 2014.

- ^ Elliott, Vicky (October 27, 2000). «Lively Petaluma festival marks Day of the Dead». The San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on July 8, 2012. Retrieved August 6, 2010.

- ^ McIntosh, Linda; Groch, Laura (October 20, 2022). «Celebrate Día de los Muertos in San Diego County with these festive events». San Diego Union-Tribune. Retrieved November 1, 2022.

- ^ «Witness historic Day of the Dead rituals in Naples, Italy». National Geographic. November 20, 2018. Retrieved November 2, 2022.

- ^ «FESTA DEI MORTI: THE SICILIAN WAY TO REMEMBER THEIR LOVED ONES». Scent of Sicily. Retrieved November 2, 2022.

- ^ «ANDREA CAMILLERI TELLS US: «THE DAY OF THE DEAD IN SICILY»«. Sicily Tourist (in Italian). Retrieved November 4, 2022.

- ^ «The Frutta Martorana, the Typical Sicilian Dessert for All Souls’ day». Visit Italy. Retrieved November 2, 2022.

- ^ «Witness historic Day of the Dead rituals in Naples, Italy». National Geographic. November 20, 2018. Retrieved November 2, 2022.

- ^ «Day of the Dead in Wellington, New Zealand». Scoop.co.nz. October 27, 2007. Archived from the original on June 4, 2009. Retrieved August 13, 2009.

- ^ «All Saints Day around the world». Guardian Weekly. November 1, 2010. Archived from the original on October 29, 2018. Retrieved October 30, 2018.

- ^ «48 Best Sugar Skull Makeup Creations To Day of the Dead». August 22, 2017. Retrieved October 14, 2019.

- ^ «Day of the Dead in Prague». Radio Czech. October 24, 2007. Archived from the original on October 24, 2007.

- ^ Guidi, Ruxandra (November 9, 2007). «Las Natitas». BBC. Archived from the original on December 6, 2008.

- ^ Smith, Fiona (November 8, 2005). «Bolivians Honor Skull-Toting Tradition». Associated Press. Archived from the original on February 18, 2008. Retrieved December 30, 2007.

- ^ «All Saints day in Bolivia – «The skull festival»«. Bolivia Line (May 2005). Archived from the original on October 23, 2008. Retrieved December 20, 2007.

- ^ Costa Rica Celebrates The Day of the Dead Outward Bound Costa Rica, 2012-11-01.

- ^ Ortiz, Gonzalo (October 30, 2010). «Diversity in Remembering the Dead». InterPress Service News Agency. Archived from the original on November 4, 2010. Retrieved October 30, 2010.

- ^ Burlingame, Betsy; Wood, Joshua. «Visit to cemetery in Guatemala». Expatexchange.com. Archived from the original on October 14, 2007. Retrieved August 13, 2009.

- ^ «Perú: así se vivió Día de todos los santos en cementerios de Lima». Peru. peru.com. January 1, 2016. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved October 30, 2017.

- ^ «Bones of the Dead Cookies — Ossa Di Morto». Savoring Italy. October 24, 2019. Retrieved November 2, 2021.

Further reading

- Andrade, Mary J. Day of the Dead A Passion for Life – Día de los Muertos Pasión por la Vida. La Oferta Publishing, 2007. ISBN 978-0-9791624-04

- Anguiano, Mariana, et al. Las tradiciones de Día de Muertos en México. Mexico City 1987.

- Brandes, Stanley (1997). «Sugar, Colonialism, and Death: On the Origins of Mexico’s Day of the Dead». Comparative Studies in Society and History. 39 (2): 270–99. doi:10.1017/S0010417500020624. S2CID 145402658.

- Brandes, Stanley (1998). «The Day of the Dead, Halloween, and the Quest for Mexican National Identity». Journal of American Folklore. 111 (442): 359–80. doi:10.2307/541045. JSTOR 541045.

- Brandes, Stanley (1998). «Iconography in Mexico’s Day of the Dead». Ethnohistory. Duke University Press. 45 (2): 181–218. doi:10.2307/483058. JSTOR 483058.

- Brandes, Stanley (2006). Skulls to the Living, Bread to the Dead. Blackwell Publishing. p. 232. ISBN 978-1-4051-5247-1.

- Cadafalch, Antoni. The Day of the Dead. Korero Books, 2011. ISBN 978-1-907621-01-7

- Carmichael, Elizabeth; Sayer, Chloe. The Skeleton at the Feast: The Day of the Dead in Mexico. Great Britain: The Bath Press, 1991. ISBN 0-7141-2503-2

- Conklin, Paul (2001). «Death Takes a Holiday». U.S. Catholic. 66: 38–41.

- Garcia-Rivera, Alex (1997). «Death Takes a Holiday». U.S. Catholic. 62: 50.

- Haley, Shawn D.; Fukuda, Curt. Day of the Dead: When Two Worlds Meet in Oaxaca. Berhahn Books, 2004. ISBN 1-84545-083-3

- Lane, Sarah and Marilyn Turkovich, Días de los Muertos/Days of the Dead. Chicago 1987.

- Lomnitz, Claudio. Death and the Idea of Mexico. Zone Books, 2005. ISBN 1-890951-53-6

- Matos Moctezuma, Eduardo, et al. «Miccahuitl: El culto a la muerte,» Special issue of Artes de México 145 (1971)

- Nutini, Hugo G. Todos Santos in Rural Tlaxcala: A Syncretic, Expressive, and Symbolic Analysis of the Cult of the Dead. Princeton 1988.

- Oliver Vega, Beatriz, et al. The Days of the Dead, a Mexican Tradition. Mexico City 1988.

- Roy, Ann (1995). «A Crack Between the Worlds». Commonwealth. 122: 13–16.

| Day of the Dead | |

|---|---|

Día de Muertos altar commemorating a deceased man in Milpa Alta, Mexico City |

|

| Observed by | Mexico, and regions with large Mexican populations |

| Type |

|

| Significance | Prayer and remembrance of friends and family members who have died |

| Celebrations | Creation of home altars to remember the dead, traditional dishes for the Day of the Dead |

| Begins | November 1 |

| Ends | November 2 |

| Date | November 2 |

| Next time | 2 November 2023 |

| Frequency | Annual |

| Related to | All Saints’ Day, All Hallows’ Eve, All Souls Day[1] |

The Day of the Dead (Spanish: Día de Muertos or Día de los Muertos)[2][3] is a holiday traditionally celebrated on November 1 and 2, though other days, such as October 31 or November 6, may be included depending on the locality.[4][5][6] It is widely observed in Mexico, where it largely developed, and is also observed in other places, especially by people of Mexican heritage. Although related to the simultaneous Christian remembrances for Hallowtide,[1] it has a much less solemn tone and is portrayed as a holiday of joyful celebration rather than mourning.[7] The multi-day holiday involves family and friends gathering to pay respects and to remember friends and family members who have died. These celebrations can take a humorous tone, as celebrants remember funny events and anecdotes about the departed.[8]

Traditions connected with the holiday include honoring the deceased using calaveras and marigold flowers known as cempazúchitl, building home altars called ofrendas with the favorite foods and beverages of the departed, and visiting graves with these items as gifts for the deceased.[9] The celebration is not solely focused on the dead, as it is also common to give gifts to friends such as candy sugar skulls, to share traditional pan de muerto with family and friends, and to write light-hearted and often irreverent verses in the form of mock epitaphs dedicated to living friends and acquaintances, a literary form known as calaveras literarias.[10]

In 2008, the tradition was inscribed in the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO.[11]

Origins, history, and similarities to other festivities

Mexican academics are divided on whether the festivity has genuine indigenous pre-Hispanic roots or whether it is a 20th-century rebranded version of a Spanish tradition developed during the presidency of Lázaro Cárdenas to encourage Mexican nationalism through an «Aztec» identity.[12][13][14] The festivity has become a national symbol in recent decades and it is taught in the nation’s school system asserting a native origin.[15] In 2008, the tradition was inscribed in the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO.[11]

Views differ on whether the festivity has indigenous pre-Hispanic roots, whether it is a more modern adaptation of an existing European tradition, or a combination of both as a manifestation of syncretism. Similar traditions can be traced back to Medieval Europe, where celebrations like All Saints’ Day and All Souls’ Day are observed on the same days in places like Spain and Southern Europe. Critics of the native American origin claim that even though pre-Columbian Mexico had traditions that honored the dead, current depictions of the festivity have more in common with European traditions of Danse macabre and their allegories of life and death personified in the human skeleton to remind us the ephemeral nature of life.[16][12] Over the past decades, however, Mexican academia has increasingly questioned the validity of this assumption, even going as far as calling it a politically motivated fabrication. Historian Elsa Malvido, researcher for the Mexican INAH and founder of the institute’s Taller de Estudios sobre la Muerte, was the first to do so in the context of her wider research into Mexican attitudes to death and disease across the centuries. Malvido completely discards a native or even syncretic origin arguing that the tradition can be fully traced to Medieval Europe. She highlights the existence of similar traditions on the same day, not just in Spain, but in the rest of Catholic Southern Europe and Latin America such as altars for the dead, sweets in the shape of skulls and bread in the shape of bones.[16]

Agustin Sanchez Gonzalez has a similar view in his article published in the INAH’s bi-monthly journal Arqueología Mexicana. Gonzalez states that, even though the «indigenous» narrative became hegemonic, the spirit of the festivity has far more in common with European traditions of Danse macabre and their allegories of life and death personified in the human skeleton to remind us the ephemeral nature of life. He also highlights that in the 19th century press there was little mention of the Day of the Dead in the sense that we know it today. All there was were long processions to cemeteries, sometimes ending with drunkenness. Elsa Malvido also points to the recent origin of the tradition of «velar» or staying up all night with the dead. It resulted from the Reform Laws under the presidency of Benito Juarez which forced family pantheons out of Churches and into civil cemeteries, requiring rich families having servants guarding family possessions displayed at altars.[16]

The historian Ricardo Pérez Montfort has further demonstrated how the ideology known as indigenismo became more and more closely linked to post-revolutionary official projects whereas Hispanismo was identified with conservative political stances. This exclusive nationalism began to displace all other cultural perspectives to the point that in the 1930s, the Aztec god Quetzalcoatl was officially promoted by the government as a substitute for the Spanish Three Kings tradition, with a person dressed up as the deity offering gifts to poor children.[12]

In this context, the Day of the Dead began to be officially isolated from the Catholic Church by the leftist government of Lázaro Cárdenas motivated both by «indigenismo» and left-leaning anti-clericalism. Malvido herself goes as far as calling the festivity a «Cardenist invention» whereby the Catholic elements are removed and emphasis is laid on indigenous iconography, the focus on death and what Malvido considers to be the cultural invention according to which Mexicans venerate death.[14][17] Gonzalez explains that Mexican nationalism developed diverse cultural expressions with a seal of tradition but which are essentially social constructs which eventually developed ancestral tones. One of these would be the Catholic Día de Muertos which, during the 20th century, appropriated the elements of an ancient pagan rite.[12]

One key element of the re-developed festivity which appears during this time is La Calavera Catrina by Mexican lithographer José Guadalupe Posada. According to Gonzalez, whereas Posada is portrayed in current times as the «restorer» of Mexico’s pre-Hispanic tradition he was never interested in Native American culture or history. Posada was predominantly interested in drawing scary images which are far closer to those of the European renaissance or the horrors painted by Francisco de Goya in the Spanish war of Independence against Napoleon than the Mexica tzompantli. The recent trans-atlantic connection can also be observed in the pervasive use of couplet in allegories of death and the play Don Juan Tenorio by 19th Spanish writer José Zorrilla which is represented on this date both in Spain and in Mexico since the early 19th century due to its ghostly apparitions and cemetery scenes.[12]

Opposing views assert that despite the obvious European influence, there exists proof of pre-Columbian festivities that were very similar in spirit, with the Aztec people having at least six celebrations during the year that were very similar to Day of the Dead, the closest one being Quecholli, a celebration that honored Mixcóatl (the god of war) and was celebrated between October 20 and November 8. This celebration included elements such as the placement of altars with food (tamales) near the burying grounds of warriors to help them in their journey to the afterlife.[13] Influential Mexican poet and Nobel prize laureate Octavio Paz strongly supported the syncretic view of the Día de Muertos tradition being a continuity of ancient Aztec festivals celebrating death, as is most evident in the chapter «All Saints, Day of the Dead» of his 1950 book-length essay The Labyrinth of Solitude.[18]

Regardless of its origin, the festivity has become a national symbol in Mexico and as such is taught in the nation’s school system, typically asserting a native origin. It is also a school holiday nationwide.[15]

Observance in Mexico

Altars (ofrendas)

During Día de Muertos, the tradition is to build private altars («ofrendas») containing the favorite foods and beverages, as well as photos and memorabilia, of the departed. The intent is to encourage visits by the souls, so the souls will hear the prayers and the words of the living directed to them. These altars are often placed at home or in public spaces such as schools and libraries, but it is also common for people to go to cemeteries to place these altars next to the tombs of the departed.[8]

Mexican cempasúchil (marigold) is the traditional flower used to honor the dead.

Plans for the day are made throughout the year, including gathering the goods to be offered to the dead. During the three-day period families usually clean and decorate graves;[19] most visit the cemeteries where their loved ones are buried and decorate their graves with ofrendas (altars), which often include orange Mexican marigolds (Tagetes erecta) called cempasúchil (originally named cempōhualxōchitl, Nāhuatl for ‘twenty flowers’). In modern Mexico the marigold is sometimes called Flor de Muerto (‘Flower of Dead’). These flowers are thought to attract souls of the dead to the offerings. It is also believed the bright petals with a strong scent can guide the souls from cemeteries to their family homes.[20][21]

Toys are brought for dead children (los angelitos, or ‘the little angels’), and bottles of tequila, mezcal or pulque or jars of atole for adults. Families will also offer trinkets or the deceased’s favorite candies on the grave. Some families have ofrendas in homes, usually with foods such as candied pumpkin, pan de muerto (‘bread of dead’), and sugar skulls; and beverages such as atole. The ofrendas are left out in the homes as a welcoming gesture for the deceased.[19][21] Some people believe the spirits of the dead eat the «spiritual essence» of the ofrendas‘ food, so though the celebrators eat the food after the festivities, they believe it lacks nutritional value. Pillows and blankets are left out so the deceased can rest after their long journey. In some parts of Mexico, such as the towns of Mixquic, Pátzcuaro and Janitzio, people spend all night beside the graves of their relatives. In many places, people have picnics at the grave site, as well.

Some families build altars or small shrines in their homes;[19] these sometimes feature a Christian cross, statues or pictures of the Blessed Virgin Mary, pictures of deceased relatives and other people, scores of candles, and an ofrenda. Traditionally, families spend some time around the altar, praying and telling anecdotes about the deceased. In some locations, celebrants wear shells on their clothing, so when they dance, the noise will wake up the dead; some will also dress up as the deceased.

Food

During Day of the Dead festivities, food is both eaten by living people and given to the spirits of their departed ancestors as ofrendas (‘offerings’).[22] Tamales are one of the most common dishes prepared for this day for both purposes.[23]

Family altar for the Day of the Dead on a patio

Pan de muerto and calaveras are associated specifically with Day of the Dead. Pan de muerto is a type of sweet roll shaped like a bun, topped with sugar, and often decorated with bone-shaped pieces of the same pastry.[24] Calaveras, or sugar skulls, display colorful designs to represent the vitality and individual personality of the departed.[23]

In addition to food, drinks are also important to the tradition of Day of the Dead. Historically, the main alcoholic drink was pulque while today families will commonly drink the favorite beverage of their deceased ancestors.[23] Other drinks associated with the holiday are atole and champurrado, warm, thick, non-alcoholic masa drinks.

Agua de Jamaica (water of hibiscus) is a popular herbal tea made of the flowers and leaves of the Jamaican hibiscus plant (Hibiscus sabdariffa), known as flor de Jamaica in Mexico. It is served cold and quite sweet with a lot of ice. The ruby-red beverage is also known as hibiscus tea in English-speaking countries.[25]

In the Yucatán Peninsula, mukbil pollo (píib chicken) is traditionally prepared on October 31 or November 1, and eaten by the family throughout the following days. It is similar to a big tamale, composed of masa and pork lard, and stuffed with pork, chicken, tomato, garlic, peppers, onions, epazote, achiote, and spices. Once stuffed, the mukbil pollo is bathed in kool sauce, made with meat broth, habanero chili, and corn masa. It is then covered in banana leaves and steamed in an underground oven over the course of several hours. Once cooked, it is dug up and opened to eat.[26][27]

Calaveras

A common symbol of the holiday is the skull (in Spanish calavera), which celebrants represent in masks, called calacas (colloquial term for skeleton), and foods such as chocolate or sugar skulls, which are inscribed with the name of the recipient on the forehead. Sugar skulls can be given as gifts to both the living and the dead.[28] Other holiday foods include pan de muerto, a sweet egg bread made in various shapes from plain rounds to skulls, often decorated with white frosting to look like twisted bones.[21]

Calaverita

In some parts of the country, especially the larger cities, children in costumes roam the streets, knocking on people’s doors for a calaverita, a small gift of candies or money; they also ask passersby for it. This custom is similar to that of Halloween’s trick-or-treating in the United States, but without the component of mischief to homeowners if no treat is given.[29]

Calaveras literarias

A distinctive literary form exists within this holiday where people write short poems in traditional rhyming verse, called calaveras literarias (lit. «literary skulls»), which are mocking, light-hearted epitaphs mostly dedicated to friends, classmates, co-workers, or family members (living or dead) but also to public or historical figures, describing interesting habits and attitudes, as well as comedic or absurd anecdotes that use death-related imagery which includes but is not limited to cemeteries, skulls, or the grim reaper, all of this in situations where the dedicatee has an encounter with death itself.[30] This custom originated in the 18th or 19th century after a newspaper published a poem narrating a dream of a cemetery in the future which included the words «and all of us were dead», and then proceeding to read the tombstones. Current newspapers dedicate calaveras literarias to public figures, with cartoons of skeletons in the style of the famous calaveras of José Guadalupe Posada, a Mexican illustrator.[28] In modern Mexico, calaveras literarias are a staple of the holiday in many institutions and organizations, for example, in public schools, students are encouraged or required to write them as part of the language class.[10]

Posada created what might be his most famous print, he called the print La Calavera Catrina («The Elegant Skull») as a parody of a Mexican upper-class female. Posada’s intent with the image was to ridicule the others that would claim the culture of the Europeans over the culture of the indigenous people. The image was a skeleton with a big floppy hat decorated with two big feathers and multiple flowers on the top of the hat. Posada’s striking image of a costumed female with a skeleton face has become associated with the Day of the Dead, and Catrina figures often are a prominent part of modern Day of the Dead observances.[28]

Theatrical presentations of Don Juan Tenorio by José Zorrilla (1817–1893) are also traditional on this day.

Local traditions

The traditions and activities that take place in celebration of the Day of the Dead are not universal, often varying from town to town. For example, in the town of Pátzcuaro on the Lago de Pátzcuaro in Michoacán, the tradition is very different if the deceased is a child rather than an adult. On November 1 of the year after a child’s death, the godparents set a table in the parents’ home with sweets, fruits, pan de muerto, a cross, a rosary (used to ask the Virgin Mary to pray for them), and candles. This is meant to celebrate the child’s life, in respect and appreciation for the parents. There is also dancing with colorful costumes, often with skull-shaped masks and devil masks in the plaza or garden of the town. At midnight on November 2, the people light candles and ride winged boats called mariposas (butterflies) to Janitzio, an island in the middle of the lake where there is a cemetery, to honor and celebrate the lives of the dead there.

In contrast, the town of Ocotepec, north of Cuernavaca in the State of Morelos, opens its doors to visitors in exchange for veladoras (small wax candles) to show respect for the recently deceased. In return the visitors receive tamales and atole. This is done only by the owners of the house where someone in the household has died in the previous year. Many people of the surrounding areas arrive early to eat for free and enjoy the elaborate altars set up to receive the visitors.

Another peculiar tradition involving children is La Danza de los Viejitos (the Dance of the Old Men) where boys and young men dressed like grandfathers crouch and jump in an energetic dance.[31]

In the 2015 James Bond film Spectre, the opening sequence features a Day of the Dead parade in Mexico City. At the time, no such parade took place in Mexico City; one year later, due to the interest in the film and the government desire to promote the Mexican culture, the federal and local authorities decided to organize an actual Día de Muertos parade through Paseo de la Reforma and Centro Historico on October 29, 2016, which was attended by 250,000 people.[32][33][34] This could be seen as an example of the pizza effect. The idea of a massive celebration was also popularized in the Disney Pixar movie Coco.

Observances outside of Mexico

America

United States

Women with calaveras makeup celebrating Día de Muertos in the Mission District of San Francisco, California

In many U.S. communities with Mexican residents, Day of the Dead celebrations are very similar to those held in Mexico. In some of these communities, in states such as Texas,[35] New Mexico,[36] and Arizona,[37] the celebrations tend to be mostly traditional. The All Souls Procession has been an annual Tucson, Arizona, event since 1990. The event combines elements of traditional Day of the Dead celebrations with those of pagan harvest festivals. People wearing masks carry signs honoring the dead and an urn in which people can place slips of paper with prayers on them to be burned.[38] Likewise, Old Town San Diego, California, annually hosts a traditional two-day celebration culminating in a candlelight procession to the historic El Campo Santo Cemetery.[39]

The festival also was held annually at historic Forest Hills Cemetery in Boston’s Jamaica Plain neighborhood. Sponsored by Forest Hills Educational Trust and the folkloric performance group La Piñata, the Day of the Dead festivities celebrated the cycle of life and death. People brought offerings of flowers, photos, mementos, and food for their departed loved ones, which they placed at an elaborately and colorfully decorated altar. A program of traditional music and dance also accompanied the community event. The Jamaica Plain celebration was discontinued in 2011.[40]

The Smithsonian Institution, in collaboration with the University of Texas at El Paso and Second Life, have created a Smithsonian Latino Virtual Museum and accompanying multimedia e-book: Día de los Muertos: Day of the Dead. The project’s website contains some of the text and images which explain the origins of some of the customary core practices related to the Day of the Dead, such as the background beliefs and the offrenda (the special altar commemorating one’s deceased loved one).[41] The Made For iTunes multimedia e-book version provides additional content, such as further details; additional photo galleries; pop-up profiles of influential Latino artists and cultural figures over the decades; and video clips[42] of interviews with artists who make Día de Muertos-themed artwork, explanations and performances of Aztec and other traditional dances, an animation short that explains the customs to children, virtual poetry readings in English and Spanish.[43][44]

In 2021, the Biden-Harris administration celebrated the Día de Muertos.[45]

California

Santa Ana, California, is said to hold the «largest event in Southern California» honoring Día de Muertos, called the annual Noche de Altares, which began in 2002.[46] The celebration of the Day of the Dead in Santa Ana has grown to two large events with the creation of an event held at the Santa Ana Regional Transportation Center for the first time on November 1, 2015.[47]

In other communities, interactions between Mexican traditions and American culture are resulting in celebrations in which Mexican traditions are being extended to make artistic or sometimes political statements. For example, in Los Angeles, California, the Self Help Graphics & Art Mexican-American cultural center presents an annual Day of the Dead celebration that includes both traditional and political elements, such as altars to honor the victims of the Iraq War, highlighting the high casualty rate among Latino soldiers. An updated, intercultural version of the Day of the Dead is also evolving at Hollywood Forever Cemetery.[48] There, in a mixture of Native Californian art, Mexican traditions and Hollywood hip, conventional altars are set up side by side with altars to Jayne Mansfield and Johnny Ramone. Colorful native dancers and music intermix with performance artists, while sly pranksters play on traditional themes.

Similar traditional and intercultural updating of Mexican celebrations are held in San Francisco. For example, the Galería de la Raza, SomArts Cultural Center, Mission Cultural Center, de Young Museum and altars at Garfield Square by the Marigold Project.[49] Oakland is home to Corazon Del Pueblo in the Fruitvale district. Corazon Del Pueblo has a shop offering handcrafted Mexican gifts and a museum devoted to Day of the Dead artifacts. Also, the Fruitvale district in Oakland serves as the hub of the Día de Muertos annual festival which occurs the last weekend of October. Here, a mix of several Mexican traditions come together with traditional Aztec dancers, regional Mexican music, and other Mexican artisans to celebrate the day.[50]

Car ofrendas on display during the Oceanside, California Dia de los Muertos festival

In San Diego, California, the city that borders Mexico, the celebrations range across the entire county. All the way up at the most northern part of the county, Oceanside celebrates their annual event which includes community and family altars built around the Oceanside Civic Center and Pier View Way, as well as events at the Mission San Luis Rey de Francia. In the more central area of San Diego, City Heights celebrates through a public festival in Jeremy Henwood Memorial Park that includes at least 35 altars, lowriders, and entertainment, all for free. Down in Chula Vista, they celebrate the tradition through a movie night at Third and Davidson streets where they will be screening “Coco.” This movie night also consists of a community altar, an Altar contest, a catrin/catrina contest, as well as lots of music, food, and vendors. Overall, San Diego is booming with colorful celebrations honoring ancestors across the county.[51]

Italy

In Italy, November 2nd is All Souls’ Day and is colloquially known as Day of the Dead or «Giorno dei Morti». While many regional nuances exist, celebrations generally consist of placing flowers at cemeteries and family burial sites and speaking to deceased relatives.[52] Some traditions also include lighting a red candle or «lumino» on the window sills at sunset and laying out a table of food for deceased relatives who will come to visit. Like other Day of the Dead traditions around the world, Giorno dei Morti is a day dedicated to honoring the lives of those who have died. Additionally, it is a tradition that teaches children not to be afraid of death.

A Sicilian cannistru dei morti