Зачем сжигают чучело Гая Фокса? Британия отпраздновала Ночь костров

Более 400 лет в Великобритании отмечают праздник, история которого весьма печальна. Ночь Гая Фокса считается одной из самых шумных в стране. Традиция — сжигать чучела и запускать фейерверки. Корни праздника уходят к 5 ноября 1605 года, когда заговорщикам не удалось взорвать парламент. В массовой культуре Гай Фокс ассоциируется прежде всего с маской из комикса Алана Мура «V — значит вендетта».

«Пороховой заговор»

В 1605 году к правлению пришел Яков I. Католики надеялись, что с ним на троне их жизнь станет лучше. Они хотели отмены штрафов и ограничений, наложенных предыдущей королевой. Яков I ничего отменять не стал. Тогда возник заговор против короля и палаты лордов. Целью было взорвать здание парламента во время ежегодной церемонии открытия заседания палаты. Если бы все сработало, то умерли бы король и остальные политики. Дальше заговорщики сменили бы власть в стране.

Для осуществления взрыва они приобрели 36 бочек с порохом, которые спрятали в подвале под палатой лордов. Именно Гай Фокс должен был поджечь фитиль и позволить всем умереть, но не успел.

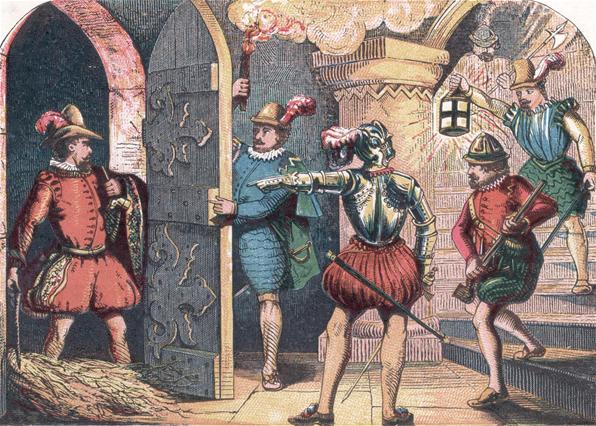

Один из участников «Порохового заговора» захотел спасти своего друга лорда и попросил его не приходить на открытие заседания. Письмо с просьбой попало в руки короля. Все подвалы парламента тут же обыскали, а Фокса поймали с поличным.

Революционера так долго и жестоко пытали, что он выдал имена всех заговорщиков. Их публично казнили, а Гая Фокса четвертовали.

https://twitter.com/scallywap/status/1190757861829296129

Некоторые считают, что Яков I придумал заговор, чтобы укрепить свою власть. Остается неизвестным, как Фокс мог незаметно внести 36 бочек с порохом в правительственное здание.

Смена традиций

Англичане были так рады спасению короля, что стали разжигать костры на улицах. С годами празднование в честь спасения монарха стало более обширным. Люди начали сжигать чучела Гая Фокса и атрибутику «Порохового заговора». Еще позже появились фейерверки и петарды. В наше время сжигают уже не только чучело Фокса. Частенько это может быть личность какого-нибудь политика, президента или певца.

Например, общество Edenbridge Bonfire прославилось своими огромными чучелами знаменитостей. За последние несколько лет они успели сжечь Дональда Трампа, Харви Вайнштейна и Бориса Джонсона. В этом году их выбор пал на ушедшего в отставку с поста спикера палаты общин Джона Беркоу. В своих руках он держит головы Бориса Джонсона и Джереми Корбина.

Для детей в этот день тоже есть развлечение. Они собирают у прохожих «монетки для Гая». Считается, что люди жертвуют деньги на костер для заговорщика. Собранные деньги дети тратят на петарды и фейерверки. Чем-то напоминает Хэллоуин, но там все обходится безобидным сбором конфет.

Многие предпочитают в Ночь Гая Фокса примерить на себя исторический образ. Кто-то одевается стражем того времени, кто-то обычным жителем XVII века. Также можно увидеть многочисленные шествия с факелами в руках. Часто на улице разыгрывают сцены задержания и заключения Гая Фокса.

Guy Fawkes night went off with a bang 🎇 #iom #isleofman #guyfawkes #fireworks pic.twitter.com/WiuHgl9jVR

— Taradean Farm (@BlomquistTara) November 2, 2019

Люди могут понаблюдать за сожжением чучел и масштабными фейерверками на каких-нибудь площадях, а могут устроить их в собственном дворе. Правда, сейчас все больше британцев требуют запрета такого грандиозного празднования. По их словам, звуки от взрыва петард и фейерверков плохо влияют на детей и животных. Домашние питомцы могут испытать большой стресс и даже умереть, а маленькие дети часто начинают плакать или забиваться в угол.

Лицо протестов

Благодаря комиксу «V — значит вендетта» и дальнейшей его экранизации образ Гая Фокса стал известен всему миру.

Главный герой комикса V носит маску, повторяющую черты Гая Фокса. Персонаж считал себя революционером и хотел продолжить дело Фокса. Маска стала символом протестующих. Этот образ укрепился после выхода фильма.

Remember, remember. Before the Dali mask, there was the Guy Fawkes mask.

[🎥 V for Vendetta] pic.twitter.com/13Kx1JExeC

— Netflix Philippines (@Netflix_PH) November 5, 2019

С годами популярность маски только растет. Так, например, выпускники в Гонконге пришли на церемонию в масках Фокса. Таким образом они выражали поддержку протестам. Во время акции «Захвати Уолл-стрит» в 2011 году улицы впервые были массово заполнены людьми в масках. Это больше не атрибут известного фильма. Для людей это символ борьбы с цензурой и коррупцией. Ну и отличный способ скрыть свое лицо.

✨Poly U HK Graduation✨

A group of Undergrads wore Guy Fawkes mask and rally with “Winnie the Pooh” and “PRC President Xi” on their Graduation Day#StandWithHongKong #FightForFreedom

📷:am730 pic.twitter.com/h11ORh0a1u

— Kings Cheung (@CheungKings) October 30, 2019

Еще один известный пример распространения маски Фокса — организация «Анонимус». Хакеры-активисты решили сделать ее символом своего движения.

Погибший революционер успел также внести вклад в английский язык. Слово guy, которое сейчас используется для обозначения парня, пришло от имени Гая Фокса. Правда, изначально им называли человека, который плохо одет.

Праздники

Великобритания

Англия

Guy Fawkes Night, also known as Guy Fawkes Day, Bonfire Night and Fireworks Night, is an annual commemoration observed on 5 November, primarily in Great Britain, involving bonfires and fireworks displays. Its history begins with the events of 5 November 1605 O.S., when Guy Fawkes, a member of the Gunpowder Plot, was arrested while guarding explosives the plotters had placed beneath the House of Lords. The Catholic plotters had intended to assassinate Protestant king James I and his parliament. Celebrating that the king had survived, people lit bonfires around London; and months later, the Observance of 5th November Act mandated an annual public day of thanksgiving for the plot’s failure.

Within a few decades Gunpowder Treason Day, as it was known, became the predominant English state commemoration. As it carried strong Protestant religious overtones it also became a focus for anti-Catholic sentiment. Puritans delivered sermons regarding the perceived dangers of popery, while during increasingly raucous celebrations common folk burnt effigies of popular hate-figures, such as the Pope. Towards the end of the 18th century reports appear of children begging for money with effigies of Guy Fawkes and 5 November gradually became known as Guy Fawkes Day. Towns such as Lewes and Guildford were in the 19th century scenes of increasingly violent class-based confrontations, fostering traditions those towns celebrate still, albeit peaceably. In the 1850s changing attitudes resulted in the toning down of much of the day’s anti-Catholic rhetoric, and the Observance of 5th November Act was repealed in 1859. Eventually the violence was dealt with, and by the 20th century Guy Fawkes Day had become an enjoyable social commemoration, although lacking much of its original focus. The present-day Guy Fawkes Night is usually celebrated at large organised events.

Settlers exported Guy Fawkes Night to overseas colonies, including some in North America, where it was known as Pope Day. Those festivities died out with the onset of the American Revolution. Claims that Guy Fawkes Night was a Protestant replacement for older customs such as Samhain are disputed.

Origins and history in Great Britain

An effigy of Fawkes, burnt on 5 November 2010 at Billericay

Guy Fawkes Night originates from the Gunpowder Plot of 1605, a failed conspiracy by a group of provincial English Catholics to assassinate the Protestant King James I of England and VI of Scotland and replace him with a Catholic head of state. In the immediate aftermath of the 5 November arrest of Guy Fawkes, caught guarding a cache of explosives placed beneath the House of Lords, James’s Council allowed the public to celebrate the king’s survival with bonfires, so long as they were «without any danger or disorder».[1] This made 1605 the first year the plot’s failure was celebrated.[2]

The following January, days before the surviving conspirators were executed, Parliament, at the initiation of James I,[3] passed the Observance of 5th November Act, commonly known as the «Thanksgiving Act». It was proposed by a Puritan Member of Parliament, Edward Montagu, who suggested that the king’s apparent deliverance by divine intervention deserved some measure of official recognition, and kept 5 November free as a day of thanksgiving while in theory making attendance at Church mandatory.[4] A new form of service was also added to the Church of England’s Book of Common Prayer, for use on that date.[5]

Little is known about the earliest celebrations. In settlements such as Carlisle, Norwich, and Nottingham, corporations (town governments) provided music and artillery salutes. Canterbury celebrated 5 November 1607 with 106 pounds (48 kg) of gunpowder and 14 pounds (6.4 kg) of match, and three years later food and drink was provided for local dignitaries, as well as music, explosions, and a parade by the local militia. Even less is known of how the occasion was first commemorated by the general public, although records indicate that in the Protestant stronghold of Dorchester a sermon was read, the church bells rung, and bonfires and fireworks lit.[6]

Early significance

According to historian and author Antonia Fraser, a study of the earliest sermons preached demonstrates an anti-Catholic concentration «mystical in its fervour».[7] Delivering one of five 5 November sermons printed in A Mappe of Rome in 1612, Thomas Taylor spoke of the «generality of his [a papist’s] cruelty», which had been «almost without bounds».[8] Such messages were also spread in printed works such as Francis Herring’s Pietas Pontifica (republished in 1610 as Popish Piety), and John Rhode’s A Brief Summe of the Treason intended against the King & State, which in 1606 sought to educate «the simple and ignorant … that they be not seduced any longer by papists».[9] By the 1620s the Fifth was honoured in market towns and villages across the country, though it was some years before it was commemorated throughout England. Gunpowder Treason Day, as it was then known, became the predominant English state commemoration. Some parishes made the day a festive occasion, with public drinking and solemn processions. Concerned though about James’s pro-Spanish foreign policy, the decline of international Protestantism, and Catholicism in general, Protestant clergymen who recognised the day’s significance called for more dignified and profound thanksgivings each 5 November.[10][11]

What unity English Protestants had shared in the plot’s immediate aftermath began to fade when in 1625 James’s son, the future Charles I, married the Catholic Henrietta Maria of France. Puritans reacted to the marriage by issuing a new prayer to warn against rebellion and Catholicism, and on 5 November that year, effigies of the pope and the devil were burnt, the earliest such report of this practice and the beginning of centuries of tradition.[a][14] During Charles’s reign Gunpowder Treason Day became increasingly partisan. Between 1629 and 1640 he ruled without Parliament, and he seemed to support Arminianism, regarded by Puritans such as Henry Burton as a step toward Catholicism. By 1636, under the leadership of the Arminian Archbishop of Canterbury William Laud, the English church was trying to use 5 November to denounce all seditious practices, and not just popery.[15] Puritans went on the defensive, some pressing for further reformation of the Church.[10]

Bonfire Night, as it was occasionally known,[16] assumed a new fervour during the events leading up to the English Interregnum. Although Royalists disputed their interpretations, Parliamentarians began to uncover or fear new Catholic plots. Preaching before the House of Commons on 5 November 1644, Charles Herle claimed that Papists were tunnelling «from Oxford, Rome, Hell, to Westminster, and there to blow up, if possible, the better foundations of your houses, their liberties and privileges».[17] A display in 1647 at Lincoln’s Inn Fields commemorated «God’s great mercy in delivering this kingdom from the hellish plots of papists», and included fireballs burning in the water (symbolising a Catholic association with «infernal spirits») and fireboxes, their many rockets suggestive of «popish spirits coming from below» to enact plots against the king. Effigies of Fawkes and the pope were present, the latter represented by Pluto, Roman god of the underworld.[18]

Following Charles I’s execution in 1649, the country’s new republican regime remained undecided on how to treat 5 November. Unlike the old system of religious feasts and State anniversaries, it survived, but as a celebration of parliamentary government and Protestantism, and not of monarchy.[16] Commonly the day was still marked by bonfires and miniature explosives, but formal celebrations resumed only with the Restoration, when Charles II became king. Courtiers, High Anglicans and Tories followed the official line, that the event marked God’s preservation of the English throne, but generally the celebrations became more diverse. By 1670 London apprentices had turned 5 November into a fire festival, attacking not only popery but also «sobriety and good order»,[19] demanding money from coach occupants for alcohol and bonfires. The burning of effigies, largely unknown to the Jacobeans,[20] continued in 1673 when Charles’s brother, the Duke of York, converted to Catholicism. In response, accompanied by a procession of about 1,000 people, the apprentices fired an effigy of the Whore of Babylon, bedecked with a range of papal symbols.[21][22] Similar scenes occurred over the following few years. On 17 November 1677, anti-Catholic fervour saw the Accession Day marked by the burning of a large effigy of the pope – his belly filled with live cats «who squalled most hideously as soon as they felt the fire» – and two effigies of devils «whispering in his ear». Two years later, as the exclusion crisis reached its zenith, an observer noted that «the 5th at night, being gunpowder treason, there were many bonfires and burning of popes as has ever been seen». Violent scenes in 1682 forced London’s militia into action, and to prevent any repetition the following year a proclamation was issued, banning bonfires and fireworks.[23]

Fireworks were also banned under James II (previously the Duke of York), who became king in 1685. Attempts by the government to tone down Gunpowder Treason Day celebrations were, however, largely unsuccessful, and some reacted to a ban on bonfires in London (born from a fear of more burnings of the pope’s effigy) by placing candles in their windows, «as a witness against Catholicism».[24] When James was deposed in 1688 by William of Orange – who, importantly, landed in England on 5 November – the day’s events turned also to the celebration of freedom and religion, with elements of anti-Jacobitism. While the earlier ban on bonfires was politically motivated, a ban on fireworks was maintained for safety reasons, «much mischief having been done by squibs».[16]

Guy Fawkes Day

The restoration of the Catholic hierarchy in 1850 provoked a strong reaction. This sketch is from an issue of Punch, printed in November that year.

William III’s birthday fell on 4 November,[b] and for orthodox Whigs the two days therefore became an important double anniversary.[25] William ordered that the thanksgiving service for 5 November be amended to include thanks for his «happy arrival» and «the Deliverance of our Church and Nation».[26] In the 1690s he re-established Protestant rule in Ireland, and the Fifth, occasionally marked by the ringing of church bells and civic dinners, was consequently eclipsed by his birthday commemorations. From the 19th century, 5 November celebrations there became sectarian in nature. (Its celebration in Northern Ireland remains controversial, unlike in Scotland where bonfires continue to be lit in various cities.)[27] In England though, as one of 49 official holidays, for the ruling class 5 November became overshadowed by events such as the birthdays of Admiral Edward Vernon, or John Wilkes, and under George II and George III, with the exception of the Jacobite Rising of 1745, it was largely «a polite entertainment rather than an occasion for vitriolic thanksgiving».[28] For the lower classes, however, the anniversary was a chance to pit disorder against order, a pretext for violence and uncontrolled revelry. In 1790 The Times reported instances of children «begging for money for Guy Faux»,[29] and a report of 4 November 1802 described how «a set of idle fellows … with some horrid figure dressed up as a Guy Faux» were convicted of begging and receiving money, and committed to prison as «idle and disorderly persons».[30] The Fifth became «a polysemous occasion, replete with polyvalent cross-referencing, meaning all things to all men».[31]

Lower class rioting continued, with reports in Lewes of annual rioting, intimidation of «respectable householders»[32] and the rolling through the streets of lit tar barrels. In Guildford, gangs of revellers who called themselves «guys» terrorised the local population; proceedings were concerned more with the settling of old arguments and general mayhem, than any historical reminiscences.[33] Similar problems arose in Exeter, originally the scene of more traditional celebrations. In 1831 an effigy was burnt of the new Bishop of Exeter Henry Phillpotts, a High Church Anglican and High Tory who opposed Parliamentary reform, and who was also suspected of being involved in «creeping popery». A local ban on fireworks in 1843 was largely ignored, and attempts by the authorities to suppress the celebrations resulted in violent protests and several injured constables.[34]

A group of children in Caernarfon, November 1962, stand with their Guy Fawkes effigy. The sign reads «Penny for the Guy» in Welsh.

On several occasions during the 19th century The Times reported that the tradition was in decline, being «of late years almost forgotten», but in the opinion of historian David Cressy, such reports reflected «other Victorian trends», including a lessening of Protestant religious zeal—not general observance of the Fifth.[29] Civil unrest brought about by the union of the Kingdoms of Great Britain and Ireland in 1800 resulted in Parliament passing the Roman Catholic Relief Act 1829, which afforded Catholics greater civil rights, continuing the process of Catholic Emancipation in the two kingdoms.[35] The traditional denunciations of Catholicism had been in decline since the early 18th century,[36] and were thought by many, including Queen Victoria, to be outdated,[37] but the pope’s restoration in 1850 of the English Catholic hierarchy gave renewed significance to 5 November, as demonstrated by the burnings of effigies of the new Catholic Archbishop of Westminster Nicholas Wiseman, and the pope. At Farringdon Market 14 effigies were processed from the Strand and over Westminster Bridge to Southwark, while extensive demonstrations were held throughout the suburbs of London.[38] Effigies of the 12 new English Catholic bishops were paraded through Exeter, already the scene of severe public disorder on each anniversary of the Fifth.[39] Gradually, however, such scenes became less popular. With little resistance in Parliament, the thanksgiving prayer of 5 November contained in the Anglican Book of Common Prayer was abolished, and in March 1859 the Anniversary Days Observance Act repealed the Observance of 5th November Act.[40][41][42]

As the authorities dealt with the worst excesses, public decorum was gradually restored. The sale of fireworks was restricted,[43] and the Guildford «guys» were neutralized in 1865, although this was too late for one constable, who died of his wounds.[37] Violence continued in Exeter for some years, peaking in 1867 when, incensed by rising food prices and banned from firing their customary bonfire, a mob was twice in one night driven from Cathedral Close by armed infantry. Further riots occurred in 1879, but there were no more bonfires in Cathedral Close after 1894.[44][45] Elsewhere, sporadic instances of public disorder persisted late into the 20th century, accompanied by large numbers of firework-related accidents, but a national Firework Code and improved public safety has in most cases brought an end to such things.[46]

Songs, Guys and decline

One notable aspect of the Victorians’ commemoration of Guy Fawkes Night was its move away from the centres of communities, to their margins. Gathering wood for the bonfire increasingly became the province of working-class children, who solicited combustible materials, money, food and drink from wealthier neighbours, often with the aid of songs. Most opened with the familiar «Remember, remember, the fifth of November, Gunpowder Treason and Plot».[47] The earliest recorded rhyme, from 1742, is reproduced below alongside one bearing similarities to most Guy Fawkes Night ditties, recorded in 1903 at Charlton on Otmoor:

Don’t you Remember,

The Fifth of November,

‘Twas Gunpowder Treason Day,

I let off my gun,

And made’em all run.

And Stole all their Bonfire away. (1742)[48]

The fifth of November, since I can remember,

Was Guy Faux, Poke him in the eye,

Shove him up the chimney-pot, and there let him die.

A stick and a stake, for King George’s sake,

If you don’t give me one, I’ll take two,

The better for me, and the worse for you,

Ricket-a-racket your hedges shall go. (1903)[47]

Organised entertainments also became popular in the late 19th century, and 20th-century pyrotechnic manufacturers renamed Guy Fawkes Day as Firework Night. Sales of fireworks dwindled somewhat during the First World War, but resumed in the following peace.[49] At the start of the Second World War celebrations were again suspended, resuming in November 1945.[50] For many families, Guy Fawkes Night became a domestic celebration, and children often congregated on street corners, accompanied by their own effigy of Guy Fawkes.[51] This was sometimes ornately dressed and sometimes a barely recognisable bundle of rags stuffed with whatever filling was suitable. A survey found that in 1981 about 23 per cent of Sheffield schoolchildren made Guys, sometimes weeks before the event. Collecting money was a popular reason for their creation, the children taking their effigy from door to door, or displaying it on street corners. But mainly, they were built to go on the bonfire, itself sometimes comprising wood stolen from other pyres—»an acceptable convention» that helped bolster another November tradition, Mischief Night.[52] Rival gangs competed to see who could build the largest, sometimes even burning the wood collected by their opponents; in 1954 the Yorkshire Post reported on fires late in September, a situation that forced the authorities to remove latent piles of wood for safety reasons.[53] Lately, however, the custom of begging for a «penny for the Guy» has almost completely disappeared.[51] In contrast, some older customs still survive; in Ottery St Mary residents run through the streets carrying flaming tar barrels,[54] and since 1679 Lewes has been the setting of some of England’s most extravagant 5 November celebrations, the Lewes Bonfire.[55]

Generally, modern 5 November celebrations are run by local charities and other organisations, with paid admission and controlled access. In 1998 an editorial in the Catholic Herald called for the end of «Bonfire Night», labelling it «an offensive act».[56] Author Martin Kettle, writing in The Guardian in 2003, bemoaned an «occasionally nannyish» attitude to fireworks that discourages people from holding firework displays in their back gardens, and an «unduly sensitive attitude» toward the anti-Catholic sentiment once so prominent on Guy Fawkes Night.[57] David Cressy summarised the modern celebration with these words: «The rockets go higher and burn with more colour, but they have less and less to do with memories of the Fifth of November … it might be observed that Guy Fawkes’ Day is finally declining, having lost its connection with politics and religion. But we have heard that many times before.»[58]

In 2012 the BBC’s Tom de Castella concluded:

It’s probably not a case of Bonfire Night decline, but rather a shift in priorities … there are new trends in the bonfire ritual. Guy Fawkes masks have proved popular and some of the more quirky bonfire societies have replaced the Guy with effigies of celebrities in the news—including Lance Armstrong and Mario Balotelli—and even politicians. The emphasis has moved. The bonfire with a Guy on top—indeed the whole story of the Gunpowder Plot—has been marginalised. But the spectacle remains.[59]

Similarities with other customs

Spectators watch a fireworks display in November 2014

Historians have often suggested that Guy Fawkes Day served as a Protestant replacement for the ancient Celtic festival of Samhain or Calan Gaeaf, pagan events that the church absorbed and transformed into All Hallow’s Eve and All Souls’ Day. In The Golden Bough, the Scottish anthropologist James George Frazer suggested that Guy Fawkes Day exemplifies «the recrudescence of old customs in modern shapes». David Underdown, writing in his 1987 work Revel, Riot, and Rebellion, viewed Gunpowder Treason Day as a replacement for Hallowe’en: «just as the early church had taken over many of the pagan feasts, so did Protestants acquire their own rituals, adapting older forms or providing substitutes for them».[60] While the use of bonfires to mark the occasion was most likely taken from the ancient practice of lighting celebratory bonfires, the idea that the commemoration of 5 November 1605 ever originated from anything other than the safety of James I is, according to David Cressy, «speculative nonsense».[61] Citing Cressy’s work, Ronald Hutton agrees with his conclusion, writing, «There is, in brief, nothing to link the Hallowe’en fires of North Wales, Man, and central Scotland with those which appeared in England upon 5 November.»[62] Further confusion arises in Northern Ireland, where some communities celebrate Guy Fawkes Night; the distinction there between the Fifth, and Halloween, is not always clear.[63] Despite such disagreements, in 2005 David Cannadine commented on the encroachment into British culture of late 20th-century American Hallowe’en celebrations, and their effect on Guy Fawkes Night:

Nowadays, family bonfire gatherings are much less popular, and many once-large civic celebrations have been given up because of increasingly intrusive health and safety regulations. But 5 November has also been overtaken by a popular festival that barely existed when I was growing up, and that is Halloween … Britain is not the Protestant nation it was when I was young: it is now a multi-faith society. And the Americanised Halloween is sweeping all before it—a vivid reminder of just how powerfully American culture and American consumerism can be transported across the Atlantic.[64]

In Northern Ireland, bonfires are lit on the Eleventh Night (11 July) by Ulster Protestants. Folklorist Jack Santino notes that the Eleventh Night is «thematically similar to Guy Fawkes Night in that it celebrates the establishment and maintenance of the Protestant state».[65]

Another celebration involving fireworks, the five-day Hindu festival of Diwali (normally observed between mid-October and November), in 2010 began on 5 November. This led The Independent to comment on the similarities between the two, its reporter Kevin Rawlinson wondering «which fireworks will burn brightest».[66]

In other countries

1768 colonial American commemoration of 5 November 1605

Gunpowder Treason Day was exported by settlers to colonies around the world, including members of the Commonwealth of Nations such as Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and various Caribbean nations.[67]

In Australia, Sydney (founded as a British penal colony in 1788)[68] saw at least one instance of the parading and burning of a Guy Fawkes effigy in 1805,[69] while in 1833, four years after its founding,[70] Perth listed Gunpowder Treason Day as a public holiday.[71] By the 1970s, Guy Fawkes Night had become less common in Australia, with the event simply an occasion to set off fireworks with little connection to Guy Fawkes. Mostly they were set off annually on a night called «cracker night»… which would include the lighting of bonfires. Some states had their fireworks night or «cracker night» at different times of the year, with some being let off on 5 November, but most often, they were let off on the Queen’s birthday. After a range of injuries to children involving fireworks, Fireworks nights and the sale of fireworks was banned in all states except the ACT by the early 1980s, which saw the end of cracker night.[72]

Some measure of celebration remains in New Zealand, Canada, and South Africa.[73] On the Cape Flats in Cape Town, South Africa, Guy Fawkes day has become associated with youth hooliganism.[74] In Canada in the 21st century, celebrations of Bonfire Night on 5 November are largely confined to the province of Newfoundland and Labrador.[75] The day is still marked in Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, and in Saint Kitts and Nevis, but a fireworks ban by Antigua and Barbuda during the 1990s reduced its popularity in that country.[76]

In North America the commemoration was at first paid scant attention, but the arrest of two boys caught lighting bonfires on 5 November 1662 in Boston suggests, in historian James Sharpe’s view, that «an underground tradition of commemorating the Fifth existed».[77] In parts of North America it was known as Pope Night, celebrated mainly in colonial New England, but also as far south as Charleston. In Boston, founded in 1630 by Puritan settlers, an early celebration was held in 1685, the same year that James II assumed the throne. Fifty years later, again in Boston, a local minister wrote «a Great number of people went over to Dorchester neck where at night they made a Great Bonfire and plaid off many fireworks», although the day ended in tragedy when «4 young men coming home in a Canoe were all Drowned». Ten years later the raucous celebrations were the cause of considerable annoyance to the upper classes and a special Riot Act was passed, to prevent «riotous tumultuous and disorderly assemblies of more than three persons, all or any of them armed with Sticks, Clubs or any kind of weapons, or disguised with vizards, or painted or discolored faces, or in any manner disguised, having any kind of imagery or pageantry, in any street, lane, or place in Boston». With inadequate resources, however, Boston’s authorities were powerless to enforce the Act. In the 1740s gang violence became common, with groups of Boston residents battling for the honour of burning the pope’s effigy. But by the mid-1760s these riots had subsided, and as colonial America moved towards revolution, the class rivalries featured during Pope Day gave way to anti-British sentiment.[78] In author Alfred Young’s view, Pope Day provided the «scaffolding, symbolism, and leadership» for resistance to the Stamp Act in 1764–65, forgoing previous gang rivalries in favour of unified resistance to Britain.[79]

The passage in 1774 of the Quebec Act, which guaranteed French Canadians free practice of Catholicism in the Province of Quebec, provoked complaints from some Americans that the British were introducing «Popish principles and French law».[80] Such fears were bolstered by opposition from the Church in Europe to American independence, threatening a revival of Pope Day.[81] Commenting in 1775, George Washington was less than impressed by the thought of any such resurrections, forbidding any under his command from participating:[82]

As the Commander in Chief has been apprized of a design form’d for the observance of that ridiculous and childish custom of burning the Effigy of the pope—He cannot help expressing his surprise that there should be Officers and Soldiers in this army so void of common sense, as not to see the impropriety of such a step at this Juncture; at a Time when we are solliciting, and have really obtain’d, the friendship and alliance of the people of Canada, whom we ought to consider as Brethren embarked in the same Cause. The defence of the general Liberty of America: At such a juncture, and in such Circumstances, to be insulting their Religion, is so monstrous, as not to be suffered or excused; indeed instead of offering the most remote insult, it is our duty to address public thanks to these our Brethren, as to them we are so much indebted for every late happy Success over the common Enemy in Canada.[83]

The tradition continued in Salem as late as 1817,[84] and was still observed in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, in 1892.[85] In the late 18th century, effigies of prominent figures such as two Prime Ministers of Great Britain, the Earl of Bute and Lord North, and the American traitor General Benedict Arnold, were also burnt.[86] In the 1880s bonfires were still being lit in some New England coastal towns, although no longer to commemorate the failure of the Gunpowder Plot. In the area around New York City, stacks of barrels were burnt on Election Day eve, which after 1845 was a Tuesday early in November.[87]

See also

- Bonfire toffee

- Gunpowder Plot in popular culture

- Push penny

- Sussex Bonfire Societies

- West Country Carnival

References

Notes

- ^ Nationally, effigies of Fawkes were subsequently joined by those of contemporary hate figures such as the pope, the sultan of Turkey, the tsar of Russia and the Irish leader Charles Stewart Parnell. In 1899 an effigy of the South African Republic leader Paul Kruger was burnt at Ticehurst, and during the 20th century effigies of militant suffragists, Kaiser Wilhelm II, Adolf Hitler, Margaret Thatcher and John Major were similarly burnt.[12] In 2014, following Russian aggression against Ukraine, effigies of Vladimir Putin were burned.[13]

- ^ Julian calendar

Footnotes

- ^ Fraser 2005, p. 207

- ^ Fraser 2005, pp. 351–352

- ^ Williamson, Philip; Mears, Natalie (2021), «Jame I and Gunpowder Treason Day», The Historical Journal, 64 (2): 185–210, doi:10.1017/S0018246X20000497, ISSN 0018-246X, S2CID 228920584

- ^ Sharpe 2005, pp. 78–79

- ^ Bond, Edward L. (2005), Spreading the gospel in colonial Virginia’, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, p. 93

- ^ Sharpe 2005, p. 87

- ^ Fraser 2005, p. 352

- ^ Sharpe 2005, p. 88

- ^ Sharpe 2005, pp. 88–89

- ^ a b Cressy 1992, p. 73

- ^ Hutton 2001, pp. 394–395

- ^ Cressy 1992, pp. 83–84; Fraser 2005, pp. 356–357; Nicholls, Mark, «The Gunpowder Plot», Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- ^ Withnall, Adam (6 November 2014), «Vladimir Putin effigies burned at Lewes Bonfire Night as the ‘new cold war’ starts to heat up», The Independent, retrieved 5 November 2022

- ^ Sharpe 2005, p. 89

- ^ Sharpe 2005, p. 90

- ^ a b c Hutton 2001, p. 395

- ^ Cressy 1992, p. 74

- ^ Sharpe 2005, p. 92

- ^ Cressy 1992, p. 75

- ^ Cressy 1992, pp. 70–71

- ^ Cressy 1992, pp. 74–75

- ^ Sharpe 2005, pp. 96–97

- ^ Sharpe 2005, pp. 98–100

- ^ Hutton 2001, p. 397

- ^ Pratt 2006, p. 57

- ^ Schwoerer, Lois G. (Spring 1990), «Celebrating the Glorious Revolution, 1689–1989», Albion: A Quarterly Journal Concerned with British Studies, The North American Conference on British Studies, 22 (1): 3, doi:10.2307/4050254, JSTOR 4050254

- ^ Rogers, Nicholas (2003), Halloween: From Pagan Ritual to Party Night, Oxford University Press, pp. 38–39, ISBN 978-0-19-516896-9

- ^ Cressy 1992, p. 77

- ^ a b Cressy 1992, pp. 79–80

- ^ «The great annoyance occasioned to the public by a set of idle fellows», The Times, vol. D, no. 5557, p. 3, 4 November 1802 – via infotrac.galegroup.com (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- ^ Cressy 1992, p. 76

- ^ Cressy 1992, p. 79

- ^ Cressy 1992, pp. 76–79

- ^ Sharpe 2005, pp. 157–159

- ^ Sharpe 2005, pp. 114–115

- ^ Sharpe 2005, pp. 110–111

- ^ a b Hutton 2001, p. 401

- ^ Sharpe 2005, p. 150

- ^ Sharpe 2005, p. 159

- ^ Cressy 1992, pp. 82–83

- ^ Fraser 2005, pp. 354–356

- ^ Anon 1859, p. 4

- ^ Cressy 1992, pp. 84–85

- ^ Bohstedt 2010, p. 252

- ^ Sharpe 2005, pp. 159–160

- ^ Hutton 2001, pp. 405–406

- ^ a b Hutton 2001, p. 403

- ^ Hutton 2001, p. 514, note 45

- ^ Cressy 1992, pp. 85–86

- ^ «Guy Fawkes’ Day», Life, Time Inc, vol. 19, no. 24, p. 43, 10 December 1945, ISSN 0024-3019

- ^ a b Sharpe 2005, p. 157

- ^ Beck, Ervin (1984), «Children’s Guy Fawkes Customs in Sheffield», Folklore, Taylor & Francis on behalf of Folklore Enterprises, 95 (2): 191–203, doi:10.1080/0015587X.1984.9716314, JSTOR 1260204

- ^ Opie 1961, pp. 280–281

- ^ Hutton 2001, pp. 406–407

- ^ Sharpe 2005, pp. 147–152

- ^ Champion 2005, p. n/a

- ^ Kettle, Martin (5 November 2003), «The real festival of Britain», The Guardian

- ^ Cressy 1992, pp. 86–87

- ^ de Castella, Tom (6 November 2012), «Has Halloween now dampened Bonfire Night?», BBC News

- ^ Underdown 1987, p. 70

- ^ Cressy 1992, pp. 69–71

- ^ Hutton 2001, p. 394

- ^ Santino, Jack (Summer 1996), «Light up the Sky: Halloween Bonfires and Cultural Hegemony in Northern Ireland», Western Folklore, Western States Folklore Society, 55 (3): 213–232, doi:10.2307/1500482, JSTOR 1500482

- ^ Cannadine, David (4 November 2005), «Halloween v Guy Fawkes Day», BBC News, archived from the original on 31 October 2010

- ^ Santino, Jack (1998), The Hallowed Eve: Dimensions of Culture in a Calendar Festival in Northern Ireland, University Press of Kentucky, p. 54

- ^ Rawlinson, Kevin (5 November 2010), «Guy Fawkes vs Diwali: Battle of Bonfire Night», The Independent

- ^ Sharpe 2005, p. 192

- ^ Phillip 1789, p. Chapter VII

- ^ «Weekly Occurrences», The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, p. 1, 10 November 1805

- ^ «The Swan River Colony», The Capricornian, p. 5, 12 December 1929

- ^ Government Notice, The Perth Gazette and Western Australian Journal, 27 April 1833, p. 66 – via Trove

- ^ Wright, Tony (30 October 2020), «Ready for a rocket?: No one’s laughing as a new Bonfire Night nears», The Sydney Morning Herald, retrieved 5 November 2021

- ^ Davis 2010, pp. 250–251

- ^ «Guy Fawkes: Reports of paint, stoning, intimidation in Cape despite warning», IOL, 5 November 2019

- ^ Atter, Heidi (5 November 2021), 17th-century Bonfire Night traditions going strong throughout N.L., and internationally, CBC News, retrieved 5 November 2021

- ^ Davis 2010, p. 250

- ^ Sharpe 2005, p. 142

- ^ Tager 2001, pp. 45–50

- ^ Young 1999, pp. 24, 93–94

- ^ Kaufman 2009, p. 99

- ^ Fuchs 1990, p. 36

- ^ Sharpe 2005, p. 145

- ^ Fitzpatrick, John C., ed. (5 November 1775), «The Writings of George Washington from the Original Manuscript Sources, 1745–1799», memory.loc.gov

- ^ Berlant 1991, p. 232 n.58, see also Robotti, Frances Diane (2009), Chronicles of Old Salem, Kessinger Publishing, LLC

- ^ Albee, John (October–December 1892), «Pope Night in Portsmouth, N. H.», The Journal of American Folklore, American Folklore Society, 5 (19): 335–336, doi:10.2307/533252, JSTOR 533252

- ^ Fraser 2005, p. 353

- ^ Eggleston, Edward (July 1885), «Social Life in the Colonies», The Century; a popular quarterly, vol. 30, no. 3, p. 400

Bibliography

- Anon (1859), The law journal for the year 1832–1949, vol. XXXVII, E. B. Ince

- Berlant, Lauren Gail (1991), The anatomy of national fantasy: Hawthorne, Utopia, and everyday life, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 978-0-226-04377-7

- Bohstedt, John (2010), The Politics of Provisions: Food Riots, Moral Economy, and Market Transition in England, C. 1550–1850, Ashgate Publishing, ISBN 978-0-7546-6581-6

- Champion, Justin (2005), «5, Bonfire Night in Lewes», Gunpowder Plots: A Celebration of 400 Years of Bonfire Night, Penguin UK, ISBN 978-0-14-190933-2

- Cressy, David (1992), «The Fifth of November Remembered», in Roy Porter (ed.), Myths of the English, Polity Press, ISBN 978-0-7456-0844-0

- Davis, John Paul (2010), Pity for the Guy: A Biography of Guy Fawkes, Peter Owen Publishers, ISBN 978-0-7206-1349-0

- Fraser, Antonia (2005) [1996], The Gunpowder Plot, Phoenix, ISBN 978-0-7538-1401-7

- Fuchs, Lawrence H. (1990), The American kaleidoscope: race, ethnicity, and the civic culture, Wesleyan University Press, ISBN 978-0-8195-6250-0

- Hutton, Ronald (2001), The stations of the sun: a history of the ritual year in Britain (reprinted, illustrated ed.), Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-285448-3

- Kaufman, Jason Andrew (2009), The origins of Canadian and American political differences, Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-03136-4

- Opie, Iona and Peter (1961), The Language and Lore of Schoolchildren, Clarendon Press

- Phillip, Arthur (1789), The Voyage of Governor Phillip To Botany Bay, John Stockdale

- Pratt, Lynda (2006), Robert Southey and the contexts of English Romanticism, Ashgate Publishing, ISBN 978-0-7546-3046-3

- Sharpe, J. A. (2005), Remember, remember: a cultural history of Guy Fawkes Day, Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-01935-5

- Tager, Jack (2001), Boston riots: three centuries of social violence, University Press of New England, ISBN 978-1-55553-461-5

- Underdown, David (1987), Revel, riot, and rebellion: popular politics and culture in England 1603–1660 (reprinted, illustrated ed.), Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-285193-4

- Young, Alfred F (1999), The shoemaker and the tea party memory and the American Revolution, Boston, ISBN 978-0-8070-7142-7

Further reading

- For information on Pope Day as it was observed in Boston, see 5th of November in Boston, The Bostonian Society

- For information on Bonfires in Newfoundland and Labrador, see Bonfire Night, collections.mun.ca

- To read further on England’s tradition of Protestant holidays, see Cressy, David (1989), Bonfires and Bells: National Memory and the Protestant Calendar in Elizabethan and Stuart England, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-06940-4. Cressy covers the same topic in Cressy, David (1994), «National Memory in Early Modern England», in John R. Gillis (ed.), Commemorations – The Politics of National Identity, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-02925-2

- For anecdotal evidence of the origins of Guy Fawkes Night as celebrated in the Bahamas in the 1950s, see Crowley, Daniel J. (July 1958), «158. Guy Fawkes Day at Fresh Creek, Andros Island, Bahamas», Man, Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, 58: 114–115, doi:10.2307/2796328, JSTOR 2796328

- A short history of Guy Fawkes celebrations: Etherington, Jim (1993), Lewes Bonfire Night, SB Publications, ISBN 978-1-85770-050-3

- Gardiner, Samuel Rawson (2009), History of England from the Accession of James I. to the Outbreak of the Civil War 1603–1642 (8), BiblioBazaar, LLC, ISBN 978-1-115-26650-5

- For comments regarding the observance of the custom in the Caribbean, see Newall, Venetia (Spring 1975), «Black Britain: The Jamaicans and Their Folklore», Folklore, Taylor & Francis, on behalf of Folklore Enterprises, 86 (1): 25–41, doi:10.1080/0015587X.1975.9715997, JSTOR 1259683

- A study of the political and social changes that affected Guy Fawkes Night: Paz, D. G. (1990), «Bonfire Night in Mid Victorian Northamptonshire: the Politics of a Popular Revel», Historical Research, 63 (152): 316–328, doi:10.1111/j.1468-2281.1990.tb00892.x

Guy Fawkes Night, also known as Guy Fawkes Day, Bonfire Night and Fireworks Night, is an annual commemoration observed on 5 November, primarily in Great Britain, involving bonfires and fireworks displays. Its history begins with the events of 5 November 1605 O.S., when Guy Fawkes, a member of the Gunpowder Plot, was arrested while guarding explosives the plotters had placed beneath the House of Lords. The Catholic plotters had intended to assassinate Protestant king James I and his parliament. Celebrating that the king had survived, people lit bonfires around London; and months later, the Observance of 5th November Act mandated an annual public day of thanksgiving for the plot’s failure.

Within a few decades Gunpowder Treason Day, as it was known, became the predominant English state commemoration. As it carried strong Protestant religious overtones it also became a focus for anti-Catholic sentiment. Puritans delivered sermons regarding the perceived dangers of popery, while during increasingly raucous celebrations common folk burnt effigies of popular hate-figures, such as the Pope. Towards the end of the 18th century reports appear of children begging for money with effigies of Guy Fawkes and 5 November gradually became known as Guy Fawkes Day. Towns such as Lewes and Guildford were in the 19th century scenes of increasingly violent class-based confrontations, fostering traditions those towns celebrate still, albeit peaceably. In the 1850s changing attitudes resulted in the toning down of much of the day’s anti-Catholic rhetoric, and the Observance of 5th November Act was repealed in 1859. Eventually the violence was dealt with, and by the 20th century Guy Fawkes Day had become an enjoyable social commemoration, although lacking much of its original focus. The present-day Guy Fawkes Night is usually celebrated at large organised events.

Settlers exported Guy Fawkes Night to overseas colonies, including some in North America, where it was known as Pope Day. Those festivities died out with the onset of the American Revolution. Claims that Guy Fawkes Night was a Protestant replacement for older customs such as Samhain are disputed.

Origins and history in Great Britain

An effigy of Fawkes, burnt on 5 November 2010 at Billericay

Guy Fawkes Night originates from the Gunpowder Plot of 1605, a failed conspiracy by a group of provincial English Catholics to assassinate the Protestant King James I of England and VI of Scotland and replace him with a Catholic head of state. In the immediate aftermath of the 5 November arrest of Guy Fawkes, caught guarding a cache of explosives placed beneath the House of Lords, James’s Council allowed the public to celebrate the king’s survival with bonfires, so long as they were «without any danger or disorder».[1] This made 1605 the first year the plot’s failure was celebrated.[2]

The following January, days before the surviving conspirators were executed, Parliament, at the initiation of James I,[3] passed the Observance of 5th November Act, commonly known as the «Thanksgiving Act». It was proposed by a Puritan Member of Parliament, Edward Montagu, who suggested that the king’s apparent deliverance by divine intervention deserved some measure of official recognition, and kept 5 November free as a day of thanksgiving while in theory making attendance at Church mandatory.[4] A new form of service was also added to the Church of England’s Book of Common Prayer, for use on that date.[5]

Little is known about the earliest celebrations. In settlements such as Carlisle, Norwich, and Nottingham, corporations (town governments) provided music and artillery salutes. Canterbury celebrated 5 November 1607 with 106 pounds (48 kg) of gunpowder and 14 pounds (6.4 kg) of match, and three years later food and drink was provided for local dignitaries, as well as music, explosions, and a parade by the local militia. Even less is known of how the occasion was first commemorated by the general public, although records indicate that in the Protestant stronghold of Dorchester a sermon was read, the church bells rung, and bonfires and fireworks lit.[6]

Early significance

According to historian and author Antonia Fraser, a study of the earliest sermons preached demonstrates an anti-Catholic concentration «mystical in its fervour».[7] Delivering one of five 5 November sermons printed in A Mappe of Rome in 1612, Thomas Taylor spoke of the «generality of his [a papist’s] cruelty», which had been «almost without bounds».[8] Such messages were also spread in printed works such as Francis Herring’s Pietas Pontifica (republished in 1610 as Popish Piety), and John Rhode’s A Brief Summe of the Treason intended against the King & State, which in 1606 sought to educate «the simple and ignorant … that they be not seduced any longer by papists».[9] By the 1620s the Fifth was honoured in market towns and villages across the country, though it was some years before it was commemorated throughout England. Gunpowder Treason Day, as it was then known, became the predominant English state commemoration. Some parishes made the day a festive occasion, with public drinking and solemn processions. Concerned though about James’s pro-Spanish foreign policy, the decline of international Protestantism, and Catholicism in general, Protestant clergymen who recognised the day’s significance called for more dignified and profound thanksgivings each 5 November.[10][11]

What unity English Protestants had shared in the plot’s immediate aftermath began to fade when in 1625 James’s son, the future Charles I, married the Catholic Henrietta Maria of France. Puritans reacted to the marriage by issuing a new prayer to warn against rebellion and Catholicism, and on 5 November that year, effigies of the pope and the devil were burnt, the earliest such report of this practice and the beginning of centuries of tradition.[a][14] During Charles’s reign Gunpowder Treason Day became increasingly partisan. Between 1629 and 1640 he ruled without Parliament, and he seemed to support Arminianism, regarded by Puritans such as Henry Burton as a step toward Catholicism. By 1636, under the leadership of the Arminian Archbishop of Canterbury William Laud, the English church was trying to use 5 November to denounce all seditious practices, and not just popery.[15] Puritans went on the defensive, some pressing for further reformation of the Church.[10]

Bonfire Night, as it was occasionally known,[16] assumed a new fervour during the events leading up to the English Interregnum. Although Royalists disputed their interpretations, Parliamentarians began to uncover or fear new Catholic plots. Preaching before the House of Commons on 5 November 1644, Charles Herle claimed that Papists were tunnelling «from Oxford, Rome, Hell, to Westminster, and there to blow up, if possible, the better foundations of your houses, their liberties and privileges».[17] A display in 1647 at Lincoln’s Inn Fields commemorated «God’s great mercy in delivering this kingdom from the hellish plots of papists», and included fireballs burning in the water (symbolising a Catholic association with «infernal spirits») and fireboxes, their many rockets suggestive of «popish spirits coming from below» to enact plots against the king. Effigies of Fawkes and the pope were present, the latter represented by Pluto, Roman god of the underworld.[18]

Following Charles I’s execution in 1649, the country’s new republican regime remained undecided on how to treat 5 November. Unlike the old system of religious feasts and State anniversaries, it survived, but as a celebration of parliamentary government and Protestantism, and not of monarchy.[16] Commonly the day was still marked by bonfires and miniature explosives, but formal celebrations resumed only with the Restoration, when Charles II became king. Courtiers, High Anglicans and Tories followed the official line, that the event marked God’s preservation of the English throne, but generally the celebrations became more diverse. By 1670 London apprentices had turned 5 November into a fire festival, attacking not only popery but also «sobriety and good order»,[19] demanding money from coach occupants for alcohol and bonfires. The burning of effigies, largely unknown to the Jacobeans,[20] continued in 1673 when Charles’s brother, the Duke of York, converted to Catholicism. In response, accompanied by a procession of about 1,000 people, the apprentices fired an effigy of the Whore of Babylon, bedecked with a range of papal symbols.[21][22] Similar scenes occurred over the following few years. On 17 November 1677, anti-Catholic fervour saw the Accession Day marked by the burning of a large effigy of the pope – his belly filled with live cats «who squalled most hideously as soon as they felt the fire» – and two effigies of devils «whispering in his ear». Two years later, as the exclusion crisis reached its zenith, an observer noted that «the 5th at night, being gunpowder treason, there were many bonfires and burning of popes as has ever been seen». Violent scenes in 1682 forced London’s militia into action, and to prevent any repetition the following year a proclamation was issued, banning bonfires and fireworks.[23]

Fireworks were also banned under James II (previously the Duke of York), who became king in 1685. Attempts by the government to tone down Gunpowder Treason Day celebrations were, however, largely unsuccessful, and some reacted to a ban on bonfires in London (born from a fear of more burnings of the pope’s effigy) by placing candles in their windows, «as a witness against Catholicism».[24] When James was deposed in 1688 by William of Orange – who, importantly, landed in England on 5 November – the day’s events turned also to the celebration of freedom and religion, with elements of anti-Jacobitism. While the earlier ban on bonfires was politically motivated, a ban on fireworks was maintained for safety reasons, «much mischief having been done by squibs».[16]

Guy Fawkes Day

The restoration of the Catholic hierarchy in 1850 provoked a strong reaction. This sketch is from an issue of Punch, printed in November that year.

William III’s birthday fell on 4 November,[b] and for orthodox Whigs the two days therefore became an important double anniversary.[25] William ordered that the thanksgiving service for 5 November be amended to include thanks for his «happy arrival» and «the Deliverance of our Church and Nation».[26] In the 1690s he re-established Protestant rule in Ireland, and the Fifth, occasionally marked by the ringing of church bells and civic dinners, was consequently eclipsed by his birthday commemorations. From the 19th century, 5 November celebrations there became sectarian in nature. (Its celebration in Northern Ireland remains controversial, unlike in Scotland where bonfires continue to be lit in various cities.)[27] In England though, as one of 49 official holidays, for the ruling class 5 November became overshadowed by events such as the birthdays of Admiral Edward Vernon, or John Wilkes, and under George II and George III, with the exception of the Jacobite Rising of 1745, it was largely «a polite entertainment rather than an occasion for vitriolic thanksgiving».[28] For the lower classes, however, the anniversary was a chance to pit disorder against order, a pretext for violence and uncontrolled revelry. In 1790 The Times reported instances of children «begging for money for Guy Faux»,[29] and a report of 4 November 1802 described how «a set of idle fellows … with some horrid figure dressed up as a Guy Faux» were convicted of begging and receiving money, and committed to prison as «idle and disorderly persons».[30] The Fifth became «a polysemous occasion, replete with polyvalent cross-referencing, meaning all things to all men».[31]

Lower class rioting continued, with reports in Lewes of annual rioting, intimidation of «respectable householders»[32] and the rolling through the streets of lit tar barrels. In Guildford, gangs of revellers who called themselves «guys» terrorised the local population; proceedings were concerned more with the settling of old arguments and general mayhem, than any historical reminiscences.[33] Similar problems arose in Exeter, originally the scene of more traditional celebrations. In 1831 an effigy was burnt of the new Bishop of Exeter Henry Phillpotts, a High Church Anglican and High Tory who opposed Parliamentary reform, and who was also suspected of being involved in «creeping popery». A local ban on fireworks in 1843 was largely ignored, and attempts by the authorities to suppress the celebrations resulted in violent protests and several injured constables.[34]

A group of children in Caernarfon, November 1962, stand with their Guy Fawkes effigy. The sign reads «Penny for the Guy» in Welsh.

On several occasions during the 19th century The Times reported that the tradition was in decline, being «of late years almost forgotten», but in the opinion of historian David Cressy, such reports reflected «other Victorian trends», including a lessening of Protestant religious zeal—not general observance of the Fifth.[29] Civil unrest brought about by the union of the Kingdoms of Great Britain and Ireland in 1800 resulted in Parliament passing the Roman Catholic Relief Act 1829, which afforded Catholics greater civil rights, continuing the process of Catholic Emancipation in the two kingdoms.[35] The traditional denunciations of Catholicism had been in decline since the early 18th century,[36] and were thought by many, including Queen Victoria, to be outdated,[37] but the pope’s restoration in 1850 of the English Catholic hierarchy gave renewed significance to 5 November, as demonstrated by the burnings of effigies of the new Catholic Archbishop of Westminster Nicholas Wiseman, and the pope. At Farringdon Market 14 effigies were processed from the Strand and over Westminster Bridge to Southwark, while extensive demonstrations were held throughout the suburbs of London.[38] Effigies of the 12 new English Catholic bishops were paraded through Exeter, already the scene of severe public disorder on each anniversary of the Fifth.[39] Gradually, however, such scenes became less popular. With little resistance in Parliament, the thanksgiving prayer of 5 November contained in the Anglican Book of Common Prayer was abolished, and in March 1859 the Anniversary Days Observance Act repealed the Observance of 5th November Act.[40][41][42]

As the authorities dealt with the worst excesses, public decorum was gradually restored. The sale of fireworks was restricted,[43] and the Guildford «guys» were neutralized in 1865, although this was too late for one constable, who died of his wounds.[37] Violence continued in Exeter for some years, peaking in 1867 when, incensed by rising food prices and banned from firing their customary bonfire, a mob was twice in one night driven from Cathedral Close by armed infantry. Further riots occurred in 1879, but there were no more bonfires in Cathedral Close after 1894.[44][45] Elsewhere, sporadic instances of public disorder persisted late into the 20th century, accompanied by large numbers of firework-related accidents, but a national Firework Code and improved public safety has in most cases brought an end to such things.[46]

Songs, Guys and decline

One notable aspect of the Victorians’ commemoration of Guy Fawkes Night was its move away from the centres of communities, to their margins. Gathering wood for the bonfire increasingly became the province of working-class children, who solicited combustible materials, money, food and drink from wealthier neighbours, often with the aid of songs. Most opened with the familiar «Remember, remember, the fifth of November, Gunpowder Treason and Plot».[47] The earliest recorded rhyme, from 1742, is reproduced below alongside one bearing similarities to most Guy Fawkes Night ditties, recorded in 1903 at Charlton on Otmoor:

Don’t you Remember,

The Fifth of November,

‘Twas Gunpowder Treason Day,

I let off my gun,

And made’em all run.

And Stole all their Bonfire away. (1742)[48]

The fifth of November, since I can remember,

Was Guy Faux, Poke him in the eye,

Shove him up the chimney-pot, and there let him die.

A stick and a stake, for King George’s sake,

If you don’t give me one, I’ll take two,

The better for me, and the worse for you,

Ricket-a-racket your hedges shall go. (1903)[47]

Organised entertainments also became popular in the late 19th century, and 20th-century pyrotechnic manufacturers renamed Guy Fawkes Day as Firework Night. Sales of fireworks dwindled somewhat during the First World War, but resumed in the following peace.[49] At the start of the Second World War celebrations were again suspended, resuming in November 1945.[50] For many families, Guy Fawkes Night became a domestic celebration, and children often congregated on street corners, accompanied by their own effigy of Guy Fawkes.[51] This was sometimes ornately dressed and sometimes a barely recognisable bundle of rags stuffed with whatever filling was suitable. A survey found that in 1981 about 23 per cent of Sheffield schoolchildren made Guys, sometimes weeks before the event. Collecting money was a popular reason for their creation, the children taking their effigy from door to door, or displaying it on street corners. But mainly, they were built to go on the bonfire, itself sometimes comprising wood stolen from other pyres—»an acceptable convention» that helped bolster another November tradition, Mischief Night.[52] Rival gangs competed to see who could build the largest, sometimes even burning the wood collected by their opponents; in 1954 the Yorkshire Post reported on fires late in September, a situation that forced the authorities to remove latent piles of wood for safety reasons.[53] Lately, however, the custom of begging for a «penny for the Guy» has almost completely disappeared.[51] In contrast, some older customs still survive; in Ottery St Mary residents run through the streets carrying flaming tar barrels,[54] and since 1679 Lewes has been the setting of some of England’s most extravagant 5 November celebrations, the Lewes Bonfire.[55]

Generally, modern 5 November celebrations are run by local charities and other organisations, with paid admission and controlled access. In 1998 an editorial in the Catholic Herald called for the end of «Bonfire Night», labelling it «an offensive act».[56] Author Martin Kettle, writing in The Guardian in 2003, bemoaned an «occasionally nannyish» attitude to fireworks that discourages people from holding firework displays in their back gardens, and an «unduly sensitive attitude» toward the anti-Catholic sentiment once so prominent on Guy Fawkes Night.[57] David Cressy summarised the modern celebration with these words: «The rockets go higher and burn with more colour, but they have less and less to do with memories of the Fifth of November … it might be observed that Guy Fawkes’ Day is finally declining, having lost its connection with politics and religion. But we have heard that many times before.»[58]

In 2012 the BBC’s Tom de Castella concluded:

It’s probably not a case of Bonfire Night decline, but rather a shift in priorities … there are new trends in the bonfire ritual. Guy Fawkes masks have proved popular and some of the more quirky bonfire societies have replaced the Guy with effigies of celebrities in the news—including Lance Armstrong and Mario Balotelli—and even politicians. The emphasis has moved. The bonfire with a Guy on top—indeed the whole story of the Gunpowder Plot—has been marginalised. But the spectacle remains.[59]

Similarities with other customs

Spectators watch a fireworks display in November 2014

Historians have often suggested that Guy Fawkes Day served as a Protestant replacement for the ancient Celtic festival of Samhain or Calan Gaeaf, pagan events that the church absorbed and transformed into All Hallow’s Eve and All Souls’ Day. In The Golden Bough, the Scottish anthropologist James George Frazer suggested that Guy Fawkes Day exemplifies «the recrudescence of old customs in modern shapes». David Underdown, writing in his 1987 work Revel, Riot, and Rebellion, viewed Gunpowder Treason Day as a replacement for Hallowe’en: «just as the early church had taken over many of the pagan feasts, so did Protestants acquire their own rituals, adapting older forms or providing substitutes for them».[60] While the use of bonfires to mark the occasion was most likely taken from the ancient practice of lighting celebratory bonfires, the idea that the commemoration of 5 November 1605 ever originated from anything other than the safety of James I is, according to David Cressy, «speculative nonsense».[61] Citing Cressy’s work, Ronald Hutton agrees with his conclusion, writing, «There is, in brief, nothing to link the Hallowe’en fires of North Wales, Man, and central Scotland with those which appeared in England upon 5 November.»[62] Further confusion arises in Northern Ireland, where some communities celebrate Guy Fawkes Night; the distinction there between the Fifth, and Halloween, is not always clear.[63] Despite such disagreements, in 2005 David Cannadine commented on the encroachment into British culture of late 20th-century American Hallowe’en celebrations, and their effect on Guy Fawkes Night:

Nowadays, family bonfire gatherings are much less popular, and many once-large civic celebrations have been given up because of increasingly intrusive health and safety regulations. But 5 November has also been overtaken by a popular festival that barely existed when I was growing up, and that is Halloween … Britain is not the Protestant nation it was when I was young: it is now a multi-faith society. And the Americanised Halloween is sweeping all before it—a vivid reminder of just how powerfully American culture and American consumerism can be transported across the Atlantic.[64]

In Northern Ireland, bonfires are lit on the Eleventh Night (11 July) by Ulster Protestants. Folklorist Jack Santino notes that the Eleventh Night is «thematically similar to Guy Fawkes Night in that it celebrates the establishment and maintenance of the Protestant state».[65]

Another celebration involving fireworks, the five-day Hindu festival of Diwali (normally observed between mid-October and November), in 2010 began on 5 November. This led The Independent to comment on the similarities between the two, its reporter Kevin Rawlinson wondering «which fireworks will burn brightest».[66]

In other countries

1768 colonial American commemoration of 5 November 1605

Gunpowder Treason Day was exported by settlers to colonies around the world, including members of the Commonwealth of Nations such as Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and various Caribbean nations.[67]

In Australia, Sydney (founded as a British penal colony in 1788)[68] saw at least one instance of the parading and burning of a Guy Fawkes effigy in 1805,[69] while in 1833, four years after its founding,[70] Perth listed Gunpowder Treason Day as a public holiday.[71] By the 1970s, Guy Fawkes Night had become less common in Australia, with the event simply an occasion to set off fireworks with little connection to Guy Fawkes. Mostly they were set off annually on a night called «cracker night»… which would include the lighting of bonfires. Some states had their fireworks night or «cracker night» at different times of the year, with some being let off on 5 November, but most often, they were let off on the Queen’s birthday. After a range of injuries to children involving fireworks, Fireworks nights and the sale of fireworks was banned in all states except the ACT by the early 1980s, which saw the end of cracker night.[72]

Some measure of celebration remains in New Zealand, Canada, and South Africa.[73] On the Cape Flats in Cape Town, South Africa, Guy Fawkes day has become associated with youth hooliganism.[74] In Canada in the 21st century, celebrations of Bonfire Night on 5 November are largely confined to the province of Newfoundland and Labrador.[75] The day is still marked in Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, and in Saint Kitts and Nevis, but a fireworks ban by Antigua and Barbuda during the 1990s reduced its popularity in that country.[76]

In North America the commemoration was at first paid scant attention, but the arrest of two boys caught lighting bonfires on 5 November 1662 in Boston suggests, in historian James Sharpe’s view, that «an underground tradition of commemorating the Fifth existed».[77] In parts of North America it was known as Pope Night, celebrated mainly in colonial New England, but also as far south as Charleston. In Boston, founded in 1630 by Puritan settlers, an early celebration was held in 1685, the same year that James II assumed the throne. Fifty years later, again in Boston, a local minister wrote «a Great number of people went over to Dorchester neck where at night they made a Great Bonfire and plaid off many fireworks», although the day ended in tragedy when «4 young men coming home in a Canoe were all Drowned». Ten years later the raucous celebrations were the cause of considerable annoyance to the upper classes and a special Riot Act was passed, to prevent «riotous tumultuous and disorderly assemblies of more than three persons, all or any of them armed with Sticks, Clubs or any kind of weapons, or disguised with vizards, or painted or discolored faces, or in any manner disguised, having any kind of imagery or pageantry, in any street, lane, or place in Boston». With inadequate resources, however, Boston’s authorities were powerless to enforce the Act. In the 1740s gang violence became common, with groups of Boston residents battling for the honour of burning the pope’s effigy. But by the mid-1760s these riots had subsided, and as colonial America moved towards revolution, the class rivalries featured during Pope Day gave way to anti-British sentiment.[78] In author Alfred Young’s view, Pope Day provided the «scaffolding, symbolism, and leadership» for resistance to the Stamp Act in 1764–65, forgoing previous gang rivalries in favour of unified resistance to Britain.[79]

The passage in 1774 of the Quebec Act, which guaranteed French Canadians free practice of Catholicism in the Province of Quebec, provoked complaints from some Americans that the British were introducing «Popish principles and French law».[80] Such fears were bolstered by opposition from the Church in Europe to American independence, threatening a revival of Pope Day.[81] Commenting in 1775, George Washington was less than impressed by the thought of any such resurrections, forbidding any under his command from participating:[82]

As the Commander in Chief has been apprized of a design form’d for the observance of that ridiculous and childish custom of burning the Effigy of the pope—He cannot help expressing his surprise that there should be Officers and Soldiers in this army so void of common sense, as not to see the impropriety of such a step at this Juncture; at a Time when we are solliciting, and have really obtain’d, the friendship and alliance of the people of Canada, whom we ought to consider as Brethren embarked in the same Cause. The defence of the general Liberty of America: At such a juncture, and in such Circumstances, to be insulting their Religion, is so monstrous, as not to be suffered or excused; indeed instead of offering the most remote insult, it is our duty to address public thanks to these our Brethren, as to them we are so much indebted for every late happy Success over the common Enemy in Canada.[83]

The tradition continued in Salem as late as 1817,[84] and was still observed in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, in 1892.[85] In the late 18th century, effigies of prominent figures such as two Prime Ministers of Great Britain, the Earl of Bute and Lord North, and the American traitor General Benedict Arnold, were also burnt.[86] In the 1880s bonfires were still being lit in some New England coastal towns, although no longer to commemorate the failure of the Gunpowder Plot. In the area around New York City, stacks of barrels were burnt on Election Day eve, which after 1845 was a Tuesday early in November.[87]

See also

- Bonfire toffee

- Gunpowder Plot in popular culture

- Push penny

- Sussex Bonfire Societies

- West Country Carnival

References

Notes

- ^ Nationally, effigies of Fawkes were subsequently joined by those of contemporary hate figures such as the pope, the sultan of Turkey, the tsar of Russia and the Irish leader Charles Stewart Parnell. In 1899 an effigy of the South African Republic leader Paul Kruger was burnt at Ticehurst, and during the 20th century effigies of militant suffragists, Kaiser Wilhelm II, Adolf Hitler, Margaret Thatcher and John Major were similarly burnt.[12] In 2014, following Russian aggression against Ukraine, effigies of Vladimir Putin were burned.[13]

- ^ Julian calendar

Footnotes

- ^ Fraser 2005, p. 207

- ^ Fraser 2005, pp. 351–352

- ^ Williamson, Philip; Mears, Natalie (2021), «Jame I and Gunpowder Treason Day», The Historical Journal, 64 (2): 185–210, doi:10.1017/S0018246X20000497, ISSN 0018-246X, S2CID 228920584

- ^ Sharpe 2005, pp. 78–79

- ^ Bond, Edward L. (2005), Spreading the gospel in colonial Virginia’, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, p. 93

- ^ Sharpe 2005, p. 87

- ^ Fraser 2005, p. 352

- ^ Sharpe 2005, p. 88

- ^ Sharpe 2005, pp. 88–89

- ^ a b Cressy 1992, p. 73

- ^ Hutton 2001, pp. 394–395

- ^ Cressy 1992, pp. 83–84; Fraser 2005, pp. 356–357; Nicholls, Mark, «The Gunpowder Plot», Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- ^ Withnall, Adam (6 November 2014), «Vladimir Putin effigies burned at Lewes Bonfire Night as the ‘new cold war’ starts to heat up», The Independent, retrieved 5 November 2022

- ^ Sharpe 2005, p. 89

- ^ Sharpe 2005, p. 90

- ^ a b c Hutton 2001, p. 395

- ^ Cressy 1992, p. 74

- ^ Sharpe 2005, p. 92

- ^ Cressy 1992, p. 75

- ^ Cressy 1992, pp. 70–71

- ^ Cressy 1992, pp. 74–75

- ^ Sharpe 2005, pp. 96–97

- ^ Sharpe 2005, pp. 98–100

- ^ Hutton 2001, p. 397

- ^ Pratt 2006, p. 57

- ^ Schwoerer, Lois G. (Spring 1990), «Celebrating the Glorious Revolution, 1689–1989», Albion: A Quarterly Journal Concerned with British Studies, The North American Conference on British Studies, 22 (1): 3, doi:10.2307/4050254, JSTOR 4050254

- ^ Rogers, Nicholas (2003), Halloween: From Pagan Ritual to Party Night, Oxford University Press, pp. 38–39, ISBN 978-0-19-516896-9

- ^ Cressy 1992, p. 77

- ^ a b Cressy 1992, pp. 79–80

- ^ «The great annoyance occasioned to the public by a set of idle fellows», The Times, vol. D, no. 5557, p. 3, 4 November 1802 – via infotrac.galegroup.com (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- ^ Cressy 1992, p. 76

- ^ Cressy 1992, p. 79

- ^ Cressy 1992, pp. 76–79

- ^ Sharpe 2005, pp. 157–159

- ^ Sharpe 2005, pp. 114–115

- ^ Sharpe 2005, pp. 110–111

- ^ a b Hutton 2001, p. 401

- ^ Sharpe 2005, p. 150

- ^ Sharpe 2005, p. 159

- ^ Cressy 1992, pp. 82–83

- ^ Fraser 2005, pp. 354–356

- ^ Anon 1859, p. 4

- ^ Cressy 1992, pp. 84–85

- ^ Bohstedt 2010, p. 252

- ^ Sharpe 2005, pp. 159–160

- ^ Hutton 2001, pp. 405–406

- ^ a b Hutton 2001, p. 403

- ^ Hutton 2001, p. 514, note 45

- ^ Cressy 1992, pp. 85–86

- ^ «Guy Fawkes’ Day», Life, Time Inc, vol. 19, no. 24, p. 43, 10 December 1945, ISSN 0024-3019

- ^ a b Sharpe 2005, p. 157

- ^ Beck, Ervin (1984), «Children’s Guy Fawkes Customs in Sheffield», Folklore, Taylor & Francis on behalf of Folklore Enterprises, 95 (2): 191–203, doi:10.1080/0015587X.1984.9716314, JSTOR 1260204

- ^ Opie 1961, pp. 280–281

- ^ Hutton 2001, pp. 406–407

- ^ Sharpe 2005, pp. 147–152

- ^ Champion 2005, p. n/a

- ^ Kettle, Martin (5 November 2003), «The real festival of Britain», The Guardian

- ^ Cressy 1992, pp. 86–87

- ^ de Castella, Tom (6 November 2012), «Has Halloween now dampened Bonfire Night?», BBC News

- ^ Underdown 1987, p. 70

- ^ Cressy 1992, pp. 69–71

- ^ Hutton 2001, p. 394

- ^ Santino, Jack (Summer 1996), «Light up the Sky: Halloween Bonfires and Cultural Hegemony in Northern Ireland», Western Folklore, Western States Folklore Society, 55 (3): 213–232, doi:10.2307/1500482, JSTOR 1500482

- ^ Cannadine, David (4 November 2005), «Halloween v Guy Fawkes Day», BBC News, archived from the original on 31 October 2010

- ^ Santino, Jack (1998), The Hallowed Eve: Dimensions of Culture in a Calendar Festival in Northern Ireland, University Press of Kentucky, p. 54

- ^ Rawlinson, Kevin (5 November 2010), «Guy Fawkes vs Diwali: Battle of Bonfire Night», The Independent

- ^ Sharpe 2005, p. 192

- ^ Phillip 1789, p. Chapter VII

- ^ «Weekly Occurrences», The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, p. 1, 10 November 1805

- ^ «The Swan River Colony», The Capricornian, p. 5, 12 December 1929

- ^ Government Notice, The Perth Gazette and Western Australian Journal, 27 April 1833, p. 66 – via Trove

- ^ Wright, Tony (30 October 2020), «Ready for a rocket?: No one’s laughing as a new Bonfire Night nears», The Sydney Morning Herald, retrieved 5 November 2021

- ^ Davis 2010, pp. 250–251

- ^ «Guy Fawkes: Reports of paint, stoning, intimidation in Cape despite warning», IOL, 5 November 2019

- ^ Atter, Heidi (5 November 2021), 17th-century Bonfire Night traditions going strong throughout N.L., and internationally, CBC News, retrieved 5 November 2021

- ^ Davis 2010, p. 250

- ^ Sharpe 2005, p. 142

- ^ Tager 2001, pp. 45–50

- ^ Young 1999, pp. 24, 93–94

- ^ Kaufman 2009, p. 99

- ^ Fuchs 1990, p. 36

- ^ Sharpe 2005, p. 145

- ^ Fitzpatrick, John C., ed. (5 November 1775), «The Writings of George Washington from the Original Manuscript Sources, 1745–1799», memory.loc.gov

- ^ Berlant 1991, p. 232 n.58, see also Robotti, Frances Diane (2009), Chronicles of Old Salem, Kessinger Publishing, LLC

- ^ Albee, John (October–December 1892), «Pope Night in Portsmouth, N. H.», The Journal of American Folklore, American Folklore Society, 5 (19): 335–336, doi:10.2307/533252, JSTOR 533252

- ^ Fraser 2005, p. 353

- ^ Eggleston, Edward (July 1885), «Social Life in the Colonies», The Century; a popular quarterly, vol. 30, no. 3, p. 400

Bibliography

- Anon (1859), The law journal for the year 1832–1949, vol. XXXVII, E. B. Ince