Ежегодно 7 ноября в России отмечается памятная дата — День Октябрьской революции 1917 года.

Формально этот праздник был учрежден в 2005 году, но на самом деле имеет давнюю историю и знаком любому человеку, родившемуся и воспитанному в Советском Союзе. С 1918 и по 1991 год день 7 ноября был главным советским праздником и носил название — День Великой Октябрьской социалистической революции.

В течение всей советской эпохи 7 ноября был «красным днем календаря», то есть государственным праздником СССР, который отмечали не только особым цветом в ежедневнике, но и обязательными демонстрациями трудящихся, проходившими в каждом городе страны. История этого праздника закончилась с распадом Советского Союза и развенчанием коммунистической идеологии.

В современной России праздник был переименован сначала в День согласия и примирения (с намеком на необходимое примирение сторонников разных идеологических взглядов), а затем и упразднен вовсе. Впрочем, в некоторых бывших республиках СССР он продолжает существовать и по сей день: в Кыргызстане 7 ноября остается выходным днем и государственным праздником (но поменял название), в Беларуси он отмечается как День Октябрьской революции.

В России 7 ноября перестало быть праздником, но вошло в перечень памятных дат. Соответствующий закон был принят в 2005 году. Ведь несмотря на спорную идеологическую подоплеку бывшего праздника, сложно отрицать значение этой даты в истории страны. Восстание в Петрограде в 1917 году, завершившееся социалистической революцией, предопределило все дальнейшее развитие не только России, но и ряда других государств мира.

Для тех, кто изучал историю уже в современной России и, возможно, уделил недостаточно вниманию этой вехе, стоит напомнить. В ночь с 7 на 8 ноября (по новому стилю, а по старом стилю это произошло с 25 на 26 октября) 1917 года в Петрограде произошло восстание. По сигналу, которым стал выстрел крейсера «Аврора», вооруженные рабочие, солдаты и матросы захватили Зимний дворец, свергли Временное правительство и провозгласили Власть Советов, которая просуществовала в стране 73 года.

В результате Октябрьской революции 1917 года изменился государственно-политический, идеологический и общественно-экономический строй страны, на большей части территории бывшей Российской империи образовалось государство, получившее в 1922 году название Союз Советских Социалистических Республик.

Кстати, легендарный крейсер — символ Октябрьской революции — в ноябре 1948 года был выведен из состава флота и поставлен на вечную стоянку у Петроградской набережной в Ленинграде (сегодня — Санкт-Петербург). Он является кораблем-музеем, филиалом Центрального военно-морского музея, а также — объектом культурного наследия Российской Федерации.

Материалы по теме в Журнале Calend.ru:

Инфографика – постер «7 ноября — День Октябрьской революции 1917 года в России»

Рассказ «Ответственная за транспаранты»

Кто-то ее по-прежнему готов называть Великой Октябрьской Социалистической революцией, кто-то – Октябрьским переворотом и началом крушения Российского государства. Любопытный факт – сами большевики первое десятилетие в активном обиходе называли этот день не иначе как «большевистским переворотом». Оставим спорщикам их споры и сначала уточним, что в результате перехода молодой Советской Республики с юлианского календаря на григорианский смена власти в России произошла в начале ноября. Вот так в нашей стране 7 ноября стало отмечаться как День Октябрьской революции. Благодаря этому месяц октябрь начал фигурировать в названиях городов, районов, поселков, улиц, культурно-массовых заведений, «заводов, газет, пароходов» и далее по списку. Названия «Октябрь» давали даже спортивным коллективам, далеким от общественно-политических коллизий. В то время как ноябрь вообще практически не упоминался в контексте революции. Например, город Ноябрьск в Тюменской области стал так называться по времени начала его строительства.

Что произошло 7 ноября

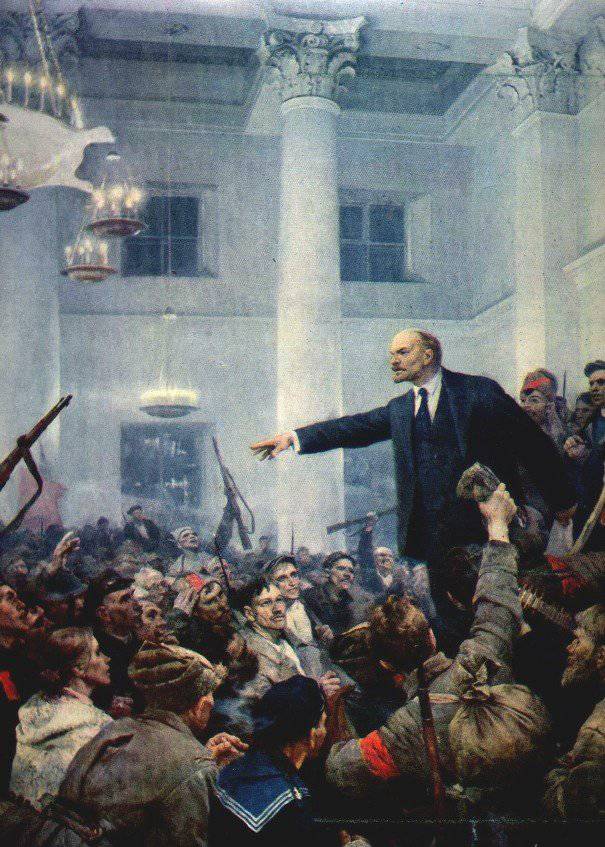

Трехсотлетняя династия Дома Романовых пала в феврале того же 1917 года в результате буржуазной революции. Пришедшее к власти либеральное правительство партии конституционных демократов объявило Россию республикой, но под спудом социально-экономических проблем и затянувшегося участия страны в Первой мировой войне уже к осени оказалось неспособным управлять государством. Набиравшая популярность за счет лозунгов, понятных большинству населения, партия большевиков за какие-то месяцы из малознакомой кому кучки теоретиков выросла до практиков, оказавшихся востребованным русским народом. Знаменитые ленинские Декреты о земле и мире стали более близкими, чем патриотические лозунги «войны до победного конца» с Германией, бывшие на вооружении у правых и центристских партий.

Таким образом, 7 ноября (25 октября по старому стилю) в России произошла насильственная, но, по свидетельству многих современников, вполне мирная смена власти. Октябрьская революция 1917 года положила начало коренному изменению государственного строя в России, а также многовековому укладу жизни народов, проживающих на территории страны. В результате стала меняться и политическая система мира. Появились государства, в основе внутренней политики которых лежали заботы об улучшении жизни широких масс. И речь здесь идет не только о странах Азии, а затем и Восточной Европы, ориентировавшихся на советскую модель. Революция дала сигнал всему капиталистическому миру о необходимости необратимых изменений в социальной сфере.

День Октябрьской революции в СССР – Мировая Пролетарская или Великая Социалистическая?

На прославление Дня Октябрьской революции в Советском Союзе были брошены все силы – от партийных и научных структур до детской литературы. Стихотворение «Круглый год» классика Самуила Маршака посвящено двенадцати месяцам, от января до декабря, где небольшие стишки-главки в одиннадцати случаях рассказывают о погодных признаках каждого из месяцев. Кроме ноября. Что радостного писать детям о хмуром небе, пустых пашнях, черных деревьях и холодном дожде со снегом, чем характеризуется обычно последний предзимний месяц? Три ноябрьских четверостишия рассказывают исключительно о праздновании Дня Октябрьской революции.

Действительно, уже в 1918 году 7 ноября было объявлено главным государственным праздником молодой Советской республики и, соответственно, выходным днем. Только назывался он не Днем Октябрьской, а Пролетарской революции. В самые первые годы Советской власти еще была сильна вера в возможность пролетариата установить свое господство не только на одной шестой части суши, но и во всем мире. Поэтому особо рьяные сторонники гегемонии рабочего класса называли праздник Днем «мировой Пролетарской революции». Спустя первое десятилетие вера в мощь и способности пролетариата значительно поубавилась даже у самых приверженных его сторонников. В постановлении ВЦИК от 26 октября 1927 года, то есть к десятилетию свержения самодержавия, 7 ноября именовалось только как «день октябрьской революции». Да, представьте себе – именно с маленькой буквы. Но от прописного знака до признания властями факта большевистского переворота – дистанция невеликая. Зато приближающаяся десятилетняя годовщина подарила для трудового народа еще один выходной – в число «красных дат» к 7 ноября добавили еще и следующий день. Сам же День Октябрьской революции на протяжении последующих шестидесяти с половиной лет на одной шестой части суши больше не трактовался как дата большевистского переворота.

Но это были еще не все изменения, касающиеся главного государственного праздника страны. В советской верхушке разворачивалась нешуточная внутрипартийная борьба. Очевидно, чтобы избежать кривотолков по поводу трактовки событий, произошедших в тот день, ровно в десятую годовщину событий Сталин официально ввел термин «Великая Октябрьская Социалистическая Революция». Знакомый многим после принятия Конституции СССР в 1936 году («Конституции победившего социализма») окончательно вытеснил понятие «мировой пролетарской революции».

Никакие последующие события так и не смогли отвоевать пальму первенства у Дня Октябрьской Революции как главного государственного праздника страны. День образования СССР (30 декабря 1922 года) так и остался чисто протокольной датой. У поистине всенародного праздника – Дня Победы в Великой Отечественной войне 9 мая – судьба сложнее. Из-за ревнивого отношения Сталина и Хрущева к популярности у советского народа маршала Жукова официальным праздником 9 мая стало только к двадцатилетнему юбилею окончания войны.

Однако чем дальше со временем отдалялась дата 7 ноября 1917 года, тем больше «вымывался» первоначальный смысл праздника. Непосредственных участников и просто свидетелей события становилось все меньше. Зато желающих получить дополнительные дни к отпуску за участие в ноябрьской демонстрации трудящихся на Красной площади постоянно росло. Два дня (7 и 8 ноября), а нередко и три, если «красные даты» в календаре примыкали к выходным, превращались в хороший отдых. С появлением цветных телевизоров трансляции народных демонстраций с участием передовиков производства становились аналогом зарубежных красочных карнавалов. Все это, да еще вечерний праздничный салют, несомненно, поднимало настроение у советских людей без какой-либо политической подоплеки. Пока главы семейства радостно шли в трудовых колоннах по брусчатке Красной площади, их домашние крутились на кухне, готовя праздничный стол. Желая поднять значимость праздника, в условиях дефицита на предприятиях повсеместно выдавались продуктовые наборы. Неизбалованный советский потребитель от души радовался баночкам с красной и черной икрой, палке финского сервелата. Дети с нетерпением ждали своих пап, которые несли домой огромные яркие воздушные шары, большие бумажные гвоздики и прочие атрибуты народной радости по поводу очередной годовщины. В такой атмосфере даже неумолимо устаревавшие черно-белые фильмы, такие как «Ленин в Октябре» или трилогия о Максиме, шли на ура.

Парады в честь дня Октябрьской революции

Первый военный парад на Красной площади в Москве состоялся 7 ноября 1918 года. Показать многочисленным врагам свой вооруженный арсенал для Советов было священным делом. Не проводились торжественные шествия в честь годовщины Октября лишь в 1920, 1921 и 1925 годах. Последний был отменен по причине траура в связи с кончиной Михаила Фрунзе. Парады принимали первые лица государства. Любопытно, что в 1923 году уже смертельно больной Ленин на торжестве был заменен на собственную гипсовую скульптуру. По мере модернизации вооруженных сил советской страны менялось и содержание ноябрьского парада.

Без всякого сомнения, самое знаменитое военное шествие в отечественной, да, пожалуй, и в мировой истории состоялось 7 ноября 1941 года. Немецко-фашистские войска вплотную подошли к Москве. Весь мир с замиранием прильнул к радиоприемникам, ловя вести из Советского Союза. Проведение парада в честь Дня Октябрьской революции в голодной и заснеженной Москве имело громадное политическое значение. Речь Сталина с обращением к памяти великих полководцев прошлого – от Александра Невского до Михаила Кутузова – не только вдохновляла шедших прямо с Красной площади на защиту столичных рубежей красноармейцев, она символизировала соединение большевистской коммунистической идеологии с историческими традициями российского государства. В конце 1941 года захватническим планам Гитлера по установлению мирового господства был нанесен один из сильнейших ударов. Стоит также упомянуть, что военные шествия в ноябре 1941 года прошли в Воронеже и Куйбышеве. Последний, в случае провала московского из-за немецких бомбежек, должен был стать основным и транслироваться по радио. Сам же факт проведения нескольких парадов в 24-ю годовщину Октября имел большой резонанс в мире. В частности, он еще больше охладил пыл союзников Германии – Турции и Японии вести военные действия против СССР.

В победном 45-м военный парад 7 ноября проводить не стали. Возможно, посчитали, что знаменитый также на весь мир Парад Победы достаточно продемонстрировал мощь и возможности Советских вооруженных сил. С 1946 по 1990 годы парад в честь Дня Октябрьской революции, наряду с демонстрацией трудящихся, входил в обязательную программу праздника.

Как отмечают 7 ноября сегодня

С распадом Советского Союза изменения коснулись и формата его главного государственного праздника. Первым делом соседний день, 8 ноября, уже в 1992 году был лишен статуса официального выходного. С самим же днем дело обстояло сложнее. Не желая вступать в острые противоречия с многочисленными политическими оппонентами, новая российская власть обратилась к глубокой истории Отечества. Выход был найден. В это же время года (начало ноября) на Руси происходили не менее драматические события, связанные с изгнанием польских интервентов. Поэтому повод придать новый смысл 7 ноября как праздничной дате искали тщательно.

В середине 90-х бывший День Октябрьской революции перебывал Днем Освобождения Москвы от польских интервентов, Днем согласия и примирения. При этом власть новой России по-прежнему не решалась покушаться на статус 7 ноября как выходного дня. Свободное от работы время верные коммунистическим идеалам силы использовали для проведения своих демонстраций. Теперь, правда, мероприятия носили протестный характер. Тягаться своей численностью с демонстрациями трудящихся в Советском Союзе они также не могли.

Следующие два десятилетия окончательно сняли с даты праздничную окраску. Выходным днем стало 4 ноября (День национального единства и согласия). В 2005 году согласно Федеральному закону «О днях воинской славы России» памятная дата 7 ноября названа Днем Октябрьской революции 1917 года. Этот же день теперь считается Днем воинской славы России как дата знаменитого военного парада на Красной площади в прифронтовой Москве морозным ноябрем 1941 года.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| День Великой Октябрьской социалистической революции Day of the Great October Socialist Revolution |

|

|---|---|

October Revolution Day in 1977 |

|

| Observed by |

|

| Type | National Day |

| Celebrations | Flag hoisting, parades, fireworks, award ceremonies, singing patriotic songs and the national anthem, speeches by the CPSU General Secretary, entertainment and cultural programs |

| Date | 7 November |

| Next time | 7 November 2023 |

| Frequency | annual |

| Related to | Great October Socialist Revolution |

Anniversary of October Revolution in Riga, Latvia, Soviet Union in 1988.

October Revolution Day (officially Day of the Great October Socialist Revolution, Russian: День Великой Октябрьской социалистической революции) was a public holiday in the Soviet Union and other Soviet-aligned states, officially observed on November 7 from 1927 to 1990,[1] commemorating the 1917 October Revolution.

For Soviet families, it was a holiday tradition to partake in a shared morning meal, and to watch the October Revolution Parade broadcast on Soviet Central Television.[1]

A holiday canon was established during the Stalinist period, and included a workers’ demonstration, the appearance of leaders on the podium of the Mausoleum, and, finally, the military parade on Red Square, which was held unfailingly every year, and most famously in 1941, as the Axis forces were advancing on Moscow.[2]

October Revolution Day, which had been the main holiday of the year and received most of its traditions during the Stalinist period, gradually became less popular in the 1970s, falling behind the Victory Day and New Year celebrations as personal and family holidays.[2]

Soviet observances[edit]

Civil-military parade[edit]

History[edit]

The 20th anniversary parade in 1937.

The first military parade took place on 7 November 1919 on the second anniversary of the revolution. The Russian civil war lasted until 1923. The parade in 1941 is particularly revered as it took place during the Battle of Moscow, during which many of the soldiers on the parade would be killed in action. In 1953, the parade took place as the first one to not be inspected by officers on horseback.[3] The practice of foreign leaders began in 1957 with Mao Zedong attending that year’s parade as part of a state visit, continuing throughout the next two decades with Ethiopian leader Mengistu Haile Mariam’s attendance in 1980 and the leaders of Warsaw Pact and USSR-allied nations in 1967, 1977 and 1987. The 1989 parade was the first to have a drill routine by the massed bands take place. During the final parade in 1990, an assassination attempt was made on the life of President Mikhail Gorbachev by Alexander Shmonov, a locksmith from Leningrad. The two bullets he fired missed as he was tackled to the ground by crowds of demonstrators.[4] The only time that a Soviet leader never attended a parade was in 1983 when Yuri Andropov did not attend the parade due to a sickness and his associate Konstantin Chernenko stood in for him.[5]

Description of the parade[edit]

The most important event of the holiday is the national military parade and demonstrations on Moscow’s Red Square, with members of the Politburo and the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union acting as the guests of honor. The celebrations begin at 9:50 am Moscow Standard Time with the arrival honors for the commander of the parade, who is greeted by the commandant of the Frunze Military Academy (now the Combined Arms Academy of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation) usually a general officer, and receives the report on the parade’s status. Once the parade commander (who is usually a Colonel General with the billet of Commander of the Moscow Military District) receives the report, he takes his position in the parade and orders the formations to stand at ease. A couple minutes later, a Communist Party and government delegation arrives at the grandstand on top of Lenin’s Mausoleum. The dignitaries include the General Secretary, Premier, the Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet, members of the entire Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, including members from the Politburo and Secretariat, the Chief of the General Staff of the Armed Forces, service branch commanders, deputy defence ministers, members of the cabinet and commanders of the support departments in the general staff, in addition to the occasional foreign head of state or party as the principal foreign guest and reviewing officer. In between the south of the grandstand is a platoon of the armed linemen and markers from the Independent Commandant’s Regiment in military overcoats whose purpose is to take post to mark the distance of the troops marching past. Seated in the stands on the west and east sides were residents of the capital, visitors from all over the Union, the diplomatic corps and military attaches and guests from allied and friendly countries with ties to the Union government. Within Red Square the more than 9,000 strong parade formation (11,000 during jubilee years) was complemented by the Massed Bands of the Moscow Garrison, conducted by the Senior Director of Music of the Military Band Service of the Armed Forces, the billet of an officer who usually held major general rank, at the start of the parade the bands were split into four sections across the expanse of the Square in between the inspecting formations. The mobile column, also present, was made up of around 170-380 vehicles and around 3,900 crews drawn from the participant units making up the segment of the parade. Until 1974 the mobile column was around 400 to 750 vehicles strong made up of around 7,500 to 9,800 crews and officers from the formations making up the column.

Badges[edit]

In November 1967 Minister of Defense Marshal Andrei Grechko announced his gratitude and of the Ministry of Defence to all those who marched on Red Square that 7 November as the country marked the golden jubilee anniversary year of the Revolution and for the first time, together with the text of gratitude, they were presented with commemorative badges «Participant of the military parade». Participants were also awarded a commemorative badge in the 1972 parade, the 100th parade to mark the golden jubilee of the foundation of the Soviet Union. A number of naval schools had custom made badges made in honor of their participation in the celebrations.[6]

Parade proper[edit]

The Leningrad parade in 1983.

As the Kremlin’s Spasskaya Tower sounds the chimes at 10am the parade commander orders the parade to present arms and look to the left for inspection. The Minister of Defence (usually a billet of a General of the Army) then is driven on a limousine to the center of the square to receive the parade report from the commander, with the combined bands playing Jubillee March of the Red Army in the background. Once the report is received, the Minister and the parade commander begin to inspect the parading formations together with the bands. The limousinesed stop at each formation in order for the minister to send his greeting to the contingents, in which they respond with a threefold «Ura» (Russian: Ура). Other than the Red Square inspection, the commander and the minister would also inspect the personnel of the mobile column on Manezhnaya Square. After the final greeting, the Massed Bands played Long Live our State by Boris Alexandrovich Alexandrov as the commander returns to his place in the parade, and the Minister driven to the grandstand while the entire parade shouts ‘Ura!’ (Russian: Ура!) repeatedly until he takes his position in the grandstand and the bands end playing (from 1945 to 1966 Slavsya from A Life for the Tsar took its place and yet again in 1990). During this time, the Corps of Drums of the Moscow Military Music College, which is an affiliate of the Suvorov Military Schools, take their place behind the parade commander’s limousine. The parade is then ordered to stand at ease and the chromatic fanfare trumpeters, together with the rest of the musicians of the massed bands, sound a fanfare call, usually Govovin’s Moscow Fanfare for the keynote address by the minister which will follow. As the minister concludes his address, he will yell «Ura!» (Russian: «Ура!») to which the entire parade repeats thrice. The Massed Bands of the Moscow Garrison then play the full version of the State Anthem of the Soviet Union while a ceremonial battery armed with the 76 mm divisional gun M1942 (ZiS-3) fire a 21-gun salute. As the anthem ends, the bands sound a second fanfare and the parade commander orders the parade to do carry out the following commands for the march past:

-

- Parade… attention! Ceremonial march past!

Form battalions! Distance by a single lineman! First battalion will remain in the right, remainder… left.. turn!

Slope.. arms!

Eyes to the right…

Quick march!

- Parade… attention! Ceremonial march past!

On the command «Quick march!», the linemen take their places at the south end of the square while the Corps of Drums of the Moscow Military Music College march to a drum tune, while the fifers and trumpeters play a specific tune, in a tradition that would go on until the late 1990s and early 2000s when the trumpets were removed. As the massed bands start playing the Corps of Drums begin to swing their drumsticks while on the eyes right led by the drum major. The Corps is immediately followed by the officers of the Frunze Military Academy whereas on jubilee parades, the massed colour guard is the first formation other than the corps on the square, followed by a historical contingent. The troops have always marched in the following order during the parade:

Order of ground march past column[edit]

Military Bands

- Massed Bands of the Moscow Military District under the direction of the Senior Director of Music of the Bands Service

- Corps of Drums of the Moscow Military Music College

Ground Column

- Parade commander holding the appointment of commanding officer of the Moscow Military District

- Color Guard Unit (in jubilee parades)

- Historical contingent (in jubilee parades)

- Red Guards

- Ex-Imperial Russian Army servicemen within the Red Army

- Sailors of the Aurora

- Red Army soldiers during the Civil War

- Great Patriotic War contingent

- Frunze Military Academy

- V.I. Lenin Military Political Academy

- Felix Dzerzhinsky Artillery Academy

- Military Armored Forces Academy Marshal Rodion Malinovsky

- Military Engineering Academy

- Military Academy of Chemical Defense and Control

- Yuri Gagarin Air Force Academy

- Prof. Nikolai Zhukovsky Air Force Engineering Academy

- Delegation of naval officer cadets from the Soviet Navy[7]

- 98th Guards Airborne Division

- Moscow Border Guards Institute of the Border Defence Forces of the KGB «Moscow City Council»

- Separate Operational Purpose Division

- 336th Marine Brigade of the Baltic Fleet

- Suvorov Military School

- Nakhimov Naval School

- Moscow Military Combined Arms Command Training School «Supreme Soviet of the Russian SFSR»

As ground column concludes, the massed bands play either Long Live our State or Song of the Motherland, with the Moscow Higher Military Command School marching past as the last formation on the square before the mobile column with Victory Day being played beforehand as their cadets march at the rear. When the ground segment ends, the bands perform an about turn and march towards the facade of the GUM department store to give way to the mobile column, which drives past as the bands play Victorious March and Moscow Salute. Once the ground mobile column is complete, the bands take their position at the western end of the square to prepare for the finale, led by the senior director of music, conductors, bandmasters and drum majors. The finale involves the massed bands marching down the square to the tune of Song of the Soviet Army or Metropolitan March and as the bands march past the grandstand, the senior director of music, conductors and bandmasters salute at the eyes right. In 1967, the massed bands marched out to the tune of My Beloved Motherland.

Order of mobile column drivepast[edit]

- 2nd Guards Motor Rifle Division

- 98th Guards Airborne Division

- 4th Guards Tank Division

- Moscow Military District Field Artillery and Rocket Forces

- Moscow Military District Ground Forces Air Defense

- 1st Moscow Air and Air Defense Forces Army

- Northern Fleet and Baltic Fleet Coastal Defense, Surface and Submarine Forces (until 1974)

- Strategic Missile Forces 27th Guards Rocket Army

Similar parade events were held in all major cities in the RSFSR as well as in the USSR, with the first secretary of the local communist party branch being the guest of honor and the commander of the regional military district or large formation acting as the parade inspector and keynote speaker, while the second-in command of the unit or command served as parade commander. The parade format is the same in these cities, with particularities being shaped to fit the specific parade ground (e.g. October Square, Minsk). Massed bands for the parade were drawn from the formation or district bands located in their respective areas. The Government of the Armenian SSR cancelled the 1989 parade in Yerevan due to extended protests, while the mobile column of the parade in the Moldovan capital of Kishinev was removed from the itinerary due to protester blocking the streets and preventing passage to vehicles.[8] A similar occurred event occurred on what is now Gediminas Avenue in Vilnius.[9]

Civil parade and workers’ demonstration[edit]

Workers demonstration in Moscow in 1977

The bands having marched off the square is the signal for the commencement of the holiday civil parade and workers’ demonstration in Red Square. In jubilee years (more frequency in the parades of the 1960s and 1970s), the civil parade kicks off with a spectacular march made up of the following components preceding the workers’ demonstration march:

- Red flag bearers

- Historical segment (present in the parades of 1967 and 1987)

- Officials, management, staff and employees of the Moscow City CPSU Committee and Moscow City Council

- Representatives of state economic enterprises and firms in Moscow

- Komsomol

- Vladimir Lenin All-Union Pioneer Organization

- DOSAAF

- Color Guard, Athletes and Coaches from the Voluntary Sports Societies of the Soviet Union

- Moscow National Central Physical Fitness and Sports School

The logo of the 1987 celebrations.

Float displays also featured prominently in the civil parades where floats were designed to promote government and party campaigns or highlight the works of various public companies, farm collectives and state economic firms. At a certain point during the civil parade, Pioneers in winter jackets and carrying flowers representing schools in Moscow and all over the country run towards the front of the Mausoleum facade and are split into two groups that ascend the staircases towards the dignitaries in the grandstand to give them flower bouquets. Following the civil parade the workers’ demonstration officially begins, wherein workers from state economic and social firms in Moscow, as well as from schools and universities, march past as part of their respective community delegations. Each delegation has a color guard unit and brass band taking part, as well as floats from the participating state enterprises. Each of Moscow’s districts march past the grandstand to greet everyone a Happy Revolution Day, especially to the dignitaries and everyone in the stands watching as balloons fly out from the crowds filing past while recorded music is played on the speakers. After an hour or two, the civil parade ends with a huge crowd bidding the principal dignitaries farewell from the grounds of the square with red flags in their hands as one final cheer resounds from the sound systems installed along the entire length of the square.

Similar civil parades occurred in all major cities and the republican capital cities following the military parades.

Post-Soviet observance[edit]

CPRF celebrations in 2009.

In Russia, the holiday was repurposed several times. In 1995, President Yeltsin reestablished a November 7 holiday to commemorate the liberation of Moscow from the Polish-Lithuanian Army in 1612.[2] The next year, it was renamed ‘Day of Accord and Reconciliation’.[2] From 2004, November 7 became one of several Days of Military Honour and ceased to be a day off.[1] The original celebrations continues to be honoured in ceremonies led by the Communist Party of the Russian Federation.

As of 2018, October Revolution Day remains an official holiday in Belarus, though the original significance has faded and it is simply regarded as a day off.[10] President Alexander Lukashenko has described the holiday as one that «strengthens social harmony».[11] Similarly, in the unrecognized Pridnestrovian Transnistrian Republic, the day is officially a public holiday, but it is regarded by locals as devoid of its original meaning.[12][citation needed] In Kyrgyzstan, the holiday was observed until 2017, when it was replaced by the ‘Days of Ancestral History and Memory’ on November 7 and 8.[13]

Observance in the United States[edit]

A handful of U.S. states[which?] designate November 7 as Victims of Communism Day. In 2022, the state of Florida in the United States, mandated that schools devote 45 minutes to teaching about communism, the role that communist leaders have had on history and «how people suffered under those regimes».[14]

See also[edit]

- Declaration of the Creation of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics

- List of October Revolution Parades in Moscow

- Victory Day (9 May)

- Golden Week (China)

- National Day of the People’s Republic of China

References[edit]

- ^ a b c «День Октябрьской революции 1917 года». РИА Новости (in Russian). 7 November 2017. Archived from the original on 2017-11-11. Retrieved 26 October 2018.

- ^ a b c d «7 ноября: пять праздников одного дня. Справка». РИА Новости (in Russian). 7 November 2008. Archived from the original on 2015-05-18. Retrieved 27 October 2018.

- ^ «Parades — November 7th». www.globalsecurity.org. Retrieved Jan 31, 2023.

- ^ Levkovich, Yevgeny (2017-02-16). «The last Soviet terrorist: The man who tried to assassinate Gorbachev». Russia Beyond The Headlines. Retrieved 2017-03-30.

- ^ Times, Serge Schmemann, Special To The New York (1983-11-08). «ANDROPOV MISSES MOSCOW PARADE, STIRRING RUMORS». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2019-10-13.

- ^ «Нагрудные знаки участникам московских парадов». izhig.ru. Retrieved 2020-07-28.

- ^ «По Брусчатке Красной Площади».

- ^ «Soviet Revolution Day celebrations disrupted». UPI. Retrieved 2017-02-11.

- ^ LordBenas (2008-05-24), 1989 sovietinis paradas Gedimino prospektu., retrieved 2017-03-20

- ^ «Минчане о 7 ноября: «Это праздник, но какой — не помню»«. Комсомольской правды (in Russian). 6 November 2016. Retrieved 26 October 2018.

- ^ https://m.eng.belta.by/president/view/lukashenko-memory-of-october-revolution-strengthens-social-harmony-125652-2019/

- ^ «7 ноября в Приднестровье по-пролетарски празднуют лишь коммунисты». Deutsche Welle (in Russian). 7 November 2009. Archived from the original on 2017-05-22. Retrieved 26 October 2018.

- ^ «Президент Киргизии постановил отмечать 7-8 ноября Дни истории и памяти предков». Interfax.ru (in Russian). 26 October 2017. Archived from the original on 2018-06-01. Retrieved 26 October 2018.

- ^ «DeSantis signs bill mandating communism lessons in class, as GOP leans on education». MSN. Retrieved 2022-05-10.

External link[edit]

Media related to October Revolution Day at Wikimedia Commons

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| День Великой Октябрьской социалистической революции Day of the Great October Socialist Revolution |

|

|---|---|

October Revolution Day in 1977 |

|

| Observed by |

|

| Type | National Day |

| Celebrations | Flag hoisting, parades, fireworks, award ceremonies, singing patriotic songs and the national anthem, speeches by the CPSU General Secretary, entertainment and cultural programs |

| Date | 7 November |

| Next time | 7 November 2023 |

| Frequency | annual |

| Related to | Great October Socialist Revolution |

Anniversary of October Revolution in Riga, Latvia, Soviet Union in 1988.

October Revolution Day (officially Day of the Great October Socialist Revolution, Russian: День Великой Октябрьской социалистической революции) was a public holiday in the Soviet Union and other Soviet-aligned states, officially observed on November 7 from 1927 to 1990,[1] commemorating the 1917 October Revolution.

For Soviet families, it was a holiday tradition to partake in a shared morning meal, and to watch the October Revolution Parade broadcast on Soviet Central Television.[1]

A holiday canon was established during the Stalinist period, and included a workers’ demonstration, the appearance of leaders on the podium of the Mausoleum, and, finally, the military parade on Red Square, which was held unfailingly every year, and most famously in 1941, as the Axis forces were advancing on Moscow.[2]

October Revolution Day, which had been the main holiday of the year and received most of its traditions during the Stalinist period, gradually became less popular in the 1970s, falling behind the Victory Day and New Year celebrations as personal and family holidays.[2]

Soviet observances[edit]

Civil-military parade[edit]

History[edit]

The 20th anniversary parade in 1937.

The first military parade took place on 7 November 1919 on the second anniversary of the revolution. The Russian civil war lasted until 1923. The parade in 1941 is particularly revered as it took place during the Battle of Moscow, during which many of the soldiers on the parade would be killed in action. In 1953, the parade took place as the first one to not be inspected by officers on horseback.[3] The practice of foreign leaders began in 1957 with Mao Zedong attending that year’s parade as part of a state visit, continuing throughout the next two decades with Ethiopian leader Mengistu Haile Mariam’s attendance in 1980 and the leaders of Warsaw Pact and USSR-allied nations in 1967, 1977 and 1987. The 1989 parade was the first to have a drill routine by the massed bands take place. During the final parade in 1990, an assassination attempt was made on the life of President Mikhail Gorbachev by Alexander Shmonov, a locksmith from Leningrad. The two bullets he fired missed as he was tackled to the ground by crowds of demonstrators.[4] The only time that a Soviet leader never attended a parade was in 1983 when Yuri Andropov did not attend the parade due to a sickness and his associate Konstantin Chernenko stood in for him.[5]

Description of the parade[edit]

The most important event of the holiday is the national military parade and demonstrations on Moscow’s Red Square, with members of the Politburo and the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union acting as the guests of honor. The celebrations begin at 9:50 am Moscow Standard Time with the arrival honors for the commander of the parade, who is greeted by the commandant of the Frunze Military Academy (now the Combined Arms Academy of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation) usually a general officer, and receives the report on the parade’s status. Once the parade commander (who is usually a Colonel General with the billet of Commander of the Moscow Military District) receives the report, he takes his position in the parade and orders the formations to stand at ease. A couple minutes later, a Communist Party and government delegation arrives at the grandstand on top of Lenin’s Mausoleum. The dignitaries include the General Secretary, Premier, the Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet, members of the entire Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, including members from the Politburo and Secretariat, the Chief of the General Staff of the Armed Forces, service branch commanders, deputy defence ministers, members of the cabinet and commanders of the support departments in the general staff, in addition to the occasional foreign head of state or party as the principal foreign guest and reviewing officer. In between the south of the grandstand is a platoon of the armed linemen and markers from the Independent Commandant’s Regiment in military overcoats whose purpose is to take post to mark the distance of the troops marching past. Seated in the stands on the west and east sides were residents of the capital, visitors from all over the Union, the diplomatic corps and military attaches and guests from allied and friendly countries with ties to the Union government. Within Red Square the more than 9,000 strong parade formation (11,000 during jubilee years) was complemented by the Massed Bands of the Moscow Garrison, conducted by the Senior Director of Music of the Military Band Service of the Armed Forces, the billet of an officer who usually held major general rank, at the start of the parade the bands were split into four sections across the expanse of the Square in between the inspecting formations. The mobile column, also present, was made up of around 170-380 vehicles and around 3,900 crews drawn from the participant units making up the segment of the parade. Until 1974 the mobile column was around 400 to 750 vehicles strong made up of around 7,500 to 9,800 crews and officers from the formations making up the column.

Badges[edit]

In November 1967 Minister of Defense Marshal Andrei Grechko announced his gratitude and of the Ministry of Defence to all those who marched on Red Square that 7 November as the country marked the golden jubilee anniversary year of the Revolution and for the first time, together with the text of gratitude, they were presented with commemorative badges «Participant of the military parade». Participants were also awarded a commemorative badge in the 1972 parade, the 100th parade to mark the golden jubilee of the foundation of the Soviet Union. A number of naval schools had custom made badges made in honor of their participation in the celebrations.[6]

Parade proper[edit]

The Leningrad parade in 1983.

As the Kremlin’s Spasskaya Tower sounds the chimes at 10am the parade commander orders the parade to present arms and look to the left for inspection. The Minister of Defence (usually a billet of a General of the Army) then is driven on a limousine to the center of the square to receive the parade report from the commander, with the combined bands playing Jubillee March of the Red Army in the background. Once the report is received, the Minister and the parade commander begin to inspect the parading formations together with the bands. The limousinesed stop at each formation in order for the minister to send his greeting to the contingents, in which they respond with a threefold «Ura» (Russian: Ура). Other than the Red Square inspection, the commander and the minister would also inspect the personnel of the mobile column on Manezhnaya Square. After the final greeting, the Massed Bands played Long Live our State by Boris Alexandrovich Alexandrov as the commander returns to his place in the parade, and the Minister driven to the grandstand while the entire parade shouts ‘Ura!’ (Russian: Ура!) repeatedly until he takes his position in the grandstand and the bands end playing (from 1945 to 1966 Slavsya from A Life for the Tsar took its place and yet again in 1990). During this time, the Corps of Drums of the Moscow Military Music College, which is an affiliate of the Suvorov Military Schools, take their place behind the parade commander’s limousine. The parade is then ordered to stand at ease and the chromatic fanfare trumpeters, together with the rest of the musicians of the massed bands, sound a fanfare call, usually Govovin’s Moscow Fanfare for the keynote address by the minister which will follow. As the minister concludes his address, he will yell «Ura!» (Russian: «Ура!») to which the entire parade repeats thrice. The Massed Bands of the Moscow Garrison then play the full version of the State Anthem of the Soviet Union while a ceremonial battery armed with the 76 mm divisional gun M1942 (ZiS-3) fire a 21-gun salute. As the anthem ends, the bands sound a second fanfare and the parade commander orders the parade to do carry out the following commands for the march past:

-

- Parade… attention! Ceremonial march past!

Form battalions! Distance by a single lineman! First battalion will remain in the right, remainder… left.. turn!

Slope.. arms!

Eyes to the right…

Quick march!

- Parade… attention! Ceremonial march past!

On the command «Quick march!», the linemen take their places at the south end of the square while the Corps of Drums of the Moscow Military Music College march to a drum tune, while the fifers and trumpeters play a specific tune, in a tradition that would go on until the late 1990s and early 2000s when the trumpets were removed. As the massed bands start playing the Corps of Drums begin to swing their drumsticks while on the eyes right led by the drum major. The Corps is immediately followed by the officers of the Frunze Military Academy whereas on jubilee parades, the massed colour guard is the first formation other than the corps on the square, followed by a historical contingent. The troops have always marched in the following order during the parade:

Order of ground march past column[edit]

Military Bands

- Massed Bands of the Moscow Military District under the direction of the Senior Director of Music of the Bands Service

- Corps of Drums of the Moscow Military Music College

Ground Column

- Parade commander holding the appointment of commanding officer of the Moscow Military District

- Color Guard Unit (in jubilee parades)

- Historical contingent (in jubilee parades)

- Red Guards

- Ex-Imperial Russian Army servicemen within the Red Army

- Sailors of the Aurora

- Red Army soldiers during the Civil War

- Great Patriotic War contingent

- Frunze Military Academy

- V.I. Lenin Military Political Academy

- Felix Dzerzhinsky Artillery Academy

- Military Armored Forces Academy Marshal Rodion Malinovsky

- Military Engineering Academy

- Military Academy of Chemical Defense and Control

- Yuri Gagarin Air Force Academy

- Prof. Nikolai Zhukovsky Air Force Engineering Academy

- Delegation of naval officer cadets from the Soviet Navy[7]

- 98th Guards Airborne Division

- Moscow Border Guards Institute of the Border Defence Forces of the KGB «Moscow City Council»

- Separate Operational Purpose Division

- 336th Marine Brigade of the Baltic Fleet

- Suvorov Military School

- Nakhimov Naval School

- Moscow Military Combined Arms Command Training School «Supreme Soviet of the Russian SFSR»

As ground column concludes, the massed bands play either Long Live our State or Song of the Motherland, with the Moscow Higher Military Command School marching past as the last formation on the square before the mobile column with Victory Day being played beforehand as their cadets march at the rear. When the ground segment ends, the bands perform an about turn and march towards the facade of the GUM department store to give way to the mobile column, which drives past as the bands play Victorious March and Moscow Salute. Once the ground mobile column is complete, the bands take their position at the western end of the square to prepare for the finale, led by the senior director of music, conductors, bandmasters and drum majors. The finale involves the massed bands marching down the square to the tune of Song of the Soviet Army or Metropolitan March and as the bands march past the grandstand, the senior director of music, conductors and bandmasters salute at the eyes right. In 1967, the massed bands marched out to the tune of My Beloved Motherland.

Order of mobile column drivepast[edit]

- 2nd Guards Motor Rifle Division

- 98th Guards Airborne Division

- 4th Guards Tank Division

- Moscow Military District Field Artillery and Rocket Forces

- Moscow Military District Ground Forces Air Defense

- 1st Moscow Air and Air Defense Forces Army

- Northern Fleet and Baltic Fleet Coastal Defense, Surface and Submarine Forces (until 1974)

- Strategic Missile Forces 27th Guards Rocket Army

Similar parade events were held in all major cities in the RSFSR as well as in the USSR, with the first secretary of the local communist party branch being the guest of honor and the commander of the regional military district or large formation acting as the parade inspector and keynote speaker, while the second-in command of the unit or command served as parade commander. The parade format is the same in these cities, with particularities being shaped to fit the specific parade ground (e.g. October Square, Minsk). Massed bands for the parade were drawn from the formation or district bands located in their respective areas. The Government of the Armenian SSR cancelled the 1989 parade in Yerevan due to extended protests, while the mobile column of the parade in the Moldovan capital of Kishinev was removed from the itinerary due to protester blocking the streets and preventing passage to vehicles.[8] A similar occurred event occurred on what is now Gediminas Avenue in Vilnius.[9]

Civil parade and workers’ demonstration[edit]

Workers demonstration in Moscow in 1977

The bands having marched off the square is the signal for the commencement of the holiday civil parade and workers’ demonstration in Red Square. In jubilee years (more frequency in the parades of the 1960s and 1970s), the civil parade kicks off with a spectacular march made up of the following components preceding the workers’ demonstration march:

- Red flag bearers

- Historical segment (present in the parades of 1967 and 1987)

- Officials, management, staff and employees of the Moscow City CPSU Committee and Moscow City Council

- Representatives of state economic enterprises and firms in Moscow

- Komsomol

- Vladimir Lenin All-Union Pioneer Organization

- DOSAAF

- Color Guard, Athletes and Coaches from the Voluntary Sports Societies of the Soviet Union

- Moscow National Central Physical Fitness and Sports School

The logo of the 1987 celebrations.

Float displays also featured prominently in the civil parades where floats were designed to promote government and party campaigns or highlight the works of various public companies, farm collectives and state economic firms. At a certain point during the civil parade, Pioneers in winter jackets and carrying flowers representing schools in Moscow and all over the country run towards the front of the Mausoleum facade and are split into two groups that ascend the staircases towards the dignitaries in the grandstand to give them flower bouquets. Following the civil parade the workers’ demonstration officially begins, wherein workers from state economic and social firms in Moscow, as well as from schools and universities, march past as part of their respective community delegations. Each delegation has a color guard unit and brass band taking part, as well as floats from the participating state enterprises. Each of Moscow’s districts march past the grandstand to greet everyone a Happy Revolution Day, especially to the dignitaries and everyone in the stands watching as balloons fly out from the crowds filing past while recorded music is played on the speakers. After an hour or two, the civil parade ends with a huge crowd bidding the principal dignitaries farewell from the grounds of the square with red flags in their hands as one final cheer resounds from the sound systems installed along the entire length of the square.

Similar civil parades occurred in all major cities and the republican capital cities following the military parades.

Post-Soviet observance[edit]

CPRF celebrations in 2009.

In Russia, the holiday was repurposed several times. In 1995, President Yeltsin reestablished a November 7 holiday to commemorate the liberation of Moscow from the Polish-Lithuanian Army in 1612.[2] The next year, it was renamed ‘Day of Accord and Reconciliation’.[2] From 2004, November 7 became one of several Days of Military Honour and ceased to be a day off.[1] The original celebrations continues to be honoured in ceremonies led by the Communist Party of the Russian Federation.

As of 2018, October Revolution Day remains an official holiday in Belarus, though the original significance has faded and it is simply regarded as a day off.[10] President Alexander Lukashenko has described the holiday as one that «strengthens social harmony».[11] Similarly, in the unrecognized Pridnestrovian Transnistrian Republic, the day is officially a public holiday, but it is regarded by locals as devoid of its original meaning.[12][citation needed] In Kyrgyzstan, the holiday was observed until 2017, when it was replaced by the ‘Days of Ancestral History and Memory’ on November 7 and 8.[13]

Observance in the United States[edit]

A handful of U.S. states[which?] designate November 7 as Victims of Communism Day. In 2022, the state of Florida in the United States, mandated that schools devote 45 minutes to teaching about communism, the role that communist leaders have had on history and «how people suffered under those regimes».[14]

See also[edit]

- Declaration of the Creation of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics

- List of October Revolution Parades in Moscow

- Victory Day (9 May)

- Golden Week (China)

- National Day of the People’s Republic of China

References[edit]

- ^ a b c «День Октябрьской революции 1917 года». РИА Новости (in Russian). 7 November 2017. Archived from the original on 2017-11-11. Retrieved 26 October 2018.

- ^ a b c d «7 ноября: пять праздников одного дня. Справка». РИА Новости (in Russian). 7 November 2008. Archived from the original on 2015-05-18. Retrieved 27 October 2018.

- ^ «Parades — November 7th». www.globalsecurity.org. Retrieved Jan 31, 2023.

- ^ Levkovich, Yevgeny (2017-02-16). «The last Soviet terrorist: The man who tried to assassinate Gorbachev». Russia Beyond The Headlines. Retrieved 2017-03-30.

- ^ Times, Serge Schmemann, Special To The New York (1983-11-08). «ANDROPOV MISSES MOSCOW PARADE, STIRRING RUMORS». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2019-10-13.

- ^ «Нагрудные знаки участникам московских парадов». izhig.ru. Retrieved 2020-07-28.

- ^ «По Брусчатке Красной Площади».

- ^ «Soviet Revolution Day celebrations disrupted». UPI. Retrieved 2017-02-11.

- ^ LordBenas (2008-05-24), 1989 sovietinis paradas Gedimino prospektu., retrieved 2017-03-20

- ^ «Минчане о 7 ноября: «Это праздник, но какой — не помню»«. Комсомольской правды (in Russian). 6 November 2016. Retrieved 26 October 2018.

- ^ https://m.eng.belta.by/president/view/lukashenko-memory-of-october-revolution-strengthens-social-harmony-125652-2019/

- ^ «7 ноября в Приднестровье по-пролетарски празднуют лишь коммунисты». Deutsche Welle (in Russian). 7 November 2009. Archived from the original on 2017-05-22. Retrieved 26 October 2018.

- ^ «Президент Киргизии постановил отмечать 7-8 ноября Дни истории и памяти предков». Interfax.ru (in Russian). 26 October 2017. Archived from the original on 2018-06-01. Retrieved 26 October 2018.

- ^ «DeSantis signs bill mandating communism lessons in class, as GOP leans on education». MSN. Retrieved 2022-05-10.

External link[edit]

Media related to October Revolution Day at Wikimedia Commons

На протяжении более 70 лет годовщина Великой Октябрьской социалистической революции была главным праздником Советского Союза. 7 ноября на протяжении всей советской эпохи был «красным днем календаря», то есть государственным праздником, отмечавшимся обязательными праздничными мероприятиями, проходившими в каждом советском городе. Так было до 1991 года, когда СССР был развален, а коммунистическую идеологию чуть было не признали преступной. В Российской Федерации этот день сначала переименовали в День согласия и примирения, намекая на необходимость завершения гражданской войны в информационном поле страны и примирение сторонников разных идеологических взглядов, а затем отменили совсем. 7 ноября перестало быть праздником, но вошло в перечень памятных дат. Соответствующий закон приняли в 2010 году. В 2005 году в связи с учреждением нового государственного праздника (Дня народного единства) 7 ноября перестало быть выходным днём.

Этот день невозможно вычеркнуть из истории России, так как восстание в Петрограде 25—26 октября (7—8 ноября по новому стилю) привело не только к свержению буржуазного Временного правительства, но и предопределило всё дальнейшее развитие как России, так и многих других государств планеты.

Краткая хроника событий

К осени 1917 года политика Временного правительства привела Российское государство на грань катастрофы. От России откалывались не только окраины, но и формировались казачьи автономии. В Киеве на власть претендовали сепаратисты. Даже в Сибири появилось собственное автономное правительство. Вооруженные силы разложились и не могли продолжать военные действия, солдаты дезертировали десятками тысяч. Фронт разваливался. Россия больше не могла противостоять коалиции центральных держав. Финансы и экономика были дезорганизованы. Начались проблемы со снабжением продовольствием городов, правительство стало проводить продразверстки. Крестьяне проводили самозахват земель, помещичьи усадьбы горели сотнями. Россия находилась в «подвешенном состоянии», так как Временное правительство отложило решение основополагающих вопросов до созыва Учредительного собрания.

Страну накрывала волна хаоса. Самодержавие, являвшееся стержнем всей империи, было разрушено. Но взамен него ничего не дали. Люди почувствовали себя свободными от всех налогов, повинностей и законов. Временное правительство, политику которого определяли деятели либерального и левого толка, не могло установить дееспособный порядок, более того, своими действиями усугубляло ситуацию. Достаточно вспомнить «демократизацию» армии во время войны. Петроград де-факто утратил контроль над страной.

Этим и решили воспользоваться большевики. До лета 1917 года они не считались серьёзной политической силой, уступая в популярности и численности кадетам и эсерам. Но к осени 1917 года их популярность выросла. Их программа была четкой и понятной народным массам. Власть в этот период могла взять фактически любая сила, которая проявила бы политическую волю. Этой силой и стали большевики.

В августе 1917 года они взяли курс на вооружённое восстание и социалистическую революцию. Это произошло на VI съезде РСДРП(б). Однако тогда партия большевиков фактически находилась в подполье. Наиболее революционные полки Петроградского гарнизона были расформированы, а сочувствовавшие большевикам рабочие были разоружены. Возможность воссоздать вооруженные структуры появилась только во время Корниловского мятежа. Замысел пришлось отложить. Только 10 (23) октября Центральный комитет принял резолюцию о подготовке восстания. 16 (29) октября расширенное заседание Центрального комитета, в котором приняли участие представители районов, подтвердило ранее принятое решение.

12 (25) октября 1917 года для защиты революции от «открыто подготавливающейся атаки военных и штатских корниловцев» по инициативе председателя Петросовета Льва Троцкого был учрежден Петроградский военно-революционный комитет. В ВРК вошли не только большевики, но и некоторые левые эсеры и анархисты. Фактически этот орган и координировал подготовку вооружённого восстания. В состав Военно-революционного комитета вошли представители ЦК, петроградских и военных партийных организаций партий большевиков и левых эсеров, делегаты президиума и солдатской секции Петросовета, представители штаба Красной гвардии, Центрального комитета Балтийского флота и Центрофлота, фабричных и заводских комитетов и т. д. ВРК подчинялись отряды Красной Гвардии, солдаты Петроградского гарнизона и матросы Балтийского флота, солдаты Петроградского гарнизона и матросы Балтийского флота. Оперативную работу осуществляло Бюро ВРК. Его формально возглавлял левый эсер Павел Лазимир, но практически все решения принимали большевики Лев Троцкий, Николай Подвойский и Владимир Антонов-Овсеенко.

При помощи ВРК большевики наладили плотную связь с солдатскими комитетами соединений Петроградского гарнизона. Фактически левые силы не только восстановили в городе доиюльское двоевластие, но и стали устанавливать свой контроль за военными силами. Когда Временное правительство решило отправить революционные полки на фронт, Петросовет назначал проверку приказа и принял решение о том, что приказ продиктован не стратегическими, а политическими мотивами. Полкам приказали остаться в Петрограде. Командующий военным округом запретил выдавать рабочим оружие из арсеналов города и пригородов, но Совет выписал ордера, и оружие выдали. Петросовет также пресек попытку Временного правительства вооружить своих сторонников с помощью арсенала Петропавловский крепости.

Части Петроградского гарнизона заявили о неподчинении Временному правительству. 21 октября прошло совещание представителей полков гарнизона, которые признали Петроградский совет единственной законной властью в городе. С этого момента ВРК стал назначать своих комиссаров в военные части, заменяя комиссаров Временного правительства. В ночь на 22 октября Военно-революционный комитет потребовал от штаба Петроградского военного округа признать полномочия своих комиссаров, а 22-го заявил о подчинении себе гарнизона. 23 октября ВРК добился права создать консультативный орган при штабе Петроградского округа. В тот же день Троцкий лично провел агитацию в Петропавловской крепости, где ещё сомневались, чью сторону принять. К 24 октября ВРК назначил своих комиссаров в 51 часть, а также на арсеналы, склады оружия, железнодорожные станции и заводы. Фактически уже к началу восстания левые силы установили военный контроль за столицей. Временное правительство было недееспособно и не смогло решительно ответить. Как впоследствии признал сам Троцкий, «вооруженное восстание совершилось в Петрограде в два приема: в первой половине октября, когда петроградские полки, подчиняясь постановлению Совета, вполне отвечавшему их собственным настроениям, безнаказанно отказались выполнить приказ главнокомандования, и 25 октября, когда понадобилось уже только небольшое дополнительное восстание, рассекавшее пуповину февральской государственности».

Поэтому значительных боестолкновений и большой крови не было, большевики просто взяли власть. Караулы Временного правительства и верные им соединения сдавались без боя или расходились по домам. Проливать свою кровь за «временщиков» никто не хотел. Так, казаки были готовы поддержать Временное правительство, но при усилении их полков пулеметами, броневиками и пехотой. В связи с невыполнением предложенных казачьими полками условий Совет казачьих войск решил никакого участия в подавлении восстания большевиков не принимать и отозвал уже отправленные 2 сотни казаков и пулеметную команду 14-го полка.

С 24 октября отряды Петроградского военно-революционного комитета заняли все ключевые пункты города: мосты, вокзалы, телеграфы, типографии, электростанции и банки. Когда глава Временного правительства Керенский приказал арестовать членов ВРК, исполнить приказ об аресте было некому. Надо сказать, что в августе-сентябре 1917 года Временное правительство имело все возможности для того, чтобы предотвратить восстание и физически ликвидировать партию большевиков. Но «февралисты» этого не сделали, пребывая в уверенности, что выступление большевиков гарантированно потерпит поражение. Правые социалисты и кадеты знали о подготовке восстания, но считали, что оно будет развиваться по июльскому сценарию — демонстраций с требованием отставки правительства. В это время планировали подтянуть верные войска и части с фронта. Но никаких митингов не было, вооруженные люди просто заняли ключевые объекты столицы, и всё это было сделано без единого выстрела, спокойно и методично. Члены Временного правительства во главе с Керенским некоторое время даже не могли понять, что происходит, так как были отрезаны от внешнего мира. О действиях революционеров можно было узнать только по косвенным признакам: в какой-то момент в Зимнем дворце пропала телефонная связь, затем — электричество. Правительство отсиживалось в Зимнем дворце, где проводило заседания, ожидало войска, которые вызвали с фронта, и запоздало рассылало обращения к населению и к гарнизону. Видимо, члены правительства надеялись отсидеться во дворце до прибытия войск с фронта. Бездарность его членов видна даже в том факте, что чиновники ничего не сделали для защиты своей последней цитадели — Зимнего дворца: не было подготовлено ни боеприпасов, ни продовольствия. Юнкеров не смогли даже накормить обедом.

К утру 25 октября (7 ноября) у Временного правительства в Петрограде остался только Зимний дворец. К концу дня его «обороняли» около 200 женщин из женского ударного батальона, 2-3 роты безусых юнкеров и несколько десятков инвалидов — георгиевских кавалеров. Охрана стала расходиться ещё до штурма. Первыми ушли казаки, смущенные тем, что самое крупное пехотное подразделение — это «бабы с ружьями». Затем ушли по приказу своего начальника юнкера Михайловского артиллерийского училища. Так оборона Зимнего дворца лишилась артиллерии. Ушла и часть юнкеров Ораниенбаумской школы. Генерал Багратуни отказался нести обязанности командующего и покинул Зимний дворец. Кадры знаменитого штурма Зимнего дворца — это красивый миф. Охрана в большинстве разошлась по домам. Весь штурм заключался в вялой перестрелке. О его масштабе можно понять по потерям: погибли шестеро солдат и одна ударница. В 2 часа ночи 26 октября (8 ноября) членов Временного правительства арестовали. Сам Керенский сбежал заранее, уехав в сопровождении автомобиля американского посла под американским же флагом.

Надо отметить, что и операция ВРК оказалась блестящей только при полной пассивности и бездарности Временного правительства. Если бы против большевиков выступил генерал наполеоновского (суворовского) типа с несколькими боеспособными частями, восстание легко бы подавили. Поддавшиеся пропаганде солдаты гарнизона и рабочие Красной гвардии не смогли бы устоять перед закаленными в боях воинами. К тому же воевать особо и не хотели. Так, ни рабочие города, ни гарнизон Петрограда в своей массе участия в восстании не принимали. А при обстреле Зимнего дворца из орудий Петропавловской крепости только 2 снаряда слегка задели карниз Зимнего дворца. Позднее Троцкий признал, что даже самые верные из артиллеристов преднамеренно стреляли мимо дворца. Провалилась и попытка использовать орудия крейсера «Аврора»: в силу своего расположения боевой корабль стрелять по Зимнему дворцу не мог. Ограничились холостым залпом. Да и сам Зимний дворец, если бы его оборону организовали хорошо, мог продержаться долго, особенно с учетом низкой боеспособности окруживших его сил. Так, Антонов-Овсеенко описывал картину «штурма» следующим образом: «Беспорядочные толпы матросов, солдат, красногвардейцев то наплывают к воротам дворца, то отхлынывают».

Одновременно с восстанием в Петрограде ВРК Московского Совета взял ключевые пункты города под свой контроль. Здесь всё пошло не столь гладко. Комитет общественной безопасности под началом председателя городской думы Вадима Руднева при поддержке юнкеров и казаков начал боевые действия против Совета. Бои продолжались до 3 ноября, когда Комитет общественной безопасности капитулировал.

В целом же советская власть была установлена в стране легко и без большого кровопролития. Революцию сразу поддержали в Центральном промышленном районе, где местные Советы рабочих депутатов уже фактически контролировали ситуацию. В Прибалтике и Белоруссии Советская власть была установлена в октябре — ноябре 1917 года, а в Центрально-Чернозёмном районе, Поволжье и Сибири — до конца января 1918 года. Этот процесс получил название «триумфального шествия Советской власти». Процесс по преимуществу мирного установления Советской власти на всей территории России стал ещё один доказательством полной деградации Временного правительства и необходимости захвата власти большевиками.

Вечером 25 октября в Смольном открылся II Всероссийский съезд Советов, который провозгласил переход всей власти к Советам. 26 октября Совет принял Декрет о мире. Всем воюющим странам предлагалось приступить к переговорам о заключении всеобщего демократического мира. Декрет о земле передавал помещичьи земли крестьянам. Все недра, леса и воды национализировались. Одновременно было сформировано правительство — Совет народных комиссаров во главе с Владимиром Лениным.

Дальнейшие события подтвердили правоту большевиков. Россия была на грани гибели. Старый проект был разрушен, и Россию мог спасти только новый проект. Его и дали большевики.

Большевиков часто обвиняют в том, что именно они уничтожили «старую Россию», но это неверно. Российскую империю убили «февралисты». В «пятую колонну» входили: часть генералитета, высшие сановники, банкиры, промышленники, представители либерально-демократических партий, многие из которых были членами масонских лож, большая часть интеллигенции, ненавидевшей «тюрьму народов». В целом большая часть «элиты» России своими руками и разрушила империю. Именно эти люди и убили «старую Россию». Большевики в этот период были маргиналами, фактически находились на обочине политической жизни. Но они смогли предложить России и её народам общий проект, программу и цель. Большевики проявили политическую волю и взяли власть, пока их конкуренты дискутировали о будущем России.