Первую половину девятнадцатого века мальчик по имени Карло Лоренцини, родом из Флоренции, провёл часть своего детства, живя здесь с родственниками, а позже, когда он стал писателем, взял себе псевдоним Карло Коллоди.

Сказка о мальчике из дерева 19-го века, теперь в новом переводе, была лозунгом всеобщего образования и итальянской государственности.

Городок Коллоди в Италии, примерно в 70 километрах к западу от Флоренции, располагается на склоне позади сказочно прекрасной виллы 17-го века. В саду, построенном как своего рода парк развлечений для семьи Гарцони и их благородных гостей, имеются террасы, цветочные клумбы, парадные лестницы, журчащие фонтаны и старинные мраморные статуи, окружающие виллу в стиле барокко.

Пройдя через туннель под виллой, и следуя по тропинке вверх по холму, можно увидеть каменные дома Коллоди, которые открывают совершенно другую реальность. Поднявшись по крутой мощёной главной улице, попадаешь на небольшую площадь с общими раковинами для стирки. Город старше виллы и, вероятно, изначально был построен на вершине холма в целях стратегической обороны. Здесь жили люди из рабочего класса, те, кто ухаживал за дворянскими виллами и садами. Трудно понять, о чём думали эти рабочие, когда брели обратно на холм после долгого дня работы на вилле. Вероятно, справедливо будет сказать, что они уставали и им было не до мыслей.

Первую половину девятнадцатого века мальчик по имени Карло Лоренцини, родом из Флоренции, провёл часть своего детства, живя здесь с родственниками, а позже, когда он стал писателем, взял себе псевдоним Карло Коллоди.

Писатель публиковал политические очерки и сатиру для взрослых, а затем, в свои 50 лет, обратил внимание на детскую литературу.

«История марионетки» впервые появилась в серийной форме, начиная с 1881 года, в детской газете Giornale per i bambini.

Вступительный абзац должен был подорвать традиционное представление о сказке, а также послать политический сигнал: «Жил-был… «Король!» — немедленно воскликнут мои маленькие читатели. Нет, дети, вы не угадали. Жил-был кусок дерева».

Волшебным «куском дерева», естественно, оказался Пиноккио, а повествование о нём стало первым всемирно известным произведением итальянской детской литературы. «Приключения Пиноккио» экранизировали 18 раз, в том числе два игровых фильма с Роберто Бениньи в главной роли. Disney и Netflix находятся в процессе создания новых версий. Большая часть населения планеты знает Пиноккио как синоним анимационного фильма Диснея 1940 года о деревянной марионетке, чей острый нос растёт каждый раз, когда он лжёт. Но в оригинальной итальянской истории речь идёт не только о лжи.

Фото: smithsonianmag.com

Пиноккио лжёт, но это всего лишь часть его плохого поведения; он эгоистичен и ненадёжен. Он негодяй, сопляк, ребёнок, который, как можно было бы сказать сегодня, делает много неверных решений. В тот момент, когда Джеппетто вырезает его из чудесного куска дерева, Пиноккио убегает и отказывается идти домой. Его выходки приводят к аресту бедного Джеппетто.

«Каждый раз, когда я в своей преподавательской деятельности касаюсь вопроса о «Пиноккио», от студентов я получаю как минимум две реакции», — говорит Мария Труглио, профессор итальянского женского и гендерного исследований в Университете штата Пенсильвания и автор книги «Итальянская детская литература и национальная идентичность: детство, меланхолия, современность».

Первая реакция — «такое удивление тем, насколько она отличается от диснеевской версии — и насколько они предпочитают оригинальную версию». Вторая реакция исходит от студентов, которые находят книгу более сложной, чем они ожидали. «Эти студенты говорят: «Я не очень много читаю и обычно не люблю книги, но мне очень понравился Пиноккио».

Анна Крачина, преподаватель университета во Флоренции, была поражена рассказом около 15 лет назад, когда читала книгу своему маленькому сыну. «Я не могла поверить, насколько богат текст», — говорит Крачина, родившаяся в Италии в семье американских художников-экспатриантов. Она рассказала Джону Хуперу, британскому журналисту и автору книги 2015 года под названием «Итальянцы», что пришло время для нового английского перевода. Он согласился. «Красота языка, литературная изобретательность Коллоди — делает то, чего я никогда не видел ни у одного автора», — говорит Хупер.

Новый перевод «Приключений Пиноккио», опубликованный в 2021 году, включает в себя обильные примечания и введение, в котором исследуются сложности этой истории.

В диснеевском фильме Джеппетто — производитель игрушек и часов с кукушкой, живущий в смутно европейском фахверковом доме. Но в книге нет ничего странного в итальянской бедности 19-го века, в которой Джеппетто — резчик по дереву. Пиноккио проводит большую часть истории, беспокоясь о том, чтобы найти что-нибудь поесть. В первый же день, после ареста Джеппетто, он испытывает «настолько реальный голод, что его можно резать ножом». Когда Джеппетто возвращается домой, он предлагает голодной марионетке три груши, которые он сам планировал съесть на завтрак. Пиноккио немедленно требует, чтобы их очистили, но в конечном итоге он жадно ест кожуру и сердцевину, усваивая урок: «Мы не должны быть слишком привередливыми или изысканными в еде».

Фото: smithsonianmag.com

Существует также определённый риск быть съеденным в мире, где все всегда голодны. Пиноккио чудом избегает быть брошенным в огонь голодным кукловодом по имени Манджафоко (Пожиратель огня), которому нужны дрова, чтобы зажарить барана на ужин. Позже Пиноккио обваливают в муке и почти обжаривают на сковороде вместе с рыбой; рыбак с нетерпением ждёт возможности попробовать эту новую «кукольную рыбу».

В другом эпизоде его превращают в осла и бросают в море, чтобы он утонул, и его владелец мог сделать из его шкуры барабан; но марионетке удаётся освободиться при помощи рыб. И, наконец, его на самом деле съедает большая акула, и он спасает Джеппетто, которого акула проглотила ранее в этой истории. Лихорадка, превращающая Пиноккио в осла, является его наказанием за то, что он пропустил школу и сбежал в Playland. Его предупреждал говорящий сверчок: «Бедный маленький глупец! Разве ты не знаешь, что обязательно вырастешь полным ослом и тебя в грош никто не будет ставить?..»

Исследователи Крачина и Хупер объясняют, что слово «осёл» в итальянском языке времён Коллоди имело двоякое значение. Людей, которым приходилось много работать, называли ослами; то же самое было с детьми, отказавшимися поступать в школу. «Послание Коллоди детям в то время, когда жизнь неквалифицированного рабочего была сплошной тяготой, — пишут они, — заключалась в том, что, если они настаивали на том, чтобы быть «осликами» в школе, они рисковали прожить жизнь и, возможно, умереть смертью осла».

Образование было делом, дорогим сердцу Коллоди. На полуострове в виде ботинка великолепной Италии в 1861 году многочисленные республики, города-государства, королевства и герцогства — каждое со своим диалектом и традициями — объединились в единую нацию. Непосредственно в классах школы дети всех этих разных провинций и штатов учились быть итальянцами. Когда страна впервые объединилась, только 25 процентов итальянцев умели читать и писать. К 1880 году бесплатное обязательное школьное образование подняло уровень грамотности почти до 40 процентов.

Но Коллоди прекрасно понимал, что нельзя ожидать, что дети будут учиться, если они голодны.

В открытом письме под названием «Хлеб и книги» он утверждал, что всем людям необходимо есть и пить, защищаться от непогоды и иметь место для сна. Этот мир был очень суровым, в котором можно было съесть или быть съеденным, и единственным выходом из него было образование.

Фото: smithsonianmag.com

Узкая флорентийская улица Виа Таддеа, где в 1826 году родился автор, представляет собой очень тёмную улицу, на которую не попадает утреннее солнце, — в этом тёмном переулке изначально жили слуги, работавшие поблизости. Мать Карло, Анджолина, была швеёй из Коллоди. Её отец управлял семейным поместьем Гарцони. Когда дочь Гардзони вышла замуж за маркиза Джинори Флорентийского, Анджолина сопровождала её в качестве швеи и компаньонки, и она вышла замуж за повара Доменико и переехала жить с ним на Виа Таддеа. Карло был первым из десяти детей пары и одним из четырёх, доживших до совершеннолетия. Жизнь была чрезвычайно тяжёлой; за четыре месяца, начиная с декабря 1838 года, умерли четверо младших братьев и сестёр Карло в возрасте от 4 месяцев до 6 лет. Дети Лоренцини проводили много времени в Коллоди с семьёй своей матери; Карло был там уже в 2 года и провёл там большую часть учебного года, когда ему было 10.

Город больше не известен прежде всего своей близостью к роскошной вилле. Он известен благодаря Пиноккио.

Здесь есть обширные сувенирные лавки, пиццерия Geppetto и таверна, названная в честь Mangiafuoco, или Fire-Eater, страшного кукловода. Существует также Parco di Pinocchio, открытый аттракцион с одним из первых в мире парков скульптур для детей. Роландо Анзилотти, мэр близлежащего посёлка, основал парк ещё в 1950-х годах. Он, конечно, вырос на этой истории.

Кастелло – маленький городок, где многие богатые люди построили изысканные виллы, чтобы спрятаться от флорентийской жары в более прохладном и зелёном месте. Брат Карло, Паоло Лоренцини, проводил там лето. Как и Карло, Паоло в детстве отправили в Коллоди, прежде чем он пошёл в среднюю школу во Флоренции в Колледже отцов Сколопи, где его поддерживала семья Джинори. Паоло стал бухгалтером, а затем управляющим фарфоровой фабрики семьи Джинори. В Кастелло Паоло арендовал место под названием «Вилла Иль Бель Рипозо», или «Вилла прекрасного отдыха». Карло жил и писал в башне виллы, хорошо просматриваемой с дороги снаружи. Там он черпал вдохновение для приключений Пиноккио.

Фото: smithsonianmag.com

Ежедневная прогулка Карло начиналась с виллы Il Bel Riposo, затем он поворачивал направо и направился вниз по холму к магазину сигар.

По словам переводчиков, Карло покупал сигары в том же магазине, что и итальянский король.

По улице Карло миновал две разные лавки, где ремесленники работали с деревом, один плотник, а другой резчик по дереву. Два владельца были хорошими друзьями, но они были сварливыми людьми и часто вступали в драки.

На первой странице «Пиноккио» кусок дерева появляется в мастерской старого плотника Антонио, известного в старых переводах как мистер Вишенка из-за его красного носа. Мистер Вишенка обнаруживает, что дерево может говорить, когда он пытается превратить его в ножку стола, только чтобы услышать, как оно протестует против удара или пореза, и от удара кончик его носа становится синим.

Итак, в главе 2 он передаёт полено своему другу Джеппетто, который хочет сделать себе марионетку, «но замечательную марионетку, которая может танцевать, фехтовать и делать сальто». Джеппетто надеется, что с помощью этой замечательной марионетки он сможет заработать на «корку хлеба и бокал вина». Озорному деревянному бруску удаётся спровоцировать ожесточённую драку между двумя мужчинами, которые оба вспыльчивы и, вероятно, их образы основаны на мастерах, мастерские которых Коллоди проходил на улице Кастелло. «Конечно, жители современного Кастелло верят, что их предки появились в Пиноккио», — говорит Крачина.

На улице, по которой проходит главная дорога в Сесто, где находился фарфоровый завод жили два «сомнительных персонажа», которые, по словам Хупера, предположительно были моделями для рассказа о Лисе и Коте. Друг Карло Джованни Фаттори, флорентийский художник, однажды нарисовал возницу, который напоминает кучера, везущего Пиноккио в злополучную поездку в Плейленд.

Фото: smithsonianmag.com

Деревянный мальчик выжил, когда его сожгли, повесили и бросили в океан. Пиноккио, безусловно, сделан из более прочного материала, чем обычный ребёнок из плоти и крови. Коллоди не всегда собирался быть милосердным к своему главному герою. Когда студенты Труглио в Пенсильванском университете доходят до сцены, где Пиноккио висит на дубе, убитый двумя ассасинами, она говорит им: «На этом конец, на этом он намеревался закончить, но редакторы журнала и читатели хотели продолжения». Её ученики неизменно удивляются.

В главах 16 и 17 Пиноккио спасает Синеволосая фея, которая первоначально появляется как Маленькая девочка с синими волосами и описывается как призрак мёртвой девочки. Есть сведения, что образцом для Синеволосой феи была Джованна Раджоньери, дочь садовника виллы Il Bel Riposo.

Крачина и Хупер предполагают, что описание Коллоди мёртвой маленькой девочки может иметь отголоски смерти одной из его сестёр, которая умерла, когда ему было около 12 лет.

По ходу книги Маленькая девочка превращается в женщину, чего его сестра никогда не смогла сделать.

После того, как Синеволосая Фея посылает помощников спасти Пиноккио от повешения — сокола, чтобы срезать его с петли, пуделя, переодетого кучером, чтобы отвезти его домой, — она понимает, что у Пиноккио высокая температура, и наливает ему лекарство. Марионетка, которая всегда ведёт себя вызывающе, отказывается принимать лекарство, потому что оно будет горьким на вкус. Фея подкупает его сахаром, но он ест сахар и продолжает твердить: «Я лучше умру, чем выпью это противное лекарство».

Наконец прибывают четыре чёрных кролика с гробом, чтобы забрать его. В этот момент Пиноккио хватает лекарство и проглатывает его. Это работает немедленно. «Через несколько минут, — рассказывает нам Коллоди, — Пиноккио спрыгнул с кровати, совершенно выздоровев, потому что деревянные куклы, видите ли, имеют привилегию редко болеть и очень быстро выздоравливать». Деревянный мальчик выжил, когда его сожгли, повесили и бросили в океан.

Какое лекарство Пиноккио так не хотел принимать? В примечаниях, которые подготовили Хупер и Крачина, слово в итальянской версии истории — пургативо (purgativo). Слабительные средства — как слабительные, так и рвотные — были популярными средствами в 19 веке и ранее и использовались во многих различных клинических ситуациях в надежде очистить организм. Они не были бы особенно эффективны в случае лихорадки или инфекции. В ситуациях, когда кому-то грозило обезвоживание, они были просто опасны.

Ближе к концу книги ещё один ребенок возвращается с грани смерти. После того, как марионетка позволяет уговорить себя прогуляться, другой мальчик бросает в Пиноккио очень тяжёлый «Трактат по арифметике», но вместо этого бьёт своего друга Юджина, очевидно убивая его. Остальные мальчики убегают, но Пиноккио остаётся с Юджином, тщетно умоляя его открыть глаза. Его прерывают два карабинера, которые арестовывают Пиноккио и довольно небрежно оставляют Юджина с какими-то рыбаками, но двумя главами позже оказывается, что Юджин полностью выздоровел. После того случая Пиноккио становится отличником.

Но ему предстоит столкнуться с последним искушением: злополучной поездкой в Playland. Он может искупить свою вину, спасая Джеппетто из чрева большой акулы. Хупер и Крачина отмечают, что собственного отца Коллоди пришлось спасать от долгов, а слово для хищных кредиторов — ростовщиков — также существует во флорентийском диалекте: pescecani. После того, как Пиноккио спасает Джеппетто, он работает, чтобы обеспечить здоровье своего отца, и усердно учится по ночам. В конце концов, он становится ragazzino per bene, хорошим маленьким ребенком в этом переводе, также иногда переводимым как приличный (или, возможно, порядочный) мальчик. Соответственно, деревянная кукла превращается в «умного, живого, красивого ребёнка с каштановыми волосами и голубыми глазами, который счастлив и радостен, как ягнёнок весной».

Фото: smithsonianmag.com

Хупер резюмирует мораль книги следующим образом: «Обучайтесь, получайте информацию, не позволяйте другим людям дёргать вас за ниточки».

Это также книга о важности заботы о других людях. «Я думаю, Коллоди говорит, что именно так вы становитесь человеком», — говорит Хупер. «Там есть сообщение о социализации, которое является абсолютно фундаментальным». Или, как выразился Джеппетто: «Когда дети перестают быть плохими и становятся хорошими, они привносят в свои семьи новую и радостную атмосферу».

Памятный знак на здании во Флоренции, где, как считается, родился Коллоди, описывает его не как писателя, а скорее как падре ди Пиноккио, отца Пиноккио. Это кажется подходящим, тем более что «Пиноккио» — это книга о необычном способе стать отцом. У Коллоди никогда не было собственных детей, хотя ходили слухи о внебрачной дочери.

О его личной жизни известно немногое; после его смерти Паоло сжёг все письма, опасаясь, что они «могли скомпрометировать дам, которые были ещё живы и очень известны». Возможно, Коллоди просто никогда не хотел остепениться. Или, возможно, он не хотел заводить собственную семью, потому что в детстве видел, как шесть его младших братьев и сестёр умерли. Только в мире Пиноккио у него была сила возвращать к жизни мёртвых детей.

Квартира, в которой Коллоди умер в возрасте 63 лет, находится над магазином фарфора Ginori во Флоренции, который существует до сих пор. Снаружи есть мемориальная доска, восхваляющая Коллоди за то, что он использовал своё остроумие и художественную чувствительность для достижения истинной цели своей жизни: «воспитать народ объединённой Италии».

В конце концов, Коллоди изменил свою страну не тем, что публиковал полемику взрослых, а тем, что обращался непосредственно к детям нации — как написано на мемориальной доске, con tenera amara virile fantasia, с нежным, горьким, мужественным воображением.

Кто написал сказку о Пиноккио?

Карло Коллоди

Когда была написана сказка Пиноккио?

7 июля 1881 года

В каком городе жил Пиноккио?

Он родился в 1826 году, так что не исключено, что еще в совсем нежном возрасте наблюдал где-нибудь на ярмарке деревянного циркача. Правда, хоть Карло был по рождению флорентийцем, детство он провел в 67 км от Флоренции — в крошечном раскинувшемся на склоне холма городке Коллоди, откуда его мать была родом.

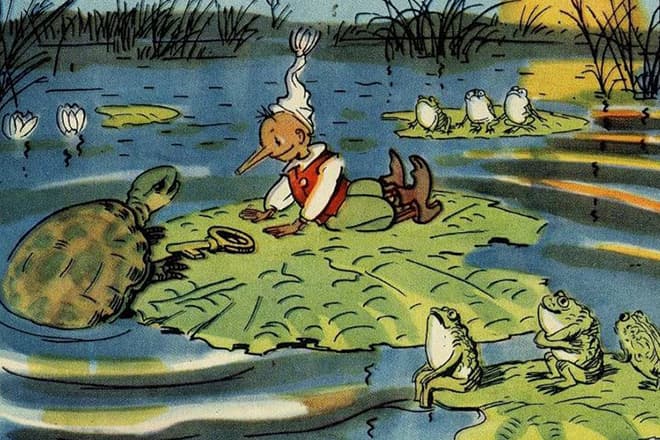

Что подарила черепаха Пиноккио?

Упав в воду, он встретился с обитательницей пруда, черепахой Тортилой. Она пожалела бедного деревянного мальчика, лишившегося денег (он узнал от неё, кто их украл), и дала ему золотой ключик, который случайно уронил в пруд Карабас Барабас.

Чем закончилась сказка о Пиноккио?

Но… в этой стране в какой-то момент у детей вдруг начинают расти ослиные уши, и они превращаются в ослов. Бедного Пиноккио – теперь уже не мальчика, а ослика – продают директору цирка, а затем из его шкуры пытаются сделать барабан. Все злоключения деревянного человечка кончаются благополучно.

Почему у Пиноккио рос нос?

Ученые обнаружили, что когда человек врет, его нос действительно увеличивается в размерах, как у Пиноккио. Это происходит потому, что увеличивается кровяное давление и клетки увеличиваются в размерах.

Почему нос становится больше?

Увеличивается нос Это происходит из-за изменений в мягких тканях, мышцах и хрящах, которые составляют его основную структуру. В отличие от кости, хрящ со временем продолжает расти. Стремительный рост приходится на период 50–60 лет. Кроме того, кончик носа с возрастом имеет свойство опускаться вниз.

Почему Мальвина с голубыми волосами?

Несмотря на это история про деревянного мальчика понравилась читателям, издатели потребовали продолжения, и вот тогда-то Коллоди превратил привидение в фею и заставил её оживить Пиноккио. А голубые волосы, которые были придуманы, чтобы подчеркнуть потустороннюю бледность зловещей девочки, так и остались голубыми.

Чему учит сказка Приключения Пиноккио?

Сказка учит слушаться родителей, слушаться старших, не слушать мошенников и обманщиков. Учит быть добрыми и помогать своим друзьям. Учит не гоняться за дурными деньгами. Учит учиться и овладевать знаниями.

Какого цвета были волосы у Мальвины?

Толстого «Золотой ключик, или Приключения Буратино» (1936), кукла с голубыми волосами и фарфоровой головой. Мальвина — это «девочка с кудрявыми голубыми волосами», «самая красивая кукла из кукольного театра синьора Карабаса Барабаса», у неё фарфоровая голова и туловище, набитое ватой.

Какой резчик по дереву создал Пиноккио?

Главную роль пожилого резчика по дереву Джепетто, который сотворил Пиноккио, исполнил лауреат премии «Оскар» Роберто Бениньи. Вообще, у Гарроне подобралась сплошь оскароносная команда.

Кто придумал Пиноккио 7 букв?

КОЛЛОДИ (Collodi) (наст. фам. — Лоренцини, Lorenzini) Карло (1826-90) итальянский писатель и критик, участник итальянского национально-освободительного движения. «Приключения Пиноккио» (1881-83) повесть для детей (по ее мотивам А.

Что увеличивает нос Пиноккио?

Исто́рия деревя́нной ку́клы» (итал. Le avventure di Pinocchio. … Главный герой книги — Пиноккио (от итал. pino «сосна» + occhio «глаз»), сделанный из дерева мальчик, нос которого увеличивается каждый раз, когда он говорит неправду.

Что искал Буратино?

Папа Карло вырезает из говорящего полена Буратино. Он сражается, скитается и ищет Золотой Ключик, которым можно открыть потайную дверь. С помощью верных друзей и черепахи Тортиллы он узнаёт, что Золотой Ключик открывает дверь в прекрасный кукольный театр за холстом в каморке Папы Карло. Главный смысл.

Что было за дверью в каморке папы Карло?

Папа Карло клеит ему одежду из цветной бумаги и покупает азбуку Буратино продает азбуку и покупает билет в кукольный театр Во время представления комедии куклы узнают Буратино Синьор Карабас Барабас вместо того, чтобы сжечь Буратино, дает ему пять золотых монет и отпускает домой

Как Буратино узнал тайну золотого ключика?

Карабас Барабас и Дуремар подкреплялись жареным поросеночком. — Там что-то чернеется, — прохрипел Карабас Барабас. … — Там что-то белеется, — подтвердил Дуремар.

Куда отправился Буратино вместо школы?

Куда отправился Буратино вместо школы? в цирк; в театр; в кино.

Кто такой Арлекино в Буратино?

Арлекин — один из героев книги А. Н. Толстого «Золотой ключик, или Приключения Буратино» и её экранизаций, самой известной из которых является телефильм 1975 года. И в сказке и экранизациях Арлекин является куклой и партнёром Пьеро по сцене.

Что такое дуремара?

Шарлатан и алчный человек Дуремар из сказки о захватывающих приключениях Буратино входит в квартет главных отрицательных героев. Продавец пиявок – прекрасный маркетолог в сфере фармакологии. И это его единственный талант.

Кого играл басов в Буратино?

Елена Санаева — лиса Алиса (74 года). Рина Зелёная — черепаха Тортила (умерла в 1991 г в возрасте 90 лет). На съемках фильма у Рина Зеленая узнала о смерти сестры,но не смотря на это снималась до конца. Владимир Басов — Дуремар (умер в 1987 году,в 64 года).

Какое лекарственное средство пропагандировал Дуремар?

Какое лекарственное средство пропагандировал Дуремар? (медицинские пиявки).

Кто играл кота Базилио в Буратино?

Ролан Быков

Кто режиссер фильма Буратино?

Леонид Алексеевич Нечаев

Сколько серий в Буратино?

«Приключе́ния Бурати́но» — советский двухсерийный музыкальный телевизионный фильм по мотивам сказки Алексея Толстого «Золотой ключик, или Приключения Буратино», созданный на киностудии «Беларусьфильм» в 1975 году. Считается культовым. Телепремьера состоялась 1-2 января 1976 года.

Кто поет песню про Буратино?

Так вот, главный хит в фильме «Приключения Буратино» исполнила Нина Бродская (певица, автор песен).

Как снимался фильм Приключения Буратино?

Отдельные эпизоды снимались в районе Ай-Петри, на ялтинской Поляне сказок, в Кореизе. В Крыму был отснят и момент, когда Буратино, сидя на сосне, кидается шишками в Карабаса-Барабаса, а у того борода приклеивается к смоле на стволе.

Содержание

- — Где снимался фильм про Буратино?

- — Кто режиссёр фильма Буратино?

- — Кому подарил говорящее полено Джузеппе Сизый нос?

- — Где жила черепаха Тортила?

- — В каком году снимался фильм Приключения Буратино?

- — Кто должен был играть Буратино?

- — Кто был первым Пиноккио или Буратино?

- — Сколько серий в Буратино?

- — Кто озвучивал Пьеро в Буратино?

- — Как Мальвина наказала Буратино за плохое поведение?

- — Откуда взялось у папы Карло говорящее полено?

- — Куда отправился Буратино вместо школы?

- — Какой ключик получил Буратино в подарок от Черепахи Тортилы?

- — Почему Буратино не утонул в пруду?

- — Что подарила черепаха Тортилла Буратино?

режиссером которой оказался Леонид Нечаев. Вопреки обыкновению, за съемки в Крыму взялись не Одесская или Ялтинская киностудия и даже не Мосфильм, а Минская. Но полуостров принимал всех, как следствие, группа провела на нем в общей сложности 93 дня.

Где снимался фильм про Буратино?

Съёмки велись в Крыму, группа объездила весь полуостров. Например, «поле чудес» снималось на территории заповедника «Херсонес Таврический», а сцена, где лиса и кот рассказывают Буратино о Стране дураков — у Байдарских ворот. Ещё съёмки велись в Ялте, в Кореизе, около горы Ай-Петри.

Кто режиссёр фильма Буратино?

Леонид Алексеевич Нечаев

Кому подарил говорящее полено Джузеппе Сизый нос?

Живущему в каморке под лестницей шарманщику Карло (Николай Гринько) его приятель, столяр Джузеппе по прозвищу Сизый Нос (Юрий Катин-Ярцев), подарил говорящее полено.

Где жила черепаха Тортила?

черепаха Тортилла — обитает в пруду около Страны Дураков; дарит Буратино золотой ключик.

В каком году снимался фильм Приключения Буратино?

Фильм Приключения Буратино (1975) — актеры и роли — советские фильмы — Кино-Театр. Ру

Кто должен был играть Буратино?

А дело было так. Первоначально на роль Буратино был утверждён Коля Кобликов. Именно он должен был сыграть этого озорного деревянного мальчика, и именно он должен был стать мегазвездой советского кинематографа.

Кто был первым Пиноккио или Буратино?

Итак, Пиноккио автора Карло Коллоди или же Буратино Алексея Толстого? Начнем с того, что они все-таки родственники, Пиноккио – старший брат русского Буратино, поскольку появился на свет в 1881 году, а его русский собрат в 1935 году, почитаем об этом здесь.

Сколько серий в Буратино?

«Приключе́ния Бурати́но» — советский двухсерийный музыкальный телевизионный фильм по мотивам сказки Алексея Толстого «Золотой ключик, или Приключения Буратино», созданный на киностудии «Беларусьфильм» в 1975 году. Считается культовым. Телепремьера состоялась 1-2 января 1976 года.

Кто озвучивал Пьеро в Буратино?

Роман Столкарц — Пьеро (51 год).

Как Мальвина наказала Буратино за плохое поведение?

Как звали пуделя у Мальвины? Как наказала Мальвина Буратино за плохое поведение? Посадила в чулан.

Откуда взялось у папы Карло говорящее полено?

Единственный друг папы Карло — старый столяр и пьяница Джузеппе (прототип — мастер Антонио, он же мастер Вишня). Как-то раз Джузеппе в очередной раз напился, и ему в руки попалось говорящее полено, которое он подарил от греха подальше своему собутыльнику Карло, предварительно с ним подравшись.

Куда отправился Буратино вместо школы?

Куда отправился Буратино вместо школы? в цирк; в театр; в кино.

Какой ключик получил Буратино в подарок от Черепахи Тортилы?

Снова заколебалась зеленая ряска, появилась черепаха, держа во рту маленький золотой ключик. Она положила его на лист у ног Буратино. — Безмозглый, доверчивый дурачок с коротенькими мыслями, — сказала Тортила, — не горюй, что лиса и кот украли у тебя золотые монеты. Я даю тебе этот ключик.

Почему Буратино не утонул в пруду?

Буратино не мог утонуть, потому что он был сделан из дерева.

Что подарила черепаха Тортилла Буратино?

Буратино и Пьеро побежали к домику Мальвины. … Она сказала: «Карабас Барабас узнал про то, что черепаха Тортила подарила ключик Буратино… Бегите отсюда поскорей».

Интересные материалы:

Когда говорить надела а когда одела?

Когда говорить вечер?

Когда говорится о а когда об?

Когда можно говорить я тебя люблю?

Когда можно говорить Христос воскрес в субботу или воскресенье?

Когда нужно говорить благодарю?

Когда нужно говорить намерение на пост?

Когда стоит говорить доброе утро?

Кому говорят спасибо Американцы в День благодарения?

Кому говорить Служу России?

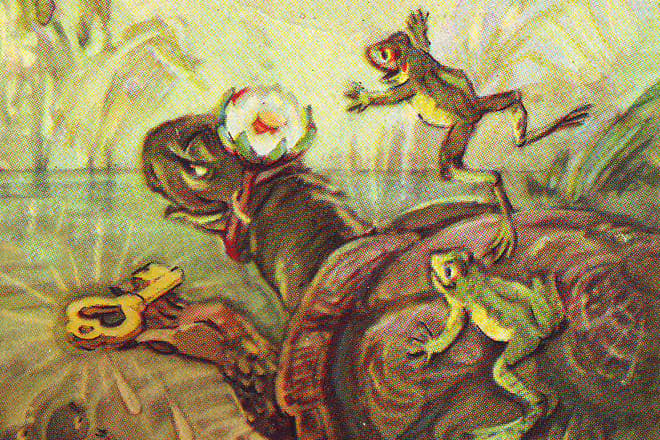

История персонажа

Второстепенный персонаж сказки «Золотой ключик, или Приключения Буратино», написанной графом Алексеем Николаевичем Толстым, литератором и общественным деятелем. Черепаха Тортила живет в пруду, волей случая играет роль хранительницы золотого ключика и передает этот предмет Буратино — главному герою.

История создания

Задумка повести о деревянном мальчике появилась у Алексея Толстого в 1923 году. В то время литератор находился в эмиграции и там занимался редактурой русского перевода сказки итальянца Карло Коллоди. Оригинальное произведение называлось «Приключения Пиноккио. История деревянной куклы» и написано было во второй половине XIX века.

Отредактированный Толстым перевод вышел в Берлине, через год, когда сам Алексей Николаевич возвратился в СССР. В этом тексте уже наблюдались некоторые отклонения от оригинальной версии: ряд моментов адаптировали к российским реалиям, в сказке появились русские поговорки, стилистические переделки. К примеру, сложное для русского уха имя отца Пиноккио — Джеппетто — заменили на более легкое для восприятия имя Карло.

В 1933 году Алексей Толстой вместе с переводчицей Ниной Петровской начинает работать над литературным пересказом «Пиноккио», которым занимается по заказу «Детгиза». В окончательной версии русского варианта сказки некоторые моменты оказываются серьезно переиначены, а кое-чего и вовсе не было в итальянском оригинале.

К примеру, золотого ключика — сюжетообразующего для русской версии предмета, который вынесен даже в название сказки. В тексте Толстого больше веселья и авантюрного духа и меньше морализаторства, чем в оригинале Коллоди.

В 1935 году законченное произведение ушло в печать. Еще через год Толстой написал для Центрального детского театра в Москве пьесу «Золотой ключик», а в 1939 году создал сценарий, по которому сняли первую, еще черно-белую киноленту о Буратино.

Биография

Черепаха Тортила в повести Алексея Толстого живет в глубоком грязном пруду, полном «лягушек, пиявок и личинок водяного жука». Сыщики-доберманы бросили в этот пруд Буратино, чтобы утопить героя. Однако деревянный мальчик не стал тонуть, а встретился вместо этого с черепахой Тортилой, которая отнеслась к герою с жалостью и отдала тому золотой ключик.

Несколько раньше Карабас-Барабас обронил этот ключик в пруд, и Тортила хранила тот на дне. От Тортилы же главный герой узнает, кто украл золотые, зарытые им на пустыре (эти злодеи — Лиса Алиса и кот Базилио). Характеристика этой героини в тексте однозначно положительная, хотя по темпераменту Тортила — типичный флегматик.

Экранизации

По сказке «Золотой ключик, или Приключения Буратино» снято некоторое количество фильмов и мультфильмов.

Классическая анимационная версия черепахи Тортилы в очках появилась в 1959 году, когда вышел советский мультфильм «Приключения Буратино». Черепаху Тортилу озвучивала актриса Анастасия Зуева.

Классическая экранизация сказки о Буратино снята в 1975 году на киностудии «Беларусьфильм». В этом двухсерийном музыкальном фильме роль черепахи Тортилы сыграла актриса Рина Зелёная. Режиссер Леонид Нечаев хотел, чтобы эту роль исполнила знаменитая Фаина Раневская, но актриса не захотела ехать в Белоруссию, где должно было сниматься кино, и отшутилась, сказав, что из-за преклонного возраста согласна работать в этом проекте только в том случае, если съемки организуют в подъезде ее собственного дома.

Для фильма было записано 13 песен. Рина Зеленая исполнила «Романс Тортилы». Во время записи произошел небольшой инцидент: актриса отказалась петь второй куплет из-за того, что в тексте упоминался преклонный возраст героини. В результате фонограмму не стали перезаписывать, но на месте второго куплета пришлось оставить один проигрыш. Позже песни из фильма выпустили отдельной пластинкой.

Фильм снят близко к тексту сказки, но есть и отличия. К примеру, злодей Карабас-Барабас о том, что черепаха Тортила отдала Буратино золотой ключик, узнает от Дуремара. В книге же Тортила сама рассказывает о произошедшем Карабасу.

В музыкальном фильме 1997 года «Новейшие приключения Буратино» роль черепахи Тортилы исполняет российская эстрадная певица Лариса Долина, а сама Тортила становится возлюбленной папы Карло (в роли которого выступает певец и актер Александр Кальянов).

Сам фильм представляет собой серию из семи клипов, место действия — некая южная страна, время — конец ХХ века. Буратино в этой интерпретации превращается в молодую певицу, которая приехала на гастроли в компании друзей и мечтает отхватить престижную музыкальную премию «Золотой ключик». Снималось кино на Канарских островах.

В 2009 году вышел еще один мюзикл о приключениях Буратино, приуроченный к празднованию Нового года. В актерском составе там тоже задействованы звезды российской эстрады, а роль Тортилы исполняет комический дуэт «Новые русские бабки».

Интересные факты

- В оригинальной сказке «Приключения Пиноккио» авторства итальянца Карло Коллоди (литературной обработкой которой и стала книга о Буратино) нет черепахи Тортилы или кого-то, хотя бы отдаленного похожего на эту героиню. Нет там и золотого ключика, вокруг которого вертятся приключения Буратино в книге Алексея Толстого.

- Сцена из фильма «Золотой ключик или приключения Буратино», где черепаха Тортила плавает в пруду, снята в Никитском ботаническом саду в Ялте.

- Костюм, в котором зрители видят Рину Зеленую в фильме, стал классическим для образа черепахи Тортилы. Детали этого костюма до сих пор воспроизводятся в карнавальных и театральных нарядах.

- Именем черепахи Тортилы назван корм для сухопутных черепах, торт и конфеты фабрики «Эврика». А визуальное воплощение героини можно увидеть на ретро-открытках серии «Золотой ключик» 1955 года выпуска с классическими иллюстрациями к изданию сказки о Буратино. Создал их художник Леонид Владимирский.

- В 1993 году вышла видеоигра в жанре графического квеста по сказке «Приключения Буратино». Черепаха Тортила в этом квесте, как и в сказке Толстого, выступает хранительницей золотого ключика.

illustration from 1883 edition by Enrico Mazzanti |

|

| Author | Carlo Collodi |

|---|---|

| Illustrator | Enrico Mazzanti |

| Country | Italy |

| Language | Italian |

| Genre | Fiction, literature, fantasy, children’s book, adventure |

|

Publication date |

July 7, 1881 – 1882 (magazine) February 1883 (novel) |

The Adventures of Pinocchio ( pin-OH-kee-oh; Italian: Le avventure di Pinocchio. Storia di un burattino, lit. ‘The Adventures of Pinocchio. Story of a Puppet’ Italian pronunciation: [le avvenˈtuːre di piˈnɔkkjo stˈɔria dˈi ˈun bʊratːˈino]; commonly shortened to Pinocchio) is a children’s fantasy novel by Italian author Carlo Collodi. It is about the mischievous adventures of an animated marionette named Pinocchio and his father, a poor woodcarver named Geppetto.

It was originally published in a serial form as The Story of a Puppet (Italian: La storia di un burattino) in the Giornale per i bambini, one of the earliest Italian weekly magazines for children, starting from 7 July 1881. The story stopped after nearly 4 months and 8 episodes at Chapter 15, but by popular demand from readers, the episodes were resumed on 16 February 1882.[1] In February 1883, the story was published in a single book. Since then, the spread of Pinocchio on the main markets for children’s books of the time has been continuous and uninterrupted, and it was met with enthusiastic reviews worldwide.[1]

A universal icon and a metaphor of the human condition, the book is considered a canonical piece of children’s literature and has had great impact on world culture. Philosopher Benedetto Croce considered it one of the greatest works of Italian literature.[2] Since its first publication, it has inspired hundreds of new editions, stage plays, merchandising, television series and movies, such as Walt Disney’s iconic animated version, and commonplace ideas such as a liar’s long nose.

According to extensive research by the Fondazione Nazionale Carlo Collodi and UNESCO sources in the late 1990s, the book has been translated into as many as 260 languages worldwide,[3][4] making it one of the world’s most translated books.[3] Likely one of the best-selling books ever published, the actual total sales since first being published are unknown due to the many reductions and different versions.[3] The story has been a public domain work in the U.S. since 1940. According to Viero Peroncini: «some sources report 35 million [copies sold], others 80, but it is only a way, even a rather idle one, of quantifying an unquantifiable success».[5] According to Francelia Butler, it also remains «the most translated Italian book and, after the Bible, the most widely read».[6]

Plot[edit]

In Tuscany, Italy, a carpenter named Master Antonio has found a block of wood that he plans to carve into a table leg. Frightened when the log cries out, he gives the log to his neighbor Geppetto, a poor man who plans to make a living as a puppeteer. Geppetto carves the block into a boy and names him «Pinocchio». As soon as Pinocchio’s feet are carved, he tries to kick Geppetto. Once the puppet has been finished and Geppetto teaches him to walk, Pinocchio runs out the door and away into the town. He is caught by a Carabiniere, who assumes Pinocchio has been mistreated and imprisons Geppetto.

Left alone, Pinocchio heads back to Geppetto’s house to get something to eat. Once he arrives at home, a talking cricket warns him of the perils of disobedience. In retaliation, Pinocchio throws a hammer at the cricket, accidentally killing it. Pinocchio gets hungry and tries to fry an egg, but a bird emerges from the egg and Pinocchio has to leave for food. He knocks on a neighbor’s door who fears he is pulling a child’s prank and instead dumps water on him. Cold and wet, Pinocchio goes home and lies down on a stove; when he wakes, his feet have burned off. Luckily, Geppetto is released from prison and makes Pinocchio a new pair of feet. In gratitude, he promises to attend school, and Geppetto sells his only coat to buy him a school book.

Geppetto is released from prison and makes Pinocchio a new pair of feet.

On his way to school the next morning, Pinocchio encounters the Great Marionette Theatre, and he sells his school book in order to buy a ticket for the show. During the performance, the puppets Harlequin, Pulcinella and Signora Rosaura on stage call out to him, angering the puppet master Mangiafuoco. Upset, he decides to use Pinocchio as firewood to cook his lamb dinner. After Pinocchio pleads for his and Harlequin’s salvation and upon learning of Geppetto’s poverty, Mangiafuoco releases him and gives him five gold pieces.

On his way home, Pinocchio meets a fox and a cat. The Cat pretends to be blind, and the Fox pretends to be lame. A white blackbird tries to warn Pinocchio of their lies, but the Cat eats the bird. The two animals convince Pinocchio that if he plants his coins in the Field of Miracles outside the city of Acchiappacitrulli (Catchfools), they will grow into a tree with gold coins. They stop at an inn, where the Fox and the Cat trick Pinocchio into paying for their meals and flee. They instruct the innkeeper to tell Pinocchio that they left after receiving a message that the Cat’s eldest kitten had fallen ill and that they would meet Pinocchio at the Field of Miracles in the morning.

The Fox and the Cat, dressed as bandits, hang Pinocchio.

As Pinocchio sets off for Catchfools, the ghost of the Talking Cricket appears, telling him to go home and give the coins to his father. Pinocchio ignores his warnings again. As he passes through a forest, the Fox and Cat, disguised as bandits, ambush Pinocchio, robbing him. The puppet hides the coins in his mouth and escapes to a white house after biting off the Cat’s paw. Upon knocking on the door, Pinocchio is greeted by a young fairy with turquoise hair who says she is dead and waiting for a hearse. Unfortunately, the bandits catch Pinocchio and hang him in a tree. After a while, the Fox and Cat get tired of waiting for the puppet to suffocate, and they leave.

The Fairy saves Pinocchio

The Fairy has Pinocchio rescued and calls in three doctors to evaluate him — one says he is alive, the other dead. The third doctor is the Ghost of the Talking Cricket who says that the puppet is fine, but has been disobedient and hurt his father. The Fairy administers medicine to Pinocchio. Recovered, Pinocchio lies to the Fairy when she asks what has happened to the gold coins, and his nose grows. The Fairy explains that Pinocchio’s lies are making his nose grow and calls in a flock of woodpeckers to chisel it down to size. The Fairy sends for Geppetto to come and live with them in the forest cottage.

When Pinocchio heads out to meet his father, he once again encounters the Fox and the Cat. When Pinocchio notices the Cat’s missing paw, the Fox claims that they had to sacrifice it to feed a hungry old wolf. They remind the puppet of the Field of Miracles, and finally, he agrees to go with them and plant his gold. Once there, Pinocchio buries his coins and leaves for the twenty minutes that it will take for his gold tree to grow. The Fox and the Cat dig up the coins and run away.

Pinocchio and the gorilla judge

Once Pinocchio returns, a parrot mocks Pinocchio for falling for the Fox and Cat’s tricks. Pinocchio rushes to the Catchfools courthouse where he reports the theft of the coins to a gorilla judge. Although he is moved by Pinocchio’s plea, the gorilla judge sentences Pinocchio to four months in prison for the crime of foolishness. Fortunately, all criminals are released early by the jailers when the Emperor of Catchfools declares a celebration following his army’s victory over the town’s enemies.

As Pinocchio heads back to the forest, he finds an enormous snake with a smoking tail blocking the way. After some confusion, he asks the serpent to move, but the serpent remains completely still. Concluding that it is dead, Pinocchio begins to step over it, but the serpent suddenly rises up and hisses at the marionette, toppling him over onto his head. Struck by Pinocchio’s fright and comical position, the snake laughs so hard he bursts an artery and dies.

Pinocchio then heads back to the Fairy’s house in the forest, but he sneaks into a farmer’s yard to steal some grapes. He is caught in a weasel trap where he encounters a glowworm. The farmer finds Pinocchio and ties him up in his doghouse. When Pinocchio foils the chicken-stealing weasels, the farmer frees the puppet as a reward. Pinocchio finally returns to the cottage, finds nothing but a gravestone, and believes that the Fairy has died.

Pinocchio and the pigeon fly to the seashore.

A friendly pigeon sees Pinocchio mourning the Fairy’s death and offers to give him a ride to the seashore, where Geppetto is building a boat in which to search for Pinocchio. Pinocchio is washed ashore when he tries to swim to his father. Geppetto is then swallowed by The Terrible Dogfish. Pinocchio accepts a ride from a dolphin to the nearest island called the Island of Busy Bees. Upon arriving on the island, Pinocchio can only get food in return for labor. Pinocchio offers to carry a lady’s jug home in return for food and water. When they get to the lady’s house, Pinocchio recognizes the lady as the Fairy, now miraculously old enough to be his mother. She says she will act as his mother, and Pinocchio will begin going to school. She hints that if Pinocchio does well in school and is good for one year, then he will become a real boy.

Pinocchio studies hard and rises to the top of his class, making the other boys jealous. They trick Pinocchio into playing hookey by saying they saw a large sea monster at the beach, the same one that swallowed Geppetto. However, the boys were lying and a fight breaks out. Pinocchio is accused of injuring another boy, so the puppet escapes. During his escape, Pinocchio saves a drowning Mastiff named Alidoro. In exchange, Alidoro later saves Pinocchio from The Green Fisherman, who was going to eat the marionette. After meeting the Snail that works for the Fairy, Pinocchio is given another chance by the Fairy.

Pinocchio does excellently in school. The Fairy promises that Pinocchio will be a real boy the next day and says he should invite all his friends to a party. He goes to invite everyone, but he is sidetracked when he meets his closest friend from school, a boy nicknamed Candlewick, who is about to go to a place called Toyland where everyone plays all day and never works. Pinocchio goes along with him and they have a wonderful time for the next five months.

One morning in the fifth month, Pinocchio and Candlewick awake with donkeys’ ears. A marmot tells Pinocchio that he has got a donkey fever: boys who do nothing but play and never study always turn into donkeys. Soon, both Pinocchio and Candlewick are fully transformed. Pinocchio is sold to a circus where he is trained to do tricks, until he falls and sprains his leg after seeing the Fairy with Turquoise Hair in one of the box seats. The ringmaster then sells Pinocchio to a man who wants to skin him and make a drum. The man throws the donkey into the sea to drown him. When the man goes to retrieve the corpse, all he finds is a living marionette. Pinocchio explains that the fish ate all the donkey skin off him and he is now a puppet again. Pinocchio dives back into the water and swims out to sea. When the Terrible Dogfish appears, Pinocchio is swallowed by it. Inside the Dogfish, Pinocchio unexpectedly finds Geppetto. Pinocchio and Geppetto escape with the help of a tuna and look for a new place to live.

Pinocchio finds Geppetto inside the Dogfish.

Pinocchio recognizes the farmer’s donkey as his friend Candlewick.

Pinocchio and Geppetto encounter the Fox and the Cat, now impoverished. The Cat has really become blind, and the Fox has really become lame. The Fox and the Cat plead for food or money, but Pinocchio rebuffs them and tells them that they have earned their misfortune. Geppetto and Pinocchio arrive at a small house, which is home to the Talking Cricket. The Talking Cricket says they can stay and reveals that he got his house from a little goat with turquoise hair. Pinocchio gets a job doing work for a farmer and recognizes the farmer’s dying donkey as his friend Candlewick.

Pinocchio becomes a real human boy.

After long months of working for the farmer and supporting the ailing Geppetto, Pinocchio goes to town with the forty pennies he has saved to buy himself a new suit. He discovers that the Fairy is ill and needs money. Pinocchio instantly gives the Snail he met back on the Island of Busy Bees all the money he has. That night, he dreams that he is visited by the Fairy, who kisses him. When he wakes up, he is a real boy. His former puppet body lies lifeless on a chair. The Fairy has also left him a new suit, boots, and a bag which contains 40 gold coins instead of pennies. Geppetto also returns to health.

Characters[edit]

- Pinocchio – Pinocchio is a marionette who gains wisdom through a series of misadventures that lead him to becoming a real human as reward for his good deeds.

- Geppetto – Geppetto is an elderly, impoverished woodcarver and the creator (and thus father) of Pinocchio. He wears a yellow wig that looks like cornmeal mush (or polendina), and subsequently the children of the neighborhood (as well as some of the adults) call him «Polendina», which greatly annoys him. «Geppetto» is a syncopated form of Giuseppetto, which in turn is a diminutive of the name Giuseppe (Italian for Joseph).

- Romeo/»Lampwick» or «Candlewick» (Lucignolo) – A tall, thin boy (like a wick) who is Pinocchio’s best friend and a troublemaker.

- The Coachman (l’Omino) – The owner of the Land of Toys who takes people there on his stagecoach pulled by twenty-four donkeys that mysteriously wear white shoes on their hooves. When the people who visit there turn into donkeys, he sells them.

- The Fairy with Turquoise Hair (la Fata dai capelli turchini) – The Blue-haired Fairy is the spirit of the forest who rescues Pinocchio and adopts him first as her brother, then as her son.

- The Terrible Dogfish (Il terribile Pesce-cane) – A mile-long, five-story-high fish. Pescecane, while literally meaning «dog fish», generally means «shark» in Italian.

- The Talking Cricket (il Grillo Parlante) – The Talking Cricket is a cricket whom Pinocchio kills after it tries to give him some advice. The Cricket comes back as a ghost to continue advising the puppet.

- Mangiafuoco – Mangiafuoco («Fire-Eater» in English) is the wealthy director of the Great Marionette Theater. He has red eyes and a black beard that reaches to the floor, and his mouth is «as wide as an oven [with] teeth like yellow fangs». Despite his appearances however, Mangiafuoco (which the story says is his given name) is not evil.

- The Green Fisherman (il Pescatore verde) – A green-skinned ogre on the Island of Busy Bees who catches Pinocchio in his fishing net and attempts to eat him.

- The Fox and the Cat (la Volpe e il Gatto) – Greedy anthropomorphic animals pretending to be lame and blind respectively, the pair lead Pinocchio astray, rob him and eventually try to hang him.

- Mastro Antonio ([anˈtɔːnjo] in Italian, ahn-TOH-nyoh in English) – Antonio is an elderly carpenter. He finds the log that eventually becomes Pinocchio, planning to make it into a table leg until it cries out «Please be careful!» The children call Antonio «Mastro Ciliegia (cherry)» because of his red nose.

- Harlequin (Arlecchino), Punch (Pulcinella), and Signora Rosaura – Harlequin, Punch, and Signora Rosaura are marionettes at the theater who embrace Pinocchio as their brother.

- The Innkeeper (l’Oste) – An innkeeper who is in tricked by the Fox and the Cat where he unknowingly leads Pinocchio into an ambush.

- The Falcon (il Falco) – A falcon who helps the Fairy with Turquoise Hair rescue Pinocchio from his hanging.

- Medoro ([meˈdɔːro] in Italian) – A poodle who is the stagecoach driver for the Fairy with Turquoise Hair. He is described as being dressed in court livery, a tricorn trimmed with gold lace was set at a rakish angle over a wig of white curls that dropped down to his waist, a jaunty coat of chocolate-colored velvet with diamond buttons and two huge pockets that were always filled with bones (dropped there at dinner by his loving mistress), breeches of crimson velvet, silk stockings, and low silver-buckled slippers completed his costume.

- The Owl (la Civetta) and the Crow (il Corvo) – Two famous doctors who diagnose Pinocchio alongside the Talking Cricket.

- The Parrot (il Pappagallo) – A parrot who tells Pinocchio of the Fox and the Cat’s trickery that they played on him outside of Catchfools and mocks him for being tricked by them.

- The Judge (il Giudice) – A gorilla venerable with age who works as a judge of Catchfools.

- The Serpent (il Serpente) – A large serpent with bright green skin, fiery eyes that glowed and burned, and a pointed tail that smoked and burned.

- The Farmer (il Contadino) – An unnamed farmer whose chickens are plagued by weasel attacks. He previously owned a watch dog named Melampo.

- The Glowworm (la Lucciola) – A glowworm that Pinocchio encounters in the farmer’s grape field.

- The Pigeon (il Colombo) – A pigeon who gives Pinocchio a ride to the seashore.

- The Dolphin (il Delfino) – A dolphin who gives Pinocchio a ride to the Island of Busy Bees. He also tells him about the Island of Busy Bees and the Terrible Dogfish.

- The Snail (la Lumaca) – A snail who works for the Fairy with Turquoise Hair. Pinocchio later gives all his money to the Snail by their next encounter.

- Alidoro ([aliˈdɔːro] in Italian, AH-lee-DORR-oh in English, literally «Golden Wings»; il can Mastino) – The old mastiff of a carabineer on the Island of Busy Bees.

- The Marmot (la Marmotta) – A Dormouse who lives in the Land of Toys. She is the one who tells Pinocchio about the donkey fever.

- The Ringmaster (il Direttore) – The unnamed ringmaster of a circus that buys Pinocchio from the Coachman.

- The Master (il Compratore) – A man who wants to make Pinocchio’s hide into a drum after the Ringmaster sold an injured Pinocchio to him.

- The Tuna Fish (il Tonno) – A tuna fish as «large as a two-year-old horse» who has been swallowed by the Terrible Shark.

- Giangio ([ˈdʒandʒo] in Italian, JAHN-joh in English) – The farmer who buys Romeo as a donkey and who Pinocchio briefly works for. He is also called Farmer John in some versions.

History[edit]

The Adventures of Pinocchio is a story about an animated puppet, boys who turn into donkeys, and other fairy tale devices. The setting of the story is the Tuscan area of Italy. It was a unique literary marriage of genres for its time. The story’s Italian language is peppered with Florentine dialect features, such as the protagonist’s Florentine name.

The third chapter of the story published on July 14, 1881 in the Giornale per i bambini.

As a young man, Collodi joined the seminary. However, the cause of Italian unification (Risorgimento) usurped his calling, as he took to journalism as a means of supporting the Risorgimento in its struggle with the Austrian Empire.[7] In the 1850s, Collodi began to have a variety of both fiction and non-fiction books published. Once, he translated some French fairy-tales so well that he was asked whether he would like to write some of his own. In 1848, Collodi started publishing Il Lampione, a newspaper of political satire. With the founding of the Kingdom of Italy in 1861, Collodi ceased his journalistic and militaristic activities and began writing children’s books.[7]

Collodi wrote a number of didactic children’s stories for the recently unified Italy, including Viaggio per l’Italia di Giannettino («Little Johnny’s voyage through Italy»; 1876), a series about an unruly boy who undergoes humiliating experiences while traveling the country, and Minuzzolo (1878).[8] In 1881, he sent a short episode in the life of a wooden puppet to a friend who edited a newspaper in Rome, wondering whether the editor would be interested in publishing this «bit of foolishness» in his children’s section. The editor did, and the children loved it.[9]

The Adventures of Pinocchio was originally published in serial form in the Giornale per i bambini, one of the earliest Italian weekly magazines for children, starting from 7 July 1881. In the original, serialized version, Pinocchio dies a gruesome death: hanged for his innumerable faults, at the end of Chapter 15. At the request of his editor, Collodi added chapters 16–36, in which the Fairy with Turquoise Hair rescues Pinocchio and eventually transforms him into a real boy, when he acquires a deeper understanding of himself, making the story more suitable for children. In the second half of the book, the maternal figure of the Blue-haired Fairy is the dominant character, versus the paternal figure of Geppetto in the first part. In February 1883, the story was published in a single book with huge success.[1]

Children’s literature was a new idea in Collodi’s time, an innovation in the 19th century. Thus in content and style it was new and modern, opening the way to many writers of the following century.

International popularity[edit]

The Adventures of Pinocchio is the world’s third most translated book (240-260 languages), [3][4] and was the first work of Italian children’s literature to achieve international fame.[10] The book has had great impact on world culture, and it was met with enthusiastic reviews worldwide. The title character is a cultural icon and one of the most reimagined characters in children’s literature.[11] The popularity of the story was bolstered by the powerful philosopher-critic Benedetto Croce, who greatly admired the tale and reputed it as one of the greatest works of Italian literature.[2]

Carlo Collodi, who died in 1890, was respected during his lifetime as a talented writer and social commentator, and his fame continued to grow when Pinocchio was first translated into English by Mary Alice Murray in 1892, whose translation was added to the widely read Everyman’s Library in 1911. Other well regarded English translations include the 1926 translation by Carol Della Chiesa, and the 1986 bilingual edition by Nicolas J. Perella. The first appearance of the book in the United States was in 1898, with publication of the first US edition in 1901, translated and illustrated by Walter S. Cramp and Charles Copeland.[1] From that time, the story was one of the most famous children’s books in the United States and an important step for many illustrators.[1]

Together with those from the United Kingdom, the American editions contributed to the popularity of Pinocchio in countries more culturally distant from Italy, such as Iceland and Asian countries.[1] In 1905, Otto Julius Bierbaum published a new version of the book in Germany, entitled Zapfelkerns Abenteuer (lit. The Adventures of Pine Nut), and the first French edition was published in 1902. Between 1911 and 1945, translations were made into all European languages and several languages of Asia, Africa and Oceania.[12][1] In 1936, Soviet writer Aleksey Nikolayevich Tolstoy published a reworked version of Pinocchio titled The Golden Key, or the Adventures of Buratino (originally a character in the commedia dell’arte), which became one of the most popular characters of Russian children’s literature.

Pinocchio puppets in a puppet shop window in Florence.

The first stage adaptation was launched in 1899, written by Gattesco Gatteschi and Enrico Guidotti and directed by Luigi Rasi.[1] Also, Pinocchio was adopted as a pioneer of cinema: in 1911, Giulio Antamoro featured him in a 45-minute hand-coloured silent film starring Polidor (an almost complete version of the film was restored in the 1990s).[1] In 1932, Noburō Ōfuji directed a Japanese movie with an experimental technique using animated puppets,[1] while in the 1930s in Italy, there was an attempt to produce a full-length animated cartoon film of the same title. The 1940 Walt Disney version was a groundbreaking achievement in the area of effects animation, giving realistic movement to vehicles, machinery and natural elements such as rain, lightning, smoke, shadows and water.

Proverbial figures[edit]

Many concepts and situations expressed in the book have become proverbial, such as:

- The long nose, commonly attributed to those who tell lies. The fairy says that «there are the lies that have short legs, and the lies that have the long nose».

- The land of Toys, to indicate cockaigne that hides another.

- The saying «burst into laughter» (also known as Ridere a crepapelle in Italian, literally «laugh to crack skin») was also created after the release of the book, in reference to the episode of the death of the giant snake.

Similarly, many of the characters have become typical quintessential human models, still cited frequently in everyday language:

- Mangiafuoco: (literally «fire eater») a gruff and irascible man.

- the Fox and the Cat: an unreliable pair.

- Lampwick: a rebellious and wayward boy.

- Pinocchio: a dishonest boy.

Literary analysis[edit]

Before writing Pinocchio, Collodi wrote a number of didactic children’s stories for the recently unified Italy, including a series about an unruly boy who undergoes humiliating experiences while traveling the country, titled Viaggio per l’Italia di Giannettino («Little Johnny’s voyage through Italy»).[8] Throughout Pinocchio, Collodi chastises Pinocchio for his lack of moral fiber and his persistent rejection of responsibility and desire for fun.

The structure of the story of Pinocchio follows that of the folk-tales of peasants who venture out into the world but are naively unprepared for what they find, and get into ridiculous situations.[13] At the time of the writing of the book, this was a serious problem, arising partly from the industrialization of Italy, which led to a growing need for reliable labour in the cities; the problem was exacerbated by similar, more or less simultaneous, demands for labour in the industrialization of other countries. One major effect was the emigration of much of the Italian peasantry to cities and to foreign countries, often as far away as South and North America.

Some literary analysts have described Pinocchio as an epic hero. According to Thomas J. Morrissey and Richard Wunderlich in Death and Rebirth in Pinocchio (1983) «such mythological events probably imitate the annual cycle of vegetative birth, death, and renascence, and they often serve as paradigms for the frequent symbolic deaths and rebirths encountered in literature. Two such symbolic renderings are most prominent: re-emergence from a journey to hell and rebirth through metamorphosis. Journeys to the underworld are a common feature of Western literary epics: Gilgamesh, Odysseus, Aeneas, and Dante all benefit from the knowledge and power they put on after such descents. Rebirth through metamorphosis, on the other hand, is a motif generally consigned to fantasy or speculative literature […] These two figurative manifestations of the death-rebirth trope are rarely combined; however, Carlo Collodi’s great fantasy-epic, The Adventures of Pinocchio, is a work in which a hero experiences symbolic death and rebirth through both infernal descent and metamorphosis. Pinocchio is truly a fantasy hero of epic proportions […] Beneath the book’s comic-fantasy texture—but not far beneath—lies a symbolic journey to the underworld, from which Pinocchio emerges whole.»[14]

The main imperatives demanded of Pinocchio are to work, be good, and study. And in the end Pinocchio’s willingness to provide for his father and devote himself to these things transforms him into a real boy with modern comforts. «as a hero of what is, in the classic sense, a comedy, Pinocchio is protected from ultimate catastrophe, although he suffers quite a few moderate calamities. Collodi never lets the reader forget that disaster is always a possibility; in fact, that is just what Pinocchio’s mentors —Geppetto, the Talking Cricket, and the Fairy— repeatedly tell him. Although they are part of a comedy, Pinocchio’s adventures are not always funny. Indeed, they are sometimes sinister. The book’s fictive world does not exclude injury, pain, or even death—they are stylized but not absent. […] Accommodate them he does, by using the archetypal birth-death-rebirth motif as a means of structuring his hero’s growth to responsible boyhood. Of course, the success of the puppet’s growth is rendered in terms of his metamorphic rebirth as a flesh-and-blood human.»[14]

Adaptations[edit]

The story has been adapted into many forms on stage and screen, some keeping close to the original Collodi narrative while others treat the story more freely. There are at least fourteen English-language films based on the story, Italian, French, Russian, German, Japanese and other versions for the big screen and for television, and several musical adaptations.

Films[edit]

- The Adventures of Pinocchio (1911), a live-action silent film directed by Giulio Antamoro, and the first movie based on the novel. Part of the film is lost.

- The Adventures of Pinocchio (1936), a historically notable, unfinished Italian animated feature film.

- Pinocchio (1940), the widely known Disney animated film, considered by many to be one of the greatest animated films ever made.

- Le avventure di Pinocchio [it] (1947), an Italian live action film with Alessandro Tomei as Pinocchio.

- Pinocchio in Outer Space (1965), Pinocchio has adventures in outer space, with an alien turtle as a friend.

- Turlis Abenteuer (1967), an East German version; in 1969 it was dubbed into English and shown in the US as Pinocchio.

- The Adventures of Pinocchio (1972); Un burattino di nome Pinocchio, literally A puppet named Pinocchio), an Italian animated film written and directed by Giuliano Cenci. Carlo Collodi’s grandchildren, Mario and Antonio Lorenzini advised the production.

- Pinocchio: The Series (1972); also known as Saban’s The Adventures of Pinocchio and known as Mock of the Oak Tree (樫の木モック, Kashi no Ki Mokku) in Japan, a 52-episode anime series by Tatsunoko Productions.

- The Adventures of Buratino (1975), a BSSR television film.

- Si Boneka Kayu, Pinokio [id] (1979), an Indonesian movie.

- Pinocchio and the Emperor of the Night (1987), an animated movie which acts as a sequel of the story.

- Pinocchio (1992), an animated movie by Golden Films.

- The Adventures of Pinocchio (1996), a film by Steve Barron starring Martin Landau as Geppetto and Jonathan Taylor Thomas as Pinocchio.

- The New Adventures of Pinocchio (1999), a direct-to-video film sequel of the 1996 movie. Martin Landau reprises his role of Geppetto, while Gabriel Thomson plays Pinocchio.

- Pinocchio (2002), a live-action Italian film directed by, co-written by and starring Roberto Benigni.

- Pinocchio 3000 (2004), a CGI animated Canadian film.

- Bentornato Pinocchio [it] (2007), an Italian animated film directed by Orlando Corradi, which acts as a sequel to the original story. Pinocchio is voiced by Federico Bebi.

- Pinocchio (2012), an Italian-Belgian-French animated film directed by Enzo D’Alò.

- Pinocchio (2015), a live-action Czech film featuring a computer-animated and female version of the Talking Cricket, given the name, Coco, who used to live in the wood Pinocchio was made out of.

- Pinocchio (2019), a live-action Italian film co-written, directed and co-produced by Matteo Garrone. It stars child actor Federico Ielapi as Pinocchio and Roberto Benigni as Geppetto. Prosthetic makeup was used to turn Ielapi into a puppet. Some actors, including Ielapi, dubbed themselves in the English-language version of the movie.

- Pinocchio: A True Story (2022), an animated Russian film. Gained infamy in the west for an English-dub by Lionsgate featuring the voices of Pauly Shore, Jon Heder, and Tom Kenny.

- Pinocchio (2022), a live-action film based on the 1940 animated Pinocchio.[15] directed and co-written by Robert Zemeckis.[16]

- Pinocchio (2022), a stop-motion musical film co-directed by Guillermo del Toro and Mark Gustafson.[17] It is a darker story set in Fascist Italy.

Television[edit]

- Spike Jones portrayed Pinocchio in a satirical version of the story aired 24 April 1954 as an episode of The Spike Jones Show.

- Pinocchio (1957), a TV musical broadcast live during the Golden Age of Television, directed and choreographed by Hanya Holm, and starring such actors as Mickey Rooney (in the title role), Walter Slezak (as Geppetto), Fran Allison (as the Blue Fairy), and Martyn Green (as the Fox). This version featured songs by Alec Wilder and was shown on NBC. It was part of a then-popular trend of musicalizing fantasy stories for television, following the immense success of the Mary Martin Peter Pan, which made its TV debut in 1955.

- The New Adventures of Pinocchio (1960), a TV series of 5-minute stop-motion animated vignettes by Arthur Rankin, Jr. and Jules Bass. The plots of the vignettes are mainly unrelated to the novel, but the main characters are the same and ideas from the novel are used as backstory.

- The Prince Street Players’ musical version, starring John Joy as Pinocchio and David Lile as Geppetto, was broadcast on CBS Television in 1965.

- Pinocchio (1968), a musical version of the story that aired in the United States on NBC, with pop star Peter Noone playing the puppet. This one bore no resemblance to the 1957 television version.

- The Adventures of Pinocchio (1972), a TV mini-series by Italian director Luigi Comencini, starring Andrea Balestri as Pinocchio, Nino Manfredi as Geppetto and Gina Lollobrigida as the Fairy.

- Pinocchio: The Series (1972), an animated series produced by Tatsunoko Productions. It has a distinctly darker, more sadistic theme, and portrays the main character, Pinocchio (Mokku), as suffering from constant physical and psychological abuse and freak accidents.

- In 1973, Piccolo, a kaiju based on Pinocchio, appeared in episode 46 of Ultraman Taro.

- Pinocchio (1976), still another live-action musical version for television, with Sandy Duncan in a trouser role as the puppet, Danny Kaye as Geppetto, and Flip Wilson as the Fox. It was telecast on CBS, and is available on DVD.

- Piccolino no Bōken (1976 animated series) Nippon Animation

- Pinocchio no Boken (1979 TV program) DAX International

- Pinocchio’s Christmas (1980), a stop-motion animated TV special.

- A 1984 episode of Faerie Tale Theatre starring Paul Reubens as the puppet Pinocchio.

- The Adventures of Pinocchio was adapted in Happily Ever After: Fairy Tales for Every Child where it takes place on the Barbary Coast.

- Geppetto (2000), a television film broadcast on The Wonderful World of Disney starring Drew Carey in the title role, Seth Adkins as Pinocchio, Brent Spiner as Stromboli, and Julia Louis-Dreyfus as the Blue Fairy.

- Pinocchio (2008), a British-Italian TV film starring Bob Hoskins as Geppetto, Robbie Kay as Pinocchio, Luciana Littizzetto as the Talking Cricket, Violante Placido as the Blue Fairy, Toni Bertorelli as the Fox, Francesco Pannofino as the Cat, Maurizio Donadoni as Mangiafuoco, and Alessandro Gassman as the original author Carlo Collodi.

- Once Upon a Time (2011), ABC television series. Pinocchio and many other characters from the story have major roles in the episodes «That Still Small Voice» and «The Stranger».

- Pinocchio appeared in GEICO’s 2014 bad motivational speaker commercial, and was revived in 2019 and 2020 for its Sequels campaign.

- Pinocchio (2014), South Korean television series starring Park Shin-hye and Lee Jong-suk, airs on SBS starting on November 12, 2014, every Wednesdays and Thursdays at 21:55 for 16 episodes. The protagonist Choi In-ha has a chronic symptom called «Pinocchio complex,» which makes her break into violent hiccups when she tells lies.

- The Enchanted Village of Pinocchio (Il villaggio incantati di Pinocchio), an Italian computer-animated television series which premiered in Italy on May 22, 2022, on Rai YoYo.

Other books[edit]

- Mongiardini-Rembadi, Gemma (1894), Il Segreto di Pinocchio, Italy. Published in the United States in 1913 as Pinocchio under the Sea.

- Cherubini, E. (1903), Pinocchio in Africa, Italy.

- Lorenzini, Paolo (1917), The Heart of Pinocchio, Florence, Italy.

- Patri, Angelo (1928), Pinocchio in America, United States.

- Della Chiesa, Carol (1932), Puppet Parade, New York.

- Tolstoy, Aleksey Nikolayevich (1936), The Golden Key, or the Adventures of Buratino, Russia, a loose adaptation. Illustrated by Alexander Koshkin, translated from Russian by Kathleen Cook-Horujy, Raduga Publishers, Moscow, 1990, 171 pages, SBN 5-05-002843-4. Leonid Vladimirsky later wrote and illustrated a sequel, Buratino in the Emerald City, bringing Buratino to the Magic Land that Alexander Melentyevich Volkov based on the Land of Oz, and which Vladimirski had illustrated.

- Marino, Josef (1940), Hi! Ho! Pinocchio!, United States.

- Coover, Robert (1991), Pinocchio in Venice,

novel, continues the story of Pinocchio, the Blue Fairy, and other characters

. - Dine, James ‘Jim’ (2006), Pinocchio, Steidl,

illustrations

. - ———— (2007), Pinocchio, PaceWildenstein.

- Winshluss (2008), Pinocchio, Les Requins Marteaux.

- Carter, Scott William (2012), Wooden Bones,

novel, described as the untold story of Pinocchio, with a dark twist. Pino, as he’s come to be known after he became a real boy, has discovered that he has the power to bring puppets to life himself

. - Morpurgo, Michael (2013), Pinocchio by Pinocchio Children’s book, illustrated by Emma Chichester Clark.

- London, Thomas (2015), Splintered: A Political Fairy Tale sets the characters of the story in modern-day Washington, D.C.

- Bemis, John Claude. Out of Abaton «duology» The Wooden Prince and Lord of Monsters (Disney Hyperion, 2016 and 2017) adapts the story to a science fiction setting.

- Carey, Edward (2021), The Swallowed Man tells the story of Pinnochio’s creation and evolution from the viewpoint of Geppetto

Theater[edit]

- «Pinocchio» (1961-1999), by Carmelo Bene.

- «Pinocchio» (2002), musical by Saverio Marconi and musics by Pooh.

- An opera, The Adventures of Pinocchio, composed by Jonathan Dove to a libretto by Alasdair Middleton, was commissioned by Opera North and premièred at the Grand Theatre in Leeds, England, on 21 December 2007.

- Navok, Lior (2009), opera,

sculptural exhibition. Two acts: actors, woodwind quintet and piano

. - Le Avventure di Pinocchio[citation needed] (2009) musical by Mario Restagno.

- Costantini, Vito (2011), The other Pinocchio,

musical, the first musical sequel to ‘Adventures of Pinocchio’

. The musical is based on The other Pinocchio, Brescia: La Scuola Editrice, 1999,book

. The composer is Antonio Furioso. Vito Costantini wrote «The other Pinocchio» after the discovery of a few sheets of an old manuscript attributed to Collodi and dated 21/10/1890. The news of the discovery appeared in the major Italian newspapers.[18] It is assumed the Tuscan artist wrote a sequel to ‘The Adventures of Pinocchio’ he never published. Starting from handwritten sheets, Costantini has reconstructed the second part of the story. In 2000 ‘The other Pinocchio’ won first prize in national children’s literature Città of Bitritto. - La vera storia di Pinocchio raccontata da lui medesimo, (2011) by Flavio Albanese, music by Fiorenzo Carpi, produced by Piccolo Teatro.

- L’altro Pinocchio (2011), musical by Vito Costantini based on L’altro Pinocchio (Editrice La Scuola, Brescia 1999).

- Pinocchio. Storia di un burattino da Carlo Collodi by Massimiliano Finazzer Flory (2012)

- Disney’s My Son Pinocchio: Geppetto’s Musical Tale (2016), a stage musical based in the 2000 TV movie Geppetto.

- Pinocchio (2017), musical by Dennis Kelly, with songs from 1940 Disney movie, directed by John Tiffany, premiered on the National Theatre, London.

Cultural influence[edit]

- Totò plays Pinocchio in Toto in Color (1952)

- The Erotic Adventures of Pinocchio, 1971 was advertised with the memorable line, «It’s not his nose that grows!»

- Weldon, John (1977), Spinnolio, a parody by National Film Board of Canada.[19]

- The 1990 movie Edward Scissorhands contains elements both of Beauty and Beast, Frankenstein and Pinocchio.

- Pinocchio’s Revenge, 1996, a horror movie where Pinocchio supposedly goes on a murderous rampage.

- Android Kikaider was influenced by Pinocchio story.

- Astro Boy (鉄腕アトム, Tetsuwan Atomu) (1952), a Japanese manga series written and illustrated by Osamu Tezuka, recasts loosely the Pinocchio theme.[20]

- Marvel Fairy Tales, a comic book series by C. B. Cebulski, features a retelling of The Adventures of Pinocchio with the robotic superhero called The Vision in the role of Pinocchio.

- The story was adapted in an episode of Simsala Grimm.

- Spielberg, Steven (2001), A.I. Artificial Intelligence, film, based on a Stanley Kubrick project that was cut short by Kubrick’s death, recasts the Pinocchio theme; in it an android with emotions longs to become a real boy by finding the Blue Fairy, who he hopes will turn him into one.[21]

- Shrek, 2001, Pinocchio is a recurrent supporting character.

- Shrek the Musical, Broadway, December 14, 2008.

- A Tree of Palme, a 2002 anime film, is an interpretation of the Pinocchio tale.

- Teacher’s Pet, 2004 contains elements and references of the 1940 adaptation and A.I. Artificial Intelligence.

- Happily N’Ever After 2: Snow White Another Bite @ the Apple, 2009 Pinocchio appears as a secondary character.

- In The Simpsons episode «Itchy and Scratchy Land», there is a parody of Pinocchio called Pinnitchio where Pinnitchio (Itchy) stabs Geppetto (Scratchy) in the eye after he fibs to not to tell lies.

- In the Rooster Teeth webtoon RWBY, the characters Penny Polendina and Roman Torchwick are based on Pinocchio and Lampwick respectively.

- He was used as the mascot for the 2013 UCI Road World Championships.

Monuments and art works dedicated to Pinocchio[edit]

A giant statue of Pinocchio at Parco di Pinocchio (it) in Pescia.

- The name of a district of the city of Ancona is «Pinocchio», long before the birth of the famous puppet. Vittorio Morelli built the Monument to Pinocchio.[22]

- Fontana a Pinocchio, 1956, fountain in Milan, with bronze statues of Pinocchio, the Cat, and the Fox.

- In Pescia, Italy, the park «Parco di Pinocchio» was built in 1956.

- Near the Lake Varese was built a metal statue depicting Pinocchio.[23]

- 12927 Pinocchio, a main-belt asteroid discovered on September 30, 1999 by M. Tombelli and L. Tesi at San Marcello Pistoiese, was named after Pinocchio.

- In the paintings series La morte di Pinocchio, Walther Jervolino, an Italian painter and engraver, shows Pinocchio being executed with arrows or decapitated, thus presenting an alternative story ending.

- In the central square of Viù, Turin, there is a wooden statue of Pinocchio which is 6.53 meters tall and weighs about 4000 kilograms.[24]

- In Collodi, the birthplace of the writer of Pinocchio, in February 2009 was installed a statue of the puppet 15 feet tall.

- At the Expo 2010 in Shanghai, in the Italian Pavilion, was exposed to more than two meters tall an aluminum sculpture called Pinocchio Art of Giuseppe Bartolozzi and Clara Thesis.

- The National Foundation Carlo Collodi together with Editions Redberry Art London has presented at the Milan Humanitarian Society the artist’s book The Adventures of Pinocchio with the works of Antonio Nocera. The exhibition was part of a Tuscany region food and fable project connected to the Milan Expo 2015.

See also[edit]

- Pinocchio paradox

- Great Books

- List of best-selling books

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j «The Adventures of Pinocchio — Fondazione Pinocchio — Carlo Collodi — Parco di Pinocchio». Fondazione Pinocchio.

- ^ a b Benedetto Croce, «Pinocchio», in Idem, La letteratura della nuova Italia, vol. V, Laterza, Bari 1957 (IV ed.), pp. 330-334.

- ^ a b c d Giovanni Gasparini. La corsa di Pinocchio. Milano, Vita e Pensiero, 1997. p. 117. ISBN 88-343-4889-3