Двенадцатой ночью заканчивается Йоль. Двенадцатая ночь — это ночь рождения нового года, нового жизненного цикла.

В двенадцатую ночь врата миров открыты, и все их жители собираются в месте празднования Йоля, чтобы веселым пиром приветствовать новую жизнь. Считается, что это самое мирное время в году, когда даже злые духи достойны уважения, приветствия и праздничного угощения.

Существует поверье, что свечи в венке Йоля должны гореть всю ночь. Горение свечей, их свет и тепло принесут в дом счастье и удачу.

Следующий день после Двенадцатой ночи считался «Днем судьбы». Новое, вернувшееся солнце снова стоит над горизонтом, день прибавляется. Все, что сказано и сделано до захода солнца, определяло все события наступившего года. Отсюда, возможно, и повелась известная присказка — как Новый год встретишь, так его и проведешь.

Считалось, что нет более верных знамений, чем те, что были явлены во время Двенадцатой ночи. Кстати, и самую большую силу имеют слова, которые были произнесены в Двенадцатую ночь.

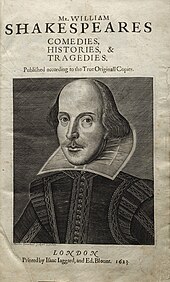

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Twelfth Night | |

|---|---|

Mervyn Clitheroe’s Twelfth Night party, |

|

| Also called | Epiphany Eve |

| Observed by | Christians |

| Type | Christian |

| Significance | evening prior to Epiphany |

| Observances |

|

| Date | 5 or 6 January |

| Frequency | annual |

| Related to |

|

Twelfth Night (also known as Epiphany Eve) is a Christian festival on the last night of the Twelve Days of Christmas, marking the coming of the Epiphany.[1] Different traditions mark the date of Twelfth Night as either 5 January or 6 January, depending on whether the counting begins on Christmas Day or 26 December.[2][3]

A superstition in some English-speaking countries suggests it is unlucky to leave Christmas decorations hanging after Twelfth Night, a tradition also variously attached to the festivals of Candlemas (2 February), Good Friday, Shrove Tuesday, and Septuagesima.[4] Other popular customs include eating king cake, singing Christmas carols, chalking the door, having one’s house blessed, merrymaking, and attending church services.[5][6]

Date[edit]

In many Western ecclesiastical traditions, Christmas Day is considered the «First Day of Christmas» and the Twelve Days are 25 December – 5 January, inclusive, making Twelfth Night on 5 January, which is Epiphany Eve.[1] In some customs, the Twelve Days of Christmas are counted from sundown on the evening of 25 December until the morning of 6 January, meaning that the Twelfth Night falls on the evening 5 January and the Twelfth Day falls on 6 January. However, in some church traditions only full days are counted, so that 5 January is counted as the Eleventh Day, 6 January as the Twelfth Day, and the evening of 6 January is counted as the Twelfth Night.[7] In these traditions, Twelfth Night is the same as Epiphany.[8] However, some such as the Church of England consider Twelfth Night to be the eve of the Twelfth Day (in the same way that Christmas Eve comes before Christmas), and thus consider Twelfth Night to be on 5 January.[9] The difficulty may come from the use of the words «eve» which is defined as «the day or evening before an event», however, especially in antiquated usage could be used to simply mean «evening».[10]

Bruce Forbes writes:

In 567 the Council of Tours proclaimed that the entire period between Christmas and Epiphany should be considered part of the celebration, creating what became known as the twelve days of Christmas, or what the English called Christmastide. On the last of the twelve days, called Twelfth Night, various cultures developed a wide range of additional special festivities. The variation extends even to the issue of how to count the days. If Christmas Day is the first of the twelve days, then Twelfth Night would be on January 5, the eve of Epiphany. If December 26, the day after Christmas, is the first day, then Twelfth Night falls on January 6, the evening of Epiphany itself.[11]

The Church of England, Mother Church of the Anglican Communion, celebrates Twelfth Night on the 5th and «refers to the night before Epiphany, the day when the nativity story tells us that the wise men visited the infant Jesus».[12][13][14]

Origins and history[edit]

Wassailing apple trees on the twelfth night to ensure a good harvest, a tradition in Maplehurst, West Sussex

A Spanish Roscón de reyes, or Kings’ ring. This size, approx. 50 cm (20 in) diameter, usually serves 8 people. This pastry is just one of the many types baked around the world for celebrations during the Twelve Days of Christmas and Twelfth Night.

In 567 A.D, the Council of Tours «proclaimed the twelve days from Christmas to Epiphany as a sacred and festive season, and established the duty of Advent fasting in preparation for the feast.»[15][16][17][18] Christopher Hill, as well as William J. Federer, states that this was done to solve the «administrative problem for the Roman Empire as it tried to coordinate the solar Julian calendar with the lunar calendars of its provinces in the east.»[19][20]

In medieval and Tudor England, Candlemas traditionally marked the end of the Christmas season,[21][22] although later, Twelfth Night came to signal the end of Christmastide, with a new but related season of Epiphanytide running until Candlemas.[23] A popular Twelfth Night tradition was to have a bean and pea hidden inside a Twelfth-night cake; the «man who finds the bean in his slice of cake becomes King for the night while the lady who finds a pea in her slice of cake becomes Queen for the night.»[24] Following this selection, Twelfth Night parties would continue and would include the singing of Christmas carols, as well as feasting.[24]

Traditions[edit]

Food and drink are the centre of the celebrations in modern times. All of the most traditional ones go back many centuries. The punch called wassail is consumed especially on Twelfth Night and throughout Christmas time, especially in the UK, and door-to-door wassailing (similar to singing Christmas carols) was common up until the 1950s.[25] Around the world, special pastries, such as the tortell and king cake, are baked on Twelfth Night, and eaten the following day for the Feast of the Epiphany celebrations. In English and French custom, the Twelfth-cake was baked to contain a bean and a pea so that those who received the slices containing them should be respectively designated king and queen of the night’s festivities.[26]

In parts of Kent, there is a tradition that an edible decoration would be the last part of Christmas to be removed in the Twelfth Night and shared amongst the family.[27]

The Theatre Royal, Drury Lane in London has had a tradition since 1795 of providing a Twelfth Night cake. The will of Robert Baddeley made a bequest of £100 to provide cake and punch every year for the company in residence at the theatre on 6 January. The tradition continues.[28]

In Ireland, it is still the tradition to place the statues of the Three Kings in the crib on the Twelfth Night or, at the latest, the following day, Little Christmas.[citation needed]

In colonial America, a Christmas wreath was always left up on the front door of each home. When taken down at the end of the Twelve Days of Christmas, any edible portions would be consumed with the other foods of the feast. The same held true in the 19th–20th centuries with fruits adorning Christmas trees. Fresh fruits were hard to come by and were therefore considered fine and proper gifts and decorations for the tree, wreaths, and home. Again, the tree would be taken down on the Twelfth Night, and such fruits, along with nuts and other local produce used, would then be consumed.[citation needed]

Modern American Carnival traditions are seen across former French colonies, most notably in New Orleans and Mobile. In the mid-twentieth century, friends gathered for weekly king cake parties. Whoever got the slice with the «king», usually in the form of a miniature baby doll (symbolic of the Christ Child, «Christ the King»), hosted the next week’s party. Traditionally, this was a bean for the king and a pea for the queen.[29] Parties centred around king cakes are no longer common and king cake today is usually brought to the workplace or served at parties, the recipient of the plastic baby being obligated to bring the next king cake to the next function. In some countries, Twelfth Night and Epiphany mark the start of the Carnival season, which lasts through Mardi Gras Day.[citation needed]

In Spain, Twelfth Night is called Cabalgata de Reyes («Parade of Kings»), and historically the «kings» would go through towns and hand out sweets.[25]

In France, La Galette des Rois («Kings’ Cake») is eaten all month long. The cakes vary depending on the region; in northern France, it is called a galette and is filled with frangipane, fruit, or chocolate. In the south, it is more of a brioche with candied fruit.[25]

Suppression[edit]

Twelfth Night in the Netherlands became so secularised, rowdy, and boisterous that public celebrations were banned by the Church.[30]

Old Twelfth Night[edit]

In some places, particularly South West England, Old Twelfth Night is still celebrated on 17 January.[31][32] This continues the custom of the Apple Wassail on the date that corresponded to 6 January on the Julian calendar at the time of the change in calendars enacted by the Calendar Act of 1750.[33]

In literature[edit]

It is unknown whether Shakespeare’s play Twelfth Night, or What You Will was written to be performed as a Twelfth Night entertainment, since there is no record of the circumstances of its composition.[34] The earliest known performance took place at Middle Temple Hall, one of the Inns of Court, on Candlemas night, 2 February 1602.[35] The play has many elements that are reversed, in the tradition of Twelfth Night, such as a woman Viola dressing as a man, and a servant Malvolio imagining that he can become a nobleman.[citation needed]

Ben Jonson’s The Masque of Blackness was performed on 6 January 1605 at the Banqueting House in Whitehall. It was originally entitled The Twelfth Nights Revells. The accompanying Masque, The Masque of Beauty was performed in the same court the Sunday night after the Twelfth Night in 1608.[36]

Robert Herrick’s poem Twelfth-Night, or King and Queene, published in 1648, describes the election of king and queen by bean and pea in a plum cake, and the homage done to them by the draining of wassail bowls of «lamb’s-wool», a drink of sugar, nutmeg, ginger, and ale.[37]

Charles Dickens’ 1843 A Christmas Carol briefly mentions Scrooge and the Ghost of Christmas Present visiting a children’s Twelfth Night party.[citation needed]

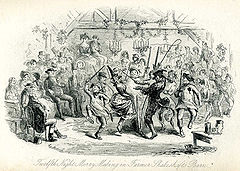

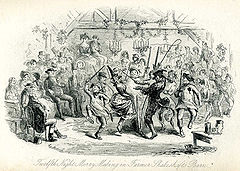

In chapter 6 of Harrison Ainsworth’s 1858 novel Mervyn Clitheroe, the eponymous hero is elected King of festivities at the Twelfth Night celebrations held in Tom Shakeshaft’s barn by receiving the slice of plum cake containing the bean; his companion Cissy obtains the pea and becomes queen, and they are seated together in a high corner to view the proceedings. The distribution has been rigged to prevent another person from gaining the role. The festivities include country dances, the introduction of a «Fool Plough», a plough decked with ribands brought into the barn by a dozen mummers together with a grotesque «Old Bessie» (played by a man), and a Fool dressed in animal skins with a fool’s hat. The mummers carry wooden swords and perform revelries. The scene in the novel is illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne («Phiz»). In the course of the evening, the fool’s antics cause a fight to break out, but Mervyn restores order. Three bowls of gin punch are disposed of. At eleven o’clock, the young men make the necessary arrangements to see the young ladies safely home across the fields.[38]

The Dead—the final, novella-length story in James Joyce’s 1914 collection Dubliners—opens on Twelfth Night, or Epiphany Eve, and extends into the early morning hours of Epiphany itself. Critics and writers consider the story «just about the finest short story in the English language»[39] and «one of the greatest short stories ever written».[40] Its adaptations include a play, a Broadway musical, and two films. The story begins at the bustling and sumptuous annual dance hosted by Kate Morkan and Julia Morkan, aunts to Gabriel Conroy, the main character. Throughout the festivities, a series of minor obligations and awkward encounters leaves Gabriel with a sense of unease, inducing self-doubt, or at least doubt in the person he presents himself as. This unease sharpens during a dinner speech in which Gabriel grandiosely ponders whether because «…we are living in a skeptical and, if I may use the phrase, a thought-tormented age», the generation currently coming of age in Ireland will begin to «lack those qualities of humanity, of hospitality, of kindly humor which belonged to an older day.» High spirits and singing soon resume. Gabriel and his wife Gretta depart for their hotel in the early morning hours. This destination for Gabriel kindles both erotic possibility and deep love. However, at the hotel, Gretta, moved by a song they had just heard sung at the party, offers a tearful, long-withheld revelation that momentarily shatters Gabriel’s feelings of warmth, leaving him shaken and bewildered. After Gretta drifts off to sleep, Gabriel, still rapt in the emotional wake of her revelation, gazes out the window at the falling snow and experiences a profound and unifying epiphany, one that reconciles the fears, doubts, and façades that had haunted him throughout the evening and, he seems to recognise, throughout his life to that point.[41]

See also[edit]

- Christmas Eve

- List of Christmas carols

- Pantomime

- Theophany

References[edit]

- ^ a b Hatch, Jane M. (1978). The American Book of Days. Wilson. ISBN 9780824205935.

January 5th: Twelfth Night or Epiphany Eve. Twelfth Night, the last evening of the traditional Twelve Days of Christmas, has been observed with festive celebration ever since the Middle Ages.

- ^ «Epiphany: Should Christmas decorations come down on 6 January?». BBC News. 6 January 2017. Retrieved 9 January 2021.

- ^ Carter, Michael. «Why it is time for an epiphany over Christmas decorations». The Tablet. Retrieved 9 January 2021.

- ^ William Alexander Barrett (1868). Flowers and Festivals, Or, Directions for the Floral Decoration of Churches. Rivingtons. pp. 170–174.

- ^ Mangan, Louise; Wyse, Nancy; Farr, Lori (2001). Rediscovering the Seasons of the Christian Year. Wood Lake Publishing Inc. p. 69. ISBN 9781551454986.

Epiphany is often heralded by «Twelfth Night» celebrations (12 days after Christmas), on the evening before the Feast of Epiphany. Some Christian communities prepare Twelfth Night festivities with drama, singing, rituals — and food! … Sometimes several congregations walk in lines from church to church, carrying candles to symbolize the light of Christ shining and spreading. Other faith communities move from house to house, blessing each home as they search for the Christ child.

- ^ Pennick, Nigel (21 May 2015). Pagan Magic of the Northern Tradition: Customs, Rites, and Ceremonies. Inner Traditions – Bear & Company. p. 176. ISBN 9781620553909.

On Twelfth Night in German-speaking countries, the Sternsinger («star singers») go around to houses carrying a paper or wooden star on a pole. They sing an Epiphany carol, then one of them writes in chalk over the door a formula consisting of the initials of the Three Wise Men in the Nativity story, Caspar, Melchior, and Balthasar, with crosses between them and the year date on either side; for example: 20 +M+B 15. This is said to protect the house and its inhabitants until the next Epiphany.

- ^ Bratcher, Dennis. «The Season of Epiphany». The Voice. Christian Resource Institute. Retrieved 4 January 2019.

- ^ Van Wagenberg-Ter Hoeven, Anke A. (1993). «The Celebration of Twelfth Night in Netherlandish Art». Simiolus: Netherlands Quarterly for the History of Art. 22 (1/2): 65–96. doi:10.2307/3780806. JSTOR 3780806.

- ^ «Epiphany». Christ Lutheran Church of Staunton, Virginia. Retrieved 4 January 2019.

- ^ «eve noun — Definition, pictures, pronunciation and usage notes | Oxford Advanced American Dictionary at OxfordLearnersDictionaries.com». www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com. Retrieved 9 January 2021.

- ^ Forbes, Bruce (2008). Christmas: A Candid History. University of California Press. p. 27. ISBN 9780520258020.

- ^ Beckford, Martin (6 January 2009). «Christmas ends in confusion over when Twelfth Night falls». The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 5 January 2010. Retrieved 26 May 2010.

- ^ «Twelve days of Christmas». Full Homely Divinity. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

We prefer, like good Anglicans, to go with the logic of the liturgy and regard January 5th as the Twelfth Day of Christmas and the night that ends that day as Twelfth Night. That does make Twelfth Night the Eve of the Epiphany, which means that, liturgically, a new feast has already begun.

- ^ Shorter Oxford English Dictionary. 1993.

…the evening of the fifth of January, preceding Twelfth Day, the eve of the Epiphany, formerly the last day of the Christmas festivities and observed as a time of merrymaking.

- ^ Fr. Francis X. Weiser. «Feast of the Nativity». Catholic Culture.

The Council of Tours (567) proclaimed the twelve days from Christmas to Epiphany as a sacred and festive season, and established the duty of Advent fasting in preparation for the feast. The Council of Braga (563) forbade fasting on Christmas Day.

- ^ Fox, Adam (19 December 2003). «‘Tis the season». The Guardian. Retrieved 25 December 2014.

Around the year 400 the feasts of St Stephen, John the Evangelist and the Holy Innocents were added on succeeding days, and in 567 the Council of Tours ratified the enduring 12-day cycle between the nativity and the epiphany.

- ^ Hynes, Mary Ellen (1993). Companion to the Calendar. Liturgy Training Publications. p. 8. ISBN 9781568540115.

In the year 567 the church council of Tours called the 13 days between December 25 and January 6 a festival season.

Martindale, Cyril Charles (1908). «Christmas». The Catholic Encyclopedia. New Advent. Retrieved 15 December 2014.The Second Council of Tours (can. xi, xvii) proclaims, in 566 or 567, the sanctity of the «twelve days» from Christmas to Epiphany, and the duty of Advent fast; …and that of Braga (563) forbids fasting on Christmas Day. Popular merry-making, however, so increased that the «Laws of King Cnut», fabricated c. 1110, order a fast from Christmas to Epiphany.

- ^ Bunson, Matthew (21 October 2007). «Origins of Christmas and Easter holidays». Eternal Word Television Network (EWTN). Retrieved 17 December 2014.

The Council of Tours (567) decreed the 12 days from Christmas to Epiphany to be sacred and especially joyous, thus setting the stage for the celebration of the Lord’s birth…

- ^ Hill, Christopher (2003). Holidays and Holy Nights: Celebrating Twelve Seasonal Festivals of the Christian Year. Quest Books. p. 91. ISBN 9780835608107.

This arrangement became an administrative problem for the Roman Empire as it tried to coordinate the solar Julian calendar with the lunar calendars of its provinces in the east. While the Romans could roughly match the months in the two systems, the four cardinal points of the solar year—the two equinoxes and solstices—still fell on different dates. By the time of the first century, the calendar date of the winter solstice in Egypt and Palestine was eleven to twelve days later than the date in Italy. As a result, the Incarnation came to be celebrated on different days in different parts of the Empire. The Western Church, in its desire to be universal, eventually took them both—one became Christmas, one Epiphany—with a resulting twelve days in between. Over time this hiatus became invested with specific Christian meaning. The Church gradually filled these days with saints, some connected to the birth narratives in Gospels (Holy Innocents’ Day, December 28, in honour of the infants slaughtered by Herod; St. John the Evangelist, «the Beloved», December 27; St. Stephen, the first Christian martyr, December 26; the Holy Family, December 31; the Virgin Mary, January 1). In 567, the Council of Tours declared the twelve days between Christmas and Epiphany to become one unified festal cycle.

Federer, William J. (6 January 2014). «On the 12th Day of Christmas». American Minute. Retrieved 25 December 2014.In 567 AD, the Council of Tours ended a dispute. Western Europe celebrated Christmas, December 25, as the holiest day of the season… but Eastern Europe celebrated Epiphany, January 6, recalling the Wise Men’s visit and Jesus’ baptism. It could not be decided which day was holier, so the Council made all 12 days from December 25 to January 6 «holy days» or «holidays,» These became known as «The Twelve Days of Christmas.»

- ^ Kirk Cameron, William Federer (6 November 2014). Praise the Lord. Trinity Broadcasting Network. Event occurs at 01:15:14. Archived from the original on 25 December 2014. Retrieved 25 December 2014.

Western Europe celebrated Christmas December 25 as the holiest day. Eastern Europe celebrated January 6 the Epiphany, the visit of the Wise Men, as the holiest day… and so they had this council and they decided to make all twelve days from December 25 to January 6 the Twelve Days of Christmas.

- ^ «LEAVE YOUR CHRISTMAS DECORATIONS UP UNTIL FEBRUARY, SAYS ENGLISH HERITAGE»

- ^ Miles, Clement A.. Christmas Customs and Traditions: Their History and Significance. Courier Dover Publications, 1976. ISBN 0-486-23354-5. Robert Herrick (1591–1674) in his poem «Ceremony upon Candlemas Eve» writes:

- «Down with the rosemary, and so

- Down with the bays and mistletoe;

- Down with the holly, ivy, all,

- Wherewith ye dress’d the Christmas Hall»

According to the Pelican Shakespeare anthology, It was written for a private performance for Elizabeth I in 1601.

As Herrick’s poem records, the eve of Candlemas (the day before 2 February) was the day on which Christmas decorations of greenery were removed from people’s homes; for any traces of berries, holly and so forth will bring death among the congregation before another year is out.

- ^ Davidson, Clifford (5 December 2016). Festivals and Plays in Late Medieval Britain. Taylor & Francis. p. 32. ISBN 9781351936613.

Playing seems to have continued after Twelfth Night, in the Epiphany season leading up to Candlemas on February 2, which sometimes was regarded as the last day of the Christmas season. We know that these weeks were an extension of the festive Christmas period.

- ^ a b Macclain, Alexia (4 January 2013). «Twelfth Night Traditions: A Cake, a Bean, and a King –». Smithsonian Libraries. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

And what happens at a Twelfth Night party? According to the 1923 Dennison’s Christmas Book, «there should be a King and a Queen, chosen by cutting a cake…» The Twelfth Night Cake has a bean and a pea baked into it. The man who finds the bean in his slice of cake becomes King for the night while the lady who finds a pea in her slice of cake becomes Queen for the night. The new King and Queen sit on a throne and «paper crowns, a scepter and, if possible, full regalia are given them.» The party continues with games such as charades as well as eating, dancing, and singing carols. For large Twelfth Night celebrations, a costume party is suggested.

- ^ a b c Derry, Johanna (4 January 2016). «Let’s bring back the glorious food traditions of Twelfth Night (largely, lots of cake)». The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 4 January 2019.

- ^ Miles & John, Hadfield (1961). The Twelve Days of Christmas. London: Cassell & Company. p. 166.

- ^ Mark Esdale. «Main Page @ Bridge Farmers’ Market».

- ^ «The Baddeley Cake». Drury Lane Theatrical Fund. Retrieved 30 November 2013.

- ^ MacClain, Alexia (4 January 2013). «Twelfth Night Traditions: A Cake, a Bean, and a King – Smithsonian Libraries Unbound». Unbound. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 4 January 2019.

- ^ Hoeven, Anke A. van Wagenberg-ter (1993). «The Celebration of Twelfth Night in Netherlandish Art». Simiolus: Netherlands Quarterly for the History of Art. 22 (1/2): 67. doi:10.2307/3780806. JSTOR 3780806.

- ^ Iain Hollingshead, Whatever happened to … wassailing?, The Guardian, 23 December 2005. Retrieved 23 May 2014

- ^ Xanthe Clay, Traditional cider: Here we come a-wassailing!, The Telegraph, 3 February 2011. Retrieved 23 May 2014

- ^ Nick Easen, Wassailing the old English apple tree, BBC Travel, 16 January 2012

- ^ White, R.S. (2014). «The Critical Backstory» in Twelfth Night: A Critical Reader ed. Findlay and Oakley-Brown. London: Bloomsbury. pp. 27–28. ISBN 9781441128782.

- ^ Shakespeare, William; Smith, Bruce R. (2001). Twelfth Night: Texts and Contexts. Boston: Bedford/St Martin’s. p. 2. ISBN 0-312-20219-9.

- ^ Herford, C. H. (1941). Percy Simpson; Evelyn Simpson (eds.). Ben Jonson. Vol. VII. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 169–201.

- ^ Herrick, Robert (1825). The Poetical Works of Robert Herrick. W. Pickering. p. 171.

- ^ Ainsworth, William Harrison (1858). Mervyn Clitheroe. G. Routledge & Company. pp. 41–55.

- ^ Barry, Dan (26 June 2014). «Singular Collection, Multiple Mysteries». The New York Times. Retrieved 28 June 2018.

- ^ «An Exploration of ‘The Dead’«. Joyce’s Dublin. UCD Humanities Institute. Retrieved 23 June 2015.

- ^ Joyce, James. «Dubliners».

Further reading[edit]

- «Christmas». Catholic Encyclopedia. Retrieved 22 December 2005. Primarily subhead Popular Merrymaking under Liturgy and Custom.

- Christmas Trivia edited by Jennie Miller Helderman, Mary Caulkins. Gramercy, 2002

- Marix-Evans, Martin. The Twelve Days of Christmas. Peter Pauper Press, 2002

- Bowler, Gerry. The World Encyclopedia of Christmas. McClelland & Stewart, 2004

- Collins, Ace. Stories Behind the Great Traditions of Christmas. Zondervan, 2003

- Wells, Robin Headlam. Shakespeare’s Humanism. Cambridge University Press, 2006

- Fosbrooke, Thomas Dudley c. 1810, Encyclopaedia of Antiquities (Publisher unknown)

- J. Brand, 1813, Popular Antiquities, 2 Vols (London)

- W. Hone, 1830, The Every-Day Book 3 Vols (London), cf Vol I pp 41–61.

Early English sources[edit]

(drawn from Hone’s Every-Day Book, references as found):

- Vox Graculi, 4to, 1623: 6 January, Masking in the Strand, Cheapside, Holbourne, or Fleet-street (London), and eating spice-bread.

- The Popish Kingdom, ‘Naogeorgus’: Baking of the twelfth-cake with a penny in it, the slices distributed to members of the household to give to the poor: whoever finds the penny is proclaimed king among them.

- Nichols, Queen Elizabeth’s Progresses: An entertainment at Sudley, temp. Elizabeth I, including Melibaeus, king of the bean, and Nisa, queen of the pea.

- Pinkerton, Ancient Scottish Poems: Letter from Sir Thomas Randolph to Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester dated 15 January 1563, mentioning that Lady Flemyng was Queen of the Beene on Twelfth-Day that year.

- Ben Jonson, Christmas, His Masque (1616, published 1641): A character ‘Baby-cake’ is attended by an usher carrying a great cake with a beane and a pease.

- Samuel Pepys, Diaries (1659/60): Epiphany Eve party, selecting of King and Queen by a cake (see King cake).

External links[edit]

- Epiphany on Catholic Encyclopedia

- The Twelve Days of Christmas at The Christian Resource Institute

- William Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Twelfth Night | |

|---|---|

Mervyn Clitheroe’s Twelfth Night party, |

|

| Also called | Epiphany Eve |

| Observed by | Christians |

| Type | Christian |

| Significance | evening prior to Epiphany |

| Observances |

|

| Date | 5 or 6 January |

| Frequency | annual |

| Related to |

|

Twelfth Night (also known as Epiphany Eve) is a Christian festival on the last night of the Twelve Days of Christmas, marking the coming of the Epiphany.[1] Different traditions mark the date of Twelfth Night as either 5 January or 6 January, depending on whether the counting begins on Christmas Day or 26 December.[2][3]

A superstition in some English-speaking countries suggests it is unlucky to leave Christmas decorations hanging after Twelfth Night, a tradition also variously attached to the festivals of Candlemas (2 February), Good Friday, Shrove Tuesday, and Septuagesima.[4] Other popular customs include eating king cake, singing Christmas carols, chalking the door, having one’s house blessed, merrymaking, and attending church services.[5][6]

Date[edit]

In many Western ecclesiastical traditions, Christmas Day is considered the «First Day of Christmas» and the Twelve Days are 25 December – 5 January, inclusive, making Twelfth Night on 5 January, which is Epiphany Eve.[1] In some customs, the Twelve Days of Christmas are counted from sundown on the evening of 25 December until the morning of 6 January, meaning that the Twelfth Night falls on the evening 5 January and the Twelfth Day falls on 6 January. However, in some church traditions only full days are counted, so that 5 January is counted as the Eleventh Day, 6 January as the Twelfth Day, and the evening of 6 January is counted as the Twelfth Night.[7] In these traditions, Twelfth Night is the same as Epiphany.[8] However, some such as the Church of England consider Twelfth Night to be the eve of the Twelfth Day (in the same way that Christmas Eve comes before Christmas), and thus consider Twelfth Night to be on 5 January.[9] The difficulty may come from the use of the words «eve» which is defined as «the day or evening before an event», however, especially in antiquated usage could be used to simply mean «evening».[10]

Bruce Forbes writes:

In 567 the Council of Tours proclaimed that the entire period between Christmas and Epiphany should be considered part of the celebration, creating what became known as the twelve days of Christmas, or what the English called Christmastide. On the last of the twelve days, called Twelfth Night, various cultures developed a wide range of additional special festivities. The variation extends even to the issue of how to count the days. If Christmas Day is the first of the twelve days, then Twelfth Night would be on January 5, the eve of Epiphany. If December 26, the day after Christmas, is the first day, then Twelfth Night falls on January 6, the evening of Epiphany itself.[11]

The Church of England, Mother Church of the Anglican Communion, celebrates Twelfth Night on the 5th and «refers to the night before Epiphany, the day when the nativity story tells us that the wise men visited the infant Jesus».[12][13][14]

Origins and history[edit]

Wassailing apple trees on the twelfth night to ensure a good harvest, a tradition in Maplehurst, West Sussex

A Spanish Roscón de reyes, or Kings’ ring. This size, approx. 50 cm (20 in) diameter, usually serves 8 people. This pastry is just one of the many types baked around the world for celebrations during the Twelve Days of Christmas and Twelfth Night.

In 567 A.D, the Council of Tours «proclaimed the twelve days from Christmas to Epiphany as a sacred and festive season, and established the duty of Advent fasting in preparation for the feast.»[15][16][17][18] Christopher Hill, as well as William J. Federer, states that this was done to solve the «administrative problem for the Roman Empire as it tried to coordinate the solar Julian calendar with the lunar calendars of its provinces in the east.»[19][20]

In medieval and Tudor England, Candlemas traditionally marked the end of the Christmas season,[21][22] although later, Twelfth Night came to signal the end of Christmastide, with a new but related season of Epiphanytide running until Candlemas.[23] A popular Twelfth Night tradition was to have a bean and pea hidden inside a Twelfth-night cake; the «man who finds the bean in his slice of cake becomes King for the night while the lady who finds a pea in her slice of cake becomes Queen for the night.»[24] Following this selection, Twelfth Night parties would continue and would include the singing of Christmas carols, as well as feasting.[24]

Traditions[edit]

Food and drink are the centre of the celebrations in modern times. All of the most traditional ones go back many centuries. The punch called wassail is consumed especially on Twelfth Night and throughout Christmas time, especially in the UK, and door-to-door wassailing (similar to singing Christmas carols) was common up until the 1950s.[25] Around the world, special pastries, such as the tortell and king cake, are baked on Twelfth Night, and eaten the following day for the Feast of the Epiphany celebrations. In English and French custom, the Twelfth-cake was baked to contain a bean and a pea so that those who received the slices containing them should be respectively designated king and queen of the night’s festivities.[26]

In parts of Kent, there is a tradition that an edible decoration would be the last part of Christmas to be removed in the Twelfth Night and shared amongst the family.[27]

The Theatre Royal, Drury Lane in London has had a tradition since 1795 of providing a Twelfth Night cake. The will of Robert Baddeley made a bequest of £100 to provide cake and punch every year for the company in residence at the theatre on 6 January. The tradition continues.[28]

In Ireland, it is still the tradition to place the statues of the Three Kings in the crib on the Twelfth Night or, at the latest, the following day, Little Christmas.[citation needed]

In colonial America, a Christmas wreath was always left up on the front door of each home. When taken down at the end of the Twelve Days of Christmas, any edible portions would be consumed with the other foods of the feast. The same held true in the 19th–20th centuries with fruits adorning Christmas trees. Fresh fruits were hard to come by and were therefore considered fine and proper gifts and decorations for the tree, wreaths, and home. Again, the tree would be taken down on the Twelfth Night, and such fruits, along with nuts and other local produce used, would then be consumed.[citation needed]

Modern American Carnival traditions are seen across former French colonies, most notably in New Orleans and Mobile. In the mid-twentieth century, friends gathered for weekly king cake parties. Whoever got the slice with the «king», usually in the form of a miniature baby doll (symbolic of the Christ Child, «Christ the King»), hosted the next week’s party. Traditionally, this was a bean for the king and a pea for the queen.[29] Parties centred around king cakes are no longer common and king cake today is usually brought to the workplace or served at parties, the recipient of the plastic baby being obligated to bring the next king cake to the next function. In some countries, Twelfth Night and Epiphany mark the start of the Carnival season, which lasts through Mardi Gras Day.[citation needed]

In Spain, Twelfth Night is called Cabalgata de Reyes («Parade of Kings»), and historically the «kings» would go through towns and hand out sweets.[25]

In France, La Galette des Rois («Kings’ Cake») is eaten all month long. The cakes vary depending on the region; in northern France, it is called a galette and is filled with frangipane, fruit, or chocolate. In the south, it is more of a brioche with candied fruit.[25]

Suppression[edit]

Twelfth Night in the Netherlands became so secularised, rowdy, and boisterous that public celebrations were banned by the Church.[30]

Old Twelfth Night[edit]

In some places, particularly South West England, Old Twelfth Night is still celebrated on 17 January.[31][32] This continues the custom of the Apple Wassail on the date that corresponded to 6 January on the Julian calendar at the time of the change in calendars enacted by the Calendar Act of 1750.[33]

In literature[edit]

It is unknown whether Shakespeare’s play Twelfth Night, or What You Will was written to be performed as a Twelfth Night entertainment, since there is no record of the circumstances of its composition.[34] The earliest known performance took place at Middle Temple Hall, one of the Inns of Court, on Candlemas night, 2 February 1602.[35] The play has many elements that are reversed, in the tradition of Twelfth Night, such as a woman Viola dressing as a man, and a servant Malvolio imagining that he can become a nobleman.[citation needed]

Ben Jonson’s The Masque of Blackness was performed on 6 January 1605 at the Banqueting House in Whitehall. It was originally entitled The Twelfth Nights Revells. The accompanying Masque, The Masque of Beauty was performed in the same court the Sunday night after the Twelfth Night in 1608.[36]

Robert Herrick’s poem Twelfth-Night, or King and Queene, published in 1648, describes the election of king and queen by bean and pea in a plum cake, and the homage done to them by the draining of wassail bowls of «lamb’s-wool», a drink of sugar, nutmeg, ginger, and ale.[37]

Charles Dickens’ 1843 A Christmas Carol briefly mentions Scrooge and the Ghost of Christmas Present visiting a children’s Twelfth Night party.[citation needed]

In chapter 6 of Harrison Ainsworth’s 1858 novel Mervyn Clitheroe, the eponymous hero is elected King of festivities at the Twelfth Night celebrations held in Tom Shakeshaft’s barn by receiving the slice of plum cake containing the bean; his companion Cissy obtains the pea and becomes queen, and they are seated together in a high corner to view the proceedings. The distribution has been rigged to prevent another person from gaining the role. The festivities include country dances, the introduction of a «Fool Plough», a plough decked with ribands brought into the barn by a dozen mummers together with a grotesque «Old Bessie» (played by a man), and a Fool dressed in animal skins with a fool’s hat. The mummers carry wooden swords and perform revelries. The scene in the novel is illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne («Phiz»). In the course of the evening, the fool’s antics cause a fight to break out, but Mervyn restores order. Three bowls of gin punch are disposed of. At eleven o’clock, the young men make the necessary arrangements to see the young ladies safely home across the fields.[38]

The Dead—the final, novella-length story in James Joyce’s 1914 collection Dubliners—opens on Twelfth Night, or Epiphany Eve, and extends into the early morning hours of Epiphany itself. Critics and writers consider the story «just about the finest short story in the English language»[39] and «one of the greatest short stories ever written».[40] Its adaptations include a play, a Broadway musical, and two films. The story begins at the bustling and sumptuous annual dance hosted by Kate Morkan and Julia Morkan, aunts to Gabriel Conroy, the main character. Throughout the festivities, a series of minor obligations and awkward encounters leaves Gabriel with a sense of unease, inducing self-doubt, or at least doubt in the person he presents himself as. This unease sharpens during a dinner speech in which Gabriel grandiosely ponders whether because «…we are living in a skeptical and, if I may use the phrase, a thought-tormented age», the generation currently coming of age in Ireland will begin to «lack those qualities of humanity, of hospitality, of kindly humor which belonged to an older day.» High spirits and singing soon resume. Gabriel and his wife Gretta depart for their hotel in the early morning hours. This destination for Gabriel kindles both erotic possibility and deep love. However, at the hotel, Gretta, moved by a song they had just heard sung at the party, offers a tearful, long-withheld revelation that momentarily shatters Gabriel’s feelings of warmth, leaving him shaken and bewildered. After Gretta drifts off to sleep, Gabriel, still rapt in the emotional wake of her revelation, gazes out the window at the falling snow and experiences a profound and unifying epiphany, one that reconciles the fears, doubts, and façades that had haunted him throughout the evening and, he seems to recognise, throughout his life to that point.[41]

See also[edit]

- Christmas Eve

- List of Christmas carols

- Pantomime

- Theophany

References[edit]

- ^ a b Hatch, Jane M. (1978). The American Book of Days. Wilson. ISBN 9780824205935.

January 5th: Twelfth Night or Epiphany Eve. Twelfth Night, the last evening of the traditional Twelve Days of Christmas, has been observed with festive celebration ever since the Middle Ages.

- ^ «Epiphany: Should Christmas decorations come down on 6 January?». BBC News. 6 January 2017. Retrieved 9 January 2021.

- ^ Carter, Michael. «Why it is time for an epiphany over Christmas decorations». The Tablet. Retrieved 9 January 2021.

- ^ William Alexander Barrett (1868). Flowers and Festivals, Or, Directions for the Floral Decoration of Churches. Rivingtons. pp. 170–174.

- ^ Mangan, Louise; Wyse, Nancy; Farr, Lori (2001). Rediscovering the Seasons of the Christian Year. Wood Lake Publishing Inc. p. 69. ISBN 9781551454986.

Epiphany is often heralded by «Twelfth Night» celebrations (12 days after Christmas), on the evening before the Feast of Epiphany. Some Christian communities prepare Twelfth Night festivities with drama, singing, rituals — and food! … Sometimes several congregations walk in lines from church to church, carrying candles to symbolize the light of Christ shining and spreading. Other faith communities move from house to house, blessing each home as they search for the Christ child.

- ^ Pennick, Nigel (21 May 2015). Pagan Magic of the Northern Tradition: Customs, Rites, and Ceremonies. Inner Traditions – Bear & Company. p. 176. ISBN 9781620553909.

On Twelfth Night in German-speaking countries, the Sternsinger («star singers») go around to houses carrying a paper or wooden star on a pole. They sing an Epiphany carol, then one of them writes in chalk over the door a formula consisting of the initials of the Three Wise Men in the Nativity story, Caspar, Melchior, and Balthasar, with crosses between them and the year date on either side; for example: 20 +M+B 15. This is said to protect the house and its inhabitants until the next Epiphany.

- ^ Bratcher, Dennis. «The Season of Epiphany». The Voice. Christian Resource Institute. Retrieved 4 January 2019.

- ^ Van Wagenberg-Ter Hoeven, Anke A. (1993). «The Celebration of Twelfth Night in Netherlandish Art». Simiolus: Netherlands Quarterly for the History of Art. 22 (1/2): 65–96. doi:10.2307/3780806. JSTOR 3780806.

- ^ «Epiphany». Christ Lutheran Church of Staunton, Virginia. Retrieved 4 January 2019.

- ^ «eve noun — Definition, pictures, pronunciation and usage notes | Oxford Advanced American Dictionary at OxfordLearnersDictionaries.com». www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com. Retrieved 9 January 2021.

- ^ Forbes, Bruce (2008). Christmas: A Candid History. University of California Press. p. 27. ISBN 9780520258020.

- ^ Beckford, Martin (6 January 2009). «Christmas ends in confusion over when Twelfth Night falls». The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 5 January 2010. Retrieved 26 May 2010.

- ^ «Twelve days of Christmas». Full Homely Divinity. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

We prefer, like good Anglicans, to go with the logic of the liturgy and regard January 5th as the Twelfth Day of Christmas and the night that ends that day as Twelfth Night. That does make Twelfth Night the Eve of the Epiphany, which means that, liturgically, a new feast has already begun.

- ^ Shorter Oxford English Dictionary. 1993.

…the evening of the fifth of January, preceding Twelfth Day, the eve of the Epiphany, formerly the last day of the Christmas festivities and observed as a time of merrymaking.

- ^ Fr. Francis X. Weiser. «Feast of the Nativity». Catholic Culture.

The Council of Tours (567) proclaimed the twelve days from Christmas to Epiphany as a sacred and festive season, and established the duty of Advent fasting in preparation for the feast. The Council of Braga (563) forbade fasting on Christmas Day.

- ^ Fox, Adam (19 December 2003). «‘Tis the season». The Guardian. Retrieved 25 December 2014.

Around the year 400 the feasts of St Stephen, John the Evangelist and the Holy Innocents were added on succeeding days, and in 567 the Council of Tours ratified the enduring 12-day cycle between the nativity and the epiphany.

- ^ Hynes, Mary Ellen (1993). Companion to the Calendar. Liturgy Training Publications. p. 8. ISBN 9781568540115.

In the year 567 the church council of Tours called the 13 days between December 25 and January 6 a festival season.

Martindale, Cyril Charles (1908). «Christmas». The Catholic Encyclopedia. New Advent. Retrieved 15 December 2014.The Second Council of Tours (can. xi, xvii) proclaims, in 566 or 567, the sanctity of the «twelve days» from Christmas to Epiphany, and the duty of Advent fast; …and that of Braga (563) forbids fasting on Christmas Day. Popular merry-making, however, so increased that the «Laws of King Cnut», fabricated c. 1110, order a fast from Christmas to Epiphany.

- ^ Bunson, Matthew (21 October 2007). «Origins of Christmas and Easter holidays». Eternal Word Television Network (EWTN). Retrieved 17 December 2014.

The Council of Tours (567) decreed the 12 days from Christmas to Epiphany to be sacred and especially joyous, thus setting the stage for the celebration of the Lord’s birth…

- ^ Hill, Christopher (2003). Holidays and Holy Nights: Celebrating Twelve Seasonal Festivals of the Christian Year. Quest Books. p. 91. ISBN 9780835608107.

This arrangement became an administrative problem for the Roman Empire as it tried to coordinate the solar Julian calendar with the lunar calendars of its provinces in the east. While the Romans could roughly match the months in the two systems, the four cardinal points of the solar year—the two equinoxes and solstices—still fell on different dates. By the time of the first century, the calendar date of the winter solstice in Egypt and Palestine was eleven to twelve days later than the date in Italy. As a result, the Incarnation came to be celebrated on different days in different parts of the Empire. The Western Church, in its desire to be universal, eventually took them both—one became Christmas, one Epiphany—with a resulting twelve days in between. Over time this hiatus became invested with specific Christian meaning. The Church gradually filled these days with saints, some connected to the birth narratives in Gospels (Holy Innocents’ Day, December 28, in honour of the infants slaughtered by Herod; St. John the Evangelist, «the Beloved», December 27; St. Stephen, the first Christian martyr, December 26; the Holy Family, December 31; the Virgin Mary, January 1). In 567, the Council of Tours declared the twelve days between Christmas and Epiphany to become one unified festal cycle.

Federer, William J. (6 January 2014). «On the 12th Day of Christmas». American Minute. Retrieved 25 December 2014.In 567 AD, the Council of Tours ended a dispute. Western Europe celebrated Christmas, December 25, as the holiest day of the season… but Eastern Europe celebrated Epiphany, January 6, recalling the Wise Men’s visit and Jesus’ baptism. It could not be decided which day was holier, so the Council made all 12 days from December 25 to January 6 «holy days» or «holidays,» These became known as «The Twelve Days of Christmas.»

- ^ Kirk Cameron, William Federer (6 November 2014). Praise the Lord. Trinity Broadcasting Network. Event occurs at 01:15:14. Archived from the original on 25 December 2014. Retrieved 25 December 2014.

Western Europe celebrated Christmas December 25 as the holiest day. Eastern Europe celebrated January 6 the Epiphany, the visit of the Wise Men, as the holiest day… and so they had this council and they decided to make all twelve days from December 25 to January 6 the Twelve Days of Christmas.

- ^ «LEAVE YOUR CHRISTMAS DECORATIONS UP UNTIL FEBRUARY, SAYS ENGLISH HERITAGE»

- ^ Miles, Clement A.. Christmas Customs and Traditions: Their History and Significance. Courier Dover Publications, 1976. ISBN 0-486-23354-5. Robert Herrick (1591–1674) in his poem «Ceremony upon Candlemas Eve» writes:

- «Down with the rosemary, and so

- Down with the bays and mistletoe;

- Down with the holly, ivy, all,

- Wherewith ye dress’d the Christmas Hall»

According to the Pelican Shakespeare anthology, It was written for a private performance for Elizabeth I in 1601.

As Herrick’s poem records, the eve of Candlemas (the day before 2 February) was the day on which Christmas decorations of greenery were removed from people’s homes; for any traces of berries, holly and so forth will bring death among the congregation before another year is out.

- ^ Davidson, Clifford (5 December 2016). Festivals and Plays in Late Medieval Britain. Taylor & Francis. p. 32. ISBN 9781351936613.

Playing seems to have continued after Twelfth Night, in the Epiphany season leading up to Candlemas on February 2, which sometimes was regarded as the last day of the Christmas season. We know that these weeks were an extension of the festive Christmas period.

- ^ a b Macclain, Alexia (4 January 2013). «Twelfth Night Traditions: A Cake, a Bean, and a King –». Smithsonian Libraries. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

And what happens at a Twelfth Night party? According to the 1923 Dennison’s Christmas Book, «there should be a King and a Queen, chosen by cutting a cake…» The Twelfth Night Cake has a bean and a pea baked into it. The man who finds the bean in his slice of cake becomes King for the night while the lady who finds a pea in her slice of cake becomes Queen for the night. The new King and Queen sit on a throne and «paper crowns, a scepter and, if possible, full regalia are given them.» The party continues with games such as charades as well as eating, dancing, and singing carols. For large Twelfth Night celebrations, a costume party is suggested.

- ^ a b c Derry, Johanna (4 January 2016). «Let’s bring back the glorious food traditions of Twelfth Night (largely, lots of cake)». The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 4 January 2019.

- ^ Miles & John, Hadfield (1961). The Twelve Days of Christmas. London: Cassell & Company. p. 166.

- ^ Mark Esdale. «Main Page @ Bridge Farmers’ Market».

- ^ «The Baddeley Cake». Drury Lane Theatrical Fund. Retrieved 30 November 2013.

- ^ MacClain, Alexia (4 January 2013). «Twelfth Night Traditions: A Cake, a Bean, and a King – Smithsonian Libraries Unbound». Unbound. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 4 January 2019.

- ^ Hoeven, Anke A. van Wagenberg-ter (1993). «The Celebration of Twelfth Night in Netherlandish Art». Simiolus: Netherlands Quarterly for the History of Art. 22 (1/2): 67. doi:10.2307/3780806. JSTOR 3780806.

- ^ Iain Hollingshead, Whatever happened to … wassailing?, The Guardian, 23 December 2005. Retrieved 23 May 2014

- ^ Xanthe Clay, Traditional cider: Here we come a-wassailing!, The Telegraph, 3 February 2011. Retrieved 23 May 2014

- ^ Nick Easen, Wassailing the old English apple tree, BBC Travel, 16 January 2012

- ^ White, R.S. (2014). «The Critical Backstory» in Twelfth Night: A Critical Reader ed. Findlay and Oakley-Brown. London: Bloomsbury. pp. 27–28. ISBN 9781441128782.

- ^ Shakespeare, William; Smith, Bruce R. (2001). Twelfth Night: Texts and Contexts. Boston: Bedford/St Martin’s. p. 2. ISBN 0-312-20219-9.

- ^ Herford, C. H. (1941). Percy Simpson; Evelyn Simpson (eds.). Ben Jonson. Vol. VII. Oxford: Clarendon Press. pp. 169–201.

- ^ Herrick, Robert (1825). The Poetical Works of Robert Herrick. W. Pickering. p. 171.

- ^ Ainsworth, William Harrison (1858). Mervyn Clitheroe. G. Routledge & Company. pp. 41–55.

- ^ Barry, Dan (26 June 2014). «Singular Collection, Multiple Mysteries». The New York Times. Retrieved 28 June 2018.

- ^ «An Exploration of ‘The Dead’«. Joyce’s Dublin. UCD Humanities Institute. Retrieved 23 June 2015.

- ^ Joyce, James. «Dubliners».

Further reading[edit]

- «Christmas». Catholic Encyclopedia. Retrieved 22 December 2005. Primarily subhead Popular Merrymaking under Liturgy and Custom.

- Christmas Trivia edited by Jennie Miller Helderman, Mary Caulkins. Gramercy, 2002

- Marix-Evans, Martin. The Twelve Days of Christmas. Peter Pauper Press, 2002

- Bowler, Gerry. The World Encyclopedia of Christmas. McClelland & Stewart, 2004

- Collins, Ace. Stories Behind the Great Traditions of Christmas. Zondervan, 2003

- Wells, Robin Headlam. Shakespeare’s Humanism. Cambridge University Press, 2006

- Fosbrooke, Thomas Dudley c. 1810, Encyclopaedia of Antiquities (Publisher unknown)

- J. Brand, 1813, Popular Antiquities, 2 Vols (London)

- W. Hone, 1830, The Every-Day Book 3 Vols (London), cf Vol I pp 41–61.

Early English sources[edit]

(drawn from Hone’s Every-Day Book, references as found):

- Vox Graculi, 4to, 1623: 6 January, Masking in the Strand, Cheapside, Holbourne, or Fleet-street (London), and eating spice-bread.

- The Popish Kingdom, ‘Naogeorgus’: Baking of the twelfth-cake with a penny in it, the slices distributed to members of the household to give to the poor: whoever finds the penny is proclaimed king among them.

- Nichols, Queen Elizabeth’s Progresses: An entertainment at Sudley, temp. Elizabeth I, including Melibaeus, king of the bean, and Nisa, queen of the pea.

- Pinkerton, Ancient Scottish Poems: Letter from Sir Thomas Randolph to Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester dated 15 January 1563, mentioning that Lady Flemyng was Queen of the Beene on Twelfth-Day that year.

- Ben Jonson, Christmas, His Masque (1616, published 1641): A character ‘Baby-cake’ is attended by an usher carrying a great cake with a beane and a pease.

- Samuel Pepys, Diaries (1659/60): Epiphany Eve party, selecting of King and Queen by a cake (see King cake).

External links[edit]

- Epiphany on Catholic Encyclopedia

- The Twelve Days of Christmas at The Christian Resource Institute

- William Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night

Двенадцатая ночь — это фестиваль в некоторых ветвях христианства, посвященных приходу Богоявления. Различные традиции отмечают дату этого праздника либо 5, либо 6 января. Церковь Англии, Матери Англиканской, празднует Двенадцатую ночь 5.01 и «относится к ночи до Богоявления, в день, когда история вертеп говорит нам, что мудрецы посетили младенца Иисуса». В традиции Западной Церкви торжество завершает 12 дней Рождества. Хотя в других, 12-я Ночь предшествует 12-му Дню. Брюс Форбс пишет:

В 567 году Совет Туров провозгласил, что весь период между Рождеством и Крещением должен рассматриваться как часть празднования, создавая то, что стало известно как 12 дней Рождества, или то, что англичане называли Christmastide. В последний из 12-ти дней, названных 12-й Ночью, различные культуры разработали широкий спектр дополнительных специальных торжеств. Вариант распространяется даже на вопрос о том, как подсчитать дни.

Другие популярные обычаи «Двенадцатая ночь» включают пение рождественских гимнов, мелование двери, благословение дома, веселье, а также посещение церковных служб.

Происхождение и история

Расселение яблонь на двенадцатой ночи, чтобы обеспечить хороший урожай, традиция в Малехерсте, Западный Сассекс Испанский РосКон де Reyes, или кольцо Королей. Этот размер диаметром около 50 см, обычно обслуживает 8 человек. Это тесто является одним из многих видов, запеченных по всему миру для празднования в течение 12-ти дней Рождества и 12-й ночи.

Традиции

Еда и напитки являются центром празднования в наше время, и все самые устоявшиеся из них возвращаются на многие столетия. Пунш под названием wassail потребляется на Двенадцатой ночи, но на протяжении всего рождественского времени, особенно в Великобритании. В целом мире, специальные пирожные, такие как tortell и король-торт, пекут на Двенадцатую ночь, и кушают на следующий день на праздник. По английскому и французскому обычаю, Двенадцатый пирог был запечен и содержал фасоль и горох, а те, кто получил их должны назначаться королем и королевой вечерних торжеств.

В отдельных частях Кента существует традиция, что съедобное украшение станет последней долей Рождества, которое удалится в Двенадцатую ночь и разделится между семьей.

В Ирландии по-прежнему остается обычаем размещать статуи Трех Королей в кроватке в Двенадцатую Ночь или, самое позднее, на следующий День.

В колониальной Америке рождественский венок всегда оставался на входной двери каждого дома, и когда его снимали в конце Двенадцати Дней праздника, любые съедобные части поглощались другими продуктами пира. То же самое имело место в XIX-XX вв. с фруктами, украшающими елки. Свежие трудно было найти, и поэтому считались прекрасными и правильными подарками украшения из дерева, венков и дома. Опять же, дерево сносится на Двенадцатую ночь, и тогда используются такие плоды, а также орехи и прочие местные продукты.

В восточных Альпах существует традиция, называемая Perchtenlaufen. От двух до трехсот молодых людей в масках мчатся по улицам с хлыстами и колокольчиками, изгоняющими злых духов. В Нюрнберге, до 1616 года, дети пугали нечисть, пробираясь по улицам и громко стуча в двери.

В отдельных странах Двенадцатая Ночь и Крещение празднуют начало сезона Карнавала, который длится через День Марди Гра.

Подавление

Двенадцатая ночь в Нидерландах стала настолько секуляризированной и шумной, что публичные торжества были запрещены в церкви.

Старая Двенадцатая ночь

Этот праздник в некоторых местах, особенно в юго-западной Англии, все еще отмечается 17 января. Это продолжается обычаем в дату, определенную юлианским календарем.

В литературе

Бен Jonson «Маска Черноты» была проведена 6 января 1605 года в Банкуэтинг Дом в Уайтхолле. Первоначально это название The Twelvth Nights Revells. Сопровождающая маска «Маска красоты» была исполнена в том же дворе в воскресенье вечером после Двенадцатой ночи в 1608.

Геррик «стихотворение Twelfe-ночь, или Король и Queene» опубликованной в 1648, описывает избрание государя и королевы по фасоли и гороху в сливовом торте, и им делали Wassail, напиток из сахара, мускатного ореха, имбиря и эля.

Чарльз Диккенс 1843 г. «Рождественская песнь» кратко упоминает Скруджа и Призрака, посещающего детскую вечеринку «Двенадцатая ночь».

Видео

Twelfth Night — название христианского праздника в Британии, отмечаемого в Крещенский вечер — в ночь с 5 на 6 января. Двенадцатая ночь завершает так называемый Йоль (др.-английский ġéol) — праздник середины зимы, 13 недель, которые древние называли «ночами духов»

В старину во время празднования Двенадцатой ночи существовало много разных обрядов и обычаев. Сейчас главный ритуал Двенадцатой ночи в Англии — проводить представление комедии Шекспира «Двенадцатая ночь».

В 2012 году Марк Райлэнс, художественный руководитель и режиссер лондонского театра «Глобус», возродил комедию Шекспира приблизительно в том виде, в каком ее играли около 1601 года, включая обстановку в театре, одежду актеров, музыку и танцы. Все женские роли исполняли мужчины, как было принято в то время. Роль Мальволио играет великолепный Стивен Фрай.

В современной Британии зимний праздничный сезон начинается в начале декабря и заканчивается в Новый год. Это настолько укоренилось в сознании, что многие уже забыли или не знали, что Рождество когда-то выглядело совсем иначе до 18 и 19 веков.

Пьеса Шекспира и песня Twelve Days of Christmas — сигнальные флажки, которые одним напоминают о старых традициях, а других побуждают интересоваться историей.

Кстати, во многих семьях сохранилась традиция выносить елку 6 января (до и после считается плохой приметой), — после Двенадцатой ночи наступает конец праздника.

Песня Twelve Days of Christmas сейчас — один из гимнов Рождества, но раньше ее пели именно в Двенадцатую ночь.

Текст песни был опубликован в 1740 году в детской книжке Mirth without Mischief, но песня была известна гораздо раньше и имеет статус народной. В песне перечисляются все подарки, которые дарились в каждый из дней праздника.

Существует много версий происхождения песни, начиная с рукописи 13 века, баллады из «Двенадцатой ночи» Шекспира и детской игры в фанты

Леди Гомм (Элис Берта Гомм — фольклорист и знаток детских игр) в 1898 году писала, что «The Twelve Days» была Рождественской игрой. Играла обычно компания родственников, взрослых и подростков, которые вечером собирались в гостиной перед застольем с традиционными Mince pie (пироги с сухофруктами и специями) и Twelfth Night Cake (настоящий «королевский» торт, с большим количеством сухофруктов, покрытый толстым слоем глазури и украшенный сахарными фигурками, внутри запекалась сухая фасоль или горох для «счастливчиков»).

Вся компания рассаживалась по разным местам комнаты. Ведущий игры произносил первую фразу первого дня. Все по очереди ее повторяли. В следующий день ведущий к первой фразе добавлял вторую. Игра продолжалась 12 дней, каждый день добавлялась новая фраза. Все должны были повторять без запинки все фразы от начала до конца. За каждую ошибку выплачивался штраф, то есть брался фант, какой-то личный предмет проштрафившегося. На двенадцатый день начинался выкуп заложенных вещей, получить которые можно было только выполнив определенные задания. В общем, игра The Twelve Days представляла из себя то, что позже стало называться «игрой в фанты»

Хит 2020 года во время локдауна

Йоль у язычников считался самым сокровенным и всемогущим праздником. В эти ночи божества всех миров собираются в Мидгарде – некоей серединной приграничной крепости между мирами. В это время вращается «веретено судьбы» и свершается «планида». Эльфы и тролли запросто общаются с людьми, а боги спускаются на землю. Завершается это единение людей и сказочных сил в Двенадцатую ночь.

Предположительно слово «йоль» происходит от скандинавского «колесо», «крутиться» и означает символ солнца. По закону жанра, или жизненного круговорота, самая длинная ночь в году обязана закончиться победой Солнца и наступлением Нового года (нового жизненного цикла).

Поэтому в это время особое значение придавали знамениям, ритуалам и загаданным желаниям, якобы, в это время все это имело необыкновенную силу.

«Говорят: под Новый год

Что ни пожелается —

Всё всегда произойдёт,

Всё всегда сбывается».

Сергей Михалков

Многие традиции празднования Рождества и Нового года тянутся еще с языческих времен. Считается, что мы блюдем христианские обычае, а на самом деле вся атрибутика заимствована у языческого йоля, в том числе колядование, ряженые и прочее.

Согласно церковным книгам, как раз в Двенадцатую ночь в Вифлием явились волхвы с дарами младенцу, а во времена празднований йоля считалось, что тот, кто найдет куколку, будет счастлив весь год.

Пожалуй, самый известный атрибут Двенадцатой ночи – йольское дерево, которое мы знаем как рождественскую или новогоднюю ель. В древности йольское дерево считалось древом желаний. Срубленную елочку или сосну приносили в дом, или же просто пересаживали во двор, украшая яркими игрушками. Праздничный убор йольского дерева сохраняется и в наши дни. Стеклянные шары символизируют желания людей, а фигурки ангелов заменили фей, которым, согласно старинным преданиям, нравилось отдыхать на веточках.

Обычай класть под елку подарки также протянулся к нам через века. Кельты и германцы считали, что таким образом порадуют эльфов, а также принесут своим подношением своеобразную жертву усопшим предкам.

Английские рождественские традиции требовали, чтобы в канун Рождества рубили большой дуб. Бревно торжественно тащили домой, причем, участвовать в его доставке должны были все члены семьи мужского пола. Каждый вечер сжигалась часть бревна. Бревна должно было хватить на все 12 дней Рождества. По поверьям поленья в камине должны были загореться при первой же попытке зажечь их, чтобы всем жителям дома весь год сопутствовала удача (торт «Рождественское полено» — отсылка к этой традиции во Франции, где придумали этот торт).

Церемония доставки Рождественского бревна. 1872 год

Ключевой частью празднования Двенадцатой ночи был, так называемый, wassailing. Слово wassail, как полагают, происходит от древнеанглийского «was hál», что означает «будь здоров» или «хорошего здоровья». Традиция wassail состоит из двух направлений: «the house-visiting wassail» и «orchard-visiting wassail».

В первом случае группы гуляк ходят от дома к дому, чтобы выпить-закусить и пожелать хозяевам здоровья и процветания. Пелись специальные песни с пожеланиями. Крестьяне могли прийти в дом помещика не за подаянием, а чтобы получить вкусную еду (чаще всего это были фиговые пудинги). По сути это было прообразам колядок.

Но такие визиты не всегда были невинными и благостными. Если хозяева не хотели одаривать гуляк выпивкой и закуской или мало давали, гуляки могли разгромить дом.

На территориях, где традиционно производили сидр, было принято петь во здравие деревьев, приносящих плоды. Гуляки шли в сад, пели песни вокруг деревьев, стучали по кастрюлям и сковородкам и получали от хозяина сада wassail (глинтвейн со специями) в специальной чаше. Считалось, что шумом прогонялись злые духи, а пение доставляло удовольствие духам деревьев. Все это делалось для того, чтобы обеспечить обильный урожай яблок, груш или слив.

Чаши wassail обычно делались в форме кубка. В песнях поется о чашах из клена, видимо, это был самый популярный материал для их изготовления. Хотя сохранились чаши и из других видов дерева. Например, с середины 17 века чаши изготавливались из бакаута (Lignum vitae), железного дерева, которое растет на Карибах и на побережье Южной Америки. Lignum vitae — самая твердая и самая тяжелая из деловой древесины. Ее традиционно использовали в судостроении, в производстве полицейских дубинок и шаров для боулинга. Благодаря своей прочности она особенно хорошо подходила для горячих жидкостей. Lignum vitae также может похвастаться лечебными свойствами, ее импортировали в Европу с 16 века как средство от ряда заболеваний, от подагры до сифилиса. Идея пить из чаши, приносящей здоровье, была модной в то время.

Были в ходу и керамические чаши

Чаша из Южного Уэльса. 1882-1888 годы. К ручкам чаши привязывали разноцветные ленты.

Наступивший после Двенадцатой ночи день называли «Днем судьбы». В этот день до захода солнца рекомендовалось очень тщательно следить за своей речью и не совершать необдуманных поступков, поскольку считалось, что именно они определяли дальнейшие события начавшегося Нового года.

Праздник Двенадцатой ночи (The Twelfth Night Feast). Ян Стин. 1662 год

Корни Двенадцатой ночи нужно искать в римских традициях.

Сатурн был римским богом земледелия. Его почитали во время празднования Сатурналии во время зимнего солнцестояния. После того, как серьезное дело посещения храма было выполнено, римляне могли веселиться до упаду. В это время отменяли все нормы приличия и общественного порядка. Хозяева обслуживали рабов, а выбранный путем жребия «король» на празднике мог требовать исполнения своих любых, даже самых нелепых желаний (например, всем танцевать нагишом). Самого апогея развлечения достигали в Двенадцатую ночь.

Ранние христиане были людьми неглупыми, они быстро смекнули, что для того, чтобы люди им поверили и приняли новую религию, не надо делать резких движений и отменять языческие праздники, а просто превратить их в свои собственные. Так «День рождения непокоренного Солнца» превратился в день рождения Христа, а Двенадцатая ночь превратилась в Богоявление, когда волхвы посетили Иисуса.

Рождеству предшествовал 40-дневный адвентистский пост, поэтому в праздничный период большое значение имела еда.

Как и у римлян, древние британцы для организации празднеств выбирали «короля» Беспорядка, который назывался Лордом Мизрула, или Королем Мизрула.

Чтобы выбрать Лорда Мизрула, внутри торта запекали боб. Тот, кто получил ломтик с бобом, был «коронован» Лордом Мизрула, также известным как Бобовый Король.

The King Drinks

Иногда также запекалась горошина, и тот, кто ее получал, объявлялся Гороховой Королевой. Эта практика была особенно популярна в ранний период Тюдоров. У Генриха VII на праздничных собраниях присутствовал Аббат Безрассудств, — другое имя Лорда Беспорядка.

К концу 18 века в Англии выбор «королевской семьи бобовых» во время Двенадцатой ночи с помощью запеченной фасоли и гороха заменили бумажные записки в торте, на одной из которых была специальная метка. Говорят, что эта традиция бумажных записок была введена в целях безопасности, чтобы не дать часто пьяным гостям случайно задохнуться до смерти твердой фасолью или монетами.

Тема Двенадцатой ночи и Бобового короля была популярной у многих художников 16-18 веков

«Двенадцатая ночь». Питер Брейгель-Младший

Twelfth Night (The King Drinks). Давид Тенирс-младший. 1634-1640.

«Двенадцатая ночь». Ян Стен. 1668 год.

«Бобовый король». Джейкоб Йорданс. 1635-1655 годы.

«Крестьяне празднуют Двенадцатую ночь». Давид Тенирс-Младший

«Двенадцатая ночь». Ян Стен. 1668 год

Популярность традиций Двенадцатой ночи стала убывать после Реформации. Двенадцатая ночь превратилась в светское застолье, но торт «Двенадцатая ночь» остался.

Иллюстрация из книги The Book of Christmas Томаса К. Херви. 1836 год

Строго говоря аутентичного рецепта не сохранилось, большинство рецептов уже адаптированы для нашего времени. Этот рецепт взят из книги Джули Дафф Cakes Regional & Traditional.

ИНГРЕДИЕНТЫ

225 г сливочного масла

225 г темного сахара мусковадо (тростниковый неочищенный сахар)

1 столовая ложка черной патоки

225 г простой муки

1 чайная ложка смешанных специй

4 больших яйца

225 г изюма

225 г смородины

225 г изюма султан

50 г измельченной смешанной цедры

50 г вишни, разрезанной пополам

50 г молотого миндаля

1 столовая ложка бренди

ПРИГОТОВЛЕНИЕ

1. Разогрейте духовку до 160 ℃.

2. Взбить сливочное масло и сахар до легкой пышной массы, а затем взбить патоку.

3. Просейте в миску муку, специи и соль. Слегка взбейте яйца вилкой, а затем аккуратно взбейте их со смесью масла и сахара вместе с мукой. Тщательно перемешав, добавьте фрукты, орехи и бренди, а затем переложите в смазанную маслом круглую форму для выпечки диаметром 18 см с выстланным пекарской бумагой дном.

4. Поместите в центр духовки. Выпекайте примерно 1,5 часа, затем уменьшите температуру до 120 ℃ и выпекайте еще 1 час или пока пирог хорошо не поднимется, не станет золотисто-коричневым и твердым на ощупь. Шампур, воткнутый в центр, должен выходить чистым.

5. Оставьте пирог остыть в форме, накрытой чистой тканью. Выложите на блюдо, когда полностью остынет

6. Обычно его едят со взбитыми сливками.

Фото автора

При желании торт можно украсить королевской глазурью, как это делает историк кулинарии Иван Дэй, создавая торты «Двенадцатая ночь» георгианской эпохи (1714—1811 годы).

В 18 и 19 веках еще не были изобретены кондитерские мешки, и торты и пирожные украшали совершенно другим способом, чем это делается сейчас. Глазурь представляла из себя сладкую пасту, похожую на жевательную резинку. Ее готовили из сахарной пудры, трагакантовой камеди (высохший на воздухе сок растений) и небольшого количества воды до состояния фарфоровой глины. Глазурь аккуратно наносилась на торт. Орнаменты вырезались деревянными формами и наклеивались пастой на глазурь. Для тортов Двенадцатой ночи были специальные орнаменты и украшения, некоторые из которых были трехмерными.

Двенадцатая ночь в Великобритании отмечаются 5 января. Это время, когда семьи по всей Британии убирают рождественские ёлки и снимают украшения, чтобы избежать неудачи в будущем году. Некоторые британцы посещают церковные службы на следующий день (на Богоявление). Прочитав статью, вы узнаете, как отмечается Двенадцатая ночь в Великобритании, а также и Богоявление здесь.

1. Середина зимы или двенадцать дней Рождества в Великобритании

На островах, которые в настоящее время образуют Соединённое Королевство, уже тысячи лет проводятся праздники и вечеринки Середины зимы. Когда люди начали обращаться в христианство, некоторые аспекты первоначальных праздников были включены в христианские празднования.

Так праздник Середины зимы, длившийся много дней, стал двенадцатью днями Рождества. В старину Рождество было не однодневным событием. На самом деле оно праздновалось в течение 12 дней, начиная от Рождества. 5 января отмечалось так же, как и само Рождество. Такова была традиция со времён Средневековья вплоть до 19 века. В настоящее время этот период начинается в День подарков (26 декабря) и длится до Богоявления (6 января).

2. Двенадцатая ночь в Великобритании

Двенадцатая ночь в Великобритании знаменует начало Богоявления, и отмечается 5 января. Согласно Англиканской церкви, Двенадцатая ночь — это вечер перед Богоявлением (Крещением), также известный как Крещенский сочельник.

В Тюдоровской Англии «король беспорядка» назначался управлять рождественскими празднествами, и Двенадцатая ночь была концом периода его правления. Общая тема заключалась в том, что нормальный порядок вещей переворачивался. Традиционные роли часто менялись, хозяева прислуживали своим слугам. Мужчинам разрешалось одеваться как женщинам, а женщинам — как мужчинам.

Ещё совсем недавно, в 1950-х годах, Двенадцатая ночь в Британии была ночью для веселья. Гуляки, как и исполнители колядок, ходили от дома к дому, распевая песни и желая своим соседям доброго здоровья.

В лондонском театре «Друри-Лейн» с 1795 года существует традиция подавать торт «Двенадцатая ночь». Роберт Бэддли, талантливый артист, служивший здесь, завещал выделять 100 фунтов стерлингов на ежегодное обеспечение тортом и пуншем труппы, работающей в театре 6 января. Традиция продолжается до сих пор.

3. Как в настоящее время отмечается Двенадцатая ночь в Великобритании?

Как это не странно, но немало людей до сих пор празднуют Двенадцатую ночь в Великобритании. Многие места по всему Соединённому Королевству проводят традицию Двенадцатой ночи под названием Вассайлинг. На Двенадцатую ночь собирается много народа, чтобы повеселиться и выпить за урожай и здоровье друг друга. Многие наряжаются в причудливые костюмы и разгуливают в них по улицам.

В некоторых местах празднование Двенадцатой ночи включает кулинарные традиции с Королевским тортом. Те, кто находят,спрятанный в торт, боб (горох), коронуются королём и королевой на этот день.

В Лондоне на берегу Темзы разыгрывается спектакль. Это может быть и пьеса Шекспира «Двенадцатая ночь». Она изначально была написана для представления в качестве развлечения Двенадцатой ночи. В конце спектакля раздаются пирожные «Двенадцатая ночь».

Однако для большинства жителей Туманного Альбиона Двенадцатая ночь — это время, когда семьи по всей стране убирают рождественские ёлки и снимают украшения, чтобы избежать неудачи в будущем году. Большинство британцев думают, что это плохая примета — оставлять свои украшения после 5-го января (после Двенадцатой ночи). Некоторые люди также считают неправильным снимать их слишком рано. В древние времена люди верили, что духи деревьев живут в падубе и плюще. После праздничного сезона их необходимо выпустить на улицу. Если их отпустят до окончания Рождества, то в результате могут возникнуть проблемы с урожаем.

Согласно одному суеверию, рождественские украшения, не снятые к Двенадцатой ночи, должны быть оставлены до дня Сретения (2 февраля). Другие говорят, что лучшее средство — оставить их до Двенадцатой ночи следующего года. Украшения в городских центрах и торговых центрах могут оставаться на витрине дольше, так как на их удаление может уйти много дней или даже недель.

4. Про Богоявление в Великобритании

Богоявление как и Двенадцатая ночь в Великобритании не является государственным праздником. 6 января официально считается последним днём Рождества в Соединённом Королевстве. Это последний день, когда ещё можно снять рождественские украшения.

Богоявленские традиции Великобритании связаны с тремя королями, которые посетили Иисуса, следуя за звездой. Богоявление имеет название «День трёх королей», в честь гостей, которые принесли младенцу Иисусу свои дары (золото, ладан и мирру). Их называют королями, царями, мудрецами и волхвами.

Согласно Евангелию от Матфея, три мудреца, Мельхиор, Каспар и Валтасар, последовали за Вифлеемской звездой через пустыню, чтобы встретить младенца Иисуса, предлагая дары золота, ладана и мирры. Дары символизировали важность рождения Иисуса. Так золото символизировало его царское положение, ладан — его божественное рождение, а мирра — его смертную жизнь. Вообще ладан, благовония и мирра, масло помазания, были традиционными дарами во времена Христа. Тела также готовили к погребению вместе с этими предметами.

Некоторые британцы на Богоявление посещают церковные службы. Также люди могут петь традиционный Богоявленский гимн, повествующий о волхвах, а дети ожидать подарков.

Вот так отмечается Двенадцатая ночь в Великобритании, а также празднуется Богоявление здесь! Читайте также:

Праздники Великобритании

Праздник трёх королей в Испании

Праздники и фестивали разных стран мира

Уважаемые читатели! Пишите комментарии! Читайте статьи на сайте «Мир праздников»!

| Двенадцатая ночь в 2023 году: |

31 декабря, воскресенье |

Более 1000 лет назад на Руси введено христианство, ставшее государственной религией. Оно пришло на смену язычеству. Современное поколение даже не знает всех богов, которым поклонялись наши предки, но некоторые праздники той эпохи (Масленица, Коляда, Ивана Купала) отмечаются и поныне 31 декабря. Все они наполнены магией и таинственностью, но самым священным и знаковым праздником считается Двенадцатая ночь, отмечаемая в череде новогодних праздников.

Йоль

У средневековых германцев и последователей неоязычества в честь зимнего солнцестояния отмечался могущественный зимний праздник Йоль, начинавшийся в самый короткий день года и длившийся 13 дней. Его окончание означало приход нового года, начало жизненного цикла. Солнце восставало из тьмы, согревало землю, давая жизнь семенам.