| Purim | |

|---|---|

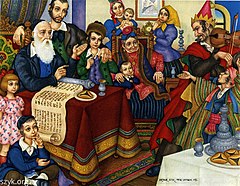

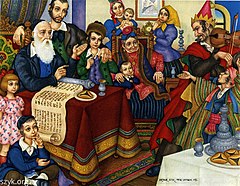

Purim by Arthur Szyk |

|

| Type | Jewish |

| Significance | Celebration of Jewish deliverance as told in the Book of Esther (megillah) |

| Celebrations |

|

| Date | 14th day of Adar (in Jerusalem and all ancient walled cities, 15th of Adar) |

| 2022 date | Sunset, 16 March – nightfall, 17 March[1] |

| 2023 date | Sunset, 6 March – nightfall, 7 March[1] |

| 2024 date | Sunset, 23 March – nightfall, 24 March[1] |

| 2025 date | Sunset, 13 March – nightfall, 14 March[1] |

| Frequency | Annual |

| Started by | Esther |

| Related to | Hanukkah, as a rabbinically decreed Jewish holiday |

Purim (; Hebrew: פּוּרִים Pūrīm, lit. ‘lots’; see Name below) is a Jewish holiday which commemorates the saving of the Jewish people from Haman, an official of the Achaemenid Empire who was planning to have all of Persia’s Jewish subjects killed, as recounted in the Book of Esther (usually dated to the 5th century BCE).

Haman was the royal vizier to Persian king Ahasuerus (Xerxes I or Artaxerxes I; «Khshayarsha» and «Artakhsher» in Old Persian, respectively).[2][3][4][5] His plans were foiled by Mordecai of the tribe of Benjamin, and Esther, Mordecai’s cousin and adopted daughter who had become queen of Persia after her marriage to Ahasuerus.[6] The day of deliverance became a day of feasting and rejoicing among the Jews.

According to the Scroll of Esther,[7] «they should make them days of feasting and gladness, and of sending portions one to another, and gifts to the poor». Purim is celebrated among Jews by:

- Exchanging gifts of food and drink, known as mishloach manot

- Donating charity to the poor, known as mattanot la-evyonim[8]

- Eating a celebratory meal, known as se’udat Purim

- Public recitation of the Scroll of Esther (Hebrew: קריאת מגילת אסתר, romanized: Kriat megillat Esther), or «reading of the Megillah», usually in synagogue

- Reciting additions to the daily prayers and the grace after meals, known as Al HaNissim

Other customs include wearing masks and costumes, public celebrations and parades (Adloyada), and eating hamantashen (transl. »Haman’s pockets»); men are encouraged to drink wine or any other alcoholic beverage.[9]

According to the Hebrew calendar, Purim is celebrated annually on the 14th day of the Hebrew month of Adar (and it is celebrated on Adar II in Hebrew leap years, which occur every two to three years), the day following the victory of the Jews over their enemies. In cities that were protected by a surrounding wall at the time of Joshua, Purim was celebrated on the 15th of the month of Adar on what is known as Shushan Purim, since fighting in the walled city of Shushan continued through the 14th day of Adar.[10] Today, only Jerusalem and a few other cities celebrate Purim on the 15th of Adar.

Name[edit]

Purim is the plural of Hebrew pur, meaning casting lots in the sense of making a random selection.[a] Its use as the name of this festival comes from Esther 3:6-7, describing the choice of date:

6: […] having been told who Mordecai’s people were, Haman plotted to do away with all the Jews, Mordecai’s people, throughout the kingdom of Ahasuerus.

7: In the first month, that is, the month of Nisan, in the twelfth year of King Ahasuerus, pur—which means “the lot”—was cast before Haman concerning every day and every month, [until it fell on] the twelfth month, that is, the month of Adar.[12]

Purim narrative[edit]

The Book of Esther begins with a six-month (180-day) drinking feast given by King Ahasuerus of the Persian Empire for the army and Media and the satraps and princes of the 127 provinces of his kingdom, concluding with a seven-day drinking feast for the inhabitants of Shushan (Susa), rich and poor, and a separate drinking feast for the women organized by Queen Vashti in the pavilion of the royal courtyard.

At this feast, Ahasuerus gets thoroughly drunk, and at the prompting of his courtiers, orders his wife Vashti to display her beauty before the nobles and populace, wearing her royal crown. The rabbis of the Oral Torah interpret this to mean that he wanted her to wear only her royal crown, meaning that she would be naked. Her refusal prompts Ahasuerus to have her removed from her post. Ahasuerus then orders all young women to be presented to him, so he could choose a new queen to replace Vashti. One of these is Esther, who was orphaned at a young age and was being fostered by her first cousin Mordecai. She finds favor in the King’s eyes, and is made his new wife. Esther does not reveal her origins or that she is Jewish as Mordecai told her not to. Since the Torah permits an uncle to marry his niece and the choice of words used in the text, some rabbinic commentators state that she was actually Mordecai’s wife.

Shortly afterwards, Mordecai discovers a plot by two palace guards Bigthan and Teresh to kill Ahasuerus. They are apprehended and hanged, and Mordecai’s service to the King is recorded in the daily record of the court.[13]

Ahasuerus appoints Haman as his viceroy. Mordecai, who sits at the palace gates, falls into Haman’s disfavor as he refuses to bow down to him. Having found out that Mordecai is Jewish, Haman plans to kill not just Mordecai but the entire Jewish minority in the empire. Obtaining Ahasuerus’ permission and funds to execute this plan, he casts lots («purim») to choose the date on which to do this — the 14th of the month of Adar. When Mordecai finds out about the plans, he puts on sackcloth and ashes, a sign of mourning, publicly weeping and lamenting, and many other Jews in Shushan and other parts of Ahasuerus’ empire do likewise, with widespread penitence and fasting. Esther discovers what has transpired; there follows an exchange of messages between her and Mordecai, with Hatach, one of the palace servants, as the intermediary. Mordecai requests that she intercede with the King on behalf of the embattled Jews; she replies that nobody is allowed to approach the King, under penalty of death.

Mordecai warns her that she will not be any safer in the palace than any other Jew, says that if she keeps silent, salvation for the Jews will arrive from some other quarter but «you and your father’s house (family line) will perish,» and suggests that she was elevated to the position of queen to be of help in just such an emergency. Esther has a change of heart, says she will fast and pray for three days and will then approach the King to seek his help, despite the law against doing so, and «if I perish, I perish.» She also requests that Mordecai tell all Jews of Shushan to fast and pray for three days together with her. On the third day, she seeks an audience with Ahasuerus, during which she invites him to a feast in the company of Haman. During the feast, she asks them to attend a further feast the next evening. Meanwhile, Haman is again offended by Mordecai’s refusal to bow to him; egged on by his wife Zeresh and unidentified friends, he builds a gallows for Mordecai, with the intention to hang him there the very next day.[14]

That night, Ahasuerus suffers from insomnia, and when the court’s daily records are read to him to help him fall asleep, he learns of the services rendered by Mordecai in the earlier plot against his life. Ahasuerus asks whether anything was done for Mordecai and is told that he received no recognition for saving the King’s life. Just then, Haman appears, and King Ahasuerus asks him what should be done for the man that the King wishes to honor. Thinking that the King is referring to Haman himself, Haman says that the honoree should be dressed in the King’s royal robes and led around on the King’s royal horse. To Haman’s horror, the king instructs Haman to render such honors to Mordecai.[15]

Later that evening, Ahasuerus and Haman attend Esther’s second banquet, at which she reveals that she is Jewish and that Haman is planning to exterminate her people, which includes her. Ahasuerus becomes enraged and instead orders Haman hanged on the gallows that Haman had prepared for Mordecai. The previous decree against the Jewish people could not be nullified, so the King allows Mordecai and Esther to write another decree as they wish. They decree that Jewish people may preemptively kill those thought to pose a lethal risk. As a result, on 13 Adar, 500 attackers and Haman’s 10 sons are killed in Shushan. Throughout the empire 75,000 of the Jewish peoples’ enemies are killed.[16] On the 14th, another 300 are killed in Shushan. No spoils are taken.[17]

Mordecai assumes the position of second in rank to Ahasuerus, and institutes an annual commemoration of the delivery of the Jewish people from annihilation.[18]

Scriptural and rabbinical sources[edit]

The primary source relating to the origin of Purim is the Book of Esther, which became the last of the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible to be canonized by the Sages of the Great Assembly. It is dated to the 4th century BCE[19] and according to the Talmud was a redaction by the Great Assembly of an original text by Mordechai.[20]

The Tractate Megillah in the Mishnah (redacted c. 200 CE) records the laws relating to Purim. The accompanying Tosefta (redacted in the same period) and Gemara (in the Jerusalem and Babylonian Talmud redacted c. 400 CE and c. 600 CE respectively)[21] record additional contextual details such as Queen Vashti having been the daughter of Belshazzar as well as details that accord with Josephus’ such as Esther having been of royal descent. Brief mention of Esther is made in Tractate Hullin (Bavli Hullin 139b) and idolatry relating to worship of Haman is discussed in Tractate Sanhedrin (Sanhedrin 61b).

The work Esther Rabbah is a Midrashic text divided in two parts. The first part dated to c. 500 CE provides an exegetical commentary on the first two chapters of the Hebrew Book of Esther and provided source material for the Targum Sheni. The second part may have been redacted as late as the 11th century CE, and contains commentary on the remaining chapters of Esther. It too contains the additional contextual material found in the Josippon (a chronicle of Jewish history from Adam to the age of Titus believed to have been written by Josippon or Joseph ben Gorion).[22]

Historical views[edit]

Traditional historians[edit]

Haman defeated (1578 engraving)

The 1st-century CE historian Josephus recounts the origins of Purim in Book 11 of his Antiquities of the Jews. He follows the Hebrew Book of Esther but shows awareness of some of the additional material found in the Greek version (the Septuagint) in that he too identifies Ahasuerus as Artaxerxes and provides the text of the king’s letter. He also provides additional information on the dating of events relative to Ezra and Nehemiah.[23] Josephus also records the Persian persecution of Jews and mentions Jews being forced to worship at Persian erected shrines.[23][24]

The Josippon, a 10th-century CE compilation of Jewish history, includes an account of the origins of Purim in its chapter 4. It too follows the original biblical account and includes additional traditions matching those found in the Greek version and Josephus (whom the author claims as a source) with the exception of the details of the letters found in the latter works. It also provides other contextual information relating to Jewish and Persian history such as the identification of Darius the Mede as the uncle and father-in-law of Cyrus.[25]

A brief Persian account of events is provided by Islamic historian Muhammad ibn Jarir al-Tabari in his History of the Prophets and Kings (completed 915 CE).[26] Basing his account on Jewish and Christian sources, al-Tabari provides additional details such as the original Persian form «Asturya» for «Esther».[27] He places events during the rule of Ardashir Bahman (Artaxerxes II),[28] but confuses him with Ardashir al-Tawil al-Ba (Artaxerxes I), while assuming Ahasuerus to be the name of a co-ruler.[27] Another brief Persian account is recorded by Masudi in The Meadows of Gold (completed 947 CE).[29] He refers to a Jewish woman who had married the Persian King Bahman (Artaxerxes II), and delivered her people,[28][30][31] thus corroborating this identification of Ahasuerus. He also mentions the woman’s daughter, Khumay, who is not known in Jewish tradition but is well remembered in Persian folklore. Al-Tabari calls her Khumani and tells how her father (Ardashir Bahman) married her. Ferdowsi in his Shahnameh (c. 1000 CE) also tells of King Bahman marrying Khumay.[32]

19th-century Bible commentaries generally identify Ahasuerus with Xerxes I of Persia.[33]

Modern scholarship views[edit]

Some historians of the Near East and Persia argue that Purim does not actually have a historical basis. Amnon Netzer and Shaul Shaked argue that the names «Mordecai» and «Esther» are similar to those of the Babylonian gods Marduk and Ishtar.[34][35] Scholars W.S. McCullough, Muhammad Dandamayev and Shaul Shaked say that the Book of Esther is historical fiction.[35][36][37] Amélie Kuhrt says the Book of Esther was composed in the Hellenistic period and it shows a perspective of Persian court identical to classical Greek books.[38] Shaul Shaked says the date of composition of the book is unknown, but most likely not much after the fall of the Achaemenid kingdom, during the Parthian period, perhaps in the 3rd or 2nd century BCE.[35] McCullough also suggests that Herodotus recorded the name of Xerxes’s queen as Amestris (the daughter of Otanes) and not as Esther.[37] Scholars Albert I. Baumgarten and S. David Sperling and R.J. Littman say that, according to Herodotus, Xerxes could only marry a daughter of one of the six allies of his father Darius I.[39][40]

Observances[edit]

Purim has more of a national than a religious character, and its status as a holiday is on a different level from those days ordained holy by the Torah. Hallel is not recited.[41] As such, according to some authorities, business transactions and even manual labor are allowed on Purim under certain circumstances.[42] A special prayer (Al ha-Nissim – «For the Miracles») is inserted into the Amidah prayers during evening, morning and afternoon prayer services, and is also included in the Birkat Hamazon («Grace after Meals»).

The four main mitzvot (obligations) of the day are:[43]

- Listening to the public reading, usually in synagogue, of the Book of Esther in the evening and again in the following morning (k’riat megillah)

- Sending food gifts to friends (mishloach manot)

- Giving charity to the poor (matanot la’evyonim)

- Eating a festive meal (se’udat mitzvah)

The three latter obligations only apply during the daytime hours of Purim.[43]

Reading of the Megillah[edit]

Children during Purim in the streets of Jerusalem (2006)

The first religious ceremony which is ordained for the celebration of Purim is the reading of the Book of Esther (the «Megillah») in the synagogue, a regulation which is ascribed in the Talmud (Megillah 2a) to the Sages of the Great Assembly, of which Mordecai is reported to have been a member. Originally this regulation was only supposed to be observed on the 14th of Adar; later, however, Rabbi Joshua ben Levi (3rd century CE) prescribed that the Megillah should also be read on the eve of Purim. Further, he obliged women to attend the reading of the Megillah, because women were also part of the miracle. The commentaries offer two reasons as to why women played a major role in the miracle. The first reason is that it was through a lady, Queen Esther, that the miraculous deliverance of the Jews was accomplished (Rashbam). The second reason is that women were also threatened by the genocidal decree and were therefore equal beneficiaries of the miracle (Tosafot).[citation needed]

In the Mishnah, the recitation of a benediction on the reading of the Megillah is not yet a universally recognized obligation. However, the Talmud, a later work, prescribed three benedictions before the reading and one benediction after the reading. The Talmud added other provisions. For example, the reader is to pronounce the names of the ten sons of Haman[44] in one breath, to indicate their simultaneous death. An additional custom that probably began in Medieval times is that the congregation recites aloud with the reader the verses Esther 2:5, Esther 8:15–16, and Esther 10:3, which relate the origin of Mordecai and his triumph.[citation needed]

The Megillah is read with a cantillation (a traditional chant) which is different from that which is used in the customary reading of the Torah. Besides the traditional cantillation, there are several verses or short phrases in the Megillah that are chanted in a different chant, the chant that is traditionally used during the reading of the book of Lamentations. These verses are particularly sad, or they refer to Jews being in exile. When the Megillah reader jumps to the melody of the book of Lamentations for these phrases, it heightens the feeling of sadness in the listener.[citation needed]

In some places,[where?] the Megillah is not chanted, but is read like a letter, because of the name iggeret («epistle»), which is applied[45] to the Book of Esther. It has been also customary since the time of the early Medieval era of the Geonim to unroll the whole Megillah before reading it, in order to give it the appearance of an epistle. According to halakha (Jewish law), the Megillah may be read in any language intelligible to the audience.[citation needed]

According to the Mishnah (Megillah 30b),[46] the story of the attack on the Jews by Amalek, the progenitor of Haman, is also to be read.[citation needed]

Blessings before Megillah reading[edit]

Before the reading of the Megillah on Purim, both at night and again in the morning, the reader of the Megillah recites the following three blessings and at the end of each blessing the congregation then responds by answering «Amen» after each of the blessings.[47] At the morning reading of the Megillah the congregation should have in mind that the third blessing applies to the other observances of the day as well as to the reading of the Megillah:[47]

| Hebrew | English |

|---|---|

|

ברוך אתה יי אלהינו מלך העולם אשר קדשנו במצותיו וצונו על מקרא מגלה |

Blessed are You, My LORD, our God, King of the universe, Who has sanctified us with His commandments and has commanded us regarding the reading of the Megillah. |

|

ברוך אתה יי אלהינו מלך העולם שעשה נסים לאבותינו בימים ההם בזמן הזה |

Blessed are You, My LORD, our God, King of the universe, Who has wrought miracles for our forefathers, in those days at this season. |

|

ברוך אתה יי אלהינו מלך העולם שהחינו וקימנו והגיענו לזמן הזה |

Blessed are You, My LORD, our God, King of the universe, Who has kept us alive, sustained us and brought us to this season. |

Blessing and recitations after Megillah reading[edit]

After the Megillah reading, each member of the congregation who has heard the reading recites the following blessing.[47] This blessing is not recited unless a minyan was present for the Megillah reading:[47]

| Hebrew | English |

|---|---|

|

ברוך אתה יי אלהינו מלך העולם האל הרב את ריבנו והדן את דיננו והנוקם את נקמתינו והמשלם גמול לכל איבי נפשנו והנפרע לנו מצרינו ברוך אתה יי הנפרע לעמו ישראל מכל צריהם האל המושיע |

Blessed are You, My LORD, our God, King of the Universe, (the God) Who takes up our grievance, judges our claim, avenges our wrong; Who brings just retribution upon all enemies of our soul and exacts vengeance for us from our foes. Blessed are You My LORD, Who exacts vengeance for His people Israel from all their foes, the God Who brings salvation. |

After the nighttime Megillah reading the following two paragraphs are recited:[47]

The first one is an acrostic poem that starts with each letter of the Hebrew alphabet, starting with «Who balked (… אשר הניא) the counsel of the nations and annulled the counsel of the cunning. When a wicked man stood up against us (… בקום עלינו), a wantonly evil branch of Amalek’s offspring …» and ending with «The rose of Jacob (ששנת יעקב) was cheerful and glad, when they jointly saw Mordechai robed in royal blue. You have been their eternal salvation (תשועתם הייתה לנצח), and their hope throughout generations.»

The second is recited at night, but after the morning Megillah reading only this is recited:

The rose of Jacob was cheerful and glad, when they jointly saw Mordechai robed in royal blue. You have been their eternal salvation, and their hope throughout generations.

At night and in the morning:

| Hebrew | English |

|---|---|

|

שושנת יעקב צהלה ושמחה בראותם יחד תכלת מרדכי. תשועתם היית לנצח ותקותם בכל דור ודור. להודיע שכל קויך לא יבשו ולא יכלמו לנצח כל החוסים בך. ארור המן אשר בקש לאבדי ברוך מרדכי היהודי. ארורה זרש אשת מפחידי ברוכה אסתר בעדי וגם חרבונה זכור לטוב |

To make known that all who hope in You will not be shamed (להודיע שכל קויך לא יבשו); nor ever be humiliated, those taking refuge in You. Accursed be Haman who sought to destroy me, blessed be Mordechai the Yehudi. Accursed be Zeresh the wife of my terrorizer, blessed be Esther who sacrificed for me—and Charvonah, too, be remembered for good (וגם חרבונה זכור לטוב) [for suggesting to the King that Haman be hanged on the gallows.[48]] |

Women and Megillah reading[edit]

Megillat Esther with Torah pointer

Women have an obligation to hear the Megillah because «they also were involved in that miracle.»[49] Most Orthodox communities, including Modern Orthodox ones, however, generally do not allow women to lead the Megillah reading. Rabbinic authorities who hold that women should not read the Megillah for themselves, because of an uncertainty as to which blessing they should recite upon the reading, nonetheless agree that they have an obligation to hear it read. According to these authorities if women, or men for that matter, cannot attend the services in the synagogue, the Megillah should be read for them in private by any male over the age of thirteen.[50] Often in Orthodox communities there is a special public reading only for women, conducted either in a private home or in a synagogue, but the Megillah is read by a man.[51]

Some Modern Orthodox leaders have held that women can serve as public Megillah readers. Women’s megillah readings have become increasingly common in more liberal Modern Orthodox Judaism, though women may only read for other women, according to Ashkenazi authorities.[52]

Blotting out Haman’s name[edit]

A wooden Purim gragger (Ra’ashan)

When Haman’s name is read out loud during the public chanting of the Megillah in the synagogue, which occurs 54 times, the congregation engages in noise-making to blot out his name. The practice can be traced back to the Tosafists (the leading French and German rabbis of the 13th century). In accordance with a passage in the Midrash, where the verse «Thou shalt blot out the remembrance of Amalek»[53] is explained to mean «even from wood and stones.» A custom developed of writing the name of Haman, the offspring of Amalek, on two smooth stones, and knocking them together until the name was blotted out. Some wrote the name of Haman on the soles of their shoes, and at the mention of the name stamped with their feet as a sign of contempt. Another method was to use a noisy ratchet, called a ra’ashan (from the Hebrew ra-ash, meaning «noise») and in Yiddish a grager. Some of the rabbis protested against these uproarious excesses, considering them a disturbance of public worship, but the custom of using a ratchet in the synagogue on Purim is now almost universal, with the exception of Spanish and Portuguese Jews and other Sephardic Jews, who consider them an improper interruption of the reading.[54]

Food gifts and charity[edit]

Gaily wrapped baskets of sweets, snacks and other foodstuffs given as mishloach manot on Purim day.

The Book of Esther prescribes «the sending of portions one man to another, and gifts to the poor».[55] According to halakha, each adult must give at least two different foods to one person, and at least two charitable donations to two poor people.[56] The food parcels are called mishloach manot («sending of portions»), and in some circles the custom has evolved into a major gift-giving event.[citation needed]

To fulfill the mitzvah of giving charity to two poor people, one can give either food or money equivalent to the amount of food that is eaten at a regular meal. It is better to spend more on charity than on the giving of mishloach manot.[56] In the synagogue, regular collections of charity are made on the festival and the money is distributed among the needy. No distinction is made among the poor; anyone who is willing to accept charity is allowed to participate. It is obligatory for the poorest Jew, even one who is himself dependent on charity, to give to other poor people.[56]

Purim meal (se’udah) and festive drinking[edit]

On Purim day, a festive meal called the Se’udat Purim is held. Fasting for non-medical reasons is prohibited on Purim.[citation needed]

There is a longstanding custom of drinking wine at the feast. The custom stems from a statement in the Talmud attributed to a rabbi named Rava that says one should drink on Purim until he can «no longer distinguish between arur Haman («Cursed is Haman») and baruch Mordechai («Blessed is Mordecai»).» The drinking of wine features prominently in keeping with the jovial nature of the feast, but also helps simulate the experience of spiritual blindness, wherein one cannot distinguish between good (Mordechai) and evil (Haman). This is based on the fact that the salvation of the Jews occurred through wine.[57] Alcoholic consumption was later codified by the early authorities, and while some advocated total intoxication, others, consistent with the opinion of many early and later rabbis, taught that one should only drink a little more than usual and then fall asleep, whereupon one will certainly not be able to tell the difference between arur Haman («cursed be Haman») and baruch Mordecai («blessed be Mordechai»). Other authorities, including the Magen Avraham, have written that one should drink until one is unable to calculate the gematria (numerical values) of both phrases.[citation needed]

Fasts[edit]

The Fast of Esther, observed before Purim, on the 13th of Adar, is an original part of the Purim celebration, referred to in Esther 9:31–32. The first who mentions the Fast of Esther is Rabbi Achai Gaon (Acha of Shabcha) (8th century CE) in She’iltot 4; the reason there given for its institution is based on an interpretation of Esther 9:18, Esther 9:31 and Talmud Megillah 2a: «The 13th was the time of gathering», which gathering is explained to have had also the purpose of public prayer and fasting. Some, however, used to fast three days in commemoration of the fasting of Esther; but as fasting was prohibited during the month of Nisan, the first and second Mondays and the Thursday following Purim were chosen. The fast of the 13th is still commonly observed; but when that date falls on Sabbath, the fast is pushed forward to the preceding Thursday, Friday being needed to prepare for Sabbath and the following Purim festival.[citation needed]

Customs[edit]

Greetings[edit]

It is common to greet one another on Purim in Hebrew with «Chag Purim Sameach», in Yiddish with «Freilichin Purim» or in Ladino with «Purim Allegre». The Hebrew greeting loosely translates to «Happy Purim Holiday» and the Yiddish and Ladino translate to «Happy Purim».[58][59]

Masquerading[edit]

Israeli girl dressed up as a cowboy while holding her Purim basket of candies (2006)

The custom of masquerading in costumes and the wearing of masks probably originated among the Italian Jews at the end of the 15th century.[60] The concept was possibly influenced by the Roman carnival and spread across Europe. The practice was only introduced into Middle Eastern countries during the 19th century. The first Jewish codifier to mention the custom was Mahari Minz (d. 1508 at Venice).[61] While most authorities are concerned about the possible infringement of biblical law if men don women’s apparel, others permit all forms of masquerades, because they are viewed as forms of merry-making. Some rabbis went as far as to allow the wearing of rabbinically-forbidden shatnez.[62]

Other reasons given for the custom: It is a way of emulating God who «disguised» his presence behind the natural events which are described in the Purim story, and it has remained concealed (yet ever-present) in Jewish history since the destruction of the First Temple. Since charity is a central feature of the day, when givers and/or recipients disguise themselves this allows greater anonymity thus preserving the dignity of the recipient. Another reason for masquerading is that it alludes to the hidden aspect of the miracle of Purim, which was «disguised» by natural events but was really the work of the Almighty.[62]

Additional explanations are based on:

- Targum on Esther (Chapter 3) which states that Haman’s hate for Mordecai stemmed from Jacob’s ‘dressing up’ like Esau to receive Isaac’s blessings;[63]

- Others who «dressed up» or hid whom they were in the story of Esther:

- Esther not revealing that she is a Jewess;[63]

- Mordecai wearing sackcloth;[63]

- Mordecai being dressed in the king’s clothing;[63]

- «[M]any from among the peoples of the land became Jews; for the fear of the Jews was fallen upon them» (Esther 8:17); on which the Vilna Gaon comments that those gentiles were not accepted as converts because they only made themselves look Jewish on the outside, as they did this out of fear;[63]

- To recall the episodes that only happened in «outside appearance» as stated in the Talmud (Megillah 12a)[64] that the Jews bowed to Haman only from the outside, internally holding strong to their Jewish belief, and likewise, God only gave the appearance as if he was to destroy all the Jews while internally knowing that he will save them (Eileh Hamitzvos #543);[63]

Burning of Haman’s effigy[edit]

As early as the 5th century, there was a custom to burn an effigy of Haman on Purim.[60] The spectacle aroused the wrath of the early Christians who interpreted the mocking and «execution» of the Haman effigy as a disguised attempt to re-enact the death of Jesus and ridicule the Christian faith. Prohibitions were issued against such displays under the reign of Flavius Augustus Honorius (395–423) and of Theodosius II (408–450).[60] The custom was popular during the Geonic period (9th and 10th centuries),[60] and a 14th century scholar described how people would ride through the streets of Provence holding fir branches and blowing trumpets around a puppet of Haman which was hanged and later burnt.[65] The practice continued into the 20th century, with children treating Haman as a sort of «Guy Fawkes.»[66] In the early 1950s, the custom was still observed in Iran and some remote communities in Kurdistan[65] where young Muslims would sometimes join in.[67]

Purim spiel[edit]

Purim spiel in Dresden, Germany (2016)

A Purim spiel (Purim play) is a comic dramatization that attempts to convey the saga of the Purim story.[68] By the 18th century, in some parts of Eastern Europe, the Purim plays had evolved into broad-ranging satires with music and dance for which the story of Esther was little more than a pretext. Indeed, by the mid-19th century, some were even based on other biblical stories. Today, Purim spiels can revolve around anything relating to Jews, Judaism, or even community gossip that will bring cheer and comic relief to an audience celebrating the day.[68][69]

Songs[edit]

Songs associated with Purim are based on sources that are Talmudic, liturgical and cultural. Traditional Purim songs include Mishenichnas Adar marbim be-simcha («When [the Hebrew month of] Adar enters, we have a lot of joy»—Mishnah Taanith 4:1) and LaYehudim haitah orah ve-simchah ve-sasson ve-yakar («The Jews had light and gladness, joy and honor»—Esther 8:16).[b] The Shoshanat Yaakov prayer is sung at the conclusion of the Megillah reading. A number of children’s songs (with non-liturgical sources) also exist: Once There Was a Wicked Wicked Man,[70][71] Ani Purim,[72] Chag Purim, Chag Purim, Chag Gadol Hu LaYehudim,[73][74] Mishenichnas Adar, Shoshanas Yaakov, Al HaNisim, VeNahafoch Hu, LaYehudim Hayesa Orah, U Mordechai Yatza, Kacha Yay’aseh, Chayav Inish, Utzu Eitzah.[75]

Traditional foods[edit]

On Purim, Ashkenazi Jews and Israeli Jews (of both Ashkenazi and Sephardic descent) eat triangular pastries called hamantaschen («Haman’s pockets») or oznei Haman («Haman’s ears»).[59] A sweet pastry dough is rolled out, cut into circles, and traditionally filled with a raspberry, apricot, date, or poppy seed filling. More recently, flavors such as chocolate have also gained favor, while non-traditional experiments such as pizza hamantaschen also exist.[76] The pastry is then wrapped up into a triangular shape with the filling either hidden or showing. Among Sephardi Jews, a fried pastry called fazuelos is eaten, as well as a range of baked or fried pastries called Orejas de Haman (Haman’s Ears) or Hojuelas de Haman.[citation needed]

Seeds, nuts, legumes and green vegetables are customarily eaten on Purim, as the Talmud relates that Queen Esther ate only these foodstuffs in the palace of Ahasuerus, since she had no access to kosher food.[77]

Kreplach, a kind of dumpling filled with cooked meat, chicken or liver and served in soup, are traditionally served by Ashkenazi Jews on Purim. «Hiding» the meat inside the dumpling serves as another reminder of the story of Esther, the only book of Hebrew scriptures besides The Song of Songs that does not contain a single reference to God, who seems to hide behind the scenes.[78]

Arany galuska, a dessert consisting of fried dough balls and vanilla custard, is traditional for Jews from Hungary and Romania, as well as their descendants.[79]

In the Middle Ages, European Jews would eat nilish, a type of blintz or waffle.[80]

Special breads are baked among various communities. In Moroccan Jewish communities, a Purim bread called ojos de Haman («eyes of Haman») is sometimes baked in the shape of Haman’s head, and the eyes, made of eggs, are plucked out to demonstrate the destruction of Haman.[81]

Among Polish Jews, koilitch, a raisin Purim challah that is baked in a long twisted ring and topped with small colorful candies, is meant to evoke the colorful nature of the holiday.[82]

Torah learning[edit]

There is a widespread tradition to study the Torah in a synagogue on Purim morning, during an event called «Yeshivas Mordechai Hatzadik» to commemorate all the Jews who were inspired by Mordechai to learn Torah to overturn the evil decree against them. Children are especially encouraged to participate with prizes and sweets due to the fact that Mordechai taught many children Torah during this time.[83]

Iranian Jews[edit]

Iranian Jews and Mountain Jews consider themselves descendants of Esther. On Purim, Iranian Jews visit the tombs of Esther and Mordechai in Hamadan. Some women pray there in the belief that Esther can work miracles.[84]

In Jerusalem[edit]

Shushan Purim[edit]

Shushan Purim falls on Adar 15 and is the day on which Jews in Jerusalem celebrate Purim.[56] The day is also universally observed by omitting the Tachanun prayer and having a more elaborate meal than on ordinary days.[85]

Purim is celebrated on Adar 14 because the Jews in unwalled cities fought their enemies on Adar 13 and rested the following day. However, in Shushan, the capital city of the Persian Empire, the Jews were involved in defeating their enemies on Adar 13–14 and rested on the 15th (Esther 9:20–22). In commemoration of this, it was decided that while the victory would be celebrated universally on Adar 14, for Jews living in Shushan, the holiday would be held on Adar 15. Later, in deference to Jerusalem, the Sages determined that Purim would be celebrated on Adar 15 in all cities which had been enclosed by a wall at the time of Joshua’s conquest of the Land of Israel. This criterion allowed the city of Jerusalem to retain its importance for Jews, and although Shushan was not walled at the time of Joshua, it was made an exception since the miracle occurred there.[56]

Today, there is debate as to whether outlying neighborhoods of Jerusalem are obliged to observe Purim on the 14th or 15th of Adar.[86] Further doubts have arisen as to whether other cities were sufficiently walled in Joshua’s era. It is therefore customary in certain towns including Hebron, Safed, Tiberias, Acre, Ashdod, Ashkelon, Beersheva, Beit She’an, Beit Shemesh, Gaza, Gush Halav, Haifa, Jaffa, Lod, Ramlah and Shechem to celebrate Purim on the 14th and hold an additional megillah reading on the 15th with no blessings.[86][87] In the diaspora, Jews in Baghdad, Damascus, Prague, and elsewhere celebrate Purim on the 14th and hold an additional megillah reading on the 15th with no blessings.[citation needed] Since today we are not sure where the walled cities from Joshua’s time are, the only city that currently celebrates only Shushan Purim is Jerusalem; however, Rabbi Yoel Elizur has written that residents of Bet El and Mevo Horon should observe only the 15th, like Jerusalem.[88]

Outside of Jerusalem, Hasidic Jews don their holiday clothing on Shushan Purim, and may attend a tish, and even give mishloach manot; however, this is just a custom and not a religious obligation.[citation needed]

Purim Meshulash[edit]

Purim Meshulash,[89] or the three-fold Purim, is a somewhat rare calendric occurrence that affects how Purim is observed in Jerusalem (and, in theory at least, in other cities that were surrounded by a wall in ancient times).[citation needed]

When Shushan Purim (Adar 15) falls on the Sabbath, the holiday is celebrated over a period of three days.[90] The megilla reading and distribution of charity takes place on the Friday (Adar 14), which day is called Purim dePrazos. The Al ha-Nissim prayer is only recited on Sabbath (Adar 15), which is Purim itself. The weekly Torah portion (Tetzaveh or Ki Tissa in regular years, Tzav in leap years) is read as usual, while the Torah portion for Purim is read for maftir, and the haftarah is the same as read the previous Shabbat, Parshat Zachor. On Sunday (Adar 16), called Purim Meshullash, mishloach manot are sent and the festive Purim meal is held.[91]

The minimum interval between occurrences of Purim Meshulash is three years (1974 to 1977; 2005 to 2008; will occur again 2045 to 2048). The maximum interval is 20 years (1954 to 1974; will occur again 2025 to 2045). Other possible intervals are four years (1977 to 1981; 2001 to 2005; 2021 to 2025; will occur again 2048 to 2052); seven years (1994 to 2001; will occur again 2123 to 2130); 13 years (1981 to 1994; 2008 to 2021; will occur again 2130 to 2143); and 17 years (1930 to 1947; will occur again 2275 to 2292).[citation needed]

Other Purims[edit]

Purim Katan[edit]

During leap years on the Hebrew calendar, Purim is celebrated in the second month of Adar. (The Karaites, however, celebrate it in the first month of Adar.) The 14th of the first Adar is then called Purim Katan («Little Purim» in Hebrew) and the 15th is Shushan Purim Katan, for which there are no set observances but it has a minor holiday aspect to it. The distinctions between the first and the second Purim in leap years are mentioned in the Mishnah.[92] Certain prayers like Tachanun, Eil Erech Apayim (when 15 Adar I is a Monday or Thursday) and Lam’nazteach (Psalm 20) are omitted during the service. When 15th Adar I is on Shabbat, «Av Harachamim» is omitted. When either 13th or 15th Adar I falls on Shabbat, «Tzidkas’cha» is omitted at Mincha. Fasting is prohibited.[93]

Communal and familial Purims[edit]

Historically, many Jewish communities around the world established local «Purims» to commemorate their deliverance from catastrophe or an antisemitic ruler or edict. One of the best known is Purim Vinz, traditionally celebrated in Frankfurt one week after the regular Purim. Purim Vinz commemorates the Fettmilch uprising (1616–1620), in which one Vincenz Fettmilch attempted to exterminate the Jewish community.[94] According to some sources, the influential Rabbi Moses Sofer (the Chasam Sofer), who was born in Frankfurt, celebrated Purim Vintz every year, even when he served as a rabbi in Pressburg.

Rabbi Yom-Tov Lipmann Heller (1579–1654) of Kraków, Poland, asked that his family henceforth celebrate a private Purim, marking the end of his many troubles, including having faced trumped-up charges.[95] Since Purim is preceded by a fast day, the rabbi also directed his descendants to have a (private) fast day, the 5th day of Tamuz, marking one of his imprisonments (1629), this one lasting for 40 days.[96][97]

The Jewish community of Hebron has celebrated two historic Purims, both from the Ottoman period. One is called Window Purim, or Purim Taka, in which the community was saved when a bag of money mysteriously appeared in a window, enabling them to pay off an extortion fee to the Ottoman Pasha. Many record the date being the 14th of the month, which corresponds the date of Purim on 14 Adar.[98][99][100] The other was called The Purim of Ibrahim Pasha, in which the community was saved during a battle.[98]

Other historic Purim celebrations in Jewish history have occurred in Yemen, Italy, Vilna and other locations.[101][102][103]

In modern history[edit]

Adolf Hitler banned and forbade the observance of Purim. In a speech made on 10 November 1938 (the day after Kristallnacht), the Nazi politician and prominent anti-Semite Julius Streicher surmised that just as «the Jew butchered 75,000 Persians» in one night, the same fate would have befallen the German people had the Jews succeeded in inciting a war against Germany; the «Jews would have instituted a new Purim festival in Germany».[104]

Nazi attacks against Jews were often coordinated with Jewish festivals. On Purim 1942, ten Jews were hanged in Zduńska Wola to «avenge» the hanging of Haman’s ten sons.[105] In a similar incident in 1943, the Nazis shot ten Jews from the Piotrków ghetto.[106] On Purim eve that same year, over 100 Jewish doctors and their families were shot by the Nazis in Częstochowa. The following day, Jewish doctors were taken from Radom and shot nearby in Szydłowiec.[106] In 1942, on Purim, the Nazis murdered over 5000 Jews, mostly children, in the Minsk Ghetto. All of the victims were shot and buried alive by the Nazis.[107]

Still, the Nazi regime was defied and Purim was celebrated in Nazi ghettos and elsewhere. [108]

In an apparent connection made by Hitler between his Nazi regime and the role of Haman, Hitler stated in a speech made on 30 January 1944, that if the Nazis were defeated, the Jews could celebrate «a second Purim».[106] Indeed, Julius Streicher was heard to sarcastically remark «Purimfest 1946» as he ascended the scaffold after Nuremberg.[109][110] According to Rabbi Mordechai Neugroschel, there is a code in the Book of Esther which lies in the names of Haman’s 10 sons. Three of the Hebrew letters—a tav, a shin and a zayin—are written smaller than the rest, while a vav is written larger. The outsized vav—which represents the number six—corresponds to the sixth millennium of the world since creation, which, according to Jewish tradition, is the period between 1240 and 2240 CE. As for the tav, shin and zayin, their numerical values add up to 707. Put together, these letters refer to the Jewish year 5707, which corresponds to the secular 1946–1947. In his research, Neugroschel noticed that ten Nazi defendants in the Nuremberg Trials were executed by hanging on 16 October 1946, which was the date of the final judgement day of Judaism, Hoshana Rabbah. Additionally, Hermann Göring, an eleventh Nazi official sentenced to death, committed suicide, parallel to Haman’s daughter in Tractate Megillah.[111][112]

There is a tale in the Hasidic Chabad movement that supposedly Joseph Stalin died as a result of some metaphysical intervention of the seventh Chabad leader, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, during the recitation of a discourse at a public Purim farbrengen.[113] Stalin was suddenly paralyzed on 1 March 1953, which corresponds to Purim 1953, and died four days later. Due to Stalin’s death, nationwide pogroms against Jews throughout the Soviet Union were averted, as Stalin’s infamous doctors’ plot was halted.[114][115]

The Cave of the Patriarchs massacre took place during Purim of 1994.[116] The Dizengoff Center suicide bombing took place on the eve of Purim killing 13 on 4 March 1996.[117]

In the media[edit]

The 1960 20th Century-Fox film Esther and the King stars Joan Collins as Esther and Richard Egan as Ahasuerus. It was filmed in Italy by director Raoul Walsh. The 2006 movie One Night with the King chronicles the life of the young Jewish girl, Hadassah, who goes on to become the Biblical Esther, the Queen of Persia, and saves the Jewish nation from annihilation at the hands of its arch enemy while winning the heart of the fiercely handsome King Xerxes.[118]

The 2006 comedy film For Your Consideration employs a film-within-a-film device in which the fictitious film being produced is titled Home for Purim, and is about a Southern Jewish family’s Purim celebration. However, once the film receives Oscar buzz, studio executives feel it is «too Jewish» and force the film to be renamed Home for Thanksgiving.[119]

Gallery[edit]

-

Purim woodcut (1741)

-

Megillah reading (1764)

-

Purim (1657 engraving)

-

Purim (1699 engraving)

-

1740 illumination of an Ashkenazic megillah reading. One man reads while another follows along and a child waves a noise-maker.

-

Frozen-themed Megillah reading (2014).

-

18th-century manuscript of the prayer of Al HaNissim on the miracles of Purim.

See also[edit]

- Jewish holidays

- Public holidays in Israel

- Jewish holidays 2000–2050

- Purim humor

Extensions of Jewish festivals which are similar to Shushan Purim and Purim Katan[edit]

- Chol HaMoed, the intermediate days between Passover and Sukkot.

- Isru chag refers to the day after each of the Three Pilgrimage Festivals.

- Mimouna, a traditional North African Jewish celebration which is held the day after Passover.

- Pesach Sheni, is exactly one month after 14 Nisan.

- Yom Kippur Katan is a practice which is observed by some Jews on the day which precedes each Rosh Chodesh or New-Moon Day.

- Yom tov sheni shel galuyot refers to the observance of an extra day of Jewish holidays outside the land of Israel.

Persian(ate) Jewry[edit]

- Persian Jews

- Judeo-Persian language

- History of the Jews in Iran

- History of the Jews in Afghanistan

- Mountain Jews

- Bukharan Jews

Notes[edit]

- ^ From the Hebrew word פור (pur), translated as ‘lot’ in the Book of Esther, perhaps related to Akkadian pūru (lit. ‘stone’ or ‘urn’);[11] also called the Festival of Lots.

- ^ A children’s song called «Light, Gladness, Joy, Honor,» based on the previously-mentioned Esther 8:16 quote, is sung in some Reform Jewish communities, but since it is based on a liturgical quote, it would not be in the list of songs above.

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d «Dates for Purim». Hebcal.com by Danny Sadinoff and Michael J. Radwin (CC-BY-3.0). Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- ^ Jewish Encyclopedia (1906). Ahasuers. JewishEncyclopedia.com. Archived from the original on 3 July 2014.

- ^ Encyclopaedia Perthensis (1816). Universal Dictionary of the Arts, Sciences, Literature etc. Vol. 9. Edinburgh: John Brown, Anchor Close (Printers). p. 82. Archived from the original on 17 October 2015.

- ^ Law, George R. (2010). Identification of Darius the Mede. US: Ready Scribe Press. pp. 94–96. ISBN 978-0982763100. Archived from the original on 17 October 2015.

- ^ First, Mitchell (2015). Esther Unmasked: Solving Eleven Mysteries of the Jewish Holidays and Liturgy (Kodesh Press), p. 163.

- ^ «Esther 2 / Hebrew – English Bible / Mechon-Mamre». www.mechon-mamre.org.

- ^ Esther 9:22

- ^ Elozor Barclay and Yitzchok Jaeger (27 January 2004). «Gifts to the Poor». Aish.com. Archived from the original on 27 April 2014. Retrieved 12 March 2014.

- ^ «Purim 2012 Guide». Chabad-Lubavitch Media Center. Archived from the original on 7 April 2012. Retrieved 5 March 2012.

- ^ Shulchan Aruch Orach Chayyim 685:1

- ^ Klein, Ernest (1966). A Comprehensive Etymological Dictionary of the English Language. Elsevier. p. 1274.

- ^ Tanakh: The Holy Scriptures, Philadelphia, PA: Jewish Publication Society, 1985, p. 1460, ISBN 9780827602526, retrieved 2 February 2023

- ^ Esther chapters 1 and 2

- ^ Esther chapters 3–5

- ^ Mindel, Nissan. The Complete Story of Purim Archived 22 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Esther chapters 9–16

- ^ Esther chapters 6–9

- ^ Esther chapters 9–10

- ^ NIV Study Bible, Introductions to the Books of the Bible, Esther, Zondervan, 2002

- ^ Babylonian Talmud, Tractate Bava Basra 15a.

- ^ Neusner, Jacob (2006). The Talmud: What It Is and What It Says. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-7425-4671-4. Retrieved 27 February 2021.

- ^ Moshe David Herr, Encyclopedia Judaica 1997 CD-ROM Edition, article Esther Rabbah, 1997

- ^ a b William Whiston, The Works of Flavius Josephus, the Learned and Authentic Jewish Historian, Milner and Sowerby, 1864, online edition Harvard University 2004. Cited in Contra Apionem which quotes a work referred to as Peri Ioudaion (On the Jews), which is credited to Hecataeus of Abdera (late fourth century BCE).

- ^ Hoschander, Jacob (1923). The Book of Esther in the Light of History. Dropsie College for Hebrew and Cognate Learning. Retrieved 27 February 2021.

- ^ David Flusser, Josephus Goridines (The Josippon) (Vols. 1–2), The Bialik Institute, 1978

- ^ Ehsan Yar-Shater, The History of al-Tabari : An Annotated Translation, SUNY Press, 1989

- ^ a b Moshe Perlmann trans., The Ancient Kingdoms, SUNY Press, 1985

- ^ a b Said Amir Arjomand, Artaxerxes, Ardasir and Bahman, The Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 118, 1998

- ^ The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition article Abd al-Hasan Ali ibn al-Husayn Masudi, Columbia University Press, 2007

- ^ Lewis Bayles Paton, Esther: Critical Exegetical Commentary, Continuum International Publishing Group, 2000

- ^ Abd al-Hasan Ali ibn al-Husayn Masudi, Murūj al-dhahab (Meadows of Gold), ed. and French transl. by F. Barbier de Meynard and Pavet du Courteille, Paris, 1861

- ^ Richard James Horatio Gottheil ed., Persian Literature, Volume 1, Comprising The Shah Nameh, The Rubaiyat, The Divan, and The Gulistan, Colonial Press, 1900

- ^ Littman, Robert J. (1975). «The Religious Policy of Xerxes and the «Book of Esther»«. The Jewish Quarterly Review. 65 (3): 145–155. doi:10.2307/1454354. JSTOR 1454354.

- ^ Netzer, Amnon. «Festivals vii. Jewish». In Encyclopædia Iranica. vol. 9, pp. 555–60.

- ^ a b c Shaked, Shaul. «Esther, Book of». In Encyclopædia Iranica. vol. 8, 1998, pp. 655–57

- ^ Dandamayev, M.A. «Bible i. As a Source for Median and Achaemenid History». In Encyclopædia Iranica. vol. 4, pp. 199–200

- ^ a b McCullough, W.S. «Ahasureus». In Encyclopædia Iranica. vol. 1, 1985. pp. 634–35

- ^ Kuhrt, Amélie, Achaemenid (in persian: Hakhamaneshian)), tr. by Morteza Thaghebfar, Tehran, 2012, p. 19

- ^ Littman, Robert J. (1975). «The Religious Policy of Xerxes and the «Book of Esther»«. The Jewish Quarterly Review. 65 (3): 145–55. doi:10.2307/1454354. JSTOR 1454354.

- ^ Sperling, S. David and Albert I Baumgarten. «scroll of esther». In Encyclopedia Judaica. vol. 18. 2nd ed. New York: Thomson Gale, 2007. 215–18. ISBN 0-02-865946-5.

- ^ Flug, Joshua. Why Don’t We Recite Hallel on Purim? Archived 22 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Yehuda Shurpin, Why Is Work Permitted on Purim? Chabad.org

- ^ a b «Purim How-To Guide – Your Purim 2019 guide contains the story of Purim, and all you need to know about the 4 mitzvahs of Purim and the other observances of the day». Archived from the original on 15 August 2017. Retrieved 21 February 2018.

- ^ Esther 9:7–10

- ^ Esther 9:26, 29

- ^ Exodus 17:8–16

- ^ a b c d e Scherman, Nosson (July 1993). The Torah: Haftoras and Five Megillos. Brooklyn, New York: Mesorah Publications, Ltd. pp. 1252, 1262. ISBN 978-0-89906-014-9.

- ^ Esther 7:9

- ^ Babylonian Talmud Megillah 4a

- ^ Chaim Rapoport, Can Women Read the Megillah? An in-depth exploration of how the mitzvah of Megillah applies to women.

- ^ Rabbi Yehuda Henkin. «Women’s Issues : Women and Megillah Reading» (PDF). Nishmat.net. Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- ^ Frimer, Aryeh A. «Women’s Megilla Reading Archived 2008-03-21 at the Wayback Machine» published in Wiskind Elper, Ora, ed. Traditions and Celebrations for the Bat Mitzvah (Jerusalem: Urim Publications, 2003), pp. 281–304.

- ^ Deuteronomy 25:19

- ^ «Comunicado sobre la actitud en los festejos de Purim». 22 February 2018.

- ^ Esther 9:22

- ^ a b c d e Barclay, Rabbi Elozor and Jaeger, Rabbi Yitzchok (2001). Guidelines: Over two hundred and fifty of the most commonly asked questions about Purim. Southfield, MI: Targum Press.

- ^ Yanki Tauber: Are Jews actually supposed to get drunk on Purim? Archived 1 January 2014 at the Wayback Machine Chabad.org (referring to the Talmudic tractate Megillah (7b)).

- ^ «Happy Purim – Traditional Purim Greetings». www.chabad.org.

- ^ a b Alhadeff, Ty (26 February 2015). «Sephardic Purim Customs from the Old World to the Pacific Northwest».

- ^ a b c d Kohler, Kaufmann; Malter, Henry (2002). «Purim». Jewish Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 7 October 2011. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- ^ Responsa no. 17, quoted by Moses Isserles on Orach Chaim 696:8.

- ^ a b Yitzchak Sender (2000). The Commentators’ Al Hanissim: Purim: Insights of the Sages on Purim and Chanukah. Jerusalem: Feldheim Publishers. pp. 236–45. ISBN 978-1-58330-411-2. Archived from the original on 17 October 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f Rabbi Moshe Taub (21 February 2018). «The Shul Chronicles». Ami Magazine. No. 356. pp. 138–139.

- ^ Megillah 12a (in Hebrew) – via Wikisource.

- ^ a b Gaster, Theodor Herzl (2007). Purim And Hanukkah in Custom And Tradition – Feast of Lots – Feast of Lights. Sutton Press. pp. 66–67. ISBN 978-1-4067-4781-2. Archived from the original on 17 October 2015.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica, 1911 edition: Purim.

- ^ Brauer, Erich (1993). Patai, Raphael (ed.). The Jews of Kurdistan. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. pp. 357–59. ISBN 978-0-8143-2392-2. Archived from the original on 17 October 2015.

- ^ a b «The Fascinating Evolution of the Purim-Spiel». ReformJudaism.org. 13 March 2014.

- ^ «Archived copy» (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 March 2016. Retrieved 11 March 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ «Haman, A Wicked Man». Musicnotes. 2001. Archived from the original on 19 March 2011. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- ^ «Wicked, Wicked Man». Zemerl. Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- ^ «Purim Songs: Ani Purim». Congregation B’nai Jeshurun. Archived from the original on 12 March 2007.

- ^ «Chag Purim». Chabad.org. 2011. Archived from the original on 16 March 2011. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- ^ «Purim Songs for the AJ Family Megillah Reading». Adath Jeshurun. 2007. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- ^ «Purim Songs». Aish.com. 2 February 2003. Archived from the original on 5 August 2011. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- ^ «Best Hamantaschen Fillings». www.kosher.com. 10 February 2020.

- ^ «Purim: The Poppy Seed Connection – Jewish Holidays». 25 February 2009.

- ^ «What Are Kreplach?». www.chabad.org.

- ^ «Golden walnut dumplings — Aranygaluska | Zserbo.com». zserbo.com.

- ^ Ari Jacobs & Abe Lederer (2013), Purim: Its Laws, Customs and Meaning, Jerusalem, Israel: Targum Press. p. 158.

- ^ «Ojos de Haman (The Eyes of Haman)». Jewish Holidays. 1 January 1970.

- ^ «Purim Traditions You’ve Never Heard Of». www.kosher.com. 5 March 2019.

- ^ «The «Mordechai Hatzaddik» Yeshiva – Jewish World». Israel National News. 16 March 2003.

- ^ «Sad Fate of Iran’s Jews». www.payvand.com. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011.

- ^ Jacobs, Joseph; Seligsohn, M. (2002). «Shushan (Susa) Purim». Jewish Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 15 February 2010. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- ^ a b Teller, Hanoch (1995). And From Jerusalem, His Word. Feldheim Publishers. p. 233. ISBN 978-1-881939-05-4. Archived from the original on 17 October 2015.

- ^ Enkin, Ari (23 February 2010). «Why I Observe Two Days of Purim». Hirhurim – Musings. Archived from the original on 11 March 2014. Retrieved 12 March 2014.

- ^ «זמני הפורים בישובים החדשים ביהודה, שומרון ובארץ בנימין / יואל אליצור». Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- ^ Aish.com: (Although grammatically it is Purim hameshulash, people usually call it ‘Purim Meshulash.’) «Purim Meshulash».

- ^ Shulchan Aruch Orach Chayyim 688:6

- ^ Yosef Zvi Rimon, Rav (21 September 2014). «A Concise Guide to the Laws of Purim Meshulash». The Israel Koschitzky Virtual Beit Midrash of Yeshivat Har Etzion. Retrieved 28 February 2018.

- ^ Megillah 1/46b; compare Orach Chayim 697.

- ^ Orenstein, Aviel (5 September 1999). Mishna brura. Feldheim Publishers. ISBN 978-0873069465 – via Google Books.

- ^ Schnettger, Matthias. «Review of: Rivka Ulmer: Turmoil, Trauma, and Triumph. The Fettmilch Uprising in Frankfurt am Main (1612–1616) According to Megillas Vintz. A Critical Edition of the Yiddish and Hebrew Text Including an English Translation» Archived 20 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine (in German). Bern / Frankfurt a.M. [u.a.]: Peter Lang 2001, in: sehepunkte 2 (2002), Nr. 7/8 [15 July 2002].

- ^ «This Day in Jewish History: Adar». Orthodox Union. Archived from the original on 12 September 2012. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- ^ Fine, Yisroel. «It Happened Today». Shamash: The Jewish Network. Archived from the original on 24 October 2007.

- ^ Rosenstein, Neil: The Feast and the Fast (1984)

- ^ a b «The Legend of the Window Purim and other Hebron Holiday Stories». the Jewish Community of Hebron. Archived from the original on 27 March 2016. Retrieved 18 March 2016.

- ^ «Purim Hebron». www.chabad.org. Archived from the original on 29 March 2016. Retrieved 18 March 2016.

- ^ Noy, Dov; Ben-Amos, Dan; Frankel, Ellen (3 September 2006). Folktales of the Jews, Volume 1: Tales from the Sephardic Dispersion. Jewish Publication Society. ISBN 978-0827608290. Archived from the original on 28 February 2018.

- ^ «When is Purim Observed?». Orthodox Union. Archived from the original on 27 March 2016. Retrieved 18 March 2016.

- ^ «Other Purims». www.chabad.org. Archived from the original on 22 March 2016. Retrieved 18 March 2016.

- ^ fasting 15 Kislev, celebrating at night/16 Kislev: Abraham Danzig (Gunpowder Purim) «Gunpowder Purim».

- ^ Bytwerk, Randall L. (2008). Landmark Speeches of National Socialism. College Station: Texas A&M University Press. p. 91. ISBN 978-1-60344-015-8. Archived from the original on 17 October 2015.

- ^ Cohen, Arthur Allen; Mendes-Flohr, Paul R., eds. (2009). 20th Century Jewish Religious Thought: Original Essays on Critical Concepts, Movements, and Beliefs. Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society of America. p. 948. ISBN 978-0-8276-0892-4. Archived from the original on 17 October 2015.

- ^ a b c Elliott Horowitz (2006). Reckless rites: Purim and the legacy of Jewish violence. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press. p. 91. ISBN 978-0-691-12491-9.

- ^ Rhodes, Richard (2002). Masters of Death: The SS-Einsatzgruppen and the Invention of the Holocaust. Random House. p. 244. ISBN 0375409009.

- ^ «MARKING THE HOLIDAY OF PURIM. Before, During and After the Holocaust», a Yad Vashem exhibition

- ^ Satinover, Jeffrey (1997). Cracking the Bible code. New York: W. Morrow. p. 189. ISBN 978-0-688-15463-9.

according to the October 16, 1946 issue of the New York Herald Tribune

- ^ Kingsbury-Smith, Joseph (16 October 1946). «The Execution of Nazi War Criminals». Nuremberg Gaol, Germany. International News Service. Retrieved 26 February 2021 – via University of Missouri–Kansas City.

- ^ «Tractate Megillah 16a». www.sefaria.org.il.

- ^ French bestseller unravels Nazi propagandist’s cryptic last words about Purim Archived 10 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Times of Israel 28 December 2012

- ^ Rich, Tracey R. (2010). «Purim». Judaism 101. Archived from the original on 9 July 2009. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- ^ Pinkus, Benjamin (1984). Frankel, Jonathan (ed.). The Soviet government and the Jews, 1948–1967: a documented study. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 107–08. ISBN 978-0-521-24713-9.

- ^ Brackman, Roman (2001). The Secret File of Joseph Stalin: A Hidden Life. Frank Cass Publishers. p. 390. ISBN 978-0-7146-5050-0.

- ^ Church, George J.; Beyer, Lisa; Hamad, Jamil; Fischer, Dean; McAllister, J.F.O. (7 March 1994). «When Fury Rules». Time. Archived from the original on 16 April 2009. Retrieved 26 February 2021.

- ^ «Behind the Headlines: a Year Without Purim; No Parades, Only Funerals». Jewish Telegraphic Agency. 5 March 1996. Archived from the original on 25 March 2016. Retrieved 18 March 2016.

- ^ Ehrlich, Carl S. (2016). «Esther in Film». In Burnette-Bletsch, Rhonda (ed.). The Bible in Motion: A Handbook of the Bible and Its Reception in Film. De Gruyter. pp. 119–36. ISBN 978-1614513261. Retrieved 28 February 2018.

- ^ For Your Consideration at AllMovie

External links[edit]

Look up Purim in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Purim.

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

- Aish HaTorah Purim Resources

- Chabad Purim Resources

- Yeshiva Laws, articles and Q&A on Purim

- Peninei Halakha The month of Adar and the holiday of Purim, minhagim (customs) and halachot (laws) by Rabbi Eliezer Melamed

- Union for Reform Judaism Purim Resources Archived 6 December 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- The United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism Purim Resources

- «Purim» . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

- Purim celebrations in the IDF, Exhibition in the IDF&defense establishment archives Archived 28 December 2019 at the Wayback Machine

| Purim | |

|---|---|

Purim by Arthur Szyk |

|

| Type | Jewish |

| Significance | Celebration of Jewish deliverance as told in the Book of Esther (megillah) |

| Celebrations |

|

| Date | 14th day of Adar (in Jerusalem and all ancient walled cities, 15th of Adar) |

| 2022 date | Sunset, 16 March – nightfall, 17 March[1] |

| 2023 date | Sunset, 6 March – nightfall, 7 March[1] |

| 2024 date | Sunset, 23 March – nightfall, 24 March[1] |

| 2025 date | Sunset, 13 March – nightfall, 14 March[1] |

| Frequency | Annual |

| Started by | Esther |

| Related to | Hanukkah, as a rabbinically decreed Jewish holiday |

Purim (; Hebrew: פּוּרִים Pūrīm, lit. ‘lots’; see Name below) is a Jewish holiday which commemorates the saving of the Jewish people from Haman, an official of the Achaemenid Empire who was planning to have all of Persia’s Jewish subjects killed, as recounted in the Book of Esther (usually dated to the 5th century BCE).

Haman was the royal vizier to Persian king Ahasuerus (Xerxes I or Artaxerxes I; «Khshayarsha» and «Artakhsher» in Old Persian, respectively).[2][3][4][5] His plans were foiled by Mordecai of the tribe of Benjamin, and Esther, Mordecai’s cousin and adopted daughter who had become queen of Persia after her marriage to Ahasuerus.[6] The day of deliverance became a day of feasting and rejoicing among the Jews.

According to the Scroll of Esther,[7] «they should make them days of feasting and gladness, and of sending portions one to another, and gifts to the poor». Purim is celebrated among Jews by:

- Exchanging gifts of food and drink, known as mishloach manot

- Donating charity to the poor, known as mattanot la-evyonim[8]

- Eating a celebratory meal, known as se’udat Purim

- Public recitation of the Scroll of Esther (Hebrew: קריאת מגילת אסתר, romanized: Kriat megillat Esther), or «reading of the Megillah», usually in synagogue

- Reciting additions to the daily prayers and the grace after meals, known as Al HaNissim

Other customs include wearing masks and costumes, public celebrations and parades (Adloyada), and eating hamantashen (transl. »Haman’s pockets»); men are encouraged to drink wine or any other alcoholic beverage.[9]

According to the Hebrew calendar, Purim is celebrated annually on the 14th day of the Hebrew month of Adar (and it is celebrated on Adar II in Hebrew leap years, which occur every two to three years), the day following the victory of the Jews over their enemies. In cities that were protected by a surrounding wall at the time of Joshua, Purim was celebrated on the 15th of the month of Adar on what is known as Shushan Purim, since fighting in the walled city of Shushan continued through the 14th day of Adar.[10] Today, only Jerusalem and a few other cities celebrate Purim on the 15th of Adar.

Name[edit]

Purim is the plural of Hebrew pur, meaning casting lots in the sense of making a random selection.[a] Its use as the name of this festival comes from Esther 3:6-7, describing the choice of date:

6: […] having been told who Mordecai’s people were, Haman plotted to do away with all the Jews, Mordecai’s people, throughout the kingdom of Ahasuerus.

7: In the first month, that is, the month of Nisan, in the twelfth year of King Ahasuerus, pur—which means “the lot”—was cast before Haman concerning every day and every month, [until it fell on] the twelfth month, that is, the month of Adar.[12]

Purim narrative[edit]

The Book of Esther begins with a six-month (180-day) drinking feast given by King Ahasuerus of the Persian Empire for the army and Media and the satraps and princes of the 127 provinces of his kingdom, concluding with a seven-day drinking feast for the inhabitants of Shushan (Susa), rich and poor, and a separate drinking feast for the women organized by Queen Vashti in the pavilion of the royal courtyard.

At this feast, Ahasuerus gets thoroughly drunk, and at the prompting of his courtiers, orders his wife Vashti to display her beauty before the nobles and populace, wearing her royal crown. The rabbis of the Oral Torah interpret this to mean that he wanted her to wear only her royal crown, meaning that she would be naked. Her refusal prompts Ahasuerus to have her removed from her post. Ahasuerus then orders all young women to be presented to him, so he could choose a new queen to replace Vashti. One of these is Esther, who was orphaned at a young age and was being fostered by her first cousin Mordecai. She finds favor in the King’s eyes, and is made his new wife. Esther does not reveal her origins or that she is Jewish as Mordecai told her not to. Since the Torah permits an uncle to marry his niece and the choice of words used in the text, some rabbinic commentators state that she was actually Mordecai’s wife.

Shortly afterwards, Mordecai discovers a plot by two palace guards Bigthan and Teresh to kill Ahasuerus. They are apprehended and hanged, and Mordecai’s service to the King is recorded in the daily record of the court.[13]

Ahasuerus appoints Haman as his viceroy. Mordecai, who sits at the palace gates, falls into Haman’s disfavor as he refuses to bow down to him. Having found out that Mordecai is Jewish, Haman plans to kill not just Mordecai but the entire Jewish minority in the empire. Obtaining Ahasuerus’ permission and funds to execute this plan, he casts lots («purim») to choose the date on which to do this — the 14th of the month of Adar. When Mordecai finds out about the plans, he puts on sackcloth and ashes, a sign of mourning, publicly weeping and lamenting, and many other Jews in Shushan and other parts of Ahasuerus’ empire do likewise, with widespread penitence and fasting. Esther discovers what has transpired; there follows an exchange of messages between her and Mordecai, with Hatach, one of the palace servants, as the intermediary. Mordecai requests that she intercede with the King on behalf of the embattled Jews; she replies that nobody is allowed to approach the King, under penalty of death.

Mordecai warns her that she will not be any safer in the palace than any other Jew, says that if she keeps silent, salvation for the Jews will arrive from some other quarter but «you and your father’s house (family line) will perish,» and suggests that she was elevated to the position of queen to be of help in just such an emergency. Esther has a change of heart, says she will fast and pray for three days and will then approach the King to seek his help, despite the law against doing so, and «if I perish, I perish.» She also requests that Mordecai tell all Jews of Shushan to fast and pray for three days together with her. On the third day, she seeks an audience with Ahasuerus, during which she invites him to a feast in the company of Haman. During the feast, she asks them to attend a further feast the next evening. Meanwhile, Haman is again offended by Mordecai’s refusal to bow to him; egged on by his wife Zeresh and unidentified friends, he builds a gallows for Mordecai, with the intention to hang him there the very next day.[14]

That night, Ahasuerus suffers from insomnia, and when the court’s daily records are read to him to help him fall asleep, he learns of the services rendered by Mordecai in the earlier plot against his life. Ahasuerus asks whether anything was done for Mordecai and is told that he received no recognition for saving the King’s life. Just then, Haman appears, and King Ahasuerus asks him what should be done for the man that the King wishes to honor. Thinking that the King is referring to Haman himself, Haman says that the honoree should be dressed in the King’s royal robes and led around on the King’s royal horse. To Haman’s horror, the king instructs Haman to render such honors to Mordecai.[15]

Later that evening, Ahasuerus and Haman attend Esther’s second banquet, at which she reveals that she is Jewish and that Haman is planning to exterminate her people, which includes her. Ahasuerus becomes enraged and instead orders Haman hanged on the gallows that Haman had prepared for Mordecai. The previous decree against the Jewish people could not be nullified, so the King allows Mordecai and Esther to write another decree as they wish. They decree that Jewish people may preemptively kill those thought to pose a lethal risk. As a result, on 13 Adar, 500 attackers and Haman’s 10 sons are killed in Shushan. Throughout the empire 75,000 of the Jewish peoples’ enemies are killed.[16] On the 14th, another 300 are killed in Shushan. No spoils are taken.[17]

Mordecai assumes the position of second in rank to Ahasuerus, and institutes an annual commemoration of the delivery of the Jewish people from annihilation.[18]

Scriptural and rabbinical sources[edit]

The primary source relating to the origin of Purim is the Book of Esther, which became the last of the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible to be canonized by the Sages of the Great Assembly. It is dated to the 4th century BCE[19] and according to the Talmud was a redaction by the Great Assembly of an original text by Mordechai.[20]

The Tractate Megillah in the Mishnah (redacted c. 200 CE) records the laws relating to Purim. The accompanying Tosefta (redacted in the same period) and Gemara (in the Jerusalem and Babylonian Talmud redacted c. 400 CE and c. 600 CE respectively)[21] record additional contextual details such as Queen Vashti having been the daughter of Belshazzar as well as details that accord with Josephus’ such as Esther having been of royal descent. Brief mention of Esther is made in Tractate Hullin (Bavli Hullin 139b) and idolatry relating to worship of Haman is discussed in Tractate Sanhedrin (Sanhedrin 61b).

The work Esther Rabbah is a Midrashic text divided in two parts. The first part dated to c. 500 CE provides an exegetical commentary on the first two chapters of the Hebrew Book of Esther and provided source material for the Targum Sheni. The second part may have been redacted as late as the 11th century CE, and contains commentary on the remaining chapters of Esther. It too contains the additional contextual material found in the Josippon (a chronicle of Jewish history from Adam to the age of Titus believed to have been written by Josippon or Joseph ben Gorion).[22]

Historical views[edit]

Traditional historians[edit]

Haman defeated (1578 engraving)

The 1st-century CE historian Josephus recounts the origins of Purim in Book 11 of his Antiquities of the Jews. He follows the Hebrew Book of Esther but shows awareness of some of the additional material found in the Greek version (the Septuagint) in that he too identifies Ahasuerus as Artaxerxes and provides the text of the king’s letter. He also provides additional information on the dating of events relative to Ezra and Nehemiah.[23] Josephus also records the Persian persecution of Jews and mentions Jews being forced to worship at Persian erected shrines.[23][24]

The Josippon, a 10th-century CE compilation of Jewish history, includes an account of the origins of Purim in its chapter 4. It too follows the original biblical account and includes additional traditions matching those found in the Greek version and Josephus (whom the author claims as a source) with the exception of the details of the letters found in the latter works. It also provides other contextual information relating to Jewish and Persian history such as the identification of Darius the Mede as the uncle and father-in-law of Cyrus.[25]

A brief Persian account of events is provided by Islamic historian Muhammad ibn Jarir al-Tabari in his History of the Prophets and Kings (completed 915 CE).[26] Basing his account on Jewish and Christian sources, al-Tabari provides additional details such as the original Persian form «Asturya» for «Esther».[27] He places events during the rule of Ardashir Bahman (Artaxerxes II),[28] but confuses him with Ardashir al-Tawil al-Ba (Artaxerxes I), while assuming Ahasuerus to be the name of a co-ruler.[27] Another brief Persian account is recorded by Masudi in The Meadows of Gold (completed 947 CE).[29] He refers to a Jewish woman who had married the Persian King Bahman (Artaxerxes II), and delivered her people,[28][30][31] thus corroborating this identification of Ahasuerus. He also mentions the woman’s daughter, Khumay, who is not known in Jewish tradition but is well remembered in Persian folklore. Al-Tabari calls her Khumani and tells how her father (Ardashir Bahman) married her. Ferdowsi in his Shahnameh (c. 1000 CE) also tells of King Bahman marrying Khumay.[32]

19th-century Bible commentaries generally identify Ahasuerus with Xerxes I of Persia.[33]

Modern scholarship views[edit]

Some historians of the Near East and Persia argue that Purim does not actually have a historical basis. Amnon Netzer and Shaul Shaked argue that the names «Mordecai» and «Esther» are similar to those of the Babylonian gods Marduk and Ishtar.[34][35] Scholars W.S. McCullough, Muhammad Dandamayev and Shaul Shaked say that the Book of Esther is historical fiction.[35][36][37] Amélie Kuhrt says the Book of Esther was composed in the Hellenistic period and it shows a perspective of Persian court identical to classical Greek books.[38] Shaul Shaked says the date of composition of the book is unknown, but most likely not much after the fall of the Achaemenid kingdom, during the Parthian period, perhaps in the 3rd or 2nd century BCE.[35] McCullough also suggests that Herodotus recorded the name of Xerxes’s queen as Amestris (the daughter of Otanes) and not as Esther.[37] Scholars Albert I. Baumgarten and S. David Sperling and R.J. Littman say that, according to Herodotus, Xerxes could only marry a daughter of one of the six allies of his father Darius I.[39][40]

Observances[edit]

Purim has more of a national than a religious character, and its status as a holiday is on a different level from those days ordained holy by the Torah. Hallel is not recited.[41] As such, according to some authorities, business transactions and even manual labor are allowed on Purim under certain circumstances.[42] A special prayer (Al ha-Nissim – «For the Miracles») is inserted into the Amidah prayers during evening, morning and afternoon prayer services, and is also included in the Birkat Hamazon («Grace after Meals»).

The four main mitzvot (obligations) of the day are:[43]

- Listening to the public reading, usually in synagogue, of the Book of Esther in the evening and again in the following morning (k’riat megillah)

- Sending food gifts to friends (mishloach manot)

- Giving charity to the poor (matanot la’evyonim)

- Eating a festive meal (se’udat mitzvah)

The three latter obligations only apply during the daytime hours of Purim.[43]

Reading of the Megillah[edit]

Children during Purim in the streets of Jerusalem (2006)