Что такое прайды, зачем они нужны, почему нет «гетеро-парадов», а России необходим ЛГБТ-карнавал, по просьбе «Таких дел» объясняет журналист, открытый ВИЧ-положительный гей и православный верующий Борис Конаков

В июне начинается не только лето, но и «Месяц гордости» (Pride Month): представители ЛГБТ+сообщества собираются по всему миру, отмечая свободу и гордость быть собой. В России прайды проводятся в дикой нервозности и опасности. Это не похоже ни на праздник, ни даже на «Стоунволлские бунты» в США, положившие начало нашей борьбе за права.

Борис КонаковФото: из личного архива

Мы не успели выдохнуть после советского уголовного преследования гомосексуалов и понять, что нам нужно. Мы, как и все постсоветские люди, жадно глотали свободу и возможности 90-х, наслаждались «сытыми» нулевыми и упустили момент, когда гомофобия стала национальной идеей.

За эти 20 лет выросло мое поколение, для которого отсутствия статьи за «мужеложество» мало, однако протестный потенциал большинства из нас подавлен опасностью преследования уже даже за лайки и репосты. Мы вынуждены по большей части мириться или высмеивать клише о «развращающих гей-парадах» и «загнивающем Западе», терпеливо объясняя вам, почему нам важно «выпячивать».

Но обо всем по порядку.

Откуда взялось название и почему в июне?

Название «Месяц гордости» придумано бисексуальной активисткой из Нью-Йорка Брендой Говард. Ее называли «Матерью Гордости» за организацию первого прайда после «Стоунволлского бунта» в июне 1969 года. Радужный флаг придуман и выполнен в 1978 году художником и дизайнером Гилбертом Бейкером по заказу Харви Милка — члена городского наблюдательного совета Сан-Франциско и первого открытого гея на руководящей должности в США.

Бейкер не копировал радугу досконально (в «традиционной» радуге — семь цветов, а не шесть, как на флаге), но вдохновлялся ей, выражая идею, что внутри сообщества все люди разные. И сейчас есть несколько версий флага, где в том числе есть полоска радуги, посвященная движению Black Lives Matter, и отметка в память о наших ребятах, погибших от пандемии СПИДа.

Что такое «Стоунволлский бунт»? Почему он произошел?

27 июня 1969 года в нью-йоркский гей-бар «Стоунволл-Инн» ворвалась полиция. По тогдашним законам геям нельзя было отпускать спиртное: они считались лицами, нарушающими общественный порядок. Фактически единственное популярное и крупное место в городе, куда попадали исключительно по рекомендации и где люди могли побыть собой, раз в месяц подвергалось плановому рейду. Полиция выбирала будний день, предупреждала владельцев (которые, кстати, не были гомосексуалами и представляли один из местных мафиозных кланов) и наносила визит. Люди переставали обниматься, готовили документы, бармены прятали алкоголь. Полицейские кого-то избивали, брали взятку, уезжали.

Однако в этот день их не ждали. Как вспоминают очевидцы, кто-то из посетителей решил, что полиции мало денег, трансперсоны устали от унизительного осмотра на определение биологического пола (если одежда не соответствовала, их задерживали), наконец, всех вымотал полицейский произвол. Среди посетителей оказалось много тех, кому, в отличие от скрывавшихся высокопоставленных геев, было нечего терять: молодые бездомные геи, травести или, к примеру, транс-персоны Марша Пи Джонсон и Сильвия Ривера, вовлеченные в проституцию. Эти героические женщины жили до самой смерти в трущобах Нью-Йорка, несмотря на мировую славу после того, как они в числе многих возглавили сопротивление полицейскому насилию.

«После стольких лет унижений это одновременно пришло в голову всем, кто оказался в ту ночь в том самом месте, и это не являлось организованным протестом… Там находились разные люди, но всех объединяло нежелание мириться с полицейским беспределом. Мы попытались вернуть себе свободу. Мы стали требовать свободу. И мы больше не собирались прятаться в ночи. Как будто что-то витало в воздухе. Это был дух свободы. И мы поняли, что мы станем бороться за нее. И мы не собирались отступать», — вспоминал активист Майкл Фейдер. Кто-то в толпе крикнул: «Gay power!» — и началось.

Газета общества Mattachine Society, защищавшего права геев с 1950-х годов, писала, что напряжение в сообществе обострилось так, что любые репрессии могли вызвать взрыв. Послевоенная «охота на ведьм» сенатора Джозефа Маккарти против коммунистов переросла в гонения на все «антиамериканское», в том числе ЛГБТ-персон. Заместитель госсекретаря США Джеймс Уэбб заявил, что мы менее устойчивы эмоционально, чем «обычные люди», поэтому мы — патология.

Были созданы списки гомосексуалов и их окружения, а также подозреваемых в «гомосексуализме». В законодательствах 22 штатов любого гея или лесбиянку могли отправить на принудительное лечение, а кое-где кастрировать или стерилизовать.

Почему это стало важным в борьбе за права ЛГБТ?

Геи, лесбиянки, бисексуалы и транс-персоны стали создавать правозащитные организации, активистские медиа. В 1970 году по всей Америке прошли первые прайды. Уже в 1972 году мы праздновали первую победу — Американская ассоциация психиатров исключила «гомосексуализм» (тогда термин официально считался корректным, потому что ВОЗ исключила гомосексуальность из списка заболеваний лишь в 1993 году) из официального перечня психических расстройств.

«Гей-парады», которыми называют прайды, — это укоренившийся миф «благодаря» андроцентричности общества — взгляда на мир с мужской точки зрения и выдачи мужских нормативных представлений за единые социальные нормы и жизненные модели. Но прайды дают видимость разным людям.

Почему ЛГБТ-прайды возможны в современной России?

Праздник гордости — естественная реакция на трагедию, а российское общество намного толерантнее и эмпатичнее, чем внушает госпропаганда.

Любые карнавалы (carrus navalis — ритуальная повозка с идолами плодородия) — про единение Жизни и Смерти. Сатурналии в честь бога плодородия Сатурна в Древнем Риме — это изобилие напитков, еды, секса. Подобные праздники уравнивали людей. На нем выбирали «короля», и им мог стать кто угодно. Но в конце он должен был погибнуть. Считалось, что это почетно. Его приветствовали прохожие в масках «мертвых», скрывающих Настоящее и Прошлое, уравновешивающих яркие «жизненные» костюмы.

Позже карнавалы в Европе или колонизированной Бразилии ознаменовывали начало Великого поста перед Пасхой — воскрешением. Они допустимы, потому что исторически вписаны в «традиционные ценности».

Термин «карнавализация» введен литературоведом Михаилом Бахтиным: это результат воздействия традиций средневекового карнавала на культуру и мышление Нового времени. Концепция Бахтина разработана тогда, когда не было прайдов, аббревиатуры ЛГБТ, слов «гей», «лесбиянка» или «гомофобия». Однако она четко «ложится» на смысл прайдов как политического, культурного и даже в некоторой степени религиозного явления.

Карнавальное, по Бахтину, противостоит трагическому и эпическому. Когда художественное или жизненное явление (борьба ЛГБТ за свои права) карнавализируется, оно становится современным. Признак карнавала (прайда) — это отражение конечности и незавершенности всего сущего, смесь пародии, развенчания (например, общественных стереотипов) и потенциала обновления (мира без насилия).

Это веселая относительность происходящего, несоответствие между внешним и внутренним (пресловутые «мужики в юбках»), условиями и условностями настоящего и предчувствие возможного иного миропорядка, таящегося за фасадом вещей, ролей, поведений и языка. Когда мы весело «выпячиваем» себя, мы уже сейчас празднуем то, что в условном «завтра» нас перестанут за это бить.

Мы высмеиваем стереотипы с помощью пародии, гротескных образов, что созвучно советскому атеизму. И, на мой взгляд, именно это неосознанно пугает гомофобно настроенную часть российского общества.

Прайды в нынешнем российском контексте намеренно могут противопоставляться официальным праздникам и системе власти. Все официальное — устаревшее, отжившее, несущее неправду и насилие, а все карнавальное — новое, живое и свободное. Однако вот цитата лингвиста, филолога и культуролога Владимира Топорова, отмечающего, что карнавал не разрушает, а созидает.

«Для мифопоэтической эпохи любой мирской праздник соотнесен с сакральными ценностями коллектива, с его сакральной историей или с прецедентом, который может подвергаться сакрализации, — пишет ученый. — Главный праздник начинается в ситуации, связанной с напряженным ожиданием катастрофы мира. Психотерапевтическая функция ритуала и сопутствующего ему праздничного действа — в снятии этого напряжения, вовлечении участников ритуала и праздника в созидание нового мира, в проверку его связей и смыслов».

Прайд — наш «мирской» праздник, на котором мы транслируем общие для всех сакральные ценности — любовь, свободу, равенство. Спустя 50 лет «Стоунволл» — наш сакральный прецедент. И мы не требуем в конце праздника жертв. Нам их хватило

Любой праздник — это сложный и многомерный феномен, имеющий культурный и социальный смысл, экзистенциальное, метафизическое измерение. Он укоренен не только в индивидуальном, личностном бытии, но и в бытии социальном и сакральном. Праздник открывает человеку бытие личности, человеческой и божественной, возможность их встречи и совместного, согласного бытия в вечности.

«Итак, если ты будешь праздновать праздники, как я тебе изобразил, и будешь причащаться Божественных Таин, как я тебе указал, то вся жизнь твоя будет одно непрерывное празднество, одна непрестающая Пасха, — прехождение от видимого к невидимому, туда, где престанут все образы, сени [знаки] и символы празднеств, бывающих в настоящей жизни, и где вечно чистые вечно имеют наслаждаться чистейшею жертвою, Христом Господом, в Боге Отце и единосущном Духе, всегда созерцая Его и видимы бывая Им, сопребывая и соцарствуя с Ним, — выше и блаженнее чего ничего нет в Царствии Его» (преподобный Симеон Новый Богослов).

Почему ЛГБТ-прайды нужны современной России?

Прайды необходимы, пока в мире меня могут посадить, убить, не взять на работу или уволить за гомосексуальность, пока происходят коррекционные изнасилования лесбиянок, пока транс-персоны занимаются проституцией, потому что не могут поменять документы, пока некоторые психиатры считают, что меня можно вылечить, пока представители конфессий называют меня «грехом», пока я низведен в России до термина «пропаганда» .

Поэтому и нет «гетеро-парадов»: вам не нужно праздновать то, что вы выжили. Ваша ориентация социально одобряема и по умолчанию примеряется на всех .

Представьте себя на моем месте. Когда я выхожу в 2013 году на Марсово поле поддержать своих и в меня летит камень из руки православного батюшки, с которым мы верим в одного Бога. Когда я еду в соседнюю страну на прайд, отвечаю на приветствия и улыбки, но чувствую себя диссидентом. Затем приезжаю, иду на Дворцовую к товарищам и вот уже, словно щенок, схвачен за шкирку и закинут в автозак. И мне крупно повезло, что я живу открыто. Кто-то не может себе позволить это всю жизнь .

Попробуйте представить, как это — десятки лет играть по вашим правилам?

Еще больше важных новостей и хороших текстов от нас и наших коллег — в телеграм-канале «Таких дел». Подписывайтесь!

Гей-прайды: зачем ходить на них в путешествиях?

Что такой прайд, зачем их посещать и на что обратить внимание. Ну и попутное развенчание основных мифов, конечно!

Алена Крылова рассказывает, почему прайд — это уникальное событие и огромная удача для путешественника, если он спонтанно на него попадает!

Откуда взялись гей-парады и что они означают

Гей-парад, или прайд, — ежегодная акция, направленная на повышение видимости ЛГБТ. Это красочный праздник, включающий в себя развлекательные и просветительские мероприятия и завершающийся шествием по главным улицам города. Люди приходят на прайды вне зависимости от сексуальной ориентации и гендерной идентичности. Кроме того, они стали выгодным коммерческим предложением и привлекают туристов со всего мира.

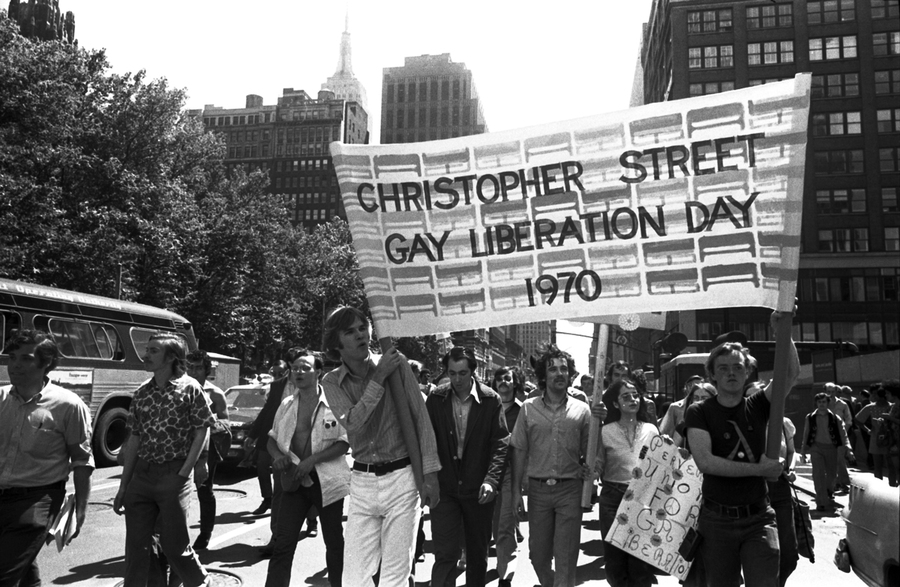

Большинство празднований традиционно проходит в июне — «месяце гордости». Это название закрепилось после Стоунволлских бунтов, прошедших в 1969 году. Формально восстания как такового не было. После очередного полицейского рейда в гей-клубе Stonewall Inn началась серия протестов и демонстраций в поддержку ЛГБТ. Представители сообщества впервые заговорили о своих правах. Спустя год в Нью-Йорке состоялась акция в память об этом событии — ее считают самым первым прайдом.

Изначально прайд был правозащитной акцией. В 1970-х годах лесбиянки, геи и трансгендеры только так могли обратить внимание на проблемы, с которыми сталкивается сообщество: о преступлениях на почве ксенофобии и повсеместной дискриминации. По мере развития ЛГБТ-движения прайды превратились в праздник, который, несмотря на кажущуюся легкомысленность, имеет глубокий бэкграунд.

Физическим символом прайда (и всего комьюнити) выступает радужный флаг. Придумал его художник и гражданский активист Гилберт Бейкер в 1978 году. Флаг состоит из шести цветов (в отличие от природной радуги, там нет голубого), каждый из которых имеет определенный смысл: красный — это жизнь, оранжевый — исцеление, желтый — солнце и так далее. Все вместе они говорят о многообразии идентичностей, входящих в состав ЛГБТ-сообщества.

Не все прайды выглядят как праздник или карнавал, и это напрямую связано с уровнем гомо- и трансфобии в стране. В частности, в Киеве и Вильнюсе шествие движется под охраной полиции, так как высока вероятность нападения провокаторов, а августовский прайд в Петербурге проходил в форме одиночных пикетов и завершился арестом десятка активистов. Такие акции, естественно, не ориентированы на туристов и играют сугубо правозащитную роль. Ту самую, с которой все начиналось в США.

Сейчас парады гордости организуют в более чем 50 странах мира. Крупнейшие проходят в Центральной и Северной Европе, США. А жителям Санкт-Петербурга ближе всего прайд в Хельсинки. Часть празднований запланирована даже на осень, потому еще есть шанс побывать на гей-параде на Мальте (14 сентября), в Роттердаме (28 сентября), Орландо или Лас-Вегасе (12 октября).

Как обычно проходит прайд?

При слове «гей-парад» многие представляют шествие с полуголыми людьми, нарушающими общественное спокойствие. Как все выглядит на самом деле? Радужные флаги развеваются над правительственными зданиями, торговые центры ломятся от товаров с ЛГБТ-тематикой, каждое второе заведение начинает позиционировать себя как гей-френдли — именно так крупные города готовятся к прайдам. В Европе и Америке они давно превратились в красочный праздник.

С точки зрения организации гей-парад проходит достаточно обыденно: примерно так выглядят народные гуляния. Разве что публика более колоритная. Участники и зрители собираются за полчаса-час до старта, в это время формируется пешая колонна, выстраиваются машины. Как и во время любых крупных праздников, перекрывают ключевые магистрали, а безопасность участников охраняют полицейские.

Маршрут стартует из центра города и проходит по нескольким улицам. Официальное открытие (речи организаторов и активистов) можно и пропустить, поэтому смело приходите с опозданием. На время шествия тротуары, ближайшие кафе, крыши домов превращаются в зрительские места. Местные наблюдают за шествием даже из окон своих квартир, а туристам удобнее всего занять место на открытой веранде. В этом случае можно лениво сидеть с чашкой кофе или бокалом вина, периодически делая фотографии. Лайфхак: стоит отойти чуть дальше по ходу шествия, и зрителей становится в разы меньше. Большая часть людей туда попросту не доходит.

Масштабные прайды включают несколько десятков колонн. Лесбиянки-феминистки, представители ЛГБТ с инвалидностью, делегаты от национальных общин и правозащитных организаций, бисексуалы, трансгендеры…. Автор этого текста хотел поступить так в Берлине и пожалел о своем желании. Спустя четыре часа удалось посмотреть две трети участников, при этом сильно устать: европейская жара, долгое нахождение на ногах, всюду толпы людей, шум, гам. Да и пик эмоций приходится на первые час-полтора.

Если душа требует движа, можно непосредственно присоединиться к параду. Ограничений и списков нет (за исключением машин-платформ), потому достаточно зайти в колонну на любом участке маршрута. Круто, если у вас будут вещи с радужной символикой. Перед прайдом можно приобрести носки, футболку или, например, маленький флажок. Впрочем, никто и слова не скажет, если вы будете выглядеть совершенно обыденно.

Негативные стороны гей-парада — перекрытые улицы, шум, мусор после шествия. Масштабные прайды напоминают фестиваль под открытым небом. Из машин доносится громкая музыка, участников осыпают дождиком и конфетти, а выпитые бутылки пива в лучшем случае складываются в одном месте. В худшем их разбивают прямо об асфальт, и любители пройтись босиком будут вытаскивать осколки где-нибудь под ближайшим деревом.

Еще прайд — это толпы людей, и в центре о тишине придется забыть. Как быть, если выйти на улицу все-таки хочется? Заранее посмотреть маршрут шествия и ничего не планировать в этом районе. В то же время на соседних улицах вполне спокойно, так что можно перемещаться по ним. Из-за перекрытых магистралей трудно (или невозможно) вызвать такси, повлияет событие и на работу автобусов и трамваев. Что касается метро, то непосредственно перед прайдом вагоны забиты участниками шествия. Все это стоит учитывать, чтобы не попасть в самое пекло.

Чем заняться на прайде?

Смотреть, смотреть и еще раз смотреть! Вот, пожалуй, главная установка для всех собирающихся на гей-парад. Ведь это самый настоящий маскарад, где каждый волен одеваться как хочет. Самые радикальные раздеваются догола и раскрашивают себя в цвета ЛГБТ-флага. Так что надо быть готовым к созерцанию обнаженных тел и к тому, что их обладатели могут захотеть обняться (личный опыт). Представители субкультур затягиваются в кожу и латекс, закрывают лица масками. Кто-то приходит в полностью радужном костюме: брюки, пиджак, кепка, сумка, зонт — кто больше.

Классические прайдовские образы связаны с единорогами и пони, стразами и блестками, обувью на высокой платформе и нарочито ярким макияжем. Последний наносят на себя вне зависимости от гендера. Так что борода в сочетании со стрелками на глазах и накладными ресницами — это вполне себе обыденная история. Растительность на лице заодно может быть выкрашена в голубой или зеленый — тут уж кому как больше нравится. Этот феномен получил название genderfuck — способ самовыражения, выражающийся в отказе от гендерных рамок.

Участники шествия с радостью позируют перед камерой и чаще всего готовы сделать совместное селфи. А когда еще представится возможность сфотографироваться с дрэг-дивой со шляпой в виде виноградных лоз или в образе радужной бабочки? Рядом с пешими участниками едут машины и платформы, представляющие общественные правозащитные движения и организации. Кто-нибудь обязательно танцует, кто-то обнимается, кто-то плавно переходит к стриптизу. В этом случае думаешь лишь: «Ну это же прайд, тут можно все!»

Pride event включает образовательные и культурные мероприятия: кинопоказы, выставки, воркшопы. Праздник завершается концертами, перфомансами и выступлениями квир-артистов. Еще одна важная составляющая прайдов — просветительская. Потому можно задавать вопросы участникам шествия (естественно, не нарушая ничьих личных границ), смело брать брошюры и флаеры.

Мифы и стереотипы: где тут правда

Собрание фриков, легальная оргия или акция борьбы? Вокруг прайдов сложилось множество заблуждений, появившихся из-за недостатка информации. Аудитория гей-парадов действительно выглядит очень ярко, нестандартно и местами эпатажно, но это личный выбор конкретных людей, которые пришли повеселиться. Развеем некоторые стереотипы, связанные с прайдами.

Геи в платьях

Чаще всего мужчины, одетые в женские наряды, — это дрэг-квин. Они могут иметь любую ориентацию, потому что платье само по себе не говорит о сексуальных предпочтениях человека. Оно сообщает лишь о том, что человеку нравятся платья. И да, это совершенно нормально для прайда. Даже после шествия можно на улицах можно встретить мужчин на каблуках и с ярко-красными губами.

Помимо этого, на шествии всегда присутствуют трансгендерные женщины (родившиеся в теле мужчины), находящиеся в стадии перехода или совершившие операцию по коррекции пола. Важно: некорректно называть их мужчинами, это вызывает сильный дискомфорт у человека и равносильно оскорблению.

Радуга, везде радуга

А вот это правда. Перед крупными прайдами город украшают так же яро, как перед Рождеством. Всюду висят радужные флаги и растяжки, а в магазинах полно товаров с соответствующей символикой. Ну а само шествие — настоящий взрыв красок. В тренде прикреплять радужные значки на радужные сумки и заодно красоваться в радужных предметах гардероба. Также организаторы и активисты часто раздают бесплатные флажки, стикеры с символикой прайда.

Прайд — пропаганда гомосексуальности?

Нет, нет и еще раз нет! Сексуальную ориентацию и гендерную идентичность нельзя продвигать. Что ориентация, что гендерная идентичность — вещи врожденные, и их нельзя изменить под чужим воздействием и по собственному желанию.

Детям здесь не место

Зависит от конкретного прайда и вовсе не связано с так называемой пропагандой. Ориентация и гендерная идентичность осознаются достаточно рано, потому ЛГБТ-дети и подростки могут идти в составе отдельного блока. Однако некоторые шествия больше напоминают шумный фестиваль с алкоголем, громкой музыкой и полупьяной молодежью. Так что если детям и не стоит туда ходить, то вовсе не из-за скопления ЛГБТ-людей. Бывают и вполне семейные прайды. Например, гей-парад в Хельсинки, куда многие приходят с детьми.

Вместо послесловия

Прайды проводятся более чем в 50 странах мира, в том числе в достаточно религиозных государствах. Старейшее и одно из крупнейших шествий проходит в Нью-Йорке, а популярными среди российских туристов являются парады в Берлине, Амстердаме, Стокгольме, Лондоне, Париже. Они собирают от 500 тысяч до миллиона человек. Чтобы попасть на парад, достаточно приехать в нужный город, узнать время начала шествия и его маршрут. Дальше — только веселье.

| Pride parade | |

|---|---|

The Stonewall Inn, in Greenwich Village, Manhattan, the site of the June 1969 Stonewall riots, which spawned the gay rights movement and pride parades around the world,[1][2][3] |

|

| Status | Active |

| Genre | Festival and parade |

| Frequency | Annually, often late June |

| Location(s) | Urban locations worldwide, incl. cities in the United States, Canada, Brazil and Japan |

| Years active | 52 |

| Inaugurated | June 27, 1970 in Chicago. June 28, 1970 in Los Angeles, New York City, and San Francisco. |

A pride parade (also known as pride march, pride event, or pride festival) is an outdoor event celebrating lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) social and self-acceptance, achievements, legal rights, and pride. The events sometimes also serve as demonstrations for legal rights such as same-sex marriage. Pride events occur in many urban areas in the United States, Canada, Brazil, Mexico, the United Kingdom, Japan, South Korea and Australia. Most occur annually while some take place every June to commemorate the 1969 Stonewall riots in New York City, a pivotal moment in modern LGBTQ social movements.[4] The parades seek to create community and honor the history of the movement.[opinion]

In 1970, pride and protest marches were held in Chicago, Los Angeles, New York City, and San Francisco around the first anniversary of Stonewall. The events became annual and grew internationally.[5] In 2019, New York and the world celebrated the largest international Pride celebration in history: Stonewall 50 — WorldPride NYC 2019, produced by Heritage of Pride commemorating the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall Riots, with five million attending in Manhattan alone. The most recent New York pride event was NYC Pride March 2022, which occurred on June 26, 2022.

Background[edit]

In 1965, the gay rights protest movement was visible at the Annual Reminder pickets, organized by members of the lesbian group Daughters of Bilitis, and the gay men’s group Mattachine Society. Mattachine members were also involved in demonstrations in support of homosexuals imprisoned in Cuban labor camps. All of these groups held protests at the United Nations and the White House, in 1965.[7] Early on the morning of Saturday, June 28, 1969, LGBTQ people rioted following a police raid on the Stonewall Inn in the Greenwich Village neighborhood of Lower Manhattan, New York City.[8][9] The Stonewall Inn was a gay bar which catered to an assortment of patrons, but which was popular with the most marginalized people in the gay community: transvestites, transgender people, effeminate young men, hustlers, and homeless youth.[10]

First pride marches[edit]

On Saturday, June 27, 1970, Chicago Gay Liberation organized a march[11] from Washington Square Park («Bughouse Square») to the Water Tower at the intersection of Michigan and Chicago avenues, which was the route originally planned, and then many of the participants spontaneously marched on to the Civic Center (now Richard J. Daley) Plaza.[12] The date was chosen because the Stonewall events began on the last Saturday of June and because organizers wanted to reach the maximum number of Michigan Avenue shoppers. Subsequent Chicago parades have been held on the last Sunday of June, coinciding with the date of many similar parades elsewhere.[citation needed]

The West Coast of the United States saw a march in San Francisco on June 27, 1970, and ‘Gay-in’ on June 28, 1970[13] and a march in Los Angeles on June 28, 1970.[14][15] In Los Angeles, Morris Kight (Gay Liberation Front LA founder), Reverend Troy Perry (Universal Fellowship of Metropolitan Community Churches founder) and Reverend Bob Humphries (United States Mission founder) gathered to plan a commemoration. They settled on a parade down Hollywood Boulevard. But securing a permit from the city was no easy task. They named their organization Christopher Street West, «as ambiguous as we could be.»[16] But Rev. Perry recalled the Los Angeles Police Chief Edward M. Davis telling him, «As far as I’m concerned, granting a permit to a group of homosexuals to parade down Hollywood Boulevard would be the same as giving a permit to a group of thieves and robbers.»[17] Grudgingly, the Police Commission granted the permit, though there were fees exceeding $1.5 million. After the American Civil Liberties Union stepped in, the commission dropped all its requirements but a $1,500 fee for police service. That, too, was dismissed when the California Superior Court ordered the police to provide protection as they would for any other group. The eleventh-hour California Supreme Court decision ordered the police commissioner to issue a parade permit citing the «constitutional guarantee of freedom of expression.» From the beginning, L.A. parade organizers and participants knew there were risks of violence. Kight received death threats right up to the morning of the parade. Unlike later editions, the first gay parade was very quiet. The marchers convened on Mccadden Place in Hollywood, marched north and turned east onto Hollywood Boulevard.[18] The Advocate reported «Over 1,000 homosexuals and their friends staged, not just a protest march, but a full-blown parade down world-famous Hollywood Boulevard.»[19]

On Sunday, June 28, 1970, at around noon, in New York gay activist groups held their own pride parade, known as the Christopher Street Liberation Day, to recall the events of Stonewall one year earlier. On November 2, 1969, Craig Rodwell, his partner Fred Sargeant, Ellen Broidy, and Linda Rhodes proposed the first gay pride parade to be held in New York City by way of a resolution at the Eastern Regional Conference of Homophile Organizations (ERCHO) meeting in Philadelphia.[20]

That the Annual Reminder, in order to be more relevant, reach a greater number of people, and encompass the ideas and ideals of the larger struggle in which we are engaged-that of our fundamental human rights-be moved both in time and location.

We propose that a demonstration be held annually on the last Saturday in June in New York City to commemorate the 1969 spontaneous demonstrations on Christopher Street and this demonstration be called «Christopher Street Liberation Day». No dress or age regulations shall be made for this demonstration.

We also propose that we contact homophile organizations throughout the country and suggest that they hold parallel demonstrations on that day. We propose a nationwide show of support.[21][22][23][24]

All attendees to the ERCHO meeting in Philadelphia voted for the march except for the Matta chine Society of New York City, which abstained.[21] Members of the Gay Liberation Front (GLF) attended the meeting and were seated as guests of Rodwell’s group, Homophile Youth Movement in Neighborhoods (HYMN).[25]

Meetings to organize the march began in early January at Rodwell’s apartment in 350 Bleecker Street.[26] At first there was difficulty getting some of the major New York organizations like Gay Activists Alliance (GAA) to send representatives. Craig Rodwell and his partner Fred Sargeant, Ellen Broidy, Michael Brown, Marty Nixon, and Foster Gunnison of Matta chine made up the core group of the CSLD Umbrella Committee (CSLDUC). For initial funding, Gunnison served as treasurer and sought donations from the national homophile organizations and sponsors, while Sargeant solicited donations via the Oscar Wilde Memorial Bookshop customer mailing list and Nixon worked to gain financial support from GLF in his position as treasurer for that organization.[27][28] Other mainstays of the GLF organizing committee were Judy Miller, Jack Waluska, Steve Gerrie and Brenda Howard.[29] Believing that more people would turn out for the march on a Sunday, and so as to mark the date of the start of the Stonewall uprising, the CSLDUC scheduled the date for the first march for Sunday, June 28, 1970.[30] With Dick Leitsch’s replacement as president of Mattachine NY by Michael Kotis in April 1970, opposition to the march by Mattachine ended.[31]

The first marches were both serious and fun, and served to inspire the widening LGBT movement; they were repeated in the following years, and more and more annual marches started up in other cities throughout the world.[opinion] In Atlanta and New York City the marches were called Gay Liberation Marches, and the day of celebration was called «Gay Liberation Day»; in Los Angeles and San Francisco they became known as ‘Gay Freedom Marches’ and the day was called «Gay Freedom Day». As more cities and even smaller towns began holding their own celebrations, these names spread. The rooted ideology behind the parades is a critique of space which has been produced to seem heteronormative and ‘straight’, and therefore any act appearing to be homosexual is considered dissident by society.[opinion] The Parade brings this queer culture into the space. The marches spread internationally, including to London where the first «gay pride rally» took place on 1 July 1972, the date chosen deliberately to mark the third anniversary of the Stonewall riots.[32]

In the 1980s, there was a cultural shift in the gay movement.[opinion] Activists of a less radical nature began taking over the march committees in different cities,[33] and they dropped «Gay Liberation» and «Gay Freedom» from the names, replacing them with «Gay Pride».

Revelers during a pride parade in Brooklyn

Description[edit]

Gay Pride Parade in New York City, 2008

Many parades still have at least some of the original political or activist character, especially in less accepting settings. The variation is largely dependent upon the political, economic, and religious settings of the area. However, in more accepting cities, the parades take on a festive or even Mardi Gras-like character, whereby the political stage is built on notions of celebration. Large parades often involve floats, dancers, drag queens and amplified music; but even such celebratory parades usually include political and educational contingents, such as local politicians and marching groups from LGBT institutions of various kinds. Other typical parade participants include local LGBT-friendly churches such as Metropolitan Community Churches, United Church of Christ, and Unitarian Universalist Churches, PFLAG, and LGBT employee associations from large businesses.[citation needed]

Even the most festive parades usually offer some aspect dedicated to remembering victims of AIDS and anti-LGBT violence. Some particularly important pride parades are funded by governments and corporate sponsors and promoted as major tourist attractions for the cities that host them. In some countries, some pride parades are now also called Pride Festivals. Some of these festivals provide a carnival-like atmosphere in a nearby park or city-provided closed-off street, with information booths, music concerts, barbecues, beer stands, contests, sports, and games. The ‘dividing line’ between onlookers and those marching in the parade can be hard to establish in some events, however, in cases where the event is received with hostility, such a separation becomes very obvious. There have been studies considering how the relationship between participants and onlookers is affected by the divide, and how space is used to critique the heteronormative nature of society.[citation needed]

Though the reality was that the Stonewall riots themselves, as well as the immediate and the ongoing political organizing that occurred following them, were events fully participated in by lesbian women, bisexual people, and transgender people, as well as by gay men of all races and backgrounds, historically these events were first named Gay, the word at that time being used in a more generic sense to cover the entire spectrum of what is now variously called the ‘queer’ or LGBT community.[34][35]

By the late 1970s and early 1980s, as many of the actual participants had grown older, moved on to other issues, or died, this passage of time led to misunderstandings as to who had actually participated in the Stonewall riots, who had actually organized the subsequent demonstrations, marches and memorials, and who had been members of early activist organizations such as Gay Liberation Front and Gay Activists Alliance. The language has become more accurate and inclusive, though these changes met with initial resistance from some in their own communities who were unaware of the historical events.[36] Changing first to Lesbian and Gay, today most are called Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender (LGBT) or simply «Pride».[citation needed] Pride parades are held in many urban areas and in many countries where the urbanization rate is at least 80%. The United States, Japan, the United Kingdom, South Korea, Canada, Australia, France, Spain, Chile, Argentina, Brazil and Mexico are the best countries for holding pride parades.

Notable pride events[edit]

Africa[edit]

Madagascar[edit]

Malawi[edit]

On 26 June 2021, a community of the LGBT community in Malawi held its first Pride Parade. The parade was held in the country’s capital city, Lilongwe.[37]

Mauritius[edit]

As of June 2006, the Rainbow Parade Mauritius is held every June in Mauritius in the town of Rose Hill. It is organized by the Collective Arc-En-Ciel, a local non-governmental LGBTI rights group, along with some other local non-governmental groups.[citation needed]

South Africa[edit]

Women marching in Joburg Pride parade in 2006

The first South African pride parade was held towards the end of the apartheid era in Johannesburg on October 13, 1990, the first such event on the African continent. Section Nine of the country’s 1996 constitution provides for equality and freedom from discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation among other factors.[38][39] The Joburg Pride organizing body disbanded in 2013 due to internal conflict about whether the event should continue to be used for political advocacy. A new committee was formed in May 2013 to organize a «People’s Pride», which was «envisioned as an inclusive and explicitly political movement for social justice».[40][41][42] Other pride parades held in the Johannesburg area include Soweto Pride which takes place annually in Meadowlands, Soweto, and Ekurhuleni Pride which takes place annually in KwaThema, a township on the East Rand. Pride parades held in other South African cities include the Cape Town Pride parade and Khumbu Lani Pride in Cape Town, Durban Pride in Durban, and Nelson Mandela Bay Pride in Port Elizabeth. Limpopo Pride is held in Polokwane, Limpopo.[citation needed]

Uganda[edit]

In August 2012, the first Ugandan pride parade was held in Entebbe to protest the government’s treatment of its LGBT citizens and the attempts by the Ugandan Parliament to adopt harsher sodomy laws, colloquially named the Kill the Gays Bill, which would include life imprisonment for aggravated homosexuality.[43] A second pride parade was held in Entebbe in August 2013.[44] The law was promulgated in December 2013 and subsequently ruled invalid by the Constitutional Court of Uganda on August 1, 2014 on technical grounds. On August 9, 2014, Ugandans held a third pride parade in Entebbe despite indications that the ruling may be appealed and/or the law reintroduced in Parliament and homosexual acts still being illegal in the country.[45]

Asia[edit]

East Timor[edit]

The first pride march in East Timor’s capital Dili was held in 2017.[46]

Hong Kong[edit]

Hong Kong pride parade 2014

The first International Day Against Homophobia pride parade in Hong Kong was held on May 16, 2005, under the theme «Turn Fear into Love», calling for acceptance and care amongst gender and sexual minorities in a diverse and friendly society.[47]

The Hong Kong Pride Parade 2008 boosted the rally count above 1,000 in the second largest East Asian Pride after Taipei’s. By now a firmly annual event, Pride 2013 saw more than 5,200 participants. The city continues to hold the event every year, except in 2010 when it was not held due to a budget shortfall.[48][49][50][non-primary source needed]

In the Hong Kong Pride Parade 2018, the event broke the record with 12,000 participants. The police arrested a participant who violated the law of «outraging public decency» by wearing only his underwear in an area of the road cordoned off for the parade.[51]

India[edit]

On June 29, 2008, four Indian cities (Delhi, Bangalore, Pondicherry, and Kolkata) saw coordinated pride events. About 2,200 people turned up overall. These were also the first pride events of all these cities except Kolkata, which had seen its first such event in 1999 — making it South Asia’s first pride walk and then had been organizing pride events every year since 2003 (although there was a gap of a year or so in-between).[52] The pride parades were successful, given that no right-wing group attacked or protested against the pride parade, although the opposition party BJP expressed its disagreement with the concept of gay pride parade. The next day, Prime Minister Manmohan Singh appealed for greater social tolerance towards homosexuals at an AIDS event. On August 16, 2008 (one day after the Independence Day of India), the gay community in Mumbai held its first-ever formal pride parade (although informal pride parades had been held many times earlier), to demand that India’s anti-gay laws be amended.[53] A high court in the Indian capital, Delhi ruled on July 2, 2009, that homosexual intercourse between consenting adults was not a criminal act,[54] although the Supreme Court later reversed its decision in 2013 under widespread pressure from powerful conservative and religious groups, leading to the re-criminalization of homosexuality in India.[55] Pride parades have also been held in smaller Indian cities such as Nagpur, Madurai, Bhubaneshwar and Thrissur. Attendance at the pride parades has been increasing significantly since 2008, with an estimated participation of 3,500 people in Delhi and 1,500 people in Bangalore in 2010.[citation needed] On September 6, 2018, sex between same-sex adults was legalized by India’s Supreme Court.

Tripura Queer Pride Walk in 1st Pride Festival in Tripura

On September 12, 2022, Tripura celebrated its first ‘Queer Pride Walk’ held in Agartala.[56] The major goal of the queer pride parade is to honor and celebrate lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender persons, as well as to raise awareness in society so that people can break free from the stigma and biases that surround them.[57] Swabhiman, a non-governmental organization, coordinated the Queer Pride Walk.[58] More than seven months after four transgender people in Tripura had a harrowing experience at a police station that went viral on social media, the state’s queer community held its first-ever pride walk on Monday in Agartala, claiming the right to live in dignity and equality, free of gender discrimination, stigma, and taboo for being different. Hundreds of lesbians, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) persons marched in the colorful pride parade, waving rainbow flags and holding banners urging people to reject gender stigma and sexuality stereotypes.[59] ‘Swabhiman’ President Sneha Gupta Roy asserted the necessity for the state to establish a Transgender Welfare Board to protect the rights of the gay community, adding, «The society must accept us as we are. We, too, are members of society and should not face discrimination. The source of societal biases, discrimination, and injustice directed at us is, surprisingly, a lack of knowledge. We, too, have the right to live with respect and dignity, and in order to do so, the Central Government must work to develop the community’s skills and create employment opportunities that will prevent members of the community from resorting to unethical means of income and thus becoming socially marginalized.»[60][61][62]

Israel[edit]

Tel Aviv hosts an annual pride parade,[63] attracting more than 260,000 people, making it the largest LGBT pride event in Asia.[64] Three Pride parades took place in Tel Aviv on the week of June 11, 2010. The main parade, which is also partly funded by the city’s municipality, was one of the largest ever to take place in Israel, with approximately 200,000 participants. The first Pride parade in Tel Aviv took place in 1993.[citation needed]

On June 30, 2005, the fourth annual Pride march of Jerusalem took place. The Jerusalem parade has been met with resistance due to the high presence of religious bodies in the city. It had originally been prohibited by a municipal ban which was canceled by the court. Many of the religious leaders of Jerusalem’s Muslim, Jewish, and Christian communities had arrived at a rare consensus asking the municipal government to cancel the permit of the parades.[citation needed]

Another parade, this time billed as an international event, was scheduled to take place in the summer of 2005, but was postponed to 2006 due to the stress on police forces during the summer of Israel’s unilateral disengagement plan. In 2006, it was again postponed due to the Israel-Hezbollah war. It was scheduled to take place in Jerusalem on November 10, 2006, caused a wave of protests by Haredi Jews around central Israel.[65] The Israel National Police had filed a petition to cancel the parade due to foreseen strong opposition. Later, an agreement was reached to convert the parade into an assembly inside the Hebrew University stadium in Jerusalem. June 21, 2007, the Jerusalem Open House organization succeeded in staging a parade in central Jerusalem after police allocated thousands of personnel to secure the general area. The rally planned afterwards was canceled due to an unrelated national fire brigade strike which prevented proper permits from being issued. The parade was postponed once more in 2014, as a result of Protective Edge Operation.[citation needed]

In 2022 local environmentalists from Tel Aviv started planning how to make the current year’s parade and future parades more sustainable, using composting stations and removing single use plastic from the largest pride parade in the Middle East.[66]

Japan[edit]

See also Pride Parade in Japan

The first Pride Parade in Japan was held on August 28, 1994, in Tokyo (while the names were not Pride Parade until 2007). In 2005, an administrative institution, the Tokyo Pride was founded to have Pride Parade constantly every year. In May 2011, Tokyo Pride was dissolved and most of the original management went on to found Tokyo Rainbow Pride.[67] The most recent Pride parade in Tokyo was Tokyo Rainbow Parade 2022, held on April 23 and 24, 2022.

- Tokyo

- 1994 –1999 Tokyo Lesbian Gay Parade, sponsored by a gay-oriented magazine

- 2000 – 2002, 2005–2006 Tokyo Lesbian & Gay Parade

- 2007 – 2010 Tokyo Pride Parade

- August 11, 2012, Save the Pride

- 2012 – present Tokyo Rainbow Pride, the successor organization to Tokyo Pride Parade and Tokyo Lesbian & Gay Parade.

- April 25 – 26, 2020 Rainbow Parade

- April 24 – 25, 2021 Rainbow Parade

- April 23 – 24, 2022 Rainbow Parade

- Other

- 1996–1999, 2001–2012 Rainbow March Sapporo

- May 13, 2006, Kobe gay parade, the Kansai’s first holding.

- 2007 LGBTIQ Pride March in Kobe 2007

- 2006 – 2007 Kansai Rainbow Parade

- May 4, 2007, Queer Rainbow Parade in Hakata

Lebanon[edit]

A rainbow flag flying in Mar Mkhayel, Beirut on May 20, 2017

Beirut Pride is the annual non-profit LGBTIQ+ pride event and militant march held in Beirut, the capital of the Lebanon, working to decriminalize homosexuality in Lebanon.[68] Since its inception in 2017, Beirut Pride has been the first and only LGBTIQ+ pride in the arabophone world, and its largest LGBTIQ+ event.[69][70] It has been the topic of four MA theses, one post-doctoral research and six documentaries, so far covered in 17 languages in 350 articles. Its first installment gathered 4,000 persons, and 2,700 people participated in the first three days of its 2018 edition,[71] before the police cracked it down and arrested its founder Hadi Damien. The next day, the prosecutor of Beirut suspended the scheduled activities, and initiated criminal proceedings against Hadi for organizing events “that incite to debauchery”.[72] Beirut Pride holds annual events adapted to the current circumstances in the country.

South Korea[edit]

Queer Culture Festivals in South Korea consist of pride parades and various other LGBT events, such as film festivals. Currently there are eight Queer Culture Festivals, including Seoul Queer Culture Festival (since 2000), Daegu Queer Culture Festival (since 2009), Busan Queer Culture Festival (since 2017), Jeju Queer Culture Festival (since 2017), Jeonju Queer Culture Festival (since 2018), Gwangju Queer Culture Festival (since 2018), and Incheon Queer Culture Festival (since 2018).[73]

Nepal[edit]

Nepal Pride Parade is organized on June 29 every year. There are also Pride Parades organized by Blue Diamond Society and Mitini Nepal. A youth-led pride parade which uses broader umbrella terms as Queer and MOGAI, is organized by Queer Youth Group and Queer Rights Collective. Blue Diamond Society’s rally on Gai Jatra is technically not considered as a Pride Parade.[74] Mitini Nepal organizes Pride Parades on Feb 14 while, a Queer Womxn Pride is also organized on International Women’s Day.[citation needed]

Philippines[edit]

In 1992, the Lesbian Collective marched during the Internal Women’s Day celebrations only to be met with opposition by progressive feminist movements marching.[75]

In 1993, UP Babaylan, a LGBT student support group, participated in the University of the Philippines Diliman’s Lantern March. Thanks to the positive reception from this march, members of UP Babaylan would participate in any future Lantern Marches.[75]

On June 26, 1994, to celebrate the 25th anniversary of the Stonewall Riots, Progressive Organization of Gays in the Philippines (Pro Gay Philippines) and Metropolitan Community Church (MCC) Manila organized the first LGBT Pride March in Philippines, marching from EDSA corner Quezon Avenue to Quezon City Memorial Circle (Quezon City, Metro Manila, Philippines) and highlighting broad social issues. At Quezon City Memorial Circle, a program was held with a Queer Pride Mass and solidarity remarks from various organizations and individuals.

In 1995, Pro Gay Philippines and MCC did not lead a pride parade. In 1996, 1997 and 1998 large and significant marches were organized and produced by Reach Out AIDS Foundation, all of which were held in Malate, Manila, Philippines.[76] These pride parades were organized a celebration of gay pride, but also were parading to raise awareness for discrimination and the misinformation surrounding AIDS.[77]

In 1999, Reach Out Aids Foundation handed its organization to a newly formed Task Force Pride Philippines (TFP), a network of LGBT and LGBT-friendly groups and individuals seeking to promote positive visibility for the LGBT community. In 2003, a decision was made to move the Pride March from June to the December Human Rights Week to coincide with related human rights activities such as World AIDS Day (December 1), Philippine National Lesbian Day (December 8), and International Human Rights Day (December 10). TFP organized the pride parades for two decades before the Metro Manila Pride organization would assume responsibility in 2016.[75]

On December 10, 2005, the First LGBT Freedom March, with the theme «CPR: Celebrating Pride and Rights» was held along the streets of España and Quiapo in Manila, Philippines. Concerned that the prevailing economic and political crisis in the country at the time presented threats to freedoms and liberties of all Filipinos, including sexual and gender minorities, LGBT individuals and groups, non-government organizations and members of various communities and sectors organized the LGBT Freedom March calling for systemic and structural change. At historic Plaza Miranda, in front of Quiapo Church, despite the pouring rain, a program with performances and speeches depicting LGBT pride was held soon after the march.

In 2007, the first transgender women’s group participated in the Metro Manila Pride March.[75]

On December 6, 2014, Philippines celebrated the 20th anniversary of the Metro Manila Pride March with the theme: Come Out for Love Kasi Pag-ibig Pa Rin (Come Out for Love Because It’s Still All About Love).[78] The theme is a reminder of the love and passion that started and sustained 20 years of taking to the streets for the recognition and respect of LGBT lives as human lives. It is also a celebration of and an invitation for families, friends, and supporters of LGBT people to claim Metro Manila Pride as a safe space to voice their support for the community, for the LGBT human rights advocacy, and for the people they love and march with every year.

Taiwan[edit]

Taipei hosts an annual Gay Pride Parade in October. Recently in 2019, the 17th Taiwan LGBT parade is the first gay parade after Taiwan ‘s same-sex marriage legislation, with attendances of over 200,000,[79] which the largest such event in East Asia.

On November 1, 2003, the first Taiwan Pride was held in Taipei with over 1,000 people attending. The parade held in September 2008 attracted around 18,000 attendances.[80] After 2008, the numbers grew rapidly. In 2009, around 5,000 people under the slogan «Love out loud» (Chinese: 同志愛很大). In 2010, despite bad weather conditions the Taiwan gay parade «Out and Vote» attracted more than 30,000 people. Other parades take place at cities throughout Taiwan in: Kaohsiung, Taichung, Tainan, Yilan, Hsinchu and East of Taiwan.[citation needed] In 2022, 120,000 people participated in the Taipei Pride march.[81]

Thailand[edit]

The first ever Pride parade was held in Bangkok on 6 June 2022.

Vietnam[edit]

On August 3, 2012, the first LGBT Viet Pride event was held in Hanoi, Vietnam with indoor activities such as film screenings, research presentations, and a bicycle rally on August 5, 2012, that attracted almost 200 people riding to support the LGBT cause. Viet Pride has since expanded, now taking place in 17 cities and provinces in Vietnam in the first weekend of August, attracting around 700 bikers in 2014 in Hanoi, and was reported on many mainstream media channels.[82]

Europe[edit]

Southeastern Europe[edit]

The first southeastern European Pride, called The Internationale Pride, was assumed to be a promotion of the human right to freedom of assembly in Croatia and some Eastern European states, where such rights of the LGBT population are not respected, and a support for organising the first Prides in those communities. Out of all ex-Yugoslav states, at that time only Slovenia and Croatia had a tradition of organising Pride events, whereas the attempt to organize such an event in Belgrade, Serbia in 2001, ended in a bloody showdown between the police and the counter-protesters, with the participants heavily beaten up. This manifestation was held in Zagreb, Croatia from June 22–25, 2006 and brought together representatives of those Eastern European and Southeastern European countries where the sociopolitical climate is not ripe for the organization of Prides, or where such a manifestation is expressly forbidden by the authorities. From 13 countries that participated, only Poland, Slovenia, Croatia, Romania and Latvia have been organizing Prides. Slovakia also hosted the pride, but encountered many problems with Slovak extremists from Slovenska pospolitost (the pride did not cross the centre of the city). North Macedonia and Albania also host Pride Parades with no major issues arising, mainly due to the protection from police. Lithuania has never had Prides before. There were also representatives from Kosovo, that participated apart from Serbia. It was the first Pride organized jointly with other states and nations, which only ten years ago have been at war with each other. Weak cultural, political and social cooperation exists among these states, with an obvious lack of public encouragement for solidarity, which organizers hoped to initiate through that regional Pride event. The host and the initiator of The Internationale LGBT Pride was Zagreb Pride, which has been held since 2002.[citation needed]

Bosnia and Herzegovina[edit]

The first Pride parade in Bosnia and Herzegovina was held on 8 September 2019 in Sarajevo under the slogan Ima Izać’ (Coming Out).[83] Around 4000 people, including foreign diplomats, members of the local government and celebrities participated amidst a strong police presence.[84] According to a 2021 study, the first LGBT+ Pride parade in Sarajevo led to increased support for LGBT activism in Sarajevo. It did not however diffuse nationwide.[83]

Bulgaria[edit]

Like the other countries from the Balkans, Bulgaria’s population is very conservative when it comes to issues like sexuality.[citation needed]

Although homosexuality was decriminalized in 1968, people with different sexual orientations and identities are still not well accepted in society.[citation needed]

In 2003 the country enacted several laws protecting the LGBT community and individuals from discrimination. In 2008, Bulgaria organized its first ever pride parade. The almost 200 people who had gathered were attacked by skinheads[citation needed]

, but police managed to prevent any injuries. The 2009 pride parade, with the motto «Rainbow Friendship» attracted more than 300 participants from Bulgaria and tourists from Greece and Great Britain. There were no disruptions and the parade continued as planned. A third Pride parade took place successfully in 2010, with close to 800 participants and an outdoor concert event.[citation needed]

Croatia[edit]

First pride parade in Croatia was held on 29 June 2002 in Zagreb and has been held annually ever since. The attendance has gradually grown from 350 in 2002 to 15.000 in 2013.[85] Pride parades are also held in Split (since 2011) and Osijek (since 2014).[citation needed]

Denmark[edit]

The Copenhagen Pride festival is held every year in August. In its current format, it has been held every year since 1996, where Copenhagen hosted EuroPride. Before 1994 the national LGBT association organised demonstration-like freedom marches. Copenhagen Pride is a colourful and festive occasion, combining political issues with concerts, films and a parade. The focal point is the City Hall Square in the city centre. It usually opens on the Wednesday of Pride Week, culminating on the Saturday with a parade and Denmark’s Mr Gay contest. In 2017, some 25,000 people took part in the parade with floats and flags, and about 300,000 were out in the streets to experience it.[86]

The smaller Aarhus Pride in held every year in June in the Jutlandic city of Aarhus.[87]

Estonia[edit]

The Baltic Pride event was held in Tallinn in 2011, 2014 and 2017.[88]

Finland[edit]

The Helsinki Pride was first organized in 1975 and called Freedom Day. It has grown into one of the biggest Nordic Pride events. Between 20,000 and 30,000 people participate in the Pride and its events annually, including a number of international participants from the Baltic countries and Russia.[89] There have been a few incidents over the years, the most serious one being a gas and pepper spray attack in 2010[90] hitting around 30 parade participants, among those children.[91] Three men were later arrested.[citation needed]

In addition to Helsinki, several other Finnish cities such as Tampere, Turku, Lahti, Oulu and Rovaniemi have hosted their own Pride events. Even small Savonian town of Kangasniemi with just 5,000 inhabitants hosted their own Pride first time in 2015.[92]

France[edit]

Paris Pride hosts an annual Gay Pride Parade last Saturday in June, with attendances of over 800,000.[93] Eighteen other parades take place at cities throughout France in: Angers, Biarritz, Bayonne, Bordeaux, Caen, Le Mans, Lille, Lyon, Marseille, Montpellier, Nancy, Nantes, Nice, Paris, Rennes, Rouen, Strasbourg, Toulouse and Tours.[94]

Germany[edit]

Both Berlin Pride and Cologne Pride claim to be one of the biggest in Europe. The first so-called Gay Freedom Day took place on June 30, 1979, in both cities. Berlin Pride parade is now held every year the last Saturday in July. Cologne Pride celebrates two weeks of supporting cultural programme prior to the parade taking place on Sunday of the first July weekend. An alternative march used to be on the Saturday prior to the Cologne Pride parade, but now takes place a week earlier. Pride parades in Germany are often called Christopher Street Days — named after the street where the Stonewall Inn was located.[95]

Greece[edit]

In Greece, endeavours were made during the 1980s and 1990s to organise such an event, but it was not until 2005 that Athens Pride was established. The Athens Pride is held every June in the centre of Athens city.[96] As of 2012, there is a second pride parade taking place in the city of Thessaloniki. The Thessaloniki Pride is also held annually every June. 2015 and 2016 brought two more pride parades, the Crete Pride taking place annually in Crete and the Patras Pride, that was held in Patras for the first time in June 2016.[97][98]

Greenland[edit]

In May 2010, Nuuk celebrated its first pride parade. Over 1,000 people attended.[99] It has been repeated every year since then, part of a festival called Nuuk Pride.[citation needed]

Iceland[edit]

First held in 1999, Reykjavík Pride celebrates its 20th anniversary in 2019. Held in early August each year, the event attracts up to 100,000 participants – approaching a third of Iceland’s population.[citation needed]

Ireland[edit]

The Dublin Pride Festival usually takes place in June. The Festival involves the Pride Parade, the route of which is from O’Connell Street to Merrion Square. However, the route was changed for the 2017 Parade due to Luas Cross City works.

The parade attracts thousands of people who line the streets each year. It gained momentum after the 2015 Marriage Equality Referendum.[citation needed]

Italy[edit]

Italian lesbian organisation Arcilesbica at the National Italian Gay Pride march in Grosseto, Italy, in 2004

The first public demonstration within the LGBT community in Italy took place in San Remo on April 5, 1972 as a protest against the International Congress on Sexual Deviance organized by the Catholic-inspired Italian Center of Sexology. The event was attended by about forty people belonging to various homophile groups, including ones from France, Belgium, Great Britain’s Gay Liberation Front, and Italy’s activist homosexual rights group Fuori! [it].[100]: 54–59

The first Italian event specifically associated with international celebrations of Gay Pride was the sixth congress of Fuori! held in Turin in late June 1978 and included a week of films on gay subjects.[100]: 103 Episodes of violence against homosexuals were frequent in Italy, such as in the summer of 1979 when two young gay men were killed in Livorno. In Pisa in November of that year, the Orfeo Collective [it] organized the first march against anti-gay violence. Around 500 gay and lesbian participants attended, and this remained the largest gathering of the kind until 1994.[100]: 122–124

Later, a system of «national Pride» observances designated one city to hold the official events, starting with Rome in 1994. Starting in 2013, the organization Onda Pride organized additional events, and in 2019 events were organized in 39 cities nationwide.[citation needed]

Latvia[edit]

On July 22, 2005, the first Latvian gay pride march took place in Riga, surrounded by protesters. It had previously been banned by the Riga City Council, and the then-Prime Minister of Latvia, Aigars Kalvītis, opposed the event, stating Riga should «not promote things like that», however a court decision allowed the march to go ahead.[101] In 2006, LGBT people in Latvia attempted a Parade but were assaulted by «No Pride» protesters, an incident sparking a storm of international media pressure and protests from the European Parliament at the failure of the Latvian authorities to adequately protect the Parade so that it could proceed.[citation needed]

In 2007, following international pressure, a Pride Parade was held once again in Riga with 4,500 people parading around Vērmane Garden, protected physically from «No Pride» protesters by 1,500 Latvian police, with ringing the inside and the outside of the iron railings of the park. Two fire crackers were detonated with one being thrown from outside at the end of the festival as participants were moving off to the buses. A man and his son were afterwards arrested by the police.[102] This caused some alarm but no injury, although participants did have to run the gauntlet of «No Pride» abuse as they ran to the buses. They were driven to a railway station on the outskirts of Riga, from where they went to a post Pride «relax» at the seaside resort of Jūrmala. Participants included MEPs, Amnesty International observers and random individuals who travelled from abroad to support LGBT Latvians and their friends and families.[citation needed]

In 2008, the Riga Pride was held in the historically potent 11. novembra krastmala (November 11 Embankment) beneath the Riga Castle. The participants heard speeches from MEPs and a message of support from the Latvian President. The embankment was not open and was isolated from the public with some participants having trouble getting past police cordons. About 300 No Pride protesters gathered on the bridges behind barricades erected by the police who kept Pride participants and the «No Pride» protesters separated. Participants were once more «bused» out but this time a 5-minute journey to central Riga.[citation needed]

In 2009, the annual Baltic Pride was launched, with the first edition being held in Riga with a march. This event and the following ones have been held without serious incidents.[103]

The 2012 Baltic Pride was held on June 2. The parade marched through Tērbatas street from the corner of Ģertrūdes street towards Vērmane Garden, where concerts and a conference were held. The events were attended by the United States Ambassador to Latvia Judith Garber and the Latvian Minister of Foreign Affairs, Edgars Rinkēvičs.[102]

In 2015, Riga hosted the pan-European EuroPride event with about 5000 participants engaging in approximately 50 cultural and entertainment events.[104]

The Baltic Pride event returned to Riga in 2018, the year of the centenary of the independence of Latvia and all three Baltic states. An estimated 8000 people took part.[105] The events took place for 100 days from March 3 to June 10 with the parade being held through the city on June 9.[106][107]

Lithuania[edit]

In 2010 first pride parade — the 2nd Baltic Pride — in Lithuania was held in Vilnius. About 300 foreign guests marched through the streets along the local participants. Law was enforced with nearly a thousand policemen.[citation needed]

The city also hosted the event in 2013 and 2016 gathering around 3 thousand participants each year.[citation needed]

The 2019 Baltic Pride was held on June 4–9 in Vilnius. An estimated 10 thousand people marched through the central part of the city.[citation needed]

Netherlands[edit]

Amsterdam’s pride parade is held in its canals

In Amsterdam, a Pride Pride has been held since 1996. The week(end)-long event involves concerts, sports tournaments, street parties and most importantly the Canal Pride, a parade on boats on the canals of Amsterdam. In 2008 three government ministers joined on their own boat, representing the whole cabinet. Mayor of Amsterdam Job Cohen also joined. About 500,000 visitors were reported. 2008 was also the first year large Dutch international corporations ING Group and TNT NV sponsored the event.[citation needed]

The Utrecht Canal Pride is the second largest gay pride in the country, organised annually since 2017.[108] Smaller Pride parades are organised in many larger cities across the country.[citation needed]

Poland[edit]

The oldest pride parade in Poland, the Equality Parade in Warsaw, has been organized since 2001. In 2005, the parade was forbidden by local authorities (including then-Mayor Lech Kaczyński) but occurred nevertheless. The ban was later declared a violation of the European Convention on Human Rights (Bączkowski and Others v. Poland). In 2008, more than 1,800 people joined the march. In 2010 EuroPride took place in Warsaw with approximately 8,000 participants. The last parade in Warsaw, in 2019, drew 80,000 people. Other Polish cities which host pride parades are Kraków, Łódź, Poznań, Gdańsk, Toruń, Wrocław, Lublin, Częstochowa, Rzeszów, Opole, Zielona Góra, Konin, Bydgoszcz, Szczecin, Kalisz, Koszalin, Olsztyn, Kielce, Gniezno, Katowice, Białystok, Radomsko, and Płock.[citation needed]

Portugal[edit]

In Lisbon, the Pride Parade, known as Marcha do Orgulho LGBTI+, has been held every year since 2000, as well as in Porto since 2006.[109] In 2017, Funchal hosted their first Pride Parade.[110]

Russia[edit]

Moscow Pride protest in 2008

Prides in Russia are generally banned by city authorities in St. Petersburg and Moscow, due to opposition from politicians and religious leaders.[citation needed] Moscow Mayor Yuri Luzhkov has described the proposed Moscow Pride as «satanic».[111] Attempted parades have led to clashes between protesters and counter-protesters, with the police acting to keep the two apart and disperse participants. In 2007 British activist Peter Tatchell was physically assaulted.[112] This was not the case in the high-profile attempted march in May 2009, during the Eurovision Song Contest. In this instance the police played an active role in arresting pride marchers. The European Court of Human Rights has ruled that Russia has until January 20, 2010 to respond to cases of pride parades being banned in 2006, 2007 and 2008.[113] In June 2012, Moscow courts enacted a hundred-year ban on pride parades.[114]

Serbia[edit]

On June 30, 2001, several Serbian LGBTQ groups attempted to hold the country’s first Pride march in Belgrade. When the participants started to gather in one of the city’s principal squares, a huge crowd of opponents attacked the event, injuring several participants and stopping the march. The police were not equipped to suppress riots or protect the Pride marchers. Some of the victims of the attack took refuge in a student cultural centre, where a discussion was to follow the Pride march. Opponents surrounded the building and stopped the forum from happening. There were further clashes between police and opponents of the Pride march, and several police officers were injured.[115][116]

Non-governmental organizations and a number of public personalities criticised the assailants, the government and security officials. Government officials did not particularly comment on the event, nor were there any consequences for the approximately 30 young men arrested in the riots.[115][116]

On July 21, 2009, a group of human rights activists announced their plans to organize second Belgrade Pride on September 20, 2009. However, due to the heavy public threats of violence made by extreme right organisations, Ministry of Internal Affairs in the morning of September 19 moved the location of the march from the city centre to a space near the Palace of Serbia therefore effectively banning the original 2009 Belgrade Pride.[117]

Belgrade Pride parade was held on October 10, 2010 with about 1000 participants[118] and while the parade itself went smoothly, a riot broke out in which 5600 police clashed with six thousand anti-gay protesters[119] at Serbia’s second ever Gay Pride march attempt, with nearly 147 policemen and around 20 civilians reported wounded in the violence. Every attempt of organizing the parade between 2010 and 2014 was banned.[120]

In 2013, the plan was to organize the parade on September 28. It was banned by the government only a day before on September 27.[121] Only a few hours after, a few hundreds of protesters gathered in front of the Serbian Government building in Nemanjina street and marched to the Parliament building in Bulevar kralja Aleksandra.[122]

In 2014, the pride parade was allowed to be held on September 28. It was protected by 7,000 police and went smoothly. There were some incidents and violence around the city, but on a smaller scale than previous times the parade was held.[123]

In 2015, the pride parade, as well as a trans pride, was held on 20 September with no incidents.[124]

In 2016, for the first time alternative pride parade called Pride Serbia was held on 25 June,[125] and the Belgrade Pride was held on 18 September. Both were held with no incidents.[126]

In 2017, three pride parades were held with no incidents, two in Belgrade[127] and one in Niš.[128]

In 2018, Belgrade Pride was attended by thousands of people and it became one of the biggest Pride Parade festival in the region.

Slovenia[edit]

Although first LGBTQ festival in Slovenia dates to 1984, namely the Ljubljana Gay and Lesbian Film Festival, the first pride parade was only organized in 2001 after a gay couple was asked to leave a Ljubljana café for being homosexual.[129] Ljubljana pride is traditionally supported by the mayor of Ljubljana and left-wing politicians.[130]

On June 30, 2019, Maribor held their first pride parade which was largely supported by several embassy ambassadors and other organizations.[131]

Spain[edit]

More than 500,000 people in Europride 2007 pride parade in Madrid

Madrid Pride Parade, known as Fiesta del Orgullo Gay (or simply Fiesta del Orgullo), Manifestación Estatal del Orgullo LGTB and Día del Orgullo Gay (or simply Día del Orgullo), is held the first Saturday after June 28[132] since 1979.[133]

The event is organised by COGAM (Madrid GLTB Collective) and FELGTB (Spanish Federation of Lesbians, Gays, Transsexuals and Bisexuals) and supported by other national and international LGTB groups. The first Gay Pride Parade in Madrid was held in June 1979 nearly four years after the death of Spain’s dictator Francisco Franco, with the gradual arrival of democracy and the de-criminalization of homosexuality. Since then, dozens of companies like Microsoft, Google and Schweppes and several political parties and trade unions, including Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party, PODEMOS, United Left, Union, Progress and Democracy, CCOO and UGT have been sponsoring and supporting the parade. Madrid Pride Parade is the biggest gay demonstration in Europe, with more than 1.5 million attendees in 2009, according to the Spanish government.[citation needed]

In 2007, Europride, the European Pride Parade, took place in Madrid. About 2.5 million people attended more than 300 events over one week in the Spanish capital to celebrate Spain as the country with the most developed LGBT rights in the world. Independent media estimated that more than 200,000 visitors came from foreign countries to join in the festivities. Madrid gay district Chueca, the biggest gay district in Europe, was the centre of the celebrations. The event was supported by the city, regional and national government and private sector which also ensured that the event was financially successful. Barcelona, Valencia and Seville hold also local Pride Parades. In 2008 Barcelona hosted the Eurogames.[citation needed]

In 2014, Winter Pride Maspalomas was held for the first time at Maspalomas, Gran Canaria, Canary Islands, one of one Europe’s most popular LGTB tourist destinations. Within a few years of its existence, Winter Pride Maspalomas became a major Pride celebration within Spain and Europe. During its 6th edition in November 2019, the Pride Walk LGBT equal rights march had over 18,000 international visitors.[134]

In 2017, Madrid hosted the WorldPride. It would be the first time WorldPride was celebrated in a Spanish city.[135][136][137][138]

Sweden[edit]

The Stockholm Pride, sometimes styled as STHLM Pride, is the biggest annual Pride event in the Nordic countries with over 60,000 participants early and 600,000 people following the parade. The Stockholm Pride is notable for several officials such as the Swedish Police Authority and Swedish Armed Forces having their own entities in the parade.[139]

Several Swedish cities have their own Pride festivals, most notably Gothenburg and Malmö. In 2018, Stockholm Pride and Gothenburg West Pride, co-hosted the 25th annual EuroPride parade.[140]

Turkey[edit]

Turkey was the first Muslim-majority country in which a gay pride march was held.[141] However, the parades have been banned nationwide since 2015. Authorities cite security concerns and threats from far-right and Islamist groups, but severe police retrubution against marchers had led to accusations of discrimination tied to the country’s increasing Islamization under Erdogan.[142]

In Istanbul (since 2003), in Ankara (since 2008) and in Izmir (since 2013) LGBT marches were being held each year with an increasing participation. Gay pride march in Istanbul started with 30 people in 2003 and in 2010 the participation became 5,000. The pride March 2011 and 2012 were attended by more than 15,000 participants.

On June 30, 2013, the pride parade attracted almost 100,000 people.[143] The protesters were joined by Gezi Park protesters, making the 2013 Istanbul Pride the biggest pride ever held in Turkey.[144] On the same day, the first Izmir Pride took place with 2000 participants.[145] Another pride took place in Antalya.[146] Politicians of the biggest opposition party, CHP and another opposition party, BDP also lent their support to the demonstration.[147] The pride march in Istanbul does not receive any support of the municipality or the government.[148]

On June 28, 2015, police in Istanbul interrupted the parade, which the organisers said was not permitted that year due to the holy month Ramadan,[149] by firing pepper spray and rubber bullets.[150][151][152]

United Kingdom[edit]

Lesbian Strength March 1983, UK

There are five main pride events in the UK LGBT pride calendar: London, Brighton, Liverpool, Manchester, and Birmingham being the largest and are the cities with the biggest gay populations.[citation needed]

Pride in London is one of the biggest in Europe and takes place on the final Saturday in June or first Saturday in July each year. London also hosted a Black Pride in August and Soho Pride or a similar event every September. During the early-1980s, there was a women-only Lesbian Strength march held each year a week before the Gay Pride march. 2012 saw World Pride coming to London.[citation needed]

Starting in 2017, there is a Pride parade for the city’s Black community that takes place the day after the main Pride parade, at the Vauxhall Gardens.[153] In February 2018, the charity Stonewall announced that they would support Black Pride instead of the main Pride parade.[154]

Brighton Pride is held on the first Saturday of August (apart from in 2012 when the event was moved to September due to the 2012 Olympics). The event starts from the seafront and culminating at Preston Park.[155]

Liverpool Pride was launched in 2010, but by 2011 it became the largest free Gay Pride festival in the United Kingdom outside London.[156][157][158] (Liverpool’s LGBT population was 94,000 by mid-2009 according to the North West Regional Development Agency.[159]

Manchester Pride has been running since 1985 and centres around the famous Canal Street. It is traditionally a four-day celebration held over the August bank holiday weekend.[citation needed]

Birmingham Pride usually takes place during the final Spring bank holiday weekend in May, and focuses on the Birmingham Gay Village area of the city, with upwards of 70,000 people in attendance annually.[citation needed]

Pride events also happen in most other major cities such as Belfast, Bristol, Cardiff, Edinburgh, Glasgow, Hull, Leeds, Leicester, Newcastle, Nottingham and Sheffield.[160]

North America[edit]

Barbados[edit]

The island nation held its first pride parade in July 2018. It attracted a diverse group, which included members of the lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) community, allies of the community, tourists and at least one member of the local clergy who came out strongly in support of the LGBT movement.[161]

Canada[edit]