Дивали (Дипавали) в Индии — один из крупнейших фестивалей индуистов, который отмечается с большим энтузиазмом. Праздник отмечают 5 дней подряд, 3 день считается самым важным — именно в это время проходит Фестиваль Огней. На праздник устраивают красочные фейерверки, зажигают традиционные лампадки дипа и свечи вокруг своих домов, чтобы привлечь богиню богатства и благоденствия Лакшми. Часто Дипавали сравнивают с европейским Новым годом.

Значение

История индийского праздника Дивали изобилует легендами, которые в большинстве своем касаются индуистских религиозных писаний. Но основная тема преданий символизирует победу добра над злом. Еще Дипавали знаменует конец сезона дождей и начало зимы. Фермеры завершали сбор урожая, а торговцы готовились к дальним путешествиям. В этот период становится важным почитание богини изобилия, богатства и процветания Лакшми.

Зажжение огней на Дивали в Индии имеет большое значение. Для индуистов тьма представляет невежество, а свет — метафора знания. Благодаря свету, раскрывается красота мира. А в большинстве религий свет — символ любого положительного опыта. Таким образом, через зажжение огней осуществляется освобождение от негативных сил: лукавства, насилия, похоти, гнева, зависти, ханжества, страха, несправедливости, угнетения и страдания. Освещение лампы — форма поклонения богу для достижения здоровья, богатства, знания, мира, доблести и славы.

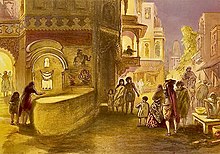

Праздник Дивали © sudarshana.ru

Пять дней Дивали

1-й день: Дханвантари Трайодаши (Дхана-Трайодаши)

Это день, когда бог Дханвантари был рожден из океана, чтобы принести человечеству знания об Аюрведе. На закате индусы должны искупаться и предложить зажженную лампу с прасадом (пища, предложенная божеству) богу Ямарадже, владыке Смерти, и молиться о защите от преждевременной смерти. Это должно быть сделано около дерева Туласи или другого священного дерева, которое растет во дворе. В этот день принято покупать украшения и посуду.

2-ой день: Нарака Чатурдаши (Чхоти-Дивали)

Во второй день празднуют победу бога Кришны над демоном Наракасурой и освобождение мира от страха. С этого дня запускают фейерверки. Следует сделать массаж тела с маслом, чтобы избавиться от усталости, искупаться и отдохнуть так, чтобы отпраздновать Дивали со всей доступной энергией. Согласно шастрам, лампаду дия в этот день зажигать не нужно. Но некоторые люди все равно ошибочно полагают, что дия всегда должна гореть перед Дипавали.

3-й день: Дивали — Лакшми Пуджа

Самый важный день фестиваля, который и есть день Дивали. В этот день поклоняются Матери Лакшми. Крайне важно, чтобы в доме было идеально убрано, так как богиня Лакшми любит чистоту и в этот день она сперва посетит наиболее чистый дом. Фонари и лампады зажигают в вечернее время для привлечения богини и освещения ее пути. Из храмов слышны звуки колоколов и барабанов. Фейерверки запускают после обеда.

Лакшми Пуджа (санскр. पूजा, Pūjā — «поклонение», «молитва») состоит из комбинированного поклонения пяти божествам — Ганеше (богу мудрости и благополучия); трем ипостасям Лакшми — Махалакшми (богине богатства и денег), Махасарасвати (богине книг и обучения), Махакали (богине-воительнице, защитнице от враждебных сил.); Кубере (богу-хранителю зарытых в земле сокровищ).

4-й день: Говардхана Пуджа

Четвертый день праздника — поклонение холму Говардхан и царю Бали Махарадже. В этот день господь Кришна поднял Говардхан Парват, чтобы защитить людей Гокула от гнева Индры, и день, когда был коронован король Викрамадитья. В храмах божествам делают молочную ванну и одевают их в блестящие одежды со сверкающими бриллиантами, жемчугами, рубинами и другими драгоценными камнями. Затем божествам подносят сладости, а затем этот прасад предлагают пришедшим.

5-й день: Йама-Двитийа или Бхайа-дуджа

Последний день Дивали посвящается любви между братьями и сестрами. Сестры готовят для своих братьев и молятся за их долгую жизнь, а братья благословляют своих сестер и дарят им подарки.

Праздник Дивали © turkey-sea.ru

Даты празднования Дивали

Даты фестиваля меняются каждый год, так как зависят от лунного календаря. По индуистскому календарю день Дивали (3 день фестиваля) приходится на новолуние (Амвасья).

- Дивали в 2016 году празднуется 30 октября;

- в 2017 — 18 ноября;

- 2018 — 7 ноября;

- 2019 — 27 октября;

- 2020 — 14 ноября.

- 2021 — 4 ноября.

Стандартный часовой пояс в Индии: +6:30

Обычаи и традиции Дипавали

Мы не будем говорить об особенностях подготовки праздничного прасада и выполнения ритуалов пуджи, но расскажем о некоторых популярных традициях и обычаях праздника огней Дипавали.

Фонари и лампады

Дипавали в буквальном переводе с санскрита означает «ряд ламп». Так что самая узнаваемая традиция фестиваля — зажжение большого количества маленьких глиняных ламп с маслом — дия (также называют дийя, дипа, дипам или дивак). В середину дийа заливают растительное масло или гхи и опускают в него фитиль из хлопка. Такие лампы можно сделать самостоятельно, просто залив в подходящую форму небольшое количество обычного растительного масла, и положив в него длинный кусочек ваты, скатанный в виде макаронины. Но будьте внимательны, не ставьте лампы рядом с легковоспламеняющимися предметами.

Праздник Дивали © goatrip.ru

Ранголи

Ранголи — рисунок-молитва, это орнамент, который наносят на пол и стены дома. Для создания рисунков используют яркие разноцветные порошки, муку и крупы. Это настолько популярное в Индии искусство, что соревнования по созданию ранголи проводят в школах и офисах. Также в домах рисуют мукой следы на полу, что символизирует ожидание прихода Лакшми.

Петарды и фейерверки

Традиция фейерверков на Дивали не очень стара, но она уже стала важной частью фестиваля огней. Считается, что фейерверки отпугивают все зло из жизни.

Азартные игры

Один из самых любопытных обычаев Дивали — потакание азартным играм. Особо популярна эта традиция в Северной Индии. Только помните, в игры играют не ради денег, а для удовольствия. По легенде, в этот день богиня Парвати играла в кости с мужем Шивой и распорядилась так, что всякий, кто сделает ставку на ночь Дипавали будет процветать в течение всего последующего года. А популярное высказывание гласит, что тот, кто не сядет играть в азартные игры родится ослом в следующей жизни. Казино и местные игорные дома ведут оживленную торговлю всю неделю Дивали.

Обмен подарками

Дарение подарков всегда было одним из важных ритуалов праздника. Дивали укрепляет связь с членами семьи, друзьями и близкими. Подарки могут быть самыми разными, но особо популярные: сладости, религиозная атрибутика, лампады дия, серебро и золото, новая одежда и украшения, открытки ручной работы.

Принятие ванны — очищение

На второй день Дивали до восхода солнца принято принимать ванну с маслом и пастой убтан, которая состоит из орехов, муки, молотых трав и масел. Необходимо очиститься и отдохнуть так, чтобы встретить праздник полным энергии.

Где распространено празднование Дивали

Фестиваль Дивали важен в индуизме, джайнизме и сикхизме, и празднуется везде, где имеются крупные общины этих религий: в Индии, Бангладеше, Шри-Ланке, Кении, Непале, Малайзии, ЮАР, Тринидад и Тобаго, Гайане, на Маврикии и Фиджи. А в связи с увеличением концентрации индийских иммигрантов и последователей вышеупомянутых религий, празднование проходит в Калифорнии, Сиэтле (США), Лондоне (Великобритания) и Сингапуре. Но лучше всего посетить Дивали именно в Индии! Если вы уже морально готовы к такой поездке, выбрать и забронировать отель в Индии можно в каталоге Planet of Hotels.

В Индии, с ее 5000-летней непростой историей, занимающей второе место по численности населения в мире, живет многонациональный народ.

На Индийском полуострове зародились системы вероисповеданий индуизма, джайнизма, буддизма и сикхизма. Последователи этих религий составляют свыше 80 % всего населения. Для них Дивали — главный праздник Индии.

Традиции и значение праздника Дивали

Имеющий глубокое религиозное и символическое значение, Дивали — «Огненный Фестиваль», знаменует победу сил света, созидания и знаний над хаосом, разрушением и невежеством. В основополагающих религиозных направлениях страны под истинными мудростью и светом подразумевают следование ортодоксальным канонам, а невежество — отступничество, олицетворяет тьму. Другие веские причины для праздника — окончание сбора урожая и наступление Нового года.

Торжество длится 5 суток и приходится на окончание осени, когда после сезона муссонных дождей наступает зимний период. Дату праздника определяют по лунному календарю.

В празднике может принять участие любой человек, независимо от национальности и вероисповедания.

Индийцы надевают новые одежды, приводят в порядок дом, украшают вход цветочными гирляндами, а у дверей устанавливают светильники.

Помимо чистоты физической требуется чистота духовная, отказ от пороков и страстей. Вожделение, жадность, гнев, эгоцентризм, излишняя любовь к прелестям материального мира не уместны в эти дни. Для гармонизации всех уровней сознания проводят медитацию. Каждый день празднования имеет свою историю, определённый ритуал и традиции.

День 1

Бог Дханвантари, родившийся из океана, принес людям знания Аюрведы. Совершив омовение на заходе солнца, индуисты подносят горящую лампу и прасад (священная пища для приношения) Ямарадже, божеству олицетворяющему Смерть, с просьбой о продлении своего существования.

Жители выбрасывают из дома старые вещи, приобретают украшения и посуду, воздушный рис и фигурки из сахара — непременную принадлежность праздничного обряда.

День 2

Кришна победил демона Наракасуру, освободив мира от ужаса.

Участники праздника делают расслабляющий масляный массаж тела, купаются и отдыхают, набираясь энергии для празднования. Начинают запуск петард.

День 3

Апогей праздника. Оказывают почести Богине богатства и счастья Лакшми. Светильники освещают ей путь и привлекают в жилище. В храмах звонят в колокола и бьют в барабаны, во второй половине дня наступает пора фейерверков.

День 4

Кришна создал холм Говардхан Парват, для защиты людей от гнева Индры. Служители святилищ омывают в молоке божества и одевают их в сверкающие одежды с драгоценными украшениями, подносят ритуальные сладости, затем предлагая их посетителям.

День 5

Заключительный день торжеств посвящен родственным отношениям сестер и братьев. Братья делают подарки и поздравляют сестер, которые, молятся за братьев и угощают их праздничной пищей.

Каждый может в эти дни воочию лицезреть и принять участие в Дивали, необязательно в Индии, но и в многочисленных индуистских и буддийских общинах, укоренившихся в ряде стран.

Отличия проведения Дивали в различных штатах

При проведении Дивали в каждом штате страны свои отличия.

-

В Западных провинциях сообщества торговцев начинают новый финансовый год. Праздничная иллюминация в ночной период заливает светом окрестности магазинов. Исстари, в этот период отправлялись за море флотилии судов, нагруженные товарами.

-

В большинстве штатов страны жене Вишну — Лакшми, Богине счастья, подносят молоко с монетами, на ночь открывают двери и окна, чтобы она не прошла мимо жилья.

-

В южных штатах вспоминают победу Кришны над сеющим хаос Наракасурой. Индусы смазывают тело маслом кокоса, символически очищаясь от греховных действий. Обряд сравним по силе со священным погружением в Ганг.

-

В Бенгалии, где находится главный храм Калигхата (по-английски Калькутта) и ряде восточных штатов, в Дивали проводят ритуал для Кали — Богини, олицетворяющей мощь вечного времени, разрушительного аспекта созидателя Шивы. Десять суток адепты молятся на священный предмет с изображением Божества, после чего верующие пьют священный напиток (вино или воду) и погружают святыню в водоем.

-

На севере мусульмане празднуют появление Лакшми праздничным огнем, игрой в карты и кости. Богиня Парвати, играя с мужем, пообещала: «Тому, кто сыграет на деньги в ночь Дивали, повезет весь год».

Ритуалы имеют глубокий смысл. Дом, освещенный ярким светом, означает наличие в нем света души.

Горящие лампады — мыслящее существо, несущее в себе базовые первоэлементы — воздух, огонь, землю, воду и всемирный эфир. Проявление огня — это душа, а горючее — духовная пища.

Зная традиции проведения народных празднеств, можно лучше понять страну и людей, в ней живущих.

Праздник Дивали в Индии сопровождается народными гуляниями, всеобщим весельем, песнями и танцами, салютами, запусками петард и фейерверков, длящимися до утра.

Никто не остается голодным и обделенным вниманием. Улицы и храмы, увешанные светящимися гирляндами, превращаются в зрелищные инсталляции, обращающие ночь в день. Ведь там где свет, нет зла!

Видео

Видео взято из открытого источника с сайта YouTube на канале Марат Нугаев

Индийцы гордятся и чтут свои религиозные верования. Все индийские праздники, так или иначе, связаны с индуизмом или буддизмом. «Комсомолка» рассказывает, как будет отмечаться главный индийский праздник Дивали, символизирующий победу добра над злом, выход людских душ из душевного сумрака, в 2023 году.

Когда отмечается Дивали в 2023 году

Как и многие памятные даты у народов с богатым историческим наследием и многовековыми обычаями, праздник Дивали, или Дипавали (что означает «глиняная лампадка с маслом») проводится уже в формате многодневного красочного фестиваля. Дивали в 2023 году приходится на 12 ноября. Но праздничные мероприятия продлятся 5 дней — с 10-го по 14-е число.

Глубокие исторические корни праздника позволяют ассоциировать Дивали с древнеязыческим почитанием осеннего урожая. Многие индусы, особенно те, кто работает в финансово-банковской сфере, считают Дивали началом своего индийского нового года. Однако современное индийское общество настолько плюралистично, что в разных частях огромного государства празднику-фестивалю без труда приписывают самые различные значения. В конце концов, главное, что у жителей Индии и многочисленной индийской диаспоры во всем мире в эти дни, как пел Владимир Высоцкий, есть хороший повод веселиться.

За время празднования Дивали в 2023 году индуисты будут отмечать многие события, связанные с их религией. Все они тесно переплетаются с богатой индийской мифологией и ее персонажами. События праздничной недели в индийском календаре расписаны на каждый дней. Причем наряду с вымышленными божествами в эту осеннюю праздничную пятидневку вспоминаются и реальные личности. Например, правитель древнеиндийской империи Мауриев, покровитель буддизма, царь Ашока.

История праздника Дивали

Непосредственно традицию празднования Дивали связывают с возвращением домой из вражеского плена легендарного царя Рамы. Поэтому, чтобы Рама и его супруга благополучно добрались домой, люди и жгли масляные лампадки. Они назывались дии и наполнялись индийским топленым маслом гхи. В индуизме топленое масло гхи играет большое значение при организации церемоний жертвоприношения.

Другая версия связывает праздник Дивали с поражением царя-демона Наракасуры, сеявшего беспорядки в древнеиндийском обществе. Злого персонажа усмирил Кришна. Сжигание чучела Наракасуры современными индийцами в праздник – один из отсылов к древней мифологии.

Во многих частях Индии в праздник вспоминают богиню достатка и процветания, супругу бога Вишны, Лакшми. По преданию, она в белом одеянии появилась из вод молочного океана, в которых в незапамятные времена боги и демоны искали эликсир бессмертия амриту. В Восточной Индии, наоборот, почитается черная богиня силы Кали. Характерно, что и с ней связаны водные мотивы. После поклонения и молитв изображения богини Кали опускают в водоемы.

Традиции праздника Дивали

Существует восемь основных традиций праздника Дивали:

- уборка дома,

- раздача соседям сладостей,

- покупки в различных магазинах,

- горящие лампады,

- красочные фейерверки в кругу добрых знакомых, родных и близких,

- вечеринки,

- всевозможные подарки. Если раньше подарком в праздник Дивали была, в основном, одежда, то сейчас ее вытеснили современная техника и подарочные сертификаты,

- ранголи — ранголи, считающиеся, пожалуй, главной опознавательной меткой праздника Дивали.

Красочный рисунок ранголи – основное украшение этих дней. Для его изготовления используют цветной песок и подкрашенную рисовую воду. Ранголи в эти дни в странах Юго-Восточной Азии можно увидеть повсюду, даже в крупных современных торговых центрах. Ранголи делают своими руками. Считается, что злые духи не могут причинить вред вашему дому, запутавшись в хитром, но красивом рисунке. Обычно рисунок ранголи наполнен различными природными мотивами и состоит из хитроумных геометрических фигур.

Особо красочно отмечают Дивали на Гоа, где существует культ победы Кришны над местным царем Наркасуром. Местные жители – большие мастера рисунков ранголи, и если повезет в эти дни попасть в их украшенные к празднику дома, то можно как следует насладиться созерцанием сложных рисунков. Заодно вас познакомят с местными обычаями и традициями.

Популярные вопросы и ответы

Где, кроме Индии, отмечают праздник Дивали?

Праздник широко отмечается в странах, где есть большие индуистские общины. Это, прежде всего, Сингапур. Сюда также относятся другие страны Юго-Восточной Азии, государства Карибского бассейна, Кения и ЮАР в Африке и острова Фиджи в Океании. Подключаются к празднованию и крупные индийские диаспоры есть в Лондоне и на западном побережье США.

Какой близкий по смыслу праздник отмечается в соседнем с Индией Непале?

Неварцы – народность, проживающая в Непале, — отмечают дату со сложно произносимым названием – Ашок Виджаядашами. В этот день, по преданию, император Ашока стал последователем буддизма.

Почему праздник Дивали еще называют праздником огней?

Праздник отмечается в период Новолуния, когда Луна еще не освещает дорогу. В память о благополучном возвращении ночью домой бога Рамы, люди и зажигают лампады. Получается настоящий праздник огней.

Просмотров 2к. Опубликовано 07.03.2013

Обновлено 13.03.2022

Дивали (Diwali, Deepavali) – фестиваль огней, один из самых главных праздников в Индии, символизирующий торжество добра, победу всего самого светлого и доброго над темным и жестоким. Празднуется в начале месяца Картик (октябре-ноябре) в течение пяти дней.

Легенда появления праздника

Дивали (Дивапали) стал праздноваться несколько веков назад, с обычаем этого праздника связано много различных легенд. Существует поверье, что Дивали тесно связан с победой бога Кришны над демоническим существом Наракасурой, грешившим похищением царевн Индии.

Кришна одолел этого демона и народ встречал его зажженными светильниками и факелами – отсюда и пришел обычай в этот день зажигать повсеместно факелы, свечи, масляные фонарики (перевод слова Дипа), фейерверки, находящиеся вблизи статуй и изображений божеств, священных животных.

Некоторые индийцы связывают праздник огней с богиней Лакшми – в ее честь накануне торжества расписывают стены, закупают ритуальные принадлежности, золото, продукты для того, чтобы богиня наградила их изобилием и богатством. Многие считают, что Дивали – это прославление божества Рамы (седьмого воплощения бога Вишну), празднование его возведения на трон и мудрого, справедливого правления.

Для каждой отдельной территории Индии фестиваль огней имеет свои особенности. Например, в Западной Индии в день праздника принято наводить порядок дома и на рабочих местах, а по вечерам витрины магазинов и частных домов светятся гирляндами, светильниками и различными электрическими приборами.

Те люди, которые верят в связь Дивали с богиней плодородия и богатства Лакшми, в день торжества делают генеральную уборку, зажигают огни, делают подношения богине из молока и опущенных в него монет, читают молитвы, а ночью не закрывают окна и двери – чтобы не чинить препятствия для Лакшми, если та решит зайти в их дом.

На южных территориях Индии считают Дивали – празднованием победы Кришны над демоном по имени Наракасура. Все индусы в этот день смазывают свое тело маслом кокоса, приравнивая это действие к омовению в священном Ганге и избавлению от имеющихся грехов.

Восток Индии поклоняется в этот день Богине Кали, выступающей олицетворением культа силы. Изображения Кали служат местом преклонения и молитв в течение 10 дней, после чего их погружают в реки и пруды.

Существующие обычаи Дивали

Само торжество Happy Deepavali длится пять дней. Вся территория страны в этот день превращается в яркое, незабываемое шоу с огнями и фейерверками. Но огни фестиваля озаряют людские сердца не только яркими красками, но и добром, ведь в этот праздник принято оказывать всем внимание, дарить подарки, помогать нуждающимся.

Нет такого праздника в Индии, в который было бы подарено столько подарков! Владельцы продуктовых лавочек устраивают распродажи для всех, кто в другой день не мог себе позволить дорогостоящую покупку, принято угощать соседей различными сладостями.

Во время Дивали существует традиция тратить деньги, но только не свои нужды, а на друзей, знакомых или соседей. Особым спросом пользуются монетки с изображением божеств, таких, как Ганеша, Лакшми, различные диковинные сувениры, предметы искусства, драгоценные украшения. Очень интересен праздник Триссур Пурам.

Для сладостей и сухофруктов в дни праздника Дивали используются специальные упаковки в форме корзинок. Такими приятными сюрпризами принято проявлять любовь и уважение к своим самым близким и дорогим людям. Никто в этот индийский праздник не должен остаться голодным и обделенным вниманием.

Видео празднования Happy Diwali

https://youtu.be/64MeBQgc7fE

Дата события уникальна для каждого года. В 2023 году эта дата — 12 ноября

Дивали или Дипавали (Diwali или Deepavali), что на санскрите означает «огненная гроздь» — фестиваль огней, повсеместно отмечаемый в Индии и символизирующий победу света над тьмой, добра над злом. Приходится на начало месяца Картик (октябрь — ноябрь) и празднуется в течение пяти дней.

Существует несколько легенд, связанных с праздником. Вишнуиты увязывают начало празднования Дивали с коронацией царевича Рамы, седьмого воплощения Вишну. В ночь его счастливого возведения на трон по всей стране была устроена иллюминация.

По другой версии, мудрое правление Рамы знаменовало избавление от духовного мрака. Зажигаемые огни символизируют возвращение человечества из тьмы к свету, благодаря легендарному царевичу.

В каждом районе Индии празднование Дивали имеет свои особенности. Для некоторых частей страны и групп населения (например, для торговых общин Западной Индии) Дивали совпадает с началом Нового года. Торговцы в этот день приводят в порядок счетоводные книги, прибирают лавки. Вечером магазины и дома иллюминируют масляными светильниками или гирляндами электрических лампочек.

На большей части территории Индии Дивали посвящается Богине Лакшми, супруге Бога Вишну (Фото: D.Shashikant, по лицензии Shutterstock.com)

На большей части территории Индии Дивали посвящается Богине богатства и плодородия Лакшми, супруге Бога Вишну. Дома тщательно убирают, зажигают все огни, так как Богиня не любит темноты, обращаются к ней с молитвой, подносят ей молоко, в которое опущены монеты, а на ночь оставляют двери и окна открытыми, чтобы ей было легче проникнуть в дом.

На Юге Индии в Дивали отмечают победу Бога Кришны над демоном Наракасурой. В этот день победы добра над злом индусы обильно смазывают себя кокосовым маслом, что очищает их от грехов, так как церемония эта считается равной по значению омовению в священном Ганге.

На Востоке Индии, и особенно в Бенгалии, Дивали посвящен поклонению черной Богине Кали, олицетворяющей культ силы. По этому случаю перед изображениями Богини десять дней совершают молитвы, а затем эти изображения погружают в воды рек или прудов.

Дивали празднуется и мусульманами, отмечающими приход Лакшми огнями и игрой в карты и кости, ведь Лакшми приносит удачу.

В этот праздник света улицы городов и сел озаряются тысячами огней и фейерверков. Воздух сотрясается от взрывов ракет, петард и хлопушек.

| Diwali | |

|---|---|

Rangoli decorations, made using coloured fine powder or sand, are popular during Diwali. |

|

| Also called | Deepavali |

| Observed by | Hindus, Jains, Sikhs,[1] some Buddhists (notably Newar Buddhists) |

| Type | Religious, cultural, seasonal |

| Significance | See below |

| Celebrations | Diya lighting, puja (worship and prayer), havan (fire offering), vrat (fasting), dāna (charity), melā (fairs/shows), home cleansing and decoration, fireworks, gifts, and partaking in a feast and sweets |

| Begins | Ashwayuja 27 or Ashwayuja 28 (amanta tradition) Kartika 12 or Kartika 13 (purnimanta tradition) |

| Ends | Kartika 2 (amanta tradition) Kartika 17 (purnimanta tradition) |

| Date | Ashvin Krishna Trayodashi, Ashvin Krishna Chaturdashi, Ashvin Amavasya, Kartik Shukla Pratipada, Kartik Shukla Dwitiya |

| 2023 date | November[2]

|

| Frequency | Annual |

| Related to | Diwali (Jainism), Bandi Chhor Divas, Tihar, Swanti, Sohrai, Bandna |

|

Hindu festival dates The Hindu calendar is lunisolar but most festival dates are specified using the lunar portion of the calendar. A lunar day is uniquely identified by three calendar elements: māsa (lunar month), pakṣa (lunar fortnight) and tithi (lunar day). Furthermore, when specifying the masa, one of two traditions are applicable, viz. amānta / pūrṇimānta. Iff a festival falls in the waning phase of the moon, these two traditions identify the same lunar day as falling in two different (but successive) masa. A lunar year is shorter than a solar year by about eleven days. As a result, most Hindu festivals occur on different days in successive years on the Gregorian calendar. |

|

Diwali (), Dewali, Divali,[3] or Deepavali (IAST: dīpāvalī), also known as the Festival of Lights,[4][5] related to Jain Diwali, Bandi Chhor Divas, Tihar, Swanti, Sohrai, and Bandna, is a religious[6] celebration in Indian religions. It is one of the most important festivals within Hinduism[7][8] where it generally lasts five days (or six in some regions of India), and is celebrated during the Hindu lunisolar months of Ashvin (according to the amanta tradition) and Kartika (between mid-October and mid-November).[9][10][11] It is a post-harvest festival celebrating the bounty following the arrival of the monsoon in the subcontinent.[12]

Diwali symbolises the spiritual «victory of light over darkness, good over evil, and knowledge over ignorance».[13][14][15][16] The festival is widely associated with Lakshmi,[17][18] goddess of prosperity and Ganesha, god of wisdom and the remover of obstacles, with many other regional traditions connecting the holiday to Sita and Rama, Vishnu, Krishna, Durga, Shiva, Kali, Hanuman, Kubera, Yama, Yami, Dhanvantari, or Vishvakarman. Furthermore, it is a celebration of the day Rama returned to his kingdom in Ayodhya with his wife Sita and his brother Lakshmana after defeating the demon Ravana.

During the festival, Hindus, Jains and Sikhs illuminate their homes, temples and workspaces with diyas (oil lamps), candles and lanterns[16] Hindus, in particular, have a ritual oil bath at dawn on each day of the festival.[19] Diwali is also marked with fireworks and the decoration of floors with rangoli designs, and other parts of the house with jhalars. Food is a major focus with families partaking in feasts and sharing mithai.[20]

The festival is an annual homecoming and bonding period not only for families,[17][18] but also for communities and associations, particularly those in urban areas, which will organise activities, events and gatherings.[21][22] Many towns organise community parades and fairs with parades or music and dance performances in parks.[23] Some Hindus, Jains and Sikhs will send Diwali greeting cards to family near and far during the festive season, occasionally with boxes of Indian confectionery.[23] Another aspect of the festival is remembering the ancestors.[24]

Originally a Hindu festival, Diwali is now also celebrated by other faiths.[7] The Jains observe their own Diwali which marks the final liberation of Mahavira,[25][26] the Sikhs celebrate Bandi Chhor Divas to mark the release of Guru Hargobind from a Mughal prison.[27] Newar Buddhists, unlike other Buddhists, celebrate Diwali by worshipping Lakshmi, while the Hindus of Eastern India and Bangladesh generally celebrate Diwali by worshipping the goddess Kali.[28][29][30]

Diwali is also a major cultural event for the Hindu, Sikh, and Jain diaspora.[31][32][33] The main day of the festival of Diwali (the day of Lakshmi Puja) is an official holiday in Fiji,[34] Guyana,[35] India, Malaysia,[a][36] Mauritius, Myanmar,[37] Nepal,[38] Pakistan,[39] Singapore,[40] Sri Lanka, Suriname, and Trinidad and Tobago.[41]

Nomenclature and dates

Diwali festivities include a celebration of sights, sounds, arts and flavours. The festivities vary between different regions.[42][43][17] |

Diwali ()[9] or Divali[44] is from the Sanskrit dīpāvali meaning «row or series of lights».[20][45] The term is derived from the Sanskrit words dīpa, «lamp, light, lantern, candle, that which glows, shines, illuminates or knowledge»[46] and āvali, «a row, range, continuous line, series».[47][b]

The five-day celebration is observed every year in early autumn after the conclusion of the summer harvest. It coincides with the new moon (amāvasyā) and is deemed the darkest night of the Hindu lunisolar calendar.[48] The festivities begin two days before amāvasyā, on Dhanteras, and extend two days after, until the second (or 17th) day of the month of Kartik.[49] (According to Indologist Constance Jones, this night ends the lunar month of Ashwin and starts the month of Kartik[50] – but see this note[c] and Amanta and Purnima systems.) The darkest night is the apex of the celebration and coincides with the second half of October or early November in the Gregorian calendar.[50]

The festival climax is on the third day and is called the main Diwali. It is an official holiday in a dozen countries, while the other festive days are regionally observed as either public or optional restricted holidays in India.[52] In Nepal, it is also a multiday festival, although the days and rituals are named differently, with the climax being called the Tihar festival by Hindus and Swanti festival by Buddhists.[53][54]

History

The five-day long festival originated in the Indian subcontinent and is likely a fusion of harvest festivals in ancient India.[50] It is mentioned in mentioned in early Sanskrit texts, such as the Padma Purana and the Skanda Purana, both of which were completed in the second half of the 1st millennium CE. The diyas (lamps) are mentioned in Skanda Kishore Purana as symbolising parts of the sun, describing it as the cosmic giver of light and energy to all life and which seasonally transitions in the Hindu calendar month of Kartik.[43][55]

Emperor Harsha refers to Deepavali, in the 7th-century Sanskrit play Nagananda, as Dīpapratipadotsava (dīpa = light, pratipadā = first day, utsava = festival), where lamps were lit and newly engaged brides and grooms received gifts.[56][57] Rajasekhara referred to Deepavali as Dipamalika in his 9th-century Kavyamimamsa, wherein he mentions the tradition of homes being whitewashed and oil lamps decorated homes, streets and markets in the night.[56]

Diwali was also described by numerous travelers from outside India. In his 11th-century memoir on India, the Persian traveler and historian Al Biruni wrote of Deepavali being celebrated by Hindus on the day of the New Moon in the month of Kartika.[58] The Venetian merchant and traveler Niccolò de’ Conti visited India in the early 15th-century and wrote in his memoir, «on another of these festivals they fix up within their temples, and on the outside of the roofs, an innumerable number of oil lamps… which are kept burning day and night» and that the families would gather, «clothe themselves in new garments», sing, dance and feast.[59][60] The 16th-century Portuguese traveler Domingo Paes wrote of his visit to the Hindu Vijayanagara Empire, where Dipavali was celebrated in October with householders illuminating their homes, and their temples, with lamps.[60] It is mentioned in the Ramayana that Diwali was celebrated for only 2 years in Ayodhya.[61]

Islamic historians of the Delhi Sultanate and the Mughal Empire era also mentioned Diwali and other Hindu festivals. A few, notably the Mughal emperor Akbar, welcomed and participated in the festivities,[62][63] whereas others banned such festivals as Diwali and Holi, as Aurangzeb did in 1665.[64][65][d][e]

Publications from the British colonial era also made mention of Diwali, such as the note on Hindu festivals published in 1799 by Sir William Jones, a philologist known for his early observations on Sanskrit and Indo-European languages.[68] In his paper on The Lunar Year of the Hindus, Jones, then based in Bengal, noted four of the five days of Diwali in the autumn months of Aswina-Cartica [sic] as the following: Bhutachaturdasi Yamaterpanam (2nd day), Lacshmipuja dipanwita (the day of Diwali), Dyuta pratipat Belipuja (4th day), and Bhratri dwitiya (5th day). The Lacshmipuja dipanwita, remarked Jones, was a «great festival at night, in honour of Lakshmi, with illuminations on trees and houses».[68][f]

Epigraphy

William Simpson labelled his chromolithograph of 1867 CE as «Dewali, feast of lamps». It showed streets lit up at dusk, with a girl and her mother lighting a street corner lamp.[69]

Sanskrit inscriptions in stone and copper mentioning Diwali, occasionally alongside terms such as Dipotsava, Dipavali, Divali and Divalige, have been discovered at numerous sites across India.[70][71][g] Examples include a 10th-century Rashtrakuta empire copper plate inscription of Krishna III (939–967 CE) that mentions Dipotsava,[72] and a 12th-century mixed Sanskrit-Kannada Sinda inscription discovered in the Isvara temple of Dharwad in Karnataka where the inscription refers to the festival as a «sacred occasion».[73] According to Lorenz Franz Kielhorn, a German Indologist known for translating many Indic inscriptions, this festival is mentioned as Dipotsavam in verses 6 and 7 of the Ranganatha temple Sanskrit inscription of the 13th-century Kerala Hindu king Ravivarman Samgramadhira. Part of the inscription, as translated by Kielhorn, reads:

«the auspicious festival of lights which disperses the most profound darkness, which in former days was celebrated by the kings Ila, Kartavirya and Sagara, (…) as Sakra (Indra) is of the gods, the universal monarch who knows the duties by the three Vedas, afterwards celebrated here at Ranga for Vishnu, resplendent with Lakshmi resting on his radiant lap.»[74][h]

Jain inscriptions, such as the 10th-century Saundatti inscription about a donation of oil to Jinendra worship for the Diwali rituals, speak of Dipotsava.[75][76] Another early 13th-century Sanskrit stone inscription, written in the Devanagari script, has been found in the north end of a mosque pillar in Jalore, Rajasthan evidently built using materials from a demolished Jain temple. The inscription states that Ramachandracharya built and dedicated a drama performance hall, with a golden cupola, on Diwali.[77][78][i]

Religious significance

Diwali is celebrated in the honour of Lakshmi, the goddess of wealth.

The religious significance of Diwali varies regionally within India.

One tradition links the festival to legends in the Hindu epic Ramayana, where Diwali is the day Rama, Sita, Lakshman and Hanuman reached Ayodhya after a period of 14 years in exile after Rama’s army of good defeated demon king Ravana’s army of evil.[79]

Per another popular tradition, in the Dvapara Yuga period, Krishna, an avatar of Vishnu, killed the demon Narakasura, who was the evil king of Pragjyotishapura, near present-day Assam, and released 16000 girls held captive by Narakasura. Diwali was celebrated as a signifier of triumph of good over evil after Krishna’s Victory over Narakasura. The day before Diwali is remembered as Naraka Chaturdasi, the day on which Narakasura was killed by Krishna.[80]

A picture of Lakshmi and Ganesha worship during Diwali

Many Hindus associate the festival with Goddess Lakshmi, the goddess of wealth and prosperity, and wife of Vishnu. According to Pintchman, the start of the 5-day Diwali festival is stated in some popular contemporary sources as the day Goddess Lakshmi was born from Samudra manthan, the churning of the cosmic ocean of milk by the Devas (gods) and the Asuras (demons) – a Vedic legend that is also found in several Puranas such as the Padma Purana, while the night of Diwali is when Lakshmi chose and wed Vishnu.[43][81] Along with Lakshmi, who is representative of Vaishnavism, Ganesha, the elephant-headed son of Parvati and Shiva of Shaivism tradition, is remembered as one who symbolises ethical beginnings and the remover of obstacles.[79]

Hindus of eastern India associate the festival with the Goddess Kali, who symbolises the victory of good over evil.[82][83][84] Hindus from the Braj region in northern India, parts of Assam, as well as southern Tamil and Telugu communities view Diwali as the day the god Krishna overcame and destroyed the evil demon king Narakasura, in yet another symbolic victory of knowledge and good over ignorance and evil.[85][86]

Trade and merchant families and others also offer prayers to Saraswati, who embodies music, literature and learning and Kubera, who symbolises book-keeping, treasury and wealth management.[43] In western states such as Gujarat, and certain northern Hindu communities of India, the festival of Diwali signifies the start of a new year.[85]

Mythical tales shared on Diwali vary widely depending on region and even within Hindu tradition,[87] yet all share a common focus on righteousness, self-inquiry and the importance of knowledge,[88][89] which, according to Lindsey Harlan, an Indologist and scholar of Religious Studies, is the path to overcoming the «darkness of ignorance».[90] The telling of these myths are reminiscent of the Hindu belief that good ultimately triumphs over evil.[91][12]

Other religions

Originally a Hindu festival, Diwali has transcended religious lines.[4] Diwali is celebrated by Hindus, Jains, Sikhs, and Newar Buddhists,[29] although for each faith it marks different historical events and stories, but nonetheless the festival represents the same symbolic victory of light over darkness, knowledge over ignorance, and good over evil.[13][14][92][93]

Jainism

A scholar of Jain and Nivethan, states that in Jain tradition, Diwali is celebrated in observance of «Mahavira Nirvana Divas», the physical death and final nirvana of Mahavira. The Jain Diwali celebrated in many parts of India has similar practices to the Hindu Diwali, such as the lighting of lamps and the offering of prayers to Lakshmi. However, the focus of the Jain Diwali remains the dedication to Mahavira.[94] According to the Jain tradition, this practice of lighting lamps first began on the day of Mahavira’s nirvana in 527 BCE,[j] when 18 kings who had gathered for Mahavira’s final teachings issued a proclamation that lamps be lit in remembrance of the «great light, Mahavira».[97][98] This traditional belief of the origin of Diwali, and its significance to Jains, is reflected in their historic artworks such as paintings.[99]

Sikhism

A hukamnama from the tenth Sikh guru, Guru Gobind Singh, requesting all of the Sikh congregation to convene in his presence on the occasion of Diwali

Sikhs celebrate Bandi Chhor Divas in remembrance of the release of Guru Hargobind from the Gwalior Fort prison by the Mughal emperor Jahangir and the day he arrived at the Golden Temple in Amritsar.[100] According to J.S. Grewal, a scholar of Sikhism and Sikh history, Diwali in the Sikh tradition is older than the sixth Guru Hargobind legend. Guru Amar Das, the third Guru of the Sikhs, built a well in Goindwal with eighty-four steps and invited Sikhs to bathe in its sacred waters on Baisakhi and Diwali as a form of community bonding. Over time, these spring and autumn festivals became the most important of Sikh festivals and holy sites such as Amritsar became focal points for annual pilgrimages.[101] The festival of Diwali, according to Ray Colledge, highlights three events in Sikh history: the founding of the city of Amritsar in 1577, the release of Guru Hargobind from the Mughal prison, and the day of Bhai Mani Singh’s martyrdom in 1738 as a result of his failure to pay a fine for trying to celebrate Diwali and thereafter refusing to convert to Islam.[102][103][k]

Buddhism

Diwali is not a festival for most Buddhists, with the exception of the Newar people of Nepal who revere various deities in Vajrayana Buddhism and celebrate Diwali by offering prayers to Lakshmi.[29][30] Newar Buddhists in Nepalese valleys also celebrate the Diwali festival over five days, in much the same way, and on the same days, as the Nepalese Hindu Diwali-Tihar festival.[106] According to some observers, this traditional celebration by Newar Buddhists in Nepal, through the worship of Lakshmi and Vishnu during Diwali, is not syncretism but rather a reflection of the freedom within Mahayana Buddhist tradition to worship any deity for their worldly betterment.[29]

Celebrations

In the lead-up to Diwali, celebrants prepare by cleaning, renovating, and decorating their homes and workplaces with diyas (oil lamps) and rangolis (colorful art circle patterns).[107] During Diwali, people wear their finest clothes, illuminate the interior and exterior of their homes with saaki (earthen lamp), diyas and rangoli, perform worship ceremonies of Lakshmi, the goddess of prosperity and wealth,[l] light fireworks, and partake in family feasts, where mithai (sweets) and gifts are shared.

The height of Diwali is celebrated on the third day coinciding with the darkest night of Ashvin or Kartika.

The common celebratory practices are known as the festival of light, however there are minor differences from state to state in India. Diwali is usually celebrated twenty days after the Vijayadashami festival, with Dhanteras, or the regional equivalent, marking the first day of the festival when celebrants prepare by cleaning their homes and making decorations on the floor, such as rangolis.[109] Some regions of India start Diwali festivities the day before Dhanteras with Govatsa Dwadashi. The second day is Naraka Chaturdashi. The third day is the day of Lakshmi Puja and the darkest night of the traditional month. In some parts of India, the day after Lakshmi Puja is marked with the Govardhan Puja and Balipratipada (Padwa). Some Hindu communities mark the last day as Bhai Dooj or the regional equivalent, which is dedicated to the bond between sister and brother,[110] while other Hindu and Sikh craftsmen communities mark this day as Vishwakarma Puja and observe it by performing maintenance in their work spaces and offering prayers.[111][112]

Diwali celebrations include puja (prayers) to Lakshmi and Ganesha. Lakshmi is of the Vaishnavism tradition, while Ganesha of the Shaivism tradition of Hinduism.[113][114]

Rituals and preparations for Diwali begin days or weeks in advance, typically after the festival of Dusshera that precedes Diwali by about 20 days.[79] The festival formally begins two days before the night of Diwali, and ends two days thereafter. Each day has the following rituals and significance:[43]

Dhanteras, Dhanatrayodashi, Yama Deepam (Day 1)

Dhanteras starts off the Diwali celebrations with the lighting of Diya or Panati lamp rows, house cleaning and floor rangoli

Dhanteras, derived from Dhan meaning wealth and teras meaning thirteenth, marks the thirteenth day of the dark fortnight of Ashwin or Kartik and the beginning of Diwali in most parts of India.[115] On this day, many Hindus clean their homes and business premises. They install diyas, small earthen oil-filled lamps that they light up for the next five days, near Lakshmi and Ganesha iconography.[115][113] Women and children decorate doorways within homes and offices with rangolis, colourful designs made from rice flour, flower petals, colored rice or colored sand,[23] while the boys and men decorate the roofs and walls of family homes, markets, and temples and string up lights and lanterns. The day also marks a major shopping day to purchase new utensils, home equipment, jewelry, firecrackers, and other items.[113][43][81] On the evening of Dhanteras, families offer prayers (puja) to Lakshmi and Ganesha, and lay offerings of puffed rice, candy toys, rice cakes and batashas (hollow sugar cakes).[113]

According to Tracy Pintchman, Dhanteras is a symbol of annual renewal, cleansing and an auspicious beginning for the next year.[115] The term Dhan for this day also alludes to the Ayurvedic icon Dhanvantari, the god of health and healing, who is believed to have emerged from the «churning of cosmic ocean» on the same day as Lakshmi.[115] Some communities, particularly those active in Ayurvedic and health-related professions, pray or perform havan rituals to Dhanvantari on Dhanteras.[115]

On Yama Deepam (also known as Yama Dipadana or Jam ke Diya), Hindus light a diya, ideally made of wheat flour and filled with sesame oil, that faces south in the back of their homes. This is believed to please Yama (Yamraj), the god of death, and to ward off untimely death.[116] Some Hindus observe Yama Deepa on the second night before the main day of Diwali.[117][118]

Naraka Chaturdashi, Kali Chaudas, Chhoti Diwali, Hanuman Puja, Roop Chaudas, Yama Deepam (Day 2)

Choti Diwali is the major shopping day for festive mithai (sweets)

Naraka Chaturdashi, also known as Chhoti Diwali, is the second day of festivities coinciding with the fourteenth day of the dark fortnight of Ashwin or Kartik.[119] The term «chhoti» means little, while «Naraka» means hell and «Chaturdashi» means «fourteenth».[120] The day and its rituals are interpreted as ways to liberate any souls from their suffering in «Naraka», or hell, as well as a reminder of spiritual auspiciousness. For some Hindus, it is a day to pray for the peace to the manes, or defiled souls of one’s ancestors and light their way for their journeys in the cyclic afterlife.[121] A mythological interpretation of this festive day is the destruction of the asura (demon) Narakasura by Krishna, a victory that frees 16,000 imprisoned princesses kidnapped by Narakasura.[120] It is also celebrated as Roop Chaudas in some North Indian households, where women bathe before sunrise, while lighting a Diya (lamp) in the bath area, they believe it helps enhance their beauty – it is a fun ritual that young girls enjoy as part of festivities. Ubtan is applied by the women which is made up of special gram flour mixed with herbs for cleansing and beautifying themselves.

Naraka Chaturdashi is also a major day for purchasing festive foods, particularly sweets. A variety of sweets are prepared using flour, semolina, rice, chickpea flour, dry fruit pieces powders or paste, milk solids (mawa or khoya) and clarified butter (ghee).[12] According to Goldstein, these are then shaped into various forms, such as laddus, barfis, halwa, kachoris, shrikhand, and sandesh, rolled and stuffed delicacies, such as karanji, shankarpali, maladu, susiyam, pottukadalai. Sometimes these are wrapped with edible silver foil (vark). Confectioners and shops create Diwali-themed decorative displays, selling these in large quantities, which are stocked for home celebrations to welcome guests and as gifts.[12][113] Families also prepare homemade delicacies for Lakshmi Pujan, regarded as the main day of Diwali.[12] Chhoti Diwali is also a day for visiting friends, business associates and relatives, and exchanging gifts.[113]

On the second day of Diwali, Hanuman Puja is performed in some parts of India especially in Gujarat. It coincides with the day of Kali Chaudas. It is believed that spirits roam around on the night of Kali Chaudas, and Hanuman, who is the deity of strength, power, and protection, is worshipped to seek protection from the spirits. Diwali is also celebrated to mark the return of Rama to Ayodhya after defeating the demon-king Ravana and completing his fourteen years of exile. The devotion and dedication of Hanuman pleased Rama so much that he blessed Hanuman to be worshipped before him. Thus, people worship Hanuman the day before Diwali’s main day.[122]

This day is commonly celebrated as Diwali in Tamil Nadu, Goa, and Karnataka. Traditionally, Marathi Hindus and South Indian Hindus receive an oil massage from the elders in the family on the day and then take a ritual bath, all before sunrise.[123] Many visit their favourite Hindu temple.[124]

Some Hindus observe Yama Deepam (also known as Yama Dipadana or Jam ke Diya) on the second day of Diwali, instead of the first day. A diya that is filled with sesame oil is lit at back of their homes facing in the southern direction. This is believed to please Yama, the god of death, and to ward off untimely death.[116][117][118]

Lakshmi Pujan, Kali Puja (Day 3)

The third day is the height of the festival,[125] and coincides with the last day of the dark fortnight of Ashwin or Kartik. This is the day when Hindu, Jain and Sikh temples and homes are aglow with lights, thereby making it the «festival of lights». The word Deepawali comes from the Sanskrit word deep, which means an Indian lantern/lamp.[48][126]

A sparkling firecracker, commonly known as ‘Kit Kat’ in India

The youngest members in the family visit their elders, such as grandparents and other senior members of the community, on this day. Small business owners give gifts or special bonus payments to their employees between Dhanteras and Lakshmi Pujan.[123][127] Shops either do not open or close early on this day allowing employees to enjoy family time. Shopkeepers and small operations perform puja rituals in their office premises. Unlike some other festivals, the Hindus typically do not fast during the five-day long Diwali including Lakshmi Pujan, rather they feast and share the bounties of the season at their workplaces, community centres, temples, and homes.[123]

Lighting candle and clay lamp in their house and at temples during Diwali night

As the evening approaches, celebrants will wear new clothes or their best outfits, teenage girls and women, in particular, wear saris and jewelry.[128] At dusk, family members gather for the Lakshmi Pujan,[128] although prayers will also be offered to other deities, such as Ganesha, Saraswati, Rama, Lakshmana, Sita, Hanuman, or Kubera.[43] The lamps from the puja ceremony are then used to light more earthenware lamps, which are placed in rows along the parapets of temples and houses,[129] while some diyas are set adrift on rivers and streams.[15][130][131] After the puja, people go outside and celebrate by lighting up patakhe (fireworks) together, and then share a family feast and mithai (sweets, desserts).[43]

The puja and rituals in the Bengali Hindu community focus on Kali, the goddess of war, instead of Lakshmi.[108][132] According to Rachel Fell McDermott, a scholar of South Asian, particular Bengali, studies, in Bengal during Navaratri (Dussehra elsewhere in India) the Durga puja is the main focus, although in the eastern and north eastern states the two are synonymous, but on Diwali the focus is on the puja dedicated to Kali. These two festivals likely developed in tandem over their recent histories, states McDermott.[108] Textual evidence suggests that Bengali Hindus worshipped Lakshmi before the colonial era, and that the Kali puja is a more recent phenomenon.[m] Contemporary Bengali celebrations mirror those found elsewhere, with teenage boys playing with fireworks and the sharing of festive food with family, but with the Shakti goddess Kali as the focus.[133]

On the night of Diwali, rituals across much of India are dedicated to Lakshmi to welcome her into their cleaned homes and bring prosperity and happiness for the coming year.[134][61] While the cleaning, or painting, of the home is in part for goddess Lakshmi, it also signifies the ritual «reenactment of the cleansing, purifying action of the monsoon rains» that would have concluded in most of the Indian subcontinent.[134] Vaishnava families recite Hindu legends of the victory of good over evil and the return of hope after despair on the Diwali night, where the main characters may include Rama, Krishna, Vamana or one of the avatars of Vishnu, the divine husband of Lakshmi.[134][135] At dusk, lamps placed earlier in the inside and outside of the home are lit up to welcome Lakshmi.[125] Family members light up firecrackers, which some interpret as a way to ward off all evil spirits and the inauspicious, as well as add to the festive mood.[136][137] According to Pintchman, who quotes Raghavan, this ritual may also be linked to the tradition in some communities of paying respect to ancestors. Earlier in the season’s fortnight, some welcome the souls of their ancestors to join the family for the festivities with the Mahalaya. The Diwali night’s lights and firecrackers, in this interpretation, represent a celebratory and symbolic farewell to the departed ancestral souls.[138]

The celebrations and rituals of the Jains and the Sikhs are similar to those of the Hindus where social and community bonds are renewed. Major temples and homes are decorated with lights, festive foods shared with all, friends and relatives remembered and visited with gifts.[127][94]

Annakut, Balipratipada (Padwa), Govardhan Puja (Day 4)

The day after Diwali is the first day of the bright fortnight of Kartik.[139] It is regionally called Annakut (heap of grain), Padwa, Goverdhan puja, Bali Pratipada, Bali Padyami, Kartik Shukla Pratipada and other names.[23][139] According to one tradition, the day is associated with the story of Bali’s defeat at the hands of Vishnu.[140][141] In another interpretation, it is thought to reference the legend of Parvati and her husband Shiva playing a game of dyuta (dice) on a board of twelve squares and thirty pieces, Parvati wins. Shiva surrenders his shirt and adornments to her, rendering him naked.[139] According to Handelman and Shulman, as quoted by Pintchman, this legend is a Hindu metaphor for the cosmic process for creation and dissolution of the world through the masculine destructive power, as represented by Shiva, and the feminine procreative power, represented by Parvati, where twelve reflects the number of months in the cyclic year, while thirty are the number of days in its lunisolar month.[139]

Annakut community meals (left), Krishna holding Govardhan Hill ritually made from cow dung, rice and flowers (right).

This day ritually celebrates the bond between the wife and husband,[142] and in some Hindu communities, husbands will celebrate this with gifts to their wives. In other regions, parents invite a newly married daughter, or son, together with their spouses to a festive meal and give them gifts.[142]

In some rural communities of the north, west and central regions, the fourth day is celebrated as Govardhan puja, honouring the legend of the Hindu god Krishna saving the cowherd and farming communities from incessant rains and floods triggered by Indra’s anger,[142] which he accomplished by lifting the Govardhan mountain. This legend is remembered through the ritual of building small mountain-like miniatures from cow dung.[142] According to Kinsley, the ritual use of cow dung, a common fertiliser, is an agricultural motif and a celebration of its significance to annual crop cycles.[114][143][144]

The agricultural symbolism is also observed on this day by many Hindus as Annakut, literally «mountain of food». Communities prepare over one hundred dishes from a variety of ingredients, which is then dedicated to Krishna before being shared among the community. Hindu temples on this day prepare and present «mountains of sweets» to the faithful who have gathered for darshan (visit).[142] In Gujarat, Annakut is the first day of the new year and celebrated through the purchase of essentials, or sabras (literally, «good things in life»), such as salt, offering prayers to Krishna and visiting temples.[142]

Bhai Duj, Bhau-Beej, Vishwakarma Puja (Day 5)

A sister ritually feeding her brother on Bhai Duj-Diwali

The last day of the festival, the second day of the bright fortnight of Kartik, is called Bhai Duj (literally «brother’s day»[145]), Bhau Beej, Bhai Tilak or Bhai Phonta. It celebrates the sister-brother bond, similar in spirit to Raksha Bandhan but it is the brother that travels to meet the sister and her family. This festive day is interpreted by some to symbolise Yama’s sister Yamuna welcoming Yama with a tilaka, while others interpret it as the arrival of Krishna at his sister Subhadra’s place after defeating Narakasura. Subhadra welcomes him with a tilaka on his forehead.[142][146]

The day celebrates the sibling bond between brother and sister.[147] On this day the womenfolk of the family gather, perform a puja with prayers for the well being of their brothers, then return to a ritual of feeding their brothers with their hands and receiving gifts. According to Pintchman, in some Hindu traditions the women recite tales where sisters protect their brothers from enemies that seek to cause him either bodily or spiritual harm.[146] In historic times, this was a day in autumn when brothers would travel to meet their sisters, or invite their sister’s family to their village to celebrate their sister-brother bond with the bounty of seasonal harvests.[43]

The artisan Hindu and Sikh community celebrates the fourth day as the Vishwakarma puja day.[n] Vishwakarma is the presiding Hindu deity for those in architecture, building, manufacturing, textile work and crafts trades.[111] [o] The looms, tools of trade, machines and workplaces are cleaned and prayers offered to these livelihood means.[150]

Other traditions and significance

During the season of Diwali, numerous rural townships and villages host melas,[151] or fairs, where local producers and artisans trade produce and goods. A variety of entertainments are usually available for inhabitants of the local community to enjoy. The women, in particular, adorn themselves in colourful attire and decorate their hands with henna. Such events are also mentioned in Sikh historical records.[152][p] In the modern day, Diwali mela are held at college, or university, campuses or as community events by members of the Indian diaspora. At such events a variety of music, dance and arts performances, food, crafts, and cultural celebrations are featured.[153][154][90]

Economics

Diwali marks a major shopping period in India,[31] and is comparable to the Christmas period in terms of consumer purchases and economic activity.[155] It is traditionally a time when households purchase new clothing, home refurbishments, gifts, gold, jewelry,[156][157] and other large purchases particularly as the festival is dedicated to Lakshmi, the goddess of wealth and prosperity, and such purchases are considered auspicious.[158][159] According to Rao, Diwali is one of the major festivals where rural Indians spend a significant portion of their annual income, and is a means for them to renew their relationships and social networks.[160] Other goods that are bought in substantial quantities during Diwali include confectionery and fireworks. In 2013, about ₹25 billion (US$310 million) of fireworks were sold to merchants for the Diwali season, an equivalent retail value of about ₹50 billion (US$630 million) according to The Times of India.[161][q] ASSOCHAM, a trade organisation in India, forecasted that online shopping alone to be over ₹300 billion (US$3.8 billion) over the 2017 Diwali season.[164] About two-thirds of Indian households, according to the ASSOCHAM forecast, would spend between ₹5,000 (US$63) and ₹10,000 (US$130) to celebrate Diwali in 2017.[165] Stock markets like NSE and BSE in India are typically closed during Diwali, with the exception of a Diwali Muhurat trading session for an hour in the evening to coincide with the beginning of the new year.[166] In 2020, the INDF ETF was launched to mark the start of Diwali.[167]

Politics

Diwali has increasingly attracted cultural exchanges, becoming occasions for politicians and religious leaders worldwide to meet Hindu or Indian origin citizens, diplomatic staff or neighbours. Many participate in other socio-political events as a symbol of support for diversity and inclusiveness. The Catholic dicastery Pontifical Council for Interreligious Dialogue, founded as Secretariat for non-Christians by Pope Paul VI, began sending official greetings and the Pope’s message to the Hindus on Diwali in the mid-1990s.[168][r]

Many governments encourage or sponsor Diwali-related festivities in their territories. For example, the Singaporean government, in association with the Hindu Endowment Board of Singapore, organises many cultural events during Diwali every year.[169] National and civic leaders such as the former Prince Charles have attended Diwali celebrations at prominent Hindu temples in the UK, such as the Swaminarayan Temple in Neasden, using the occasion to highlight contributions of the Hindu community to British society.[170][171] Since 2009, Diwali has been celebrated every year at 10 Downing Street, the residence of the British Prime Minister.[172]

Diwali was first celebrated in the White House by George W. Bush in 2003 and its religious and historical significance was officially recognized by the United States Congress in 2007.[173][174] Barack Obama became the first president to personally attend Diwali at the White House in 2009. On the eve of his first visit to India as President of the United States, Obama released an official statement sharing his best wishes with «those celebrating Diwali».[175]

Every year during Diwali, Indian forces approach their Pakistani counterparts at the border bearing gifts of traditional Indian confectionery, a gesture that is returned in kind by the Pakistani soldiers who give Pakistani sweets to the Indian soldiers.[176][s]

Issues

Burn injuries

The use of fireworks also causes an increase in the number of burn injuries in India during Diwali. One particular firework called anar (fountain) has been found to be responsible for 65% of such injuries, with adults being the typical victims. Most of the injuries sustained are Group I type burns (minor) requiring only outpatient care.[180][181]

Air pollution

The use of firecrackers on Diwali increases the concentration of dust and pollutants in the air. After firing, the fine dust particles get settled on the surrounding surfaces which are packed with chemicals like copper, zinc, sodium, lead, magnesium, cadmium and pollutants like oxides of sulfur and nitrogen.[182] These invisible yet harmful particles affect the environment and in turn, put people’s health at stake.[183]

The thick smoke generated even by the little sparklers and flowerpots can affect the respiratory tract, especially of young children. The smoke that pollutes the air can make the conditions of people who are suffering from colds and allergies much more severe.[184] It also causes congestion of the throat and chest. During Diwali, the levels of suspended particulate matter increase. When people are exposed to these pollutant particles, they may suffer from eye, nose, and throat-related problems. The air and noise pollution that is caused by firecrackers can affect people with disorders related to the heart, respiratory and nervous system. To produce colors when crackers are burst, carcinogenic and poisonous elements are used.[185] When these compounds pollute the air, they increase the risk of cancer in people. The harmful fumes while firing crackers can lead to miscarriage. Firecrackers also cause light pollution.[186] Getting exposed to harmful chemicals while firing crackers can hinder growth in people and increases the toxic levels in their bodies.[187]

See also

- Bandna – Agrarian festival that coincides with Diwali

- Bandi Chhor Divas – Sikh festival that coincides with Diwali

- Day of the Little Candles — the Colombian Catholic festival of candles

- Diwali (Jainism) – Diwali’s significance in Jainism

- Galungan – the Balinese Hindu festival of dharma’s victory over adharma

- Guy Fawkes Night — the British festival of bonfires and fireworks held on the first weekend of November. In towns with a large British Asian community, Diwali and Guy Fawkes festivities are often combined.

- Hanukkah – the Jewish festival of lights

- Kali Puja – Diwali is most commonly known as Kali Puja in West Bengal or in Bengali dominated areas

- Karthikai Deepam – the festival of lights observed by Tamils of Tamil Nadu, Puducherry, Kerala, Sri Lanka and elsewhere

- Lehyam, often prepared on the occasion of Deepavali to aid the digestion

- Lantern Festival – the Chinese festival of lanterns

- Saint Lucy’s Day – the Christian festival of lights

- Sohrai – Harvest festival that coincides with Diwali

- Swanti – Newar version of Diwali

- Tihar – Nepali version of Diwali

- Walpurgis Night – the German festival of bonfires

Notes

- ^ except Sarawak

- ^ The holiday is known as dipawoli in Assamese: দীপাৱলী, dīpabolī or dipali in Bengali: দীপাবলি/দীপালি, dīvāḷi in Gujarati: દિવાળી, divālī in Hindi: दिवाली, dīpavaḷi in Kannada: ದೀಪಾವಳಿ, Konkani: दिवाळी, dīpāvalī in Maithili: दीपावली, Malayalam: ദീപാവലി, Marathi: दिवाळी, dīpābali in Odia: ଦୀପାବଳି, dīvālī in Punjabi: ਦੀਵਾਲੀ, diyārī in Sindhi: दियारी, tīpāvaḷi in Tamil: தீபாவளி, and Telugu: దీపావళి, Galungan in Balinese and Swanti in Nepali: स्वन्ति or tihar in Nepali: तिहार and Thudar Parba in Tulu: ತುಡರ್ ಪರ್ಬ.

- ^ Historical records appear inconsistent about the name of the lunar month in which Diwali is observed. One of the earliest reports on this variation was by Wilson in 1847. He explained that though the actual Hindu festival day is the same, it is identified differently in regional calendars because there are two traditions in the Hindu calendar. One tradition starts a new month from the new moon, while the other starts it from the full moon.[51]

- ^ According to Audrey Truschke, the Sunni Muslim emperor Aurangzeb did limit «public observation» of many religious holidays such as Hindu Diwali and Holi, but also of Shia observance of Muharram and the Persian holiday of Nauruz. According to Truschke, Aurangzeb did so because he found the festivals «distasteful» and also from «concerns with public safety» lurking in the background.[66] According to Stephen Blake, a part of the reason that led Aurangzeb to ban Diwali was the practice of gambling and drunken celebrations.[65] Truschke states that Aurangzeb did not ban private practices altogether and instead «rescinded taxes previously levied on Hindu festivals» by his Mughal predecessors.[66] John Richards disagrees and states Aurangzeb, in his zeal to revive Islam and introduce strict Sharia in his empire, issued a series of edicts against Hindu festivals and shrines.[67] According to Richards, it was Akbar who abolished the discriminatory taxes on Hindu festivals and pilgrims, and it was Aurangzeb who reinstated the Mughal era discriminatory taxes on festivals and increased other religion-based taxes.[67]

- ^ Some Muslims joined the Hindu community in celebrating Diwali in the Mughal era. Illustrative Islamic records, states Stephen Blake, include those of 16th-century Sheikh Ahmad Sirhindi who wrote, «during Diwali…. the ignorant ones amongst Muslims, particularly women, perform the ceremonies… they celebrate it like their own Id and send presents to their daughters and sisters,…. they attach much importance and weight to this season [of Diwali].»[65]

- ^ Williams Jones stated that the Bhutachaturdasi Yamaterpanam is dedicated to Yama and ancestral spirits, the Lacshmipuja dipanwita to goddess Lakshmi with invocations to Kubera, the Dyuta pratipat Belipuja to Shiva-Parvati and Bali legends, and the Bhratri dwitiya to Yama-Yamuna legend and the Hindus celebrate the brother-sister relationship on this day.[68] Jones also noted that on the Diwali day, the Hindus had a mock cremation ceremony with «torches and flaming brands» called Ulcadanam, where they said goodbye to their colleagues who had died in war or in a foreign country and had never returned home. The ceremony lit the path of the missing to the mansion of Yama.[68]

- ^ Some inscriptions mention the festival of lights in Prakrit terms such as tipa-malai, sara-vilakku and others.

- ^ The Sanskrit inscription is in the Grantha script. It is well preserved on the north wall of the second prakara in the Ranganatha temple, Srirangam island, Tamil Nadu.[74]

- ^ The Diwali-related inscription is the 4th inscription and it includes the year Vikrama Era 1268 (c. 1211 CE).[77]

- ^ Scholars contest the 527 BCE date and consider Mahavira’s biographical details as uncertain. Some suggest he lived in the 5th-century BCE contemporaneously with the Buddha.[95][96]

- ^ Sikhs historically referred to this festival as Diwali. It was in early 20th-century, states Harjot Oberoi, a scholar of Sikh history, when the Khalsa Tract Society triggered by the Singh Sabha Movement sought to establish a Sikh identity distinct from the Hindus and the Muslims.[104] They launched a sustained campaign to discourage Sikhs from participating in Holi and Diwali, renaming the festivals, publishing the seasonal greeting cards in the Gurmukhi language and relinking their religious significance to Sikh historical events.[105] While some of these efforts have had a lasting impact for the Sikh community, the lighting, feasting together, social bonding, sharing and other ritual grammar of Sikh celebrations during the Diwali season are similar to those of the Hindus and Jains.[105]

- ^ Hindus of eastern and northeastern states of India associate the festival with the goddess Durga, or her fierce avatar Kali (Shaktism).[82] According to McDermott, this region also celebrated the Lakshmi puja historically, while the Kali puja tradition started in the colonial era and was particular prominent post-1920s.[108]

- ^ According to McDermott, while the Durga Puja is the largest Bengali festival and it can be traced to the 16th-century or earlier, the start of Kali puja tradition on Diwali is traceable to no earlier than about the mid-18th-century during the reign of Raja Krishnacandra Ray.[108] McDermott further writes that the older historic documents of the Bengal confirm that the Bengali Hindus have long celebrated the night of Diwali with illuminations, firecrackers, foods, new account books, Lakshmi (not Kali), inviting their friends (including Europeans during the colonial era) and gambling.[108] The Kali sarbajanin tradition on Diwali, with tantric elements in some locations, grew slowly into a popular Bengali tradition after the mid-1920s.[108]

- ^ According to a Government of Himachal Pradesh and India publication, the Vishvakarma puja is observed on the fourth day of Diwali in the Himalayan state.[148]

- ^ The Vishwakarma puja day is alternatively observed in other Hindu communities in accordance with the Hindu solar calendar, and this falls in September.[149]

- ^ Max Macauliffe, who lived in northwest Punjab area during the colonial era and is known for his work on Sikh literature and history, wrote about Diwali melas to which people visited to buy horses, seek pleasure, pray in nearby Amritsar temples for the prosperity of their children and their souls, and some on «errands, more or less worthy or unworthy character».[152]

- ^ A 2017 estimate states 50,000 tons (100 million pounds) of fireworks are exploded annually in India over the Diwali festival.[162] As a comparison, Americans explode 134,000 tons (268 million pounds) of fireworks for the 4th of July celebrations in the United States.[163]

- ^ The Pontifical Council for Interreligious Dialogue was founded as Secretariat for non-Christians by Pope Paul VI. It began sending official greetings and message to Muslims in 1967 on Id al-Fitr. About 30 years later, in the mid-1990s the Catholic authorities began sending two additional annual official greetings and message, one to the Hindus on Diwali and the other to the Buddhists on Buddha’s birthday.[168]

- ^ Diwali was not a public holiday in Pakistan from 1947 to 2016. Diwali along with Holi for Hindus, and Easter for Christians, was adopted as public holiday resolution by Pakistan’s parliament in 2016, giving the local governments and public institutions the right to declare Holi as a holiday and grant leave for its minority communities, for the first time.[177][178] Diwali celebrations have been relatively rare in contemporary Pakistan, but observed across religious lines, including by Muslims in cities such as Peshawar.[179]

References

- ^ Townsend, Charles M (2014). The Oxford Handbook of Sikh Studies. Oxford University Press. p. 440. ISBN 978-0-19-969930-8.

- ^ «2022 Diwali Puja Calendar, Deepavali Puja Calendar for New Delhi, NCT, India». Retrieved 29 October 2022.

- ^ Mead, Jean (February 2008). How and why Do Hindus Celebrate Divali?. Evans Brothers. ISBN 978-0-237-53412-7.

- ^ a b Johnson, Henry (1 June 2007). «‘Happy Diwali!’ Performance, Multicultural Soundscapes and Intervention in Aotearoa/New Zealand». Ethnomusicology Forum. 16 (1): 79. doi:10.1080/17411910701276526. ISSN 1741-1912. S2CID 191322269.

- ^ Clucas, Ann; Smith, Peter; Fleming, Marianne (25 February 2021). AQA GCSE Religious Studies A (9-1): Christianity & Hinduism Revision Guide. OUP Oxford. p. 69. ISBN 978-1-382-01499-1.

- ^ Min, Pyong Gap (5 April 2010). Preserving Ethnicity Through Religion in America: Korean Protestants and Indian Hindus Across Generations. NYU Press. p. 103. ISBN 978-0-8147-9585-9.

- ^ a b Fieldhouse, Paul (17 April 2017). Food, Feasts, and Faith: An Encyclopedia of Food Culture in World Religions [2 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. p. 150. ISBN 978-1-61069-412-4.

- ^ Stent, David (22 October 2013). Religious Studies: Made Simple. Elsevier. p. 137. ISBN 978-1-4831-8320-6.

- ^ a b The New Oxford Dictionary of English (1998) ISBN 978-0-19-861263-6 – p. 540 «Diwali /dɪwɑːli/ (also Diwali) noun a Hindu festival with lights…».

- ^ Diwali Archived 1 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine Encyclopædia Britannica (2009)

- ^ «Diwali 2020 Date in India: When is Diwali in 2020?». The Indian Express. 11 November 2020. Archived from the original on 16 November 2020. Retrieved 13 November 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Darra Goldstein 2015, pp. 222–223.

- ^ a b Vasudha Narayanan; Deborah Heiligman (2008). Celebrate Diwali. National Geographic Society. p. 31. ISBN 978-1-4263-0291-6. Archived from the original on 2 January 2017. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

All the stories associated with Deepavali, however, speak of the joy connected with the victory of light over darkness, knowledge over ignorance, and good over evil.

- ^ a b Tina K Ramnarine (2013). Musical Performance in the Diaspora. Routledge. p. 78. ISBN 978-1-317-96956-3. Archived from the original on 2 January 2017. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

Light, in the form of candles and lamps, is a crucial part of Diwali, representing the triumph of light over darkness, goodness over evil and hope for the future.

- ^ a b Jean Mead, How and why Do Hindus Celebrate Divali?, ISBN 978-0-237-53412-7

- ^ a b Constance Jones 2011, pp. 252–255

- ^ a b c Deborah Heiligman, Celebrate Diwali, ISBN 978-0-7922-5923-7, National Geographic Society, Washington, D.C.

- ^ a b Suzanne Barchers (2013). The Big Book of Holidays and Cultural Celebrations, Shell Education, ISBN 978-1-4258-1048-1

- ^ Karen-Marie Yust; Aostre N. Johnson; Sandy Eisenberg Sasso (2006). Nurturing Child and Adolescent Spirituality: Perspectives from the World’s Religious Traditions. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 232–233. ISBN 978-0-7425-4463-5. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 29 August 2018.

- ^ a b James G. Lochtefeld 2002, pp. 200–201

- ^ Christopher H. Johnson, Simon Teuscher & David Warren Sabean 2011, pp. 300–301.

- ^ Manju N. Shah 1995, pp. 41–44.

- ^ a b c d Paul Fieldhouse 2017, pp. 150–151.

- ^ Diane P. Mines; Sarah E. Lamb (2010). Everyday Life in South Asia, Second Edition. Indiana University Press. p. 243. ISBN 978-0-253-01357-6. Archived from the original on 2 July 2021. Retrieved 25 September 2018.

- ^ Sharma, S.P.; Gupta, Seema (2006). Fairs and Festivals of India. Pustak Mahal. p. 79. ISBN 978-81-223-0951-5. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- ^ Upadhye, A.N. (January–March 1982). Cohen, Richard J. (ed.). «Mahavira and His Teachings». Journal of the American Oriental Society. 102 (1): 231–232. doi:10.2307/601199. JSTOR 601199.

- ^ Geoff Teece (2005). Sikhism. p. 23. ISBN 978-1-58340-469-0. Archived from the original on 2 January 2017. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- ^ McDermott and Kripal p.72

- ^ a b c d Todd T. Lewis (7 September 2000). Popular Buddhist Texts from Nepal: Narratives and Rituals of Newar Buddhism. State University of New York Press. pp. 118–119. ISBN 978-0-7914-9243-7. Archived from the original on 2 January 2017. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- ^ a b Prem Saran (2012). Yoga, Bhoga and Ardhanariswara: Individuality, Wellbeing and Gender in Tantra. Routledge. p. 175. ISBN 978-1-136-51648-1. Archived from the original on 2 January 2017. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- ^ a b India Journal: ‘Tis the Season to be Shopping Devita Saraf, The Wall Street Journal (August 2010)

- ^ Henry Johnson 2007, pp. 71–73.

- ^ Kelly 1988, pp. 40–55.

- ^ Public Holidays Archived 16 September 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Government of Fiji

- ^ Public Holidays Archived 19 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Guyana

- ^ Public Holidays Archived 5 March 2019 at the Wayback Machine, Government of Malaysia

- ^ Public Holidays Archived 17 August 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Government of Myanmar

- ^ Public Holidays Archived 19 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Government of Nepal

- ^ Pakistan parliament adopts resolution for Holi, Diwali, Easter holidays Archived 6 March 2018 at the Wayback Machine, The Times of India (16 March 2016)

- ^ Public Gazetted Holidays Archived 19 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Government of Singapore

- ^ Official Public Holidays Archived 3 March 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Government of Trinidad & Tobago