«Праздник дураков»

«Праздник дураков»

В средние века в Европе, особенно во Франции и Италии, проводился необычный праздник, который назывался «праздником дураков». Это был веселый религиозный фестиваль-бурлеск, когда христианская месса превращалась в своеобразный фарс. Нужно отметить, что этот праздник организовывался отнюдь не врагами Церкви, а скорее самыми благочестивыми членами клира. Он обычно проходил в середине декабря и длился несколько дней.

В начале празднества самые высокие иерархические чины — епископы и архиепископы — передавались представителям низшего слоя клириков, нарушая тем самым все принятые церковные законы. Эти люди получали облачения, соответствующие их высокому сану, и вели себя так, словно они на самом деле важные церковные «шишки». Им вручались пастырские посохи и предоставлялось право на торжественное благословение прихожан.

Проводимая ими месса в городском соборе, однако, не имела ничего общего с нормальной церковной службой. Это была обманная месса, на которой ненастоящему епископу прислуживали ненастоящие священнослужители в женских одеждах. Вместо обычных торжественных молитв в храме распевали похабные песенки, а вокруг алтаря водили веселые хороводы.

Во время этой невероятной церковной службы клирики вели себя так, словно они не в храме, а где-нибудь в харчевне, так как они на ходу проглатывали горячие сосиски и на алтаре играли в карты. Вместо обычного ладана в храме жгли старую обувь.

Хотя неоднократно предпринимались усилия с целью наложения запрета на подобный обычай, он все равно пользовался громадной популярностью как среди верующих, так и у клира, и поэтому дожил в Европе до эпохи Реформации. Еще в 1645 году во Франции в некоторых монастырях отмечался «праздник дураков». Вот как его описывал один автор:

«Участники держали в руках священные книги вверх тормашками и притворялись, что читают их через очки, в которых вместо стекол были вставлены кусочки какой-то странной кожуры, при этом они что-то мямлили, путая слова, и издавали такие дикие, смешные, глупые и неприятные вопли, поднимали такой ужасный визг, что казалось, это не люди, а стадо разъяренных свиней».

Он явно осуждал такие действа:

«Лучше на самом деле пригласить в храм животных, чтобы те на свой манер вознесли славу Господу, чем выносить эту орущую толпу людей, которые, по сути дела, насмехались над Богом, делая при этом вид, что его восхваляют. Такие люди глупее и бессмысленнее, чем самые глупые и бессмысленные звери».

В кафедральном соборе французского города Сан проводился своеобразный вариант такого праздника, получивший название «праздник осла». В церковь несколько членов клира приводили осла. Во время проведения мессы осел становился центром всеобщего внимания, и вокруг него начинались всевозможные смешные церемонии в духе настоящего бурлеска. Они могли продолжаться часами.

Читайте также

Праздник Ханги

Праздник Ханги

Уборка киви продолжалась весь май. Работали во все погожие дни, включая субботы и воскресенья. Но едва начинался дождь и киви становились мокрыми, уборка сразу прекращалась. И не потому, что хозяева так уж сильно радели о здоровье своих рабочих (да и своем

Будни как праздник

Будни как праздник

За большим столом – для этого сдвинули несколько ресторанных столиков – сидели человек двадцать; это были люди разных профессий: рабочий каменоломни, повар, дежурный гостиницы, продавщица магазина, помощник бухгалтера… Их объединяли родство и

Праздник прощания

Праздник прощания

Последний день в клубе. Вот уж не думала, что буду так плакать. Япония незримо притягивает к себе, опутывая магической сетью, впитывается в плоть и кровь. Настолько сильно, что по возвращении мы не сразу можем избавиться от ставших привычными японских

Невероятный праздник повозок

Невероятный праздник повозок

Один из самык фантастических религиозных праздников проводится в городе Пури, в индийском штате Орисса. Он обычно отмечается в июне и посвящается очередной годовщине паломничества бога Вишну, которое тот совершил из Гокула в Матуру. Но во

38. Корабль дураков

38. Корабль дураков

Тишину моей одиночки через несколько дней нарушили крики зека, попавшего в соседний карцер.Сосед оказался весьма буен, он не давал покоя ни днем, ни ночью. Это был, как он сам иронически представлялся, «Владимир де Красняк, кремлевский крепостной, белый

51. Национальный праздник

51. Национальный праздник

Сегодня 1 августа — национальный праздник Швейцарии. Два швейцарских члена экипажа, Эрвин Эберсолд и я, должны как-то отметить этот день. Как именно? Разумеется костром! Этого требует традиция, которая приобрела почти что силу закона.

Праздник заклятий

Праздник заклятий

Лет двадцать назад, между 1970 и 1974-м, я имел счастье жить в панамской провинции Дарьен среди эмбера — одной из центральноамериканских народностей — и у их ближайших родственников ваунана. Опыт, приобретенный там, полностью изменил мои представления о

Главный праздник

Главный праздник

В Англии Рождество — главный праздник. Думать о нем многие начали с лета. Нетерпение оказалось так велико, что рождественское шествие жителей нашего городка прошло в ноябре.Конечно, в торговле предвкушение праздника носит коммерческий характер, ведь

Праздник смерти

Праздник смерти

Тридцать седьмой. Рубеж, символ.Год праздников и побед. Двадцатилетний юбилей Октября. Первый год новой Советской Конституции.Вторая пятилетка выполнена на девять месяцев раньше срока. Аграрная страна превратилась в мощную индустриальную державу, по

«Праздник» Пурим

«Праздник» Пурим

Первый из этих исторических примеров радикального истребления одного арийского народа большевицко-еврейскими методами приводит нам Библия. Прочтите, раскрыв пошире свои глаза, эти страницы еврейской истории, на которых повествуется о том, как евреи,

3. Есть работа хуже, чем пасти дураков

3. Есть работа хуже, чем пасти дураков

Бюрократия Россионии наших дней в общем не хуже и не лучше любой прошлой отечественной бюрократии. Её исторически преходящая специфика состоит в том, что она сейчас пребывает в той фазе своего развития, которая может быть названа

| April Fools’ Day | |

|---|---|

An April Fools’ Day prank marking the construction of the Copenhagen Metro in 2001 |

|

| Also called | April Fool’s Day |

| Type | Cultural, Western |

| Significance | Practical jokes, pranks |

| Observances | Comedy |

| Date | 1 April |

| Next time | 1 April 2023 |

| Frequency | Annual |

April Fools’ Day or All Fools’ Day is an annual custom on 1 April consisting of practical jokes and hoaxes. Jokesters often expose their actions by shouting «April Fools!» at the recipient. Mass media can be involved in these pranks, which may be revealed as such the following day. The custom of setting aside a day for playing harmless pranks upon one’s neighbour has been relatively common in the world historically.[1]

Origins[edit]

An 1857 ticket to «Washing the Lions» at the Tower of London in London. No such event ever took place.

Although the origins of April Fools’ is unknown, there are many theories surrounding it.

A disputed association between 1 April and foolishness is in Geoffrey Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales (1392).[2] In the «Nun’s Priest’s Tale», a vain cock Chauntecleer is tricked by a fox on «Since March began thirty days and two,»[3][4] i.e. 32 days since March began, which is 1 April.[5] However, it is not clear that Chaucer was referencing 1 April since the text of the «Nun’s Priest’s Tale» also states that the story takes place on the day when the sun is «in the sign of Taurus had y-rune Twenty degrees and one,» which would not be 1 April. Modern scholars believe that there is a copying error in the extant manuscripts and that Chaucer actually wrote, «Syn March was gon«.[6] If so, the passage would have originally meant 32 days after March, i.e. 2 May,[7] the anniversary of the engagement of King Richard II of England to Anne of Bohemia, which took place in 1381.

In 1508, French poet Eloy d’Amerval referred to a poisson d’avril (April fool, literally «April’s fish»), possibly the first reference to the celebration in France.[8] Some historians suggest that April Fools’ originated because, in the Middle Ages, New Year’s Day was celebrated on 25 March in most European towns,[9] with a holiday that in some areas of France, specifically, ended on 1 April,[10][11] and those who celebrated New Year’s Eve on 1 January made fun of those who celebrated on other dates by the invention of April Fools’ Day.[12] The use of 1 January as New Year’s Day became common in France only in the mid-16th century,[7] and that date was not adopted officially until 1564, by the Edict of Roussillon, as called for during the Council of Trent in 1563.[13] However, there are issues with this theory because there is an unambiguous reference to April Fools’ Day in a 1561 poem by Flemish poet Eduard de Dene of a nobleman who sends his servants on foolish errands on 1 April, predating the change.[7] April Fools’ Day was also an established tradition in Great Britain before 1 January was established as the start of the calendar year.[14][15]

In the Netherlands, the origin of April Fools’ Day is often attributed to the Dutch victory in 1572 in the Capture of Brielle, where the Spanish Duke Álvarez de Toledo was defeated. «Op 1 april verloor Alva zijn bril» is a Dutch proverb, which can be translated as: «On the first of April, Alva lost his glasses». In this case, «bril» («glasses» in Dutch) serves as a homonym for Brielle (the town where it happened). This theory, however, provides no explanation for the international celebration of April Fools’ Day.

In 1686, John Aubrey referred to the celebration as «Fooles holy day», the first British reference.[7] On 1 April 1698, several people were tricked into going to the Tower of London to «see the Lions washed».[7]

Although no biblical scholar or historian is known to have mentioned a relationship, some have expressed the belief that the origins of April Fools’ Day may go back to the Genesis flood narrative. In a 1908 edition of the Harper’s Weekly cartoonist Bertha R. McDonald wrote:

Authorities gravely back with it to the time of Noah and the ark. The London Public Advertiser of March 13, 1769, printed: «The mistake of Noah sending the dove out of the ark before the water had abated, on the first day of April, and to perpetuate the memory of this deliverance it was thought proper, whoever forgot so remarkable a circumstance, to punish them by sending them upon some sleeveless errand similar to that ineffectual message upon which the bird was sent by the patriarch».[1]

Long-standing customs[edit]

United Kingdom[edit]

On April Fools’ Day 1980, the BBC announced Big Ben’s clock face was going digital and whoever got in touch first could win the clock hands.[5]

In the UK, an April Fool prank is sometimes later revealed by shouting «April fool!» at the recipient, who becomes the «April fool». A study in the 1950s, by folklorists Iona and Peter Opie, found that in the UK, and in countries whose traditions derived from the UK, this continues to be the practice, with the custom ceasing at noon, after which time it is no longer acceptable to play pranks.[16] Thus a person playing a prank after midday is considered the «April fool» themselves.[17]

In Scotland, April Fools’ Day was originally called «Huntigowk Day«.[18] The name is a corruption of «hunt the gowk«, gowk being Scots for a cuckoo or a foolish person; alternative terms in Gaelic would be Là na Gocaireachd, «gowking day», or Là Ruith na Cuthaige, «the day of running the cuckoo». The traditional prank is to ask someone to deliver a sealed message that supposedly requests help of some sort. In fact, the message reads «Dinna laugh, dinna smile. Hunt the gowk another mile.» The recipient, upon reading it, will explain they can only help if they first contact another person, and they send the victim to this next person with an identical message, with the same result.[18]

In England a «fool» is known by a few different names around the country, including «noodle», «gob», «gobby», or «noddy».

Ireland[edit]

In Ireland, it was traditional to entrust the victim with an «important letter» to be given to a named person. That person would read the letter, then ask the victim to take it to someone else, and so on. The letter when opened contained the words «send the fool further».[19]

Italy, France, Belgium, French-speaking areas[edit]

In Italy, France, Belgium and French-speaking areas of Switzerland and Canada, the 1 April tradition is often known as «April fish» (poisson d’avril in French, april vis in Dutch or pesce d’aprile in Italian). Possible pranks include attempting to attach a paper fish to the victim’s back without being noticed. This fish feature is prominently present on many late 19th- to early 20th-century French April Fools’ Day postcards. Many newspapers also spread a false story on April Fish Day, and a subtle reference to a fish is sometimes given as a clue to the fact that it is an April Fools’ prank.[citation needed]

Germany[edit]

In Germany, an April Fool prank is sometimes later revealed by shouting «April, April!» at the recipient, who becomes the «April fool».[citation needed]

Nordic countries[edit]

Danes, Finns, Icelanders, Norwegians and Swedes celebrate April Fools’ Day (aprilsnar in Danish; aprillipäivä in Finnish; aprilsnarr in Norwegian; aprilskämt in Swedish). Most news media outlets will publish exactly one false story on 1 April; for newspapers this will typically be a first-page article but not the top headline.[20]

Poland (Prima aprilis)[edit]

In Poland, prima aprilis («First April» in Latin) as a day of pranks is a centuries-long tradition. It is a day when many pranks are played: hoaxes – sometimes very sophisticated – are prepared by people, media (which often cooperate to make the «information» more credible) and even public institutions. Serious activities are usually avoided, and generally every word said on 1 April could be untrue. The conviction for this is so strong that the Polish anti-Turkish alliance with Leopold I signed on 1 April 1683, was backdated to 31 March.[21] However, for some in Poland prima aprilis ends at noon of 1 April and prima aprilis jokes after that hour are considered inappropriate and not classy.

Ukraine[edit]

April Fools’ Day is widely celebrated in Odessa and has the special local name Humorina — in Ukrainian Гуморина (Humorina). This holiday arose in 1973.[22] An April Fool prank is revealed by saying «Первое Апреля, никому не верю» («Pervoye Aprelya, nikomu ne veryu«) — which means «First of April, I trust nobody» — to the recipient. The festival includes a large parade in the city centre, free concerts, street fairs and performances. Festival participants dress up in a variety of costumes and walk around the city fooling around and pranking passersby. One of the traditions on April Fools’ Day is to dress up the main city monument in funny clothes. Humorina even has its own logo — a cheerful sailor in a lifebelt — whose author was the artist Arkady Tsykun.[23] During the festival, special souvenirs bearing the logo are printed and sold everywhere. Since 2010, April Fools’ Day celebrations include an International Clown Festival and both celebrated as one. In 2019, the festival was dedicated to the 100th anniversary of the Odessa Film Studio and all events were held with an emphasis on cinema.[24]

Spanish-speaking countries[edit]

In many Spanish-speaking countries (and the Philippines), «Día de los Santos Inocentes» (Holy Innocents Day) is a festivity which is very similar to April Fools’ Day, but it is celebrated in late December (27, 28 or 29 depending on the location).[citation needed]

Turkey[edit]

Turkey also has a custom of April Fools’ pranks.[25] Pranks and jokes are usually verbal and are revealed by shouting «Bir Nisan!» (April 1st!).

Iran[edit]

In Iran, it is called «Dorugh-e Sizdah» (lie of Thirteen) and people and media prank on 13 Farvardin (Sizdah bedar) that is equivalent of 1 April. It is a tradition that takes place 13 days after the Persian new year Nowruz. On this day, people go out and leave their houses and have fun outside mostly in natural parks.

Pranks have reportedly been played on this holiday since 536 BC in the Achaemenid Empire.

Israel[edit]

Israel has adopted the custom of pranking on April Fools’ Day.[26]

Lebanon[edit]

In Lebanon, an April Fool prank is revealed by saying كذبة أول نيسان (which means «First of April Lie») to the recipient.

Pranks[edit]

An April Fools’ Day prank in Boston’s Public Garden warning people not to photograph sculptures, as light emitted will «erode the sculptures»

A common prank is to carefully remove the cream from an Oreo and replace it with toothpaste, and there are many similar pranks that replace an object (usually food) with another object that looks like the object but tastes different such as replacing sugar with salt and vanilla frosting with sour cream. As well as people playing pranks on one another on April Fools’ Day, elaborate pranks have appeared on radio and television stations, newspapers, and websites, and have been performed by large corporations. In one famous prank in 1957, the BBC broadcast a film in their Panorama current affairs series purporting to show Swiss farmers picking freshly-grown spaghetti, in what they called the Swiss spaghetti harvest. The BBC was soon flooded with requests to purchase a spaghetti plant, forcing them to declare the film a hoax on the news the next day.[27]

With the advent of the Internet and readily available global news services, April Fools’ pranks can catch and embarrass a wider audience than ever before.[28]

Comparable prank days[edit]

28 December[edit]

28 December, the equivalent day in Spain and Hispanic America, is also the Christian day of celebration of the Day of the Holy Innocents. The Christian celebration is a religious holiday in its own right, but the tradition of pranks is not, though the latter is observed yearly. In some regions of Hispanic America after a prank is played, the cry is made, «Inocente palomita que te dejaste engañar» («You innocent little dove that let yourself be fooled!»; not to be confused with another meaning of palomita, which means «popcorn» in some dialects).[citation needed]

In Argentina, the prankster says, «¡Que la inocencia te valga!» which roughly translates as advice to not be as gullible as the victim of the prank. In Spain, it is common to say just «¡Inocente!» (which in Spanish can mean «innocent» or «gullible»).[29]

In Colombia, the term is used as «Pásala por Inocentes«, which roughly means: «Let it go; today it’s Innocent’s Day.»[citation needed]

In Belgium, this day is also known as the «Day of the Innocent Children» or «Day of the Stupid Children». It used to be a day where parents, grandparents, and teachers would fool the children in some way. But the celebration of this day has died out in favour of April Fools’ Day.[citation needed]

Nevertheless, on the Spanish island of Menorca, Dia d’enganyar («Fooling day») is celebrated on 1 April because Menorca was a British possession during part of the 18th century. In Brazil, the «Dia da mentira» («Day of the lie») is also celebrated on 1 April[29] due to the Portuguese influence.

First day of a new month[edit]

In many English-speaking countries, mainly Britain, Ireland, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa, it is a custom to say «pinch and a punch for the first of the month» or an alternative, typically by children. The victim might respond with «a flick and a kick for being so quick», and the attacker might reply with «a punch in the eye for being so sly».[30]

Another custom in Britain and North America is to say «rabbit rabbit» upon waking on the first day of a month, for good luck.[31]

Reception[edit]

The practice of April Fool pranks and hoaxes is controversial.[17][32] The mixed opinions of critics are epitomized in the reception to the 1957 BBC «spaghetti-tree hoax», in reference to which, newspapers were split over whether it was «a great joke or a terrible hoax on the public».[33]

The positive view is that April Fools’ can be good for one’s health because it encourages «jokes, hoaxes … pranks, [and] belly laughs», and brings all the benefits of laughter including stress relief and reducing strain on the heart.[34] There are many «best of» April Fools’ Day lists that are compiled in order to showcase the best examples of how the day is celebrated.[35] Various April Fools’ campaigns have been praised for their innovation, creativity, writing, and general effort.[36]

The negative view describes April Fools’ hoaxes as «creepy and manipulative», «rude» and «a little bit nasty», as well as based on Schadenfreude and deceit.[32] When genuine news or a genuine important order or warning is issued on April Fools’ Day, there is risk that it will be misinterpreted as a joke and ignored – for example, when Google, known to play elaborate April Fools’ Day hoaxes, announced the launch of Gmail with 1-gigabyte inboxes in 2004, an era when competing webmail services offered 4-megabytes or less, many dismissed it as a joke outright.[37][38] On the other hand, sometimes stories intended as jokes are taken seriously. Either way, there can be adverse effects, such as confusion,[39] misinformation, waste of resources (especially when the hoax concerns people in danger) and even legal or commercial consequences.[40][41]

In March 2020, during the COVID-19 pandemic, various organizations and people cancelled their April Fools’ Day celebrations, or advocated against observing April Fools’ Day, as a mark of respect due to the large amount of tragic deaths that COVID-19 had caused up to that point, the wish to provide truthful information to counter the misinformation about the virus, and to pre-empt any attempts to incorporate the virus into any potential pranks.[42][43] For example, Google decided not to continue «its infamous April Fools’ jokes» tradition for that year.[44] Because the pandemic was still ongoing a year later in 2021, they also decided not to do pranks that year.[45]

In Thailand, the police warned ahead of April Fools’ in 2021 that posting or sharing fake news online could lead to maximum of five years imprisonment.[46]

Other examples of genuine news on 1 April mistaken as a hoax include:

- 1 April 1946: Warnings about the Aleutian Island earthquake’s tsunami that killed 165 people in Hawaii and Alaska.[47]

- 1 April 1984: News that the singer Marvin Gaye was shot and killed the day before his 45th birthday by his father Marvin Gay Sr. (sic) on 1 April 1984. Several people close to Gaye such as fellow singers Smokey Robinson and Jermaine Jackson, brother of Michael Jackson didn’t believe the news initially and had to phone call other people who knew Gaye to confirm the news, Al Sharpton during his interview for the VH1 documentary VH1’s Most Shocking Moments in Rock & Roll referenced the coincidence of the date when he said that Gaye’s death came «like a sick, sad joke to all of us.»[48][49][50][51][52]

- 1 April 1995: News that the singer Selena was shot and killed by the former president of her fan club Yolanda Saldívar on 31 March 1995. When radio station KEDA broke the news on 31 March 1995, many people accused the staff of lying because the next day was April Fools’ Day.[53]

- 1 April 2004: Gmail is announced to the public by Google. Some of the announced features for the service were not considered technologically possible with the technology available in 2004.[54]

- 1 April 2005: News that the comedian Mitch Hedberg had died on 29 March 2005.[55]

- 1 April 2005: Announcement about Powerpuff Girls Z, by Aniplex, Cartoon Network and Toei Animation. The TV show was an anime adaption of the cartoon The Powerpuff Girls and the idea that a cartoon would get turned into an anime was considered very outlandish in 2005 as this was the first time it happened.[56]

- 1 April 2008: Announcement that the NationStates government simulation browser game had received a cease and desist letter from the United Nations (UN) for unauthorized usage of its name and emblem for the fictional intergovernmental organization where players (as nations) can create and vote on international law within the game world and that due to this, NationStates has now changed its version of the UN into the «World Assembly» (WA) with a different emblem. On 2 April 2008, NationStates developer Max Barry revealed that the letter from the UN was in fact real and he had actually received it on 21 January 2008 but chose only to start complying with it on 1 April to deliberately fool people into thinking the announcement was the annual NationStates April Fools prank and that because the legal action was real, the changes are permanent.[57][58]

- 1 April 2009: Announcement that the long running soap opera Guiding Light was being cancelled. The date was so heavily associated with jokes and pranks that even some of the cast and crew didn’t believe the news when it was announced by CBS, the TV network that aired the show.[59]

- 1 April 2011: Isaiah Thomas declared for the NBA draft. Thomas is short and basketball players in the NBA are usually taller than average as height gives advantage to playing basketball.[60]

In popular culture[edit]

Books, films, telemovies and television episodes have used April Fools’ Day as their title or inspiration. Examples include Bryce Courtenay’s novel April Fool’s Day (1993), whose title refers to the day Courtenay’s son died. The 1990s sitcom Roseanne featured an episode titled «April Fools’ Day». This turned out to be intentionally misleading, as the episode was about Tax Day in the United States on 15 April – the last day to submit the previous year’s tax information. Although Tax Day is usually 15 April as depicted in the episode, it can be moved back a few days if that day is on a weekend or a holiday in Washington, D.C. or some states, or due to natural disasters when it can occur as late as 15 July.[61]

Further reading[edit]

- Wainwright, Martin (2007). The Guardian Book of April Fool’s Day. Aurum. ISBN 978-1-84513-155-5.

- Dundes, Alan (1988). «April Fool and April Fish: Towards a Theory of Ritual Pranks». Etnofoor. 1 (1): 4–14. JSTOR 25757645.

- Similar events documented by other Wiki languages also exist such as Poisson d’avril (France) and in the USA the International day of the joke event which is assigned the first Sunday in May.[62]

See also[edit]

- Feast of Fools, a similar medieval festival

- List of April Fools’ Day jokes

- List of practical joke topics

References[edit]

- ^ a b McDonald, Bertha R. (7 March 1908). «The Oldest Custom in the World». Harper’s Weekly. Vol. 52, no. 2672. p. 26.

- ^ Ashley Ross (31 March 2016). «No Kidding: We Have No Idea How April Fools’ Day Started». Time. Retrieved 24 March 2018.

- ^ The Nun’s Priest’s Tale

- ^ The Nun’s Priest’s Tale. Chaucer in the Twenty-First Century. University of Maine at Machias. 21 September 2007.

- ^ a b «April Fool’s Day 2021: how Chaucer, calendar confusion and Hilaria led to jokes and fake news». The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 24 September 2021.

- ^ Travis, Peter W. (1997). «Chaucer’s Chronographiae, the Confounded Reader, and Fourteenth-Century Measurements of Time». In Poster, Carol; Utz, Richard J. (eds.). Constructions of Time in the Late Middle Ages. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press. pp. 16–17. ISBN 0-8101-1541-7.

- ^ a b c d e Boese, Alex (2008). «The Origin of April Fool’s Day». Museum of Hoaxes.

- ^ Eloy d’Amerval (1991). Le Livre de la Deablerie. De maint homme et de mainte fame, poisson d’Apvril vien tost a moy. Librairie Droz. p. 70. ISBN 9782600026727.

- ^ Groves, Marsha (2005). Manners and Customs in the Middle Ages. p. 27.

- ^ «April Fools’ Day». Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ^ Santino, Jack (1972). All around the year: holidays and celebrations in American life. University of Illinois Press. p. 97. ISBN 978-0-252-06516-3.

- ^ Winick, Stephen (28 March 2016). «April Fools: The Roots of an International Tradition | Folklife Today». blogs.loc.gov. Retrieved 12 March 2022.

- ^ «April Fools’ Day». History.com. 30 March 2017.

- ^ «A brief, totally sincere history of April Fools’ Day». Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 12 March 2022.

- ^ «The Origin of April Fool’s Day». Museum of Hoaxes. Retrieved 12 March 2022.

- ^ Great Britain: Home Office (2017). Life in the United Kingdom: a guide for new residents (2014 ed.). Stationery Office. ISBN 9780113413409.

- ^ a b Archie Bland (1 April 2009). «The Big Question: How did the April Fool’s Day tradition begin, and what are the best tricks?». The Independent. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ^ a b Opie, Iona & Peter (1960). The Lore and Language of Schoolchildren. Oxford University Press. pp. 245–46. ISBN 0-940322-69-2.

- ^ Haggerty, Bridget. «April Fool’s Day». Irish Culture and Customs. Retrieved 3 April 2014.

- ^ Bora, Kukil (12 March 2012). «April Fool’s Day: 8 Interesting Things And Hoaxes You Didn’t Know». International Business Times. Retrieved 27 May 2013.

- ^ «Origin of April Fools’ Day». The Express Tribune. 3 April 2012. Retrieved 27 May 2013.

- ^ Sinelnikova, Alexandra (1 April 2019). «Humorina time». Odessitclub.

- ^ «Main festival in Odessa». 2019.

- ^ «Odessa celebrates Humorine. Picture story». 1 April 2019.

- ^ «1 Nisan şakaları 2022!». www.haberturk.com (in Turkish). 1 April 2022. Retrieved 2 April 2022.

- ^ Adam, Soclof (31 March 2011). «From the JTA Archive: April Fools’ Day lessons for Jewish pranksters». Jewish Telegraph Agency. JTA. Retrieved 3 April 2019.

- ^ «Swiss Spaghetti Harvest». Retrieved 1 November 2013.

- ^ Moran, Rob (4 April 2014). «NPR’s Brilliant April Fools’ Day Prank Was Sadly Lost On Much Of The Internet». Retrieved 6 April 2014.

- ^ a b «Avui és el Dia d’Enganyar a Menorca» [Today is Fooling Day on Minorca] (in Catalan). Vilaweb. 1 April 2003. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ^ «pinch and a punch for the first of the month — Wiktionary». en.wiktionary.org. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- ^ Willingham, AJ (July 2019). «Rabbit rabbit! Why people say this good-luck phrase at the beginning of the month». CNN. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- ^ a b Doll, Jen (1 April 2013). «Is April Fools’ Day the Worst Holiday? – Yahoo News». Yahoo! News. Retrieved 1 April 2014.

- ^ «Is this the best April Fool’s ever?». BBC News. Retrieved 1 April 2014.

- ^ «Why April Fools’ Day is Good For Your Health – Health News and Views». News.Health.com. 1 April 2013. Retrieved 1 April 2014.

- ^ «April Fools: the best online pranks | SBS News». Sbs.com.au. Retrieved 1 April 2014.

- ^ «April Fool’s Day: A Global Practice». aljazirahnews. 1 April 2019. Retrieved 8 April 2019.

- ^ Harry McCracken (1 April 2013). «Google’s Greatest April Fools’ Hoax Ever (Hint: It Wasn’t a Hoax)». Time. Archived from the original on 1 April 2013. Retrieved 1 August 2014.

- ^ Lisa Baertlein (1 April 2004). «Google: ‘Gmail’ no joke, but lunar jobs are». Reuters. Retrieved 1 August 2014.

- ^ Woods, Michael (2 April 2013). «Brazeau tweets his resignation on April Fool’s Day, causing confusion – National». Globalnews.ca. Retrieved 1 April 2014.

- ^ Hasham, Nicole (3 April 2013). «ASIC to look into prank Metgasco email from schoolgirl Kudra Falla-Ricketts». The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 3 April 2014.

- ^ «Justin Bieber’s Believe album hijacked by DJ Paz». The Sydney Morning Herald. 3 April 2014. Retrieved 3 April 2014.

- ^ «April Fools’ is Cancelled Because We Can’t Distance Fact From Fiction». CCN.com. 1 April 2020.

- ^ Willingham, A. J. (1 April 2020). «April Fools’ Day pranks are not funny right now. Don’t do them». CNN.

- ^ Gartenberg, Chaim (27 March 2020). «Google cancels its infamous April Fools’ jokes this year». The Verge.

- ^ Price, Rob. «Google is canceling its famous April Fools’ Day pranks for the 2nd year in a row». Business Insider.

- ^ «Phuket News: Police warn of prison terms for April Fool’s stories». The Phuket News. 1 April 2021. Retrieved 1 April 2021.

- ^ «1946 Aleutian Tsunami». www.usc.edu. Archived from the original on 12 January 2016. Retrieved 29 March 2022.

- ^ American Masters: What’s Going On – The Life and Death of Marvin Gaye, PBS, 2008

- ^ «Marvin Gaye Last Day». PBS. YouTube. Archived from the original on 21 December 2021. Retrieved 29 March 2022.

- ^ Behind the Music, VH1, 1998

- ^ VH1’s Most Shocking Moments in Rock & Roll, VH1, 1998

- ^ Ritz 1991, p. 334.

- ^ Patoski 1996, p. 199.

- ^ Horton, Alex. «When Gmail Was First Announced, People Thought It Was an April Fools’ Joke». ScienceAlert. Retrieved 8 November 2020.

- ^ Rusnak, Jeff (2 April 2005). «MITCH HEDBERG, 37, COMEDIAN, FILMMAKER». South Florida Sun-Sentinel. Archived from the original on 30 June 2021. Retrieved 29 March 2022.

- ^ «Powerpuff Girls Z Debut».

- ^ Andrei, Terekhov (21 January 2008). «Notice of cease and desist» (PDF). NationStates. United Nations. Retrieved 29 March 2022.

- ^ Max, Barry (2 April 2008). «The United Nations vs Me». maxbarry.com. Retrieved 29 March 2022.

- ^ «Guiding Light, Snuffed: Scene From A Dying Daytime Drama». The New York Observer. 15 September 2009.

- ^ Gould, Andrew. «Isaiah Thomas Laughs at Doubters on April Fools’ Day». Bleacher Report. Retrieved 8 November 2020.

- ^ Faler, Brian. «Trump administration moves Tax Day to July 15». POLITICO.

- ^ BBC News: International joke day

Bibliography[edit]

- Patoski, Joe Nick (1996). Selena: Como La Flor. Boston: Little Brown and Company. ISBN 978-0-316-69378-3.

- Ritz, David (1991). Divided Soul: The Life of Marvin Gaye. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-81191-X.

External links[edit]

Wikipedia victim of onslaught of April Fool’s jokes at Wikinews

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). «April-Fools’ Day» . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- «Top 100 April Fools’ Day hoaxes of all time». Museum of Hoaxes.

- «April Fools’ Day On The Web: List of all known April Fools’ Day Jokes websites from 2004 until present».

| April Fools’ Day | |

|---|---|

An April Fools’ Day prank marking the construction of the Copenhagen Metro in 2001 |

|

| Also called | April Fool’s Day |

| Type | Cultural, Western |

| Significance | Practical jokes, pranks |

| Observances | Comedy |

| Date | 1 April |

| Next time | 1 April 2023 |

| Frequency | Annual |

April Fools’ Day or All Fools’ Day is an annual custom on 1 April consisting of practical jokes and hoaxes. Jokesters often expose their actions by shouting «April Fools!» at the recipient. Mass media can be involved in these pranks, which may be revealed as such the following day. The custom of setting aside a day for playing harmless pranks upon one’s neighbour has been relatively common in the world historically.[1]

Origins[edit]

An 1857 ticket to «Washing the Lions» at the Tower of London in London. No such event ever took place.

Although the origins of April Fools’ is unknown, there are many theories surrounding it.

A disputed association between 1 April and foolishness is in Geoffrey Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales (1392).[2] In the «Nun’s Priest’s Tale», a vain cock Chauntecleer is tricked by a fox on «Since March began thirty days and two,»[3][4] i.e. 32 days since March began, which is 1 April.[5] However, it is not clear that Chaucer was referencing 1 April since the text of the «Nun’s Priest’s Tale» also states that the story takes place on the day when the sun is «in the sign of Taurus had y-rune Twenty degrees and one,» which would not be 1 April. Modern scholars believe that there is a copying error in the extant manuscripts and that Chaucer actually wrote, «Syn March was gon«.[6] If so, the passage would have originally meant 32 days after March, i.e. 2 May,[7] the anniversary of the engagement of King Richard II of England to Anne of Bohemia, which took place in 1381.

In 1508, French poet Eloy d’Amerval referred to a poisson d’avril (April fool, literally «April’s fish»), possibly the first reference to the celebration in France.[8] Some historians suggest that April Fools’ originated because, in the Middle Ages, New Year’s Day was celebrated on 25 March in most European towns,[9] with a holiday that in some areas of France, specifically, ended on 1 April,[10][11] and those who celebrated New Year’s Eve on 1 January made fun of those who celebrated on other dates by the invention of April Fools’ Day.[12] The use of 1 January as New Year’s Day became common in France only in the mid-16th century,[7] and that date was not adopted officially until 1564, by the Edict of Roussillon, as called for during the Council of Trent in 1563.[13] However, there are issues with this theory because there is an unambiguous reference to April Fools’ Day in a 1561 poem by Flemish poet Eduard de Dene of a nobleman who sends his servants on foolish errands on 1 April, predating the change.[7] April Fools’ Day was also an established tradition in Great Britain before 1 January was established as the start of the calendar year.[14][15]

In the Netherlands, the origin of April Fools’ Day is often attributed to the Dutch victory in 1572 in the Capture of Brielle, where the Spanish Duke Álvarez de Toledo was defeated. «Op 1 april verloor Alva zijn bril» is a Dutch proverb, which can be translated as: «On the first of April, Alva lost his glasses». In this case, «bril» («glasses» in Dutch) serves as a homonym for Brielle (the town where it happened). This theory, however, provides no explanation for the international celebration of April Fools’ Day.

In 1686, John Aubrey referred to the celebration as «Fooles holy day», the first British reference.[7] On 1 April 1698, several people were tricked into going to the Tower of London to «see the Lions washed».[7]

Although no biblical scholar or historian is known to have mentioned a relationship, some have expressed the belief that the origins of April Fools’ Day may go back to the Genesis flood narrative. In a 1908 edition of the Harper’s Weekly cartoonist Bertha R. McDonald wrote:

Authorities gravely back with it to the time of Noah and the ark. The London Public Advertiser of March 13, 1769, printed: «The mistake of Noah sending the dove out of the ark before the water had abated, on the first day of April, and to perpetuate the memory of this deliverance it was thought proper, whoever forgot so remarkable a circumstance, to punish them by sending them upon some sleeveless errand similar to that ineffectual message upon which the bird was sent by the patriarch».[1]

Long-standing customs[edit]

United Kingdom[edit]

On April Fools’ Day 1980, the BBC announced Big Ben’s clock face was going digital and whoever got in touch first could win the clock hands.[5]

In the UK, an April Fool prank is sometimes later revealed by shouting «April fool!» at the recipient, who becomes the «April fool». A study in the 1950s, by folklorists Iona and Peter Opie, found that in the UK, and in countries whose traditions derived from the UK, this continues to be the practice, with the custom ceasing at noon, after which time it is no longer acceptable to play pranks.[16] Thus a person playing a prank after midday is considered the «April fool» themselves.[17]

In Scotland, April Fools’ Day was originally called «Huntigowk Day«.[18] The name is a corruption of «hunt the gowk«, gowk being Scots for a cuckoo or a foolish person; alternative terms in Gaelic would be Là na Gocaireachd, «gowking day», or Là Ruith na Cuthaige, «the day of running the cuckoo». The traditional prank is to ask someone to deliver a sealed message that supposedly requests help of some sort. In fact, the message reads «Dinna laugh, dinna smile. Hunt the gowk another mile.» The recipient, upon reading it, will explain they can only help if they first contact another person, and they send the victim to this next person with an identical message, with the same result.[18]

In England a «fool» is known by a few different names around the country, including «noodle», «gob», «gobby», or «noddy».

Ireland[edit]

In Ireland, it was traditional to entrust the victim with an «important letter» to be given to a named person. That person would read the letter, then ask the victim to take it to someone else, and so on. The letter when opened contained the words «send the fool further».[19]

Italy, France, Belgium, French-speaking areas[edit]

In Italy, France, Belgium and French-speaking areas of Switzerland and Canada, the 1 April tradition is often known as «April fish» (poisson d’avril in French, april vis in Dutch or pesce d’aprile in Italian). Possible pranks include attempting to attach a paper fish to the victim’s back without being noticed. This fish feature is prominently present on many late 19th- to early 20th-century French April Fools’ Day postcards. Many newspapers also spread a false story on April Fish Day, and a subtle reference to a fish is sometimes given as a clue to the fact that it is an April Fools’ prank.[citation needed]

Germany[edit]

In Germany, an April Fool prank is sometimes later revealed by shouting «April, April!» at the recipient, who becomes the «April fool».[citation needed]

Nordic countries[edit]

Danes, Finns, Icelanders, Norwegians and Swedes celebrate April Fools’ Day (aprilsnar in Danish; aprillipäivä in Finnish; aprilsnarr in Norwegian; aprilskämt in Swedish). Most news media outlets will publish exactly one false story on 1 April; for newspapers this will typically be a first-page article but not the top headline.[20]

Poland (Prima aprilis)[edit]

In Poland, prima aprilis («First April» in Latin) as a day of pranks is a centuries-long tradition. It is a day when many pranks are played: hoaxes – sometimes very sophisticated – are prepared by people, media (which often cooperate to make the «information» more credible) and even public institutions. Serious activities are usually avoided, and generally every word said on 1 April could be untrue. The conviction for this is so strong that the Polish anti-Turkish alliance with Leopold I signed on 1 April 1683, was backdated to 31 March.[21] However, for some in Poland prima aprilis ends at noon of 1 April and prima aprilis jokes after that hour are considered inappropriate and not classy.

Ukraine[edit]

April Fools’ Day is widely celebrated in Odessa and has the special local name Humorina — in Ukrainian Гуморина (Humorina). This holiday arose in 1973.[22] An April Fool prank is revealed by saying «Первое Апреля, никому не верю» («Pervoye Aprelya, nikomu ne veryu«) — which means «First of April, I trust nobody» — to the recipient. The festival includes a large parade in the city centre, free concerts, street fairs and performances. Festival participants dress up in a variety of costumes and walk around the city fooling around and pranking passersby. One of the traditions on April Fools’ Day is to dress up the main city monument in funny clothes. Humorina even has its own logo — a cheerful sailor in a lifebelt — whose author was the artist Arkady Tsykun.[23] During the festival, special souvenirs bearing the logo are printed and sold everywhere. Since 2010, April Fools’ Day celebrations include an International Clown Festival and both celebrated as one. In 2019, the festival was dedicated to the 100th anniversary of the Odessa Film Studio and all events were held with an emphasis on cinema.[24]

Spanish-speaking countries[edit]

In many Spanish-speaking countries (and the Philippines), «Día de los Santos Inocentes» (Holy Innocents Day) is a festivity which is very similar to April Fools’ Day, but it is celebrated in late December (27, 28 or 29 depending on the location).[citation needed]

Turkey[edit]

Turkey also has a custom of April Fools’ pranks.[25] Pranks and jokes are usually verbal and are revealed by shouting «Bir Nisan!» (April 1st!).

Iran[edit]

In Iran, it is called «Dorugh-e Sizdah» (lie of Thirteen) and people and media prank on 13 Farvardin (Sizdah bedar) that is equivalent of 1 April. It is a tradition that takes place 13 days after the Persian new year Nowruz. On this day, people go out and leave their houses and have fun outside mostly in natural parks.

Pranks have reportedly been played on this holiday since 536 BC in the Achaemenid Empire.

Israel[edit]

Israel has adopted the custom of pranking on April Fools’ Day.[26]

Lebanon[edit]

In Lebanon, an April Fool prank is revealed by saying كذبة أول نيسان (which means «First of April Lie») to the recipient.

Pranks[edit]

An April Fools’ Day prank in Boston’s Public Garden warning people not to photograph sculptures, as light emitted will «erode the sculptures»

A common prank is to carefully remove the cream from an Oreo and replace it with toothpaste, and there are many similar pranks that replace an object (usually food) with another object that looks like the object but tastes different such as replacing sugar with salt and vanilla frosting with sour cream. As well as people playing pranks on one another on April Fools’ Day, elaborate pranks have appeared on radio and television stations, newspapers, and websites, and have been performed by large corporations. In one famous prank in 1957, the BBC broadcast a film in their Panorama current affairs series purporting to show Swiss farmers picking freshly-grown spaghetti, in what they called the Swiss spaghetti harvest. The BBC was soon flooded with requests to purchase a spaghetti plant, forcing them to declare the film a hoax on the news the next day.[27]

With the advent of the Internet and readily available global news services, April Fools’ pranks can catch and embarrass a wider audience than ever before.[28]

Comparable prank days[edit]

28 December[edit]

28 December, the equivalent day in Spain and Hispanic America, is also the Christian day of celebration of the Day of the Holy Innocents. The Christian celebration is a religious holiday in its own right, but the tradition of pranks is not, though the latter is observed yearly. In some regions of Hispanic America after a prank is played, the cry is made, «Inocente palomita que te dejaste engañar» («You innocent little dove that let yourself be fooled!»; not to be confused with another meaning of palomita, which means «popcorn» in some dialects).[citation needed]

In Argentina, the prankster says, «¡Que la inocencia te valga!» which roughly translates as advice to not be as gullible as the victim of the prank. In Spain, it is common to say just «¡Inocente!» (which in Spanish can mean «innocent» or «gullible»).[29]

In Colombia, the term is used as «Pásala por Inocentes«, which roughly means: «Let it go; today it’s Innocent’s Day.»[citation needed]

In Belgium, this day is also known as the «Day of the Innocent Children» or «Day of the Stupid Children». It used to be a day where parents, grandparents, and teachers would fool the children in some way. But the celebration of this day has died out in favour of April Fools’ Day.[citation needed]

Nevertheless, on the Spanish island of Menorca, Dia d’enganyar («Fooling day») is celebrated on 1 April because Menorca was a British possession during part of the 18th century. In Brazil, the «Dia da mentira» («Day of the lie») is also celebrated on 1 April[29] due to the Portuguese influence.

First day of a new month[edit]

In many English-speaking countries, mainly Britain, Ireland, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa, it is a custom to say «pinch and a punch for the first of the month» or an alternative, typically by children. The victim might respond with «a flick and a kick for being so quick», and the attacker might reply with «a punch in the eye for being so sly».[30]

Another custom in Britain and North America is to say «rabbit rabbit» upon waking on the first day of a month, for good luck.[31]

Reception[edit]

The practice of April Fool pranks and hoaxes is controversial.[17][32] The mixed opinions of critics are epitomized in the reception to the 1957 BBC «spaghetti-tree hoax», in reference to which, newspapers were split over whether it was «a great joke or a terrible hoax on the public».[33]

The positive view is that April Fools’ can be good for one’s health because it encourages «jokes, hoaxes … pranks, [and] belly laughs», and brings all the benefits of laughter including stress relief and reducing strain on the heart.[34] There are many «best of» April Fools’ Day lists that are compiled in order to showcase the best examples of how the day is celebrated.[35] Various April Fools’ campaigns have been praised for their innovation, creativity, writing, and general effort.[36]

The negative view describes April Fools’ hoaxes as «creepy and manipulative», «rude» and «a little bit nasty», as well as based on Schadenfreude and deceit.[32] When genuine news or a genuine important order or warning is issued on April Fools’ Day, there is risk that it will be misinterpreted as a joke and ignored – for example, when Google, known to play elaborate April Fools’ Day hoaxes, announced the launch of Gmail with 1-gigabyte inboxes in 2004, an era when competing webmail services offered 4-megabytes or less, many dismissed it as a joke outright.[37][38] On the other hand, sometimes stories intended as jokes are taken seriously. Either way, there can be adverse effects, such as confusion,[39] misinformation, waste of resources (especially when the hoax concerns people in danger) and even legal or commercial consequences.[40][41]

In March 2020, during the COVID-19 pandemic, various organizations and people cancelled their April Fools’ Day celebrations, or advocated against observing April Fools’ Day, as a mark of respect due to the large amount of tragic deaths that COVID-19 had caused up to that point, the wish to provide truthful information to counter the misinformation about the virus, and to pre-empt any attempts to incorporate the virus into any potential pranks.[42][43] For example, Google decided not to continue «its infamous April Fools’ jokes» tradition for that year.[44] Because the pandemic was still ongoing a year later in 2021, they also decided not to do pranks that year.[45]

In Thailand, the police warned ahead of April Fools’ in 2021 that posting or sharing fake news online could lead to maximum of five years imprisonment.[46]

Other examples of genuine news on 1 April mistaken as a hoax include:

- 1 April 1946: Warnings about the Aleutian Island earthquake’s tsunami that killed 165 people in Hawaii and Alaska.[47]

- 1 April 1984: News that the singer Marvin Gaye was shot and killed the day before his 45th birthday by his father Marvin Gay Sr. (sic) on 1 April 1984. Several people close to Gaye such as fellow singers Smokey Robinson and Jermaine Jackson, brother of Michael Jackson didn’t believe the news initially and had to phone call other people who knew Gaye to confirm the news, Al Sharpton during his interview for the VH1 documentary VH1’s Most Shocking Moments in Rock & Roll referenced the coincidence of the date when he said that Gaye’s death came «like a sick, sad joke to all of us.»[48][49][50][51][52]

- 1 April 1995: News that the singer Selena was shot and killed by the former president of her fan club Yolanda Saldívar on 31 March 1995. When radio station KEDA broke the news on 31 March 1995, many people accused the staff of lying because the next day was April Fools’ Day.[53]

- 1 April 2004: Gmail is announced to the public by Google. Some of the announced features for the service were not considered technologically possible with the technology available in 2004.[54]

- 1 April 2005: News that the comedian Mitch Hedberg had died on 29 March 2005.[55]

- 1 April 2005: Announcement about Powerpuff Girls Z, by Aniplex, Cartoon Network and Toei Animation. The TV show was an anime adaption of the cartoon The Powerpuff Girls and the idea that a cartoon would get turned into an anime was considered very outlandish in 2005 as this was the first time it happened.[56]

- 1 April 2008: Announcement that the NationStates government simulation browser game had received a cease and desist letter from the United Nations (UN) for unauthorized usage of its name and emblem for the fictional intergovernmental organization where players (as nations) can create and vote on international law within the game world and that due to this, NationStates has now changed its version of the UN into the «World Assembly» (WA) with a different emblem. On 2 April 2008, NationStates developer Max Barry revealed that the letter from the UN was in fact real and he had actually received it on 21 January 2008 but chose only to start complying with it on 1 April to deliberately fool people into thinking the announcement was the annual NationStates April Fools prank and that because the legal action was real, the changes are permanent.[57][58]

- 1 April 2009: Announcement that the long running soap opera Guiding Light was being cancelled. The date was so heavily associated with jokes and pranks that even some of the cast and crew didn’t believe the news when it was announced by CBS, the TV network that aired the show.[59]

- 1 April 2011: Isaiah Thomas declared for the NBA draft. Thomas is short and basketball players in the NBA are usually taller than average as height gives advantage to playing basketball.[60]

In popular culture[edit]

Books, films, telemovies and television episodes have used April Fools’ Day as their title or inspiration. Examples include Bryce Courtenay’s novel April Fool’s Day (1993), whose title refers to the day Courtenay’s son died. The 1990s sitcom Roseanne featured an episode titled «April Fools’ Day». This turned out to be intentionally misleading, as the episode was about Tax Day in the United States on 15 April – the last day to submit the previous year’s tax information. Although Tax Day is usually 15 April as depicted in the episode, it can be moved back a few days if that day is on a weekend or a holiday in Washington, D.C. or some states, or due to natural disasters when it can occur as late as 15 July.[61]

Further reading[edit]

- Wainwright, Martin (2007). The Guardian Book of April Fool’s Day. Aurum. ISBN 978-1-84513-155-5.

- Dundes, Alan (1988). «April Fool and April Fish: Towards a Theory of Ritual Pranks». Etnofoor. 1 (1): 4–14. JSTOR 25757645.

- Similar events documented by other Wiki languages also exist such as Poisson d’avril (France) and in the USA the International day of the joke event which is assigned the first Sunday in May.[62]

See also[edit]

- Feast of Fools, a similar medieval festival

- List of April Fools’ Day jokes

- List of practical joke topics

References[edit]

- ^ a b McDonald, Bertha R. (7 March 1908). «The Oldest Custom in the World». Harper’s Weekly. Vol. 52, no. 2672. p. 26.

- ^ Ashley Ross (31 March 2016). «No Kidding: We Have No Idea How April Fools’ Day Started». Time. Retrieved 24 March 2018.

- ^ The Nun’s Priest’s Tale

- ^ The Nun’s Priest’s Tale. Chaucer in the Twenty-First Century. University of Maine at Machias. 21 September 2007.

- ^ a b «April Fool’s Day 2021: how Chaucer, calendar confusion and Hilaria led to jokes and fake news». The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 24 September 2021.

- ^ Travis, Peter W. (1997). «Chaucer’s Chronographiae, the Confounded Reader, and Fourteenth-Century Measurements of Time». In Poster, Carol; Utz, Richard J. (eds.). Constructions of Time in the Late Middle Ages. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press. pp. 16–17. ISBN 0-8101-1541-7.

- ^ a b c d e Boese, Alex (2008). «The Origin of April Fool’s Day». Museum of Hoaxes.

- ^ Eloy d’Amerval (1991). Le Livre de la Deablerie. De maint homme et de mainte fame, poisson d’Apvril vien tost a moy. Librairie Droz. p. 70. ISBN 9782600026727.

- ^ Groves, Marsha (2005). Manners and Customs in the Middle Ages. p. 27.

- ^ «April Fools’ Day». Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ^ Santino, Jack (1972). All around the year: holidays and celebrations in American life. University of Illinois Press. p. 97. ISBN 978-0-252-06516-3.

- ^ Winick, Stephen (28 March 2016). «April Fools: The Roots of an International Tradition | Folklife Today». blogs.loc.gov. Retrieved 12 March 2022.

- ^ «April Fools’ Day». History.com. 30 March 2017.

- ^ «A brief, totally sincere history of April Fools’ Day». Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 12 March 2022.

- ^ «The Origin of April Fool’s Day». Museum of Hoaxes. Retrieved 12 March 2022.

- ^ Great Britain: Home Office (2017). Life in the United Kingdom: a guide for new residents (2014 ed.). Stationery Office. ISBN 9780113413409.

- ^ a b Archie Bland (1 April 2009). «The Big Question: How did the April Fool’s Day tradition begin, and what are the best tricks?». The Independent. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ^ a b Opie, Iona & Peter (1960). The Lore and Language of Schoolchildren. Oxford University Press. pp. 245–46. ISBN 0-940322-69-2.

- ^ Haggerty, Bridget. «April Fool’s Day». Irish Culture and Customs. Retrieved 3 April 2014.

- ^ Bora, Kukil (12 March 2012). «April Fool’s Day: 8 Interesting Things And Hoaxes You Didn’t Know». International Business Times. Retrieved 27 May 2013.

- ^ «Origin of April Fools’ Day». The Express Tribune. 3 April 2012. Retrieved 27 May 2013.

- ^ Sinelnikova, Alexandra (1 April 2019). «Humorina time». Odessitclub.

- ^ «Main festival in Odessa». 2019.

- ^ «Odessa celebrates Humorine. Picture story». 1 April 2019.

- ^ «1 Nisan şakaları 2022!». www.haberturk.com (in Turkish). 1 April 2022. Retrieved 2 April 2022.

- ^ Adam, Soclof (31 March 2011). «From the JTA Archive: April Fools’ Day lessons for Jewish pranksters». Jewish Telegraph Agency. JTA. Retrieved 3 April 2019.

- ^ «Swiss Spaghetti Harvest». Retrieved 1 November 2013.

- ^ Moran, Rob (4 April 2014). «NPR’s Brilliant April Fools’ Day Prank Was Sadly Lost On Much Of The Internet». Retrieved 6 April 2014.

- ^ a b «Avui és el Dia d’Enganyar a Menorca» [Today is Fooling Day on Minorca] (in Catalan). Vilaweb. 1 April 2003. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ^ «pinch and a punch for the first of the month — Wiktionary». en.wiktionary.org. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- ^ Willingham, AJ (July 2019). «Rabbit rabbit! Why people say this good-luck phrase at the beginning of the month». CNN. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- ^ a b Doll, Jen (1 April 2013). «Is April Fools’ Day the Worst Holiday? – Yahoo News». Yahoo! News. Retrieved 1 April 2014.

- ^ «Is this the best April Fool’s ever?». BBC News. Retrieved 1 April 2014.

- ^ «Why April Fools’ Day is Good For Your Health – Health News and Views». News.Health.com. 1 April 2013. Retrieved 1 April 2014.

- ^ «April Fools: the best online pranks | SBS News». Sbs.com.au. Retrieved 1 April 2014.

- ^ «April Fool’s Day: A Global Practice». aljazirahnews. 1 April 2019. Retrieved 8 April 2019.

- ^ Harry McCracken (1 April 2013). «Google’s Greatest April Fools’ Hoax Ever (Hint: It Wasn’t a Hoax)». Time. Archived from the original on 1 April 2013. Retrieved 1 August 2014.

- ^ Lisa Baertlein (1 April 2004). «Google: ‘Gmail’ no joke, but lunar jobs are». Reuters. Retrieved 1 August 2014.

- ^ Woods, Michael (2 April 2013). «Brazeau tweets his resignation on April Fool’s Day, causing confusion – National». Globalnews.ca. Retrieved 1 April 2014.

- ^ Hasham, Nicole (3 April 2013). «ASIC to look into prank Metgasco email from schoolgirl Kudra Falla-Ricketts». The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 3 April 2014.

- ^ «Justin Bieber’s Believe album hijacked by DJ Paz». The Sydney Morning Herald. 3 April 2014. Retrieved 3 April 2014.

- ^ «April Fools’ is Cancelled Because We Can’t Distance Fact From Fiction». CCN.com. 1 April 2020.

- ^ Willingham, A. J. (1 April 2020). «April Fools’ Day pranks are not funny right now. Don’t do them». CNN.

- ^ Gartenberg, Chaim (27 March 2020). «Google cancels its infamous April Fools’ jokes this year». The Verge.

- ^ Price, Rob. «Google is canceling its famous April Fools’ Day pranks for the 2nd year in a row». Business Insider.

- ^ «Phuket News: Police warn of prison terms for April Fool’s stories». The Phuket News. 1 April 2021. Retrieved 1 April 2021.

- ^ «1946 Aleutian Tsunami». www.usc.edu. Archived from the original on 12 January 2016. Retrieved 29 March 2022.

- ^ American Masters: What’s Going On – The Life and Death of Marvin Gaye, PBS, 2008

- ^ «Marvin Gaye Last Day». PBS. YouTube. Archived from the original on 21 December 2021. Retrieved 29 March 2022.

- ^ Behind the Music, VH1, 1998

- ^ VH1’s Most Shocking Moments in Rock & Roll, VH1, 1998

- ^ Ritz 1991, p. 334.

- ^ Patoski 1996, p. 199.

- ^ Horton, Alex. «When Gmail Was First Announced, People Thought It Was an April Fools’ Joke». ScienceAlert. Retrieved 8 November 2020.

- ^ Rusnak, Jeff (2 April 2005). «MITCH HEDBERG, 37, COMEDIAN, FILMMAKER». South Florida Sun-Sentinel. Archived from the original on 30 June 2021. Retrieved 29 March 2022.

- ^ «Powerpuff Girls Z Debut».

- ^ Andrei, Terekhov (21 January 2008). «Notice of cease and desist» (PDF). NationStates. United Nations. Retrieved 29 March 2022.

- ^ Max, Barry (2 April 2008). «The United Nations vs Me». maxbarry.com. Retrieved 29 March 2022.

- ^ «Guiding Light, Snuffed: Scene From A Dying Daytime Drama». The New York Observer. 15 September 2009.

- ^ Gould, Andrew. «Isaiah Thomas Laughs at Doubters on April Fools’ Day». Bleacher Report. Retrieved 8 November 2020.

- ^ Faler, Brian. «Trump administration moves Tax Day to July 15». POLITICO.

- ^ BBC News: International joke day

Bibliography[edit]

- Patoski, Joe Nick (1996). Selena: Como La Flor. Boston: Little Brown and Company. ISBN 978-0-316-69378-3.

- Ritz, David (1991). Divided Soul: The Life of Marvin Gaye. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-81191-X.

External links[edit]

Wikipedia victim of onslaught of April Fool’s jokes at Wikinews

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). «April-Fools’ Day» . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- «Top 100 April Fools’ Day hoaxes of all time». Museum of Hoaxes.

- «April Fools’ Day On The Web: List of all known April Fools’ Day Jokes websites from 2004 until present».

Все знают, что 1 апреля — это праздник розыгрышей. В этот день принято издеваться над ближними, смеяться и шутить, причём порой вовсе не безобидно. Откуда пошла эта странная традиция? Почему Дню дурака мы радуемся больше, чем Дню танкиста или Дню пограничника? В принципе, ответ кристально ясен: дураков в мире больше, чем пограничников. А если говорить серьёзно, то у этого праздника — глубокие корни и традиции.

Удивительно, но дольше всего традиционный День дурака отмечается в мусульманском и при этом весьма архаичном государстве — Иране. Шутить над друзьями и близкими там принято на тринадцатый день после Международного дня Новруз (Нового года у иранских и тюркских народов). Этот праздник, называющийся Сизда-Бедар, беспрерывно (или, по крайней мере, почти беспрерывно) отмечается иранцами с 536 года до н. э. Звучит невероятно, но столь «свободный» праздник успешно был принят радикальным исламом много веков спустя. Пожалуй, для мусульманских традиций подобное торжество розыгрышей и шуток скорее исключение, чем правило. Ещё более удивительно, что 13-й день после Нового года выпадает по европейскому календарю на… 1 или на 2 апреля в зависимости от года! Скорее всего, это всего лишь совпадение.

* * *

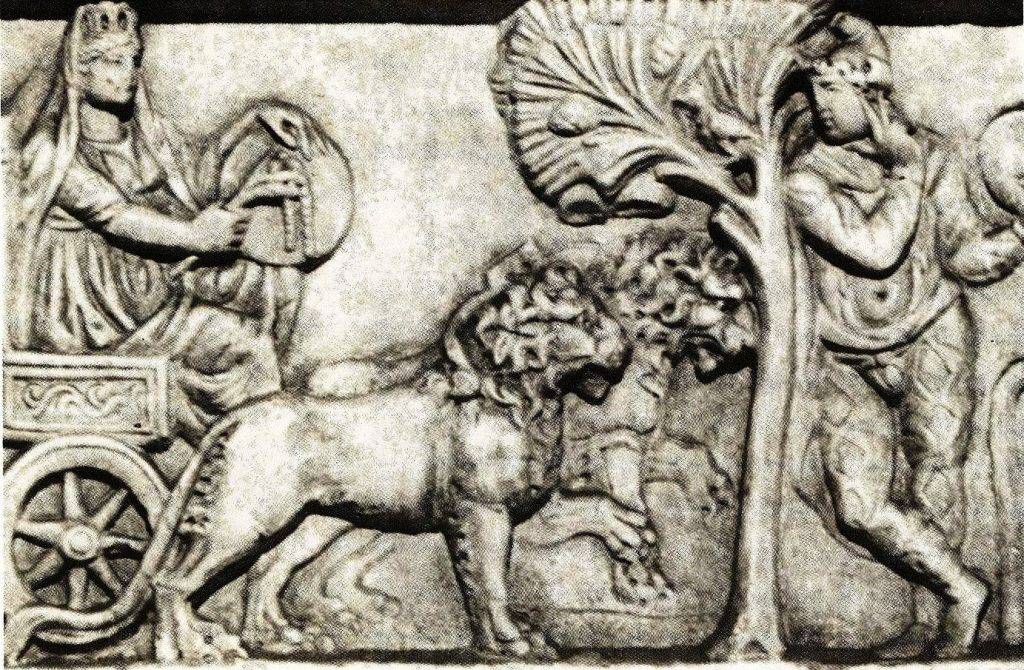

Истоки европейского праздника дураков можно найти ещё в Древнем Риме. Ежегодно в марте римляне проводили огромный религиозный фестиваль Хиларии в честь богини Кибелы, матери-природы. Сам фестиваль растягивался почти на две недели, в ходе которых приносились жертвы, проводились игрища, высаживались деревья. А вот день 25 марта, приходящийся примерно на середину фестиваля (чуть ближе к окончанию), считался «Днём радости» и посвящался Аттису, возлюбленному Кибелы. В день Аттиса было принято шутить, веселиться и — что немаловажно — разыгрывать друзей и близких.

* * *

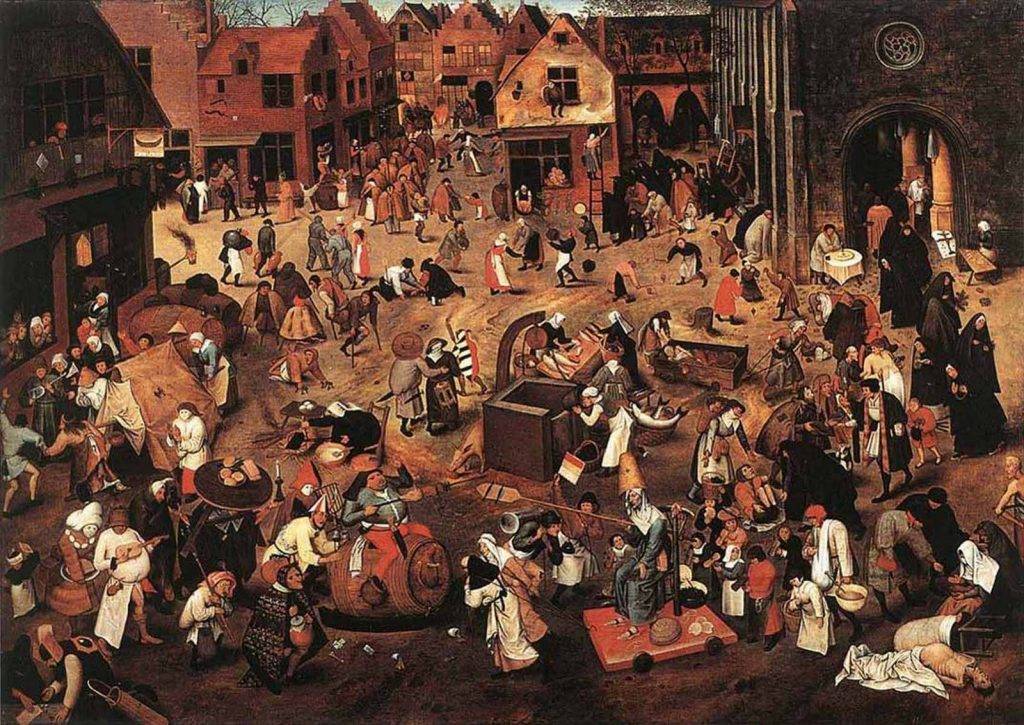

Художник: Питер Брейгель старший

В Средневековье день Аттиса нашёл своё продолжение в виде Праздника дураков (Feast of Fools). В разных странах Европы этот фестиваль проводили в разное время (но чаще всего — зимой, во второй половине декабря, незадолго до Рождества либо после него). Главой праздника назначался Лорд Бездарный Правитель — он же затем возглавлял рождественские увеселения. Церемонии и миниатюры Праздника дураков пародировали царившие в то время государственные и церковные порядки, но в этот день на сатиру и «критику» смотрели сквозь пальцы. Наиболее популярны Праздники дураков (и их аналоги — скажем, День ослов) были в Англии, Франции и Шотландии. Например, знаменитая сцена появления Квазимодо из романа «Собор Парижской богоматери» происходит именно во время Праздника дураков, проходящего в Париже.

* * *

К сожалению, церковь не могла долго смотреть на безбашенную молодёжь, издевающуюся над её устоями. В 1431 году праздники дураков были категорически запрещены Базельским собором, который был создан, чтобы пресечь успехи реформационного движения и навести в Европе религиозный порядок. В 1444 году кафедра теологии Парижского университета выпустила официальный документ о запрете празднества.

* * *

Случайные упоминания о связи дураков и апреля встречаются в различных текстах Средневековья и Возрождения. Например, в 1508 году французский поэт Элой д’Амерваль упоминает poisson d’avril («апрельского дурака»), в стихотворении Эдуарда де Дене 1539 года написания фигурирует некий дворянин, который 1 апреля разыгрывал своих слуг, в 1686 году английский писатель Джон Обри впервые упоминает 1 апреля как fooles holy day («Святой День дурака»).

* * *

Как ни странно, в течение многих лет День дурака был привязан к более известным и официальным праздникам, являясь их частью. Уже упомянутый средневековый Праздник дурака был предварением или продолжением рождественских событий. А вот 1 апреля образовалось, скорее всего, благодаря соседству с… Новым годом. Действительно, в большинстве европейских городов Новый год отмечали 25 марта, в день Благовещения Пресвятой Богородицы; в некоторых местах он длился неделю и заканчивался как раз 1 апреля, когда никакой благочинности уже не оставалось, зато пьянство и разгул были в самом разгаре. На 1 января Новый год перенесли лишь в середине XVI века.

* * *

В Россию первоапрельское празднество пришло, как несложно догадаться, при Петре I. Во время его правления в стране появилось значительное количество европейцев, принесших с собой новые обычаи. В результате в 1703 году некий дворянин-самодур разослал по Москве глашатаев, которые зазывали честной народ на невиданное прежде представление, причём совершенно бесплатно. Народ собрался перед импровизированной сценой на одной из площадей столицы, — но после того, как занавес открылся, обнаружилось, что на сцене ничего нет, кроме надписи «Первый апрель — никому не верь». С высокой долей вероятности эта история — всего лишь городская легенда, но в 2003 году совершенно официально отмечалось 300-летие Дня смеха в России. Собственно, чем плоха эта дата для начала отсчёта? Всем хороша!

* * *

Дни шуток, дураков, смеха отмечаются сегодня в самых разных государствах. Правда, не всегда эти праздники выпадают на апрель. Например, датский maj-kat отмечается 1 мая (то есть во время нашего Дня трудящихся), а Испания и часть Латинской Америки шутят и веселятся 28 декабря (собственно, это наследие средневековых фестивалей). Во времена последней правящей корейской династии Чосон (XIV–XIX вв.) ближних разыгрывали в день, когда выпадал первый снег, без привязки к конкретной дате.

* * *

В разное время устраивались розыгрыши, которые вошли в историю Дня дурака, став по-своему эталонами удачной шутки. Например, в 1996 году калифорнийская сеть ресторанов Taco Bell распространила — в рекламных целях — информацию о том, что её владелец купил у правительства США знаменитый Колокол Свободы, сзывавший жителей Филадельфии на оглашение Декларации Независимости, и переименовал его в Taco Liberty Bell. Шутка была основана на том, что эмблема Taco Bell — тоже колокол, а на момент «покупки» в США возникла угроза кризиса из-за превышения порога государственного долга. Путём приобретения национального достояния компания предполагала уменьшить госдолг и вытянуть страну из преддефолтного состояния. Информация подавалась «на полном серьёзе», в неё поверили миллионы жителей страны. В правительство посыпались возмущения и жалобы, однако в первые же два дня Taco Bell получила $1 000 000 прибыли, затратив на кампанию всего $300 000. Суммарный эффект от розыгрыша позволил компании заработать более 25 миллионов долларов.

* * *

Наиболее распространённый тип первоапрельских шуток — выдуманные географические области или животные. Таким образом над читателями издевается пресса. Например, в 1995 году журналист Тим Фолгер написал для журнала Discover статью о «горячеголовом голокожем ледяном черве-бурильщике», уникальном виде, открытом учёным по имени Эйприл Паццо (что, кстати, переводится с итальянского как «апрельский дурак»). Аналогичные розыгрыши журналисты устраивают и в России; например, широкую популярность в интернете снискал псевдоисторический материал о боевых лосях, опубликованный в 2010 году журналом «Популярная механика».

* * *

Отличный розыгрыш устроила в 1998 году компания Burger King. Незадолго до первого апреля на рекламных плакатах компании появилась официальная информация о выпуске «биг-боппера для левшей». Впоследствии многие клиенты сети заказывали бопперы, специально подчёркивая: «Мне, пожалуйста, обыкновенный, для правшей».

* * *

Порой кажется, что тот или иной праздник попадает на некую дату не без божественного умысла. Например, именно 1 апреля родились Николай Васильевич Гоголь, известный своим чувством юмора и блестящими сатирическими произведениями, и американский режиссёр Барри Зонненфельд, автор бессмертной комедии «Люди в чёрном». Но, с другой стороны, «железный канцлер» Отто фон Бисмарк тоже появился на свет первого апреля…

Если вы нашли опечатку, пожалуйста, выделите фрагмент текста и нажмите Ctrl+Enter.

Журналист, музыкант, поэт.

Показать комментарии

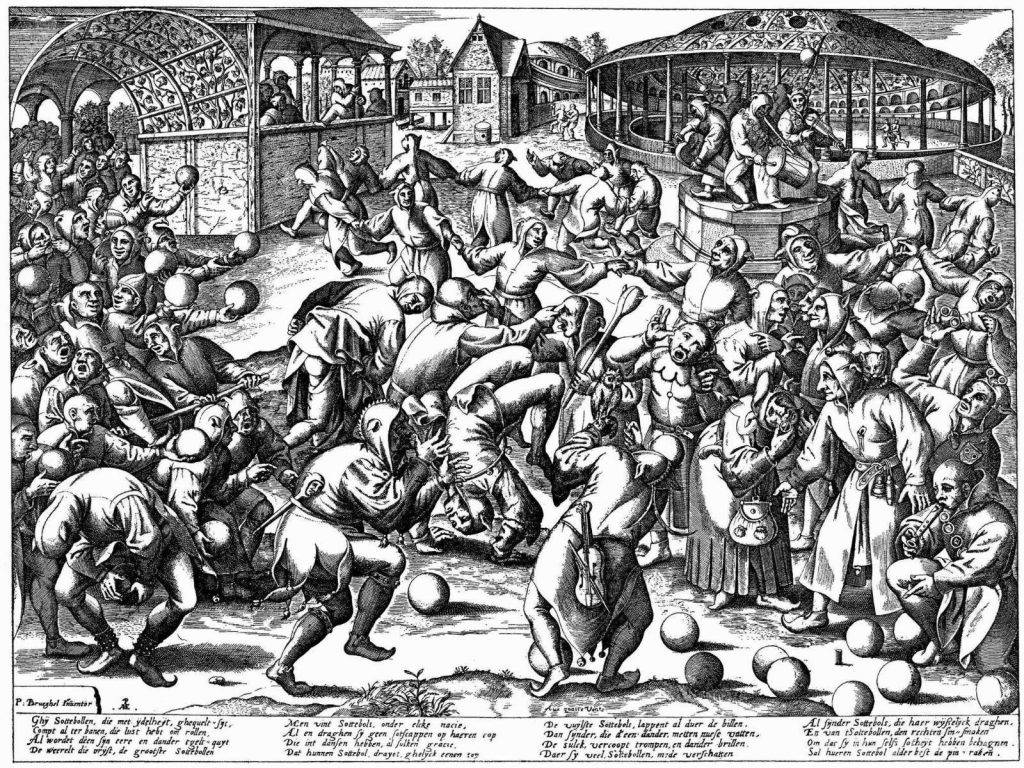

Был в Средние века в Европе такой замечательный праздник — Праздник Дураков. Очень весёлый и шумный, любимый всеми, и даже суровая католическая церковь относилась к нему весьма снисходительно. Есть даже мнение, что нынешнее 1-е апреля происходит именно оттуда. Такой вот был яркий и бесшабашный праздник, когда строить из себя идиота было не стыдно, а наоборот, ценились наиболее глупые и грубые шутки, в том числе и ниже пояса, а в церквях и на церковных папертях творились и говорились вещи, которые в любой другой день могли счесть богохульством. Но на следующее утро всё возвращалось на круги своя и народ снова возвращался к ежедневной серой рутине. Но ведь праздник, он на то и праздник, чтобы была отдушина в этой серости. Ведь правда, — хочется иногда расслабиться, не парить мозги, а просто плыть по такому вот радостному течению, делать глупости и веселиться.

Но что здесь важно — на этом празднике люди ведь вовсе не были дураками и прекрасно осознавали всю несерьёзность происходящего. А стало быть, расслабившись один день в году, знали, что жизнь таким образом прожить невозможно — ежедневная борьба за выживание, за кусок хлеба, забота о детях, в конце концов, и идиотизм, кривляние, вихляние голым задом, — вещи абсолютно несовместимые. Кстати, говорят, тем не менее, что самые смешные вещи делаются с совершенно серьёзным, прямо таки каменным выражением лица. Поэтому и стал великим комиком Бестер Китон.

А если праздник, ну прямо как по Хемингуэю, который всегда с тобой? Круглый год, да ещё под руководством массовиков затейников. Праздник дураков, но только дураков мрачных, озлобленных, серьёзных до невозможности. Дураков, которыми руководят специально приставленные массовики-затейники, главная цель которых — поддерживать уровень дурости на постоянно высоком, даже высочайшем уровне. Иначе, до дураков может внезапно дойти в каком абсурдном мире они живут, и что за существа на деле, те, кто оплачивает каторжный труд этих самых массовиков. И всё же, те самые массовики, всего лишь делают свою работу, подлую и грязную, но тем не менее весьма щедро вознаграждаемую, ибо пожалуй, у нынешнего круглогодичного праздника есть одна сверхзадача — удержать «существа» у власти. Если представить себе, что в один горестный для существ день дураки поумнеют, то день этот, несомненно окажется последним для их власти, а может, и жизни. Но не надо волноваться — такое невозможно по определению. В принципе, я полагаю, нынешние массовики могут собой гордиться — их советские предшественники могли добиться со стороны дураков только равнодушного молчания, не идущего ни в какое сомнение с нынешним энтузиазмом и «яростью благородной». Вменяемое меньшинство в массе своей, как и лет 30 назад предпочитает молчать в тряпочку.

Я, кстати, вспоминаю, по этому поводу рассказ человека, побывавшего вместе с тогда ещё советской партийной делегацией в Северной Корее. Вот у кого ещё учиться и учиться. Машину с «дорогими советскими друзьями» радостно приветствовали одетые в праздничные робы чучхейские трудящиеся, в основном женщины. В обязанности ликующих входило радостно улыбаться, хлопать в ладоши и подпрыгивать. Когда же одна из ликовавших то ли перестала подпрыгивать, то ли забыла другое какое из трёх обязательных действий, к ней подбежал сурового вида молодой человек и указал на её халатность самым наглядным способом — залепил кулаком в зубы. Действие, указание руководящего товарища, было мгновенным — утерев кровь нерадивая женщина начала скакать, хлопать в ладоши и улыбаться с удвоенной энергией. Но это так, на крайний случай, если вдруг искреннее возмущение и ненависть к врагам, скорбь по безвременно павшим снегирям и утратившим девственность старухам перестанет быть столь искренней. На тот случай, если круглогодичный праздник дураков вдруг закончиться. Ведь, рассуждая логически, так и должно было бы произойти. Ведь, как известно, праздник, если он ежедневный, тоже становится буднями, а особенно такой, какой ныне происходит в одной, отдельной, всем слишком уж известной и взятой, сами знаете за какое место стране. А кроме того, в отличие от своего средневекового предшественника, слишком уж он мрачен, а дураки там вовсе не прикидываются, а самые что ни на есть настоящие. А главное — нет того безудержного веселья, а есть тупая злоба и ярость, правда, не менее безудержные. Это становится не праздником даже, а прямо, какой-то чёрной мессой.

Именно этим, особенно, если учитывая, что в обязательное действо там входят пляски не только на хрупких косточках распятых мальчиков, снегирей и пенсионерок, но и немыслимые в своём фарисействе и лицемерии глумливые скачки на костях вполне реальных людей. Да, опять всё тот же Боинг — то, за что им никогда не знать прощения, который будет лежать проклятием на них ровно столько, сколько они будут оставаться такими вот дураками, а может быть и много дольше этого. Но им то, пожалуй, что — проклятием больше, проклятием меньше. Им — ничего, да и плевать бы на них, но топчась на костях погибших пассажиров, они топчут души их родственников, словно мало тем несчастным самого факта потери близких.

Здесь, кажется, праздник дураков доходит до своей кульминации, до верхнего предела не только запредельной глупости, но не менее запредельной подлости. Чёрт с вами, не хотите признаваться, так хоть молчите в тряпочку, потому что ваше поведение уже просто за гранью. Даже, покопавшись в истории, включая российскую и советскую, сомневаюсь, что можно найти нечто подобное. Не по количеству пролитой крови, конечно, что такое 283 человека по сравнению с ГУЛАГОМ, но такой омерзительной реакции не было никогда. Разве что Катынь, да и то…

Просто, поборов отвращение, ещё раз посмотрите на всю эту историю. На грабёж и мародёрство колорадов на месте крушения, на наспех удалённые победные реляции по поводу сбитой украинской «птички» и на кошмарные селфи местных йеху с «трофеями» с Боинга. Самолёт сбили украинцы! Почему, — потому что они плохие, а значит они сделали это. Просто так, по причине природной злости. А потом миллион версий, одна глупее и подлее другой, и как апофеоз — возмущение и протест по поводу неудержимо надвигающегося трибунала. Хотя, казалось бы, если бы там не причём, так и бояться нечего. Наоборот — истина воссияет и вы все в белом.

Но вернёмся к дуракам. Я, конечно, понимаю, что кремлёвские урки заметались и растерялись, а потому делают всё больше глупостей, погружаясь всё дальше в трясину, а руководимый ими Праздник дураков принимает совершенно уж сюрреалистические формы. Я не знаю, митинг, организованный, уж в этом я уверен, по команде Москвы на месте падения самолёта, проходил по северокорейскому сценарию, или же дураки собрались «по зову сердца». Имея в виду, что это территория «ДНР», «страны» ещё больших чудес, чем шефствующая над ней Россиюшка, допускаю оба варианта. В любом случае, просто представьте себе Чикатило, пришедшего с букетом цветов на похороны своей жертвы. И если маразм сам по себе может вызвать даже сочувствие, то омерзительная клоунада в селе Грабово Донецкой области, неподалеку от места крушения уже не смешна. Повторяю, — это за гранью. Никогда не существовавшие мальчик с пенсионеркой, снегири и фосфорные бомбы вызывают смех, но этот вот митинг, эта «скорбь» по вполне реальным людям, это нечто даже не из фильмов ужасов. Я думаю, определения этому ещё не придумали. Все эти флаги ДНР и стран, чьи граждане стали жертвами авиакатастрофы. А ещё лозунги: