С чего начать писать свой первый сценарий? Зачем нужен логлайн и что это такое? Из каких частей состоит сценарий? Как прописывать персонажей, их действия и диалоги? Что делать, когда готов первый драфт? Советы профессионалов, успешные примеры и частые ошибки в написании сценария.

Что такое сценарий?

Сценарий — это кино-драматургическое произведение, являющееся основой для съёмки проектов или театральной постановки. Сценарий является в первую очередь текстовым документом, на базе которого команда проекта выполняет свою часть работы для воплощения сценария в жизнь.

Правильный формат текста в сценарии такой: шрифт Courier New 12-ым размером. При таком форматировании каждая страница текста будет равняться одной минуте хронометража.

Сценарий полнометражного фильма обычно составляет от 90 до 120 страниц, то и длительность фильма составит от полутора до двух часов. Сценарий пишут не только к фильмам, но и к эпизодам сериалов. Ситкомы — это обычно серии на 20-30 минут, соответственно на 20-30 страниц. Драмы — 50-60 страниц.

Вы можете создать свой сценарий на основе оригинальной идей или же на основе существующих интеллектуальных прав (книг, фильмов, комиксов, журналистских статей).

Использование чужих интеллектуальных прав должно всегда оформляться договором и сопровождаться, конечно же, оплатой. Но есть произведения, за использование образов из которых, не нужно платить. Они называются общественным достоянием. Общественное достояние в России — это произведение, с года смерти автора которого прошло 70 лет. Подробно про поиск идей и интеллектуальные права мы писали здесь.

Сценарий — это чёткий план фильма или эпизода сериала. В этом работа сценариста очень сильно отличается от работы писателя.

Если на этапе разработки сценарист тоже ищет эмоциональные ходы, яркие образы, любые другие творческие решения, то на этапе написания все эти наработки все равно должны улечься в инструкцию для съемки. Хороший сценарий должен быть чётким, понятным, наглядным документом, отражающим всю предыдущую творческую подоплёку.

Ваш сценарий увидит огромная команда из продюсеров, режиссёров, актёров, постановщиков и других, и для их работы важным станет каждое написанное вами слово. Давайте ниже разберёмся вместе, как написать сценарий.

Выбор названия

Название сценария можно оставить на самый последний момент работы над ним. Но если вы всё-таки решили всё-таки чем-то назвать текстовый файл, то название должно:

- отражать жанр вашего проекта;

- быть цепким и броским;

- заявлять эмоции, которые зритель скорее всего испытает;

- быть лёгким в произношении и запоминающимся.

Логлайн

Логлайн — это основная идея вашего фильма. По старым голливудским стандартам логлайн принято формулировать не более чем в тридцать слов. То есть вставить туда все сюжетные линии, описание мира и гениальные навыки главного героя не получится. В России к этому относятся мягче – допустимо уложиться в 35-45 слов. Что же включить в логлайн:

- кратко укажите, кто герой (мальчик-волшебник, вдовец и отец пятерых детей, говорящая мышка);

- чего герой хочет (победить злого волшебника, отомстить за смерть жены, найти семью);

- что стоит на пути к достижению цели (огромная армия из злых магов, вынужденность постоянно уделять внимание детям или то, что мышка не такая как люди).

Существует такое драматургическое правило: та цель, которую вы сформулировали для героя в начале должна проходить через всю историю. Как только цель перестаёт быть важной или достигается героем, то история заканчивается. Интересная и чётко сформулированная цель главного героя поможет написать хороший сценарий.

Персонажи сценария

Когда вы знаете, о чём ваша история, пора для себя решить, кто её раскроет и покажет. Выше мы уже сформулировали логлайн и знаем, какие качества героя точно понадобятся для раскрытия темы.

На этом этапе важно выяснить, как герой изменится, и с какими своими пороками будет сражаться. С учётом логлайна поиск ответа на этот вопрос может быть таким. Например, наш главный герой отец семейства, потерявший жильё за долги. Его цель вернуть квартиру, чтобы дети смогли вновь обрести дома. Каким герой должен быть в начале, чтобы набрать столько долгов, не платить их и даже лишится квартиры? Что это за качества, которые привели его сюда? Возможно, лень, игромания, вера в удачу, безответственность? Тогда каким герой должен стать в конце, чтобы достичь цели? Возможно, он будет вынужден победить свою лень, вылечится от игромании, начать принимать ответственные решения.

Для сценарной записи вам потребуется придумать имя каждому из героев, знать приблизительно их возраст и особенности внешности. Когда вы будете презентовать героев впервые, то их имя нужно писать большими буквами, в скобках давать возраст и краткую характеристику через запятую. Например. “ЖЕКА (45), тучный мужчина в деловом костюме”.

Структура сценария

На данном этапе ещё рано создавать титульный лист в вордовском документе. Нужно провести работу над структурой сценария и расставить основные точки сюжета. Как правило, в этом помогает трёхактная структура.

Трёхактная структура — это классическая структура практически любого драматического произведения. Все остальные структуры, так или иначе основаны на ней. Так что начинающим сценаристам мы рекомендуем начать с нее. Разделите историю как минимум на начало проблем персонажа, развитие событий (попытки решения проблем) и их разрешение. Ниже мы рассмотрим, что нужно включить в каждую из частей. Обязательно запишите все эти части в виде текста, это станет хорошей основой будущего сценария.

Акт 1. Вступление и завязка истории

Первый акт может располагаться приблизительно на 20-25 страницах. Обязательно начните с интересной экспозиции, то есть описания статуса-кво персонажа. Что можно включить в экспозицию:

- показать главные черты героя;

- рассказать о его семье, социальном статусе, любых других важных для истории социальных аспектах;

- заявить второстепенных персонажей;

- продемонстрировать текущие проблемы героя или наоборот его беззаботную жизнь до того, как он окунулся в перипетии;

- обозначить первые звоночки надвигающейся проблемы на героя.

Когда всё выше готово, то пора и ударить первыми сложностями по нашему главному герою. Следующей сюжетной точкой станет катализатор — событие, которое меняет всё.

Правило для катализатора такое: нужно придумать событие, после которого герой ни сможет не решать проблемы или ни сможет не отправиться в путешествие.

Например, в начале у главного героя, главы семейства, много долгов, но из-за своей лени и плохого характера, он никак не может заработать денег и погасить их. Но за долги у него наконец-таки отбирают квартиру. До этого долги героя мало влияли на его жизнь и жизнь его семьи. Да даже после того, как тот лишится квартиры, он может и не особо против поспать в машине. Но понимая, что дети не могут жить в машине, герой вынужден изменить свой характер, чтобы справится с финансовыми сложностями. То есть перед героем в этот момент должна чётко оформиться цель, о которой мы говорили выше, и которую он будет достигать от начала до конца, а от усугубившейся проблемы уже никуда не деться.

Акт 2. Борьба главного героя со сложностями на пути к заданной цели

Основная часть сценария должна уйти под борьбу главного героя за поставленную цель. Если сказать простыми словами, то главное правило, которое существует для написания второго акта такое. Герой решает возникшую проблему, она не решается и становится всё хуже. Затем герой снова что-то делает для решения проблемы — и вновь должно стать хуже. И так до конца второго акта.

Правильным будет второй акт закончить тем, что герой опускается до самой нижней точки своего состояния. Чем хуже ему, тем лучше. В качестве примера можно вспомнить фильм “Дюна” (2021). Второй акт фильма заканчивается тем, что весь народ и семью главного героя, Пола Атрейдеса, уничтожили Харконнены. Пол остался без дома, без отца, без своего народа, без каких-либо средств к существованию, да ещё и посреди дикой неподвластной человеку пустыни, убивающей всё живое.

Акт 3. Главный герой выходит победителем

В начало третьего акта герой входит, будучи на дне. Зритель должен видеть, что все отвернулись от героя, его покинули силы, ресурсы утрачены, а злодей ликует. Но в какой-то момент у главного героя появляется некий лучик надежды, и он совершает что-то невероятное, чтобы перевернуть ситуацию с ног на голову.

Кульминация должна быть яркой, оригинальной, логичной и эмоциональной. В чём её яркость может состоять? В нетривиальных решениях. То есть герой должен сделать что-то такое, чего раньше не делал или на что не решился бы никогда. Как проявляется логика? Хорошей логичной кульминацией можно назвать ту, где именно действия героя становятся финальным источником решения проблемы, исходя из качеств и изменений героя. А также кульминация не должна наступать благодаря “богу из машины” или “роялю в кустах”. Не надо в кульминации вестерна про ковбоев и борьбу за сердце дочери местного губернатора прописывать пришельцев, которые уничтожают врага главного героя своими лазерами. О том, что такое “бог из машины” и почему использовать его надо в исключительных случаях, мы рассказывали здесь.

Кульминация — это момент, когда антагонист повержен, а герой заполучил желаемое. Но на этом фильм не заканчивается. Не забывайте про развязку.

Развязка — это то, к чему привела кульминация. Как изменился герой и его жизнь после достижения цели? Вот наконец-то желаемый Кубок огня в руках Гарри Поттера в финале Турнира трёх волшебников, и он возвращается победителем на поле Хогвартса (“Гарри Поттер и Кубок огня”). Трибуны ликуют, ведь ученики Хогвартса и Гарри получили то, что хотели — победу школы в престижнейшем и опаснейшем международном конкурсе магов. Но чем она обернулась? В руках Гарри труп Седрика Диггори, его соперника, перед глазами до сих пор жуткий процесс возрождения лорда Волан-де-Морта, и пока только Гарри знает, что самый жестокий и сильный маг современности жив и строит планы на весь мир. Победа ему уже не нужна. Седрику победа принесла смерть, а его отцу и ученикам — скорбь.

Диалоги и описание действий

Что нам поможет на этапе диалогов из предыдущей разработки? Всё, что мы знаем про персонажа. Мы уже прописали какой он, как действует, его фишки и даже особенности речи. Всё это необходимо понимать при прописывании действий и диалогов.

В этом разделе мы используем слово диалоги в общепринятом значении. На внутреннем сленге сценаристов диалогами называют собственно сам сценарий – финальный документ, где расписана вся история с действиями и репликами.

Когда вы пишите действия, то старайтесь каждое описывать отдельным абзацем, что позволит проще читать и чётко видеть, кто, куда и как направляется в рамках сцены. Сами описания действий и вообще любые другие описания должны быть краткими и лаконичными. О том, как этого можно достичь мы рассказывали здесь.

Если даже вы нашли для вашего героя увлекательные действия, с помощью которых герой круто решает свои проблемы, это не значит, что всю сцену надо превращать в сплошной набор из них. Не стесняйтесь разбивать действия ёмкими фразами, шутками, комментариями героя. Но и не увлекайтесь.

Не торопитесь начинать прописывать диалоги. Убедитесь, что все сюжетные линии продуманы, все важные события расставлены, а структура работает как надо.

Одно из главных правил диалогов в том, что он, как и действие, должен продвигать сюжет. Например, один герой уговаривает скромного друга пойти с ним на концерт рок-группы. Каждый герой будет гнуть свою линию: первый уговаривать, другой отказывать. Ни один из героев не должен повторять свои предыдущие аргументы. Более того, каждая реплика героев должна отдалять или приближать их к концерту. А в идеале диалог должен усугублять отношения между персонажами, вскрывать их обиды друг на друга, а может быть и разгораться в ссору, которая возможно сильно ударит по их отношениям или сюжету.

Ещё один важный совет при написании диалогов: не повторяйте уже известную информацию. Пример. Ваш герой входит в сцену, он избитый и окровавленный. А его мать говорит: “О, Боже, у тебя кровь!”. То есть мы потратили лишний бит и лишнюю строчку, чтобы описать то, что зритель уже увидел, а читающий прочитал.

Избегайте в диалоге длинных непонятных слов: жаргонизмов, терминов, просто заумных выражений. Зрителю будет скучно даже полминуты смотреть и слушать то, чего он не понимает и что его не продвигает по истории.

Ну и заключительная рекомендация в написании диалогов состоит в том, чтобы их проговаривать. Диалог должен произноситься естественно, без запинок, звучать приятно для ушей. При произнесении реплик вслух вы сразу почувствуете, всё ли хорошо с фразами.

Редактирование сценария

Закончили писать – пора переписывать. Редактирование и переписывание — это вторая по объёму часть работы сценариста (первая — разработка идеи).

Самостоятельно

Во-первых, перечитайте сами. Уже в первую читку вам захочется местами подправить диалоги, убрать те или иные действия, что-то будет вас раздражать в тексте по мелочам.

Во-вторых, проанализируйте, работает ли каждая сцена, эпизод, акт. Работают ли детали, которые вы указали. Всё должно быть действующим в сценарии и не должно быть лишних движений, слов, вздохов, одёргиваний юбки и подобного. Каждый раз можно спрашивать себя:

- для чего это написано?

- как это работает на историю?

- что даёт это зрителю?

В-третьих, проверьте, не нарушилась ли логика в процессе создания первого драфта сценария. Точно ли одно событие вытекает из другого? Или это только вам так кажется?

В-четвёртых, в процессе написания сценария некоторые сцены могут просто перестать быть нужными. Удаляйте их безжалостно.

В-пятых, проверьте мотивацию героев. Каждый раз ваш главный персонаж входит в сцену по какой-то причине. И если эта причина не выглядит весомой и понятной для читателя или зрителя, то она оставит негативное впечатление.

Редактор

Если у вас есть бюджет и потребность в профессиональной помощи, то можно обратиться к редактору. Он прочтёт работу от начала до конца и будет искать примерно то же, что перечислено выше. Профессиональный редактор сможет найти все нестыковки, слабые мотивации персонажей, задаст нужные вопросы к тексту и даже отметит ненужные диалоги или описания.

Часто встречающиеся ошибки

Драматургия и кинодраматургия развивается уже не первую сотню лет. Современный зритель ожидает с каждым годом всё более крутых, увлекательных и сложных проектов. Давайте обсудим, какие ошибки вы можете избежать на пути к своему первому фильму, если обратите на них внимание и что сделать, чтобы он соответствовал уровню самых искушённых зрителей.

Персонажи

Во-первых, ошибкой может быть слишком много неработающих персонажей. Не нужно для каждого безобидного взаимодействия героя создавать нового персонажа — ограничьтесь массовкой. Каждый полноценный персонаж должен нести какую-то функцию, отражаться на истории, на главном герое и даже лучше бы иметь свою понятную и законченную линию.

Во-вторых, чисто технически большое количество персонажей может запутать зрителя. А если у них ещё и похожие или плохо запоминающиеся имена, то зрителя это может ещё и раздражать.

Задавайте себе вопрос при разработке и перечитывании: нужен ли мне этот персонаж? Нужен ли он вообще? Можно ли его удалить?

Конфликты

Конфликт — это основа любой истории. Правильный конфликт — это когда два героя преследуют противоположные интересы. Убедитесь, что герой постоянно вынужден противостоять кому-то или чему-то.

Ошибкой сценариста станет слабый или поверхностный конфликт внутри истории. Если цель героя легко достижима, то ему ничего не стоит просто подойти и взять то, что ему нужно. Достигнута цель — закончилась история.

Нужно избегать и слабых антагонистов. Каждый раз зритель должен видеть усугубление и ломать голову, как же наш герой одолеет невероятно жуткого огромного монстра или вооружённого до зубов террориста. А ещё лучше бы, чтобы в эти же моменты у героя заканчивались бы все пули и укрытия.

Конфликт должен проявляться не только в виде внешнего противостояния. Например, когда герою нужно спасти мир и забрать у антагониста супер-лазер, которым он его собирается взорвать. Конфликт должен лежать внутри ценностных убеждений. Самая распространённая и довольно банальная тема, которую можно отыскать в кино — это противостояние добра и зла. Но и за этими категориями чаще стоит что-то ещё. Например, Гарри Поттер (сторона добра) смог победить Волан-де-Морта (сторона зла) с помощью любви и дружбы. В то время как тот пытался вести борьбу с помощью устрашения сторонников и силы.

Мир

Условности и законы мира должны быть понятны с первых сцен. Если вы начинаете проект в жанре сай-фай, антиутопии, фэнтэзи, хоррора, то так или иначе нужно обозначать грань того, как работают придуманные законы. Мир должен иметь свои незыблемые законы и быть опасным для главного героя.

Если у вас фильм ужасов, в котором существуют призраки, то нельзя, чтобы герой в конце их всех уничтожил магией своей взятой из ниоткуда волшебной палочки.

Антиутопии тоже подразумевают очень строгое соблюдение жанровых условий. Для создания антиутопического произведения обычно берётся какая-то одна сторона жизни людей, меняется по усмотрению автора, и мы наблюдаем, как это воздействует на остальной мир по естественным его законам. Допустим, государство приказало с этого дня сдавать всех рождённых младенцев в специальное учреждение. Звучит жутко. Это не означает, что в следующем акте государство прикажет сдавать стариков, потом решит уволить с работы и лишить собственности всех мужчин, а затем сделать президентом мышь. Это всё будет противоречить жанру, и напоминать абсурд.

Далее ошибкой может стать то, что вы не вписали своего героя и его окружение в общий исторический, мировой или национальный контекст. Может быть, иногда отсутствие сеттинга и играет на идею, но это считанные случаи. Ваш мир не может быть безликим и откровенно пластиковым. Например, в сериале “Засланец из космоса” главный герой, внеземное существо, приземляется в американский городок. Казалось бы, зачем уточнять? Американский городок — понятная категория. Внеземное существо мы тоже можем себе представить. Но чтобы сделать пребывание инопланетянина как можно более сложным, авторы поселили его в городок штата Колорадо в горах рядом с огромными ледниками. Более того, город настолько мал, что скрыть свои инопланетные способности там почти невозможно. А ещё в нём живут представители коренных народов, индейцев, погружающие главного героя в человеческие ценности.

В мире вашего сценария должно работать всё — и даже время года. Зачем в одной из сцен дождь? Что он означает? Как он помогает или мешает? Почему именно сейчас пошёл дождь? Или он нужен только для красивой картинки? Если только последнее, то сцену стоит убрать, так как её просто напросто будет дорого снять.

Диалоги

Во-первых, любой бессмысленный диалог ради болтовни станет ошибкой. Если в диалоге нет конфликта, цели и он не продвигает сюжет, то его нужно переписать.

Во-вторых, не очень хорошо, когда зритель не понимает, на чьей он стороне в диалогах. Такое бывает тогда, когда взгляды и убеждения героев размыты и плохо продуманы.

В-третьих, нельзя бросать сцену без ясного финала, то есть результата взаимодействия персонажей. К чему-то в конце должны прийти либо сами герои, либо зритель.

В-четвёртых, попробуйте закрыть рукой или удалить имена персонажей над их репликами и понять, кому принадлежит та или иная фраза. Если вы не смогли точно определить, где чьи реплики и чётко различить персонажей по их словам, то надо вновь начинать работать над описанием персонажей.

Высказывание и изменение героя

Уделите отдельное внимание высказыванию вашего сценария. Откровенно говоря, навык выражать высказывание через сюжет — это постоянная упорная работа. Поэтому лучше заранее знать, с какими ошибками можно столкнуться на пути к хорошему сценарию.

Во-первых, ошибкой будет, если ваш герой никак не изменится. Именно изменение героя транслирует определённую мысль произведения.

Во-вторых, у героя обязательно должны быть какие-то убеждения, через которые он проносит происходящее. То есть как минимум он должен реагировать на события вокруг, как-то оценивать их, делать какой-то вывод. Может эти события противоречат убеждениям героя? Или учат его чему-то? То есть реакции главного героя будут составлять ваше высказывание.

В-третьих, плохо, если у героя отсутствуют сложные дилеммы. Только через морально тяжёлый выбор герой сможет расти, побеждать свои ложные убеждения и выражать высказывание.

В-четвёртых, высказывание не должно быть слишком общим и банальным, типа “Семья — самое важное в жизни” или “Убивать нехорошо”. Зритель сразу почувствует эту натянутость и заезженность темы.

Секреты сценарного мастерства от успешных сценаристов

Есть один самый главный секрет, о котором говорит почти каждый сценарист и в России, и зарубежом. Написать хороший сценарий поможет выбор темы, которая должны быть очень личной для автора. То есть нужно придавать идее такие эмоции, которые автор уже испытывал сам и понимает их. Нельзя назвать сценариста или автора сценарной книги, который не говорил бы об этом.

Ещё одно близкое к этому правило прозвучало от Ильи Куликова, автора знаменитых сериалов “Глухарь” и “Полицейский с Рублёвки”, в подкасте “Поэпизодный клан”. Он считает, что сценарист должен писать то, о чём он знает, что он понимает и что проживает. Например, по его словам, автор не может написать сценарий о странах, в которых не был, а также о людях в этих странах, об их морали, душах, образах жизни. Простыми словами, нужно брать в качестве темы то, что вам знакомо, и это станет сильной стороной вашего проекта.

Примеры хороших сценариев

В сети Интернет выложено в свободном доступе немало сценариев российских и зарубежных фильмов. Часто это делается, когда сезон сериала закончился, или когда проект номинирован на награду в сценарной номинации. Что точно стоит почитать и посмотреть, чтобы научится писать сценарии и избежать потенциальных ошибок, мы перечислим ниже.

“Рассказ служанки”

Пилот и одну из серий 4-го сезона «Рассказа служанки», номинированную на “Эмми” можно найти в свободном доступе. Сценарии эпизодов “Рассказа служанки” отличаются лаконичностью описаний и чёткими эмоциональными битами. Особенность сцен данного проекта в том, что там мало ярких и широких внешних действий, мало драк, погонь и ругани. Эмоциональные изменение и высказывание авторы умело выражают тонкими, но говорящими, кинодействиями.

“Дюна”

В данном фильме начинающему сценаристу может быть интересна структура сценария.

Во-первых, она соответствует классической трёхактной структуре. Более того, во многом там можно найти элементы структуры Блейка Снайдера из его книги про сценарное мастерство “Спасите котика”.

Во-вторых, каждый акт и его подэлементы достаточно краткие, ёмкие и не затянутые.

В-третьих, несмотря на то, что данный проект является экранизацией одноимённой книги, автор сценария, Джон Спейтс, смог создать сразу несколько логичных завершённых сюжетных линий и не увлечься мифологией.

Отдельно хочется сказать про мир “Дюны”. Данный сценарий является хорошим примером того, как автор смог интересно передать множество сложнейших законов вселенной, не спугнуть зрителя, а также ещё и создать плацдарм для эффектной визуальной составляющей.

“Достать ножи”

Не так давно в общем доступе появился сценарий детективного фильма “Достать ножи”. Что полезного можно почерпнуть в нём?

Во-первых, Райан Джонсон, сценарист и режиссёр, смог воплотить сюжет в стиле классического детектива с соблюдением всех законов жанра.

Во-вторых, к детективному жанру автор умело добавил и комедийный элемент. Главная героиня не способна врать физически: её тошнит при произнесении любой лжи. Данная комедийная черта была использована очень сбалансировано: она использовалась для создания юморных ситуаций, в качестве препятствий для героини, но не слишком злоупотреблялась.

В-третьих, данный сценарий можно похвалить за то, как ярко и полноценно прописан каждый герой. Зритель действительно много узнаёт про всех наследников жертвы убийства: про их финансовое состояние, мотивы, отношения, боли, социальное положение и так далее. Но при этом не перегружает деталями — мы видим только то, что работает на убийство как основу сюжета.

Часто начинающие сценаристы пытаются изобрести колесо, начиная сценарий без какой-либо теоретический подготовки. Безусловно любой опыт написания станет полезным, но так или иначе начинающий сценарист будет совершать ошибки, которые до этого уже проходили другие сценаристы. Смелее приступайте к созданию своего первого сценария, используя наши советы.

Если вы уже твердо решили садиться за работу, но запутались, что и в каком порядке нужно делать, то вот вам краткий гид по начальным этапам разработки сценария

Довод ( 2020 )

Все начинается с идеи.

Идея берется откуда угодно: это набор заметок и мыслей, одна мысль или наблюдение, случай из жизни автора. Идеи не бывают плохими или бесперспективными.

Если идея у вас уже есть, проверьте, всего ли в ней хватает по этому тексту и двигайтесь дальше.

- Логлайн

Как только идея появилась и более-менее утвердилась из нее нужно сформулировать логлайн. Логлайн — это максимально емкое и краткое описание вашей истории. Подробнее о том, как его писать читайте в материале что такое логлайн >>>>>

- Синопсис

После логлайна продолжаем развивать идею в историю и раскрываем ее уже на одну страницу. Это и есть синопсис — сжатое описание истории, которое нужно продюсеру, чтобы ему было понятно что вы предлагаете, и вам, чтобы дальше было легче двигаться и разрабатывать историю.

Если вы работаете над сериалом, вам нужно в синопсис заложить трамплины, то есть вопросы на которые аудитории захочется получать ответы в течение одного или нескольких сезонов.

Потому что сериал возможен, когда история дает возможность задавать много вопросов, чтобы было много поводов для конфликтов и историй.

- Бит-шит

Следующий этап разработки сценария — разбивка вашей истории на пункты, которые называются биты. Бит-шит — это перечисление поворотных и ключевых моментов, событий в истории. Об этом у нас тоже есть отдельный материал — что такое бит шит >>>>>

- Поэпизодник

А далее идет поэпизодник. В нем ваша главная задача разложить действия на сцены, то есть обозначить, что в них происходит, что и кто делает.

Поэпизодник — это самый сложный и трудоемкий этап. Уже в нем вы закладываете юмор, саспенс или другие приемы, а также начинаете вовлекать зрителя и пробуждать его любопытство.

- Диалоги

Последний этап работы. Если поэпизодник написан плохо, диалоги, как бы вы ни старались , лучше историю не сделают.

Основной инстинкт ( 1992 )

- Экспозиция

Экспозиция — это 5-10 минут фильма, но они в разработке сценария могут быть решающими. Задача сценариста — дать в экспозиции всю ту основную информацию про героя, которая нужна зрителю, чтобы следить за историей. То есть рассказать чем он живет, каков его мир и дать о нем представление.

- Главный драматический вопрос

Главный драматический вопрос появляется после экспозиции и вырастает из первого поворотного пункта: что-то происходит и появляется вопрос.

- Поворотные пункты

В середине истории появляется центральный поворотный пункт, после него финальный поворотный пункт и далее — кульминация ( финальная битва) в которой есть еще один поворотный пункт. В кульминации также есть ложное поражение — это хороший прием, зрителю кажется что все закончилось, но на самом деле он получил ложный ответ на главный драматический момент.

- Развязка и Финал

Они завершают структуру сценария.

Первый акт — экспозиция + завязка — до возникновения драматического вопроса. Середина — второй акт, финал — третий акт. Переходов зритель не видит, их диктует ваша история.

История может быть рассказана в любой очередности, но у нее всегда есть начало середина и конец.

Дорога перемен ( 2008 )

Вся история состоит из поворотных пунктов, есть несколько их типов:

- Событие

Любое событие — это поворотный пункт.

- Действие

Действия главного героя или других персонажей: когда кто-то что-то предпринимает, нападает или знакомится. Все, что делает герой и влияет на историю должно составлять поворотные пункты.

- Информационный поворотный пункт

Визуальная или, возможно, аудио информация. Например, зрителю показывают героя в комнате, и как его беседу кто-то подслушивает или он видит фотографию главного героя со свидетелем по делу у него на стене.

- Принятие решения

Еще один тип поворотного пункта ,когда герой решает измениться, например, отправиться в путешествие, изменить пол, начать ходить в бассейн и так далее. Решение предположительно изменит его и его жизнь.

Каждый из этапов разработки сценария по-своему сложен и одинаково важен для создания успешного проекта. Именно поэтому важно понимать, в каком порядке лучше начинать работу над сценарием и какие элементы структуры учитывать

Разработка сценария мероприятия подчиняется общим законам драматургии. Но есть одно существенное отличие праздника с участием гостей от спектакля, идущего на сцене. Оно заключается в интерактивном характере торжественного события. Это обстоятельство необходимо учитывать уже на стадии написания сценария.

СОДЕРЖАНИЕ:

- С ЧЕГО НАЧАТЬ?

- КАКОЙ ДОЛЖНА БЫТЬ СТРУКТУРА СЦЕНАРИЯ?

- КАК ПИСАТЬ ВСТУПЛЕНИЕ?

- КАК ПИСАТЬ КУЛЬМИНАЦИЮ?

- СОВЕТЫ ПО ОФОРМЛЕНИЮ

- ПРАКТИЧЕСКИЕ СОВЕТЫ И РЕКОМЕНДАЦИИ

- КАК ОФОРМИТЬ ТЕКСТ СЦЕНАРИЯ: ИНСТРУКЦИЯ

- КОНКРЕТНЫЕ ИДЕИ ПО ПРОВЕДЕНИЮ ТЕМАТИЧЕСКИХ ПРАЗДНИКОВ

Золотое правило, которое отвечает на вопрос: как написать сценарий праздника, гласит: «Тексты должны быть предельно ясными, четкими и выразительными. Идеально, если они написаны короткими рифмованными строками. Хорошо воспринимаются также диалоги в форме вопрос-ответ, утверждение-отрицание».

Важно! На вопрос, как составить сценарий мероприятия, профессионалы отвечают, что его надо писать не как литературное произведение, а как схему, служащую фарватером в бурном море торжества и веселья. Условие справедливо для всех типов представлений с участием зрителей.

Воспользуйтесь для оттачивания юмористического стиля анекдотами. В них можно найти немало остроумных диалогов, которые оживят сценарий и здорово повеселят публику.

С ЧЕГО НАЧАТЬ РАБОТУ НАД СЦЕНАРИЕМ?

На помощь автору, желающему составить сценарий праздника, приходят законы, по которым строится драматургическое произведение. В данном случае они приспособлены под конкретные задачи интерактивного мероприятия.

Если вы не знаете, с чего начать и как писать сценарий, начните с ответов на вопросы и определите следующие моменты:

- Какова цель праздника? Для этого надо ответить на вопрос: чего мы хотим получить от этого мероприятия? К примеру, если это Новый год, мы хотим встретить его так, чтобы он был успешным и счастливым. Это условие ведущий оговаривает в начале торжества. Оно может быть оформлено в виде веселого договора, подписанного всеми участниками. Или в виде торжественной клятвы: «Мы… такие-то такие-то, торжественно обещаем: пить, танцевать и веселиться так, чтобы весь год быть здоровыми, бодрыми, веселыми!»

- Какова тема праздничной встречи (застолья, банкета и т. д.)? Тема определяется датой (если это календарный праздник) или поводом, по которому люди собрались веселиться. Например: празднование Масленицы посвящено встрече Весны. Тема весны определяет все дальнейшие перипетии. Определив тему, автор видит, о чем писать, в каком стиле оформить зал, какие будут номера, игры, костюмы, реквизит и так далее. Тема определяет подходящую форму праздника. Например, ту же масленицу можно решить в форме ярмарочного балагана. Отсюда рождаются тексты в виде закличек, появляются герои в костюмах балаганных дедов, коробейников и так далее.

- Что или кто мешает достичь цели? Цель — встретить счастливый Новый год. Мешает погода, Баба-яга или другие злодеи. Появляется конфликтная ситуация, вокруг которой завязываются все действия, проявляется общая заинтересованность в преодолении препятствий, компания объединяется в едином порыве, сценарий держит гостей в тонусе весь вечер.

- Каково ведущее предлагаемое обстоятельство? Вокруг чего конкретно происходит борьба? На чем держится конфликт? Куда движется сюжет? Это может быть предмет, персонаж, явление или какое-либо спорное утверждение.

Например, на празднике Знаний 1 сентября в школе можно объявить о сокровище, которое было украдено и спрятано какими-то злодеями. Чтобы его найти, надо пройти череду испытаний. На этот каркас легко и просто накладываются различные игры, концертные номера и прочие забавы.

Внимание! Классика жанра: новогоднее елочное представление, когда ведущий объявляет о том, что Снегурочку, Деда Мороза, елочку или мешок с подарками похитили какие-то злые силы. Участники под его руководством выполняют различные действия, помогающие одолеть злодеев, спасти добрых героев и получить в конце за это заслуженную награду!

Эта простейшая схема поможет правильно написать сценарий любых праздничных мероприятий. Она дает автору возможность сконцентрировать внимание на поставленной задаче, возбуждает воображение, вдохновляет на создание интересного, захватывающего сюжета!

КАКОЙ ДОЛЖНА БЫТЬ СТРУКТУРА СЦЕНАРИЯ?

Хорошо организованный праздник идет по накатанной колее так, что никто не видит поставленных ограничителей, но никто их не переходит. В сохранении баланса между организованностью и свободой и есть самая большая сложность проведения интерактивных мероприятий.

Достижение этой гармонии обычно возлагают на плечи ведущего, но лучше, если автор сценария тоже позаботится о логичной и правильной структуре, на которой будет держаться весь праздник.

Разработка сценарного плана выполняется по следующей схеме:

- Вступление.

- Кульминация.

- Заключительная часть.

Внутри и между этими компонентами выстраивается программа праздничного вечера. Можно ли назвать ее сюжетом? Да, если соблюдены законы драматургии, о которых шла речь выше.

Важно! По определению сюжет — это борьба между противоборствующими силами за достижение некоей цели. Если в программе праздника прослеживается конфликтная ситуация, можно говорить о сюжете.

Классический пример – новогодние елочные представления, когда добрые и злые персонажи пытаются привлечь детей на свою сторону.

ПИШЕМ ВСТУПЛЕНИЕ ПРАВИЛЬНО

В начале надо привлечь внимание гостей к теме, ради которой все собрались, организовать их для совместного проведения праздника, настроить на нужный лад, задать атмосферу. Это самая короткая часть вечера.

Совет: послушайте начало праздничных передач федерального или советского телевидения. Обратите внимание на то, как обставлен выход ведущих. Там это сделано очень эффектно и профессионально. Воспользуйтесь идеями и саундтреками профессионалов.

После приветствия можно провести короткий блиц-опрос зала, конкурс лучших поздравлений, игру-знакомство, игру на внимание, конкурс на лучший тост и так далее.

КАК ПИСАТЬ КУЛЬМИНАЦИЮ?

Кульминация — апогей праздника: высшая точка, самая яркая и захватывающая его часть. В сценарии этот эпизод прописывают ближе к финалу. Потому что кульминация означает победу добра над злом, достижение цели праздника, торжество справедливости, когда уже нечего делать, не за что бороться, злодеи повержены, стыдятся и раскаиваются. Пришло время завершать мероприятие и прощаться!

Важно! Участие неподготовленных гостей вносит элемент спонтанности, что требует от организаторов и ведущих быстрой реакции и умения импровизировать. Им надо быть готовыми к неожиданностям во время проведения праздника и иметь на всякий случай несколько заготовок в виде дополнительных шуток, игр, сценок, концертных номеров и так далее.

Классический пример: Дед Мороз зажигает огоньки на елке. Баба-яга и ее пособники просят прощения, исправляются и просят разрешения веселиться вместе со всеми. Веселье продолжается, но уже без артистов.

СОВЕТЫ ПО ОФОРМЛЕНИЮ

Сценарный замысел, конечно же, определяет дизайн зала, в котором будет проходить мероприятие. Составление сценария праздника зачастую идет рука об руку с другими организационными работами, возлагаемыми на автора.

Важно! Чтобы сделать интересное оформление, надо придумать необычную форму проведения мероприятия. Жанр и стилистика праздника определят его декоративную сторону.

Например, зал на юбилей или день рождения можно оформить звездными зодиакальными символами, провозвещающими виновнику торжества добро и благо!

Будет интересно, если поместить портреты юбиляра в центр астрологического круга! В таком оформлении хорошо будут смотреться сценки с гадалками, волхвами, астрологами, цыганами. В этом же ключе проводят конкурс на лучшее предсказание, аукционы, лотереи.

ПРАКТИЧЕСКИЕ СОВЕТЫ И РЕКОМЕНДАЦИИ

Праздничные сценарии, как правило, пишутся по единому шаблону. Меняется только тема, форма, персонажи, декорации, тексты. В каждом конкретном случае автор оговаривает с организаторами или заказчиками праздника отдельные детали.

Хитрость! Начинающему сценаристу можно поискать в библиотеках книжку «В помощь самодеятельности» или что-то в этом роде. Эта серия содержит огромное количество методичек и готовых сценариев на самые разные темы. Их можно использовать в качестве шаблона, чтобы набить руку и понять секреты правильного составления сценария!

Праздничные мероприятия с участием зрителей бывают следующих видов:

- застольные (свадьбы, юбилеи, корпоративы);

- торжественные, официальные;

- театрализованные.

Торжественная часть обычно предшествует застольной. Элементы театрализации могут присутствовать и в первой, и во второй частях. Главное, что требуется от автора во всех случаях, это не перегружать праздник скучными длинными речами. Даже если они очень красиво написаны.

Важно! Каждому автору и ведущему подобных вечеров надо помнить одно золотое правило: люди приходят на праздник веселиться, а не слушать умные слова. Сценарий пишут для конкретных людей. Тексты, артисты, игры, сюжет должны вести праздник, но не заслонять собой веселье и свободное общение гостей.

ИНСТРУКЦИЯ ПО ПРАВИЛЬНОМУ ОФОРМЛЕНИЮ СЦЕНАРИЯ

Сценарий любого мероприятия помимо интересного содержания должен быть правильно оформлен. Аккуратность нужна как самому автору, чтобы защитить свою идею перед заказчиком или художественным советом, так и другим участникам.

Сценарий печатают в нескольких экземплярах, чтобы раздать:

- руководителю проекта (директору клуба, администратору, заказчику);

- режиссеру, художнику, ведущим;

- звукорежиссеру, диджею, осветителю.

Перечень сотрудников зависит от масштаба праздника. Их может быть больше или меньше, но каждый должен иметь для работы свой экземпляр.

Оформление текста сценария по шагам:

- На заглавном листе вверху пишут название учреждения, по заказу которого пишется сценарий и в котором планируется проведение праздника.

- Под шапкой набирают название и имя автора-составителя.

- В нижнем колонтитуле обозначают город, в котором написан сценарий, и год написания.

Первую страницу не нумеруют. Верхний колонтитул отдают шапке, в которую вписывают следующее:

- цель мероприятия (воспитательная, просветительская, развлекательная);

- место/время проведения;

- оформление (список необходимого оборудования и реквизита);

- список персонажей, принимающих участие в театрализованном представлении).

Далее следует таблица, в которой по колонкам описывается ход мероприятия:

Пример: «Сценарий о пользе прививок против ковида».

Название: «Изгнание Коронавируса с Земли Русской».

Автор: Александр Петров. г .Самара, 2021

|

Действующие лица |

Текстовка каждого персонажа |

Авторские ремарки (пояснения: кто откуда вышел, как сказал, в какой интонации, с каким настроением и т. д.) |

Поле для заметок и примечаний |

|

Маска 1-я |

Вот уж Новый год подходит, А Ковид все не уходит! |

Звучит тревожная музыка. Выходят Маски |

|

|

Маска 2, 3, 4…. |

Надо нам его спровадить И людей от бед избавить |

Как оформить сценарий праздника? Смотрите в следующем видео:

КОНКРЕТНЫЕ ИДЕИ ПО ПРОВЕДЕНИЮ ТЕМАТИЧЕСКИХ ПРАЗДНИКОВ

На юбилее, дне рождения, любом семейном празднике, корпоративах, школьных вечеринках очень хорошо принимаются именные поздравления. Сочинить их очень легко: автор или организатор записывает имена виновников торжества и их близких родственников.

Выбирают тех, кто будет на празднике. К имени подбирается простейшая рифма: Наталия — Италия, Ольга — Волга, Николай — Играй, Желай, Григорий — Добрый и так далее. По этим простейшим созвучиям составляются позитивные четверостишия типа:

Любим нашу мы Наталию,

Как прекрасную Италию:

Всем Наташа хороша:

Блеск — фигура, свет — душа!

***

Наш Григорий — парень добрый,

И всегда готов помочь,

Оставайся сильным, бодрым,

В светлый день и в темну ночь!

Спортивный праздник можно провести в форме Олимпиады. Ведущий будет говорить как спортивный комментатор. Из числа гостей выбрать жюри, начать действо с зажжения факела, потом пронести его торжественно по залу.

Хитрость! Пусть автор посмотрит трансляцию открытия Олимпийских игр, чтобы позаимствовать оттуда интересные идеи и повторить структуру в своем сценарии!

Сценарий воспитательного направления для детей строится по такой схеме: ведущими выступают персонажи популярных мультиков. Например, Маша и Медведь, Нюша и Бараш (из Смешариков) или кто-то из семейства Барбоскиных. Один из них говорит правильные вещи, другой ему возражает.

Они призывают на помощь гостей, проводят флешмобы, конкурсы, в которых побеждает положительный и проигрывает отрицательный персонаж. В заключительной части последний понимает свои ошибки и раскаивается! Справедливость торжествует! Цель праздника достигнута! Плохой герой исправился и стал хорошим! Всем раздают призы, награды и подарки! Праздник завершается песней про дружбу!

Подписывайтесь на нас

Методическая разработка, сценарий

Методическая разработка — комплексная форма, включающая рекомендации по организации и проведению отдельных мероприятий, методические советы, сценарии, планы выступлений, выставок и т.д.

Примерная схема методической разработки:

- название разработки;

- название и форма проведения дела;

- объяснительная записка, в которой указываются задачи проводимого дела, предлагаемого метода; возраста детей, на

которых рассчитано дело; условия его осуществления; - оборудование, оформление (технические средства, варианты текстов лозунгов, плакаты, музыкальное сопровождение);

- методические советы на подготовительный период (правильное распределение поручений, работа подготовительных

штабов, советов, большие и малые дела, предшествующие основному и нацеливающие на него, роль педагогов в этот период); - сценарный план, ход проведения дела;

- сценарий дела, включающий все композиционные части, ссылки на авторов и названия источников с указанием страниц;

- методические советы организаторам и постановщикам (на какие особо важные и трудные моменты обратить внимание, каких ошибок избежать, где лучше проводить дело, варианты оформления, способы создания эмоционального настроя);

- методические советы на период ближайшего последействия (как подвести итоги, какие дела провести для закрепления полученного результата и т.п.);

- список использованной литературы;

- автор разработки, должность, место работы, год.

Сценарии — самый распространенный вид прикладной методической продукции. Сценарий — это конспективная, подробная запись праздника, линейки, любого дела. В сценарии дословно приводятся слова ведущих, чтецов, актеров, тексты песен. В ремарках даются сценические указания: художественное оформление, световая партитура, движение участников праздника на сцене и т.д.

Чтобы со сценарием было легче работать, текстовой материал размещают ближе к правой стороне листа, а сценические ремарки — ближе к левой.

Примерная схема сценария:

- название дела («Сценарий праздника «Золотая осень»);

- адресат;

- цель, воспитательные задачи дела;

- действующие лица;

- текст сценария;

- использованная литература;

- автор сценария, год.

Сценарий, как правило, снабжен методическими советами. Это дает возможность использовать сценарий не буква в букву, разрабатывать собственные варианты, не повторять возможных ошибок.

————————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

Подготовила педагог-организатор Центра «Созвездие» Палиани Г.Н., г. Советский, 2014 г.

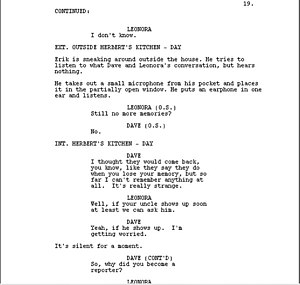

Example of a page from a screenplay formatted for a feature-length film.

Screenwriting or scriptwriting is the art and craft of writing scripts for mass media such as feature films, television productions or video games. It is often a freelance profession.

Screenwriters are responsible for researching the story, developing the narrative, writing the script, screenplay, dialogues and delivering it, in the required format, to development executives. Screenwriters therefore have great influence over the creative direction and emotional impact of the screenplay and, arguably, of the finished film. Screenwriters either pitch original ideas to producers, in the hope that they will be optioned or sold; or are commissioned by a producer to create a screenplay from a concept, true story, existing screen work or literary work, such as a novel, poem, play, comic book, or short story.

Types[edit]

The act of screenwriting takes many forms across the entertainment industry. Often, multiple writers work on the same script at different stages of development with different tasks. Over the course of a successful career, a screenwriter might be hired to write in a wide variety of roles.

Some of the most common forms of screenwriting jobs include:

Spec script writing[edit]

Spec scripts are feature film or television show scripts written on speculation of sale, without the commission of a film studio, production company or TV network. The content is usually invented solely by the screenwriter, though spec screenplays can also be based on established works or real people and events. The spec script is a Hollywood sales tool. The vast majority of scripts written each year are spec scripts, but only a small percentage make it to the screen.[1] A spec script is usually a wholly original work, but can also be an adaptation.

In television writing, a spec script is a sample teleplay written to demonstrate the writer’s knowledge of a show and ability to imitate its style and conventions. It is submitted to the show’s producers in hopes of being hired to write future episodes of the show. Budding screenwriters attempting to break into the business generally begin by writing one or more spec scripts.

Although writing spec scripts is part of any writer’s career, the Writers Guild of America forbids members to write «on speculation». The distinction is that a «spec script» is written as a sample by the writer on his or her own; what is forbidden is writing a script for a specific producer without a contract. In addition to writing a script on speculation, it is generally not advised to write camera angles or other directional terminology, as these are likely to be ignored. A director may write up a shooting script himself or herself, a script that guides the team in what to do in order to carry out the director’s vision of how the script should look. The director may ask the original writer to co-write it with him or her, or to rewrite a script that satisfies both the director and producer of the film/TV show.

Spec writing is also unique in that the writer must pitch the idea to producers. In order to sell the script, it must have an excellent title, good writing, and a great logline. A logline is one sentence that lays out what the movie is about. A well-written logline will convey the tone of the film, introduce the main character, and touch on the primary conflict. Usually the logline and title work in tandem to draw people in, and it is highly suggested to incorporate irony into them when possible. These things, along with nice, clean writing will hugely impact whether or not a producer picks up the spec script.

Commission[edit]

A commissioned screenplay is written by a hired writer. The concept is usually developed long before the screenwriter is brought on, and often has multiple writers work on it before the script is given a green light. The plot development is usually based on highly successful novels, plays, TV shows and even video games, and the rights to which have been legally acquired.

Feature assignment writing[edit]

Scripts written on assignment are screenplays created under contract with a studio, production company, or producer. These are the most common assignments sought after in screenwriting. A screenwriter can get an assignment either exclusively or from «open» assignments. A screenwriter can also be approached and offered an assignment. Assignment scripts are generally adaptations of an existing idea or property owned by the hiring company,[2] but can also be original works based on a concept created by the writer or producer.

Rewriting and script doctoring[edit]

Most produced films are rewritten to some extent during the development process. Frequently, they are not rewritten by the original writer of the script.[3] Many established screenwriters, as well as new writers whose work shows promise but lacks marketability, make their living rewriting scripts.

When a script’s central premise or characters are good but the script is otherwise unusable, a different writer or team of writers is contracted to do an entirely new draft, often referred to as a «page one rewrite». When only small problems remain, such as bad dialogue or poor humor, a writer is hired to do a «polish» or «punch-up».

Depending on the size of the new writer’s contributions, screen credit may or may not be given. For instance, in the American film industry, credit to rewriters is given only if 50% or more of the script is substantially changed.[4] These standards can make it difficult to establish the identity and number of screenwriters who contributed to a film’s creation.

When established writers are called in to rewrite portions of a script late in the development process, they are commonly referred to as script doctors. Prominent script doctors include Christopher Keane, Steve Zaillian, William Goldman, Robert Towne, Mort Nathan, Quentin Tarantino and Peter Russell.[5] Many up-and-coming screenwriters work as ghost writers.[citation needed]

Television writing[edit]

A freelance television writer typically uses spec scripts or previous credits and reputation to obtain a contract to write one or more episodes for an existing television show. After an episode is submitted, rewriting or polishing may be required.

A staff writer for a TV show generally works in-house, writing and rewriting episodes. Staff writers—often given other titles, such as story editor or producer—work both as a group and individually on episode scripts to maintain the show’s tone, style, characters, and plots.[6]

Television show creators write the television pilot and bible of new television series. They are responsible for creating and managing all aspects of a show’s characters, style, and plots. Frequently, a creator remains responsible for the show’s day-to-day creative decisions throughout the series run as showrunner, head writer or story editor.

Writing for daily series[edit]

The process of writing for soap operas and telenovelas is different from that used by prime time shows, due in part to the need to produce new episodes five days a week for several months. In one example cited by Jane Espenson, screenwriting is a «sort of three-tiered system»:[7]

- a few top writers craft the overall story arcs. Mid-level writers work with them to turn those arcs into things that look a lot like traditional episode outlines, and an array of writers below that (who do not even have to be local to Los Angeles), take those outlines and quickly generate the dialogue while adhering slavishly to the outlines.

Espenson notes that a recent trend has been to eliminate the role of the mid-level writer, relying on the senior writers to do rough outlines and giving the other writers a bit more freedom. Regardless, when the finished scripts are sent to the top writers, the latter do a final round of rewrites. Espenson also notes that a show that airs daily, with characters who have decades of history behind their voices, necessitates a writing staff without the distinctive voice that can sometimes be present in prime-time series.[7]

Writing for game shows[edit]

Game shows feature live contestants, but still use a team of writers as part of a specific format.[8] This may involve the slate of questions and even specific phrasing or dialogue on the part of the host. Writers may not script the dialogue used by the contestants, but they work with the producers to create the actions, scenarios, and sequence of events that support the game show’s concept.

Video game writing[edit]

With the continued development and increased complexity of video games, many opportunities are available to employ screenwriters in the field of video game design. Video game writers work closely with the other game designers to create characters, scenarios, and dialogue.[9]

Structural theories[edit]

Several main screenwriting theories help writers approach the screenplay by systematizing the structure, goals and techniques of writing a script. The most common kinds of theories are structural. Screenwriter William Goldman is widely quoted as saying «Screenplays are structure».

Three-act structure[edit]

According to this approach, the three acts are: the setup (of the setting, characters, and mood), the confrontation (with obstacles), and the resolution (culminating in a climax and a dénouement). In a two-hour film, the first and third acts each last about thirty minutes, with the middle act lasting about an hour, but nowadays many films begin at the confrontation point and segue immediately to the setup or begin at the resolution and return to the setup.

In Writing Drama, French writer and director Yves Lavandier shows a slightly different approach.[10] As do most theorists, he maintains that every human action, whether fictitious or real, contains three logical parts: before the action, during the action, and after the action. But since the climax is part of the action, Lavandier maintains that the second act must include the climax, which makes for a much shorter third act than is found in most screenwriting theories.

Besides the three-act structure, it is also common to use a four- or five-act structure in a screenplay, and some screenplays may include as many as twenty separate acts.

The Hero’s Journey[edit]

The hero’s journey, also referred to as the monomyth, is an idea formulated by noted mythologist Joseph Campbell. The central concept of the monomyth is that a pattern can be seen in stories and myths across history. Campbell defined and explained that pattern in his book The Hero with a Thousand Faces (1949).[11]

Campbell’s insight was that important myths from around the world, which have survived for thousands of years, all share a fundamental structure. This fundamental structure contains a number of stages, which include:

- a call to adventure, which the hero has to accept or decline,

- a road of trials, on which the hero succeeds or fails,

- achieving the goal (or «boon»), which often results in important self-knowledge,

- a return to the ordinary world, which again the hero can succeed or fail, and

- application of the boon, in which what the hero has gained can be used to improve the world.

Later, screenwriter Christopher Vogler refined and expanded the hero’s journey for the screenplay form in his book, The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers (1993).[12]

Syd Field’s paradigm[edit]

Syd Field introduced a new theory he called «the paradigm».[13] He introduced the idea of a plot point into screenwriting theory[14] and defined a plot point as «any incident, episode, or event that hooks into the action and spins it around in another direction».[15] These are the anchoring pins of the story line, which hold everything in place.[16] There are many plot points in a screenplay, but the main ones that anchor the story line in place and are the foundation of the dramatic structure, he called plot points I and II.[17][18] Plot point I occurs at the end of Act 1; plot point II at the end of Act 2.[14] Plot point I is also called the key incident because it is the true beginning of the story[19] and, in part, what the story is about.[20]

In a 120-page screenplay, Act 2 is about sixty pages in length, twice the length of Acts 1 and 3.[21] Field noticed that in successful movies, an important dramatic event usually occurs at the middle of the picture, around page sixty. The action builds up to that event, and everything afterward is the result of that event. He called this event the centerpiece or midpoint.[22] This suggested to him that the middle act is actually two acts in one. So, the three-act structure is notated 1, 2a, 2b, 3, resulting in Aristotle’s three acts being divided into four pieces of approximately thirty pages each.[23]

Field defined two plot points near the middle of Acts 2a and 2b, called pinch I and pinch II, occurring around pages 45 and 75 of the screenplay, respectively, whose functions are to keep the action on track, moving it forward, either toward the midpoint or plot point II.[24] Sometimes there is a relationship between pinch I and pinch II: some kind of story connection.[25]

According to Field, the inciting incident occurs near the middle of Act 1,[26] so-called because it sets the story into motion and is the first visual representation of the key incident.[27] The inciting incident is also called the dramatic hook, because it leads directly to plot point I.[28]

Field referred to a tag, an epilogue after the action in Act 3.[29]

Here is a chronological list of the major plot points that are congruent with Field’s Paradigm:

| What | Characterization | Example: Star Wars: Episode IV – A New Hope |

|---|---|---|

| Opening image | The first image in the screenplay should summarize the entire film, especially its tone. Screenwriters often go back and redo this as their final task before submitting the script. | In outer space, near the planet Tatooine, an Imperial Star Destroyer pursues and exchanges fire with a Rebel Tantive IV spaceship. |

| Exposition | This provides some background information to the audience about the plot, characters’ histories, setting, and theme. The status quo or ordinary world of the protagonist is established. | The settings of space and the planet Tatooine are shown; the rebellion against the Empire is described; and many of the main characters are introduced: C-3PO, R2-D2, Princess Leia Organa, Darth Vader, Luke Skywalker (the protagonist), and Ben Kenobi (Obi-Wan Kenobi). Luke’s status quo is his life on his Uncle’s moisture farm. |

| Inciting incident | Also known as the catalyst or disturbance, this is something bad, difficult, mysterious, or tragic that catalyzes the protagonist to go into motion and take action: the event that starts the protagonist on the path toward the conflict. | Luke sees the tail end of the hologram of Princess Leia, which begins a sequence of events that culminates in plot point I. |

| Plot point I | Also known as the first doorway of no return, or the first turning point, this is the last scene in Act 1, a surprising development that radically changes the protagonist’s life, and forces him or her to confront the opponent. Once the protagonist passes through this one-way door, he or she cannot go back to his or her status quo. | This is when Luke’s uncle and aunt are killed and their home is destroyed by the Empire. He has no home to go back to, so he joins the Rebels in opposing Darth Vader. Luke’s goal at this point is to help the princess. |

| Pinch I | A reminder scene at about 3/8 of the way through the script (halfway through Act 2a) that brings up the central conflict of the drama, reminding the audience of the overall conflict. | Imperial stormtroopers attack the Millennium Falcon in Mos Eisley, reminding the audience the Empire is after the stolen Death Star plans that R2-D2 is carrying, and Luke and Ben Kenobi are trying to get to the Rebel base. |

| Midpoint | An important scene in the middle of the script, often a reversal of fortune or revelation that changes the direction of the story. Field suggests that driving the story toward the midpoint keeps the second act from sagging. | Luke and his companions learn that Princess Leia is aboard the Death Star. Now that Luke knows where the princess is, his new goal is to rescue her. |

| Pinch II | Another reminder scene about 5/8 of the way through the script (halfway through Act 2b) that is somehow linked to pinch I in reminding the audience about the central conflict. | After surviving the garbage masher, Luke and his companions clash with stormtroopers again in the Death Star while en route to the Millennium Falcon. Both scenes remind us of the Empire’s opposition, and using the stormtrooper attack motif unifies both pinches. |

| Plot point II | A dramatic reversal that ends Act 2 and begins Act 3. | Luke, Leia, and their companions arrive at the Rebel base. Now that the princess has been successfully rescued, Luke’s new goal is to assist the Rebels in attacking the Death Star. |

| Moment of truth | Also known as the decision point, the second doorway of no return, or the second turning point, this is the point, about midway through Act 3, when the protagonist must make a decision. The story is, in part, about what the main character decides at the moment of truth. The right choice leads to success; the wrong choice to failure. | Luke must choose between trusting his mind or trusting The Force. He makes the right choice to let go and use the Force. |

| Climax | The point of highest dramatic tension in the action, which immediately follows the moment of truth. The protagonist confronts the main problem of the story and either overcomes it, or comes to a tragic end. | Luke’s proton torpedoes hit the target, and he and his companions leave the Death Star. |

| Resolution | The issues of the story are resolved. | The Death Star explodes. |

| Tag | An epilogue, tying up the loose ends of the story, giving the audience closure. This is also known as denouement. Films in recent decades have had longer denouements than films made in the 1970s or earlier. | Leia awards Luke and Han medals for their heroism. |

The sequence approach[edit]

The sequence approach to screenwriting, sometimes known as «eight-sequence structure», is a system developed by Frank Daniel, while he was the head of the Graduate Screenwriting Program at USC. It is based in part on the fact that, in the early days of cinema, technical matters forced screenwriters to divide their stories into sequences, each the length of a reel (about ten minutes).[30]

The sequence approach mimics that early style. The story is broken up into eight 10-15 minute sequences. The sequences serve as «mini-movies», each with their own compressed three-act structure. The first two sequences combine to form the film’s first act. The next four create the film’s second act. The final two sequences complete the resolution and dénouement of the story. Each sequence’s resolution creates the situation which sets up the next sequence.

Character theories[edit]

Michael Hauge’s categories[edit]

Michael Hauge divides primary characters into four categories. A screenplay may have more than one character in any category.

- hero: This is the main character, whose outer motivation drives the plot forward, who is the primary object of identification for the reader and audience, and who is on screen most of the time.

- nemesis: This is the character who most stands in the way of the hero achieving his or her outer motivation.

- reflection: This is the character who supports the hero’s outer motivation or at least is in the same basic situation at the beginning of the screenplay.

- romance: This is the character who is the sexual or romantic object of at least part of the hero’s outer motivation.[31]

Secondary characters are all the other people in the screenplay and should serve as many of the functions above as possible.[32]

Motivation is whatever the character hopes to accomplish by the end of the movie. Motivation exists on outer and inner levels.

- outer motivation is what the character visibly or physically hopes to achieve or accomplish by the end of the film. Outer motivation is revealed through action.

- inner motivation is the answer to the question, «Why does the character want to achieve his or her outer motivation?» This is always related to gaining greater feelings of self-worth. Since inner motivation comes from within, it is usually invisible and revealed through dialogue. Exploration of inner motivation is optional.

Motivation alone is not sufficient to make the screenplay work. There must be something preventing the hero from getting what he or she wants. That something is conflict.

- outer conflict is whatever stands in the way of the character achieving his or her outer motivation. It is the sum of all the obstacles and hurdles that the character must try to overcome in order to reach his or her objective.

- inner conflict is whatever stands in the way of the character achieving his or her inner motivation. This conflict always originates from within the character and prevents him or her from achieving self-worth through inner motivation.[33]

Format[edit]

Fundamentally, the screenplay is a unique literary form. It is like a musical score, in that it is intended to be interpreted on the basis of other artists’ performance, rather than serving as a finished product for the enjoyment of its audience. For this reason, a screenplay is written using technical jargon and tight, spare prose when describing stage directions. Unlike a novel or short story, a screenplay focuses on describing the literal, visual aspects of the story, rather than on the internal thoughts of its characters. In screenwriting, the aim is to evoke those thoughts and emotions through subtext, action, and symbolism.[34]

Most modern screenplays, at least in Hollywood and related screen cultures, are written in a style known as the master-scene format[35][36] or master-scene script.[37] The format is characterized by six elements, presented in the order in which they are most likely to be used in a script:

- Scene Heading, or Slug

- Action Lines, or Big Print

- Character Name

- Parentheticals

- Dialogue

- Transitions

Scripts written in master-scene format are divided into scenes: «a unit of story that takes place at a specific location and time».[38] Scene headings (or slugs) indicate the location the following scene is to take place in, whether it is interior or exterior, and the time-of-day it appears to be. Conventionally, they are capitalized, and may be underlined or bolded. In production drafts, scene headings are numbered.

Next are action lines, which describe stage direction and are generally written in the present tense with a focus only on what can be seen or heard by the audience.

Character names are in all caps, centered in the middle of the page, and indicate that a character is speaking the following dialogue. Characters who are speaking off-screen or in voice-over are indicated by the suffix (O.S.) and (V.O) respectively.

Parentheticals provide stage direction for the dialogue that follows. Most often this is to indicate how dialogue should be performed (for example, angry) but can also include small stage directions (for example, picking up vase). Overuse of parentheticals is discouraged.[39]

Dialogue blocks are offset from the page’s margin by 3.7″ and are left-justified. Dialogue spoken by two characters at the same time is written side by side and is conventionally known as dual-dialogue.[40]

The final element is the scene transition and is used to indicate how the current scene should transition into the next. It is generally assumed that the transition will be a cut, and using «CUT TO:» will be redundant.[41][42] Thus the element should be used sparingly to indicate a different kind of transition such as «DISSOLVE TO:».

Screenwriting applications such as Final Draft (software), Celtx, Fade In (software), Slugline, Scrivener (software), and Highland, allow writers to easily format their script to adhere to the requirements of the master screen format.

Dialogue and description[edit]

Imagery[edit]

Imagery can be used in many metaphoric ways. In The Talented Mr. Ripley, the title character talked of wanting to close the door on himself sometime, and then, in the end, he did. Pathetic fallacy is also frequently used; rain to express a character feeling depressed, sunny days promote a feeling of happiness and calm. Imagery can be used to sway the emotions of the audience and to clue them in to what is happening.

Imagery is well defined in City of God. The opening image sequence sets the tone for the entire film. The film opens with the shimmer of a knife’s blade on a sharpening stone. A drink is being prepared, The knife’s blade shows again, juxtaposed is a shot of a chicken letting loose of its harness on its feet. All symbolising ‘The One that got away’. The film is about life in the favelas in Rio — sprinkled with violence and games and ambition.

Dialogue[edit]

Since the advent of sound film, or «talkies», dialogue has taken a central place in much of mainstream cinema. In the cinematic arts, the audience understands the story only through what they see and hear: action, music, sound effects, and dialogue. For many screenwriters, the only way their audiences can hear the writer’s words is through the characters’ dialogue. This has led writers such as Diablo Cody, Joss Whedon, and Quentin Tarantino to become well known for their dialogue—not just their stories.

Bollywood and other Indian film industries use separate dialogue writers in addition to the screenplay writers.[43]

Plot[edit]

Plot, according to Aristotle’s Poetics, refers to the sequence events connected by cause and effect in a story. A story is a series of events conveyed in chronological order. A plot is the same series of events deliberately arranged to maximize the story’s dramatic, thematic, and emotional significance. E.M.Forster famously gives the example «The king died and then the queen died» is a story.» But «The king died and then the queen died of grief» is a plot.[44] For Trey Parker and Matt Stone this is best summarized as a series of events connected by «therefore» and «but».[45]

Education[edit]

A number of American universities offer specialized Master of Fine Arts and undergraduate programs in screenwriting, including USC, DePaul University, American Film Institute, Loyola Marymount University, Chapman University, NYU, UCLA, Boston University and the University of the Arts. In Europe, the United Kingdom has an extensive range of MA and BA Screenwriting Courses including London College of Communication, Bournemouth University, Edinburgh University, and Goldsmiths College (University of London).

Some schools offer non-degree screenwriting programs, such as the TheFilmSchool, The International Film and Television School Fast Track, and the UCLA Professional / Extension Programs in Screenwriting.

New York Film Academy offers both degree and non-degree educational systems with campuses all around the world.

A variety of other educational resources for aspiring screenwriters also exist, including books, seminars, websites and podcasts, such as the Scriptnotes podcast.

History[edit]

The first true screenplay is thought to be from George Melies’ 1902 film A Trip to the Moon. The movie is silent, but the screenplay still contains specific descriptions and action lines that resemble a modern-day script. As time went on and films became longer and more complex, the need for a screenplay became more prominent in the industry. The introduction of movie theaters also impacted the development of screenplays, as audiences became more widespread and sophisticated, so the stories had to be as well. Once the first non-silent movie was released in 1927, screenwriting became a hugely important position within Hollywood. The «studio system» of the 1930s only heightened this importance, as studio heads wanted productivity. Thus, having the «blueprint» (continuity screenplay) of the film beforehand became extremely optimal. Around 1970, the «spec script» was first created, and changed the industry for writers forever. Now, screenwriting for television (teleplays) is considered as difficult and competitive as writing is for feature films.[46]

Portrayed in film[edit]

Screenwriting has been the focus of a number of films:

- Crashing Hollywood (1931)—A screenwriter collaborates on a gangster movie with a real-life gangster. When the film is released, the mob doesn’t like how accurate the movie is.[47]

- Sunset Boulevard (1950)—Actor William Holden portrays a hack screenwriter forced to collaborate on a screenplay with a desperate, fading silent film star, played by Gloria Swanson.

- In a Lonely Place (1950)—Humphrey Bogart is a washed up screenwriter who gets framed for murder.

- Paris, When it Sizzles (1964)—William Holden plays a drunk screenwriter who has wasted months partying and has just two days to finish his script. He hires Audrey Hepburn to help.

- Barton Fink (1991)—John Turturro plays a naïve New York playwright who comes to Hollywood with high hopes and great ambition. While there, he meets one of his writing idols, a celebrated novelist from the past who has become a drunken hack screenwriter (a character based on William Faulkner).

- Mistress (1992)—In this comedy written by Barry Primus and J. F. Lawton, Robert Wuhl is a screenwriter/director who’s got integrity, vision, and a serious script — but no career. Martin Landau is a sleazy producer who introduces Wuhl to Robert De Niro, Danny Aiello and Eli Wallach — three guys willing to invest in the movie, but with one catch: each one wants his mistress to be the star.

- The Player (1992)—In this satire of the Hollywood system, Tim Robbins plays a movie producer who thinks he’s being blackmailed by a screenwriter whose script was rejected.

- Adaptation (2002)—Nicolas Cage portrays real-life screenwriter Charlie Kaufman (as well as his fictional brother, Donald) as Kaufman struggles to adapt an esoteric book (Susan Orlean’s real-life nonfiction work The Orchid Thief ) into an action-filled Hollywood screenplay.[48]

- Dreams on Spec (2007)—The only documentary to follow aspiring screenwriters as they struggle to turn their scripts into movies, the film also features wisdom from established scribes like James L. Brooks, Nora Ephron, Carrie Fisher, and Gary Ross.[49]

- Seven Psychopaths (2012)—In this satire, written and directed by Martin McDonagh, Colin Farrell plays a screenwriter who is struggling to finish his screenplay Seven Psychopaths, but finds unlikely inspiration after his best friend steals a Shih Tzu owned by a vicious gangster.

- Trumbo (2015)—Highly successful Hollywood screenwriter Dalton Trumbo, played in this biopic by Bryan Cranston, is targeted by the House Un-American Activities Committee for his socialist views, sent to federal prison for refusing to cooperate, and blacklisted from working in Hollywood, yet continues to write and subsequently wins two Academy Awards while using pseudonyms.

Copyright protection[edit]

United States[edit]

In the United States, completed works may be copyrighted, but ideas and plots may not be. Any document written after 1978 in the U.S. is automatically copyrighted even without legal registration or notice. However, the Library of Congress will formally register a screenplay. U.S. Courts will not accept a lawsuit alleging that a defendant is infringing on the plaintiff’s copyright in a work until the plaintiff registers the plaintiff’s claim to those copyrights with the Copyright Office.[50] This means that a plaintiff’s attempts to remedy an infringement will be delayed during the registration process.[51] Additionally, in many infringement cases, the plaintiff will not be able recoup attorney fees or collect statutory damages for copyright infringement, unless the plaintiff registered before the infringement began.[52] For the purpose of establishing evidence that a screenwriter is the author of a particular screenplay (but not related to the legal copyrighting status of a work), the Writers Guild of America registers screenplays. However, since this service is one of record keeping and is not regulated by law, a variety of commercial and non-profit organizations exist for registering screenplays. Protection for teleplays, formats, as well as screenplays may be registered for instant proof-of-authorship by third-party assurance vendors.[citation needed]