Daylight saving time regions:

Formerly used daylight saving

Never used daylight saving

Daylight saving time (DST), also referred to as daylight savings time or simply daylight time (United States, Canada, and Australia), and summer time (United Kingdom, European Union, and others), is the practice of advancing clocks (typically by one hour) during warmer months so that darkness falls at a later clock time. The typical implementation of DST is to set clocks forward by one hour in the spring («spring forward»), and to set clocks back by one hour in the fall («fall back») to return to standard time. As a result, there is one 23-hour day in early spring and one 25-hour day in the middle of autumn.

The idea of aligning waking hours to daylight hours to conserve candles was first proposed in 1784 by U.S. polymath Benjamin Franklin. In a satirical letter to the editor of The Journal of Paris, Franklin suggested that waking up earlier in the summer would economize on candle usage; and calculated considerable savings.[1][2] In 1895, New Zealand entomologist and astronomer George Hudson proposed the idea of changing clocks by two hours every spring to the Wellington Philosophical Society.[3] In 1907, British resident William Willett presented the idea as a way to save energy. After some serious consideration, it was not implemented.[4]

In 1908, Port Arthur in Ontario, Canada, started using DST.[5][6] Starting on April 30, 1916, the German Empire and Austria-Hungary each organized the first nationwide implementation in their jurisdictions. Many countries have used DST at various times since then, particularly since the 1970s energy crisis. DST is generally not observed near the Equator, where sunrise and sunset times do not vary enough to justify it. Some countries observe it only in some regions: for example, parts of Australia observe it, while other parts do not. Conversely, it is not observed at some places at high latitudes, because there are wide variations in sunrise and sunset times and a one-hour shift would relatively not make much difference. The United States observes it, except for the states of Hawaii and Arizona (within the latter, however, the Navajo Nation does observe it, conforming to federal practice).[7] A minority of the world’s population uses DST; Asia, Africa, and Latin America and the Caribbean generally do not.

Rationale[edit]

An ancient water clock that lets hour lengths vary with season.

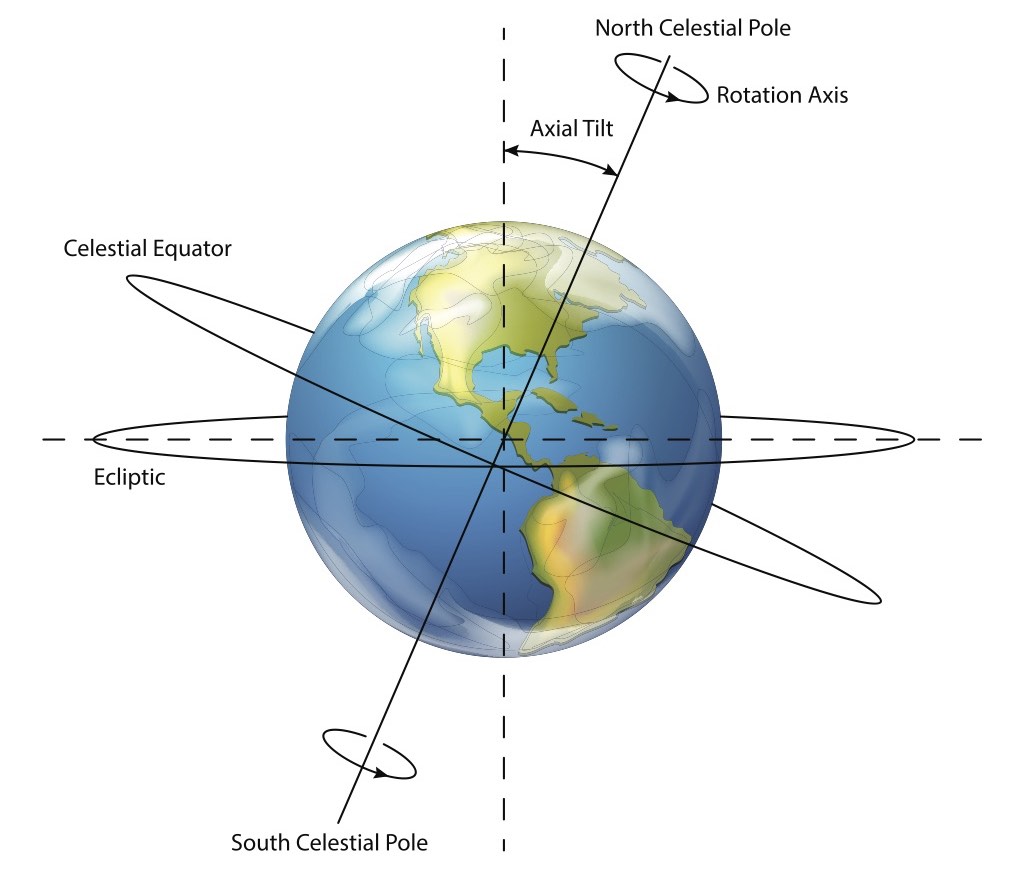

Industrialized societies usually follow a clock-based schedule for daily activities that do not change throughout the course of the year. The time of day that individuals begin and end work or school, and the coordination of mass transit, for example, usually remain constant year-round. In contrast, an agrarian society’s daily routines for work and personal conduct are more likely governed by the length of daylight hours[8][9] and by solar time, which change seasonally because of the Earth’s axial tilt. North and south of the tropics, daylight lasts longer in summer and shorter in winter, with the effect becoming greater the further one moves away from the equator.

After synchronously resetting all clocks in a region to one hour ahead of standard time, individuals following a clock-based schedule will awaken an hour earlier than they would have otherwise—or rather an hour’s worth of darkness earlier; they will begin and complete daily work routines an hour of daylight earlier: they will have available to them an extra hour of daylight after their workday activities.[10][11] They will have one less hour of daylight at the start of the workday, making the policy less practical during winter.[12][13]

Proponents of daylight saving time argue that most people prefer a greater increase in daylight hours after the typical «nine to five» workday.[14][15] Supporters have also argued that DST decreases energy consumption by reducing the need for lighting and heating, but the actual effect on overall energy use is heavily disputed.

The shift in apparent time is also motivated by practicality. In American temperate latitudes, for example, the sun rises around 04:30 at the summer solstice and sets around 19:30. Since most people are asleep at 04:30, it is seen as more practical to pretend that 04:30 is actually 05:30, thereby allowing people to wake close to the sunrise and be active in the evening light.

The manipulation of time at higher latitudes (for example Iceland, Nunavut, Scandinavia, and Alaska) has little effect on daily life, because the length of day and night changes more extremely throughout the seasons (in comparison to lower latitudes). Sunrise and sunset times become significantly out of phase with standard working hours regardless of manipulation of the clock.[16]

DST is similarly of little use for locations near the Equator, because these regions see only a small variation in daylight in the course of the year.[17] The effect also varies according to how far east or west the location is within its time zone, with locations farther east inside the time zone benefiting more from DST than locations farther west in the same time zone.[18] Neither is daylight savings of much practicality in such places as China, which—despite its width of thousands of miles—is all located within a single time zone per government mandate.

History[edit]

Ancient civilizations adjusted daily schedules to the sun more flexibly than DST does, often dividing daylight into 12 hours regardless of daytime, so that each daylight hour became progressively longer during spring and shorter during autumn.[19] For example, the Romans kept time with water clocks that had different scales for different months of the year; at Rome’s latitude, the third hour from sunrise (hora tertia) started at 09:02 solar time and lasted 44 minutes at the winter solstice, but at the summer solstice it started at 06:58 and lasted 75 minutes.[20] From the 14th century onward, equal-length civil hours supplanted unequal ones, so civil time no longer varied by season. Unequal hours are still used in a few traditional settings, such as monasteries of Mount Athos[21] and in Jewish ceremonies.[22]

Benjamin Franklin published the proverb «early to bed and early to rise makes a man healthy, wealthy, and wise,»[23][24] and published a letter in the Journal de Paris during his time as an American envoy to France (1776–1785) suggesting that Parisians economize on candles by rising earlier to use morning sunlight.[25] This 1784 satire proposed taxing window shutters, rationing candles, and waking the public by ringing church bells and firing cannons at sunrise.[26] Despite common misconception, Franklin did not actually propose DST; 18th-century Europe did not even keep precise schedules. However, this changed as rail transport and communication networks required a standardization of time unknown in Franklin’s day.[27]

In 1810, the Spanish National Assembly Cortes of Cádiz issued a regulation that moved certain meeting times forward by one hour from May 1 to September 30 in recognition of seasonal changes, but it did not change the clocks. It also acknowledged that private businesses were in the practice of changing their opening hours to suit daylight conditions, but they did so of their own volition.[28][29]

New Zealand entomologist George Hudson first proposed modern DST. His shift-work job gave him leisure time to collect insects and led him to value after-hours daylight.[3] In 1895, he presented a paper to the Wellington Philosophical Society proposing a two-hour daylight-saving shift,[10] and considerable interest was expressed in Christchurch; he followed up with an 1898 paper.[30] Many publications credit the DST proposal to prominent English builder and outdoorsman William Willett,[31] who independently conceived DST in 1905 during a pre-breakfast ride when he observed how many Londoners slept through a large part of a summer day.[15] Willett also was an avid golfer who disliked cutting short his round at dusk.[32] His solution was to advance the clock during the summer months, and he published the proposal two years later.[33] Liberal Party member of parliament Robert Pearce took up the proposal, introducing the first Daylight Saving Bill to the British House of Commons on February 12, 1908.[34] A select committee was set up to examine the issue, but Pearce’s bill did not become law and several other bills failed in the following years.[4] Willett lobbied for the proposal in the UK until his death in 1915.

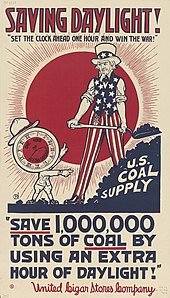

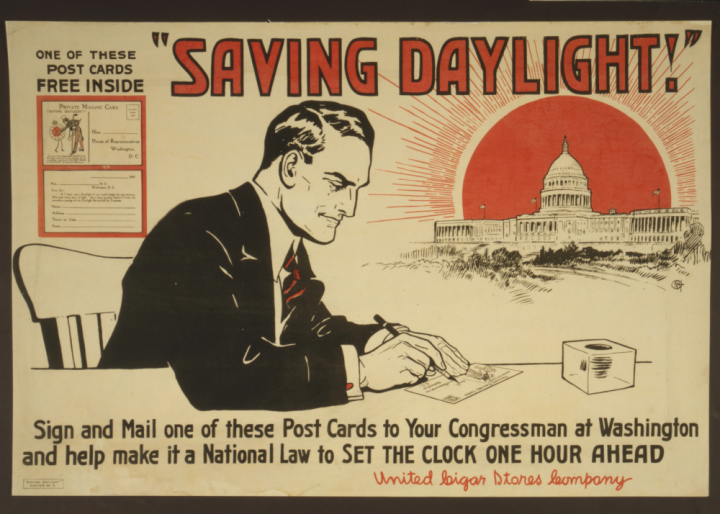

DST was first implemented in the United States to conserve energy during World War I. (poster by United Cigar Stores)

Port Arthur, Ontario, Canada, was the first city in the world to enact DST, on July 1, 1908.[5][6] This was followed by Orillia, Ontario, introduced by William Sword Frost while mayor from 1911 to 1912.[35] The first states to adopt DST (German: Sommerzeit) nationally were those of the German Empire and its World War I ally Austria-Hungary commencing April 30, 1916, as a way to conserve coal during wartime. Britain, most of its allies, and many European neutrals soon followed. Russia and a few other countries waited until the next year, and the United States adopted daylight saving in 1918. Most jurisdictions abandoned DST in the years after the war ended in 1918, with exceptions including Canada, the United Kingdom, France, Ireland, and the United States.[36] It became common during World War II (some countries adopted double summer time), and was widely adopted in America and Europe from the 1970s as a result of the 1970s energy crisis. Since then, the world has seen many enactments, adjustments, and repeals.[37]

It is a common myth in the United States that DST was first implemented for the benefit of farmers.[38][39][40] In reality, farmers have been one of the strongest lobbying groups against DST since it was first implemented.[38][39][40] The factors that influence farming schedules, such as morning dew and dairy cattle’s readiness to be milked, are ultimately dictated by the sun, so the time change introduces unnecessary challenges.[38][40][41]

DST was first implemented in the US with the Standard Time Act of 1918, a wartime measure for seven months during World War I in the interest of adding more daylight hours to conserve energy resources.[42][41] Year-round DST, or «War Time», was implemented again during World War II.[42] After the war, local jurisdictions were free to choose if and when to observe DST until the Uniform Time Act which standardized DST in 1966.[42][43] Permanent daylight saving time was enacted for the winter of 1974, but there were complaints of children going to school in the dark and working people commuting and starting their work day in pitch darkness during the winter months, and it was repealed a year later.

Procedure[edit]

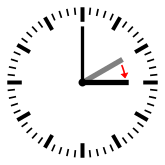

When DST observation begins, clocks are advanced by one hour (as if to skip one hour) during the very early morning.

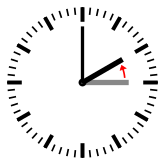

When DST observation ends and standard time observation resumes, clocks are turned back one hour (as if to repeat one hour) during the very early morning. Specific times of the clock change vary by jurisdiction.

The relevant authorities usually schedule clock changes to occur at (or soon after) midnight, and on a weekend, in order to lessen disruption to weekday schedules.[44] A one-hour change is usual, but twenty-minute and two-hour changes have been used in the past. In all countries that observe daylight saving time seasonally (i.e. during summer and not winter), the clock is advanced from standard time to daylight saving time in the spring, and they are turned back from daylight saving time to standard time in the autumn. The practice, therefore, reduces the number of civil hours in the day of the springtime change, and it increases the number of civil hours in the day of the autumnal change. For a midnight change in spring, a digital display of local time would appear to jump from 23:59:59.9 to 01:00:00.0. For the same clock in autumn, the local time would appear to repeat the hour preceding midnight, i.e. it would jump from 23:59:59.9 to 23:00:00.0.

In most countries that observe seasonal daylight saving time, the clock observed in winter is legally named «standard time»[45] in accordance with the standardization of time zones to agree with the local mean time near the center of each region.[46] An exception exists in Ireland, where its winter clock has the same offset (UTC±00:00) and legal name as that in Britain (Greenwich Mean Time)—but while its summer clock also has the same offset as Britain’s (UTC+01:00), its legal name is Irish Standard Time[47][48] as opposed to British Summer Time.[49]

While most countries that change clocks for daylight saving time observe standard time in winter and DST in summer, Morocco observes (since 2019) daylight saving time every month but Ramadan. During the holy month (the date of which is determined by the lunar calendar and thus moves annually with regard to the Gregorian calendar), the country’s civil clocks observe Western European Time (UTC+00:00, which geographically overlaps most of the nation). At the close of this month, its clocks are turned forward to Western European Summer Time (UTC+01:00), where they remain until the return of the holy month the following year.[50][51][52]

The time at which to change clocks differs across jurisdictions. Members of the European Union conduct a coordinated change, changing all zones at the same instant, at 01:00 Coordinated Universal Time (UTC), which means that it changes at 02:00 Central European Time (CET), equivalent to 03:00 Eastern European Time (EET). As a result, the time differences across European time zones remain constant.[53][54] North America coordination of the clock change differs, in that each jurisdiction change at 02:00 local time, which temporarily creates unusual differences in offsets. For example, Mountain Time is, for one hour in the autumn, zero hours ahead of Pacific Time instead of the usual one hour ahead, and, for one hour in the spring, it is two hours ahead of Pacific Time instead of one. Also, during the autumn shift from daylight saving to standard time, the hour between 01:00 and 01:59:59 occurs twice in any given time zone, whereas—during the late winter or spring shift from standard to daylight saving time—the hour between 02:00 and 02:59:59 disappears.

The dates on which clocks change vary with location and year; consequently, the time differences between regions also vary throughout the year. For example, Central European Time is usually six hours ahead of North American Eastern Time, except for a few weeks in March and October/November, while the United Kingdom and mainland Chile could be five hours apart during the northern summer, three hours during the southern summer, and four hours for a few weeks per year. Since 1996, European Summer Time has been observed from the last Sunday in March to the last Sunday in October; previously the rules were not uniform across the European Union.[54] Starting in 2007, most of the United States and Canada observed DST from the second Sunday in March to the first Sunday in November, almost two-thirds of the year.[55] Moreover, the beginning and ending dates are roughly reversed between the northern and southern hemispheres because spring and autumn are displaced six months. For example, mainland Chile observes DST from the second Saturday in October to the second Saturday in March, with transitions at 24:00 local time.[56] In some countries time is governed by regional jurisdictions within the country such that some jurisdictions change and others do not; this is currently the case in Australia, Canada, and the United States.[57][58]

From year to year, the dates on which to change clock may also move for political or social reasons. The Uniform Time Act of 1966 formalized the United States’ period of daylight saving time observation as lasting six months (it was previously declared locally); this period was extended to seven months in 1986, and then to eight months in 2005.[59][60][61] The 2005 extension was motivated in part by lobbyists from the candy industry, seeking to increase profits by including Halloween (October 31) within the daylight saving time period.[62] In recent history, Australian state jurisdictions not only changed at different local times but sometimes on different dates. For example, in 2008 most states there that observed daylight saving time changed clocks forward on October 5, but Western Australia changed on October 26.[63]

Politics, religion and sport[edit]

The concept of daylight saving has caused controversy since its early proposals.[64] Winston Churchill argued that it enlarges «the opportunities for the pursuit of health and happiness among the millions of people who live in this country»[65] and pundits have dubbed it «Daylight Slaving Time».[66] Retailing, sports, and tourism interests have historically favored daylight saving, while agricultural and evening-entertainment interests (and some religious groups[67][68][69][70]) have opposed it; energy crises and war prompted its initial adoption.[71]

The fate of Willett’s 1907 proposal illustrates several political issues. It attracted many supporters, including Arthur Balfour, Churchill, David Lloyd George, Ramsay MacDonald, King Edward VII (who used half-hour DST or «Sandringham time» at Sandringham), the managing director of Harrods, and the manager of the National Bank Ltd.[72] However, the opposition proved stronger, including Prime Minister H. H. Asquith, William Christie (the Astronomer Royal), George Darwin, Napier Shaw (director of the Meteorological Office), many agricultural organizations, and theatre-owners. After many hearings, a parliamentary committee vote narrowly rejected the proposal in 1909. Willett’s allies introduced similar bills every year from 1911 through 1914, to no avail.[73] People in the USA demonstrated even more skepticism; Andrew Peters introduced a DST bill to the House of Representatives in May 1909, but it soon died in committee.[74]

Germany together with its allies led the way in introducing DST (German: Sommerzeit) during World War I on April 30, 1916, aiming to alleviate hardships due to wartime coal shortages and air-raid blackouts. The political equation changed in other countries; the United Kingdom used DST first on May 21, 1916.[75] US retailing and manufacturing interests—led by Pittsburgh industrialist Robert Garland—soon began lobbying for DST, but railroads opposed the idea. The USA’s 1917 entry into the war overcame objections, and DST started in 1918.[76]

The end of World War I brought change in DST use. Farmers continued to dislike DST, and many countries repealed it—like Germany itself, which dropped DST from 1919 to 1939 and from 1950 to 1979.[77] Britain proved an exception; it retained DST nationwide but adjusted transition dates over the years for several reasons, including special rules during the 1920s and 1930s to avoid clock shifts on Easter mornings. As of 2009 summer time began annually on the last Sunday in March under a European Community directive, which may be Easter Sunday (as in 2016).[54] In the U.S., Congress repealed DST after 1919. President Woodrow Wilson—an avid golfer like Willett—vetoed the repeal twice, but his second veto was overridden.[78] Only a few U.S. cities retained DST locally,[79] including New York (so that its financial exchanges could maintain an hour of arbitrage trading with London), and Chicago and Cleveland (to keep pace with New York).[80] Wilson’s successor as president, Warren G. Harding, opposed DST as a «deception», reasoning that people should instead get up and go to work earlier in the summer. He ordered District of Columbia federal employees to start work at 8 am rather than 9 am during the summer of 1922. Some businesses followed suit, though many others did not; the experiment was not repeated.[11]

Since Germany’s adoption of DST in 1916, the world has seen many enactments, adjustments, and repeals of DST, with similar politics involved.[81] The history of time in the United States features DST during both world wars, but no standardization of peacetime DST until 1966.[82][83] St. Paul and Minneapolis, Minnesota, kept different times for two weeks in May 1965: the capital city decided to switch to daylight saving time, while Minneapolis opted to follow the later date set by state law.[84][85] In the mid-1980s, Clorox and 7-Eleven provided the primary funding for the Daylight Saving Time Coalition behind the 1987 extension to U.S. DST. Both senators from Idaho, Larry Craig and Mike Crapo, voted for it based on the premise that fast-food restaurants sell more French fries (made from Idaho potatoes) during DST.[86]

A referendum on the introduction of daylight saving took place in Queensland, Australia, in 1992, after a three-year trial of daylight saving. It was defeated with a 54.5% «no» vote, with regional and rural areas strongly opposed, and those in the metropolitan southeast in favor.[87]

In 2005 the Sporting Goods Manufacturers Association and the National Association of Convenience Stores successfully lobbied for the 2007 extension to U.S. DST.[88]

In December 2008 the Daylight Saving for South East Queensland (DS4SEQ) political party was officially registered in Queensland, advocating the implementation of a dual-time-zone arrangement for daylight saving in South East Queensland, while the rest of the state maintained standard time.[89] DS4SEQ contested the March 2009 Queensland state election with 32 candidates and received one percent of the statewide primary vote, equating to around 2.5% across the 32 electorates contested.[90] After a three-year trial, more than 55% of Western Australians voted against DST in 2009, with rural areas strongly opposed.[91] Queensland Independent member Peter Wellington introduced the Daylight Saving for South East Queensland Referendum Bill 2010 into the Queensland parliament on April 14, 2010, after being approached by the DS4SEQ political party, calling for a referendum at the next state election on the introduction of daylight saving into South East Queensland under a dual-time-zone arrangement.[92] The Queensland parliament rejected Wellington’s bill on June 15, 2011.[93]

In 2003, the United Kingdom’s Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents supported a proposal to observe year-round daylight saving time, but it has been opposed by some industries, by some postal workers and farmers, and particularly by those living in the northern regions of the UK.[9]

Russia declared in 2011 that it would stay in DST all year long (UTC+4:00); Belarus followed with a similar declaration.[94] (The Soviet Union had operated under permanent «summer time» from 1930 to at least 1982.) Russia’s plan generated widespread complaints due to the dark of winter-time mornings, and thus was abandoned in 2014.[95] The country changed its clocks to standard time (UTC+3:00) on October 26, 2014, intending to stay there permanently.[96]

In the United States, Arizona (with the exception of the Navajo Nation), Hawaii, and the five populated territories (American Samoa, Guam, Puerto Rico, the Northern Mariana Islands, and the US Virgin Islands) do not participate in daylight saving time.[97][98] Indiana only began participating in daylight saving time as recently as 2006. Since 2018, Florida Republican Senator Marco Rubio has repeatedly filed bills to extend daylight saving time permanently into winter, without success.[99]

Mexico observed summertime daylight saving time starting in 1996. In late 2022, the nation’s clocks «fell back» for the last time, in restoration of permanent standard time.[100]

Religion[edit]

Some religious groups and individuals have opposed DST on religious grounds. For religious Jews and Muslims it makes religious practices such as prayer and fasting more difficult or inconvenient.[101][68][69][70]

Some Muslim countries, such as Morocco, temporarily abandoned DST during Ramadan, while Iran maintains DST even during Ramadan.[70]

In Israel, DST has been a point of contention between the religious and secular, resulting in fluctuations over the years, and a shorter DST period than in the EU and US. Religious Jews prefer a shorter DST[a] due to DST delaying the time for morning prayers, thus conflicting with standard working and business hours. Additionally, DST is ended before Yom Kippur (a 25-hour fast day starting and ending at sunset, much of which is spent praying in synagogue until the fast ends at sunset) since DST would result in the day ending later, which many feel makes it more difficult.[b][68][102]

In the US, Orthodox Jewish groups have opposed extensions to DST,[103] as well as a 2022 bipartisan bill that would make DST permanent, saying it will “interfere with the ability of members of our community to engage in congregational prayers and get to their places of work on time.”[69]

Impacts[edit]

William Willett independently proposed DST in 1907 and advocated it tirelessly.[104]

Proponents of DST generally argue that it saves energy, promotes outdoor leisure activity in the evening (in summer), and is therefore good for physical and psychological health,[105] reduces traffic accidents, reduces crime or is good for business.[106] Opponents argue the actual energy savings are inconclusive.[citation needed]

A 2017 meta-analysis of 44 studies found that DST leads to electricity savings of 0.3% during the days when DST applies.[107][108] Several studies have suggested that DST increases motor fuel consumption,[109] but a 2008 United States Department of Energy report found no significant increase in motor gasoline consumption due to the 2007 United States extension of DST.[110] An early goal of DST was to reduce evening usage of incandescent lighting, once a primary use of electricity.[111] Although energy conservation remains an important goal,[112] energy usage patterns have greatly changed since then. Electricity use is greatly affected by geography, climate, and economics, so the results of a study conducted in one place may not be relevant to another country or climate.[109]

Later sunset times from DST are thought to affect behavior; for example, increasing participation in after-school sports programs or outdoor afternoon sports such as golf, and attendance at professional sporting events.[113] Advocates of daylight saving time argue that having more hours of daylight between the end of a typical workday and evening induces people to consume other goods and services.[114][106][115]

Many farmers oppose DST, particularly dairy farmers as the milking patterns of their cows do not change with the time.[116][117][118] and others whose hours are set by the sun.[119] There is concern for schoolchildren who are out in the darkness during the morning due to late sunrises.[116] DST also hurts prime-time television broadcast ratings,[120][116] drive-ins and other theaters.[121]

It has been argued that clock shifts correlate with decreased economic efficiency, and that in 2000 the daylight-saving effect implied an estimated one-day loss of $31 billion on U.S. stock exchanges,[122] Others have asserted that the observed results depend on methodology[123] and disputed the findings,[124] though the original authors have refuted points raised by disputers.[125]

Health[edit]

There are measurable adverse effects of time-shifts on human health.[126] It has been shown to disrupt human circadian rhythms,[127] negatively impacting human health in the process,[128] and that the yearly DST time-shifts can increase health risks such as heart attack,[116] and traffic accidents.[129][130]

A 2017 study in the American Economic Journal: Applied Economics estimated that «the transition into DST caused over 30 deaths at a social cost of $275 million annually», primarily by increasing sleep deprivation.[131]

A correlation between clock shifts and increase in traffic accidents has been observed in North America and the UK but not in Finland or Sweden.[132] Four reports have found that this effect is smaller than the overall reduction in traffic fatalities.[133][134][135][136] In 2018, the European Parliament, reviewing a possible abolition of DST, approved a more in-depth evaluation examining the disruption of the human body’s circadian rhythms which provided evidence suggesting the existence of an association between DST time-shirts and a modest increase of occurrence of acute myocardial infarction, especially in the first week after the spring shift.[137] However a Netherlands study found, against the majority of investigations, contrary or minimal effect.[138] Year-round standard time (not year-round DST) is proposed by some to be the preferred option for public health and safety.[139][140][141][142][143] Clock shifts were found to increase the risk of heart attack by 10 percent,[116] and to disrupt sleep and reduce its efficiency.[144] Effects on seasonal adaptation of the circadian rhythm can be severe and last for weeks.[145]

[edit]

DST likely reduces some kinds of crime, such as robbery and sexual assault, as fewer potential victims are outdoors after dusk.[146][147] Artificial outdoor lighting has a marginal and sometimes even contradictory influence on crime and fear of crime.[148]

In 2022, a publication of three replicating studies of individuals, between individuals, and transecting societies, by Ben Simon, Vallat, Rossi and Walker demonstrate that sleep loss affects the human motivation to help others, which in their fMRI findings is «associated with deactivation of key nodes within the social cognition brain network that facilitates prosociality.»

Furthermore, they detected, through analysis of over 3 million real-world charitable donations, that loss of sleep inflicted by the transition to Daylight Saving Time, reduces altruistic giving compared to controls (being states not implementing DST). They conclude that implications for cooperative, civil society are «non-trivial.»[149]

Cho, Barnes and Guanara, in their study which also took advantage of sleep manipulation due to the shift to daylight saving time in the spring, analyzed archival data from judicial punishment imposed by U.S. federal courts which showed sleep-deprived judges exact more severe penalties.[150]

Inconvenience[edit]

DST’s clock shifts have the disadvantage of complexity. People must remember to change their clocks; this can be time-consuming, particularly for mechanical clocks that cannot be moved backward safely.[151] People who work across time zone boundaries need to keep track of multiple DST rules, as not all locations observe DST or observe it the same way. The length of the calendar day becomes variable; it is no longer always 24 hours. Disruption to meetings, travel, broadcasts, billing systems, and records management is common, and can be expensive.[152] During an autumn transition from 02:00 to 01:00, a clock reads times from 01:00:00 through 01:59:59 twice, possibly leading to confusion.[153]

Remediation[edit]

Some clock-shift problems could be avoided by adjusting clocks continuously[154] or at least more gradually[155]—for example, Willett at first suggested weekly 20-minute transitions—but this would add complexity and has never been implemented. DST inherits and can magnify the disadvantages of standard time. For example, when reading a sundial, one must compensate for it along with time zone and natural discrepancies.[156] Also, sun-exposure guidelines such as avoiding the sun within two hours of noon become less accurate when DST is in effect.[157]

Terminology[edit]

As explained by Richard Meade in the English Journal of the (American) National Council of Teachers of English, the form daylight savings time (with an «s») was already in 1978 much more common than the older form daylight saving time in American English («the change has been virtually accomplished»). Nevertheless, even dictionaries such as Merriam-Webster’s, American Heritage, and Oxford, which describe actual usage instead of prescribing outdated usage (and therefore also list the newer form), still list the older form first. This is because the older form is still very common in print and preferred by many editors. («Although daylight saving time is considered correct, daylight savings time (with an «s») is commonly used.»)[158] The first two words are sometimes hyphenated (daylight-saving(s) time). Merriam-Webster’s also lists the forms daylight saving (without «time»), daylight savings (without «time»), and daylight time.[159] The Oxford Dictionary of American Usage and Style explains the development and current situation as follows: «Although the singular form daylight saving time is the original one, dating from the early 20th century—and is preferred by some usage critics—the plural form is now extremely common in AmE. […] The rise of daylight savings time appears to have resulted from the avoidance of a miscue: when saving is used, readers might puzzle momentarily over whether saving is a gerund (the saving of daylight) or a participle (the time for saving). […] Using savings as the adjective—as in savings account or savings bond—makes perfect sense. More than that, it ought to be accepted as the better form.»[160]

In Britain, Willett’s 1907 proposal[33] used the term daylight saving, but by 1911 the term summer time replaced daylight saving time in draft legislation.[104] The same or similar expressions are used in many other languages: Sommerzeit in German, zomertijd in Dutch, kesäaika in Finnish, horario de verano or hora de verano in Spanish, and heure d’été in French.[75]

The name of local time typically changes when DST is observed. American English replaces standard with daylight: for example, Pacific Standard Time (PST) becomes Pacific Daylight Time (PDT). In the United Kingdom, the standard term for UK time when advanced by one hour is British Summer Time (BST), and British English typically inserts summer into other time zone names, e.g. Central European Time (CET) becomes Central European Summer Time (CEST).

The North American English mnemonic «spring forward, fall back» (also «spring ahead …», «spring up …», and «… fall behind») helps people remember in which direction to shift the clocks.[161][64]

Computing[edit]

Changes to DST rules cause problems in existing computer installations. For example, the 2007 change to DST rules in North America required that many computer systems be upgraded, with the greatest impact on e-mail and calendar programs. The upgrades required a significant effort by corporate information technologists.[162]

Some applications standardize on UTC to avoid problems with clock shifts and time zone differences.[163] Likewise, most modern operating systems internally handle and store all times as UTC and only convert to local time for display.[164][165]

However, even if UTC is used internally, the systems still require external leap second updates and time zone information to correctly calculate local time as needed. Many systems in use today base their date/time calculations from data derived from the tz database also known as zoneinfo.

IANA time zone database[edit]

The tz database maps a name to the named location’s historical and predicted clock shifts. This database is used by many computer software systems, including most Unix-like operating systems, Java, and the Oracle RDBMS;[166] HP’s «tztab» database is similar but incompatible.[167] When temporal authorities change DST rules, zoneinfo updates are installed as part of ordinary system maintenance. In Unix-like systems the TZ environment variable specifies the location name, as in TZ=':America/New_York'. In many of those systems there is also a system-wide setting that is applied if the TZ environment variable is not set: this setting is controlled by the contents of the /etc/localtime file, which is usually a symbolic link or hard link to one of the zoneinfo files. Internal time is stored in time-zone-independent Unix time; the TZ is used by each of potentially many simultaneous users and processes to independently localize time display.

Older or stripped-down systems may support only the TZ values required by POSIX, which specify at most one start and end rule explicitly in the value. For example, TZ='EST5EDT,M3.2.0/02:00,M11.1.0/02:00' specifies time for the eastern United States starting in 2007. Such a TZ value must be changed whenever DST rules change, and the new value applies to all years, mishandling some older timestamps.[168]

Permanent daylight saving time[edit]

A move to permanent daylight saving time (staying on summer hours all year with no time shifts) is sometimes advocated and is currently implemented in some jurisdictions such as Argentina, Belarus,[169] Iceland, Kyrgyzstan, Morocco,[51] Namibia, Saskatchewan, Singapore, Turkey, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan and Yukon. Although Saskatchewan follows Central Standard Time, its capital city Regina experiences solar noon close to 13:00, in effect putting the city on permanent daylight time. Similarly, Yukon is classified as being in the Mountain Time Zone, though in effect it observes permanent Pacific Daylight Time to align with the Pacific time zone in summer, but local solar noon in the capital Whitehorse occurs nearer to 14:00, in effect putting Whitehorse on «double daylight time».

The United Kingdom and Ireland put clocks forward by an extra hour during World War II and experimented with year-round summer time between 1968 and 1971.[170] Russia switched to permanent DST from 2011 to 2014, but the move proved unpopular because of the extremely late winter sunrises; in 2014, Russia switched permanently back to standard time.[171] However, the change to permanent DST has proven popular in Turkey, with the Minister of Energy and Natural Resources saying the practice saves «millions in energy costs and reduces depression and anxiety levels associated with short exposure to daylight».[172]

In September 2018, the European Commission proposed to end seasonal clock changes as of 2019.[173] Member states would have the option of observing either daylight saving time all year round or standard time all year round. In March 2019, the European Parliament approved the commission’s proposal, while deferring implementation from 2019 until 2021.[174] In response to this proposition, the European Sleep Research Society stated «installing permanent Central European Time (CET, standard time or ‘wintertime’) is the best option for public health.»[175] As of October 2020, the decision has not been confirmed by the Council of the European Union.[176] The council has asked the commission to produce a detailed impact assessment, but the Commission considers that the onus is on the Member States to find a common position in Council.[177] As a result, progress on the issue is effectively blocked.[178]

In the United States, several states have enacted legislation to implement permanent DST, but the bills would require Congress to change federal law in order to take effect. The Uniform Time Act of 1966 permits states to opt out of DST and observe permanent standard time, it does not permit permanent DST.[97][179] Florida senator Marco Rubio in particular has promoted changing to federal law to implement permanent DST,[180] with the support of the Florida Chamber of Commerce seeking to boost evening revenue.[181] In 2022, Rubio’s «Sunshine Protection Act» passed the United States Senate without committee review by way of voice consent, with many senators afterward stating they were unaware of the vote or its topic.[182] The bill was stopped in the U.S. House, where questions were raised as to whether permanent DST or standard time would be more beneficial.[99][183]

Advocates cite the same advantages as normal DST without the problems associated with the twice yearly time shifts. Additional benefits have also been cited, including safer roadways, boosting the tourism industry, and energy savings. Detractors cite the relatively late sunrises, particularly in winter, that year-round DST entails.[13]

Experts in circadian rhythms and sleep health recommend year-round standard time as the preferred option for public health and safety.[139][140][141][142] Several chronobiology societies have published position papers against adopting DST permanently. A paper by the Society for Research on Biological Rhythms states: «based on comparisons of large populations living in DST or ST or on western versus eastern edges of time zones, the advantages of permanent ST outweigh switching to DST annually or permanently.»[184] The World Federation of Societies for Chronobiology stated that «the scientific literature strongly argues against the switching between DST and Standard Time and even more so against adopting DST permanently.»[185] The American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) holds the position that «seasonal time changes should be abolished in favor of a fixed, national, year-round standard time,»[186] and that «standard time is a better option than daylight saving time for our health, mood and well-being.»[187] The AASM’s position is endorsed by 20 other nonprofits, including the American College of Chest Physicians, National Safety Council, and National PTA.[188]

Current public opinion polls show mixed results, with few ever reporting a true majority sentiment. Surveys reported between 2021 and 2022 by the National Sleep Foundation, YouGov, CBS, and Monmouth University indicate more Americans would prefer permanent DST.[189][190][191] A 2019 survey by National Opinion Research Center and a 2021 survey by the Associated Press indicate more Americans would prefer permanent Standard Time.[192][193] The National Sleep Foundation, YouGov, and Monmouth University polls leaned significantly in favor of seeing Daylight Saving Time made permanent. The Monmouth University poll reported 44% preferring year-round DST and 13% preferring year-round standard time.[190] In 1973 and 1974, NORC found 79% of Americans to be in favor of permanent DST before its implementation during the Oil Crisis, and only 42% to support permanent DST the following February.[194]

By country and region[edit]

- Daylight saving time in Africa

- Daylight saving time in Asia

- Summer time in Europe

- Daylight saving time in the Americas

- Daylight saving time in Oceania

See also[edit]

- Analysis of daylight saving time

- Winter time (clock lag)

Notes[edit]

- ^ starting after Passover and ended before Yom Kippur (less than 180 days)

- ^ Although DST does not impact the duration of the fast, which is 25 hours regardless, many find it easier to start and end earlier rather than later.

References[edit]

- ^ «Did Ben Franklin Invent Daylight Saving Time?». The Franklin Institute. July 7, 2017. Archived from the original on June 1, 2021. Retrieved August 5, 2021.

- ^ «Full text – Benjamin Franklin – The Journal of Paris, 1784». www.webexhibits.org. Archived from the original on November 15, 2017. Retrieved August 5, 2021.

- ^ a b Gibbs, George. «Hudson, George Vernon». Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved March 22, 2015.

- ^ a b Ogle, Vanessa (2015). The Global Transformation of Time: 1870–1950. Harvard University Press. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-674-28614-6. Archived from the original on March 22, 2021. Retrieved December 4, 2020.

- ^ a b «Time to change your clocks – but why?». Northern Ontario Travel. March 8, 2018. Archived from the original on October 10, 2018. Retrieved October 9, 2018.

- ^ a b Daylight Saving Time, archived from the original on October 9, 2018, retrieved October 8, 2018

- ^ «Arizona Time Zone». Timetemperature.com. Archived from the original on November 2, 2021. Retrieved November 7, 2021.

- ^ «Daylight savings time». Session Weekly. Minnesota House Public Information Office. 1991. Archived from the original on June 16, 2016. Retrieved August 7, 2013.

- ^ a b «Single/Double Summer Time policy paper» (PDF). Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents. October 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 13, 2012.

- ^ a b G. V. Hudson (1895). «On seasonal time-adjustment in countries south of lat. 30°». Transactions and Proceedings of the New Zealand Institute. 28: 734. Archived from the original on March 30, 2019. Retrieved April 3, 2009.

- ^ a b Seize the Daylight (2005), pp. 115–118.

- ^ Mark Gurevitz (March 7, 2007). Daylight saving time (Report). Order Code RS22284. Congressional Research Service. Archived from the original on August 31, 2014.

- ^ a b Handwerk, Brian (November 6, 2011). «Permanent Daylight Saving Time? Might Boost Tourism, Efficiency». National Geographic. Archived from the original on April 9, 2019. Retrieved January 5, 2012.

- ^ Mikkelson, David (March 13, 2016). «Daylight Saving Time». Snopes. Retrieved October 17, 2016.

- ^ a b «100 years of British Summer Time». National Maritime Museum. 2008. Archived from the original on December 28, 2014.

- ^ «Bill would do away with daylight savings time in Alaska». Peninsula Clarion. March 17, 2002. Archived from the original on November 2, 2013. Retrieved January 5, 2013.

Because of our high latitudinal location, the extremities in times for sunrise and sunset are more exaggerated for Alaska than anywhere else in the country,» Lancaster said. «This makes Alaska less affected by savings from daylight-saving time.

- ^ Rosenberg, Matt (2016). «Daylight Saving Time (Also Known as Daylight Savings Time)». About. Archived from the original on November 21, 2016. Retrieved October 17, 2016.

- ^ Swanson, Anna (March 11, 2016). «Why daylight saving time isn’t as terrible as people think». The Washington Post. Archived from the original on March 11, 2018. Retrieved March 27, 2018.

- ^ Berthold (1918). «Daylight saving in ancient Rome». The Classical Journal. 13 (6): 450–451.

- ^ Jérôme Carcopino (1968). «The days and hours of the Roman calendar». Daily Life in Ancient Rome: The People and the City at the Height of the Empire. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-00031-3.

- ^ Robert Kaplan (2003). «The holy mountain». The Atlantic. 292 (5): 138–141.

- ^ Hertzel Hillel Yitzhak (2006). «When to recite the blessing». Tzel HeHarim: Tzitzit. Nanuet, NY: Feldheim. pp. 53–58. ISBN 978-1-58330-292-7.

- ^ Manser, Martin H. (2007). The Facts on File dictionary of proverbs. Infobase Publishing. p. 70. ISBN 9780816066735. Archived from the original on September 4, 2015. Retrieved October 26, 2011.

- ^ Benjamin Franklin; William Temple Franklin; William Duane (1834). Memoirs of Benjamin Franklin. McCarty & Davis. p. 477. Archived from the original on February 1, 2017. Retrieved October 20, 2016.

- ^ Seymour Stanton Block (2006). «Benjamin Franklin: America’s inventor». American History. Archived from the original on March 29, 2019. Retrieved March 9, 2009.

- ^ Benjamin Franklin, writing anonymously (April 26, 1784). «Aux auteurs du Journal». Journal de Paris (in French) (117): 511–513. Its first publication was in the journal’s «Économie» section in a French translation. The revised English version Archived November 15, 2017, at the Wayback Machine [cited February 13, 2009] is commonly called «An Economical Project», a title that is not Franklin’s; see A.O. Aldridge (1956). «Franklin’s essay on daylight saving». American Literature. 28 (1): 23–29. doi:10.2307/2922719. JSTOR 2922719.

- ^ Eviatar Zerubavel (1982). «The standardization of time: a sociohistorical perspective». The American Journal of Sociology. 88 (1): 1–23. doi:10.1086/227631. S2CID 144994119.

- ^ Luxan, Manuel (1810). Reglamento para el gobierno interior de las Cortes (PDF). Congreso de los Diputados. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 5, 2018. Retrieved September 4, 2018.

- ^ Martín Olalla, José María (September 3, 2018). «La gestión de la estacionalidad». El Mundo (in Spanish). Unidad Editorial. Archived from the original on September 4, 2018. Retrieved September 4, 2018.

- ^ G. V. Hudson (1898). «On seasonal time». Transactions and Proceedings of the New Zealand Institute. 31: 577–588. Archived from the original on May 23, 2010. Retrieved April 3, 2009.

- ^ Lee, L. P. (October 1, 1947). «New Zealand time». New Zealand Geographer. 3 (2): 198. doi:10.1111/j.1745-7939.1947.tb01466.x.

- ^ Seize the Daylight (2005), p. 3.

- ^ a b William Willett (1907). The waste of daylight (1st ed.). Archived from the original on March 30, 2019. Retrieved March 9, 2009 – via Daylight Saving Time.

- ^ «Daylight Saving Bill». Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). House of Commons. February 12, 1908. col. 155–156.

- ^ Moro, Teviah (July 16, 2009). «Faded Memories for Sale». Orillia Packet and Times. Orillia, Ontario. Archived from the original on August 26, 2016. Retrieved October 20, 2016.

- ^ League of Nations (October 20, 1923). Regulation of summer time (PDF). Geneva. pp. 5, 22–24. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 24, 2020. Retrieved September 4, 2020.

- ^ Seize the Daylight (2005), pp. 51–89.

- ^ a b c Feltman, Rachel (March 6, 2015). «Perspective | Five myths about daylight saving time». Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ a b Victor, Daniel (March 11, 2016). «Daylight Saving Time: Why Does It Exist? (It’s Not for Farming)». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ a b c Klein, Christopher. «8 Things You May Not Know About Daylight Saving Time». HISTORY. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ a b «When Daylight Saving Time Was Year-Round». Time. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ a b c A Time-Change Timeline, National Public Radio, March 8, 2007

- ^ Graphics, WSJ com News. «World War I Centenary: Daylight-Saving Time». The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved March 16, 2022.

- ^ «Information for visitors». Lord Howe Island Tourism Association. Archived from the original on May 3, 2009. Retrieved April 20, 2009.

- ^ «Time Zone Abbreviations – Worldwide List», timeanddate.com, Time and Date AS, archived from the original on August 21, 2018, retrieved May 14, 2020

- ^ MacRobert, Alan (July 18, 2006). «Time in the Sky and the Amateur Astronomer». Sky and Telescope. Archived from the original on July 11, 2020. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- ^ «Standard Time (Amendment) Act, 1971». electronic Irish Statute Book (eISB). Archived from the original on October 30, 2013. Retrieved June 3, 2019.

- ^ «Time Zones in Ireland». timeanddate.com. Time and Date AS. Archived from the original on December 31, 2019. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- ^ «Time Zones in the United Kingdom». timeanddate.com. Time and Date AS. Archived from the original on July 8, 2020. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- ^ Kasraoui, Safaa (April 16, 2019). «Morocco to Switch Clocks Back 1 Hour on May 5 for Ramadan». Morocco World News. Archived from the original on June 5, 2019. Retrieved June 5, 2019.

- ^ a b «Release of the Moroccan Official Journal» (PDF) (Press release) (in Arabic). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 26, 2019. Retrieved October 31, 2018.

- ^ «Time Zones in Morocco». timeanddate.com. Time and Date AS. Archived from the original on June 27, 2020. Retrieved May 15, 2020.

- ^ National Physical Laboratory (March 31, 2016). «At what time should clocks go forward or back for summer time (FAQ – Time)». Archived from the original on October 11, 2016. Retrieved October 17, 2016.

The time at which summer time begins and ends is given in the relevant EU Directive and UK Statutory Instrument as 1 am. Greenwich Mean Time (GMT)… All time signals are based on Coordinated Universal Time (UTC), which can be almost one second ahead of, or behind, GMT so there is a brief period in the UK when the directive is not being strictly followed.

- ^ a b c Joseph Myers (July 17, 2009). «History of legal time in Britain».

- ^ Tom Baldwin (March 12, 2007). «US gets summertime blues as the clocks go forward 3 weeks early». The Times. London. Archived from the original on April 2, 2019. Retrieved November 2, 2018.

- ^ «Historia Hora Oficial de Chile» (in Spanish). Chilean Hydrographic and Oceanographic Service. October 1, 2008. Archived from the original on April 2, 2019. Retrieved November 15, 2014.

- ^ Seize the Daylight (2005), pp. 179–180.

- ^ «Why Arizona doesn’t observe daylight-saving time». USA Today. Archived from the original on March 30, 2019. Retrieved August 26, 2017.

- ^ Downing, Michael (2018). «One Hundred Years Later, the Madness of Daylight Saving Time Endures». The Conversation. Archived from the original on February 19, 2020. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- ^ Korch, Travers (2015). «The Financial History of Daylight Saving». Bankrate. Archived from the original on July 11, 2020. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- ^ «Energy Policy Act of 2005, Public Law 109-58 § 110». August 8, 2005. Archived from the original on July 16, 2009. Retrieved July 11, 2007.

- ^ Morgan, Thad (2017). «The Sweet Relationship Between Daylight Saving Time and Halloween». History. Archived from the original on May 12, 2020. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- ^ «Implementation dates of daylight saving time within Australia». Bureau of Meteorology. September 22, 2009. Archived from the original on April 4, 2016. Retrieved July 11, 2007.

- ^ a b DST practices and controversies:

- Spring Forward (2005)

- Seize the Daylight (2005)

- ^ Winston S. Churchill (April 28, 1934). «A silent toast to William Willett». Pictorial Weekly.

- ^ Seize the Daylight (2005), p. 117.

- ^ Seize the Daylight (2005), pp. «God’s time» 106, 135, 154, 175, «religious» 208, «Jews» 212, «Israel» 221-222.

- ^ a b c

- Stoil, Rebecca Anna (2010). «Politicians fight over setting the clock back». The Jerusalem Post.

- Cohen, Benyamin (2022). «Senate passes bill to make daylight saving time permanent, complicating life for observant Jews». The Forward.

- ^ a b c

- Kornbluh, Jacob. «Orthodox groups launch uphill battle against daylight saving time bill». The Forward.

- Berman, Jesse (March 18, 2022). «What permanent daylight saving time could mean for the Jewish community». Baltimore Jewish Times.

- ^ a b c Fitzpatrick, Kyle (October 21, 2019). «When do the clocks change around the world? And why?». The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on November 1, 2020. Retrieved December 4, 2020.

Most Islamic countries do not use daylight saving time as during Ramadan it can mean that the evening dinner is delayed till later in the day.

- ^ Seize the Daylight (2005), p. xi.

- ^ Slattery, Sir Matthew (1972). The National Bank, 1835-1970 (Privately published ed.). The National Bank.

- ^ Seize the Daylight (2005), pp. 12–24.

- ^ Seize the Daylight (2005), pp. 72–73.

- ^ a b Seize the Daylight (2005), pp. 51–70.

- ^ Seize the Daylight (2005), pp. 80–101.

- ^ «Time Changes in Berlin Over the Years». timeanddate.com. Archived from the original on May 27, 2019. Retrieved May 27, 2019.

- ^ Seize the Daylight (2005), pp. 103–110.

- ^ Robert Garland (1927). Ten years of daylight saving from the Pittsburgh standpoint. Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh. OCLC 30022847. Archived from the original on September 28, 2006.

- ^ Spring Forward (2005), pp. 47–48.

- ^ David P. Baron (2005). «The politics of the extension of daylight saving time». Business and its Environment (5th ed.). Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-187355-1.

- ^ Seize the Daylight (2005), pp. 147–155, 175–180.

- ^ Ian R. Bartky; Elizabeth Harrison (1979). «Standard and daylight-saving time». Scientific American. 240 (5): 46–53. Bibcode:1979SciAm.240e..46B. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0579-46. ISSN 0036-8733.

- ^ Murray, David. «‘Chaos of time’: The history of daylight saving time, why we spring forward». Great Falls Tribune. Archived from the original on January 20, 2021. Retrieved November 9, 2020.

- ^ «Twin cities disagree over daylight savings time, 1965». St. Cloud Times. May 5, 1965. p. 1. Archived from the original on November 10, 2020. Retrieved November 9, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ James C. Benfield (May 24, 2001). «Statement to the U.S. House, Committee on Science, Subcommittee on Energy». Energy Conservation Potential of Extended and Double Daylight Saving Time. Serial 107-30. Archived from the original on August 25, 2007. Retrieved March 11, 2007.

- ^ «1992 Queensland Daylight Saving Referendum» (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 11, 2017. Retrieved July 25, 2010.

- ^ Alex Beam (July 26, 2005). «Dim-witted proposal for daylight time». Boston Globe. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved April 20, 2020.

- ^ «Daylight Saving group launched as new Qld political party». ABC News. December 14, 2008. Archived from the original on January 4, 2009. Retrieved July 25, 2010.

- ^ «Total Candidates Nominated for Election by Party – 2009 State Election». Electoral Commission of Queensland (ECQ). Archived from the original on February 26, 2011. Retrieved June 19, 2010.

- ^ Paige Taylor (May 18, 2009). «Daylight saving at a sunset out west». The Australian. Archived from the original on October 27, 2011. Retrieved March 5, 2010.

- ^ «Daylight Saving for South East Queensland Referendum Bill 2010» (PDF). April 14, 2010. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 13, 2010. Retrieved July 25, 2010.

- ^ «Daylight saving silence ‘deafening’«. June 16, 2011. Archived from the original on June 18, 2011. Retrieved June 19, 2011.

- ^ Time and Date (September 19, 2011). «Eternal Daylight Saving Time (DST) in Belarus». Archived from the original on October 19, 2017. Retrieved October 20, 2016.

- ^ «Russia abandons year-round daylight-saving time». AP. July 1, 2014. Archived from the original on September 4, 2015. Retrieved October 21, 2014.

- ^ «Russian clocks go back for last time». BBC. October 25, 2014. Archived from the original on October 26, 2014. Retrieved October 25, 2014.

- ^ a b «Daylight Saving Time State Legislation». National Conference of State Legislatures. Retrieved January 3, 2023.

- ^ «No DST in Most of Arizona». www.timeanddate.com. Retrieved February 11, 2022.

- ^ a b Howell, Jr., Tom (December 21, 2022). «Rubio to keep fighting for permanent daylight saving time after clock runs out for this Congress». Retrieved January 3, 2023.

- ^ Perlmutter, Lillian (October 27, 2022). «Mexico falls back but won’t spring forward as summer time abolished». The Guardian. Retrieved January 7, 2023.

- ^ Seize the Daylight (2005), pp. «Jews» 212, «Israel» 221-222.

- ^ Seize the Daylight (2005), p. 221.

- ^ Seize the Daylight (2005), p. 212.

- ^ a b Seize the Daylight (2005), p. 22.

- ^ Goodman, A, Page, A, Cooper, A (October 23, 2014). «Daylight saving time as a potential public health intervention: an observational study of evening daylight and objectively-measured physical activity among 23,000 children from 9 countries». International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 11: 84. doi:10.1186/1479-5868-11-84. PMC 4364628. PMID 25341643. S2CID 298351.

- ^ a b «Tired of turning clocks forward and back? You have big business to thank». CBC News. Archived from the original on December 4, 2020. Retrieved December 4, 2020.

- ^ Havranek, Tomas; Herman, Dominik; Irsova, Zuzana (June 1, 2018). «Does Daylight Saving Save Electricity? A Meta-Analysis». The Energy Journal. 39 (2). doi:10.5547/01956574.39.2.thav. ISSN 1944-9089. S2CID 58919134.

- ^ Irsova, Zuzana; Havranek, Tomas; Herman, Dominik (December 2, 2017). «Daylight saving saves no energy». VoxEU.org. Archived from the original on December 3, 2017. Retrieved December 2, 2017.

- ^ a b Myriam B.C. Aries; Guy R. Newsham (2008). «Effect of daylight saving time on lighting energy use: a literature review». Energy Policy. 36 (6): 1858–1866. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2007.05.021. Archived from the original on October 26, 2019. Retrieved September 25, 2019.

- ^ David B. Belzer; Stanton W. Hadley; Shih-Miao Chin (2008). Impact of Extended Daylight Saving Time on national energy consumption: report to Congress, Energy Policy Act of 2005, Section 110 (PDF) (Report). US Dept. of Energy. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 18, 2013.

- ^ Roscoe G. Bartlett (May 24, 2001). «Statement to the US House, Committee on Science, Subcommittee on Energy». Energy Conservation Potential of Extended and Double Daylight Saving Time. Serial 107-30. Archived from the original on August 25, 2007. Retrieved March 11, 2007.

- ^ Dilip R. Ahuja; D. P. Sen Gupta; V. K. Agrawal (2007). «Energy savings from advancing the Indian Standard Time by half an hour» (PDF). Current Science. 93 (3): 298–302. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 1, 2014. Retrieved August 20, 2013.

- ^ Downing, Michael (March 9, 2018). «One Hundred Years Later, the Madness of Daylight Saving Time Endures». Smithsonian. Archived from the original on March 11, 2018. Retrieved March 12, 2018.

Today we know that changing the clocks does influence our behavior. For example, later sunset times have dramatically increased participation in afterschool sports programs and attendance at professional sports events. In 1920, The Washington Post reported that golf ball sales in 1918—the first year of daylight saving—increased by 20 percent.

- ^ Dana Knight (April 17, 2006). «Daylight-saving time becomes daylight-spending time for many businesses». Indianapolis Star.

- ^ Bradley, Barbara (April 3, 1987). «For business, Daylight Saving Time is daylight spending time». The Christian Science Monitor.

- ^ a b c d e Brian Handwerk (December 1, 2013). «Time to Move On? The Case Against Daylight Saving Time». National Geographic News. Archived from the original on March 13, 2014. Retrieved March 9, 2014.

- ^ «Should we change the clocks?». National Farmers Union. Archived from the original on March 14, 2012. Retrieved January 6, 2012.

- ^ Crossen, Cynthia (November 6, 2003). «Daylight Saving Time Pitted Farmers Against The ‘Idle’ City Folk». The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on March 28, 2021. Retrieved December 4, 2020.

- ^ Effect on those whose hours are set by the sun:

- Spring Forward (2005), pp. 19–33

- Seize the Daylight (2005), pp. 103–110, 149–151, 198

- ^ Rick Kissell (March 20, 2007). «Daylight-saving dock ratings». Variety. Archived from the original on April 13, 2009. Retrieved April 20, 2020.

- ^ Todd D. Rakoff (2002). A Time for Every Purpose: Law and the Balance of Life. Harvard University Press. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-674-00910-3.

- ^ Mark J. Kamstra; Lisa A. Kramer; Maurice D. Levi (2000). «Losing sleep at the market: the daylight saving anomaly» (PDF). American Economic Review. 90 (4): 1005–1011. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.714.2833. doi:10.1257/aer.90.4.1005. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 21, 2017. Retrieved October 27, 2017.

- ^ Luisa Müller; Dirk Schiereck; Marc W. Simpson; Christian Voigt (2009). «Daylight saving effect». Journal of Multinational Financial Management. 19 (2): 127–138. doi:10.1016/j.mulfin.2008.09.001.

- ^ Michael J. Pinegar (2002). «Losing sleep at the market: Comment». American Economic Review. 92 (4): 1251–1256. doi:10.1257/00028280260344786. JSTOR 3083313. S2CID 16002134.

- ^ Mark J. Kamstra; Lisa A. Kramer; Maurice D. Levi (2002). «Losing sleep at the market: the daylight saving anomaly: Reply». American Economic Review. 92 (4): 1257–1263. doi:10.1257/00028280260344795. JSTOR 3083314.

- ^ Zhang, H.; Khan, A.; Edgren, G.; Rzhetsky, A. (June 8, 2020). «Measurable health effects associated with the daylight saving time shift». PLOS Comput. Biol. 16 (6): e1007927. Bibcode:2020PLSCB..16E7927Z. doi:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1007927. PMC 7302868. PMID 32511231.

- ^ Rishi, M. A.; Ahmed, O.; Barrantes Perez, J. H.; Berneking, J.; Flynn-Evans, E. E.; Gurubhagavatula, I. (2020). «Daylight saving time: an American Academy of Sleep Medicine position statement». Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 16 (10): 1781–1784. doi:10.5664/jcsm.8780. PMC 7954020. PMID 32844740.

- ^ Roenneberg T, Wirz-Justice A, Skene DJ, Ancoli-Israel S, Wright KP, Dijk DJ, Zee P, Gorman MR, Winnebeck EC, Klerman EB (2019). «Why Should We Abolish Daylight Saving Time?». Journal of Biological Rhythms. 34 (3): 227–230. doi:10.1177/0748730419854197. PMC 7205184. PMID 31170882.

- ^ Fritz, Josef; VoPham, Trang; Wright, Kenneth P.; Vetter, Céline (February 2020). «A Chronobiological Evaluation of the Acute Effects of Daylight Saving Time on Traffic Accident Risk». Current Biology. 30 (4): 729–735.e2. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2019.12.045. ISSN 0960-9822. PMID 32008905. S2CID 210956409.

- ^ Orsini, Federico; Zarantonello, Lisa; Costa, Rodolfo; Rossi, Riccardo; Montagnese, Sara (July 2022). «Driving simulator performance worsens after the Spring transition to Daylight Saving Time». iScience. 25 (7): 104666. Bibcode:2022iSci…25j4666O. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2022.104666. ISSN 2589-0042. PMC 9263509. PMID 35811844.

- ^ Smith, Austin C. (2016). «Spring Forward at Your Own Risk: Daylight Saving Time and Fatal Vehicle Crashes». American Economic Journal: Applied Economics. 8 (2): 65–91. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.676.1062. doi:10.1257/app.20140100. ISSN 1945-7782.

- ^ Fritz, Josef (2020). «A Chronobiological Evaluation of the Acute Effects of Daylight Saving Time on Traffic Accident Risk». Current Biology. 30 (4): 729–735.e2. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2019.12.045. PMID 32008905. S2CID 210956409.

- ^ Jason Varughese; Richard P. Allen (2001). «Fatal accidents following changes in daylight savings time: the American experience». Sleep Medicine. 2 (1): 31–36. doi:10.1016/S1389-9457(00)00032-0. PMID 11152980.

- ^ J. Alsousoua; T. Jenks; O. Bouamra; F. Lecky; K. Willett (2009). «Daylight savings time (DST) transition: the effect on serious or fatal road traffic collision related injuries». Injury Extra. 40 (10): 211–212. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2009.06.241.

- ^

Tuuli A. Lahti; Jari Haukka; Jouko Lönnqvist; Timo Partonen (2008). «Daylight saving time transitions and hospital treatments due to accidents or manic episodes». BMC Public Health. 8: 74. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-8-74. PMC 2266740. PMID 18302734. - ^ Mats Lambe; Peter Cummings (2000). «The shift to and from daylight savings time and motor vehicle crashes». Accident Analysis & Prevention. 32 (4): 609–611. doi:10.1016/S0001-4575(99)00088-3. PMID 10868764.

- ^ Manfredini, F.; Fabbian, F.; Cappadona, R. (2018). «Daylight saving time, circadian rhythms, and cardiovascular health». Internal and Emergency Medicine. 13 (5): 641–646. doi:10.1007/s11739-018-1900-4. PMC 6469828. PMID 29971599.

- ^ Derks, L.; Houterman, S.; Geuzebroek, G.S.C. (2021). «Daylight saving time does not seem to be associated with number of percutaneous coronary interventions for acute myocardial infarction in the Netherlands». Netherlands Heart Journal. 29 (9): 427–432. doi:10.1007/s12471-021-01566-7. PMC 8397810. PMID 33765223.

- ^ a b Cermakian, Nicolas (November 2, 2019). «Turn back the clock on Daylight Savings: Why Standard Time all year round is the healthy choice». The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on October 20, 2020. Retrieved March 4, 2020.

- ^ a b Block, Gene. «Who wants to go to work in the dark? Californians need Permanent Standard Time». The Sacramento Bee. Archived from the original on March 4, 2020. Retrieved March 4, 2020.

- ^ a b Antle, Michael (October 30, 2019). «Circadian rhythm expert argues against permanent daylight saving time». U Calgary News. Archived from the original on March 4, 2020. Retrieved March 4, 2020.

- ^ a b «Year-round daylight time will cause ‘permanent jet lag,’ sleep experts warn in letter to government». CBC News. October 31, 2019. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved March 4, 2020.

- ^ Barnes, Christopher M.; Drake, Christopher L. (November 2015). «Prioritizing Sleep Health». Perspectives on Psychological Science. 10 (6): 733–737. doi:10.1177/1745691615598509. PMID 26581727.

- ^ Tuuli A. Lahti; Sami Leppämäki; Jouko Lönnqvist; Timo Partonen (2008). «Transitions into and out of daylight saving time compromise sleep and the rest–activity cycles». BMC Physiology. 8: 3. doi:10.1186/1472-6793-8-3. PMC 2259373. PMID 18269740.

- ^ DST and circadian rhythm:

- Pablo Valdez; Candelaria Ramírez; Aída García (2003). «Adjustment of the sleep–wake cycle to small (1–2h) changes in schedule». Biological Rhythm Research. 34 (2): 145–155. doi:10.1076/brhm.34.2.145.14494. S2CID 83648787.

- Thomas Kantermann; Myriam Juda; Martha Merrow; Till Roenneberg (2007). «The human circadian clock’s seasonal adjustment is disrupted by daylight saving time» (PDF). Current Biology. 17 (22): 1996–2000. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2007.10.025. PMID 17964164. S2CID 3135927. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 16, 2020. Retrieved June 6, 2020.

- «Daylight saving hits late risers hardest». ABC News. Australia. October 25, 2007.

- ^ Doleac, Jennifer L.; Sanders, Nicholas J. (December 8, 2015). «Under the Cover of Darkness: How Ambient Light Influences Criminal Activity». Review of Economics and Statistics. 97 (5): 1093–1103. doi:10.1162/rest_a_00547. S2CID 57566972. Archived from the original on March 11, 2020. Retrieved May 22, 2020.

- ^ Grant, Laura (November 1, 2017). «Is daylight saving time worth the trouble? Research says no». The Conversation. Archived from the original on March 11, 2018. Retrieved March 12, 2018.

- ^ Rachel Pain; Robert MacFarlane; Keith Turner; Sally Gill (2006). «‘When, where, if, and but’: qualifying GIS and the effect of streetlighting on crime and fear». Environment and Planning A. 38 (11): 2055–2074. doi:10.1068/a38391. S2CID 143511067.

- ^ Simon, Eti Ben; Vallat, Raphael; Rossi, Aubrey; Walker, Matthew P. (August 23, 2022). «Sleep loss leads to the withdrawal of human helping across individuals, groups, and large-scale societies». PLOS Biology. 20 (8): e3001733. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.3001733. ISSN 1545-7885. PMC 9398015. PMID 35998121.

- ^ Cho, Kyoungmin; Barnes, Christopher M.; Guanara, Cristiano L. (December 13, 2016). «Sleepy Punishers Are Harsh Punishers». Psychological Science. 28 (2): 242–247. doi:10.1177/0956797616678437. ISSN 0956-7976. PMID 28182529. S2CID 11321574.

- ^ Joey Crandall (October 24, 2003). «Daylight saving time ends Sunday». Record–Courier. Archived from the original on February 29, 2012.

- ^ Paul McDougall (March 1, 2007). «PG&E says patching meters for an early daylight-saving time will cost $38 million». InformationWeek. Archived from the original on December 6, 2008. Retrieved February 13, 2009.

- ^ «Daylight saving time: rationale and original idea». 2008. Archived from the original on June 9, 2016. Retrieved February 13, 2009.

… Lord Balfour came forward with a unique concern: ‘Supposing some unfortunate lady was confined with twins …’

- ^ Jesse Ruderman (November 1, 2006). «Continuous daylight saving time». Archived from the original on May 4, 2016. Retrieved March 21, 2007.

- ^ «Proposal for a finer adjustment of summer time (daylight saving time)». September 28, 2011. Archived from the original on October 8, 2011. Retrieved September 28, 2011.

- ^ Albert E. Waugh (1973). Sundials: Their Theory and Construction. Dover. Bibcode:1973sttc.book…..W. ISBN 978-0-486-22947-8.

- ^ Leith Holloway (1992). «Atmospheric sun protection factor on clear days: its observed dependence on solar zenith angle and its relevance to the shadow guideline for sun protection». Photochemistry and Photobiology. 56 (2): 229–234. doi:10.1111/j.1751-1097.1992.tb02151.x. PMID 1502267. S2CID 1219032. Archived from the original on August 9, 2020. Retrieved June 6, 2020.

- ^ Seize the Daylight (2005), p. xv.

- ^ Daylight saving time and its variants:

- Richard A. Meade (1978). «Language change in this century». English Journal. 67 (9): 27–30. doi:10.2307/815124. JSTOR 815124.

- Joseph P. Pickett; et al., eds. (2000). «daylight-saving time». The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (4th ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-82517-4.

or daylight-savings time

- «daylight saving time». Merriam–Webster’s Online Dictionary. Archived from the original on June 11, 2011. Retrieved February 13, 2009.

called also daylight saving, daylight savings, daylight savings time, daylight time

- «daylight saving time». Oxford Dictionaries. Archived from the original on March 22, 2014. Retrieved March 22, 2014. «also daylight savings time»

- «15 U.S.C. § 260a notes». Archived from the original on November 9, 2021. Retrieved May 9, 2007.

Congressional Findings; Expansion of Daylight Saving Time

- ^ Garner, Bryan A. (2000). «daylight saving(s) time». Oxford Dictionary of American Usage and Style. p. 95. ISBN 9780195135084. Archived from the original on November 9, 2021. Retrieved June 6, 2020.

- ^ «Remember to Put Clocks Hour Ahead on Retiring». Brooklyn Citizen. April 25, 1936. Archived from the original on November 8, 2021. Retrieved November 7, 2021.

- ^ Steve Lohr (March 5, 2007). «Time change a ‘mini-Y2K’ in tech terms». The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 1, 2017. Retrieved February 21, 2017.

- ^ A. Gut; L. Miclea; Sz. Enyedi; M. Abrudean; I. Hoka (2006). «Database globalization in enterprise applications». 2006 IEEE International Conference on Automation, Quality and Testing, Robotics. pp. 356–359.

- ^ Ron Bean (November 2000). «The Clock Mini-HOWTO». Archived from the original on January 13, 2012. Retrieved January 10, 2012.

- ^ Raymond Chen (November 2000). «Why does Windows keep your BIOS clock on local time?». Archived from the original on January 3, 2012. Retrieved January 10, 2012.

- ^ Paul Eggert; Arthur David Olson (June 30, 2008). «Sources for time zone and daylight saving time data». Archived from the original on June 23, 2012.

- ^ «tztab(4)» (PDF). HP-UX Reference: HP-UX 11i Version 3. Hewlett–Packard Co. 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 21, 2013.

- ^ «Other environment variables». IEEE Std 1003.1–2004. The Open Group. 2004. Archived from the original on July 6, 2010. Retrieved February 17, 2007.

- ^ Parfitt, Tom (March 25, 2011). «Think of the cows: clocks go forward for the last time in Russia». The Guardian. Archived from the original on October 27, 2019. Retrieved January 5, 2012.

- ^ Hollingshead, Iain (June 2006). «Whatever happened to Double Summer Time?». The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on March 22, 2021. Retrieved March 18, 2017.

- ^ «Russia set to turn back the clocks with daylight-saving time shift». The Guardian. London. July 1, 2014. Archived from the original on December 21, 2016. Retrieved October 25, 2014.

- ^ «Turkey will not turn back the clock for daylight saving time». Daily Sabah. December 7, 2021. Retrieved September 20, 2022.

- ^ «Press corner». European Commission. September 12, 2018. Archived from the original on October 23, 2020. Retrieved October 23, 2020.

- ^ «European parliament votes to scrap daylight saving time from 2021». The Guardian (US ed.). London. March 26, 2019. Archived from the original on June 20, 2019. Retrieved July 9, 2019.

- ^ «To the EU Commission on DST» (PDF). March 2019. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 30, 2020. Retrieved November 4, 2021.

- ^ «Seasonal clock change in the EU». Mobility and Transport – European Commission. September 22, 2016. Archived from the original on June 30, 2019. Retrieved October 23, 2020.

- ^ Posaner, Joshua; Cokelaere, Hanne (October 24, 2020). «Stopping the clock on seasonal time changes? Not anytime soon». Politico. Archived from the original on October 26, 2020. Retrieved October 26, 2020.

- ^ Lawson, Patrick (November 18, 2020). «The plan to abolish the time change is «completely blocked» at European level, says specialist in European issues». Geads News. Archived from the original on February 12, 2021.

- ^ «Fall back! Daylight saving time ends Sunday». USA Today. November 1, 2018. Archived from the original on November 2, 2018. Retrieved November 2, 2018.

- ^ «Rubio’s Bill to Make Daylight Saving Time Permanent Passes Senate». rubio.senate.gov. Retrieved June 15, 2022.

- ^ Haughey, John (September 18, 2022). «Time – and money – at stake in Florida-led proposal to extend daylight saving». The Center Square Florida. Retrieved January 3, 2023.

The Florida Chamber of Commerce and state business associations maintain an extra hour of sunlight in the winter, during peak tourist season, would translate into more sales.

- ^ McLeod, Paul (March 17, 2022). «Everyone Was Surprised By The Senate Passing Permanent Daylight Saving Time. Especially The Senators». BuzzFeed. Retrieved January 3, 2023.

- ^ Schnell, Mychael (July 25, 2022). «Permanent daylight saving time hits brick wall in House». The Hill. Retrieved January 3, 2023.

- ^ Roenneberg, Till; Wirz-Justice, Anna; Skene, Debra J; etc. (June 6, 2019). «Why Should We Abolish Daylight Saving Time?». Journal of Biological Rhythms. 34 (3): 227–230. doi:10.1177/0748730419854197. PMC 7205184. PMID 31170882.

- ^ Roenneberg1, Till; Winnebeck1, Eva C.; Klerman, Elizabeth B. (August 7, 2019). «Daylight Saving Time and Artificial Time Zones – A Battle Between Biological and Social Times». Frontiers in Physiology. 10: 944. doi:10.3389/fphys.2019.00944. PMC 6692659. PMID 31447685.

- ^ Rishi, Muhammad Adeel; Ahmed, Omer; Barrantes Perez, Jairo H.; etc. (October 15, 2020). «Daylight saving time: an American Academy of Sleep Medicine position statement». J Clin Sleep Med. 16 (10): 1781–1784. doi:10.5664/jcsm.8780. PMC 7954020. PMID 32844740. S2CID 221329004.

- ^ «American Academy of Sleep Medicine opposes permanent daylight saving time bill». May 23, 2022. Retrieved January 3, 2023.

- ^ «American Academy of Sleep Medicine calls for elimination of daylight saving time». August 27, 2020. Retrieved January 3, 2023.

- ^ Davies, Claire (March 14, 2021). «Sleep Awareness Week 2021: Over 70% say Daylight Saving Time change doesn’t affect sleep». TopTenReviews. Retrieved January 11, 2023.

- ^ a b «States Object to Changing the Clocks for Daylight Saving Time». Almanac.com. January 6, 2023. Retrieved January 7, 2023.

- ^ «Daylight Saving Time: Americans want to stay permanently ‘sprung forward’ and not ‘fall back’ | YouGov». today.yougov.com. Retrieved January 9, 2023.

- ^ «Daylight Saving Time vs Standard Time». 2019. Retrieved January 7, 2023.

- ^ «Dislike for changing the clocks persists». 2021. Retrieved January 7, 2023.