Доп. материалы

11 марта 2013 г. в 06:12

СценарииКомментарии: 0

2001 год: Космическая одиссея (фильм)

2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

by Stanley Kubrick and Arthur C. Clark.

Revised draft, 12/14/65.

Скачать: Архив ZIP

Отрывок;

TITLE PART I

AFRICA

3,000,000 YEARS AGO

————————————————————————

A1

VIEWS OF AFRICAN DRYLANDS — DROUGHT

The remorseless drought had lasted now for ten million years, and would not end for another million. The reign of the terrible lizards had long since passed, but here on the continent which would one day be known as Africa, the battle for survival had reached a new climax of ferocity, and the victor was not yet in sight. In this dry and barren land, only the small or the swift or the fierce could flourish, or even hope to exist.

10/13/65 a1

————————————————————————

A2

INT & EXT CAVES — MOONWATCHER

The man-apes of the field had none of these attributes, and they were on the long, pathetic road to racial extinction. About twenty of them occupied a group of caves overlooking a small, parched valley, divided by a sluggish, brown stream.

The tribe had always been hungry, and now it was starving. As the first dim glow of dawn creeps into the cave, Moonwatcher discovers that his father has died during the night. He did not know the Old One was his father, for such a relationship was beyond his understanding. but as he stands looking down at the emaciated body he feels something, something akin to sadness. Then he carries his dead father out of the cave, and leaves him for the hyenas.

Among his kind, Moonwatcher is almost a giant. He is nearly five feet high, and though badly undernourished, weighs over a hundred pounds. His hairy, muscular body is quite man-like, and his head is already nearer man than ape. The forehead is low, and there are great ridges over the eye-sockets, yet he unmistakably holds in his genes the promise of humanity. As he looks out now upon the hostile world, there is already

10/13/65 a2

————————————————————————

A2

CONTINUED

something in his gaze beyond the grasp of any ape. In those dark, deep-set eyes is a dawning awareness-the first intimations of an intelligence which would not fulfill itself for another two million years.

10/13/65 a3

————————————————————————

A3

EXT THE STREAM — THE OTHERS

As the dawn sky brightens, Moonwatcher and his tribe reach the shallow stream.

The Others are already there. They were there on the other side every day — that did not make it any less annoying.

There are eighteen of them, and it is impossible to distinguish them from the members of Moonwatcher’s own tribe. As they see him coming, the Others begin to angrily dance and shriek on their side of the stream, and his own people reply In kind.

The confrontation lasts a few minutes — then the display dies out as quickly as it has begun, and everyone drinks his fill of the muddy water. Honor has been satisfied — each group has staked its claim to its own territory.

10/13/65 a4

————————————————————————

A4

EXT AFRICAN PLAIN — HERBIVORES

Moonwatcher and his companions search for berries, fruit and leaves, and fight off pangs of hunger, while all around them, competing with them for the samr fodder, is a potential source of more food than they could ever hope to eat. Yet all the thousands of tons of meat roaming over the parched savanna and through the brush is not only beyond their reach; the idea of eating it is beyond their imagination. They are slowly starving to death in the midst of plenty.

10/13/65 a5

————————————————————————

A5

EXT PARCHED COUNTRYSIDE — THE LION

The tribe slowly wanders across the bare, flat countryside foraging for roots and occasional berries.

Eight of them are irregularly strung out on the open plain, about fifty feet apart.

The ground is flat for miles around.

Suddenly, Moonwatcher becomes aware of a lion, stalking them about 300 yards away.

Defenceless and with nowhere to hide, they scatter in all directions, but the lion brings one to the ground.

10/13/65 a6

————————————————————————

A6

EXT DEAD TREE — FINDS HONEY

It had not been a good day, though as Moonwatcher had no real remembrance of the past he could not compare one day with another. But on the way back to the caves he finds a hive of bees in the stump of a dead tree, and so enjoys the finest delicacy his people could ever know. Of course, he also collects a good many stings, but he scacely notices them. He is now as near to contentment as he is ever likely to be; for thought he is still hungry, he is not actually weak with hunger. That was the most that any hominid could hope for.

10/13/65 a7

————————————————————————

A7

INT & EXT CAVES — NIGHT TERRORS

Over the valley, a full moon rises, and a cold wind blows down from the distant mountains. It would be very cold tonight — but cold, like hunger, was not a matter for any real concern; it was merely part of the background of life.

This Little Sun, that only shone at night and gave no warmth, was dangerous; there would be enemies abroad. Moonwatcher crawls out of the cave, clambers on to a large boulder besides the entrance, and squats there where he can survey the valley. If any hunting beast approached, he would have time to get back to the relative safety of the cave.

Of all the creatures who had ever lived on Earth, Moonwatcher’s race was the first to raise their eyes with interest to the Moon, and though he could not remember it, when he was young, Moonwatcher would reach out and try to touch its ghostly face. Now he new he would have to find a tree that was high enough.

He stirs when shrieks and screams echo up the slope from one of the lower caves, and he does not need to hear the

Нравится то, что мы делаем? Желаете помочь ЗУ? Поддержите сайт, пожертвовав на развитие — или купите футболку с хоррор-принтом!

Поддержать

Футболки

Поделись ссылкой на эту страницу — это тоже помощь

| 2001: A Space Odyssey | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster by Robert McCall |

|

| Directed by | Stanley Kubrick |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Produced by | Stanley Kubrick |

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Geoffrey Unsworth |

| Edited by | Ray Lovejoy |

|

Production |

Stanley Kubrick Productions |

| Distributed by | Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer |

|

Release dates |

|

|

Running time |

approx. 143 minutes[1] |

| Countries |

|

| Language | English |

| Budget | $10.5 million |

| Box office | $146 million |

2001: A Space Odyssey is a 1968 epic science fiction film produced and directed by Stanley Kubrick. The screenplay was written by Kubrick and science fiction author Arthur C. Clarke, and was inspired by Clarke’s 1951 short story «The Sentinel» and other short stories by Clarke. Clarke also published a novelisation of the film, in part written concurrently with the screenplay, after the film’s release. The film stars Keir Dullea, Gary Lockwood, William Sylvester, and Douglas Rain, and follows a voyage by astronauts, scientists and the sentient supercomputer HAL to Jupiter to investigate an alien monolith.

The film is noted for its scientifically accurate depiction of space flight, pioneering special effects, and ambiguous imagery. Kubrick avoided conventional cinematic and narrative techniques; dialogue is used sparingly, and there are long sequences accompanied only by music. The soundtrack incorporates numerous works of classical music, by composers including Richard Strauss, Johann Strauss II, Aram Khachaturian, and György Ligeti.

The film received diverse critical responses, ranging from those who saw it as darkly apocalyptic to those who saw it as an optimistic reappraisal of the hopes of humanity. Critics noted its exploration of themes such as human evolution, technology, artificial intelligence, and the possibility of extraterrestrial life. It was nominated for four Academy Awards, winning Kubrick the award for his direction of the visual effects. The film is now widely regarded as one of the greatest and most influential films ever made. In 1991, it was deemed «culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant» by the United States Library of Congress and selected for preservation in the National Film Registry.[2][3]

Plot[edit]

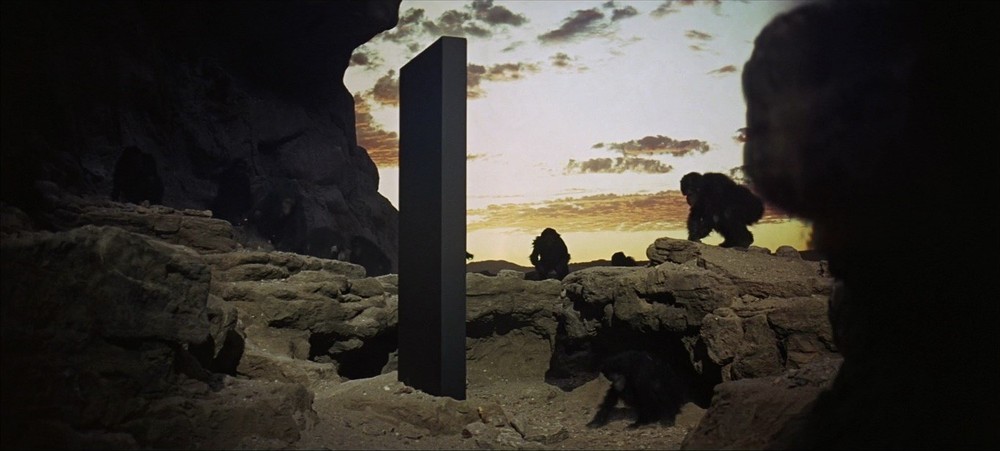

In a prehistoric veldt, a tribe of hominins is driven away from its water hole by a rival tribe. The next day, they find an alien monolith has appeared in their midst. They then learn how to use a bone as a weapon and, after their first hunt, return to drive their rivals away with it.

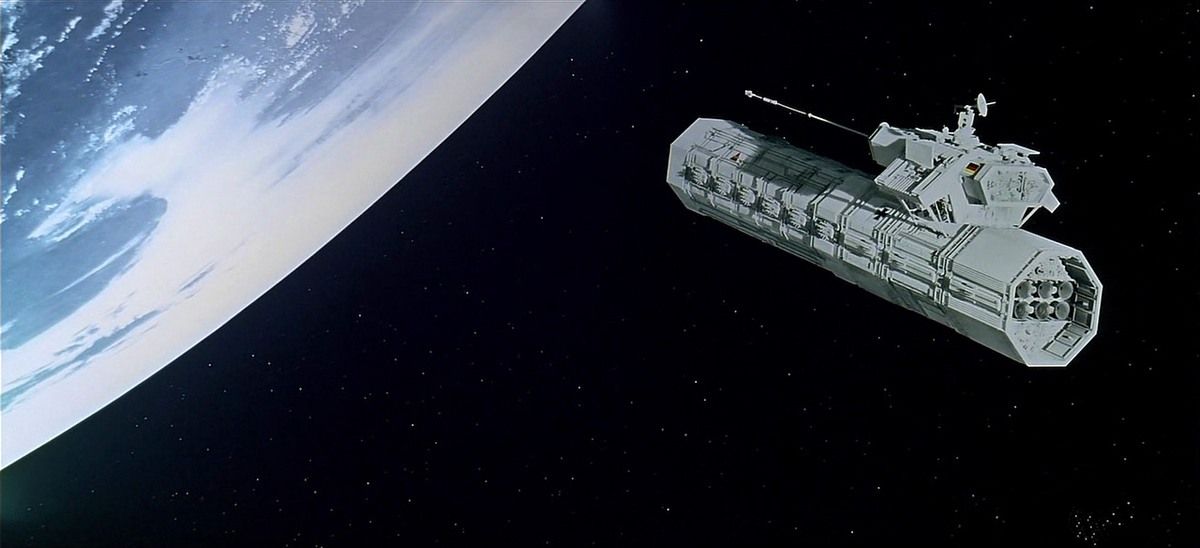

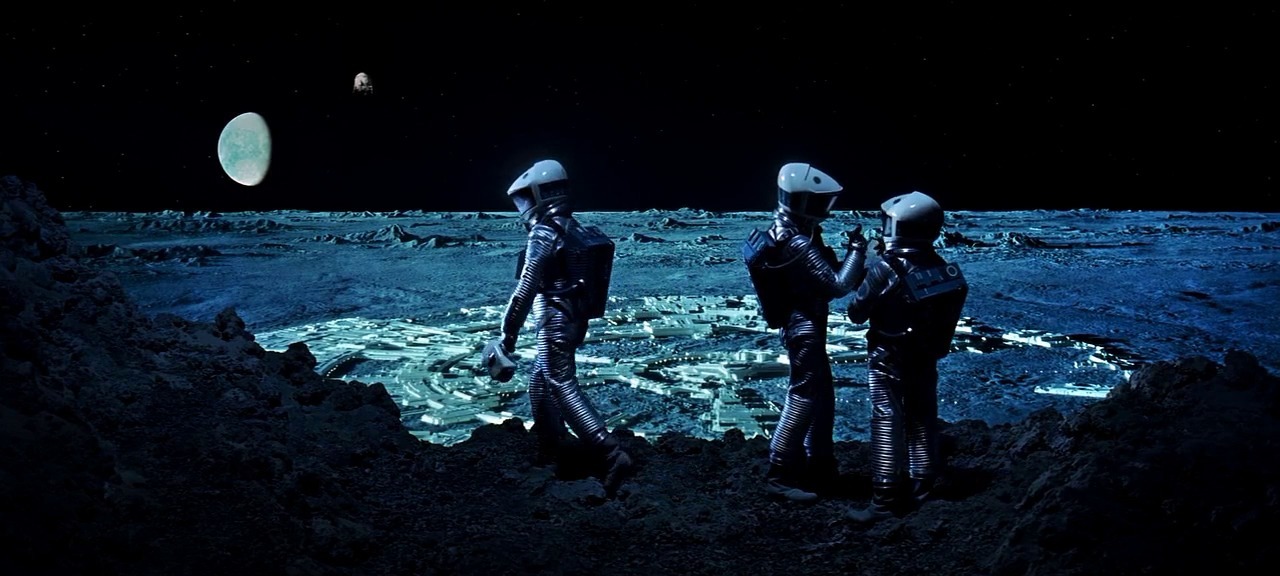

Millions of years later, Dr. Heywood Floyd, Chairman of the United States National Council of Astronautics, travels to Clavius Base, an American lunar outpost. During a stopover at Space Station 5, he meets Russian scientists who are concerned that Clavius seems to be unresponsive. He refuses to discuss rumours of an epidemic at the base. At Clavius, Heywood addresses a meeting of personnel to whom he stresses the need for secrecy regarding their newest discovery. His mission is to investigate a recently found artefact, a monolith buried four million years earlier near the lunar crater Tycho. As he and others examine the object, it is struck by sunlight, upon which it emits a high-powered radio signal.

Eighteen months later, the American spacecraft Discovery One is bound for Jupiter, with mission pilots and scientists Dr. David «Dave» Bowman and Dr. Frank Poole on board, along with three other scientists in suspended animation. Most of Discovery‘s operations are controlled by HAL, a HAL 9000 computer with a human personality. When HAL reports the imminent failure of an antenna control device, Dave retrieves it in an extravehicular activity (EVA) pod, but finds nothing wrong. HAL suggests reinstalling the device and letting it fail so the problem can be verified. Mission Control advises the astronauts that results from their twin 9000 computer indicate that HAL has made an error, but HAL blames it on human error. Concerned about HAL’s behaviour, Dave and Frank enter an EVA pod so they can talk without HAL overhearing. They agree to disconnect HAL if he is proven wrong, but HAL follows their conversation by lip reading.

While Frank is outside the ship to replace the antenna unit, HAL takes control of his pod, setting him adrift. Dave takes another pod to rescue Frank. While he is outside, HAL turns off the life support functions of the crewmen in suspended animation, killing them. When Dave returns to the ship with Frank’s body, HAL refuses to let him back in, stating that their plan to deactivate him jeopardises the mission. Dave releases Frank’s body and, despite not having a spacesuit helmet, exits his pod, crosses the vacuum and opens the ship’s emergency airlock manually. He goes to HAL’s processor core and begins disconnecting HAL’s circuits, despite HAL begging him not to. When the disconnection is complete, a prerecorded video by Heywood plays, revealing that the mission’s objective is to investigate the radio signal sent from the monolith to Jupiter.

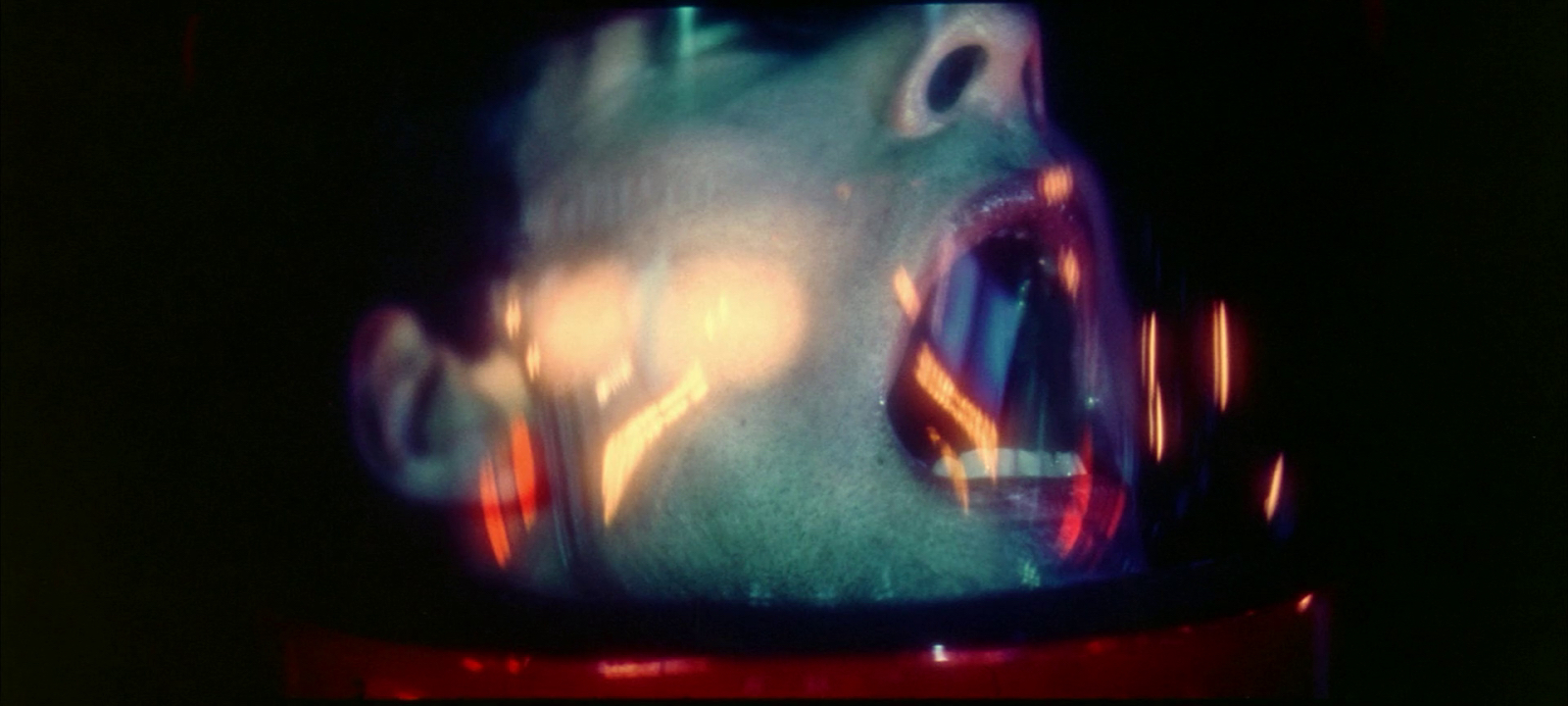

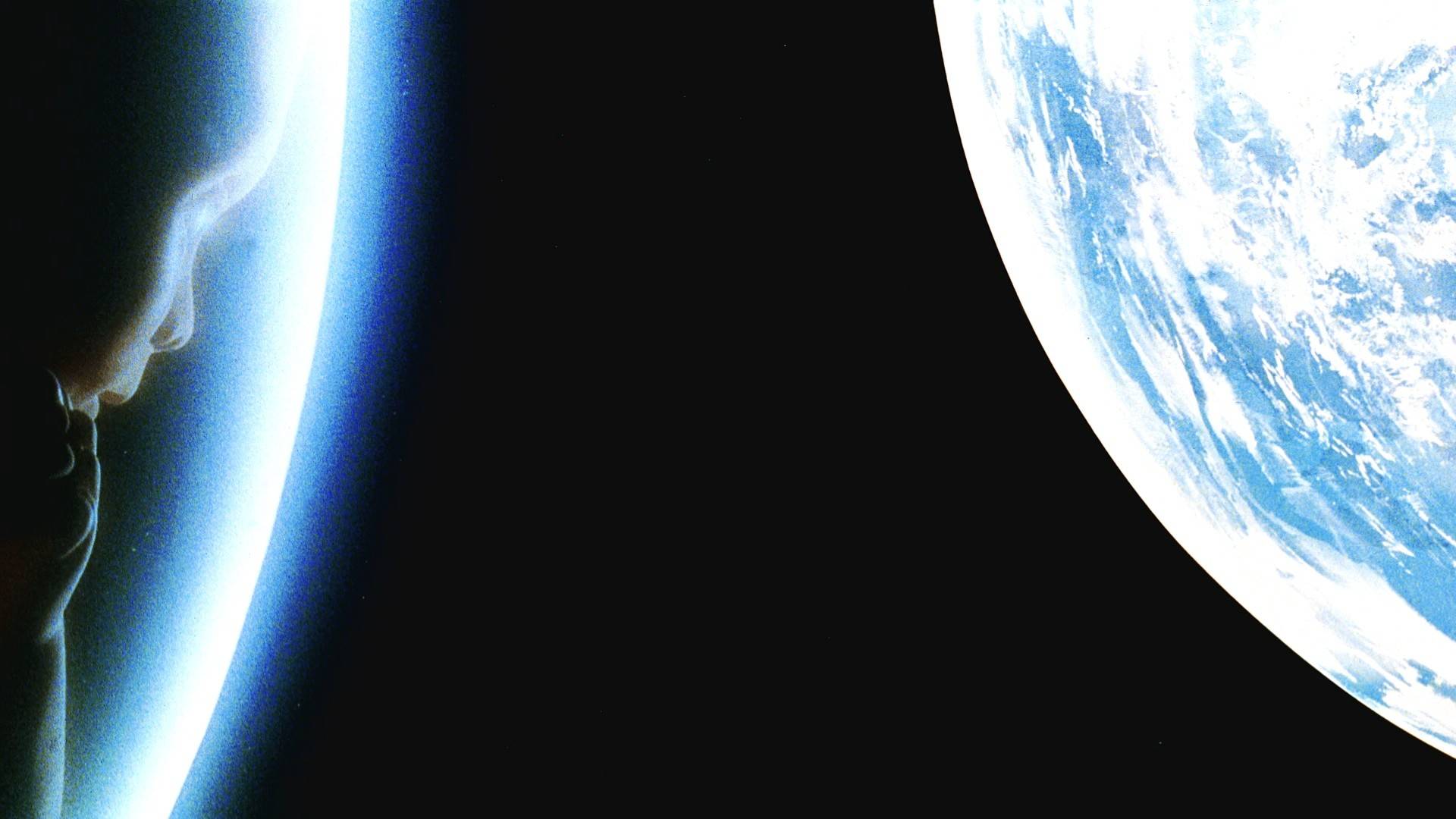

At Jupiter, Dave finds a third, much larger monolith orbiting the planet. He leaves Discovery in an EVA pod to investigate. He is pulled into a vortex of coloured light and observes bizarre cosmological phenomena and strange landscapes of unusual colours as he passes by. Finally he finds himself in a large neoclassical bedroom where he sees, and then becomes, older versions of himself: first standing in the bedroom, middle-aged and still in his spacesuit, then dressed in leisure attire and eating dinner, and finally as an old man lying in bed. A monolith appears at the foot of the bed, and as Dave reaches for it, he is transformed into a foetus enclosed in a transparent orb of light floating in space above the Earth.

Cast[edit]

- Keir Dullea as Dr. David Bowman

- Gary Lockwood as Dr. Frank Poole

- William Sylvester as Dr. Heywood Floyd

- Daniel Richter as Moonwatcher, the chief man-ape

- Leonard Rossiter as Dr. Andrei Smyslov

- Margaret Tyzack as Elena

- Robert Beatty as Dr. Ralph Halvorsen

- Sean Sullivan as Dr. Roy Michaels[4]

- Douglas Rain as the voice of HAL 9000

- Frank Miller as mission controller

- Edwina Carroll as lunar shuttle stewardess

- Penny Brahms as stewardess

- Heather Downham as stewardess

- Alan Gifford as Poole’s father

- Ann Gillis as Poole’s mother

- Maggie d’Abo as stewardess (Space Station 5 elevator) (uncredited)[5]

- Chela Matthison as Mrs. Turner, Space Station 5 reception (uncredited)[6]

- Vivian Kubrick as Floyd’s daughter, «Squirt» (uncredited)[7]

- Kenneth Kendall as BBC announcer (uncredited)[8]

Production[edit]

Development[edit]

After completing Dr. Strangelove (1964), director Stanley Kubrick told a publicist from Columbia Pictures that his next project would be about extraterrestrial life,[9] and resolved to make «the proverbial good science fiction movie».[10] How Kubrick became interested in creating a science fiction film is far from clear.[11] Biographer John Baxter notes possible inspirations in the late 1950s, including British productions featuring dramas on satellites and aliens modifying early humans, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer’s big budget CinemaScope production Forbidden Planet, and the slick widescreen cinematography and set design of Japanese kaiju (monster movie) productions (such as Godzilla and Warning from Space).[11]

Kubrick obtained financing and distribution from the American studio Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer with the selling point that the film could be marketed in their ultra widescreen Cinerama format, recently debuted with their How the West Was Won.[12][13][11] It would be filmed and edited almost entirely in southern England, where Kubrick lived, using the facilities of MGM-British Studios and Shepperton Studios. MGM had subcontracted the production of the film to Kubrick’s production company to qualify for the Eady Levy, a UK tax on box-office receipts used at the time to fund the production of films in Britain.[14]

Pre-production[edit]

Kubrick’s decision to avoid the fanciful portrayals of space found in standard popular science fiction films of the time led him to seek more realistic and accurate depictions of space travel. Illustrators such as Chesley Bonestell, Roy Carnon, and Richard McKenna were hired to produce concept drawings, sketches, and paintings of the space technology seen in the film.[15][16] Two educational films, the National Film Board of Canada’s 1960 animated short documentary Universe and the 1964 New York World’s Fair movie To the Moon and Beyond, were major influences.[15]

According to biographer Vincent LoBrutto, Universe was a visual inspiration to Kubrick.[17] The 29-minute film, which had also proved popular at NASA for its realistic portrayal of outer space, met «the standard of dynamic visionary realism that he was looking for.» Wally Gentleman, one of the special-effects artists on Universe, worked briefly on 2001. Kubrick also asked Universe co-director Colin Low about animation camerawork, with Low recommending British mathematician Brian Salt, with whom Low and Roman Kroitor had previously worked on the 1957 still-animation documentary City of Gold.[18][19] Universe‘s narrator, actor Douglas Rain, was cast as the voice of HAL.[20]

After pre-production had begun, Kubrick saw To the Moon and Beyond, a film shown in the Transportation and Travel building at the 1964 World’s Fair. It was filmed in Cinerama 360 and shown in the «Moon Dome». Kubrick hired the company that produced it, Graphic Films Corporation—which had been making films for NASA, the US Air Force, and various aerospace clients—as a design consultant.[15] Graphic Films’ Con Pederson, Lester Novros, and background artist Douglas Trumbull airmailed research-based concept sketches and notes covering the mechanics and physics of space travel, and created storyboards for the space flight sequences in 2001.[15] Trumbull became a special effects supervisor on 2001.[15]

Writing[edit]

Searching for a collaborator in the science fiction community for the writing of the script, Kubrick was advised by a mutual acquaintance, Columbia Pictures staff member Roger Caras, to talk to writer Arthur C. Clarke, who lived in Ceylon. Although convinced that Clarke was «a recluse, a nut who lives in a tree,» Kubrick allowed Caras to cable the film proposal to Clarke. Clarke’s cabled response stated that he was «frightfully interested in working with [that] enfant terrible«, and added «what makes Kubrick think I’m a recluse?»[17][21] Meeting for the first time at Trader Vic’s in New York on 22 April 1964, the two began discussing the project that would take up the next four years of their lives.[22] Clarke kept a diary throughout his involvement with 2001, excerpts of which were published in 1972 as The Lost Worlds of 2001.[23]

Arthur C. Clarke in 1965, photographed in the Discovery‘s pod bay

Kubrick told Clarke he wanted to make a film about «Man’s relationship to the universe»,[24] and was, in Clarke’s words, «determined to create a work of art which would arouse the emotions of wonder, awe … even, if appropriate, terror».[22] Clarke offered Kubrick six of his short stories, and by May 1964, Kubrick had chosen «The Sentinel» as the source material for the film. In search of more material to expand the film’s plot, the two spent the rest of 1964 reading books on science and anthropology, screening science fiction films, and brainstorming ideas.[25] They created the plot for 2001 by integrating several different short story plots written by Clarke, along with new plot segments requested by Kubrick for the film development, and then combined them all into a single script for 2001.[26][27] Clarke said that his 1953 story «Encounter in the Dawn» inspired the film’s «Dawn of Man» sequence.[28]

Kubrick and Clarke privately referred to the project as How the Solar System Was Won, a reference to how it was a follow-on to MGM’s Cinerama epic How the West Was Won.[11] On 23 February 1965, Kubrick issued a press release announcing the title as Journey Beyond The Stars.[29] Other titles considered included Universe, Tunnel to the Stars, and Planetfall. Expressing his high expectations for the thematic importance which he associated with the film, in April 1965, eleven months after they began working on the project, Kubrick selected 2001: A Space Odyssey; Clarke said the title was «entirely» Kubrick’s idea.[30] Intending to set the film apart from the «monsters-and-sex» type of science-fiction films of the time, Kubrick used Homer‘s The Odyssey as both a model of literary merit and a source of inspiration for the title. Kubrick said, «It occurred to us that for the Greeks the vast stretches of the sea must have had the same sort of mystery and remoteness that space has for our generation.»[31]

How much would we appreciate La Gioconda today if Leonardo had written at the bottom of the canvas: «This lady is smiling slightly because she has rotten teeth» — or «because she’s hiding a secret from her lover»? It would shut off the viewer’s appreciation and shackle him to a reality other than his own. I don’t want that to happen to 2001.

—Stanley Kubrick, Playboy, 1968[32]

Originally, Kubrick and Clarke had planned to develop a 2001 novel first, free of the constraints of film, and then write the screenplay. They planned the writing credits to be «Screenplay by Stanley Kubrick and Arthur C. Clarke, based on a novel by Arthur C. Clarke and Stanley Kubrick» to reflect their preeminence in their respective fields.[33] In practice, the screenplay developed in parallel with the novel, with only some elements being common to both. In a 1970 interview, Kubrick said:

There are a number of differences between the book and the movie. The novel, for example, attempts to explain things much more explicitly than the film does, which is inevitable in a verbal medium. The novel came about after we did a 130-page prose treatment of the film at the very outset. … Arthur took all the existing material, plus an impression of some of the rushes, and wrote the novel. As a result, there’s a difference between the novel and the film … I think that the divergences between the two works are interesting.[34]

In the end, Clarke and Kubrick wrote parts of the novel and screenplay simultaneously, with the film version being released before the book version was published. Clarke opted for clearer explanations of the mysterious monolith and Star Gate in the novel; Kubrick made the film more cryptic by minimising dialogue and explanation.[35] Kubrick said the film is «basically a visual, nonverbal experience» that «hits the viewer at an inner level of consciousness, just as music does, or painting».[36]

The screenplay credits were shared whereas the 2001 novel, released shortly after the film, was attributed to Clarke alone. Clarke wrote later that «the nearest approximation to the complicated truth» is that the screenplay should be credited to «Kubrick and Clarke» and the novel to «Clarke and Kubrick».[37] Early reports about tensions involved in the writing of the film script appeared to reach a point where Kubrick was allegedly so dissatisfied with the collaboration that he approached other writers who could replace Clarke, including Michael Moorcock and J. G. Ballard. But they felt it would be disloyal to accept Kubrick’s offer.[38] In Michael Benson’s 2018 book Space Odyssey: Stanley Kubrick, Arthur C. Clarke, and the Making of a Masterpiece, the actual relation between Clarke and Kubrick was more complex, involving an extended interaction of Kubrick’s multiple requests for Clarke to write new plot lines for various segments of the film, which Clarke was expected to withhold from publication until after the release of the film while receiving advances on his salary from Kubrick during film production. Clarke agreed to this, though apparently he did make several requests for Kubrick to allow him to develop his new plot lines into separate publishable stories while film production continued, which Kubrick consistently denied on the basis of Clarke’s contractual obligation to withhold publication until release of the film.[27]

Astronomer Carl Sagan wrote in his 1973 book The Cosmic Connection that Clarke and Kubrick had asked him how to best depict extraterrestrial intelligence. While acknowledging Kubrick’s desire to use actors to portray humanoid aliens for convenience’s sake, Sagan argued that alien life forms were unlikely to bear any resemblance to terrestrial life, and that to do so would introduce «at least an element of falseness» to the film. Sagan proposed that the film should simply suggest extraterrestrial superintelligence, rather than depict it. He attended the premiere and was «pleased to see that I had been of some help.»[39] Sagan had met with Clarke and Kubrick only once, in 1964; and Kubrick subsequently directed several attempts to portray credible aliens, only to abandon the idea near the end of post-production. Benson asserts it is unlikely that Sagan’s advice had any direct influence.[27] Kubrick hinted at the nature of the mysterious unseen alien race in 2001 by suggesting that given millions of years of evolution, they progressed from biological beings to «immortal machine entities» and then into «beings of pure energy and spirit» with «limitless capabilities and ungraspable intelligence».[40]

In a 1980 interview (not released during Kubrick’s lifetime), Kubrick explains one of the film’s closing scenes, where Bowman is depicted in old age after his journey through the Star Gate:

The idea was supposed to be that he is taken in by godlike entities, creatures of pure energy and intelligence with no shape or form. They put him in what I suppose you could describe as a human zoo to study him, and his whole life passes from that point on in that room. And he has no sense of time. … [W]hen they get finished with him, as happens in so many myths of all cultures in the world, he is transformed into some kind of super being and sent back to Earth, transformed and made some kind of superman. We have to only guess what happens when he goes back. It is the pattern of a great deal of mythology, and that is what we were trying to suggest.[41]

The script went through many stages. In early 1965, when backing was secured for the film, Clarke and Kubrick still had no firm idea of what would happen to Bowman after the Star Gate sequence. Initially all of Discovery‘s astronauts were to survive the journey; by 3 October, Clarke and Kubrick had decided to make Bowman the sole survivor and have him regress to infancy. By 17 October, Kubrick had come up with what Clarke called a «wild idea of slightly fag robots who create a Victorian environment to put our heroes at their ease.»[37] HAL 9000 was originally named Athena after the Greek goddess of wisdom and had a feminine voice and persona.[37]

Early drafts included a prologue containing interviews with scientists about extraterrestrial life,[42] voice-over narration (a feature in all of Kubrick’s previous films),[a] a stronger emphasis on the prevailing Cold War balance of terror, and a different and more explicitly explained breakdown for HAL.[44][45] Other changes include a different monolith for the «Dawn of Man» sequence, discarded when early prototypes did not photograph well; the use of Saturn as the final destination of the Discovery mission rather than Jupiter, discarded when the special effects team could not develop a convincing rendition of Saturn’s rings; and the finale of the Star Child exploding nuclear weapons carried by Earth-orbiting satellites,[45] which Kubrick discarded for its similarity to his previous film, Dr. Strangelove.[42][45] The finale and many of the other discarded screenplay ideas survived in Clarke’s novel.[45]

Kubrick made further changes to make the film more nonverbal, to communicate on a visual and visceral level rather than through conventional narrative.[32] By the time shooting began, Kubrick had removed much of the dialogue and narration.[46] Long periods without dialogue permeate the film: the film has no dialogue for roughly the first and last twenty minutes,[47] as well as for the 10 minutes from Floyd’s Moonbus landing near the monolith until Poole watches a BBC newscast on Discovery. What dialogue remains is notable for its banality (making the computer HAL seem to have more emotion than the humans) when juxtaposed with the epic space scenes.[46] Vincent LoBrutto wrote that Clarke’s novel has its own «strong narrative structure» and precision, while the narrative of the film remains symbolic, in accord with Kubrick’s final intentions.[48]

Filming[edit]

Principal photography began on 29 December 1965, in Stage H at Shepperton Studios, Shepperton, England. The studio was chosen because it could house the 60-by-120-by-60-foot (18 m × 37 m × 18 m) pit for the Tycho crater excavation scene, the first to be shot. In January 1966, the production moved to the smaller MGM-British Studios in Borehamwood, where the live-action and special-effects filming was done, starting with the scenes involving Floyd on the Orion spaceplane;[49] it was described as a «huge throbbing nerve center … with much the same frenetic atmosphere as a Cape Kennedy blockhouse during the final stages of Countdown.»[50] The only scene not filmed in a studio—and the last live-action scene shot for the film—was the skull-smashing sequence, in which Moonwatcher (Richter) wields his newfound bone «weapon-tool» against a pile of nearby animal bones. A small elevated platform was built in a field near the studio so that the camera could shoot upward with the sky as background, avoiding cars and trucks passing by in the distance.[51][52] The Dawn of Man sequence that opens the film was shot at Borehamwood with John Alcott as cinematographer after Geoffrey Unsworth left to work on other projects.[53][54] The still photographs used as backgrounds for the Dawn of Man sequence were taken in Namibia.[55]

Filming of actors was completed in September 1967,[56] and from June 1966 until March 1968, Kubrick spent most of his time working on the 205 special-effects shots in the film.[34] He ordered the special-effects technicians to use the painstaking process of creating all visual effects seen in the film «in camera», avoiding degraded picture quality from the use of blue screen and travelling matte techniques. Although this technique, known as «held takes», resulted in a much better image, it meant exposed film would be stored for long periods of time between shots, sometimes as long as a year.[57] In March 1968, Kubrick finished the «pre-premiere» editing of the film, making his final cuts just days before the film’s general release in April 1968.[34]

The film was announced in 1965 as a «Cinerama»[58] film and was photographed in Super Panavision 70 (which uses a 65 mm negative combined with spherical lenses to create an aspect ratio of 2.20:1). It would eventually be released in a limited «roadshow» Cinerama version, then in 70 mm and 35 mm versions.[59][60] Colour processing and 35 mm release prints were done using Technicolor’s dye transfer process. The 70 mm prints were made by MGM Laboratories, Inc. on Metrocolor. The production was $4.5 million over the initial $6 million budget and 16 months behind schedule.[61]

For the opening sequence involving tribes of apes, professional mime Daniel Richter played the lead ape and choreographed the movements of the other man-apes, who were mostly portrayed by his mime troupe.[51]

Kubrick and Clarke consulted IBM on plans for HAL, though plans to use the company’s logo never materialised.[55]

Post-production[edit]

For cuts made after the film premiered, see the Theatrical run section below.

The film was edited before it was publicly screened, cutting out, among other things, a painting class on the lunar base that included Kubrick’s daughters, additional scenes of life on the base, and Floyd buying a bush baby for his daughter from a department store via videophone.[62] A ten-minute black-and-white opening sequence featuring interviews with scientists, including Freeman Dyson discussing off-Earth life,[63] was removed after an early screening for MGM executives.[64]

Music[edit]

From early in production, Kubrick decided that he wanted the film to be a primarily nonverbal experience[65] that did not rely on the traditional techniques of narrative cinema, and in which music would play a vital role in evoking particular moods. About half the music in the film appears either before the first line of dialogue or after the final line. Almost no music is heard during scenes with dialogue.[66]

The film is notable for its innovative use of classical music taken from existing commercial recordings. Most feature films, then and now, are typically accompanied by elaborate film scores or songs written specially for them by professional composers. In the early stages of production, Kubrick commissioned a score for 2001 from Hollywood composer Alex North, who had written the score for Spartacus and also had worked on Dr. Strangelove.[67] During post-production, Kubrick chose to abandon North’s music in favour of the now-familiar classical pieces he had earlier chosen as temporary music for the film. North did not learn that his score had been abandoned until he saw the film’s premiere.[66]

Design and special effects[edit]

Costumes and set design[edit]

Kubrick involved himself in every aspect of production, even choosing the fabric for his actors’ costumes,[68] and selecting notable pieces of contemporary furniture for use in the film. When Floyd exits the Space Station 5 elevator, he is greeted by an attendant seated behind a slightly modified George Nelson Action Office desk from Herman Miller’s 1964 «Action Office» series.[b][69][c] Danish designer Arne Jacobsen designed the cutlery used by the Discovery astronauts in the film.[70][71][72]

Other examples of modern furniture in the film are the bright red Djinn chairs seen prominently throughout the space station[73][74] and Eero Saarinen’s 1956 pedestal tables. Olivier Mourgue, designer of the Djinn chair, has used the connection to 2001 in his advertising; a frame from the film’s space station sequence and three production stills appear on the homepage of Mourgue’s website.[75] Shortly before Kubrick’s death, film critic Alexander Walker informed Kubrick of Mourgue’s use of the film, joking to him «You’re keeping the price up».[76] Commenting on their use in the film, Walker writes:

Everyone recalls one early sequence in the film, the space hotel, primarily because the custom-made Olivier Mourgue furnishings, those foam-filled sofas, undulant and serpentine, are covered in scarlet fabric and are the first stabs of colour one sees. They resemble Rorschach «blots» against the pristine purity of the rest of the lobby.[77]

Detailed instructions in relatively small print for various technological devices appear at several points in the film, the most visible of which are the lengthy instructions for the zero-gravity toilet on the Aries Moon shuttle. Similar detailed instructions for replacing the explosive bolts also appear on the hatches of the EVA pods, most visibly in closeup just before Bowman’s pod leaves the ship to rescue Frank Poole.[d]

The film features an extensive use of Eurostile Bold Extended, Futura and other sans serif typefaces as design elements of the 2001 world.[79] Computer displays show high-resolution fonts, colour, and graphics that were far in advance of what most computers were capable of in the 1960s, when the film was made.[78]

Design of the monolith[edit]

Kubrick was personally involved in the design of the monolith and its form for the film. The first design for the monolith for the 2001 film was a transparent tetrahedral pyramid. This was taken from the short story «The Sentinel» that the first story was based on.[80][81]

A London firm was approached by Kubrick to provide a 12-foot (3.7 m) transparent plexiglass pyramid, and due to construction constraints they recommended a flat slab shape. Kubrick approved, but was disappointed with the glassy appearance of the transparent prop on set, leading art director Anthony Masters to suggest making the monolith’s surface matte black.[27]

Models[edit]

Modern replica of the Discovery One spaceship model

To heighten the reality of the film, very intricate models of the various spacecraft and locations were built. Their sizes ranged from about two-foot-long models of satellites and the Aries translunar shuttle up to the 55-foot (17 m)-long model of the Discovery One spacecraft. «In-camera» techniques were again used as much as possible to combine models and background shots together to prevent degradation of the image through duplication.[82][83]

In shots where there was no perspective change, still shots of the models were photographed and positive paper prints were made. The image of the model was cut out of the photographic print and mounted on glass and filmed on an animation stand. The undeveloped film was re-wound to film the star background with the silhouette of the model photograph acting as a matte to block out where the spaceship image was.[82]

Shots where the spacecraft had parts in motion or the perspective changed were shot by directly filming the model. For most shots the model was stationary and camera was driven along a track on a special mount, the motor of which was mechanically linked to the camera motor—making it possible to repeat camera moves and match speeds exactly. Elements of the scene were recorded on the same piece of film in separate passes to combine the lit model, stars, planets, or other spacecraft in the same shot. In moving shots of the long Discovery One spacecraft, in order to keep the entire model in focus (and preserve its sense of scale), the camera’s aperture was stopped down for maximum depth-of-field, and each frame was exposed for several seconds.[84] Many matting techniques were tried to block out the stars behind the models, with filmmakers sometimes resorting to hand-tracing frame by frame around the image of the spacecraft (rotoscoping) to create the matte.[82][85]

Some shots required exposing the film again to record previously filmed live-action shots of the people appearing in the windows of the spacecraft or structures. This was achieved by projecting the window action onto the models in a separate camera pass or, when two-dimensional photographs were used, projecting from the backside through a hole cut in the photograph.[84]

All of the shots required multiple takes so that some film could be developed and printed to check exposure, density, alignment of elements, and to supply footage used for other photographic effects, such as for matting.[82][85]

Rotating sets[edit]

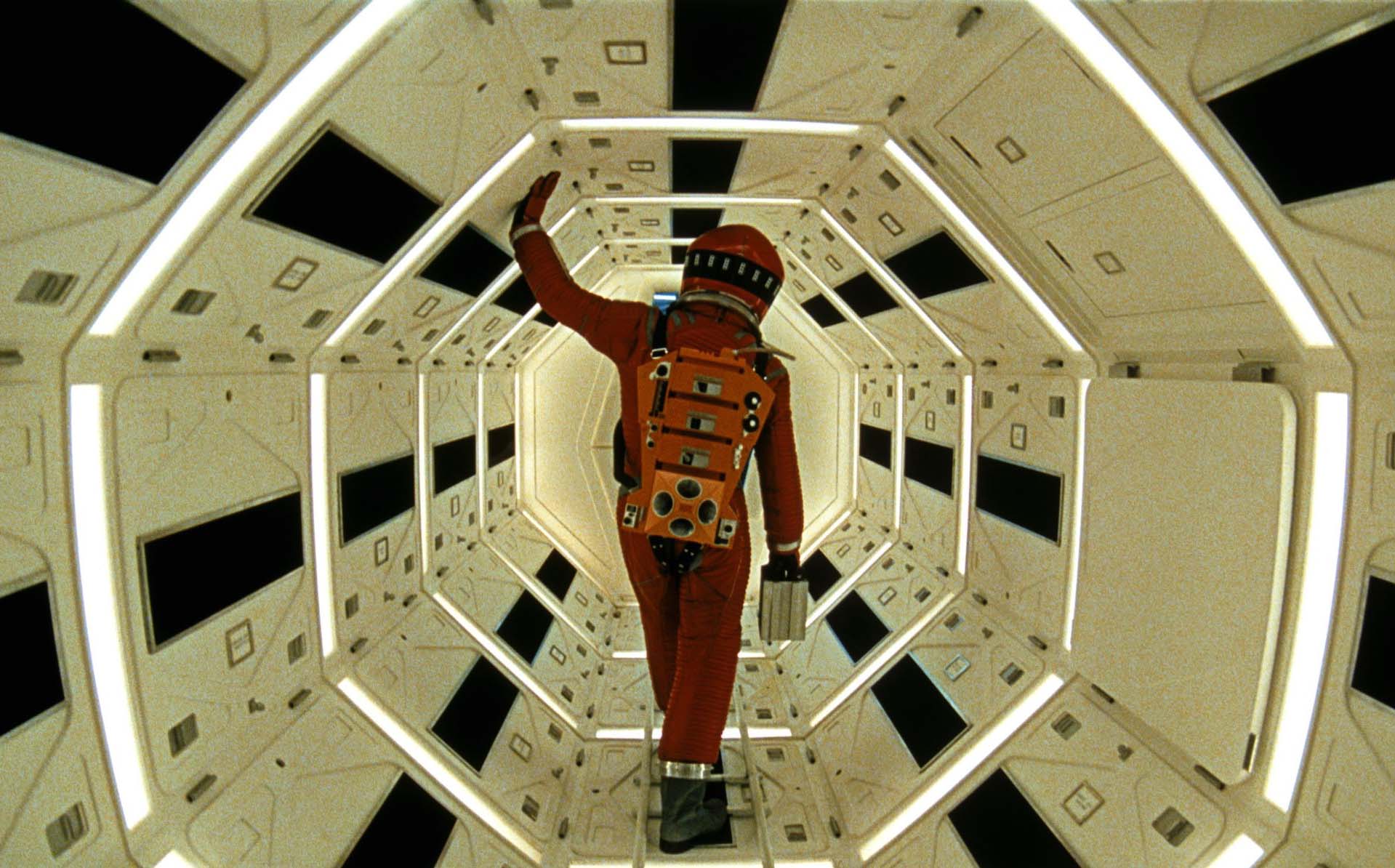

The «centrifuge» set used for filming scenes depicting interior of the spaceship Discovery

For spacecraft interior shots, ostensibly containing a giant centrifuge that produces artificial gravity, Kubrick had a 30-short-ton (27 t) rotating «ferris wheel» built by Vickers-Armstrong Engineering Group at a cost of $750,000. The set was 38 feet (12 m) in diameter and 10 feet (3.0 m) wide.[86] Various scenes in the Discovery centrifuge were shot by securing set pieces within the wheel, then rotating it while the actor walked or ran in sync with its motion, keeping him at the bottom of the wheel as it turned. The camera could be fixed to the inside of the rotating wheel to show the actor walking completely «around» the set, or mounted in such a way that the wheel rotated independently of the stationary camera, as in the jogging scene where the camera appears to alternately precede and follow the running actor.[87]

The shots where the actors appear on opposite sides of the wheel required one of the actors to be strapped securely into place at the «top» of the wheel as it moved to allow the other actor to walk to the «bottom» of the wheel to join him. The most notable case is when Bowman enters the centrifuge from the central hub on a ladder, and joins Poole, who is eating on the other side of the centrifuge. This required Gary Lockwood to be strapped into a seat while Keir Dullea walked toward him from the opposite side of the wheel as it turned with him.[87]

Another rotating set appeared in an earlier sequence on board the Aries trans-lunar shuttle. A stewardess is shown preparing in-flight meals, then carrying them into a circular walkway. Attached to the set as it rotates 180 degrees, the camera’s point of view remains constant, and she appears to walk up the «side» of the circular walkway, and steps, now in an «upside-down» orientation, into a connecting hallway.[88]

Zero-gravity effects[edit]

The realistic-looking effects of the astronauts floating weightless in space and inside the spacecraft were accomplished by suspending the actors from wires attached to the top of the set and placing the camera beneath them. The actors’ bodies blocked the camera’s view of the wires and appeared to float. For the shot of Poole floating into the pod’s arms during Bowman’s recovery of him, a stuntman on a wire portrayed the movements of an unconscious man and was shot in slow motion to enhance the illusion of drifting through space.[89] The scene showing Bowman entering the emergency airlock from the EVA pod was done similarly: an off-camera stagehand, standing on a platform, held the wire suspending Dullea above the camera positioned at the bottom of the vertically oriented airlock. At the proper moment, the stage-hand first loosened his grip on the wire, causing Dullea to fall toward the camera, then, while holding the wire firmly, jumped off the platform, causing Dullea to ascend back toward the hatch.[90]

The methods used were alleged to have placed stuntman Bill Weston’s life in danger. Weston recalled that he filmed one sequence without air-holes in his suit, risking asphyxiation. «Even when the tank was feeding air into the suit, there was no place for the carbon dioxide Weston exhaled to go. So it simply built up inside, incrementally causing a heightened heart rate, rapid breathing, fatigue, clumsiness, and eventually, unconsciousness.»[91] Weston said Kubrick was warned «we’ve got to get him back» but reportedly replied, «Damn it, we just started. Leave him up there! Leave him up there!»[92] When Weston lost consciousness, filming ceased, and he was brought down. «They brought the tower in, and I went looking for Stanley, … I was going to shove MGM right up his … And the thing is, Stanley had left the studio and sent Victor [Lyndon, the associate producer] to talk to me.» Weston claimed Kubrick fled the studio for «two or three days. … I know he didn’t come in the next day, and I’m sure it wasn’t the day after. Because I was going to do him.»[93]

«Star Gate» sequence[edit]

During the «Jupiter and Beyond the Infinite» sequence, Bowman takes a trip through the «Star Gate» that involves the innovative use of slit-scan photography to create the visual effects.

The coloured lights in the Star Gate sequence were accomplished by slit-scan photography of thousands of high-contrast images on film, including Op art paintings, architectural drawings, Moiré patterns, printed circuits, and electron-microscope photographs of molecular and crystal structures. Known to staff as «Manhattan Project», the shots of various nebula-like phenomena, including the expanding star field, were coloured paints and chemicals swirling in a pool-like device known as a cloud tank, shot in slow motion in a dark room.[94] The live-action landscape shots were filmed in the Hebridean islands, the mountains of northern Scotland, and Monument Valley. The colouring and negative-image effects were achieved with different colour filters in the process of making duplicate negatives in an optical printer.[95]

Visual effects[edit]

A bone-club and orbiting satellite are juxtaposed in the film’s famous match cut

«Not one foot of this film was made with computer-generated special effects. Everything you see in this film or saw in this film was done physically or chemically, one way or the other.»

— Keir Dullea (2014)[96]

2001 contains a famous example of a match cut, a type of cut in which two shots are matched by action or subject matter.[97][98] After Moonwatcher uses a bone to kill another ape at the watering hole, he throws it triumphantly into the air; as the bone spins in the air, the film cuts to an orbiting satellite, marking the end of the prologue.[99] The match cut draws a connection between the two objects as exemplars of primitive and advanced tools respectively, and demonstrates humanity’s technological progress since the time of early hominids.[100]

2001 pioneered the use of front projection with retroreflective matting. Kubrick used the technique to produce the backdrops in the Africa scenes and the scene when astronauts walk on the Moon.[101][54]

The technique consisted of a separate scenery projector set at a right angle to the camera and a half-silvered mirror placed at an angle in front that reflected the projected image forward in line with the camera lens onto a backdrop of retroreflective material. The reflective directional screen behind the actors could reflect light from the projected image 100 times more efficiently than the foreground subject did. The lighting of the foreground subject had to be balanced with the image from the screen, so that the part of the scenery image that fell on the foreground subject was too faint to show on the finished film. The exception was the eyes of the leopard in the «Dawn of Man» sequence, which glowed due to the projector illumination. Kubrick described this as «a happy accident».[102]

Front projection had been used in smaller settings before 2001, mostly for still photography or television production, using small still images and projectors. The expansive backdrops for the African scenes required a screen 40 feet (12 m) tall and 110 feet (34 m) wide, far larger than had been used before. When the reflective material was applied to the backdrop in 100-foot (30 m) strips, variations at the seams of the strips led to visual artefacts; to solve this, the crew tore the material into smaller chunks and applied them in a random «camouflage» pattern on the backdrop. The existing projectors using 4-×-5-inch (10 × 13 cm) transparencies resulted in grainy images when projected that large, so the crew worked with MGM’s special-effects supervisor Tom Howard to build a custom projector using 8-×-10-inch (20 × 25 cm) transparencies, which required the largest water-cooled arc lamp available.[102] The technique was used widely in the film industry thereafter until it was replaced by blue/green screen systems in the 1990s.[102]

Soundtrack[edit]

The initial MGM soundtrack album release contained none of the material from the altered and uncredited rendition of Ligeti’s Aventures used in the film, used a different recording of Also sprach Zarathustra (performed by the Berlin Philharmonic conducted by Karl Böhm) from that heard in the film, and a longer excerpt of Lux Aeterna than that in the film.[103]

In 1996, Turner Entertainment/Rhino Records released a new soundtrack on CD that included the film’s rendition of «Aventures», the version of «Zarathustra» used in the film, and the shorter version of Lux Aeterna from the film. As additional «bonus tracks» at the end, the CD includes the versions of «Zarathustra» and Lux Aeterna on the old MGM soundtrack album, an unaltered performance of «Aventures», and a nine-minute compilation of all of HAL’s dialogue.[103]

Alex North’s unused music was first released in Telarc’s issue of the main theme on Hollywood’s Greatest Hits, Vol. 2, a compilation album by Erich Kunzel and the Cincinnati Pops Orchestra. All of the music North originally wrote was recorded commercially by his friend and colleague Jerry Goldsmith with the National Philharmonic Orchestra and released on Varèse Sarabande CDs shortly after Telarc’s first theme release and before North’s death. Eventually, a mono mix-down of North’s original recordings was released as a limited-edition CD by Intrada Records.[104]

Theatrical run and post-premiere cuts[edit]

Original trailer for 2001: A Space Odyssey.

The film’s world premiere was on 2 April 1968,[105][106] at the Uptown Theater in Washington, D.C. with a 160-minute cut.[107] It opened the next day at the Loew’s Capitol in New York and the following day at the Warner Hollywood Theatre in Los Angeles.[107] The original version was also shown in Boston.

Kubrick and editor Ray Lovejoy edited the film between 5 April and 9, 1968. Kubrick’s rationale for trimming the film was to tighten the narrative. Reviews suggested the film suffered from its departure from traditional cinematic storytelling.[108] Kubrick said, «I didn’t believe that the trims made a critical difference. … The people who like it like it no matter what its length, and the same holds true for the people who hate it.»[62] The cut footage is reported as being 19[109][110] or 17[111] minutes long. It includes scenes revealing details about life on Discovery: additional space walks, Bowman retrieving a spare part from an octagonal corridor, elements from the Poole murder sequence—including space-walk preparation and HAL turning off radio contact with Poole—and a close-up of Bowman picking up a slipper during his walk in the alien room.[62] Jerome Agel describes the cut scenes as comprising «Dawn of Man, Orion, Poole exercising in the centrifuge, and Poole’s pod exiting from Discovery.»[112] The new cut was approximately 143 minutes long,[1] around 88 minutes for the first section, followed by an intermission, and 55 minutes in the second section.[113] Detailed instructions were sent to theatre owners already showing the film so that they could make the specified trims themselves.[citation needed] Some of the cuts may have been poorly done in a particular theatre, possibly causing the version seen by viewers early in the film’s run to vary from theatre to theatre.

According to his brother-in-law, Jan Harlan, Kubrick was adamant that the trims were never to be seen and had the negatives, which he had kept in his garage, burned shortly before his death. This was confirmed by former Kubrick assistant Leon Vitali: «I’ll tell you right now, okay, on Clockwork Orange, The Shining, Barry Lyndon, some little parts of 2001, we had thousands of cans of negative outtakes and print, which we had stored in an area at his house where we worked out of, which he personally supervised the loading of it to a truck and then I went down to a big industrial waste lot and burned it. That’s what he wanted.»[114] However, in December 2010, Douglas Trumbull, the film’s visual effects supervisor, announced that Warner Bros. had found 17 minutes of lost footage from the post-premiere cuts, «perfectly preserved», in a Kansas salt mine vault used by Warners for storage.[115][112][111] No plans have been announced for the rediscovered footage.[116]

The revised version was ready for the expansion of the roadshow release to four other U.S. cities (Chicago, Denver, Detroit and Houston), on 10 April 1968, and internationally in five cities the following day,[112][117] where the shortened version was shown in 70mm format in the 2.21:1 aspect ratio and used a six-track stereo magnetic soundtrack.[112]

By the end of May, the film had opened in 22 cities in the United States and Canada and in another 36 in June.[118] The general release of the film in its 35 mm anamorphic format took place in autumn 1968 and used either a four-track magnetic stereo soundtrack or an optical monaural one.[119]

The original 70-millimetre release, like many Super Panavision 70 films of the era such as Grand Prix, was advertised as being in «Cinerama» in cinemas equipped with special projection optics and a deeply curved screen. In standard cinemas, the film was identified as a 70-millimetre production. The original release of 2001: A Space Odyssey in 70-millimetre Cinerama with six-track sound played continually for more than a year in several venues, and for 103 weeks in Los Angeles.[119]

As was typical of most films of the era released both as a «roadshow» (in Cinerama format in the case of 2001) and general release (in 70-millimetre in the case of 2001), the entrance music, intermission music (and intermission altogether), and postcredit exit music were cut from most prints of the latter version, although these have been restored to most DVD releases.[120][121]

Reception[edit]

Box office[edit]

In its first nine weeks from 22 locations, it grossed $2 million in the United States and Canada.[118] The film earned $8.5 million in theatrical gross rentals from roadshow engagements throughout 1968,[122][123] contributing to North American rentals of $16.4 million and worldwide rentals of $21.9 million during its original release.[124] The film’s high costs, in excess of $10 million,[105][61] meant that the initial returns from the 1968 release left it $800,000 in the red; but the successful re-release in 1971 made it profitable.[125][126][127] By June 1974, the film had rentals from the United States and Canada of $20.3 million (gross of $58 million)[125] and international rentals of $7.5 million.[113] The film had a reissue on a test basis on 24 July 1974 at the Cinerama Dome in Los Angeles and grossed $53,000 in its first week, which led to an expanded reissue.[113] Further re-releases followed, giving a cumulative gross of over $60 million in the United States and Canada.[128] Taking its re-releases into account, it is the highest-grossing film of 1968 in the United States and Canada.[129] Worldwide, it has grossed $146 million across all releases,[e] although some estimates place the gross higher, at over $190 million.[131]

Critical response[edit]

Upon release, 2001 polarised critical opinion, receiving both praise and derision, with many New York-based critics being especially harsh. Kubrick called them «dogmatically atheistic and materialistic and earthbound».[132] Some critics viewed the original 161-minute cut shown at premieres in Washington D.C., New York, and Los Angeles.[133] Keir Dullea says that during the New York premiere, 250 people walked out; in L.A., Rock Hudson not only left early but «was heard to mutter, ‘What is this bullshit?‘«[132] «Will someone tell me what the hell this is about?»[134] «But a few months into the release, they realised a lot of people were watching it while smoking funny cigarettes. Someone in San Francisco even ran right through the screen screaming: ‘It’s God!’ So they came up with a new poster that said: ‘2001 – the ultimate trip!‘«[135]

In The New Yorker, Penelope Gilliatt said it was «some kind of great film, and an unforgettable endeavor … The film is hypnotically entertaining, and it is funny without once being gaggy, but it is also rather harrowing.»[136] Charles Champlin of the Los Angeles Times wrote that it was «the picture that science fiction fans of every age and in every corner of the world have prayed (sometimes forlornly) that the industry might some day give them. It is an ultimate statement of the science fiction film, an awesome realization of the spatial future … it is a milestone, a landmark for a spacemark, in the art of film.»[137] Louise Sweeney of The Christian Science Monitor felt that 2001 was «a brilliant intergalactic satire on modern technology. It’s also a dazzling 160-minute tour on the Kubrick filmship through the universe out there beyond our earth.»[138] Philip French wrote that the film was «perhaps the first multi-million-dollar supercolossal movie since D.W. Griffith’s Intolerance fifty years ago which can be regarded as the work of one man … Space Odyssey is important as the high-water mark of science-fiction movie making, or at least of the genre’s futuristic branch.»[139] The Boston Globe‘s review called it «the world’s most extraordinary film. Nothing like it has ever been shown in Boston before or, for that matter, anywhere … The film is as exciting as the discovery of a new dimension in life.»[140] Roger Ebert gave the film four stars in his original review, saying the film «succeeds magnificently on a cosmic scale.»[47] He later put it on his Top 10 list for Sight & Sound.[141] Time provided at least seven different mini-reviews of the film in various issues in 1968, each one slightly more positive than the preceding one; in the final review dated 27 December 1968, the magazine called 2001 «an epic film about the history and future of mankind, brilliantly directed by Stanley Kubrick. The special effects are mindblowing.»[142]

Others were unimpressed. Pauline Kael called it «a monumentally unimaginative movie.»[143] Stanley Kauffmann of The New Republic described it as «a film that is so dull, it even dulls our interest in the technical ingenuity for the sake of which Kubrick has allowed it to become dull.»[144] The Soviet film director Andrei Tarkovsky found the film to be an inadequate addition to the science fiction genre of filmmaking.[27] Renata Adler of The New York Times wrote that it was «somewhere between hypnotic and immensely boring.»[145] Variety‘s Robert B. Frederick (‘Robe’) believed the film was a «[b]ig, beautiful, but plodding sci-fi epic … A major achievement in cinematography and special effects, 2001 lacks dramatic appeal to a large degree and only conveys suspense after the halfway mark.»[108] Andrew Sarris called it «one of the grimmest films I have ever seen in my life … 2001 is a disaster because it is much too abstract to make its abstract points.»[146] (Sarris reversed his opinion upon a second viewing, and declared, «2001 is indeed a major work by a major artist.»[147]) John Simon felt it was «a regrettable failure, although not a total one. This film is fascinating when it concentrates on apes or machines … and dreadful when it deals with the in-betweens: humans … 2001, for all its lively visual and mechanical spectacle, is a kind of space-Spartacus and, more pretentious still, a shaggy God story.»[148] Historian Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr. deemed the film «morally pretentious, intellectually obscure and inordinately long … a film out of control».[149] In a 2001 review, the BBC said that its slow pacing often alienates modern audiences more than it did upon its initial release.[150]

On review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, the film has a «Certified Fresh» rating of 92% based on 116 reviews, with an average rating of 9.2/10. The website’s critical consensus reads: «One of the most influential of all sci-fi films – and one of the most controversial – Stanley Kubrick’s 2001 is a delicate, poetic meditation on the ingenuity – and folly – of mankind.»[106] Review aggregator Metacritic, which uses a weighted average, has assigned the film a score of 84 out of 100, based on 25 critic reviews, indicating «universal acclaim».[151]

2001 was the only science fiction film to make Sight & Sound‘s 2012 list of the ten best films,[152] and tops the Online Film Critics Society list of greatest science fiction films of all time.[153] In 2012, the Motion Picture Editors Guild listed the film as the 19th best-edited film of all time based on a survey of its membership.[154] Other lists that include the film are 50 Films to See Before You Die (#6), The Village Voice 100 Best Films of the 20th century (#11), and Roger Ebert’s Top Ten (1968) (#2). In 1995, the Vatican named it one of the 45 best films ever made (and included it in a sub-list of the «Top Ten Art Movies» of all time.)[155] In 1998, Time Out conducted a reader’s poll and 2001: A Space Odyssey was voted as #9 on the list of «greatest films of all time».[156] Entertainment Weekly voted it no. 26 on their list of 100 Greatest Movies of All Time.[157] In 2017, Empire magazine’s readers’ poll ranked the film 21st on its list of «The 100 Greatest Movies».[158] In the Sight & Sound poll of 480 directors published in December 2022, 2001: A Space Odyssey was voted as the Greatest Film of All Time, ahead of Citizen Kane and The Godfather.[159][160]

Science fiction writers[edit]

The film won the Hugo Award for best dramatic presentation, as voted by science fiction fans and published science-fiction writers.[161] Ray Bradbury praised the film’s photography, but disliked the banality of most of the dialogue, and believed that the audience does not care when Poole dies.[162] Both he and Lester del Rey disliked the film’s feeling of sterility and blandness in the human encounters amidst the technological wonders, while both praised the pictorial element of the film. Reporting that «half the audience had left by intermission», Del Rey described the film as dull, confusing, and boring («the first of the New Wave-Thing movies, with the usual empty symbols»), predicting «[i]t will probably be a box-office disaster, too, and thus set major science-fiction movie making back another ten years».[163] Samuel R. Delany was impressed by how the film undercuts the audience’s normal sense of space and orientation in several ways. Like Bradbury, Delany noticed the banality of the dialogue (he stated that characters say nothing meaningful), but regarded this as a dramatic strength, a prelude to the rebirth at the conclusion of the film.[164] Without analysing the film in detail, Isaac Asimov spoke well of it in his autobiography and other essays. James P. Hogan liked the film but complained that the ending did not make any sense to him, leading to a bet about whether he could write something better: «I stole Arthur’s plot idea shamelessly and produced Inherit the Stars.»[165]

Awards and honours[edit]

In 1969, a United States Department of State committee chose 2001 as the American entry at the 6th Moscow International Film Festival.[174]

2001 was ranked 15th on the American Film Institute’s 2007 100 Years … 100 Movies[175] (22 in 1998),[176] was no. 40 on its 100 Years, 100 Thrills,[177] was included on its 100 Years, 100 Quotes (no. 78 «Open the pod bay doors, HAL.»),[178] and HAL 9000 was the no. 13 villain in 100 Years … 100 Heroes and Villains.[179] The film was also no. 47 on AFI’s 100 Years … 100 Cheers[180] and the no. 1 science fiction film on AFI’s 10 Top 10.[181]

Interpretations[edit]

Since its premiere, 2001: A Space Odyssey has been analysed and interpreted by professional critics and theorists, amateur writers, and science fiction fans. In his monograph for BFI analysing the film, Peter Krämer summarised the diverse interpretations as ranging from those who saw it as darkly apocalyptic in tone to those who saw it as an optimistic reappraisal of the hopes of mankind and humanity.[182] Questions about 2001 range from uncertainty about its implications for humanity’s origins and destiny in the universe[183] to interpreting elements of the film’s more enigmatic scenes, such as the meaning of the monolith, or the fate of astronaut David Bowman. There are also simpler and more mundane questions about the plot, in particular the causes of HAL’s breakdown (explained in earlier drafts but kept mysterious in the film).[184][41][185][186]

Audiences vs. critics[edit]

A spectrum of diverse interpretative opinions would form after the film’s release, appearing to divide theatre audiences from the opinions of critics. Krämer writes: «Many people sent letters to Kubrick to tell him about their responses to 2001, most of them regarding the film—in particular the ending—as an optimistic statement about humanity, which is seen to be born and reborn. The film’s reviewers and academic critics, by contrast, have tended to understand the film as a pessimistic account of human nature and humanity’s future. The most extreme of these interpretations state that the foetus floating above the Earth will destroy it.»[187]

Closing scene of Dr. Strangelove and Kubrick’s sardonic fulfilment of a nuclear nightmare

Some of the critics’ cataclysmic interpretations were informed by Kubrick’s prior direction of the Cold War film Dr. Strangelove, immediately before 2001, which resulted in dark speculation about the nuclear weapons orbiting the Earth in 2001. These interpretations were challenged by Clarke, who said: «Many readers have interpreted the last paragraph of the book to mean that he (the foetus) destroyed Earth, perhaps for the purpose of creating a new Heaven. This idea never occurred to me; it seems clear that he triggered the orbiting nuclear bombs harmlessly …».[182] In response to Jeremy Bernstein’s dark interpretation of the film’s ending, Kubrick said: «The book does not end with the destruction of the Earth.»[182]

Regarding the film as a whole, Kubrick encouraged people to make their own interpretations and refused to offer an explanation of «what really happened». In a 1968 interview with Playboy magazine, he said:

You’re free to speculate as you wish about the philosophical and allegorical meaning of the film—and such speculation is one indication that it has succeeded in gripping the audience at a deep level—but I don’t want to spell out a verbal road map for 2001 that every viewer will feel obligated to pursue or else fear he’s missed the point.[40]

In a subsequent discussion of the film with Joseph Gelmis, Kubrick said his main aim was to avoid «intellectual verbalization» and reach «the viewer’s subconscious.» But he said he did not strive for ambiguity—it was simply an inevitable outcome of making the film nonverbal. Still, he acknowledged this ambiguity was an invaluable asset to the film. He was willing then to give a fairly straightforward explanation of the plot on what he called the «simplest level,» but unwilling to discuss the film’s metaphysical interpretation, which he felt should be left up to viewers.[188]

Meaning of the monolith[edit]

For some readers, Clarke’s more straightforward novel based on the script is key to interpreting the film. The novel explicitly identifies the monolith as a tool created by an alien race that has been through many stages of evolution, moving from organic form to biomechanical, and finally achieving a state of pure energy. These aliens travel the cosmos assisting lesser species to take evolutionary steps. Conversely, film critic Penelope Houston wrote in 1971 that because the novel differs in many key aspects from the film, it perhaps should not be regarded as the skeleton key to unlock it.[189]

Multiple interpretations of the meaning of the monolith have been examined in the critical reception of the film

Carolyn Geduld writes that what «structurally unites all four episodes of the film» is the monolith, the film’s largest and most unresolvable enigma.[190] Vincent LoBrutto’s biography of Kubrick says that for many, Clarke’s novel supplements the understanding of the monolith which is more ambiguously depicted in the film.[191] Similarly, Geduld observes that «the monolith … has a very simple explanation in Clarke’s novel», though she later asserts that even the novel does not fully explain the ending.[190]

Bob McClay’s Rolling Stone review describes a parallelism between the monolith’s first appearance in which tool usage is imparted to the apes (thus ‘beginning’ mankind) and the completion of «another evolution» in the fourth and final encounter[192] with the monolith. In a similar vein, Tim Dirks ends his synopsis saying «[t]he cyclical evolution from ape to man to spaceman to angel-starchild-superman is complete.»[193]

Humanity’s first and second encounters with the monolith have visual elements in common; both the apes, and later the astronauts, touch it gingerly with their hands, and both sequences conclude with near-identical images of the Sun appearing directly over it (the first with a crescent moon adjacent to it in the sky, the second with a near-identical crescent Earth in the same position), echoing the Sun–Earth–Moon alignment seen at the very beginning of the film.[194] The second encounter also suggests the triggering of the monolith’s radio signal to Jupiter by the presence of humans, echoing the premise of Clarke’s source story «The Sentinel».[195]

The monolith is the subject of the film’s final line of dialogue (spoken at the end of the «Jupiter Mission» segment): «Its origin and purpose still a total mystery.» Reviewers McClay and Roger Ebert wrote that the monolith is the main element of mystery in the film; Ebert described «the shock of the monolith’s straight edges and square corners among the weathered rocks,» and the apes warily circling it as prefiguring man reaching «for the stars.»[47] Patrick Webster suggests the final line relates to how the film should be approached as a whole: «The line appends not merely to the discovery of the monolith on the Moon, but to our understanding of the film in the light of the ultimate questions it raises about the mystery of the universe.»[196]

According to other scholars, «the monolith is a representation of the actual wideframe cinema screen, rotated 90 degrees … a symbolic cinema screen».[197] «It is at once a screen and the opposite of a screen, since its black surface only absorbs, and sends nothing out. … and leads us … to project ourselves, our emotions».[198]

«A new heaven»[edit]

Clarke indicated his preferred reading of the ending of 2001 as oriented toward the creation of «a new heaven» provided by the Star Child.[182] His view was corroborated in a posthumously released interview with Kubrick.[41] Kubrick says that Bowman is elevated to a higher level of being that represents the next stage of human evolution. The film also conveys what some viewers have described as a sense of the sublime and numinous.[47] Ebert writes in his essay on 2001 in The Great Movies:

The Star Child looking upon the Earth

North’s [rejected] score, which is available on a recording, is a good job of film composition, but would have been wrong for 2001 because, like all scores, it attempts to underline the action—to give us emotional cues. The classical music chosen by Kubrick exists outside the action. It uplifts. It wants to be sublime; it brings a seriousness and transcendence to the visuals.[47]

In a book on architecture, Gregory Caicco writes that Space Odyssey illustrates how our quest for space is motivated by two contradictory desires, a «desire for the sublime» characterised by a need to encounter something totally other than ourselves—»something numinous»—and the conflicting desire for a beauty that makes us feel no longer «lost in space,» but at home.[199] Similarly, an article in The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Science Fiction and Fantasy, titled «Sense of Wonder,» describes how 2001 creates a «numinous sense of wonder» by portraying a universe that inspires a sense of awe but that at the same time we feel we can understand.[200] Christopher Palmer wrote that «the sublime and the banal» coexist in the film, as it implies that to get into space, people had to suspend the «sense of wonder» that motivated them to explore it.[201]

HAL’s breakdown[edit]

One of HAL 9000’s interfaces

The reasons for HAL’s malfunction and subsequent malignant behaviour have elicited much discussion. He has been compared to Frankenstein’s monster. In Clarke’s novel, HAL malfunctions because of being ordered to lie to the crew of Discovery and withhold confidential information from them, namely the confidentially programmed mission priority over expendable human life, despite being constructed for «the accurate processing of information without distortion or concealment». This would not be addressed on film until the 1984 follow-up, 2010: The Year We Make Contact. Film critic Roger Ebert wrote that HAL, as the supposedly perfect computer, is actually the most human of the characters.[47] In an interview with Joseph Gelmis in 1969, Kubrick said that HAL «had an acute emotional crisis because he could not accept evidence of his own fallibility».[202]

«Star Child» symbolism[edit]

Multiple allegorical interpretations of 2001 have been proposed. The symbolism of life and death can be seen through the final moments of the film, which are defined by the image of the «Star Child,» an in utero foetus that draws on the work of Lennart Nilsson.[203] The Star Child signifies a «great new beginning,»[203] and is depicted naked and ungirded but with its eyes wide open.[204] Leonard F. Wheat sees 2001 as a multi-layered allegory, commenting simultaneously on Nietzsche, Homer, and the relationship of man to machine.[205] Rolling Stone reviewer Bob McClay sees the film as like a four-movement symphony, its story told with «deliberate realism».[206]

Military satellites[edit]

Kubrick originally planned a voice-over to reveal that the satellites seen after the prologue are nuclear weapons,[207] and that the Star Child would detonate the weapons at the end of the film[208] but felt this would create associations with Dr. Strangelove and decided not to make it obvious that they were «war machines». A few weeks before the film’s release, the U.S. and Soviet governments had agreed not to put any nuclear weapons into outer space.[209]

In a book he wrote with Kubrick’s assistance, Alexander Walker states that Kubrick eventually decided that nuclear weapons had «no place at all in the film’s thematic development», being an «orbiting red herring» that would «merely have raised irrelevant questions to suggest this as a reality of the twenty-first century».[207]

Kubrick scholar Michel Ciment, discussing Kubrick’s attitude toward human aggression and instinct, observes: «The bone cast into the air by the ape (now become a man) is transformed at the other extreme of civilization, by one of those abrupt ellipses characteristic of the director, into a spacecraft on its way to the moon.»[210] In contrast to Ciment’s reading of a cut to a serene «other extreme of civilization», science fiction novelist Robert Sawyer, in the Canadian documentary 2001 and Beyond, says he sees it as a cut from a bone to a nuclear weapons platform, explaining that «what we see is not how far we’ve leaped ahead, what we see is that today, ‘2001’, and four million years ago on the African veldt, it’s exactly the same—the power of mankind is the power of its weapons. It’s a continuation, not a discontinuity in that jump.»[211]

Legacy and influence[edit]

2001: A Space Odyssey is widely regarded as among the greatest and most influential films ever made.[212] It is considered one of the major artistic works of the 20th century, with many critics and filmmakers considering it Kubrick’s masterpiece.[213] In the 1980s,[214] critic David Denby compared Kubrick to the monolith from 2001: A Space Odyssey, calling him «a force of supernatural intelligence, appearing at great intervals amid high-pitched shrieks, who gives the world a violent kick up the next rung of the evolutionary ladder».[215] By the start of the 21st century, 2001: A Space Odyssey had become recognised as among the best films ever made by such sources as the British Film Institute (BFI). The Village Voice ranked the film at number 11 in its Top 250 «Best Films of the Century» list in 1999, based on a poll of critics.[216] In January 2002, the film was voted no. 1 on the list of the «Top 100 Essential Films of All Time» by the National Society of Film Critics.[217][218] Sight & Sound magazine ranked the film 12th in its greatest films of all-time list in 1982,[219] tenth in 1992 critics’ poll of greatest films,[220] sixth in the top ten films of all time in its 2002,[221] 2012[222] and 2022 critics’ polls editions;[160] it also tied for second and first place in the magazine’s 2012[222] and 2022 directors’ poll.[160] The film was voted no. 43 on the list of «100 Greatest Films» by the prominent French magazine Cahiers du cinéma in 2008.[223] In 2010, The Guardian named it «the best sci-fi and fantasy film of all time».[224] The film ranked 4th in BBC’s 2015 list of the 100 greatest American films.[225] In 1991, it was deemed «culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant» by the United States Library of Congress and selected for preservation in the National Film Registry.[226] In 2010, it was named the greatest film of all time by The Moving Arts Film Journal.[227]

Stanley Kubrick made the ultimate science fiction movie, and it is going to be very hard for someone to come along and make a better movie, as far as I’m concerned. On a technical level, it [Star Wars] can be compared, but personally I think that 2001 is far superior.

—George Lucas, 1977[119]

The influence of 2001 on subsequent filmmakers is considerable. Steven Spielberg, George Lucas, and others—including many special effects technicians—discuss the impact the film has had on them in a featurette titled Standing on the Shoulders of Kubrick: The Legacy of 2001, included in the 2007 DVD release of the film. Spielberg calls it his film generation’s «big bang», while Lucas says it was «hugely inspirational», calling Kubrick «the filmmaker’s filmmaker». Director Martin Scorsese has listed it as one of his favourite films of all time.[228] Sydney Pollack calls it «groundbreaking», and William Friedkin says 2001 is «the grandfather of all such films». At the 2007 Venice film festival, director Ridley Scott said he believed 2001 was the unbeatable film that in a sense killed the science fiction genre.[229] Similarly, film critic Michel Ciment in his essay «Odyssey of Stanley Kubrick» wrote, «Kubrick has conceived a film which in one stroke has made the whole science fiction cinema obsolete.»[230]

Others credit 2001 with opening up a market for films such as Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Alien, Blade Runner, Contact, and Interstellar, proving that big-budget «serious» science-fiction films can be commercially successful, and establishing the «sci-fi blockbuster» as a Hollywood staple.[231] Science magazine Discover‘s blogger Stephen Cass, discussing the film’s considerable impact on subsequent science fiction, writes that «the balletic spacecraft scenes set to sweeping classical music, the tarantula-soft tones of HAL 9000, and the ultimate alien artifact, the monolith, have all become enduring cultural icons in their own right».[232] Trumbull said that when working on Star Trek: The Motion Picture he made a scene without dialogue because of «something I really learned with Kubrick and 2001: Stop talking for a while, and let it all flow».[233]

Kubrick did not envision a sequel to 2001. Fearing the later exploitation and recycling of his material in other productions (as was done with the props from MGM’s Forbidden Planet), he ordered all sets, props, miniatures, production blueprints, and prints of unused scenes destroyed.[citation needed] Most of these materials were lost, with some exceptions: a 2001 spacesuit backpack appeared in the «Close Up» episode of the Gerry Anderson series UFO,[209][234][235][236] and one of HAL’s eyepieces is in the possession of the author of Hal’s Legacy, David G. Stork. In 2012, Lockheed engineer Adam Johnson, working with Frederick I. Ordway III, science adviser to Kubrick, wrote the book 2001: The Lost Science, which for the first time featured many of the blueprints of the spacecraft and film sets that previously had been thought destroyed. Clarke wrote three sequel novels: 2010: Odyssey Two (1982), 2061: Odyssey Three (1987), and 3001: The Final Odyssey (1997). The only filmed sequel, 2010: The Year We Make Contact, released in 1984, was based on Clarke’s 1982 novel. Kubrick was not involved; it was directed as a spin-off by Peter Hyams in a more conventional style. The other two novels have not been adapted for the screen, although actor Tom Hanks in June 1999 expressed a passing interest in possible adaptations.[237]

To commemorate the 50th anniversary of the film’s release, an exhibit called «The Barmecide Feast» opened on 8 April 2018, in the Smithsonian Institution’s National Air and Space Museum. The exhibit features a fully realised, full-scale reflection of the neo-classical hotel room from the film’s penultimate scene.[238][239] Director Christopher Nolan presented a mastered 70 mm print of 2001 for the film’s 50th anniversary at the 2018 Cannes Film Festival on 12 May.[240][241] The new 70 mm print is a photochemical recreation made from the original camera negative, for the first time since the film’s original theatrical run.[242][243] Further, an exhibit entitled «Envisioning 2001: Stanley Kubrick’s Space Odyssey» presented at the Museum of the Moving Image in Astoria, Queens, New York City opened in January 2020.[244]