This article is about the 1972 film. For the original novel on which the film is based, see The Godfather (novel). For other uses, see Godfather.

| The Godfather | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster |

|

| Directed by | Francis Ford Coppola |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Based on | The Godfather by Mario Puzo |

| Produced by | Albert S. Ruddy |

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Gordon Willis |

| Edited by |

|

| Music by | Nino Rota |

|

Production |

|

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures |

|

Release dates |

|

|

Running time |

175 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $6–7.2 million[N 1] |

| Box office | $250–291 million[N 2] |

The Godfather is a 1972 American crime film[2] directed by Francis Ford Coppola, who co-wrote the screenplay with Mario Puzo, based on Puzo’s best-selling 1969 novel of the same title. The film stars Marlon Brando, Al Pacino, James Caan, Richard Castellano, Robert Duvall, Sterling Hayden, John Marley, Richard Conte, and Diane Keaton. It is the first installment in The Godfather trilogy, chronicling the Corleone family under patriarch Vito Corleone (Brando) from 1945 to 1955. It focuses on the transformation of his youngest son, Michael Corleone (Pacino), from reluctant family outsider to ruthless mafia boss.

Paramount Pictures obtained the rights to the novel for $80,000, before it gained popularity.[3][4] Studio executives had trouble finding a director; the first few candidates turned down the position before Coppola signed on to direct the film but disagreement followed over casting several characters, in particular, Vito (Marlon Brando) and Michael (Al Pacino). Filming took place primarily on location around New York City and in Sicily, and was completed ahead of schedule. The musical score was composed principally by Nino Rota, with additional pieces by Carmine Coppola.

The Godfather premiered at the Loew’s State Theatre on March 14, 1972, and was widely released in the United States on March 24, 1972. It was the highest-grossing film of 1972, and was for a time the highest-grossing film ever made, earning between $250 and $291 million at the box office. The film received universal acclaim from critics and audiences, with praise for the performances, particularly those of Brando and Pacino, direction, screenplay, cinematography, editing, score, and portrayal of the mafia. The Godfather acted as a catalyst for the successful careers of Coppola, Pacino, and other relative newcomers in the cast and crew. The film also revitalized Brando’s career, which had declined in the 1960s, and he went on to star in films such as Last Tango in Paris, Superman, and Apocalypse Now. At the 45th Academy Awards, the film won Best Picture, Best Actor (Brando), and Best Adapted Screenplay (for Puzo and Coppola). In addition, the seven other Oscar nominations included Pacino, Caan, and Duvall all for Best Supporting Actor, and Coppola for Best Director.

The Godfather is regarded as one of the greatest and most influential films ever made, as well as a landmark of the gangster genre.[5] It was selected for preservation in the U.S. National Film Registry of the Library of Congress in 1990, being deemed «culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant» and is ranked the second-greatest film in American cinema (behind Citizen Kane) by the American Film Institute. It was followed by sequels The Godfather Part II (1974) and The Godfather Part III (1990).

Plot[edit]

In 1945 New York City, Corleone crime family don Vito Corleone listens to requests during his daughter Connie’s wedding to Carlo. Michael, Vito’s youngest son and a former Marine, introduces his girlfriend, Kay Adams, to his family at the reception. Johnny Fontane, a popular singer and Vito’s godson, seeks Vito’s help in securing a movie role. Vito sends his consigliere, Tom Hagen, to persuade studio head Jack Woltz to offer Johnny the part. Woltz refuses Hagen’s request at first, but soon complies after finding the severed head of his prized racing horse in his bed.

Near Christmas, drug baron Sollozzo asks Vito to invest in his narcotics business and for protection from the law. Vito declines, citing that involvement in narcotics would alienate his political connections. Suspicious of Sollozzo’s partnership with the Tattaglia crime family, Vito sends his enforcer Luca Brasi to the Tattaglias on an espionage mission. Brasi is garroted to death during the initial meeting. Later, enforcers gun down Vito and kidnap Hagen. With Vito’s first-born Sonny now in command, Sollozzo pressures Hagen to persuade Sonny to accept the narcotics deal. Sonny retaliates for Brasi’s death with a hit on Bruno Tattaglia. Vito survives the shooting and is visited in the hospital by Michael, who finds him unprotected after NYPD officers on Sollozzo’s payroll cleared out Vito’s guards. Michael thwarts another attempt on his father’s life but is beaten by corrupt police captain Mark McCluskey. Sollozzo and McCluskey request to meet with Michael and settle the dispute. Michael feigns interest and agrees to meet, but hatches a plan with Sonny and Corleone capo Clemenza to kill them and go into hiding. Michael meets Sollozzo and McCluskey at a Bronx restaurant; after retrieving a handgun planted in the bathroom by Clemenza, he shoots both men dead.

Despite a clampdown by the authorities for the killing of a police captain, the Five Families erupt in open warfare. Michael takes refuge in Sicily and Fredo, Vito’s second son, is sheltered by Moe Greene in Las Vegas. Sonny publicly attacks and threatens Carlo for physically abusing Connie. When he abuses her again, Sonny speeds to their home but is ambushed and murdered by gangsters at a highway toll booth. In Sicily, Michael meets and marries a local woman, Apollonia, but she is killed shortly thereafter by a car bomb intended for him.

Devastated by Sonny’s death and tired of war, Vito sets a meeting with the Five Families. He assures them that he will withdraw his opposition to their narcotics business and forgo avenging Sonny’s murder. His safety guaranteed, Michael returns home to enter the family business and marry Kay. Kay gives birth to two children in the early 1950s. With his father nearing the end of his life and Fredo not suited to lead, Michael assumes the position of head of the Corleone family. Vito reveals to Michael that it was Don Barzini who ordered the hit on Sonny and warns him that Barzini would try to kill him at a meeting organized by a traitorous Corleone capo. With Vito’s support, Michael relegates Hagen to managing operations in Las Vegas as he is not a «wartime consigliere». Michael travels to Las Vegas to buy out Greene’s stake in the family’s casinos and is dismayed to see that Fredo is more loyal to Greene than to his own family.

In 1955, Vito dies of a heart attack while playing with his grandchild. At Vito’s funeral, Tessio asks Michael to meet with Barzini, signaling his betrayal. The meeting is set for the same day as the baptism of Connie’s baby. While Michael stands at the altar as the child’s godfather, Corleone hitmen murder the dons of the Five Families, plus Greene, and Tessio is executed (offscreen) for his treachery. Michael extracts Carlo’s confession to playing a part in Sonny’s murder, assuring Carlo he is only being exiled, not murdered; afterward, Clemenza garrotes Carlo to death. Connie confronts Michael about Carlo’s death while Kay is in the room. Kay asks Michael if Connie is telling the truth and is relieved when he denies it. As Kay leaves, capos enter the office and pay reverence to Michael as «Don Corleone» before closing the door.

Cast[edit]

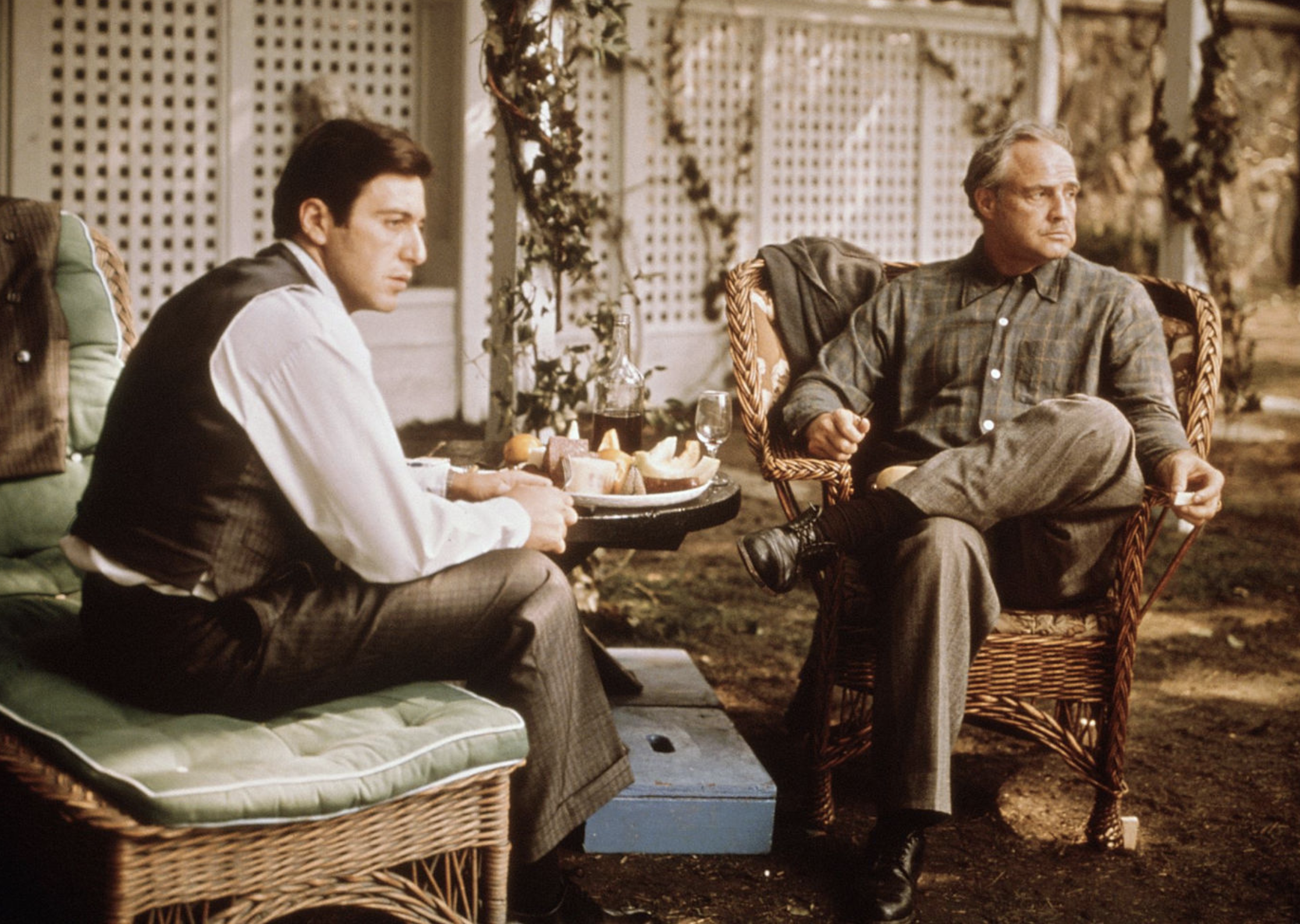

Brando (right) and Pacino as Don Vito and Michael Corleone, respectively

- Marlon Brando as Vito Corleone: crime boss and patriarch of the Corleone family

- Al Pacino as Michael Corleone: Vito’s youngest son

- James Caan as Sonny Corleone: Vito’s eldest son

- Richard Castellano as Peter Clemenza: a caporegime in the Corleone crime family, Sonny’s godfather

- Robert Duvall as Tom Hagen: Corleone consigliere, lawyer, and unofficial adopted member of the Corleone family

- Sterling Hayden as Captain McCluskey: a corrupt police captain on Sollozzo’s payroll

- John Marley as Jack Woltz: Hollywood film producer who is intimidated by the Corleones

- Richard Conte as Emilio Barzini: a crime boss of a rival family

- Al Lettieri as Virgil Sollozzo: an adversary who pressures Vito to get into the drug business, backed by the Tattaglia family

- Diane Keaton as Kay Adams-Corleone: Michael’s girlfriend and, later, second wife

- Abe Vigoda as Salvatore Tessio: a caporegime in the Corleone crime family

- Talia Shire as Connie Corleone: Vito’s only daughter

- Gianni Russo as Carlo Rizzi: Connie’s abusive husband

- John Cazale as Fredo Corleone: Vito’s middle son

- Rudy Bond as Cuneo: a crime boss of a rival family

- Al Martino as Johnny Fontane: a singer

- Morgana King as Mama Corleone: Vito’s wife

- Lenny Montana as Luca Brasi: Vito’s enforcer

- Johnny Martino as Paulie Gatto: a soldier in the Corleone crime family

- Salvatore Corsitto as Amerigo Bonasera: the undertaker who asks for a favor at Connie’s wedding

- Richard Bright as Neri: the soldier in the Corleone crime family who becomes Michael’s enforcer

- Alex Rocco as Moe Greene

- Tony Giorgio as Bruno Tattaglia

- Vito Scotti as Nazorine

- Tere Livrano as Theresa Hagen: Tom’s wife

- Victor Rendina as Philip Tattaglia: head of the Tattaglia crime family and prostitution crime boss

- Jeannie Linero as Lucy Mancini

- Julie Gregg as Sandra Corleone

- Ardell Sheridan as Mrs. Clemenza

Other actors playing smaller roles in the Sicilian sequence are Simonetta Stefanelli as Apollonia Vitelli-Corleone, Angelo Infanti as Fabrizio, Corrado Gaipa as Don Tommasino, Franco Citti as Calò and Saro Urzì as Vitelli.[6][7]

Production[edit]

Development[edit]

The film is based on Mario Puzo’s The Godfather, which remained on The New York Times Best Seller list for 67 weeks and sold over nine million copies in two years.[8][9][10] Published in 1969, it became the best selling published work in history for several years.[11] Paramount Pictures originally found out about Puzo’s novel in 1967 when a literary scout for the company contacted then Paramount Vice President of Production Peter Bart about Puzo’s unfinished sixty-page manuscript.[9] Bart believed the work was «much beyond a Mafia story» and offered Puzo a $12,500 option for the work, with an option for $80,000 if the finished work were to be made into a film.[9][12] Despite Puzo’s agent telling him to turn down the offer, Puzo was desperate for money and accepted the deal.[9][12] Paramount’s Robert Evans relates that, when they met in early 1968, he offered Puzo the $12,500 deal for the 60-page manuscript titled Mafia after the author confided in him that he urgently needed $10,000 to pay off gambling debts.[13]

In March 1967, Paramount announced that they backed Puzo’s upcoming work in the hopes of making a film.[9] In 1969, Paramount confirmed their intentions to make a film out of the novel for the price of $80,000,[N 3][12][14][15][16] with aims to have the film released on Christmas Day in 1971.[17] On March 23, 1970, Albert S. Ruddy was officially announced as the film’s producer, in part because studio executives were impressed with his interview and because he was known for bringing his films in under budget.[18][19][20]

Direction[edit]

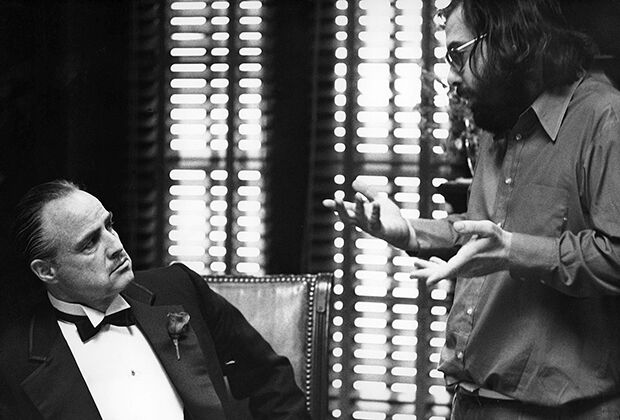

Evans wanted the picture to be directed by an Italian American to make the film «ethnic to the core».[21][22] Paramount’s latest mafia movie, The Brotherhood, had done very poorly at the box office;[10][23] Evans believed that the reason for its failure was its almost complete lack of cast members or creative personnel of Italian descent (the director Martin Ritt and star Kirk Douglas were not Italian).[13] Sergio Leone was Paramount’s first choice to direct the film.[24][25] Leone turned down the option, in order to work on his own gangster film Once Upon a Time in America.[24][25] Peter Bogdanovich was then approached but he also declined the offer because he was not interested in the mafia.[26][27][28] In addition, Peter Yates, Richard Brooks, Arthur Penn, Costa-Gavras, and Otto Preminger were all offered the position and declined.[29][30] Evans’ chief assistant Peter Bart suggested Francis Ford Coppola, as a director of Italian ancestry who would work for a low sum and budget after the poor reception of his latest film The Rain People.[31][21] Coppola initially turned down the job because he found Puzo’s novel sleazy and sensationalist, describing it as «pretty cheap stuff».[13][32] At the time Coppola’s studio, American Zoetrope,[33] owed over $400,000 to Warner Bros. for budget overruns with the film THX 1138 and when coupled with his poor financial standing, along with advice from friends and family, Coppola reversed his initial decision and took the job.[30][34][35] Coppola was officially announced as director of the film on September 28, 1970.[36] Coppola agreed to receive $125,000 and six percent of the gross rentals.[37][38] Coppola later found a deeper theme for the material and decided that the film should not be about organized crime but a family chronicle, a metaphor for capitalism in America.[21]

Coppola and Paramount[edit]

Before The Godfather was in production, Paramount had been going through an unsuccessful period.[10] In addition to the failure of The Brotherhood, other recent films that were produced or co-produced by Paramount had greatly exceeded their budgets: Darling Lili,[19] Paint Your Wagon, and Waterloo.[10][23] The budget for the film was originally $2.5 million but as the book grew in popularity Coppola argued for and ultimately received a larger budget.[N 1][29][39][41] Paramount executives wanted the movie to be set in contemporary Kansas City and shot in the studio backlot in order to cut down on costs.[29][19][39] Coppola objected and wanted to set the movie in the same time period as the novel, the 1940s and 1950s;[19][29][35][36] Coppola’s reasons included: Michael Corleone’s Marine Corps stint, the emergence of corporate America, and America in the years after World War II.[36] The novel was becoming increasingly successful and so Coppola’s wishes were eventually granted.[19][39] The studio heads subsequently let Coppola film on location in New York City and Sicily.[47]

Gulf+Western executive Charles Bluhdorn was frustrated with Coppola over the number of screen tests he had performed without finding a person to play the various roles.[42] Production quickly fell behind because of Coppola’s indecisiveness and conflicts with Paramount, which led to costs being around $40,000 per day.[42] With costs rising, Paramount had then-Vice President Jack Ballard keep a close eye on production expenses.[48] While filming, Coppola stated that he felt he could be fired at any point as he knew Paramount executives were not happy with many of the decisions he had made.[29] Coppola was aware that Evans had asked Elia Kazan to take over directing the film because he feared that Coppola was too inexperienced to cope with the increased size of the production.[49] Coppola was also convinced that the film editor, Aram Avakian, and the assistant director, Steve Kestner, were conspiring to get him fired. Avakian complained to Evans that he could not edit the scenes correctly because Coppola was not shooting enough footage. Evans was satisfied with the footage being sent to the West Coast and authorized Coppola to fire them both. Coppola later explained: «Like the godfather, I fired people as a preemptory strike. The people who were angling the most to have me fired, I had fired.»[50] Brando threatened to quit if Coppola was fired.[29][48]

Paramount wanted The Godfather to appeal to a wide audience and threatened Coppola with a «violence coach» to make the film more exciting. Coppola added a few more violent scenes to keep the studio happy. The scene in which Connie smashes crockery after finding out Carlo has been cheating was added for this reason.[35]

Writing[edit]

On April 14, 1970, it was revealed that Puzo was hired by Paramount for $100,000, along with a percentage of the film’s profits, to work on the screenplay for the film.[20][51][52] Working from the book, Coppola wanted to have the themes of culture, character, power, and family at the forefront of the film, whereas Puzo wanted to retain aspects from his novel[53] and his initial draft of 150 pages was finished on August 10, 1970.[51][52] After Coppola was hired as director, both Puzo and Coppola worked on the screenplay, but separately.[54] Puzo worked on his draft in Los Angeles, while Coppola wrote his version in San Francisco.[54] Coppola created a book where he tore pages out of Puzo’s book and pasted them into his book.[55][54] There, he made notes about each of the book’s fifty scenes, which related to major themes prevalent in the scene, whether the scene should be included in the film, along with ideas and concepts that could be used when filming to make the film true to Italian culture.[54][48] The two remained in contact while they wrote their respective screenplays and made decisions on what to include and what to remove for the final version.[54] A second draft was completed on March 1, 1971, and was 173 pages long.[51][56] The final screenplay was finished on March 29, 1971,[52] and wound up being 163 pages long,[51][54] 40 pages over what Paramount had asked for.[57] When filming, Coppola referred to the notebook he had created over the final draft of the screenplay.[54][48] Screenwriter Robert Towne did uncredited work on the script, particularly on the Pacino-Brando garden scene.[58] Despite finishing the third draft, some scenes in the film were still not written yet and were written during production.[59]

The Italian-American Civil Rights League, led by mobster Joseph Colombo, maintained that the film emphasized stereotypes about Italian-Americans, and wanted all uses of the words «mafia» and «Cosa Nostra» to be removed from the script.[60][17][61][62][63] The league also requested that all the money earned from the premiere be donated to the league’s fund to build a new hospital.[62][63] Coppola claimed that Puzo’s screenplay only contained two instances of the word «mafia» being used, while «Cosa Nostra» was not used at all.[62][63] They were removed and replaced with other terms, without compromising the story.[62][63] The league eventually gave its support for the script.[62][63] Earlier, the windows of producer Albert S. Ruddy’s car had been shot out with a note left on the dashboard which essentially said, «shut down the movie—or else.»[21]

Casting[edit]

Puzo was first to show interest in having Marlon Brando portray Don Vito Corleone by sending a letter to Brando in which he stated Brando was the «only actor who can play the Godfather».[64] Despite Puzo’s wishes, the executives at Paramount were against having Brando,[33] partly because of the poor performance of his recent films and also his short temper.[39][65] Coppola favored Brando or Laurence Olivier for the role,[66][67] but Olivier’s agent refused the role claiming Olivier was sick;[68] however, Olivier went on to star in Sleuth later that year.[67] The studio mainly pushed for Ernest Borgnine to receive the part.[66] Others considered were George C. Scott, Richard Conte, Anthony Quinn and Orson Welles.[66][69][70] Welles was Paramount’s preferred choice for the role.[71]

After months of debate between Coppola and Paramount over Brando, the two finalists for the role were Borgnine and Brando,[72] the latter of whom Paramount president Stanley Jaffe required to perform a screen test.[73][74] Coppola did not want to offend Brando and stated that he needed to test equipment in order to set up the screen test at Brando’s California residence.[74][75] For make-up, Brando stuck cotton balls in his cheeks,[72] put shoe polish in his hair to darken it, and rolled his collar.[76] Coppola placed Brando’s audition tape in the middle of the videos of the audition tapes as the Paramount executives watched them.[77] The executives were impressed with Brando’s efforts and allowed Coppola to cast Brando for the role if Brando accepted a lower salary and put up a bond to ensure he would not cause any delays in production.[72][77][78] Brando earned $1.6 million from a net participation deal.[79]

From the start of production, Coppola wanted Robert Duvall to play the part of Tom Hagen.[17][80][81] After screen testing several other actors, Coppola eventually got his wish and Duvall was awarded the part.[80][81] Al Martino, a then famed singer in nightclubs, was notified of the character Johnny Fontane by a friend who read the novel and felt Martino represented the character of Johnny Fontane. Martino then contacted producer Albert S. Ruddy, who gave him the part. However, Martino was stripped of the part after Coppola became director and then awarded the role to singer Vic Damone. According to Martino, after being stripped of the role, he went to Russell Bufalino, his godfather and a crime boss, who then orchestrated the publication of various news articles that claimed Coppola was unaware of Ruddy giving Martino the part.[21] Damone eventually dropped the role because he did not want to provoke the mob, in addition to being paid too little.[21][82] Ultimately, the part of Johnny Fontane was given to Martino.[21][82]

Robert De Niro originally was given the part of Paulie Gatto.[83][72] A spot in The Gang That Couldn’t Shoot Straight opened up after Al Pacino quit the project in favor of The Godfather, which led De Niro to audition for the role and leave The Godfather after receiving the part.[83][84] De Niro also cast for the role of Sonny Corleone.[85][86][87] After De Niro quit, Johnny Martino was given the role of Gatto.[21] Coppola cast Diane Keaton for the role of Kay Adams owing to her reputation for being eccentric.[88] John Cazale was given the part of Fredo Corleone after Coppola saw him perform in an Off Broadway production.[88] Gianni Russo was given the role of Carlo Rizzi after he was asked to perform a screen test in which he acted out the fight between Rizzi and Connie.[89]

Nearing the start of filming on March 29, Michael Corleone had yet to be cast.[90] Paramount executives wanted a popular actor, either Warren Beatty or Robert Redford.[91][72][92] Producer Robert Evans wanted Ryan O’Neal to receive the role, owing in part to his recent success in Love Story.[92][93] Pacino was Coppola’s favorite for the role[33] as he could picture him roaming the Sicilian countryside, and wanted an unknown actor who looked like an Italian-American.[35][92][93] However, Paramount executives found Pacino to be too short to play Michael.[17][21] Dustin Hoffman, Martin Sheen, and James Caan also auditioned.[88] Burt Reynolds was offered the role of Michael, but Marlon Brando threatened to quit if Reynolds was hired, so Reynolds turned down the role.[94] Jack Nicholson was also offered the role, but turned it down as he felt that an Italian-American actor should play the role.[95][96] Caan was well received by the Paramount executives and was given the part of Michael initially, while the role of Sonny Corleone was awarded to Carmine Caridi.[21] Coppola still pushed for Pacino to play Michael after the fact and Evans eventually conceded, allowing Pacino to have the role of Michael as long as Caan played Sonny.[97] Evans preferred Caan over Caridi because Caan was seven inches shorter than Caridi, which was much closer to Pacino’s height.[21] Despite agreeing to play Michael Corleone, Pacino was contracted to star in MGM’s The Gang That Couldn’t Shoot Straight, but the two studios agreed on a settlement and Pacino was signed by Paramount three weeks before shooting began.[98]

Coppola gave several roles in the film to family members.[21] He gave his sister, Talia Shire, the role of Connie Corleone.[99][100] His daughter Sofia played Michael Francis Rizzi, Connie’s and Carlo’s newborn son.[21][101] Carmine Coppola, his father, appeared in the film as an extra playing a piano during a scene.[102] Coppola’s wife, mother, and two sons all appeared as extras in the picture.[21]

Several smaller roles, like Luca Brasi, were cast after the filming had started.[103]

Filming[edit]

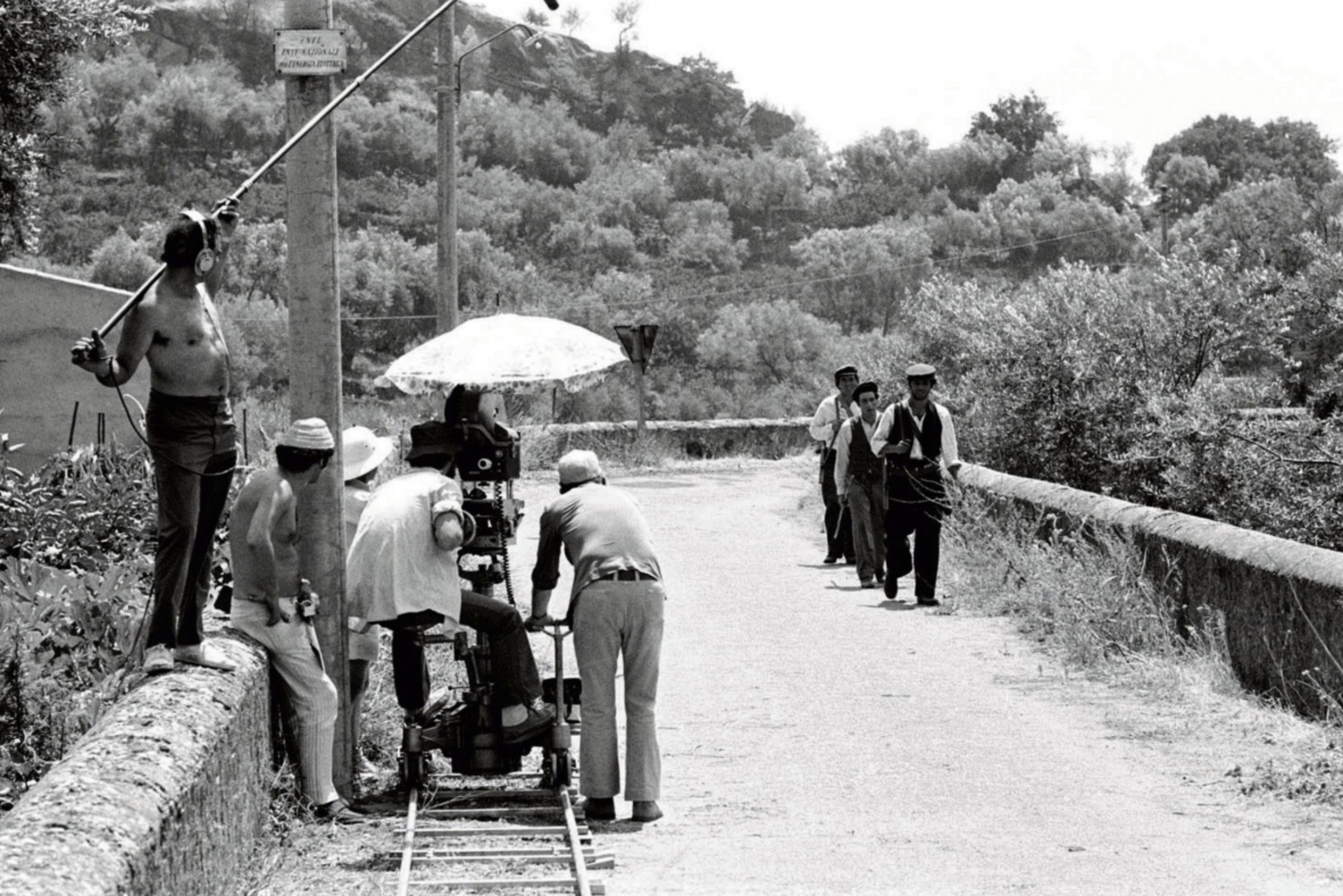

Before the filming began, the cast received a two-week period for rehearsal, which included a dinner where each actor and actress had to assume character for its duration.[104] Filming was scheduled to begin on March 29, 1971, with the scene between Michael Corleone and Kay Adams as they leave Best & Co. in New York City after shopping for Christmas gifts.[105][106] The weather on March 23 predicted snow flurries, which caused Ruddy to move the filming date forward; snow did not materialize and a snow machine was used.[106] Principal filming in New York continued until July 2, 1971.[107][108] Coppola asked for a three-week break before heading overseas to film in Sicily.[107] Following the crew’s departure for Sicily, Paramount announced that the release date would be moved to early 1972.[109]

Cinematographer Gordon Willis initially turned down the opportunity to film The Godfather because the production seemed «chaotic» to him.[111][97] After Willis later accepted the offer, he and Coppola agreed to not use any modern filming devices, helicopters, or zoom lenses.[112] Willis and Coppola chose to use a «tableau format» of filming to make it seem as if it was viewed like a painting.[112] He made use of shadows and low light levels throughout the film to showcase psychological developments.[112] Willis and Coppola agreed to interplay light and dark scenes throughout the film.[42] Willis underexposed the film in order to create a «yellow tone».[112] The scenes in Sicily were shot to display the countryside and «display a more romantic land,» giving these scenes a «softer, more romantic» feel than the New York scenes.[113]

One of the film’s most shocking moments involved an actual, severed, horse’s head.[35][114] The filming location for this scene is contested, as some sources indicate it was filmed at the Beverly Estate, while others indicate it was filmed at Sands Point Preserve on Long Island.[115][116][117] Coppola received some criticism for the scene, although the head was obtained from a dog-food company from a horse that was to be killed regardless of the film.[118] On June 22, the scene where Sonny is killed was shot on a runway at Mitchel Field in Uniondale, where three tollbooths were built, along with guard rails, and billboards to set the scene.[119] Sonny’s car was a 1941 Lincoln Continental with holes drilled in it to resemble bullet holes.[120][121] The scene took three days to film and cost over $100,000.[122][121]

Coppola’s request to film on location was observed; approximately 90 percent was shot in New York City and its surrounding suburbs,[123][124] using over 120 distinct locations.[125] Several scenes were filmed at Filmways in East Harlem.[126] The remaining portions were filmed in California, or on-site in Sicily. The scenes set in Las Vegas were not shot on location because there were insufficient funds.[123][127] Savoca and Forza d’Agrò were the Sicilian towns featured in the film.[128] The opening wedding scene was shot in a Staten Island neighborhood using almost 750 locals as extras.[124][129] The house used as the Corleone household and the wedding location was at 110 Longfellow Avenue in the Todt Hill neighborhood of Staten Island.[130][129][60] The wall around the Corleone compound was made from styrofoam.[129] Scenes set in and around the Corleone olive oil business were filmed on Mott Street.[125][131]

After filming had ended on August 7,[132] post-production efforts were focused on trimming the film to a manageable length.[133] In addition, producers and director were still including and removing different scenes from the end product, along with trimming certain sequences.[134] In September, the first rough cut of the film was viewed.[133] Many of the scenes removed from the film were centered around Sonny, which did not advance the plot.[135] By November, Coppola and Ruddy finished the semi-final cut.[135] Debates over personnel involved with the final editing remained even 25 years after the release of the film.[136] The film was shown to Paramount staff and exhibitors in late December 1971 and January 1972.[137]

Music[edit]

Coppola hired Italian composer Nino Rota to create the underscore for the film, including «Love Theme from The Godfather«.[138][139] For the score, Rota was to relate to the situations and characters in the film.[138][139] Rota synthesized new music for the film and took some parts from his 1958 Fortunella film score, in order to create an Italian feel and evoke the tragedy within the film.[140] Paramount executive Evans found the score to be too «highbrow» and did not want to use it; however, it was used after Coppola managed to get Evans to agree.[138][139] Coppola believed that Rota’s musical piece gave the film even more of an Italian feel.[139] Coppola’s father, Carmine, created some additional music for the film,[141] particularly the music played by the band during the opening wedding scene.[139][140]

Incidental music includes, «C’è la luna mezzo mare» and Cherubino’s aria, «Non so più cosa son» from Le Nozze di Figaro.[140] There was a soundtrack released for the film in 1972 in vinyl form by Paramount Records, on CD in 1991 by Geffen Records, and digitally by Geffen on August 18, 2005.[142] The album contains over 31 minutes of music that was used in the film, most of which was composed by Rota, along with a song from Coppola and one by Johnny Farrow and Marty Symes.[143][144][145] AllMusic gave the album five out of five, with editor Zach Curd saying it is a «dark, looming, and elegant soundtrack».[143] An editor for Filmtracks believed that Rota was successful in relating the music to the film’s core aspects.[145]

Release[edit]

Theatrical[edit]

The world premiere for The Godfather took place at Loews’s State Theatre in New York City on Tuesday, March 14, 1972, almost three months after the planned release date of Christmas Day in 1971,[146][147][7] with profits from the premiere donated to The Boys Club of New York.[148] Before the film premiered, the film had already made $15 million from advance rentals from over 400 theaters.[39] The following day,[33] the film opened in five theaters in New York (Loew’s State I and II, Orpheum, Cine and Tower East).[149][21][7] Next was the Imperial Theatre in Toronto[146] on March 17[150] and then Los Angeles at two theaters on March 22.[151] The Godfather was released on March 24, 1972 throughout the rest of the United States[149][7] reaching 316 theaters five days later.[152]

Home media[edit]

The television rights were sold for a record $10 million to NBC for one showing over two nights.[153] The theatrical version of The Godfather debuted on American network television on NBC with only minor edits.[154] The first half of the film aired on Saturday, November 16, 1974, and the second half two days later.[155] The television airings attracted a large audience with an average Nielsen rating of 38.2 and audience share of 59% making it the eighth most-watched film on television, with the broadcast of the second half getting the third-best rating for a film on TV behind Airport and Love Story with a rating of 39.4 and 57% share.[155] The broadcast helped generate anticipation for the upcoming sequel.[154] The next year, Coppola created The Godfather Saga expressly for American television in a release that combined The Godfather and The Godfather Part II with unused footage from those two films in a chronological telling that toned down the violent, sexual, and profane material for its NBC debut on November 18, 1977.[156] In 1981, Paramount released the Godfather Epic boxed set, which also told the story of the first two films in chronological order, again with additional scenes, but not redacted for broadcast sensibilities.[156] The Godfather Trilogy was released in 1992, in which the films are fundamentally in chronological order.[157]

The Godfather Family: A Look Inside was a 73-minute documentary released in 1991.[158] Directed by Jeff Warner, the film featured some behind the scenes content from all three films, interviews with the actors, and screen tests.[158] The Godfather DVD Collection was released on October 9, 2001, in a package that contained all three films—each with a commentary track by Coppola—and a bonus disc containing The Godfather Family: A Look Inside.[159] The DVD also held a Corleone family tree, a «Godfather» timeline, and footage of the Academy Award acceptance speeches.[159]

The Godfather: The Coppola Restoration[edit]

During the film’s original theatrical release, the original negatives were worn down due to the reel being printed so much to meet demand.[160][161] In addition, the duplicate negative was lost in Paramount archives.[161] In 2006 Coppola contacted Steven Spielberg—whose studio DreamWorks had recently been bought out by Paramount—about restoring The Godfather.[160][161] Robert A. Harris was hired to oversee the restoration of The Godfather and its two sequels, with the film’s cinematographer Willis participating in the restoration.[162][163] Work began in November 2006 by repairing the negatives so they could go through a digital scanner to produce high resolution 4K files. If a negative were damaged and discolored, work was done digitally to restore it to its original look.[160][161] After a year and a half of working on the restoration, the project was complete.[161] Paramount called the finished product The Godfather: The Coppola Restoration and released it to the public on September 23, 2008, on both DVD and Blu-ray Disc.[162][163] Dave Kehr of The New York Times believed the restoration brought back the «golden glow of their original theatrical screenings».[162] As a whole, the restoration of the film was well received by critics and Coppola.[160][161][162][163][164] The Godfather: The Coppola Restoration contains several new special features that play in high definition, (including additional scenes, behind the scenes footage, etc).[164]

Paramount Pictures restored and remastered The Godfather, The Godfather Part II, and The Godfather Coda: The Death of Michael Corleone (a re-edited cut of the third film) for a limited theatrical run and home media release on Blu-ray and 4K Blu-ray to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the premiere of The Godfather. The disc editions were released on March 22, 2022.[165]

Reception[edit]

Box office[edit]

The Godfather was a blockbuster, breaking many box office records to become the highest grossing film of 1972.[166] The film’s opening day gross from five theaters was $57,829 with ticket prices increased from $3 to $3.50.[146] Prices in New York increased further at the weekend to $4, and the number of showings increased from four times a day to seven times a day.[146] The film grossed $61,615 in Toronto for the weekend[146] and $240,780 in New York,[167] for an opening weekend gross of $302,395. The film grossed $454,000 for the week in New York[146] and $115,000 in Toronto[150] for a first week gross of $568,800, which made it number one at the U.S. box office for the week.[168] In its first five days of national release, it grossed $6.8 million, taking its gross up to $7,397,164.[169] A week later its gross had reached $17,291,705[170] with the one week gross of around $10 million being an industry record.[171] It grossed another $8.7 million by April 9 to take its gross to $26,000,815.[172] After 18 weeks at number one in the United States, the film had grossed $101 million, the fastest film to reach that milestone.[173][174] Some news articles at the time proclaimed it was the first film to gross $100 million in North America,[151] but such accounts are erroneous; this record belongs to The Sound of Music, released in 1965.[175] It remained at number one in the US for another five weeks to bring its total to 23 consecutive weeks at number one before being unseated by Butterflies Are Free for one week before becoming number one for another three weeks.[176][177]

The film eventually earned $81.5 million in theatrical rentals in the US and Canada during its initial release,[166][178] increasing its earnings to $85.7 million through a reissue in 1973,[179] and including a limited re-release in 1997,[180] it ultimately earned an equivalent exhibition gross of $135 million, with a production cost of $6.5 million.[149] It displaced Gone with the Wind to claim the record as the top rentals earner,[166] a position it would retain until the release of Jaws in 1975.[151][181] The film repeated its native success overseas, earning in total an unprecedented $142 million in worldwide theatrical rentals, to become the highest net earner.[182] Profits were so high for The Godfather that earnings for Gulf & Western Industries, Inc., which owned Paramount, jumped from 77 cents per share to $3.30 a share for the year, according to a Los Angeles Times article, dated December 13, 1972.[151] Re-released eight more times since 1997, it has grossed between $250 million and $291 million in worldwide box office receipts,[N 2] and adjusted for ticket price inflation in North America, ranks among the top 25 highest-grossing films.[183]

Critical response[edit]

The Godfather has received overwhelming critical acclaim and is seen as one of the greatest and most influential films of all time, particularly of the gangster genre.[184] On review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds a 97% approval rating based on 148 reviews, with an average rating of 9.40/10. The website’s critics consensus reads, «One of Hollywood’s greatest critical and commercial successes, The Godfather gets everything right; not only did the movie transcend expectations, it established new benchmarks for American cinema.»[185] Metacritic, which uses a weighted average, has assigned the film a score of 100 out of 100 based on 16 critic reviews, indicating «universal acclaim».[186]

Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun Times praised Coppola’s efforts to follow the storyline of the novel, the choice to set the film in the same time as the novel, and the film’s ability to «absorb» the viewer over its three-hour run time.[187] Ebert named The Godfather «The best film of 1972».[188] The Chicago Tribune‘s Gene Siskel gave the film four out of four, commenting that it was «very good».[189]

The Village Voice‘s Andrew Sarris believed Brando portrayed Vito Corleone well and that his character dominated each scene it appeared in, but felt Puzo and Coppola had the character of Michael Corleone too focused on revenge.[190] In addition, Sarris stated that Richard Castellano, Robert Duvall, and James Caan were good in their respective roles.[190] Pauline Kael of The New Yorker wrote «If ever there was a great example of how the best popular movies come out of a merger of commerce and art, “The Godfather” is it.»[191]

Desson Howe of The Washington Post called the film a «jewel» and wrote that Coppola deserves most of the credit for the film.[192] Writing for The New York Times, Vincent Canby felt that Coppola had created one of the «most brutal and moving chronicles of American life» and went on to say that it «transcends its immediate milieu and genre».[193][194] Director Stanley Kubrick thought the film had the best cast ever and could be the best movie ever made.[195] Stanley Kauffmann of The New Republic wrote negatively of the film in a contemporary review, claiming that Pacino «rattles around in a part too demanding for him,» while also criticizing Brando’s make-up and Rota’s score.[196]

Previous mafia films had looked at the gangs from the perspective of an outraged outsider.[197] In contrast, The Godfather presents the gangster’s perspective of the Mafia as a response to corrupt society.[197] Although the Corleone family is presented as immensely rich and powerful, no scenes depict prostitution, gambling, loan sharking or other forms of racketeering.[198] George De Stefano argues that the setting of a criminal counterculture allows for unapologetic gender stereotyping (such as when Vito tells a weepy Johnny Fontane to «act like a man») and is an important part of the film’s appeal.[199]

Remarking on the fortieth anniversary of the film’s release, film critic John Podhoretz praised The Godfather as «arguably the great American work of popular art» and «the summa of all great moviemaking before it».[200] Two years before, Roger Ebert had written in his journal that it «comes closest to being a film everyone agrees… is unquestionably great».[201]

Accolades[edit]

The Godfather was nominated for seven awards at the 30th Golden Globe Awards: Best Picture – Drama, James Caan for Best Supporting Actor, Al Pacino and Marlon Brando for Best Actor – Drama, Best Score, Best Director, and Best Screenplay.[202] When the winners were announced on January 28, 1973, the film had won the categories for: Best Screenplay, Best Director, Best Actor – Drama (Brando), Best Original Score, and Best Picture – Drama.[203][204]

Rota’s score was also nominated for Grammy Award for Best Original Score for a Motion Picture or TV Special at the 15th Grammy Awards.[205][206] Rota was announced the winner of the category on March 3 at the Grammys’ ceremony in Nashville, Tennessee.[205][206]

When the nominations for the 45th Academy Awards were revealed on February 12, 1973, The Godfather was nominated for eleven awards.[207][208] The nominations were for: Best Picture, Best Costume Design, Marlon Brando for Best Actor, Mario Puzo and Francis Ford Coppola for Best Adapted Screenplay, Pacino, Caan, and Robert Duvall for Best Supporting Actor, Best Film Editing, Nino Rota for Best Original Score, Coppola for Best Director, and Best Sound.[207][208][209] Upon further review of Rota’s love theme from The Godfather, the Academy found that Rota had used a similar score in Eduardo De Filippo’s 1958 comedy Fortunella.[210][211][212] This led to re-balloting, where members of the music branch chose from six films: The Godfather and the five films that had been on the shortlist for best original dramatic score but did not get nominated. John Addison’s score for Sleuth won this new vote, and thus replaced Rota’s score on the official list of nominees.[213] Going into the awards ceremony, The Godfather was seen as the favorite to take home the most awards.[203] From the nominations that The Godfather had remaining, it only won three of the Academy Awards: Best Actor for Brando, Best Adapted Screenplay, and Best Picture.[209][214]

Brando, who had also not attended the Golden Globes ceremony two months earlier,[212][215] boycotted the Academy Awards ceremony and refused to accept the Oscar,[33] becoming the second actor to refuse a Best Actor award after George C. Scott in 1970.[216][217] Brando sent American Indian Rights activist Sacheen Littlefeather in his place, to announce at the awards podium Brando’s reasons for declining the award, which were based on his objection to the depiction of American Indians by Hollywood and television.[216][217][218] Pacino also boycotted the ceremony;[33] he was insulted at being nominated for the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor, when he had more screen time than his co-star and Best Actor-winner Brando, and thus should have received the nomination for Best Actor.[219]

The Godfather had five nominations for awards at the 26th British Academy Film Awards. The nominees were: Pacino for Most Promising Newcomer, Rota for the Anthony Asquith Award for Film Music, Duvall for Best Supporting Actor, and Brando for Best Actor, the film’s costume designer Anna Hill Johnstone for Best Costume Design. The only nomination to win was that of Rota.[220]

List of accolades[edit]

| Award | Category | Nominee | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 45th Academy Awards | Best Picture | Albert S. Ruddy | Won |

| Best Director | Francis Ford Coppola | Nominated | |

| Best Actor | Marlon Brando (declined award) | Won | |

| Best Supporting Actor | James Caan | Nominated | |

| Robert Duvall | Nominated | ||

| Al Pacino | Nominated | ||

| Best Adapted Screenplay | Mario Puzo and Francis Ford Coppola | Won | |

| Best Costume Design | Anna Hill Johnstone | Nominated | |

| Best Film Editing | William Reynolds and Peter Zinner | Nominated | |

| Best Sound | Bud Grenzbach, Richard Portman and Christopher Newman | Nominated | |

| Best Original Dramatic Score | Nino Rota | Revoked | |

| 26th British Academy Film Awards | Best Actor | Marlon Brando (Also for The Nightcomers) | Nominated |

| Best Supporting Actor | Robert Duvall | Nominated | |

| Most Promising Newcomer to Leading Film Roles | Al Pacino | Nominated | |

| Best Film Music | Nino Rota | Won | |

| Best Costume Design | Anna Hill Johnstone | Nominated | |

| 25th Directors Guild of America Awards | Outstanding Directorial Achievement in Motion Pictures | Francis Ford Coppola | Won |

| 30th Golden Globe Awards | Best Motion Picture – Drama | Won | |

| Best Director – Motion Picture | Francis Ford Coppola | Won | |

| Best Motion Picture Actor – Drama | Marlon Brando | Won | |

| Al Pacino | Nominated | ||

| Best Supporting Actor – Motion Picture | James Caan | Nominated | |

| Best Screenplay | Mario Puzo and Francis Ford Coppola | Won | |

| Best Original Score | Nino Rota | Won | |

| 15th Grammy Awards | Best Original Score Written for a Motion Picture or TV Special | Nino Rota | Won |

| 25th Writers Guild of America Awards | Best Drama Adapted from Another Medium | Mario Puzo and Francis Ford Coppola[221] | Won |

American Film Institute recognition[edit]

- 1998 AFI’s 100 Years…100 Movies – No. 3[222]

- 2001 AFI’s 100 Years…100 Thrills – No. 11[223]

- 2005 AFI’s 100 Years…100 Movie Quotes:

- «I’m going to make him an offer he can’t refuse.» – No. 2[224]

- 2006 AFI’s 100 Years of Film Scores – No. 5[225]

- 2007 AFI’s 100 Years…100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition) – No. 2[226]

- 2008 AFI’s 10 Top 10 – No. 1 Gangster Film[227]

Other recognition[edit]

- 1990 Selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry as being deemed «culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant».[228]

- 1992 The Godfather ranked 6th in Sight & Sound Greatest Films of All Time director’s poll.[229]

- 1998 Time Out conducted a poll and The Godfather was voted the best film of all time.[230]

- The Village Voice ranked The Godfather at number 12 in its Top 250 «Best Films of the Century» list in 1999, based on a poll of critics.[231]

- 1999 Entertainment Weekly named it the greatest film ever made.[232][233][234]

- 2002 Sight & Sound polled film directors and they voted the film and its sequel as the second best film ever;[235] the critics poll separately voted it fourth.[236]

- 2002 The Godfather was ranked the second best film of all time by Film4, after Star Wars Episode V: The Empire Strikes Back.[237]

- 2002 the film (along with The Godfather Part II) was voted at No. 39 on the list of the «Top 100 Essential Films of All Time» by the National Society of Film Critics.[238][239]

- 2005 Named one of the 100 greatest films of the last 80 years by Time magazine (the selected films were not ranked).[240][241]

- 2006 The Writers Guild of America, West agreed, voting it the number two in its list of the 101 greatest screenplays, after Casablanca.[242]

- 2008 Voted in at No. 1 on Empire magazine’s list of The 500 Greatest Movies of All Time.[243]

- 2008 Voted at No. 50 on the list of «100 Greatest Films» by the prominent French magazine Cahiers du cinéma.[244]

- 2009 The Godfather was ranked at No. 1 on Japanese film magazine kinema Junpo’s Top 10 Non-Japanese Films of All Time list.[245]

- 2010 The Guardian ranked the film 15th in its list of 25 greatest arthouse films.[246]

- 2012 The Motion Picture Editors Guild listed The Godfather as the sixth best-edited film of all time based on a survey of its membership.[247]

- 2012 The film ranked at number seven on Sight & Sound directors’ top ten poll. On the same list it was ranked at number twenty one by critics.[248][249][250]

- 2014 The Godfather was voted the greatest film in a Hollywood Reporter poll of 2120 industry members, including every studio, agency, publicity firm and production house in Hollywood in 2014.[251]

- 2015 Second on the BBC’s «100 Greatest American Films», voted by film critics from around the world.[252]

Cultural influence and legacy[edit]

Although many films about gangsters preceded The Godfather, Coppola steeped his film in Italian immigrant culture, and his portrayal of mobsters as persons of considerable psychological depth and complexity was unprecedented.[253] Coppola took it further with The Godfather Part II, and the success of those two films, critically, artistically and financially, was a catalyst for the production of numerous other depictions of Italian Americans as mobsters, including films such as Martin Scorsese’s Goodfellas and TV series such as David Chase’s The Sopranos.

A comprehensive study of Italian-American culture in film from 1914 to 2014 was conducted by the Italic Institute of America showing the influence of The Godfather.[254][255] Over 81 percent of films, 430 films, featuring Italian Americans as mobsters (87 percent of which were fictional) had been produced since The Godfather, an average of 10 per year, while only 98 films were produced preceding The Godfather.

The Godfather epic, encompassing the original trilogy and the additional footage that Coppola incorporated later, has been thoroughly integrated into American life. Together with a succession of mob-theme imitators, it has resulted in a stereotyped concept of Italian-American culture biased toward the criminal networks. The first film had the largest effect. Unlike any film before it, its portrayal of the many poor Italians who immigrated to the United States in the early decades of the 20th century is perhaps attributable to Coppola and expresses his understanding of their experience. The films explore the integration of fictional Italian-American criminals into American society. Though set in the period of mass Italian immigration to America, the film explores the specific family of the Corleones, who live outside the law. Although some critics have considered the Corleone story to portray some universal elements of immigration, other critics have suggested that it resulted in viewers overly associating organized crime with Italian-American culture. Produced in a period of intense national cynicism and self-criticism, the film struck a chord about the dual identities felt by many descendants of immigrants.[256] The Godfather has been cited as an influence in an increase in Hollywood’s negative portrayals of immigrant Italians, and was a recruiting tool for organized crime.[257]

The concept of a mafia «Godfather» was a creation of Mario Puzo, and the film resulted in this term being added to the common language. Don Vito Corleone’s line, «I’m gonna make him an offer he can’t refuse», was voted the second-most memorable line in cinema history in AFI’s 100 Years…100 Movie Quotes by the American Film Institute, in 2014.[258] The concept was not unique to the film. French writer Honoré de Balzac, in his novel Le Père Goriot (1835), wrote that Vautrin told Eugène: «In that case I will make you an offer that no one would decline.»[259] An almost identical line was used in the John Wayne Western, Riders of Destiny (1933), where Forrest Taylor states, «I’ve made Denton an offer he can’t refuse.»[260] In 2014, the film also was selected as the greatest film by 2,120 industry professionals in a Hollywood survey undertaken by The Hollywood Reporter.[251]

Gangsters reportedly responded enthusiastically to the film.[261] Salvatore «Sammy the Bull» Gravano, the former underboss in the Gambino crime family,[262] said: «I left the movie stunned … I mean I floated out of the theater. Maybe it was fiction, but for me, then, that was our life. It was incredible. I remember talking to a multitude of guys, made guys, who felt exactly the same way.» According to Anthony Fiato, after seeing the film, Patriarca crime family members Paulie Intiso and Nicky Giso altered their speech patterns to imitate that of Vito Corleone. Intiso was known to swear frequently and use poor grammar; but after seeing the movie, he began to improve his speech and philosophize more.[263]

Representation in other media[edit]

The film has been referenced and parodied in various kinds of media.[264]

- John Belushi appeared in a Saturday Night Live sketch as Vito Corleone in a therapy session; he said of the Tattaglia Family, «Also, they shot my son Santino 56 times».[265]

- In the television show The Sopranos, Silvio Dante’s topless bar is named Bada Bing!, a phrase popularized by James Caan’s character Sonny Corleone in The Godfather.[21]

- In the animated television series The Simpsons, there have been many references to the film. For instance, in the season 3 episode «Lisa’s Pony», Lisa wakes up to find a horse in her bed and starts screaming, a reference to a scene in The Godfather. In the season 4 episode «Mr. Plow», Bart Simpson is pelted with snowballs in mimicry of Sonny Corleone’s killing.[266][267][268]

- The film’s baptism sequence was parodied in the season 4 episode «Fulgencio», of the comedy series Modern Family.[269]

- The 2006 video game The Godfather is based upon this film and tells the story of an original character, Aldo Trapani, whose rise through the ranks of the Corleone family intersects with the plot of the film on numerous occasions.[270][271] Duvall, Caan, and Brando supplied voiceovers and their likenesses,[272] but Pacino did not.[272] Francis Ford Coppola openly voiced his disapproval of the game.[273]

- On April 28, 2022, a 10-episode drama series The Offer premiered on Paramount+, about the production told from the perspective of producer Ruddy.[274]

See also[edit]

- List of films set in Las Vegas

Notes[edit]

- ^ a b Sources disagree on both the amount of the original budget and the final budget. The starting budget has been recorded as $1 million,[19] $2 million,[17][39][40][12] and $2.5 million,[21][41] while Coppola later demanded—and received—a $5 million budget.[29] The final budget has been named at $6 million,[29][21][42][43] $6.5 million,[39][44] $7 million,[45] and $7.2 million.[46]

- ^ a b Sources disagree on the amount grossed by the film.

- 1974: Newsweek. Vol. 84. 1974. p. 74.

The original Godfather has grossed a mind-boggling $285 million…

- 1991: Von Gunden, Kenneth (1991). Postmodern auteurs: Coppola, Lucas, De Palma, Spielberg, and Scorsese. McFarland & Company. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-89950-618-0.

Since The Godfather had earned over $85 million in U.S.-Canada rentals (the worldwide box-office gross was $285 million), a sequel, according to the usual formula, could be expected to earn approximately two-thirds of the original’s box-office take (ultimately Godfather II had rentals of $30 million).

- Releases: «The Godfather (1972)». Box Office Mojo. Retrieved March 17, 2022.

Original release: $243,862,778; 1997 re-release: $1,267,490; 2009 re-release: $121,323; 2011 re-release: $818,333; 2014 re-release: $29,349; 2018 re-release: $21,701; 2020 re-release: $4,323; 2022 re-release: $3,999,963; Budget: $6,000,000

- 1974: Newsweek. Vol. 84. 1974. p. 74.

- ^ Sources disagree on the date where Paramount confirmed their intentions to make Mario Puzo’s novel The Godfather into a feature-length film. Harlan Lebo’s work states that the announcement came in January 1969,[12] while Jenny Jones’ book puts the date of the announcement three months after the novel’s publication, in June 1969.[14]

References[edit]

- ^ «THE GODFATHER (18)». British Board of Film Classification. Archived from the original on June 12, 2016. Retrieved March 26, 2022.

- ^ «The Godfather | Plot, Cast, Oscars, & Facts | Britannica». www.britannica.com. Retrieved December 31, 2021.

- ^ Allan, John H. (April 17, 1972). «‘Godfather’ gives boost to G&W profit picture». Milwaukee Journal. (New York Times). p. 16, part 2. Archived from the original on November 21, 2018. Retrieved July 19, 2018.

- ^ Allan, John H. (April 16, 1972). «Profits of ‘The Godfather’«. The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 10, 2018. Retrieved September 10, 2018.

- ^ Gambino, Megan (January 31, 2012). «What is The Godfather Effect?». Smithsonian. Archived from the original on September 10, 2018. Retrieved September 10, 2018.

- ^ «The Godfather (1972)». The New York Times. 2014. Archived from the original on April 18, 2014. Retrieved March 19, 2020.

- ^ a b c d «The Godfather». AFI. American Film Institute. Archived from the original on July 17, 2014. Retrieved July 15, 2014.

- ^ Lebo 2005, p. 5–6.

- ^ a b c d e Jones 2007, p. 10.

- ^ a b c d ««The Godfather» Turns 40″. CBS News. March 15, 2012. Archived from the original on July 17, 2014. Retrieved July 15, 2014.

- ^ Lebo 2005, p. 7.

- ^ a b c d e Lebo 2005, p. 6.

- ^ a b c Phillips 2004, p. 88.

- ^ a b Jones 2007, p. 10–11.

- ^ O’Brian, Jack (January 25, 1973). «Not First Lady on TV». The Spartanburg Herald. p. A4. Archived from the original on November 21, 2018. Retrieved July 15, 2014.

- ^ Michael L. Geczi and Martin Merzer (April 10, 1978). «Hollywood business is blockbuster story». St. Petersburg Times. p. 11B. Archived from the original on November 14, 2020. Retrieved July 15, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Italie, Hillel (December 24, 1990). «‘Godfather’ films have their own saga». The Daily Gazette. Associated Press. p. A7. Archived from the original on November 14, 2020. Retrieved July 15, 2014.

- ^ Jones 2007, p. 14.

- ^ a b c d e f Phillips 2004, p. 92.

- ^ a b Lebo 2005, p. 11.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Mark Seal (March 2009). «The Godfather Wars». Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved July 15, 2014.

- ^ Welsh, Phillips & Hill 2010, p. 104.

- ^ a b Jones 2007, p. 12.

- ^ a b Fristoe, Roger. «Sergio Leone Profile». Turner Classic Movies. Archived from the original on July 16, 2014. Retrieved July 16, 2014.

- ^ a b Bozzola, Lucia (2014). «Sergio Leone». Movies & TV Dept. The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 16, 2014. Retrieved July 16, 2014.

- ^ James, Clive (November 30, 2004). «Peter Bogdanovich». The Guardian. Archived from the original on August 27, 2013. Retrieved July 16, 2014.

- ^ «Peter Bogdanovich – Hollywood survivor». BBC News. January 7, 2005. Archived from the original on September 3, 2010. Retrieved July 16, 2014.

- ^ Webb, Royce (July 28, 2008). «10 BQs: Peter Bogdanovich». ESPN. Archived from the original on November 10, 2013. Retrieved July 16, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Horne, Philip (September 22, 2009). «The Godfather: ‘Nobody enjoyed one day of it’«. The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on September 24, 2009. Retrieved July 15, 2014.

- ^ a b ««The Godfather» Turns 40″. CBS News. March 15, 2012. Archived from the original on July 17, 2014. Retrieved July 15, 2014.

- ^ Phillips 2004, p. 89.

- ^ Lebo 1997, p. 23.

- ^ a b c d e f Itzkoff, Dave (March 14, 2022). «He Came Out of Nowhere And Was Quickly Someone». The New York Times. p. 10(L). Gale A696504953.

- ^ Hearn, Marcus (2005). The Cinema of George Lucas. New York City: Harry N. Abrams Inc. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-8109-4968-3.

- ^ a b c d e The Godfather DVD commentary featuring Francis Ford Coppola, [2001]

- ^ a b c Jones 2007, p. 18.

- ^ Lebo 2005, p. 25.

- ^ Cowie 1997, p. 11.

- ^ a b c d e f g «Backstage Story of ‘The Godfather’«. Lodi News-Sentinel. United Press International. March 14, 1972. p. 9. Archived from the original on November 21, 2018. Retrieved July 15, 2014.

- ^ Cowie 1997, p. 9.

- ^ a b «Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather opens». History (U.S. TV network). Archived from the original on July 4, 2014. Retrieved July 16, 2014.

- ^ a b c d Jones 2007, p. 19.

- ^ «The Godfather, Box Office Information». Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on January 28, 2012. Retrieved January 21, 2012.

Worldwide Gross: $245,066,411

- ^ Phillips 2004, p. 93.

- ^ «The Godfather (1972) – Financial Information». The Numbers. Archived from the original on March 14, 2019. Retrieved January 22, 2020.

- ^ Block & Wilson 2010, p. 527

- ^ Phillips 2004, p. 92–93.

- ^ a b c d Jones 2007, p. 20.

- ^ Phillips 2004, p. 96.

- ^ Phillips 2004, p. 100.

- ^ a b c d Jones 2007, p. 11.

- ^ a b c Jones 2007, p. 252.

- ^ Lebo 1997, p. 30.

- ^ a b c d e f g Phillips 2004, p. 90.

- ^ Coppola 2016.

- ^ Cowie 1997, p. 26.

- ^ «The making of The Godfather». The Week. THE WEEK Publications, Inc. July 15, 1988. Archived from the original on July 21, 2014. Retrieved June 15, 2012.

- ^ Lebo 1997, p. 162.

- ^ Lebo 1997, p. 36.

- ^ a b Ferretti, Fred (March 23, 1971). «Corporate Rift in ‘Godfather Filming». The New York Times. p. 28. Retrieved January 24, 2023.

- ^ Gage, Nicholas (March 19, 1972). «A Few Family Murders, but That’s Show Biz». The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 25, 2014. Retrieved June 15, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e Parker, Jerry (June 27, 1971). «They’re Having a Ball Making ‘Godfather’«. Toledo Blade. p. 2. Archived from the original on November 21, 2018. Retrieved July 15, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Parker, Jerry (May 30, 1971). «About ‘The Godfather’… It’s Definitely Not Irish-American». The Victoria Advocate. p. 13. Archived from the original on November 14, 2020. Retrieved July 15, 2014.

- ^ Santopietro 2012, p. 2.

- ^ Santopietro 2012, p. 1.

- ^ a b c Williams 2012, p. 187.

- ^ a b «What Could Have Been… 10 Movie Legends Who Almost Worked on The Godfather Trilogy». Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. April 2, 2012. Archived from the original on March 30, 2013. Retrieved July 15, 2014.

- ^ Stanley 2014, p. 83.

- ^ Mayer, Geoff (2012). Historical Dictionary of Crime Films. Scarecrow Press. p. 176. ISBN 978-0-8108-6769-7. Archived from the original on February 14, 2017. Retrieved January 19, 2017.

- ^ World Features Syndicate (May 13, 1991). «Marlon Brando played Don Vito Corleone in «The Godfather…» Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on July 15, 2014. Retrieved July 15, 2014.

- ^ «An alternate Godfather could have starred Robert Redford and Elvis Pressley». NPR. March 14, 2022. Retrieved October 19, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Williams 2012, p. 188.

- ^ Santopietro 2012, p. 2–3.

- ^ a b Gelmis 1971, p. 52.

- ^ Santopietro 2012, p. 3–4.

- ^ Santopietro 2012, p. 4.

- ^ a b Santopietro 2012, p. 5.

- ^ Gelmis 1971, p. 53.

- ^ «Brando’s $3-Mil Year». Variety. January 9, 1974. p. 1.

- ^ a b Lebo 1997, p. 53-55.

- ^ a b Jones 2007, p. 173.

- ^ a b Jones 2007, p. 50.

- ^ a b Jones 2007, p. 147.

- ^ ««The Godfather» Turns 40″. CBS News. March 15, 2012. Archived from the original on July 16, 2014. Retrieved July 15, 2014.

- ^ Entretenimiento (April 20, 2017). «Robert De Niro revela el secreto para conseguir su papel en ‘El Padrino’«. Cnnespanol.cnn.com. Retrieved February 6, 2022.

- ^ «El Padrino: Mirá la fallida audición de Robert De Niro para el rol de Sonny Corleone». Indiehoy.com. September 19, 2020. Retrieved February 6, 2022.

- ^ «Esta es la audición que hizo Robert De Niro para ser Sonny Corleone… ¡Por la que fue rechazado!». Boldamania.com. Retrieved February 6, 2022.

- ^ a b c The Godfather DVD Collection documentary A Look Inside, [2001]

- ^ Cowie 1997, p. 20-21.

- ^ Lebo 1997, p. 61.

- ^ Cowie 1997, p. 23.

- ^ a b c Jones 2007, p. 133.

- ^ a b Nate Rawlings (March 14, 2012). «The Anniversary You Can’t Refuse: 40 Things You Didn’t Know About The Godfather». Time. Archived from the original on January 2, 2014. Retrieved January 2, 2014.

- ^ Sippell, Margeaux (September 6, 2018). «Roles Burt Reynolds Turned Down, From Bond to Solo».

- ^ «Godfather role was an offer Al Pacino could refuse | The Godfather | The Guardian». www.theguardian.com. October 29, 2014.

- ^ Staff, Movieline (November 2, 2004). «Jack Nicholson: A Chat With Jack».

- ^ a b Cowie 1997, p. 24.

- ^ ««The Godfather» Turns 40″. CBS News. March 15, 2012. Archived from the original on July 16, 2014. Retrieved July 15, 2014.

- ^ Lebo 1997, p. 59.

- ^ Welsh, Phillips & Hill 2010, p. 236.

- ^ «Sofia Coppola Mimics Hollywood Life in ‘Somewhere’«. NPR. December 20, 2010. Archived from the original on June 26, 2013. Retrieved July 15, 2014.

- ^ Cowie 1997, p. 22.

- ^ Lebo 1997, p. 60.

- ^ Lebo 1997, p. 87-88.

- ^ Santopietro 2012, p. 128.

- ^ a b Lebo 1997, p. 93.

- ^ a b Lebo 2005, p. 184.

- ^ Lebo 1997, p. 109.

- ^ Lebo 1997, p. 185.

- ^ Lebo 2005, p. 181.

- ^ Feeney, Mark (2006). «A Study in Contrasts». WUTC. Archived from the original on July 20, 2014. Retrieved July 19, 2014.

- ^ a b c d Lebo 1997, p. 70.

- ^ Cowie 1997, p. 59.

- ^ Lebo 1997, p. 137.

- ^ «Inside The Former Hearst Mansion On The Market For $195 Million». Guest of a Guest. Retrieved January 5, 2023.

- ^ Warren, Katie. «The iconic mansion from ‘The Godfather’ is back on the market at a $105 million discount. Look inside the Beverly Hills estate». Business Insider. Retrieved January 5, 2023.

- ^ Sands Point Preserve Conservancy Information about TV and film productions that took place at Sands Point Preserve

- ^ Phillips 2004, p. 102.

- ^ Lebo 2005, p. 174.

- ^ Lebo 2005, p. 176.

- ^ a b Cowie 1997, p. 50.

- ^ Lebo 1997, p. 172.

- ^ a b Lebo 1997, p. 26.

- ^ a b «Secrets of ‘The Godfather’ Filming Now Revealed». Atlanta Daily World. June 11, 1972. p. 10.

- ^ a b Jim and Shirley Rose Higgins (May 7, 1972). «Movie Fan’s Guide to Travel». Chicago Tribune. p. F22.

- ^ Jones 2007, p. 24.

- ^ Lebo 1997, p. 132.

- ^ «In search of… The Godfather in Sicily». The Independent. Independent Digital News and Media Limited. April 26, 2003. Archived from the original on May 11, 2015. Retrieved February 12, 2016.

- ^ a b c Jones 2007, p. 30.

- ^ «You Can Stay in the Godfather House for Just $50 a Night». Town & Country. July 19, 2022. Retrieved January 24, 2023.

- ^ Lebo 2005, p. 115.

- ^ Cowie 1997, p. 57.

- ^ a b Lebo 1997, p. 192.

- ^ Lebo 1997, p. 192, 194-196.

- ^ a b Lebo 1997, p. 197.

- ^ Lebo 1997, p. 197-198.

- ^ Lebo 1997, p. 198.

- ^ a b c Phillips 2004, p. 107.

- ^ a b c d e Welsh, Phillips & Hill 2010, p. 222.

- ^ a b c Lebo 1997, p. 191.

- ^ Phillips 2004, p. 355.

- ^ «The Godfather (Original Motion Picture Soundtrack)». Apple. January 1991. Archived from the original on July 20, 2014. Retrieved April 16, 2013.

- ^ a b Curd, Zach. «Nino Rota – The Godfather [Original Soundtrack]». Allmusic. All Media Network. Archived from the original on July 20, 2014. Retrieved July 20, 2014.

- ^ «Nino Rota – The Godfather [Original Soundtrack]». Allmusic. All Media Network. Archived from the original on July 20, 2014. Retrieved July 20, 2014.

- ^ a b «The Godfather». Filmtracks. Christian Clemmensen (Filmtracks Publications). October 3, 2009. Archived from the original on July 20, 2014. Retrieved July 20, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f «It’s Everybody’s ‘Godfather’«. Variety. March 22, 1972. p. 5.

- ^ Cowie 1997, p. 60.

- ^ Lebo 1997, p. 200.

- ^ a b c Block & Wilson 2010, pp. 518, 552.

- ^ a b «‘Godfather’ Record $115,000, Toronto». Variety. March 22, 1972. p. 16.

- ^ a b c d «The Godfather (1972) – Notes». Turner Classic Movies. Archived from the original on October 29, 2013. Retrieved July 16, 2014.

- ^ Lebo 1997, p. 204.

- ^ Murphy, A.D. (November 13, 1974). «Frank Yablans Resigns Par Presidency». Variety. p. 3.

- ^ a b Lebo 2005, p. 245.

- ^ a b «Hit Movies on U.S. TV Since 1961». Variety. January 24, 1990. p. 160.

- ^ a b Lebo 2005, p. 247.

- ^ Lebo 2005, p. XIV.

- ^ a b Duncan, Alice (2015). «The Godfather Family: A Look Inside (1991)». Movies & TV Dept. The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 23, 2015. Retrieved July 16, 2014.

- ^ a b Duncan, Alice (October 9, 2001). «The Godfather DVD Collection». Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on August 23, 2015. Retrieved July 16, 2014.

- ^ a b c d Snider, Mike (September 23, 2008). «‘Godfather’ films finally restored to glory». USA Today. Archived from the original on July 21, 2014. Retrieved July 15, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f Kaplan, Fred (September 30, 2008). «Your DVD Player Sleeps With the Fishes». Slate. Archived from the original on July 21, 2014. Retrieved July 15, 2014.

- ^ a b c d Kehr, Dave (September 22, 2008). «New DVDs: ‘The Godfather: The Coppola Restoration’«. The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 21, 2014. Retrieved July 15, 2014.

- ^ a b c Phipps, Keith (October 7, 2008). «The Godfather: The Coppola Restoration». The A.V. Club. Onion Inc. Archived from the original on July 21, 2014. Retrieved July 15, 2014.

- ^ a b Noller, Matt (September 26, 2008). «The Godfather Collection: The Coppola Restoration». Slant Magazine. Archived from the original on July 21, 2014. Retrieved July 15, 2014.

- ^ «‘The Godfather Trilogy Releasing to 4k, Finally». January 13, 2022. Retrieved March 14, 2022.

- ^ a b c Frederick, Robert B. (January 3, 1973). «‘Godfather’: & Rest of Pack». Variety. p. 7.

- ^ «Unprecedented boxoffice! (advert)». Variety. March 22, 1972. p. 12.

- ^ «50 Top-Grossing Films». Variety. March 29, 1972. p. 21.

- ^ «‘Godfather’ B.O. $7,397,164″. Daily Variety. March 30, 1972. p. 1.

- ^ «The Godfather is now a phenomenon (advert)». Variety. April 5, 1972. pp. 12–13.

- ^ Green, Abel (April 5, 1972). «‘Godfather’: Boon To All Pix». Variety. p. 3.

- ^ «‘Godfather’ B.O. Beyond $26 Mil». Daily Variety. April 11, 1972. p. 1.

- ^ «‘Godfather-Part II’ Preems March 24, ’74». Variety. August 2, 1972. p. 1.

- ^ «Motion Picture History Has Been Made (advertisement)». Variety. August 2, 1972. p. 10.

- ^ «Robert Wise – The Sound of Music (1965)». American Film Institute. Archived from the original on November 4, 2015. Retrieved November 20, 2012.

- ^ «50 Top-Grossing Films». Variety. September 6, 1972. p. 11.

- ^ «50 Top-Grossing Films». Variety. September 27, 1972. p. 9.

- ^ Wedman, Len (January 24, 1973). «Birth of a Nation classic proves it’s still fantastic». The Vancouver Sun. p. 39.

- ^ «Godfather 1 all-time earner». The Gazette. Montreal. Reuters. January 9, 1975. p. 21.

- ^ «The Godfather (Re-issue) (1997)». Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on March 21, 2013. Retrieved November 20, 2012.

North America:$1,267,490

- ^ Dirks, Tim. «Top Films of All-Time: Part 1 – Box-Office Blockbusters». AMC Filmsite.org. Archived from the original on October 14, 2013. Retrieved May 31, 2012.

- ^ Jacobs, Diane (1980). Hollywood Renaissance. Dell Publishing. p. 115. ISBN 978-0-440-53382-5. Archived from the original on June 5, 2019. Retrieved August 6, 2019.

The Godfather catapulted Coppola to overnight celebrity, earning three Academy Awards and a then record-breaking $142 million in worldwide sales

- ^ «All Time Box Office Adjusted for Ticket Price Inflation». Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on May 4, 2009. Retrieved November 20, 2012.

- ^ «The Mafia in Popular Culture». History. A&E Television Networks. 2009. Archived from the original on July 17, 2014. Retrieved July 16, 2014.

- ^ «The Godfather (1972)». Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Archived from the original on July 22, 2019. Retrieved March 29, 2021.

- ^ «The Godfather (1972)». Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on September 29, 2017. Retrieved July 19, 2019.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (January 1, 1972). «The Godfather». Roger Ebert.com. Ebert Digital. Archived from the original on July 19, 2014. Retrieved January 1, 2014.

- ^ «Ebert’s 10 Best Lists: 1967–present». Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on September 8, 2006.

- ^ Siskel, Gene (October 15, 1999). «The Movie Reviews». Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on July 1, 2014. Retrieved August 23, 2015.

- ^ a b Sarris, Andrew (March 16, 1972). «Films in Focus». The Village Voice. Village Voice, LLC. Archived from the original on October 24, 2013. Retrieved January 1, 2014.

- ^ «The Godfather». The New Yorker.

- ^ Howe, Desson (March 21, 1997). «‘Godfather’: Offer Accepted». The Washington Post. Archived from the original on July 20, 2014. Retrieved January 1, 2014.

- ^ Canby, Vincent (March 16, 1972). «‘Godfather’: Offer Accepted». The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 20, 2014. Retrieved January 1, 2014.

- ^ Canby, Vincent (March 16, 1972). «Moving and Brutal ‘Godfather’ Bows». The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 16, 2018. Retrieved November 4, 2018.

- ^ Wrigley, Nick (February 14, 2014). «Stanley Kubrick, cinephile – redux». BFI. British Film Institute. Archived from the original on July 16, 2014. Retrieved June 1, 2014.

- ^ Kauffmann, Stanley (April 1, 1972). ««The Godfather» and the Decline of Marlon Brando». The New Republic. Archived from the original on March 20, 2017. Retrieved March 20, 2017.

- ^ a b De Stefano 2006, p. 68.

- ^ De Stefano 2006, p. 119.

- ^ De Stefano 2006, p. 180.

- ^ Podhoretz, John (March 26, 2012). «Forty Years On: Why ‘The Godfather’ is a classic, destined to endure». The Weekly Standard., p. 39.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (July 18, 2010). «Whole Lotta Cantin’ Going On». Archived from the original on June 2, 2013. Retrieved June 25, 2013.

- ^ «The 30th Annual Golden Globe Awards (1973)». HFPA. Hollywood Foreign Press Association. Archived from the original on July 17, 2014. Retrieved July 15, 2014.

- ^ a b «‘Godfather’ Wins Four Globe Awards». The Telegraph. Associated Press. January 30, 1973. p. 20. Archived from the original on November 14, 2020. Retrieved July 15, 2014.

- ^ «Ruth Bizzi Cited By Golden Globes». The Age. Associated Press. February 1, 1973. p. 14. Archived from the original on November 14, 2020. Retrieved July 15, 2014.

- ^ a b «Roberta Flack Is Big Winner in Awarding Of ‘Grammys’«. Sarasota Herald-Tribune. Associated Press. March 5, 1973. p. 11–A. Archived from the original on November 21, 2018. Retrieved July 15, 2014.

- ^ a b Edward W. Coker Jr. (March 9, 1973). «Roberta Flack Is Big Winner in Awarding Of ‘Grammys’«. The Spokesman-Review. Archived from the original on November 21, 2018. Retrieved July 15, 2014.

- ^ a b Russell, Bruce (February 13, 1973). «‘Godfather’ Gets 11 Oscar Nominations». Toledo Blade. Reuters. p. P-2. Archived from the original on November 14, 2020. Retrieved September 2, 2014.

- ^ a b «Godfather Gets 11 Oscar Nominations». The Michigan Daily. United Press International. February 14, 1971. p. 3. Archived from the original on November 14, 2020. Retrieved July 15, 2014.

- ^ a b «The 45th Academy Awards (1973) Nominees and Winners». Oscars. Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on July 17, 2014. Retrieved July 16, 2014.

- ^ «‘Godfather’ Song Used Before». Daytona Beach Morning Star. Associated Press. March 2, 1973. p. 10. Archived from the original on November 21, 2018. Retrieved July 15, 2014.

- ^ «Godfather, Superfly music out of Oscars». The Montreal Gazette. Associated Press. March 7, 1973. p. 37. Archived from the original on November 21, 2018. Retrieved July 16, 2014.

- ^ a b Tapley, Kris (January 21, 2008). «Jonny Greenwood’s ‘Blood’ score disqualified by AM-PAS». Variety. Archived from the original on September 15, 2012. Retrieved March 4, 2010.

- ^ «100 Years of Paramount: Academy Awards». Paramount Pictures. Archived from the original on June 4, 2013. Retrieved June 16, 2013.

- ^ «The Godfather». The Val d’Or Star. October 26, 1977. p. 2. Archived from the original on November 14, 2020. Retrieved July 15, 2014.

- ^ «Brando Expected To Skip Oscar Award Rites». The Morning Record. Associated Press. March 26, 1973. p. 7. Archived from the original on November 21, 2018. Retrieved July 16, 2014.

- ^ a b «Brando Rejects Oscar Award». The Age. March 29, 1973. p. 10. Archived from the original on November 21, 2018. Retrieved July 15, 2014.

- ^ a b «Brando snubs Hollywood, rejects Oscar». The Montreal Gazette. Gazette. March 28, 1973. p. 1. Archived from the original on January 4, 2021. Retrieved July 15, 2014 – via Google News.

- ^ «Only the most talented actors have the nerve to tackle roles that push them to their physical and mental limits». The Irish Independent. November 26, 2011. Archived from the original on November 29, 2011. Retrieved December 6, 2011.

- ^ Grobel; p. xxi

- ^ «BAFTA Awards Search». British Academy of Film and Television Arts. Archived from the original on July 17, 2014. Retrieved July 15, 2014.

- ^ «Previous Nominees & Winners». The Writers Guilds Awards. Writers Guild of America. Archived from the original on March 7, 2016. Retrieved March 13, 2018.

- ^ «AFI’s 100 Years…100 Movies» (PDF). American Film Institute. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 12, 2019. Retrieved November 14, 2014.

- ^ «AFI’s 100 Years…100 Thrills» (PDF). American Film Institute. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 28, 2014. Retrieved November 14, 2014.

- ^ «AFI’s 100 Years…100 Movie Quotes» (PDF). American Film Institute. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 13, 2011. Retrieved November 14, 2014.

- ^ «AFI’s 100 Years of Film Scores» (PDF). American Film Institute. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 3, 2016. Retrieved November 14, 2014.