Ку-клукс-клан ( Ku — Klux — Klan ) всегда ассоциировался с чем-то зловещим и угрожающим, отвечая намерениям его создателей. Тема истории ку-клукс-клана в нашей стране являлась не совсем благодарной, и если об этой организации и говорили, то только в отрицательном духе, что, впрочем, соответствовало действительности…

Однако призадумаемся – что мы знаем о ку-клукс-клане? Как правило, справочники сообщают нам, что это была тайная расистская террористическая организация, направленная на борьбу против негров. Единственное, что многие знали о возникновении такого названия (звук затвора винтовки) и то оказалось вымыслом. Если любознательный читатель пытался найти какие-либо дополнительные сведения, его ждало разочарование. Несомненно, что отсутствие информации по какой-либо проблеме всегда вызывает к ней интерес, тем более что до сих пор подлинная история Ку-клукс-клана еще не написана; многое в его деятельности остается неизвестным.

Предлагаю узнать об этом побольше …

История Соединенных Штатов Америки, довольно молодого государства, содержит большое количество драматичных и тайных страниц. Одним из наиболее критичных моментов в истории страны была гражданская война, которая разгорелась между свободным Севером и рабовладельцами Юга. Началась она в 1860 году, когда отношения между двумя сторонами накалились до предела. На Севере появилось много влиятельных партий, которые поддерживали проведение радикальных демократических реформ, одной из которых была отмена рабства. Возглавлял движение А.Линкольн, который и был избран президентом. Но консервативно настроенные силы Юга не подержали его и объявили демократам войну. Кровопролитное противостояние длилось 4 года и, унеся более полумиллиона жизней, завершилось формальной капитуляцией и подписанием мира в 1865 году. Таким образом, рабство было отменено, чернокожее население получило свободу и конституционные права. Однако расовое противостояние на этом не закончилось.

Создание Ку-клукс-клана и его организационная структура.

До появления Ку-клукс-клана, в 40-х гг. XIX в. на Юге США существовало множество тайных организаций, проводивших террористические акты против офицеров, солдат федеральных войск и лиц, боровшихся за права черного населения Америки. Во время Гражданской войны (1861-1865) эти организации участвовали в борьбе с северянами – «Голубые ложи», «Сыны Юга», «Социальный союз». Наибольшую известность приобрели «Рыцари золотого круга» — в ноябре 1860 г. в ней состояло 115,0 тыс. чел. Практически все они исчезли – по тем или иным причинам – во время войны. После поражения Юга в Гражданской войне в истории США начался новый период – Реконструкция Юга (1865-1877).

Разумеется, на Юге осталось большое количество людей разного социального положения, проявлявших недовольство по поводу освобождения негров, вчерашних рабов. Поэтому появление новой антинегритянской организации оказалось закономерным.

24 декабря 1865 г. (2 июня прекратили сопротивления все войска южан) в городе Пьюласки (штат Теннеси) судья Томас Л. Джонс и 6 других лиц (почти все – бывшие офицеры армии Конфедерации) создали ку-клукс-клан, о чем свидетельствует мемориальная доска на стене здания местного суда.

Ими было принято решение о создании тайного общества, которое должно было защищать «утраченную справедливость», то есть патриархальные порядки, существовавшие на Юге. Немаловажным было и придумать особое название для организации, которое подчеркивало бы связь общества и традициями тайных обществ прошлого. Так и получился «Куклос-клан» (первое слово в переводе с греческого означает «круг» — любимый символ заговорщиков, а второе – английское слово клан, то есть, родовая община).

Однако заговорщики на этом не остановились и, желая придать названию еще больше таинственности, немного видоизменили написание слов. Так и получился «Ку-клукс-клан».

Но «Рыцари круга» очень сильно походило на другое общество, «Рыцари золотого круга». Тогда другой «учредитель», капитан Кеннеди, шотландец, предложил внести в название слово «клан», обозначавшее на его исторической родине род, группу близких родственников (не даром же один киногерой-шотландец говорил о себе: «Я – Дункан Маклауд, из клана Маклаудов»). Так было придумано наименование новой организации – Ку-клукс-клан – надолго вошедшей в историю. Поэтому А. Конан-Дойл в рассказе о Шерлоке Холмсе «Пять апельсиновых зернышек», скорее всего, был не прав, когда говорил, что название «ку- клукс-клан» «основано на сходстве со своеобразным звуком взводимого ружейного затвора». Несомненно, наименование организации было очень странным и не характерным для американцев. Как говорил один из американских историков кланизма, Д.Л. Вильсон, даже «…в самом названии ку-клукс- клана существовало какая-то роковая сила. Пусть читатель произнесет это слово вслух. Оно напоминает звук ударяющегося друг о друга костей скелета».

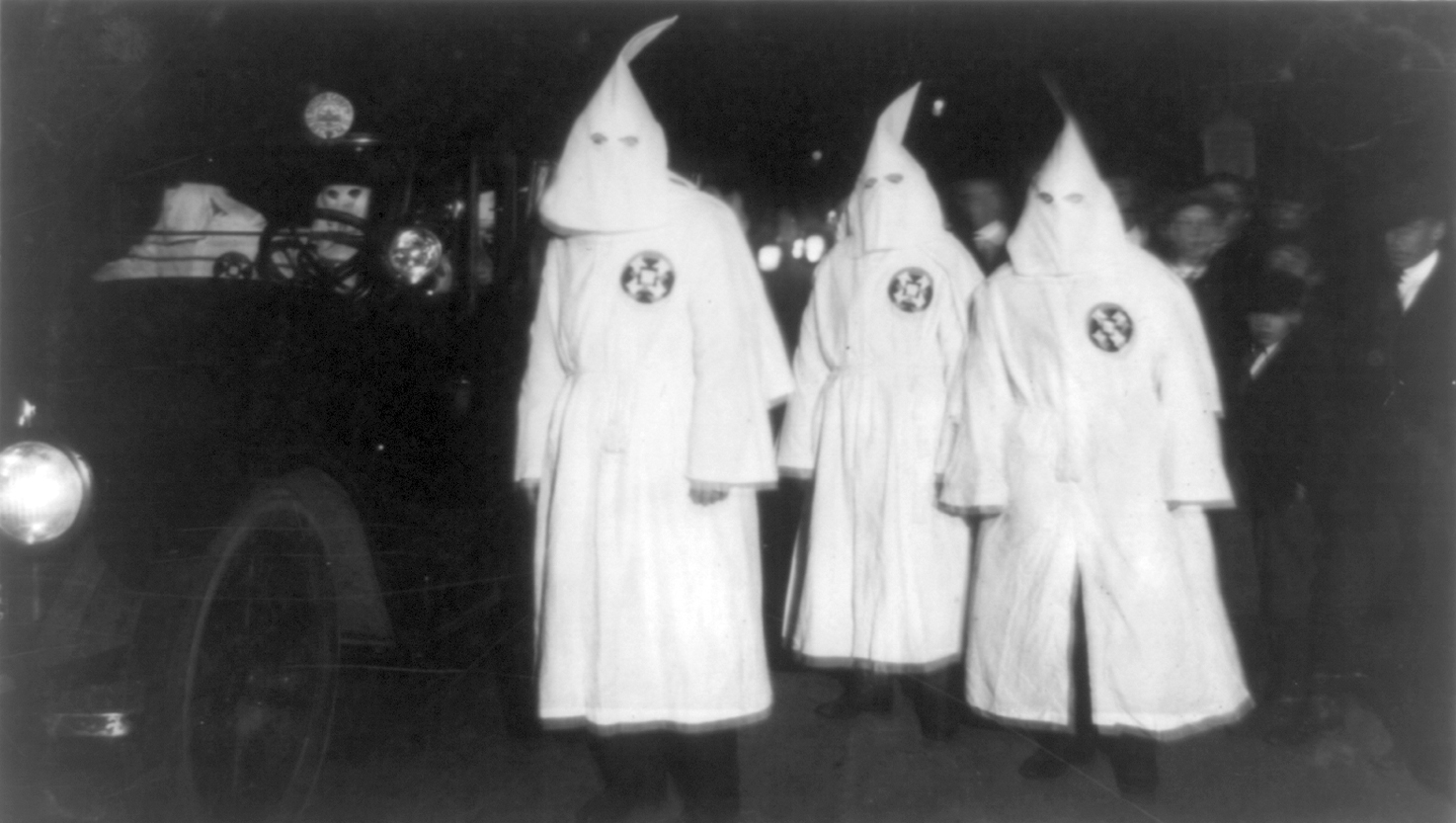

Желая отпраздновать создание своей террористической организации, ночью «отцы-учредители» закутались в белые простыни, сели на лошадей и принялись скакать по улицам города. Они от души смеялись над изумлением, которое произвело их шествие на жителей, и испытали еще большее удовольствие от страха негров, встречавшихся им по пути. В первое время суеверные негры принимали клановцев за души погибших конфедератов (т.е. южан). Страх у негров прошел, только когда среди клановцев появились убитые и раненые. После первого массового явления народу в ку-клукс-клане появился обычай носить белые маски с отверстиями для глаз и носа, высокие шапки, сшитые так, чтобы увеличить рост человека, и белую мантию (балахон), полностью закрывавший фигуру. В экипировку обязательно входил свисток, которым подавались команды; был специально разработан особый код условных сигналов.

Один из первых актов устрашения клановцев оказался довольно «невинным». Наказанию подвергся негр, ухаживавший за белой школьной учительницей. Клановцы вывезли его за город, сделали ему внушение, чтобы он перестал встречаться с белыми женщинами, и бросили его в реку.

Ку-клукс-клан быстро приобрел популярность, особенно среди бывших офицеров и солдат армии Конфедерации, убежденных расистов, и бывших членов тайных организаций типа «Рыцари золотого круга». В 1865-1867 гг., т.е. почти за два года существования численность клановцев уверенно растет – первоначальных ячеек клана насчитывалось более сотни. К 1868 г. вокруг ку-клукс-клана объединились все террористические организации южан. Социальная база клана являлась очень широкой – от самых беднейших крестьян (заработная плата которых резко упала из-за появления на рынке труда дешевой рабочей силы в виде освободившихся негров) до богачей.

В апреле 1867 г. в истории ку-клукс-клана произошло очередное важное событие – в городе Нашвилл прошел первый, нелегальный, «конгресс» организации. Согласно легенде, собрание прошло в 10-м номере отеля Максуэлла. На «конгрессе» присутствовали делегаты от Теннеси, Алабамы и Джорджии. Результатом «конференции» явилось принятие «устава» и «конституции» ку-клукс-клана. В документе говорилось, что клан возник, чтобы «остановить гибель нашей несчастной страны и избавить белую расу от тех невыносимых условий, в которые она поставлена в последнее время. Нашей основной задачей является поддержка верховенства белой расы… Америка была создана белыми и для белых, и любая попытка передать власть в руки черной расы является одновременно нарушением и Конституции [имеется в виду Конституция США], и божьей воли… Права негров должны быть признаны и защищены, но белые должны оставить себе привилегию определить объем этих политических прав. И до тех пор, пока негры не ответят, как они понимают свои политические права, Клан поклялся не допустить политического равенства чернокожих». «Конгресс» выработал и структуру организации. Ку-клукс-клан объявлялся «Невидимой империей», управляющейся «великим магом», при котором имелся совет (с функциями штаба), состоявший из 10 «гениев».

Власть главы «империи» являлась абсолютной, и принятые им решения подлежали немедленному исполнению. «Империя» делилась на «королевства», охватывавшие штат, во главе с «великим драконом» и его штабом из 8 «гидр». «Королевство» подразделялось на «домены», равные избирательному округу по выборам в Конгресс США. Во главе «домена» стоял «великий титан» с помощниками, именовавшиеся «фуриями». «Домены» делились на «провинции», возглавляемые «великим гигантом» и 4 «домовыми». Первоначальной ячейкой Клана являлась «пещера» во главе с «великим циклопом» и 2 «ночными ястребами». Имелись и другие должностные лица: «великий волхв» (замещавший «циклопа» в его отсутствие), «великий монах», исполнявший функции главы «пещеры» в случае отсутствия «циклопа» и «волхва». «Великий казначей», как видно из названия, распоряжался финансами; «великий Турок» оповещал «вампиров» — рядовых членов Клана – о предстоящих собраниях; «великий страж» являлся привратником «пещеры»; «великий знаменосец» хранил и оберегал «великое знамя», т.е. регалии. Вопрос финансирования «Невидимой империи» остается неизвестным. Часть денег клансмены добывали контрабандой, не брезговали и ограблениями, захватывая и оружие с боеприпасами. Во всяком случае, денег Клан имел всегда достаточно.

Ку-клукс-клан становится на ноги.

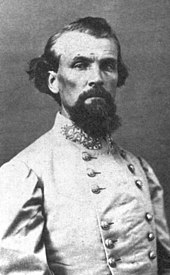

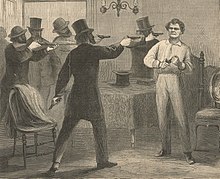

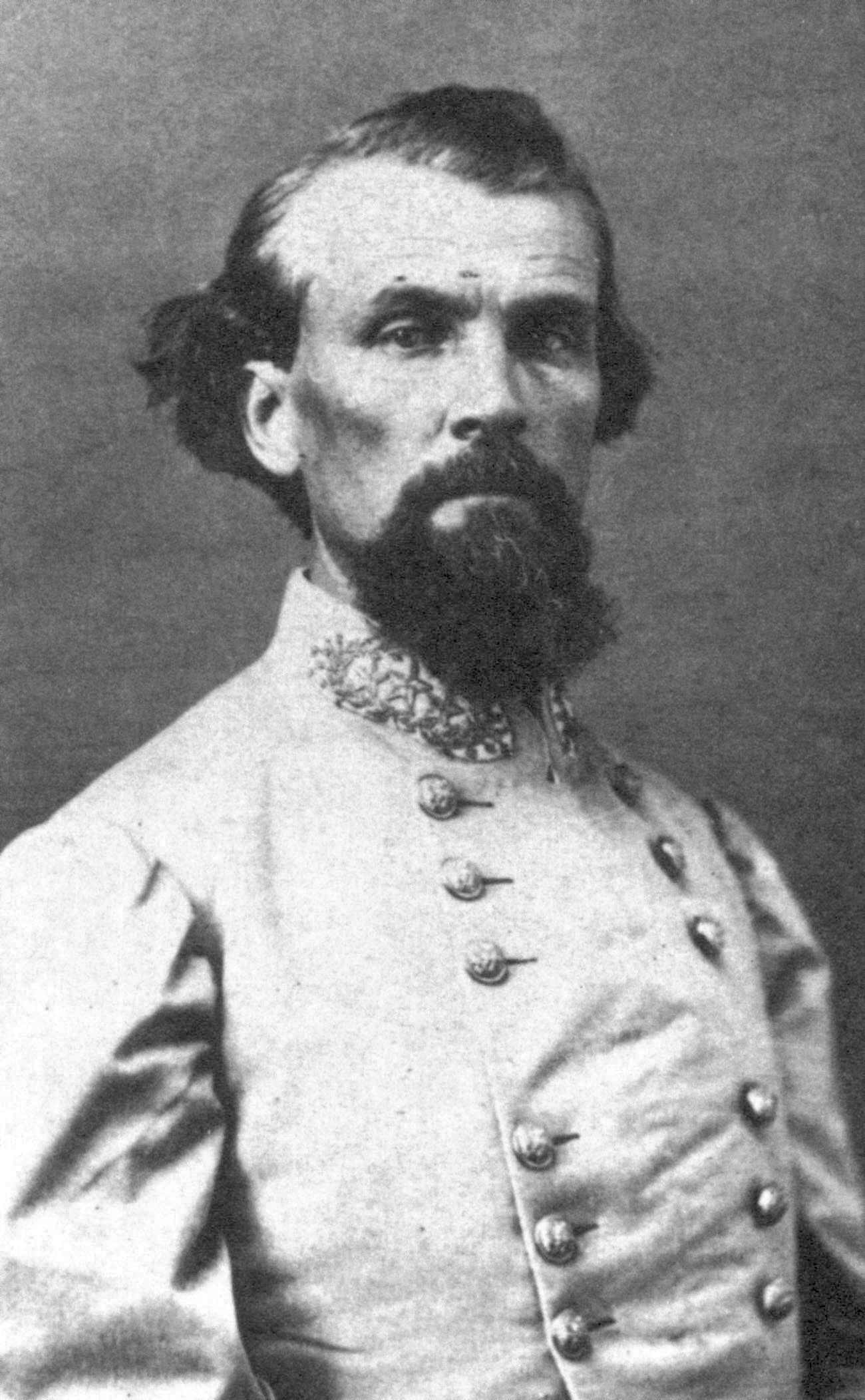

Первым лидером Ку-клукс-клана его «учредители» намеревались сделать известного и талантливого главнокомандующего армии Конфедерации Р. Ли, потерпевшего поражение в сражение при Геттисберге. Однако генерал предпочел не вмешиваться в деятельность новой террористической организации, отделавшись остроумной фразой, что «останется невидимым главой «Невидимой империи». Поэтому на пост первого «великого мага» был назначен бывший генерал Конфедерации Н.Б. Форрест, имевший большую популярность на Юге и прославившийся жестокостью во время Гражданской войны по отношению к неграм, захваченным в составе войск Севера (на другие должности были поставлены также бывшие офицеры и генералы армии Конфедерации).

В 1871 г., на заседании комиссии Конгресса, расследовавшей деятельность Ку- клукс-клана, Форрест скажет: «Я люблю старый строй [т.е. строй, существовавший до Гражданской войны на Юге], я люблю старую Конституцию. Я думаю, что правительство Конфедерации было самым лучшим правительством во всем мире». Ку-клукс-клан быстро завоевывал популярность, и в 1868 г. устав был пересмотрен. Теперь в качестве районов деятельности Клана входили, кроме 11 штатов Конфедерации, и новые – Мериленд, Массачусетс, Кентукки. Наибольшее распространение Клан получил в Теннеси, Алабаме, Северной Каролине и Луизиане.

С 70-х гг. XIX в. Ку-клукс-клан заявляет о себе почти открыто; «пещеры» оформлялись в виде политических или спортивных клубов. По данным Форреста, в Клане состояло свыше 550,0 тыс. чел, по другим данным – 2,0 млн. Клан действовал под разными названиями, чтобы люди, состоящие в них, могли без опаски клясться в суде, что они не состоят в ку-клукс-клане – «Белое братство», «Рыцари черного креста», «Стражи Конституции», «Рыцари белой камелии» и др. Наиболее характерными чертами Клана стали секретность и таинственность. Они были необходимы для конспирации «вампиров», и в качестве некоего пугала для негров и их «пособников». Второму обстоятельству придавалось первостепенное значение.

Марш Ку-клукс-клана в Вашингтоне, 1920-е годы.

Во многих случаях жертве достаточно было намекнуть, что ее присутствие нежелательно, как человек сразу же переезжал в другое место (именно об этом и рассказывает А. Конан-Дойл в рассказе «Пять апельсиновых зернышек»). Клановцы пытались всегда и везде подчеркивать таинственность организации, о ее связях с мистикой. Особенно клановцы предпочитали ночные шествия – в полном молчании, в белых балахонах и колпаках, верхом на лошадях, они ездили по пустынным улицам. Зрелище, надо отметить, производило определенное впечатление. «Невидимая империя» была окутана плотной завесой секретности. За даже малейшую попытку предать огласке секреты Ку-клукс-клана полагалась только смерть. Никогда клановцы не собирались подряд несколько раз в одном и том же месте. Для встреч друг с другом они разрабатывали запасные явки, проникнуть на которые мог только тот, кто знал многочисленные пароли и опознавательные знаки. В целях конспирации, на встречах между собой и для проведения террористических акций, клановцы надевали белые, черные или полосатые балахоны и колпаки с отороченными красными прорезями для глаз, носа и рта, иногда увенчанные несколькими рогами. Ку-клукс-клан – в «действии».

Основным «занятием» Ку-клукс-клана являлись террористические акты. Из- за необычайной разветвленности организации «вампиры» обладали исчерпывающей информацией, на базе которой они проводили убийства, поджоги, избиения. В оперативном отношении «Невидимая империя» имела следующую структуру – графство (административно-территориальная единица США) делилось на несколько округов, каждый из которых являлся «лагом», т.е. низшей боевой ячейкой, возглавляемой «капитаном». Клановцы действовали мобильными группами (в зависимости от обстоятельств) – от 10-12 чел до 200-500 чел чрезвычайно оперативно; свидетелей в живых не оставляли. Убийства негров (особенно тех, кто служил в армии) и борющихся за их права (в т.ч. и белых) совершались с невиданной жестокостью – они расстреливали, калечили, вешали. Как правило, предпочитали бросать жертву в воду с камнем на шее. Губернатор Флориды Флемминг рассказывает, что как-то раз, после того, как одного несчастного негра сварили в котле заживо, его кости хирург- клановец собрал в единый скелет, который «вампиры» повесили на перекрестке дорог для устрашения. Впоследствии, только по официальным фактам комиссии Конгресса было установлено, что в период с 1865 по 1870 гг. Ку-клукс-клан совершил более 15,0 тыс. убийств.

В 1880 г. член палаты представителей Г. Вильсон свидетельствовал, что только за политическую деятельность в южных штатах было убито 130,0 тыс. чел. Смерть ожидала не только рядовых граждан США, но и политических деятелей.

В 1868 г. в Джорджии был убит кандидат от республиканской партии на пост губернатора штата. В том де году в Алабаме было совершено нападение на двух членов Законодательного корпуса. Одного застрелили, другой, оставшийся в живых, свернул свою деятельность.

В 1869 г. клановцы убили одного сенатора и члена Законодательного собрания. Опасаясь покушения, один из радикалов во Флориде Гиббс, устроил дома настоящий арсенал, окружив себя охранниками. Но и это не помогло – Гиббса отравили. В результате к середине 70-х гг. XIX в. клановцы устроили тотальный террор, добившись небывалого могущества «Невидимой империи» почти во всех штатах Юга. Поэтому федеральное правительство было вынуждено активно вмешаться в деятельность Ку-клукс-клана, достигнув на этом поприще больших успехов. Значительно способствовала запрещению «Невидимой империи» и смерть «великого мага» Форреста в октябре 1877 г. (незадолго перед смертью освободивший «вампиров» от всех клятв), т.е. когда завершался период Реконструкции Юга. Однако если Ку-клукс-клан исчез, то ненадолго. Вскоре он снова появился. Ку-клукс-клан: второе рождение и начало заката.

Второе рождение «Невидимой империи» произошло во время Первой Мировой войны. Хотя Ку-клукс-клан уже не функционировал около 30 лет, память о нем на Юге осталась самая «благоприятная» среди ярых сторонников антинегритянского и движения. Немного спустя после ликвидации Ку-клукс- клана в свет вышли несколько книжек, прославляющих деятельность «Невидимой империи», восхваляя его как «инструмент справедливости», верного защитника прав и цивилизации южан. Так, в 1884 г. в Нашвилле вышла в свет книга одного из основателей Клана капитана Дж. Листера. Новым «отцом» Ку-клукс-клана стал некий Уильямс Симмонс – блестящий оратор, участник американо-испанской войны 1898 г. (на войну ушел добровольцем). 28 октября 1915 г. в офисе И.Р. Кларксона, адвоката Симмонса, под председательством спикера Законодательного собрания штата Джорджия Д.У. Бейла, в присутствии 36 чел (из которых двое являлись «вампирами» при «великом маге» Форресте) состоялось «учредительное собрание» нового Ку-клукс-клана. Участники встречи подписали петицию, в которой просили власти штата Джорджия разрешения учредить организацию «Рыцари Ку-клукс-клана» как «патриотический, благотворительный социальный братский орден».

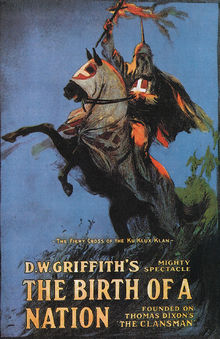

Ноябрьской ночью в День благодарения, на вершину Стоун-Маунтин, в 10 милях от Атланты (столица штата Джорджия) поднялось 16 чел. Они провели ритуальное действие – соорудили из камней алтарь, на который положили американский флаг, саблю и Библию. Рядом водрузили деревянный крест, облитый керосином, который подожгли. Второе рождение Ку-клукс-клана произошло по нескольким причинам. Одной из главных причин реинкарнации оказалась живучесть в сердцах новых южан воспоминаний о Клане как борце с неграми, к которым на Юге не питали большой любви; и еще больше обострившейся во время Первой Мировой войны. Во-вторых, в начале ХХ в. началась массовая миграция негров с Юга на Север, вызвавшая крайнее неодобрение у северян. Толчком к возрождению «Невидимой империи» явилась небывалая популярность художественной киноленты американского режиссера (южанина) Д.У. Гриффита «Рождение нации» (1915). Гриффит оставил в мировой кинематографе большой след. Вместе со знаменитостями киноэкрана начала ХХ в. — Ч. Чаплином, М. Пикфорд, Д. Фербенксом – он создал кинокомпанию « United Artists », существующую до сих пор. Гриффит разработал новые приемы операторской работы (крупный план, затемнение, наплывы, использовал движущуюся камеру). 8 марта 1915 г. Гриффит впервые продемонстрировал свое полотно широкой публике, которая получила повсеместное одобрение, особенно на Юге. Как писал один критик, «люди кричали, вопили, орали и стреляли в экран, чтобы спасти Флору Каперон [героиню фильма] от черного насильника». Резонанс после просмотра кинокартины, прославлявший белого человека и формирующий образ чернокожего человека как жестокого убийцы, бандита и грабителя, оказался небывало высоким. Радикальные организации пытались запретить показ «Рождения нации», но – удивительное дело! – президенту США В. Вильсону (южанину) и председателю Верховного суда США Э. Уайту (тоже южанин) кинофильм понравился. Это во многом и определило успех творения Гриффита (справедливости ради отметим, что в 1918 г. он создал новую картину, под названием «Сердца мира», в которой утверждал единство белых и негров).

4 декабря 1915 г. «Невидимая империя» получила право на легальное существование и на использование прежних атрибутов, традиций, регалий Клана. Словно в подтверждение необходимости функционирования организации, на следующий день, 5 декабря, в Атланте прошел первый показ кинофильма «Рождение нации»; через три недели фильм побил все рекорды по посещаемости. Возродившись, Клан частично принял другие формы существования, совершенно неприемлемые ранее. Лидеры «Невидимой империи» всячески подчеркивали, что их движение – это «стопроцентный американизм», что они проповедуют истинно патриотические и религиозные чувства. Клан призывал к закону и порядку, выдвинул лозунги борьбы против проституции, в защиту морали, что привлекло к «империи» многих американцев, и особенно женщин. Один из «великих магов» в этот период, Эванс, сказал: «Мы – движение простого народа. Мы требуем (и мы надеемся победить) вернуть власть в руки среднего гражданина, потомка пионеров…». Кроме слов, Ку-клукс-клан занимался и делом – на благотворительность в 1921 г. он затратил 1 млн. долларов.

Вместе с тем не стоит идеализировать «Невидимую империю» — победа большевиков в 1917 г. привела к росту антикоммунистических настроений, экономическая нестабильность в стране в 1919-1920 гг. – бесчисленные банкротства. Во всех бедах Клан винил «красных», иностранцев, и конечно, «черномазых», разжигая шовинизм, проповедуя национализм. Поэтому, в силу неблагоприятного внутреннего положения в США, к концу 1920 г. в Клан люди вступали сотнями тысяч человек, искренне полагая, что именно он сможет исправить ситуацию. В 1919-1920 гг. деятельностью Клана заинтересовались федеральные власти, в т.ч. небезызвестное ФБР; к суду были привлечены многие «вампиры», в т.ч. Симмонс. Однако дальше слушаний и формальных разбирательств дело не пошло – всего шесть дней потребовалось суду (с 11 по 17 октября 1921 г.), чтобы закрыть дело. Впоследствии Симмонс сказал: «Конгресс дал нам наилучшую паблисити, которые мы когда-либо получали. Конгресс создал нас». И это было не простая бравада. Когда Симмонс прибыл в Джорджию из Вашингтона, его завалил поток писем, в которых многочисленные поклонники просили разрешения создать в своей местности кланистские «пещеры». Рост численности членов Клана проходил постоянно. Иногда в «империю» в течение недели вступало около 100,0 тыс. чел! К 1924 г. в Клане насчитывалось от 6 до 9 млн. чел. Даже в одной из тюрем штата Колорадо была организована кланистская ячейка – «клаверна» — в которую входили как заключенные, так и некоторые охранники и часть тюремной администрации!

Ку-клукс-клан парад, Вашингтон 1926

В 20-е гг. Клан пользовался бешеной популярностью в стране. В июне 1923 г. был организован «Женский Ку-клукс-клан», в 1924 г. – «Младший Ку-клукс-клан» для мальчиков и юношей в возрасте от 12 до 18 лет. Количественный рост «вампиров» происходил и в городе, и в деревне. С 1920 по 1925 гг. доходы только от членских взносов составили 90,0 млн. долларов, т.е. в год – 15 млн.! Как и прежде, Ку-клукс-клан отличала антинегритянская направленность. Однако, в отличие от «классического» варианта существования, когда несчастных негров убивали десятками человек, в 20-е гг. подобного не существовало. Так, если в 60-70-е гг. XIX в. в год погибало около 3,0 тыс. чел, в 1918 г. – 70 чел, с 1919 по 1922 гг. – 239 чел.

В 1938- 1940 гг. в штате Джорджия клановцы провели более 50 террористических актов. Как и прежде, «вампиры» пользовались поддержкой «сильных мира сего». Клан располагал огромными средствами. Для подкупа, на проведение выборов в высшие законодательные органы клановцы тратили сотни и сотни тысяч долларов. По-прежнему их ставленники пробирались во власть – от самых низовых органов до Конгресса. В 1922 г. на посты губернаторов штатов Джорджия, Алабама, Калифорния и Орегона прошли люди, сочувствующие делу Клана. В 1924 г. число губернаторов-«вампиров» увеличилось за счет Колорадо, Мена, Огайо, Луизианы.

В том же, в 1924 г. «великий казначей» «империи» ассигновал для поддержки сенатора от штата Джорджия 500,0 тыс. долларов. Когда противник будущего сенатора узнал, что его соперник поддерживается Кланом, он сразу «выбросил белый флаг», т.е. предпочел уступить. Во время Второй Мировой войны деятельность Клана из-за лишней реакционности пошла на убыль, и 28 апреля 1944 г., в связи с невыплатой налогов в размере 685.305 долларов 8 центов, «Невидимая империя» объявила в Атланте о финансовой несостоятельности и самороспуске. Правда, ненадолго. Третье рождение Ку-клукс-клана: окончательный закат. Третье рождение Ку-клукс-клана произошло в 1946 г., в той же Атланте. Одним из последних «великих магов» Клана стал Сэмуэл Грин, «вампир» с 1922 г., ставший «великим драконом» Джорджии в начале 30-х гг. Однако единой, централизованной «Невидимой империи» наступил закономерный финал. Еще под председательством Грина Клан являлся более или менее послушным в его руках, но основательно трещал по всем швам. В 40-е гг. во всех организациях Клана на территории штатов Южная Каролина, Теннеси, Флорида, Алабама состояло 10,0 тыс. чел.

Сбор участников Ку-клукс-клана в Рамфорде, штат Мэн, 1987 год.

В 1949 г. Грин умер, и «империя» рухнула. В южных штатах образовываются отдельные, независимые друг от друга кланистские организации. Самым известным «королевством» стали «Рыцари Ку-клукс- клана Америки», возникшие в 1949 г. в Алабаме, претендовавшие на роль лидера Ку-клукс-клана Соединенных Штатов. Раскол происходил и внутри этих небольших организаций. Так, в «королевстве» Джорджии отделились местные «клаверны» в Колумбусе и Манчестере, образовав «Подлинные южные кланы Америки», во главе которых встал 23-летний ветеран Второй Мировой войны Элтон Пейт, который провозгласил «беспощадную борьбу с учением коммунистической партией», защиту американского протестантизма и выступал против национальных меньшинств. Огромное недовольство всех кланистов вызвала отмена в 1954 г. сегрегации школы, т.е. в данном случае – раздельное обучение белых и черных детей. Несмотря на ссоры и распри внутри Клана, «вампиры» все как один являлись, как в былые времена, ярыми ненавистниками «неамериканцев», в т.ч. негров. Так, в городе Мобил (Алабама) в январе 1957 г. Клан взорвал за одну ночь три дома, совершил вооруженные налеты на три жилища негров, спалил негритянский дом и здание школы.

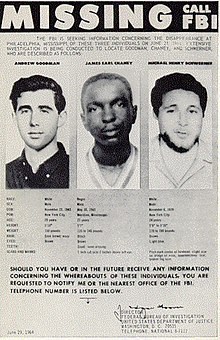

Всего с 1955 по 1965 гг. расисты Юга убили 85 чел, из них 69 негров и 8 белых борцов за права «цветного населения» США.

Тем не менее, попытки возродить клан делались и в 1960-е годы, когда наиболее радикальные члены организации проводили борьбу против секс-меньшинств, а заодно и уничтожали других борцов за гражданские права. Но тогда клановцы вновь переборщили с активностью, и их вновь запретили.

Новый всплеск активности организации пришелся на 1970-е годы, когда отдельные небольшие расистские группы при помощи террора попытались вести борьбу против чернокожего населения, которое отстаивало свои права. Но тогда на высоте оказалось ФБР, которое за короткий период времени арестовало наиболее активных клановцев.

В настоящее время Ку-клукс-клан остается активным членом «гражданского общества». Участники движения уверяют, что не прибегают больше к насилию, а заняты лишь тем, чтобы охранять христианство и свои города от преступников и иммигрантов. Большая часть клановцев – это гражданская милиция. Их насчитывается примерно 250 тысяч человек. Примерно 100-150 тысяч состоит в нелегальных и полулегальных организациях. Время от времени эти организации закрывают, а вожди «белого движения» попадают за решетку на длительные сроки.

На сегодняшний день официально в различных группировках клана состоит около 5 тысяч человек. Однако реальная цифра тех, кто поддерживает движение и активно участвует в жизни клана, достигает более одного миллиона человек. Официальное число говорит лишь о том, что различные антифашистские и прочие цветные организации и движения предъявляют судебные иски клановцам. Речь идет о миллионах долларов. Для того чтобы эти выплаты уменьшить, официальное общество намерено занижает свою численность, чтобы таким образом вполне законно снизить до минимума судовые выплаты (мотивируя это малочисленностью и бедностью организации).

Одним из таких исков стало дело Джордана Грувера. В 2006 году четыре участника движения «императорский Ку-клукс-клан» в небольшом городке Бранденбург, расположенном в штате Кентукки, якобы проводили миссионерскую деятельность (но почему-то ночью). По пути они встретили шестнадцатилетнего подростка-индейца. Не очень задумываясь о правильности своих действий, «миссионеры» избили его, затем облив спиртом, попытались сжечь заживо. Но мальчику повезло, мимо проезжала полицейская машина. В результате жизнь Джордана была спасена, а клановцы на три года попали за решетку. В свою защиту они в ходе судебных разбирательств говорили о том, что мальчик сам пытался напасть на них. И это на здоровых мужчин, двое из которых имели под два метра роста и весили более ста килограммов, при этом рост мальчика не дотягивал даже до 160 сантиметров, а вес – 45 килограммов.

Помимо тюремного заключения, на саму организацию был наложен штраф – «императорский Ку-клукс-клан» должен был выплатить 1,5 миллиона долларов самому Груверу, а кроме того, еще 1 миллионов в казну штата.

В 2010 году был арестован лидер «императорского клана» пастор Рон Эдвардс и его жена. Его обвинили в хранении и распространении метамфетамина. Клановцы уверяли, что наркотики им были подброшены сотрудниками ФБР. Но тогда пастору удалось отделаться всего лишь домашним арестом.

Еще один такой случай, но с гораздо более плачевным финалом, произошел в 2011 году, когда в тюрьме Хантсвилла был казнен один из наиболее активных участников клана Лоуренс Брювер. В 1998 году он вместе с двумя своими сообщниками жестоко расправился с чернокожим мужчиной Джеймсом Бердом. Его заманили в автомобиль, на котором вывезли в безлюдное место и подвергли пыткам. Затем пристегнули его наручниками к машине и волочили тело до тех пор, пока мужчина не умер.

Многие задаются вопросом: как так получается, что подобная организация, многими принимаемая исключительно как пережиток эпохи, возрождается снова и снова? А все очень просто – периодически она требуется официальным властям. И под названием «Ку-клукс-клан» скрывается не одна, а сразу несколько законспирированных организаций. Самой крупной из них являются «Рыцари Ку-клукс-клана», которые действуют в Арканзасе. Во главе организации стоит пастор Том Робб. Клановцы имеют серьезную юридическую поддержку, которую им предоставляет Американский союз гражданских свобод. Но в то же время, достигнуть былого размаха организации пока не удается. Впрочем, клановцы не унывают, утверждая, что численность для них – не самое главное. Вполне может быть, что Ку-клукс-клан ожидает долгая жизнь, потому как организации нужна многим…

[источники]

http://www.calend.ru/event/4657/

http://www.vokrugsveta.ru/telegraph/history/1083/

http://www.velesova-sloboda.org/right/ku-klux-klan.html

http://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D0%9A%D1%83-%D0%BA%D0%BB%D1%83%D0%BA%D1%81-%D0%BA%D0%BB%D0%B0%D0%BD

http://wap.alcofans.forum24.ru/?1-12-0-00000023-000-0-0-1193064356

http://www.ridus.ru/news/151838

Еще немного истории Америки: вот например Теракт на Уолл-стрит, а вот Нефтяная лихорадка в Калифорнии и Почему в США не перешли на метрическую систему. Давайте вспомним еще про Взятие Вашингтона а так же про Запрещенные эксперименты над людьми в США

Оригинал статьи находится на сайте ИнфоГлаз.рф Ссылка на статью, с которой сделана эта копия — http://infoglaz.ru/?p=86073

-

-

December 24 2019, 11:00

- История

- Общество

- Cancel

В этот день на свет появился «Ку-клукс-клан»

В этот день в 1865 – году в США родилось движение Ку-клукс-клан.

За белыми капюшонами с прорезями для глаз скрывались мстительные южане и тайная расистская организация Америки. Ветераны Гражданской войны хотели вернуть былое величие и запугать безжалостными методами своих бывших чернокожих рабов. Кстати, знаете одну из самых главных причин, почему в США были освобождены рабы?

Первый Ку-клукс-клан был основан в 1860-х годах на юге США. Первый Ку-клукс-клан был основан в 1860-х годах на юге США, но уже в начале 1870-х движение перестало существовать. Творившими беззаконие людьми руководил Великий маг, которому подчинялись великие драконы, титаны и циклопы.

Один из первых актов был довольно мягким. Наказанию подвергся негр, ухаживавший за белой школьной учительницей. Его вывезли за город, сделали внушение со стороны спины и бросили в реку. Но клан быстро перешел на зверские избиения и казни, а со временем пополнился вооруженными покушениями и террористическими взрывами.

Объектом террора являлись не только люди негроидной расы, но и белые республиканцы. Любой белый, прибывший с севера для работы среди чернокожих, подвергался нападениям. В 1869 г. клановцы убили одного сенатора и члена Законодательного собрания.

По данным «Великого Магистра» Форреста (1868 год), в Клане состояло свыше 550 тыс. чел, по другим данным — 2 млн. К концу 1868 года число его членов достигло 600 тыс. человек. В большинстве своём это были солдаты и офицеры армии южан.

Конан-Дойл в рассказе о Шерлоке Холмсе «Пять апельсиновых зернышек», объяснил странное название просто — «ку- клукс-клан» «основано на сходстве со своеобразным звуком взводимого ружейного затвора».

Ациям членов ку-клукс-клана обычно предшествовало предупреждение. Это была дубовая ветка с листьями, или семена дыни или зёрнышки апельсина. Получив такое предупреждение, жертва могла либо отречься от своих прежних взглядов, либо покинуть страну. Если человек игнорировал предупреждение, его ждала смерть.

В середине XX века Ку-клукс-клан выступал также против американских католиков и коммунизма. С этой организацией связывают появление понятия суд Линча, который отменили ВНИМАНИЕ в конце 50-х ПРОШЛОГО века.

В городе Мобил (Алабама) в январе 1957 г. Клан взорвал за одну ночь три дома, совершил вооруженные налеты на три жилища негров, спалил негритянский дом и здание школы.

Многие задаются вопросом: как так получается, что подобная организация, многими принимаемая исключительно как пережиток эпохи, возрождается снова и снова? А все очень просто – она требуется официальным властям. На них и на их право «свободы» и фанатизм можно свалить все что угодно и списать любое преступление.

В сегодняшнем Ку-клукс-клане состоят от 4 до 6 тысяч американцев и как считают в США «остается активным членом гражданского общества»… )))

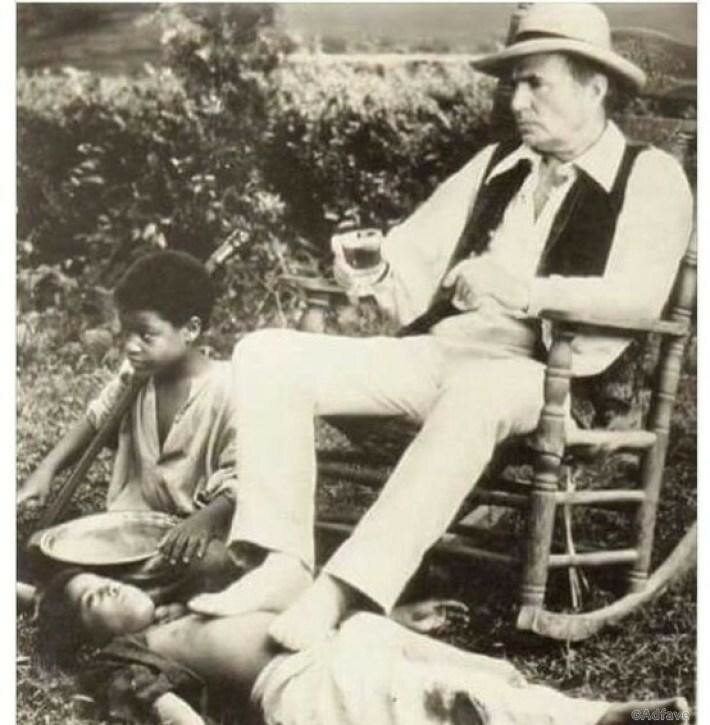

Краткая история американской работорговли с картинками и фотографиями

Бежавшему и пойманному рабу отрезали уши. Рабам запрещали передвигаться группами более чем в 7 человек без сопровождения белых. Любой белый, встретивший негра вне плантации, должен был потребовать у него отпускной билет, а если такого не было, мог дать 20 ударов плетью.

В случае, если негр пытался защищаться или ответить на удар, он подлежал казни. За нахождение вне дома после 9 часов вечера негров в Виргинии подвергали четвертованию.

Негры работали до 18−19 часов в сутки. На ночь их запирали и спускали собак. Средняя продолжительность жизни негра-раба на плантациях составляла 10 лет, а в XIX веке — 7 лет. За плохую работу раба, отрубали руки и ноги его детям.

Всего с 1955 по 1965 гг. расисты Юга убили 85 чел, из них 69 негров и 8 белых борцов за права «цветного населения» США.

Такие вот дерьмократы живут в США…

США ● Путешествие туриста по стране. Города, национальные парки, лайфхаки…

Инфа и фото (С) интернет

The Duke Flag, used by some in the Third Klan and named after former Klan leader David Duke. The Blood Drop Cross is shown in the centre.[1] |

|

| In existence |

|

|---|---|

| Members |

|

| Political ideologies |

After 1915:

After 1950:

|

| Political position | Far-right |

| Espoused religion |

|

The Ku Klux Klan (),[c] commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is an American white supremacist, right-wing terrorist, and hate group whose primary targets are African Americans, Jews, Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans,[43] and Catholics, as well as immigrants, leftists, homosexuals,[44][45] Muslims,[46] atheists,[27][28][29][30] and abortion providers.[47][48][49]

The Klan has existed in three distinct eras. Each has advocated extremist reactionary positions such as white nationalism, anti-immigration and—especially in later iterations—Nordicism,[50][51] antisemitism, anti-Catholicism, Prohibition, right-wing populism, anti-communism, homophobia,[52][53][54][55][56] anti-atheism,[27][28][29][30] Islamophobia, and anti-progressivism. The first Klan founded by Confederate veterans[57] used terrorism—both physical assault and murder—against politically active Black people and their allies in the Southern United States in the late 1860s. The second iteration of the Klan originated in the 1910s, and was the first to use cross burnings and hooded robes. During the First Red Scare, the Klan integrated anti-communism into its doctrine.[58] [59] The third Klan used murders and bombings from the late 1940s to the early 1960s to achieve its aims. All three movements have called for the «purification» of American society, and are all considered far-right extremist organizations.[60][61][62][63] In each era, membership was secret and estimates of the total were highly exaggerated by both friends and enemies.

The first Klan was established in the wake of the American Civil War and was a defining organization of the Reconstruction era. Organized in numerous chapters across the Southern United States, federal law enforcement suppressed it around 1871. It sought to overthrow the Republican state governments in the South, especially by using voter intimidation and targeted violence against African-American leaders. Each chapter was autonomous and highly secretive about membership and plans. Members made their own, often colorful, costumes: robes, masks and conical hats, designed to be terrifying and to hide their identities.[64][65]

The second Klan started in 1915 as a small group in Georgia. It grew after 1920 and flourished nationwide in the early and mid-1920s, including urban areas of the Midwest and West. Taking inspiration from D. W. Griffith’s 1915 silent film The Birth of a Nation, which mythologized the founding of the first Klan, it employed marketing techniques and a popular fraternal organization structure. Rooted in local Protestant communities, it sought to maintain white supremacy, often took a pro-Prohibition and pro-compulsory public education[66][67][68] stance, and it opposed Jews, while also stressing its opposition to the alleged political power of the pope and the Catholic Church. This second Klan flourished both in the south and northern states; it was funded by initiation fees and selling its members a standard white costume. The chapters did not have dues. It used K-words which were similar to those used by the first Klan, while adding cross burnings and mass parades to intimidate others. It rapidly declined in the latter half of the 1920s.

The third and current manifestation of the KKK emerged after 1950, in the form of localized and isolated groups that use the KKK name. They have focused on opposition to the civil rights movement, often using violence and murder to suppress activists. This manifestation is classified as a hate group by the Anti-Defamation League and the Southern Poverty Law Center.[69] As of 2016, the Anti-Defamation League puts total KKK membership nationwide at around 3,000, while the Southern Poverty Law Center puts it at 6,000 members total.[70]

The second and third incarnations of the Ku Klux Klan made frequent references to a false mythologized perception of America’s «Anglo-Saxon» blood, hearkening back to 19th-century nativism.[71] Although members of the KKK swear to uphold Christian morality, Christian denominations widely denounce them.[72]

Overview

First KKK

Depiction of Ku Klux Klan in North Carolina in 1870, based on a photograph taken under the supervision of a federal officer who seized Klan costumes

The first Klan was founded in Pulaski, Tennessee, on December 24, 1865,[73] by six former officers of the Confederate army:[74] Frank McCord, Richard Reed, John Lester, John Kennedy, J. Calvin Jones, and James Crowe.[75] It started as a fraternal social club inspired at least in part by the then largely defunct Sons of Malta. It borrowed parts of the initiation ceremony from that group, with the same purpose: «ludicrous initiations, the baffling of public curiosity, and the amusement for members were the only objects of the Klan», according to Albert Stevens in 1907.[76] The manual of rituals was printed by Laps D. McCord of Pulaski.[77] The origins of the hood are uncertain; it may have been appropriated from the Spanish capirote hood,[78] or it may be traced to the uniform of Southern Mardi Gras celebrations.[79]

According to The Cyclopædia of Fraternities (1907), «Beginning in April, 1867, there was a gradual transformation. … The members had conjured up a veritable Frankenstein. They had played with an engine of power and mystery, though organized on entirely innocent lines, and found themselves overcome by a belief that something must lie behind it all—that there was, after all, a serious purpose, a work for the Klan to do.»[76]

Although there was little organizational structure above the local level, similar groups rose across the South and adopted the same name and methods.[clarification needed][80] Klan groups spread throughout the South as an insurgent movement promoting resistance and white supremacy during the Reconstruction Era. For example, Confederate veteran John W. Morton founded a chapter in Nashville, Tennessee.[81] As a secret vigilante group, the Klan targeted freedmen and their allies; it sought to restore white supremacy by threats and violence, including murder. «They targeted white Northern leaders, Southern sympathizers and politically active Blacks.»[82] In 1870 and 1871, the federal government passed the Enforcement Acts, which were intended to prosecute and suppress Klan crimes.[83]

The first Klan had mixed results in terms of achieving its objectives. It seriously weakened the Black political leadership through its use of assassinations and threats of violence, and it drove some people out of politics. On the other hand, it caused a sharp backlash, with passage of federal laws that historian Eric Foner says were a success in terms of «restoring order, reinvigorating the morale of Southern Republicans, and enabling Blacks to exercise their rights as citizens».[84] Historian George C. Rable argues that the Klan was a political failure and therefore was discarded by the Democratic Party leaders of the South. He says:

The Klan declined in strength in part because of internal weaknesses; its lack of central organization and the failure of its leaders to control criminal elements and sadists. More fundamentally, it declined because it failed to achieve its central objective – the overthrow of Republican state governments in the South.[85]

After the Klan was suppressed, similar insurgent paramilitary groups arose that were explicitly directed at suppressing Republican voting and turning Republicans out of office: the White League, which started in Louisiana in 1874; and the Red Shirts, which started in Mississippi and developed chapters in the Carolinas. For instance, the Red Shirts are credited with helping elect Wade Hampton as governor in South Carolina. They were described as acting as the military arm of the Democratic Party and are attributed with helping white Democrats regain control of state legislatures throughout the South.[86]

Second KKK

KKK rally near Chicago in the 1920s

In 1915, the second Klan was founded atop Stone Mountain, Georgia, by William Joseph Simmons. While Simmons relied on documents from the original Klan and memories of some surviving elders, the revived Klan was based significantly on the wildly popular film The Birth of a Nation. The earlier Klan had not worn the white costumes and had not burned crosses; these aspects were introduced in the book on which the film was based. When the film was shown in Atlanta in December of that year, Simmons and his new klansmen paraded to the theater in robes and pointed hoods – many on robed horses – just like in the film. These mass parades became another hallmark of the new Klan that had not existed in the original Reconstruction-era organization.[87]

Beginning in 1921, it adopted a modern business system of using full-time, paid recruiters and it appealed to new members as a fraternal organization, of which many examples were flourishing at the time. The national headquarters made its profit through a monopoly on costume sales, while the organizers were paid through initiation fees. It grew rapidly nationwide at a time of prosperity. Reflecting the social tensions pitting urban versus rural America, it spread to every state and was prominent in many cities. The second KKK preached «One Hundred Percent Americanism» and demanded the purification of politics, calling for strict morality and better enforcement of Prohibition. Its official rhetoric focused on the threat of the Catholic Church, using anti-Catholicism and nativism.[7] Its appeal was directed exclusively toward white Protestants; it opposed Jews, Black people, Catholics, and newly arriving Southern and Eastern European immigrants such as Italians, Russians, and Lithuanians, many of whom were Jewish or Catholic.[88] Some local groups threatened violence against rum runners and those they deemed «notorious sinners»; the violent episodes generally took place in the South.[89] The Red Knights were a militant group organized in opposition to the Klan and responded violently to Klan provocations on several occasions.[90]

The «Ku Klux Number» of Judge, August 16, 1924

The second Klan was a formal fraternal organization, with a national and state structure. During the resurgence of the second Klan in the 1920s, its publicity was handled by the Southern Publicity Association. Within the first six months of the Association’s national recruitment campaign, Klan membership had increased by 85,000.[91] At its peak in the mid-1920s, the organization’s membership ranged from three to eight million members.[92]

In 1923, Simmons was ousted as leader of the KKK by Hiram Wesley Evans. From September 1923 there were two Ku Klux Klan organizations: the one founded by Simmons and led by Evans with its strength primarily in the southern United States, and a breakaway group led by Grand Dragon D. C. Stephenson based in Indiana with its membership primarily in the midwestern United States.[93]

Internal divisions, criminal behavior by leaders – especially Stephenson’s conviction for the abduction, rape, and murder of Madge Oberholtzer – and external opposition brought about a collapse in the membership of both groups. The main group’s membership had dropped to about 30,000 by 1930. It finally faded away in the 1940s.[94] Klan organizers also operated in Canada, especially in Saskatchewan in 1926–1928, where Klansmen denounced immigrants from Eastern Europe as a threat to Canada’s «Anglo-Saxon» heritage.[95][96]

Third KKK

The «Ku Klux Klan» name was used by numerous independent local groups opposing the civil rights movement and desegregation, especially in the 1950s and 1960s. During this period, they often forged alliances with Southern police departments, as in Birmingham, Alabama; or with governor’s offices, as with George Wallace of Alabama.[97] Several members of Klan groups were convicted of murder in the deaths of civil rights workers in Mississippi in 1964 and of children in the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham in 1963.

The United States government still considers the Klan to be a «subversive terrorist organization».[98][99][100][101] In April 1997, FBI agents arrested four members of the True Knights of the Ku Klux Klan in Dallas for conspiracy to commit robbery and for conspiring to blow up a natural gas processing plant.[102] In 1999, the city council of Charleston, South Carolina, passed a resolution declaring the Klan a terrorist organization.[103]

The existence of modern Klan groups has been in a state of consistent decline due to a variety of factors from the American public’s negative distaste of the group’s image, platform, and history, infiltration and prosecution by law enforcement, civil lawsuit forfeitures, and the radical right-wing’s perception of the Klan as outdated and unfashionable. The Southern Poverty Law Center reported that just between 2016 and 2019 the number of Klan groups in America dropped from 130 to just 51.[104] A 2016 report by the Anti-Defamation League claims an estimate of just over 30 active Klan groups existing in the United States.[105] Estimates of total collective membership range from about 3,000[105] to 8,000.[106] In addition to its active membership, the Klan has an «unknown number of associates and supporters».[105]

History

Origin of the name

The name was probably formed by combining the Greek kyklos (κύκλος, which means circle) with clan.[107][108] The word had previously been used for other fraternal organizations in the South such as Kuklos Adelphon.

First Klan: 1865–1871

Creation and naming

Six Confederate veterans from Pulaski, Tennessee, created the original Ku Klux Klan on December 24, 1865, shortly after the Civil War, during the Reconstruction of the South.[109][110] The group was known for a short time as the «Kuklux Clan». The Ku Klux Klan was one of a number of secret, oath-bound organizations using violence, which included the Southern Cross in New Orleans (1865) and the Knights of the White Camelia (1867) in Louisiana.[111]

Historians generally classify the KKK as part of the post-Civil War insurgent violence related not only to the high number of veterans in the population, but also to their effort to control the dramatically changed social situation by using extrajudicial means to restore white supremacy. In 1866, Mississippi governor William L. Sharkey reported that disorder, lack of control, and lawlessness were widespread; in some states armed bands of Confederate soldiers roamed at will. The Klan used public violence against Black people and their allies as intimidation. They burned houses and attacked and killed Black people, leaving their bodies on the roads.[112] While racism was a core belief of the Klan, anti-Semitism was not. Many prominent southern Jews identified wholly with southern culture, resulting in examples of Jewish participation in the Klan.[113]

This Frank Bellew cartoon links the Democratic Party with secession and the Confederate cause.[114]

At an 1867 meeting in Nashville, Tennessee, Klan members gathered to try to create a hierarchical organization with local chapters eventually reporting to a national headquarters. Since most of the Klan’s members were veterans, they were used to such military hierarchy, but the Klan never operated under this centralized structure. Local chapters and bands were highly independent.

Former Confederate brigadier general George Gordon developed the Prescript, which espoused white supremacist belief. For instance, an applicant should be asked if he was in favor of «a white man’s government», «the reenfranchisement and emancipation of the white men of the South, and the restitution of the Southern people to all their rights».[115] The latter is a reference to the Ironclad Oath, which stripped the vote from white persons who refused to swear that they had not borne arms against the Union.

Confederate general Nathan Bedford Forrest was elected the first grand wizard, and claimed to be the Klan’s national leader.[74][116] In an 1868 newspaper interview, Forrest stated that the Klan’s primary opposition was to the Loyal Leagues, Republican state governments, people such as Tennessee governor William Gannaway Brownlow, and other «carpetbaggers» and «scalawags».[117] He argued that many Southerners believed that Black people were voting for the Republican Party because they were being hoodwinked by the Loyal Leagues.[118] One Alabama newspaper editor declared «The League is nothing more than a nigger Ku Klux Klan.»[119]

Despite Gordon’s and Forrest’s work, local Klan units never accepted the Prescript and continued to operate autonomously. There were never hierarchical levels or state headquarters. Klan members used violence to settle old personal feuds and local grudges, as they worked to restore general white dominance in the disrupted postwar society. The historian Elaine Frantz Parsons describes the membership:

Lifting the Klan mask revealed a chaotic multitude of anti-Black vigilante groups, disgruntled poor white farmers, wartime guerrilla bands, displaced Democratic politicians, illegal whiskey distillers, coercive moral reformers, sadists, rapists, white workmen fearful of Black competition, employers trying to enforce labor discipline, common thieves, neighbors with decades-old grudges, and even a few freedmen and white Republicans who allied with Democratic whites or had criminal agendas of their own. Indeed, all they had in common, besides being overwhelmingly white, southern, and Democratic, was that they called themselves, or were called, Klansmen.[120]

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

Historian Eric Foner observed: «In effect, the Klan was a military force serving the interests of the Democratic party, the planter class, and all those who desired restoration of white supremacy. Its purposes were political, but political in the broadest sense, for it sought to affect power relations, both public and private, throughout Southern society. It aimed to reverse the interlocking changes sweeping over the South during Reconstruction: to destroy the Republican party’s infrastructure, undermine the Reconstruction state, reestablish control of the Black labor force, and restore racial subordination in every aspect of Southern life.[121] To that end they worked to curb the education, economic advancement, voting rights, and right to keep and bear arms of Black people.[121] The Klan soon spread into nearly every Southern state, launching a reign of terror against Republican leaders both Black and white. Those political leaders assassinated during the campaign included Arkansas Congressman James M. Hinds, three members of the South Carolina legislature, and several men who served in constitutional conventions.»[122]

Activities

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

Klan members adopted masks and robes that hid their identities and added to the drama of their night rides, their chosen time for attacks. Many of them operated in small towns and rural areas where people otherwise knew each other’s faces, and sometimes still recognized the attackers by voice and mannerisms. «The kind of thing that men are afraid or ashamed to do openly, and by day, they accomplish secretly, masked, and at night.»[124] The KKK night riders «sometimes claimed to be ghosts of Confederate soldiers so, as they claimed, to frighten superstitious Blacks. Few freedmen took such nonsense seriously.»[125]

The Klan attacked Black members of the Loyal Leagues and intimidated Southern Republicans and Freedmen’s Bureau workers. When they killed Black political leaders, they also took heads of families, along with the leaders of churches and community groups, because these people had many roles in society. Agents of the Freedmen’s Bureau reported weekly assaults and murders of Black people.

«Armed guerrilla warfare killed thousands of Negroes; political riots were staged; their causes or occasions were always obscure, their results always certain: ten to one hundred times as many Negroes were killed as whites.» Masked men shot into houses and burned them, sometimes with the occupants still inside. They drove successful Black farmers off their land. «Generally, it can be reported that in North and South Carolina, in 18 months ending in June 1867, there were 197 murders and 548 cases of aggravated assault.»[126]

Klan violence worked to suppress Black voting, and campaign seasons were deadly. More than 2,000 people were killed, wounded, or otherwise injured in Louisiana within a few weeks prior to the Presidential election of November 1868. Although St. Landry Parish had a registered Republican majority of 1,071, after the murders, no Republicans voted in the fall elections. White Democrats cast the full vote of the parish for President Grant’s opponent. The KKK killed and wounded more than 200 Black Republicans, hunting and chasing them through the woods. Thirteen captives were taken from jail and shot; a half-buried pile of 25 bodies was found in the woods. The KKK made people vote Democratic and gave them certificates of the fact.[127]

In the April 1868 Georgia gubernatorial election, Columbia County cast 1,222 votes for Republican Rufus Bullock. By the November presidential election, Klan intimidation led to suppression of the Republican vote and only one person voted for Ulysses S. Grant.[128]

Klansmen killed more than 150 African Americans in a county[which?] in Florida, and hundreds more in other counties.[which?] Florida Freedmen’s Bureau records provided a detailed recounting of Klansmen’s beatings and murders of freedmen and their white allies.[129]

Milder encounters, including some against white teachers, also occurred. In Mississippi, according to the Congressional inquiry:

One of these teachers (Miss Allen of Illinois), whose school was at Cotton Gin Port in Monroe County, was visited … between one and two o’clock in the morning in March 1871, by about fifty men mounted and disguised. Each man wore a long white robe and his face was covered by a loose mask with scarlet stripes. She was ordered to get up and dress which she did at once and then admitted to her room the captain and lieutenant who in addition to the usual disguise had long horns on their heads and a sort of device in front. The lieutenant had a pistol in his hand and he and the captain sat down while eight or ten men stood inside the door and the porch was full. They treated her «gentlemanly and quietly» but complained of the heavy school-tax, said she must stop teaching and go away and warned her that they never gave a second notice. She heeded the warning and left the county.[130]

By 1868, two years after the Klan’s creation, its activity was beginning to decrease.[131] Members were hiding behind Klan masks and robes as a way to avoid prosecution for freelance violence. Many influential Southern Democrats feared that Klan lawlessness provided an excuse for the federal government to retain its power over the South, and they began to turn against it.[132] There were outlandish claims made, such as Georgian B. H. Hill stating «that some of these outrages were actually perpetrated by the political friends of the parties slain.»[131]

Resistance

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

Union Army veterans in mountainous Blount County, Alabama, organized «the anti-Ku Klux». They put an end to violence by threatening Klansmen with reprisals unless they stopped whipping Unionists and burning Black churches and schools. Armed Black people formed their own defense in Bennettsville, South Carolina, and patrolled the streets to protect their homes.[133]

National sentiment gathered to crack down on the Klan, even though some Democrats at the national level questioned whether the Klan really existed, or believed that it was a creation of nervous Southern Republican governors.[134] Many southern states began to pass anti-Klan legislation.[135]

In January 1871, Pennsylvania Republican senator John Scott convened a congressional committee which took testimony from 52 witnesses about Klan atrocities, accumulating 12 volumes. In February, former Union general and congressman Benjamin Franklin Butler of Massachusetts introduced the Civil Rights Act of 1871 (Ku Klux Klan Act). This added to the enmity that Southern white Democrats bore toward him.[136] While the bill was being considered, further violence in the South swung support for its passage. The governor of South Carolina appealed for federal troops to assist his efforts in keeping control of the state. A riot and massacre occurred in a Meridian, Mississippi, courthouse, from which a Black state representative escaped by fleeing to the woods.[137] The 1871 Civil Rights Act allowed the president to suspend habeas corpus.[138]

In 1871, President Ulysses S. Grant signed Butler’s legislation. The Ku Klux Klan Act and the Enforcement Act of 1870 were used by the federal government to enforce the civil rights provisions for individuals under the constitution. The Klan refused to voluntarily dissolve after the 1871 Klan Act, so President Grant issued a suspension of habeas corpus and stationed federal troops in nine South Carolina counties by invoking the Insurrection Act of 1807. The Klansmen were apprehended and prosecuted in federal court. Judges Hugh Lennox Bond and George S. Bryan presided over the trial of KKK members in Columbia, South Carolina, during December 1871.[139] The defendants were given from three months to five years of incarceration with fines.[140] More Black people served on juries in federal court than on local or state juries, so they had a chance to participate in the process.[138][141] Hundreds of Klan members were fined or imprisoned during the crackdown.

End of the first Klan

Klan leader Nathan Bedford Forrest boasted that the Klan was a nationwide organization of 550,000 men and that he could muster 40,000 Klansmen within five days’ notice. However, the Klan had no membership rosters, no chapters, and no local officers, so it was difficult for observers to judge its membership.[142] It had created a sensation by the dramatic nature of its masked forays and because of its many murders.

In 1870, a federal grand jury determined that the Klan was a «terrorist organization»[143] and issued hundreds of indictments for crimes of violence and terrorism. Klan members were prosecuted, and many fled from areas that were under federal government jurisdiction, particularly in South Carolina.[143] Many people not formally inducted into the Klan had used the Klan’s costume to hide their identities when carrying out independent acts of violence. Forrest called for the Klan to disband in 1869, arguing that it was «being perverted from its original honorable and patriotic purposes, becoming injurious instead of subservient to the public peace».[144] Historian Stanley Horn argues that «generally speaking, the Klan’s end was more in the form of spotty, slow, and gradual disintegration than a formal and decisive disbandment».[145] A Georgia-based reporter wrote in 1870: «A true statement of the case is not that the Ku Klux are an organized band of licensed criminals, but that men who commit crimes call themselves Ku Klux».[146]

In many states, officials were reluctant to use Black militia against the Klan out of fear that racial tensions would be raised.[141] Republican governor of North Carolina William Woods Holden called out the militia against the Klan in 1870, adding to his unpopularity. This and extensive violence and fraud at the polls caused the Republicans to lose their majority in the state legislature. Disaffection with Holden’s actions contributed to white Democratic legislators impeaching him and removing him from office, but their reasons for doing so were numerous.[147]

Klan operations ended in South Carolina[132] and gradually withered away throughout the rest of the South. Attorney General Amos Tappan Ackerman led the prosecutions.[148]

Foner argues that:

By 1872, the federal government’s evident willingness to bring its legal and coercive authority to bear had broken the Klan’s back and produced a dramatic decline in violence throughout the South. So ended the Reconstruction career of the Ku Klux Klan.[149]

New groups of insurgents emerged in the mid-1870s, local paramilitary organizations such as the White League, Red Shirts, saber clubs, and rifle clubs, that intimidated and murdered Black political leaders.[150] The White League and Red Shirts were distinguished by their willingness to cultivate publicity, working directly to overturn Republican officeholders and regain control of politics.

In 1882, the Supreme Court ruled in United States v. Harris that the Klan Act was partially unconstitutional. It ruled that Congress’s power under the Fourteenth Amendment did not include the right to regulate against private conspiracies. It recommended that persons who had been victimized should seek relief in state courts, which were entirely unsympathetic to such appeals.[151]

Klan costumes, also called «regalia», disappeared from use by the early 1870s,[152] after Grand Wizard Forrest called for their destruction as part of disbanding the Klan. The Klan was broken as an organization by 1872.[153] In 1915, William Joseph Simmons held a meeting to revive the Klan in Georgia; he attracted two aging former members, and all other members were new.[154]

Second Klan: 1915–1944

Refounding in 1915

In 1915 the film The Birth of a Nation was released, mythologizing and glorifying the first Klan and its endeavors. The second Ku Klux Klan was founded in 1915 by William Joseph Simmons at Stone Mountain, near Atlanta, with fifteen «charter members».[155] Its growth was based on a new anti-immigrant, anti-Catholic, Prohibitionist and anti-Semitic agenda, which reflected contemporary social tensions, particularly recent immigration. The new organization and chapters adopted regalia featured in The Birth of a Nation; membership was kept secret by wearing masks in public.

The Birth of a Nation

«The Fiery Cross of old Scotland’s hills!» Illustration from the first edition of The Clansman, by Arthur I. Keller. Note figures in background.

Movie poster for The Birth of a Nation, which has been widely credited with inspiring the 20th-century revival of the Ku Klux Klan.

Director D. W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation glorified the original Klan. The film was based on the book and play The Clansman: A Historical Romance of the Ku Klux Klan, as well as the book The Leopard’s Spots, both by Thomas Dixon Jr. Much of the modern Klan’s iconography is derived from it, including the standardized white costume and the burning cross. Its imagery was based on Dixon’s romanticized concept of old England and Scotland, as portrayed in the novels and poetry of Sir Walter Scott. The film’s influence was enhanced by a false claim of endorsement by President Woodrow Wilson. Dixon was an old friend of Wilson’s and, before its release, there was a private showing of the film at the White House. A publicist claimed that Wilson said, «It is like writing history with lightning, and my only regret is that it is all so terribly true.» Wilson strongly disliked the film and felt he had been tricked by Dixon. The White House issued a denial of the «lightning» quote, saying that he was entirely unaware of the nature of the film and at no time had expressed his approbation of it.[156]

Goals

Three Ku Klux Klan members at a 1922 parade

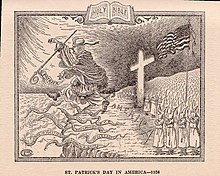

In this 1926 cartoon, the Ku Klux Klan chases the Catholic Church, personified by St. Patrick, from the shores of America. Among the «snakes» are various supposed negative attributes of the Church, including superstition, the union of church and state, control of public schools, and intolerance.

The first and third Klans were primarily Southeastern groups aimed against Black people. The second Klan, in contrast, broadened the scope of the organization to appeal to people in the Midwestern and Western states who considered Catholics, Jews, and foreign-born minorities to be anti-American.[73]

The Second Klan saw threats from every direction. According to historian Brian R. Farmer, «two-thirds of the national Klan lecturers were Protestant ministers».[157] Much of the Klan’s energy went into guarding the home, and historian Kathleen Blee says that its members wanted to protect «the interests of white womanhood».[158] Joseph Simmons published the pamphlet ABC of the Invisible Empire in Atlanta in 1917; in it, he identified the Klan’s goals as «to shield the sanctity of the home and the chastity of womanhood; to maintain white supremacy; to teach and faithfully inculcate a high spiritual philosophy through an exalted ritualism; and by a practical devotedness to conserve, protect and maintain the distinctive institutions, rights, privileges, principles and ideals of a pure Americanism».[159] Such moral-sounding purpose underlay its appeal as a fraternal organization, recruiting members with a promise of aid for settling into the new urban societies of rapidly growing cities such as Dallas and Detroit.[160] During the 1930s, particularly after James A. Colescott of Indiana took over as imperial wizard, opposition to Communism became another primary aim of the Klan.[73]

Organization

New Klan founder William J. Simmons joined 12 different fraternal organizations and recruited for the Klan with his chest covered with fraternal badges, consciously modeling the Klan after fraternal organizations.[161] Klan organizers called «Kleagles» signed up hundreds of new members, who paid initiation fees and received KKK costumes in return. The organizer kept half the money and sent the rest to state or national officials. When the organizer was done with an area, he organized a rally, often with burning crosses, and perhaps presented a Bible to a local Protestant preacher. He left town with the money collected. The local units operated like many fraternal organizations and occasionally brought in speakers.

Simmons initially met with little success in either recruiting members or in raising money, and the Klan remained a small operation in the Atlanta area until 1920. The group produced publications for national circulation from its headquarters in Atlanta: Searchlight (1919–1924), Imperial Night-Hawk (1923–1924), and The Kourier.[162][163][164]

Perceived moral threats

The second Klan grew primarily in response to issues of declining morality typified by divorce, adultery, defiance of Prohibition, and criminal gangs in the news every day.[41] It was also a response to the growing power of Catholics and American Jews and the accompanying proliferation of non-Protestant cultural values. The Klan had a nationwide reach by the mid-1920s, with its densest per capita membership in Indiana. It became most prominent in cities with high growth rates between 1910 and 1930, as rural Protestants flocked to jobs in Detroit and Dayton in the Midwest, and Atlanta, Dallas, Memphis, and Houston in the South. Close to half of Michigan’s 80,000 Klansmen lived in Detroit.[165]

Members of the KKK swore to uphold American values and Christian morality, and some Protestant ministers became involved at the local level. However, no Protestant denomination officially endorsed the KKK;[166] indeed, the Klan was repeatedly denounced by the major Protestant magazines, as well as by all major secular newspapers. Historian Robert Moats Miller reports that «not a single endorsement of the Klan was found by the present writer in the Methodist press, while many of the attacks on the Klan were quite savage. …The Southern Baptist press condoned the aims but condemned the methods of the Klan.» National denominational organizations never endorsed the Klan, but they rarely condemned it by name. Many nationally and regionally prominent churchmen did condemn it by name, and none endorsed it.[167]

The second Klan was less violent than either the first or third Klan were. However, the second Klan, especially in the Southeast, was not an entirely non-violent organization. The most violent Klan was in Dallas, Texas. In April 1921, shortly after they began gaining popularity in the area, the Klan kidnapped Alex Johnson, a Black man who had been accused of having sex with a white woman. They burned the letters «KKK» into his forehead and gave him a severe beating by a riverbed. The police chief and district attorney refused to prosecute, explicitly and publicly stating they believed that Johnson deserved this treatment. Encouraged by the approval of this whipping, the Dallas KKK whipped 68 people by the riverbed in 1922 alone. Although Johnson had been Black, most of the Dallas KKK’s whipping victims were white men who were accused of offenses against their wives such as adultery, wife beating, abandoning their wives, refusing to pay child support or gambling. Far from trying to hide its vigilante activity, the Dallas KKK loved to publicize it. The Dallas KKK often invited local newspaper reporters to attend their whippings so they could write a story about it in the next day’s newspaper.[168][169][170]

The Alabama KKK was less chivalrous than the Dallas KKK was and whipped both white and Black women who were accused of fornication or adultery. Although many people in Alabama were outraged by the whippings of white women, no Klansmen were ever convicted for the violence.[171][172]

Rapid growth

In 1920, Simmons handed the day-to-day activities of the national office over to two professional publicists, Elizabeth Tyler and Edward Young Clarke.[173] The new leadership invigorated the Klan and it grew rapidly. It appealed to new members based on current social tensions, and stressed responses to fears raised by defiance of Prohibition and new sexual freedoms. It emphasized anti-Jewish, anti-Catholic, anti-immigrant and later anti-Communist positions. It presented itself as a fraternal, nativist and strenuously patriotic organization; and its leaders emphasized support for vigorous enforcement of Prohibition laws. It expanded membership dramatically to a 1924 peak of 1.5 million to 4 million, which was between 4–15% of the eligible population.[174]

By the 1920s, most of its members lived in the Midwest and West. Nearly one in five of the eligible Indiana population were members.[174] It had a national base by 1925. In the South, where the great majority of whites were Democrats, the Klansmen were Democrats. In the rest of the country, the membership comprised both Republicans and Democrats, as well as independents. Klan leaders tried to infiltrate political parties; as Cummings notes, «it was non-partisan in the sense that it pressed its nativist issues to both parties».[175] Sociologist Rory McVeigh has explained the Klan’s strategy in appealing to members of both parties:

Klan leaders hope to have all major candidates competing to win the movement’s endorsement. … The Klan’s leadership wanted to keep their options open and repeatedly announced that the movement was not aligned with any political party. This non-alliance strategy was also valuable as a recruiting tool. The Klan drew its members from Democratic as well as Republican voters. If the movement had aligned itself with a single political party, it would have substantially narrowed its pool of potential recruits.[176]

Religion was a major selling point. Kelly J. Baker argues that Klansmen seriously embraced Protestantism as an essential component of their white supremacist, anti-Catholic, and paternalistic formulation of American democracy and national culture. Their cross was a religious symbol, and their ritual honored Bibles and local ministers. But no nationally prominent religious leader said he was a Klan member.[41]

Economists Fryer and Levitt argue that the rapid growth of the Klan in the 1920s was partly the result of an innovative, multi-level marketing campaign. They also argue that the Klan leadership focused more intently on monetizing the organization during this period than fulfilling the political goals of the organization. Local leaders profited from expanding their membership.[174]

Prohibition

Historians agree that the Klan’s resurgence in the 1920s was aided by the national debate over Prohibition.[177] The historian Prendergast says that the KKK’s «support for Prohibition represented the single most important bond between Klansmen throughout the nation».[178] The Klan opposed bootleggers, sometimes with violence. In 1922, two hundred Klan members set fire to saloons in Union County, Arkansas. Membership in the Klan and in other Prohibition groups overlapped, and they sometimes coordinated activities.[179]

Urbanization

A significant characteristic of the second Klan was that it was an organization based in urban areas, reflecting the major shifts of population to cities in the North, West, and the South. In Michigan, for instance, 40,000 members lived in Detroit, where they made up more than half of the state’s membership. Most Klansmen were lower- to middle-class whites who feared the waves of newcomers to the industrial cities: immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe, who were mostly Catholic or Jewish; and Black and white migrants from the South. As new populations poured into cities, rapidly changing neighborhoods created social tensions. Because of the rapid pace of population growth in industrializing cities such as Detroit and Chicago, the Klan grew rapidly in the Midwest. The Klan also grew in booming Southern cities such as Dallas and Houston.[160]

In the medium-size industrial city of Worcester, Massachusetts, in the 1920s, the Klan ascended to power quickly but declined as a result of opposition from the Catholic Church. There was no violence and the local newspaper ridiculed Klansmen as «night-shirt knights». Half of the members were Swedish Americans, including some first-generation immigrants. The ethnic and religious conflicts among more recent immigrants contributed to the rise of the Klan in the city. Swedish Protestants were struggling against Irish Catholics, who had been entrenched longer, for political and ideological control of the city.[180]

In some states, historians have obtained membership rosters of some local units and matched the names against city directory and local records to create statistical profiles of the membership. Big city newspapers were often hostile and ridiculed Klansmen as ignorant farmers. Detailed analysis from Indiana showed that the rural stereotype was false for that state:

Indiana’s Klansmen represented a wide cross section of society: they were not disproportionately urban or rural, nor were they significantly more or less likely than other members of society to be from the working class, middle class, or professional ranks. Klansmen were Protestants, of course, but they cannot be described exclusively or even predominantly as fundamentalists. In reality, their religious affiliations mirrored the whole of white Protestant society, including those who did not belong to any church.[181]

The Klan attracted people but most of them did not remain in the organization for long. Membership in the Klan turned over rapidly as people found out that it was not the group which they had wanted. Millions joined and at its peak in the 1920s the organization claimed numbers that amounted to 15% of the nation’s eligible population. The lessening of social tensions contributed to the Klan’s decline.

Costumes and the burning cross

The distinctive white costume permitted large-scale public activities, especially parades and cross-burning ceremonies, while keeping the membership rolls a secret. Sales of the costumes provided the main financing for the national organization, while initiation fees funded local and state organizers.

The second Klan embraced the burning Latin cross as a dramatic display of symbolism, with a tone of intimidation.[182] No crosses had been used as a symbol by the first Klan, but it became a symbol of the Klan’s quasi-Christian message. Its lighting during meetings was often accompanied by prayer, the singing of hymns, and other overtly religious symbolism.[183] In his novel The Clansman, Thomas Dixon Jr. borrows the idea that the first Klan had used fiery crosses from ‘the call to arms’ of the Scottish Clans,[184] and film director D.W. Griffith used this image in The Birth of a Nation; Simmons adopted the symbol wholesale from the movie, and the symbol and action have been associated with the Klan ever since.[185]

Women