| Все дипломные спектакли Выпуск 2007 |

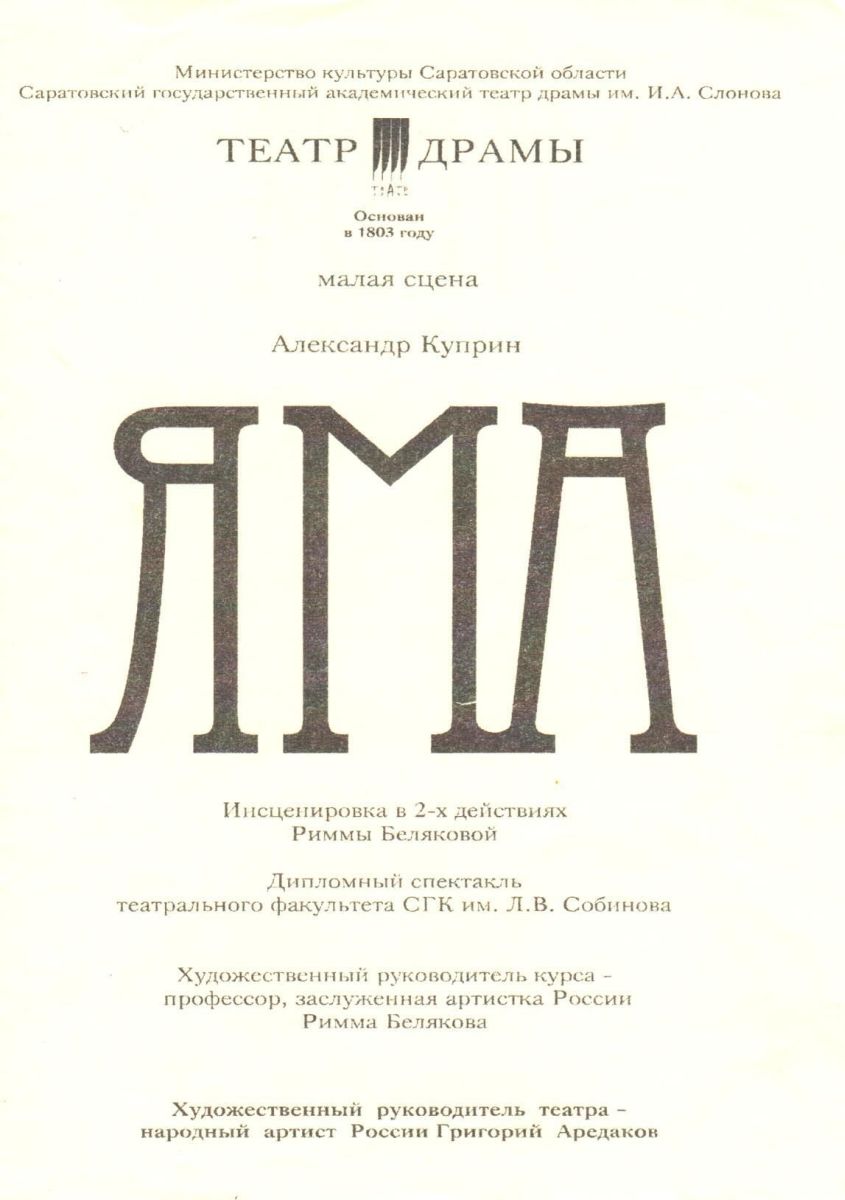

| ЯМА |

Александр Куприн Александр КупринЯма Инсценировка в двух действиях Риммы Беляковой

дипломный спектакль выпуска 2007 премьера состоялась 20 декабря 2006 года спектакль шёл на Малой сцене Саратовского академического театра драмы им. Слонова |

| ОПИСАНИЕ |

| В основе спектакля — известная повесть Александра Куприна. Римма Белякова, художественный руководитель курса, поставила спектакль по собственной инсценировке классического произведения — трагической истории девушек легкого поведения. Куприн создал повесть на грани притчи, при этом отдал дань натурализму. Повесть многие современники писателя считали безнравственной. И лишь через век поняли, насколько оправдано обращение писателя к теме.

По словам профессора Риммы |

| ДЕЙСТВУЮЩИЕ ЛИЦА И ИСПОЛНИТЕЛИ |

|

| СЦЕНЫ ИЗ СПЕКТАКЛЯ |

|

УРОК – ДИСПУТ

В 11 КЛАССЕ

«Яма зла и пороков»

по повести А. И. Куприна «Яма»

Подготовила

учитель литературы

Галанскова Галина Николаевна

Звучит соната Бетховена №2. На её фоне — отрывок из повести Куприна «Гранатовый браслет»

«Вот сейчас я вам покажу в нежных звуках жизнь, которая покорно и

радостно обрекла себя на мучения, страдания и смерть. Ни жалобы, ни упрека, ни боли самолюбия я не знал. Я перед тобою — одна молитва: «Да святится имя Твое».

Вспоминаю каждый твой шаг, улыбку, взгляд, звук твоей походки. Сладкой грустью, тихой, прекрасной грустью обвеяны мои последние воспоминания. Но я не причиню тебе горя. «Да святится имя Твое».

Успокойся, дорогая, успокойся, успокойся. Ты обо мне помнишь? Помнишь? Ты ведь моя единая и последняя любовь. Успокойся, я с тобой. Подумай обо мне, и я буду с тобой, потому что мы с тобой любили друг друга только одно мгновение, но навеки. Ты обо мне помнишь? Помнишь? Помнишь? Вот я чувствую твои слезы. Успокойся».

Откуда эти трепетные строки, наполненные любовью, нежностью и теплотой?

Есть у Бунина и Куприна одна заветная тема. Они прикасаются к ней целомудренно, благоговейно. Да иначе и нельзя. Эта тема – Любовь.

— Что же это такое в понимании этих авторов?

Любовь- «лёгкое дыхание», посетившее сей мир и готовое в любой миг исчезнуть. Бунин «Лёгкое дыхание»

Любовь – некий высший, напряжённый момент бытия: подобно зарницам в ночи, она озаряет всю жизнь человека. Бунин «Тёмные аллеи»

Любовь настоящая – это непременно гармония, неразрывность «небесного и земного», души и тела. Бунин «Митина любовь»

Любовь даёт много наслаждений. Но никогда , никогда она не бывает так остра, тонка и нежна, как тогда, когда ещё не высказана и не разделена. Куприн «Святая любовь»

Любовь всегда трагедия, всегда борьба и достижение, всегда радость и страх, воскрешение и смерть. Куприн

Любовь – это полное слияние умов, мыслей, душ, интересов, а не только тел одних. Куприн «Яма»

Иногда кажется, что о любви в мировой литературе сказано всё. Что можно сказать после «Тристана и Изольды», «Ромео и Джульетты», «Анны Карениной»? но у любви тысячи аспектов, и в каждом из них – свой свет, своя печаль, своё счастье и своё благоухание.

Правда, есть у любви, впрочем, можно ли это назвать любовью, и ещё одно уродливое лицо.

Тема нашей пресс-конференции «Поругание любви и красоты». Яма зла и пороков – Проституция.

В обсуждении этой проблемы примут участие специалисты-эксперты:

Правовед, психолог, литературный критик, журналист, а также наши слушатели, которые представят нам персонажей повести Куприна.

Итак, обратимся к теме, имевшей в русской литературе более чем вековую историю.

О том, какое отражение в творчестве многих писателей нашла эта проблема, нам расскажет литературный критик того времени.

Петухова Ольга Викторовна – сотрудница петербургского журнала «Вопросы пола»

1.Ещё в конце 18 века А.Н. Радищев в своей книге «Путешествие…» гневно заклеймил «наёмное удовлетворение любовной страсти».

2. Нездоровый интерес к вопросам пола. Нажива на произведениях, содержащих пикантные ситуации.

3. Иначе подходили к этой теме большие, честные писатели: А.П. Чехов «Припадок», А.Блок «Униженные», М. Горький в 1899 году писал: «Быть может, найдутся люди, которые с брезгливой миной скажут: «Зачем это печатать? Нелепая идея! В литературе совсем нет места проституткам…»

Это будут глупые и лживые слова. Литература есть трибуна для всякого человека, имеющего горячее желание поведать людям о неустройстве жизни и страданиях человеческих…»

4. В годы столыпинской реакции, когда в буржуазном обществе росли всевозможные лиги свободной любви, проституция приняла чудовищные размеры. «Со всех уголков России, — писала петербургская газета бегут телеграммы о разнузданной эпидемии половых преступлений.» (1909г.)

5. В этом же 1909 году Куприн пишет «Яму», стремится познакомить читателя с жизнью публичного дома как бы изнутри, день за днём.

— Какую оценку даёт литературная критика этому произведению?

Многие критики, писатели, в том числе и Л.Н. Толстой, чьим мнением особенно дорожил Куприн, дали отрицательную оценку этому произведению, считая его безнравственным и непривычным. Некоторые утверждали, что такие описания публичных домов скорее способствуют распространению проституции, чем её искоренению.

— А как вы считаете, напрасен труд, затраченный на эту повесть7

-Что по этому поводу скажут эксперты?

А вот, что по этому поводу писал Куприн: «Во всяком случае я твёрдо верю, что своё дело я сделал. Возможно, что грязь, но надо же очиститься от неё. И если бы сам Л.Н.Толстой написал с гениальностью великого художника о проституции, он сделал бы великое дело, так как к нему прислушались бы больше, чем ко мне».

— С какими словами обращается Куприн в начале повести к читателям?

— Почему он посвящает это произведение матерям и юношеству?

— Объясните смысл названия повести.

«Что такое я? Какая-то всемирная плевательница, помойная яма, отхожее место»

Что же такое проституция? Блажной бред больших городов или это вековечное историческое явление? Прекратится ли она когда-нибудь?

Или она умрёт только со смертью всего человечества? Кто мне ответит на это?

Проституция – это ещё более страшное зло, чем война. Война пройдёт, но проституция живёт веками.

Проституция – одно из величайших бедствий человечества, и в этом зле виноваты не женщины, а мы мужчины, потому что спрос родит предложение» (Ярченко)

Очень сложно понять психологию тех людей, которые пошли по этой дороге

— Что толкало их на это?

(Можно вспомнить Бунина «Митина любовь» — Катя, Алёна)

_ А как объясняет это психология? (Слово предоставляется психологу. Можно вспомнить Сонечку Мармеладову)

Чтобы понять весь этот сложный механизм, давайте поподробней познакомимся с героями повести Куприна «Яма». (выступление учащихся)

Анна Марковна

— Проститутка –экономка – хозяйка публичного дома.

— Семья: муж Исай Саввич, дочь Берта.

— Описание публичного дома, положение девушек.

— Цель жизни – благополучие дочери.

Диалог с залом

Есть ли у Анны Марковны друзья? Как они относятся к её профессии?

Что можно сказать о посетителях этого заведения?

Что не хватает этим людям в жизни? Зачем они идут сюда, в эту помойную яму?

— Слово экспертам.

2.Что же это за девушки, выброшенные обществом, проклятые семьёй? Кто они, жертвы общественного темперамента?

Люба

Вот история девушки, которая пыталась изменить свой образ жизни.

Это некрасивая, в веснушках, но крепкая и свежая телом девушка. Страховой агент, у которого она служила, толкнул её на путь проституции. Жизнь в публичном доме ей не нравится. Она с удовольствием помогает кухарке убираться, ласкает и кормит собаку.

— Жизнь любы с Лихониным. Разлад.

— Пыталась ли Люба сама изменить свою жизнь?

— Почему она отказывает Соловьёву, который хочет на ней жениться?

Комментарии экспертов.

Женя.

— Описание внешности, интересы.

— Положение в публичном доме, отношение к клиентам.

— Считают ли эти девушки себя ничуть не хуже так называемых порядочных женщин?

— Крик души: « А ведь я – человек».

— Болезнь. « Этих двуногих подлецов я нарочно заражаю каждый вечер… «

А потом появился Коля Гладышев . Разговор Коли с Женей (Инсценировка)

— Коля не говорит о настоящей причине. Что послужило этому? Перелом в жизни Коли.

— Она не смогла его заразить, пожалела, а теперь не понимает почему. Поэтому и обращается за помощью к Платонову.

— Сцена разговора Жени с Платоновым.

— Совет Платонова.

Женя уходит из жизни.

Платонов

— Появление в публичном доме. (Обучение Берты, наблюдения за жизнью девушек в публичном доме)

— Платонов в обществе студентов.

Беседы о проституции.

— Глава 12 — « Когда она прекратится…» — Платонов

«Ведь только в одной русской душе могут ужиться такие противоречия» — Платонов

« А что делать теперь? Сидеть сложа руки? Мириться, махнуть рукой?

(Лихонин)

Теория Лихонина: « Чем хуже, тем лучше, тем ближе к концу.»

Почему же сегодня мне кажется, что я сам виноват в зле проституции,-

Виноват своим молчанием, своим равнодушием, своим косвенным попустительством?

— Осознают ли мужчины, посещающие публичный дом, низость своих поступков?

Рамзин:

« Виноват же во всём случившемся, а значит, и в моей смерти, только один я, потому что, повинуясь минутному скотскому влечению, взял женщину без любви, за деньги. Потому я и заслужил наказание, которое сам на себя налагаю»

Пока существует брак, не умрёт и проституция.

А как бы ответили вы на эти вопросы?

(зал, эксперты)

Вопросы на доске.

Перед нами прошли эпизоды из жизни публичного дома.

Какое впечатление они произвели на вас, о чём заставили задуматься?

Таковы ужасы «любви» без любви.

Куприн затронул тему, актуальную и в наше время. Ведь честность и ложь, отвага и трусость, благородство и низость, нравственность и разврат по-прежнему ведут между собой непримиримую борьбу. И всё так же безостановочно течёт в своих берегах «река жизни», требуя от нас ежедневного решения и выбора: «За» или «Против».

Мы представляем слово журналисту, которого тоже волнует эта проблема.

В классической литературе прошлого века много рассказывается о любви но, соединяя любящих, писатели ставят точку. Публичное обсуждение интимной жизни приравнивалось к подглядыванию в замочную скважину и всячески осуждалось обществом. Наше время распахнуло двери спальни, мы можем купить книги «про это»,посмотреть фильм с откровенными сценами. То, что недавно было тайной двоих, перестало быть тайной.

В нашем обществе растёт и быстро распространяется равнодушие, апатия, зависть, озлобленность. Всё это говорит об остром дефиците любви, о явном её обеднении и сужении во всех сферах.

Любовь, как дитя цивилизации, цивилизацией и губится. В наш нигилистический век на пьедестал возведён его Величество Секс. Святая, чистая любовь брошена в жертву открытым любовным отношениям, порнографии, диким экспериментам в области любовных отношений. Пресыщенное человечество подхлёстывает себя алкоголем, наркотиками, крикливой рекламой интимных отношений.

Ужасно то, что обществом эта проблема сейчас почти не осуждается. Быть проституткой стало престижно, об этом свидетельствует и социологический опрос, проведённый в одной из московских школ. Ежегодно на улицы столицы выходит около 6.000 проституток. Их возраст от 14 лет. А сколько их в дорогих гостиницах, валютных барах, неофициальных борделях. Многие девушки имеют высшее образование, а то и не одно, неплохо подкованы в юридических и экономических вопросах, знают по несколько иностранных языков. Они даже мечтают организовать свой профсоюз. Легализация проституток.

Вот мнение на этот счёт некоторых известных людей.

(Газеты «Московский комсомолец»,»АИФ», «Спид-Инфо»

Журнал «Любовь» — барии Алибасов

Журнал «Спид –Инфо» — Любовь Полищук, Татьяна Догилева, «Блестящие»

— Хотелось бы узнать ваше мнение по этому вопросу?

Наш земляк Иван Шелухин в своём творчестве тоже касается этой проблемы.

Страсть желаний

И ласкает меня, и клянёт

За мгновения боль и усладу.

И всё крепче к груди моей льнёт,

И целует, как будто в награду.

Страсть желаний угасла в ночи.

Я, смущаясь, шепчу ей покорно

А она говорит:

— Помолчи!

Что естественно, то — не позорно.

— Что естественно, но по любви,-

Отвечает ей тихо, несмело,

И огонь возбужденья в крови

От любви истекает по телу.

А иначе – животные мы.

Если страстью звериною пышем…

Мы остались с любовью людьми,

А дождинки горошат по крыше.

«Исчезнет ли когда-нибудь это зло?», — спрашивает Куприн

— Что думают по этому поводу эксперты?

— Что же изменилось за это время?

Изменилось отношение общества к этой проблеме, а зло не исчезло. Но ведь на протяжении веков именно женщины добивались для себя права принадлежать одному мужчине, а не всем. Человечество следует по пути прогресса, ещё в первобытнообщинном строе ушло от беспорядочных половых связей. Стоит ли возвращаться к ним в 21 веке.

Звучит песня.

Каждый выбирает для себя…

Это стихотворение Ю.Левитанского на музыку Виктора Берковского

Каждый выбирает для себя

Женщину, религию, дорогу.

Дьяволу служить или пророку —

Каждый выбирает для себя.

Каждый выбирает по себе

Шпагу для дуэли, меч для битвы.

Слово для любви и для молитвы

Каждый выбирает по себе.

Каждый выбирает по себе

Щит и латы, посох и заплаты.

Меру окончательной расплаты

Каждый выбирает по себе.

Каждый выбирает для себя

Выбираю тоже как умею

Ни к кому претензий не имею

Каждый выбирает для себя

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

1916 edition |

|

| Author | Alexander Kuprin |

|---|---|

| Original title | Яма |

| Country | Russia |

| Language | Russian |

| Publisher | Moscow Book Publishers Zemlya almanac |

|

Publication date |

1909; 1914–1915 |

The Pit (Russian: Яма, romanized: Yama, published in English as Yama: The Pit) is a novel by Alexander Kuprin published in installments between 1909 and 1915, in Zemlya almanacs (Part 1 in 1909 and Parts 2–3 in 1914–1915). The book, centering on a brothel, owned by a woman named Anna Markovna, caused much controversy in its time.[1][2]

Background[edit]

Alexander Kuprin started collecting the material for his work in Kiev in 1890s, and it is in this city that the novel’s action takes place. Speaking in 1909 to a local newspaper correspondent about prototypes, he commented: «Characters I’ve made cannot be seen as copying real people. I picked up a lot of small details from the real life, but that was by no means copying the reality, which is something I detest doing.» He added that his observations were by no means restricted to Kiev. «The Pit is [about] Odessa, Petersburg and Kiev,» Kuprin said.[3]

The real life episode similar to that of singer Rovinskaya and her friends making a visit to a brothel happened in Saint Petersburg. According to the critic Alexander Izmaylov, the author was relating it to his friends as far back as 1905.[4] Zhenya’s character (according to biographer O.Mstislavskaya) was partly inspired by Kuprin’s encounter with his neighbour landlord’s niece in Danilovskoye, his Nizny Novgorod region estate. In 1908 he asked his friend Fyodor Batyushkov for Z.Vorontsova’s book Memoirs of a Café-chantant Singer (1908) which provided him numerous details, some of which he used while creating the Tamara character.[1] Platonov’s monologues echo the discussions concerning prostitution that were going on in the Russian press in 1908-1909; similar views were expressed by the Saint Petersburg doctor P.E. Oboznenko.[1]

History[edit]

Kuprin was planning to start The Pit in the early 1900s and in 1902 he asked Mir Bozhy‘s editor Batyushkov if the magazine would publish a novel of that kind. As Batyushkov expressed doubts, the work was postponed. In 1907 Kuprin brought Part 1 of the novel to Mir Bozhy and the magazine announced its publication as planned for 1908, but then cancelled the publication. Kuprin signed a new deal with G.Blumenberg and D.Rebrik of the Moskovskoye Knogoizdatelstvo (Moscow Book Publishers) according to which the company would start publishing The Complete Kuprin series and include The Pit into their literary almanac Zemlya (The Land).[1]

In November 1908, while in Gatchina, the author finished Chapters 1 and 2, in December — Chapters 3 and 4. «The going gets hard. The difficulty lies in the fact that the first, say, ten chapters’ action is supposed to be squeezed into just one day,» Kuprin complained, speaking to Alexander Izmaylov in January.[5] Later, in order to get closer to the subject matter, Kuprin moved to Zhitomir, a city famous for its organised crime gangs engaged in the local sex industry.[6][7]

His financial situation at the time was a dire one: the Moscow Book Publishers insisted that he’d break his contract with Saint Petersburg Progress which was planning to issue The Pit as a separate edition. Until then the MBP refused to pay him the advance and at some point Kuprin had to pawn some of his property to make ends meet.[1] In March 1909, as the deadline approached, only 9 of 12 chapters of Part 1 were ready. Kurpin had to work hectically hoping that he’ll be able to improve the text while proofreading, but eventually failed to do that. He was dissatisfied with the general quality of the text and with growing apprehension anticipated Lev Tolstoy’s possible reaction. «Should he prove to be unsympathetic [to Part 1 of the novel], my writing process will be hindered. L.N.’s opinion is very important to me,» Kuprin said in an interview.»[8]

The novel’s first reviewer though happened to be V.I.Istomin, a member of the Moscow censorial committee. In his report he noted that there were fragments in the novel «which give us reasons to regard it as immoral and indecent… as well as fragments belying the author’s intention to treat the problem of prostitution in the most serious manner.» The list of indecencies featured all the episodes of officials and officers attending a brothel. On April 25, 1909, the committee’s special meeting took place. Eventually the publication of The Vol.3 of Zemlya almanac was permitted.[9] Still, when preparing The Pit for the inclusion into the Volumes VIII and IX of Adolf Marks-published The Collected Works by A.I. Kuprin (1912, 1915), Kuprin took into consideration the censorial report and removed all the bits in which the officials, officers and cadets’ visiting the brothel were mentioned.[1]

Parts 2 and 3[edit]

After finishing Part 1, Kuprin started writing Part 2, which he intended to make «astonishingly frank» and «devoid of didacticism» (according to his letter to Ivan Bunin in June, 1909). While in Zhitomir he discussed possible plotlines and new ideas with visiting journalists and writers. For a while the work was going on fast. Then Kuprin read some reviews, was told of Tolstoy’s opinion (who, having read the novel’s first several chapters, said: «Very poor, brutal and unnecessarily dirty»)[10]), and in the autumn stopped writing. «Read too much of criticism, so much that I became sick of my own work,» he wrote to Batyushkov.

Besides, another novel on prostitution came out, The Red Lantern (known in Russia under several other titles, «From Darkness Into the Light» and «The Dung-Beatle» among them), by the Austrian author Else Jerusalem. Some critics rated it higher than The Pit, much to Kuprin’s dismay. «The Pit ripens, then bursts. These reviewers and E.Jerusalem have eaten me up,» he wrote to V.S.Klestov, of the Moscow Book Publishers.[1]

On February 26, 1910, Kuprin moved to Moscow, with the view to «find some quiet rooms» and start working on the Part 2 of The Pit. But in March he returned to Odessa and informed Klestov that he’d «done nothing in Moscow, being dragged down by petty scurry and bustle.» The MBP, riled by Kuprin’s failure to meet the deadline, stopped paying him advances. He dropped the novel, to concentrate upon short stories and articles. «Now I am very poor indeed. Pawned everything. What am I to live on? And how can I write The Pit? Willy-nilly I have to produce all manner of rubbish, publishing it in all kinds of places,» Kuprin complained to Batyushkov. In summer 1910 Kuprin started writing The Garnet Bracelet which he finished in the autumn to send to Zemlya. After publishing the novelette in 1911, G.Blyumenberg found it unsuitable to go back to The Pit the publication of which had been interrupted two years ago. He advised Kuprin to make it a totally different novel. Kuprin came up with a title, «The Demise» (Гибель), but soon decided against «creating a host of new characters while others would hang in the air,» as he noted in an autumn 1910 letter to Klestov).[1]

In the course of 1911 Kuprin was working on The Pit in fits and starts, being too busy preparing texts for the forthcoming Complete A. Kuprin series by the Marks Publishing House. The first half of 1912 he spent abroad, and after the return started publishing sketches («The Azure Shores») for Retch (Speech) newspaper. In 1912 the Saint Petersburg press came out with the sensational news that the author known as Count Amori (real name Hyppolite Rapgof) released his own book called «The Final Chapters of The Pit by I.A.Kuprin», featuring all the episodes the author was talking about while confiding with his literary friends in Zhitomir. The scandal apparently gave the author a much needed impetus. All through 1913 Kuprin was working upon The Pit and in December he came to Moscow to drive the work to completion. In spring 1914 the novel was finished. Blumenberg decided to break it in two and publish it in two issues of Zemlya. Kuprin detested the idea of having to go through the censorship committee twice. «First they’ll cut an arm, then a leg,» he complained. Indeed, the publication of Part 2’s second part was stopped by censors; only in half a year the publishers received the censors’ permission for the Vol.15 of Zemlya’s release. Simultaneously the permission for the release of the Book 16 of Zemlya, featuring the novel’s final chapters, was received.[1]

In 1917, while working on the novel’s text, preparing it for Volume XII of the Moscow Book Publishers’ The Complete A.Kuprin edition, the author returned all the bits that he had to remove from Volumes XVIII and IX of the Marks’ series, and made some stylistic changes to parts 2 and 3. This authorized version has been used in re-issues and compilations ever since.[1]

Critical reception[edit]

The Vol.3 of Zemlya almanac with the Part 1 of Yama came out in Spring 1909 and caused quite a stir. «In Moscow people talk of just one thing: The Pit,» Ivan Bunin informed Kuprin in a letter, dated May 22, 1909. All the major Russian periodicals reviewed the novel.[1]

Alexander Izmaylov argued that never since The Kreutzer Sonata had a Russian novel «touched so daringly upon morbid wounds of life.» «Against the demon of lie, lust and evil greed does the Russian writer Kuprin wage his war,» the critic concluded.[11] Volynh praised The Pit as a damning social document. «Horror, shuddering horror rules this kingdom of champing toads,» the reviewer Botsyanovsky wrote.[12] Droog (Friend) magazine hailed the novel as «a powerful warning for parents and youngsters.» The literary historian P.Kogan maintained that «before Kuprin nobody had even made an attempt to trace — hour by hour, day by day, — the everyday life of such places.»[13]

There was a wave of negative response too. Volynh (No.295, October 27, 1909), as well as Vestnik Literatury later (No.8, August, 1911) argued that such naturalistic descriptions of the life in a brothel could serve only for the spreading of prostitution, not its eradication. Vatslav Vorovsky accused Kuprin of idealizing prostitutes; the Marxist critic found the whole style of the novel uncharacteristically sentimental.[14] The Pit was severely criticized by both pro-monarchist Novoye Vremya and the Symbolist Vesy magazine. The latter’s reviewer Boris Sadovskoy saw the novel as ‘a pit’ of Kuprin’s weaknesses: his «tendency to daub real life sketches, being prone to textbook didacticism and having a taste for the ugliest things in life.» «Into The Pit Kuprin has stuck all that he’s got and what did he get? — another Duel,» the critic argued.[1]

Parts 2 and 3 of The Pit, published in 1915, made no resonance. Reviewers deplored what they saw as the lack of compositional integrity, the disparity of motifs and the author’s eagerness to rely on literary clichés. «Something feuilleton-like, petty and derivative is there in the garishness of many scenes, and the general drift of the story is banal,» wrote Russkiye Zapisky (Russian Notes, 1915, No.1) reviewer.[1]

One of the few critics who assessed the novel’s second and third parts highly was Korney Chukovsky. «That is a different kind of Yama, it has little in common with the one we read several years ago. In the former all the action took place in just one tiny hole. This time the author takes us through thousand places — from a café-chantant to a graveyard, a morgue, a police station, a student dormitory. And this motley canvas knit of myriad of faces is based on one grandiose theme, one powerful feeling. Each character stands out in relief, you can almost touch it and that is why all this affects you so… Karbesh, Sonjka the Rule, Anna Markovna, Emma and Semyon Horizont — all of them are portrayed in such a way that I would recognize each and every one of them in a huge crowd,» the critic wrote.[15]

Kuprin’s response[edit]

Kuprin, who had to deal with a lot of criticism, conceded the novel had its weaknesses and faults, but maintained he never regretted the huge amount of time he spent on it. «I certainly believe I’ve done an important job. Prostitution is a worse evil than war of famine: wars come and go, but prostitution stays with us through centuries,» he told Birzhevyie Vedomosti in 1915. Speaking of Lev Tolstoy’s original negative response, he added, «This might be dirt, but one has to wash it off. Should Lev Tolstoy have written of prostitution, using all the power of his genius, he’d have done a highly important job, for people would have listened to him more than they do to me. Alas, my pen is weak…»[16]

In 1918, responding to the question of the novel’s ideological relevance poised by the veteran worker P.I. Ivanov, Kuprin said: «I’ll tell you confidentially, I am not good at teaching people how to live their lives. I’ve mangled my own life as bad as I could. My readers see me mostly as a good friend and an engaging storyteller, that is all.»[1]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Rothstain, E. Commentaries to The Pit. The Complete A.I.Kuprin, in 9 volumes. Pravda Publishers. Ogonyok magazine library. Moscow. 1964. Pp.453-456.

- ^ Luker, Nicholas J.T. «1905 and After». kuprin.gatchina3000. Retrieved 2014-01-13.

- ^ Kievskiye Vesti, 1909, No. 156, June 14

- ^ Birzhevye Vedomosti, 1915, No.14943, August 4.

- ^ Rodnoy Mir, 1909, No.1, January.

- ^ Peterburgskaya Gazeta, 1908, No.303, November 8.

- ^ Kuprin’s Letter to F.D.Batyshkov, 1909, April 14, ИРЛИ

- ^ Kiyevskiye Vesti,1909, No.449. June 14.

- ^ The Moscow Regional Historical Archive. Fund 31. Section 3, File No.2200

- ^ Gusev, N. The Chronicle of Lev Tolstoy’s Life and Work. The May 6, 1909 entry.

- ^ Russkoye Slovo, 1909, No.91, April, 22

- ^ Volynh newspaper, 1909, No.113, April 27.

- ^ Kogan, P. Sketches on the History of Modern Russian Literature. Vol. 3, 1910.

- ^ Vorovsky, V. Literary Criticism. Moscow, 1956. P.283

- ^ Niva, 1914, No.45, November 6

- ^ Birzhevye Vedomosti, 1915, No.14855, May 21

External Links[edit]

- Yama: The Pit at Standard Ebooks

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

1916 edition |

|

| Author | Alexander Kuprin |

|---|---|

| Original title | Яма |

| Country | Russia |

| Language | Russian |

| Publisher | Moscow Book Publishers Zemlya almanac |

|

Publication date |

1909; 1914–1915 |

The Pit (Russian: Яма, romanized: Yama, published in English as Yama: The Pit) is a novel by Alexander Kuprin published in installments between 1909 and 1915, in Zemlya almanacs (Part 1 in 1909 and Parts 2–3 in 1914–1915). The book, centering on a brothel, owned by a woman named Anna Markovna, caused much controversy in its time.[1][2]

Background[edit]

Alexander Kuprin started collecting the material for his work in Kiev in 1890s, and it is in this city that the novel’s action takes place. Speaking in 1909 to a local newspaper correspondent about prototypes, he commented: «Characters I’ve made cannot be seen as copying real people. I picked up a lot of small details from the real life, but that was by no means copying the reality, which is something I detest doing.» He added that his observations were by no means restricted to Kiev. «The Pit is [about] Odessa, Petersburg and Kiev,» Kuprin said.[3]

The real life episode similar to that of singer Rovinskaya and her friends making a visit to a brothel happened in Saint Petersburg. According to the critic Alexander Izmaylov, the author was relating it to his friends as far back as 1905.[4] Zhenya’s character (according to biographer O.Mstislavskaya) was partly inspired by Kuprin’s encounter with his neighbour landlord’s niece in Danilovskoye, his Nizny Novgorod region estate. In 1908 he asked his friend Fyodor Batyushkov for Z.Vorontsova’s book Memoirs of a Café-chantant Singer (1908) which provided him numerous details, some of which he used while creating the Tamara character.[1] Platonov’s monologues echo the discussions concerning prostitution that were going on in the Russian press in 1908-1909; similar views were expressed by the Saint Petersburg doctor P.E. Oboznenko.[1]

History[edit]

Kuprin was planning to start The Pit in the early 1900s and in 1902 he asked Mir Bozhy‘s editor Batyushkov if the magazine would publish a novel of that kind. As Batyushkov expressed doubts, the work was postponed. In 1907 Kuprin brought Part 1 of the novel to Mir Bozhy and the magazine announced its publication as planned for 1908, but then cancelled the publication. Kuprin signed a new deal with G.Blumenberg and D.Rebrik of the Moskovskoye Knogoizdatelstvo (Moscow Book Publishers) according to which the company would start publishing The Complete Kuprin series and include The Pit into their literary almanac Zemlya (The Land).[1]

In November 1908, while in Gatchina, the author finished Chapters 1 and 2, in December — Chapters 3 and 4. «The going gets hard. The difficulty lies in the fact that the first, say, ten chapters’ action is supposed to be squeezed into just one day,» Kuprin complained, speaking to Alexander Izmaylov in January.[5] Later, in order to get closer to the subject matter, Kuprin moved to Zhitomir, a city famous for its organised crime gangs engaged in the local sex industry.[6][7]

His financial situation at the time was a dire one: the Moscow Book Publishers insisted that he’d break his contract with Saint Petersburg Progress which was planning to issue The Pit as a separate edition. Until then the MBP refused to pay him the advance and at some point Kuprin had to pawn some of his property to make ends meet.[1] In March 1909, as the deadline approached, only 9 of 12 chapters of Part 1 were ready. Kurpin had to work hectically hoping that he’ll be able to improve the text while proofreading, but eventually failed to do that. He was dissatisfied with the general quality of the text and with growing apprehension anticipated Lev Tolstoy’s possible reaction. «Should he prove to be unsympathetic [to Part 1 of the novel], my writing process will be hindered. L.N.’s opinion is very important to me,» Kuprin said in an interview.»[8]

The novel’s first reviewer though happened to be V.I.Istomin, a member of the Moscow censorial committee. In his report he noted that there were fragments in the novel «which give us reasons to regard it as immoral and indecent… as well as fragments belying the author’s intention to treat the problem of prostitution in the most serious manner.» The list of indecencies featured all the episodes of officials and officers attending a brothel. On April 25, 1909, the committee’s special meeting took place. Eventually the publication of The Vol.3 of Zemlya almanac was permitted.[9] Still, when preparing The Pit for the inclusion into the Volumes VIII and IX of Adolf Marks-published The Collected Works by A.I. Kuprin (1912, 1915), Kuprin took into consideration the censorial report and removed all the bits in which the officials, officers and cadets’ visiting the brothel were mentioned.[1]

Parts 2 and 3[edit]

After finishing Part 1, Kuprin started writing Part 2, which he intended to make «astonishingly frank» and «devoid of didacticism» (according to his letter to Ivan Bunin in June, 1909). While in Zhitomir he discussed possible plotlines and new ideas with visiting journalists and writers. For a while the work was going on fast. Then Kuprin read some reviews, was told of Tolstoy’s opinion (who, having read the novel’s first several chapters, said: «Very poor, brutal and unnecessarily dirty»)[10]), and in the autumn stopped writing. «Read too much of criticism, so much that I became sick of my own work,» he wrote to Batyushkov.

Besides, another novel on prostitution came out, The Red Lantern (known in Russia under several other titles, «From Darkness Into the Light» and «The Dung-Beatle» among them), by the Austrian author Else Jerusalem. Some critics rated it higher than The Pit, much to Kuprin’s dismay. «The Pit ripens, then bursts. These reviewers and E.Jerusalem have eaten me up,» he wrote to V.S.Klestov, of the Moscow Book Publishers.[1]

On February 26, 1910, Kuprin moved to Moscow, with the view to «find some quiet rooms» and start working on the Part 2 of The Pit. But in March he returned to Odessa and informed Klestov that he’d «done nothing in Moscow, being dragged down by petty scurry and bustle.» The MBP, riled by Kuprin’s failure to meet the deadline, stopped paying him advances. He dropped the novel, to concentrate upon short stories and articles. «Now I am very poor indeed. Pawned everything. What am I to live on? And how can I write The Pit? Willy-nilly I have to produce all manner of rubbish, publishing it in all kinds of places,» Kuprin complained to Batyushkov. In summer 1910 Kuprin started writing The Garnet Bracelet which he finished in the autumn to send to Zemlya. After publishing the novelette in 1911, G.Blyumenberg found it unsuitable to go back to The Pit the publication of which had been interrupted two years ago. He advised Kuprin to make it a totally different novel. Kuprin came up with a title, «The Demise» (Гибель), but soon decided against «creating a host of new characters while others would hang in the air,» as he noted in an autumn 1910 letter to Klestov).[1]

In the course of 1911 Kuprin was working on The Pit in fits and starts, being too busy preparing texts for the forthcoming Complete A. Kuprin series by the Marks Publishing House. The first half of 1912 he spent abroad, and after the return started publishing sketches («The Azure Shores») for Retch (Speech) newspaper. In 1912 the Saint Petersburg press came out with the sensational news that the author known as Count Amori (real name Hyppolite Rapgof) released his own book called «The Final Chapters of The Pit by I.A.Kuprin», featuring all the episodes the author was talking about while confiding with his literary friends in Zhitomir. The scandal apparently gave the author a much needed impetus. All through 1913 Kuprin was working upon The Pit and in December he came to Moscow to drive the work to completion. In spring 1914 the novel was finished. Blumenberg decided to break it in two and publish it in two issues of Zemlya. Kuprin detested the idea of having to go through the censorship committee twice. «First they’ll cut an arm, then a leg,» he complained. Indeed, the publication of Part 2’s second part was stopped by censors; only in half a year the publishers received the censors’ permission for the Vol.15 of Zemlya’s release. Simultaneously the permission for the release of the Book 16 of Zemlya, featuring the novel’s final chapters, was received.[1]

In 1917, while working on the novel’s text, preparing it for Volume XII of the Moscow Book Publishers’ The Complete A.Kuprin edition, the author returned all the bits that he had to remove from Volumes XVIII and IX of the Marks’ series, and made some stylistic changes to parts 2 and 3. This authorized version has been used in re-issues and compilations ever since.[1]

Critical reception[edit]

The Vol.3 of Zemlya almanac with the Part 1 of Yama came out in Spring 1909 and caused quite a stir. «In Moscow people talk of just one thing: The Pit,» Ivan Bunin informed Kuprin in a letter, dated May 22, 1909. All the major Russian periodicals reviewed the novel.[1]

Alexander Izmaylov argued that never since The Kreutzer Sonata had a Russian novel «touched so daringly upon morbid wounds of life.» «Against the demon of lie, lust and evil greed does the Russian writer Kuprin wage his war,» the critic concluded.[11] Volynh praised The Pit as a damning social document. «Horror, shuddering horror rules this kingdom of champing toads,» the reviewer Botsyanovsky wrote.[12] Droog (Friend) magazine hailed the novel as «a powerful warning for parents and youngsters.» The literary historian P.Kogan maintained that «before Kuprin nobody had even made an attempt to trace — hour by hour, day by day, — the everyday life of such places.»[13]

There was a wave of negative response too. Volynh (No.295, October 27, 1909), as well as Vestnik Literatury later (No.8, August, 1911) argued that such naturalistic descriptions of the life in a brothel could serve only for the spreading of prostitution, not its eradication. Vatslav Vorovsky accused Kuprin of idealizing prostitutes; the Marxist critic found the whole style of the novel uncharacteristically sentimental.[14] The Pit was severely criticized by both pro-monarchist Novoye Vremya and the Symbolist Vesy magazine. The latter’s reviewer Boris Sadovskoy saw the novel as ‘a pit’ of Kuprin’s weaknesses: his «tendency to daub real life sketches, being prone to textbook didacticism and having a taste for the ugliest things in life.» «Into The Pit Kuprin has stuck all that he’s got and what did he get? — another Duel,» the critic argued.[1]

Parts 2 and 3 of The Pit, published in 1915, made no resonance. Reviewers deplored what they saw as the lack of compositional integrity, the disparity of motifs and the author’s eagerness to rely on literary clichés. «Something feuilleton-like, petty and derivative is there in the garishness of many scenes, and the general drift of the story is banal,» wrote Russkiye Zapisky (Russian Notes, 1915, No.1) reviewer.[1]

One of the few critics who assessed the novel’s second and third parts highly was Korney Chukovsky. «That is a different kind of Yama, it has little in common with the one we read several years ago. In the former all the action took place in just one tiny hole. This time the author takes us through thousand places — from a café-chantant to a graveyard, a morgue, a police station, a student dormitory. And this motley canvas knit of myriad of faces is based on one grandiose theme, one powerful feeling. Each character stands out in relief, you can almost touch it and that is why all this affects you so… Karbesh, Sonjka the Rule, Anna Markovna, Emma and Semyon Horizont — all of them are portrayed in such a way that I would recognize each and every one of them in a huge crowd,» the critic wrote.[15]

Kuprin’s response[edit]

Kuprin, who had to deal with a lot of criticism, conceded the novel had its weaknesses and faults, but maintained he never regretted the huge amount of time he spent on it. «I certainly believe I’ve done an important job. Prostitution is a worse evil than war of famine: wars come and go, but prostitution stays with us through centuries,» he told Birzhevyie Vedomosti in 1915. Speaking of Lev Tolstoy’s original negative response, he added, «This might be dirt, but one has to wash it off. Should Lev Tolstoy have written of prostitution, using all the power of his genius, he’d have done a highly important job, for people would have listened to him more than they do to me. Alas, my pen is weak…»[16]

In 1918, responding to the question of the novel’s ideological relevance poised by the veteran worker P.I. Ivanov, Kuprin said: «I’ll tell you confidentially, I am not good at teaching people how to live their lives. I’ve mangled my own life as bad as I could. My readers see me mostly as a good friend and an engaging storyteller, that is all.»[1]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Rothstain, E. Commentaries to The Pit. The Complete A.I.Kuprin, in 9 volumes. Pravda Publishers. Ogonyok magazine library. Moscow. 1964. Pp.453-456.

- ^ Luker, Nicholas J.T. «1905 and After». kuprin.gatchina3000. Retrieved 2014-01-13.

- ^ Kievskiye Vesti, 1909, No. 156, June 14

- ^ Birzhevye Vedomosti, 1915, No.14943, August 4.

- ^ Rodnoy Mir, 1909, No.1, January.

- ^ Peterburgskaya Gazeta, 1908, No.303, November 8.

- ^ Kuprin’s Letter to F.D.Batyshkov, 1909, April 14, ИРЛИ

- ^ Kiyevskiye Vesti,1909, No.449. June 14.

- ^ The Moscow Regional Historical Archive. Fund 31. Section 3, File No.2200

- ^ Gusev, N. The Chronicle of Lev Tolstoy’s Life and Work. The May 6, 1909 entry.

- ^ Russkoye Slovo, 1909, No.91, April, 22

- ^ Volynh newspaper, 1909, No.113, April 27.

- ^ Kogan, P. Sketches on the History of Modern Russian Literature. Vol. 3, 1910.

- ^ Vorovsky, V. Literary Criticism. Moscow, 1956. P.283

- ^ Niva, 1914, No.45, November 6

- ^ Birzhevye Vedomosti, 1915, No.14855, May 21

External Links[edit]

- Yama: The Pit at Standard Ebooks