5 и 6 декабря в Австрии, Германии, Венгрии и некоторых странах Европы отмечается «Крампус» — антипод Рождеству, основанный на образе злобного спутника Санта Клауса. Россиянам такого не видать, РПЦ не разрешит.

Крампус — волосатый, жуткий, похожий на дьявола образ существа из немецкого фольклора. Он выходит на улицы вместе со Святым Николаем (Санта-Клаусом), похищает плохих детей, избивает, подвешивает на деревья или уносит их в пещеру, чтобы сожрать.

5 и 6 декабря Австрии, Германии, Венгрии, Чехии, а с некоторых пор в США и Италии, принято устраивать обряды в его честь. Мужчины, но иногда и смелые женщины, наряжаются в жуткие и отвратительные костюмы Крампуса, ходят по улице, звенят цепями, розгами и колокольчиками, и до чертиков пугают всех детей в округе. Вплоть до 50-х годов XX века католическая церковь не особо поощряла такие празднества, но сейчас успокоилась и не мешает людям потешаться во славу сатанинской твари.

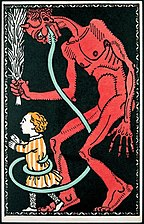

Коммерциализация «Крампуса» произошла в конце XIX века, когда австрийское правительство разрешило печатать марки частным компаниям и на них стали появляться образы дьявольского существа. На некоторых демона рисовали с мешком на спине, подобном рождественскому, только он не носил в нем подарки, а таскал там непослушных детей. В то же время появлялись и ироничные изображения с Крампусом: где-то он даже демонстрировался как страстный любовник для одиноких женщин, оставшихся без мужа в праздничную ночь.

- В этом году съезд фанатов Крампуса прошел 21 ноября в Словении

- В традиционном шестии по улицам приняли участие костюмированные приезжие из Венгрии, Германии, Австрии, Италии, Хорватии и еще десятка стран

- А это уже парад в Зальцбурге, Австрия, 28 ноября

- Многие участники изготавливают костюмы сильно заранее, порой работая над ними несколько месяцев

- Нередко для празднующих выделяют целую территорию, чтобы там они могли жечь фаеры, танцевать и напиваться

- Многие из них действительно верят в то, что с помощью таких обрядов можно отогнать демонов зимы и обеспечить благоприятный новый год

Подлинное веселье начинается в ночь с 5 на 6 декабря, когда австрийские мужики напиваются, одеваются в омерзительные инфернальные наряды, водят хороводы и устраивают настоящие уличные парады. «Крампус» перестает быть детским праздником и превращается в полуночную пьяную вечеринку для взрослых, которые ходят по домам и барам, и требуют, чтобы им непременно налили. Грубо говоря, это более жуткий, опасный и страшный аналог «Хэллоуина», только вместо костюма «Железного Человека» сосед надевает рога, вместо конфет просит бутылку «Джим Бима», а вместо объятий может дать по морде.

Но и так не везде: в Техасе, например, «Крампус» отметили достаточно мирно. Взрослые нарядились в нужные костюмы и пугали нерадивых детей, попутно наливая им газировку и кормя конфетами. Потом малышей, правда, отправили спать, а родители направились в местный бар

А вот так гулянки прошли в Италии в 2012 году, для них это был один из первых подобных обрядов

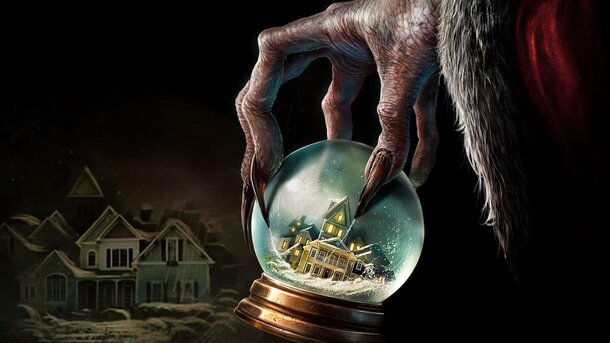

Сейчас «Крампус» становится все популярнее во всем мире, а, следовательно, и в массовой культуре. Образ рогатого рождественского монстра мелькал в сериалах «Гримм» и «Зов крови», над ним шутили в «Американском папаше», а 1 января в российский прокат выйдет одноименный ужастик про похитителя детей.

Появившийся в альпийских мифах и изначально дикий для людей демонический праздник, похоже, набирает обороты и почти наверняка придет и в Россию. Но, судя по реакции на невинный «Хэллоуин», произойдет это не так скоро, как хотелось бы.

НОЧЬ КРАМПУСА

Крампус, он же дьявол или чёрт — легендарное существо в фольклоре стран альпийского региона, спутник и в то же время антипод Николая Чудотворца, заменяющего Санта-Клауса и Деда Мороза. Ежегодно в ночь с 5 на 6 декабря эта парочка осуществляет по отношению к подрастающему поколению воспитательную функцию, делая это методом кнута и пряника — Чудотворец награждает хороших детей подарками, в то время как его напарник Крампус пугает их и наказывает за непослушание.

Изображать Крампуса принято в Австрии, Южной Баварии, Венгрии, Словении, Чехии, некоторых северных областях Италии (Больцано) и Хорватии. Облик этого создания и его прозвище варьируется в зависимости от местности. Как правило, в альпийском регионе Крампуса изображают как классического чёрта — рогатое и косматое звероподобное чудовище дьявольской внешности.

Ежегодно в ноябре и январе жители западных регионов Австрии одеваются в костюмы Перхтен (также известные в некоторых регионах, как Крампус или Тюифль) дабы осуществить древний языческий ритуал, которому уже более пятнадцати столетий, и с его помощью разогнать призраков приближающейся зимы. Этот ритуал — удивительная культурная достопримечательность Австрии, привлекающая в страну ежегодно толпы туристов. Каждый костюм изготавливается вручную и состоит из дюжины овечьих или козьих шкур, мастер может сконструировать до трёх костюмов за один день. Стоимость каждого костюма составляет примерно 500-600 евро. Резчику же по дереву требуется около 15 часов чтобы создать уникальную дьявольскую маску, которая которая обычно изготавливается из кедра и украшается козьими рогами. Маска стоит дополнительно 600 евро.

Традиционно мужчины наряжаются в наряд Крампуса в первую неделю декабря, а особенно в ночь с 5 (День Крампуса) на 6 декабря (День Св. Николая) и бродят по улицам, стращая детей звоном цепей и колокольчиков.

Легенды гласят, что когда Крампус находит капризного ребёнка, он засовывает его в свой мешок и уносит напуганное дитя в пещеру, предположительно чтобы съесть на рождественский ужин. В более старых версиях легенд Крампус похищает детей и уносит в свой жуткий замок, а останки потом сбрасывает в море.

Упоминания о Крампусе присутствуют ещё в дохристианском германском фольклоре. По некоторым характеристикам он проявляет сходство и с сатирами из древнегреческой мифологии. Во времена инквизиции католическая церковь запрещала празднования с участием ряженых, изображающих рогатых существ. Однако традиция изображения Крампуса сохранилась, и к XVII веку он утвердился в рождественских празднованиях как спутник Святого Николая.

В XX веке австрийское правительство также не поощряло культ Крампуса. После гражданской войны 1934 года режим Дольфуса наложил запрет на данную традицию. Тем не менее, к концу века традиция проведения празднований и гуляний с участием Крампуса обрела вторую жизнь и сейчас остаётся весьма популярной. При этом в Австрии проводилась общественная дискуссия на тему допустимости использования образа Крампуса для маленьких детей.

При всех различиях в изображении Крампуса некоторые его характеристики остаются общими: он покрыт шерстью, обычно бурой или чёрной, у него козлиные рога и раздвоенные копыта. Из пасти вываливается длинный заострённый язык.

Нередко Крампус несёт цепь, что символизирует оковы на дьяволе в христианской традиции. Для достижения большего эффекта он потрясает цепями. Цепи могут также дополняться колокольчиками разного размера. К языческим представлениям восходит такой атрибут Крампуса, как связки берёзовых розог, которыми он стегает детей. Наказание розгами играло важную роль в дохристианском обряде инициации. Розги могут заменяться хлыстом. Иногда Крампус появляется с мешком или лоханью за спиной — они предназначены для того, чтобы унести непослушных детей для их последующего поедания, утопления или отправления в преисподнюю.

За последние несколько десятилетий в Австрии как грибы выросли многочисленные деревенские Крампус-ассоциации с числом участников, превышающих сотню. Несмотря на все исторические препятствия карнавальная традиция растёт и укрепляется.

Якуб Рожальски (Jakub Rozalski) — «На стыке времен»

Источник

Кто такой Крампус, и как отмечают его день?

31 декабря 2021 13:20

Киноафиша рассказывает про скандинавскую мифологию Крампуса и ее отражения в кинематографе.

Во многих европейских странах набирает популярность жутковатый предновогодний праздник – День Крампуса. Этот мифический персонаж зародился несколько тысяч лет назад в дохристианском скандинавском фольклоре. В большинстве современных источников его описывают как «рождественского черта» – злобного духа с рогами и козлиной бородой, приходящего в мир каждую зиму вместе со Святым Николаем.

Он является своего рода антиподом добродушного старика Санты, а вместо подарков для послушных детей приносит разнообразные наказания для «плохих» мальчиков и девочек. Некоторых жертв он уносит в свое логово в мешке, подвешивает за ноги и медленно поедает. По другим версиям, Крампус мстит не только детям, но и взрослым, не верящим в чудеса и утратившим дух Рождества.

В древности Ночь Крампуса отмечали в самую долгую ночь в году – на 22 декабря. А самим этим персонажем пугали непослушных ребятишек. Сегодня отношение к Крампусу в мире значительно поменялось. Ему посвятили отдельный праздник, который в Германии, Австрии и Венгрии продолжается целых два дня – 5 и 6 декабря. Причем участвуют в этом торжестве отнюдь не дети. Ночь Крампуса стала своеобразной версией Хэллоуина. Взрослые мужчины и женщины наряжаются в Крампуса, цепляют на себя козлиные рога и жуткие бороды и бродят по улицам, выпивая, шумя и требуя гостинцы у прохожих.

Из Северной Европы праздник распространяется и по другим странам. Сейчас его уже отмечают в Чехии, Италии и США. Изображения Крампуса печатают на открытках и почтовых марках, в форме него выпускают игрушки и коллекционные фигурки. В России Ночь Крампуса пока не так популярна, но этот мифологический образ постепенно пробирается с запада и в нашу культуру. Например, в некоторых барах в канун Хэллоуина или Нового года уже можно встретить ряженых в костюмах «рождественского черта».

Конечно, свое отражение этот образ находит и в кинематографе. В 2015 году на экраны вышел полнометражный американский фильм ужасов под названием «Крампус». Он рассказывает о семействе Энджел, которое воочию повстречалось с этим жутким божеством. По сюжету двенадцатилетний мальчик Макс не ладит со своими многочисленными родными. Семья ссорится прямо за рождественским столом, что приводит к кошмарным последствиям. Старшую сестру, а затем и брата Макса похищает и жестоко убивает загадочный злой дух. Пожилая бабушка – глава семейства – опознает в нем самого Крампуса и дает советы родным, как с ним бороться. Фильм имеет запутанный сюжет и неоднозначное завершение. С одной стороны, можно подумать, что пережитый кошмар оказывается лишь сном героя. Но, с другой стороны, многое указывает на то, что последнее слово все же остается за Крампусом.

Этот фильм понравится не только любителям сказок о Крампусе, но и поклонникам классических ужастиков и атмосферных рождественских фильмов.

Культура

Дьявол из Европы. Кто такой Крампус

Если говорить о самых интересных традиционных мероприятиях Европы, то невозможно не упомянуть довольно старинный праздник «День Крампуса». Крампус выступает в фольклоре альпийского региона как спутник Святого Николая, который был полной его противоположностью и нужен был для создания равновесия в мире. Иными словами, если Святой Николай дарил подарки хорошим детишкам, то Крампус наказывал непослушных.

Проходит праздник в ночь с 5 на 6 декабря. Его отмечают в Австрии, Чехии, Венгрии, Словении, Южной Баварии, северных областях Хорватии и Италии.

Каждый год в эту ночь организуется шествие Крампусов, которые проходят по городу с демоническими огнями, танцами и песнями. А все желающие могут поучаствовать в конкурсе на самый жуткий костюм и самый страшный рык.

«День Крампуса» считается одним из наиболее увлекательных и самых ожидаемых праздников. Посмотреть на него приезжает множество туристов, а местные жители с удовольствием покидают свои дома, чтобы повеселиться на параде страшных дьяволов.

Вот так выглядит процесс изготовления маски дьявола.

Для этого резчика по дереву традиция переодеваться Крампусом является неплохим способом заработать. Костюм ручной работы будет стоить прилично — порядка 500-600 евро, но и на изготовление его уходит целых 15 часов.

В разных районах Крампуса изображаю по-разному, но чаще всего он представляет собой косматое, покрытое шерстью чудовище, на голове которого дьявольские рога.

В ночь празднования на улицах можно увидеть множество самых разных устрашающих обличий Крампуса. Мужчины переодеваются в костюмы, чтобы пугать детей, гремя цепями и колокольчиками.

Согласно легенде, Крампус наказывал непослушных детей максимально строго. Он находил их, кидал в свой мешок и уносил в пещеру, где съедал их на рождественский ужин. В более старых сказаниях говорится, что демон забирал детей в свой замок, после чего сбрасывал их в море.

Нельзя не заметить, что некоторые черты внешности Крампуса похожи на сатиров — существ из древнегреческой мифологии.

Так проходил праздник в Словении в 2015 году.

Это фото сделано во время празднования в австрийском городе Хубен в 2014 году.

Резчики по дереву создают настоящие шедевры искусства. Только взгляните на эти потрясающие маски!

Крампусы идут по улицам Зальцбурга (Австрия), 2015 год.

Еще одно фото дьявола из Зальцбурга.

Крампус пугает зрителей огнем, Словения, 2015 год.

Присоединяйся к нашему сообществу в телеграмме, нас уже более 1 млн человек 😍

Ссылка на тематические чаты тут https://t.me/+69dR1AvDfdM0MTYy

Крампуснахт отмечается 5 декабря каждого года в Германии, других европейских странах и Австралии. Это происходит в ночь перед празднованием праздника Святого Николая, в ночь, когда люди наряжаются дьяволом Крампусом и гоняют непослушных детей по улицам. Крампус отчитывает детей и дает связки «рутен», связку веток, чтобы они не забыли Крампуса после его ухода. Этот праздник становится все более популярным и в Америке, потому что он передает немного волнения и жути Хэллоуина прямо перед рождественским сезоном. Праздник Крампуснахт — история, как отмечать, узнайте в следующей статье на kakogo-chisla.ru.

Содержание

- Какого числа Крампуснахт

- История Крампуснахта

- Почему важен Крампуснахт

- Как отметить Крампуснахт

- Интересные факты про Крампуснахт

Какого числа Крампуснахт

Какого числа отмечают Крампуснахт? Узнайте, на какой день выпадает Крампуснахт в 2022, 2023, 2024, 2025 и 2026 годах.

| Год | Дата | День |

|---|---|---|

| 2022 | 5 декабря | Понедельник |

| 2023 | 5 декабря | Вторник |

| 2024 | 5 декабря | Четверг |

| 2025 | 5 декабря | Пятница |

| 2026 | 5 декабря | Суббота |

История Крампуснахта

Крампуснахт отмечается каждый год 5 декабря, в ночь перед празднованием праздника Святого Николая. Этот праздник в основном отмечается в Германии, Австрии, Хорватии и некоторых других странах Европы. Он также популярен в Австралии, и с годами популярность Крампуснахта выросла и в Северной Америке.

Крампуснахт — это праздник дьявола Крампуса, который, как полагают, является существом, которое является наполовину человеком, наполовину козлом. Он изображен волосатым, с большими рогами, козлиными копытами, красными глазами и клыками. Однако изображения Крампуса варьируются от региона к региону. На некоторых изображениях Крампус показан в цепях, и люди в костюмах Крампуса часто бьются в цепях для максимального эффекта. Цепи должны представлять связывание Дьявола Иисусом Христом в христианской мифологии.

Крампус носит связки «рутен» или веток, которыми он шлепает непослушных детей. По праздникам эти свертки раздают семьям, чтобы дети помнили об угрозе Крампуса в течение всего года и вели себя прилично. В странах, где празднуется Крампуснахт, Святой Николай дарит детям подарки, но если они плохо себя ведут, появляется Крампус, чтобы забрать подарки и вместо этого дать детям уголь и рутен. Всю ночь на 5 декабря мужчины наряжаются Крампусами, пьют алкоголь и празднуют на улицах.

Хотя происхождение Крампуса неясно, идея рогатой демонической сущности является дохристианской. Такое языческое существо могло быть поглощено сезонными традициями, чтобы стать частью празднования, предшествующего Рождеству.

Почему важен Крампуснахт

- Это герой для детей

Крампус используется как предупреждение для детей, чтобы они вели себя прилично в течение всего наступающего года. Это также просто забавный повод для взрослых, чтобы расслабиться и повеселиться!

- Мы любим прославлять фольклор

Дохристианские альпийские народные традиции сохраняются в современных праздниках, таких как Крампуснахт. Это связь с прошлым.

- Это веселый, праздничный день

Лучший способ привлечь больше людей к веселью Крампуснахта — отпраздновать его самим. Подготовьте свои лучшие костюмы и присоединяйтесь к празднику.

Советуем почитать: День рождения Гарри Поттера

Как отметить Крампуснахт

- Сделайте запасы шнапса

Мужчины в снаряжении Крампуса ходят от дома к дому, устраивая шум. По традиции, прежде чем они продолжат, угощают их шнапсом, поэтому убедитесь, что вы поставили немного шнапса!

- Оденьтесь как Крампус

Что может быть лучше, чем отпраздновать Крампуснахт, превратившись в самого Крампуса? Наденьте свой лучший костюм демона и пугайте непослушных детей на улицах.

- Устройте костюмированную вечеринку

Соберите своих друзей на костюмированную вечеринку в ночь на 5 декабря. Каждый может одеться как Крампус, а человек с лучшим костюмом будет коронован как «Крампус года».

Интересные факты про Крампуснахт

- Слово «Крампус» означает «коготь»

Крампус происходит от древнегерманского слова «крампен», что означает коготь и относится к устрашающему виду Крампуса.

- У карт Крампуса есть имена

Рождественские открытки, на которых изображен Крампус, называются «Krampuskarten».

- Крампус приходит со святым Николаем

Поскольку Крампуснахт — это ночь перед праздником Святого Николая, в некоторых регионах Крампус посещает дома со Святым Николаем.

- Крампус приезжает на две недели

Хотя Крампуснахт является официальным праздником, Крампус посещает улицы и бродит по улицам в течение первых двух недель декабря.

- Крампус в популярных СМИ

От поздравительных открыток до фильмов и даже видеоигр, Крампус появлялся во многих средствах массовой информации, поскольку популярность празднования Крампуснахта растет с каждым годом.

Крампуснахт — повод веселиться!

Post Views: 62

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

This article is about the folklore figure. For the film, see Krampus (film).

1900s illustration of Saint Nicholas and Krampus visiting a child

Krampus is a horned, anthropomorphic figure in the Central and Eastern Alpine folklore of Europe who, during the Advent season, scares children who have misbehaved. Assisting Saint Nicholas, or Santa Claus, the pair visit children on the night of 6 December, with Saint Nicholas rewarding the well-behaved children with modest gifts such as oranges, dried fruit, walnuts and chocolate, while the badly behaved ones only receive punishment from Krampus with birch rods. Krampus day itself, on the other hand, is on the 5th of December.[1]

The origin of the figure is unclear; some folklorists and anthropologists have postulated it as having pre-Christian origins.[2] In traditional parades and in such events as the Krampuslauf (English: Krampus run), young men dressed as Krampus attempt to scare the audience with their antics.[3] Such events occur annually in most Alpine towns.[4] Krampus is featured on holiday greeting cards called Krampuskarten.

The figure has been imported into American popular culture, and has appeared in movies, TV and video games.

Etymology[edit]

Krampus is thought to come from either Bavarian: krampn, meaning «dead», «rotten», or from the German: kramp/krampen, meaning «claw».[5][6][7]

Origins[edit]

A person dressed as Krampus at Morzger Pass, Salzburg, Austria

The history of the Krampus figure has been theorized as stretching back to pre-Christian Alpine traditions,[2][7] with celebrations involving Krampus dating back to the 6th or 7th century CE.[7] Though there are no written sources before the end of the 16th century.[8]

Discussing his observations in 1975 while in Irdning, a small town in Styria, anthropologist John J. Honigmann wrote that:

The Saint Nicholas festival we are describing incorporates cultural elements widely distributed in Europe, in some cases going back to pre-Christian times. Nicholas himself became popular in Germany around the eleventh century. The feast dedicated to this patron of children is only one winter occasion in which children are the objects of special attention, others being Martinmas, the Feast of the Holy Innocents, and New Year’s Day. Masked devils acting boisterously and making nuisances of themselves are known in Germany since at least the sixteenth century while animal masked devils combining dreadful-comic (schauriglustig) antics appeared in Medieval church plays. A large literature, much of it by European folklorists, bears on these subjects. …

Austrians in the community we studied are quite aware of «heathen» elements being blended with Christian elements in the Saint Nicholas customs and in other traditional winter ceremonies. They believe Krampus derives from a pagan supernatural who was assimilated to the Christian devil.[9]

The Krampus figures persisted, and by the 17th century Krampus had been incorporated into Christian winter celebrations by pairing Krampus with St. Nicholas.[10]

Modern history[edit]

In the aftermath of the 1932 election in Austria, the Krampus tradition was prohibited by the Dollfuss regime[11] under the clerical fascist Fatherland’s Front (Vaterländische Front) and the Christian Social Party. In the 1950s, the government distributed pamphlets titled «Krampus Is an Evil Man».[12] Towards the end of the century, a popular resurgence of Krampus celebrations occurred and continues today.[13]

The Krampus tradition is being revived in Bavaria as well, along with a local artistic tradition of hand-carved wooden masks.[14][15] In 2019 there were reports of drunken or disorderly conduct by masked Krampuses in some Austrian towns.[16]

Appearance[edit]

A 1900s greeting card reading ‘Greetings from Krampus!’

Although Krampus appears in many variations, most share some common physical characteristics. He is hairy, usually brown or black, and has the cloven hooves and horns of a goat. His long, pointed tongue lolls out,[17][18] and he has fangs.[19]

Krampus carries chains, thought to symbolize the binding of the Devil by the Christian Church. He thrashes the chains for dramatic effect. The chains are sometimes accompanied with bells of various sizes.[20] Of more pagan origins is the Rute, a bundle of birch branches that Krampus carries and with which he occasionally swats children.[17] The Rute may have had significance in pre-Christian pagan initiation rites.[17] The birch branches are replaced with a whip in some representations. Sometimes Krampus appears with a sack or a basket strapped to his back; this is to cart off evil children for drowning, eating, or transport to Hell. Some of the older versions make mention of naughty children being put in the bag and taken away.[17] This quality can be found in other companions of Saint Nicholas such as Zwarte Piet.[21]

Krampusnacht[edit]

The Feast of St. Nicholas is celebrated in parts of Europe on 6 December.[22] On the preceding evening of 5 December, Krampus Night or Krampusnacht, the wicked hairy devil appears on the streets. Sometimes accompanying St. Nicholas and sometimes on his own, Krampus visits homes and businesses.[17] The Saint usually appears in the Eastern Rite vestments of a bishop, and he carries a golden ceremonial staff. Unlike North American versions of Santa Claus, in these celebrations Saint Nicholas concerns himself only with the good children, while Krampus is responsible for the bad. Nicholas dispenses gifts, while Krampus supplies coal and the Rute.[23]

A seasonal play that spread throughout the Alpine regions was known as the Nikolausspiel [de] («Nicholas play»). Inspired by Paradise plays,[citation needed] which focused on Adam and Eve’s encounter with a tempter, the Nicholas plays featured competition for the human souls and played on the question of morality. In these Nicholas plays, Saint Nicholas would reward children for scholarly efforts rather than for good behavior.[24] This is a theme that grew in Alpine regions where the Roman Catholic Church had significant influence.[citation needed]

Perchtenlauf and Krampuslauf[edit]

There were already established pagan traditions in the Alpine regions that became intertwined with Catholicism. People would masquerade as a devilish figure known as Percht, a two-legged humanoid goat with a giraffe-like neck, wearing animal furs.[24] People wore costumes and marched in processions known as Perchtenlaufen, which are regarded as an earlier form of the Krampus runs. Perchtenlaufen were looked at with suspicion by the Catholic Church and banned by some civil authorities. Due to sparse population and rugged environments within the Alpine region, the ban was not effective or easily enforced, rendering the ban useless. Eventually the Perchtenlauf, inspired by the Nicholas plays, introduced Saint Nicholas and his set of good morals. The Percht transformed into what is now known as the Krampus and was made to be subjected to Saint Nicholas’ will.[25]

It is customary to offer a Krampus schnapps, a strong distilled fruit brandy.[17] These runs may include Perchten, similarly wild pagan spirits of Germanic folklore and sometimes female in representation, although the Perchten are properly associated with the period between winter solstice and 6 January.

Krampuskarten[edit]

Europeans have been exchanging greeting cards featuring Krampus since the 19th century.[26] Sometimes introduced with Gruß vom Krampus (Greetings from Krampus), the cards usually have humorous rhymes and poems. Krampus is often featured looming menacingly over children. He is also shown as having one human foot and one cloven hoof. In some, Krampus has sexual overtones; he is pictured pursuing buxom women.[27] Over time, the representation of Krampus in the cards has changed; older versions have a more frightening Krampus, while modern versions have a cuter, more Cupid-like creature.[citation needed] Krampus has also adorned postcards and candy containers.[28]

Regional variation[edit]

Krampus appears in the folklore of Austria, Bavaria, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Northern Italy, Autonomous Province of Trento and South Tyrol, Slovakia, and Slovenia.[29]

In Styria, the Rute is presented by Krampus to families. The twigs are painted gold and displayed year-round in the house—a reminder to any child who has temporarily forgotten Krampus. In smaller, more isolated villages, the figure has other beastly companions, such as the antlered «wild man» figures, and St Nicholas is nowhere to be seen. These Styrian companions of Krampus are called Schabmänner or Rauhen.[17]

A toned-down version of Krampus is part of the popular Christmas markets in Austrian urban centres like Salzburg. In these, more tourist-friendly interpretations, Krampus is more humorous than fearsome.[30]

Dallas Krampus Society Walk, 2016

North American Krampus celebrations are a growing phenomenon.[31]

Similar figures are recorded in neighboring areas. Strohbart in Bavaria, Klaubauf(mann) in Austria and Bavaria, while Bartl or Bartel, Niglobartl, and Wubartl are used in the southern part of the country. Other names include Barrel or Bartholomeus (Styria), Schmutzli (German-speaking Switzerland), Pöpel or Hüllepöpel (Würzburg), Zember (Cheb), Belzmärte and Pelzmärtel (Swabia and Franconia). In most parts of Slovenia, whose culture was greatly affected by Austrian culture, Krampus is called parkelj and is one of the companions of Miklavž, the Slovenian form of St. Nicholas.[17][32]

In many parts of Croatia, Krampus is described as a devil wearing a cloth sack around his waist and chains around his neck, ankles, and wrists. As a part of a tradition, when a child receives a gift from St. Nicholas he is given a golden branch to represent his good deeds throughout the year; however, if the child has misbehaved, Krampus will take the gifts for himself and leave only a silver branch to represent the child’s bad acts.[33][34][35][36]

In popular culture[edit]

The character of Krampus has been imported and modified for various North American media,[19][37] including print (e.g. Krampus: The Devil of Christmas, a collection of vintage postcards by Monte Beauchamp in 2004;[38][26] Krampus: The Yule Lord, a 2012 novel by Gerald Brom[39]); Krampus, a comic series from Image Comics in 2013 created by Dean Kotz and Brian Joines, television – both live action («A Krampus Carol», a 2012 episode of The League[37]) and animation («A Very Venture Christmas», a 2004 episode of The Venture Bros.,[19] «Minstrel Krampus», a 2013 episode of American Dad![40])–video games (CarnEvil, a 1998 arcade game,[41] The Binding of Isaac: Rebirth, a 2014 video game[42]), and film (Krampus, a 2015 Christmas comedy horror movie from Universal Pictures[43]).

Criticism[edit]

Every year there are arguments during Krampus runs. Occasionally spectators take revenge for whippings and attack Krampuses. In 2013, after several Krampus runs in East Tyrol, a total of eight injured people (mostly with broken bones) were admitted to the Lienz district hospital and over 60 other patients were treated on an outpatient basis.[44]

Gallery[edit]

-

Krampus mit Kind («Krampus with a child») postcard from around 1911

-

Nikolaus and Krampus in Austria in the early 20th century

-

Washington DC Krampusnacht walk (2016)

-

A St. Nicholas procession with Krampus, and other characters, c. 1910

-

St. Nikolaus with 12 Krampuses in Berchtesgadener Land, Germany (2016)

-

-

A modern Krampus at the Perchtenlauf in Klagenfurt (2006)

See also[edit]

[edit]

- Belsnickel – German Christmas gift-bringer, another West Germanic figure associated with the midwinter period

- Perchta – German Alpine goddess, a female figure in West Germanic folklore whose procession (Perchtenlauf) occurs during the midwinter period

- Pre-Christian Alpine traditions

- Germanic paganism – Ethnic religion practiced by the Germanic peoples from the Iron Age until Christianisation

- Goatman – a malevolent figure in urban folklore originating in Southern United States, like Maryland

- Green Man – Sculpture or other representation of a face surrounded by or made from foliage

- Holly King and Oak King – Personifications of winter and summer

- Yule goat – Scandinavian decorative Christmas straw goat, a goat associated with the midwinter period among the North Germanic peoples

- Namahage – Japanese folklore character associated with new year’s ritual

- Nuuttipukki – Creature in Finnish folklore

- Kallikantzaros – Malevolent goblin in Southeastern European and Anatolian folklore – Creature in Balkan folklore

- Knecht Ruprecht – A companion of Saint Nicholas in Germanic folklore

- Koliada – Ancient pre-Christian Slavic winter festival, an ancient pre-Christian Slavic festival where participants wear masks and costumes and run around.

- Turoń – Creature in Polish folklore

- Ded Moroz – Christmas figure in eastern Slavic cultures

- Sinterklaas – Legendary figure based on Saint Nicholas, celebrated in the Low Countries on 5 or 6 December. He has a companion called Zwarte Piet (Black Pete), who used to punish bad children with a «roe», and kidnap them in bags to Spain. But nowadays they are just as friendly as Sinterklaas («de Sint»), and give sweets and presents to all children.

- Kurentovanje

- Wild man – Mythical figure

- Silvesterklaus, a Swiss New Year’s Eve celebration featuring a musical procession of performers in grotesque costumes.

- Wendigo – Mythical being in Native American folklore.

Other[edit]

- Bogeyman – Mythical creature

- Demon

- Horned deity

References[edit]

- ^ Billock, Jennifer (4 December 2015). «The Origin of Krampus, Europe’s Evil Twist on Santa». The Smithsonian Magazine. The Smithsonian.

- ^ a b Forcher, Michael; Peterlini, Hans Karl (2010). Südtirol in Geschichte und Gegenwart [South Tyrol past and present] (in German). Haymon Verlag. p. 399.

- ^ «What is the Karmpuslauf?». Travel Dudes. 16 May 2019.

- ^ Crimmins, Peter (15 December 2011). «Horror For The Holidays: Meet The Anti-Santa». NPR. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- ^ Novak, Laura (December 2008). «Arrivano I Krampus: Un Inno Alla Mostruosità» [The Krampus arrive: A Hymn to Monstrosity]. Instoria (in Italian).

- ^ [«I Krampus» [The Krampus]. Friulani.net (in Italian). 28 October 2011.

- ^ a b c Muckerman, Anna (8 December 2018). «The man behind the Krampus mask». BBC.

- ^ Schubladen, Hans (1983–1984). «Zur Geschichte von Perchtenbräuchen im Berchtesgadener Land, in Tirol und Salzburg vom 16. bis zum 19. Jahrhundert. Grundlagen zur Analyse heutigen Traditionsverständnisses» [On the history of Perchten customs in the Berchtesgadener Land, in Tyrol and Salzburg from the 16th to the 19th century. Basics for the analysis of today’s understanding of tradition]. Bayerische Hefte für Volkskunde [Bavarian issues for folklore] (in German): 1–29.

- ^ Honigmann, John J. (Autumn 1977). «The Masked Face». Ethos. 5 (3): 263–80. doi:10.1525/eth.1977.5.3.02a00020.

- ^ «Run, Kris Kringle, Krampus is Coming!». Der Spiegel Online. 2 December 2008. Retrieved 17 December 2011.

- ^ «Krampus disliked in Fascist Austria; Genial Black and Red Devil, Symbol of Christmas Fun, Is Frowned Upon». The New York Times. 23 December 1934.

- ^ «Throw Out Krampus». Time. 7 December 1953. p. 41. Archived from the original on 22 December 2008. Retrieved 18 December 2011.

- ^ Silver, Marc (30 November 2009). «Merry Krampus?». NGM Blog Central. National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on 22 September 2010. Retrieved 17 December 2011.

- ^ Olsen, Erik (21 December 2014). «In Bavaria, Krampus Catches the Naughty». The New York Times. Archived from the original on 8 November 2020.

- ^ Alexandra, Zawadil (6 December 2006). «Santa’s evil sidekick? Who knew?». Reuters. Archived from the original on 2 November 2017.

- ^ Oltermann, Philip (8 December 2019). «Austria struggles with marauding Krampus demons gone rogue: Police record rising violence and drunkenness in relation to traditional folkloric festivities». The Guardian. Retrieved 8 December 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Bruce, Maurice (March 1958). «The Krampus in Styria». Folklore. 69 (1): 44–47. doi:10.1080/0015587X.1958.9717121.

- ^ Zeller, Tom (24 December 2000). «Have a Very Scary Christmas». The New York Times.

- ^ a b c Basu, Tanya (17 December 2013). «Who is Krampus? Explaining the Horrific Christmas Devil». National Geographic Magazine. National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on 20 February 2014. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- ^ Gatzke, Gretchen (1 December 2009). «Krampus? Who’s That?». The Vienna Review. Retrieved 17 December 2011.

- ^ Davis, Robert (2004). Christian Slaves, Muslim Masters: White Slavery in the Mediterranean, the Barbary Coast, and Italy, 1500–1800. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1403945518.

- ^ «Horror for the Holidays: Meet the Anti Santa». NPR. National Public Radio. Retrieved 22 December 2011.

- ^ Siefker, Phyllis (1997). Santa Claus, last of the Wild Men: the origins and evolution of Saint Nicholas. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Co. pp. 155–159. ISBN 978-0-7864-0246-5.

- ^ a b Ridenour 2016, p. 191.

- ^ Ridenour 2016, pp. 97–99.

- ^ a b Little, Becky (5 December 2018). «Meet Krampus, the Christmas Devil Who Punishes Naughty Children: The Alpine legend is the original bad Santa». History. Retrieved 17 December 2022.

- ^ Beauchamp, Monte (2004). The Devil in Design: The Krampus Postcards. Seattle, Washington: Fantagraphics. pp. 14–29, 32. ISBN 978-1-56097-542-7.

- ^ Apkarian-Russell, Pamela (2001). Postmarked yesteryear: art of the holiday postcard. Portland, Oregon: Collectors Press. p. 136. ISBN 978-1-888054-54-5.

- ^ Williams, Victoria (2016). Celebrating Life Customs around the World: From Baby Showers to Funerals. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. p. 222. ISBN 978-1-4408-3659-6 – via Google Books.

- ^ Haid, Oliver (2006). «Christmas markets in the Tyrolean Alps: Representing regional traditions in a newly created world of Christmas». In Picard, David; Robinson, Mike (eds.). Festivals, tourism and social change: remaking worlds. Buffalo, New York: Channel View Publications. pp. 216–19. ISBN 978-1-84541-048-3.

- ^ Crimmins, Peter (10 December 2011). «Horror for the Holidays: Meet the Anti-Santa». National Public Radio.

- ^ Miles, Clement A. (1912). «VIII». Christmas in ritual and tradition: Christian and Pagan. Toronto: Bell and Cockburn. pp. 227–29. ISBN 978-0-665-81125-8.

- ^ «Dobili ste šibu u čizmici? Evo tko je Krampus koji ju je ostavio» [Got a kick in the boot? This is who the Krampus who left her is]. Index.hr (in Croatian). 6 December 2015. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

- ^ «Sveti Nikola – Mikulaš» [Saint Nicholas — Mikulas]. www.hrvatskarijec.rs (in Croatian).

- ^ «Krampus nije baš tako loš kao što se čini, on samo opominje» [Krampus isn’t as bad as he seems, he just warns]. www.24sata.hr (in Croatian).

- ^ «FOTO: Sveti Nikola i Krampus stigli su morem i nagradili dobru djecu» [PHOTO: Saint Nicholas and Krampus arrived by sea and rewarded good children]. Liburnija.net (in Croatian). 26 November 2016. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

- ^ a b «Joines & Kotz’s «Krampus!» Terrorizes Christmas at Image». Comic Book Resources. 19 November 2013. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 21 December 2014.

- ^ Hix, Lisa (11 December 2012). «You’d Better Watch Out: Krampus Is Coming to Town». Collectors Weekly. Retrieved 4 December 2018.

- ^ Hoffert, Barbara (3 May 2012). «Fiction Previews, November 2012, Pt. 1: McCall Smith, Mayle, Munro, and More». Library Journal. Retrieved 21 December 2014.

- ^ McFarland, Kevin (16 December 2013). «American Dad: «Minstrel Krampus»«. The A.V. Club. Retrieved 5 September 2020.

- ^ Reed, Ashley; Houghton, David (19 December 2014). «12 games where you beat the everloving cheer out of Santa Claus». GamesRadar. Retrieved 21 December 2014.

- ^ «Krampus – Binding of Isaac: Rebirth Wiki». 18 November 2016. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

- ^ McNary, Dave (4 December 2015). «Box Office: Christmas Horror-Comedy ‘Krampus’ Jingles its Way to $16 Million Cancer». Variety. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

- ^ Mittermayr, Helmut (8 December 2013). «70 Verletzte bei Krampuslauf» [70 injured in Krampus run]. Tiroler Tageszeitung (in German).

Bibliography[edit]

- Ridenour, Al (2016). The Krampus and the Old Dark Christmas: Roots and Rebirth of the Folkloric Devil. Port Townsend, WA: Feral House. ISBN 978-1-62731-034-5.

External links[edit]

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Krampus.

This audio file was created from a revision of this article dated 23 November 2015, and does not reflect subsequent edits.

- Roncero, Miguel. «Trailing the Krampus», Vienna Review, 2 December 2013

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

This article is about the folklore figure. For the film, see Krampus (film).

1900s illustration of Saint Nicholas and Krampus visiting a child

Krampus is a horned, anthropomorphic figure in the Central and Eastern Alpine folklore of Europe who, during the Advent season, scares children who have misbehaved. Assisting Saint Nicholas, or Santa Claus, the pair visit children on the night of 6 December, with Saint Nicholas rewarding the well-behaved children with modest gifts such as oranges, dried fruit, walnuts and chocolate, while the badly behaved ones only receive punishment from Krampus with birch rods. Krampus day itself, on the other hand, is on the 5th of December.[1]

The origin of the figure is unclear; some folklorists and anthropologists have postulated it as having pre-Christian origins.[2] In traditional parades and in such events as the Krampuslauf (English: Krampus run), young men dressed as Krampus attempt to scare the audience with their antics.[3] Such events occur annually in most Alpine towns.[4] Krampus is featured on holiday greeting cards called Krampuskarten.

The figure has been imported into American popular culture, and has appeared in movies, TV and video games.

Etymology[edit]

Krampus is thought to come from either Bavarian: krampn, meaning «dead», «rotten», or from the German: kramp/krampen, meaning «claw».[5][6][7]

Origins[edit]

A person dressed as Krampus at Morzger Pass, Salzburg, Austria

The history of the Krampus figure has been theorized as stretching back to pre-Christian Alpine traditions,[2][7] with celebrations involving Krampus dating back to the 6th or 7th century CE.[7] Though there are no written sources before the end of the 16th century.[8]

Discussing his observations in 1975 while in Irdning, a small town in Styria, anthropologist John J. Honigmann wrote that:

The Saint Nicholas festival we are describing incorporates cultural elements widely distributed in Europe, in some cases going back to pre-Christian times. Nicholas himself became popular in Germany around the eleventh century. The feast dedicated to this patron of children is only one winter occasion in which children are the objects of special attention, others being Martinmas, the Feast of the Holy Innocents, and New Year’s Day. Masked devils acting boisterously and making nuisances of themselves are known in Germany since at least the sixteenth century while animal masked devils combining dreadful-comic (schauriglustig) antics appeared in Medieval church plays. A large literature, much of it by European folklorists, bears on these subjects. …

Austrians in the community we studied are quite aware of «heathen» elements being blended with Christian elements in the Saint Nicholas customs and in other traditional winter ceremonies. They believe Krampus derives from a pagan supernatural who was assimilated to the Christian devil.[9]

The Krampus figures persisted, and by the 17th century Krampus had been incorporated into Christian winter celebrations by pairing Krampus with St. Nicholas.[10]

Modern history[edit]

In the aftermath of the 1932 election in Austria, the Krampus tradition was prohibited by the Dollfuss regime[11] under the clerical fascist Fatherland’s Front (Vaterländische Front) and the Christian Social Party. In the 1950s, the government distributed pamphlets titled «Krampus Is an Evil Man».[12] Towards the end of the century, a popular resurgence of Krampus celebrations occurred and continues today.[13]

The Krampus tradition is being revived in Bavaria as well, along with a local artistic tradition of hand-carved wooden masks.[14][15] In 2019 there were reports of drunken or disorderly conduct by masked Krampuses in some Austrian towns.[16]

Appearance[edit]

A 1900s greeting card reading ‘Greetings from Krampus!’

Although Krampus appears in many variations, most share some common physical characteristics. He is hairy, usually brown or black, and has the cloven hooves and horns of a goat. His long, pointed tongue lolls out,[17][18] and he has fangs.[19]

Krampus carries chains, thought to symbolize the binding of the Devil by the Christian Church. He thrashes the chains for dramatic effect. The chains are sometimes accompanied with bells of various sizes.[20] Of more pagan origins is the Rute, a bundle of birch branches that Krampus carries and with which he occasionally swats children.[17] The Rute may have had significance in pre-Christian pagan initiation rites.[17] The birch branches are replaced with a whip in some representations. Sometimes Krampus appears with a sack or a basket strapped to his back; this is to cart off evil children for drowning, eating, or transport to Hell. Some of the older versions make mention of naughty children being put in the bag and taken away.[17] This quality can be found in other companions of Saint Nicholas such as Zwarte Piet.[21]

Krampusnacht[edit]

The Feast of St. Nicholas is celebrated in parts of Europe on 6 December.[22] On the preceding evening of 5 December, Krampus Night or Krampusnacht, the wicked hairy devil appears on the streets. Sometimes accompanying St. Nicholas and sometimes on his own, Krampus visits homes and businesses.[17] The Saint usually appears in the Eastern Rite vestments of a bishop, and he carries a golden ceremonial staff. Unlike North American versions of Santa Claus, in these celebrations Saint Nicholas concerns himself only with the good children, while Krampus is responsible for the bad. Nicholas dispenses gifts, while Krampus supplies coal and the Rute.[23]

A seasonal play that spread throughout the Alpine regions was known as the Nikolausspiel [de] («Nicholas play»). Inspired by Paradise plays,[citation needed] which focused on Adam and Eve’s encounter with a tempter, the Nicholas plays featured competition for the human souls and played on the question of morality. In these Nicholas plays, Saint Nicholas would reward children for scholarly efforts rather than for good behavior.[24] This is a theme that grew in Alpine regions where the Roman Catholic Church had significant influence.[citation needed]

Perchtenlauf and Krampuslauf[edit]

There were already established pagan traditions in the Alpine regions that became intertwined with Catholicism. People would masquerade as a devilish figure known as Percht, a two-legged humanoid goat with a giraffe-like neck, wearing animal furs.[24] People wore costumes and marched in processions known as Perchtenlaufen, which are regarded as an earlier form of the Krampus runs. Perchtenlaufen were looked at with suspicion by the Catholic Church and banned by some civil authorities. Due to sparse population and rugged environments within the Alpine region, the ban was not effective or easily enforced, rendering the ban useless. Eventually the Perchtenlauf, inspired by the Nicholas plays, introduced Saint Nicholas and his set of good morals. The Percht transformed into what is now known as the Krampus and was made to be subjected to Saint Nicholas’ will.[25]

It is customary to offer a Krampus schnapps, a strong distilled fruit brandy.[17] These runs may include Perchten, similarly wild pagan spirits of Germanic folklore and sometimes female in representation, although the Perchten are properly associated with the period between winter solstice and 6 January.

Krampuskarten[edit]

Europeans have been exchanging greeting cards featuring Krampus since the 19th century.[26] Sometimes introduced with Gruß vom Krampus (Greetings from Krampus), the cards usually have humorous rhymes and poems. Krampus is often featured looming menacingly over children. He is also shown as having one human foot and one cloven hoof. In some, Krampus has sexual overtones; he is pictured pursuing buxom women.[27] Over time, the representation of Krampus in the cards has changed; older versions have a more frightening Krampus, while modern versions have a cuter, more Cupid-like creature.[citation needed] Krampus has also adorned postcards and candy containers.[28]

Regional variation[edit]

Krampus appears in the folklore of Austria, Bavaria, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Northern Italy, Autonomous Province of Trento and South Tyrol, Slovakia, and Slovenia.[29]

In Styria, the Rute is presented by Krampus to families. The twigs are painted gold and displayed year-round in the house—a reminder to any child who has temporarily forgotten Krampus. In smaller, more isolated villages, the figure has other beastly companions, such as the antlered «wild man» figures, and St Nicholas is nowhere to be seen. These Styrian companions of Krampus are called Schabmänner or Rauhen.[17]

A toned-down version of Krampus is part of the popular Christmas markets in Austrian urban centres like Salzburg. In these, more tourist-friendly interpretations, Krampus is more humorous than fearsome.[30]

Dallas Krampus Society Walk, 2016

North American Krampus celebrations are a growing phenomenon.[31]

Similar figures are recorded in neighboring areas. Strohbart in Bavaria, Klaubauf(mann) in Austria and Bavaria, while Bartl or Bartel, Niglobartl, and Wubartl are used in the southern part of the country. Other names include Barrel or Bartholomeus (Styria), Schmutzli (German-speaking Switzerland), Pöpel or Hüllepöpel (Würzburg), Zember (Cheb), Belzmärte and Pelzmärtel (Swabia and Franconia). In most parts of Slovenia, whose culture was greatly affected by Austrian culture, Krampus is called parkelj and is one of the companions of Miklavž, the Slovenian form of St. Nicholas.[17][32]

In many parts of Croatia, Krampus is described as a devil wearing a cloth sack around his waist and chains around his neck, ankles, and wrists. As a part of a tradition, when a child receives a gift from St. Nicholas he is given a golden branch to represent his good deeds throughout the year; however, if the child has misbehaved, Krampus will take the gifts for himself and leave only a silver branch to represent the child’s bad acts.[33][34][35][36]

In popular culture[edit]

The character of Krampus has been imported and modified for various North American media,[19][37] including print (e.g. Krampus: The Devil of Christmas, a collection of vintage postcards by Monte Beauchamp in 2004;[38][26] Krampus: The Yule Lord, a 2012 novel by Gerald Brom[39]); Krampus, a comic series from Image Comics in 2013 created by Dean Kotz and Brian Joines, television – both live action («A Krampus Carol», a 2012 episode of The League[37]) and animation («A Very Venture Christmas», a 2004 episode of The Venture Bros.,[19] «Minstrel Krampus», a 2013 episode of American Dad![40])–video games (CarnEvil, a 1998 arcade game,[41] The Binding of Isaac: Rebirth, a 2014 video game[42]), and film (Krampus, a 2015 Christmas comedy horror movie from Universal Pictures[43]).

Criticism[edit]

Every year there are arguments during Krampus runs. Occasionally spectators take revenge for whippings and attack Krampuses. In 2013, after several Krampus runs in East Tyrol, a total of eight injured people (mostly with broken bones) were admitted to the Lienz district hospital and over 60 other patients were treated on an outpatient basis.[44]

Gallery[edit]

-

Krampus mit Kind («Krampus with a child») postcard from around 1911

-

Nikolaus and Krampus in Austria in the early 20th century

-

Washington DC Krampusnacht walk (2016)

-

A St. Nicholas procession with Krampus, and other characters, c. 1910

-

St. Nikolaus with 12 Krampuses in Berchtesgadener Land, Germany (2016)

-

-

A modern Krampus at the Perchtenlauf in Klagenfurt (2006)

See also[edit]

[edit]

- Belsnickel – German Christmas gift-bringer, another West Germanic figure associated with the midwinter period

- Perchta – German Alpine goddess, a female figure in West Germanic folklore whose procession (Perchtenlauf) occurs during the midwinter period

- Pre-Christian Alpine traditions

- Germanic paganism – Ethnic religion practiced by the Germanic peoples from the Iron Age until Christianisation

- Goatman – a malevolent figure in urban folklore originating in Southern United States, like Maryland

- Green Man – Sculpture or other representation of a face surrounded by or made from foliage

- Holly King and Oak King – Personifications of winter and summer

- Yule goat – Scandinavian decorative Christmas straw goat, a goat associated with the midwinter period among the North Germanic peoples

- Namahage – Japanese folklore character associated with new year’s ritual

- Nuuttipukki – Creature in Finnish folklore

- Kallikantzaros – Malevolent goblin in Southeastern European and Anatolian folklore – Creature in Balkan folklore

- Knecht Ruprecht – A companion of Saint Nicholas in Germanic folklore

- Koliada – Ancient pre-Christian Slavic winter festival, an ancient pre-Christian Slavic festival where participants wear masks and costumes and run around.

- Turoń – Creature in Polish folklore

- Ded Moroz – Christmas figure in eastern Slavic cultures

- Sinterklaas – Legendary figure based on Saint Nicholas, celebrated in the Low Countries on 5 or 6 December. He has a companion called Zwarte Piet (Black Pete), who used to punish bad children with a «roe», and kidnap them in bags to Spain. But nowadays they are just as friendly as Sinterklaas («de Sint»), and give sweets and presents to all children.

- Kurentovanje

- Wild man – Mythical figure

- Silvesterklaus, a Swiss New Year’s Eve celebration featuring a musical procession of performers in grotesque costumes.

- Wendigo – Mythical being in Native American folklore.

Other[edit]

- Bogeyman – Mythical creature

- Demon

- Horned deity

References[edit]

- ^ Billock, Jennifer (4 December 2015). «The Origin of Krampus, Europe’s Evil Twist on Santa». The Smithsonian Magazine. The Smithsonian.

- ^ a b Forcher, Michael; Peterlini, Hans Karl (2010). Südtirol in Geschichte und Gegenwart [South Tyrol past and present] (in German). Haymon Verlag. p. 399.

- ^ «What is the Karmpuslauf?». Travel Dudes. 16 May 2019.

- ^ Crimmins, Peter (15 December 2011). «Horror For The Holidays: Meet The Anti-Santa». NPR. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- ^ Novak, Laura (December 2008). «Arrivano I Krampus: Un Inno Alla Mostruosità» [The Krampus arrive: A Hymn to Monstrosity]. Instoria (in Italian).

- ^ [«I Krampus» [The Krampus]. Friulani.net (in Italian). 28 October 2011.

- ^ a b c Muckerman, Anna (8 December 2018). «The man behind the Krampus mask». BBC.

- ^ Schubladen, Hans (1983–1984). «Zur Geschichte von Perchtenbräuchen im Berchtesgadener Land, in Tirol und Salzburg vom 16. bis zum 19. Jahrhundert. Grundlagen zur Analyse heutigen Traditionsverständnisses» [On the history of Perchten customs in the Berchtesgadener Land, in Tyrol and Salzburg from the 16th to the 19th century. Basics for the analysis of today’s understanding of tradition]. Bayerische Hefte für Volkskunde [Bavarian issues for folklore] (in German): 1–29.

- ^ Honigmann, John J. (Autumn 1977). «The Masked Face». Ethos. 5 (3): 263–80. doi:10.1525/eth.1977.5.3.02a00020.

- ^ «Run, Kris Kringle, Krampus is Coming!». Der Spiegel Online. 2 December 2008. Retrieved 17 December 2011.

- ^ «Krampus disliked in Fascist Austria; Genial Black and Red Devil, Symbol of Christmas Fun, Is Frowned Upon». The New York Times. 23 December 1934.

- ^ «Throw Out Krampus». Time. 7 December 1953. p. 41. Archived from the original on 22 December 2008. Retrieved 18 December 2011.

- ^ Silver, Marc (30 November 2009). «Merry Krampus?». NGM Blog Central. National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on 22 September 2010. Retrieved 17 December 2011.

- ^ Olsen, Erik (21 December 2014). «In Bavaria, Krampus Catches the Naughty». The New York Times. Archived from the original on 8 November 2020.

- ^ Alexandra, Zawadil (6 December 2006). «Santa’s evil sidekick? Who knew?». Reuters. Archived from the original on 2 November 2017.

- ^ Oltermann, Philip (8 December 2019). «Austria struggles with marauding Krampus demons gone rogue: Police record rising violence and drunkenness in relation to traditional folkloric festivities». The Guardian. Retrieved 8 December 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Bruce, Maurice (March 1958). «The Krampus in Styria». Folklore. 69 (1): 44–47. doi:10.1080/0015587X.1958.9717121.

- ^ Zeller, Tom (24 December 2000). «Have a Very Scary Christmas». The New York Times.

- ^ a b c Basu, Tanya (17 December 2013). «Who is Krampus? Explaining the Horrific Christmas Devil». National Geographic Magazine. National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on 20 February 2014. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

- ^ Gatzke, Gretchen (1 December 2009). «Krampus? Who’s That?». The Vienna Review. Retrieved 17 December 2011.

- ^ Davis, Robert (2004). Christian Slaves, Muslim Masters: White Slavery in the Mediterranean, the Barbary Coast, and Italy, 1500–1800. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1403945518.

- ^ «Horror for the Holidays: Meet the Anti Santa». NPR. National Public Radio. Retrieved 22 December 2011.

- ^ Siefker, Phyllis (1997). Santa Claus, last of the Wild Men: the origins and evolution of Saint Nicholas. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Co. pp. 155–159. ISBN 978-0-7864-0246-5.

- ^ a b Ridenour 2016, p. 191.

- ^ Ridenour 2016, pp. 97–99.

- ^ a b Little, Becky (5 December 2018). «Meet Krampus, the Christmas Devil Who Punishes Naughty Children: The Alpine legend is the original bad Santa». History. Retrieved 17 December 2022.

- ^ Beauchamp, Monte (2004). The Devil in Design: The Krampus Postcards. Seattle, Washington: Fantagraphics. pp. 14–29, 32. ISBN 978-1-56097-542-7.

- ^ Apkarian-Russell, Pamela (2001). Postmarked yesteryear: art of the holiday postcard. Portland, Oregon: Collectors Press. p. 136. ISBN 978-1-888054-54-5.

- ^ Williams, Victoria (2016). Celebrating Life Customs around the World: From Baby Showers to Funerals. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. p. 222. ISBN 978-1-4408-3659-6 – via Google Books.

- ^ Haid, Oliver (2006). «Christmas markets in the Tyrolean Alps: Representing regional traditions in a newly created world of Christmas». In Picard, David; Robinson, Mike (eds.). Festivals, tourism and social change: remaking worlds. Buffalo, New York: Channel View Publications. pp. 216–19. ISBN 978-1-84541-048-3.

- ^ Crimmins, Peter (10 December 2011). «Horror for the Holidays: Meet the Anti-Santa». National Public Radio.

- ^ Miles, Clement A. (1912). «VIII». Christmas in ritual and tradition: Christian and Pagan. Toronto: Bell and Cockburn. pp. 227–29. ISBN 978-0-665-81125-8.

- ^ «Dobili ste šibu u čizmici? Evo tko je Krampus koji ju je ostavio» [Got a kick in the boot? This is who the Krampus who left her is]. Index.hr (in Croatian). 6 December 2015. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

- ^ «Sveti Nikola – Mikulaš» [Saint Nicholas — Mikulas]. www.hrvatskarijec.rs (in Croatian).

- ^ «Krampus nije baš tako loš kao što se čini, on samo opominje» [Krampus isn’t as bad as he seems, he just warns]. www.24sata.hr (in Croatian).

- ^ «FOTO: Sveti Nikola i Krampus stigli su morem i nagradili dobru djecu» [PHOTO: Saint Nicholas and Krampus arrived by sea and rewarded good children]. Liburnija.net (in Croatian). 26 November 2016. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

- ^ a b «Joines & Kotz’s «Krampus!» Terrorizes Christmas at Image». Comic Book Resources. 19 November 2013. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 21 December 2014.

- ^ Hix, Lisa (11 December 2012). «You’d Better Watch Out: Krampus Is Coming to Town». Collectors Weekly. Retrieved 4 December 2018.

- ^ Hoffert, Barbara (3 May 2012). «Fiction Previews, November 2012, Pt. 1: McCall Smith, Mayle, Munro, and More». Library Journal. Retrieved 21 December 2014.

- ^ McFarland, Kevin (16 December 2013). «American Dad: «Minstrel Krampus»«. The A.V. Club. Retrieved 5 September 2020.

- ^ Reed, Ashley; Houghton, David (19 December 2014). «12 games where you beat the everloving cheer out of Santa Claus». GamesRadar. Retrieved 21 December 2014.

- ^ «Krampus – Binding of Isaac: Rebirth Wiki». 18 November 2016. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

- ^ McNary, Dave (4 December 2015). «Box Office: Christmas Horror-Comedy ‘Krampus’ Jingles its Way to $16 Million Cancer». Variety. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

- ^ Mittermayr, Helmut (8 December 2013). «70 Verletzte bei Krampuslauf» [70 injured in Krampus run]. Tiroler Tageszeitung (in German).

Bibliography[edit]

- Ridenour, Al (2016). The Krampus and the Old Dark Christmas: Roots and Rebirth of the Folkloric Devil. Port Townsend, WA: Feral House. ISBN 978-1-62731-034-5.

External links[edit]

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Krampus.

This audio file was created from a revision of this article dated 23 November 2015, and does not reflect subsequent edits.

- Roncero, Miguel. «Trailing the Krampus», Vienna Review, 2 December 2013