Спасибо что зашли на наш сайт, перед тем как начать чтение вы можете подписаться на интересную православную mail рассылку, для этого вам необходимо кликнуть по этой ссылке «Подписаться»

Вечер накануне этого дня издавна известен, как Васильев: ведь это также день памяти свт. Василия Великого, любимого многими святого, создателя чина литургии. Кроме того, 14 января – так называемый «старый Новый год», то есть 1 января «старого» стиля, по так называемому юлианскому календарю (в отличие от гражданского, «григорианского») принятому страной до 1918 г., а Церковью – до наших дней. А вот о важном духовном значении праздника Обрезания Господня, также отмечаемого 14 января, знают далеко не все.

Содержание страницы

- Почему праздник Обрезания Господня не имеет статус двунадесятого

- Когда отмечают Обрезание Господне

- Событие праздника, который отмечают 14 января

- Значение Евангельского свидетельства об обрезании Богомладенца

- История ветхозаветного ритуала

- Что такое обрезание

- Когда делают обрезание в иудаизме?

- Зачем нужна такая процедура?

- Духовный смысл праздника в христианстве

- Когда ритуал сделали необязательным для христиан

- Чем заменили процедуру обрезания

- Богослужебные особенности

- Коротко о новолетии

- Тропарь, кондак, величание

- Тропарь, кондак, величание

- Икона праздника

- Что нельзя делать в этот день

- Похожие статьи

Почему праздник Обрезания Господня не имеет статус двунадесятого

Дело здесь не только в общем духовном невежестве многих наших современников, поколениями оторванных от традиции за годы атеизма. Ведь еще в начале XX в., когда было немало верующих, помнивших дореволюционные времена, митрополит Вениамин (Федченков) писал:

«Может быть, даже многие и не знают этого праздника. Во всяком случае, в сознании верующих этот праздник – один из самых затененных. Точно и не праздник он для богомольцев… Ясно, что Обрезание как-то мало захватывает нашу душу по самому существу своему…»

Иногда говорят, что само празднование так «незаметно» потому, что приходится между двумя великими «двунадесятыми» (то есть из числа установленных Церковью главнейших праздников). Это Рождество (7 января) и Крещение Иисуса Христа (19 января).

Но дело не только в этом. Церковь с IV в. установила, что праздник принадлежит к числу «великих», но не входит в число двенадцати главных. Вероятно, потому, что:

- событие относится к исполнению Господом нормы Ветхого Завета; на том, что Закон Моисеев (содержащий более 600 различный предписаний, включая обрезание) во всей его полноте не может, не должен более исполняться христианами, настаивал сначала ап. Павел, проповедник Истинного Бога среди язычников, затем – о том же прямо говорит Первый Апостольский Собор (49 г.);

- кроме того, событие относилось к земной жизни Спасителя, а христиане уже с I в. исходили из слов того же Павла: «отныне мы никого не знаем по плоти;если же и знали Христа по плоти, то ныне уже не знаем.Итак, кто во Христе, тот новая тварь; древнее прошло, теперь все новое» (2 Кор. 5:16-17).

Вместе с тем, события земной жизни Господа, включая это, были всегда дороги Его ученикам, потому праздник все-таки «великий».

Когда отмечают Обрезание Господне

Это ровно 8 день после Рождества Христова – день, когда по Закону иудейскому всякий младенец мужского пола должен был пройти через обрезание крайней плоти.

Из всех Евангелистов его описывает только св. Лука. Оно очень кратко:

«По прошествии восьми дней, когда надлежало обрезать Младенца, дали Ему имя Иисус, нареченное Ангелом прежде зачатия Его во чреве» (Лк.2:21).

При этом для Евангелиста принципиален не сам ритуал, а именно наречение имени: Иисус (по-еврейски – Иехошуа, то есть «Иегова спасает»).

О самом же совершенном обрезании Евангелист практически ничего не говорит. Связано это, конечно, с отношением христиан вообще к Закону, как «детоводителю ко Христу», исполнение которого для христиан не необходимо.

Значение Евангельского свидетельства об обрезании Богомладенца

Уже с конца I в. оно имело значение апологетическое: Церковь смущали еретики, приверженцы учения так называемого докетизма (от греческого «казаться»), считавшие, что Воплощение Христа на земле было «призрачным». Обрезание по Закону, которое Он, Младенец, претерпел, как раз показывало: Иисус – Совершенный Человек. Отголосок этой полемики – не только статус праздника, пусть «ветхозаветного», но все же «великого», но также его греческое наименование:

«Ή κατά σάρκα Περιτομή τού Κυρίου καί Θεού καί Σωτήρος ημών Ιησού Χριστού», буквально переведенное на славянский как «Еже по плоти Обрезание Господа и Бога и Спаси нашего Иисуса Христа». Именно – «по плоти».

История ветхозаветного ритуала

Она восходит к самому началу религии евреев, когда повеление совершать его было дано праотцу Аврааму непосредственно Богом:

«Сей есть завет Мой, который вы должны соблюдать между Мною и между вами и между потомками твоими после тебя [в роды их]: да будет у вас обрезан весь мужеский пол; обрезывайте крайнюю плоть вашу: и сие будет знамением завета между Мною и вами. Восьми дней от рождения да будет обрезан у вас в роды ваши всякий младенец мужеского пола… Необрезанный же мужеского пола, который не обрежет крайней плоти своей [в восьмой день], истребится душа та из народа своего, ибо он нарушил завет Мой» (Быт. 17:10-14).

Эти слова были сказаны Аврааму, когда старцу было уже 99 лет. Тогда же он, все мужчины его семьи прошли через ритуал.

Исход из Египта. Обрезание Елиезера, сына Моисея. Роспись Сикстинской капеллы, Ватикан. Ок. 1482 г. Худож. П. Перуджино

Прошел год, его супруга Сарра, несмотря на старость, родила праотцу сына – Исаака, что стало видимым знаком особого Божия благоволения к праведнику. С того времени иудеи строго блюди заповедь, данную на столетия раньше Закона Моисеева.

Что такое обрезание

Это, по сути, хирургическая операция удаления крайней плоти у мальчиков или же мужчин. Последнее чаще всего встречается сейчас при прохождении ими так называемого гиюра – перехода в иудаизм тех, кто по рождению не является евреем. Обрезание сейчас может происходить:

- · в синагоге, после молитвы утром;

- · дома; при этом должны присутствовать 10 мужчин (к таковым принадлежат все иудеи старше 13 лет);

- · в больнице, но с присутствием раввина

Совершать ритуал может любой иудей, или даже (если мужчины нет рядом) женщина иудейской веры. На практике же это делает специально обученный человек, именуемый моэлем, или же обычный врач, если все происходит в больнице. Особый участник ритуала – тот, кто держит на руках младенца во время него. Такой человек именуется «сандак». Это слово, про происхождению греческое, значит «защитник» или даже «одновременно родивший», по сути, второй отец.

Когда делают обрезание в иудаизме?

Это происходит на 8 день после рождения ребенка, но лишь тогда, когда он полностью здоров. Если ребенок болен, обрезание откладывается.

Зачем нужна такая процедура?

Смысл ее – прежде всего, духовный. Библия прямо указывает: «… душа всякого тела есть кровь его, она душа его» (Лев. 17:14). Кровь, истекающая из органа мужского дела, дающего жизнь, есть посвящение всего человека, его помыслов, действий, Создателю. Завет Бога с человеком – договор двоих. Со стороны человека он скрепляется кровью, тем, в чем жизнь, Господом же дарованная.

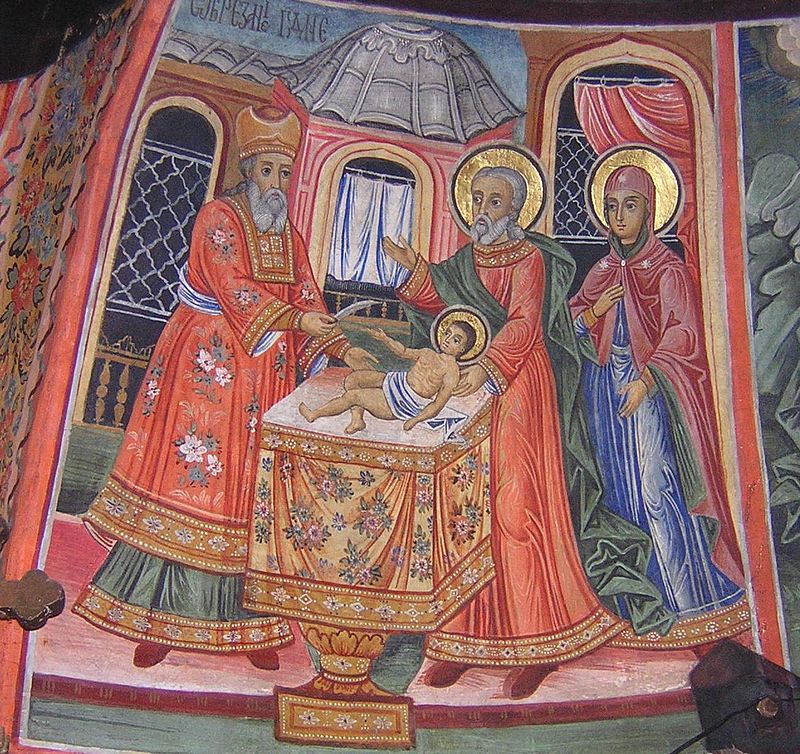

Обрезание. Художник Тинторетто 1518—1594. Фрагмент картины

Кроме того, со времен Авраама «необрезанный» означало «неверующий», непосвященный, не член Израильского общества; обрезание отделяло израильтян от прочих, языческих народов;

Духовный смысл праздника в христианстве

Кроме того, что оно говорит о Христе как реальном, а не «кажущемся», как учили докеты, Человеке, событие Обрезания:

- · свидетельствует о глубоком смирении Господа, принимающего на Себя исполнение Закона, Им же установленного;

Митр. Вениамин (Федченков) пишет: «Тот, кто намерен жить по новым законам, тот сначала должен исполнить старые. Это покажет, что он действительно «законопослушный» человек, а не своеволец. Тот лишь имеет право устанавливать новое, кто исполнил старое. Господь пришел установить Новый Закон, и Он необходимо должен был исполнить Ветхий».

- · оно же – начало страданий Сына Божия, прообразующее Его Крестный путь, жертву ради спасения людей;

- · наконец, это – пример христианам; путь к Богу начинается с исполнения церковных установлений: вот ты заставил себя встать пораньше, чтобы прийти на службу, вот ограничил себя в пище во время поста, а вот прошло время – и ты понудил душу подумать о грехах на исповеди;это уже – начало ее преображения.

К сожалению, многие, несколько расслабившиеся после Рождественского Поста, мало задумываются об этом на праздник Обрезания, такой «малозаметный» среди других.

Когда ритуал сделали необязательным для христиан

Начальная история Церкви, описанная св. Лукой в «Деяниях Апостолов», свидетельствует, что первые десятилетия существования христианских общин были временем дискуссии – местами довольно бурной – об обрезании вновь присоединяющихся к Церкви бывших язычников, да вообще – о соблюдении ими Закона. Проблема встала сразу после того, как новое учение вышло за пределы Палестины, народа Израиля, став достоянием жителей Римской империи самых разных национальностей.

Проповедь апостола Павла. Мозаика

Многие проповедовавшие Христа смущали язычников, требуя от них исполнения Закона, и, прежде всего, обрезания. Для решения вопроса пришлось собирать Собор Апостолов. К этому времени:

- · уже произошла история с Крещением сотника-язычника Корнилия, более того, всего его дома, от руки ап. Петра, имевшего пред тем особое небесное видение, которым, к его смущению, Апостолу предлагалось вкусить ритуально нечистой (по Закону) пищи; затем глас с неба трижды проговорил: «Что Бог очистил, того ты не почитай нечистым!» (Деян.10:15);

Говоря о Крещении язычников, св. Петр восклицает: «Сердцеведец Бог дал им свидетельство, даровав им Духа Святого, как и нам;и не положил никакого различия между нами и ими, верою очистив сердца их.Что же вы ныне искушаете Бога, желая возложить на выи учеников иго, которого не могли понести ни отцы наши, ни мы?»

- · крестил множество «необрезанных» другой Апостол, Павел.

Именно их мнение стало главным при принятии следующего решения Собора, обращенного к христианам из язычников:

«Апостолы и пресвитеры и братия – находящимся в Антиохии, Сирии и Киликии братиям из язычников: радоваться. Поелику мы услышали, что некоторые, вышедшие от нас, смутили вас своими речами и поколебали ваши души, говоря, что должно обрезываться и соблюдать закон, чего мы им не поручали,то мы, собравшись, единодушно рассудили, избрав мужей, послать их к вам с возлюбленными нашими Варнавою и Павлом, человеками, предавшими души свои за имя Господа нашего Иисуса Христа…

Ибо угодно Святому Духу и нам не возлагать на вас никакого бремени более, кроме сего необходимого:воздерживаться от идоложертвенного и крови, и удавленины, и блуда, и не делать другим того, чего себе не хотите. Соблюдая сие, хорошо сделаете. Будьте здравы».

Это постановление полностью отменяет обрезание для христиан из язычников. Впрочем, известно, что Иерусалимская община, состоявшая из евреев, продолжала соблюдать весь Закон Моисея. После разрушения города (70 г. н.э.) значение этой, самой авторитетной, из Церквей, упало, а традиция обрезания не продолжилась.

Чем заменили процедуру обрезания

Это Таинство Крещения. С древности оно, как обрезание, также совершалось – по возможности – на 8 день по рождении. К иудейской практике восходит также традиция иметь восприемника (того, кто принимает новокрещенного от купели).

Фото Анны Колесниковой

Смысл Таинства тот же – посвящение себя Богу. Но крови человека здесь уже не нужно: ее пролил за людей Сам Христос. Но доныне широко известно повторяемое многими святыми отцами выражение: «Даждь кровь и прими Дух!». Оно не говорит о собственно кровавой жертве, но означает: отдай Богу свое сердце, вручи Ему жизнь – тогда Господь дарует тебе Благодать.

Богослужебные особенности

Они определяются сочетанием двух праздников сразу – это Обрезание и память свт. Василия Великого. Поэтому:

- · служится литургия, создание которой приписывается святому;

- · на ней читаются два зачала (фрагмента) из Евангелия; один из них – праздничный, другой же посвящен святителю;

- · накануне, ввиду великого праздника, служат всенощное бдение;

- · отпуст (заключительные слова службы, которыми иерей «отпускает» собравшихся верующих) начинается со слов «Иже в осьмый день плотию обрезатися изволивый нашего ради спасения Христос, истинны Бог наш…»

Коротко о новолетии

Собственно церковный год начинается с 1 сентября. Традиция отмечать «старый Новый год», скорее, народная, возникшая после перехода России с юлианского на григорианский календарь 14 февраля 1918 г. При этом Разница между двумя календарями составляет 13 дней.

Церковь сохранила юлианский календарь. Вместе с тем, последние десятилетия традиционными становятся ночные литургии с 31 декабря на 1 января, а также предновогодние молебны. Они служатся по гражданскому (григорианскому) календарю. На «старый Новый год» особых чинов не совершается.

Тропарь, кондак, величание

Тропарь, кондак, величание

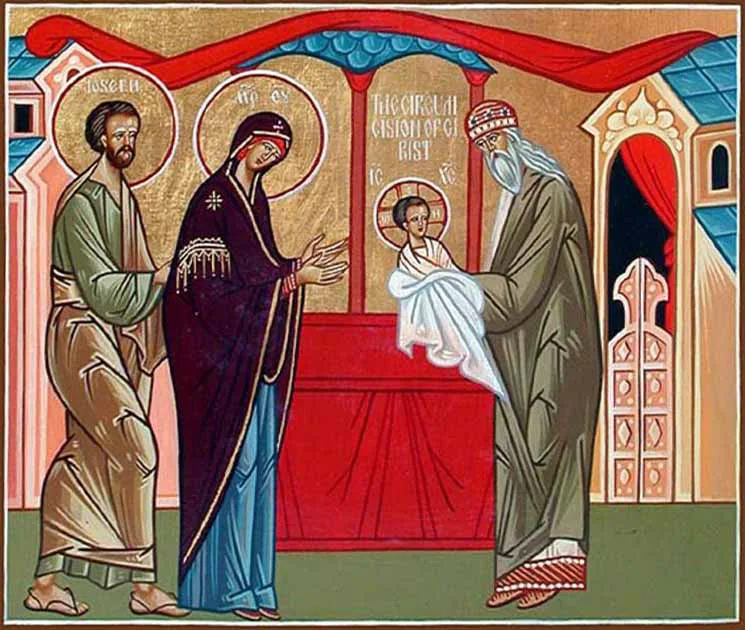

Икона праздника

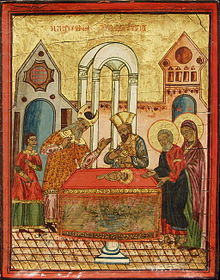

Многие образы похожи на иконографию Сретения: Богородица, держащая на руках Младенца, прав. Иосиф, мнимый Отец Господа, встречающий их священник. Однако по центру иконы находится стол со специальным ножом.

Обрезание Господне, Преображенский монастырь, Болгария

Существует также вариант иконы, где Младенец написан уже лежащим на нем, ожидающим обряда. На Нем – белое одеяние, рука жестом покорности протянута к старцу, совершающему ритуал.

Что нельзя делать в этот день

Существуют различные суеверия, правда, связанные с новолетием по «старому стилю». Они запрещают уборку, даже – вынос мусора из дома. Все они, конечно, неразумны, к христианству не имеют отношения. Особых церковных запретов этого дня не существует – за исключением всегдашнего негативного отношения к «народной» практике разного рода гаданий от Рождества до Крещения – этот запрет относится к Обрезанию тоже.

Что делать можно? Если христианин не занят на работе – посвятить день богослужению, возможно, причаститься. И уж точно – подумать о значении события, о том, что ныне – по сути, именины Господа, а еще начало пути его земного служения.

Наталья Сазонова

Похожие статьи

Хотим привлечь ваше внимание к проблеме разрушенных храмов, пострадавших в безбожные годы. Более 4000 старинных церквей по всей России ждут восстановления, многие находятся в критическом положении, но их все еще можно спасти.

Один из таких храмов, находится в городе Калач, это церковь Успения Божией Матери XVIII века. Силами неравнодушных людей храм начали восстанавливать, но средств на все работы катастрофически не хватает, так как строительные и реставрационные работы очень дорогие. Поэтому мы приглашаем всех желающих поучаствовать в благом деле восстановления храма в честь Пресвятой Богородицы. Сделать это можно на сайте храма

Помочь храму

Рекомендуем статьи по теме

На восьмой день после Рождества, 14 января, верующие отмечают Обрезание Господне — великий праздник для православной церкви. В 2023 году он приходится на субботу. В чем смысл торжества и самого христианского обряда — объясняют «Известия».

Обрезание Господне – 2023 — история праздника

Обряд обрезания пришел в христианство еще из Ветхого Завета. Библия гласит, что Господь, явившись к праведнику Аврааму и жене его Саре, предрек их роду быть богоизбранным народом. По словам Творца, потомков у пары будет столько же, сколько звезд на небе. Он нарек избранников Авраамом и Саррой и повелел в знак их договора учредить обряд обрезания крайней плоти.

С тех пор все дети-израильтяне мужского пола на восьмой день рождения проходили обрезание и ритуал имянаречения. Не стал исключением и Иисус. Имя же его предрек Ангел, явившийся к Деве Марии еще до зачатия. И в день обрезания младенец был наречен.

В Новом Завете обряд обрезания сменяется Крещением, «обрезанием сердца». Таким образом Иисус провозглашает главенство духа над плотью.

Обрезание Господне – 2023 — традиции праздника

В 49 году православная церковь официально упразднила обряд обрезания. С этого момента обязательным для христиан стало лишь крещение. Тем не менее некоторые верующие и по сей день придерживаются древней традиции.

Священнослужители в день праздника проводят ночь в молитвах, днем проводится литургия, а затем читается молебен о новолетии, поскольку праздник по старому стилю выпадал на 1 января. По новому же календарю торжество также приходится на старый Новый год.

Обрезание Господне – 2023 — что можно и нельзя делать

Накануне праздника в доме полагается провести уборку и окропить жилище святой водой. В ночь на 14 января в народе принято гадать и загадывать желания.

На стол в день праздника можно подавать не только постные продукты, но мясо и выпечку, но лучше обойтись без рыбы и птицы.

К гостям и близким нужно проявлять щедрость и великодушие, угостить домочадцев и соседей, не отказывать просящему. Если человек просит прощения за свои проступки, обязательно нужно пойти ему навстречу.

Однако, как и в другие церковные праздники, в день Обрезания нельзя сквернословить и ругаться, желать другому зла и осуществлять дурные помыслы. Считается, что если дать деньги взаймы, то весь год пройдет в долгах. Нельзя и заниматься серьезными подсчетами, решение финансовых вопросов лучше отложить на потом.

Также в народе верили, что мусор из дома выносить нельзя, потому что вместе с ним можно выкинуть и свое счастье.

Не стоит в день праздника браться за уборку и тяжелые дела по дому, а также заниматься рукоделием.

4 декабря верующие отмечали Введение во храм Пресвятой Богородицы — праздник, символизирующий день, когда юную Деву Марию посвятили Богу. «Известия» рассказывали читателям об истории и традициях знаменательной даты. С грядущими церковными праздниками 2023 года можно познакомиться в специальном календаре.

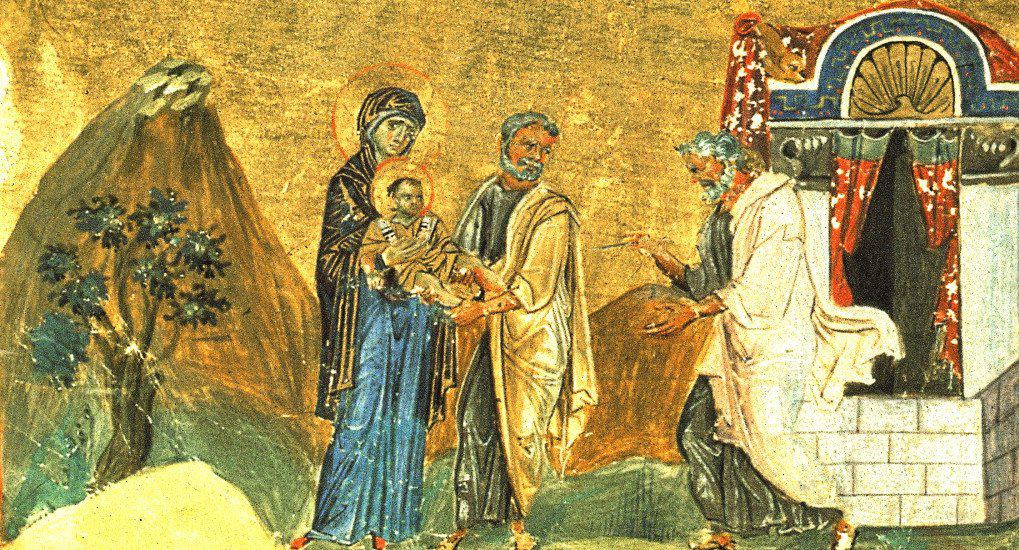

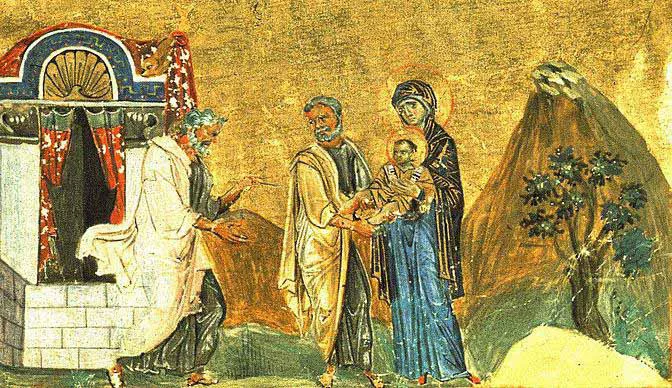

Фрагмент миниатюры Минология Василия II. Константинополь. 985 г. Ватиканская библиотека. Рим.

Обрезание: история и христианские смыслы

Приблизительное время чтения: 2 мин.

14 января Русская Православная Церковь отмечает праздник Обрезания Господня. Христиане придают ему особое значение, и видят в этом празднике сразу несколько важных для себя смыслов.

Для начала обратимся к ветхозаветному пониманию самого обрезания как религиозного обряда. По установленному Богом Закону каждый еврейский мальчик должен был быть обрезан на восьмой день после своего рождения в знак Завета Бога с праведным Авраамом и его потомками (Быт. 17, 10-14; Лев. 12, 3). Этот обряд включал человека в общество Израиля. Потому пройти его должен был и Спаситель, ведь по плоти Он был со Своим народом, происходя по материнской линии из рода царя Давида. При обрезании, как было заведено в то время у народа Израиля, Ему было дано имя — Иисус. Об этом нам сообщает Евангелие от Луки (Лк. 2, 21).

Однако, помимо ветхозаветного значения, в празднике Обрезания скрыто немало важных христианских символов. Апостол Павел в своем Послании к Колоссянам проводит параллель между обрезанием и христианским Таинством Крещения, замечая, что ветхозаветный обряд не отринут, а лишь уступил место новозаветному Таинству. По слову апостола, плотское обрезание иудеев заменяется у христиан обрезанием духовным: «обрезаны обрезанием нерукотворенным, совлечением греховного тела плоти, обрезанием Христовым» (Кол. 2, 11).

Праздник Обрезания сыграл важную историческую роль в конце первого века нашей эры, когда среди христиан возникла одна из первых ересей — докетизм. Ее название происходит от греческого «докео», что означает «казаться»: последователи докетизма считали Христа не реальным человеком, а призраком или духом, который лишь казался воплотившимся. Евангельское свидетельство о том, что Он прошел обрезание в спорах того времени стало важным свидетельством того, что плоть Христа была осязаемой, а значит и Сам Он был истинно воплощенным.

И, пожалуй, еще один важный момент. Обрезание по своей форме — это определенное ограничение, удаление. Принимая плотское обрезание по Закону, Христос тем самым показал людям необходимость духовного обрезания (то есть удаления, ограничения) от себя своих греховных страстей — эгоизма, гордыни, самости и иных рождающихся от них.

Что касается истории включения праздника Обрезания Господня в церковный календарь, то считается, что это произошло в IV веке. Канон празднику был написан преподобным Стефаном Савваитом. Это событие, в конечном счете, и вошло в Церковь в виде великого праздника.

Подробнее о смысле праздника читайте:

Проповеди на праздник Обрезание Господне

Загрузка…

Теги: Праздники Праздники

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Depiction of the Circumcision of Jesus by Fra Angelico (c. 1450)

The circumcision of Jesus is an event from the life of Jesus, according to the Gospel of Luke chapter 2, which states:

And when eight days were fulfilled to circumcise the child, his name was called Jesus, the name called by the angel before he was conceived in the womb.[1]

The eight days after his birth is traditionally observed January 1. This is in keeping with the Jewish law which holds that males should be circumcised eight days after birth during a Brit milah ceremony, at which they are also given their name. The circumcision of Christ became a very common subject in Christian art from the 10th century onwards, one of numerous events in the Life of Christ to be frequently depicted by artists. It was initially seen only as a scene in larger cycles, but by the Renaissance might be treated as an individual subject for a painting, or form the main subject in an altarpiece.

The event is celebrated as the Feast of the Circumcision in the Eastern Orthodox Church on January 1 in whichever calendar is used, and is also celebrated on the same day by many Anglicans. It is celebrated by Roman Catholics as the Feast of the Holy Name of Jesus, in recent years on January 3 as an Optional Memorial, though it was for long celebrated on January 1, as some other churches still do. A number of relics claiming to be the Holy Prepuce, the foreskin of Jesus, have surfaced.

Biblical accounts[edit]

Mid-18th-century Russian icon

Luke’s account of Jesus’s circumcision is extremely short, particularly compared to Paul the Apostle’s much fuller description of his own circumcision in the third chapter of his Epistle to the Philippians. This led theologians Friedrich Schleiermacher and David Strauss to speculate that the author of the Gospel of Luke might have assumed the circumcision to be historical fact, or might have been relating it as recalled by someone else.[2]

In addition to the canonical account in the Gospel of Luke, the apocryphal Arabic Infancy Gospel contains the first reference to the survival of Christ’s severed foreskin. The second chapter has the following story: «And when the time of his circumcision was come, namely, the eighth day, on which the law commanded the child to be circumcised, they circumcised him in a cave. And the old Hebrew woman took the foreskin (others say she took the navel-string), and preserved it in an alabaster-box of old oil of spikenard. And she had a son who was a druggist, to whom she said, «Take heed thou sell not this alabaster box of spikenard-ointment, although thou shouldst be offered three hundred pence for it. Now this is that alabaster-box which Mary the sinner procured, and poured forth the ointment out of it upon the head and feet of our Lord Jesus Christ, and wiped it off with the hairs of her head».[3]

Depictions in art[edit]

The circumcision controversy in early Christianity was resolved in the 1st century, so that non-Jewish Christians were not obliged to be circumcised. Saint Paul, the leading proponent of this position, discouraged circumcision as a qualification for conversion to Christianity. Circumcision soon became rare in most of the Christian world, except the Coptic Church of Egypt (where circumcision was a tradition dating to pre-Christian times) and for Judeo-Christians.[4] Perhaps for this reason, the subject of the circumcision of Christ was extremely rare in Christian art of the 1st millennium, and there appear to be no surviving examples until the very end of the period, although literary references suggest it was sometimes depicted.[5]

One of the earliest depictions to survive is a miniature in an important Byzantine illuminated manuscript of 979–984, the Menologion of Basil II in the Vatican Library. This has a scene which shows Mary and Joseph holding the baby Jesus outside a building, probably the Temple of Jerusalem, as a priest comes towards them with a small knife.[6] This is typical of the early depictions, which avoid showing the operation itself. At the period of Jesus’s birth, the actual Jewish practice was for the operation to be performed at home, usually by the father,[7] and Joseph is shown using the knife in an enamelled plaque from the Klosterneuburg Altar (1181) by Nicolas of Verdun, where it is next to plaques showing the very rare scenes (in Christian art) of the circumcisions of Isaac and Samson.[8] Like most later depictions these are shown taking place in a large building, probably representing the Temple, though in fact the ceremony was never performed there. Medieval pilgrims to the Holy Land were told Jesus had been circumcised in the church at Bethlehem.[7]

The scene gradually became increasingly common in the art of the Western church, and increasingly rare in Orthodox art. Various themes in theological exegesis of the event influenced the treatment in art. As the first drawing of Christ’s blood, it was also seen as a forerunner of, or even the first scene of, the Passion of Christ, and was one of the Seven Sorrows of Mary. Other interpretations developed based on it as the naming ceremony equivalent to Christian baptism, the aspect which was eventually to become most prominent in Catholic thinking. Both in this respect and in terms of finding a place in a pictorial cycle, consideration of the circumcision put it in a kind of competition with the much better established Presentation of Jesus; eventually the two scenes were to be conflated in some paintings.[9]

An influential book by Leo Steinberg, The Sexuality of Christ in Renaissance Art and in Modern Oblivion (1983, 2nd edition 1996), explores the explicit depiction of Christ’s penis in art, which he argues became a new focus of attention in late medieval art, initially covered only by a transparent veil in the early 14th century, and by the second half of the century completely uncovered, and often being the subject of the gaze or gestures of other figures in the scene. This emphasis is, among other things, a demonstration of Christ’s humanity when it appears in depictions of the Madonna and Child and other scenes of Christ’s childhood, and also a foreshadowing of Christ’s Passion to come in the context of the Circumcision.[10]

Having borrowed the large architectural setting in the Temple of the Presentation, later scenes may show the high priest alone holding the baby, as he or a mohel performs the operation, as in the St Wolfgang altarpiece by Michael Pacher (1481), or Dürer’s painting (right) and his influential woodcut from his series on the Life of the Virgin. This reflected what had by then become, and remains, standard Jewish practice, where the ceremony is performed in the synagogue and the baby is held by the seated rabbi as the mohel performs the operation.[9] Such an arrangement is seen in a miniature from a German Pentateuch in Hebrew from about 1300, showing the Circumcision of Isaac.[11] Other depictions show the baby held by Mary or Joseph, or both. Many show another baby in the background, presumably the next in the queue.

Other late medieval and Renaissance depictions of circumcision in general show antipathy towards Judaism; caricatures show the procedure as being grotesquely cruel and the mohel as a threatening figure; Martin Luther’s anti-Judaic treatise of 1543, On the Jews and Their Lies, devotes many pages to circumcision.[12] Some late-medieval German depictions depict the Circumcision of Christ in a similar vein, with the baby not held by his parents and the officiating Jewish officials given stereotypic features. In at least one manuscript miniature women are shown performing the rite, which has been interpreted as a misogynistic trope, with circumcision represented as a form of emasculation.[13]

By the 15th century the scene was often prominent in large polyptych altarpieces with many scenes in Northern Europe, and began to be the main scene on the central panel in some cases, usually when commissioned by lay confraternities dedicated to the Holy Name of Jesus, which were found in many cities. These often included donor portraits of members, though none are obvious in Luca Signorelli’s Circumcision of Christ commissioned by the confraternity at Volterra. The devotion to the Holy Name was a strong feature of the theatrical and extremely popular preaching of Saint Bernardino of Siena, who adopted Christ’s IHS monogram as his personal emblem, which was also used by the Jesuits; this often appears in paintings, as may a scroll held by an angel reading Vocatum est nomen eius Jesum.[14]

A smaller composition in a horizontal format originated with the Venetian painter Giovanni Bellini in about 1500 and was extremely popular, with at least 34 copies or versions being produced over the following decades;[15] the nearest to a prime version is in the National Gallery, London, though attributed to his workshop. These appear to have been commissioned for homes, possibly as votive offerings for the safe birth of an eldest son, although the reason for their popularity remains unclear. They followed some other depictions in showing Simeon, the prophet of the Presentation, regarded by then as a High Priest of the Temple, performing the operation on Jesus held by Mary. In other depictions he is a figure in the background, sometimes holding up his hands and looking to heaven, as in the Signorelli.[16] An altarpiece of 1500 by another Venetian painter, Marco Marziale (National Gallery, London), is a thoroughgoing conflation of the Circumcision and Presentation, with the text of Simeon’s prophecy, the Nunc dimittis, shown as if in mosaic on the vaults of the temple setting. There were a number of comparable works, some commissioned in circumstances where it is clear that the iconography would have had to pass learned scrutiny, so the conflation was evidently capable of theological approval, although some complaints are also recorded.[17]

The scene was often included in Protestant art, where this included narrative scenes. It appears on baptismal fonts because of the connection made by theologians with baptism. A painting (1661, National Gallery of Art, Washington[18]) and an etching (1654) by Rembrandt are both unusual in showing the ceremony taking place in a stable.[19] By this period large depictions were rarer in Catholic art, not least because the interpretation of the decrees of the final session of the Council of Trent in 1563 discouraged nudity in religious art, even that of the infant Jesus, which made depicting the scene difficult.[20] Even before this, 16th-century depictions like those of Bellini, Dürer and Signorelli tended to discreetly hide Jesus’s penis from view, in contrast to earlier compositions, where this evidence of his humanity is clearly displayed.

Poems on the subject included John Milton’s Upon the Circumcision and his contemporary Richard Crashaw’s Our Lord in His Circumcision to His Father, which both expounded the traditional symbolism.[21]

Theological beliefs and celebrations[edit]

The circumcision of Jesus has traditionally been seen, as explained in the popular 14th-century work the Golden Legend, as the first time the blood of Christ was shed, and thus the beginning of the process of the redemption of man, and a demonstration that Christ was fully human, and of his obedience to Biblical law.[22] Medieval and Renaissance theologians repeatedly stressed this, also drawing attention to the suffering of Jesus as a demonstration of his humanity and a foreshadowing of his Passion.[23] These themes were continued by Protestant theologians like Jeremy Taylor, who in a treatise of 1657 argued that Jesus’s circumcision proved his human nature while fulfilling the law of Moses. Taylor also notes that had Jesus been uncircumcised, it would have made Jews substantially less receptive to his Evangelism.[24]

The «Feast of the Circumcision of our Lord» is a Christian celebration of the circumcision, eight days (according to the Semitic and southern European calculation of intervals of days)[25] after his birth, the occasion on which the child was formally given his name, Jesus, a name derived from Hebrew meaning «salvation» or «saviour».[26][27] It is first recorded from a church council held at Tours in 567, although it was clearly already long-established.

The feast day appears on 1 January in the liturgical calendar of the Eastern Orthodox Church.[28] It also appears in the pre-1960 General Roman Calendar and is celebrated by churches of the Anglican Communion (though in many revised Anglican calendars, such as the 1979 calendar of the Episcopal Church, there is a tendency toward associating the day more with the Holy Name of Jesus[29]) and virtually all Lutheran churches. Johann Sebastian Bach wrote several cantatas for this Feast, «Beschneidung des Herrn» («Circumcision of the Lord»), including Singet dem Herrn ein neues Lied, BWV 190, for 1 January 1724 in Leipzig.

It finds no place in the present Roman Calendar of the ordinary form of the Roman Rite, replaced on January 1 by the Solemnity of Mary, Mother of God, but is still celebrated by Old Catholics and also by traditionalist Catholics who worship according to the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite (that follows the General Roman Calendar promulgated in 1962). It was for many centuries combined on January 1 with the Feast of the Holy Name of Jesus, before the two were separated, and now that the Feast of the Circumcision has disappeared as such from the official Catholic calendar, the other feast may be regarded as celebrating this too.

Relics[edit]

At various points in history, relics purporting to be the holy prepuce, the foreskin of Christ, have surfaced and various miraculous powers have been ascribed to it. A number of churches in Europe have claimed to possess Jesus’ foreskin, sometimes at the same time.[30] The best known was in the Lateran Basilica in Rome, whose authenticity was confirmed by a vision of Saint Bridget of Sweden. In its gold reliquary, it was looted in the Sack of Rome in 1527, but eventually recovered.[31]

Most of the Holy Prepuces were lost or destroyed during the Reformation and the French Revolution.[32] The Prepuce of Calcata is noteworthy, as the reliquary containing the Holy Foreskin was paraded through the streets of this Italian village as recently as 1983 on the Feast of the Circumcision, which was formerly marked by the Roman Catholic Church around the world on January 1 each year, and is now renamed as the Feast of the Holy Name of Jesus. The practice ended, however, when thieves stole the jewel-encrusted case, contents and all.[32] Following this theft, it is unclear whether any purported Holy Prepuces still exist.

Other philosophers contended that with the Ascension of Jesus, all of his body parts – even those no longer attached – ascended as well. One, Leo Allatius, reportedly went so far as to contend that the foreskin became the rings of Saturn; however, this reference is unverifiable.[33]

Gallery[edit]

-

Scene from a German painted wood altarpiece

-

-

Die Beschneidung Christi, Rubens, 1605

See also[edit]

- Chronology of Jesus

Notes[edit]

- ^

21 - ^ «The contrast however between the fullness of detail with which this point is elaborated and coloured in the life of the Baptist, and the barrenness with which it is stated in reference to Jesus, is striking, and may justify an agreement with the remark of Schleiermacher, that here, at least, the author of the first chapter is no longer the originator.» — Strauss, 217

- ^ «The Lost Books of the Bible,» New York: Bell Publishing Company, 1979

- ^ Pritz, pp. 108–109.

- ^ Schiller, 89

- ^ Schiller, 88–89, and plate 225

- ^ a b Schiller, 89; Penny, 116

- ^ Schiller, 89; Schreckenberg, 78–79

- ^ a b Schiller, 89; Penny, 107, 117–118

- ^ Kendrick, 11–15

- ^ Image of Isaac’s circumcision, Regensburg c1300, Regensburg Pentateuch, Israel Museum, Jerusalem; Cod. 180/52, fol. 81b. This image is discussed at length by Eva Frojmovic in pp. 228–238 of Framing the Family: Narrative and Representation in the Medieval and Early Modern Periods, Rosalynn Voaden (ed), 2005, Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies. She says she knows of only one other medieval Jewish image of the subject.

- ^ Glick, 91-92; 98–102

- ^ Schreckenberg illustrates four examples on pp. 143–146, two from manuscripts of c. 1400 (performed by a woman) and c. 1440, and two panels from altarpieces of c. 1450 and 1519. See also Abramson and Hannon, pp. 98, 102–108; Penny, 117.

- ^ Penny, 117

- ^ Penny, 119; Bartolomeo Veneto’s Circoncision’ and Bellini’s La Circoncision are two of them

- ^ Penny, 118–119

- ^ Penny, 118. The Marziale altarpiece is the subject of Penny’s very comprehensive catalogue entry on pp. 104–121; National Gallery page on Marziale Circumcision

- ^ Rembrandt from NGA Washington

- ^ Schiller, 90

- ^ Blunt, 118, citing Molanus

- ^ Milton text, Bartleby.com

- ^ Penny, 116-117

- ^ Glick, 93-96

- ^ «But so mysterious were all the actions of Jesus, that this one [his circumcision] served many ends. For 1. It gave demonstration of the verity of human nature. 2. So he began to fulfill the law. 3. And took from himself the scandal of uncircumcision, which would eternally have prejudiced the Jews against his entertainment and communion. 4. And then he took upon him that name, which declared him to be the Savior of the world; which as it was consummate in the blood of the cross, so it was inaugurated in the blood of circumcision: for «when eight days were accomplished for circumcising of the Child, his name was called Jesus.» — Taylor, 51

- ^ In the northern European calculation, which abstracts from the day from which the count begins, the interval was of seven days.

- ^ Luke 2:21: «On the eighth day, when it was time to circumcise the child, he was named Jesus, the name the angel had given him before he was conceived.» (NIV)

- ^ Catholic Encyclopedia: Feast of the Circumcision

- ^ Greek Orthodox Archdiocese calendar of Holy Days Archived February 13, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Calendar of the Church Year, according to the Episcopal Church

- ^ Glick, 96, says that «there were at least a dozen or so available for veneration».

- ^ Glick, 96

- ^ a b «Fore Shame», David Farley, Slate.com, Tuesday, Dec. 19, 2006

- ^ Palazzo, Robert P. (2005). «The Veneration of the Sacred Foreskin(s) of Baby Jesus — A Documented Analysis». In James P. Helfers (ed.). Multicultural Europe and Cultural Exchange in the Middle Ages and Renaissance. Turnhout: Brepols. p. 157. ISBN 2503514707. Archived from the original on 2013-11-21.

References[edit]

- Abramson, Henry; Hannon, Carrie. «Depicting the Ambiguous Wound: Circumcision in Medieval Art». In Mark, Elizabeth Wyner. The Covenant of Circumcision: New Perspectives on an Ancient Jewish Rite, 2003, Lebanon, New Hampshire, Brandeis University Press, ISBN 1-58465-307-8.

- Blunt, Anthony, Artistic Theory in Italy, 1450-1660, 1940 (refs to 1985 edn), OUP, ISBN 0-19-881050-4

- Glick, Leonard. Marked in Your Flesh: Circumcision from Ancient Judea to Modern America, OUP America, 2005

- Kendrick, Laura. Chaucerian play: comedy and control in the Canterbury tales, 1988, University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-06194-2, ISBN 978-0-520-06194-1, Internet Archive

- Penny, Nicholas. National Gallery Catalogues (new series): The Sixteenth Century Italian Paintings, Volume I, 2004, National Gallery Publications Ltd, ISBN 1-85709-908-7

- Pritz, Ray. Nazarene Jewish Christianity, 1992, The Magnes Press, Jerusalem, ISBN 965-223-798-1

- Schiller, Gertud. Iconography of Christian Art, Vol. I, 1971 (English trans from German), Lund Humphries, London, ISBN 0-85331-270-2

- Schreckenburg, Heinz, The Jews in Christian Art, 1996, Continuum, New York, ISBN 0-8264-0936-9

- Strauss, David Friedrich. The Life of Jesus: Critically Examined, Chapman and Brothers, London, 1846.

- Taylor, Jeremy. The Whole works; with an essay biographical and critical, Volume 1 (1657). Frederick Westley and A.H. Davis, London, 1835.

Further reading[edit]

- Baxter, Roger (1823). «Circumcision of Jesus» . Meditations For Every Day In The Year. New York: Benziger Brothers. pp. 101–107.

- Leo Steinberg, The Sexuality of Christ in Renaissance Art and in Modern Oblivion, 1996 (2nd edition), University of Chicago Press

External links[edit]

- Ancient Jew Review: On the Eighth Day of Christmas[permanent dead link]

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Depiction of the Circumcision of Jesus by Fra Angelico (c. 1450)

The circumcision of Jesus is an event from the life of Jesus, according to the Gospel of Luke chapter 2, which states:

And when eight days were fulfilled to circumcise the child, his name was called Jesus, the name called by the angel before he was conceived in the womb.[1]

The eight days after his birth is traditionally observed January 1. This is in keeping with the Jewish law which holds that males should be circumcised eight days after birth during a Brit milah ceremony, at which they are also given their name. The circumcision of Christ became a very common subject in Christian art from the 10th century onwards, one of numerous events in the Life of Christ to be frequently depicted by artists. It was initially seen only as a scene in larger cycles, but by the Renaissance might be treated as an individual subject for a painting, or form the main subject in an altarpiece.

The event is celebrated as the Feast of the Circumcision in the Eastern Orthodox Church on January 1 in whichever calendar is used, and is also celebrated on the same day by many Anglicans. It is celebrated by Roman Catholics as the Feast of the Holy Name of Jesus, in recent years on January 3 as an Optional Memorial, though it was for long celebrated on January 1, as some other churches still do. A number of relics claiming to be the Holy Prepuce, the foreskin of Jesus, have surfaced.

Biblical accounts[edit]

Mid-18th-century Russian icon

Luke’s account of Jesus’s circumcision is extremely short, particularly compared to Paul the Apostle’s much fuller description of his own circumcision in the third chapter of his Epistle to the Philippians. This led theologians Friedrich Schleiermacher and David Strauss to speculate that the author of the Gospel of Luke might have assumed the circumcision to be historical fact, or might have been relating it as recalled by someone else.[2]

In addition to the canonical account in the Gospel of Luke, the apocryphal Arabic Infancy Gospel contains the first reference to the survival of Christ’s severed foreskin. The second chapter has the following story: «And when the time of his circumcision was come, namely, the eighth day, on which the law commanded the child to be circumcised, they circumcised him in a cave. And the old Hebrew woman took the foreskin (others say she took the navel-string), and preserved it in an alabaster-box of old oil of spikenard. And she had a son who was a druggist, to whom she said, «Take heed thou sell not this alabaster box of spikenard-ointment, although thou shouldst be offered three hundred pence for it. Now this is that alabaster-box which Mary the sinner procured, and poured forth the ointment out of it upon the head and feet of our Lord Jesus Christ, and wiped it off with the hairs of her head».[3]

Depictions in art[edit]

The circumcision controversy in early Christianity was resolved in the 1st century, so that non-Jewish Christians were not obliged to be circumcised. Saint Paul, the leading proponent of this position, discouraged circumcision as a qualification for conversion to Christianity. Circumcision soon became rare in most of the Christian world, except the Coptic Church of Egypt (where circumcision was a tradition dating to pre-Christian times) and for Judeo-Christians.[4] Perhaps for this reason, the subject of the circumcision of Christ was extremely rare in Christian art of the 1st millennium, and there appear to be no surviving examples until the very end of the period, although literary references suggest it was sometimes depicted.[5]

One of the earliest depictions to survive is a miniature in an important Byzantine illuminated manuscript of 979–984, the Menologion of Basil II in the Vatican Library. This has a scene which shows Mary and Joseph holding the baby Jesus outside a building, probably the Temple of Jerusalem, as a priest comes towards them with a small knife.[6] This is typical of the early depictions, which avoid showing the operation itself. At the period of Jesus’s birth, the actual Jewish practice was for the operation to be performed at home, usually by the father,[7] and Joseph is shown using the knife in an enamelled plaque from the Klosterneuburg Altar (1181) by Nicolas of Verdun, where it is next to plaques showing the very rare scenes (in Christian art) of the circumcisions of Isaac and Samson.[8] Like most later depictions these are shown taking place in a large building, probably representing the Temple, though in fact the ceremony was never performed there. Medieval pilgrims to the Holy Land were told Jesus had been circumcised in the church at Bethlehem.[7]

The scene gradually became increasingly common in the art of the Western church, and increasingly rare in Orthodox art. Various themes in theological exegesis of the event influenced the treatment in art. As the first drawing of Christ’s blood, it was also seen as a forerunner of, or even the first scene of, the Passion of Christ, and was one of the Seven Sorrows of Mary. Other interpretations developed based on it as the naming ceremony equivalent to Christian baptism, the aspect which was eventually to become most prominent in Catholic thinking. Both in this respect and in terms of finding a place in a pictorial cycle, consideration of the circumcision put it in a kind of competition with the much better established Presentation of Jesus; eventually the two scenes were to be conflated in some paintings.[9]

An influential book by Leo Steinberg, The Sexuality of Christ in Renaissance Art and in Modern Oblivion (1983, 2nd edition 1996), explores the explicit depiction of Christ’s penis in art, which he argues became a new focus of attention in late medieval art, initially covered only by a transparent veil in the early 14th century, and by the second half of the century completely uncovered, and often being the subject of the gaze or gestures of other figures in the scene. This emphasis is, among other things, a demonstration of Christ’s humanity when it appears in depictions of the Madonna and Child and other scenes of Christ’s childhood, and also a foreshadowing of Christ’s Passion to come in the context of the Circumcision.[10]

Having borrowed the large architectural setting in the Temple of the Presentation, later scenes may show the high priest alone holding the baby, as he or a mohel performs the operation, as in the St Wolfgang altarpiece by Michael Pacher (1481), or Dürer’s painting (right) and his influential woodcut from his series on the Life of the Virgin. This reflected what had by then become, and remains, standard Jewish practice, where the ceremony is performed in the synagogue and the baby is held by the seated rabbi as the mohel performs the operation.[9] Such an arrangement is seen in a miniature from a German Pentateuch in Hebrew from about 1300, showing the Circumcision of Isaac.[11] Other depictions show the baby held by Mary or Joseph, or both. Many show another baby in the background, presumably the next in the queue.

Other late medieval and Renaissance depictions of circumcision in general show antipathy towards Judaism; caricatures show the procedure as being grotesquely cruel and the mohel as a threatening figure; Martin Luther’s anti-Judaic treatise of 1543, On the Jews and Their Lies, devotes many pages to circumcision.[12] Some late-medieval German depictions depict the Circumcision of Christ in a similar vein, with the baby not held by his parents and the officiating Jewish officials given stereotypic features. In at least one manuscript miniature women are shown performing the rite, which has been interpreted as a misogynistic trope, with circumcision represented as a form of emasculation.[13]

By the 15th century the scene was often prominent in large polyptych altarpieces with many scenes in Northern Europe, and began to be the main scene on the central panel in some cases, usually when commissioned by lay confraternities dedicated to the Holy Name of Jesus, which were found in many cities. These often included donor portraits of members, though none are obvious in Luca Signorelli’s Circumcision of Christ commissioned by the confraternity at Volterra. The devotion to the Holy Name was a strong feature of the theatrical and extremely popular preaching of Saint Bernardino of Siena, who adopted Christ’s IHS monogram as his personal emblem, which was also used by the Jesuits; this often appears in paintings, as may a scroll held by an angel reading Vocatum est nomen eius Jesum.[14]

A smaller composition in a horizontal format originated with the Venetian painter Giovanni Bellini in about 1500 and was extremely popular, with at least 34 copies or versions being produced over the following decades;[15] the nearest to a prime version is in the National Gallery, London, though attributed to his workshop. These appear to have been commissioned for homes, possibly as votive offerings for the safe birth of an eldest son, although the reason for their popularity remains unclear. They followed some other depictions in showing Simeon, the prophet of the Presentation, regarded by then as a High Priest of the Temple, performing the operation on Jesus held by Mary. In other depictions he is a figure in the background, sometimes holding up his hands and looking to heaven, as in the Signorelli.[16] An altarpiece of 1500 by another Venetian painter, Marco Marziale (National Gallery, London), is a thoroughgoing conflation of the Circumcision and Presentation, with the text of Simeon’s prophecy, the Nunc dimittis, shown as if in mosaic on the vaults of the temple setting. There were a number of comparable works, some commissioned in circumstances where it is clear that the iconography would have had to pass learned scrutiny, so the conflation was evidently capable of theological approval, although some complaints are also recorded.[17]

The scene was often included in Protestant art, where this included narrative scenes. It appears on baptismal fonts because of the connection made by theologians with baptism. A painting (1661, National Gallery of Art, Washington[18]) and an etching (1654) by Rembrandt are both unusual in showing the ceremony taking place in a stable.[19] By this period large depictions were rarer in Catholic art, not least because the interpretation of the decrees of the final session of the Council of Trent in 1563 discouraged nudity in religious art, even that of the infant Jesus, which made depicting the scene difficult.[20] Even before this, 16th-century depictions like those of Bellini, Dürer and Signorelli tended to discreetly hide Jesus’s penis from view, in contrast to earlier compositions, where this evidence of his humanity is clearly displayed.

Poems on the subject included John Milton’s Upon the Circumcision and his contemporary Richard Crashaw’s Our Lord in His Circumcision to His Father, which both expounded the traditional symbolism.[21]

Theological beliefs and celebrations[edit]

The circumcision of Jesus has traditionally been seen, as explained in the popular 14th-century work the Golden Legend, as the first time the blood of Christ was shed, and thus the beginning of the process of the redemption of man, and a demonstration that Christ was fully human, and of his obedience to Biblical law.[22] Medieval and Renaissance theologians repeatedly stressed this, also drawing attention to the suffering of Jesus as a demonstration of his humanity and a foreshadowing of his Passion.[23] These themes were continued by Protestant theologians like Jeremy Taylor, who in a treatise of 1657 argued that Jesus’s circumcision proved his human nature while fulfilling the law of Moses. Taylor also notes that had Jesus been uncircumcised, it would have made Jews substantially less receptive to his Evangelism.[24]

The «Feast of the Circumcision of our Lord» is a Christian celebration of the circumcision, eight days (according to the Semitic and southern European calculation of intervals of days)[25] after his birth, the occasion on which the child was formally given his name, Jesus, a name derived from Hebrew meaning «salvation» or «saviour».[26][27] It is first recorded from a church council held at Tours in 567, although it was clearly already long-established.

The feast day appears on 1 January in the liturgical calendar of the Eastern Orthodox Church.[28] It also appears in the pre-1960 General Roman Calendar and is celebrated by churches of the Anglican Communion (though in many revised Anglican calendars, such as the 1979 calendar of the Episcopal Church, there is a tendency toward associating the day more with the Holy Name of Jesus[29]) and virtually all Lutheran churches. Johann Sebastian Bach wrote several cantatas for this Feast, «Beschneidung des Herrn» («Circumcision of the Lord»), including Singet dem Herrn ein neues Lied, BWV 190, for 1 January 1724 in Leipzig.

It finds no place in the present Roman Calendar of the ordinary form of the Roman Rite, replaced on January 1 by the Solemnity of Mary, Mother of God, but is still celebrated by Old Catholics and also by traditionalist Catholics who worship according to the extraordinary form of the Roman Rite (that follows the General Roman Calendar promulgated in 1962). It was for many centuries combined on January 1 with the Feast of the Holy Name of Jesus, before the two were separated, and now that the Feast of the Circumcision has disappeared as such from the official Catholic calendar, the other feast may be regarded as celebrating this too.

Relics[edit]

At various points in history, relics purporting to be the holy prepuce, the foreskin of Christ, have surfaced and various miraculous powers have been ascribed to it. A number of churches in Europe have claimed to possess Jesus’ foreskin, sometimes at the same time.[30] The best known was in the Lateran Basilica in Rome, whose authenticity was confirmed by a vision of Saint Bridget of Sweden. In its gold reliquary, it was looted in the Sack of Rome in 1527, but eventually recovered.[31]

Most of the Holy Prepuces were lost or destroyed during the Reformation and the French Revolution.[32] The Prepuce of Calcata is noteworthy, as the reliquary containing the Holy Foreskin was paraded through the streets of this Italian village as recently as 1983 on the Feast of the Circumcision, which was formerly marked by the Roman Catholic Church around the world on January 1 each year, and is now renamed as the Feast of the Holy Name of Jesus. The practice ended, however, when thieves stole the jewel-encrusted case, contents and all.[32] Following this theft, it is unclear whether any purported Holy Prepuces still exist.

Other philosophers contended that with the Ascension of Jesus, all of his body parts – even those no longer attached – ascended as well. One, Leo Allatius, reportedly went so far as to contend that the foreskin became the rings of Saturn; however, this reference is unverifiable.[33]

Gallery[edit]

-

Scene from a German painted wood altarpiece

-

-

Die Beschneidung Christi, Rubens, 1605

See also[edit]

- Chronology of Jesus

Notes[edit]

- ^

21 - ^ «The contrast however between the fullness of detail with which this point is elaborated and coloured in the life of the Baptist, and the barrenness with which it is stated in reference to Jesus, is striking, and may justify an agreement with the remark of Schleiermacher, that here, at least, the author of the first chapter is no longer the originator.» — Strauss, 217

- ^ «The Lost Books of the Bible,» New York: Bell Publishing Company, 1979

- ^ Pritz, pp. 108–109.

- ^ Schiller, 89

- ^ Schiller, 88–89, and plate 225

- ^ a b Schiller, 89; Penny, 116

- ^ Schiller, 89; Schreckenberg, 78–79

- ^ a b Schiller, 89; Penny, 107, 117–118

- ^ Kendrick, 11–15

- ^ Image of Isaac’s circumcision, Regensburg c1300, Regensburg Pentateuch, Israel Museum, Jerusalem; Cod. 180/52, fol. 81b. This image is discussed at length by Eva Frojmovic in pp. 228–238 of Framing the Family: Narrative and Representation in the Medieval and Early Modern Periods, Rosalynn Voaden (ed), 2005, Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies. She says she knows of only one other medieval Jewish image of the subject.

- ^ Glick, 91-92; 98–102

- ^ Schreckenberg illustrates four examples on pp. 143–146, two from manuscripts of c. 1400 (performed by a woman) and c. 1440, and two panels from altarpieces of c. 1450 and 1519. See also Abramson and Hannon, pp. 98, 102–108; Penny, 117.

- ^ Penny, 117

- ^ Penny, 119; Bartolomeo Veneto’s Circoncision’ and Bellini’s La Circoncision are two of them

- ^ Penny, 118–119

- ^ Penny, 118. The Marziale altarpiece is the subject of Penny’s very comprehensive catalogue entry on pp. 104–121; National Gallery page on Marziale Circumcision

- ^ Rembrandt from NGA Washington

- ^ Schiller, 90

- ^ Blunt, 118, citing Molanus

- ^ Milton text, Bartleby.com

- ^ Penny, 116-117

- ^ Glick, 93-96

- ^ «But so mysterious were all the actions of Jesus, that this one [his circumcision] served many ends. For 1. It gave demonstration of the verity of human nature. 2. So he began to fulfill the law. 3. And took from himself the scandal of uncircumcision, which would eternally have prejudiced the Jews against his entertainment and communion. 4. And then he took upon him that name, which declared him to be the Savior of the world; which as it was consummate in the blood of the cross, so it was inaugurated in the blood of circumcision: for «when eight days were accomplished for circumcising of the Child, his name was called Jesus.» — Taylor, 51

- ^ In the northern European calculation, which abstracts from the day from which the count begins, the interval was of seven days.

- ^ Luke 2:21: «On the eighth day, when it was time to circumcise the child, he was named Jesus, the name the angel had given him before he was conceived.» (NIV)

- ^ Catholic Encyclopedia: Feast of the Circumcision

- ^ Greek Orthodox Archdiocese calendar of Holy Days Archived February 13, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Calendar of the Church Year, according to the Episcopal Church

- ^ Glick, 96, says that «there were at least a dozen or so available for veneration».

- ^ Glick, 96

- ^ a b «Fore Shame», David Farley, Slate.com, Tuesday, Dec. 19, 2006

- ^ Palazzo, Robert P. (2005). «The Veneration of the Sacred Foreskin(s) of Baby Jesus — A Documented Analysis». In James P. Helfers (ed.). Multicultural Europe and Cultural Exchange in the Middle Ages and Renaissance. Turnhout: Brepols. p. 157. ISBN 2503514707. Archived from the original on 2013-11-21.

References[edit]

- Abramson, Henry; Hannon, Carrie. «Depicting the Ambiguous Wound: Circumcision in Medieval Art». In Mark, Elizabeth Wyner. The Covenant of Circumcision: New Perspectives on an Ancient Jewish Rite, 2003, Lebanon, New Hampshire, Brandeis University Press, ISBN 1-58465-307-8.

- Blunt, Anthony, Artistic Theory in Italy, 1450-1660, 1940 (refs to 1985 edn), OUP, ISBN 0-19-881050-4

- Glick, Leonard. Marked in Your Flesh: Circumcision from Ancient Judea to Modern America, OUP America, 2005

- Kendrick, Laura. Chaucerian play: comedy and control in the Canterbury tales, 1988, University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-06194-2, ISBN 978-0-520-06194-1, Internet Archive

- Penny, Nicholas. National Gallery Catalogues (new series): The Sixteenth Century Italian Paintings, Volume I, 2004, National Gallery Publications Ltd, ISBN 1-85709-908-7

- Pritz, Ray. Nazarene Jewish Christianity, 1992, The Magnes Press, Jerusalem, ISBN 965-223-798-1

- Schiller, Gertud. Iconography of Christian Art, Vol. I, 1971 (English trans from German), Lund Humphries, London, ISBN 0-85331-270-2

- Schreckenburg, Heinz, The Jews in Christian Art, 1996, Continuum, New York, ISBN 0-8264-0936-9

- Strauss, David Friedrich. The Life of Jesus: Critically Examined, Chapman and Brothers, London, 1846.

- Taylor, Jeremy. The Whole works; with an essay biographical and critical, Volume 1 (1657). Frederick Westley and A.H. Davis, London, 1835.

Further reading[edit]

- Baxter, Roger (1823). «Circumcision of Jesus» . Meditations For Every Day In The Year. New York: Benziger Brothers. pp. 101–107.

- Leo Steinberg, The Sexuality of Christ in Renaissance Art and in Modern Oblivion, 1996 (2nd edition), University of Chicago Press

External links[edit]

- Ancient Jew Review: On the Eighth Day of Christmas[permanent dead link]

Источник: Храм Иконы Божией Матери «Неопалимая купина»

Между двумя Великими праздниками – Рождества Христова и Крещения Господня незаметно, как звезда, слабо различимая при свете солнца, стоит праздник Обрезания по плоти Господа Иисуса Христа. Это событие из жизни Спасителя не является Великим двунадесятым праздником. У него даже нет ни предпразднства, ни попразднства, всего лишь один только день, и среди верующих он известен не настолько хорошо, как любой из других Великих церковных праздников.

История праздника Обрезание Господне

По прошествии восьми дней после Рождества Христова, которое произошло в Вифлиемской пещере, Святая Мария и Ее обручник Иосиф пришли в Иерусалимский храм с Младенцем. Они должны были исполнить обязательный иудейский обряд – обрезание крайней плоти. По закону, при обрезании, Младенец получил имя Иисус. В переводе с еврейского, Спаситель (Иисус — греческое слово от еврейского) — Иехошуа (или сокращенно Иешуа, Иешу), что значит «Бог Спаситель». Это имя Ему дал архангел Гавриил еще при Благовещении Деве Марии.

После этого ритуала обрезания Младенец стал официально считаться полноценным потомком Авраама, Он получил право быть настоящим Мессией для соплеменников и наставлять их. А в Церкви этот праздник стал называться Обрезание по плоти Господа Иисуса Христа. В этот день прославляется и наречение чудодейственного имени.

Духовный смысл праздника Обрезания Господня

Самому обряду обрезанию, который исходил из Божиего завета Аврааму, уже много веков. В Библии об этом завете говорится так:

«Обрежется от вас всякий мужеск пол, и обрежете плоть крайнюю вашу. И будет в знамение завета между Мною и вами. И младенец осми дней обрежется вам… И будет завет Мой на плоти вашей в завет вечен. Необрезанный же мужеский пол, еже не обрежет плоти своея крайния в день осмый, погубится душа та от рода своего: яко завет Мой разори» (Быт. 17:10 — 14).

Крайняя плоть считается очагом страстности, а ее обрезание символизирует непорочную жизнь и свержение греховности для тех, кто хочет жить по Божеским заветам. Обрезанием символизируется утверждение любви к Богу, преданость Ему и, если это необходимо, готовность принести себя и свою жизнь в жертву Господу.

Спаситель пришел к людям, чтобы установить Новый Закон и Новую Церковь. Но, чтобы люди поверили Ему, необходимо было соблюсти Ветхий Закон.

Тот, кто устанавливает законы и следит за их выполнением, сам должен быть образцом для их исполнения. В жизни мы, конечно, часто видим обратную картину – закон выполняется только там, где выгодно, а если нет – придумываются новые правила.

Иисус Христос, сразу же после рождения, выполнил первое священное действие – обрезание. Закон был исполнен!

Богочеловек показал нам пример подчинения законам для нашей же пользы. Вряд ли кто захочет подумать, что Иисус Христос имел необходимость совершать какой-либо религиозный ритуал. Но без исполнения основ, Отец новой Церкви не имел права требовать от своих последователей настоящей веры.

Таким образом, Спаситель «ветхого» человека делает его «новым», а Новый Завет зарождается из Старого. Поэтому праздник Обрезания Господня стоит именно после Рождества не столько из-за того, что этот обряд проводится на восьмой день, а больше по смыслу цепочки событий: прежде всего Рождение, затем подтверждение начала Служения людям (Обрезание), а потом – Крещение.

«Не постыдился Всеблагой Бог плотским обрезанием обрезаться, но Самим Собой показал образ и начертание спасения: Творец закона — закон исполняет».

Молитвословия в праздник Обрезания Господня

Стихира празднику Обрезания Господня

Сходяй Спас к роду человеческому, прият пеленами повитие, не возгнушася плотскаго обрезания, осмодневен по Матери, безначальный по Отцу. Тому вернии возопиим: Ты еси Бог наш, помилуй нас.

Тропарь, глас 1

На престоле огнезрачнем в вышних седяй со Отцем безначальным и Божественным Твоим Духом, благоволил еси родитися на земли от Отроковицы, неискусомужныя Твоя Матере, Иисусе; сего ради и обрезан был еси яко человек осмодневный. Слава всеблагому Твоему совету, слава смотрению Твоему, слава снизхождению Твоему, едине Человеколюбче.

Кондак, глас 3

Всех Господь обрезание терпит, и человеческая прегрешения яко Благ обрезует, дает спасение днесь миру; радуется же в вышних и Создателев иерарх и светоносный Божественный таинник Христов Василий.

Величание

Величание: Величаем Тя, Живодавче Христе, и почитаем пречистыя плоти Твоея законное обрезание.