The brit milah (Hebrew: בְּרִית מִילָה bərīṯ mīlā, pronounced [bʁit miˈla]; Ashkenazi pronunciation: Hebrew pronunciation: [bʁis ˈmilə], «covenant of circumcision»; Yiddish pronunciation: bris Yiddish pronunciation: [bʀɪs]) is the ceremony of circumcision in Judaism.[1] According to the Book of Genesis, God commanded the biblical patriarch Abraham to be circumcised, an act to be followed by his male descendants on the eighth day of life, symbolizing the covenant between God and the Jewish people.[1] Today, it is generally performed by a mohel on the eighth day after the infant’s birth and is followed by a celebratory meal known as seudat mitzvah.[2]

Brit Milah is considered among the most important and central commandments in Judaism, and the rite has played a central role in the formation and history of Jewish civilization. The Talmud, when discussing the importance of Brit Milah, compares it to being equal to all other mitzvot (commandments) based on the gematria for brit of 612.[3] Jews who voluntarily fail to undergo Brit Milah, barring extraordinary circumstances, are believed to suffer Kareth in Jewish theology: the extinction of the soul and denial of a share in the world to come.[4][5][6][7] Judaism does not see circumcision as a universal moral law. Rather, the commandment is exclusive to followers of Judaism and the Jewish people; Gentiles who follow the Noahide Laws are believed to have a portion in the World to Come.[8]

Conflicts between Jews and European civilizations (both Christian and Pagan) have occurred several times over Brit Milah.[7] There have been multiple campaigns of Jewish ethnic, cultural, and religious persecution over the subject, with subsequent bans and restrictions on the practice as an attempted means of forceful assimilation, conversion, and ethnocide, most famously in the Maccabean Revolt by the Seleucid Empire.[7][9][10] According to historian Michael Livingston, «In Jewish history, the banning of circumcision (brit mila) has historically been a first step toward more extreme and violent forms of persecution».[10] These periods have generally been linked to suppression of Jewish religious, ethnic, and cultural identity and subsequent «punishment at the hands of government authorities for engaging in circumcision».[9] The Maccabee victory in the Maccabean Revolt — ending the prohibition against circumcision — is celebrated in Hanukkah.[7][11]

Circumcision rates are near-universal among Jews.[12]

Origins (Unknown to 515 BCE)[edit]

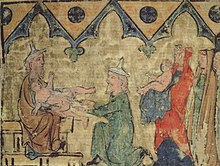

«Isaac’s Circumcision», Regensburg Pentateuch, c1300

The origin of circumcision is not known with certainty; however, artistic and literary evidence from ancient Egypt suggests it was practiced in the ancient Near East from at least the Sixth Dynasty (ca. 2345–ca. 2181 BCE).[13] According to some scholars, it appears that it only appeared as a sign of the covenant during the Babylonian Exile.[14][15][16] Scholars who posit the existence of a hypothetical J source (likely composed during the seventh century BCE) of the Pentateuch in Genesis 15 hold that it would not have mentioned a covenant that involves the practice of circumcision. Only in the P source (likely composed during the sixth century BCE) of Genesis 17 does the notion of circumcision become linked to a covenant.[14][15][16][17]

Some scholars have argued that it originated as a replacement for child sacrifice.[15][17][18][19][20]

Biblical references[edit]

According to the Hebrew Bible, Adonai commanded the biblical patriarch Abraham to be circumcised, an act to be followed by his descendants:

This is My covenant, which ye shall keep, between Me and you and thy seed after thee: every male among you shall be circumcised. And ye shall be circumcised in the flesh of your foreskin; and it shall be a token of a covenant betwixt Me and you. And he that is eight days old shall be circumcised among you, every male throughout your generations, he that is born in the house, or bought with money of any foreigner, that is not of thy seed. He that is born in thy house, and he that is bought with thy money, must needs be circumcised; and My covenant shall be in your flesh for an everlasting covenant. And the uncircumcised male who is not circumcised in the flesh of his foreskin, that soul shall be cut off from his people; he hath broken My covenant.

— Genesis 17:10–14[21]

Leviticus 12:3 says: «And in the eighth day the flesh of his foreskin shall be circumcised.»[22]

According to the Hebrew Bible, it was «a reproach» for an Israelite to be uncircumcised.[23] The plural term arelim («uncircumcised») is used opprobriously, denoting the Philistines and other non-Israelites[24] and used in conjunction with tameh (unpure) for heathen.[25] The word arel («uncircumcised» [singular]) is also employed for «impermeable»;[26] it is also applied to the first three years’ fruit of a tree, which is forbidden.[27]

However, the Israelites born in the wilderness after the Exodus from Egypt were not circumcised. Joshua 5:2–9, explains, «all the people that came out» of Egypt were circumcised, but those «born in the wilderness» were not. Therefore, Joshua, before the celebration of the Passover, had them circumcised at Gilgal specifically before they entered Canaan. Abraham, too, was circumcised when he moved into Canaan.

The prophetic tradition emphasizes that God expects people to be good as well as pious, and that non-Jews will be judged based on their ethical behavior, see Noahide Law. Thus, Jeremiah 9:25–26 says that circumcised and uncircumcised will be punished alike by the Lord; for «all the nations are uncircumcised, and all the house of Israel are uncircumcised in heart.»

The penalty of non-observance is kareth (spiritual excision from the Jewish nation), as noted in Genesis 17:1-14.[28] Conversion to Judaism for non-Israelites in Biblical times necessitated circumcision, otherwise one could not partake in the Passover offering.[29] Today, as in the time of Abraham, it is required of converts in Orthodox, Conservative and Reform Judaism.[30]

As found in Genesis 17:1–14, brit milah is considered to be so important that should the eighth day fall on the Sabbath, actions that would normally be forbidden because of the sanctity of the day are permitted in order to fulfill the requirement to circumcise.[31] The Talmud, when discussing the importance of Milah, compares it to being equal to all other mitzvot (commandments) based on the gematria for brit of 612.[3]

Covenants in ancient times were sometimes sealed by severing an animal, with the implication that the party who breaks the covenant will suffer a similar fate. In Hebrew, the verb meaning «to seal a covenant» translates literally as «to cut». It is presumed by Jewish scholars that the removal of the foreskin symbolically represents such a sealing of the covenant.[32]

Ceremony[edit]

Mohel[edit]

A mohel is a Jew trained in the practice of brit milah, the «covenant of circumcision.» According to traditional Jewish law, in the absence of a grown free Jewish male expert, anyone who has the required skills is also authorized to perform the circumcision, if they are Jewish.[33][34] Yet, most streams of non-Orthodox Judaism allow female mohels, called mohalot (Hebrew: מוֹהֲלוֹת, plural of מוֹהֶלֶת mohelet, feminine of mohel), without restriction. In 1984, Deborah Cohen became the first certified Reform mohelet; she was certified by the Berit Mila program of Reform Judaism.[35]

Time and place[edit]

It is customary for the brit to be held in a synagogue, but it can also be held at home or any other suitable location. The brit is performed on the eighth day from the baby’s birth, taking into consideration that according to the Jewish calendar, the day begins at the sunset of the day before. If the baby is born on Sunday before sunset, the brit will be held the following Sunday. However, if the baby is born on Sunday night after sunset, the brit is on the following Monday. The brit takes place on the eighth day following birth even if that day is Shabbat or a holiday. A brit is traditionally performed in the morning, but it may be performed any time during daylight hours.[36]

Postponement for health reasons[edit]

Family circumcision set and trunk, ca. eighteenth century Wooden box covered in cow hide with silver implements: silver trays, clip, pointer, silver flask, spice vessel.

The Talmud explicitly instructs that a boy must not be circumcised if he had two brothers who died due to complications arising from their circumcisions,[37] and Maimonides says that this excluded paternal half-brothers. This may be due to a concern about hemophilia.[37]

An Israeli study found a high rate of urinary tract infections if the bandage is left on too long.[38]

If the child is born prematurely or has other serious medical problems, the brit milah will be postponed until the doctors and mohel deem the child strong enough for his foreskin to be surgically removed.

Adult circumcision[edit]

In recent years, the circumcision of adult Jews who were not circumcised as infants has become more common than previously thought.[39] In such cases, the brit milah will be done at the earliest date that can be arranged. The actual circumcision will be private, and other elements of the ceremony (e.g., the celebratory meal) may be modified to accommodate the desires of the one being circumcised.

Circumcision for the dead[edit]

According to Halacha, a baby who dies before they had time to circumcise him must be circumcised before burial. Several reasons were given for this commandment.[40] Some have written that there is no need for this circumcision.

Anesthetic[edit]

Most prominent acharonim rule that the mitzvah of brit milah lies in the pain it causes, and anesthetic, sedation, or ointment should generally not be used.[41] However, it is traditionally common to feed the infant a drop of wine or other sweet liquid to soothe him.[42][43]

Eliezer Waldenberg, Yechiel Yaakov Weinberg, Shmuel Wosner, Moshe Feinstein and others agree that the child should not be sedated, although pain relieving ointment may be used under certain conditions; Shmuel Wosner particularly asserts that the act ought to be painful, per Psalms 44:23.[41]

In a letter to the editor published in The New York Times on January 3, 1998, Rabbi Moshe David Tendler disagrees with the above and writes, «It is a biblical prohibition to cause anyone unnecessary pain». Rabbi Tendler recommends the use of an analgesic cream.[44] Lidocaine should not be used, however, because lidocaine has been linked to several pediatric near-death episodes.[45][46]

Kvatter[edit]

The title of kvater (Yiddish: קוואַטער) among Ashkenazi Jews is for the person who carries the baby from the mother to the father, who in turn carries him to the mohel. This honor is usually given to a couple without children, as a merit or segula (efficacious remedy) that they should have children of their own. The origin of the term is Middle High German gevater/gevatere («godfather»).[47]

Seudat Mitzah at a brit (1824 Czechia).

Seudat mitzvah[edit]

After the ceremony, a celebratory meal takes place. At the birkat hamazon, additional introductory lines, known as Nodeh Leshimcha, are added. These lines praise God and request the permission of God, the Torah, Kohanim and distinguished people present to proceed with the grace. When the four main blessings are concluded, special ha-Rachaman prayers are recited. They request various blessings by God that include:

- the parents of the baby, to help them raise him wisely;

- the sandek (companion of child);

- the baby boy to have strength and grow up to trust in God and perceive Him three times a year;

- the mohel for unhesitatingly performing the ritual;

- to send the Messiah in Judaism speedily in the merit of this mitzvah;

- to send Elijah the prophet, known as «The Righteous Kohen», so that God’s covenant can be fulfilled with the re-establishment of the throne of King David.

Ritual components[edit]

Uncovering, priah[edit]

At the neonatal stage, the inner preputial epithelium is still linked with the surface of the glans.[48]

The mitzvah is executed only when this epithelium is either removed, or permanently peeled back to uncover the glans.[49]

On medical circumcisions performed by surgeons, the epithelium is removed along with the foreskin,[50] to prevent post operative penile adhesion and its complications.[51]

However, on ritual circumcisions performed by a mohel, the epithelium is most commonly peeled off only after the foreskin has been amputated. This procedure is called priah (Hebrew: פריעה), which means: ‘uncovering’. The main goal of «priah» (also known as «bris periah»), is to remove as much of the inner layer of the foreskin as possible and prevent the movement of the shaft skin, what creates the look and function of what is known as a «low and tight» circumcision.[52]

According to Rabbinic interpretation of traditional Jewish sources,[53] the ‘priah’ has been performed as part of the Jewish circumcision since the Israelites first inhabited the Land of Israel.[54]

The Oxford Dictionary of the Jewish Religion states that many Hellenistic Jews attempted to restore their foreskins, and that similar action was taken during the Hadrianic persecution, a period in which a prohibition against circumcision was issued. The writers of the dictionary hypothesize that the more severe method practiced today was probably begun in order to prevent the possibility of restoring the foreskin after circumcision, and therefore the rabbis added the requirement of cutting the foreskin in periah.[55]

According to Shaye J. D. Cohen, the Torah only commands milah.[56] David Gollaher has written that the rabbis added the procedure of priah to discourage men from trying to restore their foreskins: «Once established, priah was deemed essential to circumcision; if the mohel failed to cut away enough tissue, the operation was deemed insufficient to comply with God’s covenant,» and «Depending on the strictness of individual rabbis, boys (or men thought to have been inadequately cut) were subjected to additional operations.»[2]

Engraving of a brit (1657)

Metzitzah[edit]

- note: alternate spellings Metzizah[57] or Metsitsah[58] are also used to refer to this.

In the Metzitzah (Hebrew: מְצִיצָה), the guard is slid over the foreskin as close to the glans as possible to allow for maximum removal of the former without any injury to the latter. A scalpel is used to detach the foreskin. A tube is used for metzitzah

In addition to milah (the initial cut amputating the akroposthion) and p’riah and subsequent circumcision, mentioned above, the Talmud (Mishnah Shabbat 19:2) mentions a third step, metzitzah, translated as suction, as one of the steps involved in the circumcision rite. The Talmud writes that a «Mohel (Circumciser) who does not suck creates a danger, and should be dismissed from practice».[59][60] Rashi on that Talmudic passage explains that this step is in order to draw some blood from deep inside the wound to prevent danger to the baby.[61]

There are other modern antiseptic and antibiotic techniques—all used as part of the brit milah today—which many say accomplish the intended purpose of metzitzah, however, since metzitzah is one of the four steps to fulfill Mitzvah, it continues to be practiced by a minority of Orthodox and Hassidic Jews.[62]

Metzitzah B’Peh (oral suction)[edit]

- This has also been abbreviated as MBP.[63]

The ancient method of performing metzitzah b’peh (Hebrew: מְצִיצָה בְּפֶה)—or oral suction[64][65]—has become controversial. The process has the mohel place his mouth directly on the infant’s genital wound to draw blood away from the cut. The vast majority of Jewish circumcision ceremonies do not use metzitzah b’peh,[66] but some Haredi Jews continue to use it.[67][68][57] It has been documented that the practice poses a serious risk of spreading herpes to the infant.[69][70][71][72] Proponents maintain that there is no conclusive evidence that links herpes to Metzitza,[73] and that attempts to limit this practice infringe on religious freedom.[74][75][76]

The practice has become a controversy in both secular and Jewish medical ethics. The ritual of metzitzah is found in Mishnah Shabbat 19:2, which lists it as one of the four steps involved in the circumcision rite. Rabbi Moses Sofer, also known as the Chatam Sofer (1762–1839), observed that the Talmud states that the rationale for this part of the ritual was hygienic — i.e., to protect the health of the child. The Chatam Sofer issued a leniency (Heter) that some consider to have been conditional, to perform metzitzah with a sponge to be used instead of oral suction in a letter to his student, Rabbi Lazar Horowitz of Vienna. This letter was never published among Rabbi Sofer’s responsa but rather in the secular journal Kochvei Yitzchok.[77][78] along with letters from Dr. Wertheimer, the chief doctor of the Viennese General Hospital. It relates the story that a mohel (who was suspected of transmitting herpes via metzizah to infants) was checked several times and never found to have signs of the disease and that a ban was requested because of the «possibility of future infections».[79] Moshe Schick (1807–1879), a student of Moses Sofer, states in his book of Responsa, She’eilos u’teshuvos Maharam Schick (Orach Chaim 152,) that Moses Sofer gave the ruling in that specific instance only because the mohel refused to step down and had secular government connections that prevented his removal in favor of another mohel, and the Heter may not be applied elsewhere. He also states (Yoreh Deah 244) that the practice is possibly a Sinaitic tradition, i.e., Halacha l’Moshe m’Sinai. Other sources contradict this claim, with copies of Moses Sofer’s responsa making no mention of the legal case or of his ruling applying in only one situation. Rather, that responsa makes quite clear that «metzizah» was a health measure and should never be employed where there is a health risk to the infant.[80]

Chaim Hezekiah Medini, after corresponding with the greatest Jewish sages of the generation, concluded the practice to be Halacha l’Moshe m’Sinai and elaborates on what prompted Moses Sofer to give the above ruling.[81] He tells the story that a student of Moses Sofer, Lazar Horowitz, Chief Rabbi of Vienna at the time and author of the responsa Yad Elazer, needed the ruling because of a governmental attempt to ban circumcision completely if it included metztitzah b’peh. He therefore asked Sofer to give him permission to do brit milah without metzitzah b’peh. When he presented the defense in secular court, his testimony was erroneously recorded to mean that Sofer stated it as a general ruling.[82] The Rabbinical Council of America (RCA), which claims to be the largest American organization of Orthodox rabbis, published an article by mohel Dr Yehudi Pesach Shields in its summer 1972 issue of Tradition magazine, calling for the abandonment of Metzitzah b’peh.[83] Since then the RCA has issued an opinion that advocates methods that do not involve contact between the mohel’s mouth and the infant’s genitals, such as the use of a sterile syringe, thereby eliminating the risk of infection.[67] According to the Chief Rabbinate of Israel[84] and the Edah HaChareidis[85] metzitzah b’peh should still be performed.

The practice of metzitzah b’peh posed a serious risk in the transfer of herpes from mohelim to eight Israeli infants, one of whom suffered brain damage.[69][86] When three New York City infants contracted herpes after metzizah b’peh by one mohel and one of them died, New York authorities took out a restraining order against the mohel requiring use of a sterile glass tube, or pipette.[57][87] The mohel’s attorney argued that the New York Department of Health had not supplied conclusive medical evidence linking his client with the disease.[87][88] In September 2005, the city withdrew the restraining order and turned the matter over to a rabbinical court.[89] Dr. Thomas Frieden, the Health Commissioner of New York City, wrote, «There exists no reasonable doubt that ‘metzitzah b’peh’ can and has caused neonatal herpes infection….The Health Department recommends that infants being circumcised not undergo metzitzah b’peh.»[90] In May 2006, the Department of Health for New York State issued a protocol for the performance of metzitzah b’peh.[91] Dr. Antonia C. Novello, Commissioner of Health for New York State, together with a board of rabbis and doctors, worked, she said, to «allow the practice of metzizah b’peh to continue while still meeting the Department of Health’s responsibility to protect the public health.»[92] Later in New York City in 2012 a 2-week-old baby died of herpes because of metzitzah b’peh.[93]

In three medical papers done in Israel, Canada, and the US, oral suction following circumcision was suggested as a cause in 11 cases of neonatal herpes.[69][94][95] Researchers noted that prior to 1997, neonatal herpes reports in Israel were rare, and that the late incidences[spelling?] were correlated with the mothers carrying the virus themselves.[69] Rabbi Doctor Mordechai Halperin implicates the «better hygiene and living conditions that prevail among the younger generation,» which lowered to 60% the rate of young Israeli Chareidi mothers who carry the virus. He explains that an «absence of antibodies in the mothers’ blood means that their newborn sons received no such antibodies through the placenta, and therefore are vulnerable to infection by HSV-1.»[96]

Barriers[edit]

Because of the risk of infection, some rabbinical authorities have ruled that the traditional practice of direct contact should be replaced by using a sterile tube between the wound and the mohel’s mouth, so there is no direct oral contact. The Rabbinical Council of America, the largest group of Modern Orthodox rabbis, endorses this method.[97] The RCA paper states: «Rabbi Schachter even reports that Rav Yosef Dov Soloveitchik reports that his father, Rav Moshe Soloveitchik, would not permit a mohel to perform metzitza be’peh with direct oral contact, and that his grandfather, Rav Chaim Soloveitchik, instructed mohelim in Brisk not to do metzitza be’peh with direct oral contact. However, although Rav Yosef Dov Soloveitchik also generally prohibited metzitza be’peh with direct oral contact, he did not ban it by those who insisted upon it.» The sefer Mitzvas Hametzitzah[98] by Rabbi Sinai Schiffer of Baden, Germany, states that he is in possession of letters from 36 major Russian (Lithuanian) rabbis that categorically prohibit Metzitzah with a sponge and require it to be done orally. Among them is Rabbi Chaim Halevi Soloveitchik of Brisk.

In September 2012, the New York Department of Health unanimously ruled that the practice of metztizah b’peh should require informed consent from the parent or guardian of the child undergoing the ritual.[99] Prior to the ruling, several hundred rabbis, including Rabbi David Neiderman, the executive director of the United Jewish Organization of Williamsburg, signed a declaration stating that they would not inform parents of the potential dangers that came with metzitzah b’peh, even if informed consent became law.[100]

In a motion for preliminary injunction with intent to sue, filed against New York City Department of Health & Mental Hygiene, affidavits by Awi Federgruen,[101][102] Brenda Breuer,[103][104] and Daniel S. Berman[105][106] argued that the study on which the department passed its conclusions is flawed.[107][108][109][110]

The «informed consent» regulation was challenged in court. In January 2013 the U.S. District court ruled that the law did not specifically target religion and therefore must not pass strict scrutiny. The ruling was appealed to the Court of Appeals.[111]

On August 15, 2014, the Second Circuit Court of Appeals reversed the decision by the lower court, and ruled that the regulation does have to be reviewed under strict scrutiny to determine whether it infringes on Orthodox Jews’ freedom of religion.[112]

On September 9, 2015, after coming to an agreement with the community The New York City Board of Health voted to repeal the informed consent regulation.[113]

Hatafat dam brit[edit]

A brit milah is more than circumcision; it is a sacred ritual in Judaism, as distinguished from its non-ritual requirement in Islam. One ramification is that the brit is not considered complete unless a drop of blood is actually drawn. The standard medical methods of circumcision through constriction do not meet the requirements of the halakhah for brit milah, because they are done with hemostasis, i.e., they stop the flow of blood. Moreover, circumcision alone, in the absence of the brit milah ceremony, does not fulfill the requirements of the mitzvah. Therefore, in cases involving a Jew who was circumcised outside of a brit milah, an already-circumcised convert, or an aposthetic (born without a foreskin) individual, the mohel draws a symbolic drop of blood (Hebrew: הטפת דם, hatafat-dam) from the penis at the point where the foreskin would have been or was attached.[114]

Milah L’shem Giur[edit]

Set of brit milah implements, Göttingen city museum

A milah l’shem giur is a «circumcision for the purpose of conversion». In Orthodox Judaism, this procedure is usually done by adoptive parents for adopted boys who are being converted as part of the adoption or by families with young children converting together. It is also required for adult converts who were not previously circumcised, e.g., those born in countries where circumcision at birth is not common. The conversion of a minor is valid in both Orthodox and Conservative Judaism until a child reaches the age of majority (13 for a boy, 12 for a girl); at that time the child has the option of renouncing his conversion and Judaism, and the conversion will then be considered retroactively invalid. He must be informed of his right to renounce his conversion if he wishes. If he does not make such a statement, it is accepted that the boy is halakhically Jewish. Orthodox rabbis will generally not convert a non-Jewish child raised by a mother who has not converted to Judaism.[115]

The laws of conversion and conversion-related circumcision in Orthodox Judaism have numerous complications, and authorities recommend that a rabbi be consulted well in advance.

In Conservative Judaism, the milah l’shem giur procedure is also performed for a boy whose mother has not converted, but with the intention that the child be raised Jewish. This conversion of a child to Judaism without the conversion of the mother is allowed by Conservative interpretations of halakha. Conservative Rabbis will authorize it only under the condition that the child be raised as a Jew in a single-faith household. Should the mother convert, and if the boy has not yet reached his third birthday, the child may be immersed in the mikveh with the mother, after the mother has already immersed, to become Jewish. If the mother does not convert, the child may be immersed in a mikveh, or body of natural waters, to complete the child’s conversion to Judaism. This can be done before the child is even one year old. If the child did not immerse in the mikveh, or the boy was too old, then the child may choose of their own accord to become Jewish at age 13 as a Bar Mitzvah, and complete the conversion then.[116]

- The ceremony, when performed l’shem giur, does not have to be performed on a particular day, and does not override Shabbat and Jewish Holidays.[117][118]

- In Orthodox Judaism, there is a split of authorities on whether the child receives a Hebrew name at the Brit ceremony or upon immersion in the Mikvah. According to Zichron Brit LeRishonim, naming occurs at the Brit with a different formula than the standard Brit Milah. The more common practice among Ashkenazic Jews follows Rabbi Moshe Feinstein, with naming occurring at immersion.

Where the procedure was performed but not followed by immersion or other requirements of the conversion procedure (e.g., in Conservative Judaism, where the mother has not converted), if the boy chooses to complete the conversion at Bar Mitzvah, a milah l’shem giur performed when the boy was an infant removes the obligation to undergo either a full brit milah or hatafat dam brit.

Controlling male sexuality[edit]

The desire to control male sexuality has been central to Milah throughout history. Jewish theologians, philosophers, and ethicists have often justified the practice by claiming that the ritual substantially reduces male sexual pleasure and desire.[119][120][121][122][123][124]

The political scientist Thomas Pangle concluded:[119]

As Maimonides — the greatest legal scholar, and also the preeminent medical authority, in traditional Judaism — teaches, the most obvious purpose of circumcision is the weakening of the male sexual capacity and pleasure… Closely related would appear to be the aim of setting before any potential adult male convert the trial of submitting to a mark that incurs shame among most if not all other peoples, as well as being frighteningly painful: «Now a man does not perform this act upon himself or upon a son of his unless it be in consequence of a genuine belief… Finally, this mark, and the gulf it establishes, not only distinguishes but unifies the chosen people. The peculiar nature of the pain, of the debility, and of the shame serves to underline the fact that dedication to God calls for a severe mastery over and ruthless subordination of sexual appetite and pleasure. It is surely no accident, Maimonides observes in the same passage just quoted, it was the chaste Abraham who was the first to be called upon to enact ritual circumcision. But of course we must add since the commandment applies to Ishmael as well as to Issac, circumcision is the mark uniting those singular peoples, descended from Abraham, who recall not only his chastity but above all his dread in the presence of God; who share in that dread, and who understand the dread and the circumcision to be in part their response as mortal, hence reproductive, hence sexual creatures — created in the image of God — to the presence of the holy or pure God Who as Creator utterly transcends His mortal, reproductive creatures, and especially their sexuality.

The Jewish philosopher Philo Judaeus argued that Milah is a way to «mutilate the organ» in order to eliminate «all superfluous and excessive pleasure.»[120][121][125]

Similarly, while not claiming that circumcision limited sexual pleasure, Maimonides proposed that two important purposes of circumcision are to temper sexual desire and to join in an affirmation of faith and the covenant of Abraham:[126][127]

Visible symbol of a covenant[edit]

Rabbi Saadia Gaon considers something to be «complete» if it lacks nothing, but also has nothing that is unneeded. He regards the foreskin an unneeded organ that God created in man, and so by amputating it, the man is completed.[128] The author of Sefer ha-Chinuch[129] provides three reasons for the practice of circumcision:

- To complete the form of man, by removing what he claims to be a redundant organ;

- To mark the chosen people, so that their bodies will be different as their souls are. The organ chosen for the mark is the one responsible for the sustenance of the species.

- The completion effected by circumcision is not congenital, but left to the man. This implies that as he completes the form of his body, so can he complete the form of his soul.

Talmud professor Daniel Boyarin offered two explanations for circumcision. One is that it is a literal inscription on the Jewish body of the name of God in the form of the letter «yud» (from «yesod»). The second is that the act of bleeding represents a feminization of Jewish men, significant in the sense that the covenant represents a marriage between Jews and (a symbolically male) God.[130]

Other reasons[edit]

In Of the Special Laws, Book 1, the Jewish philosopher Philo additionally gave other reasons for the practice of circumcision.[125]

He attributes four of the reasons to «men of divine spirit and wisdom.» These include the idea that circumcision:

- Protects against disease,

- Secures cleanliness «in a way that is suited to the people consecrated to God,»

- Causes the circumcised portion of the penis to resemble a heart, thereby representing a physical connection between the «breath contained within the heart [that] is generative of thoughts, and the generative organ itself [that] is productive of living beings,» and

- Promotes prolificness by removing impediments to the flow of semen.

- «Is a symbol of a man’s knowing himself.»

Judaism, Christianity, and the Early Church (4 BCE – 150 CE)[edit]

The 1st-century Jewish author Philo Judaeus defended Jewish circumcision on several grounds. He thought that circumcision should be done as early as possible as it would not be as likely to be done by someone’s own free will. He claimed that the foreskin prevented semen from reaching the vagina and so should be done as a way to increase the nation’s population. He also noted that circumcision should be performed as an effective means to reduce sexual pleasure.[120][121][122][123]

There was also division in Pharisaic Judaism between Hillel the Elder and Shammai on the issue of circumcision of proselytes.[131]

According to the Gospel of Luke, Jesus was circumcised on the 8th day.

After eight days had passed, it was time to circumcise the child; and he was called Jesus, the name given by the angel before he was conceived in the womb.

— Luke 2:21[132]

According to saying 53 of the Gospel of Thomas,[133][134]

His disciples said to him, «is circumcision useful or not?» He said to them, «If it were useful, their father would produce children already circumcised from their mother. Rather, the true circumcision in spirit has become profitable in every respect.»

Foreskin was considered a sign of beauty, civility, and masculinity throughout the Greco-Roman world; it was custom to spend an hour a day or so exercising nude in the gymnasium and in Roman baths; many Jewish men did not want to be seen in public deprived of their foreskins, where matters of business and politics were discussed.[135] To expose one’s glans in public was seen as indecent, vulgar, and a sign of sexual arousal and desire.[15][136][135] Classical, Hellenistic, and Roman culture widely found circumcision to be barbaric, cruel, and utterly repulsive in nature.[15][136][137][138] By the period of the Maccabees, many Jewish men attempted to hide their circumcisions through the process of epispasm due to the circumstances of the period, although Jewish religious writers denounced these practices as abrogating the covenant of Abraham in 1 Maccabees and the Talmud.[15][135] After Christianity and Second Temple Judaism split apart from one another, Milah was declared spiritually unnecessary as a condition of justification by Christian writers such as Paul the Apostle and subsequently in the Council of Jerusalem, while it further increased in importance for Jews.[15]

In the mid-2nd century CE, the Tannaim, the successors of the newly ideologically dominant Pharisees, introduced and made mandatory a secondary step of circumcision known as the Periah.[15][139][1][2] Without it circumcision was newly declared to have no spiritual value.[1] This new form removed as much of the inner mucosa as possible, the frenulum and its corresponding delta from the penis, and prevented the movement of shaft skin, in what creates a «low and tight» circumcision.[15][52] It was intended to make it impossible to restore the foreskin.[15][139][1] This is the form practiced among the large majority of Jews today, and, later, became a basis for the routine neonatal circumcisions performed in the United States.[15][139]

The steps, justifications, and imposition of the practice have dramatically varied throughout history; commonly cited reasons for the practice have included it being a way to control male sexuality by reducing sexual pleasure and desire, as a visual marker of the covenant of the pieces, as a metaphor for mankind perfecting creation, and as a means to promote fertility.[14][2][15][119][120] The original version in Judaic history was either a ritual nick or cut done by a father to the acroposthion, the part of the foreskin that overhangs the glans penis. This form of genital nicking or cutting, known as simply milah, became adopted among Jews by the Second Temple period and was the predominant form until the second century CE.[15][139][1][140] The notion of milah being linked to a biblical covenant is generally believed to have originated in the 6th century BCE as a product of the Babylonian captivity; the practice likely lacked this significance among Jews before the period.[14][15][16][17]

Reform Judaism[edit]

The Reform societies established in Frankfurt and Berlin regarded circumcision as barbaric and wished to abolish it. However, while prominent rabbis such as Abraham Geiger believed the ritual to be barbaric and outdated, they refrained from instituting any change in this matter. In 1843, when a father in Frankfurt refused to circumcise his son, rabbis of all shades in Germany stated it was mandated by Jewish law; even Samuel Holdheim affirmed this.[141] By 1871, Reform rabbinic leadership in Germany reasserted «the supreme importance of circumcision in Judaism,» while affirming the traditional viewpoint that non-circumcised Jews are Jews nonetheless. Although the issue of circumcision of converts continues to be debated, the necessity of Brit Milah for Jewish infant boys has been stressed in every subsequent Reform rabbis manual or guide.[142] Since 1984 Reform Judaism has trained and certified over 300 of their own practicing mohalim in this ritual.[143][144]

Criticism and legality[edit]

Criticism[edit]

Among Jews[edit]

A growing number of contemporary Jews have chosen not to circumcise their sons.[145][146][147][148][149][150]

Among the reasons for their choice is the claim that circumcision is a form of bodily and sexual harm forced on men and violence against helpless infants, a violation of children’s rights, and their opinion that circumcision is a dangerous, unnecessary, painful, traumatic and stressful event for the child, which can cause even further psychophysical complications down the road, including serious disability and even death.[151][152][153][154] They are assisted by a number of Reform, Liberal, and Reconstructionist rabbis, and have developed a welcoming ceremony that they call the Brit shalom («Covenant [of] Peace») for such children,[153][155][149] also accepted by Humanistic Judaism.[156][157] The ceremony of Brit shalom is not officially approved of by the Reform or Reconstructionist rabbinical organizations, who make the recommendation that male infants should be circumcised, though the issue of converts remains controversial[158][159] and circumcision of converts is not mandatory in either movement.[160]

The connection of the Reform movement to an anti-circumcision, pro-symbolic stance is a historical one.[58] From the early days of the movement in Germany and Eastern Europe,[58][161] some classical Reformers hoped to replace ritual circumcision «with a symbolic act, as has been done for other bloody practices, such as the sacrifices».[162] In the US, an official Reform resolution in 1893 announced converts are no longer mandated to undergo the ritual,[163] and this ambivalence toward the practice has carried over to classical-minded Reform Jews today. In Elyse Wechterman’s essay A Plea for Inclusion, she argues that, even in the absence of circumcision, committed Jews should never be turned away, especially by a movement «where no other ritual observance is mandated.» She goes on to advocate an alternate covenant ceremony, brit atifah, for both boys and girls as a welcoming ritual into Judaism.[164] With a continuing negativity towards circumcision still present within a minority of modern-day Reform, Judaic scholar Jon Levenson has warned that if they «continue to judge brit milah to be not only medically unnecessary but also brutalizing and mutilating … the abhorrence of it expressed by some early Reform leaders will return with a vengeance», proclaiming that circumcision will be «the latest front in the battle over the Jewish future in America».[165]

Many European Jewish fathers during the nineteenth century chose not to circumcise their sons, including Theodor Herzl.[166][151] However, unlike many other forms of religious observance, it remained one of the last rituals Jewish communities could enforce. In most of Europe, both the government and the unlearned Jewish masses believed circumcision to be a rite akin to baptism, and the law allowed communities not to register uncircumcised children as Jewish. This legal maneuver spurred several debates addressing the advisibility of its use, since many parents later chose to convert to Christianity. In early 20th-century Russia, Chaim Soloveitchik advised his colleagues to reject this measure, stating that uncircumcised Jewish males are no less Jewish than Jews who violate other commandments.[141] Since the 18th century, multiple Jewish philosophers and theologians have criticized the practice of circumcision, advocating an abolishment of the practice and alternatives such as Brit Shalom.[167][168] Circumcision rates are near-universal among Jews.[12]

Brit shalom (Hebrew: ברית שלום; «Covenant of Peace»), also called alternative brit, brit ben, brit chayim, brit tikkun, or bris in Yiddish and Ashkenazi Hebrew, refers to a range of newly created naming ceremonies for self-identified Jewish families that involve rejecting the traditional Jewish rite of circumcision.[169][170][171][172][173] There is no universally agreed upon form of Brit Shalom. Brit shalom ceremonies are performed by a rabbi or a lay person; in this context, rabbi does not necessarily imply belief in God, as some celebrants belong to Humanistic Judaism.[174] Brit shalom is recognized by secular Jewish organizations affiliated with Humanistic Judaism like the International Institute for Secular Humanistic Judaism, Congress of Secular Jewish Organizations, and Society for Humanistic Judaism.

The actual number of brit shalom ceremonies performed per year is unknown. Filmmaker Eli Ungar-Sargon, who is opposed to circumcision, said in 2011, regarding its current popularity, that «calling it a marginal phenomenon would be generous.»[175] Its popularity in the United States, where it has been promoted by groups such as Beyond the Bris and Jews Against Circumcision,[176][177] is increasing, however.[178][179][180] The first known ceremony was celebrated by Rabbi Sherwin Wine, the founder of the Society for Humanistic Judaism, around 1970.[181]

Outside Jews[edit]

In 2017, Iceland proposed a bill banning circumcision especially for non-medical reasons,[182] with a six-year jail term for anyone carrying out a circumcision[183] for non-medical reasons, as well as anyone guilty of removing a child’s sexual organs in whole or in part, arguing that the practice violates the child’s rights.[182] Religious groups have condemned the bill because it goes against their traditions.[184]

See also[edit]

- Circumcision of Jesus

- Khitan (circumcision)

- History of male circumcision

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f Hirsch, Emil; Kohler, Kaufmann; Jacobs, Joseph; Friedenwald, Aaron; Broydé, Isaac (1906). «Circumcision: The Cutting Away». The Jewish Encyclopedia. Retrieved October 13, 2020.

In order to prevent the obliteration of the «seal of the covenant» on the flesh, as circumcision was henceforth called, the Rabbis, probably after the war of Bar Kokba (see Yeb. l.c.; Gen. R. xlvi.), instituted the «peri’ah» (the laying bare of the glans), without which circumcision was declared to be of no value (Shab. xxx. 6).

- ^ a b c d Gollaher, David (2001). Circumcision: A History Of The World’s Most Controversial Surgery. United States: Basic Books. pp. 1–30. ISBN 978-0-465-02653-1.

- ^ a b Tractate Nedarim 32a

- ^ Harlow, Daniel; Collins, John (2010). «Circumcision». The Eerdmans Dictionary of Early Judaism. William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. ISBN 978-1-4674-6609-7.

- ^ Hamilton, Victor (1990). The Book of Genesis, Chapters 1-17. Eerdmans Publishing Company. p. 473. ISBN 978-0-8028-2521-6.

In fact, circumcision is only one of two performative commands, the neglect of which bring the kareth penalty. (The other is the failure to be cleansed from corpse contamination, umb. 19:11-22.)

- ^ Mark, Elizabeth (2003). «Frojmovic/Travelers to the Circumcision». The Covenant of Circumcision: New Perspectives on an Ancient Jewish Rite. Brandeis University Press. p. 141. ISBN 978-1-58465-307-3.

Circumcision became the single most important commandment… the one without which… no Jew could attain the world to come.

- ^ a b c d Rosner, Fred (2003). Encyclopedia of Jewish Medical Ethics. Feldheim Publishers. p. 196. ISBN 978-1-58330-592-8.

Several eras in subsequent Jewish history were associated with forced conversions and with prohibitions against ritual circumcision… Jews endangered their lives during such times and exerted strenuous efforts to nullify such edicts. When they succeeded, they celebrated by declaring a holiday. Throughout most of history, Jews never doubted their obligation to observe circumcision… [those who attempted to reverse it or failed to perform the ritual were called] voiders of the covenant of Abraham our father, and they have no portion in the World to Come.

- ^ Oliver, Isaac W. (2013-05-14). «Forming Jewish Identity by Formulating Legislation for Gentiles». Journal of Ancient Judaism. 4 (1): 105–132. doi:10.30965/21967954-00401005. ISSN 1869-3296.

- ^ a b Wilson, Robin (2018). The Contested Place of Religion in Family Law. Cambridge University Press. p. 174. ISBN 978-1-108-41760-0.

Jews have a long history of suffering punishment at the hands of government authorities for engaging in circumcision. Muslims have also experienced suppression of their identities through suppression of this religious practice.

- ^ a b Livingston, Michael (2021). Dreamworld or Dystopia: The Nordic Model and Its Influence in the 21st Century. Cambridge University Press. p. 87. ISBN 978-1-108-75726-3.

In Jewish history, the banning of circumcision (brit mila) has historically been a first step toward more extreme and violent forms of persecution.

- ^ «What Is Hanukkah?». Chabad-Lubavitch Media Center.

In the second century BCE, the Holy Land was ruled by the Seleucids (Syrian-Greeks), who tried to force the people of Israel to accept Greek culture and beliefs instead of mitzvah observance and belief in G‑d. Against all odds, a small band of faithful but poorly armed Jews, led by Judah the Maccabee, defeated one of the mightiest armies on earth, drove the Greeks from the land, reclaimed the Holy Temple in Jerusalem and rededicated it to the service of G‑d. … To commemorate and publicize these miracles, the sages instituted the festival of Chanukah.

- ^ a b Cohen-Almagor, Raphael (9 November 2020). «Should liberal government regulate male circumcision performed in the name of Jewish tradition?». SN Social Sciences. 1 (1): 8. doi:10.1007/s43545-020-00011-7. ISSN 2662-9283. S2CID 228911544.

Protagonists and critics of male circumcision agree on some things and disagree on many others… They also do not underestimate the importance of male circumcision for the relevant communities…. Even the most critical voices of male circumcision do not suggest putting a blanket ban on the practice as they understand that such a ban, very much like the 1920–1933 prohibition laws in the United States, would not be effective… Protagonists and critics of male circumcision debate whether the practice is morally acceptable… They assign different weights to harm as well as to medical risks and to non-medical benefits. The different weights to risks and benefits conform to their underlying views about the practices… Protagonists and critics disagree about the significance of medical reasons for circumcision…

- ^ Gollaher, David, 1949- (2000). Circumcision : a history of the world’s most controversial surgery. New York: Basic Books. p. 2. ISBN 0-465-04397-6. OCLC 42040798.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d Karris, Robert (1992). The Collegeville Bible Commentary: Old Testament. United States: Liturgical Press. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-8146-2210-0.

Circumcision only became an important sign of the covenant during the Babylonian Exile; it is doubtful that it always had this significance for Israel.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Glick, Leonard (2005). Marked in Your Flesh: Circumcision from Ancient Judea to Modern America. United States: Oxford University Press. pp. 1–3, 15–35. ISBN 978-0-19-517674-2.

- ^ a b c Eilberg-Schwartz, Howard (1990). The Savage in Judaism: An Anthropology of Israelite Religion and Ancient Judaism. United States: Indiana University Press. p. 172. ISBN 978-0-253-31946-3.

- ^ a b c Glick, Nansi S. (2006), «Zipporah and the Bridegroom of Blood: Searching for the Antecedents of Jewish Circumcision», Bodily Integrity and the Politics of Circumcision, Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, pp. 37–47, doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-4916-3_3, ISBN 978-1-4020-4915-6, retrieved December 21, 2020

- ^ Stavrakopoulou, Francesca (2012). King Manasseh and Child Sacrifice: Biblical Distortions of Historical Realities. Germany: Walter de Gruyter. pp. 198–200, 282–283, 305–306, et al. ISBN 978-3-11-089964-1.

- ^ Barker, Margaret (2012). The Mother of the Lord: Volume 1: The Lady in the Temple. T&T Clark. p. 130. ISBN 978-0-567-36246-9.

It seems that in the biblical tradition… child sacrifice was replaced by circumcision…

- ^ Edinger, Edward (1986). The Bible and the Psyche: Individuation Symbolism in the Old Testament. Inner City Books. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-919123-23-6.

- ^ Genesis 17:10–14

- ^ Leviticus 12:3

- ^ Joshua 5:9.

- ^ I Samuel 14:6, 31:4; II Samuel 1:20

- ^ Isaiah 52:1

- ^ Leviticus 26:41, «their uncircumcised hearts»; compare Jeremiah 9:25; Ezekiel 44:7, 9

- ^ Leviticus 19:23

- ^ Genesis 17:1–14

- ^ Exodus 12:48

- ^ Genesis 34:14–16

- ^ «Tractate Shabbat: Chapter 19». Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved 2022-07-23.

- ^ «Circumcision.» Mark Popovsky. Encyclopedia of Psychology and Religion. Ed. David A. Leeming, Kathryn Madden and Stanton Marlan. New York: Springer, 2010. pp. 153–54.

- ^ Talmud Avodah Zarah 26b; Menachot 42a; Maimonides’ Mishneh Torah, Milah, ii. 1; Shulkhan Arukh, Yoreh De’ah, l.c.

- ^ Lubrich, Naomi, ed. (2022). Birth Culture. Jewish Testimonies from Rural Switzerland and Environs (in German and English). Basel. pp. 54–123. ISBN 978-3-7965-4607-5.

- ^ «Berit Mila Program of Reform Judaism». 2013-10-07. Archived from the original on 2013-10-07. Retrieved 2022-07-23.

- ^ «The Circumcision Procedure and Blessings – Performing the Bris Milah – The Handbook to Circumcision». Chabad.org. Archived from the original on 2012-01-16. Retrieved 2012-04-25.

- ^ a b

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Singer, Isidore; et al., eds. (1901–1906). «Morbidity». The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

- ^ Ilani, Ofri (2008-05-12). «Traditional circumcision raises risk of infection, study shows». Haaretz. Archived from the original on 20 August 2009. Retrieved 15 August 2009.

- ^ Kreimer, Susan (2004-10-22). «In New Trend, Adult Emigrés Seek Ritual Circumcision». The Jewish Daily Forward. Retrieved 24 August 2015.

- ^ Reiner, Rami (2022). «A baby boy who dies before reaching eight [days] is circumcised with a flint or reed at his grave» (Shulḥan ‘Arukh, Yoreh De’ah 263:5): From Women’s Custom to Rabbinic Law». Journal of the Goldstein-Goren International Center for Jewish Thought. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- ^ a b Rabbi Yaakov Montrose. Halachic World – Volume 3: Contemporary Halachic topics based on the Parshah. «Lech Lecha – No Pain, No Bris?» Feldham Publishers 2011, pp. 29–32

- ^ Rich, Tracey. «Judaism 101 – Birth and the First month of Life». jewfaq.org. Archived from the original on 1 June 2016. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- ^ Harris, Patricia (June 11, 1999). «Study confirms that wine drops soothe boys during circumcision». J. The Jewish News of Northern California. Archived from the original on 13 August 2016. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- ^ «Pain and Circumcision». The New York Times. January 3, 1998. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved June 11, 2014.

- ^ Berger, Itai; Steinberg, Avraham (May 2002). «Neonatal mydriasis: intravenous lidocaine adverse reaction». J Child Neurol. 17 (5): 400–01. doi:10.1177/088307380201700520. PMID 12150593. S2CID 2169066.[dead link]

- ^ Rezvani, Massoud; Finkelstein, Yaron (2007). «Generalized seizures following topical lidocaine administration during circumcision: establishing causation». Paediatr Drugs. 9 (2): 125–27. doi:10.2165/00148581-200709020-00006. PMID 17407368. S2CID 45481923.

- ^ Beider, Alexander (2015). Origins of Yiddish Dialects. Oxford University Press. p. 153.

- ^ Øster, Jakob (April 1968). «Further Fate of the Foreskin». 43. Archives of Disease in Childhood: 200–02. Archived from the original on 2010-06-29. Retrieved 2010-11-14.

- ^ Mishnah Shabbat 19:6.

circumcised but did not perform priah, it is as if he did not circumcise.

The Jerusalem Talmud there adds: «and is punished kareth!» - ^ Circumcision Policy Statement Archived 2009-03-20 at the Wayback Machine of The American Academy of Pediatrics notes that «there are three methods of circumcision that are commonly used in the newborn male,» and that all three include «bluntly freeing the inner preputial epithelium from the epithelium of the glans,» to be later amputated with the foreskin.

- ^ Gracely-Kilgore, Katharine A. (May 1984). «Further Fate of the Foreskin». 5 (2). Nurse Practitioner: 4–22. Archived from the original on 2010-06-28. Retrieved 2010-11-14.

- ^ a b «Styles – Judaism and Islam». Circlist. 2014-03-07. Archived from the original on 2014-05-15. Retrieved 2014-06-11.

- ^ Glick, Leonard B. (2005-06-30). Marked in Your Flesh: Circumcision from Ancient Judea to Modern America. pp. 46–47. ISBN 978-0-19-517674-2.

the rabbis go on to dedicate all of chapter 19 to circumcision .. milah, peri’ah, and metsitsah. This is the first text specifying peri’ah as an absolute requirement. The same chapter is where we first find mention of the warning that leaving even «shreds» of foreskin renders the procedure «invalid.»

(note: section 19.2 from Moed tractate Shabbat (Talmud) is quoted) - ^ Rabbah b. Isaac in the name of Rab. «71b». Talmud Bavli Tractate Yebamoth.

The commandment of uncovering the corona at circumcision was not given to Abraham; for it is said, At that time the Lord said unto Joshua: ‘Make thee knives of flint etc.’ But is it not possible [that this applied to] those who were not previously circumcised; for it is written, For all the people that came out were circumcised, but all the people that were born etc.? — If so, why the expression. ‘Again!’ Consequently it must apply to the uncovering of the corona.

- ^ Werblowsky, R.J. Zwi; Wigoder, Geoffrey (1997). The Oxford Dictionary of the Jewish Religion. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Cohen, Shaye J.D (2005-09-06). Why Aren’t Jewish Women Circumcised?: Gender and Covenant in Judaism. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-520-21250-3.

These mishniac requirements have three sources: the Torah, which requires circumcision (milah); the rabbis themselves, who added the requirement of completely uncovering the corona (peri’ah); and ancient medical beliefs about the treatment of wounds (suctioning, bandaging, cumin). The Torah demands circumcision but does not specify exactly what should be cut or how much.

- ^ a b c Hartog, Kelly (February 18, 2005). «Death Spotlights Old Circumcision Rite». The Jewish Journal of Greater Los Angeles. Archived from the original on December 13, 2006. Retrieved 2006-11-22.

Metzizah b’peh — loosely translated as oral suction — is the part of the circumcision ceremony where the mohel removes the blood from the baby’s member; these days the removal of the blood is usually done using a sterilized glass tube, instead of with the mouth, as the Talmud suggests.

- ^ a b c

In the first half of the nineteenth century, various European governments considered regulating, if not banning, berit milah on the grounds that it posed potential medical dangers. In the 1840s, radical Jewish reformers in Frankfurt asserted that circumcision should no longer be compulsory. This controversy reached Russia in the 1880s. Russian Jewish physicians expressed concern over two central issues: the competence of those carrying out the procedure and the method used for metsitsah. Many Jewish physicians supported the idea of procedural and hygienic reforms in the practice, and they debated the question of physician supervision during the ceremony. Most significantly, many advocated carrying out metsitsah by pipette, not by mouth. In 1889, a committee on circumcision convened by the Russian Society for the Protection of Health, which included leading Jewish figures, recommended educating the Jewish public about the concerns connected with circumcision, in particular, the possible transmission of diseases such as tuberculosis and syphilis through the custom of metsitsah by mouth.

Veniamin Portugalov, who—alone among Russian Jewish physicians—called for the abolition of circumcision, set off these discussions. Portugalov not only denied all medical claims regarding the sanitary advantages of circumcision but disparaged the practice as barbaric, likening it to pagan ritual mutilation. Ritual circumcision, he claimed, stood as a self-imposed obstacle to the Jews’ attainment of true equality with the other peoples of Europe. - ^ Tractate Shabbos 133b

- ^ Rambam – Maimonides in his «book of laws» Laws of Milah Chapter 2, paragraph 2: «…and afterwards he sucks the circumcision until blood comes out from far places, in order not to come to danger, and anyone who does not suck, we remove him from practice.»

- ^ Rashi and others on Tractate Shabbos 173a and 173b

- ^ «Denouncing City’s Move to Regulate Circumcision». The New York Times. September 12, 2012. Archived from the original on January 27, 2013. Retrieved 2013-03-01.

- ^ Goldberger, Frimet (18 February 2014). «Why My Son Underwent Metzitzah B’Peh». Forward.com.

MBP is believed to be a commandment from God .. Chasam Sofer clearly stated his position on MBP .. I do not know all the answers, but banning MBP is not one of them.

- ^ Nussbaum Cohen, Debra (October 14, 2005). «City Risking Babies’ Lives With Brit Policy: Health Experts». The Jewish Week. Archived from the original on 2007-05-22.

- ^ Nussbaum Cohen, Debra; Cohler-Esses, Larry (December 23, 2005). «City Challenged On Ritual Practice». The Jewish Week. Archived from the original on 2006-11-20. Retrieved 2007-04-19.

- ^ «N.Y. newborn contracts herpes from controversial circumcision rite». Jewish Telegraphic Agency. February 2, 2014. Archived from the original on February 19, 2014.

- ^ a b Eliyahu Fink and Eliyahu Federman (Sep 29, 2013). «Controversial circumcisions». Haaretz. Archived from the original on 2014-02-10.

- ^ «Metzitza Be’Peh – Halachic Clarification». Rabbinical Council of America. June 7, 2005. Archived from the original on April 15, 2007. Retrieved 2007-04-06.

The poskim consulted by the RCA agree that the normative halacha permits using a glass tube, and that it is proper for mohalim to do so given the health issues involved.

- ^ a b c d Gesundheit, B.; et al. (August 2004). «Neonatal Genital Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1 Infection After Jewish Ritual Circumcision: Modern Medicine and Religious Tradition» (PDF). Pediatrics. 114 (2): e259–63. doi:10.1542/peds.114.2.e259. ISSN 1098-4275. PMID 15286266. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2006-07-23. Retrieved 2006-06-28.

- ^ «Another Jewish baby has contracted herpes through bris». New York Daily News. Archived from the original on 2015-12-08.

- ^ Staff (8 June 2012) Should extreme Orthodox Jewish circumcision be illegal? Archived 2016-03-05 at the Wayback Machine The Week, Retrieved 30 June 2012

- ^ «NYC, Orthodox Jews in talks over ritual after herpes cases». USA Today. Archived from the original on 2016-07-10.

- ^ «Archived copy». Archived from the original on 2012-06-17. Retrieved 2012-07-09.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ «Lawsuit Unites Jewish Groups». collive.com. Oct 24, 2012. Archived from the original on 2015-12-08. Retrieved 2013-01-01.

- ^ «City Urges Requiring Consent for Jewish Rite». The New York Times. June 12, 2012. Archived from the original on June 25, 2017. Retrieved 2013-02-01.

- ^ «Assault on Bris Milah Unites Jewish Communities». CrownHeights.info. October 25, 2012. Archived from the original on October 1, 2014. Retrieved September 29, 2014.

- ^ «Editorial & Opinion». The Jewish Week. Archived from the original on November 20, 2006. Retrieved 2012-04-25.

- ^ Macdowell, Mississippi Fred (2010-04-26). «On the Main Line: Rabbi Moshe Sofer’s responsum on metzitzah». On the Main Line. Retrieved 2022-05-23.

- ^ Katz, Jacob (1998). Divine Law in Human Hands. ISBN 978-9652239808.

- ^ «The Chasam Sofer’s ruling on Metzitzah Be-peh». onthemainline.blogspot.com. April 16, 2012. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 23, 2015.

- ^ Sdei Chemed vol. 8 p. 238

- ^ «Kuntres Hamiliuim». Dhengah.org. Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2012-04-25.

- ^ «The Making of Metzitzah». Tradition. Archived from the original on 2014-05-02. Retrieved 2014-05-02.

- ^ «Archived copy». Archived from the original on 2014-02-22. Retrieved 2013-04-26.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ «Archived copy». Archived from the original on 2014-02-22. Retrieved 2013-04-26.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ «Rare Circumcision Ritual Carries Herpes Risk». WebMD. Archived from the original on September 20, 2005. Retrieved 2012-04-25.

- ^ a b Newman, Andy (August 26, 2005). «City Questions Circumcision Ritual After Baby Dies». The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 15, 2013. Retrieved 2006-11-23.

- ^ Clarke, Suzan (June 21, 2006). «State offers new guidelines on oral-suction circumcision». The Journal News. Archived from the original on 2006-07-06. Retrieved 2006-06-28.

- ^ Nussbaum Cohen, Debra (September 23, 2005). «City: Brit Case To Bet Din». The Jewish Week. Archived from the original on 2006-11-20. Retrieved 2006-11-23.

- ^ Nussbaum Cohen, Debra (February 23, 2006). «Controversy rages in New York over circumcision practice». The Jewish Ledger. Archived from the original on April 29, 2006. Retrieved 2006-11-23.

- ^ «Circumcision Protocol Regarding the Prevention of Neonatal Herpes Transmission». Department of Health, New York State. November 2006. Archived from the original on February 5, 2007. Retrieved 2006-11-23.

The person performing metzizah b’peh must do the following: Wipe around the outside of the mouth thoroughly, including the labial folds at the corners, with a sterile alcohol wipe, and then discard in a safe place. Wash hands with soap and hot water for 2–6 minutes. Within 5 minutes before metzizah b’peh, rinse mouth thoroughly with a mouthwash containing greater than 25% alcohol (for example, Listerine) and hold the rinse in mouth for 30 seconds or more before discarding it.

- ^ Novello, Antonia C. (May 8, 2006). «Dear Rabbi Letter». Department of Health, New York State. Archived from the original on February 18, 2007. Retrieved 2006-11-23.

The meetings have been extremely helpful to me in understanding the importance of metzizah b’peh to the continuity of Jewish ritual practice, how the procedure is performed, and how we might allow the practice of metzizah b’peh to continue while still meeting the Department of Health’s responsibility to protect the public health. I want to reiterate that the welfare of the children of your community is our common goal and that it is not our intent to prohibit metzizah b’peh after circumcision, rather our intent is to suggest measures that would reduce the risk of harm, if there is any, for future circumcisions where metzizah b’peh is the customary procedure and the possibility of an infected mohel may not be ruled out. I know that successful solutions can and will be based on our mutual trust and cooperation.

- ^ Susan Donaldson James (March 12, 2012). «Baby Dies of Herpes in Ritual Circumcision By Orthodox Jews». abcnews.go.com. Archived from the original on April 19, 2017.

- ^ Rubin LG, Lanzkowsky P. Cutaneous neonatal herpes simplex infection associated with ritual circumcision. Pediatric Infectious Diseases Journal. 2000. 19(3) 266–67.

- ^ Distel R, Hofer V, Bogger-Goren S, Shalit I, Garty BZ. Primary genital herpes simplex infection associated with Jewish ritual circumcision. Israel Medical Association Journal. 2003 Dec;5(12):893-4 Archived October 21, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Halperin, Mordechai (Winter 2006). Translated by Lavon, Yocheved. «Metzitzah B’peh Controversy: The View from Israel». Jewish Action. 67 (2): 25, 33–39. Archived from the original on March 6, 2012. Retrieved February 15, 2007.

The mohel brings the baby’s organ into his mouth immediately after the excision of the foreskin and sucks blood from it vigorously. This action lowers the internal pressure in the tissues of the organ, in the blood vessels of the head of the organ and in the exposed ends of the arterioles that have just been cut. Thus, the difference between the pressure in the blood vessels in the base of the organ and the pressure in the blood vessels at its tip is increased. This requirement has deep religious significance as well as medical benefits….Immediately after incising or injuring an artery, the arterial walls contract and obstruct, or at least reduce, the flow of blood. Since the arterioles of the orlah, or the foreskin, branch off from the dorsal arteries (the arteries of the upper side of the organ), cutting away the foreskin can result in a temporary obstruction in these dorsal arteries. This temporary obstruction, caused by arterial muscle contraction, continues to develop into a more enduring blockage as the stationary blood begins to clot. The tragic result can be severe hypoxia (deprivation of the supply of blood and oxygen) of the glans penis.28 If the arterial obstruction becomes more permanent, gangrene follows; the baby may lose his glans, and it may even become a life-threatening situation. Such cases have been known to occur. Only by immediately clearing the blockage can one prevent such clotting from happening. Performing metzitzah immediately after circumcision lowers the internal pressure within the tissues and blood vessels of the glans, thus raising the pressure gradient between the blood vessels at the base of the organ and the blood vessels at its distal end—the glans as well as the excised arterioles of the foreskin, which branch off of the dorsal arteries. This increase in pressure gradient (by a factor of four to six!) can resolve an acute temporary blockage and restore blood flow to the glans, thus significantly reducing both the danger of immediate, acute hypoxia and the danger of developing a permanent obstruction by means of coagulation. How do we know when a temporary blockage has successfully been averted? When the «blood in the further reaches [i.e., the proximal dorsal artery] is extracted,» as Rambam has stated.

- ^ «Metzitza Be’Peh – Halachic Clarification Regarding Metzitza Be’Peh, RCA Clarifies Halachic Background to Statement of March 1, 2005». Rabbis.org. Archived from the original on January 17, 2012. Retrieved 2012-04-25.

- ^ The book was originally published in German, Die Ausübung der Mezizo, Frankfurt a.M. 1906; It was subsequently translated into Hebrew, reprinted in Jerusalem in 1966 under the title «Mitzvas Hametzitzah» and appended to the back of Dvar Sinai, a book written by the author’s grandson, Sinai Adler.

- ^ admin (2012-09-13). «New York, NY – City Approves Metzitzah B’Peh Consent Form (full video NYC DOH debate)». VINnews. Retrieved 2022-07-23.

- ^ Witty, Allison C. (2012-09-02). «New York – Rabbis Say They’ll Defy Law On Metzitzah B’peh». VINnews. Retrieved 2022-07-23.

- ^ «Archived copy» (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-05-15. Retrieved 2013-04-17.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ «Docket for Central Rabbinical Congress of the USA & Canada v. New York City Department of Health & Mental…, 1:12-cv-07590». CourtListener. Archived from the original on 8 May 2018. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- ^ «Archived copy» (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-05-15. Retrieved 2013-04-17.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ «Docket for Central Rabbinical Congress of the USA & Canada v. New York City Department of Health & Mental…, 1:12-cv-07590». CourtListener. Archived from the original on 8 May 2018. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- ^ «Archived copy» (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-05-15. Retrieved 2013-04-17.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ «Docket for Central Rabbinical Congress of the USA & Canada v. New York City Department of Health & Mental…, 1:12-cv-07590». CourtListener. Archived from the original on 8 May 2018. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- ^ «No Conclusive Evidence on Circumcision Rite and Herpes». forward.com. Archived from the original on 20 October 2015. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- ^ Maimon, Debbie (26 December 2012). «Bris Milah Lawsuit: Court To Rule On Temporary Injuction Against Anti-MBP Law». yated.com. Archived from the original on 8 May 2018. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- ^ «Judge Rejects Injunction in Landmark Milah Suit». hamodia.com. Jewish News – Israel News – Israel Politics. 10 January 2013. Archived from the original on 26 October 2017. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- ^ Federgruen, Dr. Daniel Berman and Prof. Brenda Breuer and Prof. Awi. «Consent Forms For Metzitzah B’Peh – Empowering Parents Or Interfering In Religious Practice?». jewishpress.com. Archived from the original on 22 November 2017. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- ^ «Central Rabbinical Congress v. New York City Department of Health & Mental Hygiene». becketlaw.org. Archived from the original on 18 March 2018. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- ^ «U.S. Court revives challenge to New York City circumcision law». Reuters. 2014-08-15. Archived from the original on 2015-09-30. Retrieved 2017-06-30.

- ^ Grynbaum, Michael M. (9 September 2015). «New York City Health Board Repeals Rule on Consent Forms for Circumcision Ritual». The New York Times. Archived from the original on 16 July 2017 – via NYTimes.com.

- ^ Shulchan Aruch, Yoreh De’ah, 263:4

- ^ Rabbi Paysach J. Krohn, Bris Milah Mesorah Publications Ltd, 1985, pp. 103–105.

- ^ Rabbi Avram Israel Reisner, On the conversion of adoptive and patrilineal children Archived 2010-11-27 at the Wayback Machine, Rabbinical Assembly Committee on Jewish Law and Standards, 1988

- ^ «Can a brit take place on Yom Kippur? – holidays general information holiday information life cycle circumcision the brit». Askmoses.com. Archived from the original on 2012-02-21. Retrieved 2012-04-25.

- ^ «The Mitzvah of Brit Milah (Bris)». Ahavat Israel. Archived from the original on 2012-02-04. Retrieved 2012-04-25.

- ^ a b c Pangle, Thomas (2007). Political Philosophy and the God of Abraham. Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 151–152. ISBN 978-0-8018-8761-1.

- ^ a b c d Bruce, Frederick (1990). The Acts of the Apostles: The Greek Text with Introduction and Commentary. William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. p. 329. ISBN 978-0-8028-0966-7.

- ^ a b c Darby, Robert (2013). A Surgical Temptation:The Demonization of the Foreskin and the Rise of Circumcision in Britain. University of Chicago Press. p. 205. ISBN 978-0-226-10978-7.

The view that circumcision had the effect of reducing sexual pleasure, and had even been instituted with this objective in mind, was both widely held in the nineteenth century and in accordance with traditional religious teaching. Both Philo and Maimondies had written to this effect, and Herbert Snow quoted the contemporary Dr. Asher… as stating that chastity was the moral objective of the alteration.

- ^ a b Borgen, Peder; Neusner, Jacob (1988). The Social World of Formative Christianity and Judaism. Fortress Press. p. 127. ISBN 978-0-8006-0875-0.

- ^ a b Earp, Brian (June 7, 2020). «Male and Female Genital Cutting: Controlling Sexuality». YouTube. Archived from the original on 2021-11-23. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

It is agreed among scholars that the original purpose within Judaism… was precisely to dull the sexual organ.

- ^ Yanklowitz, Shmuly (2014). Soul of Jewish Social Justice. Urim Publications. p. 135. ISBN 9789655241860.

- ^ a b Philo of Alexandria; Colson, F.H. (trans.) (1937). Of the special laws, Book I (i and ii), in Works of Philo. Vol. VII. Loeb Classical Library: Harvard University Press. pp. 103–05. ISBN 978-0-674-99250-4.

- ^ Friedländer, Michael (January 1956). Guide for the Perplexed. Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-20351-5.

- ^ Maimonides, Moses, 1135–1204 (1974-12-15). The Guide of the Perplexed. Pines, Shlomo, 1908-1990,, Strauss, Leo, Bollingen Foundation Collection (Library of Congress). [Chicago]. ISBN 0-226-50230-9. OCLC 309924.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Gaon, Saadia; Rosenblatt, Samuel (trans.) (1958). «article III chapter 10». the Book of Beliefs and Opinions. Yale Judaica. ISBN 978-0-300-04490-4.

- ^ 2nd commandment

- ^ Boyarin, Daniel. «‘This We Know to Be the Carnal Israel’: Circumcision and the Erotic Life of God and Israel», Critical Inquiry. (Spring, 1992), 474–506.

- ^ «The Proselyte Who Comes». Jewish Ideas. Retrieved November 26, 2020.

- ^ Luke 2:21

- ^ Dominic Crossan, John (1999). The Birth of Christianity. Bloomsbury Academic. p. 327. ISBN 978-0-567-08668-6.

- ^ Pagels, Elaine (2004). Beyond Belief: The Secret Gospel of Thomas. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. p. 234. ISBN 978-1-4000-7908-7.

- ^ a b c Hall, Robert (August 1992). «Epispasm: Circumcision in Reverse». Bible Review. 8 (4): 52–57.

- ^ a b

Circumcised barbarians, along with any others who revealed the glans penis, were the butt of ribald humor. For Greek art portrays the foreskin, often drawn in meticulous detail, as an emblem of male beauty; and children with congenitally short foreskins were sometimes subjected to a treatment, known as epispasm, that was aimed at elongation.

— Approaches to Ancient Judaism, New Series: Religious and Theological Studies (1993), p. 149, Scholars Press.

- ^ Rubin, Jody P. (July 1980). «Celsus’ Decircumcision Operation: Medical and Historical Implications». Urology. Elsevier. 16 (1): 121–4. doi:10.1016/0090-4295(80)90354-4. PMID 6994325. Retrieved 4 January 2020.

- ^ Fredriksen, Paula (2018). When Christians Were Jews: The First Generation. London: Yale University Press. pp. 10–11. ISBN 978-0-300-19051-9.

- ^ a b c d Kimmel, Michael (2005). The Gender of Desire: Essays on Male Sexuality. United States: State University of New York Press. p. 183. ISBN 978-0-7914-6337-6.

- ^ Baky Fahmy, Mohamed (2020). Normal and Abnormal Prepuce. Springer International Publishing. p. 13. ISBN 978-3-030-37621-5.

…Brit Milah is just [ritually] nicking or amputating the protruding tip of the prepuce…

- ^ a b Judith Bleich, «The Circumcision Controversy in Classical Reform in Historical Context», KTAV Publishing House, 2007. pp. 1–28.

- ^ «Circumcision of Infants». Central Conference of American Rabbis. 1982. Archived from the original on 2012-03-15. Retrieved 2010-09-12.

- ^ Niebuhr, Gustav (June 28, 2001). «Reform Rabbis’ Vote Reflects Expanding Interest in Rituals». The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 30, 2013. Retrieved 2007-10-03.

- ^ «Berit Mila Program of Reform Judaism». National Association of American Mohalim. 2010. Archived from the original on 2013-10-07. Retrieved 2010-01-23.

- ^ Greenberg, Zoe (2017-07-25). «When Jewish Parents Decide Not to Circumcise». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2017-09-14. Retrieved 2022-07-31.

- ^ Chernikoff, Helen (October 3, 2007). «Jewish «intactivists» in U.S. stop circumcising». Reuters. Archived from the original on December 27, 2008. Retrieved 2019-04-03.

- ^ Ahituv, Netta (2012-06-14). «Even in Israel, More and More Parents Choose Not to Circumcise Their Sons». Haaretz. Archived from the original on 2022-05-25. Retrieved 2022-07-31.

- ^ Kasher, Rani (23 August 2017). «It’s 2017. Time to Talk About Circumcision». Haaretz. Tel Aviv. Archived from the original on 4 September 2017. Retrieved 4 September 2017.

- ^ a b Oryszczuk, Stephen (28 February 2018). «The Jewish parents cutting out the bris». The Times of Israel. Jerusalem. Retrieved 4 August 2018.

- ^ Silvers, Emma (2012-01-06). «Brit shalom is catching on, for parents who dont want to circumcise their child». J. The Jewish News of Northern California. San Francisco Jewish Community Publications Inc. Archived from the original on 2022-07-29. Retrieved 2022-07-30.

- ^ a b Goldman, Ronald (1997). «Circumcision: A Source of Jewish Pain». Jewish Circumcision Resource Center. Jewish Spectator. Retrieved 26 December 2019.

- ^ Goodman, Jason (January 1999). «Jewish circumcision: an alternative perspective». BJU International. 83 (1: Supplement): 22–27. doi:10.1046/j.1464-410x.1999.0830s1022.x. PMID 10349411. S2CID 29022100. Retrieved 26 December 2019.

- ^ a b Kimmel, Michael S. (May–June 2001). «The Kindest Un-Cut: Feminism, Judaism, and My Son’s Foreskin». Tikkun. 16 (3): 43–48. Retrieved 26 December 2019.

- ^ Boyle, Gregory J.; Svoboda, J. Steven; Price, Christopher P.; Turner, J. Neville (2000). «Circumcision of Healthy Boys: Criminal Assault?». Journal of Law and Medicine. 7: 301–310. Retrieved 22 November 2018.