From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Oldboy | |

|---|---|

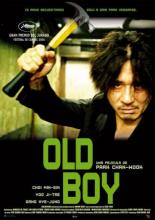

Theatrical release poster |

|

| Hangul |

올드보이 |

| Revised Romanization | Oldeuboi |

| McCune–Reischauer | Oldŭboi |

| Directed by | Park Chan-wook |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Based on |

Old Boy

|

| Produced by | Lim Seung-yong |

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Chung Chung-hoon |

| Edited by | Kim Sang-bum |

| Music by | Cho Young-wuk |

|

Production |

Egg Film |

| Distributed by | Show East |

|

Release date |

|

|

Running time |

120 minutes[1] |

| Country | South Korea |

| Language | Korean |

| Budget | $3 million[2] |

| Box office | $15 million[3] |

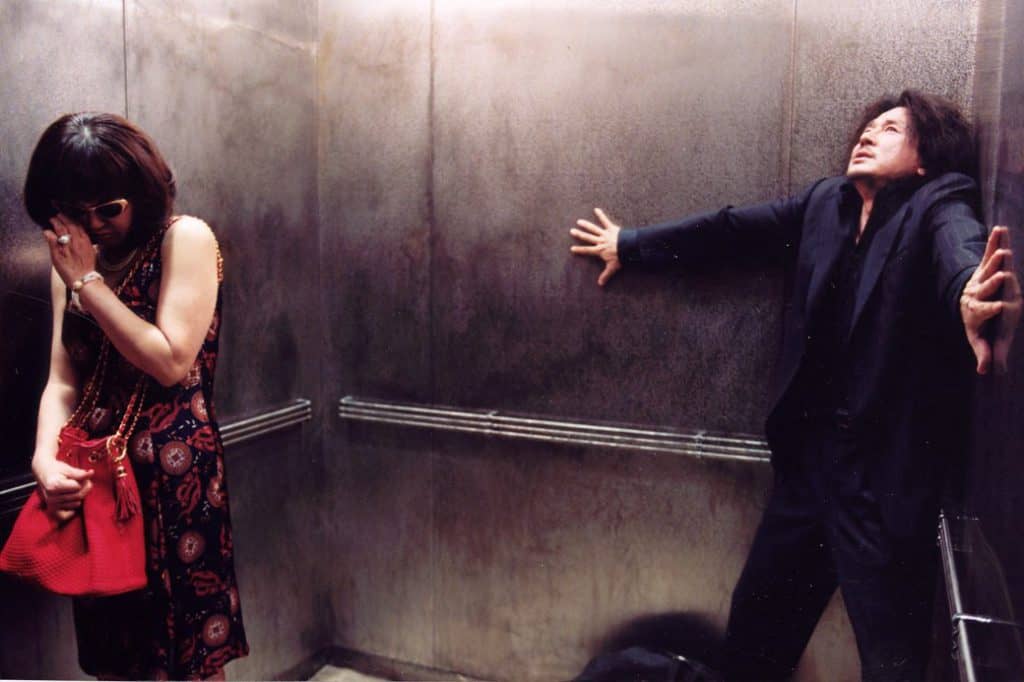

Oldboy (Korean: 올드보이; RR: Oldeuboi; MR: Oldŭboi) is a 2003 South Korean neo-noir action thriller film[4][5] directed and co-written by Park Chan-wook. A loose adaptation of the Japanese manga of the same name, the film follows the story of Oh Dae-su (Choi Min-sik), who is imprisoned in a cell which resembles a hotel room for 15 years without knowing the identity of his captor nor his captor’s motives. When he is finally released, Dae-su finds himself still trapped in a web of conspiracy and violence. His own quest for vengeance becomes tied in with romance when he falls in love with an attractive young sushi chef, Mi-do (Kang Hye-jung).

The film won the Grand Prix at the 2004 Cannes Film Festival and high praise from the president of the jury, director Quentin Tarantino. The film has received widespread acclaim in the United States, with film critic Roger Ebert stating that Oldboy is a «powerful film not because of what it depicts, but because of the depths of the human heart which it strips bare».[6] It also received praise for its action sequences, most notably the single shot corridor fight sequence.[7]

It has been regarded as one of the best films of all time and listed among the best films of the 2000s in several publications.[8] The film has had two remakes, an unauthorised 2006 Hindi film and a 2013 American film. The film is the second installment of Park’s The Vengeance Trilogy, preceded by Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance (2002) and followed by Lady Vengeance (2005).

Plot[edit]

In 1988, businessman Oh Dae-su is arrested for drunkenness, missing his daughter’s fourth birthday. After his friend Joo-hwan picks him up from the police station, Dae-su is kidnapped and wakes up in a sealed hotel room, where food is delivered through a pet door. Dae-su learns that his wife has been murdered and that he has been framed as a prime suspect by his captors. As years of imprisonment pass, Dae-su hallucinates, grows deranged from solitude, and eventually attempts suicide. While unconscious after slashing his wrists, Dae-su is resuscitated and bandaged, prevented from dying in order to ensure that he continues to live in agony. After this, Dae-su passes the time practicing shadowboxing and attempting to dig an escape tunnel in order to seek vengeance against his captors.

In 2003, Dae-su is suddenly released after being sedated and hypnotized. Dae-su wakes up and, after testing his fighting skills on a group of thugs, a mysterious beggar gives him money and a cell phone. Dae-su enters a sushi restaurant where he meets Mi-do, a young chef. He receives a taunting phone call from his captor, collapses, and is taken in by Mi-do. Dae-su attempts to leave Mi-do’s apartment, but Mi-do, now interested in Dae-su, stops him. They reconcile and begin to form a bond. After he recovers, Dae-su attempts to find his daughter, but gives up on trying to contact her after learning she was adopted after his kidnapping. Now focused on identifying his captors, Dae-su locates the Chinese restaurant that made his prison food and finds the prison by following a deliveryman.

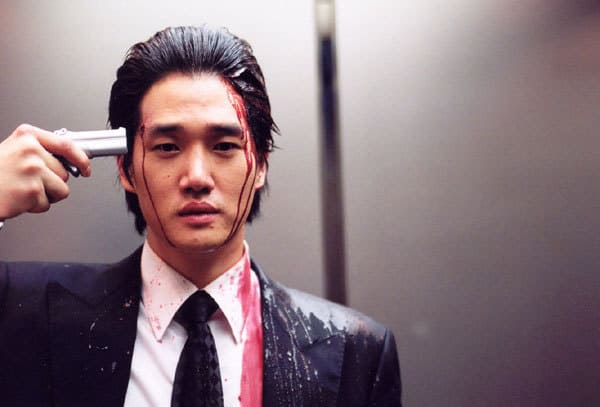

Dae-su learns the hotel he was held in is a private prison, where people pay to have others incarcerated. He tortures and interrogates the warden, Mr. Park Cheol-woong, who divulges that Dae-su was imprisoned for «talking too much». Mr. Park’s guards come to attack Dae-su, and they fight fiercely in the hotel corridor; Dae-su is stabbed but manages to defeat all of them. Dae-su’s captor is revealed to be a wealthy businessman named Lee Woo-jin. Woo-jin gives him an ultimatum: if Dae-su can uncover the motive for his imprisonment within five days, Woo-jin will kill himself; otherwise, he will kill Mi-do. Dae-su and Mi-do get close and have sex. Meanwhile, Joo-hwan tries to contact Dae-su with important information, but is murdered by Woo-jin. Dae-su eventually recalls that he and Woo-jin went to the same high school, and that he witnessed Woo-jin committing incest with his own sister. Dae-su told Joo-hwan what he saw, which led to his classmates gossiping about it. Rumors spread and Woo-jin’s sister committed suicide, leading a grief-stricken Woo-jin to seek revenge. In the present, Woo-jin cuts off Mr. Park’s hand, leading Mr. Park and his gang to join forces with Dae-su. Dae-su leaves Mi-do with Mr. Park and sets out to face Woo-jin.

At Woo-jin’s penthouse, he shows Dae-su a purple box containing a family album containing photos of Dae-su, his wife, and his infant daughter together from years ago, progressing to show how his daughter grew up. Woo-jin then reveals that Mi-do is actually Dae-su’s daughter, and that he had orchestrated everything, using hypnosis to guide Dae-su to the restaurant so he and Mi-do would fall in love, so that Dae-su would experience the same pain of incest that he did. Woo-jin reveals that Mr. Park is still working for him and threatens to tell the truth to Mi-do. Dae-su apologizes for being the source of the rumor that caused the death of Woo-jin’s sister, and humiliates himself by imitating a dog and begging. When Woo-jin is unimpressed, Dae-su cuts out his own tongue as a sign of penance. Woo-jin finally accepts Dae-su’s apology and tells Mr. Park to hide the truth from Mi-do. He then drops the device he claims is the remote to his pacemaker and walks away. Dae-su activates the device in an attempt to kill Woo-jin, only to find it is actually a remote for loudspeakers, which play an audio recording of Dae-su and Mi-do having sex. As Dae-su collapses in despair, Woo-jin enters the elevator, where he recalls his sister’s suicide and kills himself by handgun.

Some time later, Dae-su finds the hypnotist and asks her to erase his knowledge of Mi-do being his daughter so that they can stay happy together. To persuade her, he repeats the question he heard from the man on the rooftop, and the hypnotist agrees. Afterward, Mi-do finds Dae-su lying in snow, but there are no signs of the hypnotist. Mi-do confesses her love for him and the two embrace. Dae-su breaks into a wide smile, which is slowly replaced by a more ambiguous expression.

Cast[edit]

- Choi Min-sik as Oh Dae-su, a businessman who seeks revenge after being held in a mysterious prison for 15 years. Choi Min-sik lost and gained weight for his role depending on the filming schedule, trained for six weeks, and did most of his own stunt work.

- Oh Tae-kyung as young Dae-su

- Yoo Ji-tae as Lee Woo-jin, the man behind Oh Dae-su’s imprisonment. Park Chan-wook’s ideal choice for Woo-jin had been actor Han Suk-kyu, who previously played a rival to Choi Min-sik in Shiri and No. 3. Choi then suggested Yoo Ji-tae for the role, despite Park believing he was too young for the part.[9]

- Yoo Yeon-seok as young Woo-jin

- Kang Hye-jung as Mi-do, Dae-su’s love interest.

- Ji Dae-han as No Joo-hwan, Dae-su’s friend and the owner of an internet café.

- Woo Il-han as young Joo-hwan

- Kim Byeong-ok as Mr. Han, Woo-jin’s bodyguard.

- Yoon Jin-seo as Lee Soo-ah, Woo-jin’s sister.

- Oh Dal-su as Park Cheol-woong, the private prison’s warden.

Production[edit]

|

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (November 2018) |

The corridor fight scene took seventeen takes in three days to perfect and was one continuous take; there was no editing of any sort except for the knife that was stabbed in Oh Dae-su’s back, which was computer-generated imagery.

The script originally called for full male frontal nudity, but Yoo Ji-tae changed his mind after the scenes had been shot.

Other computer-generated imagery in the film includes the ant coming out of Dae-su’s arm (according to the making-of feature on the DVD, the whole arm was CGI) and the ants crawling over him afterwards. The octopus being eaten alive was not computer-generated; four were used during the filming of this scene. Actor Choi Min-sik, a Buddhist, said a prayer for each one. The eating of squirming octopuses (called san-nakji (산낙지) in Korean) as a delicacy exists in East Asia, although it is usually killed and cut, not eaten whole and alive; the squirming is a result of posthumous nerve activity in the octopus’ tentacles.[10][11][12] When asked in DVD commentary if he felt sorry for Choi, director Park Chan-wook stated he felt more sorry for the octopus.

The final scene’s snowy landscape was filmed in New Zealand.[13] The ending is deliberately ambiguous, and the audience is left with several questions: specifically, how much time has passed, if Dae-su’s meeting with the hypnotist really took place, whether he successfully lost the knowledge of Mi-do’s identity, and whether he will continue his relationship with Mi-do. In an interview with Park (included with the European release of the film), he says that the ambiguous ending was deliberate and intended to generate discussion; it is completely up to each individual viewer to interpret what isn’t shown.

Reception and analysis[edit]

Critical response[edit]

Oldboy received generally positive reviews from critics. Review aggregation website Rotten Tomatoes gives the film a score of 81% based on 151 reviews with an average rating of 7.40/10. The site’s consensus is «Violent and definitely not for the squeamish, Park Chan-Wook’s visceral Oldboy is a strange, powerful tale of revenge.»[14] Metacritic gives the film an average score of 77 out of 100, based on 32 reviews.[15]

Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times gave the film four out of four stars. Ebert remarked: «We are so accustomed to ‘thrillers’ that exist only as machines for creating diversion that it’s a shock to find a movie in which the action, however violent, makes a statement and has a purpose.»[6] James Berardinelli of ReelViews gave the film three out of four stars, saying that it «isn’t for everyone, but it offers a breath of fresh air to anyone gasping on the fumes of too many traditional Hollywood thrillers.»[16]

Stephanie Zacharek of Salon.com praised the film, calling it «anguished, beautiful, and desperately alive» and «a dazzling work of pop-culture artistry.»[17] Peter Bradshaw gave it 5/5 stars, commenting that this is the first time in which he could actually identify with a small live octopus. Bradshaw summarizes his review by referring to Oldboy as «cinema that holds an edge of cold steel to your throat.»[18] David Dylan Thomas points out that rather than simply trying to «gross us out», Oldboy is «much more interested in playing with the conventions of the revenge fantasy and taking us on a very entertaining ride to places that, conceptually, we might not want to go.»[19] Sean Axmaker of the Seattle Post-Intelligencer gave Oldboy a score of «B−», calling it «a bloody and brutal revenge film immersed in madness and directed with operatic intensity,» but felt that the questions raised by the film are «lost in the battering assault of lovingly crafted brutality.»[20]

MovieGazette lists 10 features on its «It’s Got» list for Oldboy and summarizes its review of Oldboy by saying, «Forget ‘The Punisher’ and ‘Man on Fire’ – this mesmerising revenger’s tragicomedy shows just how far-reaching the tentacles of mad vengeance can be.» MovieGazette also comments that it «needs to be seen to be believed.»[21] Jamie Russell of the BBC movie review calls it a «sadistic masterpiece that confirms Korea’s current status as producer of some of the world’s most exciting cinema.»[22] In 2019 on The Hankyoreh, Kim Hyeong-seok said that Oldboy was the ‘zeitgeist of the vigorous Korean cinema in early 2000s’, and a ‘boiling point that led history of Korean cinema to new state’.[23] Manohla Dargis of the New York Times gave a lukewarm review, saying that «there is not much to think about here, outside of the choreographed mayhem.»[24] J.R. Jones of the Chicago Reader was also not impressed, saying that «there’s a lot less here than meets the eye.»[25]

In 2008, Oldboy was placed 64th on an Empire list of the top 500 movies of all time.[26] The same year, voters on CNN named it one of the ten best Asian films ever made.[27] It was ranked #18 in the same magazine’s «The 100 Best Films of World Cinema» in 2010.[28] In a 2016 BBC poll, critics voted the film the 30th greatest since 2000.[29] In 2020, The Guardian ranked it number 3 among the classics of modern South Korean Cinema.[30]

Oedipus the King inspiration[edit]

Park Chan-wook stated that he named the main character Oh Dae-su «to remind the viewer of Oedipus.»[31] In one of the film’s iconic shots, Yoo Ji-tae, who played Woo-jin, strikes an extraordinary yoga pose. Park Chan-wook said he designed this pose to convey «the image of Apollo.»[32] It was Apollo’s prophecy that revealed Oedipus’ fate in Sophocles’ Oedipus the King. The link to Oedipus Rex is only a minor element in most English-language criticism of the movie, while Koreans have made it a central theme. Sung Hee Kim wrote «Family seen through Greek tragedy and Korean movie – Oedipus the King and Old Boy.»[33] Kim Kyungae offers a different analysis, with Dae-su and Woo-jin both representing Oedipus.[34] Besides the theme of unknown incest revealed, Oedipus gouges his eyes out to avoid seeing a world that despises the truth, while Oh Dae-su cuts off his tongue to avoid revealing the truth to his world.

More parallels with Greek tragedy include the fact that Lee Woo-jin looks relatively young as compared to Oh Dae-su when they are supposed to be contemporaries at school, which makes Lee Woo-jin look like an immortal Greek god whereas Oh Dae-su is merely an aged mortal. Indeed, throughout the movie Lee Woo-jin is portrayed as an obscenely rich young man who lives in a lofty tower and is omnipresent due to having planted listening devices on Oh Dae-Su and others, which again furthers the parallel between his character and the secrecy of Greek gods.

Mido, who throughout the movie comes across as a strong-willed, young and innocent girl, which is not too far from Sophocles’ Antigone, Oedipus’ daughter, who, though she does not commit incest with her father, remains faithful and loyal to him which reminds us of the bittersweet ending where Mido reunites with Oh Dae-Su and takes care of him in the wilderness (cf. Oedipus at Colonus, the second installment of the Oedipus trilogy). Another interesting character is the hypnotist, who, apart from being able to hypnotise people, also has the power to make people fall in love (e.g. Dae-Su and Mido), which is characteristic of the power of Aphrodite, the goddess of love, whose classic act is to make Paris and Helen fall in love before and during the Trojan War.[35]

Box office performance[edit]

In South Korea, the film was seen by 3,260,000 filmgoers and ranks fifth for the highest-grossing film of 2003.[36]

It grossed a total of US$14,980,005 worldwide.[3]

Home media[edit]

In the United Kingdom, the film was watched by 300,000 television viewers on Channel 4 in 2011. This made it the year’s most-watched foreign-language film on a non-BBC television channel in the UK.[37]

Awards and nominations[edit]

Soundtrack[edit]

| Original Motion Picture Soundtrack from Oldboy | |

|---|---|

| Soundtrack album by

Jo Yeong-wook |

|

| Released | 9 December 2003 |

| Recorded | 2003 Seoul |

| Genre | Contemporary classical |

| Length | 60:00 |

| Label | EMI Music Korea Ltd. |

| Producer | Jo Yeong-wook Shim Hyeon-jeong Lee Ji-soo Choi Seung-hyun |

Nearly all the music cues that are composed by Shim Hyeon-jeong, Lee Ji-soo and Choi Seung-hyun are titled after films, many of them film noirs.

- Track listing

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | «Look Who’s Talking» (opening song) | 1:41 |

| 2. | «Somewhere in the Night» | 1:29 |

| 3. | «The Count of Monte Cristo» | 2:34 |

| 4. | «Jailhouse Rock» | 1:57 |

| 5. | «In a Lonely Place» (Oh Dae-su’s theme) | 3:29 |

| 6. | «It’s Alive» | 2:36 |

| 7. | «The Searchers» | 3:29 |

| 8. | «Look Back in Anger» | 2:11 |

| 9. | «»Vivaldi» – Four Seasons Concerto Concerto No. 4 in F minor, Op. 8, RV 297, «L’inverno» (Winter)» | 3:03 |

| 10. | «Room at the Top» | 1:36 |

| 11. | «Cries and Whispers» (Lee Woo-jin’s theme) | 3:32 |

| 12. | «Out of Sight» | 1:00 |

| 13. | «For Whom the Bell Tolls» | 2:45 |

| 14. | «Out of the Past» | 1:25 |

| 15. | «Breathless» (Lee Woo-jin’s theme [reprise]) | 4:21 |

| 16. | «The Old Boy» (Oh Dae-su’s theme [reprise]) | 3:44 |

| 17. | «Dressed to Kill» | 2:00 |

| 18. | «Frantic» | 3:28 |

| 19. | «Cul-de-Sac» | 1:32 |

| 20. | «Kiss Me Deadly» | 3:57 |

| 21. | «Point Blank» | 0:27 |

| 22. | «Farewell, My Lovely» (Lee Woo-jin’s theme [reprise]) | 2:47 |

| 23. | «The Big Sleep» | 1:34 |

| 24. | «The Last Waltz» (Mi-do’s theme) | 3:23 |

| Total length: | 60:00 |

Remakes[edit]

| Oldboy (2003) (Korean) |

Zinda (2006) (Hindi) |

Oldboy (2013) (English) |

| Choi Min-sik | Sanjay Dutt | Josh Brolin |

| Kang Hye-jung | Lara Dutta | Elizabeth Olsen |

| Yoo Ji-tae | John Abraham | Sharlto Copley |

Controversy over Zinda[edit]

Zinda, the Bollywood film directed by writer-director Sanjay Gupta, also bears a striking resemblance to Oldboy but is not an officially sanctioned remake. It was reported in 2005 that Zinda was under investigation for violation of copyright. A spokesman for Show East, the distributor of Oldboy, said, «If we find out there’s indeed a strong similarity between the two, it looks like we’ll have to talk with our lawyers.»[44] Show East, the producers of Oldboy, who had already sold the film’s rights to DreamWorks in 2004, initially expressed legal concerns but no legal action was taken as the studio had shut down.[45][46][47]

American film remake[edit]

Steven Spielberg originally intended to make a version of the movie starring Will Smith in 2008. He commissioned screenwriter Mark Protosevich to work on the adaptation. Spielberg pulled out of the project in 2009.[48] An American remake directed by Spike Lee was released on 27 November 2013.[49] The remake generally received negative reviews with a 39 percent on Rotten Tomatoes.[50]

See also[edit]

- East Asian cinema

- Greek tragedy

- Kafkaesque

- List of Korean-language films

- List of South Korean films of 2003

- Revenge play

- List of cult films

References[edit]

- ^ «Oldboy». British Board of Film Classification. Archived from the original on 31 January 2020. Retrieved 26 March 2018.

- ^ «Oldboy (2003) — Financial Information». The Numbers. Archived from the original on 16 February 2019. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- ^ a b «Oldboy (2005)». Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on 27 October 2017. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- ^ «OLDBOY (2003)». British Board of Film Classification. Archived from the original on 10 November 2020. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- ^ «From Mind-Numbing Thrillers To Refreshing Rom-Coms, 15 Korean Movies You Need To Watch ASAP!». Indiatimes. 30 March 2019. Archived from the original on 13 July 2019. Retrieved 7 August 2019.

- ^ a b Ebert, Roger (24 March 2005). «Korea’s ‘Oldboy’ digs deeper than average mystery/thriller». Roger Ebert. Archived from the original on 26 November 2021. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- ^ «7 of the Best One-Shot Action Sequences, From ‘Oldboy’ to ‘The Revenant’«. IndieWire. 25 July 2017. Archived from the original on 27 May 2018. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- ^ Boman, Björn (December 2020). Valsiner, Jaan (ed.). «From Oldboy to Burning: Han in South Korean films». Culture & Psychology. SAGE Publications. 26 (4): 919–932. doi:10.1177/1354067X20922146. eISSN 1461-7056. ISSN 1354-067X.

- ^ Cine21 Interview about Park’s revenge trilogy; 27 April 2007.

- ^ Rosen, Daniel Edward (4 May 2010). «Korean restaurant’s live Octopus dish has animal rights activists squirming». New York Daily News. Archived from the original on 11 February 2019. Retrieved 3 June 2017.

- ^ Han, Jane (14 May 2010). «Clash of culture? Sannakji angers US animal activists». The Korea Times. Archived from the original on 20 December 2019. Retrieved 4 June 2017.

- ^ Compton, Natalie B. (17 June 2016). «Eating a Live Octopus Wasn’t Nearly as Difficult As It Sounds». VICE. Archived from the original on 23 February 2022. Retrieved 23 February 2022.

- ^ Baillie, Russell (9 April 2005). «Oldboy». The New Zealand Herald. Archived from the original on 23 February 2022. Retrieved 23 February 2022.

- ^ «Oldboy Movie Reviews, Pictures». Rotten Tomatoes. Flixster. Archived from the original on 26 June 2012. Retrieved 22 June 2012.

- ^ «Oldboy (2005): Reviews». Metacritic. CBS interactive. Archived from the original on 24 May 2008. Retrieved 20 May 2008.

- ^ Review by James Berardinelli Archived 24 February 2021 at the Wayback Machine, ReelViews.

- ^ Stephanie Zacharek (25 March 2005). «Thunder out of Korea». Salon. Archived from the original on 15 June 2008. Retrieved 23 February 2022.

- ^ Bradshaw, Peter (15 October 2004). «Film of the week: Oldboy». The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 25 February 2017. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

- ^ «Oldboy». Filmcritic.com. Archived from the original on 27 October 2011. Retrieved 25 September 2012.

- ^ Sean Axmaker (21 April 2005). «‘Oldboy’ story of revenge is beaten down by its own brutality». Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Archived from the original on 23 February 2022. Retrieved 23 February 2022.

- ^ «Oldboy – Movie Review». Movie-gazette.com. 24 October 2004. Archived from the original on 14 August 2021. Retrieved 23 February 2022.

- ^ Jamie Russell (8 October 2004). «Films – Old Boy». BBC. Archived from the original on 27 August 2012. Retrieved 25 September 2012.

- ^ Kim, Hyeong-seok (29 May 2019). ««누구냐 너» 금기 깬 혼돈의 매력…예열 끝낸 박찬욱의 ‘작가본색’» (in Korean). The Hankyoreh. Archived from the original on 30 January 2020. Retrieved 21 March 2021.

- ^ Dargis, Manohla (25 March 2005). «The Violence (and the Seafood) Is More Than Raw». The New York Times. Archived from the original on 23 February 2022. Retrieved 23 February 2022.

- ^ Review by J.R. Jones Archived 4 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Chicago Reader.

- ^ Sciretta, Peter (5 October 2008). «Empire Magazine’s 500 Greatest Movies Of All Time». /Film. Archived from the original on 23 February 2022. Retrieved 23 February 2022.

- ^ Plaza, Gerry (12 November 2008). «CNN: ‘Himala’ best Asian film in history». The Philippine Inquirer. Archived from the original on 22 August 2015. Retrieved 23 February 2022.

- ^ Green, Willow (23 September 2019). «The 100 Best Films Of World Cinema». Empire. Archived from the original on 23 November 2015. Retrieved 23 February 2022.

- ^ «The 21st century’s 100 greatest films». BBC. 23 August 2016. Archived from the original on 31 January 2017. Retrieved 8 November 2016.

- ^ Bradshaw, Peter (13 February 2020). «Classics of modern South Korean cinema – ranked!». The Guardian. Archived from the original on 30 May 2020. Retrieved 16 March 2020.

- ^ «Sympathy for the Old Boy… An Interview with Park Chan Wook» Archived 14 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine by Choi Aryong

- ^ «IKONEN : Interview Park Chan Wok Old Boy Lady Vengeance JSA Choi Aryong». Ikonenmagazin.de. Archived from the original on 14 October 2014. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ^ «그리스비극과 한국영화를 통해 본 가족 – 드라마연구 – 한국드라마학회 : 전자저널 논문». 한국표면공학회지. 35 (6): 363–370. December 2002. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ^ «〈올드보이〉에 나타난 여섯 개의 이미지 – 문학과영상 – 문학과영상학회 : 전자저널 논문». Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ^ «Greek tragedy in East Asia: Oldboy (2003)». 17 April 2015. Archived from the original on 24 September 2017. Retrieved 23 September 2017.

- ^ «Korean Movie Reviews for 2003: Save the Green Planet, Memories of Murder, A Tale of Two Sisters, Oldboy, Silmido, and more». www.koreanfilm.org. Archived from the original on 28 July 2010. Retrieved 18 August 2007.

- ^ «BFI Statistical Yearbook 2012» (PDF). British Film Institute (BFI). 2012. p. 125. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ Denis, Fernand (10 January 2005). «La victoire de «Poulpe fiction»«. La Libre Belgique (in French). Archived from the original on 1 March 2022. Retrieved 26 October 2012.

- ^ «Awards (2004)». Bergen International Film Festival. Archived from the original on 13 February 2007. Retrieved 10 April 2007.

- ^ «Oldboy». www.cinemasie.com. Archived from the original on 25 September 2016. Retrieved 3 October 2012.

- ^ «Winners (2004)». The British Independent Film Awards. Archived from the original on 7 April 2007. Retrieved 10 April 2007.

- ^ «All The Awards (2004)». Cannes Film Festival. Archived from the original on 30 November 2006. Retrieved 10 April 2007.

- ^ «The Nominations (2004)». The European Film Awards. Archived from the original on 9 December 2006. Retrieved 10 April 2007.

- ^ Oldboy Makers Plan Vengeance on Zinda Archived September 14, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, TwitchFilm.

- ^ «Spielberg Still Has Oldboy Plans Despite Korean Suit». Anime News Network. Archived from the original on 8 November 2020. Retrieved 26 September 2020.

- ^ Elley, Derek (6 February 2006). «Zinda». Archived from the original on 17 November 2017. Retrieved 25 November 2021.

- ^ Kim, Hyun-rok (16 November 2005). 표절의혹 ‘올드보이’, 제작사 법적대응 고려 [Plagiarism Doubts, ‘Oldboy’ Production Company Considers Legal Confrontation] (in Korean). Star News. Archived from the original on 9 April 2021. Retrieved 26 August 2009.

- ^ Kate Aurthur (30 November 2013). «Adapting «Oldboy»: Its Screenwriter Talks About Twists And Spoilers». Buzzfeed. Archived from the original on 25 February 2017. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ^ «Spike Lee Confirmed to Direct ‘Oldboy’«. /Film. 11 July 2011. Archived from the original on 1 March 2022. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- ^ «Oldboy(2013)». rottentomatoes. Archived from the original on 22 July 2021. Retrieved 27 April 2021.

External links[edit]

- Oldboy at IMDb

- Oldboy at the Korean Movie Database

- Oldboy at HanCinema

- Oldboy at AllMovie

- Oldboy at Rotten Tomatoes

- Oldboy at Metacritic

- Oldboy at Box Office Mojo

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Oldboy | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster |

|

| Hangul |

올드보이 |

| Revised Romanization | Oldeuboi |

| McCune–Reischauer | Oldŭboi |

| Directed by | Park Chan-wook |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Based on |

Old Boy

|

| Produced by | Lim Seung-yong |

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Chung Chung-hoon |

| Edited by | Kim Sang-bum |

| Music by | Cho Young-wuk |

|

Production |

Egg Film |

| Distributed by | Show East |

|

Release date |

|

|

Running time |

120 minutes[1] |

| Country | South Korea |

| Language | Korean |

| Budget | $3 million[2] |

| Box office | $15 million[3] |

Oldboy (Korean: 올드보이; RR: Oldeuboi; MR: Oldŭboi) is a 2003 South Korean neo-noir action thriller film[4][5] directed and co-written by Park Chan-wook. A loose adaptation of the Japanese manga of the same name, the film follows the story of Oh Dae-su (Choi Min-sik), who is imprisoned in a cell which resembles a hotel room for 15 years without knowing the identity of his captor nor his captor’s motives. When he is finally released, Dae-su finds himself still trapped in a web of conspiracy and violence. His own quest for vengeance becomes tied in with romance when he falls in love with an attractive young sushi chef, Mi-do (Kang Hye-jung).

The film won the Grand Prix at the 2004 Cannes Film Festival and high praise from the president of the jury, director Quentin Tarantino. The film has received widespread acclaim in the United States, with film critic Roger Ebert stating that Oldboy is a «powerful film not because of what it depicts, but because of the depths of the human heart which it strips bare».[6] It also received praise for its action sequences, most notably the single shot corridor fight sequence.[7]

It has been regarded as one of the best films of all time and listed among the best films of the 2000s in several publications.[8] The film has had two remakes, an unauthorised 2006 Hindi film and a 2013 American film. The film is the second installment of Park’s The Vengeance Trilogy, preceded by Sympathy for Mr. Vengeance (2002) and followed by Lady Vengeance (2005).

Plot[edit]

In 1988, businessman Oh Dae-su is arrested for drunkenness, missing his daughter’s fourth birthday. After his friend Joo-hwan picks him up from the police station, Dae-su is kidnapped and wakes up in a sealed hotel room, where food is delivered through a pet door. Dae-su learns that his wife has been murdered and that he has been framed as a prime suspect by his captors. As years of imprisonment pass, Dae-su hallucinates, grows deranged from solitude, and eventually attempts suicide. While unconscious after slashing his wrists, Dae-su is resuscitated and bandaged, prevented from dying in order to ensure that he continues to live in agony. After this, Dae-su passes the time practicing shadowboxing and attempting to dig an escape tunnel in order to seek vengeance against his captors.

In 2003, Dae-su is suddenly released after being sedated and hypnotized. Dae-su wakes up and, after testing his fighting skills on a group of thugs, a mysterious beggar gives him money and a cell phone. Dae-su enters a sushi restaurant where he meets Mi-do, a young chef. He receives a taunting phone call from his captor, collapses, and is taken in by Mi-do. Dae-su attempts to leave Mi-do’s apartment, but Mi-do, now interested in Dae-su, stops him. They reconcile and begin to form a bond. After he recovers, Dae-su attempts to find his daughter, but gives up on trying to contact her after learning she was adopted after his kidnapping. Now focused on identifying his captors, Dae-su locates the Chinese restaurant that made his prison food and finds the prison by following a deliveryman.

Dae-su learns the hotel he was held in is a private prison, where people pay to have others incarcerated. He tortures and interrogates the warden, Mr. Park Cheol-woong, who divulges that Dae-su was imprisoned for «talking too much». Mr. Park’s guards come to attack Dae-su, and they fight fiercely in the hotel corridor; Dae-su is stabbed but manages to defeat all of them. Dae-su’s captor is revealed to be a wealthy businessman named Lee Woo-jin. Woo-jin gives him an ultimatum: if Dae-su can uncover the motive for his imprisonment within five days, Woo-jin will kill himself; otherwise, he will kill Mi-do. Dae-su and Mi-do get close and have sex. Meanwhile, Joo-hwan tries to contact Dae-su with important information, but is murdered by Woo-jin. Dae-su eventually recalls that he and Woo-jin went to the same high school, and that he witnessed Woo-jin committing incest with his own sister. Dae-su told Joo-hwan what he saw, which led to his classmates gossiping about it. Rumors spread and Woo-jin’s sister committed suicide, leading a grief-stricken Woo-jin to seek revenge. In the present, Woo-jin cuts off Mr. Park’s hand, leading Mr. Park and his gang to join forces with Dae-su. Dae-su leaves Mi-do with Mr. Park and sets out to face Woo-jin.

At Woo-jin’s penthouse, he shows Dae-su a purple box containing a family album containing photos of Dae-su, his wife, and his infant daughter together from years ago, progressing to show how his daughter grew up. Woo-jin then reveals that Mi-do is actually Dae-su’s daughter, and that he had orchestrated everything, using hypnosis to guide Dae-su to the restaurant so he and Mi-do would fall in love, so that Dae-su would experience the same pain of incest that he did. Woo-jin reveals that Mr. Park is still working for him and threatens to tell the truth to Mi-do. Dae-su apologizes for being the source of the rumor that caused the death of Woo-jin’s sister, and humiliates himself by imitating a dog and begging. When Woo-jin is unimpressed, Dae-su cuts out his own tongue as a sign of penance. Woo-jin finally accepts Dae-su’s apology and tells Mr. Park to hide the truth from Mi-do. He then drops the device he claims is the remote to his pacemaker and walks away. Dae-su activates the device in an attempt to kill Woo-jin, only to find it is actually a remote for loudspeakers, which play an audio recording of Dae-su and Mi-do having sex. As Dae-su collapses in despair, Woo-jin enters the elevator, where he recalls his sister’s suicide and kills himself by handgun.

Some time later, Dae-su finds the hypnotist and asks her to erase his knowledge of Mi-do being his daughter so that they can stay happy together. To persuade her, he repeats the question he heard from the man on the rooftop, and the hypnotist agrees. Afterward, Mi-do finds Dae-su lying in snow, but there are no signs of the hypnotist. Mi-do confesses her love for him and the two embrace. Dae-su breaks into a wide smile, which is slowly replaced by a more ambiguous expression.

Cast[edit]

- Choi Min-sik as Oh Dae-su, a businessman who seeks revenge after being held in a mysterious prison for 15 years. Choi Min-sik lost and gained weight for his role depending on the filming schedule, trained for six weeks, and did most of his own stunt work.

- Oh Tae-kyung as young Dae-su

- Yoo Ji-tae as Lee Woo-jin, the man behind Oh Dae-su’s imprisonment. Park Chan-wook’s ideal choice for Woo-jin had been actor Han Suk-kyu, who previously played a rival to Choi Min-sik in Shiri and No. 3. Choi then suggested Yoo Ji-tae for the role, despite Park believing he was too young for the part.[9]

- Yoo Yeon-seok as young Woo-jin

- Kang Hye-jung as Mi-do, Dae-su’s love interest.

- Ji Dae-han as No Joo-hwan, Dae-su’s friend and the owner of an internet café.

- Woo Il-han as young Joo-hwan

- Kim Byeong-ok as Mr. Han, Woo-jin’s bodyguard.

- Yoon Jin-seo as Lee Soo-ah, Woo-jin’s sister.

- Oh Dal-su as Park Cheol-woong, the private prison’s warden.

Production[edit]

|

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (November 2018) |

The corridor fight scene took seventeen takes in three days to perfect and was one continuous take; there was no editing of any sort except for the knife that was stabbed in Oh Dae-su’s back, which was computer-generated imagery.

The script originally called for full male frontal nudity, but Yoo Ji-tae changed his mind after the scenes had been shot.

Other computer-generated imagery in the film includes the ant coming out of Dae-su’s arm (according to the making-of feature on the DVD, the whole arm was CGI) and the ants crawling over him afterwards. The octopus being eaten alive was not computer-generated; four were used during the filming of this scene. Actor Choi Min-sik, a Buddhist, said a prayer for each one. The eating of squirming octopuses (called san-nakji (산낙지) in Korean) as a delicacy exists in East Asia, although it is usually killed and cut, not eaten whole and alive; the squirming is a result of posthumous nerve activity in the octopus’ tentacles.[10][11][12] When asked in DVD commentary if he felt sorry for Choi, director Park Chan-wook stated he felt more sorry for the octopus.

The final scene’s snowy landscape was filmed in New Zealand.[13] The ending is deliberately ambiguous, and the audience is left with several questions: specifically, how much time has passed, if Dae-su’s meeting with the hypnotist really took place, whether he successfully lost the knowledge of Mi-do’s identity, and whether he will continue his relationship with Mi-do. In an interview with Park (included with the European release of the film), he says that the ambiguous ending was deliberate and intended to generate discussion; it is completely up to each individual viewer to interpret what isn’t shown.

Reception and analysis[edit]

Critical response[edit]

Oldboy received generally positive reviews from critics. Review aggregation website Rotten Tomatoes gives the film a score of 81% based on 151 reviews with an average rating of 7.40/10. The site’s consensus is «Violent and definitely not for the squeamish, Park Chan-Wook’s visceral Oldboy is a strange, powerful tale of revenge.»[14] Metacritic gives the film an average score of 77 out of 100, based on 32 reviews.[15]

Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times gave the film four out of four stars. Ebert remarked: «We are so accustomed to ‘thrillers’ that exist only as machines for creating diversion that it’s a shock to find a movie in which the action, however violent, makes a statement and has a purpose.»[6] James Berardinelli of ReelViews gave the film three out of four stars, saying that it «isn’t for everyone, but it offers a breath of fresh air to anyone gasping on the fumes of too many traditional Hollywood thrillers.»[16]

Stephanie Zacharek of Salon.com praised the film, calling it «anguished, beautiful, and desperately alive» and «a dazzling work of pop-culture artistry.»[17] Peter Bradshaw gave it 5/5 stars, commenting that this is the first time in which he could actually identify with a small live octopus. Bradshaw summarizes his review by referring to Oldboy as «cinema that holds an edge of cold steel to your throat.»[18] David Dylan Thomas points out that rather than simply trying to «gross us out», Oldboy is «much more interested in playing with the conventions of the revenge fantasy and taking us on a very entertaining ride to places that, conceptually, we might not want to go.»[19] Sean Axmaker of the Seattle Post-Intelligencer gave Oldboy a score of «B−», calling it «a bloody and brutal revenge film immersed in madness and directed with operatic intensity,» but felt that the questions raised by the film are «lost in the battering assault of lovingly crafted brutality.»[20]

MovieGazette lists 10 features on its «It’s Got» list for Oldboy and summarizes its review of Oldboy by saying, «Forget ‘The Punisher’ and ‘Man on Fire’ – this mesmerising revenger’s tragicomedy shows just how far-reaching the tentacles of mad vengeance can be.» MovieGazette also comments that it «needs to be seen to be believed.»[21] Jamie Russell of the BBC movie review calls it a «sadistic masterpiece that confirms Korea’s current status as producer of some of the world’s most exciting cinema.»[22] In 2019 on The Hankyoreh, Kim Hyeong-seok said that Oldboy was the ‘zeitgeist of the vigorous Korean cinema in early 2000s’, and a ‘boiling point that led history of Korean cinema to new state’.[23] Manohla Dargis of the New York Times gave a lukewarm review, saying that «there is not much to think about here, outside of the choreographed mayhem.»[24] J.R. Jones of the Chicago Reader was also not impressed, saying that «there’s a lot less here than meets the eye.»[25]

In 2008, Oldboy was placed 64th on an Empire list of the top 500 movies of all time.[26] The same year, voters on CNN named it one of the ten best Asian films ever made.[27] It was ranked #18 in the same magazine’s «The 100 Best Films of World Cinema» in 2010.[28] In a 2016 BBC poll, critics voted the film the 30th greatest since 2000.[29] In 2020, The Guardian ranked it number 3 among the classics of modern South Korean Cinema.[30]

Oedipus the King inspiration[edit]

Park Chan-wook stated that he named the main character Oh Dae-su «to remind the viewer of Oedipus.»[31] In one of the film’s iconic shots, Yoo Ji-tae, who played Woo-jin, strikes an extraordinary yoga pose. Park Chan-wook said he designed this pose to convey «the image of Apollo.»[32] It was Apollo’s prophecy that revealed Oedipus’ fate in Sophocles’ Oedipus the King. The link to Oedipus Rex is only a minor element in most English-language criticism of the movie, while Koreans have made it a central theme. Sung Hee Kim wrote «Family seen through Greek tragedy and Korean movie – Oedipus the King and Old Boy.»[33] Kim Kyungae offers a different analysis, with Dae-su and Woo-jin both representing Oedipus.[34] Besides the theme of unknown incest revealed, Oedipus gouges his eyes out to avoid seeing a world that despises the truth, while Oh Dae-su cuts off his tongue to avoid revealing the truth to his world.

More parallels with Greek tragedy include the fact that Lee Woo-jin looks relatively young as compared to Oh Dae-su when they are supposed to be contemporaries at school, which makes Lee Woo-jin look like an immortal Greek god whereas Oh Dae-su is merely an aged mortal. Indeed, throughout the movie Lee Woo-jin is portrayed as an obscenely rich young man who lives in a lofty tower and is omnipresent due to having planted listening devices on Oh Dae-Su and others, which again furthers the parallel between his character and the secrecy of Greek gods.

Mido, who throughout the movie comes across as a strong-willed, young and innocent girl, which is not too far from Sophocles’ Antigone, Oedipus’ daughter, who, though she does not commit incest with her father, remains faithful and loyal to him which reminds us of the bittersweet ending where Mido reunites with Oh Dae-Su and takes care of him in the wilderness (cf. Oedipus at Colonus, the second installment of the Oedipus trilogy). Another interesting character is the hypnotist, who, apart from being able to hypnotise people, also has the power to make people fall in love (e.g. Dae-Su and Mido), which is characteristic of the power of Aphrodite, the goddess of love, whose classic act is to make Paris and Helen fall in love before and during the Trojan War.[35]

Box office performance[edit]

In South Korea, the film was seen by 3,260,000 filmgoers and ranks fifth for the highest-grossing film of 2003.[36]

It grossed a total of US$14,980,005 worldwide.[3]

Home media[edit]

In the United Kingdom, the film was watched by 300,000 television viewers on Channel 4 in 2011. This made it the year’s most-watched foreign-language film on a non-BBC television channel in the UK.[37]

Awards and nominations[edit]

Soundtrack[edit]

| Original Motion Picture Soundtrack from Oldboy | |

|---|---|

| Soundtrack album by

Jo Yeong-wook |

|

| Released | 9 December 2003 |

| Recorded | 2003 Seoul |

| Genre | Contemporary classical |

| Length | 60:00 |

| Label | EMI Music Korea Ltd. |

| Producer | Jo Yeong-wook Shim Hyeon-jeong Lee Ji-soo Choi Seung-hyun |

Nearly all the music cues that are composed by Shim Hyeon-jeong, Lee Ji-soo and Choi Seung-hyun are titled after films, many of them film noirs.

- Track listing

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | «Look Who’s Talking» (opening song) | 1:41 |

| 2. | «Somewhere in the Night» | 1:29 |

| 3. | «The Count of Monte Cristo» | 2:34 |

| 4. | «Jailhouse Rock» | 1:57 |

| 5. | «In a Lonely Place» (Oh Dae-su’s theme) | 3:29 |

| 6. | «It’s Alive» | 2:36 |

| 7. | «The Searchers» | 3:29 |

| 8. | «Look Back in Anger» | 2:11 |

| 9. | «»Vivaldi» – Four Seasons Concerto Concerto No. 4 in F minor, Op. 8, RV 297, «L’inverno» (Winter)» | 3:03 |

| 10. | «Room at the Top» | 1:36 |

| 11. | «Cries and Whispers» (Lee Woo-jin’s theme) | 3:32 |

| 12. | «Out of Sight» | 1:00 |

| 13. | «For Whom the Bell Tolls» | 2:45 |

| 14. | «Out of the Past» | 1:25 |

| 15. | «Breathless» (Lee Woo-jin’s theme [reprise]) | 4:21 |

| 16. | «The Old Boy» (Oh Dae-su’s theme [reprise]) | 3:44 |

| 17. | «Dressed to Kill» | 2:00 |

| 18. | «Frantic» | 3:28 |

| 19. | «Cul-de-Sac» | 1:32 |

| 20. | «Kiss Me Deadly» | 3:57 |

| 21. | «Point Blank» | 0:27 |

| 22. | «Farewell, My Lovely» (Lee Woo-jin’s theme [reprise]) | 2:47 |

| 23. | «The Big Sleep» | 1:34 |

| 24. | «The Last Waltz» (Mi-do’s theme) | 3:23 |

| Total length: | 60:00 |

Remakes[edit]

| Oldboy (2003) (Korean) |

Zinda (2006) (Hindi) |

Oldboy (2013) (English) |

| Choi Min-sik | Sanjay Dutt | Josh Brolin |

| Kang Hye-jung | Lara Dutta | Elizabeth Olsen |

| Yoo Ji-tae | John Abraham | Sharlto Copley |

Controversy over Zinda[edit]

Zinda, the Bollywood film directed by writer-director Sanjay Gupta, also bears a striking resemblance to Oldboy but is not an officially sanctioned remake. It was reported in 2005 that Zinda was under investigation for violation of copyright. A spokesman for Show East, the distributor of Oldboy, said, «If we find out there’s indeed a strong similarity between the two, it looks like we’ll have to talk with our lawyers.»[44] Show East, the producers of Oldboy, who had already sold the film’s rights to DreamWorks in 2004, initially expressed legal concerns but no legal action was taken as the studio had shut down.[45][46][47]

American film remake[edit]

Steven Spielberg originally intended to make a version of the movie starring Will Smith in 2008. He commissioned screenwriter Mark Protosevich to work on the adaptation. Spielberg pulled out of the project in 2009.[48] An American remake directed by Spike Lee was released on 27 November 2013.[49] The remake generally received negative reviews with a 39 percent on Rotten Tomatoes.[50]

See also[edit]

- East Asian cinema

- Greek tragedy

- Kafkaesque

- List of Korean-language films

- List of South Korean films of 2003

- Revenge play

- List of cult films

References[edit]

- ^ «Oldboy». British Board of Film Classification. Archived from the original on 31 January 2020. Retrieved 26 March 2018.

- ^ «Oldboy (2003) — Financial Information». The Numbers. Archived from the original on 16 February 2019. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- ^ a b «Oldboy (2005)». Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on 27 October 2017. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- ^ «OLDBOY (2003)». British Board of Film Classification. Archived from the original on 10 November 2020. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- ^ «From Mind-Numbing Thrillers To Refreshing Rom-Coms, 15 Korean Movies You Need To Watch ASAP!». Indiatimes. 30 March 2019. Archived from the original on 13 July 2019. Retrieved 7 August 2019.

- ^ a b Ebert, Roger (24 March 2005). «Korea’s ‘Oldboy’ digs deeper than average mystery/thriller». Roger Ebert. Archived from the original on 26 November 2021. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- ^ «7 of the Best One-Shot Action Sequences, From ‘Oldboy’ to ‘The Revenant’«. IndieWire. 25 July 2017. Archived from the original on 27 May 2018. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- ^ Boman, Björn (December 2020). Valsiner, Jaan (ed.). «From Oldboy to Burning: Han in South Korean films». Culture & Psychology. SAGE Publications. 26 (4): 919–932. doi:10.1177/1354067X20922146. eISSN 1461-7056. ISSN 1354-067X.

- ^ Cine21 Interview about Park’s revenge trilogy; 27 April 2007.

- ^ Rosen, Daniel Edward (4 May 2010). «Korean restaurant’s live Octopus dish has animal rights activists squirming». New York Daily News. Archived from the original on 11 February 2019. Retrieved 3 June 2017.

- ^ Han, Jane (14 May 2010). «Clash of culture? Sannakji angers US animal activists». The Korea Times. Archived from the original on 20 December 2019. Retrieved 4 June 2017.

- ^ Compton, Natalie B. (17 June 2016). «Eating a Live Octopus Wasn’t Nearly as Difficult As It Sounds». VICE. Archived from the original on 23 February 2022. Retrieved 23 February 2022.

- ^ Baillie, Russell (9 April 2005). «Oldboy». The New Zealand Herald. Archived from the original on 23 February 2022. Retrieved 23 February 2022.

- ^ «Oldboy Movie Reviews, Pictures». Rotten Tomatoes. Flixster. Archived from the original on 26 June 2012. Retrieved 22 June 2012.

- ^ «Oldboy (2005): Reviews». Metacritic. CBS interactive. Archived from the original on 24 May 2008. Retrieved 20 May 2008.

- ^ Review by James Berardinelli Archived 24 February 2021 at the Wayback Machine, ReelViews.

- ^ Stephanie Zacharek (25 March 2005). «Thunder out of Korea». Salon. Archived from the original on 15 June 2008. Retrieved 23 February 2022.

- ^ Bradshaw, Peter (15 October 2004). «Film of the week: Oldboy». The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 25 February 2017. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

- ^ «Oldboy». Filmcritic.com. Archived from the original on 27 October 2011. Retrieved 25 September 2012.

- ^ Sean Axmaker (21 April 2005). «‘Oldboy’ story of revenge is beaten down by its own brutality». Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Archived from the original on 23 February 2022. Retrieved 23 February 2022.

- ^ «Oldboy – Movie Review». Movie-gazette.com. 24 October 2004. Archived from the original on 14 August 2021. Retrieved 23 February 2022.

- ^ Jamie Russell (8 October 2004). «Films – Old Boy». BBC. Archived from the original on 27 August 2012. Retrieved 25 September 2012.

- ^ Kim, Hyeong-seok (29 May 2019). ««누구냐 너» 금기 깬 혼돈의 매력…예열 끝낸 박찬욱의 ‘작가본색’» (in Korean). The Hankyoreh. Archived from the original on 30 January 2020. Retrieved 21 March 2021.

- ^ Dargis, Manohla (25 March 2005). «The Violence (and the Seafood) Is More Than Raw». The New York Times. Archived from the original on 23 February 2022. Retrieved 23 February 2022.

- ^ Review by J.R. Jones Archived 4 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Chicago Reader.

- ^ Sciretta, Peter (5 October 2008). «Empire Magazine’s 500 Greatest Movies Of All Time». /Film. Archived from the original on 23 February 2022. Retrieved 23 February 2022.

- ^ Plaza, Gerry (12 November 2008). «CNN: ‘Himala’ best Asian film in history». The Philippine Inquirer. Archived from the original on 22 August 2015. Retrieved 23 February 2022.

- ^ Green, Willow (23 September 2019). «The 100 Best Films Of World Cinema». Empire. Archived from the original on 23 November 2015. Retrieved 23 February 2022.

- ^ «The 21st century’s 100 greatest films». BBC. 23 August 2016. Archived from the original on 31 January 2017. Retrieved 8 November 2016.

- ^ Bradshaw, Peter (13 February 2020). «Classics of modern South Korean cinema – ranked!». The Guardian. Archived from the original on 30 May 2020. Retrieved 16 March 2020.

- ^ «Sympathy for the Old Boy… An Interview with Park Chan Wook» Archived 14 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine by Choi Aryong

- ^ «IKONEN : Interview Park Chan Wok Old Boy Lady Vengeance JSA Choi Aryong». Ikonenmagazin.de. Archived from the original on 14 October 2014. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ^ «그리스비극과 한국영화를 통해 본 가족 – 드라마연구 – 한국드라마학회 : 전자저널 논문». 한국표면공학회지. 35 (6): 363–370. December 2002. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ^ «〈올드보이〉에 나타난 여섯 개의 이미지 – 문학과영상 – 문학과영상학회 : 전자저널 논문». Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ^ «Greek tragedy in East Asia: Oldboy (2003)». 17 April 2015. Archived from the original on 24 September 2017. Retrieved 23 September 2017.

- ^ «Korean Movie Reviews for 2003: Save the Green Planet, Memories of Murder, A Tale of Two Sisters, Oldboy, Silmido, and more». www.koreanfilm.org. Archived from the original on 28 July 2010. Retrieved 18 August 2007.

- ^ «BFI Statistical Yearbook 2012» (PDF). British Film Institute (BFI). 2012. p. 125. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ Denis, Fernand (10 January 2005). «La victoire de «Poulpe fiction»«. La Libre Belgique (in French). Archived from the original on 1 March 2022. Retrieved 26 October 2012.

- ^ «Awards (2004)». Bergen International Film Festival. Archived from the original on 13 February 2007. Retrieved 10 April 2007.

- ^ «Oldboy». www.cinemasie.com. Archived from the original on 25 September 2016. Retrieved 3 October 2012.

- ^ «Winners (2004)». The British Independent Film Awards. Archived from the original on 7 April 2007. Retrieved 10 April 2007.

- ^ «All The Awards (2004)». Cannes Film Festival. Archived from the original on 30 November 2006. Retrieved 10 April 2007.

- ^ «The Nominations (2004)». The European Film Awards. Archived from the original on 9 December 2006. Retrieved 10 April 2007.

- ^ Oldboy Makers Plan Vengeance on Zinda Archived September 14, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, TwitchFilm.

- ^ «Spielberg Still Has Oldboy Plans Despite Korean Suit». Anime News Network. Archived from the original on 8 November 2020. Retrieved 26 September 2020.

- ^ Elley, Derek (6 February 2006). «Zinda». Archived from the original on 17 November 2017. Retrieved 25 November 2021.

- ^ Kim, Hyun-rok (16 November 2005). 표절의혹 ‘올드보이’, 제작사 법적대응 고려 [Plagiarism Doubts, ‘Oldboy’ Production Company Considers Legal Confrontation] (in Korean). Star News. Archived from the original on 9 April 2021. Retrieved 26 August 2009.

- ^ Kate Aurthur (30 November 2013). «Adapting «Oldboy»: Its Screenwriter Talks About Twists And Spoilers». Buzzfeed. Archived from the original on 25 February 2017. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ^ «Spike Lee Confirmed to Direct ‘Oldboy’«. /Film. 11 July 2011. Archived from the original on 1 March 2022. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- ^ «Oldboy(2013)». rottentomatoes. Archived from the original on 22 July 2021. Retrieved 27 April 2021.

External links[edit]

- Oldboy at IMDb

- Oldboy at the Korean Movie Database

- Oldboy at HanCinema

- Oldboy at AllMovie

- Oldboy at Rotten Tomatoes

- Oldboy at Metacritic

- Oldboy at Box Office Mojo

Этот корейский фильм начинается, как комедия, и, пройдя через стадии детектива, драмы и психологического триллера, поднимается на уровень кровавых шекспировских трагедий типа «Тита Андроника». Он получил множество престижных премий и удостоился восторженных отзывов критиков и простых зрителей. Кого-то приводят в восторг жестокие драки или шевелящиеся щупальца осьминога, торчащие изо рта главного героя; кого-то – зловещий и таинственный враг, много лет продержавший несчастного Олдбоя в застенках. Но все едины в одном: чувства после просмотра фильма иным словом, чем «потрясение», не передашь. И дело не в фонтанах крови или съеденных моллюсках – просто сила мести и любви, родившей эту месть, не отпускает, словно порочный ночной кошмар.

Кто такой Олдбой?

Слово «Олдбой» переводится с английского и как «старина», «дружище», и как «старый ученик школы». В отношении главного героя верны оба перевода. Он и в самом деле «наш старый добрый парень», вызывающий улыбку и симпатию. Но, чтобы понять причину обрушившихся на него несчастий, Олдбою придётся вернуться в прошлое, в школьные годы.

Зовут его О Дэ Су, то есть «живущий одним днём». Таким он и предстаёт перед нами в начале фильма – весёлый, милый, безответственный шалопай. Первые кадры – хроника из полицейского участка: голоса полицейских за кадром уговаривают его успокоиться, а он брыкается, пытается помочиться в угол, дразнит стражей правопорядка. Наш «старина» напился в день рождения дочки, но не забыл купить ей подарок – смешные игрушечные крылья ангелочка. Что ещё сделать с таким милашкой? Только «понять и простить». Но, едва покинув стены участка, наш «старина» попадает в кошмар, который затянется на 14 лет.

Месть, как она есть

Тема мести невольно возвращает нашу память к «Графу Монте-Кристо». Как и несчастный Эдмон Дантес, Олдбой попал в тюремные застенки за вину, которой он не знал и не понимал. Как и герой Дюма, он от тупого отчаянья и бунта перешёл к анализу своей жизни, попытке побега и самообразованию, только роль всеведущего аббата Фариа для него играл телевизор. Как и для графа Монте-Кристо, главным в жизни Олдбоя стала месть человеку, засадившему его в застенки. Но здесь сходство заканчивается.

Олдбой – мститель и жертва мести одновременно. Его жизнь разбита. Неизвестный могущественный враг отнял его свободу, убил его жену, свалив всю вину на О Дэ Су, и теперь ему безопаснее в этой тюрьме, чем на воле, где его немедленно схватят и посадят в ещё худшую камеру. Он не знает, что стало с его дочерью, а главное – не знает, кто и за что подверг его такому страшному наказанию. Вырвавшись на свободу, он мечтает о мести, но мечты оборачиваются против него.

Враг Олдбоя – Ли У Чжин – страшен не потому, что богат и всесилен. Он – другое лицо всё того же графа Монте-Кристо, с его болезненным желанием отомстить и принесшим всю свою жизнь в жертву этой страсти. Его юный облик кажется неестественным, но в этом – особый психологический смысл: жизнь У Чжина остановилась, он не живёт, не стареет. Он умер когда-то в юности, в страшный момент смерти сестры, и с тех пор, подчинив все мысли мести, отказался от собственной жизни. Слова о мести как о блюде, подаваемом в холодном виде, не оправдываются в «Олдбое». Спустя много лет чувства героев всё так же обострены и горячи, а действия далеки от рассудка.

Преступление и наказание

Первый психологический слой фильма состоит в том, что месть бесплодна и разрушает психику. Второй – касается адекватности преступления и наказания, и того, что случается с человеком, когда он берёт на себя функции судьи, следователя и палача одновременно. В чём, строго говоря, виновен О Дэ Су? «В том, что много говорил», — отвечает его палач. Случайно, походя, просто от того, что молодой парнишка не смог удержать язык за зубами, он разрушил чью-то жизнь. Разрушил, сам не зная об этом. Но ещё хуже – он забыл. Забыл напрочь действующих лиц истории, в которую ввязался случайно.

Любое наше действие может иметь разрушительные последствия. Любое слово, сказанное нами, может стать причиной самых кардинальных изменений в жизни людей, о которых мы толком ничего не знаем. Как эффект «домино» — только тронь одну костяшку, и начнётся стремительное движение. Как круги от камня, небрежно брошенного в воду. Вот только в случае с О Дэ Су, бросившему маленький камешек в чужой пруд, лёгкая зыбь на воде превратилась в цунами.

Презумпция виновности

Виновен ли Дэ Су? Если суд обязан подходить к обвиняемому с позиций презумпции невиновности, то он сам себя уже считает виноватым. Сидя в тюрьме, Олдбой составляет списки людей, которых мог обидеть, и которые могли затаить на него злость. Список получается весьма внушительным. Так ли мил и хорош наш «старина», как это казалось нам в начале?

Насколько виноват в произошедшем У Чжин? В основе случившегося лежат его грехи: он занимался любовными играми с родной сестрой, он не удержал её в момент падения с плотины. Казалось бы, он мечтает свалить свою вину на болтливого О Дэ Су, разгласившего их с сестрой постыдную тайну. 14 лет он терпеливо ждёт, когда в списках Олдбоя появится его имя; не дождавшись, отпускает его на свободу и продолжает играть с ним, как кошка с мышкой. Совершив месть и насладившись ею, У Чжин казнит сам себя, оставив Дэ Су жить в полном сознании своей вины. Он добился, чего хотел, и теперь вынес себе окончательный приговор. Потому ли, что потерял дальнейший смысл жизни, или потому, что хочет понести свою долю ответственности – остаётся судить зрителю.

Олдбой 2003 vs Олдбой 2013

10 лет спустя после триумфа «Олдбоя» в Голливуде был снят ремейк, провалившийся в прокате. Ряд существенных расхождений в сценариях привёл и к расхождениям в психологическом смысле фильмов. Герой голливудского варианта, рекламщик Джо Дюссе, не вызывает никакой симпатии с первых кадров, как и его антагонист.

Психологический подтекст американского фильма получился плоским и утрированным; Спайк Ли снял обычный триллер, к тому же изменив концовку. В американском варианте Олдбой добровольно возвращается в тюрьму, материально обеспечив будущее своей дочери. Корейский вариант тем и хорош, что материальная сторона заботит героев меньше всего; пошли О Дэ Су бриллианты Ми До, она выбросила бы их на помойку, как мусор.

Смысл концовки фильма

Страшная правда, открывшаяся О Дэ Су, не сломила его, как кажется на первый взгляд. Он идёт на крайнюю степень унижения, только бы сохранить её в тайне от дочери. Он находит единственный выход – обратиться к женщине-гипнотизёру, которая работала на У Чжина, чтобы та заставила его забыть то, что он узнал от своего мучителя, и попытаться жить дальше.

Дэ Су, несмотря ни на что, не пытается покончить с собой, он старается сохранить оставшиеся крупицы достоинства. Ведь, в сущности, он не убийца и не садист.

Секунды счастливого непонимания и блаженная улыбка на лице Олдбоя сменяются гримасой. Складывается впечатление, что на этот раз могучая сила гипноза на него не подействовала. Возможно, потому, что есть вещи, которые невозможно забыть ни за что и никогда. А может быть, и потому, что теперь Дэ Су физически отторгает забвение, которое слишком дорого ему обошлось.

Олдбой (фильм, 2003)

Oldeuboi

В 1988 году бизнесмен О Дэ Су торопится домой, чтобы отпраздновать День рождения свой маленькой дочки.

В 1993 году исполнительный директор по рекламе алкогольных напитков Джозеф Дюссе напивается после потери крупного заказа. Прежде чем потерять сознание, он видит женщину с жёлтым зонтиком. Проснувшись, он обнаруживает, что заперт в комнате, похожей на гостиничный номер. Его невидимые тюремщики обеспечивают его едой, водкой и предметами личной гигиены, но не объясняют, почему он находится в заточении. Джозеф видит в новостях сообщение о том, что его бывшая жена была изнасилована и убита, и что он является главным подозреваемым, а их 3-летняя дочь Миа была удочерена через систему социального обеспечения.

В течение следующих 20 лет Дюссе бросает пить и приходит в форму, намереваясь сбежать из заточения и отомстить. Попутно он составляет список тех, кто, возможно, хотел посадить его в тюрьму, и пишет письма, чтобы потом передать их Мии. Однажды он видит телевизионное интервью с Мией, которая говорит, что простит своего отца, если когда-нибудь увидит его.

Вскоре после этого Джозефа усыпляют газом и отпускают посреди поля с мобильным телефоном и небольшой суммой денег в кармане. Он замечает женщину с жёлтым зонтиком и бросается в погоню, но теряет её, при этом встречая медсестру Мари, которая предлагает ему свою помощь; Дюссе отказывается от помощи, но берет её визитную карточку. Джозеф идет в бар своего друга Чаки и объясняет, что произошло. Находясь там, Дюссе получает звонок по мобильному телефону от человека, называющего себя «Незнакомцем», который издевается над ним. Джозеф тратит много усилий, чтобы определить, является ли кто-нибудь из мужчин в его списке тем самым «Незнакомцем», но безуспешно. Дюссе падает в обморок от обезвоживания, и Чаки зовет Мари на помощь. Пока он выздоравливает, Мари, прочитав письма Джозефа к Мии, проникается к нему и предлагает дальнейшую помощь. Она помогает ему определить китайский ресторан, который снабжал его едой, пока он был в тюрьме.

Джозеф следует за доставщиком из ресторана на склад, который оказывается нелегальной «тюрьмой» для самых разных людей. Он убивает нескольких охранников, пытает владельца «тюрьмы» Чейни и тот признаётся, что «Незнакомец» организовал как пленение Джозефа, так и его недавнее освобождение. Вернувшись в бар Чаки, Дюссе застаёт там «Незнакомца» с женщиной с жёлтым зонтиком, которая оказывается его телохранителем. «Незнакомец» говорит, что они похитили Мию, но если Дюссе сможет за 46 часов определить его личность и понять, почему он держал Джозефа в плену в течение 20 лет, он освободит Мию, даст Джозефу 20 миллионов долларов бриллиантами и доказательство его невиновности в убийстве бывшей жены, и совершит самоубийство.

«Незнакомец» также сообщает Джозефу о том, что Чейни и его люди хотят отомстить, напав на Мари. Джозеф мчится к ней домой и попадает в плен к Чейни, тот собирается его пытать, но «Незнакомец» звонит Чейни и предлагает деньги за освобождение Джозефа и Мари. Джозеф прячет Мари в отеле и они занимаются сексом, не подозревая, что Эдриан наблюдает за ними через скрытые камеры.

Используя приложение для распознавания музыки, Мари определяет, что мелодия звонка «Незнакомца» — это гимн бывшей академии «Evergreen», в которую ходил Джозеф. Посетив директора, Джозеф пролистывает фотоальбом и узнаёт в «Незнакомце» студента Эдриана Прайса. Чаки ищет это имя в Интернете и приходит к выводу, что дело в сестре Эдриана Аманде. В голосовом сообщении Джозефу он называет Аманду грубым словом и тогда Эдриан, который перехватил сообщение, приезжает в бар и душит его проволокой от пианино.

Ночью Джозеф и Мари проникают в здание академии и просматривают архивы; Джозеф вспоминает, как случайно увидел Аманду занимавшейся сексом со взрослым мужчиной и рассказал об этом одноклассникам. Отец Эдриана и Аманды Артур Прайс, как выяснилось, сексуально надругался над своими детьми. После событий в школе семья переехала в Люксембург, где Артур позже застрелил обоих детей и жену и покончил с собой, однако Эдриан выжил. Эдриан полагал, что их отношения в семье были выражением любви и винит в разрушении своей семьи Джозефа, раскрывшего их тайну.

Джозеф идёт в пентхаус Эдриана, убивает его охранницу и правильно отвечает на вопросы о личности «Незнакомца» и причинах заточения. Эдриан передаёт ему бриллианты и улики и сопровождает его туда, где должна находиться Миа. Эдриан показывает, что интервью с «Мией» было ненастоящим и эта девушка была наёмной актрисой. Родной дочерью Джозефа на самом деле является Мари. Эдриан объясняет Джозефу, что этим он хотел показать ему, каково это — потерять всё, и после этого кончает жизнь самоубийством.

Джозеф пишет Мари письмо, в котором говорит, что они больше никогда не увидятся и оставляет ей большую часть бриллиантов; остальные бриллианты он использует, чтобы заплатить Чейни за возвращение обратно в «тюрьму».

Похожие фильмы и сериалы

Список популярных актёров, режиссёров и сценаристов.

Сергей Барковский

Сергей Шнырев

Жюльет Бинош

Павел Москаль

Илья Олейников

Фатих Акин

Брюс Уиллис

Ребекка Холл

Санжар Мадиев

Александр Новиков

Римма Маркова

Клаус Мария Брандауэр

Джош Стюарт

Юрий Поляков

Ольга Спиридонова

Ирина Лачина

Анатолий Дзиваев

Александр Митта