Праздник Успения Богородицы, 15 августа – один из основных религиозных праздников греков. Пожалуй, нет – он больше, шире, глобальнее религиозного праздника, это скорее – одна из дат, непосредственно связанных с родной матерью, которые никогда не забываешь, и которые память хранит так же свято, как и даты, связанные с родными детьми.

Богородица – родная мать всех греков, их столиц, городов, деревень, это защитница и покровительница, каковой в Древнем мире для афинян была Афина-Паллада: недаром Парфенон в христианские времена был преобразован в храм, посвященный Афинской Богоматери, и даже в эпоху франкского, католического завоевания назывался «Санта Мария ди Атене».

День 15 августа греки называют «второй пасхой». И потому, что ему предшествует обязательный строгий пост (пусть всего двухнедельный), и потому, что сам День Успения Богоматери празднуется пышно, обильно, с барашками на вертеле, текущим рекой вином и излишествами и салатными яствами.

В этот день греческие города выглядят особенно нарядными, а церкви – особенно к Благовещению, Успению и посвященные Рождению Богородицы – украшаются как к пышной свадьбе. Можно утверждать со всем правом, что именно 15 августа, как и пасха, знаменует собой наступление нового периода, последнюю треть года, когда лето идет на убыль и надвигается очередной девятый вал с началом школьного, студенческого, рабочего года.

Как бы там ни было, а эту дату обойти мы не имели никакого морального права. Тем более, что имя Панагии греки употребляют на каждом шагу – прося, заклиная, угрожая. Ведь Панагия-Богородица многолика, как многолик и почитаемый ее греческий мир.

Сон богопослушной Пелагии

Религиозной столицей Греции считается остров Тинос в Кикладском Архипелаге, остров Панагии с ее величественным Благовещенским собором, к которому стремятся страждущие, надеющиеся, молящие со всего света, а прибегающие к помощи Панагии, как к последней на Земле инстанции – ползут на коленях аж от самого морского порта.

Панагия Тиноса (Благовещенский собор на острове Тинос). Фото с сайта – el.wikipedia.org/wiki

Панагия, можно сказать, сама избрала себе «резиденцию» на Тиносе, и случилось это ровно 190 лет назад, когда по указке Богородицы, в 1823 революционном году, была обнаружена на вспаханном и засеянном крестьянском поле ее чудотворная икона, работы, как гласит предание, самого евангелиста Луки.

Богородица явилась во всей своей величественной красе монахине Пелагее, поповской дочери, в миру Лукии Негрепонти, с 15 лет посвятившей себя Господу. Пелагея родилась в 1752 году (в прошлом году Тинос отпраздновал 260-летие со дня ее рождения), но пророческий сон пришел к ней довольно поздно, когда Пелагее было 70 лет, и она уже отсчитывала «назад» отпущенные ей Господом леты.

Пелагея сну не поверила, решив, что усталые от молитв глаза начинают ей отказывать и не связала ночное посещение царского роста и вида женщины с событиями на материке и началом вооруженного восстания против турок. «Вставай! – приказала ей явившаяся «царица». — Веди народ на поле Антониса Доксараса, где в земле лежит мой лик. Достаньте его и выстройте мне дом».

Никакой народ Пелагия никуда, конечно, не повела, так что Богородице пришлось приходить к ней еще дважды, и только на третий раз Пелагия подчинилась приказу «свыше».

Это случилось в июле 1822 года. Копали-копали всем островом на участке Антониса Доксараса, да так ничего и не нашли, и только через полгода, 30 января 1823 года заступ одного из крестьян наткнулся на дерево иконной рамы. Существует предание, согласно которому икона Благовещения была защищена стеклом, и самые первые счастливцы, которым выпал жребий это стекло разбить и прикоснуться к чудотворной иконе, навсегда излечились от всех изводящих их недугов.

Слух о чудотворной иконе мгновенно облетел охваченную Революцией Грецию, и на поклон к ней явились по очереди ее вожди с изъеденными пороховой пылью лицами. Свои посвящения оставили у ее оклада адмиралы Мьяулисы и Канарис, генералы Макрияннис и Колокотронис: последний преподнес Панагии кольцо, которое и по сей день хранится в Благовещенском соборе на Тиносе.

Интересно, что Благовещенский собор был построен на месте нахождения чудотворной иконы, в том самом месте, где в древности стоял театр Диониса, а затем – раннехристианский храм Иоанна Предтечи. Кроме того, сам остров Тинос считался священным задолго до того, как монахиня Пелагея увидела вещий сон: ведь здесь находилось один из древнейших паломнических святилищ, посвященных Посейдону и Амфитрите, могущественной морской божественной паре.

Рассказов о чудесах, свершенных Панагией острова Тиноса – великое множество. Все это – частные истории отдельных людей, верить которым или сомневаться в них – право каждого. Но вот в очевидности одного чуда сомневаться не приходится, так как оно – самое настоящее «историческое чудо» — случилось на глазах тысяч паломников, собравшихся в тот блаженный день 15 августа 1940 года отметить День Успения Богородицы.

Греция находилась в состоянии «воинствующего» мира с фашистской Италией, но диктатор Греции Иоаннис Метаксас еще не ответил громовым «ОХИ» («НЕТ») на предложение Италии о капитуляции, и до начала греко-итальянской войны оставались три с половиной месяца. Итальянская подводная лодка «Delfino», точно ждущая своего часа акула, лежала в морской толще у священного кикладского острова. К берегу Тиноса радостно плыли два празднично украшенных пассажирских корабля, «Эсперос» и «Эльза» с паломниками на борту, каждый из которых заготавливал свою речь, которую он произнесет в краткий миг свидания с чудотворной иконой. В порту острова стоял на якоре крейсер «ЭЛЛИ», с которого вот-вот должен был ступить на берег десант для сопровождения Благовещенской иконы.

Как вдруг… случилось невероятное! Итальянцы открыли огонь по греческим «целям», выпустив сразу несколько торпед! Две торпеды полетели прямо к пассажирским судам с паломниками, где, началась паника. Однако, ни одна из торпед цели не достигла! Они врезались в окружающие порт скалы, подняв в воздух тонны воды. Поразившая же крейсер «ЭЛЛИ» торпеда унесла 10 жизней – моряков и офицеров, находившихся непосредственно в сфере удара торпеды.

Богородица сделала в день своего праздника, что могла: без ее защиты жертв было бы несравненно больше.

Когда откроется сотая дверь…

О посвященных Богородице греческих храмах можно рассказывать бесконечно: у нее столько же имен, сколько и статей в словаре греческих топонимов. Но есть среди них и храмы знаменитые, собирающие в День Ее Успения десятки тысяч верующих и зрителей. Таким храмом является великая Панагия Сумела на Понте и ее филиал на севере Греции,

Панагия Сумела. Фото с сайта — eirinika.gr

монастырский комплекс Панагия Хозовиотисса на маленьком островке Аморгос,

Панагия Хозовиотисса на маленьком островке Аморгос,

Таким храмом является Стовратная Панагия (Экатондапилиани) на соседнем с Тиносом острове Паросе, один из наиболее хорошо сохранившихся и наиболее крупных раннехристианских памятников в Греции.

Согласно традиции, этот храм выстроил еще в IV веке византийский император Константин Великий, исполняя просьбу своей матери, Святой Елены, которая, отправляясь на паломничество к Святым местам, потерпела крушение и спаслась от верной гибели на берегах Пароса.

Спасшаяся императрица-мать Елена пообещала защитнице Константинополя Панагии выстроить в честь нее на Паросе Успенский храм, ничуть не уступающий в убранстве храмам столичным, царьградским. Еще два века спустя архитектор императора Юстиниана достроил храм по современным образам, и традиция гласит, что этим зодчим был лучший ученик архитектора Святой Софии, превзошедший в мастерстве своего учителя.

Успенский собор на Паросе с XVI века получил название «Стовратного»: 99 дверей храма видны любому посетителю, а вот 100-ая дверь – невидима, она откроется и обнаружится лишь тогда, когда откроется потайная дверь в захваченной турками 560 лет назад, в 1453 году, Святой Софии Константинопольской.

Что же это за такая потайная дверь? Легенда гласит, что 29 мая 1453 года, когда турки захватили Константинополь, за потайной дверью укрылся служивший в тот момент службу священник, захватив с собой чашу для причащений. Та же легенда, как и греческие народные песни, гласит, что дверь откроется в том момент, когда Святая София вновь перейдет в греческие руки…

Так вот, в настоящее время константинольские (стамбульские) документалисты снимают фильм под зданием Святой Софии, в катакомбах, вьющихся под одним из старейших построек мира. Фильм выйдет на экраны в 2014 году, а пока… режиссер фильма рассказал журналистам центральной стамбульской газеты «Milliyet» о тайнах, с которыми им довелось столкнуться под священной землей, о потайных комнатах, погребениях, заполненных водой колодцах. Группе удалось пройти пока лишь 238 метров по подземным галереям и обнаружить с два десятка разветвлений, неизвестно куда ведущих.

Так вот, один из входов в сеть переплетенных галерей, был запечатан мраморной плитой-дверью, располагающейся около мраморного источника под фундаментом храма…

Та ли это дверь, о которой гласит легенда?

И, если та, то, может быть, нам доведется стать свидетелями космоисторичсеких событий.

The festival calendar of Classical Athens involved the staging of many festivals each year. This includes festivals held in honor of Athena, Dionysus, Apollo, Artemis, Demeter, Persephone, Hermes, and Herakles. Other Athenian festivals were based around family, citizenship, sacrifice and women. There were at least 120 festival days each year.

Athena[edit]

The Panathenaea (Ancient Greek: Παναθήναια, «all-Athenian festival») was the most important festival for Athens and one of the grandest in the entire ancient Greek world. Except for slaves, all inhabitants of the polis could take part in the festival. This holiday of great antiquity is believed to have been the observance of Athena’s birthday and honoured the goddess as the city’s patron divinity, Athena Polias (‘Athena of the city’). A procession assembled before dawn at the Dipylon Gate in the northern sector of the city. The procession, led by the Kanephoros, made its way to the Areopagus and in front of the Temple of Athena Nike next to the Propylaea. Only Athenian citizens were allowed to pass through the Propylaea and enter the Acropolis. The procession passed the Parthenon and stopped at the great altar of Athena in front of the Erechtheum. Every four years a newly woven peplos was dedicated to Athena.

Dionysus[edit]

The Dionysia was a large religious festival in ancient Athens in honor of the god Dionysus, the central event of which was the performance of tragedies and, from 487 BCE, comedies. It was the second-most important festival after the Panathenaia. The Dionysia actually comprised two related festivals, the Rural Dionysia and the City Dionysia, which took place in different parts of the year. They were also an essential part of the Dionysian Mysteries.

The Lenaia (Ancient Greek: Λήναια) was an annual festival with a dramatic competition but one of the lesser festivals of Athens and Ionia in ancient Greece. The Lenaia took place (in Athens) in the month of Gamelion, roughly corresponding to January. The festival was in honour of Dionysus Lenaius. Lenaia probably comes from lenai, another name for the Maenads, the female worshippers of Dionysus.

The Anthesteria, one of the four Athenian festivals in honour of Dionysus (collectively the Dionysia), was held annually for three days, the eleventh to thirteenth of the month of Anthesterion (the January/February full moon);[1] it was preceded by the Lenaia.[2] At the centre of this wine-drinking festival was the celebration of the maturing of the wine stored at the previous vintage, whose pithoi were now ceremoniously opened, and the beginning of spring. Athenians of the Classical age were aware that the festival was of great antiquity; Walter Burkert points out that the mythic reflection of this is the Attic founder-king Theseus’ release of Ariadne to Dionysus,[3] but this is no longer considered a dependable sign that the festival had been celebrated in the Minoan period. Since the festival was celebrated by Athens and all the Ionian cities, it is assumed that it must have preceded the Ionian migration of the late eleventh or early tenth century BCE.

Apollo and Artemis[edit]

The Boedromia (Ancient Greek: Βοηδρόμια) was an ancient Greek festival held at Athens on the 7th of Boedromion (summer) in the honour of Apollo Boedromios (the helper in distress). The festival had a military connotation, and thanks the god for his assistance to the Athenians during wars. It could also commemorate a specific intervention at the origin of the festival. The event in question, according to the ancient writers, could be the help brought to Theseus in his war against the Amazons, or the assistance provided to the king Erechtheus during his struggle against Eumolpus. During the event, sacrifices were also made to Artemis Agrotera.

The Thargelia (Ancient Greek: Θαργήλια) was one of the chief Athenian festivals in honour of the Delian Apollo and Artemis, held on their birthdays, the 6th and 7th of the month Thargelion (about 24 and 25 May). Essentially an agricultural festival, the Thargelia included a purifying and expiatory ceremony. While the people offered the first-fruits of the earth to the god in token of thankfulness, it was at the same time necessary to propitiate him, lest he might ruin the harvest by excessive heat, possibly accompanied by pestilence. The purificatory preceded the thanksgiving service. On the 6th a sheep was sacrificed to Demeter Chloe on the Acropolis, and perhaps a swine to the Fates, but the most important ritual was the following: Two men, the ugliest that could be found (the Pharmakoi) were chosen to die, one for the men, the other (according to some, a woman) for the women. On the day of the sacrifice they were led round with strings of figs on their necks, and whipped on the genitals with rods of figwood and squills. When they reached the place of sacrifice on the shore, they were stoned to death, their bodies burnt, and the ashes thrown into the sea (or over the land, to act as a fertilizing influence).

Aphrodite and Adonis[edit]

Aphrodite and her mortal lover Adonis

The Adonia (Ἀδώνια), or Adonic feasts, were ancient feasts instituted in honour of Aphrodite and Adonis, and observed with great solemnity among the Greeks, Egyptians, etc. The festival took place in the late summer and lasted between one and eight days. The event was run by women and attended exclusively by them. All Athenian women were allowed to attend, including widows, wives and unmarried women of different social classes.[4] On the first day, they brought into the streets statues of Adonis, which were laid out as corpses; and they observed all the rites customary at funerals, beating themselves and uttering lamentations, in imitation of the cries of Aphrodite for the death of her paramour. The second day was spent in merriment and feasting; because Adonis was allowed to return to life, and spend half of the year with Aphrodite. The Adonis festival was held annually to honor the death of Adonis, Aphrodite’s mortal lover who was killed by a boar. Women would participate in the festival by planting their own gardens of Adonis inside of fractured pottery vessels to transport to the rooftops where the ceremonies took place.[5] The women would march through the city to the sea, where Adonis was born and buried. This was preceded by wailing on the rooftops that could be heard throughout the city. The Adonis was an event where women were allowed unusual freedom and independence, as they could socialize without constraint under their own terms.[6]

Demeter and Persephone[edit]

The Thesmophoria was a festival held in Greek cities, in honour of the goddesses Demeter and her daughter Persephone. The name derives from thesmoi, or laws by which men must work the land.[7] The Thesmophoria were the most widespread festivals and the main expression of the cult of Demeter, aside from the Eleusinian Mysteries. The Thesmophoria commemorated the third of the year when Demeter abstained from her role of goddess of the harvest and growth in mourning for her daughter who was in the realm of the Underworld. Their distinctive feature was the sacrifice of pigs.[8]

The festival of the Skira or Skirophoria in the calendar of ancient Athens, closely associated with the Thesmophoria, marked the dissolution of the old year in May/June.[9] At Athens, the last month of the year was Skirophorion, after the festival. Its most prominent feature was the procession that led out of Athens to a place called Skiron near Eleusis, in which the priestess of Athena and the priest of Poseidon took part, under a ceremonial canopy called the skiron, which was held up by the Eteoboutadai.[10] Their joint temple on the Acropolis was the Erechtheum, where Poseidon embodied as Erechtheus remained a numinous presence.[11]

Hermes[edit]

The Hermaea (Ancient Greek: Ἔρμαια) were ancient Greek festivals held annually in honour of Hermes, notably at Pheneos at the foot of Mt Cyllene in Arcadia. Usually the Hermaea honoured Hermes as patron of sport and gymnastics, often in conjunction with Heracles. They included athletic contests of various kinds and were normally held in gymnasia and palaestrae. The Athenian Hermaea were an occasion for relatively unrestrained and rowdy competitions for the ephebes, and Solon tried to prohibit adults from attending.[12][13]

Heracles[edit]

The Heracleia were ancient festivals honouring the divine hero Heracles. The ancient Athenians celebrated the festival, which commemorated the death of Heracles, on the second day of the month of Metageitnion (which would fall in late July or early August), at the Κυνοσαργες (Kynosarges) gymnasium at the demos Diomeia outside the walls of Athens, in a sanctuary dedicated to Heracles. His priests were drawn from the list of boys who were not full Athenian citizens (nothoi).

Citizenship festivals[edit]

The Apaturia (Greek: Ἀπατούρια) were Ancient Greek festivals held annually by all the Ionian towns, except Ephesus and Colophon who were excluded due to acts of bloodshed. The festivals honored the origins and the families of the men who were sent to Ionia by the kings[clarification needed] and were attended exclusively by the descendants of these men. In these festivals, men would present their sons to the clan to swear an oath of legitimacy. The oath was made to preserve the purity of the bloodline and their connection to the original settlers. The oath was followed by a sacrifice of either a sheep or a goat, and then the sons’ names getting inscribed in the register.[14]

At Athens, the Apaturia, a Greek citizenship festival took place on the 11th, 12th and 13th days of the month Pyanepsion (mid-October to mid-November). At this festival, the various phratries, or clans, of Attica met to discuss their affairs, along with initiating the sons into the clans.[15]

Family festivals[edit]

The Amphidromia was a ceremonial feast celebrated on the fifth or seventh day after the birth of a child. It was a family festival of the Athenians, at which the newly born child was introduced into the family, and children of poorer families received its name. Children of wealthier families held a naming ceremony on the tenth day called dekate. This ceremony, unlike the Amphidromia, was open to the public by invitation. No particular day was fixed for this solemnity; but it did not take place very soon after the birth of the child, for it was believed that most children died before the seventh day, and the solemnity was therefore generally deferred till after that period, that there might be at least some probability of the child remaining alive.

Women in Athenian festivals[edit]

Athenian women were allowed to attend the majority of festivals, but often had limited participation in the festivities or feasts. They would have been escorted by a family member or husband to the male domination festivals, as it would have been seen as inappropriate for an unmarried girl or married woman to go unsupervised. Non-citizen women and slaves would be present as prostitutes or workers for the male guests, but were not included in the actual festival.[16]

Select male festivals would include women in their festivities. Often it was high-born women who were allowed to attend the Panathenaia as basket-bearers, but would not participate in the feast itself. The public festivals of Anthesteria and Dionysia, included women both in attendance and rites of sacrifice.[17] The festival of Argive held in honor of Hera was attended by both men and women. The men and women’s involvement in Argive was close to equal, as they shared rites of feasting and sacrifice.[18]

Athenian women held their own festivals that often excluded men, such as the Thesmophoria, Adonia, and Skira. Festivals hosted by women were not supported by the state and instead were private festivals run and funded by wealthy women. For this reason they were often hosted inside homes and held at night.[19] The Thesmophoria was a major women’s festival held in the honour of Demeter. Women’s festivals were often dedicated to a goddess and were held as a way of social, religious and personal expression for women. Wealthy women would sponsor the events and elect other women to preside over the festival. Common themes of festivals hosted by women were the transitioning from a girl to a woman, as well as signs of fertility.

There were festivals held as a way to protest the power of the men in Athens, and empower the women in the community. The Skira was an example of a woman-only event that was held annually in the summer as an opposition to men. This festival was held in honor of the Goddesses Athena and Demeter, where women would eat garlic as it was linked to sexual abstinence to oppose the men in the community and their husbands.[20]

Sacrifice in Athenian festivals[edit]

Blood sacrifices were a common occurrence in Athenian festivals. Athenians used blood sacrifices to make the accord between gods and men, and it renewed the bonds of the community. Many animals were sacrificed in Athenian festivals, but the most common animals were sheep, lamb, and goat. This is because they were readily available in Athens and the cost of them was minimal. Bigger sacrifices included bulls and oxen. These animals were reserved for larger festivals like Buphonia. Goats were commonly sacrificed at the festivals of Dionysus, Apotropaiso, Lykeios, and Pythois.[21]

Sacrifice in Athenian festivals was very formal, and the act was less focused on violence or aggression, and more focused on ritual. Women and men had very specific roles in sacrifices. Only female virgins, called kanephoroi, could lead the procession as they were required to carry the sacred implements and provisions at the sacrifices. The kanephoroi was also required to raise the ololuge, a screaming howl in which the woman would perform as the man would begin killing the animal. The men were the sacrificers; they would cut their hair as an offering, then butcher the animal on the altar. The animal would be skinned and then cooked over the altar for the participants to consume.[22] Ritual sacrifice in Athens had three main steps: the preparation of the sacrifice, the distribution, and consumption of the sacrificial animal.[23]

Other forms of sacrifice took place at Athenian festivals, such as food and other items. Offerings of agricultural products took place at the Proerosia, the Thargelia, the Pyanospia, the Thalysia and the Pithoigia. These offerings were made to ask for help in the production of crops and the breeding animals from Gods and Goddesses such as Demeter, Apollo, and Artemis. The offerings were more likely to happen in areas prone to frost, drought, rain and hailstorms. The offerings consisted of liquid and solid food, and was usually presented daily or at common feasts.[24]

Number[edit]

Jon D. Mikalson in his book, The Sacred and Civil Calendar of the Athenian Year, states “The total number of positively dated festival days (i.e., the total in the two lists) is 120, which constitutes 33 percent of the days of the year”.[25]

Other known festivals[edit]

- Delphinia

- Haloa

- Pandia (festival)

- Synoikia

References[edit]

- ^ Thucydides (ii.15) noted that «the more ancient Dionysia were celebrated on the twelfth day of the month of Anthesterion in the temple of Dionysus Limnaios («Dionysus in the Marshes»).

- ^ Walter Burkert, Greek Religion 1985 §V.2.4, pp 237–42, offers a concise assessment, with full bibliography.

- ^ Burkert 1985: §II.7.7, p 109.

- ^ Fredal, James (2002). «Herm Choppers, the Adonia, and Rhetorical Action in Ancient Greece». College English. 64 (5): 590–612. doi:10.2307/3250755. JSTOR 3250755.

- ^ Smith, Tyler Jo (June 2017). «The Athenian Adonia in Context: The Adonis Festival as Cultural Practice». Religious Studies Review (2 ed.). 43: 163–164 – via Ebsco.

- ^ Fredal, James (2002). «Herm Choppers, the Adonia, and Rhetorical Action in Ancient Greece». College English. 64 (5): 590–612. doi:10.2307/3250755. JSTOR 3250755.

- ^ For a fuller discussion of the name considering multiple interpretations, cf. A.B. Stallsmith’s article «Interpreting the Thesmophoria» in Classical Bulletin.

- ^ «Pig bones, votive pigs, and terracottas, which show a votary or the goddess herself holding the piglet in her arms, are the archaeological signs of Demeter sanctuaries everywhere.»(Burkert p 242).

- ^ The festival is analysed by Walter Burkert, in Homo Necans (1972, tr. 1983:143-49), with bibliography p 143, note 33.

- ^ L. Deubner, Attische Feste (Berlin 1932:49–50); their accompanier in late descriptions, the priest of Helios, Walter Burkert regards as a Hellenistic innovation rather than an archaic survival (Burkert 1983:)

- ^ See Poseidon#The foundation of Athens; the connection was an early one: in the Odyssey (vii.81), Athena was said to have «entered the house of Erechtheus» (noted by Burkert 1983:144).

- ^ William Smith (editor). «Hermaea» Archived May 29, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (1870), p.604.

- ^ C. Daremberg & E. Saglio. «Hermaia», Dictionnaire des antiquités grecques et romaines (1900), tome III, volume 1, pp.134–5.

- ^ Herodotus i. 147.

- ^

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). «Apaturia». Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 2 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 160.

- ^ Burton, Joan (1998). «Women’s Commensality in the Ancient Greek World». Greece and Rome. 45 (2): 148–149. doi:10.1017/S0017383500033659 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Burton, Joan (1998). «Women’s Commensality in the Ancient Greek World». Greece and Rome. 45 (2): 150. doi:10.1017/S0017383500033659 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Burton, Joan (1998). «Women’s Commensality in the Ancient Greek World». Greece and Rome. 45 (2): 157. doi:10.1017/S0017383500033659 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Burton, Joan (1998). «Women’s Commensality in the Ancient Greek World». Greece and Rome. 45 (2): 152. doi:10.1017/S0017383500033659 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Burton, Joan (1998). «Women’s Commensality in the Ancient Greek World». Greece and Rome. 45 (2): 151. doi:10.1017/S0017383500033659 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Osborne, Robin (1993). «Women and Sacrifice in Classical Greece». The Classical Quarterly (2 ed.). 43 (2): 392–405. doi:10.1017/S0009838800039914 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Osborne, Robin (1993). «Women and Sacrifice in Classical Greece». The Classical Quarterly (2 ed.). 43 (2): 392–405. doi:10.1017/S0009838800039914 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Demaris, Richard. E (2013). «Sacrifice, an Ancient Mediterranean Ritual». Biblical Theology Bulletin (2 ed.). 43 (2): 60–73. doi:10.1177/0146107913482279. S2CID 143693807.

- ^ Wagner- Hasel, B (2016). «GIFTS FOR THE GODS». The Classical Review (2 ed.). 66: 468–470 – via ProQuest.

- ^ Mikalson, Jon (1976). The Sacred and Civil Calendar of the Athenian Year. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691644691. JSTOR j.ctt13x10wg.

The festival calendar of Classical Athens involved the staging of many festivals each year. This includes festivals held in honor of Athena, Dionysus, Apollo, Artemis, Demeter, Persephone, Hermes, and Herakles. Other Athenian festivals were based around family, citizenship, sacrifice and women. There were at least 120 festival days each year.

Athena[edit]

The Panathenaea (Ancient Greek: Παναθήναια, «all-Athenian festival») was the most important festival for Athens and one of the grandest in the entire ancient Greek world. Except for slaves, all inhabitants of the polis could take part in the festival. This holiday of great antiquity is believed to have been the observance of Athena’s birthday and honoured the goddess as the city’s patron divinity, Athena Polias (‘Athena of the city’). A procession assembled before dawn at the Dipylon Gate in the northern sector of the city. The procession, led by the Kanephoros, made its way to the Areopagus and in front of the Temple of Athena Nike next to the Propylaea. Only Athenian citizens were allowed to pass through the Propylaea and enter the Acropolis. The procession passed the Parthenon and stopped at the great altar of Athena in front of the Erechtheum. Every four years a newly woven peplos was dedicated to Athena.

Dionysus[edit]

The Dionysia was a large religious festival in ancient Athens in honor of the god Dionysus, the central event of which was the performance of tragedies and, from 487 BCE, comedies. It was the second-most important festival after the Panathenaia. The Dionysia actually comprised two related festivals, the Rural Dionysia and the City Dionysia, which took place in different parts of the year. They were also an essential part of the Dionysian Mysteries.

The Lenaia (Ancient Greek: Λήναια) was an annual festival with a dramatic competition but one of the lesser festivals of Athens and Ionia in ancient Greece. The Lenaia took place (in Athens) in the month of Gamelion, roughly corresponding to January. The festival was in honour of Dionysus Lenaius. Lenaia probably comes from lenai, another name for the Maenads, the female worshippers of Dionysus.

The Anthesteria, one of the four Athenian festivals in honour of Dionysus (collectively the Dionysia), was held annually for three days, the eleventh to thirteenth of the month of Anthesterion (the January/February full moon);[1] it was preceded by the Lenaia.[2] At the centre of this wine-drinking festival was the celebration of the maturing of the wine stored at the previous vintage, whose pithoi were now ceremoniously opened, and the beginning of spring. Athenians of the Classical age were aware that the festival was of great antiquity; Walter Burkert points out that the mythic reflection of this is the Attic founder-king Theseus’ release of Ariadne to Dionysus,[3] but this is no longer considered a dependable sign that the festival had been celebrated in the Minoan period. Since the festival was celebrated by Athens and all the Ionian cities, it is assumed that it must have preceded the Ionian migration of the late eleventh or early tenth century BCE.

Apollo and Artemis[edit]

The Boedromia (Ancient Greek: Βοηδρόμια) was an ancient Greek festival held at Athens on the 7th of Boedromion (summer) in the honour of Apollo Boedromios (the helper in distress). The festival had a military connotation, and thanks the god for his assistance to the Athenians during wars. It could also commemorate a specific intervention at the origin of the festival. The event in question, according to the ancient writers, could be the help brought to Theseus in his war against the Amazons, or the assistance provided to the king Erechtheus during his struggle against Eumolpus. During the event, sacrifices were also made to Artemis Agrotera.

The Thargelia (Ancient Greek: Θαργήλια) was one of the chief Athenian festivals in honour of the Delian Apollo and Artemis, held on their birthdays, the 6th and 7th of the month Thargelion (about 24 and 25 May). Essentially an agricultural festival, the Thargelia included a purifying and expiatory ceremony. While the people offered the first-fruits of the earth to the god in token of thankfulness, it was at the same time necessary to propitiate him, lest he might ruin the harvest by excessive heat, possibly accompanied by pestilence. The purificatory preceded the thanksgiving service. On the 6th a sheep was sacrificed to Demeter Chloe on the Acropolis, and perhaps a swine to the Fates, but the most important ritual was the following: Two men, the ugliest that could be found (the Pharmakoi) were chosen to die, one for the men, the other (according to some, a woman) for the women. On the day of the sacrifice they were led round with strings of figs on their necks, and whipped on the genitals with rods of figwood and squills. When they reached the place of sacrifice on the shore, they were stoned to death, their bodies burnt, and the ashes thrown into the sea (or over the land, to act as a fertilizing influence).

Aphrodite and Adonis[edit]

Aphrodite and her mortal lover Adonis

The Adonia (Ἀδώνια), or Adonic feasts, were ancient feasts instituted in honour of Aphrodite and Adonis, and observed with great solemnity among the Greeks, Egyptians, etc. The festival took place in the late summer and lasted between one and eight days. The event was run by women and attended exclusively by them. All Athenian women were allowed to attend, including widows, wives and unmarried women of different social classes.[4] On the first day, they brought into the streets statues of Adonis, which were laid out as corpses; and they observed all the rites customary at funerals, beating themselves and uttering lamentations, in imitation of the cries of Aphrodite for the death of her paramour. The second day was spent in merriment and feasting; because Adonis was allowed to return to life, and spend half of the year with Aphrodite. The Adonis festival was held annually to honor the death of Adonis, Aphrodite’s mortal lover who was killed by a boar. Women would participate in the festival by planting their own gardens of Adonis inside of fractured pottery vessels to transport to the rooftops where the ceremonies took place.[5] The women would march through the city to the sea, where Adonis was born and buried. This was preceded by wailing on the rooftops that could be heard throughout the city. The Adonis was an event where women were allowed unusual freedom and independence, as they could socialize without constraint under their own terms.[6]

Demeter and Persephone[edit]

The Thesmophoria was a festival held in Greek cities, in honour of the goddesses Demeter and her daughter Persephone. The name derives from thesmoi, or laws by which men must work the land.[7] The Thesmophoria were the most widespread festivals and the main expression of the cult of Demeter, aside from the Eleusinian Mysteries. The Thesmophoria commemorated the third of the year when Demeter abstained from her role of goddess of the harvest and growth in mourning for her daughter who was in the realm of the Underworld. Their distinctive feature was the sacrifice of pigs.[8]

The festival of the Skira or Skirophoria in the calendar of ancient Athens, closely associated with the Thesmophoria, marked the dissolution of the old year in May/June.[9] At Athens, the last month of the year was Skirophorion, after the festival. Its most prominent feature was the procession that led out of Athens to a place called Skiron near Eleusis, in which the priestess of Athena and the priest of Poseidon took part, under a ceremonial canopy called the skiron, which was held up by the Eteoboutadai.[10] Their joint temple on the Acropolis was the Erechtheum, where Poseidon embodied as Erechtheus remained a numinous presence.[11]

Hermes[edit]

The Hermaea (Ancient Greek: Ἔρμαια) were ancient Greek festivals held annually in honour of Hermes, notably at Pheneos at the foot of Mt Cyllene in Arcadia. Usually the Hermaea honoured Hermes as patron of sport and gymnastics, often in conjunction with Heracles. They included athletic contests of various kinds and were normally held in gymnasia and palaestrae. The Athenian Hermaea were an occasion for relatively unrestrained and rowdy competitions for the ephebes, and Solon tried to prohibit adults from attending.[12][13]

Heracles[edit]

The Heracleia were ancient festivals honouring the divine hero Heracles. The ancient Athenians celebrated the festival, which commemorated the death of Heracles, on the second day of the month of Metageitnion (which would fall in late July or early August), at the Κυνοσαργες (Kynosarges) gymnasium at the demos Diomeia outside the walls of Athens, in a sanctuary dedicated to Heracles. His priests were drawn from the list of boys who were not full Athenian citizens (nothoi).

Citizenship festivals[edit]

The Apaturia (Greek: Ἀπατούρια) were Ancient Greek festivals held annually by all the Ionian towns, except Ephesus and Colophon who were excluded due to acts of bloodshed. The festivals honored the origins and the families of the men who were sent to Ionia by the kings[clarification needed] and were attended exclusively by the descendants of these men. In these festivals, men would present their sons to the clan to swear an oath of legitimacy. The oath was made to preserve the purity of the bloodline and their connection to the original settlers. The oath was followed by a sacrifice of either a sheep or a goat, and then the sons’ names getting inscribed in the register.[14]

At Athens, the Apaturia, a Greek citizenship festival took place on the 11th, 12th and 13th days of the month Pyanepsion (mid-October to mid-November). At this festival, the various phratries, or clans, of Attica met to discuss their affairs, along with initiating the sons into the clans.[15]

Family festivals[edit]

The Amphidromia was a ceremonial feast celebrated on the fifth or seventh day after the birth of a child. It was a family festival of the Athenians, at which the newly born child was introduced into the family, and children of poorer families received its name. Children of wealthier families held a naming ceremony on the tenth day called dekate. This ceremony, unlike the Amphidromia, was open to the public by invitation. No particular day was fixed for this solemnity; but it did not take place very soon after the birth of the child, for it was believed that most children died before the seventh day, and the solemnity was therefore generally deferred till after that period, that there might be at least some probability of the child remaining alive.

Women in Athenian festivals[edit]

Athenian women were allowed to attend the majority of festivals, but often had limited participation in the festivities or feasts. They would have been escorted by a family member or husband to the male domination festivals, as it would have been seen as inappropriate for an unmarried girl or married woman to go unsupervised. Non-citizen women and slaves would be present as prostitutes or workers for the male guests, but were not included in the actual festival.[16]

Select male festivals would include women in their festivities. Often it was high-born women who were allowed to attend the Panathenaia as basket-bearers, but would not participate in the feast itself. The public festivals of Anthesteria and Dionysia, included women both in attendance and rites of sacrifice.[17] The festival of Argive held in honor of Hera was attended by both men and women. The men and women’s involvement in Argive was close to equal, as they shared rites of feasting and sacrifice.[18]

Athenian women held their own festivals that often excluded men, such as the Thesmophoria, Adonia, and Skira. Festivals hosted by women were not supported by the state and instead were private festivals run and funded by wealthy women. For this reason they were often hosted inside homes and held at night.[19] The Thesmophoria was a major women’s festival held in the honour of Demeter. Women’s festivals were often dedicated to a goddess and were held as a way of social, religious and personal expression for women. Wealthy women would sponsor the events and elect other women to preside over the festival. Common themes of festivals hosted by women were the transitioning from a girl to a woman, as well as signs of fertility.

There were festivals held as a way to protest the power of the men in Athens, and empower the women in the community. The Skira was an example of a woman-only event that was held annually in the summer as an opposition to men. This festival was held in honor of the Goddesses Athena and Demeter, where women would eat garlic as it was linked to sexual abstinence to oppose the men in the community and their husbands.[20]

Sacrifice in Athenian festivals[edit]

Blood sacrifices were a common occurrence in Athenian festivals. Athenians used blood sacrifices to make the accord between gods and men, and it renewed the bonds of the community. Many animals were sacrificed in Athenian festivals, but the most common animals were sheep, lamb, and goat. This is because they were readily available in Athens and the cost of them was minimal. Bigger sacrifices included bulls and oxen. These animals were reserved for larger festivals like Buphonia. Goats were commonly sacrificed at the festivals of Dionysus, Apotropaiso, Lykeios, and Pythois.[21]

Sacrifice in Athenian festivals was very formal, and the act was less focused on violence or aggression, and more focused on ritual. Women and men had very specific roles in sacrifices. Only female virgins, called kanephoroi, could lead the procession as they were required to carry the sacred implements and provisions at the sacrifices. The kanephoroi was also required to raise the ololuge, a screaming howl in which the woman would perform as the man would begin killing the animal. The men were the sacrificers; they would cut their hair as an offering, then butcher the animal on the altar. The animal would be skinned and then cooked over the altar for the participants to consume.[22] Ritual sacrifice in Athens had three main steps: the preparation of the sacrifice, the distribution, and consumption of the sacrificial animal.[23]

Other forms of sacrifice took place at Athenian festivals, such as food and other items. Offerings of agricultural products took place at the Proerosia, the Thargelia, the Pyanospia, the Thalysia and the Pithoigia. These offerings were made to ask for help in the production of crops and the breeding animals from Gods and Goddesses such as Demeter, Apollo, and Artemis. The offerings were more likely to happen in areas prone to frost, drought, rain and hailstorms. The offerings consisted of liquid and solid food, and was usually presented daily or at common feasts.[24]

Number[edit]

Jon D. Mikalson in his book, The Sacred and Civil Calendar of the Athenian Year, states “The total number of positively dated festival days (i.e., the total in the two lists) is 120, which constitutes 33 percent of the days of the year”.[25]

Other known festivals[edit]

- Delphinia

- Haloa

- Pandia (festival)

- Synoikia

References[edit]

- ^ Thucydides (ii.15) noted that «the more ancient Dionysia were celebrated on the twelfth day of the month of Anthesterion in the temple of Dionysus Limnaios («Dionysus in the Marshes»).

- ^ Walter Burkert, Greek Religion 1985 §V.2.4, pp 237–42, offers a concise assessment, with full bibliography.

- ^ Burkert 1985: §II.7.7, p 109.

- ^ Fredal, James (2002). «Herm Choppers, the Adonia, and Rhetorical Action in Ancient Greece». College English. 64 (5): 590–612. doi:10.2307/3250755. JSTOR 3250755.

- ^ Smith, Tyler Jo (June 2017). «The Athenian Adonia in Context: The Adonis Festival as Cultural Practice». Religious Studies Review (2 ed.). 43: 163–164 – via Ebsco.

- ^ Fredal, James (2002). «Herm Choppers, the Adonia, and Rhetorical Action in Ancient Greece». College English. 64 (5): 590–612. doi:10.2307/3250755. JSTOR 3250755.

- ^ For a fuller discussion of the name considering multiple interpretations, cf. A.B. Stallsmith’s article «Interpreting the Thesmophoria» in Classical Bulletin.

- ^ «Pig bones, votive pigs, and terracottas, which show a votary or the goddess herself holding the piglet in her arms, are the archaeological signs of Demeter sanctuaries everywhere.»(Burkert p 242).

- ^ The festival is analysed by Walter Burkert, in Homo Necans (1972, tr. 1983:143-49), with bibliography p 143, note 33.

- ^ L. Deubner, Attische Feste (Berlin 1932:49–50); their accompanier in late descriptions, the priest of Helios, Walter Burkert regards as a Hellenistic innovation rather than an archaic survival (Burkert 1983:)

- ^ See Poseidon#The foundation of Athens; the connection was an early one: in the Odyssey (vii.81), Athena was said to have «entered the house of Erechtheus» (noted by Burkert 1983:144).

- ^ William Smith (editor). «Hermaea» Archived May 29, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (1870), p.604.

- ^ C. Daremberg & E. Saglio. «Hermaia», Dictionnaire des antiquités grecques et romaines (1900), tome III, volume 1, pp.134–5.

- ^ Herodotus i. 147.

- ^

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). «Apaturia». Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 2 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 160.

- ^ Burton, Joan (1998). «Women’s Commensality in the Ancient Greek World». Greece and Rome. 45 (2): 148–149. doi:10.1017/S0017383500033659 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Burton, Joan (1998). «Women’s Commensality in the Ancient Greek World». Greece and Rome. 45 (2): 150. doi:10.1017/S0017383500033659 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Burton, Joan (1998). «Women’s Commensality in the Ancient Greek World». Greece and Rome. 45 (2): 157. doi:10.1017/S0017383500033659 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Burton, Joan (1998). «Women’s Commensality in the Ancient Greek World». Greece and Rome. 45 (2): 152. doi:10.1017/S0017383500033659 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Burton, Joan (1998). «Women’s Commensality in the Ancient Greek World». Greece and Rome. 45 (2): 151. doi:10.1017/S0017383500033659 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Osborne, Robin (1993). «Women and Sacrifice in Classical Greece». The Classical Quarterly (2 ed.). 43 (2): 392–405. doi:10.1017/S0009838800039914 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Osborne, Robin (1993). «Women and Sacrifice in Classical Greece». The Classical Quarterly (2 ed.). 43 (2): 392–405. doi:10.1017/S0009838800039914 – via JSTOR.

- ^ Demaris, Richard. E (2013). «Sacrifice, an Ancient Mediterranean Ritual». Biblical Theology Bulletin (2 ed.). 43 (2): 60–73. doi:10.1177/0146107913482279. S2CID 143693807.

- ^ Wagner- Hasel, B (2016). «GIFTS FOR THE GODS». The Classical Review (2 ed.). 66: 468–470 – via ProQuest.

- ^ Mikalson, Jon (1976). The Sacred and Civil Calendar of the Athenian Year. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691644691. JSTOR j.ctt13x10wg.

Из Симферополя и Белогорска, Кировского и Керчи сегодня приехали крымские греки в Чернополье. Здесь всегда много гостей в День святых Константина и Елены. Престольный праздник в небольшом сельском храме — значительное событие для греческой общины полуострова. Об этом сообщает корреспондент «Вести-Крым».

По традиции, после утренней литургии духовенство, прихожане и гости идут крестным ходом через всё село. Все, кто приезжает в Чернополье, непременно посещают этнографический музей.

Раньше это был действующий центр греческой культуры. Сегодня — здание на замке. Ирина Зекова, организатор и хранитель музея, открывает входную дверь нечасто. Музей представляет собой традиционный греческий дом — такой, каким запомнили его самые старшие представители греческой общины.

В 1944 году греки, как и другие малые народы Крыма, были отправлены в ссылку. Вернувшись на Родину, Ирина Зекова лично искала предметы греческого быта по окрестным деревням. Чтобы не потерять свою культуру, не утратить связь времен.

Здание музея не отапливается, появились плесень и сырость. В таких условиях невозможно обеспечить сохранность экспозиции, собранной буквально по крупицам. Уникальный музей греческой культуры может стать центром этнографического туризма, объектом культурного наследия. Важно это наследие сохранить, а не потерять — из-за сырости, холода и равнодушия.

Спасибо что зашли на наш сайт, перед тем как начать чтение вы можете подписаться на интересную православную mail рассылку, для этого вам необходимо кликнуть по этой ссылке «Подписаться»

Панагия — греческое слово вошло в славянский язык без перевода, а буквально означает «Всесвятая». Так говорят о Пречистой Богородице – но не только о Ней.

Содержание страницы

- Значение

- Что такое Панагия в православии

- Икона Божией Матери «Великая Панагия»

- Чин возношения в церкви

- Панагия епископа

- Греческий праздник

- Церковь Панагии Теоскепасти

- Монастырь Панагия Сумела

- На Меле

- В Верии

- Озеро и урочище в Крыму

- Мыс в Анапе

- Другие

- Похожие статьи

Значение

Эпитет «Всесвятая» означает высшую степень благодатности, святости, превышающую праведность всех святых, и даже – Ангелов.

Что такое Панагия в православии

Этим словом обозначают:

- саму Пречистую Деву, подчеркивая Её святость;

- особый тип Её икон;

- просфору, из которой во время литургии изымается частица, посвященная Матери Божией;

- у греков – любые храмы, посвященные Богородице;

- кроме этого, тем же словом называют нагрудный медальон с изображением Богородицы, а также Христа; в России это – принадлежность архиерейского облачения, а вот в Греции подобные носят также настоятели некоторых особенно значимых монастырей, к примеру, на Афоне.

Икона Божией Матери «Великая Панагия»

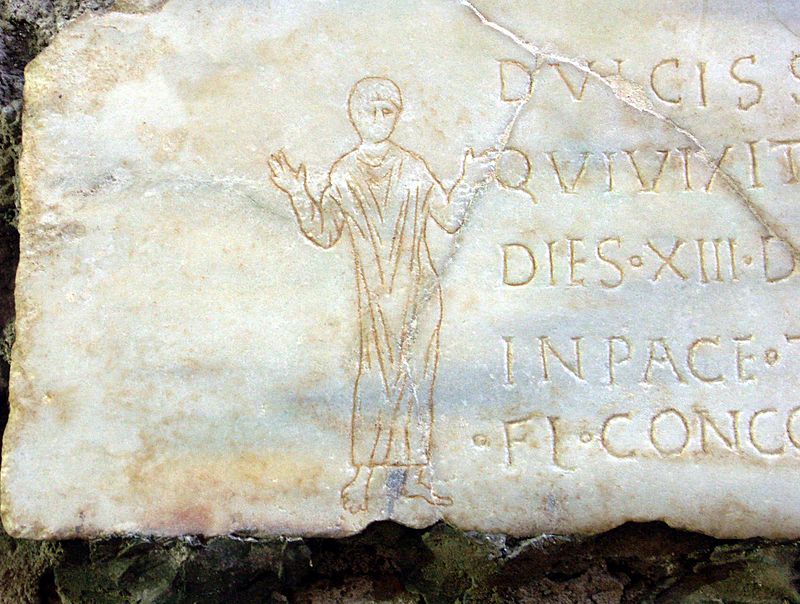

Считается, что древнейшее изображение Богородицы такого типа относится к IV в.: фреска найдена в одной из катакомб Рима, где древние христиане совершали моления, укрываясь от гонителей.

Оранта. Изображение в катакомбах Домитиллы, Рим

Пречистая представлена молящейся, с воздетыми руками, с изображением перед грудью Христа как Отрока. Древнее изображение – поясное, однако позже появились подобные иконы, где:

- Богородица написана в полный рост;

- образ Христа на Её груди заключен в круг («медальон»).

Несколько столетий такие ростовые и поясные иконы этого типа имели другие названия:

- греки именовали этот тип изображений Орантой, или молящейся Богородицей, а также Платитерой, что значит буквально «шире» или «просторнее; это именование обращает взор молящегося к изображению Христа: Богородица, чье чрево «пространнее небес», представлена как принимающая в Себя Бога, в момент Его Воплощения;

- на Руси утвердилось иное именование поясных икон Пречистой с воздетыми руками – «Знамение»; происхождение названия связано, с одной стороны, с пророчеством св. Исайи «Сам Господь даст вам знамение: се, дева во чреве приимет и родит сына, и нарекут ему имя Еммануил»; но кроме этого, есть и событие XI в., когда от такого образа 25 февраля 1170 г. последовало знамение милости Божией Новгороду, осажденному войсками князя Андрея Боголюбского; во время крестного хода по стенам города стрела ударила в икону, она развернулась к осажденным и источила слезы; одновременно осаждающие, объятые страхом, начали беспорядочно отступать.

Ростовые образы Великой Панагии часто можно увидеть в алтарях древних храмах, в апсидах. Чаще всего Богородица изображается в конхе – верхней закругленной части апсиды, таким образом, возвышаясь над престолом, благословляя его. А поясные иконы, как правило, пишутся на досках, их можно увидеть практически в любой церкви.

Богоматерь Великая Панагия (Оранта). Из Спасо-Преображенского монастыря в Ярославле. Первая треть XIII века. Государственная Третьяковская галерея

Чин возношения в церкви

Его центр – просфора в честь Богородицы, также называемая Панагией. Происхождение обычая восходит к Апостолам: по церковному преданию, они после Вознесения Господа во время каждой трапезы отделяли часть, предназначенную Учителю, Христу. По окончании трапезы они с молитвой возносили этот хлеб, а затем разделяли между собой. После Успения Богородицы и Её явления им часть трапезы таким же образом стали отделять в честь Матери Божией.

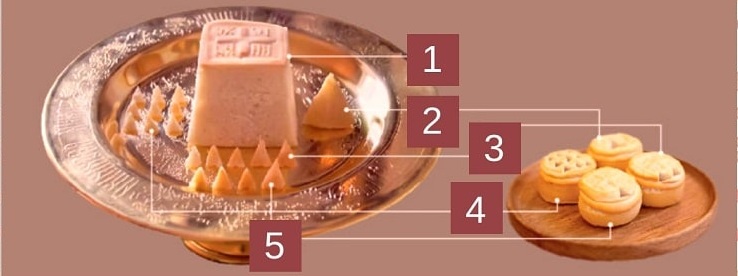

1. Агничная просфора

2. Богородичная просфора

3. Девятичинная просфора

4. Заздравная просфора

5. Заупокойная просфора

Сейчас части просфоры, из которой вырезается Агнец – претворяющийся в Тело и Кровь Господа – называются антидором, и благоговейно потребляются верующими сразу по Причастии. Богородичную же просфору принято также употреблять по окончании богослужения, но уже не в храме. В первые века обычая этого придерживались монастыри, мирские приходы, кроме того, Чин возвышения совершался при дворе византийского императора, русских царей до XVII в.

Сейчас же его можно увидеть только в монастырях по воскресным, праздничным дням.

Часть Чина о Панагии видят миряне, собравшиеся у храма после богослужения: братия попарно выходят из церкви вслед за настоятелем. Перед ними – монах, несущий панагиар с Богородичной просфорой. Это может быть как сам настоятель, так и один и иеромонахов. При этом принято петь псалом 144, однако, если храм посвящен Богородице, это может быть также песнопение в Её честь. Если совершается праздник, могут петься его тропари и кондаки. Процессию сопровождает колокольный звон.

По приходе в трапезную следуют:

- пение «Отче наш» с благословением пищи;

- сама трапеза, которая сопровождается чтением житий святых; все это время сосуд с просфорой находится на особом месте;

- по ее окончании – краткое благодарение, после чего совершается само «возвышение Панагии».

Устав предписывает делать это диакону (по древней Апостольской традиции, именно диаконы были «служителями при трапезе»), или монастырскому келарю. По благословении настоятеля он поднимает Богородичную просфору сначала перед иконой Троицы со словами «Велико имя…» (фразу заканчивает братия или настоятель: «… Святыя Троицы»), затем – Богородицы. Звучат Апостольские слова, впервые сказанные учениками Христа, когда Матерь Божия явилась им по Своем Успении:

«Пресвятая Богородице, помогай нам!».

Затем просфора разделяется на части и с благодарением принимается братией.

Панагия епископа

Совпадение именований Богородичной просфоры и нагрудного Её изображения – не случайно. В древности панагиар износил из храма настоятель монастыря или епископ, а носился он на груди, как особый закрытый ковчежец, на шнуре или цепи. Постепенно панагией стали называть вообще ковчежец для ношения святыни – например, частиц мощей. Такой сосуд украшали иконами Св. Троицы – на одной стороне, Богородицы – на другой. Позже Богородичную просфору стали носить в особом сосуде – а нагрудные иконы как отличительная черта облачения епископа, сохранились.

Впоследствии, в Российской империи, панагия архиерея получила еще значение награды. Например, за особые заслуги епископ мог быть награжден панагией с портретом императора на оборотной стороне. А архиереи, отличившиеся во время войны, могли получать панагии на георгиевской ленте.

Греческий праздник

У глубоко любящих Пречистую греков «месяцем Панагии» именуется август. Центральный его праздник – Успение Матери Божией, которое Элладская Церковь празднует, исходя из дат григорианского календаря, то есть 15 августа. 1 числа которого начинается строгий пост, который завершается церковным торжеством. Особенно торжественно Успение отмечается в храмах, посвященных Богородице, которых в стране великое множество.

Церковь Панагии Теоскепасти

Дословно именование этого храма на о. Кипр, в городе Пафос, переводится, как «Пресвятая, Укрытая Богом». Небольшая церковь времен Византийской империи – очень древняя, стоит на небольшой скале, в 800 м – развалины крепости также времен Византию. Чудо, благодаря которому храм стал известен, относится к 649 г. Тогда на Кипр впервые напали арабы-мусульмане, практически полностью уничтожившие как дома жителей, так и все укрепления Пафоса. Богородичная церковь единственная осталась невредимой, о причинах чего существует два различных предания:

- первое из них, собственно, дало название храму: согласно ему, завоеватели просто не заметили его, так как здание скрыл неизвестно откуда взявшийся туман;

- согласно другому рассказу, один из арабов все же после этого храм нашел, и, увидев богатые украшения, пожертвованные людьми к чудотворной иконе Пречистой, попытался забрать их; вдруг как бы из ниоткуда появился меч, и отсек кощуннику обе руки.

Нынешняя Теоксепасти – постройки 1920-х гг., хотя и копирует архитектурный стиль Византии. Прежний храм VII в. прекратил существование с 1878 г., совершенно разрушенный землетрясением. Но образ, к которому даже до наших дней притекают паломники, сохранился до наших дней. Местные жители говорят, что эта древняя иконы Матери Божией в серебряном окладе относится к I в., и, может быть, даже создана Евангелистом Лукой. Сейчас увидеть святыню можно в иконостасе храма, на левой стороне от царских врат.

Монастырь Панагия Сумела

Это именование обители и чудотворной иконы Матери Божией переводится с греческого как «Богоматерь с Черной горы». Существует два места с таким названием

На Меле

Это бывший греческий монастырь чуть более, чем в 40 км от турецкого города Трабзона (ранее Трапезунд). Его основание связано с еще одной иконой Божией Матери, по преданию, написанной Евангелистом Лукой.После его мученической кончины образ хранился в Ахаии, затем попал в Афины.

Сумельская икона Богородицы

Отсюда в конце IV в., по прямому указанию Пречистой, вышли священник Василий (во иночестве Варсонофий) и его племянник диакон Сотирихий (после пострига – Софроний). Они считаются основателями обители – но место для нее выбрала Сама Матерь Божия – ее чудотворная икона чудесным образом привела иноков к горе Мела. Затем из горы пробился целительный источник воды. Монастырь действовал до 1922 г. Затем, по договору об обмену населением между Грецией и Турцией, монахи вынуждены были покинуть эти места, впрочем, им удалось скрыть святыни монастыря.

В Верии

Это город греческой области Македония, где христианство появилось еще во времена Апостола Павла. Именно сюда ушли иноки Сумельской обители – а в 1931 г. у них появилась возможность вернуться и забрать святыни. Так образ Панагия Сумела был спасен и попал в Грецию. Здесь образовался одноименный прежней обители монастырь, где святыня пребывает с 1952 г. наших дней.

Озеро и урочище в Крыму

Топонимы, связанные с греческим именованием Богородицы, встречаются также там, где с древности были колонии греков. Одно из таких мест – полуостров Крым. Здесь в 30 км от города Судак есть урочище и озеро с таким названием. Добраться до него, как говорят туристы, можно только на такси – необходимо ехать до поселка Зеленогорье. От его окраины ведут две дороги – направо, к знаменитым Арпатским водопадам, налево – к урочищу, где среди скал находится небольшое озеро с зеленоватой водой.

Озеро Панагия

Есть легенда, что некогда здесь мог быть православный монастырь в честь Богородицы. Кроме того, многие приезжающие говорят, что в лунном свете на одной из скал как бы проявляется подобие изображения Богоматери. Вот один из таких рассказов:

«Еще перед поездкой я вычитала, что вечером при свете Луны можно разглядеть изображение Божьей Матери на озерной глади или на склонах гор. И нам посчастливилось увидеть нечто подобное! С наступлением темноты мы вели неспешную беседу за бутылочной хорошего коктебельского вина, и вдруг я перевела взгляд на скалу поблизости. Видение пробирало до мурашек – в горах будто и правда сидела Богоматерь с ребенком на руках. Мой спутник подтвердил, что видит тоже, что и я, поэтому сомнений не оставалось… Утром видения развеялись, в месте, где мы разглядели Богоматерь, по-прежнему возвышалась белая скала. Правда, если приглядеться, в её очертаниях можно было узреть что-то необычное….»

Мыс в Анапе

Он расположен на Таманском полуострове близ Анапы в Краснодарском крае, считается памятником природы. Он расположен на границе Азовском и Черного морей, и имеет высоту 30 м.

Сейчас мыс, по сути, представляет собой гигантскую окаменелость, образованную некогда бывшей здесь огромной колонией животных, подобных морским звездам – мшанок. Название его, очевидно, связано с какими-либо храмами времен раннего христианства, возможно, даже с жившими здесь монахами, ведь и в этой части Причерноморья тоже было множество греческих колоний.

Другие

На карте Греции топонимов с названием «Панагия» есть еще несколько. Это:

- остров Кира Панагия; он принадлежит Святой Горе Афон, с 2017 г. здесь восстановлен древний монастырь;

- еще один островок с этим именованием есть в Ионическом море близ острова Паксос; здесь действует древний храм Богородицы;

- Панагия также – другое название острова Пасас в Эгейском море;

- на карте страны также по крайней мере 5 деревень, называемых именем Богородицы – и у каждой своя история, связанная с Ней, Ее иконами, храмами.

Подобные истории могут рассказать и жители почти каждого города России – издревле именовавшей себя «домом Пресвятой Богородицы», ведь чудеса Её помощи людям – неисчислимы. Именно поэтому и на нашей земле множество храмов, чудотворных икон, хотя имеющих не греческие, а русские названия.

Наталья Сазонова

Похожие статьи

Хотим привлечь ваше внимание к проблеме разрушенных храмов, пострадавших в безбожные годы. Более 4000 старинных церквей по всей России ждут восстановления, многие находятся в критическом положении, но их все еще можно спасти.

Один из таких храмов, находится в городе Калач, это церковь Успения Божией Матери XVIII века. Силами неравнодушных людей храм начали восстанавливать, но средств на все работы катастрофически не хватает, так как строительные и реставрационные работы очень дорогие. Поэтому мы приглашаем всех желающих поучаствовать в благом деле восстановления храма в честь Пресвятой Богородицы. Сделать это можно на сайте храма

Помочь храму

Рекомендуем статьи по теме