Почему праздник Пасхи не является государственным праздником?

Объясните мне, пожалуйста, почему праздник Пасхи не объявлен государственным праздником, как например праздник Рождества? Виктор.

Отвечает протоиерей Александр Ильяшенко:

Здравствуйте, Виктор! Христос воскресе!

Думаю, Ваш вопрос уместнее было бы задать депутатам Государственной Думы, которые принимали поправки в Трудовой Кодекс, где были установлены праздничные дни, в том числе и празднование Рождества Христова как государственного праздника. Я же могу только предположить, что Пасха не отнесена к праздничным дням потому, что и так приходится на воскресный день, то есть нерабочий, день, и поэтому особо выделять этот праздник не стали. А праздник Рождества Христова может выпасть на любой день недели, поэтому, возможно, и было принято решение считать этот день праздничным и нерабочим.

С уважением, протоиерей Александр Ильяшенко.

- Много лет как безвозмездный донор сдаю кровь. Богоугодно ли это?

- Как себя вести, когда тебя оскорбляют в коллективе, покинуть который нельзя? Как быть смиренным и не стать всеобщим посмешищем?

- Можно ли заниматься сетевым маркетингом?

- Можно ли и нужно ли подавать милостыню?

Выходные дни на Пасху:

- 23.04 — суббота накануне праздника;

- 24.04 — Светлое Христово Воскресение.

В понедельник, 25 апреля, почти всем работающим гражданам придется выйти на службу.

Праздник Пасхи всегда выпадает на воскресенье, но многих волнует вопрос: переносится Пасха на понедельник в России — нет, нормами Трудового кодекса РФ это не предусмотрено. Но в некоторых регионах РФ действуют специальные нормы, по которым главные религиозные христианские и мусульманские праздники объявлены нерабочими днями.

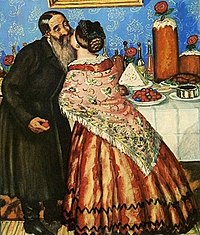

История и традиции

Сам праздник Светлого Христова Воскресения очень старый — ему больше тысячи лет, но в современную Россию он пришел в полной мере только после распада СССР. Хотя граждане и раньше пекли куличи, делали творожные пасхи, красили яйца, они редко соблюдали настоящие православные каноны, присущие этому торжеству. Сейчас же большинство православных россиян соблюдают праздничные дни на Пасху: ходят в церковь на всенощную службу, соблюдают пост перед праздником, посещают кладбища и поминают своих умерших родных.

Очевидно, что для исполнения всех пасхальных традиций мало одного воскресенья, на который он всегда выпадает. Но отдых в понедельник после Пасхи доступен для немногих граждан России, сама религиозная дата не является официальным государственным праздничным нерабочим днем. Это связано с тем, что Российская Федерация — многоконфессиональное государство, и религиозных поводов для торжества у ее граждан очень много, даже таких важных и значимых, как Светлое Воскресение. Более того, в статье 14 Конституции РФ Россия признана светским государством, в котором ни одна из церквей не вправе занимать лидирующее положение. Но есть в России регионы, где традиции верующих разных конфессий учтены при составлении производственного календаря, и Пасха считается праздничным днем в рабочем календаре, как и другие православные праздничные даты — Рождество и Троица. В некоторых регионах дополнительно дают людям нерабочий день на Радоницу, чтобы они могли посетить кладбище и помянуть умерших родных.

Торжество в 2022 году

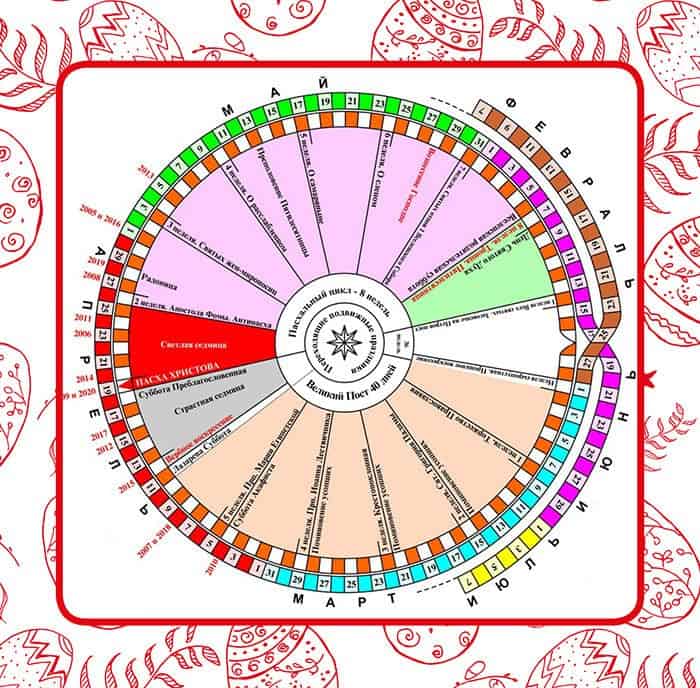

В 2022 году Светлое Христово Воскресение православные будут отмечать 24 апреля. У этого религиозного события нет строго установленной даты, она ежегодно меняется. Выбирают день для празднования служители церкви. Для этого они используют особую методику, которая применяется уже много лет. В ней учитываются другие важные религиозные события и природные явления (полнолуние, солнцестояние). В ТК РФ указано, является ли Пасха государственным праздником, — нет, она не входит в закрытый перечень указанных там дат.

Государственные праздничные нерабочие дни

Все праздничные нерабочие даты перечислены в статье 112 Трудового кодекса РФ. Всего таких дат 8, но дней для отдыха больше, в честь новогодних каникул Россия отдыхает целых 5 дней. Полный перечень праздничных нерабочих дат из этой статьи выглядит так:

- 1-5 января — Новый год;

- 7 января — Рождество;

- 23 февраля — День защитника Отечества;

- 8 марта — Международный женский день;

- 1 мая — Праздник Весны и Труда;

- 9 мая — День Победы;

- 12 июня — День России;

- 4 ноября — День народного единства.

Из этого списка очевидно, что дополнительные выходные на Пасху в России официально не предусмотрены. А значит, не действует и норма статьи 112 ТК РФ о переносе выходного, совпавшего с праздником, на другую дату. Но сам праздник всегда совпадает с воскресеньем — календарным выходным днем, поэтому нет сомнений, как будем отдыхать на Пасху в 2022 году: в субботу и воскресенье.

Но есть регионы, в которых дела обстоят иначе, их власти на местном уровне определяют, Пасха выходной день или нет, ежегодно.

Пасхальные выходные дни в регионах РФ

Субъекты РФ, в соответствии с Конституцией, вправе устанавливать собственные праздничные нерабочие дни. К примеру, Светлое Христово Воскресение — национальный праздник в Республике Крым. И если смотреть, когда выходные на Пасху в этом регионе, то их три:

- суббота — 23 апреля;

- воскресенье — 24-ое число;

- понедельник — 25.04.

Кстати, в этих регионах проживают много мусульман. Их главные религиозные праздники отмечены в местных производственных календарях как нерабочие даты. В других российских регионах с преобладающим мусульманским населением, в частности, в Татарстане, Адыгее, Дагестане, Ингушетии, Кабардино-Балкарии, Карачаево-Черкесии, Чечне и Башкортостане, все граждане отдыхают в дни Курбан-Байрама и Ураза-Байрама. Возможно, в недалеком будущем регионы РФ с преобладающим православным населением примут такие же местные законы, и Светлое Христово Воскресение станет праздничным нерабочим днем, а значит, и ответ на вопрос, сколько дней отдыхают на Пасху в России, — 3 дня, станет общим для большинства субъектов РФ.

Подробнее о региональных праздниках и выходных днях: «Как отдыхаем в 2022: официальные выходные в России и субъектах РФ».

Дидух Юлия

бухгалтер, юрист

В 1998 году закончила КГАУ, экономический факультет по специальности бухгалтер. В 2006 году ТНУ, юридический факультет по специальности гражданское и предпринимательское право. Опыт работы бухгалтером с 1998 по 2007 год. Пишу статьи с 2012 года

Все статьи автора

This article is about the Christian and cultural festival. For other uses, see Easter (disambiguation).

| Easter | |

|---|---|

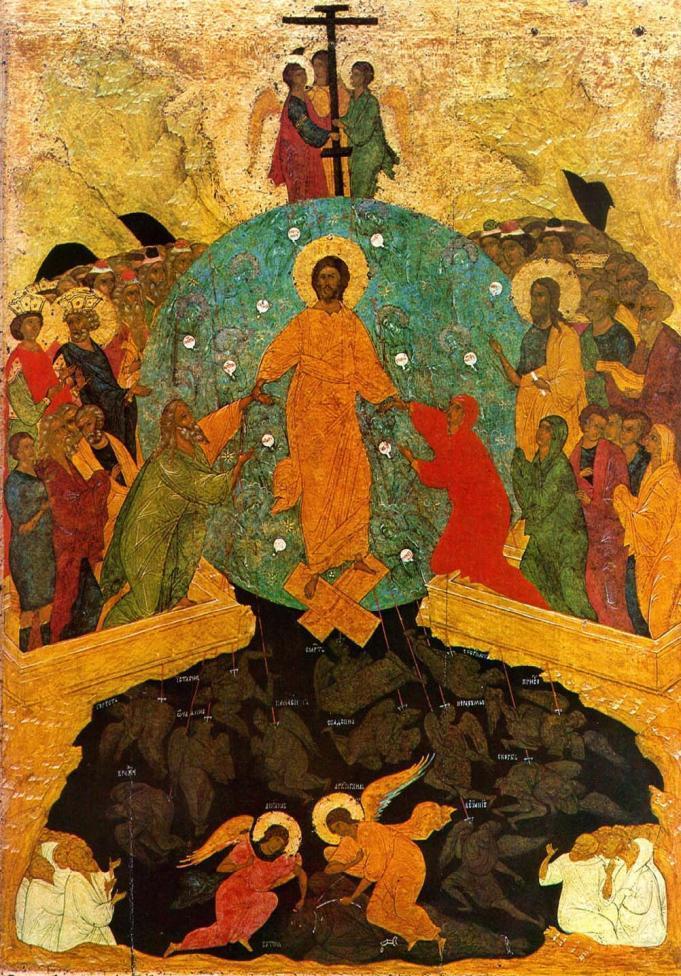

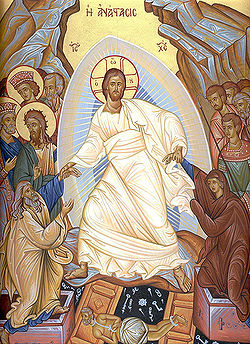

Icon of the Resurrection depicting Christ having destroyed the gates of hell and removing Adam and Eve from the grave. Christ is flanked by saints, and Satan, depicted as an old man, is bound and chained. |

|

| Observed by | Christians |

| Significance | Celebrates the resurrection of Jesus |

| Celebrations | Church services, festive family meals, Easter egg decoration, and gift-giving |

| Observances | Prayer, all-night vigil, sunrise service |

| Date | Variable, determined by the Computus |

| 2022 date |

|

| 2023 date |

|

| 2024 date |

|

| 2025 date |

|

| Related to | Passover, Septuagesima, Sexagesima, Quinquagesima, Shrove Tuesday, Ash Wednesday, Clean Monday, Lent, Great Lent, Palm Sunday, Holy Week, Maundy Thursday, Good Friday, and Holy Saturday which lead up to Easter; and Divine Mercy Sunday, Ascension, Pentecost, Trinity Sunday, Corpus Christi and Feast of the Sacred Heart which follow it. |

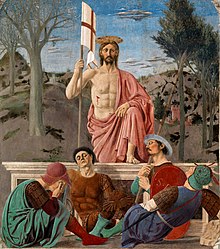

Easter,[nb 1] also called Pascha[nb 2] (Aramaic, Greek, Latin) or Resurrection Sunday,[nb 3] is a Christian festival and cultural holiday commemorating the resurrection of Jesus from the dead, described in the New Testament as having occurred on the third day of his burial following his crucifixion by the Romans at Calvary c. 30 AD.[12][13] It is the culmination of the Passion of Jesus Christ, preceded by Lent (or Great Lent), a 40-day period of fasting, prayer, and penance.

Easter-observing Christians commonly refer to the week before Easter as Holy Week, which in Western Christianity begins on Palm Sunday (marking the entrance of Jesus in Jerusalem), includes Spy Wednesday (on which the betrayal of Jesus is mourned),[14] and contains the days of the Easter Triduum including Maundy Thursday, commemorating the Maundy and Last Supper,[15][16] as well as Good Friday, commemorating the crucifixion and death of Jesus.[17] In Eastern Christianity, the same days and events are commemorated with the names of days all starting with «Holy» or «Holy and Great»; and Easter itself might be called «Great and Holy Pascha», «Easter Sunday», «Pascha» or «Sunday of Pascha». In Western Christianity, Eastertide, or the Easter Season, begins on Easter Sunday and lasts seven weeks, ending with the coming of the 50th day, Pentecost Sunday. In Eastern Christianity, the Paschal season ends with Pentecost as well, but the leave-taking of the Great Feast of Pascha is on the 39th day, the day before the Feast of the Ascension.

Easter and its related holidays are moveable feasts, not falling on a fixed date; its date is computed based on a lunisolar calendar (solar year plus Moon phase) similar to the Hebrew calendar. The First Council of Nicaea (325) established only two rules, namely independence from the Hebrew calendar and worldwide uniformity. No details for the computation were specified; these were worked out in practice, a process that took centuries and generated a number of controversies. It has come to be the first Sunday after the ecclesiastical full moon that occurs on or soonest after 21 March.[18] Even if calculated on the basis of the more accurate Gregorian calendar, the date of that full moon sometimes differs from that of the astronomical first full moon after the March equinox.[19]

The English term is derived from the Saxon spring festival Ēostre; Easter is also linked to the Jewish Passover by its name (Hebrew: פֶּסַח pesach, Aramaic: פָּסחָא pascha are the basis of the term Pascha), by its origin (according to the synoptic Gospels, both the crucifixion and the resurrection took place during the week of Passover)[20][21] and by much of its symbolism, as well as by its position in the calendar. In most European languages, both the Christian Easter and the Jewish Passover are called by the same name; and in the older English versions of the Bible, as well, the term Easter was used to translate Passover.[22] Easter customs vary across the Christian world, and include sunrise services, midnight vigils, exclamations and exchanges of Paschal greetings, clipping the church (England),[23] decoration and the communal breaking of Easter eggs (a symbol of the empty tomb).[24][25][26] The Easter lily, a symbol of the resurrection in Western Christianity,[27][28] traditionally decorates the chancel area of churches on this day and for the rest of Eastertide.[29] Additional customs that have become associated with Easter and are observed by both Christians and some non-Christians include Easter parades, communal dancing (Eastern Europe), the Easter Bunny and egg hunting.[30][31][32][33][34] There are also traditional Easter foods that vary by region and culture.

Etymology

The modern English term Easter, cognate with modern Dutch ooster and German Ostern, developed from an Old English word that usually appears in the form Ēastrun, -on, or -an; but also as Ēastru, -o; and Ēastre or Ēostre.[nb 4] Bede provides the only documentary source for the etymology of the word, in his eighth-century The Reckoning of Time. He wrote that Ēosturmōnaþ (Old English ‘Month of Ēostre’, translated in Bede’s time as «Paschal month») was an English month, corresponding to April, which he says «was once called after a goddess of theirs named Ēostre, in whose honour feasts were celebrated in that month».[35]

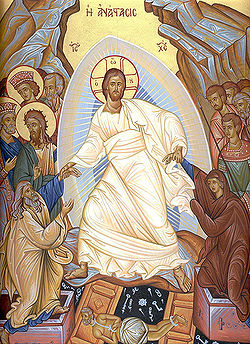

In Latin and Greek, the Christian celebration was, and still is, called Pascha (Greek: Πάσχα), a word derived from Aramaic פסחא (Paskha), cognate to Hebrew פֶּסַח (Pesach). The word originally denoted the Jewish festival known in English as Passover, commemorating the Jewish Exodus from slavery in Egypt.[36][37] As early as the 50s of the 1st century, Paul the Apostle, writing from Ephesus to the Christians in Corinth,[38] applied the term to Christ, and it is unlikely that the Ephesian and Corinthian Christians were the first to hear Exodus 12 interpreted as speaking about the death of Jesus, not just about the Jewish Passover ritual.[39] In most languages, Germanic languages such as English being exceptions, the feast is known by names derived from Greek and Latin Pascha.[9][40] Pascha is also a name by which Jesus himself is remembered in the Orthodox Church, especially in connection with his resurrection and with the season of its celebration.[41] Others call the holiday «Resurrection Sunday» or «Resurrection Day,» after the Greek: Ἀνάστασις, romanized: Anastasis, lit. ‘Resurrection’ day.[10][11][42][43]

Theological significance

Easter celebrates Jesus’ supernatural resurrection from the dead, which is one of the chief tenets of the Christian faith.[44] The resurrection established Jesus as the Son of God and is cited as proof that God will righteously judge the world.[45] Paul writes that, for those who trust in Jesus’s death and resurrection, «death is swallowed up in victory.» The First Epistle of Peter declares that God has given believers «a new birth into a living hope through the resurrection of Jesus Christ from the dead». Christian theology holds that, through faith in the working of God, those who follow Jesus are spiritually resurrected with him so that they may walk in a new way of life and receive eternal salvation, and can hope to be physically resurrected to dwell with him in the Kingdom of Heaven.[45]

Easter is linked to Passover and the Exodus from Egypt recorded in the Old Testament through the Last Supper, sufferings, and crucifixion of Jesus that preceded the resurrection.[40] According to the three Synoptic Gospels, Jesus gave the Passover meal a new meaning, as in the upper room during the Last Supper he prepared himself and his disciples for his death.[40] He identified the bread and cup of wine as his body, soon to be sacrificed, and his blood, soon to be shed. The Apostle Paul states, in his First Epistle to the Corinthians, «Get rid of the old yeast that you may be a new batch without yeast—as you really are. For Christ, our Passover lamb, has been sacrificed. This refers to the requirement in Jewish law that Jews eliminate all chametz, or leavening, from their homes in advance of Passover, and to the allegory of Jesus as the Paschal lamb.[46][47]

Early Christianity

The Last Supper celebrated by Jesus and his disciples. The early Christians, too, would have celebrated this meal to commemorate Jesus’s death and subsequent resurrection.

As the Gospels affirm that both the crucifixion and resurrection of Jesus during the week of Passover, the first Christians timed the observance of the annual celebration of the resurrections in relation to Passover.[48] Direct evidence for a more fully formed Christian festival of Pascha (Easter) begins to appear in the mid-2nd century. Perhaps the earliest extant primary source referring to Easter is a mid-2nd-century Paschal homily attributed to Melito of Sardis, which characterizes the celebration as a well-established one.[49] Evidence for another kind of annually recurring Christian festival, those commemorating the martyrs, began to appear at about the same time as the above homily.[50]

While martyrs’ days (usually the individual dates of martyrdom) were celebrated on fixed dates in the local solar calendar, the date of Easter was fixed by means of the local Jewish[51] lunisolar calendar. This is consistent with the celebration of Easter having entered Christianity during its earliest, Jewish, period, but does not leave the question free of doubt.[52]

The ecclesiastical historian Socrates Scholasticus attributes the observance of Easter by the church to the perpetuation of pre-Christian custom, «just as many other customs have been established», stating that neither Jesus nor his Apostles enjoined the keeping of this or any other festival. Although he describes the details of the Easter celebration as deriving from local custom, he insists the feast itself is universally observed.[53]

Date

A stained-glass window depicting the Passover Lamb, a concept integral to the foundation of Easter[40][54]

Easter and the holidays that are related to it are moveable feasts, in that they do not fall on a fixed date in the Gregorian or Julian calendars (both of which follow the cycle of the sun and the seasons). Instead, the date for Easter is determined on a lunisolar calendar similar to the Hebrew calendar. The First Council of Nicaea (325) established two rules, independence of the Jewish calendar and worldwide uniformity, which were the only rules for Easter explicitly laid down by the Council. No details for the computation were specified; these were worked out in practice, a process that took centuries and generated a number of controversies. (See also Computus and Reform of the date of Easter.) In particular, the Council did not decree that Easter must fall on Sunday, but this was already the practice almost everywhere.[55][incomplete short citation]

In Western Christianity, using the Gregorian calendar, Easter always falls on a Sunday between 22 March and 25 April,[56] within about seven days after the astronomical full moon.[57] The following day, Easter Monday, is a legal holiday in many countries with predominantly Christian traditions.[58]

Eastern Orthodox Christians base Paschal date calculations on the Julian Calendar. Because of the thirteen-day difference between the calendars between 1900 and 2099, 21 March corresponds, during the 21st century, to 3 April in the Gregorian Calendar. Since the Julian calendar is no longer used as the civil calendar of the countries where Eastern Christian traditions predominate, Easter varies between 4 April and 8 May in the Gregorian calendar. Also, because the Julian «full moon» is always several days after the astronomical full moon, the eastern Easter is often later, relative to the visible lunar phases, than western Easter.[59]

Among the Oriental Orthodox, some churches have changed from the Julian to the Gregorian calendar and the date for Easter, as for other fixed and moveable feasts, is the same as in the Western church.[60]

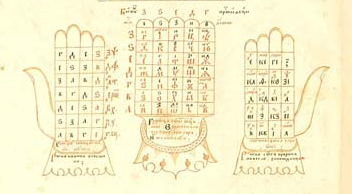

Computations

In 725, Bede succinctly wrote, «The Sunday following the full Moon which falls on or after the equinox will give the lawful Easter.»[61] However, this does not precisely reflect the ecclesiastical rules. The full moon referred to (called the Paschal full moon) is not an astronomical full moon, but the 14th day of a lunar month. Another difference is that the astronomical equinox is a natural astronomical phenomenon, which can fall on 19, 20 or 21 March,[62] while the ecclesiastical date is fixed by convention on 21 March.[63]

In applying the ecclesiastical rules, Christian churches use 21 March as the starting point in determining the date of Easter, from which they find the next full moon, etc. The Eastern Orthodox and Oriental Orthodox Churches continue to use the Julian calendar. Their starting point in determining the date of Orthodox Easter is also 21 March but according to the Julian reckoning, which in the current century corresponds to 3 April in the Gregorian calendar.[citation needed]

In addition, the lunar tables of the Julian calendar are currently five days behind those of the Gregorian calendar. Therefore, the Julian computation of the Paschal full moon is a full five days later than the astronomical full moon. The result of this combination of solar and lunar discrepancies is divergence in the date of Easter in most years (see table).[64]

Easter is determined on the basis of lunisolar cycles. The lunar year consists of 30-day and 29-day lunar months, generally alternating, with an embolismic month added periodically to bring the lunar cycle into line with the solar cycle. In each solar year (1 January to 31 December inclusive), the lunar month beginning with an ecclesiastical new moon falling in the 29-day period from 8 March to 5 April inclusive is designated as the paschal lunar month for that year.[65]

Easter is the third Sunday in the paschal lunar month, or, in other words, the Sunday after the paschal lunar month’s 14th day. The 14th of the paschal lunar month is designated by convention as the Paschal full moon, although the 14th of the lunar month may differ from the date of the astronomical full moon by up to two days.[65] Since the ecclesiastical new moon falls on a date from 8 March to 5 April inclusive, the paschal full moon (the 14th of that lunar month) must fall on a date from 22 March to 18 April inclusive.[64]

The Gregorian calculation of Easter was based on a method devised by the Calabrian doctor Aloysius Lilius (or Lilio) for adjusting the epacts of the Moon,[66] and has been adopted by almost all Western Christians and by Western countries which celebrate national holidays at Easter. For the British Empire and colonies, a determination of the date of Easter Sunday using Golden Numbers and Sunday letters was defined by the Calendar (New Style) Act 1750 with its Annexe. This was designed to match exactly the Gregorian calculation.[citation needed]

Controversies over the date

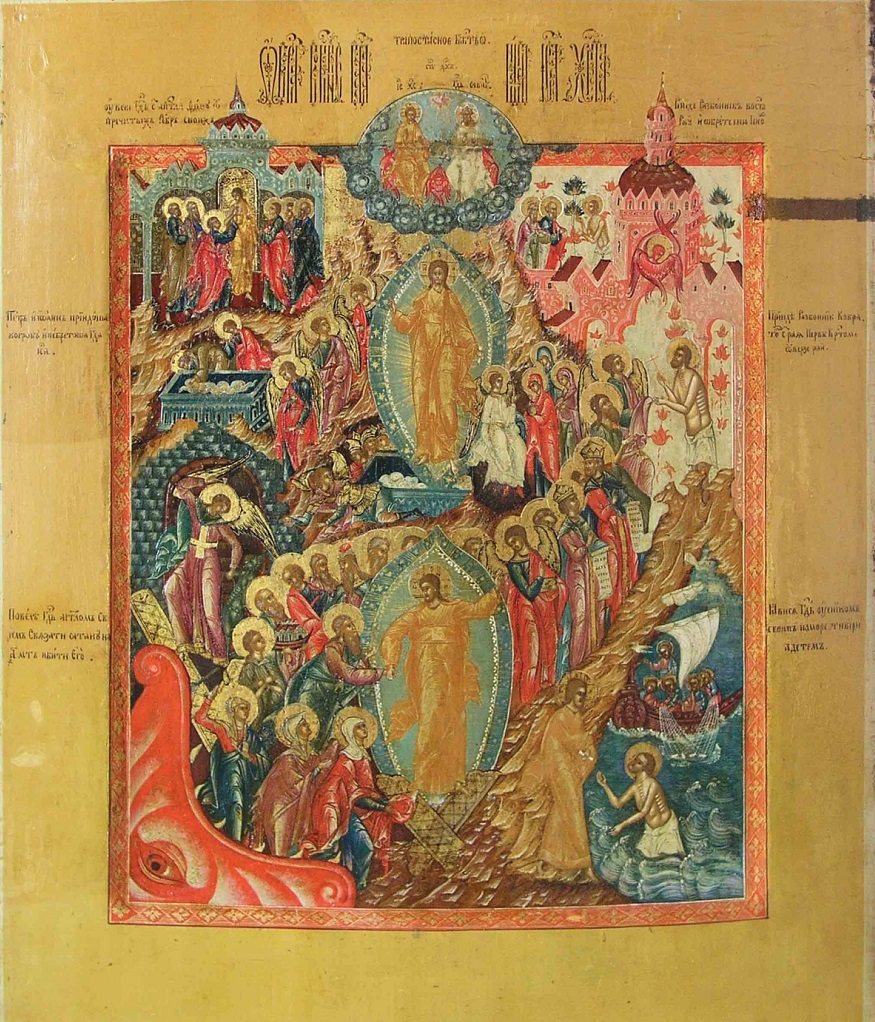

A five-part Russian Orthodox icon depicting the Easter story.

Eastern Orthodox Christians use a different computation for the date of Easter than the Western churches.

The precise date of Easter has at times been a matter of contention. By the later 2nd century, it was widely accepted that the celebration of the holiday was a practice of the disciples and an undisputed tradition. The Quartodeciman controversy, the first of several Easter controversies, arose concerning the date on which the holiday should be celebrated.[citation needed]

The term «Quartodeciman» refers to the practice of ending the Lenten fast on Nisan 14 of the Hebrew calendar, «the LORD‘s passover».[67] According to the church historian Eusebius, the Quartodeciman Polycarp (bishop of Smyrna, by tradition a disciple of John the Apostle) debated the question with Anicetus (bishop of Rome). The Roman province of Asia was Quartodeciman, while the Roman and Alexandrian churches continued the fast until the Sunday following (the Sunday of Unleavened Bread), wishing to associate Easter with Sunday. Neither Polycarp nor Anicetus persuaded the other, but they did not consider the matter schismatic either, parting in peace and leaving the question unsettled.[citation needed]

Controversy arose when Victor, bishop of Rome a generation after Anicetus, attempted to excommunicate Polycrates of Ephesus and all other bishops of Asia for their Quartodecimanism. According to Eusebius, a number of synods were convened to deal with the controversy, which he regarded as all ruling in support of Easter on Sunday.[68] Polycrates (circa 190), however, wrote to Victor defending the antiquity of Asian Quartodecimanism. Victor’s attempted excommunication was apparently rescinded, and the two sides reconciled upon the intervention of bishop Irenaeus and others, who reminded Victor of the tolerant precedent of Anicetus.[citation needed]

Quartodecimanism seems to have lingered into the 4th century, when Socrates of Constantinople recorded that some Quartodecimans were deprived of their churches by John Chrysostom[69] and that some were harassed by Nestorius.[70]

It is not known how long the Nisan 14 practice continued. But both those who followed the Nisan 14 custom, and those who set Easter to the following Sunday, had in common the custom of consulting their Jewish neighbors to learn when the month of Nisan would fall, and setting their festival accordingly. By the later 3rd century, however, some Christians began to express dissatisfaction with the custom of relying on the Jewish community to determine the date of Easter. The chief complaint was that the Jewish communities sometimes erred in setting Passover to fall before the Northern Hemisphere spring equinox.[71][72] The Sardica paschal table[73] confirms these complaints, for it indicates that the Jews of some eastern Mediterranean city (possibly Antioch) fixed Nisan 14 on dates well before the spring equinox on multiple occasions.[74]

Because of this dissatisfaction with reliance on the Jewish calendar, some Christians began to experiment with independent computations.[nb 5] Others, however, believed that the customary practice of consulting Jews should continue, even if the Jewish computations were in error.[citation needed]

First Council of Nicaea (325 AD)

This controversy between those who advocated independent computations, and those who wished to continue the custom of relying on the Jewish calendar, was formally resolved by the First Council of Nicaea in 325, which endorsed changing to an independent computation by the Christian community in order to celebrate in common. This effectively required the abandonment of the old custom of consulting the Jewish community in those places where it was still used. Epiphanius of Salamis wrote in the mid-4th century:

the emperor … convened a council of 318 bishops … in the city of Nicaea … They passed certain ecclesiastical canons at the council besides, and at the same time decreed in regard to the Passover [i.e., Easter] that there must be one unanimous concord on the celebration of God’s holy and supremely excellent day. For it was variously observed by people; some kept it early, some between [the disputed dates], but others late. And in a word, there was a great deal of controversy at that time.[77]

Canons[78] and sermons[79] condemning the custom of computing Easter’s date based on the Jewish calendar indicate that this custom (called «protopaschite» by historians) did not die out at once, but persisted for a time after the Council of Nicaea.

Dionysius Exiguus, and others following him, maintained that the 318 bishops assembled at Nicaea had specified a particular method of determining the date of Easter; subsequent scholarship has refuted this tradition.[80] In any case, in the years following the council, the computational system that was worked out by the church of Alexandria came to be normative. The Alexandrian system, however, was not immediately adopted throughout Christian Europe. Following Augustalis’ treatise De ratione Paschae (On the Measurement of Easter), Rome retired the earlier 8-year cycle in favor of Augustalis’ 84-year lunisolar calendar cycle, which it used until 457. It then switched to Victorius of Aquitaine’s adaptation of the Alexandrian system.[81][82]

Because this Victorian cycle differed from the unmodified Alexandrian cycle in the dates of some of the Paschal Full Moons, and because it tried to respect the Roman custom of fixing Easter to the Sunday in the week of the 16th to the 22nd of the lunar month (rather than the 15th to the 21st as at Alexandria), by providing alternative «Latin» and «Greek» dates in some years, occasional differences in the date of Easter as fixed by Alexandrian rules continued.[81][82] The Alexandrian rules were adopted in the West following the tables of Dionysius Exiguus in 525.[citation needed]

Early Christians in Britain and Ireland also used an 84-year cycle. From the 5th century onward this cycle set its equinox to 25 March and fixed Easter to the Sunday falling in the 14th to the 20th of the lunar month inclusive.[83][84] This 84-year cycle was replaced by the Alexandrian method in the course of the 7th and 8th centuries. Churches in western continental Europe used a late Roman method until the late 8th century during the reign of Charlemagne, when they finally adopted the Alexandrian method. Since 1582, when the Roman Catholic Church adopted the Gregorian calendar while most of Europe used the Julian calendar, the date on which Easter is celebrated has again differed.[85]

The Greek island of Syros, whose population is divided almost equally between Catholics and Orthodox, is one of the few places where the two Churches share a common date for Easter, with the Catholics accepting the Orthodox date—a practice helping considerably in maintaining good relations between the two communities.[86] Conversely, Orthodox Christians in Finland celebrate Easter according to the Western Christian date.[87]

Reform of the date

In the 20th century, some individuals and institutions have propounded changing the method of calculating the date for Easter, the most prominent proposal being the Sunday after the second Saturday in April. Despite having some support, proposals to reform the date have not been implemented.[88] An Orthodox congress of Eastern Orthodox bishops, which included representatives mostly from the Patriarch of Constantinople and the Serbian Patriarch, met in Constantinople in 1923, where the bishops agreed to the Revised Julian calendar.[89]

The original form of this calendar would have determined Easter using precise astronomical calculations based on the meridian of Jerusalem.[90][91] However, all the Eastern Orthodox countries that subsequently adopted the Revised Julian calendar adopted only that part of the revised calendar that applied to festivals falling on fixed dates in the Julian calendar. The revised Easter computation that had been part of the original 1923 agreement was never permanently implemented in any Orthodox diocese.[89]

In the United Kingdom, Parliament passed the Easter Act 1928 to change the date of Easter to be the first Sunday after the second Saturday in April (or, in other words, the Sunday in the period from 9 to 15 April). However, the legislation has not been implemented, although it remains on the Statute book and could be implemented, subject to approval by the various Christian churches.[92]

At a summit in Aleppo, Syria, in 1997, the World Council of Churches (WCC) proposed a reform in the calculation of Easter which would have replaced the present divergent practices of calculating Easter with modern scientific knowledge taking into account actual astronomical instances of the spring equinox and full moon based on the meridian of Jerusalem, while also following the tradition of Easter being on the Sunday following the full moon.[93] The recommended World Council of Churches changes would have sidestepped the calendar issues and eliminated the difference in date between the Eastern and Western churches. The reform was proposed for implementation starting in 2001, and despite repeated calls for reform, it was not ultimately adopted by any member body.[94][95]

In January 2016, the Anglican Communion, Coptic Orthodox Church, Greek Orthodox Church, and Roman Catholic Church again considered agreeing on a common, universal date for Easter, while also simplifying the calculation of that date, with either the second or third Sunday in April being popular choices.[96]

In November 2022, the Patriarch of Constantinople said that conversations between the Roman Catholic Church and the Orthodox Churches had begun to determine a common date for the celebration of Easter. The agreement is expected to be reached for the 1700th anniversary of the Council of Nicaea in 2025.[97]

Table of the dates of Easter by Gregorian and Julian calendars

The WCC presented comparative data of the relationships:

| Year | Full Moon | Jewish Passover [note 1] | Astronomical Easter [note 2] | Gregorian Easter | Julian Easter |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 8 April | 15 April | |||

| 2002 | 28 March | 31 March | 5 May | ||

| 2003 | 16 April | 17 April | 20 April | 27 April | |

| 2004 | 5 April | 6 April | 11 April | ||

| 2005 | 25 March | 24 April | 27 March | 1 May | |

| 2006 | 13 April | 16 April | 23 April | ||

| 2007 | 2 April | 3 April | 8 April | ||

| 2008 | 21 March | 20 April | 23 March | 27 April | |

| 2009 | 9 April | 12 April | 19 April | ||

| 2010 | 30 March | 4 April | |||

| 2011 | 18 April | 19 April | 24 April | ||

| 2012 | 6 April | 7 April | 8 April | 15 April | |

| 2013 | 27 March | 26 March | 31 March | 5 May | |

| 2014 | 15 April | 20 April | |||

| 2015 | 4 April | 5 April | 12 April | ||

| 2016 | 23 March | 23 April | 27 March | 1 May | |

| 2017 | 11 April | 16 April | |||

| 2018 | 31 March | 1 April | 8 April | ||

| 2019 | 20 March | 20 April | 24 March | 21 April | 28 April |

| 2020 | 8 April | 9 April | 12 April | 19 April | |

| 2021 | 28 March | 4 April | 2 May | ||

| 2022 | 16 April | 17 April | 24 April | ||

| 2023 | 6 April | 9 April | 16 April | ||

| 2024 | 25 March | 23 April | 31 March | 5 May | |

| 2025 | 13 April | 20 April | |||

|

Position in the church year

Western Christianity

Easter and other named days and day ranges around Lent and Easter in Western Christianity, with the fasting days of Lent numbered

In most branches of Western Christianity, Easter is preceded by Lent, a period of penitence that begins on Ash Wednesday, lasts 40 days (not counting Sundays), and is often marked with fasting. The week before Easter, known as Holy Week, is an important time for observers to commemorate the final week of Jesus’ life on earth.[99] The Sunday before Easter is Palm Sunday, with the Wednesday before Easter being known as Spy Wednesday (or Holy Wednesday). The last three days before Easter are Maundy Thursday, Good Friday and Holy Saturday (sometimes referred to as Silent Saturday).[100]

Palm Sunday, Maundy Thursday and Good Friday respectively commemorate Jesus’s entry in Jerusalem, the Last Supper and the crucifixion. Maundy Thursday, Good Friday, and Holy Saturday are sometimes referred to as the Easter Triduum (Latin for «Three Days»). Many churches begin celebrating Easter late in the evening of Holy Saturday at a service called the Easter Vigil.

The week beginning with Easter Sunday is called Easter Week or the Octave of Easter, and each day is prefaced with «Easter», e.g. Easter Monday (a public holiday in many countries), Easter Tuesday (a much less widespread public holiday), etc. Easter Saturday is therefore the Saturday after Easter Sunday. The day before Easter is properly called Holy Saturday. Eastertide, or Paschaltide, the season of Easter, begins on Easter Sunday and lasts until the day of Pentecost, seven weeks later.

Eastern Christianity

In Eastern Christianity, the spiritual preparation for Easter/Pascha begins with Great Lent, which starts on Clean Monday and lasts for 40 continuous days (including Sundays). Great Lent ends on a Friday, and the next day is Lazarus Saturday. The Vespers which begins Lazarus Saturday officially brings Great Lent to a close, although the fast continues through the following week, i.e. Holy Week. After Lazarus Saturday comes Palm Sunday, Holy Week, and finally Easter/Pascha itself, and the fast is broken immediately after the Paschal Divine Liturgy.[citation needed]

The Paschal Vigil begins with the Midnight Office, which is the last service of the Lenten Triodion and is timed so that it ends a little before midnight on Holy Saturday night. At the stroke of midnight the Paschal celebration itself begins, consisting of Paschal Matins, Paschal Hours, and Paschal Divine Liturgy.[101]

The liturgical season from Easter to the Sunday of All Saints (the Sunday after Pentecost) is known as the Pentecostarion (the «50 days»). The week which begins on Easter Sunday is called Bright Week, during which there is no fasting, even on Wednesday and Friday. The Afterfeast of Easter lasts 39 days, with its Apodosis (leave-taking) on the day before the Feast of the Ascension. Pentecost Sunday is the 50th day from Easter (counted inclusively).[102] In the Pentecostarion published by Apostoliki Diakonia of the Church of Greece, the Great Feast Pentecost is noted in the synaxarion portion of Matins to be the 8th Sunday of Pascha. However, the Paschal greeting of «Christ is risen!» is no longer exchanged among the faithful after the Apodosis of Pascha.

Liturgical observance

Western Christianity

The Easter festival is kept in many different ways among Western Christians. The traditional, liturgical observation of Easter, as practised among Roman Catholics, Lutherans,[103] and some Anglicans begins on the night of Holy Saturday with the Easter Vigil which follows an ancient liturgy involving symbols of light, candles and water and numerous readings form the Old and New Testament.[104]

Services continue on Easter Sunday and in a number of countries on Easter Monday. In parishes of the Moravian Church, as well as some other denominations such as the Methodist Churches, there is a tradition of Easter Sunrise Services[105] often starting in cemeteries[106] in remembrance of the biblical narrative in the Gospels, or other places in the open where the sunrise is visible.[107]

In some traditions, Easter services typically begin with the Paschal greeting: «Christ is risen!» The response is: «He is risen indeed. Alleluia!»[108]

Eastern Christianity

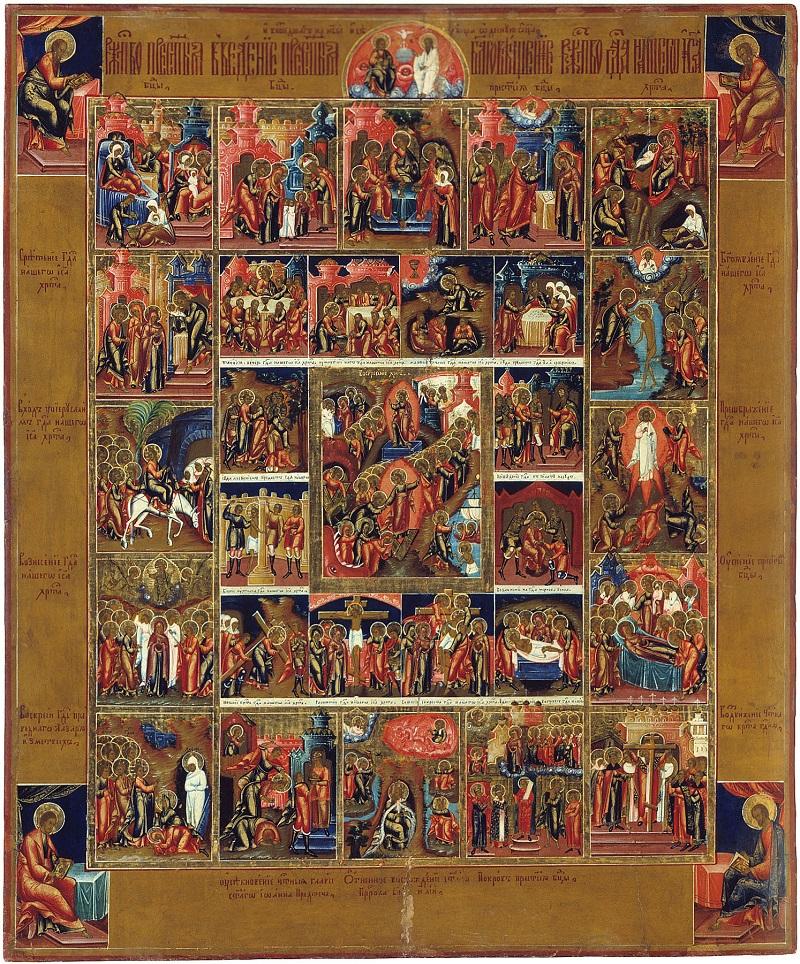

Icon of the Resurrection by an unknown 17th-century Bulgarian artist

Eastern Orthodox, Eastern Catholics and Byzantine Rite Lutherans have a similar emphasis on Easter in their calendars, and many of their liturgical customs are very similar.[109]

Preparation for Easter begins with the season of Great Lent, which begins on Clean Monday.[110] While the end of Lent is Lazarus Saturday, fasting does not end until Easter Sunday.[111] The Orthodox service begins late Saturday evening, observing the Jewish tradition that evening is the start of liturgical holy days.[111]

The church is darkened, then the priest lights a candle at midnight, representing the resurrection of Jesus Christ. Altar servers light additional candles, with a procession which moves three times around the church to represent the three days in the tomb.[111] The service continues early into Sunday morning, with a feast to end the fasting. An additional service is held later that day on Easter Sunday.[111]

Non-observing Christian groups

Many Puritans saw traditional feasts of the established Anglican Church, such as All Saints’ Day and Easter, as abominations because the Bible does not mention them.[112][113] Conservative Reformed denominations such as the Free Presbyterian Church of Scotland and the Reformed Presbyterian Church of North America likewise reject the celebration of Easter as a violation of the regulative principle of worship and what they see as its non-Scriptural origin.[114][115]

Members of the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers), as part of their historic testimony against times and seasons, do not celebrate or observe Easter or any traditional feast days of the established Church, believing instead that «every day is the Lord’s Day,» and that elevation of one day above others suggests that it is acceptable to do un-Christian acts on other days.[116][117] During the 17th and 18th centuries, Quakers were persecuted for this non-observance of Holy Days.[118]

Groups such as the Restored Church of God reject the celebration of Easter, seeing it as originating in a pagan spring festival adopted by the Roman Catholic Church.[119][non-primary source needed]

Jehovah’s Witnesses maintain a similar view, observing a yearly commemorative service of the Last Supper and the subsequent execution of Christ on the evening of Nisan 14 (as they calculate the dates derived from the lunar Hebrew calendar). It is commonly referred to by many Witnesses as simply «The Memorial». Jehovah’s Witnesses believe that such verses as Luke 22:19–20 and 1 Corinthians 11:26 constitute a commandment to remember the death of Christ though not the resurrection.[120][non-primary source needed]

Easter celebrations around the world

In countries where Christianity is a state religion, or those with large Christian populations, Easter is often a public holiday. As Easter always falls on a Sunday, many countries in the world also recognize Easter Monday as a public holiday. Some retail stores, shopping malls, and restaurants are closed on Easter Sunday. Good Friday, which occurs two days before Easter Sunday, is also a public holiday in many countries, as well as in 12 U.S. states. Even in states where Good Friday is not a holiday, many financial institutions, stock markets, and public schools are closed — the few banks that are normally open on regular Sundays are closed on Easter.[citation needed]

In the Nordic countries Good Friday, Easter Sunday, and Easter Monday are public holidays,[121] and Good Friday and Easter Monday are bank holidays.[122] In Denmark, Iceland and Norway Maundy Thursday is also a public holiday. It is a holiday for most workers, except those operating some shopping malls which keep open for a half-day. Many businesses give their employees almost a week off, called Easter break.[123] Schools are closed between Palm Sunday and Easter Monday. According to a 2014 poll, 6 of 10 Norwegians travel during Easter, often to a countryside cottage; 3 of 10 said their typical Easter included skiing.[124]

In the Netherlands both Easter Sunday and Easter Monday are national holidays. Like first and second Christmas Day, they are both considered Sundays, which results in a first and a second Easter Sunday, after which the week continues to a Tuesday.[125]

In Greece Good Friday and Saturday as well as Easter Sunday and Monday are traditionally observed public holidays. It is custom for employees of the public sector to receive Easter bonuses as a gift from the state.[126]

In Commonwealth nations Easter Day is rarely a public holiday, as is the case for celebrations which fall on a Sunday. In the United Kingdom both Good Friday and Easter Monday are bank holidays, except for Scotland, where only Good Friday is a bank holiday.[127] In Canada, Easter Monday is a statutory holiday for federal employees. In the Canadian province of Quebec, either Good Friday or Easter Monday are statutory holidays (although most companies give both).[128]

In Australia, Easter is associated with harvest time.[129] Good Friday and Easter Monday are public holidays across all states and territories. «Easter Saturday» (the Saturday before Easter Sunday) is a public holiday in every state except Tasmania and Western Australia, while Easter Sunday itself is a public holiday only in New South Wales. Easter Tuesday is additionally a conditional public holiday in Tasmania, varying between award, and was also a public holiday in Victoria until 1994.[130]

In the United States, because Easter falls on a Sunday, which is already a non-working day for federal and state employees, it has not been designated as a federal or state holiday.[131] Easter parades are held in many American cities, involving festive strolling processions.[30]

Easter eggs

Traditional customs

The egg is an ancient symbol of new life and rebirth.[132] In Christianity it became associated with Jesus’s crucifixion and resurrection.[133] The custom of the Easter egg originated in the early Christian community of Mesopotamia, who stained eggs red in memory of the blood of Christ, shed at his crucifixion.[134][135] As such, for Christians, the Easter egg is a symbol of the empty tomb.[25][26] The oldest tradition is to use dyed chicken eggs.

In the Eastern Orthodox Church Easter eggs are blessed by a priest[136] both in families’ baskets together with other foods forbidden during Great Lent and alone for distribution or in church or elsewhere.

-

Traditional red Easter eggs for blessing by a priest

-

A priest blessing baskets with Easter eggs and other foods forbidden during Great Lent

-

A priest distributing blessed Easter eggs after blessing the Soyuz rocket

Easter eggs are a widely popular symbol of new life among the Eastern Orthodox but also in folk traditions in Slavic countries and elsewhere. A batik-like decorating process known as pisanka produces intricate, brilliantly colored eggs. The celebrated House of Fabergé workshops created exquisite jewelled Easter eggs for the Russian Imperial family from 1885 to 1916.[137]

Modern customs

A modern custom in the Western world is to substitute decorated chocolate, or plastic eggs filled with candy such as jellybeans; as many people give up sweets as their Lenten sacrifice, individuals enjoy them at Easter after having abstained from them during the preceding forty days of Lent.[138]

-

Easter eggs, a symbol of the empty tomb, are a popular cultural symbol of Easter.[24]

-

Marshmallow rabbits, candy eggs and other treats in an Easter basket

Manufacturing their first Easter egg in 1875, British chocolate company Cadbury sponsors the annual Easter egg hunt which takes place in over 250 National Trust locations in the United Kingdom.[139][140] On Easter Monday, the President of the United States holds an annual Easter egg roll on the White House lawn for young children.[141]

Easter Bunny

In some traditions the children put out their empty baskets for the Easter bunny to fill while they sleep. They wake to find their baskets filled with candy eggs and other treats.[142][31] A custom originating in Germany,[142] the Easter Bunny is a popular legendary anthropomorphic Easter gift-giving character analogous to Santa Claus in American culture. Many children around the world follow the tradition of coloring hard-boiled eggs and giving baskets of candy.[31] Historically, foxes, cranes and storks were also sometimes named as the mystical creatures.[142] Since the rabbit is a pest in Australia, the Easter Bilby is available as an alternative.[143]

Music

|

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (March 2021) |

- Marc-Antoine Charpentier:

- Messe pour le samedi de Pâques, for soloists, chorus and continuo, H.8 (1690).

- Prose pour le jour de Pâques, for 3 voices and continuo, H.13 (1670)

- Chant joyeux du temps de Pâques, for soloists, chorus, 2 treble viols, and continuo, H.339 (1685).

- O filii à 3 voix pareilles, for 3 voices, 2 flutes, and continuo, H.312 (1670).

- Pour Pâques, for 2 voices, 2 flutes, and continuo, H.308 (1670).

- O filii pour les voix, violons, flûtes et orgue, for soloists, chorus, flutes, strings, and continuo, H.356 (1685 ?).

- Louis-Nicolas Clérambault: Motet pour le Saint jour de Pâques, in F major, opus 73

- André Campra: Au Christ triomphant, cantata for Easter

- Dieterich Buxtehude: Cantatas BuxWV 15 and BuxWV 62

- Carl Heinrich Graun: Easter Oratorio

- Henrich Biber: Missa Christi resurgentis C.3 (1674)

- Michael Praetorius: Easter Mass

- Johann Sebastian Bach: Christ lag in Todesbanden, BWV 4; Der Himmel lacht! Die Erde jubilieret, BWV 31; Oster-Oratorium, BWV 249.

- Georg Philipp Telemann, more than 100 cantatas for Eastertide.

- Jacques-Nicolas Lemmens: Sonata n° 2 «O Filii», Sonata n° 3 «Pascale», for organ.

- Charles Gounod: Messe solennelle de Pâques (1883).

- Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov: La Grande Pâque russe, symphonic overture (1888).

- Sergueï Vassilievitch Rachmaninov: Suite pour deux pianos n°1 – Pâques, op. 5, n° 4 (1893).

See also

- Divine Mercy Sunday

- Life of Jesus in the New Testament

- List of Easter hymns

- Movable Eastern Christian Observances

- Regina Caeli

- Category:Film portrayals of Jesus’ death and resurrection

Footnotes

- ^ Traditional names for the feast in English are «Easter Day», as in the Book of Common Prayer; «Easter Sunday», used by James Ussher (The Whole Works of the Most Rev. James Ussher, Volume 4[3]) and Samuel Pepys (The Diary of Samuel Pepys, Volume 2[4]), as well as the single word «Easter» in books printed in 1575,[5] 1584,[6] and 1586.[7]

- ^ In the Eastern Orthodox Church, the Greek word Pascha is used for the celebration; in English, the analogous word is Pasch.[8][9]

- ^ The term «Resurrection Sunday» is used particularly by Christian communities in the Middle East.[10][11]

- ^ Old English pronunciation: [ˈæːɑstre, ˈeːostre]

- ^ Eusebius reports that Dionysius, Bishop of Alexandria, proposed an 8-year Easter cycle, and quotes a letter from Anatolius, Bishop of Laodicea, that refers to a 19-year cycle.[75] An 8-year cycle has been found inscribed on a statue unearthed in Rome in the 17th century, and since dated to the 3rd century.[76]

References

- ^ Selected Christian Observances, 2023, U.S. Naval Observatory Astronomical Applications Department

- ^ When is Orthodox Easter?, Calendarpedia

- ^ Archived 1 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Archived 9 June 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Archived 1 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Archived 1 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Archived 1 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ferguson, Everett (2009). Baptism in the Early Church: History, Theology, and Liturgy in the First Five Centuries. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 351. ISBN 978-0802827487. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 23 April 2014.

The practices are usually interpreted in terms of baptism at the pasch (Easter), for which compare Tertullian, but the text does not specify this season, only that it was done on Sunday, and the instructions may apply to whenever the baptism was to be performed.

- ^ a b Norman Davies (1998). Europe: A History. HarperCollins. p. 201. ISBN 978-0060974688.

In most European languages Easter is called by some variant of the late Latin word Pascha, which in turn derives from the Hebrew pesach, meaning passover.

- ^ a b Gamman, Andrew; Bindon, Caroline (2014). Stations for Lent and Easter. Kereru Publishing Limited. p. 7. ISBN 978-0473276812.

Easter Day, also known as Resurrection Sunday, marks the high point of the Christian year. It is the day that we celebrate the resurrection of Jesus Christ from the dead.

- ^ a b Boda, Mark J.; Smith, Gordon T. (2006). Repentance in Christian Theology. Liturgical Press. p. 316. ISBN 978-0814651759. Archived from the original on 4 August 2020. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

Orthodox, Catholic, and all Reformed churches in the Middle East celebrate Easter according to the Eastern calendar, calling this holy day «Resurrection Sunday,» not Easter.

- ^ Bernard Trawicky; Ruth Wilhelme Gregory (2000). Anniversaries and Holidays. American Library Association. ISBN 978-0838906958. Archived from the original on 12 October 2017. Retrieved 17 October 2020.

Easter is the central celebration of the Christian liturgical year. It is the oldest and most important Christian feast, celebrating the Resurrection of Jesus Christ. The date of Easter determines the dates of all movable feasts except those of Advent.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Aveni, Anthony (2004). «The Easter/Passover Season: Connecting Time’s Broken Circle», The Book of the Year: A Brief History of Our Seasonal Holidays. Oxford University Press. pp. 64–78. ISBN 0-19-517154-3. Archived from the original on 8 February 2021. Retrieved 17 October 2020.

- ^ Cooper, J.HB. (23 October 2013). Dictionary of Christianity. Routledge. p. 124. ISBN 9781134265466.

Holy Week. The last week in LENT. It begins on PALM SUNDAY; the fourth day is called SPY WEDNESDAY; the fifth is MAUNDY THURSDAY or HOLY THURSDAY; the sixth is GOOD FRIDAY; and the last ‘Holy Saturday’, or the ‘Great Sabbath’.

- ^ Peter C. Bower (2003). The Companion to the Book of Common Worship. Geneva Press. ISBN 978-0664502324. Archived from the original on 8 June 2021. Retrieved 11 April 2009.

Maundy Thursday (or le mandé; Thursday of the Mandatum, Latin, commandment). The name is taken from the first few words sung at the ceremony of the washing of the feet, «I give you a new commandment» (John 13:34); also from the commandment of Christ that we should imitate His loving humility in the washing of the feet (John 13:14–17). The term mandatum (maundy), therefore, was applied to the rite of foot-washing on this day.

- ^ Gail Ramshaw (2004). Three Day Feast: Maundy Thursday, Good Friday, and Easter. Augsburg Fortress. ISBN 978-1451408164. Archived from the original on 5 November 2021. Retrieved 11 April 2009.

In the liturgies of the Three Days, the service for Maundy Thursday includes both, telling the story of Jesus’ last supper and enacting the footwashing.

- ^ Leonard Stuart (1909). New century reference library of the world’s most important knowledge: complete, thorough, practical, Volume 3. Syndicate Pub. Co. Archived from the original on 5 November 2021. Retrieved 11 April 2009.

Holy Week, or Passion Week, the week which immediately precedes Easter, and is devoted especially to commemorating the passion of our Lord. The Days more especially solemnized during it are Holy Wednesday, Maundy Thursday, Good Friday, and Holy Saturday.

- ^ «Frequently asked questions about the date of Easter». Archived from the original on 22 April 2011. Retrieved 22 April 2009.

- ^ Woodman, Clarence E. (1923). «Clarence E. Woodman, «Easter and the Ecclesiastical Calendar» in Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, Vol. 17, p.141″. Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada. 17: 141. Bibcode:1923JRASC..17..141W. Archived from the original on 12 May 2019. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- ^ «5 April 2007: Mass of the Lord’s Supper | BENEDICT XVI». www.vatican.va. Archived from the original on 5 April 2021. Retrieved 1 April 2021.

- ^ Reno, R. R. (14 April 2017). «The Profound Connection Between Easter and Passover». The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on 17 December 2021. Retrieved 1 April 2021.

- ^ Weiser, Francis X. (1958). Handbook of Christian Feasts and Customs. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company. p. 214. ISBN 0-15-138435-5.

- ^ Simpson, Jacqueline; Roud, Steve (2003). «clipping the church». Oxford Reference. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780198607663.001.0001. ISBN 9780198607663. Archived from the original on 12 April 2020. Retrieved 31 March 2013.

- ^ a b Anne Jordan (2000). Christianity. Nelson Thornes. ISBN 978-0748753208. Archived from the original on 8 February 2021. Retrieved 7 April 2012.

Easter eggs are used as a Christian symbol to represent the empty tomb. The outside of the egg looks dead but inside there is new life, which is going to break out. The Easter egg is a reminder that Jesus will rise from His tomb and bring new life. Eastern Orthodox Christians dye boiled eggs red to represent the blood of Christ shed for the sins of the world.

- ^ a b The Guardian, Volume 29. H. Harbaugh. 1878. Archived from the original on 4 August 2020. Retrieved 7 April 2012.

Just so, on that first Easter morning, Jesus came to life and walked out of the tomb, and left it, as it were, an empty shell. Just so, too, when the Christian dies, the body is left in the grave, an empty shell, but the soul takes wings and flies away to be with God. Thus you see that though an egg seems to be as dead as a sone, yet it really has life in it; and also it is like Christ’s dead body, which was raised to life again. This is the reason we use eggs on Easter. (In olden times they used to color the eggs red, so as to show the kind of death by which Christ died, – a bloody death.)

- ^ a b Gordon Geddes, Jane Griffiths (2002). Christian belief and practice. Heinemann. ISBN 978-0435306915. Archived from the original on 29 July 2020. Retrieved 7 April 2012.

Red eggs are given to Orthodox Christians after the Easter Liturgy. They crack their eggs against each other’s. The cracking of the eggs symbolizes a wish to break away from the bonds of sin and misery and enter the new life issuing from Christ’s resurrection.

- ^ Collins, Cynthia (19 April 2014). «Easter Lily Tradition and History». The Guardian. Archived from the original on 17 August 2020. Retrieved 20 April 2014.

The Easter Lily is symbolic of the resurrection of Jesus Christ. Churches of all denominations, large and small, are filled with floral arrangements of these white flowers with their trumpet-like shape on Easter morning.

- ^ Schell, Stanley (1916). Easter Celebrations. Werner & Company. p. 84.

We associate the lily with Easter, as pre-eminently the symbol of the Resurrection.

- ^ Luther League Review: 1936–1937. Luther League of America. 1936. Archived from the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ^ a b Duchak, Alicia (2002). An A–Z of Modern America. Rutledge. p. 372. ISBN 978-0415187558. Archived from the original on 27 December 2021. Retrieved 17 October 2020.

- ^ a b c Sifferlin, Alexandra (21 February 2020) [2015]. «What’s the Origin of the Easter Bunny?». Time. Archived from the original on 22 October 2021. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

- ^ Vicki K. Black (2004). The Church Standard, Volume 74. Church Publishing, Inc. ISBN 978-0819225757. Archived from the original on 4 August 2020. Retrieved 7 April 2012.

In parts of Europe, the eggs were dyed red and were then cracked together when people exchanged Easter greetings. Many congregations today continue to have Easter egg hunts for the children after the services on Easter Day.

- ^ The Church Standard, Volume 74. Walter N. Hering. 1897. Archived from the original on 30 August 2020. Retrieved 7 April 2012.

When the custom was carried over into Christian practice the Easter eggs were usually sent to the priests to be blessed and sprinkled with holy water. In later times the coloring and decorating of eggs was introduced, and in a royal roll of the time of Edward I., which is preserved in the Tower of London, there is an entry of 18d. for 400 eggs, to be used for Easter gifts.

- ^ Brown, Eleanor Cooper (2010). From Preparation to Passion. ISBN 978-1609577650. Archived from the original on 4 August 2020. Retrieved 7 April 2012.

So what preparations do most Christians and non-Christians make? Shopping for new clothing often signifies the belief that Spring has arrived, and it is a time of renewal. Preparations for the Easter Egg Hunts and the Easter Ham for the Sunday dinner are high on the list too.

- ^ Wallis, Faith (1999). Bede: The Reckoning of Time. Liverpool University Press. p. 54. ISBN 0853236933.

- ^ «History of Easter». The History Channel website. A&E Television Networks. Archived from the original on 31 May 2013. Retrieved 9 March 2013.

- ^ Karl Gerlach (1998). The Antenicene Pascha: A Rhetorical History. Peeters Publishers. p. xviii. ISBN 978-9042905702. Archived from the original on 8 August 2021. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

The second century equivalent of easter and the paschal Triduum was called by both Greek and Latin writers «Pascha (πάσχα)», a Greek transliteration of the Aramaic form of the Hebrew פֶּסַח, the Passover feast of Ex. 12.

- ^ 1 Corinthians 5:7

- ^ Karl Gerlach (1998). The Antenicene Pascha: A Rhetorical History. Peters Publishers. p. 21. ISBN 978-9042905702. Archived from the original on 28 December 2021. Retrieved 17 October 2020.

For while it is from Ephesus that Paul writes, «Christ our Pascha has been sacrificed for us,» Ephesian Christians were not likely the first to hear that Ex 12 did not speak about the rituals of Pesach, but the death of Jesus of Nazareth.

- ^ a b c d Vicki K. Black (2004). Welcome to the Church Year: An Introduction to the Seasons of the Episcopal Church. Church Publishing, Inc. ISBN 978-0819219664. Archived from the original on 8 August 2021. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

Easter is still called by its older Greek name, Pascha, which means «Passover», and it is this meaning as the Christian Passover-the celebration of Jesus’s triumph over death and entrance into resurrected life-that is the heart of Easter in the church. For the early church, Jesus Christ was the fulfillment of the Jewish Passover feast: through Jesus, we have been freed from slavery of sin and granted to the Promised Land of everlasting life.

- ^ Orthros of Holy Pascha, Stichera: «Today the sacred Pascha is revealed to us. The new and holy Pascha, the mystical Pascha. The all-venerable Pascha. The Pascha which is Christ the Redeemer. The spotless Pascha. The great Pascha. The Pascha of the faithful. The Pascha which has opened unto us the gates of Paradise. The Pascha which sanctifies all faithful.»

- ^ «Easter or Resurrection day?». Simply Catholic. 17 January 2019. Archived from the original on 8 June 2021. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

- ^ «Easter: 5 facts you need to know about resurrection sunday». Christian Post. 1 April 2018. Archived from the original on 22 November 2021. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

- ^ Torrey, Reuben Archer (1897). «The Resurrection of Christ». Torrey’s New Topical Textbook. Archived from the original on 20 November 2021. Retrieved 31 March 2013. (interprets primary source references in this section as applying to the Resurrection)

«The Letter of Paul to the Corinthians». Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 24 April 2015. Retrieved 10 March 2013. - ^ a b «Jesus Christ». Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 3 May 2015. Retrieved 11 March 2013.

- ^ Barker, Kenneth, ed. (2002). Zondervan NIV Study Bible. Grand Rapids: Zondervan. p. 1520. ISBN 0-310-92955-5.

- ^ Karl Gerlach (1998). The Antenicene Pascha: A Rhetorical History. Peeters Publishers. pp. 32, 56. ISBN 978-9042905702. Archived from the original on 27 December 2021. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

- ^ Landau, Brent. «Why Easter is called Easter, and other little-known facts about the holiday». The Conversation. Archived from the original on 12 August 2021. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- ^

Melito of Sardis. «Homily on the Pascha». Kerux. Northwest Theological Seminary. Archived from the original on 12 March 2007. Retrieved 28 March 2007. - ^ Cheslyn Jones, Geoffrey Wainwright, Edward Yarnold, and Paul Bradshaw, Eds., The Study of Liturgy, Revised Edition, Oxford University Press, New York, 1992, p. 474.

- ^ Genung, Charles Harvey (1904). «The Reform of the Calendar». The North American Review. 179 (575): 569–583. JSTOR 25105305.

- ^ Cheslyn Jones, Geoffrey Wainwright, Edward Yarnold, and Paul Bradshaw, Eds., The Study of Liturgy, Revised Edition, Oxford University Press, New York, 1992, p. 459:»[Easter] is the only feast of the Christian Year that can plausibly claim to go back to apostolic times … [It] must derive from a time when Jewish influence was effective … because it depends on the lunar calendar (every other feast depends on the solar calendar).»

- ^ Socrates, Church History, 5.22, in Schaff, Philip (13 July 2005). «The Author’s Views respecting the Celebration of Easter, Baptism, Fasting, Marriage, the Eucharist, and Other Ecclesiastical Rites». Socrates and Sozomenus Ecclesiastical Histories. Calvin College Christian Classics Ethereal Library. Archived from the original on 16 March 2010. Retrieved 28 March 2007.

- ^ Karl Gerlach (1998). The Antenicene Pascha: A Rhetorical History. Peeters Publishers. p. 21. ISBN 978-9042905702. Archived from the original on 8 August 2021. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

Long before this controversy, Ex 12 as a story of origins and its ritual expression had been firmly fixed in the Christian imagination. Though before the final decades of the 2nd century only accessible as an exegetical tradition, already in the Pauline letters the Exodus saga is deeply involved with the celebration of bath and meal. Even here, this relationship does not suddenly appear, but represents developments in ritual narrative that must have begun at the very inception of the Christian message. Jesus of Nazareth was crucified during Pesach-Mazzot, an event that a new covenant people of Jews and Gentiles both saw as definitive and defining. Ex 12 is thus one of the few reliable guides for tracing the synergism among ritual, text, and kerygma before the Council of Nicaea.

- ^ Sozomen, Book 7, Chapter 18

- ^ Caroline Wyatt (25 March 2016). «Why Can’t the Date of Easter be Fixed». BBC. Archived from the original on 24 November 2021. Retrieved 13 April 2017.

- ^ The Date of Easter Archived 14 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Article from United States Naval Observatory (27 March 2007).

- ^ «Easter Monday in Hungary in 2021». Office Holidays. Archived from the original on 5 November 2021. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- ^ «calendar — The early Roman calendar | Britannica». www.britannica.com. Archived from the original on 16 April 2022. Retrieved 16 April 2022.

- ^ «The Church in Malankara switched entirely to the Gregorian calendar in 1953, following Encyclical No. 620 from Patriarch Mor Ignatius Aphrem I, dt. December 1952.» Calendars of the Syriac Orthodox Church Archived 24 February 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 22 April 2009

- ^ Wallis, Faith (1999). Bede: The Reckoning of Time. Liverpool University Press. p. 148. ISBN 0853236933.

- ^ Why is Easter so early this year? Archived 19 April 2021 at the Wayback Machine, EarthSky, Bruce McClure in Astronomy Essentials, 30 March 2018.

- ^ Paragraph 7 of Inter gravissimas ISO.org Archived 14 July 2022 at the Wayback Machine to «the vernal equinox, which was fixed by the fathers of the [first] Nicene Council at XII calends April [21 March]». This definition can be traced at least back to chapters 6 & 59 of Bede’s De temporum ratione (725).

- ^ a b «Date of Easter». The Anglican Church of Canada. Archived from the original on 26 December 2021. Retrieved 5 April 2021.

- ^ a b Montes, Marcos J. «Calculation of the Ecclesiastical Calendar» Archived 3 November 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 12 January 2008.

- ^ G Moyer (1983), «Aloisius Lilius and the ‘Compendium novae rationis restituendi kalendarium'» Archived 12 October 2021 at the Wayback Machine, pp. 171–188 in G.V. Coyne (ed.).

- ^ Leviticus 23:5

- ^ Eusebius, Church History 5.23.

- ^ Socrates, Church History, 6.11, at Schaff, Philip (13 July 2005). «Of Severian and Antiochus: their Disagreement from John». Socrates and Sozomenus Ecclesiastical Histories. Calvin College Christian Classics Ethereal Library. Archived from the original on 13 October 2010. Retrieved 28 March 2009.

- ^ Socrates, Church History 7.29, at Schaff, Philip (13 July 2005). «Nestorius of Antioch promoted to the See of Constantinople. His Persecution of the Heretics». Socrates and Sozomenus Ecclesiastical Histories. Calvin College Christian Classics Ethereal Librar. Archived from the original on 13 October 2010. Retrieved 28 March 2009.

- ^ Eusebius, Church History, 7.32.

- ^ Peter of Alexandria, quoted in the Chronicon Paschale. In Alexander Roberts and James Donaldson, eds., Ante-Nicene Christian Library, Volume 14: The Writings of Methodius, Alexander of Lycopolis, Peter of Alexandria, And Several Fragments, Edinburgh, 1869, p. 326, at Donaldson, Alexander (1 June 2005). «That Up to the Time of the Destruction of Jerusalem, the Jews Rightly Appointed the Fourteenth Day of the First Lunar Month». Gregory Thaumaturgus, Dionysius the Great, Julius Africanus, Anatolius and Minor Writers, Methodius, Arnobius. Calvin College Christian Classics Ethereal Library. Archived from the original on 15 April 2009. Retrieved 28 March 2009.

- ^ MS Verona, Biblioteca Capitolare LX(58) folios 79v–80v.

- ^ Sacha Stern, Calendar and Community: A History of the Jewish Calendar Second Century BCE – Tenth Century CE, Oxford, 2001, pp. 124–132.

- ^ Eusebius, Church History, 7.20, 7.31.

- ^ Allen Brent, Hippolytus and the Roman Church in the Third Century, Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1995.

- ^ Epiphanius, Adversus Haereses, Heresy 69, 11,1, in Willams, F. (1994). The Panarion of Epiphianus of Salamis Books II and III. Leiden: E.J. Brill. p. 331.

- ^ Apostolic Canon 7: «If any bishop, presbyter, or deacon shall celebrate the holy day of Easter before the vernal equinox with the Jews, let him be deposed.» A Select Library of Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers of the Christian Church, Second Series, Volume 14: The Seven Ecumenical Councils, Eerdmans, 1956, p. 594.

- ^ St. John Chrysostom, «Against those who keep the first Passover», in Saint John Chrysostom: Discourses against Judaizing Christians, translated by Paul W. Harkins, Washington, DC, 1979, pp. 47ff.

- ^ Mosshammer, Alden A. (2008). The Easter Computus and the Origins of the Christian Era. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 50–52, 62–65. ISBN 978-0-19-954312-0.

- ^ a b Mosshammer, Alden A. (2008). The Easter Computus and the Origins of the Christian Era. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 239–244. ISBN 978-0-19-954312-0.

- ^ a b Holford-Strevens, Leofranc, and Blackburn, Bonnie (1999). The Oxford Companion to the Year. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 808–809. ISBN 0-19-214231-3.

- ^ Mosshammer, Alden A. (2008). The Easter Computus and the Origins of the Christian Era. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 223–224. ISBN 978-0-19-954312-0.

- ^ Holford-Strevens, Leofranc, and Blackburn, Bonnie (1999). The Oxford Companion to the Year. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 870–875. ISBN 0-19-214231-3.

- ^ «Orthodox Easter: Why are there two Easters?». BBC Newsround. 20 April 2020. Archived from the original on 23 December 2021. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

- ^ «Easter: A date with God». The Economist. 20 April 2011. Archived from the original on 23 April 2018. Retrieved 23 April 2011.

Only in a handful of places do Easter celebrants alter their own arrangements to take account of their neighbours. Finland’s Orthodox Christians mark Easter on the Western date. And on the Greek island of Syros, a Papist stronghold, Catholics and Orthodox alike march to Orthodox time. The spectacular public commemorations, involving flower-strewn funeral biers on Good Friday and fireworks on Saturday night, bring the islanders together, rather than highlighting division.

- ^ «Easter: A date with God». The Economist. 20 April 2011. Archived from the original on 23 April 2018. Retrieved 23 April 2011.

Finland’s Orthodox Christians mark Easter on the Western date.

- ^ «Easter (holiday)». Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 3 May 2015. Retrieved 9 March 2013.

- ^ a b Hieromonk Cassian, A Scientific Examination of the Orthodox Church Calendar, Center for Traditionalist Orthodox Studies, 1998, pp. 51–52, ISBN 0-911165-31-2.

- ^ M. Milankovitch, «Das Ende des julianischen Kalenders und der neue Kalender der orientalischen Kirchen», Astronomische Nachrichten 200, 379–384 (1924).

- ^ Miriam Nancy Shields, «The new calendar of the Eastern churches Archived 24 March 2015 at the Wayback Machine», Popular Astronomy 32 (1924) 407–411 (page 411 Archived 12 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine). This is a translation of M. Milankovitch, «The end of the Julian calendar and the new calendar of the Eastern churches», Astronomische Nachrichten No. 5279 (1924).

- ^ «Hansard Reports, April 2005, regarding the Easter Act of 1928». United Kingdom Parliament. Archived from the original on 8 June 2021. Retrieved 14 March 2010.

- ^ WCC: Towards a common date for Easter Archived 13 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ «Why is Orthodox Easter on a different day?». U.S. Catholic magazine. 3 April 2015. Archived from the original on 9 May 2021. Retrieved 5 April 2021.

- ^ Iati, Marisa (20 April 2019). «Why isn’t Easter celebrated on the same date every year?». Washington Post. Archived from the original on 10 December 2020. Retrieved 5 April 2021.

- ^ «Christian Churches to Fix Common Date for Easter» Archived 9 June 2021 at the Wayback Machine (18 January 2016). CathNews.com. Retrieved 18 September 2018.

- ^ Hertz, Joachin Meisner (16 November 2022). «Patriarch of Constantinople: Conversations Are Underway for Catholics and Orthodox to Celebrate Easter on the Same Date». ZENIT — English. Retrieved 18 November 2022.

- ^ «Towards a Common Date for Easter». Aleppo, Syria: World Council of Churches (WCC) / Middle East Council of Churches Consultation (MECC). 10 March 1997.

- ^ MacKinnon, Grace (March 2003). «The Meaning of Holy Week». Catholic Education Resource Center. Archived from the original on 12 May 2021. Retrieved 16 April 2022.

- ^ Sfetcu, Nicolae (2 May 2014). Easter Traditions. Nicolae Sfetcu.

- ^ Lash, Ephrem (Archimandrite) (25 January 2007). «On the Holy and Great Sunday of Pascha». Monastery of Saint Andrew the First Called, Manchester, England. Archived from the original on 9 April 2007. Retrieved 27 March 2007.

- ^ «Pentecost Sunday». About.com. Archived from the original on 29 March 2013. Retrieved 28 March 2013.

- ^ Notes for the Easter Vigil Archived 21 November 2021 at the Wayback Machine, website of Lutheran pastor Weitzel

- ^ Catholic Activity: Easter Vigil Archived 15 September 2021 at the Wayback Machine, entry on catholicculture.org

- ^ Easter observed at Sunrise Celebration Archived 25 December 2019 at the Wayback Machine, report of Washington Post April 2012

- ^ Sunrise Service At Abington Cemetery Is An Easter Tradition Archived 24 January 2021 at the Wayback Machine, report of Hartford Courant newspaper of 4 April 2016

- ^ «Easter sunrise services: A celebration of resurrection». The United Methodist Church. 5 April 2019. Archived from the original on 23 December 2021. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

- ^ «The Easter Liturgy». The Church of England. Archived from the original on 19 October 2021. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

- ^ Moroz, Vladimir (10 May 2016). Лютерани східного обряду: такі є лише в Україні (in Ukrainian). РІСУ – Релігійно-інформаційна служба України. Archived from the original on 15 August 2020. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

В українських лютеран, як і в ортодоксальних Церквах, напередодні Великодня є Великий Піст або Чотиридесятниця.

- ^ «Easter». History.com. History. Archived from the original on 9 December 2021. Retrieved 20 April 2019.

- ^ a b c d Olp, Susan. «Celebrating Easter looks different for Eastern Orthodox, Catholic and Protestant churches». The Billings Gazette. Archived from the original on 29 November 2021. Retrieved 20 April 2019.

- ^ Daniels, Bruce Colin (1995). Puritans at Play: Leisure and Recreation in Colonial New England. Macmillan, p. 89, ISBN 978-0-31216124-8

- ^ Roark, James; Johnson, Michael; Cohen, Patricia; Stage, Sarah; Lawson, Alan; Hartmann, Susan (2011). Understanding the American Promise: A History, Volume I: To 1877. Bedford/St. Martin’s. p. 91.

Puritans mandated other purifications of what they considered corrupt English practices. They refused to celebrate Christmas or Easter because the Bible did not mention either one.

- ^ «The Regulative Principle of Worship». Free Presbyterian Church of Scotland. Archived from the original on 14 February 2022. Retrieved 12 April 2022.

Those who adhere to the Regulative Principle by singing exclusively the psalms, refusing to use musical instruments, and rejecting «Christmas», «Easter» and the rest, are often accused of causing disunity among the people of God. The truth is the opposite. The right way to move towards more unity is to move to exclusively Scriptural worship. Each departure from the worship instituted in Scripture creates a new division among the people of God. Returning to Scripture alone to guide worship is the only remedy.

- ^ Minutes of Session of 1905. Reformed Presbyterian Church of North America. 1905. p. 130.

WHEREAS, There is a growing tendency in Protestant Churches, and to some extent in our own, to observe days and ceremonies, as Christmas and Easter, that are without divine authority; we urge our people to abstain from all such customs as are popish in their origin and injurious as lending sacredness to rites that come from paganism; that ministers keep before the minds of the people that only institutions that are Scriptural and of Divine appointment should be used in the worship of God.

- ^ Brownlee, William Craig (1824). «A Careful and Free Inquiry into the True Nature and Tendency of the …» Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ^ «See Quaker Faith & practice of Britain Yearly Meeting, Paragraph 27:42″. Archived from the original on 8 June 2021. Retrieved 21 April 2014.

- ^ Quaker life, December 2011: «Early Quaker Top 10 Ways to Celebrate (or Not) «the Day Called Christmas» by Rob Pierson Archived 6 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Pack, David. «The True Origin of Easter». The Restored Church of God. Archived from the original on 26 April 2011. Retrieved 24 March 2011.

- ^ «Easter or the Memorial – Which Should You Observe?». Watchtower Magazine. Watch Tower Bible and Tract Society of Pennsylvania. 1 April 1996. Archived from the original on 18 April 2014. Retrieved 11 April 2014.

- ^ Public holidays in Scandinavian countries, for example; «Public holidays in Sweden». VisitSweden. Archived from the original on 13 April 2014. Retrieved 10 April 2014.

«Public holidays [in Denmark]». VisitDenmark. Archived from the original on 25 July 2018. Retrieved 10 April 2014. - ^ «Bank Holidays». Nordea Bank AB. Archived from the original on 13 April 2014. Retrieved 10 April 2014.

- ^ «Lov om detailsalg fra butikker m.v.» (in Danish). retsinformation.dk. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 10 April 2014.

- ^ Mona Langset (12 April 2014) Nordmenn tar påskeferien i Norge Archived 10 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine (in Norwegian) VG

- ^ «Dutch Easter traditions – how the Dutch celebrate Easter». Dutch Community. Archived from the original on 13 April 2014. Retrieved 10 April 2014.

- ^ webteam (6 April 2017). «Τι προβλέπει η νομοθεσία για την καταβολή του δώρου του Πάσχα | Ελληνική Κυβέρνηση» (in Greek). Archived from the original on 28 July 2021. Retrieved 23 April 2022.

- ^ «UK bank holidays». gov.uk. Archived from the original on 21 September 2012. Retrieved 10 April 2014.

- ^ «Statutory holidays». CNESST. Archived from the original on 1 January 2022. Retrieved 1 January 2022.

- ^ «Easter 2016». Public Holidays Australia. Archived from the original on 22 December 2021. Retrieved 1 June 2015.

- ^ Public holidays Archived 4 January 2015 at the Wayback Machine, australia.gov.au