-

-

April 27 2011, 13:13

- Искусство

- Праздники

- Cancel

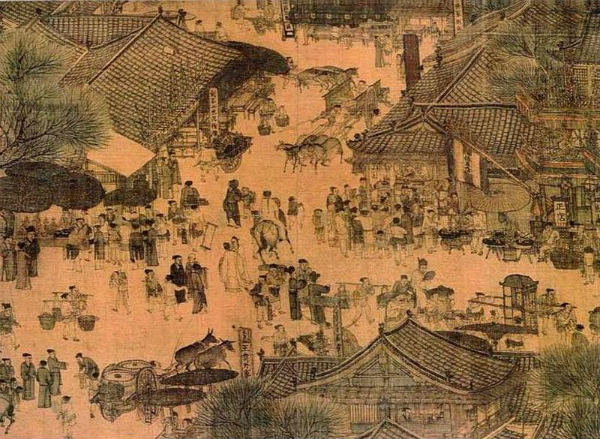

Шедевр классического искусства — картина «Праздник Цинмин на реке Бяньхэ «清明上河图»»

Картина «Праздник Цинмин на реке Бяньхэ» является бесценным уникумом в истории китайской живописи. Она была выполнена художником Сунской династии Чжан Цзэдуанем на шелковом полотке высотой 24,8 см и шириной 528 см. Картина отличается детальным изображением городского быта, показывает пышный расцвет города Бяньляна — столицы династии Северная Сун. Работа эта не теряет своего блеска и по сей день. Однако с течением времени появилось немало копий этой картины.

В 1950 г. в провинции Ляонин эксперт Ян Жэнькай исследовал три работы и нашёл оригинальное полотно кисти Чжан Цзэдуаня. В 1953 г. оригинальная картина «Праздник Цинмин на реке Бяньхэ» демонстрировалась в музее Гугун в Пекине.

К ещё большему удивлению эксперта Ян Жэнькая, среди вышеупомянутых трёх работ одна работа оказалась выполненной художником Минской династии Цю Ином. Следуя оригиналу Чжан Цзэдуаня, Цю Ин изобразил общественную жизнь в южно-китайском городе Сучжоу. По мнению эксперта в истории большинство копий картины «Праздник Цинмин на реке Бяньхэ» сделано именно с картины Цю Ина.

Согласно статистике, в настоящее время в Китае и за рубежом существует более 30 копий картины «Праздник Цинмин на реке Бяньхэ», которые находятся в музеях и частных коллекциях.(http://russian.cri.cn)

начнем с названия.

оригинальное название свитка (китайский): 清明上河图

дословный перевод:

清 — чистый, светлый, спокойный

明 — светлый; ясный

上 — подниматься, восходить [на]

河- река, Хуанхэ (река)

图 — рисунок

или первая пара может быть одним словом (остальное так же):

清明 —

- светлый, ясный; безмятежный; чистый, прозрачный

- спокойный, размеренный; правильный; трезвый (об уме); в порядке

- законный

- ясные дни (период года с 5 или 6 апреля, отнесён к первой половине 3-го лунного месяца)

- дни [весенних] поминок

известные названия по-английски:

- The Qingming Scroll

- Quingming Festival on the River

- Going Upriver on the Qingming Festival,

- Life along the Bian River at the Qingming Festival,

- Life Along the Bian River at the Pure Brightness Festival,

- Riverside Scene at Qingming Festival,

- Upper River during Qing Ming Festival,

- Spring Festival on the River,

- Spring Festival Along the River, or alternatively,

- Peace Reigns Over the River.

- Peace Reigns on the River

(про последние 2 — будет ниже)

известные русские названия:

- По реке в День поминовения усопших

- Праздник Цинмин на реке Бянъхэ

- Праздник Цинмин на реке Бяньхэ (разница в одной букве)

- Праздник Цинмин на реке

- Цинмин на реке

- Берег реки

получается, что первую пару знаков в исходном название можно читать как «в праздник цинмин…», так и «светлый день…». а можно и «спокойный, размеренный, правильный, в порядке, законный день…». одна из версий, приписывает название свитка неверно понятой подписи-каллиграфии поэта более поздней династии.

в любом случае, надо согласиться с критиками, что именно праздником на свитке — даже не пахнет. в разгаре рабочий день.

к слову, в русских вариантах, название без праздника даже не упоминается. просто поражает уровень нашего интереса, к великому южному соседу.

в начале привел все названия, что бы было с чего начинать при поиске источников. но не надо забывать, что свиток имеет бесчисленное количество ремейков и копий (включая мою), так что хорошо бы с начала начать отличать главные, корневые экземпляры.

теперь про авторство, которое тоже оспаривается.

рискну предложить свою версию, которая строго перпендикулярна академическим: у свитка больше одного автора. возможно помогал ученик, а может кто из заказчиков приложил руку.

дело в деревьях. все деревья на свитке, можно разделить на 2 группы: с прямыми ветками, и с ветками-черточками.

и только одно дерево в центре свитка, под поворотом реки, выбивается из этого набора, и больше похоже на арабскую вязь (может даже кто-то сможет прочитать). такой стиль использован не только в этом месте, есть еще пара точек, где этой же рукой дописаны ветки.

ветки крупным планом — сравнивайте.

Советская Красная Армия

и еще одна интересная деталь. пара китайских источников пишет: «сундуки императора Пу И, набитые историческими сокровищами Китая, были захвачены Советской Красной Армией, и переданы Народному Правительству Китая». подтверждение данному факту найти трудно, но 39-я армия (оперативное объединение Сухопутных войск (армия) в составе Вооружённых cил СССР, созданная во время Великой Отечественной войныю wiki), на самом деле могла это сделать. так что в истории свитка есть и русская рука, причем у нее очень позитивная роль, в отличии от.

Женщина молится на кладбище Бабаошань в Пекине. Фото: South China Morning Post

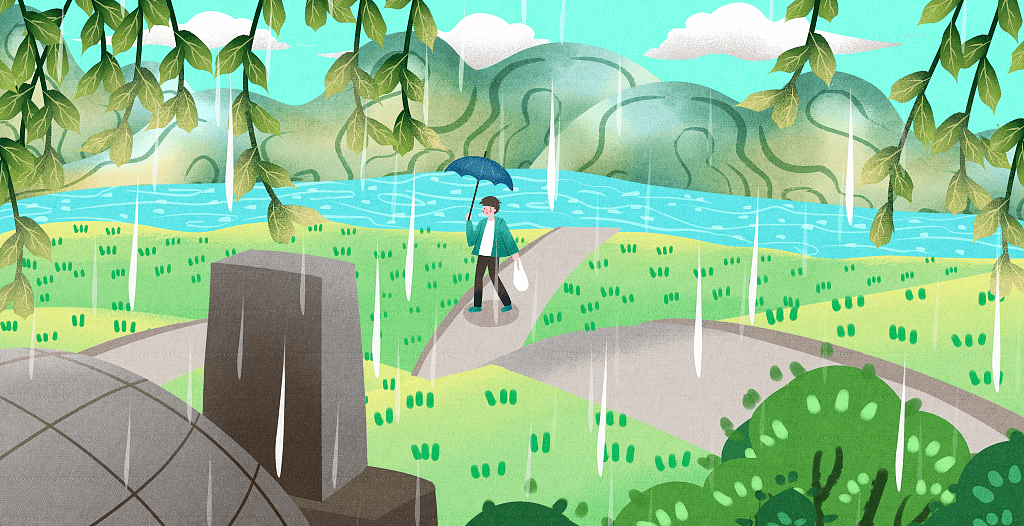

Дни с 4 по 6 апреля являются выходными в Китае. Дело в том, что в это время отмечается праздник Цинмин, который еще называют Днем поминовения усопших. С праздником связано множество ритуалов, чьи корни уходят в глубокую древность, а кроны впитывают все социальные изменения и тенденции в стране, поэтому иностранцу непросто разобраться в том, что творится вокруг в эти три весенних дня. Если вы еще не были в КНР или находитесь там, но не понимаете, что происходит, читайте гид по празднику Цинмин от ЭКД.

1. Происхождение и смысл

Цинмин Цзе (清明节;Qīngmíngjié) буквально переводится как «праздник чистого света». Он отмечается на 15-й день после весеннего равноденствия, который выпадает либо на 4-е, либо на 5-е апреля. В 2015 году он попал на 5-е число, но по традиции выходными всегда считаются три дня с 4 по 6 апреля.

В древнем Китае почитание умерших предков было важнейшим обрядом, на него не жалели ни средств, ни времени, и проводился он регулярно, в некоторых населенных пунктах едва ли не каждые две недели. И это не считая других праздников и фестивалей. В 732 году император династии Тан по имени Сюань-цзун решил положить конец этой расточительности, и установил единый для всей страны День поминовения усопших — праздник Цинмин — когда людям было позволено посещать могилы предков. Эта традиция сохраняется до сих пор.

Основатель праздника Цинмин, танский император Сюань-цзун. Фото: Википедиа

После прихода к власти в 1949 году, китайское коммунистическое правительство пыталось бороться с этим праздником, как с пережитком прошлого, однако неофициально люди продолжали отмечать этот день. В 2008 году Цинмин снова стал государственным.

2. Ритуалы

Уход за могилами

В дни Цинмин дороги, ведущие к большим кладбищам, обычно перегружены транспортом, так как люди спешат убрать старые листья с надгробий усопших родственников, обновить надписи и украсить могилу венками или цветами. Этот ритуал считается одним из проявлений сыновьей почтительности, однако в последние годы коммерция бросает вызов вековым ценностям.

Фото: bukitbrown.com

В прошлом году на Taobao.com — крупнейшей в стране площадке электронной торговли — появились магазины, предлагающие услуги по уходу за могилами предков в праздник Цинмин. Идея предпринимателей заключается в том, что многие жители современных мегаполисов слишком заняты и часто не успевают на кладбище, поэтому за плату от 100 до 1000 юаней ($16-161) они могут заказать уборку, возжигание благовоний, совершение поклонов и другие ритуалы. Однако не многие китайцы считают такой вариант приемлемым.

Сжигание жертвенных денег

Жертвенные гаджеты из картона на пачках ритуальных денег. Фото: China Daily

Китайцы — прагматичный народ, поэтому считают, что деньги нужны и на этом, и на том свете. Обычно для жертвоприношений используют копии купюр существующих валют несуществующих номиналов, например 5 млрд юаней. С развитием высоких технологий люди начали приносить в жертву усопшим близким не только «игрушечные» деньги, но и вырезанные из картона фотокамеры, смартфоны, игровые консоли и другие предметы, которыми пользуется любой современный житель КНР.

Однако в последнее время эту трогательную традицию пытаются (пока безуспешно) упразднить. Есть мнение, что единовременное сжигание огромного количества бумаги по всей стране ухудшает качество воздуха в городах. С другой стороны, есть подозрение, что одна угольная электростанция в день выбрасывает больше, чем люди в состоянии нажечь за сто цинминов.

3. Еда

Цинмин — это не только память об умерших, это еще и радостный праздник наступления весны, поэтому многие китайцы устраивают пикник или семейный обед в этот день. Традиционные блюда разнятся в зависимости от региона.

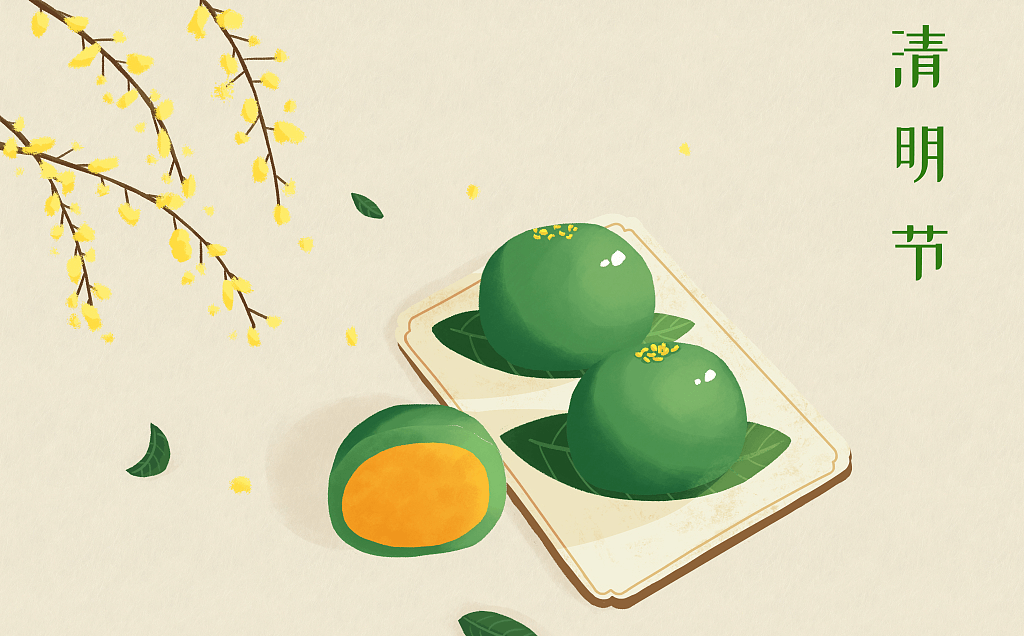

Цинминские фрукты (清明果;Qīngmíngguǒ)

Фото: Синьхуа

Формой они напоминают пельмени, но вкус совсем другой. Тесто делается из выжимки полыни, риса и рисового крахмала. Внутрь заворачивают начинку из сладких красных бобов, готовят на пару. Также встречаются варианты с беконом, стеблями бамбука и грибами.

Черный рис Ужэнь (乌稔饭;wūrěn fàn)

Фото: dqdaily.com

Это блюдо популярно у представителей национальности Шэ, которые живут в восточной провинции Фуцзянь. В День поминовения усопших каждая семья готовит Ужэнь фань и передает друг другу в качестве подарка. Что-то вроде крашенных яиц на Пасху в России. Рис готовится вместе с местным сортом голубики, из которой выжимают сок, окрашивающий блюдо в черный цвет.

Рисовые шарики Цинтуань (青团;qīnɡ tuán)

Фото: bendibao.com

Типичное для Шанхая блюдо представляет собой рисовый шарик с начинкой из сладкой бобовой пасты. По сути тоже, что и цинминские фрукты, но для придания особого вкуса, при готовке в пароварку добавляют листья тростника.

Жареные нити из теста Саньцзы (馓子;sǎnzǐ)

Фото: xjass.com

Это блюдо одинаково распространено по всей стране, хотя сейчас считается более типичным для уйгуров. В старые времена Саньцзы называли «холодной пищей» и связывали с праздником Ханьши, который отмечается 4 апреля, и чья история еще более древняя. Но со временем жареное тесто вписалось в традиции Цинмин также, как и Ханьши.

Улитки Цинмин Луо (清明螺;Qīngmíngluó)

Фото: smmail.cn

Все просто: в начале апреля улитки в Китае особенно жирные. Как гласит народная поговорка: «В Цинмин улитки огромные как гуси». Блюдо типично для сельской местности. Сначала крестьяне вытаскивают мясо с помощью специальной иголки, а затем бросают пустые раковины на крышу. Стук раковин распугивает мышей, а если в доме не будет грызунов, крестьяне смогут спокойно выращивать коконы шелкопрядов.

Спринг-роллы Чуньбин (春饼;chūn bǐnɡ)

Фото: hujiang.com

Блинчики со свежими и маринованными овощами едят в Цинмин на севере Китая. С одной стороны, это подходящий символ наступившей весны, с другой — бюджетная альтернатива пекинской утке.

Финиковый кекс (枣糕;zǎo ɡāo)

Традиционный десерт города Сучжоу. Фото: hujiang.com

Знаменитый десерт из Сучжоу готовится из яиц, муки, сахара и масла. В качестве наполнителя используют кедровые орешки, китайский финик жужуб и другую фруктовую мякоть. Кекс пекут на медленном огне. Он получается достаточно сладким, но не жирным. Обычно его дарят друзьям и родственникам.

4. Воздушные змеи

Фото: CCTV News

В дни празднования Цинмина в Китае, особенно на севере, дует сильный ветер, что дает людям возможность провести выходные с детьми, запуская воздушных змеев.

По легенде, воздушных змеев изобрел знаменитый китайский плотник по имени Лу Бань около 2000 лет назад. Первые змеи делались из дерева, и их называли Му Юань — деревянные ястребы. Позже появились бумажные змеи, которых стали называть Чжи Юань — бумажные ястребы.

Во времена правления последней династии Цин было принято запускать змея как можно выше и отпускать его в верхней точке. Считалось, что вместе с ним улетают проблемы и болезни. И напротив, человек, поднявший чужого змея с земли, обрекал себя на несчастья.

Сегодня некоторые энтузиасты запускают воздушных змеев ночью, привязывая к ним маленькие бумажные фонарики.

5. Цинмин в китайском искусстве

Праздник, установленный в эпоху Тан, вдохновлял поэтов того времени. Ярким примером служит произведение Хань Хуна.

Летят повсюду лепестки. Спустился в город вечер.

Восточный ветер во дворе ветвями ив играет.

Лишь только во дворце Ханьгун зажгли сегодня свечи,

В дома Пяти Маркизов-Хоу их легкий дым вплывает…

Фрагмент картины «Праздник Цинмин на реке». Фото: Википедия

Сцены празднования Цинмина зафиксированы на многих классических китайский полотнах. Самым известным, пожалуй, является шелковый свиток «Праздник Цинмин на реке» работы придворного живописца эпохи Сун Чжана Цзэдуаня. Сейчас полотно хранится в Запретном городе в Пекине.

Дария Остаева

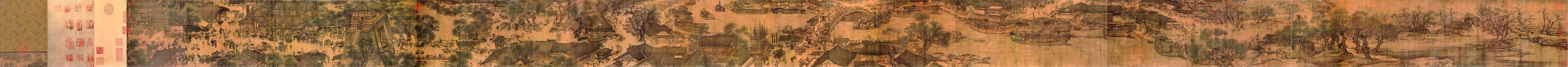

«По реке в день поминовения усопших» (кит. трад. 清明上河圖, упр. 清明上河图, пиньинь: Qīngmíng Shànghé Tú, палл.: Цинмин Шанхэ ту) — живописная панорама, созданная в XII веке при дворе династии Сун, очевидно, художником по имени Чжан Цзэдуань. На свитке запечатлена повседневная жизнь обитателей императорской столицы, Кайфына, в день празднования Цинмина (5 апреля).

Описание

Свиток длиной в 528 см в мельчайших подробностях изображает занятия самых разных сословий. Здесь нашли отражение и крестьянский труд, и столичная суета. В общей сложности можно разглядеть 814 человеческих фигур, 28 лодок, 94 животных и 170 деревьев. Свиток Цзэдуаня настолько полюбился одному из императоров династии Юань, что он собственноручно начертал на обороте своё стихотворение.

Репродукция XVIII века

История

В продолжение последующих столетий было создано несколько десятков вариаций на эту тему. Во времена династии Мин был изготовлен обновлённый вариант свитка длиной в 670 см. При династии Цин он воспроизводился с ещё большим размахом: один из вариантов, длиной в 11 метров, изображает более четырёх тысяч людей. К XX веку слава свитка была уже настолько велика, что европейцы именовали его не иначе как «китайской Моной Лизой».

Последний император Пу И увёз оригинальный свиток с собой в Маньчжоу-го. В 1945 году он был выкуплен правительством и ныне находится на сохранении в дворцовом музее Запретного города, где экспонируется перед толпой любопытствующих по праздничным случаям, как правило, один раз в несколько лет.

Панорамы

Свиток Чжана Цзэдуаня XII века.

Репродукция XVIII века.

Литература

- Fairbank, John y Gila Sharony (1996). China: una nueva historia. Barcelona: Andrés Bello. ISBN 84-89691-05-3.

Ссылки

| По реке в День поминовения усопших на Викискладе? |

- Интерактивная панорама «По реке в день поминовения усопших»

- Панорама на сайте Колумбийского университета

-color: rgb(255, 255, 255);Картина, написанная в эпоху Северная Сун художником Чжан Цзэдуанем на шелке в технике «дань шэсэ» («бледное заполнение цветом» контура из туши). Размеры — 24,8 см на 528,7 см. В настоящее время хранится в Пекинском музее императорского дворца (Гугун). Картина отображает красочное многообразие бытовых сцен и природных ландшафтов города Кайфэн (Бяньлан), столицы Северной Сун, и берегов реки Бяньхэ в праздник Цинмин (День поминовения усопших). Картина состоит из трех фрагментов. Первый из них изображает весенний пейзаж в окрестностях столицы: в редколесье, полускрытые дымкой, видны соломенные хижины, мостики, ручьи, старые деревья, лодочки. В изображении людей и пейзажа подчеркнуты специфика момента — праздника Цинмин — и свойственные ему обычаи, что является своеобразным прологом к картине в целом. Центральный фрагмент демонстрирует оживленную суету, царящую на пристани реки Бяньхэ. Здесь можно увидеть множество людей и домов, лодки с зерном, теснящиеся на реке. Через реку Бяньхэ перекинут огромный деревянный мост — изысканной конструкции, изогнутый, словно радуга, он носит название Хунцяо, что означает «Радужный мост». Здесь и находится знаменитая пристань у моста Хунцяо, самый настоящий центр речных перевозок, где всегда царит шумная сутолока и оживление. Последний фрагмент живописует оживленные городские улицы, в деталях изображая стройные ряды домов, самые разные заведения и лавки, шумную толчею на улицах и площадях, нескончаемые потоки людей. Купцы, шэньши, чиновники, лоточники… здесь изображены люди всех сословий и занятий, приверженцы всех вероисповеданий и философских течений. Видны всевозможные транспортные средства — паланкины, верблюды, рикши, повозки, запряженные быками и лошадьми. -color: rgb(255, 255, 255);Выполненная в традиционной для китайской живописи форме длинного свитка с использованием композиционной техники «рассеянной перспективы», эта картина объединяет многочисленные и разнообразные сцены в единое исполненное динамики полотно. На ней изображено свыше 500 персонажей — в разной одежде, с разными выражениями лиц и к тому же занятых самыми разными делами, что придает картине необыкновенную сценичность. Композиции картины присущи ритмичность и метрическая динамика — чередуются сюжетно насыщенные и спокойные участки. Живописная техника демонстрирует высочайший уровень мастера. «По реке в День поминовения усопших» — это реалистическая жанровая картина, на которой изображен один из уголков столичного города эпохи Северная Сун. Эта картина обладает высочайшей исторической и художественной ценностью. Существует точка зрения, согласно которой картина изображает не сцены праздника Цинмин, а метафорически — «чистое и ясное» (цинмин) управление государством в эпоху Северная Сун, царящие в обществе покой и процветание.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Qingming | |

|---|---|

Burning paper gifts for the departed. |

|

| Official name | Qingming Jie (清明节) Ching Ming Festival (清明節) Tomb Sweeping Day (掃墳節) |

| Observed by | Han Chinese, Chitty[1] and Ryukyuans |

| Type | Cultural, Asian |

| Significance | Remembering ancestors |

| Observances | Cleaning and sweeping of graves, ancestor worship, offering food to deceased, burning joss paper |

| Date | 15th day from the Spring Equinox 4, 5 or 6 April |

| Qingming Festival | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 清明節 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 清明节 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | «Pure Brightness Festival» | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Qingming festival[2] or Ching Ming Festival,[3] also known as Tomb-Sweeping Day in English (sometimes also called Chinese Memorial Day or Ancestors’ Day),[4][5] is a traditional Chinese festival observed by the Han Chinese of mainland China, Hong Kong, and Macau, and by the ethnic Chinese of Taiwan, Malaysia, Singapore, Cambodia, Indonesia, Philippines, Thailand, Vietnam and Panama. It falls on the first day of the fifth solar term of the traditional Chinese lunisolar calendar. This makes it the 15th day after the Spring Equinox, either 4, 5 or 6 April in a given year.[6][7][8] During Qingming, Chinese families visit the tombs of their ancestors to clean the gravesites, pray to their ancestors and make ritual offerings. Offerings would typically include traditional food dishes and the burning of joss sticks and joss paper. The holiday recognizes the traditional reverence of one’s ancestors in Chinese culture.

The Qingming Festival has been observed by the Chinese for over 2500 years, although the observance has changed significantly. It became a public holiday in mainland China in 2008, where it is associated with the consumption of qingtuan, green dumplings made of glutinous rice and Chinese mugwort or barley grass.

In Taiwan, the public holiday was in the past observed on 5 April to honor the death of Chiang Kai-shek on that day in 1975, but with Chiang’s popularity waning, this convention is not being observed. A confection called caozaiguo or shuchuguo, made with Jersey cudweed, is consumed there.

A similar holiday is observed in the Ryukyu Islands, called Shīmī in the local language.[9]

Origin[edit]

The festival originated from the Cold Food or Hanshi Festival which remembered Jie Zitui, a nobleman of the state of Jin (modern Shanxi) during the Spring and Autumn Period. Amid the Li Ji Unrest, he followed his master Prince Chong’er in 655 BC to exile among the Di tribes and around China. Supposedly, he once even cut flesh from his own thigh to provide his lord with soup. In 636 BC, Duke Mu of Qin invaded Jin and enthroned Chong’er as its duke, where he was generous in rewarding those who had helped him in his time of need. Owing either to his own high-mindedness or to the duke’s neglect, however, Jie was long passed over. He finally retired to the forest around Mount Mian with his elderly mother. The duke went to the forest in 636 BC but could not find them. He then ordered his men to set fire to the forest in order to force Jie out. When Jie and his mother were killed instead, the duke was overcome with remorse and erected a temple in his honor. The people of Shanxi subsequently revered Jie as an immortal and avoided lighting fires for as long as a month in the depths of winter, a practice so injurious to children and the elderly that the area’s rulers unsuccessfully attempted to ban it for centuries. A compromise finally developed where it was restricted to 3 days around the Qingming solar term in mid-spring.

The present importance of the holiday is credited to Emperor Xuanzong of Tang. Wealthy citizens in China were reportedly holding too many extravagant and ostentatiously expensive ceremonies in honor of their ancestors. In AD 732, Xuanzong sought to curb this practice by declaring that such respects could be formally paid only once a year, on Qingming.[10]

Observance[edit]

Qingming at the cemetery by Kolkata Chinese

Qingming Festival is when Chinese people traditionally visit ancestral tombs to sweep them. This tradition has been legislated by the Emperors who built majestic imperial tombstones for every dynasty. For thousands of years, the Chinese imperials, nobility, peasantry, and merchants alike have gathered together to remember the lives of the departed, to visit their tombstones to perform Confucian filial piety by tombsweeping, to visit burial grounds, graveyards or in modern urban cities, the city columbaria, to perform groundskeeping and maintenance and to commit to pray for their ancestors in the uniquely Chinese concept of the afterlife and to offer remembrances of their ancestors to living blood relatives, their kith and kin. In some places, people believe that sweeping the tomb is only allowed during this festival, as they believe the dead will get disturbed if the sweeping is done on other days.

The young and old alike kneel down to offer prayers before tombstones of the ancestors, offer the burning of joss in both the forms of incense sticks (joss-sticks) and silver-leafed paper (joss paper), sweep the tombs and offer food, tea, wine, chopsticks, and/or libations in memory of the ancestors. Depending on the religion of the observers, some pray to a higher deity to honour their ancestors, while others may pray directly to the ancestral spirits.

These rites have a long tradition in Asia, especially among the imperialty who legislated these rituals into a national religion. They have been preserved especially by the peasantry and are most popular with farmers today, who believe that continued observances will ensure fruitful harvests ahead by appeasing the spirits in the other world.

Religious symbols of ritual purity, such as pomegranate and willow branches, are popular at this time. Some people carry willow branches with them on Qingming or stick willow branches on their gates and/or front doors. There are similarities to palm leaves used on Palm Sundays in Christianity; both are religious rituals. Furthermore, the belief is that the willow branches will help ward off the unappeased, troubled and troubling spirits, and/or evil spirits that may be wandering in the earthly realms on Qingming.

After gathering on Qingming to perform Confucian clan and family duties at the tombstones, graveyards or columbaria, participants spend the rest of the day in clan or family outings, before they start the spring plowing. They often sing and dance. Qingming is also a time when young couples traditionally start courting. Another popular thing to do is to fly kites in the shapes of animals or characters from Chinese opera.[11] Another common practice is to carry flowers instead of burning paper, incense, or firecrackers.[12]

Traditionally, a family will burn spirit money(joss paper) and paper replicas of material goods such as cars, homes, phones and paper servants. This action usually happens during the Qingming festival.[13] In Chinese culture, it is believed that people still need all of those things in the afterlife. Then family members take turns to kowtow three to nine times (depending on the family adherence to traditional values) before the tomb of the ancestors. The Kowtowing ritual in front of the grave is performed in the order of patriarchal seniority within the family. After the ancestor worship at the grave site, the whole family or the whole clan feast on the food and drink they have brought for the worship either at the site or in nearby gardens in the memorial park, signifying the family’s reunion with its ancestors. Another ritual related to the festival is the cockfight,[14] as well as being available within that historic and cultural context at Kaifeng Millennium City Park (Qingming Riverside Landscape Garden).[15][16]

The holiday is often marked by people paying respects to those who are considered national or legendary heroes or those exemplary Chinese figures who died in events considered politically sensitive.[17] The April Fifth Movement and the Tiananmen Incident were major events in Chinese history which occurred on Qingming. After Premier Zhou Enlai died in 1976, thousands honored him during the festival to pay their respects. Many also pay respects to victims of the Tiananmen Square protests in 1989 and Zhao Ziyang.[18]

Malaysia and Singapore[edit]

Colored papers placed on a grave during Qingming Festival, Bukit Brown Cemetery, Singapore

Despite the festival having no official status, the overseas Chinese communities in Southeast Asian nations, such as those in Singapore and Malaysia, take this festival seriously and observe its traditions faithfully. Some Qingming rituals and ancestral veneration decorum observed by the overseas Chinese in Malaysia and Singapore can be dated back to Ming and Qing dynasties, as the overseas communities were not affected by the Cultural Revolution in Mainland China. Qingming in Malaysia is an elaborate family function or a clan feast (usually organized by the respective clan association) to commemorate and honour recently deceased relatives at their grave sites and distant ancestors from China at home altars, clan temples or makeshift altars in Buddhist or Taoist temples. For the overseas Chinese community, the Qingming festival is very much a solemn family event and, at the same time, a family obligation. They see this festival as a time of reflection for honouring and giving thanks to their forefathers. Overseas Chinese normally visit the graves of their recently deceased relatives on the weekend nearest to the actual date. According to the ancient custom, grave site veneration is only permissible ten days before and after the Qingming Festival. If the visit is not on the actual date, normally veneration before Qingming is encouraged. The Qingming Festival in Malaysia and Singapore normally starts early in the morning by paying respect to distant ancestors from China at home altars. This is followed by visiting the graves of close relatives in the country. Some follow the concept of filial piety to the extent of visiting the graves of their ancestors in mainland China.

Other customs[edit]

Games[edit]

During the Tang dynasty, Emperor Xuanzong of Tang promoted large-scale tug of war games, using ropes of up to 167 metres (548 ft) with shorter ropes attached and more than 500 people on each end of the rope. Each side also had its own team of drummers to encourage the participants.[19] In honor of these customs, families often go hiking or kiting, play Chinese soccer or tug-of-war and plant trees.[20]

Buddhism[edit]

The Qingming festival is also a part of spiritual and religious practices in China. For example, Buddhism teaches that those who die with guilt are unable to eat in the afterlife, except on the day of the Qingming festival.[21]

Chinese tea culture[edit]

The Qingming festival holiday has a significance in the Chinese tea culture since this specific day divides the fresh green teas by their picking dates. Green teas made from leaves picked before this date are given the prestigious ‘pre-qingming’ (清明前) designation which commands a much higher price tag. These teas are prized for having much lighter and subtler aromas than those picked after the festival.[citation needed]

Weather[edit]

The Qingming festival was originally considered the day with the best spring weather, when many people would go out and travel. The Old Book of Tang describes this custom and mentions of it may be found in ancient poetry.[22]

In painting[edit]

The famous Song dynasty Qingming scroll attributed to Zhang Zeduan may portray Kaifeng city, the capital of the Song Dynasty, but does not include any of the activities associated with the holiday, however, and the term «Qingming» may not refer to the holiday.

In literature[edit]

Qingming was frequently mentioned in Chinese literature. Among these, the most famous one is probably Du Mu’s poem (simply titled «Qingming»):

| Traditional Chinese | Simplified Chinese | Pinyin | English translation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 清明時節雨紛紛 | 清明时节雨纷纷 | qīng míng shí jié yǔ fēn fēn | Drizzling during Qingming |

| 路上行人欲斷魂 | 路上行人欲断魂 | lù shàng xíng rén yù duàn hún | Dwellers on the road seem lifeless |

| 借問酒家何處有 | 借问酒家何处有 | jiè wèn jiǔ jiā hé chù yǒu | Please sir, where can I find a bar |

| 牧童遙指杏花村 | 牧童遥指杏花村 | mù tóng yáo zhǐ xìng huā cūn | A herdsboy pointing to a village afar — the Apricot Flowers. |

Although the date is not presently a holiday in Vietnam, the Qingming festival is mentioned (under the name Thanh Minh) in the epic poem The Tale of Kieu, when the protagonist Kieu meets a ghost of a dead old lady. The description of the scenery during this festival is one of the best-known passages of Vietnamese literature:

| Hán Nôm | Vietnamese | English translation |

|---|---|---|

| 𣈜春𡥵燕迻梭, | Ngày xuân con én đưa thoi | Swift swallows and spring days were shuttling by; |

| 韶光𠃩𨔿㐌外𦒹𨑮。 | Thiều quang chín chục đã ngoài sáu mươi | Of ninety radiant ones three score had fled. |

| 𦹵𡽫撑羡蹎𡗶, | Cỏ non-xanh tận chân trời | Young grass spread all its green to heaven’s rim; |

| 梗梨𤽸點沒𢽼花, | Cành lê trắng điểm một vài bông hoa | Some blossoms marked pear branches with white dots. |

| 清明𥪞節𣎃𠀧, | Thanh Minh trong tiết tháng ba | Now came the Feast of Light in the third month |

| 礼羅掃墓,噲羅踏清。 | Lễ là Tảo mộ, hội là Đạp thanh | With graveyard rites and junkets on the green. |

| 𧵆賒奴㘃燕, | Gần xa nô nức yến oanh | As merry pilgrims flocked from near and far, |

| 姉㛪懺所步行制春。 | Chị em sắm sửa bộ hành chơi xuân | The sisters and their brother went for a stroll. |

See also[edit]

- Along the River During Ching Ming Festival by Zhang Zeduan

- Cold Food Festival, three consecutive days starting the day before the Qingming Festival

- Day of the Dead, a Mexican celebration similar to the Qingming Festival

- Double Ninth Festival, the other day to visit and clean up the cemeteries in Hong Kong

- Bon Festival, the Japanese counterpart of the Ghost Festival

- Hansik, a related Korean holiday on the same day

- Dust Clearing, a similar ritual in the Middle-East

- Radonitsa / Pomynky, a similar holiday of Eastern Slavs

- Traditional Chinese holidays

- Filial piety in Chinese culture

- The Parentalia in Roman culture

References and further reading[edit]

- Aijmer, Göran (1978), «Ancestors in the Spring the Qingming Festival in Central China», Journal of the Hong Kong Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 18: 59–82, JSTOR 23889632

Notes[edit]

- ^ «Meet the Chetti Melaka, or Peranakan Indians, striving to save their vanishing culture». Channel News Asia. 21 October 2018.

- ^ «Qingming Festival». Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- ^ «108 years of Ching Ming Festival continuous holiday traffic evacuation information». Northeast and Yilan Coast National Scenic Area Administration. 25 March 2019.

- ^ «General holidays for 2015». GovHK. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ^ «Macau Government Tourist Office». Macau Tourism. Archived from the original on 16 March 2016. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ^ «Traditional Chinese Festivals». china.org.cn. 5 April 2007. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ^ «Tomb Sweeping Day». Taiwan.gov.tw. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ^ «Ching Ming Festival | Hong Kong Tourism Board».

- ^ «Festivals and Rituals of Okinawa — Seimei Ritual (Shiimii) -«. www.wonder-okinawa.jp. Archived from the original on 15 December 2007. Retrieved 14 January 2022.

- ^ «寒食清明节:纪念晋国大夫介之推». Cathay.ce.cn. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ^ «中华人民共和国外交部». Archived from the original on 15 April 2009. Retrieved 8 April 2009.

- ^ «Asia News — South Asia News — Latest headlines – News, Photos, Videos». UPIAsia.com. 22 July 2012. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ^ Chung, Sheng Kuan; Li, Dan (2 November 2017). «An Artistic and Spiritual Exploration of Chinese Joss Paper». Art Education. 70 (6): 28–35. doi:10.1080/00043125.2017.1361770. ISSN 0004-3125. S2CID 187756852.

- ^ «Festival of Pure Brightness». Uiowa.edu. Archived from the original on 19 November 2014. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ^ «Millennium City Park, Kaifeng, Henan». Travelchinaguide.com. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ^ «Qingming Riverside Landscape Garden». Cultural-china.com. Archived from the original on 12 August 2015. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ^ «Celebration». China Daily. 3 March 2013. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- ^ «China clamps down on Qing Ming». Straits Times. 8 April 2009. Archived from the original on 20 March 2014. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- ^ Tang dynasty Feng Yan: Notes of Feng, volume 6

- ^ «Chinese Traditional Holidays». Qingming Festival Customs. China Internet News Center.

- ^ «Buddhism and Qingming Festival». Chinese Scholars. Retrieved 26 March 2019.

- ^ Xu, Liu. «Old Book of Tang»: 13.

External links[edit]

Media related to Qingming Festival at Wikimedia Commons

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Qingming | |

|---|---|

Burning paper gifts for the departed. |

|

| Official name | Qingming Jie (清明节) Ching Ming Festival (清明節) Tomb Sweeping Day (掃墳節) |

| Observed by | Han Chinese, Chitty[1] and Ryukyuans |

| Type | Cultural, Asian |

| Significance | Remembering ancestors |

| Observances | Cleaning and sweeping of graves, ancestor worship, offering food to deceased, burning joss paper |

| Date | 15th day from the Spring Equinox 4, 5 or 6 April |

| Qingming Festival | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 清明節 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 清明节 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | «Pure Brightness Festival» | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Qingming festival[2] or Ching Ming Festival,[3] also known as Tomb-Sweeping Day in English (sometimes also called Chinese Memorial Day or Ancestors’ Day),[4][5] is a traditional Chinese festival observed by the Han Chinese of mainland China, Hong Kong, and Macau, and by the ethnic Chinese of Taiwan, Malaysia, Singapore, Cambodia, Indonesia, Philippines, Thailand, Vietnam and Panama. It falls on the first day of the fifth solar term of the traditional Chinese lunisolar calendar. This makes it the 15th day after the Spring Equinox, either 4, 5 or 6 April in a given year.[6][7][8] During Qingming, Chinese families visit the tombs of their ancestors to clean the gravesites, pray to their ancestors and make ritual offerings. Offerings would typically include traditional food dishes and the burning of joss sticks and joss paper. The holiday recognizes the traditional reverence of one’s ancestors in Chinese culture.

The Qingming Festival has been observed by the Chinese for over 2500 years, although the observance has changed significantly. It became a public holiday in mainland China in 2008, where it is associated with the consumption of qingtuan, green dumplings made of glutinous rice and Chinese mugwort or barley grass.

In Taiwan, the public holiday was in the past observed on 5 April to honor the death of Chiang Kai-shek on that day in 1975, but with Chiang’s popularity waning, this convention is not being observed. A confection called caozaiguo or shuchuguo, made with Jersey cudweed, is consumed there.

A similar holiday is observed in the Ryukyu Islands, called Shīmī in the local language.[9]

Origin[edit]

The festival originated from the Cold Food or Hanshi Festival which remembered Jie Zitui, a nobleman of the state of Jin (modern Shanxi) during the Spring and Autumn Period. Amid the Li Ji Unrest, he followed his master Prince Chong’er in 655 BC to exile among the Di tribes and around China. Supposedly, he once even cut flesh from his own thigh to provide his lord with soup. In 636 BC, Duke Mu of Qin invaded Jin and enthroned Chong’er as its duke, where he was generous in rewarding those who had helped him in his time of need. Owing either to his own high-mindedness or to the duke’s neglect, however, Jie was long passed over. He finally retired to the forest around Mount Mian with his elderly mother. The duke went to the forest in 636 BC but could not find them. He then ordered his men to set fire to the forest in order to force Jie out. When Jie and his mother were killed instead, the duke was overcome with remorse and erected a temple in his honor. The people of Shanxi subsequently revered Jie as an immortal and avoided lighting fires for as long as a month in the depths of winter, a practice so injurious to children and the elderly that the area’s rulers unsuccessfully attempted to ban it for centuries. A compromise finally developed where it was restricted to 3 days around the Qingming solar term in mid-spring.

The present importance of the holiday is credited to Emperor Xuanzong of Tang. Wealthy citizens in China were reportedly holding too many extravagant and ostentatiously expensive ceremonies in honor of their ancestors. In AD 732, Xuanzong sought to curb this practice by declaring that such respects could be formally paid only once a year, on Qingming.[10]

Observance[edit]

Qingming at the cemetery by Kolkata Chinese

Qingming Festival is when Chinese people traditionally visit ancestral tombs to sweep them. This tradition has been legislated by the Emperors who built majestic imperial tombstones for every dynasty. For thousands of years, the Chinese imperials, nobility, peasantry, and merchants alike have gathered together to remember the lives of the departed, to visit their tombstones to perform Confucian filial piety by tombsweeping, to visit burial grounds, graveyards or in modern urban cities, the city columbaria, to perform groundskeeping and maintenance and to commit to pray for their ancestors in the uniquely Chinese concept of the afterlife and to offer remembrances of their ancestors to living blood relatives, their kith and kin. In some places, people believe that sweeping the tomb is only allowed during this festival, as they believe the dead will get disturbed if the sweeping is done on other days.

The young and old alike kneel down to offer prayers before tombstones of the ancestors, offer the burning of joss in both the forms of incense sticks (joss-sticks) and silver-leafed paper (joss paper), sweep the tombs and offer food, tea, wine, chopsticks, and/or libations in memory of the ancestors. Depending on the religion of the observers, some pray to a higher deity to honour their ancestors, while others may pray directly to the ancestral spirits.

These rites have a long tradition in Asia, especially among the imperialty who legislated these rituals into a national religion. They have been preserved especially by the peasantry and are most popular with farmers today, who believe that continued observances will ensure fruitful harvests ahead by appeasing the spirits in the other world.

Religious symbols of ritual purity, such as pomegranate and willow branches, are popular at this time. Some people carry willow branches with them on Qingming or stick willow branches on their gates and/or front doors. There are similarities to palm leaves used on Palm Sundays in Christianity; both are religious rituals. Furthermore, the belief is that the willow branches will help ward off the unappeased, troubled and troubling spirits, and/or evil spirits that may be wandering in the earthly realms on Qingming.

After gathering on Qingming to perform Confucian clan and family duties at the tombstones, graveyards or columbaria, participants spend the rest of the day in clan or family outings, before they start the spring plowing. They often sing and dance. Qingming is also a time when young couples traditionally start courting. Another popular thing to do is to fly kites in the shapes of animals or characters from Chinese opera.[11] Another common practice is to carry flowers instead of burning paper, incense, or firecrackers.[12]

Traditionally, a family will burn spirit money(joss paper) and paper replicas of material goods such as cars, homes, phones and paper servants. This action usually happens during the Qingming festival.[13] In Chinese culture, it is believed that people still need all of those things in the afterlife. Then family members take turns to kowtow three to nine times (depending on the family adherence to traditional values) before the tomb of the ancestors. The Kowtowing ritual in front of the grave is performed in the order of patriarchal seniority within the family. After the ancestor worship at the grave site, the whole family or the whole clan feast on the food and drink they have brought for the worship either at the site or in nearby gardens in the memorial park, signifying the family’s reunion with its ancestors. Another ritual related to the festival is the cockfight,[14] as well as being available within that historic and cultural context at Kaifeng Millennium City Park (Qingming Riverside Landscape Garden).[15][16]

The holiday is often marked by people paying respects to those who are considered national or legendary heroes or those exemplary Chinese figures who died in events considered politically sensitive.[17] The April Fifth Movement and the Tiananmen Incident were major events in Chinese history which occurred on Qingming. After Premier Zhou Enlai died in 1976, thousands honored him during the festival to pay their respects. Many also pay respects to victims of the Tiananmen Square protests in 1989 and Zhao Ziyang.[18]

Malaysia and Singapore[edit]

Colored papers placed on a grave during Qingming Festival, Bukit Brown Cemetery, Singapore

Despite the festival having no official status, the overseas Chinese communities in Southeast Asian nations, such as those in Singapore and Malaysia, take this festival seriously and observe its traditions faithfully. Some Qingming rituals and ancestral veneration decorum observed by the overseas Chinese in Malaysia and Singapore can be dated back to Ming and Qing dynasties, as the overseas communities were not affected by the Cultural Revolution in Mainland China. Qingming in Malaysia is an elaborate family function or a clan feast (usually organized by the respective clan association) to commemorate and honour recently deceased relatives at their grave sites and distant ancestors from China at home altars, clan temples or makeshift altars in Buddhist or Taoist temples. For the overseas Chinese community, the Qingming festival is very much a solemn family event and, at the same time, a family obligation. They see this festival as a time of reflection for honouring and giving thanks to their forefathers. Overseas Chinese normally visit the graves of their recently deceased relatives on the weekend nearest to the actual date. According to the ancient custom, grave site veneration is only permissible ten days before and after the Qingming Festival. If the visit is not on the actual date, normally veneration before Qingming is encouraged. The Qingming Festival in Malaysia and Singapore normally starts early in the morning by paying respect to distant ancestors from China at home altars. This is followed by visiting the graves of close relatives in the country. Some follow the concept of filial piety to the extent of visiting the graves of their ancestors in mainland China.

Other customs[edit]

Games[edit]

During the Tang dynasty, Emperor Xuanzong of Tang promoted large-scale tug of war games, using ropes of up to 167 metres (548 ft) with shorter ropes attached and more than 500 people on each end of the rope. Each side also had its own team of drummers to encourage the participants.[19] In honor of these customs, families often go hiking or kiting, play Chinese soccer or tug-of-war and plant trees.[20]

Buddhism[edit]

The Qingming festival is also a part of spiritual and religious practices in China. For example, Buddhism teaches that those who die with guilt are unable to eat in the afterlife, except on the day of the Qingming festival.[21]

Chinese tea culture[edit]

The Qingming festival holiday has a significance in the Chinese tea culture since this specific day divides the fresh green teas by their picking dates. Green teas made from leaves picked before this date are given the prestigious ‘pre-qingming’ (清明前) designation which commands a much higher price tag. These teas are prized for having much lighter and subtler aromas than those picked after the festival.[citation needed]

Weather[edit]

The Qingming festival was originally considered the day with the best spring weather, when many people would go out and travel. The Old Book of Tang describes this custom and mentions of it may be found in ancient poetry.[22]

In painting[edit]

The famous Song dynasty Qingming scroll attributed to Zhang Zeduan may portray Kaifeng city, the capital of the Song Dynasty, but does not include any of the activities associated with the holiday, however, and the term «Qingming» may not refer to the holiday.

In literature[edit]

Qingming was frequently mentioned in Chinese literature. Among these, the most famous one is probably Du Mu’s poem (simply titled «Qingming»):

| Traditional Chinese | Simplified Chinese | Pinyin | English translation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 清明時節雨紛紛 | 清明时节雨纷纷 | qīng míng shí jié yǔ fēn fēn | Drizzling during Qingming |

| 路上行人欲斷魂 | 路上行人欲断魂 | lù shàng xíng rén yù duàn hún | Dwellers on the road seem lifeless |

| 借問酒家何處有 | 借问酒家何处有 | jiè wèn jiǔ jiā hé chù yǒu | Please sir, where can I find a bar |

| 牧童遙指杏花村 | 牧童遥指杏花村 | mù tóng yáo zhǐ xìng huā cūn | A herdsboy pointing to a village afar — the Apricot Flowers. |

Although the date is not presently a holiday in Vietnam, the Qingming festival is mentioned (under the name Thanh Minh) in the epic poem The Tale of Kieu, when the protagonist Kieu meets a ghost of a dead old lady. The description of the scenery during this festival is one of the best-known passages of Vietnamese literature:

| Hán Nôm | Vietnamese | English translation |

|---|---|---|

| 𣈜春𡥵燕迻梭, | Ngày xuân con én đưa thoi | Swift swallows and spring days were shuttling by; |

| 韶光𠃩𨔿㐌外𦒹𨑮。 | Thiều quang chín chục đã ngoài sáu mươi | Of ninety radiant ones three score had fled. |

| 𦹵𡽫撑羡蹎𡗶, | Cỏ non-xanh tận chân trời | Young grass spread all its green to heaven’s rim; |

| 梗梨𤽸點沒𢽼花, | Cành lê trắng điểm một vài bông hoa | Some blossoms marked pear branches with white dots. |

| 清明𥪞節𣎃𠀧, | Thanh Minh trong tiết tháng ba | Now came the Feast of Light in the third month |

| 礼羅掃墓,噲羅踏清。 | Lễ là Tảo mộ, hội là Đạp thanh | With graveyard rites and junkets on the green. |

| 𧵆賒奴㘃燕, | Gần xa nô nức yến oanh | As merry pilgrims flocked from near and far, |

| 姉㛪懺所步行制春。 | Chị em sắm sửa bộ hành chơi xuân | The sisters and their brother went for a stroll. |

See also[edit]

- Along the River During Ching Ming Festival by Zhang Zeduan

- Cold Food Festival, three consecutive days starting the day before the Qingming Festival

- Day of the Dead, a Mexican celebration similar to the Qingming Festival

- Double Ninth Festival, the other day to visit and clean up the cemeteries in Hong Kong

- Bon Festival, the Japanese counterpart of the Ghost Festival

- Hansik, a related Korean holiday on the same day

- Dust Clearing, a similar ritual in the Middle-East

- Radonitsa / Pomynky, a similar holiday of Eastern Slavs

- Traditional Chinese holidays

- Filial piety in Chinese culture

- The Parentalia in Roman culture

References and further reading[edit]

- Aijmer, Göran (1978), «Ancestors in the Spring the Qingming Festival in Central China», Journal of the Hong Kong Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 18: 59–82, JSTOR 23889632

Notes[edit]

- ^ «Meet the Chetti Melaka, or Peranakan Indians, striving to save their vanishing culture». Channel News Asia. 21 October 2018.

- ^ «Qingming Festival». Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- ^ «108 years of Ching Ming Festival continuous holiday traffic evacuation information». Northeast and Yilan Coast National Scenic Area Administration. 25 March 2019.

- ^ «General holidays for 2015». GovHK. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ^ «Macau Government Tourist Office». Macau Tourism. Archived from the original on 16 March 2016. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ^ «Traditional Chinese Festivals». china.org.cn. 5 April 2007. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ^ «Tomb Sweeping Day». Taiwan.gov.tw. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ^ «Ching Ming Festival | Hong Kong Tourism Board».

- ^ «Festivals and Rituals of Okinawa — Seimei Ritual (Shiimii) -«. www.wonder-okinawa.jp. Archived from the original on 15 December 2007. Retrieved 14 January 2022.

- ^ «寒食清明节:纪念晋国大夫介之推». Cathay.ce.cn. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ^ «中华人民共和国外交部». Archived from the original on 15 April 2009. Retrieved 8 April 2009.

- ^ «Asia News — South Asia News — Latest headlines – News, Photos, Videos». UPIAsia.com. 22 July 2012. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ^ Chung, Sheng Kuan; Li, Dan (2 November 2017). «An Artistic and Spiritual Exploration of Chinese Joss Paper». Art Education. 70 (6): 28–35. doi:10.1080/00043125.2017.1361770. ISSN 0004-3125. S2CID 187756852.

- ^ «Festival of Pure Brightness». Uiowa.edu. Archived from the original on 19 November 2014. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ^ «Millennium City Park, Kaifeng, Henan». Travelchinaguide.com. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ^ «Qingming Riverside Landscape Garden». Cultural-china.com. Archived from the original on 12 August 2015. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ^ «Celebration». China Daily. 3 March 2013. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- ^ «China clamps down on Qing Ming». Straits Times. 8 April 2009. Archived from the original on 20 March 2014. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- ^ Tang dynasty Feng Yan: Notes of Feng, volume 6

- ^ «Chinese Traditional Holidays». Qingming Festival Customs. China Internet News Center.

- ^ «Buddhism and Qingming Festival». Chinese Scholars. Retrieved 26 March 2019.

- ^ Xu, Liu. «Old Book of Tang»: 13.

External links[edit]

Media related to Qingming Festival at Wikimedia Commons

Expro International Business LTD

Tianhe North road 615, office 1208

Guanzou, China

$$$

+86 13178888875

4.5

10

Праздник Цинмин ( «qīngmíngjié», 清明节) — День поминовения усопших, один из традиционных праздников КНР, который отмечается ежегодно по лунному календарю на 104-й день после зимнего солнцестояния или 15-й день после весеннего равноденствия.

Происхождение названия этого праздника связано с климатом и природой весеннего времени в Китае, когда на улице становится намного теплее и светлее — иероглиф 清 означает «светлый» , 明 — «ясный» .

Сегодня «Праздник Света» особенно почитается в Китае и среди членов китайских общин по всему миру. Помимо Китая, праздник Цинмин, отмечают во Вьетнаме, Южной Корее, Малайзии, Сингапуре и др.

Дата праздника ежегодно может немного меняться — обычно он выпадает на начало апреля, между 3 и 5 числом.

В 2022 году фестиваль Цинмин приходится на 5 апреля.

Официальные выходные дни в 2022г. с 3 по 5 апреля 2022 года.

В русском народном календаре есть свой религиозных аналог этого праздника — Красная горка, который также является днем поминовения умерших, отведенный на церковные службы, посещение могил усопших родственников и приготовление особой поминальной трапезы.

Происхождение праздника Цинмин

Считается, что фестиваль Цинмин берет свое начало от церемоний жертвоприношений у могил древних императоров и полководцев во времена династии Чжоу (周代) более 2 500 лет назад. Тогда высшие представители власти и чиновники обращались к величественным предкам и просили благословить их страну на процветание, мир и хороший урожай.

В VIII в н.э. император Сюаньцзун (玄宗)династии Тан (唐代)учредил для народа один единственный день под исполнение поминальных обрядов. С тех пор традиции посещения захоронений и уборки могил распространились на простых людей и закрепились в культуре на долгие века вперед.

С 2008 г. праздник Цинмин был официально закреплен в государственном календаре официальных праздников КНР.

Несмотря на исторические корни и немного грустный оттенок этого праздника, сегодня это также радостный день, когда китайцы могут воспользоваться выходным и стать немного ближе к природе. Издревле предки китайской нации стремились к гармоничному единству «неба, земли и людей» , и праздник Цинмин воспел эти стремления в рамках одного дня.

Основные обычаи

Праздник Цинмин на протяжении долгих лет остается важным днем в Китае, предоставляя многим людям возможность отдать дань уважения своим предкам и провести время, наслаждаясь природой.

В этот день в КНР принято посещать могилы предков для того, чтобы привести их в порядок ( «sǎomù» 扫墓 ), принести цветы, сделать подношения в виде овощей и фруктов, зажечь благовония и сжечь бумагу в виде ненастоящих денег. Подношения и сжигания бумаги олицетворяют передачу земельных богатств в Царство мертвых и даже несмотря на тысячелетнюю историю пользуются большой популярностью среди современных китайцев.

Практика посещения могил умерших тесно переплетается с китайскими традициями, связанными с сыновьей почтительностью и поклонением предкам. Уход за могилами своих родственников является очень важной частью праздника Цинмин, но, поскольку обычаи захоронения в китайской деревне сильно отличаются от городских, процесс поминовения может различаться — в сельской местности и отдаленных городах, где все еще разрешено (пусть и не официально) хоронить в земле, китайцы часто ходят на кладбища или к захоронениям, которые располагаются за городом на возвышенностях (- благоприятных местах, с точки зрения фэншуй); в городах, где предпочтения отдают кремации — в особые центры, где в ряд за рядом стоят каменные плиты с урнами.

Также во время фестиваля Цинмин буддисты украшают двери и входные ворота ветвями ивы, как Гуаньинь, которая использовала эти ветви для того, чтобы отпугивать злых духов.

Второй немаловажной частью этого дня является выход на природу ( «tàqīng» 踏青) и организация маленького пикника, для того чтобы расслабиться и ощутить первое тепло этого года. В этот день многие китайцы любят запускать воздушных змеев: с древних времен люди верили, что такими образом в этот день они могут посылать привет своим усопшим близким.

Сегодня запуск змеев в Праздник Цинмин скорее отожествляют с надеждами на удачу и излечение от болезней. Считается, что если перерезать веревку у воздушного змея, то он унесет все несчастья с собой в небо. Такое занятие присуще абсолютно всем — задорным детям и пожилым пенсионерам, сельским работягам и жителям мегаполисов — в светлое и темное время суток (особенно впечатляют в ночное время подсвеченные фонариками змеи на фоне темного неба).

Также во многих сельских местностях до сих пор сохранилась традиция посадки деревьев — китайцы говорят, что посаженные в этот день саженцы имеют высокую приживаемость и быстро растут.

Традиционные блюда праздника Цинмин

Во времена династии Тан (唐代)день накануне фестиваля Цинмин назывался Hánshíjié (寒食节) ,дословно Днем холодной пищи. В этот день люди не пользовались огнем и ели только холодную пищу. Эти обычаи во многом сохранились и до современного времени.

Сегодня во время праздника Цинмин на юге Китая люди обычно едят цинтуань («qīngtuán» 青团) — круглые, липкие и слегка сладковатые зеленые шарики, приготовленные из клейкого риса и травы ячменя или китайской полыни. Внутри эти пампушки чаще всего начинены сладкими бобами.

Как на севере, так и на юге страны также популярно есть саньцзы( «sǎnzi» 馓子)- обжаренные во фритюре соломки из соленого теста, которые готовят заранее, чтобы перед употреблением дать им остыть и высохнуть. Их едят холодными и часто приправляют семенами кунжута. У некоторых китайских этнических меньшинств в Синьцзяне, Ганьсу, Юньнани и Нинся саньцзы славятся разнообразием своих неповторимых вкусов.

Помимо этого в некоторых регионах КНР люди едят улиток с имбирем в соевом соусе («qīngmíngluó»清明螺), весенние блины с начинкой из овощей и лука( «chūnbǐng» 春饼) , сладкие финиковые кексы или печенья ( «zǎogāo» 枣糕), рисовую кашу из цветков персика ( «táohuā zhōu» 桃花粥), а у отдельных национальных меньшинств есть такие свои особенные блюда, которые присущи только их малым народностям.

![Image [36] Image [36]](https://ic.pics.livejournal.com/bastrakof/29687960/212227/212227_original.jpg)

![Image [35] Image [35]](https://ic.pics.livejournal.com/bastrakof/29687960/211995/211995_original.jpg)

![Image [32] Image [32]](https://ic.pics.livejournal.com/bastrakof/29687960/212501/212501_original.jpg)

![Image [33] Image [33]](https://ic.pics.livejournal.com/bastrakof/29687960/212889/212889_original.jpg)

![Image [34] Image [34]](https://ic.pics.livejournal.com/bastrakof/29687960/213199/213199_original.jpg)