Санкюлотиды

«Санкюлотиды» — дополнительные дни календарного года. Для согласования длины календарного года с продолжительностью солнечного необходимо было в конце каждого простого года добавлять еще 5, а в високосном — 6 дней. Весь этот период с 17 по 22 сентября был назван в честь восставшего народа «санкюлотидами» объявлен нерабочим, и каждый из его дней посвящался особому празднику.

Первый день санкюлотид (17 сентября) был праздником Гения, во время которого восхвалялись выдающиеся победы человеческого ума: открытия и изобретения, сделанные за год в науках, искусствах и ремеслах.

Вторая санкюлотида (18 сентября) называлась праздником Труда и посвящалась героям труда.

Третья (19 сентября) отмечалась как праздник Подвигов. В этот день прославлялись проявления личного мужества и отваги.

Четвертая (20 сентября) была праздником Наград. Во время ее совершались церемонии публичного признания и национальной благодарности в отношении всех тех, кто был прославлен в предыдущие три дня.

Пятая санкюлотида (21 сентября) — праздник Мнения, веселый и грозный день общественной критики. Горе должностным лицам, если они не оправдают оказанного им доверия.

Шестая санкюлотида (22 сентября), отмечаемая только в високосные годы, называлась просто Санкюлотидой и посвящалась спортивным играм и состязаниям.

День взятия Бастилии (14 июля)

Единственный революционный праздник, сохранившийся до наших дней. Официально его стали праздновать лишь в конце 19 века, но впервые отметили уже в 1790 году под названием «Праздник Федерации».

Проходил он не на развалинах Бастилии, а на Марсовом поле, которое в то время находилось вне Парижа. Усилиями добровольцев его удалось полностью преобразить для праздника.

В начале праздника отслужил мессу епископ Талейран, после чего генерал Лафайет принес клятву верности конституции. За ним последовал король. После окончания официальной церемонии по всему Парижу начались народные гуляния, фейерверки и танцы.

В последующие революционные годы день падения Бастилии отмечали народными гуляниями, а потом с 1793 по 1803 вместо этого праздника отмечали «день Республики» 1-го вандемьера (22 сентября).

Наконец, в 1880 году день взятия Бастилии был вновь объявлен официальным национальным праздником.

День принятия Конституции

10 августа 1793 года – годовщина восстания на Марсовом поле, которое дало импульс к свержению монархии и день принятия Республиканской Конституции, написанной Эро де Сешелем и другими.

Публичная присяга Конституции состоялась на развалинах Бастилии. Как и многие другие сценарии революционных праздников, программа была придумана Давидом.

На развалинах Бастилии была сооружена статуя Природы, из груди которой бил фонтан.

Туда же пришли депутаты Конвента под предводительством председателя Эро де Сешеля.

Де Сешель набрал из фонтана у подножия статуи Природы воды и выпил первым, произнеся небольшую речь, его примеру последовали депутаты и делегаты из провинций.

Далее процессия прошла по парижским улицам до площади Революции, где была установлена статуя Свободы. Возле нее Эро де Сешель произнес вторую речь и присягнул на верность Конституции.

По окончании официальных церемоний на улицах города повсеместно были акрыты столы для общественных трапез, за которыми последовали танцы и песни до глубокой ночи.

Праздник Разума – 10 ноября 1793

Осенью 1793 года в стране развернулось движение дехристианизации, противопоставившее католическому культу культ Разума. В ноябре того же когда коммуна Парижа издала декрет о запрете католического богослужения и закрытии церквей. В них открывали «святилища Разума».

Праздник проходил одновременно во многих церквях, в которых было закрыто все, тчо напоминало о христианстве. Центральная церемония прошла в Соборе Парижской Богоматери.

В нем установили храм с надписью «философия», бюсты философов и зажгли «факел Истины».

Их «храма» вышли сперва девушки в белом, а потом – «Богиня Разума», олицетворявшая свободу и на самом деле бывшая актрисой. Такие же «богини» присутствовали на всех церемониях в других храмах и также были известными актрисами и куртизанками. Праздник закончился трапезами на городских улицах, танцами и гуляниями.

После праздника Конвент решил преобразовать Нотр-Дам де Партии в Храм Разума. Такие же празднества шли по всей стране. Они проходили в форме карнавалов с обязательным участием «богинь Разума», с принуждением священников публично отрекаться от церкви и сана после чего следовало краткое «богослужение» и все те же гуляния. Во многих селениях и департаментах жители протестовали против уничтожения католической религии, начались легкие волнения.

21 ноября 1793 года Робеспьер осудил действия дехристианизаторов. 6—7 декабря 1793 года Конвент официально осудил меры насилия, «противоречащие свободе культов». В марте 1794 года культ Разума был запрещён.

Праздник Верховного Существа — 8 июня 1794

Культ Верховного Существа утверждался властями в борьбе, во-первых, с христианством, а во-вторых, с Культом Разума. С идейной стороны культ Верховного Существа наследовал деизму Просвещения (Вольтер) и философским взглядам Руссо, допускавшего божественный промысел. Он опирался на понятия естественной религии и рационализма. Целью культа, включавшего также ряд праздников в честь республиканских добродетелей, было «развитие гражданственности и республиканской морали». Термин «Бог» избегался и заменялся на термин «Верховное Существо».

Ярым сторонником культа Верховного существа был Робеспьер, ставший и одним из инициаторов праздника. Цели у Робеспьера были, в основном политические.

Внутри страны в провинциях нарастало недовольство борьбой якобинцев с католической церковью, священниками и обрядами. Дехристианизация также играла Франции дурную службу на внешнеполитической арене, восстанавливая против нее не только европейских политиков, но и европейские народы.

Праздник Верховного существа должен был, с одной стороны, учредить новый главенствующий религиозный культ, схожий с католическим и призванный заменить его, а с другой стороны, показать, что Республика настроена миролюбиво по отношению к религии и прочим культам, существующим в стране и не является атеистическим государством. Таким образом, Робеспьер намеревался учредить новую главенствующую государственную религию.

В день праздника Робеспьер был избран председателем Конвента, и тем самым ему отводилось первое место в празднике, которым должен был руководить Конвент.

Праздничная церемония открылась речью Робеспьера.

После речи Робеспьера под музыку была сожжена «гидра атеизма». Чучела, изображавшие атеизм, символы честолюбия, эгоизма и гордыни, были сожжены Робеспьером, как первосвященником, или жрецом, а на их месте появилось изображение Мудрости. Затем Робеспьер произнес вторую речь, на этот раз против атеизма, который «короли хотели утвердить во Франции».

Этот пышный праздник был ошибкой Робеспьера. Его враги сочли, что Робеспьер перестал довольствоваться тем, что он глава политической власти, и стремился еще сделаться жрецом новой национальной церкви. Его стремление к неограниченной и единоличной власти отвратило от него все больше союзников.

Когда Робеспьер шел во главе процессии, депутаты Конвента перешептывались между собой, называя его «диктатором», что он прекрасно слышал, и вернулся с него в дурном расположении духа, по воспоминаниям современников.

Деревья Свободы

Праздник, не имевший точной календарной даты и проводившийся в провинциях вразнобой. Объединяла его лишь идея посадки «деревьев свободы» — традиция, очевидно унаследованная от «майских деревеьев» Бельтайна.

Как и в канун мая, участники торжества сажали живые деревья .или втыкали в землю длинный шест и украшали его цветами, венками, лентами и революционными эмблемами, а вокруг разворачивалось народное гуляние.

Такой обряд появился в январе 1790 г. в провинции Перигор, а затем широко распространился по всей Франции.

В Париже первое дерево свободы посажено в 1790 году, дерево торжественно увенчали красным колпаком и пели вокруг него революционные песни. Уже в мае 1790 года почти в каждой деревне был торжественно посажен молодой дубок как постоянное напоминание о свободе.

Мученики свободы

Как и в предыдущем случае, революционеры пытались дать старой традиции новый смысл. В частности, святым должны были прийти на смену «мученики свободы», а изображение Свободы могло соседствовать в жилищах рядом с изображением Девы Марии.

«Мучеников свободы» было трое: убитый Шарлоттой Корде в июле 1793 года Марат, убитый роялистом в январе 1793 года Лепелетье, и казненный в мятежном Лионе в июле того же года глава местных якобинцев Шалье.

Культ мучеников особенно усилился в разгар дехристианизации, когда с закрытием церквей на время было запрещено совершение католических обрядов. Обряды в честь «мучеников свободы» совершались с поистине религиозной пышностью, с торжественными кортежами и участием хоров.

Вместе с тем, подмена старых святых новыми сопровождалась дехристианизацией: на похоронах Шалье, чей пепел возложили на алтарь и поклонялись ему, как святыне, зажгли огромный костер, куда бросили Евангелие, жития святых, церковные облачения и утварь. По окончании церемонии бюст Шалье водрузили в церкви вместо разбитого изображения Христа.

Дерево свободы (фр. arbre de la liberté, нем. Freiheitsbaum) — революционный символ.

История

Ведет свое происхождение от распространённого у многих европейских народов обычая встречать наступление весны, а также больших праздников насаждением зелёных деревьев (майские деревья). Символический смысл свободы дерево впервые получило во время американской войны за независимость, в начале которой жители Бостона собирались под подобным деревом для совещаний.

Посадка дерева свободы в 1790.

По рассказу аббата Грегуара, автора «Essai historique et patriotique sur les arbres de la liberté», первое Дерево свободы было посажено во время французской революции Норбертом Прессаком, священником в департаменте Виенны. В мае 1790 года почти в каждой деревне был торжественно посажен молодой дубок как постоянное напоминание о свободе. В Париже первое дерево свободы посажено якобинцами в 1790 году, увенчавшими его красной шапкой и певшими вокруг него революционные песни. Национальный конвент декретом 4 плювиоза II г. постановил, чтобы каждая община заменила непринявшиеся деревья новыми к 1 жерминалю, дабы повсюду зеленел символ свободы. Некоторым из таких деревьев давалось название «Деревья братства» (arbres de la fraternité). Хотя при реставрации все деревья свободы должны были быть уничтожены, но ещё в 1830 году в Париже, в предместье Ст.-Антуан, было украшено трёхцветным знаменем дерево, посаженное в первые времена революции.

Июльская революция вызвала и в Германии, особенно в прирейнской Баварии, водружение дерев свободы. Во время революции 1848 года также были посажены во многих местах деревья свободы, но правительственным распоряжением 1850 г. уничтожены. Такая же участь постигла деревья свободы, посаженные в 1848 года в Италии. При провозглашении республики в 1870 году были также посажены деревья свободы, особенно в южной Франции.

Источники

- Дерево свободы // Энциклопедический словарь Брокгауза и Ефрона: В 86 томах (82 т. и 4 доп.). — СПб., 1890—1907.

Дерево свободы (фр. (b) arbre de la liberté, нем. (b) Freiheitsbaum) — революционный символ.

История

Ведет своё происхождение от распространённого у многих европейских народов обычая встречать наступление весны, а также больших праздников насаждением зелёных деревьев (майские деревья (b) ). Символический смысл свободы дерево впервые получило во время американской войны за независимость (b) , в начале которой жители Бостона собирались под подобным деревом для совещаний.

По рассказу аббата Грегуара (b) , автора «Essai historique et patriotique sur les arbres de la liberté», первое Дерево свободы было посажено во время французской революции (b) Норбертом Прессаком, священником в департаменте Виенны. В мае 1790 года почти в каждой деревне был торжественно посажен молодой дубок как постоянное напоминание о свободе. В Париже (b) первое дерево свободы посажено якобинцами (b) в 1790 году (b) , увенчавшими его красной шапкой и певшими вокруг него революционные песни. Национальный конвент декретом 4 плювиоза (b) II г. постановил, чтобы каждая община заменила непринявшиеся деревья новыми к 1 жерминалю (b) , дабы повсюду зеленел символ свободы. Некоторым из таких деревьев давалось название «Деревья братства» (arbres de la fraternité). Хотя при реставрации все деревья свободы должны были быть уничтожены, но ещё в 1830 году (b) в Париже, в предместье Ст.-Антуан, было украшено трёхцветным знаменем дерево, посаженное в первые времена революции.

Июльская революция (b) вызвала и в Германии, особенно в прирейнской Баварии, водружение дерев свободы. Во время революции 1848 года (b) также были посажены во многих местах деревья свободы, но правительственным распоряжением 1850 (b) г. уничтожены. Такая же участь постигла деревья свободы, посаженные в 1848 года (b) в Италии. При провозглашении республики в 1870 году (b) были также посажены деревья свободы, особенно в южной Франции.

Источники

- Дерево свободы // Энциклопедический словарь Брокгауза и Ефрона (b) : в 86 т. (82 т. и 4 доп.). — СПб., 1890—1907.

Великая французская революция открыла новую эру в истории человечества. Казалось, настал триумф свободы, равенства и братства. Однако решительный разрыв с многовековым монархическим укладом дался нелегко. С 1789 по 1794 г. вся жизнь народа — особенно в столице, где решались судьбы страны, — протекала на улицах. Полные надежд на будущее идейные вожди этого грандиозного переворота стремились превратить его в нескончаемый всенародный праздник — карнавал, растянувшийся на пять лет.

Замечательным воплощением этого великого революционного замысла стали многочисленные «деревья Свободы». У крестьян издавна существовала традиция сажать по разным поводам (свадьба, сбор урожая) «майские деревья» — для этой цели годилось любое дерево и даже врытый в землю столб, — веря, что они приносят плодородие, радость и успех. В дни революции дерево стало символом уничтожения феодальной системы, эмблемой Свободы. Какой же праздник без него! Каждый город сажал свое дерево, украшая его трехцветными лентами, кокардами, флагами, красными колпаками и листовками с текстом Декларации прав человека и гражданина. Под его ветвями праздновали освобождение, водили хороводы. Посадка священного в глазах народа «дерева Свободы» превращалась в торжество, часто завершавшееся песнями и фарандолой.

Вообще песни, которыми, как правило, сопровождаются все народные танцы, занимали особое место в жизни этой революционной эпохи. За пять лет их было сложено более двух тысяч. В стране, где каждый второй был неграмотным, они служили мощным средством полемики. Воздух улиц буквально звенел от патриотических, политических и сатирических куплетов; порой разгоралась настоящая песенная война: революционные песни «сражались» против роялистских. Уличного певца, где бы он ни появлялся, тут же окружала толпа, подхватывавшая песню, тем более что мелодия чаще всего была старая, всем известная, менялись только слова.

«Станцуем Карманьолу! Да здравствует гром пушек!»

Люди пели повсюду и по любому поводу: на площадях, в залах заседаний и народных собраний, в тюрьмах, театрах и даже… на трибуне Учредительного собрания. Однажды, когда какой-то гражданин запел, стоя перед судом, Дантон, не выдержав этого «песенного помешательства», взорвался: «В моем характере тоже хватает галльской веселости, — воскликнул он, — но я требую, чтобы впредь здесь звучали только прозаические доводы». Пели обо всем: о политике, меняющихся настроениях, декретах Учредительного собрания. Все перипетии борьбы внутри страны и за ее пределами находили отражение в песнях тех лет.

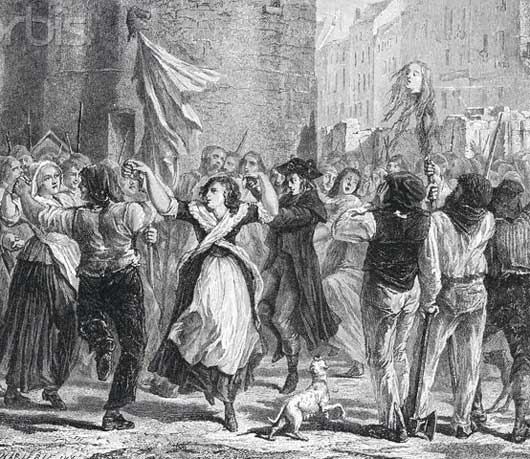

Без этого непременного атрибута любого собрания и праздника не обходилось ни одно народное восстание. Случалось, что особенно важные революционные выступления заканчивались спонтанным торжеством, как это было 5—6 октября 1789 г., когда демонстрация около семи тысяч решительно настроенных парижан, главным образом женщин, завершилась «захватом» королевского дворца в Версале.

Поход женщин на Версаль

Людовика XVI сопровождало в Париж настоящее праздничное шествие — смеющееся, бурлящее, танцующее. За его каретой бежали тысячи горожан. «Везут!» — кричали они уличным зевакам. Взобравшиеся на пушки женщины в шапках подоспевших на выручку гренадеров Национальной гвардии почетным эскортом проплывали мимо толпы. За ними следовало несколько возов с зерном, мукой и бочками вина. Это был день всеобщего ликования и братания, символом которого стали тополиные ветки; их втыкали в ружейные стволы, несли в руках. Веселье не омрачали даже торчавшие повсюду отрубленные головы солдат королевской охраны, насаженные на острия пик в назидание тем, кто осмелится противиться воле народа.

Это были не только военные трофеи, но и предупреждение. Луи Себастьен Мерсье в своем сочинении «Картины Парижа» пишет: «Парижане находят в этом водовороте событий повод для веселья». В самом деле, протесты народа, решившего, по словам Мерсье, в один прекрасный день сбросить вековое ярмо, зачастую облекались в форму самых невероятных шуток и выходок. Представим себе на миг странный королевский кортеж, протискивающийся сквозь запрудившую улицы огромную толпу, лица горожан, застывшие в изумлении перед этим «устрашающим весельем масс», превративших в пленника своего монарха — последнего Богом данного государя.

Подобные народные шествия удивительно похожи на карнавал. Люди выражают свою радость в неистовых танцах и движениях, в революционном экстазе они выставляют на посмешище все, что считалось священным в — увы! — отжившем обществе. И пусть вокруг войны, смерть и кровь — смешаем в пляске радость и ярость. Будем плясать, чтобы не думать о своем прошлом.

Во время восстания 10 августа 1792 г., с которого собственно и началась Республика, парижане разграбили дворец Тюильри, перебили швейцарцев из королевской охраны, открывших огонь по толпе, и тут же, насадив их головы на пики, пустились в пляс, празднуя победу над монархией. Дух этой «второй революции» как нельзя лучше передает знаменитая «Карманьола», которую поют и сегодня. Ее припев: «Станцуем Карманьолу! Да здравствует гром пушек!» — дает полное представление об этом времени, радостном и жестоком. На месте казни Людовика XVI, прозванного Людовиком последним, 21 января 1793 г. народ лихо отплясывал фарандолу.

Эти народные праздники, которые имели огромное воздействие на современников, были, несомненно, одним из способов борьбы с религией. В 1790 г. «Гражданское устройство духовенства» разделило верующих на тех, кто его принял, и тех, кто после протеста папы римского отказался его признать. Постепенно значительная часть духовенства перешла на сторону контрреволюции; так в глазах народа церковь стала врагом свободы.

Прежних святых сменили новые — так называемые мученики свободы, отдавшие жизнь за революцию. Среди них депутат Учредительного собрания Лепелетье де Сен-Фаржо, журналист Марат (издатель популярной газеты «Друг народа») и представитель муниципалитета Шарлье. Все трое погибли в 1793 г. от руки оппозиционеров и были особо почитаемы народом: их бюсты украшали перекрестки и площади, залы собраний и театры, к ним приносили цветы — «гражданские венки», — в их честь устраивались процессии, сочинялись гимны. Именами этих героев Республики нарекались новорожденные.

10 ноября 1793 г. в Соборе Парижской Богоматери состоялся грандиозный праздник Свободы. Роль богини разума исполняла одна из оперных примадонн. Под пение гимнов, в сопровождении кортежа из украшенных цветами колесниц, санкюлотов, детей, членов народных обществ и разных учреждений она приблизилась к подножию сооруженной на площади горы и «освободила» от цепей чернокожего раба. Атрибуты королевской власти и религиозные символы полетели в костер, вокруг которого до зари танцевали и поднимали бокалы за всеобщее братство парижане. После этого праздника Собор переименовали в Храм Разума. Новый «культ» быстро распространялся в провинции; церкви повсюду закрывали.

На этом фоне в первой половине второго года Республики (осень 1793—весна 1794 г.) по стране прокатилась волна антирелигиозных выступлений. В Париже и в сельской местности то тут, то там устраивались шутовские карнавальные шествия. Их участники, вырядившись в священнические одежды, восседая на ослах, свиньях и козлах, увешанных крестами и библиями, с миртами на головах изображали епископов и папу, подвергая жестокому осмеянию церковь и все институты власти. Они разыгрывали пантомимы, пили из потиров, шумели, возили с собой на повозках кропильницы, исповедальни, дароносицы, статуи святых, кресты, гербы своих бывших господ, скульптурные изображения лилии (символ монархии), чучела чужеземных королей и папы римского…

Вся эта причудливая поклажа гибла, в конце концов, в веселом пламени костра. Вокруг него и вокруг «дерева Свободы» танцевали фарандолу и пили вино — «святую воду республиканцев».

Эти праздники разрушения и духовного перерождения не могли не беспокоить политических лидеров страны. Они пытались как-то упорядочить подобные проявления чувств, слишком напоминавшие вакханалии. Чтобы смягчить их откровенно атеистический характер, в 1794 г. был принят закон о введении праздника «Верховного существа» (Бога). Таким образом, провозглашался как бы универсальный культ природы, торжественно объявлялось, что «французский народ признает бессмертие души». Теперь в духе педагогических принципов Руссо и его идеи социальной общности организация праздников передавалась самому народу, который участвовал в них и как зритель, и как актер. (Кстати, этими вопросами до сих пор занимается комитет народного образования Национального собрания.)

Нужно было подчеркнуть разрыв со старым, основанным на неравенстве строем и воспеть новую социальную гармонию и республиканские «добродетели»: любовь к человеку, природе и отечеству, дружбу, справедливость, а также ненависть к монархам и тиранам. Так, праздники, посвященные наиболее памятным моментам революции (например, 14 июля и 10 августа), знаменовали собой разрыв с прошлым и отмечали крупнейшие вехи создания Республики. Что касается праздников, устраивавшихся в конце каждой декады месяца по республиканскому календарю и представлявших собой своего рода республиканские «литургии», прославляющие народы Древнего Рима и Древней Греции, духовным наследником которых был объявлен французский народ, то считалось, что они утверждают новый моральный кодекс: среди них были праздники, посвященные целомудрию, истине, супружеской любви, причем все они непременно сопровождались песнями и гражданскими клятвами примерно одинакового содержания.

Вот одна из них. Ее произносили, вытянув руку по направлению к бюсту Брута (убившего Цезаря, чтобы спасти Римскую республику): «Брут, клянемся следовать твоему примеру, клянемся сохранить Республику единой и неделимой. Долой королей, долой самозванцев! Свобода или смерть!»

Эти праздники включали элементы народных традиций («дерево Свободы», костры), а также символику санкюлотов (фригийский колпак, пика), которые наполнялись политическим и социальным содержанием с неизменным акцентом на единство страны.

Так, первая годовщина народного восстания 10 августа 1792 г., завершившегося свержением монархии, отмечалась в Париже под истинно республиканским лозунгом — «Единство и Неделимость». Стремясь максимально воссоздать атмосферу памятного дня, участники праздничного шествия маршировали с оружием в руках.

В течение нескольких часов процессия следовала по украшенным гирляндами дубовых листьев улицам столицы, время от времени делая остановки: первую — у фонтана Возрождения на том месте, где стояла Бастилия; затем у триумфальной арки, воздвигнутой в честь парижанок — участниц событий 5—6 октября 1789 г., изображенных увенчанными лавровыми венками в окружении пушек. Третья остановка — на площади Революции (ныне площадь Согласия). Здесь манифестанты выпустили в небо тысячи птиц и побросали символы монархии и феодального строя в пламя огромного костра, разожженного перед изображением Свободы во фригийском колпаке с пикой в руке. Следующая остановка — перед Домом инвалидов, где была установлена огромная скульптура с дубиной и фасцией, символизирующая французский народ, раздавивший гидру аристократии. И наконец, последняя, пятая остановка — на Марсовом поле, где перед алтарем отечеству 200 тыс. парижан произнесли клятву: «Свобода, Равенство, Братство или смерть!» Праздник завершился дружеским пикником и прославлением победы революционных армий над коалицией тиранов.

Автор: Лоранс Кудар.

P. S. Старинные летописи рассказывают: Впрочем, некоторые люди и в наше время отмечают годовщину великой французской революции, порой это даже повод для каких-нибудь подарков, таких как скажем, штоф в СПб – наборы для различных алкогольных напитков.

Схожі статті:

Символизм во Французской революции был средством выделить и прославить (или очернить) основные черты Французской революции .и обеспечить общественную идентификацию и поддержку. Чтобы эффективно проиллюстрировать различия между новой республикой и старым режимом, лидерам необходимо было внедрить новый набор символов, которые следует отмечать вместо старой религиозной и монархической символики. С этой целью символы были заимствованы из исторических культур и переопределены, а символы старого режима либо уничтожены, либо переприписаны приемлемым характеристикам. Были введены новые символы и стили, чтобы отделить новую республиканскую страну от монархии прошлого. Эти новые и пересмотренные символы использовались, чтобы привить публике новое чувство традиции и благоговения перед Просвещением и Республикой. [1]

Фасции

Фасции , как и многие другие символы Французской революции, имеют римское происхождение. Фасции представляют собой пучок березовых прутьев с жертвенным топором. В римские времена фасции символизировали власть магистратов, представляя союз и согласие с Римской республикой. Французская Республика продолжала использовать этот римский символ для обозначения государственной власти, справедливости и единства. [2]

Во время революции изображение фасции часто использовалось в сочетании со многими другими символами. Хотя его видели на протяжении всей Французской революции, возможно, наиболее известным французским воплощением фасций является фасция, увенчанная фригийской шапкой. В этом образе нет ни топора, ни сильного центрального государства; скорее, он символизирует власть освобожденных людей, помещая Кепку Свободы поверх классического символа власти. [2]

Трехцветная кокарда

Трехцветная кокарда была создана в июле 1789 года. Белый (королевский цвет) был добавлен, чтобы национализировать более ранний сине-красный дизайн.

Кокарды широко носили революционеры, начиная с 1789 года. Теперь они прикололи сине-красную кокарду Парижа к белой кокарде Ancien Régime , таким образом получив оригинальную кокарду Франции . Позже отличительные цвета и стили кокарды указывали на фракцию владельца, хотя значения различных стилей не были полностью одинаковыми и несколько различались в зависимости от региона и периода.

Трехцветный флаг происходит от кокарды, использовавшейся в 1790-х годах. Это были круглые розеткообразные эмблемы, прикрепленные к шляпе. Камиль Демулен попросил своих последователей носить зеленые кокарды 12 июля 1789 года. Парижское ополчение, сформированное 13 июля, приняло сине-красную кокарду. Синий и красный — традиционные цвета Парижа, и они используются на гербе города. Кокарды различной расцветки применялись при штурме Бастилии 14 июля. [3] Сине-красная кокарда была вручена королю Людовику XVI в Hôtel de Ville 17 июля. Лафайет выступал за добавление белой полосы, чтобы «национализировать» дизайн. [4]27 июля трехцветная кокарда была принята как часть униформы Национальной гвардии , национальной полиции, пришедшей на смену ополчению. [5]

Общество женщин-революционеров-республиканцев , крайне левая воинствующая группа, потребовала в 1793 году принятия закона, обязывающего всех женщин носить трехцветную кокарду, чтобы продемонстрировать свою лояльность Республике. Закон был принят, но против него выступили другие группы женщин. Якобинцы, возглавлявшие правительство, решили, что женщинам нет места в государственных делах, и в октябре 1793 г. распустили все женские организации.

Кепка свободы

В революционной Франции кепка или красная шляпа были впервые замечены публично в мае 1790 года на фестивале в Труа , украшающем статую, представляющую нацию, и в Лионе на копье, которое несет богиня Либертас . [7] По сей день национальная эмблема Франции, Марианна , изображена во фригийском колпаке. [8] Шапки часто вязали женщины, известные как Tricoteuse , которые сидели рядом с гильотиной во время публичных казней в Париже во время Французской революции, предположительно продолжая вязать между казнями.

Шапка Liberty, также известная как фригийская кепка или пилеус , представляет собой войлочную кепку без полей конической формы с выдвинутым вперед кончиком. Шапку изначально носили древние римляне, греки, иллирийцы [9] и до сих пор носят в Албании и Косово . Шапка подразумевает облагораживающий эффект, как видно из ее ассоциации с гомеровским Улиссом и мифическими близнецами Кастором и Поллуксом . Популярность эмблемы во время Французской революции отчасти объясняется ее важностью в Древнем Риме: ее использование намекает на римский ритуал освобождения рабов, в котором освобожденный раб получает шляпу как символ своей вновь обретенной свободы. Римская трибунаЛуций Апулей Сатурнин подстрекал рабов к восстанию, показывая пилеус, как если бы это был штандарт. [10]

Шляпка пилеуса часто красного цвета. Этот тип кепки носили революционеры при падении Бастилии. Согласно Revolutions de Paris, он стал «символом освобождения от всех рабств, знаком объединения всех врагов деспотизма». [11] Пилеус конкурировал с фригийской шапкой, аналогичной шапкой, закрывавшей уши и затылок, за популярность. Фригийская шапка со временем вытеснила пилеус и узурпировала его символику, став синонимом республиканской свободы.

Одежда

Здесь Людовик XIV изображен в традиционных красных туфлях на каблуках, связанных с его двором. Такие каблуки стали символом Людовика XIV, королевского двора и монархии в целом. [12]

Раннее изображение триколора в руках санкюлота во время Французской революции.

По мере того, как радикалы и якобинцы становились все более могущественными, возникло отвращение к высокой моде из-за ее экстравагантности и связи с королевской властью и аристократией. На смену ему пришла своего рода «антимода» для мужчин и женщин, подчеркивающая простоту и скромность. Мужчины были одеты в простую темную одежду и с короткими ненапудренными волосами. Во время террора 1794 повседневная одежда санкюлотов символизировала эгалитаризм якобинцев. Sans-culotte буквально переводится как «бриджи без колен», согласно Британской энциклопедии , имея в виду длинные брюки, которые носили революционеры, которые использовали свою одежду, чтобы дистанцироваться от французской аристократии и аристократии в целом, которые традиционно носили брюки-кюлоты. , или шелковые бриджи до колен. [13]Такие длинные штаны были символом рабочего человека. Высокая мода и экстравагантность вернулись при Директории 1795–1799 годов с ее «директорским» стилем ; мужчины не вернулись к экстравагантным обычаям. [14] Еще одним символом французской аристократии был высокий каблук. До Французской революции высокие каблуки были одним из основных элементов мужской моды, их носили те, кто мог себе их позволить, чтобы обозначить высокое социальное положение. Людовик XIV популяризировал и регламентировал ношение высоких каблуков при своем дворе. Сам король, как и многие представители знати при его дворе, носил красные туфли на высоких каблуках, причем красный цвет использовался, чтобы «… продемонстрировать, что дворяне не пачкают свою обувь …» [15] [ нужна страница ] согласно Филип Мансел, специалист по судебной истории. Однако во время революции эти стили вышли из моды для мужчин, поскольку монархия становилась все более непопулярна, а ассоциации с монархией становились все более опасными. Такая мода также стала символом легкомыслия, что сделало ее непопулярным среди среднего французского человека.

Дерево Свободы

Дерево Свободы , официально принятое в 1792 году, является символом вечной Республики, национальной свободы и политической революции. [11] Он имеет исторические корни в революционной Франции, а также в Америке, как символ, который разделяли две зарождающиеся республики. [16] Дерево было выбрано в качестве символа Французской революции, потому что оно символизирует плодородие во французском фольклоре, [17] что обеспечивало простой переход от почитания его по одной причине к другой. Американские колонии также использовали идею Дерева Свободы, чтобы отпраздновать свои собственные восстания против британцев, начиная с бунта против Закона о гербовых марках в 1765 году .

Кульминацией беспорядков стало повешение чучел двух политиков, действовавших в соответствии с Законом о гербовых марках, на большом вязе. Вяз стал прославляться как символ свободы в американских колониях. [19] Он был принят как символ, который должен был жить и расти вместе с Республикой. С этой целью дерево изображается в виде саженца, обычно дуба во французской интерпретации. Дерево Свободы служит постоянным праздником духа политической свободы.

Выше приведена гравюра 1831 года гипсовой модели предполагаемого памятника Слону Бастилии, посвященного падению тюрьмы Бастилии.

Слон Бастилии

Падение Бастилии 14 июля 1789 года стало важным моментом для французского народа. Выдающийся символ монархического правления, Бастилия изначально служила политической тюрьмой. Однако со временем Бастилия превратилась из тюрьмы в помещение, в котором в основном хранилось оружие, хотя символика осталась, и здание стало синонимом французской монархии и тиранического правления. [20] [21] Падение памятника привело к бегству нескольких дворян из Франции и жестоким нападениям на богатых. [22] Слон Бастилии был возведен в ознаменование падения Бастилии , спроектированной Наполеоном как символ его собственных побед, которую он построил из орудий своих врагов вБитва при Фридланде . [23] Слон был снесен в 1846 году и заменен Июльской колонной , которая сейчас стоит в Париже на первоначальном основании слона. Эта колонна была создана во времена правления короля Луи-Филиппа I в честь июльской революции 1830 года и установления Июльской монархии .

Геркулес

Символ Геркулеса был впервые принят Старым режимом для обозначения монархии. [24] Геракл был древнегреческим героем, который символизировал силу и могущество. Символ использовался для представления суверенной власти короля над Францией во время правления монархов Бурбонов . [25] Однако монархия была не единственной правящей силой во французской истории, которая использовала символ Геркулеса для объявления своей власти.

Во время революции символ Геркулеса был возрожден, чтобы представлять зарождающиеся революционные идеалы. Первое использование Геркулеса в качестве революционного символа было во время фестиваля, посвященного победе Национального собрания над федерализмом 10 августа 1793 года. [26] «Федерализм» был движением, направленным на ослабление центрального правительства. [27] Этот фестиваль единства состоял из четырех станций вокруг Парижа, на которых были представлены символы, представляющие основные события революции, которые воплощали революционные идеалы свободы, единства и власти. [28]

Статуя Геракла, установленная на вокзале в память о падении Людовика XVI , символизировала власть французского народа над своими бывшими угнетателями. Нога статуи была поставлена на горло Гидры , которая олицетворяла тиранию федерализма , побежденную новой республикой . В одной руке статуя сжимала дубинку, символ власти, а в другой — фасции, символизирующие единство французского народа. Образ Геракла помог новой республике установить свою новую республиканскую моральную систему. Таким образом, Геракл превратился из символа суверенитета монарха в символ новой суверенной власти во Франции: французского народа. [29]

Этот переход был осуществлен легко по двум причинам. Во-первых, поскольку Геракл был известным мифологическим персонажем и ранее использовался монархией, его легко узнавали образованные французские наблюдатели. Революционному правительству не нужно было воспитывать французский народ на фоне символа. Кроме того, Геракл напомнил классическую эпоху греков и римлян, период, который революционеры отождествляли с республиканскими и демократическими идеалами. Эти коннотации сделали Геркулеса легким выбором для представления могущественного нового суверенного народа Франции. [25]

Во время более радикальной фазы революции с 1793 по 1794 год использование и изображение Геракла изменилось. Эти изменения символа были связаны с тем, что революционные лидеры считали, что символ подстрекает к насилию среди простых граждан. Триумфальные сражения Геракла и преодоление врагов Республики стали менее заметными. В дискуссиях о том, какой символ использовать для печати Республики, рассматривался образ Геракла, но в конечном итоге он был исключен в пользу Марианны . [30]

Геркулес был на монете Республики. Однако этот Геракл не был тем же самым образом, что и дотеррорные этапы Революции. Новый образ Геракла был более прирученным. Он казался более отеческим, старше и мудрее, чем образы воина на ранних этапах Французской революции. В отличие от его 24-футовой статуи на Фестивале Верховного Существа, теперь он был того же размера, что и Свобода и Равенство. [30]

Также язык на монете с Гераклом сильно отличался от риторики дореволюционных изображений. На монетах были использованы слова «объединение свободы и равенства». Это противоречит резкому языку ранней революционной риторики и риторике монархии Бурбонов. К 1798 году Совет Древних обсудил «неизбежное» изменение проблемного образа Геракла, и в конечном итоге Геракл был заменен на еще более послушный образ. [30]

Марсельеза

Руже де Лиль, композитор Марсельезы, впервые поет ее в 1792 году.

|

|

Гимн Франции «Марсельеза » ; текст на французском языке. |

|

Проблемы с воспроизведением этого файла? См . справку по СМИ . |

«Марсельеза» ( французское произношение: [ la maʁsɛjɛːz] ) стала национальным гимном Франции. Песня была написана и сочинена в 1792 году Клодом Жозефом Руже де Лилем и первоначально называлась « Chant de guerre pour l’Armée du Rhin ». Французское национальное собрание приняло его в качестве гимна Первой республики в 1795 году. Свое прозвище он получил после того, как его спели в Париже добровольцы из Марселя , маршировавшие на столицу.

Песня является первым примером гимнического стиля «Европейский марш». Вызывающая воспоминания мелодия и текст гимна привели к его широкому использованию в качестве песни революции и включению во многие произведения классической и популярной музыки. Серуло говорит, что «замысел «Марсельезы» приписывают французскому генералу Страсбургу, который, как говорят, поручил де Лилю, составителю гимна, «сочинить один из тех гимнов, который доносит до души народа энтузиазм, который она (музыка) предлагает »» [31] .

Гильотина

Как показано в этой британской карикатуре Исаака Круикшанка , гильотина стала пренебрежительным символом насильственных эксцессов во времена правления террора. На трехцветной ленте сверху написано: «Нет Бога! Нет религии! Нет короля! Нет Конституции!» Под лентой и его фригийской шапкой с трехцветной кокардой находятся два окровавленных топора, прикрепленных к гильотине, лезвие которой подвешено над пылающим миром. Истощенный мужчина и пьяная женщина, одетые в лохмотья, служат геральдическими «сторонниками», радостно танцуя на сброшенных царских и церковных регалиях.

Хэнсон отмечает: «Гильотина является главным символом террора во время Французской революции». [32] Изобретенная врачом во время революции как более быстрая, более эффективная и более характерная форма казни, гильотина стала частью массовой культуры и исторической памяти. Левые прославляли его как народного мстителя, а правые проклинали как символ Царства Террора . [33] Его деятельность стала популярным развлечением, которое привлекало большие толпы зрителей. Продавцы продавали программы с именами тех, кто должен был умереть. Многие люди приходили день за днем и соперничали за лучшие места, откуда можно было наблюдать за происходящим; вязание женское ( трикотаж) сформировали кадры хардкорных завсегдатаев, разжигающих толпу. Родители часто приводили своих детей. К концу Террора толпы резко поредели. Повторение притупило даже это самое ужасное из развлечений, и зрителям стало скучно. [34]

То, что пугает людей, со временем меняется. Дойл комментирует:

- Даже уникальный ужас гильотины затмевается газовыми камерами Холокоста, организованной жестокостью ГУЛАГа, массовым запугиванием культурной революции Мао или камбоджийскими полями смерти. [35]

Вулкан

На риторику насилия во время Французской революции сильно повлияла тенденция обращаться к явлениям мира природы для описания и объяснения изменений в обществе. В мире быстрых политических и культурных изменений выдающиеся деятели революции активно использовали определенные языковые средства для создания политического языка, находящего отклик у публики. Многие из них также были знакомы с развивающимися научными областями естествознания либо благодаря развитому интересу, либо стремлению сделать карьеру в области естественных наук. Следовательно, природные образы стали средством как «воображения, так и объяснения революции». [36]

Таким образом, метафора вулкана расцвела в революционном воображении. Первоначально вулкан символизировал «необузданную силу и разрушение, но разрушение, которое могло работать и против Франции, и для нее». [37] Однако по мере развития революции менялся и образ вулкана, и его значение для развития человечества. Из источника потенциальных разрушений и катастроф вулкан позже стал символом «конструктивной революционной трансформации» во время правления террора.. Когда политическая ситуация снова изменилась, образ вулкана в конечном итоге вернулся к своему статусу силы безжалостной силы. Меняющиеся символические значения вулкана сами по себе представляют революцию как источник непредсказуемого и неизбежного разрушения, неподвластного человеческому контролю. [38]

Однако на фоне враждебности французов, их растущего политического недовольства и беспокойства даже метафора раскаленного вулкана меркнет. Даже метафоры, взятые из яростного великолепия природы, не могли описать свирепость нации и ее презираемых людей. Эта метафорическая трансформация отражена в жанрах всего литературного спектра, включая рождение и растущую популярность романа как формы выражения. [39]

Эти яркие сравнения между социальной трансформацией и природной катастрофой не были редкостью. За двадцать лет до Ассамблеи знати 1787 года политический философ Жан Жак Руссо подчеркивал сейсмическую активность, такую как вулканические толчки, взрывы и пирокластические выбросы, как ключевую силу, стоящую за распространением ранней человеческой цивилизации. Согласно его Второй беседе, стихийные бедствия не только сблизили сообщества, укрепив их узы сотрудничества, но и позволили таким сообществам стать свидетелями силы горения как важнейшего ресурса для возможного производства рабочих инструментов. [40]Оптимистическое видение Руссо натурализованных изменений, потрясений как порождающей и прогрессивной стадии жизненного цикла управления находит отклик, но не разделяется британской радикальной прессой. Когда изображение вулкана стало кодифицированным как французский штамп, революционная угроза неясна, однако многочисленные цитаты можно проследить в рекламных листовках, выпущенных в период с 1788 по 1830 год. Французской революции» и сожалеет о том дне, когда «наша (британская) власть (будет) парализована такими стихийными бедствиями». [41]

Примечания

- ↑ Censer and Hunt, компакт-диск «Как читать изображения» с Censer, Джеком; Линн Хант (2001). Свобода, равенство, братство: изучение Французской революции . Пенсильвания: Издательство Пенсильванского государственного университета.

- ^ a b Кадило и Хант, компакт-диск «Как читать изображения»

- ↑ Крауди , Терри, Французская революционная пехота 1789–1802 гг ., с. 42 (2004).

- ↑ Мари Жозеф Поль Ив Рох Жильбер Дю Мотье Лафайет (маркиз де), Мемуары, переписка и рукописи генерала Лафайета, том. 2, с. 252.

- ↑ Клиффорд, Дейл, «Может ли униформа сделать гражданина? Париж, 1789–1791», Исследования восемнадцатого века , 2001, с. 369.

- ^ Дарлин Гей Леви, Гарриет Брэнсон Эпплуайт и Мэри Дарем Джонсон, ред. Женщины в революционном Париже, 1789–1795 (1981), стр. 143–49.

- ↑ Дженнифер Харрис, «Красная шапка свободы: исследование платья, которое носили французские революционные партизаны 1789-94». Исследования восемнадцатого века (1981): 283–312. в JSTOR

- ↑ Ричард Ригли, «Преобразования революционной эмблемы: Кепка Свободы во Французской революции, French History 11 (2) 1997: 131-169.

- ^ статья Британской энциклопедии

- ^ Уильям Дж. Купер и Джон Маккарделл . «Шапки свободы и деревья свободы». Прошлое и настоящее 146.1 (1995): 66-102.

- ^ a b Кадило и Хант, «Как читать изображения» LEF CD-ROM

- ^ Мансел, Филип (2005). Одеты по правилам: королевские и придворные костюмы от Людовика XIV до Елизаветы II . Нью-Хейвен: издательство Йельского университета . ISBN 0-300-10697-1. OCLC 57319508 .

- ^ «Санкюлот | Французская революция» . Британская энциклопедия . Проверено 25 ноября 2019 г. .

- ↑ Джеймс А. Лейт, «Мода и антимода во Французской революции», Консорциум революционной Европы 1750–1850: Избранные статьи (1998), стр. 1–18

- ^ Мансел, Филип (2005). Одетые по правилам: королевские и придворные костюмы от Людовика XIV до Елизаветы II . Издательство Йельского университета. ISBN 978-0-300-10697-8.

- ^ Купер и Маккарделл. «Шапки свободы и деревья свободы». (1995): 75–77.

- ↑ Озуф, «Фестивали и Французская революция» 123.

- ^ Купер и Маккарделл. «Шапки свободы и деревья свободы». (1995): 75

- ^ Купер и Маккарделл. «Шапки свободы и деревья свободы». (1995): 88

- ^ Рид, Дональд (1998). «Обзор Бастилии: история символа деспотизма и свободы». Французская политика и общество . 16 (2): 81–84. ISSN 0882-1267 . JSTOR 42844714 .

- ↑ Кларк, Кеннет, 1903–1983 гг. (2005). Цивилизация: личный взгляд . Джон Мюррей. ISBN 0719568447. OCLC 62306592 .

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: несколько имен: список авторов ( ссылка ) - ^ «III. От района к разделу», Французская революция в миниатюре , Princeton University Press, 1984-12-31, стр. 76–103, doi : 10.1515/9781400856947.76 , ISBN 9781400856947

- ^ Карадонна, JL (27 августа 2008 г.). «История личности: Франция, 1715-1815». Французская история . 22 (4): 494–495. doi : 10.1093/fh/crn050 . ISSN 0269-1191 .

- ^ Хант 1984, 89.

- ^ а б Хант 1984, 101–102

- ^ Хант 1984, 96

- ↑ Билл Эдмондс, «Федерализм и городское восстание во Франции в 1793 году», Journal of Modern History (1983) 55 № 1, стр. 22-53.

- ^ Хант 1984, 92

- ↑ Хант 1984, 97, 103.

- ^ а б в Охота 1984, 113

- ^ Карен А. Церуло, «Символы и мировая система: национальные гимны и флаги». Социологический форум (1993) 8 № 2 стр. 243-271.

- ^ Пол Р. Хэнсон (2007). Французская революция от А до Я. Пугало Пресс. п. 151. ISBN 9781461716068.

- ^ Р. По-чиа Ся, Линн Хант, Томас Р. Мартин, Барбара Х. Розенвейн и Бонни Г. Смит, Создание Запада, народов и культуры, Краткая история, Том II: с 1340 г., (2-е изд., 2007), с. 664.

- ^ Опи РФ, Гильотина (2003)

- ^ Уильям Дойл (2001). Французская революция: очень краткое введение . Оксфорд УП. п. 22. ISBN 9780191578373.

- ^ Миллер, Мэри Эшберн (2009). «Гора, стань вулканом: образ вулкана в риторике Французской революции». Французские исторические исследования . 32 (4): 555–585 (стр. 558). doi : 10.1215/00161071-2009-009 .

- ^ Миллер, Мэри Эшберн (2009). «Гора, стань вулканом: образ вулкана в риторике Французской революции». Французские исторические исследования . 32 (4): 555–585, (стр. 559). doi : 10.1215/00161071-2009-009 .

- ^ Миллер, Мэри Эшберн (2009). «Гора, стань вулканом: образ вулкана в риторике Французской революции». Французские исторические исследования . 32 (4): 555–585 (стр. 585). doi : 10.1215/00161071-2009-009 .

- ^ Розадор, фон; Тецели, Курт (1 июня 1988 г.). «Метафорические изображения Французской революции в викторианской художественной литературе» . Литература девятнадцатого века . 43 (1): 1–23. дои : 10.2307/3044978 . ISSN 0891-9356 . JSTOR 3044978 .

- ^ Руссо, Жан-Жак (1781). ESSAI SUR L’ORIGINE DES LANGUES, или il est parlé de la Mélodie, et de l’Imitation Musicale .

- ^ Петтит, Клэр (июнь 2020 г.). Серийные формы: Незавершенный проект современности, 1815-1848 гг . Издательство Оксфордского университета. ISBN 978-0-19-883042-9.

Дальнейшее чтение

- Кейдж, Э. Клэр. «Портняжное Я: неоклассическая мода и гендерная идентичность во Франции, 1797–1804». Исследования восемнадцатого века 42.2 (2009): 193–215.

- Курильница, Джек; Линн Хант (2001). Свобода, равенство, братство: изучение Французской революции . Пенсильвания: Издательство Пенсильванского государственного университета.; функция компакт-диска «Как читать изображения»

- Купер, Уильям Дж. и Джон Маккарделл. «Шапки свободы и деревья свободы». Прошлое и настоящее 146 № 1 (1995): 66–102. в JSTOR

- Германи, Ян. «Постановочные сражения: представления о войне в театре и на фестивалях Французской революции». Европейский обзор истории — Européenne d’Histoire (2006) 13 № 2 стр: 203–227.

- Гермер, Стефан. «Сферы в посттермидорной Франции». Художественный бюллетень 74.1 (1992): 19–36. онлайн

- Харрис, Дженнифер. «Красная шапка свободы: исследование одежды, которую носили французские революционные партизаны 1789-94». Исследования восемнадцатого века (1981): 283–312. в JSTOR

- Хендерсон, Эрнест Ф. Символ и сатира во Французской революции (1912 г.), со 171 иллюстрацией онлайн бесплатно .

- Хант, Линн. «Геркулес и радикальный образ во Французской революции», « Представления » (1983), № 2, стр. 95–117 в JSTOR .

- Хант, Линн. «Священное и Французская революция». Дюркгеймовская социология: культурология (1988): 25–43.

- Коршак, Ивонн. «Шапка Свободы как революционный символ в Америке и Франции». Смитсоновские исследования американского искусства (1987): 53–69.

- Ландес, Джоан Б. Визуализация нации: гендер, представительство и революция во Франции восемнадцатого века (2003)

- Озуф, Мона. Фестивали и Французская революция (издательство Гарвардского университета, 1991)

- Райхардт, Рольф и Хубертус Коле. Визуализация революции: политика и изобразительное искусство во Франции конца восемнадцатого века (Reaktion Books, 2008); охватывающий все искусства и включая элитарные, религиозные и народные традиции; 187 иллюстраций, 46 цветных.

- Робертс, Уоррен. Жак-Луи Давид и Жан-Луи Приер, художники-революционеры: общественность, народные массы и образы Французской революции (SUNY Press, 2000)

- Ригли, Ричард. Политика внешности: представления об одежде в революционной Франции (Берг, 2002 г.)

-

-

October 13 2013, 13:56

- Путешествия

- Cancel

Дерево свободы

Я вернулась.

Отпуск в целом удался

Также я совершила некоторое количество «ритуальных действий», в частности станцевала под деревом свободы:

Дерево свободы стоит в музее Рисорджименто в Турине, в зале, посвященном Французской революции и итальянским якобинцам.

Это ничего, что оно — современная реконструкция и что оно в музее — там при желании (и наличии достаточного числа граждан, чтоб все витрины охватить) можно и хоровод вокруг него устроить, место есть

От настоящего дерева свободы (которое вырубили русские с австрийцами, войдя в Турин) остался фригийский колпак 1796 года.

Вообще, конечно, у меня ощущение, что чем дальше, тем больше я путешествую по какой-то «внутренней Италии», и как её показать (да и надо ли, да и интересно ли это кому-то кроме меня самой), я понятия не имею. Но, надеюсь, некоторое количество рассказов с картинками воспоследует в ближайщее время

Всем привет. Рада буду вас снова видеть.

Всю френдленту за две недели я вряд ли успею отмотать, так что если я пропустила что-то важное или интересное — кидайтесь ссылками!

For other uses, see French Revolution (disambiguation).

| Date | 1789–1799 |

|---|---|

| Location | France |

| Participants | French society |

| Outcome |

|

The French Revolution (French) was a period of radical social and political upheaval in France from 1789 to 1799 that had a fundamental impact on French history and on modern history worldwide.

Experiencing an economic crisis exacerbated by the Seven Years’ War and the American Revolutionary War, the common people of France became increasingly frustrated by the ineptitude of King Louis XVI and the continued decadence of the aristocracy. This resentment, coupled with burgeoning Enlightenment ideals, fueled radical sentiments and launched the Revolution in 1789 with the convocation of the Estates-General in May. The first year of the Revolution saw members of the Third Estate proclaiming the Tennis Court Oath in June, the assault on the Bastille in July, the passage of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen in August, and an epic march on Versailles that forced the royal court back to Paris in October. The next few years were dominated by struggles between various liberal assemblies and right-wing supporters of the monarchy intent on thwarting major reforms. A republic was proclaimed in September 1792 and King Louis XVI was executed the next year.

External threats shaped the course of the Revolution profoundly. The Revolutionary Wars began in 1792 and ultimately featured spectacular French victories that facilitated the conquest of the Italian Peninsula, the Low Countries and most territories west of the Rhine – achievements that had eluded previous French governments for centuries. Internally, popular agitation radicalized the Revolution significantly, culminating in the rise of Maximilien Robespierre and the Jacobins. The dictatorship imposed by the Committee of Public Safety during the Reign of Terror, from 1793 until 1794, caused up to 40,000 deaths inside France,[1] abolished slavery in the colonies, and secured the borders of the new republic from its enemies. The bloody rule of the Jacobins sparked an internal backlash and ultimately sent Robespierre to the guillotine. After the fall of the Jacobins, the Directory assumed control of the French state in 1795 and held power until 1799. In that year, which marks the traditional conclusion of the Revolution, Napoleon Bonaparte overthrew the Directory in the Brumaire coup and established the Consulate. The primary successor state of the Revolution, the First Empire under Napoleon, emerged in 1804 and spread the new revolutionary principles all over Europe during the Napoleonic Wars. The First Empire finally collapsed in 1815 when the forces of reaction succeeded in restoring the Bourbons, albeit under a constitutional monarchy.

The modern era has unfolded in the shadow of the French Revolution. French society itself underwent an epic transformation as feudal, aristocratic, and religious privileges evaporated under a sustained assault from various left-wing political groups, the masses on the streets, and peasants in the countryside.[2] Old ideas about tradition and hierarchy regarding monarchs, aristocrats, and the Catholic Church were abruptly overthrown under the mantra of «Liberté, égalité, fraternité.» Globally, the Revolution accelerated the rise of republics and democracies, the spread of liberalism and secularism, the development of modern ideologies, and the adoption of total war.[3] Some of its central documents, like the Declaration of the Rights of Man, expanded the arena of human rights to include women and slaves.[4] The fallout from the Revolution had permanent consequences for human history: the Latin American independence wars, the Louisiana Purchase by the United States, and the Revolutions of 1848 are just a few of the numerous events that ultimately depended upon the eruption of 1789.

Causes

The French government faced a fiscal crisis in the 1780s, and King Louis XVI was criticized for his handling of these affairs.

Adherents of most historical models identify many of the same features of the Ancien Régime as being among the causes of the Revolution. Historians at one time emphasized class conflicts from a Marxist perspective; that interpretation fell out of favour in the late 19th century. The economy was not healthy; poor harvests, rising food prices, and an inadequate transportation system made food even more expensive. The sequence of events leading to the revolution involved the national government’s virtual bankruptcy due to its poor tax system and the mounting debts caused by numerous large wars. The attempt to challenge British naval and commercial power in the Seven Years’ War was a costly disaster, with the loss of France’s colonial possessions in continental North America and the destruction of the French Navy. French forces were rebuilt and performed more successfully in the American Revolutionary War, but only at massive additional cost, and with no real gains for France except the knowledge that Britain had been humbled. France’s inefficient and antiquated financial system was unable to finance this debt. Faced with a financial crisis, the king called an Assembly of Notables in 1787 for the first time in over a century.

Meanwhile, the royal court at Versailles was isolated from, and indifferent to the escalating crisis. While in theory King Louis XVI was an absolute monarch, in practice he was often indecisive and known to back down when faced with strong opposition. While he did reduce government expenditures, opponents in the parlements successfully thwarted his attempts at enacting much needed reforms. Those who were opposed to Louis’ policies further undermined royal authority by distributing pamphlets (often reporting false or exaggerated information) that criticized the government and its officials, stirring up public opinion against the monarchy.[5]

Many other factors involved resentments and aspirations given focus by the rise of Enlightenment ideals. These included resentment of royal absolutism; resentment by peasants, laborers and the bourgeoisie toward the traditional seigneurial privileges possessed by the nobility; resentment of the Catholic Church’s influence over public policy and institutions; aspirations for freedom of religion; resentment of aristocratic bishops by the poorer rural clergy; aspirations for social, political and economic equality, and (especially as the Revolution progressed) republicanism; hatred of Queen Marie-Antoinette, who was falsely accused of being a spendthrift and an Austrian spy; and anger toward the King for firing finance minister Jacques Necker, among others, who were popularly seen as representatives of the people.[6]

Financial crisis

Caricature of the Third Estate carrying the First Estate (clergy) and the Second Estate (nobility) on its back.

Louis XVI ascended to the throne amidst a financial crisis; the state was nearing bankruptcy and outlays outpaced income.[7] This was because of France’s financial obligations stemming from involvement in the Seven Years’ War and its participation in the American Revolutionary War.[8] In May 1776, finance minister Turgot was dismissed, after he failed to enact reforms. The next year, Jacques Necker, a foreigner, was appointed Comptroller-General of Finance. He could not be made an official minister because he was a Protestant.[9]

Necker realized that the country’s extremely regressive tax system subjected the lower classes to a heavy burden,[9] while numerous exemptions existed for the nobility and clergy.[10] He argued that the country could not be taxed higher; that tax exemptions for the nobility and clergy must be reduced; and proposed that borrowing more money would solve the country’s fiscal shortages. Necker published a report to support this claim that underestimated the deficit by roughly 36 million livres, and proposed restricting the power of the parlements.[9]

This was not received well by the King’s ministers, and Necker, hoping to bolster his position, argued to be made a minister. The King refused, Necker was fired, and Charles Alexandre de Calonne was appointed to the Comptrollership.[9] Calonne initially spent liberally, but he quickly realized the critical financial situation and proposed a new tax code.[11]

The proposal included a consistent land tax, which would include taxation of the nobility and clergy. Faced with opposition from the parlements, Calonne organised the summoning of the Assembly of Notables. But the Assembly failed to endorse Calonne’s proposals and instead weakened his position through its criticism. In response, the King announced the calling of the Estates-General for May 1789, the first time the body had been summoned since 1614. This was a signal that the Bourbon monarchy was in a weakened state and subject to the demands of its people.[12]

Estates-General of 1789

Main article: Estates-General of 1789

The Estates-General was organized into three estates: the clergy, the nobility, and the rest of France.[13] On the last occasion that the Estates-General had met, in 1614, each estate held one vote, and any two could override the third. The Parlement of Paris feared the government would attempt to gerrymander an assembly to rig the results. Thus, they required that the Estates be arranged as in 1614.[14]

The 1614 rules differed from practices of local assemblies, where each member had one vote and third estate membership was doubled. For example, in the Dauphiné the provincial assembly agreed to double the number of members of the third estate, hold membership elections, and allow one vote per member, rather than one vote per estate.[15]

Prior to the assembly taking place, the «Committee of Thirty,» a body of liberal Parisians, began to agitate against voting by estate. This group, largely composed of the wealthy, argued for the Estates-General to assume the voting mechanisms of Dauphiné. They argued that ancient precedent was not sufficient, because «the people were sovereign.»[16] Necker convened a Second Assembly of Notables, which rejected the notion of double representation by a vote of 111 to 333.[16] The King, however, agreed to the proposition on 27 December; but he left discussion of the weight of each vote to the Estates-General itself.[17]

Elections were held in the spring of 1789; suffrage requirements for the Third Estate were for French-born or naturalised males only, at least 25 years of age, who resided where the vote was to take place and who paid taxes.

Pour être électeur du tiers état, il faut avoir 25 ans, être français ou naturalisé, être domicilié au lieu de vote et compris au rôle des impositions.[18]

Strong turnout produced 1,201 delegates, including: «291 nobles, 300 clergy, and 610 members of the Third Estate.»[17] To lead delegates, «Books of grievances» (cahiers de doléances) were compiled to list problems.[13] The books articulated ideas which would have seemed radical only months before; however, most supported the monarchical system in general. Many assumed the Estates-General would approve future taxes, and Enlightenment ideals were relatively rare.[14][19]

Pamphlets by liberal nobles and clergy became widespread after the lifting of press censorship.[16] The Abbé Sieyès, a theorist and Catholic clergyman, argued the paramount importance of the Third Estate in the pamphlet Qu’est-ce que le tiers état? («What is the Third Estate?«), published in January 1789. He asserted: «What is the Third Estate? Everything. What has it been until now in the political order? Nothing. What does it want to be? Something.»[14][20]

The meeting of the Estates General on 5 May 1789 in Versailles.

The Estates-General convened in the Grands Salles des Menus-Plaisirs in Versailles on 5 May 1789 and opened with a three-hour speech by Necker. The Third Estate demanded that the verification of deputies’ credentials should be undertaken in common by all deputies, rather than each estate verifying the credentials of its own members internally; negotiations with the other estates failed to achieve this.[19] The commoners appealed to the clergy who replied they required more time. Necker asserted that each estate verify credentials and «the king was to act as arbitrator.»[21] Negotiations with the other two estates to achieve this, however, were unsuccessful.[22]

National Assembly (1789)

Main article: National Assembly (French Revolution)

The National Assembly taking the Tennis Court Oath (sketch by Jacques-Louis David).

On 10 June 1789, Abbé Sieyès moved that the Third Estate, now meeting as the Communes (English: «Commons»), proceed with verification of its own powers and invite the other two estates to take part, but not to wait for them. They proceeded to do so two days later, completing the process on 17 June.[23] Then they voted a measure far more radical, declaring themselves the National Assembly, an assembly not of the Estates but of «the People.» They invited the other orders to join them, but made it clear they intended to conduct the nation’s affairs with or without them.[24]

In an attempt to keep control of the process and prevent the Assembly from convening, Louis XVI ordered the closure of the Salle des États where the Assembly met, making an excuse that the carpenters needed to prepare the hall for a royal speech in two days. Weather did not allow an outdoor meeting, so the Assembly moved their deliberations to a nearby indoor real tennis court, where they proceeded to swear the Tennis Court Oath (20 June 1789), under which they agreed not to separate until they had given France a constitution.[25]

A majority of the representatives of the clergy soon joined them, as did 47 members of the nobility. By 27 June, the royal party had overtly given in, although the military began to arrive in large numbers around Paris and Versailles. Messages of support for the Assembly poured in from Paris and other French cities.[25]

National Constituent Assembly (1789–1791)

Main article: National Constituent Assembly

Storming of the Bastille

By this time, Necker had earned the enmity of many members of the French court for his overt manipulation of public opinion. Marie Antoinette, the King’s younger brother the Comte d’Artois, and other conservative members of the King’s privy council urged him to dismiss Necker as financial advisor. On 11 July 1789, after Necker published an inaccurate account of the government’s debts and made it available to the public, the King fired him, and completely restructured the finance ministry at the same time.[26]

Many Parisians presumed Louis’s actions to be aimed against the Assembly and began open rebellion when they heard the news the next day. They were also afraid that arriving soldiers – mostly foreign mercenaries – had been summoned to shut down the National Constituent Assembly. The Assembly, meeting at Versailles, went into nonstop session to prevent another eviction from their meeting place. Paris was soon consumed by riots, chaos, and widespread looting. The mobs soon had the support of some of the French Guard, who were armed and trained soldiers.[27]

The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen of 26 August 1789

On 14 July, the insurgents set their eyes on the large weapons and ammunition cache inside the Bastille fortress, which was also perceived to be a symbol of royal power. After several hours of combat, the prison fell that afternoon. Despite ordering a cease fire, which prevented a mutual massacre, Governor Marquis Bernard de Launay was beaten, stabbed and decapitated; his head was placed on a pike and paraded about the city. Although the fortress had held only seven prisoners (four forgers, two noblemen kept for immoral behavior, and a murder suspect), the Bastille served as a potent symbol of everything hated under the Ancien Régime. Returning to the Hôtel de Ville (city hall), the mob accused the prévôt des marchands (roughly, mayor) Jacques de Flesselles of treachery and butchered him.[28]

The King, alarmed by the violence, backed down, at least for the time being. The Marquis de la Fayette took up command of the National Guard at Paris. Jean-Sylvain Bailly, president of the Assembly at the time of the Tennis Court Oath, became the city’s mayor under a new governmental structure known as the commune. The King visited Paris, where, on 17 July he accepted a tricolore cockade, to cries of Vive la Nation («Long live the Nation») and Vive le Roi («Long live the King»).[29]

Necker was recalled to power, but his triumph was short-lived. An astute financier but a less astute politician, Necker overplayed his hand by demanding and obtaining a general amnesty, losing much of the people’s favour.

As civil authority rapidly deteriorated, with random acts of violence and theft breaking out across the country, members of the nobility, fearing for their safety, fled to neighboring countries; many of these émigrés, as they were called, funded counter-revolutionary causes within France and urged foreign monarchs to offer military support to a counter-revolution.[30]

By late July, the spirit of popular sovereignty had spread throughout France. In rural areas, many commoners began to form militias and arm themselves against a foreign invasion: some attacked the châteaux of the nobility as part of a general agrarian insurrection known as «la Grande Peur» («the Great Fear«). In addition, wild rumours and paranoia caused widespread unrest and civil disturbances that contributed to the collapse of law and order.[31]

Working toward a constitution

Main article: French Revolution from the abolition of feudalism to the Civil Constitution of the Clergy

On 4 August 1789, the National Constituent Assembly abolished feudalism (although at that point there had been sufficient peasant revolts to almost end feudalism already), in what is known as the August Decrees, sweeping away both the seigneurial rights of the Second Estate and the tithes gathered by the First Estate. In the course of a few hours, nobles, clergy, towns, provinces, companies and cities lost their special privileges.

On 26 August 1789, the Assembly published the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, which comprised a statement of principles rather than a constitution with legal effect. The National Constituent Assembly functioned not only as a legislature, but also as a body to draft a new constitution.

Necker, Mounier, Lally-Tollendal and others argued unsuccessfully for a senate, with members appointed by the crown on the nomination of the people. The bulk of the nobles argued for an aristocratic upper house elected by the nobles. The popular party carried the day: France would have a single, unicameral assembly. The King retained only a «suspensive veto«; he could delay the implementation of a law, but not block it absolutely. The Assembly eventually replaced the historic provinces with 83 départements, uniformly administered and roughly equal in area and population.

Amid the Assembly’s preoccupation with constitutional affairs, the financial crisis had continued largely unaddressed, and the deficit had only increased. Honoré Mirabeau now led the move to address this matter, and the Assembly gave Necker complete financial dictatorship.

Women’s March on Versailles

Main article: The Women’s March on Versailles

Engraving of the Women’s March on Versailles, 5 October 1789

Fueled by rumors of a reception for the King’s bodyguards on 1 October 1789 at which the national cockade had been trampled upon, on 5 October 1789 crowds of women began to assemble at Parisian markets. The women first marched to the Hôtel de Ville, demanding that city officials address their concerns.[32] The women were responding to the harsh economic situations they faced, especially bread shortages. They also demanded an end to royal efforts to block the National Assembly, and for the King and his administration to move to Paris as a sign of good faith in addressing the widespread poverty.

Getting unsatisfactory responses from city officials, as many as 7,000 women joined the march to Versailles, bringing with them cannons and a variety of smaller weapons. Twenty thousand National Guardsmen under the command of La Fayette responded to keep order, and members of the mob stormed the palace, killing several guards.[33] La Fayette ultimately persuaded the king to accede to the demand of the crowd that the monarchy relocate to Paris.

On 6 October 1789, the King and the royal family moved from Versailles to Paris under the «protection» of the National Guards, thus legitimizing the National Assembly.

Revolution and the Church

Main articles: Dechristianisation of France during the French Revolution and Civil Constitution of the Clergy

In this caricature, monks and nuns enjoy their new freedom after the decree of 16 February 1790

The Revolution caused a massive shift of power from the Roman Catholic Church to the state. Under the Ancien Régime, the Church had been the largest single landowner in the country, owning about 10% of the land in the kingdom.[34] The Church was exempt from paying taxes to the government, while it levied a tithe—a 10% tax on income, often collected in the form of crops—on the general population, only a fraction of which it then redistributed to the poor.[34] The power and wealth of the Church was highly resented by some groups. A small minority of Protestants living in France, such as the Huguenots, wanted an anti-Catholic regime and revenge against the clergy who discriminated against them. Enlightenment thinkers such as Voltaire helped fuel this resentment by denigrating the Catholic Church and destabilizing the French monarchy.[35] As historian John McManners argues, «In eighteenth-century France throne and altar were commonly spoken of as in close alliance; their simultaneous collapse … would one day provide the final proof of their interdependence.»[36]

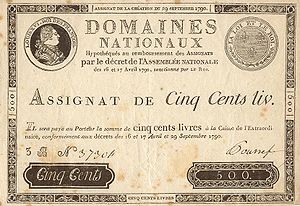

This resentment toward the Church weakened its power during the opening of the Estates General in May 1789. The Church composed the First Estate with 130,000 members of the clergy. When the National Assembly was later created in June 1789 by the Third Estate, the clergy voted to join them, which perpetuated the destruction of the Estates General as a governing body.[37] The National Assembly began to enact social and economic reform. Legislation sanctioned on 4 August 1789 abolished the Church’s authority to impose the tithe. In an attempt to address the financial crisis, the Assembly declared, on 2 November 1789, that the property of the Church was «at the disposal of the nation.»[38] They used this property to back a new currency, the assignats. Thus, the nation had now also taken on the responsibility of the Church, which included paying the clergy and caring for the poor, the sick and the orphaned.[39] In December, the Assembly began to sell the lands to the highest bidder to raise revenue, effectively decreasing the value of the assignats by 25% in two years.[40] In autumn 1789, legislation abolished monastic vows and on 13 February 1790 all religious orders were dissolved.[41] Monks and nuns were encouraged to return to private life and a small percentage did eventually marry.[42]

The Civil Constitution of the Clergy, passed on 12 July 1790, turned the remaining clergy into employees of the state. This established an election system for parish priests and bishops and set a pay rate for the clergy. Many Catholics objected to the election system because it effectively denied the authority of the Pope in Rome over the French Church. Eventually, in November 1790, the National Assembly began to require an oath of loyalty to the Civil Constitution from all the members of the clergy.[42] This led to a schism between those clergy who swore the required oath and accepted the new arrangement and those who remained loyal to the Pope. Overall, 24% of the clergy nationwide took the oath.[43] Widespread refusal led to legislation against the clergy, «forcing them into exile, deporting them forcibly, or executing them as traitors.»[40] Pope Pius VI never accepted the Civil Constitution of the Clergy, further isolating the Church in France.

During the Reign of Terror, extreme efforts of de-Christianization ensued, including the imprisonment and massacre of priests and destruction of churches and religious images throughout France. An effort was made to replace the Catholic Church altogether, with civic festivals replacing religious ones. The establishment of the Cult of Reason was the final step of radical de-Christianization. These events led to a widespread disillusionment with the Revolution and to counter-rebellions across France. Locals often resisted de-Christianization by attacking revolutionary agents and hiding members of the clergy who were being hunted. Eventually, Robespierre and the Committee of Public Safety were forced to denounce the campaign,[44] replacing the Cult of Reason with the deist but still non-Christian Cult of the Supreme Being. The Concordat of 1801 between Napoleon and the Church ended the de-Christianization period and established the rules for a relationship between the Catholic Church and the French State that lasted until it was abrogated by the Third Republic via the separation of church and state on 11 December 1905. The persecution of the Church led to a counter-revolution known as the Revolt in the Vendée, whose suppression is considered by some to be the first modern genocide.[45]

Intrigues and radicalism

Factions within the Assembly began to clarify. The aristocrat Jacques Antoine Marie de Cazalès and the abbé Jean-Sifrein Maury led what would become known as the right wing, the opposition to revolution (this party sat on the right-hand side of the Assembly). The «Royalist democrats» or monarchiens, allied with Necker, inclined toward organising France along lines similar to the British constitutional model; they included Jean Joseph Mounier, the Comte de Lally-Tollendal, the comte de Clermont-Tonnerre, and Pierre Victor Malouet, comte de Virieu.