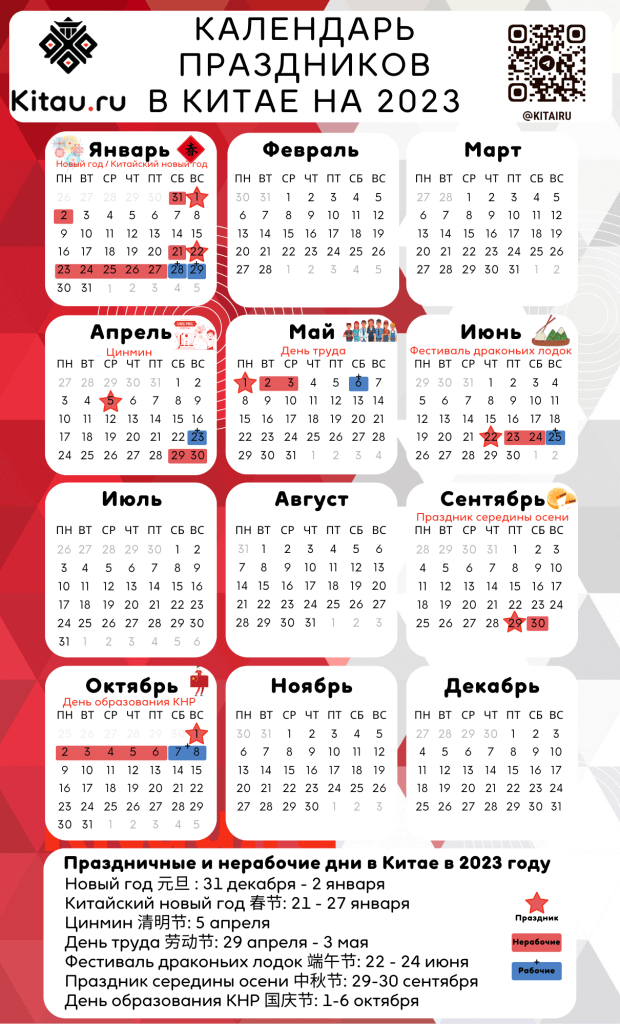

Праздник драконьих лодок находится пятый лунный день пятого месяца по лунному календарью, в 2022 году настутит на 3июня, на пятницу.Выходные дни длятся с 3июня по 5июня в Китае. Праздник драконьих лодок, также известный как Праздник Дуаньу- традиционный и важный праздник в Китае. Это официальный выходной день для большинства китайцев.

Общие данные о празднике драконьих лодок

· Название праздника на китайском языке: 端午节 Duānwǔ Jié / Дуаньу цзе/

· Дата празднования: 5-е число 5 месяца по лунному календарю

· История: более 2000 лет

· Празднование: гонки на драконьих лодках, деятельность, укрепляющая здоровье, проявление почтения Цюй Юаню и др.

· Праздничная еда: цзунцзы (лакомство из клейкого риса с разнообразными начинками в бамбуковых листьях)

Подробнее о празднике драконьих лодок

Это народный праздник, богатый традициями и суевериями, который ознаменовывает жизнь и смерть известного китайского ученого Цюй Юаня (Чу Юань). Истоки праздника, возможно, восходят к поклонению дракону. Это важное событие в китайском спортивном календаре и день памяти и поклонения Цюй Юаню. Праздник драконьих лодок в Китае является традиционным празднеством уже более 2000 лет.

30 октября 2009 г. этот праздник был включен в список Всемирного нематериального культурного наследия ЮНЕСКО.

Даты: Когда отмечается праздник драконьих лодок?

Дата праздника Дуаньу (праздника драконьих лодок) приходится на 5-й день 5 месяца по Китайскому лунному календарю. Поэтому дата празднования по грегорианскому календарю ежегодно разная. Ниже представлены даты празднования на ближайшие несколько лет.

|

Год |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2022 |

2022 |

2023 |

|

Дата |

18 июня |

7 июня |

25 июня |

14 июня |

3 июня |

22 июня |

|

Выходные |

16-18 июня |

7-9 июня |

25-27 июня |

12-14 июня |

3-5 июня |

22-24 июня |

Происхождение и история: почему отмечается праздник драконьих лодок?

На протяжении более 2000 лет этот праздник отмечался как день гигиены – люди использовали травы для лечения болезней и вирусов. Однако наиболее распространенное мнение гласит, что происхождение праздника тесно связано с великим поэтом Цюй Юанем, жившем в период Сражающихся царств (475 – 221 гг. до н.э.). Чтобы увековечить память о его смерти в 5-й день 5 лунного месяца, китайцы отмечают праздник драконьих лодок, при этом вариации празднования очень отличаются. Великие мужи У Цзысюй и Цао Э, также умерли в этот день, поэтому в некоторых регионах Китая люди также вспоминают их и отдают дань памяти во время праздника.

Легенда о празднике драконьих лодок: с чего всё началось?

Цюй Юань (340 – 278 гг. до н.э.) был поэтом-патриотом и ссыльным чиновником во времена периода Сражающихся царств в Древнем Китае. Он утонул в реке Мило на 5-й день 5 лунного месяца, когда любимое им царство Чу пало перед царством Цинь.

Местные жители делали отчаянные попытки спасти Цюй Юаня или восстановить его тело, но безуспешно. Каждый 5-й день 5 лунного месяца, чтобы почтить память Цюй Юаня, китайцы бьют в барабаны и устраивают соревнования в гребле на лодках по реке, как в те давние времена, чтобы не дать рыбам и злым духам навредить телу поэта.

Традиции и обычаи: Как китайцы отмечают праздник драконьих лодок?

На протяжении более 2000 лет этот праздник отмечался как день гигиены – люди использовали травы для лечения болезней и вирусов. Однако наиболее распространенное мнение гласит, что происхождение праздника тесно связано с великим поэтом Цюй Юанем, жившем в период Сражающихся царств (475 – 221 гг. до н.э.). Чтобы увековечить память о его смерти в 5-й день 5 лунного месяца, китайцы отмечают праздник драконьих лодок, при этом вариации празднования очень отличаются. Великие мужи У Цзысюй и Цао Э, также умерли в этот день, поэтому в некоторых регионах Китая люди также вспоминают их и отдают дань памяти во время праздника.

Что едят в праздник драконьих лодок?- Попробуйте цзунцзы

Цзунцзы – наиболее традиционное угощение на праздник драконьих лодок. Цзунцзы связаны с традицией почитания Цюй Юаня – согласно легенде люди бросали в реку горсти риса для того, чтобы остановить рыб от поедания утонувшего тела Цюй Юаня.

Цзунцзы – это лакомство из клейкого риса с разнообразными начинками, завернутое в бамбуковые листья в форме пирамидки. Это особое праздничное угощение. В северном Китае люди предпочитают финики в качестве начинки, в то время как южане подслащивают бобовую пасту, свежее мясо или яичный желток. Сегодня цзунцзы стали обычной едой, которую можно купить в любом супермаркете. Однако некоторые семьи и по сей день сохраняют традицию готовить цзунцзы в праздничный день.

Выпейте вино с добавлением реальгара

Старая поговорка гласит: «Употребление вина с добавлением реальгара избавляет от болезней и злых духов!». Вино с добавлением реальгара – это китайский алкогольный напиток, состоящий из ферментированных злаков и порошкового реальгара.

В древние времена китайцы верили, что реальгар – это противоядие от всех видов ядов, он эффективен для борьбы с насекомыми и способен изгонять злых духов. Поэтому каждый мог вкусить немного вина из реальгара во время праздника Дуаньу.

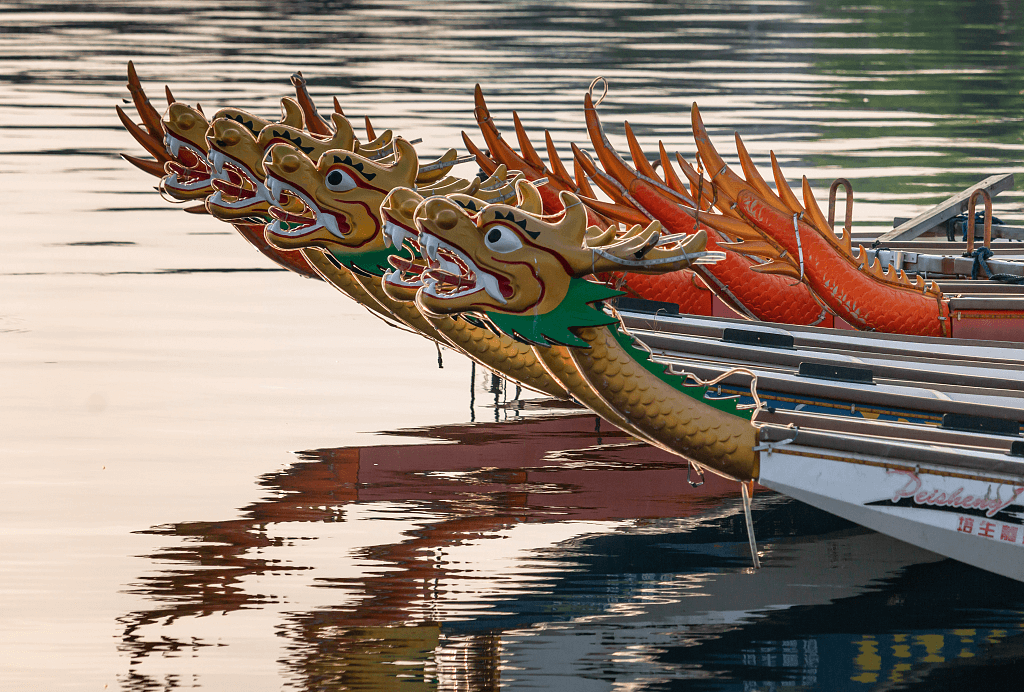

Гонки на драконьих лодках

Драконьи лодки получили такое название благодаря тому, что нос и корма лодок выполнены в форме традиционного китайского дракона. Команда гребцов работает на веслах, пытаясь добраться до финиша раньше других команд. Один из членов команды сидит в носовой части лодки и отбивает ритм на барабане, чтобы поддерживать моральный дух гребцов и следить за тем, чтобы все успевали друг за другом. Легенда гласит, что подобный соревновательный заплыв берёт свое начало от события, когда люди гребли на своих лодках, чтобы спасти тонувшего Цюй Юаня. Сегодня гонки на драконьих лодках стали большим спортивным событием, которое проводится не только в Китае, но и в Японии, Вьетнаме и в Британии.

Где можно увидеть гонки на драконьих лодках?

Лучшие места, где Вы сможете увидеть гонки на драконьих лодках:

А) Международные гонки на драконьих лодках в городе Юэян. Центр гонок на драконьих лодках по реке Мило, город Юэян провинции Хунань.

B) Гонки на драконьих лодках в поселке Цзыгуй. Залив Сюйцзячун, поселок Цзуйгуй, город Ичан провинции Хубэй.

C) Международный фестиваль каноэ народности мяо. Река Циншуй, провинция Гуйчжоу

D) Гонки на драконьих лодках Сиси в городе Ханчжоу (Xixi Wetland Park).

Другие интересные статья о Празднике Китая

Китай славится своей богатейшей культурой, особенное место в которой занимают многочисленные фестивали и народные торжества. Одним из самых эффектных и ярких мероприятий стал Праздник драконьих лодок, что сегодня привлекает массу зрителей, а также тысячи иностранных туристов.

Однако многие современные участники фестиваля и представить не могут, что это торжество зародилось около 2000 года до нашей эры, во времена правления династии Ся. Со временем традиции обогащались и утверждались, что и создало Праздник драконьих лодок, что мы знаем сегодня. Как же проходит этот фестиваль в Китае? С чем связаны история и предания о Празднике драконьих лодок?

Зарождение праздника

Праздник драконьих лодок (в Китае его называют Дуань-у) в народе именуют “двумя пятёрками”, поскольку торжество попадает на пятый день пятого месяца лунного календаря. Он связан не только с лодками, однако такой перевод названия указывает на главную традицию фестиваля. Как правило, праздник этот связан с именем Цюй Юаня, знаменитого китайского поэта, а также встречей лета.

Изначально Дуань-у связывался именно со сменой сезонов. Поскольку летом в Древнем Китае появлялась опасность распространения различных заболеваний, народ стремился обезопасить себя за счёт особенных ритуалов и оберегов.

В Праздник драконьих лодок немало традиций было связано с детьми. Их необходимо было защитить от тёмных сил и злых духов, что могли вызвать болезни и принести неприятности. Для самых маленьких членов семей китайцы изготавливали ожерелья из цветных нитей. Вместе с детьми родители изготавливали игрушечные луки и стрелы, что считались защитой от всего плохого, что может приблизиться к ребёнку.

Появление традиций

В день Дуань-у своим приближённым и верным подданным императоры преподносили подарки. В одном из своих стихотворений Ду Фу рассказывает о наряде, что преподнёс ему император. Поэт был очарован тонкой и дорогой тканью, но главное – подарок был знаком его преданной службы, которую оценили по достоинству.

В период правления династии Тан (а это попадает на VII-X века) императоры несколько изменили прежние традиции. Теперь чиновникам преподносили жёсткие пояса с чёрными украшениями, что являлись символом долговечности и силы. Такой подарок от правителя красноречиво говорил о признании, о вере в мужество и решимость человека, что могут пригодиться его родине.

До наших дней в Китае сохранился обычай покупать и дарить друг другу бумажные веера, посвящённые Празднику драконьих лодок. Связана традиция со случаем, что произошёл в период правления императора Тай-цзуна.

Двум своим придворным властитель передал в качестве подарка именно такие веера, на которых лично начертал иероглифы. “Пускай ветер раздувает ваши добродетельные деяния”, – заметил император. Вскоре о произошедшем узнали и за пределами дворца, после чего бумажные веера, преподнесенные в качестве подарка, стали доброй традицией Дуань-у.

Легенды о Празднике драконьих лодок

Как я уже сказала, Праздник драконьих лодок связан с историями о Цюй Юане. Великий китайский поэт был министром царства Чу. Все силы он направлял на борьбу с коррупцией и происками предателей страны. Его дела заслужили уважение правителя, но, увы, злые языки сыграли свою роль в судьбе Цюй Юаня. Из-за подлой клеветы, он был отправлен в изгнание.

Император, не послушавший мудрых наставлений министра, вскоре был свергнут, а само царство Чу пришло к упадку. Узнав о распаде своего государства, которому посвятил жизнь, Цюй Юань утопился в реке Мило. Случилось это как раз в пятый день пятого лунного месяца.

Как гласят предания, народ царства Чу пытался спасти своего любимого министра. К сожалению, поиски по реке на длинных лодках не дали результата. Однако с тех времён в Китае установился обычай в Праздник драконьих лодок бить в барабаны и совершать церемониальное шествие по реке – в память о великом Цюй Юане.

Основные обычаи

Хотя Праздник драконьих лодок имеет многовековую историю, лишь с 2007 года он был отмечен как официальное торжество, в честь которого устанавливаются выходные дни. В наши дни пятое число пятого лунного месяца – это не просто дата, но и культурное наследие китайцев.

В 2021 году праздник драконьих лодок пройдет с 12 по 14 июня.

Проведение праздника связано с рядом старинных традиций. Конечно, главным обычаем остаются неизменные гонки на лодка-драконах. Каждое из таких транспортных средств выполнено в форме священного мифического животного Китая

Каждая из лодок вмещает 20 гребцов, которые под звуки барабана спешат к финишу. Всем участникам хочется продемонстрировать свои навыки, ловкость и мастерство. Что примечательно, участники должны не только показать превосходный результат в скорости своей лодки, но и создать из неё истинный шедевр. В цветах декора лодки должны присутствовать священные цвета Китая: золотой, красный, зелёный.

Помимо гонок, китайцы непременно придерживаются ещё одного древнего обычая. Это – украшение дома защитными талисманами. Как и их далёкие предки, жители Китая развешивают в домах обереги из полыни, растения, что укрепляет здоровье и отгоняет злых духов.

Праздник драконьих лодок – удивительное зрелище, на котором побывать мечтают не только китайцы, но и жители самых разных стран мира. Это неудивительно, ведь такой фестиваль позволяет проникнуться историей и культурой Поднебесной, приобщиться к древним и интересным традициям одного из самых загадочных народов нашей планеты.

-

This year, June 14 marks the fifth day of the fifth month of the lunar calendar–the day of the annual Dragon Boat Festival, or Duanwujie. Today’s Doodle celebrates this ancient tradition, which has a history that is more than 2,000 years old.

The Dragon Boat Festival is a high-spirited tradition where competitors paddle long, vibrantly-painted long wooden boats into rivers and race to the finish. The team of dragon boat sailors row as fast as they can toward a finish line while one team member sits toward the front of the ship and beats a drum to maintain their pace and keep energy high. Spectators and racers alike enjoy zongzi, a tetrahedron-shaped sticky rice treat wrapped in reed or bamboo stalks believed to bring good fortune. In some cultures, revelers add another friendly contest to the day—egg balancing. Noon is said to be the best time to keep the egg standing!

Good luck to everyone competing today and Happy Dragon Boat Festival!

Early concepts and drafts of the Doodle below

-

This day in history

For dragon boating as a sport, see Dragon boat. For the Cambodian festival with dragon boat races, see Bon Om Touk.

| Dragon Boat Festival | |

|---|---|

Dragon Boat Festival (18th century) |

|

| Observed by | Chinese |

| Type | Cultural |

| Observances | Dragon boat racing, consumption of realgar wine and zongzi |

| Date | Fifth day of the fifth lunar month |

| 2022 date | 3 June |

| 2023 date | 22 June |

| 2024 date | 31 May |

| 2025 date | 30 June |

| Frequency | Annual |

| Related to | Tango no sekku, Dano, Tết Đoan Ngọ, Yukka Nu Hii |

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 端午节 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 端午節 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | «The very mid point of the year Festival» | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Dragon Boat Festival | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 龙船节 / 龙舟节 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 龍船節 / 龍舟節 | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Double Fifth Festival Fifth Month Festival Fifth Day Festival |

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 重五节 / 双五节 五月节 五日节 |

||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 重五節 / 雙五節 五月節 五日節 |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Dumpling Festival | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 肉粽节 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 肉糭節 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Meat Zongzi Festival | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Portuguese name | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Portuguese | Festividade do Barco-Dragão |

The Dragon Boat Festival (simplified Chinese: 端午节; traditional Chinese: 端午節) is a traditional Chinese holiday which occurs on the fifth day of the fifth month of the Chinese calendar, which corresponds to late May or June in the Gregorian calendar.

Names[edit]

The English language name for the holiday is Dragon Boat Festival,[1] used as the official English translation of the holiday by the People’s Republic of China.[2] It is also referred to in some English sources as Double Fifth Festival which alludes to the date as in the original Chinese name.[3]

Chinese names by region[edit]

Duanwu (Chinese: 端午; pinyin: duānwǔ), as the festival is called in Mandarin Chinese, literally means «starting/opening horse», i.e., the first «horse day» (according to the Chinese zodiac/Chinese calendar system) to occur on the month;[4][a] however, despite the literal meaning being wǔ, «the [day of the] horse in the animal cycle», this character has also been interchangeably construed as wǔ (Chinese: 五; pinyin: wǔ) meaning «five». Hence Duanwu, the «festival on the fifth day of the fifth month».[7]

The Mandarin Chinese name of the festival is «端午節» (simplified Chinese: 端午节; traditional Chinese: 端午節; pinyin: Duānwǔjié; Wade–Giles: Tuan Wu chieh)[b] in Mainland China and Taiwan,[8][6][9] and «Tuen Ng Festival» for Hong Kong, Macao,[10] Malaysia and Singapore.[11]

It is pronounced variously in different Chinese dialects. In Cantonese, it is romanized as Tuen1 Ng5 Jit3 in Hong Kong and Tung1 Ng5 Jit3 in Macau. Hence the «Tuen Ng Festival» in Hong Kong[11] Tun Ng (Festividade do Barco-Dragão in Portuguese) in Macao.[12][13]

History[edit]

Origin[edit]

The fifth lunar month is considered an unlucky month. People believed that natural disasters and illnesses are common in the fifth month. To get rid of the misfortune, people would put calamus, Artemisia, pomegranate flowers, Chinese ixora and garlic above the doors on the fifth day of the fifth month.[citation needed] Calamus is believed to be able to remove evil spirits because of its sword-like shape and strong garlic smell.

Hanging wormwood leaves on top of a door to deter insects.

Another explanation to the origin of the Dragon Boat Festival comes from before the Qin Dynasty (221–206 BC). The fifth month of the lunar calendar was regarded as a bad month and the fifth day of the month a bad day. Venomous animals were said to appear starting from the fifth day of the fifth month, such as snakes, centipedes, and scorpions; people also supposedly get sick easily after this day. Therefore, during the Dragon Boat Festival, people try to avoid this bad luck. For example, people may paste pictures of the five poisonous creatures on the wall and stick needles in them. People may also make paper cutouts of the five creatures and wrap them around the wrists of their children.[14] Big ceremonies and performances developed from these practices in many areas, making the Dragon Boat Festival a day for getting rid of disease and bad luck.

Qu Yuan[edit]

The story best known in modern China holds that the festival commemorates the death of the poet and minister Qu Yuan (c. 340–278 BC) of the ancient state of Chu during the Warring States period of the Zhou dynasty.[15] A cadet member of the Chu royal house, Qu served in high offices. However, when the emperor decided to ally with the increasingly powerful state of Qin, Qu was banished for opposing the alliance and even accused of treason.[15] During his exile, Qu Yuan wrote a great deal of poetry. Twenty-eight years later, Qin captured Ying, the Chu capital. In despair, Qu Yuan committed suicide by drowning himself in the Miluo River.

It is said that the local people, who admired him, raced out in their boats to save him, or at least retrieve his body. This is said to have been the origin of dragon boat races. When his body could not be found, they dropped balls of sticky rice into the river so that the fish would eat them instead of Qu Yuan’s body. This is said to be the origin of zongzi.[15]

During World War II, Qu Yuan began to be treated in a nationalist way as «China’s first patriotic poet». The view of Qu’s social idealism and unbending patriotism became canonical under the People’s Republic of China after 1949 Communist victory in the Chinese Civil War.

Wu Zixu[edit]

Despite the modern popularity of the Qu Yuan origin theory, in the former territory of the Kingdom of Wu, the festival commemorated Wu Zixu (died 484 BC), the Premier of Wu. Xi Shi, a beautiful woman sent by King Goujian of the state of Yue, was much loved by King Fuchai of Wu. Wu Zixu, seeing the dangerous plot of Goujian, warned Fuchai, who became angry at this remark. Wu Zixu was forced to commit suicide by Fuchai, with his body thrown into the river on the fifth day of the fifth month. After his death, in places such as Suzhou, Wu Zixu is remembered during the Dragon Boat Festival.

Cao E[edit]

The front of the Cao E Temple, facing east, toward Cao’e River, in Shangyu, Zhejiang, China.

Although Wu Zixu is commemorated in southeast Jiangsu and Qu Yuan elsewhere in China, much of Northeastern Zhejiang including the cities of Shaoxing, Ningbo and Zhoushan celebrates the memory of the young girl Cao E (曹娥; AD 130–144) instead. Cao E’s father Cao Xu (曹盱) was a shaman who presided over local ceremonies at Shangyu. In 143, while presiding over a ceremony commemorating Wu Zixu during the Dragon Boat Festival, Cao Xu accidentally fell into the Shun River. Cao E, in an act of filial piety, decided to find her father in the river, searching for 3 days trying to find him. After five days, she and her father were both found dead in the river from drowning. Eight years later, in 151, a temple was built in Shangyu dedicated to the memory of Cao E and her sacrifice for filial piety. The Shun River was renamed Cao’e River in her honor.[16]

Cao E is depicted in the Wu Shuang Pu (無雙譜; Table of Peerless Heroes) by Jin Guliang.

Pre-existing holiday[edit]

Some modern research suggests that the stories of Qu Yuan or Wu Zixu were superimposed onto a pre-existing holiday tradition. The promotion of these stories might be encouraged by Confucian scholars, seeking to legitimize and strengthen their influence in China. The relationship between zongzi, Qu Yuan and the festival, first appeared during the early Han dynasty.[17]

The stories of both Qu Yuan and Wu Zixu were recorded in Sima Qian’s Shiji, completed 187 and 393 years after the events, respectively, because historians wanted to praise both characters.

Another theory, advanced by Wen Yiduo, is that the Dragon Boat Festival originated from dragon worship. Support is drawn from two key traditions of the festival: the tradition of dragon boat racing and zongzi. The food may have originally represented an offering to the dragon king, while dragon boat racing naturally reflects a reverence for the dragon and the active yang energy associated with it. This was merged with the tradition of visiting friends and family on boats.

Another suggestion is that the festival celebrates a widespread feature of east Asian agrarian societies: the harvest of winter wheat. Offerings were regularly made to deities and spirits at such times: in the ancient Yue, dragon kings; in the ancient Chu, Qu Yuan; in the ancient Wu, Wu Zixu (as a river god); in ancient Korea, mountain gods (see Dano). As interactions between different regions increased, these similar festivals eventually merged into one holiday.

Early 20th century[edit]

In the early 20th Century the Dragon Boat Festival was observed from the first to the fifth days of the fifth month, and also known as the

Festival of Five Poisonous Insects (simplified Chinese: 毒虫节; traditional Chinese: 毒蟲節; pinyin: Dúchóng jié).

Yu Der Ling writes in chapter 11 of her 1911 memoir Two Years in the Forbidden City:

The first day of the fifth moon was a busy day for us all, as from the first to the fifth of the fifth moon was the festival of five poisonous insects, which I will explain later—also called the Dragon Boat Festival. … Now about this Feast. It is also called the Dragon Boat Feast. The fifth of the fifth moon at noon was the most poisonous hour for the poisonous insects, and reptiles such as frogs, lizards, snakes, hide in the mud, for that hour they are paralyzed. Some medical men search for them at that hour and place them in jars, and when they are dried, sometimes use them as medicine. Her Majesty told me this, so that day I went all over everywhere and dug into the ground, but found nothing.[18]

21st century[edit]

In 2004 the Dragon Boat Festival was elevated to a national holiday in China.

Public holiday[edit]

ROC (Taiwan) President Ma Ying-jeou visits Liang Island before Dragon Boat Festival (2010)

‘恭祝總統端節愉快‘ (‘Respectfully Wishing the President a Joyous Dragon Boat Festival’)

The festival was long marked as a cultural festival in China and is a public holiday in China, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, and Taiwan (ROC). The People’s Republic of China government established in 1949 did not initially recognize the Dragon Boat Festival as a public holiday but reintroduced it in 2008 alongside two other festivals in a bid to boost traditional culture.[19][20]

Dragon Boat Festival is unofficially observed by the Chinese communities of Southeast Asia, including Singapore and Malaysia. Equivalent and related official festivals include the Korean Dano, Japanese Children’s Day, and Vietnamese Tết Đoan Ngọ.[citation needed]

Practices and activities[edit]

Three of the most widespread activities conducted during the Dragon Boat Festival are eating (and preparing) zongzi, drinking realgar wine, and racing dragon boats.[21]

Dragon boat racing[edit]

Dragon boat racing has a rich history of ancient ceremonial and ritualistic traditions, which originated in southern central China more than 2500 years ago. The legend starts with the story of Qu Yuan, who was a minister in one of the Warring State governments, Chu. He was slandered by jealous government officials and banished by the king. Out of disappointment in the Chu monarch, he drowned himself into the Miluo River. The common people rushed to the water and tried to recover his body. In commemoration of Qu Yuan, people hold dragon boat races yearly on the day of his death according to the legend. They also scattered rice into the water to feed the fish, to prevent them from eating Qu Yuan’s body, which is one of the origins of zongzi.

Zongzi (traditional Chinese rice dumpling)[edit]

A notable part of celebrating Dragon Boat Festival is making and eating zongzi with family members and friends. People traditionally wrap zongzi in leaves of reed, bamboo, forming a pyramid shape. The leaves also give a special aroma and flavor to the sticky rice and fillings. Choices of fillings vary depending on regions. Northern regions in China prefer sweet or dessert-styled zongzi, with bean paste, jujube, and nuts as fillings. Southern regions in China prefer savory zongzi, with a variety of fillings including marinated pork belly, sausage, and salted duck eggs.

Zongzi appeared before the Spring and Autumn Period and was originally used to worship ancestors and gods; in the Jin Dynasty, Zongzi became a festive food for the Dragon Boat Festival. Jin Dynasty, dumplings were officially designated as the Dragon Boat Festival food. At this time, in addition to glutinous rice, the raw materials for making zongzi are also added with Chinese medicine Yizhiren. The cooked zongzi is called «yizhi zong».[22]

The reason why the Chinese eat zongzi on this special day has many statements. The folk version is to hold a memorial ceremony for Quyuan. While in fact, Zongzi has been regarded as an oblation for the ancestor even before the Chunqiu period. From the Jin dynasty, Zongzi officially became the festival food and long last until now.

[edit]

‘Wu’ (午) in the name ‘Duanwu’ in Chinese has a similar pronunciation as the number 5 in multiple dialects, and thus many regions have traditions of eating food that is related to the number 5. For example, the Guangdong and Hong Kong regions have the tradition of having congee made from 5 different beans.

Realgar wine[edit]

Realgar wine or Xiong Huang wine is a Chinese alcoholic drink that is made from Chinese yellow wine dosed with powdered realgar, a yellow-orange arsenic sulfide mineral also known as «rice wine». It is often used as a pesticide against mosquitoes and other biting insects during the hot summers, and as a common antidote against poison in ancient Asia.

5-colored silk-threaded braid[edit]

In some regions of China, parents braid silk threads of 5 colors and put them on their children’s wrists, on the day of the Dragon Boat Festival. People believe that this will help keep bad spirits and diseases away.

Other common activities include hanging up icons of Zhong Kui (a mythic guardian figure), hanging mugwort and calamus, taking long walks, and wearing perfumed medicine bags.[23] Other traditional activities include a game of making an egg stand at noon (this «game» implies that if someone succeeds in making the egg stand at exactly 12:00 noon, that person will receive luck for the next year), and writing spells. All of these activities, together with the drinking of realgar wine or water, were regarded by the ancients and some today as effective in preventing disease or evil while promoting health and well-being.

In the early years of the Republic of China, Duanwu was celebrated as the «Poets’ Day» due to Qu Yuan’s status as China’s first known poet. The Taiwanese also sometimes conflate the spring practice of egg-balancing with Duanwu.[24]

The sun is considered to be at its strongest around the time of summer solstice, as the daylight in the northern hemisphere is the longest. The sun, like the Chinese dragon, traditionally represents masculine energy, whereas the moon, like the phoenix, traditionally represents feminine energy. The summer solstice is considered the annual peak of male energy while the winter solstice, the longest night of the year, represents the annual peak of feminine energy. The masculine image of the dragon has thus associated with the Dragon Boat Festival.[25]

Gallery[edit]

-

Activities to avoid bad luck

-

A bodice worn by kids with symbols of the Five Poisonous Insects on it to deter poisonous insects, and reptiles such as frogs, lizards, snakes.

-

A dragon boat racing in San Francisco, 2008.

-

Raw Rice Dumpling

See also[edit]

- Bon Om Touk

- Dano (Korean festival)

- Traditional Chinese holidays

Explanatory notes[edit]

- ^ Also suggested to mean «Beginning of Noon»,[5] or «High Noon Festival»,[6] since «horse» also marks the hours 11:00–13:00 each day.

- ^ Romanized in pinyin with inflection as Duānwǔjié.

References[edit]

- Citations

- ^ Chittick (2011), p. 1.

- ^ Chinese Government’s Official Web Portal. «Holidays Archived May 2, 2012, at the Wayback Machine». 2012. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

- ^ «Double Fifth (Dragon Boat) Festival Archived May 6, 2008, at the Wayback Machine».

- ^ Inahata, Kōichirō [in Japanese] (2007). Tango 端午 (たんご). Heibonsha World Encyclopedia 世界大百科事典 (revised, new ed.). Heibonsha. via Japanknowledge.

- ^ Lowe (1983), p. 141.

- ^ a b «Dragon Boat Festival». Taiwan Today. Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Republic of China (Taiwan). 1 June 1967.

- ^ Chen, Sanping (January–March 2016). «Were ‘Ugly Slaves’ in Medieval China Really Ugly?». Journal of the American Oriental Society. 136 (1): 30–31. doi:10.7817/jameroriesoci.136.1.117. JSTOR 10.7817/jameroriesoci.136.1.117.

- ^ General Office of the State Council of the People’s Republic of China. 《国务院办公厅关于2011年部分节假日安排的通知国办发明电〔2010〕40号》. 9 December 2010. Retrieved 3 November 2013. (in Chinese)

- ^ Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Republic of China (Taiwan). «Holidays and Festivals in Taiwan Archived 2014-02-21 at the Wayback Machine Archived 2014-02-16 at the Wayback Machine». Retrieved 3 November 2013. (in Chinese and English).

- ^ Special Administrative Region of Macao. Office of the Chief Executive. 《第60/2000號行政命令》. 3 October 2000. Retrieved 3 November 2013. (in Chinese)

- ^ a b GovHK. »

General holidays for 2014″. 2013. Retrieved 1 November 2013. - ^ Macau Government Tourist Office. «Calendar of Events». 2013. Retrieved 3 November 2013.

- ^ Special Administrative Region of Macao. Office of the Chief Executive. «Ordem Executiva n.º 60/2000». 3 October 2000. Retrieved 3 November 2013. (in Portuguese)

- ^ Liu, L. (2011). ‘Beijing Review’ Color Photographs. vol. 54, issue 23. pp. 42–43.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ a b c SCMP.» Earthquake and floods make for the muted festival. Retrieved on 9 June 2008. Archived 25 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ «The river in which she jumped was renamed as Cao’s River». Archived from the original on 4 April 2017.

- ^ «The Legends Behind the Dragon Boat Festival». Smithsonian. 14 May 2009.

- ^ Yü, Der Ling (1911). Two Years in the Forbidden City. T. F. Unwin. Project Gutenberg

- ^ People’s Daily. «Peopledaily.» China to revive traditional festivals to boost traditional culture. Retrieved on 9 June 2008.

- ^ Xinhua Net. «First day-off for China’s Dragon Boat Festival helps revive tradition Archived 2013-12-22 at the Wayback Machine.» Xinhua News Agency. Published 8 June 2008. Retrieved 9 June 2008.

- ^ «Dragon Boat Festival». China Internet Information Center. Retrieved 12 June 2013.

- ^ Yuan, He (2015). «Textual Research on the Origin of Zongzi». Journal of Nanning Polytechnic.

- ^ «Dragon Boat Festival keeps the beast at bay». chinadailyhk.

- ^ Huang, Ottavia. Hmmm, This Is What I Think: «Dragon Boat Festival: Time to Balance an Egg». 24 June 2012. Retrieved 3 November 2013.

- ^ Chan, Arlene & al. Paddles Up! Dragon Boat Racing in Canada, p. 27. Dundurn Press Ltd., 2009. ISBN 978-1-55488-395-0. Retrieved 1 June 2011.

- Bibliography

- Chittick, Andrew (2011). «The Song Navy and the Invention of Dragon Boat Racing». Journal of Song-Yuan Studies. 2011 (41): 1–28. doi:10.1353/sys.2011.0025. JSTOR 23496206. S2CID 162282148.

- Lowe, H. Y. (aka Lü Hsing-yüan 慮興源) (2014) [1983]. «The Dragon Boat Festival». The Adventures of Wu: The Life Cycle of a Peking Man. Translated by Bodde, Derk. Princeton University Press. pp. 141–148. doi:10.2307/j.ctt7ztjmr.20. ISBN 9781400855896. JSTOR j.ctt7ztjmr.20.

External links[edit]

Media related to Duanwu Festival at Wikimedia Commons

For dragon boating as a sport, see Dragon boat. For the Cambodian festival with dragon boat races, see Bon Om Touk.

| Dragon Boat Festival | |

|---|---|

Dragon Boat Festival (18th century) |

|

| Observed by | Chinese |

| Type | Cultural |

| Observances | Dragon boat racing, consumption of realgar wine and zongzi |

| Date | Fifth day of the fifth lunar month |

| 2022 date | 3 June |

| 2023 date | 22 June |

| 2024 date | 31 May |

| 2025 date | 30 June |

| Frequency | Annual |

| Related to | Tango no sekku, Dano, Tết Đoan Ngọ, Yukka Nu Hii |

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 端午节 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 端午節 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | «The very mid point of the year Festival» | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Dragon Boat Festival | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 龙船节 / 龙舟节 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 龍船節 / 龍舟節 | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Double Fifth Festival Fifth Month Festival Fifth Day Festival |

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 重五节 / 双五节 五月节 五日节 |

||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 重五節 / 雙五節 五月節 五日節 |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Dumpling Festival | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 肉粽节 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 肉糭節 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Meat Zongzi Festival | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Portuguese name | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Portuguese | Festividade do Barco-Dragão |

The Dragon Boat Festival (simplified Chinese: 端午节; traditional Chinese: 端午節) is a traditional Chinese holiday which occurs on the fifth day of the fifth month of the Chinese calendar, which corresponds to late May or June in the Gregorian calendar.

Names[edit]

The English language name for the holiday is Dragon Boat Festival,[1] used as the official English translation of the holiday by the People’s Republic of China.[2] It is also referred to in some English sources as Double Fifth Festival which alludes to the date as in the original Chinese name.[3]

Chinese names by region[edit]

Duanwu (Chinese: 端午; pinyin: duānwǔ), as the festival is called in Mandarin Chinese, literally means «starting/opening horse», i.e., the first «horse day» (according to the Chinese zodiac/Chinese calendar system) to occur on the month;[4][a] however, despite the literal meaning being wǔ, «the [day of the] horse in the animal cycle», this character has also been interchangeably construed as wǔ (Chinese: 五; pinyin: wǔ) meaning «five». Hence Duanwu, the «festival on the fifth day of the fifth month».[7]

The Mandarin Chinese name of the festival is «端午節» (simplified Chinese: 端午节; traditional Chinese: 端午節; pinyin: Duānwǔjié; Wade–Giles: Tuan Wu chieh)[b] in Mainland China and Taiwan,[8][6][9] and «Tuen Ng Festival» for Hong Kong, Macao,[10] Malaysia and Singapore.[11]

It is pronounced variously in different Chinese dialects. In Cantonese, it is romanized as Tuen1 Ng5 Jit3 in Hong Kong and Tung1 Ng5 Jit3 in Macau. Hence the «Tuen Ng Festival» in Hong Kong[11] Tun Ng (Festividade do Barco-Dragão in Portuguese) in Macao.[12][13]

History[edit]

Origin[edit]

The fifth lunar month is considered an unlucky month. People believed that natural disasters and illnesses are common in the fifth month. To get rid of the misfortune, people would put calamus, Artemisia, pomegranate flowers, Chinese ixora and garlic above the doors on the fifth day of the fifth month.[citation needed] Calamus is believed to be able to remove evil spirits because of its sword-like shape and strong garlic smell.

Hanging wormwood leaves on top of a door to deter insects.

Another explanation to the origin of the Dragon Boat Festival comes from before the Qin Dynasty (221–206 BC). The fifth month of the lunar calendar was regarded as a bad month and the fifth day of the month a bad day. Venomous animals were said to appear starting from the fifth day of the fifth month, such as snakes, centipedes, and scorpions; people also supposedly get sick easily after this day. Therefore, during the Dragon Boat Festival, people try to avoid this bad luck. For example, people may paste pictures of the five poisonous creatures on the wall and stick needles in them. People may also make paper cutouts of the five creatures and wrap them around the wrists of their children.[14] Big ceremonies and performances developed from these practices in many areas, making the Dragon Boat Festival a day for getting rid of disease and bad luck.

Qu Yuan[edit]

The story best known in modern China holds that the festival commemorates the death of the poet and minister Qu Yuan (c. 340–278 BC) of the ancient state of Chu during the Warring States period of the Zhou dynasty.[15] A cadet member of the Chu royal house, Qu served in high offices. However, when the emperor decided to ally with the increasingly powerful state of Qin, Qu was banished for opposing the alliance and even accused of treason.[15] During his exile, Qu Yuan wrote a great deal of poetry. Twenty-eight years later, Qin captured Ying, the Chu capital. In despair, Qu Yuan committed suicide by drowning himself in the Miluo River.

It is said that the local people, who admired him, raced out in their boats to save him, or at least retrieve his body. This is said to have been the origin of dragon boat races. When his body could not be found, they dropped balls of sticky rice into the river so that the fish would eat them instead of Qu Yuan’s body. This is said to be the origin of zongzi.[15]

During World War II, Qu Yuan began to be treated in a nationalist way as «China’s first patriotic poet». The view of Qu’s social idealism and unbending patriotism became canonical under the People’s Republic of China after 1949 Communist victory in the Chinese Civil War.

Wu Zixu[edit]

Despite the modern popularity of the Qu Yuan origin theory, in the former territory of the Kingdom of Wu, the festival commemorated Wu Zixu (died 484 BC), the Premier of Wu. Xi Shi, a beautiful woman sent by King Goujian of the state of Yue, was much loved by King Fuchai of Wu. Wu Zixu, seeing the dangerous plot of Goujian, warned Fuchai, who became angry at this remark. Wu Zixu was forced to commit suicide by Fuchai, with his body thrown into the river on the fifth day of the fifth month. After his death, in places such as Suzhou, Wu Zixu is remembered during the Dragon Boat Festival.

Cao E[edit]

The front of the Cao E Temple, facing east, toward Cao’e River, in Shangyu, Zhejiang, China.

Although Wu Zixu is commemorated in southeast Jiangsu and Qu Yuan elsewhere in China, much of Northeastern Zhejiang including the cities of Shaoxing, Ningbo and Zhoushan celebrates the memory of the young girl Cao E (曹娥; AD 130–144) instead. Cao E’s father Cao Xu (曹盱) was a shaman who presided over local ceremonies at Shangyu. In 143, while presiding over a ceremony commemorating Wu Zixu during the Dragon Boat Festival, Cao Xu accidentally fell into the Shun River. Cao E, in an act of filial piety, decided to find her father in the river, searching for 3 days trying to find him. After five days, she and her father were both found dead in the river from drowning. Eight years later, in 151, a temple was built in Shangyu dedicated to the memory of Cao E and her sacrifice for filial piety. The Shun River was renamed Cao’e River in her honor.[16]

Cao E is depicted in the Wu Shuang Pu (無雙譜; Table of Peerless Heroes) by Jin Guliang.

Pre-existing holiday[edit]

Some modern research suggests that the stories of Qu Yuan or Wu Zixu were superimposed onto a pre-existing holiday tradition. The promotion of these stories might be encouraged by Confucian scholars, seeking to legitimize and strengthen their influence in China. The relationship between zongzi, Qu Yuan and the festival, first appeared during the early Han dynasty.[17]

The stories of both Qu Yuan and Wu Zixu were recorded in Sima Qian’s Shiji, completed 187 and 393 years after the events, respectively, because historians wanted to praise both characters.

Another theory, advanced by Wen Yiduo, is that the Dragon Boat Festival originated from dragon worship. Support is drawn from two key traditions of the festival: the tradition of dragon boat racing and zongzi. The food may have originally represented an offering to the dragon king, while dragon boat racing naturally reflects a reverence for the dragon and the active yang energy associated with it. This was merged with the tradition of visiting friends and family on boats.

Another suggestion is that the festival celebrates a widespread feature of east Asian agrarian societies: the harvest of winter wheat. Offerings were regularly made to deities and spirits at such times: in the ancient Yue, dragon kings; in the ancient Chu, Qu Yuan; in the ancient Wu, Wu Zixu (as a river god); in ancient Korea, mountain gods (see Dano). As interactions between different regions increased, these similar festivals eventually merged into one holiday.

Early 20th century[edit]

In the early 20th Century the Dragon Boat Festival was observed from the first to the fifth days of the fifth month, and also known as the

Festival of Five Poisonous Insects (simplified Chinese: 毒虫节; traditional Chinese: 毒蟲節; pinyin: Dúchóng jié).

Yu Der Ling writes in chapter 11 of her 1911 memoir Two Years in the Forbidden City:

The first day of the fifth moon was a busy day for us all, as from the first to the fifth of the fifth moon was the festival of five poisonous insects, which I will explain later—also called the Dragon Boat Festival. … Now about this Feast. It is also called the Dragon Boat Feast. The fifth of the fifth moon at noon was the most poisonous hour for the poisonous insects, and reptiles such as frogs, lizards, snakes, hide in the mud, for that hour they are paralyzed. Some medical men search for them at that hour and place them in jars, and when they are dried, sometimes use them as medicine. Her Majesty told me this, so that day I went all over everywhere and dug into the ground, but found nothing.[18]

21st century[edit]

In 2004 the Dragon Boat Festival was elevated to a national holiday in China.

Public holiday[edit]

ROC (Taiwan) President Ma Ying-jeou visits Liang Island before Dragon Boat Festival (2010)

‘恭祝總統端節愉快‘ (‘Respectfully Wishing the President a Joyous Dragon Boat Festival’)

The festival was long marked as a cultural festival in China and is a public holiday in China, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, and Taiwan (ROC). The People’s Republic of China government established in 1949 did not initially recognize the Dragon Boat Festival as a public holiday but reintroduced it in 2008 alongside two other festivals in a bid to boost traditional culture.[19][20]

Dragon Boat Festival is unofficially observed by the Chinese communities of Southeast Asia, including Singapore and Malaysia. Equivalent and related official festivals include the Korean Dano, Japanese Children’s Day, and Vietnamese Tết Đoan Ngọ.[citation needed]

Practices and activities[edit]

Three of the most widespread activities conducted during the Dragon Boat Festival are eating (and preparing) zongzi, drinking realgar wine, and racing dragon boats.[21]

Dragon boat racing[edit]

Dragon boat racing has a rich history of ancient ceremonial and ritualistic traditions, which originated in southern central China more than 2500 years ago. The legend starts with the story of Qu Yuan, who was a minister in one of the Warring State governments, Chu. He was slandered by jealous government officials and banished by the king. Out of disappointment in the Chu monarch, he drowned himself into the Miluo River. The common people rushed to the water and tried to recover his body. In commemoration of Qu Yuan, people hold dragon boat races yearly on the day of his death according to the legend. They also scattered rice into the water to feed the fish, to prevent them from eating Qu Yuan’s body, which is one of the origins of zongzi.

Zongzi (traditional Chinese rice dumpling)[edit]

A notable part of celebrating Dragon Boat Festival is making and eating zongzi with family members and friends. People traditionally wrap zongzi in leaves of reed, bamboo, forming a pyramid shape. The leaves also give a special aroma and flavor to the sticky rice and fillings. Choices of fillings vary depending on regions. Northern regions in China prefer sweet or dessert-styled zongzi, with bean paste, jujube, and nuts as fillings. Southern regions in China prefer savory zongzi, with a variety of fillings including marinated pork belly, sausage, and salted duck eggs.

Zongzi appeared before the Spring and Autumn Period and was originally used to worship ancestors and gods; in the Jin Dynasty, Zongzi became a festive food for the Dragon Boat Festival. Jin Dynasty, dumplings were officially designated as the Dragon Boat Festival food. At this time, in addition to glutinous rice, the raw materials for making zongzi are also added with Chinese medicine Yizhiren. The cooked zongzi is called «yizhi zong».[22]

The reason why the Chinese eat zongzi on this special day has many statements. The folk version is to hold a memorial ceremony for Quyuan. While in fact, Zongzi has been regarded as an oblation for the ancestor even before the Chunqiu period. From the Jin dynasty, Zongzi officially became the festival food and long last until now.

[edit]

‘Wu’ (午) in the name ‘Duanwu’ in Chinese has a similar pronunciation as the number 5 in multiple dialects, and thus many regions have traditions of eating food that is related to the number 5. For example, the Guangdong and Hong Kong regions have the tradition of having congee made from 5 different beans.

Realgar wine[edit]

Realgar wine or Xiong Huang wine is a Chinese alcoholic drink that is made from Chinese yellow wine dosed with powdered realgar, a yellow-orange arsenic sulfide mineral also known as «rice wine». It is often used as a pesticide against mosquitoes and other biting insects during the hot summers, and as a common antidote against poison in ancient Asia.

5-colored silk-threaded braid[edit]

In some regions of China, parents braid silk threads of 5 colors and put them on their children’s wrists, on the day of the Dragon Boat Festival. People believe that this will help keep bad spirits and diseases away.

Other common activities include hanging up icons of Zhong Kui (a mythic guardian figure), hanging mugwort and calamus, taking long walks, and wearing perfumed medicine bags.[23] Other traditional activities include a game of making an egg stand at noon (this «game» implies that if someone succeeds in making the egg stand at exactly 12:00 noon, that person will receive luck for the next year), and writing spells. All of these activities, together with the drinking of realgar wine or water, were regarded by the ancients and some today as effective in preventing disease or evil while promoting health and well-being.

In the early years of the Republic of China, Duanwu was celebrated as the «Poets’ Day» due to Qu Yuan’s status as China’s first known poet. The Taiwanese also sometimes conflate the spring practice of egg-balancing with Duanwu.[24]

The sun is considered to be at its strongest around the time of summer solstice, as the daylight in the northern hemisphere is the longest. The sun, like the Chinese dragon, traditionally represents masculine energy, whereas the moon, like the phoenix, traditionally represents feminine energy. The summer solstice is considered the annual peak of male energy while the winter solstice, the longest night of the year, represents the annual peak of feminine energy. The masculine image of the dragon has thus associated with the Dragon Boat Festival.[25]

Gallery[edit]

-

Activities to avoid bad luck

-

A bodice worn by kids with symbols of the Five Poisonous Insects on it to deter poisonous insects, and reptiles such as frogs, lizards, snakes.

-

A dragon boat racing in San Francisco, 2008.

-

Raw Rice Dumpling

See also[edit]

- Bon Om Touk

- Dano (Korean festival)

- Traditional Chinese holidays

Explanatory notes[edit]

- ^ Also suggested to mean «Beginning of Noon»,[5] or «High Noon Festival»,[6] since «horse» also marks the hours 11:00–13:00 each day.

- ^ Romanized in pinyin with inflection as Duānwǔjié.

References[edit]

- Citations

- ^ Chittick (2011), p. 1.

- ^ Chinese Government’s Official Web Portal. «Holidays Archived May 2, 2012, at the Wayback Machine». 2012. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

- ^ «Double Fifth (Dragon Boat) Festival Archived May 6, 2008, at the Wayback Machine».

- ^ Inahata, Kōichirō [in Japanese] (2007). Tango 端午 (たんご). Heibonsha World Encyclopedia 世界大百科事典 (revised, new ed.). Heibonsha. via Japanknowledge.

- ^ Lowe (1983), p. 141.

- ^ a b «Dragon Boat Festival». Taiwan Today. Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Republic of China (Taiwan). 1 June 1967.

- ^ Chen, Sanping (January–March 2016). «Were ‘Ugly Slaves’ in Medieval China Really Ugly?». Journal of the American Oriental Society. 136 (1): 30–31. doi:10.7817/jameroriesoci.136.1.117. JSTOR 10.7817/jameroriesoci.136.1.117.

- ^ General Office of the State Council of the People’s Republic of China. 《国务院办公厅关于2011年部分节假日安排的通知国办发明电〔2010〕40号》. 9 December 2010. Retrieved 3 November 2013. (in Chinese)

- ^ Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Republic of China (Taiwan). «Holidays and Festivals in Taiwan Archived 2014-02-21 at the Wayback Machine Archived 2014-02-16 at the Wayback Machine». Retrieved 3 November 2013. (in Chinese and English).

- ^ Special Administrative Region of Macao. Office of the Chief Executive. 《第60/2000號行政命令》. 3 October 2000. Retrieved 3 November 2013. (in Chinese)

- ^ a b GovHK. »

General holidays for 2014″. 2013. Retrieved 1 November 2013. - ^ Macau Government Tourist Office. «Calendar of Events». 2013. Retrieved 3 November 2013.

- ^ Special Administrative Region of Macao. Office of the Chief Executive. «Ordem Executiva n.º 60/2000». 3 October 2000. Retrieved 3 November 2013. (in Portuguese)

- ^ Liu, L. (2011). ‘Beijing Review’ Color Photographs. vol. 54, issue 23. pp. 42–43.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ a b c SCMP.» Earthquake and floods make for the muted festival. Retrieved on 9 June 2008. Archived 25 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ «The river in which she jumped was renamed as Cao’s River». Archived from the original on 4 April 2017.

- ^ «The Legends Behind the Dragon Boat Festival». Smithsonian. 14 May 2009.

- ^ Yü, Der Ling (1911). Two Years in the Forbidden City. T. F. Unwin. Project Gutenberg

- ^ People’s Daily. «Peopledaily.» China to revive traditional festivals to boost traditional culture. Retrieved on 9 June 2008.

- ^ Xinhua Net. «First day-off for China’s Dragon Boat Festival helps revive tradition Archived 2013-12-22 at the Wayback Machine.» Xinhua News Agency. Published 8 June 2008. Retrieved 9 June 2008.

- ^ «Dragon Boat Festival». China Internet Information Center. Retrieved 12 June 2013.

- ^ Yuan, He (2015). «Textual Research on the Origin of Zongzi». Journal of Nanning Polytechnic.

- ^ «Dragon Boat Festival keeps the beast at bay». chinadailyhk.

- ^ Huang, Ottavia. Hmmm, This Is What I Think: «Dragon Boat Festival: Time to Balance an Egg». 24 June 2012. Retrieved 3 November 2013.

- ^ Chan, Arlene & al. Paddles Up! Dragon Boat Racing in Canada, p. 27. Dundurn Press Ltd., 2009. ISBN 978-1-55488-395-0. Retrieved 1 June 2011.

- Bibliography

- Chittick, Andrew (2011). «The Song Navy and the Invention of Dragon Boat Racing». Journal of Song-Yuan Studies. 2011 (41): 1–28. doi:10.1353/sys.2011.0025. JSTOR 23496206. S2CID 162282148.

- Lowe, H. Y. (aka Lü Hsing-yüan 慮興源) (2014) [1983]. «The Dragon Boat Festival». The Adventures of Wu: The Life Cycle of a Peking Man. Translated by Bodde, Derk. Princeton University Press. pp. 141–148. doi:10.2307/j.ctt7ztjmr.20. ISBN 9781400855896. JSTOR j.ctt7ztjmr.20.

External links[edit]

Media related to Duanwu Festival at Wikimedia Commons

Рубрика : «ПОВЕСТКА ДНЯ»

端午节 — Duānwǔ Jié – Фестиваль драконьих лодок

Традиционное название торжества — Праздник начала лета — 5 день 5 месяца по лунному календарю. В 2021 году праздник выпал на 14 число, поэтому китайцы в этом году отдыхают также как и мы, три дня — с 12 по 14 июня. Дальше вас ждет короткая легенда возникновения этого праздника и интересные факты о том, как наши друзья из поднебесной отмечают 端午节.

Легенда возникновения праздника

Давным-давно, задолго до нашей эры, в крайне смутные времена, когда за царский трон велись кровопролитные битвы, в Китае жил чудесный поэт Цюй Юань. Он гордился великим царством и любил его всем сердцем, а свой патриотический дух отражал в прекрасных стихах. Народ безмерно уважал и ценил Цюй Юаня за воспевание красот Китая, поднятие боевого духа и борьбу за свободу населения.

Но настали темные времена, когда царский трон захватила вражеская сторона. Цюй так близко к сердцу воспринял произошедшее, так его это ранило, что не смог он смириться с этим, и в отчаянии бросился в реку, где и утонул.

Смерть Цюй Юаня потрясла народ, и весь город бросился искать тело любимого поэта с верой в чудо. Запрыгнув в лодки, они проплыли всю реку, бросая рыбам рис, чтобы отвлечь их, дабы они не съели тело поэта. Но помимо рыб народу следовало задобрить еще и дух Дракона, для этого они решили подливать в реку рисовое вино, чтобы Дракон расплылся в улыбке и не серчал. Но ведь рисовое вино надо чем-то закусывать?! А весь рис под расчет и причитается рыбам, как же его уберечь от дракона?! Находчивые женщины прятали рис, заворачивая их в пирамидки из листьев тростника. Это блюдо с разными начинками позже получит название 粽子 — zòngzi – цзунцзы.

Празднование фестиваля

Тело поэта так и не нашли, но чтобы память о нем жила вечно, китайцы ежегодно стали проводить гонки на драконьих лодках, у которых нос и корма выполнены в форме драконьей головы. Гонки символизируют поиски поэта и проходит под бой барабанов. Задача каждой из команд как можно быстрее догрести до финиша.

Традиционное лакомство сегодняшнего дня, как вы уже догадались — 粽子 — zòngzi – цзунцзы. Завернутый клейкий рис в пирамидки из листьев тростника также снабжают разнообразной начинкой: мясо, рыба, яйца, финики и т.д.

Фестиваль Tuen Ng, также известный как Дуаньу или праздник драконьих лодок, отмечается в пятый день пятого месяца китайского лунного календаря на протяжении тысячелетий.

| Год | Дата | День | Праздник |

| 2020 | 25 Июня | Чт | Праздник драконьих лодок |

| 2021 | 14 Июня | Пн | Праздник драконьих лодок |

| 2022 | 3 Июня | Пт | Праздник драконьих лодок |

| 2023 | 22 Июня | Чт | Праздник драконьих лодок |

| 2024 | 10 Июня | Пн | Праздник драконьих лодок |

| 2025 | 31 Мая | Сб | Праздник драконьих лодок |

История праздника драконьих лодок

Легенда гласит, что люди пытались спасти своего уважаемого государственного деятеля, преследуя его вниз по реке, с били в барабаны, чтобы отпугнуть рыбу, и бросали пельмени в реку, чтобы рыба не съела его тело. Сегодняшние торжества символизируют тщетные попытки друзей и граждан, которые мчались вниз по реке, чтобы спасти Чу Юань.

Как празднуется Праздник драконьих лодок

Лодка-дракон — это огромное военное каноэ, традиционно сделанное из тика, с вырезанной на носу головой дракона и хвостом дракона на корме. Лодки могут различаться по размеру и иметь длину до 100 футов и вмещать от 20 до 80 гребцов. Перед гонкой проводится сакральный ритуал — лодке рисуются глаза, что, как говорят, «оживляет лодку» и «дает ей жизнь». В каждой лодке в середине сидит барабанщик, который ударами в свой барабан задаёт ритм гребле.

Выстрел стартера отрывает лодки от берега, а бой барабанов и тарелок, с переполненных людьми берегов, наполняют гавань шумом. Гонки длятся весь день; на берегах Гонконга люди отмечают праздник живой песней и танцами, болея за свою команду.

Считается, что Праздники драконьих лодок отпугивает зло и приносят удачу в летние месяцы.

Zongzi

Похоже, что ниодин важный фестиваль в Юго-Восточной Азии не обходится без рисовых клецок, и Праздник драконьих лодок не является исключением. Популярная традиция, связанная с Праздником драконьих лодок — это рисовые клецки под названием цзунцзы.

Они часто выдаются в качестве небольших подарков во время фестиваля и доступны в большинстве магазинов.

Клейкий рис заворачивается в листья бамбука или лотоса и приправляется в зависимости от региона. На севере Китая цзунцзы обычно сладкие; в то время как на юге Китая цзунцзы с более пикантным вкусом. На Тайване они могут быть сделаны с арахисом, каштанами и кальмарами.

Приблизительно через неделю после праздника драконьих лодок в Гонконге специальные международные гонки на лодках-драконах проводятся по всей Азии и США. В США их можно найти в Бостоне, Нью-Йорке и Колорадо. В настоящее время 68 стран являются членами Международной федерации драконьих лодок, демонстрируя популярность гонки.

В 2009 году этот фестиваль был включен в список ЮНЕСКО, представляющий нематериальное культурное наследие человечества.

Ниже перечислены страны, которые отмечают праздник драконьих лодок как государственный.

Expro International Business LTD

Tianhe North road 615, office 1208

Guanzou, China

$$$

+86 13178888875

4.5

10

Праздник Дуаньу или Праздник драконьих лодок ( «duānwǔjié» 端午节 или Dragon Boat Festival) — один из четырех традиционных праздников, который наряду с Фестивалем Весны(春节), Праздником Цинмин(清明节) и Праздником Середины осени(中秋节) глубоко почитают в Китае.

Он празднуется ежегодно на 5-ый день 5-го месяца по Лунному календарю (поэтому его часто называют «праздником двойной пятерки»). Жители Поднебесной с большой радостью встречают этот день, так как он символизирует наступление долгожданного лета. В Григорианском календаре он чаще всего выпадает на конец мая или начало июня.

⠀

В 2006 года Госсоветом КНР он был включен в национальный список нематериального культурного наследия, а с 2008 стал одним из государственных официальных праздников, на который выделили 3 выходных дня.

В 2023 году праздник Дуаньу приходится на 22 июня.

Официальные выходные дни в 2022г. с 22 по 24 июня 2023 года.

Несмотря на то, что день Дуаньу является традиционным китайским праздником, он также приобрел популярность в странах, которые исторически имеют культурные связи с китайской цивилизацией – Корее, Японии, Вьетнаме, Малайзии, Индонезии, Сингапуре и др.

Происхождение Праздника драконьих лодок

Происхождение праздника связывают с личностью поэта Цюй Юаня (屈原), который жил в государстве Чу в период Сражающихся царств с 343 по 278гг. до н.э. Он был очень важным человеком, которого уважали не только за его талант, но и за мудрые мысли, к которым прислушивались правители во время войны с соседними государствами. Его не раз выгоняли со двора в связи с, как сейчас бы сказали, «утратой доверия» из-за заговоров придворных, но он на протяжении всей сознательной жизни оставался верен своим идеалам и крайне патриотично относился к родине. Когда же государство Чу потерпело поражение от вражеского Царства Цинь, он настолько отчаялся, что бросился в реку Милоу. Произошло это на 5-ые сутки 5 лунного месяца.

Люди, которые очень любили поэта, тут же бросились его искать: одни гребли на лодках, другие били в барабаны, третьи бросали в воду рис – делали все, чтобы распугнуть морских обитателей и найти тело Цюй Юаня, но у них ничего не вышло. Уже после трагедии друзья выдающегося деятеля рассказали, что его дух явился к ним и рассказал, что его тело съел речной дракон.

С тех самых пор в Китае зародилась традиция гребли, поедания риса (который предложили заворачивать в твердые листья тростника, которые «не по вкусу» морским обитателям), и ассоциировать этот день с драконами.

Существует и вторая версия зарождения праздника, которая не так романтична, как первая. Суть ее заключается в том, что в древние времена 5-ый лунный месяц среди простого народа был известен как самый опасный, с точки зрения распространения болезней. Мало того, что из-за резкого начала жары люди легче заболевали и распространяли инфекции, так еще после зимних холодов на свет выползали различные рептилии, которые распространяли яды ( «wǔdú» 五毒)и представляли чрезвычайную опасность для жизни. Поэтому поклонники этой теории ассоциируют праздник с днем противостояния болезням и недугам, когда следует поклонятся богам и просить у них лучшей (в значении «здоровой») жизни.

Основные обычаи. Как проводят Фестиваль Драконьих лодок в Китае

Праздник драконьих лодок широко известен традиционными соревнованиями по гребле на лодках («sàilóngzhōu» 赛龙舟), которые проходят перед оживленной толпой под гром барабанов. Команды гребцов от 20 до 60 человек (в составе обязательно присутствуют рулевой, барабанщик и гребцы с веслами) соревнуются не только в том, кто первый достигнет финиша, но и в украшении своей лодки в виде дракона («lóngzhōu» 龙舟). На носу лодки располагается голова мифического зверя, а на корме – хвост. Все остальное – это туловище, которое также ярко и красочно разукрашивают. Каждый, кому посчастливится понаблюдать за ходом соревнований, как правило, уносит с собой незабываемые впечатления.

Существует мнение, что именно после появления традиции подобных соревнований в Китае, они настолько понравились людям по всему миру, что стали международным видом спорта, который сегодня практикуют в США, Канаде, Австралии и Европе.

Традицией, которая имеет связь со «здоровыми» корнями праздника, является обычай вывешивать листья полыни у входа в свое жилье в качестве оберега от злых духов и болезней. Некоторые также верят, что ветви полыни способны приносить в дом удачу и благосостояние.

Где посмотреть традиционные соревнования по гребле

Соревнования на лодках проходят практически во всех городах, где есть водоемы, но самые яркие и востребованные среди туристов, конечно, имеют место в Гуанчжоу, Ханчжоу и Гонконге.

Если же Вы являетесь поклонником аутентичного Китая и любите путешествовать вне рамок популярных туристических маршрутов, обязательно отправляйтесь в одно из этих мест, чтобы разделить традиционную праздничную атмосферу и дух соревнования с местным населением.

- г. Милоу, провинция Хунань (湖南汨罗)

- г. Юаньлин, провинция Хунань (湖南沅陵)

- г. Дунгуань, провинция Гуандун (广东东莞)

- г.Тунжэнь, провинция Гуйчжоу(贵州铜仁)

- г. Сянъян, провинция Хубэй (湖北襄阳)

- г. Фучжоу, провинция Фуцзянь(福建福州)

- г. Сюпу, провинция Хунань(湖南溆浦)

- г. Цяньдуннань, провинцияГуйчжоу (贵州黔东南)

- г. Ухань, Хубэй(武汉汉江)

- уезд Саньцзао, г. Чжухай(珠海三灶镇)

Традиционные блюда праздника Дуаньу. Китайские цзунцзы (zongzi)

Главным угощением Фестиваля драконьих лодок являются цзунцзы («zòngzi»粽子)– треугольные конвертики из клейкого риса с различными начинками, завернутыми в листья тростника, бамбука или лотоса. Многим они напоминают пирамидки, а из-за основной идеи приготовления их также называют своеобразными пельменями. По вкусу они бывают сладкими (с бобами), солеными (с грибами, мясом, яйцами) и даже острыми (с добавлением перца), в зависимости от наполнения и специфических предпочтений жителей того или иного региона КНР.

Приобрести их можно в кафе, ресторанах и кондитерских, их также продают в замороженном виде в супермаркетах, хотя очень многие традиционные китайские семьи продолжают готовить их самостоятельно даже в современные дни.

⠀

Помимо этого лакомства на столе обязательно присутствует вино, которое считается противоядием от болезней и отравлений.