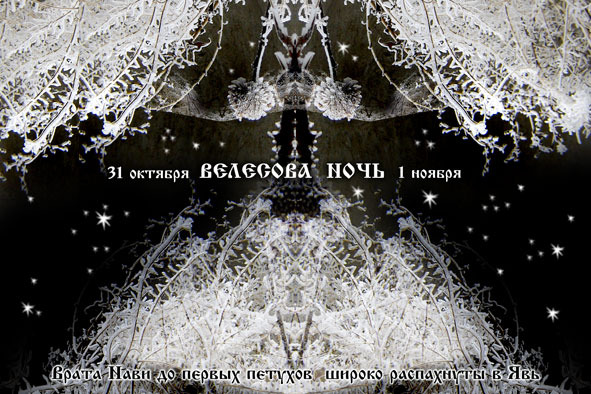

МАРИНА НОЧЬ (ВЕЛЕСОВА НОЧЬ) — чародейная ночь с 31 октября на 1 ноября, когда Белобог окончательно передаёт Коло Лета (Года) — Чернобогу, а Врата Нави до первых петухов (либо до самого рассвета) широко распахнуты в Явь. Следующий день (1 ноября) называют Мариным днём.

Также, 31 октября — День Мудрых Странников

ВЕЛЕС И МАРА

Сыпят ели снег с иголок

Серебро в нощи искрится

На санях сквозь вьюжный морок

Вещий Бог над Земью мчитсяШапка золотом сияет

Иней блещет на ресницах

Шуба сива с плеч спадает

Над главою — бела птицаЛюты волки — очи вслед

Из-за древ горят как угли

Вещий Бог — как Месяц сед

Снегопад — зимы хоругвиРасступаются леса

В белом мертвенном убранстве

Ясны Вещего глаза

Духов круг — Нощное БратствоМара смотрит вдаль с холма

В Небе — Звёздные Дороги

Волохатая, легла

Шуба Вещего под ноги…Марин Глас — в нощи звенят

Колокольцы ледяные

Кони Вещего летят

Ввысь — в Просторы Неземные…Велеслав

САМХЕЙН (САМАЙН)

В дохристианскую эпоху земли современной Англии, Ирландии и Франции населяли кельтские племена. Год у них состоял из двух частей — лета и зимы. Они почитали Бога Солнца, который, по приданию, в течение каждой зимы находился в плену у Самхэйна — властелина мертвых и князя тьмы.

Именно в день, соответствующий нашему 31 октября, древние кельты отмечали свой главный праздник — Самхэйн (Samhain). Этому празднику кельты придавали очень большое значение, так как он означал окончание сбора урожая и символизировал конец старого и начало нового года.

Еще Самхэйн — это ворота в зиму. Мы до сих пор склонны воспринимать зиму с неприязнью. Кажется, что всё живое умирает. Являясь язычниками, кельты верили в зарождение жизни из смерти, а приход смерти рассматривали в этот день как приход жизни.

По легенде, белая пустыня, где живёт Самхэйн, необычайно красива. Она освобождена от всего лишнего, наносного. Его время — это время сбросить груз забот и сует, накопившихся за лето и потерявших свое значение, следуя примеру деревьев, которые освобождаются от листьев, отживших свой срок. Ведь если деревья не сбросят их, мёртвые листья не дадут им возможность ожить вновь весной.

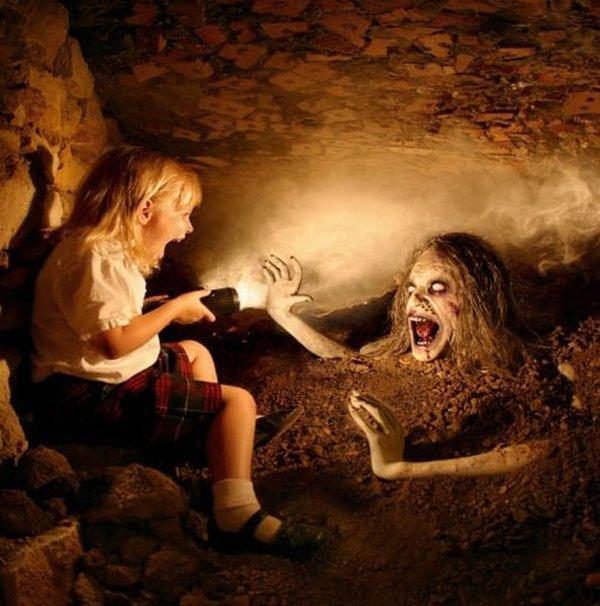

Легенда гласит, что в эту ночь Самхэйн открывает ворота в прошлое и будущее. 31 октября лето сменялось зимой, день — ночью, жизнь — смертью, и все барьеры между материальным и сверхъестественным мирами устранялись, ворота между ними открывались на одну ночь. Две стихии становятся доступны в настоящем. Это время, когда человек не ограничен клеткой своего времени и может осознать своё место в паутине вечности. Однако переход в другое пространство или время обычно бывает болезненным. Ворота хорошо охраняются. Ведьмы и демоны — герои Хэллоуина — это тени хранителей ворот…

Исследователи истории кельтов полагают также, что в день Самхэйна люди тушили весь огонь в домах, чтобы вновь зажечь его от огня друидов — своих жрецов, являвшихся одновременно учеными, поэтами и духовными вождями (согласно другим источникам, друиды являлись ещё и неким мистический орденом, контролировавших все аспекты жизни кельтского народа).

Также считалось, что в ночь Самхэйна завеса, разделяющая мир людей и мир сидов (волшебных существ, настроенных по отношению к людям нейтрально или враждебно), становится на столько тонкой, что люди и сиды могут проникать в миры друг друга. Поэтому, с точки зрения кельтов, риск встретить сида в ночь Самхэйна был очень велик. Другими словами, это был день, когда потревоженные духи, демоны, гоблины и прочие мистические существа могли с наибольшей легкостью прийти в материальный мир. Именно поэтому люди одевались так же, как эти существа, и ходили по домам, прося еду для умиротворения нечистой силы. Поскольку Самхэйн олицетворял конец года, то он являлся наиболее удобным временем для общения с духами и умершими. Наконец, в Самайн устраивались разнообразные гадания.

В I в. нашей эры, когда римляне завоевали кельтскую территорию, кельты уже праздновали Самхэйн на протяжении нескольких веков. Римляне не стали выступать против этого праздника, потому что он совпадал с их собственным Днем Помоны — богини растений. В некоторых областях римляне и кельты жили вместе, поэтому вполне логично, что Самхэйн стал постепенно «растворяться» в римской традиции.

Христианизация островов Британии и Ирландии привела к тому, что населению пришлось отказаться от кельтских языческих обычаев. Однако память о Самайне осталась жить в поколениях обитателей Ирландии и Шотландии.

«Самхейн»

— Месяц-друид, предскажи мне судьбу

Россыпью звёзд-рун,

Кончен мой путь, иль воскреснуть могу?

Сколько мне ждать лун?

Сколько метаться меж светом и тьмой,

Падать, взмывать ввысь?

Что меня ждёт, долгожданный покой,

Или опять — жизнь?— Только в Самхейн ты получишь ответ,

В ночь, что длинней дней,

Что перевесит — Тьма или Свет,

В блудной душе твоей.Саваном белым укрыты холмы,

Холод струится с полей…

Вечные призраки, духи зимы,

Ждут, что придет Самхейн…Неждана Юрьева

Хеллуин

Дальше нас история забрасывает в IX век, когда Папой Григорием III было перенесено празднование Дня всех святых с 13 мая на 1 ноября (тогда этот день посвящали тем святым, у которых не было своего праздника в течение года). День накануне — 31 октября — в средневековом английском языке получил название All Hallows Even, или All Hallows Eve (что означает «вечер всех святых»). Позже его стали называть Hallowe’en, и в конце концов — Halloween.

К этому времени кельты уже не представляли физической опасности для Империи, друиды также исчезли. «Совместив» христианский и языческий праздники, Папа, видимо, надеялся на постепенное искоренение языческих традиций. Но, как оказалось, совпадение дат привело к тому, что языческий праздник не только выжил, но и неразрывно сросся в народном сознании с праздником церковным, из-за чего Хэллоуин приобрел окраску Самхэйна и буйно отмечался.

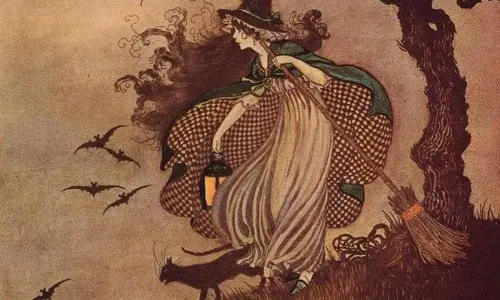

При этом представления о сидах, проникающих в мир людей, в средневековом христианском сознании превратились в представления о нечистой силе, выходящей в этот день пугать благочестивых обывателей. Именно поэтому в эпохи Средневековья и Нового времени Хэллоуин облюбовали ведьмы, обязательно устраивавшие в этот день шабаш. Чтобы не стать добычей мёртвой тени, люди гасили очаги в домах и наряжались как можно страшнее — в звериные шкуры и головы, надеясь распугать привидения, переползшие открытую границу. Духам выставляли угощение на улицу, чтобы они удовлетворились этим и не ломились в дом. А сами жители собирались у костров, которые разводили друиды, кельтские священники. В эту ночь делались предсказания, приносились в жертву животные, а потом каждый брал в свой дом язычок священного пламени, чтобы зажечь зимний очаг.

К 43 году н.э. римляне заняли большинство кельтских территорий. За те 400 лет, которые они провели на землях кельтов, смешалось не только население, но и традиции: с Новым годом соединились два римских праздника. Первый — Фералия, отмечавшийся в конце октября, нечто вроде дня поминовения усопших, и второй — в честь богини фруктов и деревьев Помоны. Её символом было яблоко, и отсюда пошла современная хэллоуинская традиция устраивать игры с яблоками.

С постепенным превращением Самхэйна в День всех святых родилась игра «Угощай или пожалеешь». Она заключается в том, чтобы «откупиться» сладостями от детей, которые настойчиво стучат в дверь. В случае отказа весьма велика вероятность обнаружить ручки дверей полностью вымазанными сажей… Кроме того, появилась традиция вырезать на картофелинах или репках страшные рожицы и помещать внутрь свечи — получался своеобразный фонарь.

Легенда гласит, что его изобрел скупой и хитрый ирландский кузнец по имени Джек. Он сумел два раза обмануть Дьявола и получил от него обещание не покушаться на собственную душу. Однако за свою греховную мирскую жизнь ирландец не был допущен и в Рай. В ожидании Судного дня Джек должен был бродить по Земле, освещая себе путь кусочком угля, защищенным от дождя обыкновенной тыквой. Отсюда и название фонаря — Jack-o-lanterns.

Очередной этап распространения праздника связывают с 1517 годом и с «95 Тезисами» Мартина Лютера, положившими начало протестантской религии. Кроме того, большое влияние на распространение праздника оказало открытие Америки…

Считается, что в современном виде праздник состоялся лишь в XIX веке благодаря европейским эмигрантам, привезшим с собой в США обычай буйствовать на Хэллоуин и соблюдать связанные с этим праздником суеверия. Однако на новом месте жительства праздник вновь претерпел небольшие изменения — например, обнаружилось, что тыквы гораздо удобнее, чем репки.

Первыми большими городами, где в 20-х годах XX века прошло празднование Хэллоуина, стали Нью-Йорк и Лос-Анджелес. К началу XX в. во всех городах США стала распространяться мода устраивать на Хэллоуин акции мелкого вандализма — бить стекла, поджигать деревья и т.п.

Популярность этого сумасшествия была настолько велика, что в 20-е годы американским бойскаутам пришла в голову идея пропагандировать отказ от вандализма в этот день, не отказываясь от самого праздника; их лозунг гласил: «Sane Halloween!» (Да здравствует здоровый Хэллоуин!). Хулиганство бойскауты заменили маскарадом и попрошайничеством конфет. С середины этого же века Хэллоуин становится ещё и выгодным коммерческим предприятием. Костюмы, свечи, украшения, поздравительные открытки и тыквы пользуются огромной популярностью, несмотря на то, что праздник до сих пор не является официальным. С этих пор Хэллоуин и стал любимым праздником американских школьников…

Источники:

http://kapitan.ru/halloween…

http://kuking.net/20021031.htm

А по Ведическому Календарю (Коляды Дару) это День Мудрых Странников — опять же All Hallows Even

Сантия Пятая

16 (80). И пошлют к ним Боги… Великого Странника,

любовь несущего, но жрецы Золотого Тура

придадут его смерти мученической.

И по смерти его, объявят БОГОМ его…

и создадут Веру новую, построенную

на лжи, крови и угнетении…

И объявят все народы низшими и грешными,

и призовут пред ликом ими созданного Бога

каяться, и просить прощения за деяния

свершенные и не совершенные…

Да не погаснет свет в такой ночи

И на пороге-шелухи ржаной немного.

Смотри, как в тёплом трепетании свечи,

Горит воссозданая памятью дорога.

Подай просящему легко большой ломоть

И выбрось прочь изломанные вещи,

Лежит на алтаре рябины красной гроздь,

Сегодня души предков с нами вместе.

Прими от них, как встарь, ещё один урок,

А также от родни прими благословенье.

Один раз в год и на короткий очень срок,

Соприкоснись с великим обновленьем.

Граница стёрта и прозрачна меж миров,

Нет разницы между живым и мёртвым.

Врата открыты и до первой песни петухов,

Дух посвящения горит в крови народной.

Мир сформирован мириадом людских душ,

Они родились в нём и долго славно жили.

Поэт, солдат, историк, врач и чей-то муж,

Они придут домой по звёздной яркой пыли.

Не позабудь про удалившихся во тьму,

И принявших в обиде тёмные истоки.

Мир разделен чертой, вердиктом — посему

Любой из половинок честно правят боги

.

В такую ночь надейся на родной совет,

На силу памяти и на прощенье предков.

Пусть тёмное уйдёт в алеющий рассвет,

Оставив на пороге шелуху и тыкву деткам.

Сергей Брандт

Источник — https://my.mail.ru/community/beregina/3D36A847E8A168E7.html

31.10

В 2016 году очищение было не столь заметным, так как негативных систем было еще очень много, и они успели «подготовиться», создав много блокировок, которые включились именно 31 октября. Но и тогда очистилось достаточно много систем, хотя объем проведенной работы составил только 40-50% по сравнению с 2015 годом.

В этом году произошел наиболее сильный прорыв в очищении, начиная с конца 2015 года. Предполагаемый план по очищению был перевыполнен в 26 раз. Очещение затронуло все искаженные системы управления горизонталью. Среди них — различные глобальные искусственные интеллекты, искаженные системы управления Играми 25 и 100 уровня, глобальные «игровые поля» для негативных экспериментов, затрагивавшие всю материю. Также были зачищены искаженные системы и подпространства в дробных мерностях Земли, и многие другие искаженные системы, на существование которых мало кто даже обращал внимание.

Масштаб произошедших изменений еще предстоит оценить, но уже видно, что там, где раньше были, грубо говоря, орды чертей, легионы роботов искусственного интеллекта и прочие армии «врагов» — их уже просто нет.

На данный момент запускаются процессы восстановления пространства материальной вселенной, подобно тому, как заживает орган, который до этого был поражен тяжелой болезнью. Затягиваются пустоты, на месте которых раньше были искаженные миры, сворачиваются пространства, где раньше находились блокирующие системы. Происходит уплотнение и коцентрация пространства, восстанавливается полноценный энергообмен между всеми уровнями от Абсолюта до нижних мерностей.

Следующими этапами очищения должны стать непосредственные изменения на физическом плане. Их сроки, как уже говорилось, уже напрямую зависят от способности людей принять эти изменения, о готовности к ним.

Источник — https://mirai8.livejournal.com/75591.html

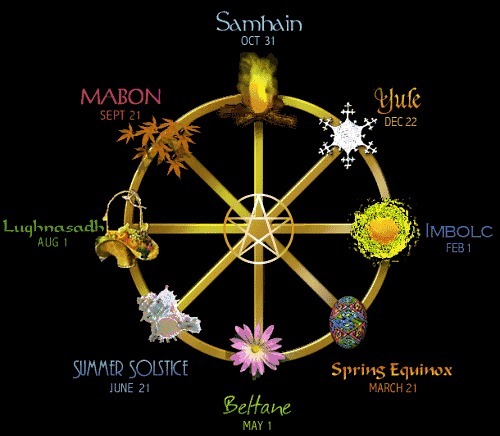

Праздник Самайн — торжество древних кельтов, означающее конец времени уборки урожая и начало зимы. Он отмечается обычно с вечера 31 октября на 1 ноября, так как день у кельтов, как правило, и начинался, и заканчивался на закате солнца. Происходило это где-то на половине пути: между осенним равноденствием и следующим за ним зимним солнцестоянием.

Содержание

- Самайн — праздник древних кельтов

- Сегодня мало кто знает, что в Ирландии

- Дух Самайна

- Традиции Самайна

- Ритуалы и обряды на Самайн

- Викканская молитва и слова для обряда

- Пир Самайна

- Магия Самайна

- Самайн у разных народов

- Связь Самайна и Хэллоуина

- Праздник мертвых или как Самайн превратился в день всех святых

Самайн — праздник древних кельтов

Что такое Cамайн и откуда его корни? Издревле это праздничное действо, как и следующий за ним Бельтайн (весеннее продолжение Самайна), широко отмечалось по всей территории Ирландии, Шотландии, а также — на острове Мэн.

Кельтский праздник Самайн очень много значил и до сих пор значит для людей, утративших близких, потому что именно в эти дни, согласно легенде, все мертвые души могут навещать своих родственников, оставшихся на земле, и наблюдать при этом за ними. Однако срок пребывания духов умерших среди живых всегда ограничен: на рассвете 1 ноября они снова должны уйти туда, откуда пришли: в мир иной.

Как мы уже знаем, отмечается Самайн 31 октября – 1 ноября. Считается, что он имеет кельтское языческое происхождение. Если заглянуть в историю Ирландии и в ее мифологию, то можно встретить много связанных с ним интересных фактов. Именно в это время обычно крупный рогатый скот возвращался с летних пастбищ и забивался на зиму. Параллельно с забоем скота разжигались специальные костры. Они являлись священными: защитными и очищающими силами, которые сопровождались различными ритуалами.

Как и Белтайн, Самайн рассматривался людьми как определенное мгновение, когда границу между этим миром и иным можно пересечь. Это означало, что духи и феи (Aos и Sí) и другие мифические существа могли каким-то образом пробраться в нашу реальность и даже на некоторое время в ней задержаться.

Большинство исследователей рассматривают Aos и Sí как остатки языческих богов и духов природы, которых, как и духов усопших, нужно умиротворить, чтобы люди и их скот спокойно и в достатке пережили зиму. Во время Самайна за праздничными столами даже отводили и оставляли специальные почетные места, на которые приглашались души умерших родственников.

Сегодня мало кто знает, что в Ирландии

около 2000 лет назад Самайн (Бельтайн) был неким водоразделом в году: между более легкой его половиной (летом) и более темной половиной года (зимой). Именно в этот день условная черта разделения между нашим и потусторонним миром считалась самой тонкой, позволяющей духам легко сквозь нее проходить.

Торжество Самайна или «праздника огней» по времени совпадает и с празднованием индуистского Нового года, а также знаменует собою конец и начало нового кельтского года.

Дух Самайна

Древние кельты верили, что ночь предшествует дню, и поэтому их празднества проходили исключительно накануне дня наступающего. Именно это торжество для дохристианских ирландцев было самым важным и решающим из всех в течение года: наполненным особой магией и символическим значением.

С этим днем у кельтов связано очень многое:

- легенды и повествования;

- ритуалы и жертвоприношения;

- священные огни;

- пышные трапезы.

С давних пор дни этого праздненства считались, тем не менее, нечестивым периодом, потому что все ведьмы, колдуны и разные сверхъестественные сущности устраивали в это время свой пир и шабаш.

Во время праздника Самайн отмечалось также и новое Колесо Года. Каждый день в этот период считался магическим, наполненным самыми фантастическими событиями и явлениями, ставшими во многом уже предметами мифологии.

Согласно календарю ведьм, после жаркого лета в течение восьми суток длилось так называемое Колесо Года, которое также также считалось большим праздником. В течение этих мистических восьми дней можно было наблюдать за циклом, по которому происходит движение солнца.

Идея о том, что Самайн (или Самхейн дикая охота, — как называли еще это время кельты) – есть соединение двух половин года, наводила людей на мысль и о том, что этот временной период приобретает некий уникальный статус эдакой своеобразной приостановки времени и не принадлежит, в конечном итоге, ни к старому году, ни к новому.

Можно сказать, что в этот час время действительно будто бы останавливалось, естественный порядок жизни превращался в хаос, а земной мир живых безнадежно запутывался в мире мертвых. Мир же умерших был населен не только духами усопших, но и множеством богов, фей и других существ неопределенной природы.

Любой путешественник, находившийся далеко от дома в эту ночь, мог неожиданно столкнуться с одним или несколькими из этих существ, поэтому для людей было всегда предпочтительней оставаться в этот период в помещении. Призраки бродят повсюду, они могут быть дружелюбными или наоборот: озлобленными по отношению к живым.

Традиции Самайна

В ночь Самайна в доме нужно зажечь особый ритуальный огонь. Это может быть обычный очаг в камине, горящая свеча или даже лампадка. Можно развести большой костер и на улице. Когда костер потухнет, домой стоит взять из него пару угольков. Такая традиция священна, поскольку именно огонь символизирует силу и считается главным оберегом дома от злых духов.

Надо сказать, что традиционно разжигавшиеся повсюду в это время костры символизировали кратковременное господство сил тьмы и попытку хоть как-то осветить окружающее людей пространство: весь мир погружался в темноту, и мертвые, как мы знаем, могли переходить границу между мирами.

Пренебрегать такими традициями не стоит, ведь злой дух может негативно повлиять на урожай, здоровье семьи или скота. Многие вообще считали, что Самайн — это некий демон. Другие же лишь сравнивали его с шабашем, на котором ведьмы проводят свое празднование. Третьи — наоборот: придумывали разные украшения для дома и своей обители, чтобы на Самайн задобрить духов усопших предков.

Ритуалы и обряды на Самайн

Повсеместные гадания на самайнский праздник или в ночь Дикой Охоты были приняты, вероятно, еще и потому, что именно этот промежуток времени суток был насквозь пронизан магией и колдовством. В такое время можно избавиться от всего негатива и зла, которое накапливалось у людей целый год. И все, что потребуется для такого избавления — это всего лишь написать все свои недостатки и беды на бумаге, после чего сжечь эту бумажку над ритуальной свечой.

Главное условие здесь – правильный подбор цветовой гаммы, и, в особенности, — оттенка горящей свечи. Она должна быть оранжевой. Также есть традиция с наступлением праздника рассчитываться по долгам.

Практика гадания на Самайн, рассказывающая о будущем, была важной частью жизненного уклада кельтов, и несомненно, что это искусство стало центральной частью всего этого празднества.

Ритуалы на Самайн были самые разнообразные. И одним из самых популярных и распространенных считается переодевание. На улицах и площадях кельтских городов в этот период можно повсюду встретить переодетых людей и детей, идущих от двери до двери в костюмах и масках. Возможно, такие традиции помогали живым каким-то образом слиться с мертвыми и призраками, чтобы те не смогли причинить людям вреда. Гадания и игры на Самайн также были большой частью этого праздника.

Горящие повсюду костры и пышная ритуальная еда играли в таких празднествах большую роль. Кости убитого скота сбрасывались в общий огонь, домашние очаги разжигались от углей с ритуальных пожарищ. Пища, приготовленная и для живых, и для мертвых, аккуратно располагалась на столах.

Викканская молитва и слова для обряда

Молитва в конце ритуала могла произноситься на любом языке, в зависимости и согласно верованиям человека. Существует даже универсальный стих викканская молитва, в котором прославляются кельтские обычаи, дикая охота, колесо года. А также — приглашаются в дом умершие: для угощения праздничными яствами, водой и вином.

Существует множество разных обычаев, исполняемых в процессе праздника Самайн. Главный их смысл — это установка связи с умершими. Для такого действия обычно делался круг, в котором проводился некий колдовской обряд: нужно было стать в этот круг, развести руки и просто говорить с усопшими.

Надо отметить, что каких-то специальных слов, заговоров или речей на Самайн не существует. Все, о чем хочется рассказать или спросить, произносится человеком в произвольной форме. Важно при этом не разозлить духов. После такого ритуала для спокойствия и умиротворения призраков обязательно проговаривается молитва.

Пир Самайна

В ночь Самайна на праздничный стол обычно ставятся традиционные народные блюда. Готовятся они из овощей, фруктов, мяса скота. Кухня должна быть повседневной, потому что угощать призраков нужно знакомыми им лакомствами. Для застолья подбирается хорошее красное вино. Также необходимо поставить тарелку с карамельными яблоками. Орехи и яблоки как раз созревают в этот период, поэтому эти плоды должны присутствовать на столе непременно. Приветствуются и молочные продукты, в особенности, — сливочное масло.

Магия Самайна

Ночь Самайна или ночь Велеса, действительно, полностью пропитана магией и колдовством. Чтобы поддержать настроение, нужно всего лишь украсить и дополнить свою обитель некими декорациями в виде цветов, атрибутов и символов в стиле смерти, можно инициировать даже шабаш ведьм, облачившись в ведьмины одежды.

Важно навестить в это время и могилы усопших близких, чтобы почтить их память и пригласить их к себе на праздничный ужин. Цвета для декораций стоит подбирать тщательно и даже щепетильно, чтобы они понравились приглашенным духам. Идеально подойдет в этом случае коричневый, оранжевый цвет. Также актуально будет смотреться фиолетовый, черный и темно-синий.

Обязательно нужно зажечь огни Самайна, поскольку именно они имеют самое важное значение. Разжигание такого огня в своем доме есть своеобразное очищение от негатива и жилища, и даже своих мыслей. На стол в эту ночь всегда подается мясо. Это некого рода жертвоприношение духам в знак благодарности за хороший урожай и уродившуюся живность.

Самайн у разных народов

Все знают, что на Самайн все миры пребывают в равновесии и равно открыты друг для друга, поэтому стоит отдать должное этому промежутку времени. Каждый народ празднует Ночь Охоты по-своему. Одним из похожих торжеств является праздник Велесова ночь: своеобразный славянский Хэллоуин. Так же отмечают День Мертвых в Мексике, Хэллоуин в Америке и многие другие подобные обычаи практически по всему миру.

Связь Самайна и Хэллоуина

Самайн и Хэллоуин в целом — очень похожие между собой празднования. Ношение костюмов и масок для защиты от вредных духов Самайна существует и в Хэллоуине. В это торжество перекочевали также многие самайнские обряды и ритуалы.

Надо отметить, что произошло это не случайно. В XIX веке ирландцы в большом количестве эмигрировали в Америку, особенно большое их количество покинуло Ирландию во времена голода в этой стране в 1840-х годах. Они-то и принесли свои традиции в США, где Хэллоуин сегодня — один из главных праздников года, с которым теперь сочетается также и обычай сбора урожая, ознаменованный также известной традицией вырезания тыкв.

И все же — между этими двумя праздниками есть некое отличие. И заключается оно в том, что в день Хэллоуина (в канун Дня всех Святых) люди веселятся и торжествуют, а в ночь Самайна они стараются обрести покой и проводят ее тихо, чтобы не потревожить духов и прочих сверхъестественных сущностей.

Праздник мертвых или как Самайн превратился в день всех святых

Пообщаться с мертвыми и призраками, действительно, можно только единожды в году, и это — в ночь Самайна или Хэллоуина – канун Дня всех Святых. В такие мгновения грань между потусторонним и реальным миром настолько тонка, что если правильно выполнить все соответствующие традиции, то наверняка можно почувствовать присутствие рядом с собою разных сверхъестественных персонажей.

Сегодня Хэллоуин (Ночь Дикой Охоты) празднуют практически так же, как и День всех Святых. Почему? Да просто потому, что пришедшее на смену язычеству христианство также включило почитание мертвых в свой христианский календарь: День всех Святых празднуется у христиан также 1 ноября.

Автор и создатель сайта Extranorm Pro

Задать вопрос

Кельтский праздник Самайн знаменовал собой окончание сбора урожая, одновременно будучи окончанием одного сельскохозяйственного года и началом нового.

Название Самайн происходит от кельтского месяца samhain — третьего месяца осени, аналогичного ноябрю. Это же название ноября сохранилось у шотландцев и ирландцев. Новый год кельты праздновали неделю подряд. Три дня подготовки к празднику, а основное празднование приходилось на три дня (точнее, первые три ночи) месяца Самайна. Потому и сейчас время Самайна приходится на 31 октября — 2 ноября.

ВСЁ ДЛЯ ПОДГОТОВКИ К САМАЙНУ

Несмотря на то, что он возник еще в языческие времена, Самайн не утратил своего значения и с приходом христианства, только обрел новые черты — связь этого дня с темой смерти и почитанием умерших у кельтов перешла в отмечание Дня всех святых у христиан. Со временем менялись масштабы празднования, обряды и названия, но основная суть Самайна сохраняется до сих пор и, похоже, будет существовать, пока существует смена времен года.

- праздник окончания сбора урожая;

- кельтский новый год;

- праздник почитания умерших предков.

Ирландский эпос подтверждает огромное значение Самайна в жизни кельтов. Это истории о схватках и сражениях, происходивших в Самайн и менявших не только судьбу Ирландии, но и ее ландшафт. Легенда о “Последнем пире в Таре” рассказывает о том, что на короля Диармайда по каким-то причинам обрушился гнев ирландских монахов, которые пришли в Тару в дни Самайна и прокляли ее, и с тех пор оттуда ушли короли и воины, а пиры больше не устраивались.

Связь Самайна и Хэллоуина

Кельты верили, что после смерти человек оказывается в стране счастья и молодости — Тир нан Ог. Именно в конце октября, по верованиям кельтов, границы между реальным и нереальным на время исчезали, вращение вселенной приостанавливалось, открывались магические двери, и духи мертвых и создания божественные свободно перемещались в мире людей, вмешиваясь в их жизни.

Откуда взялся современный Хэллоуин, который отмечается также в ночь с 31 октября на 1 ноября?

Так как у кельтов не было ни рая, ни ада, ни соответственно демонов и чертей, то и о демонических темных культах, которые некоторые приписывают кельтским традициям, речи быть не могло. Потому и нападки на Хэллоуин как на сатанинский праздник не имеют под собой оснований. Хэллоуин никак не связан с дьяволом, но действительно имеет под собой религиозные корни, идущие от кельтского язычества. Верования кельтов включали богов и духов, фэйри и монстров, которые могли быть опасными, но не являлись силами зла. Легенды Самайна рассказывают, что феи порой в эти заманивают людей в свои холмы и леса, завораживают и заставляют заблудиться, оставшись там навсегда.

Где же связь между популярным Хэллоуином и древним Самайном?

Но мы сейчас говорим не о популярном празднике, который нынче отмечают в мегаполисах, а об изначальном, древнем праздновании Самайна, его сакральном смысле и магических практиках, которые были свойственны древним кельтам.

Эксперты магазина «Ведьмино Счастье» рекомендуют:

Дух Самайна

Вся ритуалика Самайна вращается вокруг восполняемости жизненного ресурса, смерти старого и расчищения пространства для возрождения. Легенды рассказывают о том, как призраки и существа тонкого мира собираются в ночь Самайна для своих дел.

Самайн — хорошее время для того, чтобы уединиться, разобраться в себе, отбросить старый мусор и все отжившее, все старые помехи, чтобы сделать шаг к новым возможностям. Перед Самайном становится ясно, что стало лишним и как от этого лучше избавиться, появляется возможность это сделать.

Традиции Самайна

Изначально традиции Самайна зародились в период преобладания скотоводства у кельтов. Самайн был окончанием пастбищного сезона. Стада в конце октября возвращали обратно в стойло, а часть уходила на убой и сохранение на зиму. В Самайн собирались все — простой народ, вожди, а короли устраивали пиры и соревнования.

В Самайн люди стремились расстаться с долгами прошедшего года, чтобы войти в новый год свободными. Было принято приносить дары из своих запасов, которые могли быть использованы на пиру.

Ритуальная сторона Самайна включала разжигание огня “чистым” методом — от камней или трения, чтобы этот новый огонь потом разнести по своим домам.

Другие элементы ритуала включали жертвоприношения, головы убитых врагов насаживали на ограду крепости для отпугивания темных сил. В жертву чаще приносили скот, но случались и человеческие жертвоприношения — это преступники, пленные и подобные “лишние” люди. Со временем (еще до прихода христианства) человеческие жертвы стали заменять на чучело или ритуал перепрыгивания через костер выбранной “жертвы”

Пища на Самайн

С другой стороны — это специальная ритуальная еда, которая применялась в обрядах и воспринималась как магическое средство (которое могло потом использоваться в течение года). К такой пище относился специальный хлеб, выпекаемый на углях от ритуальных костров, в других местах это были цельнозерновые лепешки. Такой хлеб нес магические целебные и защитные свойства, по куску получали не только все члены семьи, но и домашние животные, а определенная часть приносилась в дар богам, духам и душам умерших.

Разжигание священного огня

Как уже упоминалось, ритуал огня был центральным на Самайн. Как и в иные праздники Колеса года, огонь разжигался “чистый”, или “новый” — от искры либо трения, и затем разносился по всем домам. Перед этим всюду гасился огонь, и было строго-настрого запрещено его зажигать до момента, когда жрецы проведут ритуал разведения священного огня.

Затем с помощью факелов огонь разносили по всем дворам и разжигали очаги, обходили поля и деревни с факельными шествиями, таким образом защищая владения от нечистой силы, колдовства и всего вредоносного. Дым от ритуального огня помогал очистить жилище через окуривание, скот проводили через дым для очищения и исцеления, а золу и угли сохраняли как магические инструменты.

Жертвоприношения

Мы уже упоминали, что человеческие жертвоприношения у кельтов имели место, но не везде, а в основном в роли жертвы выступали пленные или преступники. Чаще в качестве жертвы использовали домашний скот.

Цель жертвоприношения ясна — это подношения даров богам, либо в качестве благодарности за помощь, либо для усмирения гнева и защиты от вредоносного вмешательства, если например речь идет о духах мертвых.

Пир Самайна

Пир в ночь Самайна был главным действом всего праздника. “Хлеба и зрелищ!” — эта фраза применима не только к римлянам. Люди рассаживались на шкуры по кругу, в центре проходили поединки и игрища, играли музыканты, а еда раздавалась на специальных деревянных или глиняных подносах. Было много мяса, рыбы, молочных продуктов, фруктов и орехов. Из напитков — вино, пиво и медовуха. Это был последний пир до следующей весны.

Самайн у разных народов

Как и у кельтов, у славян верили, что в определенные дни года граница между миром Яви и Нави стирается, и духи могут проникать между ними. Чтобы все было хорошо, живым следовало внимательно отнестись к духам мертвых, встретить их, угостить и не забыть проводить обратно. Деды отмечались несколько раз в год, в том числе и осенью.

Празднование напоминало поминки. В этот день не работали, только готовили еду. За столом нельзя было громко разговаривать, веселиться, шуметь и ходить туда-сюда. Острыми предметами не пользовались, куски ломали руками, а дверь и печку держали открытыми. По окончании ужина обязательно провожали дедов за порог со специальными словами прощания.

Эксперты магазина «Ведьмино Счастье» рекомендуют:

Современное празднование Самайна

Подготовка — уборка

Энергетическая чистка

Здесь можно провести классическую чистку помещения с помощью свечей. Мы в нашем блоге уже описывали, как это можно сделать.

Есть еще вариант чистки солью — когда соль либо рассыпается по углам, либо расставляется там в чашках и плошках со словами “Откуда пришло — туда и ушло” на ночь. Утром соль следует прокалить на сковороде по максимуму, а потом унести подальше от дома и людского присутствия, и там высыпать, по дороге не отвлекаясь ни на кого и ни на что. Остатки соли по углам, если они есть, сметаются к порогу, собираются, растворяются в воде и этой водой моется пол. Далее можно применять окуривание травами (например, полынью) вдоль периметра дома по часовой стрелке и проветривание.

Огонь Самайна

Вместо ритуального костра можно зажечь свечи, вспоминая умерших близких людей. Огонь лучше всего зажигать от искры или трения, как в старые времена. Свечу можно оставить на алтаре и на окне, чтобы помочь духам найти выход.

Приготовить лепешки, пригласить пришедших духов к трапезе. Положить немного еды на алтарь.

На стол накрывают, ставя прибор для того из близких, кто в этом году (или в последнее время) ушел из вашей жизни.

Если кто-то случайно оказался поблизости вашего застолья, его следует угостить.

Хорошо проводить трапезу в тишине или в спокойном звуковом сопровождении, без шума и танцев.

Просьбы, которые поступают в это время, лучше удовлетворять по возможности.

Медитация

Медитация в ночь Самайна может быть связана с прошлым — с пересмотром каких-то событий прошлого, себя и своих эмоций в них. Пусть события и образы сами всплывают в памяти, достаточно спокойно дышать, отпуская от себя связанные с ними чувства и эмоции. Темами медитации могут стать смерть и трансформация, изменчивость.

Цвета Самайна:

- огненный;

- рыжий;

- коричневый;

- черный;

- желтый;

- цвета огня и горящего факела.

Магия Самайна

С точки зрения магических практик ночь Самайна является одной из сильнейших в году. Духи и силы, привлекаемые к магическим ритуалам, становятся доступными. Это время, пластичное к изменениям, они отлично подходит для:

- магии очищения;

- свечной магии;

- зеркальных магических действий;

- защитной практики;

- практики прошлых жизней;

- очищения пути от препятствий;

- достижения покоя и гармонии;

- визуализации;

- мантики на картах и рунах.

Эксперты магазина «Ведьмино Счастье» рекомендуют:

Расклады для Самайна

Расклад Таро «Ворон»

Расклад основан на стихотворении Эдгара По «Ворон». Карты выкладывают в виде клюва ворона.

1 ************************

****** 2 *****************

************** 3 *********

8 ********************** 4

*************** 5 ********

******* 6 ****************

7 ************************

- 1. Любимая Ленор – Какое влияние прошлое оказывает на вашу жизнь.

- 2. Стук в дверь – На что вы должны обратить внимание.

- 3. Величественный ворон – Ваш самый глубокий страх.

- 4. Эхо из тьмы – основа ваших страхов.

- 5. Дом Посещаемым Ужасом – Почему Вы держитесь на свои страхи.

- 6. Зловещая Птица Былого – Что вы должны понять и увидеть.

- 7. Тени на Полу – Что Вы отказываетесь видеть

- 8. Каркнул Ворон: «Никогда!» – Как страхи будут влиять на вашу жизнь, если Вы не будете противостоять им.

Расклад Таро «Тыква»

******1*******

****2*3*4****

**5*******7**

***6**9**8***

- 1. Вырезать и снять крышку. Что требуется сделать в первую очередь, чтобы вы могли видеть себя яснее.

- 2. Замерзшая мякоть. Над чем надо работать до конца.

- 3. Семена. Ваш потенциал роста.

- 4. Удаляемая мякоть. Препятствия на вашем пути.

- 5. Пустота. Тень внутри. То, что вы в себе не видите.

- 6. Резьба. На что стоит обратить внимание.

- 7. Свеча. Ваш внутренний свет. Позитивные качества. Как начать светить.

- 8. Замена крышки. Как изменения отразятся в вас.

- 9. Размещение в окне. Как изменения будут оценены со стороны.

Расклад Таро «Дом с привидениями»

*****7*****

***5***6***

**3*****4**

**1**8**2**

- 1. Скелет в шкафу — секрет, который ты стараешься уберечь.

- 2. Крысы в подвале — секрет, в котором ты даже себе признаться не можешь.

- 3. Черный кот в прихожей — что заставляет тебя «выпускать когти»?

- 4. Тыква на кухне — во что или в кого ты готов «воткнуть нож» и оторваться по полной?

- 5. Привидение в спальне — Кто или что завладело твоими мыслями.

- 6. Паук в ванной — что выводит тебя из себя?

- 7. Летучие мыши на чердаке — что сводит тебя с ума?

- 8. Передняя дверь — выход из всего этого безумия… а может, вход?

Еще один расклад на Самайн Этот расклад посвящен традиционному языческому / неоязыческому европейскому празднику перехода от осени к зиме, приходящемуся на 1-2 ноября. Это период подведения итогов прошлых событий и деяний, окончательный выбор и принятие решения, прощание с тем, что отжило и подготовка к тяжелому периоду зимы. Также это время контакта мира живых с миром мертвых, с иным миром… представление о котором сохранилось по всей Европе, от кельтского Самайна и исландского альвблота (праздника почитания альвов 2 ноября) до славянского поминания дедов (2 ноября).

*****3*****6*****7*****

1**********4**********9

*****2*****5*****8*****

- 1. Урожай осени — плоды, которыми можно воспользоваться.

- 2. Неприкосновенный запас — что должно быть отложено до весны.

- 3. Испытания Зимы — испытания.

- 4. Проход между мирами — новые пути действия.

- 5. Подарки Самайна — бонусы от периода или действия.

- 6. Встреча с неведомым — с чем предстоит встретиться.

- 7. C чем проститься…

- 8. О чем помнить…

- 9. Итоги.

Желаем вам плодотворного праздника!

Чтобы понять, что же это за праздник такой — ночь 31 октября , придется нам заглянуть в глубь веков, в дохристианскую эпоху.

Земли Ирландии, Северной Франции и Англии населяли тогда племена кельтов. Их год состоял из двух частей — лета и зимы. Переход одного сезона в другой ознаменовывался праздником окончания сбора урожая, он отмечался 31 октября.

Это было, как бы, начало нового года, потому что после праздника в свои права вступала зима.Ночь на 1 ноября была особой: только в эту ночь, которую называли Самхэйн или Самайн, грань между мирами живых и мертвых стиралась.

Кельты придавали празднику большое значение и, чтобы не стать добычей мертвых наряжались в звериные головы и шкуры, гасили очаги в своих домах и собирались у костров, которые разводили кельтские жрецы — друиды.

В эту ночь приносили жертвы, делали предсказания и зажигали зимний очаг. Традиция празднования передавалась из века в век до тех пор, пока в I в. нашей эры римляне не завоевали территорию кельтов.Обращенные в христианскую веру, жители островов Ирландии и Британии, вынуждены были отказаться от многих языческих обычаев. Однако воспоминания о Самайне продолжали жить и передаваться от поколения к поколению.

А когда в IX веке Папа Григорий III перенес с 13 мая на 1 ноября празднование Дня всех святых, Самхэйн начали праздновать вновь. Предшествующая празднику ночь, в средневековом английском языке, именовалась All Hallows Even (Вечер всех святых), в сокращении — Hallowe’en, и совсем кратко Halloween.С тех пор, Хэллоуин отмечался повсеместно в лучших традициях Самхэйна, а саму ночь празднования облюбовали ведьмы, которые в эту ночь обязательно устраивали шабаш.

В Америке Хэллоуин долгое время не отмечали: там было слишком много пуритан, осуждавших шумное «языческое» веселье. Но во второй половине XIX столетия в США хлынули бедные шотландцы и ирландцы, которые привезли в Новый свет свои традиции.

Так Хэллоуин стал частью американской культуры, а благодаря Голливуду этот праздник начали отмечать по всему миру. И дело тут не столько в «проклятой поп-культуре», сколько в глубинной потребности человека «присвоить» смерть, сделать не страшной и в конце концов победить.

В эту мистическую ночь, с 31 октября на 1 ноября, принято наряжаться в костюмы представителей потусторонних сил: Дракулы, вампиров, ведьм и т.д. Преобладающие цвета костюмов – черный, фиолетовый и красный. Ужас и кровь…Таким переодеванием, да и чествованием самого праздника мы обязаны кельтским легендам.

Во многих культурах октябрь — месяц переходный: из осени в зиму. Люди до сих пор зачастую воспринимают зиму с некой неприязнью, с тоскливыми ассоциациями, что все живое умирает. Однако без смерти нет рождения, если деревья не сбросят мертвые листья, те не дадут возможность ожить им новой весной.

Так вот одна из легенд гласит, что в эту ночь (с 31 октября на 1 ноября) открываются ворота в прошлое и будущее, и получается, что в настоящем сходятся все три составные Времени. А значит, в эту ночь человек не ограничен привычной клеткой своего времени, он может осознать себя в величайшей паутине безвременной вечности.

Однако не все так просто: ворота хорошо охраняются. Герои октябрьского праздника — ведьмы, демоны, нечисть разная — это тени хранителей Врат. По эту сторону Врат они кажутся нам ужасающими, но если перейти на Ту сторону, кого увидим мы?..

Интрига и желание увидеть большее, чем мы привыкли, — в этом «соль» этой ночи…

Согласно легендам, в ночь на 1 ноября в дубовых рощах собирались духи живой природы – друиды.

Они жгли костры, приносили жертвы злым духам. Утром друиды раздавали угли от этих костров для разжигания очагов в их домах. Считалось, что огонь от угольков друидов согревал дома в течение долгой зимы и охранял дом от нечистой силы. Самым плохим предзнаменованием считался упавший подсвечник, кельты верили, что так злые духи хотели погасить огонь в доме.

А такие тени, по поверьям кельтов, появляются один раз в год, когда открыта граница между двумя мирами: миром мертвых и миром живых. Эти «тени» надо было и напугать, и задобрить.

Поэтому для отпугивания люди надевали на себя шкуры и головы зверей. А задабривали жертвоприношениями – выносили еду на улицы.

Верили, что после этого нечисть не проникнет в жилище. А еще друиды предсказывали будущее в эту ночь, глядя на пламя костра.

Все это нашло отражение в Хэллоуине. Угольки друидов – это светильник Джека.

Главный атрибут современного праздника. Изготавливают его из тыквы – делают прорези для глаз, носа, рта.

Чем страшнее будет выглядеть «Джек», тем лучше. Внутрь тыквы помещают свечу. Джек – герой ирландской легенды, который сумел перехитрить дьявола, заманив в ловушку.

За свою свободу дьявол пообещал, что не заберет душу Джека в ад. Слово свое дьявол сдержал. Но Джеку от этого лучше не стало – в рай его не приняли. С тех пор скитается Джек по белу свету, ожидая Судный день. А освещает ему путь фонарь – уголек в репе.

Поэтому раньше в Ирландии и Шотландии светильники Джека изготавливали из репы. Тыквенные светильники – заслуга американцев.

Светильник Джека принято считать оберегом и от неприкаянной души Джека, и от всей нечисти.

Хэллоуин, Самайн, Кельтский Новый год, Праздник смерти, канун Дня всех святых, Велесова Ночь — все эти праздники ведут свое начало от одной мистической ночи, когда открываются врата, соединяющие мир мёртвых с миром живых. Ночь, когда любым нечеловеческим сущностям, от фей и эльфов до сил преисподней, позволено свободно разгуливать по земле.

Ночь, когда становится возможным невозможное и странное. От кельтского праздника урожая к единственному дню в году, когда смерть становится не страшной, и даже забавной — путь, пройденный праздником в человеческом сознании, впечатляет.

В Ирландии в этот день пекут пироги, начинка которых – мелкие предметы. Если достанется кусок с монетой – разбогатеете; кусочек ткани – предостережение: не стоит сорить деньгами.

В Мексике посещают кладбища. 31 октября для мексиканцев – День мертвых.

В Румынии чествуют Дракулу. Место паломничества в этот праздник – Трансильвания.

В Америке празднуют Хэллоуин, отдавая предпочтение костюмированным вечеринкам и проведению обряда – «Пакость или подарок». Дети ходят по домам, крича: «Угощай или пожалеешь!» Откупиться можно сладостями. В противном случае «пакость» хозяевам дома обеспечена.

В России 31 октября отмечают свой праздник — Велесову Ночь. Велесова ночь – это ночь великой силы, когда истончаются границы между мирами, когда духи наших предков и тех, что будут жить после нас, предстают неотъемлемым целым, вместе с умирающим и обновляющимся миром, со стихиями и их мощью. Праздник отмечается шумными гуляниями и игрищами с огнем. А заканчивается душевными посиделками, на которых вспоминают ушедших близких, друзей, родственников, но без сожаления.

Автор Наталья Берилова

| Halloween | |

|---|---|

Carving a jack-o’-lantern is a common Halloween tradition |

|

| Also called |

|

| Observed by | Western Christians and many non-Christians around the world[1] |

| Type | Christian |

| Significance | First day of Allhallowtide |

| Celebrations | Trick-or-treating, costume parties, making jack-o’-lanterns, lighting bonfires, divination, apple bobbing, visiting haunted attractions. |

| Observances | Church services,[2] prayer,[3] fasting,[1] and vigil[4] |

| Date | 31 October |

| Related to | Samhain, Hop-tu-Naa, Calan Gaeaf, Allantide, Day of the Dead, Reformation Day, All Saints’ Day, Mischief Night (cf. vigil) |

Halloween or Hallowe’en (less commonly known as Allhalloween,[5] All Hallows’ Eve,[6] or All Saints’ Eve)[7] is a celebration observed in many countries on 31 October, the eve of the Western Christian feast of All Saints’ Day. It begins the observance of Allhallowtide,[8] the time in the liturgical year dedicated to remembering the dead, including saints (hallows), martyrs, and all the faithful departed.[9][10][11][12]

One theory holds that many Halloween traditions were influenced by Celtic harvest festivals, particularly the Gaelic festival Samhain, which are believed to have pagan roots.[13][14][15][16] Some go further and suggest that Samhain may have been Christianized as All Hallow’s Day, along with its eve, by the early Church.[17] Other academics believe Halloween began solely as a Christian holiday, being the vigil of All Hallow’s Day.[18][19][20][21] Celebrated in Ireland and Scotland for centuries, Irish and Scottish immigrants took many Halloween customs to North America in the 19th century,[22][23] and then through American influence Halloween had spread to other countries by the late 20th and early 21st century.[24][25]

Popular Halloween activities include trick-or-treating (or the related guising and souling), attending Halloween costume parties, carving pumpkins or turnips into jack-o’-lanterns, lighting bonfires, apple bobbing, divination games, playing pranks, visiting haunted attractions, telling scary stories, and watching horror or Halloween-themed films.[26] Some people practice the Christian religious observances of All Hallows’ Eve, including attending church services and lighting candles on the graves of the dead,[27][28][29] although it is a secular celebration for others.[30][31][32] Some Christians historically abstained from meat on All Hallows’ Eve, a tradition reflected in the eating of certain vegetarian foods on this vigil day, including apples, potato pancakes, and soul cakes.[33][34][35][36]

Etymology

The word Halloween or Hallowe’en («Saints’ evening»[37]) is of Christian origin;[38][39] a term equivalent to «All Hallows Eve» is attested in Old English.[40] The word hallowe[‘]en comes from the Scottish form of All Hallows’ Eve (the evening before All Hallows’ Day):[41] even is the Scots term for «eve» or «evening»,[42] and is contracted to e’en or een;[43] (All) Hallow(s) E(v)en became Hallowe’en.

History

Christian origins and historic customs

Halloween is thought to have influences from Christian beliefs and practices.[44][45] The English word ‘Halloween’ comes from «All Hallows’ Eve», being the evening before the Christian holy days of All Hallows’ Day (All Saints’ Day) on 1 November and All Souls’ Day on 2 November.[46] Since the time of the early Church,[47] major feasts in Christianity (such as Christmas, Easter and Pentecost) had vigils that began the night before, as did the feast of All Hallows’.[48][44] These three days are collectively called Allhallowtide and are a time when Western Christians honour all saints and pray for recently departed souls who have yet to reach Heaven. Commemorations of all saints and martyrs were held by several churches on various dates, mostly in springtime.[49] In 4th-century Roman Edessa it was held on 13 May, and on 13 May 609, Pope Boniface IV re-dedicated the Pantheon in Rome to «St Mary and all martyrs».[50] This was the date of Lemuria, an ancient Roman festival of the dead.[51]

In the 8th century, Pope Gregory III (731–741) founded an oratory in St Peter’s for the relics «of the holy apostles and of all saints, martyrs and confessors».[44][52] Some sources say it was dedicated on 1 November,[53] while others say it was on Palm Sunday in April 732.[54][55] By 800, there is evidence that churches in Ireland[56] and Northumbria were holding a feast commemorating all saints on 1 November.[57] Alcuin of Northumbria, a member of Charlemagne’s court, may then have introduced this 1 November date in the Frankish Empire.[58] In 835, it became the official date in the Frankish Empire.[57] Some suggest this was due to Celtic influence, while others suggest it was a Germanic idea,[57] although it is claimed that both Germanic and Celtic-speaking peoples commemorated the dead at the beginning of winter.[59] They may have seen it as the most fitting time to do so, as it is a time of ‘dying’ in nature.[57][59] It is also suggested the change was made on the «practical grounds that Rome in summer could not accommodate the great number of pilgrims who flocked to it», and perhaps because of public health concerns over Roman Fever, which claimed a number of lives during Rome’s sultry summers.[60][44]

On All Hallows’ Eve, Christians in some parts of the world visit cemeteries to pray and place flowers and candles on the graves of their loved ones.[61] Top: Christians in Bangladesh lighting candles on the headstone of a relative. Bottom: Lutheran Christians praying and lighting candles in front of the central crucifix of a graveyard.

By the end of the 12th century, the celebration had become known as the holy days of obligation in Western Christianity and involved such traditions as ringing church bells for souls in purgatory. It was also «customary for criers dressed in black to parade the streets, ringing a bell of mournful sound and calling on all good Christians to remember the poor souls».[62] The Allhallowtide custom of baking and sharing soul cakes for all christened souls,[63] has been suggested as the origin of trick-or-treating.[64] The custom dates back at least as far as the 15th century[65] and was found in parts of England, Wales, Flanders, Bavaria and Austria.[66] Groups of poor people, often children, would go door-to-door during Allhallowtide, collecting soul cakes, in exchange for praying for the dead, especially the souls of the givers’ friends and relatives. This was called «souling».[65][67][68] Soul cakes were also offered for the souls themselves to eat,[66] or the ‘soulers’ would act as their representatives.[69] As with the Lenten tradition of hot cross buns, soul cakes were often marked with a cross, indicating they were baked as alms.[70] Shakespeare mentions souling in his comedy The Two Gentlemen of Verona (1593).[71] While souling, Christians would carry «lanterns made of hollowed-out turnips», which could have originally represented souls of the dead;[72][73] jack-o’-lanterns were used to ward off evil spirits.[74][75] On All Saints’ and All Souls’ Day during the 19th century, candles were lit in homes in Ireland,[76] Flanders, Bavaria, and in Tyrol, where they were called «soul lights»,[77] that served «to guide the souls back to visit their earthly homes».[78] In many of these places, candles were also lit at graves on All Souls’ Day.[77] In Brittany, libations of milk were poured on the graves of kinfolk,[66] or food would be left overnight on the dinner table for the returning souls;[77] a custom also found in Tyrol and parts of Italy.[79][77]

Christian minister Prince Sorie Conteh linked the wearing of costumes to the belief in vengeful ghosts: «It was traditionally believed that the souls of the departed wandered the earth until All Saints’ Day, and All Hallows’ Eve provided one last chance for the dead to gain vengeance on their enemies before moving to the next world. In order to avoid being recognized by any soul that might be seeking such vengeance, people would don masks or costumes».[80] In the Middle Ages, churches in Europe that were too poor to display relics of martyred saints at Allhallowtide let parishioners dress up as saints instead.[81][82] Some Christians observe this custom at Halloween today.[83] Lesley Bannatyne believes this could have been a Christianization of an earlier pagan custom.[84] Many Christians in mainland Europe, especially in France, believed «that once a year, on Hallowe’en, the dead of the churchyards rose for one wild, hideous carnival» known as the danse macabre, which was often depicted in church decoration.[85] Christopher Allmand and Rosamond McKitterick write in The New Cambridge Medieval History that the danse macabre urged Christians «not to forget the end of all earthly things».[86] The danse macabre was sometimes enacted in European village pageants and court masques, with people «dressing up as corpses from various strata of society», and this may be the origin of Halloween costume parties.[87][88][89][72]

In Britain, these customs came under attack during the Reformation, as Protestants berated purgatory as a «popish» doctrine incompatible with the Calvinist doctrine of predestination. State-sanctioned ceremonies associated with the intercession of saints and prayer for souls in purgatory were abolished during the Elizabethan reform, though All Hallow’s Day remained in the English liturgical calendar to «commemorate saints as godly human beings».[90] For some Nonconformist Protestants, the theology of All Hallows’ Eve was redefined; «souls cannot be journeying from Purgatory on their way to Heaven, as Catholics frequently believe and assert. Instead, the so-called ghosts are thought to be in actuality evil spirits».[91] Other Protestants believed in an intermediate state known as Hades (Bosom of Abraham).[92] In some localities, Catholics and Protestants continued souling, candlelit processions, or ringing church bells for the dead;[46][93] the Anglican church eventually suppressed this bell-ringing.[94] Mark Donnelly, a professor of medieval archaeology, and historian Daniel Diehl write that «barns and homes were blessed to protect people and livestock from the effect of witches, who were believed to accompany the malignant spirits as they traveled the earth».[95] After 1605, Hallowtide was eclipsed in England by Guy Fawkes Night (5 November), which appropriated some of its customs.[96] In England, the ending of official ceremonies related to the intercession of saints led to the development of new, unofficial Hallowtide customs. In 18th–19th century rural Lancashire, Catholic families gathered on hills on the night of All Hallows’ Eve. One held a bunch of burning straw on a pitchfork while the rest knelt around him, praying for the souls of relatives and friends until the flames went out. This was known as teen’lay.[97] There was a similar custom in Hertfordshire, and the lighting of ‘tindle’ fires in Derbyshire.[98] Some suggested these ‘tindles’ were originally lit to «guide the poor souls back to earth».[99] In Scotland and Ireland, old Allhallowtide customs that were at odds with Reformed teaching were not suppressed as they «were important to the life cycle and rites of passage of local communities» and curbing them would have been difficult.[22]

In parts of Italy until the 15th century, families left a meal out for the ghosts of relatives, before leaving for church services.[79] In 19th-century Italy, churches staged «theatrical re-enactments of scenes from the lives of the saints» on All Hallow’s Day, with «participants represented by realistic wax figures».[79] In 1823, the graveyard of Holy Spirit Hospital in Rome presented a scene in which bodies of those who recently died were arrayed around a wax statue of an angel who pointed upward towards heaven.[79] In the same country, «parish priests went house-to-house, asking for small gifts of food which they shared among themselves throughout that night».[79] In Spain, they continue to bake special pastries called «bones of the holy» (Spanish: Huesos de Santo) and set them on graves.[100] At cemeteries in Spain and France, as well as in Latin America, priests lead Christian processions and services during Allhallowtide, after which people keep an all night vigil.[101] In 19th-century San Sebastián, there was a procession to the city cemetery at Allhallowtide, an event that drew beggars who «appeal[ed] to the tender recollectons of one’s deceased relations and friends» for sympathy.[102]

Gaelic folk influence

Today’s Halloween customs are thought to have been influenced by folk customs and beliefs from the Celtic-speaking countries, some of which are believed to have pagan roots.[103] Jack Santino, a folklorist, writes that «there was throughout Ireland an uneasy truce existing between customs and beliefs associated with Christianity and those associated with religions that were Irish before Christianity arrived».[104] The origins of Halloween customs are typically linked to the Gaelic festival Samhain.[105]

Samhain is one of the quarter days in the medieval Gaelic calendar and has been celebrated on 31 October – 1 November[106] in Ireland, Scotland and the Isle of Man.[107][108] A kindred festival has been held by the Brittonic Celts, called Calan Gaeaf in Wales, Kalan Gwav in Cornwall and Kalan Goañv in Brittany; a name meaning «first day of winter». For the Celts, the day ended and began at sunset; thus the festival begins the evening before 1 November by modern reckoning.[109] Samhain is mentioned in some of the earliest Irish literature. The names have been used by historians to refer to Celtic Halloween customs up until the 19th century,[110] and are still the Gaelic and Welsh names for Halloween.

Snap-Apple Night, painted by Daniel Maclise in 1833, shows people feasting and playing divination games on Halloween in Ireland.[111]

Samhain marked the end of the harvest season and beginning of winter or the ‘darker half’ of the year.[112][113] It was seen as a liminal time, when the boundary between this world and the Otherworld thinned. This meant the Aos Sí, the ‘spirits’ or ‘fairies’, could more easily come into this world and were particularly active.[114][115] Most scholars see them as «degraded versions of ancient gods […] whose power remained active in the people’s minds even after they had been officially replaced by later religious beliefs».[116] They were both respected and feared, with individuals often invoking the protection of God when approaching their dwellings.[117][118] At Samhain, the Aos Sí were appeased to ensure the people and livestock survived the winter. Offerings of food and drink, or portions of the crops, were left outside for them.[119][120][121] The souls of the dead were also said to revisit their homes seeking hospitality.[122] Places were set at the dinner table and by the fire to welcome them.[123] The belief that the souls of the dead return home on one night of the year and must be appeased seems to have ancient origins and is found in many cultures.[66] In 19th century Ireland, «candles would be lit and prayers formally offered for the souls of the dead. After this the eating, drinking, and games would begin».[124]

Throughout Ireland and Britain, especially in the Celtic-speaking regions, the household festivities included divination rituals and games intended to foretell one’s future, especially regarding death and marriage.[125] Apples and nuts were often used, and customs included apple bobbing, nut roasting, scrying or mirror-gazing, pouring molten lead or egg whites into water, dream interpretation, and others.[126] Special bonfires were lit and there were rituals involving them. Their flames, smoke, and ashes were deemed to have protective and cleansing powers.[112] In some places, torches lit from the bonfire were carried sunwise around homes and fields to protect them.[110] It is suggested the fires were a kind of imitative or sympathetic magic – they mimicked the Sun and held back the decay and darkness of winter.[123][127][128] They were also used for divination and to ward off evil spirits.[74] In Scotland, these bonfires and divination games were banned by the church elders in some parishes.[129] In Wales, bonfires were also lit to «prevent the souls of the dead from falling to earth».[130] Later, these bonfires «kept away the devil».[131]

A plaster cast of a traditional Irish Halloween turnip (rutabaga) lantern on display in the Museum of Country Life, Ireland[132]

From at least the 16th century,[133] the festival included mumming and guising in Ireland, Scotland, the Isle of Man and Wales.[134] This involved people going house-to-house in costume (or in disguise), usually reciting verses or songs in exchange for food. It may have originally been a tradition whereby people impersonated the Aos Sí, or the souls of the dead, and received offerings on their behalf, similar to ‘souling’. Impersonating these beings, or wearing a disguise, was also believed to protect oneself from them.[135] In parts of southern Ireland, the guisers included a hobby horse. A man dressed as a Láir Bhán (white mare) led youths house-to-house reciting verses – some of which had pagan overtones – in exchange for food. If the household donated food it could expect good fortune from the ‘Muck Olla’; not doing so would bring misfortune.[136] In Scotland, youths went house-to-house with masked, painted or blackened faces, often threatening to do mischief if they were not welcomed.[134] F. Marian McNeill suggests the ancient festival included people in costume representing the spirits, and that faces were marked or blackened with ashes from the sacred bonfire.[133] In parts of Wales, men went about dressed as fearsome beings called gwrachod.[134] In the late 19th and early 20th century, young people in Glamorgan and Orkney cross-dressed.[134]

Elsewhere in Europe, mumming was part of other festivals, but in the Celtic-speaking regions, it was «particularly appropriate to a night upon which supernatural beings were said to be abroad and could be imitated or warded off by human wanderers».[134] From at least the 18th century, «imitating malignant spirits» led to playing pranks in Ireland and the Scottish Highlands. Wearing costumes and playing pranks at Halloween did not spread to England until the 20th century.[134] Pranksters used hollowed-out turnips or mangel wurzels as lanterns, often carved with grotesque faces.[134] By those who made them, the lanterns were variously said to represent the spirits,[134] or used to ward off evil spirits.[137][138] They were common in parts of Ireland and the Scottish Highlands in the 19th century,[134] as well as in Somerset (see Punkie Night). In the 20th century they spread to other parts of Britain and became generally known as jack-o’-lanterns.[134]

Spread to North America

Lesley Bannatyne and Cindy Ott write that Anglican colonists in the southern United States and Catholic colonists in Maryland «recognized All Hallow’s Eve in their church calendars»,[140][141] although the Puritans of New England strongly opposed the holiday, along with other traditional celebrations of the established Church, including Christmas.[142] Almanacs of the late 18th and early 19th century give no indication that Halloween was widely celebrated in North America.[22]

It was not until after mass Irish and Scottish immigration in the 19th century that Halloween became a major holiday in America.[22] Most American Halloween traditions were inherited from the Irish and Scots,[23][143] though «In Cajun areas, a nocturnal Mass was said in cemeteries on Halloween night. Candles that had been blessed were placed on graves, and families sometimes spent the entire night at the graveside».[144] Originally confined to these immigrant communities, it was gradually assimilated into mainstream society and was celebrated coast to coast by people of all social, racial, and religious backgrounds by the early 20th century.[145] Then, through American influence, these Halloween traditions spread to many other countries by the late 20th and early 21st century, including to mainland Europe and some parts of the Far East.[24][25][146]

Symbols

Development of artifacts and symbols associated with Halloween formed over time. Jack-o’-lanterns are traditionally carried by guisers on All Hallows’ Eve in order to frighten evil spirits.[73][147] There is a popular Irish Christian folktale associated with the jack-o’-lantern,[148] which in folklore is said to represent a «soul who has been denied entry into both heaven and hell»:[149]

On route home after a night’s drinking, Jack encounters the Devil and tricks him into climbing a tree. A quick-thinking Jack etches the sign of the cross into the bark, thus trapping the Devil. Jack strikes a bargain that Satan can never claim his soul. After a life of sin, drink, and mendacity, Jack is refused entry to heaven when he dies. Keeping his promise, the Devil refuses to let Jack into hell and throws a live coal straight from the fires of hell at him. It was a cold night, so Jack places the coal in a hollowed out turnip to stop it from going out, since which time Jack and his lantern have been roaming looking for a place to rest.[150]

In Ireland and Scotland, the turnip has traditionally been carved during Halloween,[151][152] but immigrants to North America used the native pumpkin, which is both much softer and much larger, making it easier to carve than a turnip.[151] The American tradition of carving pumpkins is recorded in 1837[153] and was originally associated with harvest time in general, not becoming specifically associated with Halloween until the mid-to-late 19th century.[154]

The modern imagery of Halloween comes from many sources, including Christian eschatology, national customs, works of Gothic and horror literature (such as the novels Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus and Dracula) and classic horror films such as Frankenstein (1931) and The Mummy (1932).[155][156] Imagery of the skull, a reference to Golgotha in the Christian tradition, serves as «a reminder of death and the transitory quality of human life» and is consequently found in memento mori and vanitas compositions;[157] skulls have therefore been commonplace in Halloween, which touches on this theme.[158] Traditionally, the back walls of churches are «decorated with a depiction of the Last Judgment, complete with graves opening and the dead rising, with a heaven filled with angels and a hell filled with devils», a motif that has permeated the observance of this triduum.[159] One of the earliest works on the subject of Halloween is from Scottish poet John Mayne, who, in 1780, made note of pranks at Halloween; «What fearfu’ pranks ensue!», as well as the supernatural associated with the night, «bogles» (ghosts),[160] influencing Robert Burns’ «Halloween» (1785).[161] Elements of the autumn season, such as pumpkins, corn husks, and scarecrows, are also prevalent. Homes are often decorated with these types of symbols around Halloween. Halloween imagery includes themes of death, evil, and mythical monsters.[162] Black cats, which have been long associated with witches, are also a common symbol of Halloween. Black, orange, and sometimes purple are Halloween’s traditional colors.[163]

Trick-or-treating and guising

Trick-or-treaters in Sweden

Trick-or-treating is a customary celebration for children on Halloween. Children go in costume from house to house, asking for treats such as candy or sometimes money, with the question, «Trick or treat?» The word «trick» implies a «threat» to perform mischief on the homeowners or their property if no treat is given.[64] The practice is said to have roots in the medieval practice of mumming, which is closely related to souling.[164] John Pymm wrote that «many of the feast days associated with the presentation of mumming plays were celebrated by the Christian Church.»[165] These feast days included All Hallows’ Eve, Christmas, Twelfth Night and Shrove Tuesday.[166][167] Mumming practiced in Germany, Scandinavia and other parts of Europe,[168] involved masked persons in fancy dress who «paraded the streets and entered houses to dance or play dice in silence».[169]

Girl in a Halloween costume in 1928, Ontario, Canada, the same province where the Scottish Halloween custom of guising was first recorded in North America

In England, from the medieval period,[170] up until the 1930s,[171] people practiced the Christian custom of souling on Halloween, which involved groups of soulers, both Protestant and Catholic,[93] going from parish to parish, begging the rich for soul cakes, in exchange for praying for the souls of the givers and their friends.[67] In the Philippines, the practice of souling is called Pangangaluluwa and is practiced on All Hallow’s Eve among children in rural areas.[26] People drape themselves in white cloths to represent souls and then visit houses, where they sing in return for prayers and sweets.[26]

In Scotland and Ireland, guising – children disguised in costume going from door to door for food or coins – is a traditional Halloween custom.[172] It is recorded in Scotland at Halloween in 1895 where masqueraders in disguise carrying lanterns made out of scooped out turnips, visit homes to be rewarded with cakes, fruit, and money.[152][173] In Ireland, the most popular phrase for kids to shout (until the 2000s) was «Help the Halloween Party».[172] The practice of guising at Halloween in North America was first recorded in 1911, where a newspaper in Kingston, Ontario, Canada, reported children going «guising» around the neighborhood.[174]

American historian and author Ruth Edna Kelley of Massachusetts wrote the first book-length history of Halloween in the US; The Book of Hallowe’en (1919), and references souling in the chapter «Hallowe’en in America».[175] In her book, Kelley touches on customs that arrived from across the Atlantic; «Americans have fostered them, and are making this an occasion something like what it must have been in its best days overseas. All Halloween customs in the United States are borrowed directly or adapted from those of other countries».[176]

While the first reference to «guising» in North America occurs in 1911, another reference to ritual begging on Halloween appears, place unknown, in 1915, with a third reference in Chicago in 1920.[177] The earliest known use in print of the term «trick or treat» appears in 1927, in the Blackie Herald, of Alberta, Canada.[178]

The thousands of Halloween postcards produced between the turn of the 20th century and the 1920s commonly show children but not trick-or-treating.[179] Trick-or-treating does not seem to have become a widespread practice in North America until the 1930s, with the first US appearances of the term in 1934,[180] and the first use in a national publication occurring in 1939.[181]

A popular variant of trick-or-treating, known as trunk-or-treating (or Halloween tailgating), occurs when «children are offered treats from the trunks of cars parked in a church parking lot», or sometimes, a school parking lot.[100][182] In a trunk-or-treat event, the trunk (boot) of each automobile is decorated with a certain theme,[183] such as those of children’s literature, movies, scripture, and job roles.[184] Trunk-or-treating has grown in popularity due to its perception as being more safe than going door to door, a point that resonates well with parents, as well as the fact that it «solves the rural conundrum in which homes [are] built a half-mile apart».[185][186]

Costumes

Halloween costumes were traditionally modeled after figures such as vampires, ghosts, skeletons, scary looking witches, and devils.[64] Over time, the costume selection extended to include popular characters from fiction, celebrities, and generic archetypes such as ninjas and princesses.

Halloween shop in Derry, Northern Ireland, selling masks

Dressing up in costumes and going «guising» was prevalent in Scotland and Ireland at Halloween by the late 19th century.[152] A Scottish term, the tradition is called «guising» because of the disguises or costumes worn by the children.[173] In Ireland and Scotland, the masks are known as ‘false faces’,[38][187] a term recorded in Ayr, Scotland in 1890 by a Scot describing guisers: «I had mind it was Halloween . . . the wee callans were at it already, rinning aboot wi’ their fause-faces (false faces) on and their bits o’ turnip lanthrons (lanterns) in their haun (hand)».[38] Costuming became popular for Halloween parties in the US in the early 20th century, as often for adults as for children, and when trick-or-treating was becoming popular in Canada and the US in the 1920s and 1930s.[178][188]

Eddie J. Smith, in his book Halloween, Hallowed is Thy Name, offers a religious perspective to the wearing of costumes on All Hallows’ Eve, suggesting that by dressing up as creatures «who at one time caused us to fear and tremble», people are able to poke fun at Satan «whose kingdom has been plundered by our Saviour». Images of skeletons and the dead are traditional decorations used as memento mori.[189][190]

«Trick-or-Treat for UNICEF» is a fundraising program to support UNICEF,[64] a United Nations Programme that provides humanitarian aid to children in developing countries. Started as a local event in a Northeast Philadelphia neighborhood in 1950 and expanded nationally in 1952, the program involves the distribution of small boxes by schools (or in modern times, corporate sponsors like Hallmark, at their licensed stores) to trick-or-treaters, in which they can solicit small-change donations from the houses they visit. It is estimated that children have collected more than $118 million for UNICEF since its inception. In Canada, in 2006, UNICEF decided to discontinue their Halloween collection boxes, citing safety and administrative concerns; after consultation with schools, they instead redesigned the program.[191][192]

The yearly New York’s Village Halloween Parade was begun in 1974; it is the world’s largest Halloween parade and America’s only major nighttime parade, attracting more than 60,000 costumed participants, two million spectators, and a worldwide television audience.[193]

Since the late 2010s, ethnic stereotypes as costumes have increasingly come under scrutiny in the United States.[194] Such and other potentially offensive costumes have been met with increasing public disapproval.[195][196]

Pet costumes

According to a 2018 report from the National Retail Federation, 30 million Americans will spend an estimated $480 million on Halloween costumes for their pets in 2018. This is up from an estimated $200 million in 2010. The most popular costumes for pets are the pumpkin, followed by the hot dog, and the bumblebee in third place.[197]

Games and other activities

In this 1904 Halloween greeting card, divination is depicted: the young woman looking into a mirror in a darkened room hopes to catch a glimpse of her future husband.

There are several games traditionally associated with Halloween. Some of these games originated as divination rituals or ways of foretelling one’s future, especially regarding death, marriage and children. During the Middle Ages, these rituals were done by a «rare few» in rural communities as they were considered to be «deadly serious» practices.[198] In recent centuries, these divination games have been «a common feature of the household festivities» in Ireland and Britain.[125] They often involve apples and hazelnuts. In Celtic mythology, apples were strongly associated with the Otherworld and immortality, while hazelnuts were associated with divine wisdom.[199] Some also suggest that they derive from Roman practices in celebration of Pomona.[64]

Children bobbing for apples at Hallowe’en

The following activities were a common feature of Halloween in Ireland and Britain during the 17th–20th centuries. Some have become more widespread and continue to be popular today.