День Святого Антония в Испании Events

Сегодня в Испании отмечали день покровителя домашних животных святого Антония. Святой Антоний прославился тем, что стал одним из первых, кто опробовал аскетическую жизнь в пустыне, будучи полностью оторванным от цивилизации.

День Святого Антония — церковный праздник, который проходит в дни католического Карнавала. В этот день священники благословляют домашний скот, который хозяева приводят к церкви. По всей стране проходят праздничные процессии, на которых хозяева в сопровождении своих собак, кошек, лошадей, ослов, красочно украшенных лентами, плюмажами и колокольчиками, ходят вокруг храма перед тем, как священник с паперти благословит их.

В деревне Сан-Бартоломео существует обряд, имеющий многовековую традицию — жители деревни, мужчины и женщины, скачут на лошадях через пылающий костер.

Photo: Susana Vera / Reuters

День Святого Антония в деревне Сан-Бартоломео (Photo: Raúl Sanchidrián / EFE)

Празднества сопровождаются «братскими пиршествами». По вечерам у костров и жаровней, выставленных прямо на улице, прохожим раздают куски мяса и колбасы, которые тут же обильно запиваются вином.

Прежде такие праздники устраивались только 17 января. Сейчас они растягиваются на несколько дней, так как настоящее время в Испании не хватает католического духовенства и священникам требуется время, чтобы объездить все храмы и благословить домашних животных.

17.01.08

19:20

автор: grishin

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

|

Saint Bartholomew the Apostle |

|

|---|---|

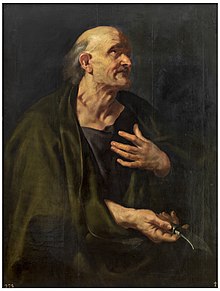

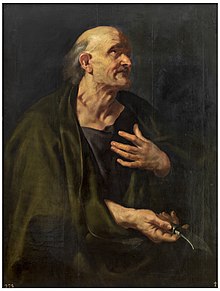

St Bartholomew (c. 1611) by Peter Paul Rubens |

|

| Apostle and Martyr | |

| Born | c. 1 AD Cana, Galilee, Roman Empire |

| Died | c. 69 AD Albanopolis, Kingdom of Armenia[1][2][3][4] |

| Venerated in | All Christian denominations which venerate saints |

| Major shrine | Saint Bartholomew Monastery in historical Armenia, Saint Bartholomew Church in Baku, Relics at Basilica of San Bartolomeo in Benevento, Italy, Holy Myrrhbearers Cathedral in Baku, Azerbaijan, Saint Bartholomew-on-the-Tiber Church, Rome, Canterbury Cathedral, the Cathedrals in Frankfurt and Plzeň, and San Bartolomeo Cathedral in Lipari |

| Feast | 24 August (Western Christianity) 11 June (with St. Barnabas) (Eastern Christianity) 25 August (Translation of relics, with Saint Titus) (Eastern Christianity) |

| Attributes | Knife and his flayed skin, Red Martyrdom |

| Patronage | Armenia; Azerbaijan; bookbinders; butchers; Florentine cheese and salt merchants; Gambatesa, Italy; Catbalogan, Samar; Magalang, Pampanga; Malabon, Metro Manila; Nagcarlan, Laguna; San Leonardo, Nueva Ecija, Philippines; Għargħur, Malta; leather workers; neurological diseases; skin diseases; dermatology; plasterers; shoemakers; curriers; tanners; trappers; twitching; whiteners; Los Cerricos (Spain); Barva, Costa Rica |

Bartholomew (Aramaic: ܒܪ ܬܘܠܡܝ; Ancient Greek: Βαρθολομαῖος, romanized: Bartholomaîos; Latin: Bartholomaeus; Armenian: Բարթողիմէոս; Coptic: ⲃⲁⲣⲑⲟⲗⲟⲙⲉⲟⲥ; Hebrew: בר-תולמי, romanized: bar-Tôlmay; Arabic: بَرثُولَماوُس, romanized: Barthulmāwus) was one of the twelve apostles of Jesus according to the New Testament. Some identify Bartholomew as Nathanael or Nathaniel,[5] who appears in the Gospel of John (1:45-51; cf. 21:2), although this is not supported by the Gospels, Acts, or any early, reliable Christian tradition.[6]

New Testament references[edit]

The name Bartholomew (Greek: Βαρθολομαῖος, transliterated «Bartholomaios») comes from the Imperial Aramaic: בר-תולמי bar-Tolmay «son of Talmai»[7] or «son of the furrows».[7] Bartholomew is listed in the New Testament among the Twelve Apostles of Jesus in the three Synoptic Gospels: Matthew,[10:1–4] Mark,[3:13–19] and Luke,[6:12–16] and in Acts of the Apostles.[1:13]

Tradition[edit]

Eusebius of Caesarea’s Ecclesiastical History (5:10) states that after the Ascension, Bartholomew went on a missionary tour to India, where he left behind a copy of the Gospel of Matthew. Tradition records him as serving as a missionary in Mesopotamia and Parthia, as well as Lycaonia and Ethiopia in other accounts.[8]

Popular traditions say that Bartholomew preached the Gospel in India and then went to Greater Armenia.[7]

Mission to India[edit]

Two ancient testimonies exist about the mission of Saint Bartholomew in India. These are of Eusebius of Caesarea (early 4th century) and of Saint Jerome (late 4th century). Both of these refer to this tradition while speaking of the reported visit of Saint Pantaenus to India in the 2nd century.[9] The studies of Fr A.C. Perumalil SJ and Moraes hold that the Bombay region on the Konkan coast, a region which may have been known as the ancient city Kalyan, was the field of Saint Bartholomew’s missionary activities. Previously the consensus among scholars was against the apostolate of Saint Bartholomew the Apostle in India. The majority of the scholars are skeptical about the mission of Saint Bartholomew the Apostle in India. Stallings (1703), Neander (1853), Hunter (1886), Rae (1892), Zaleski (1915) are the authors who supported the Apostolate of Saint Bartholomew in India. Scholars such as Sollerius (1669), Carpentier (1822), Harnack (1903), Medlycott (1905), Mingana (1926), Thurston (1933), Attwater (1935), etc. do not support this hypothesis. The main argument is that the India that Eusebius and Jerome refer to should be identified as Ethiopia or Arabia Felix.[9]

In Armenia[edit]

Along with his fellow apostle Jude «Thaddeus», Bartholomew is reputed to have brought Christianity to Armenia in the 1st century. Thus, both saints are considered the patron saints of the Armenian Apostolic Church. According to tradition, he is the 2nd Catholicos-Patriarch of the Armenian Apostolic Church .[10]

Christian tradition has three stories about Bartholomew’s death: «One speaks of his being kidnapped, beaten unconscious, and cast into the sea to drown. Another account states that he was crucified upside down, and another says that he was skinned alive and beheaded in Albac or Albanopolis, near Baku, Azerbaijan[11] or Başkale, Turkey.»[12]

The most prominent tradition has it that Apostle Bartholomew was executed in Albanopolis in Armenia. According to popular hagiography, the apostle was flayed alive and beheaded. According to other accounts, he was crucified upside down (head downward) like St. Peter. He is said to have been martyred for having converted Polymius, the king of Armenia, to Christianity. Enraged by the monarch’s conversion, and fearing a Roman backlash, King Polymius’s brother, Prince Astyages, ordered Bartholomew’s torture and execution, which Bartholomew endured. However, there are no records of any Armenian king of the Arsacid dynasty of Armenia with the name «Polymius». Current scholarship indicates that Bartholomew is more likely to have died in Kalyan in India, where there was an official named «Polymius».[13][14]

The 13th-century Saint Bartholomew Monastery was a prominent Armenian monastery constructed at the site of the martyrdom of Apostle Bartholomew in Vaspurakan, Greater Armenia (now in southeastern Turkey).[15]

In Azerbaijan[edit]

Saint Bartholomew Church (Baku) was built in 1892 at the expense of donations from the local Christian population on the site where the Apostle Bartholomew was believed to have been killed.[16] It is believed that in this area near the Maiden Tower, the apostle Bartholomew was crucified and killed by pagans around 71 AD.[17] The church continued to operate until 1936, then it was demolished as a part of the Soviet campaign against religion.

Veneration[edit]

According to the Synaxarium of the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria, Bartholomew’s martyrdom is commemorated on the first day of the Coptic calendar (i.e., the first day of the month of Thout), which currently falls on 11 September (corresponding to 29 August in the Julian calendar). Eastern Christianity honours him on June 11 and the Catholic Church honours him on 24 August.

Bartholomew the Apostle is remembered in the Church of England with a Festival on 24 August.[18][19] The Armenian Apostolic Church honours Saint Bartholomew and Saint Thaddeus as its patron saints.

The Catholic Church of Azerbaijan[20] and Russian Orthodox Eparchy of Baku and Azerbaijan[21] honour Saint Bartholomew as the Patron Saint of Azerbaijan and regard him as the bringer of Christianity to the region of Caucasian Albania, modern-day Azerbaijan. The feast day of the Apostle is solemnly celebrated therein on 24 August by the Christian laity and the Church officials alike.[22]

Relics[edit]

Altar of San Bartolomeo Basilica in Benevento, containing the relics of Bartholomew

The 6th-century writer Theodorus Lector averred that in about 507, the Byzantine emperor Anastasius I Dicorus gave the body of Bartholomew to the city of Daras, in Mesopotamia, which he had recently refounded.[23] The existence of relics at Lipari, a small island off the coast of Sicily, in the part of Italy controlled from Constantinople, was explained by Gregory of Tours[24] by his body having miraculously washed up there. A large piece of his skin and many bones that were kept in the Cathedral of St. Bartholomew in Lipari, were translated to Benevento in 838, where they are still kept now in the Basilica San Bartolomeo. A portion of the relics was given in 983 by Otto II, Holy Roman Emperor, to Rome, where it is conserved at San Bartolomeo all’Isola, which was founded on the temple of Asclepius, an important Roman medical centre. This association with medicine in course of time caused Bartholomew’s name to become associated with medicine and hospitals.[25] Some of Bartholomew’s alleged skull was transferred to the Frankfurt Cathedral, while an arm was venerated in Canterbury Cathedral.[citation needed]

In 2003, Patriarch Bartholomew I of Constantinople brought some of the remains of St. Bartholomew to Baku as a gift to Azerbaijani Christians, and these remains are now kept in the Holy Myrrhbearers Cathedral.[26]

Miracles[edit]

Saint Bartholomew has been credited with several miracles.[27]

Art and literature[edit]

In artistic depictions, Bartholomew is most commonly depicted holding his flayed skin and the knife with which he was skinned.

St. Bartholomew is the most prominent flayed Christian martyr;[28] During the 16th century, images of the flaying of Bartholomew were so popular that it came to signify the saint in works of art.[29] Consequently, Saint Bartholomew is most often represented being skinned alive.[30] Symbols associated with the saint include knives and his own skin, which Bartholomew holds or drapes around his body.[29] Similarly, the ancient herald of Bartholomew is known by «flaying knives with silver blades and gold handles, on a red field.»[31] As in Michelangelo’s Last Judgement, the saint is often depicted with both the knife and his skin.[30] Representations of Bartholomew with a chained demon are common in Spanish painting.[29]

Saint Bartholomew is often depicted in lavish medieval manuscripts.[32] Manuscripts, which are literally made from flayed and manipulated skin, hold a strong visual and cognitive association with the saint during the medieval period and can also be seen as depicting book production.[32] Florentine artist Pacino di Bonaguida, depicts his martyrdom in a complex and striking composition in his Laudario of Sant’Agnese, a book of Italian Hymns produced for the Compagnia di Sant’Agnese c. 1340.[28] In the five scene, narrative based image three torturers flay Bartholomew’s legs and arms as he is immobilised and chained to a gate. On the right, the saint wears his own flesh tied around his neck while he kneels in prayer before a rock, his severed head fallen to the ground. Another example includes the Flaying of St. Bartholomew in the Luttrell Psalter c.1325–1340. Bartholomew is depicted on a surgical table, surrounded by tormentors while he is flayed with golden knives.[33]

Reliquary shutters with the Martyrdoms of St. Francis, St. Claire, St. Bartholomew, and St. Catherine of Alexandria by Guido da Siena

Due to the nature of his martyrdom, Bartholomew is the patron saint of tanners, plasterers, tailors, leatherworkers, bookbinders, farmers, housepainters, butchers, and glove makers.[34][29] In works of art the saint has been depicted being skinned by tanners, as in Guido da Siena’s reliquary shutters with the Martyrdoms of St. Francis, St. Claire, St. Bartholomew, and St. Catherine of Alexandria.[35] Popular in Florence and other areas in Tuscany, the saint also came to be associated with salt, oil, and cheese merchants.[36]

Although Bartholomew’s death is commonly depicted in artworks of a religious nature, his story has also been used to represent anatomical depictions of the human body devoid of flesh. An example of this can be seen in Marco d’Agrate’s St Bartholomew Flayed (1562) where Bartholomew is depicted wrapped in his own skin with every muscle, vein and tendon clearly visible, acting as a clear description of the muscles and structure of the human body.[37]

The Martyrdom of Saint Bartholomew (1634) by Jusepe de Ribera depicts Bartholomew’s final moments before being flayed alive. The viewer is meant to empathize with Bartholomew, whose body seemingly bursts through the surface of the canvas, and whose outstretched arms embrace a mystical light that illuminates his flesh. His piercing eyes, open mouth, and petitioning left hand bespeak an intense communion with the divine; yet this same hand draws our attention to the instruments of his torture, symbolically positioned in the shape of a cross. Transfixed by Bartholomew’s active faith, the executioner seems to have stopped short in his actions, and his furrowed brow and partially illuminated face suggest a moment of doubt, with the possibility of conversion.[38] The representation of Bartholomew’s demise in the National Gallery painting differs significantly from all other depictions by Ribera. By limiting the number of participants to the main protagonists of the story—the saint, his executioner, one of the priests who condemned him, and one of the soldiers who captured him—and presenting them halflength and filling the picture space, the artist rejected an active, movemented composition for one of intense psychological drama. The cusping along all four edges shows that the painting has not been cut down: Ribera intended the composition to be just such a tight, restricted presentation, with the figures cut off and pressed together.[39]

The idea of using the story of Bartholomew being skinned alive to create an artwork depicting an anatomical study of a human is still common amongst contemporary artists with Gunther Von Hagens’s The Skin Man (2002) and Damien Hirst’s Exquisite Pain (2006). Within Gunther Von Hagens’s body of work called Body Worlds a figure reminiscent of Bartholomew holds up his skin. This figure is depicted in actual human tissues (made possible by Hagens’s plastination process) to educate the public about the inner workings of the human body and to show the effects of healthy and unhealthy lifestyles.[40] In Exquisite Pain 2006, Damien Hirst depicts St Bartholomew with a high level of anatomical detail with his flayed skin draped over his right arm, a scalpel in one hand and a pair of scissors in the other. The inclusion of scissors was inspired by Tim Burton’s film Edward Scissorhands (1990).[41]

Bartholomew plays a part in Francis Bacon’s Utopian tale New Atlantis, about a mythical isolated land, Bensalem, populated by a people dedicated to reason and natural philosophy. Some twenty years after the ascension of Christ the people of Bensalem found an ark floating off their shore. The ark contained a letter as well as the books of the Old and New Testaments. The letter was from Bartholomew the Apostle and declared that an angel told him to set the ark and its contents afloat. Thus the scientists of Bensalem received the revelation of the Word of God.[42]

-

Saint Bartholomew displaying his flayed skin in Michelangelo’s The Last Judgment.

-

-

The Martyrdom of St. Bartolomew or the Double Martydom Aris Kalaizis, 2015

Culture[edit]

The festival in August has been a traditional occasion for markets and fairs, such as the Bartholomew Fair which was held in Smithfield, London, from the Middle Ages,[43] and which served as the scene for Ben Jonson’s 1614 homonymous comedy.[citation needed]

St Bartholomew’s Street Fair is held in Crewkerne, Somerset, annually at the start of September.[44] The fair dates back to Saxon times and the major traders’ market was recorded in the Domesday Book. St Bartholomew’s Street Fair, Crewkerne is reputed to have been granted its charter in the time of Henry III (1207–1272). The earliest surviving court record was made in 1280, which can be found in the British Library.[citation needed]

In Islam[edit]

The Qur’anic account of the disciples of Jesus does not include their names, numbers, or any detailed accounts of their lives. Muslim exegesis, however, more or less agrees with the New Testament list and holds that the disciples included Peter, Philip, Thomas, Bartholomew, Matthew, Andrew, James, Jude, James the Less, John and Simon the Zealot.[45]

See also[edit]

- Gospel of Bartholomew

- Questions of Bartholomew

- Acts of Andrew and Bartholomew

- St. Bartholomew’s Day massacre

- St Bartholomew’s Hospital

- Bertil

- Saint Bartholomew the Apostle, patron saint archive

References[edit]

Notes[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ «Saint Bartholomew | Christian Apostle | Britannica». www.britannica.com. Retrieved 30 November 2022.

- ^ Sacred Lives, Batholomew

- ^ Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible by David Noel Freedman, Allen C. Myers, and Astrid B. Beck ,2000,page 152: «… Bartholomew preached to the Indians and died at Albanopolis in Armenia). It was condemned in the Gelasian decree, referred …»

- ^ The Untold Story of the New Testament Church: An Extraordinary Guide to Understanding the New Testament by Frank Viola,page 170: «… one of the Twelve, is beaten and crucified in Albanopolis, Armenia. …»

- ^ Green, McKnight & Marshall 1992, p. 180.

- ^ Raymond F. Collins, «Nathanael 3,» in The Anchor Bible Dictionary, vol. 4 (New York: Doubleday), p. 1031.

- ^ a b c Butler & Burns 1998, p. 232.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica, Micropædia. vol. 1, p. 924. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 1998. ISBN 0-85229-633-9.

- ^ a b «Mission of Saint Bartholomew, the Apostle in India». Nasranis. 10 October 2014. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- ^ Gilman, Ian; Klimkeit, Hans-Joachim (11 January 2013). Christians in Asia before 1500. ISBN 9781136109782.

- ^ In the Life of apostle Bartholomew Baku is identified as Alban. Some historians assume that Baku during the existence of Caucasian Albania was called Albanopolis.

- ^ Teunis 2003, p. 306.

- ^ Fenlon 1907.

- ^ Spilman 2017.

- ^ «The Condition of the Armenian Historical Monuments in Turkey». raa.am. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- ^ «Bakıda məzarı tapılan İsa peyğəmbərin apostolu Varfolomey». qaynarinfo.az. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- ^ «Проповедь Святого Апостола Варфоломея». udi.az. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- ^ «The Calendar». The Church of England. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- ^ Damo-Santiago 2014.

- ^ «24 AVQUST – MÜQƏDDƏS HƏVARİ BARTALMAYIN BAYRAMI». catholic.az.

- ^ «24 iyun – Bakı şəhərinin səmavi qoruyucusu Həvari Varfolomeyin Xatirə Günü». pravoslavie.az.

- ^ «Azərbaycanda yaşayan pravoslavlar Müqəddəs Varfolomeyi anıblar». interfax.az.

- ^ Smith & Cheetham 1875, p. 179.

- ^ Gregory, De Gloria Martyrum, i.33.

- ^ Attwater & John 1995.

- ^ «KONSTANTİNOPOL PATRİARXI I VARFOLOMEY AZƏRBAYCANA GƏLMİŞDİR». azertag.az. 16 April 2003. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- ^ «Golden Legend: Life of St. Bartholomew the Apostle». www.christianiconography.info. Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- ^ a b Mittman & Sciacca 2017, pp. viii, 141.

- ^ a b c d Giorgi 2003, p. 51.

- ^ a b Crane 2014, p. 5.

- ^ Post 2018, p. 12.

- ^ a b Kay 2006, pp. 35–74.

- ^ Mittman & Sciacca 2017, pp. 42.

- ^ Bissell 2016.

- ^ Decker & Kirkland-Ives 2017, p. ii.

- ^ West 1996.

- ^ «The statue of St Bartholomew in the Milan Duomo». Duomo di Milano. 29 June 2018. Archived from the original on 31 October 2018. Retrieved 30 October 2018.

- ^ «The Martyrdom of Saint Bartholomew». nga.gov. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- ^ DeGrazia & Garberson 1996, p. 410.

- ^ «Philosophy». Body Worlds. Archived from the original on 9 June 2019. Retrieved 30 October 2018.

- ^ Dorkin 2003.

- ^ Bacon 1942.

- ^ Cavendish 2005.

- ^ «About the Fair». Crewkerne Charter Fair, Somerset – (Formerly St.Bartholomew’s Street Fair). Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- ^ Noegel & Wheeler 2002, p. 86: Muslim exegesis identifies the disciples of Jesus as Peter, Andrew, Matthew, Thomas, Philip, John, James, Bartholomew, and Simon

Cite error: A list-defined reference named «timelineindex.com» is not used in the content (see the help page).

Sources[edit]

- Attwater, Donald; John, Catherine Rachel (1995). The Penguin Dictionary of Saints. Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-051312-7.

- Bacon, Francis (1942). New Atlantis. New York: W. J. Black.

- Benedict XVI (4 October 2006). «General Audience». vatican.va. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- Bissell, Tom (1 March 2016). «A Most Violent Martyrdom». Lapham’s Quarterly. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- Butler, Alban; Burns, Paul (1998). Butler’s Lives of the Saints: August. A&C Black. ISBN 978-0-86012-257-9.

- Cavendish, Richard (9 September 2005). «London’s Last Bartholomew Fair». History Today. Vol. 55, no. 9.

- Crane, Thomas Frederick (2014). Tales from Italy: When Christianity Met Italy. M&J. ISBN 979-11-951749-4-2.

- Damo-Santiago, Corazon (28 August 2014). «Saint Bartholomew the Apostle skinned alive for spreading his faith». BusinessMirror. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- Decker, John R.; Kirkland-Ives, Mitzi (2017). «Death, Torture and the Broken Body in European Art, 1300–1650 «. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-351-57009-1.

- DeGrazia, Diane; Garberson, Eric (1996). Italian Paintings of the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries. Edgar Peters Bowron, Peter Lukehart, Mitchell Merling. National Gallery of Art. ISBN 978-0-89468-241-4.

- de Voragine, Jacobus; Duffy, Eamon (2012). The Golden Legend: Readings on the Saints. Translated by William Granger Ryan. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-4205-6.

- Dorkin, Molly (2003), «Sotheby’s», Oxford Art Online, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.t079852

- Fabricius, Johann Albert (1703). Codex Apocryphus Novi Testamenti: collectus, castigatus testimoniisque, censuris & animadversionibus illustratus. sumptib. B. Schiller.

- Fenlon, John Francis (1907). «St. Bartholomew» . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 2. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Giorgi, Rosa (2003). Saints in Art. Getty Publications. ISBN 978-0-89236-717-7. OCLC 50982363.

- Green, Joel B.; McKnight, Scot; Marshall, I. Howard (1992). Dictionary of Jesus and the Gospels: A Compendium of Contemporary Biblical Scholarship. InterVarsity Press. ISBN 978-0-8308-1777-1.

- Kay, S. (2006). «Original Skin: Flaying, Reading, and Thinking in the Legend of Saint Bartholomew and Other Works». Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies. 36 (1): 35–74. doi:10.1215/10829636-36-1-35. ISSN 1082-9636.

- Lillich, Meredith Parsons (2011). The Gothic Stained Glass of Reims Cathedral. Penn State Press. ISBN 978-0-271-03777-6.

- Meier, John P. (1991). A Marginal Jew: Companions and competitors. Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-46993-7.

- Mittman, Asa Simon; Sciacca, Christine (2017). Tracy, Larissa (ed.). Flaying in the Pre-modern World: Practice and Representation. Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 978-1-84384-452-5.

- Noegel, Scott B.; Wheeler, Brannon M. (2002). Historical Dictionary of Prophets in Islam and Judaism. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow. ISBN 978-0-8108-4305-9.

- Post, W. Ellwood (2018). Saints, Signs, and Symbols. Papamoa Press. ISBN 978-1-78720-972-5.

- Smith, Dwight Moody (1999). Abingdon New Testament Commentaries. Vol. 4: John. Abingdon Press. ISBN 978-0-687-05812-9.

- Smith, William; Cheetham, Samuel (1875). A Dictionary of Christian Antiquities: A-Juv. J. Murray.

- Spilman, Frances (2017). The Twelve: Lives and Legends of The Apostles. Lulu.com. ISBN 978-1-365-64043-8.

- Teunis, D. A. (2003). Satan’s Secret: Exposing the Master of Deception and the Father of Lies. AuthorHouse. ISBN 978-1-4107-3580-5.

- West, Shearer (1996). The Bloomsbury Guide to Art. Bloomsbury. OCLC 246967494.

Further reading[edit]

- Hanks, Patrick; Hodges, Flavia; Hardcastle, Kate (2016). A Dictionary of First Names. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-880051-4.

- Perumalil, A. C. (1971). The Apostles in India. Jaipur: Xavier Teachers’ Training Institute.

External links[edit]

- The Martyrdom of the Holy and Glorious Apostle Bartholomew, attributed to Pseudo-Abdias, one of the minor Church Fathers

- St. Bartholomew’s Connections in India

- St. Bartholomew at the Christian Iconography web site.’

- «The Life of St. Bartholomew the Apostle» in the Caxton translation of the Golden Legend

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

|

Saint Bartholomew the Apostle |

|

|---|---|

St Bartholomew (c. 1611) by Peter Paul Rubens |

|

| Apostle and Martyr | |

| Born | c. 1 AD Cana, Galilee, Roman Empire |

| Died | c. 69 AD Albanopolis, Kingdom of Armenia[1][2][3][4] |

| Venerated in | All Christian denominations which venerate saints |

| Major shrine | Saint Bartholomew Monastery in historical Armenia, Saint Bartholomew Church in Baku, Relics at Basilica of San Bartolomeo in Benevento, Italy, Holy Myrrhbearers Cathedral in Baku, Azerbaijan, Saint Bartholomew-on-the-Tiber Church, Rome, Canterbury Cathedral, the Cathedrals in Frankfurt and Plzeň, and San Bartolomeo Cathedral in Lipari |

| Feast | 24 August (Western Christianity) 11 June (with St. Barnabas) (Eastern Christianity) 25 August (Translation of relics, with Saint Titus) (Eastern Christianity) |

| Attributes | Knife and his flayed skin, Red Martyrdom |

| Patronage | Armenia; Azerbaijan; bookbinders; butchers; Florentine cheese and salt merchants; Gambatesa, Italy; Catbalogan, Samar; Magalang, Pampanga; Malabon, Metro Manila; Nagcarlan, Laguna; San Leonardo, Nueva Ecija, Philippines; Għargħur, Malta; leather workers; neurological diseases; skin diseases; dermatology; plasterers; shoemakers; curriers; tanners; trappers; twitching; whiteners; Los Cerricos (Spain); Barva, Costa Rica |

Bartholomew (Aramaic: ܒܪ ܬܘܠܡܝ; Ancient Greek: Βαρθολομαῖος, romanized: Bartholomaîos; Latin: Bartholomaeus; Armenian: Բարթողիմէոս; Coptic: ⲃⲁⲣⲑⲟⲗⲟⲙⲉⲟⲥ; Hebrew: בר-תולמי, romanized: bar-Tôlmay; Arabic: بَرثُولَماوُس, romanized: Barthulmāwus) was one of the twelve apostles of Jesus according to the New Testament. Some identify Bartholomew as Nathanael or Nathaniel,[5] who appears in the Gospel of John (1:45-51; cf. 21:2), although this is not supported by the Gospels, Acts, or any early, reliable Christian tradition.[6]

New Testament references[edit]

The name Bartholomew (Greek: Βαρθολομαῖος, transliterated «Bartholomaios») comes from the Imperial Aramaic: בר-תולמי bar-Tolmay «son of Talmai»[7] or «son of the furrows».[7] Bartholomew is listed in the New Testament among the Twelve Apostles of Jesus in the three Synoptic Gospels: Matthew,[10:1–4] Mark,[3:13–19] and Luke,[6:12–16] and in Acts of the Apostles.[1:13]

Tradition[edit]

Eusebius of Caesarea’s Ecclesiastical History (5:10) states that after the Ascension, Bartholomew went on a missionary tour to India, where he left behind a copy of the Gospel of Matthew. Tradition records him as serving as a missionary in Mesopotamia and Parthia, as well as Lycaonia and Ethiopia in other accounts.[8]

Popular traditions say that Bartholomew preached the Gospel in India and then went to Greater Armenia.[7]

Mission to India[edit]

Two ancient testimonies exist about the mission of Saint Bartholomew in India. These are of Eusebius of Caesarea (early 4th century) and of Saint Jerome (late 4th century). Both of these refer to this tradition while speaking of the reported visit of Saint Pantaenus to India in the 2nd century.[9] The studies of Fr A.C. Perumalil SJ and Moraes hold that the Bombay region on the Konkan coast, a region which may have been known as the ancient city Kalyan, was the field of Saint Bartholomew’s missionary activities. Previously the consensus among scholars was against the apostolate of Saint Bartholomew the Apostle in India. The majority of the scholars are skeptical about the mission of Saint Bartholomew the Apostle in India. Stallings (1703), Neander (1853), Hunter (1886), Rae (1892), Zaleski (1915) are the authors who supported the Apostolate of Saint Bartholomew in India. Scholars such as Sollerius (1669), Carpentier (1822), Harnack (1903), Medlycott (1905), Mingana (1926), Thurston (1933), Attwater (1935), etc. do not support this hypothesis. The main argument is that the India that Eusebius and Jerome refer to should be identified as Ethiopia or Arabia Felix.[9]

In Armenia[edit]

Along with his fellow apostle Jude «Thaddeus», Bartholomew is reputed to have brought Christianity to Armenia in the 1st century. Thus, both saints are considered the patron saints of the Armenian Apostolic Church. According to tradition, he is the 2nd Catholicos-Patriarch of the Armenian Apostolic Church .[10]

Christian tradition has three stories about Bartholomew’s death: «One speaks of his being kidnapped, beaten unconscious, and cast into the sea to drown. Another account states that he was crucified upside down, and another says that he was skinned alive and beheaded in Albac or Albanopolis, near Baku, Azerbaijan[11] or Başkale, Turkey.»[12]

The most prominent tradition has it that Apostle Bartholomew was executed in Albanopolis in Armenia. According to popular hagiography, the apostle was flayed alive and beheaded. According to other accounts, he was crucified upside down (head downward) like St. Peter. He is said to have been martyred for having converted Polymius, the king of Armenia, to Christianity. Enraged by the monarch’s conversion, and fearing a Roman backlash, King Polymius’s brother, Prince Astyages, ordered Bartholomew’s torture and execution, which Bartholomew endured. However, there are no records of any Armenian king of the Arsacid dynasty of Armenia with the name «Polymius». Current scholarship indicates that Bartholomew is more likely to have died in Kalyan in India, where there was an official named «Polymius».[13][14]

The 13th-century Saint Bartholomew Monastery was a prominent Armenian monastery constructed at the site of the martyrdom of Apostle Bartholomew in Vaspurakan, Greater Armenia (now in southeastern Turkey).[15]

In Azerbaijan[edit]

Saint Bartholomew Church (Baku) was built in 1892 at the expense of donations from the local Christian population on the site where the Apostle Bartholomew was believed to have been killed.[16] It is believed that in this area near the Maiden Tower, the apostle Bartholomew was crucified and killed by pagans around 71 AD.[17] The church continued to operate until 1936, then it was demolished as a part of the Soviet campaign against religion.

Veneration[edit]

According to the Synaxarium of the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria, Bartholomew’s martyrdom is commemorated on the first day of the Coptic calendar (i.e., the first day of the month of Thout), which currently falls on 11 September (corresponding to 29 August in the Julian calendar). Eastern Christianity honours him on June 11 and the Catholic Church honours him on 24 August.

Bartholomew the Apostle is remembered in the Church of England with a Festival on 24 August.[18][19] The Armenian Apostolic Church honours Saint Bartholomew and Saint Thaddeus as its patron saints.

The Catholic Church of Azerbaijan[20] and Russian Orthodox Eparchy of Baku and Azerbaijan[21] honour Saint Bartholomew as the Patron Saint of Azerbaijan and regard him as the bringer of Christianity to the region of Caucasian Albania, modern-day Azerbaijan. The feast day of the Apostle is solemnly celebrated therein on 24 August by the Christian laity and the Church officials alike.[22]

Relics[edit]

Altar of San Bartolomeo Basilica in Benevento, containing the relics of Bartholomew

The 6th-century writer Theodorus Lector averred that in about 507, the Byzantine emperor Anastasius I Dicorus gave the body of Bartholomew to the city of Daras, in Mesopotamia, which he had recently refounded.[23] The existence of relics at Lipari, a small island off the coast of Sicily, in the part of Italy controlled from Constantinople, was explained by Gregory of Tours[24] by his body having miraculously washed up there. A large piece of his skin and many bones that were kept in the Cathedral of St. Bartholomew in Lipari, were translated to Benevento in 838, where they are still kept now in the Basilica San Bartolomeo. A portion of the relics was given in 983 by Otto II, Holy Roman Emperor, to Rome, where it is conserved at San Bartolomeo all’Isola, which was founded on the temple of Asclepius, an important Roman medical centre. This association with medicine in course of time caused Bartholomew’s name to become associated with medicine and hospitals.[25] Some of Bartholomew’s alleged skull was transferred to the Frankfurt Cathedral, while an arm was venerated in Canterbury Cathedral.[citation needed]

In 2003, Patriarch Bartholomew I of Constantinople brought some of the remains of St. Bartholomew to Baku as a gift to Azerbaijani Christians, and these remains are now kept in the Holy Myrrhbearers Cathedral.[26]

Miracles[edit]

Saint Bartholomew has been credited with several miracles.[27]

Art and literature[edit]

In artistic depictions, Bartholomew is most commonly depicted holding his flayed skin and the knife with which he was skinned.

St. Bartholomew is the most prominent flayed Christian martyr;[28] During the 16th century, images of the flaying of Bartholomew were so popular that it came to signify the saint in works of art.[29] Consequently, Saint Bartholomew is most often represented being skinned alive.[30] Symbols associated with the saint include knives and his own skin, which Bartholomew holds or drapes around his body.[29] Similarly, the ancient herald of Bartholomew is known by «flaying knives with silver blades and gold handles, on a red field.»[31] As in Michelangelo’s Last Judgement, the saint is often depicted with both the knife and his skin.[30] Representations of Bartholomew with a chained demon are common in Spanish painting.[29]

Saint Bartholomew is often depicted in lavish medieval manuscripts.[32] Manuscripts, which are literally made from flayed and manipulated skin, hold a strong visual and cognitive association with the saint during the medieval period and can also be seen as depicting book production.[32] Florentine artist Pacino di Bonaguida, depicts his martyrdom in a complex and striking composition in his Laudario of Sant’Agnese, a book of Italian Hymns produced for the Compagnia di Sant’Agnese c. 1340.[28] In the five scene, narrative based image three torturers flay Bartholomew’s legs and arms as he is immobilised and chained to a gate. On the right, the saint wears his own flesh tied around his neck while he kneels in prayer before a rock, his severed head fallen to the ground. Another example includes the Flaying of St. Bartholomew in the Luttrell Psalter c.1325–1340. Bartholomew is depicted on a surgical table, surrounded by tormentors while he is flayed with golden knives.[33]

Reliquary shutters with the Martyrdoms of St. Francis, St. Claire, St. Bartholomew, and St. Catherine of Alexandria by Guido da Siena

Due to the nature of his martyrdom, Bartholomew is the patron saint of tanners, plasterers, tailors, leatherworkers, bookbinders, farmers, housepainters, butchers, and glove makers.[34][29] In works of art the saint has been depicted being skinned by tanners, as in Guido da Siena’s reliquary shutters with the Martyrdoms of St. Francis, St. Claire, St. Bartholomew, and St. Catherine of Alexandria.[35] Popular in Florence and other areas in Tuscany, the saint also came to be associated with salt, oil, and cheese merchants.[36]

Although Bartholomew’s death is commonly depicted in artworks of a religious nature, his story has also been used to represent anatomical depictions of the human body devoid of flesh. An example of this can be seen in Marco d’Agrate’s St Bartholomew Flayed (1562) where Bartholomew is depicted wrapped in his own skin with every muscle, vein and tendon clearly visible, acting as a clear description of the muscles and structure of the human body.[37]

The Martyrdom of Saint Bartholomew (1634) by Jusepe de Ribera depicts Bartholomew’s final moments before being flayed alive. The viewer is meant to empathize with Bartholomew, whose body seemingly bursts through the surface of the canvas, and whose outstretched arms embrace a mystical light that illuminates his flesh. His piercing eyes, open mouth, and petitioning left hand bespeak an intense communion with the divine; yet this same hand draws our attention to the instruments of his torture, symbolically positioned in the shape of a cross. Transfixed by Bartholomew’s active faith, the executioner seems to have stopped short in his actions, and his furrowed brow and partially illuminated face suggest a moment of doubt, with the possibility of conversion.[38] The representation of Bartholomew’s demise in the National Gallery painting differs significantly from all other depictions by Ribera. By limiting the number of participants to the main protagonists of the story—the saint, his executioner, one of the priests who condemned him, and one of the soldiers who captured him—and presenting them halflength and filling the picture space, the artist rejected an active, movemented composition for one of intense psychological drama. The cusping along all four edges shows that the painting has not been cut down: Ribera intended the composition to be just such a tight, restricted presentation, with the figures cut off and pressed together.[39]

The idea of using the story of Bartholomew being skinned alive to create an artwork depicting an anatomical study of a human is still common amongst contemporary artists with Gunther Von Hagens’s The Skin Man (2002) and Damien Hirst’s Exquisite Pain (2006). Within Gunther Von Hagens’s body of work called Body Worlds a figure reminiscent of Bartholomew holds up his skin. This figure is depicted in actual human tissues (made possible by Hagens’s plastination process) to educate the public about the inner workings of the human body and to show the effects of healthy and unhealthy lifestyles.[40] In Exquisite Pain 2006, Damien Hirst depicts St Bartholomew with a high level of anatomical detail with his flayed skin draped over his right arm, a scalpel in one hand and a pair of scissors in the other. The inclusion of scissors was inspired by Tim Burton’s film Edward Scissorhands (1990).[41]

Bartholomew plays a part in Francis Bacon’s Utopian tale New Atlantis, about a mythical isolated land, Bensalem, populated by a people dedicated to reason and natural philosophy. Some twenty years after the ascension of Christ the people of Bensalem found an ark floating off their shore. The ark contained a letter as well as the books of the Old and New Testaments. The letter was from Bartholomew the Apostle and declared that an angel told him to set the ark and its contents afloat. Thus the scientists of Bensalem received the revelation of the Word of God.[42]

-

Saint Bartholomew displaying his flayed skin in Michelangelo’s The Last Judgment.

-

-

The Martyrdom of St. Bartolomew or the Double Martydom Aris Kalaizis, 2015

Culture[edit]

The festival in August has been a traditional occasion for markets and fairs, such as the Bartholomew Fair which was held in Smithfield, London, from the Middle Ages,[43] and which served as the scene for Ben Jonson’s 1614 homonymous comedy.[citation needed]

St Bartholomew’s Street Fair is held in Crewkerne, Somerset, annually at the start of September.[44] The fair dates back to Saxon times and the major traders’ market was recorded in the Domesday Book. St Bartholomew’s Street Fair, Crewkerne is reputed to have been granted its charter in the time of Henry III (1207–1272). The earliest surviving court record was made in 1280, which can be found in the British Library.[citation needed]

In Islam[edit]

The Qur’anic account of the disciples of Jesus does not include their names, numbers, or any detailed accounts of their lives. Muslim exegesis, however, more or less agrees with the New Testament list and holds that the disciples included Peter, Philip, Thomas, Bartholomew, Matthew, Andrew, James, Jude, James the Less, John and Simon the Zealot.[45]

See also[edit]

- Gospel of Bartholomew

- Questions of Bartholomew

- Acts of Andrew and Bartholomew

- St. Bartholomew’s Day massacre

- St Bartholomew’s Hospital

- Bertil

- Saint Bartholomew the Apostle, patron saint archive

References[edit]

Notes[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ «Saint Bartholomew | Christian Apostle | Britannica». www.britannica.com. Retrieved 30 November 2022.

- ^ Sacred Lives, Batholomew

- ^ Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible by David Noel Freedman, Allen C. Myers, and Astrid B. Beck ,2000,page 152: «… Bartholomew preached to the Indians and died at Albanopolis in Armenia). It was condemned in the Gelasian decree, referred …»

- ^ The Untold Story of the New Testament Church: An Extraordinary Guide to Understanding the New Testament by Frank Viola,page 170: «… one of the Twelve, is beaten and crucified in Albanopolis, Armenia. …»

- ^ Green, McKnight & Marshall 1992, p. 180.

- ^ Raymond F. Collins, «Nathanael 3,» in The Anchor Bible Dictionary, vol. 4 (New York: Doubleday), p. 1031.

- ^ a b c Butler & Burns 1998, p. 232.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica, Micropædia. vol. 1, p. 924. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 1998. ISBN 0-85229-633-9.

- ^ a b «Mission of Saint Bartholomew, the Apostle in India». Nasranis. 10 October 2014. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- ^ Gilman, Ian; Klimkeit, Hans-Joachim (11 January 2013). Christians in Asia before 1500. ISBN 9781136109782.

- ^ In the Life of apostle Bartholomew Baku is identified as Alban. Some historians assume that Baku during the existence of Caucasian Albania was called Albanopolis.

- ^ Teunis 2003, p. 306.

- ^ Fenlon 1907.

- ^ Spilman 2017.

- ^ «The Condition of the Armenian Historical Monuments in Turkey». raa.am. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- ^ «Bakıda məzarı tapılan İsa peyğəmbərin apostolu Varfolomey». qaynarinfo.az. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- ^ «Проповедь Святого Апостола Варфоломея». udi.az. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- ^ «The Calendar». The Church of England. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- ^ Damo-Santiago 2014.

- ^ «24 AVQUST – MÜQƏDDƏS HƏVARİ BARTALMAYIN BAYRAMI». catholic.az.

- ^ «24 iyun – Bakı şəhərinin səmavi qoruyucusu Həvari Varfolomeyin Xatirə Günü». pravoslavie.az.

- ^ «Azərbaycanda yaşayan pravoslavlar Müqəddəs Varfolomeyi anıblar». interfax.az.

- ^ Smith & Cheetham 1875, p. 179.

- ^ Gregory, De Gloria Martyrum, i.33.

- ^ Attwater & John 1995.

- ^ «KONSTANTİNOPOL PATRİARXI I VARFOLOMEY AZƏRBAYCANA GƏLMİŞDİR». azertag.az. 16 April 2003. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- ^ «Golden Legend: Life of St. Bartholomew the Apostle». www.christianiconography.info. Retrieved 21 December 2021.

- ^ a b Mittman & Sciacca 2017, pp. viii, 141.

- ^ a b c d Giorgi 2003, p. 51.

- ^ a b Crane 2014, p. 5.

- ^ Post 2018, p. 12.

- ^ a b Kay 2006, pp. 35–74.

- ^ Mittman & Sciacca 2017, pp. 42.

- ^ Bissell 2016.

- ^ Decker & Kirkland-Ives 2017, p. ii.

- ^ West 1996.

- ^ «The statue of St Bartholomew in the Milan Duomo». Duomo di Milano. 29 June 2018. Archived from the original on 31 October 2018. Retrieved 30 October 2018.

- ^ «The Martyrdom of Saint Bartholomew». nga.gov. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- ^ DeGrazia & Garberson 1996, p. 410.

- ^ «Philosophy». Body Worlds. Archived from the original on 9 June 2019. Retrieved 30 October 2018.

- ^ Dorkin 2003.

- ^ Bacon 1942.

- ^ Cavendish 2005.

- ^ «About the Fair». Crewkerne Charter Fair, Somerset – (Formerly St.Bartholomew’s Street Fair). Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- ^ Noegel & Wheeler 2002, p. 86: Muslim exegesis identifies the disciples of Jesus as Peter, Andrew, Matthew, Thomas, Philip, John, James, Bartholomew, and Simon

Cite error: A list-defined reference named «timelineindex.com» is not used in the content (see the help page).

Sources[edit]

- Attwater, Donald; John, Catherine Rachel (1995). The Penguin Dictionary of Saints. Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-051312-7.

- Bacon, Francis (1942). New Atlantis. New York: W. J. Black.

- Benedict XVI (4 October 2006). «General Audience». vatican.va. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- Bissell, Tom (1 March 2016). «A Most Violent Martyrdom». Lapham’s Quarterly. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- Butler, Alban; Burns, Paul (1998). Butler’s Lives of the Saints: August. A&C Black. ISBN 978-0-86012-257-9.

- Cavendish, Richard (9 September 2005). «London’s Last Bartholomew Fair». History Today. Vol. 55, no. 9.

- Crane, Thomas Frederick (2014). Tales from Italy: When Christianity Met Italy. M&J. ISBN 979-11-951749-4-2.

- Damo-Santiago, Corazon (28 August 2014). «Saint Bartholomew the Apostle skinned alive for spreading his faith». BusinessMirror. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- Decker, John R.; Kirkland-Ives, Mitzi (2017). «Death, Torture and the Broken Body in European Art, 1300–1650 «. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-351-57009-1.

- DeGrazia, Diane; Garberson, Eric (1996). Italian Paintings of the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries. Edgar Peters Bowron, Peter Lukehart, Mitchell Merling. National Gallery of Art. ISBN 978-0-89468-241-4.

- de Voragine, Jacobus; Duffy, Eamon (2012). The Golden Legend: Readings on the Saints. Translated by William Granger Ryan. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-4205-6.

- Dorkin, Molly (2003), «Sotheby’s», Oxford Art Online, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.t079852

- Fabricius, Johann Albert (1703). Codex Apocryphus Novi Testamenti: collectus, castigatus testimoniisque, censuris & animadversionibus illustratus. sumptib. B. Schiller.

- Fenlon, John Francis (1907). «St. Bartholomew» . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 2. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Giorgi, Rosa (2003). Saints in Art. Getty Publications. ISBN 978-0-89236-717-7. OCLC 50982363.

- Green, Joel B.; McKnight, Scot; Marshall, I. Howard (1992). Dictionary of Jesus and the Gospels: A Compendium of Contemporary Biblical Scholarship. InterVarsity Press. ISBN 978-0-8308-1777-1.

- Kay, S. (2006). «Original Skin: Flaying, Reading, and Thinking in the Legend of Saint Bartholomew and Other Works». Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies. 36 (1): 35–74. doi:10.1215/10829636-36-1-35. ISSN 1082-9636.

- Lillich, Meredith Parsons (2011). The Gothic Stained Glass of Reims Cathedral. Penn State Press. ISBN 978-0-271-03777-6.

- Meier, John P. (1991). A Marginal Jew: Companions and competitors. Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-46993-7.

- Mittman, Asa Simon; Sciacca, Christine (2017). Tracy, Larissa (ed.). Flaying in the Pre-modern World: Practice and Representation. Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 978-1-84384-452-5.

- Noegel, Scott B.; Wheeler, Brannon M. (2002). Historical Dictionary of Prophets in Islam and Judaism. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow. ISBN 978-0-8108-4305-9.

- Post, W. Ellwood (2018). Saints, Signs, and Symbols. Papamoa Press. ISBN 978-1-78720-972-5.

- Smith, Dwight Moody (1999). Abingdon New Testament Commentaries. Vol. 4: John. Abingdon Press. ISBN 978-0-687-05812-9.

- Smith, William; Cheetham, Samuel (1875). A Dictionary of Christian Antiquities: A-Juv. J. Murray.

- Spilman, Frances (2017). The Twelve: Lives and Legends of The Apostles. Lulu.com. ISBN 978-1-365-64043-8.

- Teunis, D. A. (2003). Satan’s Secret: Exposing the Master of Deception and the Father of Lies. AuthorHouse. ISBN 978-1-4107-3580-5.

- West, Shearer (1996). The Bloomsbury Guide to Art. Bloomsbury. OCLC 246967494.

Further reading[edit]

- Hanks, Patrick; Hodges, Flavia; Hardcastle, Kate (2016). A Dictionary of First Names. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-880051-4.

- Perumalil, A. C. (1971). The Apostles in India. Jaipur: Xavier Teachers’ Training Institute.

External links[edit]

- The Martyrdom of the Holy and Glorious Apostle Bartholomew, attributed to Pseudo-Abdias, one of the minor Church Fathers

- St. Bartholomew’s Connections in India

- St. Bartholomew at the Christian Iconography web site.’

- «The Life of St. Bartholomew the Apostle» in the Caxton translation of the Golden Legend

Часть 2.

«Праздник четок» действительно получился у Дюрера очень необычным. Это многофигурная композиция, где далеко не все персонажи в настоящее время могут быть идентифицированы. Но попробуем все-таки разобраться, что здесь происходит, и кто есть кто.

Итак, в центре композиции совершенно логично и оправдано находится Богоматерь. Она восседает на троне под зеленым балдахином, который за трогательные красные шнурочки с кисточками поддерживают ангелочки-путти. Яркий насыщенный зеленый цвет балдахина символизирует жизнь и надежду ( а также, возможно, и Богоявление). Еще двое ангелочков держат над головой Богоматери корону, причем это корона династии Габсбургов.

Богоматерь со светлыми вьющимися волосами, очень похожая на венецианку, одета в потрясающей красоты ярко-голубое платье, украшенное золотой брошью с красными и зелеными драгоценными камнями. На ее коленях довольно игриво расположился Младенец Иисус. В полном соответствии с сутью праздника Богоматерь возлагает венок из роз на голову императора Священной Римской империи Фридриха III, а Иисус — на голову папы римского Юлия II. Любопытно, что Фридриха Дюрер написал с лицом его сына, императора Максимилиана I (хотя у отца и сына достаточно сильно фамильное сходство), причем довольно точно, хотя лично он тогда императора он еще не видел, но мог основываться на рисунке художника Амброджо де Предиса, а вот Юлия изобразил без соблюдения портретного сходства. Это принято объяснять тем, что Венеция, где Дюрер работал над созданием картины, в то время враждовала с папой Юлием II.

Присутствие именно этих двух исторических лиц, возглавляющих две процессии мирян, движущихся к престолу Богоматери слева и справа, объясняется тем, что и папа Юлий, и император Фридрих способствовали утверждению в Германии Братства Розария (Молитвенное Братство Розария было основано Якобом Шпренгером в Кельне в 1475 году).

Венки, которые Богоматерь и Иисус возлагают на головы императора и папы, а также ангелы раздают всем участницам действа, сплетены из роз белого и красного (а, точнее ярко-розового) цвета. Белые являются символом чистоты Марии, а красные означают страдания Христа. Считается, что сплетённые вместе они знаменуют собой объединение всех христиан в вере.

Еще одним персонажем, раздающим венки из роз является святой Доминик, покровитель Розария, с чьим именем и связано появление этой католической традиции. Он изображен в традиционном одеянии монаха своего ордена (белая туника и черный плащ) с белыми лилиями на длинном стебле. Эти цветы, символ Девы Марии, традиционно сопровождают изображения св.Доминика.

Из остальных персонажей картины с более-менее достаточной степенью уверенности можно идентифицировать лишь нескольких. Во-первых, это патриарх (иначе говоря епископ с особыми полномочиями) Венеции Антонио Сориано. Он изображен у левого края полотна преклонившим колени с руками, сложенными для молитвы. Рядом с ним справа, обернувшись к нему, стоит Буркхард фон Шпеер, который был капелланом церкви Сан-Бартоломео.

Человек, держащий в руке крест, на голову которого венок возложил святой Доминик — это венецианский кардинал Доменико Гримани, известный покровитель искусств.

У правого края картины под деревом стоит сам Альбрехт Дюрер. Он одет в экзотический наряд, нечто вроде розовой мантии с золотистым меховым воротником и эффектными полосатыми, черно-розовыми рукавами. Он носит волосы до плеч, как и на более ранних автопортретах, но теперь отрастил ещё и элегантную бородку.

Есть версия, что персонаж в черном одеянии, который расположен в нижнем ряду последним у левого края картины — это архитектор Джироламо Тедеско, по проекту которого было построено здание Фондако-деи-Тедески в 1228 голу.

Продолжение следует…

-

-

December 22 2018, 19:32

- Архитектура

- Путешествия

- История

- Религия

- Cancel

В 1000 году на острове Тиберина по приказу Оттона III, германского короля и императора Священной Римской империи, похороненного, кстати, в Аахенском соборе, была возведена церковь святого Варфоломея. Старинные римские церкви строились не на пустом месте, а часто на месте античных храмов. Так было и с этой церковью, возведённой на месте святилища бога врачевания, Эскулапа.

01.

В течение столетий церковь несколько раз реставрировалась, в 1583 г. после наводнения. После реставрации в 1624 году церковь приобрела свой нынешний облик. Реставрационные работы в барочном стиле внутри церкви проводились в 1720-1739 гг. В 1852-1865 гг. внутреннее убранство было переделано в стиле историзма. В интерьере церкви сохранились четырнадцать римских колонн.

Перед алтарём в ступенях, ведущим к алтарю стоит цвета слоновой кости колодец, некогда находившийся в храме бога Эскулапа. В 10-11 вв. 12-метровый колодец был украшен барельефами Христа, императора Оттона III с короной и со скипетром в руках и апостола Варфоломея. В ступени, ведущей к алтарю, находится средневековая мраморная чаша, которая, возможно, служила крышкой колодца. Справа от нее стоит бронзовый арабской работы сосуд, в котором Оттон перевозил из Беневенто мощи Св. Варфоломея, одного из двенадцати апостолов Христа. В алтаре в порфировом саркофаге, античной ванне, находятся мощи апостола Варфаломея.

В 2002 году папа Иоанн Павел II посвятил Сан-Бартоломео новым мученикам XX века, в алтарое икона в честь их. В каждой из боковых капелл выставлены реликвии, связанные с новомучениками. В числе новомучеников протоиерей РПЦ, богослов Александр Мень (1935-1990), убиённый 9 сентября 1990 года топором. До сих пор не ясен мотив убийства, преступника не нашли…

Римские колонны и барочный орган.

Потрясающей красоты кассетный потолок.

Древний обелиск в центре острова был разрушен в средние века. В 1868 году папа Пий IX приказал заменить его новой колонной. Архитектор Игнацио Якометти создал монумент, украшенный статуями четырех святых: Варфоломея, Павлина Ноланского, Франциска Ассизского, Иоанна Божьего. Фрагменты античного обелиска сейчас хранятся в музее Неаполя.

02.

Внутрь церкви я не попала, три ненумированных кадра из Википедии.

См. ГЕРМАНИЯ. Аахенский собор — чудо архитектуры.

Описание произведения.

Библейский сюжет, который лег в основу произведения Дюрера, красив и наполнен глубоким символизмом. Распространённое на территории Европы братство чёток, по легенде было основано святым Домиником, которому в 1214 г. явилась Богоматерь. По этому случаю в октябре традиционно устраивался праздник Девы Марии Розария. Иными словами праздник четок или венков из роз. Во время праздничного богослужения произносились молитвы Розария и перебирались четки, которые для членов братства были не просто молитвенным инструментом, но глубоким символом. Считалось, что каждая белая бусина – это роза, символизирующая невинность Богоматери, а красная – цветок-символ крови Спасителя, пролитой за человечество.

На картине представлена сцена увенчания венками. Пречистая Дева возлагает венок на голову папы римского Юлия II, а младенец-Иисус – на чело Максимилиану I. Над головой Марии два херувима держат тяжеловесную корону – венец Габсбургов. Рядом с Богородицей и младенцем мы видим Святого Доминика, который раздаёт венки мирянам. В сцене изображен также сам художник. Дюрер представил себя справа в виде человека в красивых одеждах. Кроме себя, художник изобразил знаменитого архитектора Иеронима, кардинала Гримани и самих купцов-заказчиков.

В композиции присутствует персонаж, который не характерен для Дюрера, но является традиционным для итальянской школы живописи. Это херувим с лютней – дань тому, что художник почерпнул за время работы в стране. Картина преисполнена яркими тонами, атмосфера полотна представляется невероятно живой и динамичной, поистине праздничной.

История создания.

Вначале 1500-х Дюрер совершает путешествие по Италии, знакомясь с местными мастерами, искусство которых в то время признавалось эталонным. В Венеции художник получает заказ на картину от немецких купцов, которые давно обосновались в этом городе. Именно в Венеции Дюрер пишет алтарный образ для церкви Сан-Бартоломео, что находилась близ немецкого торгового дома Фондако Тедески.

Исследователи отмечают значимое влияние итальянских мастеров на Дюрера при создании этого произведения. В частности, ангел, который музицирует у ног Марии, является частым лейтмотивом полотен итальянских мастеров. После того, как картина была завершена, Дюрер пишет из Венеции своему другу в Нюрнберг гордые слова, в которых ощущается удовлетворение законченным «Праздником четок»: «Заявляю вам, что лучше моей Марианской картины, вы не найдете на целом свете...» По словам самого Дюрера, эта работа заставила признать тех художников, кто считал его лишь гравёром, что он также настоящий живописец.

Позднее в 1585 картину «Праздник венков из роз» приобрел император Рудольф II. За свою пятисотлетнюю историю великолепная картина пережила ряд повреждений и реконструкций. Сегодня полностью восстановленное полотно хранится в национальной галерее Праги.

Отношение автора к вере.

С юных лет Альбрехт Дюрер предавался глубоким рассуждениям на тему вопросов бытия и своего предназначения. Многочисленные автопортреты художника свидетельствуют о его стремлении заглянуть вглубь своей природы и воспитать свою личность соразмерно таланту, который был дарован ему Богом. На одном из ранних автопортретов, который был создан в тринадцатилетнем возрасте, мастер предстает задумчивым юношей, тонко и глубоко чувствующим. Позднее поиски самоопределения живописца особенно ярко проявляются в мысли о том, что художник является творцом, подобно Богу. Альбрехт Дюрер вел нравственную жизнь глубоко верующего христианина. Один из современников так писал о художнике: «За всю жизнь не известно ни одного поступка, который бы заслужил порицания или хотя бы снисхождения. Он был безупречен вполне».

При этом художник жил в сложную эпоху Реформации, когда каждому человеку предстояло сделать выбор — поддерживать революционные изменения религиозных уставов или отстаивать непреложные основы христианской веры. Изначально, прельстившись новыми идеями, живописец примкнул к лютеровскому движению, но впоследствии разочаровался в Реформации. В итоге евангельская тема становится лейтмотивом творчества Дюрера, бывшего духовно очень чутким человеком. В конце своего творчества художник сделал надпись на одной из картин, ставшей своеобразным завещанием будущим поколениям: «Все мирские правители в эти опасные времена пусть остерегаются, чтобы не принять за божественное слово человеческие заблуждения». Сказанное было особенно важно в ту эпоху, когда Нюрнберг официально принял Реформацию. Тогда люди самых разных направлений новой веры стали проповедовать свои учения. Живописец призывал современников и потомков к внутренней стойкости в борьбе с лжепророками, которые ставили под угрозу весь строй духовной и материальной культуры. Твердой основой и истинной жизненной опорой человечества Альбрехт Дюрер считал библейское слово, не искаженное домыслами современности.

Биография.

Альбрехт Дюрер родился 21 мая 1471 г. в Нюрнберге, главном центре немецкого гуманизма. Его художественное дарование, деловые качества и мировоззрение формировались под влиянием трех людей, сыгравших наиболее важную роль в его жизни: отца, венгерского ювелира; крестного Кобергера, оставившего ювелирное искусство и занявшегося издательским делом; и ближайшего друга Дюрера, Вилибальда Пиркхаймера — выдающегося гуманиста, познакомившего молодого художника с новыми ренессансными идеями и произведениями итальянских мастеров.

Дюрер освоил основы живописи и ксилографии в мастерской художника Михаэля Вольгемута. 1492-1494 годы он провел в Базеле, крупнейшем центре производства иллюстрированных книг. Здесь молодой художник увлекся ксилографией и гравюрой на меди. В 1494 году, после посещения Страсбурга, Дюрер вернулся на родину, но вскоре отправился в Венецию. По дороге мастер выполнил несколько замечательных акварельных пейзажей, которые являются одними из первых произведений этого жанра в западноевропейском искусстве.

Вернувшись в Нюрнберг в 1495 году, художник открыл собственную мастерскую и стал делать рисунки, по которым его ученики изготавливали ксилографии. Печатая значительное количество оттисков, Дюрер с 1497 года начал прибегать к услугам агентов, продававших его гравюры по всей Европе. Таким образом, он стал не только художником, но и издателем; его славу упрочило издание в 1498 году серии гравюр на дереве «Апокалипсис».

В 1506 году, возможно, спасаясь от чумы, Дюрер снова приехал в Венецию. Здесь он создает выдающиеся полотна «Христос среди учителей» и «Праздник четок». Вернувшись в Нюрнберг, Дюрер продолжал заниматься гравюрой, однако среди его произведений 1507-1511 годов более важное место занимают картины. По всей видимости, художника не привлекал получивший широкое распространение в эти годы прием сфумато, и он продолжал писать в жестком линеарном стиле. Известный диптих «Адам и Ева» (1507 г.) был создан именно в это период.

Годы 1511-1514 были посвящены преимущественно гравюре. Дюрер выпустил второе издание «Апокалипсиса», цикл из двадцати гравюр на дереве «Жизнь Марии», двенадцать гравюр серии «Большие Страсти» и тридцать семь гравюр на тот же сюжет – «Малые Страсти». В этот период его стиль становится более уверенным, контрасты света и тени сильнее. В 1513-1514 годах художник создал три самых знаменитых своих листа: «Рыцарь, смерть и дьявол»; «Св. Иероним в келье» и «Меланхолия I».

В 1514 году Дюрер стал придворным художником императора Максимилиана I. Дюрер продолжал писать и картины, создав замечательный «Портрет императора Максимилиана» и образ «Богоматерь с Младенцем и св. Анной» (1519-1520 гг.).

В конце своей жизни Дюрер приступил к теоретическому осмыслению своих наблюдений и написал трактаты о пропорциях человеческого тела и о перспективе — проблемах, занимавших его еще со времен первой поездки в Италию. Художник ушел из жизни в Нюрнберге 6 апреля 1528 года.

Автор текста: Миненко Евгения Владимировна.