Праздник любования луной ещё имеет также названия «Фестиваль луны Цукими» или «Праздник середины осени». Его японское название «Tsukimi» переводится как «Просмотр луны». Это не удивительно, так у японцев принято «любоваться окружающим миром». Это и, известное на весь мир, любование цветами сакуры (О-Ханами), а также — любование снегом в горячем источнике (Юкими онсен). Вообще, у японцев вошло в привычку сидеть вместе и любоваться приметами уходящих сезонов. Прочитав статью, вы узнаете историю Праздника любования луной (Цукими), а также познакомитесь с традициями этого необычного праздника.

1. Сказка о кролике на Луне

Считается, что праздник любования луной появился благодаря одной фольклорной сказке о кролике на Луне. Эта история известна не только в Японии, но и в Китае. В таком виде она дошла до наших дней.

Однажды лунный старец спустился на Землю, чтобы испытать доброту трёх друзей — животных (обезьяны, кролика и лисы). Превратившись в нищего, лунный старик захотел узнать, кто из них самый добрый. Он подошел к друзьям, сидевшим у костра, и спросил, нет ли у них лишней еды. Обезьяна собрала много фруктов для нищего. Лис принёс человеку рыбу.

Но кролику нечего было дать, и он предложил принести себя в жертву голодному человеку. Он хотел броситься в костер из зажариться на нём, чтобы нищий поел. Но прежде чем кролик успел это сделать, нищий снова стал лунным старцем. Он сказал, что кролик — очень добрая душа, и взял его с собой на Луну.

Эта история, передаваемая из поколения в поколение, соответствует старому японскому убеждению, что «кролики пришли с Луны». В современном высокотехнологичном мире все тайны, которые когда-то были связаны с Луной, уже давно раскрыты. Тем не менее, полная осенняя Луна всё ещё вызывает чувство радости и удивления у японцев. Когда японские люди смотрят на Луну, они видят форму кролика и верят в «сказку».

2. История праздника любования луной (Цукими) в Японии

Праздник любования луной (Цукими) начал отмечаться очень давно. Фестиваль, как говорят, праздновался сначала в период Нара (710-794 гг. н. э.).

Ещё в те времена восьмой солнечный месяц (соответствующий сентябрю по современному Григорианскому календарю) был лучшим временем для того, чтобы смотреть на Луну. Это связано с тем, что относительное положение главных светил в сентябре «заставят Луну» казаться особенно яркой.

Однако только в период Хэйан (794-1185 гг.) Цукими стал популярным среди аристократов, которые восхищались отражением Луны в воде. Японская придворная знать праздновала Цукими, проводя щедрые банкеты на лодках или рядом с прудом, который отражает лунный свет. Праздник сопровождался музыкальными и поэтическими выступлениями, посвящёнными ночной небесной красавице.

С окончанием периода Хэйан празднества не закончились. До 1683 года по японскому календарю его отмечали в полнолуние, которое приходилось на 13-й день каждого месяца. Однако в 1684 году календарь был изменен таким образом, что новолуние приходилось на первый день каждого месяца, а полнолуние — на пятнадцатый.

В то время некоторые люди в Эдо (современный Токио) перенесли празднование Цукими на 15-й день месяца, другие продолжали его отмечать на 13-й день. Кроме того, в некоторых частях Японии в 17-й день месяца проводились различные региональные обряды, а также буддийские обряды. Некоторые японцы использовали их, в качестве предлогов для частых ночных вечеринок осенью в течение всего этого периода. Этот обычай был быстро прекращен в период Мэйдзи…

Прочитать кратко об истории Японии можно по ссылке ниже:

Читать статью: «Национальные праздники Японии»

3. Традиции Праздника любования луной (Цукими) в Японии

Праздник любования луной (Цукими) в Японии сохранился до нынешнего времени. Цукими означает «просмотр Луны» на японском языке. Согласно лунному календарю, Луна наиболее красива около 15 сентября, когда она находится в самом полном виде и ближе всего к Осеннему равноденствию. Однако каждый год дата празднования меняется, так как она вычисляется по лунному календарю. Например, В 2018 году Цукими отмечался 24 сентября.

В настоящее время праздник,конечно, несколько изменил свою трактовку. Современный праздник Цукими — это не только «любование луной». Это день выражения благодарности и признательности природе за её дары. Поэтому луну в это время ещё называют «Урожайной луной». Также не случайно Цукими называют Праздником середины осени или Осенним фестивалем урожая.

Японцы празднуют Цукими со своими семьями, наблюдая за Луной и наслаждаясь сладостями Моти или Цукими данго. Есть более чем 10 видов Моти. Но те, которые едят в ночь Цукими должны быть особенными! Другие популярные продукты на Цукими: каштаны, тыква, бобы, также саке.

Комнату обычно украшают зерновыми культурами, а также сусуки, японской пампасной травой или серебристой травой. Пампасная трава когда-то использовалась японцами для соломы крыш и кормления животных. Говорят, что она отгоняет плохих духов, и её обычно ставят в вазу у входной двери. Японские мужчины верят, что серебряная трава защитит дом от зла. Она также служит в качестве приношения Богу Луны.

Просмотр Луны является торжественным и тихим делом. Возможно, на это влияет прохлада ночного ветра, ставшего ещё холоднее с переходом с лета в осень. Или, может быть, это глубокое, необъяснимое чувство тоски, которое люди испытывают, глядя на мучительно красивое сияние луны.

В японском языке существуют специальные термины, обозначающие случаи, когда Луна не видна традиционным осенним вечером. Когда не видно Луну совсем, то это Мугецу. Луна во время дождя — это Угецу. Однако даже когда Луна не видна, проводятся вечеринки Цукими.

В некоторых местах Японии имеются возможности отметить праздник, как в эпоху Хэйан. Например, в садах Йокогаме можно насладиться музыкальными выступлениями под Луной. Здесь можно услышать разнообразную музыку от гагаку (старинную придворную музыку), до выступлений кото (фортепианных и саксофонных исполнений японских песен). Подобные концерты обязательно порадует каждую артистическую душу.

Самые популярные места в Японии во время Фестиваля середины осени — святыни и храмы. Люди одеваются в традиционные костюмы и ходят в храмы, чтобы зажечь благовония (джоссы), поблагодарить природу за хороший урожай и попросить о счастье. Почти в каждой святыне Японии проводится большое представление, состоящее из традиционных песен и танцев. А некоторые из них даже проводят экстравагантный парад.

Какова бы ни была причина, наслаждаться фестивалем Цукими в Японии — это чудесный «романтический опыт», который нельзя пропустить!

Вот так отмечается праздник любования луной в Японии!

Читайте также:

Праздник середины осени в Китае

Праздники Японии

Праздники и фестивали разных стран мира

Уважаемые читатели! Пишите комментарии! Читайте статьи на сайте «Мир праздников»!

| Mid-Autumn Festival | |

|---|---|

Festival decorations in Beijing |

|

| Also called | Moon Festival, Mooncake Festival |

| Observed by | Mainland China, Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan (similar holidays celebrated in Japan, Korea, and Southeast Asia) |

| Type | Cultural, religious, Asian |

| Significance | Celebrates the end of the autumn harvest |

| Celebrations | Lantern lighting, mooncake making and sharing, courtship and matchmaking, fireworks, family gathering, dragon dances, family meal, visiting friends and relatives, gift giving |

| Observances | Consumption of mooncakes Consumption of cassia wine |

| Date | 15th day of the 8th month of the Chinese lunar calendar |

| 2023 date | 29 September[1] |

| 2024 date | 7 September[1] |

| Frequency | Annual |

| Related to | Chuseok (Korea), Tsukimi (Japan), Tết Trung Thu (Vietnam), Uposatha of Ashvini or Krittika (Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Sri Lanka, and Thailand) |

| Mid-Autumn Festival | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

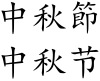

«Mid-Autumn Festival» in traditional (top) and simplified (bottom) Chinese characters |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 中秋節 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 中秋节 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | «Mid-Autumn Festival» | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Min Chinese alternate name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 八月節 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | «Festival of the Eighth Month» | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Mid-Autumn Festival (Chinese: 中秋節 / 中秋节), also known as the Moon Festival or Mooncake Festival, is a traditional festival celebrated in Chinese culture. Similar holidays are celebrated in Japan (Tsukimi), Korea (Chuseok), Vietnam (Tết Trung Thu), and other countries in East and Southeast Asia.

It is one of the most important holidays in Chinese culture; its popularity is on par with that of Chinese New Year. The history of the Mid-Autumn Festival dates back over 3,000 years.[2][3] The festival is held on the 15th day of the 8th month of the Chinese lunisolar calendar with a full moon at night, corresponding to mid-September to early October of the Gregorian calendar.[4] On this day, the Chinese believe that the Moon is at its brightest and fullest size, coinciding with harvest time in the middle of Autumn.[5]

Lanterns of all size and shapes, are carried and displayed – symbolic beacons that light people’s path to prosperity and good fortune. Mooncakes, a rich pastry typically filled with sweet-bean, egg yolk, meat or lotus-seed paste, are traditionally eaten during this festival.[6][7][8] The Mid-Autumn Festival is based on the legend of Chang’e, the Moon goddess in Chinese mythology.

Etymology[edit]

- The Mid-Autumn Festival is so-named as it is held on the 15th of the 8th lunar month in the Chinese calendar around the autumn equinox.[3] Its name is pronounced in Mandarin as Zhōngqiū Jié (simplified Chinese: 中秋节; traditional Chinese: 中秋節), Jūng-chāu Jit in Cantonese, and Tiong-chhiu-cheh in Hokkien. It is also called Peh-goe̍h-cheh (八月節; ‘Eighth Month Festival’) in Hokkien.

- Chuseok (추석 / 秋夕; Autumn Eve), Korea festival celebrated on the same day in the Chinese and other East Asian lunisolar calendars.[9]

- Tsukimi (月見; ‘moon viewing’), Japanese variant of the Mid-Autumn Festival celebrated on the same day in the Chinese lunisolar calendar.

- Moon Festival or Harvest Moon Festival, because of the celebration’s association with the full moon on this night, as well as the traditions of Moon worship and Moon viewing.

- Tết Trung Thu (節中秋 in Chữ Nôm, Mid-Autumn Tet), in Vietnamese.

- Also known as The Children’s Festival in Vietnam. Most festival songs are sung by the children.[10]

- Lantern Festival, a term sometimes used in Singapore, Malaysia and Indonesia,[11] which is not to be confused with the Lantern Festival in China that occurs on the 15th day of the first month of the Chinese calendar.

- However, ‘Mid-Autumn Festival’ is more widely used by locals when referring to the festival in English and ‘Zhōngqiū Jié’ is used when referring to the festival in Chinese.[citation needed]

- Bon Om Touk, or The Water and Moon Festival in Cambodian. The festival is held each year in November for 3 days.[12]

Meanings[edit]

The festival celebrates three fundamental concepts that are closely connected:

- Gathering, such as family and friends coming together, or harvesting crops for the festival. It is said the Moon is the brightest and roundest on this day which means family reunion. Consequently, this is the main reason why the festival is thought to be important.

- Thanksgiving, to give thanks for the harvest, or for harmonious unions

- Praying (asking for conceptual or material satisfaction), such as for babies, a spouse, beauty, longevity, or for a good future

Traditions and myths surrounding the festival are formed around these concepts,[13] although traditions have changed over time due to changes in technology, science, economy, culture, and religion.[13] It’s about well being together.

Origins and development[edit]

The Chinese have celebrated the harvest during the autumn full moon since the Shang dynasty (c. 1600–1046 BCE).[13][14] The term mid-autumn (中秋) first appeared in Rites of Zhou, a written collection of rituals of the Western Zhou dynasty (1046–771 BCE).[4] As for the royal court, it was dedicated to the goddess Taiyinxingjun (太陰星君; Tàiyīn xīng jūn). This is still true for Taoism and Chinese folk religion.[15][16]

The celebration as a festival only started to gain popularity during the early Tang dynasty (618–907 CE).[4] One legend explains that Emperor Xuanzong of Tang started to hold formal celebrations in his palace after having explored the Moon-Palace.[13]

In the Northern Song Dynasty, the Mid Autumn Festival has become a popular folk festival, and officially designated the 15th day of the eighth month of the lunar calendar as the Mid Autumn Festival.

By the Ming and Qing Dynasties, the mid autumn festival had become one of the main folk festivals in China. The Empress Dowager Cixi (late 19th century) enjoyed celebrating Mid-Autumn Festival so much that she would spend the period between the thirteenth and seventeenth day of the eighth month staging elaborate rituals.[3]

Moon worship[edit]

Chang’e, the Moon Goddess of Immortality

Houyi helplessly looking at his wife Chang’e flying off to the Moon after she drank the elixir.

An important part of the festival celebration is Moon worship. The ancient Chinese believed in rejuvenation being associated with the Moon and water, and connected this concept to the menstruation of women, calling it «monthly water».[17] The Zhuang people, for example, have an ancient fable saying the Sun and Moon are a couple and the stars are their children, and when the Moon is pregnant, it becomes round, and then becomes crescent after giving birth to a child. These beliefs made it popular among women to worship and give offerings to the Moon on this evening.[17] In some areas of China, there are still customs in which «men do not worship the moon and the women do not offer sacrifices to the kitchen gods.»[17]

In China, the Mid-Autumn festival symbolizes the family reunion and on this day, all families will appreciate the Moon in the evening, because it is the 15th day of the eighth month of the Chinese lunisolar calendar, when the moon is at its fullest. There is a beautiful myth about the Mid-Autumn festival, that is Chang’e flying to the Moon.

Offerings are also made to a more well-known lunar deity, Chang’e, known as the Moon Goddess of Immortality. The myths associated with Chang’e explain the origin of Moon worship during this day. One version of the story is as follows, as described in Lihui Yang’s Handbook of Chinese Mythology:[18]

In the ancient past, there was a hero named Hou Yi who was excellent at archery. His wife was Chang’e. One year, the ten suns rose in the sky together, causing great disaster to the people. Yi shot down nine of the suns and left only one to provide light. An immortal admired Yi and sent him the elixir of immortality. Yi did not want to leave Chang’e and be immortal without her, so he let Chang’e keep the elixir. However, Peng Meng, one of his apprentices, knew this secret. So, on the fifteenth of August in the Chinese lunisolar calendar, when Yi went hunting, Peng Meng broke into Yi’s house and forced Chang’e to give the elixir to him. Chang’e refused to do so. Instead, she swallowed it and flew into the sky. Since she loved her husband and hoped to live nearby, she chose the moon for her residence. When Yi came back and learned what had happened, he felt so sad that he displayed the fruits and cakes Chang’e liked in the yard and gave sacrifices to his wife. People soon learned about these activities, and since they also were sympathetic to Chang’e they participated in these sacrifices with Yi.

“when people learned of this story, they burnt incense on a long altar and prayed to Chang’e, now the goddess of the Moon, for luck and safety. The custom of praying to the Moon on Mid-Autumn Day has been handed down for thousands of years since that time.»[19]

Handbook of Chinese Mythology also describes an alternate common version of the myth:[18]

After the hero Houyi shot down nine of the ten suns, he was pronounced king by the thankful people. However, he soon became a conceited and tyrannical ruler. In order to live long without death, he asked for the elixir from Xiwangmu. But his wife, Chang’e, stole it on the fifteenth of August because she did not want the cruel king to live long and hurt more people. She took the magic potion to prevent her husband from becoming immortal. Houyi was so angry when discovered that Chang’e took the elixir, he shot at his wife as she flew toward the moon, though he missed. Chang’e fled to the moon and became the spirit of the moon. Houyi died soon because he was overcome with great anger. Thereafter, people offer a sacrifice to Chang’e on every fifteenth day of eighth month to commemorate Chang’e’s action.

Celebration[edit]

The festival was a time to enjoy the successful reaping of rice and wheat with food offerings made in honor of the moon. Today, it is still an occasion for outdoor reunions among friends and relatives to eat mooncakes and watch the Moon, a symbol of harmony and unity. During a year of a solar eclipse, it is typical for governmental offices, banks, and schools to close extra days in order to enjoy the extended celestial celebration an eclipse brings.[20] The festival is celebrated with many cultural or regional customs, among them:

- Burning incense in reverence to deities including Chang’e.

- Performance of dragon and lion dances, which is mainly practiced in southern China.[4]

Lanterns[edit]

For information on a different festival that also involves lanterns, see Lantern Festival

Mid-Autumn Festival lanterns in Chinatown, Singapore

Mid-Autumn Festival lanterns at a shop in Hong Kong

A notable part of celebrating the holiday is the carrying of brightly lit lanterns, lighting lanterns on towers, or floating sky lanterns.[4] Another tradition involving lanterns is to write riddles on them and have other people try to guess the answers (simplified Chinese: 灯谜; traditional Chinese: 燈謎; pinyin: dēng mí; lit. ‘lantern riddles’).[21]

It is difficult to discern the original purpose of lanterns in connection to the festival, but it is certain that lanterns were not used in conjunction with Moon-worship prior to the Tang dynasty.[13] Traditionally, the lantern has been used to symbolize fertility, and functioned mainly as a toy and decoration. But today the lantern has come to symbolize the festival itself.[13] In the old days, lanterns were made in the image of natural things, myths, and local cultures.[13] Over time, a greater variety of lanterns could be found as local cultures became influenced by their neighbors.[13]

As China gradually evolved from an agrarian society to a mixed agrarian-commercial one, traditions from other festivals began to be transmitted into the Mid-Autumn Festival, such as the putting of lanterns on rivers to guide the spirits of the drowned as practiced during the Ghost Festival, which is observed a month before.[13] Hong Kong fishermen during the Qing dynasty, for example, would put up lanterns on their boats for the Ghost Festival and keep the lanterns up until Mid-Autumn Festival.[13]

Mooncakes[edit]

Typical lotus bean-filled mooncakes eaten during the festival

Making and sharing mooncakes is one of the hallmark traditions of this festival. In Chinese culture, a round shape symbolizes completeness and reunion. Thus, the sharing and eating of round mooncakes among family members during the week of the festival signifies the completeness and unity of families.[22] In some areas of China, there is a tradition of making mooncakes during the night of the Mid-Autumn Festival.[23] The senior person in that household would cut the mooncakes into pieces and distribute them to each family member, signifying family reunion.[23] In modern times, however, making mooncakes at home has given way to the more popular custom of giving mooncakes to family members, although the meaning of maintaining familial unity remains.[citation needed]

Although typical mooncakes can be around a few centimetres in diameter, imperial chefs have made some as large as 8 meters in diameter, with its surface pressed with designs of Chang’e, cassia trees, or the Moon-Palace.[20] One tradition is to pile 13 mooncakes on top of each other to mimic a pagoda, the number 13 being chosen to represent the 13 months in a full Chinese lunisolar year.[20] The spectacle of making very large mooncakes continues in modern China.[24]

According to Chinese folklore, a Turpan businessman offered cakes to Emperor Taizong of Tang in his victory against the Xiongnu on the fifteenth day of the eighth Chinese lunisolar month. Taizong took the round cakes and pointed to the moon with a smile, saying, «I’d like to invite the toad to enjoy the hú (胡) cake.» After sharing the cakes with his ministers, the custom of eating these hú cakes spread throughout the country.[25] Eventually these became known as mooncakes. Although the legend explains the beginnings of mooncake-giving, its popularity and ties to the festival began during the Song dynasty (906–1279 CE).[13]

Another popular legend concerns the Han Chinese’s uprising against the ruling Mongols at the end of the Yuan dynasty (1280–1368 CE), in which the Han Chinese used traditional mooncakes to conceal the message that they were to rebel on Mid-Autumn Day.[21] Because of strict controls upon Han Chinese families imposed by the Mongols in which only 1 out of every 10 households was allowed to own a knife guarded by a Mongolian, this coordinated message was important to gather as many available weapons as possible.

Other foods and food displays[edit]

Cassia wine is the traditional choice for «reunion wine» drunk during Mid-Autumn Festival

Vietnamese rice figurines, known as tò he

Imperial dishes served on this occasion included nine-jointed lotus roots which symbolize peace, and watermelons cut in the shape of lotus petals which symbolize reunion.[20] Teacups were placed on stone tables in the garden, where the family would pour tea and chat, waiting for the moment when the full moon’s reflection appeared in the center of their cups.[20] Owing to the timing of the plant’s blossoms, cassia wine is the traditional choice for the «reunion wine» drunk on the occasion. Also, people will celebrate by eating cassia cakes and candy. In some places, people will celebrate by drinking osmanthus wine and eating osmanthus mooncakes.[26][27][28]

Food offerings made to deities are placed on an altar set up in the courtyard, including apples, pears, peaches, grapes, pomegranates, melons, oranges, and pomelos.[29] One of the first decorations purchased for the celebration table is a clay statue of the Jade Rabbit. In Chinese folklore, the Jade Rabbit was an animal that lived on the Moon and accompanied Chang’e. Offerings of soy beans and cockscomb flowers were made to the Jade Rabbit.[20]

Nowadays, in southern China, people will also eat some seasonal fruit that may differ in different district but carrying the same meaning of blessing.

Courtship and matchmaking[edit]

The Mid-Autumn moon has traditionally been a choice occasion to celebrate marriages. Girls would pray to Moon deity Chang’e to help fulfill their romantic wishes.[3]

In some parts of China, dances are held for young men and women to find partners. For example, young women are encouraged to throw their handkerchiefs to the crowd, and the young man who catches and returns the handkerchief has a chance at romance.[4] In Daguang, in southwest Guizhou Province, young men and women of the Dong people would make an appointment at a certain place. The young women would arrive early to overhear remarks made about them by the young men. The young men would praise their lovers in front of their fellows, in which finally the listening women would walk out of the thicket. Pairs of lovers would go off to a quiet place to open their hearts to each other.[17]

Games and activities[edit]

During the 1920s and 1930s, ethnographer Chao Wei-pang conducted research on traditional games among men, women and children on or around the Mid-Autumn day in the Guangdong Province. These games relate to flights of the soul, spirit possession, or fortunetelling.[20]

- One type of activity, «Ascent to Heaven» (Chinese: 上天堂 shàng tiāntáng) involves a young lady selected from a circle of women to «ascend» into the celestial realm. While being enveloped in the smoke of burning incense, she describes the beautiful sights and sounds she encounters.[20]

- Another activity, «Descent into the Garden» (Chinese: 落花园 luò huāyuán), played among younger girls, detailed each girl’s visit to the heavenly gardens. According to legend, a flower tree represented her, and the number and color of the flowers indicated the sex and number of children she would have in her lifetime.[20]

- Men played a game called «Descent of the Eight Immortals» (jiangbaxian), where one of the Eight Immortals took possession of a player, who would then assume the role of a scholar or warrior.[20]

- Children would play a game called «Encircling the Toad» (guanxiamo), where the group would form a circle around a child chosen to be a Toad King and chanted a song that transformed the child into a toad. He would jump around like a toad until water was sprinkled on his head, in which he would then stop.[20]

Practices by regions and cultures[edit]

Mid-Autumn Festival at the Botanical Garden, Montreal

China[edit]

Xiamen[edit]

A unique tradition is celebrated quite exclusively in the island city of Xiamen. During the festival, families and friends gather to play Bo Bing, a gambling sort of game involving 6 dice. People take turns in rolling the dice in a ceramic bowl with the results determining what they win. The number 4 is mainly what determines how big the prize is.[30]

Hong Kong and Macau[edit]

In Hong Kong and Macau, the day after the Mid-Autumn Festival is a public holiday rather than the festival date itself (unless that date falls on a Sunday, then Monday is also a holiday), because many celebration events are held at night. There are a number of festive activities such as lighting lanterns, but mooncakes are the most important feature there. However, people don’t usually buy mooncakes for themselves, but to give their relatives as presents. People start to exchange these presents well in advance of the festival. Hence, mooncakes are sold in elegant boxes for presentation purpose. Also, the price for these boxes are not considered cheap—a four-mooncake box of the lotus seeds paste with egg yolks variety, can generally cost US$40 or more.[31] However, as environmental protection has become a concern of the public in recent years, many mooncake manufacturers in Hong Kong have adopted practices to reduce packaging materials to practical limits.[32] The mooncake manufacturers also explore in the creation of new types of mooncakes, such as ice-cream mooncake and snow skin mooncake.

There are also other traditions related to the Mid-Autumn Festival in Hong Kong. Neighbourhoods across Hong Kong set impressive lantern exhibitions with traditional stage shows, game stalls, palm readings, and many other festive activities. The grandest celebrations take place in Victoria Park (Hong Kong).[33] One of the brightest rituals is the Fire Dragon Dance dating back to the 19th century and recognised as a part of China’s intangible cultural heritage.[34][35] The 200 foot-long fire dragon requires more than 300 people to operate, taking turns. The leader of the fire dragon dance would pray for peace, good fortune through blessings in Hakka. After the ritual ceremony, fire-dragon was thrown into the sea with lanterns and paper cards, which means the dragon would return to sea and take the misfortunes away.[35]

Before 1941, There were also some celebration of Mid-Autumn Festival held in small villages in Hong Kong. Sha Po would celebrate Mid Autumn Festival in every 15th day of the 8th Chinese lunisolar month.[36] People called Mid Autumn Festival as Kwong Sin Festival, they hold Pok San Ngau Tsai at Datong Pond in Sha Po. Pok San Ngau Tsai was a celebration event of Kwong Sin Festival, people would gather around to watch it. During the event, someone would play the percussions, Some villagers would then acted as possessed and called themselves as «Maoshan Masters». They burnt themselves with incense sticks and fought with real blades and spears.

Ethnic minorities in China[edit]

- Korean minorities living in Yanbian Korean Autonomous Prefecture have a custom of welcoming the Moon, where they put up a large conical house frame made of dry pine branches and call it a «moon house». The moonlight would shine inside for gazers to appreciate.[17]

- The Bouyei people call the occasion «Worshiping Moon Festival», where after praying to ancestors and dining together, they bring rice cakes to the doorway to worship the Moon Grandmother.[17]

- The Tu people practice a ceremony called «Beating the Moon», where they place a basin of clear water in the courtyard to reflect an image of the Moon, and then «beat» the water surface with branches.[17]

- The Maonan people tie a bamboo near the table, on which a grapefruit is hung, with three lit incense sticks on it. This is called «Shooting the Moon».[17]

Taiwan[edit]

In Taiwan, and its outlying islands Penghu, Kinmen, and Matsu, the Mid-Autumn Festival is a public holiday. Outdoor barbecues have become a popular affair for friends and family to gather and enjoy each other’s company.[37] Children also make and wear hats made of pomelo rinds. It is believed Chang’e, the lady in the moon, will notice children with her favorite fruit and bestow good fortune upon them. [38]

Similar traditions in other countries[edit]

Similar traditions are found in other parts of Asia and also revolve around the full moon. These festivals tend to occur on the same day or around the Mid-Autumn Festival.

East Asia[edit]

Japan[edit]

The Japanese moon viewing festival, o-tsukimi (お月見, «moon viewing»), is also held at this time. People picnic and drink sake under the full moon to celebrate the harvest.

Korea[edit]

Chuseok (추석; 秋夕; [tɕʰu.sʌk̚]), literally «Autumn eve», once known as hangawi (한가위; [han.ɡa.ɥi]; from archaic Korean for «the great middle (of autumn)»), is a major harvest festival and a three-day holiday in North Korea and South Korea celebrated on the 15th day of the 8th month of the Chinese lunisolar calendar on the full moon. It was celebrated as far back as during the Three Kingdoms period in Silla. As a celebration of the good harvest, Koreans visit their ancestral hometowns, honor their ancestors in a family ceremony (차례), and share a feast of Korean traditional food such as songpyeon (송편), tohrangook (토란국), and rice wines such as sindoju and dongdongju.[citation needed]

Southeast Asia[edit]

Many festivals revolving around a full moon are also celebrated in Cambodia, Laos, and Myanmar. Like the Mid-Autumn Festival, these festivals have Buddhist origins and revolve around the full moon. However, unlike their East Asian counterparts they occur several times a year to correspond with each full moon as opposed to one day each year. The festivals that occur in the lunar months of Ashvini and Kṛttikā generally occur during the Mid-Autumn Festival.[39][40]

Cambodia[edit]

In Cambodia, it is more commonly called «The Water and Moon Festival» Bon Om Touk.[41] The Water and Moon festival is celebrated in November of every year. It is a three-day celebration, starting with the boat race that last the first two days of the festival. The boat races are colorfully painted with bright colors and is in various designs being most popular the neak, Cambodian sea dragon. Hundreds of Cambodian males take part in rowing the boats and racing them at the Tonle Sap River. When night falls the streets are filled with people buying food and attending various concerts.[42] In the evening is the Sampeah Preah Khae: the salutation to the moon or prayers to the moon.[43] The Cambodian people set an array of offerings that are popular for rabbits, such and various fruits and a traditional dish called Ak Ambok in front of their homes with lit incenses to make wishes to the Moon.[44] Cambodians believe the legend of The Rabbit and the Moon, and that a rabbit who lives on the Moon watches over the Cambodian people. At midnight everyone goes up to the temple to pray and make wishes and enjoy their Ak Ambok together. Cambodians would also make homemade lanterns that are usually made into the shape of the lotus flowers or other more modern designs. Incense and candles light up the lanterns and Cambodians make prayers and then send if off into the river for their wishes and prayers to be heard and granted.[45][46][47]

Laos[edit]

In Laos, many festivals are held on the day of the full moon. The most popular festival known as That Luang Festival is associated with Buddhist legend and is held at Pha That Luang temple in Vientiane. The festival often lasts for three to seven days. A procession occurs and many people visit the temple.[48]

Mid-Autumn Festival Decorations at Gardens by the Bay, Singapore.

Myanmar[edit]

In Myanmar, numerous festivals are held on the day of the full moon. However, the Thadingyut Festival is the most popular one and occurs in the month of Thadingyut. It also occurs around the time of the Mid-Autumn Festival, depending on the lunar calendar. It is one of the biggest festivals in Myanmar after the New Year festival, Thingyan. It is a Buddhist festival and many people go to the temple to pay respect to the monks and offer food.[49] It is also a time for thanksgiving and paying homage to Buddhist monks, teachers, parents and elders.[50]

Singapore[edit]

Informally observed but not a government holiday.

Vietnam[edit]

Vietnamese children celebrating the Tết Trung Thu with traditional 5-pointed star-shaped lantern

In Vietnam, children participate in parades in the dark under the full moon with lanterns of various forms, shapes, and colors. Traditionally, lanterns signified the wish for the sun’s light and warmth to return after winter.[51] In addition to carrying lanterns, the children also don masks. Elaborate masks were made of papier-mâché, though it is more common to find masks made of plastic nowadays.[52] Handcrafted shadow lanterns were an important part of Mid-Autumn displays since the 12th-century Lý dynasty, often of historical figures from Vietnamese history.[52] Handcrafted lantern-making declined in modern times due to the availability of mass-produced plastic lanterns, which often depict internationally recognizable characters from children’s shows and video games.[52]

The Mid-Autumn Festival is known as Tết Trung Thu (Chữ Nôm: 節中秋) in Vietnamese. It is also commonly referred to as the «Children’s Festival».[10] The Vietnamese traditionally believed that children, being the most innocent, had the closest connection to the sacred, pure and natural beauty of the world. The celebration of the children’s spirit was seen as a way to connect to that world still full of wonder, mystery, teachings, joy, and sadness. Animist spirits, deities and Vietnamese folk religions are also observed during the festival.[51]

In its most traditional form, the evening commemorates the dragon who brings rain for the crops.[52] Celebrants would observe the moon to divine the future of the people and the harvests. Eventually the celebration came to symbolize a reverence for fruitfulness, with prayers given for bountiful harvests, increase in livestock, and fertility. Over time, the prayers for children evolved into the celebration of children.[52] Historical Confucian scholars continued the tradition of gazing at the Moon, but to sip wine and improvise poetry and song.[52] However, by the early twentieth century in Hanoi, the festival had begun to assume its identity as the quintessential children’s festival.[52]

Aside from the story of Chang’e (Vietnamese: Hằng Nga), there are two other popular folktales associated with the festival. The first describes the legend of Cuội, whose wife accidentally urinated on a sacred banyan tree. The tree began to float towards the Moon, and Cuội, trying to pull it back down to Earth, floated to the Moon with it, leaving him stranded there. Every year, during the Mid-Autumn Festival, children light lanterns and participate in a procession to show Cuội the way back to Earth.[53] The other tale involves a carp who wanted to become a dragon, and as a result, worked hard throughout the year until he was able to transform himself into a dragon.[10]

One important event before and during the festival are lion dances. Dances are performed by both non-professional children’s groups and trained professional groups. Lion dance groups perform on the streets, going to houses asking for permission to perform for them. If the host consents, the «lion» will come in and start dancing as a blessing of luck and fortune for the home. In return, the host gives lucky money to show their gratitude.[citation needed] Cakes and fruits are not only consumed, but elaborately prepared as food displays. For example, glutinous rice flour and rice paste are molded into familiar animals. Pomelo sections can be fashioned into unicorns, rabbits, or dogs.[52] Villagers of Xuân La, just north of Hanoi, produce tò he, figurines made from rice paste and colored with natural food dyes.[52] Into the early decades of the twentieth century of Vietnam, daughters of wealthy families would prepare elaborate center pieces filled with treats for their younger siblings. Well-dressed visitors could visit to observe the daughter’s handiwork as an indication of her capabilities as a wife in the future. Eventually the practice of arranging centerpieces became a tradition not just limited to wealthy families.[52]

Into the early decades of the twentieth century Vietnam, young men and women used the festival as a chance to meet future life companions. Groups would assemble in a courtyard and exchange verses of song while gazing at the moon. Those who performed poorly were sidelined until one young man and one young woman remained, after which they would win prizes as well as entertain matrimonial prospects.[52]

South Asia[edit]

India[edit]

Main article: Onam

Onam is an annual Harvest festival in the state of Kerala in India. It falls on the 22nd nakshatra Thiruvonam in the Malayalam calendar month of Chingam, which in Gregorian calendar overlaps with August–September. According to legends, the festival is celebrated to commemorate King Mahabali, whose spirit is said to visit Kerala at the time of Onam.[citation needed]

Onam is a major annual event for Malayali people in and outside Kerala. It is a harvest festival, one of three major annual Hindu celebrations along with Vishu and Thiruvathira, and it is observed with numerous festivities. Onam celebrations include Vallam Kali (boat races), Pulikali (tiger dances), Pookkalam (flower Rangoli), Onathappan (worship), Onam Kali, Tug of War, Thumbi Thullal (women’s dance), Kummattikali (mask dance), Onathallu (martial arts), Onavillu (music), Kazhchakkula (plantain offerings), Onapottan (costumes), Atthachamayam (folk songs and dance), and other celebrations.

Onam is the official state festival of Kerala with public holidays that start four days from Uthradom (Onam eve). Major festivities take place across 30 venues in Thiruvananthapuram, capital of Kerala. It is also celebrated by Malayali diaspora around the world. Though a Hindu festival, non-Hindu communities of Kerala participate in Onam celebrations considering it as a cultural festival.

Sharad Purnima is a harvest festival celebrated on the full moon day of the Hindu lunar month of Ashvin (September–October), marking the end of the monsoon season.

Sri Lanka[edit]

Main article: Poya

In Sri Lanka, a full moon day is known as Poya and each full moon day is a public holiday. Shops and businesses are closed on these days as people prepare for the full moon.[54][better source needed] Exteriors of buildings are adorned with lanterns and people often make food and go to the temple to listen to sermons.[55] The Binara Full Moon Poya Day and Vap Full Moon Poya Day occur around the time of the Mid-Autumn Festival and like other Buddhist Asian countries, the festivals celebrate the ascendance and culmination of the Buddha’s visit to heaven and for the latter, the acknowledgement of the cultivation season known as «Maha».[56][57][58]

Israel and Jewish Diaspora[edit]

The harvest festival of Sukkot is a cognate celebration, beginning on the full moon of the lunar month Tishrei, which is the seventh month of the Hebrew Calendar.

North America[edit]

Canada and the United States[edit]

As late as 2014, the Mid-Autumn Festival generally went unnoticed outside of Asian supermarkets and food stores,[59] but it has gained popularity since then in areas with significant ethnic Chinese overseas populations, such as New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, and San Francisco.[60] Unlike traditions in China, celebrations in the United States are usually limited to daylight hours, and generally conclude by early evening.[61]

| City | District | Since | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Boston | Chinatown | [62] | |

| Chicago | Chinatown | 2005 | [63] |

| Los Angeles | Chinatown | 1938 | [64] |

| New York City | Mott Street, Flushing, and Sunset Park | 2019 | [60][65] |

| Philadelphia | Chinatown | 1995 | [66] |

| San Francisco | Chinatown | 1991 | [67] |

| Toronto | Cadillac Fairview shopping areas | [68][69] | |

| Vancouver | Dr. Sun Yat-Sen Classical Chinese Garden | [70] |

Dates[edit]

The Mid-Autumn Festival is held on the 15th day of the eighth month in the Han calendar—essentially the night of a full moon—which falls near the Autumnal Equinox (on a day between 8 September and 7 October in the Gregorian calendar). In 2018, it fell on 24 September. It will occur on these days in coming years:[71]

- 2021: 21 September (Tuesday)

- 2022: 10 September (Saturday)

- 2023: 29 September (Friday)

See also[edit]

- Dragon Boat Festival

- Agriculture in China

- Agriculture in Vietnam

- Chinese holidays

- Vietnamese holidays

- List of harvest festivals

Notes[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b https://www.timeanddate.com/holidays/china/mid-autumn-festival

- ^ «Moon Festival – The Chinese Mid Autumn Festival». 3 June 2021.

- ^ a b c d Roy, Christian (2005). Traditional Festivals: A Multicultural Encyclopedia, Volume 1. ABC-CLIO. pp. 282–286. ISBN 978-1576070895.

- ^ a b c d e f Yang, Fang. «Mid-Autumn Festival and its traditions». Archived from the original on 13 April 2012.

The festival, celebrated on the 15th day of the eighth month of the Chinese calendar, has no fixed date on the Western calendar, but the day always coincides with a full moon.

- ^ «Mooncakes, lanterns and legends: Your guide to the Mid-Autumn Festival in Singapore». AsiaOne. 19 September 2020.

- ^ «Mid-Autumn Festival in Other Asian Countries». www.travelchinaguide.com.

- ^ «A Chinese Symbol of Reunion: Moon Cakes – China culture». kaleidoscope.cultural-china.com. Archived from the original on 5 May 2017. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- ^ «Back to Basics: Baked Traditional Moon Cakes». Guai Shu Shu. 10 August 2014. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- ^ «Chuseok — Korean Harvest Festival». Chuseok.org. Chuseok.org.

- ^ a b c Lee, Jonathan H. X.; Nadeau, Kathleen M., eds. (2011). Encyclopedia of Asian American Folklore and Folklife. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. p. 1180. ISBN 978-0313350665.

- ^ «Lantern Festival | Definition, History, Traditions, & Facts | Britannica». www.britannica.com. Retrieved 30 November 2021.

- ^ «Water and Moon Festival (Bon Om Tuk, Bondet Protit, Sam Peah Preah Khae)». intocambodia.org. Retrieved 30 June 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Siu, K. W. Michael (1999). «Lanterns of the mid-Autumn Festival: A Reflection of Hong Kong Cultural Change». The Journal of Popular Culture. 33 (2): 67–86. doi:10.1111/j.0022-3840.1999.3302_67.x.

- ^ Yu, Jose Vidamor B. (2000). Inculturation of Filipino-Chinese culture mentality. Roma: Pontificia università gregoriana. pp. 111–112. ISBN 978-8876528484.

- ^ Overmyer, Daniel L. (1986). Religions of China: The World as a Living System. New York: Harper & Row. p. 51. ISBN 9781478609896.

- ^ Fan, Lizhu; Chen, Na (2013). «The Revival of Indigenous Religion in China» (PDF). China Watch: 23.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Li, Xing (2006). «Chapter VI: Women’s Festivals». Festivals of China’s Ethnic Minorities. China Intercontinental Press. pp. 124–127. ISBN 978-7508509990.

- ^ a b Yang, Lihui; Deming An (2005). Handbook of Chinese mythology. Santa Barbara, Calif. [u.a.]: ABC-Clio. pp. 89–90. ISBN 978-1576078068.

- ^ Lemei, Yang (2006). «China’s Mid-Autumn Day». Journal of Folklore Research. 43 (3): 263–270. doi:10.2979/JFR.2006.43.3.263. ISSN 0737-7037. JSTOR 4640212. S2CID 161494297.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Stepanchuk, Carol; Wong, Charles (1991). Mooncakes and hungry ghosts: festivals of China. San Francisco: China Books & Periodicals. pp. 51–60. ISBN 978-0835124812.

- ^ a b Yang, Lemei (September–December 2006). «China’s Mid-Autumn Day». Journal of Folklore Research. 43 (3): 263–270. doi:10.2979/jfr.2006.43.3.263. JSTOR 4640212. S2CID 161494297.

- ^ «中秋节传统习俗:吃月饼». www.huaxia.com. Retrieved 24 September 2018.

- ^ a b «中秋食品». Academy of Chinese Studies. Retrieved 16 December 2012.

- ^ Yan, Alice (4 September 2016). «Chinese city’s record 2.4-metre-wide Mid-Autumn Festival mooncake cut down to size for hungry fans». South China Morning Post. Retrieved 25 December 2017.

- ^ Wei, Liming; Lang, Tao (2011). Chinese festivals (Updated ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521186599.

- ^ Li Zhengping. Chinese Wine, p. 101. Cambridge University Press (Cambridge), 2011. Accessed 8 November 2013.

- ^ Qiu Yaohong. Origins of Chinese Tea and Wine, p. 121. Asiapac Books (Singapore), 2004. Accessed 7 November 2013.

- ^ Liu Junru. Chinese Food, p. 136. Cambridge Univ. Press (Cambridge), 2011. Accessed 7 November 2013.

- ^ Tom, K.S. (1989). Echoes from old China: life, legends, and lore of the Middle Kingdom. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0824812850.

- ^ «Xiamen rolls the dice, parties for Moon Festival». www.shanghaidaily.com. Retrieved 8 October 2016.

- ^ «10 must-order mooncakes for Mid-Autumn Festival 2017». Lifestyle Asia – Hong Kong. 9 August 2017.

- ^ «Voluntary Agreement on Management of Mooncake Packaging». Environmental Protection Department of Hong Kong. 18 March 2013. Retrieved 10 September 2013.

- ^ «Mid-Autumn Festival». Hong Kong Tourism Board.

- ^ «Mid-Autumn Festival». rove.me.

- ^ a b «Local Festivals: 8th Lunar Month». Hong Kong Memory. Retrieved 5 March 2019.

- ^ https://www.hkmemory.hk/collections/oral_history/All_Items_OH/oha_104/highlight/index.html Hong Kong memory

- ^ Yeo, Joanna (20 September 2012). «Traditional BBQ for Mid-Autumn Festival?». Makansutra. Retrieved 10 November 2012.

- ^ Ciaran McEneaney (7 January 2019). «5 Taiwanese Customs to Celebrate Moon Festival». Culture Trip. Retrieved 5 September 2022.

- ^ «How the world celebrates Mid-Autumn Festival – Chinese News». chinesetimesschool.com.

- ^ «上海百润投资控股集团股份有限公司». www.bairun.net.

- ^ Aquino, Michael. «Water and Moon Fest». chanbokeo.com. Retrieved 15 November 2019.

- ^ Craig (5 November 2019). «Cambodian Water Festival (Bon Om Touk)». pharecircus.org. Retrieved 15 November 2019.

- ^ Cassie (21 November 2018). «Cambodia’s Water Festival (Bon Om Touk)». movetocambodia.com. Retrieved 15 November 2019.

- ^ Carruthers, Marissa (22 October 2018). «No, not Songkran – that other water festival, in Cambodia, and its thrills». scmp.com. Retrieved 15 November 2019.

- ^ «Asian Mid Autumn Festival». Blog’s GoAsiaDayTrip. 25 August 2016.

- ^ «Moon Festival in Cambodia – An Unforgettable Experience». travelcambodiaonline.com.

- ^ «Water and Moon Festival and Boat Racing». tourismcambodia.com. Retrieved 15 November 2019.

- ^ «That Luang Festival – Event Carnival».

- ^ Long, Douglas (23 October 2015). «Thadingyut: Festival of Lights».

- ^ «Myanmar Festivals 2016–2017».

- ^ a b Cohen, Barbara (1 October 1995). «Mid-Autumn Children’s Festival». Archived from the original on 21 January 2013. Retrieved 10 November 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Nguyen, Van Huy (2003), «The Mid-Autumn Festival (Tet Trung Thu), Yesterday and Today», in Kendall, Laurel (ed.), Vietnam: Journeys of Body, Mind, and Spirit, University of California Press, pp. 93–106, ISBN 978-0520238725

- ^ Wong, Bet Key. «Tet Trung Thu». FamilyCulture.com. Archived from the original on 23 June 2012. Retrieved 14 November 2010.

- ^ 冯明惠. «How the world celebrates Mid-Autumn Festival». Chinadaily.com.cn.

- ^ «Mid-Autumn Festival Traditions». All China Women’s Federation.

- ^ «Poya – Sri Lanka – Office Holidays».

- ^ «september calendar».

- ^ «Today is Vap Full Moon Poya Day».

- ^ Vuong, Zen (13 September 2014). «Mid-Autumn Festival and being Chinese-American». Daily Bulletin. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- ^ a b «Feature: Mid-Autumn Festival gives Americans a taste of China». Xinhua. 14 September 2019. Archived from the original on 17 September 2019. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- ^ «Celebration in America». Mid-Autumn Festival (AAS 220). Stonybrook. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- ^ «Annual August Moon Festival: Chinatown 2019 (Tips, Reviews, Local Guide)». www.bostoncentral.com.

- ^ «About Moon Fest Chicago». Moon Festival Chicago. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- ^ «81st Annual Mid-Autumn Moon Festival (2019-09-14)».

- ^ Snook, Raven (5 August 2014). «Chinese Mid-Autumn Moon Festivals in New York City: Moon Cakes and Flying Lanterns». MommyPoppins.com.

- ^ «Join in a lantern parade at annual Mid-Autumn Festival in Chinatown». 19 September 2017.

- ^ «About». MoonFestival.org. Chinatown Merchants Association. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- ^ Fairview, Cadillac. «Cadillac Fairview Celebrates the Mid-Autumn Festival». www.newswire.ca.

- ^ «Celebrate Mid-Autumn Festival». www.cfshops.com.

- ^ «Mid-Autumn Festival celebration held in Vancouver – Xinhua | English.news.cn». www.xinhuanet.com. Archived from the original on 11 August 2020.

- ^ «Gregorian-Lunar Calendar Conversion Table». Hong Kong Observatory. Retrieved 10 November 2012.

External links[edit]

- San Francisco Chinatown Autumn Moon Festival

- Moon Viewing Festival on YouTube at Sumiyoshi-taisha, Osaka, Japan

- Brief video about the history and traditions of Mid-Autumn Festival on YouTube

- Origin and Development of the Mid-Autumn Festival

| Mid-Autumn Festival | |

|---|---|

Festival decorations in Beijing |

|

| Also called | Moon Festival, Mooncake Festival |

| Observed by | Mainland China, Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan (similar holidays celebrated in Japan, Korea, and Southeast Asia) |

| Type | Cultural, religious, Asian |

| Significance | Celebrates the end of the autumn harvest |

| Celebrations | Lantern lighting, mooncake making and sharing, courtship and matchmaking, fireworks, family gathering, dragon dances, family meal, visiting friends and relatives, gift giving |

| Observances | Consumption of mooncakes Consumption of cassia wine |

| Date | 15th day of the 8th month of the Chinese lunar calendar |

| 2023 date | 29 September[1] |

| 2024 date | 7 September[1] |

| Frequency | Annual |

| Related to | Chuseok (Korea), Tsukimi (Japan), Tết Trung Thu (Vietnam), Uposatha of Ashvini or Krittika (Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Sri Lanka, and Thailand) |

| Mid-Autumn Festival | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

«Mid-Autumn Festival» in traditional (top) and simplified (bottom) Chinese characters |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 中秋節 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 中秋节 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | «Mid-Autumn Festival» | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Min Chinese alternate name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 八月節 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | «Festival of the Eighth Month» | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Mid-Autumn Festival (Chinese: 中秋節 / 中秋节), also known as the Moon Festival or Mooncake Festival, is a traditional festival celebrated in Chinese culture. Similar holidays are celebrated in Japan (Tsukimi), Korea (Chuseok), Vietnam (Tết Trung Thu), and other countries in East and Southeast Asia.

It is one of the most important holidays in Chinese culture; its popularity is on par with that of Chinese New Year. The history of the Mid-Autumn Festival dates back over 3,000 years.[2][3] The festival is held on the 15th day of the 8th month of the Chinese lunisolar calendar with a full moon at night, corresponding to mid-September to early October of the Gregorian calendar.[4] On this day, the Chinese believe that the Moon is at its brightest and fullest size, coinciding with harvest time in the middle of Autumn.[5]

Lanterns of all size and shapes, are carried and displayed – symbolic beacons that light people’s path to prosperity and good fortune. Mooncakes, a rich pastry typically filled with sweet-bean, egg yolk, meat or lotus-seed paste, are traditionally eaten during this festival.[6][7][8] The Mid-Autumn Festival is based on the legend of Chang’e, the Moon goddess in Chinese mythology.

Etymology[edit]

- The Mid-Autumn Festival is so-named as it is held on the 15th of the 8th lunar month in the Chinese calendar around the autumn equinox.[3] Its name is pronounced in Mandarin as Zhōngqiū Jié (simplified Chinese: 中秋节; traditional Chinese: 中秋節), Jūng-chāu Jit in Cantonese, and Tiong-chhiu-cheh in Hokkien. It is also called Peh-goe̍h-cheh (八月節; ‘Eighth Month Festival’) in Hokkien.

- Chuseok (추석 / 秋夕; Autumn Eve), Korea festival celebrated on the same day in the Chinese and other East Asian lunisolar calendars.[9]

- Tsukimi (月見; ‘moon viewing’), Japanese variant of the Mid-Autumn Festival celebrated on the same day in the Chinese lunisolar calendar.

- Moon Festival or Harvest Moon Festival, because of the celebration’s association with the full moon on this night, as well as the traditions of Moon worship and Moon viewing.

- Tết Trung Thu (節中秋 in Chữ Nôm, Mid-Autumn Tet), in Vietnamese.

- Also known as The Children’s Festival in Vietnam. Most festival songs are sung by the children.[10]

- Lantern Festival, a term sometimes used in Singapore, Malaysia and Indonesia,[11] which is not to be confused with the Lantern Festival in China that occurs on the 15th day of the first month of the Chinese calendar.

- However, ‘Mid-Autumn Festival’ is more widely used by locals when referring to the festival in English and ‘Zhōngqiū Jié’ is used when referring to the festival in Chinese.[citation needed]

- Bon Om Touk, or The Water and Moon Festival in Cambodian. The festival is held each year in November for 3 days.[12]

Meanings[edit]

The festival celebrates three fundamental concepts that are closely connected:

- Gathering, such as family and friends coming together, or harvesting crops for the festival. It is said the Moon is the brightest and roundest on this day which means family reunion. Consequently, this is the main reason why the festival is thought to be important.

- Thanksgiving, to give thanks for the harvest, or for harmonious unions

- Praying (asking for conceptual or material satisfaction), such as for babies, a spouse, beauty, longevity, or for a good future

Traditions and myths surrounding the festival are formed around these concepts,[13] although traditions have changed over time due to changes in technology, science, economy, culture, and religion.[13] It’s about well being together.

Origins and development[edit]

The Chinese have celebrated the harvest during the autumn full moon since the Shang dynasty (c. 1600–1046 BCE).[13][14] The term mid-autumn (中秋) first appeared in Rites of Zhou, a written collection of rituals of the Western Zhou dynasty (1046–771 BCE).[4] As for the royal court, it was dedicated to the goddess Taiyinxingjun (太陰星君; Tàiyīn xīng jūn). This is still true for Taoism and Chinese folk religion.[15][16]

The celebration as a festival only started to gain popularity during the early Tang dynasty (618–907 CE).[4] One legend explains that Emperor Xuanzong of Tang started to hold formal celebrations in his palace after having explored the Moon-Palace.[13]

In the Northern Song Dynasty, the Mid Autumn Festival has become a popular folk festival, and officially designated the 15th day of the eighth month of the lunar calendar as the Mid Autumn Festival.

By the Ming and Qing Dynasties, the mid autumn festival had become one of the main folk festivals in China. The Empress Dowager Cixi (late 19th century) enjoyed celebrating Mid-Autumn Festival so much that she would spend the period between the thirteenth and seventeenth day of the eighth month staging elaborate rituals.[3]

Moon worship[edit]

Chang’e, the Moon Goddess of Immortality

Houyi helplessly looking at his wife Chang’e flying off to the Moon after she drank the elixir.

An important part of the festival celebration is Moon worship. The ancient Chinese believed in rejuvenation being associated with the Moon and water, and connected this concept to the menstruation of women, calling it «monthly water».[17] The Zhuang people, for example, have an ancient fable saying the Sun and Moon are a couple and the stars are their children, and when the Moon is pregnant, it becomes round, and then becomes crescent after giving birth to a child. These beliefs made it popular among women to worship and give offerings to the Moon on this evening.[17] In some areas of China, there are still customs in which «men do not worship the moon and the women do not offer sacrifices to the kitchen gods.»[17]

In China, the Mid-Autumn festival symbolizes the family reunion and on this day, all families will appreciate the Moon in the evening, because it is the 15th day of the eighth month of the Chinese lunisolar calendar, when the moon is at its fullest. There is a beautiful myth about the Mid-Autumn festival, that is Chang’e flying to the Moon.

Offerings are also made to a more well-known lunar deity, Chang’e, known as the Moon Goddess of Immortality. The myths associated with Chang’e explain the origin of Moon worship during this day. One version of the story is as follows, as described in Lihui Yang’s Handbook of Chinese Mythology:[18]

In the ancient past, there was a hero named Hou Yi who was excellent at archery. His wife was Chang’e. One year, the ten suns rose in the sky together, causing great disaster to the people. Yi shot down nine of the suns and left only one to provide light. An immortal admired Yi and sent him the elixir of immortality. Yi did not want to leave Chang’e and be immortal without her, so he let Chang’e keep the elixir. However, Peng Meng, one of his apprentices, knew this secret. So, on the fifteenth of August in the Chinese lunisolar calendar, when Yi went hunting, Peng Meng broke into Yi’s house and forced Chang’e to give the elixir to him. Chang’e refused to do so. Instead, she swallowed it and flew into the sky. Since she loved her husband and hoped to live nearby, she chose the moon for her residence. When Yi came back and learned what had happened, he felt so sad that he displayed the fruits and cakes Chang’e liked in the yard and gave sacrifices to his wife. People soon learned about these activities, and since they also were sympathetic to Chang’e they participated in these sacrifices with Yi.

“when people learned of this story, they burnt incense on a long altar and prayed to Chang’e, now the goddess of the Moon, for luck and safety. The custom of praying to the Moon on Mid-Autumn Day has been handed down for thousands of years since that time.»[19]

Handbook of Chinese Mythology also describes an alternate common version of the myth:[18]

After the hero Houyi shot down nine of the ten suns, he was pronounced king by the thankful people. However, he soon became a conceited and tyrannical ruler. In order to live long without death, he asked for the elixir from Xiwangmu. But his wife, Chang’e, stole it on the fifteenth of August because she did not want the cruel king to live long and hurt more people. She took the magic potion to prevent her husband from becoming immortal. Houyi was so angry when discovered that Chang’e took the elixir, he shot at his wife as she flew toward the moon, though he missed. Chang’e fled to the moon and became the spirit of the moon. Houyi died soon because he was overcome with great anger. Thereafter, people offer a sacrifice to Chang’e on every fifteenth day of eighth month to commemorate Chang’e’s action.

Celebration[edit]

The festival was a time to enjoy the successful reaping of rice and wheat with food offerings made in honor of the moon. Today, it is still an occasion for outdoor reunions among friends and relatives to eat mooncakes and watch the Moon, a symbol of harmony and unity. During a year of a solar eclipse, it is typical for governmental offices, banks, and schools to close extra days in order to enjoy the extended celestial celebration an eclipse brings.[20] The festival is celebrated with many cultural or regional customs, among them:

- Burning incense in reverence to deities including Chang’e.

- Performance of dragon and lion dances, which is mainly practiced in southern China.[4]

Lanterns[edit]

For information on a different festival that also involves lanterns, see Lantern Festival

Mid-Autumn Festival lanterns in Chinatown, Singapore

Mid-Autumn Festival lanterns at a shop in Hong Kong

A notable part of celebrating the holiday is the carrying of brightly lit lanterns, lighting lanterns on towers, or floating sky lanterns.[4] Another tradition involving lanterns is to write riddles on them and have other people try to guess the answers (simplified Chinese: 灯谜; traditional Chinese: 燈謎; pinyin: dēng mí; lit. ‘lantern riddles’).[21]

It is difficult to discern the original purpose of lanterns in connection to the festival, but it is certain that lanterns were not used in conjunction with Moon-worship prior to the Tang dynasty.[13] Traditionally, the lantern has been used to symbolize fertility, and functioned mainly as a toy and decoration. But today the lantern has come to symbolize the festival itself.[13] In the old days, lanterns were made in the image of natural things, myths, and local cultures.[13] Over time, a greater variety of lanterns could be found as local cultures became influenced by their neighbors.[13]

As China gradually evolved from an agrarian society to a mixed agrarian-commercial one, traditions from other festivals began to be transmitted into the Mid-Autumn Festival, such as the putting of lanterns on rivers to guide the spirits of the drowned as practiced during the Ghost Festival, which is observed a month before.[13] Hong Kong fishermen during the Qing dynasty, for example, would put up lanterns on their boats for the Ghost Festival and keep the lanterns up until Mid-Autumn Festival.[13]

Mooncakes[edit]

Typical lotus bean-filled mooncakes eaten during the festival

Making and sharing mooncakes is one of the hallmark traditions of this festival. In Chinese culture, a round shape symbolizes completeness and reunion. Thus, the sharing and eating of round mooncakes among family members during the week of the festival signifies the completeness and unity of families.[22] In some areas of China, there is a tradition of making mooncakes during the night of the Mid-Autumn Festival.[23] The senior person in that household would cut the mooncakes into pieces and distribute them to each family member, signifying family reunion.[23] In modern times, however, making mooncakes at home has given way to the more popular custom of giving mooncakes to family members, although the meaning of maintaining familial unity remains.[citation needed]

Although typical mooncakes can be around a few centimetres in diameter, imperial chefs have made some as large as 8 meters in diameter, with its surface pressed with designs of Chang’e, cassia trees, or the Moon-Palace.[20] One tradition is to pile 13 mooncakes on top of each other to mimic a pagoda, the number 13 being chosen to represent the 13 months in a full Chinese lunisolar year.[20] The spectacle of making very large mooncakes continues in modern China.[24]

According to Chinese folklore, a Turpan businessman offered cakes to Emperor Taizong of Tang in his victory against the Xiongnu on the fifteenth day of the eighth Chinese lunisolar month. Taizong took the round cakes and pointed to the moon with a smile, saying, «I’d like to invite the toad to enjoy the hú (胡) cake.» After sharing the cakes with his ministers, the custom of eating these hú cakes spread throughout the country.[25] Eventually these became known as mooncakes. Although the legend explains the beginnings of mooncake-giving, its popularity and ties to the festival began during the Song dynasty (906–1279 CE).[13]

Another popular legend concerns the Han Chinese’s uprising against the ruling Mongols at the end of the Yuan dynasty (1280–1368 CE), in which the Han Chinese used traditional mooncakes to conceal the message that they were to rebel on Mid-Autumn Day.[21] Because of strict controls upon Han Chinese families imposed by the Mongols in which only 1 out of every 10 households was allowed to own a knife guarded by a Mongolian, this coordinated message was important to gather as many available weapons as possible.

Other foods and food displays[edit]

Cassia wine is the traditional choice for «reunion wine» drunk during Mid-Autumn Festival

Vietnamese rice figurines, known as tò he

Imperial dishes served on this occasion included nine-jointed lotus roots which symbolize peace, and watermelons cut in the shape of lotus petals which symbolize reunion.[20] Teacups were placed on stone tables in the garden, where the family would pour tea and chat, waiting for the moment when the full moon’s reflection appeared in the center of their cups.[20] Owing to the timing of the plant’s blossoms, cassia wine is the traditional choice for the «reunion wine» drunk on the occasion. Also, people will celebrate by eating cassia cakes and candy. In some places, people will celebrate by drinking osmanthus wine and eating osmanthus mooncakes.[26][27][28]

Food offerings made to deities are placed on an altar set up in the courtyard, including apples, pears, peaches, grapes, pomegranates, melons, oranges, and pomelos.[29] One of the first decorations purchased for the celebration table is a clay statue of the Jade Rabbit. In Chinese folklore, the Jade Rabbit was an animal that lived on the Moon and accompanied Chang’e. Offerings of soy beans and cockscomb flowers were made to the Jade Rabbit.[20]

Nowadays, in southern China, people will also eat some seasonal fruit that may differ in different district but carrying the same meaning of blessing.

Courtship and matchmaking[edit]

The Mid-Autumn moon has traditionally been a choice occasion to celebrate marriages. Girls would pray to Moon deity Chang’e to help fulfill their romantic wishes.[3]

In some parts of China, dances are held for young men and women to find partners. For example, young women are encouraged to throw their handkerchiefs to the crowd, and the young man who catches and returns the handkerchief has a chance at romance.[4] In Daguang, in southwest Guizhou Province, young men and women of the Dong people would make an appointment at a certain place. The young women would arrive early to overhear remarks made about them by the young men. The young men would praise their lovers in front of their fellows, in which finally the listening women would walk out of the thicket. Pairs of lovers would go off to a quiet place to open their hearts to each other.[17]

Games and activities[edit]

During the 1920s and 1930s, ethnographer Chao Wei-pang conducted research on traditional games among men, women and children on or around the Mid-Autumn day in the Guangdong Province. These games relate to flights of the soul, spirit possession, or fortunetelling.[20]

- One type of activity, «Ascent to Heaven» (Chinese: 上天堂 shàng tiāntáng) involves a young lady selected from a circle of women to «ascend» into the celestial realm. While being enveloped in the smoke of burning incense, she describes the beautiful sights and sounds she encounters.[20]

- Another activity, «Descent into the Garden» (Chinese: 落花园 luò huāyuán), played among younger girls, detailed each girl’s visit to the heavenly gardens. According to legend, a flower tree represented her, and the number and color of the flowers indicated the sex and number of children she would have in her lifetime.[20]

- Men played a game called «Descent of the Eight Immortals» (jiangbaxian), where one of the Eight Immortals took possession of a player, who would then assume the role of a scholar or warrior.[20]

- Children would play a game called «Encircling the Toad» (guanxiamo), where the group would form a circle around a child chosen to be a Toad King and chanted a song that transformed the child into a toad. He would jump around like a toad until water was sprinkled on his head, in which he would then stop.[20]

Practices by regions and cultures[edit]

Mid-Autumn Festival at the Botanical Garden, Montreal

China[edit]

Xiamen[edit]

A unique tradition is celebrated quite exclusively in the island city of Xiamen. During the festival, families and friends gather to play Bo Bing, a gambling sort of game involving 6 dice. People take turns in rolling the dice in a ceramic bowl with the results determining what they win. The number 4 is mainly what determines how big the prize is.[30]

Hong Kong and Macau[edit]

In Hong Kong and Macau, the day after the Mid-Autumn Festival is a public holiday rather than the festival date itself (unless that date falls on a Sunday, then Monday is also a holiday), because many celebration events are held at night. There are a number of festive activities such as lighting lanterns, but mooncakes are the most important feature there. However, people don’t usually buy mooncakes for themselves, but to give their relatives as presents. People start to exchange these presents well in advance of the festival. Hence, mooncakes are sold in elegant boxes for presentation purpose. Also, the price for these boxes are not considered cheap—a four-mooncake box of the lotus seeds paste with egg yolks variety, can generally cost US$40 or more.[31] However, as environmental protection has become a concern of the public in recent years, many mooncake manufacturers in Hong Kong have adopted practices to reduce packaging materials to practical limits.[32] The mooncake manufacturers also explore in the creation of new types of mooncakes, such as ice-cream mooncake and snow skin mooncake.

There are also other traditions related to the Mid-Autumn Festival in Hong Kong. Neighbourhoods across Hong Kong set impressive lantern exhibitions with traditional stage shows, game stalls, palm readings, and many other festive activities. The grandest celebrations take place in Victoria Park (Hong Kong).[33] One of the brightest rituals is the Fire Dragon Dance dating back to the 19th century and recognised as a part of China’s intangible cultural heritage.[34][35] The 200 foot-long fire dragon requires more than 300 people to operate, taking turns. The leader of the fire dragon dance would pray for peace, good fortune through blessings in Hakka. After the ritual ceremony, fire-dragon was thrown into the sea with lanterns and paper cards, which means the dragon would return to sea and take the misfortunes away.[35]

Before 1941, There were also some celebration of Mid-Autumn Festival held in small villages in Hong Kong. Sha Po would celebrate Mid Autumn Festival in every 15th day of the 8th Chinese lunisolar month.[36] People called Mid Autumn Festival as Kwong Sin Festival, they hold Pok San Ngau Tsai at Datong Pond in Sha Po. Pok San Ngau Tsai was a celebration event of Kwong Sin Festival, people would gather around to watch it. During the event, someone would play the percussions, Some villagers would then acted as possessed and called themselves as «Maoshan Masters». They burnt themselves with incense sticks and fought with real blades and spears.

Ethnic minorities in China[edit]

- Korean minorities living in Yanbian Korean Autonomous Prefecture have a custom of welcoming the Moon, where they put up a large conical house frame made of dry pine branches and call it a «moon house». The moonlight would shine inside for gazers to appreciate.[17]

- The Bouyei people call the occasion «Worshiping Moon Festival», where after praying to ancestors and dining together, they bring rice cakes to the doorway to worship the Moon Grandmother.[17]

- The Tu people practice a ceremony called «Beating the Moon», where they place a basin of clear water in the courtyard to reflect an image of the Moon, and then «beat» the water surface with branches.[17]

- The Maonan people tie a bamboo near the table, on which a grapefruit is hung, with three lit incense sticks on it. This is called «Shooting the Moon».[17]

Taiwan[edit]

In Taiwan, and its outlying islands Penghu, Kinmen, and Matsu, the Mid-Autumn Festival is a public holiday. Outdoor barbecues have become a popular affair for friends and family to gather and enjoy each other’s company.[37] Children also make and wear hats made of pomelo rinds. It is believed Chang’e, the lady in the moon, will notice children with her favorite fruit and bestow good fortune upon them. [38]

Similar traditions in other countries[edit]

Similar traditions are found in other parts of Asia and also revolve around the full moon. These festivals tend to occur on the same day or around the Mid-Autumn Festival.

East Asia[edit]

Japan[edit]

The Japanese moon viewing festival, o-tsukimi (お月見, «moon viewing»), is also held at this time. People picnic and drink sake under the full moon to celebrate the harvest.

Korea[edit]

Chuseok (추석; 秋夕; [tɕʰu.sʌk̚]), literally «Autumn eve», once known as hangawi (한가위; [han.ɡa.ɥi]; from archaic Korean for «the great middle (of autumn)»), is a major harvest festival and a three-day holiday in North Korea and South Korea celebrated on the 15th day of the 8th month of the Chinese lunisolar calendar on the full moon. It was celebrated as far back as during the Three Kingdoms period in Silla. As a celebration of the good harvest, Koreans visit their ancestral hometowns, honor their ancestors in a family ceremony (차례), and share a feast of Korean traditional food such as songpyeon (송편), tohrangook (토란국), and rice wines such as sindoju and dongdongju.[citation needed]

Southeast Asia[edit]

Many festivals revolving around a full moon are also celebrated in Cambodia, Laos, and Myanmar. Like the Mid-Autumn Festival, these festivals have Buddhist origins and revolve around the full moon. However, unlike their East Asian counterparts they occur several times a year to correspond with each full moon as opposed to one day each year. The festivals that occur in the lunar months of Ashvini and Kṛttikā generally occur during the Mid-Autumn Festival.[39][40]

Cambodia[edit]

In Cambodia, it is more commonly called «The Water and Moon Festival» Bon Om Touk.[41] The Water and Moon festival is celebrated in November of every year. It is a three-day celebration, starting with the boat race that last the first two days of the festival. The boat races are colorfully painted with bright colors and is in various designs being most popular the neak, Cambodian sea dragon. Hundreds of Cambodian males take part in rowing the boats and racing them at the Tonle Sap River. When night falls the streets are filled with people buying food and attending various concerts.[42] In the evening is the Sampeah Preah Khae: the salutation to the moon or prayers to the moon.[43] The Cambodian people set an array of offerings that are popular for rabbits, such and various fruits and a traditional dish called Ak Ambok in front of their homes with lit incenses to make wishes to the Moon.[44] Cambodians believe the legend of The Rabbit and the Moon, and that a rabbit who lives on the Moon watches over the Cambodian people. At midnight everyone goes up to the temple to pray and make wishes and enjoy their Ak Ambok together. Cambodians would also make homemade lanterns that are usually made into the shape of the lotus flowers or other more modern designs. Incense and candles light up the lanterns and Cambodians make prayers and then send if off into the river for their wishes and prayers to be heard and granted.[45][46][47]

Laos[edit]

In Laos, many festivals are held on the day of the full moon. The most popular festival known as That Luang Festival is associated with Buddhist legend and is held at Pha That Luang temple in Vientiane. The festival often lasts for three to seven days. A procession occurs and many people visit the temple.[48]

Mid-Autumn Festival Decorations at Gardens by the Bay, Singapore.

Myanmar[edit]