Шабат, или Шаббат (иврит: שַׁבָּת) — седьмой день творения, он же — седьмой день недели, еврейская Суббота. В иудаизме Шаббат — святой день, который заповедано чтить и соблюдать в знак того, что шесть дней Б-г творил этот мир, а в седьмой — отдыхал. Само слово «шабат»/«шаббат» происходит от ивритского корневого глагола «лишбот» и означает «отдыхал», «прекратил деятельность», что имеет общий корень с «шева» — «семь» (отсюда, например, «швиит» — заповедь соблюдения седьмого, «субботнего» года). Традиционно Шаббат — это день отдыха, день субботнего покоя: в Шаббат запрещено совершать 39 видов деятельности (т.н. 39 видов работ). Евреи отмечают Шаббат как праздник: встречают Субботу зажиганием свечей, устраивают трапезы с шаббатними песнями, посвящают Шаббат духовному росту, изучению Торы, проводят время с семьей и близкими друзьями, непременно желая друг другу «Шабат шалом!» (традиционное субботнее приветствие, пожелание мира в Шаббат) или «гут Шабес!» (на идиш — «хорошей субботы!»). Соблюдение Субботы считается одной из базовых заповедей иудаизма: соблюдая Шаббат и отстраняясь от работы в этот день, еврей провозглашает веру в то, что Б-г — Творец мира, который управляет всеми процессами в нем.

СУББОТА — Шаббат, седьмой день недели

Суббота, седьмой день недели, день отдыха… На иврите все дни называются по числу их отстранения от Субботы — первый, второй и т. д., но имя собственное есть только у одного дня — Субботы.

Согласно Торе, заповедь соблюдать субботу установлена Всевышним, Который, закончив за шесть дней Творение мира, благословил и освятил седьмой день. Читаем в книге Шмот, в главе о получении евреями на горе Синае Десяти заповедей: «Помни субботний день, чтобы освящать его. Шесть дней работай и делай любое свое дело. Но седьмой день — суббота Всевышнему: не делай никакого дела, — ни твой сын, ни твоя дочь, ни твой слуга, ни твоя служанка, ни твой скот, ни твой пришелец, который в твоих воротах. Ибо шесть дней создавал Всевышний небо, землю, море и все, что в них, а в седьмой день отдыхал. Поэтому благословил Всевышний субботний день и освятил его».

Тора называет субботу праздником, в который запрещено делать работу — даже в разгар полевой страды; кроме того, в субботу запрещено зажигать огонь. Всякий, нарушивший эти запреты, строго наказывается судом. В тех местах Торы, где перечисляются праздники, суббота упоминается первой. Пророк Йешаяу предвидел, что еврейский народ будет возвеличен, если будет считать субботу своей отрадой, святым Б-жьим днем (см. 58:13).

Лишенный будничных забот, субботний день предназначен для духовных занятий. Субботняя молитва провозглашает: «Да возрадуются в Твоем царстве все, кто хранят субботу, народ, освящающий седьмой день… Ты назвал этот день украшением дней».

Евреи во все времена столь ревностно относились к выполнению субботней заповеди, что в глазах инородцев соблюдение субботы стало самым характерным признаком еврейства. Римляне называли евреев «сабаториями», субботниками. Сенека, Тацит, Овидий в открытую издевались над евреями за их привязанность к этому дню. Интересно, что ненависть чужеземных властителей к иудеям всегда сопровождалась запретами на субботу. Впрочем, все эти гонения в античные времена кончились тем, что семидневную неделю с заключительным днем отдыха приняли все народы Средиземноморья. Неделю, но не субботу. Соблюдение шаббата осталось чисто еврейской заповедью.

Предлагаем вашему вниманию подборку статей и аудиоуроков по теме «Шаббат», представленных на сайте Толдот Йешурун.

Запрет стирки в субботу

статья р. Моше Пантелята

Выжимание одежды в субботу

статья р. Моше Пантелята

Работа «даш» («молотьба») в субботу

статья р. Моше Пантелята

Укутывание кастрюли для сохранения тепла в субботу

статья р. Моше Пантелята

Установка кастрюли на огонь до наступления субботы

статья р. Моше Пантелята

Пища, сваренная в субботу

статья р. Моше Пантелята

Водяные нагреватели в субботу

статья р. Моше Пантелята

Запрет варки в субботу

статья р. Моше Пантелята

Перенос грузов в субботу

статья р. Моше Пантелята

Запрет земледельческих работ в субботу

статья р. Моше Пантелята

Запрещенные в субботу работы, связанные в Мишкане с изготовлением ткани

статья р. Моше Пантелята

Субботние запреты, связанные с изготовлением одежды

статья р. Моше Пантелята

Запрещенные в субботу работы, связанные в Мишкане с обработкой кож

статья р. Моше Пантелята

Запрет писать и стирать в субботу в субботу

статья р. Моше Пантелята

«Сотер» и «Боне» в субботу

статья р. Моше Пантелята

Как греть сухую еду в шабат?

ответ р. Бенциона Зильбера

Суббота в лагере.

воспоминания рава Ицхака Зильбера о том, как он соблюдал субботу в лагере

Суббота — не день отдыха!

глава из книги «Царица Суббота» р. Моше Пантелята

Общие принципы законов Субботы

глава из книги «Царица Суббота» р. Моше Пантелята

Суббота. Законы Торы и законы Мудрецов.

глава из книги «Царица Суббота» р. Моше Пантелята

Суть Cубботы, Её райский вкус

Рав М. Пантелят

Четвёртая заповедь. Волшебная сила субботы.

статья Ефима Свирского

Субботний кидуш

статья руководителя московской ешивы «Торат Хаим» р. Моше Лебеля

Субботние свечи

статья руководителя московской ешивы «Торат Хаим» р. Моше Лебеля

Видеоуроки о законах субботы, проведённые р. Элияу Левиным

Субботние запреты. Запрет «провеивание» в субботу — «зорэ»

Субботние запреты. Запрет «молотить» в субботу — «даш». Часть 6 Субботние запреты. Запрет «молотить» в субботу — «даш». Часть 5

Субботние запреты. Запрет «молотить» в субботу — «даш». Часть 4

Субботние запреты. Запрет «молотить» в субботу — «даш». Часть 3

Субботние запреты. Запрет «молотить» в субботу — «даш». Часть 2

Субботние запреты. Запрет «молотить» в субботу — «даш». Часть 1

Субботние запреты. Запрет «сбор в снопы» в субботу — «меамер»

Субботние запреты. Запрет «сбор урожая — жатва» в субботу — «коцер». Часть 3

Субботние запреты. Запрет «сбор урожая — жатва» в субботу — «коцер». Часть 2

Запрет «сбор урожая — жатва» в субботу — «коцер». Часть 1

Субботние запреты. Запрет «вспахивать» в субботу — «хореш». Часть 2

Субботние запреты. Запрет «вспахивать» в субботу — «хореш». Часть 1

Субботние запреты. Запрет «сеять» в субботу — «зореа». Часть 2

Субботние запреты. Запрет «сеять» в субботу — «зореа». Часть 1

Суббота. Классификация субботних запретов. Вступление

Суббота. Источник субботних запретов. Вступление

Суббота. Суть субботних запретов. Вступление

Исход субботы. Законы авдалы (продолжение)

Исход субботы. Законы авдалы

Пост в субботу. Молитва о бедах в субботу. Штей микра эхад таргум. Необходимость посвятить в Субботу время для духовного роста

Три субботние трапезы

Суббота. Cвязь между кидушем и трапезой

Суббота. Законы Кидуша (продолжение)

Суббота. Законы Кидуша

Суббота. Встреча субботы. Вечерняя молитва. Заповедь: «Помни день субботний»

Суббота. Подробности заповеди зажигания свечей

Суббота. Смысл зажигания свечей

Суббота. Виды работ разрешенных после захода солнца , до выхода звезд

Время субботы. Принятие субботы . Исход субботы

Канун субботы. Принятие душа, Миква. Стрижка волос и ногтей

Канун субботы. Пост перед субботой. Когда можно есть перед субботой

Канун субботы. До какого времени можно отправляться в пятницу в дальнюю поездку и когда надо прибыть к месту назначения.

Канун субботы. С какого времени и какие работы не следует делать в пятницу

Законы субботы. Канун субботы. Подготовка к cубботе

Законы Субботы. Канун субботы

Законы Субботы. Заповедь подготовки к Субботе

Законы субботы. Вступление. Часть 2

Законы субботы. Вступление. Часть 1

1. Шабат продолжается

от захода солнца в пятницу до наступления темноты и выхода первых звезд в

субботу

Каждую неделю в течение 25 часов, начиная

незадолго до захода солнца в пятницу и до наступления темноты и выхода первых

звезд в субботу, евреи празднуют Шабат. Это время отдыха, покоя и духовного обновления.

Вот слова о Шабате пророка Йешаяу:

«Если

удержишь в субботу ногу свою, (удержишься) от исполнения дел твоих в святой

день Мой, и назовешь субботу отрадой, святой (день) Господа – почитаемым, и

почтишь ее, не занимаясь делами своими, не отыскивая дело себе и не говоря ни

слова (об этом), То наслаждаться будешь в Господе, и Я возведу тебя на высоты

земли, и питать буду тебя наследием Яакова, отца твоего, потому что уста Господа изрекли (это)» (58:13-14).

2. Предыдущий день тоже особенный

«Тот, кто трудится в канун Шабата, – говорят

мудрецы, – будет наслаждаться яствами в Шабат».

Царица Шабат у нас традиционно считается

почетной гостьей, и в пятницу (а у некоторых даже еще в четверг вечером) в

еврейском доме обычно свободное от официальной работы время посвящают

подготовке к ее приходу. Поэтому

пятница не просто йом шиши (шестой день), а совершенно особенный день – канун Шабата:

это как прелюдия в музыке. И так это ведется с древних времен.

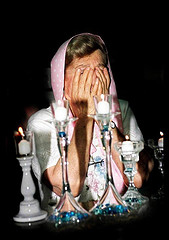

3. В честь Царицы Шабат зажигают свечи

В пятницу в диаспорах за 18 минут до захода

солнца еврейские женщины и девушки (когда женщин в доме нет, то и мужчины)

зажигают субботние свечи. Чаще всего это делается в столовой, где потом будет проходить праздничная трапеза, чтобы можно было наслаждаться их

светом.

Одинокие девушки и женщины зажигают по одной

свече, а замужние не меньше двух (некоторые добавляют еще по одной за каждого

ребенка).

4. 4-я из 10 заповедей

Шабат 4-я из 10 заповедей, и она столько раз

упоминается в Торе, что это говорит о

ней, как об одним из важнейших элементов иудаизма.

Фактически Шабат настолько важен для

еврейской жизни, что термин шомер Шабат (наблюдатель

Шабата) обычно подразумевает «религиозного еврея».

5. Как правильно назвать

Еврейский термин, определяющий этот святой для евреев день, англичане адаптировали, превратив его просто в Субботу. К счастью, на иврите и идише этого не произошло. Ашкеназы (евреи европейского происхождения) говорят Шабас (или Шабес,Шабос), а сефарды (евреи восточного происхождения) и говорящие на современном иврите произносят Шабат.

Само

слово Шабат происходит

от ивритского корневого глагола «лишбоах», что означает «отдыхать», «прекратить

деятельность», а это имеет общий корень со словом «шева» — «семь».

6. Есть несколько субботних приветствий

«Шабат шалом!» обычно произносят сефарды и те, кто предпочитает современный иврит. Это пожелание «Субботнего мира!»

Шалом – на иврите «мир». Это может быть, например, мир между Богом и человеком, между людьми или странами, а также внутренний мир или ментальный баланс

индивидуума (целостность, гармония).

Традиционное идишское приветствие

ашкеназов звучит как «Гут

Шабес», что означает «Хорошей

Субботы!». Оно используется вместо слов «привет» и «до свидания», впрочем, при

расставании иногда может слегка меняться, например, на «А гутен

Шабес».

В случае, если вы не сможете вспомнить нюансы

идиша, просто скажите: «Хорошего Шабеса!»

– и все вас отлично поймут.

7. Тора дает нам два основания для Шабата

Десять заповедей (Десять речений, Декалог) перечислены

в Торе дважды: сначала в книге

Шмот (20;1-14), а

затем и в Дварим (5:6-18).

В Шмот нам заповедано: «Помни день субботний, чтобы освящать его… Ибо в шесть дней создал

Господь небо и землю, море и все, что в них, и отдыхал в день седьмой. Потому

благословил Господь день субботний и освятил его».

А в Дварим сказано по-другому: «Соблюдай день субботний, чтобы освящать его, как повелел тебе Господь, Б-г твой… И помни, что рабом был ты на земле Египта, и вывел тебя Господь, Бог твой, оттуда рукою крепкою и мышцею

простертой…».

В первом случае сказано,

что мы обязаны помнить и освящать Шабат, потому что Бог шесть дней создавал

Свое творение, а на седьмой отдыхал. А во втором случае повеление соблюдать

Шабат, помня то, что Бог освободил нас из рабства.

8. Откровение на Синае происходило в

субботу

Самым значительным моментом в истории евреев

было Откровение на Синае, когда Бог сообщил Десять заповедей и заключил Завет с

еврейским народом после того, как вывел их из Египта. Мудрецы Талмуда

говорят, что это невероятное событие произошло в Шабат.

9. В Шабат запрещено 39 видов млахот (работ)

В определенном смысле работа – это процесс превращения одного вида энергии в

другой, в обычном смысле – вообще нахождение в действии, что

требует значительной энергии. Однако работа, которой мы избегаем в Шабат,

определяется несколько шире.

Мудрецы Талмуда перечисляют 39 запрещенных

творческих актов, каждый из которых является в некотором смысле «отцом» («ав»;

как бы породившим их) со многими «потомками» (то есть другими видами работ, производными

от главных 39-и), также запрещенными из-за их сущностного сходства с «родителями».

10. В трактате Шабат целых 24 главы!

39 млахот и

их производные рассматриваются в Талмуде, одном из главных трудов раввинского

иудаизма. В трактате Шабат 24 главы,

и это одна из крупнейших частей Талмуда. Больше него только трактат Келим,

в котором 30 глав.

11. 3 трапезы: вечером, не позже полудня и

на исходе Шабата

Действительно, праздничные трапезы – большая

часть соблюдения Шабата, и время их довольно регламентировано.

Мы едим в Шабат 3 раза: первый раз в пятницу

вечером, после молитвы Маарив; второй раз на следующий день – трапеза начинается

не позже, чем через считанные минуты после полудня, хотя вполне может быть и

значительно раньше; и еще одна трапеза, относительно легкая, начинается ближе к

вечеру, перед заходом солнца и исходом Шабата.

12. В пятницу вечером нас посещают ангелы

Традиция гласит, что 2 ангела, белый и

черный, сопровождают нас на пути к первой вечерней трапезе. Когда

дом убран, к Шабату приготовлены особенные блюда, белый ангел говорит: «Да

будет так и в следующий раз!» – и черному ангелу остается сказать только

«амейн». А если не дай Бог дом запущен и никто не думает о Шабате, тогда черный

ангел говорит: «Да будет так и в следующий раз», – и тогда белому ангелу

приходится ответить «амейн».

Это породило классическую субботнюю песню Шалом алейхем» , в

которой мы приветствуем ангелов в своем доме, просим их благословить нас, а

затем провожаем.

Как правило, за этим следует Эшет Хаиль – знаменитая

ода царя

Шломо доблестной женщине,

глубокий мистический текст со многими аллегориями.

13. Кидуш

– мы освящаем Шабат, произнося благословение на вино

Тора повелевает нам: «Помни день субботний,

чтобы освящать его…». Мудрецы объясняют это так, что мы обязаны провозгласить

Шабат святым днем и в пятницу вечером, прежде чем сядем обедать, должны произнести

особое благословение на вино – совершить ритуал, известный как Кидуш (освящение). Кидуш повторяется

и на следующий день, только в сокращении.

14. Приступаем к еде, начиная с благословения

на 2 халы

После Кидуша

каждую субботнюю трапезу мы начинаем тем, что произносим благословение Амоци на 2

батона хлеба. Традиционно используют

плетеный хлеб, который называется хала, но может быть и другой. После

благословения на хлеб его нарезают, затем каждый кусочек обмакивают в соль и

раздают всем присутствующим.

15. Обычно сначала едят рыбу

Первым блюдом субботней трапезы чаще всего

бывает рыба, приготовленная различными способами, К примеру, марокканские евреи

делают вкусное блюдо тажин, а традиционное блюдо ашкеназов – это гефилте фиш,

фаршированная рыба. Фаворитом современного субботнего стола часто бывает

суши-салат, приготовленный из кошерных сортов

постной белой рыбы, риса и кусочков овощей.

16. Любимые горячие блюда – куриный суп и чолнт

Хотя в Шабат горячую пищу готовить запрещено,

при определенных условиях разрешается оставлять горячую пищу, приготовленную

перед Шабатом, на огне или на специальном субботнем электрическом плато. Таким

образом,

вечером в пятницу у

ашкеназов принято наслаждаться куриным супом с шариками из мацы (кнедлех, клецки). На дневную

трапезу и сефарды, и ашкеназы чаще всего подают

чолнт, ассорти из мяса, бобов, ячменя, картофеля и др., это блюдо томится с

пятницы и ждет своего часа. Сефардский эквивалент

чолнта называется хамин.

17. Шабат встречают как царицу и как

невесту

В пятницу, когда уже зажжены свечи, после псалмов

принято петь гимн, приветствующий

наступление Шабата, Леха

доди – «Выйди, мой возлюбленный» (автор Шломо Галеви Алкабец, каббалист и поэт 16 в.).

Гимн очень многозначен. Под «возлюбленным»

прежде всего подразумевается Сам Всевышний. Он как жених в отношении народа

Израиля, который для Него как невеста. И мы воспеваем сладость Шабата, спускающуюся

к нам с небес, и обращаемся к Шабату, как к прекрасной невесте и любимой царице.

В этом гимне народ Израиля просит Бога

послать великую Субботу спасения, когда придет

Машиах.

Пение Леха

доди предваряет вечернюю молитву Маарив.

Концепция этого гимна полностью согласуется с

Талмудом, где мы читаем, как в канун Шабата рабби Ханина нарядился в

праздничную одежду и произнес: «Приходите, и мы пойдем приветствовать Шабат – Царицу».

Другой мудрец, рав Янай, надевал

праздничную одежду в канун Шабата и повторял: «Входи, о, невеста! Входи,

о невеста!»

18. Утренние богослужения – самые продолжительные

за неделю

Еврейский народ ежедневно молится в синагоге

утром, днем и вечером. Так

и в Шабат. Однако субботнее богослужение более продолжительное: в дополнение к утренней

Шахарит читается молитва Мусаф. Большая часть литургии поется, и есть дополнения

в молитвах.

19. Читаем

соответствующую недельную главу Торы – паршат

Основной момент

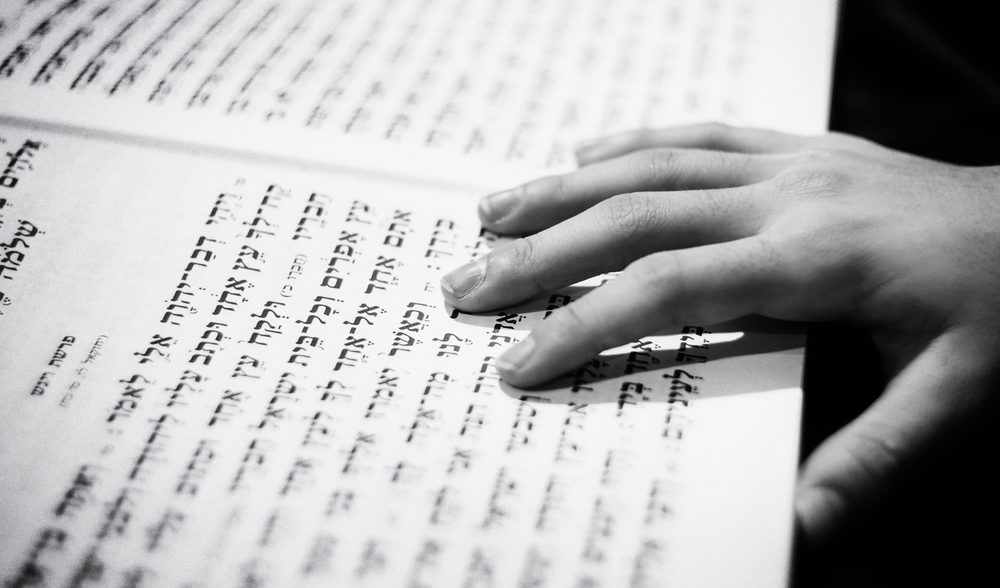

утренней службы в Шабат – это когда из Ковчега извлекается свиток Торы, его торжественно

проносят через синагогу, кладут на биму и читают вслух.

Тора разделена на 53 части (иногда на 54). Каждую

неделю мы читаем очередную часть, называемую паршат, или глава, и так ежегодно прочитываем весь

свиток.

У каждой главы есть название, взятое из ее первых слов. И если в течение недели изучают и читают в синагоге части из недельной главы, то в Субботу всю главу читают полностью.

20. Дневная трапеза

После утренних богослужений не всегда, но

часто следует общий обед. Это может быть и легкий перекус, и обильная праздничная

трапеза, все зависит от возможностей общины. А

главное, это время, чтобы гости общины и ее прихожане могли насладиться неспешным шабатним

общением.

21. Сладость дневного субботнего сна

Есть мнение, что слово Шабат является аббревиатурой

слов Шейна бе-Шабат таануг – «спать

в Шабат удовольствие». Излюбленные занятия в Шабат

– это изучение Торы, сон и прогулка. Приятное

времяпровождение в кругу семьи и друзей также уникальный дар Шабата.

22. Не носим вещи вне эрува

Одно из 39 запрещенных действий в Шабат –

перенос любого предмета на расстояние в 4 локтя (4 м 57 см) и более в

общественном владении. Это

включает еще передачу вещей из частного владения в общественное и наоборот.

Надо сказать, в этом контексте «частный» и

«общественный» имеют мало общего с тем, что мы привыкли под этим понимать.

Небольшие жилые районы могут быть условно превращены

в частные владения при помощи создания специального барьера, который называется

эрув.

Сегодня многие еврейские кварталы окружены эрувом, позволяющим

людям возить коляски с детьми, носить книги в синагогу, а также ключи, когда

отправляются на прогулку.

23. Шабат провожают с вином, специями и огнем

Точно так же, как с самого начала мы выделяем

Шабат Кидушем, делая его на вино, мы совершаем это и при помощи Авдалы,

которая является окончанием Шабата. Это

короткая, но прекрасная церемония отделения святого от будничного: мы вдыхаем

аромат душистых специй (часто это гвоздика, высушенный этрог и проч.), чтобы

восстановить силы, которые были ослаблены уходящим Шабатом – ведь нам на весь

этот день дается дополнительная душа, а теперь мы простились с ней до

следующего раза. Затем мы произносим благословение на огонь и зажигаем его, а

после Авдалы можем снова приступать к будничным делам и пользоваться огнем, как

обычно.

24. Вечер после Шабата тоже особенный!

Вечер после Авдалы на иврите называют моцей

Шабат – «уход Шабата», и мы все еще наслаждаемся приятными воспоминаниями

минувшего дня.

В этот вечер принято устраивать Мелаве Малку

(«Сопровождение Королевы») – это трапеза в память об ушедшем Шабате.

Мы зажигаем одну свечу и ставим ее на стол.

В эту трапезу принято рассказывать о

праведниках, сведения о которых сохранились в нашей истории, и, конечно, о выдающихся

современниках.

25. Шабат – прелюдия к эре Машиаха

Шабат, день отдыха и духовного блаженства, это

прелюдия к тому наслаждению, которое мы испытаем в эпоху Машиаха, когда мирная

жизнь и изобилие станут нормой, а присутствие Бога в нашем мире очевидным для

всех. И

неудивительно, что нам обещают в качестве награды за соблюдение Шабата именно приход

Машиаха.

Пусть же это случится как можно скорей, в наши дни! Амейн!

Было ли это полезно?

«Цимес» разбирается, как принято встречать субботу, какое она имеет значение в еврейской традиции и что можно, а что нельзя делать еврею в этот день

Шаббат (иногда произносят Шаббес или Шаббос) — одна из самых известных практик иудаизма.

Это еженедельный праздник (что? да!), длящийся 25 часов. Как все праздники, подчиняющиеся еврейскому календарю, Шаббат начинается накануне вечером — незадолго до захода солнца в пятницу — и продолжается до захода солнца в субботу плюс ещё чуть-чуть. Поскольку всюду в мире солнце заходит в разное время, существует календарь зажигания субботних свечей, с которым можно свериться.

Вообще, это день физической и духовной радости, который должен подчеркнуть ряд ключевых концепций в иудейском видении мира.

В традиционных стихах и песнях суббота сравнивается с невестой, с царицей. Шаббат в Торе — это венец творения вселенной, седьмой день, в который Г-дь отдыхал, сотворив мир за шесть предыдущих дней.

До сих пор в иврите только у Шаббата есть собственное имя — остальные дни недели просто называются «день первый», «день второй» и т. д. Соблюдение Шаббата — напоминание о том, что мир полон смысла и что люди созданы не просто так.

Так было всегда?

Как и многое другое в иудаизме, практики Шаббата взялись из Торы, где суббота описывается в основном как день свободы от труда. Пророки описывают Шаббат также как день радостей и удовольствий. Мудрецы же, осмысляя это в течение веков, пришли к чёткому описанию того, что в Шаббат запрещено, а также расписали, как надо вести себя в этот день, сколько раз принимать пищу, какие проводить церемонии и читать благословения. Шаббат в разных общинах, веках и направлениях иудаизма праздновался немного по-разному и иллюстрировал адаптацию евреев к окружающей их реальности и к незнакомым идеям.

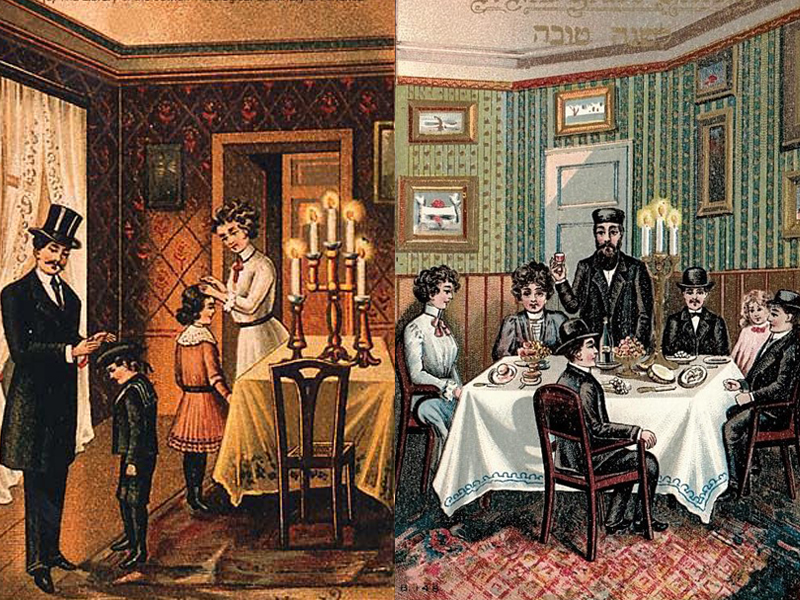

Одна общая вещь для всех, вне зависимости от века и места, — это встреча субботы дома, с семьёй и гостями.

И как встречают?

Во многих семьях готовиться начинают ещё с середины недели — покупают продукты, планируют меню, пекут пироги, убирают дом. Талмуд предписывает в Шаббат принимать пищу трижды.

Сейчас это не выглядит как что-то особенное, но в древности люди ели максимум два раза в день, так что предписания Шаббата делали этот день особенным и роскошным, даже если трапезы были самыми скромными.

Нельзя покупать в Шаббат (использовать деньги), так что все покупки делают днём в пятницу и тогда же готовят на сутки вперёд, чтобы хватило на три субботние трапезы. Поскольку электричеством пользоваться тоже нельзя, делают и еду, которую не надо подогревать, и еду, которая всю субботу томится на слабом огне в духовке (как знаменитый чолнт). Используют также «субботнюю плату» — специальный электрический прибор для поддержания тепла. Включают все эти приборы до наступления Шаббата и выключают, когда он заканчивается, — так же как и лампочки в тех помещениях, где в субботу может понадобиться свет.

А что делают в синагоге?

Проводят специальную службу каббалат шаббат («встреча субботы») в пятницу вечером, а на следующий вечер — специальную службу проводов Шаббата. Используются особые мелодии и литургия, обычные молитвы перемежаются прозаическими и поэтическими пассажами, благодарящими Б-га за дар Шаббата и его удовольствий. На службе утром в субботу читается недельный отрывок из Торы и отрывок из Пророков.

А что там со свечами?

Прибытие Шаббата в пятницу вечером встречают церемонией зажигания свечей. Это принято делать ради соблюдения заповедей шлом байт («мир в доме», семейная гармония) и онег шаббат («субботняя радость»). Зажигают свечи в той же комнате, где будут совершать трапезу. Делает это традиционно мать семейства, но может и любая девушка старше 12 лет. Если женщины в семье нет, зажечь свечи может и мужчина (а в либеральных общинах — вообще любой взрослый еврей).

Обычно свечи зажигают за 18 минут до захода солнца. Нужны две свечи — в честь первых слов заповедей в Торе, имеющих отношение к Шаббату: шамор («хранить») и захор («помнить»). В некоторых общинах свечей зажигают больше, например по одной за каждого ребёнка в семье, и если однажды зажёг определённое число свечей в Шаббат, их число уменьшать не принято.

Как правильно зажечь?

- Собственно, зажечь свечи.

- Проделать пассы руками вокруг пламени и к лицу от одного до семи раз (обычно три).

- Закрыть глаза руками.

- Произнести благословение.

Тут есть интересный нюанс. Обычно благословение произносят перед тем, как что-то сделать. Но поскольку благословение на свечи одновременно тот самый акт, который официально начинает Шаббат, после него зажечь свечи уже будет нельзя, потому что после начала Шаббата запрещено зажигать огонь (это один из видов работ, не разрешённых в субботу).

Традиционное разрешение парадокса — зажечь свечи и закрыть глаза, пока произносишь благословение. Тогда после того как откроешь глаза, свечи предстанут перед тобой во всей своей красе и ты словно увидишь их впервые — и благословение сказано, и Шаббат не нарушен.

А когда уже можно поесть?

После зажигания свечей семья и гости собираются за столом, произносится несколько традиционных формул — субботний гимн «Шалом алейхем» и специальный гимн «Эшет хаиль», восхваление жены, которое произносят муж и сыновья хозяйки дома.

На столе обязательно должны быть две халы, накрытые тканью (в честь двух порций манны небесной, посылаемых Б-гом евреям ежедневно во время их блуждания по пустыне), и вино или виноградный сок. Традиционно мужчина — но в либеральных общинах и женщина — произносит особое благословение (кидуш) на вино, отпивает и даёт отпить остальным. Потом все омывают руки, мужчина произносит благословение на халу, отрывает кусок, обмакивает в соль, ест и даёт остальным. После этого можно приступить к праздничному ужину.

А когда заканчивается Шаббат?

Шаббат заканчивается после захода солнца в субботу коротким ритуалом (авдала), церемонией, призванной отделить святость субботы от рутины обычных дней. Начинается авдала, когда на тёмном небе восходят три звезды, но обычно время исхода субботы в вашей местности можно узнать заранее в еврейском календаре. Снова зажигают свечу (обычно с несколькими фитилями), пьют вино, нюхают пряности, хранящиеся в специальном футляре, — чтобы нести воспоминание о Шаббате дальше, в рабочую неделю, — и произносят благословение. После этого можно делать всё, что в Шаббат было запрещено.

Что, правда ничего нельзя делать?

Это самая известная фишка — что в Шаббат иудеям нельзя работать. Но что считается работой? В Торе в качестве запрещённого указан труд, связанный с земледелием, виноделием, сельским хозяйством, торговлей, перемещением предметов, путешествиями и разжиганием огня.

Как обычно, мудрецы переосмыслили заповеди и выделили 39 категорий запрещённых действий (с кучей подробностей) — а в современном мире их переосмыслили снова.

Например, запрет водить машину относится к категории «разжигание огня», потому что двигатель запускается посредством искры, поджигающей пары бензина. А многие современные соблюдающие иудеи выкручивают перед субботой лампочку в холодильнике — чтобы она не зажигалась, когда открываешь дверцу.

Средневековые раввины понимали заповеди расширенно и охраняли святость субботы путём налагания запретов даже на действия, только напоминающие запретные, — поэтому нельзя, например, залезать на деревья, ведь это может привести к ломанию веток, которое напоминает сбор урожая, то есть отделение части растения от других его частей. Или составлять букеты — потому что это напоминает укладку сена в стог. Или наносить макияж — напоминает окрашивание тканей. В общинах, где Шаббат соблюдается строго, множество вещей в субботу нельзя даже трогать — деньги или чеки, ножницы и молотки, карандаши и ручки, телефоны и компьютеры. И даже спички — сразу после того как зажжены субботние свечи.

Не все общины настолько буквально соблюдают предписания тысячелетней давности, так что не удивляйтесь, если встретите в Шаббат в синагоге женщину при полном макияже — даже в Иерусалиме.

Кроме того, как обычно в иудаизме, в Шаббат действует принцип пикуах нефеш («спасение души») — то есть святость субботы можно и нужно нарушить, если от этого зависит жизнь человека.

Разные течения иудаизма относятся к Шаббату с разной степенью строгости, но во всех соблюдающих и даже в некоторых светских еврейских семьях этот день считают праздником и так или иначе отделяют от других дней. Для многих современных евреев Шаббат — это просто семейный день общения и отдыха, который начинается со вкусного ужина в пятницу вечером.

Подготовила Мария Вуль

Читайте также:

- Шаббат в большом городе: как получить удовольствие от еврейского дня отдыха

- На чём держится кипа, что делают с крайней плотью после обрезания и ещё 5 стыдных вопросов евреям

- Хала-принц и еврейка на кухне: лучшие блоги, инстаграмы и тиктоки с рецептами

Шабат – еврейский праздник соблюдения субботнего дня и единения с Богом. Это национальная традиция, которую стараются соблюдать практически все евреи, где бы они ни жили, по всему миру. Он имеет большое значение для иудеев, его несоблюдение в древние времена каралось смертной казнью. Конечно, в наше время нет такого строгого наказания за невыполнение правил шабата, тем не менее, глубоко верующие евреи неукоснительно следуют наставления Торы и древним традициям.

История и значение праздника

Началось все с исхода евреев из трех тысячелетнего египетского рабства. Вместе с крижалями на горе Сион евреям была дана заповедь соблюдения субботнего дня. Как напоминание о тех давних событиях, с одной стороны, с другой – как почитание Всевышнего и следование его действиям при создании мира. Когда Бог создавал вселенную, он работал в течение 6 дней, а на седьмой, субботний, почивал от всяких дел. В следование этому все евреи чтят последний день недели, и строго соблюдают его правила, прописанные в Торе – главном своде законов религии.

Когда иудеи 40 лет шли по пустыне перед обретением своей земли обетованной, их кормила манна, которую Бог посылал с небес. В субботу она не посылалась, чтобы люди не работали, зато в пятницу выпадала в двойной мере, чтобы люди в субботний день, когда нельзя трудится, не голодали. Даже при строительстве скинии (переносного храма) соблюдались эти правила.

Суть шабата: люди заботятся о материальных благах семьи в шесть дней недели, но седьмой посвящают Богу, чтобы не забывать о своей духовности. В субботний день человек как бы отделяет себя от материального мира, его проблем и забот, соединяясь с Господом, погружаясь в духовные размышления, наполняется мудростью, терпением и силой для следующей «материальной» недели.

Кто соблюдает Шаббат

Строгость соблюдения правил субботы зависит от нескольких факторов. В первую очередь это мера религиозности человека, его семьи и окружения. Вторая – то, где он проживает. К примеру, если в Иерусалиме шабат соблюдают все по правилам Торы, то в Тель-Авиве, городе более светском, в субботний день работают кафе, рестораны, и полно праздношатающихся людей. Только отдельные семьи замыкаются в своем домашнем мирке, общаются, читают своды законов, чтят правила, и проводят день в тишине, любви, общении и духовных размышлениях.

Как проходит Шабат в Израиле, что нельзя делать

Суббота в Израиле – праздник общий и семейный. Все замирает с заходом солнца в пятницу: закрываются магазины, не ходит общественный транспорт, не ездят автомобили, не работают никакие заведения. На улицах не встретишь людей, кругом тишина, покой, и даже воздух, кажется, пронизан мировым спокойствием и величественным созерцанием вселенной. Заканчивается все в субботу вечером церемонией Авдал, отделяющей Шабат от остальных дней недели. Это означает возвращение к будничной обычной жизни до следующего седьмого священного дня. Неделя начинается с воскресенья, называемого в иудаизме Йом Ришон.

Интересно

Почему именно вечером начало Шабата? Это указано в Ветхом завете: «был вечер, и было утро». То есть, день начинался именно с вечера.

Как происходит встреча Шаббата – «Маарив»

Самое важное – своевременное зажжение свечей. За 18 минут до заката старшая женщина в семье зажигает их в двух экземплярах, следуя правилам – за день субботний и за его соблюдение. После этого женщины накрывают столы, мужчину идут в синагогу, на чтение молитвы «Минха». По возвращении домой все приветствуют друг друга словами «Шабат, шалом!», и происходит традиционное омовение. При этом необходимо трижды обмакнуть в воду левую и правую руки, вытереть их, произнося благодарение Господу, и тогда все приступают к трапезе.

Столы накрывают праздничной скатертью, на них располагаются в первую очередь традиционные продукты. Это кошерное вино, 2 халы (выпечка в виде косы), соль. Кроме них, на застолье могут присутствовать разные яства – мясные, рыбные, овощные, молочные. Главное правило – они должны быть кошерными, и подают их поочередно, не смешивая.

Кошерность пищи – отдельная история, присущая только еврейскому народу. У них есть прописанные правила, какой должна быть еда, чтобы ее было позволительно употреблять. К примеру, в пищу разрешено мясо животных жующих парнокопытных (овца, коза, лань), домашней птицы, рыбы с чешуей. Существуют также правила забоя и так далее. Главное – еда должна быть здоровой, приготовленной по правилам, а вино – собранное с виноградника, которому больше 7 лет.

Обязательно

На Шабат все заранее готовят нарядную одежду и самые изысканные продукты. Даже последний бедняк должен иметь 2 свечи, и что поставить на стол. Если у него нет этого, синагога обязательно ему все необходимое выдаст для соблюдения правил.

Традиции и особенности праздника

Отец семейства благословляет детей, возложив им на голову руки, затем произносит благословение над вином (кидуш), надрезает халу, также творя соответствующую молитву. Затем разрезает плетенку, макает кусочек в соль, съедает его и раздает остальные ее части всем за столом.

Далее все едят, общаются на духовные темы, поют традиционные песни. День посвящен Богу и общению в семье. Особенно его любят дети. Ведь именно в субботу родители отделяются от всех дел и забот, и посвящают время всем членам семьи, проявляя любовь и заботу. Ничто мирское не должно заботить в этот день, запрещено работать, и думать о мирской суете. В конце застолья опять произносятся соответствующие молитвы и благодарение Господа за пищу и все ниспосланные дары.

Двойная хала

Означает две порции манны, подаваемой евреям в пустыне в пятницу перед шабатом. Соль – напоминание о разрушенном в Иерусалиме когда-то храме.

Какая работа запрещена в субботу

Шабат – чудный семейный праздник и строгий ритуал, он имеет центральное значение в жизни евреев. Все отходят от ежедневной суеты, не звонят телефоны, не включаются телевизоры, не заводятся автомобили, даже кнопки лифта в этот день не включают – забывают о всех благах цивилизации. День посвящен только духовной составляющей, семье и Богу.

Не всякая работа запрещена в субботу. Есть два понятия: авода (простой физический труд) и мелаха (работа творческая, созидательная), не разрешена именно она. То есть, человек не должен ничего делать, что меняет окружающий мир, «созидать», оставляя это Богу. В Торе прописано 39 видов работ, которые нельзя делать в шабат. К ним относятся, в частности:

- шитье;

- готовка еды;

- стирка;

- уборка;

- строительство;

- зажигание огня;

- включение электричества;

- торговля и т.д.

Шабат – древний еврейский праздник, главный символ иудаизма, означающий создание еврейской нации. Соблюдение субботы позволило им выдержать трехвековое рабство, претерпеть мучения и гонения, и сохранить свое единство. В Израиле эта традиции особенно сильна и чтима, ее строго соблюдает большинство жителей.

Встречаются раввин, поп и мулла:

- Я отпускаю человеческие грехи. От меня люди выходят очищенными, — рассказывает поп.

- А я прощаю прегрешения наперед, разрешаю мужчинам возжелать жену ближнего своего, — отвечает ему мулла.

- Да что там! Я вот могу менять дни недели! — заявляет раввин.

- Как это? — изумляются поп и мулла.

- А вот так: иду я по улице в Шаббат. Вижу, кошелек на земле лежит. Плотненький такой… Ну, нельзя же в этот день нагибаться, чтобы что-то поднять с земли. Взмолился я господу, и услышал меня Всевышний. И, о, чудо! У всех Шаббат, а у меня среда!

По субботами евреи не работают, не включают свет в своих домах, не завязывают шнурки, ездят на лифтах без кнопок и пользуются специальной плитой, которая поддерживает заданную температуру и не выключается. Магазины закрыты, на дорогах мало автомобилей, на улицах практически нет людей. Шаббат шалом!

Про Шаббат у евреев

Неделя в Израиле начинается в воскресенье. Шаббат [שַבָּת] — последний ее день. Иудеи в это время должны воздерживаться от работы. Праздник Шаббат у евреев — это одна из 10 главных заповедей, которые Моисей получил на горе Синай.

Создатель трудился над сотворением мира шесть дней, а в седьмой отдыхал. «Шаббат» с иврита на самом деле переводится не как «суббота», а как «остановился». Иудеи считают, что рождение мира произошло в воскресенье. Значит, суббота — это седьмой день, в который надо остановиться и отдохнуть.

Есть историки, которые уверены, что евреи праздновали этот день даже в Древнем Египте. Ученые утверждают, что Моисей, много лет наблюдавший за изнурительным рабским трудом своих собратьев, попросил фараона разрешить им отдыхать один день в неделю, и тот согласился.

Во сколько Шаббат начинается? В пятницу, когда на небе появляются три звезды. Их специально вычисляют и печатают в календарях, газетах, а время напоминают по телевизору.

За вечером пятницы следует праздник Шаббат. Вдруг все затихает, особенно в городах, где много религиозных людей. Повсюду только и слышно «Шаббат шалом!». В переводе это означает «Мирной субботы».

Что делать в Шаббат?

Женщина играет важную роль в подготовке к празднику. В субботу, Шаббат, нельзя готовить или подогревать еду, поэтому она заранее собирает стол к празднику утром в пятницу. Готовит лучшие блюда. Печет две халы в память о двойном количестве хлеба, которую евреи получили в пустыне от Всевышнего. Женщина обязательно пробует блюда и в это время произносит благословения. Она накрывает стол белой скатертью и расставляет еду.

Перед праздником мужчины и женщины обязательно купаются. Если они не успевают сделать это, то умывают лицо и руки. Зажигают свечи женщины. И делают это они до захода солнца.

Праздник начинают с трапезы. Мужчины читают благословение, разливают вино, преломляют халу. Семья сидит за столом. Люди забывают о проблемах и тяготах, наслаждаются общением с близкими и трапезой, поют песни. Царит радостная и спокойная атмосфера.

Читайте также: Еврейские мудрые и смешные цитаты и афоризмы

Что нельзя в Шаббат?

В Торе перечислены 39 видов работы, которую запрещается делать евреям в этот праздник. Правда, этот перечень на сегодняшний день утратил свою актуальность. Сейчас же нельзя:

- работать;

- пользоваться электроприборами;

- путешествовать на общественных транспортных средствах;

- готовить еду;

- заводить мотор авто (а если другой человек сделает это, ехать разрешается);

В этот день иудеи даже не пишут. Благо, читать им можно в Шаббат, но только определенную литературу. И даже белье развешивать запрещено.

Тема того, что можно и нельзя делать в этот священный день, очень обширна. Каждая ситуация требует детального рассмотрения, и ее истолковывают раввины. Можно долго перечислять, что нельзя в Шаббат делать. В общем, запрещено что-то изменять или созидать.

В Интернете есть забавные истории евреев, которые не живут в Израиле, но традицию соблюдают. Они рассказывают, как по субботам им приходится ждать, пока кто-то не откроет замок подъездной двери или нажмет кнопку вызова лифта.

Несмотря на запреты праздника, экстренные и медслужбы в этот день работают. Евреи считают, что самое главное — это человеческая жизнь. И никакие заповеди не могут быть выше нее.

Читайте также: Крылатые фразы и выражения на иврите с переводом и транскрипцией

Шаббат шалом!

В субботу Всевышний создал мир, а потом решил отдохнуть. Иудеи должны поступать так же. Они посвящают Шаббат Создателю, близким и родным. Даже нерелигиозные израильтяне с радостью собираются за столом, преломляют халу, пьют виноградный сок или разливают вино и проводят свое время в кругу семьи и друзей. Это священный праздник с особой атмосферой, которая царит повсюду. Шаббат шалом!

Популярные статьи в блоге:

- Еврейская песня ХАВА НАГИЛА слова на иврите с переводом на русский

- Я тебя люблю на иврите

- Имена на иврите. Мужские и женские имена на иврите

- Как узнать как дела на иврите? 5 вариантов спросить как дела с транскрипцией и переводом

- Прости на иврите — СЛИХА…

This article is about the rest day in Judaism. For the general day of rest in Abrahamic religions, see Sabbath. For Sabbath in the Bible, see Biblical Sabbath. For the Talmudic tractate, see Shabbat (Talmud).

Kiddush cup, Shabbat candles and challah cover |

|

| Halakhic texts relating to this article | |

|---|---|

| Torah: | Exodus 20:7–10, Deut 5:12–14, numerous others.[1] |

| Mishnah: | Shabbat, Eruvin |

| Babylonian Talmud: | Shabbat, Eruvin |

| Jerusalem Talmud: | Shabbat, Eruvin |

| Mishneh Torah: | Sefer Zmanim, Shabbat 1–30; Eruvin 1–8 |

| Shulchan Aruch: | Orach Chayim, Shabbat 244–344; Eruvin 345–395; Techumin 396–416 |

| Other rabbinic codes: | Kitzur Shulchan Aruch ch. 72–96 |

Shabbat (, , or ; Hebrew: שַׁבָּת, romanized: Šabbāṯ, [ʃa’bat], lit. ‘rest’ or ‘cessation’) or the Sabbath (), also called Shabbos (, ) by Ashkenazim, is Judaism’s day of rest on the seventh day of the week—i.e., Saturday. On this day, religious Jews remember the biblical stories describing the creation of the heaven and earth in six days and the redemption from slavery and The Exodus from Egypt, and look forward to a future Messianic Age. Since the Jewish religious calendar counts days from sunset to sunset, Shabbat begins in the evening of what on the civil calendar is Friday.

Shabbat observance entails refraining from work activities, often with great rigor, and engaging in restful activities to honour the day. Judaism’s traditional position is that the unbroken seventh-day Shabbat originated among the Jewish people, as their first and most sacred institution. Variations upon Shabbat are widespread in Judaism and, with adaptations, throughout the Abrahamic and many other religions.

According to halakha (Jewish religious law), Shabbat is observed from a few minutes before sunset on Friday evening until the appearance of three stars in the sky on Saturday night.[2] Shabbat is ushered in by lighting candles and reciting a blessing. Traditionally, three festive meals are eaten: The first one is held on Friday evening, the second is traditionally a lunch meal on Saturday, and the third is held later in the afternoon. The evening meal and the early afternoon meal typically begin with a blessing called kiddush and another blessing recited over two loaves of challah. The third meal does not have the kiddush recited but all have the two loaves. Shabbat is closed Saturday evening with a havdalah blessing.

Shabbat is a festive day when Jews exercise their freedom from the regular labours of everyday life. It offers an opportunity to contemplate the spiritual aspects of life and to spend time with family.

Etymology[edit]

The word Shabbat derives from the Hebrew root ש־ב־ת. Although frequently translated as «rest» (noun or verb), another accurate translation is «ceasing [from work].»[3] The notion of active cessation from labour is also regarded[by whom?] as more consistent with an omnipotent God’s activity on the seventh day of creation according to Genesis.

Origins[edit]

Babylon[edit]

A cognate Babylonian Sapattum or Sabattum is reconstructed from the lost fifth Enūma Eliš creation account, which is read as: «[Sa]bbatu shalt thou then encounter, mid[month]ly». It is regarded as a form of Sumerian sa-bat («mid-rest»), rendered in Akkadian as um nuh libbi («day of mid-repose»).[4]

Connection to Sabbath observance has been suggested in the designation of the seventh, fourteenth, nineteenth, twenty-first and twenty-eight days of a lunar month in an Assyrian religious calendar as a ‘holy day’, also called ‘evil days’ (meaning «unsuitable» for prohibited activities). The prohibitions on these days, spaced seven days apart (except the nineteenth), include abstaining from chariot riding, and the avoidance of eating meat by the King. On these days officials were prohibited from various activities and common men were forbidden to «make a wish», and at least the 28th was known as a «rest-day».[5][6]

The Universal Jewish Encyclopedia advanced a theory of Assyriologists like Friedrich Delitzsch[7] (and of Marcello Craveri)[8] that Shabbat originally arose from the lunar cycle in the Babylonian calendar[9][10] containing four weeks ending in a Sabbath, plus one or two additional unreckoned days per month.[11] The difficulties of this theory include reconciling the differences between an unbroken week and a lunar week, and explaining the absence of texts naming the lunar week as Sabbath in any language.[12]

Egypt[edit]

Seventh-day Shabbat did not originate with the Egyptians, to whom it was unknown;[13] and other origin theories based on the day of Saturn, or on the planets generally, have also been abandoned.[12]

Hebrew Bible[edit]

Sabbath is given special status as a holy day at the very beginning of the Torah in Genesis 2:1-3.[14] It is first commanded after The Exodus from Egypt, in Exodus 16:26[15] (relating to the cessation of manna) and in Exodus 16:29[16] (relating to the distance one may travel by foot on the Sabbath), as also in Exodus 20:8-11[17] (as one of the Ten Commandments). Sabbath is commanded and commended many more times in the Torah and Tanakh; double the normal number of animal sacrifices are to be offered on the day.[18] Sabbath is also described by the prophets Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, Hosea, Amos, and Nehemiah.

The longstanding Jewish position is that unbroken seventh-day Shabbat originated among the Jewish people, as their first and most sacred institution.[7] The origins of Shabbat and a seven-day week are not clear to scholars; the Mosaic tradition claims an origin from the Genesis creation narrative.[19][20]

The first non-Biblical reference to Sabbath is in an ostracon found in excavations at Mesad Hashavyahu, which has been dated to approximately 630 BCE.[21]

Status as a Jewish holy day[edit]

The Tanakh and siddur describe Shabbat as having three purposes:[citation needed]

- To commemorate God’s creation of the universe, on the seventh day of which God rested from (or ceased) his work;

- To commemorate the Israelites’ Exodus and redemption from slavery in ancient Egypt;

- As a «taste» of Olam Haba (the Messianic Age).

Judaism accords Shabbat the status of a joyous holy day. In many ways, Jewish law gives Shabbat the status of being the most important holy day in the Hebrew calendar:[22]

- It is the first holy day mentioned in the Bible, and God was the first to observe it with the cessation of creation (Genesis 2:1–3).

- Jewish liturgy treats Shabbat as a «bride» and «queen» (see Shekhinah); some sources described it as a «king».[23]

- The Sefer Torah is read during the Torah reading which is part of the Shabbat morning services, with a longer reading than during the week. The Torah is read over a yearly cycle of 54 parashioth, one for each Shabbat (sometimes they are doubled). On Shabbat, the reading is divided into seven sections, more than on any other holy day, including Yom Kippur. Then, the Haftarah reading from the Hebrew prophets is read.

- A tradition states that the Jewish Messiah will come if every Jew properly observes two consecutive Shabbatoth.[24]

- The punishment in ancient times for desecrating Shabbat (stoning) is the most severe punishment in Jewish law.[25]

- On this day an offering of two lambs was brought to the temple in Jerusalem.[26]

Rituals[edit]

«Shabbat dinner» redirects here. For the film, see Shabbat Dinner.

Welcoming Shabbat[edit]

Honoring Shabbat (kavod Shabbat) on Preparation Day (Friday) includes bathing, having a haircut and cleaning and beautifying the home (with flowers, for example).

Days in the Jewish calendar start at nightfall, therefore many Jewish holidays begin at such time.[27] According to Jewish law, Shabbat starts a few minutes before sunset. Candles are lit at this time. It is customary in many communities to light the candles 18 minutes before sundown (tosefet Shabbat, although sometimes 36 minutes), and most printed Jewish calendars adhere to this custom.

The Kabbalat Shabbat service is a prayer service welcoming the arrival of Shabbat. Before Friday night dinner, it is customary to sing two songs, one «greeting» two Shabbat angels into the house[28] («Shalom Aleichem» -«Peace Be Upon You») and the other praising the woman of the house for all the work she has done over the past week («Eshet Ḥayil» -«Women Of Valour»).[29] After blessings over the wine and challah, a festive meal is served. Singing is traditional at Sabbath meals.[30] In modern times, many composers have written sacred music for use during the Kabbalat Shabbat observance, including Robert Strassburg[31] and Samuel Adler.[32]

According to rabbinic literature, God via the Torah commands Jews to observe (refrain from forbidden activity) and remember (with words, thoughts, and actions) Shabbat, and these two actions are symbolized by the customary two Shabbat candles. Candles are lit usually by the woman of the house (or else by a man who lives alone). Some families light more candles, sometimes in accordance with the number of children.[33]

Other rituals[edit]

«Oyneg Shabes» and «Oneg Shabbat» redirect here. For the collection of documents from the Warsaw Ghetto collected and preserved by the group known by the code name Oyneg Shabes, see Ringelblum Archive.

Shabbat is a day of celebration as well as prayer. It is customary to eat three festive meals: Dinner on Shabbat eve (Friday night), lunch on Shabbat day (Saturday), and a third meal (a Seudah shlishit[34]) in the late afternoon (Saturday). It is also customary to wear nice clothing (different from during the week) on Shabbat to honor the day.

Many Jews attend synagogue services on Shabbat even if they do not do so during the week. Services are held on Shabbat eve (Friday night), Shabbat morning (Saturday morning), and late Shabbat afternoon (Saturday afternoon).

With the exception of Yom Kippur, days of public fasting are postponed or advanced if they coincide with Shabbat. Mourners sitting shivah (week of mourning subsequent to the death of a spouse or first-degree relative) outwardly conduct themselves normally for the duration of the day and are forbidden to display public signs of mourning.

Although most Shabbat laws are restrictive, the fourth of the Ten Commandments in Exodus is taken by the Talmud and Maimonides to allude to the positive commandments of Shabbat. These include:

- Honoring Shabbat (kavod Shabbat): on Shabbat, wearing festive clothing and refraining from unpleasant conversation. It is customary to avoid talking on Shabbat about money, business matters, or secular things that one might discuss during the week.[35][36]

- Recitation of kiddush over a cup of wine at the beginning of Shabbat meals, or at a reception after the conclusion of morning prayers (see the list of Jewish prayers and blessings).

- Eating three festive meals. Meals begin with a blessing over two loaves of bread (lechem mishneh, «double bread»), usually of braided challah, which is symbolic of the double portion of manna that fell for the Jewish people on the day before Sabbath during their 40 years in the desert after the Exodus from Ancient Egypt. It is customary to serve meat or fish, and sometimes both, for Shabbat evening and morning meals. Seudah Shlishit (literally, «third meal»), generally a light meal that may be pareve or dairy, is eaten late Shabbat afternoon.

- Enjoying Shabbat (oneg Shabbat): Engaging in pleasurable activities such as eating, singing, sleeping, spending time with the family, and marital relations. Sometimes referred to as «Shabbating».

- Recitation of havdalah.

Bidding farewell[edit]

Observing the closing havdalah ritual in 14th-century Spain

Havdalah (Hebrew: הַבְדָּלָה, «separation») is a Jewish religious ceremony that marks the symbolic end of Shabbat, and ushers in the new week. At the conclusion of Shabbat at nightfall, after the appearance of three stars in the sky, the havdalah blessings are recited over a cup of wine, and with the use of fragrant spices and a candle, usually braided. Some communities delay havdalah later into the night in order to prolong Shabbat. There are different customs regarding how much time one should wait after the stars have surfaced until the sabbath technically ends. Some people hold by 72 minutes later and other hold longer and shorter than that.

Prohibited activities[edit]

Jewish law (halakha) prohibits doing any form of melakhah (מְלָאכָה, plural melakhoth) on Shabbat, unless an urgent human or medical need is life-threatening. Though melakhah is commonly translated as «work» in English, a better definition is «deliberate activity» or «skill and craftmanship». There are 39 categories of melakhah:[37]

- plowing earth

- sowing

- reaping

- binding sheaves

- threshing

- winnowing

- selecting

- grinding

- sifting

- kneading

- baking

- shearing wool

- washing wool

- beating wool

- dyeing wool

- spinning

- weaving

- making two loops

- weaving two threads

- separating two threads

- tying

- untying

- sewing stitches

- tearing

- trapping

- slaughtering

- flaying

- tanning

- scraping hide

- marking hide

- cutting hide to shape

- writing two or more letters

- erasing two or more letters

- building

- demolishing

- extinguishing a fire

- kindling a fire

- putting the finishing touch on an object, and

- transporting an object (between private and public domains, or over 4 cubits within public domain)

The 39 melakhoth are not so much activities as «categories of activity». For example, while «winnowing» usually refers exclusively to the separation of chaff from grain, and «selecting» refers exclusively to the separation of debris from grain, they refer in the Talmudic sense to any separation of intermixed materials which renders edible that which was inedible. Thus, filtering undrinkable water to make it drinkable falls under this category, as does picking small bones from fish (gefilte fish is one solution to this problem).

The categories of labors prohibited on Shabbat are exegetically derived – on account of Biblical passages juxtaposing Shabbat observance (Exodus 35:1–3) to making the Tabernacle (Exodus 35:4 etc.) – that they are the kinds of work that were necessary for the construction of the Tabernacle. They are not explicitly listed in the Torah; the Mishnah observes that «the laws of Shabbat … are like mountains hanging by a hair, for they are little Scripture but many laws».[38] Many rabbinic scholars have pointed out that these labors have in common activity that is «creative», or that exercises control or dominion over one’s environment.[39]

In addition to the 39 melakhot, additional activities were prohibited by the rabbis for various reasons.

The term shomer Shabbat is used for a person (or organization) who adheres to Shabbat laws consistently. The (strict) observance of the Sabbath is often seen as a benchmark for orthodoxy and indeed has legal bearing on the way a Jew is seen by an orthodox religious court regarding their affiliation to Judaism.[40]

Specific applications[edit]

Electricity[edit]

Teddy bear lamp in the collection of the Jewish Museum of Switzerland. The cap can be twisted, which covers the lightbulb with a dark shell and dims the light in a way arguably acceptable on the sabbath.

Orthodox and some Conservative authorities rule that turning electric devices on or off is prohibited as a melakhah; however, authorities are not in agreement about exactly which one(s). One view is that tiny sparks are created in a switch when the circuit is closed, and this would constitute lighting a fire (category 37). If the appliance is purposed for light or heat (such as an incandescent bulb or electric oven), then the lighting or heating elements may be considered as a type of fire that falls under both lighting a fire (category 37) and cooking (i.e., baking, category 11). Turning lights off would be extinguishing a fire (category 36). Another view is that completing an electrical circuit constitutes building (category 35) and turning off the circuit would be demolishing (category 34). Some schools of thought consider the use of electricity to be forbidden only by rabbinic injunction, rather than a melakhah.

A common solution to the problem of electricity involves preset timers (Shabbat clocks) for electric appliances, to turn them on and off automatically, with no human intervention on Shabbat itself. Some Conservative authorities[41][42][43] reject altogether the arguments for prohibiting the use of electricity. Some Orthodox also hire a «Shabbos goy», a Gentile to perform prohibited tasks (like operating light switches) on Shabbat.

Automobiles[edit]

Orthodox and many Conservative authorities completely prohibit the use of automobiles on Shabbat as a violation of multiple categories, including lighting a fire, extinguishing a fire, and transferring between domains (category 39). However, the Conservative movement’s Committee on Jewish Law and Standards permits driving to a synagogue on Shabbat, as an emergency measure, on the grounds that if Jews lost contact with synagogue life they would become lost to the Jewish people.

A halakhically authorized Shabbat mode added to a power-operated mobility scooter may be used on the observance of Shabbat for those with walking limitations, often referred to as a Shabbat scooter. It is intended only for individuals whose limited mobility is dependent on a scooter or automobile consistently throughout the week.

Modifications[edit]

Seemingly «forbidden» acts may be performed by modifying technology such that no law is actually violated. In Sabbath mode, a «Sabbath elevator» will stop automatically at every floor, allowing people to step on and off without anyone having to press any buttons, which would normally be needed to work. (Dynamic braking is also disabled if it is normally used, i.e., shunting energy collected from downward travel, and thus the gravitational potential energy of passengers, into a resistor network.) However, many rabbinical authorities consider the use of such elevators by those who are otherwise capable as a violation of Shabbat, with such workarounds being for the benefit of the frail and handicapped and not being in the spirit of the day.

Many observant Jews avoid the prohibition of carrying by use of an eruv. Others make their keys into a tie bar, part of a belt buckle, or a brooch, because a legitimate article of clothing or jewelry may be worn rather than carried. An elastic band with clips on both ends, and with keys placed between them as integral links, may be considered a belt.

Shabbat lamps have been developed to allow a light in a room to be turned on or off at will while the electricity remains on. A special mechanism blocks out the light when the off position is desired without violating Shabbat.

The Shabbos App is a proposed Android app claimed by its creators to enable Orthodox Jews, and all Jewish Sabbath-observers, to use a smartphone to text on the Jewish Sabbath. It has met with resistance from some authorities.[44][45][46][47]

Permissions[edit]

If a human life is in danger (pikuach nefesh), then a Jew is not only allowed, but required,[48][49] to violate any halakhic law that stands in the way of saving that person (excluding murder, idolatry, and forbidden sexual acts). The concept of life being in danger is interpreted broadly: for example, it is mandated that one violate Shabbat to bring a woman in active labor to a hospital. Lesser rabbinic restrictions are often violated under much less urgent circumstances (a patient who is ill but not critically so).

We did everything to save lives, despite Shabbat. People asked: «Why are you here? There are no Jews here,» but we are here because the Torah orders us to save lives …. We are desecrating Shabbat with pride.

Various other legal principles closely delineate which activities constitute desecration of Shabbat. Examples of these include the principle of shinui («change» or «deviation»): A violation is not regarded as severe if the prohibited act was performed in a way that would be considered abnormal on a weekday. Examples include writing with one’s nondominant hand, according to many rabbinic authorities. This legal principle operates bedi’avad (ex post facto) and does not cause a forbidden activity to be permitted barring extenuating circumstances.

Reform and Reconstructionist views[edit]

Generally, adherents of Reform and Reconstructionist Judaism believe that the individual Jew determines whether to follow Shabbat prohibitions or not. For example, some Jews might find activities, such as writing or cooking for leisure, to be enjoyable enhancements to Shabbat and its holiness, and therefore may encourage such practices. Many Reform Jews believe that what constitutes «work» is different for each person, and that only what the person considers «work» is forbidden.[51] The radical Reform rabbi Samuel Holdheim advocated moving Sabbath to Sunday for many no longer observed it, a step taken by dozens of congregations in the United States in late 19th century.[52]

More rabbinically traditional Reform and Reconstructionist Jews believe that these halakhoth in general may be valid, but that it is up to each individual to decide how and when to apply them. A small fraction of Jews in the Progressive Jewish community accept these laws in much the same way as Orthodox Jews.

Encouraged activities[edit]

The Talmud, especially in tractate Shabbat, defines rituals and activities to both «remember» and «keep» the Sabbath and to sanctify it at home and in the synagogue. In addition to refraining from creative work, the sanctification of the day through blessings over wine, the preparation of special Sabbath meals, and engaging in prayer and Torah study were required as an active part of Shabbat observance to promote intellectual activity and spiritual regeneration on the day of rest from physical creation. The Talmud states that the best food should be prepared for the Sabbath, for «one who delights in the Sabbath is granted their heart’s desires» (BT, Shabbat 118a-b).[53][54]

All Jewish denominations encourage the following activities on Shabbat:

- Reading, studying, and discussing Torah and commentary, Mishnah and Talmud, and learning some halakha and midrash.

- Synagogue attendance for prayers.

- Spending time with other Jews and socializing with family, friends, and guests at Shabbat meals (hachnasat orchim, «hospitality»).

- Singing zemiroth or niggunim, special songs for Shabbat meals (commonly sung during or after a meal).

- Sex between husband and wife.[55]

- Sleeping.

Special Shabbat[edit]

Special Shabbatot are the Shabbatot that precede important Jewish holidays: e.g., Shabbat HaGadol (Shabbat preceding Pesach), Shabbat Zachor (Shabbat preceding Purim), and Shabbat Shuvah (Shabbat between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur).

In other religions[edit]

Christianity[edit]

Most Christians do not observe Saturday Sabbath, but instead observe a weekly day of worship on Sunday, which is often called the «Lord’s Day». Several Christian denominations, such as the Seventh-day Adventist Church, the Church of God (7th Day), the Seventh Day Baptists, and others, observe seventh-day Sabbath. This observance is celebrated from Friday sunset to Saturday sunset.

Samaritans[edit]

|

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (December 2022) |

Samaritans also observe Shabbat.[56][57]

Lunar Sabbath[edit]

Some hold the biblical sabbath was not connected to a 7-day week like the Gregorian calendar. The Seven-Day Week. Instead the New Moon marks the starting point for counting and the shabat falls consistently on the 8th, 15th, 22nd, 29th of each month. Biblical text to support using the moon, a light in the heavens, to determine days include Genesis 1:14, Psalm 104:19, and Sirach 43:6-8 See references:

[58]

[59]

[60]

Rabbinic Jewish tradition and practice does not hold of this, holding the sabbath to be based of the days of creation, and hence a wholly separate cycle from the monthly cycle, which does not occur automatically and must be rededicated each month.[61] See kiddush hachodesh.

See also[edit]

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Shabbat.

- List of Shabbat topics

- Baqashot

- Jewish greetings

- Jewish prayer #Prayer on Shabbat

- Shmita

- Uposatha

References[edit]

- ^ Other Biblical sources include: Exodus 16:22–30, Exodus 23:12, Exodus 31:12–17, Exodus 34:21, and Exodus 35: 12–17; Leviticus 19:3, Leviticus 23:3, Leviticus 26:2 and Numbers 15:32–26

- ^ Shulchan Aruch, Orach Chayim 293:2

- ^ Sabbath, Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ Pinches, T.G. (2003). «Sabbath (Babylonian)». In Hastings, James (ed.). Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics. Vol. 20. Selbie, John A., contrib. Kessinger Publishing. pp. 889–891. ISBN 978-0-7661-3698-4. Retrieved 2009-03-17.

It has been argued that the association of the number seven with creation itself derives from the circumstance that the Enuma Elish was recorded on seven tablets.

«emphasized by Professor Barton, who says: ‘Each account is arranged in a series of sevens, the Babylonian in seven tablets, the Hebrew in seven days. Each of them places the creation of man in the sixth division of its series.» Albert T. Clay, The Origin of Biblical Traditions: Hebrew Legends in Babylonia and Israel, 1923, p. 74. - ^ «Histoire du peuple hébreu». André Lemaire. Presses Universitaires de France 2009 (8e édition), p. 66

- ^ Eviatar Zerubavel (1985). The Seven Day Circle: The History and Meaning of the Week. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-98165-7.

- ^ a b Landau, Judah Leo. The Sabbath. Johannesburg, South Africa: Ivri Publishing Society, Ltd. pp. 2, 12. Retrieved 2009-03-26.

- ^ Craveri, Marcello (1967). The Life of Jesus. Grove Press. p. 134.

- ^ Joseph, Max (1943). «Holidays». In Landman, Isaac (ed.). The Universal Jewish Encyclopedia: An authoritative and popular presentation of Jews and Judaism since the earliest times. Vol. 5. Cohen, Simon, compiler. The Universal Jewish Encyclopedia, Inc. p. 410.

- ^ Joseph, Max (1943). «Sabbath». In Landman, Isaac (ed.). The Universal Jewish Encyclopedia: An authoritative and popular presentation of Jews and Judaism since the earliest times. Vol. 9. Cohen, Simon, compiler. The Universal Jewish Encyclopedia, Incv. p. 295.

- ^ Cohen, Simon (1943). «Week». In Landman, Isaac (ed.). The Universal Jewish Encyclopedia: An authoritative and popular presentation of Jews and Judaism since the earliest times. Vol. 10. Cohen, Simon, compiler. The Universal Jewish Encyclopedia, Inc. p. 482.

- ^ a b Sampey, John Richard (1915). «Sabbath: Critical Theories». In Orr, James (ed.). The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia. Howard-Severance Company. p. 2630. Retrieved 2009-08-13.

- ^ Bechtel, Florentine (1912). «Sabbath». The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 13. New York City: Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved 2009-03-26.

- ^ Genesis 2:1–3

- ^ Exodus 16:26

- ^ Exodus 16:29

- ^ Exodus 20:8–11

- ^ Every Person’s Guide to Shabbat, by Ronald H. Isaacs, Jason Aronson, 1998, p. 6

- ^ Graham, I. L. (2009). «The Origin of the Sabbath». Presbyterian Church of Eastern Australia. Archived from the original on December 3, 2008. Retrieved 2009-03-26.

- ^ «Jewish religious year: The Sabbath». Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 2009. Retrieved 2009-03-26.

According to biblical tradition, it commemorates the original seventh day on which God rested after completing the creation. Scholars have not succeeded in tracing the origin of the seven-day week, nor can they account for the origin of the Sabbath.

- ^ «Mezad Hashavyahu Ostracon, c. 630 BCE». Archived from the original on 2013-01-30. Retrieved 2012-09-12.

- ^ One measure is the number of people called up to Torah readings at the Shachrit/morning service. Three is the smallest number, e.g. Mondays and Thursdays. Five on the Holy days of Passover, Shavuoth, Succoth. Yom Kippur: Six. Shabbat: Seven.

- ^ The Talmud (Shabbat 119a) describes rabbis going out to greet the Shabbat Queen, and the Lekhah Dodi poem describes Shabbat as a «bride» and «queen». However, Maimonides (Mishneh Torah Hilchot Shabbat 30:2) speaks of greeting the «Shabbat King», and two independent commentaries on Mishneh Torah (Maggid Mishneh and R’ Zechariah haRofeh) quote the Talmud as speaking of the «Shabbat King». The words «King» and «Queen» in Aramaic differ by just one letter, and it seems that these understandings result from different traditions regarding spelling the Talmudic word. See full discussion.

- ^ Shabbat 118

- ^ See e.g. Numbers 15:32–36.

- ^ Numbers 28:9.

- ^ Moss, Aron. «Why do Jewish holidays begin at nightfall?». Chabad.org. Chabad.org. Retrieved 25 September 2020.

- ^ Shabbat 119b

- ^ Proverbs 31:10–31

- ^ Ferguson, Joey (May 20, 2011). «Jewish lecture series focuses on Sabbath Course at Chabad center focuses on secrets of sabbath’s serenity». Deseret News.

The more we are able to invest in it, the more we are able to derive pleasure from the Sabbath.» Jewish belief is based on understanding that observance of the Sabbath is the source of all blessing, said Rabbi Zippel in an interview. He referred to the Jewish Sabbath as a time where individuals disconnect themselves from all endeavors that enslave them throughout the week and compared the day to pressing a reset button on a machine. A welcome prayer over wine or grape juice from the men and candle lighting from the women invokes the Jewish Sabbath on Friday at sundown.

- ^ «Strassburg, Robert». Milken Archive of Jewish Music. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ^ «Milken Archive of Jewish Music – People – Samuel Adler». Retrieved 2 August 2015.

- ^ Shulchan Aruch, Orach Chaim 261.

- ^ Since it is this meal that changes the other two from meals of a two-per-day nature to two of a trio

- ^ Ein Yaakov: The Ethical and Inspirational Teachings of the Talmud. 1999. ISBN 1461628245.

- ^ Derived from Isaiah 58:13–14.

- ^ Mishnah Tractate Shabbat 7:2

- ^ Chagigah 1:8.

- ^ Klein, Miriam (April 27, 2011). «Sabbath Offers Serenity in a Fast-Paced World». Triblocal. Chicago Tribune.

- ^ See Yosef Dov Soloveitchik’s «Beis HaLevi» commentary on parasha Ki Tissa for further elaboration regarding the legal ramifications.

- ^ Neulander, Arthur (1950). «The Use of Electricity on the Sabbath». Proceedings of the Rabbinical Assembly. 14: 165–171.

- ^ Adler, Morris; Agus, Jacob; Friedman, Theodore (1950). «Responsum on the Sabbath». Proceedings of the Rabbinical Assembly. 14: 112–137.

- ^ Klein, Isaac. A Guide to Jewish Religious Practice. The Jewish Theological Seminary of America: New York, 1979.

- ^ Hannah Dreyfus (October 2, 2014). «New Shabbos App Creates Uproar Among Orthodox Circles». The Jewish Week. Archived from the original on October 7, 2014. Retrieved October 12, 2014.

- ^ David Shamah (October 2, 2014). «App lets Jewish kids text on Sabbath – and stay in the fold; The ‘Shabbos App’ is generating controversy in the Jewish community – and a monumental on-line discussion of Jewish law». The Times of Israel. Retrieved October 3, 2014.

- ^ Daniel Koren (October 2, 2014). «Finally, Now You Can Text on Saturdays Thanks to New ‘Shabbos App’«. Shalom Life. Archived from the original on October 7, 2014. Retrieved October 12, 2014.

- ^ «Will the Shabbos App Change Jewish Life, Raise Rabbinic Ire, or Both?». Jewish Business News. October 2, 2014. Retrieved October 12, 2014.

- ^ 8 saved during «Shabbat from hell» Archived 2010-01-19 at the Wayback Machine (January 17, 2010) in Israel 21c Innovation News Service Retrieved 2010–01–18

- ^ ZAKA rescue mission to Haiti ‘proudly desecrating Shabbat’ Religious rescue team holds Shabbat prayer with members of international missions in Port au-Prince. Retrieved 2010–01–22

- ^ Levy, Amit (17 January 2010). «ZAKA mission to Haiti ‘proudly desecrating Shabbat’«. Ynetnews. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ^ Faigin, Daniel P. (2003-09-04). «Soc.Culture.Jewish Newsgroups Frequently Asked Questions and Answers». Usenet. p. 18.4.7. Archived from the original on 2006-02-22. Retrieved 2009-03-27.

- ^ «The Sunday-Sabbath Movement in American Reform Judaism: Strategy or Evolution» (PDF). Americanjewisharchives.org. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ^ Birnbaum, Philip (1975). «Sabbath». A Book of Jewish Concepts. New York, NY: Hebrew Publishing Company. pp. 579–581. ISBN 088482876X.

- ^ «Judaism — The Sabbath». Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-07-28.

- ^ Shulkhan Arukh, Orach Chaim 280:1

- ^ «Sabbat Observance». AB Institute for Samaritan Studies, supported by the Israeli Ministry of Culture. Retrieved 20 December 2022.

- ^ «Dying Out: The Last Of The Samaritan Tribe – Full Documentary». Little Dot Studios. Retrieved 20 December 2022.

- ^ «Sabbath’s Consistent Lunar Month Dates». 4 February 2015. Retrieved Dec 27, 2021.

the sacred seventh-day Sabbaths are forever fixed to the count from one New Moon to the next, causing them to consistently fall upon the 8th, 15th, 22nd, and 29th lunar calendar dates.

- ^ Biblical Proof for the Lunar Sabbath — John D. Keyser

- ^ Cipriani, Roshan (Oct 1, 2015). Lunar Sabbath: The Seventy-Two Lunar Sabbaths: Sabbath Observance By The Phases Of The Moon. Scotts Valley, CA: CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. ISBN 978-1517080372.[unreliable source?]

- ^ «tefilla — No Mekadesh Yisrael on Shabbat». Mi Yodeya. Retrieved 2022-06-22.

This article is about the rest day in Judaism. For the general day of rest in Abrahamic religions, see Sabbath. For Sabbath in the Bible, see Biblical Sabbath. For the Talmudic tractate, see Shabbat (Talmud).

Kiddush cup, Shabbat candles and challah cover |

|

| Halakhic texts relating to this article | |

|---|---|

| Torah: | Exodus 20:7–10, Deut 5:12–14, numerous others.[1] |

| Mishnah: | Shabbat, Eruvin |

| Babylonian Talmud: | Shabbat, Eruvin |

| Jerusalem Talmud: | Shabbat, Eruvin |

| Mishneh Torah: | Sefer Zmanim, Shabbat 1–30; Eruvin 1–8 |

| Shulchan Aruch: | Orach Chayim, Shabbat 244–344; Eruvin 345–395; Techumin 396–416 |

| Other rabbinic codes: | Kitzur Shulchan Aruch ch. 72–96 |

Shabbat (, , or ; Hebrew: שַׁבָּת, romanized: Šabbāṯ, [ʃa’bat], lit. ‘rest’ or ‘cessation’) or the Sabbath (), also called Shabbos (, ) by Ashkenazim, is Judaism’s day of rest on the seventh day of the week—i.e., Saturday. On this day, religious Jews remember the biblical stories describing the creation of the heaven and earth in six days and the redemption from slavery and The Exodus from Egypt, and look forward to a future Messianic Age. Since the Jewish religious calendar counts days from sunset to sunset, Shabbat begins in the evening of what on the civil calendar is Friday.

Shabbat observance entails refraining from work activities, often with great rigor, and engaging in restful activities to honour the day. Judaism’s traditional position is that the unbroken seventh-day Shabbat originated among the Jewish people, as their first and most sacred institution. Variations upon Shabbat are widespread in Judaism and, with adaptations, throughout the Abrahamic and many other religions.