Праздник щедрой осени

Самый популярный праздник в Словении, связанный с виноделием и культурой потребления вина, — День Святого Мартина. Торжества начинаются 11 ноября и продолжаются всю неделю, а то и две. Таких осенних гуляний вы не встретите нигде в Европе, так что побывать на этом празднике, безусловно, стоит. Отметьте этот особый праздник там, где зреют виноград, вино – на виноградниках в гостях у виноделов. Праздник Святого Мартина отмечается не только в винодельческих регионах Словении, но и по всей стране — от Средиземного моря до Паннонских равнин.

Когда сусло превращается в вино

Принято считать, что праздник Святого Мартина зародился в стародавние времена: у кельтов было принято в осеннее время чествовать поля и виноградники. А донес эту традицию до новейших времен Святой Мартин, епископ французского города Тур, венгр по происхождению. Торжества, проходящие в Словении по случаю превращения сусла в молодое вино, по их размаху трудно сравнить с каким бы то ни было другим праздником, ведь почти каждый седьмой житель Словении занимается виноградарством, и даже в словенских сериалах в качестве героев, как правило, выступают представители винодельческих династий.

Праздник Святого Мартина пахнет вином и лакомствами

Праздник Святого Мартина – это не только новый урожай вина. В этот период принято готовить характерные блюда местной кухни, самым распространенным из которых является запеченный гусь или утка с «млинцами» и тушеной краснокочанной капустой. В словенских ресторанах вас ждут специальные праздничные меню, в которых вы обязательно найдете выпечку: это «погача», «потица» и другие сладости.

Винные сюжеты Словении

Виноградарство и виноделие Словении представлено тремя винодельческими регионами, в рамках которых насчитывается 14 винодельческих территории. Первые письменные свидетельства о том, что в Словении выращивали виноград, относятся к третьему веку до нашей эры. С тех самых пор здесь делали и вино – в Словении его много, и оно отменное. Многие словенские виноделы завоевывают самые престижные награды и призы на глобальных винных ярмарках и фестивалях. В Словении имеется и ряд особых сортов винограда, из которых получают особенное вино. Уникальными являются «Крашки Теран» и «Доленьский Цвичек», а есть еще «Зелен», «Пинела», «Грганья», «Кларница» и другие редкие сорта. Вам они еще не известны? Праздник Святого Мартина – прекрасный случай для того, чтобы их попробовать.

Узнать больше

Где можно попробовать словенские вина?

В период празднеств в честь Святого Мартина, которые охватывают всю Словению, можно отведать молодого вина. Вы сможете не только побывать на дегустациях вина нового урожая в различных ресторанах, трактирах, винных погребах и на специально организованных мероприятиях, но и познакомиться с изысканными винами в не совсем обычном формате.

Праздник Святого Мартина в Словении

В период празднования Дня Святого Мартина в Словении проходит великое множество интересных мероприятий. Узнайте о том, где можно поднять бокалы, полные молодого вина.

Праздник Святого Мартина – торжества в честь щедрой осени

Откройте для себя традиции виноградарства и виноделия – посетите Праздник Святого Мартина. Одна-две недели в Словении будут проходить именно под знаком вина нового урожая. Словения – это винодельческая Европа в миниатюре.

Хочу получать электронные новости

Информация об отдыхе в Словении, сезонных предложениях, текущих событиях, возможностях для экскурсий и путешествий. Добавьте уголок зеленой Словении в свое онлайн-пространство.

Настройки конфиденциальности

Настройки конфиденциальности

Самым большим событием осенью в Словении является День святого Мартина (11 ноября). Этот праздник знаменует собой символическое завершение всех усилий виноделов страны. В День святого Мартина многие города и поселки Словении (Любляна, Марибор, Птуй, Ормож, Горня-Радгона и др.) проводят винные и кулинарные фестивали. Прочитав статью, вы узнаете, как отмечается День святого Мартина в разных городах Словении. А также познакомитесь с тем, как проходят основные торжества в Мариборе.

1. Как День святого Мартина отмечают в Словении?

День святого Мартина в Словении не является национальным праздником, хотя он пользуется здесь популярностью. Это связано с многочисленными винными и кулинарными фестивалями, которые проходят в этот день в Любляне, Мариборе, Птуе, Орможе, Горня-Радгоне и других местах.

Осенний праздник День святого Мартина в Словении является событием, на котором местные производители виноградного напитка предлагают свой продукт участникам праздника. 11 ноября в столице Словении — городе Любляне проходит Фестиваль вина. Более 150 виноделен представляют здесь для дегустации свои уникальные вина нового урожая. Вместе с ними местные кулинары предлагают свою продукцию участникам праздника.

В поселке Шмартно (регион Горишка Брда) торжества проводятся на центральной площади. Здесь проходят концертная и развлекательная программы. Для любителей покушать открыты кулинарные ряды. А в поселке Виполже организуется экскурсионная поездка, во время которой гости могут узнать много интересного о вине, оливковом масле, хурме и других продуктах.

Празднование в Орможе включает в себя фестиваль, посвящённый вину и гастрономии. Он включает в себя также культурно-развлекательную программу. Праздничные мероприятия также пройдут в Горня-Радгоне, где можно продегустировать молодое вино и узнать некоторую интересную информации о производстве вина.

2. Основные мероприятия в День святого Мартина в Мариборе

Традиционный фестиваль виноградной лозы в Мариборе проводит на День святого Мартина свой завершающий этап. Благодаря своей обширной программе он известен не только в свой стране, но и за её пределами. По оценкам организаторов, праздник посещают более 20 тысяч человек со всей Словении и зарубежных стран, независимо от дня недели.

В дни праздника рынок на площади Леона Штукля (Trg Leona Štuklja) заполняется музыкантами и киосками, предлагающими осенние продукты и деликатесы. Основные мероприятия проходят на площади Леона Штукля. Они начинаются 11 ноября ровно в 11:00 часов утра. Организаторы устраивают настоящее веселье в Штирийском стиле.

Здесь происходит торжественное «крещение» нового вина, а также «приезд винной королевы».

Шествие «винной королевы», сборщиков урожая, фольклористов, фермерских женщин, сплавщиков и представителей «винных орденов и ассоциаций» проходит по центру города. Затем участники присоединяются к празднованиям, принося свою продукцию в качестве символической «дани осени».

Местные жители, гости из близлежащих городов и деревень, а также туристы присоединяются к церемониальному «благословению сусла». Затем они участвуют в дегустации местных блюд и вин, предлагаемых на прилавках местных кулинаров и виноделов, в компании известных музыкантов и самодеятельных коллективов.

Заметим, что словенское вино — это в основном высококачественное вино без добавления сахара, которое на 75% является белым. В стране выращивается 53 сорта лозы.Словенцы занимаются культивированием, как общеевропейских сортов винограда, таких как совиньон, шардоне, пино-блан и пино-гри, так и местных сортов.

3. Чем ещё известен Марибор?

11 ноября в Мариборе — это День святого Мартина, который «превратил виноградный сок в вино». Антон Мартин Сломшек, ставший первым епископом города в 1846 году, известен здесь тем, что написал популярную застольную песню. В городе есть две статуи Вакха, бога вина. Словенцы шутят, что посетители могут напиться, просто вдыхая здешний воздух.

В Музее старой лозы города проводятся дегустации словенских сортов винограда, таких как Пино Гри, Гевюрцтраминер и Мускат. Также проводятся дегустации в одном из самых больших винных погребов Европы (Vinag). В нём хранится более 50 миллионов литров вина в 21.2 километрах туннелей под городской площадью Свободы. В их числе находится Рислинг, изготовленный во время Второй Мировой войны.

Словенская кухня — это интересное сочетание Балканской и средиземноморской кухни. В старейших ресторанах Марибора можно отведать филе судака с полентой и спаржей, фаршированные кальмары, горячий венгерский суп-гуляш, разновидности варенников, ореховый рулет Потица… В Мариборе, помимо вина, есть и отличное пиво!

Два хороших винных бара на верхнем этаже гостиницы «Славия» — это шикарное пространство с великолепным обзором. Оба подают деликатный Шипон белого цвета, приготовленный бенедиктинскими монахами на винодельне (Dveri Pax) в нескольких милях к северу от города. На берегу реки Драва, в водонапорной башне 16-го века, теперь находится романтический винный бар с живым джазом и пролетающими лебедями.

Вот так в Словении проходит День святого Мартина! По большому счёту, это больше напоминает винно-гастрономический фестиваль! О разных традициях на День святого Мартина, а также о самом Мартине вы можете прочитать, перейдя по ссылкам ниже:

Читать статью: «День святого Мартина в Венгрии»

Читать статью: «Праздник святого Мартина в Германии»

Читайте также:

Праздники и фестивали разных стран мира

Уважаемые читатели! Пишите комментарии! Читайте статьи на сайте «Мир праздников»!

St Martin’s Day Kermis by Peeter Baltens (16th century), shows peasants celebrating by drinking the first wine of the season, and a horseman representing the saint

Saint Martin’s Day or Martinmas, sometimes historically called Old Halloween or Old Hallowmas Eve,[1][2] is the feast day of Saint Martin of Tours and is celebrated in the liturgical year on 11 November. In the Middle Ages and early modern period, it was an important festival in many parts of Europe, particularly Germanic-speaking regions. In these regions, it marked the end of the harvest season and beginning of winter.[3] and the «winter revelling season». Traditions include feasting on ‘Martinmas goose’ or ‘Martinmas beef’, drinking the first wine of the season, and mumming. In some German and Dutch-speaking towns, there are processions of children with lanterns (Laternelaufen), sometimes led by a horseman representing St Martin. The saint was also said to bestow gifts on children. In the Rhineland, it is also marked by lighting bonfires.

Martin of Tours (died 397) was a Roman soldier who was baptized as an adult and became a bishop in Gaul. He is best known for the tale whereby he cut his cloak in half with his sword, to give half to a beggar who was dressed in only rags in the depth of winter. That night Martin had a vision of Jesus Christ wearing the half-cloak.[4][5]

Customs[edit]

A tradition on St Martin’s Eve or Day is to share a goose for dinner.

Traditionally, in many parts of Europe, St Martin’s Day marked the end of the harvest and the beginning of winter. The feast coincides with the end of the Octave of Allhallowtide.

Feasting and drinking[edit]

Martinmas was traditionally when livestock were slaughtered for winter provision.[6] It may originally have been a time of animal sacrifice, as the Old English name for November was Blōtmōnaþ (‘sacrifice month’).[7]

Goose is eaten at Martinmas in most places. There is a legend that St Martin, when trying to avoid being ordained bishop, hid in a pen of geese whose cackling gave him away. Once a key medieval autumn feast, a custom of eating goose on the day spread to Sweden from France. It was primarily observed by the craftsmen and noblemen of the towns. In the peasant community, not everyone could afford this, so many ate duck or hen instead.[8]

In winegrowing regions of Europe, the first wine was ready around the time of Martinmas. Although there was no mention of a link between St Martin and winegrowing by Gregory of Tours or other early hagiographers, St Martin is widely credited in France with helping to spread winemaking throughout the region of Tours (Touraine) and facilitating vine-planting. The old Greek tale that Aristaeus discovered the advantage of pruning vines after watching a goat has been appropriated to St Martin.[9] He is credited with introducing the Chenin blanc grape, from which most of the white wine of western Touraine and Anjou is made.[9]

Bonfires and lanterns[edit]

Bonfires are lit on St Martin’s Eve in the Rhineland region of Germany. In the fifteenth century, these bonfires were so numerous that the festival was nicknamed Funkentag (spark day).[7] In the nineteenth century it was recorded that young people danced around the fire and leapt through the flames, and that the ashes were strewn on the fields to make them fertile.[7] Similar customs were part of the Gaelic festival Samhain (1 November).

In some German and Dutch-speaking towns, there are nighttime processions of children carrying paper lanterns or turnip lanterns and singing songs of St Martin.[7] These processions are known in German as Laternelaufen.

Gift-bringers[edit]

In parts of Flanders and the Rhineland, processions are led by a man on horseback representing St Martin, who may give out apples, nuts, cakes or other sweets for children.[7] Historically, in Ypres, children hung up stockings filled with hay on Martinmas Eve, and awoke the next morning to find gifts in them. These were said to have been left by St Martin as thanks for the fodder provided for his horse.[7]

In the Swabia and Ansbach regions of Germany, a character called Pelzmärten (‘pelt Martin’ or ‘skin Martin’) appeared at Martinmas until the 19th century. With a black face and wearing a cow bell, he ran about frightening children, and he dealt out blows as well as nuts and apples.[7]

Eve of St Martin’s Lent[edit]

In the 6th century, church councils began requiring fasting on all days, except Saturdays and Sundays, from Saint Martin’s Day to Epiphany (elsewhere, the Feast of the Three Wise Men for the stopping of the star over Bethlehem)[10] on January 6 (56 days). An addition to and an equivalent to the 40 days fasting of Lent, given its weekend breaks, this was called Quadragesima Sancti Martini (Saint Martin’s Lent, or literally «the fortieth of»).[11] This is rarely observed now. This period was shortened to begin on the Sunday before December and became the current Advent within a few centuries.[12]

Celebrations by culture[edit]

Germanic[edit]

Austrian[edit]

In Austria, St Martin’s Day is celebrated the same way as in Germany. The nights before and on the night of 11 November, children walk in processions carrying lanterns, which they made in school, and sing Martin songs.[citation needed] Martinloben is celebrated as a collective festival. Events include art exhibitions, wine tastings, and live music. Martinigansl (roasted goose) is the traditional dish of the season.[13]

Dutch and Flemish[edit]

In the Netherlands, on the evening of 11 November, children go door to door (mostly under parental supervision) with lanterns made of hollowed-out sugar beet or, more recently, paper, singing songs such as «Sinte(re) Sinte(re) Maarten», to receive sweets or fruit in return. In the past, poor people would visit farms on 11 November to get food for the winter. In the 1600s, the city of Amsterdam held boat races on the IJ, where 400 to 500 light craft, both rowing boats and sailboats, took part with a vast crowd on the banks. St Martin is the patron saint of the city of Utrecht, and St Martin’s Day is celebrated there with a big lantern parade.[citation needed]

In Flanders, the Dutch-speaking part of Belgium, St Martin’s Eve is celebrated on the evening of 10 November, mainly in West Flanders and around Ypres. Children go through the streets with paper lanterns and candles, and sing songs about St Martin. Sometimes, a man dressed as St Martin rides on a horse in front of the procession.[14] The children receive presents from either their friends or family as supposedly coming from St Martin.[citation needed] In some areas, there is a traditional goose meal.[citation needed]

In Wervik, children go from door to door, singing traditional «Séngmarténg» songs, sporting a hollow beetroot with a carved face and a candle inside called «Bolle Séngmarténg»; they gather at an evening bonfire. At the end the beetroots are thrown into the fire, and pancakes are served.[citation needed]

English[edit]

Martinmas was widely celebrated on 11 November in medieval and early modern England. In his study «Medieval English Martinmesse: The Archaeology of a Forgotten Festival», Martin Walsh describes Martinmas as a festival marking the end of the harvest season and beginning of winter.[6] He suggests it had pre-Christian roots.[6] Martinmas ushered in the «winter revelling season» and involved feasting on the meat of livestock that had been slaughtered for winter provision (especially ‘Martlemas beef’), drinking, storytelling, and mumming.[6] It was a time for saying farewell to travelling ploughmen, who shared in the feast along with the harvest-workers.[6]

According to Walsh, Martinmas eventually died out in England as a result of the English Reformation, the emergence of Guy Fawkes Night (5 November), as well as changes in farming and the Industrial Revolution.[6] Today, 11 November is Remembrance Day.

German[edit]

A widespread custom in Germany is to light bonfires, called Martinsfeuer, on St Martin’s Eve. In recent years, the processions that accompany those fires have been spread over almost a fortnight before Martinmas (Martinstag). At one time, the Rhine River valley would be lined with fires on the eve of Martinmas. In the Rhineland, Martin’s day is celebrated traditionally with a get-together during which a roasted suckling pig is shared with the neighbours.

The nights before and on the eve itself, children walk in processions called Laternelaufen, carrying lanterns, which they made in school, and sing St Martin’s songs. Usually, the walk starts at a church and goes to a public square. A man on horseback representing St Martin accompanies the children. When they reach the square, Martin’s bonfire is lit and Martin’s pretzels are distributed.[15]

In the Rhineland, the children also go from house to house with their lanterns, sing songs and get candy in return. The origin of the procession of lanterns is unclear. To some, it is a substitute for the Martinmas bonfire, which is still lit in a few cities and villages throughout Europe. It formerly symbolized the light that holiness brings to the darkness, just as St Martin brought hope to the poor through his good deeds. Even though the bonfire tradition is gradually being lost, the procession of lanterns is still practiced.[16]

A Martinsgans («St Martin’s goose»), is typically served on St Martin’s Eve following the procession of lanterns. «Martinsgans» is usually served in restaurants, roasted, with red cabbage and dumplings.[16]

The traditional sweet of Martinmas in the Rhineland is Martinshörnchen, a pastry shaped in the form of a croissant, which recalls both the hooves of St Martin’s horse and, by being the half of a pretzel, the parting of his mantle. In some areas, these pastries are instead shaped like men (Stutenkerl or Weckmänner).

St Martin’s Day is also celebrated in German Lorraine and Alsace, which border the Rhineland and are now part of France. Children receive gifts and sweets. In Alsace, in particular the Haut-Rhin mountainous region, families with young children make lanterns out of painted paper that they carry in a colourful procession up the mountain at night. Some schools organise these events, in particular schools of the Rudolf Steiner (Waldorf education) pedagogy. In these regions, the day marks the beginning of the holiday season.[citation needed] In the German speaking parts of Belgium, notably Eupen and Sankt Vith, processions similar to those in Germany take place.[citation needed]

German American[edit]

In the United States, St. Martin’s Day celebrations are uncommon, but are typically held by German American communities.[17] Many German restaurants feature a traditional menu with goose and Glühwein (a mulled red wine). St Paul, Minnesota celebrates with a traditional lantern procession around Rice Park. The evening includes German treats and traditions that highlight the season of giving.[18] In Dayton, Ohio the Dayton Liederkranz-Turner organization hosts a St Martin’s Family Celebration on the weekend before with an evening lantern parade to the singing of St Martin’s carols, followed by a bonfire.[19]

Swedish[edit]

St Martin’s Day or St Martin’s Eve (Mårtensafton) was an important medieval autumn feast in Sweden. In early November, geese are ready for slaughter, and on St Martin’s Eve it is tradition to have a roast goose dinner. The custom is particularly popular in Scania in southern Sweden, where goose farming has long been practised, but it has gradually spread northwards. A proper goose dinner also includes svartsoppa (a heavily spiced soup made from geese blood) and apple charlotte.[20]

Slavic[edit]

Croatian[edit]

In Croatia, St. Martin’s Day (Martinje, Martinovanje) marks the day when the must traditionally turns to wine. The must is usually considered impure and sinful, until it is baptised and turned into wine. The baptism is performed by someone who dresses up as a bishop and blesses the wine; this is usually done by the host. Another person is chosen as the godfather of the wine.

Czech[edit]

A Czech proverb connected with the Feast of St. Martin – Martin přijíždí na bílém koni (transl. «Martin is coming on a white horse») – signifies that the first half of November in the Czech Republic is the time when it often starts to snow. St. Martin’s Day is the traditional feast day in the run-up to Advent. Restaurants often serve roast goose as well as young wine from the recent harvest known as Svatomartinské víno, which is similar to Beaujolais nouveau as the first wine of the season. Wine shops and restaurants around Prague pour the first of the St. Martin’s wines at 11:11 a.m. Many restaurants offer special menus for the day, featuring the traditional roast goose.[21]

Polish[edit]

Procession of Saint Martin in Poznań, 2006

In Poland, 11 November is National Independence Day. St. Martin’s Day (Dzień Świętego Marcina) is celebrated mainly in the city of Poznań where its citizens buy and eat considerable amounts of croissants filled with almond paste with white poppy seeds, the Rogal świętomarciński or St. Martin’s Croissants. Legend has it that this centuries-old tradition commemorates a Poznań baker’s dream which had the saint entering the city on a white horse that lost its golden horseshoe. The next morning, the baker whipped up horseshoe-shaped croissants filled with almonds, white poppy seeds and nuts, and gave them to the poor. In recent years, competition amongst local patisseries has become fierce. The product is registered under the European Union Protected Designation of Origin and only a limited number of bakers hold an official certificate. Poznanians celebrate the festival with concerts, parades and a fireworks show on Saint Martin’s Street. Goose meat dishes are also eaten during the holiday.[22]

Slovene[edit]

The biggest event in Slovenia is the St. Martin’s Day celebration in Maribor which marks the symbolic winding up of all the wine growers’ endeavours. There is the ceremonial «christening» of the new wine, and the arrival of the Wine Queen. The square Trg Leona Štuklja is filled with musicians and stalls offering autumn produce and delicacies.[23]

Celtic[edit]

Irish[edit]

In some parts[24] of Ireland, on the eve of St. Martin’s Day (Lá Fhéile Mártain in Irish), it was tradition to sacrifice a cockerel by bleeding it. The blood was collected and sprinkled on the four corners of the house.[25][24] Also in Ireland, no wheel of any kind was to turn on St. Martin’s Day, because Martin was said by some people[24] to have been thrown into a mill stream and killed by the wheel and so it was not right to turn any kind of wheel on that day. A local legend in Co. Wexford says that putting to sea is to be avoided as St. Martin rides a white horse across Wexford Bay bringing death by drowning to any who see him.[26]

Welsh[edit]

In Welsh mythology the day is associated with the Cŵn Annwn, the spectral hounds who escort souls to the otherworld (Annwn). St Martin’s Day was one of the few nights the hounds would engage in a Wild Hunt, stalking the land for criminals and villains.[27] The supernatural character of the day in Welsh culture is evident in the number omens associated with it. Marie Trevelyan recorded that if the hooting of an owl was heard on St Martin’s Day it was seen as a bad omen for that district. If a meteor was seen, then there would be trouble for the whole nation.[28]

Latvian[edit]

Mārtiņi (Martin’s) is traditionally celebrated by Latvians on 10 November, marking the end of the preparations for winter, such as salting meat and fish, storing the harvest and making preserves. Mārtiņi also marks the beginning of masquerading and sledding, among other winter activities.

Maltese[edit]

A Maltese «Borża ta’ San Martin»

St. Martin’s Day (Jum San Martin in Maltese) is celebrated in Malta on the Sunday nearest to 11 November. Children are given a bag full of fruits and sweets associated with the feast, known by the Maltese as Il-Borża ta’ San Martin, «St. Martin’s bag». This bag may include walnuts, hazelnuts, almonds, chestnuts, dried or processed figs, seasonal fruit (like oranges, tangerines, apples and pomegranates) and «Saint Martin’s bread roll» (Maltese: Ħobża ta’ San Martin). In old days, nuts were used by the children in their games.

There is a traditional rhyme associated with this custom:

Ġewż, Lewż, Qastan, Tin

Kemm inħobbu lil San Martin.

(Walnuts, Almonds, Chestnuts, Figs

I love Saint Martin so much.)

A feast is celebrated in the village of Baħrija on the outskirts of Rabat, including a procession led by the statue of Saint Martin. There is also a fair, and a show for local animals. San Anton School, a private school on the island, organises a walk to and from a cave especially associated with Martin in remembrance of the day.

Portuguese and Galician[edit]

In Portugal, St. Martin’s Day (Dia de São Martinho) is commonly associated with the celebration of the maturation of the year’s wine, being traditionally the first day when the new wine can be tasted. It is celebrated, traditionally around a bonfire, eating the magusto, chestnuts roasted under the embers of the bonfire (sometimes dry figs and walnuts), and drinking a local light alcoholic beverage called água-pé (literally «foot water», made by adding water to the pomace left after the juice is pressed out of the grapes for wine – traditionally by stomping on them in vats with bare feet, and letting it ferment for several days), or the stronger jeropiga (a sweet liquor obtained in a very similar fashion, with aguardente added to the water). Água-pé, though no longer available for sale in supermarkets and similar outlets (it is officially banned for sale in Portugal), is still generally available in small local shops from domestic production.[citation needed]

Leite de Vasconcelos regarded the magusto as the vestige of an ancient sacrifice to honor the dead and stated that it was tradition in Barqueiros to prepare, at midnight, a table with chestnuts for the deceased family members to eat.[29] The people also mask their faces with the dark wood ashes from the bonfire.[citation needed]

A typical Portuguese saying related to Saint Martin’s Day:

É dia de São Martinho;

comem-se castanhas, prova-se o vinho.

(It is St. Martin’s Day,

we’ll eat chestnuts, we’ll taste the wine.)

This period is also quite popular because of the usual good weather period that occurs in Portugal in this time of year, called Verão de São Martinho (St. Martin’s Summer). It is frequently tied to the legend since Portuguese versions of St. Martin’s legend usually replace the snowstorm with rain (because snow is not frequent in most parts of Portugal, while rain is common at that time of the year) and have Jesus bringing the end of it, thus making the «summer» a gift from God.[citation needed]

St Martin’s Day is widely celebrated in Galicia. It is the traditional day for slaughtering fattened pigs for the winter. This tradition has given way to the popular saying «A cada cerdo le llega su San Martín from Galician A cada porquiño chégalle o seu San Martiño («Every pig gets its St Martin»). The phrase is used to indicate that wrongdoers eventually get their comeuppance.

Sicilian[edit]

In Sicily, November is the winemaking season. On the day Sicilians eat anise, hard biscuits dipped into Moscato, Malvasia or Passito. l’Estate di San Martino (Saint Martin’s Summer) is the traditional reference to a period of unseasonably warm weather in early to mid November, possibly shared with the Normans (who founded the Kingdom of Sicily) as common in at least late English folklore. The day is celebrated in a special way in a village near Messina and at a monastery dedicated to Saint Martin overlooking Palermo beyond Monreale.[30] Other places in Sicily mark the day by eating fava beans.[citation needed]

In art[edit]

Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s physically largest painting is The Wine of Saint Martin’s Day, which depicts the saint giving charity.

There is a closely similar painting by Peeter Baltens, which can be seen here.

See also[edit]

- St. Catherine’s Day

References[edit]

- ^ Bulik, Mark (1 January 2015). The Sons of Molly Maguire: The Irish Roots of America’s First Labor War. Fordham University Press. p. 43. ISBN 9780823262243.

- ^ Carlyle, Thomas (11 November 2010). The Works of Thomas Carlyle. Cambridge University Press. p. 356. ISBN 9781108022354.

- ^ George C. Homans, English Villagers of the Thirteenth Century, 2nd ed. 1991, «The Husbandman’s year» p355f.

- ^ Sulpicius Severus (397). De Vita Beati Martini Liber Unus [On the Life of St. Martin]. Retrieved 2 November 2021.

- ^ Dent, Susie (2020). Word Perfect: Etymological Entertainment For Every Day of the Year. John Murray. ISBN 978-1-5293-1150-1.

- ^ a b c d e f Walsh, Martin (2000). «Medieval English Martinmesse: The Archaeology of a Forgotten Festival». Folklore. 111 (2): 231–249. doi:10.1080/00155870020004620. S2CID 162382811.

- ^ a b c d e f g Miles, Clement A. (1912). Christmas in Ritual and Tradition. Chapter 7: All Hallow Tide to Martinmas. Reproduced by Internet Sacred Text Archive.

- ^ «St Martin’s Day – or ‘Martin Goose'» Lilja, Agneta. Sweden.se magazine-format website

- ^ a b For instance, in Hugh Johnson, Vintage: The Story of Wine 1989, p 97.

- ^ per Matthew 2:1–2:12

- ^ Philip H. Pfatteicher, Journey into the Heart of God (Oxford University Press 2013 ISBN 978-0-19999714-5)

- ^ «Saint Martin’s Lent». Encyclopædia Britannica. Britannica. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ^ «Autumn Feast of St. Martin», Austrian Tourism Board

- ^ Thomson, George William. Peeps At Many Lands: Belgium, Library of Alexandria, 1909

- ^ «St. Martin’s Day traditions honor missionary», Kaiserlautern American, 7 November 2008

- ^ a b «Celebrating St. Martin’s Day on November 11», German Missions in the United States Archived 2012-01-06 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ German traditions in the US for St. Martin’s Day

- ^ «St. Martin’s Day», St. Paul Star Tribune, November 5, 2015

- ^ «St. Martin’s Day Family Celebration». Dayton Liederkranz-Turner. Retrieved 2021-11-02.

- ^ «Mårten Gås», Sweden.SE

- ^ «St. Martin’s Day specials at Prague restaurants», Prague Post, 11 November 2011

- ^ «St. Martin’s Day Celebrations»

- ^ «St. Martin’s Day Celebrations in Maribor», Slovenian Tourist Board

- ^ a b c Marion McGarry (11 November 2020). «Why blood sacrifice rites were common in Ireland on 11 November». RTE. Retrieved 13 November 2020.

Opinion: Blood sacrifices involving pigs, sheep or geese were practiced in Ireland well into living memory on Martinmas. … the custom extended from North Connacht, down to Kerry, and across the midlands and was rarer in Ulster or on the east coast. … some say the saint met his death by being crushed between two wheels

- ^ Súilleabháin, Seán Ó (2012). Miraculous Plenty; Irish Religious Folktales and Legends. Four Courts Press. pp. 183-191 and 269. ISBN 978-0-9565628-2-1.

- ^ «A Wexford Legend — St Martin’s Eve».

- ^ Matthews, John; Matthews, Caitlín (2005). The Element Encyclopedia of Magical Creatures. HarperElement. p. 119. ISBN 978-1-4351-1086-1.

- ^ Trevelyan, Marie (1909). Folk Lore And Folk Stories Of Wales. p. 13. ISBN 9781497817180.

- ^ Leite de Vasconcelos, Opúsculos Etnologia — volumes VII, Lisboa, Imprensa Nacional, 1938

- ^ Gangi, Roberta. «The Joys of St Martin’s Summer», Best of Sicily Magazine, 2010

External links[edit]

Media related to St. Martin’s Day at Wikimedia Commons

- How to make a St. Martin’s Day lantern

- UK History of Martinmas

- St. Martin’s Day in Germany

- St. Martin of Tours

- Alice’s Medieval Feasts & Fasts

St Martin’s Day Kermis by Peeter Baltens (16th century), shows peasants celebrating by drinking the first wine of the season, and a horseman representing the saint

Saint Martin’s Day or Martinmas, sometimes historically called Old Halloween or Old Hallowmas Eve,[1][2] is the feast day of Saint Martin of Tours and is celebrated in the liturgical year on 11 November. In the Middle Ages and early modern period, it was an important festival in many parts of Europe, particularly Germanic-speaking regions. In these regions, it marked the end of the harvest season and beginning of winter.[3] and the «winter revelling season». Traditions include feasting on ‘Martinmas goose’ or ‘Martinmas beef’, drinking the first wine of the season, and mumming. In some German and Dutch-speaking towns, there are processions of children with lanterns (Laternelaufen), sometimes led by a horseman representing St Martin. The saint was also said to bestow gifts on children. In the Rhineland, it is also marked by lighting bonfires.

Martin of Tours (died 397) was a Roman soldier who was baptized as an adult and became a bishop in Gaul. He is best known for the tale whereby he cut his cloak in half with his sword, to give half to a beggar who was dressed in only rags in the depth of winter. That night Martin had a vision of Jesus Christ wearing the half-cloak.[4][5]

Customs[edit]

A tradition on St Martin’s Eve or Day is to share a goose for dinner.

Traditionally, in many parts of Europe, St Martin’s Day marked the end of the harvest and the beginning of winter. The feast coincides with the end of the Octave of Allhallowtide.

Feasting and drinking[edit]

Martinmas was traditionally when livestock were slaughtered for winter provision.[6] It may originally have been a time of animal sacrifice, as the Old English name for November was Blōtmōnaþ (‘sacrifice month’).[7]

Goose is eaten at Martinmas in most places. There is a legend that St Martin, when trying to avoid being ordained bishop, hid in a pen of geese whose cackling gave him away. Once a key medieval autumn feast, a custom of eating goose on the day spread to Sweden from France. It was primarily observed by the craftsmen and noblemen of the towns. In the peasant community, not everyone could afford this, so many ate duck or hen instead.[8]

In winegrowing regions of Europe, the first wine was ready around the time of Martinmas. Although there was no mention of a link between St Martin and winegrowing by Gregory of Tours or other early hagiographers, St Martin is widely credited in France with helping to spread winemaking throughout the region of Tours (Touraine) and facilitating vine-planting. The old Greek tale that Aristaeus discovered the advantage of pruning vines after watching a goat has been appropriated to St Martin.[9] He is credited with introducing the Chenin blanc grape, from which most of the white wine of western Touraine and Anjou is made.[9]

Bonfires and lanterns[edit]

Bonfires are lit on St Martin’s Eve in the Rhineland region of Germany. In the fifteenth century, these bonfires were so numerous that the festival was nicknamed Funkentag (spark day).[7] In the nineteenth century it was recorded that young people danced around the fire and leapt through the flames, and that the ashes were strewn on the fields to make them fertile.[7] Similar customs were part of the Gaelic festival Samhain (1 November).

In some German and Dutch-speaking towns, there are nighttime processions of children carrying paper lanterns or turnip lanterns and singing songs of St Martin.[7] These processions are known in German as Laternelaufen.

Gift-bringers[edit]

In parts of Flanders and the Rhineland, processions are led by a man on horseback representing St Martin, who may give out apples, nuts, cakes or other sweets for children.[7] Historically, in Ypres, children hung up stockings filled with hay on Martinmas Eve, and awoke the next morning to find gifts in them. These were said to have been left by St Martin as thanks for the fodder provided for his horse.[7]

In the Swabia and Ansbach regions of Germany, a character called Pelzmärten (‘pelt Martin’ or ‘skin Martin’) appeared at Martinmas until the 19th century. With a black face and wearing a cow bell, he ran about frightening children, and he dealt out blows as well as nuts and apples.[7]

Eve of St Martin’s Lent[edit]

In the 6th century, church councils began requiring fasting on all days, except Saturdays and Sundays, from Saint Martin’s Day to Epiphany (elsewhere, the Feast of the Three Wise Men for the stopping of the star over Bethlehem)[10] on January 6 (56 days). An addition to and an equivalent to the 40 days fasting of Lent, given its weekend breaks, this was called Quadragesima Sancti Martini (Saint Martin’s Lent, or literally «the fortieth of»).[11] This is rarely observed now. This period was shortened to begin on the Sunday before December and became the current Advent within a few centuries.[12]

Celebrations by culture[edit]

Germanic[edit]

Austrian[edit]

In Austria, St Martin’s Day is celebrated the same way as in Germany. The nights before and on the night of 11 November, children walk in processions carrying lanterns, which they made in school, and sing Martin songs.[citation needed] Martinloben is celebrated as a collective festival. Events include art exhibitions, wine tastings, and live music. Martinigansl (roasted goose) is the traditional dish of the season.[13]

Dutch and Flemish[edit]

In the Netherlands, on the evening of 11 November, children go door to door (mostly under parental supervision) with lanterns made of hollowed-out sugar beet or, more recently, paper, singing songs such as «Sinte(re) Sinte(re) Maarten», to receive sweets or fruit in return. In the past, poor people would visit farms on 11 November to get food for the winter. In the 1600s, the city of Amsterdam held boat races on the IJ, where 400 to 500 light craft, both rowing boats and sailboats, took part with a vast crowd on the banks. St Martin is the patron saint of the city of Utrecht, and St Martin’s Day is celebrated there with a big lantern parade.[citation needed]

In Flanders, the Dutch-speaking part of Belgium, St Martin’s Eve is celebrated on the evening of 10 November, mainly in West Flanders and around Ypres. Children go through the streets with paper lanterns and candles, and sing songs about St Martin. Sometimes, a man dressed as St Martin rides on a horse in front of the procession.[14] The children receive presents from either their friends or family as supposedly coming from St Martin.[citation needed] In some areas, there is a traditional goose meal.[citation needed]

In Wervik, children go from door to door, singing traditional «Séngmarténg» songs, sporting a hollow beetroot with a carved face and a candle inside called «Bolle Séngmarténg»; they gather at an evening bonfire. At the end the beetroots are thrown into the fire, and pancakes are served.[citation needed]

English[edit]

Martinmas was widely celebrated on 11 November in medieval and early modern England. In his study «Medieval English Martinmesse: The Archaeology of a Forgotten Festival», Martin Walsh describes Martinmas as a festival marking the end of the harvest season and beginning of winter.[6] He suggests it had pre-Christian roots.[6] Martinmas ushered in the «winter revelling season» and involved feasting on the meat of livestock that had been slaughtered for winter provision (especially ‘Martlemas beef’), drinking, storytelling, and mumming.[6] It was a time for saying farewell to travelling ploughmen, who shared in the feast along with the harvest-workers.[6]

According to Walsh, Martinmas eventually died out in England as a result of the English Reformation, the emergence of Guy Fawkes Night (5 November), as well as changes in farming and the Industrial Revolution.[6] Today, 11 November is Remembrance Day.

German[edit]

A widespread custom in Germany is to light bonfires, called Martinsfeuer, on St Martin’s Eve. In recent years, the processions that accompany those fires have been spread over almost a fortnight before Martinmas (Martinstag). At one time, the Rhine River valley would be lined with fires on the eve of Martinmas. In the Rhineland, Martin’s day is celebrated traditionally with a get-together during which a roasted suckling pig is shared with the neighbours.

The nights before and on the eve itself, children walk in processions called Laternelaufen, carrying lanterns, which they made in school, and sing St Martin’s songs. Usually, the walk starts at a church and goes to a public square. A man on horseback representing St Martin accompanies the children. When they reach the square, Martin’s bonfire is lit and Martin’s pretzels are distributed.[15]

In the Rhineland, the children also go from house to house with their lanterns, sing songs and get candy in return. The origin of the procession of lanterns is unclear. To some, it is a substitute for the Martinmas bonfire, which is still lit in a few cities and villages throughout Europe. It formerly symbolized the light that holiness brings to the darkness, just as St Martin brought hope to the poor through his good deeds. Even though the bonfire tradition is gradually being lost, the procession of lanterns is still practiced.[16]

A Martinsgans («St Martin’s goose»), is typically served on St Martin’s Eve following the procession of lanterns. «Martinsgans» is usually served in restaurants, roasted, with red cabbage and dumplings.[16]

The traditional sweet of Martinmas in the Rhineland is Martinshörnchen, a pastry shaped in the form of a croissant, which recalls both the hooves of St Martin’s horse and, by being the half of a pretzel, the parting of his mantle. In some areas, these pastries are instead shaped like men (Stutenkerl or Weckmänner).

St Martin’s Day is also celebrated in German Lorraine and Alsace, which border the Rhineland and are now part of France. Children receive gifts and sweets. In Alsace, in particular the Haut-Rhin mountainous region, families with young children make lanterns out of painted paper that they carry in a colourful procession up the mountain at night. Some schools organise these events, in particular schools of the Rudolf Steiner (Waldorf education) pedagogy. In these regions, the day marks the beginning of the holiday season.[citation needed] In the German speaking parts of Belgium, notably Eupen and Sankt Vith, processions similar to those in Germany take place.[citation needed]

German American[edit]

In the United States, St. Martin’s Day celebrations are uncommon, but are typically held by German American communities.[17] Many German restaurants feature a traditional menu with goose and Glühwein (a mulled red wine). St Paul, Minnesota celebrates with a traditional lantern procession around Rice Park. The evening includes German treats and traditions that highlight the season of giving.[18] In Dayton, Ohio the Dayton Liederkranz-Turner organization hosts a St Martin’s Family Celebration on the weekend before with an evening lantern parade to the singing of St Martin’s carols, followed by a bonfire.[19]

Swedish[edit]

St Martin’s Day or St Martin’s Eve (Mårtensafton) was an important medieval autumn feast in Sweden. In early November, geese are ready for slaughter, and on St Martin’s Eve it is tradition to have a roast goose dinner. The custom is particularly popular in Scania in southern Sweden, where goose farming has long been practised, but it has gradually spread northwards. A proper goose dinner also includes svartsoppa (a heavily spiced soup made from geese blood) and apple charlotte.[20]

Slavic[edit]

Croatian[edit]

In Croatia, St. Martin’s Day (Martinje, Martinovanje) marks the day when the must traditionally turns to wine. The must is usually considered impure and sinful, until it is baptised and turned into wine. The baptism is performed by someone who dresses up as a bishop and blesses the wine; this is usually done by the host. Another person is chosen as the godfather of the wine.

Czech[edit]

A Czech proverb connected with the Feast of St. Martin – Martin přijíždí na bílém koni (transl. «Martin is coming on a white horse») – signifies that the first half of November in the Czech Republic is the time when it often starts to snow. St. Martin’s Day is the traditional feast day in the run-up to Advent. Restaurants often serve roast goose as well as young wine from the recent harvest known as Svatomartinské víno, which is similar to Beaujolais nouveau as the first wine of the season. Wine shops and restaurants around Prague pour the first of the St. Martin’s wines at 11:11 a.m. Many restaurants offer special menus for the day, featuring the traditional roast goose.[21]

Polish[edit]

Procession of Saint Martin in Poznań, 2006

In Poland, 11 November is National Independence Day. St. Martin’s Day (Dzień Świętego Marcina) is celebrated mainly in the city of Poznań where its citizens buy and eat considerable amounts of croissants filled with almond paste with white poppy seeds, the Rogal świętomarciński or St. Martin’s Croissants. Legend has it that this centuries-old tradition commemorates a Poznań baker’s dream which had the saint entering the city on a white horse that lost its golden horseshoe. The next morning, the baker whipped up horseshoe-shaped croissants filled with almonds, white poppy seeds and nuts, and gave them to the poor. In recent years, competition amongst local patisseries has become fierce. The product is registered under the European Union Protected Designation of Origin and only a limited number of bakers hold an official certificate. Poznanians celebrate the festival with concerts, parades and a fireworks show on Saint Martin’s Street. Goose meat dishes are also eaten during the holiday.[22]

Slovene[edit]

The biggest event in Slovenia is the St. Martin’s Day celebration in Maribor which marks the symbolic winding up of all the wine growers’ endeavours. There is the ceremonial «christening» of the new wine, and the arrival of the Wine Queen. The square Trg Leona Štuklja is filled with musicians and stalls offering autumn produce and delicacies.[23]

Celtic[edit]

Irish[edit]

In some parts[24] of Ireland, on the eve of St. Martin’s Day (Lá Fhéile Mártain in Irish), it was tradition to sacrifice a cockerel by bleeding it. The blood was collected and sprinkled on the four corners of the house.[25][24] Also in Ireland, no wheel of any kind was to turn on St. Martin’s Day, because Martin was said by some people[24] to have been thrown into a mill stream and killed by the wheel and so it was not right to turn any kind of wheel on that day. A local legend in Co. Wexford says that putting to sea is to be avoided as St. Martin rides a white horse across Wexford Bay bringing death by drowning to any who see him.[26]

Welsh[edit]

In Welsh mythology the day is associated with the Cŵn Annwn, the spectral hounds who escort souls to the otherworld (Annwn). St Martin’s Day was one of the few nights the hounds would engage in a Wild Hunt, stalking the land for criminals and villains.[27] The supernatural character of the day in Welsh culture is evident in the number omens associated with it. Marie Trevelyan recorded that if the hooting of an owl was heard on St Martin’s Day it was seen as a bad omen for that district. If a meteor was seen, then there would be trouble for the whole nation.[28]

Latvian[edit]

Mārtiņi (Martin’s) is traditionally celebrated by Latvians on 10 November, marking the end of the preparations for winter, such as salting meat and fish, storing the harvest and making preserves. Mārtiņi also marks the beginning of masquerading and sledding, among other winter activities.

Maltese[edit]

A Maltese «Borża ta’ San Martin»

St. Martin’s Day (Jum San Martin in Maltese) is celebrated in Malta on the Sunday nearest to 11 November. Children are given a bag full of fruits and sweets associated with the feast, known by the Maltese as Il-Borża ta’ San Martin, «St. Martin’s bag». This bag may include walnuts, hazelnuts, almonds, chestnuts, dried or processed figs, seasonal fruit (like oranges, tangerines, apples and pomegranates) and «Saint Martin’s bread roll» (Maltese: Ħobża ta’ San Martin). In old days, nuts were used by the children in their games.

There is a traditional rhyme associated with this custom:

Ġewż, Lewż, Qastan, Tin

Kemm inħobbu lil San Martin.

(Walnuts, Almonds, Chestnuts, Figs

I love Saint Martin so much.)

A feast is celebrated in the village of Baħrija on the outskirts of Rabat, including a procession led by the statue of Saint Martin. There is also a fair, and a show for local animals. San Anton School, a private school on the island, organises a walk to and from a cave especially associated with Martin in remembrance of the day.

Portuguese and Galician[edit]

In Portugal, St. Martin’s Day (Dia de São Martinho) is commonly associated with the celebration of the maturation of the year’s wine, being traditionally the first day when the new wine can be tasted. It is celebrated, traditionally around a bonfire, eating the magusto, chestnuts roasted under the embers of the bonfire (sometimes dry figs and walnuts), and drinking a local light alcoholic beverage called água-pé (literally «foot water», made by adding water to the pomace left after the juice is pressed out of the grapes for wine – traditionally by stomping on them in vats with bare feet, and letting it ferment for several days), or the stronger jeropiga (a sweet liquor obtained in a very similar fashion, with aguardente added to the water). Água-pé, though no longer available for sale in supermarkets and similar outlets (it is officially banned for sale in Portugal), is still generally available in small local shops from domestic production.[citation needed]

Leite de Vasconcelos regarded the magusto as the vestige of an ancient sacrifice to honor the dead and stated that it was tradition in Barqueiros to prepare, at midnight, a table with chestnuts for the deceased family members to eat.[29] The people also mask their faces with the dark wood ashes from the bonfire.[citation needed]

A typical Portuguese saying related to Saint Martin’s Day:

É dia de São Martinho;

comem-se castanhas, prova-se o vinho.

(It is St. Martin’s Day,

we’ll eat chestnuts, we’ll taste the wine.)

This period is also quite popular because of the usual good weather period that occurs in Portugal in this time of year, called Verão de São Martinho (St. Martin’s Summer). It is frequently tied to the legend since Portuguese versions of St. Martin’s legend usually replace the snowstorm with rain (because snow is not frequent in most parts of Portugal, while rain is common at that time of the year) and have Jesus bringing the end of it, thus making the «summer» a gift from God.[citation needed]

St Martin’s Day is widely celebrated in Galicia. It is the traditional day for slaughtering fattened pigs for the winter. This tradition has given way to the popular saying «A cada cerdo le llega su San Martín from Galician A cada porquiño chégalle o seu San Martiño («Every pig gets its St Martin»). The phrase is used to indicate that wrongdoers eventually get their comeuppance.

Sicilian[edit]

In Sicily, November is the winemaking season. On the day Sicilians eat anise, hard biscuits dipped into Moscato, Malvasia or Passito. l’Estate di San Martino (Saint Martin’s Summer) is the traditional reference to a period of unseasonably warm weather in early to mid November, possibly shared with the Normans (who founded the Kingdom of Sicily) as common in at least late English folklore. The day is celebrated in a special way in a village near Messina and at a monastery dedicated to Saint Martin overlooking Palermo beyond Monreale.[30] Other places in Sicily mark the day by eating fava beans.[citation needed]

In art[edit]

Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s physically largest painting is The Wine of Saint Martin’s Day, which depicts the saint giving charity.

There is a closely similar painting by Peeter Baltens, which can be seen here.

See also[edit]

- St. Catherine’s Day

References[edit]

- ^ Bulik, Mark (1 January 2015). The Sons of Molly Maguire: The Irish Roots of America’s First Labor War. Fordham University Press. p. 43. ISBN 9780823262243.

- ^ Carlyle, Thomas (11 November 2010). The Works of Thomas Carlyle. Cambridge University Press. p. 356. ISBN 9781108022354.

- ^ George C. Homans, English Villagers of the Thirteenth Century, 2nd ed. 1991, «The Husbandman’s year» p355f.

- ^ Sulpicius Severus (397). De Vita Beati Martini Liber Unus [On the Life of St. Martin]. Retrieved 2 November 2021.

- ^ Dent, Susie (2020). Word Perfect: Etymological Entertainment For Every Day of the Year. John Murray. ISBN 978-1-5293-1150-1.

- ^ a b c d e f Walsh, Martin (2000). «Medieval English Martinmesse: The Archaeology of a Forgotten Festival». Folklore. 111 (2): 231–249. doi:10.1080/00155870020004620. S2CID 162382811.

- ^ a b c d e f g Miles, Clement A. (1912). Christmas in Ritual and Tradition. Chapter 7: All Hallow Tide to Martinmas. Reproduced by Internet Sacred Text Archive.

- ^ «St Martin’s Day – or ‘Martin Goose'» Lilja, Agneta. Sweden.se magazine-format website

- ^ a b For instance, in Hugh Johnson, Vintage: The Story of Wine 1989, p 97.

- ^ per Matthew 2:1–2:12

- ^ Philip H. Pfatteicher, Journey into the Heart of God (Oxford University Press 2013 ISBN 978-0-19999714-5)

- ^ «Saint Martin’s Lent». Encyclopædia Britannica. Britannica. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ^ «Autumn Feast of St. Martin», Austrian Tourism Board

- ^ Thomson, George William. Peeps At Many Lands: Belgium, Library of Alexandria, 1909

- ^ «St. Martin’s Day traditions honor missionary», Kaiserlautern American, 7 November 2008

- ^ a b «Celebrating St. Martin’s Day on November 11», German Missions in the United States Archived 2012-01-06 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ German traditions in the US for St. Martin’s Day

- ^ «St. Martin’s Day», St. Paul Star Tribune, November 5, 2015

- ^ «St. Martin’s Day Family Celebration». Dayton Liederkranz-Turner. Retrieved 2021-11-02.

- ^ «Mårten Gås», Sweden.SE

- ^ «St. Martin’s Day specials at Prague restaurants», Prague Post, 11 November 2011

- ^ «St. Martin’s Day Celebrations»

- ^ «St. Martin’s Day Celebrations in Maribor», Slovenian Tourist Board

- ^ a b c Marion McGarry (11 November 2020). «Why blood sacrifice rites were common in Ireland on 11 November». RTE. Retrieved 13 November 2020.

Opinion: Blood sacrifices involving pigs, sheep or geese were practiced in Ireland well into living memory on Martinmas. … the custom extended from North Connacht, down to Kerry, and across the midlands and was rarer in Ulster or on the east coast. … some say the saint met his death by being crushed between two wheels

- ^ Súilleabháin, Seán Ó (2012). Miraculous Plenty; Irish Religious Folktales and Legends. Four Courts Press. pp. 183-191 and 269. ISBN 978-0-9565628-2-1.

- ^ «A Wexford Legend — St Martin’s Eve».

- ^ Matthews, John; Matthews, Caitlín (2005). The Element Encyclopedia of Magical Creatures. HarperElement. p. 119. ISBN 978-1-4351-1086-1.

- ^ Trevelyan, Marie (1909). Folk Lore And Folk Stories Of Wales. p. 13. ISBN 9781497817180.

- ^ Leite de Vasconcelos, Opúsculos Etnologia — volumes VII, Lisboa, Imprensa Nacional, 1938

- ^ Gangi, Roberta. «The Joys of St Martin’s Summer», Best of Sicily Magazine, 2010

External links[edit]

Media related to St. Martin’s Day at Wikimedia Commons

- How to make a St. Martin’s Day lantern

- UK History of Martinmas

- St. Martin’s Day in Germany

- St. Martin of Tours

- Alice’s Medieval Feasts & Fasts

МАРТИНОВАНЬЕ В СЛОВЕНИИ

Ну вот и закончилась пора сбора урожая! Поля чисты и отдыхают, готовясь к следующему посеву, виноград собран, молодое вино пока еще в виде сусла разлито по бочкам, а крестьянские погреба наполнены разной всячиной…

Винное сусло, из которого потом получается вино, в Словении называется Мошт (Mošt). Этот слабоалкогольный напиток (4-6%) продается в Словении на каждом углу и пользуется большой популярностью как у местного населения, так и у туристов. Главное — попробовать его до 11 ноября, а то он же в вино превратится! 🙂

ОТ ЯЗЫЧНИКОВ И ДО НАШИХ ДНЕЙ

Даже трудно себе представить, когда люди начали отмечать праздник окончания сбора урожая. Известно, что он был широко распространен еще у древних кельтов, как праздник Сайман: языческие племена, занимавшие обширную территорию в Западной и Центральной Европе на рубеже эр (в том числе и территорию нынешней Словении), в этот день благодарили богов за хороший урожай и просили их повторить обилие в следующем году.

Потом в эти земли стало проникать христианство, но праздник был настолько популярен среди простых людей, что церковь не стала его отменять, а только придала более торжественный характер, заменив языческих идолов христианским святым. Этим святым стал Мартин Турский – покровитель бедных, нищих, беженцев, пастухов, мельников и виноградарей, и один из самых почитаемых святых Западной Европы.

Кстати, такая подмена произходила со многими церковными праздниками.

СВЯТОЙ МАРТИН

Родившийся в начале IV века в Паннонии (сегодня часть Венгрии), в семье римского трибуна, Мартин с детства мечтал стать монахом, но волею отца был направлен служить в Римскую армию. Отважный, крепкий и благородный юноша быстро снискал уважение сослуживцев и вскоре возглавил конный отряд римских легионеров.

Как-то раз зимой, проезжая со своим отрядом через ворота города, Мартин встретил полуобнаженного нищего. На глазах смеющихся солдат Мартин сорвал с себя плащ, и разорвав его на двое, отдал одну половину нищему. Ночью во время сна Мартину явился Иисус, обернутый половиной его плаща: «Взгляни Мартин, не та ли эта половина, которую ты отдал нищему у ворот?».

И пока Мартин стоял в благоговейном безмолвии, Христос обратился от него к стоящим перед ним ангелам и громко сказал:

— Сим плащом одел меня Мартин, хотя он еще только оглашенный.

Эта легенда, олицетворяющая дух, благородство и милосердие Мартина Турского, сегодня отображена на многих иконах, картинах и статуях. А Мартин же, после этого случая ушел в проповедники и вскоре основал свое аббатство (аббатство Мармутье), которое существует и поныне.

В дополнении ко всему, в 371 году Мартин стал епископом французского города Тур.

Вообще, епископам того времени приписывали многие чудеса, однако самым большим чудом надо считать сохранение сельского хозяйства, важной частью которого было виноделие. Святой Мартин стал не только епископом, но и тем человеком, который зародил виноделие в Туре.

В своем аббатстве он сам стал возделывать виноград и производить прекрасные вина. Скорее всего, именно поэтому Святой Мартин и стал покровителем всех виноделов.

Введение обрезания виноградных лоз приписывают именно Святому Мартину.

Умер Мартин Турский 8 ноября 397 года и был захоронен в Туре 11 ноября. На похороны Святого собралось более 2 тысяч монахов, что явно говорит о размахе его деятельности в деле распространения христианского просвещения.

МАРТИНОВАНЬЕ — ПРАЗДНИК МОЛОДОГО ВИНА

Любой словенец, даже самый маленький, удивленно вскинет брови, если его спросят: «А что это за праздник — Мартинованье?» Да и не мудрено. Пройдя сквозь тысячелетия, и обретя своего покровителя, праздник окончания сбора урожая и праздник молодого вина в этой стране знает каждый. 11 ноября — по преданию, именно в этот день, третий после смерти Святого Мартина, винное «грешное» сусло превращается в настоящее вино.

А так как праздник напрямую связан с окончанием сельскохозяйственных работ, он предполагает обильное угощение. В этот день в Словении к столу обычно подают жареного гуся, тушеную кислую красную капусту и млинцы — печеные, тонко нарезанные лепешки, залитые гусином жиром. Ну а запивается вся эта вкуснота, естественно, молодым вином.

Говорят, что когда жители Тура пришли провозгласить Мартина своим епископом, тот, не желая этого, спрятался от них в гусятник, но гуси своими криками выдали местонахождение святого, и Мартину пришлось подчиниться воле народа. Может быть гусей подают к столу именно поэтому. ))

МАРТИНОВАНЬЕ В СЛОВЕНИИ

Не зря Словения считается винной державой. Во время празднования Мартинованья вино здесь просто льется рекой. Во всех винных регионах, крупных городах страны, да и в маленьких деревушках проходят фестивали вина, дегустации, гулянья…

Господи! Это бесполезно описывать, это обязательно надо посетить! Тем более, что Мартинованье продолжается не один день!

Добро пожаловать в Словению на праздник молодого вина!

p.s. Кстати, моя дочка тоже родилась 11 ноября… может это знак?! )))

Сегодня многие страны Европы празднуют день святого Мартина — покровителя виноделов.

Словения — не исключение.

На этих выходных по всей стране проходят разнообразные винные фестивали. Считается, что именно в этот день, который также называют Мартинованьем, сусло (о котором я упоминал в сентябре) превращается в вино.

К слову, к этому моменту срок годности самого мошта уже истекает.

Конечно, традиции везде разные, и в будущем хотелось бы попасть на этот праздник куда-нибудь поближе к знаменитым винным регионам Словении (Ормож, долина Випава, Горишка Брда). Но всему свое время, а пока ограничились вчерашними винными мероприятиями Любляны.

В столице организовывают так называемый «винный путь» — некоторые центральные площади и улицы превращаются в подобие рынка, работающего с 10:00 до 17:00.

Помимо вина, здесь также изредка продают другую продукцию — колбасные изделия, масла и прочее. Но, конечно, это мало кому интересно в такой день.

Правила такие: берем в аренду бокал за 10 евро + покупаем не менее 5 купонов на вино (каждый стоит 1 евро). Обязательно сохраняем чек. С купленными купонами подходим к виноделам и… угадайте что.

Кстати, большинство предлагает сперва «немного» попробовать (но наливают вполне себе от души).

100 мл = 1–2 купона, «цены» устанавливают сами виноделы. Конечно, покупать можно и бутылки. Я тоже две прикупил. До 17:00 бокал (если удалось сохранить его целым) можно вернуть, получив 10 евро назад.

Наша компания предполагала, что большинство вин будет стоить 2–4 купона, потому взяли сразу по 10 (на 10 евро каждый). Но уже после первых 3–4 бокалов стало ясно, что с однокупонных нужно срочно переходить хотя бы на двухкупонные, а дороже даже не встречали.

К слову, начали мы впетяром (чисто мужской компанией, в то время как непьющие женщины с детьми отправились в соседнее кафе), но за вечер вполне ожидаемо встретили несколько десятков знакомых.

Отдельно хочется сказать о поведении людей.

Праздник проходит на улице, местами это очень громко, где-то поют и играют на музыкальных инструментах, но самое главное — за весь день мы не встретили никакого неадекватного поведения.

Вообще словенцы пьют очень много, но за год я видел шатающихся от алкогольного опьянения людей всего несколько раз. А конфликтов не встречали вообще.

И дух вчерашнего алкогольного мероприятия лишь усилил нашу веру в адекватность словенцев — исключительно сплошной позитив, абсолютное отсутствие понятия «пьяное быдло», все очень цивилизованно и культурно.

В общем, кто не живет в Словении — заезжайте к нам на Мартинованье.

Поднимите бокалы в честь молодого вина! Праздник щедрой осени

Самый популярный праздник в Словении, связанный с виноделием и культурой потребления вина, — День Святого Мартина. Торжества начинаются 11 ноября и продолжаются всю неделю, а то и две. Таких осенних гуляний вы не встретите нигде в Европе, так что побывать на этом празднике, безусловно, стоит. Отметьте этот особый праздник там, где зреют виноград, вино – на виноградниках в гостях у виноделов. Праздник Святого Мартина отмечается не только в винодельческих регионах Словении, но и по всей стране — от Средиземного моря до Паннонских равнин. Погрузитесь в атмосферу ликования в честь рождения нового вина!

Когда сусло превращается в вино

Принято считать, что праздник Святого Мартина зародился в стародавние времена: у кельтов было принято в осеннее время чествовать поля и виноградники. А донес эту традицию до новейших времен Святой Мартин, епископ французского города Тур, венгр по происхождению. Торжества, проходящие в Словении по случаю превращения сусла в молодое вино, по их размаху трудно сравнить с каким бы то ни было другим праздником, ведь почти каждый седьмой житель Словении занимается виноградарством, и даже в словенских сериалах в качестве героев, как правило, выступают представители винодельческих династий.

Праздник Святого Мартина пахнет вином и лакомствами

Праздник Святого Мартина – это не только новый урожай вина. В этот период принято готовить характерные блюда местной кухни, самым распространенным из которых является запеченный гусь или утка с «млинцами» и тушеной краснокочанной капустой. В словенских ресторанах вас ждут специальные праздничные меню, в которых вы обязательно найдете выпечку: это «погача», «потица» и другие сладости.

Торжества в честь Святого Мартина под открытым небом

Ну, а поскольку праздник посвящен рождению нового вина, то в этот день его принято «крестить», и для этого по всей Словении организуются пышные празднества под открытым небом. Одним из самых ярких осенних событий в городе Марибор, где растет виноградная лоза, которой уже исполнилось 450 лет, является ежегодный Фестиваль Старой Лозы. Завершается он торжественным ужином в День Святого Мартина, украшением которого являются богатый ассортимент вкусных блюд и музыкальная программа.

Из Мариборa, второго по величине города Словении, расположенного на востоке страны, в котором растет старейшая виноградная лоза в мире, отправьтесь в город Птуй, гордящийся самым древним винным погребом в Словении – он был устроен монахами. На юге страны, среди щедрых виноградных холмов Посавья и Доленьского региона, также кипит веселье, в центре столицы Любляны тоже можно пройти «винным маршрутом» и продегустировать вино. В Средиземноморской Словении с наибольшим размахом празднуют в Новой Горице (куда стекаются и сельские жители из винодельческого региона Випавской Долины), на Красе и в местности Брда, где тоже можно посетить старинные винные погреба в живописной средневековой деревушке Шмартно, подышать их неповторимой атмосферой. Весело будет и в городе Копер.

Винные сюжеты Словении

Виноградарство и виноделие Словении представлено тремя винодельческими регионами, в рамках которых насчитывается 14 винодельческих территории. Первые письменные свидетельства о том, что в Словении выращивали виноград, относятся к третьему веку до нашей эры. С тех самых пор здесь делали и вино – в Словении его много, и оно отменное. Многие словенские виноделы завоевывают самые престижные награды и призы на глобальных винных ярмарках и фестивалях. В Словении имеется и ряд особых сортов винограда, из которых получают особенное вино. Уникальными являются «Крашки Теран» и «Доленьский Цвичек», а есть еще «Зелен», «Пинела», «Грганья», «Кларница» и другие редкие сорта. Вам они еще не известны? Праздник Святого Мартина – прекрасный случай для того, чтобы их попробовать.

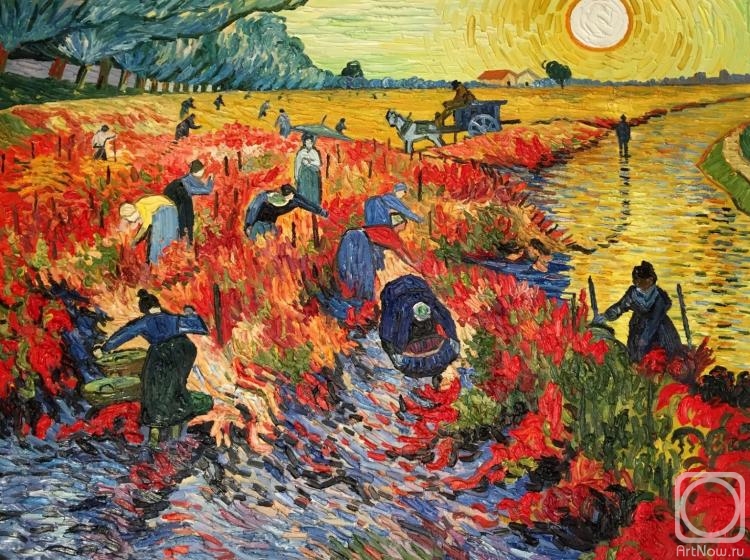

Винсент Ван Гог. Красные виноградники в Арле

День святого Мартина, посвященный завершению сбора винограда, впервые после двухлетнего перерыва отметили жители Словении, 12 ноября сообщает ТАСС.

Одно из главных мероприятий праздника прошло в словенском муниципалитете Горишка Брда, где расположена самая крупная винодельческая компания страны Klet Brda. В празднованиях приняли участие более 1,2 тыс. человек.

«Я очень рад, что после двух лет перерыва мы снова собрались все вместе. В праздновании Дня святого Мартина также участвуют представители различных компаний из Словении, а также других стран Европы», — отметил глава муниципалитета Франц Мужич.

Праздник знаменует завершение работы сборщиков винограда. Считается, что в этот праздник виноградное сусло становится вином. День святого Мартина, названный в честь епископа Мартина Турского, является одним из главных народных праздников Словении, рассказал директор Klet Brda Сильван Першолья.

День святого Мартина

11 Ноября,

Суббота

День святого Мартина (англ. St. Martin’s Day) — международный праздник в честь дня памяти об епископе Мартине Турском. Отмечается ежегодно 11 ноября во многих странах, преимущественно католических. Праздничные мероприятия включают в себя торжественные шествия по улицам, детские фонарики из тыквы или современных материалов со свечой внутри, подача к ужину печёного гуся и кондитерскую выпечку.

В кельтской общине существовал праздник Самайн, который во время христианизации Европы трансформировался в — День почитания святого Мартина. Язычники отмечали время окончания сбора урожая и начала зимы — жжением костров, ритуальными песнями и празднованиями, принесением в жертву животных с последующим пиром.

День святого Мартина

День святого Мартина в другие годы

-

2021

11 Ноября,

Четверг

-

2022

11 Ноября,

Пятница

-

2024

11 Ноября,

Понедельник

День святого Мартина в других странах

- Австрия

- Италия

- Австрия

- Албания

- Андорра

- Антигуа и Барбуда

- Аргентина

- Бельгия

- Болгария

- Боливия

- Бонэйре

- Ботсвана

- Бразилия

- Ватикан

- Великобритания

- Венесуэла

- Виргинские Острова США

- Гайана

- Гвинея

- Гренада

- Дания

- Доминика

- Доминиканская Республика

- Ирландия

- Исландия

- Испания

- Италия

- Коста Рика

- Куба

- Латвия

- Литва

- Мексика

- Норвегия

- Польша

- Румыния

- США

- Словакия

- Уругвай

- Франция

- Французская Полинезия

- Черногория

- Чехия

- Чили

- Швейцария

- Швеция

- Эквадор

- Эритрея

- Эфиопия

Показать больше