Sinterklaas (Dutch: [ˌsɪntərˈklaːs]) or Sint-Nicolaas (Dutch: [sɪnt ˈnikoːlaːs] (listen)) is a legendary figure based on Saint Nicholas, patron saint of children. Other Dutch names for the figure include De Sint («The Saint»), De Goede Sint («The Good Saint») and De Goedheiligman («The Good Holy Man»). Many descendants and cognates of «Sinterklaas» or «Saint Nicholas» in other languages are also used in the Low Countries, nearby regions, and former Dutch colonies.[note 1]

The feast of Sinterklaas celebrates the name day of Saint Nicholas on 6 December. The feast is celebrated annually with the giving of gifts on St. Nicholas’ Eve (5 December) in the Netherlands and on the morning of 6 December, Saint Nicholas Day, Belgium, Luxembourg, western Germany, northern France (French Flanders, Lorraine, Alsace and Artois), and Hungary. The tradition is also celebrated in some territories of the former Dutch Empire, including Aruba.

Sinterklaas is one of the sources of the popular Christmas icon of Santa Claus.[1][2]

Figures[edit]

Sinterklaas[edit]

Sinterklaas is based on the historical figure of Saint Nicholas (270–343), a Greek bishop of Myra in present-day Turkey. He is depicted as an elderly, stately and serious man with white hair and a long, full beard. He wears a long red cape or chasuble over a traditional white bishop’s alb and a sometimes-red stole, dons a red mitre and ruby ring, and holds a gold-coloured crosier, a long ceremonial shepherd’s staff with a fancy curled top.[3]

He traditionally rides a white horse. In the Netherlands, the last horse was called Amerigo, but he was «pensioned» (i.e., died) in 2019 and replaced with a new horse called Ozosnel («oh so fast»), after a passage in a well-known Sinterklaas song.[4] In Belgium, the horse is named Slecht weer vandaag, meaning «bad weather today»[5] or Mooi weer vandaag («nice weather today»).[6]

Sinterklaas carries a big, red book which records whether each child has been good or naughty in the past year.[7]

Zwarte Piet[edit]

Sinterklaas is assisted by Zwarte Piet («Black Pete»), a helper dressed in Moorish attire and in blackface. Zwarte Piet first appeared in print as the nameless servant of Saint Nicholas in Sint-Nikolaas en zijn knecht («St. Nicholas and His Servant»), published in 1850 by Amsterdam schoolteacher Jan Schenkman; however, the tradition appears to date back at least as far as the early 19th century.[8] Zwarte Piet’s colourful dress is based on 16th-century noble attire, with a ruff (lace collar) and a feathered cap. He is typically depicted carrying a bag which contains candy for the children, which he tosses around, a tradition supposedly originating in the story of Saint Nicholas saving three young girls from prostitution by tossing golden coins through their window at night to pay their dowries.

Traditionally, he would also carry a birch rod (Dutch: roe), a chimney sweep’s broom made of willow branches, used to spank children who had been naughty. Some of the older Sinterklaas songs make mention of naughty children being put in Zwarte Piet’s bag and being taken back to Spain. This part of the legend refers to the times that the Moors raided the European coasts, and as far as Iceland, to abduct the local people into slavery. This quality can be found in other companions of Saint Nicholas such as Krampus and Père Fouettard.[9] In modern versions of the Sinterklaas feast, however, Zwarte Piet no longer carries the roe and children are no longer told that they will be taken back to Spain in Zwarte Piet’s bag if they have been naughty.

Over the years many stories have been added, and Zwarte Piet has developed into a valuable assistant to the absent-minded saint. In modern adaptations for television, Sinterklaas has developed a Zwarte Piet for every function, such as a Head Piet (Hoofdpiet), a Navigation Piet (Wegwijspiet) to navigate the steamboat from Spain to the Netherlands, a Presents Piet (Pakjespiet) to wrap all the gifts, and Acrobatic Piet to climb roofs and chimneys.[10] Traditionally Zwarte Piet’s face is said to be black because he is a Moor from Spain.[11] Today, some children are told that his face is blackened with soot because he has to climb through chimneys to deliver gifts for Sinterklaas.

Since the 2010s, the traditions surrounding the holiday of Sinterklaas have been the subject of a growing number of editorials, debates, documentaries, protests and even violent clashes at festivals.[12] Some large cities and television channels now only display Zwarte Piet characters with some soot smudges on the face rather than full blackface, so-called roetveegpieten («soot-smudge Petes») or schoorsteenpieten («chimney Petes»).[13][14]

In a 2013 survey, 92 per cent of the Dutch public did not perceive Zwarte Piet as racist or associate him with slavery, and 91 per cent were opposed to altering the character’s appearance.[15] In a similar survey in 2018, between 80 and 88 per cent of the Dutch public did not perceive Zwarte Piet as racist, and between 41 and 54 per cent were happy with the character’s modernised appearance (a mix of roetveegpieten and blackface).[16][17]

A June 2020 survey saw a drop in support for leaving the character’s appearance unaltered: 47 per cent of those surveyed supported the traditional appearance, compared to 71 per cent in a similar survey held in November 2019.[18] Prime Minister Mark Rutte stated in a parliamentary debate on 5 June 2020 that he had changed his opinion on the issue and now has more understanding for people who consider the character’s appearance to be racist.[19]

Celebration[edit]

Arrival from Spain[edit]

Sinterklaas and his Zwarte Piet helpers arriving by steamboat from Spain

The festivities traditionally begin each year in mid-November (the first Saturday after 11 November), when Sinterklaas «arrives» by a steamboat at a designated seaside town, supposedly from Spain. In the Netherlands this takes place in a different port each year, whereas in Belgium it always takes place in the city of Antwerp. The steamboat anchors, then Sinterklaas disembarks and parades through the streets on his horse, welcomed by children cheering and singing traditional Sinterklaas songs.[20] His Zwarte Piet assistants throw candy and small, round, gingerbread-like cookies, either kruidnoten or pepernoten, into the crowd. The event is broadcast live on national television in the Netherlands and Belgium.

Following this national arrival, other towns celebrate their own intocht van Sinterklaas (arrival of Sinterklaas). Local arrivals usually take place later on the same Saturday of the national arrival, the next day (Sunday), or one weekend after the national arrival. In places a boat cannot reach, Sinterklaas arrives by train, horse, horse-drawn carriage or even a fire truck.

Sinterklaas is said to come from Spain, possibly because in 1087, half of Saint Nicholas’ relics were transported to the Italian city of Bari, which later formed part of the Spanish Kingdom of Naples. Others suggest that mandarin oranges, traditionally gifts associated with St. Nicholas, led to the misconception that he must have been from Spain. This theory is backed by a Dutch poem documented in 1810 in New York and provided with an English translation:[21][22]

Sinterklaas, goedheiligman! |

Saint Nicholas, good holy man! |

The text presented here comes from a pamphlet that John Pintard released in New York in 1810. It is the earliest source mentioning Spain in connection to Sinterklaas. Pintard wanted St. Nicholas to become patron saint of New York and hoped to establish a Sinterklaas tradition. Apparently he got help from the Dutch community in New York, that provided him with the original Dutch Sinterklaas poem. Strictly speaking, the poem does not state that Sinterklaas comes from Spain, but that he needs to go to Spain to pick up the oranges and pomegranates. So the link between Sinterklaas and Spain goes through the oranges, a much appreciated treat in the 19th century. Later the connection with the oranges got lost, and Spain became his home.

Period leading up to Saint Nicholas’ Eve[edit]

In the weeks between his arrival and 5 December, Sinterklaas visits schools, hospitals, and shopping centers. He is said to ride his white-grey horse over the rooftops at night, delivering gifts through the chimney to the well-behaved children. Traditionally, naughty children risked being caught by Black Pete, who carried a jute bag and willow cane for that purpose.[23]

Before going to bed, children each leave a single shoe next to the fireplace chimney of the coal-fired stove or fireplace (or in modern times close to the central heating radiator, or a door). They leave the shoe with a carrot or some hay in it and a bowl of water nearby «for Sinterklaas’ horse», and the children sing a Sinterklaas song. The next day they find some candy or a small present in their shoes.

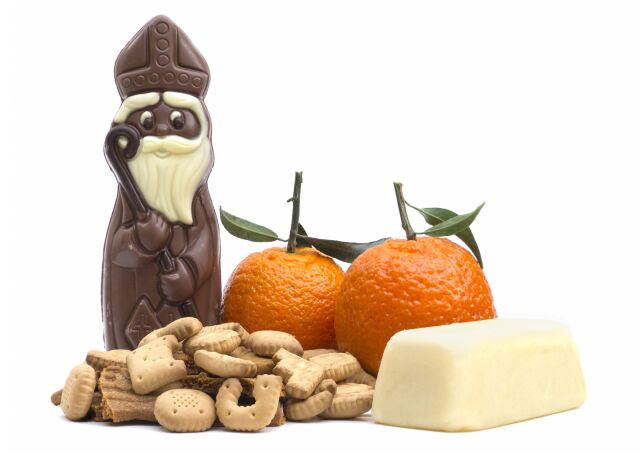

Typical Sinterklaas treats traditionally include mandarin oranges, pepernoten, speculaas (sometimes filled with almond paste), banketletter (pastry filled with almond paste) or a chocolate letter (the first letter of the child’s name made out of chocolate), chocolate coins, suikerbeest (animal-shaped figures made of sugary confection), and marzipan figures. Newer treats include gingerbread biscuits or and a figurine of Sinterklaas made of chocolate and wrapped in coloured aluminium foil.

Saint Nicholas’ Eve and Saint Nicholas’ Day[edit]

In the Netherlands, Saint Nicholas’ Eve, 5 December, became the chief occasion for gift-giving during the winter holiday season. The evening is called Sinterklaasavond («Sinterklaas evening») or Pakjesavond («gifts evening», or literally «packages evening»).

On the evening of 5 December, parents, family, friends or acquaintances pretend to act on behalf of «Sinterklaas», or his helpers, and fool the children into thinking that «Sinterklaas» has really given them presents. This may be done through a note that is «found», explaining where the presents are hidden, as though Zwarte Piet visited them and left a burlap sack of presents with them. Sometimes a neighbour will knock on the door (pretending to be a Zwarte Piet) and leave the sack outside for the children to retrieve; this varies per family. When the presents arrive, the living room is decked out with them, much as on Christmas Day in English-speaking countries. On 6 December «Sinterklaas» departs without any ado, and all festivities are over.

In the Southern Netherlands and Belgium, most children have to wait until the morning of 6 December to receive their gifts, and Sinterklaas is seen as a festivity almost exclusively for children. The shoes are filled with a poem or wish list for Sinterklaas and carrots, hay or sugar cubes for the horse on the evening of the fifth and in Belgium often a bottle of beer for Zwarte Piet and a cup of coffee for Sinterklaas are placed next to them. Also in some areas, when it is time for children to give up their pacifier, they place it into his or her shoe («safekeeping by Sinterklaas») and it is replaced with chocolate the next morning.

The present is often creatively disguised by being packaged in a humorous, unusual or personalised way. This is called a surprise (from the French).[24][25]

Poems from Sinterklaas usually accompany gifts, bearing a personal message for the receiver. It is usually a humorous poem which often teases the recipient for well-known bad habits or other character deficiencies.

In recent years, influenced by North-American media and the Anglo-Saxon Christmas tradition, when the children reach the age where they get told «the big secret of Sinterklaas», some people will shift to Christmas Eve or Christmas Day for the present giving. Older children in Dutch families where the children are too old to believe in Sinterklaas any more, also often celebrate Christmas with presents instead of pakjesavond. Instead of such gifts being brought by Sinterklaas, family members ordinarily draw names for an event comparable to Secret Santa. Because of the popularity of his «older cousin» Sinterklaas, Santa Claus is however not commonly seen in the Netherlands and Belgium.

History[edit]

Pre-Christian Europe[edit]

Municipal ban on Sint-Nicolaas pastry in the town of Utrecht during 1–8 December 1655 (to combat Catholic idolatry).

Jacob Grimm,[26] Hélène Adeline Guerber and others have drawn parallels between Sinterklaas and his helpers and the Wild Hunt of Wodan or Odin,[27] a major god among the Germanic peoples, who was worshipped in Northern and Western Europe prior to Christianization. Riding the white horse Sleipnir he flew through the air as the leader of the Wild Hunt, always accompanied by two black ravens, Huginn and Muninn.[28] Those helpers would listen, just like Zwarte Piet, at the chimney – which was just a hole in the roof at that time – to tell Wodan about the good and bad behaviour of the mortals.[29][unreliable source?][30] Historian Rita Ghesquiere asserts that it is likely that certain pre-christian elements survived in the honouring of Saint Nicholas.[31] Indeed, it seems clear that the tradition contains a number of elements that are not ecclesiastical in origin.[32]

Middle Ages[edit]

The Sinterklaasfeest arose during the Middle Ages. The feast was both an occasion to help the poor, by putting money in their shoes (which evolved into putting presents in children’s shoes) and a wild feast, similar to Carnival, that often led to costumes, a «topsy-turvy» overturning of daily roles, and mass public drunkenness.

In early traditions, students elected one of their classmates as «bishop» on St. Nicholas Day, who would rule until 28 December (Innocents Day), and they sometimes acted out events from the bishop’s life. As the festival moved to city streets, it became more lively.[33]

Illustration from the 1850 book St. Nikolaas en zijn knecht («Saint Nicholas and his servant»), by Jan Schenkman, 1850

16th and 17th centuries[edit]

During the Reformation in 16th- and 17th-century Europe, Protestant reformers like Martin Luther changed the Saint gift bringer to the Christ Child or Christkindl and moved the date for giving presents from 6 December to Christmas Eve. Certain Protestant municipalities and clerics forbade Saint Nicholas festivities, as the Protestants wanted to abolish the cult of saints and saint adoration, while keeping the midwinter gift-bringing feast alive.[34][35][36]

After the successful revolt of the largely Protestant northern provinces of the Low Countries against the rule of Roman Catholic king Philip II of Spain, the new Calvinist regents, ministers and clericals prohibited celebration of Saint Nicholas. The newly independent Dutch Republic officially became a Protestant country and abolished public Catholic celebrations. Nevertheless, the Saint Nicholas feast never completely disappeared in the Netherlands. In Amsterdam, where the public Saint Nicholas festivities were very popular, main events like street markets and fairs were kept alive with persons impersonating Nicholas dressed in red clothes instead of a bishop’s tabard and mitre. The Dutch government eventually tolerated private family celebrations of Saint Nicholas’ Day, as can be seen on Jan Steen’s painting The Feast of Saint Nicholas.

19th century[edit]

In the 19th century, the saint emerged from hiding and the feast became more secularised at the same time.[33] The modern tradition of Sinterklaas as a children’s feast was likely confirmed with the illustrated children’s book Sint-Nicolaas en zijn knecht (‘Saint Nicholas and his servant’), written in 1850 by the teacher Jan Schenkman (1806–1863). Some say he introduced the images of Sinterklaas’ delivering presents by the chimney, riding over the roofs of houses on a grey horse, and arriving from Spain by steamboat, which at that time was an exciting modern invention. Perhaps building on the fact that Saint Nicholas historically is the patron saint of the sailors (many churches dedicated to him have been built near harbours), Schenkman could have been inspired by the Spanish customs and ideas about the saint when he portrayed him arriving via the water in his book. Schenkman introduced the song Zie ginds komt de stoomboot («Look over yonder, the steamboat is arriving»), which is still popular in the Netherlands.

In Schenkman’s version, the medieval figures of the mock devil, which later changed to Oriental or Moorish helpers, was portrayed for the first time as black African and called Zwarte Piet (Black Pete).[33]

World War II[edit]

During the German occupation of the Netherlands (1940–1945) many of the traditional Sinterklaas rhymes were rewritten to reflect current events.[37] The Royal Air Force (RAF) was often celebrated. In 1941, for instance, the RAF dropped boxes of candy over the occupied Netherlands. One classical poem turned contemporary was the following:

Sinterklaas, kapoentje,

R.A.F. Kapoentje, |

Sinterklaas, little capon,

R.A.F. little Capon, |

This is a variation of one of the best-known traditional Sinterklaas rhymes, with «RAF» replacing «Sinterklaas» in the first line (the two expressions have the same metrical characteristics in the first and second, and in the third and fourth lines). The Dutch word kapoentje (little rascal) is traditional to the rhyme, but in this case it also alludes to a capon. The second line is straight from the original rhyme, but in the third and fourth line the RAF is encouraged to drop bombs on the Moffen (slur for Germans, like «krauts» in English) and candy over the Netherlands. Many of the Sinterklaas poems of this time noted the lack of food and basic necessities, and the German occupiers having taken everything of value; others expressed admiration for the Dutch Resistance.[38]

Originally Sinterklaas was only accompanied by one (or sometimes two) Zwarte Pieten, but just after the liberation of the Netherlands, Canadian soldiers organised a Sinterklaas party with many Zwarte Pieten, and ever since this has been the custom, each Piet normally having his own dedicated task.[39]

Sinterklaas in the former Dutch colonies[edit]

In Curaçao, Dutch-style Sinterklaas events were organised until 2020. The Zwarte Piet costumes were purple, gold, blue, yellow and orange but especially black and dark black.[40] Prime Minister Ivar Asjes has spoken negatively of the tradition.[41] In 2011, the government of Gerrit Schotte threatened to withdraw the grant for the Dutch tradition after the Curaçaoan activist Quinsy Gario was arrested, when he protested in Dordrecht against the use of Zwarte Piet.[42] Since 2020, the Sinterklaas feast is no longer nationally celebrated in Curaçao and has been replaced by Children’s Day on 20 November.[43]

Dutch-style Sinterklaas events were also organised in Suriname.[44] In 1970 the Surinamese playwright Eugène Drenthe envisioned the character of Gudu Ppa («Father of Riches» in Sranantongo) as a postcolonial replacement of Sinterklaas.[45] Instead of a white man, Gudu Ppa was black. His helpers symbolised Suriname’s different ethnic groups, replacing Zwarte Piet. Although promoted by the military regime in the eighties, Gudu Ppa never really caught on.[citation needed] In 2011, opposition member of parliament and former president Ronald Venetiaan called for an official ban on Sinterklaas because he considered Zwarte Piet to be a racist element.[46] Since 2013, the Sinterklaas feast on 5 December has been replaced by Kinderdag («Children’s Day») in Suriname.[47]

The Saint Nicholas Society of New York celebrates a feast on 6 December to this day. In the Hudson Valley region of New York, Sinterklaas is celebrated annually in the towns of Rhinebeck and Kingston because of the region’s Dutch heritage. It includes Sinterklaas’ crossing the Hudson River and then a parade.[48]

Sinterklaas as a source for Santa Claus[edit]

Sinterklaas is the basis for the North American figure of Santa Claus. It is often claimed that during the American War of Independence, the inhabitants of New York City, a former Dutch colonial town (New Amsterdam), reinvented their Sinterklaas tradition, as Saint Nicholas was a symbol of the city’s non-English past.[49] In the 1770s the New York Gazetteer noted that the feast day of «St. a Claus» was celebrated «by the descendants of the ancient Dutch families, with their usual festivities.»[50] In a study of the «children’s books, periodicals and journals» of New Amsterdam, the scholar Charles Jones did not find references to Saint Nicholas or Sinterklaas.[51] Not all scholars agree with Jones’ findings, which he reiterated in a book in 1978.[52] Howard G. Hageman, of New Brunswick Theological Seminary, maintains that the tradition of celebrating Sinterklaas in New York existed in the early settlement of the Hudson Valley. He agrees that «there can be no question that by the time the revival of St. Nicholas came with Washington Irving, the traditional New Netherlands observance had completely disappeared.»[53] However, Irving’s stories prominently featured legends of the early Dutch settlers, so while the traditional practice may have died out, Irving’s St. Nicholas may have been a revival of that dormant Dutch strand of folklore. In his 1812 revisions to A History of New York, Irving inserted a dream sequence featuring St. Nicholas soaring over treetops in a flying wagon – a creation others would later dress up as Santa Claus.

In New York, two years earlier John Pintard published a pamphlet with illustrations of Alexander Anderson in which he calls for making Saint Nicholas the patron Saint of New York and starting a Sinterklaas tradition. He was apparently assisted by the Dutch because in his pamphlet he included an old Dutch Sinterklaas poem with an English translation. In the Dutch poem, Saint Nicholas is referred to as ‘Sancta Claus’.[22] Ultimately, his initiative helped Sinterklaas to pop up as Santa Claus in the Christmas celebration, which returned – freed of episcopal dignity and ties – via England and later Germany to Europe again.

During the Reformation in 16th–17th-century Europe, many Protestants changed the gift bringer from Sinterklaas to the Christ Child or Christkindl (corrupted in English to Kris Kringle). Similarly, the date of giving gifts changed from 5 or 6 December to Christmas Eve.[54]

Sinterklaas in fiction[edit]

In a scene in the 1947 film Miracle on 34th Street, a Dutch girl recognises Macy’s department store Santa as Sinterklaas. They converse in Dutch and sing a Sinterklaas song while she sits on his lap.[55]

Santa Claus is portrayed as Sinterklaas in the 1985 film One Magic Christmas: he and his wife have Dutch accents, and she calls him Nicolaas.[56] In lieu of elves, his helpers are «Christmas angels» who are deceased people of all nationalities.[56]

Sinterklaas has been the subject of a number of Dutch novels, films and television series, primarily aimed at children. Sinterklaas-themed children’s films include Winky’s Horse (2005) and the sequel Where Is Winky’s Horse? (2007).[57][58]

Sinterklaas-themed films aimed at adults include the drama Makkers Staakt uw Wild Geraas (1960), which won a Silver Bear award at the 11th Berlin International Film Festival; the romantic comedy Alles is Liefde (2007) and its Belgian remake Zot van A. (2010); and the Dick Maas-directed horror film Sint (2010).[59]

De Club van Sinterklaas is a Sinterklaas-themed soap opera aimed at children. The popular television series has run since 1999 and has had a number of spin-off series. Since 2001, a Sinterklaas «news» program aimed at children is broadcast daily on Dutch television during the holiday season, the Sinterklaasjournaal. The Dutch-Belgian Nickelodeon series Slot Marsepeinstein has aired since 2009.

Much of the first half of A War of Gifts by Orson Scott Card is about the Sinterklaas tradition, including chapter 4 «Sinterklaas Eve» and 5 «Sinterklaas Day».[60]

In the fourth episode of the television series The Librarians («And Santa’s Midnight Ride»), Santa (Bruce Campbell) is an «immortal avatar» who has existed in many different incarnations throughout history. After experiencing mistletoe poisoning, he briefly turns into Sinterklaas, using his magic to play tricks and make toys appear in people’s shoes, before regaining control of his current incarnation.[citation needed]

Sinterklaas also appeared in Sesamstraat, the Dutch version of Sesame Street.[citation needed]

[edit]

Other holiday figures based on Saint Nicholas are celebrated in some parts of Germany and Austria (Sankt Nikolaus); the Czech Republic (Mikuláš); Hungary (Mikulás); Switzerland (Samichlaus); Italy (San Nicola in Bari, South Tyrol, Alpine municipalities, and many others); parts of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia and Serbia (Sveti Nikola); Slovenia (Sveti Nikolaj or Sveti Miklavž); Greece (Agios Nikolaos); Romania (Moș Nicolae); Albania (Shën Kolli, Nikolli), among others. See further: Saint Nicholas Day.

See also[edit]

- Companions of Saint Nicholas

- Folklore of the Low Countries

References[edit]

- ^ Clark, Cindy Dell (1 November 1998). Flights of Fancy, Leaps of Faith: Children’s Myths in Contemporary America. University of Chicago Press. p. 26. ISBN 9780226107783.

- ^ Ghesquiere 1989, pp. 84–85.

- ^ «Sinterklaas», Landelijk Centrum voor Cultuur van Alledag (LECA)

- ^ «Oh zo Snel |». www.ad.nl. Retrieved 22 November 2019.

- ^ «25 jaar geleden kwam de 1e aflevering van «Dag Sinterklaas» op tv», Alexander Verstraete, VRT NWS, 26 November 2017

- ^ «Sint met paard en koets op Markt», Het Laatste Nieuws, 4 December 2014

- ^ «Sinterklaas gedichten | Kies nu jouw leuke sinterklaasgedicht!». www.1001gedichten.nl. Retrieved 28 October 2016.

- ^ E. Boer-Dirks, «Nieuw licht op Zwarte Piet. Een kunsthistorisch antwoord op de vraag naar de herkomst», Volkskundig Bulletin, 19 (1993), pp. 1–35; 2–4, 10, 14.

- ^ Christian Slaves, Muslim Masters: White Slavery in the Mediterranean, the Barbary Coast, and Italy, 1500–1800, Robert Davis, 2004

- ^ nos.nl; Wie is die Zwarte Piet eigenlijk?, 23 October 2013

- ^ Forbes, Bruce David (2007). Christmas: A Candid History. University of California Press.

- ^ Morse, Felicity. «Zwarte Piet: Opposition Grows To ‘Racist Black Pete’ Dutch Tradition». HuffPost. UK. Retrieved 27 October 2012.

- ^ http://www.rtlnieuws.nl/nederland/rtl-stopt-met-zwarte-piet-voortaan-alleen-pieten-met-roetvegen ; «RTL stopt met Zwarte Piet, voortaan alleen pieten met roetvegen», 24 October 2016

- ^ http://nos.nl/artikel/2141314-geen-zwarte-piet-meer-in-amsterdam-alleen-schoorsteenpieten.html ; «Geen Zwarte Piet meer in Amsterdam, alleen Schoorsteenpieten», 4 November 2016

- ^ «VN wil einde Sinterklaasfeest – Binnenland | Het laatste nieuws uit Nederland leest u op Telegraaf.nl [binnenland]». De Telegraaf. 22 October 2013. Archived from the original on 20 December 2013. Retrieved 19 December 2013.

- ^ «Onderzoek: Zwarte Piet is genoeg aangepast». Een Vandaag. 16 November 2018. Retrieved 30 November 2018.

- ^ «Onderzoek: Rapportage Zwarte Piet» (PDF). Een Vandaag. 15 November 2018. Retrieved 18 February 2019.

- ^ «Niet alleen Rutte is van mening veranderd: de steun voor traditionele Zwarte Piet is gedaald — weblog Gijs Rademaker». Een Vandaag. 17 June 2020. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- ^ «Rutte: ik ben anders gaan denken over Zwarte Piet». NOS Nieuws. 5 June 2020. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- ^ «Sinterklaas Arrival—Amsterdam, the Netherlands». St. Nicholas Center. 2008.

- ^ «Knickerbocker Santa Claus». St. Nicholas Center. 4 December 1953. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ^ a b www.stnicholascenter.org https://web.archive.org/web/20081208115421/http://www.stnicholascenter.org/stnic/images/alexander-anderson-1810b.jpg. Archived from the original on 8 December 2008.

- ^ «Netherlands». St. Nicholas Center.

- ^ «Artikel: Sinterklaas Gaming Surprises» (in Dutch). Female-Gamers.nl. 15 November 2011. Archived from the original on 26 April 2012. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ^ «Examples of typical surprises» (in Dutch). knutselidee.nl.

- ^ Ghesquiere 1989, p. 72.

- ^ «Wat heeft Sinterklaas met Germaanse mythologie te maken?» (in Dutch). historianet.nl. 3 December 2011. Retrieved 8 December 2012.

- ^ Guerber, Hélène Adeline. «huginn and muninn ‘Myths of the Norsemen’ from». Retrieved 26 November 2012 – via Project Gutenberg.

- ^ Booy, Frits (2003). «Lezing met dia’s over ‘op zoek naar zwarte piet’ (in search of Zwarte Piet)» (in Dutch). Archived from the original on 12 October 2011. Retrieved 29 November 2007. Almekinders, Jaap (2005). «Wodan en de oorsprong van het Sinterklaasfeest (Wodan and the origin of Saint Nicolas’ festivity)» (in Dutch). Archived from the original on 26 April 2012. Retrieved 28 November 2011. Christina, Carlijn (2006). «St. Nicolas and the tradition of celebrating his birthday». Archived from the original on 26 April 2012. Retrieved 28 November 2011.

- ^ «Artikel: sinterklaas and Germanic mythology» (in Dutch). historianet.nl. 3 December 2011. Retrieved 8 December 2012.

- ^ Ghesquiere 1989, p. 77.

- ^ Meertens Instituut, Piet en Sint – veelgestelde vragen, meertens.knaw.nl. Retrieved 19 November 2013; J. de Jager, Rituelen & Tradities: Sinterklaas, jefdejager.nl. Retrieved 19 November 2013. According to E. Boer-Dirks, «Nieuw licht op Zwarte Piet. Een kunsthistorisch antwoord op de vraag naar de herkomst», Volkskundig Bulletin, 19 (1993), pp. 1–35, this tradition is derived from German folkloristic research of the first decades of the 19th century (p. 2). This happened relatively early; already in 1863, the Dutch lexicographer Eelco Verwijs is found comparing the feast of St. Nicholas with Germanic pagan traditions and noting that the appearance of Wodan and Eckart in December reminds him of that of St. Nicholas and «his servant Ruprecht» (De christelijke feesten: Eene bijdrage tot de kennis der germaansche mythologie. I. Sinterklaas (The Hague, 1863), p. 40). An older reference to a possible pagan origin of a «St. Nicholas and his black servant with chains», apparently in a Dutch setting, is found in L. Ph. C. van den Bergh, Nederlandsche volksoverleveringen en godenleer (Utrecht, 1836), p. 74 («…de verschijning van den zwarten knecht van St. Nikolaas met kettingen, die de kinders verschrikt, … acht ik van heidenschen oorsprong»).

- ^ a b c Hauptfleisch, Temple; Lev-Aladgem, Shulamith; Martin, Jacqueline; Sauter, Willmar; Schoenmakers, Henri (2007). Festivalising!: Theatrical Events, Politics and Culture. Amsterdam and New York: International Federation for Theatre Research. p. 291. ISBN 978-9042022218.

- ^ Forbes, Bruce David, Christmas: a candid history, University of California Press, 2007, ISBN 0-520-25104-0, pp. 68–79.

- ^ Köhler, Erika. Martin Luther und der Festbrauch, Cologne, 1959. OCLC 613003275.

- ^ «Martin Luther soll das Christkind erfunden haben». Stiftung Luthergedenkstätten in Sachsen-Anhalt – Staatliche Geschäftsstelle «Luther 2017». Retrieved 5 March 2018.

- ^ Some of these were collected, published in 2009 by Hinke Piersma, a researcher at the Dutch Institute for War Documentation.

- ^ Budde, Sjoukje (4 December 2008). «Hitler heeft den strijd gestart, maar aan ‘t eind krijgt hij de gard». De Volkskrant. Amsterdam. Retrieved 5 December 2008.

- ^ Sijs, Nicoline van der (2009) Cookies, Coleslaw, and Stoops. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. p. 254.

- ^ «In Willemstad is piet vooral donker zwart en sint wit geschminkt». Volkskrant.n. 18 November 2017.

- ^ «Zwarte en gekleurde Pieten op Curaçao». Nu.nl. 16 November 2013.

- ^ «Op Curaçao hebben ze al regenboogpieten». Algemeen Dagblad.

- ^ «Geen sinterklaasviering meer op Curaçao». NOS. 20 September 2020.

- ^ «Surinaamse Sint ruilt Piet in voor suikerfee». Trouw. 2 December 2014.

- ^ «Leidse Courant – 19 november 1980 – pagina 15». Historische Kranten, Erfgoed Leiden en Omstreken.

- ^ «Starnieuws — NDP ondersteunt Venetiaan met afschaffing Sinterklaas». www.starnieuws.com.

- ^ «Sint en Piet niet meer op Surinaamse scholen». Trouw. 6 December 2013.

- ^ «Sinterklaas!». Sinterklaashudsonvalley.com. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ Lendering, Jona (20 November 2008). «Saint Nicholas, Sinterklaas, Santa Claus». Livius.org. Archived from the original on 13 May 2011. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ^ Shorto, Russell. The Island at the Center of the World. Random House LLC, 2005.

- ^ Jones, Charles W. «Knickerbocker Santa Claus». The New-York Historical Society Quarterly. Vol. XXXVIII, no. 4.

- ^ Charles W. Jones, Saint Nicholas of Myra, Bari, and Manhattan: Biography of a Legend (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1978)

- ^ Hageman, Howard G. (1979). «Review of Saint Nicholas of Myra, Bari, and Manhattan: Biography of a Legend«. Theology Today. Vol. 36, no. 3. Princeton: Princeton Theological Seminary. Archived from the original on 7 December 2008. Retrieved 5 December 2008.

- ^ Forbes, Bruce David (2007). Christmas: A Candid History. University of California Press. pp. 68–79. ISBN 978-0-520-25104-5.

- ^ Miracle on 34th Street (DVD). Los Angeles, California: 20th Century Fox. 2 May 1947. Event occurs at 23:40.

- ^ a b One Magic Christmas (DVD). Burbank, California: Buena Vista Distribution. 22 November 1985. Event occurs at TBD.

- ^ Winky’s Horse at IMDb

- ^ Where Is Winky’s Horse at IMDb

- ^ Guido Franken, «Sinterklaas in de Nederlandse film», Neerlands Filmdoek, 29 November 2013 (Dutch)

- ^ Card, Orson Scott (November 2007). A War of Gifts: An Ender Story. Tor / Tom Doherty Associates. pp. 47–81. ISBN 978-0-7653-1282-2.

Notes[edit]

- ^ Those include Sanikolas in Papiamento; Saint Nicolas in French; Sinteklaas in West Frisian; Sinterklaos in Limburgs; Sunterklaos or Sünnerklaas in Low Saxon; Sintekloai in West Flemish; Kleeschen and Zinniklos in Luxembourgish; Sankt Nikolaus or Nikolaus in German; and Sint Nicholas in Afrikaans.

Bibliography[edit]

- Ghesquiere, Rita (1989). Van Nicolaas van Myra tot Sinterklaas. Acco. ISBN 9789061525561.

External links[edit]

Media related to Sinterklaas (figure) at Wikimedia Commons

Sinterklaas (Dutch: [ˌsɪntərˈklaːs]) or Sint-Nicolaas (Dutch: [sɪnt ˈnikoːlaːs] (listen)) is a legendary figure based on Saint Nicholas, patron saint of children. Other Dutch names for the figure include De Sint («The Saint»), De Goede Sint («The Good Saint») and De Goedheiligman («The Good Holy Man»). Many descendants and cognates of «Sinterklaas» or «Saint Nicholas» in other languages are also used in the Low Countries, nearby regions, and former Dutch colonies.[note 1]

The feast of Sinterklaas celebrates the name day of Saint Nicholas on 6 December. The feast is celebrated annually with the giving of gifts on St. Nicholas’ Eve (5 December) in the Netherlands and on the morning of 6 December, Saint Nicholas Day, Belgium, Luxembourg, western Germany, northern France (French Flanders, Lorraine, Alsace and Artois), and Hungary. The tradition is also celebrated in some territories of the former Dutch Empire, including Aruba.

Sinterklaas is one of the sources of the popular Christmas icon of Santa Claus.[1][2]

Figures[edit]

Sinterklaas[edit]

Sinterklaas is based on the historical figure of Saint Nicholas (270–343), a Greek bishop of Myra in present-day Turkey. He is depicted as an elderly, stately and serious man with white hair and a long, full beard. He wears a long red cape or chasuble over a traditional white bishop’s alb and a sometimes-red stole, dons a red mitre and ruby ring, and holds a gold-coloured crosier, a long ceremonial shepherd’s staff with a fancy curled top.[3]

He traditionally rides a white horse. In the Netherlands, the last horse was called Amerigo, but he was «pensioned» (i.e., died) in 2019 and replaced with a new horse called Ozosnel («oh so fast»), after a passage in a well-known Sinterklaas song.[4] In Belgium, the horse is named Slecht weer vandaag, meaning «bad weather today»[5] or Mooi weer vandaag («nice weather today»).[6]

Sinterklaas carries a big, red book which records whether each child has been good or naughty in the past year.[7]

Zwarte Piet[edit]

Sinterklaas is assisted by Zwarte Piet («Black Pete»), a helper dressed in Moorish attire and in blackface. Zwarte Piet first appeared in print as the nameless servant of Saint Nicholas in Sint-Nikolaas en zijn knecht («St. Nicholas and His Servant»), published in 1850 by Amsterdam schoolteacher Jan Schenkman; however, the tradition appears to date back at least as far as the early 19th century.[8] Zwarte Piet’s colourful dress is based on 16th-century noble attire, with a ruff (lace collar) and a feathered cap. He is typically depicted carrying a bag which contains candy for the children, which he tosses around, a tradition supposedly originating in the story of Saint Nicholas saving three young girls from prostitution by tossing golden coins through their window at night to pay their dowries.

Traditionally, he would also carry a birch rod (Dutch: roe), a chimney sweep’s broom made of willow branches, used to spank children who had been naughty. Some of the older Sinterklaas songs make mention of naughty children being put in Zwarte Piet’s bag and being taken back to Spain. This part of the legend refers to the times that the Moors raided the European coasts, and as far as Iceland, to abduct the local people into slavery. This quality can be found in other companions of Saint Nicholas such as Krampus and Père Fouettard.[9] In modern versions of the Sinterklaas feast, however, Zwarte Piet no longer carries the roe and children are no longer told that they will be taken back to Spain in Zwarte Piet’s bag if they have been naughty.

Over the years many stories have been added, and Zwarte Piet has developed into a valuable assistant to the absent-minded saint. In modern adaptations for television, Sinterklaas has developed a Zwarte Piet for every function, such as a Head Piet (Hoofdpiet), a Navigation Piet (Wegwijspiet) to navigate the steamboat from Spain to the Netherlands, a Presents Piet (Pakjespiet) to wrap all the gifts, and Acrobatic Piet to climb roofs and chimneys.[10] Traditionally Zwarte Piet’s face is said to be black because he is a Moor from Spain.[11] Today, some children are told that his face is blackened with soot because he has to climb through chimneys to deliver gifts for Sinterklaas.

Since the 2010s, the traditions surrounding the holiday of Sinterklaas have been the subject of a growing number of editorials, debates, documentaries, protests and even violent clashes at festivals.[12] Some large cities and television channels now only display Zwarte Piet characters with some soot smudges on the face rather than full blackface, so-called roetveegpieten («soot-smudge Petes») or schoorsteenpieten («chimney Petes»).[13][14]

In a 2013 survey, 92 per cent of the Dutch public did not perceive Zwarte Piet as racist or associate him with slavery, and 91 per cent were opposed to altering the character’s appearance.[15] In a similar survey in 2018, between 80 and 88 per cent of the Dutch public did not perceive Zwarte Piet as racist, and between 41 and 54 per cent were happy with the character’s modernised appearance (a mix of roetveegpieten and blackface).[16][17]

A June 2020 survey saw a drop in support for leaving the character’s appearance unaltered: 47 per cent of those surveyed supported the traditional appearance, compared to 71 per cent in a similar survey held in November 2019.[18] Prime Minister Mark Rutte stated in a parliamentary debate on 5 June 2020 that he had changed his opinion on the issue and now has more understanding for people who consider the character’s appearance to be racist.[19]

Celebration[edit]

Arrival from Spain[edit]

Sinterklaas and his Zwarte Piet helpers arriving by steamboat from Spain

The festivities traditionally begin each year in mid-November (the first Saturday after 11 November), when Sinterklaas «arrives» by a steamboat at a designated seaside town, supposedly from Spain. In the Netherlands this takes place in a different port each year, whereas in Belgium it always takes place in the city of Antwerp. The steamboat anchors, then Sinterklaas disembarks and parades through the streets on his horse, welcomed by children cheering and singing traditional Sinterklaas songs.[20] His Zwarte Piet assistants throw candy and small, round, gingerbread-like cookies, either kruidnoten or pepernoten, into the crowd. The event is broadcast live on national television in the Netherlands and Belgium.

Following this national arrival, other towns celebrate their own intocht van Sinterklaas (arrival of Sinterklaas). Local arrivals usually take place later on the same Saturday of the national arrival, the next day (Sunday), or one weekend after the national arrival. In places a boat cannot reach, Sinterklaas arrives by train, horse, horse-drawn carriage or even a fire truck.

Sinterklaas is said to come from Spain, possibly because in 1087, half of Saint Nicholas’ relics were transported to the Italian city of Bari, which later formed part of the Spanish Kingdom of Naples. Others suggest that mandarin oranges, traditionally gifts associated with St. Nicholas, led to the misconception that he must have been from Spain. This theory is backed by a Dutch poem documented in 1810 in New York and provided with an English translation:[21][22]

Sinterklaas, goedheiligman! |

Saint Nicholas, good holy man! |

The text presented here comes from a pamphlet that John Pintard released in New York in 1810. It is the earliest source mentioning Spain in connection to Sinterklaas. Pintard wanted St. Nicholas to become patron saint of New York and hoped to establish a Sinterklaas tradition. Apparently he got help from the Dutch community in New York, that provided him with the original Dutch Sinterklaas poem. Strictly speaking, the poem does not state that Sinterklaas comes from Spain, but that he needs to go to Spain to pick up the oranges and pomegranates. So the link between Sinterklaas and Spain goes through the oranges, a much appreciated treat in the 19th century. Later the connection with the oranges got lost, and Spain became his home.

Period leading up to Saint Nicholas’ Eve[edit]

In the weeks between his arrival and 5 December, Sinterklaas visits schools, hospitals, and shopping centers. He is said to ride his white-grey horse over the rooftops at night, delivering gifts through the chimney to the well-behaved children. Traditionally, naughty children risked being caught by Black Pete, who carried a jute bag and willow cane for that purpose.[23]

Before going to bed, children each leave a single shoe next to the fireplace chimney of the coal-fired stove or fireplace (or in modern times close to the central heating radiator, or a door). They leave the shoe with a carrot or some hay in it and a bowl of water nearby «for Sinterklaas’ horse», and the children sing a Sinterklaas song. The next day they find some candy or a small present in their shoes.

Typical Sinterklaas treats traditionally include mandarin oranges, pepernoten, speculaas (sometimes filled with almond paste), banketletter (pastry filled with almond paste) or a chocolate letter (the first letter of the child’s name made out of chocolate), chocolate coins, suikerbeest (animal-shaped figures made of sugary confection), and marzipan figures. Newer treats include gingerbread biscuits or and a figurine of Sinterklaas made of chocolate and wrapped in coloured aluminium foil.

Saint Nicholas’ Eve and Saint Nicholas’ Day[edit]

In the Netherlands, Saint Nicholas’ Eve, 5 December, became the chief occasion for gift-giving during the winter holiday season. The evening is called Sinterklaasavond («Sinterklaas evening») or Pakjesavond («gifts evening», or literally «packages evening»).

On the evening of 5 December, parents, family, friends or acquaintances pretend to act on behalf of «Sinterklaas», or his helpers, and fool the children into thinking that «Sinterklaas» has really given them presents. This may be done through a note that is «found», explaining where the presents are hidden, as though Zwarte Piet visited them and left a burlap sack of presents with them. Sometimes a neighbour will knock on the door (pretending to be a Zwarte Piet) and leave the sack outside for the children to retrieve; this varies per family. When the presents arrive, the living room is decked out with them, much as on Christmas Day in English-speaking countries. On 6 December «Sinterklaas» departs without any ado, and all festivities are over.

In the Southern Netherlands and Belgium, most children have to wait until the morning of 6 December to receive their gifts, and Sinterklaas is seen as a festivity almost exclusively for children. The shoes are filled with a poem or wish list for Sinterklaas and carrots, hay or sugar cubes for the horse on the evening of the fifth and in Belgium often a bottle of beer for Zwarte Piet and a cup of coffee for Sinterklaas are placed next to them. Also in some areas, when it is time for children to give up their pacifier, they place it into his or her shoe («safekeeping by Sinterklaas») and it is replaced with chocolate the next morning.

The present is often creatively disguised by being packaged in a humorous, unusual or personalised way. This is called a surprise (from the French).[24][25]

Poems from Sinterklaas usually accompany gifts, bearing a personal message for the receiver. It is usually a humorous poem which often teases the recipient for well-known bad habits or other character deficiencies.

In recent years, influenced by North-American media and the Anglo-Saxon Christmas tradition, when the children reach the age where they get told «the big secret of Sinterklaas», some people will shift to Christmas Eve or Christmas Day for the present giving. Older children in Dutch families where the children are too old to believe in Sinterklaas any more, also often celebrate Christmas with presents instead of pakjesavond. Instead of such gifts being brought by Sinterklaas, family members ordinarily draw names for an event comparable to Secret Santa. Because of the popularity of his «older cousin» Sinterklaas, Santa Claus is however not commonly seen in the Netherlands and Belgium.

History[edit]

Pre-Christian Europe[edit]

Municipal ban on Sint-Nicolaas pastry in the town of Utrecht during 1–8 December 1655 (to combat Catholic idolatry).

Jacob Grimm,[26] Hélène Adeline Guerber and others have drawn parallels between Sinterklaas and his helpers and the Wild Hunt of Wodan or Odin,[27] a major god among the Germanic peoples, who was worshipped in Northern and Western Europe prior to Christianization. Riding the white horse Sleipnir he flew through the air as the leader of the Wild Hunt, always accompanied by two black ravens, Huginn and Muninn.[28] Those helpers would listen, just like Zwarte Piet, at the chimney – which was just a hole in the roof at that time – to tell Wodan about the good and bad behaviour of the mortals.[29][unreliable source?][30] Historian Rita Ghesquiere asserts that it is likely that certain pre-christian elements survived in the honouring of Saint Nicholas.[31] Indeed, it seems clear that the tradition contains a number of elements that are not ecclesiastical in origin.[32]

Middle Ages[edit]

The Sinterklaasfeest arose during the Middle Ages. The feast was both an occasion to help the poor, by putting money in their shoes (which evolved into putting presents in children’s shoes) and a wild feast, similar to Carnival, that often led to costumes, a «topsy-turvy» overturning of daily roles, and mass public drunkenness.

In early traditions, students elected one of their classmates as «bishop» on St. Nicholas Day, who would rule until 28 December (Innocents Day), and they sometimes acted out events from the bishop’s life. As the festival moved to city streets, it became more lively.[33]

Illustration from the 1850 book St. Nikolaas en zijn knecht («Saint Nicholas and his servant»), by Jan Schenkman, 1850

16th and 17th centuries[edit]

During the Reformation in 16th- and 17th-century Europe, Protestant reformers like Martin Luther changed the Saint gift bringer to the Christ Child or Christkindl and moved the date for giving presents from 6 December to Christmas Eve. Certain Protestant municipalities and clerics forbade Saint Nicholas festivities, as the Protestants wanted to abolish the cult of saints and saint adoration, while keeping the midwinter gift-bringing feast alive.[34][35][36]

After the successful revolt of the largely Protestant northern provinces of the Low Countries against the rule of Roman Catholic king Philip II of Spain, the new Calvinist regents, ministers and clericals prohibited celebration of Saint Nicholas. The newly independent Dutch Republic officially became a Protestant country and abolished public Catholic celebrations. Nevertheless, the Saint Nicholas feast never completely disappeared in the Netherlands. In Amsterdam, where the public Saint Nicholas festivities were very popular, main events like street markets and fairs were kept alive with persons impersonating Nicholas dressed in red clothes instead of a bishop’s tabard and mitre. The Dutch government eventually tolerated private family celebrations of Saint Nicholas’ Day, as can be seen on Jan Steen’s painting The Feast of Saint Nicholas.

19th century[edit]

In the 19th century, the saint emerged from hiding and the feast became more secularised at the same time.[33] The modern tradition of Sinterklaas as a children’s feast was likely confirmed with the illustrated children’s book Sint-Nicolaas en zijn knecht (‘Saint Nicholas and his servant’), written in 1850 by the teacher Jan Schenkman (1806–1863). Some say he introduced the images of Sinterklaas’ delivering presents by the chimney, riding over the roofs of houses on a grey horse, and arriving from Spain by steamboat, which at that time was an exciting modern invention. Perhaps building on the fact that Saint Nicholas historically is the patron saint of the sailors (many churches dedicated to him have been built near harbours), Schenkman could have been inspired by the Spanish customs and ideas about the saint when he portrayed him arriving via the water in his book. Schenkman introduced the song Zie ginds komt de stoomboot («Look over yonder, the steamboat is arriving»), which is still popular in the Netherlands.

In Schenkman’s version, the medieval figures of the mock devil, which later changed to Oriental or Moorish helpers, was portrayed for the first time as black African and called Zwarte Piet (Black Pete).[33]

World War II[edit]

During the German occupation of the Netherlands (1940–1945) many of the traditional Sinterklaas rhymes were rewritten to reflect current events.[37] The Royal Air Force (RAF) was often celebrated. In 1941, for instance, the RAF dropped boxes of candy over the occupied Netherlands. One classical poem turned contemporary was the following:

Sinterklaas, kapoentje,

R.A.F. Kapoentje, |

Sinterklaas, little capon,

R.A.F. little Capon, |

This is a variation of one of the best-known traditional Sinterklaas rhymes, with «RAF» replacing «Sinterklaas» in the first line (the two expressions have the same metrical characteristics in the first and second, and in the third and fourth lines). The Dutch word kapoentje (little rascal) is traditional to the rhyme, but in this case it also alludes to a capon. The second line is straight from the original rhyme, but in the third and fourth line the RAF is encouraged to drop bombs on the Moffen (slur for Germans, like «krauts» in English) and candy over the Netherlands. Many of the Sinterklaas poems of this time noted the lack of food and basic necessities, and the German occupiers having taken everything of value; others expressed admiration for the Dutch Resistance.[38]

Originally Sinterklaas was only accompanied by one (or sometimes two) Zwarte Pieten, but just after the liberation of the Netherlands, Canadian soldiers organised a Sinterklaas party with many Zwarte Pieten, and ever since this has been the custom, each Piet normally having his own dedicated task.[39]

Sinterklaas in the former Dutch colonies[edit]

In Curaçao, Dutch-style Sinterklaas events were organised until 2020. The Zwarte Piet costumes were purple, gold, blue, yellow and orange but especially black and dark black.[40] Prime Minister Ivar Asjes has spoken negatively of the tradition.[41] In 2011, the government of Gerrit Schotte threatened to withdraw the grant for the Dutch tradition after the Curaçaoan activist Quinsy Gario was arrested, when he protested in Dordrecht against the use of Zwarte Piet.[42] Since 2020, the Sinterklaas feast is no longer nationally celebrated in Curaçao and has been replaced by Children’s Day on 20 November.[43]

Dutch-style Sinterklaas events were also organised in Suriname.[44] In 1970 the Surinamese playwright Eugène Drenthe envisioned the character of Gudu Ppa («Father of Riches» in Sranantongo) as a postcolonial replacement of Sinterklaas.[45] Instead of a white man, Gudu Ppa was black. His helpers symbolised Suriname’s different ethnic groups, replacing Zwarte Piet. Although promoted by the military regime in the eighties, Gudu Ppa never really caught on.[citation needed] In 2011, opposition member of parliament and former president Ronald Venetiaan called for an official ban on Sinterklaas because he considered Zwarte Piet to be a racist element.[46] Since 2013, the Sinterklaas feast on 5 December has been replaced by Kinderdag («Children’s Day») in Suriname.[47]

The Saint Nicholas Society of New York celebrates a feast on 6 December to this day. In the Hudson Valley region of New York, Sinterklaas is celebrated annually in the towns of Rhinebeck and Kingston because of the region’s Dutch heritage. It includes Sinterklaas’ crossing the Hudson River and then a parade.[48]

Sinterklaas as a source for Santa Claus[edit]

Sinterklaas is the basis for the North American figure of Santa Claus. It is often claimed that during the American War of Independence, the inhabitants of New York City, a former Dutch colonial town (New Amsterdam), reinvented their Sinterklaas tradition, as Saint Nicholas was a symbol of the city’s non-English past.[49] In the 1770s the New York Gazetteer noted that the feast day of «St. a Claus» was celebrated «by the descendants of the ancient Dutch families, with their usual festivities.»[50] In a study of the «children’s books, periodicals and journals» of New Amsterdam, the scholar Charles Jones did not find references to Saint Nicholas or Sinterklaas.[51] Not all scholars agree with Jones’ findings, which he reiterated in a book in 1978.[52] Howard G. Hageman, of New Brunswick Theological Seminary, maintains that the tradition of celebrating Sinterklaas in New York existed in the early settlement of the Hudson Valley. He agrees that «there can be no question that by the time the revival of St. Nicholas came with Washington Irving, the traditional New Netherlands observance had completely disappeared.»[53] However, Irving’s stories prominently featured legends of the early Dutch settlers, so while the traditional practice may have died out, Irving’s St. Nicholas may have been a revival of that dormant Dutch strand of folklore. In his 1812 revisions to A History of New York, Irving inserted a dream sequence featuring St. Nicholas soaring over treetops in a flying wagon – a creation others would later dress up as Santa Claus.

In New York, two years earlier John Pintard published a pamphlet with illustrations of Alexander Anderson in which he calls for making Saint Nicholas the patron Saint of New York and starting a Sinterklaas tradition. He was apparently assisted by the Dutch because in his pamphlet he included an old Dutch Sinterklaas poem with an English translation. In the Dutch poem, Saint Nicholas is referred to as ‘Sancta Claus’.[22] Ultimately, his initiative helped Sinterklaas to pop up as Santa Claus in the Christmas celebration, which returned – freed of episcopal dignity and ties – via England and later Germany to Europe again.

During the Reformation in 16th–17th-century Europe, many Protestants changed the gift bringer from Sinterklaas to the Christ Child or Christkindl (corrupted in English to Kris Kringle). Similarly, the date of giving gifts changed from 5 or 6 December to Christmas Eve.[54]

Sinterklaas in fiction[edit]

In a scene in the 1947 film Miracle on 34th Street, a Dutch girl recognises Macy’s department store Santa as Sinterklaas. They converse in Dutch and sing a Sinterklaas song while she sits on his lap.[55]

Santa Claus is portrayed as Sinterklaas in the 1985 film One Magic Christmas: he and his wife have Dutch accents, and she calls him Nicolaas.[56] In lieu of elves, his helpers are «Christmas angels» who are deceased people of all nationalities.[56]

Sinterklaas has been the subject of a number of Dutch novels, films and television series, primarily aimed at children. Sinterklaas-themed children’s films include Winky’s Horse (2005) and the sequel Where Is Winky’s Horse? (2007).[57][58]

Sinterklaas-themed films aimed at adults include the drama Makkers Staakt uw Wild Geraas (1960), which won a Silver Bear award at the 11th Berlin International Film Festival; the romantic comedy Alles is Liefde (2007) and its Belgian remake Zot van A. (2010); and the Dick Maas-directed horror film Sint (2010).[59]

De Club van Sinterklaas is a Sinterklaas-themed soap opera aimed at children. The popular television series has run since 1999 and has had a number of spin-off series. Since 2001, a Sinterklaas «news» program aimed at children is broadcast daily on Dutch television during the holiday season, the Sinterklaasjournaal. The Dutch-Belgian Nickelodeon series Slot Marsepeinstein has aired since 2009.

Much of the first half of A War of Gifts by Orson Scott Card is about the Sinterklaas tradition, including chapter 4 «Sinterklaas Eve» and 5 «Sinterklaas Day».[60]

In the fourth episode of the television series The Librarians («And Santa’s Midnight Ride»), Santa (Bruce Campbell) is an «immortal avatar» who has existed in many different incarnations throughout history. After experiencing mistletoe poisoning, he briefly turns into Sinterklaas, using his magic to play tricks and make toys appear in people’s shoes, before regaining control of his current incarnation.[citation needed]

Sinterklaas also appeared in Sesamstraat, the Dutch version of Sesame Street.[citation needed]

[edit]

Other holiday figures based on Saint Nicholas are celebrated in some parts of Germany and Austria (Sankt Nikolaus); the Czech Republic (Mikuláš); Hungary (Mikulás); Switzerland (Samichlaus); Italy (San Nicola in Bari, South Tyrol, Alpine municipalities, and many others); parts of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia and Serbia (Sveti Nikola); Slovenia (Sveti Nikolaj or Sveti Miklavž); Greece (Agios Nikolaos); Romania (Moș Nicolae); Albania (Shën Kolli, Nikolli), among others. See further: Saint Nicholas Day.

See also[edit]

- Companions of Saint Nicholas

- Folklore of the Low Countries

References[edit]

- ^ Clark, Cindy Dell (1 November 1998). Flights of Fancy, Leaps of Faith: Children’s Myths in Contemporary America. University of Chicago Press. p. 26. ISBN 9780226107783.

- ^ Ghesquiere 1989, pp. 84–85.

- ^ «Sinterklaas», Landelijk Centrum voor Cultuur van Alledag (LECA)

- ^ «Oh zo Snel |». www.ad.nl. Retrieved 22 November 2019.

- ^ «25 jaar geleden kwam de 1e aflevering van «Dag Sinterklaas» op tv», Alexander Verstraete, VRT NWS, 26 November 2017

- ^ «Sint met paard en koets op Markt», Het Laatste Nieuws, 4 December 2014

- ^ «Sinterklaas gedichten | Kies nu jouw leuke sinterklaasgedicht!». www.1001gedichten.nl. Retrieved 28 October 2016.

- ^ E. Boer-Dirks, «Nieuw licht op Zwarte Piet. Een kunsthistorisch antwoord op de vraag naar de herkomst», Volkskundig Bulletin, 19 (1993), pp. 1–35; 2–4, 10, 14.

- ^ Christian Slaves, Muslim Masters: White Slavery in the Mediterranean, the Barbary Coast, and Italy, 1500–1800, Robert Davis, 2004

- ^ nos.nl; Wie is die Zwarte Piet eigenlijk?, 23 October 2013

- ^ Forbes, Bruce David (2007). Christmas: A Candid History. University of California Press.

- ^ Morse, Felicity. «Zwarte Piet: Opposition Grows To ‘Racist Black Pete’ Dutch Tradition». HuffPost. UK. Retrieved 27 October 2012.

- ^ http://www.rtlnieuws.nl/nederland/rtl-stopt-met-zwarte-piet-voortaan-alleen-pieten-met-roetvegen ; «RTL stopt met Zwarte Piet, voortaan alleen pieten met roetvegen», 24 October 2016

- ^ http://nos.nl/artikel/2141314-geen-zwarte-piet-meer-in-amsterdam-alleen-schoorsteenpieten.html ; «Geen Zwarte Piet meer in Amsterdam, alleen Schoorsteenpieten», 4 November 2016

- ^ «VN wil einde Sinterklaasfeest – Binnenland | Het laatste nieuws uit Nederland leest u op Telegraaf.nl [binnenland]». De Telegraaf. 22 October 2013. Archived from the original on 20 December 2013. Retrieved 19 December 2013.

- ^ «Onderzoek: Zwarte Piet is genoeg aangepast». Een Vandaag. 16 November 2018. Retrieved 30 November 2018.

- ^ «Onderzoek: Rapportage Zwarte Piet» (PDF). Een Vandaag. 15 November 2018. Retrieved 18 February 2019.

- ^ «Niet alleen Rutte is van mening veranderd: de steun voor traditionele Zwarte Piet is gedaald — weblog Gijs Rademaker». Een Vandaag. 17 June 2020. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- ^ «Rutte: ik ben anders gaan denken over Zwarte Piet». NOS Nieuws. 5 June 2020. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- ^ «Sinterklaas Arrival—Amsterdam, the Netherlands». St. Nicholas Center. 2008.

- ^ «Knickerbocker Santa Claus». St. Nicholas Center. 4 December 1953. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ^ a b www.stnicholascenter.org https://web.archive.org/web/20081208115421/http://www.stnicholascenter.org/stnic/images/alexander-anderson-1810b.jpg. Archived from the original on 8 December 2008.

- ^ «Netherlands». St. Nicholas Center.

- ^ «Artikel: Sinterklaas Gaming Surprises» (in Dutch). Female-Gamers.nl. 15 November 2011. Archived from the original on 26 April 2012. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ^ «Examples of typical surprises» (in Dutch). knutselidee.nl.

- ^ Ghesquiere 1989, p. 72.

- ^ «Wat heeft Sinterklaas met Germaanse mythologie te maken?» (in Dutch). historianet.nl. 3 December 2011. Retrieved 8 December 2012.

- ^ Guerber, Hélène Adeline. «huginn and muninn ‘Myths of the Norsemen’ from». Retrieved 26 November 2012 – via Project Gutenberg.

- ^ Booy, Frits (2003). «Lezing met dia’s over ‘op zoek naar zwarte piet’ (in search of Zwarte Piet)» (in Dutch). Archived from the original on 12 October 2011. Retrieved 29 November 2007. Almekinders, Jaap (2005). «Wodan en de oorsprong van het Sinterklaasfeest (Wodan and the origin of Saint Nicolas’ festivity)» (in Dutch). Archived from the original on 26 April 2012. Retrieved 28 November 2011. Christina, Carlijn (2006). «St. Nicolas and the tradition of celebrating his birthday». Archived from the original on 26 April 2012. Retrieved 28 November 2011.

- ^ «Artikel: sinterklaas and Germanic mythology» (in Dutch). historianet.nl. 3 December 2011. Retrieved 8 December 2012.

- ^ Ghesquiere 1989, p. 77.

- ^ Meertens Instituut, Piet en Sint – veelgestelde vragen, meertens.knaw.nl. Retrieved 19 November 2013; J. de Jager, Rituelen & Tradities: Sinterklaas, jefdejager.nl. Retrieved 19 November 2013. According to E. Boer-Dirks, «Nieuw licht op Zwarte Piet. Een kunsthistorisch antwoord op de vraag naar de herkomst», Volkskundig Bulletin, 19 (1993), pp. 1–35, this tradition is derived from German folkloristic research of the first decades of the 19th century (p. 2). This happened relatively early; already in 1863, the Dutch lexicographer Eelco Verwijs is found comparing the feast of St. Nicholas with Germanic pagan traditions and noting that the appearance of Wodan and Eckart in December reminds him of that of St. Nicholas and «his servant Ruprecht» (De christelijke feesten: Eene bijdrage tot de kennis der germaansche mythologie. I. Sinterklaas (The Hague, 1863), p. 40). An older reference to a possible pagan origin of a «St. Nicholas and his black servant with chains», apparently in a Dutch setting, is found in L. Ph. C. van den Bergh, Nederlandsche volksoverleveringen en godenleer (Utrecht, 1836), p. 74 («…de verschijning van den zwarten knecht van St. Nikolaas met kettingen, die de kinders verschrikt, … acht ik van heidenschen oorsprong»).

- ^ a b c Hauptfleisch, Temple; Lev-Aladgem, Shulamith; Martin, Jacqueline; Sauter, Willmar; Schoenmakers, Henri (2007). Festivalising!: Theatrical Events, Politics and Culture. Amsterdam and New York: International Federation for Theatre Research. p. 291. ISBN 978-9042022218.

- ^ Forbes, Bruce David, Christmas: a candid history, University of California Press, 2007, ISBN 0-520-25104-0, pp. 68–79.

- ^ Köhler, Erika. Martin Luther und der Festbrauch, Cologne, 1959. OCLC 613003275.

- ^ «Martin Luther soll das Christkind erfunden haben». Stiftung Luthergedenkstätten in Sachsen-Anhalt – Staatliche Geschäftsstelle «Luther 2017». Retrieved 5 March 2018.

- ^ Some of these were collected, published in 2009 by Hinke Piersma, a researcher at the Dutch Institute for War Documentation.

- ^ Budde, Sjoukje (4 December 2008). «Hitler heeft den strijd gestart, maar aan ‘t eind krijgt hij de gard». De Volkskrant. Amsterdam. Retrieved 5 December 2008.

- ^ Sijs, Nicoline van der (2009) Cookies, Coleslaw, and Stoops. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. p. 254.

- ^ «In Willemstad is piet vooral donker zwart en sint wit geschminkt». Volkskrant.n. 18 November 2017.

- ^ «Zwarte en gekleurde Pieten op Curaçao». Nu.nl. 16 November 2013.

- ^ «Op Curaçao hebben ze al regenboogpieten». Algemeen Dagblad.

- ^ «Geen sinterklaasviering meer op Curaçao». NOS. 20 September 2020.

- ^ «Surinaamse Sint ruilt Piet in voor suikerfee». Trouw. 2 December 2014.

- ^ «Leidse Courant – 19 november 1980 – pagina 15». Historische Kranten, Erfgoed Leiden en Omstreken.

- ^ «Starnieuws — NDP ondersteunt Venetiaan met afschaffing Sinterklaas». www.starnieuws.com.

- ^ «Sint en Piet niet meer op Surinaamse scholen». Trouw. 6 December 2013.

- ^ «Sinterklaas!». Sinterklaashudsonvalley.com. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ Lendering, Jona (20 November 2008). «Saint Nicholas, Sinterklaas, Santa Claus». Livius.org. Archived from the original on 13 May 2011. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ^ Shorto, Russell. The Island at the Center of the World. Random House LLC, 2005.

- ^ Jones, Charles W. «Knickerbocker Santa Claus». The New-York Historical Society Quarterly. Vol. XXXVIII, no. 4.

- ^ Charles W. Jones, Saint Nicholas of Myra, Bari, and Manhattan: Biography of a Legend (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1978)

- ^ Hageman, Howard G. (1979). «Review of Saint Nicholas of Myra, Bari, and Manhattan: Biography of a Legend«. Theology Today. Vol. 36, no. 3. Princeton: Princeton Theological Seminary. Archived from the original on 7 December 2008. Retrieved 5 December 2008.

- ^ Forbes, Bruce David (2007). Christmas: A Candid History. University of California Press. pp. 68–79. ISBN 978-0-520-25104-5.

- ^ Miracle on 34th Street (DVD). Los Angeles, California: 20th Century Fox. 2 May 1947. Event occurs at 23:40.

- ^ a b One Magic Christmas (DVD). Burbank, California: Buena Vista Distribution. 22 November 1985. Event occurs at TBD.

- ^ Winky’s Horse at IMDb

- ^ Where Is Winky’s Horse at IMDb

- ^ Guido Franken, «Sinterklaas in de Nederlandse film», Neerlands Filmdoek, 29 November 2013 (Dutch)

- ^ Card, Orson Scott (November 2007). A War of Gifts: An Ender Story. Tor / Tom Doherty Associates. pp. 47–81. ISBN 978-0-7653-1282-2.

Notes[edit]

- ^ Those include Sanikolas in Papiamento; Saint Nicolas in French; Sinteklaas in West Frisian; Sinterklaos in Limburgs; Sunterklaos or Sünnerklaas in Low Saxon; Sintekloai in West Flemish; Kleeschen and Zinniklos in Luxembourgish; Sankt Nikolaus or Nikolaus in German; and Sint Nicholas in Afrikaans.

Bibliography[edit]

- Ghesquiere, Rita (1989). Van Nicolaas van Myra tot Sinterklaas. Acco. ISBN 9789061525561.

External links[edit]

Media related to Sinterklaas (figure) at Wikimedia Commons

Больше всего День святого Николая (Sinterklaasavond), который ежегодно отмечается 6 декабря, любят голландские дети. Вечером 5 декабря люди анонимно дарят друг другу красиво упакованные подарки.

По сведениям «голландской мифологии», Синта — Синтерклаас — святой Николай — является близким родственником Санта-Клауса. В прошлом голландцы перенесли в Америку многие свои обычаи, которые за прошедшее время изрядно трансформировались. Выходцы из Нидерландов, переселившиеся в 17 веке в Нью-Амстердам (будущий Нью-Йорк) в Америке, «забрали» с собой популярного святого Николая, защитника от всяких невзгод. Святой «прижился» на новой родине и трансформировался со временем, вобрав в себя элементы различных культур, в Санта-Клауса.

Сам святой Николай как историческая фигура родился в 3 веке нашей эры на территории современной Турции и был епископом города Миры. Все свое богатство, доставшееся в наследство от родителей, он раздал бедным. Был очень любим народом, в особенности детьми, для которых творил настоящие чудеса. Епископ умер 6 декабря 342 года, а в 1089 году его останки были перевезены в Италию. С тех пор 6 декабря считается его праздником и праздником детей.

По народным голландским поверьям, Санта-Клаус — это святой покровитель с белой бородой, который приезжает из Испании (почему именно из Испании — никто не знает). Компанию ему составляют слуги, которых называют Черные Питы (Zwarte Pieten). Черный Пит одет как средневековый паж, на голове у него шляпа с пером. В наше время принято считать, что кроме них еще существуют Синие и Зеленые Питы.

Гости прибывают в Нидерланды 6 декабря с моря, через Роттердам, а встречают их в крошечной рыбацкой деревушке Монникэндам, расположенной недалеко от столицы, не только горожане, но и власти.

Вместе с главными героями на пристань спускается многочисленная свита. Их приветствуют выстрелами, салютом, звоном колоколов на ратуше. На набережной их встречают самые настоящие члены городского правления — бургомистр, альдермен, иные должностные лица. Святому подводят белого коня, он умело поднимается в седло, и процессия движется через весь город. Слуги-мавры придают процессии особый колорит — все они, кроме черного Пита, одеты в «сверхсовременные» костюмы и гордо восседают на трескучих мопедах. В день прибытия процессия движется по главной улице города, затем начинает посещать детские учреждения.

Ближе к Рождеству Клаус и Пит появляются и в частных домах. Когда приближается час прихода Санты, родители стараются занять чем-нибудь детей, оставив их в гостиной. Дверь приоткрывается, и в нее просовывается черная рука, которая разбрасывает сладости и фрукты. Пока дети их собирают, важно входит святой Николай. Он расспрашивает детей об их успехах и поведении, и при этом, как настоящий святой, уже все про них знает. Он дает оценку поведению и поступкам детей, произносит наставление и уходит.

Во многих странах с преобладающим католическим населением День святого Николая отмечается 6 декабря. Однако в Нидерландах основные торжества проходят 5 декабря, в канун Дня святого Николая. В этот день Синтерклаас (так его здесь зовут) приносит детям подарки. Прочитав статью, вы познакомитесь с тем, как в Нидерландах встречают приезд в страну святого Николая и его помощников. А также, как здесь проводятся основные торжества, посвящённые Дню святого Николая.

1. Прибытие святого Николая в Нидерланды

Прибытие святого Николая в Нидерланды осуществляется во вторую субботу ноября (первая суббота после 11 числа). В этот день святой Николай (Синтерклаас) прибывает на корабле (это может быть катер или даже пароход) в какой-то город или городок в Нидерландах. Это событие транслируется в прямом эфире на телевидении. Нидерланды издавна были страной моряков, и Святой Николай, который считается покровителем моряков, почитается здесь очень высоко.

Голландская традиция гласит, что святой Николай живет в Мадриде (Испания). Каждый год он выбирает одну из гаваней в Нидерланды, чтобы как можно больше детей смогли встретить его. Амстердам и другие портовые города обычно проводят большие торжества, чтобы возвестить о прибытие святого Николая, включая парады, звон церковных колоколов и детские вечеринки.

Отметим, Синтерклаас — не то же самое, что Санта-Клаус. Святой Николай выглядит совсем иначе, чем весёлый человек, изображённый в западной культуре. Нидерландцы считают его совсем другим лицом, чем Санта-Клаус, которого они называют Керстман. Синтерклаас высок и строен, он носит темно-красные одежды и шляпу, похожую на одеяние епископа. Во многих традиционных изображениях он пожилой и имеет длинную белую бороду.

Святого Николая сопровождает его помощник Чёрный Пит или Чёрный Питер (Zwarte Piet). Он одет в испанскую одежду 16-го века, чтобы символизировать доминирование Испании над Нидерландами в ту эпоху. Лицо Чёрного Питера покрыто сажей. Его одежда резко контрастирует с более радостными цветами одеяния святого Николая.

Когда Синтерклаас и Чёрный Пит выходят на берег с корабля, все местные церковные колокола звонят в честь праздника. Святой Николай, одетый в свои красные одежды, верхом на белом коне и Чёрный Пит на муле, проезжают через город. В каждом городе Нидерландов есть несколько помощников Синтерклааса, одетых так же, как Синтерклаас, которые помогают раздавать подарки. Иногда можно увидеть несколько Чёрных Питов с Синтерклаас.

Детям говорят, что Чёрный Пит записывают всё, что они сделали за последний год, в Большую книгу. Хорошие дети получат подарки от Синтерклааса, а плохих детей положат в мешок… Затем Чёрный Питер увезёт их в Испанию на год, чтобы научить их, как себя вести!

В тот вечер, когда святой Николай приезжает в Нидерланды, дети оставляют обувь у камина или иногда на подоконнике и поют песни Синтерклааса. Дети в Нидерландах думают, что Синтерклаас и Чёрный Пит будут посещают их еженедельно… Поэтому во все последующие субботы до главной вечеринки Синтерклааса (5 декабря) они будут это делать.

Дети также считают, что если они оставят немного сена и моркови в своих ботинках для лошади Синтерклааса, им оставят сладости. Детям в Нидерландах говорят, что ночью святой Николай ездит по крышам на своей лошади. А Чёрный Пит спускается по трубе или проникает через окно в дом и затем кладёт подарки и конфеты в их обувь.

2. Канун Дня святого Николая в Нидерландах

Канун Святого Николая или Синтерклаас Авонд отмечается ежегодно 5 декабря. Дети в Нидерландах получают свои подарки в течение всего вечера. Может раздаться стук в дверь, и там обнаружится мешок, полный подарков! Их оставляет Синтерклаас, который путешествует по домам каждого ребенка в Нидерландах.

В канун Святого Николая во многих семьях устраиваются вечеринки для детей. На них проводят различные игры, связанные с охотой за сокровищами, стихами и загадками, дающими ключи для поиска. Дети следуют за подсказками, чтобы найти маленькие подарки, оставленные Синтерклаасом.

На вечеринке детей угощают специальным печеньем и сладостями. Для всей семьи организуются щедрые ужины на Синтерклаас Avond, которые обычно включают оленину или жареного гуся, свинину, овощи и домашний хлеб. Также популярны вареные каштаны, фрукты, миндальная паста, хлеб (керстстол), похожий на марципан, и печенье. Многие семьи выпекают торты в форме первой буквы имени каждого члена семьи, чтобы добавить личное и вкусное блюдо к праздничному столу. Также популярны булочки из смородины и торт с фруктами и орехами (штоллен).

3. Сюрпризы в День святого Николая (6 декабря) в Нидерландах

В День святого Николая (6 декабря) школьникам также преподносят сюрпризы. Обычно это делается на вечеринках Синтерклааса, часто в классах школы. Сюрприз заключается в том, что имя каждого участника вечеринки помещается в шляпу. Все по очереди вытягивают имя человека, который получает сюрприз. Подарками часто являются предметы, связанные с их любимым хобби. Они приходят со стихотворением внутри, что дает ключ к тому, кто мог бы отправить подарок, но всё это должно быть тайной!

Подобные подарки-сюрпризы на День Святого Николая дома могут включать причудливые стихи, чтобы сделать каждый подарок уникальным и захватывающим. Они могут быть скрыты или замаскированы для большего веселья.

6 декабря святой Николай покидает Нидерланды на корабле через порт Роттердам (крупнейший порт Европы), чтобы вернуться в Испанию.

День Святого Николая в Нидерландах пользуется большой популярностью. Синтерклаас не ощущает никакой конкуренции от своего двоюродного брата с Северного полюса — Санта-Клауса. Заметим, что два Деда Мороза существует и в других соседних странах, например, в Бельгии. Вы можете прочитать об этом, перейдя по ссылке ниже:

Читать статью: «Как в Бельгии отмечают Рождество?»

Читайте также:

Праздники и фестивали Нидерландов

День святого Николая в Польше

Праздники и фестивали разных стран мира

Уважаемые читатели! Пишите комментарии! Читайте статьи на сайте «Мир праздников»!

Конец ноября во многих странах Европы становится временем преображения городов и улиц. В этот период начинается активная подготовка к Рождеству, однако голландцы пошли дальше. Они в декабре праздную не один, а целых два праздника. В Нидерландах н менее значимым, чем праздник Рождества, стал Синтерклаас, который приходится на начало первого зимнего месяца.

Посвящён он святому покровителю, Николаю, однако благодаря самобытным традициям сильно отличается от Дня Святого Николая в других странах. Как же принято праздновать Синтерклаас? Что особенного в этом голландском празднике?

Синтерклаас – кто он?

Синтерклаас ежегодно отмечается в Нидерландах и Бельгии, причём у голландцев он приходится на 5 декабря, а бельгийцы празднуют его на день позже. Покровителем торжества является Святой Николай или Санта-Клаус, как принято называть его в Европе и Америке.

Именно он выступает в качестве главного действующего лица на Синтерклаас. Всем известно, что Николай является добрым святым, который раздаёт подарки малышам. Голландские дети с нетерпением ждут прихода его праздника. Есть даже предание о том, что в Синтерклаас Николай прибывает на пароходе из Испании.