27 января во всем мире отмечают Международный день памяти жертв Холокоста. Эта дата напоминает нам о леденящих кровь преступлениях фашистской Германии – массовых убийствах евреев. С 1943 по 1945 год нацисты уничтожили около шести миллионов узников, находившихся в гетто и лагерях смерти.

В материале РЕН ТВ расскажем об истории и значении Холокоста, а также о том, как вспоминали это время те, кому удалось спастись.

Когда отмечают Международный день памяти жертв Холокоста

Международный день памяти жертв Холокоста ежегодно отмечается 27 января. Дата была выбрана неслучайно – именно в этот день в 1945 году советские солдаты освободили узников нацистского концлагеря Освенцим.

Праздник утвердили на съезде Генеральной ассамблеи ООН в 2005 году. Тогда генсек организации, Кофи Аннан, призвал навсегда сохранить память о жертвах Холокоста и подвигах солдат, отдавших свои жизни во имя борьбы с нацизмом. Эту память, по его словам, необходимо передавать из поколения в поколение, чтобы ужасы фашизма не повторились вновь.

Фото: © ТАСС/Наталия Федосенко

Холокост в истории

Слово «холокост» переводится как «всесожжение». Этот термин обозначает преследование и уничтожение евреев нацистами после прихода к власти Гитлера. Зверства фашистов и их пособников продолжались с 1933 по 1945 год. За это время более шести миллионов евреев были стерты с лица земли.

Начало преследования евреев

В конце XIX века в Германии стала набирать популярность идея расового антисемитизма. По мнению ее сторонников, евреи были низшей расой и представляли угрозу существованию германской нации. Придя к власти в 1933 году, Адольф Гитлер сделал антисемитизм основой своей идеологии.

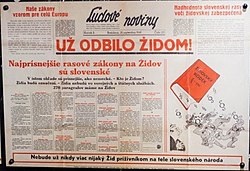

Так, евреев стали воспринимать как людей второго сорта и начали преследовать. В 1935 году появились два «Нюрнбергских закона», согласно которым гражданином рейха мог быть только человек с «германской кровью». С того момента евреи и цыгане, проживающие в Германии, были лишены гражданства, имущества и всех прав.

Фото: © Global Look Press/Scherl

В ночь с 9 на 10 ноября 1938 года по всей Германии прошли погромы. Охваченные ненавистью немцы безжалостно разрушали дома и магазины, которыми владели евреи. Это событие вошло в историю как Хрустальная ночь. Поводом для антиеврейской истерии стало убийство немецкого дипломата Эрнста фом Рата польским евреем. Трагедия сыграла нацистам на руку – под звучным девизом «Месть за убийство фом Рата» они начали громить еврейские общины.

В 1939 году Гитлер приказал выдворить всех евреев из Германии – на осуществление плана было отведено четыре года. Однако ехать им было некуда. Большинство стран отказывались принимать беженцев: мир разделился на те места, где евреи могли жить, и те, куда въезд им был запрещен.

Изоляция евреев

Важно понимать, что антиеврейская истерия не накрыла Европу стихийно. Нацисты внушали ненависть к евреям долго и планомерно, и спустя годы машина Холокоста заработала. Многие успели сбежать в Прибалтику, Польшу, Украину или Белоруссию, но после того, как армия Гитлера захватила эти земли, евреев начали безжалостно истреблять и там.

Фото: © Global Look Press/via www.imago-images.de/www.imago-images.de

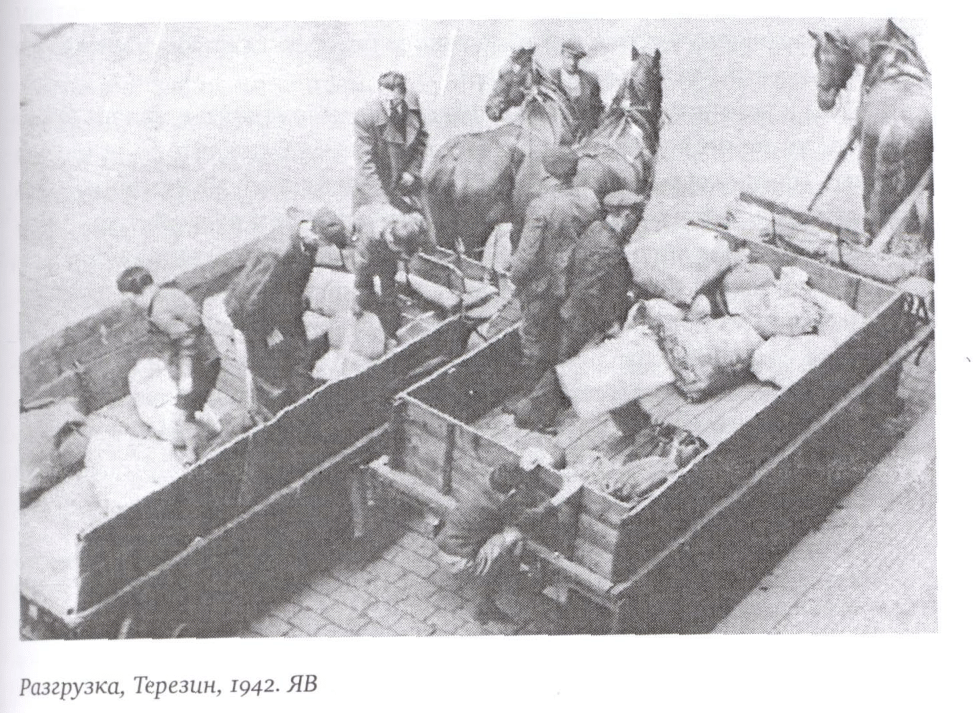

Чтобы упростить «решение еврейского вопроса», нацисты построили гетто – части поселков или городов, где евреи жили в тесноте и антисанитарных условиях. Эти территории огораживали, а охранники не позволяли узникам покидать гетто без разрешения. Лишенные человеческого достоинства, узники гетто переставали жить и начинали существовать. У них отобрали свободу, семью, дом и даже имя (взамен выдавали номер), а потом забирали и жизнь. Люди занимались изнурительным трудом, сотнями умирали от голода и свирепствующих болезней.

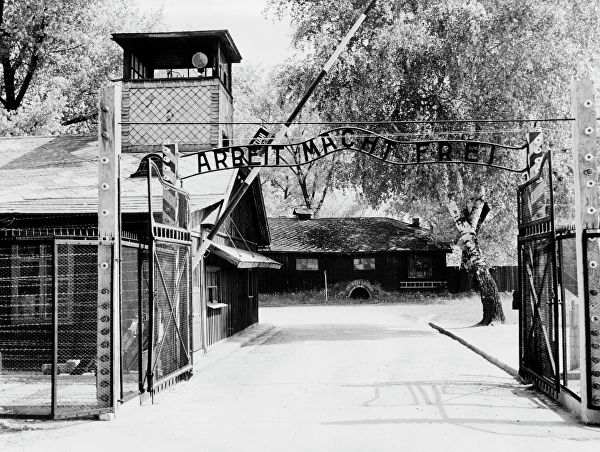

Самая страшная участь ждала тех, кто попадал в концлагеря, лагеря смерти. В таких местах был построен отлаженный конвейер, который превращал в пепел по нескольку тысяч человек в сутки. Узников жестоко истязали, травили угарным газом в специальных камерах, расстреливали и сжигали заживо. Самыми известными концлагерями считаются Бухенвальд, Освенцим, Берген-Бельзен и Арбайтсдорф.

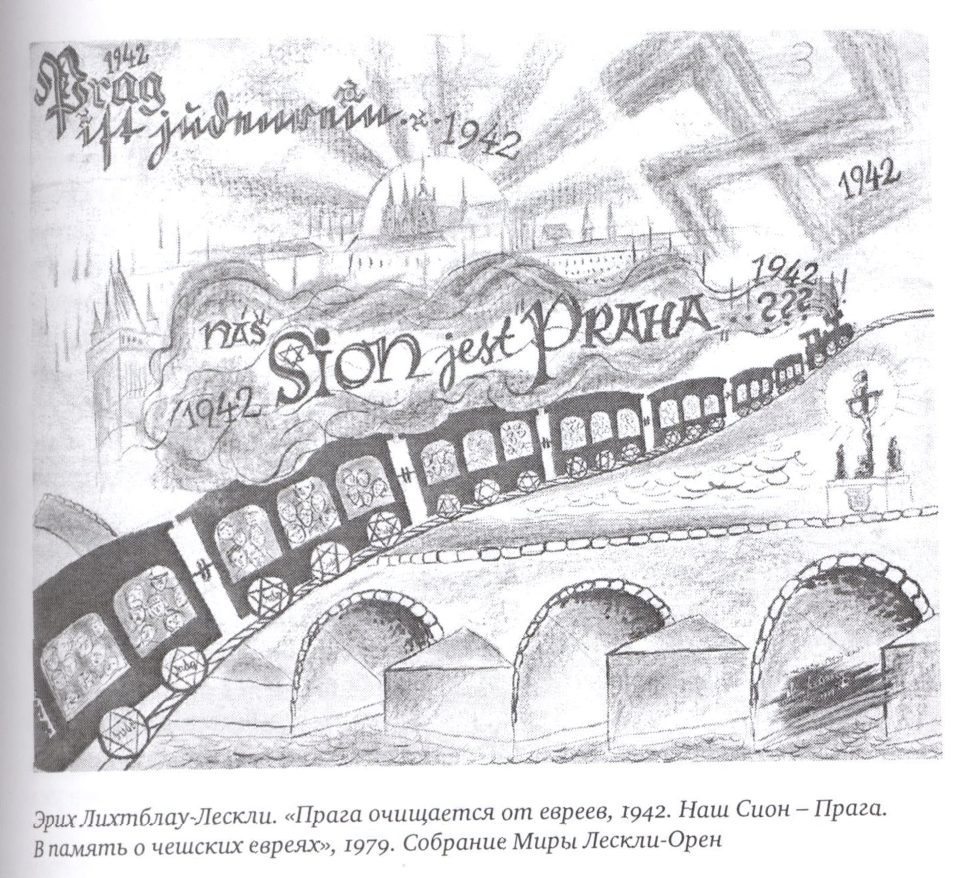

«Агрегат по обработке человеческого сырья… Волосами можно набить подушки, с зубов снять золотые коронки, перелить в обручальные кольца, из подкожного жира варить мыло. Человек не поступал в обработку голым – на нем была одежда и обувь. Снятые с себя вещи нужно было положить в ящики, они предназначались для последующей сортировки», – рассказывается в книге «3000 судеб. Депортация евреев из терезинского гетто в Ригу».

Фото: © Global Look Press/IMAGO/United Archives / Erich An

Узники концлагерей

Помимо евреев, жертвами концлагерей стали около десяти миллионов граждан СССР. В лагеря смерти попадали и участники Сопротивления, и советские военнопленные, и даже поданные США и стран Европы. Среди погибших есть даже известные спортсмены – немецкий футболист Юлиус Хирш и олимпийская чемпионка 1928 года из Нидерландов Эстелла Агстергриббе.

Узниками фашистских концлагерей стали и российские эмигранты: общественный деятель Илья Фондаминский и личный секретарь Григория Распутина Арон Симанович.

Освобождение и спасение узников концлагерей 27 января 1945 года

27 января 1945 года войска 60-й армии во главе с маршалом Иваном Коневым начали освобождение концлагеря Освенцим в Польше. Это произошло ровно через год после полного снятия блокады Ленинграда. Спасением узников польского лагеря смерти занималась 107-я дивизия под командованием генерал-лейтенанта Василия Петренко. Впоследствии советский герой-освободитель несколько раз посещал Израиль и всегда был там желанным гостем, несмотря на то, что страна не поддерживала дипломатических отношений с Советским Союзом.

Фото: © Global Look Press/Ilker Gurer/ZUMAPRESS.com

Суд над военными преступниками

В 1943 году США, Британия и СССР подписали Московскую декларацию о преступлениях нацистской Германии против человечества. Согласно документу, после прекращения войны все фашисты должны быть переданы государству, на территории которого они совершали преступления, осуждены и наказаны по закону. А главным военным преступникам союзные государства решили выносить приговор совместно.

В августе 1945 года Франция, СССР, Британия и США подписали Лондонское соглашение и Нюрнбергскую хартию. В немецком городе Нюрнберг создали Международный военный трибунал. Там судили нацистов, совершивших особо тяжкие преступления: убийства, истребление и порабощение людей, также гонения по религиозным и политическим мотивам.

Самым известным судом над военными преступниками считается Нюрнбергский процесс, который начался 20 ноября 1945 года. Приговор 22 нацистским лидерам был вынесен 1 октября 1946 года. Девятнадцать подсудимых были приговорены к смертной казни – среди них были Юлиус Штрейхер, Герман Геринг и Ганс Франк.

Фото: © Global Look Press/Agentur Voller Ernst/dpa-Zentralbild

После этого суды над военными преступниками продолжились, провели еще 12 процессов. Историки называют их Малыми Нюрнбергскими процессами.

Дети Холокоста

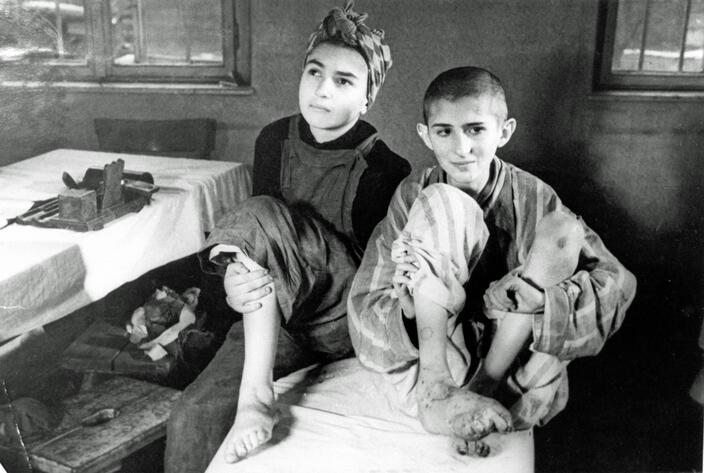

Маленькие дети всегда были самыми легкоуязвимыми жертвами нацистов. Их убийство рассматривалось как часть расовой борьбы. Во время Холокоста было уничтожено около полутора миллиона детей. Некоторые из них, особенно близнецы, использовались нацистами для медицинских экспериментов. Шансы на выживание были лишь у подростков – их могли использовать как рабочую силу в трудовых лагерях.

Однако некоторым ребятам все же удалось спастись. Многие дети участвовали в акциях подпольного сопротивления, совершали побег из концлагерей с родителями или родственниками, чтобы присоединиться к отрядам еврейских партизан.

С 1938 по 1940 год существовала кампания по спасению детей-беженцев «Киндертранспорт», благодаря которой тысячи детей были переправлены в Британию. Иногда евреев укрывали сами европейцы, в основном это были семьи католических священников или религиозные люди. Таким образом, много детей было спасено в Италии и Бельгии.

Фото: © Global Look Press/imago stock&people

Воспоминания выживших

Несмотря на нечеловеческую жестокость нацисткой армии, некоторым евреям удалось пережить Холокост. Спастись смогли лишь единицы – они выжили по разным причинам: благодаря помощи других людей или счастливому стечению обстоятельств.

В руки специалистов попадали письма, хранящие воспоминания тех, кто смог пройти через ад Холокоста и выжить.

«Пришло время, когда я не прошел селекцию в Кайзервальде, и меня отправили в изолятор ждать своей участи. Это было в женском лагере. Все там плакали и стенали. Это был шок. Поздно вечером я увидел немецкого еврея, который молился всем сердцем, не обращая внимания на окружающее. Около него был маленький ребенок. Религиозный еврей сказал: наше дело молиться. Меня же беспокоил ребенок. Рядом сидел другой зэк, и мы до рассвета втроем говорили о том, как быть с верой и как быть с ребенком. Мы уговорили религиозного еврея пропихнуть ребенка в женское гетто. И мы это сделали. Потом явились машины, комендант отсчитал 11 мужчин, всех остальных – на убой. Я был одним из одиннадцати», – написал Оскар Бередикт.

Фото: © Global Look Press/imago stock&people

«В Штутгофе была газовая камера. Мы увидели горы детской и женской обуви. В этом лагере я пробыл до конца февраля 1945 года. Оттуда нас отправили в Германию. Марш смерти. Русские были рядом. Я потерял сознание. Через два дня я пришел в себя и увидел в окно русские танки», – рассказал он историю своего спасения.

Память о Холокосте

После победы над фашизмом мир долго пытался оправиться от ужасов войны. В ООН и других международных организациях были убеждены: важно хранить и передавать из поколения в поколение память о жертвах Холокоста и солдатах-освободителях, сражавшихся за мир.

О трагическом моменте в истории, Холокосте, написано немало книг и снято множество фильмов. Среди них картины «Список Шиндлера» Стивена Спилберга, «Тяжелый песок» по роману Анатолия Рыбакова и фильм «Папа» по произведению Александра Галича «Матросская тишина».

Фото: © Global Look Press/Daniel Hohlfeld/CHROMORANGE

По всему миру созданы так называемые музеи Холокоста. Их специалисты изучают и хранят письма и вещи выживших, исторические документы и другие важные предметы, связанные с Холокостом. Для всех желающих проводятся выставки. Самые крупные и известные музеи находятся в США, Израиле, Бельгии, Германии и России. В Москве можно посетить научно-просветительный центр «Холокост» и Музей еврейского наследия и Холокоста в Мемориальной синагоге на Поклонной горе.

Вечный огонь

Фото: «Толк»

Холокост – одна из величайших трагедий в истории человечества. На протяжении 12 лет нацисты Германии и их союзники из разных стран пытались полностью истребить целую нацию – евреев

Международный день памяти жертв Холокоста 27 января отмечают в честь освобождения в этот день в 1945 году узников польского концентрационного лагеря Освенцим.

Что такое холокост

Понятие «холокост» берет свое начало из греческого языка и означает «всесожжение». Почему Гитлер ненавидел еврейский народ, историки спорят до сих пор. Придя к власти, фюрер поставил себе целью буквально испепелить всех евреев дотла. Но холокост коснулся не только евреев фашистской Германии и Европы.

С 1933 по 1944 год нацисты истребляли поляков, цыган, чернокожих жителей Германии, советских военнопленных. Кроме того, Гитлер, мечтавший вывести чистую арийскую расу, «выбраковывал» и немцев, не попадавших под определение идеального арийца. Нацисты истребляли инвалидов, сексуальные меньшинства, масонов, свидетелей Иеговы.

Свеча. Траур

Фото: pixabay.com

Когда начался холокост

Все началось 9 ноября 1938 года. Эта ночь вошла в историю как Хрустальная ночь, или Ночь разбитого стекла. По всей Германии и Австрии нацисты злобно нападали на еврейские общины. Они разрушили, разграбили и сожгли более 1 тыс. синагог и 7 тыс. еврейских предприятий. Также они разрушили еврейские больницы, школы, кладбища и дома. Когда все закончилось, 96 евреев были убиты и 30 тыс. арестованы. Позднее министерство финансов конфисковало всю еврейскую собственность.

Концентрационные лагеря

Существовало несколько типов лагерей: трудовые лагеря и лагеря усиленного труда, транзитные лагеря и лагеря для военнопленных. Концентрационный лагерь был всего лишь одним из них. С 1941 года фашисты начали создавать лагеря смерти, «фабрики смерти», единственной целью которых было методичное убийство европейских евреев. Для этого они оснащались газовыми камерами и крематориями. Лагеря находились на территории Восточной Европы, в основном в Польше. Самый знаменитый из них – Освенцим, сообщает «Энциклопедия холокоста». В комплексе Освенцим было убито более миллиона человек, больше чем в любом другом месте. Комплекс включал три больших лагеря: Освенцим, Биркенау и Моновиц.

Огонь.

Фото: Pexel

Шокирующие факты о холокосте

- Советские солдаты первыми освободили лагеря смерти. 23 июля 1944 года они освободили Майданек. Большая часть мира поначалу отказывалась верить советским сообщениям об ужасах, которые они там обнаружили.

- В таких лагерях смерти был построен отлаженный конвейер, превращавший в пепел по несколько тысяч человек в сутки. К ним относятся Майданек, Освенцим, Треблинка и другие, пишет РИА Новости.

- За 12 лет холокоста было сожжено в крематориях, расстреляно, удушено в газовых камерах и убито в пытках около 11 млн человек, 6 млн из них – евреи.

- Жертвами холокоста оказались 1,1 млн детей.

- Самый страшный день был в сентябре 1941 года: в ущелье Бабий Яр недалеко от Киева всего за два дня было убито более 33 тыс. евреев. Их заставили раздеться, пройти к краю оврага, где их и расстреливали. А затем нацисты зарыли овраг, захоронив мертвых и живых. Многих детей бросали в овраг живыми.

- При входе в каждый лагерь смерти происходил процесс отбора. Беременные женщины, маленькие дети, больные, инвалиды и старики немедленно приговаривались к смерти.

- Выживший в холокосте Иегуда Бэкон рассказал, что рассмеялся во время первой похоронной процессии, которую он увидел после освобождения:

«Люди сумасшедшие. Для одного человека делают гроб и играют торжественную музыку? Несколько недель назад я видел тысячи тел, сложенных для сожжения, как хлам».

Гвоздики. Цветы.

Фото: Pexels

Доктор Смерть

Йозеф Менгеле – немецкий врач, проводивший медицинские опыты на узниках концлагеря Освенцим во время Второй мировой войны. Менгеле лично занимался отбором узников, прибывающих в лагерь, проводил эксперименты над заключенными. Его жертвами стали сотни тысяч человек.

- Тех, кто выживал в экспериментах доктора Йозефа Менгеле, почти всегда убивали и препарировали. В этих экспериментах многие дети были искалечены или парализованы, сотни умерли.

- Доктор приносил детям конфеты и игрушки, прежде чем убить их.

- Близнецы очаровывали нацистского доктора. Есть свидетельство, что он сшил спинами пару близнецов по имени Гвидо и Ина, которым было около 4 лет. Так он пытался создать сиамских близнецов. Родители близнецов смогли получить морфий и убить их, чтобы положить конец детским страданиям.

- Йозеф Менгеле умер в 1979 году в результате несчастного случая, когда утонул в Бразилии, сообщает vsefakty.ru.

Кладбище. Памятник. Цветы

Фото: photosforyou с сайта Pixabay

Память о холокосте

В письмах и документах нацисты никогда не использовали слова «истребление» или «убийство». Вместо этого они использовали такие кодовые слова, как «окончательное решение», «эвакуация» или «особое лечение». Эти термины прочно вошли в историю как обозначение холокоста.

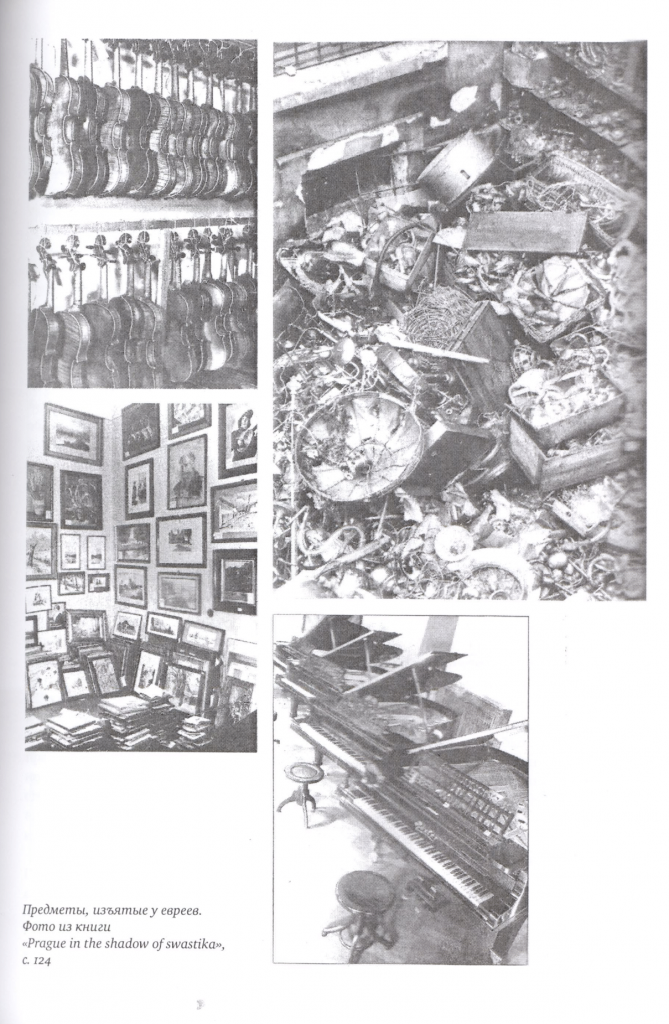

После холокоста сохранилось много ужасающих фотографий, но одна из самых запоминающихся – снимок, на котором запечатлели несколько тысяч обручальных колец, снятых с заключенных-смертников. В Сети можно отыскать и другие исторические фото холокоста с похожим сюжетом: горы оставшейся от заключенных одежды, горы обуви, горы истощенных тел.

27 января – Международный день памяти жертв Холокоста. Эта памятная дата призвана напомнить о наиболее последовательном геноциде в мировой истории, она была установлена Генассамблеей ООН и отсылает к событиям, произошедшим в этот день в 1945 г., когда войска Красной Армии освободили несколько тысяч узников Аушвица (Освенцима, если по-польски).

Необходимо пояснить, к чему отсылает эта памятная дата. Всего в годы Второй мировой войны в результате агрессии на оккупированных нацистской Германией территориях преднамеренно истреблено около 20 млн человек, в том числе примерно 7,4 млн советских граждан. Из этих 20 млн примерно 6 млн – евреи (2,8 млн советских евреев), которые ввиду этнической принадлежности подлежали уничтожению. В годы второй мировой о страданиях евреев знали многие, однако одни не верили в сообщаемые сведения, другие не подозревали масштаба, третьи считали уничтожение целого народа невозможным. Только после окончания войны стали закрепляться специальные термины, отсылающие к убийству евреев. Наиболее известный – американизм «холокост» (от греческого «всесожжение»). Другой термин – «шоа», в переводе с иврита – «катастрофа, бедствие». Оба понятия употребляются как синонимы, однако некоторые намеренно отказываются от употребления слова «холокост», т.к. оно содержит религиозный подтекст, связано с жертвоприношением. Но разве можно считать таковым бессмысленное убийство миллионов детей, женщин, стариков?

Существует множество попыток объяснить, почему истребительная политика нацизма стала возможной. Постараемся кратко перечислить причины. Во-первых, виной тому сама идеология нацизма, в основу которой была положена смесь представлений «органического» национализма и расизма. Такой национализм предполагает, что каждая нация есть единство не просто культурное, но и биологическое, органическое (как популяция собак). Тем самым культурные отличия (в языке, устоявшихся традициях, нормах и пр.) объяснялись через отсылку к «крови». Конкретный человек определяется не по его личным представлениям, убеждениям, воспринятым культурным нормам, а только в силу рождения «не таким». Расизм же восходит к эпохе колониальных империй и предполагает деление наций на «высших» и «низших». Нацисты просто сделали шаг вперед и перенесли ту логику, которую европейцы применяли в колониях, непосредственно на саму Европу. Если вы делите людей на замкнутые органические группы, если некоторые из этих групп считаются опасными, то становится логичным призыв эти группы победить, исключить и даже уничтожить.

Во-вторых, для того чтобы пройти путь от пропаганды к массовым казням, необходим аппарат насилия, причем собственно государственные структуры (армия, полиция) мало подходят для этого. Поэтому нацисты выстроили параллельную систему квазигосударственного насилия в виде СС, которая быстро развивалась и стала включать военизированные формирования, создавать концентрационные лагеря и другие учреждения.

В-третьих, необходимо не только заставить, но и убедить миллионы людей стать соучастниками преступлений. Для этого есть эффективная система пропаганды, которая создавала яркий образ врага и дегуманизировала противника. Каждый человек встраивался в систему нацистского террора: поддержка варьировалась от выражения согласия и выполнения канцелярских обязанностей до расстрелов на местах. И каждый мог при этом считать, что он только выполняет приказы и не несет за происходящее ответственности. Неготовность выносить собственное моральное суждение о своих поступках стала главным залогом ужасов нацистского режима.

Как можно предположить только на основе представленных выше цифр, стать жертвами нацистской политики и геноцида могли многие социальные группы, причем выделенные по разным основаниям. Например, когда в 1933 г. Гитлер пришел к власти, то по всей стране был развязан террор против левой (коммунисты и социал-демократы) оппозиции. Затем к числу жертв добавились те, кого считали преступниками и асоциальными элементами. Это могли быть и мелкие мошенники, и простые граждане, против которых имелись подозрения в совершении преступлений. Людей арестовывали без суда и следствия, кидали бессрочно в специально создаваемые концентрационные лагеря СС (наиболее известные, созданные до войны, – Дахау, Бухенвальд, Заксенхаузен, Маутхаузен, Равенсбрюк, Флоссенбюрг). Здесь людей мучали, над ними издевались, могли доводить до самоубийства.

Первые массовые убийства произошли в 1939-1941 гг., и их жертвами стали сами немцы. В рамках программы T-4 были хладнокровно убиты (инъекциями, в газовых камерах) 250 тыс. тех, кого считали «психическими больными», «с врожденными отклонениями», «неизлечимыми» и т.д. С началом Второй мировой войны истреблению подверглась польская интеллигенция, т.к. немцы считали, что, убив всех образованных людей, они сделают невозможным сопротивление оккупационной политике. Затем настал черед цыган, несколько сотен тысяч сгинули в газовых камерах.

Однако подлинный масштаб убийства приняли с нападением гитлеровской Германии и ее союзников на СССР. Целенаправленные репрессии были развязаны против партработников, коммунистов и вообще политического руководства. В отдельную группу нужно выделить советских военнопленных, которых задействовали на самых тяжелых работах и содержали в ужаснейших условиях. Около 3,3 млн советских людей погибли в лагерях для военнопленных (примерно 60% от их общего числа). Несомненно, это было актом геноцида, поскольку солдаты и офицеры других государств антигитлеровской коалиции содержались в условиях намного лучших.

С нападением на СССР на практике стала реализовываться политика «окончательного решения еврейского вопроса», т.е. уничтожения европейских евреев.

Притеснения евреев в самом Третьем Рейхе начались уже в 1933 г., т.е. вскоре после прихода нацистов к власти. Сначала им запрещали работать на госслужбе, в 1935 г. приняли Нюрнбергские законы. Теперь евреи не могли вступать в брак с арийцами, были лишены политических и ряда социальных прав. Затем давление лишь усилилось: произошел запрет на профессии (например, банкира, адвоката), на право обучать детей вместе с немцами, на возможность посещения культурных мероприятий, сама собственность подлежала обязательной регистрации.

Происходило методичное вытеснение евреев из общественной жизни. Во-первых, они вытеснялись ментально посредством создания яркого негативного образа евреев как извечных врагов немцев, повинных во всех бедах Германии. Во-вторых, это было вытеснение социальное и юридическое, которое лишало представителей определенной этнической группы прав и положения в обществе. И только затем началось вытеснение пространственное. Это уже связано с периодом Второй мировой войны, когда на оккупированных территориях в 1939 г. и в начале 40-х гг. создавались крупные резервации евреев, т.н. гетто. Вскоре туда стали выселять евреев и из других европейских стран, включая Германию. Поначалу нацистский режим метался в поисках «окончательного решения» еврейского вопроса: то предполагалось сосредоточить всех евреев в районе Люблина, то – отвезти их на Мадагаскар. Все эти планы по разным обстоятельствам не реализовались. Гитлер хотел добиться двух целей: одна из них – ограбить евреев, а другая – уничтожить. Точно так же между идеологическим императивом тотального уничтожения и экономическими императивами (воюющей стране нужны дешевые рабочие руки) металась и вся нацистская система.

Выбор в пользу определенного решения был сделан во время войны против СССР, когда на местах стали уничтожать еврейское население. Вслед за армией двигались специальные части (айнзатцгруппы), на которые возлагалась ответственность по уничтожению партийных и советских работников, диверсантов и убийству евреев. Методы убийств были самыми жестокими: мужчин избивали, женщин насиловали, над согнанными евреями всячески издевались, после чего расстреливали, сваливая тела в специальных ямах. На детей и младенцев не тратили пули – просто убивали ударами прикладов или разбивая головы об деревья. Наиболее активными помощниками оказывались местные коллаборационисты. На территории Прибалтики и Украины они были ответственны наряду с гитлеровцами за большую часть убийств.

Массовые расстрелы были осуществлены 29-30 сентября 1941 г. в Киеве – на окраине под названием Бабий Яр. Здесь за несколько дней убили около 33 тыс. евреев (в дальнейшем тут же расстреливали подпольщиков, партизан, военнопленных и других «врагов рейха»). На территории современной России самая крупная антиеврейская акция была осуществлена в августе 1942 г. в Ростове-на-Дону, вернее, на его окраине – в Змиевской балке. Здесь были убиты более 10 тыс. евреев, а если считать всех жителей, погибших тут за период оккупации, то общая цифра, по официальным оценкам, достигает 27 тыс. человек.

Далеко не всех евреев убивали сразу. Большинство сгоняли в специально созданные гетто (около 1 000 по всему СССР). Евреев лишали собственности, заставляли работать на наиболее тяжелых, опасных и малооплачиваемых работах. По сравнению с остальным населением, привлеченным к работам, они получали меньше денег, имели меньше прав, жили в худших условиях.

Под влиянием событий на территории СССР уже осенью 1941 г. Гитлер принял окончательное решение об уничтожении всех европейских евреев. Технические детали об убийстве 12 млн человек были согласованы с ответственными партийными и государственными работниками 20 января 1942 г. на совещании (конференции) в Ванзее, которое и считается отправной точкой начала Холокоста. Для реализации этого решения на территории оккупированной Польши (генерал-губернаторство) были созданы три лагеря смерти – Белжец, Майданек и Собибор. Кроме того, с декабря 1941 г. функционировал еще один лагерь смерти в Хелмно (около Лодзи, территория Третьего Рейха), куда в основном отправлялись «лишние евреи» из Лодзинского гетто. В качестве лагерей смерти функционировали также концлагеря Майданек (в 1942-1944 гг.) и Аушвиц (вернее, его подразделение Аушвиц-2 – Биркенау).

Разница между концлагерем и лагерем смерти состояла в том, что первый существовал для того, чтобы заставить узников сначала работать (массовая смертность и намеренное уничтожение людей становились «побочным эффектом»), вторые изначально создавались для уничтожения. Узники не жили более 2 часов. Именно столько времени занимал путь от станции до газовой камеры. Временно в живых оставляли лишь единицы (для поддержания функционирования лагерей смерти). Как правило, перед депортациями (из городов или гетто) людям говорили, что их везут на работы, в семейные лагеря. Эту иллюзию поддерживали до самого последнего. Людей просили написать открытки родным или знакомым домой. Затем направляли на дезинфекцию (в концлагерях она представляла собою душ и обработку специальным раствором). При этом женщинам остригали волосы (их потом использовали частные фирмы для производства канатов или тканей). И только потом жертвы попадали в «душевые», где их травили газом, а трупы сжигали. Если, например, в Аушвице и Майданеке использовали сильнодействующий газ «Циклон Б», то в Собиборе – угарный газ от дизельного мотора. В Хелмно применялись газенвагены-душегубки: людей сажали в кузова грузовиков, и по пути на место сожжения трупов в лесу все они погибали, т.к. выхлопные газы шли внутрь грузовика. Крематории могли существовать параллельно с другими методами уничтожения трупов, например, сожжения на специальных кострах. Так, в Собиборе, где за 1,5 года убили 250 тыс. евреев, крематория вообще не было.

Для того чтобы убийцы морально не страдали от участия в расстрелах детей и женщин (после войны некоторые преступники напрямую заявляли, что именно они были «главными жертвами», т.к. испытывали мучения, убивая невинных), стали уже летом искать более «эффективные методы». Таковой нашелся в виде газа. «Инновацию» в виде газа «Циклон Б» впервые протестировали в Аушвице в конце августа 1941 г. Тогда погибли советские военнопленные. Методическая и рациональная организация убийств – вот, что больше всего поражало современников и потомков в этой истории. Для убийств тратились серьезные ресурсы. Даже летом 1944 г. нацистами были приложены большие усилия для того, чтобы сотни тысяч венгерских евреев отправились в газовые камеры Аушвица.

История Холокоста знает множество трагических и героических страниц. Как правило, речь идет либо об организации самой системы уничтожения, либо об актах сопротивления ей. Например, во всем мире знают о восстании в Варшавском гетто весной 1943 г. Тогда уже проводились массовые депортации из него в лагерь смерти Треблинка, и остававшиеся пока в живых евреи решили оказать сопротивление и умереть с честью. Меньше в мире знают о восстании в Белостокском гетто.

Только в последние годы стали уделять должное внимание подвигу в Собиборе. Именно здесь 14 октября 1943 г. состоялось единственное успешное восстание в лагерях смерти. Его поднял и возглавил советский военнопленный Александр Печерский. Да, в лагере, где около 600 заключенных временно были оставлены в живых для различных работ, существовало подполье во главе с Л. Фельдхендлером. Но оно не знало, как действовать. Прибытие в конце сентября 1943 г. советских евреев-военнопленных изменило ситуацию. На первый план выдвинулся А. А. Печерский, который принял принципиальное решение: восстание, а не побег. В случае выбора последнего мог бы спастись он с отдельными своими товарищами, однако остальные были обречены на смерть, которая незамедлительно бы последовала в качестве возмездия. Заговорщикам удалось убить значительное число эсэсовцев, а затем начать прорыв. Всего бежали около 300 человек. Немногим более 50 удалось дожить до конца войны. Остальных поймали или выдали местные жители. Однако удалось сделать главное: спасти человеческие жизни и отомстить (в ходе восстания убили 11 эсэсовцев и еще больше охранников из числа коллаборационистов). Более того, после восстания из Берлина пришел указ закрыть сам лагерь смерти Собибор и сровнять его с землей.

История восстания в Собиборе для нас сегодня важна и потому, что она позволяет подчеркнуть то, что очень часто остается за пределами дискуссий о Холокосте. Ведь помимо преступников и жертв была и третья сторона, та, которая несла освобождение. Холокост не был прекращен в один момент, эта машина остановилась не по желанию немцев, а после краха самой нацистской Германии. Краха, который был вызван не внутренними причинами, а внешними – давлением союзнических войск и прежде всего Красной Армии. Так, именно она начала счет освобожденным гетто (в декабре 1941 г. были выпущены узники гетто в Калуге). Именно ее боевой путь пролегал там, где находились все лагеря смерти. Например, в Майданеке последние расстрелы (несколько сотен человек) произошли летом 1944 г., за несколько дней до прихода Красной Армии. Когда 27 января 1945 г. был освобожден Аушвиц, туда были направлены сразу же два госпиталя для ухода за узниками. Этот список можно продолжать, ведь из 12 млн евреев, которых на совещании в Ванзее планировали уничтожить, успели убить только половину. Довольно легко представить, что могло произойти, если бы не было грандиозных побед под Сталинградом или Курском. Именно поэтому данная международная памятная дата имеет огромное значение для России. Холокост – это трагедия и российского народа (ведь почти половина всех уничтоженных евреев были советскими людьми), и одновременно одна из историй, подчеркивающая освободительный и спасительный для миллионов людей характер освободительной миссии Красной Армии.

Источник фото: РИА Новости

Международный день памяти жертв Холокоста отмечается ежегодно 27 января. В этот день в 1945 году Красная армия освободила крупнейший концентрационный лагерь нацистов Аушвиц-Биркенау, более известный в мире как Освенцим.

Как говорил президент Федерации еврейских общин России (ФЕОР) раввин Александр Борода, 27 января 1945 года связано не только с завершением проводимой гитлеровцами и их пособниками политики Холокоста в отношении евреев, но и с освобождением советскими солдатами узников концентрационных лагерей. Таким образом, дата напоминает о подвиге Красной армии, ее неоценимом вкладе в освобождении народов Европы из фашистского рабства.

Эта дата объединяет память о миллионах разных людей, о разных народах и об их общем подвиге

— отметил Борода.

Сам термин «холокост» означает политику властей Третьего рейха и их пособников из числа коллаборационистов в разных странах Европы, направленную на уничтожение этнических евреев. Фашистская Германия последовательно проводила ее с 1933 по 1945 год. За это время было уничтожено примерно шесть миллионов человек, в том числе полтора миллиона детей.

Как объявило Министерство просвещения России, с этого года Международный день памяти жертв Холокоста включен в школах нашей стране в календарный план воспитательной работы.

Вчера накануне печальной даты Генеральный секретарь ООН Антониу Гутерриш посетил одну из синагог Нью-Йорка, чтобы принять участие в памятных мероприятиях.

Давайте все вместе дадим обещание помнить о Холокосте и не допускать, чтобы о нем забывали другие

— призвал собравшихся глава пока еще самой влиятельной международной организации.

Редакция «Военного обозрения», как все нормальные люди планеты, скорбит по жертвам Холокоста и по всем, кто погиб от рук фашистов. Мы надеемся, что подобное больше никогда не повторится.

| The Holocaust | |

|---|---|

| Part of World War II | |

From the Auschwitz Album: Hungarian Jews arriving at Auschwitz II in German-occupied Poland, May 1944. Most were «selected» to go to the gas chambers. Camp prisoners are visible in their striped uniforms.[1] |

|

| Location | German Reich and German-occupied Europe |

| Description | Genocide of the European Jews |

| Date | 1941–1945[2] |

|

Attack type |

|

| Deaths | Around 6 million Jews |

| Perpetrators | Adolf Hitler Nazi Germany and its collaborators List of major perpetrators of the Holocaust |

| Motive |

|

| Trials | Nuremberg trials, Subsequent Nuremberg trials, Trial of Adolf Eichmann, and others |

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah,[a] was the genocide of European Jews during World War II.[b] Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe;[c] around two-thirds of Europe’s Jewish population.[d] The murders were carried out in pogroms and mass shootings; by a policy of extermination through labor in concentration camps; and in gas chambers and gas vans in German extermination camps, chiefly Auschwitz-Birkenau, Bełżec, Chełmno, Majdanek, Sobibór, and Treblinka in occupied Poland.[4]

Germany implemented the persecution in stages. Following Adolf Hitler’s appointment as chancellor on 30 January 1933, the regime built a network of concentration camps in Germany for political opponents and those deemed «undesirable», starting with Dachau on 22 March 1933.[5] After the passing of the Enabling Act on 24 March,[6] which gave Hitler dictatorial plenary powers, the government began isolating Jews from civil society; this included boycotting Jewish businesses in April 1933 and enacting the Nuremberg Laws in September 1935. On 9–10 November 1938, eight months after Germany annexed Austria, Jewish businesses and other buildings were ransacked or set on fire throughout Germany and Austria on what became known as Kristallnacht (the «Night of Broken Glass»). After Germany invaded Poland in September 1939, triggering World War II, the regime set up ghettos to segregate Jews. Eventually, thousands of camps and other detention sites were established across German-occupied Europe.

The segregation of Jews in ghettos culminated in the policy of extermination the Nazis called the Final Solution to the Jewish Question, discussed by senior government officials at the Wannsee Conference in Berlin in January 1942. As German forces captured territories in the East, all anti-Jewish measures were radicalized. Under the coordination of the SS, with directions from the highest leadership of the Nazi Party, killings were committed within Germany itself, throughout occupied Europe, and within territories controlled by Germany’s allies. Paramilitary death squads called Einsatzgruppen, in cooperation with the German Army and local collaborators, murdered around 1.3 million Jews in mass shootings and pogroms from the summer of 1941. By mid-1942, victims were being deported from ghettos across Europe in sealed freight trains to extermination camps where, if they survived the journey, they were gassed, worked or beaten to death, or killed by disease, starvation, cold, medical experiments, or during death marches. The killing continued until the end of World War II in Europe in May 1945.

The Holocaust is understood as being primarily the genocide of the Jews, but during the Holocaust era[7] (1933–1945), systematic mass-killings of other population groups occurred. These included Roma, Poles, Ukrainians, Soviet civilians and prisoners of war, and other targeted populations. Smaller groups were also victims of deadly Nazi persecution, such as Jehovah’s Witnesses, Black Germans, disabled people, communists, and homosexuals.[8][9]

Terminology and scope

Terminology

The first recorded use of the term holocaust in its modern sense was in 1895 by The New York Times to describe the massacre of Armenian Christians by Ottoman forces.[10] The term comes from the Greek: ὁλόκαυστος, romanized: holókaustos; ὅλος hólos, «whole» + καυστός kaustós, «burnt offering».[e] The biblical term shoah (Hebrew: שׁוֹאָה), meaning «calamity» (and also used to refer to «destruction» since the Middle Ages), became the standard Hebrew term for the murder of the European Jews. According to Haaretz, the writer Yehuda Erez may have been the first to describe events in Germany as the shoah. Davar and later Haaretz both used the term in September 1939.[12][f]

On 3 October 1941 the American Hebrew used the phrase «before the Holocaust», apparently to refer to the situation in France,[14] and in May 1943 the New York Times, discussing the Bermuda Conference, referred to the «hundreds of thousands of European Jews still surviving the Nazi Holocaust».[15] In 1968 the Library of Congress created a new category, «Holocaust, Jewish (1939–1945)».[16]

The term was popularised in the United States by the NBC mini-series Holocaust (1978) about a fictional family of German Jews,[17] and in November that year the President’s Commission on the Holocaust was established.[18] As non-Jewish groups began to include themselves as Holocaust victims, many Jews chose to use the Hebrew terms Shoah or Churban.[19][g] The Nazis used the phrase «Final Solution to the Jewish Question» (German: die Endlösung der Judenfrage).[21]

Definition

Holocaust historians commonly define the Holocaust as the genocide of the European Jews by Nazi Germany and its collaborators between 1941 and 1945.[b] Donald Niewyk and Francis Nicosia, in The Columbia Guide to the Holocaust (2000), favor a definition that includes the Jews, Roma, and disabled people: «the systematic, state-sponsored murder of entire groups determined by heredity».[28][h]

Other groups targeted after Hitler became Chancellor of Germany in January 1933[31] include those whom the Nazis viewed as inherently inferior (some Slavic people, particularly Poles and Russians,[32] the Roma, and the disabled), and those targeted because of their beliefs or behavior (such as Jehovah’s Witnesses, communists, and homosexuals).[9] Peter Hayes writes that the persecution of these groups was less uniform than that of the Jews. For example, the Nazis’ treatment of the Slavs consisted of «enslavement and gradual attrition», while some Slavs were favored; Hayes lists Bulgarians, Croats, Slovaks, and some Ukrainians.[33] In contrast, according to historian Dan Stone, Hitler regarded the Jews as «a Gegenrasse: a ‘counter-race’ … not really human at all».[8]

Distinctive features

Genocidal state

The logistics of the mass murder turned Germany into what Michael Berenbaum called a «genocidal state».[34] Eberhard Jäckel wrote in 1986 that it was the first time a state had thrown its power behind the idea that an entire people should be wiped out.[i] In total, 165,200 German Jews were murdered.[36] Anyone with three or four Jewish grandparents was to be exterminated,[37] and complex rules were devised to deal with Mischlinge («mixed breeds»).[38] Bureaucrats identified who was a Jew, confiscated property, and scheduled trains to deport them. Companies fired Jews and later used them as slave labor. Universities dismissed Jewish faculty and students. German pharmaceutical companies tested drugs on camp prisoners; other companies built the crematoria.[34] As prisoners entered the death camps, they surrendered all personal property,[39] which was cataloged and tagged before being sent to Germany for reuse or recycling.[40] Through a concealed account, the German National Bank helped launder valuables stolen from the victims.[41]

Medical experiments

The 23 defendants during the Doctors’ trial, Nuremberg, 9 December 1946 – 20 August 1947

At least 7,000 camp inmates were subjected to medical experiments; most died during them or as a result.[42] The experiments, which took place at Auschwitz, Buchenwald, Dachau, Natzweiler-Struthof, Neuengamme, Ravensbrück, and Sachsenhausen, sought to uncover strategies to counteract chemical weapons, survive harsh environments, develop new vaccines and drugs and treat wounds. Many men and women were also involuntarily sterilized.[42]

After the war, 23 senior physicians and other medical personnel were charged at Nuremberg with crimes against humanity. They included the head of the German Red Cross, tenured professors, clinic directors, and biomedical researchers.[43] The most notorious physician was Josef Mengele, an SS officer who became the Auschwitz camp doctor on 30 May 1943.[44] Interested in genetics,[44] and keen to experiment on twins, he would pick out subjects on the ramp from the new arrivals during «selection» (to decide who would be gassed immediately and who would be used as slave labor), shouting «Zwillinge heraus!» (twins step forward!).[45] The twins would be measured, killed, and dissected. One of Mengele’s assistants said in 1946 that he was told to send organs of interest to the directors of the «Anthropological Institute in Berlin-Dahlem». This is thought to refer to Mengele’s academic supervisor, Otmar Freiherr von Verschuer, director from October 1942 of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute of Anthropology, Human Heredity, and Eugenics in Berlin-Dahlem.[46][j]

Origins

Antisemitism and the völkisch movement

Throughout the Middle Ages in Europe, Jews were subjected to antisemitism based on Christian theology, which blamed them for killing Jesus. Even after the Reformation, Catholicism and Lutheranism continued to persecute Jews, accusing them of blood libels and subjecting them to pogroms and expulsions.[49] The second half of the 19th century saw the emergence, in the German empire and Austria-Hungary, of the völkisch movement, developed by such thinkers as Houston Stewart Chamberlain and Paul de Lagarde. The movement embraced a pseudo-scientific racism that viewed Jews as a race whose members were locked in mortal combat with the Aryan race for world domination.[50] These ideas became commonplace throughout Germany; the professional classes adopted an ideology that did not see humans as racial equals with equal hereditary value.[51] The Nazi Party (the Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or National Socialist German Workers’ Party) originated as an offshoot of the völkisch movement, and it adopted that movement’s antisemitism.[52]

Germany after World War I, Hitler’s world view

After World War I (1914–1918), many Germans did not accept that their country had been defeated. A stab-in-the-back myth developed, insinuating that disloyal politicians, chiefly Jews and communists, had orchestrated Germany’s surrender. Inflaming the anti-Jewish sentiment was the apparent over-representation of Jews in the leadership of communist revolutionary governments in Europe, such as Ernst Toller, head of a short-lived revolutionary government in Bavaria. This perception contributed to the canard of Jewish Bolshevism.[53]

Early antisemites in the Nazi Party included Dietrich Eckart, publisher of the Völkischer Beobachter, the party’s newspaper, and Alfred Rosenberg, who wrote antisemitic articles for it in the 1920s. Rosenberg’s vision of a secretive Jewish conspiracy ruling the world would influence Hitler’s views of Jews by making them the driving force behind communism.[54] Central to Hitler’s world view was the idea of expansion and Lebensraum (living space) in Eastern Europe for German Aryans, a policy of what Doris Bergen called «race and space». Open about his hatred of Jews, he subscribed to common antisemitic stereotypes.[55] From the early 1920s onwards, he compared the Jews to germs and said they should be dealt with in the same way. He viewed Marxism as a Jewish doctrine, said he was fighting against «Jewish Marxism», and believed that Jews had created communism as part of a conspiracy to destroy Germany.[56]

Rise of Nazi Germany

Dictatorship and repression (January 1933)

With the appointment in January 1933 of Adolf Hitler as Chancellor of Germany and the Nazi’s seizure of power, German leaders proclaimed the rebirth of the Volksgemeinschaft («people’s community»).[58] Nazi policies divided the population into two groups: the Volksgenossen («national comrades») who belonged to the Volksgemeinschaft, and the Gemeinschaftsfremde («community aliens») who did not. Enemies were divided into three groups: the «racial» or «blood» enemies, such as the Jews and Roma; political opponents of Nazism, such as Marxists, liberals, Christians, and the «reactionaries» viewed as wayward «national comrades»; and moral opponents, such as gay men, the work-shy, and habitual criminals. The latter two groups were to be sent to concentration camps for «re-education», with the aim of eventual absorption into the Volksgemeinschaft. «Racial» enemies could never belong to the Volksgemeinschaft; they were to be removed from society.[59]

Before and after the March 1933 Reichstag elections, the Nazis intensified their campaign of violence against opponents,[60] setting up concentration camps for extrajudicial imprisonment.[61] One of the first, at Dachau, opened on 22 March 1933.[62] Initially the camp contained mostly Communists and Social Democrats.[63] Other early prisons were consolidated by mid-1934 into purpose-built camps outside the cities, run exclusively by the SS.[64] The camps served as a deterrent by terrorizing Germans who did not support the regime.[65]

Throughout the 1930s, the legal, economic, and social rights of Jews were steadily restricted.[66] On 1 April 1933, there was a boycott of Jewish businesses.[67] On 7 April 1933, the Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service was passed, which excluded Jews and other «non-Aryans» from the civil service.[68] Jews were disbarred from practicing law, being editors or proprietors of newspapers, joining the Journalists’ Association, or owning farms.[69] In Silesia, in March 1933, a group of men entered the courthouse and beat up Jewish lawyers; Friedländer writes that, in Dresden, Jewish lawyers and judges were dragged out of courtrooms during trials.[70] Jewish students were restricted by quotas from attending schools and universities.[68] Jewish businesses were targeted for closure or «Aryanization», the forcible sale to Germans; of the approximately 50,000 Jewish-owned businesses in Germany in 1933, about 7,000 were still Jewish-owned in April 1939. Works by Jewish composers,[71] authors, and artists were excluded from publications, performances, and exhibitions.[72] Jewish doctors were dismissed or urged to resign. The Deutsches Ärzteblatt (a medical journal) reported on 6 April 1933: «Germans are to be treated by Germans only.»[73]

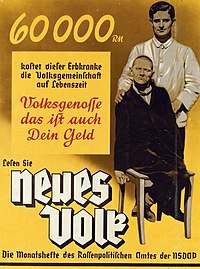

Sterilization Law, Aktion T4

The poster (c. 1937) reads: «60,000 RM is what this person with hereditary illness costs the community in his lifetime. Fellow citizen, that is your money too. Read Neues Volk, the monthly magazine of the Office of Racial Policy of the Nazi Party.»[74]

The economic strain of the Great Depression led Protestant charities and some members of the German medical establishment to advocate compulsory sterilization of the «incurable» mentally and physically disabled,[75] people the Nazis called Lebensunwertes Leben (life unworthy of life).[76] On 14 July 1933, the Law for the Prevention of Hereditarily Diseased Offspring (Gesetz zur Verhütung erbkranken Nachwuchses), the Sterilization Law, was passed.[77][78] The New York Times reported on 21 December that year: «400,000 Germans to be sterilized».[79] There were 84,525 applications from doctors in the first year. The courts reached a decision in 64,499 of those cases; 56,244 were in favor of sterilization.[80] Estimates for the number of involuntary sterilizations during the whole of the Third Reich range from 300,000 to 400,000.[81]

In October 1939 Hitler signed a «euthanasia decree» backdated to 1 September 1939 that authorized Reichsleiter Philipp Bouhler, the chief of Hitler’s Chancellery, and Karl Brandt, Hitler’s personal physician, to carry out a program of involuntary euthanasia. After the war this program came to be known as Aktion T4,[82] named after Tiergartenstraße 4, the address of a villa in the Berlin borough of Tiergarten, where the various organizations involved were headquartered.[83] T4 was mainly directed at adults, but the euthanasia of children was also carried out.[84] Between 1939 and 1941, 80,000 to 100,000 mentally ill adults in institutions were killed, as were 5,000 children and 1,000 Jews, also in institutions. There were also dedicated killing centers, where the deaths were estimated at 20,000, according to Georg Renno, deputy director of Schloss Hartheim, one of the euthanasia centers, or 400,000, according to Frank Zeireis, commandant of the Mauthausen concentration camp.[85] Overall, the number of mentally and physically disabled people murdered was about 150,000.[86]

Although not ordered to take part, psychiatrists and many psychiatric institutions were involved in the planning and carrying out of Aktion T4.[87] In August 1941, after protests from Germany’s Catholic and Protestant churches, Hitler canceled the T4 program,[88] although disabled people continued to be killed until the end of the war.[86] The medical community regularly received bodies for research; for example, the University of Tübingen received 1,077 bodies from executions between 1933 and 1945. The German neuroscientist Julius Hallervorden received 697 brains from one hospital between 1940 and 1944: «I accepted these brains of course. Where they came from and how they came to me was really none of my business.»[89]

Nuremberg Laws, Jewish emigration

Czechoslovakian Jews at Croydon airport, England, 31 March 1939, before deportation[90]

On 15 September 1935, the Reichstag passed the Reich Citizenship Law and the Law for the Protection of German Blood and German Honor, known as the Nuremberg Laws. The former said that only those of «German or kindred blood» could be citizens. Anyone with three or more Jewish grandparents was classified as a Jew.[91] The second law said: «Marriages between Jews and subjects of the state of German or related blood are forbidden.» Sexual relationships between them were also criminalized; Jews were not allowed to employ German women under the age of 45 in their homes.[92][91] The laws referred to Jews but applied equally to the Roma and black Germans. Although other European countries—Bulgaria, Independent State of Croatia, Hungary, Italy, Romania, Slovakia, and Vichy France—passed similar legislation,[91] Gerlach notes that «Nazi Germany adopted more nationwide anti-Jewish laws and regulations (about 1,500) than any other state.»[93]

By the end of 1934, 50,000 German Jews had left Germany,[94] and by the end of 1938, approximately half the German Jewish population had left,[95] among them the conductor Bruno Walter, who fled after being told that the hall of the Berlin Philharmonic would be burned down if he conducted a concert there.[96] Albert Einstein, who was in the United States when Hitler came to power, never returned to Germany; his citizenship was revoked and he was expelled from the Kaiser Wilhelm Society and Prussian Academy of Sciences.[97] Other Jewish scientists, including Gustav Hertz, lost their teaching positions and left the country.[98]

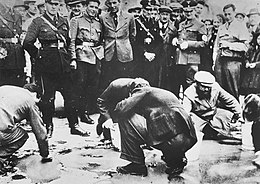

Anschluss (12 March 1938)

March or April 1938: Jews are forced to scrub the pavement in Vienna, Austria.

On 12 March 1938, Germany annexed Austria. Ninety percent of Austria’s 176,000 Jews lived in Vienna.[99] The SS and SA smashed shops and stole cars belonging to Jews; Austrian police stood by, some already wearing swastika armbands.[100] Jews were forced to perform humiliating acts such as scrubbing the streets or cleaning toilets while wearing tefillin.[101] Around 7,000 Jewish businesses were «Aryanized», and all the legal restrictions on Jews in Germany were imposed in Austria.[102] The Évian Conference was held in France in July 1938 by 32 countries, to help German and Austrian Jewish refugees, but little was accomplished and most countries did not increase the number of refugees they would accept.[103] In August that year, Adolf Eichmann was appointed manager (under Franz Walter Stahlecker) of the Central Agency for Jewish Emigration in Vienna (Zentralstelle für jüdische Auswanderung in Wien).[104] Sigmund Freud and his family arrived in London from Vienna in June 1938, thanks to what David Cesarani called «Herculean efforts» to get them out.[105]

Kristallnacht (9–10 November 1938)

Potsdamer Straße 26, Berlin, the day after Kristallnacht, November 1938

On 7 November 1938, Herschel Grynszpan, a Polish Jew, shot the German diplomat Ernst vom Rath in the German Embassy in Paris, in retaliation for the expulsion of his parents and siblings from Germany.[106][k] When vom Rath died on 9 November, the synagogue and Jewish shops in Dessau were attacked. According to Joseph Goebbels’ diary, Hitler decided that the police should be withdrawn: «For once the Jews should feel the rage of the people,» Goebbels reported him as saying.[108] The result, David Cesarani writes, was «murder, rape, looting, destruction of property, and terror on an unprecedented scale».[109]

Known as Kristallnacht («Night of Broken Glass»), the pogrom on 9–10 November 1938 saw over 7,500 Jewish shops (out of 9,000) looted and attacked, and over 1,000 synagogues damaged or destroyed. Groups of Jews were forced by the crowd to watch their synagogues burn; in Bensheim they were made to dance around it and in Laupheim to kneel before it.[110] At least 90 Jews were murdered. The damage was estimated at 39 million Reichsmark.[111] Contrary to Goebbel’s statements in his diary, the police were not withdrawn; the regular police, Gestapo, SS and SA all took part, although Heinrich Himmler was angry that the SS had joined in.[112] Attacks took place in Austria too.[113] The extent of the violence shocked the rest of the world. The Times of London stated on 11 November 1938:

No foreign propagandist bent upon blackening Germany before the world could outdo the tale of burnings and beatings, of blackguardly assaults upon defenseless and innocent people, which disgraced that country yesterday. Either the German authorities were a party to this outbreak or their powers over public order and a hooligan minority are not what they are proudly claimed to be.[114]

Between 9 and 16 November, 30,000 Jews were sent to the Buchenwald, Dachau, and Sachsenhausen concentration camps.[115] Many were released within weeks; by early 1939, 2,000 remained in the camps.[116] German Jewry was held collectively responsible for restitution of the damage; they also had to pay an «atonement tax» of over a billion Reichsmark. Insurance payments for damage to their property were confiscated by the government. A decree on 12 November 1938 barred Jews from most remaining occupations.[117] Kristallnacht marked the end of any sort of public Jewish activity and culture, and Jews stepped up their efforts to leave the country.[118]

Resettlement

Before World War II, Germany considered mass deportation from Europe of German, and later European, Jewry.[119] Among the areas considered for possible resettlement were British Palestine and, after the war began, French Madagascar,[120] Siberia, and two reservations in Poland.[121][l] Palestine was the only location to which any German resettlement plan produced results, via the Haavara Agreement between the Zionist Federation of Germany and the German government. Between November 1933 and December 1939, the agreement resulted in the emigration of about 53,000 German Jews, who were allowed to transfer RM 100 million of their assets to Palestine by buying German goods, in violation of the Jewish-led anti-Nazi boycott of 1933.[123]

Outbreak of World War II

Invasion of Poland (1 September 1939)

Ghettos

Between 2.7 and 3 million Polish Jews were murdered during the Holocaust, out of a population of 3.3 – 3.5 million.[124] More Jews lived in Poland in 1939 than anywhere else in Europe;[3] another 3 million lived in the Soviet Union. When the German Wehrmacht (armed forces) invaded Poland on 1 September 1939, triggering declarations of war from the UK and France, Germany gained control of about two million Jews in the territory it occupied. The rest of Poland was occupied by the Soviet Union, which invaded Poland from the east on 17 September 1939.[125]

Jews in the Warsaw Ghetto march to the Umschlagplatz before being sent to a camp, April or May 1943.

The Wehrmacht in Poland was accompanied by seven SS Einsatzgruppen der Sicherheitspolitizei («special task forces of the Security Police») and an Einsatzkommando, numbering 3,000 men in all, whose role was to deal with «all anti-German elements in hostile country behind the troops in combat».[126] German plans for Poland included expelling non-Jewish Poles from large areas, settling Germans on the emptied lands,[127] sending the Polish leadership to camps, denying the lower classes an education, and confining Jews.[128] The Germans sent Jews from all territories they had annexed (Austria, the Czech lands, and western Poland) to the central section of Poland, which was termed the General Government.[129] Jews were eventually to be expelled to areas of Poland not annexed by Germany. Still, in the meantime, they would be concentrated in major cities ghettos to achieve, according to an order from Reinhard Heydrich dated 21 September 1939, «a better possibility of control and later deportation».[130][m] From 1 December, Jews were required to wear Star of David armbands.[129]

The Germans stipulated that each ghetto be led by a Judenrat of 24 male Jews, who would be responsible for carrying out German orders.[132] These orders included, from 1942, facilitating deportations to extermination camps.[133] The Warsaw Ghetto was established in November 1940, and by early 1941 it contained 445,000 people;[134] the second largest, the Łódź Ghetto, held 160,000 as of May 1940.[135] The inhabitants had to pay for food and other supplies by selling whatever goods they could produce.[134] In the ghettos and forced-labor camps, at least half a million died of starvation, disease, and poor living conditions.[136] Although the Warsaw Ghetto contained 30 percent of the city’s population, it occupied only 2.4 percent of its area,[137] averaging over nine people per room.[138] Over 43,000 residents died there in 1941.[139]

Pogroms in occupied eastern Poland

Peter Hayes writes that the Germans created a «Hobbesian world» in Poland in which different parts of the population were pitted against each other.[141] A perception among ethnic Poles that the Jews had supported the Soviet invasion[142] contributed to existing antisemitism,[143] which Germany exploited, redistributing Jewish homes and goods, and converting synagogues, schools and hospitals in Jewish areas into facilities for non-Jews.[144] The Germans ordered the death penalty for anyone helping Jews. Informants pointed out who was Jewish and the Poles who were helping to hide them[145] during the Judenjagd (hunt for the Jews).[146] Despite the dangers, thousands of Poles helped Jews.[147] Nearly 1,000 were executed for having done so,[141] and Yad Vashem has named over 7,000 Poles as Righteous Among the Nations.[148]

Pogroms occurred throughout the occupation. During the Lviv pogroms in Lwów, occupied eastern Poland (later Lviv, Ukraine)[n] in June and July 1941—the population was 157,490 Polish; 99,595 Jewish; and 49,747 Ukrainian[149]—some 6,000 Jews were murdered in the streets by the Ukrainian nationalists (specifically, the OUN)[150] and Ukrainian People’s Militia, aided by local people.[151] Jewish women were stripped, beaten, and raped.[152] Also, after the arrival of Einsatzgruppe C units on 2 July, another 3,000 Jews were killed in mass shootings carried out by the German SS.[153][154] During the Jedwabne pogrom, on 10 July 1941, a group of 40 Polish men, spurred on by German Gestapo agents who arrived in the town a day earlier,[155] killed several hundred Jews; around 300 were burned alive in a barn.[156] According to Hayes, this was «one of sixty-six nearly simultaneous such attacks in the province of Suwałki alone and some two hundred similar incidents in the Soviet-annexed eastern provinces».[142]

German Nazi Extermination camps in Poland

Jews arrive with their belongings at the Auschwitz II extermination camp, summer 1944, thinking they were being resettled.

At the end of 1941, the Germans began building extermination camps in Poland: Auschwitz II,[157] Bełżec,[158] Chełmno,[159] Majdanek,[160] Sobibór,[161] and Treblinka.[162] Gas chambers had been installed by the spring or summer of 1942.[163] The SS liquidated most of the ghettos of the General Government area in 1942–1943 (the Łódź Ghetto was liquidated in mid-1944),[164] and shipped their populations to these camps, along with Jews from all over Europe.[165][o] The camps provided locals with employment and with black-market goods confiscated from Jewish families who, thinking they were being resettled, arrived with their belongings. According to Hayes, dealers in currency and jewellery set up shop outside the Treblinka extermination camp (near Warsaw) in 1942–1943, as did prostitutes.[144] By the end of 1942, most of the Jews in the General Government area were dead.[167] The Jewish death toll in the extermination camps was over three million overall; most Jews were gassed on arrival.[168]

Invasion of Norway and Denmark

Germany invaded Norway and Denmark on 9 April 1940, during Operation Weserübung. Denmark was overrun so quickly that there was no time for a resistance to form. Consequently, the Danish government stayed in power and the Germans found it easier to work through it. Because of this, few measures were taken against the Danish Jews before 1942.[169] By June 1940 Norway was completely occupied.[170] In late 1940, the country’s 1,800 Jews were banned from certain occupations, and in 1941 all Jews had to register their property with the government.[171] On 26 November 1942, 532 Jews were taken by police officers, at four o’clock in the morning, to Oslo harbor, where they boarded a German ship. From Germany they were sent by freight train to Auschwitz. According to Dan Stone, only nine survived the war.[172]

Invasion of France and the Low Countries

In May 1940, Germany invaded the Netherlands, Luxembourg, Belgium, and France. After Belgium’s surrender, the country was ruled by a German military governor, Alexander von Falkenhausen, who enacted anti-Jewish measures against its 90,000 Jews, many of them refugees from Germany or Eastern Europe.[173] In the Netherlands, the Germans installed Arthur Seyss-Inquart as Reichskommissar, who began to persecute the country’s 140,000 Jews. Jews were forced out of their jobs and had to register with the government. In February 1941, non-Jewish Dutch citizens staged a strike in protest that was quickly crushed.[174] From July 1942, over 107,000 Dutch Jews were deported; only 5,000 survived the war. Most were sent to Auschwitz; the first transport of 1,135 Jews left Holland for Auschwitz on 15 July 1942. Between 2 March and 20 July 1943, 34,313 Jews were sent in 19 transports to the Sobibór extermination camp, where all but 18 are thought to have been gassed on arrival.[175]

France had approximately 330,000 Jews, divided between the German-occupied north and the unoccupied collaborationist southern areas in Vichy France (named after the town Vichy), more than half this Jewish population were not French citizens, but refugees who had fled Nazi persecution in other countries. The occupied regions were under the control of a military governor, and there, anti-Jewish measures were not enacted as quickly as they were in the Vichy-controlled areas.[176] In July 1940, the Jews in the parts of Alsace-Lorraine that had been annexed to Germany were expelled into Vichy France.[177] Vichy France’s government implemented anti-Jewish measures in Metropolitan France, in French Algeria and in the two French Protectorates of Tunisia and Morocco.[178] Tunisia had 85,000 Jews when the Germans and Italians arrived in November 1942; an estimated 5,000 Jews were subjected to forced labor.[179] The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum estimates that between 72,900 and 74,000 Jews were murdered during the Holocaust in France.[36]

Madagascar Plan

The fall of France gave rise to the Madagascar Plan in the summer of 1940, when French Madagascar in Southeast Africa became the focus of discussions about deporting all European Jews there; it was thought that the area’s harsh living conditions would hasten deaths.[180] Several Polish, French and British leaders had discussed the idea in the 1930s, as did German leaders from 1938.[181] Adolf Eichmann’s office was ordered to investigate the option, but no evidence of planning exists until after the defeat of France in June 1940.[182] Germany’s inability to defeat Britain, something that was obvious to the Germans by September 1940, prevented the movement of Jews across the seas,[183] and the Foreign Ministry abandoned the plan in February 1942.[184]

Invasion of Yugoslavia and Greece

Greek Jews from Saloniki are forced to exercise or dance, July 1942.

Yugoslavia and Greece were invaded in April 1941 and surrendered before the end of the month. Germany, Italy and Bulgaria divided Greece into occupation zones but did not eliminate it as a country. The pre-war Greek Jewish population had been between 72,000 and 77,000. By the end of the war, some 10,000 remained, representing the lowest survival rate in the Balkans and among the lowest in Europe.[185]

Yugoslavia, home to 80,000 Jews, was dismembered; regions in the north were annexed by Germany and Hungary, regions along the coast were made part of Italy, Kosovo and western Macedonia were given to Albania, while Bulgaria received eastern Macedonia. The rest of the country was divided into the Independent State of Croatia (NDH), an Italian-German puppet state whose territory comprised Croatia and Bosnia-Herzegovina, with the Croatian fascist Ustaše party placed in power; and German occupied Serbia, governed by German military and police administrators[186] who appointed the Serbian collaborationist puppet government, Government of National Salvation, headed by Milan Nedić.[187][188][189] In August 1942 Serbia was declared free of Jews,[190] after the Wehrmacht and German police, assisted by collaborators of the Nedić government and others such as Zbor, a pro-Nazi and pan-Serbian fascist party, had murdered nearly the entire population of 17,000 Jews.[187][188][189]

In the Independent State of Croatia (NDH), the Nazi regime demanded that its rulers, the Ustaše, adopt antisemitic racial policies, persecute Jews and set up several concentration camps. NDH leader Ante Pavelić and the Ustaše accepted Nazi demands. By the end of April 1941 the Ustaše required all Jews to wear insignia, typically a yellow Star of David[191] and started confiscating Jewish property in October 1941.[192] During the same time as their persecution of Serbs and Roma, the Ustaše took part in the Holocaust, and killed the majority of the country’s Jews;[193] the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum estimates that 30,148 Jews were murdered.[36] According to Jozo Tomasevich, the Jewish community in Zagreb was the only one to survive out of 115 Jewish religious communities in Yugoslavia in 1939–1940.[194]

The state broke away from Nazi antisemitic policy by promising honorary Aryan citizenship, and thus freedom from persecution, to Jews who were willing to contribute to the «Croat cause». Marcus Tanner states that the «SS complained that at least 5,000 Jews were still alive in the NDH and that thousands of others had emigrated, by buying ‘honorary Aryan’ status».[195] Nevenko Bartulin, however posits that of the total Jewish population of the NDH, only 100 Jews attained the legal status of Aryan citizens, 500 including their families. In both cases a relatively small portion out of a Jewish population of 37,000.[196]

In the Bulgarian annexed zones of Macedonia and Thrace, upon demand of the German authorities, the Bulgarians handed over the entire Jewish population, about 12,000 Jews to the military authorities, all were deported.[197]

Invasion of the Soviet Union (22 June 1941)

Reasons

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

Germany invaded the Soviet Union on 22 June 1941, a day Timothy Snyder called «one of the most significant days in the history of Europe … the beginning of a calamity that defies description».[198] German propaganda portrayed the conflict as an ideological war between German National Socialism and Jewish Bolshevism, and as a racial war between the Germans and the Jewish, Romani, and Slavic Untermenschen («sub-humans»).[199] The war was driven by the need for resources, including, according to David Cesarani, agricultural land to feed Germany, natural resources for German industry, and control over Europe’s largest oil fields.[200]

Between early fall 1941 and late spring 1942, Jürgen Matthäus writes, 2 million of the 3.5 million Soviet POWs captured by the Wehrmacht had been executed or had died of neglect and abuse. By 1944 the Soviet death toll was at least 20 million.[201]

Mass shootings

As the method of widespread execution was shooting rather than gas chamber, the Holocaust in the Soviet Union is sometimes referred to as the Holocaust by bullets.

As German troops advanced, the mass shooting of «anti-German elements» was assigned, as in Poland, to the Einsatzgruppen, this time under the command of Reinhard Heydrich.[202] The point of the attacks was to destroy the local Communist Party leadership and therefore the state, including «Jews in the Party and State employment», and any «radical elements».[p] Cesarani writes that the killing of Jews was at this point a «subset» of these activities.[204]

Typically, victims would undress and give up their valuables before lining up beside a ditch to be shot, or they would be forced to climb into the ditch, lie on a lower layer of corpses, and wait to be killed.[205] The latter was known as Sardinenpackung («packing sardines»), a method reportedly started by SS officer Friedrich Jeckeln.[206]

According to Wolfram Wette, the German army took part in these shootings as bystanders, photographers, and active shooters.[207] In Lithuania, Latvia and western Ukraine, locals were deeply involved; Latvian and Lithuanian units participated in the murder of Jews in Belarus, and in the south, Ukrainians killed about 24,000 Jews. Some Ukrainians went to Poland to serve as guards in the camps.[208]

Einsatzgruppe A arrived in the Baltic states (Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania) with Army Group North; Einsatzgruppe B in Belarus with Army Group Center; Einsatzgruppe C in Ukraine with Army Group South; and Einsatzgruppe D went further south into Ukraine with the 11th Army.[209] Each Einsatzgruppe numbered around 600–1,000 men, with a few women in administrative roles.[210] Traveling with nine German Order Police battalions and three units of the Waffen-SS,[211] the Einsatzgruppen and their local collaborators had murdered almost 500,000 people by the winter of 1941–1942. By the end of the war, they had killed around two million, including about 1.3 million Jews and up to a quarter of a million Roma.[212]

Notable massacres include the July 1941 Ponary massacre near Vilnius (Soviet Lithuania), in which Einsatgruppe B and Lithuanian collaborators shot at least 70,000 Jews, 20,000 Poles and 8,000 Russians.[213] In the Kamianets-Podilskyi massacre (Soviet Ukraine), nearly 24,000 Jews were killed between 27 and 30 August 1941.[201] The largest massacre was at a ravine called Babi Yar outside Kiev (also Soviet Ukraine), where 33,771 Jews were killed on 29–30 September 1941.[214][215] The Germans used the ravine for mass killings throughout the war; up to 100,000 may have been killed there.[216]

Toward the Holocaust

At first the Einsatzgruppen targeted the male Jewish intelligentsia, defined as male Jews aged 15–60 who had worked for the state and in certain professions. The commandos described them as «Bolshevist functionaries» and similar. From August 1941 they began to murder women and children too.[218] Christopher Browning reports that on 1 August 1941, the SS Cavalry Brigade passed an order to its units: «Explicit order by RF-SS [Heinrich Himmler, Reichsführer-SS]. All Jews must be shot. Drive the female Jews into the swamps.»[219]

Two years later, in a speech on 6 October 1943 to party leaders, Heinrich Himmler said he had ordered that women and children be shot, but according to Peter Longerich and Christian Gerlach, the murder of women and children began at different times in different areas, suggesting local influence.[220]

Historians agree that there was a «gradual radicalization» between the spring and autumn of 1941 of what Longerich calls Germany’s Judenpolitik, but they disagree about whether a decision—Führerentscheidung (Führer’s decision)—to murder the European Jews had been made at this point.[221][q] According to Browning, writing in 2004, most historians say there was no order, before the invasion of the Soviet Union, to kill all the Soviet Jews.[223] Longerich wrote in 2010 that the gradual increase in brutality and numbers killed between July and September 1941 suggests there was «no particular order». Instead, it was a question of «a process of increasingly radical interpretations of orders».[224]

Concentration and labor camps

Germany first used concentration camps as places of terror and unlawful incarceration of political opponents.[226] Large numbers of Jews were not sent there until after Kristallnacht in November 1938.[227] After war broke out in 1939, new camps were established, many outside Germany in occupied Europe.[228] Most wartime prisoners of the camps were not Germans but belonged to countries under German occupation.[229]

After 1942, the economic function of the camps, previously secondary to their penal and terror functions, came to the fore. Forced labor of camp prisoners became commonplace.[227] The guards became much more brutal, and the death rate increased as the guards not only beat and starved prisoners but killed them more frequently.[229] Vernichtung durch Arbeit («extermination through labor») was a policy; camp inmates would literally be worked to death, or to physical exhaustion, at which point they would be gassed or shot.[230] The Germans estimated the average prisoner’s lifespan in a concentration camp at three months, as a result of lack of food and clothing, constant epidemics, and frequent punishments for the most minor transgressions.[231] The shifts were long and often involved exposure to dangerous materials.[232]

Transportation to and between camps was often carried out in closed freight cars with little air or water, long delays and prisoners packed tightly.[233] In mid-1942 work camps began requiring newly arrived prisoners to be placed in quarantine for four weeks.[234] Prisoners wore colored triangles on their uniforms, the color denoting the reason for their incarceration. Red signified a political prisoner, Jehovah’s Witnesses had purple triangles, «asocials» and criminals wore black and green, and gay men wore pink.[235] Jews wore two yellow triangles, one over another to form a six-pointed star.[236] Prisoners in Auschwitz were tattooed on arrival with an identification number.[237]

Germany’s allies

Romania

Bodies being pulled out of a train carrying Romanian Jews from the Iași pogrom, July 1941

Romania ranks first among Holocaust perpetrator countries other than Germany.[238] Romanian antisemitic legislation was not an attempt to placate the Germans, but rather entirely home-grown, preceding German hegemony and Nazi Germany itself. The ascendance of Germany enabled Romania to disregard the minorities treaties that were imposed upon the country after the First World War. Antisemitic legislation in Romania was usually aimed at exploiting Jews rather than humiliating them as in Germany.[239]

At the end of 1937, the Government of Octavian Goga came to power, Romania thus becoming the second overtly antisemitic state in Europe.[240][241] Romania was the second country in Europe after Germany to enact antisemitic legislation, and the only one besides Germany to do so before the 1938 Anschluss.[242][243] Romania was the only country other than Germany itself that «implemented all the steps of the destruction process, from definitions to killings.»[244][245]

According to Dan Stone, the murder of Jews in Romania was «essentially an independent undertaking».[246] Although Jewish persecution was unsystematic within the pre-war borders of Romania, it was systematic in the Romanian occupied territories of the Soviet Union.[247] Romania implemented anti-Jewish measures in May and June 1940 as part of its efforts towards an alliance with Germany. By March 1941 all Jews had lost their jobs and had their property confiscated.[248] In June 1941 Romania joined Germany in its invasion of the Soviet Union and within the first few weeks of the invasion, almost the entire rural Jewish population of Bessarabia and Bukovina were decimated.[247][249]