Недавно мы рассказывали о современных хиппи, их философии, мировоззрении и самых известных коммунах и поселениях, куда можно приехать и поближе познакомиться с культурой “детей цветов”.

Единение с природой, жизнь в мире и согласии и любовь к свободе и творческому самовыражению – основные принципы идеологии хиппи – воплотились в традиции проведения музыкальных фестивалей, зародившейся в 1966 году. О самых крупных и известных из них мы расскажем в этой статье.

Содержание

- Bonnaroo Music Festival

- Burning Man

- Oregon Country Fair

- Starwood Festival

- Rainbow Gathering

- Российская радуга

- Mystic Rising

- Electric Forest

- Beloved Festival

- Shangri-La

- Gathering of the Vibes

Содержание

- Bonnaroo Music Festival

- Burning Man

- Oregon Country Fair

- Starwood Festival

- Rainbow Gathering

- Российская радуга

- Mystic Rising

- Electric Forest

- Beloved Festival

- Shangri-La

- Gathering of the Vibes

Bonnaroo Music Festival

Bonnaroo Music and Arts Festival – ежегодный четырехдневный фестиваль под открытым небом, который проходит с 2002 года на территории Грэйт Стейдж Парк в Манчестере (Теннесси, США). Фестиваль традиционно начинается во второй четверг июня. На нескольких сценах с полудня и до рассвета проходят концерты живой музыки самых разных жанров: инди-рок, хип-хоп, джаз, американа, кантри, фолк, госпел, регги, поп – список можно продолжать.

За годы существования фестиваля на его сцене выступали такие легенды музыки, как Red Hot Chili Peppers, Radiohead, Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers, Phish, Bob Dylan, Willie Nelson и многие другие. В перерывах между концертами скучать тоже не приходится: можно посетить ярмарку ремесел и приобрести товары, изготовленные своими руками, принять участие в многочисленных воркшопах или позаниматься йогой, сходить на дискотеку или посмотреть кино и даже покататься на колесе обозрения. Ежегодно фестиваль принимает около 100 тысяч гостей.

По теме: Экопоселения: европейский опыт

Burning Man

Burning Man – ежегодный фестиваль, проходящий в пустыне Блэк-Рок, штат Невада.

Это социальный и художественный эксперимент, основы которого заложены в 10 главных принципах, включающих “радикальную” вовлеченность в жизнь сообщества, самостоятельность и самовыражение, кооперацию и уменьшение ущерба для окружающей среды.

Впервые фестиваль прошел в 1986 году на Baker Beach в Сан-Франциско – тогда это было совсем небольшое мероприятие, организованное Ларри Харви с группой единомышленников. С тех пор он проводится ежегодно между последним воскресеньем августа и первым понедельником сентября: так, Burning Man 2016 прошел с 28 августа до 5 сентября.

Burning Man – современное выражение альтернативной культуры, близкое по духу к мероприятиям хиппи. Фестиваль ежегодно превращает участок пустыни в настоящий город с причудливыми кемпингами, арт-объектами и художественно оформленными транспортными средствами. Участники выражают свою индивидуальность через необычные и яркие костюмы, частью которых практически всегда становятся защитная маска и очки – в пустыне нередки песчаные бури.

По слухам, с Burning man связана идея выкупа 4000 акров земли и образования на этой территории постоянной коммуны, живущей по принципам и законам фестиваля. Некоторые источники называют в качестве инициаторов изобретателя Илона Маска и основателя Google Сергея Брина. Таким образом, у ежегодного мероприятия есть все шансы однажды превратиться в бесконечный праздник.

Oregon Country Fair

“Хиппи не исчезли – они просто переехали в Орегон” – так говорят в этом штате, где хиппи чуть ли не больше, чем остального населения, а отношение к ним самое дружелюбное. Особого внимания заслуживает город Юджин, в свое время ставший вторым домом для легендарной рок-группы Grateful Dead.

В Юджине провел свои студенческие годы и называл его своим родным городом Кен Кизи, которому здесь установлен памятник. Скульптурная композиция «Рассказчик» (Storyteller) изображает Кизи читающим книгу своим внукам.

В окрестностях города Венета, в 15 милях к западу от Юджина, каждый год проходит одно из главных событий хиппи – Oregon Country Fair (OCF) – трехдневная ярмарка, история которой началась с расцветом движения хиппи – в 1969 году. Организованная для сбора средств для школы, костюмированная ярмарка превратилась в центр альтернативного искусства и представлений, а в 1972 и 1982 годы принимала концерты Grateful Dead.

Oregon Country Fair традиционно проходит во второй уикенд июля. Здесь можно посмотреть выступления музыкантов, артистов и фокусников, попробовать вкуснейшую экологическую еду, а также приобрести сувениры, украшения и предметы искусства, сделанные своими руками.

Каждый год мероприятие, известное своей контркультурной направленностью и заботой об окружающей среде, посещает более 45 тысяч людей.

Starwood Festival

The Starwood Festival – семидневный неоязыческий фестиваль, посвященный культурному разнообразию, альтернативному образу жизни, духовным практикам и верованиям.

В 2016 году мероприятие прошло 12-18 июля на территории Wisteria Campground and Event Site в городе Померой, Огайо.

Участники живут в кемпинге и участвуют во множестве воркшопов, классов и церемоний под руководством известных преподавателей. Воркшопы делятся на пять групп: «Новые рубежи», «Магия и дух», «Музыка, ритм и движение», «Ремесло и творчество», «Здоровье и исцеление» и включают в себя как эзотерические руководства, так и неожиданно прагматичные курсы вроде «Создания собственного бизнеса».

Также проводятся музыкальные live-концерты местных талантов и исполнителей мирового уровня. Неделю танцев, игры на барабане и других инструментах, презентаций и прочих мероприятий, не последнее место среди которых занимает общение и обмен опытом с самыми необычными людьми, увенчивает костер, который традиционно собирает вокруг себя участников фестиваля в субботнюю ночь.

Rainbow Gathering

Rainbow Gathering – ежегодное собрание единомышленников во многих странах мира. Они следуют идеалам мира, любви, уважения, гармонии, свободы и человеческого единства и позиционируют себя как альтернативу потребительскому обществу, капитализму и господству масс-медиа. Примкнуть к «Семье Радуги» может любой желающий.

Первое Собрание племен Радуги (Rainbow Gathering of the Tribes) произошло в Колорадо в июле 1972 года и продлилось четыре дня, объединив более 20 тысяч людей вопреки протестам полиции. С тех пор мероприятие проводится регулярно, собирая всевозможных представителей контркультурных движений, нью-эйдж и хиппи.

Их идеологические корни можно найти в утопических традициях XIX века – и в «пророчествах индейцев хопи», предрекающих появление на «заболевшей» Земле племени «Воинов Радуги», которое объединит людей разных культур, верящих в дело, а не в слово, и исцелит мир. Некоторые считают пророчество журналистской фикцией, но индейские ритуалы и традиции прочно легли в основу движения, которое с тех пор разрослось и впитало в себя этнические особенности множества культур.

Несмотря на то, что местные жители часто негативно относятся к этим собраниям, а СМИ еще с 1980-х годов пренебрежительно называют Семью Радуги «постаревшими хиппи» и акцентируют внимание на самых спорных сторонах сообщества – наркотиках, нудизме, происшествиях и так далее – Rainbow Gatherings существуют вот уже 40 лет, оставаясь международным феноменом.

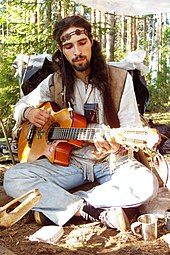

Российская радуга

Российская Радуга — региональное ответвление Rainbow Gathering и крупнейшее собрание хиппи и других представителей контркультуры в России. Она проводится с 1990 года в разных регионах страны и достаточно сильно отличается от своих западных аналогов. В частности, это в меньшей степени эзотерическое и нью-эйдж движение и в большей – просто палаточный лагерь единомышленников со своими обычаями и традициями. Здесь собирается молодежь, верящая в гармоничный мир, общечеловеческие ценности, любовь и понимание, заядлые путешественники и те, кто желает расширить свои горизонты, вырвавшись из привычной обстановки. Не все из участников причисляют себя к движению хиппи, но это мероприятие определенно близко по духу к фестивалям 1960-1970-х годов.

Обычно в год Радугу посещает около 2-3 тысяч человек. Помимо Радуги, российские хиппи собираются на фестивалях «Пустые Холмы», «Чаща всего», «ИнЛакЕш» и других.

Mystic Rising

Фестиваль Mystic Rising появился 17 лет назад на горячих источниках Велспрингс в Эшленде – все в том же «хиппейском рае» Орегоне. Его ключевые темы – здоровый образ жизни, забота об экологии, гармония, творчество и самопознание через духовные практики. В этом году на нем выступят Chris Berry & Bana Kuma Orchestra, Freedom Tribe, Jah Levi, Sasha “Butterfly”, Bhagavan Das и многие другие, также организуется множество мастер-классов, церемонии, танцы и уроки йоги. По мнению организаторов, опыт пребывания на всевозможных фестивалях, собраниях и мероприятиях и общение с единомышленниками может открывать участникам новые горизонты, учить их прислушиваться к себе и жить более яркую и здоровую жизнь.

В 2016 году фестиваль состоится уже в десятый раз. Он прошло 5-7 августа.

Electric Forest

Electric Forest Festival – четырехдневное многожанровое мероприятие, на котором выступают в основном электронные и jam-группы.

С 2008 года он традиционно проводится в Ротбери, Мичиган, на территории курорта Double JJ, и изначально назывался Rothbury Festival. Несмотря на то, что участники живут в кемпинге, условия более чем привлекательные, а поблизости находятся поле для гольфа, озеро и аквапарк. Фестиваль продолжает психоделическую традицию, заложенную еще «Кислотными тестами» Кизи: те, кому посчастливилось там побывать, сравнивают его с «Алисой в Стране чудес» и фильмами Тима Бертона. Неоновая подсветка леса создает галлюциногенный эффект не хуже пресловутых ЛСД и превращает Electric Forest в очень атмосферное мероприятие.

В 2015 году на фестиваль приехало более 45 тысяч посетителей.

Beloved Festival

Очередное орегонское мероприятие – музыкальный Beloved Festival, проходящий у небольшого городка Тайдуотер к западу от Корваллиса. Фестиваль длится четыре дня и посвящен всему «святом и божественному».

Все ожидающиеся группы, от Total Experience Gospel Choir до DJ Anjali и the Incredible Kid, так или иначе можно отнести к формам «священной музыки», служащей для духовного поиска и объединения сообщества. «Расцвет электронной танцевальной музыки в наше время стал для миллионов людей языком их народа, места и времени», – считают организаторы.

В отличие от большинства современных фестивалей, организующих концерты на нескольких сценах, на Beloved Festival сцена только одна. По мнению организаторов, сцена – это эпицентр фестиваля, который должен аккумулировать энергию на всей его протяженности, вместо того чтобы позволять ей рассеиваться в разных направлениях.

Немузыкальная часть фестиваля разделена между разными видами экспериментального искусства. Известными писателями, мыслителями и художниками будет проведена серия лекций и мероприятий с такими интригующими названиями, как «Руководство квантового активиста по социальному предпринимательству» и «Знакомство с водой». И, конечно же, в программе фестиваля много разнообразных уроков йоги.

Фестиваль прошел 12-15 августа 2016 года.

Shangri-La

«Шангри-Ла известна как мифическая утопия и рай на земле, изолированная от окружающего мира страна, где люди вечно молоды, вечно счастливы и практически бессмертны. Это место великой красоты и умиротворения» – пишут организаторы этого фестиваля, ставя себе целью хотя бы на один уикенд перенести участников в эту волшебную страну.

Wookiefoot, Nahko and Medicine for the People, Stick Figure, The Flobots, TAUK и другие заявлены в списке исполнителей, которые должны превратить трехдневный фестиваль в незабываемое переживание.

Ближайшее мероприятие состоится 8-10 сентября в Harmony Park, Кларкс Гроув, Миннесота.

Gathering of the Vibes

Gathering of the Vibes (GOTV) – ежегодный четырехдневный фестиваль-кемпинг, посвященный музыке и искусствам.

Фестиваль восходит к традициям легендарных Grateful Dead, вокруг которых образовалась целая фан-субкультура Deadhead. Смерть вокалиста группы Джерри Гарсии в 1995 году стала ударом для многих фанатов, поэтому идея мемориального концерта под названием «Deadhead Heaven – A Gathering of the Tribe» была встречена с большим энтузиазмом и вскоре превратилась в ежегодный фестиваль «Gathering of the Vibes».

С 1996 года GOTV собирает множество групп, выступающих в жанре рок, фанк, блюграсс, джаз, регги, R&B и фолк. На двух главных сценах музыка не смолкает весь день и большую часть ночи, а если прогуляться по береговой линии, можно послушать самых талантливых исполнителей северо-востока США на Green Vibes Stage.

В промежутке между концертами следует заглянуть на местную Shakedown Street. Такие пространства, названные в честь песни Grateful Dead, встречаются на многих фестивалях – как правило, на парковках. Исторически это было место, где фанаты Grateful Dead и Phish продавали и обменивали всевозможные вещи, от предметов одежды до наркотиков, чтобы заработать денег на следующий концерт или бензин – так им удавалось проводить в поездках долгие месяцы. Кроме того, такая торговля между участниками фестиваля играла объединительную роль, предоставляя фанатам площадку для общения и дискуссий. Сейчас там можно приобрести сувениры и предметы искусства, произведенные вручную.

Следующий фестиваль Gathering of the Vibes пройдет в 2017 году.

[tp]

[/tp]

Читайте также

Лучшие музыкальные фестивали Европы. Лето 2016

Вечный праздник: волонтерство на карнавалах

Весело и вкусно: волонтерство на фестивалях еды

Все о Карнавале в Рио

Волонтерство на Карнавале в Рио-де-Жанейро

Виктория Позднякова

Содержание:

- Оформление

- Фотозона

- Пригласительные

- Костюмы

- Меню, сервировка

- Развлечения

Духовная свобода и телесная раскованность, единение с природой и позитивный настрой. Нет соперничеству. Нет запретам. Нет разрушениям. Вечеринка в стиле хиппи – оригинальная тема для проведения любого праздника в кругу друзей. Особенно на природе, в объятиях леса, на день рождения у воды или в атмосферном сельском домике.

Оформление

Начните оформление с организации пространства: мусорная корзина, костер, туалет, зона отдыха. Проникнитесь духом субкультуры – отношение к Природе должно быть бережным. Уголь привезите с собой или наберите сушняка, ведь рубить деревья совсем не в стиле хиппи. Декор для вечеринки закрепляйте веревками или скотчем, не используя гвозди.

Если планируете остаться на ночь, прихватите с собой теплые одеяла и позаботьтесь о месте для палаток, индийских типи или тенте. Можно взять напрокат или сделать своими руками из яркой ткани, цветастых платков.

Для комфорта, если не хочется сидеть на пледах/бревнах, привезите с собой мебель из ротанга. Пластиковые столы/стулья задрапируйте тканью с этническим орнаментом. Разложите яркие подушки, разбросайте марокканские и полосатые «бабушкины» коврики.

Украсьте деревья бумажными фонариками, гирляндами – цветочными, тематическими из бумаги, электрическими на батарейках. Расставьте большие свечи в глиняных/деревянных плошках. Иллюминация на вечеринке будет весьма эффектной!

Можно украсить бутылки наклейками, раскрасить акрилом – силуэты хиппи, цветы, кляксы, символ пацифистов. Или просто покрасить бутылки/банки, чтобы свет получился цветным. Такие «подсвечники» можно использовать и в доме, расставив по комнате или развесив под потолком.

Погода не располагает к отдыху на свежем воздухе? В помещении хиппи-декор тоже уместен, ведь дети цветов не все время проводили под открытым небом. Только уберите лишнее, по возможности. Почти все следующие идеи для хиппи вечеринки можно воплотить и на природе, если описанного выше недостаточно.

- спрячьте громоздкие шкафы, современные обои. Для этой цели используйте фото хиппи 60-х, легендарных Rolling Stones и Beatles, тематические постеры, плакаты. Нарисуйте абстрактные картины в стиле хиппи – для вечеринки подойдет даже ватман с психоделическими разводами/кляксами. Если «кислотность» нежелательна, нарисуйте яркие цветы, солнце, облака;

Слишком яркие «кислотные» цвета – это скорее утрированное представление. Хиппи ценили натуральность, близость к природе. Но для стилизации можно выбрать и этот вариант. Только без перебора – обилие кричащих оттенков порой создает давящую атмосферу.

- украсьте потолок гирляндами ленточек, бумажных картинок (автобус, гитара, пацифика), помпонов, ватных облаков. Для антуража хаотично закрепите на гирляндах фенечки, деревянные бусы, нити бисера, кусочки джинсовой ткани, кисточки, монетки;

- замените текстиль натуральными тканями, разложите яркие подушки, коврики. То, о чем мы уже говорили выше;

- расставьте живые цветы, идеально – горшечные, не срезанные. Можно своими руками раскрасить в стиле хиппи небольшие кадки/ящики, насыпать земли и посадить растения. Получится оригинальный декор для вечеринки – яркий и целиком в тему;

- используйте в оформлении элементы, намекающие на тематику праздника: фигурки хиппи, индийские статуэтки, ловцы снов, картонные музыкальные инструменты и т.п. Отлично впишутся лавовые и ароматические лампы, кальян (необязательно курить, просто для антуража). Замечательно, если удастся найти гитару, барабан, губные гармошки, маракасы и другие этнические инструменты – пригодятся для фото и развлечения гостей;

- принесите пару настольных ламп и торшер, с абажурами под ретро. О свечах мы говорили выше. Верхний свет приглушите (бумажные, плотные тканевые чехлы на плафоны).

Фотозона

Подготовьте для друзей забавные аксессуары на палочках-держателях, с ними фото получатся оригинальными и веселыми: картонные очки, губки, пацифика, таблички с лозунгами. Для тематической вечеринки в стиле хиппи фотозону можно организовать так:

- цветастый микроавтобус Volkswagen. На день рождения можно арендовать настоящий и, прямо как хиппи, покататься по городу! А можно просто нарисовать его на плотном картоне, вырезать окошки, поставить сзади опоры;

- фон с хиппи-узорами, разводами, цветами, радугой. Повесьте несколько гирлянд, хаотично напишите «Make love, not war», «Hell No, We Won’t Go!» и другие лозунги. Можно нарисовать известных хиппи или музыкантов 60-х, вырезать окошки лиц – получится тантамареска;

- отличной фотозоной станет хиппи-палатка или типпи. Цветные платки, коврики, подушки, гитара, блюдо фруктов – стилизованный этнический декор. Ее легко соорудить в одном из углов помещения. Перед типпи пусть «горит» картонный костер. Помимо фото, тут смогут отдохнуть гости вечеринки.

Пригласительные

Приглашение на хиппи-вечеринку должно быть ярким, тематически узнаваемым – тот же автобус, гитара, палатка. Нарисуйте или распечатайте картинку, приклейте на основу. Можно вырезать символ пацифистов, написать текст по кругу.

Вместо обычного бумажного приглашения можно сделать миниатюрные топиарии, а текст написать прямо на горшочке. Или отправить друзьям почтовых голубей (символ мира). Конечно, не настоящих – фигурки или открытки, сделанные своими руками.

Костюмы

Главные принципы стиля хиппи – одежда должна быть удобной, не сковывающей движений, преимущественно из натуральных тканей. Цвета костюмов лучше выбирать яркие, но природные – «кислотными» были украшения, и то не всегда. Приветствуется смешение этнических стилей, бохо, творческая небрежность.

Модно одеться на вечеринку в стиле хиппи не составит труда – сегодня это направление очень популярно! Девушкам подойдут длинные юбки, свободные сарафаны, туники. Парням – легкие рубашки, туники, футболки. Независимо от пола, актуальны майки, жилеты, джинсы, свободные штаны, клеш. Обувь – босоножки, сандалии, мокасины, сапоги.

Косметику хиппи не уважали – это не натурально, производство вредит Природе, да еще и бедные лабораторные животные! Поэтому макияж лучше nude, совсем-совсем натуральный. Прическа без сложных деталей, естественной формы (тоже «nude»).

Помимо одежды, не забудьте аксессуары в стиле хиппи. Их легко собрать/сплести своими руками. Украшения носили все, независимо от пола:

- хайратник, не дающий волосам лезть в глаза. Плетеный из кожи, полосок ткани;

- этнические бусы, подвески на шее;

- много разноцветных фенечек/браслетов на запястьях и щиколотках, если обувь открытая;

- серьги из перьев, бисера, деревянных бусин. Драгоценные камни и металлы неуместны – хиппи презирали материальные ценности. А вот фурнитура под серебро и полудрагоценные камни целиком в стиле;

- платок на шее или вокруг талии, сумка с бахромой, круглые ретро-очки с цветными линзами.

Меню, сервировка

Для тематической вечеринки оформлять стол в стиле хиппи… не надо вообще! Конечно, если вам интересна достоверность. Да и от стола можно избавиться, заменив его накрытой «поляной», будто вы на пикнике. На природе тем более не стоит устраивать пышное застолье – хиппи скромно питались, считая чревоугодие недостойным их культуры (а может, просто денег не всегда хватало?).

Если все-таки стол, то накройте его льняной скатертью. Расставьте полевые цветы, глиняные блюда, разномастные вазочки, металлические емкости. Должно сложиться впечатление, будто посуду собирали тут и там, с каждого «по нитке». Уместна одноразовая посуда, но обязательно картонная – пластик вреден Земле.

Хиппи любят создавать что-то своими руками. Например, можно подарить вторую жизнь виниловым пластикам – атмосферный декор:

С другой стороны, речь идет о вечеринке. Поэтому в стиле хиппи можно украсить буквально все! Получится сумасшедше-ярко, особенно если накупить всего и побольше. Наборы посуды, шары, скатерти, трубочки, карточки для оформления блюд, наклейки – все есть в магазинах для организации вечеринок.

Над меню ломать голову не стоит. Изысканные блюда и гастрономические шедевры не в стиле детей цветов. Простые идеи:

- меню хиппи – натуральная еда, много овощей и фруктов, любые напитки. Все самобытное, даже деревенское;

- подача такая, будто вы на природе – в общих больших тарелках, на подносах (горками, рядочками);

- конфеты в ярких фантиках положите в прозрачные банки, украсьте блюда конопляными листочками (бутафорскими);

- горячее и салаты можно раскладывать прямо из кастрюли;

- придумайте некоторым угощениям названия, сделайте таблички: «Радужное настроение», «Не грусти – похрусти!», «Может содержать следы запрещенных веществ»;

- на день рождения закажите торт в стиле хиппи – вкусный сюрприз имениннику и всем гостям!

Развлечения

Один из главных постулатов хиппи – никакого соперничества. Но так как это вечеринка, можно добавить в сценарий пару-тройку конкурсов. На дружеской ноте, без награждения победителей. Памятные мелочи лучше вручить в конце вечеринки, всем гостям.

Зажигательная и расслабляющая музыка в стиле хиппи создаст неповторимую атмосферу! Легендарные Beatles и Rolling Stones, The Doors, Grateful Dead и другие популярные группы 60-х. Из нашего – музыка и песни групп «Машина времени», «Ковчег», Калинов мост», «Аквариум». Несколько композиций инди, регги, джаз, блюз, этническая музыка – выбор огромен.

Музыка для хиппи – способ самовыражения. Любые исполнители подойдут, если их песни отражают вкусы и настроение вашей компании.

Непременно спойте наш супер хиппи-гимн из «Бременских музыкантов». Мультик создавался под влиянием именно этой субкультуры и группы Битлз:

Весь сценарий вечеринки в стиле хиппи может быть построен на творческих развлечениях:

- пойте под гитару и караоке, танцуйте, сочиняйте тематические тосты;

- все вместе раскрасьте футболку в технике тай-дай. На день рождения напишите поздравления поверх украшенных своими руками джинсов, майки или платка;

- можно украсить бутылку или шкатулку, собирайте бусы, плетите фенечки и хайратники, делайте обереги, раскрасьте игрушечный автобус или настоящую гитару.

Конкурсы, как мы уже говорили, без особого соперничества. Несколько идей для сценария:

Посвящение в хиппи

Для разогрева проведите викторину на знание темы. Вопросы такого рода: кто на фото (известные хиппи, музыканты), что означает слово (сленг хиппи), любимое занятие хиппи (кто что придумает).

А у нас коммуна!

Все люди братья и в таком духе (для подводки). А мы (гости вечеринки) так вообще одна большая дружная семья! Под веселую музыку надо стать «единым целым». Для этого бельевую веревку нужно пропустить через рукава так, чтобы все гости оказались «связаны» вместе цепочкой.

Любовь-морковь

Делимся с миром любовью! Но для начала – со своими друзьями, гостям хиппи-вечеринки. Возможно несколько сценариев: две команды, тройки или пары. Для каждой команды приготовьте тазик, терку, одноразовые перчатки и много очищенной моркови (такой вот рифмованный символ любви).

Выбираем по одному из членов команд. Они быстро натирают морковь в свои тазики, не забыв надеть перчатки. Остальные быстро едят морковь. В конце подсчитать, в чьей кучке осталось меньше «любви» (кто щедрее раздавал, тот и молодец).

И вновь любовь

Парный конкурс, смешной и не совсем пуританский. По очереди, ведущий засекает время. Цель – справиться как можно быстрее.

Понадобится много цветных прищепок, на обычные легко приклеить яркие цветочки. Или использовать детские заколочки, которые можно «прищипнуть» на одежду. Паре участников завязывают глаза. Ведущий на обоих цепляет прищепки, десятка по два. Пара влюбленных/друзей должна снять эти «украшения» друг с друга наощупь. Степень «развязности» конкурса зависит от фантазии ведущего, который будет крепить прищепки.

Дети, и не только цветов

Море волнуется раз, бутылочка, твистер, крокодил, яблоко на веревочке и карандаш на ней же, но пониже спины. Стульев опять нехватка, яйцо из ложки выпадает, а спичечный коробок накрепко «завис» на носу! Детсадовские развлечения будто придумывали хиппи – такие игры целиком в стиле вечеринки. Веселитесь!

Идеи для улицы, для самых смелых:

- фанты «с прохожими». Сделай комплимент, подари цветок, обменяй бусы на еду и т.п.

- облагородить… да хоть собственный двор! Шумной компанией разбить клумбу под окнами – то еще зрелище!

- организовать благотворительный сбор в пользу… да любой организации, детдома, приюта животных.

Мир, любовь и свобода — вечеринка в стиле хиппи

Когда-то движение хиппи – яркое, свободное привлекало тысячи людей по всему миру. Сейчас оно превратилось в бохо – более эстетичное и утончённое направление. Но кое-что остаётся общим: стремление к свободе и самовыражению. Вечеринка в стиле хиппи позволит почувствовать, что по-настоящему значит атмосфера.

- Дизайн и интерьер

- Как подготовить праздник на природе

- Вечеринка в стиле бохо дома

- Фотозона

- Образы на вечеринку

- Для девушек

- Для мужчин

- Еда и напитки

- Что делать во время вечеринки

- Конкурсы и игры

Дизайн и интерьер

Хиппи называли детьми цветом. Они любили единение с природой и много путешествовали. Для хиппи-вечеринки идеальная пора – конец весны или лето. Если устроить праздник в лесу или у реки, получится в полной мере почувствовать дух хиппи.

Однако если не позволяет погода или вы не хотите уезжать, празднование дома или в кафе – тоже хороший вариант. Однако придётся большее внимание уделить интерьеру и оформлению помещения. Компромиссный вариант – вечеринка на даче. Это позволит побыть на природе, но укрыться в помещении и отдохнуть, как только захочется.

Если вы задумали вечеринку в кафе или баре, подбирайте не гламурное, не тёмное и не пафосное место. Пусть в нём будет много воздуха и простора.

Как подготовить праздник на природе

На вечеринку в стиле хиппи придётся подготовиться, так как именно через детали вы сможете передать ту особую атмосферу. Именно оформление задаёт тон. Однако многое можно сделать своими руками.

Если вы устраиваете вечер на природе, подготовьте палатки или тенты. Украсьте их тканями, платками и цветами. Вместо мебели используйте брёвна и пледы. Однако если вам хочется удобства, привозите с собой мебель из ротанга или пластиковую мебель, задрапированную тканью. На траве разбросайте подушки и коврики.

На деревья повесьте фонарики и гирлянды: из цветов, бумаги или электрические. В сумерках будут красиво смотреться свечи в глиняных или деревянных подставках. Красивый свет получается, если свечи поставить внутрь бутылок, раскрашенных краской. На них можно нарисовать цветы, кляксы или символ мира.

Вечеринка в стиле бохо дома

Прежде всего уберите или задекорируйте все современные детали интерьера. То, что нельзя вынести, спрячьте под плакатами с группами 1960-х, тематическими постерами, фотографиями хиппи. Самый простой вариант – взять ватман и нарисовать на нём абстракцию. Кстати, это можно использовать как интерактив, если дать гостям возможность дополнить картину.

Важно! Принято считать, что хиппи – это всё яркое. Цвета должны быть близкими к кислотным и притягивать внимание. На самом деле они ценили всё естественное и близкое к природе. Для декора выбирайте те цвета, которые можно встретить в природной палитре. Атмосфера должна получиться лёгкой и воздушной.

Как организовать помещение правильно:

- Разложите повсюду подушки и коврики, текстиль замените на натуральные ткани.

- Потолок украсьте лентами и бумажными картинами в виде автобуса, гитары, пацифика и т.д.

- Разложите повсюду фенечки, бисер, деревянные бусы, кусочки джинсовый ткани и т.д. Хорошо впишутся аромалампы, музыкальные инструменты, ловцы снов, индийские статуэтки. Однако не переборщите с деталями, чтобы не перегрузить интерьер.

- Здорово будут смотреться цветы в горшках, раскрашенных в соответствующем стиле.

Фотозона

После такой яркой вечеринки нужно обязательно оставить воспоминания. Подготовьте фотозону, где каждый желающий сможет сфотографироваться. Подойдут:

- Плакаты с лозунгами про мир, свободу и любовь.

- Тантамареска в виде цветастого автобуса.

- Картонный фон с надписями, разводами, узорами, радугой.

- Палатка с ковриками, подушками, гитарой.

Образы на вечеринку

Костюмы подбирайте на основе нескольких принципов: простота, практичность, натуральность, удобство. Чаще всего хиппи носили старые отреставрированные вещи, а при необходимости делали на них яркие заплаты.

В костюмах и девушки, и парня часто присутствовали абстрактные рисунки и этнические мотивы. Они носили самодельные украшения и не боялись смешивать одежду разных культур. Сейчас, превратившись в бохо, эта культура стала более аккуратной и продуманной. В образе должна сквозить этакая творческая небрежность.

Для девушек

Девушке наряд подобрать достаточно просто, подойдут практически любые летние вещи. Как одеться, женские образы:

- Подойдут длинные свободные сарафаны, лёгкие летящие платья, расклешённые джинсы, майки-оверсайз, кофты с цветочным принтом, плетёная одежда.

- Из обуви – это плетёные босоножки, сандалии. Часто хиппи ходили босиком.

- Для культуры характерно обилие украшений: фенечек, шнурков, бус, подвесок, кулонов. Один из самых характерных аксессуаров – очки с круглыми стёклами. Дополнить образ можно повязкой на лоб и крупными серьгами. В волосы можно вплести цветы, бусины или перья.

- Сделайте лёгкий нюдовый макияж или приходите без косметики.

Для мужчин

Мужской костюм может выглядеть так:

- Джинсы-клёш или широкие штаны, рваные джинсы с заплатами, разноцветные футболки, свободные рубашки и жилеты.

- На ноги наденьте мокасины, лёгкие парусные туфли, старые кроссовки.

- И для девушек, и для мужчин было характерно обилие аксессуаров. Яркий образ можно создать с помощью повязок на голову и круглых очков. Дополните его фенечками на руках.

Еда и напитки

Прелесть хиппи-вечеринки в том, что для неё не нужна сервировка вообще. И стол не нужен тоже. На природе устройте пикник, а дома положите яркую скатерть прямо на пол, точно вы собрались у костра.

Если же стол остаётся, постелите на него льняную скатерть. Поставьте полевые цветы. Стеклянную посуду замените глиняной. Блюда подавала в вазочка и металлических тарелках. Оформление должно получиться разномастным, точно по кусочку от каждой культуры. Если вы хотите использовать одноразовую посуду, то подойдёт только деревянная – хиппи старались не использовать пластик.

Многие из них были вегетарианцами и никогда не стремились к изыскам. Меню должно быть простым и лёгким:

- Свежие и печёные овощи. Обилие трав: петрушка, укроп, базилик, сельдерей и т.д.

- Маринованные или печёные грибы.

- Лёгкие канапе.

- Барбекю, отварное мясо, рыба, запечённая в фольге.

- На десерт – ягоды и фрукты.

- Из напитков – зелёный или травяной чай, сок, ягодные отвары.

Обратите внимание на подачу блюд. Можно делать это на больших тарелках или подносах, точно вы находитесь на природе. Горячие и салаты раскладывайте из кастрюли. Положите деревянные приборы или ешьте руками, если блюда это позволяют. Мясо или рыбу стоит заранее нарезать.

Что делать во время вечеринки

Сценарий для вечеринок просто обязателен. Да, досуг хиппи был прост: песни, разговоры у костра – однако, чтобы гости не заскучали, организацию продумать необходимо, и несколько конкурсов и игр не помешают.

Продумайте тайминг вечера, чтобы хватило времени и на разговоры, и на танцы, и на конкурсы. Однако не делайте его слишком жёстким: гости должны веселиться и не чувствовать ограничения.

Подготовку сценария начните с музыкальной составляющей. Музыка задаёт настроение и помогает почувствовать атмосферу. Для разговоров и застолья подберите более лёгкие спокойные композиции, для активной части вечера – весёлые и бодрые.

Настоящая классика – это рок-н-ролл, в меньшей степени – регги, инди и джаз. Составьте подборку из таких исполнителей и групп, как: Джимми Хендрикс, Джон Ленном, Джим Моррисон, Rolling Stones,The Beatles, The Doors и др. Из русской музыки подойдут «Аквариум», «Машина времени», «Калинов мост».

Под конец вечера можно включить музыку для медитаций. Здорово, если кто-то играет на гитаре – так воссоздать атмосферу получится наиболее правдоподобно. Если вы вместе споёте под гитару, это оставит тёплые приятные воспоминания.

Конкурсы и игры

Хиппи не хотели соперничать, они жили в мире, поэтому при выборе конкурсов и игр сделайте упор на то, чтобы они были весёлыми, а не разжигали спортивный интерес.

- Аквагрим. Подготовьте краски и кисточки. Разбейтесь на пары и нарисуйте на любой части тела друг друга пацифик, сердце, цветок, напишите название любимой группы или лозунг и т.д.

- «Лотерейный билет». Каждый пишет на листочке задание: спеть, станцевать, обнять прохожего и т.д. Все бумажки складываются в мешок и перемешиваются, затем каждый вытягивают по заданию.

- «Застывшая фигура». Эта игра из детства очень подойдёт к вечеринке. Участники танцуют под музыку, затем она неожиданно останавливается. Каждый должен застыть в одной позе. Игроки с помощью голоса и мимики пытаются расшевелить друг друга. Зашевелившийся выбывает, а побеждает самый стойкий.

- Фенечки. Проведите мастер-класс по плетению фенечек. Для этого понадобятся бисер, бусины и леска. Такая фенечка станет хорошим памятным сувениром о прошедшем вечере.

- Посвящение в хиппи. Проведите викторину на знание культуры хиппи: что означает слово, кто изображён на фото, различные вопросы о движении и т.д.

- «Лимбо». Два человека встают по разные стороны. Они держат в руках ленточку или верёвку. Включается музыка, и третий участник должен пройти под ней, наклонившись. С каждым разом лента или верёвка опускаются всё нижи.

Вечеринка в стиле хиппи получается лёгкой и весёлой. Удобство, простота и натуральность – под таким девизом она проходит. Чтобы воплотить ту самую атмосферу, стоит заранее продумать интерьер помещения и подобрать образ, составить сценарий. Если вы хотите отдыхать не только во время праздника, но и при его подготовке, команда PartyToday поможет с организацией яркой запоминающейся вечеринки.

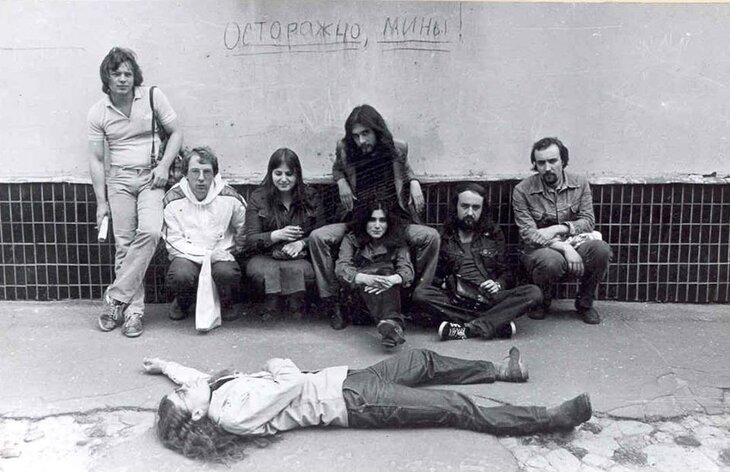

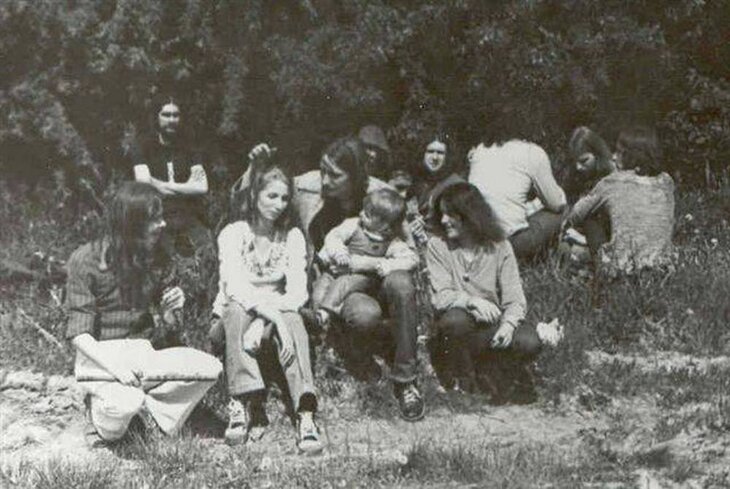

Фото из архива Александра Литвиненко

Уже много лет подряд, а точнее, как зафиксировано в хрониках – с 1981 года, в первый день лета, на большой поляне в парке «Царицыно» собираются сотни людей. Пожилых и молодых, волосатых и не очень, обвешанных «фенечками» и расписанных всеми цветами радуги, а порой и абсолютно цивильного вида. Все они приходят сюда, чтобы в День детей, отпраздновать свой праздник – День детей цветов, проще говоря, хиппи. «Олдовые», разменявшие шестой, а то и седьмой десяток, приходят на свою на свою «земляничную поляну», чтобы как близкие родственники порадоваться и погрустить по поводу изменения их количества.

Мальчики и девочки 70-80-х стоят, сидят, беседуют и обнимаются, рядом с нынешней дредастой молодежью, на чьих плечах уже появился свежий крымский загар, а сандалии запылились на новых трассах.

Разговоры о том, что одна из самых ярких субкультур испарилась вместе с молодостью первопроходцев движения – всего лишь разговоры. Хиппи живы до тех пор пока на свете есть любовь, музыка и дороги к новым городам, морям и странам. Накануне Дня хиппи обозреватель m24.ru встретился с теми, для кого хипповская система, рожденная в начале семидесятых, стала главной системой жизненных координат.

Мамедовна и Йоко

– Давайте с самого начала: как вы дошли до жизни такой?

Йоко: Перед институтом, в 1976 году я работала в архиве. Там и познакомилась с волосатыми ребятами. А встретить таких людей давно хотелось. В 1977 году пришла на тусовку, в систему, в общем, нашла, что искала. Никто никуда не втягивал. Исключительно добровольно.

Мамедовна: У меня примерно в то же время, чуть позже… И началось все с «Машины времени» (во всем виновата «Машина», ха!), которая приехала играть к нам на сейшн в Менделеевке. Мы, студенточки, тогда с подругой былиТатьяной Ц. Она блондинка, я брюнетка – прямо «АББА». И к нам подошел знакомиться звуковик «Машины» и пригласил на следующий концерт. Конечно, мы не отказались, а потом вообще очень подружились с Наилем, благодаря чему бывали почти на всех концертах «Машины», которые проходили тогда в основном на окраинах или в Подмосковье. Веселое время было. Я, помню, рванула с практики из славного города Ровно на московский рок-фест, никого не предупредив. Жила несколько дней по флэтам, а родители объявили меня во всесоюзный розыск. Что удивительно, нашли на генеральской флэте подруги недалеко от дома. А летом 77-го или 78-го (не помню), узнав, что «Машина» будет рядом с Гурзуфом на какой-то базе, мы туда рванули с подругой. В Гурзуфе тогда была чуть не вся московская системная тусовка. Там мы и познакомились с легендарным Эдиком Маминым, Гариком Прайсом, Филом, Смайлом и другими. Причем, тусовка это была именно «центровая – стритовая»: Пушка, Труба, Квадрат, в отличие от Ароматской (Вавилонской) тусовки Йоко. Вот так это все и началось.

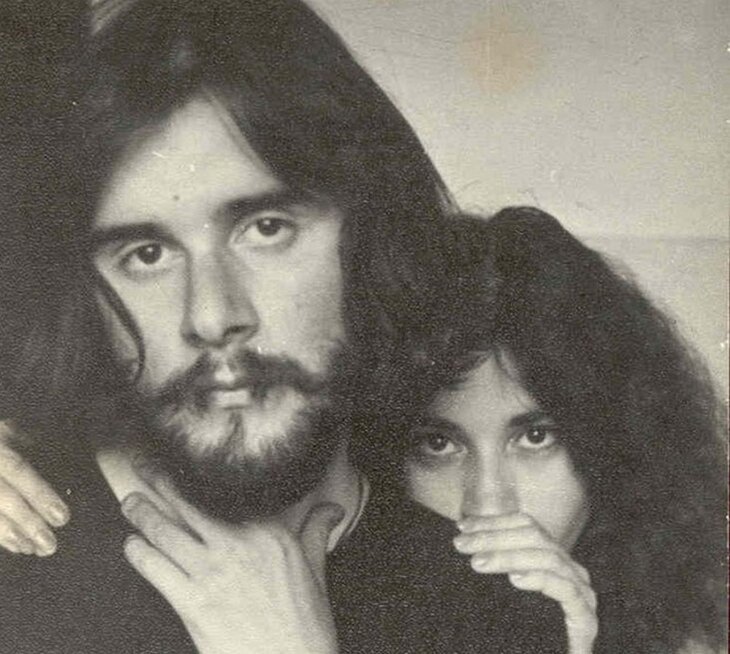

Йоко и Мамедовна, 2016 год

Йоко: Нет, почему, я на Пушке тоже была, но мне там очень быстро не понравилось, и я оттуда резко скипнула.

Мамедовна : Ну да, там тусовались в основном «дринкачи»: Солнце, Красноштан, Юрай, мама Ира, Галя Рыбий Глаз, Бася…. И много других замечательных и талантливых людей!

Йоко: Ну, не моя там была публика.

– Может сложиться ошибочное впечатление, что у хиппи были свои кафе на манер клубов…

Йоко: …Были тусовочные места: кафе «Аромат» на Суворовском, он же «Вавилон». «Этажерка» на стриту, потом уже «Чайник», «Турист», кафе на Ослиных ушах (напротив памятника Крупской на Сретенском бульваре) Но «Вавилон» был для меня самым первым и главным. Там можно было сидеть целыми днями, попивая чаек из огромного самовара, как-то очень было уютно, и несмотря на то, что периодически винтили, чувствовала я себя там, как дома. Конечно, перед Олимпиадой его закрыли как бы на ремонт и больше не открыли. Этот «рассадник» всем, «кому надо» уже глаза намозолил.

Мамедовна: Ну и Гоголя… Но я туда позже стала ходить, когда уже с мужем Сергеем познакомилась. Кстати, 3 раза нас пытались знакомить именно по ФИО: он Мамедов, я Мамедовна, и лишь на третий раз удалось. Благодаря братьям-художникам Анохиным, у которых я частенько бывала, а Серега жил по соседству. Вместе с Серегой я получила еще более обширный круг знакомых и друзей среди системных. Причем среди самых олдовых и суперолдовых, ибо мы были уже третьей волной.

Мы и хиппи-то себя не называли. Хотя именно так и выглядели. С одной стороны, стрит с его неизменным аском, сейшены (спасибо Эдику, всегда нас проводил), тусовки, выставки, хиппятники в Царицыно, марши мира, хэппенинги. В «Аромат» тоже захаживали, но редко. Ходили на культовые фильмы, на том же «И все таки я верю» или «Обыкновенном фашизме», на мульфильмах Норштейна можно было почти всю тусню встретить… Кстати, в книге Василия Лонга «Мы –Хиппи!» четко и интересно описаны некоторые моменты стритовой и вообще хиппово-системной жизни.

С другой стороны, мы были такими «полудомашними хиппи» – ни в Среднюю Азию, ни на Гаую, ни по стране стопом не ездили… Но у нас на флэту кто только ни собирался: художники, музыканты, поэты, киношники, ну, в общем, богема всякая. Читали ксероксный самиздат, говорили о культовых режиссерах типа Фассбиндера, Йонаса Лукаса и куче других, щеголяли такими именами, как Джерри Рубин, Эбби Хоффман и т.п., много читали. Сам-то Сергей был художником недоучившимся, но знал массу всего. Даже в иняз меня потом готовил. Хиппи же всегда были в авангарде, да еще плюс внутренняя свобода. И ощущение того, что ты живешь в параллельном мире. И полный пофигизм. И в совок только по надобности…

Йоко. Фото из архива

Йоко: Антисоветчины у всех хватало. На флэту у Олеси Троянской, к примеру. К нам с Джузи как-то пришли оперативники под видом хиппарей, но у них на рожах все было написано. И начинается: «Можно вписаться? Мы из Питера». – «Ну ладно». Сидим, еще гости какие-то, но все уже понятно. Мы, конечно, не сильно испугались, но состояние неприятное, потому что у нас лежала фотокопия «Архипелага ГУЛАГа» Солженицына. Джузи быстренько ее под рубашку и к родителям. Мама с папой сидят, телевизор смотрят, говорят ему: «Ленька, опять наркотики?» – «Нет, мама, это антисоветчина!» – «А-а, ну ладно».

Мамедовна: Самое интересное, что у Троянской мы с Йоко не пересеклись. Были в разные периоды. Йоко – в 1978-79, а мы в начале 80-х.

Йоко: После того, как Олеся рассталась с Сережей, мы перестали у нее бывать. А потом встретились как-то мельком, через несколько лет.

Мамедовна: Звонок в четыре часа ночи нам с Сережей: «Привет, это Троянская, что делаете?» – «Как что делаем? Спим, блин». – «Так, быстро ловите тачку и ко мне, я продала дачу, гуляем». И вот мы с Сережей, я уж не помню, ночью ли, утром ли, рванули к Олесе и, наверное, на две недели там и зависли. Вообще к Олесе на флэт на денек приехать и зависнуть на недельку-две, это в порядке вещей. Народец там постоянно разный тусовался, вписывался, найтал, жил.

Йоко: Квартира была абсолютно мистической, бывало, что в пустоте слышались какие-то шорохи, странные звуки. И люди там бывали самые разные. Диссиденты, хиппи, наркоманы, музыканты, художники, в общем, всякой твари по паре. Настоящий Ноев ковчег.

Мамедовна и Сергей. Фото из архива

Мамедовна: Ну да… Пипл всякий… Можно было заснуть с фенечками, браслетами на руках и с сережками в ушах. А проснуться уже без оных. Мистика!!!

– Но все-таки костяк хиппарей составляли люди из какого-то определенного сословия?

Йоко: Самые разные. В основном, дети интеллигенции, но это вовсе необязательно. Вообще-то никогда не озадачивалась этим вопросом, кто из какой семьи вышел.

Мамедовна: С самого начала это была в основном «золотая молодежь». Дети, внуки дипломатов, генералов-адмиралов, партработников, актеров и т.д. В общем, совэлиты. Те, кто мог выезжать за бугор и привозить пластинки, журналы о той жизни. У них были родные джинсы, не самострок. Классные музинструменты, не самопал. А потом уже разные попадались. Я, например, из простой семьи инженеров, а вот мой муж был из очень непростой семьи. Ну как-то и вправду на этом никто не циклился.

– Темы для разговоров и для общих тусовок должны были быть общими, как вы вычленяли своих?

Йоко: Общность взглядов на мир, на жизнь, и конечно, музыка. Хотелось как-то отстраниться еще и от серого, унылого совка.

Мамедовна: Ну, про разговоры я уже упоминала… Своих узнавали в том числе и по внешним атрибутам. Я не могу сказать, что все тогда ходили в фенечках, пацификах и расшитых штанах. Ходили, конечно. Сами шили и расшивали, один дзен-баптист чего стоит! Но мы с Серегой , например, носили черные водолазки или свитера или джинсовый прикид, тем не менее нас свои всегда узнавали. Как-то шли по Гоголя, вдруг навстречу необычная троица чуваков. Подошли к Сереге: «Привет-привет!» и разошлись. Мы прифигели. Потому что это был БГ с друзьями. То есть мы его знать не знали и знакомы не были, но по внешним атрибутам (хаер, хайратник, джинса рваная и особое выражение лица) они сразу признали своих.

Йоко: Кстати сказать, помимо общего живописного вида, были и кое-какие отличия. В Москве предпочитали вышивку и аппликации на одежде, а в Питере и Прибалтике – просторные свитера и джинсы. Еще питерские предпочитали ходить с регланами. Где они их брали, до сих пор для меня загадка. И какие-нибудь две-три изящные фенечки.

Мамедовна: А в Москве-то еще и на Тишинке одевались. Тогда там барахолка была – и классные, как сейчас говорят, винтажные вещи можно было откопать.

Йоко: Да, тогда совсем другая Тишинка была…

Фото из архива

– Вы уже упоминали Олесю Троянскую – культового персонажа в среде московских хиппи. Расскажите о ней.

Йоко: Олеся была сложным человеком, довольно злая на язык, но голос у нее был уникальный! Когда она была в ударе, это было что-то потрясающее! Я так жалею, что не успела ее записать. Хотя где-то наверняка сохранились ее записи. Не только же я хотела это записать. Просто тогда эти катушечные бандуры вроде «Маяка» таскать было сложно. Так вот, она просто брала гитару, и что творилось дальше – передать невозможно!

Мамедовна: Да, язычок у Олеси был весьма острый. И вообще Олеся была атаманшей. Как ее мужики слушались – не передать! Со свитой всегда ходила. И очень четко видела людей. А голос – да… Иногда мы выходили на улицу большой командой, Олеська с гитарой и пела прямо на ходу. Народ обалдевал! Такой голос с хрипотцой, как у Дженис. Она вообще артистичная натура была, очень любила устраивать всякие представления, хеппенинги. Кстати, Олеся рассказывала, что именно она учила петь Агузарову, когда та у нее на вписке была.

– Если говорить про музыку, то это?

Йоко: классика рок-музыки, которую можно долго перечислять – битлы, роллинги, «Лед Зеппелин»…

Мамедовна: По роллингам у нас Эдик асом был… Ну еще Пёпл, Криденсы, Грэнд фанк, , Кинг Кримсон, Йес, Юрай Хип..… ой, нет .. длиннющий список.. На рок-фестивали ходили. Лужники. Марш мира, где Сантана выступал. Тушино уже позже.

Йоко: У Джузи был друг и сосед, занимался дисками, большая часть новой музыки шла от него.

Мамедовна: А у нас с Серегой была целая коллекция рок-винила. И даже если иногда пластинки бились, то мы конверты не выбрасывали, потому что они тоже ценились, особенно, если родные. Откуда мы весь этот винил брали, точно не помню, но явно не покупали – меняли, частенько даже и на фотки. К нам один классный чувак приходил, он сейчас старец, не буду говорить где. Так вот он просто приходил, ставил рекорда, тихо садился в углу и слушал музыку. А коллекцию потом у нас украли. Местная урла. Тупо взломали замок . Их нашли потом, но от коллекции осталось всего несколько пластинок.

– А российские команды?

Мамедовна: «Машина», «Високосники», «Воскресение», «Рубины», «Удачное приобретение», «ДК», «Веселые картинки»… Куда удавалось попасть и что удавалось послушать… Конечно, Олесино «Смещение». Еще она записывала песни с «Автоматическими удовлетворителями». И эти композиции есть в Сети. А что касается сейшенов, то в те годы никто не знал наверняка, сколько продлится действо. Мы один раз с Серегой приехали на «Смещение», опоздали на полчаса, а там уже концерт прекратили, и всех свинтили.

«Машина времени». Фото: Наталья Георгадзе

– Какими проблемами это могло обернуться?

Мамедовна: Ну, забирали в ментовку, если докапывались, то составляли протокол, допустим «в нетрезвом виде» или «нарушение общественного порядка», могли написать в институт, на работу… Если кто учился, работал. А если нет – могли припаять за тунеядство Тогда статья была. Поэтому все старались где-то числиться.

Йоко: Во-первых, винтили настолько часто, что это уже переставало быть проблемой, а во-вторых, большинство работало на таких работах, что это мало, чем могло навредить «карьере». Дворниками, сторожами, натурщиками….

Мамедовна: Я, например, была «молодой специалист в ящике». И в таком статусе загремела в ментовку за то, что укусила мента за палец на собственном флэту на собственном безнике. Народ гуляет, я уже сплю, пятый сон вижу – и вдруг кто-то тормошит. Ну и я цапнула… Оказался мент Якушкин, которого вызвал сосед (тоже мент) и который составил на меня протокол. Всех забрали, потом всех отпустили, а меня оставили найтать в ментовке. Протокол же ж. Хулиганство, а то и легкие телесные. Но менты какие-то добрые попались, чаем напоили, шинелькой накрыли, а наутро в суд повезли. И вот стою я перед судом, такая несчастная, красивая и хрупкая (не как сейчас), и вид у меня невинный, а вокруг синяки да алкаши. И видит судья, что если мне впаять 15 суток, ничего с меня не возьмешь, а если штраф, то всем хорошо. Вызвала к себе в комнатку. «Деньги есть?» – «Не-е-еет, но у меня сегодня зарпла-а-та…» Так, быстро метнулась туда сюда и привезла мне штраф 30 рублей. Прямо в руки. Ну, я метнулась, привезла, отдала – и на свободу с чистой совестью. И никакой телеги на работу не пришло. А могли бы.

А вообще сосед-мент – это было что-то. Как я уже говорила, народ у нас собирался очень разный. И разговорчики были стремные. А мент под дверью подслушивал и постоянно стучал на нас в места посерьезнее. И все ждал, когда ж нас всех окончательно повяжут и отвезут на Лубянку, и наши гости перестанут таскать у него еду из холодильника. А нас все не вязали и не везли. Ну, мент же не знал, что дед у Сереги был отставным генералом из тех серьезных мест, поэтому ментовские доносы рубились на корню или растворялись в воздухе.

Фото из архива

Йоко: Да, жизнь была сплошным приключением. Сидели это мы как-то раз в бомбоубежище на Чехова, было одно время такое теплое местечко, собирались ехать в Азию, и вдруг прибегает один наш друг и зовет в гости, в Мурманск. У него мама оттуда, а папа из Туапсе, вот мама как раз к морю и уехала, он ее случайно на вокзале встретил. «Ребята – говорит, – поехали, там флэт свободный! Недели на две». Азия отпала сама собой, команда собралась, и поехали. Добрались до Мурманска, по пути прихватив еще одну львовскую барышню. Приехали, весело пожили пару дней, погуляли по городу, а потом нас всех взяли прямо из дома и посадили на 10 суток, толком ничего не объяснив. Повод был стандартный: «сопротивление властям», которым, разумеется, никто не собирался сопротивляться. Они там просто никогда таких, как мы не видели, и предпочли на всякий случай от нас избавиться.

Слегка придя в себя, мы нарисовали карты, и все 10 суток, в основном, резались в покер, и развлекались, как могли. Держались дружно, поэтому нас не только не трогали, а даже вполне дружелюбно восприняли товарки по несчастью. Выпустили нас через 10 суток, прямо в засыпанный белым снегом город. Разноцветные сопки стали белыми, а мы от холода – синими. И выглядели как остатки наполеоновской армии: кто в чем, кто в плед завернут, кто в шинельке неподрубленной, у одной барышни вообще на ногах сабо, и каблук все время отлетает. В общем, доехали мы до Кандалакши, на дальнейшую дорогу денег не было. До Петрозаводска добирались на попутном товарняке, под открытым небом, когда ночью приехали, пальцы не сгибались, чтобы за железную лесенку ухватиться, еле выползли. А потом до Питера на электричках, и домой.

Мамедовна: Ой, а у меня один раз Серега с утра за пивом пошел и пропал на целый день. Я уж заволновалась, где что, мобильных-то не было… А он мне вечером из Питера звонит. Попили пивка и рванули командой.

– Одним из самых знаменитых для выездов мест был хипповский лагерь в Латвии на реке Гауе. Почему именно там?

Йоко: Почему именно там? Просто так получилось, до этого собирались в Эстонии, было такое место Вилянди. Но там вроде винтили. Решили собраться на Чудском, в местечке Муствэ. Народ приехал, собралось нас немало, но всех в тот же вечер свинтили и увезли в Кохтла-Ярве. Ночь продержали, взяли у всех подписку покинуть Эстонию в 24 часа и вывезли в Ленобласть. А там нас уже встречали менты областные. Снова всех посадили и вывезли на тихий эстонский полустанок, в какую-то немыслимую глушь, не обращая внимания на наши протесты. Тогда решили поехать на Витрупе, под Ригой, место это было уже кое-кому знакомо, и мы потихоньку, разделив общий скарб, стали перебираться туда парами и поодиночке. Место и впрямь оказалось чудным, на берегу моря, в сторонке от кемпинга. Стояли там несколько дней, народ подтягивался и подтягивался. Спасибо, Миша Бомбин из Риги взял на все свои отпускные палатки в прокате, так что все устроились замечательно. Потом под видом туристов приехали граждане из уфимских компетентных органов. В футбол они играли неподалеку от нас, и уфимские даже подарили им журнал «Футбол–Хоккей». И когда потом дружную уфимскую команду стали дергать и спрашивать, был ли кто на Витрупе, все, конечно, отказывались, а этот журнал стал железной уликой!

Потом приехал какой-то мужик, явно кагебешник, присел, поболтал и сказал, что все хорошо, но погода портится. Конечно, все стали уверять, что он ошибается, но мужик твердо пообещал, что погода испортится завтра-послезавтра, и намек был понят. Вот тогда Миша Бомбин и рижане и предложили Гаую. Место дивное, укромное, с озерами, соснами, до моря не так далеко. Мы оставили в кемпинге несколько человек, посмотреть, что будет, и уехали. Так и началась Гауя. А за нами действительно приезжали, если бы мы остались, погода для нас уж точно бы испортилась.

– Для расширения сознания и приятного времяпрепровождения использовали портвейн?

Мамедовна: Портвейн был в то время натуральный и самый доступный по цене (сушняк тогда никто и за вино-то не держал). Схема выглядела так: вышел на стрит, встретил себе подобных, нааскал ( один или в паре), часть заныкал бывало (на джинсы), на оставшиеся купил то, на что нааскал, остальные сели на хвост и все выпили по бульку. Как говорил Сеня Скорпион: «А на оставшиеся деньги оптом дешевого портвешку!» Бася хорошо аскала, Рыба, а также Прайс – высший пилотаж. Про него тогда статья вышла в газете «Принц–нищий». Стрелял иногда по чирику. Угощал потом шартрезом в баре на последнем этаже гостиницы «Москва». Но не портвейном единым… Ибо выпив свой бульк, кто-то мог начать читать свои стихи, телеги рассказывать. У некоторых был (и есть) настоящий поэтический и литературный дар. Как, например, у Сени, Миши Красноштана, у многих других. Вот и проводились эдакие «портвейно-литературные чтения» в каком-нибудь элитном парадняке за Елисеевском или в саду Эрмитаж. Да много мест было, не только Пешков-стрит. Частенько ехали к кому-то на флэт музыку послушать.

– Наркотики появились позже?

Йоко: Наркотики появились почти сразу. Хотя очень многие вообще ничего не употребляли, должна заметить. А кто-то только курил, да и то нечасто. Как-то это не было всеобщим поветрием. Самая страшная, на мой взгляд, штука «винт», появилась во второй половине 80-х. Я его всегда боялась. Он был распространен не то что массово, но у меня перед глазами было несколько примеров, когда замечательные люди действительно начисто съезжали крышей или просто пропадали… Последствия были страшные!

– На какое время, на ваш взгляд, пришелся пик хипповского движения?

Йоко: Мне кажется, на 75-78-й годы, но это на мой взгляд. Потому что есть старшие товарищи, и у них свои пики

Мамедовна: А у меня был свой такой длинный пик – с конца 70-х и до конца 80-х. Но, как уже сказала Йоко, у более олдовых, для коих мы пионеры, иные пики. Некоторые говорят, что к концу 70-х уже все закончилось. Исчезла контркультурная составляющая и т.п.

Фото из архива

– Хиппи – это люди крупных городов, насколько они были в большей степени порождением Москвы, Питера, Таллинна?

Йоко: Совсем необязательно. Была своя большая и дружная тусовка в Могилеве, Смоленске, с легкой руки Паши Смоленского сотоварищи были львовские, минские, уфимские, казанские, иркутские и ангарские. Может, забыла какие-то еще, прошу простить! Большое уважение вызывали уфимские и казанские, из-за обилия в этих городах абсолютно дикой урлы.

– Кто на ваш взгляд максимально точно передал дух тусовки хиппи тех лет?

Йоко: Из поэтов – Гуру, Шамиль, Сеня Скорпион, хотя, конечно, это далеко не все, кого хотелось бы и стоило бы упомянуть. Что поделаешь, склероз!

Мамедовна: Умка. Олеся.

Йоко: Умка глубже, но Олеся, конечно, эмоциональнее!

Мамедовна: Скорпион, Солдат, Шамиль, Кест, Вася Лонг, Володя Борода. Еще целый ряд. Очень много талантливых людей среди хиппи, умеющих передать дух.. Я даже и не перечислю тут всех..

Йоко: Диверсант! Он и рисовал, и стихи писал замечательные.

Мамедовна: Саша Пессимист, Мата Хари.

Йоко: Да, Пессимист очень талантливый человек. Система вообще была богата на таланты. И трудно перечислить всех поэтов, художников и музыкантов, это тема отдельная. Кстати, много интересного можно найти в журнале «Забриски Райдер».

– Фильм Гарика Сукачева «Дом Cолнца» хотя бы в какой степени отразил эпоху?

Йоко: Он ее в какой-то степени затронул и сделал розовую сказочку в конфетном фантике.

Мамедовна: Фильм был ужасно раскритикован хиппарями именно за свою сказочность и однобокость. Лично мне фильм понравился, пусть сказочка, но хоть что-то. Гарик – молодец! (И Ваня тоже.) Хоть он и не совсем точно отразил те события, но это достаточно позитивный взгляд, без чернухи. Иначе бы фильм вряд ли вышел на экраны.

[html][/html]

Видео: Youtube/пользователь: Дом Солнца

– Каждый год 1 июня вы собираетесь в Царицыно. Значит что-то вас сильно удерживает, несмотря на то что времена хиппи все-таки прошли?

Мамедовна: Для старичков, как мне кажется, это просто ностальгия по молодости, тому времени, стремление держаться друг друга – «своих» из тех, кто еще жив… В силу общей ментальности, общего прошлого. Для молодежи – это такая прикольная тусовка, и для них времена хиппи в самом разгаре, и у них свои пики. А вообще атмосфера на поляне совершенно необычная, позволяющая снова окунуться в тот параллельный мир, в котором мы ранее пребывали. Выходя с поляны, попадаешь в иную, серую и скучную, реальность.

Йоко: Хочется повидать тех, с кем были связаны самые яркие и лучшие годы жизни. И снова ощутить атмосферу праздника.

Мамедовна: Хочу добавить, что, говоря о том времени, я упоминаю лишь свой скромный специфический круг общения в своем временном отрезке. И это крайне малая часть того, что происходило тогда. К тому же память подводит. И трудно восстановить хронологию. И вспомнить всех, с кем тогда общались. Вспоминаются наиболее яркие моменты. Было очень много интересного и до, и во время, были потрясающие люди. Некоторые из них еще живы и могут рассказать гораздо подробнее и увлекательнее о системе хиппи.

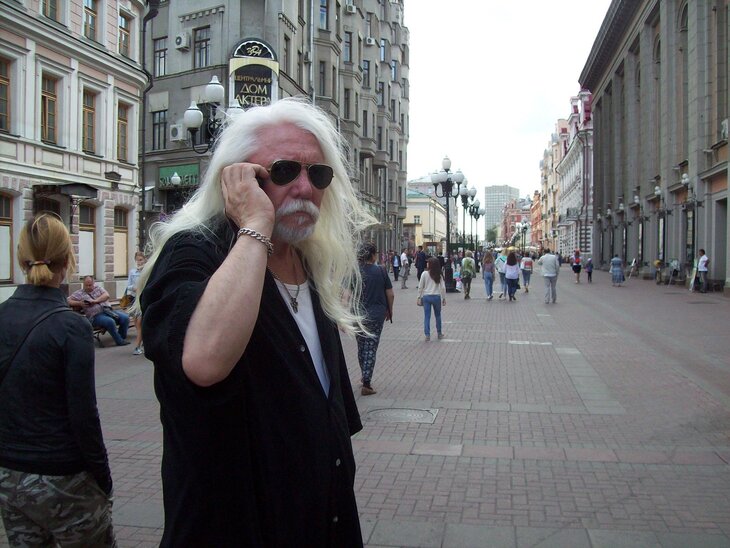

Боксер (Александр Литвиненко)

Семья у меня была специфическая. Мама музыкой увлекалась. Отец был чиновником, в Министерстве сельского хозяйства Узбекской ССР работал в Средней Азии. В Ташкенте я и родился. Бабушка окончила Первый медицинский в Москве. Дед – полковник-артиллерист, истребитель танков.

Фото предоставлено Александром Литвиненко

Хорошая библиотека была в доме, так что я был готов морально весь мир внутренним оком окинуть. Дядька мой был стилягой и музыкантом, очень увлекался Элвисом. Не знаю, откуда он брал пластинки, но у меня все началось именно с тех ритмов специфических, мое восприятие и внутренний мир стали формироваться.

Отца перевели работать в Москву. Наш дом тоже был населен публикой специфической. Очень хорошо помню как у соседей появилась пластинка The Beatles. У парня, у которого родители работали в Лондоне были, и интересные шмотки, и гитара у него была хорошая, ну а пластинки – в полном ассортименте.

[html][/html]

Видео: Youtube/пользователь: DrSotosOctopus

В школе я учился с младшим братом известного Юрия Солнце. Это было в девятом классе – 1969-1970 учебный год.

Вообще мне кажется, что все было сильно замешано на фирменных штанах и пластинках, на возможности общении с разными европейскими студентами. Я в свое время с немецким пареньком поменялся майками просто посреди улицы, на ней было написано «Карнаби стрит». Оказалось, что это улица, которая работает на продвинутую хипповую одежду.

Заезжала в Москву американская молодежь. Ходила в штанах клеш с волосами длинными, селились в бюджетных отелях. Как я понимаю, приезжали сюда по студенческому обмену через комсомольский «Спутник».

Откуда взялись пацифистские идеи: у меня и дед, и отец – фронтовики, воевали за Родину, что было понятно и естественно. Меня же, когда советские войска вошли в 1968 году в Чехословакию, повергло в шок. Что-то у меня как-то сдвинулось в сознании в сторону и воевать резко расхотелось. Наверное, уже был перегружен этими маршами, разрывами бомб настолько, что моя генетическая линия устала. Я драчуном был, в волейбол играл и ничего особенно не боялся, но во всей этой политике партии и правительства такая фальшь и натянутость!

Ну, а дальше – журнал «Америка» с типажами длинноволосыми на берегу моря, Californian girls. Вообще длинные волосы и хулиганы носили, и рабочие парни, и интеллектуалы. Так же, как и клеши. Другое дело, что они отличались по качеству и по свойству. Мы их (майки), выкручивали, варили, чтобы получались с пятнами, с разводами. Фенечки плели. Но самое главное – джинсы! Я увидел их в вестерне у Джона Уэйна в «Дилижансе». Весь он такой там был в этих делах джинсовых, в хороших ковбойских сапогах, в шляпе и с винчестером. В общем, тлетворное влияние Запада, понятное дело. Я это осознаю, признаю, конечно, что виноват, поддался и так далее. Как же они потрясающе были поданы! Эти типажи меня устраивали куда больше, чем серая масса на улицах с кислыми мордахами.

Серьезным толчком для меня была встреча с Сережей Баски из «Рубиновой Атаки», тогда они еще были «Рубинами» Он всего на два года старше меня, но все равно это такая преемственность поколений. Мы как бы присматривали друг за другом, что чего.

Сережа Баски. Фото из архива Александра Литвиненко

Я постоянно посещал кинотеатр «Иллюзион», потому что очень любил кино. Вообще, конечно, молодежь нашей формации в основном состояла из гуманитариев. При этом стычки происходили постоянно. Нашу публику ставили на учет в милиции, в детских комнатах, и мы уже были потенциальные нарушители правопорядка. Шел отлов в кафе, на улицах фиксировали на ходу. Просто останавливали и фотографировали нас. Ну, а потом, в 1971-72 годах, дали распоряжение, чтобы они с нами слились. Им дали распоряжение одеваться и отпускать волосы. Благо, реквизита завались! Вот он – из конфискатов. Говорили, что и магазин у них был в подвале Петровки, 38, в котором диски The Beatles продавались по три рубля, в то время когда на свежем воздухе они стоили 60-80 рублей. Ну далее – хороший пиджачок, джинсы из конфиската, часы Seiko и Citizen. В общем, модные пошли опера, нафарцованные, нафаршированные шмотьем. Вот только смешаться с толпой они опять не смогли!

Была и беготня от них, и драки с ними, когда была возможность, понятное дело. Шпана – дело другое.

В Питере много хиппового народа, но особенно много в Прибалтике. Латыши, эстонцы, литовцы были буквально заражены этой темой! Была у нас девочка Илона Рижская, свободных нравов! Я это не в упрек говорю, по тем временам – хорошая девочка, нормальная во всех отношениях, но любвеобильная. Времена Peace, Love & Rock’n’roll!

Наркотики не помню, как-то мимо нашей компании они прошли. Траву иногда курили. Да, еще был циклодол. Это такие таблетки типа транквилизаторов. Один раз попробовал, и меня это не устроило совершенно.

«Рубиновая атака». Фото из архива Александра Литвиненко

Хватало все того же рок-н-ролла! Макаревич со своей «Машиной времени» еще только начинали (в сейшенах участвовали, разогревая «Рубинов»), «Оловянные солдатики», «Второе дыхание», Градский со “Скоморохами”, “Воскресение”. Все были модные, стильные, джинсовые, лохматенькие. Все думали о хорошей аппаратуре, о хорошем звуке.

[html][/html]

Видео: Youtube/Канал пользователя marivana3000

Все началось на Маяковке, потом Пушка, ну и два психодрома – в скверике возле 1-го и 2-го корпусов МГУ, на Моховой. Где памятник стоит Ломоносову – это был первый. А второй психодром – площадочка, где лавочки стояли у забора, их сейчас убрали, ворота закрыты. Раньше всюду можно было пройти, как-то демократичнее было. Сейчас все напряженнее, заборов нагородили дополнительных ,замков навесили, охрана повсюду стоит. Раньше этого не было и пройти можно было в любую аудиторию.

Пик, наверное, пришелся на ту известную демонстрацию 1971 года. Я на ней не был, потому что на движения ее организатора Солнца я, честно говоря, не очень велся. Моя компания его называла Подсолнухом. Что там было на самом деле с этой демонстрацией, история темная, но после 1971 года, когда людей по дурдомам рассовали, по тюрьмам и в армию отправили. Наверное, это и был финал.

Вот только ничего этим не добились и ничего на самом деле не разогнали. Единственное, кто-то перешел в разряд конкретных пьяниц, кто-то сел на наркоту, а кто-то пошел трудиться на производстве. Многие, но не все. Конечно, нас пытались отсечь, как опухоль, влияние капиталистического образа жизни. При этом забывалось другое, что при всем нашем непривычном для них внешнем виде, любви к рок-н-роллу, мы же были советскими людьми. Мы же не были предателями Родины! Да, у нас был свой стиль, да, мы не хотели быть в коллективе, предпочитая компании, да, мы были индивидуалистами! Зачем мне демонстрация, если я больше любил пообщаться наедине?

Когда я попал на Запад и в США, поразился тому, насколько мы похожи с тамошними волосатыми. Они такие же агрессивные в хорошем смысле на полицию, на публику, несущую государственную функцию и при этом – очень мягкие со своими. Встретил одного такого в Голландии. Причем человек был из Христиании, ехавший из Дании через Амстердам в Лондон, а я из Москвы через Германию приехал в Амстердам.

Фото : Алексей Субботин

Я сидел в 7 часов утра, освещенный солнцем, как сейчас помню, извините за высокий стиль. Шляпа на мне была большая, и меня перекрыла тень от точно такой же шляпы. Напротив сидел на корточках чувачок, взрослый, он старше меня лет на пять где-то, Джон, как он представился потом. Площадка была пустая совершенно, я один на ней был. Когда он узнал, что я из России, для него это был дикий кайф!

Я считаю, что все получилось, как надо. Свободная волна, родившаяся тогда, никуда не исчезла. Комсомольцы сделали свой мир с капитализмом под лозунгом «Грабь награбленное» и «Это все наше, но на всех не хватит». Мне это никогда не было интересно. Я картины пишу, кукол своих рок-н-ролльных делаю, и я максимально в своей стезе. Да и женщины у меня такие, другие меня раздражали, и с другими я не мог ужиться.

Творческий народ вокруг меня – вот, что меня устраивает. Ну и плюс возможность передвижения по миру. Там я ни с кем не сплетаюсь, для того чтобы Россию полоскать. Я люблю эту землю, живу здесь, здесь предки все мои похоронены. Я в настрое, мозг совершенно свежий и не загаженный штампами. Так что, все нормально!

Young people near the Woodstock music festival in August 1969

A hippie, also spelled hippy,[1] especially in British English,[2] is someone associated with the counterculture of the 1960s, originally a youth movement that began in the United States during the mid-1960s and spread to different countries around the world.[3] The word hippie came from hipster and was used to describe beatniks[4] who moved into New York City’s Greenwich Village, in San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury district, and Chicago’s Old Town community. The term hippie was used in print by San Francisco writer Michael Fallon, helping popularize use of the term in the media, although the tag was seen elsewhere earlier.[5][6]

The origins of the terms hip and hep are uncertain. By the 1940s, both had become part of African American jive slang and meant «sophisticated; currently fashionable; fully up-to-date».[7][8][9] The Beats adopted the term hip, and early hippies inherited the language and countercultural values of the Beat Generation. Hippies created their own communities, listened to psychedelic music, embraced the sexual revolution, and many used drugs such as marijuana and LSD to explore altered states of consciousness.[10][11]

In 1967, the Human Be-In in Golden Gate Park, San Francisco, and Monterey Pop Festival[12]

popularized hippie culture, leading to the Summer of Love on the West Coast of the United States, and the 1969 Woodstock Festival on the East Coast. Hippies in Mexico, known as jipitecas, formed La Onda and gathered at Avándaro, while in New Zealand, nomadic housetruckers practiced alternative lifestyles and promoted sustainable energy at Nambassa. In the United Kingdom in 1970, many gathered at the gigantic third Isle of Wight Festival with a crowd of around 400,000 people.[13] In later years, mobile «peace convoys» of New Age travellers made summer pilgrimages to free music festivals at Stonehenge and elsewhere. In Australia, hippies gathered at Nimbin for the 1973 Aquarius Festival and the annual Cannabis Law Reform Rally or MardiGrass. «Piedra Roja Festival», a major hippie event in Chile, was held in 1970.[14] Hippie and psychedelic culture influenced 1960s and early 1970s youth culture in Iron Curtain countries in Eastern Europe (see Mánička).[15]

Hippie fashion and values had a major effect on culture, influencing popular music, television, film, literature, and the arts. Since the 1960s, mainstream society has assimilated many aspects of hippie culture. The religious and cultural diversity the hippies espoused has gained widespread acceptance, and their pop versions of Eastern philosophy and Asiatic spiritual concepts have reached a larger group.

The vast majority of people who had participated in the golden age of the hippie movement were those born during the 1940s. These included the oldest of the Baby Boomers as well as the youngest of the Silent Generation; the latter who were the actual leaders of the movement as well as the pioneers of rock music.[16]

Etymology[edit]

Lexicographer Jesse Sheidlower, the principal American editor of the Oxford English Dictionary, argues that the terms hipster and hippie are derived from the word hip, whose origins are unknown.[17] The word hip in the sense of «aware, in the know» is first attested in a 1902 cartoon by Tad Dorgan,[18] and first appeared in prose in a 1904 novel by George Vere Hobart[19] (1867–1926), Jim Hickey: A Story of the One-Night Stands, where an African-American character uses the slang phrase «Are you hip?»

The term hipster was coined by Harry Gibson in 1944.[20] By the 1940s, the terms hip, hep and hepcat were popular in Harlem jazz slang, although hep eventually came to denote an inferior status to hip.[21] In Greenwich Village in the early 1960s, New York City, young counterculture advocates were named hips because they were considered «in the know» or «cool», as opposed to being square, meaning conventional and old-fashioned. In the April 27, 1961 issue of The Village Voice, «An open letter to JFK & Fidel Castro», Norman Mailer utilizes the term hippies, in questioning JFK’s behavior. In a 1961 essay, Kenneth Rexroth used both the terms hipster and hippies to refer to young people participating in black American or Beatnik nightlife.[22] According to Malcolm X’s 1964 autobiography, the word hippie in 1940s Harlem had been used to describe a specific type of white man who «acted more Negro than Negroes».[23] Andrew Loog Oldham refers to «all the Chicago hippies,» seemingly about black blues/R&B musicians, in his rear sleeve notes to the 1965 LP The Rolling Stones, Now!

Although the word hippies made other isolated appearances in print during the early 1960s, the first use of the term on the West Coast appeared in the article «A New Paradise for Beatniks» (in the San Francisco Examiner, issue of September 5, 1965) by San Francisco journalist Michael Fallon. In that article, Fallon wrote about the Blue Unicorn Cafe (coffeehouse) (located at 1927 Hayes Street in the Haight-Ashbury district of San Francisco), using the term hippie to refer to the new generation of beatniks who had moved from North Beach into the Haight-Ashbury district.[24][25]

History[edit]

Origins[edit]

A July 1968 Time magazine study on hippie philosophy credited the foundation of the hippie movement with historical precedent as far back as the sadhu of India, the spiritual seekers who had renounced the world and materialistic pursuits by taking «Sannyas». Even the counterculture of the Ancient Greeks, espoused by philosophers like Diogenes of Sinope and the cynics were also early forms of hippie culture.[26] It also named as notable influences the religious and spiritual teachings of Buddha, Hillel the Elder, Jesus, St. Francis of Assisi, Henry David Thoreau, Gandhi and J.R.R. Tolkien.[26]

The first signs of modern «proto-hippies» emerged at turn of the 19th century in Europe. Late 1890s to early 1900s, a German youth movement arose as a countercultural reaction to the organized social and cultural clubs that centered around «German folk music». Known as Der Wandervogel («wandering bird»), this hippie movement opposed the formality of traditional German clubs, instead emphasizing folk music and singing, creative dress, and outdoor life involving hiking and camping.[27] Inspired by the works of Friedrich Nietzsche, Goethe, and Hermann Hesse, Wandervogel attracted thousands of young Germans who rejected the rapid trend toward urbanization and yearned for the pagan, back-to-nature spiritual life of their ancestors.[28] During the first several decades of the 20th century, Germans settled around the United States, bringing the values of this German youth culture. Some opened the first health food stores, and many moved to southern California where they introduced an alternative lifestyle. One group, called the «Nature Boys», took to the California desert and raised organic food, espousing a back-to-nature lifestyle like the Wandervogel.[29] Songwriter eden ahbez wrote a hit song called Nature Boy inspired by Robert Bootzin (Gypsy Boots), who helped popularize health-consciousness, yoga, and organic food in the United States.

American tourists in Thailand, the early 1970s

The hippie movement in the United States began as a youth movement. Composed mostly of white teenagers and young adults between 15 and 25 years old,[30][31] hippies inherited a tradition of cultural dissent from bohemians and beatniks of the Beat Generation in the late 1950s.[31] Beats like Allen Ginsberg crossed over from the beat movement and became fixtures of the burgeoning hippie and anti-war movements. By 1965, hippies had become an established social group in the U.S., and the movement eventually expanded to other countries,[32][33] extending as far as the United Kingdom and Europe, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, Japan, Mexico, and Brazil.[34] The hippie ethos influenced The Beatles and others in the United Kingdom and other parts of Europe, and they in turn influenced their American counterparts.[35] Hippie culture spread worldwide through a fusion of rock music, folk, blues, and psychedelic rock; it also found expression in literature, the dramatic arts, fashion, and the visual arts, including film, posters advertising rock concerts, and album covers.[36] In 1968, self-described hippies represented just under 0.2% of the U.S. population[37] and dwindled away by mid-1970s.[32]

Along with the New Left and the Civil Rights Movement, the hippie movement was one of three dissenting groups of the 1960s counterculture.[33] Hippies rejected established institutions, criticized middle class values, opposed nuclear weapons and the Vietnam War, embraced aspects of Eastern philosophy,[38] championed sexual liberation, were often vegetarian and eco-friendly, promoted the use of psychedelic drugs which they believed expanded one’s consciousness, and created intentional communities or communes. They used alternative arts, street theatre, folk music, and psychedelic rock as a part of their lifestyle and as a way of expressing their feelings, their protests, and their vision of the world and life. Hippies opposed political and social orthodoxy, choosing a gentle and nondoctrinaire ideology that favored peace, love, and personal freedom,[39][40] expressed for example in The Beatles’ song «All You Need is Love».[41] Hippies perceived the dominant culture as a corrupt, monolithic entity that exercised undue power over their lives, calling this culture «The Establishment», «Big Brother», or «The Man».[42][43][44] Noting that they were «seekers of meaning and value», scholars like Timothy Miller have described hippies as a new religious movement.[45]

There are echoes of the term «hippie» in «preppy» (with particular cultural currency as a 1950s fashion trend) and «yuppie» (1980s), both of which embraced rather than rejected establishment culture.

1958–1967: Early hippies[edit]

Escapin’ through the lily fields

I came across an empty space

It trembled and exploded

Left a bus stop in its place

The bus came by and I got on

That’s when it all began

There was cowboy Neal

At the wheel

Of a bus to never-ever land

– Grateful Dead, lyrics from «That’s It for the Other One»[46]