12 апреля 2012 года, в четверг Страстной седмицы, Святейший Патриарх Московский и всея Руси Кирилл совершил Литургию святителя Василия Великого в кафедральном соборном Храме Христа Спасителя, сообщает Патриархия.ru. По окончании богослужения Предстоятель Русской Церкви обратился к верующим с проповедью.

Этот день в середине Страстной седмицы мы именуем великим праздником, и он действительно является таковым наравне с двунадесятыми, потому что воспоминание о событии, которое легло в основу этого празднования, живет в Церкви особым образом.

Многое, что приходит к нам из прошлого, содержится в летописях, в книгах. Открывая их, мы можем узнать о том, что было до нас, что было в прошлом, и это возбуждает наше воображение — мы стараемся представить себе древних героев, вождей, полководцев, императоров, князей. Такое воспоминание, которое порождается чтением, осуществляется в нашем сознании, в нашей памяти, в том числе силой нашего воображения.

Но Господь Иисус Христос, совершив Тайную Вечерю, сказал Своим ученикам: «Сие творите в Мое воспоминание; и когда вы будете есть хлеб сей и вкушать от чаши сей, то вы смерть Мою будете возвещать до тех пор, пока Я не приду» (см. 1 Кор. 11:26). Совершенно очевидно, что воспоминание о Тайной Вечере — это не то воспоминание, которым мы связываем себя с прошлым. Если нечто совершается до скончания века, то это уже не воспоминание — это некая связь с той реальностью, которая была тогда, когда Христос произнес эти слова.

И действительно, из слов Священного Писания, из великой святоотеческой традиции мы знаем, что воспоминание, которое творит Святая Церковь, совершая Святую Евхаристию, подобно Господу и Спасителю освящая хлеб и вино, пресуществляя их в истинное Тело и Кровь Спасителя, есть не ментальное воспоминание на уровне разума, сознания, памяти. В этом действии присутствует Дух Святой, и Он непостижимым образом вводит нас, людей XXI века, соединяющихся в храме вокруг своего епископа или священника, в соприкосновение с той Тайной Вечерей, которую совершил Господь. Находясь в храме, будучи отделены временем и пространством от той Тайной Вечери, мы силой Святого Духа становимся не зрителями, вспоминающими только сознанием своим, но реальными соучастниками той Тайной Вечери, которую Господь совершил с учениками Своими.

Вот почему воспоминание о Тайной Вечере, Таинстве Святой Евхаристии мы именуем Таинством Церкви. Не сегодня появилось это определение — оно появилось в святоотеческой древности, потому что Церковь призвана все то, что совершил Господь Иисус Христос не силой человеческой, а силой Духа Святого, актуализировать, делать достоянием каждого последующего поколения. И, подобно апостолам, мы с вами были сегодня на Тайной Вечере, оставаясь здесь, в этом храме, отделенные от Тайной Вечери двумя тысячами лет. Силой Святого Духа мы совершили то, что совершил Господь Иисус Христос, учредив Таинство Святой Евхаристии.

А почему преподобный Симеон Новый Богослов и вслед него многие другие учителя Церкви именуют Евхаристию Таинством Церкви? Да потому что Церковь есть Тело Христово, по слову апостола (1 Кор. 12:27), и оно являет себя как Тело Христово, совершая Таинство Евхаристии. Мы Церковь, когда мы вместе молимся и когда мы от единого Хлеба и от единой Чаши причащаемся подлинного Тела и подлинной Крови Христовых.

В этот момент происходит нечто опять-таки непонятное человеческому уму. Причащаясь от единого Хлеба и Чаши, мы входим друг с другом во Единого Духа причастие, мы входим в нерасторжимое единство. Именно в этом Божественное обоснование единства Церкви, именно из этого факта проистекает осуждение всяких расколов, ересей, которые препятствуют людям участвовать в этой священной Евхаристической трапезе. Тот, кто разделяет Тело Христово, тот разрушает Святую Евхаристию, тот идет против Бога, против Его заповедей, против всего того, что запечатлено мудростью святых отцов и кровью мучеников, — против единства Церкви Христовой.

Поэтому сегодняшний праздник установления Святой Евхаристии есть праздник Церкви, праздник молящейся евхаристической общины, праздник нашего нерасторжимого единства, и никому не дано этого единство поколебать, несмотря на соблазны века сего, ложь, клевету, сомнения, которые сеются врагом рода человеческого. Именно из этого проистекает учение Церкви о том, что всякое разделение наносит непоправимый духовный ущерб, является несмываемым грехом для того, кто вступает на путь разделения. Но каким бы ни было по масштабу это разделение, будь то единицы, сотни или даже тысячи людей, никакое разделение неспособно разрушить единую Святую Соборную и Апостольскую Церковь, которая будет до скончания века, ибо по обетованию Спасителя «врата ада не одолеют ю» (Мф. 16:18).

Пусть сегодняшний день, осознанное духовное переживание Таинства Святой Евхаристии, Таинства нашего участия в жизни, страданиях, смерти и Воскресении Спасителя, Таинства нашего участия в Его последней вечери с апостолами укрепит каждого в вере, единомыслии, твердости и непоколебимой решимости, следуя за Христом, соблюдать все то, что Он передал нам, все то, что Духом Святым укоренено в жизни Церкви и в сознании верных, сохраняя единство духа в союзе мира (Еф. 4:3). Аминь.

Пресс-служба Патриарха Московского и всея Руси

Ваше Блаженство, Ваши Преосвященства, отцы, братия и сестры!

Первым праздником как днем, свободным от работы, днем отдыха, днем покоя (а именно так и воспринимает современный человек любой праздник) был день, последствовавший шести дням творения: И совершил Бог к седьмому дню дела Свои, которые Он делал, и почил в день седьмый от всех дел Своих, которые делал. И благословил Бог седьмой день, и освятил его(Быт. 2. 2-3).

Жизнь первозданной четы в раю проходила в контексте субботнего покоя. Человек еще не должен был трудиться в поте лица своего, чтобы добывать необходимые средства к существованию. Он находился в непрестанном богообщении, а окружающий мир — в состоянии гармонии.

Однако грехопадение повлекло за собой нарушение этого райского состояния. Большую часть времени человек стал уделять трудам, необходимым для удовлетворения своих жизненных потребностей. Для общения же с Богом, главным содержанием которого было благодарение (по-гречески — евхаристия), выделялись особые дни, что подтверждается библейским описанием жертвоприношения Каина и Авеля. Значит, уже тогда существовал ритуал праздника-жертвоприношения, приуроченный к определенному времени года, существовал круг обязанностей человека по отношению к Богу, которые выражались в благодарении через жертву.

Библия неоднократно говорит о жертвах, совершенных людьми в благодарность Творцу за явленные Им благодеяния. Здесь и жертвоприношение Ноя по окончании Всемирного потопа (см.: Быт. 8. 20-22), и Авраама — близ Вефиля (см.: Быт. 12. 8), у дубравы Мамре, что в Хевроне (см.: Быт. 13. 18), в Вирсавии (см.: Быт. 26. 23-25); Иаков поставил жертвенник в Сихеме (см. Быт. 33. 18-20). Господь повелел Иакову устроить жертвенник в Вефиле, где ранее явился ему, когда тот бежал от Исава (см.: Быт. 35. 1), и др.

Однако установление праздников, связанных с ними богослужений и жертвоприношений и подробная регламентация поведения народа Божия в эти дни относится уже ко времени его исхода из Египта.

Так, в дарованном избранному народу Декалоге заповедь о субботе 2-й главы Книги Бытия конкретизируется: Помни день субботний, чтобы святить его. Шесть дней работай, и делай в них всякие дела твои; а день седьмый — суббота Господу Богу твоему: не делай в оный никакого дела ни ты, ни сын твой, ни дочь твоя, ни раб твой, ни рабыня твоя, ни скот твой, ни пришлец, который в жилищах твоих. Ибо в шесть дней создал Господь небо и землю, море и все, что в них, а в день седьмый почил. Посему благословил Господь день субботний и освятил его (Исх. 20. 8-11).

Таким образом, первый в истории человечества праздник имел в основе своей божественное установление, но вместе с тем он носил и естественный характер как необходимый для трудящегося отдых.

То, что Сам Господь установил праздничный календарь, говорит о важности праздника в нашей жизни. Ведь совершая праздник, народ Божий не только вспоминает какое-либо событие своей истории, но и свидетельствует о том, что он помнит о делах Божиих, живет этим воспоминанием, актуализирует его в современности. Но праздник — не только обращение к памяти народа. Это и обращение к «памяти» Бога, «напоминание» Ему о Его любви к Своему народу, призыв сохранить и возобновить те милости, которые Он даровал отцам. Важно отметить, что заповедь о субботе, как и о других, позднейших праздниках, содержит в себе два аспекта: служение Богу и отказ от земных забот и дел.

Важнейшими ветхозаветными праздниками были Пасха и Пятидесятница. А важнейшей частью любого празднования являлась трапеза.

И первая Евхаристия, совершенная Самим Христом, была продолжением и развитием праздничной пасхальной трапезы, имевший священный характер, потому что на ней доминировали религиозные переживания, и традиционные праздничные блюда были подчинены религиозной идее. Вправленная в формат ветхозаветной пасхальной вечери, содержавшей воспоминания об исходе Израиля из Египта, Новая Пасха своим смысловым центром имела распятие и воскресение Сына Божия. И Спаситель заповедал ученикам совершать Пасху не в воспоминание об исходе из Египта, а в воспоминание о Нем — о Его исходе от смерти к жизни. Пасхальный агнец был одновременно и жертвой благодарения за избавление от египетского плена, и жертвой прошения в умилостивление за грехи народа, и главной частью праздничной трапезы. Все эти три элемента — благодарение, прошение и трапеза — присутствуют в Евхаристии.

В раннехристианской Церкви годовой богослужебный круг также основывался на Пасхе и Пятидесятнице. Унаследованные от иудейской традиции, эти праздники приобрели новое содержание: Пасха с самого начала была празднованием Воскресения Христа, а Пятидесятница — воспоминанием сошествия Святого Духа на апостолов, установления Нового Завета между Богом и Новым Израилем — христианами.

Во II веке Церковь начинает почитать мучеников, выделяя в календаре дни их молитвенного поминовения. Древнейшим свидетельством этого является «Мученичество святого Поликарпа Смирнского», относящееся к середине II века. Характерно, что почитание мучеников не отделяется в этом памятнике от поклонения Христу: «Мы поклоняемся Ему как Сыну Божию; а мучеников как учеников и подражателей Господних достойно любим за непобедимую приверженность (их) своему Царю и Учителю. Да даст Бог и нам быть их сообщниками и соучениками!» («Мученичество Поликарпа Смирнского» 17). И хотя первоначально культ каждого мученика был привязан ко дню его кончины, церковное воспоминание этого события всегда носило праздничный характер. В конце повествования о кончине святого Поликарпа авторы говорят: «Мы взяли затем кости его, которые драгоценнее дорогих камней и благороднее золота, положили где следовало. Там, по возможности, Господь даст и нам, собравшимся в весели и радости, отпраздновать день рождения Его мученика, в память подвизавшихся до нас и в наставление и приготовление для будущих (подвижников)» («Мученичество…» 18).

В течение IV века богослужебный круг христианских Церквей существенно расширяется благодаря введению новых праздников, переосмыслению старых, добавлению памятей новых святых, «обмену праздниками» между поместными Церквами. И, конечно же, центром каждого празднования было богослужение — Евхаристия.

Каждый из Святых Отцов этого периода оставил нам проповеди на те или иные праздники. Одновременно происходило и осмысление самого феномена христианского праздника. И в этом выдающуюся роль сыграл святитель Григорий Богослов. В проповеди на Рождество Христово он говорит о годичном круге церковных праздников и о том, как в течение литургического года перед глазами верующего проходит вся жизни Иисуса:

«Ведь немного позже (выражение «немного позже» указывает на ближайший к Рождеству праздник Крещения Господня — День Светов — прим.) ты увидишь Иисуса и очищающимся в Иордане… увидишь и разверзающиеся небеса (Мк. 1. 10); увидишь Его принимающим свидетельство от родственного Ему Духа, искушаемым и побеждающим искусителя, принимающим служение Ангелов, исцеляющим всякую болезнь и всякую немощь в людях (Мф. 4. 23), животворящим мертвых… изгоняющим демонов… немногими хлебами насыщающим тысячи, ходящим по морю, предаваемым, распинаемым и распинающим мой грех, приносимым (в жертву) как агнец и приносящим как священник, погребаемым как человек и восстающим как Бог, а потом и восходящим на небо и приходящим со славой Своей. Вот сколько у меня праздников по поводу каждого таинства Христова! Но главное в них одно: мой путь к совершенству, воссоздание и возвращение к первому Адаму» (Григорий Богослов. Слово 38, 16, 1-19. SС 358, 140-142. Творения. Т. 1. С. 531).

Святитель Григорий учит, что каждый церковный праздник должен служить для верующего новой ступенью на пути к совершенству, новым прозрением в жизнь и искупительный подвиг Иисуса.

В этом же Слове святитель подчеркивает, что христианский праздник состоит не в том, чтобы устраивать пиршества, наедаться роскошными блюдами и напиваться дорогостоящими винами. Для верующего праздник заключается в том, чтобы прийти в храм и там насладиться словом Божиим.

Именно в храме, по мысли другого великого святителя, Иоанна Златоуста, и совершается праздничный пир — пир веры. Здесь, участвуя в Евхаристии, мы не только встречаемся со Спасителем, реально пребывающим с нами в Святых Дарах, но и приобщаемся Его Пречистого Тела и Честной Крови, становясь участниками истинной праздничной трапезы.

«Итак, все — войдите в радость Господа своего! И первые, и последние, примите награду; богатые и бедные, друг с другом ликуйте; воздержные и беспечные, равно почтите этот день; постившиеся и непостившиеся, возвеселитесь ныне! Трапеза обильна, насладитесь все! Телец упитанный, никто не уходи голодным! Все насладитесь пиром веры, все воспримите богатство благости!» — призывает учитель Церкви христиан в своем знаменитом Слове огласительном на Святую Пасху.

И если Евхаристия является центром и смыслом христианского праздника, то участие в праздновании не мыслится без участия в Евхаристии. Об этом говорят преподобные Никодим Святогорец и Макарий Коринфский: «Те, которые хотя и постятся перед Пасхой, но на Пасху не причащаются, такие люди Пасху не празднуют. Те, которые не подготовлены каждый праздник причащаться Тела и Крови Господних, не могут по-настоящему праздновать и воскресные дни, и другие праздники в году, потому что эти люди не имеют в себе причины и повода праздника, которым является Сладчайший Иисус Христос, и не имеют той духовной радости, которая рождается от Божественного приобщения» (Макарий Коринфский, Никодим Святогорец. «О непрестанном причащении», с. 54).

Каждый день, по мнению преподобных Никодима и Макария, может стать праздником: «Хочешь праздновать каждый день? Хочешь праздновать святую Пасху когда пожелаешь и радоваться радостью неизреченной в этой прискорбной жизни? Непрестанно прибегай к Таинству и причащайся с должной подготовкой, и тогда ты насладишься тем, чего желаешь. Ведь истинная Пасха и истинный праздник души — это Христос, который приносится в жертву в Таинстве» (там же. 2, с. 52-53).

Здесь почти дословно воспроизводится учение Симеона Нового Богослова о жизни как о непрестанном празднике приобщения к Богу. Преподобный Симеон пишет: «Если ты так празднуешь, так и Святые Таины принимаешь, вся жизнь твоя да будет единым праздником, но даже не праздником, но начатком праздника и единой Пасхи, переходом и переселением от видимого к умопостигаемому» (Слово нравственное 14, 54).

Рассуждая о христианских праздниках, невозможно избежать темы взаимодействия временного и вечного в нашей жизни. Сын Божий, рожденный Отцом вне времени и прежде всякого времени, прежде всех век, в Своем воплощении соединяет временное и вечное, земное и небесное. И праздник, и Евхаристия преодолевают время и являют вечность тем, кто участвует в них.

Евхаристия — не просто благочестивое воспоминание о Тайной Вечере, совершаемое Церковью в нарочитые дни, не ее дидактическая инсценировка, но ее постоянное повторение.

Совершителем Таинства является Сам Иисус Христос, и каждая совершаемая Литургия является не просто символическим воспоминанием об этом событии, но его продолжением и актуализацией. Хотя Евхаристия совершается в разное время и в разных местах, она остается единой, преодолевая временные и пространственные границы. Об этом говорит святитель Иоанн Златоуст: «Веруйте, что ныне совершается та же вечеря, на которой Сам Он возлежал. Одна от другой ничем не отличается. Нельзя сказать, что эту совершает человек, а ту совершил Христос; напротив, ту и другую совершает Сам Он. Когда видишь, что священник преподает тебе Дары, представляй, что не священник делает это, но Христос простирает к тебе руку». (Иоанн Златоуст. Беседы на Мф. (50, 30). Творения. Т. 7. С. 423).

По словам святителя, «мы постоянно приносим одного и того же Агнца, а не одного сегодня, другого завтра, но всегда одного и того же. Таким образом, эта жертва одна. Хотя она приносится во многих местах, но разве много Христов? Нет, один Христос везде, и здесь полный, и там полный, одно Тело Его. И как приносимый во многих местах Он — одно Тело, а не много тел, так и жертва одна. Он наш Первосвященник, принесший жертву, очищающую нас; ее приносим и мы теперь, тогда принесенную, но не оскудевающую… Не другую жертву, как тогдашний первосвященник, но ту же приносим постоянно…» (Иоанн Златоуст. Беседы на Евр. (17, 3). Творения. Т. 12. Кн. 1. С. 153).

В другом месте Златоуст подчеркивает: «Предстоит Христос и теперь; Кто учредил ту трапезу, Тот же теперь устрояет и эту. Не человек претворяет предложенное в Тело и Кровь Христовы, но Сам распятый за нас Христос. Представляя Его образ, стоит священник, произносящий те слова, а действует сила и благодать Божия» (Иоанн Златоуст. О предательстве Иуды 1, 6. Творения. Т. 2. Кн. 2. С. 423).

Евхаристия — не просто воспоминание о Голгофской жертве, но ее постоянное воспроизведение, на что указывают тексты евхаристических молитв. Эти молитвы пронизаны темой жертвы, которая приносится «о всех и за вся», что опять-таки сближает Евхаристию с древним храмовым богослужением, центром которого было жертвоприношение.

В молитве «по поставлении святых даров» литургии Василия Великого предстоящий священнослужитель просит Бога принять службу участвующих в Литургии так же, как Он приял «Авелевы дары» — принесение Авелем жертвы Богу (см.: Быт. 4. 4), «Ноевы жертвы» — жертвоприношение Ноя по окончании потопа (см.: Быт. 8. 20-22), «Аврваамова всеплодия» — принесение Авраамом в жертву сына своего Исаака (см.: Быт. 22. 1-14), «Моисеева и Аронова священства» — священство Моисея и Аарона (см.: Пс. 98. 6), «Самуилова мирная» — мирные жертвы, принесенные Самуилом (см.: 1 Цар. 11. 14-15). Здесь упоминаются пять сюжетов Священной истории, в христианской традиции воспринимаемые как прообразы Евхаристии. Со времени Тайной Вечери Евхаристия является той единственной жертвой, которая необходима для спасения и которая заменяет все ветхозаветные жертвы и всесожжения.

Цитированная молитва раскрывает смысл Литургии как таинства Нового Завета, соединяющего всю историю человечества от сотворения мира с эсхатологическим ожиданием Страшного Суда. Молитва устанавливает преемство между ветхозаветным культом всесожжений и жертв и новозаветной Евхаристиией, прообразом которой эти жертвы являлись.

Прообразом христианского праздника, говорит святитель Григорий Богослов, является ветхозаветный «юбилей» — год оставления. По закону Моисееву, каждый седьмой год считался годом покоя, когда не разрешалось засевать поля и собирать виноград; каждый пятидесятый год объявлялся юбилейным — годом праздника, когда люди возвращались в свои владения, должникам прощались долги, а рабов отпускали на свободу. Назначение юбилейного года, особым образом посвященного Богу, состояло не только в том, чтобы дать людям отдых, но и в том, чтобы, насколько возможно, исправить неравенство и несправедливость, существующие в человеческом обществе. Юбилей был годом подведения итогов, когда люди давали отчет Богу и друг другу в том, как они строят свою жизнь, и перестраивали ее в большем соответствии с заповедями Божиими. Юбилей, таким образом, становился прообразом жизни людей в будущем веке, где нет социального неравенства, рабов и господ, заимодавцев и должников:

«Число семь почитают чада народа еврейского на основании закона Моисеева… Почитание это у них простирается не только на дни, но и на годы. Что касается дней, то евреи постоянно чтут субботу… что же касается лет, то каждый седьмой год у них — год оставления. И не только седмицы, но и седмицы седмиц чтут они — так же в отношении дней и лет. Итак, седмицы дней рождают Пятидесятницу, которую они называют святым днем, а седмицы лет — год, называемый у них юбилеем, когда отдыхает земля, рабы получают свободу, а земельные владения возвращаются прежним хозяевам. Ибо не только начатки плодов и первородных, но и начатки дней и лет посвящает Богу этот народ. Так почитаемое число семь привело и к чествованию Пятидесятницы. Ибо число семь, помноженное на себя, дает пятьдесят без одного дня, который занят нами у будущего века, будучи одновременно восьмым и первым, лучше же сказать — единым и нескончаемым» (Григорий Богослов. Слово 41, 2, 4-35. SC 358, 324; 346. Творения. Т. 1. С. 576)

В христианской традиции Пятидесятница есть праздник Святого Духа — Утешителя, Который приходит на смену Христу, вознесшемуся на небо. Дела Христовы на земле окончились, и для Христа как человека с момента Его погребения наступила суббота покоя. Для христиан же после Воскресения Христова наступила эра юбилея — нескончаемый пятидесятый год, начинающийся на земле и перетекающий в вечность. Эра юбилея характеризуется прежде всего активным обновляющим действием Святого Духа. Под воздействием благодати Духа люди кардинальным образом меняются, превращаясь из пастухов в пророков, из рыбаков в апостолов. Святитель Григорий считает, что христианский праздник никогда не должен кончаться. Об этом он говорит, завершая проповедь на Пятидесятницу:

«Нам уже пора распускать собрание, ибо достаточно сказано; торжество же пусть никогда не прекратится, но будем праздновать — ныне телесно, а в скором времени вполне духовно, когда и причины праздника узнаем чище и яснее в Самом Слове и Боге и Господе нашем Иисусе Христе — истинном празднике и весели спасаемых…» (Григорий Богослов. Слово 41, 18, 2-10. SC 358, 352-354. Творения. Т. 1. С. 587).

Вся жизнь христианина должна стать непрестанным праздником, непрекращающейся Пятидесятницей, юбилейным годом, начинающимся в момент крещения и не имеющим конца. Земная жизнь может стать для христианина нескончаемым празднеством приобщения Богу через Церковь и Евхаристию. Годичный круг церковных праздников, так же как и таинства Церкви, способствует постепенному переходу человека из времени в вечность, постепенному отрешению от земного и приобщению к небесному. Но настоящий праздник и истинное таинство наступит только там — за пределом времени, где человек встретится с Богом лицом к лицу. Истинный праздник есть Сам Господь Иисус Христос, Которого в непрестанном ликовании созерцают верующие в Царствии Божием, где сыны Царствия уже не будут причащаться Тела и Крови Христовых под видом хлеба и вина, но будут «истее» причащаться Самого Христа — Источника жизни и бессмертия.

Вячеслав Пономарев

Таинство причащения (Евхаристия)

В православном катехизисе дается следующее определение этого Таинства: Причащение

есть Таинство, в котором верующий под видом хлеба и вина вкушает (причащается) Самого Тела и Крови Господа нашего Иисуса Христа во оставление грехов и в Жизнь Вечную.

Приготовление Святых Даров для Причащения совершается на Евхаристии (греч. благодарение), почему это Таинство и имеет двойное название – Причащение, или Евхаристия.

Причащение (Причастие, принятие Святых Тела и Крови Христовых) – это такое Таинство, при котором православный христианин не символически, а реально и живо соединяется со Христом Богом в той степени, в какой он подготовлен к этому. Чем лучше верующий человек подготовит себя к личной встрече с Богом, тем благодатнее она будет. Образ этого соединения непостижим для рационального восприятия, как непредставима тайна преложения хлеба и вина в Пречистые Тело и Кровь Христову: «Веруем, что в сем священнодействии предлежит Господь наш Иисус Христос, не символически, не образно, не преизбытком благодати, как в прочих Таинствах, не одним наитием, как это некоторые Отцы говорили о Крещении, и не чрез “проницание” хлеба, так, чтобы Божество Слова “входило” в предложенный для Евхаристии хлеб существенно, как последователи Лютера26 довольно неискусно и недостойно но изъясняют: но истинно и действительно, так что по освящении хлеба и вина, хлеб прелагается, пресуществляется, претворяется, преобразуется в самое истинное Тело Господа, которое родилось в Вифлееме от Приснодевы, крестилось во Иордане, пострадало, погребено, воскресло, вознеслось, седит одесную Бога Отца, имеет явиться на облаках небесных; а вино претворяется и пресуществляется в самую истинную Кровь Господа, которая, во время страдания Его на Кресте, излилась за жизнь мира. Еще веруем, что по освящении хлеба и вина остаются уже не самый хлеб и вино, но самое Тело и Кровь Господа, под видом и образом хлеба и вина» («Послание восточных патриархов»).

В Святых Тайнах Христос присутствует всецело

Для верующих факт действительного преложения хлеба и вина, принесенных на Литургию, в Тело и Кровь Христову несомненен. В том же «Послании восточных патриархов» говорится о Таинстве Евхаристии следующее: «Веруем, что в каждой части до малейшей частицы преложенного хлеба и вина находится не какая-либо отдельная часть Тела и Крови Господней, но Тело Христово, всегда целое и во всех частях единое, и Господь Христос присутствует по Существу Своему, то есть с Душой и Божеством, как совершенный Бог и совершенный человек. Потому хотя в одно и то же время бывает много священнодействий во вселенной, но не много Тел Христовых, а один и тот же Христос присутствует истинно и действительно, одно Тело Его и одна Кровь во всех отдельных церквах верных. И это не потому, что Тело Господа, находящееся на Небесах, нисходит на жертвенники, но потому, что хлеб предложения, приготовляемый порознь во всех церквах и по освящении претворяемый и прелагаемый, делается одним и тем же с Телом, сущим на Небесах. Ибо всегда у Господа одно Тело, а не многие во многих местах. Потому-то Таинство это, по общему мнению, есть самое чудесное, постигаемое одной верой, а не умствованиями человеческой мудрости, суетность и безумие изысканий которой о Божественном отвергает эта Святая и свыше определенная за нас Жертва».

Богослужение Таинства – Литургия

Богослужение, на котором совершается Евхаристия, называется Литургией

(греч. лито́ с – общественный и э́ргон – служба). Если в других общественных богослужениях (утрени, вечерни, часов) Господь Иисус Христос присутствует только Своей благодатью, на Литургии Он присутствует всецело Своими Пречистыми Телом и Кровью.

Плоды Таинства

Причащение – главнейшее из христианских Таинств, установленное самим Господом Иисусом Христом. Как уже упоминалось, это Таинство является центральным не только в Евангельских повествованиях (Ин. 6; 51–58, Мф. 26; 26–28, Mp. 14; 22–24, Лк. 22; 19, 20 и 1Кор. 11; 23–25), но и в Православной сотериологии27. К Таинству Причащения в Православной Церкви допускаются все ее члены, после того как приготовятся к нему постом и покаянием. Православная Церковь преподает Таинство и младенцам (причащая их одной Кровью Иисуса Христа).

Спасительные плоды достойного Причащения Святых Тайн следующие.

1. Теснейшее соединение с Господом (Ин. 6; 55–56). Причащение, по учению Церкви, делает причастников «стелесниками» Иисуса Христа, христоносцами, участниками Божественного естества.

2. Возрастание в духовной жизни (Ин. 6; 57). Причастие оживляет душу, освящает ее, делает человека твердым в подвигах добра.

3. Залог всеобщего Воскресения и блаженной вечной жизни (Ин. 6; 58).

Но недостойно приступающим к Таинству Причащение приносит большее осуждение: Ибо, кто ест и пьет недостойно, тот ест и пьет осуждение себе, не рассуждая о Теле Господнем (1Кор. 11; 29).

Православная Церковь учит, что Тело и Кровь Христовы – это умилостивительная Жертва, приносимая Богу за живых и умерших. Это та же Жертва, что была принесена Господом на Голгофском Кресте, различаемая лишь по образу и обстоятельствам Жертвоприношения. Отличие в том, что Господь Своим Жертвоприношением на Кресте искупил весь род человеческий, а Евхаристическая жертва усвояет это искупление конкретному человеку, прибегающему к ней.

Свойства Евхаристической жертвы

Крестная жертва, будучи венцом всех ветхозаветных жертв (но в тоже время являясь для них и первообразом), обнимает собою все их виды: хвалебно-благодарственные, умилостивительные за всех живых и умерших и просительные.

1. Хвалебно-благодарственная жертва. Само название Евхаристии означает в переводе с греческого «благодарение». Священное Писание свидетельствует о том, что при установлении Таинства Евхаристии Иисус взял хлеб и, благословив, преломил и, раздавая ученикам, сказал: приимите, ядите: сие есть Тело Мое. И взяв чашу и благодарив (п/ж – ред.), подал им и сказал: пейте из нее все (Мф. 26; 26, 27). За каждой Литургией звучат хвалебно-благодарственные молитвословия: «Достойно и праведно покланятися Отцу и Сыну и Святому Духу…» и «Тебе поем, Тебе благословим, Тебе благодарим, Господи…». В Постановлениях апостольских (глава

2. Умилостивительная жертва. Эта жертва имеет силу преклонять к нам милость Божью. Когда она приносится, поминаются не только живые, но и умершие, причем не только те, за которых мы молимся, но и те, в молитвах которых мы нуждаемся.

3. Просительная жертва. Она очень близка по своей форме к жертве умилостивительной, поскольку, призывая милость Божью, мы храним уверенность в том, что Господь исполнит наши прошения «во благо».

Литургия как средоточие жизни Церкви

Как в древнейшие, апостольские времена, так и в период роста и расцвета церковного сознания, в Византии и в древней Руси все, совершавшееся в церковной жизни христиан, сосредоточивалось вокруг Литургии.

Об этом свидетельствует тот факт, что все Таинства Православной Церкви включались в состав Литургии или находились в тесной органической связи с ней.

1. Так Крещение катихуменов (оглашенных) совершалось во время Литургии во дни Пасхи, Рождества, Богоявления и некоторых других праздников. Свидетельства о «крещальных Литургиях» находим у таких духовных писателей II и последующих веков, как святой мученик Иустин Философ, Сильвия Аквитанка и др.

2. Венчание совершалось до Евхаристического канона, во время Литургии оглашенных, скорее всего, после малого входа, приблизительно тогда, когда читались Апостол и Евангелие. В конце Литургии молодые причащались Святых Тайн.

3. Елеосвящение начиналось с освящения елея во время проскомидии28, а оканчивалось помазанием после заамвонной молитвы29.

4. Миро для совершения Таинства Миропомазания и в настоящее время освящается во время Литургии сразу же после преложения Даров в Великий Четверг.

5. Таинство Священства также совершается в определенные моменты чинопоследования Литургии.

Кроме того, так или иначе приурочиваются ко времени Литургии или вводятся в ее состав такие священнодействия как освящение храма, освящение антиминса, богоявленское освящение воды, пострижение в монашество. Отпевание усопших также обычно предваряется заупокойной Литургией.

Природа самой Церкви – евхаристична, поскольку Церковь – это Тело Христово, а Евхаристия – есть Таинство Причащения Христова Тела. Поэтому без Евхаристии нет Церкви, но и Евхаристия немыслима вне Церкви.

Церковь как общество христиан, объединенных общей верой, не может быть сведена только к административным рамкам. Все члены Тела Христова, то есть Церкви, получают настоящую жизнь только через соединение со Христом в Таинстве Причащения Его Плоти и Крови. «Нельзя только относиться к Церкви или числиться в ней, надо в ней (то есть ею) жить. Надо живо, реально, конкретно участвовать в жизни Церкви, то есть в жизни мистического Тела Христа. Надо быть живой частью этого Тела. Надо быть участником, то есть причастником этого Тела» (Ю. Ф. Самарин).

В единой Православной Церкви – единая Евхаристия, но, вместе с тем, при многочисленности Поместных Церквей, при разнообразии входящих в них многих племен и народов, исторически оформилось огромное количество разных типов Евхаристических молитв, или анафор30. Единство Церкви и Евхаристии не требует полной тождественности в богослужебном чине; варианты, поместные особенности не только возможны, но и важны, как проявление соборной природы Церкви.

Богословская наука классифицировала все это многообразие и все варианты в несколько групп (литургических фамилий) и изучила происхождение и историю их развития.

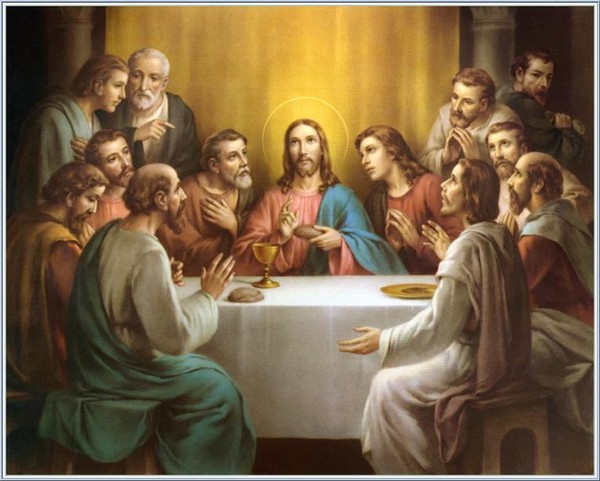

История установления Таинства Причащения

Евхаристия получила свое начало во дни, предшествующие Голгофской Жертве Спасителя, незадолго до Его Распятия. Первое Таинство Евхаристии было совершено самим Иисусом Христом в Сионской горнице, где состоялась Тайная Вечеря Господа с учениками-апостолами. Корень Литургии – повторение этой вечери, о которой Христом было сказано: сие творите в Мое воспоминание (Лк. 22; 19). Составить представление о том, каким был первоначальный чин Литургии можно, рассмотрев обряды еврейской пасхальной вечери, так как внешне Тайная Вечеря была ей практически идентична.

Еврейская пасхальная вечеря

Обычай ветхозаветного закона, отраженный в Пятикнижии Моисеевом, требовал совершения вечери стоя (Исх. 12; 11), но ко времени Христа уже традиционно за вечерей возлежали. Предлагаемая последовательность совершения пасхальной вечери дается по изложению архимандрита Киприана (Керна)31. В ней порядок молитв, обрядов и яств описывается приблизительно так.

1. Употреблялась первая чаша, смешанная с водой. Глава семейства произносил молитву «киддуш» (евр. освящение). Читалось благодарение над вином и благодарение праздника. B Мишне32 были даны такие благодарения, как:

а) благословение над вином: «Благословен Ты, Господи Боже наш, Царь вселенной, создавший плод виноградной лозы…»;

б) над хлебом: «Благословен Ты, Господи Боже наш, Царь вселенной, выводящий хлеб из земли…»;

в) благословение праздника: «Благословен… избравший нас из всех народов, и возвысивший нас над всеми языками, и освятивший нас Своими заповедями…».

2. Омывались руки (омовение совершалось трижды и в разные моменты).

3. Глава семейства омокал горькие травы в солило33, в котором находился харосэт – приправа из миндаля, орехов, фиг и сладких плодов – и подавал их прочим членам семейства.

4. Он же разламывал один из опресноков34 (средний из трех), половину которого отлагал до конца вечери; эта половина называлась афигомон. Блюдо с опресноками поднималось со словами: «Это хлеб страданий, который вкушали наши отцы в земле египетской». После возвышения хлеба глава семьи клал обе руки на хлебы.

5. Наполнялась вторая чаша. Младший член семьи спрашивал, чем эта ночь отличается от других ночей.

6. Глава семьи произносил кагаду – рассказывал историю рабства и исхода из Египта.

7. Поднималась вторая чаша со словами: «Мы должны благодарить, хвалить, славословить…». Затем чаша опускалась и вновь поднималась.

8. Пелась первая часть Галлела35

(псалмы со 112 (стих 1) по 113 (стих 8)).

9. Пили вторую чашу.

10. Омывали руки.

11. Совершали праздничное вкушение пищи: глава семьи подавал ее членам части опресноков, горькие травы, омоченные в харосэт, и пасхального агнца.

12. Разделялся остаток афигомона.

13. Пили третью чашу с послетрапезной молитвой.

14. Пели вторую часть Галлела (псалмы 115–118).

15. Наполняли четвертую чашу.

16. По желанию прибавлялась и пятая чаша с пением псалма 135.

Именно на Тайной Вечере, совершавшейся с соблюдением порядка еврейской пасхальной вечери, было установлено Таинство Евхаристии: И когда они ели, Иисус, взяв Хлеб, благословил, преломил, дал им и сказал: приимите, ядите; сие есть Тело Мое. И взяв чашу, благодарив, подал им: и пили из нее все. И сказал им: сие есть Кровь Моя Нового Завета, за многих изливаемая. Истинно говорю вам: Я уже не буду пить от плода виноградного до того дня, когда буду пить новое вино в Царствии Божием (Мк. 14; 22–25).

Произошло это при наступлении праздника иудейской Пасхи в первый же день опресночный (Мф. 26; 17) в Сионской горнице, где Спаситель в присутствии своих учеников установил Святейшее Таинство. Но еще до этого события апостолы Христовы слышали из уст Учителя прикровенные свидетельства о Таинстве Его Тела и Крови: Истинно, истинно говорю вам: если не будете есть Плоти Сына Человеческого и пить Крови Его, то не будете иметь в себе жизни. Ядущий Мою Плоть и пиющий Мою Кровь имеет жизнь вечную, и Я воскрешу его в последний день. Ибо Плоть Моя истинно есть пища, и Кровь Моя истинно есть питие. Ядущий Мою Плоть и пиющий Мою Кровь пребывает во Мне, и Я в нем (Ин. 6; 53–56).

Первая Евхаристия

Первоначально Евхаристия была совершена следующим образом.

1. Иисус Христос взял хлеб в Свои Пречистые руки, возвел очи горе (то есть вверх) и воздал Небесному Отцу хвалу и благодарение.

2. Господь разломил хлеб на части и дал его ученикам со словами: «Приимите, ядите; сие есть Тело Мое, еже за вы ломимое во оставление грехов«36.

3. Ученики, получив Хлеб от Господа, вкусили Его.

4. Спаситель взял Чашу с вином и, согласно апостольскому преданию, растворил его водой.

5. Воздав благодарение Своему Отцу, Христос сказал ученикам: »Пийте от нея вси: сия есть Кровь Моя Нового Завета, яже за вы и за многия изливаемая во оставление грехов«37.

6. И пили из нее все (Мк. 14; 23).

Вопрос о том, как располагались на Тайной Вечери Учитель и ученики евангелистами не обсуждается. Но некоторые заключения об этом исходя из контекста сделать можно. Нужно только иметь в виду несколько фактов.

1. Схема, по которой расставлялись столы для вечери, представляла собой «триклинию» – три стола, стоящие в виде подковы.

2. Во времена Христа полагалось возлежать у стола (на особом ложе) на левом локте, чтобы иметь правую руку свободной; кроме того, евангельская притча (См.: Лк. 14; 7

11) свидетельствует, что евреями соблюдался обычай занимать места в известной последовательности.

3. Уйти до окончания вечери, никого не беспокоя, можно было только с определенных мест, так как на большинстве других мест ученики возлежали «в затылок друг другу».

4. Все евангелисты свидетельствуют о том, что Иуда свободно ушел, не дожидаясь окончания вечери, после того как Господь подал ему кусок хлеба, омоченный в солило.

Исходя из этих фактов, естественно предположить, что ближе всех ко Христу должны были быть самые любимые Его ученики и Иуда. Евангельские тексты не противоречат той версии, что наиболее близко к Спасителю возлежали трое: Иоанн, Петр и Иуда Предатель.

Архимандрит Киприан (Керн) пишет по этому поводу: «Наиболее для нас авторитетный и исторически верный Лагранж так и предполагает: Иоанн – одесную Господа, Петр скорее всего – одесную Иоанна, Иуда – поблизости от Господа, во главе другого ряда возлежащих учеников и так, чтобы он мог бы легко уйти, никого не беспокоя. Все предположения об остальных местах Лагранж считает просто праздными и тщетными».

Во времена апостольские

Евхаристия оставалась вечерей, хотя ритуал пасхальной вечери для нее не совершался, а использовались более простые ее формы: субботняя или даже обычная. В такой форме совершение Евхаристии осуществлялось приблизительно до середины II века. Свидетельство об этом есть в письме Плиния к Траяну (между 111–113 гг.) о вифинских христианах.

После дня Пятидесятницы новоначальные христиане постоянно пребывали в учении Апостолов, в общении и преломлении хлеба и в молитвах (Деян. 2; 42).

История сохранила для нас изложение древнего ритуала Евхаристии, которое дано в 9-й и 10-й главах «Учения двенадцати апостолов» (Дидахе). В 14-й главе этого памятника I – начала II веков даются общие наставления о Евхаристии: «В Господень день, то есть в воскресенье, собравшись, преломляйте хлеб и благодарите, предварительно исповедав свои грехи, чтобы жертва ваша была чистой. Всякий имеющий недоразумение с братом да не сходится с вами до тех пор, пока они не примирятся, чтобы не осквернилась ваша жертва. Ибо Господь сказал о ней: на всяком месте и во всякое время приносите Мне жертву чистую, ибо Я Царь велик, и Имя Мое хвально среди народов». Есть там и такое указание: «Никто да не вкушает, да не пьет от вашей Евхаристии, но лишь крещенные во Имя Господне, ибо об этом Господь сказал: не давайте святыни псам».

Как в древнееврейской Мишне были различные благодарения, так были они и в чине Евхаристии.

1. Над чашей: Благословляем Тебя, Отче наш, за святую Лозу Давида, отрока Твоего, Которую Ты явил нам чрез Своего Отрока Иисуса. Тебе слава во веки.

2. Над хлебом: Благословляем Тебя, Отче наш, за жизнь и ведение, которое Ты явил нам чрез Своего Отрока Иисуса. Тебе слава во веки. Как этот хлеб был рассеян по холмам и был собран в одно, так да соберется Церковь Твоя от пределов земли во Твое Царство. Ибо Твоя слава и сила чрез Иисуса Христа во веки.

3. После совершения Евхаристии: Благословляем Тебя, Отче Святый, за Святое Твое Имя, Которое Ты вселил в наших сердцах, и также за ведение, веру и бессмертие, которые Ты явил нам чрез Своего Отрока. Тебе слава во веки. Ты, Господи, Вседержитель, сотворил все ради Имени Твоего, подал людям пищу и питие, нам же Ты, чрез Своего Отрока, даровал духовную пищу и питие, и вечную жизнь. За все благословляем Тебя, особенно же за то, что Ты Всемогущ. Тебе слава во веки. Помяни, Господи, Церковь Твою, чтобы избавить ее от всякого зла и усовершить ее в любви Твоей, собери ее освященную (Тобою) от четырех ветров во Твое Царство, которое Ты уготовал ей. Ибо Твоя сила и слава во веки. Да приидет благодать и прейдет этот мир. Осанна Богу Давида. Кто свят, тот да подходит, а кто нет, да кается. Маран афа (Господь наш грядет). Аминь. Пророкам позволяйте благодарить, сколько они хотят.

К 150–155 годам относится подробное описание чинопоследования Литургии, которое дано в Апологии святого мученика Иустина Философа (II в.). Дошедшие до нас тексты излагают чин Евхаристии в связи с Таинством Крещения и празднованием дня Господня (воскресенья). В воскресный день Литургия совершалась следующим образом: «В так называемый день солнца бывает у нас собрание в одно место всех живущих по городам и селам; при этом читаются памятные записки апостолов или писания пророков, сколько позволяет время. Потом, когда читающий престанет, предстоятель посредством слова делает наставление и увещание подражать слышанному доброму. Затем все вообще встаем и воссылаем молитвы.

Когда же окончим молитву, тогда приносятся хлеб, вино и вода и предстоятель также воссылает молитвы и благодарения, сколько он может, а народ подтверждает, говоря: аминь. Затем следует раздаяние каждому и причащение Даров, над которыми совершено благодарение, а к не присутствовавшим они посылаются чрез диаконов. Между тем достаточные и желающие, каждый по своему произволению, дают, что хотят, и собранное складывается у предстоятеля, а он имеет попечение о сиротах и вдовах, о всех нуждающихся вследствие болезни или по другим причинам, о находящихся в узах, о пришедших издалека чужестранцах, – вообще печется о всех находящихся в нужде.

В день же именно солнца творим собрание таким образом все вообще потому, что это первый день, в который Бог, изменив мрак и вещество, сотворил мир, а Иисус Христос, Спаситель наш, в тот же день воскрес из мертвых, так как распяли Его накануне дня Кроноса; а после Кроносова дня, так как этот день – солнца, Он явился Своим апостолам и ученикам и научил их тому, что мы представили теперь на ваше усмотрение».

Таким образом, Евхаристическое собрание в воскресный день, по свидетельству святого Иустина, состояло

1) из чтения Священного Писания;

2) проповеди;

3) молитвы;

4) причащения Святых Христовых Таин.

На Евхаристии, в чинопоследование которой включалось Таинство Крещения, не было чтения Писания и проповеди.

Слово «Собрание» приблизительно с середины II века в течение нескольких столетий употреблялось как название Евхаристии. Так «Таинством собрания и приобщения» называет Евхаристию Дионисий Ареопагит в своей книге «О церковной иерархии» (конец V – начало VI веков). Впрочем, Евхаристию первых времен христианства именовали самыми различными терминами, как, например: Господня Вечеря, Преломление хлеба, Приношение, Призывание, Вечеря, Трапеза Господня, Литургия (греч. общее дело), Анафора (греч. возношение), Агапа (греч. любовь), Синаксис (греч. собрание) и т. д.

После Пятидесятницы количество присоединяемых к Церкви полностью совпадало с числом новых участников Евхаристического собрания. Состоять в Церкви означало участвовать в Евхаристии.

Остатки древней Вечери Господней были широко распространены в Александрийском церковном округе в IV-V веках. По свидетельству Сократа Схоластика (V в.) «Египтяне причащаются Святых Тайн не так, как обычно христиане: после того, как насытятся и поедят всякой пищи, причащаются вечером, когда совершается Приношение».

В других африканских Церквах Вечеря Господня с Таинством Евхаристии совершалась только в Великий Четверг. Евхаристия в этот день совершалась вечером, и причащались, уже поев. Ныне в Православной Церкви напоминанием древнехристианской Вечери Господней является чин возношения Панагии, когда раздается Богородичная просфора. Сейчас этот чин совершается только в монастырях.

По 50-у правилу Карфагенского собора Причащение должно быть только натощак. В Древней Церкви причащались отдельно Тела Христова, которое священник давал причащающемуся в руки, сложенные крестообразно, и Святой Крови, которую преподавали дьяконы из общей Чаши.

Такая практика существовала еще во времена Трулльского («Пято-Шестого») Собора 691 г. Когда стали причащать вместе и Телом, и Кровью Христовой – неизвестно. 23-е правило VI Вселенского Собора запрещает брать плату за Причастие.

По примеру, данному Господом Иисусом Христом на Тайной Вечере, Причащение в древней Церкви совершалось после преломления евхаристийного хлеба. У греков преломление хлеба на четыре части следовало непосредственно за освящением Тела и Крови Христовой; в других Церквах это совершалось перед раздачей Святых Даров причащающимся.

В некоторых других местах на Востоке хлеб преломлялся дважды: на три части после освящения Даров; и каждая из этих трех – на небольшие части перед Причащением. Мозарабы38 делили хлеб на девять частей, каждая из которых символизировала одно из событий жизни Иисуса Христа.

Подходили к Причастию в строгом порядке: сначала епископ, за ним – пресвитеры, дьяконы, остальной клир, аскеты; затем женщины – диакониссы, девы и вдовы; затем дети и все остальные, присутствовавшие на Литургии.

В Апостольских постановлениях есть свидетельства того, что Дары раздавал сам епископ, но во времена Иустина Мученика (то есть во II веке) епископ уже лишь освящал Дары, а раздавали Их дьяконы.

В дальнейшем существовала практика раздачи Святого Хлеба епископами и священниками, а дьяконы подавали причастникам Чашу с Вином. Иногда дьяконы с разрешения епископа преподавали мирянам Святые Дары под контролем священнослужителей.

В разное время и в разных Поместных Церквах порядок Причащения клириков и мирян отличался некоторыми деталями.

1. В Испании и у греков в алтаре причащались только священники и дьяконы; прочие клирики приобщались на клиросе, а миряне – на амвоне.

2. В Галлии миряне и даже женщины причащались на клиросе.

3. Миряне причащались стоя или коленопреклоненно; пресвитеры – стоя, но сделав перед Причастием земной поклон.

4. Женщины принимали Тело Христово в особый белый плат, после чего уже полагали его себе в рот. Правилом Оксерского собора женщине было запрещено брать Тело Христово голой рукой.

5. Святую Кровь в первые века всасывали из Чаши с помощью особой, золотой или серебряной, трубки. Впрочем есть предположение, что Причащение Святой Кровью могло осуществляться непосредственно из подаваемой диаконом большой Чаши.

6. До IV века из-за гонений на христиан верные совершали Таинства в катакомбах и после Причастия уносили домой оставшиеся частицы Святого Хлеба, которыми сами причащались дома, когда имели в этом нужду (об этом свидетельствовали Иустин Мученик, Тертуллиан, Киприан Карфагенский). Святитель Василий Великий писал, что в его время «в Александрии и в Египте вообще всякий даже мирянин имеет сосуд (koinonia) специально для домашнего Причастия, и причащается когда хочет».

7. В случае болезни или других обстоятельств, мешавших причащаться в храме, дьякон, или низший клирик, а иногда даже и мирянин приносил Святые Дары больному на дом. Верные, по свидетельству Григория Великого, могли брать Их с собой в путешествие. Клирики и миряне несли Святые Дары в чистом полотенце (oraria) или в сумке, повешенной через шею на ленте, а иногда – в золотой, серебряной или глиняной чаше.

8. 43-е правило Карфагенского Собора (397 г.) предписывает совершать Причащение до принятия пищи, а 6-е правило Маконского Собора (585 г.) определило подвергать отлучению тех пресвитеров, которые нарушают это правило.

Чины Божественной литургии

Святейшее Таинство Евхаристии совершается на Литургии верных – третьей части Божественной литургии, – являясь, таким образом, ее важнейшей составляющей. С первых лет христианства в разных Поместных Церквах (и даже в пределах одной и той же Церкви) стали оформляться отличные друг от друга чины Литургии. Существовали персидские, египетские, сирийские, западные и многие другие чинопоследования, внутри которых также наблюдались различия. Только сирийских чинов насчитывалось более шестидесяти. Но такое их разнообразие не является свидетельством разности в вероучении. Будучи едины по своей сути, они различались лишь в подробностях, деталях, образующих форму конкретного чина.

Самыми значимыми были древние последования, послужившие основой для Литургий святых Василия Великого и Иоанна Златоустого.

1. Климентова Литургия (ее чинопоследование находится в VIII книге Апостольских постановлений).

2. Литургия святого апостола Иакова, брата Господня по плоти (совершалась в Иерусалимской и Антиохийской Церквах).

3. Литургия апостола и евангелиста Марка (совершалась в Египетских Церквах).

В I-II веках чины многочисленных Литургий не были письменно зафиксированы и передавались в устной форме. Но с момента появления ересей возникла потребность в письменной фиксации и, более того, унификации последований различных чинов.

Эта миссия была выполнена святителями Василием Великим (ок. 330–379) и Иоанном Златоустом (ок. 347 –14 сентября 407), которые стяжали славу учителей Церкви. Ими были составлены стройные чины Литургий, называемые теперь их именами, в которых Божественная служба была изложена в строгой последовательности и гармоничности ее частей. По мнению некоторых толкователей, одна из целей при составлении этих последований состояла в том, чтобы сократить Литургию до апостольского чина, сохранив его основное содержание. К VI веку Литургии святителей Василия Великого и Иоанна Златоуста совершались по всему православному Востоку.

Но современные чины святительских Литургий сильно отличаются от первоначальных. Процесс таких изменений естественен и охватывает все стороны жизни Церкви. В частности, все части чина, предшествующие малому входу, – позднего происхождения; Трисвятое добавлено не раньше 438–439 года; молитва входа заимствована из Литургии апостола Иакова; Херувимские песни («Иже херувимы» и «Вечери Твоея») введены в 565–578 годах и т. д.

В некоторых Поместных Церквах в день памяти святого апостола Иакова (23 октября) совершается Литургия его имени. То, что ее чинопоследование сохранилось до наших дней – чрезвычайно важно для нас, ведь оно является памятником литургической деятельности всех апостолов, имевших со святым Иаковом теснейшее общение.

В Православной Церкви существует еще один чин Литургии – Преждеосвященных Даров39. Связано его появление с соблюдением поста, заповеданного Господом для всех Его последователей. 49-е правило Лаодакийского Собора предписывает не совершать полной Божественной литургии в дни Святой Четыредесятницы40. Таким образом, на христиан во время Великого поста как бы накладывается епитимья, и они не могут приступать к Причастию так часто, как они это делают в обычные дни41.

Преждеосвященная Литургия – апостольского происхождения. Вот что писал об этом святой Софроний, Патриарх Иерусалимский: «одни говорили, что она Иакова, именуемого братом Господним, другие – Петра, верховного апостола, иные иначе».

Для Александрийской Церкви последование Преждеосвященной Литургии было составлено апостолом и евангелистом Марком. В древнейших рукописных памятниках чин содержащейся там Преждеосвященной Литургии надписан именем апостола Иакова. В IV веке святитель Василий Великий переработал это чинопоследование, с одной стороны, сократив его, а с другой, – внеся в него свои молитвы. И уже это чинопоследование переработал для западной части Православной Церкви святой Григорий Двоеслов, папа Римский42. Переработав этот чин и переведя его на латынь, святитель Григорий ввел его в повсеместное употребление на Западе. Сугубое уважение к трудам Григория Двоеслова стало причиной того, что в названии Литургии Преждеосвященных Даров закрепилось его имя.

Время совершения Литургии

Литургия может совершаться ежедневно, кроме некоторых особо оговоренных Уставом дней.

Литургии не положено в следующие дни.

1. В среду и пятницу Сырной седмицы.

2. В понедельник, вторник и четверг седмиц Великого поста.

3. В Великий Пяток, если этот день не совпадает с Благовещением Пресвятой Богородицы 25 марта (7 апреля по н. ст.), когда положена Литургия святителя Иоанна Златоуста.

4. В пятницу, предваряющую праздники Рождества Христова и Богоявления Господня, если сами дни праздников выпадают на воскресенье или понедельник.

Литургия святого Василия Великого совершается десять раз в году.

1. В навечерие Рождества Христова или в самый день праздника, если он приходится на воскресенье или понедельник.

2. В навечерие Богоявления или в самый день праздника, если он приходится на воскресенье или понедельник.

3. В день памяти святителя Василия Великого – 1 (14 по н. ст.) января.

4. В воскресные дни 1, 2, 3, 4 и 5 седмиц Великого поста.

5. В Великий Четверг и Великую Субботу.

Литургия Преждеосвященных Даров совершается Великим постом.

1. В среду и пятницу первых шести седмиц.

2. Во вторник или четверг 5-й седмицы.

3. В первые три дня Страстной седмицы.

4. В предпразднство Благовещения, если оно бывает в среду или пяток.

5. Литургия Преждеосвященных Даров может совершаться также в понедельник, вторник и четверг, начиная со 2-й седмицы Великого поста, если эти дни совпадают с полиелейными праздниками (в частности, в день памяти Сорока мучеников Севастийских, 9 (22 по н. ст.) марта или в день Обретения главы Предтечи и Крестителя Спасова Иоанна, 24 февраля (9 марта по н. ст.), если он выпадает на дни Великого поста, когда Литургии не положено).

6. В некоторые другие дни, точно определяемые Уставом.

Непредвиденных Литургий Преждеосвященных Даров не может быть, все дни ее совершения четко определены Уставом.

В остальное время церковного года совершается Литургия святителя Иоанна Златоуста.

По обычаю Евхаристическое приношение начинают утром. По древнему правилу было положено делать это в третий (девятый по современному исчислению) час, но можно начинать Литургию и раньше, и позже указанного времени. Единственное жесткое правило – она не может быть совершена ранее рассвета и после полудня. Исключение из этого правила составляют несколько дней церковного года, когда Литургия совершается «порану» (то есть ночью) или соединяется с вечерней службой, которая начинается около 11 часов вечера. Это бывает:

1) в день Святой Пасхи;

2) во дни Святой Четыредесятницы, когда совершается Литургия Преждеосвященных Даров;

3) в день навечерия Рождества Христова;

4) в день навечерия Богоявления;

5) в Великую Субботу;

6) в день Пятидесятницы.

Литургия обязательно должна совершаться во все воскресные и праздничные дни, а также по средам и пятницам Великого Поста (Литургия Преждеосвященных Даров).

Место совершения Божественной литургии

Местом совершения Литургии является освященный архиереем в соответствии с Канонами храм. Литургия не может совершаться в храме, оскверненном убийством, самоубийством, пролитием крови, вторжением язычников или еретиков. По особому благословению архиерея, Литургия может быть совершена на освященном антиминсе в жилом доме или другом пригодном для этого помещении, а также под открытым небом.

На одном Престоле (в одном храмовом приделе) в один день может быть совершена только одна Литургия. Объясняется это тем, что Крестная Жертва Господа Иисуса Христа одна на все времена до скончания века. Священник не может совершать две Литургии в день. Также он не может участвовать в соборном служении второй Литургии.

Евхаристический пост

Человеку, желающему причаститься, нужно соблюсти перед этим так называемый евхаристический пост. В настоящее время та его часть, что относится к телесному посту представляет собой воздержание от скоромной пищи (мяса, молока, масла животного происхождения, яиц, рыбы) в течение нескольких дней. Чем реже человек причащается, тем дольше должен быть телесный пост, и наоборот. Семейные и социальные обстоятельства, такие, как жизнь в нецерковной семье либо тяжелый физический труд, могут быть причиной ослабления поста. Кроме качественных ограничений в пище, должно уменьшить и количество съедаемого, а также избегать посещения театра, просмотра развлекательных фильмов и передач, прослушивания светской музыки, других мирских удовольствий.

Вместо всего этого рекомендуется посвятить свободное время богомыслию, размышлениям о своей жизни и совершенных грехах, а также путях их исправления. Супругам в течение поста необходимо воздерживаться от телесного общения.

Накануне Таинства, начиная с 12 часов ночи, нужно полностью отказаться от пищи, питья и курения (тем, кто страдает этой дурной привычкой) до времени Причастия. Если есть возможность, то накануне Причащения нужно побывать на вечернем богослужении; перед Литургией (накануне вечером или утром перед ее совершением) – прочесть содержащееся в любом православном молитвослове правило ко Причащению43

. Утром в день Причастия следует прийти в храм заранее, до начала богослужения. Перед Причастием нужно исповедаться или вечером, или непосредственно перед Божественной литургией.

Готовящийся ко Святому Причащению должен примириться со всеми и беречь себя от злобы и раздражения, осуждения и всяких непотребных мыслей, а также пустых разговоров. Готовясь к Причастию, полезно вспоминать и совет праведного Иоанна Кронштадтского: «Некоторые поставляют все свое благополучие и исправность пред Богом в вычитывании всех положенных молитв, не обращая внимания на готовность сердца для Бога – на внутреннее исправление свое; например, многие так вычитывают правило ко Причащению. Между тем здесь прежде всего надо смотреть на исправление нашей жизни и готовность сердца к принятию Святых Таин. Если сердце право стало во утробе твоей, по милости Божией, если оно готово встретить Жениха, то и слава Богу, хотя и не успел ты вычитать всех молитв. Царство Божие не в слове, а в силе (1Кор. 4; 20)».

Некоторые церковные правила преподания верующим Святых Таин

1. Ни священнослужитель, ни мирянин ни в коем случае не должен причащаться дважды в один и тот же день.

2. Диаконы не имеют право причащать верующих ни в коем случае.

3. 58-е правило VI Вселенского Собора гласит: «Никто из состоящих в разряде мирян да не преподает себе Божественныя Тайны; дерзающий же на что-либо таковое, как поступающий противу чиноположения, на едину неделю да будет отлучен от общения церковнаго, вразумляяся тем не мудрствовати паче, еже подобает мудрствовати».

4. До семилетнего возраста младенцев причащают без положенного для взрослых приготовления. Если младенец мал настолько, что не может принять частицу Тела Господня, его причащают под одним видом – Крови. Это правило является причиной другого правила: младенцев не приобщают на Литургии Преждеосвященных Даров, когда в Чаше находится вино44, не пресуществленное в Кровь Христову.

5. Младенец, крещенный мирянином «страха ради смертного», может быть причащен Святых Таин только после Миропомазания, совершенного православным священником.

6. Чтобы при Причащении младенца Святые Тайны были им проглочены, необходимо подносить его к Чаше на правой руке и лицом вверх и в таком положении причащать. Родителям надо внимательнейшим образом контролировать, чтобы младенец проглотил Дары!

7. Причащать заболевших детей, не достигших семи лет, на дому нельзя, так как чин Причащения больных запасными Дарами неприменим к детям указанного возраста.

8. Душевнобольных следует причащать под двумя видами – Тела и Крови Христовых, так как в правилах церковных противоположное не указано.

9. Супруги, имевшие во время говения супружеское общение, а также женщины в период очищения к Причастию не допускаются.

10. Причастники должны приступать к Святой Чаше чинно и в глубоком смирении, повторяя за священником произносимые им молитвы: «Верую, Господи…», «Вечери Твоея Тайныя…» и «Да не в суд.».

11. Перед тем как приступить к Чаше, надо сделать один земной поклон Господу Иисусу Христу, присутствующему тут же в Святых Тайнах, и после этого сложить крестообразно руки на груди так, чтобы правая рука была поверх левой.

12. Приняв Святые Тайны, нужно сразу Их проглотить и после того, как дьякон вытрет уста платом, поцеловать нижний край Святой Чаши, как ребро Христово, из которого истекли Кровь и вода (руку же священника целовать не надо!).

13. Отступив немного от Чаши после Причастия, нужно сделать поклон, но не до земли, ради принятых Святых Таин, а затем запить Дары теплотой.

14. Если в храме по окончании службы не читают благодарственные молитвы «по святом Причащении» или если их не удалось прослушать, то, придя домой, необходимо первым делом прочесть эти молитвы.

15. В день Причастия не принято делать земных поклонов, за исключением тех случаев, когда они обязательно предписываются Уставом: Великим постом при чтении молитвы Ефрема Сирина; перед Плащаницей Христовой в Великую Субботу и во время коленопреклонных молитв в день Святой Троицы.

Вещество Таинства

Веществом Таинства Евхаристии является пшеничный квасной (то есть не пресный, а приготовленный на дрожжах) хлеб и красное виноградное вино. Основание для этого находим в Новом Завете, где в описании Тайной Вечери употребляется греческое слово «артос» (квасной хлеб). Если бы речь здесь шла об опресноках в тексте бы стояло слово «азимон» (пресный хлеб).

Древний обычай приносить в храм хлеб и вино для совершения Таинства Таинств дал первой части Литургии название «проскомидия», что, как уже отмечалось, означает в переводе с греческого «приношение». В настоящее время для совершения проскомидии употребляются пять хлебцев, называемых богослужебными просфорами. В отличие от малых просфор, употребляемых для вынимания на проскомидии частиц за живых и усопших, богослужебные имеют большие размеры. Внешне просфора должна быть кругловидной и двухсоставной в ознаменование двух естеств в Господе Иисусе Христе – Божественного и человеческого. На верхней части Агничной просфоры изображается крест, а по его сторонам имеется надпись:

ИС. ХС. (Иисус Христос)

НИ. КА. (Победитель (побеждает)).

На остальных просфорах могут быть изображения Божьей Матери и святых. Выпекание просфор осуществляется в особом помещении (просфорне) специально назначенными для этого церковнослужителями.

Красное виноградное вино, употребляемое в Таинстве, соединяется на проскомидии с чистой водой в воспоминание истекших из прободенного ребра Спасителя Крови и воды.

Как часто нужно причащаться?

Этот вопрос получал разное разрешение в разные эпохи существования Церкви. Например, первохристианская практика подразумевала Причащение верующих либо за каждой Литургией, либо четыре раза в неделю, либо каждый воскресный день. А в XIX веке чада Русской Церкви причащались большей частью один раз в год, Великим постом. В данный исторический момент не существует единой, устоявшейся точки зрения на обозначенную проблему.

Одна из главных причин, декларируемых противниками частого Причащения, заключается в том, что современный человек «не достоин» приступать к столь Великому дару без длительной подготовки. Ущербность такой точки зрения обнаруживается в их уверенности, что человек может своими силами стать «достойным» Бога и основной фактор, способствующий этому, – количество времени, которое отводится на такую подготовку.

Святой Иоанн Кассиан Римлянин в V веке говорил: «Мы не должны устраняться от Причащения Господня из-за того, что сознаем себя грешными. Но еще более и более надобно поспешить к нему для уврачевания души и очищения духа, однако же с таким смирением духа и веры, чтобы, считая себя недостойными принятия такой благодати, мы желали более уврачевания наших ран. А иначе и однажды в год нельзя достойно принимать Причащение, как некоторые делают… оценивая достоинство, освящение и благотворность Небесных Тайн так, что думают, будто принимать Их должны только святые и непорочные; а лучше бы думать, что эти Таинства сообщением благодати делают нас чистыми и святыми. Они подлинно выказывают больше гордости, нежели смирения, как им кажется, потому что, когда принимают Их, считают себя достойными принятия Их. Гораздо правильнее было бы, если бы мы со смирением сердца, по которому веруем и исповедуем, что мы никогда не можем достойно прикасаться Святых Тайн, в каждый воскресный день принимали Их для врачевания наших недугов, нежели… верить, что мы после годичного срока бываем достойны принятия Их».

Такой подход к проблеме регулярности Причащения наиболее корректен. В любом случае каждым христианином этот вопрос должен решаться индивидуально со своим духовником. При отсутствии такого духовного наставника, нужно придерживаться общих рекомендаций, вытекающих из практики современной Церкви, и причащаться раз в три-четыре недели.

Причащение больных45

В случае тяжелой болезни и невозможности присутствовать в храме при совершении Таинства, христианина, согласно его желанию, можно и нужно причащать на дому. Такая практика сложилась уже в древней Церкви и сейчас существует почти в том же виде, как и в первые века христианства.

По обычаю Православной Церкви, Святые Дары для больных приготовляются либо в Великий Четверток (по преимуществу), либо во всякое другое время церковного года, когда совершается полная (то есть святителя Иоанна Златоуста либо святителя Василия Великого) Литургия. Для этой цели на проскомидии приготовляется второй Агнец либо при ежедневном совершении Литургии в храме отлагается часть прелагаемого литургийного Агнца. Совершается это таким же образом, как и для Литургии Преждеосвященных Даров Великим постом.

Чинопоследование причащения больных имеет такой порядок.

1. Священник влагает часть Святых Таин в Потир и вливает туда немного вина.

2. Читаются «обычное начало», «Приидите, поклонимся» (трижды), Символ веры и молитвы ко Святому Причащению.

3. Совершается Исповедь больного.

4. Больному преподаются Святые Тайны.

5. Затем читаются следующие молитвословия: «Ныне отпущаеши…», Трисвятое, «Отче наш», тропарь дня и Богородичен.

6. Священник творит отпуст настоящего дня.

Чинопоследование Таинства Евхаристии

Чинопоследование Литургии включает в себя три части.

1. Проскомидию.

2. Литургию оглашенных.

3. Литургию верных.

Таинство Евхаристии совершается с определенного момента Литургии верных. Последование Литургии едино и совершать Евхаристию в отрыве от ее остальных частей невозможно. Поэтому рассматривать чинопоследование Таинства необходимо в контексте всех остальных, подготовительных тайнодействий Литургии.

Что касается совершительной части Таинства, то оно тоже делится на несколько частей.

1. Возносится хвала и благодарение Богу за все неисчислимые благодеяния, явленные Им человеческому роду в творении, Божественном промысле и особенно в воплощении Спасителя – это песнопения «Достойно и праведно Тя Пети» и «Сый Владыко Господи Боже, Отче Вседержителю…».

2. Произносятся слова установления Таинства: «Приидите, ядите…» и «Пийте от нея вси…», в которых выражается всемогущая воля Спасителя о преложении хлеба и вина в Его Тело и Кровь.

3. Происходит призывание Духа Святого на предложенные Святые Дары: «Низпосли Духа Твоего Святаго на ны и на предлежащие Дары сия».

4. Троекратно благословляются Святые Дары: «И сотвори убо хлеб сей, честное Тело Христа Твоего, а еже в чаши сей, честную Кровь Христа Твоего, преложив Духом Твоим Святым».

Основание для такого порядка совершения Таинства находим в Священном Писании, которое, описывая Тайную Вечерю, отмечает, что Спаситель не просто преподал апостолам хлеб и вино, а прежде воздал хвалу Господу (Лк. 22; 19), а потом благословил и освятил их (Мф. 26; 26, 27 и Мк. 14; 22).

Краткий устав-схема Литургии святителя Иоанна Златоуста

Проскомидия (совершается в алтаре).

Литургия оглашенных

Отверзается завеса Царских врат.

Каждение алтаря и храма.

Дьякон: «Благослови, владыко».

Священник: «Благословено Царство…».

Дьякон – ектенья великая: «Миром Господу помолимся…».

Священник читает тайную молитву: «Господи Боже наш, егоже держава…».

Возглас: «Яко подобает Тебе…».

Хор – первый антифон (стихи 102-го псалма): «Благослови, душе моя, Господа.».

Дьякон – ектенья малая: «Паки и паки миром Господу помолимся».

Священник читает тайную молитву: «Господи Боже наш…».

Возглас: «Яко Твоя держава…».

Хор – второй антифон (стихи 145-го псалма): «Хвали, душе моя, Господа.», «Единородный Сыне…».

Священник читает тайную молитву: «Иже общая сия…».

Дьякон – ектенья малая: «Паки и паки миром Господу помолимся».

Возглас: «Яко Благ и Человеколюбец…».

Хор – третий антифон: Блаженны.

Отверзаются Царские врата.

Малый вход (с Евангелием).

Священник читает молитву входа (тайную): «Владыко Господи, Боже наш…».

Хор – входное: «Приидите, поклонимся и припадем ко Христу. Спаси ны, Сыне Божий…».

Тропари и кондаки.

Возглас: «Яко Свят еси Боже наш…».

Хор – Трисвятое: «Святый Боже…».

Чтец или дьякон: Прокимен.

Чтец или дьякон: Чтение Апостола.

Каждение.

Аллилуиарий.

Священник читает тайную молитву перед Евангелием: «Возсияй в сердцах…».

Дьякон: Чтение Евангелия.

Дьякон – ектенья сугубая: «Рцем вси…».

Священник читает тайную молитву прилежного моления.

Возглас: «Яко Милостив и Человеколюбец…».

[Дьякон – ектенья заупокойная: «Помилуй нас, Боже…». Священник читает молитву: «Боже духов…».

Возглас: «Яко Ты еси Воскресение…»46.]

Закрываются Царские врата.

Дьякон – ектенья об оглашенных: «Помолитеся, оглашеннии…».

Священник читает молитву об оглашенных: «Да и тии с нами славят…».

Дьякон: «Ели́цы оглашеннии, изыдите…».

Литургия верных

Дьякон – ектенья: «Елицы верныи, паки и паки…». Священник читает тайную молитву верных (первую). Возглас: «Яко подобает Тебе…».

Дьякон – ектенья малая: «Паки и паки…».

Священник читает тайную молитву верных (вторую). Возглас: «Яко да под державою Твоею…».

Отверзаются Царские врата.

Хор: «Иже Херувимы…» (священник читает тайную молитву: «Никтоже достоин…»).

Великий вход.

Поминовение Святейшего Патриарха, епархиального архиерея и всех православных христиан.

Закрытие Царских врат и завесы.

Хор: «Яко да Царя всех подымем…».

Дьякон – ектенья: «Исполним молитву нашу…». Священник читает тайную молитву приношения. Возглас: «Щедротами Единородного Сына…». Священник: «Мир всем».

Дьякон: «Возлюбим друг друга…».

Хор: «Отца и Сына и Святаго Духа…».

Дьякон: «Двери, двери, премудростию вонмем». Отверзается завеса.

Дьякон с народом – Символ веры: «Верую во Единого Бога Отца…».

Дьякон: «Станем до́бре…».

Хор: «Милость мира…».

Священник: «Благодать Господа…».

Хор: «И со духом твоим».

Священник: «Горе имеим сердца».

Хор: «Имамы ко Господу».

Совершение Таинства

Священник: «Благодарим Господа».

Хор: «Достойно и праведно…».

Священник тайно читает Евхаристическую молитву: «Достойно и праведно…».

Священник произносит вслух. «Победную песнь поюще…». Хор: «Свят, Свят, Свят…».

Священник читает продолжение Евхаристической молитвы: «С сими и мы…».

Священник: «Приимите, ядите, сие есть Тело Мое, еже за вы ломимое во оставление грехов».

Хор: «Аминь».

Священник: «Пийте от нея вси, сия есть Кровь Моя Новаго Завета, яже за вы и за многия изливаемая, во оставление грехов».

Хор: «Аминь».

Священник читает тайную молитву: «Поминающе убо…».

Священник произносит вслух: «Твоя от Твоих, Тебе приносяще о всех и за вся».

Хор: «Тебе поем, Тебе благословим…».

Освящение Даров (в алтаре), после чего:

Священник: «Изрядно о Пресвятей…».

Хор: «Достойно есть…».

Священник читает тайную молитву: «О Святем Иоанне Пророце…».

Священник произносит вслух: «В первых помяни, Господи…».

Хор: «И всех, и вся».

Священник произносит вслух: «И даждь нам единеми усты…».

Хор: «Аминь».

Священник: «И да будут милости…».

Хор: «И со духом твоим».

Дьякон – ектенья: «Вся святыя помянувше…». Священник читает тайную молитву: «Тебе предлагаем…».

Священник: «И сподоби нас, Владыко…».

Дьякон с народом: «Отче наш…».

Возглас: «Яко Твое есть Царство…».

Священник: «Мир всем».

Хор: «И духови твоему».

Дьякон: «Главы ваша Го́сподеви приклоните».

Хор: «Тебе, Господи».

Священник читает тайную молитву: «Благодарим Тя, Царю Невидимый…».

Возглас: «Благодатию, и щедротами…».

Хор: «Аминь».

Священник читает тайную молитву: «Вонми, Господи…».

Дьякон: «Вонмем».

Задергивается завеса.

Священник: «Святая святым».

Хор: «Един Свят, един Господь…».

Причастен.

Причащение священнослужителей в алтаре.

Отверзаются Царские врата.

Дьякон: «Со страхом Божиим и верою приступите».

Хор: «Благословен Грядый во Имя Господне…».

Причащение мирян.

Священник: «Спаси, Боже, люди Твоя…».

Хор: «Видехом Свет Истинный…».

Священник: «Всегда, ныне и присно…».

Хор: «Да исполнятся уста наша…».

Дьякон – ектенья: «Про́сти, прии́мше Божественных…».

Возглас: «Яко Ты еси Освящение наше…».

Священник: «С миром изыдем. О имени Господни».

Дьякон: «Господу помолимся».

Хор: «Господи, помилуй».

Священник читает заамвонную молитву: «Благословляяй благословящыя Тя, Господи…».

Хор: «Буди Имя Господне…», «Благословлю Господа…» (псалом 33).

Священник: «Благословение Господне на вас…», «Слава Тебе, Христе Боже…».

Хор: «Слава, и ныне», «Господи, помилуй» (трижды), «Благослови».

Отпуст великий.

Хор: Многолетие.

Закрываются Царские врата и завеса.

Совершение Таинства

Центральной частью христианской Литургии, во время которой происходит преложение Святых Даров, является Анафора (Евхаристическая молитва, Евхаристический канон). Древнейшая по своему происхождению она является наиболее важным моментом всего православного богослужения в целом.

Несмотря на большое разнообразие Литургических чинопоследований, во всех Анафорах можно выделить несколько основных частей.

1. Praefatio (лат. введение) – начальная молитва, содержащая славословие и благодарение Богу (должна быть обращена к Богу-Отцу, хотя, в постановлениях Константинопольского Собора 1156 г. говорится о том, что Евхаристическая Жертва приносится всей Пресвятой Троице).

2. Sanctus (лат. святой) – гимн «Свят, Свят, Свят.».

3. Anamnesis (лат. воспоминание) – воспоминание Тайной Вечери с произнесением тайноустановительных слов Иисуса Христа.

4. Epiclesis (лат. призывание) – призывание Святого Духа на «предлежащие» Дары.

5. Intercessio (лат. заступничество, ходатайство) – молитвы за живых и усопших, составляющих Церковь, с воспоминанием Богородицы и всех святых.

Евхаристический канон

Совершение Святого Таинства начинается возгласом священника «Благодарим Господа», призывающим участвующих в Евхаристии христиан к благодарению, поскольку и Сам Спаситель начал священнодействие Бескровной Жертвы благодарением Своему Отцу.

Хор: «Достойно и праведно есть поклонятися Отцу и Сыну и Святому Духу, Троице Единосущней и Нераздельней».

Священник читает тайную молитву: «Достойно и праведно Тя пети, Тя благословити, Тя хвалити, Тя благодарити…».

В этой молитве священник от лица всех предстоящих благодарит Господа за сотворение мира, за искупительный подвиг Его Сына, за все милости, явленные Им роду человеческому и за то, что Ему угодно принять от верующих в Него эту службу.

Священник произносит вслух: «Победную песнь поюще…».

Хор поет слова ангельской победной песни: «Свят, Свят, Свят Господь Саваоф, испол нь небо и земля славы Твоея!..».

Во время пения славословия «Свят, Свят, Свят…» священник продолжает читать Евхаристическую молитву: «С сими и мы блаженными Силами, Владыко Человеколюб-че, вопием и глаголем: Свят еси и Пресвят, Ты и Единородный Твой Сын, и Дух Твой Святый…. даде святым Своим учеником и апостолом, рек:

(далее священник произносит вслух слова Спасителя, являющиеся установительными словами Таинства)

«Приимите, яди́те, Сие есть Тело Мое, е́же за вы ломи́мое, во оставление грехов».

Хор: «Аминь».

Священник (тихо):

«Подо́бне и Чашу по вечери, глаголя:

(и вслух)

“Пи́йте от нея вси, Сия есть Кровь Моя Новаго Завета, я́же за вы и за многия изливаемая во оставление грехов”».

Хор: «Аминь».

Возношение Святых Даров

Священник читает тайную молитву: «Поминающе убо спасительную сию заповедь.».

Священник произносит вслух: «Твоя от Твоих Тебе приносяще о всех и за вся».

При произнесении этих слов дьякон, а если его нет, то сам священник берет правой рукой дискос, а левой (перекрещивая руки) – Потир, поднимая их над Престолом.

Это – возношение Святых Даров в жертву Богу от всех верующих. Слова священника «Твоя» – означают «Твои Дары» (то есть хлеб и вино), а «от Твоих» – от лица Твоих верных и из Твоих многих даров выбранное мы приносим Тебе в благодарственную жертву за всех нас и за все Твои благодеяния прошедшие, настоящие, и будущие.

Преложение Святых Даров

Хор: «Тебе поем, Тебе благословим, Тебе благодарим, Господи, и молим Ти ся, Боже наш».

После возношения Даров священник начинает читать

молитву эпиклезиса