Приблизительное время чтения: 17 мин.

Причастие. Кто-то годами не решается к нему приступить, кого-то останавливает сложная подготовка, кто-то считает его не более обязательным, чем «купание» в проруби на Крещение, кто-то решается причаститься только в период тяжелой болезни или при приближении смерти… А тем временем это то, ради чего существует земная Церковь. О Причастии, или Евхаристии, центре и средоточии христианской жизни, вопросах и недоумениях, возникающих вокруг этого Таинства, мы говорим с митрополитом Волоколамским Иларионом (Алфеевым), председателем Отдела внешних церковных связей Московского Патриархата.

Объяснить необъяснимое

— Владыка Иларион, лично Вы помните Ваше первое причастие, и изменилось ли Ваше отношение к нему с годами?

— Первого причастия я не помню, но могу сказать, что моя жизнь изменилась радикально после того, как я стал причащаться, — примерно в тринадцатилетнем возрасте. В одиннадцать лет я был крещен, где-то с тринадцати начал регулярно причащаться, и думаю, что это коренным образом изменило меня: именно это, в конечном итоге, привело меня к решению посвятить всю жизнь Церкви и Богу.

— Говорят, людям некрещеным не стоит раскрывать суть Таинств, тем более Таинства таинств — Причащения. Сколько в этом правды? И если это так, то откуда эта секретность?

— Начнем с того, что в древней Церкви существовала традиция оглашения (кстати, сегодня она возрождается), то есть подготовки людей, желающих стать христианами (оглашенных), к таинству Крещения. На протяжении какого-то времени им в определенном порядке излагались основы веры: говорилось о Боге Отце, о воплощении Бога Сына, о действии Бога Святого Духа, и объяснялся сам чин Крещения. О других Таинствах Церкви, и в особенности о Евхаристии, рассказывалось уже после Крещения. Например, в цикле огласительных бесед святителя Кирилла Иерусалимского, святого IV века, наряду с восемнадцатью огласительными поучениями есть и пять поучений тайноводственных, т. е. раскрывающих смысл Таинств, — это преподавалось человеку уже крестившемуся.

— Почему о главном таинстве Церкви рассказывалось только после Крещения?

— Потому что иначе человек ничего не поймет: природа Таинств вообще находится за пределами человеческого разума и человеческого постижения. Их смысл невозможно уяснить из книг, из бесед — только из личного опыта. Поэтому до тех пор, пока человек сам не начнет жить тáинственной жизнью Церкви — а это доступно только принявшему Крещение — нет смысла говорить ему о Таинствах: любые разговоры будут для него пустым звуком.

В особенности это касается Евхаристии. Как объяснить словами природу этого союза между Богом и человеком, который начинается тогда, когда Тело Христа становится частью нашего тела и Его Кровь начинает течь в наших жилах?

— Сегодня не все крещеные люди имеют понятие об этом. Не могли бы Вы рассказать, что такое Причастие, и почему оно называется «Таинством таинств»?

— Евхаристия — это самое тесное, какое только возможно здесь, на земле, соединение человека с Богом, причем соединение не только интеллектуальное и эмоциональное, но даже физическое. Господь дал нам его через привычный для человека способ — трапезу. И как в обычной трапезе употребляемая нами пища в процессе ее усвоения преобразуется в ткани нашего организма, так что природа человека соединяется с природой пищи, так и в Евхаристии: мы незримо соединяемся со Христом, приобщаемся Ему.

И это то, что делает православное богословие не отвлеченной теорией, а живым переживанием, реальным общением с Богом, а христианскую Церковь — уникальным явлением, без которого существование нашего мира не имело бы никакого смысла и оправдания. Христос с людьми не как память или абстрактная идея, Он с нами в полном смысле этого слова, через Евхаристию. Поэтому именно в ней главная ценность и стержень бытия Церкви.

— Как исторически сложилось это Таинство? Христос Сам установил его?

— Исторически оно пришло на смену древнееврейской пасхальной трапезе: евреи собирались семьей и закалывали ягненка как жертву, и употребляли его в пищу в ночь перед Пасхой. И Христос называется в Писании Агнцем, потому что как бы заменил Собой того жертвенного агнца, от которого вкушали евреи в память об избавлении их от египетского рабства.

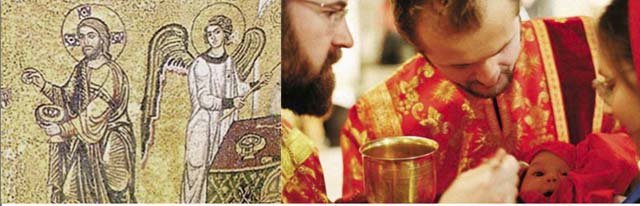

Евхаристия, какой мы ее знаем, появилась еще до страданий Спасителя, на Тайной вечере, где собрались апостолы, чтобы исполнить ветхозаветный пасхальный обычай. Иисус Христос, подавая им хлеб и вино, сказал: Примите, ядите, сие есть Тело Мое, которое за вас предается; пейте из нее все, ибо сие есть Кровь Моя Нового Завета, за многих изливаемая во оставление грехов (Лк 22:19—20, Мф 26:26—28). Эти собрания-трапезы продолжили Его ученики: каждый первый день недели — день, когда воскрес Христос, — они собирались для «преломления хлеба». Постепенно, по мере роста христианских общин, Евхаристия трансформировалась из трапезы в богослужение, которое мы сегодня знаем.

Почему Таинство — страшное?

— В молитвах мы читаем, что Причастие — страшное Таинство. Почему страшное? Чего бояться?

— Мы должны бояться не какой-то кары, а того, что, получив великое сокровище, тут же его потеряем, что оно не принесет плода! Мы забываем, что Причастие очень ко многому обязывает: человек, приняв внутрь себя Бога, должен жить не так, как он жил до этого. Причастием его соединение с Богом не кончается: очень важно то, чтó следует за отпустом Литургии, когда человек возвращается в мир. Он же возвращается, чтобы нести людям тот свет и ту благодать, которую получил!

Но бывает и по-другому. Есть люди, которые, неправильно воспринимая это Таинство (как традицию, ритуал или «религиозный долг»), причащаются как бы впустую: их жизнь не меняется. Вот этого и надо бояться, это страшно.

— Может ли быть причиной этому привычка? Человек, как говорится, ко всему привыкает.

— Вы знаете, я думаю, в этом смысле можно сравнить жизнь верующего с жизнью музыканта. Музыкант из года в год исполняет одни и те же произведения. Представьте себе, допустим, пианиста, который в 20 лет впервые играет рапсодию Брамса и в 70 лет играет ее уже в 455-й раз. Если он к ней привыкнет, если он после сотого раза начнет ее исполнять как неинтересное для него самого произведение, которые лично ему уже ничего не говорит, это мгновенно передастся слушателям: на его концерты просто перестанут ходить. Но ведь все великие исполнители на протяжении десятилетий играли одни и те же вещи, при этом ни они не уставали, ни публика. Вот в чем здесь секрет?

Секрет в том, что в каждом серьезном музыкальном произведении заложена определенная духовно-нравственная истина и определенные жизненные силы, которые приводятся в движение всякий раз, когда оно исполняется. Если музыкант перестает чувствовать это, значит проблема не в произведении, а в нем самом.

То же самое происходит и в религиозной жизни. Ведь богослужение в основных своих частях является неизменным, и в этом есть большая сила. В отличие от концерта, на который человек часто идет, чтобы послушать нечто новое, мы, приходя на Литургию, знаем, чтó и в какой последовательности будет происходить. Но в то же время, Причастие — это встреча с Богом, которая всякий раз бывает новой для человека.

— Что значит «причаститься в осуждение»? О чем здесь речь?

— Первым человеком, который причастился в осуждение, был Иуда. Он участвовал в Тайной вечере, он так же, как и все апостолы, принял Тело и Кровь Христа. И после этого совершил преступление, ставшее результатом его внутренней раздвоенности, следствием того, что он приступил к Евхаристии, замыслив предательство, а не с чистым сердцем и не с чистыми помыслами. Поэтому Таинство не оказалось для него спасительным.

— Для нас оно тоже может не оказаться спасительным? Причастие «во осуждение» означает какие-то кары — как говорит апостол, ибо, кто ест и пьет недостойно, тот ест и пьет осуждение себе, не рассуждая о Теле Господнем. Оттого многие из вас немощны и больны и немало умирает(1 Кор 11:29-30).

— Эти слова нельзя понимать как призыв воздерживаться от причащения из страха своего недостоинства. Напротив, это призыв причащаться, но при этом жить не расслабленно и кое-как, а — в постоянном духовном напряжении.

— Существует ли объективное действие Причастия, которое мы должны ощутить?

— Да, оно заключается в том, что человек с каждым причащением должен становиться лучше. Но не обязательно он должен это чувствовать, даже наоборот: чем лучше он становится в духовном отношении, тем более ясно видит свои недостатки и сознает свое недостоинство. Но зато окружающие люди понимают, что его религиозная жизнь оказывает преображающее действие и на него самого, и на всех вокруг.

От нас требуется не оценка своих успехов, а стремление всегда жить на такой высоте духовной жизни, чтобы тяга к богослужениям, тяга к Причастию никуда не уходили, не исчезали, а, наоборот, возрастали.

— Часто случается, что родные умирающего или тяжело больного человека хотят причастить его, несмотря на то, что тот никогда в Церковь не ходил и не понимает, зачем это нужно. Как в такой ситуации лучше поступать?

— Когда человек приближается к смерти, у него происходит переоценка ценностей: он начинает вспоминать свою жизнь, на второй план отходят многолетние земные заботы, могут исчезать всякие предубеждения. И я сам не раз сталкивался с ситуациями, когда меня приглашали причащать тяжело больного или умирающего человека, который никогда прежде не причащался, не исповедовался, может быть, и в храм-то заходил всего один раз в жизни. Но он совершенно сознательно подходил к Причастию, потому что уже чувствовал близость смерти, и в душе у него происходила очень важная работа по переоценке ценностей. Пускай лишь на смертном одре, но человек наконец-то понимал: самое главное, что ему необходимо сделать за этот краткий, оставшийся ему отрезок его земной жизни, это соединиться с Богом до того, как будет пройдена черта, отделяющая жизнь от смерти.

Поэтому, конечно, надо причащать умирающих. Но не надо ждать того момента, когда человек станет недееспособным: не будет в состоянии ни исповедоваться, ни даже принять Причастие. Мне всегда было очень горько и обидно, когда меня приглашали причащать умирающего, я приходил и видел перед собой человека, уже не говорящего, ничего не сознающего и даже не способного глотать. Я в таких случаях спрашивал людей: «А почему вы ждали так долго?» — «Мы боялись его огорчить».

Вот этого не должно быть! Часто бывает, что родственники боятся пригласить к тяжело больному человеку священника, чтоб не огорчить этого человека, — приближение священника в массовом сознании ассоциируется с приближением смерти. Но умирающему человеку никогда не надо внушать, как это часто делают люди, что он никогда не умрет! Даже если он не умрет сейчас, он все равно умрет, рано или поздно, и лучше дать ему возможность подготовиться к смерти, сознательно встретить это самое важное событие в жизни, чем оставить его жить с иллюзиями.

Не надо бояться огорчить человека приходом священника и причащением Святых Христовых Тайн. Потому что самое лучшее, что мы можем сделать для тяжелобольного или умирающего, — это как раз причастить его.

— Кто сегодня может причащаться? Любой крещеный человек, даже если не осознает, к чему приступает?

— Можно не понимать величия и смысла этого Таинства, можно ощущать себя внутренне неготовым, но если у человека есть доверие к Церкви, желание открыться навстречу Богу, он может к этому Таинству приступать. Потому что оно как раз способствует духовному росту. У того, кто постоянно причащается, начинают происходит некие внутренние изменения, которые очень трудно бывает описать или передать другим людям. И со временем на смену простому доверию приходит религиозный опыт, наступает момент, когда христианин говорит: «Я убежден, что это Тело и Кровь Христа — и не потому только, что Церковь так говорит, но потому что я это пережил, испытал, и я точно знаю, что не простого хлеба причащаюсь и не простое вино принимаю из Чаши».

Неподъемная подготовка?

— Существует ли такое понятие как неготовность в Причащению? И может ли человек сам себе поставить такой «диагноз»?

— Да, такое понятие существует. Человека может оценить в этом плане его духовник. Он может сказать: «Я считаю, что ты не готов к Причастию». Есть грехи, за которые христианин должен быть отлучен от Причастия хотя бы на какое-то время. Человек и сам себя может оценить. Но если все же он чувствует, что находится не в очень хорошем духовном состоянии, существует Таинство исповеди — Бог принимает всех.

— Исповедь делает человека достойным Причащения?

— Никогда несовершенный человек не будет достоин соединения с совершенным Богом. Наше человеческое естество всегда будет неадекватным по отношению к этому Таинству. Подлинная подготовка — не в проверке своей готовности, а в осознании своего недостоинства, своей греховности, и в глубоком покаянии.

Если человек сам не видит своих недостатков, есть очень хороший способ: спросить у других — у духовника, у близких. Следующим шагом будет решимость избавляться от этих недостатков, работа над собой. Причем когда она производится только собственными силами, то, как правило, не приносит ощутимых плодов. Но она должна совершаться с помощью Божьей, и вот такая синергия (соработничество) будет успешна. А получает человек эту помощь через Евхаристию, через сознательное приобщение Богу.

— Владыка, получается набор неприятных ощущений: осознание своей «плохости» и страх причаститься и потом не сохранить эту святыню в себе. Разве так должно быть?

— Вы забываете о радости человека, который обрел Бога. Она не поддается определению, описанию, в нее можно только войти, и Евхаристия как раз является вхождением в эту радость.

Здесь есть парадокс и тайна Евхаристии: мы причащаемся с чувством своей греховности и одновременно с радостью о том, что Бог к нам нисходит, очищает нас, освящает, дает духовные силы, несмотря на все наше недостоинство. Это дар и милость Божия, прежде всего.

— Довольно часто подготовка к Евхаристии становится препятствием для нее: кому-то трудно поститься, трудно «вычитывать» каноны. Как с этим быть?

— Я категорически не согласен с теми духовниками, которые налагают на людей чрезмерные требования, связанные с подготовкой к Причастию. Например, три дня поста, чтение не только последования, но еще и трех канонов, и акафиста, иногда — в каждый из трех дней. Это действительно может оттолкнуть человека от Причастия. И самое главное, эти требования не основываются на церковном предании. Постных дней в календаре более чем достаточно — примерно половина года, и Церковь очень ясно установила их: это четыре больших поста, а также среды и пятницы. Добавлять к этому еще дополнительные постные дни я считаю абсолютно неоправданным.

— Откуда вообще пошла традиция поститься перед причастием? И зачем? Разве еда оскверняет человека?

— Само по себе невкушение той или иной пищи — не самоцель. Пост, телесное воздержание должно вести к укреплению духа, это элемент духовной подготовки. Мы знаем, что Христос начал Свое служение после сорокадневного поста в пустыне. Смысл же и цель нашего говения заключаются в том, чтобы, подражая Христу, очищая душу и тело, мы оказывались более способными воспринимать Бога, Его благодать, посылаемую нам. Причащение натощак — это древняя традиция, восходящая к той эпохе, когда Литургия стала совершаться в утренние часы. Другое дело, что поститься несколько дней перед каждым Причастием — это русская традиция, связанная с тем, что в синодальный период (XVII—XIX вв.) у нас сложился обычай крайне редко причащаться. Когда будущий святитель Игнатий Брянчанинов, живший в XIX столетии, поведал своему духовнику о желании причащаться каждое воскресенье, это привело того в крайнее замешательство. Причастие в то время стали воспринимать как событие экстраординарное, совершаемое, например, четыре раза в год, в каждый пост, или вообще раз в году. Поэтому и пост перед Причащением был обязательным. Например, до революции на первой неделе Великого поста все говели, потом причащались в субботу после 5 дней строгого поста, и на этом все заканчивалось: считалось, что «религиозный долг» выполнен. Причастие было формальным подтверждением принадлежности человека к православной Церкви.

— Исповедь перед каждым Причастием имеет такие же корни?

— Да. И сегодня абсолютное большинство наших прихожан исповедуются перед каждым причащением, хотя изначально эти Таинства — Исповедь и Причастие — были разведены, и во многих Поместных Православных Церквах они до сих пор не связаны напрямую.

Но наша русская практика сама по себе очень правильная: это возможность для человека оценить свою жизнь за период, прошедший с предыдущей исповеди, может быть, взять на себя какие-то нравственные обязательства, возможность очистить свою совесть, примириться с Богом перед тем, как приступить к Причастию. Если только исповедь не превращается в формальность, в то, что один богослов XX века назвал «билетом на Причастие»…

— «Билет на Причастие», обязаловка… Кажется, ничто не мешает и сегодня воспринимать Причастие как религиозный долг?

— Причастие — это не религиозный долг, оно должно быть желанным, а не тягостным. К нему христианин должен стремиться, жаждать его. Если мы любим человека, а нам скажут: «Вот и хорошо! И встречайтесь с ним раз в год», мы удовлетворимся таким советом? Конечно, нет! Я не думаю, что надо заставлять себя любить своих детей или своих родителей. Их надо просто любить. Так же и в религиозной жизни: нельзя принудить себя любить Бога. Нужно научиться Его любить, жить так, чтобы любовь к Богу пронизывала всю твою жизнь. Тогда и соединение с Ним станет потребностью, а не тяжелой обязанностью.

— Есть ли тут место работе над собой, какой-то обязательности, постоянности, или любовь — дело порыва?

— У человека помимо желаний и порывов, исходящих из его сердца, должна быть и самодисциплина — иначе он потеряет свою духовную форму! Как спортсмен должен быть всегда в хорошей физической форме, или как музыканту необходимо соответствующее эмоциональное настроение, чтобы он мог передать заложенные в музыке чувства, так и верующему человеку нужно всегда находиться в состоянии «боевой готовности», чтобы все свои мысли, слова и поступки выстраивать по Евангелию.

Это то, что мы называем подвигом. Когда о подвиге говорят люди светские, подразумевается нечто экстраординарное: подвиг — это то, что совершает герой, имя которого остается в веках. А на христианском аскетическом языке это означает ежедневный незаметный труд человека, подвижничество, за которое ему не поставят памятника, не будут дарить букеты цветов. К такому труду призван каждый христианин.

— К чему конкретно?

— К тому, чтобы не жить в расслаблении, пребывая в мечтах о завтрашнем дне, а полноценно и полнокровно переживать настоящий момент, переживать свою связь с Богом и Его присутствие в этом мире. Для этого нет более сильного средства, чем Евхаристия. Ее не могут заменить ни чтение Евангелия, ни молитвы, ни посты.

Христос прямо говорит: Если не будете есть Плоти Сына Человеческого и пить Крови Его, то не будете иметь в себе жизни (Ин 6:54). Поэтому наша встреча со Спасителем не должна быть эпизодическим свиданием. Это постоянное напряженное устремление к Богу, желание жить с Ним.

О частоте причащения

— Как часто Вы бы рекомендовали причащаться?

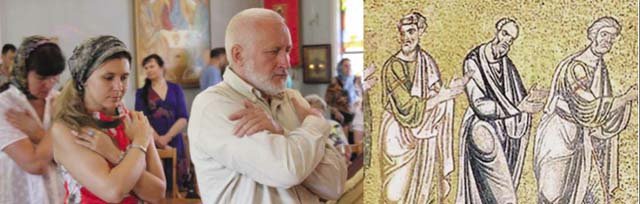

— Каждый человек должен для себя определить ритм своей духовной жизни и ритм причащения. В идеале нужно причащаться за каждой Литургией. Ведь вся Литургия является подготовкой к этому Таинству, так же как и всенощная, совершенная накануне. Много раз в течение богослужения Христос через священника призывает собравшихся людей причащаться: Примите, ядите, сие есть Тело Мое, за вас ломимое. Пейте от нее вси, сия есть Кровь Моя…. Ведь не сказано «пейте от нее те, которые подготовились», «пейте от нее только самые достойные», «пейте от нее только раз в год». А — пейте от нее вси. Сия есть Кровь Моя Нового Завета, яже за вы и за многие изливаемая. То есть «за вас, здесь присутствующих». Поэтому в древней Церкви вообще не было такого, чтобы человек пришел на Литургию, отстоял службу и не причастился. Не допускались к Чаше только оглашенные и кающиеся, которые стояли в притворе, но они и уходили раньше, чем начиналось само Причащение. А члены общины участвовали в Таинстве, причем у каждой общины был свой внутренний ритм, единый для ее членов. Например, в Кесарии Каппадокийской в IV веке приступали к Таинству четыре раза в неделю.

— С этими разными ритмами связаны различия евхаристических традиций в разных Поместных Церквах?

— Они действительно связаны с разной историей церквей: в результате где-то люди причащаются регулярно, а где-то вообще не причащаются или — крайне редко. Я участвовал в богослужении в одной из Поместных Церквей, где на богослужении на престольный праздник причастились только священники. Чаша для мирян даже не выносилась, часть Литургии, где священник говорит: «Со страхом Божиим и верою приступите», была вообще опущена.

А ведь Литургия всегда была общим делом («Литургия» — «общее дело» в переводе с греческого. — Ред.): причащаясь Христа, мы соединяемся со всеми членами общины. И отдельные поместные Церкви соединяются в единое Тело через Евхаристию.

Сегодня общинность в церковной жизни ослаблена, и, конечно, в современных условиях трудно найти некий единый стандарт, определить частоту причащения для всех: каждый человек должен сам чувствовать свой внутренний ритм и определить, как часто ему причащаться.

— Несмотря на все различия, что самое важное, на Ваш взгляд?

— Важно, чтобы Причастие не превращалось в редкое явление, исключительный случай. Надо понимать, что Евхаристия — это вершина. Более тесного соединения с Богом в земной жизни быть не может. Только от нас зависит, как мы переживаем это соединение, насколько глубоко мы его чувствуем. Мы не знаем, как будет человек причащаться Богу в жизни будущей. Есть такие слова в Пасхальном каноне Иоанна Дамаскина: «Подавай нам истее Тебе причащатися в невечернем дни Царствия Твоего». «Истее» — значит «еще полнее». Означает ли это просто, что исчезнет материя хлеба и вина, или это означает какое-то еще более полное соединение человека со Христом? Мы живем верой и надеждой в то, что за порогом смерти нас ждет полнота общения с Богом и Творцом. Но максимально тесное соединение с Ним в нашей земной жизни — это то, которое мы получаем в Причастии. И для христианина не может быть ничего более ценного и более радостного.

Иллюстрации: фрагмент иконы Андрея Рублева «Троица»; фрагмент мозаики Михайловского собора Михайловского Златоверхого монастыря в Киеве.

Фото: Владимира Ештокина; с сайта azbuka.ru; с сайта Свято-Воскресенского Русского Православного Собора, Ванкувер, Канада.

На на заставке фрагмент фото flickr.com/massalim

Другие тексты о таинстве Евхаристии читайте в рубрике Причастие

https://ria.ru/20211001/prichastie-1752746213.html

Причастие: в чем суть и как его совершать правильно — ответ священников

Причащение в православной церкви: как проходит таинство причастия и как к нему подготовиться

Причастие: в чем суть и как его совершать правильно — ответ священников

Святое причастие — одно из таинств православной церкви. Почему его называют Евхаристией, как проходит причащение в храме, каким образом к нему подготовиться и… РИА Новости, 01.10.2021

2021-10-01T20:58

2021-10-01T20:58

2021-10-01T21:34

общество

русская православная церковь

иисус христос

религия

/html/head/meta[@name=’og:title’]/@content

/html/head/meta[@name=’og:description’]/@content

https://cdnn21.img.ria.ru/images/07e5/0a/01/1752738034_0:133:3036:1841_1920x0_80_0_0_e46570486c25a349a2cceca1cb607425.jpg

МОСКВА, 1 окт — РИА Новости. Святое причастие — одно из таинств православной церкви. Почему его называют Евхаристией, как проходит причащение в храме, каким образом к нему подготовиться и что нельзя делать после — в материале РИА Новости.Что являет собой причащениеПричастие — христианское таинство, во время которого верующий вкушает белый хлеб и вино, символизирующие тело и кровь Иисуса Христа.Религиозный философ-славянофил XIX века Алексей Хомяков, подчеркивая важность причастия, говорил: «Церковь — это стены, воздвигнутые вокруг Евхаристической чаши».История таинстваСлово «евхаристия» происходит от греческого eucharistia, означающего «благодарение». Этот термин возник в I или II веке нашей эры, когда первые христиане вспоминали Тайную вечерю Христа.Согласно Библии, в ночь перед тем, как Христос был распят, он и двенадцать его учеников вкушали хлеб, запивая вином.В Евангелии от Матфея говорится: «когда они ели, Иисус взял хлеб и, благословив, преломил и, раздавая ученикам, сказал: приимите, ядите: сие есть тело Мое. И, взяв чашу и благодарив, подал им и сказал: пейте из нее все, ибо сие есть кровь Моя Нового Завета, за многих изливаемая во оставление грехов».В христианской религии существует множество названий таинства причастия. Некоторые протестантские церкви (англикане, лютеране, пресвитериане и объединенные методисты) и православные используют термин «евхаристия». В Римско-католической церкви причастие иногда называют «Мессой», хотя это слово также означает всю церковную службу.Методы совершения Евхаристии также различаются. Обычно подают хлеб, потом вино. При этом католическая, православная и многие протестантские церкви используют именно вино, а баптисты — виноградный сок. В некоторых конфессиях хлеб и вино употребляются индивидуально, в то время как в других — коллективно после молитвы.Верующие считают, что на литургии хлеб и вино — это не просто символы, а именно самые настоящие тело и кровь Бога. «Происходит чудо, хлеб и вино пресуществляются в Христовы тело и кровь, к сущности хлеба и вина прилагается сущность тела и крови Господа», — добавляет эксперт.Егор Дегтярев объясняет: «Еще один аспект Евхаристии: принесение Даров. В иудейской религии, продолжателями которой являются христиане, наказание за грех — смерть, поэтому Богу за грехи человека приносили в жертву животных, как гласил Договор между Богом и человеком («Ветхий Завет»). Но пришел Христос и принес себя самого в жертву за грехи всех людей: за тех, которые умерли, которые живут, которые будут жить. Он стал жертвенным ягненком, исполнив этим Ветхий Договор. Верующим остается только принять этот дар и воспользоваться спасением, принося бескровную жертву, как он повелел, хлеб и вино. Принимая их в пищу во время причащения, человек приобщается к той безграничной жертве Христа».Зачем нужно причащатьсяВ Евангелии от Иоанна сказано: «Истинно, истинно говорю вам: если не будете есть плоти Сына Человеческого и пить крови Его, то не будете иметь в себе жизни. Ядущий Мою плоть и пиющий Мою кровь имеет жизнь вечную, и Я воскрешу его в последний день. Ибо плоть Моя истинно есть пища, и кровь Моя истинно есть питие. Ядущий Мою плоть и пиющий Мою кровь пребывает во Мне, и Я в нем».Итак, причастие — это таинство, помогающее верующему соединиться с Богом, очистить душу от грехов и обрести вечную жизнь.В какой день можно причаститьсяДля всех желающих принять причастие в церкви определен специальный день: Великий Четверг на Страстной неделе. Однако причащаться можно и в любой день недели, когда проводится божественная литургия.Как правильно подготовитьсяПрежде чем отправиться на причастие, необходимо провести некоторую подготовку души и тела. К таинству допускаются только крещеные православные христиане.Клирик храма Матроны Московской в Уфе Алексей Федянин отмечает: «День причащения — важный день для христианской души, когда она особым образом соединяется со Христом. В это время необходимо больше молчать, находиться в тишине и вести себя благопристойно. В день причастия ни в коем случае нельзя ругаться, танцевать, ходить в увеселительные заведения, развлекаться, пить спиртное. От всего этого следует воздержаться до следующего дня».»Если человек не бывает в храме, но решает принять причастие в Чистый четверг, потому что так положено, то ему необходимо посоветоваться со священником, который на исповеди определит глубину его намерений», — рассказывает ректор Киевской Духовной академии епископ Сильвестр (Стойчев).»Если у человека на данный момент благоговения нет, то лучше таинство отложить, чтобы не было греха ни на этом человеке, ни на священнике, который благословил подходить к причастию», — добавляет он.ПостСтрогий пост выдерживается в течение трех дней. К употреблению запрещаются яйца, мясо, рыба и молочные продукты. Допускается хотя бы за шесть часов до таинства не принимать пищу и не пить. Кроме того, стоит отказаться от развлечений и плотских отношений.МолитвыВо время поста желательно читать молитвы. В любом молитвослове есть раздел под названием «Последование ко Святому Причащению», где можно найти все необходимое.ИсповедьСчитается, что перед причастием лучше всего сходить на исповедь. Без этого причащаются только дети до семи лет.О необходимости такого шага есть разные мнения. Например, Егор Дегтярев отмечает: «Сейчас традиционно в РПЦ распространилось заблуждение, что перед причастием нужно обязательно исповедоваться. Я считаю, это не так. Исповедь и причастие — совершенно разные и несвязанные таинства. Ведь тело и кровь — это дар Божий, который Он дает людям по своему милосердию и любви к нам! Чтобы получить этот дар, не нужно никакого «пропуска» в качестве исповеди. Подарки же мы получаем не за что-то, а просто так, из-за любви дающего. Поэтому лучшая подготовка к причастию — участие в службе».Благочинный церквей Красногорского округа Московской епархии, настоятель Успенского храма Красногорска протоиерей Константин Островский, в свою очередь, добавляет: «Обычай исповедоваться перед причастием в наших условиях я считаю разумным и нужным, но надо понимать, что это именно обычай, а не канон и не догмат. И прихожанин, про которого я знаю, что он серьезно относится к своей духовной жизни, может просто подойти ко мне и сказать: «Батюшка, благословите причаститься». И я благословляю».Последование ко Святому ПричащениюПоследование ко Святому Причащению представляет собой специальный сборник молитв.По правилам причащающийся должен их прочитать дома перед таинством, кроме двух последних частей. Благодарственные молитвы нужно либо выслушать в храме после службы, либо читать самому. Но исторически предполагалась несколько иная последовательность. Изначально все части Последования причащающиеся читали единолично во время службы, чтение должно было продолжаться также сразу после таинства.Сейчас считается плохим тоном, когда кто-то, не слушая литургию, утыкается в молитвослов. Значит, прихожанин не успел все положенное прочитать дома.Однако так было не всегда, целостность и неразрывность Последования ко Святому Причащению предполагает погружение причастника именно в частную молитву, а не в общую. Дело в том, что после IV века нашей эры римские императоры прекратили гонения на христиан и численность общин значительно выросла. Меньше чем за столетие христианство превратилось из гонимой религии в религию большинства населения Римской империи. Поменялись и правила богослужений. Это уже не встреча нескольких верующих в небольшом доме или другом неприметном месте, а многолюдное собрание, торжественно проходившее в специально построенной для этого церкви.Но у этого триумфа христианства была и обратная сторона. Ранее люди сознательно становились последователями религии, понимая, что за это можно поплатиться жизнью, и вели себя на службах с должным смирением и благоговением.После распространения христианства сознательных верующих стало значительно меньше. Неподобающее поведение было особенно видно на больших церковных празднествах, когда собиралось много прихожан. Во время литургии большое количество причастников кричали и толкались, стараясь побыстрее совершить таинство и уйти.Иоанн Златоуст отмечал, что таким поведением они только усугубляли свои грехи, вместо того чтобы очистить душу.Именно для того, чтобы исключить такое недостойное поведение, проповедники и богословы того времени предложили прихожанам не торопясь ждать окончания богослужения и спокойно подходить к причастию, а время ожидания заполнять личными молитвами.Сначала эти молитвы не были воссоединены и точечно встречались в различных молитвословах. Информация о Последовании появилась только во второй половине XI века, а окончательно оно сформировалось и стало самостоятельным в XII-XIV веках.К тому моменту количество составляющих его молитв настолько выросло, что стало невозможным читать Последование в церкви. Возникло правило совершать часть его до литургии и часть после нее, которое применяется и сейчас.Сейчас Последование ко Святому Причащению состоит из:Отступления от правил подготовки к причастию разрешены нескольким категориям. Больным людям, беременным и кормящим женщинам разрешается не придерживаться поста, старые и немощные прихожане также могут сократить пост и количество молитв перед таинством. Детям до семи лет позволено никак не готовиться к причастию, так как суть обряда заключается не в том, чтобы утомить себя молитвами и обессилить постом, а получить радость от встречи с Богом.Как проходит таинствоТаинство причащения состоит из трех основных частей:Как вести себя на причастии:Как подходить к Святой ЧашеПелагея Тюренкова, религиозный публицист, религиовед, автор диссертации «Образ современной женщины в православных российских СМИ» отмечает: «К Чаше мы подходим с благоговением, обязательно получив благословение священника (обычно после исповеди), не едим и не пьем воду до и стараемся провести благочестивый день после».Подходить к Святой Чаше нужно с правой стороны, оставляя левую свободной, в порядке очереди. Нельзя толпиться, толкаться, разговаривать. Женщины обязаны стереть губную помаду, если она есть. Стоя у Святой Чаши, нужно прочитать про себя молитву «Господи Иисусе Христе, Сыне Божий, помилуй мя грешнаго» и снова сделать земной поклон (если людей много, можно сделать его заранее).У Чаши внятно назвать свое имя, данное при крещении, и открыть рот. Проглотив Святые Дары, поцеловать нижний край чаши, который символизирует проткнутое ребро Христа, из которого текла кровь, смешанная с водой. Находясь у Чаши, нельзя целовать руку священника, браться за сосуд руками, креститься, чтобы не опрокинуть и не пролить Чашу. В старину за такое саму церковь сжигали, а священнослужителя отправляли в монастырь.Отходить от Чаши нужно оставляя руки скрещенными. Возле иконы Спасителя снова поклониться в землю, после этого можно подходить к столу с просфорами и вином (соком). Съев хлеб и запив его, причастник должен прополоскать рот, чтобы все частички просфоры были проглочены. И только после этого можно разговаривать и целовать иконы.После причастия важно достоять службу до конца.Егор Дегтярев рассказывает: «Говоря о внешних обычаях, сообщу, что мы традиционно подходим к Чаше со сложенными на груди руками (правая поверх левой), но это не принципиально. Не крестимся перед самой Чашей, чтобы не задеть ее. В очереди к Причастию стоим благоговейно, молимся, не болтаем. Обычно первыми причащаются дети, в некоторых храмах после детей идут мужчины, а потом уже женщины; в некоторых идут семьями, не делятся по полам. Но если вы нарушите традицию того или иного храма, ничего страшного не произойдет, просто могут сделать замечание. Поэтому о традициях лучше заранее спросить в церковной лавке».Что делать после таинстваДень причащения является праздником, поэтому все дела откладываются. После таинства стоит провести оставшееся время в молитвах. Есть правила, которые важно соблюдать, но без преувеличения и излишнего усердия.Что можно и что нельзя делать после причастия»Вопреки распространенным заблуждениям, после причастия можно и целовать иконы, и чистить зубы, и есть мясо… Но, как однажды сказал мой учитель, чтец Василий Анатольевич Соболев, после причастия нельзя лгать, вынашивать злобу, лицемерить, завидовать и много еще чего нельзя. Причащайтесь и побольше улыбайтесь», — говорит Егор Дегтярев.Некоторые преувеличенно осторожны и стараются не только не плевать после Евхаристии, но и все несъедобные части пищи, которые побывали во рту, съесть, а то, что не удается (например, кости) — сжечь. Подобного церковный устав не требует.Еще одно заблуждение: после причастия нельзя целовать иконы, мощи угодников, друг друга. Это опровергается обычаем священников после Евхаристии подходить к архиерею за благословением и целовать ему руку.»С тем, что можно делать, а что нельзя после причастия, связано много мифов. Я даже слышал, что нельзя принимать душ. Логики в подобных утверждениях, безусловно, нет. Время после Причастия нужно провести в целомудрии, тишине, в чтении духовной литературы», — отмечает епископ Сильвестр (Стойчев).В первые два часа после причастия лучше всего не переедать, вести себя тихо, избегать шумных увеселений.Как часто надо причащатьсяОбычно частота причащения определяется индивидуально для каждого его духовником. Чаще всего прихожане принимают причастие во время многодневных постов, в храмовые праздники и каждое воскресенье. Наиболее распространенный вариант — не реже двух раз в месяц.Причащение больныхБольным разрешается принимать причастие без соблюдения поста и чтения молитв. Священник одновременно с таинством отпускает им грехи.Причастить больного священнослужитель обязан в любой момент, даже прервав свою службу в храме, если в том есть необходимость. Прерывать нельзя только литургию.Если отлученный от церкви находится на грани смерти или тяжело болен, ему не откажут в причащении. В том случае когда такой человек выздоравливает, на него накладывается епитимья (держать строгий пост и читать молитвы), по окончании которой церковь снова примет его в свое лоно.Причащение детейДети до семи лет принимают причастие без каких-либо приготовлений, причем если ребенок еще не умеет жевать, ему дают только сок. Поэтому на Литургии Преждеосвященных Даров малышей не причащают, так как вином (кровью) пропитаны частицы хлеба (тела), которые ребенок не сможет проглотить.Младенцы причащаются сразу после крещения либо в следующий возможный день.Сколько стоитТаинство причастия проводится совершенно бесплатно.

https://ria.ru/20210920/venchanie-1751045041.html

https://ria.ru/20210814/post-1745739797.html

https://ria.ru/20210413/patriarkh-1728113276.html

РИА Новости

internet-group@rian.ru

7 495 645-6601

ФГУП МИА «Россия сегодня»

https://xn--c1acbl2abdlkab1og.xn--p1ai/awards/

2021

РИА Новости

internet-group@rian.ru

7 495 645-6601

ФГУП МИА «Россия сегодня»

https://xn--c1acbl2abdlkab1og.xn--p1ai/awards/

Новости

ru-RU

https://ria.ru/docs/about/copyright.html

https://xn--c1acbl2abdlkab1og.xn--p1ai/

РИА Новости

internet-group@rian.ru

7 495 645-6601

ФГУП МИА «Россия сегодня»

https://xn--c1acbl2abdlkab1og.xn--p1ai/awards/

https://cdnn21.img.ria.ru/images/07e5/0a/01/1752738034_305:0:3036:2048_1920x0_80_0_0_eb6f898470365289eb4715e90740d994.jpg

РИА Новости

internet-group@rian.ru

7 495 645-6601

ФГУП МИА «Россия сегодня»

https://xn--c1acbl2abdlkab1og.xn--p1ai/awards/

РИА Новости

internet-group@rian.ru

7 495 645-6601

ФГУП МИА «Россия сегодня»

https://xn--c1acbl2abdlkab1og.xn--p1ai/awards/

общество, русская православная церковь, иисус христос, религия

Общество, Русская православная церковь, Иисус Христос, Религия

МОСКВА, 1 окт — РИА Новости. Святое причастие — одно из таинств православной церкви. Почему его называют Евхаристией, как проходит причащение в храме, каким образом к нему подготовиться и что нельзя делать после — в материале РИА Новости.

Что являет собой причащение

Причастие — христианское таинство, во время которого верующий вкушает белый хлеб и вино, символизирующие тело и кровь Иисуса Христа.

Религиозный философ-славянофил XIX века Алексей Хомяков, подчеркивая важность причастия, говорил: «Церковь — это стены, воздвигнутые вокруг Евхаристической чаши».

История таинства

Слово «евхаристия» происходит от греческого eucharistia, означающего «благодарение». Этот термин возник в I или II веке нашей эры, когда первые христиане вспоминали Тайную вечерю Христа.

Согласно Библии, в ночь перед тем, как Христос был распят, он и двенадцать его учеников вкушали хлеб, запивая вином.

В Евангелии от Матфея говорится: «когда они ели, Иисус взял хлеб и, благословив, преломил и, раздавая ученикам, сказал: приимите, ядите: сие есть тело Мое. И, взяв чашу и благодарив, подал им и сказал: пейте из нее все, ибо сие есть кровь Моя Нового Завета, за многих изливаемая во оставление грехов».

В христианской религии существует множество названий таинства причастия. Некоторые протестантские церкви (англикане, лютеране, пресвитериане и объединенные методисты) и православные используют термин «евхаристия». В Римско-католической церкви причастие иногда называют «Мессой», хотя это слово также означает всю церковную службу.

Методы совершения Евхаристии также различаются. Обычно подают хлеб, потом вино. При этом католическая, православная и многие протестантские церкви используют именно вино, а баптисты — виноградный сок. В некоторых конфессиях хлеб и вино употребляются индивидуально, в то время как в других — коллективно после молитвы.

«Христос сам дал заповедь ученикам, следовательно, и нам: есть его тело и пить его кровь во оставление наших грехов и совершать это в память о нем. Тогда, на Тайной вечере, в чаше было красное виноградное вино, а ели пресный пшеничный хлеб. Сейчас же в Русской православной церкви для богослужения используют специальное красное вино кагор и дрожжевой пшеничный хлеб — просфору», — рассказывает Егор Дегтярев, чтец РПЦ, теолог и богослов.

Верующие считают, что на литургии хлеб и вино — это не просто символы, а именно самые настоящие тело и кровь Бога. «Происходит чудо, хлеб и вино пресуществляются в Христовы тело и кровь, к сущности хлеба и вина прилагается сущность тела и крови Господа», — добавляет эксперт.

Егор Дегтярев объясняет: «Еще один аспект Евхаристии: принесение Даров. В иудейской религии, продолжателями которой являются христиане, наказание за грех — смерть, поэтому Богу за грехи человека приносили в жертву животных, как гласил Договор между Богом и человеком («Ветхий Завет»). Но пришел Христос и принес себя самого в жертву за грехи всех людей: за тех, которые умерли, которые живут, которые будут жить. Он стал жертвенным ягненком, исполнив этим Ветхий Договор. Верующим остается только принять этот дар и воспользоваться спасением, принося бескровную жертву, как он повелел, хлеб и вино. Принимая их в пищу во время причащения, человек приобщается к той безграничной жертве Христа».

Зачем нужно причащаться

В Евангелии от Иоанна сказано: «Истинно, истинно говорю вам: если не будете есть плоти Сына Человеческого и пить крови Его, то не будете иметь в себе жизни. Ядущий Мою плоть и пиющий Мою кровь имеет жизнь вечную, и Я воскрешу его в последний день. Ибо плоть Моя истинно есть пища, и кровь Моя истинно есть питие. Ядущий Мою плоть и пиющий Мою кровь пребывает во Мне, и Я в нем».

Итак, причастие — это таинство, помогающее верующему соединиться с Богом, очистить душу от грехов и обрести вечную жизнь.

В какой день можно причаститься

Для всех желающих принять причастие в церкви определен специальный день: Великий Четверг на Страстной неделе. Однако причащаться можно и в любой день недели, когда проводится божественная литургия.

Как правильно подготовиться

Прежде чем отправиться на причастие, необходимо провести некоторую подготовку души и тела. К таинству допускаются только крещеные православные христиане.

Клирик храма Матроны Московской в Уфе Алексей Федянин отмечает: «День причащения — важный день для христианской души, когда она особым образом соединяется со Христом. В это время необходимо больше молчать, находиться в тишине и вести себя благопристойно. В день причастия ни в коем случае нельзя ругаться, танцевать, ходить в увеселительные заведения, развлекаться, пить спиртное. От всего этого следует воздержаться до следующего дня».

«Если человек не бывает в храме, но решает принять причастие в Чистый четверг, потому что так положено, то ему необходимо посоветоваться со священником, который на исповеди определит глубину его намерений», — рассказывает ректор Киевской Духовной академии епископ Сильвестр (Стойчев).

«Если у человека на данный момент благоговения нет, то лучше таинство отложить, чтобы не было греха ни на этом человеке, ни на священнике, который благословил подходить к причастию», — добавляет он.

Пост

Строгий пост выдерживается в течение трех дней. К употреблению запрещаются яйца, мясо, рыба и молочные продукты. Допускается хотя бы за шесть часов до таинства не принимать пищу и не пить. Кроме того, стоит отказаться от развлечений и плотских отношений.

Молитвы

Во время поста желательно читать молитвы. В любом молитвослове есть раздел под названием «Последование ко Святому Причащению», где можно найти все необходимое.

Исповедь

Считается, что перед причастием лучше всего сходить на исповедь. Без этого причащаются только дети до семи лет.

О необходимости такого шага есть разные мнения. Например, Егор Дегтярев отмечает: «Сейчас традиционно в РПЦ распространилось заблуждение, что перед причастием нужно обязательно исповедоваться. Я считаю, это не так. Исповедь и причастие — совершенно разные и несвязанные таинства. Ведь тело и кровь — это дар Божий, который Он дает людям по своему милосердию и любви к нам! Чтобы получить этот дар, не нужно никакого «пропуска» в качестве исповеди. Подарки же мы получаем не за что-то, а просто так, из-за любви дающего. Поэтому лучшая подготовка к причастию — участие в службе».

«Однако тот, кто никогда не причащался или причащался пару раз, далек от церкви, но хочет прибегнуть к таинству, обязательно перед причащением должен сходить на исповедь, поговорить со священником», — заключает эксперт.

Благочинный церквей Красногорского округа Московской епархии, настоятель Успенского храма Красногорска протоиерей Константин Островский, в свою очередь, добавляет: «Обычай исповедоваться перед причастием в наших условиях я считаю разумным и нужным, но надо понимать, что это именно обычай, а не канон и не догмат. И прихожанин, про которого я знаю, что он серьезно относится к своей духовной жизни, может просто подойти ко мне и сказать: «Батюшка, благословите причаститься». И я благословляю».

Последование ко Святому Причащению

Последование ко Святому Причащению представляет собой специальный сборник молитв.

По правилам причащающийся должен их прочитать дома перед таинством, кроме двух последних частей. Благодарственные молитвы нужно либо выслушать в храме после службы, либо читать самому. Но исторически предполагалась несколько иная последовательность. Изначально все части Последования причащающиеся читали единолично во время службы, чтение должно было продолжаться также сразу после таинства.

Сейчас считается плохим тоном, когда кто-то, не слушая литургию, утыкается в молитвослов. Значит, прихожанин не успел все положенное прочитать дома.

Однако так было не всегда, целостность и неразрывность Последования ко Святому Причащению предполагает погружение причастника именно в частную молитву, а не в общую. Дело в том, что после IV века нашей эры римские императоры прекратили гонения на христиан и численность общин значительно выросла. Меньше чем за столетие христианство превратилось из гонимой религии в религию большинства населения Римской империи. Поменялись и правила богослужений. Это уже не встреча нескольких верующих в небольшом доме или другом неприметном месте, а многолюдное собрание, торжественно проходившее в специально построенной для этого церкви.

Но у этого триумфа христианства была и обратная сторона. Ранее люди сознательно становились последователями религии, понимая, что за это можно поплатиться жизнью, и вели себя на службах с должным смирением и благоговением.

После распространения христианства сознательных верующих стало значительно меньше. Неподобающее поведение было особенно видно на больших церковных празднествах, когда собиралось много прихожан. Во время литургии большое количество причастников кричали и толкались, стараясь побыстрее совершить таинство и уйти.

Иоанн Златоуст отмечал, что таким поведением они только усугубляли свои грехи, вместо того чтобы очистить душу.

Именно для того, чтобы исключить такое недостойное поведение, проповедники и богословы того времени предложили прихожанам не торопясь ждать окончания богослужения и спокойно подходить к причастию, а время ожидания заполнять личными молитвами.

Сначала эти молитвы не были воссоединены и точечно встречались в различных молитвословах. Информация о Последовании появилась только во второй половине XI века, а окончательно оно сформировалось и стало самостоятельным в XII-XIV веках.

К тому моменту количество составляющих его молитв настолько выросло, что стало невозможным читать Последование в церкви. Возникло правило совершать часть его до литургии и часть после нее, которое применяется и сейчас.

Сейчас Последование ко Святому Причащению состоит из:

-

—

псалмов № 22, 23, 50, 115;

-

—

канона;

-

—

десяти молитв;

-

—

молитвы святого Иоанна Златоуста;

-

—

благодарственных молитв для чтения после таинства.

Отступления от правил подготовки к причастию разрешены нескольким категориям. Больным людям, беременным и кормящим женщинам разрешается не придерживаться поста, старые и немощные прихожане также могут сократить пост и количество молитв перед таинством. Детям до семи лет позволено никак не готовиться к причастию, так как суть обряда заключается не в том, чтобы утомить себя молитвами и обессилить постом, а получить радость от встречи с Богом.

Как проходит таинство

Таинство причащения состоит из трех основных частей:

-

—

Проскомидия. Выносятся хлеб и вино. Хлеб — пять просфор (напоминание о пяти хлебах из Евангелия), красное виноградное вино разбавлено водой (по телу распятого Христа текла кровь, смешанная с водой). Начинается молитва о тех, кто пришел на причастие.

-

—

Литургия оглашенных. Священник выносит из Алтаря Евангелие (малый выход), пришедшие на службу сейчас должны вспомнить о своих близких и помолиться об их здравии.

-

—

Литургия верных. Начинается с хождения священников, символизирующего шествие Христа к кресту. Происходит благословление хлеба и вина. После того как священнослужители примут причастие за закрытой занавеской (напоминание о Тайной вечере), начинается Евхаристия для прихожан.

Как вести себя на причастии:

-

—

В день причащения верующему необходимо прийти к началу утренней службы и присутствовать на ней от начала до конца.

-

—

Во время выноса священником Святых Даров, поклониться до земли, достав рукой пол.

-

—

Еще один земной поклон совершается после чтения молитвы «Верую, Господи, и исповедую…».

-

—

Как только открываются Царские Врата, начинается процедура причастия. Каждый причастник должен сложить руки на груди крестом так, чтобы правая рука была поверх левой.

-

—

В первую очередь причастие принимают священнослужители и дети.

Как подходить к Святой Чаше

Пелагея Тюренкова, религиозный публицист, религиовед, автор диссертации «Образ современной женщины в православных российских СМИ» отмечает: «К Чаше мы подходим с благоговением, обязательно получив благословение священника (обычно после исповеди), не едим и не пьем воду до и стараемся провести благочестивый день после».

Подходить к Святой Чаше нужно с правой стороны, оставляя левую свободной, в порядке очереди. Нельзя толпиться, толкаться, разговаривать. Женщины обязаны стереть губную помаду, если она есть. Стоя у Святой Чаши, нужно прочитать про себя молитву «Господи Иисусе Христе, Сыне Божий, помилуй мя грешнаго» и снова сделать земной поклон (если людей много, можно сделать его заранее).

У Чаши внятно назвать свое имя, данное при крещении, и открыть рот. Проглотив Святые Дары, поцеловать нижний край чаши, который символизирует проткнутое ребро Христа, из которого текла кровь, смешанная с водой. Находясь у Чаши, нельзя целовать руку священника, браться за сосуд руками, креститься, чтобы не опрокинуть и не пролить Чашу. В старину за такое саму церковь сжигали, а священнослужителя отправляли в монастырь.

Отходить от Чаши нужно оставляя руки скрещенными. Возле иконы Спасителя снова поклониться в землю, после этого можно подходить к столу с просфорами и вином (соком). Съев хлеб и запив его, причастник должен прополоскать рот, чтобы все частички просфоры были проглочены. И только после этого можно разговаривать и целовать иконы.

После причастия важно достоять службу до конца.

Егор Дегтярев рассказывает: «Говоря о внешних обычаях, сообщу, что мы традиционно подходим к Чаше со сложенными на груди руками (правая поверх левой), но это не принципиально. Не крестимся перед самой Чашей, чтобы не задеть ее. В очереди к Причастию стоим благоговейно, молимся, не болтаем. Обычно первыми причащаются дети, в некоторых храмах после детей идут мужчины, а потом уже женщины; в некоторых идут семьями, не делятся по полам. Но если вы нарушите традицию того или иного храма, ничего страшного не произойдет, просто могут сделать замечание. Поэтому о традициях лучше заранее спросить в церковной лавке».

Что делать после таинства

День причащения является праздником, поэтому все дела откладываются. После таинства стоит провести оставшееся время в молитвах. Есть правила, которые важно соблюдать, но без преувеличения и излишнего усердия.

Что можно и что нельзя делать после причастия

«Вопреки распространенным заблуждениям, после причастия можно и целовать иконы, и чистить зубы, и есть мясо… Но, как однажды сказал мой учитель, чтец Василий Анатольевич Соболев, после причастия нельзя лгать, вынашивать злобу, лицемерить, завидовать и много еще чего нельзя. Причащайтесь и побольше улыбайтесь», — говорит Егор Дегтярев.

Некоторые преувеличенно осторожны и стараются не только не плевать после Евхаристии, но и все несъедобные части пищи, которые побывали во рту, съесть, а то, что не удается (например, кости) — сжечь. Подобного церковный устав не требует.

Еще одно заблуждение: после причастия нельзя целовать иконы, мощи угодников, друг друга. Это опровергается обычаем священников после Евхаристии подходить к архиерею за благословением и целовать ему руку.

«С тем, что можно делать, а что нельзя после причастия, связано много мифов. Я даже слышал, что нельзя принимать душ. Логики в подобных утверждениях, безусловно, нет. Время после Причастия нужно провести в целомудрии, тишине, в чтении духовной литературы», — отмечает епископ Сильвестр (Стойчев).

В первые два часа после причастия лучше всего не переедать, вести себя тихо, избегать шумных увеселений.

Как часто надо причащаться

Обычно частота причащения определяется индивидуально для каждого его духовником. Чаще всего прихожане принимают причастие во время многодневных постов, в храмовые праздники и каждое воскресенье. Наиболее распространенный вариант — не реже двух раз в месяц.

«Православный христианин не представляет своей жизни без причастия и литургии. Это центр христианской жизни. Это величайший дар и спасение. Поэтому причащаться нужно часто, на каждой божественной литургии. Ведь сам Христос на каждой литургии обращается к нам: «Приимите, ядите…» Бывать на литургии следует минимум раз в две недели. Я обязательно причащаюсь каждое воскресенье и чаще. Но обстоятельства и возможности у всех разные, поэтому Шестой Вселенский собор постановил, что те, кто без уважительной причины не причащается больше трех недель, автоматически отлучают себя от церкви. Снова войти в церковь можно, только исповедовавшись. Пост в течение трех дней перед причастием положен тем, кто причащается редко», — отмечает Егор Дегтярев.

Причащение больных

Больным разрешается принимать причастие без соблюдения поста и чтения молитв. Священник одновременно с таинством отпускает им грехи.

Причастить больного священнослужитель обязан в любой момент, даже прервав свою службу в храме, если в том есть необходимость. Прерывать нельзя только литургию.

Если отлученный от церкви находится на грани смерти или тяжело болен, ему не откажут в причащении. В том случае когда такой человек выздоравливает, на него накладывается епитимья (держать строгий пост и читать молитвы), по окончании которой церковь снова примет его в свое лоно.

Причащение детей

Дети до семи лет принимают причастие без каких-либо приготовлений, причем если ребенок еще не умеет жевать, ему дают только сок. Поэтому на Литургии Преждеосвященных Даров малышей не причащают, так как вином (кровью) пропитаны частицы хлеба (тела), которые ребенок не сможет проглотить.

Младенцы причащаются сразу после крещения либо в следующий возможный день.

Сколько стоит

Таинство причастия проводится совершенно бесплатно.

Смысл жизни каждого православного христианина заключается в единении с Господом Иисусом Христом. Добиться его помогает таинство причастия или Евхаристии. Эта процедура считается основным церковным таинством. Важно учитывать, что это не просто внешний обряд или магическое действо. Поклонение внешней стороне церковной жизни ничего не принесет человеку. Итак, причастие в церкви – что это такое и как проходит эта процедура?

Содержание

- 1 Зачем это нужно

- 2 Подготовка к причащению

- 3 Процесс причащения

- 4 Что делать после этой процедуры

- 5 Стоимость услуги

Зачем это нужно

Причастие представляет собой таинство, которое по-настоящему соединяет человека с Господом. Об этом сказано в 6 главе Евангелия от Иоанна. Как говорит преподобный Иоанн Дамаскин, Тело и Кровь Христа помогают человеку очиститься от скверны и изгоняют любое зло. По словам святого апостола Петра, это позволяет людям стать «причастниками Божества». Они становятся «своими» для Господа, превращаясь в его народ.

При этом данная процедура также помогает соединиться людям. Это связано с тем, что все, кто причащается от общего хлеба, становятся единым Телом Христовым. Люди превращаются в единую кровь, становясь членами друг друга.

Новый Завет обозначает Церковь Божию как Тело Христово. Находиться там допускается исключительно через настоящее единение с Христом. Для этого и требуется такое таинство, как причастие.

Людям обязательно необходимо причащаться, поскольку этот обряд дарит спасение и наследование вечной жизни. Тем более что в православной религии спасение представляет собой не внешнее воздействие на человека, а внутренний процесс, который направлен на достижение полноты любви и благодати через единение с Господом Богом.

Подготовка к причащению

Чтобы таинство прошло правильно, необходимо правильно подготовиться к нему. Для этого стоит делать следующее:

- Ознакомиться с сутью причастия и желать его всей душой. Человек, который готовится пройти это таинство, должен четко понимать, что это за процедура и для чего она требуется. Причастие требуется для единения с Господом Богом. С помощью этой процедуры удается начать общение с Творцом, получить Тело и Кровь Христа для освящения и избавления от грехов. К тому же важно обладать настоящим внутренним желанием, которое должно быть искренним. Не стоит ориентироваться на чувство долга или советы других людей.

- Жить в мире с другими людьми. Запрещено проходить обряд в состоянии ненависти. Нельзя враждовать с окружающими.

- Не допускать смертных грехов, которые отлучают от таинства. Прежде всего, это касается убийства, включая аборты. Также нельзя нарушать супружескую верность или посещать гадалок и экстрасенсов. При отступлении важно, прежде всего, соединиться с церковью, исповедовавшись у священника.

- Ежедневно жить в соответствии с христианскими законами. Чтобы пройти таинство, не следует как-то специально готовиться. Важно жить так, чтобы сама обыденная жизнь сочеталась с систематическим участием в Господней Трапезе. Обязательным элементом такой жизни считается каждодневная личная молитва. Также нужно читать и изучать Библию, следовать заповедям Бога и постоянно сражаться с «ветхим человеком», живущим в каждом. К неотъемлемым элементам духовной жизни относят каждодневное испытание совести и систематические исповеди. Правильная духовная жизнь заключается в том, что человек должен стремиться жить не для себя, а для других. Немаловажное значение имеет внутренняя честность, смирение и правдивость. Свой образ жизни требуется соизмерять с необходимостью служения Богу. При этом важно соблюдать общепринятые посты и принимать участие в праздничных богослужениях, которые происходят не только по воскресеньям.

- Пройти литургический пост. С давних времен проходить таинство причастия принято натощак. Это правило называется литургическим постом. Обычно отказываться от употребления еды и напитков требуется с полуночи перед процедурой. Если рассматривать требование Священного Синода РПД, длительность такого поста должна составлять минимум 6 часов. Важно учитывать, что это требование касается только здоровых людей. К примеру, при наличии диабета разрешается с утра поесть. Также допускается принимать перед таинством лекарства, которые нужны человеку по жизненным показаниям. Стоит отметить, что Тайная Вечеря и евхаристические трапезы людей, стоявших у истоков христианства, проходили по вечерам – после еды. Священники отмечают, что во время подготовки к таинству первостепенное значение имеет состояние души и сердца, а не желудка.

- Исповедоваться. Обычно перед причастием требуется исповедоваться. Этот обряд проводят прямо перед литургией, накануне вечером или за несколько дней. Прихожанам, которых батюшка знает как истинных христиан, можно причащаться и без исповеди.

- Совершать молитвенную подготовку. Она подразумевает произнесение канона и молитв. Это рекомендуется делать вечером или с утра перед литургией. Здоровый человек должен накануне посетить храм для вечернего богослужения. В ходе литургии в храме необходимо молиться совместно с другими людьми, а не читать свое правило. Читать другие молитвы каждый верующий решает самостоятельно.

- Соблюдать требование телесного воздержания. В ночь перед причастием супругам не рекомендуется вступать в телесные отношения.

Процесс причащения

Таинство включает 3 составляющие:

- Проскомидия – на этом этапе выносят хлеб и вино. Хлеб представляет собой 5 просфор, которые являются отсылкой к 5 хлебам, упоминаемым в Евангелии. Красное вино разбавляется водой. Это вызывает ассоциации со смесью крови и воды, которая текла по телу Христа. На этом этапе начинается молитва людей, которые пришли на таинство.

- Литургия оглашенных – на этом этапе батюшка выносит Евангелие из Алтаря. При этом людям, которые посетили службу, требуется вспомнить своих близких и прочитать молитву об их здравии.

- Литургия верных – этот обряд начинается с хождения священнослужителей, которое считается символом шествия Христа к кресту. При этом благословляются хлеб и вино. После принятия причастия священниками за закрытой занавесью начинается таинство для прихожан.

Христианам нужно соблюдать на причастии такие правила:

- В день таинства прийти в храм. Это требуется сделать к началу утренней службы. На ней нужно отстоять до конца.

- Во время вынесения батюшкой Святых Даров склониться до земли. При этом важно дотянуться рукой до пола.

- После молитвы «Верую, Господи, и исповедую…» опять нужно совершить поклон до земли.

- После открытия Царских Врат происходит таинство. Каждый человек, который его проходит, должен расположить руки крестом на груди. Это требуется сделать таким образом, чтобы правая рука размещалась поверх левой.

- Вначале причастие принимают священники и дети.

Довольно часто возникает вопрос, как нужно подходить к чаше. Эксперты и религиоведы отмечают, что это требуется делать с благоговением. Предварительно непременно нужно получить благословение священника.

Приближаться к Святой Чаше требуется с правой стороны. При этом левая часть должна оставаться свободной. Делать это рекомендуется по очереди. Толпиться, отталкивать других людей или говорить в это время нельзя. Женщинам требуется стереть губную помаду в случае ее наличия. Стоя около Святой Чаши, важно прочитать молитву «Господи Иисусе Христе, Сыне Божий, помилуй мя грешнаго», после чего требуется снова поклониться до земли. При большом количестве людей поклон допустимо сделать заблаговременно.

Около Чаши требуется внятно произнести свое имя, данное при крещении, и открыть рот. После проглатывания Святых Даров нужно приложиться к нижней части чаши, который является символом проткнутого ребра Христа – именно оттуда текла кровь, которая смешивалась с водой. Около Чаши запрещено целовать руку священнослужителя, дотрагиваться до сосуда руками или совершать крестное знамение, поскольку есть опасность уронить и разлить содержимое. В давние времена такой поступок приводил к тому, что храм сжигали, а священника отправляли в монастырь.

Отходить от Чаши требуется со скрещенными руками. Около иконы Спасителя нужно опять склониться к земле. Затем можно подходить к столу, на котором стоят просфоры и вино. Когда хлеб съеден, а вино выпито, требуется ополоснуть рот, чтобы проглотить все частицы просфоры. Лишь после этого можно говорить и прикладываться к иконам.

Что делать после этой процедуры

После таинства причастия разрешается употреблять любую пищу. При этом соблазн грешить попросту исчезнет. В это время тело и душа человека представляют собой одно целое с Господом. Причащение помогает отогнать всех демонов и бесов. Они просто боятся приблизиться к верующему с искушениями.

Вечером после таинства нужно прочесть еще одно молитвенное правило – благодарственные молитвы. Это поможет выразить благодарность Господу за то, что он стал с христианином одной плотью, несмотря на все слабости и несовершенства.

Стоит отметить, что правила поведения после обряда связаны с большим количеством суеверий. К ним относят запреты на чистку зубов, поцелуи и даже мытье. Безусловно, обращать внимание на подобные вымыслы не нужно. Самое главное правило, которому требуется следовать после таинства, – это максимально долгое сохранение в себе радости единства с Богом.

Стоимость услуги

Церковь оказывает эту услугу бесплатно. При этом ее стоимость оценить невозможно. За таинство причастия людям не нужно платить деньги, тогда как Господь пожертвовал Своим Сыном, чтобы каждый мог стать с Ним одной плотью и духом.

Причастие представляет собой важнейшее христианское таинство, суть которого заключается в достижении единства с Господом Богом. При этом данный обряд имеет определенные особенности. Чтобы пройти его, нужно правильно подготовиться и придерживаться ряда правил в процессе.

The Eucharist (; from Greek εὐχαριστία, eucharistía, lit. ‘thanksgiving’), also known as Holy Communion and the Lord’s Supper, is a Christian rite that is considered a sacrament in most churches, and as an ordinance in others. According to the New Testament, the rite was instituted by Jesus Christ during the Last Supper; giving his disciples bread and wine during a Passover meal, he commanded them to «do this in memory of me» while referring to the bread as «my body» and the cup of wine as «the blood of my covenant, which is poured out for many».[1][2][3]

The elements of the Eucharist, sacramental bread (leavened or unleavened) and wine (or non-alcoholic grape juice in some Protestant traditions), are consecrated on an altar or a communion table and consumed thereafter. Christians generally recognize a special presence of Christ in this rite, though they differ about exactly how, where, and when Christ is present.

The Catholic Church states that the Eucharist is the body and blood of Christ under the species of bread and wine. It maintains that by the consecration, the substances of the bread and wine actually become the substances of the body and blood of Jesus Christ (transubstantiation) while the appearances or «accidents» of the bread and wine remain unaltered (e.g. colour, taste, feel, and smell). The Eastern Orthodox and Oriental Orthodox churches agree that an objective change occurs of the bread and wine into the body and blood of Christ. Lutherans believe the true body and blood of Christ are really present «in, with, and under» the forms of the bread and wine (sacramental union).[4] Reformed Christians believe in a real spiritual presence of Christ in the Eucharist.[5] Anglican eucharistic theologies universally affirm the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist, though Evangelical Anglicans believe that this is a spiritual presence, while Anglo-Catholics hold to a corporeal presence.[6][7] Others, such as the Plymouth Brethren, take the act to be only a symbolic reenactment of the Last Supper and a memorial.[8] As a result of these different understandings, «the Eucharist has been a central issue in the discussions and deliberations of the ecumenical movement.»[2]

Terminology[edit]

Eucharist[edit]

The New Testament was originally written in the Greek language and the Greek noun εὐχαριστία (eucharistia), meaning «thanksgiving», appears a few times in it,[10] while the related Greek verb εὐχαριστήσας is found several times in New Testament accounts of the Last Supper,[11][12][13][14][15]: 231 including the earliest such account:[12]

For I received from the Lord what I also delivered to you, that the Lord Jesus on the night when he was betrayed took bread, and when he had given thanks (εὐχαριστήσας), he broke it, and said, «This is my body which is for you. Do this in remembrance of me».

— 1 Corinthians 11:23–24[16]

The term eucharistia (thanksgiving) is that by which the rite is referred to[12] in the Didache (a late 1st or early 2nd century document),[17]: 51 [18][19]: 437 [20]: 207 and by Ignatius of Antioch (who died between 98 and 117)[19][21] and by Justin Martyr (First Apology written between 155 and 157).[22][19][23] Today, «the Eucharist» is the name still used by Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, Catholics, Anglicans, Presbyterians, and Lutherans. Other Protestant denominations rarely use this term, preferring either «Communion», «the Lord’s Supper», «Remembrance», or «the Breaking of Bread». Latter-day Saints call it «the Sacrament».[24]

Lord’s Supper[edit]

In the First Epistle to the Corinthians Paul uses the term «Lord’s Supper,» in Greek Κυριακὸν δεῖπνον (Kyriakon deipnon), in the early 50s of the 1st century,[12][13]:

When you come together, it is not the Lord’s Supper you eat, for as you eat, each of you goes ahead without waiting for anybody else. One remains hungry, another gets drunk.

— 1 Corinthians 11:20–21[25]

So Paul’s use of the term “Lord’s supper” in reference to the Corinthian banquet is powerful and interesting; but to be an actual name for the Christian meal, rather than a meaningful phrase connected with an ephemeral rhetorical contrast, it would have to have some history, previous or subsequent.[26] Nevertheless, given its existence in the biblical text, «Lord’s Supper» came into use after the Protestant Reformation and remains the predominant term among Evangelicals, such as Baptists and Pentecostals.[27]: 123 [28]: 259 [29]: 371 They also refer to the observance as an ordinance rather than a sacrament.

A Kremikovtsi Monastery fresco (15th century) depicting the Last Supper celebrated by Jesus and his disciples. The early Christians too would have celebrated this meal to commemorate Jesus’ death and subsequent resurrection.

Communion[edit]

Use of the term Communion (or Holy Communion) to refer to the Eucharistic rite began by some groups originating in the Protestant Reformation. Others, such as the Catholic Church, do not formally use this term for the rite, but instead mean by it the act of partaking of the consecrated elements;[30] they speak of receiving Holy Communion at Mass or outside of it, they also use the term First Communion when one receives the Eucharist for the first time. The term Communion is derived from Latin communio («sharing in common»), translated from the Greek κοινωνία (koinōnía) in 1 Corinthians 10:16:

The cup of blessing which we bless, is it not the communion of the blood of Christ? The bread which we break, is it not the communion of the body of Christ?

— 1 Corinthians 10:16

Other terms[edit]

Breaking of bread[edit]

The phrase κλάσις τοῦ ἄρτου (klasis tou artou, ‘breaking of the bread’; in later liturgical Greek also ἀρτοκλασία artoklasia) appears in various related forms five times in the New Testament[31] in contexts which, according to some, may refer to the celebration of the Eucharist, in either closer or symbolically more distant reference to the Last Supper.[32] This term is used by the Plymouth Brethren.[33]

Sacrament or Blessed Sacrament[edit]

The «Blessed Sacrament», the «Sacrament of the Altar», and other variations, are common terms used by Catholics,[34] Lutherans[35] and some Anglicans (Anglo-Catholics)[36] for the consecrated elements, particularly when reserved in a tabernacle. In the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints the term «The Sacrament» is used of the rite.[24]

Mass[edit]

The term «Mass» is used in the Catholic Church, the Lutheran churches (especially those of Sweden, Norway and Finland), and by some Anglicans. It derives from the Latin word missa, a dismissal: «Ite missa est,» or «go, it is sent,» the very last phrase of the service.[37] That Latin word has come to imply «mission» as well because the congregation is sent out to serve Christ.[38]

At least in the Catholic Church, the Mass is a long rite in two parts: the Liturgy of the Word and the Liturgy of the Eucharist. The former consists of readings from the Bible and a homily, or sermon, given by a priest or deacon. The latter, which follows seamlessly, includes the «Offering» of the bread and wine at the altar, their consecration by the priest through prayer, and their reception by the congregation in Holy Communion.[39] Among the many other terms used in the Catholic Church are «Holy Mass», «the Memorial of the Passion, Death and Resurrection of the Lord», the «Holy Sacrifice of the Mass», and the «Holy Mysteries».[40]

Divine Liturgy and Divine Service[edit]

The term Divine Liturgy (Greek: Θεία Λειτουργία) is used in Byzantine Rite traditions, whether in the Eastern Orthodox Church or among the Eastern Catholic Churches. These also speak of «the Divine Mysteries», especially in reference to the consecrated elements, which they also call «the Holy Gifts».[a]

The term Divine Service (German: Gottesdienst) has often been used to refer to Christian worship more generally and is still used in Lutheran churches, in addition to the terms «Eucharist», «Mass» and «Holy Communion».[41] Historically this refers (like the term «worship» itself) to service of God, although more recently it has been associated with the idea that God is serving the congregants in the liturgy.[42]

Other Eastern rites[edit]

Some Eastern rites have yet more names for Eucharist. Holy Qurbana is common in Syriac Christianity and Badarak[43] in the Armenian Rite; in the Alexandrian Rite, the term Prosfora (from the Greek προσφορά) is common in Coptic Christianity and Keddase in Ethiopian and Eritrean Christianity.[44]

History[edit]

Biblical basis[edit]

The Last Supper appears in all three Synoptic Gospels: Matthew, Mark, and Luke. It also is found in the First Epistle to the Corinthians,[2][45][46] which suggests how early Christians celebrated what Paul the Apostle called the Lord’s Supper. Although the Gospel of John does not reference the Last Supper explicitly, some argue that it contains theological allusions to the early Christian celebration of the Eucharist, especially in the chapter 6 Bread of Life Discourse but also in other passages.[47] Other New Testament passages depicting Jesus eating with crowds or after the resurrection also have eucharistic overtones.[citation needed]

Gospels[edit]

In the synoptic gospels, Mark 14:22–25,[48] Matthew 26:26–29[49] and Luke 22:13–20[50] depict Jesus as presiding over the Last Supper prior to his crucifixion. The versions in Matthew and Mark are almost identical,[51] but the Gospel of Luke presents a textual difference, in that a few manuscripts omit the second half of verse 19 and all of verse 20 («given for you […] poured out for you»), which are found in the vast majority of ancient witnesses to the text.[52] If the shorter text is the original one, then Luke’s account is independent of both that of Paul and that of Matthew/Mark. If the majority longer text comes from the author of the third gospel, then this version is very similar to that of Paul in 1 Corinthians, being somewhat fuller in its description of the early part of the Supper,[53] particularly in making specific mention of a cup being blessed before the bread was broken.[54]

In the one prayer given to posterity by Jesus, the Lord’s Prayer, the word epiousios—which is otherwise unknown in Classical Greek literature—was interpreted by some early Christian writers as meaning «super-substantial», and hence a possible reference to the Eucharist as the Bread of Life, .[55]

In the Gospel of John, however, the account of the Last Supper does not mention Jesus taking bread and «the cup» and speaking of them as his body and blood; instead, it recounts other events: his humble act of washing the disciples’ feet, the prophecy of the betrayal, which set in motion the events that would lead to the cross, and his long discourse in response to some questions posed by his followers, in which he went on to speak of the importance of the unity of the disciples with him, with each other, and with God.[56][57] Some would find in this unity and in the washing of the feet the deeper meaning of the Communion bread in the other three gospels.[58] In John 6:26–65,[59] a long discourse is attributed to Jesus that deals with the subject of the living bread; John 6:51–59[60] also contains echoes of Eucharistic language.

First Epistle to the Corinthians[edit]

1 Corinthians 11:23–25[61] gives the earliest recorded description of Jesus’ Last Supper: «The Lord Jesus on the night when he was betrayed took bread, and when he had given thanks, he broke it and said, ‘This is my body, which is for you. Do this in remembrance of me.'» The Greek word used in the passage for ‘remembrance’ is ἀνάμνησιν (anamnesis), which itself has a much richer theological history than the English word «remember».

Early Christian painting of an Agape feast.

The expression «The Lord’s Supper», derived from Paul’s usage in 1 Corinthians 11:17–34,[62] may have originally referred to the Agape feast (or love feast), the shared communal meal with which the Eucharist was originally associated.[63] The Agape feast is mentioned in Jude 12[64] but «The Lord’s Supper» is now commonly used in reference to a celebration involving no food other than the sacramental bread and wine.

Early Christian sources[edit]