Исходным

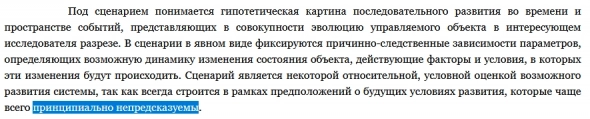

этапом прогнозирования является

прогнозный сценарий. Его задача —

разработка серии гипотез, предполагающих

и обосновывающих наиболее вероятные

изменения существующих демографических

процессов и явлений.

Сценарий

также содержит условия, определяющие

предполагаемую динамику прогнозируемых

процессов.

Избранная

гипотеза определяет использование

конкретного прогнозного метода.

Пример прогнозного

сценария.

Суммарный коэффициент

рождаемости для города и села на

протяжении ближайших двадцати лет будет

неизменным, а именно:

-

Для города —

1,682; -

Для села — 2,334.

Ожидаемая

продолжительность жизни при рождении

для мужского и женского населения в

городских и сельских районах на протяжении

ближайших двадцати лет останется без

изменений, а именно:

• ожидаемая

продолжительность жизни для мужчин

будет составлять:

для города — 66, 2

года;

для села — 64,2 года.

• ожидаемая

продолжительность жизни для женщин

будет составлять:

для города — 74,9

года;

для села — 74,6

года.

Этот

сценарий оценивают как оптимистический,

но маловероятный для ситуации в Украине.

Так,

суммарный коэффициент рождаемости не

может не уменьшаться на фоне значительного

спада производства, резкого обнищания

населения, ухудшения жилищных условий,

недостаточного обеспечения полноценным

питанием и соответствующим медицинским

обслуживанием. Эти причины, наряду с

кризисной экологической ситуацией,

делают невозможным повышение ожидаемой

продолжительности жизни в прогнозном

периоде. Потому этот сценарий расценивается

как наиболее желаемый уровень развития

демографической ситуации в Украине.

Варианты прогнозов

предусматривают предположение разных

тенденций в динамике основных показателей,

то есть они могут считаться неизменными

(как в примере), увеличиваться или

снижаться.

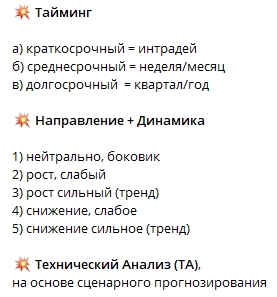

Конкретное

содержание прогнозного сценария зависит

от длительности периода, на который

разрабатывается прогноз. В краткосрочном

прогнозе целесообразно

применять так называемый метод

экстраполяций, то есть перенесение

тенденций ретроспективного периода на

перспективу. Но бывают случаи резкого

изменения условий, влияющих на

демографические процессы, т.е. нарушается

их плавность. Тогда применять этот метод

нецелесообразно, поскольку краткосрочный

прогноз должен давать достаточно точные

показатели.

В

среднесрочном прогнозе учитывается

влияние социально-экономических факторов

на динамику демографических процессов.

В связи с этим разрабатывается несколько

вариантов прогнозов. Сценарием должна

быть определенная вероятность отдельных

из них, потому, как правило, различают

пессимистический, средний и оптимистический

варианты прогноза. Пессимистический

вариант прогноза можно рассматривать

как прогноз-предостережение, с тем,

чтобы привлечь внимание к негативным

последствиям при сохранении негативных

тенденций, углублении неблагоприятных

условий.

Долгосрочные

прогнозы имеют аналитический характер

и разрабатываются для групп стран или

даже континентов. Их задача — создание

определенной базы для формирования

направлений социальной, экономической,

экологической, демографической политики

в глобальных масштабах.

Важнейшим итоговым

показателем демографического

прогнозирования является количество

населения, а это предусматривает

необходимость прогнозирования рождаемости

и смертности с учетом возрастного и

полового состава населения. Потому для

одновременного учета влияния изменений

как возрастно-половой структуры

населения, так и изменений тенденций

рождаемости и смертности используется

метод «передвижки возрастов», или «метод

компонент».

Метод

передвижки возрастов учитывает как

старение (возрастную передвижку)

населения, так и миграционные потоки

между регионами. Метод основан на том,

что, на исходный расчетный момент времени

t,

возрастная

структура численности населения задана

для всех регионов и страны в целом.

Чтобы

получить возрастную структуру численности

населения на следующий момент времени

t

+ 1,

для каждого региона делается

последовательная передвижка возрастных

когорт: возрастная когорта, составляющая

численность населения в возрасте от х

до

х

+

1 передвигается на место когорты

численности возрастов от х

+ 1

до х

+ 2 за

вычетом умерших в рассматриваемой

когорте за период времени от t

до

t

+ 1.

Кроме того, из этой когорты вычитаются

все выбывшие в другие регионы за этот

же период и прибавляются все прибывшие

соответствующего возраста из других

регионов. Также на место первой возрастной

когорты (младенцы) в каждом регионе

подставляется численность новорожденных

в данном регионе за вычетом числа умерших

младенцев.

В

результате на каждый следующий момент

времени должна получаться полная

возрастная структура численности

населения с учетом рождаемости, смертности

и миграции по всем рассматриваемым

регионам. Таким образом, метод «передвижки

возрастов» дает возможность получить

количество населения в перспективном

периоде по возрасту и половому составу

и на

базе годового приращения позволяет

осуществить подготовку одного из

вариантов демографического прогноза.

Схема вариантного расчета численности

населения методом передвижки возрастов

нуждается в прогностическом обосновании

основных демографических показателей.

В

демографическом прогнозировании

применяется метод аналогий

или

метод референтного прогноза. Допускают,

что динамика определенного демографического

процесса, происходящего в населении

одного региона, будет происходить таким

же образом, как это было в населении

другого региона. Основа метода —

последовательность состояний эволюционного

развития населения, то есть концепция

демографического перехода. При

использовании метода аналогий требуется

обоснованный выбор населения двух

регионов для сравнения, то есть учет

особенностей и отличий социально-экономического

развития регионов, население которых

сравнивается, а также степень подобия

у них демографических процессов. На

практике даже близкие по значению

показатели режима воспроизводства

населения разных периодов времени

фактически не будут совпадать по всем

параметрам, поэтому данный метод

используют в качестве приближенного

способа разработки сценариев

демографического прогноза.

Более

широко используется метод экспертных

оценок.

Он базируется на использовании для

сценариев мнений многих специалистов

по разным отраслям науки относительно

наиболее вероятных перспективных

изменений в динамике рождаемости,

смертности, миграции. Преимуществом

этого метода является обеспечение

большей обоснованности гипотез, на

которых основаны сценарии прогнозов.

Важное место в

демографическом прогнозировании

занимают прогнозы показателей,

характеризующих семейную структуру

населения. Семья — основной потребитель

многих товаров длительного использования.

Для расчета спроса на них необходимы

знания будущего количества одиночек и

семей разного типа, в частности молодых

семей с детьми, семей с тремя поколениями

и т. п. Прогноз количества и состава

семей, а также их доходов и потребностей

необходим для оценки перспектив жилищного

строительства. Методология разработки

этого раздела демографического прогноза

находится на стадии становления. В

большинстве стран мира объектом

статистического наблюдения и прогноза

является не семья, а домохозяйство. В

определении домохозяйства нет требования

родственных уз между его членами,

одновременно допускается домохозяйство

одного человека. По мнению специалистов,

прогноз семьи должен учитывать три

категории: семью, одиночек, и членов

семей, которые живут отдельно.

При

прогнозировании семейной структуры

применяют метод экстраполяции

разных

характеристик деления семей по величине.

Другой подход базируется на зависимости

между возрастно-половым составом

населения и его семейной структурой.

Применяется также способ, который

опирается на так называемые коэффициенты

главенства. Эти коэффициенты рассчитываются

на основе количества глав семей,

определенных во время переписи населения.

В дальнейшем количество глав семей

распределяется по полу и возрасту, затем

определяются доли глав семей в числе

лиц этого пола и возраста. Полученные

результаты и составляют коэффициенты

главенства. Экстраполируя вычисленные

коэффициенты на прогнозируемое количество

населения, можно определить прогнозное

количество семей. Теоретически наиболее

совершенным, но недостаточно разработанным

методом прогноза является моделирование

воспроизводства семейной структуры

населения.

Методы демографического

прогнозирования населения мира, отдельных

стран и территорий, принятые ООН (United

Nations Population Division), основаны на использовании

информационной статистической базы

государств — членов ООН, а также на

результатах собственных аналитических

исследований.

Важной характеристикой

прогноза является точность исходной

информации, а также обоснованность

гипотез об ожидаемых изменениях

социально-экономических факторов,

влияющих на демографические процессы.

Точность демографических прогнозов

зависит от прогнозируемого периода: на

период до 10 лет расчеты могут быть

выполнены достаточно точно, на 25-30 лет

— степень точности снижается. Определенное

значение для точности прогнозных

расчетов имеет состояние демографического

перехода населения данной территории.

На точность прогнозов влияют также

разного рода катаклизмы стихийного,

биологического и другого характера.

В

целом точность демографических прогнозов

значительно ниже точности расчетов

фактического населения. Если точность

прогнозных расчетов составляет до 5 %,

прогноз

считается удачным (точность переписей

население определяет в 1-2 %).

Достоверность

прогноза напрямую зависит от качества

методов его выполнения, учета максимально

возможного числа факторов,

его

определяющих, гипотез и сценарных

подходов к определению тенденций

демографических изменений и в меньшей

степени от математического обеспечения.

Современные

программы значительно экономят время,

необходимое для проведения прогнозных

расчетов, дают возможность просчитывать

разные сценарии возможной динамики

населения, а также делать расчеты в

случае неполных или дефектных данных.

Практика

свидетельствует, что демографические

составляющие еще не нашли достойного

места в социально-экономическом

прогнозировании. Демографы же отмечают

исключительную важность демографической

экспертизы для различных решений.

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

Scenario planning, scenario thinking, scenario analysis,[1] scenario prediction[2] and the scenario method[3] all describe a strategic planning method that some organizations use to make flexible long-term plans. It is in large part an adaptation and generalization of classic methods used by military intelligence.[4]

In the most common application of the method, analysts generate simulation games for policy makers. The method combines known facts, such as demographics, geography and mineral reserves, with military, political, and industrial information, and key driving forces identified by considering social, technical, economic, environmental, and political («STEEP») trends.

In business applications, the emphasis on understanding the behavior of opponents has been reduced while more attention is now paid to changes in the natural environment. At Royal Dutch Shell for example, scenario planning has been described as changing mindsets about the exogenous part of the world prior to formulating specific strategies.[5][6]

Scenario planning may involve aspects of systems thinking, specifically the recognition that many factors may combine in complex ways to create sometimes surprising futures (due to non-linear feedback loops). The method also allows the inclusion of factors that are difficult to formalize, such as novel insights about the future, deep shifts in values, and unprecedented regulations or inventions.[7] Systems thinking used in conjunction with scenario planning leads to plausible scenario storylines because the causal relationship between factors can be demonstrated.[8] These cases, in which scenario planning is integrated with a systems thinking approach to scenario development, are sometimes referred to as «dynamic scenarios».

Critics of using a subjective and heuristic methodology to deal with uncertainty and complexity argue that the technique has not been examined rigorously, nor influenced sufficiently by scientific evidence. They caution against using such methods to «predict» based on what can be described as arbitrary themes and «forecasting techniques».

A challenge and a strength of scenario-building is that «predictors are part of the social context about which they are trying to make a prediction and may influence that context in the process».[9] As a consequence, societal predictions can become self-destructing. For example, a scenario in which a large percentage of a population will become HIV infected based on existing trends may cause more people to avoid risky behavior and thus reduce the HIV infection rate, invalidating the forecast (which might have remained correct if it had not been publicly known). Or, a prediction that cybersecurity will become a major issue may cause organizations to implement more secure cybersecurity measures, thus limiting the issue.[9]

Principle[edit]

Crafting scenarios[edit]

Combinations and permutations of fact and related social changes are called «scenarios». Scenarios usually include plausible, but unexpectedly important, situations and problems that exist in some nascent form in the present day. Any particular scenario is unlikely. However, futures studies analysts select scenario features so they are both possible and uncomfortable. Scenario planning helps policy-makers and firms anticipate change, prepare responses, and create more robust strategies.[10][11]

Scenario planning helps a firm anticipate the impact of different scenarios and identify weaknesses. When anticipated years in advance, those weaknesses can be avoided or their impacts reduced more effectively than when similar real-life problems are considered under the duress of an emergency. For example, a company may discover that it needs to change contractual terms to protect against a new class of risks, or collect cash reserves to purchase anticipated technologies or equipment. Flexible business continuity plans with «PREsponse protocols» can help cope with similar operational problems and deliver measurable future value.

Zero-sum game scenarios[edit]

Strategic military intelligence organizations also construct scenarios. The methods and organizations are almost identical, except that scenario planning is applied to a wider variety of problems than merely military and political problems.

As in military intelligence, the chief challenge of scenario planning is to find out the real needs of policy-makers, when policy-makers may not themselves know what they need to know, or may not know how to describe the information that they really want.

Good analysts design wargames so that policy makers have great flexibility and freedom to adapt their simulated organisations.[12] Then these simulated organizations are «stressed» by the scenarios as a game plays out. Usually, particular groups of facts become more clearly important. These insights enable intelligence organizations to refine and repackage real information more precisely to better serve the policy-makers’ real-life needs. Usually the games’ simulated time runs hundreds of times faster than real life, so policy-makers experience several years of policy decisions, and their simulated effects, in less than a day.

This chief value of scenario planning is that it allows policy-makers to make and learn from mistakes without risking career-limiting failures in real life. Further, policymakers can make these mistakes in a safe, unthreatening, game-like environment, while responding to a wide variety of concretely presented situations based on facts. This is an opportunity to «rehearse the future», an opportunity that does not present itself in day-to-day operations where every action and decision counts.

How military scenario planning or scenario thinking is done[edit]

- Decide on the key question to be answered by the analysis. By doing this, it is possible to assess whether scenario planning is preferred over the other methods. If the question is based on small changes or a very small number of elements, other more formalized methods may be more useful.

- Set the time and scope of the analysis. Take into consideration how quickly changes have happened in the past, and try to assess to what degree it is possible to predict common trends in demographics, product life cycles. A usual timeframe can be five to 10 years.

- Identify major stakeholders. Decide who will be affected and have an interest in the possible outcomes. Identify their current interests, whether and why these interests have changed over time in the past.

- Map basic trends and driving forces. This includes industry, economic, political, technological, legal, and societal trends. Assess to what degree these trends will affect your research question. Describe each trend, how and why it will affect the organisation. In this step of the process, brainstorming is commonly used, where all trends that can be thought of are presented before they are assessed, to capture possible group thinking and tunnel vision.

- Find key uncertainties. Map the driving forces on two axes, assessing each force on an uncertain/(relatively) predictable and important/unimportant scale. All driving forces that are considered unimportant are discarded. Important driving forces that are relatively predictable (ex. demographics) can be included in any scenario, so the scenarios should not be based on these. This leaves you with a number of important and unpredictable driving forces. At this point, it is also useful to assess whether any linkages between driving forces exist, and rule out any «impossible» scenarios (ex. full employment and zero inflation).

- Check for the possibility to group the linked forces and if possible, reduce the forces to the two most important. (To allow the scenarios to be presented in a neat xy-diagram)

- Identify the extremes of the possible outcomes of the two driving forces and check the dimensions for consistency and plausibility. Three key points should be assessed:

- Time frame: are the trends compatible within the time frame in question?

- Internal consistency: do the forces describe uncertainties that can construct probable scenarios.

- Vs the stakeholders: are any stakeholders currently in disequilibrium compared to their preferred situation, and will this evolve the scenario? Is it possible to create probable scenarios when considering the stakeholders? This is most important when creating macro-scenarios where governments, large organisations et al. will try to influence the outcome.

- Define the scenarios, plotting them on a grid if possible. Usually, two to four scenarios are constructed. The current situation does not need to be in the middle of the diagram (inflation may already be low), and possible scenarios may keep one (or more) of the forces relatively constant, especially if using three or more driving forces. One approach can be to create all positive elements into one scenario and all negative elements (relative to the current situation) in another scenario, then refining these. In the end, try to avoid pure best-case and worst-case scenarios.

- Write out the scenarios. Narrate what has happened and what the reasons can be for the proposed situation. Try to include good reasons why the changes have occurred as this helps the further analysis. Finally, give each scenario a descriptive (and catchy) name to ease later reference.

- Assess the scenarios. Are they relevant for the goal? Are they internally consistent? Are they archetypical? Do they represent relatively stable outcome situations?

- Identify research needs. Based on the scenarios, assess where more information is needed. Where needed, obtain more information on the motivations of stakeholders, possible innovations that may occur in the industry and so on.

- Develop quantitative methods. If possible, develop models to help quantify consequences of the various scenarios, such as growth rate, cash flow etc. This step does of course require a significant amount of work compared to the others, and may be left out in back-of-the-envelope-analyses.

- Converge towards decision scenarios. Retrace the steps above in an iterative process until you reach scenarios which address the fundamental issues facing the organization. Try to assess upsides and downsides of the possible scenarios.

Use by managers[edit]

The basic concepts of the process are relatively simple. In terms of the overall approach to forecasting, they can be divided into three main groups of activities (which are, generally speaking, common to all long range forecasting processes):[13]

- Environmental analysis

- Scenario planning

- Corporate strategy

The first of these groups quite simply comprises the normal environmental analysis. This is almost exactly the same as that which should be undertaken as the first stage of any serious long-range planning. However, the quality of this analysis is especially important in the context of scenario planning.

The central part represents the specific techniques – covered here – which differentiate the scenario forecasting process from the others in long-range planning.

The final group represents all the subsequent processes which go towards producing the corporate strategy and plans. Again, the requirements are slightly different but in general they follow all the rules of sound long-range planning.

Applications[edit]

Business[edit]

In the past, strategic plans have often considered only the «official future», which was usually a straight-line graph of current trends carried into the future. Often the trend lines were generated by the accounting department, and lacked discussions of demographics, or qualitative differences in social conditions.[5]

These simplistic guesses are surprisingly good most of the time, but fail to consider qualitative social changes that can affect a business or government. Paul J. H. Schoemaker offers a strong managerial case for the use of scenario planning in business and had wide impact.[14]

The approach may have had more impact outside Shell than within, as many others firms and consultancies started to benefit as well from scenario planning. Scenario planning is as much art as science, and prone to a variety of traps (both in process and content) as enumerated by Paul J. H. Schoemaker.[14] More recently scenario planning has been discussed as a tool to improve the strategic agility, by cognitively preparing not only multiple scenarios but also multiple consistent strategies.[10]

Military[edit]

Scenario planning is also extremely popular with military planners. Most states’ department of war maintains a continuously updated series of strategic plans to cope with well-known military or strategic problems. These plans are almost always based on scenarios, and often the plans and scenarios are kept up-to-date by war games, sometimes played out with real troops. This process was first carried out (arguably the method was invented by) the Prussian general staff of the mid-19th century.

Finance[edit]

In economics and finance, a financial institution might use scenario analysis to forecast several possible scenarios for the economy (e.g. rapid growth, moderate growth, slow growth) and for financial market returns (for bonds, stocks and cash) in each of those scenarios. It might consider sub-sets of each of the possibilities. It might further seek to determine correlations and assign probabilities to the scenarios (and sub-sets if any). Then it will be in a position to consider how to distribute assets between asset types (i.e. asset allocation); the institution can also calculate the scenario-weighted expected return (which figure will indicate the overall attractiveness of the financial environment). It may also perform stress testing, using adverse scenarios.[15]

Depending on the complexity of the problem, scenario analysis can be a demanding exercise. It can be difficult to foresee what the future holds (e.g. the actual future outcome may be entirely unexpected), i.e. to foresee what the scenarios are, and to assign probabilities to them; and this is true of the general forecasts never mind the implied financial market returns. The outcomes can be modeled mathematically/statistically e.g. taking account of possible variability within single scenarios as well as possible relationships between scenarios. In general, one should take care when assigning probabilities to different scenarios as this could invite a tendency to consider only the scenario with the highest probability.[16]

Geopolitics[edit]

In politics or geopolitics, scenario analysis involves reflecting on the possible alternative paths of a social or political environment and possibly diplomatic and war risks.

History of use by academic and commercial organizations[edit]

Most authors attribute the introduction of scenario planning to Herman Kahn through his work for the US Military in the 1950s at the RAND Corporation where he developed a technique of describing the future in stories as if written by people in the future. He adopted the term «scenarios» to describe these stories. In 1961 he founded the Hudson Institute where he expanded his scenario work to social forecasting and public policy.[17][18][19][20][21] One of his most controversial uses of scenarios was to suggest that a nuclear war could be won.[22] Though Kahn is often cited as the father of scenario planning, at the same time Kahn was developing his methods at RAND, Gaston Berger was developing similar methods at the Centre d’Etudes Prospectives which he founded in France. His method, which he named ‘La Prospective’, was to develop normative scenarios of the future which were to be used as a guide in formulating public policy. During the mid-1960s various authors from the French and American institutions began to publish scenario planning concepts such as ‘La Prospective’ by Berger in 1964[23] and ‘The Next Thirty-Three Years’ by Kahn and Wiener in 1967.[24] By the 1970s scenario planning was in full swing with a number of institutions now established to provide support to business including the Hudson Foundation, the Stanford Research Institute (now SRI International), and the SEMA Metra Consulting Group in France. Several large companies also began to embrace scenario planning including DHL Express, Dutch Royal Shell and General Electric.[19][21][25][26]

Possibly as a result of these very sophisticated approaches, and of the difficult techniques they employed (which usually demanded the resources of a central planning staff), scenarios earned a reputation for difficulty (and cost) in use. Even so, the theoretical importance of the use of alternative scenarios, to help address the uncertainty implicit in long-range forecasts, was dramatically underlined by the widespread confusion which followed the Oil Shock of 1973. As a result, many of the larger organizations started to use the technique in one form or another. By 1983 Diffenbach reported that ‘alternate scenarios’ were the third most popular technique for long-range forecasting – used by 68% of the large organizations he surveyed.[27]

Practical development of scenario forecasting, to guide strategy rather than for the more limited academic uses which had previously been the case, was started by Pierre Wack in 1971 at the Royal Dutch Shell group of companies – and it, too, was given impetus by the Oil Shock two years later. Shell has, since that time, led the commercial world in the use of scenarios – and in the development of more practical techniques to support these. Indeed, as – in common with most forms of long-range forecasting – the use of scenarios has (during the depressed trading conditions of the last decade) reduced to only a handful of private-sector organisations, Shell remains almost alone amongst them in keeping the technique at the forefront of forecasting.[28]

There has only been anecdotal evidence offered in support of the value of scenarios, even as aids to forecasting; and most of this has come from one company – Shell. In addition, with so few organisations making consistent use of them – and with the timescales involved reaching into decades – it is unlikely that any definitive supporting evidenced will be forthcoming in the foreseeable future. For the same reasons, though, a lack of such proof applies to almost all long-range planning techniques. In the absence of proof, but taking account of Shell’s well documented experiences of using it over several decades (where, in the 1990s, its then CEO ascribed its success to its use of such scenarios), can be significant benefit to be obtained from extending the horizons of managers’ long-range forecasting in the way that the use of scenarios uniquely does.[13]

Process[edit]

The part of the overall process which is radically different from most other forms of long-range planning is the central section, the actual production of the scenarios. Even this, though, is relatively simple, at its most basic level. As derived from the approach most commonly used by Shell,[29] it follows six steps:[30]

- Decide drivers for change/assumptions

- Bring drivers together into a viable framework

- Produce 7–9 initial mini-scenarios

- Reduce to 2–3 scenarios

- Draft the scenarios

- Identify the issues arising

Step 1 – decide assumptions/drivers for change[edit]

The first stage is to examine the results of environmental analysis to determine which are the most important factors that will decide the nature of the future environment within which the organisation operates. These factors are sometimes called ‘variables’ (because they will vary over the time being investigated, though the terminology may confuse scientists who use it in a more rigorous manner). Users tend to prefer the term ‘drivers’ (for change), since this terminology is not laden with quasi-scientific connotations and reinforces the participant’s commitment to search for those forces which will act to change the future. Whatever the nomenclature, the main requirement is that these will be informed assumptions.

This is partly a process of analysis, needed to recognise what these ‘forces’ might be. However, it is likely that some work on this element will already have taken place during the preceding environmental analysis. By the time the formal scenario planning stage has been reached, the participants may have already decided – probably in their sub-conscious rather than formally – what the main forces are.

In the ideal approach, the first stage should be to carefully decide the overall assumptions on which the scenarios will be based. Only then, as a second stage, should the various drivers be specifically defined. Participants, though, seem to have problems in separating these stages.

Perhaps the most difficult aspect though, is freeing the participants from the preconceptions they take into the process with them. In particular, most participants will want to look at the medium term, five to ten years ahead rather than the required longer-term, ten or more years ahead. However, a time horizon of anything less than ten years often leads participants to extrapolate from present trends, rather than consider the alternatives which might face them. When, however, they are asked to consider timescales in excess of ten years they almost all seem to accept the logic of the scenario planning process, and no longer fall back on that of extrapolation. There is a similar problem with expanding participants horizons to include the whole external environment.

Brainstorming

In any case, the brainstorming which should then take place, to ensure that the list is complete, may unearth more variables – and, in particular, the combination of factors may suggest yet others.

A very simple technique which is especially useful at this – brainstorming – stage, and in general for handling scenario planning debates is derived from use in Shell where this type of approach is often used. An especially easy approach, it only requires a conference room with a bare wall and copious supplies of 3M Post-It Notes.

The six to ten people ideally taking part in such face-to-face debates should be in a conference room environment which is isolated from outside interruptions. The only special requirement is that the conference room has at least one clear wall on which Post-It notes will stick. At the start of the meeting itself, any topics which have already been identified during the environmental analysis stage are written (preferably with a thick magic marker, so they can be read from a distance) on separate Post-It Notes. These Post-It Notes are then, at least in theory, randomly placed on the wall. In practice, even at this early stage the participants will want to cluster them in groups which seem to make sense. The only requirement (which is why Post-It Notes are ideal for this approach) is that there is no bar to taking them off again and moving them to a new cluster.

A similar technique – using 5″ by 3″ index cards – has also been described (as the ‘Snowball Technique’), by Backoff and Nutt, for grouping and evaluating ideas in general.[31]

As in any form of brainstorming, the initial ideas almost invariably stimulate others. Indeed, everyone should be encouraged to add their own Post-It Notes to those on the wall. However it differs from the ‘rigorous’ form described in ‘creative thinking’ texts, in that it is much slower paced and the ideas are discussed immediately. In practice, as many ideas may be removed, as not being relevant, as are added. Even so, it follows many of the same rules as normal brainstorming and typically lasts the same length of time – say, an hour or so only.

It is important that all the participants feel they ‘own’ the wall – and are encouraged to move the notes around themselves. The result is a very powerful form of creative decision-making for groups, which is applicable to a wide range of situations (but is especially powerful in the context of scenario planning). It also offers a very good introduction for those who are coming to the scenario process for the first time. Since the workings are largely self-evident, participants very quickly come to understand exactly what is involved.

Important and uncertain

This step is, though, also one of selection – since only the most important factors will justify a place in the scenarios. The 80:20 Rule here means that, at the end of the process, management’s attention must be focused on a limited number of most important issues. Experience has proved that offering a wider range of topics merely allows them to select those few which interest them, and not necessarily those which are most important to the organisation.

In addition, as scenarios are a technique for presenting alternative futures, the factors to be included must be genuinely ‘variable’. They should be subject to significant alternative outcomes. Factors whose outcome is predictable, but important, should be spelled out in the introduction to the scenarios (since they cannot be ignored). The Important Uncertainties Matrix, as reported by Kees van der Heijden of Shell, is a useful check at this stage.[32]

At this point it is also worth pointing out that a great virtue of scenarios is that they can accommodate the input from any other form of forecasting. They may use figures, diagrams or words in any combination. No other form of forecasting offers this flexibility.

Step 2 – bring drivers together into a viable framework[edit]

The next step is to link these drivers together to provide a meaningful framework. This may be obvious, where some of the factors are clearly related to each other in one way or another. For instance, a technological factor may lead to market changes, but may be constrained by legislative factors. On the other hand, some of the ‘links’ (or at least the ‘groupings’) may need to be artificial at this stage. At a later stage more meaningful links may be found, or the factors may then be rejected from the scenarios. In the most theoretical approaches to the subject, probabilities are attached to the event strings. This is difficult to achieve, however, and generally adds little – except complexity – to the outcomes.

This is probably the most (conceptually) difficult step. It is where managers’ ‘intuition’ – their ability to make sense of complex patterns of ‘soft’ data which more rigorous analysis would be unable to handle – plays an important role. There are, however, a range of techniques which can help; and again the Post-It-Notes approach is especially useful:

Thus, the participants try to arrange the drivers, which have emerged from the first stage, into groups which seem to make sense to them. Initially there may be many small groups. The intention should, therefore, be to gradually merge these (often having to reform them from new combinations of drivers to make these bigger groups work). The aim of this stage is eventually to make 6–8 larger groupings; ‘mini-scenarios’. Here the Post-It Notes may be moved dozens of times over the length – perhaps several hours or more – of each meeting. While this process is taking place the participants will probably want to add new topics – so more Post-It Notes are added to the wall. In the opposite direction, the unimportant ones are removed (possibly to be grouped, again as an ‘audit trail’ on another wall). More important, the ‘certain’ topics are also removed from the main area of debate – in this case they must be grouped in clearly labelled area of the main wall.

As the clusters – the ‘mini-scenarios’ – emerge, the associated notes may be stuck to each other rather than individually to the wall; which makes it easier to move the clusters around (and is a considerable help during the final, demanding stage to reducing the scenarios to two or three).

The great benefit of using Post-It Notes is that there is no bar to participants changing their minds. If they want to rearrange the groups – or simply to go back (iterate) to an earlier stage – then they strip them off and put them in their new position.

Step 3 – produce initial mini-scenarios[edit]

The outcome of the previous step is usually between seven and nine logical groupings of drivers. This is usually easy to achieve. The ‘natural’ reason for this may be that it represents some form of limit as to what participants can visualise.

Having placed the factors in these groups, the next action is to work out, very approximately at this stage, what is the connection between them. What does each group of factors represent?

Step 4 – reduce to two or three scenarios[edit]

The main action, at this next stage, is to reduce the seven to nine mini-scenarios/groupings detected at the previous stage to two or three larger scenarios

There is no theoretical reason for reducing to just two or three scenarios, only a practical one. It has been found that the managers who will be asked to use the final scenarios can only cope effectively with a maximum of three versions! Shell started, more than three decades ago, by building half a dozen or more scenarios – but found that the outcome was that their managers selected just one of these to concentrate on. As a result, the planners reduced the number to three, which managers could handle easily but could no longer so easily justify the selection of only one! This is the number now recommended most frequently in most of the literature.

Complementary scenarios

As used by Shell, and as favoured by a number of the academics, two scenarios should be complementary; the reason being that this helps avoid managers ‘choosing’ just one, ‘preferred’, scenario – and lapsing once more into single-track forecasting (negating the benefits of using ‘alternative’ scenarios to allow for alternative, uncertain futures). This is, however, a potentially difficult concept to grasp, where managers are used to looking for opposites; a good and a bad scenario, say, or an optimistic one versus a pessimistic one – and indeed this is the approach (for small businesses) advocated by Foster. In the Shell approach, the two scenarios are required to be equally likely, and between them to cover all the ‘event strings’/drivers. Ideally they should not be obvious opposites, which might once again bias their acceptance by users, so the choice of ‘neutral’ titles is important. For example, Shell’s two scenarios at the beginning of the 1990s were titled ‘Sustainable World’ and ‘Global Mercantilism'[xv]. In practice, we found that this requirement, much to our surprise, posed few problems for the great majority, 85%, of those in the survey; who easily produced ‘balanced’ scenarios. The remaining 15% mainly fell into the expected trap of ‘good versus bad’. We have found that our own relatively complex (OBS) scenarios can also be made complementary to each other; without any great effort needed from the teams involved; and the resulting two scenarios are both developed further by all involved, without unnecessary focusing on one or the other.

Testing

Having grouped the factors into these two scenarios, the next step is to test them, again, for viability. Do they make sense to the participants? This may be in terms of logical analysis, but it may also be in terms of intuitive ‘gut-feel’. Once more, intuition often may offer a useful – if academically less respectable – vehicle for reacting to the complex and ill-defined issues typically involved. If the scenarios do not intuitively ‘hang together’, why not? The usual problem is that one or more of the assumptions turns out to be unrealistic in terms of how the participants see their world. If this is the case then you need to return to the first step – the whole scenario planning process is above all an iterative one (returning to its beginnings a number of times until the final outcome makes the best sense).

Step 5 – write the scenarios[edit]

The scenarios are then ‘written up’ in the most suitable form. The flexibility of this step often confuses participants, for they are used to forecasting processes which have a fixed format. The rule, though, is that you should produce the scenarios in the form most suitable for use by the managers who are going to base their strategy on them. Less obviously, the managers who are going to implement this strategy should also be taken into account. They will also be exposed to the scenarios, and will need to believe in these. This is essentially a ‘marketing’ decision, since it will be very necessary to ‘sell’ the final results to the users. On the other hand, a not inconsiderable consideration may be to use the form the author also finds most comfortable. If the form is alien to him or her the chances are that the resulting scenarios will carry little conviction when it comes to the ‘sale’.

Most scenarios will, perhaps, be written in word form (almost as a series of alternative essays about the future); especially where they will almost inevitably be qualitative which is hardly surprising where managers, and their audience, will probably use this in their day to day communications. Some, though use an expanded series of lists and some enliven their reports by adding some fictional ‘character’ to the material – perhaps taking literally the idea that they are stories about the future – though they are still clearly intended to be factual. On the other hand, they may include numeric data and/or diagrams – as those of Shell do (and in the process gain by the acid test of more measurable ‘predictions’).

Step 6 – identify issues arising[edit]

The final stage of the process is to examine these scenarios to determine what are the most critical outcomes; the ‘branching points’ relating to the ‘issues’ which will have the greatest impact (potentially generating ‘crises’) on the future of the organisation. The subsequent strategy will have to address these – since the normal approach to strategy deriving from scenarios is one which aims to minimise risk by being ‘robust’ (that is it will safely cope with all the alternative outcomes of these ‘life and death’ issues) rather than aiming for performance (profit) maximisation by gambling on one outcome.

Use of scenarios[edit]

It is important to note that scenarios may be used in a number of ways:

a) Containers for the drivers/event strings

Most basically, they are a logical device, an artificial framework, for presenting the individual factors/topics (or coherent groups of these) so that these are made easily available for managers’ use – as useful ideas about future developments in their own right – without reference to the rest of the scenario. It should be stressed that no factors should be dropped, or even given lower priority, as a result of producing the scenarios. In this context, which scenario contains which topic (driver), or issue about the future, is irrelevant.

b) Tests for consistency

At every stage it is necessary to iterate, to check that the contents are viable and make any necessary changes to ensure that they are; here the main test is to see if the scenarios seem to be internally consistent – if they are not then the writer must loop back to earlier stages to correct the problem. Though it has been mentioned previously, it is important to stress once again that scenario building is ideally an iterative process. It usually does not just happen in one meeting – though even one attempt is better than none – but takes place over a number of meetings as the participants gradually refine their ideas.

c) Positive perspectives

Perhaps the main benefit deriving from scenarios, however, comes from the alternative ‘flavors’ of the future their different perspectives offer. It is a common experience, when the scenarios finally emerge, for the participants to be startled by the insight they offer – as to what the general shape of the future might be – at this stage it no longer is a theoretical exercise but becomes a genuine framework (or rather set of alternative frameworks) for dealing with that.

Scenario planning compared to other techniques[edit]

The flowchart to the right provides a process for classifying a phenomenon as a scenario in the intuitive logics tradition.[33]

Process for classifying a phenomenon as a scenario in the Intuitive Logics tradition.

Scenario planning differs from contingency planning, sensitivity analysis and computer simulations.[34]

Contingency planning is a «What if» tool, that only takes into account one uncertainty. However, scenario planning considers combinations of uncertainties in each scenario. Planners also try to select especially plausible but uncomfortable combinations of social developments.

Sensitivity analysis analyzes changes in one variable only, which is useful for simple changes, while scenario planning tries to expose policy makers to significant interactions of major variables.

While scenario planning can benefit from computer simulations, scenario planning is less formalized, and can be used to make plans for qualitative patterns that show up in a wide variety of simulated events.

During the past 5 years, computer supported Morphological Analysis has been employed as aid in scenario development by the Swedish Defence Research Agency in Stockholm.[35] This method makes it possible to create a multi-variable morphological field which can be treated as an inference model – thus integrating scenario planning techniques with contingency analysis and sensitivity analysis.

Scenario analysis[edit]

Scenario analysis is a process of analyzing future events by considering alternative possible outcomes (sometimes called «alternative worlds»). Thus, scenario analysis, which is one of the main forms of projection, does not try to show one exact picture of the future. Instead, it presents several alternative future developments. Consequently, a scope of possible future outcomes is observable. Not only are the outcomes observable, also the development paths leading to the outcomes. In contrast to prognoses, the scenario analysis is not based on extrapolation of the past or the extension of past trends. It does not rely on historical data and does not expect past observations to remain valid in the future. Instead, it tries to consider possible developments and turning points, which may only be connected to the past. In short, several scenarios are fleshed out in a scenario analysis to show possible future outcomes. Each scenario normally combines optimistic, pessimistic, and more and less probable developments. However, all aspects of scenarios should be plausible. Although highly discussed, experience has shown that around three scenarios are most appropriate for further discussion and selection. More scenarios risks making the analysis overly complicated.[36][37] Scenarios are often confused with other tools and approaches to planning. The flowchart to the right provides a process for classifying a phenomenon as a scenario in the intuitive logics tradition.[38]

Principle[edit]

Scenario-building is designed to allow improved decision-making by allowing deep consideration of outcomes and their implications.

A scenario is a tool used during requirements analysis to describe a specific use of a proposed system. Scenarios capture the system, as viewed from the outside

Scenario analysis can also be used to illuminate «wild cards.» For example, analysis of the possibility of the earth being struck by a meteor suggests that whilst the probability is low, the damage inflicted is so high that the event is much more important (threatening) than the low probability (in any one year) alone would suggest. However, this possibility is usually disregarded by organizations using scenario analysis to develop a strategic plan since it has such overarching repercussions.

Combination of Delphi and scenarios[edit]

Scenario planning concerns planning based on the systematic examination of the future by picturing plausible and consistent images of that future. The Delphi method attempts to develop systematically expert opinion consensus concerning future developments and events. It is a judgmental forecasting procedure in the form of an anonymous, written, multi-stage survey process, where feedback of group opinion is provided after each round.

Numerous researchers have stressed that both approaches are best suited to be combined.[39][40] Due to their process similarity, the two methodologies can be easily combined. The output of the different phases of the Delphi method can be used as input for the scenario method and vice versa. A combination makes a realization of the benefits of both tools possible. In practice, usually one of the two tools is considered the dominant methodology and the other one is added on at some stage.

The variant that is most often found in practice is the integration of the Delphi method into the scenario process (see e.g. Rikkonen, 2005;[41] von der Gracht, 2008;[42]). Authors refer to this type as Delphi-scenario (writing), expert-based scenarios, or Delphi panel derived scenarios. Von der Gracht (2010)[43] is a scientifically valid example of this method. Since scenario planning is “information hungry”, Delphi research can deliver valuable input for the process. There are various types of information output of Delphi that can be used as input for scenario planning. Researchers can, for example, identify relevant events or developments and, based on expert opinion, assign probabilities to them. Moreover, expert comments and arguments provide deeper insights into relationships of factors that can, in turn, be integrated into scenarios afterwards. Also, Delphi helps to identify extreme opinions and dissent among the experts. Such controversial topics are particularly suited for extreme scenarios or wildcards.

In his doctoral thesis, Rikkonen (2005)[41] examined the utilization of Delphi techniques in scenario planning and, concretely, in construction of scenarios. The author comes to the conclusion that the Delphi technique has instrumental value in providing different alternative futures and the argumentation of scenarios. It is therefore recommended to use Delphi in order to make the scenarios more profound and to create confidence in scenario planning. Further benefits lie in the simplification of the scenario writing process and the deep understanding of the interrelations between the forecast items and social factors.

Critique[edit]

While there is utility in weighting hypotheses and branching potential outcomes from them, reliance on scenario analysis without reporting some parameters of measurement accuracy (standard errors, confidence intervals of estimates, metadata, standardization and coding, weighting for non-response, error in reportage, sample design, case counts, etc.) is a poor second to traditional prediction. Especially in “complex” problems, factors and assumptions do not correlate in lockstep fashion. Once a specific sensitivity is undefined, it may call the entire study into question.

It is faulty logic to think, when arbitrating results, that a better hypothesis will render empiricism unnecessary. In this respect, scenario analysis tries to defer statistical laws (e.g., Chebyshev’s inequality Law), because the decision rules occur outside a constrained setting. Outcomes are not permitted to “just happen”; rather, they are forced to conform to arbitrary hypotheses ex post, and therefore there is no footing on which to place expected values. In truth, there are no ex ante expected values, only hypotheses, and one is left wondering about the roles of modeling and data decision. In short, comparisons of «scenarios» with outcomes are biased by not deferring to the data; this may be convenient, but it is indefensible.

“Scenario analysis” is no substitute for complete and factual exposure of survey error in economic studies. In traditional prediction, given the data used to model the problem, with a reasoned specification and technique, an analyst can state, within a certain percentage of statistical error, the likelihood of a coefficient being within a certain numerical bound. This exactitude need not come at the expense of very disaggregated statements of hypotheses. R Software, specifically the module “WhatIf,”[44] (in the context, see also Matchit and Zelig) has been developed for causal inference, and to evaluate counterfactuals. These programs have fairly sophisticated treatments for determining model dependence, in order to state with precision how sensitive the results are to models not based on empirical evidence.

Another challenge of scenario-building is that «predictors are part of the social context about which they are trying to make a prediction and may influence that context in the process».[45] As a consequence, societal predictions can become self-destructing.[45] For example, a scenario in which a large percentage of a population will become HIV infected based on existing trends may cause more people to avoid risky behavior and thus reduce the HIV infection rate, invalidating the forecast (which might have remained correct if it had not been publicly known). Or, a prediction that cybersecurity will become a major issue may cause organizations to implement more secure cybersecurity measures, thus limiting the issue.

Critique of Shell’s use of scenario planning[edit]

In the 1970s, many energy companies were surprised by both environmentalism and the OPEC cartel, and thereby lost billions of dollars of revenue by mis-investment. The dramatic financial effects of these changes led at least one organization, Royal Dutch Shell, to implement scenario planning. The analysts of this company publicly estimated that this planning process made their company the largest in the world.[46] However other observers[who?] of Shell’s use of scenario planning have suggested that few if any significant long-term business advantages accrued to Shell from the use of scenario methodology[citation needed]. Whilst the intellectual robustness of Shell’s long term scenarios was seldom in doubt their actual practical use was seen as being minimal by many senior Shell executives[citation needed]. A Shell insider has commented «The scenario team were bright and their work was of a very high intellectual level. However neither the high level «Group scenarios» nor the country level scenarios produced with operating companies really made much difference when key decisions were being taken».[citation needed]

The use of scenarios was audited by Arie de Geus’s team in the early 1980s and they found that the decision-making processes following the scenarios were the primary cause of the lack of strategic implementation[clarification needed]), rather than the scenarios themselves. Many practitioners today spend as much time on the decision-making process as on creating the scenarios themselves.[47]

See also[edit]

- ACEGES – an agent-based model for scenario analysis

- Counter-revolutionary

- Decentralized planning (economics)

- Disruptive innovation

- Hoshin Kanri#Hoshin planning

- Futures studies

- Global Scenario Group

- Resilience (organizational)

- Robust decision-making

- Scenario (computing)

Similar terminology[edit]

- Feedback loop

- System dynamics (also known as Stock and flow)

- System thinking

Analogous concepts[edit]

- Delphi method, including Real-time Delphi

- Game theory

- Horizon scanning

- Morphological analysis

- Rational choice theory

- Stress testing

- Twelve leverage points

Examples[edit]

- CIM-10 Bomarc (relied on Semi-Automatic Ground Environment)

- Climate change mitigation scenarios – possible futures in which global warming is reduced by deliberate actions

- Covert United States foreign regime change actions

- Dynamic Analysis and Replanning Tool

- Energy modeling – the process of building computer models of energy systems

- Floodplain

- Nijinomatsubara

- Pentagon Papers

References[edit]

- ^ Palomino, Marco A.; Bardsley, Sarah; Bown, Kevin; De Lurio, Jennifer; Ellwood, Peter; Holland‐Smith, David; Huggins, Bob; Vincenti, Alexandra; Woodroof, Harry; Owen, Richard (1 January 2012). «Web‐based horizon scanning: concepts and practice». Foresight. 14 (5): 355–373. doi:10.1108/14636681211269851. ISSN 1463-6689. Retrieved 16 May 2021.

- ^ Kovalenko, Igor; Davydenko, Yevhen; Shved, Alyona (2019-04-12). «Development of the procedure for integrated application of scenario prediction methods». Eastern-European Journal of Enterprise Technologies. 2 (4 (98)): 31–38. doi:10.15587/1729-4061.2019.163871. S2CID 188383713.

- ^ Spaniol, Matthew J.; Rowland, Nicholas J. (2018-01-01). «The scenario planning paradox». Futures. 95: 33–43. doi:10.1016/j.futures.2017.09.006. ISSN 0016-3287. S2CID 148708423.

- ^ Bradfield, Ron; Wright, George; Burt, George; Cairns, George; Heijden, Kees Van Der (2005). «The origins and evolution of scenario techniques in long range business planning». Futures. 37 (8): 795–812. doi:10.1016/j.futures.2005.01.003.

- ^ a b «Living in the Futures». Harvard Business Review. 2013-05-01. Retrieved 2018-01-12.

- ^ Schoemaker, Paul J. H. (1993-03-01). «Multiple scenario development: Its conceptual and behavioral foundation». Strategic Management Journal. 14 (3): 193–213. doi:10.1002/smj.4250140304. ISSN 1097-0266.

- ^ Mendonça, Sandro; Cunha, Miguel Pina e; Ruff, Frank; Kaivo-oja, Jari (2009). «Venturing into the Wilderness». Long Range Planning. 42 (1): 23–41. doi:10.1016/j.lrp.2008.11.001.

- ^ Gausemeier, Juergen; Fink, Alexander; Schlake, Oliver (1998). «Scenario Management». Technological Forecasting and Social Change. 59 (2): 111–130. doi:10.1016/s0040-1625(97)00166-2.

- ^ a b Overland, Indra (2019-03-01). «The geopolitics of renewable energy: Debunking four emerging myths». Energy Research & Social Science. 49: 36–40. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2018.10.018. ISSN 2214-6296.

- ^ a b Lehr, Thomas; Lorenz, Ullrich; Willert, Markus; Rohrbeck, René (2017). «Scenario-based strategizing: Advancing the applicability in strategists’ teams». Technological Forecasting and Social Change. 124: 214–224. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2017.06.026.

- ^ Ringland, Gill (2010). «The role of scenarios in strategic foresight». Technological Forecasting and Social Change. 77 (9): 1493–1498. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2010.06.010.

- ^ Schwarz, Jan Oliver (2013). «Business wargaming for teaching strategy making». Futures. 51: 59–66. doi:10.1016/j.futures.2013.06.002.

- ^ a b Mercer, David. «Simpler Scenarios,» Management Decision. Vol. 33 Issue 4:1995, pp 32-40.

- ^ a b Schoemaker, Paul J.H. “Scenario Planning: A Tool for Strategic Thinking,” Sloan Management Review. Winter: 1995, pp. 25-40.

- ^ «Scenario Analysis in Risk Management», Bertrand Hassani, Published by Springer, 2016, ISBN 978-3-319-25056-4, [1]

- ^ The Art of the Long View: Paths to Strategic Insight for Yourself and Your Company, Peter Schwartz, Published by Random House, 1996, ISBN 0-385-26732-0 Google book

- ^ Schwartz, Peter. . The Art of the Long View: Planning for the Future in an Uncertain World New York: Currency Doubleday, 1991.

- ^ «Herman Kahn.» The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition. 2008. Retrieved November 30, 2009 from Encyclopedia.com: http://www.encyclopedia.com/doc/1E1-Kahn-Her.html

- ^ a b Chermack, Thomas J., Susan A. Lynham, and Wendy E. A. Ruona. «A Review of Scenario Planning Literature.» Futures Research Quarterly 7 2 (2001): 7-32.

- ^ Lindgren, Mats, and Hans Bandhold. Scenario Planning: The Link between Future and Strategy. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003.

- ^ a b Bradfield, Ron, et al. «The Origins and Evolution of Scenario Techniques in Long Range Business Planning.» Futures 37 8 (2005): 795-812.

- ^ Kahn, Herman. Thinking About the Unthinkable. New York: Horizon Press, 1965.

- ^ Berger, G. «Phénoménologies du Temps et Prospectives.» Presse Universitaires de France, 1964.

- ^ Kahn, Herman, and Anthony J. Wiener. «The Next Thirty-Three Years: A Framework for Speculation.» Daedalus 96 3 (1967): 705-32.

- ^ Godet, Michel, and Fabrice Roubelat. «Creating the Future :The Use and Misuse of Scenarios.» Long Range Planning 29 2 (1996): 164-71.

- ^ Godet, Michel, Fabrice Roubelat, and Guest Editors. «Scenario Planning: An Open Future.» Technological Forecasting and Social Change 65 1 (2000): 1-2.

- ^ Diffenbach, John. «Corporate Environmental Analysis in Large US Corporations,» Long Range Planning. 16 (3), 1983.

- ^ Wack, Peter. «Scenarios: Uncharted Waters Ahead,» Harvard Business Review. September–October, 1985.

- ^ Shell (2008). «Scenarios: An Explorer’s Guide» (PDF). www.shell.com/scenarios. Shell Global. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ Meinert, Sacha (2014). Field manual — Scenario building (PDF). Brussels: Etui. ISBN 978-2-87452-314-4. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ Backoff, R.W. and P.C. Nutt. «A Process for Strategic Management with Specific Application for the Non-Profit Organization,» Strategic Planning: Threats and Opportunities for Planners. Planners Press, 1988.

- ^ van der Heijden, Kees. Scenarios: The Art of Strategic Conversation. Wiley & Sons, 1996.

- ^ Spaniol, Matthew J.; Rowland, Nicholas J. (2018). «Defining Scenario». Futures & Foresight Science. 1: e3. doi:10.1002/ffo2.3.

- ^ Schoemaker, Paul J.H. Profiting from Uncertainty. Free Press, 2002.

- ^ T. Eriksson & T. Ritchey, «Scenario Development using Computer Aided Morphological Analysis» (PDF). Adapted from a Paper Presented at the Winchester International OR Conference, England, 2002.

- ^ Aaker, David A. (2001). Strategic Market Management. New York: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 108 et seq. ISBN 978-0-471-41572-5.

- ^ Bea, F.X., Haas, J. (2005). Strategisches Management. Stuttgart: Lucius & Lucius. pp. 279 and 287 et seq.

- ^ Spaniol, Matthew J.; Rowland, Nicholas J. (2019). «Defining Scenario». Futures & Foresight Science. 1: e3. doi:10.1002/ffo2.3.

- ^ Nowack, Martin; Endrika, Jan; Edeltraut, Guenther (2011). «Review of Delphi-based scenario studies: Quality and design considerations». Technological Forecasting and Social Change. 78 (9): 1603–1615. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2011.03.006.

- ^ Renzi, Adriano B.; Freitas, Sydney (2015). «The Delphi Method for Future Scenarios Construction». Procedia Manufacturing. 3: 5785–5791. doi:10.1016/j.promfg.2015.07.826.

- ^ a b Rikkonen, P. (2005). Utilisation of alternative scenario approaches in defining the policy agenda for future agriculture in Finland. Turku School of Economics and Business Administration, Helsinki.

- ^ von der Gracht, H. A. (2008) The future of logistics: scenarios for 2025. Dissertation. Gabler, ISBN 978-3-8349-1082-0

- ^ von der Gracht, H. A./ Darkow, I.-L.: Scenarios for the Logistics Service Industry: A Delphi-based analysis for 2025. In: International Journal of Production Economics, Vol. 127, No. 1, 2010, 46-59.

- ^ Stoll, Heather; King, Gary; Zeng, Langche (August 12, 2010). «WhatIf: Software for Evaluating Counterfactuals» (PDF). Journal of Statistical Software. Retrieved 2022-04-23.

- ^ a b Overland, Indra (2019-03-01). «The geopolitics of renewable energy: Debunking four emerging myths». Energy Research & Social Science. 49: 36–40. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2018.10.018. ISSN 2214-6296.

- ^ Schwartz, Peter. The Art of the Long View. Doubleday, 1991.

- ^ Cornelius, Peter, Van de Putte, Alexander, and Romani, Mattia. «Three Decades of Scenario Planning in Shell,» California Management Review. Vol. 48 Issue 1:Fall 2005, pp 92-109.

Additional Bibliography[edit]

- D. Erasmus, The future of ICT in financial services: The Rabobank ICT scenarios (2008).

- M. Godet, Scenarios and Strategic Management, Butterworths (1987).

- M. Godet, From Anticipation to Action: A Handbook of Strategic Prospective. Paris: Unesco, (1993).

- Adam Kahane, Solving Tough Problems: An Open Way of Talking, Listening, and Creating New Realities (2007)

- H. Kahn, The Year 2000, Calman-Levy (1967).

- Herbert Meyer, «Real World Intelligence», Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1987,

- National Intelligence Council (NIC) Archived 2012-07-28 at the Wayback Machine, «Mapping the Global Future», 2005,

- M. Lindgren & H. Bandhold, Scenario planning – the link between future and strategy, Palgrave Macmillan, 2003

- G. Wright& G. Cairns, Scenario thinking: practical approaches to the future, Palgrave Macmillan, 2011

- A. Schuehly, F. Becker t& F. Klein, Real Time Strategy: When Strategic Foresight Meets Artificial Intelligence, Emerald, 2020*

- A. Ruser, Sociological Quasi-Labs: The Case for Deductive Scenario Development, Current Sociology Vol63(2): 170-181, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0011392114556581

Scientific Journals[edit]

- Foresight

- Futures

- Futures & Foresight Science

- Journal of Futures Studies

- Technological Forecasting and Social Change

External links[edit]

- Wikifutures wiki; Scenario page—wiki also includes several scenarios (GFDL licensed)

- ScenarioThinking.org —more than 100 scenarios developed on various global issues, on a wiki for public use

- Shell Scenarios Resources—Resources on what scenarios are, Shell’s new and old scenario’s, explorer’s guide and other scenario resources

- Learn how to use Scenario Manager in Excel to do Scenario Analysis

Further reading[edit]

- «Learning from the Future: Competitive Foresight Scenarios», Liam Fahey and Robert M. Randall, Published by John Wiley and Sons, 1997, ISBN 0-471-30352-6, Google book

- «Shirt-sleeve approach to long-range plans.», Linneman, Robert E, Kennell, John D.; Harvard Business Review; Mar/Apr77, Vol. 55 Issue 2, p141

Scenario planning, scenario thinking, scenario analysis,[1] scenario prediction[2] and the scenario method[3] all describe a strategic planning method that some organizations use to make flexible long-term plans. It is in large part an adaptation and generalization of classic methods used by military intelligence.[4]

In the most common application of the method, analysts generate simulation games for policy makers. The method combines known facts, such as demographics, geography and mineral reserves, with military, political, and industrial information, and key driving forces identified by considering social, technical, economic, environmental, and political («STEEP») trends.

In business applications, the emphasis on understanding the behavior of opponents has been reduced while more attention is now paid to changes in the natural environment. At Royal Dutch Shell for example, scenario planning has been described as changing mindsets about the exogenous part of the world prior to formulating specific strategies.[5][6]

Scenario planning may involve aspects of systems thinking, specifically the recognition that many factors may combine in complex ways to create sometimes surprising futures (due to non-linear feedback loops). The method also allows the inclusion of factors that are difficult to formalize, such as novel insights about the future, deep shifts in values, and unprecedented regulations or inventions.[7] Systems thinking used in conjunction with scenario planning leads to plausible scenario storylines because the causal relationship between factors can be demonstrated.[8] These cases, in which scenario planning is integrated with a systems thinking approach to scenario development, are sometimes referred to as «dynamic scenarios».

Critics of using a subjective and heuristic methodology to deal with uncertainty and complexity argue that the technique has not been examined rigorously, nor influenced sufficiently by scientific evidence. They caution against using such methods to «predict» based on what can be described as arbitrary themes and «forecasting techniques».

A challenge and a strength of scenario-building is that «predictors are part of the social context about which they are trying to make a prediction and may influence that context in the process».[9] As a consequence, societal predictions can become self-destructing. For example, a scenario in which a large percentage of a population will become HIV infected based on existing trends may cause more people to avoid risky behavior and thus reduce the HIV infection rate, invalidating the forecast (which might have remained correct if it had not been publicly known). Or, a prediction that cybersecurity will become a major issue may cause organizations to implement more secure cybersecurity measures, thus limiting the issue.[9]

Principle[edit]

Crafting scenarios[edit]

Combinations and permutations of fact and related social changes are called «scenarios». Scenarios usually include plausible, but unexpectedly important, situations and problems that exist in some nascent form in the present day. Any particular scenario is unlikely. However, futures studies analysts select scenario features so they are both possible and uncomfortable. Scenario planning helps policy-makers and firms anticipate change, prepare responses, and create more robust strategies.[10][11]

Scenario planning helps a firm anticipate the impact of different scenarios and identify weaknesses. When anticipated years in advance, those weaknesses can be avoided or their impacts reduced more effectively than when similar real-life problems are considered under the duress of an emergency. For example, a company may discover that it needs to change contractual terms to protect against a new class of risks, or collect cash reserves to purchase anticipated technologies or equipment. Flexible business continuity plans with «PREsponse protocols» can help cope with similar operational problems and deliver measurable future value.

Zero-sum game scenarios[edit]

Strategic military intelligence organizations also construct scenarios. The methods and organizations are almost identical, except that scenario planning is applied to a wider variety of problems than merely military and political problems.

As in military intelligence, the chief challenge of scenario planning is to find out the real needs of policy-makers, when policy-makers may not themselves know what they need to know, or may not know how to describe the information that they really want.

Good analysts design wargames so that policy makers have great flexibility and freedom to adapt their simulated organisations.[12] Then these simulated organizations are «stressed» by the scenarios as a game plays out. Usually, particular groups of facts become more clearly important. These insights enable intelligence organizations to refine and repackage real information more precisely to better serve the policy-makers’ real-life needs. Usually the games’ simulated time runs hundreds of times faster than real life, so policy-makers experience several years of policy decisions, and their simulated effects, in less than a day.

This chief value of scenario planning is that it allows policy-makers to make and learn from mistakes without risking career-limiting failures in real life. Further, policymakers can make these mistakes in a safe, unthreatening, game-like environment, while responding to a wide variety of concretely presented situations based on facts. This is an opportunity to «rehearse the future», an opportunity that does not present itself in day-to-day operations where every action and decision counts.

How military scenario planning or scenario thinking is done[edit]

- Decide on the key question to be answered by the analysis. By doing this, it is possible to assess whether scenario planning is preferred over the other methods. If the question is based on small changes or a very small number of elements, other more formalized methods may be more useful.

- Set the time and scope of the analysis. Take into consideration how quickly changes have happened in the past, and try to assess to what degree it is possible to predict common trends in demographics, product life cycles. A usual timeframe can be five to 10 years.

- Identify major stakeholders. Decide who will be affected and have an interest in the possible outcomes. Identify their current interests, whether and why these interests have changed over time in the past.

- Map basic trends and driving forces. This includes industry, economic, political, technological, legal, and societal trends. Assess to what degree these trends will affect your research question. Describe each trend, how and why it will affect the organisation. In this step of the process, brainstorming is commonly used, where all trends that can be thought of are presented before they are assessed, to capture possible group thinking and tunnel vision.

- Find key uncertainties. Map the driving forces on two axes, assessing each force on an uncertain/(relatively) predictable and important/unimportant scale. All driving forces that are considered unimportant are discarded. Important driving forces that are relatively predictable (ex. demographics) can be included in any scenario, so the scenarios should not be based on these. This leaves you with a number of important and unpredictable driving forces. At this point, it is also useful to assess whether any linkages between driving forces exist, and rule out any «impossible» scenarios (ex. full employment and zero inflation).

- Check for the possibility to group the linked forces and if possible, reduce the forces to the two most important. (To allow the scenarios to be presented in a neat xy-diagram)

- Identify the extremes of the possible outcomes of the two driving forces and check the dimensions for consistency and plausibility. Three key points should be assessed:

- Time frame: are the trends compatible within the time frame in question?

- Internal consistency: do the forces describe uncertainties that can construct probable scenarios.

- Vs the stakeholders: are any stakeholders currently in disequilibrium compared to their preferred situation, and will this evolve the scenario? Is it possible to create probable scenarios when considering the stakeholders? This is most important when creating macro-scenarios where governments, large organisations et al. will try to influence the outcome.