Друзья и коллеги!

Завтра, 14 октября, в нашем сообществе стартует 1-й «Осенний ДРАМАФОН».

Пока не могу раскрыть его условия. Но, в качестве подготовки к забегу, давайте вспомним, что такое трёхактная и пятиактная структура сценария (или пьесы).

Замечание. Количество страниц в приведенном ниже тексте соответствует американской сценарной лесенке. Думаю, для пьесы надо делить это количество на 2-3, в зависимости от ее объема.

Источник.

Пятиактная парадигма, или о чём вам не рассказал Сид Филд

В своей статье, известный режиссер Рашид Нагуманов («Игла») критически анализирует классическую трёхактную структуру сценария и предлагает «пятиактную парадигму». В статье проиллюстрирована схемами и примерами из фильма «Китайский квартал» (автор сценария Р. Таун).

Как внесистемный кинематографист, я предлагаю профессиональным сценаристам всего мира внимательнее взглянуть на классическую 3-актную структуру, описанную Сидом Филдом в книге «Киносценарий»:

начало середина конец

1-й акт 2-й акт 3-й акт

———x—|———————x—|————

завязка противостояние развязка

стр. 1-30 стр. 30-90 стр. 90-120

Поворот 1 Поворот 2

стр. 25-27 стр. 85-90

Эта парадигма была поднята на щит и de facto признана стандартом в Голливуде. В то же время немало критики высказано в адрес её примитивизма и неспособности ответить на сложные требования современного кино. И вправду, вообразите эту парадигму картиной на стене, и сразу возникают трудные вопросы:

Фильм идёт уже полчаса (одна страница правильно сформатированного сценария соответствует одной минуте экранного времени), а мы всё ещё в «начале», как и тридцать, и двадцать пять, и двадцать минут назад?

Первый сюжетный поворот случается на странице 25. Мы что, до сих пор ехали гладко, и нас не заносило?

2-й акт состоит из 60 страниц противостояния — одно препятствие за другим на протяжении часа! Не утомительно?

Развязка — что это? Просто «конец», который длится тридцать минут?

И так далее, в том же духе…

Как бы отвечая критикам, Сид Филд позже предложил более детализированную структуру в рамках всё той же парадигмы (книга «Разрешение сценарных проблем»):

1-й акт 2-й акт 3-й акт

1-я половина 2-я половина

———x—|————|———x—|————

завязка противостояние развязка

Поворот 1 Середина Поворот 2

(стр. 20-30) (стр. 60) (стр. 80-90)

2-й акт выглядит более разработанным и разделён на две части «срединной точкой». Уже легче, но вопросы остаются.

2-й акт теперь имеет две половинки, но точка поворота по-прежнему одна — во второй. А что в первой половине акта?

Теперь первый поворот может случиться раньше (начиная с 20-й страницы). Это делает завязку более динамичной, но мы всё еще чувствуем дискомфорт из-за отсутствия точки отсчета и слишком затянутого начала. Как быть с этим? Парадигма не даёт ответа.

Куда отнести «срединную точку» — к первой половине 2-го акта или ко второй его половине? Или она просто разрезает весь сценарий пополам?

Развязка — когда она происходит? В самом конце линии, после чего фильм немедленно заканчивается и идут финальные титры? Или же это непрерывный процесс развязки в течение тридцати минут, узел за узлом?

Подобные вопросы лишают парадигму полного счастья, которым она могла бы одарить сценаристов, ведь в целом она рисует четкую, сбалансированную картину сценария. Возникает ощущение, что мы видим конструкцию сюжета на расстоянии, не различая жизненно важных, решающих деталей. Так и хочется шагнуть к «картине на стене» и приглядеться поближе.

Сделаем этот шаг.

ЗАВЯЗКА: 10 ИЛИ 30 СТРАНИЦ?

Вглядевшись в 1-й акт, немедленно выделяешь «самую важную часть сценария» — его первые десять страниц. Именно в течение первых десяти страниц (или десяти минут фильма) обычно понимаешь, нравится тебе то, что ты видишь, или нет. Давайте отобразим это на картине:

1-й акт

стр. 10

—-|——x—|

завязка

Поворот 1

(стр. 20-30)

Сид Филд учит, что в течение первых десяти минут драматического действия нужно показать читателю главного героя, драматическую предпосылку истории (о чём она) и драматическую ситуацию (обстоятельства, окружающие историю). Герой, предпосылка, ситуация — всё это вместе определяется одним словом: «завязка».

Каждый поворот истории — это функция главного героя. В том числе и отправная точка — т.е. некое событие, которое запускает главного героя в движение. В сценарии «Чайнатауна» этот момент происходит на 7-й странице, когда Джиттс (Джек Николсон) принимает предложение лже-госпожи Малрей (Фэй Данауэй) расследовать дело: «Ну хорошо. Посмотрим, что можно сделать.»

Отправная точка в подавляющем большинстве голливудских фильмов случается не позже десятой минуты:

10-мин. завязка

———-x—|

Отправная точка

Схема выглядит подозрительно знакомо, не правда ли? Точно. Так выглядит акт в парадигме Сида Филда. Это и есть акт. Вследствие его важности, этот элемент драматического действия следует рассматривать именно как отдельный акт. В нем вы должны определить главного героя, предпосылку, ситуацию и жанр. Вся история должна завязаться в этом акте, иначе читатель забросит ваш сценарий, а зритель возненавидит ваш фильм.

Запишите и запомните: первые десять страниц завязки — это 1-й акт.

Исключительная важность завязки для всего сценария заслуживает ещё нескольких слов.

Как отдельный акт, завязка состоит из трех ясно различимых частей: первая сцена, отправная сцена и сцена сюжетного вопроса.

В «Чайнатауне» первая сцена содержит четыре страницы диалога между Джиттсом и Курли в кабинете Джиттса. Отправная сцена происходит в кабинете Даффи и Уолша от страницы 5 до отправной точки на странице 7. А сцена, в которой звучит главный сюжетный вопрос, происходит на публичных слушаниях в ратуше, и вопрос этот задаёт какой-то фермер: «Кто вам платит, мистер Малрей, хотел бы я знать?»

Первая сцена не обязательно показывает нам главного героя. Её главная задача — показать мир, в который нас забросило, а также определить жанр фильма. Иначе говоря, заложить фундамент для отправной сцены. А вот отправная сцена всегда связана с главным героем (даже если этот главный герой — неодушевленный предмет, вроде фестиваля в Вудстоке или войны во Вьетнаме). Отправная точка, которую она содержит — это первое действие протагониста, после чего немедленно следует сцена вопроса.

Сюжетный вопрос, в свою очередь, необязательно звучит из уст протагониста. Он может быть задан партнером, а иногда (как в «Чайнатауне») даже проходным, эпизодным персонажем. Единожды прозвучав, это вопрос закрывает завязку, и нас ждёт…

2-Й АКТ: ИНТРИГА

Прежде чем приступить к этому захватывающему этапу сценарной работы, спросите себя: Можно ли назвать следующие двадцать страниц сценария, которые теперь составляют 2-й акт, «завязкой»?

Готов поклясться, ответ вы уже знаете: Нет.

Современного зрителя раздражает завязка, которая тянется полчаса. Нужно делать это за десять минут. Как же в таком случае назвать следующие двадцать минут драматического действия, которые завершаются знаменитой «поворотной точкой номер 1»?

Очень просто: интрига.

Задавшись вопросом, который впоследствии окажется центральным для всей истории, наш герой отправляется в путь. Вопрос этот никогда не получает ответа в данном акте, но череда неожиданных событий приводит его к первой поворотной точке сюжета. Главный герой неожиданно для себя оказывается в центре интриги. Он — её часть!

Первый поворот является прямым результатом отправной точки в завязке. Протагонист отправился в путь, не вполне понимая, на что или куда он идет, и теперь перед ним точка, за которой нет возврата. Поворот номер 1 — это ничто другое, как решение главного героя преступить эту черту.

В «Чайнатауне» Джиттс после предварительного расследования понимает, что он стал актером в чужой игре. При этом самой большой неожиданностью для него становится появление настоящей госпожи Малрей в его кабинете. Некоторые ошибочно принимают это событие за первый поворот. Запомните: сюжет является функцией главного героя. Каким бы неожиданным ни было её появление, это еще не поворот сюжета. Джиттс пока ещё не меняет направления своего пути, решение ещё не пришло. По сути, это — проверка. Проверка решимости Джиттса на поиск истины. Настоящий первый поворот в «Чайнатауне» случается на странице 27 во время их второй встречи, когда госпожа Малрей предлагает отозвать иск. Вот теперь у Джиттса есть выбор. Чтобы сохранить проактивность героя, в каждом поворотном пункте должен присутствовать выбор: вернуться к привычной жизни или ступить на новую, неизведанную территорию. Джиттс делает свой выбор: «Я не хочу отказываться.»

Первый поворот не ведет напрямую в следующий акт. Прежде нужно завершить 2-й акт, и чаще всего он захлопывается с треском. Нас ожидает последняя неожиданность интриги, самая сильная. Сожгите мост перед глазами героя. Дайте нам почувствовать, что его жизнь уже никогда не будет прежней.

Убейте Малрея.

БУММ!…

Теперь, когда принято решение, пройдена точка возврата и мосты сожжены, главному герою не остётся ничего другого, как…

3-Й АКТ: TERRA INCOGNITA, ИЛИ УЧЕБА

Эта неизведанная территория в середине сценария может быть столь же малознакома автору сценария, как и его герою! И начинающие писатели, и матерые сценаристы часто признаются, что написали замечательную завязку и развязку, но совершенно потерялись в этом длиннющем, чудовищном 60-страничном среднем акте, а всё, что предлагают гуру от сценаристики — это швырять булыжники в главного героя и строить перед ним одно препятствие за другим, называя всё это «противостоянием». Булыжники — это хорошо, но много ли пользы от таких советов? Не очень.

Но есть один секрет, который превратит работу над средней частью вашего сценария в увлекательное, легкое и приятное занятие. Секрет заключается в том, что не надо писать шестьдесят страниц; в 3-м акте их всего тридцать.

Взгляните еще раз на то, что у Сида Филда называется «первой половиной» и «второй половиной» 2-го акта:

2-й акт

1-я половина 2-я половина

————-|———-x—|

Середина Поворот 2

На самом деле, мы видим 3-й и 4-й акты, с их собственными сюжетными поворотами:

3-й акт 4-й акт

———-x—|———-x—|

Середина Поворот 2

Вы можете сказать с недоверием: «Два акта противостояния вместо одного? Это еще хуже!»

Дело в том, что 3-й и 4-й акты вовсе не о противостоянии! С детских лет мы прекрасно знаем, что настоящее противостояние случается в конце фильма. Все мы помним эти «последние битвы», где наш герой сходится в смертельной схватке со злом, чем бы ни было это зло и в чем бы ни заключалась эта схватка.

О чем же тогда эти два срединных акта?

Как уже упомянуто, 3-й акт повествует о новой, неизведанной территории, куда ступает наш герой и которую он вынужден исследовать. Это акт об учебе.

Разумеется, в процессе исследования герой встречает одно препятствие за другим (вспомните школу!) Разумеется, он попадет не в одну серьезную переделку. Да, враг может послать герою несколько серьезных предупреждений, обычно через посредников (незнакомый коротыш порежет Джиттсу ноздрю), чтобы заставить того изменить своё решение и уйти с неведомой территории — территории врага. И разумеется, старый добрый мир исчезнет как дым. Но это еще не противостояние лицом к лицу с главным врагом. Это процесс узнавания нового, и герой обязан пройти его, чтобы успешно сразиться со злом в финале.

Несмотря на все тяжести и опасности учебы, этот опыт по большей части вдохновляющий. Герой делает успехи, и ему это нравится. (На странице 51 Джиттс говорит буквально следующее: «Я чуть не лишился носа, черт побери. Но мне нравится. Нравится дышать всем этим.»). Вот это и есть срединная точка сценария.

Очень часто срединная точка менее артикулирована, чем 1-я и 2-я. В ней может не произойти решающего сюжетного поворота. 3-й акт не обязательно заканчивается ударом. Именно по этой причине девственным сценаристам, озабоченным швырянием булыжников в героя, бывает трудно найти середину драматургического действия иным способом, кроме механического складывания сценария пополам, — и тем самым еще более запутываясь в нем.

Истина заключается в том, что срединная точка сценария не разделяет два акта; это такой же сюжетный поворот, как другие, пусть он и менее ярок. Как мы уже знаем, в каждом акте перед завершением существует поворотная точка. Мы также знаем, что любой сюжетный поворот — это функция главного героя. Средняя точка принадлежит 3-му акту. Она имеет отношение к учебному опыту героя. При этом она случается на его взлете. Исходя из всего этого, ищите точку там, где герой доволен происходящим или получает какой-то важный урок, который в конце концов приведет его к победе.

Как завершить 3-й акт? На ваше усмотрение. Можно придумать ударную сцену без особых серьезных открытий, просто предложив очередное препятствие и успешно преодолев его. Можете даже дать в нем зрителю почувствовать вкус грядущей битвы. А можно отдать предпочтение и тонкой психологической сцене. Главное — помнить, что на этой сцене успешная учеба героя заканчивается. И самое важное — свяжите эту сцену с той, откуда мы пришли сюда, с сюжетным поворотом номер 1.

3-й акт «Чайнатауна» заканчивается словами Джиттса: «Раньше я крутил краны с горячей и холодной водой, ничего не понимая». Красиво.

Середина. Уверенный прогресс. Всё идет хорошо, завтра будет ещё лучше. Победа не за горами. Мы любуемся нашим героем. Мы болеем за него; мы ставим на него и уверены в своем выборе.

Не так быстро!

Наступила пора испытать серьезные — вы правы…

4-Й АКТ: НЕПРИЯТНОСТИ

Ну что, еще тридцать страниц «булыжников, препятствий и переделок», пока не доберемся до сюжетного поворота номер 2?

С легкостью.

В этот момент влезьте в шкуру главного злодея. Не зашёл ли герой слишком далеко? А то как же. Не пора ли ударить по-настоящему? Еще как пора!

4-й акт обычно начинается сценой, в которой дается иная, негативная оценка достижений героя.

4-й акт «Чайнатауна» начинается на странице 58, где Джиттс отправляется в гости к Ною Кроссу, который в конце концов окажется злодеем. Именно Кросс негативно отзовётся об усилиях Джиттса: «Ты можешь думать, что знаешь, с чем имеешь дело, но поверь мне, это не так.»

С этого момента герой покатится под гору, всё быстрее и быстрее, пока не достигнет самой низкой точки падения во всем сюжете. Здесь он столкнется с самым крупным препятствим, какое он до сих пор видел. Оно покажется ему непреодолимым. Возможно, он к своему смятению обнаружит, что двигался в неверном направлении. Что бы то ни было, герой испытает самые печальные минуты своей жизни. Все предыдущие усилия покажутся пустыми и тщетными.

Джиттс признается: «Мне казалось, я защищал кого-то, а на самом деле сделал всё возможное, чтобы навредить.»

И вновь появляется альтернатива: сдаться или сделать такое, чего никогда ещё в жизни не делал.

Вы знаете, что выберет герой. И этот выбор станет вторым главным поворотным пунктом сюжета. (В нашей уточнённой парадигме это пункт номер 4, но давайте пока держаться нумерации Сида Филда).

Большинство сценаристов без труда определяют второй сюжетный поворот. В этой сцене протагонист оставляет позади все колебания и идет навстречу главной проблеме, антагонисту, злодею, злоумышленнику, злу, немезису…

5-Й АКТ: ПРОТИВОСТОЯНИЕ

Да, именно в последнем акте происходит подлинное противостояние. Сид Филд называет его «развязкой». Но на деле развязка приходит в самом конце финальной битвы. Ведь если это не так, и мы узнаем о развязке в начале битвы, разве она сумеет нас захватить?

Развязка — это сюжетный поворот в конце 5-го акта. Это последнее действие нашего героя: победный удар, финальное открытие, конечная цель. Это ответ на вопрос, который впервые всплыл в завязке. Это разрешение 5-го акта и последняя точка всей истории.

После развязки может последовать завершительная сцена, а может и не последовать. Сюжет сам подскажет вам верное решение. Роберту Тауну понадобилась всего одна фраза, чтобы закончить историю: «Забудь, Джейк. Это Чайнатаун.»

Однако во многих шедеврах можно обнаружить отдельную завершительную сцену после развязки. Часто встречаются и фильмы, которые в конце прокладывают мостик к продолжению, по сути предлагают первую сцену нового сюжета. Ваша история вам продиктует. А иногда — ваш продюсер, режиссер или прокатчик. Так или иначе, но как только закончен 5-й акт, а с ним и вся история, вы вправе с гордостью напечатать самое долгожданное из всех слов: КОНЕЦ.

ЗАКЛЮЧЕНИЕ: ТАК ЧТО ЖЕ НА КАРТИНЕ?

А вот что:

1-й акт 2-й акт 3-й акт 4-й акт 5-й акт

——x-|———-x—|————x—|————x—|————x-

завязка интрига учеба неприятности противостояние

Начало Поворот 1 Середина Поворот 2 Конец

(стр. 5-10) (стр. 20-30) (стр.50-60) (стр. 80-90) (стр. 115-120)

Это и есть 5-актная парадигма. Вы сразу заметите, что её конструкция полностью совместима с 3-актной парадигмой. По сути это 3-актная парадигма на близком расстоянии. Пользуйтесь ей. Она даст вам инструменты, которых 3-актная парадигма просто не в состоянии предложить.

Анализируйте её. Вот разбивка «Чайнатауна»:

1-й акт (завязка): стр. 1-9

первая сцена — стр. 1-4

Отправная точка — стр. 7 («Посмотрим, что можно сделать.»)

сюжетный вопрос — стр. 9 («Кто вам платит, м-р Малрей?»)

2 акт (интрига): стр. 9-31

Поворот 1 — стр. 27 («Не хочу отказываться.»)

ударная сцена — стр. 30-31 (Малрей найден мертвым)

3-й акт (учеба): стр. 32-57

Середина — стр. 51 («Мне нравится.»)

4-й акт (неприятности): стр. 58-91

негативная оценка — стр. 64 (Ноя Кросс)

Поворот 2 — стр. 87 (Джиттс идет за г-жой Малрей.)

5-й акт (противостояние): стр. 91-118

Финальная точка — стр. 118 («Он за всё в ответе!»)

Вот «Матрица» (поставьте DVD и проиграйте, применяя 5-актную парадигму):

1-й акт (завязка): 1-11 мин

первая сцена — 1-6 мин

Отправная точка -9 мин («Конечно, я иду» — за Белым Кроликом)

сюжетный вопрос — 11 мин («Что такое Матрица?»)

2-й акт (интрига): 11-34 мин

Поворот 1 — 28 мин (Нео выбирает красную пилюлю.)

ударная сцена — 29-34 мин (отключение Нео от Матрицы)

3-й акт (учеба): 34-58 мин

Середина — 56 мин («Там, где у них сбой, ты преуспеешь.»)

4-й акт (неприятности): 58-93 мин

негативная оценка — 60 мин (Сайфер: «Если увидишь агента, беги.»)

Поворот 2 — 91 мин («Я пойду освобождать его.»)

5-й акт (противостояние): 93-124 мин

Финальная точка — 120 мин (Нео контролирует Матрицу.)

Возьмите в аренду 100 самых популярных DVD и убедитесь, что каждый блокбастер в точности сконструирован в соответствии с 5-актной парадигмой.

Вылечите свой сценарий парадигмой. Она сработает.

Исследуйте парадигму под микроскопом. Поделитесь своими открытиями.

Хотите снять персональный, авторский или авангардистский фильм? Всё равно изучите правила — а потом нарушайте их со знанием.

Удачи!

ПРОЦИТИРОВАННЫЕ РАБОТЫ

Field, Syd. Screenplay. New York: Dell, 1982.

Field, Syd. The Screenwriter’s Problem Solver. New York: Dell, 1998.

Towne, Robert. Chinatown (the screenplay).

НАПИСАНО 10 августа 2001

ОПУБЛИКОВАНО в книге Screenwriting for a Global Market, University of California Press, 2004

АВТОРСКИЙ ПЕРЕВОД Р. Нугманова 9 сентября 2006

Хемингуэй говорил, что проза — это архитектура, а не внутренний декор. Красивые слова и забавные шутки работают, но без структуры все разваливается. Она помогает контролировать, что именно узнает читатель и в какой момент.

Бывает, хочешь рассказать о чем-то классном, но мысли прыгают из начала в конец. И только ты понимаешь, что произошло и где смеяться. У хорошо написанной истории есть правила — они работают и для романов, и для мультиков, и для рекламы внедорожников.

Расскажем о 3-4-5-6-9-актных структурах, которые закрывают любые потребности сторителлера. Подробнее всего разберем четырехактную — если понять ее, получится красиво разложить любой сюжет.

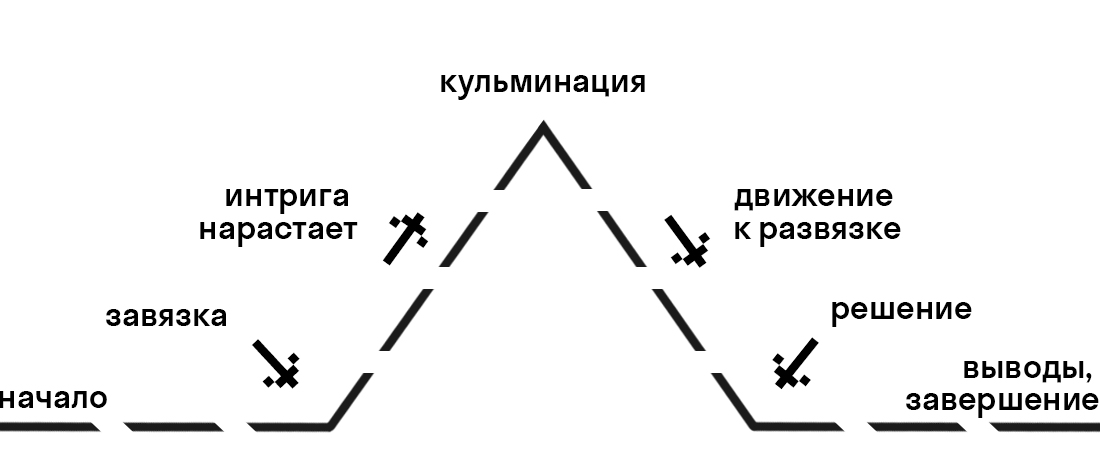

Трехактная структура

В школе нам говорили о трех обязательных актах истории: завязка, кульминация, развязка. На трехактной структуре до сих пор строят простую рекламу: сетап, проблема, решение.

Первый акт. Завязка (проблема)/сетап — когда пишешь Jeep на iOS, выскакивает невнятная машинка-пирожок.

Второй акт. Кульминация/кризис — что бы ты ни писал со словом Jeep, там все равно возникает пирожок. Это бесит.

Третий акт. Развязка/решение — Jeep договорились с Apple, emoji отвязали от слова. Жизнь наладилась.

Эта структура годится, если нужно показать простую связку «было-стало». Чтобы передать более сложную историю, но при этом не запутаться, лучше использовать четырехтактную.

Четырехактная структура

Четырехактная структура помогает рассказать историю в красках, показав, что в жизни все не так просто и прямолинейно.

Мы расписали базовые составляющие каждого акта. Сторителлер сам решает, какому пункту уделить больше внимания. Но каждый этап обязательный — если из этого списка что-то выбросить, нарушится логика истории.

Описание четырех актов звучит довольно сложно (кажется, что это для романа в двух томах или как минимум финала «Мстителей»). Чтобы объяснить их, а не запутать еще больше, будем двигаться по примеру Bud Light, который уместил все четыре акта в одну минуту:

Акт #1 — Завязка

Экспозиция. Нужно обрисовать ситуацию и героев на момент начала истории. Дать контекст. Ты сам выбираешь, что рассказать, но этого должно быть достаточно, чтобы аудитория поняла самое важное о герое и его мире.

Зацепка. Интересный факт, что-то неожиданное, что вызывает любопытство. Это может быть сюжетная фишка, хорошая шутка или необычный визуал.

Начало кризиса. История без драмы — не история. В конце первого акта нужно обрисовать проблему, показать, с чего начинается кризис.

За первые 7 секунд в рекламе-примере мы узнали, что есть какое-то средневековое королевство, которое варит много пива Bud Light, но без добавления кукурузного сиропа. Кризис начинается, когда они понимают, что им по ошибке доставили чужой сироп.

Акт #2 — Прогрессия усложнения

Первый план решения проблемы. Герой придумывает план выхода из кризиса.

Проверка реальностью. Герой осуществляет задуманное. На этом этапе можно лучше раскрыть второстепенных персонажей, добавить фактажа о мире героя, союзниках и противниках.

Провал. Что-то идет не так, очевидные решения не работают, простые пути заводят в тупик, союзники предают, а силы заканчиваются.

За одну секунду герои формулируют первый план: отвезти сироп в другое королевство Miller Lite, которое тоже варит пиво, но с кукурузным сиропом. Там говорят, что свою посылку уже забрали. Везите дальше. Первый план провалился.

Акт #3 — Кризис

Затишье/Разрушительное поведение. Эту часть относят то к концу второго, то к началу третьего акта. Смысл остается — какое-то время герои просто живут в мире после провала. Кажется, что они сдались.

Эскалация/Кризис. Противодействие усиливается, все становится хуже, чем когда-либо. Это может быть как и внутреннее состояние героя, так и какие-то внешние факторы.

В четырехактной структуре применяется формула американского драматурга Дэйва Либера: героя нужно привести в самую нижнюю точку, чтобы поворот событий был особенно ярким. Провал одной или даже нескольких попыток справиться с проблемой отлично усиливает восприятие кризиса.

Новый план. Герой собирается с силами и придумывает новое решение.

Эту часть относят то к концу третьего, то к началу четвертого акта.

Секунду группа в отчаянии, но потом принимает решение все-таки доставить бочку сиропа предполагаемым владельцам в новое отдаленное королевство — Coors Lite.

Акт #4 — Развязка

Последний рывок. Воплощение нового плана. Экшн.

Проблема решена!/Все пропало. К концу четвертого акта равновесие восстанавливается — герой или победил, или окончательно проиграл.

Завершение. Выводы из истории, изменения, которые произошли после развязки. В этой структуре завершение зачастую схематично и укорочено.

По пути рыцаря Bud Light бьет током, на путешественников нападает гигантский осьминог, но они не сдаются. Сироп доставлен по адресу. Герои, которые не портят свое пиво кукурузными добавками, могут спокойно идти домой.

У саги «Гарри Поттер» в семи томах и одноминутной рекламы Bud Light одна и та же структура — четырехактная.

Пятиактная структура

У стандартного описания пятиактной структуры другая логика, хотя элементы внутри совпадают с подпунктами четырехактной.

Акт #1 — Завязка. Контекст истории.

Акт #2 — Возрастание действия. События, которые ведут к кульминации.

Акт #3 — Кульминация. Ключевое событие, которое все меняет.

Акт #4 — Спад действия. События в результате кульминации, которые ведут к развязке.

Акт #5 — Развязка. Счастливый или не очень финал.

Завершение выделено и усилено. Такой подход использует Pixar. В большинстве их мультфильмов много экранного времени отдано развязке с завершением.

Мультфильм «Тайна Коко» — отличный пример. В конце — длинная сцена под названием «Год спустя». Этот пятый акт длится три минуты — почти столько же, сколько кульминация и решение проблемы.

В удлиненном финале есть смысл — мы переживали за героев и хотим порадоваться, наблюдая, как у них наконец все хорошо.

Пятиактную структуру еще называют пирамидой Густава Фрейтага, немецкого писателя середины-конца XIX века.

Шестиактная структура

В шестиактной структуре между вступлением и нарастанием интриги нужно выделить стадию конфликта. В четырех- и пятиактных вариациях обычно это конец первого акта — то самое «начало кризиса».

Памела Дуглас, автор книги «Искусство сериала», говорит, что шестиактные структуры появились, чтобы можно было затянуть сюжет и вставить побольше рекламы. Ей можно верить — Памела 12 лет была сценаристом сериала «Звездный путь».

Девятиактная структура

Девятиактная структура использует некоторые подпункты четырехактной как самостоятельные части и обязательно содержит два ключевых поворота сюжета.

В девятиактном сценарии целых четыре первых акта выделены на сетап и раскрытие персонажа. А вот завершение может быть очень коротким.

Некоторые писатели, например Дэвид Сигал, уверяют, что эта структура отличается не только формой, но и сутью. Сценарий фокусируется не на кризисах, а на сменах целей главного героя.

Звучит неплохо, но цели меняются, потому что предыдущие не сработали для решения проблем. А это возвращает нас к базовой четырехактной структуре с провалами и победами.

Структура истории — обязательная часть любого внятного рассказа, текстового или визуального. Но это не волшебная таблетка, которая обеспечит сотни репостов, а только каркас, на котором все держится.

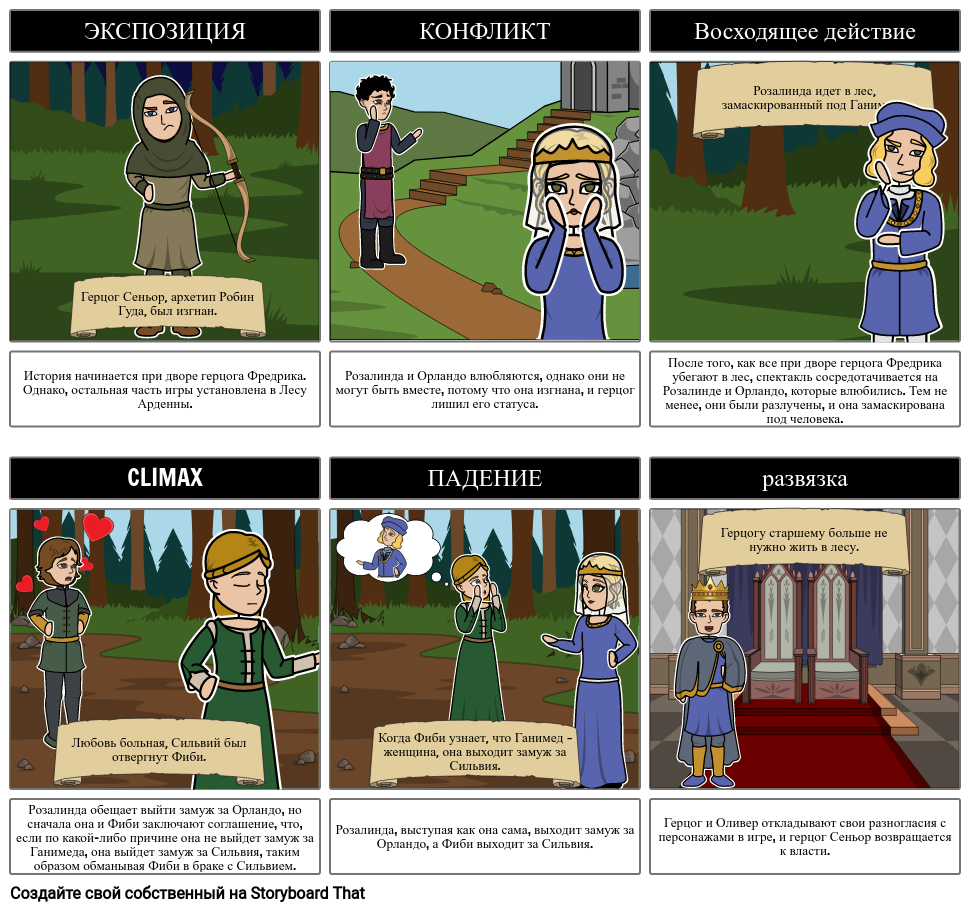

Структуры игры

Игры впервые зародились в древней Греции. Аристотель был одним из первых, кто написал о драме и описал три ее сегмента: начало, середину и конец. Со временем драмы развились, римский поэт Гораций выступал за пять актов, а много веков спустя немецкий драматург Густав Фрейтаг разработал структуру из пяти актов, обычно используемую сегодня для анализа классических и шекспировских драм. Образец этой пятиактной структуры можно увидеть на знакомой сюжетной диаграмме:

Три акта структура

Аристотель считал, что каждый кусочек поэзии или драмы должен иметь начало, середину и конец. Эти подразделения были разработаны римлянами Элием Донатом и назывались Протазисом, Эпитазом и Катастрофой. Структура с тремя действиями пережила возрождение в последние годы, поскольку киноблокеры и популярные телешоу приняли это.

Структура пяти актов

Структура из пяти актов расширяет классические деления и может быть наложена на традиционную сюжетную диаграмму, поскольку она следует тем же пяти частям. Шекспировские пьесы особенно известны тем, что следуют этой структуре.

На приведенном выше рисунке повествовательная арка сюжетной диаграммы находится между структурой пяти актов (вверху) и делениями Аристотеля (внизу).

Формат пятиактной структуры

Акт 1: Экспозиция

Здесь аудитория изучает настройку (время / место), персонажи развиваются и возникает конфликт.

Акт 2: Восходящее действие

Действие этого акта приводит зрителей к кульминации. Обычно возникают осложнения или когда главный герой сталкивается с препятствиями.

Акт 3: Климакс

Это поворотный момент в игре. Кульминация характеризуется наибольшим количеством неизвестности.

Акт 4: Падающее Действие

В противоположность Rising Action, в Falling Action история заканчивается, и любые неизвестные детали или повороты сюжета раскрываются и оборачиваются.

Акт 5: Развязка или разрешение

Это окончательный результат драмы. Здесь авторский тон о его или ее предмете раскрывается, и иногда мораль или урок усваиваются.

Примеры структуры из пяти актов с пьесами Шекспира

Ромео и Джульетта

Акт 1: Экспозиция

- Окружение: Верона, Италия, XVI или XVII век

- Персонажи: Капулетти и Монтекки, в частности, Ромео и Джульетта

- Конфликт: Монтекки и Капулеты враждуют

Акт 2: Восходящее действие

- Ромео и Джульетта влюбляются, но не могут быть вместе, потому что их семьи не любят друг друга. Они решают пожениться в тайне.

Акт 3: Климакс

- После провала вечеринки Капулетти Тибальт идет за командой Монтегю и убивает Меркуцио.

- Чтобы отомстить за своего друга, Ромео сражается и убивает Тибальта — двоюродного брата Джульетты.

- Ромео изгнан, но перед тем как уйти, он дает Джульетте правильную брачную ночь!

Акт 4: Падающее Действие

- Родители Джульетты устраивают для нее брак в Париж.

- У нее и у монаха есть продуманный план, чтобы вытащить ее из второго брака, притворяясь ее смертью. Частью этого плана является то, что Ромео получит письмо, в котором говорится, что она не умерла.

- Ромео, так и не получив письмо, думает, что Джульетта умерла (см. Нашу статью о драматической иронии ).

- Ромео покупает яд и идет к своей могиле, чтобы совершить самоубийство.

Акт 5: Развязка или разрешение

- Ромео противостоит Парижу у могилы Джульетты и убивает его, прежде чем покончить с собой.

- Джульетта просыпается от своего снотворного зелья и видит, что Ромео покончил жизнь самоубийством.

- Она берет его кинжал и убивает себя.

- Брат и медсестра объясняют семьям Капулетти и Монтегю, что двое влюбленных тайно поженились.

- Обе семьи опечалены ситуацией и обещают положить конец своей давней вражде.

Как вам это нравится

Акт 1: Экспозиция

- Урегулирование: Франция, история начинается в суде Герцога Фредрика, однако, остальная часть игры установлена в Лесу Арденны.

- Персонажи: герцог Фредерик, герцог старший, Росиленд, Селия, Орландо, Оливер, Тачстоун и Жак

- Конфликт: герцог Фредерик сослал своего леса, герцога старшего, в лес. Его дочь, Росиланд, вскоре после этого изгнана. Орландо должен избежать преследований своего старшего брата Оливера.

Акт 2: Восходящее действие

- Розалинда маскируется под юношу, Ганимед.

- В лесу много ошибочных личностей, и многие персонажи влюбляются в людей, которые их не любят.

Акт 3: Климакс

- Розалинда / Ганимед хитроумно устраивает ряд обещаний, чтобы все поженились, и никто не разочаровался.

- Розалинда раскрывает свою истинную личность другим персонажам.

Акт 4: Падающее Действие

- Орландо спасает своего брата от льва, и оба помирились. Оливер влюбляется в Алиену.

- Существует гигантская свадьба для всех пар.

Акт 5: Развязка или разрешение

- Все персонажи, кроме Фридриха и Жака, которые становятся религиозными отшельниками, возвращаются в герцогство.

Макбет: «Шотландская пьеса»

Акт 1: Экспозиция

- Окружение: Шотландия, в конце войны

- Персонажи: Макбет и его друг Банко представлены.

- Конфликт: Три ведьмы задумали злой заговор с участием Макбета, и они говорят ему, что он будет королем!

Акт 2: Восходящее действие

- Макбет и его жена убивают короля и занимают трон.

- Они идут на тираническое веселье убийства. Действие возрастает, когда зрители видят, какими амбициозными стали Макбет и Леди Макбет.

Акт 3: Климакс

- Макбет проводит банкет и видит призрака Банко (которого Макбет убил).

- Леди Макбет становится психически неуравновешенной, и пара начинает бояться последствий своих убийственных поступков.

Акт 4: Падающее Действие

- Макдуф спровоцировал восстание, чтобы восстановить трон изгнанного сына Дункана.

- Макбет узнает еще один набор пророчеств от ведьм и начинает думать, что он будет спасен.

Акт 5: Развязка или разрешение

- Предсказания трех ведьм сбываются, и замок штурмуется. Макбет убит.

Общие основные стандарты

- ELA-Literacy.RL.6.2: Determine a theme or central idea of a text and how it is conveyed through particular details; provide a summary of the text distinct from personal opinions or judgments

- ELA-Literacy.RL.7.2: Determine a theme or central idea of a text and analyze its development over the course of the text; provide an objective summary of the text

- ELA-Literacy.RL.8.2: Determine a theme or central idea of a text and analyze its development over the course of the text, including its relationship to the characters, setting, and plot; provide an objective summary of the text

- ELA-Literacy.RL.9-10.2: Determine a theme or central idea of a text and analyze in detail its development over the course of the text, including how it emerges and is shaped and refined by specific details; provide an objective summary of the text

- ELA-Literacy.RL.11-12.2: Determine two or more themes or central ideas of a text and analyze their development over the course of the text, including how they interact and build on one another to produce a complex account; provide an objective summary of the text

- ELA-Literacy.RL.6.5: Analyze how a particular sentence, chapter, scene, or stanza fits into the overall structure of a text and contributes to the development of the theme, setting, or plot

- ELA-Literacy.RL.7.5: Analyze how a drama’s or poem’s form or structure (e.g., soliloquy, sonnet) contributes to its meaning

- ELA-Literacy.RL.8.5: Compare and contrast the structure of two or more texts and analyze how the differing structure of each text contributes to its meaning and style

- ELA-Literacy.RL.9-10.5: Analyze how an author’s choices concerning how to structure a text, order events within it (e.g., parallel plots), and manipulate time (e.g., pacing, flashbacks) create such effects as mystery, tension, or surprise

- ELA-Literacy.RL.11-12.5: Analyze how an author’s choices concerning how to structure specific parts of a text (e.g., the choice of where to begin or end a story, the choice to provide a comedic or tragic resolution) contribute to its overall structure and meaning as well as its aesthetic impact

- ELA-Literacy.RL.9-10.6: Analyze a particular point of view or cultural experience reflected in a work of literature from outside the United States, drawing on a wide reading of world literature

- ELA-Literacy.RL.11-12.6: Analyze a case in which grasping a point of view requires distinguishing what is directly stated in a text from what is really meant (e.g., satire, sarcasm, irony, or understatement)

Найдите больше подобных занятий в нашей категории 6-12 ELA!

*(Это начнется с бесплатной пробной версии за 2 недели — без кредитной карты)

https://www.storyboardthat.com/ru/articles/e/пятиактной-структура

© 2023 — Clever Prototypes, LLC — Все права защищены.

StoryboardThat является товарным знаком Clever Prototypes , LLC и зарегистрирован в Бюро по патентам и товарным знакам США.

Пять актов Нугманова

Пятиактная структура, предложенная Рашидом Нугмановым— подробно на сайте автора).

В оригинальном тексте кинематографисты говорят о завязке как о первых 10 страницах сценария (это 10 минут фильма). Поскольку для рисованной истории ни страницы сценария, ни минуты не являются ориентиром, я заменил это на 10%. Не очень точно, но тут особой точности не требуется. Скорее, важен сам принцип. Таким образом, для 46 полосной РИ 10-25-50-75 процентов приблизительно соответствуют 3-12-23-36 полосам. Итак (картинка моя, текст Р.Нугманова, постскриптум мой):

Нужно представить читателю главного героя, дать понять, о чём будет история и какие обстоятельства эту историю окружают. Завязка состоит из трёх ясно различимых частей: первая сцена, отправная сцена и сцена сюжетного вопроса. Задача – показать мир, в который нас забросило, а также определить жанр фильма. Отправная сцена всегда связана с главным героем. Отправная точка, которую она содержит – это первое действие протагониста, после чего немедленно следует сцена вопроса.

>>>>> Интрига

Задавшись вопросом, герой отправляется в путь и неожиданно для себя оказывается в центре интриги. Первый поворот является прямым результатом отправной точки в завязке. Протагонист отправился в путь, не вполне понимая, на что или куда он идет, и теперь перед ним точка, за которой нет возврата. Поворот номер 1 – это ничто другое, как решение главного героя преступить эту черту.

>>>>> Учёба

Герой встречает одно препятствие за другим и попадает не в одну серьёзную переделку. Но это еще не противостояние лицом к лицу с главным врагом. Враг действует через посредников. Это процесс узнавания нового, и герой обязан пройти его, чтобы успешно сразиться со злом в финале. Центральная точка сценария имеет отношение к учебному опыту героя. При этом она случается на его взлёте. Исходя из всего этого, ищите точку там, где герой доволен происходящим или получает какой-то важный урок, который в конце концов приведёт его к победе. Акт завершается сценой, которая даёт понять, что успешная учёба героя заканчивается.

>>>>> Неприятности

Этот акт обычно начинается сценой, в которой даётся иная, негативная оценка достижений героя. С этого момента герой покатится под гору, всё быстрее и быстрее, пока не достигнет самой низкой точки падения во всем сюжете. Здесь он столкнётся с самым крупным препятствием, какое он до сих пор видел. Оно покажется ему непреодолимым. Возможно, он к своему смятению обнаружит, что двигался в неверном направлении. Что бы то ни было, герой испытает самые печальные минуты своей жизни. Все предыдущие усилия покажутся пустыми и тщетными. И вновь появляется альтернатива: сдаться или сделать такое, чего никогда ещё в жизни не делал. Этот выбор станет вторым главным поворотным пунктом сюжета. В этой сцене протагонист оставляет позади все колебания и идёт навстречу главной проблеме (антагонисту).

>>>>> Противостояние (и развязка)

В последнем акте происходит подлинное противостояние. Развязка – это сюжетный поворот в конце акта. Это последнее действие нашего героя: победный удар, финальное открытие, конечная цель. Это ответ на вопрос, который впервые всплыл в завязке. Это последняя точка всей истории. После развязки может последовать завершительная сцена, а может и не последовать. Иногда можно обнаружить отдельную завершительную сцену после развязки. Часто встречаются и фильмы, которые в конце прокладывают мостик к продолжению, по сути предлагают первую сцену нового сюжета.

=============== PS

Что может быть проблемой для рисованной истории(комикса).

Три страницы на завязку — это маловато. Особенно, для одиночного 46-полосного альбома. Для второго-третьего-четвёртого альбома в серии это нормально, так как герой уже был представлен читателю в предыдущей серии и в повторном представлении не нуждается. Для альбома, объёмом 56-62 полосы 10% на завязку уже приемлемо, а для более объёмных — совсем хорошо.

С другой стороны, авторы РИ очень любят начинать с пространных вступлений и двигаться в ритме улитки до самой середины истории. Есть повод подумать о том, как сделать историю динамичнее.

Как вариант, можно увеличить завязку за счёт пятого акта — подрезать его на две-четыре страницы. Это можно сделать за счёт традиционного монолога злодея, в котором он долго рассказывает пленному главному герою о своих коварных планах.

Структура сценария — это не мифология или спасение котика. Это основные инструменты, c помощью которых сценарист может рассказать свою историю. Все эти типы структуры применимы к любому жанру.

Попробуем разрушить некоторые стереотипы и предложить приемы, которые вы сможете взять на вооружение.

Будем честны. Даже если разрушить все до основания, история все-равно будет иметь начало, середину и конец. Это структура, которой следовали с тех пор, как древние люди рассказывали истории вокруг костра или создавали наскальные рисунки, изображающие сюжеты охоты на добычу (начало), противостояние добыче (середина) и победу над ней (конец). Больше о том, что такое трехактная структура >>>>>

Трехактная структура в кино — простая и понятная структура, которой следуют большинство фильмов, независимо от того, что потом говорят об этом эксперты и критики. Есть экспозиция, конфронтация и развязка. Четырех, пяти и семи-актные структуры, как и другие варианты для телевизионных фильмов, просто продолжают трехактную структуру.

Девять структур, которые приводятся ниже, тоже разбиваются на три акта, просто в каждой это работает по-разному.

Когда автор решает использовать трехактную структуру, он предлагает самый простой и доступный для аудитории сюжет.

Каждая сцена имеет значение.

Каждая сцена переходит к следующей, двигая историю вперед с естественным развитием — без каких-то дополнительных приемов. Существует экспозиция персонажей и мира, далее следует конфликт, с которым они вынуждены столкнуться, и в конце все приходит к развязке.

Вместо того, чтобы создавать сценарий только с использованием самых важных частей истории, как это делают в трехактной структуре, можно представить свою историю в непрерывном повествовании и реальном времени.

Примеры:

- 12 Разгневанных мужчин (1956 )

- Мой ужин с Андре ( 1981 )

- В последний момент ( 1995 )

- Потерянный рейс ( 2006 )

- Ровно в полдень (1952 )

Нет перерывов в повествовании, нет флэшбэков, нет срезок, нет пробросов времени или чего-то подобного.

История представлена цельной и неотфильтрованной. Каждая мелочь важна, и сценаристы, которые применяют эту структуру к своим историям, должны это понимать.

Эти типы сценариев сложны, поэтому сценаристу часто приходится искать возможности, чтобы управлять действием и мотивацией персонажей. Обратный отсчет времени – лучший инструмент в данном случае.

Если посмотреть на фильм «Ровно в полдень» и, особенно, на «В последний момент», то видно, что действие и драма превращаются в единый механизм из-за эффекта тикающих часов.

В фильме «Ровно в полдень» в определённое время что-то произойдет и маршал должен успеть подготовиться.

А в фильме «В последний момент» отец вынужден выполнять то, что говорит злодей, если он хочет снова увидеть свою дочь. Часы в прямом смысле тикают.

Ровно в полдень ( 1952 )

Если решите рассказать свою историю в формате структуры реального времени, имейте в виду — ни одна секунда в выбранный момент жизни персонажа не может быть упущена.

Преимущество этой структуры в том, что напряженность истории постоянно растет и выглядит намного более убедительно. Особенно, если сценаристу удалось сделать все честно.

Это, пожалуй, одна из самых сложных структур. В ней несколько различных историй смешиваются вместе.

Примеры:

- Нетерпимость ( 1916)

- Фонтан ( 2006 )

- Облачный атлас ( 2012 )

- Крестный отец 2 ( 1974 )

Эти фильмы охватывают одновременно несколько историй, которые могут происходить в разное время.

Все эти истории объединены темами, эмоциями, смыслом, но не всегда связаны напрямую. События одной истории не всегда влияют на остальные.

Единственная связь между ними — общие темы, эмоции и смыслы. Кроме этого, возможно использование одних и тех же актеров для отображения разных персонажей, демонстрация одинаковых мест в разные периоды времени и т. д.

Магия заключается в том, что у аудитории создается ощущение, что жизнь во Вселенной каким-то образом связана.

Если решите связать сюжетные линии, как это сделал Фрэнсис Форд Коппола во второй части Крестного отца, то каждая история будет иметь более глубокий смысл. Когда мы видим подъем власти Майкла Корлеоне …

Крестный отец 2 ( 1974 )

… в сочетании с более коварным и незаметным подъемом власти его отца …

Крестный отец 2 ( 1974 )

… начинаем ощущать двойственность этих историй, которые могли бы существовать в других разных фильмах сами по себе.

Решите вы связывать истории из нескольких хронологий или нет, эта структура в любом случае предполагает выход за рамки обычного повествования.

Истории со взаимосвязанной структурой работают по принципу домино. Каждая кость домино падает, заставляя падать следующую и следующую, и следующую, и так до конца.

Примеры:

- Магнолия ( 1999 )

- Столкновение ( 2004 )

- Вавилон ( 2006 )

Некоторые истории, которые были в фильмах «Магнолия», «Столкновение» и «Вавилон», похожи на фильмы, созданные по структуре множества сюжетных линий. Но отличие заключается в том, что все истории связаны между собой как несколько разных рядов падающих домино. Они взаимодействуют друг с другом так, что вместе приводят к развязке. События каждой отдельной линии ведут всю историю фильма целиком.

Этот тип структуры дает аудитории ощущение того, что наши жизни могут быть невероятно взаимосвязаны. Причины и следствия поступков, могут иметь параллельные причины и следствия в жизни других людей.

В «Магнолии» Пол Томас Андерсон создал историю, в которой восемь персонажей и их рассказы медленно соединяются по мере развития сюжета.

Магнолия ( 1999)

Главным в структуре взаимосвязей является то, что к концу каждый сюжет и персонаж должны мастерски воздействовать на других, и если удалить одну сюжетную линию или персонажа, то вся история целиком не сработает.

Сценарий со структурой взаимосвязей делает чтение сценария невероятно увлекательным, так как захватывает читателя с самого начала, он задается вопросом, действительно ли эти истории и персонажи связаны между собой.

Возможно, вы не слышали о такой структуре, но на самом деле она распространена больше, чем кажется на первый взгляд.

Примеры:

- Бойцовский клуб ( 1999 )

- Казино ( 1995 )

- Красота по-американски ( 1999 )

- Славные парни ( 2016 )

- Форест Гамп ( 1994 )

- Интервью с вампиром ( 1994 )

- Гражданин Кейн ( 1941 )

Эта структура пришла в Голливуд из России, основываясь на терминах, которые возникли из русского формализма и используются в нарратологии, где создается повествовательное построение сюжета.

Фабула — сама история, а сюжет — повествование и то, как устроена история.

Эта специфическая структура, используемая американским кино, она имеет оригинальную организацию, сначала демонстрируя конец. А уже после экспозиции, которая представлена финалом фильма зрители видят, как герои туда попали.

«Гражданин Кейн» начинается со смерти главного персонажа, когда он бормочет «Роузбуд» на смертном одре. Жизнь затем представлена через воспоминания, с вкраплениями журналистских расследований жизни Кейна.

Гражданин Кейн ( 1941 )

Фабула фильма — это реальная история о жизни Кейна, как это происходило в хронологическом порядке. В то же время сюжет — это то, как рассказывается история на протяжении всего фильма.

«Форрест Гамп» открывается почти финалом истории, когда Форрест ждет автобуса. Зритель изучает фабулу через воспоминания, когда он рассказывает спутникам на автобусной остановке о некоторых историях из жизни.

Сюжет присутствует в сценах, когда автобусная остановка переплетается с этими историями о жизни. Если бы фильм был представлен в трехактной структуре, мы бы встретились с Форрестом Гампом в детстве и дошли до того момента, когда он сидит на автобусной остановке. Сцены с Форрестом, где он разговаривает с людьми на остановке, были бы лишними, а голос за кадром можно было бы не использовать.

Форрест Гамп (1994)

«Интервью с вампиром» начинается со знакомства с вампиром Луи, с которым беседует Маллой. Луи вспоминает о днях в качестве вампира за сотни лет до этого момента, прожитых с его создателем Лестатом. Это и есть фабула истории, а события интервью представляют собой сюжет. События истории (фабула) сами существуют, независимо от того, как их рассказывать (сюжет).

Интервью с вампиром ( 1994 )

Это уникальная структура, которая часто используется в реальных историях, но также может быть креативно применена к вымышленным.

Структура Фабула/Сюжет дает дополнительное ощущение повествования и оправдывает использование закадрового голоса. Поэтому, если нужен голос за кадром в сценарии, один из лучших способов сделать это — написать сценарий по структуре Фабула / Сюжет.

Больше о том, что такое структура в материале что такое акт в сценарии >>>>>. Во второй части статьи разберем структуры:

- С реверсивной драматургией

- Расёмон

- Цикличная (круговая)

- Нелинейная

- Сновидений

Перевод статьи Кена Миямото сценарного ридера и аналитика компании Sony Pictures, оригинал статьи

Перевод статьи: Илья Глазунов, Вадим Комиссарук

Читать вторую часть >>>>

В своей статье, известный режиссер Рашид Нагуманов («Игла») критически анализирует классическую трёхактную структуру сценария и предлагает «пятиактную парадигму». В статье проиллюстрирована схемами и примерами из фильма «Китайский квартал» (автор сценария Р. Таун).

Как внесистемный кинематографист, я предлагаю профессиональным сценаристам всего мира внимательнее взглянуть на классическую 3-актную структуру, описанную Сидом Филдом в книге «Киносценарий»:

начало середина конец

1-й акт 2-й акт 3-й акт

———x—|———————x—|————

завязка противостояние развязка

стр. 1-30 стр. 30-90 стр. 90-120

Поворот 1 Поворот 2

стр. 25-27 стр. 85-90

Эта парадигма была поднята на щит и de facto признана стандартом в Голливуде. В то же время немало критики высказано в адрес её примитивизма и неспособности ответить на сложные требования современного кино. И вправду, вообразите эту парадигму картиной на стене, и сразу возникают трудные вопросы:

Фильм идёт уже полчаса (одна страница правильно сформатированного сценария соответствует одной минуте экранного времени), а мы всё ещё в «начале», как и тридцать, и двадцать пять, и двадцать минут назад?

Первый сюжетный поворот случается на странице 25. Мы что, до сих пор ехали гладко, и нас не заносило?

2-й акт состоит из 60 страниц противостояния — одно препятствие за другим на протяжении часа! Не утомительно?

Развязка — что это? Просто «конец», который длится тридцать минут?

И так далее, в том же духе…

Как бы отвечая критикам, Сид Филд позже предложил более детализированную структуру в рамках всё той же парадигмы (книга «Разрешение сценарных проблем»):

1-й акт 2-й акт 3-й акт

1-я половина 2-я половина

———x—|————|———x—|————

завязка противостояние развязка

Поворот 1 Середина Поворот 2

(стр. 20-30) (стр. 60) (стр. 80-90)

2-й акт выглядит более разработанным и разделён на две части «срединной точкой». Уже легче, но вопросы остаются.

2-й акт теперь имеет две половинки, но точка поворота по-прежнему одна – во второй. А что в первой половине акта?

Теперь первый поворот может случиться раньше (начиная с 20-й страницы). Это делает завязку более динамичной, но мы всё еще чувствуем дискомфорт из-за отсутствия точки отсчета и слишком затянутого начала. Как быть с этим? Парадигма не даёт ответа.

Куда отнести «срединную точку» – к первой половине 2-го акта или ко второй его половине? Или она просто разрезает весь сценарий пополам?

Развязка – когда она происходит? В самом конце линии, после чего фильм немедленно заканчивается и идут финальные титры? Или же это непрерывный процесс развязки в течение тридцати минут, узел за узлом?

Подобные вопросы лишают парадигму полного счастья, которым она могла бы одарить сценаристов, ведь в целом она рисует четкую, сбалансированную картину сценария. Возникает ощущение, что мы видим конструкцию сюжета на расстоянии, не различая жизненно важных, решающих деталей. Так и хочется шагнуть к «картине на стене» и приглядеться поближе.

Сделаем этот шаг.

ЗАВЯЗКА: 10 ИЛИ 30 СТРАНИЦ?

Вглядевшись в 1-й акт, немедленно выделяешь «самую важную часть сценария» – его первые десять страниц. Именно в течение первых десяти страниц (или десяти минут фильма) обычно понимаешь, нравится тебе то, что ты видишь, или нет. Давайте отобразим это на картине:

1-й акт

стр. 10

—-|——x—|

завязка

Поворот 1

(стр. 20-30)

Сид Филд учит, что в течение первых десяти минут драматического действия нужно показать читателю главного героя, драматическую предпосылку истории (о чём она) и драматическую ситуацию (обстоятельства, окружающие историю). Герой, предпосылка, ситуация – всё это вместе определяется одним словом: «завязка».

Каждый поворот истории – это функция главного героя. В том числе и отправная точка – т.е. некое событие, которое запускает главного героя в движение. В сценарии «Чайнатауна» этот момент происходит на 7-й странице, когда Джиттс (Джек Николсон) принимает предложение лже-госпожи Малрей (Фэй Данауэй) расследовать дело: «Ну хорошо. Посмотрим, что можно сделать.»

Отправная точка в подавляющем большинстве голливудских фильмов случается не позже десятой минуты:

10-мин. завязка

———-x—|

Отправная точка

Схема выглядит подозрительно знакомо, не правда ли? Точно. Так выглядит акт в парадигме Сида Филда. Это и есть акт. Вследствие его важности, этот элемент драматического действия следует рассматривать именно как отдельный акт. В нем вы должны определить главного героя, предпосылку, ситуацию и жанр. Вся история должна завязаться в этом акте, иначе читатель забросит ваш сценарий, а зритель возненавидит ваш фильм.

Запишите и запомните: первые десять страниц завязки — это 1-й акт.

Исключительная важность завязки для всего сценария заслуживает ещё нескольких слов.

Как отдельный акт, завязка состоит из трех ясно различимых частей: первая сцена, отправная сцена и сцена сюжетного вопроса.

В «Чайнатауне» первая сцена содержит четыре страницы диалога между Джиттсом и Курли в кабинете Джиттса. Отправная сцена происходит в кабинете Даффи и Уолша от страницы 5 до отправной точки на странице 7. А сцена, в которой звучит главный сюжетный вопрос, происходит на публичных слушаниях в ратуше, и вопрос этот задаёт какой-то фермер: «Кто вам платит, мистер Малрей, хотел бы я знать?»

Первая сцена не обязательно показывает нам главного героя. Её главная задача – показать мир, в который нас забросило, а также определить жанр фильма. Иначе говоря, заложить фундамент для отправной сцены. А вот отправная сцена всегда связана с главным героем (даже если этот главный герой — неодушевленный предмет, вроде фестиваля в Вудстоке или войны во Вьетнаме). Отправная точка, которую она содержит – это первое действие протагониста, после чего немедленно следует сцена вопроса.

Сюжетный вопрос, в свою очередь, необязательно звучит из уст протагониста. Он может быть задан партнером, а иногда (как в «Чайнатауне») даже проходным, эпизодным персонажем. Единожды прозвучав, это вопрос закрывает завязку, и нас ждёт…

2-Й АКТ: ИНТРИГА

Прежде чем приступить к этому захватывающему этапу сценарной работы, спросите себя: Можно ли назвать следующие двадцать страниц сценария, которые теперь составляют 2-й акт, «завязкой»?

Готов поклясться, ответ вы уже знаете: Нет.

Современного зрителя раздражает завязка, которая тянется полчаса. Нужно делать это за десять минут. Как же в таком случае назвать следующие двадцать минут драматического действия, которые завершаются знаменитой «поворотной точкой номер 1»?

Очень просто: интрига.

Задавшись вопросом, который впоследствии окажется центральным для всей истории, наш герой отправляется в путь. Вопрос этот никогда не получает ответа в данном акте, но череда неожиданных событий приводит его к первой поворотной точке сюжета. Главный герой неожиданно для себя оказывается в центре интриги. Он – её часть!

Первый поворот является прямым результатом отправной точки в завязке. Протагонист отправился в путь, не вполне понимая, на что или куда он идет, и теперь перед ним точка, за которой нет возврата. Поворот номер 1 – это ничто другое, как решение главного героя преступить эту черту.

В «Чайнатауне» Джиттс после предварительного расследования понимает, что он стал актером в чужой игре. При этом самой большой неожиданностью для него становится появление настоящей госпожи Малрей в его кабинете. Некоторые ошибочно принимают это событие за первый поворот. Запомните: сюжет является функцией главного героя. Каким бы неожиданным ни было её появление, это еще не поворот сюжета. Джиттс пока ещё не меняет направления своего пути, решение ещё не пришло. По сути, это — проверка. Проверка решимости Джиттса на поиск истины. Настоящий первый поворот в «Чайнатауне» случается на странице 27 во время их второй встречи, когда госпожа Малрей предлагает отозвать иск. Вот теперь у Джиттса есть выбор. Чтобы сохранить проактивность героя, в каждом поворотном пункте должен присутствовать выбор: вернуться к привычной жизни или ступить на новую, неизведанную территорию. Джиттс делает свой выбор: «Я не хочу отказываться.»

Первый поворот не ведет напрямую в следующий акт. Прежде нужно завершить 2-й акт, и чаще всего он захлопывается с треском. Нас ожидает последняя неожиданность интриги, самая сильная. Сожгите мост перед глазами героя. Дайте нам почувствовать, что его жизнь уже никогда не будет прежней.

Убейте Малрея.

БУММ!…

Теперь, когда принято решение, пройдена точка возврата и мосты сожжены, главному герою не остётся ничего другого, как…

3-Й АКТ: TERRA INCOGNITA, ИЛИ УЧЕБА

Эта неизведанная территория в середине сценария может быть столь же малознакома автору сценария, как и его герою! И начинающие писатели, и матерые сценаристы часто признаются, что написали замечательную завязку и развязку, но совершенно потерялись в этом длиннющем, чудовищном 60-страничном среднем акте, а всё, что предлагают гуру от сценаристики – это швырять булыжники в главного героя и строить перед ним одно препятствие за другим, называя всё это «противостоянием». Булыжники – это хорошо, но много ли пользы от таких советов? Не очень.

Но есть один секрет, который превратит работу над средней частью вашего сценария в увлекательное, легкое и приятное занятие. Секрет заключается в том, что не надо писать шестьдесят страниц; в 3-м акте их всего тридцать.

Взгляните еще раз на то, что у Сида Филда называется «первой половиной» и «второй половиной» 2-го акта:

2-й акт

1-я половина 2-я половина

————-|———-x—|

Середина Поворот 2

На самом деле, мы видим 3-й и 4-й акты, с их собственными сюжетными поворотами:

3-й акт 4-й акт

———-x—|———-x—|

Середина Поворот 2

Вы можете сказать с недоверием: «Два акта противостояния вместо одного? Это еще хуже!»

Дело в том, что 3-й и 4-й акты вовсе не о противостоянии! С детских лет мы прекрасно знаем, что настоящее противостояние случается в конце фильма. Все мы помним эти «последние битвы», где наш герой сходится в смертельной схватке со злом, чем бы ни было это зло и в чем бы ни заключалась эта схватка.

О чем же тогда эти два срединных акта?

Как уже упомянуто, 3-й акт повествует о новой, неизведанной территории, куда ступает наш герой и которую он вынужден исследовать. Это акт об учебе.

Разумеется, в процессе исследования герой встречает одно препятствие за другим (вспомните школу!) Разумеется, он попадет не в одну серьезную переделку. Да, враг может послать герою несколько серьезных предупреждений, обычно через посредников (незнакомый коротыш порежет Джиттсу ноздрю), чтобы заставить того изменить своё решение и уйти с неведомой территории – территории врага. И разумеется, старый добрый мир исчезнет как дым. Но это еще не противостояние лицом к лицу с главным врагом. Это процесс узнавания нового, и герой обязан пройти его, чтобы успешно сразиться со злом в финале.

Несмотря на все тяжести и опасности учебы, этот опыт по большей части вдохновляющий. Герой делает успехи, и ему это нравится. (На странице 51 Джиттс говорит буквально следующее: «Я чуть не лишился носа, черт побери. Но мне нравится. Нравится дышать всем этим.»). Вот это и есть срединная точка сценария.

Очень часто срединная точка менее артикулирована, чем 1-я и 2-я. В ней может не произойти решающего сюжетного поворота. 3-й акт не обязательно заканчивается ударом. Именно по этой причине девственным сценаристам, озабоченным швырянием булыжников в героя, бывает трудно найти середину драматургического действия иным способом, кроме механического складывания сценария пополам, – и тем самым еще более запутываясь в нем.

Истина заключается в том, что срединная точка сценария не разделяет два акта; это такой же сюжетный поворот, как другие, пусть он и менее ярок. Как мы уже знаем, в каждом акте перед завершением существует поворотная точка. Мы также знаем, что любой сюжетный поворот – это функция главного героя. Средняя точка принадлежит 3-му акту. Она имеет отношение к учебному опыту героя. При этом она случается на его взлете. Исходя из всего этого, ищите точку там, где герой доволен происходящим или получает какой-то важный урок, который в конце концов приведет его к победе.

Как завершить 3-й акт? На ваше усмотрение. Можно придумать ударную сцену без особых серьезных открытий, просто предложив очередное препятствие и успешно преодолев его. Можете даже дать в нем зрителю почувствовать вкус грядущей битвы. А можно отдать предпочтение и тонкой психологической сцене. Главное – помнить, что на этой сцене успешная учеба героя заканчивается. И самое важное – свяжите эту сцену с той, откуда мы пришли сюда, с сюжетным поворотом номер 1.

3-й акт «Чайнатауна» заканчивается словами Джиттса: «Раньше я крутил краны с горячей и холодной водой, ничего не понимая». Красиво.

Середина. Уверенный прогресс. Всё идет хорошо, завтра будет ещё лучше. Победа не за горами. Мы любуемся нашим героем. Мы болеем за него; мы ставим на него и уверены в своем выборе.

Не так быстро!

Наступила пора испытать серьезные – вы правы…

4-Й АКТ: НЕПРИЯТНОСТИ

Ну что, еще тридцать страниц «булыжников, препятствий и переделок», пока не доберемся до сюжетного поворота номер 2?

С легкостью.

В этот момент влезьте в шкуру главного злодея. Не зашёл ли герой слишком далеко? А то как же. Не пора ли ударить по-настоящему? Еще как пора!

4-й акт обычно начинается сценой, в которой дается иная, негативная оценка достижений героя.

4-й акт «Чайнатауна» начинается на странице 58, где Джиттс отправляется в гости к Ною Кроссу, который в конце концов окажется злодеем. Именно Кросс негативно отзовётся об усилиях Джиттса: «Ты можешь думать, что знаешь, с чем имеешь дело, но поверь мне, это не так.»

С этого момента герой покатится под гору, всё быстрее и быстрее, пока не достигнет самой низкой точки падения во всем сюжете. Здесь он столкнется с самым крупным препятствим, какое он до сих пор видел. Оно покажется ему непреодолимым. Возможно, он к своему смятению обнаружит, что двигался в неверном направлении. Что бы то ни было, герой испытает самые печальные минуты своей жизни. Все предыдущие усилия покажутся пустыми и тщетными.

Джиттс признается: «Мне казалось, я защищал кого-то, а на самом деле сделал всё возможное, чтобы навредить.»

И вновь появляется альтернатива: сдаться или сделать такое, чего никогда ещё в жизни не делал.

Вы знаете, что выберет герой. И этот выбор станет вторым главным поворотным пунктом сюжета. (В нашей уточнённой парадигме это пункт номер 4, но давайте пока держаться нумерации Сида Филда).

Большинство сценаристов без труда определяют второй сюжетный поворот. В этой сцене протагонист оставляет позади все колебания и идет навстречу главной проблеме, антагонисту, злодею, злоумышленнику, злу, немезису…

5-Й АКТ: ПРОТИВОСТОЯНИЕ

Да, именно в последнем акте происходит подлинное противостояние. Сид Филд называет его «развязкой». Но на деле развязка приходит в самом конце финальной битвы. Ведь если это не так, и мы узнаем о развязке в начале битвы, разве она сумеет нас захватить?

Развязка – это сюжетный поворот в конце 5-го акта. Это последнее действие нашего героя: победный удар, финальное открытие, конечная цель. Это ответ на вопрос, который впервые всплыл в завязке. Это разрешение 5-го акта и последняя точка всей истории.

После развязки может последовать завершительная сцена, а может и не последовать. Сюжет сам подскажет вам верное решение. Роберту Тауну понадобилась всего одна фраза, чтобы закончить историю: «Забудь, Джейк. Это Чайнатаун.»

Однако во многих шедеврах можно обнаружить отдельную завершительную сцену после развязки. Часто встречаются и фильмы, которые в конце прокладывают мостик к продолжению, по сути предлагают первую сцену нового сюжета. Ваша история вам продиктует. А иногда – ваш продюсер, режиссер или прокатчик. Так или иначе, но как только закончен 5-й акт, а с ним и вся история, вы вправе с гордостью напечатать самое долгожданное из всех слов: КОНЕЦ.

ЗАКЛЮЧЕНИЕ: ТАК ЧТО ЖЕ НА КАРТИНЕ?

А вот что:

1-й акт 2-й акт 3-й акт 4-й акт 5-й акт

——x-|———-x—|————x—|————x—|————x-

завязка интрига учеба неприятности противостояние

Начало Поворот 1 Середина Поворот 2 Конец

(стр. 5-10) (стр. 20-30) (стр.50-60) (стр. 80-90) (стр. 115-120)

Это и есть 5-актная парадигма. Вы сразу заметите, что её конструкция полностью совместима с 3-актной парадигмой. По сути это 3-актная парадигма на близком расстоянии. Пользуйтесь ей. Она даст вам инструменты, которых 3-актная парадигма просто не в состоянии предложить.

Анализируйте её. Вот разбивка «Чайнатауна»:

1-й акт (завязка): стр. 1-9

первая сцена — стр. 1-4

Отправная точка — стр. 7 («Посмотрим, что можно сделать.»)

сюжетный вопрос — стр. 9 («Кто вам платит, м-р Малрей?»)

2 акт (интрига): стр. 9-31

Поворот 1 — стр. 27 («Не хочу отказываться.»)

ударная сцена — стр. 30-31 (Малрей найден мертвым)

3-й акт (учеба): стр. 32-57

Середина — стр. 51 («Мне нравится.»)

4-й акт (неприятности): стр. 58-91

негативная оценка — стр. 64 (Ноя Кросс)

Поворот 2 — стр. 87 (Джиттс идет за г-жой Малрей.)

5-й акт (противостояние): стр. 91-118

Финальная точка — стр. 118 («Он за всё в ответе!»)

Вот «Матрица» (поставьте DVD и проиграйте, применяя 5-актную парадигму):

1-й акт (завязка): 1-11 мин

первая сцена — 1-6 мин

Отправная точка —9 мин («Конечно, я иду» — за Белым Кроликом)

сюжетный вопрос — 11 мин («Что такое Матрица?»)

2-й акт (интрига): 11-34 мин

Поворот 1 — 28 мин (Нео выбирает красную пилюлю.)

ударная сцена — 29-34 мин (отключение Нео от Матрицы)

3-й акт (учеба): 34-58 мин

Середина — 56 мин («Там, где у них сбой, ты преуспеешь.»)

4-й акт (неприятности): 58-93 мин

негативная оценка — 60 мин (Сайфер: «Если увидишь агента, беги.»)

Поворот 2 — 91 мин («Я пойду освобождать его.»)

5-й акт (противостояние): 93-124 мин

Финальная точка — 120 мин (Нео контролирует Матрицу.)

Возьмите в аренду 100 самых популярных DVD и убедитесь, что каждый блокбастер в точности сконструирован в соответствии с 5-актной парадигмой.

Вылечите свой сценарий парадигмой. Она сработает.

Исследуйте парадигму под микроскопом. Поделитесь своими открытиями.

Хотите снять персональный, авторский или авангардистский фильм? Всё равно изучите правила – а потом нарушайте их со знанием.

Удачи!

ПРОЦИТИРОВАННЫЕ РАБОТЫ

Field, Syd. Screenplay. New York: Dell, 1982.

Field, Syd. The Screenwriter’s Problem Solver. New York: Dell, 1998.

Towne, Robert. Chinatown (the screenplay).

НАПИСАНО 10 августа 2001

ОПУБЛИКОВАНО в книге Screenwriting for a Global Market, University of California Press, 2004

АВТОРСКИЙ ПЕРЕВОД Р. Нугманова 9 сентября 2006

Метки: Сид Филд, структура

Example of a page from a screenplay formatted for a feature-length film.

Screenwriting or scriptwriting is the art and craft of writing scripts for mass media such as feature films, television productions or video games. It is often a freelance profession.

Screenwriters are responsible for researching the story, developing the narrative, writing the script, screenplay, dialogues and delivering it, in the required format, to development executives. Screenwriters therefore have great influence over the creative direction and emotional impact of the screenplay and, arguably, of the finished film. Screenwriters either pitch original ideas to producers, in the hope that they will be optioned or sold; or are commissioned by a producer to create a screenplay from a concept, true story, existing screen work or literary work, such as a novel, poem, play, comic book, or short story.

Types[edit]

The act of screenwriting takes many forms across the entertainment industry. Often, multiple writers work on the same script at different stages of development with different tasks. Over the course of a successful career, a screenwriter might be hired to write in a wide variety of roles.

Some of the most common forms of screenwriting jobs include:

Spec script writing[edit]

Spec scripts are feature film or television show scripts written on speculation of sale, without the commission of a film studio, production company or TV network. The content is usually invented solely by the screenwriter, though spec screenplays can also be based on established works or real people and events. The spec script is a Hollywood sales tool. The vast majority of scripts written each year are spec scripts, but only a small percentage make it to the screen.[1] A spec script is usually a wholly original work, but can also be an adaptation.

In television writing, a spec script is a sample teleplay written to demonstrate the writer’s knowledge of a show and ability to imitate its style and conventions. It is submitted to the show’s producers in hopes of being hired to write future episodes of the show. Budding screenwriters attempting to break into the business generally begin by writing one or more spec scripts.

Although writing spec scripts is part of any writer’s career, the Writers Guild of America forbids members to write «on speculation». The distinction is that a «spec script» is written as a sample by the writer on his or her own; what is forbidden is writing a script for a specific producer without a contract. In addition to writing a script on speculation, it is generally not advised to write camera angles or other directional terminology, as these are likely to be ignored. A director may write up a shooting script himself or herself, a script that guides the team in what to do in order to carry out the director’s vision of how the script should look. The director may ask the original writer to co-write it with him or her, or to rewrite a script that satisfies both the director and producer of the film/TV show.

Spec writing is also unique in that the writer must pitch the idea to producers. In order to sell the script, it must have an excellent title, good writing, and a great logline. A logline is one sentence that lays out what the movie is about. A well-written logline will convey the tone of the film, introduce the main character, and touch on the primary conflict. Usually the logline and title work in tandem to draw people in, and it is highly suggested to incorporate irony into them when possible. These things, along with nice, clean writing will hugely impact whether or not a producer picks up the spec script.

Commission[edit]

A commissioned screenplay is written by a hired writer. The concept is usually developed long before the screenwriter is brought on, and often has multiple writers work on it before the script is given a green light. The plot development is usually based on highly successful novels, plays, TV shows and even video games, and the rights to which have been legally acquired.

Feature assignment writing[edit]

Scripts written on assignment are screenplays created under contract with a studio, production company, or producer. These are the most common assignments sought after in screenwriting. A screenwriter can get an assignment either exclusively or from «open» assignments. A screenwriter can also be approached and offered an assignment. Assignment scripts are generally adaptations of an existing idea or property owned by the hiring company,[2] but can also be original works based on a concept created by the writer or producer.

Rewriting and script doctoring[edit]

Most produced films are rewritten to some extent during the development process. Frequently, they are not rewritten by the original writer of the script.[3] Many established screenwriters, as well as new writers whose work shows promise but lacks marketability, make their living rewriting scripts.

When a script’s central premise or characters are good but the script is otherwise unusable, a different writer or team of writers is contracted to do an entirely new draft, often referred to as a «page one rewrite». When only small problems remain, such as bad dialogue or poor humor, a writer is hired to do a «polish» or «punch-up».

Depending on the size of the new writer’s contributions, screen credit may or may not be given. For instance, in the American film industry, credit to rewriters is given only if 50% or more of the script is substantially changed.[4] These standards can make it difficult to establish the identity and number of screenwriters who contributed to a film’s creation.

When established writers are called in to rewrite portions of a script late in the development process, they are commonly referred to as script doctors. Prominent script doctors include Christopher Keane, Steve Zaillian, William Goldman, Robert Towne, Mort Nathan, Quentin Tarantino and Peter Russell.[5] Many up-and-coming screenwriters work as ghost writers.[citation needed]

Television writing[edit]

A freelance television writer typically uses spec scripts or previous credits and reputation to obtain a contract to write one or more episodes for an existing television show. After an episode is submitted, rewriting or polishing may be required.

A staff writer for a TV show generally works in-house, writing and rewriting episodes. Staff writers—often given other titles, such as story editor or producer—work both as a group and individually on episode scripts to maintain the show’s tone, style, characters, and plots.[6]

Television show creators write the television pilot and bible of new television series. They are responsible for creating and managing all aspects of a show’s characters, style, and plots. Frequently, a creator remains responsible for the show’s day-to-day creative decisions throughout the series run as showrunner, head writer or story editor.

Writing for daily series[edit]

The process of writing for soap operas and telenovelas is different from that used by prime time shows, due in part to the need to produce new episodes five days a week for several months. In one example cited by Jane Espenson, screenwriting is a «sort of three-tiered system»:[7]

- a few top writers craft the overall story arcs. Mid-level writers work with them to turn those arcs into things that look a lot like traditional episode outlines, and an array of writers below that (who do not even have to be local to Los Angeles), take those outlines and quickly generate the dialogue while adhering slavishly to the outlines.

Espenson notes that a recent trend has been to eliminate the role of the mid-level writer, relying on the senior writers to do rough outlines and giving the other writers a bit more freedom. Regardless, when the finished scripts are sent to the top writers, the latter do a final round of rewrites. Espenson also notes that a show that airs daily, with characters who have decades of history behind their voices, necessitates a writing staff without the distinctive voice that can sometimes be present in prime-time series.[7]

Writing for game shows[edit]

Game shows feature live contestants, but still use a team of writers as part of a specific format.[8] This may involve the slate of questions and even specific phrasing or dialogue on the part of the host. Writers may not script the dialogue used by the contestants, but they work with the producers to create the actions, scenarios, and sequence of events that support the game show’s concept.

Video game writing[edit]

With the continued development and increased complexity of video games, many opportunities are available to employ screenwriters in the field of video game design. Video game writers work closely with the other game designers to create characters, scenarios, and dialogue.[9]

Structural theories[edit]

Several main screenwriting theories help writers approach the screenplay by systematizing the structure, goals and techniques of writing a script. The most common kinds of theories are structural. Screenwriter William Goldman is widely quoted as saying «Screenplays are structure».

Three-act structure[edit]

According to this approach, the three acts are: the setup (of the setting, characters, and mood), the confrontation (with obstacles), and the resolution (culminating in a climax and a dénouement). In a two-hour film, the first and third acts each last about thirty minutes, with the middle act lasting about an hour, but nowadays many films begin at the confrontation point and segue immediately to the setup or begin at the resolution and return to the setup.

In Writing Drama, French writer and director Yves Lavandier shows a slightly different approach.[10] As do most theorists, he maintains that every human action, whether fictitious or real, contains three logical parts: before the action, during the action, and after the action. But since the climax is part of the action, Lavandier maintains that the second act must include the climax, which makes for a much shorter third act than is found in most screenwriting theories.

Besides the three-act structure, it is also common to use a four- or five-act structure in a screenplay, and some screenplays may include as many as twenty separate acts.

The Hero’s Journey[edit]