Испания богата уникальными режиссёрами, но очень немногие из них находят отклик на международном кинорынке. Один из самых известных – Педро Альмодовар. Его работы признаны шедеврами мировой кинопрессой, критиками и зрителями.

Отчасти его успех – результат сложившихся обстоятельств. Альмодовар начал снимать в период постфранкистского раскрепощения и развития контркультурного движения «мовида». При этом он создал вместе с братом продюсерскую компанию «El Deseo», обеспечив себе независимость от испанской киноиндустрии и возможность развивать свой уникальный голос и провокационные ракурсы.

Альмодовар снял десятки фильмов и удостоился самых престижных национальных и международных кинопремий. У него нет идеальных героев, но все они уникальны и полны чувств. Режиссёр ведёт их по лабиринтам экзотических страстей и поднимает общечеловеческие темы, говоря на языке, понятном во всём мире.

В этом списке двенадцать самых важных работ, отражающих технические, культурные и личные ориентиры испанского кинорежиссёра. Предлагаем убедиться в том, насколько красив и интересен мир фильмов Альмодовара – от дерзких и провокационных комедий до серьёзных глубоких драм.

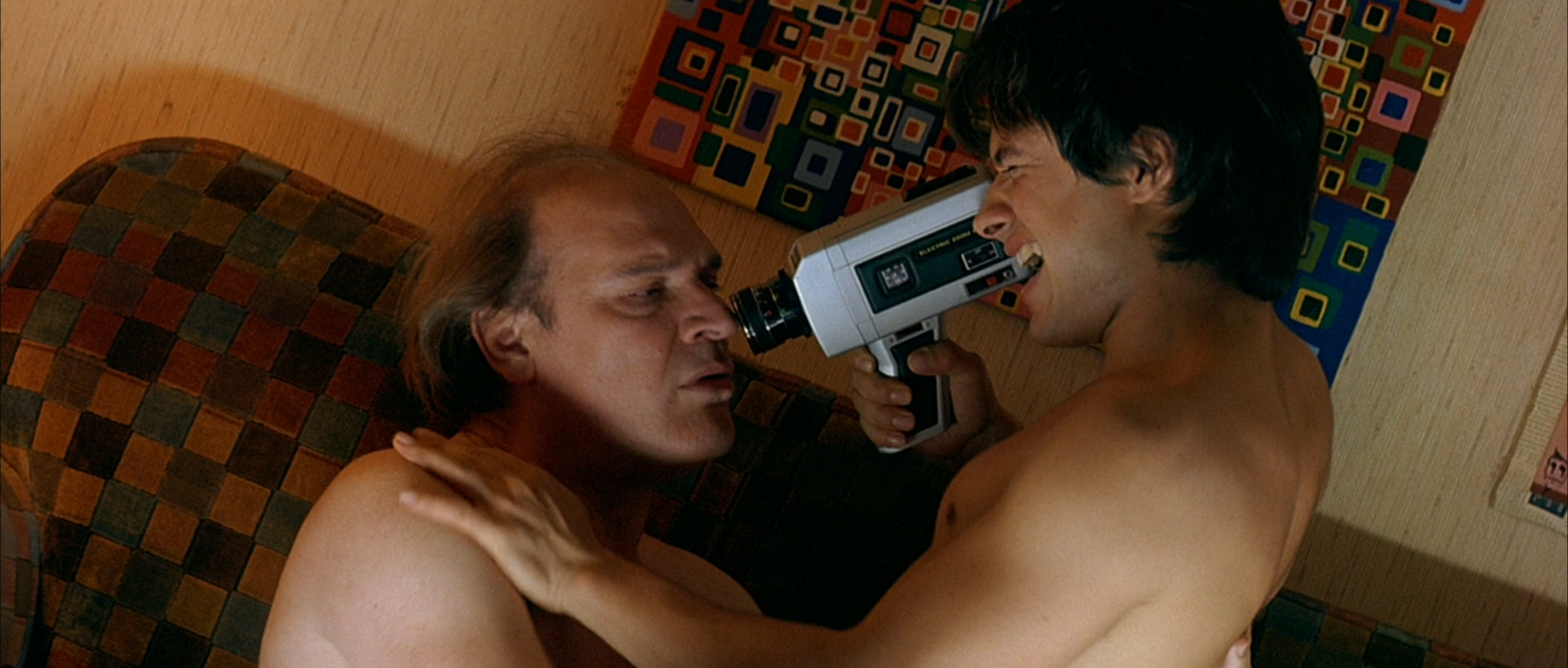

Свяжи меня! / ?Atame! (1990)

Рики (Антонио Бандерас) покидает психиатрическую клинику и отправляется на поиски бывшей порнозвезды Марины (Виктория Абриль). Он её похищает и держит связанной, но в итоге героиня влюбляется в своего насильника. Феминистки ополчились против этой картины, да и критики восприняли её противоречиво. Наибольшему осуждению подверглись сцены секса. Но, не смотря на эпатирующую смелость, фильм служит художественной цели. Можно сказать, это версия «Красавицы и Чудовища» от маэстро Альмодовара.

Возвращение / Volver (2006)

Место действия – Ла-Манча, родные края Альмодовара, где стоят мельницы, напоминающие о Дон Кихоте. Сюжет же сосредоточен на Раймунде (Пенелопа Крус) и её сестре Соледад (Лола Дуэньяс). Одна открывает ресторан и прячет труп своего мужа, а вторая трудится в парикмахерской и принимает на работу призрака своей матери Ирен (Кармен Маура), которая вернулась после смерти, чтобы завершить незаконченные дела.

Альмодовар смешал неореализм с историями о призраках, чтобы изучить женщин, не способных скрывать скелеты в своих шкафах. Картина удостоилась множества премий; коллективная награда «Лучшая актриса» на Каннском кинофестивале досталась сразу шести исполнительницам.

Женщины на грани нервного срыва / Mujeres al borde de un ataque de nervios (1988)

Актриса дубляжа Пепа Маркос (Кармен Маура) отчаянно пытается найти бросившего её любовника Ивана (Фернандо Гильен). Но она сталкивается с серией неприятностей, включая острый гаспачо и шиитских террористов.

С «Женщинами на грани нервного срыва» Альмодовар укрепился в репутации сумасбродного режиссёра. В фильме плавно объединились зарубежные веяния с испанскими мотивами, создав новый образ в испанском кинематографе. К сожалению, он также отмечен уходом Мауры, которая вернётся к работе с Альмодоваром в 2006 году в картине «Возвращение».

Всё о моей матери / Todo sobre mi madre (1999)

Мануэла (Сесилия Рот) – скорбящая мать, чей сын смертельно ранен в результате несчастного случая. Она жертвует его органы для трансплантации и переоценивает свой консервативный образ жизни. Мануэла решает покинуть Мадрид и вернуться в Барселону, чтобы встретиться с отцом погибшего сына, который никогда не знал о его существовании.

Картина получила приз Каннского кинофестиваля за лучшую режиссуру, а также премии «Оскар», «Сезар», «Золотой глобус» и BAFTA за лучший фильм на иностранном языке.

Кожа, в которой я живу / La piel que habito (2011)

В этом научно-фантастическом фильме Антонио Бандерас играет талантливого пластического хирурга-психопата, который разрабатывает новую форму человеческой кожи, устойчивую к травмам. А Елена Анайя исполняет роль его подопытной, которую он тайно держит взаперти. После гибели жены в автокатастрофе хирург начинает свои зловещие эксперименты.

Эта работа не похожа на другие творения Педро Альмодовара. Она более сложная, так как сочетает в себе элементы мистики, ужасов, сдвиги во времени, тему сумасшедшего доктора, историю любви и секреты, которые зрителю предстоит разгадать.

Лабиринт страстей / Laberinto de pasiones (1982)

Поп-звезда Сексилия (Сесилия Рот) страдает нимфоманией и ищет удовольствие в оргиях. Риса (Иманоль Ариас) – ближневосточный принц гей, который скрывается в Испании от террористов и способен покорить любого мужчину. Их неожиданная встреча должна стать поворотной в судьбе обоих. Сексилия попытается побороть свою нимфоманию, а Риса – сменить ориентацию на гетеро.

В этом фильме Альмодовар изобразил прогрессивный сексуальный образ Испании начала 80-х. Андеграундный тон придаёт картине странную чувственность, которая будет дорабатываться на протяжении многих лет. «Лабиринт страстей» – одна из лучших секс-комедий Альмодовара.

Матадор / Matador (1986)

Бывший матадор Диего Монтес (Начо Мартинес) после травмы не может вернуться на арену, но сексуальное удовольствие для него неразрывно связано с убийством. Для адвоката Марии Карденаль (Ассумпта Серна) высшее наслаждение так же невозможно без смерти партнёра. Встреча этой пары ведёт к неминуемой трагедии.

Эту провокационную картину Альмодовар назвал одной из двух самых слабых работ в своей фильмографии (наряду с «Кикой»). Но здесь он представил интересный образ испанской культуры, уходящей корнями к кровавой корриде.

За что мне это? / ?Que he hecho yo para merecer esto? (1984)

Глория (Кармен Маура) – женщина, увязшая в браке без любви и бытовых трудностях. Она живёт в многоэтажке унылого спального района в Мадриде вместе с мужем таксистом, восхищающемся немолодой певицей, двумя сыновьями, один из которых продаёт наркотики, а второй спит с мужчинами, и с крайне чудаковатой свекровью (Чус Лампреаве).

Чёрная комедия «За что мне это?» – первый международный хит и самый социальный из фильмов Альмодовара, в котором режиссёр исследует фрустрацию героини через объектив неореализма, изучая гендерные и классовые проблемы.

Цветок моей тайны / La flor de mi secreto (1995)

Лео (Мариса Паредес) пишет «розовые романы», которые публикует под псевдонимом Аманда Грис, но её жизнь далеко не так счастлива, как у её героинь. Пытаясь экспериментировать в писательстве, она создаёт спорные работы и при этом осознаёт, что её брак распадается.

«Цветок моей тайны» – душевный и глубоко эмоционально фильм, ставший началом зрелого периода Альмодовара.

Закон желания / La ley del deseo (1987)

Режиссёр и сценарист Пабло Кинтеро (Эусебио Понсела) делит успех с сестрой Тиной (Кармен Маура) и своим любовником Хуаном (Мигель Молина). Но Пабло увлекается своим поклонником Антонио (Антонио Бандерас), что приводит к убийству Хуана.

Этот фильм о любовном треугольнике трёх мужчин полон романтики, тепла и огня. Маура создала многогранный портрет транссексуалки, обладающей собственными представлениями о женственности. «Закон желания» – первый фильм, произведённый продюсерской компанией «El Deseo», которую Педро Альмодовар основал вместе со своим братом, получив полный контроль над будущими проектами.

Дурное воспитание / La mala educacion (2004)

К преуспевающему режиссёру Энрике (Феле Мартинес) приходит человек, который представляется его школьным товарищем Игнасио (Гаэль Гарсия Берналь). Давний друг предлагает Энрике в качестве основы для сценария рассказ о том, как в школе-интернате он подвергся сексуальному насилию со стороны падре. Между ними растёт взаимное влечение, но Энрике впадает в ступор, узнав, кто на самом деле выдаёт себя за его школьного товарища.

«Дурное воспитание» – самый личный из фильмов режиссёра. Очевидно, что Энрике во многом похож на Альмодовара и остаётся лишь гадать, насколько сценарий заимствован из реальной жизни.

Поговори с ней / Hable con ella (2002)

Бениньо (Хавьер Камара) и Марко (Дарио Грандинетти) ухаживают за двумя находящимися в коме женщинами – танцовщицей Алисией (Леонор Уотлинг) и тореадором Лидией (Росарио Флорес). Мужчины разговаривают с ними, надеясь, что те вернутся к жизни. Но откровения и обвинение в изнасиловании приводят к разрыву отношений между четырьмя персонажами.

Фильм собрал престижнейшие кинопремии, в том числе «Оскар» за лучший оригинальный сценарий. Он стал величайшим достижением Альмодовара, смешавшего все свои характерные темы и элементы в изящный и восторженно воспринятый критиками шедевр.

Смотрите также:

- 12 фильмов братьев Коэн, которые точно стоит посмотреть

- 15 лучших фильмов, воплотивших философские идеи Жана Бодрийяра

- 10 титулованных фильмов Мартина Скорсезе, которые делают нас лучше

- 10 самых смешных фильмов Вуди Аллена. Остроумное кино от отца интеллектуальной комедии

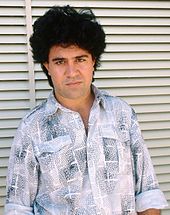

In this Spanish name, the first or paternal surname is Almodóvar and the second or maternal family name is Caballero.

|

Pedro Almodóvar |

|

|---|---|

Almodóvar in 2017 |

|

| Born |

Pedro Almodóvar Caballero 25 September 1949 (age 73) Calzada de Calatrava, Francoist Spain |

| Occupation | Filmmaker |

| Years active | 1974–present |

| Partner | Fernando Iglesias (2002–present) |

Pedro Almodóvar Caballero (Spanish pronunciation: [ˈpeðɾo almoˈðoβaɾ kaβaˈʝeɾo]; born 25 September 1949)[1] is a Spanish filmmaker. His films are marked by melodrama, irreverent humour, bold colour, glossy décor, quotations from popular culture, and complex narratives. Desire, passion, family, and identity are among Almodóvar’s most prevalent subjects in his films. Acclaimed as one of the most internationally successful Spanish filmmakers, Almodóvar and his films have gained worldwide interest and developed a cult following.

Almodóvar’s career came to during La Movida Madrileña, a cultural renaissance that followed after the end of Francoist Spain. His early films characterised the sense of sexual and political freedom of the period. In 1986, he established his own film production company, El Deseo, with his younger brother Agustín Almodóvar, who has been responsible for producing all of his films since Law of Desire (1987). His breakthrough film was Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown (1988), which was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film.

He achieved further success often collaborating with actors Antonio Banderas and Penélope Cruz. He directed Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down! (1989), High Heels (1991), and Live Flesh (1997). His next two films, All About My Mother (1999) and Talk to Her (2002), earned him an Academy Award each for Best International Feature Film and Best Original Screenplay, respectively. His later films include Volver (2006), Broken Embraces (2009), The Skin I Live In (2011), Julieta (2016), Pain and Glory (2019), and Parallel Mothers (2021).

Almodóvar has received numerous accolades including two Academy Awards, five BAFTA Awards, two Emmy Awards, two Golden Globe Awards, nine Goya Awards. He has also received the French Legion of Honour in 1997, the Gold Medal of Merit in the Fine Arts in 1999, and the European Film Academy Achievement in World Cinema Award in 2013[2] and was awarded the Golden Lion in 2019.[3][4][5] He’s also received an honorary doctoral degrees from Harvard University in 2009[6] and from University of Oxford in 2016.[7]

Early life[edit]

Pedro Almodóvar Caballero was born on 25 September 1949 in Calzada de Calatrava, a small rural town of Ciudad Real, a province of Castile-La Mancha in Spain.[8] He has two older sisters, Antonia and María Jesús,[9] and one brother Agustín.[10] His father, Antonio Almodóvar, was a winemaker,[11] and his mother, Francisca Caballero, who died in 1999, was a letter reader and transcriber for illiterate neighbours.[12]

When Almodóvar was eight years old, the family sent him to study at a religious boarding school in the city of Cáceres, Extremadura, in western Spain,[6] with the hope that he might someday become a priest. His family eventually joined him in Cáceres, where his father opened a gas station and his mother opened a bodega in which she sold her own wine.[11][13] Unlike Calzada, there was a cinema in Cáceres.[14] «Cinema became my real education, much more than the one I received from the priest», he said later in an interview.[15] Almodóvar was influenced by Luis Buñuel.[16]

Against his parents’ wishes, Almodóvar moved to Madrid in 1967 to become a filmmaker. When the Spanish dictator, Francisco Franco, closed the National School of Cinema in Madrid, Almodóvar became self-taught.[6] To support himself, Almodóvar had a number of jobs, including selling used items in the famous Madrid flea market El Rastro and as an administrative assistant with the Spanish phone company Telefónica, where he worked for 12 years.[17] Since he worked only until three in the afternoon, he had the rest of the day to pursue his film-making.[6]

Early career[edit]

In the early 1970s, Almodóvar became interested in experimental cinema and theatre. He collaborated with the vanguard theatrical group Los Goliardos, in which he played his first professional roles and met actress Carmen Maura.[18] Madrid’s flourishing alternative cultural scene became the perfect scenario for Almodóvar’s social talents. He was a crucial figure in La Movida Madrileña (the Madrilenian Movement), a cultural renaissance that followed the death of Francisco Franco. Alongside Fabio McNamara, Almodóvar sang in a glam rock parody duo.[19]

Almodóvar also penned various articles for major newspapers and magazines, such as El País, Diario 16 and La Luna as well as contributing to comic strips, articles and stories in counterculture magazines, such as Star, El Víbora and Vibraciones.[20]

He published a novella, Fuego en las entrañas (Fire in the Guts)[21] and kept writing stories that were eventually published in a compilation volume entitled El sueño de la razón (The Dream of Reason).[22]

Almodóvar bought his first camera, a Super-8, with his first paycheck from Telefónica when he was 22 years old, and began to make hand-held short films.[23] Around 1974, he made his first short film, and by the end of the 1970s they were shown in Madrid’s night circuit and in Barcelona. These shorts had overtly sexual narratives and no soundtrack: Dos putas, o, Historia de amor que termina en boda (Two Whores, or, A Love Story that Ends in Marriage) in 1974; La caída de Sodoma (The Fall of Sodom) in 1975; Homenaje (Homage) in 1976; La estrella (The Star) in 1977; Sexo Va: Sexo viene (Sex Comes and Goes); and Complementos (Shorts) in 1978, his first film in 16mm.[24]

He remembers, «I showed them in bars, at parties… I could not add a soundtrack because it was very difficult. The magnetic strip was very poor, very thin. I remember that I became very famous in Madrid because, as the films had no sound, I took a cassette with music while I personally did the voices of all the characters, songs and dialogues».[25]

After four years of working with shorts in Super-8 format, Almodóvar made his first full-length film Folle, folle, fólleme, Tim (Fuck Me, Fuck Me, Fuck Me, Tim) in Super-8 in 1978, followed by his first 16 mm short Salomé.[26]

Film career[edit]

1980s[edit]

Pepi, Luci, Bom (1980)

Almodóvar made his first feature film Pepi, Luci, Bom (1980) with a very low budget of 400,000 pesetas,[27] shooting it in 16 mm and later blowing it up into 35 mm.[28] The film was based on a comic strip titled General Erections that he had written and revolves around the unlikely friendship between Pepi (Carmen Maura), who wants revenge on a corrupt policeman who raped her, a masochistic housewife named Luci (Eva Siva), and Bom (Alaska), a lesbian punk rock singer. Inspired by La Movida Madrileña, Pepi, Luci, Bom expressed the sense of cultural and sexual freedom of the time with its many kitsch elements, campy style, outrageous humour and explicit sexuality (there is a golden shower scene in the middle of a knitting lesson).

The film was noted for its lack of polished filming technique, but Almodóvar looked back fondly on the film’s flaws. «When a film has only one or two [defects], it is considered an imperfect film, while when there is a profusion of technical flaws, it is called style. That’s what I said joking around when I was promoting the film, but I believe that that was closer to the truth».[29]

Pepi, Luci, Bom premiered at the 1980 San Sebastián International Film Festival[30] and despite negative reviews from conservative critics, the film amassed a cult following in Spain. It toured the independent circuits before spending three years on the late night showing of the Alphaville Theater in Madrid.[31] The film’s irreverence towards sexuality and social mores has prompted contemporary critics to compare it to the 1970s films of John Waters.[32]

Labyrinth of Passion (1982)

His second feature Labyrinth of Passion (1982) focuses on nymphomaniac pop star, Sexila (Cecilia Roth), who falls in love with a gay middle-eastern prince, Riza Niro (Imanol Arias). Their unlikely destiny is to find one another, overcome their sexual preferences and live happily ever after on a tropical island. Framed in Madrid during La Movida Madrileña, between the dissolution of Franco’s authoritarian regime and the onset of AIDS consciousness, Labyrinth of Passion caught the spirit of liberation in Madrid and it became a cult film.[33]

The film marked Almodóvar’s first collaboration with cinematographer Ángel Luis Fernandez as well as the first of several collaborations with actor Antonio Banderas. Labyrinth of Passion premiered at the 1982 San Sebastian Film Festival[34] and while the film received better reviews than its predecessor, Almodóvar later acknowledged: «I like the film even if it could have been better made. The main problem is that the story of the two leads is much less interesting than the stories of all the secondary characters. But precisely because there are so many secondary characters, there’s a lot in the film I like».[33]

Dark Habits (1983)

For his next film Dark Habits (1983), Almodóvar was approached by multi-millionaire Hervé Hachuel who wanted to start a production company to make films starring his girlfriend, Cristina Sánchez Pascual.[35] Hachuel set up Tesuaro Production and asked Almodóvar to keep Pascual in mind.[citation needed] Almodóvar had already written the script for Dark Habits and was hesitant to cast Pascual in the leading role due to her limited acting experience.[citation needed] When she was cast, he felt it necessary to make changes to the script so his supporting cast were more prominent in the story.[citation needed]

The film heralded a change in tone to somber melodrama with comic elements.[according to whom?] Pascual stars as Yolanda, a cabaret singer who seeks refuge in a convent of eccentric nuns, each of whom explores a different sin. This film has an almost all-female cast including Carmen Maura, Julieta Serrano, Marisa Paredes and Chus Lampreave, actresses who Almodóvar would cast again in later films. This is Almodóvar’s first film in which he used popular music to express emotion: in a pivotal scene, the mother superior and her protégé sing along with Lucho Gatica’s bolero «Encadenados».

Dark Habits premiered at the Venice Film Festival and was surrounded in controversy due its subject matter.[36] Despite religious critics being offended by the film, it went on to become a modest critical and commercial success, cementing Almodóvar’s reputation as the enfant terrible of the Spanish cinema.[citation needed]

What Have I Done to Deserve This? (1984)

Carmen Maura stars in What Have I Done to Deserve This?, Almodóvar’s fourth film, as Gloria, an unhappy housewife who lives with her ungrateful husband Antonio (Ángel de Andrés López), her mother in law (Chus Lampreave), and her two teenage sons. Verónica Forqué appears as her prostitute neighbor and confidante.

Almodóvar has described his fourth film as a homage to Italian neorealism, although this tribute also involves jokes about paedophilia, prostitution, and a telekinetic child. The film, set in the tower blocks around Madrid in post-Franco Spain, depicts female frustration and family breakdown, echoing Jean-Luc Godard’s Two or Three Things I Know About Her and strong story plots from Roald Dahl’s Lamb to the slaughter and Truman Capote’s A Day’s work,[37] but with Almodóvar’s unique approach to film making.

Matador (1986)

Almodóvar’s growing success caught the attention of emerging Spanish film producer Andrés Vicente Gómez, who wanted to join forces to make his next film Matador (1986).[citation needed] The film centres on the relationship between a former bullfighter and a murderous female lawyer, who both find sexual fulfillment through acts of murder.[citation needed]

Written together with Spanish novelist Jesús Ferrero, Matador drew away from the naturalism and humour of the director’s previous work into a deeper and darker terrain.[citation needed] Almodóvar cast several of his regulars actors in key roles: Antonio Banderas was hired for the role of Ángel, a bullfighting student who, after an attempted rape incident, falsely confesses to a series of murders that he did not commit; Julieta Serrano appears as Ángel’s very religious mother; while Carmen Maura, Chus Lampreave, Verónica Forqué and Eusebio Poncela also appear in minor roles. Newcomers Nacho Martínez and Assumpta Serna, who would later work with Almodóvar again, had minor roles in the film. Matador also marked the first time Almodóvar included a notable cinematic reference, using King Vidor’s Duel in the Sun in one scene.[citation needed]

The film premiered in 1986 and drew some controversy due to its subject matter. Almodóvar justified his use of violence, explaining «The moral of all my films is to get to a stage of greater freedom». Almodóvar went on to note: «I have my own morality. And so do my films. If you see Matador through the perspective of traditional morality, it’s a dangerous film because it’s just a celebration of killing. Matador is like a legend. I don’t try to be realistic; it’s very abstract, so you don’t feel identification with the things that are happening, but with the sensibility of this kind of romanticism».[38]

Law of Desire (1987)

Following the success of Matador, Almodóvar solidified his creative independence by starting his own production company, El Deseo, together with his brother Agustín Almodóvar in 1986. El Deseo’s first major release was Law of Desire (1987), a film about the complicated love triangle between a gay filmmaker (Eusebio Poncela), his transsexual sister (Carmen Maura), and a repressed murderously obsessive stalker (Antonio Banderas).

Taking more risk from a visual standpoint, Almodóvar’s growth as a filmmaker is clearly on display. In presenting the love triangle, Almodóvar drew away from most representations of homosexuals in films. The characters neither come out nor confront sexual guilt or homophobia; they are already liberated. The same can be said for the complex way he depicted transgender characters on screen. Almodóvar said about Law of Desire: «It’s the key film in my life and career. It deals with my vision of desire, something that’s both very hard and very human. By this I mean the absolute necessity of being desired and the fact that in the interplay of desires it’s rare that two desires meet and correspond».[39]

Law of Desire made its premiere at the Berlin International Film Festival in 1987, where it won the festival’s first ever Teddy Award, which recognises achievement in LGBT cinema. The film was a hit in art-house theatres and received much praise from critics.[citation needed]

Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown (1988)

Almodóvar’s first major critical and commercial success internationally came with the release of Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown (1988).The film debuted at the 45th Venice film festival. This feminist light comedy of rapid-fire dialogue and fast-paced action further established Almodóvar as a «women’s director» in the same vein as George Cukor and Rainer Werner Fassbinder. Almodóvar has said that women make better characters: «women are more spectacular as dramatic subjects, they have a greater range of registers, etc.»[40]

Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown centres on Pepa (Carmen Maura), a woman who has been abruptly abandoned by her married boyfriend Iván (Fernando Guillén). Over two days, Pepa frantically tries to track him down. In the course, she discovers some of his secrets and realises her true feelings. Almodóvar included many of his usual actors, including Antonio Banderas, Chus Lampreave, Rossy de Palma, Kiti Mánver and Julieta Serrano as well as newcomer María Barranco.[citation needed]

The film was released in Spain in March 1988, and became a hit in the US, making over $7 million when it was released later that same year,[41] bringing Almodóvar to the attention of American audiences. Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown won five Goya Awards, Spain’s top film honours, for Best Film, Best Original Screenplay, Best Editing (José Salcedo), Best Actress (Maura), and Best Supporting Actress (Barranco). The film won an award for best screenplay at the Venice film festival and two awards at the European Film Awards as well as being nominated for Best Foreign Language Film at the BAFTAs and Golden Globes. It also gave Almodóvar his first Academy Award nomination for Best Foreign Language Film.[42]

1990s[edit]

Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down! (1990)

Almodóvar’s next film marked the end of the collaboration between him and Carmen Maura, and the beginning of a fruitful collaboration with Victoria Abril. Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down! (1990) tells the story about a recently released psychiatric patient, Ricky (Antonio Banderas), who kidnaps a porn star, Marina (Abril), in order to make her fall in love with him.[citation needed]

Rather than populate the film with many characters, as in his previous films, here the story focuses on the compelling relationship at its center: the actress and her kidnapper literally struggling for power and desperate for love. The film’s title line Tie Me Up! is unexpectedly uttered by the actress as a genuine request. She does not know if she will try to escape or not, and when she realizes she has feelings for her captor, she prefers not to be given a chance. In spite of some dark elements, Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down! can be described as a romantic comedy, and the director’s most clear love story, with a plot similar to William Wyler’s thriller The Collector.[citation needed]

Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down! made its world premiere at the Berlin Film Festival to a polarized critical reaction. In the United States, the film received an X rating by the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA), and the stigma attached to the X rating marginalized the distribution of the film in the country. Miramax, who distributed the film in the US, filed a lawsuit against the MPAA over the X rating, but lost in court. However, in September 1990, the MPAA replaced the X rating with the NC-17 rating. This was helpful to films of explicit nature, like Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down!, that were previously categorized with pornography because of the X rating.[43]

High Heels (1991)

High Heels (1991) is built around the fractured relationship between a famous singer, Becky del Páramo (Marisa Paredes), and her news reporter daughter, Rebeca (Victoria Abril), as the pair get caught up in a murder mystery. Rebeca struggles with constantly being in her mother’s shadow. The fact that Rebeca is married to Becky’s former lover only adds to the tension between the two.[citation needed]

The film was partly inspired by old Hollywood mother-daughter melodramas like Stella Dallas, Mildred Pierce, Imitation of Life and particularly Autumn Sonata, which is quoted directly in the film. Production took place in 1990; Almodóvar enlisted Alfredo Mayo to shoot the film as Jose Luis Alcaine was unavailable.[citation needed] Japanese composer Ryuichi Sakamoto created a score that infused popular songs and boleros. High Heels also contains a prison yard dance sequence.[citation needed]

While High Heels was a box office success in Spain, the film received poor reviews from Spanish film critics due to its melodramatic approach and unsuspecting tonal shifts.[citation needed] The film got a better critical reception in Italy and France and won France’s César Award for Best Foreign Film. In the US, Miramax’s lack of promotional effort was blamed for the film’s underperformance in the country. It was however nominated for the Golden Globe for Best Foreign Language Film.[citation needed]

Kika (1993)

His next film Kika (1993) centres on the good-hearted, but clueless, makeup artist named Kika (Verónica Forqué) who gets herself tangled in the lives of an American writer (Peter Coyote) and his stepson (Àlex Casanovas). A fashion conscious TV reporter (Victoria Abril), who is constantly in search of sensational stories, follows Kika’s misadventures. Almodóvar used Kika as a critique of mass media, particularly its sensationalism.[citation needed]

The film is infamous for its rape scene that Almodóvar used for comic effect to set up a scathing commentary on the selfish and ruthless nature of media. Kika made its premiere in 1993 and received very negative reviews from film critics worldwide;[citation needed] not just for its rape scene which was perceived as both misogynistic and exploitative, but also for its overall sloppiness. Almodóvar would later refer to the film as one of his weakest works.[citation needed]

The Flower of My Secret (1995)

In The Flower of My Secret (1995), the story focuses on Leo Macías (Marisa Paredes), a successful romance writer who has to confront both a professional and personal crisis. Estranged from her husband, a military officer who has volunteered for an international peacekeeping role in Bosnia and Herzegovina to avoid her, Leo fights to hold on to a past that has already eluded her, not realising she has already set her future path by her own creativity and by supporting the creative efforts of others.[citation needed]

This was the first time that Almodóvar utilized composer Alberto Iglesias and cinematographer Affonso Beato, who became key figures in some future films. The Flower of My Secret is the transitional film between his earlier and later style.[citation needed]

The film premiered in Spain in 1995 where, despite receiving 7 Goya Award nominations, was not initially well received by critics.

Live Flesh (1997)

Live Flesh (1997) was the first film by Almodóvar that had an adapted screenplay. Based on Ruth Rendell’s novel Live Flesh, the film follows a man who is sent to prison after crippling a police officer and seeks redemption years later when he is released. Almodóvar decided to move the book’s original setting of the UK to Spain, setting the action between the years 1970, when Franco declared a state of emergency, to 1996, when Spain had completely shaken off the restrictions of the Franco regime.[citation needed]

Live Flesh marked Almodóvar’s first collaboration with Penélope Cruz, who plays the prostitute who gives birth to Victor. Additionally, Almodóvar cast Javier Bardem as the police officer David and Liberto Rabal as Víctor, the criminal seeking redemption. Italian actress Francesca Neri plays a former drug addict who sparks a complicated love triangle with David and Víctor.

Live Flesh premiered at the New York Film Festival in 1997. The film did modestly well at the international box office and also earned Almodóvar his second BAFTA nomination for Best Film Not in the English Language.

All About My Mother (1999)

Almodóvar’s next film, All About My Mother (1999), grew out of a brief scene in The Flower of My Secret. The premise revolves around a woman Manuela (Cecilia Roth), who loses her teenage son, Esteban (Eloy Azorín) in a tragic accident. Filled with grief, Manuela decides to track down Esteban’s transgender mother, Lola (Toni Cantó), and notify her about the death of the son she never knew she had. Along the way Manuela encounters an old friend, Agrado (Antonia San Juan), and meets up with a pregnant nun, Rosa (Penélope Cruz).

The film revisited Almodóvar’s familiar themes of the power of sisterhood and of family. Almodóvar shot parts of the film in Barcelona and used lush colors to emphasise the richness of the city. Dedicated to Bette Davis, Romy Schneider and Gena Rowlands, All About My Mother is steeped in theatricality, from its backstage setting to its plot, modeled on the works of Federico García Lorca and Tennessee Williams, to the characters’ preoccupation with modes of performance. Almodóvar inserts a number of references to American cinema. One of the film’s key scenes, where Manuela watches her son die, was inspired by John Cassavetes’ 1977 film Opening Night. The film’s title is also a nod to All About Eve, which Manuela and her son are shown watching in the film. The comic relief of the film centers on Agrado, a pre-operative transgender woman. In one scene, she tells the story of her body and its relationship to plastic surgery and silicone, culminating with a statement of her own philosophy: «you get to be more authentic the more you become like what you have dreamed of yourself».[44]

All About My Mother opened at the 1999 Cannes Film Festival, where Almodóvar won both the Best Director and the Ecumenical Jury prizes.[45] The film garnered a strong critical reception and grossed over $67 million worldwide.[46] All About My Mother has accordingly received more awards and honours than any other film in the Spanish motion picture industry,[47] including Almodóvar’s very first Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film, the Golden Globe in the same category, the BAFTA Awards for Best Direction and Best Film Not in the English Language as well as 6 Goyas in his native Spain.[47]

2000s[edit]

Talk to Her (2002)

After the success of All About My Mother, Almodóvar took a break from filmmaking to focus on his production company El Deseo.[citation needed] During this break, Almodóvar had an idea for Talk to Her (2002), a film about two men, played by Javier Cámara and Darío Grandinetti, who become friends while taking care of the comatose women they love, played by Leonor Watling and Rosario Flores. Combining elements of modern dance and silent filmmaking with a narrative that embraces coincidence and fate,[citation needed] in the film, Almodóvar plots the lives of his characters, thrown together by unimaginably bad luck, towards an unexpected conclusion.

Talk to Her was released in April 2002 in Spain, followed by its international premiere at the Telluride Film Festival in September of that year. It was hailed by critics and embraced by arthouse audiences, particularly in America.[48] The unanimous praise for Talk to Her resulted in Almodóvar winning his second Academy Award, this time for Best Original Screenplay, as well as being nominated in the Best Director category.[48] The film also won the César Award for Best Film from the European Union and both the BAFTA Award and Golden Globe Award for Best Foreign Language Film.[48] Talk to Her made over $51 million worldwide.[49]

Bad Education (2004)

Two years later, Almodóvar followed with Bad Education (2004), tale of child sexual abuse and mixed identities, starring Gael García Bernal and Fele Martínez. In the drama film, two children, Ignácio and Enrique, discover love, cinema, and fear in a religious school at the start of the 1960s. Bad Education has a complex structure that not only uses film within a film, but also stories that open up into other stories, real and imagined to narrate the same story: A tale of child molestation and its aftermath of faithlessness, creativity, despair, blackmail and murder. Sexual abuse by Catholic priests, transsexuality, drug use, and a metafiction are also important themes and devices in the plot.

Almodóvar used elements of film noir, borrowing in particular from Double Indemnity.[citation needed] The film’s protagonist, Juan (Gael Garcia Bernal), was modeled largely on Patricia Highsmith’s most famous character, Tom Ripley,[50] as played by Alain Delon in René Clément’s Purple Noon. A criminal without scruples, but with an adorable face that betrays nothing of his true nature. Almodóvar explains : «He also represents a classic film noir character – the femme fatale. Which means that when other characters come into contact with him, he embodies fate, in the most tragic and noir sense of the word».[51] Almodóvar claimed he worked on the film’s screenplay for over ten years before starting the film.[52]

Bad Education premiered in March 2004 in Spain before opening in the 57th Cannes Film Festival, the first Spanish film to do so, two months later.[53] The film grossed more than $40 million worldwide,[54] despite its NC-17 rating in the US. It won the GLAAD Media Award for Outstanding Film – Limited Release and was nominated for the BAFTA Award for Best Film Not in the English Language; it also received 7 European Film Award nominations and 4 Goya nominations.[citation needed]

Volver (2006)

Volver (2006), a mixture of comedy, family drama and ghost story, is set in part in La Mancha (the director’s native region) and follows the story of three generations of women in the same family who survive wind, fire, and even death. The film is an ode to female resilience, where men are literally disposable. Volver stars Penélope Cruz, Lola Dueñas, Blanca Portillo, Yohana Cobo and Chus Lampreave in addition to reunited the director with Carmen Maura, who had appeared in several of his early films.

The film was very personal to Almodóvar as he used elements of his own childhood to shape parts of the story.[original research?] Many of the characters in the film were variations of people he knew from his small town.[citation needed] Using a colorful backdrop, the film tackled many complex themes such as sexual abuse, grief, secrets and death. The storyline of Volver appears as both a novel and movie script in Almodóvar’s earlier film The Flower of My Secret.[citation needed] Many of Almodóvar’s stylistic hallmarks are present: the stand-alone song (a rendition of the Argentinian tango song «Volver»), references to reality TV, and an homage to classic film (in this case Luchino Visconti’s Bellissima).[citation needed]

Volver received a rapturous reception when it played at the 2006 Cannes Film Festival, where Almodóvar won the Best Screenplay prize while the entire female ensemble won the Best Actress prize. Penélope Cruz also received an Academy Award nomination for Best Actress, making her the first Spanish woman ever to be nominated in that category. Volver went on to earn several critical accolades and earned more than £85 million internationally, becoming Almodóvar’s highest-grossing film worldwide.[55]

Broken Embraces (2009)

Almodóvar’s next film, Broken Embraces (2009) a romantic thriller which centres on a blind novelist, Harry Caine (Lluís Homar), who uses his works to recount both his former life as a filmmaker, and the tragedy that took his sight. A key figure in Caine’s past is Lena (Penélope Cruz), an aspiring actress who gets embroiled in a love triangle with Caine and a paranoid millionaire, Ernesto (José Luis Gómez). The film has a complex structure, mixing past and present and film within a film. Almodóvar previously used this type of structure in Talk to Her and Bad Education.

Jose Luis Alcaine was unable to take part in the production, so Almodóvar hired Mexican cinematographer Rodrigo Prieto to shoot the film.[56] Distinctive shading and shadows help to differentiate the various time periods within Broken Embraces, as Almodóvar’s narrative jumps between the early 1990s and the late 2000s. Broken Embraces was accepted into the main selection at the 2009 Cannes Film Festival in competition for the Palme d’Or, his third film to do so and fourth to screen at the festival.[57] The film earned £30 million worldwide,[58] and received critical acclaim among critics with Roger Ebert giving the film his highest rating, 4 stars, writing, «Broken Embraces» is a voluptuary of a film, drunk on primary colors…using the devices of a Hitchcock to distract us with surfaces while the sinister uncoils beneath. As it ravished me, I longed for a freeze frame to allow me to savor a shot.»[59]

Despite the film failing to receive an Academy Award nomination, the film was nominated for both the British Academy Film Award and the Golden Globe Award for Best Foreign Language Film.[60][61]

2010s[edit]

The Skin I Live In (2011)

Loosely based on the French novel Tarantula by Thierry Jonquet,[62] The Skin I Live In (2011) is the director’s first incursion into the psychological horror genre[63] Inspired to make his own horror film, The Skin I Live In revolves around a plastic surgeon, Robert (Antonio Banderas), who becomes obsessed with creating skin that can withstand burns. Haunted by past tragedies, Robert believes that the key to his research is the patient who he mysteriously keeps prisoner in his mansion.[64] The film marked a long-awaited reunion between Almodóvar and Antonio Banderas, reunited after 21 years.[65] Penélope Cruz was initially slated for the role of the captive patient Vera Cruz, but she was unable to take part as she was pregnant with her first child. As a result, Elena Anaya, who had appeared in Talk to Her, was cast.[66]

The Skin I Live In has many cinematic influences, most notably the French horror film Eyes Without a Face directed by Georges Franju,[63] but also refers to Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo, and the style of the films of David Cronenberg, Dario Argento, Mario Bava, Umberto Lenzi and Lucio Fulci while also paying tribute to the films of Fritz Lang and F. W. Murnau.[63] After making its premiere at the 2011 Cannes Film Festival, the film grossed $30 million worldwide.[67] The Skin I Live In received the BAFTA Award for Best Film Not in the English Language and a Golden Globe Award nomination in the same category.[68][69]

I’m So Excited (2013)

After a long period of dramatic and serious feature films, Almodóvar’s next film was a comedy. I’m So Excited (2013) is set almost entirely on an aircraft in flight,[70] whose first-class passengers, pilots, and trio of gay stewards all try to deal with the fact that landing gears are malfunctioning. During the ordeal, they talk about love, themselves, and a plethora of things while getting drunk on Valencia cocktails. With its English title taken from a song by the Pointer Sisters, Almodóvar openly embraced the campy humor that was prominent in his early works.[71]

The film’s cast was a mixture of Almodóvar regulars such as Cecilia Roth, Javier Cámara, and Lola Dueñas, Blanca Suárez and Paz Vega as well as Antonio Banderas and Penélope Cruz who make cameo appearances in the film’s opening scene. Shot on a soundstage, Almodóvar amplified the campy tone by incorporating a dance number and oddball characters like Dueñas’ virginal psychic.[citation needed] The film premiered in Spain in March 2013 and had its international release during the summer of that year. Despite mixed reviews from critics, the film did fairly well at the international box office.[72]

Julieta (2016)

For his 20th feature film,[73] Almodóvar decided to return to drama and his «cinema of women».[74] Julieta (2016) stars Emma Suárez and Adriana Ugarte, who play the older and younger versions of the film’s titular character,[75] as well as regular Rossy de Palma, who has a supporting role in the film.[76] This film was originally titled «Silencio» (Silence) but the director changed the name to prevent confusion with another recent release by that name.[77]

The film was released in April 2016 in Spain to positive reviews and received its international debut at the 2016 Cannes Film Festival. It was Almodóvar’s fifth film to compete for the Palme d’Or. The film was also selected by the Spanish Academy as the entry for the Best Foreign Language Film at the 89th Academy Awards,[78] but it did not make the shortlist.

Pain and Glory (2019)

Almodóvar’s next film—Pain and Glory (Dolor y gloria)—was released in Spain on 22 March 2019 by Sony Pictures Releasing.[79] It first was selected to compete for the Palme d’Or at the 2019 Cannes Film Festival.[80] The film centers around an aging film director, played by Antonio Banderas who is suffering from chronic illness and writer’s block as he reflects on his life in flashbacks to his childhood. Penelope Cruz plays Jacinta, the mother of the aging film director, in the film’s flashbacks. The film has been described as semi-autobiographical, according to Almodóvar.[81] The film was nominated for the Academy Award for Best International Feature Film, though it ultimately lost to Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite.

2020s[edit]

In July 2020, Agustín Almodóvar announced that his brother had finished the script for his next full-length feature Parallel Mothers during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown.[82] Once again starring Penelope Cruz, the drama turns on two mothers who give birth the same day and follows their parallel lives over their first and second years raising their children. Madres paralelas began shooting in February 2021 and opened the 78th Venice International Film Festival where Cruz won the Volpi Cup for Best Actress. The film has received near universal acclaim with David Rooney of The Hollywood Reporter writing, «It’s a testament to the consummate gifts of one of the world’s most treasured filmmakers — now entering the fifth decade of a career still going strong — that he can constantly delight your eye with no risk of losing your involvement in the emotional lives of characters he so clearly adores.»[83] The film has been nominated for the Golden Globe Award and Independent Spirit Award for Best International Film.

The shoot delayed Almodóvar’s previously announced feature-length adaptation of Lucia Berlin’s short story collection A Manual for Cleaning Women starring Cate Blanchett which is set to be his first feature in English.[82]

Artistry[edit]

«Almodóvar has consolidated his own, very recognizable universe, forged by repeating themes and stylistic features», wrote Gerard A. Cassadó in Fotogramas, Spanish film magazine, in which the writer identified nine key features which recur in Almodóvar’s films: homosexuality; sexual perversion; female heroines; sacrilegious Catholicism; lipsyncing; familial cameos; excessive kitsch and camp; narrative interludes; and intertextuality.[84]

June Thomas from Slate magazine also recognised that illegal drug use, letter-writing, spying, stalking, prostitution, rape, incest, transsexuality, vomiting, movie-making, recent inmates, car accidents and women urinating on screen are frequent motifs recurring in his work.[85]

Almodóvar has also been distinguished for his use of bold colours and inventive camera angles, as well as using «cinematic references, genre touchstones, and images that serve the same function as songs in a musical, to express what cannot be said».[86] Elaborate décor and the relevance of fashion in his films are additionally important aspects informing the design of Almodóvar’s mise-en-scène.[87]

Music is also a key feature; from pop songs to boleros to original compositions by Alberto Iglesias.[88] While some criticise Almodóvar for obsessively returning to the same themes and stylistic features, others have applauded him for having «the creativity to remake them afresh every time he comes back to them».[85] Internationally, Almodóvar has been hailed as an auteur by film critics, who have coined the term «Almodovariano» (which would translate as Almodovarian) to define his unique style.[89][90]

Almodóvar has taken influences from various filmmakers, including figures in North American cinema, particularly old Hollywood directors George Cukor and Billy Wilder,[91] and the underground, transgressive cinema of John Waters and Andy Warhol.[92] The influence of Douglas Sirk’s melodramas and the stylistic appropriations of Alfred Hitchcock are also present in his work.[93][94] He also takes inspiration from figures in the history of Spanish cinema, including directors Luis García Berlanga, Fernando Fernán Gómez, Edgar Neville as well as dramatists Miguel Mihura and Enrique Jardiel Poncela;[94][95][96] many also hail Almodóvar as «the most celebrated Spanish filmmaker since Luis Buñuel».[88][90] Other foreign influences include filmmakers Ingmar Bergman, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Federico Fellini and Fritz Lang.[97]

References to film and allusions to theatre, literature, dance, painting, television and advertising «are central to the world that Almodóvar constructs on screen».[98] Film critic José Arroyo noted that Almodóvar «borrows indiscriminately from film history».[98]

Almodóvar has acknowledged that «cinema is always present in my films [and that] certain films play an active part in my scripts. When I insert an extract from a film, it isn’t a homage but outright theft. It’s part of the story I’m telling, and becomes an active presence rather than a homage which is always something passive. I absorb the films I’ve seen into my own experience, which immediately becomes the experience of my characters».[99]

Almodóvar has alluded to the work of many different artists and genres in his work; sometimes works have been referenced diagetically or evoked through less direct methods.[98] Almodóvar has additionally made self-references to films within his own oeuvre.[100]

Working with some of Spain’s best-known actresses including Carmen Maura, Victoria Abril, Marisa Paredes and Penélope Cruz, Almodóvar has become famous for his female-centric films, his «sympathetic portrayals of women»[85] and his elevation of «the humdrum spaces of overworked women».[101] He was heavily influenced by classic Hollywood films in which everything happens around a female main character, and aims to continue in that tradition.[23] Almodóvar has frequently spoken about how he was surrounded by powerful women in his childhood: «Women were very happy, worked hard and always spoke. They handed me the first sensations and forged my character. The woman represented everything to me, the man was absent and represented authority. I never identified with the male figure: maternity inspires me more than paternity».[102]

Almodóvar in popular culture

A critic from Popmatters notes that Almodóvar is interested in depicting women overcoming tragedies and adversities and the power of close female relationships.[103] Ryan Vlastelica from AVClub wrote: «Many of his characters track a Byzantine plot to a cathartic reunion, a meeting where all can be understood, if not forgiven. They seek redemption».[86] Almodóvar stated that he does not usually write roles for specific actors, but after casting a film, he custom-tailors the characters to suit the actors;[104] he believes his role as a director is a «mirror for the actors – a mirror that can’t lie».[104]

Critics believe Almodóvar has redefined perceptions of Spanish cinema and Spain.[105] Many typical images and symbols of Spain, such as bullfighting, gazpacho and flamenco, have been featured in his films; the majority of his films have also been shot in Madrid.[106] Spanish people have been divided in their opinion of Almodóvar’s work: while some believe that «Almodóvar has renegotiated what it means to be Spanish and reappropriated its ideals» in a post-Franco Spain,[100] others are concerned with how their essence might be dismissed as «another quirky image from a somewhat exotic and colorful culture» to a casual foreigner.[89] Almodóvar has however acknowledged: «[M]y films are very Spanish, but on the other hand they are capriciously personal. You cannot measure Spain by my films».[107] Almodóvar is generally better received by critics outside of Spain, particularly in France and the USA.[89]

Asked to explain the success of his films, Almodóvar says that they are very entertaining: «It’s important not to forget that films are made to entertain. That’s the key».[23] He has also been noted for his tendency to shock audiences in his films by featuring outrageous situations or characters, which have served a political or commercial purpose to «tell viewers that if the people on the screen could endure these terrible travails and still communicate, so could they».[85]

Almodóvar believes all his films to be political, «even the most frivolous movie», but claimed that he had never attempted to pursue outright political causes or fight social injustice in his films; merely wanting to entertain and generate emotion.[104] «I’m not a political director. As a filmmaker, my commitment was to want to create free people, completely autonomous from a moral point of view. They are free regardless of their social class or their profession», remarked Almodóvar.[94] However, he admitted that in his earlier films, which were released just after Franco’s death, he wanted to create a world on film in which Franco and his repression did not exist,[108] thereby «providing a voice for Spain’s marginalized groups».[86]

Almodóvar has incorporated elements of underground and LGBT culture into mainstream forms with wide crossover appeal;[109] academics have recognised the director’s significance in queer cinema.[110][111] Almodóvar dislikes being pigeonholed as a gay filmmaker, but Courtney Young from Pop Matters claimed that he has pushed boundaries by playing with the expectations of gender and sexuality, which places his work in the queer cinematic canon.[112] Young also commented on Almodóvar’s fluid idea of sexuality; within his films, LGBT characters do not need to come out as they are already sexually liberated, «enlivening the narrative with complex figures that move beyond trite depictions of the LGBTQI experience».[112] She also wrote about the importance of the relationships between gay men and straight women in Almodóvar’s films.[112] In conclusion, Young stated, «Almodóvar is an auteur that designates the queer experience as he sees it the dignity, respect, attention, and recognition it so deserves».[112]

He served as the President of the Jury for the 2017 Cannes Film Festival,[113][114] He was elected a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 2001.[1]

Frequent collaborators[edit]

Almodóvar often casts certain actors in many of his films. Actors who have performed in his films 3 or more times in either lead, supporting or cameo roles include Chus Lampreave (8),[115] Antonio Banderas (8), Rossy de Palma (8), Carmen Maura (7), Cecilia Roth (7), Penélope Cruz (7), Julieta Serrano (6), Kiti Manver (5), Fabio McNamara (5), Marisa Paredes (5), Eva Silva (5), Victoria Abril (4), Lola Dueñas (4), Lupe Barrado (4), Bibiana Fernández (Bibi Andersen) (4), Loles León (3) and Javier Cámara (3).[116] Almodóvar is particularly noted for his work with Spanish actresses and they have become affectionately known as «Almodóvar girls» (chicas Almodóvar).[117]

After setting up El Deseo in 1986, Agustín Almodóvar, Pedro’s brother, has produced all of his films since Law of Desire (1986).[118] Esther García has also been involved in the production of Almodóvar films since 1986.[119] Both of them regularly appear in cameo roles in their films.[119][120] His mother, Francisca Caballero, made cameos in four films before she died.

Film editor José Salcedo was responsible for editing all of Almodóvar’s films from 1980 until his death in 2017.[121] Cinematographer José Luis Alcaine has collaborated on a total of six films with Almodóvar, particularly his most recent films. Their earliest collaboration was on Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown (1988), and their most recent on The Human Voice (2020).[122] Angel Luis Fernández was responsible for cinematography in five of Almodóvar’s earlier films in the 1980s, from Labyrinth of Passion (1982) until Law of Desire (1987).[123] In the 1990s, Almodóvar collaborated with Alfredo Mayo on two films and Affonso Beato on three films.

Composer Bernardo Bonezzi wrote the music for six of his earlier films from Labyrinth of Passion (1982) until Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown (1988).[124] His musical style is intertextually imbued with the compositional language of various classical and film composers such as Erik Satie, Igor Stravinsky, Bernard Hermann and Nino Rota.[125] Since The Flower of My Secret (1995), Alberto Iglesias has composed the music for all of Almodóvar’s films.[126]

Art design on Almodóvar’s films has invariably been the responsibility of Antxón Gomez in recent years,[127] though other collaborators include Román Arango, Javier Fernández and Pin Morales. Almodóvar’s frequent collaborators for costume design include José María de Cossío, Sonia Grande and Paco Delgado. Almodóvar has also worked with designers Jean Paul Gaultier and Gianni Versace on a few films.

|

Work Actor |

1980 | 1982 | 1983 | 1984 | 1986 | 1987 | 1988 | 1990 | 1991 | 1993 | 1995 | 1997 | 1999 | 2002 | 2004 | 2006 | 2009 | 2011 | 2013 | 2016 | 2019 | 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Pepi, Luci, Bom |

Labyrinth of Passion |

Dark Habits |

What Have I Done to Deserve This? |

Matador |

Law of Desire |

Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown |

Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down! |

High Heels |

Kika |

The Flower of My Secret |

Live Flesh |

All About My Mother |

Talk to Her |

Bad Education |

Volver |

Broken Embraces |

The Skin I Live In |

I’m So Excited! |

Julieta |

Pain and Glory |

Parallel Mothers |

|

| Victoria Abril | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Antonio Banderas | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lupe Barrado | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Javier Cámara | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Penélope Cruz | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lola Dueñas | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bibiana Fernández | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chus Lampreave | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Loles León | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Fabio McNamara | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kiti Manver | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Carmen Maura | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rossy de Palma | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Marisa Paredes | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cecilia Roth | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Julieta Serrano | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Eva Siva | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Paz Vega |

Personal life[edit]

Almodóvar is openly gay.[128] He describes himself as having been actively bisexual until the age of 34.[129] He has been with his partner, the actor and photographer Fernando Iglesias, since 2002, and often casts him in small roles in his films.[130] The pair live in separate dwellings in neighbouring districts of Madrid; Almodóvar in Argüelles and Iglesias in Malasaña.[131] Almodóvar used to live on Calle de O’Donnell on the eastern side of the city but moved to his €3 million apartment on Paseo del Pintor Rosales in the west in 2007.[132] Almodóvar endorsed Democratic candidate Hillary Clinton in the run-up for the 2016 U.S. presidential election.[133]

In 2009, Almodóvar signed a petition in support of film director Roman Polanski, calling for his release after Polanski was arrested in Switzerland in relation to his 1977 charge for drugging and raping a 13-year-old girl.[134]

Panama Papers scandal

In April 2016, a week before his film Julieta was to be released in Spain, Pedro and Agustín Almodóvar were listed in the leak of the Panama Papers from the database of the offshore law firm Mossack Fonseca; their names showed up on the incorporation documents of a company based in the British Virgin Islands between 1991 and 1994.[135] As a result, Pedro cancelled scheduled press, interviews and photocalls he had made for the release of Julieta in Spain.[136] Agustín released a statement in which he declared himself fully responsible, saying that he has always taken charge of financial matters while Pedro has been dedicated to the creative side and hoping that this would not tarnish his brother’s reputation.[137]

He also stressed that the brothers have always abided by Spanish tax laws. «On the legal front there are no worries», he explained. «It’s a reputation problem which I’m responsible for. I’m really sorry that Pedro has had to suffer the consequences. I have taken full responsibility for what has happened, not because I’m his brother or business partner, but because the responsibility is all mine. I hope that time will put things in its place. We are not under any tax inspection».[138]

The week after the release of Julieta, Pedro gave an interview in which he stated that he knew nothing about the shares as financial matters were handled by his brother, Agustín. However, he emphasised that his ignorance was not an excuse and took full responsibility.[139] Agustín later admitted that he believed Julieta‘s box office earnings in Spain suffered as a result,[138] as the film reportedly had the worst opening of an Almodóvar film at the Spanish box office in 20 years.[140]

Filmography[edit]

Films[edit]

| Year | English title | Director | Writer | Producer | Original title |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | Pepi, Luci, Bom | Yes | Yes | No | Pepi, Luci, Bom y otras chicas del montón |

| 1982 | Labyrinth of Passion | Yes | Yes | Yes | Laberinto de pasiones |

| 1983 | Dark Habits | Yes | Yes | No | Entre tinieblas |

| 1984 | What Have I Done to Deserve This? | Yes | Yes | No | ¿Qué he hecho yo para merecer esto? |

| 1986 | Matador | Yes | Yes | No | Matador |

| 1987 | Law of Desire | Yes | Yes | No | La ley del deseo |

| 1988 | Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown | Yes | Yes | Yes | Mujeres al borde de un ataque de nervios |

| 1989 | Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down! | Yes | Yes | No | ¡Átame! |

| 1991 | High Heels | Yes | Yes | No | Tacones lejanos |

| 1993 | Kika | Yes | Yes | No | Kika |

| 1995 | The Flower of My Secret | Yes | Yes | No | La flor de mi secreto |

| 1997 | Live Flesh | Yes | Yes | No | Carne trémula |

| 1999 | All About My Mother | Yes | Yes | No | Todo sobre mi madre |

| 2002 | Talk to Her | Yes | Yes | No | Hable con ella |

| 2004 | Bad Education | Yes | Yes | Yes | La mala educación |

| 2006 | Volver | Yes | Yes | No | Volver |

| 2009 | Broken Embraces | Yes | Yes | No | Los abrazos rotos |

| 2011 | The Skin I Live In | Yes | Yes | No | La piel que habito |

| 2013 | I’m So Excited! | Yes | Yes | No | Los amantes pasajeros |

| 2016 | Julieta | Yes | Yes | No | Julieta |

| 2019 | Pain and Glory | Yes | Yes | No | Dolor y gloria |

| 2021 | Parallel Mothers | Yes | Yes | Yes | Madres paralelas |

Short films[edit]

| Year | Title | Director | Writer | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1974 | Film político | Yes | Yes | |

| Dos putas, o historia de amor que termina en boda | Yes | Yes | ||

| 1975 | La caída de Sódoma | Yes | Yes | |

| Homenaje | Yes | Yes | ||

| El sueño, o la estrella | Yes | Yes | ||

| Blancor | Yes | Yes | ||

| 1976 | Sea caritativo | Yes | Yes | |

| Muerte en la carretera | Yes | Yes | ||

| 1977 | Sexo va, sexo viene | Yes | Yes | |

| 1978 | Salomé | Yes | Yes | |

| 1996 | Pastas Ardilla | Yes | Yes | TV advert |

| 2009 | La concejala antropófaga | Yes | Yes | Credited as «Mateo Blanco» (director) and as «Harry ‘Huracán’ Caine» (writer) |

| 2020 | The Human Voice | Yes | Yes | |

| TBA | Strange Way of Life | Yes | Yes |

Awards and nominations[edit]

| Year | Title | Academy Awards | BAFTA Awards | Golden Globe Awards | Goya Awards | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominations | Wins | Nominations | Wins | Nominations | Wins | Nominations | Wins | ||

| 1986 | Matador | 1 | |||||||

| 1988 | Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown | 1 | 1 | 1 | 16 | 5 | |||

| 1991 | High Heels | 1 | 5 | ||||||

| 1997 | Live Flesh | 1 | 3 | 1 | |||||

| 1999 | All About My Mother | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 14 | 7 |

| 2002 | Talk to Her | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 7 | 1 | |

| 2004 | Bad Education | 1 | 4 | ||||||

| 2006 | Volver | 1 | 2 | 2 | 14 | 5 | |||

| 2009 | Broken Embraces | 1 | 1 | 5 | 1 | ||||

| 2011 | The Skin I Live In | 1 | 1 | 1 | 16 | 4 | |||

| 2013 | I’m So Excited! | 1 | |||||||

| 2016 | Julieta | 1 | 7 | 1 | |||||

| 2019 | Pain and Glory | 2 | 1 | 2 | 16 | 7 | |||

| 2021 | Parallel Mothers | 2 | 1 | 2 | 8 | ||||

| Total | 9 | 2 | 14 | 5 | 12 | 1 | 117 | 32 |

References[edit]

- ^ a b «Book of Members, 1780–2010: Chapter A» (PDF). American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 15 April 2011.

- ^ «Winners 2013». European Film Awards. European Film Academy. Retrieved 9 December 2013.

- ^ «Biennale Cinema 2019 | Pedro Almodóvar, Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement». La Biennale di Venezia. 14 June 2019. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ Vivarelli, Nick (14 June 2019). «Pedro Almodovar to Receive Lifetime Achievement Award at Venice Film Festival». Variety. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ Wiseman, Andreas (14 June 2019). «Pedro Almodóvar To Receive Venice Film Festival Golden Lion For Lifetime Achievement». Deadline. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- ^ a b c d Ten honorary degrees awarded at Commencement | Harvard Gazette. News.harvard.edu. Retrieved on 22 May 2014.

- ^ Luis Martínez (29 March 2016). «Pedro Almodóvar, doctor honoris causa por Oxford | Cultura | EL MUNDO». Elmundo.es. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ «Pedro Almodóvar Biography». Biography.com. Archived from the original on 28 January 2019. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- ^ José Luis Romo (8 April 2016). «Agustín Almodóvar, ‘Todo sobre mi hermano’ | loc | EL MUNDO». Elmundo.es. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ Chitra Ramaswamy (28 April 2013). «Pedro Almodóvar on his new film ‘I’m so Excited!’«. Scotsman.com. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- ^ a b Lynn Hirschberg (5 September 2004). «The Redeemer : Pedro Almodovar : Cannes: The Slow Drive to Triumph». The New York Times. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- ^ Giles Tremlett (27 April 2013). «Pedro Almodóvar: ‘It’s my gayest film ever’ | Film». The Guardian. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- ^ D’Lugo, Pedro Almodóvar, p. 13

- ^ Allison, A Spanish Labyrinth, p. 7

- ^ D’Lugo, Pedro Almodóvar, p. 14

- ^ «Almodóvar rescatará tres filmes en súper 8 anteriores a su primera película». Elmundo.es. 18 October 2006. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- ^ «Pedro Almodóvar interview for The Skin I Live In». The Telegraph. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- ^ Andrew Dickson (10 December 2014). «Women on the verge of song and dance: Almodóvar’s world is pure theatre | Stage». The Guardian. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- ^ «Almodóvar no da crédito: Su principal compañero de la ‘Movida’ se ha convertido en «portavoz delirante de Gallardón» : Periódico digital progresista». Archived from the original on 29 December 2014. Retrieved 29 December 2014.

- ^ «Pedro Almodóvar, el genio del cine español». Elmundo.es. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- ^ «The Call of the Wild How Did Pedro Almodovar Go From Phone-company Worker To Spain’s Hottest Director?». Articles.philly.com. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- ^ «Almodóvar celebrates 61 years with «I’m So Excited» (Video)» (in Spanish). Laopinion.com. Archived from the original on 3 January 2015. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- ^ a b c Sigal Ratner-Arias (19 November 2009), Director Pedro Almodovar is haunted by one taboo, Associated Press

- ^ Edwards, Almodóvar: Labyrinth of Passion, p. 12

- ^ Almodóvar Secreto: Cobos and Marias, p. 76- 78

- ^ Allison, A Spanish Labyrinth, p. 9

- ^ Raphael Abraham (2 January 2015). «Tea with the FT: Pedro Almodóvar». FT.com. Archived from the original on 11 December 2022. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- ^ «Pepi, Luci, Bom – Film Calendar». The Austin Chronicle. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ D’Lugo, Pedro Almodóvar, p. 19

- ^ «FILM – Carmen Maura – Good Times for a ‘Bad Woman’«. The New York Times. SPAIN. 23 October 1988. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ D’Lugo, Pedro Almodóvar, p. 26

- ^ «Early Almodóvar – Harvard Film Archive». Hcl.harvard.edu. Archived from the original on 6 May 2016. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ a b Almodóvar on Almodóvar: Strauss, p.28

- ^ Dorothy Chartrand (3 November 2011). «Antonio Banderas takes a leap of faith in The Skin I Live In | Georgia Straight Vancouver’s News & Entertainment Weekly». Straight.com. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ David Parkinson (29 May 2013). «Dark Habits – A Sister Act of Sacrilegious Salvation». Moviemail.com. Archived from the original on 13 May 2016. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ Almodóvar, Pedro (7 August 1996). «Vuelve ‘Entre tinieblas’ | Edición impresa | EL PAÍS». El País. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ «Ted Anton on Truman Capote’s «A Day’s Work»«. Assay: A Journal of Nonfiction Studies. 27 April 2015. Retrieved 19 December 2017.

- ^ D’Lugo, Pedro Almodóvar, p. 96

- ^ Strauss, Almodóvar on Almodóvar, p. 15

- ^ Almodóvar Secreto: Cobos and Marias, p.100

- ^ «Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown (1988)». Box Office Mojo. 11 November 1988. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ «The 61st Academy Awards (1989) Nominees and Winners». oscars.org. Archived from the original on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 20 August 2015.

- ^ «X Film Rating Dropped and Replaced by NC-17 : Movies: Designation would bar children under 17. Move expected to clear the way for strong adult themes. – latimes». Articles.latimes.com. 27 September 1990. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- ^ Pedro Almodóvar, All About my Mother

- ^ «Festival de Cannes: All About My Mother». festival-cannes.com. Archived from the original on 22 August 2011. Retrieved 8 October 2009.

- ^ «All About My Mother (1999)». Box Office Mojo. 28 August 2002. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ a b D’Lugo, Pedro Almodóvar, p. 105

- ^ a b c Lyttelton, Oliver (14 October 2011). «The Films of Pedro Almodóvar: A Retrospective». IndieWire. Archived from the original on 8 January 2012. Retrieved 20 November 2012.

- ^ «Talk to Her (2002)». Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ D’Lugo, Pedro Almodóvar, p. 117

- ^ Strauss, Almodóvar on Almodóvar, p. 212

- ^ De La Fuente, Anna Marie (4 November 2004). «Almodovar puts ‘Education’ to use». Variety. Archived from the original on 20 June 2009. Retrieved 20 June 2009.

- ^ «Festival de Cannes: Bad Education». festival-cannes.com. Archived from the original on 10 October 2012. Retrieved 5 December 2009.

- ^ «Bad Education (2004)». Box Office Mojo. 25 April 2005. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ «Volver (2006)». Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ «Review: Broken Embraces». Film Comment. Retrieved 22 November 2020.

- ^ «Festival de Cannes: Broken Embraces». festival-cannes.com. Archived from the original on 4 July 2009. Retrieved 9 May 2009.

- ^ «Broken Embraces (2009)». Box Office Mojo. 27 May 2010. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ «Broken Embraces movie review». rogerebert.com. Retrieved 22 November 2020.

- ^ «Bafta Film Awards: 2010 winners». BBC News. 21 February 2010. Retrieved 22 November 2020.

- ^ «Golden Globes nominations: the 2010 list in full». The Guardian. 15 December 2009. Retrieved 22 November 2020.

- ^ «Mygale (Tarantula) (The Skin I Live In) – Thierry Jonquet». Complete-review.com. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- ^ a b c Almodóvar, Some Notes About The Skin I Live In, p. 94-95

- ^ «Review: The Skin I Live In». Film Comment. Retrieved 22 November 2020.

- ^ Barton, Steve (5 May 2010). «Antonio Banderas To Carve Up The Skin I Live In». Dreadcentral.com. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- ^ «Pedro Almodóvar Finally Unites Penélope Cruz and Antonio Banderas». W Magazine. Retrieved 22 November 2020.

- ^ «The Skin I Live In (2011)». Box Office Mojo. 29 March 2012. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ «Almodóvar hoping for fifth Bafta with «The Skin I Live In»«. thinkSpain. Archived from the original on 30 November 2020. Retrieved 22 November 2020.

- ^ «The Skin I Live In». Goldenglobes.com. Retrieved 22 November 2020.

- ^ Sarda, Juan. (14 February 2012) Almodovar laughs with The Brief Lovers | News | Screen. Screendaily.com. Retrieved on 22 May 2014.

- ^ «Out of Frame: I’m So Excited». dcist. Archived from the original on 21 September 2020. Retrieved 22 November 2020.

- ^ «I’m So Excited (2013)». Box Office Mojo. 7 November 2013. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ «Pedro Almodovar Announces New Cast for Film ‘Silencio’ : Entertainment». Latinpost.com. 29 March 2015. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- ^ Raphael Abraham (2 January 2015). «Tea with the FT: Pedro Almodóvar». FT.com. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- ^ «‘Silencio’: Pedro Almodóvar is filming | In English | EL PAÍS». Elpais.com. 27 March 2015. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- ^ «Rossy de Palma: «A Almodóvar nunca le he pedido nada» | Vanity Fair». Revistavanityfair.es. 16 January 2015. Archived from the original on 24 January 2015. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- ^ Schonfeld, Zach (23 December 2016). «Review: ‘Julieta’ is Pedro Almodovar’s Best Film in Years». Newsweek.

- ^ Belinchón, Gregorio (7 September 2016). «‘Julieta’ representará a España en los Oscar». El País. Retrieved 20 September 2016.

- ^ Marie De La Fuente, Anna (13 December 2018). «Sony Pictures to Release Pedro Almodovar’s ‘Pain & Glory’ (EXCLUSIVE)». Variety. Retrieved 13 December 2018.

- ^ «Cannes festival 2019: full list of films». The Guardian. Retrieved 18 April 2019.

- ^ «Director Pedro Almodóvar on semi-autobiographical film ‘Pain and Glory – and refusing to work in Hollywood». Channel 4. 23 August 2019. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- ^ a b Hopewell, John (30 June 2020). «Pedro Almodovar, Penelope Cruz Look to Team Up on Motherhood-Themed ‘Madres Paralelas’«. Variety. Retrieved 9 July 2020.

- ^ «Penélope Cruz in Pedro Almodóvar’s ‘Parallel Mothers’ (‘Madres Paralelas’): Film Review — Venice 2021». The Hollywood Reporter. September 2021. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- ^ «Los 9 temas más reconocibles del cine de Almodóvar — Cinefilia — Fotogramas». Archived from the original on 25 April 2016. Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- ^ a b c d Thomas, June (13 October 2011). «Pedro Almodovar’s filmography: What I learned from watching all his films». Slate.com. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ a b c Vlastelica, Ryan (11 January 2016). «A beginner’s guide to the twisty melodrama of Pedro Almodóvar · Primer». Avclub.com. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ Limnander, Armand (30 April 2009). «ABCD». The New York Times. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ a b [1][dead link]

- ^ a b c «Lost in Translation». PopMatters. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ a b «All About Almodóvar». Dga.org. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ «Almodovar Looks To Films of Wilder For Motivation». Articles.chicagotribune.com. 2 March 1989. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ «Pedro Almodóvar : ‘Mis influencias han sido Andy Warhol y Lola Flores’«. Elcultural.com. 13 November 2008. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ Tim Robey; David Gritten. «Love in a time of intolerance». The Telegraph. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ a b c «ALMODOVAR : SA GRANDE CONFESSION | Le meilleur magazine de cinéma du monde». Sofilm.fr. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ «Pedro Almodóvar • Great Director profile • Senses of Cinema». Sensesofcinema.com. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ John Hopewell (15 October 2014). «Pedro Almodóvar Talks About Spanish Cinema He Loves». Variety. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ «Viva Pedro: The Almodóvar Interview». PopMatters. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ a b c «Referencing & Recycling». PopMatters. 16 November 2009. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ Almodóvar on Almódovar: Strauss, p. 45

- ^ a b «Pedro Almodovar’s Renegotiation of the Spanish Identity». Movies in 203. 11 January 2011. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ Crooke, Daniel (15 May 2017). «Pedro Party: What Have I Done To Deserve This? & Volver». filmexpereince.net. Retrieved 15 May 2017.

- ^ «Almodóvar: puedo sobrevivir sin Palma de Oro pero no sin cine | La Nación». Lanacion.com.py. 7 May 2016. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ «Woman or Object: Selected Female Roles in the Films of Pedro Almodóvar». PopMatters. 17 November 2009. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ a b c «Pedro Almodovar Discusses Career Influences, Women’s Natural Acting Skills». Hollywood Reporter. 18 November 2012. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ Film: Bergan, p.252

- ^ Benji Lanyado. «All about Madrid | Travel». The Guardian. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ Almodovar, Pedro (Spring 1994). «Interview with Ela Troyano». BOMB Magazine. Archived from the original on 25 May 2012. Retrieved 4 May 2012.

- ^ Jim Nelson; Ruven Afandor (29 May 2013). «The GQ+A: Pedro Almodovar». GQ. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ «Almodóvar y el sexo». Elmundo.es. 22 December 2006. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ «Pedro Almodóvar: queer pioneer – Parade@Portsmouth». Eprints.port.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 1 July 2016. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ «Lambda Literary». Lambda Literary. 5 August 2015. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ a b c d Bad Education (17 November 2009). «Pedro Almodóvar’s Quintessentially Pansexual Oeuvre». PopMatters. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ «Pedro Almodóvar President of the Jury of the 70th Festival de Cannes». Cannes. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 31 January 2017.

- ^ «Pedro Almodóvar, Leone d’oro a Venezia: «Sarà la mia mascotte insieme ai gatti»«. La Repubblica. 14 June 2019. Retrieved 14 June 2019.

- ^ Thomas, June (4 April 2016). «Almodovar muse Chus Lampreave is dead at 85». Slate.com. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ «Heroines of Cinema: Almodóvar’s Seven Favorite Actresses». Indiewire. 14 November 2013. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ Lindo, Elvira (31 October 2015). «Ser chica Almodóvar | Estilo | EL PAÍS». El País. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ Esteban Ramón (19 December 2013). «Agustín Almodóvar: «Hemos perdido el derecho moral sobre nuestras películas»«. RTVE.es. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ a b «Esther García (El Deseo): «Almodóvar convierte en una obra cinematográfica lo que quiere con total libertad»«. Europapress.es (in Spanish). 20 November 2015. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ Raphael Abraham (2 January 2015). «Tea with the FT: Pedro Almodóvar». Financial Times. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ «Actualidad en el cine español». Archived from the original on 26 April 2016. Retrieved 19 April 2016.