ПРОЛОГ

ИЗ ЗАТЕМНЕНИЯ

НАТ. КСЭНАДУ — РАССВЕТ — 1940 (МИНИАТЮРА)

Фильм открывается мрачными аккордами авторства композитора Бернарда Херрманна. Все вокруг это почти полностью черный экран. Теперь, когда камера медленно движется в сторону окна, которое в кадре почти как почтовая марка, появляются другие предметы; колючая проволока, циклон ограждений, и на фоне раннего утреннего неба, огромная железная решетка. Камера перемещается вверх, и в кадре появляется знак гигантских пропорций, который находится на вершине ограждения — это огромная начальная буква “К” (в слове КСЭНАДУ), которая становится все темнее и темнее. Благодаря рассвету мы видим сказочную горную вершину в “Ксэнаду”, а на туманном холме видим зубчатый силуэт замка, расположенного на вершине этого холма.

СМЕНА КАДРА

(СЕРИЯ СМЕНЯЮЩИХСЯ КАДРОВ, КАЖДЫЙ РАЗ ВСЕ КРУПНЕЕ)

Все, что мы видим является частной собственностью ЧАРЛЬЗА ФОСТЕРА КЕЙНА.

Сцена напоминает готический фильм ужасов, в котором такой замок вполне бы мог принадлежать графу Дракуле.

Территория, где построен особняк, раскинулась почти на сорок миль на побережье Мексиканского залива, и это действительно огромная территория, невозможно разглядеть где ее граница.

Это была скучная болотистая местность пока Кейн не выкупил эту территорию и невероятно сильно преобразил ее — теперь это красивое место с холмами, горами и это все штучное. Вся земля была украшена вечнозелеными растениями, которые растут в парках. Также было создано озеро, где водилось много разнообразной рыбы. На самом верху самой высокой горы расположился замок, а точнее комплекс замков — они невероятно огромны, красивые, оформлены в европейском стиле.

СМЕНА КАДРА

ПОЛЕ ДЛЯ ГОЛЬФА

Теперь мы видим большое и красивое поле для гольфа, которое зарастает зеленью и дикими тропическими сорняками, за которыми не смотрят уже длительный период.

СМЕНА КАДРА

ТО ЧТО РАНЬШЕ БЫЛО БОЛЬШИМ ЗООПАРКОМ

Огромная красивая территория окруженная рвами, которая использовалась как зоопарк, со множеством диких животных, которые бродили здесь. По табличкам можно понять, что здесь когда-то были тигры, львы, жирафы).

СМЕНА КАДРА

ТЕРРАСА ОБЕЗЬЯН

На ветке сидит обезьяна, она почесывается медленно, задумчиво, смотрит куда-то вдаль владений Чарльза Кейна. Вторая обезьяна смотрит на свет в далеко расположенном замке, свет исходит от одного единственного светящегося окна в замке.

СМЕНА КАДРА

КАНАВА АЛЛИГАТОРОВ

Куча больших аллигаторов, спящих у озера. В мутной воде отражение светящегося окна в замке.

СМЕНА КАДРА

ЛАГУНА

Мутная вода в лагуне. Старые газеты плавают на поверхности воды — копии “New York Enquirer”. Лодка покачивается. В воде снова отражение светящегося окна в замке, но уже размера побольше, что говорит что мы находимся ближе к замку.

СМЕНА КАДРА

БОЛЬШОЙ БАССЕЙН

Емкость бассейна пуста — воды нет. На дне емкости валяются газеты, которые ветер бросает по стенкам.

КОТТЕДЖИ

Несколько коттеджей находящихся в тени замка. Мы видим, что их двери и окна заколочены и заперты, с тяжелыми балками на дверях для дополнительной защиты.

СМЕНА ПЛАНА

ПОДЪЕМНЫЙ МОСТ

Этот красивый мост расположен над широким рвом, в настоящий момент заросший сорняками и травой. Мы продвигаемся по мосту и попадаем в красивые ворота, которые ведут в прекрасный сад. Сад сохранился в отличном состоянии, хотя и заметно по некоторым местам, что за садом уже длительное время никто не смотрит. Поскольку мы передвигаемся все ближе к освещенному окну в замке мы замечаем, что в саду много экзотических и редкостных растений, которые были завезены из тропических лесов.

СМЕНА ПЛАНА

ОКНО

Вот мы уже почти у самого окна. Вдруг свет внутри комнаты гаснет. Это останавливает движение камеры и прекращает звучание музыки, сопровождавшей нас все это время. В окне мы видим отражение тусклого ландшафта усадьбы Мистера Кейна.

СМЕНА ПЛАНА

ИНТ. СПАЛЬНЯ КЕЙНА — РАССВЕТ — 1940

Очень длинный выступ огромной кровати Кейна вырисовывается из огромного окна.

СМЕНА ПЛАНА

ИНТ. СПАЛЬНЯ КЕЙНА — РАССВЕТ — 1940

Снежная сцена. Идет невероятно красивый крупный снег. Большие хлопья снега падают на землю, украшая дом, вдруг резко камера выхватывает дом и мы видим, что это стеклянная игрушка, которая продается в магазинах.

ГОЛОС СТАРОГО КЕЙНА

Розовый бутон.

Игрушка в руке — рука принадлежит Кейну, он расслабляет руку и игрушка выпадает и падает на мраморный пол где и разбивается на мелкие кусочки.

Видим ноги Кейна на кровати.

В отражении на стекле мы видим входную дверь в спальню. Дверь распахивается и в комнату заходит МЕДСЕСТРА. Она спокойно подходит к мертвому телу Кейна и накрывает его простыней.

ЗАТМ.

ИЗ ЗАТМ.

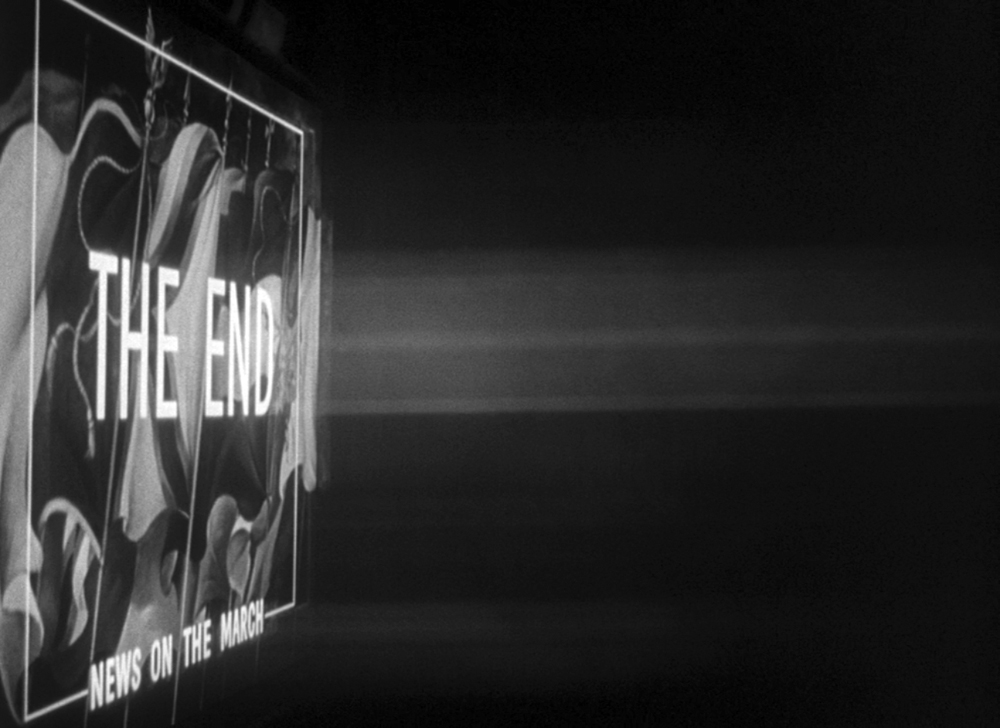

ИНТ. АППАРАТНАЯ

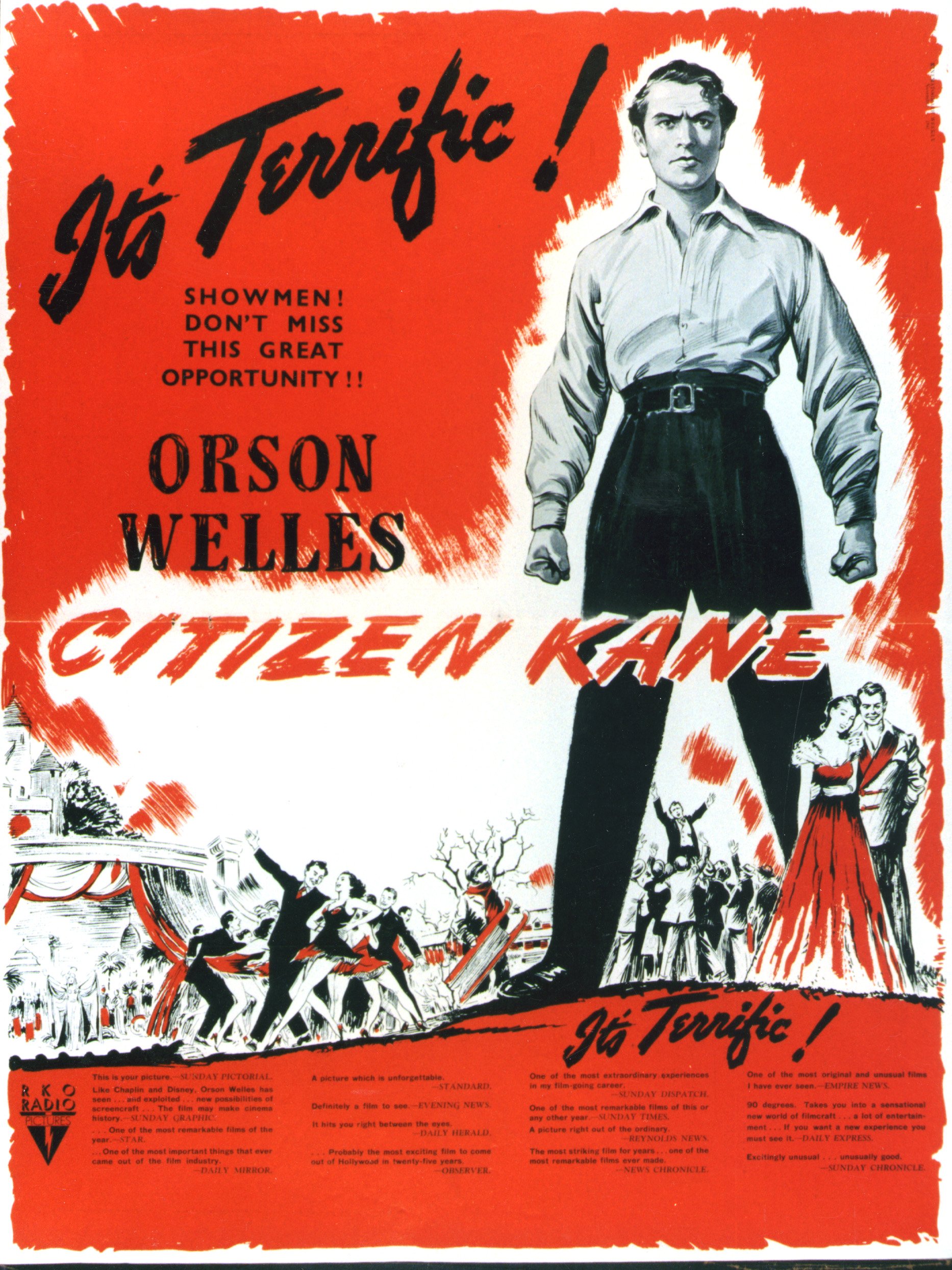

На экране появляется ОСНОВНОЕ НАЗВАНИЕ фильма. Затем под саундтрек появляется огромная надпись ПОСЛЕДНИЕ НОВОСТИ

ПРИМЕЧАНИЕ:

Здесь идет типичная сводка новостей ежемесячных газет, которые рассказывают о публичных людях и мероприятиях. Они отличаются от обычных тем, что они полностью отредактированы, разработаны и с сюжетом. Например, газета используемая здесь, отлично подобрала информацию о произошедшем, информация использована этой газетой, была собрана из многих других мелких газет, что мы и будем видеть. Рассказчик будет использовать названия этих газет и заглавия статей и будет объяснять их значения.

ТИТР

Новости на марше.

ТИТР: НАЗВАНИЕ СТАТЬИ

Некролог “Владелец “Ксэнаду”.

РАССКАЗЧИК

В поместье “Ксэнаду” Кубла Хан воздвиг величественный дворец удовольствий.

(цитирует описание)

Поместье “Ксэнаду”, воздвигнутое Кубла Ханом, стало легендарным. Сегодня этот дворец во Флориде — самое большое частное владение. Здесь, на пустынных берегах, построили частную гору для Кейна. 100 тысяч деревьев, 20 тысяч тон мрамора являются основой горы.

РАССКАЗЧИК

Дворец ”Ксэнаду” украшают картины, статуи, экспонаты частных коллекций в таком количестве, что не скоро все это можно будет оценить и каталогизировать. Тут хватит на 10 музеев. Живой инвентарь. Пернатые твари. Рыбы морские. Всякого рода животные. Самый большой частный зоопарк со времен Ноя.

СЕРИЯ кадром, показывающих различные аспекты поместья “Ксэнаду”

РАССКАЗЧИК

Подобно фараонам, хозяин заготовил камни для собственной гробницы. Со времен пирамид, это самый дорогой монумент, который человек возводил для себя. На прошлой неделе в “Ксэнаду” прошли самые роскошные и странные похороны 1941 года. На прошлой неделе отошел в мир иной владелец “Ксэнаду”.

Все, что Рассказчик рассказывает, мы видим на экране.

РАССКАЗЧИК

Один из столпов нашего века, американский Кубла Хан — Чарльз Фостер Кейн.

ТИТР:

Для 44 миллионов американских читателей сам Кейн был значительно интересней, чем любая знаменитость, о которой писали его газеты.

РАССКАЗЧИК

Свою карьеру он начал в ветхом здании этой газетенки. А теперь империя Кейна насчитывает 37 газет, 2 печатных агенства, радиостанцию.

На экране показываются такие события:

1891-1911 — карта США, охватывающих весь экран, которая в анимированой схеме показывает как империя Кейна распространяется от города к городу. Начиная от Нью-Йорка, затем Чикаго, Детройт, Сент-Луис, Лос-Анджелес, Сан Франциско, Вашингтон, Атланта, Эль-Пасо, и т.д.

Кадр из большой шахты работающей на полную мощность, дымоходы выпускаю дым, поезда движутся и так далее.

Кадры Томаса Фостера Кейна и его жены Марии, в день их свадьбы. Аналогичная картина Мария Kейн — прошло уже около четырех или пяти лет, с ней мальчик, Чарльз Фостер Кейн.

РАССКАЗЧИК

Своего рода империя в империи. Он владел бакалейными лавками, бумажными фабриками, жилыми домами,заводами, лесами, океанскими лайнерами. В течение 50-ти лет империю Кейна питал бесконечный поток золота из третьего по величине золотоносного рудника. О происхождении богатств Кейна ходит легенда. В 1868 году хозяйка гостиницы Мэри Кейн получила от задолжавшего постояльца ничего не стоящие документы на заброшенный рудник “Колорадо”.

КРУПНЫЙ ПЛАН ЛИЦА КЕЙНА.

Изображение на первой титульной странице газеты “Enquirer”. Текс говорит о том, что умер самый влиятельный человек.

Далее следуют вырезки из различных газет. Большое количество заголовков, разного шрифта, на на разных языках, но все они освещают смерть Кейна. Все статьи сопровождают фотографии Кейна. Важный факт — многие из этих газет имеют противоречивые мнения о Кейне. Таким образом, заголовки содержат такие слова “патриот”, “демократ”, “пацифист”, “предатель”, “идеалист”, “американец” и т.д.

РАССКАЗЧИК

57 лет спустя, выступая в сенатской комиссии, Уолтер Тэтчер, бывший много лет мишенью для нападок газет Кейна, вспоминал о поездке, совершенной в юности.

Вставка из Капитолия, в Вашингтоне округ Колумбия.

Вставка из Конгресса Следственного комитета. Уолтер П. Тэтчер на стенде. Он находится рядом возле своего сына, Уолтера Тэтчера младшего, и другими партнерами. В настоящее время он ведет дискуссию с конгрессменом Мэрри Эндрю.

ТЕТЧЕР

Миссис Кейн поручила моей фирме управление крупной суммой денег, а также заботу о своем сыне — Чарльзе Фостере Кейне.

ОБВИНИТЕЛЬ

Что по этому случаю этот Кейн напал на Вас и ударил в живот санками?

Гул смеха.

ТЕТЧЕР

Господин председатель, я должен зачитать подготовленное заявление. Я отказываюсь отвечать на другие вопросы.

Молодой помощник подносит ему листок бумаги. Тетчер читает с листа.

ТЕТЧЕР

(читает)

Мистер Чарльз Фостер Кейн, нападающий на американские традиции частной собственности и инициативы, по сути своих убеждений является самым махровым коммунистом.

СМЕНА ПЛАНА

НАТ. ОГРОМНАЯ ПЛОЩАДЬ — ДЕНЬ

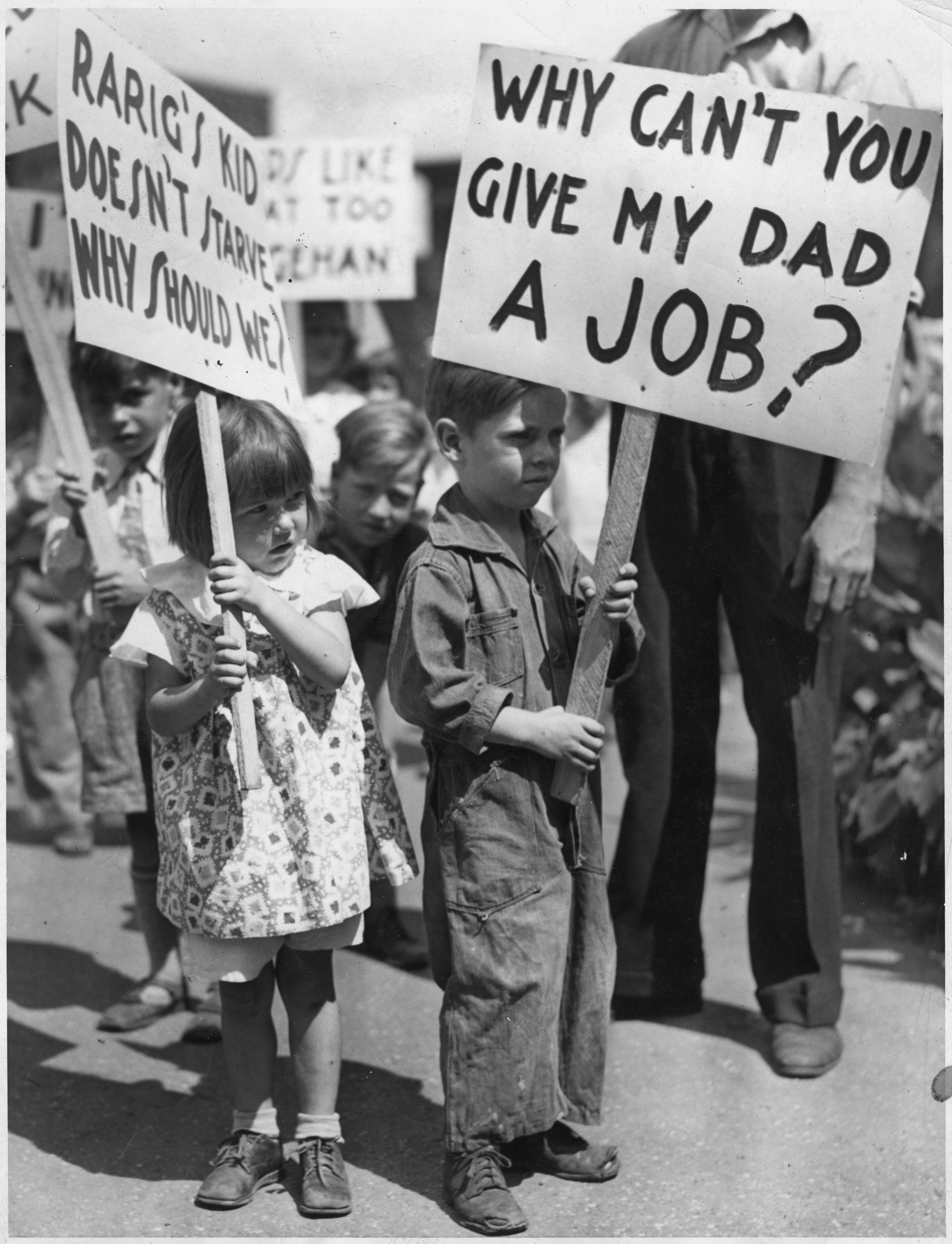

Огромная толпа людей ходят по площади с плакатами и призывами бойкотировать газеты Кейна.

РАССКАЗЧИК

В тот же месяц на Юнион-квер…

На трибуне установленной на площади, стоит молодой человек СПИКЕР, и обращается к толпе.

СПИКЕР

Слова “Чарльз Фостер Кейн” стали угрозой для американского рабочего. Кейн такой, каким был всегда, и таким останется — фашистом.

РАССКАЗЧИК

А вот другое мнение:

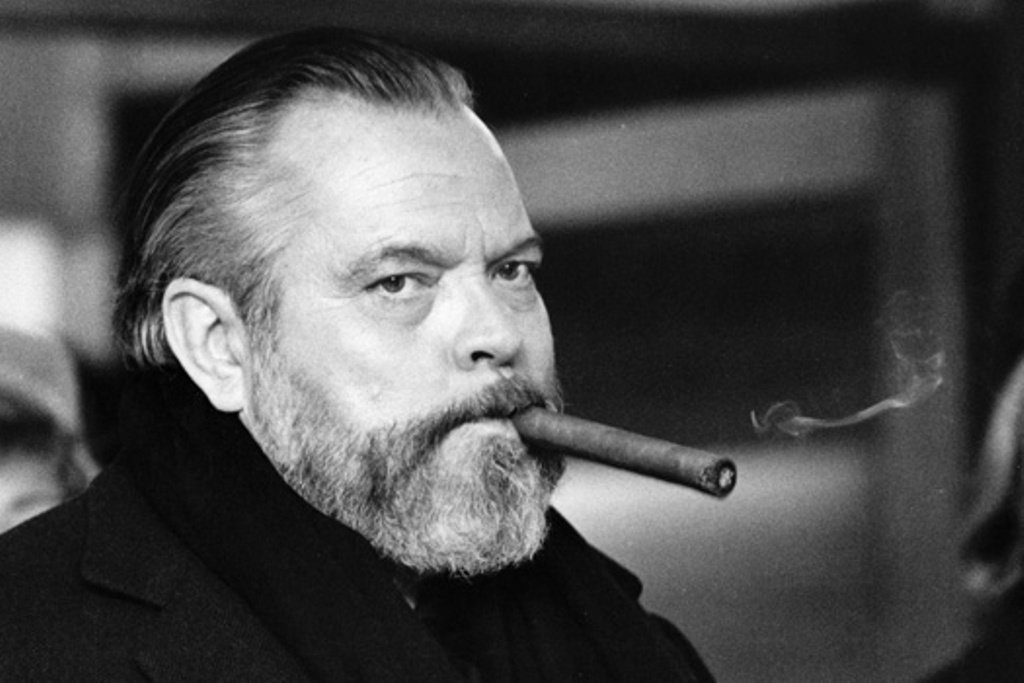

Без звучный кадр, когда Кейн стоит на платформе, установленной у здания редакции газеты “Enquirer”. Кейн одет великолепно. Мы не слышим, что он говорит.

ТИТР НА ВЕСЬ ЭКРАН:

“Я всегда был и буду только американцем”. Ч.Ф. Кейн.

СМЕНА КАДРА

ИНТ. ЭЛИТНОЕ ЗАВЕДЕНИЕ — ВЕЧЕР

Кейн жмет руку какому-то важному человеку. Здесь он выглядит уже постарше, толще. Он уставший, выглядит одиноким и несчастным в разгар веселья.

РАССКАЗЧИК

1895 по 1941 — все эти годы он скрывал, кем является. Кейн подталкивал страну вступить в одну войну, отговаривал от участия в другой. Выиграл выборы не для одного президента. Боролся за интересы миллионов. Еще больше — ненавидели его. За 40 лет не было такого общественного деятеля, о котором газеты Кейна не писали бы. Часто этих людей сам Кейн поддерживал, а потом разоблачал. Часто поддерживал… а потом разоблачал.

ТИТР: Его частная жизнь стала достоянием народа.

ВСТАВКА

Несколько кадров с Емили Нортон (1900)

РАССКАЗЧИК

Дважды женился, дважды разводился. На племяннице президента Эмили Нортон. Бросила его в 1916 году. Погибла с сыном в автокатастрофе в 1918 году. Через 16 лет после первого брака, 2 недели после первого развода Кейн женится на певице театра Трентона в Нью-Джерси.

СМЕНА КАДРА

Реконструкция событий в виде кинохроники без слов.

Кейн, Сьюзен и Бернштейн появляются в дверном проеме здания мэрии, их окружают пресс-фотографы, репортеры и т.д. Кейн выглядит встревоженным, он подходит к одному из репортеров, выхватывает палку с микрофоном и начинает отбиваться от репортеров, размахивает ею по сторонам пытаясь зацепить каждого присутствующего.

РАССКАЗЧИК

Для нее, оперной певицы Cьюзан Александер, Кейн построил здание Городской оперы в Чикаго, стоявшее ему 3 миллиона долларов. Замок “Ксэнаду”, сооруженный для Cьюзан Александер Кейн, о стоимости которого можно лишь догадываться, так и не был достроен.

НАРЕЗКА ЭПИЗОДОВ ИЗ ПОЛИТИЧЕСКОЙ ЖИЗНИ КЕЙНА

Испано-американская война (кадры из взрывами, 1898)

Кладбище во Франции погибших в Первой мировой войне и множество крестов. (1919)

Кадры из политической карьеры. Много газетных заголовков, с которых мы понимает, что у Кейна активная политическая карьера.

РАССКАЗЧИК

В политике он был чуть-чуть в тени. Кейн, творец общественного мнения, в жизни был обойден избирателями. Однако его газеты имели большой вес. За ним,баллотировавшимся в губернаторы в 1916 году, стояли лучшие люди страны. Белый Дом был следующим шагом в его политической карьере. Но внезапно, за неделю до выборов, постыдный оглушительный провал отодвинул на 20 лет реформы в США. Навсегда отказав в политической карьере Кейну.

Вставка кадра: ночью среди большой площади толпа людей палит чучело, очень похожее на Чарльза Кейна. Он горит, затем заваливается и догорает.

ЗАТМ.

ИЗ ЗАТМ.

Кадры кинохроники — огромные толпы в здании Мэдисон Сквер Гарден, звучат выстрелы, стрелок выстрелил в огромный плакат на котором изображен Кейн.

Несколько кадров портретов маленьких детей Кейна. Толпа ликует.

РАССКАЗЧИК

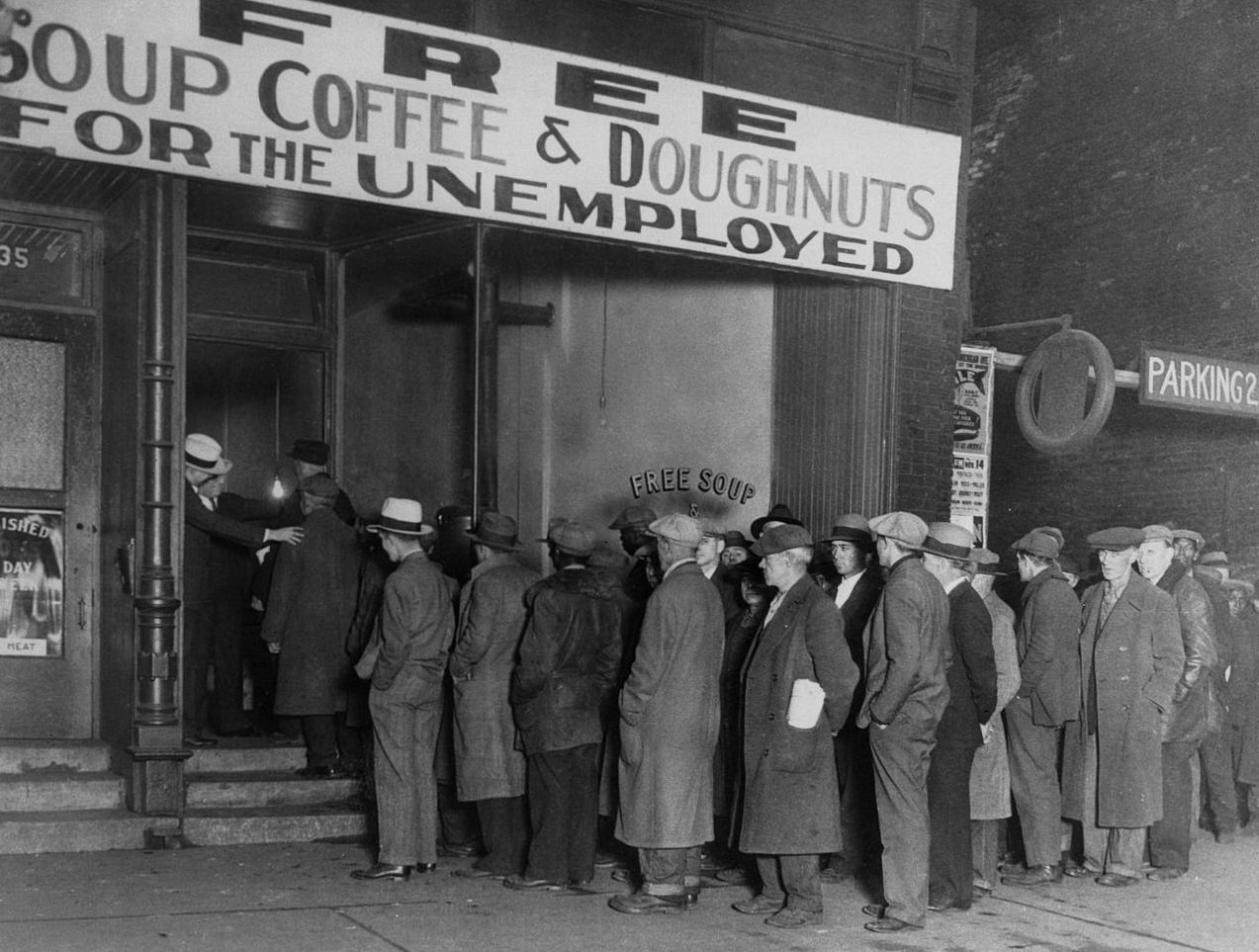

Затем, в первый год великой депрессии, закрываются газеты Кейна. Исчезло 11 газет Кейна. Еще больше продано или влачат жалкое существование. Но Америка их читает, а он сам остается главной новостью.

Нарезка эпизодов.

Фотография Кейна в газете во время его доклада….

Несколько вставок газетных заголовков. На фотографиях изображены Кейн и Сюзан.

Видим как печатается газета, статья в которой осветляет тему Большой Депрессии.

Показываем карту США 1932-1939 гг.. Вдруг карта изображающая владения империи Кейна, начинает показывать, что империя сокращается.

Дверь офиса большой известной газеты на которой написано: “Закрыто”

РАССКАЗЧИК

Кейн помог изменить мир. Но теперь мир Кейна ушел в историю, и жизнь самого магната стала достоянием истории. Один в своем недостроенном дворце, никем не навещаемый, не фотографируемый, он пытался управлять разваливающейся империей. Он тщетно пытался повлиять на судьбу нации, она перестала слушать его, перестала верить.

ИНТ. ЗАЛ ДЛЯ ПРЕСС-КОНФЕРЕНЦИЙ — ДЕНЬ

Большой зал. В зале много народа, в основном это репортеры и журналисты. Все они смотрят и фотографирую Кейна.

Он стоит на сцене и отвечает на вопросы.

РЕПОРТЕР

Это правда?

КЕЙН

Не верьте радио, читайте “Инквайер”.

ДРУГОЙ РЕПОРТЕР

Ваша оценка экономических условий в Европе?

КЕЙН

Как я оцениваю экономические условия, Мистер Бомс? Как оценщик.

ТРЕТИЙ РЕПОРТЕР

Вы рады, что вернулись?

КЕЙН

Я всегда рад, я же американец. И всегда им был. Что-нибудь еще? Когда я был репортером, мы задавали вопросы быстрее.

ЧЕТВЕРТЫЙ РЕПОРТЕР

Возможна война в Европе?

КЕЙН

Я встречался с руководителями Англии, Франции, Германии, Италии. Они благоразумны и не допустят гибели цивилизации. Могу поручиться — войны не будет.

СМЕНА КАДРА

СЕРИЯ КАДРОВ, кадры современные, на них нервный и расстроен Кейн сидит закутанным в плед, затем он встает и гуляет среди кустов духмяной розы.

РАССКАЗЧИК

И вот, на прошлой неделе, к Чарльзу Фостеру Кейну тихо и обыденно пришла смерть.

Конец новостей на марше.

СМЕНА КАДРА

ИНТ. ПРОСТОРНЫЙ ЗАЛ — ДЕНЬ — 1940

Черный экран. По мере того как камера отъезжает, в кадре появляется большой портрет Кейна. Затем портрет становится все меньше и мы постепенно оказываемся в просторной комнате, где сидят несколько пожилых мужчин. Они сидят за большим столом посреди комнаты.

Примечание: за столом находятся редакторы “News Digest” и несколько человек из журнала “Роулстон” (Rawlston). Некоторые мужчины сидят, другие встают и передвигаются по комнате.

Довольно просторный зал. Все эти люди только что смотрели кино, документальное кино о жизни Чарльза Кейна. Все, что было до данного момента, это был фильм о жизни Кейна.

Еще один человек находится у телефона и разговаривает по нем.

ТРЕТИЙ МУЖЧИНА

(по телефону)

Ну и все. Не уходите, я наберу вас, если нам понадобится взглянуть этот фильм еще раз.

(вешает трубку)

ТОМПСОН

Что скажите, мистер Роулстон?

Маленькая пауза.

МУЖСКОЙ ГОЛОС

Трудно уместить в одном ролике 70 лет жизни человека.

Начинается гул, все собравшиеся мужчины соглашаются с этим предложением.

Роулстон встает из-за стола и исчезает где-то в комнате. Мы видим мужчин, они беседуют друг с другом и разобрать о чем они говорят не реально. На экране застыло изображение Кейна.

Но все же некоторые реплики все таки можно различить.

ГОЛОС

Хороший ролик.

МУЖСКОЙ ГОЛОС

Только нужно найти угол зрения.

ДРУГОЙ ГОЛОС

Мы видели, что Кейн умер.

ЕЩЕ ОДИН ГОЛОС

Я читал об этом в газетах.

ДРУГОЙ ГОЛОС

Мало сказать, что сделал человек, интересно, каким он был.

ГОЛОС

Нужен ракурс.

Снова все превращается в сплошной гул голосов.

РОУЛСТОН (ВПЗ)

Минутку…

Все затихают и переводят взгляд на мистера Роулстона.

РОУЛСТОН

Помните последние слова Кейна?

Тишина, каждый пытается вспомнить последние слова Кейна.

ТОМПСОН

Может, на смертном одре он рассказал нам о себе?

РОУЛСТОН

Может да, а может нет. Это большой американец. Он отличается от Форда, Херса, рядового американца. Его последними словами были…

Наступает тишина. Роулстон обращается ко всем.

ЧЕЙ-ТО ГОЛОС

Что? Да вы не читаете газеты.

ЕЩЕ ЧЕЙ-ТО ГОЛОС

Одна фраза; “Розовый бутон”.

РОУЛСТОН

Да, он сказал: “Розовый бутон”.

ГОЛОС

Сильный парень.

РОУЛСТОН

Этот человек мог стать президентом. Его любили и ненавидели одновременно. Но у него на уме только розовый бутон. Что это значит?

ГОЛОС

Может имя лошади? Она не пришла первой.

РОУЛСТОН

Розовый бутон? Попридержите это неделю.

(решительно)

Раскопайте про розовый бутон. Свяжитесь со всеми, кто хорошо знал его — с управляющим, Берштайном, с его второй женой.

ЧЕЙ-ТО ГОЛОС

Она еще жива.

РОУЛСТОН

Cьюзан Александер Кейн. Cо всеми: с кем он когда-либо работал, с теми, кто любил его, ненавидел. Адресная книга здесь не поможет.

ТОМПСОН

Я займусь этим.

РОУЛСТОН

Розовый бутон — живой или мертвый. Наверняка что-то обыденное.

СМЕНА КАДРА

ЗАТМ.

ИЗ ЗАТМ.

НАТ. ДЕШЕВОЕ КАБАРЕ — “ЭЛЬ РАНЧО” — АТЛАНТИК СИТИ — НОЧЬ — 1940 — ДОЖДЬ

Первое что, мы видим это плакат на котором изображено лицо женщины. Затем мы видим надпись, которая светится неоном на фоне ночного города.

НАДПИСЬ:

Дважды за вечер выступает Cьюзан Александер Кейн.

На улице идет сильный дождь, звучат раскаты грома и это создает мистику происходящему.

Через панорамное окно этого кабаре мы видим столики. Спускаемся еще ближе.

ИНТ. КАБАРЕ “ЭЛЬ РАНЧО” — НОЧЬ

Через окно в потолке мы попадаем во внутрь кабаре и видим, что здесь все столики свободны, лишь за одним столиком сидид одинокая женщина.

Музыка звучит громко.

Заходит Официант (КАПИТАН) и становится возле женщины.

В зал заходит еще один мужчина, это Томпсон.

КАПИТАН

Мисс Александер. Это мистер Томпсон.

Сьюзен смотрит на Томпсона. Ей 50 лет, но она пытается выглядеть намного моложе этих лет. Блондинка. Одета в очень дорогое вечернее платье.

СЬЮЗЕН

(Капитану)

Я хочу еще выпить.

КАПИТАН

Сейчас. Что вы будете пить, мистер Томпсон?

ТОМПСОН

Виски с содовой.

Собирается присесть рядом с Сьюзен.

СЬЮЗЕН

Кто разрешил Вам сесть?

ТОМПСОН

Я думал, мы можем поговорить.

СЬЮЗЕН

Подумайте еще.

СЬЮЗЕН

Оставьте меня. Я занимаюсь своим делом, а Вы своим.

ТОМПСОН

Позвольте поговорить с Вами.

СЬЮЗЕН

Убирайтесь. Убирайтесь!

ТОМПСОН

Извините. Может, в другой раз?

СЬЮЗЕН

Убирайтесь.

КАПИТАН

Джим! Принеси еще виски. Она ни с кем говорить не будет.

ТОМПСОН

Хорошо.

ОФИЦИАНТ

Еще двойной?

КАПИТАН

Да. Она должна еще выпить.

Они направляются к выходу.

КАПИТАН

После смерти, она стала говорить о нем, как об обычном человеке.

ТОМПСОН

Я навещу ее через неделю или около того. Вы можете помочь мне.

КАПИТАН

Да, сэр.

ТОМПСОН

Когда она спускается сюда и говорит о Кейне — Она не упоминала о розовом бутоне?

КАПИТАН

О розовом бутоне?

Томпсон передает ему счет. Капитан прячет его в карман.

КАПИТАН

Спасибо, мистер Томпсон. В тот день, когда газеты написали о его кончине, я спросил ее. Она ничего не знала о розовом бутоне.

ИНТ. ТЕЛЕФОННАЯ БУДКА НА УЛИЦЕ — НОЧЬ — ДОЖДЬ

Обычная телефонная будка. В ней находится Томпсон, он разговаривает по телефону.

ТОМПСОН

Мистер Роулстон? Вторая миссис Кейн говорить не желает. Я в Атлантик-Сити. Завтра еду в библиотеку Тетчера, ознакомиться с его личным дневником. В Нью-Йорке встречаюсь с управляющим Кейна. Встречусь со всеми, если они живы. До свидания.

ЗАТМ.

ИЗ ЗАТМ.

ИНТ. МЕМОРИАЛ БИБЛИОТЕКИ ТЕТЧЕР — ДЕНЬ — 1940

Роскошное здание.На самом видном месте стоит памятник основателю библиотеки мистера Тетчера, созданного из дорогого мрамора. Статуя сидит на стульях и взгляд опушен вниз. Это очень большой постамент. Надпись на статуи “Вальтер Паркс Тетчер”.

Сразу возле постамента мы видим лицо пожилой женщины, это БЕРТА Андерсон. Она сидит за столом. Рядом с ней стоит, держа в руке свою шляпу, Томпсон. Берта разговаривает по телефону.

БЕРТА

(в телефон)

Да, я передам ему.

(кладет трубку и смотрит на Томпсона)

Руководство библиотеки просило напомнить Вам об условиях, на которых Вам разрешили ознакомиться с мемуарами мистера Тэтчера.

ТОМПСОН

Я помню их.

БЕРТА

Да, сейчас. Вы не имеете права нигде и никогда цитировать рукописи.

Берта встает из-за стола и направляется к стеллажам книг и записей, которые находятся за вальяжно обрамленной дверью.

БЕРТА

Пойдемте.

Томпсон следует за ней.

ИНТ. ХРАНИЛИЩЕ БИБЛИОТЕКИ — ДЕНЬ — 1940

Комната оформленная в стиле гробницы Наполеона. Это большая и длинная комната. Все сделано из мрамора и это придает комнате мрачную обстановку. Освещения мало. Также здесь есть дорогой и гигантский стол, сделан из красного дерева. Он находится по центру комнаты. Дальше в мраморной стене встроен сейф, из которого Охранник с пистолетом в кобуре извлекает журнал Уолтера Тетчера. Он несет его Берте, при этом несет его так, как будто это ценный кусок золота.

Во время всего этого действия Берта говорит.

БЕРТА

Мы надеемся, что в рукописях вы ограничитесь только главами, касающимися мистера Кейна.

ТОМПСОН

Только это меня и интересует.

Подходит Охранник к Берте и кладет журнал на стол.

БЕРТА

(Охраннику)

Спасибо. Страницы с 85 по 142.

Томпсон открывает нужные страницы.

БЕРТА

Вы должны покинуть эту комната в четыре тридцать.

Она уходит.

Томпсон закуривает. Охранник смотрит на него, затем качает головой.

Томсон наклоняется над журналом и читает рукопись.

Там аккуратно и четко написано:

“Чарльз Фостер Кейн.

Когда этот текст появится в печати, через пятьдесят лет после моей смерти, я уверен, что весь мир согласится с мои мнением о Чарльзе Фостере Кейне, предполагая, что он еще не будет забыт. Хорошая сделка Абсурда появилась, когда я впервые увидел Кейна, тогда ему было шесть лет. Факты просты. Зимой 1870 года…”

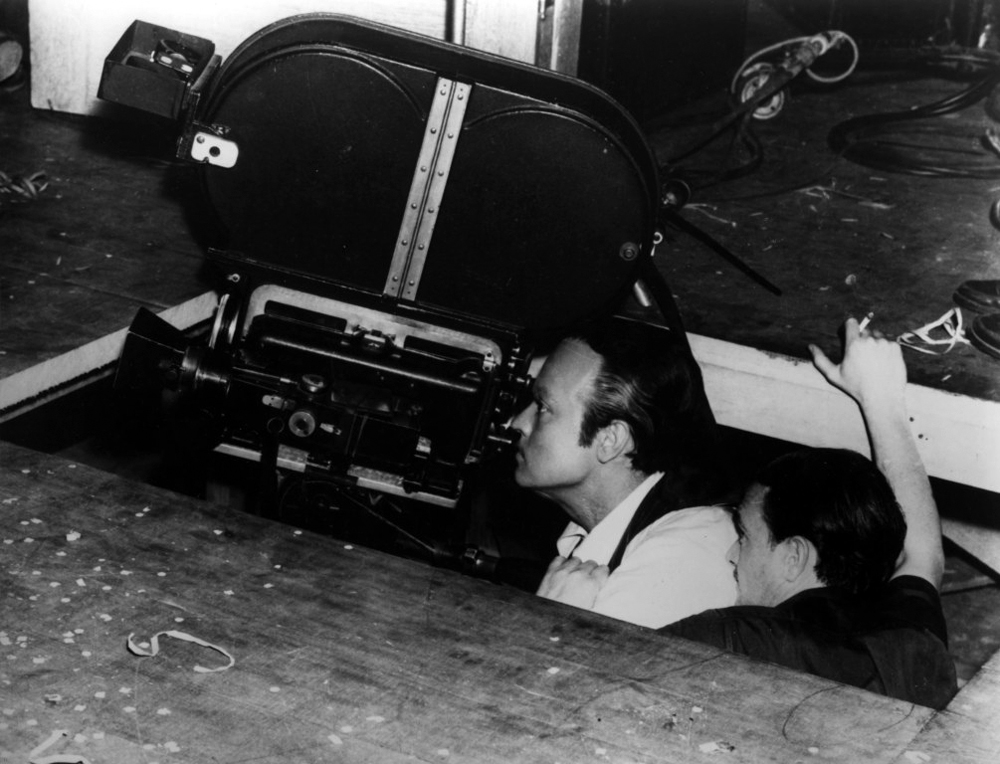

Камера наплывает на страницу журнала до тех пор пока весь экран не стает белым.

СМЕНА КАДРА:

НАТ. ПАНСИОНАТ МИССИС КЕЙН — ДЕНЬ — 1870

Белые заснеженные поля пансионата. На фоне этого белого чуда природы появляется крошечная фигура Чарльза Фостера Кейна, в возрасте до пяти лет. Он готовится бросать снежку в камеру. Снежка летит над нами и мы видим большую вывеску:

ПАНСИОНАТ МИССИС КЕЙН

ВЫСОКИЙ КЛАСС ЕДЫ И ПРОЖИВАНИЯ

СПРАШИВАЙТЕ ВНУТРИ

Снежка, брошенная Кейном, попадает точно в знак.

ИНТ. ПРИЁМНАЯ — ПАНСИОНАТ МИССИС КЕЙН — ДЕНЬ — 1870

Через окно приёмной пансионата мы видим заснеженный двор, где гуляет в снежки маленький Кейн. Он бросается снежками.

В приёмной у окна сидит молодая девушка — МИССИС КЕЙН (28). Она смотрит на сына.

МАЛЕНЬКИЙ КЕЙН

(на улице)

Давайте, ребята, в атаку!

Миссис Кейн наблюдает за сыном.

МИССИС КЕЙН

(кричит из окна)

Осторожнее, Чарльз.

ТЕТЧЕР (ЗК)

Миссис Кейн.

МИССИС КЕЙН

(продолжает кричать сыну)

Поправь шарф.

Но маленький Кейн не обращает внимания на слова мамы, он счастливо играется в снежки.

Миссис Кейн поворачивается в сторону зовящего ее голоса. Мы видим, что у нее очень уставшее лицо, но при этом очень доброе.

ТЕТЧЕР

Думаю, нужно сказать ему.

Возле нее стоит высокий молодой человек. Это ТЕТЧЕР (36), консервативного типа мужчина, одет дорого и очень презентабельно. Он держит в руках документы.

МИССИС КЕЙН

Да. Я сейчас же подпишу документы.

МИСТЕР КЕЙН

Вы забыли, что я его отец.

Все переводят внимание на Мистера Кейна, стоящего немного в сторонке.

Мистер Кейн выглядит ухоженным, элегантно.

Снаружи мы слышим радостные и слегка дикие крики мальчика, играющего в снегу.

МИССИС КЕЙН

Будет так, как я сказала. Нет ничего зазорного в Колорадо. Теперь есть деньги, и мы сами воспитаем сына.

МИСТЕР КЕЙН

Если надо, я подам в суд. Имею право. Жилец оставил эту ничего не стоящую бумагу. Она и моя тоже. Знай Фред Грег, что она станет ценной, выписал бы ее на нас обоих.

ТЕТЧЕР

Но она на миссис Кейн.

МИСТЕР КЕЙН

Но был должен двоим.

ТЕТЧЕР

Решение банка…

МИСТЕР КЕЙН

(перебивает)

Не хочу, чтобы распорядителем был банк!

Миссис Кейн смотрит на мужа. Она одержала победу на ним и это выражается в ее неспособности закончить предложение.

МИССИС КЕЙН

Прекрати нести чепуху, Джим.

ТЕТЧЕР

Решение относительно образования, места жительства Вашего сына.

МИСТЕР КЕЙН

(перебивает)

Банк будет распоряжаться…

МИССИС КЕЙН

Не говори чепуху.

ТЕТЧЕР

(продолжает говорить)

Берем на себя управление рудником, владелицей которого являетесь Вы.

Мистер Кейн хочет что-то сказать, открывает рот, но ловит на себе взгляд Миссис Кейн.

МИССИС КЕЙН

Где подписать?

ТЕТЧЕР

Здесь.

МИСТЕР КЕЙН

(грозно)

И не говори, что я не предупреждал тебя.

Успокаивается.

Миссис Кейн берет гусиное перо для росписи.

МИСТЕР КЕЙН

Мэри, прошу тебя. Все подумают, что я плохой муж и отец.

Миссис Кейн смотрит на него.

ТЕТЧЕР

На протяжении вашей жизни, вам будет выплачиваться 50 тысяч долларов ежегодно.

Миссис Кейн подписывает бумаги.

МИСТЕР КЕЙН

Надеюсь, все это к лучшему.

МИССИС КЕЙН

Да.

Кейн подходит к окну и смотрит на своего сына. Тот наслаждается игрой в снежки. Его радостные вопли мешают разговорам в комнате. Он смотрит несколько секунд на мальчика. Затем Мистер Кейн закрывает окно.

МИСТЕР КЕЙН

Почему я должен отдавать его банку?

ТЕТЧЕР

По доверенности основным капиталом и доходами за него будет управлять банк. Когда ему исполнится 25 лет, он вступит во владение состоянием.

Миссис Кейн встает и подходит к окну.

МИССИС КЕЙН

Продолжайте.

Тетчер продолжает в то время как Миссис Кейн открывает окно на улицу. Смотрит на мальчика.

Тот играет в снежки и кажется ему все равно, что происходит здесь в комнате. Он бросает снежкой в снеговика, затем падает на землю и ползет к снеговику.

ТЕТЧЕР

Уже 5 часов. Не пора ли познакомиться с мальчиком?

Тетчер подходит ближе к Миссис Кейн.

МИССИС КЕЙН

Вещи собраны.

(она вздыхает)

Еще неделю назад.

Она больше ничего не может сказать. Она отходит от окна к центру комнаты.

Мистер Кейн смотрит на нее — он понятия не имеет как ее успокоить.

ТЕТЧЕР

Воспитатель встретит нас в Чикаго.

Тетчер прекращает говорить, так как видит, что миссис Кейн не обращает на него никакого внимания. Она просто открывает двери и выходит из комнаты.

Мужчины переглядываются и следуют за миссис Кейн.

НАТ. ПАНСИОНАТ МИССИС КЕЙН — ДЕНЬ — 1870

Маленький Кейн играется в снежном сугробе. Он играется со снеговиком.

Теперь мы можем видеть здание пансионата — это ветхое, потрепанное двухэтажное здание с деревянной пристройкой. Миссис Кейн подходит к сыну. Мистер Кейн и Тетчер следуют за ней.

МАЛЕНЬКИЙ КЕЙН

Привет, мам.

Миссис Кейн улыбается.

МИССИС КЕЙН

Чарльз, иди в дом, сынок.

Маленький Кейн становится возле снеговика.

МАЛЕНЬКИЙ КЕЙН

Смотри, мама. Это же настоящий снеговик!

МИССИС КЕЙН

Ты сам его слепил?

МАЛЕНЬКИЙ КЕЙН

Я еще сделаю зубы и бакенбарды.

МИССИС КЕЙН

Это мистер Тэтчер.

ТЕТЧЕР

Привет, Чарльз.

МАЛЕНЬКИЙ КЕЙН

Здравствуй.

МИСТЕР КЕЙН

Он приехал с Востока.

МИССИС КЕЙН

Чарльз!

МАЛЕНЬКИЙ КЕЙН

Да, мама.

МИССИС КЕЙН

Он возьмет тебя в путешествие. Ты поедешь на 10 номере.

МИСТЕР КЕЙН

Это поезд с горящими огнями.

МАЛЕНЬКИЙ КЕЙН

Ты поедешь?

ТЕТЧЕР

Нет, но твоя мама…

МАЛЕНЬКИЙ КЕЙН

Куда я еду?

МИСТЕР КЕЙН

Ты увидишь Чикаго, Нью-Йорк, Вашингтон. Не так ли, мистер Тетчер?

ТЕТЧЕР

Конечно. Когда я был маленьким мальчиком…

МАЛЕНЬКИЙ КЕЙН

Почему ты не едешь?

МИССИС КЕЙН

Мы должны остаться.

МИСТЕР КЕЙН

Ты будешь жить с мистером Тэтчером. Будешь богатым. Мы с мамой решили, что тут тебе не стоит жить. Станешь самым богатым в Америке. Тебе надо учиться.

МИССИС КЕЙН

Ты не будешь одинок, Чарльз.

ТЕТЧЕР

Будем вместе, мы проведем много прекрасного времени вместе.

Маленький Кейн пялится на Мистера Тетчера.

ТЕТЧЕР

Пожмем руки, Чарльз.

(протягивает ему свою руку)

Я совсем не страшный. Давай, не упрямься.

Тетчер стоит с протянутой рукой к Чарльзу. Чарльз хватает санки и ударяет ими Тетчера в живот. Удар был сильный и Тетчер хватается за больное место, тяжело дышит.

ТЕТЧЕР

(с болью в голосе)

Чарльз, мне больно.

(делает вдох)

Санки не для битья людей. На санках нужно кататься.

Он подходит к Чарльзу и пытается положить руку ему на плечо. Как только он делает это Чарльз бьет его по ноге.

МИССИС КЕЙН

Чарльз!

Он бросается в объятья своей матери. Миссис Кейн обнимает его очень крепко.

МАЛЕНЬКИЙ КЕЙН

Мама, мама!!

МИССИС КЕЙН

Все хорошо, Чарльз, все хорошо.

Тетчер смотрит на них с возмущением, иногда склоняется потереть лодыжку.

МИСТЕР КЕЙН

Извините. Ему надо дать хорошую взбучку.

МИССИС КЕЙН

Ты думаешь?

МИСТЕР КЕЙН

Да.

Миссис Кейн смотрит на своего мужа.

МИССИС КЕЙН

Поэтому он будет подальше от тебя.

1870 — НОЧЬ

Крупный план вращающихся старомодных железнодорожных колес.

ИНТ. ПОЕЗД — СТАРОМОДНОЕ КУПЕ — НОЧЬ — 1870

Тетчер, с досадой и сочувствием на лице, стоит над рыдающем в подушку маленьким Кейном. Они находятся в старомодном красивом купе поезда.

МАЛЕНЬКИЙ КЕЙН

Мама, мама!!

РЕЗКАЯ СМЕНА КАДРА

Белая страница рукописи Тетчера. Мы читаем такие слова:

“ОН БЫЛ, ПОВТОРЯЮ, АФЕРИСТОМ, ИЗБАЛОВАННЫМ, НЕДОБРОСОВЕСТНЫМ, БЕЗОТВЕТСТВЕННЫМ”

Эти слова плавно переходят в заголовок газеты “Enquirer”.

ИНТ. РЕДАКЦИЯ ГАЗЕТЫ ENQUIRER — ДЕНЬ — 1898

Крупный план заголовка газеты. Мы читаем “ИСПАНСКИЕ ГАЛИОНЫ ПОКИНУЛИ ДЖЕРСИ”

Тетчер делает копию этой газеты. Он стоит рядом с редакционным столом, за которым сидят члены редакции, среди них Райли, Леланд и Кейн. Они обедают.

Испанские галионы покинули Джерси.

ТЕТЧЕР

(холодно)

По-твоему, так руководят газетой?

КЕЙН

Не знаю, мистер Тетчер. Делаю все, что приходит в голову.

ТЕТЧЕР

(читает газету)

“Испанские галионы покинули Джерси”. Ты прекрасно знаешь, что этому нет доказательств.

КЕЙН

Можете опровергнуть?

БЕРШТАЙН проходит рядом. У него в руке кабель. Он останавливается когда заметил Тетчера.

КЕЙН

Мистер Берштайн. Познакомьтесь с мистером Тетчером.

БЕРШТАЙН

Здравствуйте, мистер Тетчер.

ТЕТЧЕР

Как поживаете?

БЕРШТАЙН

Мы только что созванивались с Кубой, мистер Кейн.

Запинается, чувствует, что сказал лишнее.

КЕЙН

Ничего страшного. Он мой бывший опекун. Мистер Тетчер один из наших самых верных читателей. Знает, что не так с каждым номером.

БЕРШТАЙН

Девушки на Кубе — пальчики оближешь. Мог бы послать поэму в стихах, но жаль тратить деньги. Войны нет. Виллер.

КЕЙН

Дорогой Виллер, обеспечьте поэму, я обеспечу войну.

Все за столом и присутствующие в редакции начинают смеяться.

БЕРШТАЙН

Остроумно, мистер Кейн.

КЕЙН

Мне тоже нравится.

Майк И Берштайн покидают комнату. Кейн смотрит на Тетчера, который уже не может себя контролировать. Он сильно возмущен. Он решает сделать последнюю попытку.

ТЕТЧЕР

Чарльз, поговорим о том, что твоя газета затеяла против “Паблик Транзит”.

КЕЙН

Не желаете выйти из офиса и зайти ко мне в кабинет?

Они направляются в сторону кабинета Кейна.

ТЕТЧЕР

Напомню тебе о том, что ты забыл. Ты один из самых крупных акционеров этой компании.

ИНТ. КАБИНЕТ КЕЙНА — ДЕНЬ — 1898

Кейн придерживает дверь для Тетчера. Они заходят в офис.

КЕЙН

Мистер Тетчер, не все, что я пишу в газете является абсолютной правдой?

ТЕТЧЕР

Они все часть вашей атаки — бессмысленной атаки — на все и вся, кто зарабатывает больше десяти центов. Они–

КЕЙН

Беда в том, мистер Тетчер, что вы разговариваете с двумя разными людьми.

Кейн ходит возле своего стола. Тетчер не понимает, смотрит на него.

КЕЙН

Первый Чарльз Фостер Кейн, у которого 82 364 акции компании, я знаю объемы своих авуаров. Вы мне симпатичны. Ч.Ф. Кейн — мошенник. Его газету нужно изгнать из города. Я не могу тратить время на такую чушь.

ТЕТЧЕР

(раздраженно)

Чарльз, мое время слишком ценно для меня–

КЕЙН

(прерывает)

И другой человек — я и издатель “Инквайера”. И по сему — это мой долг. Мне приятно видеть, как порядочные обычные люди, зарабатывают свои кровные деньги. Только потому, что их не обкрадывают мошенники. Раскрою Вам еще маленький секрет: я тот кто это сделает. У меня есть деньги и собственность.

Тетчер не понимает о чем говорит Кейн.

КЕЙН

Если не я буду отстаивать интересы неимущих, то кто-нибудь без денег и собственности сделает это, что будет очень плохо.

Тетчер смотрит на него, не в силах ответить.

Кейн начинает танцевать.

Тетчер надевает свою шляпу.

ТЕТЧЕР

Чарльз, я думал, что сегодня увижу твое заявление.

КЕЙН

Неужели?

ТЕТЧЕР

Скажи честно, мой мальчик, разумно продолжать выпуск газеты, которая приносит тебе миллион долларов убытка в год.

КЕЙН

Вы правы, я потерял миллион долларов в этом году, еще миллион в следующем. Мистер Тетчер, даже при этом, я буду вынужден закрыть газету только через 60 лет.

ИНТ. ДОМ ТЕТЧЕРА — ДЕНЬ

За окном бущует снежная буря. Все вокруг засыпано снегом.

В окно на улицу смотрит мистер Тетчер. Он оборачивается к сидящему у пылающего камина маленькому Кейну. Тот распаковывает подарки.

ТЕТЧЕР

Что ж, Чарльз. С Рождеством!

КЕЙН

Рождеством.

ТЕТЧЕР

И с Новым годом! Позволь напомнить, что скоро тебе исполнится 25 лет. Ты будешь независим от фирмы “Тэтчер и компания”. Сам будешь отвечать за свое состояние — 6-ое в мире по величине. Записали?

Рядом за столом сидит юрист и записывает все, что ему говорит Тетчер.

ЮРИСТ

6-ое по величине.

ТЕТЧЕР

Чарльз, вряд ли ты понимаешь положение, которое скоро займешь. Посылаю тебе список твоего имущества.

ЧЕРЕЗ НЕКОТОРОЕ ВРЕМЯ

Мистер Тетчер уже заметно постарел. Он сидит за своим столом. Рядом с ним его помощники.

ПОМОЩНИК

От мистера Кейна.

ТЕТЧЕР

Читай.

ПОМОЩНИК

Извините, но рудники, недвижимость меня не интересуют…

ТЕТЧЕР

Не интересуют?!

Он выхватывает письмо из рук Помощника и принимается читать сам.

ТЕТЧЕР

Только один пункт: газетенка “Нью-Иорк Инквайер”, которую мы купили за долги. Не продавайте ее. Думаю, будет забавно руководить газетой.

Эта фраза сильно злит Тетчера.

ТЕТЧЕР

(дразнит)

Думаю, будет забавно руководить газетой.

ДАЛЕЕ СЛЕДУЕТ НАРЕЗКА ЭПИЗОДОВ

Мистер Тетчер едет в поезде, где почти все пассажиры читают одну и ту же газету.

Мистер Тетчер смотрит на заглавие:

Махинации в “Тракшнтраст”.

ДАЛЕЕ ЭПИЗОД В РЕСТОРАНЕ

КРУПНЫЙ ПЛАН ЗАГЛАВИЯ ГАЗЕТЫ

“Тракшнтраст” обобрал народ.

СНОВА КРУПНЫЙ ПЛАН ПЕРВОЙ СТРАНИЦЫ ГАЗЕТЫ

“Инквайер” разнес в пух и прах “Тракшнтраст”.

Мистер Тетчер сидит у камина.

КРУПНЫЙ ПЛАН ПЕРВОЙ СТРАНИЦЫ ГАЗЕТЫ

Домовладельцы не вывозят мусор.

Тетчер выбрасывает газету в камин.

КРУПНЫЙ ПЛАН

“Инквайер” открывает борьбу за мусор.

КРУПНЫЙ ПЛАН ПЕРВОЙ СТРАНИЦЫ

Махинации на Уолт-Отрит.

Суд над грабителями.

ИНТ. КАБИНЕТ ТЕТЧЕРА — ДЕНЬ

Большой и просторный кабинет.

Надпись на бумаге КРУПНЫМ ПЛАНОМ — Зимой 1929 года.

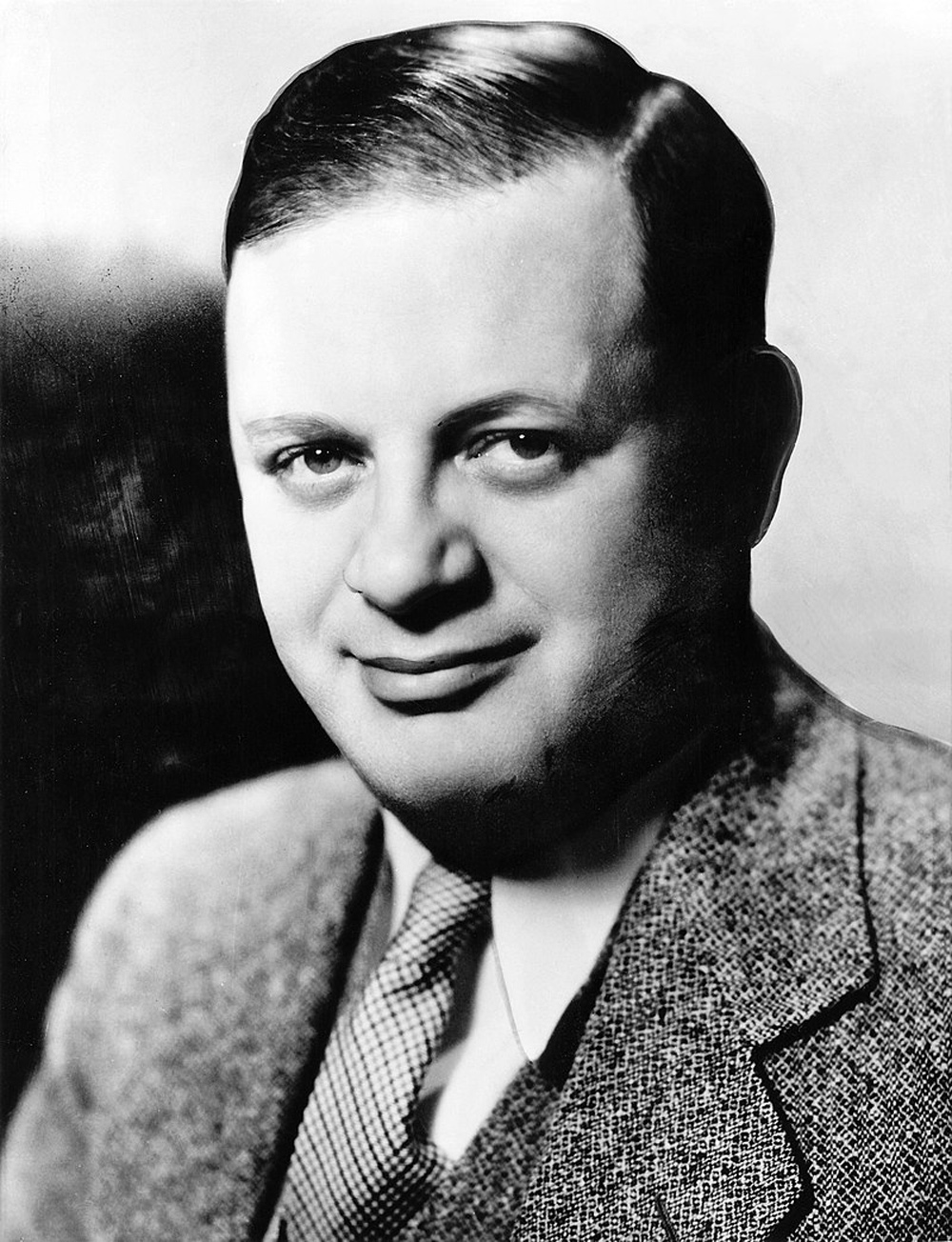

В кабинете находятся Тетчер, заметно постаревший, Берштайн и Кейн.

БЕРШТАЙН

(читает)

С уважением к вышеназванным газетам, Чарльз Фостер Кейн отказывается от всяческого контроля над с ними, над их профсоюзами, а также всеми другими газетами и любого рода издательствами. От имущественных претензий.

ТЕТЧЕР

Мы разорены. Нет наличности.

КЕЙН

Я читал это, мистер Тэтчер.

ТЕТЧЕР

Давайте подпишу и пойду домой. Ты стар, чтобы называть меня так, Чарльз.

КЕЙН

Вы стары, чтобы называть по-другому. Всегда были старым.

БЕРШТАЙН

(продолжает читать)

За это ‘”Тэтчер и компания” согласны выплачивать Ч.Ф. Кейну пожизненно сумму…

КЕЙН

Моя стипендия.

ТЕТЧЕР

Ты продолжишь выпускать свои газеты. Это только метод контроля. Метод контроля. Мы будем советоваться с тобой. Этот кризис, я думаю, временный. Есть шанс, что ты умрешь более богатым, чем я.

КЕЙН

Более богатым, чем родился.

ТЕТЧЕР

Мы никогда не теряли все заработанное. Да, но Ваши методы… Чарльз, ты никогда не делал инвестиций, а использовал деньги, чтобы…

КЕЙН

Покупать вещи. Покупать вещи. Выбрать бы маме менее надежного банкира.

(подписывает бумаги)

Что ж. Я высмеиваю тех, кто родился в рубашке. Мистер Берштайн, не будь я так богат…, стал бы по-настоящему великим человеком.

БЕРШТАЙН

Ну, да?

КЕЙН

Я сделал бы максимум возможного.

ТЕТЧЕР

Кем бы хотел быть?

КЕЙН

Тем, кого Вы ненавидите.

ИНТ. ХРАНИЛИЩЕ — МЕМОРИАЛЬНАЯ БИБЛИОТЕКА ТЕТЧЕРА — ДЕНЬ

Томпсон за столом. С досадой он закрывает рукопись. Он встает из-за стола и натыкается на мисс Андерсон, которая зашла сюда совсем незаметно.

ТОМПСОН

Прошу прошения, что Вы сказали?

БЕРТА

Вам пора, не так ли?

ТОМПСОН

Да, мэм.

БЕРТА

Это редкая привилегия. Нашли то, что искали?

ТОМПСОН

Нет. Вы ведь не розовый бутон?

БЕРТА

Что?

ТОМПСОН

Ваша фамилия Дженкинс?

БЕРТА

Да, сэр.

ТОМПСОН

Всем до свидания. Спасибо за помощь.

Он надевает свою шляпу, щакуривает и направляется к выходу. Берта наблюдает за ним.

ЗАТМ:

ИЗ ЗАТМ:

ИНТ. ОФИС БЕРНШТАЙНА — НЕБОСКРЕБ ЕНКВАЙЕР — ДЕНЬ — 1940

Крупным планом лицо старого Кейна. Но затем камера отъезжает и мы видим, что это портрет на стене. На портретом скрещены два американских флага.

Под портретом сидит Бернштайн. Его низкорослая челюсть теперь кажется еще меньше, чем в молодости. Он лыс, как яйцо, с невероятно подвижными глазами.

Напротив него стоит Томпсон.

БЕРШТАЙН

(криво усмехается)

Председатель совета занятой человек? Времени у меня полно. Что Вас интересует?

ТОМПСОН

Мистер Берштайн, мы думали, если узнаем про его последние слова.

БЕРШТАЙН

Про розовый бутон. Может это… девушка. Их было много в юности.

ТОМПСОН

Не верится, познакомившись с какой-то девушкой, через 50 лет…

БЕРШТАЙН

О, Вы наивны, мистер…

(вспоминает имя)

мистер Томпсон. Люди помнят такое, о чем трудно догадаться. Я, например, в 1896 году переправлялся на пароме в Джерси. Навстречу плыл другой паром, на котором я увидел девушку.

(медленно)

В белом платье и с белым зонтиком от солнца. Я видел ее секунду. Она меня вообще не заметила. Клянусь, не проходит и месяца, как я вспоминаю ее.

(смеется)

Итак, что вам стало известно о Розовом бутоне, мистер Томсон?

ТОМПСОН

Я опрашиваю людей которые знали Мистера Кейна. Сейчас я хочу расспросить вас.

БЕРШТАЙН

С кем еще встречались?

ТОМПСОН

Я был в Атлантик-Сити.

БЕРШТАЙН

У Сьюзи? Спасибо. После его смерти я позвонил ей. Кто-то ведь должен был.

(грустно)

Не сняла трубку.

ТОМПСОН

Собираюсь еще через пару дней к ней заехать. Насчет розового бутона. Не расскажите ли Вы мне все, что помните. Вы с ним с самого начала.

БЕРШТАЙН

Больше, чем с самого начала. А теперь и после его конца. Еще с кем-нибудь встречались?

ТОМПСОН

Я познакомился с дневником Уолтера Тетчера.

БЕРШТАЙН

Это самый большой кретин, которого я встречал.

ТОМПСОН

Он заработал кучу денег.

БЕРШТАЙН

Немудрено, если вам только и нужно… заработать кучу денег. Например, Кейн. Ему нужны были не деньги. У него было необычное чувство юмора. Тэтчер не понял его, и я не всегда понимал. Как в ту ночь, когда открылось здание оперы в Чикаго… Вы знаете, что оперный театр он построил для Сьюзи, она собиралась стать оперной певицей. Это было несколько лет спустя в 1914 году. Миссис Кейн играла главную роль в опре и она была ужасна. Но никто не осмелился сказать ей об этом — даже критики. Мистер Кейн был большой шишкой в то время. Но только один человек, его друг, Бранфорд Лиланд… Вам нужно повидать мистера Лиланда. Это его близкий друг. Вместе ходили в школу.

ТОМПСОН

В Гарвард?

БЕРШТАЙН

В Гарвардский, Ельский — его исключали из многих университетов. У Лиланда не было ни гроша. У его отца было 10 миллионов. Но пустил пулю в лоб, оставив только долги. Со мной и мистером Кейном он работал в “Инквайер” с первых дней.

ИНТ. КОМНАТА — ОФИС ИНКВАЙЕРА — ДЕНЬ — 1891

Одна большая комната, которая занимает большую часть этажа. Несмотря на то, что на улице светит солнце, в комнате света очень мало, так как солнце попадает сюда мало из-за очень маленьких и узких окон.

В комнате около десятка столов и стульев все они разнообразные от старомодных до современных. Два стола находящиеся немного на возвышении, очевидно принадлежат главным редакторам этой газеты. Слева находится дверь, которая ведет в офис другой газеты.

Кейн и Лиланд заходят в комнату и в этот момент тучный мужчина за возвышенным столом ударяет в колокол и все обитатели этой комнаты — мужчины одного возраста с Кейном, поднимаются и приветствуют вошедшего.

КАРТЕР

Добро пожаловать, мистер Кейн! Добро пожаловать. Я Герберт Картер, главный редактор.

КЕЙН

Спасибо. Это мистер Лиланд.

КАРТЕР

(здоровается)

Здравствуйте!

КЕЙН

Наш новый театральный критик. Ты ведь хотел им быть?

ЛИЛАНД

Да.

КЕЙН

(смотрит на стоящих мужчин)

Они стоят из-за меня?

КАРТЕР

Я думал это будет уместно.

КЕЙН

Попросите всех сесть.

КАРТЕР

Господа, можете продолжить работу.

(к Кейну)

Я не знал Ваших планов…

КЕЙН

И я их не знаю. У меня нет планов.

Он поднимается с Картером на платформу.

КЕЙН

Я хочу выпускать газету.

Слышен ужасный треск в дверях. Они все поворачиваются в сторону шума — у входа стоит Берштайн с постельным бельем, чемоданом и двумя картинами.

КЕЙН

Мистер Берштайн?

БЕРШТАЙН

Да.

Берштайн смотрит на Кейна.

КЕЙН

Мистер Картер, это мистер Берштайн. Мой управляющий.

Берштайн подходит к платформе.

КАРТЕР

Управляющий? Здравствуйте.

БЕРШТАЙН

Мистер Картер…

КЕЙН

Мистер Картер…

КАРТЕР

Да, мистер Берштайн, Кейн.

КЕЙН

Посмотри, Джедидайя, здесь все будет иначе. Идем.

НАТ. УЛИЦА ВОЗЛЕ РЕДАКЦИИ “ИНКВАЙЕРА” — ДЕНЬ

Прекрасное солнечное утро. К зданию редакции подъезжает повозка с одним человеком на борту. Это Берштайн.

Повозка останавливается.

КУЧЕР

Тут комнаты не сдаются. Это редакция.

БЕРШТАЙН

Вам платят за перевозку клиентов.

Он вылазит из повозки.

ИНТ. РЕДАКЦИЯ ГАЗЕТЫ — ДЕНЬ

КЕЙН

Мистер Картер, это Ваш кабинет?

КАРТЕР

Мой маленький кабинет в Вашем распоряжении. Вам понравится.

В кабинет начинают заносить вещи. Картеру это не понятно.

КАРТЕР

Извините. Кажется, я не понимаю.

КЕЙН

Я буду жить в Вашем кабинете, сколько понадобиться.

ЛИЛАНД

Мистер Картер…

КАРТЕР

Жить здесь? Извините. Но утренняя газета, мистер Кейн?

ЛИЛАНД

Извините.

КАРТЕР

Мы закрыты практически 24 часа в день.

КЕЙН

Это придется изменить. Новости должны выходить 24 часа в день.

КАРТЕР

24?

КЕЙН

Именно, мистер Картер.

Порой молодым людям требуется насладиться сексом с безупречно голыми проститутками. Они шикарные шлюхи предлагают вам воспользоваться своими предложениями интимного характера.

ЛИЛАНД

Извините. Извините.

КАРТЕР

Это невозможно.

ЧЕРЕЗ НЕКОТОРОЕ ВРЕИЯ

В кабинете мистера Картера, который уже обставлен по вкусу Кейна.

Заходит Лиланд с большим плакатом.

ЛИЛАНД

Я нарисовал это. Я плохой карикатурист.

КЕЙН

Ничего подобного. Ты театральный критик.

ЛИЛАНД

Все пишешь?

КЕЙН

Я хочу есть.

(рассматривает газету)

Первая полоса “Кроникл” посвящена пропавшей миссис Сильверстоун. Вероятно, она убита. Почему нет подобного в “Инквайере”?

КАРТЕР

Мы выпускаем газету…а не портянку из скандалов.

КЕЙН

Джозеф! Я ужасно хочу есть. Мистер Картер, в “Кроникл” передовица в три колонки, а в “Инквайере”?

КАРТЕР

Не было больших новостей.

КЕЙН

Мистер Картер, если передовица будет большая, то и новости.

БЕРШТАЙН

Это верно.

КЕЙН

Убийство миссис Сильверстоун.

КАРТЕР

Нет доказательств.

КЕЙН

Соседи высказывают подозрения.

КАРТЕР

Не наше дело печатать сплетни. Так мы могли бы выпускать газету дважды в день.

КЕЙН

Отныне только такие вещи будут привлекать нас. Пошлите человека к мистеру Сильверстоуну. Пусть скажет ему, что если он не покажет свою жену, “Инквайер” добъется его ареста. Пусть скажет, что он детектив из центрального управления. Если Сильверстоун попросит показать значок, пусть назовет его убийцей. Громко, чтобы слышали соседи.

(поднимается)

Идем обедать, Джедидайя.

КАРТЕР

Зачем уважающей себя газете…

КЕЙН

Вы были самым понятливым. Большое спасибо.

КАРТЕР

До свидания.

НАТ. У ВХОДА В РЕДАКЦИЮ ГАЗЕТЫ

Мистер Картер стоит со своими вещами на выходе из редакции. Он одевает шляпу и направляется по дороге домой. Проходит возле парня — газетчика.

ГАЗЕТЧИК

Покупайте специальный выпуск. Читайте подробности о том, что утром писала “Кроникл”. Читайте все о тайне женщины, которая пропала в Бруклине.

ИНТ. РЕДАКЦИЯ ГАЗЕТЫ — ТО ЖЕ ВРЕМЯ

Лиланд и Кейн сидят у окна и смотрят как уходит Картер.

ЛИЛАНД

Скоро отдохнем, Чарли. Еще 10 минут.

БЕРШТАЙН

Работали почти 4 часа, но все же сделали.

КЕЙН

Тяжелый день.

БЕРШТАЙН

Да, тяжелый. Вы переделывали передовицу 4 раза.

Он смотрит на Лиланд несколько секунд затем возвращается к своим записям.

Бернштайн подошел и стал рядом с Кейном. Оба стоят и смотрят.

КЕЙН

Я немного изменил передовицу. Этого мало. Я должен кое-что поместить в эту газету. “Инквайер” будет так важен для Нью-Иорка, как газ для лампы.

ЛИЛАНД

Что намерен делать?

Лиланд присоединяется к ним с другой стороны. Их три головы вырисовывались на фоне неба.

КЕЙН

Создать свою “Декларация принципов”. Не смейся. У меня тут все написано.

БЕРШТАЙН

Давая обещания, нужно их сдерживать.

КЕЙН

Я сдержу.

(делает паузу)

Я дам жителям города газету, которая будет честно сообщать им новости.

(пишет что-то; читает написанное)

Также…

ЛИЛАНД

Предложение с “я”.

КЕЙН

(продолжает)

Пусть знают, кто виноват. Люди будут узнавать правду быстро, просто.

(говорит с убеждением)

Ничто не помешает этому. Я стану борцом за гражданские права моих читателей.

Кейн подписывает последнее предложение.

КЕЙН

Соли!

Подходит СОЛИ (30).

СОЛИ

Да, мистер Кейн.

КЕЙН

Помести это заявление на первой полосе.

СОЛИ

На первой полосе утреннего выпуска?

КЕЙН

Именно, а значит нам придется переделать передовицу. Иди вниз и скажи наборщикам.

СОЛИ

Да, мистер Кейн.

Соли хочет уйти, но его останавливает Лиланд.

ЛИЛАНД

Соли, когда закончишь верни мне текст.

Соли кивает и уходит.

ЛИЛАНД

Я бы хотел сохранить этот необычный листок бумаги. Мне кажется он станет очень важной вещью. Документом, подобным Декларации Независимости и моим первым репортерским удостоверением в школе.

Лиланд смотрит на Кейна, Кейн поворачивает голову и смотрит в глаза Лиланду.

Бернштайн закуривает сигарету.

СМЕНА КАДРА:

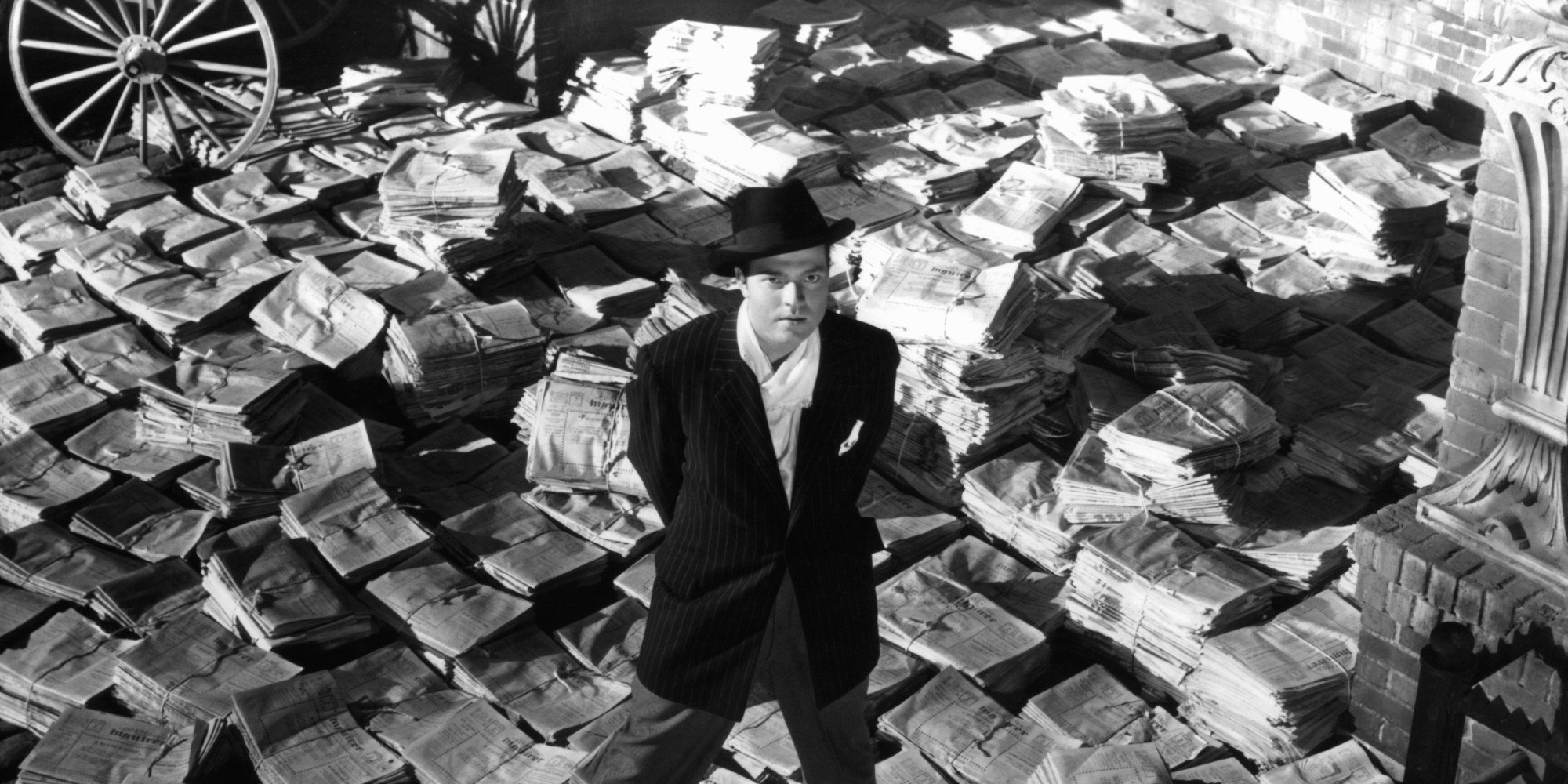

Первая страница “Enquirer” пестрит большим заголовком:

МОИ ПРИНЦИПЫ — ДЕКЛАРАЦИЯ ЧАРЛЬЗА ФОСТЕРА КЕЙНА

Мы видим, что это верхняя газета в стопке газет. Затем мы видим что эта стопка газет лежит на полу в большом цеху. Это печатный цех, где выпускается газета “Enquirer”.

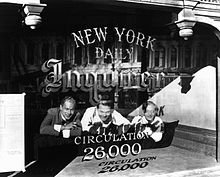

Также видим, что по всему цеху разбросаны огромные стопки газет, все 26000 копий, готовых к распространению.

Вагон с большой надписью:

“Инквайер” — Тираж 26000

Затем мы переключаемся на улицу города. На деревянном поломанном ящыке на углу дома лежит стопка газет свежего выпуска “Инквайера”. Это бедный район города.

Затем мы видим старую деревянную дверь возле которой стоит старомодный велосипед с огромным передним колесом. Копия газеты “Инквайер” лежит на ступеньке.

Стол для завтрака — красивая скатерть и красивые серебряные приборы — все в этом доме говорит, о том, что это дом богатого человека. Через окно кто-то просунул копию газеты “Инквайер”.

И все эти газеты с одним заголовком на главной странице — МОИ ПРИНЦИПЫ — ДЕКЛАРАЦИЯ ЧАРЛЬЗА ФОСТЕРА КЕЙНА.

Деревянный пол железнодорожной станции, который то освещается то снова покрывается темнотой, в зависимости от того, проезжает рядом поезд или нет. На полу лежит брошенная связка газеты “Нью-Йорк Enquirer». Снова видно заголовок о декларации принципов.

Сельская местность. И снова железнодорожная станция. Проезжают поезда, на одном из них мы замечаем новую надпись “Тираж — 31000”. Затем мы переходим к следующем вагоне на котором уже написано Тираж 40000, затем на следующем поезде надпись — 55000, и вот уже на следующем надпись — 62000.

Каждый раз, как меняется вагон поезда и надпись тиража, мы слышим на заднем фоне шум трафика Нью-Йорка; цокот колес по брусчатке; велосипедные звонок; пение птиц и конечно звук проезжающего поезда.

Последняя надпись “Тираж 62000” уже напечатана на последней странице газеты “Инсквайер” и мы плавно переходим:

НАТ. УЛИЦА И РЕДАКЦИЯ ГАЗЕТЫ — ДЕНЬ — 1895

Угол здания редакции газеты — художник на люльке ставит последний ноль в цифре “62000” на огромном знаке, рекламирующем газету “Инквайер”. На знаке мы читаем:

ИНКВАЙЕР

ВЫБОР НАРОДА

ТИРАЖ 62000

Затем мы плавно переходим на другое здание, на котором мы читаем:

ЧИТАЙТЕ ИНКВАЙЕР

САМЫЙ БОЛЬШОЙ ТИРАЖ АМЕРИКИ

62000

Затем мы снова перемещаемся немного ниже по зданию и оказываемся у главного входа в редакцию газеты “КРОНИКЛ”. В большом стеклянном окне мы видим отображение фигур Лиланда, Кейна и Бернштайна, которые смотрят на вход и жуют орешки.

За окном, в здании, мы видим большой плакат на котором изображены сотрудники газеты “Кроникал” по центру которых сидит Рейли.

Надпись на плакате;

РЕДАКТОРЫ И ИСПОЛНИТЕЛЬНАЯ КОМАНДА ГАЗЕТЫ КРОНИКЛ

Внизу плаката продолжение надписи:

САМОЙ БОЛЬШОЙ ГАЗЕТЫ В МИРЕ

также написан тираж газеты

БЕРШТАЙН

(смотрит на свою надпись, счастливо)

62000

ЛИЛАНД

Звучит вполне не плохо.

КЕЙН

Будем надеяться, что им это будет видно.

БЕРШТАЙН

С этой точки этого здания — наша надпись самая большая из всех, которые они могут увидеть. Будьте уверены — они увидят.

КЕЙН

(указывает на надпись над плакатом)

Посмотрите на это.

ЛИЛАНД

“Кроникл” хорошая газета.

КЕЙН

“Кроникл” — хорошая идея для газеты.

(присматривается к надписи)

Посмотрите на тираж.

БЕРШТАЙН

Тираж 495 тысяч. Но посмотрите, кто работает на “Кроникл”. С ними тираж вполне оправдан.

КЕЙН

Вы правы, мистер Барштайн.

БЕРШТАЙН

Знаете, сколько “Кроникл” шел к этому — 20 лет.

КЕЙН

20 лет? Что ж…

Кейн смеется, хакуривает сигарету.

КЕЙН (ЗК)

Смотря на фотографию самых великих газетчиков, я чувствовал себя мальчишкой у кондитерской. 6 лет спустя, эта кондитерская принадлежит мне.

Кейн продолжает смотреть в окно. Затем мы плавно наезжаем камерой на плакат с редакторами газеты, на фоне которых отображается улыбка Кейна.

ИНТ. РЕДАКЦИЯ ГАЗЕТЫ “ЕНКВАЙЕР” — НОЧЬ — 1895

Девять мужчин, выстроенные в ряд, как на предыдущем плакате, только сейчас с излучающим свет Кейном по центру. Мужчин, кто с бородой, кто с шикарными усами, кто лысый и т.д. легко идентифицировать как-будто это редакторы газеты “Кроникл” с мистером Рейли.

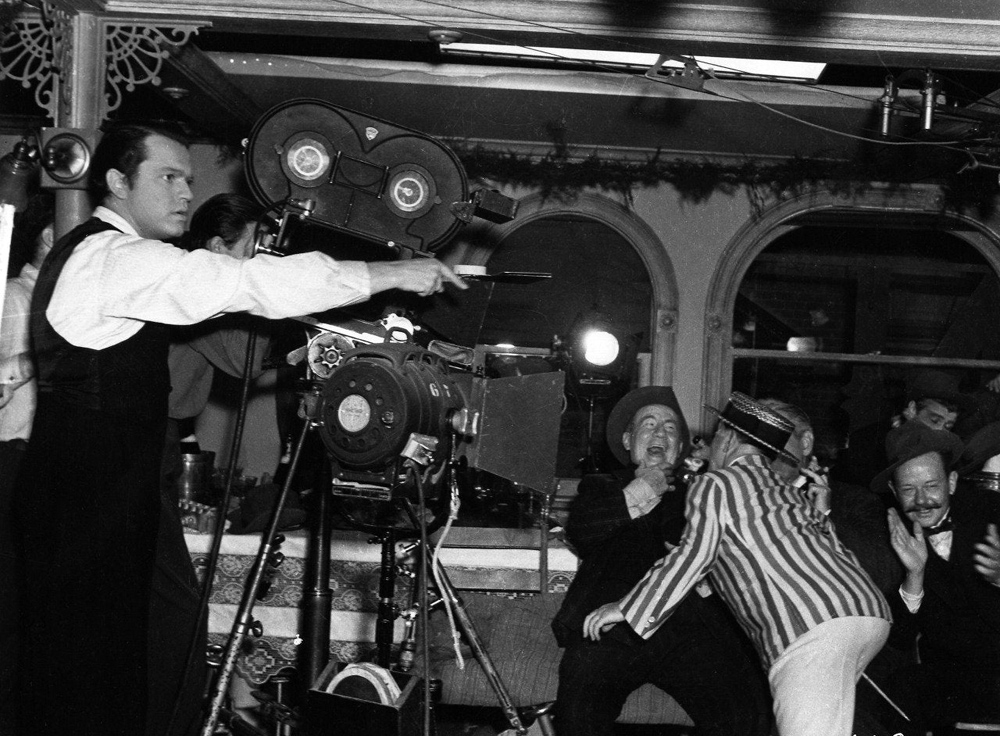

Мы видим, что ни стоят по центру комнаты и готовы фотографироваться. Возле них бегает старый фотограф. Чтобы сделать эту фотографию, поставили столы в угол комнаты. По часам становится ясно, что сейчас 1:30 ночи.

Они стоят возле большого банкетного стола, на котором находятся еще остатки еды. За столом сидит Берштайн и Лиланд, они и еще несколько человек наблюдают за фотосессией.

ФОТОГРАФ

Это все, господа! Спасибо.

Фотограф поднимает все свои прибамбасы.

КЕЙН

(вдруг выдает)

Один экземпляр пошлите в “Кроникл”.

Усмехнувшись и сияя, он направляется к своему месту за банкетным столом. Остальные уже сидят за столом.

Кейн привлекает внимание своих гостей постукиваем ножом по столу.

КЕЙН

Джентльмены “Инквайера”. Думаю будет уместно поприветствовать уважаемых нами журналистов

(указывает на плакат с изображением редакторов “Кроникл”)

и мистера Рейди лично, которые являются последними дополнениями в наши ряды. Они будут счастливы, узнав, что тираж “Инквайера” сегодня утром перевалил за двести тысяч.

БЕРШТАЙН

210 тысяч 647 экземпляров.

Всеобщее аплодисменты.

КЕЙН

Верно. Все вы — новые и старые — Вы все получаете лучшие зарплаты в городе. Ни один из вас не был принят на работу по лояльности или связям. Все из-за вашего таланта, в котором я очень заинтересован, и который сделает “Инквайер” лучшей газетой в мире.

Очередные аплодисменты.

КЕЙН

Однако, я думаю, вы уже достаточно наслушались и газетах и газетном бизнесе этой ночью. В мире есть и другие темы для обсуждения.

Он засовывает два пальца в рот и начинает свистеть. Это сигнал. В комнату заходит группа молодых и очень привлекательных девиц, одетых дерзко, они поют частушки. Остальная часть этого эпизода будет показана позже. Суть его состоит в том, чтобы показать, что Кейн здоровый и счастливый молодой человек, проводивший отлично время.

Одна из девиц подходит к мужчинам и берет одного из них для приватного танца.

РАСТВОРЕНИЕ КАДРА

Плавно кадр появляется из большой надписи:

НЕПРЕВЗОЙДЁННАЯ АМЕРИКАНСКАЯ ГАЗЕТА ВЫШЛА ТИРАЖОМ 274 321

Танцующий Кейн держит девушку за руку и они растворяются в кадре. Мы видим улицу города и на одном из зданий висит плакат:

ЧИТАЙТЕ ИНКВАЙЕР ВЕЛИЧАЙШУЮ ГАЗЕТУ В МИРЕ

Несколько секунд кадры панорамы города.

Думаю, вы простите меня за то, что уезжаю в отпуск за границу. Я обещал приехать своему лечащему врачу, как только смогу.

ДАЛЕЕ СЛЕДУЕТ НАРЕЗКА ЭПИЗОДОВ, ПОКАЗЫВАЮЩИХ ПЕРИОД МЕЖДУ 1891 — 1900 ГГ.

Следуют кадры в которых мы можем понят рост популярности газеты “Инквайер” и личный рост Кейна.

Кадр показывающий факельное шествие молодых парней (парни идут на испано-американскую войну). Факелы отображаются в окне салуна — внутри находится духовой оркестр, исполняющий “Эта горячая пора”.

На окне салуна висит плакат с надписью: “ПОМНИМ МЭЙН”

ВСТАВКА: Рисунок американских парней, похожих на те, что сейчас идут на параде, с надписью “Наши парни”.

Залняя часть автомобиля для наблюдений. Кадр поздравления Кейна Тедди Рузвельтом.

Деревянный пол железнодорожной платформы — из вагона движущего поезда выбрасывается огромная стопка газеты “Инквайер”. Она падает на пол и мы видим огромную фотографию на первой странице: Кейн пожимает руку Тедди. Заголовок сообщает о том, что Куба была сдана.

ИНТ. РЕДАКЦИЯ ИНКВАЙЕРА

Мультфильм, весьма драматический, с подписями, этикетками и символическими фигурами — “Капиталистическая Жадность”. Этот мультфильм почти закончен и находится на чертежной доске, перед которой стоят Кейн и сам художник. Кейн усмехается над предложение, которое он сам сделал.

СМЕНА КАДРА

Мультфильм уже закончен и теперь копируется на страницах газеты “Инквайер” совсем рядом с лицами редакторской группы. Номер газеты выполнен в злом и провокационном стиле.

РЕЗКАЯ СМЕНА КАДРА

ИНТ. РЕДАКЦИЯ ИНКВАЙЕР

Мультипликатор и Кейн работают над комиксом “Монах Джонни”.

СМЕНА

Пол в квартире — Двое детей сидят на полу и расматривают в газете известный нам комикс.

Смена плана

Свежий номер газеты с большой фотографией на главной странице. Номер газеты читает в мужской парикмахерской, мужчина которому делают маникюр, стрижку и так далее. Хныкающая девушка на картинке в газете говорит:

Я НЕ ЗНАЛА, ЧТО ДЕЛАЮ. ВСЕ СТАЛО КРАСНЫМ”.

Далее мы видим — Овальная картинка в виде оружия, входит и выходит в плоть красивой девушки, в картинке надпись: “СМЕРТЕЛЬНОЕ ОРУЖИЕ”

РАСТВОРЕНИЕ КАДРА

УЛИЦА — СНИМОК ВЕДРА ПОЖАРНОЙ БРИГАДЫ

Снимок Кейна, в дорогом вечернем костюме, он в опасном положении, мы видим, что он находится на фоне бущующего огня в многоквартирном доме.

ВСТАВКА: Заголовок в газете о несовершенности современного пожарного оборудования.

СМЕНА КАДРА

ЗВУК НОВОГО ПАРОВОГО ДВИГАТЕЛЯ РЕВУЩЕГО НА УГЛУ УЛИЦЫ

КРУПНЫЙ ПЛАН РЕШЕТОК НА ОКНЕ. Мы в тюремной камере. Дверь в камеру открыта и мы видим осужденного, священника, надзирателя и нескольких парней из обслуживающего персонала. Дальше по коридору мы видим сестру Кейна, самого Кейна и несколько фотографов. Фотографы делают несколько снимков с могучей старомодной пороховой вспышкой Кейна на фоне камеры осужденного. Смертник (осужденный) ослепляется от такого яркого света.

СМЕНА КАДРА

Копия свежего номера “Исквайера” разложена на столе. На странице газеты написана статья об убийце, а рядом другая статья о новом паровом двигателе.

Рядом с газетой стоит чашка кофе и пончик. Сотрудница работает над выпуском и нечаянно задевает чашку кофе.

Балл Beaux Art. Много дам и господ преклонного возраста собираются на бал. Они все в мехах и дорогих платьях и костюмах. Прислуги помогают снять эти все дорогие меха, прежде чем войти на бал, и напоминают, что нужно быть в маске. Леди и джентльмены охотно соглашаются и надевают свои маски — это выглядит очень забавно. Среди этих всех людей мы видим мистера Тетчера, он лысый. Затем изображение застывает и мы переносимся на страницу газеты, это как-бы репортаж об этом событии.

Над иллюстрированной копией этого номера мы видим свежее кофейное пятно в виде рыбы — ужасное зрелище. Газета скомкана и выброшена в мусорный бак.

Крупный план надписи: “ПРОФЕССИЯ — ЖУРНАЛИСТ”

Камера отъезжает и мы видим открытый паспорт с фотографией Кейна, датой рождения, регистрацией, национальностью. Обложка паспорта закрыта, но понятно, что это американский паспорт.

НАТ. МОРСКОЙ ПОРТ — ТРАПЫ ОКЕАНСКОГО ЛАЙНЕРА — НОЧЬ — 1900

Большой морской порт, много народа, среди них мы видим Кейна, Берштайна и Лиланда. В порту шумиха и суета. Все готовятся подняться на борт шикарного океанского лайнера.

Мы видим надпись “ПЕРВЫЙ КЛАСС”. Кейн и его напарники направляются туда.

Слышны крики стюардов, слышен звук свистка, гонг.

СТЮАРД

О, вы здесь, мистер Кейн. Весь багаж доставлен.

КЕЙН

Спасибо.

Кейн, Лиланд и Берштайн заходят на трап.

СТЮАРД

Хорошего отдыха, мистер Кейн.

КЕЙН

Спасибо.

БЕРШТАЙН

Раз уж Вы даете обещания, в Европе осталась масса не купленных Вами картин и статуй.

КЕЙН

В этом я не виноват. Статуи создавались 2 тысячи лет, а я покупаю их всего 5.

БЕРШТАЙН

Обещайте, мистер Кейн.

КЕЙН

Обещаю.

БЕРШТАЙН

Спасибо.

Кейн оставляет Лиланд и Бернштайна на полпути трапа, оглядывается.

КЕЙН

Мистер Бернштайн, вы думаете, что я сдержу эти обещания?

БЕРШТАЙН

Нет!

Кейн поворачивается и продолжает подниматься по трапу. Лиланд и Берштайн провожают его взглядом.

Кейн скрывается в толпе народа на лайнере.

Берштайна и Лиланд стоят и смотрят на этот красивый лайнер. Затем идут в сторону выхода из порта.

БЕРШТАЙН

Почему Вы не поехали?

ЛИЛАНД

Пусть сам развлекается.

Пауза.

ЛИЛАНД

Мистер Берштайн, я хочу спросить у вас кое-что и хочу получить правдивый ответ.

Они смотрят друг на друга.

ЛИЛАНД

Разве я ничтожество? Лицемер с лошадиной рожей? Сельская учительница?

БЕРШТАЙН

Да.

Такой ответ сильно удивил Лиланд. Он смотрит на Берштайна с удивлением.

БЕРШТАЙН

Ошибаетесь, думая, что я отвечу иначе, чем это сказал мистер Кейн.

ЛИЛАНД

Вы в заговоре против меня. И всегда были.

Он продолжают идти. Звук лайнера звучит очень громко.

ЛИЛАНД

Ладно. Не знал, что Чарли коллекционирует алмазы.

БЕРШТАЙН

Скорее тех, кто коллекционирует алмазы. Он коллекционирует не только статуи. А когда он встречает мисс, то всегда пытается поцеловать ее. Кто-то покупает еду, кто-то покупает выпивку, а кто-то думает, что деньги созданы, чтобы их тратить.

КЕЙН

Сейчас прошу вашего пристального внимания, господа. Мы объявим войну Испании.

ЛИЛАНД

Что? Убейте меня, пока я счастлив.

КЕЙН

Я сказал: мы объявим войну Испании или нет?

БЕРШТАЙН

“Инквайер” уже объявил.

Лиланд в шоке такое услышать.

ЛИЛАНД

(Кейну)

Ты унылый и плохо одетый анархист.

КЕЙН

Разве плохо?

ЛИЛАНД

Бернштайн, посмотрите на его галстук.

К их столику подходят две девушки из группы танцовщиц. Это ДЖОРДЖИ (40) не молодая, но достаточно привлекательная женщина. Она держит за руку молодую, красивую и стеснительную девушку — ЕТЕЛЬ (21).

Джорджи представляет молодую даму Лиланду. На фоне звучит фортепианная музыка.

ДЖОРДЖИ

Етель — этот господин очень хотел встретится с тобой — это Етель.

ЕТЕЛЬ

Здравствуйте, мистер Лиланд.

Оно здороваются.

Затем кто-то в зале кричит на весь зал.

КТО-ТО

А давайте споем песню о Чарли.

ДРУГАЯ ДЕВУШКА

Мистер Кейн. Давайте послушаем.

Все обращают свое внимание на Кейна. Он поворачивается к Берштайну и Лмланду.

КЕЙН

Стоит купить пончиков, и о вас сочиняют песни.

В зале звучит музыка. Девицы поют песню; “Ох, мистер Кейн”.

Все пытаются подпевать. Выходит очень забавно. Песня хорошая и она поднимает настроение не только Кейну.

Затем Кейн подсаживается поближе к Лиланду. Говорит с ним персонально.

КЕЙН

Скажем так, Брэд. У меня есть идея идея.

ЛИЛАНД

Да.

КЕЙН

Точнее у меня есть работка для вас.

ЛИЛАНД

Отлично.

КЕЙН

Вы не желаете воевать с другими корреспондентами — как на счет стать литературным критиком?

ЛИЛАНД

(с усмешкой)

С удовольствием, сэр.

Продолжается песня о Кейне.

НАПЛЫВ

ИНТ. СИТИ РУМ — ИНКВАЙЕР — НОЧЬ — 1895

Вечеринка (продолжение вечеринки с девушками танцовщицами)

В этот раз вечеринка освещается с точки зрения Лиланда, который сидит в конце стола. Кейн говорит свою речь.

КЕЙН

Ни один из вас не был принят на работу по лояльности или связям. Все из-за вашего таланта, в котором я очень заинтересован, и который сделает “Инквайер” лучшей газетой в мире.

АПЛОДИСМЕНТЫ.

Берштайн поворачивается к Лиланду.

БЕРШТАЙН

Великолепная вечеринка, правда?

ЛИЛАНД

Да.

Но затем тон голоса Кейна заставляет его прислушивается к Кейну.

КЕЙН (ЗК)

Однако, я думаю, вы уже достаточно наслушались и газетах и газетном бизнесе этой ночью. В мире есть и другие темы для обсуждения.

Затем Берштайн снова обращает свое внимание на Лиланда.

БЕРШТАЙН

Что такое?

ЛИЛАНД

Мистер Берштайн, люди из “Кроникл” сейчас в “Инквайер”. Эти люди разве не были преданы политике “Кроникл”, как сейчас нашей политике?

БЕРШТАЙН

Конечно. Они такие же, как все. Идут на работу и работают.

(с гордостью)

Это лучшие люди в журналистике.

Слышно свист Кейна. В зал заходят девицу в красивых платьях и поют частушки.

ЛИЛАНД

Мы боремся за те же идеалы, что и “Кроникл”?

БЕРШТАЙН

Конечно, нет. Мистер Кейн обратит их в свою веру за неделю.

ЛИЛАНД

Но есть шанс, что и наоборот. Он и не заметит.

Кейн подходит к Берштайну и Лиланду. Садится рядом и закуривает сигарету.

ИНТ. СИТИ РУМ — РЕДАКЦИЯ ИНКВАЙЕР — ДЕНЬ — 1900

Большая комната, но оформлена со вкусом. В комнате несколько десятков столом, на которых накрыты праздничные закуски и выпивка. За столами сидят сотрудники редакции газеты. В комнате есть огромное окно, через которое в комнату попадает много солнечного света.

Кейн и Берштайн входят в комнату. При входе они останавливаются. Кейн выглядит отлично — он отдохнувший, загорелый, его глаза сияют. Одет в новый костюм английского стиля.

Зайдя в комнату весь персонал поднимается и приветствует Кейна.

БЕРШТАЙН

Добро пожаловать домой. От всех 467-ми сотрудников “Инквайера”.

Сотрудники хлопают и приветствуют Кейна.

КЕЙН

Привет всем!

Берштайн и Кейн проходят к своим столам. Подходят к своему столу — за столом сидят несколько человек, среди них Лиланд. Кейн здоровается с ним. Присматривается к нему.

КЕЙН

У тебя усы?

ЛИЛАНД

Знаю.

КЕЙН

Какой кошмар.

ЛИЛАНД

Никакой не кошмар.

Затем Берштайн представляет незнакомую женщину за столом.

БЕРШТАЙН

Мисс Таунсен, это мистер Кейн.

Мисс Таунсен смотрит вверх и так удивляется увидим незнакомого ей человека рядом с Берштайном.

Затем она начинает поднимается, но ее ноги подкашиваются и она начинает падать, но удержав равновесие он хватается за все попало за столом.

КЕЙН

(приятным голосом)

Мисс Таунсен, меня давно тут не было. Я многое забыл.

Его голос ее успокаивает и она стоит прямо и уверенно.

КЕЙН

У меня маленькое объявление для светской хроники, как и любое другое.

Рн протягивает ей конверт. Она нервничает и берет конверт. Руки трясутся.

КЕЙН

Прочитайте его, мисс Таунсен. И помните — регулярное лечение. Увидимся в девять часов, мистер Берштайн.

Кейн уходит. Берштайн смотрит ему вслед, а затем на конверт в руке. Мисс Таунсен удается открыть конверт. Она с Берштайном изучает написанное.

МИСС ТАУНСЕН

Это объявление

(читает)

“Мистер и миссис Томас Монро Нортон объявляют о помолвке их дочери Эмили с мистером Ч.Ф. Кейном.”

БЕРШТАЙН

Эмили Монро Нортон — племянница президента США.

Он переглядывается с мисс Таунсен.

МИСС ТАУНСЕН

Племянница президента.

Они снова переглядываются. Подходят к окно и смотрят вниз на улицу.

НАТ. УЛИЦА ВОЗЛЕ РЕДАКЦИИ ЕНКВАЙЕРА — ДЕНЬ — 1900

Видно мисс Таунсен и Берштайна выглядывающих из окна редакции. Она смотрят на Кейна, который садится элегантный автомобиль, в котором уже сидит мисс Эмили Нортон. Он целует ее в губы, прежде чем сесть. Она немного удивленна таким поведением Кейна, но затем она смотрит на него с обожанием. Кейн поворачивает голову в сторону окна с которого смотрят на него Берштайн. Он машет им рукой.

ИНТ. РЕДАКЦИЯ ИНКВАЙЕРА — ДЕНЬ — 1900

Берштайн и Мисс Таунсен стоят у окна.

БЕРШТАЙН

Эта девушка, поверьте мне, она счастливица. Племянница президента говорите вы, ха-ха… Она будет женой президента.

Мисс Таунсен смотрит на Берштайна. Затем переводит взгляд на уезжающею влюбленную парочку.

СМЕНА КАДРА

Титульная страница газеты “Инквайер”. На большом фото молодая пара — Кейн и Эмили — они очень счастливы.

СМЕНА КАДРА

ИНТ. ОФИС БЕРШТАЙНА — ИНКВАЙЕР — ДЕНЬ — 1940

Берштайн и Томпсон. Как только появляется кадр слышим голос Берштайна.

БЕРШТАЙН

Нет смысла говорить, что мисс Эмили не была розовым бутоном.

ТОМПСОН

Брак не удался?

БЕРШТАЙН

Да.

(маленькая пауза)

Потом была Сьюзи. И этот тоже.

(пауза; смотрит в глаза Томпсону)

Я вот что подумал. Этот розовый бутон…

ТОМПСОН

Да?

БЕРШТАЙН

Может что-то потерянное? Он потерял почти все, что имел.

(пауза)

Поговорите с Лиландом. Они смотрели на вещи по-разному. Например, испано-американская война. Думаю, Лиланд был прав. Это была война Кейна. Воевать было не за что. А если и было. Думаете, мы бы получили Панамский канал? Где сейчас Лиланд? Давно ничего не слышал о нем. Возможно, он умер?

ТОМПСОН

Он сейчас в городской больнице Ханингтона.

БЕРШТАЙН

А я и не знал.

ТОМПСОН

Ничего особенного. Мне сказали…

БЕРШТАЙН

…состарился.

(смеется)

Это единственная болезнь, от которой нет лекарства.

ЗАТМ.

ИЗ ЗАТМ.

НАТ. БАЛКОН ГОСПИТАЛЯ — ДЕНЬ — 1940

Госпиталь Ханингтона. Томпсон сидит в кресле на балконе и смотрит в небо. Слышим голос Лиланд, но еще его не видно.

ЛИЛАНД (ЗК)

Я абсолютно все помню. Это мое проклятье. Память — самое страшное проклятье рода человеческого. Я был его старинным другом, а он вел себя как свинья. Он не был грубым, просто делал грубые вещи. Если не меня, то кого же назвать другом? Наверное, я был тем, кого называют ”компаньон”.

Теперь Лиланд видно — он сидит в инвалидном кресле закутан в одеяло. Он разговаривает с Томпсоном.

Они находятся на балконе. Также с ними есть несколько других пациентов этой больницы и обслуживающий персонал. Все они греются на солнце.

Лиланд смотрит на Томпсона.

ТОМПСОН

Вы хотели что-то сказать о розовом бутоне.

ЛИЛАНД

У Вас нет хорошей сигары? Врач хочет, чтобы я бросил курить.

ТОМПСОН

Боюсь нет. Извините.

ЛИЛАНД

Я сменил тему. Каким нудным стариком я стал. Вы, журналисты, хотите знать, что я думаю о Чарльзе Кейне. Что ж. В нем было благородство. Но он таил его.

(ухмыляется)

Не открывался до конца. Ничего не отдавал. Оставил нам конец веревки. У него была щедрая душа. Имел множество мнений. Но он всегда верил и полагался только на Чарли Кейна. Думаю, он умер, веря только в себя. Большинство приходит к смерти без представления о ней. Но мы знаем, зачем живем, во что верим.

(смотрит на Томпсона резко)

У Вас точно нет сигары?

ТОМПСОН

Извините, мистер Лиланд.

ЛИЛАНД

Ничего.

ТОМПСОН

Что вы знаете о розовом бутоне?

ЛИЛАНД

О розовом бутоне?

ТОМПСОН

Его предсмертные слова. Я читал об этом в “Инквайере”.

ЛИЛАНД

Давно не верю тому, что пишет “Инквайер”. Что-нибудь еще? Могу рассказать об Эмили. Ходил с ней в танцевальную школу. Мы говорили о первой миссис Кейн.

ТОМПСОН

Какая она была?

ЛИЛАНД

Как все девушки в школе. Очень красивые, но Эмили красивее. Через пару месяцев совместной жизни, он стал редко с ней видеться. Только за завтраком. Их брак не отличался от других.

СМЕНА КАДРА/НАПЛЫВ

ИНТ. ОСОБНЯК КЕЙНА — УТРО

Красивая комната с огромном особняке Кейна. В комнату попадает много солнечного света через огромные окна от пола до потолка.

По центру комнаты стоит не большой стол. За столом сидит ЭМИЛИ, красивая молодая девушка. Он завтракает. Наливает себе кофе.

Заходит Кейн и приносит десерт.

ЭМИЛИ

Чарльз.

КЕЙН

Ты прекрасна.

ЭМИЛИ

Да, что ты.

КЕЙН

Очень красива.

ЭМИЛИ

Не была на 6 вечеринках за вечер. Не ложилась так поздно.

КЕЙН

Привыкнешь.

ЭМИЛИ

Что подумают слуги?

КЕЙН

Что мы веселились. Ведь так?

ЭМИЛИ

Почему тебе нужно быть в редакции?

КЕЙН

Ты напрасно вышла за газетчика. Это хуже, чем за моряка. Обожаю тебя…

ЭМИЛИ

Чарльз, даже газетчикам нужно спать.

КЕЙН

Попрошу отменить дневные встречи. Который час?

ЭМИЛИ

Не знаю. Поздно.

КЕЙН

Рано.

ЧЕРЕЗ НЕКОТОРОЕ ВРЕМЯ

(ДАННОЕ СОБЫТИЕ БУДЕТ ПОКАЗАНО С ПОМОЩЬЮ ПРОЕЗЖАЮЩЕГО БЕЗ ЗВУКА

ПОЕЗДА СО СВЕТЯЩИМИСЯ ВАГОНАМИ)

Кейн выглядит немного иначе- у него другая прическа. Он закуривает трубку.

ЭМИЛИ

Чарльз… Знаешь, сколько я тебя ждала, когда ты ушел в редакцию на 10 минут? Что там делать среди ночи?

КЕЙН

Эмили, дорогая, твой единственный соперник — мой “Инквайер”.

ВСТАВКА

СНОВА ПРОЕЗЖАЮЩИЙ ПОЕЗД/ЧЕРЕЗ НЕКОТОРОЕ ВРЕМЯ

Кейн в дорогом халате сидит в саду.

ЭМИЛИ

Лучше иметь соперника из плоти и крови.

КЕЙН

Я не много времени уделяю газете.

ЭМИЛИ

Дело в том, что ты печатаешь, нападая на президента.

КЕЙН

На дядюшку Джона?

ЭМИЛИ

На президента США.

КЕЙН

Он по-прежнему дядюшка Джон и большой болван. Кто управляет его администрацией?

ЭМИЛИ

Он президент, Чарльз, не ты.

КЕЙН

Это мы исправим на днях.

ВСТАВКА

СНОВА ПРОЕЗЖАЮЩИЙ ПОЕЗД/ЧЕРЕЗ НЕКОТОРОЕ ВРЕМЯ

Эмили в прекрасном вечернем наряде сидит за столом.

ЭМИЛИ

Вчера твой мистер Бернштайн прислал малышу гадость. Не могу оставить ее в детской.

Кейн в строгом деловом черном костюме. Он сама серьёзность.

КЕЙН

Он намерен посетить детскую.

ЭМИЛИ

Это необходимо?

КЕЙН

Да.

ВСТАВКА

СНОВА ПРОЕЗЖАЮЩИЙ ПОЕЗД/ЧЕРЕЗ НЕКОТОРОЕ ВРЕМЯ

ЭМИЛИ

Чарльз, люди подумают, что…

КЕЙН

То, что я им скажу.

ВСТАВКА

СНОВА ПРОЕЗЖАЮЩИЙ ПОЕЗД/ЧЕРЕЗ НЕКОТОРОЕ ВРЕМЯ

На этот раз Кейн и Эмили сидят молча за столом и читают газеты. Не смотрят друг на друга.

НАЗАД К ЛИЛАНДУ И ТОМПСОНУ

ТОМПСОН

Он любил ее?

ЛИЛАНД

Женился по любви. Любовь. Все делал по любви. Пошел в политику. Хотел, чтобы его любили избиратели. Ему нужна была только любовь. Это история Чарли. Ему больше нечего было дать. Конечно, он любил Чарли Кейна. Искренне. И свою мать любил.

ТОМПСОН

А вторую жену?

ЛИЛАНД

Сьюзен Александер? Знаете, как он ее называл? После их знакомства, он рассказал мне о ней. Она была типичной американкой. Думаю, она его чем-то пленила. В их первую ночь, по словам Чарли, у нее была зубная боль.

ПЛАВНЫЙ ПЕРЕХОД

НАТ. УЛИЦА ГОРОДА — УГОЛ ДОМА И АПТЕКИ — ВЕЧЕР — 1909

Ночной город. На улице уже не ходят пешеходы. Кроме одинокого Кейна. Он стоит и курит трубку.

Из аптеки выходит СЬЮЗЕН (21). Она делает несколько шагов, останавливается и трогает свой больной зуб. Затем снова продолжает идти и проходит возле Кейна.

Она смеется и держит в руках таблетки.

Девушка подходит ближе к Кейну. Продолжает смеяться. Это замечает Кейн.

КЕЙН

Почему Вы смеетесь? Что с Вами?

СЬЮЗЕН

Зубная боль.

КЕЙН

Что?

СЬЮЗЕН

Зубная боль.

КЕЙН

Зубная боль. О, так у Вас болят зубы. Что смешного?

СЬЮЗЕН

Вы, мистер. У Вас грязь на лице.

КЕЙН

Глина.

Он с ног до головы испачкан грязью. Вытирается.

СЬЮЗЕН

Может горячей воды? Я тут живу.

КЕЙН

Что такое?

СЬЮЗЕН

Не желаете горячей воды? Могу дать… немного воды.

КЕЙН

Большое спасибо.

Они направляются в квартиру.

ИНТ. КВАРТИРА СЬЮЗЕН — ВЕЧЕР

Красивая уютная квартира. Горит яркий свет. Здесь есть все для нормального проживания — кровать, большой стол. На стене несколько красивых картин.

Сьюзен стоит у зеркала и пытается что-то сделать со своим больным зубом.

Из ванной выходит Кейн, вытирает лицо полотенцем.

КЕЙН

Я выгляжу лучше?

СЬЮЗЕН

Такое лечение впустую.

КЕЙН

Надо не думать о боли.

Кейн закрывает дверь. Но через несколько секунд дверь снова открывается.

СЬЮЗЕН

Домохозяйка требует не закрываться, когда в гостях мужчина.

КЕЙН

Опять зубная боль?

СЬЮЗЕН

Разумеется.

КЕЙН

Посмейтесь надо мной. Я все еще смешной.

СЬЮЗЕН

Вы же не хотите.

КЕЙН

Не хочу, чтобы болели зубы.

КЕЙН

Посмотрите. Видите?

СЬЮЗЕН

Что Вы делаете?

КЕЙН

Шевелю ушами одновременно.

Этот трюк срабатывает и Сьюзен смеется.

КЕЙН

Правильно. Два года учебы в лучшем колледже для мальчиков. Научивший меня — президент Венесуэлы. Вот так.

Кейн играет со Сьюзен в игру “Угадай животного по тени”. Он все еще пытается смешить ее.