| Halloween | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster by Robert Gleason |

|

| Directed by | John Carpenter |

| Written by |

|

| Produced by | Debra Hill |

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Dean Cundey |

| Edited by |

|

| Music by | John Carpenter |

|

Production |

|

| Distributed by |

|

|

Release date |

|

|

Running time |

91 minutes[5] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $300,000–325,000[6][7][8] |

| Box office | $70 million[6][7] |

Halloween is a 1978 American independent slasher film directed and scored by John Carpenter, co-written with producer Debra Hill, and starring Jamie Lee Curtis (in her film debut) and Donald Pleasence, with P. J. Soles and Nancy Loomis in supporting roles. The plot centers on a mental patient, Michael Myers, who was committed to a sanitarium for murdering his babysitting teenage sister on Halloween night when he was six years old. Fifteen years later, he escapes and returns to his hometown, where he stalks a female babysitter and her friends while under pursuit by his psychiatrist.

Filming took place in Southern California in May 1978. The film premiered in October, whereupon it grossed $70 million, becoming one of the most profitable independent films of all time. Primarily praised for Carpenter’s direction and score, many critics credit the film as the first in a long line of slasher films inspired by Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960) and Bob Clark’s Black Christmas (1974). It is considered one of the greatest and most influential horror films ever made. In 2006, Halloween was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being «culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant».[9][10]

Halloween spawned a film franchise comprising thirteen films which helped construct an extensive backstory for its antagonist Michael Myers, sometimes narratively diverging entirely from previous installments. A direct sequel of the film was released in 1981. A remake was released in 2007. An eleventh installment, which serves as a direct sequel to the original film that retcons all previous sequels, was released in 2018. Additionally, a novelization, a video game and comic book series have been based on the film.

Plot[edit]

On Halloween night in 1963, in the fictional suburban town of Haddonfield, Illinois, six-year-old Michael Myers stabs his teenage sister Judith to death with a chef’s knife. For fifteen years, Michael is incarcerated at Smith’s Grove Sanitarium, during which time he never speaks a word. On October 30, 1978, Michael’s psychiatrist, Dr. Samuel Loomis, arrives at the sanitarium to escort Michael to court for a hearing; Loomis hopes that Michael will be imprisoned for life. Michael escapes Smith’s Grove and steals Loomis’s car and escapes, killing a mechanic for his coveralls on the way back to Haddonfield. Upon arriving, he steals knives, ropes, and a white, expressionless mask from a hardware store.

On Halloween, Michael sees high school student Laurie Strode drop off a key at the long-abandoned Myers house that her father is trying to sell. Laurie notices Michael stalking her throughout the day, but her friends Annie Brackett and Lynda Van Der Klok dismiss her concerns. Loomis arrives in Haddonfield and finds Judith’s tombstone missing from the cemetery. He meets with Annie’s father, Sheriff Leigh Brackett, and they investigate Michael’s house, where Loomis tells Brackett that in the 15 years he has known Michael, he has realized that he is pure evil. Loomis and Brackett find a dead partially eaten dog in the house furthering Loomis’s suspicious that Michael is in Haddonfield. Brackett is doubtful of the danger but goes to patrol the streets, while Loomis waits at the house, expecting Michael to return. That night, Laurie babysits Tommy Doyle, while Annie babysits Lindsey Wallace across the street.

Michael follows them, spying on Annie and killing the Wallaces’ dog. Tommy sees Michael from the windows and thinks he is the boogeyman, but Laurie does not believe him. Annie later takes Lindsey over to the Doyle house to spend the night, so she can pick up her boyfriend Paul. When she gets into her car, Michael appears from the back seat, strangling her and slitting her throat. Soon after, Lynda and her boyfriend Bob arrive at the Wallace house and find it empty. After having sex, Bob goes downstairs to get a beer, where Michael kills him by pinning him to the wall with a kitchen knife. Michael then poses as Bob in a ghost costume and confronts Lynda, who teases him to no effect. Annoyed, she calls Laurie to find out what happened to Annie, but Michael strangles her to death with the phone cord while Laurie listens on the other end, thinking it is a joke.

Loomis discovers the stolen car and searches the streets. Suspicious of the phone call, Laurie goes to the Wallace house and finds her friends’ bodies, as well as Judith’s headstone, in the upstairs bedroom. She flees to the hallway, where Michael appears in the dark and slashes her arm, causing her to fall over the stairway banister. Dazed and injured Laurie manages to escape and runs back to the Doyle house, but finds she lost the keys to the front door during the altercation with Michael. Tommy lets her into the house. Laurie orders Tommy and Lindsey to hide and tries to use the telephone for help, only to find the phone dead.

Michael sneaks in through the window and attacks her again, but she incapacitates him by stabbing him in the neck with a knitting needle. Thinking he is dead, Laurie staggers upstairs to check on the children, but is shocked when Michael approaches to attack her again. She tells the children to hide in the bathroom while Laurie hides in the bedroom closet, but Michael finds her. Laurie pokes his eye out with a coat hanger, causing Michael to drop the knife, which Laurie uses to stab him in the chest. She then tells Tommy and Lindsey to go down the street to a neighbor’s house to call the police. After they leave, Michael awakens once again and slowly approaches an unsuspecting Laurie. Loomis sees the children running from the house and goes to investigate, only to see Michael attempting to strangle Laurie.

Laurie snatches Michael’s mask off, distracting him as he seeks to put it back on. Loomis shoots Michael once in the head and five more times in the chest, knocking him off the balcony. Laurie asks Loomis if Michael was the «boogeyman», which Loomis confirms. Loomis walks to the balcony and looks down to see that Michael has vanished. Unsurprised, he stares off into the night as Laurie sobs.

Cast[edit]

- Donald Pleasence as Dr. Samuel «Sam» Loomis

- Jamie Lee Curtis as Laurie Strode

- Nick Castle as The Shape (Michael Myers masked)

- Tony Moran as Michael Myers – age 21 (mistakenly 23 in credits) (Michael Myers unmasked at the end of the film)

- Will Sandin as Michael Myers – age 6

- P. J. Soles as Lynda Van Der Klok

- Nancy Loomis as Annie Brackett

- Charles Cyphers as Sheriff Leigh Brackett

- Kyle Richards as Lindsey Wallace

- Brian Andrews as Tommy Doyle

- John Michael Graham as Bob Simms

- Nancy Stephens as Marion Chambers

- Arthur Malet as Angus Taylor

- Mickey Yablans as Richie Castle

- Brent Le Page as Lonnie Elam

- Adam Hollander as Keith

- Robert Phalen as Dr. Terence Wynn

- Sandy Johnson as Judith Myers

- David Kyle as Danny Hodges

- Peter Griffith as Morgan Strode, Laurie’s father

Production[edit]

Concept[edit]

After viewing Carpenter’s film Assault on Precinct 13 (1976) at the Milan Film Festival, independent film producer Irwin Yablans and financier Moustapha Akkad sought out Carpenter to direct a film for them about a psychotic killer that stalked babysitters.[11][12] In an interview with Fangoria magazine, Yablans stated: «I was thinking what would make sense in the horror genre, and what I wanted to do was make a picture that had the same impact as The Exorcist.»[11] Carpenter agreed to direct the film contingent on his having full creative control,[13] and was paid $10,000 for his work, which included writing, directing, and scoring the film.[14] He and his then-girlfriend Debra Hill began drafting the story of Halloween.[15][16][17] There is an urban myth that the film at one point was supposed to be called The Babysitter Murders but Yablans has since debunked this stating that it was always intended to be called (and take place on) Halloween.[18] Carpenter said of the basic concept: «Halloween night. It has never been the theme in a film. My idea was to do an old haunted house film.»[19]

Film director Bob Clark suggested in an interview released in 2005[20] that Carpenter had asked him for his own ideas for a sequel to his 1974 film Black Christmas (written by Roy Moore) that featured an unseen and motiveless killer murdering students in a university sorority house. As also stated in the 2009 documentary Clarkworld (written and directed by Clark’s former production designer Deren Abram after Clark’s tragic death in 2007), Carpenter directly asked Clark about his thoughts on developing the anonymous slasher in Black Christmas:

… I did a film about three years later, started a film with John Carpenter, it was his first film for Warner Bros. (which picked up Black Christmas), he asked me if I was ever gonna do a sequel and I said no. I was through with horror, I didn’t come into the business to do just horror. He said, ‘Well what would you do if you did do a sequel?’ I said it would be the next year and the guy would have actually been caught, escape from a mental institution, go back to the house and they would start all over again. And I would call it Halloween. The truth is John didn’t copy Black Christmas, he wrote a script, directed the script, did the casting. Halloween is his movie and besides, the script came to him already titled anyway. He liked Black Christmas and may have been influenced by it, but in no way did John Carpenter copy the idea. Fifteen other people at that time had thought to do a movie called Halloween but the script came to John with that title on it.

— Bob Clark, 2005 interview, Icons of Fright[20]

Screenplay[edit]

It took approximately 10 days to write the screenplay.[15] Yablans and Akkad ceded most of the creative control to writers Carpenter and Hill (whom Carpenter wanted as producer), but Yablans did offer several suggestions. According to a Fangoria interview with Hill, «Yablans wanted the script written like a radio show, with ‘boos’ every 10 minutes.»[11] By Hill’s recollection, the script took three weeks to write,[21] and much of the inspiration behind the plot came from Celtic traditions of Halloween such as the festival of Samhain. Although Samhain is not mentioned in the plot of the first film, Hill asserts that:

… the idea was that you couldn’t kill evil, and that was how we came about the story. We went back to the old idea of Samhain, that Halloween was the night where all the souls are let out to wreak havoc on the living, and then came up with the story about the most evil kid who ever lived. And when John came up with this fable of a town with a dark secret of someone who once lived there, and now that evil has come back, that’s what made Halloween work.[22]

I met this six-year-old child with this blank, pale, emotionless face, and the blackest eyes; the devil’s eyes … I realized what was living behind that boy’s eyes was purely and simply … evil.

—Loomis’ description of a young Michael was inspired by John Carpenter’s experience with a real life mental patient[23]

Hill, who had worked as a babysitter during her teenage years, wrote most of the female characters’ dialogue,[24] while Carpenter drafted Loomis’ speeches on the soullessness of Michael Myers. Many script details were drawn from Carpenter’s and Hill’s own backgrounds and early careers: The fictional town of Haddonfield, Illinois was derived from Haddonfield, New Jersey, where Hill was raised,[25] while several of the street names were taken from Carpenter’s hometown of Bowling Green, Kentucky.[25] Laurie Strode was allegedly the name of one of Carpenter’s old girlfriends,[26] while Michael Myers was the name of an English producer who had previously entered, with Yablans, Assault on Precinct 13 in various European film festivals.[11] Homage is paid to Alfred Hitchcock with two characters’ names: Tommy Doyle is named after Lt. Det. Thomas J. Doyle (Wendell Corey) from Rear Window (1954),[27] and Dr. Loomis’ name was derived from Sam Loomis (John Gavin) from Psycho, the boyfriend of Marion Crane (Janet Leigh, who is the real-life mother of Jamie Lee Curtis).[28][15] Sheriff Leigh Brackett shared the name of a Hollywood screenwriter and frequent collaborator of Howard Hawks.[29]

In devising the backstory for the film’s villain, Michael Myers, Carpenter drew on «haunted house» folklore that exists in many small American communities: «Most small towns have a kind of haunted house story of one kind or another,» he stated. «At least that’s what teenagers believe. There’s always a house down the lane that somebody was killed in, or that somebody went crazy in.»[30] Carpenter’s inspiration for the «evil» that Michael embodied came from a visit he had taken during college to a psychiatric institution in Kentucky.[31] There, he visited a ward with his psychology classmates where «the most serious, mentally ill patients» were held.[31] Among those patients was an adolescent boy, who possessed a blank, «schizophrenic stare.»[23] Carpenter’s experience inspired the characterization that Loomis gave of Michael to Sheriff Brackett in the film.[23] Debra Hill has stated the scene where Michael kills the Wallaces’ German Shepherd was done to illustrate how he is «really evil and deadly».[32]

The ending scene of Michael being shot six times, and then disappearing after falling off the balcony, was meant to terrify the imagination of the audience. Carpenter tried to keep the audience guessing as to who Michael Myers really is—he is gone, and everywhere at the same time; he is more than human; he may be supernatural, and no one knows how he got that way. To Carpenter, keeping the audience guessing was better than explaining away the character with «he’s cursed by some…»[32]

Carpenter has described Halloween as: «True crass exploitation. I decided to make a film I would love to have seen as a kid, full of cheap tricks like a haunted house at a fair where you walk down the corridor and things jump out at you.»[33]

Casting[edit]

The cast of Halloween included veteran actor Donald Pleasence and then-unknown actress Jamie Lee Curtis.[25] The low budget limited the number of big names that Carpenter could attract, and most of the actors received very little compensation for their roles. Pleasence was paid the highest amount at $20,000, Curtis received $8,000, and Nick Castle earned $25 a day.[11] The role of Dr. Loomis was originally intended for Peter Cushing, who had recently appeared as Grand Moff Tarkin in Star Wars (1977); Cushing’s agent rejected Carpenter’s offer due to the low salary.[34] Christopher Lee was approached for the role; he too turned it down, although the actor later told Carpenter and Hill that declining the role was the biggest mistake he made during his career.[35] Yablans then suggested Pleasence, who agreed to star because his daughter Lucy, a guitarist, had enjoyed Assault on Precinct 13 for Carpenter’s score.[36]

In an interview, Carpenter admits that «Jamie Lee wasn’t the first choice for Laurie. I had no idea who she was. She was 19 and in a TV show at the time, but I didn’t watch TV.» He originally wanted to cast Anne Lockhart, the daughter of June Lockhart from Lassie, as Laurie Strode. However, Lockhart had commitments to several other film and television projects.[25] Hill says of learning that Jamie Lee was the daughter of Psycho actress Janet Leigh: «I knew casting Jamie Lee would be great publicity for the film because her mother was in Psycho.»[37] Curtis was cast in the part, though she initially had reservations as she felt she identified more with the other female characters: «I was very much a smart alec, and was a cheerleader in high school, so [I] felt very concerned that I was being considered for the quiet, repressed young woman when in fact I was very much like the other two girls.»[38]

Another relatively unknown actress, Nancy Kyes (credited in the film as Nancy Loomis), was cast as Laurie’s outspoken friend Annie Brackett, daughter of Haddonfield sheriff Leigh Brackett (Charles Cyphers).[39] Kyes had previously starred in Assault on Precinct 13 (as had Cyphers) and happened to be dating Halloween’s art director Tommy Lee Wallace when filming began.[40] Carpenter chose P. J. Soles to play Lynda Van Der Klok, another loquacious friend of Laurie’s, best remembered in the film for dialogue peppered with the word «totally.»[41] Soles was an actress known for her supporting role in Carrie (1976) and her minor part in The Boy in the Plastic Bubble (1976) and would subsequently play Riff Randall in the 1979 film Rock ‘n Roll High School.[42] According to Soles, she was told after being cast that Carpenter had written the role with her in mind.[43] Soles’s then-husband, actor Dennis Quaid, was considered for the role of Bob Simms, Lynda’s boyfriend, but was unable to perform the role due to prior work commitments.[44]

The role of «The Shape»—as the masked Michael Myers character was billed in the end credits—was played by Nick Castle, who befriended Carpenter while they attended the University of Southern California.[45] After Halloween, Castle became a director, taking the helm of films such as The Last Starfighter (1984), The Boy Who Could Fly (1986), Dennis the Menace (1993), and Major Payne (1995).[46] Tony Moran plays the unmasked Michael at the end of the film. Moran was a struggling actor before he got the role.[47] At the time, he had a job on Hollywood and Vine dressed up as Frankenstein.[48] Moran had the same agent as his sister, Erin, who played Joanie Cunningham on Happy Days. When Moran went to audition for the role of Michael, he met for an interview with Carpenter and Yablans. He later got a call back and was told he had got the part.[49] Moran was paid $250 for his appearance. Will Sandin played the unmasked young Michael in the beginning of the film. Carpenter also provided uncredited voice work as Paul, Annie’s boyfriend.

Filming[edit]

Akkad agreed to put up $300,000 for the film’s budget, which was considered low at the time[50][11] (Carpenter’s previous film, Assault on Precinct 13, had an estimated budget of $100,000). Akkad worried over the tight, four-week schedule, low budget, and Carpenter’s limited experience as a filmmaker, but told Fangoria: «Two things made me decide. One, Carpenter told me the story verbally and in a suspenseful way, almost frame for frame. Second, he told me he didn’t want to take any fees, and that showed he had confidence in the project». Carpenter received $10,000 for directing, writing, and composing the music, retaining rights to 10 percent of the film’s profits.[51]

The film’s $300,000 budget would translate to 1.4 million dollars in 2022.

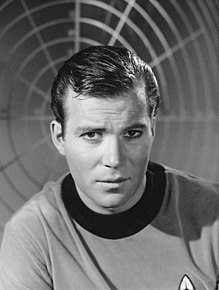

Production designer Tommy Lee Wallace used a mask modeled after Captain Kirk from the Star Trek series (pictured), making various modifications such as painting it white, widening its eyes, and altering its hair

Because of the low budget, wardrobe and props were often crafted from items on hand or that could be purchased inexpensively. Carpenter hired Tommy Lee Wallace as production designer, art director, location scout and co-editor.[52] Wallace created the trademark mask worn by Michael Myers throughout the film from a Captain Kirk mask[53] purchased for $1.98 from a costume shop on Hollywood Boulevard.[11][54] Carpenter recalled how Wallace «widened the eye holes and spray-painted the flesh a bluish white. In the script it said Michael Myers’s mask had ‘the pale features of a human face’ and it truly was spooky looking. I can only imagine the result if they hadn’t painted the mask white. Children would be checking their closet for William Shatner after Tommy got through with it.»[11] Hill adds that the «idea was to make him almost humorless, faceless—this sort of pale visage that could resemble a human or not.»[11] Many of the actors wore their own clothes, and Curtis’ wardrobe was purchased at J.C. Penney for around $100.[11] Wallace described the filming process as uniquely collaborative, with cast members often helping move equipment, cameras, and helping facilitate set-ups.[55] The vehicle stolen by Michael Myers from Dr Loomis and Nurse Marion Chambers at the Smith Grove Sanitarium was an Illinois government-owned 1978 Ford LTD station wagon rented for two weeks of filming. When filming was complete, the car was returned to the rental company who put it up for auction. Its next owner left it in a barn for decades until selling it to its new owner who has completely restored both its interior and exterior.[56]

Halloween was filmed in 20 days over a four-week period in May 1978.[57][58] Much of the filming was completed using a Panaglide, a clone of the Steadicam, the then-new camera that allowed the filmmakers to move around spaces smoothly.[59] Filming locations included South Pasadena, California; Garfield Elementary School in Alhambra, California; and the cemetery at Sierra Madre, California. An abandoned house owned by a church stood in as the Myers house. Two homes on Orange Grove Avenue (near Sunset Boulevard) in the Spaulding Square neighborhood of Hollywood were used for the film’s climax, as the street had few palm trees, and thus closely resembled a Midwestern street.[60] Some palm trees, however, are visible in the film’s earlier establishing scenes.[61] The crew had difficulty finding pumpkins in the spring, and artificial fall leaves had to be reused for multiple scenes.[62] Local families dressed their children in Halloween costumes for trick-or-treat scenes.[11]

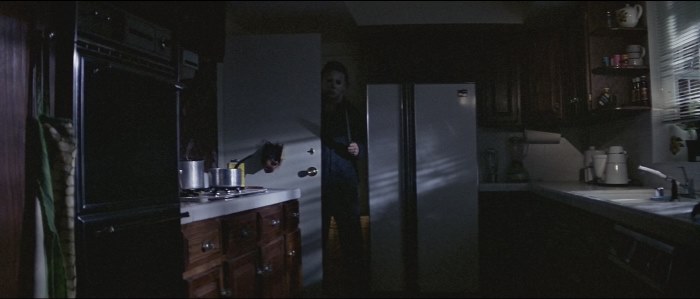

Carpenter worked with the cast to create the desired effect of terror and suspense. According to Curtis, Carpenter created a «fear meter» because the film was shot out-of-sequence and she was not sure what her character’s level of terror should be in certain scenes. «Here’s about a 7, here’s about a 6, and the scene we’re going to shoot tonight is about a 91/2«, remembered Curtis. She had different facial expressions and scream volumes for each level on the meter.[11] Carpenter’s direction for Castle in his role as Myers was minimal.[63] For example, when Castle asked what Myers’ motivation was for a particular scene, Carpenter replied that his motivation was to walk from one set marker to another and «not act.»[64] By Carpenter’s account the only direction he gave Castle was during the murder sequence of Bob, in which he told Castle to tilt his head and examine the corpse as if it «were a butterfly collection.»[65]

Musical score[edit]

Instead of utilizing a more traditional symphonic soundtrack, the film’s score consists primarily of a piano melody played in a 10/8 or «complex 5/4» time signature, composed and performed by director John Carpenter.[19][66] It took Carpenter three days to compose and record the entire score for the film. Following the film’s critical and commercial success, the «Halloween Theme» became recognizable apart from the film.[67] Critic James Berardinelli calls the score «relatively simple and unsophisticated», but admits that «Halloween‘s music is one of its strongest assets».[68] Carpenter once stated in an interview, «I can play just about any keyboard, but I can’t read or write a note.»[69] In Halloween‘s end credits, Carpenter bills himself as the «Bowling Green Philharmonic Orchestra», but he also received assistance from composer Dan Wyman, a music professor at San José State University.[11][70]

Some non-score songs can be heard in the film, one an untitled song performed by Carpenter and a group of his friends in a band called The Coupe De Villes. The song can be heard as Laurie steps into Annie’s car on her way to babysit Tommy Doyle.[11] Another song, «(Don’t Fear) The Reaper» by classic rock band Blue Öyster Cult, also appears in the film.[71] It plays on the car radio as Annie drives Laurie through Haddonfield with Myers in silent pursuit.

The soundtrack was first released in the United States in October 1983, by Varèse Sarabande/MCA.[citation needed] It was subsequently released on CD in 1985, re-released in 1990, and reissued again in 2000.[citation needed] On the film’s 40th anniversary, coinciding with the release of Anthology: Movie Themes 1974–1998, a cover of the theme by Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross was released.[72]

Release[edit]

Ad, The Village Voice, November 6, 1978: only known, published window for date of film’s New York City premiere («Held over … 2nd week»)[a]

Theatrical distribution[edit]

Halloween premiered on October 24, 1978, in downtown Kansas City, Missouri, at the AMC Empire theatre. Regional distribution in the Philadelphia and New York City metropolitan areas was acquired by Aquarius Releasing.[4] It grossed $1,270,000 from 198 theatres across the U.S. (including 72 in New York City and 98 in Southern California) in its opening week.[74] The film grossed $47 million in the United States[8] and an additional $23 million internationally, making the theatrical total $70 million, making it one of the most successful independent films of all time.[75][7]

On September 7, 2012, the official Halloween Movies Facebook page announced that the original Halloween would be re-released starting October 25, 2013, in celebration of the film’s 35th anniversary in 2013. A new documentary was screened before the film at all locations, titled You Can’t Kill the Boogeyman: 35 Years of Halloween, written and directed by HalloweenMovies.com webmaster Justin Beahm.[76][77]

Television rights[edit]

In 1980, the television rights to Halloween were sold to NBC for approximately $3 million.[78] After a debate among Carpenter, Hill and NBC’s Standards and Practices over censoring of certain scenes, Halloween appeared on television for the first time in October 1981.[79] To fill the two-hour time slot, Carpenter filmed twelve minutes of additional material during the production of Halloween II. The newly filmed scenes include Dr. Loomis at a hospital board review of Michael Myers and Dr. Loomis talking to a then-6-year-old Michael at Smith’s Grove, telling him, «You’ve fooled them, haven’t you, Michael? But not me.» Another extra scene features Dr. Loomis at Smith’s Grove examining Michael’s abandoned cell after his escape and seeing the word «Sister» scratched into the door.[78] Finally, a scene was added in which Lynda comes over to Laurie’s house to borrow a silk blouse before Laurie leaves to babysit, just as Annie telephones asking to borrow the same blouse. The new scene had Laurie’s hair hidden by a towel, since Curtis was by then wearing a much shorter hairstyle than she had worn in 1978.[80]

In August 2006, Fangoria reported that Synapse Films had discovered boxes of negatives containing footage cut from the film. One was labeled «1981» suggesting that it was additional footage for the television version of the film. Synapse owner Don May Jr. said, «What we’ve got is pretty much all the unused original camera negative from Carpenter’s original Halloween. Luckily, Billy [Kirkus] was able to find this material before it was destroyed. The story on how we got the negative is a long one, but we’ll save it for when we’re able to showcase the materials in some way. Kirkus should be commended for pretty much saving the Holy Grail of horror films».[81] He later claimed: «We just learned from Sean Clark, long time Halloween genius, that the footage found is just that: footage. There is no sound in any of the reels so far, since none of it was used in the final edit».[82]

Critical response[edit]

Contemporaneous[edit]

Upon its initial release, Halloween performed well with little advertising, relying mostly on word-of-mouth, but many critics seemed uninterested or dismissive of the film. Pauline Kael wrote a scathing review in The New Yorker suggesting that «Carpenter doesn’t seem to have had any life outside the movies: one can trace almost every idea on the screen to directors such as Hitchcock and Brian De Palma and to the Val Lewton productions» and musing that «Maybe when a horror film is stripped of everything but dumb scariness—when it isn’t ashamed to revive the stalest device of the genre (the escaped lunatic)—it satisfies part of the audience in a more basic, childish way than sophisticated horror pictures do.»[83]

Roger Ebert, an often vocal critic of slasher films,[84] praised Halloween upon its release

The Los Angeles Times deemed the film a «well-made but empty and morbid thriller»,[85] while Bill von Maurer of The Miami Times felt it was «surprisingly good», noting: «Taken on its own level, Halloween is a terrifying movie—if you are the right age and the right mood.»[86] Susan Stark of the Detroit Free Press branded Halloween a burgeoning cult film at the time of its release, describing it as «moody in the extreme» and praising its direction and music.[87]

Gene Siskel of the Chicago Tribune gave the film three and a half stars out of four and called it «a beautifully made thriller» that «works because director Carpenter knows how to shock while making us smile. He repeatedly sets up anticipation of a shock and delays the shock for varying lengths of time. The tension is considerable. More than once during the movie I looked around just to make sure that no one weird was sitting behind me.»[88] Gary Arnold of The Washington Post was negative, writing «Since there is precious little character or plot development to pass the time between stalking sequences, one tends to wish the killer would get on with it. Presumably, Carpenter imagines he’s building up spine-tingling anticipation, but his techniques are so transparent and laborious that the result is attenuation rather than tension.»[89]

Lou Cedrone of The Baltimore Evening Sun referred to it as «tediously familiar» and whose only notable element is «Jamie Lee Curtis, whose performance as the intended fourth victim, is well above the rest of the film.»[90]

Tom Allen of The Village Voice praised the film in his November 1978 review, noting it as sociologically irrelevant but praising its Hitchcock-like technique as effective and «the most honest way to make a good schlock film». Allen pointed out the stylistic similarities to Psycho and George A. Romero’s Night of the Living Dead (1968).[91]

The following month, Voice lead critic Andrew Sarris wrote a follow-up feature on cult films, citing Allen’s appraisal of Halloween and writing in the lead sentence that the film «bids fair to become the cult discovery of 1978. Audiences have been heard screaming at its horrifying climaxes».[92] Roger Ebert gave the film similar praise in his 1979 review in the Chicago Sun-Times, referring to it as «a visceral experience—we aren’t seeing the movie, we’re having it happen to us. It’s frightening. Maybe you don’t like movies that are really scary: Then don’t see this one.»[93] Ebert also selected it as one of his top 10 films of 1978.[94] Once-dismissive critics became impressed by Carpenter’s choice of camera angles and simple music, and surprised by the lack of blood and graphic violence.[68]

Retrospective[edit]

Years after its debut, Halloween is considered by many critics as one of the best films of 1978.[94][95][96][97][98] On the review aggregation website Rotten Tomatoes, Halloween holds a 96% approval rating based on 78 critic reviews, with an average rating of 8.60/10. The consensus reads: «Scary, suspenseful, and viscerally thrilling, Halloween set the standard for modern horror films.»[99] On Metacritic, the film has a weighted average score of 87 out of 100 based on 21 critics, indicating «universal acclaim».[100]

Many compared the film with the work of Alfred Hitchcock, although TV Guide calls comparisons made to Psycho «silly and groundless»[101] and some critics in the late 1980s and early 1990s blamed the film for spawning the slasher subgenre, which they felt had rapidly descended into sadism and misogyny.[102][103] Scholars such as Adam Rockoff dispute the recurring descriptions of Halloween as overtly violent or gory, commenting that the film is in fact «one of the most restrained horror films», showing very little onscreen violence.[104] Almost a decade after its premiere, Mick Martin and Marsha Porter critiqued the first-person camera shots that earlier film reviewers had praised and later slasher-film directors used for their own films (for example, 1980’s Friday the 13th). Claiming it encouraged audience identification with the killer, Martin and Porter pointed to the way «the camera moves in on the screaming, pleading victim, ‘looks down’ at the knife, and then plunges it into chest, ear, or eyeball. Now that’s sick.»[103]

Home media[edit]

Since Halloween‘s premiere, it has been released in several home video formats. Early VHS versions were released by Media Home Entertainment.[105] This release subsequently became a collectors’ item, with one copy from 1979 selling on eBay for $13,220 in 2013.[105] On August 3, 1995, Blockbuster Video issued a commemorative edition of the film on VHS.[106]

As stated, the film was first released on VHS in 1979 and again in 1981 by Media Home Entertainment.[107] The synopsis on the back misspelled Myers as Meyers. The film was also released on Betamax around that same time. It was not released in CED format (capacitance electronic disc), unlike Halloween II and Halloween III, but it was released on Laser Disc.[108]

The film was released for the first time on DVD in the United States by Anchor Bay Entertainment on October 28, 1997.[109][110] To date, that DVD release is the only one to feature the original mono audio track as heard in theaters in 1978 and on most home video releases that preceded it. Anchor Bay re-released the film on DVD in various other editions; among these were an «extended edition,» which features the original theatrical release with the scenes that were shot for the broadcast TV version edited in at their proper places.[111] In 1999, Anchor Bay issued a two-disc limited edition, which featured both the theatrical and «extended editions,» as well as lenticular cover art and lobby cards.[112] In 2003, Anchor Bay released a two-disc «25th Anniversary edition» with improved DiviMax picture and audio, along with an audio commentary by Carpenter, Curtis and Hill, among other features.[113]

On October 2, 2007, the film was released for the first time on Blu-ray by Anchor Bay.[114] The following year, a «30th Anniversary Commemorative Set» was issued, containing DVD and Blu-ray versions of the film, the sequels Halloween 4: The Return of Michael Myers and Halloween 5: The Revenge of Michael Myers, and a replica Michael Myers mask.[115] A 35th-anniversary Blu-ray was released in October 2013, featuring a new transfer supervised by cinematographer Dean Cundey.[116] This release earned a Saturn Award for Best Classic Film Release.[117] In September 2014, Scream Factory teamed with Anchor Bay Entertainment to release the film as part of a Blu-ray boxed set featuring every film in the series (up to 2009’s Halloween II), made available in a standard and limited edition.[118]

The film was released by Lionsgate Home Entertainment in an Ultra HD Blu-ray and Blu-ray edition for the film’s 40th anniversary. It is also available online for computer and other devices viewing (streaming rentals) and downloadable files through Amazon.com, Apple’s iTunes Store download application and Vudu.com computer servers.

In September 2021, Scream Factory released a new 4K Ultra HD Dolby Vision scan of the film, as well as its first four sequels.[119]

Accolades[edit]

Halloween was nominated for the Saturn Award for Best Horror Film by the Academy of Science Fiction, Fantasy & Horror Films in 1979, but lost to The Wicker Man (1973).[120] In 2001, Halloween ranked #68 on the American Film Institute TV program 100 Years … 100 Thrills.[121] The film was #14 on Bravo’s The 100 Scariest Movie Moments (2004).[122] Similarly, the Chicago Film Critics Association named it the 3rd scariest film ever made.[123] In 2006, Halloween was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being «culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant.»[124] In 2008, the film was selected by Empire magazine as one of The 500 Greatest Movies of All Time.[125] In 2010, Total Film selected the film as one of The 100 Greatest Movies of All Time.[126] In 2017, Complex magazine named Halloween the best slasher film of all time.[127] The following year, Paste listed it the best slasher film of all time,[128] while Michael Myers was ranked the greatest slasher villain of all time by LA Weekly.[129]

American Film Institute lists

- AFI’s 100 Years … 100 Thrills – #68

- AFI’s 100 Years … 100 Heroes & Villains:

- Michael Myers – Nominated Villain

- AFI’s 100 Years … 100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition) – Nominated

Analysis[edit]

Themes[edit]

Scholar Carol J. Clover has argued that the film, and its genre at large, links sexuality with danger, saying that killers in slasher films are fueled by a «psychosexual fury»[130] and that all the killings are sexual in nature. She reinforces this idea by saying that «guns have no place in slasher films» and when examining the film I Spit on Your Grave she notes that «a hands-on killing answers a hands-on rape in a way that a shooting, even a shooting preceded by a humiliation, does not.»[131] Equating sex with violence is important in Halloween and the slasher genre according to film scholar Pat Gill, who made a note of this in her essay «The Monstrous Years: Teens, Slasher Films, and the Family». She remarks that Laurie’s friends «think of their babysitting jobs as opportunities to share drinks and beds with their boyfriends. One by one they are killed … by Michael Myers an asylum escapee who years ago at the age of six murdered his sister for preferring sex to taking care of him.»[132] Carpenter has distanced himself from these interpretations, saying «It has been suggested that I was making some kind of moral statement. Believe me, I’m not. In Halloween, I viewed the characters as simply normal teenagers.»[17] In another interview, Carpenter said that readings of the film as a morality play «completely missed the point,» adding, «The one girl who is the most sexually uptight just keeps stabbing this guy with a long knife. She’s the most sexually frustrated. She’s the one that’s killed him. Not because she’s a virgin but because all that sexually repressed energy starts coming out. She uses all those phallic symbols on the guy.»[133]

Some feminist critics, according to historian Nicholas Rogers, «have seen the slasher movies since Halloween as debasing women in as decisive a manner as hard-core pornography.»[102] Critics such as John Kenneth Muir state that female characters such as Laurie Strode survive not because of «any good planning» or their own resourcefulness, but sheer luck. Although she manages to repel the killer several times, in the end, Strode is rescued in Halloween and Halloween II only when Dr. Loomis arrives to shoot Myers.[134] However, Clover has argued that despite the violence against women, Halloween and other slasher films turned women into heroines.[135] In many pre-Halloween horror films, women are depicted as helpless victims and are not safe until they are rescued by a strong masculine hero. Despite the fact that Loomis saves Strode, Clover asserts that Halloween initiates the role of the «final girl» who ultimately triumphs in the end. Strode fights back against Myers and severely wounds him.[136] Had Myers been a normal man, Strode’s attacks would have killed him; even Loomis, the male hero of the story, who shoots Michael repeatedly with a revolver, cannot kill him.[137] Aviva Briefel argued that moments such as when Michael’s face was temporarily revealed are meant to give pleasure to the male viewer. Briefel further argues that these moments are masochistic in nature and give pleasure to men because they are willingly submitting themselves to the women of the film; they submit themselves temporarily because it will make their return to authority even more powerful.[138]

Critics, such as Gill, see Halloween as a critique of American social values. She remarks that parental figures are almost entirely absent throughout the film, noting that when Laurie is attacked by Michael while babysitting, «No parents, either of the teenagers or of the children left in their charge, call to check on their children or arrive to keen over them.»[132]

According to Gill, the dangers of suburbia is another major theme that runs throughout the film and the slasher genre at large: Gill states that slasher films «seem to mock white flight to gated communities, in particular the attempts of parents to shield their children from the dangerous influences represented by the city.»[139] Halloween and slasher films, generally, represent the underside of suburbia to Gill.[140] Myers was raised in a suburban household and after he escapes the mental hospital he returns to his hometown to kill again; Myers is a product of the suburban environment, writes Gill.[139]

Michael is thought by some to represent evil in the film. This is based on the common belief that evil never dies, nor does evil show remorse. This idea is demonstrated in the film when Dr. Loomis discusses Michael’s history with the sheriff. Loomis states, «I spent eight years trying to reach him [Michael Myers], and then another seven trying to keep him locked up because I realized that what was living behind that boy’s eyes was purely and simply … evil.» Loomis also refers to Michael as «evil» when he steals his car at the sanitarium.[141]

Aesthetic elements[edit]

Judith Myers and her boyfriend, as viewed from the point-of-view of young Michael Myers; this voyeuristic perspective is a distinguishing feature of the film’s opening scene

Historian Nicholas Rogers notes that film critics contend that Carpenter’s direction and camera work made Halloween a «resounding success.»[142] Roger Ebert remarks, «It’s easy to create violence on the screen, but it’s hard to do it well. Carpenter is uncannily skilled, for example, at the use of foregrounds in his compositions, and everyone who likes thrillers knows that foregrounds are crucial . … «[93]

The opening title, featuring a jack-o’-lantern placed against a black backdrop, sets the mood for the entire film. The camera slowly moves toward the jack-o’-lantern’s left eye as the main title theme plays. After the camera fully closes in, the jack-o’-lantern’s light dims and goes out. Film historian J.P. Telotte says that this scene «clearly announces that [the film’s] primary concern will be with the way in which we see ourselves and others and the consequences that often attend our usual manner of perception.»[143] Carpenter’s first-person point-of-view compositions were employed with steadicam; Telotte argues, «As a result of this shift in perspective from a disembodied, narrative camera to an actual character’s eye … we are forced into a deeper sense of participation in the ensuing action.»[144] Along with the 1974 Canadian horror film Black Christmas, Halloween made use of seeing events through the killer’s eyes.[145]

The first scene of the young Michael’s voyeurism is followed by the murder of Judith seen through the eye holes of Michael’s clown costume mask. According to scholar Nicholas Rogers, Carpenter’s «frequent use of the unmounted first-person camera to represent the killer’s point of view … invited [viewers] to adopt the murderer’s assaultive gaze and to hear his heavy breathing and plodding footsteps as he stalked his prey.»[142] Film analysts have noted its delayed or withheld representations of violence, characterized as the «false startle» or «the old tap-on-the-shoulder routine» in which the stalkers, murderers, or monsters «lunge into our field of vision or creep up on a person.»[146] Critic Susan Stark described the film’s opening sequence in her 1978 review:

In a single, wonderfully fluid tracking shot, the camera establishes the quiet character of a suburban street, the sexual hanky-panky going on between a teenage couple in one of the staid-looking homes, the departure of the boyfriend, a hand in the kitchen drawer removing a butcher’s knife, the view on the way upstairs from behind the eye-slits of a Halloween mask, the murder of a half-nude young girl seated at her dressing table, the descent downstairs and whammo! The killer stands speechless on the lawn, holding the bloody knife, a small boy in a satin clown suit with a newly-returned parent on each side shrieking in an attempt to find out what the spectacle means.[87]

Legacy[edit]

Halloween is a widely influential film within the horror genre; it was largely responsible for the popularization of slasher films in the 1980s and helped develop the slasher genre. Halloween popularized many tropes that have become completely synonymous with the slasher genre. Halloween helped to popularize the final girl trope, the killing off of characters who are substance abusers or sexually promiscuous,[147] and the use of a theme song for the killer. Carpenter also shot many scenes from the perspective of the killer in order to build tension. These elements have become so established that many historians argue that Halloween is responsible for the new wave of horror that emerged during the 1980s.[148][149] Due to its popularity, Halloween became a blueprint for success that many other horror films, such as Friday the 13th and A Nightmare on Elm Street, followed, and that others like Scream satirized.[citation needed]

The major themes present in Halloween also became common in the slasher films it inspired. Film scholar Pat Gill notes that in Halloween, there is a theme of absentee parents[132] but films such as A Nightmare on Elm Street and Friday the 13th feature the parents becoming directly responsible for the creation of the killer.[150]

There are slasher films that predated Halloween, such as Silent Night, Bloody Night (1972), The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974) and Black Christmas (1974) which contained prominent elements of the slasher genre; both involving a group of teenagers being murdered by a stranger as well as having the final girl trope. Halloween, however, is considered by historians as being responsible for the new wave of horror films, because it not only used these tropes but also pioneered many others.[148][149] Rockoff notes that it is «difficult to overestimate the importance of Halloween,» noting its pioneering use of the final girl character, subjective point-of-view shots, and holiday setting.[151] Rockoff considers the film «the blueprint for all slashers and the model against which all subsequent films are judged.»[151]

[edit]

Novelization and video game[edit]

A mass market paperback novelization of the same name, written by Curtis Richards (a pseudonym that was used by author Richard Curtis), was published by Bantam Books in 1979. It was reissued in 1982.[152] it later went out of print. The novelization adds aspects not featured in the film, such as the origins of the curse of Samhain and Michael Myers’ life in Smith’s Grove Sanatorium, which contradict its source material. For example, the novel’s version of Michael speaks during his time at the sanitarium;[153] in the film, Dr. Loomis states, «He hasn’t spoken a word in fifteen years.»

In 1983, Halloween was adapted as a video game for the Atari 2600 by Wizard Video.[154] None of the main characters in the game were named. Players take on the role of a teenage babysitter who tries to save as many children as possible from an unnamed, knife-wielding killer.[155] In another effort to save money, most versions of the game did not even have a label on the cartridge. It was simply a piece of tape with «Halloween» written in marker.[156] The game contained more gore than the film, however. When the babysitter is killed, her head disappears and is replaced by blood pulsating from the neck as she runs around exaggeratedly. The game’s primary similarity to the film is the theme music that plays when the killer appears onscreen.[157]

Sequels and remake[edit]

Halloween spawned seven sequels.[158][159] Of these films, only the first sequel was written by Carpenter and Hill. It begins exactly where Halloween ends and was intended to finish the story of Michael Myers and Laurie Strode. Carpenter did not direct any of the subsequent films in the Halloween series, although he did produce Halloween III: Season of the Witch, the plot of which is unrelated to the other films in the series due to the absence of Michael Myers.[160] He, along with Alan Howarth, also composed the music for the second and third films. After the negative critical and commercial reception for Season of the Witch, the filmmakers brought back Michael Myers in Halloween 4: The Return of Michael Myers.[161] Financier Moustapha Akkad continued to work closely with the Halloween franchise, acting as executive producer of every sequel until his death in the 2005 Amman bombings.[162]

With the exception of Halloween III, the sequels further develop the character of Michael Myers and the Samhain theme. Even without considering the third film, the Halloween series contains continuity issues, which some sources attribute to the different writers and directors involved in each film.[163]

A remake was released in 2007, directed by Rob Zombie, which itself was followed by a 2009 sequel.[164]

An eleventh installment was released in the United States in 2018. The film, directed by David Gordon Green, is a direct sequel to the original film while disregarding the previous sequels from canon, and retconning the ending of the first film.[165] It was followed by two direct sequels: Halloween Kills (2021) and Halloween Ends (2022).[166]

Notes[edit]

- ^ While the review gives no New York City premiere date or specific theater, a display advertisement on page 72 reads: «Held over! 2nd week of horror! At a Flagship Theatre near you». Per the movie listings on pages 82, 84 and 85, respectively, it played at four since-defunct theaters: the Essex, located at 375 Grand Street in Chinatown, per Cinema Treasures: Essex Theatre; the RKO 86th Street Twin, on East 86th Street near Lexington Avenue; the Rivoli, located at 1620 Broadway, in the Times Square area, per Cinema Treasures: Rivoli Theatre; and the Times Square Theater, located at 217 West 42nd Street, per Treasures:Times Square Theater[73]

References[edit]

- ^ a b «Film Releases…Print Results». Variety Insight. Archived from the original on October 18, 2018. Retrieved October 23, 2018.

- ^ a b «Halloween». AFI Catalog of Feature Films. Archived from the original on October 23, 2018. Retrieved October 23, 2018.

- ^ «Halloween (1978)». British Film Institute. Archived from the original on October 11, 2018. Retrieved October 23, 2018.

- ^ a b Muir 2012, p. 15.

- ^ «Halloween». British Board of Film Classification. Archived from the original on February 9, 2015. Retrieved January 15, 2015.

- ^ a b «Debra Hill, 54, Film Producer Who Helped Create ‘Halloween,’ Dies». The New York Times. Associated Press. March 8, 2005. Archived from the original on May 29, 2015. Retrieved February 2, 2015.

- ^ a b c «Halloween (1978) – Financial Information». The Numbers. Archived from the original on May 15, 2018. Retrieved March 22, 2012.

- ^ a b «Halloween (1978)». Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on June 6, 2011. Retrieved July 25, 2011.

- ^ «Complete National Film Registry Listing». Library of Congress. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved April 30, 2020.

- ^ «Librarian of Congress Adds Home Movie, Silent Films and Hollywood Classics to Film Preservation List». Library of Congress. Archived from the original on April 12, 2020. Retrieved April 30, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n «Behind the Scenes». HalloweenMovies.com. Trancas International Films, Inc. 2001. Archived from the original on December 20, 2006. Retrieved August 28, 2018.

- ^ Smith 2003, event occurs at 6:40.

- ^ Smith 2003, event occurs at 7:18.

- ^ Smith 2003, event occurs at 7:15—7:40.

- ^ a b c Muir 2012, p. 13.

- ^ Smith 2003, event occurs at 7:22.

- ^ a b «Syfy – Watch Full Episodes | Imagine Greater». Scifi.com. Archived from the original on February 10, 2006. Retrieved March 7, 2015.

- ^ Frost, Benjamin J.; Volk-Weiss, Brian (October 2021). «Halloween». The Movies That Made Us. Season 3. Episode 1. Netflix.

- ^ a b «John Carpenter: Press: Rolling Stone: 6–28–79». Theofficialjohncarpenter.com. June 28, 1979. Archived from the original on February 28, 2015. Retrieved March 7, 2015.

- ^ a b «Bob Clark Interview». May 2005. Archived from the original on February 22, 2020. Retrieved February 22, 2020.

- ^ Smith 2003, event occurs at 9:30.

- ^ Salisbury, Mark (October 17, 2002). «Done to death». The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on September 8, 2018. Retrieved August 28, 2018.

- ^ a b c Smith 2003, event occurs at 29:09–30:10.

- ^ Smith 2003, event occurs at 10:21.

- ^ a b c d Rockoff 2011, p. 53.

- ^ Le Blanc & Odell 2001, p. 28.

- ^ Muir 2012, p. 17.

- ^ «DEBRA HILL’S SPEECH – A 1998 INTRODUCTION TO HALLOWEEN». Archived from the original on October 16, 2007. Retrieved December 4, 2018.

- ^ Muir 2012, p. 14.

- ^ Smith 2003, event occurs at 9:50.

- ^ a b Smith 2003, event occurs at 29:28–30:10.

- ^ a b John Carpenter, Debra Hill, Nick Castle, Jamie Lee Curtis, and Tommy Lee Wallace (2003). A Cut Above the Rest (Halloween: 25th Anniversary Edition DVD Special Features) (DVD (Region 2)). United States: Anchor Bay.

- ^ «John Carpenter: Press: Chic Magazine: August 1979». Theofficialjohncarpenter.com. Archived from the original on November 4, 2015. Retrieved March 7, 2015.

- ^ Smith 2003, event occurs at 17:44.

- ^ Smith 2003, event occurs at 18:00.

- ^ Smith 2003, event occurs at 18:18—19:30.

- ^ Clarke, Frederick S., ed. (August 1998). «John Carpenter Discusses «Halloween: H20»«. Cinefantastique. Vol. 30. F.S. Clarke. p. 7. ISSN 0145-6032.

- ^ Smith 2003, event occurs at 14:40.

- ^ Smith 2003, event occurs at 15:48.

- ^ Smith 2003, event occurs at 15:55.

- ^ Smith 2003, event occurs at 17:18.

- ^ Smith 2003, event occurs at 16:03.

- ^ Smith 2003, event occurs at 16:38.

- ^ Smith 2003, event occurs at 17:09.

- ^ Smith 2003, event occurs at 38:40.

- ^ Nick Castle casting information at HalloweenMovies.com; last accessed April 19, 2006.

- ^ «First Look at Horror Icon: Inside Michael’s Mask with Tony Moran». DreadCentral.com. October 7, 2010. Archived from the original on November 15, 2019. Retrieved November 27, 2010.

- ^ R.S Rhine«Michael Myers vs. Pumpkinhead». girlsandcorpsed.com. Archived from the original on January 30, 2019. Retrieved November 27, 2010.

- ^ Will Broaddus«‘Halloween’ villain Michael Myers at Salem gallery». salemnews.com. March 23, 2009. Archived from the original on March 2, 2014. Retrieved November 27, 2010.

- ^ Audio commentary by John Carpenter and Debra Hill in The Fog, 2002 special edition DVD

- ^ Moustapha Akkad, Fangoria interview, quoted at HalloweenMovies.com; last accessed April 19, 2006.

- ^ Muir 2012, p. 84.

- ^ Leeder 2014, p. 68.

- ^ Smith 2003, event occurs at 42:20.

- ^ Smith 2003, event occurs at 22:30.

- ^ Squires, John (July 14, 2021). «The Original Station Wagon from ‘Halloween’ is Driving into Flashback Weekend Later This Month!». Bloody Disgusting. Retrieved November 12, 2021.

- ^ Smith 2003, event occurs at 21:11.

- ^ Thomas, Bob (October 20, 1978). «A scary step into cinema». Courier-Post. Camden, New Jersey: Associated Press. p. 5. Archived from the original on September 9, 2018. Retrieved September 8, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Smith 2003, event occurs at 31:00.

- ^ Allerman 2013, pp. 246–247.

- ^ Smith 2003, event occurs at 35:47.

- ^ Smith 2003, event occurs at 36:00.

- ^ Smith 2003, event occurs at 40:10.

- ^ Smith 2003, event occurs at 40:15.

- ^ Smith 2003, event occurs at 41:01.

- ^ Burnand & Mena 2004, p. 59.

- ^ «Killing His Contemporaries: Dissecting The Musical Worlds Of John Carpenter». Archived from the original on June 13, 2006.

- ^ a b Berardinelli, James. «review of Halloween«. ReelViews. Archived from the original on September 8, 2018. Retrieved September 5, 2018.

- ^ Larson 1985, p. 287.

- ^ «Dr. Daniel Wyman». Faculty and Staff. San José State University. Archived from the original on July 20, 2011. Retrieved September 23, 2010.

- ^ Halloween Soundtrack information from HalloweenMovies.com; last accessed April 19, 2006.

- ^ Kreps, Daniel (October 13, 2017). «Hear Trent Reznor, Atticus Ross’ Chilling Take on ‘Halloween’ Theme». Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on August 11, 2018. Retrieved August 10, 2018.

- ^ Allen, Tom (November 6, 1978). «The Sleeper That’s Here to Stay». The Village Voice. pp. 67, 70 – via Google News.

- ^ «‘Halloween’ $1,270,000″. Variety. November 8, 1978. p. 7.

- ^ «Halloween». Houseofhorrors.com. Archived from the original on April 6, 2015. Retrieved March 7, 2015.

- ^ «Here’s the Poster for Halloween Re-Release». Shock Till You Drop. September 13, 2012. Archived from the original on September 15, 2012. Retrieved September 13, 2012.

- ^ Turek, Ryan (September 13, 2012). «John Carpenter’s Halloween Returning to Theaters This Fall». ComingSoon.net. Archived from the original on September 12, 2017. Retrieved September 8, 2018.

- ^ a b Muir 2012, p. 16.

- ^ Leeder 2014, p. 32.

- ^ Taylor, Michael Edward (October 22, 2016). «15 Things You Didn’t Know About John Carpenter’s Halloween». Screen Rant. Archived from the original on November 30, 2016. Retrieved September 6, 2018.

- ^ «Synapse Finds Complete Halloween Negatives». Fangoria. August 29, 2006. Archived from the original on February 28, 2007.

- ^ «Holy Grail of Halloween Footage Found». Dread Central. August 29, 2006. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007.

- ^ Kael, Pauline (1979). «Halloween». The New Yorker. p. 128. ISSN 0028-792X.

- ^ Paul, Zachary (February 27, 2018). «Ebert at the Horror Movies: The Late Critic’s Thoughts On Horror Classics». Bloody Disgusting. Archived from the original on June 20, 2018. Retrieved August 28, 2018.

- ^ «Calendar: Movies: Halloween». Los Angeles Times. November 5, 1978. p. 44. Archived from the original on September 9, 2018. Retrieved September 8, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Von Maurer, Bill (November 21, 1978). «‘Halloween’ packs a few shivers in with cliches». The Miami Times. Miami, Florida. p. 6B. Archived from the original on September 9, 2018. Retrieved September 8, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Stark, Susan (December 1, 1978). «‘Halloween’: A cult film is born». Detroit Free Press. Detroit, Michigan. p. 2B. Archived from the original on September 9, 2018. Retrieved September 8, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Siskel, Gene (November 22, 1978). «‘Halloween’ — Some Tricks, A Lot of Treats». Chicago Tribune. p. III-7 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Arnold, Gary (November 24, 1978). «‘Halloween’: A Trickle of Treats». The Washington Post. p. B5. Archived from the original on October 6, 2019.

- ^ Cedrone, Lou (November 28, 1978). «One Is For Squirrels, The Other Is For Birds». The Baltimore Evening Sun. Baltimore, MD. p. B5. Archived from the original on September 9, 2018. Retrieved September 8, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Allen, Tom (November 1979). «Halloween». Village Voice – via criterion.com.

- ^ Sarris, Andrew (December 18, 1978). «Those Wild and Crazy Cult Movies». The Village Voice. p. 60 – via Google News.

- ^ a b Ebert, Roger (October 31, 1979). «Halloween». Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on October 15, 2018. Retrieved September 8, 2018 – via RogerEbert.com.

- ^ a b «Roger Ebert’s 10 Best Lists: 1967–present». RogerEbert.com. Archived from the original on November 13, 2005. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

- ^ «Gene Siskel’s 10 Best Lists: 1969–1998». Archived from the original on July 17, 2011. Retrieved August 29, 2018 – via California Institute of Technology.

- ^ «The Greatest Films of 1978». AMC Filmsite. AMC. Archived from the original on December 10, 2005. Retrieved September 5, 2018.

- ^ «The 10 Best Movies of 1978». Film.com. Archived from the original on July 1, 2010. Retrieved April 13, 2010.

- ^ «The Best Movies of 1978 by Rank». Films101.com. Archived from the original on March 22, 2016. Retrieved April 13, 2010.

- ^ «Halloween (1978)». Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango. Archived from the original on August 14, 2019. Retrieved October 29, 2019.

- ^ «Halloween (1978) Reviews». Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on June 17, 2018. Retrieved October 20, 2018.

- ^ TV Guide Staff. «Halloween (review)». TV Guide. Archived from the original on November 14, 2015. Retrieved September 6, 2018.

- ^ a b Rogers 2002, pp. 117–118.

- ^ a b Martin & Porter 1986, p. 60.

- ^ Rockoff 2011, p. 57.

- ^ a b Miska, Brad (June 3, 2013). «[WTF] Original 1979 MEDIA ‘Halloween’ VHS Sells For Whopping $13,000 On Ebay!». Bloody Disgusting. Archived from the original on September 9, 2018. Retrieved September 5, 2018.

- ^ Halloween (VHS). Blockbuster Video. 1995. ASIN B000O8SO24.

- ^ «Halloween- Video Distribution». www.angelfire.com. Retrieved October 24, 2021.

- ^ «Halloween- Video Distribution». www.angelfire.com. Retrieved October 24, 2021.

- ^ IMDB: Halloween 1978, Company Credits

- ^ Halloween DVD (First Release), retrieved September 20, 2022

- ^ Naugle, Patrick (August 24, 2001). «Halloween: Extended Version». DVD Verdict. Archived from the original on February 18, 2004. Retrieved October 5, 2014.

- ^ Halloween (DVD). Anchor Bay Entertainment. 1999. ASIN 6305546797.

- ^ «Halloween: 25th Anniversary Edition DVD». Film Threat. August 14, 2003. Archived from the original on September 8, 2018. Retrieved September 5, 2018.

- ^ Maltz, Greg (October 19, 2007). «Halloween Blu-ray Review». Blu-ray.com. Archived from the original on September 9, 2018. Retrieved September 7, 2018.

- ^ Paper Staff (October 30, 2008). «Halloween: 30th Anniversary Commemorative DVD». Paper. Archived from the original on September 9, 2018. Retrieved September 6, 2018.

- ^ Serafini, Matt (June 11, 2013). «Dean Cundey will supervise Halloween 35th anniversary Blu-ray». Dread Central. Archived from the original on December 13, 2013. Retrieved June 12, 2013.

- ^ «The 40th Saturn Awards Winners». Saturn Awards. Archived from the original on February 21, 2012. Retrieved June 27, 2014.

- ^ Miska, Brad (July 21, 2014). «Full Specs For ‘Halloween: The Complete Collection’«. Bloody Disgusting. Archived from the original on July 25, 2014. Retrieved August 28, 2018.

- ^ Hunt, Bill (July 6, 2021). «Scream bow the Halloween films in 4K, plus our big ultra HD catalog update for the rest of 2021 & remembering Richard Donner». Retrieved October 30, 2021.

- ^ Saturn Award Nominees and Winners, 1979 at Internet Movie Database; last accessed April 19, 2006.

- ^ «AFI’s 100 Years … 100 Thrills» (PDF). American Film Institute. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 19, 2012. Retrieved May 22, 2010.

- ^ «Bravo’s 100 Scariest Movie Moments». Bravo TV. Archived from the original on October 30, 2007. Retrieved September 8, 2010.

- ^ «Chicago Critics’ Scariest Films». AltFilmGuide.com. Archived from the original on June 4, 2015. Retrieved May 22, 2010.

- ^ «Films Selected to The National Film Registry, 1989–2010». National Film Registry. Library of Congress. Archived from the original on December 23, 2017. Retrieved December 27, 2017.

- ^ «Empire‘s 500 Greatest Movies of All Time». Empire. Archived from the original on November 7, 2011. Retrieved July 31, 2011.

- ^ «Film features: 100 Greatest Movies Of All Time». Total Film. Archived from the original on October 29, 2013. Retrieved July 2, 2010.

- ^ Barone, Matt (October 23, 2017). «The Best Slasher Films of All Time». Complex. Archived from the original on December 12, 2018. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- ^ Vorel, Jim (August 8, 2018). «The Best Slasher Movies of All Time». Paste. Archived from the original on July 12, 2019. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- ^ Byrnes, Chad (October 22, 2018). «A Killer List: The Greatest Movie Slashers of All Time». LA Weekly. Archived from the original on July 3, 2019. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- ^ Clover 1987, p. 194.

- ^ Clover 1987, p. 198.

- ^ a b c Gill 2002, p. 22.

- ^ Jones 2005, p. 102.

- ^ Muir 1998, p. 104.

- ^ Clover 1993, p. 46.

- ^ Clover 1993, pp. 25–33.

- ^ Clover 1993, p. 189.

- ^ Briefel 2005, pp. 17–18.

- ^ a b Gill 2002, p. 16.

- ^ Gill 2002, pp. 15–17.

- ^ «‘Reel Terror’ Is Quite the Hatchet Job». PopMatters. December 19, 2012. Archived from the original on October 5, 2018. Retrieved October 5, 2018.

- ^ a b Rogers 2002, p. 111.

- ^ Telotte 1992, p. 116.

- ^ Telotte 1992, pp. 116–117.

- ^ Muir 2011, p. 315.

- ^ Diffrient 2004, p. 61.

- ^ Williams 1996, pp. 164–165.

- ^ a b Clover 1993, p. 24.

- ^ a b Conrich 2004, p. 92.

- ^ Gill 2002, p. 26.

- ^ a b Rockoff 2011, p. 55.

- ^ Richard, Curtis (1982) [1979]. Halloween. New York: Bantam Books. ISBN 978-0-553-26296-4.

- ^ Richard, Curtis (1979). Halloween. New York: Bantam Books. ISBN 978-0-553-13226-7.

- ^ Perron 2009, p. 5.

- ^ Bradley-Tschirgi, Mat (May 30, 2017). «9 Spooky Horror Atari 2600 Games That Are Worth a Damn». Dread Central. Archived from the original on August 23, 2017. Retrieved September 8, 2018.

- ^ Panico, Sam (July 15, 2017). «Unearthing Wizard Video’s Halloween and Texas Chainsaw Massacre Atari Cartridges». That’s Not Current. Archived from the original on September 8, 2018. Retrieved August 30, 2018.

- ^ George, Gregory D. (October 31, 2001). «History of Horror: A Primer of Horror Games for Your Atari». The Atari Times. Archived from the original on April 22, 2006.

- ^ Leeder 2014, p. 12.

- ^ King, Susan (August 29, 2009). «Malcolm McDowell has a laugh in ‘Halloween II’«. Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on February 1, 2015. Retrieved September 8, 2018.

- ^ Muir 2012, p. 195.

- ^ Leeder 2014, pp. 12–14.

- ^ «Moustapha Akkad (obituary)». The Daily Telegraph. London. November 12, 2005. Archived from the original on September 8, 2018. Retrieved September 8, 2018.

- ^ Mendelson, Scott (June 7, 2018). «‘Halloween’ Is The ‘Choose Your Own Adventure’ Of Horror Movie Franchises». Forbes. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved July 9, 2018.

- ^ Hale, Mike (August 28, 2009). «Masked Slasher Is Back: Rampage Is Inevitable». The New York Times. Retrieved November 3, 2021.

- ^ Bierly, Mandi (November 13, 2017). «Danny McBride on ‘Halloween’: ‘I just hope that we don’t f*** it up and piss people off’«. Yahoo!. Archived from the original on November 13, 2017. Retrieved November 14, 2017.

- ^ D’Alessandro, Anthony (July 8, 2020). «Blumhouse & Universal Move ‘Halloween Kills’, ‘Forever Purge’ & More To Later Release Dates». Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on September 27, 2020. Retrieved October 20, 2021.

Works cited[edit]

- Allerman, Richard (2013). Hollywood: The Movie Lover’s Guide: The Ultimate Insider Tour of Movie L.A. New York: Crown/Archetype. ISBN 978-0-8041-3777-5.

- Badley, Linda (1995). Film, Horror, and the Body Fantastic. Westport, Connecticut, United States: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-27523-4.

- Baird, Robert (Spring 2000). «The Startle Effect: Implications for Spectator Cognition and Media Theory». Film Quarterly. 3 (53): 12–24. doi:10.2307/1213732. JSTOR 1213732. S2CID 28472020.

- Briefel, Aviva (Spring 2005). «Monster Pains: Masochism, Menstruation, and Identification in the Horror Film». Film Quarterly. 58 (3): 16–27. doi:10.1525/fq.2005.58.3.16. S2CID 191609222.

- Burnand, David; Mena, Miguel (2004). «Fast and Cheap? The Film Music of John Carpenter». In Conrich, Ian; Woods, David (eds.). The Cinema of John Carpenter: The Technique of Terror. London: Wallflower Press. pp. 49–65. ISBN 978-1-904764-14-4.

- Clover, Carol (Autumn 1987). «Her Body, Himself: Gender in the Slasher Film». Representations (20): 87–228. doi:10.2307/2928507. JSTOR 2928507. S2CID 44603757.

- Clover, Carol (1993). Men, Women, and Chainsaws: Gender in the Modern Horror Film. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. OCLC 748991864.

- Conrich, Ian (2004). «Killing Time and Time Again: The Popular Appeal of Carpenters Horror’s and the Impact of the Thing and Halloween». In Conrich, Ian; Woods, David (eds.). The Cinema of John Carpenter: The Technique of Terror. London: Wallflower Press. pp. 91–106. ISBN 978-1-904764-14-4.

- Cumbow, Robert C. (2000). Order in the Universe: The Films of John Carpenter (2nd ed.). Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-3719-5.

- Diffrient, David Scott (2004). «A Film is Being Beaten: Notes on the Shock Cut and the Material Violence of Horror». In Hantke, Steffen (ed.). Horror Film: Creating and Marketing Fear. Jackson, Mississippi: University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-57806-692-6.

- Gill, Pat (Winter 2002). «The Monstrous Years: Teens, Slasher Films, and the Family». Journal of Film and Video. 54 (4): 16–30. JSTOR 20688391. S2CID 190071369.

- Johnson, Kenneth (1993). «The Point of View of the Wandering Camera». Cinema Journal. 2 (32, Winter 1993): 49–56. doi:10.2307/1225604. JSTOR 1225604. S2CID 147402792.

- Jones, Alan (2005). The Rough Guide to Horror Movies. New York: Rough Guides. ISBN 978-1-84353-521-8.

- Karney, Robin (2000). Cinema: Year by Year, 1894–2000 (3rd ed.). London: DK Pub. ISBN 978-0-7894-6118-6.

- King, Stephen (1981). Danse Macabre. New York City: Berkley Books. ISBN 978-0-425-10433-0.

- Larson, Randall D. (1985). Musique Fantastique: A Survey of Film Music in the Fantastic Cinema. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-1728-9.

- Le Blanc, Michelle; Odell, Colin (2001). John Carpenter. New York: Pocket Essentials. ISBN 978-1-903047-37-8.

- Leeder, Murray (2014). Halloween. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-1-906733-86-5.

- Martin, Mick; Porter, Marsha (1986). Video Movie Guide 1987. New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0-345-33872-3.

- Muir, John Kenneth (1998). Wes Craven: The Art of Horror. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-1923-4.

- Muir, John Kenneth (2011). Horror Films of the 1970s. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-9156-8.

- Muir, John Kenneth (2012). The Films of John Carpenter. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-9348-7.

- Noël, Carroll (Autumn 1987). «The Nature of Horror». Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism. 1 (46): 51–59. doi:10.1515/9781942401209-006. S2CID 239368695.

- Perron, Bernard (2009). Horror Video Games: Essays on the Fusion of Fear and Play. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-5479-2.

- Prince, Stephen (2004). The Horror Film. New Brunswick, New Jersey, United States: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-3363-6.

- Rockoff, Adam (2011). Going to Pieces: The Rise and Fall of the Slasher Film. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-6932-1.

- Rogers, Nicholas (2002). Halloween: From Pagan Ritual to Party Night. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-516896-9.

- Schneider, Steven Jay (2004). Horror Film and Psychoanalysis: Freud’s Worst Nightmare. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-82521-4.

- Smith, Steve; et al. (2003). Halloween: A Cut Above the Rest (Documentary). Prometheus Entertainment. OCLC 929885060.

- Telotte, J.P. (1992). «Through a Pumpkin’s Eye: The Reflexive Nature of Horror». In Waller, Gregory (ed.). American Horrors: Essays on the Modern American Horror Film. Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-01448-2.

- Williams, Tony (1996a). «Trying to Survive on the Darker Side: 1980s Family Horror». In Grant, Barry K. (ed.). The Dread of Difference: Gender and the Horror Film. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-72794-6.

- Williams, Tony (1996b). Hearths of Darkness: The Family in the American Horror Film. Rutherford, New Jersey, United States: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 978-0-8386-3564-3.

External links[edit]

| Halloween | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster by Robert Gleason |

|

| Directed by | John Carpenter |

| Written by |

|

| Produced by | Debra Hill |

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Dean Cundey |

| Edited by |

|

| Music by | John Carpenter |

|

Production |

|

| Distributed by |

|

|

Release date |

|

|

Running time |

91 minutes[5] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $300,000–325,000[6][7][8] |

| Box office | $70 million[6][7] |

Halloween is a 1978 American independent slasher film directed and scored by John Carpenter, co-written with producer Debra Hill, and starring Jamie Lee Curtis (in her film debut) and Donald Pleasence, with P. J. Soles and Nancy Loomis in supporting roles. The plot centers on a mental patient, Michael Myers, who was committed to a sanitarium for murdering his babysitting teenage sister on Halloween night when he was six years old. Fifteen years later, he escapes and returns to his hometown, where he stalks a female babysitter and her friends while under pursuit by his psychiatrist.

Filming took place in Southern California in May 1978. The film premiered in October, whereupon it grossed $70 million, becoming one of the most profitable independent films of all time. Primarily praised for Carpenter’s direction and score, many critics credit the film as the first in a long line of slasher films inspired by Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960) and Bob Clark’s Black Christmas (1974). It is considered one of the greatest and most influential horror films ever made. In 2006, Halloween was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being «culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant».[9][10]

Halloween spawned a film franchise comprising thirteen films which helped construct an extensive backstory for its antagonist Michael Myers, sometimes narratively diverging entirely from previous installments. A direct sequel of the film was released in 1981. A remake was released in 2007. An eleventh installment, which serves as a direct sequel to the original film that retcons all previous sequels, was released in 2018. Additionally, a novelization, a video game and comic book series have been based on the film.

Plot[edit]

On Halloween night in 1963, in the fictional suburban town of Haddonfield, Illinois, six-year-old Michael Myers stabs his teenage sister Judith to death with a chef’s knife. For fifteen years, Michael is incarcerated at Smith’s Grove Sanitarium, during which time he never speaks a word. On October 30, 1978, Michael’s psychiatrist, Dr. Samuel Loomis, arrives at the sanitarium to escort Michael to court for a hearing; Loomis hopes that Michael will be imprisoned for life. Michael escapes Smith’s Grove and steals Loomis’s car and escapes, killing a mechanic for his coveralls on the way back to Haddonfield. Upon arriving, he steals knives, ropes, and a white, expressionless mask from a hardware store.

On Halloween, Michael sees high school student Laurie Strode drop off a key at the long-abandoned Myers house that her father is trying to sell. Laurie notices Michael stalking her throughout the day, but her friends Annie Brackett and Lynda Van Der Klok dismiss her concerns. Loomis arrives in Haddonfield and finds Judith’s tombstone missing from the cemetery. He meets with Annie’s father, Sheriff Leigh Brackett, and they investigate Michael’s house, where Loomis tells Brackett that in the 15 years he has known Michael, he has realized that he is pure evil. Loomis and Brackett find a dead partially eaten dog in the house furthering Loomis’s suspicious that Michael is in Haddonfield. Brackett is doubtful of the danger but goes to patrol the streets, while Loomis waits at the house, expecting Michael to return. That night, Laurie babysits Tommy Doyle, while Annie babysits Lindsey Wallace across the street.

Michael follows them, spying on Annie and killing the Wallaces’ dog. Tommy sees Michael from the windows and thinks he is the boogeyman, but Laurie does not believe him. Annie later takes Lindsey over to the Doyle house to spend the night, so she can pick up her boyfriend Paul. When she gets into her car, Michael appears from the back seat, strangling her and slitting her throat. Soon after, Lynda and her boyfriend Bob arrive at the Wallace house and find it empty. After having sex, Bob goes downstairs to get a beer, where Michael kills him by pinning him to the wall with a kitchen knife. Michael then poses as Bob in a ghost costume and confronts Lynda, who teases him to no effect. Annoyed, she calls Laurie to find out what happened to Annie, but Michael strangles her to death with the phone cord while Laurie listens on the other end, thinking it is a joke.