| Caligula | |

|---|---|

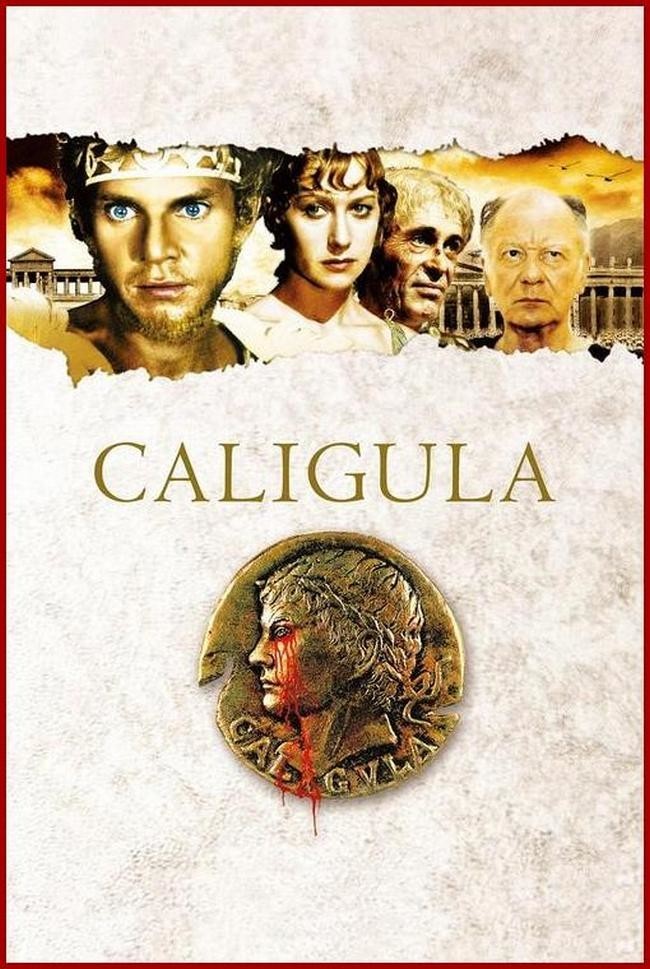

Theatrical release poster |

|

| Directed by |

|

| Screenplay by |

|

| Story by | Gore Vidal (original screenplay) |

| Based on | Life of Caligula |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Silvano Ippoliti |

| Edited by |

|

| Music by |

|

|

Production |

|

| Distributed by |

|

|

Release dates |

|

|

Running time |

156 minutes |

| Countries |

|

| Languages |

|

| Budget | $17.5 million[9] |

| Box office | $23.4 million[10] |

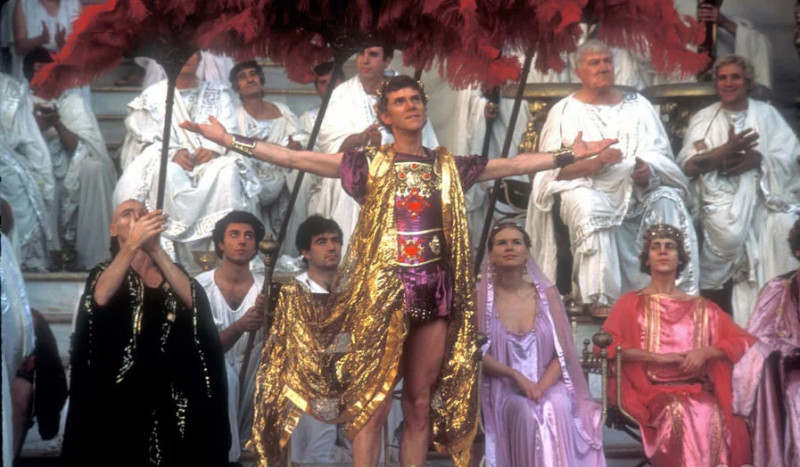

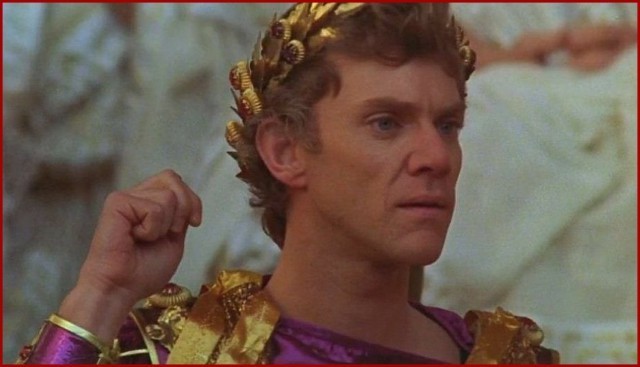

Caligula (Italian: Caligola) is a 1979 erotic historical drama film focusing on the rise and fall of the Roman Emperor Caligula. The film stars Malcolm McDowell in the title role, alongside Teresa Ann Savoy, Helen Mirren, Peter O’Toole, John Steiner and John Gielgud. Producer Bob Guccione, the founder of Penthouse magazine, intended to produce an erotic feature film narrative with high production values and name actors.

Gore Vidal originated the idea for a film about the controversial Roman emperor and produced a draft screenplay under the working title Gore Vidal’s Caligula. The director, Tinto Brass, extensively altered Vidal’s original screenplay, however, leading Vidal to disavow the film. The final screenplay focuses on the idea that «absolute power corrupts absolutely». The producers did not allow Brass to edit the film, and changed its tone and style significantly, adding graphic unsimulated sex scenes featuring Penthouse Pets as extras filmed in post-production by Guccione and Giancarlo Lui. Brass had refused to film those sequences, as both he and Vidal disagreed with their inclusion. The version of the film released in Italian cinemas in 1979 and in American cinemas the following year, disregarded Brass’s intentions to present the film as a political satire, prompting him to disavow the film as well.[11]

Caligula‘s release was met with legal issues and controversies over its violent and sexual content; multiple cut versions were released worldwide, while its uncut form remains banned in several countries.[12] Despite the generally negative reception, with some critics also citing it among the worst movies ever made, the film is considered to be a cult classic[13] with significant merit for its political content and historical portrayal.[14]

The script was later adapted into a novelisation written by William Johnston under the pseudonym William Howard.[15] In 2018, Penthouse announced that a new Director’s Cut of the film was being edited by Alexander Tuschinski, with the approval of Brass’s family.[16] No release date for that cut has been confirmed. In 2020, another version of the film was announced to be released in the fall of that year, edited by author and historian Thomas Negovan to follow more closely Gore Vidal’s original screenplay instead of Tinto Brass’s or Bob Guccione’s vision.[17]

Plot[edit]

Caligula is the young heir to the throne of his great uncle, the Emperor Tiberius. One morning, a blackbird flies into his room; Caligula considers this a bad omen. Shortly afterward, one of the heads of the Praetorian Guard, Naevius Sutorius Macro, tells Caligula that Tiberius demands his immediate presence at Capri, where the Emperor lives with his close friend Nerva, dim-witted relative Claudius, and Caligula’s adopted son (Tiberius’s grandson) Gemellus. Fearing assassination, Caligula is afraid to leave but his sister and lover Drusilla persuades him to go.

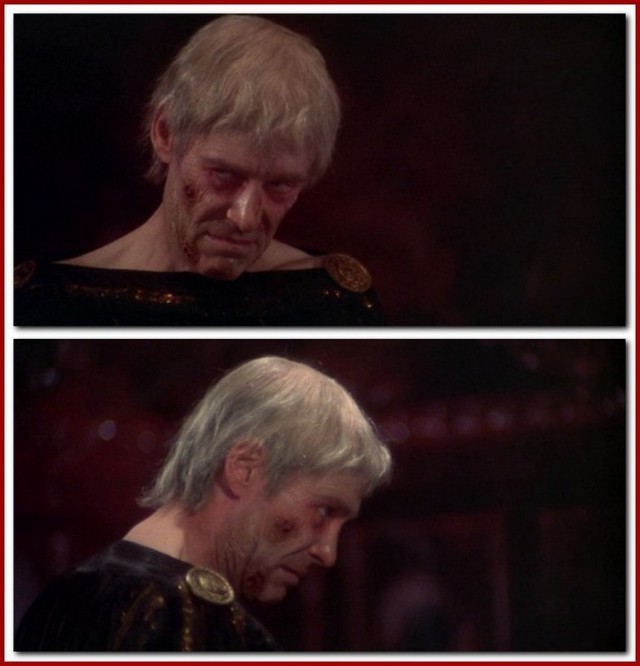

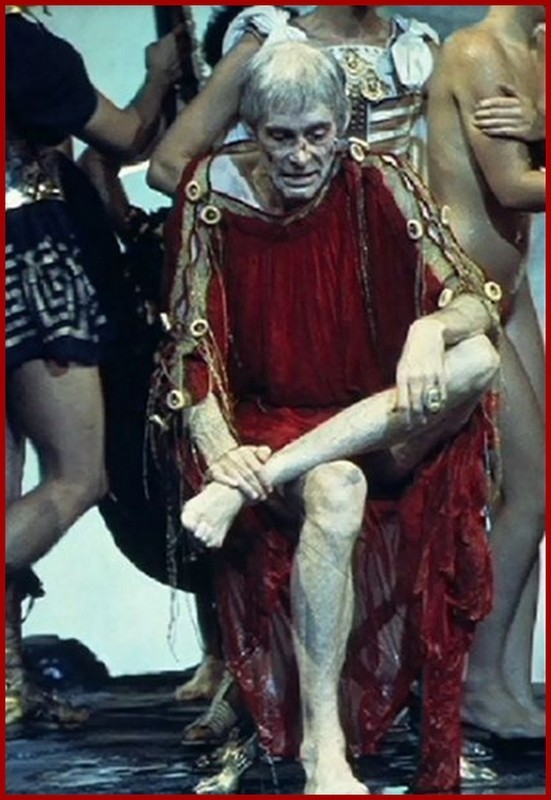

At Capri, Caligula finds that Tiberius has become depraved, showing signs of advanced venereal diseases, and embittered with Rome and politics. Tiberius enjoys swimming with naked youths and watching degrading sex shows that include deformed people and animals. Caligula observes with fascination and horror. Tensions rise when Tiberius tries to poison Caligula in front of Gemellus. Nerva commits suicide and Caligula tries to kill Tiberius but loses his nerve. Proving his loyalty to Caligula, Macro kills Tiberius instead with Gemellus as a witness.

After Tiberius’ death and burial, Caligula is proclaimed the new Emperor, then proclaims Drusilla as his equal, to the apparent disgust of the Roman Senate. Drusilla, fearful of Macro’s influence, persuades Caligula to get rid of him. Caligula sets up a mock trial in which Gemellus is intimidated into testifying that Macro murdered Tiberius, then has Macro’s wife Ennia banished from Rome. After Macro is executed in a gruesome public game, Caligula appoints Tiberius’ former adviser Longinus as his personal assistant while pronouncing the docile Senator Chaerea as the new head of the Praetorian Guard.

Drusilla tries to find Caligula a wife among the priestesses of the goddess Isis, the cult they secretly practice. Caligula wants to marry Drusilla, but she insists they cannot marry because she is his sister. Instead, Caligula marries Caesonia, a priestess and notorious courtesan, after she bears him an heir. Drusilla reluctantly supports their marriage. Meanwhile, despite Caligula’s popularity with the masses, the Senate expresses disapproval for what initially seem to be light eccentricities. Darker aspects of Caligula’s personality emerge when he rapes a bride and groom on their wedding day in a minor fit of jealousy and orders Gemellus’s execution to provoke a reaction from Drusilla.

After discovering that Caesonia is pregnant, Caligula develops a severe fever. Drusilla nurses him back to health. Just as he fully recovers, Caesonia bears him a daughter, Julia Drusilla. During the celebration, Drusilla collapses with the same fever he had had. Soon afterward, Caligula receives another ill omen in the form of a blackbird. Despite his praying to Isis out of desperation, Drusilla dies from her fever. Initially unable to accept her death, Caligula has a nervous breakdown and rampages through the palace, destroying a statue of Isis while clutching Drusilla’s body.

Now in a deep depression, Caligula walks the Roman streets disguised as a beggar; he causes a disturbance after watching an amateur performance mocking his relationship with Drusilla. After a brief stay in a city gaol, Caligula proclaims himself a god and becomes determined to destroy the senatorial class, which he has come to loathe. The new reign he leads becomes a series of humiliations against the foundations of Rome—senators’ wives are forced to work in the service of the state as prostitutes, estates are confiscated, the old religion is desecrated, and the army is made to embark on a mock invasion of Britain. Unable to further tolerate his actions, Longinus conspires with Chaerea to assassinate Caligula.

Caligula enters his bedroom where a nervous Caesonia awaits him. Another blackbird appears but only Caesonia is frightened of it. The next morning, after rehearsing an Egyptian play, Caligula and his family are attacked in a coup headed by Chaerea. Caesonia and Julia are murdered, and Chaerea stabs Caligula in the stomach. With his final breath, the Emperor defiantly whimpers «I live!» as Caligula and his family’s bodies are thrown down the stadium’s steps and their blood is washed off the marble floor. Claudius witnesses the entire ordeal and is horrified even after being proclaimed Emperor by the Praetorian Guard.

Cast[edit]

- Malcolm McDowell as Caligula

- Teresa Ann Savoy as Drusilla

- Guido Mannari as Macro

- Patrick Allen as Macro (English dub voice) (uncredited)[3]

- John Gielgud as Nerva

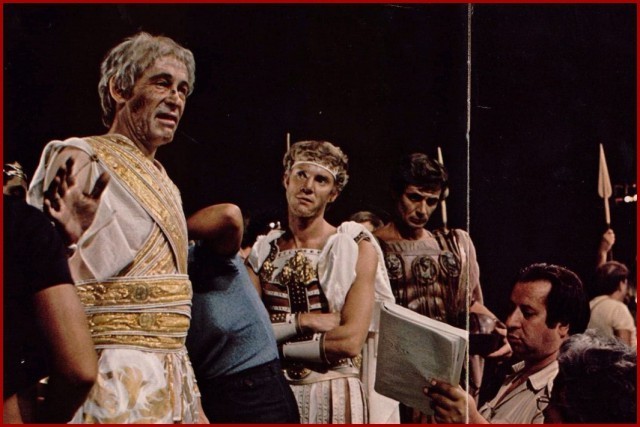

- Peter O’Toole as Tiberius

- Giancarlo Badessi as Claudius

- Bruno Brive as Gemellus

- Adriana Asti as Ennia

- Leopoldo Trieste as Charicles

- Paolo Bonacelli as Cassius Chaerea

- Joss Ackland as Cassius Chaerea (English dub voice) (uncredited)

- John Steiner as Longinus

- Mirella D’Angelo as Livilla

- Helen Mirren as Caesonia

- Richard Parets as Mnester

- Paula Mitchell as Subura Singer

- Osiride Pevarello as Giant

- Donato Placido as Proculus

- Anneka Di Lorenzo as Messalina

- Lori Wagner as Agrippina

- Valerie Rae Clark as Imperial Brothel Worker

- Susanne Saxon as Imperial Brothel Worker

- Jane Hargrave as Imperial Brothel Worker

- Carolyn Patsis as Imperial Brothel Worker

- Bonnie Dee Wilson as Imperial Brothel Worker

Production[edit]

Development[edit]

Gore Vidal was paid $200,000 to write the screenplay for Caligula;[18] ultimately, the film credited no official screenwriter, only that it was «adapted from a screenplay» by Vidal.

The men’s magazine Penthouse had long been involved in film funding, helping invest in films made by other studios, including Chinatown, The Longest Yard and The Day of the Locust, but it had never produced a film on its own.[18] The magazine’s founder Bob Guccione wanted to produce an explicit adult film within a feature film narrative that had high production values; he decided to produce a film about the rise and fall of the Roman emperor Caligula.[19] Development began under producer Franco Rossellini, the nephew of filmmaker Roberto Rossellini.[18] A screenplay was written by Lina Wertmüller, but Guccione rejected Wertmüller’s script and paid Gore Vidal to write a new screenplay.[20] Vidal’s script had a strong focus on homosexuality, leading Guccione to demand rewrites which toned down the homosexual content for wider audience appeal. Guccione was concerned that Vidal’s script contained several homosexual sex scenes and only one scene of heterosexual sex, which was between Caligula and his sister Drusilla.[20][21] Vidal was paid US$200,000 for his screenplay, which was titled Gore Vidal’s Caligula.[18]

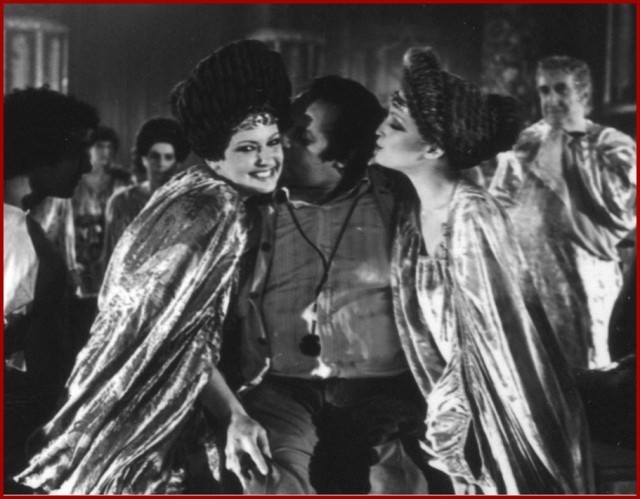

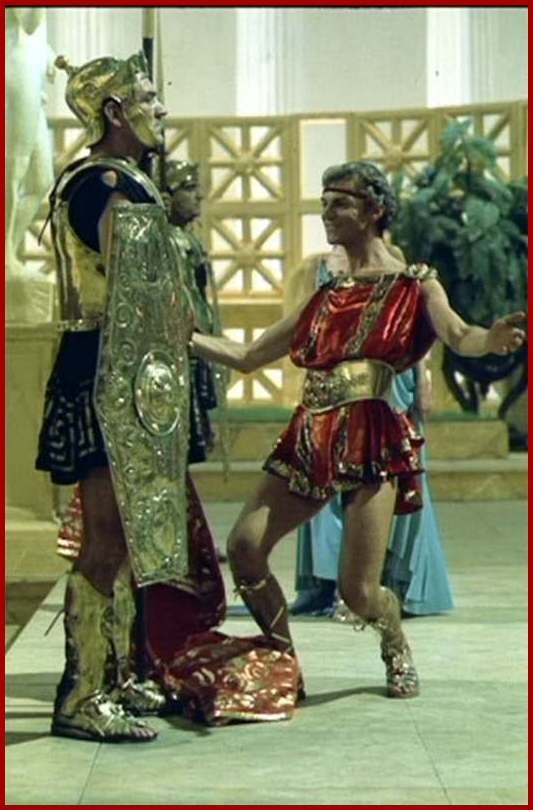

Elaborate sets were built by production designer Danilo Donati, who also designed the film’s costumes, jewelry, hairstyles, wigs, and makeup.[18] Several mainstream actors were cast, Guccione intending to make a film that he felt, like Citizen Kane, would be a landmark in cinematic history.[21] Guccione offered directing duties to John Huston and Lina Wertmüller, both of whom rejected the film.[18] After viewing scenes from the film Salon Kitty, Guccione agreed to have lunch with that film’s director Tinto Brass, believing Brass would be the ideal person to direct Caligula.[21] Brass had a reputation for being difficult to deal with on film sets but Guccione thought the film’s epic scope would «keep [Brass] in line» and that Brass understood the concept of the film enough to direct it.[18] Brass described Vidal’s screenplay as «the work of an aging arteriosclerotic» and agreed to direct only if he was allowed to rewrite Vidal’s screenplay.[21] Brass’s screenplay expanded the sexual content to include orgies, decorative phalluses, and much female nudity.[21] Guccione said Brass’s rewrites were done out of necessity to the film’s visual narrative and did not alter the dialogue or content.[18]

In an interview for Time magazine, Vidal said that in film production, directors were «parasites» and a film’s author was its screenwriter; in response, Brass demanded Vidal’s removal from the set and Guccione agreed.[18] Guccione considered the film to be a «collective effort, involving the input of a great number of artists and craftsmen», and the director to be the leader of a «team effort».[18] Vidal filed a contractual dispute over the film because of Brass’s rewrites;[18] Guccione said Vidal had demanded 10% of the film’s profits, which Vidal said was not the case.[20] Vidal distanced himself from the production, calling Brass a «megalomaniac». Brass publicly stated, «If I ever really get mad at Gore Vidal, I’ll publish his script».[22] Vidal’s name was removed from the film’s title; the credits were changed to state that the film was «adapted from a screenplay by Gore Vidal», crediting no official screenwriter.[23] Guccione said, «Gore’s work was basically done and Tinto’s work was about to begin».[18]

Themes and significance[edit]

What shall it profit a man if he should gain the whole world and lose his own soul?

Mark 8:36, quoted at the film’s beginning,[24] establishing the film’s theme that «absolute power corrupts absolutely»[25]

The film’s primary theme is «absolute power corrupts absolutely».[25] Vidal’s script presented Caligula as a good man driven to madness by absolute power;[21] Brass’s screenplay envisioned Caligula as a «born monster».[21] In The Encyclopedia of Epic Films, author Djoymi Baker describes Brass’s screenplay as «an antiepic with an antihero, on a path of self-inflicted, antisocial descent».[26] Guccione said this final draft was more violent than sexual, stating, «I maintain the film is actually anti-erotic … in every one of its scenes you’ll find a mixture of gore or violence or some other rather ugly things».[25]

Casting[edit]

Orson Welles was initially offered $1 million to star as Tiberius,[27] a figure which would have been his highest ever salary, but he refused on moral grounds when he read the script. Gore Vidal expressed disbelief that this could have ever been the case as he felt that Welles could not have portrayed Tiberius, but then recalled Kenneth Tynan remarking to him at the time that Welles was «upset» by the script.[28] Renowned actors who did accept roles in the film included Malcolm McDowell, Helen Mirren, Peter O’Toole and Sir John Gielgud, with Maria Schneider cast as Caligula’s doomed sister Drusilla.[22] Schneider became uncomfortable with appearing nude and in sexual scenes, and left the production, to be replaced by Teresa Ann Savoy, whom Brass had previously worked with on Salon Kitty.[22] Schneider had also apparently angered Brass by sewing up the open tunics she was supposed to wear on camera.[29] Gielgud was also offered the role of Tiberius, which he declined, as he felt Vidal’s script was «pornographic», but he later accepted the shorter role of Nerva.[30] Director Tinto Brass cast his own acquaintances as senators and noblemen, including ex-convicts, thieves and anarchists.[18][31] Guccione cast Penthouse Pets as female extras in sexual scenes.[18]

Filming[edit]

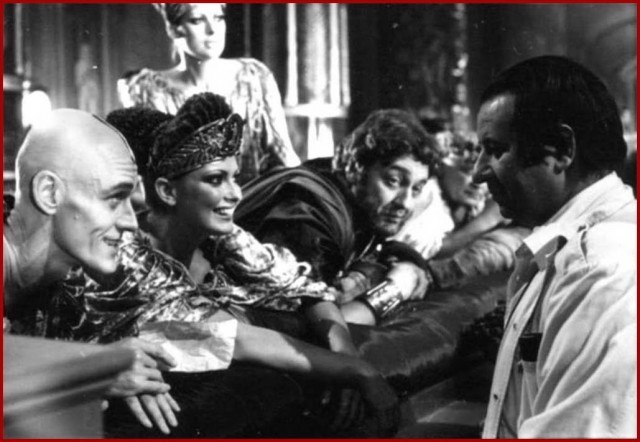

Principal photography began in 1976 in Rome.[18] McDowell got along well with Tinto Brass, while Peter O’Toole immediately disliked the director. John Gielgud and Helen Mirren were indifferent to Brass; they ultimately trusted his direction and focused on their own performances.[18] O’Toole had stopped drinking alcohol before filming, but Guccione described O’Toole as being «strung out on something» and said the actor was not sober during the entire filming schedule.[18]

Guccione later complained about McDowell’s behavior, calling the actor «shallow» and «stingy». According to Guccione, during the film’s production, McDowell took members of the production to dinner at an expensive restaurant to celebrate England’s win in a football match against the Italian team, and left the choreographer to pay for the meal, saying he had forgotten to bring enough money.[18] Also according to Guccione, at the end of the production, McDowell gave his dresser a pendant bearing her name, but it was misspelled and she gave it back to him. McDowell offered her a signet ring, a prop from the film. She refused because it belonged to the production company.[18]

Brass decided not to focus much on Danilo Donati’s elaborate sets, and intentionally kept the Penthouse Pets in the background during sex scenes, sometimes not filming them at all. Guccione later said that Brass, apparently as a joke, would focus on «fat, ugly and wrinkled old women» and have them play the «sensual parts» intended for the Penthouse Pets.[18] Brass and Guccione disagreed about the film’s approach to sexual content; Guccione preferred unsimulated sexual content that Brass did not want to film.[32]

Post-production[edit]

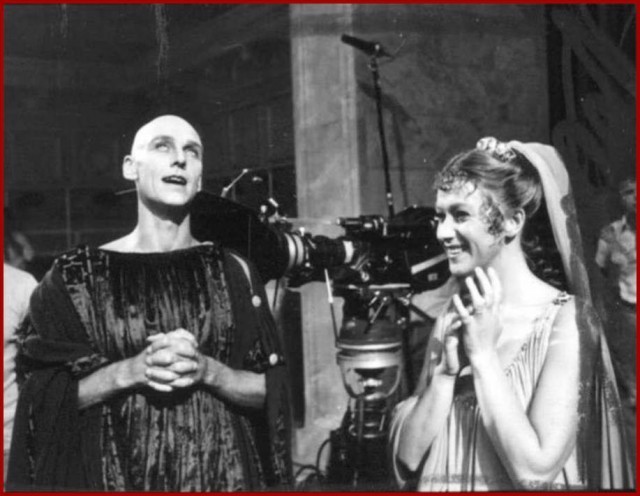

Tinto Brass served as the film’s director, but disowned the film in post-production, and was credited only for «principal photography».[33]

Filming concluded on 24 December 1976.[18] Guccione said Brass shot enough film to «make the original version of Ben-Hur about 50 times over».[18] Brass started editing the film but was not allowed to continue after he had edited approximately the first hour of it. His rough cut was disassembled, and the film was edited by several editors, changing its tone and structure significantly by removing and re-arranging many scenes, using different takes, a slower editing style, and music other than Brass intended.[34]

A few weeks after filming had concluded, Guccione and Giancarlo Lui returned to Rome along with several Penthouse Pets. Guccione and Lui «hired a skeleton crew, snuck back into the studios at night, raided the prop room»[18] and shot a number of hardcore sex scenes to be edited into the film.[31][32] The new unsimulated sex scenes included Penthouse pets Anneka Di Lorenzo and Lori Wagner, who appeared as supporting characters in Brass’ original footage. Both performed a lesbian scene together.[18] Brass ultimately disowned the film[33] as a result, and the credits only list «principal photography by Tinto Brass».[35]

Although there were a number of editors on the film, their names were not credited. Instead, the credit «Editing by the Production» is given during the opening credits.[citation needed]

As it was intended for an international release, the film was shot entirely in English. It was shot without sound, like the majority of Italian films, with the main English-speaking actors re-recording their lines later. However, as many of the supporting actors/actresses were Italian, their lines needed to be dubbed in English by other performers.[36]

Peter O’Toole was reluctant to re-record his English dialogue; he avoided the film’s producers, though they eventually tracked him down to Canada where they «dragged him in front of a mike» to record his dialogue. After production ended, O’Toole expressed his dislike of the film (although according to Guccione he hadn’t even seen the rushes) and doubted that it would ever be released.[18]

Caligula spent so much time in post-production that the film’s co-producer Franco Rossellini feared that it would never be released. Rossellini then decided to make Caligula‘s expensive sets and costumes profitable by using them in Messalina, Messalina!, a sex comedy directed by Bruno Corbucci. That film was released in Italy in 1977, two years before Caligula could be shown to the public. In some territories, it was released after Caligula and falsely marketed as its sequel. Anneka Di Lorenzo (as the title character) and Lori Wagner both reprised their roles from Caligula in Corbucci’s film. Danilo Donati’s sets and costumes were reused without his permission.[37]

Soundtrack[edit]

| Caligula: The Music | |

|---|---|

| Soundtrack album by

Paul Clemente |

|

| Released | 1980 |

| Recorded |

|

| Genre | Film score, neoclassical, pop, disco |

| Length | 36:22 |

| Label | Penthouse Records |

| Producer | Toni Biggs |

The film was scored by Bruno Nicolai under the name Paul Clemente.[3][4] According to Kristopher Spencer, the score «is gloriously dramatic, capturing both the decadent atmosphere of ancient Rome and the twisted tragedy of its true story».[4] The score also featured music by Aram Khachaturian (from Spartacus) and Sergei Prokofiev (from Romeo and Juliet).[4] In November 1980, Guccione formed Penthouse Records to release a double album soundtrack to Caligula.[38] The album featured Nicolai’s score and two versions—one in a disco style—of a love theme titled «We Are One», which did not appear in the film.[4][39]

Track listing[edit]

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Vocals | Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | «We Are One (Caligula Love Theme)» | Toni Biggs | Lydia Van Huston | 3:18 |

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Vocals | Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | «We Are One (Caligula Love Theme Dance Version)» | Toni Biggs | Lydia Van Huston | 4:33 |

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | «Wood Sequence (Intro/Spartacus/Romeo & Juliet)» | Paul Clemente, Aram Khatchaturian, Sergei Prokofiev | 4:20 |

| 2. | «Caligula & Ennia (Anfitrione)» | Paul Clemente | 1:52 |

| 3. | «Caligula’s Dance (Marziale)» | Paul Clemente | 1:20 |

| 4. | «Drusilla’s Bedroom (Spartacus)» | Aram Khatchaturian | 0:55 |

| 5. | «Isis Pool (Oblio)» | Paul Clemente | 4:15 |

| 6. | «Livia/Proculus Wedding (Movimento)» | Paul Clemente | 3:37 |

| 7. | «Caesonia’s Dance (Primitivo)» | Paul Clemente | 1:25 |

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | «Drusilla’s Death — Main Theme (Spartacus)» | Aram Khatchaturian | 5:48 |

| 2. | «Orgy On Ship (Cinderella/Midnight Waltz)» | Sergei Prokofiev | 1:52 |

| 3. | «Orgy On Ship — Part II (Orgia)» | Paul Clemente | 2:28 |

| 4. | «Battle Of Britain (Spartan War)» | John Leach | 1:26 |

| 5. | «Play/Stadium (Equiziana)» | Paul Clemente | 2:47 |

| 6. | «Caligula’s Death (Romeo & Juliet)» | Sergei Prokofiev | 3:32 |

| 7. | «Reprise (Spartacus [Main Theme])» | Aram Khatchaturian | 0:45 |

Release[edit]

Helen Mirren was cast as Caesonia, wife of Caligula. Mirren described the film as an «irresistible mix of art and genitals».[40]

An edited version of the film had a limited run in a small town near Forlì, Italy before opening in Rome on Sunday, November 11, 1979.[41] In Rome, it was the highest-grossing film of the weekend, with a gross of $59,950 from 6 theaters.[42][41] The film was confiscated by Italian police on November 15 with the Pubblico Ministero calling many scenes in the film «flagrantly obscene».[41]

In the United States, Guccione refused to submit Caligula to the MPAA because he did not want the film to receive a rating—even X—which he considered to be «demeaning».[9] Instead, Guccione applied his own «Mature Audiences» rating to the film, instructing theater owners not to admit anyone under the age of 18.[43] The film premiered in the United States on 1 February 1980, at the Trans Lux East Theatre, which Guccione had rented exclusively to screen the film; he changed the theater’s name to Penthouse East.[8]

Rather than leasing prints to exhibitors, the distributor rented theaters that specialized in foreign and art films for the purpose of screening Caligula exclusively[44] in order to keep the film out of theaters that showed pornographic films.[43][44][45] In 1981, the Brazilian Board of Censors approved the establishment of special theaters to screen In the Realm of the Senses and Caligula because they were international box office hits.[46]

Caligula grossed US$23 million[10] at the box office.[10][47] The film was a financial success in France, Germany, Switzerland, Belgium, the Netherlands and Japan.[38] A 105-minute R-rated version without the explicit sexual material was released in 1981.[23][48][49]

The script was adapted into a novelization written by William Johnston under the pseudonym William Howard.[15]

Legal problems[edit]

In 1979, when Guccione tried to import the film’s footage into the U.S., customs officials seized it. Federal officials did not declare the film to be obscene.[45] When the film was released in New York City, the anti-pornography organization Morality in Media unsuccessfully filed a lawsuit against these federal officials.[45]

In Boston, authorities seized the film.[45] Penthouse took legal action, partly because Guccione thought the legal challenges and moral controversies would provide «the kind of [marketing] coverage money can never buy».[50] Penthouse won the case when a Boston Municipal Court ruled that Caligula had passed the Miller test and was not obscene.[50] While the Boston judge said the film «lacked artistic and scientific value» because of its depiction of sex and considered it to «[appeal] to prurient interests», he said the film’s depiction of ancient Rome contained political values which enabled it to pass the Miller test in its depiction of corruption in ancient Rome, which dramatized the political theme that «absolute power corrupts absolutely».[25] A Madison, Wisconsin, district attorney declined an anti-pornography crusader’s request to prevent the release of Caligula on the basis that «the most offensive portions of the film are those explicitly depicting violent, and not sexual conduct, which is not in any way prohibited by the criminal law».[25]

Atlanta prosecutors threatened legal action if the film was to be screened in the city, but experts testified in court on behalf of the film, and Atlanta, too, declared that the film was not obscene.[45] Citizens for Decency through Law, a private watchdog group that protested against films that it deemed immoral, sought to prevent the film’s exhibition in Fairlawn, Ohio, on the grounds that it would be a «public nuisance», leading Penthouse to withdraw the film from exhibition there to avoid another trial.[25] CDL’s lawyer advised against attempting to prosecute Penthouse for obscenity and instead recommended a civil proceeding, because the film would not be placed against the Miller test.[25] The Penthouse attorney described the Fairlawn events as being driven by conservative morality reinforced by Ronald Reagan’s presidential victory, stating: «Apparently, these extremists have interpreted a change by the administration to mean a clarion call for a mandate to shackle the public’s mind again.»[25] The uncut film was granted a certificate by the British Board of Film Classification in 2008. The film was banned in Australia, where it continues to be banned in its uncut form as of 2014.[51]

In 1981, Anneka Di Lorenzo, who played Messalina, sued Guccione, claiming sexual harassment. In 1990, after protracted litigation, a New York state court awarded her $60,000 in compensatory damages and $4 million in punitive damages. On appeal, the court vacated the award, ruling that punitive damages were not allowed by the law governing the case.[52]

Contemporary reviews[edit]

Caligula received generally negative reviews. The films holds a 22% rating on Rotten Tomatoes based on thirty-two reviews. The site’s consensus states: «Endlessly perverse and indulgent, Caligula throws in hardcore sex every time the plot threatens to get interesting.»[53] Roger Ebert gave it zero stars, calling it «sickening, utterly worthless, shameful trash». Ebert wrote: «In the two hours of this film that I saw, there were no scenes of joy, natural pleasure, or good sensual cheer. There was, instead, a nauseating excursion into base and sad fantasies.»[54] It was one of the few films Ebert ever walked out of—he walked out 2 hours into its 170-minute length after feeling «disgusted and unspeakably depressed».[54] He and Gene Siskel selected the film as one of their «dogs of the year» in a 1980 episode of Sneak Previews.[55] Hank Werba of Variety described the film as a «moral holocaust» in his review.[56][57] Rex Reed called Caligula «a trough of rotten swill».[31] Jay Scott, reviewing Caligula for The Globe and Mail, said, «Caligula doesn’t really work on any level».[58] Scott unfavourably compared Caligula with In the Realm of the Senses, describing the latter film as a better treatment of extreme sexuality.[58] Scott’s review went on to say «Rome would seem to be at least as fecund a territory for the cinematic exploration of sex, death and money, as pre-war Japan … but what’s missing from Caligula, which is rife with all three, is any connective tissue (also any point of view, any thought, any meaning)».[58] Scott concluded his review by claiming the whole film’s production was «a boondoggle of landmark proportions».[58] New York critic David Denby described the film as «an infinitely degraded version of Fellini Satyricon«.[33] Tom Milne (Monthly Film Bulletin) stated that the film was «by no means so awesomely bad as most critics have been pleased to report—but pretty bad all the same» and found the film to be «notable chiefly for the accuracy with which it reflects [Caligula’s] anonymity».[59]

Legacy[edit]

Caligula continued to garner negative reception long after its release, though it has been reappraised by some critics, and attempts have been made to reconstruct a version of the film that more closely resembles the visions of either Tinto Brass or Gore Vidal. Review aggregate Rotten Tomatoes gives the film a score of 22% based on 32 reviews, with an average rating of 3.9/10. The site’s critical consensus reads: «Endlessly perverse and indulgent, Caligula throws in hardcore sex every time the plot threatens to get interesting.»[53] Leslie Halliwell said Caligula was «a vile curiosity of interest chiefly to sado-masochists».[60] Time Out London called it «a dreary shambles».[61] Positive criticism of the film came from Moviehole reviewer Clint Morris, who awarded it 3 stars out of 5, calling it «[a] classic in the coolest sense of the word».[53] New Times critic Gregory Weinkauf gave the film 3 out of 5, calling it «Kinda dumb and tacky, but at least it’s a real movie».[53] Arkansas Democrat-Gazette reviewer Philip Martin also gave the film 3 out of 5.[53]

Writers for The Hamilton Spectator and St. Louis Post-Dispatch said Caligula was one of the worst films they’d seen.[62][63] Writing for The A.V. Club, Keith Phipps said, «As a one-of-a-kind marriage of the historical epic and the porn film … Caligula deserves a look. But it might be better to let Guccione’s savagely unpleasant folly fade into the century that spawned it».[64]

Several films were released in the following years as attempts to cash in on Caligula‘s reputation, including Caligula and Messalina (1981), directed by Bruno Mattei and Caligula… The Untold Story (1982), directed by Joe D’Amato. Like Caligula, D’Amato’s film exists in several softcore and hardcore versions.[65]

In 1985, the hardcore version of Caligula was broadcast in France on Canal+, making it the first film with unsimulated sex scenes ever shown on French television. The film, which had been broadcast as a test, became the starting point of Canal+’s tradition of showing one pornographic film at midnight every month.[66][67]

Retrospective recognition[edit]

Caligula has been described as a «cult classic» by William Hawes in a book about the film.[13] Helen Mirren has defended her involvement in the making of Caligula and even described the final product of the film as «an irresistible mix of art and genitals».[40] In 2005, artist Francesco Vezzoli produced a fake trailer for an alleged remake called Gore Vidal’s Caligula as a promotion for Versace’s new line of accessories; the remake was to star Helen Mirren as «the Empress Tiberius», Gerard Butler as Chaerea, Milla Jovovich as Drusilla, Courtney Love as Caligula, and Karen Black as Agrippina the Elder and featuring an introduction by Gore Vidal. The fake trailer was screened worldwide, including New York City’s Whitney Museum of American Art’s 2006 Whitney Biennial.[68]

Leonardo DiCaprio has cited Caligula as an influence on his performance as Jordan Belfort in The Wolf of Wall Street.[69]

Reconstruction attempts[edit]

In 2007, Caligula was released on DVD and Blu-ray in an «Imperial Edition»,[70] which featured the unrated theatrical release version and a new version featuring alternative sequencing from the original theatrical release and without the explicit sexual content shot by Guccione, marking the first attempt to reconstruct the film into a version closer to Brass’s intentions. This edition also includes audio commentaries featuring Malcolm McDowell and Helen Mirren, and interviews with the cast and crew.[71]

In February 2018, Penthouse announced that a new cut of the film was being edited by Alexander Tuschinski.[72] Tuschinski will use 85 minutes of Brass’s original workprint and edit the remainder of the film himself.[73] Brass’s family supports Tuschinski’s effort, but it remains unconfirmed if Brass will be directly involved with the edit.[74] However, the edit is an attempt to realize Brass’s original vision for the film.[16]

In July 2018, Alexander Tuschinski released his documentary Mission: Caligula on Vimeo. The film explores his relationship with Caligula, the process of reconstructing Brass’s vision, and Penthouse CEO Kelly Holland’s backing of the project.[16]

In 2020, another version of the film was announced to be released in the fall of that year, edited by E. Elias Merhige to follow more closely Gore Vidal’s original screenplay instead of Tinto Brass’s or Bob Guccione’s vision.[75]

See also[edit]

- List of films considered the worst

- Unsimulated sex

References[edit]

- ^ William Hawes (2008). Caligula and the Fight for Artistic Freedom: The Making, Marketing and Impact of the Bob Guccione Film. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-5240-8.

- ^ The film’s titles credit both Baragli and «The Production», a credit possibly referring to Bob Guccione and his production assistants, with editing.

- ^ a b c William Hawes (2008). Caligula and the Fight for Artistic Freedom: The Making, Marketing and Impact of the Bob Guccione Film. McFarland. p. 233. ISBN 978-0-7864-5240-8.

- ^ a b c d e Kristopher Spencer (2008). Film and Television Scores, 1950–1979: A Critical Survey by Genre. McFarland. p. 125. ISBN 978-0-7864-5228-6.

- ^ Annuario del cinema italiano & audiovisivi (in Italian), Centro di studi di cultura, promozione e difusione del cinema, p. 59, OCLC 34869836

- ^ Anthony Slide (2014). The New Historical Dictionary of the American Film Industry. Routledge. p. 11. ISBN 978-1-135-92554-3.

- ^ William Hawes (2008). Caligula and the Fight for Artistic Freedom: The Making, Marketing and Impact of the Bob Guccione Film. McFarland. p. 195. ISBN 978-0-7864-5240-8.

- ^ a b William Hawes (2008). Caligula and the Fight for Artistic Freedom: The Making, Marketing and Impact of the Bob Guccione Film. McFarland. p. 196. ISBN 978-0-7864-5240-8.

- ^ a b John Heidenry (2002). What Wild Ecstasy. Simon and Schuster. p. 268. ISBN 978-0-7432-4184-7.

- ^ a b c «Caligula box office at the-numbers.com». the-numbers.com.

- ^ What Culture#14 Archived August 6, 2020, at the Wayback Machine: Caligula

- ^ «Film Censorship: Caligula (1979)». Refused-Classification.com. Retrieved June 9, 2012.

- ^ a b Hawes, William (2008). Caligula and the Fight for Artistic Freedom: The Making, Marketing and Impact of the Bob Guccione Film. McFarland. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-7864-5240-8.

- ^ Stephen Prince (1980–1989). A New Pot of Gold: Hollywood Under the Electronic Rainbow. p. 350.

- ^ a b Spencer, David (January–February 2010). «IAMTW’s Grand Master Scribe Award, The Faust, Goes to the Genre’s Most Prolific Practitioner» (PDF). Tied-In: The Newsletter of the International Association of Media Tie-in Writers. Calabasas, California: International Association of Media Tie-in Writers. 4 (1). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 4, 2016. Retrieved August 26, 2015.

- ^ a b c Tuschinski, Alexander (July 26, 2018), Mission: Caligula, retrieved July 27, 2018

- ^ «Caligula MMXX — announcement on website for 2020 re-release». Retrieved January 5, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y Ernest Volkman (May 1980). «Bob Guccione Caligula Interview from Penthouse May 1980». Penthouse: 112–118, 146–115. Archived from the original on August 8, 2014. Retrieved June 9, 2012.

- ^ Constantine Santas; James M. Wilson; Maria Colavito; Djoymi Baker (2014). The Encyclopedia of Epic Films. Scarecrow Press. p. 115. ISBN 978-0-8108-8248-5.

- ^ a b c «New York Magazine». Newyorkmetro.com. New York Media, LLC: 85. March 26, 1979. ISSN 0028-7369.

- ^ a b c d e f g h John Heidenry (2002). What Wild Ecstasy. Simon and Schuster. p. 266. ISBN 978-0-7432-4184-7.

- ^ a b c «Will the Real Caligula Stand Up?». Time (magazine). January 3, 1977. Archived from the original on January 19, 2008. Retrieved June 9, 2012.

- ^ a b Michael Weldon (1996). The Psychotronic Video Guide To Film. St. Martin’s Press. p. 87. ISBN 978-0-312-13149-4.

- ^ Stanley E. Porter (2007). Dictionary of Biblical Criticism and Interpretation. Routledge. p. 331. ISBN 978-1-134-63556-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Stephen Prince (2002). A New Pot of Gold: Hollywood Under the Electronic Rainbow, 1980–1989. University of California Press. pp. 350. ISBN 978-0-520-23266-2.

- ^ a b Constantine Santas; James M. Wilson; Maria Colavito; Djoymi Baker (2014). The Encyclopedia of Epic Films. Scarecrow Press. p. 118. ISBN 978-0-8108-8248-5.

- ^ Brady, Frank (1990) Citizen Welles, London: Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 9780340513897. p. 563

- ^ Vidal, Gore (1989) «Remembering Orson Welles», New York Review of Books, June 1, 1989

- ^ «Stracult Movie — Therese Ann Savoy» Archived November 1, 2022, at the Wayback Machine, Video Rai TV (July 31, 2012)

- ^ a b William Hawes (2008). Caligula and the Fight for Artistic Freedom: The Making, Marketing and Impact of the Bob Guccione Film. McFarland. p. 105. ISBN 978-0-7864-5240-8.

- ^ a b c Thomas Vinciguerra (September 6, 1999). «Porn Again». nymag.com. Retrieved June 9, 2012.

- ^ a b Jeffrey Richards (2008). Hollywood’s Ancient Worlds. A&C Black. p. 157. ISBN 978-1-84725-007-0.

- ^ a b c «New York Magazine». Newyorkmetro.com. New York Media, LLC: 61. February 25, 1980. ISSN 0028-7369.

- ^ «Analysis and reconstruction of Tinto Brass’ intended version of Caligula (PDF, 15,2 MB, 106 pages)» (PDF). Retrieved September 9, 2014.

- ^ Deborah Cartmell, Ashley D. Polasek, A Companion to the Biopic, John Wiley & Sons Inc, 2019, p. 180

- ^ William Hawes (2008). Caligula and the Fight for Artistic Freedom: The Making, Marketing and Impact of the Bob Guccione Film. McFarland. p. 108. ISBN 978-0-7864-5240-8.

- ^ Howard Hughes (April 30, 2011). Cinema Italiano: The Complete Guide from Classics to Cult. I.B.Tauris, 2011, p. 288. ISBN 9780857730442.

- ^ a b Billboard. Nielsen Business Media, Inc. November 15, 1980. p. 8. ISSN 0006-2510.

- ^ Jerry Osborne (2002). Movie/TV Soundtracks and Original Cast Recordings Price and Reference Guide. Jerry Osborne Enterprises. p. 92. ISBN 978-0-932117-37-3.

- ^ a b William Hawes (2008). Caligula and the Fight for Artistic Freedom: The Making, Marketing and Impact of the Bob Guccione Film. McFarland. p. 191. ISBN 978-0-7864-5240-8.

- ^ a b c «Guccioni, Rossellini ‘Caligula’ Seized As ‘Flagrantly Obscene’«. Variety. November 21, 1979. p. 3.

- ^ «‘Caligula’ Big In Rome Debut, At $59,950; ‘Manhattan’ 44G, 2d». Variety. November 21, 1979. p. 43.

- ^ a b Stephen Vaughn (2006). Freedom and Entertainment: Rating the Movies in an Age of New Media. Cambridge University Press. p. 73. ISBN 978-0-521-85258-6.

- ^ a b Stephen Prince. A New Pot of Gold: Hollywood Under the Electronic Rainbow, 1980–1989. p. 349.

- ^ a b c d e Stephen Vaughn (2006). Freedom and Entertainment: Rating the Movies in an Age of New Media. Cambridge University Press. p. 74. ISBN 978-0-521-85258-6.

- ^ Lisa Shaw; Stephanie Dennison (2014). Brazilian National Cinema. Routledge. p. 100. ISBN 978-1-134-70210-7.

- ^ Joyce L. Vedral (1990). Uncle John’s Third Bathroom Reader. St. Martin’s Press. p. 155. ISBN 978-0-312-04586-9.

- ^ William Hawes (2008). Caligula and the Fight for Artistic Freedom: The Making, Marketing and Impact of the Bob Guccione Film. McFarland. p. 205. ISBN 978-0-7864-5240-8.

- ^ David Welling (2010). Cinema Houston: From Nickelodeon to Megaplex. University of Texas Press. p. 249. ISBN 978-0-292-77398-1.

- ^ a b Stephen Prince (2002). A New Pot of Gold: Hollywood Under the Electronic Rainbow, 1980–1989. University of California Press. pp. 349. ISBN 978-0-520-23266-2.

- ^ Robert Cetti (2014). Offensive to a Reasonable Adult: Film Censorship and Classification in Australia. Robert Cettl. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-9872425-5-6.

- ^ «Marjorie Lee Thoreson A/K/A Anneka Dilorenzo, Appellant-Respondent, V. Penthouse International, Ltd. And Robert C. Guccione, Respondents-Appellants». law.cornell.edu. Retrieved January 19, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e «Caligula (1979)». Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved July 3, 2014.

- ^ a b Roger Ebert (September 22, 1980). «Caligula». Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved June 9, 2012.

- ^ «Siskel & Ebert org — Worst of 1980». Archived from the original on January 8, 2018. Retrieved February 1, 2015.

- ^ Werba, Hank (November 21, 1979). «Film Reviews: Caligula». Variety. p. 24.

- ^ «100 Most Controversial Films of All Time».

- ^ a b c d Jay Scott, The Globe and Mail, February 7, 1980.

- ^ Milne, Tom (1980). «Caligula». Monthly Film Bulletin. Vol. 47, no. 552. British Film Institute. p. 232. ISSN 0027-0407.

- ^ Photoplay Magazine, Volume 38, 1987 (p.38)

- ^ «Caligula (1979)». Time Out. Retrieved June 9, 2012.

- ^ «Lowest:100 Really Bad Moments in 20th Century Entertainment». The Hamilton Spectator, July 24, 1999 (p. W17).

- ^ Joe Holleman, «Roman Warriors roam the big screen again». St. Louis Post-Dispatch May 5, 2000 (p. E1).

- ^ Keith Phipps

(April 23, 2002) Caligula Archived November 1, 2022, at the Wayback Machine. The AV Club. Retrieved January 12, 2014. - ^ Grattarola, Franco; Napoli, Andrea (2014). Luce Rossa. La nascita e le prime fasi del cinema pornografico in Italia. Roma: Iacobelli Editore, pp. 278-280

- ^ Du carré blanc au film porno de Canal+, une brève histoire du sexe à la télévision Archived June 1, 2022, at the Wayback Machine, Le Parisien, 30 October 2021

- ^ la recherche du porno perdu Archived June 3, 2022, at the Wayback Machine, Libération, 14 October 2019

- ^ Linda Yablonsky (February 26, 2006). «‘Caligula’ Gives a Toga Party (but No One’s Really Invited)». The New York Times. Retrieved June 9, 2012.

- ^ «Leonardo DiCaprio channelled Caligula for Wolf of Wall Street». WENN.com. December 18, 2013. Archived from the original on December 8, 2015.

- ^ Monica S. Cyrino (2013). Screening Love and Sex in the Ancient World. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 148. ISBN 978-1-137-29960-4.

- ^ Martin M. Winkler (2009). Cinema and Classical Texts: Apollo’s New Light. Cambridge University Press. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-521-51860-4.

- ^ AVN, Mark Kernes. «Penthouse Event Previews New Version of Classic Film ‘Caligula’ | AVN». AVN. Retrieved March 12, 2018.

- ^ «Film-Analyses / Caligula». alexander-tuschinski.de. Retrieved March 12, 2018.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: MISSION CALIGULA Q&A at Hollywood Reel Independent Film Festival — February 26, 2018, February 28, 2018, retrieved March 12, 2018

- ^ «Caligula MMXX — announcement on website for 2020 re-release». Retrieved January 5, 2020.

External links[edit]

| Caligula | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster |

|

| Directed by |

|

| Screenplay by |

|

| Story by | Gore Vidal (original screenplay) |

| Based on | Life of Caligula |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Silvano Ippoliti |

| Edited by |

|

| Music by |

|

|

Production |

|

| Distributed by |

|

|

Release dates |

|

|

Running time |

156 minutes |

| Countries |

|

| Languages |

|

| Budget | $17.5 million[9] |

| Box office | $23.4 million[10] |

Caligula (Italian: Caligola) is a 1979 erotic historical drama film focusing on the rise and fall of the Roman Emperor Caligula. The film stars Malcolm McDowell in the title role, alongside Teresa Ann Savoy, Helen Mirren, Peter O’Toole, John Steiner and John Gielgud. Producer Bob Guccione, the founder of Penthouse magazine, intended to produce an erotic feature film narrative with high production values and name actors.

Gore Vidal originated the idea for a film about the controversial Roman emperor and produced a draft screenplay under the working title Gore Vidal’s Caligula. The director, Tinto Brass, extensively altered Vidal’s original screenplay, however, leading Vidal to disavow the film. The final screenplay focuses on the idea that «absolute power corrupts absolutely». The producers did not allow Brass to edit the film, and changed its tone and style significantly, adding graphic unsimulated sex scenes featuring Penthouse Pets as extras filmed in post-production by Guccione and Giancarlo Lui. Brass had refused to film those sequences, as both he and Vidal disagreed with their inclusion. The version of the film released in Italian cinemas in 1979 and in American cinemas the following year, disregarded Brass’s intentions to present the film as a political satire, prompting him to disavow the film as well.[11]

Caligula‘s release was met with legal issues and controversies over its violent and sexual content; multiple cut versions were released worldwide, while its uncut form remains banned in several countries.[12] Despite the generally negative reception, with some critics also citing it among the worst movies ever made, the film is considered to be a cult classic[13] with significant merit for its political content and historical portrayal.[14]

The script was later adapted into a novelisation written by William Johnston under the pseudonym William Howard.[15] In 2018, Penthouse announced that a new Director’s Cut of the film was being edited by Alexander Tuschinski, with the approval of Brass’s family.[16] No release date for that cut has been confirmed. In 2020, another version of the film was announced to be released in the fall of that year, edited by author and historian Thomas Negovan to follow more closely Gore Vidal’s original screenplay instead of Tinto Brass’s or Bob Guccione’s vision.[17]

Plot[edit]

Caligula is the young heir to the throne of his great uncle, the Emperor Tiberius. One morning, a blackbird flies into his room; Caligula considers this a bad omen. Shortly afterward, one of the heads of the Praetorian Guard, Naevius Sutorius Macro, tells Caligula that Tiberius demands his immediate presence at Capri, where the Emperor lives with his close friend Nerva, dim-witted relative Claudius, and Caligula’s adopted son (Tiberius’s grandson) Gemellus. Fearing assassination, Caligula is afraid to leave but his sister and lover Drusilla persuades him to go.

At Capri, Caligula finds that Tiberius has become depraved, showing signs of advanced venereal diseases, and embittered with Rome and politics. Tiberius enjoys swimming with naked youths and watching degrading sex shows that include deformed people and animals. Caligula observes with fascination and horror. Tensions rise when Tiberius tries to poison Caligula in front of Gemellus. Nerva commits suicide and Caligula tries to kill Tiberius but loses his nerve. Proving his loyalty to Caligula, Macro kills Tiberius instead with Gemellus as a witness.

After Tiberius’ death and burial, Caligula is proclaimed the new Emperor, then proclaims Drusilla as his equal, to the apparent disgust of the Roman Senate. Drusilla, fearful of Macro’s influence, persuades Caligula to get rid of him. Caligula sets up a mock trial in which Gemellus is intimidated into testifying that Macro murdered Tiberius, then has Macro’s wife Ennia banished from Rome. After Macro is executed in a gruesome public game, Caligula appoints Tiberius’ former adviser Longinus as his personal assistant while pronouncing the docile Senator Chaerea as the new head of the Praetorian Guard.

Drusilla tries to find Caligula a wife among the priestesses of the goddess Isis, the cult they secretly practice. Caligula wants to marry Drusilla, but she insists they cannot marry because she is his sister. Instead, Caligula marries Caesonia, a priestess and notorious courtesan, after she bears him an heir. Drusilla reluctantly supports their marriage. Meanwhile, despite Caligula’s popularity with the masses, the Senate expresses disapproval for what initially seem to be light eccentricities. Darker aspects of Caligula’s personality emerge when he rapes a bride and groom on their wedding day in a minor fit of jealousy and orders Gemellus’s execution to provoke a reaction from Drusilla.

After discovering that Caesonia is pregnant, Caligula develops a severe fever. Drusilla nurses him back to health. Just as he fully recovers, Caesonia bears him a daughter, Julia Drusilla. During the celebration, Drusilla collapses with the same fever he had had. Soon afterward, Caligula receives another ill omen in the form of a blackbird. Despite his praying to Isis out of desperation, Drusilla dies from her fever. Initially unable to accept her death, Caligula has a nervous breakdown and rampages through the palace, destroying a statue of Isis while clutching Drusilla’s body.

Now in a deep depression, Caligula walks the Roman streets disguised as a beggar; he causes a disturbance after watching an amateur performance mocking his relationship with Drusilla. After a brief stay in a city gaol, Caligula proclaims himself a god and becomes determined to destroy the senatorial class, which he has come to loathe. The new reign he leads becomes a series of humiliations against the foundations of Rome—senators’ wives are forced to work in the service of the state as prostitutes, estates are confiscated, the old religion is desecrated, and the army is made to embark on a mock invasion of Britain. Unable to further tolerate his actions, Longinus conspires with Chaerea to assassinate Caligula.

Caligula enters his bedroom where a nervous Caesonia awaits him. Another blackbird appears but only Caesonia is frightened of it. The next morning, after rehearsing an Egyptian play, Caligula and his family are attacked in a coup headed by Chaerea. Caesonia and Julia are murdered, and Chaerea stabs Caligula in the stomach. With his final breath, the Emperor defiantly whimpers «I live!» as Caligula and his family’s bodies are thrown down the stadium’s steps and their blood is washed off the marble floor. Claudius witnesses the entire ordeal and is horrified even after being proclaimed Emperor by the Praetorian Guard.

Cast[edit]

- Malcolm McDowell as Caligula

- Teresa Ann Savoy as Drusilla

- Guido Mannari as Macro

- Patrick Allen as Macro (English dub voice) (uncredited)[3]

- John Gielgud as Nerva

- Peter O’Toole as Tiberius

- Giancarlo Badessi as Claudius

- Bruno Brive as Gemellus

- Adriana Asti as Ennia

- Leopoldo Trieste as Charicles

- Paolo Bonacelli as Cassius Chaerea

- Joss Ackland as Cassius Chaerea (English dub voice) (uncredited)

- John Steiner as Longinus

- Mirella D’Angelo as Livilla

- Helen Mirren as Caesonia

- Richard Parets as Mnester

- Paula Mitchell as Subura Singer

- Osiride Pevarello as Giant

- Donato Placido as Proculus

- Anneka Di Lorenzo as Messalina

- Lori Wagner as Agrippina

- Valerie Rae Clark as Imperial Brothel Worker

- Susanne Saxon as Imperial Brothel Worker

- Jane Hargrave as Imperial Brothel Worker

- Carolyn Patsis as Imperial Brothel Worker

- Bonnie Dee Wilson as Imperial Brothel Worker

Production[edit]

Development[edit]

Gore Vidal was paid $200,000 to write the screenplay for Caligula;[18] ultimately, the film credited no official screenwriter, only that it was «adapted from a screenplay» by Vidal.

The men’s magazine Penthouse had long been involved in film funding, helping invest in films made by other studios, including Chinatown, The Longest Yard and The Day of the Locust, but it had never produced a film on its own.[18] The magazine’s founder Bob Guccione wanted to produce an explicit adult film within a feature film narrative that had high production values; he decided to produce a film about the rise and fall of the Roman emperor Caligula.[19] Development began under producer Franco Rossellini, the nephew of filmmaker Roberto Rossellini.[18] A screenplay was written by Lina Wertmüller, but Guccione rejected Wertmüller’s script and paid Gore Vidal to write a new screenplay.[20] Vidal’s script had a strong focus on homosexuality, leading Guccione to demand rewrites which toned down the homosexual content for wider audience appeal. Guccione was concerned that Vidal’s script contained several homosexual sex scenes and only one scene of heterosexual sex, which was between Caligula and his sister Drusilla.[20][21] Vidal was paid US$200,000 for his screenplay, which was titled Gore Vidal’s Caligula.[18]

Elaborate sets were built by production designer Danilo Donati, who also designed the film’s costumes, jewelry, hairstyles, wigs, and makeup.[18] Several mainstream actors were cast, Guccione intending to make a film that he felt, like Citizen Kane, would be a landmark in cinematic history.[21] Guccione offered directing duties to John Huston and Lina Wertmüller, both of whom rejected the film.[18] After viewing scenes from the film Salon Kitty, Guccione agreed to have lunch with that film’s director Tinto Brass, believing Brass would be the ideal person to direct Caligula.[21] Brass had a reputation for being difficult to deal with on film sets but Guccione thought the film’s epic scope would «keep [Brass] in line» and that Brass understood the concept of the film enough to direct it.[18] Brass described Vidal’s screenplay as «the work of an aging arteriosclerotic» and agreed to direct only if he was allowed to rewrite Vidal’s screenplay.[21] Brass’s screenplay expanded the sexual content to include orgies, decorative phalluses, and much female nudity.[21] Guccione said Brass’s rewrites were done out of necessity to the film’s visual narrative and did not alter the dialogue or content.[18]

In an interview for Time magazine, Vidal said that in film production, directors were «parasites» and a film’s author was its screenwriter; in response, Brass demanded Vidal’s removal from the set and Guccione agreed.[18] Guccione considered the film to be a «collective effort, involving the input of a great number of artists and craftsmen», and the director to be the leader of a «team effort».[18] Vidal filed a contractual dispute over the film because of Brass’s rewrites;[18] Guccione said Vidal had demanded 10% of the film’s profits, which Vidal said was not the case.[20] Vidal distanced himself from the production, calling Brass a «megalomaniac». Brass publicly stated, «If I ever really get mad at Gore Vidal, I’ll publish his script».[22] Vidal’s name was removed from the film’s title; the credits were changed to state that the film was «adapted from a screenplay by Gore Vidal», crediting no official screenwriter.[23] Guccione said, «Gore’s work was basically done and Tinto’s work was about to begin».[18]

Themes and significance[edit]

What shall it profit a man if he should gain the whole world and lose his own soul?

Mark 8:36, quoted at the film’s beginning,[24] establishing the film’s theme that «absolute power corrupts absolutely»[25]

The film’s primary theme is «absolute power corrupts absolutely».[25] Vidal’s script presented Caligula as a good man driven to madness by absolute power;[21] Brass’s screenplay envisioned Caligula as a «born monster».[21] In The Encyclopedia of Epic Films, author Djoymi Baker describes Brass’s screenplay as «an antiepic with an antihero, on a path of self-inflicted, antisocial descent».[26] Guccione said this final draft was more violent than sexual, stating, «I maintain the film is actually anti-erotic … in every one of its scenes you’ll find a mixture of gore or violence or some other rather ugly things».[25]

Casting[edit]

Orson Welles was initially offered $1 million to star as Tiberius,[27] a figure which would have been his highest ever salary, but he refused on moral grounds when he read the script. Gore Vidal expressed disbelief that this could have ever been the case as he felt that Welles could not have portrayed Tiberius, but then recalled Kenneth Tynan remarking to him at the time that Welles was «upset» by the script.[28] Renowned actors who did accept roles in the film included Malcolm McDowell, Helen Mirren, Peter O’Toole and Sir John Gielgud, with Maria Schneider cast as Caligula’s doomed sister Drusilla.[22] Schneider became uncomfortable with appearing nude and in sexual scenes, and left the production, to be replaced by Teresa Ann Savoy, whom Brass had previously worked with on Salon Kitty.[22] Schneider had also apparently angered Brass by sewing up the open tunics she was supposed to wear on camera.[29] Gielgud was also offered the role of Tiberius, which he declined, as he felt Vidal’s script was «pornographic», but he later accepted the shorter role of Nerva.[30] Director Tinto Brass cast his own acquaintances as senators and noblemen, including ex-convicts, thieves and anarchists.[18][31] Guccione cast Penthouse Pets as female extras in sexual scenes.[18]

Filming[edit]

Principal photography began in 1976 in Rome.[18] McDowell got along well with Tinto Brass, while Peter O’Toole immediately disliked the director. John Gielgud and Helen Mirren were indifferent to Brass; they ultimately trusted his direction and focused on their own performances.[18] O’Toole had stopped drinking alcohol before filming, but Guccione described O’Toole as being «strung out on something» and said the actor was not sober during the entire filming schedule.[18]

Guccione later complained about McDowell’s behavior, calling the actor «shallow» and «stingy». According to Guccione, during the film’s production, McDowell took members of the production to dinner at an expensive restaurant to celebrate England’s win in a football match against the Italian team, and left the choreographer to pay for the meal, saying he had forgotten to bring enough money.[18] Also according to Guccione, at the end of the production, McDowell gave his dresser a pendant bearing her name, but it was misspelled and she gave it back to him. McDowell offered her a signet ring, a prop from the film. She refused because it belonged to the production company.[18]

Brass decided not to focus much on Danilo Donati’s elaborate sets, and intentionally kept the Penthouse Pets in the background during sex scenes, sometimes not filming them at all. Guccione later said that Brass, apparently as a joke, would focus on «fat, ugly and wrinkled old women» and have them play the «sensual parts» intended for the Penthouse Pets.[18] Brass and Guccione disagreed about the film’s approach to sexual content; Guccione preferred unsimulated sexual content that Brass did not want to film.[32]

Post-production[edit]

Tinto Brass served as the film’s director, but disowned the film in post-production, and was credited only for «principal photography».[33]

Filming concluded on 24 December 1976.[18] Guccione said Brass shot enough film to «make the original version of Ben-Hur about 50 times over».[18] Brass started editing the film but was not allowed to continue after he had edited approximately the first hour of it. His rough cut was disassembled, and the film was edited by several editors, changing its tone and structure significantly by removing and re-arranging many scenes, using different takes, a slower editing style, and music other than Brass intended.[34]

A few weeks after filming had concluded, Guccione and Giancarlo Lui returned to Rome along with several Penthouse Pets. Guccione and Lui «hired a skeleton crew, snuck back into the studios at night, raided the prop room»[18] and shot a number of hardcore sex scenes to be edited into the film.[31][32] The new unsimulated sex scenes included Penthouse pets Anneka Di Lorenzo and Lori Wagner, who appeared as supporting characters in Brass’ original footage. Both performed a lesbian scene together.[18] Brass ultimately disowned the film[33] as a result, and the credits only list «principal photography by Tinto Brass».[35]

Although there were a number of editors on the film, their names were not credited. Instead, the credit «Editing by the Production» is given during the opening credits.[citation needed]

As it was intended for an international release, the film was shot entirely in English. It was shot without sound, like the majority of Italian films, with the main English-speaking actors re-recording their lines later. However, as many of the supporting actors/actresses were Italian, their lines needed to be dubbed in English by other performers.[36]

Peter O’Toole was reluctant to re-record his English dialogue; he avoided the film’s producers, though they eventually tracked him down to Canada where they «dragged him in front of a mike» to record his dialogue. After production ended, O’Toole expressed his dislike of the film (although according to Guccione he hadn’t even seen the rushes) and doubted that it would ever be released.[18]

Caligula spent so much time in post-production that the film’s co-producer Franco Rossellini feared that it would never be released. Rossellini then decided to make Caligula‘s expensive sets and costumes profitable by using them in Messalina, Messalina!, a sex comedy directed by Bruno Corbucci. That film was released in Italy in 1977, two years before Caligula could be shown to the public. In some territories, it was released after Caligula and falsely marketed as its sequel. Anneka Di Lorenzo (as the title character) and Lori Wagner both reprised their roles from Caligula in Corbucci’s film. Danilo Donati’s sets and costumes were reused without his permission.[37]

Soundtrack[edit]

| Caligula: The Music | |

|---|---|

| Soundtrack album by

Paul Clemente |

|

| Released | 1980 |

| Recorded |

|

| Genre | Film score, neoclassical, pop, disco |

| Length | 36:22 |

| Label | Penthouse Records |

| Producer | Toni Biggs |

The film was scored by Bruno Nicolai under the name Paul Clemente.[3][4] According to Kristopher Spencer, the score «is gloriously dramatic, capturing both the decadent atmosphere of ancient Rome and the twisted tragedy of its true story».[4] The score also featured music by Aram Khachaturian (from Spartacus) and Sergei Prokofiev (from Romeo and Juliet).[4] In November 1980, Guccione formed Penthouse Records to release a double album soundtrack to Caligula.[38] The album featured Nicolai’s score and two versions—one in a disco style—of a love theme titled «We Are One», which did not appear in the film.[4][39]

Track listing[edit]

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Vocals | Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | «We Are One (Caligula Love Theme)» | Toni Biggs | Lydia Van Huston | 3:18 |

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Vocals | Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | «We Are One (Caligula Love Theme Dance Version)» | Toni Biggs | Lydia Van Huston | 4:33 |

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | «Wood Sequence (Intro/Spartacus/Romeo & Juliet)» | Paul Clemente, Aram Khatchaturian, Sergei Prokofiev | 4:20 |

| 2. | «Caligula & Ennia (Anfitrione)» | Paul Clemente | 1:52 |

| 3. | «Caligula’s Dance (Marziale)» | Paul Clemente | 1:20 |

| 4. | «Drusilla’s Bedroom (Spartacus)» | Aram Khatchaturian | 0:55 |

| 5. | «Isis Pool (Oblio)» | Paul Clemente | 4:15 |

| 6. | «Livia/Proculus Wedding (Movimento)» | Paul Clemente | 3:37 |

| 7. | «Caesonia’s Dance (Primitivo)» | Paul Clemente | 1:25 |

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | «Drusilla’s Death — Main Theme (Spartacus)» | Aram Khatchaturian | 5:48 |

| 2. | «Orgy On Ship (Cinderella/Midnight Waltz)» | Sergei Prokofiev | 1:52 |

| 3. | «Orgy On Ship — Part II (Orgia)» | Paul Clemente | 2:28 |

| 4. | «Battle Of Britain (Spartan War)» | John Leach | 1:26 |

| 5. | «Play/Stadium (Equiziana)» | Paul Clemente | 2:47 |

| 6. | «Caligula’s Death (Romeo & Juliet)» | Sergei Prokofiev | 3:32 |

| 7. | «Reprise (Spartacus [Main Theme])» | Aram Khatchaturian | 0:45 |

Release[edit]

Helen Mirren was cast as Caesonia, wife of Caligula. Mirren described the film as an «irresistible mix of art and genitals».[40]

An edited version of the film had a limited run in a small town near Forlì, Italy before opening in Rome on Sunday, November 11, 1979.[41] In Rome, it was the highest-grossing film of the weekend, with a gross of $59,950 from 6 theaters.[42][41] The film was confiscated by Italian police on November 15 with the Pubblico Ministero calling many scenes in the film «flagrantly obscene».[41]

In the United States, Guccione refused to submit Caligula to the MPAA because he did not want the film to receive a rating—even X—which he considered to be «demeaning».[9] Instead, Guccione applied his own «Mature Audiences» rating to the film, instructing theater owners not to admit anyone under the age of 18.[43] The film premiered in the United States on 1 February 1980, at the Trans Lux East Theatre, which Guccione had rented exclusively to screen the film; he changed the theater’s name to Penthouse East.[8]

Rather than leasing prints to exhibitors, the distributor rented theaters that specialized in foreign and art films for the purpose of screening Caligula exclusively[44] in order to keep the film out of theaters that showed pornographic films.[43][44][45] In 1981, the Brazilian Board of Censors approved the establishment of special theaters to screen In the Realm of the Senses and Caligula because they were international box office hits.[46]

Caligula grossed US$23 million[10] at the box office.[10][47] The film was a financial success in France, Germany, Switzerland, Belgium, the Netherlands and Japan.[38] A 105-minute R-rated version without the explicit sexual material was released in 1981.[23][48][49]

The script was adapted into a novelization written by William Johnston under the pseudonym William Howard.[15]

Legal problems[edit]

In 1979, when Guccione tried to import the film’s footage into the U.S., customs officials seized it. Federal officials did not declare the film to be obscene.[45] When the film was released in New York City, the anti-pornography organization Morality in Media unsuccessfully filed a lawsuit against these federal officials.[45]

In Boston, authorities seized the film.[45] Penthouse took legal action, partly because Guccione thought the legal challenges and moral controversies would provide «the kind of [marketing] coverage money can never buy».[50] Penthouse won the case when a Boston Municipal Court ruled that Caligula had passed the Miller test and was not obscene.[50] While the Boston judge said the film «lacked artistic and scientific value» because of its depiction of sex and considered it to «[appeal] to prurient interests», he said the film’s depiction of ancient Rome contained political values which enabled it to pass the Miller test in its depiction of corruption in ancient Rome, which dramatized the political theme that «absolute power corrupts absolutely».[25] A Madison, Wisconsin, district attorney declined an anti-pornography crusader’s request to prevent the release of Caligula on the basis that «the most offensive portions of the film are those explicitly depicting violent, and not sexual conduct, which is not in any way prohibited by the criminal law».[25]

Atlanta prosecutors threatened legal action if the film was to be screened in the city, but experts testified in court on behalf of the film, and Atlanta, too, declared that the film was not obscene.[45] Citizens for Decency through Law, a private watchdog group that protested against films that it deemed immoral, sought to prevent the film’s exhibition in Fairlawn, Ohio, on the grounds that it would be a «public nuisance», leading Penthouse to withdraw the film from exhibition there to avoid another trial.[25] CDL’s lawyer advised against attempting to prosecute Penthouse for obscenity and instead recommended a civil proceeding, because the film would not be placed against the Miller test.[25] The Penthouse attorney described the Fairlawn events as being driven by conservative morality reinforced by Ronald Reagan’s presidential victory, stating: «Apparently, these extremists have interpreted a change by the administration to mean a clarion call for a mandate to shackle the public’s mind again.»[25] The uncut film was granted a certificate by the British Board of Film Classification in 2008. The film was banned in Australia, where it continues to be banned in its uncut form as of 2014.[51]

In 1981, Anneka Di Lorenzo, who played Messalina, sued Guccione, claiming sexual harassment. In 1990, after protracted litigation, a New York state court awarded her $60,000 in compensatory damages and $4 million in punitive damages. On appeal, the court vacated the award, ruling that punitive damages were not allowed by the law governing the case.[52]

Contemporary reviews[edit]

Caligula received generally negative reviews. The films holds a 22% rating on Rotten Tomatoes based on thirty-two reviews. The site’s consensus states: «Endlessly perverse and indulgent, Caligula throws in hardcore sex every time the plot threatens to get interesting.»[53] Roger Ebert gave it zero stars, calling it «sickening, utterly worthless, shameful trash». Ebert wrote: «In the two hours of this film that I saw, there were no scenes of joy, natural pleasure, or good sensual cheer. There was, instead, a nauseating excursion into base and sad fantasies.»[54] It was one of the few films Ebert ever walked out of—he walked out 2 hours into its 170-minute length after feeling «disgusted and unspeakably depressed».[54] He and Gene Siskel selected the film as one of their «dogs of the year» in a 1980 episode of Sneak Previews.[55] Hank Werba of Variety described the film as a «moral holocaust» in his review.[56][57] Rex Reed called Caligula «a trough of rotten swill».[31] Jay Scott, reviewing Caligula for The Globe and Mail, said, «Caligula doesn’t really work on any level».[58] Scott unfavourably compared Caligula with In the Realm of the Senses, describing the latter film as a better treatment of extreme sexuality.[58] Scott’s review went on to say «Rome would seem to be at least as fecund a territory for the cinematic exploration of sex, death and money, as pre-war Japan … but what’s missing from Caligula, which is rife with all three, is any connective tissue (also any point of view, any thought, any meaning)».[58] Scott concluded his review by claiming the whole film’s production was «a boondoggle of landmark proportions».[58] New York critic David Denby described the film as «an infinitely degraded version of Fellini Satyricon«.[33] Tom Milne (Monthly Film Bulletin) stated that the film was «by no means so awesomely bad as most critics have been pleased to report—but pretty bad all the same» and found the film to be «notable chiefly for the accuracy with which it reflects [Caligula’s] anonymity».[59]

Legacy[edit]

Caligula continued to garner negative reception long after its release, though it has been reappraised by some critics, and attempts have been made to reconstruct a version of the film that more closely resembles the visions of either Tinto Brass or Gore Vidal. Review aggregate Rotten Tomatoes gives the film a score of 22% based on 32 reviews, with an average rating of 3.9/10. The site’s critical consensus reads: «Endlessly perverse and indulgent, Caligula throws in hardcore sex every time the plot threatens to get interesting.»[53] Leslie Halliwell said Caligula was «a vile curiosity of interest chiefly to sado-masochists».[60] Time Out London called it «a dreary shambles».[61] Positive criticism of the film came from Moviehole reviewer Clint Morris, who awarded it 3 stars out of 5, calling it «[a] classic in the coolest sense of the word».[53] New Times critic Gregory Weinkauf gave the film 3 out of 5, calling it «Kinda dumb and tacky, but at least it’s a real movie».[53] Arkansas Democrat-Gazette reviewer Philip Martin also gave the film 3 out of 5.[53]

Writers for The Hamilton Spectator and St. Louis Post-Dispatch said Caligula was one of the worst films they’d seen.[62][63] Writing for The A.V. Club, Keith Phipps said, «As a one-of-a-kind marriage of the historical epic and the porn film … Caligula deserves a look. But it might be better to let Guccione’s savagely unpleasant folly fade into the century that spawned it».[64]

Several films were released in the following years as attempts to cash in on Caligula‘s reputation, including Caligula and Messalina (1981), directed by Bruno Mattei and Caligula… The Untold Story (1982), directed by Joe D’Amato. Like Caligula, D’Amato’s film exists in several softcore and hardcore versions.[65]

In 1985, the hardcore version of Caligula was broadcast in France on Canal+, making it the first film with unsimulated sex scenes ever shown on French television. The film, which had been broadcast as a test, became the starting point of Canal+’s tradition of showing one pornographic film at midnight every month.[66][67]

Retrospective recognition[edit]

Caligula has been described as a «cult classic» by William Hawes in a book about the film.[13] Helen Mirren has defended her involvement in the making of Caligula and even described the final product of the film as «an irresistible mix of art and genitals».[40] In 2005, artist Francesco Vezzoli produced a fake trailer for an alleged remake called Gore Vidal’s Caligula as a promotion for Versace’s new line of accessories; the remake was to star Helen Mirren as «the Empress Tiberius», Gerard Butler as Chaerea, Milla Jovovich as Drusilla, Courtney Love as Caligula, and Karen Black as Agrippina the Elder and featuring an introduction by Gore Vidal. The fake trailer was screened worldwide, including New York City’s Whitney Museum of American Art’s 2006 Whitney Biennial.[68]

Leonardo DiCaprio has cited Caligula as an influence on his performance as Jordan Belfort in The Wolf of Wall Street.[69]

Reconstruction attempts[edit]

In 2007, Caligula was released on DVD and Blu-ray in an «Imperial Edition»,[70] which featured the unrated theatrical release version and a new version featuring alternative sequencing from the original theatrical release and without the explicit sexual content shot by Guccione, marking the first attempt to reconstruct the film into a version closer to Brass’s intentions. This edition also includes audio commentaries featuring Malcolm McDowell and Helen Mirren, and interviews with the cast and crew.[71]

In February 2018, Penthouse announced that a new cut of the film was being edited by Alexander Tuschinski.[72] Tuschinski will use 85 minutes of Brass’s original workprint and edit the remainder of the film himself.[73] Brass’s family supports Tuschinski’s effort, but it remains unconfirmed if Brass will be directly involved with the edit.[74] However, the edit is an attempt to realize Brass’s original vision for the film.[16]

In July 2018, Alexander Tuschinski released his documentary Mission: Caligula on Vimeo. The film explores his relationship with Caligula, the process of reconstructing Brass’s vision, and Penthouse CEO Kelly Holland’s backing of the project.[16]

In 2020, another version of the film was announced to be released in the fall of that year, edited by E. Elias Merhige to follow more closely Gore Vidal’s original screenplay instead of Tinto Brass’s or Bob Guccione’s vision.[75]

See also[edit]

- List of films considered the worst

- Unsimulated sex

References[edit]

- ^ William Hawes (2008). Caligula and the Fight for Artistic Freedom: The Making, Marketing and Impact of the Bob Guccione Film. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-5240-8.

- ^ The film’s titles credit both Baragli and «The Production», a credit possibly referring to Bob Guccione and his production assistants, with editing.

- ^ a b c William Hawes (2008). Caligula and the Fight for Artistic Freedom: The Making, Marketing and Impact of the Bob Guccione Film. McFarland. p. 233. ISBN 978-0-7864-5240-8.

- ^ a b c d e Kristopher Spencer (2008). Film and Television Scores, 1950–1979: A Critical Survey by Genre. McFarland. p. 125. ISBN 978-0-7864-5228-6.

- ^ Annuario del cinema italiano & audiovisivi (in Italian), Centro di studi di cultura, promozione e difusione del cinema, p. 59, OCLC 34869836

- ^ Anthony Slide (2014). The New Historical Dictionary of the American Film Industry. Routledge. p. 11. ISBN 978-1-135-92554-3.

- ^ William Hawes (2008). Caligula and the Fight for Artistic Freedom: The Making, Marketing and Impact of the Bob Guccione Film. McFarland. p. 195. ISBN 978-0-7864-5240-8.

- ^ a b William Hawes (2008). Caligula and the Fight for Artistic Freedom: The Making, Marketing and Impact of the Bob Guccione Film. McFarland. p. 196. ISBN 978-0-7864-5240-8.

- ^ a b John Heidenry (2002). What Wild Ecstasy. Simon and Schuster. p. 268. ISBN 978-0-7432-4184-7.

- ^ a b c «Caligula box office at the-numbers.com». the-numbers.com.

- ^ What Culture#14 Archived August 6, 2020, at the Wayback Machine: Caligula

- ^ «Film Censorship: Caligula (1979)». Refused-Classification.com. Retrieved June 9, 2012.

- ^ a b Hawes, William (2008). Caligula and the Fight for Artistic Freedom: The Making, Marketing and Impact of the Bob Guccione Film. McFarland. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-7864-5240-8.

- ^ Stephen Prince (1980–1989). A New Pot of Gold: Hollywood Under the Electronic Rainbow. p. 350.

- ^ a b Spencer, David (January–February 2010). «IAMTW’s Grand Master Scribe Award, The Faust, Goes to the Genre’s Most Prolific Practitioner» (PDF). Tied-In: The Newsletter of the International Association of Media Tie-in Writers. Calabasas, California: International Association of Media Tie-in Writers. 4 (1). Archived from the original (PDF) on March 4, 2016. Retrieved August 26, 2015.

- ^ a b c Tuschinski, Alexander (July 26, 2018), Mission: Caligula, retrieved July 27, 2018

- ^ «Caligula MMXX — announcement on website for 2020 re-release». Retrieved January 5, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y Ernest Volkman (May 1980). «Bob Guccione Caligula Interview from Penthouse May 1980». Penthouse: 112–118, 146–115. Archived from the original on August 8, 2014. Retrieved June 9, 2012.

- ^ Constantine Santas; James M. Wilson; Maria Colavito; Djoymi Baker (2014). The Encyclopedia of Epic Films. Scarecrow Press. p. 115. ISBN 978-0-8108-8248-5.

- ^ a b c «New York Magazine». Newyorkmetro.com. New York Media, LLC: 85. March 26, 1979. ISSN 0028-7369.

- ^ a b c d e f g h John Heidenry (2002). What Wild Ecstasy. Simon and Schuster. p. 266. ISBN 978-0-7432-4184-7.