История, разделенная на три главы, начинается в Париже. Лиза (Стэйси Мартин) встречается с Симоном (Пьер Нинэ), который зарабатывает на жизнь продажей наркотиков. Когда один из клиентов умирает от передозировки, парень решает покинуть страну без любимой девушки. Спустя время герои встречаются снова — на этот раз на тропическом острове. Лиза замужем за обеспеченным мужчиной Лео (Бенуа Мажимель), а Симон тем временем работает при отеле. Бывшие влюбленные совершенно предсказуемо вступают на опасный путь соблазна, лжи и обреченных отношений.

Стейси Мартен в роли Лизы на кадре из фильма «Любовники»

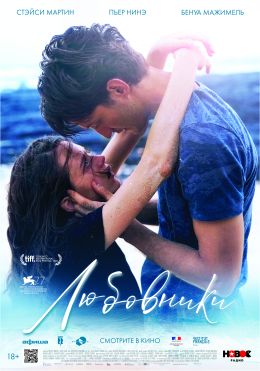

На протяжении всей картины неоднократно упоминается гравюра Кацусики Хокусая «Большая волна в Канагаве». Казалось бы, для чего наполнять французский фильм японским искусством? Как главенствующие темы восточной работы – борьба со стихией и единство противоположностей – могут быть вплетены в фестивальную историю любви? На самом деле все довольно прозаично: Николь Гарсия, режиссерка ленты, с самого начала настраивает зрителей на определенный финал. Если в «Большой волне» человек вступает в битву с силами природы, то в «Любовниках» двое борются со своими чувствами. Любовь Лизы и Симона, как огромный всплеск, накрывает их с головы до ног. Даже на постере персонажи изображены на фоне синего моря — на первый взгляд безмятежного, но неизбежно олицетворяющего угрозу. Фильм наполнен ощущением фатальности, которая позволяет сюжету хоть немного сдвинуться с мертвой точки и проявить подобие напряжения.

Пьер Нине в роли Саймона на кадре из фильма «Любовники»

В остальном же холодная картина Гарсия представляет собой безжизненное и лишенное страсти кино, где трое персонажей наматывают круги вокруг безнадежных отношений. В каком-то смысле перед нами консервативная и старомодная история о любовном треугольнике. Здесь есть и состоятельный муж, современная инкарнация Каренина, и двое привлекательных молодых людей, чьи обнаженные тела переплетаются в укромных квартирках. Режиссерка изредка затрагивает такие темы, как поиск идентичности, пропасть между социальными классами, влияние капитализма на отношения, а также размышляет про красоту, которая может быть одновременно силой и бременем женщин. Однако все это оказывается на обочине, и остаются только томные взгляды актеров, которым — давайте будем честны — здесь нечего играть.

Гарсия рисует портрет человеческих отношений, разбивающих сердца. Контраст между двумя романами Лизы очевиден — страсть, бьющая через край, и суровые реалии бедности в противовес комфортной жизни с нелюбимым человеком, полной отчаяния. В этом ключе снова вспоминается работа художника Хокусая. На втором плане гравюры виднеется Фудзи, в отличие от бушующей волны, олицетворяющий стабильность. Мечась между двумя мужчинами, Лиза в конце концов, как и любой из нас, заслуживает гармонии. Хочется верить, что режиссерка за несколькими слоями угнетающей драмы припрятала простую мысль: какой бы из героев в итоге ни стал победителем, самым правильным будет сделать выбор в пользу себя.

| Amantes | |

|---|---|

Spanish theatrical release poster |

|

| Directed by | Vicente Aranda |

| Written by | Carlos Pérez Marinero Alvaro del Amo Vicente Aranda |

| Produced by | Pedro Costa, Televisión Española (TVE) |

| Starring | Victoria Abril, Jorge Sanz, Maribel Verdú |

| Cinematography | José Luis Alcaine |

| Edited by | Teresa Font |

| Music by | José Nieto |

| Distributed by | Aries Films (1992) (USA) (subtitled), Columbia TriStar |

|

Release dates |

|

|

Running time |

103 minutes |

| Country | Spain |

| Language | Spanish |

| Budget | P208,120,000 |

Lovers (Spanish: Amantes) is a 1991 Spanish film noir written and directed by Vicente Aranda, starring Victoria Abril, Jorge Sanz and Maribel Verdú. The film brought Aranda to widespread attention in the English-speaking world. It won two Goya Awards (Best Film and Best Director) and is considered one of the best Spanish films of the 1990s.

Plot[edit]

In Madrid, in the mid-1950s, Paco — a handsome young man from the provinces, serving the last days of his military service — is in search of both lodging and a steady job. He is engaged to be married to his major’s maid, Trini, who is not only sweet and pretty, but has also saved up a sizable amount of money through years of hard work and frugal living, which will enable her and Paco to start their lives together comfortably. With a factory job lined up, Paco moves out of his barracks and looks for somewhere to live until the wedding. Trini unwittingly refers him to Luisa, a beautiful widow who periodically takes in boarders and rents him a spare bedroom.

Besides supplementing her income with boarders, Luisa engages in swindles with underworld contracts, and is not above cheating her partners by skimming money off her illicit earnings. Instantly smitten by Paco, the attractive Luisa quickly seduces her new tenant. Frustrated by his unfruitful job hunt and by Trini’s refusal to sleep with him until they are married, Paco offers little resistance when Luisa seduces him, initiating an affair. He is dazzled with the sexual delight to which she introduces him. So intense is Paco’s attraction for Luisa, that he abandons Trini for long periods, finally showing up at the major’s house to spend Christmas Eve with her. Trini feels a distance between herself and Paco, and while the couple are strolling in the street, she is surprised to see the ‘old widow’ and immediately guesses that she and Paco are having a relationship.

Trini seeks the advice of the major’s wife, who tells her that she should use her own sexual powers to win Paco back. Waiting for Luisa to leave the apartment, Trini goes to Paco’s room and gives herself to him, making sure that Luisa later sees her leaving. At first, her tactic works and Paco re-affirms his love for her, and they leave to visit Trini’s mother in her village. However, Trini is no match for her rival as a lover, and Paco cannot get Luisa out of his mind.

When Paco and Trini come back to Madrid, he is willing to continue his twin relationship, but Luisa — who knows of Trini’s existence — is wildly jealous of her rival. Things become more complicated for Paco by Luisa’s shady business dealings with Minuta and Gordo, members of a gang of swindlers to whom she owes money. They have threatened her life, and Paco, attempting to aid his lover, suggests that he get the money by swindling Trini of her savings. Luisa would prefer that they simply kill Trini, but proposes that Paco should marry Trini, then steal her savings and run away with Luisa. Paco uneasily agrees.

The plan is for Paco to propose marriage to Trini and bring her to the provincial city of Aranda del Duero, where they have planned to purchase a bar. Under that pretense, Paco and Trini leave Madrid. Luisa follows them, unsure of Paco’s resolve. While Trini is asleep, Paco steals the money from her handbag. He offers it to Luisa, but pulls out of their plan to flee together. Very upset, Luisa tells him he has botched the plan, and when he tells her to wait and, ‘Things will be okay,’ she excitedly utters, ‘Kill her!’, and walks away, tossing the money at her feet – it is Paco she wants. Paco retrieves the money, and, driven by guilt, he returns to Trini to explain the situation. After the disappearance of the money, Trini realises the fraud and understands that her love for Paco is doomed.

When Paco comes back to the hotel room and confesses the plan, Trini locks herself in the bathroom and attempts to commit suicide using Paco’s razor. She is thwarted by Paco breaking the window and snatching the razor from her. Later, as the two sit in the rain on a bench in front of the cathedral of the town, Trini refuses to forgive Paco, and tells him she prefers death to abandonment. Thwarted in her attempt to cut her own wrist with Paco’s razor, she begs him to kill her since that is what he really wants. He does so, then rushes to the train station to prevent Luisa from leaving. Placing his bloody hands on her compartment window, signalling to Luisa that the mission has been accomplished, she gets off the moving train. The couple embraces passionately on the platform, as the train pulls out. A title informs viewers that the police captured the pair, three days later.

Production and background[edit]

Amantes had its origin in La Huella del Crimen (The Trace of the Crime), a Spanish television series depicting infamous crimes that happened in Spain, and for which Vicente Aranda had directed the chapter El Crimen del Capitán Sánchez (Captain Sánchez’s Crime) in 1984. The success of this production, made for TVE, compelled producer Pedro Costa to develop a follow-up.[1] In the new installment of the series, there was to be an episode called Los Amantes de Tetuán (The Lovers of Tetuán), the story of a real life crime committed by a couple living in the district of Tetuán de las Victorias, a working class sector of Madrid. The actual crime took place in 1949 in La Canal, a small village near Burgos, and so it was also dubbed as ‘El Crimen de La Canal’ (‘Crime at La Canal’).

The event itself concerned a widow, Francisca Sánchez Morales, engaged in blackmailing and who persuaded a young man, José García San Juan, to kill his young wife, Dominga del Pino Rodríguez. Three days later, the couple were caught and never saw each other again. They were condemned to capital punishment, still prevailing by those years in Spain (not even their attorney wanted to defend them). Eventually, they got their sentences commuted and they served between ten and twelve years. The widow died of a heart attack just after leaving jail, and the young man started a new, anonymous and prosperous life in Zaragoza.

A re-interpretation of the crime was built up during the pre-production of Los Amantes de Tetuán. The script was written by Aranda, Alvaro del Amo, and Carlos Perez Merinero, using some elements of the actual crime and reinventing many others to recreate the background of the characters, about which little was known. The television project was halted from 1987 to 1990, and when the time came to start production, Los Amantes de Tetuán took a separate life from La Huella del Crimen. It was going to be the last chapter to be filmed because Vicente Aranda was immersed in the making of a mini-series for TVE. By then, Aranda was initially reluctant to make another production for television, and proposed to expand the script and make it into a full feature film for the big screen.[1] Thanks to the recent success of his television mini-series, Los Jinetes del Alba, the project was approved by TVE.

The original title, Los Amantes de Tetuán, was shortened to simply Amantes to avoid confusion with the North African city of the same name. The events were moved from the 1940s to an unspecific time in the 1950s.[2] for both economic and dramatic reasons. It was cheaper to recreate the period of the 1950s, and Aranda considered the decade more appealing for modern audiences. The real life crime story was treated in the same way Billy Wilder used the facts that inspired his adaptation of Double Indemnity, the novel by James M. Cain. Las Edades de Lulu, a movie directed by Bigas Luna and which had been seen by Aranda, inspired the eroticism of the film.

The most famous sequence of the film in which Luisa introduces a handkerchief in Paco’s anus, to withdraw it in the moment of climax, was not in the script. Aranda explained:

- ‘I told the actors that I felt something was lacking and that we needed something more explicit, a novelty. I opened a kind of contest and each one gave different options. Jorge Sanz came out with the idea of the handkerchief. The production was successful team collaboration. From the beginning at the preparation of the film, there was a spirit of team collaboration, something very positive that made our work fun. I don’t know why, but we all knew we were making a film that was going to be important.[3]

The intense and tragic climax was benefited by the weather, with a snowstorm that was not scheduled at all for the shooting, as producer Costa explained through the DVD commentaries. That scene, filmed in front of the famous Burgos Cathedral, was articulated around two popular Spanish Christmas carols, Dime, Niño, de Quién Eres and La Marimorena, whose traditional cheerful melody, by contrast, is changed for the score into one that is elegiac and sad. The score was composed by Jose Nieto, often working with Aranda (Intruso, Celos, Juana la Loca and Carmen) and the film editor was Aranda’s regular, his wife Teresa Font. Equally noteworthy is the film’s striking cinematography by Jose Luis Alcaine, with whom Aranda had previously worked on no fewer than five films. Alcaine is especially adept at evoking the ‘sooty’ look of Madrid winters, which convey the somber qualities of urban life during the early years of Francoist Spain.[4]

Cast[edit]

Victoria Abril, here in her ninth collaboration with Vicente Aranda, was thought of from the beginning for the role of Trini, the virginal maid, while Concha Velasco was offered the role of Luisa. When Velasco declined, Aranda deemed Victoria was mature enough to play Luisa and proposed her to switch roles and take that of the widow. She was reluctant, saying that she saw herself more as Trini, the sacrificial maid rather than the wicked widow. Abril was pregnant; by the time she gave birth, she was ready to start the film, had had a change of heart and agreed to be Luisa.[5]

The role of Trini fell on Maribel Verdú, a young actress who had made her film debut with Aranda in El Crimen del Capitán Sánchez (Captain Sánchez’s Crime) in 1984, as the younger sister of Victoria Abril’s character, and who was the leading actress of that film. Maribel Verdú, whose artistic culmination maybe is Ricardo Franco’s La Buena Estrella (1997), is better known internationally for her roles in Alfonso Cuarón’s Y tu mamá también (2000) and in Guillermo del Toro’s Pan’s Labyrinth (2006).

At first, Aranda thought about Antonio Banderas as Paco, but the actor had already undertaken work on Arne Glimcher’s The Mambo Kings (1992), and the role was assigned to Jorge Sanz, who would later become best known to English-speaking audiences playing the role of the young soldier who falls in love with four sisters in Belle Époque (1993), which won the Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film. Sanz had won a Goya Award as Best Actor for Aranda’s Si Te Dicen que Caí, which also starred Abril. The three lead actors of Amantes had acted together before in another love triangle, in Aranda’s previous project, Los Jinetes del Alba.

- Victoria Abril — Luisa

- Jorge Sanz — Paco

- Maribel Verdú — Trini

- Enrique Cerro — commandant

- Mabel Escaño — commandant’s wife

- Alicia Agut -Trini’s mother

- Jose Cerro — Minuta

- Gabriel Latorre — Gordo

- Saturnino Garcia — Pueblerino

Themes[edit]

One of the main themes of Amantes is the destructive potential of obsessive passion and sexual desire a topic further explore by Aranda in La Pasion Turca (1994). Amantes forms — with Intruso (1993) and Celos (1999) — a trilogy of films about love as uncontrollable passion that ends tragically. These three films, directed by Aranda, are loosely based on real crime stories.

Analysis[edit]

In Amantes, Aranda focuses tightly on his three leading actors, effectively conveying the dreadful, consuming power of passion. The films portrays a mortal struggle between a strong phallic widow and a younger patriarchal woman for the love of a young man in a romantic love triangle. The widow derives her power from an intense sexuality and the religious idealism belongs to the young victim.[6] Set in film noir genre, it depicts the young man, Paco, not as the master of the two women who love him, but as the malleable object of their competing scenarios.[6] Luisa is introduced with a mouthful of candy, and draped with Christmas tinsel, almost as though she were a gift to the sexually frustrated Paco. Aranda thus sets up his central conflict with precision and power. Despite the physical beauty of the two women, it is the handsome young man who is treated as the primary object of desire. He is seduced by both women and is the object of the camera’s erotic gaze.[7] He embodies the 1950s generation torn between ‘two Spains’, represented by the two female rivals. Identified with the images of rural Spain, Trini is the traditionally stoically self-sacrificing embodiment of Catholic Spain, versus the modern vision of a newly emerging industrialized Spain, incarnated in Luisa, who is identified with the city and with the iconography of foreign culture (kimono, Christmas tree ornaments), representing the modernizing version of Spain.[4] Though the narrative eventually cast Luisa as the heartless instigator of Trini’s murder, she can also be perceived as a rebel against the oppression of a macho culture while Paco, a traditional tragic film noir hero, is turned into a murderer by the two women who love him.

Despite being positioned as the opposing stereotypes of virgin and whore, Trini and Luisa are equally passionate and strong willed. Both are frequently robed in blue, a color feature in traditional pictorial representations of the virgin, and Trini takes with her a painting of the Immaculate Conception, hanging it in the hotel room just before her death. While Luisa directs her violent passions outwards, confessing to Paco that she murdered her husband, Trini turns them inwards on herself, following in the footsteps of her lame mother, who threw herself in front of a cart after learning of her husband’s infidelity.[7] Just as Luisa forced Paco to take hold of his penis in their pursuits of pleasure, Trini coerces him to wield the razor that will release her from pain.

The sexual scenes of the film are designed to underscore the female domination of the male, even in terms of his sexual identity.[8] Amantes forcefully depicts the subversive power of Luisa’s sexuality. From the moment she opens the door to Paco, wearing a colorful dark blue robe and draped with glittering streamers she is using to decorate a Christmas tree, Luisa appears as a profane alternative to the Madonna. Her body substitutes for the Christmas tree and all of its religious symbolism, offering eroticism in place of religious ecstasy. Not only is she the sexual subject who actively pursues her own desire and who first seduces Paco, but she continues to control the love-making. In a graphic sex scene, we see her penetrating his anus with a silk handkerchief and then withdrawing it in the moments of ecstasy. Despite her sexually dominating her young lover, Luisa remains loving and emotionally vulnerable. Paco’s response not only makes him obsessed, but he rejects the more traditional passive sexuality of his fiancéé Trini.

The murder scene is remarkable for its under-stated approach. Staged on a bench in front of the cathedral of Burgos (the small town of Aranda del Duero, in the film), the murder retains the aura of Christian ritual, especially since the minimalist representation of violence is limited to a few close-ups of the victim’s barefoot and a few drops of bright red blood falling on the pure white snow. Earlier, Paco had sat on the same bench praying, observed by a beautiful young mother who was carrying a bright blue umbrella and tying the shoelace of her young son, a symbolic Madonna who seems to foresee the murder.[9]

In the final scene, Paco goes to the train station to find Luisa. Pressing his bloody hands against the window, he draws her off the train for a final murderous embrace, a shot that is held, then blurs and finally freezes, signifying the triumph of their passion. A printed epilogue delivers the ironic moralizing punch line to the narrative. Three days later, Paco and Luisa were arrested in Valladolid (a city well known for its right-wing sentiments) and they never saw each other again.

Amantes and other films[edit]

Amantes has elements from Double Indemnity; Luisa frequently wears dark glasses, like the character played by Barbara Stanwyck. There are also similarities to François Truffaut’s La Femme d’à côté, another amour fou film in which a lame older woman’s own story foretells the tragic end.

Vicente Aranda’s cold style portraying unrestrained passions has also been compared to the similar approach to passion in Ingmar Bergman’s films. The American movie To Die For, was inspired by the Pamela Smart case (the most famous crime in New Hampshire history) was compared to the similar plot of Amantes.

Reception[edit]

Amantes opened in February 1991 at the 41st Berlin International Film Festival where Victoria Abril won the Silver Bear for Best Actress.[10] In Spain it was a great success with critics and audiences and won two Goya Awards including Best Film and Best director.

Amantes was the first of Aranda’s films to get an American release, opening in March 1992 and becoming an important art house hit, getting more than one and a half million dollars at the box-office. The movie shocked audiences because of the frankness of its sex scenes.

The film remains Vicente Aranda’s best-regarded work; he explained ‘Whenever someone wants to flatter me, they bring up the subject of Amantes. I haven’t been able to make a film that takes its place.’[5]

Awards and nominations[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b Guarner, José Luis: El Inquietante Cine de Vicente Aranda, Imagfic, D.L.1985, p. 66

- ^ In the film dialogue, Trini and Paco mention going to the movies to watch Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (film), which came out in May 1955. The setting would then be from Christmas 1955 to January 1956

- ^ Vicente Aranda, 2006 Declaración de Intenciones

- ^ a b D’Lugo, Marvin: Guide to the Cinema of Spain, Greenwood Press, 1997, p.32

- ^ a b Vicente Aranda, 2006 Declaración de Intenciones www.vicentearanda.es.

- ^ a b Kinder, Marsha: Blood Cinema: The Reconstruction of National Identity in Spain, Berkeley University Press, 1993. p. 206

- ^ a b Kinder, Marsha: Blood Cinema: The Reconstruction of National Identity in Spain, Berkeley University Press, 1993. p. 207

- ^ D’Lugo, Marvin: Guide to the Cinema of Spain, Greenwood Press, 1997, p.31

- ^ Kinder, Marsha: Blood Cinema: The Reconstruction of National Identity in Spain, Berkeley University Press, 1993. p. 208

- ^ a b «Berlinale: 1991 Prize Winners». berlinale.de. Retrieved 2011-03-21.

- ^ «Palmarés 1991». premiosondas.com. Retrieved 8 February 2022.

- ^ «Amantes». premiosgoya.com. Retrieved 8 February 2022.

- ^ «‘Amantes’ recibe el premio Fotogramas a la mejor película». El País. 25 February 1992.

Bibliography[edit]

- Alvarez, Rosa y Frias Belen, Vicente Aranda: El Cine Como Pasión, Huelva, XX Festival de Cine Iberoamericano de Huelva, 1994

- Cánovás Belchí, Joaquín (ed.), Varios Autores,: Miradas sobre el cine de Vicente Aranda, Murcia: Universidad de Murcia, 2000.P. Madrid

- Colmena, Enrique: Vicente Aranda, Cátedra, Madrid, 1986, ISBN 84-376-1431-7

- Guarner, José Luis: El Inquietante Cine de Vicente Aranda,Imagfic, D.L.1985.

- Kinder, Marsha: Blood Cinema: The Reconstruction of National Identity in Spain, Berkeley University Press, 1993. ISBN 0-520-08157-9

- D’Lugo, Marvin: Guide to the Cinema of Spain, Greenwood Press, 1997.ISBN 0-313-29474-7

External links[edit]

- Vicente Aranda at IMDB

- Web Oficial de Vicente Aranda

- Amantes at IMDb

| Amantes | |

|---|---|

Spanish theatrical release poster |

|

| Directed by | Vicente Aranda |

| Written by | Carlos Pérez Marinero Alvaro del Amo Vicente Aranda |

| Produced by | Pedro Costa, Televisión Española (TVE) |

| Starring | Victoria Abril, Jorge Sanz, Maribel Verdú |

| Cinematography | José Luis Alcaine |

| Edited by | Teresa Font |

| Music by | José Nieto |

| Distributed by | Aries Films (1992) (USA) (subtitled), Columbia TriStar |

|

Release dates |

|

|

Running time |

103 minutes |

| Country | Spain |

| Language | Spanish |

| Budget | P208,120,000 |

Lovers (Spanish: Amantes) is a 1991 Spanish film noir written and directed by Vicente Aranda, starring Victoria Abril, Jorge Sanz and Maribel Verdú. The film brought Aranda to widespread attention in the English-speaking world. It won two Goya Awards (Best Film and Best Director) and is considered one of the best Spanish films of the 1990s.

Plot[edit]

In Madrid, in the mid-1950s, Paco — a handsome young man from the provinces, serving the last days of his military service — is in search of both lodging and a steady job. He is engaged to be married to his major’s maid, Trini, who is not only sweet and pretty, but has also saved up a sizable amount of money through years of hard work and frugal living, which will enable her and Paco to start their lives together comfortably. With a factory job lined up, Paco moves out of his barracks and looks for somewhere to live until the wedding. Trini unwittingly refers him to Luisa, a beautiful widow who periodically takes in boarders and rents him a spare bedroom.

Besides supplementing her income with boarders, Luisa engages in swindles with underworld contracts, and is not above cheating her partners by skimming money off her illicit earnings. Instantly smitten by Paco, the attractive Luisa quickly seduces her new tenant. Frustrated by his unfruitful job hunt and by Trini’s refusal to sleep with him until they are married, Paco offers little resistance when Luisa seduces him, initiating an affair. He is dazzled with the sexual delight to which she introduces him. So intense is Paco’s attraction for Luisa, that he abandons Trini for long periods, finally showing up at the major’s house to spend Christmas Eve with her. Trini feels a distance between herself and Paco, and while the couple are strolling in the street, she is surprised to see the ‘old widow’ and immediately guesses that she and Paco are having a relationship.

Trini seeks the advice of the major’s wife, who tells her that she should use her own sexual powers to win Paco back. Waiting for Luisa to leave the apartment, Trini goes to Paco’s room and gives herself to him, making sure that Luisa later sees her leaving. At first, her tactic works and Paco re-affirms his love for her, and they leave to visit Trini’s mother in her village. However, Trini is no match for her rival as a lover, and Paco cannot get Luisa out of his mind.

When Paco and Trini come back to Madrid, he is willing to continue his twin relationship, but Luisa — who knows of Trini’s existence — is wildly jealous of her rival. Things become more complicated for Paco by Luisa’s shady business dealings with Minuta and Gordo, members of a gang of swindlers to whom she owes money. They have threatened her life, and Paco, attempting to aid his lover, suggests that he get the money by swindling Trini of her savings. Luisa would prefer that they simply kill Trini, but proposes that Paco should marry Trini, then steal her savings and run away with Luisa. Paco uneasily agrees.

The plan is for Paco to propose marriage to Trini and bring her to the provincial city of Aranda del Duero, where they have planned to purchase a bar. Under that pretense, Paco and Trini leave Madrid. Luisa follows them, unsure of Paco’s resolve. While Trini is asleep, Paco steals the money from her handbag. He offers it to Luisa, but pulls out of their plan to flee together. Very upset, Luisa tells him he has botched the plan, and when he tells her to wait and, ‘Things will be okay,’ she excitedly utters, ‘Kill her!’, and walks away, tossing the money at her feet – it is Paco she wants. Paco retrieves the money, and, driven by guilt, he returns to Trini to explain the situation. After the disappearance of the money, Trini realises the fraud and understands that her love for Paco is doomed.

When Paco comes back to the hotel room and confesses the plan, Trini locks herself in the bathroom and attempts to commit suicide using Paco’s razor. She is thwarted by Paco breaking the window and snatching the razor from her. Later, as the two sit in the rain on a bench in front of the cathedral of the town, Trini refuses to forgive Paco, and tells him she prefers death to abandonment. Thwarted in her attempt to cut her own wrist with Paco’s razor, she begs him to kill her since that is what he really wants. He does so, then rushes to the train station to prevent Luisa from leaving. Placing his bloody hands on her compartment window, signalling to Luisa that the mission has been accomplished, she gets off the moving train. The couple embraces passionately on the platform, as the train pulls out. A title informs viewers that the police captured the pair, three days later.

Production and background[edit]

Amantes had its origin in La Huella del Crimen (The Trace of the Crime), a Spanish television series depicting infamous crimes that happened in Spain, and for which Vicente Aranda had directed the chapter El Crimen del Capitán Sánchez (Captain Sánchez’s Crime) in 1984. The success of this production, made for TVE, compelled producer Pedro Costa to develop a follow-up.[1] In the new installment of the series, there was to be an episode called Los Amantes de Tetuán (The Lovers of Tetuán), the story of a real life crime committed by a couple living in the district of Tetuán de las Victorias, a working class sector of Madrid. The actual crime took place in 1949 in La Canal, a small village near Burgos, and so it was also dubbed as ‘El Crimen de La Canal’ (‘Crime at La Canal’).

The event itself concerned a widow, Francisca Sánchez Morales, engaged in blackmailing and who persuaded a young man, José García San Juan, to kill his young wife, Dominga del Pino Rodríguez. Three days later, the couple were caught and never saw each other again. They were condemned to capital punishment, still prevailing by those years in Spain (not even their attorney wanted to defend them). Eventually, they got their sentences commuted and they served between ten and twelve years. The widow died of a heart attack just after leaving jail, and the young man started a new, anonymous and prosperous life in Zaragoza.

A re-interpretation of the crime was built up during the pre-production of Los Amantes de Tetuán. The script was written by Aranda, Alvaro del Amo, and Carlos Perez Merinero, using some elements of the actual crime and reinventing many others to recreate the background of the characters, about which little was known. The television project was halted from 1987 to 1990, and when the time came to start production, Los Amantes de Tetuán took a separate life from La Huella del Crimen. It was going to be the last chapter to be filmed because Vicente Aranda was immersed in the making of a mini-series for TVE. By then, Aranda was initially reluctant to make another production for television, and proposed to expand the script and make it into a full feature film for the big screen.[1] Thanks to the recent success of his television mini-series, Los Jinetes del Alba, the project was approved by TVE.

The original title, Los Amantes de Tetuán, was shortened to simply Amantes to avoid confusion with the North African city of the same name. The events were moved from the 1940s to an unspecific time in the 1950s.[2] for both economic and dramatic reasons. It was cheaper to recreate the period of the 1950s, and Aranda considered the decade more appealing for modern audiences. The real life crime story was treated in the same way Billy Wilder used the facts that inspired his adaptation of Double Indemnity, the novel by James M. Cain. Las Edades de Lulu, a movie directed by Bigas Luna and which had been seen by Aranda, inspired the eroticism of the film.

The most famous sequence of the film in which Luisa introduces a handkerchief in Paco’s anus, to withdraw it in the moment of climax, was not in the script. Aranda explained:

- ‘I told the actors that I felt something was lacking and that we needed something more explicit, a novelty. I opened a kind of contest and each one gave different options. Jorge Sanz came out with the idea of the handkerchief. The production was successful team collaboration. From the beginning at the preparation of the film, there was a spirit of team collaboration, something very positive that made our work fun. I don’t know why, but we all knew we were making a film that was going to be important.[3]

The intense and tragic climax was benefited by the weather, with a snowstorm that was not scheduled at all for the shooting, as producer Costa explained through the DVD commentaries. That scene, filmed in front of the famous Burgos Cathedral, was articulated around two popular Spanish Christmas carols, Dime, Niño, de Quién Eres and La Marimorena, whose traditional cheerful melody, by contrast, is changed for the score into one that is elegiac and sad. The score was composed by Jose Nieto, often working with Aranda (Intruso, Celos, Juana la Loca and Carmen) and the film editor was Aranda’s regular, his wife Teresa Font. Equally noteworthy is the film’s striking cinematography by Jose Luis Alcaine, with whom Aranda had previously worked on no fewer than five films. Alcaine is especially adept at evoking the ‘sooty’ look of Madrid winters, which convey the somber qualities of urban life during the early years of Francoist Spain.[4]

Cast[edit]

Victoria Abril, here in her ninth collaboration with Vicente Aranda, was thought of from the beginning for the role of Trini, the virginal maid, while Concha Velasco was offered the role of Luisa. When Velasco declined, Aranda deemed Victoria was mature enough to play Luisa and proposed her to switch roles and take that of the widow. She was reluctant, saying that she saw herself more as Trini, the sacrificial maid rather than the wicked widow. Abril was pregnant; by the time she gave birth, she was ready to start the film, had had a change of heart and agreed to be Luisa.[5]

The role of Trini fell on Maribel Verdú, a young actress who had made her film debut with Aranda in El Crimen del Capitán Sánchez (Captain Sánchez’s Crime) in 1984, as the younger sister of Victoria Abril’s character, and who was the leading actress of that film. Maribel Verdú, whose artistic culmination maybe is Ricardo Franco’s La Buena Estrella (1997), is better known internationally for her roles in Alfonso Cuarón’s Y tu mamá también (2000) and in Guillermo del Toro’s Pan’s Labyrinth (2006).

At first, Aranda thought about Antonio Banderas as Paco, but the actor had already undertaken work on Arne Glimcher’s The Mambo Kings (1992), and the role was assigned to Jorge Sanz, who would later become best known to English-speaking audiences playing the role of the young soldier who falls in love with four sisters in Belle Époque (1993), which won the Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film. Sanz had won a Goya Award as Best Actor for Aranda’s Si Te Dicen que Caí, which also starred Abril. The three lead actors of Amantes had acted together before in another love triangle, in Aranda’s previous project, Los Jinetes del Alba.

- Victoria Abril — Luisa

- Jorge Sanz — Paco

- Maribel Verdú — Trini

- Enrique Cerro — commandant

- Mabel Escaño — commandant’s wife

- Alicia Agut -Trini’s mother

- Jose Cerro — Minuta

- Gabriel Latorre — Gordo

- Saturnino Garcia — Pueblerino

Themes[edit]

One of the main themes of Amantes is the destructive potential of obsessive passion and sexual desire a topic further explore by Aranda in La Pasion Turca (1994). Amantes forms — with Intruso (1993) and Celos (1999) — a trilogy of films about love as uncontrollable passion that ends tragically. These three films, directed by Aranda, are loosely based on real crime stories.

Analysis[edit]

In Amantes, Aranda focuses tightly on his three leading actors, effectively conveying the dreadful, consuming power of passion. The films portrays a mortal struggle between a strong phallic widow and a younger patriarchal woman for the love of a young man in a romantic love triangle. The widow derives her power from an intense sexuality and the religious idealism belongs to the young victim.[6] Set in film noir genre, it depicts the young man, Paco, not as the master of the two women who love him, but as the malleable object of their competing scenarios.[6] Luisa is introduced with a mouthful of candy, and draped with Christmas tinsel, almost as though she were a gift to the sexually frustrated Paco. Aranda thus sets up his central conflict with precision and power. Despite the physical beauty of the two women, it is the handsome young man who is treated as the primary object of desire. He is seduced by both women and is the object of the camera’s erotic gaze.[7] He embodies the 1950s generation torn between ‘two Spains’, represented by the two female rivals. Identified with the images of rural Spain, Trini is the traditionally stoically self-sacrificing embodiment of Catholic Spain, versus the modern vision of a newly emerging industrialized Spain, incarnated in Luisa, who is identified with the city and with the iconography of foreign culture (kimono, Christmas tree ornaments), representing the modernizing version of Spain.[4] Though the narrative eventually cast Luisa as the heartless instigator of Trini’s murder, she can also be perceived as a rebel against the oppression of a macho culture while Paco, a traditional tragic film noir hero, is turned into a murderer by the two women who love him.

Despite being positioned as the opposing stereotypes of virgin and whore, Trini and Luisa are equally passionate and strong willed. Both are frequently robed in blue, a color feature in traditional pictorial representations of the virgin, and Trini takes with her a painting of the Immaculate Conception, hanging it in the hotel room just before her death. While Luisa directs her violent passions outwards, confessing to Paco that she murdered her husband, Trini turns them inwards on herself, following in the footsteps of her lame mother, who threw herself in front of a cart after learning of her husband’s infidelity.[7] Just as Luisa forced Paco to take hold of his penis in their pursuits of pleasure, Trini coerces him to wield the razor that will release her from pain.

The sexual scenes of the film are designed to underscore the female domination of the male, even in terms of his sexual identity.[8] Amantes forcefully depicts the subversive power of Luisa’s sexuality. From the moment she opens the door to Paco, wearing a colorful dark blue robe and draped with glittering streamers she is using to decorate a Christmas tree, Luisa appears as a profane alternative to the Madonna. Her body substitutes for the Christmas tree and all of its religious symbolism, offering eroticism in place of religious ecstasy. Not only is she the sexual subject who actively pursues her own desire and who first seduces Paco, but she continues to control the love-making. In a graphic sex scene, we see her penetrating his anus with a silk handkerchief and then withdrawing it in the moments of ecstasy. Despite her sexually dominating her young lover, Luisa remains loving and emotionally vulnerable. Paco’s response not only makes him obsessed, but he rejects the more traditional passive sexuality of his fiancéé Trini.

The murder scene is remarkable for its under-stated approach. Staged on a bench in front of the cathedral of Burgos (the small town of Aranda del Duero, in the film), the murder retains the aura of Christian ritual, especially since the minimalist representation of violence is limited to a few close-ups of the victim’s barefoot and a few drops of bright red blood falling on the pure white snow. Earlier, Paco had sat on the same bench praying, observed by a beautiful young mother who was carrying a bright blue umbrella and tying the shoelace of her young son, a symbolic Madonna who seems to foresee the murder.[9]

In the final scene, Paco goes to the train station to find Luisa. Pressing his bloody hands against the window, he draws her off the train for a final murderous embrace, a shot that is held, then blurs and finally freezes, signifying the triumph of their passion. A printed epilogue delivers the ironic moralizing punch line to the narrative. Three days later, Paco and Luisa were arrested in Valladolid (a city well known for its right-wing sentiments) and they never saw each other again.

Amantes and other films[edit]

Amantes has elements from Double Indemnity; Luisa frequently wears dark glasses, like the character played by Barbara Stanwyck. There are also similarities to François Truffaut’s La Femme d’à côté, another amour fou film in which a lame older woman’s own story foretells the tragic end.

Vicente Aranda’s cold style portraying unrestrained passions has also been compared to the similar approach to passion in Ingmar Bergman’s films. The American movie To Die For, was inspired by the Pamela Smart case (the most famous crime in New Hampshire history) was compared to the similar plot of Amantes.

Reception[edit]

Amantes opened in February 1991 at the 41st Berlin International Film Festival where Victoria Abril won the Silver Bear for Best Actress.[10] In Spain it was a great success with critics and audiences and won two Goya Awards including Best Film and Best director.

Amantes was the first of Aranda’s films to get an American release, opening in March 1992 and becoming an important art house hit, getting more than one and a half million dollars at the box-office. The movie shocked audiences because of the frankness of its sex scenes.

The film remains Vicente Aranda’s best-regarded work; he explained ‘Whenever someone wants to flatter me, they bring up the subject of Amantes. I haven’t been able to make a film that takes its place.’[5]

Awards and nominations[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b Guarner, José Luis: El Inquietante Cine de Vicente Aranda, Imagfic, D.L.1985, p. 66

- ^ In the film dialogue, Trini and Paco mention going to the movies to watch Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (film), which came out in May 1955. The setting would then be from Christmas 1955 to January 1956

- ^ Vicente Aranda, 2006 Declaración de Intenciones

- ^ a b D’Lugo, Marvin: Guide to the Cinema of Spain, Greenwood Press, 1997, p.32

- ^ a b Vicente Aranda, 2006 Declaración de Intenciones www.vicentearanda.es.

- ^ a b Kinder, Marsha: Blood Cinema: The Reconstruction of National Identity in Spain, Berkeley University Press, 1993. p. 206

- ^ a b Kinder, Marsha: Blood Cinema: The Reconstruction of National Identity in Spain, Berkeley University Press, 1993. p. 207

- ^ D’Lugo, Marvin: Guide to the Cinema of Spain, Greenwood Press, 1997, p.31

- ^ Kinder, Marsha: Blood Cinema: The Reconstruction of National Identity in Spain, Berkeley University Press, 1993. p. 208

- ^ a b «Berlinale: 1991 Prize Winners». berlinale.de. Retrieved 2011-03-21.

- ^ «Palmarés 1991». premiosondas.com. Retrieved 8 February 2022.

- ^ «Amantes». premiosgoya.com. Retrieved 8 February 2022.

- ^ «‘Amantes’ recibe el premio Fotogramas a la mejor película». El País. 25 February 1992.

Bibliography[edit]

- Alvarez, Rosa y Frias Belen, Vicente Aranda: El Cine Como Pasión, Huelva, XX Festival de Cine Iberoamericano de Huelva, 1994

- Cánovás Belchí, Joaquín (ed.), Varios Autores,: Miradas sobre el cine de Vicente Aranda, Murcia: Universidad de Murcia, 2000.P. Madrid

- Colmena, Enrique: Vicente Aranda, Cátedra, Madrid, 1986, ISBN 84-376-1431-7

- Guarner, José Luis: El Inquietante Cine de Vicente Aranda,Imagfic, D.L.1985.

- Kinder, Marsha: Blood Cinema: The Reconstruction of National Identity in Spain, Berkeley University Press, 1993. ISBN 0-520-08157-9

- D’Lugo, Marvin: Guide to the Cinema of Spain, Greenwood Press, 1997.ISBN 0-313-29474-7

External links[edit]

- Vicente Aranda at IMDB

- Web Oficial de Vicente Aranda

- Amantes at IMDb

Чувства и чувствительность. «Любовник», режиссер Валерий Тодоровский

|

Просыпайтесь, мужчина! Финальная реплика в фильме «Любовник»

Да, кино получилось, в принципе, мужское. А значит, главная героиня — женщина. В последних кадрах мужчина (О.Янковский), измученный перестановкой акцентов в прошедшей семейной жизни, засыпает навсегда в пустом обмороженном трамвае. Сюжет — практически анекдот из разряда «вернулся муж из командировки», только с летальным исходом. Недаром его придумал сценарист Г. Островский, известный сочинением не только кино-, но и телесценариев. Подобные истории на- верняка встречались уже и в кухонных дискуссиях Валерия Комиссарова. Но разыгран бродячий бытовой сюжет практически как трагедия. Недаром фильм снял режиссер, не слишком торопившийся выпускать новое кино «в духе времени». Хотя, как мне кажется, именно Тодоровскому этот дух удалось передать — возможно, потому, что, в отличие от генерации нашего «нового глянцевого кино», он совершенно не стремился быть модным и прогрессивным. Он взял вневременной сюжет из жизни «немодной» социально-возрастной группы. Однако эта группа и является носителем буржуазных ценностей, а вовсе не молодые да ранние, которым как раз сам бог велел бунтовать против буржуазности. Крупно, панорамно показанный «мелкий» быт и укрупненный до безбытной экзистенциальной драмы «случай из жизни» складываются в семейный ребус в традициях Бергмана. Драма героев, не имеющая никакого отношения к тебе лично, оказывается неожиданно близкой. Все начинается с точки в конце истории. Мы узнаем об измене и о том, что уже ничего нельзя изменить. Главная героиня умирает в первых кадрах картины, и зритель так никогда и не увидит лица этой роковой (роковой ли?) женщины. Все очень просто и непонятно. Муж, сидя за письменным столом, томно разминает шею — голова побаливает. Ремонтный рабочий гулко, с нежилым эхом в наполовину разоренной квартире требует: «Хозяйка, я за краской…» И вот оно — страшное в своей всег-дашней неожиданности, несвоевременности, непоправимости. Опрокинутая турка с закипевшим кофе, длинные волосы, разметавшиеся по полу кухни, розовый халат. Этот яркий утренний цвет — последний теплый оттенок картины. Дальше будет безжалостное серо-синее освещение на помятых жизнью лицах двух мужчин и землисто-коричневая гамма поздней провинциальной осени. В сущности, Тодоровский с самого начала очень сильно рискует из-за графоманской загадочности драматургии: эта Лена, успевшая дожить до тридцати семи, совершенно абстрактна, и не потому, что у нее нет лица, а потому, что подробности, которые узнает обманутый покойницей муж, абсолютно не проясняют ее характер. Однако если подробности абстрактны, как откровения в программе «Моя семья», то безнадежный, запоздалый и совсем не элегантный конфликт немолодых «соперников» полон подлинного отчаяния. Вроде бы что интересного в нюансах того, как провинциальный, уверенный в себе, самовлюбленный стареющий плейбой с местного филфака (можно ли было себе представить таким Янковского с его врожденным маскулинным гламуром?) узнает, что жена наставляла ему рога всю их совместную (теперь это слово звучит для него издевательски) жизнь. Ну ловко морочила голову, ну в одночасье ушла от ответа — какой спрос с мертвой? И что прикажете делать актеру в кадре, когда его герой, докурив все оставшиеся от поминок бычки, в поисках спрятанной (доктора запретили) трубки находит письмо к любовнику, да еще составленное в таких выражениях, будто эта женщина, кроме переводных любовных романов, ничего не читала? «Мой дорогой, любимый человек», — написано в трамвае по пути домой от этого «человека», связь с которым длится столько же, сколько и брак с обманутым мужем. Конечно же, в письме — фальшивые эмоции. А вот в том, как тяжело и сипло дышит Янковский, прочитав его, — правда. Дальше можно просто составить таблицу, которая покажет, как легко (по видимому результату, только по нему) режиссер превращает надуманное, бумажное в выстраданное, визуально емкое. Бред сивой кобылы (вернее, курицы), закадычной подруги: «Леночка смотрит на нас с облачка и радуется!» Чудесная Вера Воронкова бормочет это, ни разу не поперхнувшись, сверкая убежденно сумасшедшим взглядом прирожденной дуры набитой, чтобы попытаться поднять доставшиеся ей опереточные реплики до уровня «блаженных откровений». И величественное кладбище, которое богаче, чем реальная жизнь; эти гранитные «мойдодыры» мощно придавили к земле по-настоящему дорогих покойников. Точная метафора: здесь правит жесткая власть общественных установок («чтобы все было прилично, как у людей»), власть молвы и фарисейского знания чужой интимной тайны. Во время похорон муж начинает догадываться, что всем был известен этот любовник Иван — как имя и портрет умершей на надгробии. Но чтобы понять, почему все было так, а не иначе, ему придется самому отправиться на тот свет. «Просыпайтесь, мужчина!» Моментальный, как подготовленный к экзамену, ответ: «Помню», — на вопрос мужа к пожилому кондуктору: «Помните, здесь женщина ездила с синими глазами?» Похоже, что даже трамвайное депо было в курсе адюльтера. И величественные трамваи того самого маршрута, на котором пять остановок туда и столько же обратно проезжала жена и любовница, плывут в тумане, разметая опавшие листья, как бы навстречу друг другу, но в разные стороны, по наезженной рельсовой колее. Маршрут человеческой жизни может насчитывать и меньше остановок, это кому как повезет. Но соскочить с рельсов можно разве что в гроб или в безумие, да и это лишь видимость. Сын Петя, которому только заикание (еще один искусственный двигатель сюжета — повод для ничем не закончившегося выяснения отцовства) помогает справиться с таким вот докладом о проделанной работе: «Я прочитал в медицинской энциклопедии, что разрыв сердца может быть от стресса» (в сценарии он это прочитал, а не в энциклопедии). И двое мужчин на фоне стены с огромными окнами, заколоченными досками; их темные силуэты, отделившись от фасада, становятся неотличимыми тенями, оставшимися от так и не увиденной нами женщины. «Я хочу знать правду», — говорят они по очереди, потому что жизнь их стала плоской, потеряла объем, трехмерность, утратив одну из сторон банальнейшего любовного треугольника. Вот он, дух времени, которому не нужна глянцевая оболочка: никто сейчас не хочет уходить от банальности жизни, а, наоборот, мечтает именно о ней. Это и есть буржуазные ценности, а вовсе не холодные хайтековские интерьеры и модельные девочки в качестве образов «нашей современницы». Для чего в телевикторине «хотят стать миллионером»? Чтобы дать дочке образование, купить домик в деревне, съездить, в конце концов, с семьей в Париж (и не умереть). Отчего страдают в программе «Жди меня»? Родной человек свернул с колеи, и след его исчез в тумане лет, а так хочется встретиться вновь. Зачем подсматривают за соседями в «Моей семье»? Да затем, чтобы узнать, что, в общем-то, у них ничего особенного не происходит — все как у людей. Отставной военный Иван (его играет Сергей Гармаш), превратившийся в жэковского работника ради испепеляющей страсти, — смеетесь, что ли? Страсть испепеляет, когда кругом пампасы, водопады, океанические волны и автомобили с открытым верхом. В средней полосе России, в трамвае и в комнатах с обшарпанными стенами, на продавленном диване под привычное бульканье телевизора страсть тлеет, как торф. То есть чадит, а дым глаза ест. Этот дым и есть подлинная буржуазная сентиментальность, если иметь в виду ее культурный эквивалент. При всем сожалении о слабостях сценария то, как сильная мужская пара Янковский — Гармаш играет тот самый «дым», лично у меня вызывает даже зрительский азарт. Особенно, учитывая некоторую парадоксальность кастинга. Само собой, более очевидным решением было бы переставить актеров: Янковскому дать роль загадочного любовника, а Гармашу предложить быть на экране самодовольным растяпой, скрестив своих «сериальных» злодеев со своими же хорошими парнями из «ментовки». Однако такой фильм легко представить, но незачем снимать. Да и нашему «первому любовнику» в очередной раз тянуть лямку амплуа, пожалуй, не стоило. Неожиданная роль Янковского, сделанная из ничего, из пустоты и обиняков — из чего, собственно, и скроена любая обыденность, — становится по-настоящему главной в фильме. И дело не в заурядно бытовом сюжете, а в том, как деликатно масштаб актерской личности укрупняет несоразмерную ему самому личность героя. В таких условиях задачей Гармаша, конечно, было подыграть, не обыгрывая. Что не менее сложно, поскольку ему досталось все сюжетное «мясо» — от сломанной педали у клубного пианино в воинской части (с чего началась их роковая любовь с музыкантшей Леной) до пресловутого заикания, которым страдает наряду с сыном его покойной любовницы и дочка Ивана от неудачного, краткосрочного брака. Возможно, Тодоровскому стоило бы до минимума убрать слова из своего фильма. У его актеров, к счастью, есть глаза, походка, жесты, которые говорят больше, чем псевдолингвистическая (о профессии обманутого мужа сценарист знает столько же, сколько о медицинских диагнозах) белиберда про «деньги-капусту» и «сучку-течку». «Золотое» мужское молчание — главный козырь его строгой и изящной картины про чувства и чувствительность.

«Любовник» Автор сценария Г. Островский Режиссер В. Тодоровский Оператор С. Михальчук Художник В. Гудилин Композитор А. Айги Звукооператор С. Чупров В ролях: О. Янковский, С. Гармаш, А. Смирнов, В. Воронкова и другие «Рекун-кино», РТР Россия 2002

.jpg)

.jpg)