| A Clockwork Orange | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster by Bill Gold |

|

| Directed by | Stanley Kubrick |

| Screenplay by | Stanley Kubrick |

| Based on | A Clockwork Orange by Anthony Burgess |

| Produced by | Stanley Kubrick |

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | John Alcott |

| Edited by | Bill Butler |

| Music by | Wendy Carlos[a] |

|

Production |

|

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. (US) Columbia-Warner Distributors (UK) |

|

Release dates |

|

|

Running time |

136 minutes[2] |

| Countries |

|

| Language | English |

| Budget | $1.3 million[4] |

| Box office | $114 million[4] |

A Clockwork Orange is a 1971 dystopian crime film adapted, produced, and directed by Stanley Kubrick, based on Anthony Burgess’s 1962 novel of the same name. It employs disturbing, violent images to comment on psychiatry, juvenile delinquency, youth gangs, and other social, political, and economic subjects in a dystopian near-future Britain.

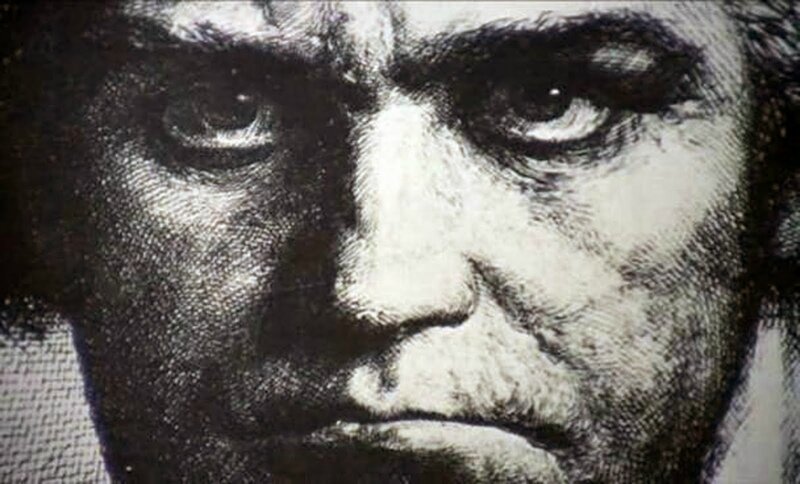

Alex (Malcolm McDowell), the central character, is a charismatic,[5] antisocial delinquent whose interests include classical music (especially Beethoven), committing rape, theft, and ultra-violence. He leads a small gang of thugs, Pete (Michael Tarn), Georgie (James Marcus), and Dim (Warren Clarke), whom he calls his droogs (from the Russian word друг, which is «friend», «buddy»). The film chronicles the horrific crime spree of his gang, his capture, and attempted rehabilitation via an experimental psychological conditioning technique (the «Ludovico Technique») promoted by the Minister of the Interior (Anthony Sharp). Alex narrates most of the film in Nadsat, a fractured adolescent slang composed of Slavic languages (especially Russian), English, and Cockney rhyming slang.

The film premiered in New York City on 19 December 1971 and was released in the United Kingdom on 13 January 1972. The film was met with polarised reviews from critics and was controversial due to its depictions of graphic violence. After it was cited as having inspired copycat acts of violence, the film was withdrawn from British cinemas at Kubrick’s behest, and it was also banned in several other countries. In the years following, the film underwent a critical re-evaluation and gained a cult following. It received several awards and nominations, including four nominations at the 44th Academy Awards, including Best Picture.

In 2020, the film was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress.

Plot[edit]

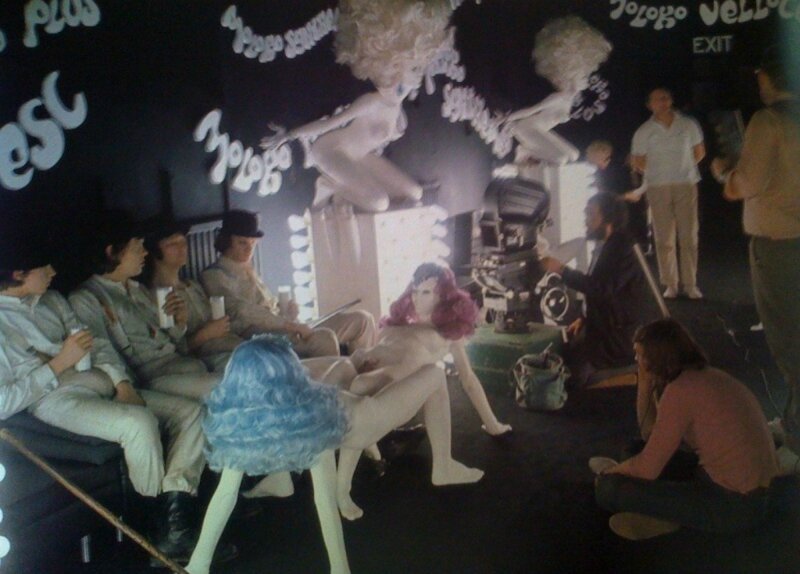

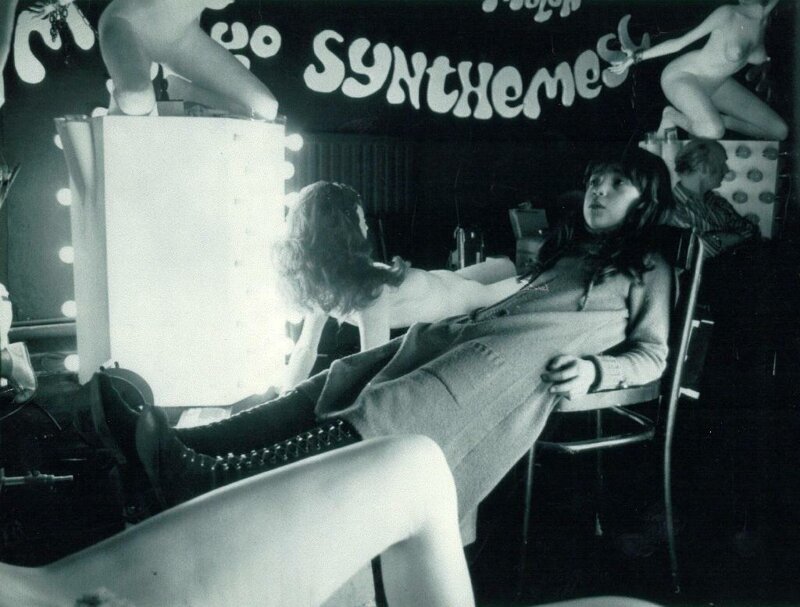

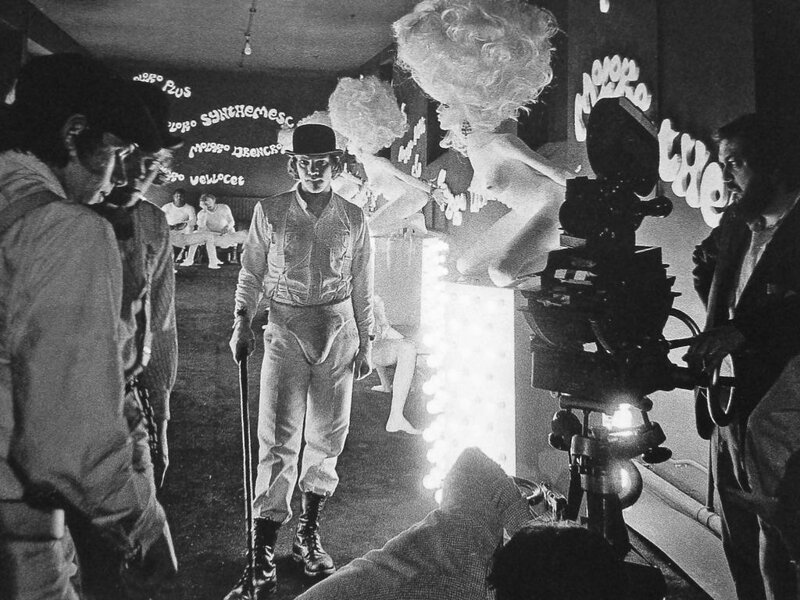

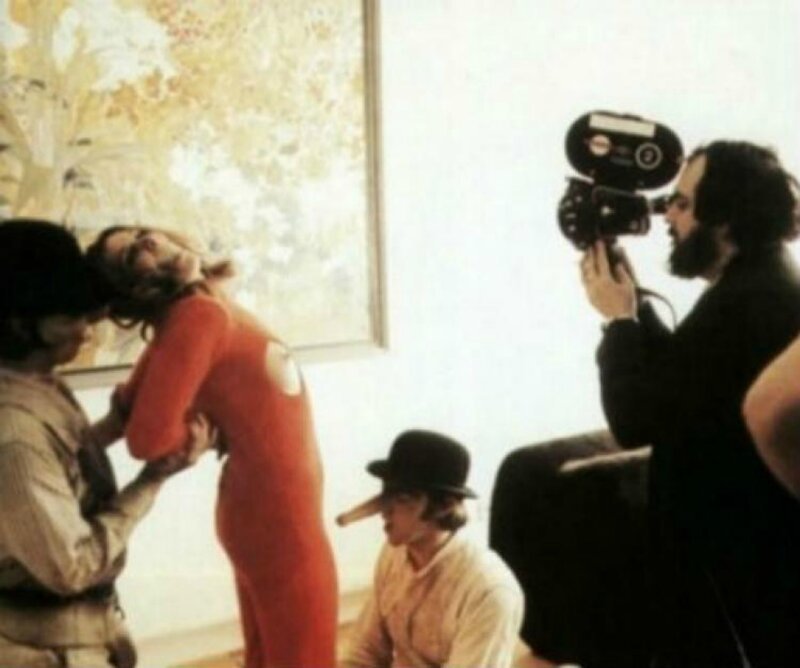

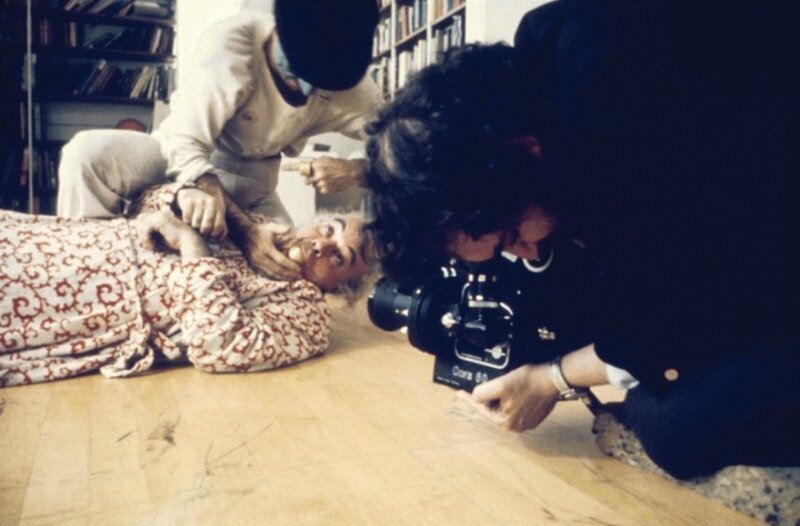

In a futuristic Britain, Alex DeLarge is the leader of a gang of «droogs»: Georgie, Dim and Pete. One night, after getting intoxicated on drug-laden «milk-plus», they engage in an evening of «ultra-violence», which includes a fight with a rival gang. They drive to the country home of writer Frank Alexander and trick his wife into letting them inside. They beat Alexander to the point of crippling him, and Alex violently rapes Alexander’s wife while singing «Singin’ in the Rain». The next day, while truant from school, Alex is approached by his probation officer, PR Deltoid, who is aware of Alex’s activities and cautions him.

Alex’s droogs express discontent with petty crime and want more equality and high-yield thefts, but Alex asserts his authority by attacking them. Later, Alex invades the home of a wealthy «cat-lady» and bludgeons her with a phallic sculpture while his droogs remain outside. On hearing sirens, Alex tries to flee but Dim smashes a bottle in his face, stunning Alex and leaving him to be arrested. Deltoid brings word that the woman has died of her injuries, and Alex is convicted of murder and sentenced to 14 years in prison.

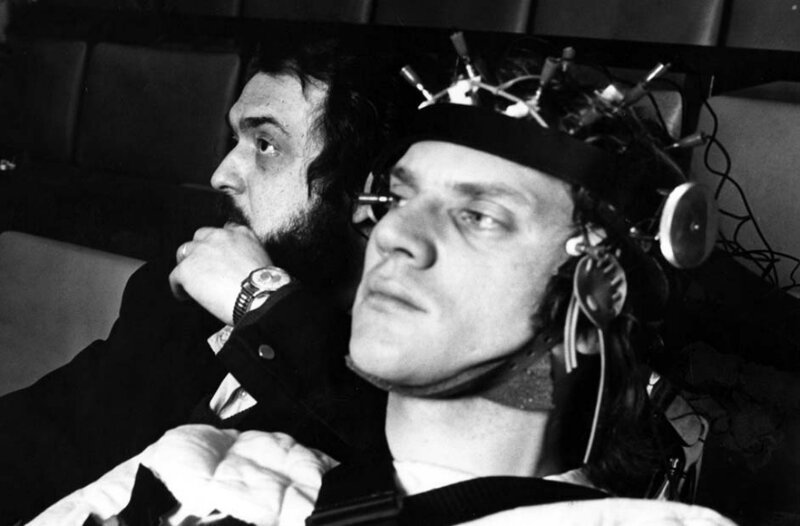

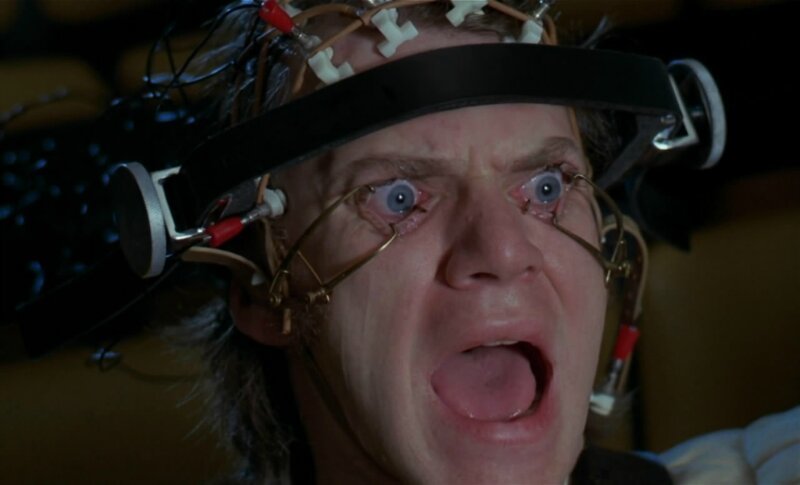

Two years into the sentence, Alex eagerly takes up an offer to be a test subject for the Minister of the Interior’s new Ludovico technique, an experimental aversion therapy for rehabilitating criminals within two weeks. Alex is strapped to a chair, his eyes are clamped open and he is injected with drugs. He is then forced to watch films of sex and violence, some of which are accompanied by the music of his favourite composer, Ludwig van Beethoven. Making the association between the violent scenes and Beethoven, Alex becomes traumatized and nauseated by the films and, fearing the technique will make him sick upon hearing Beethoven, begs for an end to the treatment.

Two weeks later, the Minister demonstrates Alex’s rehabilitation to a gathering of officials. Alex is unable to fight back against an actor who taunts and attacks him and becomes ill wanting sex with a topless woman. The prison chaplain complains that Alex has been robbed of his free will; the Minister asserts that the Ludovico technique will cut crime and alleviate crowding in prisons.

Alex is released from prison, only to find that the police have sold his possessions to provide compensation to his victims and his parents have let out his room. Alex encounters an elderly vagrant whom he attacked years earlier, and the vagrant and his friends attack him. Alex is saved by two policemen but is shocked to find they are his former droogs Dim and Georgie. They drive him to the countryside, beat him, and nearly drown him before abandoning him. Alex barely makes it to the doorstep of a nearby home before collapsing.

Alex wakes up to find himself in the home of Mr Alexander, who is now using a wheelchair. Alexander does not recognise Alex from the previous attack but knows of him and the Ludovico technique from the newspapers. He sees Alex as a political weapon and prepares to present him to his colleagues. While bathing, Alex breaks into «Singin’ in the Rain», causing Alexander to realise that Alex was the person who assaulted his wife and him. With help from his colleagues, Alexander drugs Alex and locks him in an upstairs bedroom. He then plays Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony loudly from the floor below. Unable to withstand the sickening pain, Alex attempts suicide by jumping out of the window.

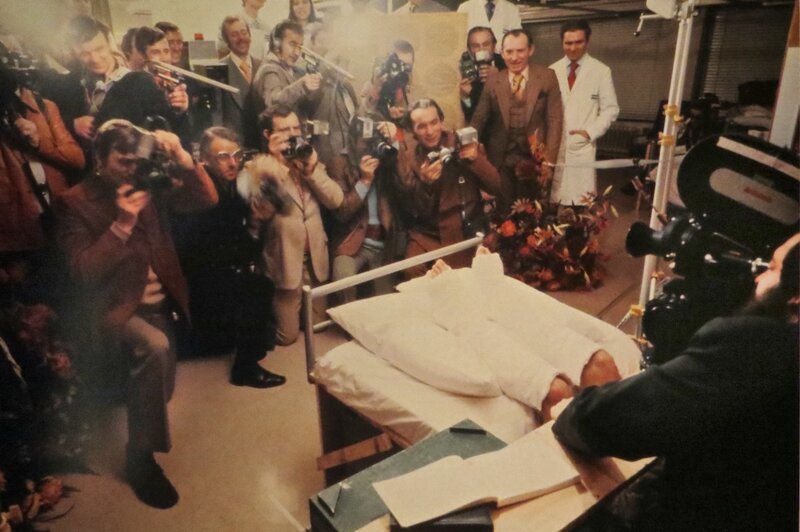

Alex survives the attempt and wakes up in hospital with multiple injuries. While being given a series of psychological tests, he finds that he no longer has aversions to violence and sex. The Minister arrives and apologises to Alex. He offers to take care of Alex and get him a job in return for his co-operation with his election campaign and public relations counter-offensive. As a sign of goodwill, the Minister brings in a stereo system playing Beethoven’s Ninth. Alex then contemplates violence and has vivid thoughts of having sex with a woman in front of an approving crowd, thinking to himself, «I was cured, all right!»

Cast[edit]

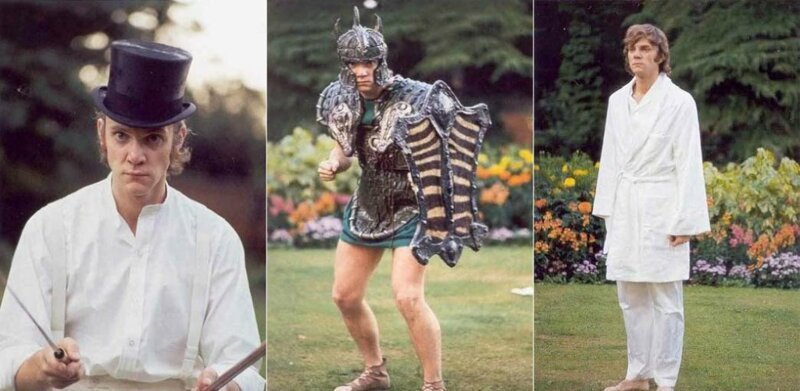

Malcolm McDowell as Alex DeLarge.

- Malcolm McDowell as Alex DeLarge

- Patrick Magee as Frank Alexander

- Michael Bates as Chief Guard Barnes

- Warren Clarke as Dim

- John Clive as Stage Actor

- Adrienne Corri as Mary Alexander

- Carl Duering as Dr Brodsky

- Paul Farrell as Tramp

- Clive Francis as Joe the Lodger

- Michael Gover as Prison Governor

- Miriam Karlin as «Catlady» Weathers

- James Marcus as Georgie

- Aubrey Morris as P. R. Deltoid

- Godfrey Quigley as Prison Chaplain

- Sheila Raynor as Mum

- Madge Ryan as Dr Branom

- John Savident as Conspirator Dolin

- Anthony Sharp as Frederick, Minister of the Interior

- Philip Stone as Dad

- Pauline Taylor as Dr Taylor

- Margaret Tyzack as Conspirator Rubinstein

There were early roles for Steven Berkoff, David Prowse, and Carol Drinkwater.[6]

Themes[edit]

Morality[edit]

The film’s central moral question is the definition of «goodness» and whether it makes sense to use aversion therapy to stop immoral behaviour.[7] Stanley Kubrick, writing in Saturday Review, described the film: «A social satire dealing with the question of whether behavioural psychology and psychological conditioning are dangerous new weapons for a totalitarian government to use to impose vast controls on its citizens and turn them into little more than robots.»[8] Similarly, on the production’s call sheet, Kubrick wrote: «It is a story of the dubious redemption of a teenage delinquent by condition-reflex therapy. It is, at the same time, a running lecture on free-will.»

After aversion therapy, Alex behaves like a good member of society, though not through choice. His goodness is involuntary; he has become the titular clockwork orange—organic on the outside, mechanical on the inside. After Alex has undergone the Ludovico technique, the chaplain criticises his new attitude as false, arguing that true goodness must come from within. This leads to the theme of abusing liberties—personal, governmental, civil—by Alex, with two conflicting political forces, the Government and the Dissidents, both manipulating Alex purely for their own political ends.[9] The story portrays the «conservative» and «leftist» parties as equally worthy of criticism. The writer Frank Alexander, a victim of Alex and his gang, wants revenge against Alex and sees him as a means of definitively turning the populace against the incumbent government and its new regime. He fears the new government and in a telephone conversation, he says: «Recruiting brutal young roughs into the police; proposing debilitating and will-sapping techniques of conditioning. Oh, we’ve seen it all before in other countries; the thin end of the wedge! Before we know where we are, we shall have the full apparatus of totalitarianism.»

On the other side, the Minister of the Interior (the Government) jails Mr Alexander (the Dissident Intellectual) on the excuse of his endangering Alex (the People), rather than the government’s totalitarian regime (described by Mr Alexander). It is unclear whether or not he has been harmed; however, the Minister tells Alex that the writer has been denied the ability to write and produce «subversive» material that is critical of the incumbent government and meant to provoke political unrest.

Psychology[edit]

Ludovico technique apparatus

The film critiques the behaviourism or «behavioural psychology» propounded by psychologists John B. Watson and B. F. Skinner. Burgess disapproved of behaviourism, calling Skinner’s book Beyond Freedom and Dignity (1971) «one of the most dangerous books ever written». Although behaviourism’s limitations were conceded by its principal founder, Watson, Skinner argued that behaviour modification—specifically, operant conditioning (learned behaviours via systematic reward-and-punishment techniques) rather than the «classical» Watsonian conditioning—is the key to an ideal society. The film’s Ludovico technique is widely perceived as a parody of aversion therapy, which is a form of classical conditioning.[10]

Author Paul Duncan said: «Alex is the narrator so we see everything from his point of view, including his mental images. The implication is that all of the images, both real and imagined, are part of Alex’s fantasies.»[11]

Psychiatrist Aaron Stern, the former head of the MPAA rating board, believed that Alex represents man in his natural state, the unconscious mind. Alex becomes «civilised» after receiving his Ludovico «cure» and the sickness in the aftermath Stern considered to be the «neurosis imposed by society».[12]

Kubrick told film critics Philip Strick and Penelope Houston: «Alex makes no attempt to deceive himself or the audience as to his total corruption or wickedness. He is the very personification of evil. On the other hand, he has winning qualities: his total candour, his wit, his intelligence, and his energy; these are attractive qualities and ones, I might add, which he shares with Richard III.»[13]

Society[edit]

The society depicted in the film was perceived by some as Communist (as Michel Ciment pointed out in an interview with Kubrick) due to its slight ties to Russian culture. The teenage slang has a heavily Russian influence, as in the novel; Burgess explains the slang as being, in part, intended to draw a reader into the world of the book’s characters and to prevent the book from becoming outdated. There is some evidence to suggest that the society is a socialist one or perhaps a society evolving from a failed socialism into an authoritarian society. In the novel, streets have paintings of working men in the style of Russian socialist art, and the film shows a mural of socialist artwork with obscenities drawn on it. As Malcolm McDowell points out on the DVD commentary, Alex’s residence was shot on failed municipal architecture and the name «Municipal Flat Block 18A, Linear North» alludes to socialist-style housing.[14][15]

When the new right-wing government takes power, the atmosphere is certainly more authoritarian than the anarchist air of the beginning. Kubrick’s response to Ciment’s question remained ambiguous as to what kind of society it is. Kubrick asserted that the film held comparisons between both ends of the political spectrum and that there is little difference between the two. Kubrick stated: «The Minister, played by Anthony Sharp, is clearly a figure of the Right. The writer, Patrick Magee, is a lunatic of the Left… They differ only in their dogma. Their means and ends are hardly distinguishable.»[14]

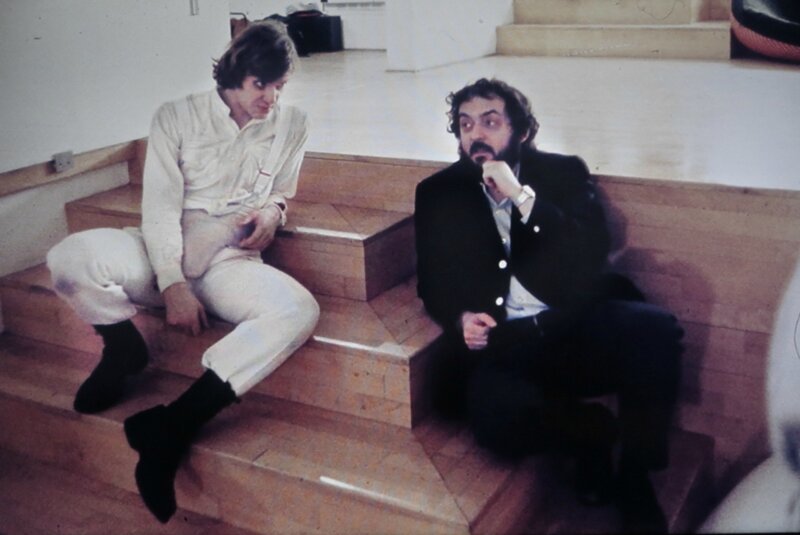

Production[edit]

Anthony Burgess sold the film rights of his novel for US$500 (equivalent to $4,500 in 2021), shortly after its publication in 1962.[16] Originally, the film was projected to star the rock band The Rolling Stones, with the band’s lead singer Mick Jagger expressing interest in playing the lead role of Alex, and British filmmaker Ken Russell attached to direct.[16] However, this never came to fruition due to problems with the British Board of Film Classification (BBFC), and the rights ultimately fell to Kubrick.[16]

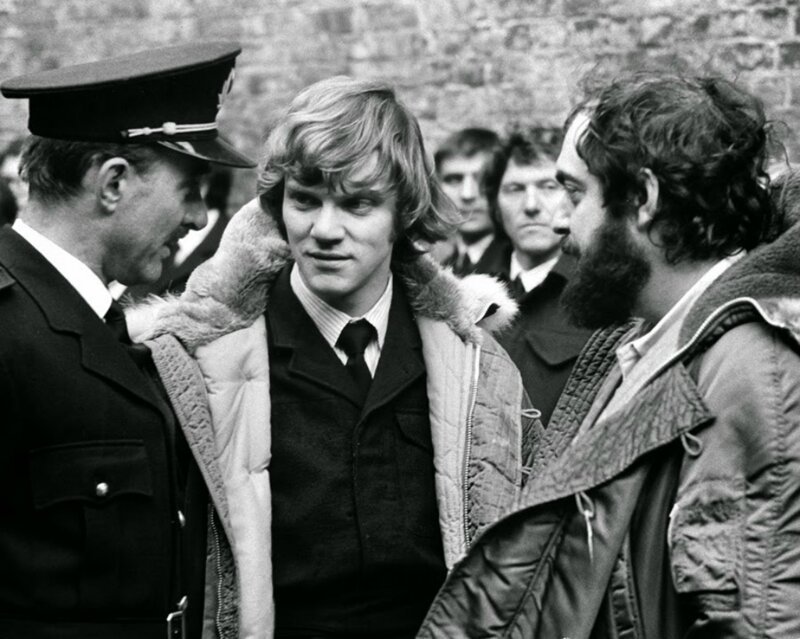

McDowell was chosen for the role of Alex after Kubrick saw him in the film if…. (1968). When asking why he was picked for the role, Kubrick told him: «You can exude intelligence on the screen.»[17] He also helped Kubrick on the uniform of Alex’s gang, when he showed Kubrick the cricket whites he had. Kubrick asked him to put the box (jockstrap) not under but on top of the costume.[18][19]

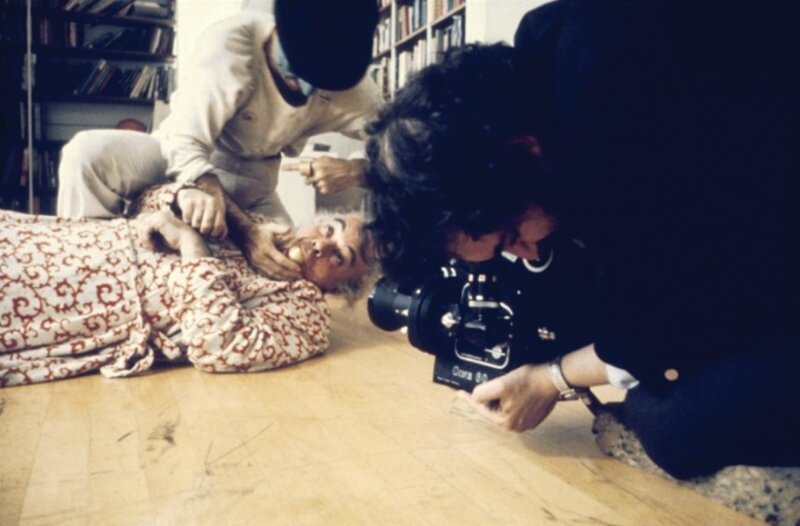

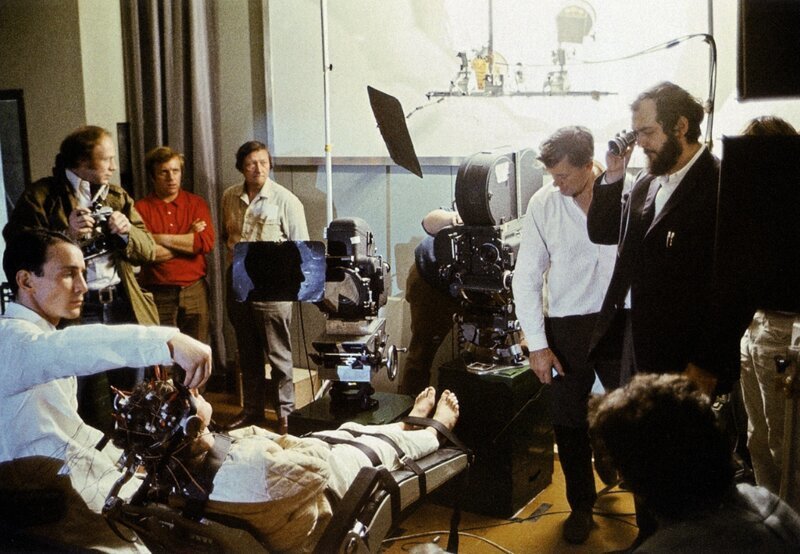

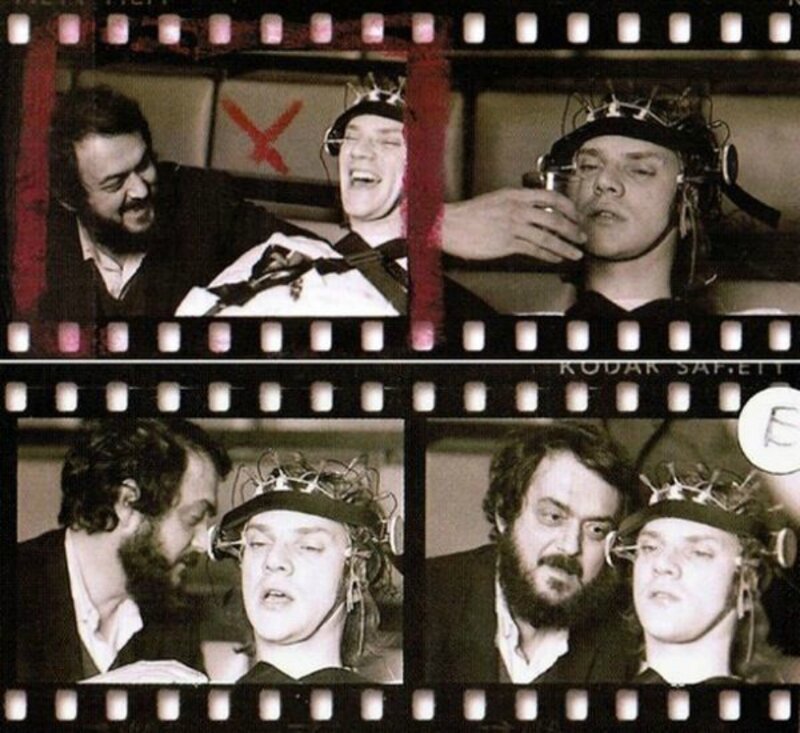

During the filming of the Ludovico technique scene, McDowell scratched a cornea[20] and was temporarily blinded. The doctor standing next to him in the scene, dropping saline solution into Alex’s forced-open eyes, was a real physician present to prevent the actor’s eyes from drying. McDowell also cracked some ribs filming the humiliation stage show.[21] A unique special effect technique was used when Alex jumps out of the window in a suicide attempt, showing the camera approaching the ground from Alex’s point of view. This effect was achieved by dropping a Newman-Sinclair clockwork camera in a box, lens-first, from the third storey of the Corus Hotel. To Kubrick’s surprise, the camera survived six takes.[22]

Adaptation[edit]

The cinematic adaptation of A Clockwork Orange (1962) was not initially planned. Screenplay writer Terry Southern gave Kubrick a copy of the novel, but, as he was developing a Napoleon Bonaparte-related project, Kubrick put it aside. Kubrick’s wife, in an interview, said she had given Kubrick the novel after having read it. Kubrick said: «I was excited by everything about it: the plot, the ideas, the characters, and, of course, the language. The story functions, of course, on several levels: political, sociological, philosophical, and, what’s most important, on a dreamlike psychological-symbolic level.» Kubrick wrote a screenplay faithful to the novel, saying: «I think whatever Burgess had to say about the story was said in the book, but I did invent a few useful narrative ideas and reshape some of the scenes.»[23] Kubrick based the script on the shortened US edition of the book, which omitted the final chapter.[16]

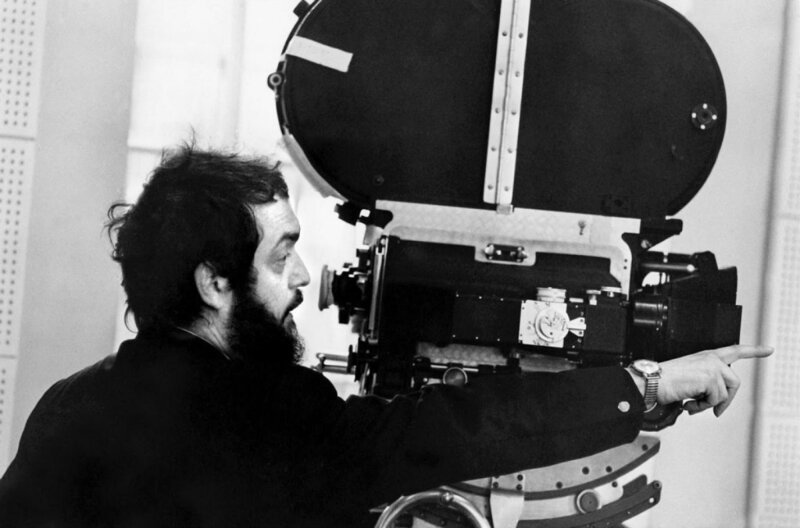

Direction[edit]

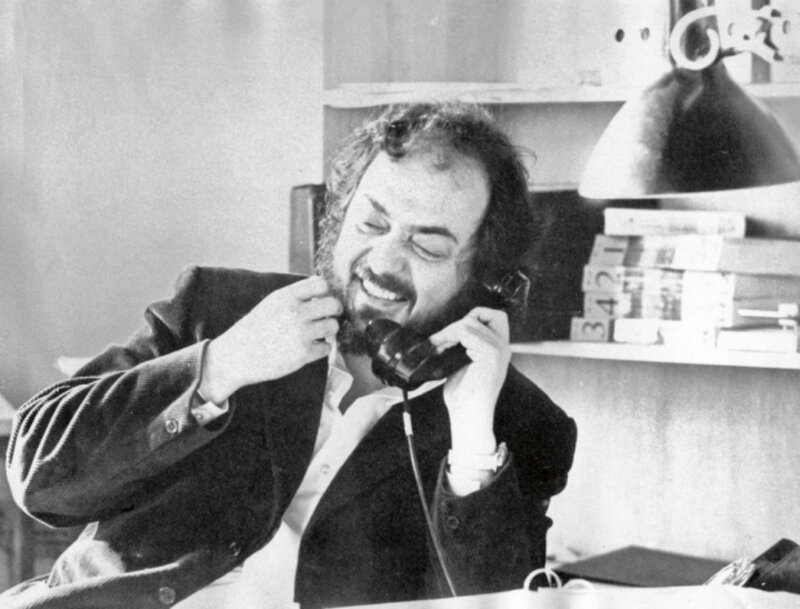

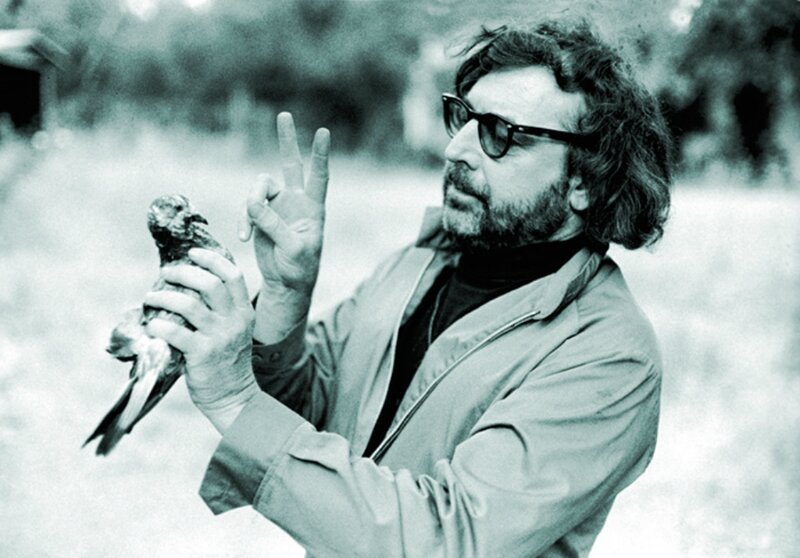

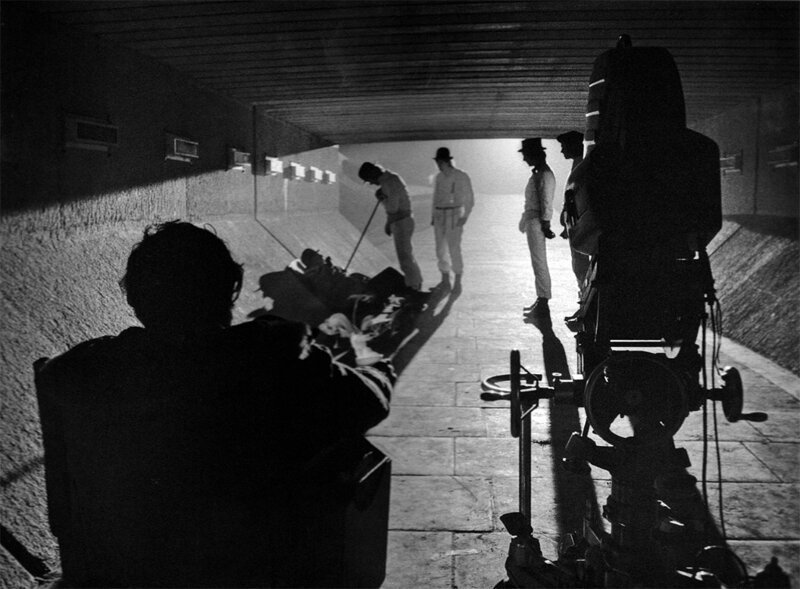

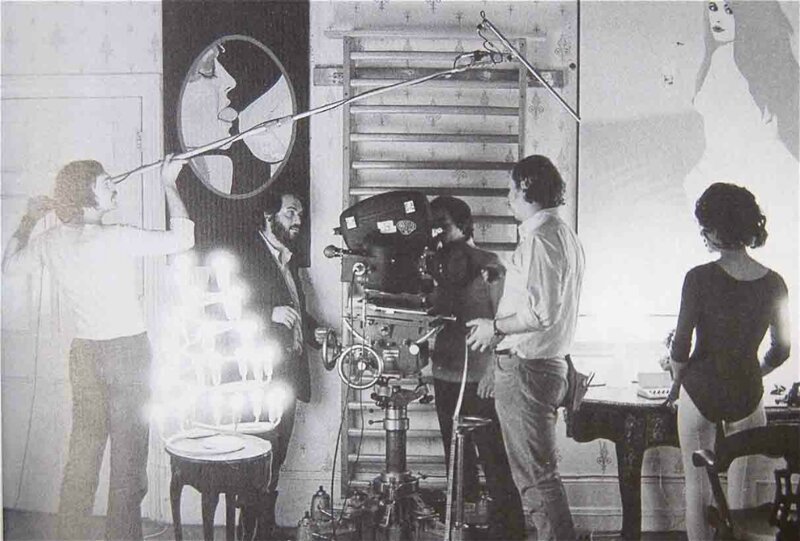

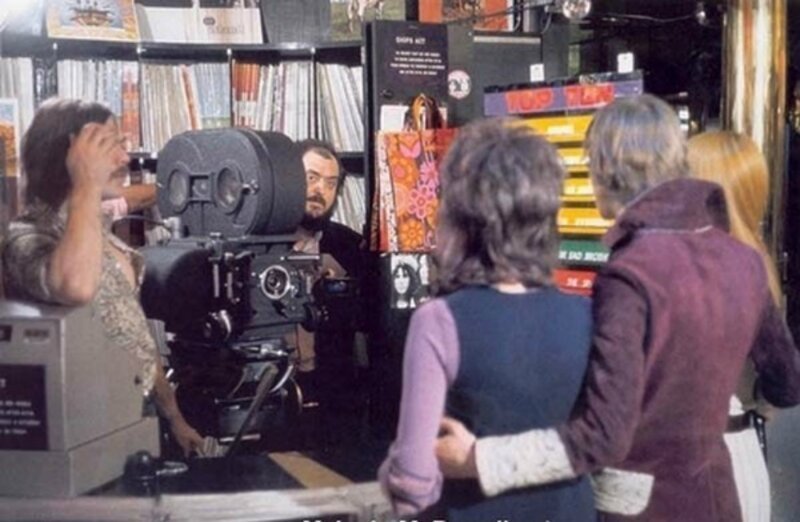

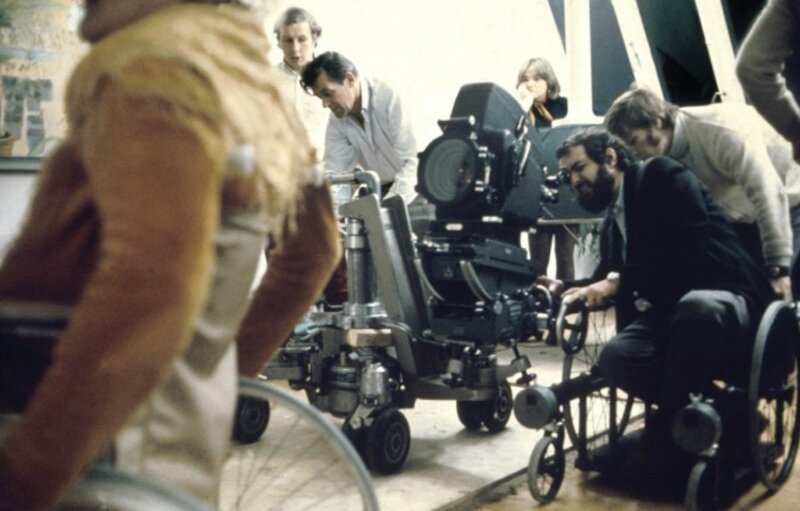

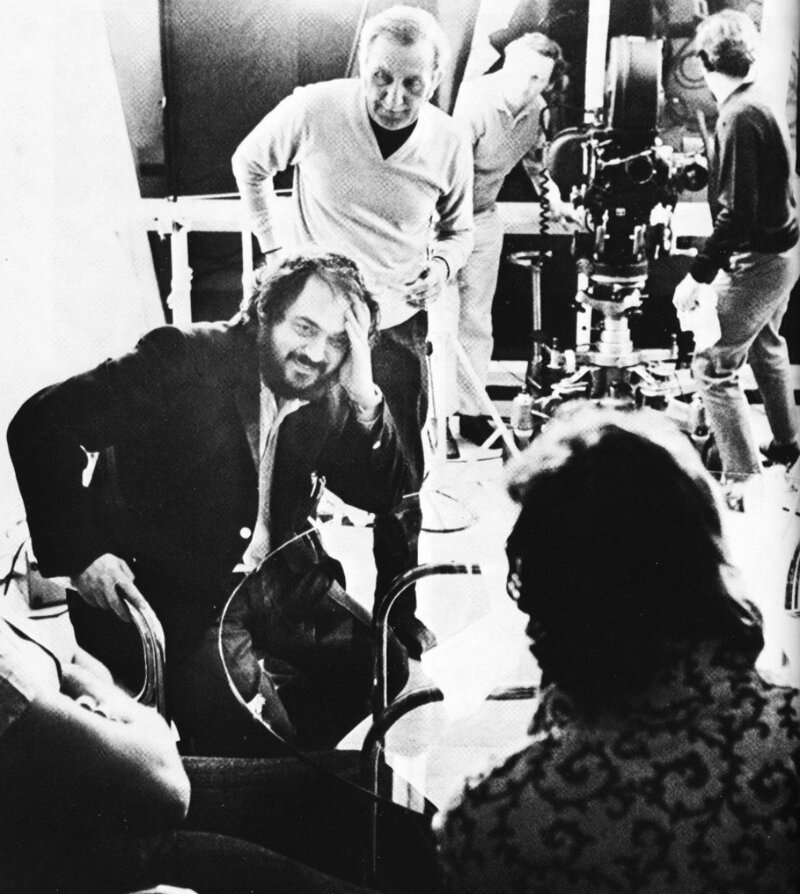

Thamesmead South Housing Estate where Alex knocks his rebellious droogs into the lake

Kubrick was a perfectionist who researched meticulously, with thousands of photographs taken of potential locations, and many scene takes. Like Malcolm McDowell, he usually «got it right» early on, so there were few takes. He was so meticulous that McDowell stated: «If Kubrick hadn’t been a film director he’d have been a General Chief of Staff of the US Forces. No matter what it is—even if it’s a question of buying a shampoo it goes through him. He just likes total control.»[24] Filming took place between September 1970 and April 1971, making A Clockwork Orange the quickest film shoot in his career. Technically, to achieve and convey the fantastic, dream-like quality of the story, he filmed with extreme wide-angle lenses such as the Kinoptik Tegea 9.8 mm for 35 mm Arriflex cameras.[25][26]

Music[edit]

The main theme is an electronic arrangement of Henry Purcell’s Music for the Funeral of Queen Mary, and the soundtrack has two of Edward Elgar’s Pomp and Circumstance Marches.[citation needed]

Alex is fanatical about Ludwig van Beethoven in general and his Ninth Symphony in particular, and the soundtrack includes an electronic version specially arranged by Wendy Carlos of the Scherzo and other parts of the Symphony. The soundtrack contains more music by Rossini than by Beethoven. The fast-motion sex scene with the two girls, the slow-motion fight between Alex and his Droogs, the fight with Billy Boy’s gang, the drive to the writer’s home («playing ‘hogs of the road'»), the invasion of the Cat Lady’s home, and the scene where Alex looks into the river and contemplates suicide before being approached by the beggar are all accompanied by Rossini’s William Tell Overture or The Thieving Magpie Overture.[27][28]

Reception[edit]

Original trailer for A Clockwork Orange

Critical reception[edit]

On release, A Clockwork Orange was met with mixed reviews.[16] Vincent Canby of The New York Times praised the film: «McDowell is splendid as tomorrow’s child, but it is always Mr. Kubrick’s picture, which is even technically more interesting than 2001. Among other devices, Mr. Kubrick constantly uses what I assume to be a wide-angle lens to distort space relationships within scenes, so that the disconnection between lives, and between people and environment, becomes an actual, literal fact.»[29] The following year, after the film won the New York Film Critics Award, he called it «a brilliant and dangerous work, but it is dangerous in a way that brilliant things sometimes are».[30] The film also had notable detractors. Film critic Stanley Kauffmann commented, «Inexplicably, the script leaves out Burgess’ reference to the title».[31] Roger Ebert gave A Clockwork Orange two stars out of four, calling it an «ideological mess».[32] In her New Yorker review titled «Stanley Strangelove», Pauline Kael called it pornographic because of how it dehumanised Alex’s victims while highlighting the sufferings of the protagonist. Kael derided Kubrick as a «bad pornographer», noting the Billyboy’s gang extended stripping of the very buxom woman they intended to rape, claiming it was offered for titillation.[33]

John Simon noted that the novel’s most ambitious effects were based on language and the alienating effect of the narrator’s Nadsat slang, making it a poor choice for a film. Concurring with some of Kael’s criticisms about the depiction of Alex’s victims, Simon noted that the character of Mr Alexander, who was young and likeable in the novel, was played by Patrick Magee, «a very quirky and middle-aged actor who specialises in being repellent». Simon comments further that «Kubrick over-directs the basically excessive Magee until his eyes erupt like missiles from their silos and his face turns every shade of a Technicolor sunset».[34]

Over the years, A Clockwork Orange gained a status as a cult classic. For The Guardian, Philip French stated that the film’s controversial reputation likely stemmed from the fact that it was released during a time when fear of teenage delinquency was high.[35] Adam Nayman of The Ringer wrote that the film’s themes of delinquency, corrupt power structures and dehumanisation are relevant in today’s society.[36] Simon Braund of Empire praised the «dazzling visual style» and McDowell’s «simply astonishing» portrayal of Alex.[37] Roger Ebert softend on the film years after first viewing it declaring on his talk show that while he still thought the film had «all head and no heart», he felt Kubrick’s detachments from the violence more so than he did in the first viewing.[38]

On review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds an approval rating of 88% based on 80 reviews, with an average rating of 8.8/10. The website’s critical consensus reads: «Disturbing and thought-provoking, A Clockwork Orange is a cold, dystopian nightmare with a very dark sense of humor».[39] Metacritic gives the film a score of 77 out of 100, based on reviews by 21 critics, indicating «generally favorable reviews».[40]

Box office[edit]

The film was a box-office success, grossing $41 million in the United States and about $73 million overseas for a worldwide total of $114 million on a budget of $1.3 million.[4]

The film was also successful in the United Kingdom, playing for over a year at the Warner West End in London. After two years of release, the film had earned Warner Bros. rentals of $2.5 million in the United Kingdom and was the number three film for 1973 behind Live and Let Die and The Godfather.[1]

The film was the most popular film of 1972 in France with 7,611,745 admissions.[41]

The film was re-released in North America in 1973 and earned $1.5 million in rentals.[42]

Controversies[edit]

American version[edit]

In the United States, A Clockwork Orange was given an X rating in its original release in 1972. Later, Kubrick replaced approximately 30 seconds of sexually explicit footage from two scenes with less explicit action to obtain an R rating re-release later in 1972.[16][43]

Because of the explicit sex and violence, The National Catholic Office for Motion Pictures rated it C («condemned»), a rating which forbade Roman Catholics seeing the film. In 1982, the office abolished the «condemned» rating. Subsequently, films deemed to have unacceptable levels of sex and violence by the Conference of Bishops are rated O, «morally offensive».[44]

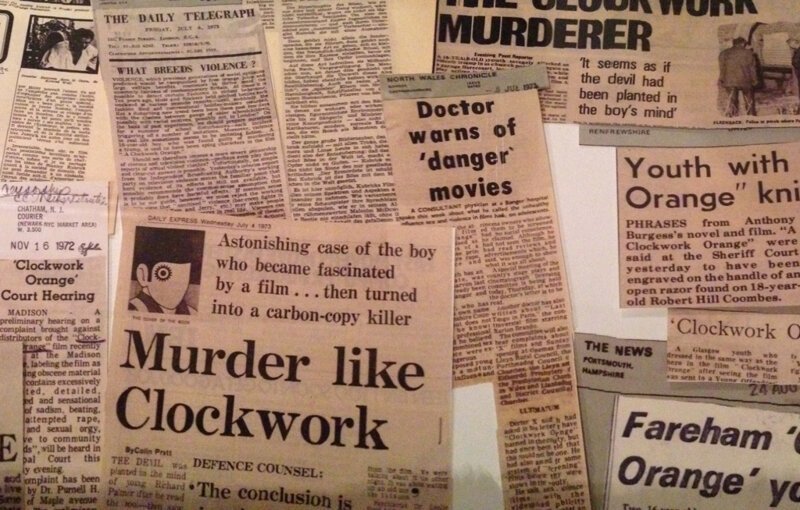

British withdrawal[edit]

Although it was passed uncut for UK cinemas in December 1971, British authorities considered the sexual violence in the film to be extreme. In March 1972, during the trial of a 14-year-old boy accused of the manslaughter of a classmate, the prosecutor referred to A Clockwork Orange, suggesting that the film had a macabre relevance to the case.[45] The film was linked to the murder of an elderly vagrant by a 16-year-old boy in Bletchley, Buckinghamshire, who pleaded guilty after telling police that friends had told him of the film «and the beating up of an old boy like this one». Roger Gray, for the defence, told the court that «the link between this crime and sensational literature, particularly A Clockwork Orange, is established beyond reasonable doubt».[46] The press also blamed the film for a rape in which the attackers sang «Singin’ in the Rain» as «Singin’ in the Rape».[47] Christiane Kubrick, the director’s wife, has said that the family received threats and had protesters outside their home.[48]

The film was withdrawn from British release in 1973 by Warner Bros at the request of Kubrick.[49] In response to allegations that the film was responsible for copycat violence Kubrick stated:

To try and fasten any responsibility on art as the cause of life seems to me to put the case the wrong way around. Art consists of reshaping life, but it does not create life, nor cause life. Furthermore, to attribute powerful suggestive qualities to a film is at odds with the scientifically accepted view that, even after deep hypnosis in a posthypnotic state, people cannot be made to do things which are at odds with their natures.[50]

The Scala Cinema Club went into receivership in 1993 after losing a legal battle following an unauthorised screening of the film.[51] In the same year, Channel 4 broadcast Forbidden Fruit, a 27-minute documentary about the withdrawal of the film in Britain.[52] It contains footage from A Clockwork Orange. It was difficult to see A Clockwork Orange in the United Kingdom for 27 years. It was only after Kubrick died in 1999 that the film was re-released theatrically, on VHS, and on DVD. On 4 July 2001, the uncut version premiered on Sky TV’s Sky Box Office, where it ran until mid-September.

Censorship in other countries[edit]

In Ireland, the film was banned on 10 April 1973. Warner Bros. decided against appealing the decision. Eventually, the film was passed uncut for cinema on 13 December 1999 and released on 17 March 2000.[53][54][55] The re-release poster, a replica of the original British version, was rejected due to the words «ultra-violence» and «rape» in the tagline. Head censor Sheamus Smith explained his rejection to The Irish Times: «I believe that the use of those words in the context of advertising would be offensive and inappropriate.»[56]

In Singapore, the film was banned for over 30 years, before an attempt at release was made in 2006. However, the submission for an M18 rating was rejected, and the ban was not lifted.[57] The ban was later lifted and the film was shown uncut (with an R21 rating) on 28 October 2011, as part of the Perspectives Film Festival.[58][59]

In South Africa, it was banned under the apartheid regime for 13 years, then in 1984 was released with one cut and only made available to people over the age of 21.[60] It was banned in South Korea[57] and in the Canadian provinces of Alberta and Nova Scotia.[61] The Maritime Film Classification Board also reversed the ban eventually. Both jurisdictions now grant an R rating to the film.

In Brazil, the film was banned under the military dictatorship until 1978, when the film was released in a version with black dots covering the genitals and breasts of the actors in the nude scenes.[62]

In Spain, the film debuted at the 1975 Valladolid International Film Festival under the dictatorship of Francisco Franco. It was expected to be screened in the University of Valladolid but, due to student protests, the university had been closed for two months. The final screenings were in the commercial festival venues, with long queues of expectant students. After the festival, the film went into the arthouse circuit and later in commercial cinemas successfully.[63]

In Malta, a ban on the film was lifted in 2000, when it was shown in local cinemas for the first time.[64] The film was brought up during the compilation of evidence on the rape and murder of Paulina Dembska, which took place on 2 January 2022 in Sliema, for the accused attacker compared himself to Alex during police interrogation.[65][66]

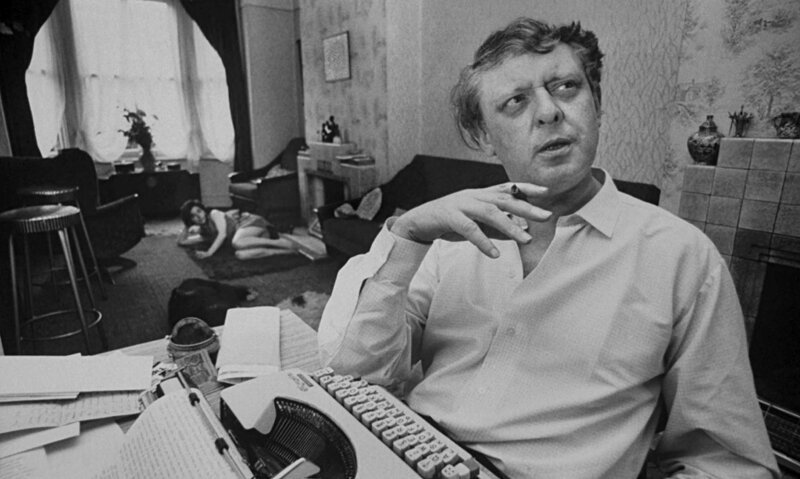

Novelist’s response[edit]

Burgess had mixed reception about the film adaptation of his novel, publicly saying he loved Malcolm McDowell and Michael Bates, and the use of music. He praised it as so «brilliant» that it might be dangerous. He was concerned that it lacked the novel’s redemptive final chapter, an absence he blamed upon his American publisher and not Kubrick. All US editions of the novel prior to 1986 omit the final chapter. Kubrick called the missing chapter «an extra chapter» and claimed that he had not read the original version until he had virtually finished the screenplay, and that he had never seriously considered using it.[67] In Kubrick’s opinion – as in the opinion of other readers, including the original American editor – the final chapter was unconvincing and inconsistent with the book.[68]

Burgess reports in his autobiography You’ve Had Your Time (1990) that he and Kubrick at first enjoyed a good relationship, each holding similar philosophical and political views and each very interested in literature, cinema, music, and Napoleon Bonaparte. Burgess’s novel Napoleon Symphony (1974) was dedicated to Kubrick. Their relationship soured when Kubrick left Burgess to defend the film from accusations of glorifying violence. A lapsed Catholic, Burgess tried many times to explain the Christian moral points of the story to outraged Christian organisations and to defend it against newspaper accusations that it supported fascist dogma. He also went to receive awards given to Kubrick on his behalf. He was in no way involved in the production of the film. The only profit he made directly from the film was the initial $500 that had been given to him for the rights to the adaptation.[citation needed]

Burgess’s own stage adaptation of the novel, A Clockwork Orange: A Play with Music (1984), contains a direct reference to Kubrick. In the final moment of the play Alex joins in a song with the other characters. In the script’s stage directions it states that while this happens: «A man bearded like Stanley Kubrick comes on playing, in exquisite counterpoint, ‘Singin’ in the Rain’ on the trumpet. He is kicked off the stage.»[69][70]

Accolades[edit]

Comparison of film and novel[edit]

Kubrick’s film is relatively faithful to the Burgess novel, omitting only the final, positive chapter, in which Alex matures and outgrows sociopathy. While the film ends with Alex being offered an open-ended government job, implying he remains a sociopath at heart, the novel ends with Alex’s positive change in character. This plot discrepancy occurred because Kubrick based his screenplay on the novel’s American edition, in which the final chapter had been deleted on the insistence of its American publisher.[83] He claimed not to have read the complete, original version of the novel until he had almost finished writing the screenplay, and that he never considered using it. The introduction to the 1996 edition of A Clockwork Orange says that Kubrick found the end of the original edition too blandly optimistic and unrealistic.

- Critic Randy Rasmussen has argued that the government in the film is in a shambolic state of desperation, whereas the government in the novel is quite strong and self-confident. The former reflects Kubrick’s preoccupation with the theme of acts of self-interest masked as simply following procedure.[84]

One example of this would be differences in the portrayal of P. R. Deltoid, Alex’s «post-corrective advisor». In the novel, P. R. Deltoid appears to have some moral authority (although not enough to prevent Alex from lying to him or engaging in crime, despite his protests). In the film, Deltoid is slightly sadistic and seems to have a sexual interest in Alex, interviewing him in his parents’ bedroom and smacking him in the crotch. - In the film, Alex has a pet snake. There is no mention of this in the novel.[85]

- In the novel, F. Alexander recognises Alex through several careless references to the previous attack (such as his wife then claiming they did not have a telephone). In the film, Alex is recognised when singing the song ‘Singing in the Rain’ in the bath, which he had hauntingly done while attacking F. Alexander’s wife. The song does not appear at all in the book, as it was an improvisation by actor Malcolm McDowell when Kubrick complained that the rape scene was too «stiff».[86]

Home media[edit]

In the US the film has been widely available on home video since 1980 and was re-released several times on VHS. It was first released on DVD in the US on 29 June 1999.

In the UK the film was eventually released by Warner Home Video on 13 November 2000 (on both VHS and DVD), individually and as part of The Stanley Kubrick Collection DVD set.[87] Due to negative comments from fans, Warner Bros re-released the film, its image digitally restored and its soundtrack remastered. A limited-edition collector’s set with a soundtrack disc, film poster, booklet, and film strip followed, and was discontinued. In 2005, a British re-release, packaged as an «Iconic Film» in a limited-edition slipcase was published, identical to the remastered DVD set, except for different package cover art. In 2006, Warner Bros announced the September publication of a two-disc special edition featuring a Malcolm McDowell commentary, and the releases of other two-disc sets of Stanley Kubrick films. Several British retailers had set the release date as 6 November 2006. The release was delayed and re-announced for 2007 Holiday Season.

An HD DVD, Blu-ray, and DVD version was re-released on 23 October 2007, alongside four other Kubrick classics, with 1080p video transfers and remixed Dolby TrueHD 5.1 (for HD DVD) and uncompressed 5.1 PCM (for Blu-ray) audio tracks.[88] Unlike the previous version, the DVD re-release edition is anamorphically enhanced. The Blu-ray was reissued for the 40th anniversary of the film’s release, identical to the previously released Blu-ray, plus a Digibook and the Stanley Kubrick: A Life in Pictures documentary as a bonus feature.[88]

In 2021, a 4K restoration was completed with Kubrick’s former assistant Leon Vitali working closely with Warner Bros.[89] It was released in the US on 21 September 2021 and 4 October 2021 in the UK.

Legacy and influence[edit]

Along with Bonnie and Clyde (1967), Night of the Living Dead (1968), The Wild Bunch (1969), Soldier Blue (1970), Dirty Harry (1971), and Straw Dogs (1971), the film is considered a landmark in the relaxation of control on violence in cinema.[90]

A Clockwork Orange remains an influential work in cinema and other media. The film is frequently referenced in popular culture, which Adam Chandler of The Atlantic attributes to Kubrick’s «genre-less» directing techniques that brought novel innovation in filming, music, and production that had not been seen at the time of the film’s original release.[91]

The Village Voice ranked A Clockwork Orange at number 112 in its Top 250 «Best Films of the Century» list in 1999, based on a poll of critics.[92] The film appears several times on the American Film Institute’s (AFI) top movie lists. The film was listed at No. 46 in the 1998 AFI’s 100 Years… 100 Movies,[93] at No. 70 in the 2007 second listing.[94] «Alex DeLarge» is listed 12th in the villains section of the AFI’s 100 Years… 100 Heroes and Villains.[95] In 2008, the AFI’s 10 Top 10 rated A Clockwork Orange as the 4th greatest science-fiction movie to date.[96] The film was also placed 21st in the AFI’s 100 Years… 100 Thrills[97]

In the British Film Institute’s 2012 Sight & Sound polls of the world’s greatest films, A Clockwork Orange was ranked 75th in the directors’ poll and 235th in the critics’ poll.[98] In 2010, Time magazine placed it 9th on their list of the Top 10 Ridiculously Violent Movies.[99] In 2008, Empire ranked it 37th on their list of «The 500 Greatest Movies of All Time», and in 2013, Empire ranked it 11th on their list of «The 100 Best British Films Ever».[100] In 2010, The Guardian ranked the film 6th in its list of 25 greatest arthouse films.[101] The Spanish director Luis Buñuel praised the film highly. He once said: «A Clockwork Orange is my current favourite. I was predisposed against the film. After seeing it, I realised it is only a movie about what the modern world really means».[13]

A Clockwork Orange was added to the National Film Registry in 2020 as a work considered to be of «culturally, historically or aesthetically» significance.[102]

See also[edit]

- Violence in art

- List of cultural references to A Clockwork Orange

- List of films featuring home invasions

- BFI Top 100 British films

Notes[edit]

- ^ The film credits her birth name of Walter

References[edit]

- ^ a b «Think ‘Orange’ Took $2,500,000 In Gt. Britain». Variety. 16 January 1974.

- ^ «A Clockwork Orange». BBFC. 13 February 2019. Retrieved 6 August 2021.

- ^ a b «A Clockwork Orange (1971)». British Film Institute. Archived from the original on 11 August 2014. Retrieved 20 September 2014.

- ^ a b c «Kubrick Keeps ’em in Dark with ‘Eyes Wide Shut’«. Los Angeles Times. 29 September 1998. p. 2. Archived from the original on 12 January 2019. Retrieved 15 April 2021.

- ^ Romney, Jonathan (8 January 2012). «A Clockwork Orange at 40». The Independent. Retrieved 13 January 2023.

- ^ «A Clockwork Orange (1971)». AFI Catalog of Feature Films. Retrieved 28 May 2022.

- ^ «Should We Cure Bad Behavior?». Reason. 1 June 2005. Archived from the original on 6 June 2011. Retrieved 23 December 2009.

- ^ Saturday Review, 25 December 1971[full citation needed]

- ^ «Books of The Times». The New York Times. 19 March 1963. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 4 February 2017.

- ^ Theodore Dalrymple (1 January 2006). «A Prophetic and Violent Masterpiece». City Journal. Archived from the original on 1 February 2011. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- ^ Duncan 2003, p. 142.

- ^ Duncan 2003, p. 128.

- ^ a b Duncan 2003, p. 129.

- ^ a b Ciment 1982. Online at: Kubrick on A Clockwork Orange: An interview with Michel Ciment Archived 17 April 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Zicari, Greta; MacPherson, Tom (31 March 2017). «In the presence of stars: Famous filming locations near Sprachcaffe schools». Archived from the original on 15 June 2018. Retrieved 15 June 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f «AFI|Catalog — A Clockwork Orange». American Film Institute. Archived from the original on 27 October 2020. Retrieved 27 November 2020.

- ^ Malcolm McDowell talks ‘A Clockwork Orange’ at 50 — NME

- ^ «Malcolm McDowell and Leon Vitali Talk A CLOCKWORK ORANGE on the 40th Anniversary». Collider.com. 18 May 2011. Archived from the original on 13 April 2015. Retrieved 13 April 2015.

- ^ «McDowell’s cricket gear inspired ‘Clockwork’ thug». Washington Times. 19 May 2011. Archived from the original on 25 April 2015. Retrieved 13 April 2015.

- ^ «Art Adams interview». «The Mutant Report.» Volume 3. Marvel Age #71 (February 1989). Marvel Comics. pp. 12–15.

- ^ «Misc». Worldtv.com. Archived from the original on 12 April 2011. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- ^ Strick, Philip; Houston, Penelope. «Interview with Stanley Kubrick regarding A Clockwork Orange». Sight&Sound (Spring 1972). Archived from the original on 20 December 2018. Retrieved 13 April 2015.

- ^ «The Kubrick Site: The ACO Controversy in the UK». Visual-memory.co.uk. Archived from the original on 10 September 2012. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- ^ Baxter 1997, pp. 6–7.

- ^ «A Clockwork Orange». Chicago Sun-Times. 11 February 1972. Archived from the original on 28 November 2012. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- ^ «A Clockwork Orange». Chalkthefilm.com. Archived from the original on 8 July 2011. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- ^ McDougal 2003, p. 123.

- ^ «You’ve heard Gioachino Rossini’s music, even if you’ve never heard of him». Christian Science Monitor. 29 February 2012. Archived from the original on 6 March 2013. Retrieved 26 September 2014.

- ^ Canby, Vincent (20 December 1971). «A Clockwork Orange (1971) ‘A Clockwork Orange’ Dazzles the Senses and Mind». The New York Times. Archived from the original on 16 May 2012. Retrieved 4 February 2017.

- ^ Canby, Vincent (9 January 1972). «Orange — Disorienting But Human Comedy». The New York Times. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 4 February 2017.

Stanley Kubrick’s ninth film, ‘A Clockwork Orange,’ which has just won the New York Film Critics Award as the best film of 1971, is a brilliant and dangerous work, but it is dangerous in a way that brilliant things sometimes are. …

- ^ Walker, John (2005). Halliwell’s Film, Video & DVD Guide 2006. HarperCollins. p. 223. ISBN 0-00-720550-3.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (11 February 1972). «A Clockwork Orange». RogerEbert.com. Ebert Digital LLC. Archived from the original on 1 July 2019. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- ^ Kael, Pauline (January 1972). «Stanley Strangelove». The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 25 November 2012. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- ^ Simon, John (1982). Reverse-Angel A decade of American film. New York: Potter. ISBN 9780517546970. OCLC 1036817554.

- ^ French, Philip (28 February 2000). «You looking at me?». The Guardian. Archived from the original on 29 April 2018. Retrieved 27 November 2020.

- ^ Nayman, Adam (13 March 2019). «‘A Clockwork Orange’ in the Age of Cancellation». The Ringer. Archived from the original on 8 November 2020. Retrieved 27 November 2020.

- ^ Braund, Simon (1 January 2000). «EMPIRE ESSAY: A Clockwork Orange Review». Empire. Archived from the original on 20 June 2021. Retrieved 27 November 2020.

- ^ «Cult Movies on Videocassete, 1987». Siskel And Ebert Movie Reviews. Retrieved 17 November 2022.

- ^ «A Clockwork Orange (1971)». Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Archived from the original on 22 May 2016. Retrieved 9 August 2022.

- ^ «A Clockwork Orange Reviews». Metacritic. Archived from the original on 13 November 2020. Retrieved 24 November 2020.

- ^ Soyer, Renaud (22 July 2016). «Box Office France 1972 Top 10». Box Office Story. Archived from the original on 8 June 2019. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- ^ «Big Rental Films of 1973». Variety. 9 January 1974. Archived from the original on 29 June 2019. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- ^ Frederick, Robert B. (3 January 1973). «‘Godfather’: & Rest of Pack». Variety. p. 7.

- ^ Gillis, Chester (1999). Roman Catholicism in America. United States of America: Columbia University Press. p. 226. ISBN 0-231-10870-2.

- ^ «Serious pockets of violence at London school, QC says», The Times, 21 March 1972.

- ^ » ‘Clockwork Orange’ link with boy’s crime», The Times, 4 July 1973.

- ^ «A Clockwork Orange: Context». SparkNotes. 7 March 1999. Archived from the original on 14 February 2011. Retrieved 13 March 2011.

- ^ Barnes, Henry; Brooks, Xan (20 May 2011). «Cannes 2011: Re-winding A Clockwork Orange with Malcolm McDowell – video». The Guardian. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011. Retrieved 21 May 2011.

- ^ Bradshaw, Peter (23 March 2000). «The old ultra-violence». The Guardian. Archived from the original on 22 April 2019. Retrieved 8 October 2016.

- ^ Duncan 2003, p. 136.

- ^ «Scala’s History». scala-london.co.uk. Archived from the original on 24 October 2007. Retrieved 12 November 2007.

- ^ «Without Walls: Forbidden Fruit (1993) A Clockwork Orange BBC Special – Steven Berkoff». Archived from the original on 22 October 2009.

- ^ «Ireland : The Banning and Unbanning of Films». merlin.obs.coe.int. Archived from the original on 1 October 2018. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- ^ «Banned like Clockwork». Come Here To Me!. 21 July 2013. Archived from the original on 4 March 2018. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- ^ Dwyer, Michael (14 December 1999). «Passed like ‘Clockwork’ following a 26-year delay». The Irish Times.

- ^ Dwyer, Michael (4 March 2000). «Kubrick film arrives – minus its poster». The Irish Times.

- ^ a b Davis, Laura (16 August 2009). «Gratuitous Gore and Sex». Tonight. New Zealand: Tonight & Independent Online. Retrieved 19 March 2010.[permanent dead link]

- ^ «Perspective Film Festival 2011 Brochure». Archived from the original on 21 December 2011. Retrieved 28 November 2011.

- ^ Tan, Jeanette (11 October 2011). «‘A Clockwork Orange’ to premiere at S’pore film fest». Yahoo!. Yahoo! Singapore. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 2 October 2014.

- ^ «The Kubrick Site: Censorship of Kubrick’s Films in South Africa». Archived from the original on 6 June 2019. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- ^ Censored! Only in Canada, Malcolm Dean, Virgo Press, 1981.

- ^ «Filmes Censurados pela Ditadura Militar». Cinem(ação) (in Brazilian Portuguese). 5 October 2018. Archived from the original on 12 January 2021. Retrieved 11 January 2021.

- ^ Camazón, Alba (15 August 2021). «El estreno de ‘La Naranja Mecánica’ en España: universitarios sin clases, un antiguo festival cristiano y una falsa amenaza de bomba». ElDiario.es (in Spanish). Retrieved 17 August 2021.

- ^ «Film Conversation — A Clockwork Orange plus Q&A with Malcolm McDowell». Fondazzjoni Kreattività. Retrieved 22 January 2022.

- ^ Cacciottolo, Diana. «Sliema murder: Aquilina told police he didn’t want to hurt victim ‘that much’«. Times of Malta. Archived from the original on 21 January 2022. Retrieved 22 January 2022.

- ^ Agius, Matthew. «Dembska murder: Accused told police his mind was a ‘cooker’ and received ‘frequencies’«. MaltaToday.com.mt. Archived from the original on 21 January 2022. Retrieved 22 January 2022.

- ^ Ciment, Michel (1981). «Kubrick on A Clockwork Orange«. The Kubrick Site. Archived from the original on 24 December 2012. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- ^ Zicari, Greta; MacPherson, Tom (31 March 2017). «In the presence of stars: Famous filming locations near Sprachcaffe schools». Archived from the original on 15 June 2018. Retrieved 15 June 2018.

- ^ «A Clockwork Orange on Stage webpage on The International Anthony Burgess Foundation website». Archived from the original on 17 May 2021. Retrieved 17 May 2021.

- ^ Burgess, Anthony (January 1998). A Clockwork Orange. Bloomsbury Methuen Drama. pp. 50–51. ISBN 978-0-413-73590-4. Archived from the original on 20 June 2021. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- ^ «BAFTA Awards: Film in 1973». BAFTA. 1973. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- ^ «24th DGA Awards». Directors Guild of America Awards. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ «A Clockwork Orange – Golden Globes». HFPA. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ «The Hugo Awards: 1972». The Hugo Awards. 26 July 2007. Archived from the original on 12 June 2010. Retrieved 1 November 2008.

- ^ «KCFCC Award Winners – 1970-79». kcfcc.org. 14 December 2013. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- ^ «Past Awards». National Society of Film Critics. 19 December 2009. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ «1969 New York Film Critics Circle Awards». Mubi. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ «Film Hall of Fame Productions». Online Film & Television Association. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- ^ «2007 Rondo Awards». Rondo Hatton Classic Horror Awards. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

- ^ «2011 Satellite Awards». Satellite Awards. International Press Academy. Retrieved 10 July 2021.

- ^ a b c «Past Saturn Awards». Saturn Awards Organization. Archived from the original on 19 December 2008. Retrieved 1 November 2008.

- ^ «Awards Winners». Writers Guild of America. Archived from the original on 5 December 2012. Retrieved 6 June 2010.

- ^ «The Kubrick FAQ Part 2». Visual-memory.co.uk. Archived from the original on 18 August 2008. Retrieved 1 May 2006.

- ^ Rasmussen, Randy. Kubrick: Seven Films Analyzed. p. 112.[full citation needed]

- ^ Baxter, John. Stanley Kubrick. p. 255.[full citation needed]

- ^ LoBrutto, Vincent. Stanley Kubrick. pp. 365–366.[full citation needed] and Alexander Walker; Sybil Taylor; Ulrich Ruchti. Stanley Kubrick, director. p. 204.[full citation needed]

- ^ «Home Video: Stanley Kubrick, a Film Odyssey». The New York Times. 8 June 2001. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

- ^ a b «A Clockwork Orange». DVD Beaver. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

- ^ Lovitt, Maggie (3 August 2021). «Stanley Kubrick’s ‘A Clockwork Orange’ Gets a 4K Ultra HD Release Date». Collider. Retrieved 15 January 2022.

- ^ MacDonald, Ian. Revolution in the Head. Pimlico. p. 235.[full citation needed]

- ^ Chandler, Adam (2 February 2012). «‘A Clockwork Orange’ Strikes 40″. The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 6 October 2017. Retrieved 6 October 2017.

- ^ «Take One: The First Annual Village Voice Film Critics’ Poll». The Village Voice. 1999. Archived from the original on 26 August 2007. Retrieved 27 July 2006.

- ^ «AFI’s 100 Years…100 Movies» (PDF). afi.com. American Film Institute. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 April 2019. Retrieved 14 January 2015.

- ^ «AFI’s 100 Years…100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition)» (PDF). afi.com. American Film Institute. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 June 2013. Retrieved 14 January 2015.

- ^ «AFI’s 100 Years…100 Heroes & Villains» (PDF). afi.com. American Film Institute. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 March 2014. Retrieved 14 January 2015.

- ^ «AFI’s 10 Top 10: Top 10 Sci-Fi». afi.com. American Film Institute. Archived from the original on 28 March 2014. Retrieved 14 January 2015.

- ^ «AFI’s 100 Years…100 Thrills» (PDF). afi.com. American Film Institute. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 March 2014. Retrieved 14 January 2015.

- ^ «A Clockwork Orange». Archived from the original on 10 July 2014. Retrieved 6 July 2014.

- ^ «Top 10 Ridiculously Violent Movies». Time. 3 September 2010. Archived from the original on 17 February 2013. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

- ^ «The 100 Best British Films Ever» Archived 23 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine. Empire. Retrieved 5 January 2013

- ^ Patterson, John (20 October 2010). «A Clockwork Orange: No 6 best arthouse film of all time». theguardian.

- ^ McNary, Dave (14 December 2020). «‘Dark Knight,’ ‘Shrek,’ ‘Grease,’ ‘Blues Brothers’ Added to National Film Registry». Variety. Archived from the original on 18 February 2021. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- Bibliography

- Baxter, John (1997). Stanley Kubrick: A Biography. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-00-638445-8.

- Duncan, Paul (2003). Stanley Kubrick: The Complete Films. Taschen GmbH. ISBN 978-3836527750.

- McDougal, Stuart Y. (2003). Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-57488-4.

Further reading[edit]

- Burgess, Anthony (2000). Stanley Kubrick’s a Clockwork Orange: Based on the Novel by Anthony Burgess. ScreenPress Books. ISBN 978-1-901680-47-8.

- Heide, Thomas von der (1 June 2006). A Clockwork Orange — The presentation and the impact of violence in the novel and in the film. GRIN Verlag. ISBN 978-3-638-50681-6.

- Volkmann, Maren (16 October 2006). «A Clockwork Orange» in the Context of Subculture. GRIN Verlag. ISBN 978-3-638-55498-5.

- A Clockwork Orange has been cited in a murder case. It is not the first time — Times of Malta 21 January 2022

External links[edit]

- A Clockwork Orange at IMDb

- A Clockwork Orange at AllMovie

- A Clockwork Orange at the TCM Movie Database

- A Clockwork Orange at the American Film Institute Catalog

- A Clockwork Orange at Rotten Tomatoes

- A Clockwork Orange at Metacritic

- A Clockwork Orange at the BFI’s Screenonline

- A Clockwork Orange at Discogs (list of releases)

- «One on One with Malcolm McDowell» from HoboTrashcan.com (2008)

| A Clockwork Orange | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster by Bill Gold |

|

| Directed by | Stanley Kubrick |

| Screenplay by | Stanley Kubrick |

| Based on | A Clockwork Orange by Anthony Burgess |

| Produced by | Stanley Kubrick |

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | John Alcott |

| Edited by | Bill Butler |

| Music by | Wendy Carlos[a] |

|

Production |

|

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. (US) Columbia-Warner Distributors (UK) |

|

Release dates |

|

|

Running time |

136 minutes[2] |

| Countries |

|

| Language | English |

| Budget | $1.3 million[4] |

| Box office | $114 million[4] |

A Clockwork Orange is a 1971 dystopian crime film adapted, produced, and directed by Stanley Kubrick, based on Anthony Burgess’s 1962 novel of the same name. It employs disturbing, violent images to comment on psychiatry, juvenile delinquency, youth gangs, and other social, political, and economic subjects in a dystopian near-future Britain.

Alex (Malcolm McDowell), the central character, is a charismatic,[5] antisocial delinquent whose interests include classical music (especially Beethoven), committing rape, theft, and ultra-violence. He leads a small gang of thugs, Pete (Michael Tarn), Georgie (James Marcus), and Dim (Warren Clarke), whom he calls his droogs (from the Russian word друг, which is «friend», «buddy»). The film chronicles the horrific crime spree of his gang, his capture, and attempted rehabilitation via an experimental psychological conditioning technique (the «Ludovico Technique») promoted by the Minister of the Interior (Anthony Sharp). Alex narrates most of the film in Nadsat, a fractured adolescent slang composed of Slavic languages (especially Russian), English, and Cockney rhyming slang.

The film premiered in New York City on 19 December 1971 and was released in the United Kingdom on 13 January 1972. The film was met with polarised reviews from critics and was controversial due to its depictions of graphic violence. After it was cited as having inspired copycat acts of violence, the film was withdrawn from British cinemas at Kubrick’s behest, and it was also banned in several other countries. In the years following, the film underwent a critical re-evaluation and gained a cult following. It received several awards and nominations, including four nominations at the 44th Academy Awards, including Best Picture.

In 2020, the film was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress.

Plot[edit]

In a futuristic Britain, Alex DeLarge is the leader of a gang of «droogs»: Georgie, Dim and Pete. One night, after getting intoxicated on drug-laden «milk-plus», they engage in an evening of «ultra-violence», which includes a fight with a rival gang. They drive to the country home of writer Frank Alexander and trick his wife into letting them inside. They beat Alexander to the point of crippling him, and Alex violently rapes Alexander’s wife while singing «Singin’ in the Rain». The next day, while truant from school, Alex is approached by his probation officer, PR Deltoid, who is aware of Alex’s activities and cautions him.

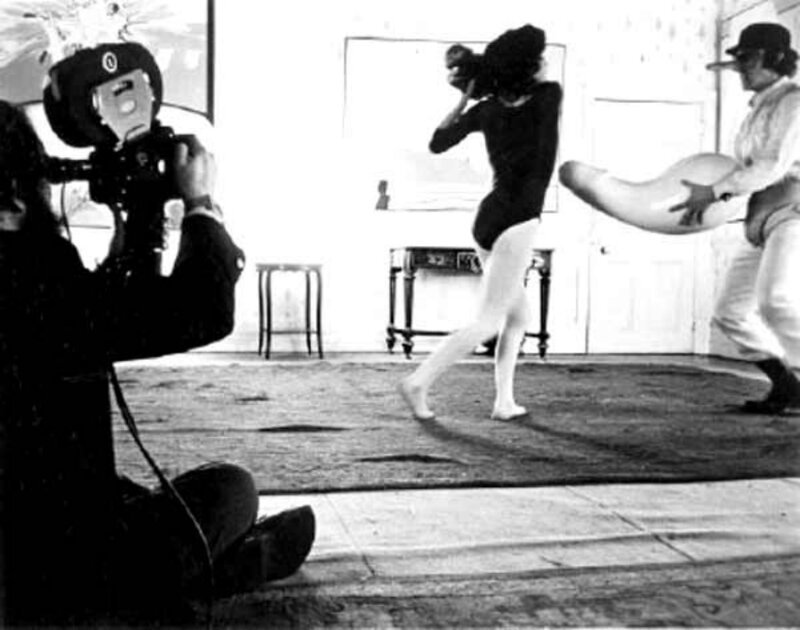

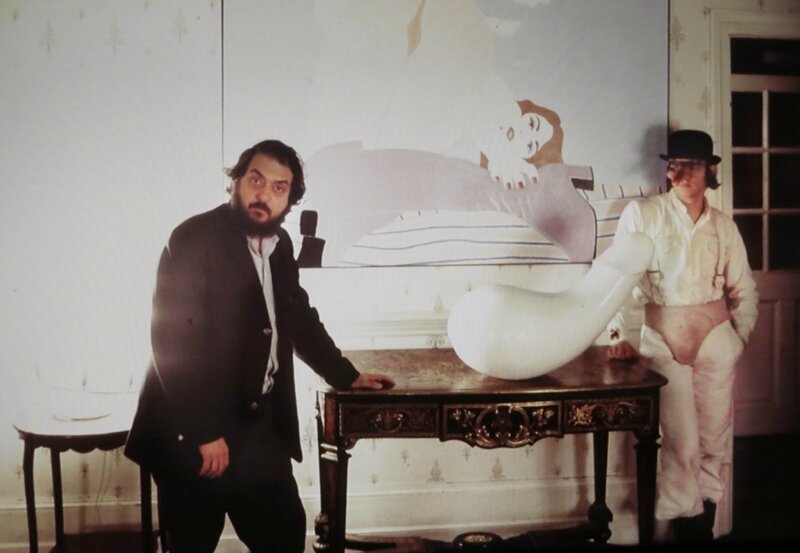

Alex’s droogs express discontent with petty crime and want more equality and high-yield thefts, but Alex asserts his authority by attacking them. Later, Alex invades the home of a wealthy «cat-lady» and bludgeons her with a phallic sculpture while his droogs remain outside. On hearing sirens, Alex tries to flee but Dim smashes a bottle in his face, stunning Alex and leaving him to be arrested. Deltoid brings word that the woman has died of her injuries, and Alex is convicted of murder and sentenced to 14 years in prison.

Two years into the sentence, Alex eagerly takes up an offer to be a test subject for the Minister of the Interior’s new Ludovico technique, an experimental aversion therapy for rehabilitating criminals within two weeks. Alex is strapped to a chair, his eyes are clamped open and he is injected with drugs. He is then forced to watch films of sex and violence, some of which are accompanied by the music of his favourite composer, Ludwig van Beethoven. Making the association between the violent scenes and Beethoven, Alex becomes traumatized and nauseated by the films and, fearing the technique will make him sick upon hearing Beethoven, begs for an end to the treatment.

Two weeks later, the Minister demonstrates Alex’s rehabilitation to a gathering of officials. Alex is unable to fight back against an actor who taunts and attacks him and becomes ill wanting sex with a topless woman. The prison chaplain complains that Alex has been robbed of his free will; the Minister asserts that the Ludovico technique will cut crime and alleviate crowding in prisons.

Alex is released from prison, only to find that the police have sold his possessions to provide compensation to his victims and his parents have let out his room. Alex encounters an elderly vagrant whom he attacked years earlier, and the vagrant and his friends attack him. Alex is saved by two policemen but is shocked to find they are his former droogs Dim and Georgie. They drive him to the countryside, beat him, and nearly drown him before abandoning him. Alex barely makes it to the doorstep of a nearby home before collapsing.

Alex wakes up to find himself in the home of Mr Alexander, who is now using a wheelchair. Alexander does not recognise Alex from the previous attack but knows of him and the Ludovico technique from the newspapers. He sees Alex as a political weapon and prepares to present him to his colleagues. While bathing, Alex breaks into «Singin’ in the Rain», causing Alexander to realise that Alex was the person who assaulted his wife and him. With help from his colleagues, Alexander drugs Alex and locks him in an upstairs bedroom. He then plays Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony loudly from the floor below. Unable to withstand the sickening pain, Alex attempts suicide by jumping out of the window.

Alex survives the attempt and wakes up in hospital with multiple injuries. While being given a series of psychological tests, he finds that he no longer has aversions to violence and sex. The Minister arrives and apologises to Alex. He offers to take care of Alex and get him a job in return for his co-operation with his election campaign and public relations counter-offensive. As a sign of goodwill, the Minister brings in a stereo system playing Beethoven’s Ninth. Alex then contemplates violence and has vivid thoughts of having sex with a woman in front of an approving crowd, thinking to himself, «I was cured, all right!»

Cast[edit]

Malcolm McDowell as Alex DeLarge.

- Malcolm McDowell as Alex DeLarge

- Patrick Magee as Frank Alexander

- Michael Bates as Chief Guard Barnes

- Warren Clarke as Dim

- John Clive as Stage Actor

- Adrienne Corri as Mary Alexander

- Carl Duering as Dr Brodsky

- Paul Farrell as Tramp

- Clive Francis as Joe the Lodger

- Michael Gover as Prison Governor

- Miriam Karlin as «Catlady» Weathers

- James Marcus as Georgie

- Aubrey Morris as P. R. Deltoid

- Godfrey Quigley as Prison Chaplain

- Sheila Raynor as Mum

- Madge Ryan as Dr Branom

- John Savident as Conspirator Dolin

- Anthony Sharp as Frederick, Minister of the Interior

- Philip Stone as Dad

- Pauline Taylor as Dr Taylor

- Margaret Tyzack as Conspirator Rubinstein

There were early roles for Steven Berkoff, David Prowse, and Carol Drinkwater.[6]

Themes[edit]

Morality[edit]

The film’s central moral question is the definition of «goodness» and whether it makes sense to use aversion therapy to stop immoral behaviour.[7] Stanley Kubrick, writing in Saturday Review, described the film: «A social satire dealing with the question of whether behavioural psychology and psychological conditioning are dangerous new weapons for a totalitarian government to use to impose vast controls on its citizens and turn them into little more than robots.»[8] Similarly, on the production’s call sheet, Kubrick wrote: «It is a story of the dubious redemption of a teenage delinquent by condition-reflex therapy. It is, at the same time, a running lecture on free-will.»

After aversion therapy, Alex behaves like a good member of society, though not through choice. His goodness is involuntary; he has become the titular clockwork orange—organic on the outside, mechanical on the inside. After Alex has undergone the Ludovico technique, the chaplain criticises his new attitude as false, arguing that true goodness must come from within. This leads to the theme of abusing liberties—personal, governmental, civil—by Alex, with two conflicting political forces, the Government and the Dissidents, both manipulating Alex purely for their own political ends.[9] The story portrays the «conservative» and «leftist» parties as equally worthy of criticism. The writer Frank Alexander, a victim of Alex and his gang, wants revenge against Alex and sees him as a means of definitively turning the populace against the incumbent government and its new regime. He fears the new government and in a telephone conversation, he says: «Recruiting brutal young roughs into the police; proposing debilitating and will-sapping techniques of conditioning. Oh, we’ve seen it all before in other countries; the thin end of the wedge! Before we know where we are, we shall have the full apparatus of totalitarianism.»

On the other side, the Minister of the Interior (the Government) jails Mr Alexander (the Dissident Intellectual) on the excuse of his endangering Alex (the People), rather than the government’s totalitarian regime (described by Mr Alexander). It is unclear whether or not he has been harmed; however, the Minister tells Alex that the writer has been denied the ability to write and produce «subversive» material that is critical of the incumbent government and meant to provoke political unrest.

Psychology[edit]

Ludovico technique apparatus

The film critiques the behaviourism or «behavioural psychology» propounded by psychologists John B. Watson and B. F. Skinner. Burgess disapproved of behaviourism, calling Skinner’s book Beyond Freedom and Dignity (1971) «one of the most dangerous books ever written». Although behaviourism’s limitations were conceded by its principal founder, Watson, Skinner argued that behaviour modification—specifically, operant conditioning (learned behaviours via systematic reward-and-punishment techniques) rather than the «classical» Watsonian conditioning—is the key to an ideal society. The film’s Ludovico technique is widely perceived as a parody of aversion therapy, which is a form of classical conditioning.[10]

Author Paul Duncan said: «Alex is the narrator so we see everything from his point of view, including his mental images. The implication is that all of the images, both real and imagined, are part of Alex’s fantasies.»[11]

Psychiatrist Aaron Stern, the former head of the MPAA rating board, believed that Alex represents man in his natural state, the unconscious mind. Alex becomes «civilised» after receiving his Ludovico «cure» and the sickness in the aftermath Stern considered to be the «neurosis imposed by society».[12]

Kubrick told film critics Philip Strick and Penelope Houston: «Alex makes no attempt to deceive himself or the audience as to his total corruption or wickedness. He is the very personification of evil. On the other hand, he has winning qualities: his total candour, his wit, his intelligence, and his energy; these are attractive qualities and ones, I might add, which he shares with Richard III.»[13]

Society[edit]

The society depicted in the film was perceived by some as Communist (as Michel Ciment pointed out in an interview with Kubrick) due to its slight ties to Russian culture. The teenage slang has a heavily Russian influence, as in the novel; Burgess explains the slang as being, in part, intended to draw a reader into the world of the book’s characters and to prevent the book from becoming outdated. There is some evidence to suggest that the society is a socialist one or perhaps a society evolving from a failed socialism into an authoritarian society. In the novel, streets have paintings of working men in the style of Russian socialist art, and the film shows a mural of socialist artwork with obscenities drawn on it. As Malcolm McDowell points out on the DVD commentary, Alex’s residence was shot on failed municipal architecture and the name «Municipal Flat Block 18A, Linear North» alludes to socialist-style housing.[14][15]

When the new right-wing government takes power, the atmosphere is certainly more authoritarian than the anarchist air of the beginning. Kubrick’s response to Ciment’s question remained ambiguous as to what kind of society it is. Kubrick asserted that the film held comparisons between both ends of the political spectrum and that there is little difference between the two. Kubrick stated: «The Minister, played by Anthony Sharp, is clearly a figure of the Right. The writer, Patrick Magee, is a lunatic of the Left… They differ only in their dogma. Their means and ends are hardly distinguishable.»[14]

Production[edit]

Anthony Burgess sold the film rights of his novel for US$500 (equivalent to $4,500 in 2021), shortly after its publication in 1962.[16] Originally, the film was projected to star the rock band The Rolling Stones, with the band’s lead singer Mick Jagger expressing interest in playing the lead role of Alex, and British filmmaker Ken Russell attached to direct.[16] However, this never came to fruition due to problems with the British Board of Film Classification (BBFC), and the rights ultimately fell to Kubrick.[16]

McDowell was chosen for the role of Alex after Kubrick saw him in the film if…. (1968). When asking why he was picked for the role, Kubrick told him: «You can exude intelligence on the screen.»[17] He also helped Kubrick on the uniform of Alex’s gang, when he showed Kubrick the cricket whites he had. Kubrick asked him to put the box (jockstrap) not under but on top of the costume.[18][19]

During the filming of the Ludovico technique scene, McDowell scratched a cornea[20] and was temporarily blinded. The doctor standing next to him in the scene, dropping saline solution into Alex’s forced-open eyes, was a real physician present to prevent the actor’s eyes from drying. McDowell also cracked some ribs filming the humiliation stage show.[21] A unique special effect technique was used when Alex jumps out of the window in a suicide attempt, showing the camera approaching the ground from Alex’s point of view. This effect was achieved by dropping a Newman-Sinclair clockwork camera in a box, lens-first, from the third storey of the Corus Hotel. To Kubrick’s surprise, the camera survived six takes.[22]

Adaptation[edit]

The cinematic adaptation of A Clockwork Orange (1962) was not initially planned. Screenplay writer Terry Southern gave Kubrick a copy of the novel, but, as he was developing a Napoleon Bonaparte-related project, Kubrick put it aside. Kubrick’s wife, in an interview, said she had given Kubrick the novel after having read it. Kubrick said: «I was excited by everything about it: the plot, the ideas, the characters, and, of course, the language. The story functions, of course, on several levels: political, sociological, philosophical, and, what’s most important, on a dreamlike psychological-symbolic level.» Kubrick wrote a screenplay faithful to the novel, saying: «I think whatever Burgess had to say about the story was said in the book, but I did invent a few useful narrative ideas and reshape some of the scenes.»[23] Kubrick based the script on the shortened US edition of the book, which omitted the final chapter.[16]

Direction[edit]

Thamesmead South Housing Estate where Alex knocks his rebellious droogs into the lake

Kubrick was a perfectionist who researched meticulously, with thousands of photographs taken of potential locations, and many scene takes. Like Malcolm McDowell, he usually «got it right» early on, so there were few takes. He was so meticulous that McDowell stated: «If Kubrick hadn’t been a film director he’d have been a General Chief of Staff of the US Forces. No matter what it is—even if it’s a question of buying a shampoo it goes through him. He just likes total control.»[24] Filming took place between September 1970 and April 1971, making A Clockwork Orange the quickest film shoot in his career. Technically, to achieve and convey the fantastic, dream-like quality of the story, he filmed with extreme wide-angle lenses such as the Kinoptik Tegea 9.8 mm for 35 mm Arriflex cameras.[25][26]

Music[edit]

The main theme is an electronic arrangement of Henry Purcell’s Music for the Funeral of Queen Mary, and the soundtrack has two of Edward Elgar’s Pomp and Circumstance Marches.[citation needed]

Alex is fanatical about Ludwig van Beethoven in general and his Ninth Symphony in particular, and the soundtrack includes an electronic version specially arranged by Wendy Carlos of the Scherzo and other parts of the Symphony. The soundtrack contains more music by Rossini than by Beethoven. The fast-motion sex scene with the two girls, the slow-motion fight between Alex and his Droogs, the fight with Billy Boy’s gang, the drive to the writer’s home («playing ‘hogs of the road'»), the invasion of the Cat Lady’s home, and the scene where Alex looks into the river and contemplates suicide before being approached by the beggar are all accompanied by Rossini’s William Tell Overture or The Thieving Magpie Overture.[27][28]

Reception[edit]

Original trailer for A Clockwork Orange

Critical reception[edit]

On release, A Clockwork Orange was met with mixed reviews.[16] Vincent Canby of The New York Times praised the film: «McDowell is splendid as tomorrow’s child, but it is always Mr. Kubrick’s picture, which is even technically more interesting than 2001. Among other devices, Mr. Kubrick constantly uses what I assume to be a wide-angle lens to distort space relationships within scenes, so that the disconnection between lives, and between people and environment, becomes an actual, literal fact.»[29] The following year, after the film won the New York Film Critics Award, he called it «a brilliant and dangerous work, but it is dangerous in a way that brilliant things sometimes are».[30] The film also had notable detractors. Film critic Stanley Kauffmann commented, «Inexplicably, the script leaves out Burgess’ reference to the title».[31] Roger Ebert gave A Clockwork Orange two stars out of four, calling it an «ideological mess».[32] In her New Yorker review titled «Stanley Strangelove», Pauline Kael called it pornographic because of how it dehumanised Alex’s victims while highlighting the sufferings of the protagonist. Kael derided Kubrick as a «bad pornographer», noting the Billyboy’s gang extended stripping of the very buxom woman they intended to rape, claiming it was offered for titillation.[33]

John Simon noted that the novel’s most ambitious effects were based on language and the alienating effect of the narrator’s Nadsat slang, making it a poor choice for a film. Concurring with some of Kael’s criticisms about the depiction of Alex’s victims, Simon noted that the character of Mr Alexander, who was young and likeable in the novel, was played by Patrick Magee, «a very quirky and middle-aged actor who specialises in being repellent». Simon comments further that «Kubrick over-directs the basically excessive Magee until his eyes erupt like missiles from their silos and his face turns every shade of a Technicolor sunset».[34]

Over the years, A Clockwork Orange gained a status as a cult classic. For The Guardian, Philip French stated that the film’s controversial reputation likely stemmed from the fact that it was released during a time when fear of teenage delinquency was high.[35] Adam Nayman of The Ringer wrote that the film’s themes of delinquency, corrupt power structures and dehumanisation are relevant in today’s society.[36] Simon Braund of Empire praised the «dazzling visual style» and McDowell’s «simply astonishing» portrayal of Alex.[37] Roger Ebert softend on the film years after first viewing it declaring on his talk show that while he still thought the film had «all head and no heart», he felt Kubrick’s detachments from the violence more so than he did in the first viewing.[38]

On review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds an approval rating of 88% based on 80 reviews, with an average rating of 8.8/10. The website’s critical consensus reads: «Disturbing and thought-provoking, A Clockwork Orange is a cold, dystopian nightmare with a very dark sense of humor».[39] Metacritic gives the film a score of 77 out of 100, based on reviews by 21 critics, indicating «generally favorable reviews».[40]

Box office[edit]

The film was a box-office success, grossing $41 million in the United States and about $73 million overseas for a worldwide total of $114 million on a budget of $1.3 million.[4]

The film was also successful in the United Kingdom, playing for over a year at the Warner West End in London. After two years of release, the film had earned Warner Bros. rentals of $2.5 million in the United Kingdom and was the number three film for 1973 behind Live and Let Die and The Godfather.[1]

The film was the most popular film of 1972 in France with 7,611,745 admissions.[41]

The film was re-released in North America in 1973 and earned $1.5 million in rentals.[42]

Controversies[edit]

American version[edit]

In the United States, A Clockwork Orange was given an X rating in its original release in 1972. Later, Kubrick replaced approximately 30 seconds of sexually explicit footage from two scenes with less explicit action to obtain an R rating re-release later in 1972.[16][43]

Because of the explicit sex and violence, The National Catholic Office for Motion Pictures rated it C («condemned»), a rating which forbade Roman Catholics seeing the film. In 1982, the office abolished the «condemned» rating. Subsequently, films deemed to have unacceptable levels of sex and violence by the Conference of Bishops are rated O, «morally offensive».[44]

British withdrawal[edit]

Although it was passed uncut for UK cinemas in December 1971, British authorities considered the sexual violence in the film to be extreme. In March 1972, during the trial of a 14-year-old boy accused of the manslaughter of a classmate, the prosecutor referred to A Clockwork Orange, suggesting that the film had a macabre relevance to the case.[45] The film was linked to the murder of an elderly vagrant by a 16-year-old boy in Bletchley, Buckinghamshire, who pleaded guilty after telling police that friends had told him of the film «and the beating up of an old boy like this one». Roger Gray, for the defence, told the court that «the link between this crime and sensational literature, particularly A Clockwork Orange, is established beyond reasonable doubt».[46] The press also blamed the film for a rape in which the attackers sang «Singin’ in the Rain» as «Singin’ in the Rape».[47] Christiane Kubrick, the director’s wife, has said that the family received threats and had protesters outside their home.[48]

The film was withdrawn from British release in 1973 by Warner Bros at the request of Kubrick.[49] In response to allegations that the film was responsible for copycat violence Kubrick stated:

To try and fasten any responsibility on art as the cause of life seems to me to put the case the wrong way around. Art consists of reshaping life, but it does not create life, nor cause life. Furthermore, to attribute powerful suggestive qualities to a film is at odds with the scientifically accepted view that, even after deep hypnosis in a posthypnotic state, people cannot be made to do things which are at odds with their natures.[50]

The Scala Cinema Club went into receivership in 1993 after losing a legal battle following an unauthorised screening of the film.[51] In the same year, Channel 4 broadcast Forbidden Fruit, a 27-minute documentary about the withdrawal of the film in Britain.[52] It contains footage from A Clockwork Orange. It was difficult to see A Clockwork Orange in the United Kingdom for 27 years. It was only after Kubrick died in 1999 that the film was re-released theatrically, on VHS, and on DVD. On 4 July 2001, the uncut version premiered on Sky TV’s Sky Box Office, where it ran until mid-September.

Censorship in other countries[edit]

In Ireland, the film was banned on 10 April 1973. Warner Bros. decided against appealing the decision. Eventually, the film was passed uncut for cinema on 13 December 1999 and released on 17 March 2000.[53][54][55] The re-release poster, a replica of the original British version, was rejected due to the words «ultra-violence» and «rape» in the tagline. Head censor Sheamus Smith explained his rejection to The Irish Times: «I believe that the use of those words in the context of advertising would be offensive and inappropriate.»[56]

In Singapore, the film was banned for over 30 years, before an attempt at release was made in 2006. However, the submission for an M18 rating was rejected, and the ban was not lifted.[57] The ban was later lifted and the film was shown uncut (with an R21 rating) on 28 October 2011, as part of the Perspectives Film Festival.[58][59]

In South Africa, it was banned under the apartheid regime for 13 years, then in 1984 was released with one cut and only made available to people over the age of 21.[60] It was banned in South Korea[57] and in the Canadian provinces of Alberta and Nova Scotia.[61] The Maritime Film Classification Board also reversed the ban eventually. Both jurisdictions now grant an R rating to the film.

In Brazil, the film was banned under the military dictatorship until 1978, when the film was released in a version with black dots covering the genitals and breasts of the actors in the nude scenes.[62]

In Spain, the film debuted at the 1975 Valladolid International Film Festival under the dictatorship of Francisco Franco. It was expected to be screened in the University of Valladolid but, due to student protests, the university had been closed for two months. The final screenings were in the commercial festival venues, with long queues of expectant students. After the festival, the film went into the arthouse circuit and later in commercial cinemas successfully.[63]

In Malta, a ban on the film was lifted in 2000, when it was shown in local cinemas for the first time.[64] The film was brought up during the compilation of evidence on the rape and murder of Paulina Dembska, which took place on 2 January 2022 in Sliema, for the accused attacker compared himself to Alex during police interrogation.[65][66]

Novelist’s response[edit]

Burgess had mixed reception about the film adaptation of his novel, publicly saying he loved Malcolm McDowell and Michael Bates, and the use of music. He praised it as so «brilliant» that it might be dangerous. He was concerned that it lacked the novel’s redemptive final chapter, an absence he blamed upon his American publisher and not Kubrick. All US editions of the novel prior to 1986 omit the final chapter. Kubrick called the missing chapter «an extra chapter» and claimed that he had not read the original version until he had virtually finished the screenplay, and that he had never seriously considered using it.[67] In Kubrick’s opinion – as in the opinion of other readers, including the original American editor – the final chapter was unconvincing and inconsistent with the book.[68]