Культурно-досуговая

программа является универсальной формой

художественного моделирования

действительности, а его драматургической

основой – сценарий.

Если

обратиться к этимологии слова, то

сценарий (от итал. scenario, от лат. scaena –

сцена) – краткое изложение событий,

которые происходят по ходу действия в

спектакле. Слово «сце¬нарий» первоначально

обозначало развернутый план спектакля.

Сценарий

определял основной порядок действия,

ключе¬вые моменты развития интриги,

очередность выходов на сце¬ну персонажей

импровизационного театра. Непосредствен¬ный

текст создавался самими актерами в

процессе спектакля или репетиций; при

этом он жестко не фиксировался, а

варьировался в зависимости от реакций

и отклика зрителей. По сценарному

принципу строились практически все

виды народного театра, особенно

комедийного (древнерусского – театр

скоморохов, европейского и славянского

– кукольного театра, французского –

ярмарочного, итальянского – зна¬ме¬ни¬той

комедии дель арте и т.д.).

В

начале XVII века даже начали выпускаться

отдельные сборники сценариев для

представлений комедии дель арте, авторами

которых чаще всего были ведущие актеры

трупп. Первый сборник, выпущенный Ф.Скала

в 1611 году, содер¬жал 50 сценариев, по

которым могло развиваться сценичес¬кое

действие.

в

широком смысле слова сценарий представляет

собой особый сло¬вес¬ный текст,

своеобразный перевод, осуществляемый

с языка сло¬весного вида искусства на

язык аудиовизуального, зре¬лищ¬ного

искусства. Будучи драматургической

основой куль¬тур¬но-досуговой программы,

сценарий «фиксирует» будущее единое

драматургическое действие во всем

объеме вырази¬тельных средств.

Сценарий

культурно-досуговой программы – это

подроб¬ная литературная разработка

драматургического действия,

пред¬на-значенного для постановки на

сценической площадке, на основе которого

создаются различные формы культурно-досуговых

программ.

8. Сценарный замысел и его составляющие элементы.

Зарождение

замысла – сложный процесс, связанный

с ин¬ди-видуальными особенностями

творческой личности, его ми¬ро-восприятием

и мироощущением. Возникновение замысла

придает поначалу хаотичной работе

целенаправленность, не ограничивая при

этом воображение, интуицию, фантазию.

Толковый

словарь русского языка под ред. Д.Н.Ушакова

трактует замысел как «нечто задуманное,

замышленное, как цель работы, деятельности».

Толковый

словарь русского языка С.И.Ожегова

определяет замысел в двух значениях:

1.

Задуманный план действий, деятельности,

намерение.

2.

Заложенный в произведении смысл, идея.

Словарь

литературоведческих терминов характеризует

твор¬ческий замысел как представление

об основных чертах и свойствах

художественного произведения, его

содержании и фор¬ме, как творческий

набросок, намечающий основу произ¬ведения.

Тема

(от греч. théma – то, что положено в основу)

В

замысле культурно-досуговой программы

присутствуют не только личность

сценариста, его видение мира, но и

конечное звено творческого процесса –

зритель, аудитория. Не случайно Ю. Борев

отметил, что творчество – это процесс

отчуждения замысла от художника и

передачи его через произведение читателю,

зрителю, слушателю.

Таким

образом, в основе сценарного замысла

культурно-досуговой программы прежде

всего лежит ее (программы) тема и идея.

В.И.Даль

определяет тему как «положение, задача,

о коей рассуждается или которую

разъясняют». Другими словами, тема

культурно-досуговой программы – это

круг жизненных явлений, вопросов,

проблем, которые волнуют автора и

аудиторию, причем наиболее актуальных

и художественно осмысленных.

Выбор

темы досуговой программы определяется

миро¬ощу¬ще¬нием автора сценария, его

жизненными ценностными ориен¬тациями,

теми явлениями и связями, которые он

счи¬та¬ет наиболее важными.

Тема

неразрывно связана с идеей драматургического

про¬из-ведения, которая характеризуется

как его содержательно-смысловая

целостность и продукт эмоционального

пережи¬ва¬ния и освоения жизни автором

Однако

идея не может быть сведена лишь к главной

автор¬ской мысли. Она – ракурс, точка

зрения автора на «факты жиз¬ни».

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

A screenplay, or script, is a written work by screenwriters for a film, television show, or video game (as opposed to a stage play). A screenplay written for television is also known as a teleplay. Screenplays can be original works or adaptations from existing pieces of writing. A screenplay is a form of narration in which the movements, actions, expressions and dialogue of the characters are described in a certain format. Visual or cinematographic cues may be given, as well as scene descriptions and scene changes.

History[edit]

In the early silent era, before the turn of the 20th century, «scripts» for films in the United States were usually a synopsis of a film of around one paragraph and sometimes as short as one sentence.[1] Shortly thereafter, as films grew in length and complexity, film scenarios (also called «treatments» or «synopses»[2]: 92 ) were written to provide narrative coherence that had previously been improvised.[1] Films such as A Trip to the Moon (1902) and The Great Train Robbery (1903) had scenarios consisting respectively of a list of scene headings or scene headings with a detailed explication of the action in each scene.[1] At this time, scripts had yet to include individual shots or dialogue.[1]

These scenario scripts evolved into continuity scripts, which listed a number of shots within each scene, thus providing continuity to streamline the filmmaking process.[1] While some productions, notably D. W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation (1915), were made without a script, preapproved «continuities» allowed the increasingly powerful studio executives to more accurately budget for film productions.[1] Movie industry revolutionary Thomas H. Ince, a screenwriter himself, invented movie production by introducing an «assembly line» system of filmmaking that utilized far more detailed written materials, clearly dedicated to «separating conception from execution».[1] Film researcher Andrew Kenneth Gay posits that, «The process of scripting for the screen did not so much emerge naturally from other literary forms such as the play script, the novel, or poetry nor to meet the artistic needs of filmmakers but developed primarily to address the manufacturing needs of industrial production.»[1]

With the advent of sound film, dialogue quickly dominated scripts, with what had been specific instructions for the filmmaker initially regressed to a list of master shots.[1] However, screenwriters soon began to add the shot-by-shot details that characterized continuities of the films of the later silent era.[1] Casablanca (1942), is written in this style, with detailed technical instructions interwoven with dialogue.[1] The first use of the term «screenplay» dates to this era;[2]: 86 the term «screen play» (two words) was used as early as 1916 in the silent era to refer to the film itself, i.e. a play shown on a screen.[2]: 82 [1]

With the end of the studio system in the 1950s and 1960s, these continuities were gradually split into a master-scene script, which includes all dialogue but only rudimentary scene descriptions and a shooting script devised by the director after a film is approved for production.[1] While studio era productions required the explicit visual continuity and strict adherence to a budget that continuity scripts afforded, the master-scene script was more readable, which is of importance to an independent producer seeking financing for a project.[1] By the production of Chinatown (1974), this change was complete.[1] Andrew Kenneth Gay argues that this shift has raised the status of directors as auteurs and lowered the profile of screenwriters.[1] However, he also notes that since the screenplay is no longer a technical document, screenwriting is more of a literary endeavour.[1]

Format and style[edit]

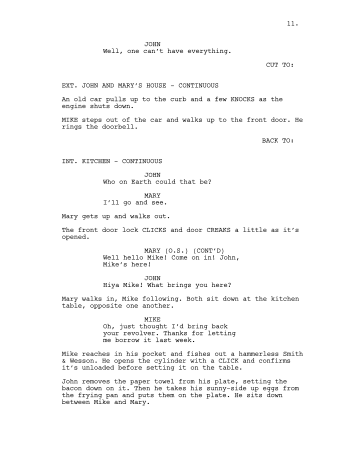

Page from a screenplay, showing dialogue and action descriptions, as well as scene cuts

The format is structured so that (as a ballpark estimate) one page equates to roughly one minute of screen time, though this often bears little resemblance to the runtime of the final production.[3] The standard font is 12 point, 10 pitch Courier typeface.[4] Wide margins of at least one inch are employed (usually larger for the left to accommodate hole punches).

The major components are action (sometimes called «screen direction») and dialogue. The action is written in the present tense and is limited to what can be heard or seen by the audience, for example descriptions of settings, character movements, or sound effects. The dialogue is the words the characters speak, and is written in a center column.

Unique to the screenplay (as opposed to a stage play) is the use of slug lines. A slug line, also called a master scene heading, occurs at the start of each scene and typically contains 3 pieces of information: whether the scene is set inside or outside (INT. or EXT.; interior or exterior), the specific location, and the time of day. Each slug line begins a new scene. In a «shooting script» the slug lines are numbered consecutively for ease of reference.[5]

Physical format[edit]

US[edit]

American screenplays are printed single-sided on three-hole-punched paper using the standard American letter size (8.5 x 11 inch). They are then held together with two brass brads in the top and bottom hole. The middle hole is left empty as it would otherwise make it harder to quickly read the script.

UK[edit]

In the United Kingdom, double-hole-punched A4 paper is normally used, which is slightly taller and narrower than US letter size. Some UK writers format the scripts for use in the US letter size, especially when their scripts are to be read by American producers since the pages would otherwise be cropped when printed on US paper. Because each country’s standard paper size is difficult to obtain in the other country, British writers often send an electronic copy to American producers, or crop the A4 size to US letter.

A British script may be bound by a single brad at the top left-hand side of the page, making flicking through the paper easier during script meetings. Screenplays are usually bound with a light card stock cover and back page, often showing the logo of the production company or agency submitting the script, covers are there to protect the script during handling which can reduce the strength of the paper. This is especially important if the script is likely to pass through the hands of several people or through the post.

Other[edit]

Increasingly, reading copies of screenplays (that is, those distributed by producers and agencies in the hope of attracting finance or talent) are distributed printed on both sides of the paper (often professionally bound) to reduce paper waste. Occasionally they are reduced to half-size to make a small book which is convenient to read or put in a pocket; this is generally for use by the director or production crew during shooting.

Although most writing contracts continue to stipulate physical delivery of three or more copies of a finished script, it is common for scripts to be delivered electronically via email. Electronic copies allow easier copyright registration and also documenting «authorship on a given date».[6] Authors can register works with the WGA’s Registry,[7] and even television formats using the FRAPA’s system.[8][9]

Screenplay formats[edit]

Screenplays and teleplays use a set of standardizations, beginning with proper formatting. These rules are in part to serve the practical purpose of making scripts uniformly readable «blueprints» of movies, and also to serve as a way of distinguishing a professional from an amateur.

Feature film[edit]

Motion picture screenplays intended for submission to mainstream studios, whether in the US or elsewhere in the world, are expected to conform to a standard typographical style known widely as the studio format which stipulates how elements of the screenplay such as scene headings, action, transitions, dialogue, character names, shots and parenthetical matter should be presented on the page, as well as font size and line spacing.

One reason for this is that, when rendered in studio format, most screenplays will transfer onto the screen at the rate of approximately one page per minute. This rule of thumb is widely contested — a page of dialogue usually occupies less screen time than a page of action, for example, and it depends enormously on the literary style of the writer — and yet it continues to hold sway in modern Hollywood.

There is no single standard for studio format. Some studios have definitions of the required format written into the rubric of their writer’s contract. The Nicholl Fellowship, a screenwriting competition run under the auspices of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, has a guide to screenplay format.[10] A more detailed reference is The Complete Guide to Standard Script Formats.[11]

Speculative screenplay[edit]

A speculative screenplay or «spec script» is a script written to be sold on the open market with no upfront payment, or promise of payment. The content is usually invented solely by the screenwriter, though spec screenplays can also be based on established works or real people and events.[12]

Television[edit]

For American TV shows, the format rules for hour-long dramas and single-camera sitcoms are essentially the same as for motion pictures. The main difference is that TV scripts have act breaks. Multi-camera sitcoms use a different, specialized format that derives from stage plays and radio. In this format, dialogue is double-spaced, action lines are capitalized, and scene headings, character entrances and exits, and sound effects are capitalized and underlined.

Drama series and sitcoms are no longer the only formats that require the skills of a writer. With reality-based programming crossing genres to create various hybrid programs, many of the so-called «reality» programs are in a large part scripted in format. That is, the overall skeleton of the show and its episodes are written to dictate the content and direction of the program. The Writers Guild of America has identified this as a legitimate writer’s medium, so much so that they have lobbied to impose jurisdiction over writers and producers who «format» reality-based productions. Creating reality show formats involves storytelling structure similar to screenwriting, but much more condensed and boiled down to specific plot points or actions related to the overall concept and story.

Documentaries[edit]

The script format for documentaries and audio-visual presentations which consist largely of voice-over matched to still or moving pictures is different again and uses a two-column format which can be particularly difficult to achieve in standard word processors, at least when it comes to editing or rewriting. Many script-editing software programs include templates for documentary formats.

Screenwriting software[edit]

Various screenwriting software packages are available to help screenwriters adhere to the strict formatting conventions. Detailed computer programs are designed specifically to format screenplays, teleplays, and stage plays. Such packages include BPC-Screenplay, Celtx, Fade In, Final Draft, FiveSprockets, Montage, Movie Draft SE, Movie Magic Screenwriter, Movie Outline 3.0, Scrivener, and Zhura. Software is also available as web applications, accessible from any computer, and on mobile devices, such as Fade In Mobile Scripts Pro and Studio Binder.

The first screenwriting software was SmartKey, a macro program that sent strings of commands to existing word processing programs, such as WordStar, WordPerfect and Microsoft Word. SmartKey was popular with screenwriters from 1982 to 1987, after which word processing programs had their own macro features.

Script coverage[edit]

Script coverage is a filmmaking term for the analysis and grading of screenplays, often within the script-development department of a production company. While coverage may remain entirely verbal, it usually takes the form of a written report, guided by a rubric that varies from company to company. The original idea behind coverage was that a producer’s assistant could read a script and then give their producer a breakdown of the project and suggest whether they should consider producing the screenplay or not.[13]

See also[edit]

- Pre-production – phase of producing a film or television show

- Closet screenplay – screenplay read by a person or aloud in a group rather than performed

- Dreams on Spec – documentary film about screenwriters

- Screenwriter’s salary – how screenwriters are paid

- Scriptment – written work by a screenwriter

- Storyboard – form of ordering graphics in media

- Outline of film – overview and topical guide to film

- List of screenwriting awards for film – wikimedia list article

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Andrew Kenneth Gay. «History of scripting and the screenplay» at Screenplayology: An Online Center for Screenplay Studies. Retrieved 15 December 2021.

- ^ a b c Steven Maras. Screenwriting: History, Theory and Practice. Wallflower Press, 2009. ISBN 9781905674824

- ^ JohnAugust.com «How accurate is the page-per-minute rule?

- ^ JohnAugust.com «Hollywood Standard Formatting»

- ^ Schumach, Murray (August 28, 1960). «HOLLYWOOD USAGE Experts Analyze the Pros and Cons Of Time-Tested ‘Master’ Scene». The New York Times. Retrieved April 6, 2021.

- ^ Zerner ESQ, Larry. «Writers Guild of America-West Registration vs. Copyright Registration». www.writersstore.com. Retrieved 2020-03-29.

If the writer registers the script with the Copyright Office only after the infringement has taken place, he will be barred from recovering attorneys fees or statutory damages in the lawsuit.

- ^ «WGA West Registry». Writers Guild of America West. Retrieved 2020-03-29.

Any file may be registered to assist you in documenting the creation of your work. Some examples of registerable material include scripts, treatments, synopses, and outlines… The WGAW Registry also accepts stageplays, novels, books, short stories, poems, commercials, lyrics, drawings, music and various media work such as Web series, code, and other digital content.

- ^ Sonia Castang; Richard Deakin; Tony Forster; Andrea Gibb; Olivia Hetreed (Chair); Guy Hibbert; Kathy Hill; Terry James; Line Langebek; Dominic Minghella; Phil Nodding; Phil O’Shea; Sam Snape (April 2016). «Writing Film : A Good Practice Guide» (PDF). Writers’ Guild of Great Britain. p. 11. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

In the UK there is no legal necessity to register your work – copyright is automatic. Registration is more important if you intend to offer your work to overseas producers. The Writers Guild of America in New York and Los Angeles offer a cheap and easy-to-use internet-based script registration system that involves uploading a digital copy. If you are offering your work in the USA you should also register it with the US Copyright Office – if you don’t, your right to legal damages for copyright infringement may be much reduced.

- ^ Ricolfi, Marco; Morando, Federico; Rubiano, Camilo; Hsu, Shirley; Ouma, Marisella; De Martin, Juan Carlos (September 9, 2011). «Survey of Private Copyright Documentation Systems and Practices» (PDF). World Intellectual Property Organization. p. 24. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 June 2013. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

Established in 1927, Writers Guild of America, West Registry (WGAWR) is one of the oldest private copyright registries.

Alt URL - ^ Guide to screenplay format from the website of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences

- ^ The Complete Guide to Standard Script Formats (2002) Cole and Haag, SCB Distributors, ISBN 0-929583-00-0.

- ^ «Spec Script». Act Four Screenplays. 29 July 2010. Retrieved August 10, 2012.

- ^ «What is Script Coverage?». WeScreenplay. Retrieved 5 July 2016.

Further reading[edit]

- David Trottier (1998). The Screenwriter’s Bible: A Complete Guide to Writing, Formatting, and Selling Your Script. Silman-James Press. ISBN 1-879505-44-4. — Paperback

- Yves Lavandier (2005). Writing Drama, A Comprehensive Guide for Playwrights and Scritpwriters. Le Clown & l’Enfant. ISBN 2-910606-04-X. — Paperback

- Judith H. Haag, Hillis R. Cole (1980). The Complete Guide to Standard Script Formats: The Screenplay. CMC Publishing. ISBN 0-929583-00-0. — Paperback

- Jami Bernard (1995). Quentin Tarantino: The Man and His Movies. HarperCollins publishers. ISBN 0-00-255644-8. — Paperback

- Luca Bandirali, Enrico Terrone (2009), Il sistema sceneggiatura. Scrivere e descrivere i film, Turin (Italy): Lindau. ISBN 978-88-7180-831-4.

- Riley, C. (2005) The Hollywood Standard: the complete and authoritative guide to script format and style. Michael Weise Productions. Sheridan Press. ISBN 0-941188-94-9.

External links[edit]

- Writing section from the MovieMakingManual (MMM) Wikibook, especially on formatting.

- «Credits Survival Guide: Everything you wanted to know about the credits process but didn’t ask.’ | BEFORE YOU MAKE A DEAL». Writers Guild of America West. Retrieved 2020-03-29.

- American Screenwriters Association

- Screenplays at Curlie

- All Movie Scripts on IMSDb (A-Z) imsdb.com

- All Tamil Movie Scripts on Thiraikathai (A-Z) Thiraikathai.com

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

A screenplay, or script, is a written work by screenwriters for a film, television show, or video game (as opposed to a stage play). A screenplay written for television is also known as a teleplay. Screenplays can be original works or adaptations from existing pieces of writing. A screenplay is a form of narration in which the movements, actions, expressions and dialogue of the characters are described in a certain format. Visual or cinematographic cues may be given, as well as scene descriptions and scene changes.

History[edit]

In the early silent era, before the turn of the 20th century, «scripts» for films in the United States were usually a synopsis of a film of around one paragraph and sometimes as short as one sentence.[1] Shortly thereafter, as films grew in length and complexity, film scenarios (also called «treatments» or «synopses»[2]: 92 ) were written to provide narrative coherence that had previously been improvised.[1] Films such as A Trip to the Moon (1902) and The Great Train Robbery (1903) had scenarios consisting respectively of a list of scene headings or scene headings with a detailed explication of the action in each scene.[1] At this time, scripts had yet to include individual shots or dialogue.[1]

These scenario scripts evolved into continuity scripts, which listed a number of shots within each scene, thus providing continuity to streamline the filmmaking process.[1] While some productions, notably D. W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation (1915), were made without a script, preapproved «continuities» allowed the increasingly powerful studio executives to more accurately budget for film productions.[1] Movie industry revolutionary Thomas H. Ince, a screenwriter himself, invented movie production by introducing an «assembly line» system of filmmaking that utilized far more detailed written materials, clearly dedicated to «separating conception from execution».[1] Film researcher Andrew Kenneth Gay posits that, «The process of scripting for the screen did not so much emerge naturally from other literary forms such as the play script, the novel, or poetry nor to meet the artistic needs of filmmakers but developed primarily to address the manufacturing needs of industrial production.»[1]

With the advent of sound film, dialogue quickly dominated scripts, with what had been specific instructions for the filmmaker initially regressed to a list of master shots.[1] However, screenwriters soon began to add the shot-by-shot details that characterized continuities of the films of the later silent era.[1] Casablanca (1942), is written in this style, with detailed technical instructions interwoven with dialogue.[1] The first use of the term «screenplay» dates to this era;[2]: 86 the term «screen play» (two words) was used as early as 1916 in the silent era to refer to the film itself, i.e. a play shown on a screen.[2]: 82 [1]

With the end of the studio system in the 1950s and 1960s, these continuities were gradually split into a master-scene script, which includes all dialogue but only rudimentary scene descriptions and a shooting script devised by the director after a film is approved for production.[1] While studio era productions required the explicit visual continuity and strict adherence to a budget that continuity scripts afforded, the master-scene script was more readable, which is of importance to an independent producer seeking financing for a project.[1] By the production of Chinatown (1974), this change was complete.[1] Andrew Kenneth Gay argues that this shift has raised the status of directors as auteurs and lowered the profile of screenwriters.[1] However, he also notes that since the screenplay is no longer a technical document, screenwriting is more of a literary endeavour.[1]

Format and style[edit]

Page from a screenplay, showing dialogue and action descriptions, as well as scene cuts

The format is structured so that (as a ballpark estimate) one page equates to roughly one minute of screen time, though this often bears little resemblance to the runtime of the final production.[3] The standard font is 12 point, 10 pitch Courier typeface.[4] Wide margins of at least one inch are employed (usually larger for the left to accommodate hole punches).

The major components are action (sometimes called «screen direction») and dialogue. The action is written in the present tense and is limited to what can be heard or seen by the audience, for example descriptions of settings, character movements, or sound effects. The dialogue is the words the characters speak, and is written in a center column.

Unique to the screenplay (as opposed to a stage play) is the use of slug lines. A slug line, also called a master scene heading, occurs at the start of each scene and typically contains 3 pieces of information: whether the scene is set inside or outside (INT. or EXT.; interior or exterior), the specific location, and the time of day. Each slug line begins a new scene. In a «shooting script» the slug lines are numbered consecutively for ease of reference.[5]

Physical format[edit]

US[edit]

American screenplays are printed single-sided on three-hole-punched paper using the standard American letter size (8.5 x 11 inch). They are then held together with two brass brads in the top and bottom hole. The middle hole is left empty as it would otherwise make it harder to quickly read the script.

UK[edit]

In the United Kingdom, double-hole-punched A4 paper is normally used, which is slightly taller and narrower than US letter size. Some UK writers format the scripts for use in the US letter size, especially when their scripts are to be read by American producers since the pages would otherwise be cropped when printed on US paper. Because each country’s standard paper size is difficult to obtain in the other country, British writers often send an electronic copy to American producers, or crop the A4 size to US letter.

A British script may be bound by a single brad at the top left-hand side of the page, making flicking through the paper easier during script meetings. Screenplays are usually bound with a light card stock cover and back page, often showing the logo of the production company or agency submitting the script, covers are there to protect the script during handling which can reduce the strength of the paper. This is especially important if the script is likely to pass through the hands of several people or through the post.

Other[edit]

Increasingly, reading copies of screenplays (that is, those distributed by producers and agencies in the hope of attracting finance or talent) are distributed printed on both sides of the paper (often professionally bound) to reduce paper waste. Occasionally they are reduced to half-size to make a small book which is convenient to read or put in a pocket; this is generally for use by the director or production crew during shooting.

Although most writing contracts continue to stipulate physical delivery of three or more copies of a finished script, it is common for scripts to be delivered electronically via email. Electronic copies allow easier copyright registration and also documenting «authorship on a given date».[6] Authors can register works with the WGA’s Registry,[7] and even television formats using the FRAPA’s system.[8][9]

Screenplay formats[edit]

Screenplays and teleplays use a set of standardizations, beginning with proper formatting. These rules are in part to serve the practical purpose of making scripts uniformly readable «blueprints» of movies, and also to serve as a way of distinguishing a professional from an amateur.

Feature film[edit]

Motion picture screenplays intended for submission to mainstream studios, whether in the US or elsewhere in the world, are expected to conform to a standard typographical style known widely as the studio format which stipulates how elements of the screenplay such as scene headings, action, transitions, dialogue, character names, shots and parenthetical matter should be presented on the page, as well as font size and line spacing.

One reason for this is that, when rendered in studio format, most screenplays will transfer onto the screen at the rate of approximately one page per minute. This rule of thumb is widely contested — a page of dialogue usually occupies less screen time than a page of action, for example, and it depends enormously on the literary style of the writer — and yet it continues to hold sway in modern Hollywood.

There is no single standard for studio format. Some studios have definitions of the required format written into the rubric of their writer’s contract. The Nicholl Fellowship, a screenwriting competition run under the auspices of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, has a guide to screenplay format.[10] A more detailed reference is The Complete Guide to Standard Script Formats.[11]

Speculative screenplay[edit]

A speculative screenplay or «spec script» is a script written to be sold on the open market with no upfront payment, or promise of payment. The content is usually invented solely by the screenwriter, though spec screenplays can also be based on established works or real people and events.[12]

Television[edit]

For American TV shows, the format rules for hour-long dramas and single-camera sitcoms are essentially the same as for motion pictures. The main difference is that TV scripts have act breaks. Multi-camera sitcoms use a different, specialized format that derives from stage plays and radio. In this format, dialogue is double-spaced, action lines are capitalized, and scene headings, character entrances and exits, and sound effects are capitalized and underlined.

Drama series and sitcoms are no longer the only formats that require the skills of a writer. With reality-based programming crossing genres to create various hybrid programs, many of the so-called «reality» programs are in a large part scripted in format. That is, the overall skeleton of the show and its episodes are written to dictate the content and direction of the program. The Writers Guild of America has identified this as a legitimate writer’s medium, so much so that they have lobbied to impose jurisdiction over writers and producers who «format» reality-based productions. Creating reality show formats involves storytelling structure similar to screenwriting, but much more condensed and boiled down to specific plot points or actions related to the overall concept and story.

Documentaries[edit]

The script format for documentaries and audio-visual presentations which consist largely of voice-over matched to still or moving pictures is different again and uses a two-column format which can be particularly difficult to achieve in standard word processors, at least when it comes to editing or rewriting. Many script-editing software programs include templates for documentary formats.

Screenwriting software[edit]

Various screenwriting software packages are available to help screenwriters adhere to the strict formatting conventions. Detailed computer programs are designed specifically to format screenplays, teleplays, and stage plays. Such packages include BPC-Screenplay, Celtx, Fade In, Final Draft, FiveSprockets, Montage, Movie Draft SE, Movie Magic Screenwriter, Movie Outline 3.0, Scrivener, and Zhura. Software is also available as web applications, accessible from any computer, and on mobile devices, such as Fade In Mobile Scripts Pro and Studio Binder.

The first screenwriting software was SmartKey, a macro program that sent strings of commands to existing word processing programs, such as WordStar, WordPerfect and Microsoft Word. SmartKey was popular with screenwriters from 1982 to 1987, after which word processing programs had their own macro features.

Script coverage[edit]

Script coverage is a filmmaking term for the analysis and grading of screenplays, often within the script-development department of a production company. While coverage may remain entirely verbal, it usually takes the form of a written report, guided by a rubric that varies from company to company. The original idea behind coverage was that a producer’s assistant could read a script and then give their producer a breakdown of the project and suggest whether they should consider producing the screenplay or not.[13]

See also[edit]

- Pre-production – phase of producing a film or television show

- Closet screenplay – screenplay read by a person or aloud in a group rather than performed

- Dreams on Spec – documentary film about screenwriters

- Screenwriter’s salary – how screenwriters are paid

- Scriptment – written work by a screenwriter

- Storyboard – form of ordering graphics in media

- Outline of film – overview and topical guide to film

- List of screenwriting awards for film – wikimedia list article

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Andrew Kenneth Gay. «History of scripting and the screenplay» at Screenplayology: An Online Center for Screenplay Studies. Retrieved 15 December 2021.

- ^ a b c Steven Maras. Screenwriting: History, Theory and Practice. Wallflower Press, 2009. ISBN 9781905674824

- ^ JohnAugust.com «How accurate is the page-per-minute rule?

- ^ JohnAugust.com «Hollywood Standard Formatting»

- ^ Schumach, Murray (August 28, 1960). «HOLLYWOOD USAGE Experts Analyze the Pros and Cons Of Time-Tested ‘Master’ Scene». The New York Times. Retrieved April 6, 2021.

- ^ Zerner ESQ, Larry. «Writers Guild of America-West Registration vs. Copyright Registration». www.writersstore.com. Retrieved 2020-03-29.

If the writer registers the script with the Copyright Office only after the infringement has taken place, he will be barred from recovering attorneys fees or statutory damages in the lawsuit.

- ^ «WGA West Registry». Writers Guild of America West. Retrieved 2020-03-29.

Any file may be registered to assist you in documenting the creation of your work. Some examples of registerable material include scripts, treatments, synopses, and outlines… The WGAW Registry also accepts stageplays, novels, books, short stories, poems, commercials, lyrics, drawings, music and various media work such as Web series, code, and other digital content.

- ^ Sonia Castang; Richard Deakin; Tony Forster; Andrea Gibb; Olivia Hetreed (Chair); Guy Hibbert; Kathy Hill; Terry James; Line Langebek; Dominic Minghella; Phil Nodding; Phil O’Shea; Sam Snape (April 2016). «Writing Film : A Good Practice Guide» (PDF). Writers’ Guild of Great Britain. p. 11. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

In the UK there is no legal necessity to register your work – copyright is automatic. Registration is more important if you intend to offer your work to overseas producers. The Writers Guild of America in New York and Los Angeles offer a cheap and easy-to-use internet-based script registration system that involves uploading a digital copy. If you are offering your work in the USA you should also register it with the US Copyright Office – if you don’t, your right to legal damages for copyright infringement may be much reduced.

- ^ Ricolfi, Marco; Morando, Federico; Rubiano, Camilo; Hsu, Shirley; Ouma, Marisella; De Martin, Juan Carlos (September 9, 2011). «Survey of Private Copyright Documentation Systems and Practices» (PDF). World Intellectual Property Organization. p. 24. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 June 2013. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

Established in 1927, Writers Guild of America, West Registry (WGAWR) is one of the oldest private copyright registries.

Alt URL - ^ Guide to screenplay format from the website of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences

- ^ The Complete Guide to Standard Script Formats (2002) Cole and Haag, SCB Distributors, ISBN 0-929583-00-0.

- ^ «Spec Script». Act Four Screenplays. 29 July 2010. Retrieved August 10, 2012.

- ^ «What is Script Coverage?». WeScreenplay. Retrieved 5 July 2016.

Further reading[edit]

- David Trottier (1998). The Screenwriter’s Bible: A Complete Guide to Writing, Formatting, and Selling Your Script. Silman-James Press. ISBN 1-879505-44-4. — Paperback

- Yves Lavandier (2005). Writing Drama, A Comprehensive Guide for Playwrights and Scritpwriters. Le Clown & l’Enfant. ISBN 2-910606-04-X. — Paperback

- Judith H. Haag, Hillis R. Cole (1980). The Complete Guide to Standard Script Formats: The Screenplay. CMC Publishing. ISBN 0-929583-00-0. — Paperback

- Jami Bernard (1995). Quentin Tarantino: The Man and His Movies. HarperCollins publishers. ISBN 0-00-255644-8. — Paperback

- Luca Bandirali, Enrico Terrone (2009), Il sistema sceneggiatura. Scrivere e descrivere i film, Turin (Italy): Lindau. ISBN 978-88-7180-831-4.

- Riley, C. (2005) The Hollywood Standard: the complete and authoritative guide to script format and style. Michael Weise Productions. Sheridan Press. ISBN 0-941188-94-9.

External links[edit]

- Writing section from the MovieMakingManual (MMM) Wikibook, especially on formatting.

- «Credits Survival Guide: Everything you wanted to know about the credits process but didn’t ask.’ | BEFORE YOU MAKE A DEAL». Writers Guild of America West. Retrieved 2020-03-29.

- American Screenwriters Association

- Screenplays at Curlie

- All Movie Scripts on IMSDb (A-Z) imsdb.com

- All Tamil Movie Scripts on Thiraikathai (A-Z) Thiraikathai.com

Содержание

- 1 Сценарий — определение

- 2 Кинематографический сценарий — кадры, которые планируется показать зрителю

- 3 Сценарий в прогнозировании

- 4 Компьютерная программа как сценарий

- 5 Сценарий сервиса и услуги

- 6 Использование сценариев

- 7 Сценарий педагогической деятельности

- 8 Сценарии совместной сетевой деятельности

Сценарий — определение

Детальный план, сюжетная схема пьесы, оперы, балета, фильма или другого действия со множеством участников. Театральный сценарий — изложение событий и действий, свершающихся по ходу действия в спектакле. Кинематографический сценарий — литературно-драматическое произведение, написанное как основа для постановки кино- или телефильма. Последовательность действий – это буквально все ходы партии, которые должны сыграть участники этой игры.

Первоначально термин использовался применительно к миру театра, однако, позднее сценарий (скрипт) как подробный план и схема деятельности начинают использовать для описания различных видов деятельности:

- сценарии рабочей деятельности

- сценарий компьютерной программы

- психологический сценарий в психологии детско-родительских отношений

Кинематографический сценарий — кадры, которые планируется показать зрителю

Из журнала «Советский Экран» № 46, 13 ноября 1928 года Потомок Чингис-Хана

- 52. Поворот лестницы. Пробежал монгол.

- 53. Лестница. Поднялись солдаты.

- 54. Дверь. Проскочил монгол.

- 55. Комната. Пробежал монгол.

- 56. Дверь. Выскочил монгол.

- 57. Поворот лестницы. Бегут солдаты

- …

- 157. Ракурс кричащего лица лейтенанта. — Поймать

- 158. Лев — скульптура.

- 159. Лев на флаге.

- 160 — 161. Кадры тревоги из первой части. — Уничтожить.

- 162 — 163. Кадры тревоги из первой части.

- 164 — 165. Бешенные облака и сверкание.

- 166. Скачущий Баир размножается.

- 167 — 169. Растущий ветер.

Сценарий в прогнозировании

- Сценарии — это внутренне непротиворечивое представление о том, каким может оказаться будущее — не прогноз, а один из вариантов будущих последствий”

- Сценарий – это описание картины будущего, состоящей из согласованных, логически взаимоувязанных событий и последовательности шагов, с определенной вероятностью ведущих к прогнозируемому конечному состоянию (образу организации в будущем). Как правило, сценарии представляют собой качественное описание, хотя и детализированное, содержащее отдельные количественные оценки. Этим они отличаются от обычных прогнозов, в большинстве которых упор делается на количественные показатели.

- под сценарием понимают динамическую последовательность возможных событий, фокусирующую внимание на причинно-следственной связи между этими событиями и точками принятия решений, способных изменить их ход и траекторию движения во времени всей рассматриваемой системы в целом или отдельных ее подсистем».

Компьютерная программа как сценарий

Многие языки программирования используют сценарный подход и программа представляет собой последовательность действий, которые нужно совершить. Последовательность действий может быть задана либо цифровой последовательностью, либо указанием сигнала, после получения которого данный исполнитель должен совершить свои действия. Например, на следующем рисунке представлен сценарий действий, которые должен совершить компьютерный спрайт в среде Scratch.

Сценарий сервиса и услуги

Услуги можно рассматривать как сценарии. Все услуги оказываются в соответствии с сценарием, который управляет всеми действиями участников. Сценарий для еды в ресторане:

- резервируем столик

- приходим в ресторан и занимаем зарезервированный стол

- изучаем меню,

- делаем заказ официанту,

- на стол доставляется еда

- едим

- просим счет

- платим

- уходим

Инновации сервисов происходят в результате переписывания сценариев, так что в результате деятельность разворачивается и идет другим путем. Например, ресторан быстрого обслуживания работает по другому сценарию:

- читаем меню,

- делаем заказ

- платим,

- сами приносим пищу на столик,

- едим

- убираем за собой мусор,

- уходим.

Большинство сценариев государственных и общественных услуг – такие как образование – не меняются в течение многих десятилетий:

- пришел в класс

- сел за парту

- слушаешь учителя

- читаешь текст на доске

- пишешь упражнение

- бежишь на игровую площадку

Сценарии взаимодействия с пользователями полиции, больницы, библиотеки пишутся профессионалами, создателями и управленцами, а не пользователями. От пользователей сервисов ожидается только то, что они будут следовать этим сценариям.

Чарльз Лидбиттер показывает, что в истории общества многие инновации связаны с тем, что пользователи услуги или сервиса начинают использовать этот сервис в соответствии со своими собственными представлениями, совсем не так как планировал создатель этого средства или услуги. Например, первоначально использование СМС-сообщений предполагалось только в крайних случаях для обращения к аварийным и спасательным службам, но пользователи нашли, что этот сервис удобен для их личного обмена сообщениями.

В открытым обществе главная роль правительства заключается в том, чтобы способствовать выработку коллективных решений внутри общества, которое хочет более широкие возможности для самоорганизации и проведению инициатив, направленных снизу вверх. Необходимо найти новый баланс отношений между центральным управлением, которое распространяется сверху вниз, и местными инициативами, которые развиваются снизу вверх. Как найти этот новый баланс.

Использование сценариев

Го и Кэролл выделяли и анализировали следующие области использования сценариев:

- Стратегическое планирование и тут ключевое значение имели работы Германа Кана. Кан использует сценарии как инструмент анализа, описания, социальной и политической оценки. Сценарий позволяет увидеть одновременно сразу несколько аспектов проблемы. Используя развивающиеся сценарии аналитик сможет почувствовать значение событий и точек ветвления зависящих от критического выбора. Примеры использования сценарного анализа для прогнозирования и планирования были описаны в работах Пьера Вака

- Go, Kentaro, и John M. Carroll. «The blind men and the elephant: views of scenario-based system design». interactions 11, № 6 (2004): 44–53. doi:10.1145/1029036.1029037.

- Wack, Pierre. Scenarios: Uncharted Waters Ahead. Harvard Business Review, 1985.

- Взаимодействие людей и компьютеров. В рамках этого подхода, актерам в сценариях приписывались свойства людей, которые выполняют реальныезадачи. Чтобы представить себе использование системы, которая еще не была построена, сценаристы должны были подробно описать потенциальных пользователей и те действия, которые те могут совершать с системой. Обычно для такого описания использовался формат «Один день из жизни» — что, когда и как делает пользователь за компьютером. Повторяющийся процесс написания сценария и его анализа на основании психологических потребностей пользователей. Насколько сценарий и перечисленные в нем особенности инструментов и объектов удовлетворяют психологическим потребностям пользователей. ДиСесса использовал сценарный подход для описания и анализа действий ученика в Лого-подобной среде.

- Carroll, John M., ред. Scenario-based design: envisioning work and technology in system development. New York, NY, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1995.

- Программные требования — область, в которой описывается поведение составных частей компьютерной программы. Сценарии являются частью технической документации, описывающей поведение программы.

- Объектно-ориентированный анализ и дизайн систем основанный на разборе примеров поведения различных агентов.

Сценарий педагогической деятельности

- Язык описания учебной деятельности IMS Global LD

- Язык педагогического дизайна MISA

Сценарии совместной сетевой деятельности

В 20 веке работа с общественными или корпоративными знаниями базировалась на сценарии, когда извлечение, вербализация и представление знаний было делом специальных людей — инженеры по знаниям, эксперты, профессиональные писатели, музыканты, издатели = авторы контента, авторы хитов. С развитием цифровой среды и сети интернет появляются возможности неограниченного пространства для хранения информации.

С появлением социальных сервисов у компаний, государства и общества появляются новые возможности для работы со знаниями своих сотрудников и своих граждан.

- У организаций появляется возможность вовлекать всех своих сотрудников в создание, обновление и использование корпоративных знаний.

- У общества и государства появляется возможность вовлекать граждан в создание и использование общественных знаний.

Эти новые возможности требуют разработки не только новых средств для деятельности, но и новых сценариев совместной сетевой деятельности. Ключевой вопрос разработки сценария совместной деятельности: как поддержать и мотивировать совместную деятельность участников?