Когда советские историки балета и хореографы добрались до первоначального либретто «Щелкунчика», оно оказалось едва ли не сценарием праздника в честь Великой французской революции.

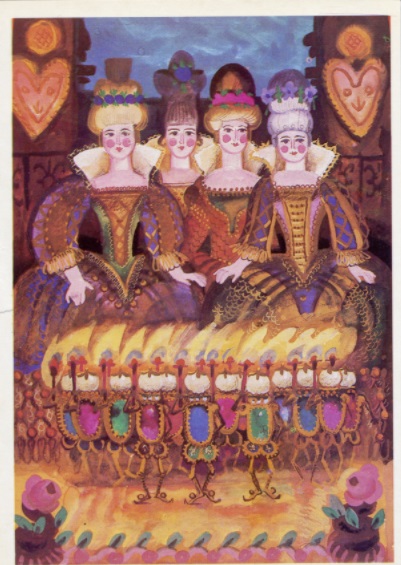

В Императорских театрах это было невозможно: исследователи решили, что балетмейстер Петипа и композитор Чайковский в 1892 году едва не готовили первую русскую революцию.

Ниже рассказывается история создания «Щелкунчика» — и объясняется, как на придворную сцену попала французская крамола.

Казус Лопухова

Черновой вариант сценария «Щелкунчика» достоин того, чтобы привести его целиком.

“В «Щелкунчике» господин директор сказал: «Открываются ящики, и из них выходят оловянные солдатики. Выскакивают они с помощью трамплина».

На ящиках надписи: «Оловянные солдатики».

Сюжет. Дерево будет за дверью. Когда они ушли, в комнате темно (черное). Входит молодая девушка в халате с подсвечником в руке. Свечу она заслоняет рукой, таким образом, комната остается в темноте. Дверь открывается, и видна большая елка, которая только свечой и освещена. Появляются крысы с мышиным царем. Часовой на елке стреляет из ружья. Другой часовой бьет тревогу. Ящики (коробки) раскрываются, и оловянные солдатики выскакивают оттуда.

Председатель

Крак! (трещит орех)

Ужасные куик! куик!

Шесть пушек

Пушки

Орудийный залп

Картечь

Она развязывает и снимает с ноги туфлю и изо всех сил…

Страшный снаряд попал в мышиного короля, который повержен в прах, в ту же минуту и король, и войско, и победители, и побежденные исчезают бесследно.

Царство кукол

Марципаны

Леденцы

Ячменный сахар

Лес рождественских елок

Фисташки и миндальное пирожное

Роща вареньяАкт II

Приют гармонии.

В глубине фонтаны.

Танец карамели.

Трубочки с кремом

Танец сквозь века

Паспье королевы

Толпа полишинелей

Карманьола

Две феи

Добрый путь, милый дю Молле!

Если бы «Щелкунчик» действительно был поставлен так, ему бы не было цены, — но в конце XIX века хореографы и зрители так думать еще не умели.

«Господин директор» — это Иван Александрович Всеволожский (или Всеволожской, как предпочитал себя называть он сам). Сегодня его назвали бы интендантом — не функционер во главе хлопотного казенного хозяйства, а человек, лично определявший художественную политику вверенных ему Императорских театров.

Всеволожский придумал сценарий балета «Спящая красавица» и сделал заказ на музыку Петру Ильичу Чайковскому, который после полуудачи «Лебединого озера» боялся балета пуще смерти, но которого господин директор ставил выше всех отечественных композиторов.

Всеволожский инициировал заказ новой двойной работы Чайковского: балет с оперой в один вечер, в модном парижском духе, «Иоланта» со «Щелкунчиком».

Жемчужины балета “Лебединое озеро” П. И. Чайковского

«Добрый путь, милый дю Молле» — песня французского композитора Дезожье — исполнялась в его водевиле «Отъезд в Сен-Мало» и быстро стала частью фольклора; после 1830 года герой песни стал прочно ассоциироваться с Карлом Х, который в тот год отрекся от престола и сбежал в Англию.

«Приют гармонии» отсылает к аллегорическим празднествам Великой французской революции, а карманьола была главной песней всех революционных событий во Франции, начиная с падения Тюильри.

В 1971 году в Советском Союзе выходит первая монография, посвященная Мариусу Петипа. Сценарии балетов Петипа для издания комментирует Федор Лопухов, старейшина советских хореографов, почитавшийся как главный знаток дореволюционного балета.

Мариус Петипа: «Россия – рай земной, да и только»

В сценарии «Щелкунчика» изумленный Лопухов оставляет приписки: «Еще сильнее!», «Еще значительнее», «Все очень глубокомысленно!» Карманьолу и вообще все французские аллюзии либретто он связывает с детскими воспоминаниями Петипа, который родился в городе, давшем миру «Марсельезу», и в 12-летнем возрасте застал революционные волнения в Брюсселе.

Исчезновение столь дорогих сердцу хореографа идей Лопухов оставляет на совести Всеволожского. Для советского исследователя это был единственно возможный ход мысли: не мог ведь директор Императорских театров (царедворец, притеснитель устремлений подлинного Художника) действовать заодно с Петипа, то есть с собственно Художником.

Проект Всеволожского

Казус Лопухова первой описала Юлия Яковлева в книгах «Мариинский театр. Балет. ХХ век» и «Создатели и зрители. Русский балет эпохи шедевров», к которым отсылаем всех интересующихся. Здесь скажем кратко: к началу последнего десятилетия XIX века Россия потеряла главного европейского союзника в лице Германии — власть Бисмарка закончилась, новое германское правительство от сотрудничества с Россией отказалось.

Внешнеполитический крейсер был спешно развернут в сторону Франции: генералитеты двух стран договариваются о поставках оружия и совместных маневрах, а летом 1891 года в Кронштадте русский царь приветствует французскую эскадру.

«Щелкунчик», с очевидностью, задумывался как часть парадного спектакля. Это был особый жанр спектаклей-подарков в честь визитов высочайших иностранных гостей, коронаций или бракосочетаний членов царской фамилии:

Императорские театры всегда оставались парадной витриной государства и дипломатическим инструментом правительства. Отсюда и сравнительно небольшие пропорции балета — два кратких акта против четырех-пяти в обычных репертуарных новинках.

В парадном спектакле «Щелкунчик» шел бы еще с одним балетиком, актом из оперы либо даже новой небольшой оперой — и с обязательным фейерверком по наступлении сумерек.

Франция в те годы бурно отмечала столетие своей первой революции — и балет-презент должен был обыгрывать праздничный повод в форме каприччио, театральной фантазии. Для франкомана Всеволожского это был проект чести, обещание нового, вслед за «Спящей красавицей», триумфа, залогом которого было участие лучшего хореографа (француза по национальности) и лучшего композитора.

Судя по всему, идею маскарада в честь Французской революции не одобрило Министерство двора, которому Всеволожский подчинялся напрямую, а масштаб предстоящих дипломатических визитов был, очевидно, не столь высок, чтобы готовить парадный спектакль. Глава Франции добрался до Петербурга только в 1897-м. Замысел господина директора осуществлен не был, но для «Щелкунчика» не прошел бесследно.

Почему Франция — и вдруг «Щелкунчик», Гофман, сон немецкого романтического разума?

В премьерной программе отца героини именовали президентом Зильбергаусом, а не советником Штальбаумом, как то было у Гофмана. Звание президента пришло как раз из времен Конвента. В балетный сценарий оно попало из франкоязычной сказки «История Щелкунчика», написанной Александром Дюма-отцом и впервые изданной в 1844 году. Именно вольное переложение гофмановской новеллы, сделанное Дюма, имели в виду Всеволожский и Петипа, когда обсуждали новый балет.

Понятно ведь, что напрямую следовать перипетиям сказки в балете никто не собирался: хореографы и сценаристы XIX века так не работали, ими руководили чисто хореографические законы и доводы, литература была только поводом для сочинения балетного каприччио. Следовать «букве и духу» первоисточника хореографы начнут уже в ХХ веке. Вот почему фраза «либретто Петипа по сказке Гофмана», что встречается на афише каждого второго «Щелкунчика», — неправда.

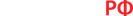

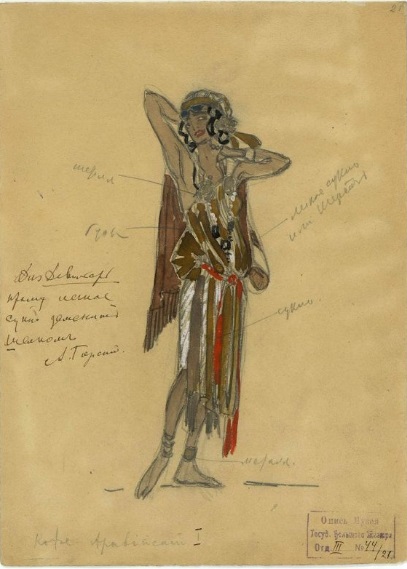

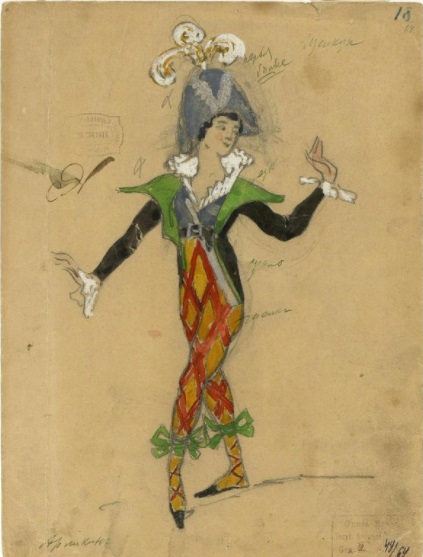

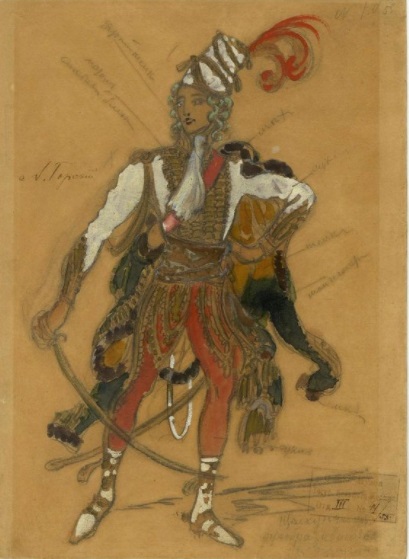

В первой постановке чета Зильбергаусов и их гости одеты в стиле инкруаяблей и мервейёзов. Les Incroyables et les Merveilleuses, «невероятные и великолепные» — модники времен Директории: псевдоантичные платья-хитоны и гротескные головные уборы у дам; у кавалеров — сюртуки с огромными воротниками, шейные платки на пол-лица, треуголки и прически oreilles de chien, то есть длинные волосы на ушах и косичка сзади.

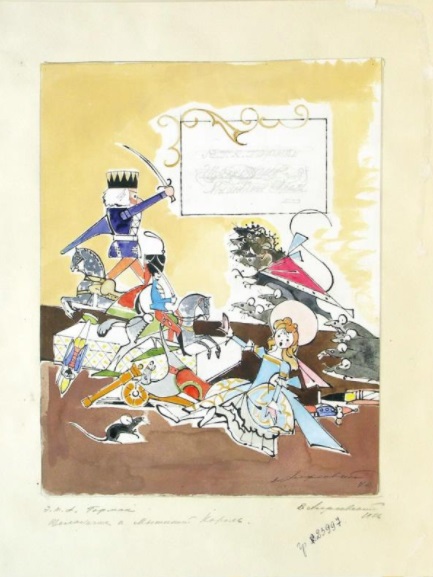

Эскизы костюмов, на условиях анонимности, рисовал лично Всеволожский, он же сочинил костюмы «Спящей красавицы» и еще нескольких балетов Петипа 1890-х.

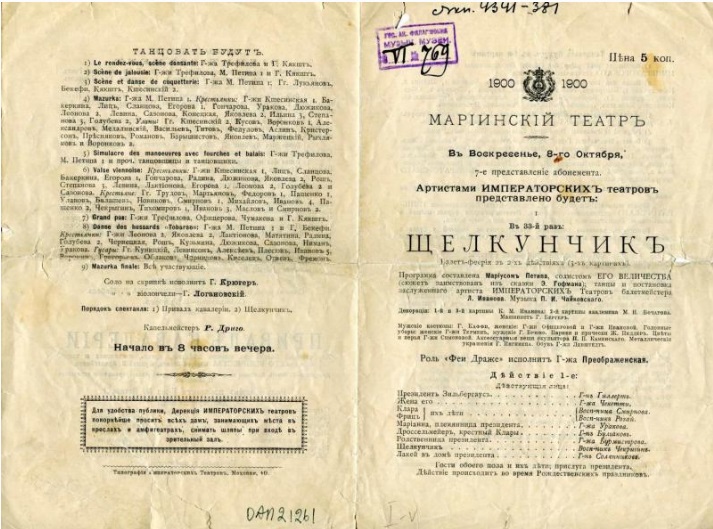

Гостей в «Щелкунчике» он изобразил с оптикой карикатуриста и знаниями историка, не забыв даже вручить инкруаяблям в руки надлежащие корявые палки вместо тростей. Он и Дроссельмейера изобразил в том же духе, а Щелкунчику надел на деревянную голову красный фригийский колпак — еще один символ Французской революции, атрибут Свободы на баррикадах.

Первая постановка вскорости исчезла, а Щелкунчика в бывшем Мариинском театре таким и оставили. Обратите внимание, как выглядит заглавный персонаж в нынешнем спектакле Василия Вайнонена: на квадратных сувенирных щелкунчиков в треуголках не похож, зато красный колпак носит по-прежнему.

Песни Чайковского

Следы дипломатического замысла остались и в партитуре, как застывшие в янтаре доисторические насекомые. Чайковский, конечно, не цитировал карманьолу: на балетных подмостках она прозвучит в «Пламени Парижа» уже совсем в другую эпоху. Однако несколько популярных французских песен в партитуре аранжированы — и публика на премьере в Императорском Мариинском театре наверняка эти песни узнала.

Действительно ли Лопухов не слышал в музыке «Щелкунчика» мотив «Месье дю Молле», если так удивился, обнаружив «песенку антиправительственного содержания» в черновике Петипа?

В окончательном плане, который Петипа передал для работы Чайковскому, есть помета «В добрый путь, мосье Дюмолле (16 или 24 такта)». Помета перечеркнута рукой композитора, но песня в балете все-таки звучит — это танец родителей в первом акте.

Еще две популярные галльские песни звучат в номере «Мамаша Жигонь и паяцы». Написанный в духе французского канкана, он завершает череду разнохарактерных танцев второго акта — и обычно первым попадает под нож: хореографы просто не знают, чтó на эту музыку ставить.

Жигонь — персонаж французского театра, символ плодородия, тетка с безразмерным платьем, у которой из-под подола являются все новые и новые дети. Такой она изображена и на эскизе Всеволожского. Такой, например, ее вывел в своей нью-йоркской постановке Джордж Баланчин, воспитанник петербургской балетной школы, ребенком выходивший на сцену в самом первом «Щелкунчике».

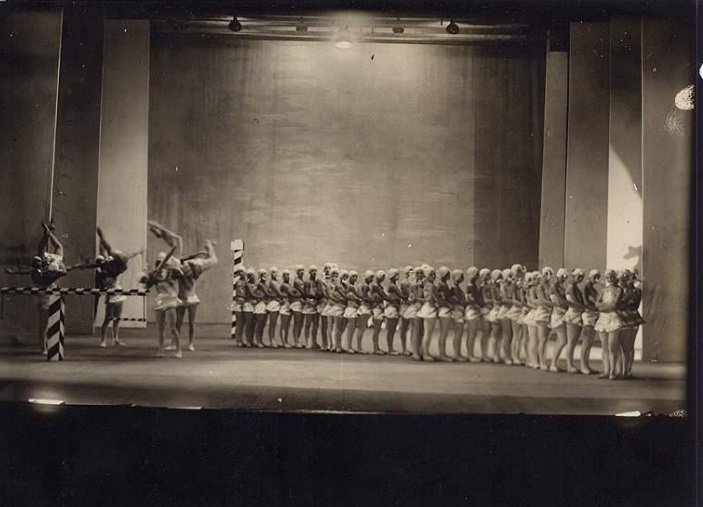

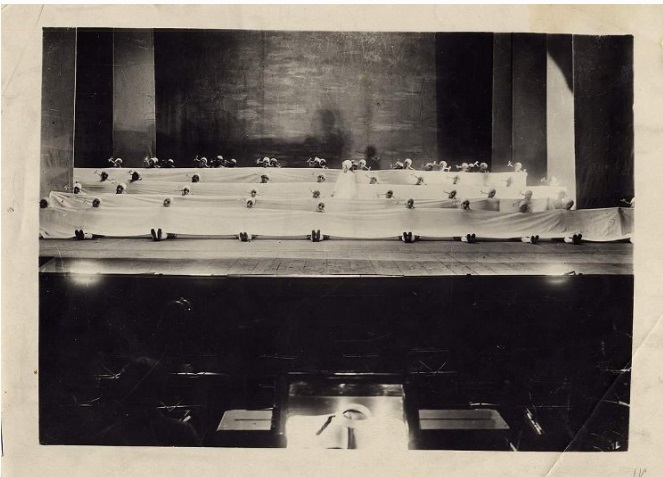

Столь экстравагантное антре в «Щелкунчике» отвечало сразу нескольким задачам. На сцену выходили дети, то есть воспитанники Театрального училища (нынешней Академии Вагановой), чье участие в новых балетах входило в набор обязательных зрительских удовольствий.

Вновь возникала отсылка к французским празднествам, а в оркестре вновь звучали мотивы французских песен. Чайковский использовал две: в крайних частях звучит «Жирофле-жирофля», а в средней — написанная в 1792 году «Кадет Руссель», в которой выведен реальный персонаж, «добрый революционер» Гийом Руссель.

Сегодня редкий зритель «Щелкунчика» опознает эту мелодию, а в советское время ее разучивали на уроках музыки в русском переводе.

История любви к трем апельсинам

Резон Петипа

Петипа в конечном итоге отказался от постановки, отдав ее второму балетмейстеру Императорского балета, Льву Иванову, — его мы знаем в качестве автора «белых» картин «Лебединого озера» (да и то условно: за 120 лет от ивановской хореографии остались одни контуры).

Общепринятая версия: 74-летний Петипа хворал, а накануне постановки потерял 15-летнюю дочь и воспитанницу Евгению, подававшую большие надежды на танцевальном поприще.

Спектакль Иванова прошел со скромным успехом, удостоившись от балетоманской прессы характеристик вроде «балет для тех, кто любит пряники и не боится мышей». Сколь ни обещал Петипа вернуться к «Щелкунчику», сколь ни интриговали на страницах газет петербургские балетоманы, призывая дирекцию Императорских театров к переделке «Щелкунчика», ничего не случилось.

Очевидно, главным аргументом для отказа честолюбивого Петипа от работы была музыка.

Чайковского и Петипа с советских времен принято воображать эдакими Рабочим и Колхозницей, что вывели русский балет, косный и обстрелянный всей прогрессивной русской мыслью от Некрасова до Толстого, к подлинным высотам духа. Но, судя по всему, музыка Чайковского была для Петипа слишком затейливо устроена. Классический балет, как его мыслил Петипа и каким его привел к концу XIX века, требовал стандартных музыкальных и пластических форм — не в косности дело, а в незыблемых законах композиции и восприятия.

Проще и грубее: не требовалось сквозного симфонического развития, контрапунктических ухищрений, изысканной инструментовки. Идеалом Петипа была музыка Людвига Минкуса (блистательного профессионала и редкого мелодиста, почем зря растоптанного советскими искусствоведами), а позже — Риккардо Дриго.

В «Спящей красавице» Чайковский следовал плану-сценарию Петипа и соблюдал традиционную разбивку по номерам. В «Щелкунчике» план-сценарий вновь исполнен с безупречной точностью, но заданные номера спрессованы, почти весь первый акт идет без пауз — и все закручено в тугую спираль, так что хореографы до сих пор ломают головы и ноги об эту музыку.

Спектакль Иванова несколько раз возобновлялся, последний раз уже в 1920-е годы. Потребовалось два десятка лет, чтобы в этом слабом, как считалось, балете обнаружил себя шедевр — «Вальс снежных хлопьев», которому балетный критик и искусствовед Аким Волынский посвятил отдельное эссе.

Где смотреть классическую версию «Щелкунчика»

Постановка Иванова утеряна. Балетмейстеры Юрий Бурлака и Василий Медведев предприняли попытку восстановить ее, но количество постановочных вольностей в нем слишком велико, а наличный состав Берлинского балета слишком малочислен, чтобы говорить о реконструкции.

Так что канонической, классической, исчерпывающей версии «Щелкунчика» — каковые есть у «Спящей красавицы» или «Баядерки», — не существует. Это не мешает исполнять «Щелкунчика» каждой балетной труппе мира, даром что все постановки похожи друг на друга: треугольная конструкция изображает елку, пляшут дети, скачут мыши, героиня по ходу спектакля переодевается из длинной ночнушки в усыпанную стразами пачку, а уважаемые телезрители, попавшие в театр, радостно узнают в музыке балеринской вариации саундтрек из рекламы шоколадных драже.

Популярных российских версий три. Спектакль Юрия Григоровича с 1964 года остается в репертуаре Большого театра: попытки увидеть его в новогодние дни обречены, билеты исчезают на вторую минуту продаж.

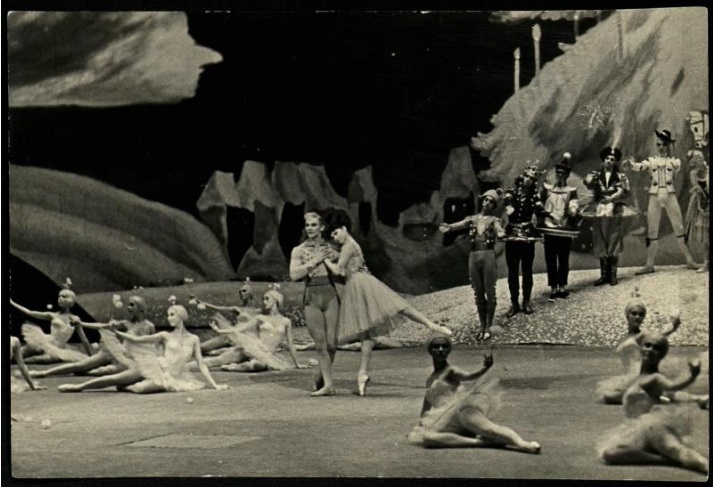

Сразу два спектакля идут в Мариинском театре. Постановка Василия Вайнонена в оформлении Симона Вирсаладзе — сладкая греза, все оттенки розового, три акта в церемонно медленных темпах. Эту версию по очереди исполняют труппа Мариинского театра и студенты Академии Вагановой, она растиражирована по всей России и ближнему зарубежью, — но стоит присмотреться, с каким пластическим остроумием и музыкальностью Вайнонен сочинил танцы финального акта, а «Вальсу снежных хлопьев» придал классическую простоту и законченность (говорят, Вайнонен подсмотрел его в спектакле Иванова, который застал при последнем возобновлении в 1923-м).

В качестве контраста — спектакль Михаила Шемякина, в свое время свалившийся на петербургского зрителя как черный снег на голову. Знаменитый художник выступил здесь и автором декораций-костюмов, и сценаристом, и режиссером, оставив хореографу Кириллу Симонову небольшое поле деятельности, — но это первая в российском театре состоятельная попытка вернуть «Щелкунчика» из сферы детских книжек с картинками в темные глубины музыки Чайковского.

Илона Ковязина, VTBRussia.Ru

Балет в двух действиях с прологом

Композитор: П.И.Чайковский

Либретто: Мариус Петип по мотивам сказки Э. Т. А. Гофмана «Щелкунчик и мышиный король»

Первая постановка: Санкт-Петербург, Мариинский театр, 18 декабря 1892 года.

Действующие лица:

Штальбаум.

Его жена.

их дети:

Клара (Мари, Маша), принцесса

Фриц (Миша)

Марианна, племянница

Няня.

Дроссельмейер.

Щелкунчик, принц

Фея Драже

Принц Коклюш

Кукла.

Паяц (шут).

Король мышей.

Кордебалет: гости, родственники, слуги, маски, пажи, цветы, игрушки, солдатики и т. д.

Пролог

В канун Рождества, в красивом доме доктора Штальбаума начинают собираться гости. За взрослыми на цыпочках следуют девочки с куклами и маршируют мальчики с саблями.

Действие I

Дети доктора Штальбаума Мари и Фриц, как и другие дети, с нетерпением ждут подарков. Последний из гостей — Дроссельмейер. Он входит в цилиндре, с тростью и в маске. Его способность оживлять игрушки не только забавляет детей, но и пугает их. Дроссельмейер снимает маску. Мари и Фриц узнают своего любимого крестного.

Мари хочет поиграть с куклами, но с огорчением узнает, что они все убраны. Чтобы успокоить девочку, крестный дарит ей Щелкунчика. Странное выражение лица куклы забавляет её. Шалун и озорник Фриц нечаянно ломает куклу. Мари расстроена. Она укладывает полюбившуюся ей куклу спать. Фриц вместе с друзьями надевают маски мышей и начинают дразнить Мари.

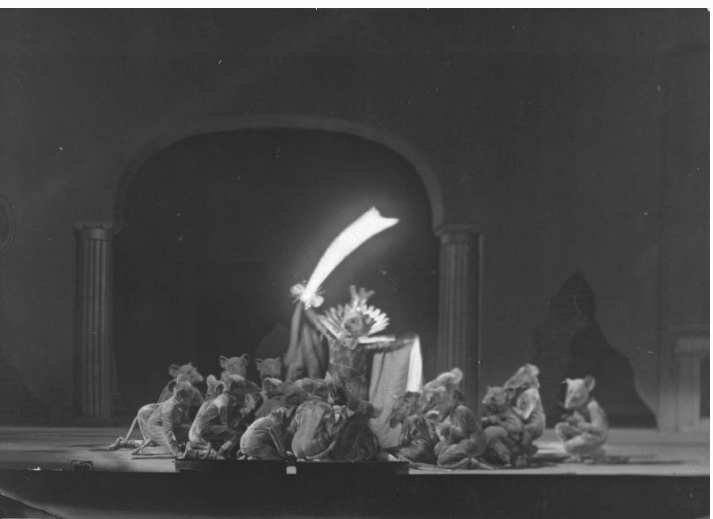

Праздник заканчивается, и гости танцуют традиционный танец «Гросс-Фатер», после чего все расходятся по домам. Наступает ночь. Комната, в которой находится ёлка, наполняется лунным светом. Мари возвращается, она обнимает Щелкунчика. И тут появляется Дроссельмейер. Он уже не крестный, а добрый волшебник. Он взмахивает рукой и в комнате начинает все меняться: стены раздвигаются, ёлка начинает расти, ёлочные игрушки оживают и становятся солдатиками. Внезапно появляются мыши под предводительством Мышиного короля. Отважный Щелкунчик ведет солдатиков в бой.

Щелкунчик и Мышиный король встречаются в смертельной схватке. Мари видит, что армия мышей превосходит армию солдатиков.

В отчаянии она снимает с себя туфельку и со всей силой бросает её в Мышиного короля. Он напуган и убегает вместе со своей армией. Армия солдатиков победила. Они триумфально несут Мари на плечах к Щелкунчику. Внезапно лицо Щелкунчика начинает меняться. Он перестает быть уродливой куклой и превращается в прекрасного Принца. Мари и оставшиеся в живых куклы оказываются под звездным небом и фантастически красивой ёлкой, вокруг кружатся снежинки.

Действие II

Мари и Принц любуются красотой звездного неба. Внезапно их атакуют мыши. И вновь, Принц наносит им поражение. Все танцуют и веселятся, празднуют победу над мышиным войском.

Испанская, Индийская и Китайская куклы благодарят Мари за то, что она спасла им жизнь. Вокруг танцуют прекрасные феи и пажи.

Появляется Дроссельмейер, он опять меняет все вокруг. Все готовятся к королевской свадьбе Мари и Принца. Мари просыпается. Щелкунчик всё ещё у неё в руках. Она сидит в Знакомой комнате. Увы, это был всего лишь сказочный сон…

Но также есть так называемый Фрейдитский вариант балета разработаный Нуреевым. Согласно ему, после танца с принцем, Мари просыпается и щелкунчиком оказывается помолодевший Дроссельмайер.

Приблизительное время чтения: 10 мин.

Что это такое

Один из самых известных русских балетов. Рассказанная музыкой история о том, что в мире бюргеров 1 есть место чуду. Гофмановская сказка о любви доброй девочки и заколдованного юноши усилиями композитора Петра Чайковского (1840–1893) и либреттиста Мариуса Петипа 2 превратилась в балет-сновидение. «Щелкунчик» разделил историю балета на «до» и «после», став к тому же самым известным балетом на тему Рождества.

Литературная основа

Сказка Эрнста Теодора Амадея Гофмана «Щелкунчик и Мышиный король» была опубликована в 1816 году. Позже она вошла во второй раздел первого тома гофмановского сборника «Серапионовы братья» (1819–1921). В этой книге рассказчиком сказки о Щелкунчике писатель сделал одного из членов литературного «братства» — Лотара, прототипом которого обычно считают литератора Фридриха де ла Мотт Фуке, автора знаменитой сказочной повести «Ундина».

Описанный в сказке Щелкунчик — это одновременно игрушка и столовая утварь для колки орехов. Такие фигурки под названием Nussknacker были распространены в Германии и Австрии с XVIII века.

Гофмановская манера причудливо соединять в одном тексте два мира — реальный и фантастический — проявилась и в «Щелкунчике»: старший советник суда Дроссельмейер оказывается придворным часовщиком из полусказочного Нюрнберга, а деревянный щелкунчик — принцем Марципанового замка. В отличие от других гофмановских сказок («Золотой горшок», «Крошка Цахес», «Повелитель блох»), в «Щелкунчике» практически не звучат иронические мотивы в адрес главных героев — это один из самых поэтичных текстов в творчестве Гофмана.

Первые два русских перевода «Щелкунчика» появились практически одновременно, оба — в 1835 году. Однако основой для балетного либретто послужили вовсе не они. В 1844 году гофмановскую сказку по-своему пересказал Александр Дюма («История Щелкунчика»). Он освободил причудливую гофмановскую фантазию от множества сюжетных деталей, а принца-щелкунчика сделал лихим рыцарем, в чём-то похожим на героев собственных романов. Именно версию Дюма и навязал Чайковскому и балетмейстеру Мариусу Петипа директор императорских театров Иван Всеволожский. За либретто 3 принялся Петипа.

Либретто

На первом этапе Петипа задумал ввести в балет революционную тематику, даже использовать в одном из фрагментов мелодию «Карманьолы» 4. Шел 1891 год, буквально только что было столетие Великой французской революции. Из планов Петипа к «Щелкунчику»: «Толпа полишинелей. Карманьола. Станцуем карманьолу! Да здравствует гул пушек! Паспье королевы. В добрый путь, милый дю Молле». Последнее — слова из детской песенки, намекающие на бегство Карла Х в Англию после Июльской революции 1830 года во Франции.

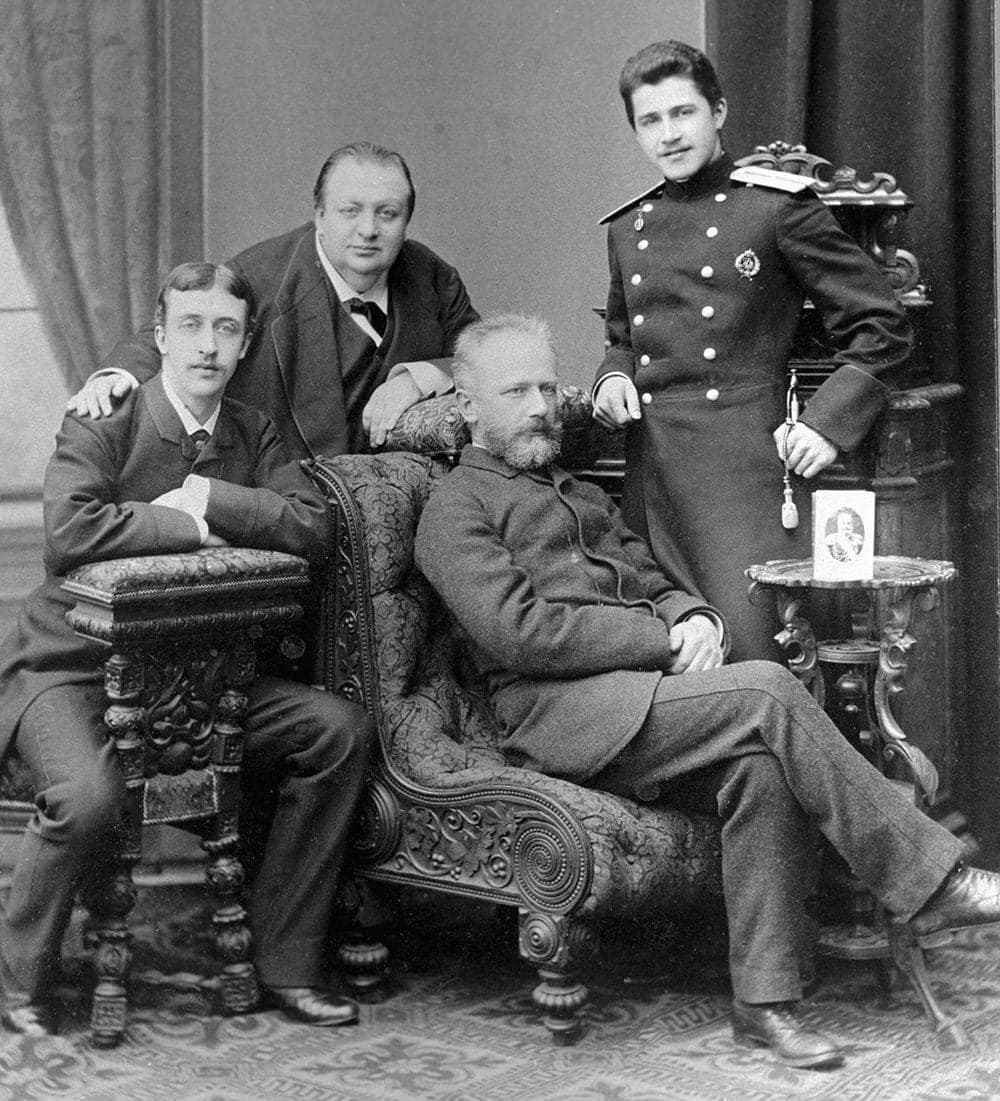

Мариус Петипа в партии Таора. 1862 г.

Но мы-то помним, что сюжет о Щелкунчике пришёл к Петипа из дирекции императорских театров. Балету с революционной тематикой доступ на императорскую сцену был бы закрыт. Так что из окончательного сценария Петипа все революционные мотивы были изгнаны.

Сюжет Гофмана-Дюма также пострадал: из сказки выпала вся предыстория заколдованного юноши. Зато общая канва истории стала компактной и стройной. В первом действии главная героиня получает в подарок Щелкунчика, который с наступлением ночи вместе с оловянными солдатиками ведет бой против мышей во главе с Мышиным королем. В конце первого действия девочка спасает Щелкунчика, он превращается в прекрасного принца и ведет девочку за собой в сказочную страну. В финале она просыпается — это был всего лишь сон.

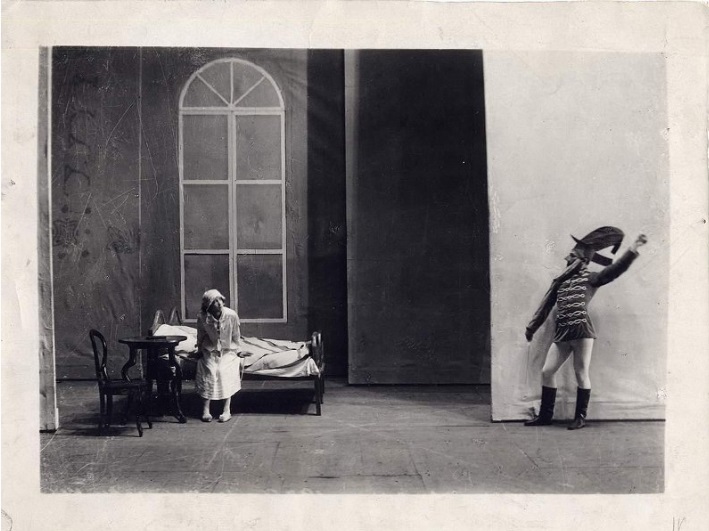

Сцена из балета «Щелкунчик». Мариинский театр, 1892

Многие мотивы из либретто Петипа проходят мимо большинства постановок «Щелкунчика». Так, например, снежная буря, которая обрушивается на главных героев (ведь счастья можно добиться, только пройдя через испытания), обычно превращается в безобидный «вальс снежных хлопьев». Исчезает игрушечный трамплин, выталкивающий на сцену оловянных солдатиков, готовых к бою с мышами. Знаменитое Адажио в оригинале танцуют не главная героиня и Принц, как можно подумать, а Фея Драже и принц Оршад 5, которого уже на премьере переименовали в принца Коклюша (в переводе с французского — «любимчик»).

В сказке Гофмана имя главной героини — Мари, а одну из её кукол зовут Кларой. Петипа назвал Кларой саму девочку. На этом сложности с именем не закончились: в советские времена возникла традиция звать главную героиню русифицированным именем Маша. Потом героиню стали называть и по-гофмановски — Мари. Аутентичным следует считать имя Клара, которое фигурирует в сценарии Петипа и в партитуре Чайковского.

Музыка

Музыка сочинялась тяжело. В феврале 1891 года Чайковский сообщает брату: «Я работаю изо всей мочи, начинаю примиряться с сюжетом балета». В марте: «Главное — отделаться от балета». В апреле: «Я тщательно напрягал все силы для работы, но ничего не выходило, кроме мерзости». Ещё позже: «А вдруг окажется, что… ‘’Щелкунчик’’ — гадость…»

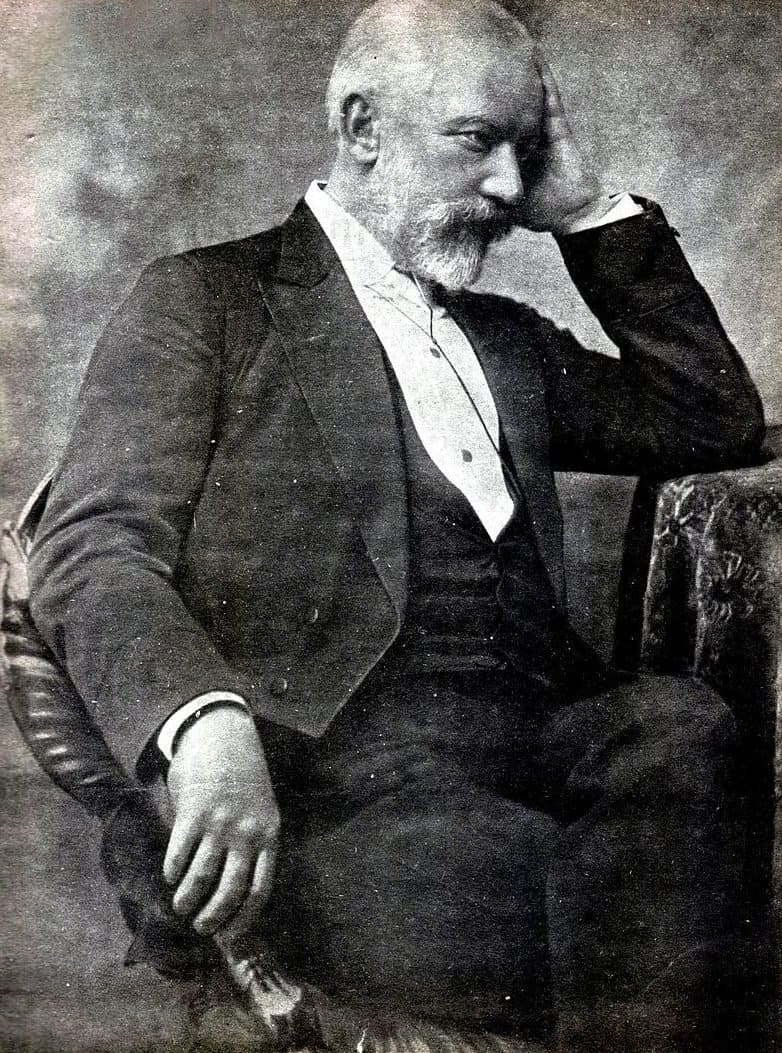

П. И. Чайковский, 1893

Начало 1890-х стали для композитора временем размышлений о жизни и смерти. В 1891 году умирает его сестра Александра Давыдова-Чайковская, и ее смерть он воспринял очень болезненно. Впереди были самые трагические сочинения композитора — «Пиковая дама» и Шестая симфония. В музыковедении последних лет высказывается идея, что «Щелкунчик» — это сочинение из того же ряда, балет о смерти и бессмертии, а всё, что случается с героиней, происходит в некоем ином мире. Возможно, снежная буря — метафора перехода из земной жизни в другое состояние, а Конфитюренбург — это рай. В Вальсе снежных хлопьев и в знаменитом Адажио есть, кстати, музыка весьма страшная, даром что мажорная.

Первая часть балета — это действие в чистом виде. Второе же, за исключением финала, представляет собой обычный для балета того времени дивертисмент 6. Идея кондитерского дивертисмента в Конфитюренбурге, городе сладостей, не слишком нравилась самому Чайковскому; впрочем, с поставленной задачей он справился блестяще.

Александра Ильинична Давыдова, сестра Петра Ильича Чайковского

В музыке «Щелкунчика» есть несколько пластов. Есть сцены детские и взрослые, фантастические и романтические, есть танцы дивертисмента. В музыке много аллюзий на культуру XVIII века: это, например, и галантный Танец пастушков, и Китайский танец, который, скорее, псевдокитайский (есть такой термин «шинуазри», то есть «китайщина»). А романтические фрагменты, наиболее связанные с эмоциональной сферой, становятся для композитора поводом для личных, очень интимных высказываний. Их суть непросто разгадать и очень интересно интерпретировать.

На пути симфонизации музыки композитор зашёл очень далеко даже по сравнению с «Лебединым озером» (1876) и «Спящей красавицей» (1889). Композитор обрамляет дивертисмент, который требовал от него балетмейстер, музыкой, насыщенной подлинным драматизмом. Сцена роста елки в первом акте сопровождается музыкой симфонического размаха: из тревожного, «ночного» звучания вырастает прекрасная, бесконечно льющаяся мелодия. Кульминацией всего балета стало Адажио, которое по замыслу Петипа танцевали Фея Драже и принц Оршад.

В марте 1892 года публике была представлена сюита из балета 7. Она имела большой успех: из шести номеров пять по требованию публики были повторены.

Первая трактовка

«Щелкунчик» и Петипа разминулись. Считается, что хореограф, пребывая в депрессии после смерти дочери, переложил всю работу на своего ассистента Льва Иванова. В сотрудничестве с ним Чайковский и заканчивал свой балет.

Впоследствии, уже после премьеры, газеты сообщали, что Петипа намерен представить его новую версию. Однако этим замыслам не суждено было осуществиться: балетмейстер так и не вернулся к своему проекту.

Премьера балета состоялась 6 декабря (18 декабря по новому стилю) 1892 года в Мариинском театре в Санкт-Петербурге в один вечер с оперой «Иоланта». Роли Клары и Фрица исполняли дети, учащиеся петербургского Императорского театрального училища.

Фрагмент спектакля «Щелкунчик» в постановке Императорского Мариинского театра, 1892

Вопрос о том, сколько идей Петипа перешло в хореографию Иванова, дискуссионный. Иванов в основном иллюстрировал сюжет, не обращая внимания на драматические возможности партитуры. Именно у него снежная буря и превратилась в безобидный вальс снежных хлопьев. Второе действие балета критики назвали вульгарным: балетные артистки, одетые сдобными булочками-бриошами, были восприняты как вызов хорошему вкусу. Сам Чайковский также остался недоволен постановкой. Последний раз спектакль Иванова возобновляли в 1923 году, после чего он навсегда исчез со сцены Мариинского театра.

Другие интерпретации

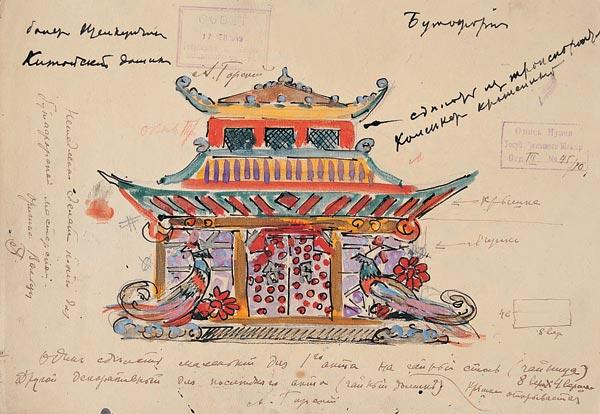

Новый взгляд на балет Чайковского представили балетмейстер Александр Горский и художник Константин Коровин (1919, Большой театр). В их спектакле сцена представляла собой сервированный стол с огромным кофейным сервизом, из которого выходили танцоры. В финале Горский оставлял Клару в мистическом сне. Вместо Феи Драже и принца Коклюша Горский отдал Адажио маленьким героям — Кларе и принцу Щелкунчику. Эта идея оказалась настолько хороша, что прочно прижилась в России.

К.А. Коровин. Эскиз бутафории к балету «Щелкунчик» П.И. Чайковского. Китайский домик. 1919, Третьяковская галерея

Ещё дальше пошёл Василий Вайнонен 8. Он откорректировал сюжет Петипа, заставив детей в финале первого акта повзрослеть, и выявил в балете историю девочки, полюбившей уродливую куклу (он назвал её Машей, и это имя надолго прижилось в отечественных постановках). Вслед за Горским Вайнонен убрал Коклюша с Феей Драже. Общая тональность спектакля была светлой; это был идеальный детский спектакль с фантастическими фокусами, яркими куклами и ёлкой, сверкающей праздничными огнями. Трагические мотивы балетмейстер оставил без внимания. В финале Щелкунчик и Маша, как и положено в сказке, превращались в Принца и Принцессу. Этот спектакль стал своего рода эмблемой Мариинского театра.

Юрий Григорович 9, отталкиваясь от музыки Чайковского, в очередной раз переписал либретто, заимствовав лучшие идеи у Горского и Вайнонена. Григорович первым в России создал из «Щелкунчика» философскую притчу о недостижимости идеального счастья. В этом спектакле Маша, простившаяся во сне со своим детством, в финале просыпалась в своей комнате — снова девочка и снова среди игрушек. Эта история изумительно точно и гармонично легла на музыку Чайковского, выявив её драматический потенциал.

Между тем традиции пышного дореволюционного «Щелкунчика» продолжил великий реформатор балета Джордж Баланчин, создатель бессюжетных хореографических постановок, который оказал значительное влияние на развитие хореографической школы в США (1954, Нью-Йорк Сити балет). Когда-то, ещё будучи учеником балетного училища в Петербурге, он участвовал в том самом спектакле, который разочаровал Чайковского. Спустя многие годы он решил оттолкнуться от идей Иванова и поставить пышный дивертисмент, в котором сам сюжет убрал на второй план. У Баланчина дети, попав в кондитерский рай, остаются детьми и смотрят на происходящие чудеса со стороны. Адажио танцуют Фея Драже и Кавалер (так Баланчин обозвал принца Коклюша). Хотя в философские смыслы музыки Чайковского хореограф не углублялся, его версия стала самой популярной в США: на неё до сих пор ориентируются многие американские постановщики «Щелкунчика».

В 1973 году балет «Щелкунчик» соединился с искусством анимации (режиссёр мультфильма — Борис Степанцев). Зрителей поразила — и поражает до сих пор — фантазия его авторов: в начальном эпизоде вместе с Машей танцует метла, а в Вальсе цветов Принц и Маша взлетают в небеса, подобно героям Шагала. И пусть главная героиня вопреки Гофману, Дюма и Петипа превратилась в девочку-служанку, эта версия «Щелкунчика» стала в России не менее классической, чем балет Григоровича.

Из версий XXI века отметим постановку «Щелкунчика» художником Михаилом Шемякиным и хореографом Кириллом Симоновым 10. Идеолог спектакля Шемякин вольно обошёлся с сюжетом, зато подспудно воскресил дух Гофмана, поставив балет как злой гротеск про мышиное царство. В финале крысы съедают Машу и Щелкунчика, превратившихся в засахаренных куколок.

П. Чайковский. «Щелкунчик». Мариинский театр. Музыкальный руководитель и дирижер Валерий Гергиев, декорации, костюмы и постановка Михаила Шемякина, хореография Кирилла Симонова. Сцена из спектакля. Фото Н. Разиной

Память о том, что премьера «Щелкунчика» прошла в один вечер с премьерой «Иоланты», сподвигла режиссёра Сергея Женовача вновь соединить вместе эти два произведения. В 2015 году, поставив «Иоланту» в Большом театре, он предварил её сюитой из «Щелкунчика» и заставил слепую Иоланту вслушиваться в музыку балета и сопереживать ей.

Музыку из «Щелкунчика» мы можем слышать не только в оперных или концертных залах. Она звучит за кадром во многих фильмах («Один дома»), мультфильмах («Том и Джерри»), телесериалах («Друзья»).

Рождественский балет

Есть несколько музыкально-сценических произведений, которые воспринимаются во всём мире как рождественские или новогодние. В Германии такова опера «Гензель и Гретель» Энгельберта Хумпердинка (хотя её сюжет не имеет отношения к Рождеству), в Австрии — оперетта «Летучая мышь» Иоганна Штрауса, в США и России — балет «Щелкунчик».

«Щелкунчик», Большой театр, 2014

Американская традиция давать «Щелкунчика» к Рождеству обязана своим возникновением Баланчину. «Щелкунчик» в США — это синоним Рождества и зимних детских каникул. Любая, даже самая маленькая, балетная компания, каждая балетная школа показывает в декабре свой вариант балета. По смыслу многие из них восходят к пышной постановке Баланчина и мало отличаются друг от друга.

В советское время «Щелкунчик» по понятным причинам считался новогодним балетом. Многие культурные феномены, хоть сколько-нибудь связанные с праздником Рождества, в те годы привязывались к новогодней теме. Билеты на новогодние представления «Щелкунчика» в Большом, Мариинском, Михайловском театрах, в Музыкальном театре Станиславского и Немировича-Данченко раскупались задолго до Нового года.

После 1990-х, когда Рождество вновь стало официальным праздником, балет «Щелкунчик» мгновенно обрёл статус главного рождественского балета. И пусть его содержание выходит далеко за рамки религиозного праздника — «Щелкунчик» всегда дарит зрителям и слушателям самое настоящее рождественское чудо.

Примечания:

1 — горожан, обывателей

2 — 1811–1910; французский и российский солист балета, балетмейстер и педагог

3 — литературная основа большого музыкального сочинения

4- анонимная песня, написанная в 1792 году, очень популярная во времена Великой французской революции

5 — напиток, который готовится на основе орехов — миндального молока

6- избранные фрагменты, составившие короткий цикл

7 — театральное представление, состоящее из различных танцевальных номеров, в дополнение к основному представлению

8 — 1934 — Кировский театр, 1938 — Большой театр

9 — 1966, Большой театр

10 — 2001, Мариинский театр

«Щелкунчик»:

путешествие во времени

Долгая история самого новогоднего балета

Уже больше 125 лет балет «Щелкунчик» живет на театральной сцене — и все это время балетмейстеры продолжают искать новые подходы к музыке Петра Чайковского, а сказка Эрнста Гофмана раз за разом получает новые оригинальные воплощения.

В специальном проекте портала «Культура.РФ» вы узнаете, как рождался самый новогодний русский балет и что скрывал Чайковский от коллег-композиторов, а также услышите легендарную музыку из «Щелкунчика» в редких записях фирмы «Мелодия» и увидите старинные фотографии первых постановок балета, которые сохранились в ГЦТМ им. А.А. Бахрушина.

Уже больше 125 лет балет «Щелкунчик» живет на театральной сцене — и все это время балетмейстеры продолжают искать новые подходы к музыке Петра Чайковского, а сказка Эрнста Гофмана раз за разом получает новые оригинальные воплощения.

В специальном проекте портала «Культура.РФ» вы узнаете, как рождался самый новогодний русский балет и что скрывал Чайковский от коллег-композиторов, а также услышите легендарную музыку из «Щелкунчика» в редких записях фирмы «Мелодия» и увидите старинные фотографии первых постановок балета, которые сохранились в ГЦТМ им. А.А. Бахрушина.

Уже больше 125 лет балет «Щелкунчик» живет на театральной сцене — и все это время балетмейстеры продолжают искать новые подходы к музыке Петра Чайковского, а сказка Эрнста Гофмана раз за разом получает новые оригинальные воплощения.

В специальном проекте портала «Культура.РФ» вы узнаете, как рождался самый новогодний русский балет и что скрывал Чайковский от коллег-композиторов, а также услышите легендарную музыку из «Щелкунчика» в редких записях фирмы «Мелодия» и увидите старинные фотографии первых постановок балета, которые сохранились в ГЦТМ им. А.А. Бахрушина.

Секреты новой постановки «Щелкунчика» в МАМТе

Портал «Культура.РФ» и МАМТ представляют серию коротких видео в VK Клипах о новой постановке балета «Щелкунчик». Пользователи узнают, как создавался спектакль — от задумки до постановки на сцене. Официальный хештег проекта — #СекретыЩелкунчика.

Идея сказочного балета

В 1890 году Петр Чайковский получил от дирекции Императорских театров заказ на одноактную оперу и двухактный балет. Композитор, находившийся тогда на пике популярности после успешных премьер балета «Спящая красавица» и оперы «Пиковая дама», должен был написать музыку для так называемого сборного спектакля: оперу и балет планировали представить в один вечер в декабре 1891 года.

Для оперы Чайковский сам выбрал полюбившийся ему сюжет драмы датского писателя Генрика Герца — «Дочь короля Рене». А создать балет по сказке Гофмана «Щелкунчик и Мышиный король» ему предложили директор Императорских театров Иван Всеволожский и знаменитый балетмейстер Мариус Петипа. У последнего уже был примерный сценарий постановки, который, правда, сильно изменился в процессе работы.

Для оперы Чайковский сам выбрал полюбившийся ему сюжет драмы датского писателя Генрика Герца — «Дочь короля Рене». А создать балет по сказке Гофмана «Щелкунчик и Мышиный король» ему предложили директор Императорских театров Иван Всеволожский и знаменитый балетмейстер Мариус Петипа. У последнего уже был примерный сценарий постановки, который, правда, сильно изменился в процессе работы.

Чайковский согласился, поскольку со сказкой Гофмана был уже знаком. Сохранилось письмо, в котором композитор благодарил музыкального критика Сергея Флёрова, приславшего ему издание «Щелкунчика и Мышиного короля» на русском языке, и отзывался о книге как о «превосходнейшем переводе превосходной сказки».

Петр Чайковский. Балет «Щелкунчик»

Исполняет Государственный симфонический оркестр СССР, дирижер Евгений Светланов

1988 год, запись из архива Фирмы «Мелодия»

«Щелкунчик» и мотивы со всего света

По задумке Мариуса Петипа, новогодняя «пряничная» сказка про волшебный город Конфитюренбург должна была стать совершенно не такой, какой мы ее знаем. На создание либретто балетмейстера вдохновила тема Великой французской революции, столетие которой отмечали в 1889 году. Судя по записям Петипа, во втором акте балета должны были звучать популярные французские революционные песни — «Карманьола» и «Добрый путь, милый дю Молле!». Однако балет на революционную тематику в царской России конца XIX века поставить было невозможно, и многие идеи Петипа остались только на бумаге. Хотя мотив из песни «Добрый путь, милый дю Молле!» Чайковский по просьбе балетмейстера в партитуре сохранил.

Тамара Старженецкая. Эскиз декорации «Занавес» к балету Петра Чайковского «Щелкунчик». 1978 год

Изображение: tchaikovskyhome.ru

Ирина Старженецкая. Эскиз декорации II акта к балету Петра Чайковского «Щелкунчик». 1969 год

Изображение: tchaikovskyhome.ru

Тамара Старженецкая. Эскиз декорации «Бой мышей» к балету Петра Чайковского «Щелкунчик». 1978 год

Изображение: tchaikovskyhome.ru

Ирина Старженецкая. Эскиз декорации I акта к балету Петра Чайковского «Щелкунчик». 1969 год

Изображение: tchaikovskyhome.ru

Валерий Доррер. Эскиз декорации II акта к балету Петра Чайковского «Щелкунчик». 1947 год

Изображение: tchaikovskyhome.ru

Музыка к «Щелкунчику» в целом богата на цитаты. Например, арабский танец «Кофе» из второго акта балета основан на традиционной грузинской колыбельной песне. Ее мелодию Чайковский лично слышал в Грузии: его брат Анатолий был вице-губернатором Тбилиси, и композитор несколько раз бывал у него в гостях.

В танце родителей и гостей звучит немецкая мелодия «Grossvater Tanz» («Танец дедушки»), которую до этого использовал в одном из своих произведений Роберт Шуман — один из любимых композиторов Чайковского. Мелодия «Grossvater Tanz» появилась в XVII веке, однако до сих пор доподлинно неизвестно, был ли этот танец народным или принадлежал авторству Карла Готлиба Геринга. На протяжении несколько веков лирический «Grossvater Tanz» исполняли в конце свадебной церемонии.

Петр Чайковский. Балет «Щелкунчик»

Большой симфонический оркестр Центрального телевидения и Всесоюзного радио, дирижер Владимир Федосеев

1986 год, запись из архива Фирмы «Мелодия»

Приключения челесты в России

В партитуре «Щелкунчика» Чайковский использовал новые для русской музыки второй половины XIX века инструменты. Внимание композитора привлекла французская челеста — клавишный металлофон. Ее Чайковский услышал на премьере драмы «Буря» Эрнеста Шоссона и остался очарован сказочным звучанием инструмента. О неожиданной находке он написал в 1891 году музыкальному издателю Петру Юргенсону:

«Я открыл в Париже новый оркестровый инструмент, нечто среднее между маленьким фортепиано и глокеншпилем, с божественно чудным звуком… Называется он Celesta Mustel и стоит тысячу двести франков. Купить его можно только в Париже у господина Мюстэля… Так как инструмент этот нужен будет в Петербурге раньше, чем в Москве, то желательно, чтобы его послали из Парижа к Осипу Ивановичу. Но при этом я желал бы, чтобы его никому не показывали, ибо боюсь, что Римский-Корсаков и Глазунов пронюхают и раньше меня воспользуются его необыкновенными эффектами».

Челеста звучит в знаменитом «Танце феи Драже». Она, как было указано в либретто Мариуса Петипа, подражает «звуку падающих капель».

Петр Чайковский. Балет «Щелкунчик»

Оркестр Большого театра СССР, дирижер Геннадий Рождественский

1960 год, запись из архива Фирмы «Мелодия»

«Главное — отделаться от балета»

Вскоре после начала работы над постановкой «Щелкунчика» от нее отказался Мариус Петипа, и балет передали второму балетмейстеру Мариинского театра Льву Иванову, который ранее ставил «Половецкие пляски» в «Князе Игоре» Александра Бородина и танцы в опере-балете Николая Римского-Корсакова «Млада».

Чайковскому работа над «Щелкунчиком» тоже давалась непросто: он долгое время не понимал, как соединить сложную симфоническую музыку и балет, второй акт которого представлял собой довольно наивный дивертисмент — набор танцев без сквозного сюжета и драматургии. По просьбе композитора премьеру постановки перенесли на год, а директор Императорских театров Всеволожский даже несколько раз извинялся перед Чайковским за то, что привлек его к столь «несерьезному» проекту. В 1891 году композитор писал: «Я работаю изо всей мочи, начинаю примиряться с сюжетом балета». Он мечтал: «Главное — отделаться от балета».

Партитуру балета Чайковский завершил в 1892 году. В премьерной постановке «Щелкунчика» было два акта и три картины. Первая показывала праздник в доме родителей Мари, вторая — сон девочки, в котором Щелкунчик воевал с крысиным войском и в финале превращался в прекрасного принца, а третья — сказочный город, куда попадали Мари и Щелкунчик.

Почему в балете в качестве антагонистов выступали крысы, а не мыши, как в сказке Гофмана, до сих пор остается загадкой. В рабочих материалах Петипа сохранилась лишь запись «Появляются крысы с мышиным царем» без каких-либо пояснений.

-

«Иногда мы безобидно и незаметно для зрителя шутим. Во втором акте есть проходка восьми мышей по заднику. Бывало, если в последней кулисе сидела девочка в роли Снежинки и переодевала пуанты, мыши хватали эту Снежинку на руки и, закрывая ее от зрителя спинами, перебегали по сцене в противоположную кулису. Зритель никогда такого озорства не замечал, ведь артисты работали опытные».

Петр Чайковский. Фрагменты из балета «Щелкунчик»

Академический симфонический оркестр Ленинградской государственной филармонии,

дирижер Евгений Мравинский

1981 год, запись из архива Фирмы «Мелодия»

«Невообразимая по безвкусию постановка»

В декабре 1892 года «Щелкунчик» предстал перед публикой на сцене Мариинского театра, который входил в состав Императорских театров России. Критика была разгромной. Уровень искусства театральной постановки не соответствовал сложной симфонической музыке Чайковского, да и талант композитора рецензенты подвергли сомнению.

Иван Всеволожский. Эскиз костюмов Клары и ее брата Фрица. 1892 год

Изображение: sorokastore.com

Иван Всеволожский. Эскиз костюмов феи Драже и Принца Коклюша

Изображение: sorokastore.com

Иван Всеволожский. Эскизы костюмов для балета Петра Чайковского «Щелкунчик»

Изображение: sorokastore.com

Иван Всеволожский. Эскиз костюмов Клары и ее брата Фрица. 1892 год

Изображение: sorokastore.com

Иван Всеволожский. Эскиз костюмов феи Драже и Принца Коклюша

Изображение: sorokastore.com

Иван Всеволожский. Эскизы костюмов для балета Петра Чайковского «Щелкунчик»

Изображение: sorokastore.com

«Вообще «Щелкунчик» поставлен преимущественно для детей — для танцовщиц в нем было весьма мало, для искусства — ровно ничего. Даже музыка оказалась довольно слабою», — писал Константин Скальковский в «Биржевой газете».

«Трудно представить себе что-нибудь скучнее и бессмысленнее «Щелкунчика», — отзывался Николай Безобразов из «Петербургской газете».

Но самый известный критик той эпохи дал балету положительный отзыв. Александр Бенуа писал брату Анатолию о генеральной репетиции «Щелкунчика»: «Государь был в восхищении, призывал в ложу и наговорил массу сочувственных слов. Постановка… великолепна и в балете даже слишком великолепна — глаза устают от этой роскоши».

Партию Мари исполнила Станислава Белинская, а Щелкунчика — Сергей Легат. Оба танцовщика на тот момент еще учились на балетном отделении Петербургского театрального училища: Легату было 17 лет, а Белинской — всего 12. Критики были беспощадны и к ним.

Но самый известный критик той эпохи дал балету положительный отзыв. Александр Бенуа писал брату Анатолию о генеральной репетиции «Щелкунчика»: «Государь был в восхищении, призывал в ложу и наговорил массу сочувственных слов. Постановка… великолепна и в балете даже слишком великолепна — глаза устают от этой роскоши».

Партию Мари исполнила Станислава Белинская, а Щелкунчика — Сергей Легат. Оба танцовщика на тот момент еще учились на балетном отделении Петербургского театрального училища: Легату было 17 лет, а Белинской — всего 12. Критики были беспощадны и к ним.

Сам Чайковский в письмах друзьям и родным отмечал, что даже внешне балет выглядел аляповато и безвкусно, вспоминал, что ему было сложно смотреть на сцену.

«После ряда удачных постановок, как «Пиковая дама» и «Спящая красавица», появилась невообразимая по безвкусию постановка балета Чайковского «Щелкунчик», в последней картине которого некоторые балетные артистки были одеты сдобными бриошами из булочной Филиппова», — писал будущий директор Императорских театров Владимир Теляковский.

Балет «Щелкунчик». Дорина в роли

Государственный центральный театральный музей им. А.А. Бахрушина, Москва

Балет «Щелкунчик». Дорина в роли. Обратная сторона фотографии

Государственный центральный театральный музей им. А.А. Бахрушина, Москва

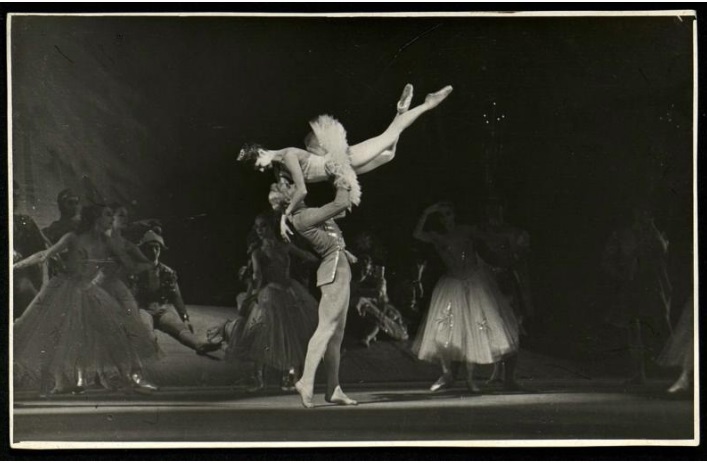

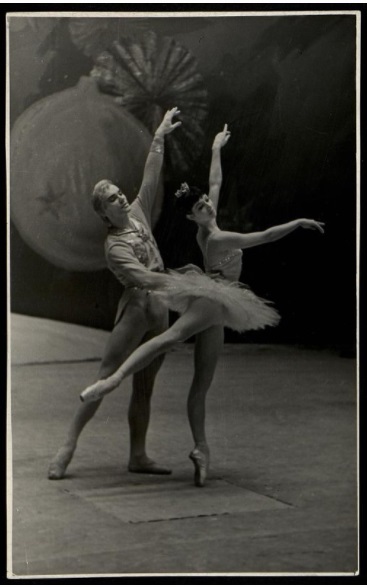

Балет «Щелкунчик». Ольга Преображенская и Сергей Легат в ролях. 1900 год

Государственный центральный театральный музей им. А.А. Бахрушина, Москва

Балет «Щелкунчик». Дорина в роли

Государственный центральный театральный музей им. А.А. Бахрушина, Москва

Балет «Щелкунчик». Дорина в роли. Обратная сторона фотографии

Государственный центральный театральный музей им. А.А. Бахрушина, Москва

Балет «Щелкунчик». Ольга Преображенская и Сергей Легат в ролях. 1900 год

Государственный центральный театральный музей им. А.А. Бахрушина, Москва

Впрочем, несмотря на оглушительный провал, «Щелкунчик» продержался в репертуаре Мариинского театра более 30 лет.

-

«В детстве я ни разу не видел полномасштабный классический балет. Спектакль «Щелкунчик» я увидел, уже будучи учеником МГАХ. С тех пор этот спектакль так устойчиво закрепился в моей артистической жизни, что Новый год для меня ассоциируется именно с «Щелкунчиком».

Петр Чайковский. Сюита из балета «Щелкунчик»

Государственный симфонический оркестр СССР, дирижер Евгений Светланов

1987 год, запись из архива Фирмы «Мелодия»

«Щелкунчик» в России и за рубежом

-

В 1919 году по-новому интерпретировать «Щелкунчика» решился балетмейстер Александр Горский на сцене московского Большого театра. Постановка, появившаяся в разгар революционных событий, прожила недолго.

1919 год

-

В 1923 году в Петербурге появилась новая версия спектакля от балетмейстера Федора Лопухова. На сцене царил авангард: декорации представляли собой восемь разноцветных щитов на колесиках. Спектакль показали всего девять раз.

1923 год

-

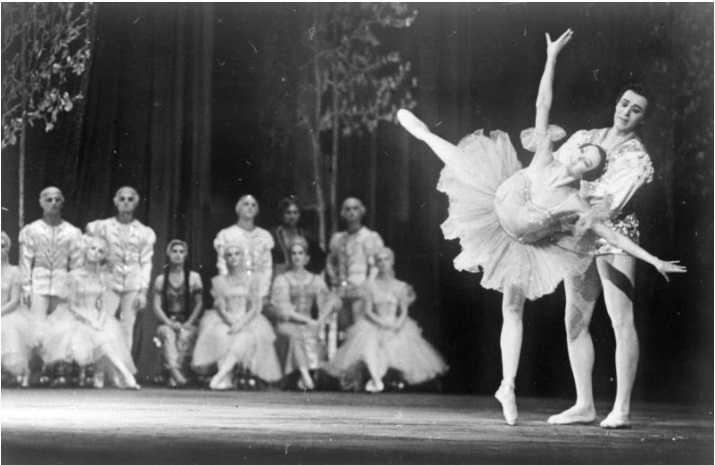

В 1934 году «Щелкунчик» снова предстал на сцене Мариинки. Вернуть его в репертуар поручили балетмейстеру Василию Вайнонену. В целом постановка была похожа на первоначальную версию Петипа — Иванова, но оказалась более удачной. Главные партии на премьере исполнили Галина Уланова и Константин Сергеев. На родной сцене «Щелкунчик» Вайнонена идет до сих пор — уже более 80 лет.

1934 год

-

В 1934 году «Щелкунчика» впервые реконструировали за границей. Свою версию балета в Лондоне представил Николай Сергеев, эмигрировавший после Октябрьской революции.

1934 год

-

Воспитанник Мариинки Джордж Баланчин поставил «Щелкунчика» в Нью-Йорке в 1954 году. Его версия целиком и полностью опиралась на сценарий Петипа, в который постановщик добавил новые танцы и мизансцены. Балет уже больше полувека с постоянным успехом идет каждую зиму на нью-йоркской сцене. В экранизации его постановки 1993 года главную партию танцевал ученик балетной школы Баланчина — Маколей Калкин, тогда уже снявшийся в известном фильме «Один дома».

1954 год

-

В 1967 году в Англию «Щелкунчика» вернул Рудольф Нуреев в 1967 году. Сперва новый балет показали на сцене Королевской шведской оперы в Стокгольме, а потом постановка Нуреева обосновалась в лондонском Ковент-Гардене. Еще через несколько лет балет смогли увидеть зрители миланского театра Ла Скала. Став директором балетной труппы Парижской оперы, Нуреев поставил «Щелкунчика» и там. В его версии сказка стала ближе к оригиналу Гофмана: менее «пряничной» и куда более готичной.

1967 год

-

Свою версию «Щелкунчика» на сцене нью-йоркского Американского театра балета в 1976 году представил Михаил Барышников. Главную партию в балете он исполнил сам. Премьера «Щелкунчика» Барышникова прошла с успехом, но, когда в 1989 году он ушел из Американского театра балета, его постановки убрали из репертуара. Зато видеоверсия спектакля сохранилась до наших дней.

1976 год

-

«Я пересматривал большое количество видеозаписей с артистами старшего поколения и должен признать, что многое почерпнул для своей роли в плане нюансов, манеры, настроений. Однако передо мной не стояла задача подражать кому-то из великих, я пытался создать своего Принца. При этом я не забываю, что моего Принца придумывает в своем воображении Маша, в её голове я идеален. А знаете, как непросто соответствовать ожиданиям опытных прим-балерин Большого?!»

Петр Чайковский. Сюита из балета «Щелкунчик»

Оркестр Ленинградского академического театра им. С. Кирова, дирижер Валерий Гергиев

1988 год, запись из архива Фирмы «Мелодия»

Современная сценография

В 1966 году в Большом театре появилась постановка Юрия Григоровича, которую историки театра считают почти идеальным решением партитуры Чайковского. Взяв за основу сценарий Петипа, Григорович создал сквозной сюжет всего спектакля. Второй акт из дивертисмента превратился в сказочное путешествие героев по елке, которое завершалось венчанием Маши и Щелкунчика.

Балет «Щелкунчик». Екатерина Максимова в роли Маши и Владимир Васильев в роли Принца. Государственный Большой театр оперы и балета, Москва. 1966 год

Государственный центральный театральный музей им. А.А. Бахрушина, Москва

Балет «Щелкунчик». Александр Рубашкин, Галина Уланова, Екатерина Максимова в роли Маши и Владимир Васильев в роли Принца на поклонах. Юбилей Галины Улановой. 1980 год

Государственный центральный театральный музей им. А.А. Бахрушина, Москва

Балет «Щелкунчик». Галина Уланова в роли Маши. Государственный академический театр оперы и балета, Москва. 1934 год

Государственный центральный театральный музей им. А.А. Бахрушина, Москва

Балет «Щелкунчик». Екатерина Максимова в роли Маши и Владимир Васильев в роли Принца. Государственный Большой театр оперы и балета, Москва. 1966 год

Государственный центральный театральный музей им. А.А. Бахрушина, Москва

Балет «Щелкунчик». Александр Рубашкин, Галина Уланова, Екатерина Максимова в роли Маши и Владимир Васильев в роли Принца на поклонах. Юбилей Галины Улановой. 1980 год

Государственный центральный театральный музей им. А.А. Бахрушина, Москва

Балет «Щелкунчик». Галина Уланова в роли Маши. Государственный академический театр оперы и балета, Москва. 1934 год

Государственный центральный театральный музей им. А.А. Бахрушина, Москва

Сам балетмейстер еще во время учебы в Ленинградском хореографическом училище в 1930-х годах танцевал в «Щелкунчике» Вайнонена. «Мы, дети, очень любили этот балет и хорошо знали, что когда закончим танцевать и подойдем к накрытому на сцене праздничному столу, то обязательно найдем на нем приготовленные для нас настоящие сладости», — вспоминал Григорович.

Сцена из балета Петра Чайковского «Щелкунчик». Московский государственный академический детский музыкальный театр им. Н.И. Сац, Москва

Фотография: Елена Лапина / teatr-sats.ru

Сцена из балета Петра Чайковского «Щелкунчик». Государственный академический Большой театр России, Москва

Фотография: theatrehd.ru

Сцена из балета Петра Чайковского «Щелкунчик». Государственный академический Большой театр России, Москва

Фотография: theatrehd.ru

Сцена из балета Петра Чайковского «Щелкунчик». Государственный академический Большой театр России, Москва

Фотография: theatrehd.ru

Сцена из балета Петра Чайковского «Щелкунчик». Государственный академический Мариинский театр, Санкт-Петербург

Фотография: mariinsky.ru

В постановке Григоровича танцевала главная пара советского балета тех лет — Владимир Васильев и Екатерина Максимова. Именно эта версия «Щелкунчика» идет и в наши дни на сцене Большого театра.

Сцена из балета Петра Чайковского «Щелкунчик». Академия Русского балета им. А.Я. Вагановой, Санкт-Петербург

Фотография: mariinsky.ru

Сцена из балета Петра Чайковского «Щелкунчик». Государственный академический Большой театр России, Москва

Фотография: coolconnections.ru

Сцена из балета Петра Чайковского «Щелкунчик». Государственный академический Большой театр России, Москва

Фотография: theatrehd.ru

Сцена из балета Петра Чайковского «Щелкунчик». Государственный академический Большой театр России, Москва

Фотография: theatrehd.ru

Сцена из балета Петра Чайковского «Щелкунчик». Государственный академический Мариинский театр, Санкт-Петербург

Фотография: mariinsky.ru

В 2001 году на второй сцене Мариинского театра появилась одна из самых необычных вариаций «Щелкунчика». Либретто Мариуса Петипа переработал Михаил Шемякин, значительно «гофманизировав» спектакль. Хореограф добавил в знакомую сказку множество фантасмагорических образов, гротескных персонажей и совсем не детских тем.

Михаил Шемякин. Эскиз костюма к балету Петра Чайковского «Щелкунчик». Крысенок в головке сыра. 2000 год

Изображение: artchive.ru

Эскиз костюма к балету Петра Чайковского «Щелкунчик». Крыс-ветеран. 2000 год

Изображение: artchive.ru

Михаил Шемякин. Эскиз костюма к балету Петра Чайковского «Щелкунчик». Мухолов. 2000 год

Изображение: artchive.ru

Михаил Шемякин. Эскиз костюма к балету Петра Чайковского «Щелкунчик». Крысенок в головке сыра. 2000 год

Изображение: artchive.ru

Эскиз костюма к балету Петра Чайковского «Щелкунчик». Крыс-ветеран. 2000 год

Изображение: artchive.ru

Михаил Шемякин. Эскиз костюма к балету Петра Чайковского «Щелкунчик». Мухолов. 2000 год

Изображение: artchive.ru

Шемякин писал, что в центре его балета — история одинокой девочки в чуждом для нее мире, который она не может и не хочет принять. Маша в этой версии «Щелкунчика» предстает нелюбимой дочерью, которую не принимают ни родители, ни сверстники. Поэтому в финале она превращается в сахарную фигурку на торте, чтобы никогда не возвращаться в безрадостный реальный мир.

Балет Петра Чайковского «Щелкунчик» в постановке Михаила Шемякина. Государственный академический Мариинский театр, Санкт-Петербург

Фотография: mariinsky.ru

Валерия Мартынюк в роли Маши и Алексей Недвига в роли Щелкунчика-куклы. Балет Петра Чайковского «Щелкунчик» в постановке Михаила Шемякина. Государственный академический Мариинский театр, Санкт-Петербург

Фотография: mariinsky.ru

Действие первое. Сцена «Панорама». Маша и Щелкунчик отправляются в путешествие в дедушкином башмаке. Балет Петра Чайковского «Щелкунчик» в постановке Михаила Шемякина. Государственный академический Мариинский театр, Санкт-Петербург

Фотография: mariinsky.ru

Действие первое. Сцена вторая. «Рождественский праздник». Балет Петра Чайковского «Щелкунчик» в постановке Михаила Шемякина. Государственный академический Мариинский театр, Санкт-Петербург

Фотография: mariinsky.ru

Действие первое. Сцена третья «Баталия». Балет Петра Чайковского «Щелкунчик» в постановке Михаила Шемякина. Государственный академический Мариинский театр, Санкт-Петербург

Фотография: mariinsky.ru

Вальс цветов. Вальс цветов. Балет Петра Чайковского «Щелкунчик» в постановке Михаила Шемякина. Государственный академический Мариинский театр, Санкт-Петербург

Фотография: mariinsky.ru

Pas de trois пчелок. Балет Петра Чайковского «Щелкунчик» в постановке Михаила Шемякина. Государственный академический Мариинский театр, Санкт-Петербург

Фотография: mariinsky.ru

Анастасия Петушкова в роли Королевы снежинок. Балет Петра Чайковского «Щелкунчик» в постановке Михаила Шемякина. Государственный академический Мариинский театр, Санкт-Петербург

Фотография: mariinsky.ru

-

«Спектакль «Щелкунчик» Григоровича я впервые увидел, когда уже был приглашен в Большой театр. У меня ни один другой спектакль не пробуждает такие чувства и мысли о волшебстве. Мы, взрослые, которые, как нам кажется, знают эту жизнь с ее цинизмом и неурядицами, вдруг погружаемся в атмосферу, где создается магия. Здесь мы снова превращаемся в детей с их чистыми мечтами и искренней верой в чудеса. Здесь можно загадывать желания, которые исполняются».

Петр Чайковский. Концертная сюита из балета «Щелкунчик»

Переложение для фортепиано Михаила Плетнева

Михаил Плетнев, фортепиано

1978 год, запись из архива Фирмы «Мелодия»

«Щелкунчик» на слух

Слушайте литературно-музыкальную композицию «Щелкунчик» и беседу о балете от фирмы «Мелодия».

Петр Чайковский. Балет «Щелкунчик»

Беседа о музыке для общеобразовательных школ

1968 год, запись из архива Фирмы «Мелодия»

Музыкально-литературная композиция

по балету Петра Чайковского и сказке Эрнста Гофмана

1966 год, запись из архива Фирмы «Мелодия»

Постановки «Щелкунчика» в российских театрах

Смотрите две видеоверсии спектакля в постановке Юрия Григоровича — главные партии в них исполнили Владимир Васильев и Екатерина Максимова. А еще знакомьтесь с другими интерпретациями классического балета. Государственный Московский Театр балета классической хореографии создал на его основе детское представление, а режиссер Петр Базарон из екатеринбургского театра «Щелкунчик» перенес действие спектакля в современность.

-

«Щелкунчик»

Государственный академический Большой театр России

1966 год -

«Щелкунчик»

Государственный академический Большой театр России

1977 год -

«Щелкунчик»

Муниципальный театр балета «Щелкунчик»

2019 год -

«Щелкунчик»

Московский театр балета классической хореографии

2020 год

-

«Щелкунчик»

Государственный академический Большой театр России

1966 год -

«Щелкунчик»

Государственный академический Большой театр России

1977 год -

«Щелкунчик»

Муниципальный театр балета «Щелкунчик»

2019 год -

«Щелкунчик»

Московский театр балета классической хореографии

2020 год

Автор текста: Полина Пендина

Автор проекта: Екатерина Тарасова

Верстка: Кристина Мацевич

«Щелку́нчик» — балет Петра Ильича

Чайковского в двух актах на либретто

Мариуса Петипа по мотивам сказки Э. Т.

А. Гофмана «Щелкунчик и мышиный король».

Либретто к балету создано Мариусом

Петипа (1816 год).

Премьера балета состоялась 6 (18) декабря

1892 года в Мариинском театре в

Санкт-Петербурге. Роли Клары и Фрица

исполняли дети, учащиеся Петербургского

Императорского театрального училища,

которое оба закончили лишь через

несколько лет в 1899 году: Клара — Станислава

Белинская, Фриц — Василий Стуколкин.

Другие исполнители: Щелкунчик — С. Г.

Легат, фея Драже — А.Дель-Эра, принц

Коклюш — П. Гердт, Дроссельмейер — Т.

Стуколкин, племянница Марианна — Лидия

Рубцова; балетмейстер Иванов, дирижёр

Дриго, художники Бочаров и К. Иванов,

костюмы — Всеволожский и Пономарев.

Хореограф: Мариус Петипа

Последующие редакции: Л.И.Иванов, А.А.

Горский, Ф.В. Лопухов, В.И. Вайнонен,

Ю.Н.Григорович

В разных редакцих есть разночтения в

имени главной героини: Клара и Мари. В

оригинальном произведении Гофмана имя

девочки Мари, а Клара — это ее любимая

кукла.

В постановках в СССР с середины 1930-х

годов, в связи с общей идеологической

установкой сюжет балета русифицировался,

и главная героиня стала зваться Машей.

Премьера балета «Щелкунчик»

состоялась в декабре 1892 года в Мариинском

театре (Санкт-Петербург). С тех пор балет

пережил рекордное количество постановок,

как классических, так и новаторских.

Вашему вниманию предлагается постановка

1994 года.

«Щелкунчик» П. И. Чайковского —

классика балетного искусства, неизменно

привлекающая зрителей всех возрастов.

Очень интересна история создания балета.

В конце 19 века директор императорских

театров И. А. Всеволожский задумал

создать представление, в котором будут

объединены опера «Иоланта» и балет

«Щелкунчик». Эта постановка,

задуманная как пышное, роскошное

представление-феерия, должна была стать

главным событием сезона. Таким образом,

Чайковский получил заказ на музыку к

«Иоланте» и «Щелкунчику».

Однако работа над балетом затягивалась,

поскольку композитор не сразу нашел

подход к музыкальной интерпретации

сказки Гофмана. В основу балета был

положен сценарий Петипа. Произведение

Чайковского получило восторженную

оценку критики, однако некоторые

современники композитора сомневались

в возможности постановки балета. Музыка

«Щелкунчика» сложнее других

произведений Чайковского, написанных

для балета. Композитора недаром называли

реформатором балетной музыки, привнесшего

в нее динамику, сквозное развитие образов

и музыкальных тем.

К услугам Иванова был сценарий,

составленный Петипа по сказке Т. А.

Гофмана, и музыка, казалось бы, послушная

сценарию, на деле же постоянно подымавшаяся

над его заданиями.В сценарии вновь

сталкивались силы добра и зла, как и в

«Спящей красавице», но здесь борьба

протекала более статично. Девочка Клара

получала на рождество подарки, и больше

всего ей нравился Щелкунчик, разгрызающий

деревянными челюстями орехи. Ночью

Кларе снилось, что на игрушек пошли

войной мыши и оборону игрушек возглавил

Щелкунчик. Клара бросала башмачок в

короля мышей. Благодарный Щелкунчик

вел ее в царство игрушек и сластей. Во

втором акте героиня спектакля становилась

зрительницей всевозможных чудес, а

центральное адажио исполняли балерина-фея

Драже и ее партнер-принц Коклюш. Детство

с его доверчивым и причудливым восприятием

мира являлось единственной темой

сценария. Чайковский преступил узкое

задание. Безгранично раздвигая права

балетной музыки, он дал симфоническую

картину, где радости и горести детства

были только зачином музыкальной темы.

Дальше тема уходила в большой поэтический

и философский мир, превосходя и «Спящую

красавицу» с ее заранее подсказанным

безмятежным финалом. В «Щелкунчике»

человеческая душа выходила из детства

в область дерзаний, порой окрашенных

предчувствием трагедии. Кульминацией

темы являлось центральное адажио.Музыка

«Щелкунчика» требовала от постановщика

равных ей поэтических обобщений в танце.

Лев Иванов, для которого вершиной до

сих пор был «Очарованный лес» Дриго,

столкнулся с непосильной, казалось бы,

задачей. Он и не осилил ее целиком, прежде

всего потому, что был обязан выполнить

условия сценария, да и не помышлял о

том, чтобы от них отступить. Он искренне

почитал эстетику Петипа непреложной и

поставил «Щелкунчика» так, как то

предусматривал сценарий.В первом

акте игры детей и гроссфатер взрослых,

танцы заводных кукол, война мышей и

лягушек-все было изобретательно, изящно

и вызывало чуть юмористическое отношение

к происходящему. Второй акт являл собой

дивертисмент сластей. Костюмы исполнителей

изображали карамель, ячменный сахар,

нугу, мятные лепешки, печенье и т. п.

Испанский танец назывался «шоколад»,

арабский-«кофе», китайский-«чай».

В вальсе кондитерские персонажи

рассыпались и складывались в

калейдоскопические узоры, подготовляя

pas de deux феи Драже и принца Коклюша. Адажио

напоминало танец Авроры с четырьмя

принцами, как его воплотил Петипа:

основным хореографическим мотивом

также был аттитюд в разных ракурсах и

поворотах.

Но как бы ни была гармонична пластика

феи Драже, она не передавала вдохновенной

глубины музыки,- музыка неизмеримо

возвышалась над сценарными задачами

второго акта и вообще далеко превосходила

смысловые возможности pas de deux в балетном

спектакле XIX века.Только в одной

танцевальной сцене, выключенной из

сюжета, но углубляющей музыкально-симфоническое

действие, Иванов достиг подлинно

новаторских результатов. Это был вальс

снежных хлопьев в конце первого акта;

там выступало около шестидесяти

танцовщиц. Как писал критик А. Л.

Волынский, вальс был «разработан

балетмейстером с такою графическою

правильностью, с такою гармоническою

цельностью, что глазу легко воспринять

его во всех деталях». В нем виделись

«мелькания морозной пыли, штрихи и

узоры снежных кристаллов, вензеля и

арабески морозной пластики». Основным

движением являлся мягкий pas de basque, в

котором кордебалет составлял фигуры

параллельных и пересекающихся линий,

большие и малые круги, звезды, кресты.

Вальс создавал образ волшебного сна

зимней природы.

Все сказочно развивало тему колыбельной

песенки, которой Клара убаюкивала

Щелкунчика. Просветленные голоса

детского хора за сценой как бы взмывали

над плавным танцем, давая ощутить простор

зимней ночи.

Велики заслуги Иванова в симфонизации

русского балета, в усилении выразительности

классического танца. Особенно ярко это

проявилось при работе над балетами П.

Й. Чайковского — «Щелкунчик» и «Лебединое

озеро».

С 1885 второй балетмейстер Мариинского

театра, помощник М. И. Петипа. В 1887 поставил

в традициях романтизма балеты «Очарованный

лес» Дриго и «Гарлемский тюльпан» Шеля.

Исключительная музыкальность позволила

И. создать выдающиеся образцы

симфонической разработки танца

— характерного (половецкие пляски в

опере «Князь Игорь» Бородина, 1890) и

классического (танец снежных хлопьев

— «Щелкунчик», 1892, сцены на озере —

«Лебединое озеро», 1895, Чайковского).

Поэтическое содержание образов

воплощалось балетмейстером в совершенную

хореографическую форму. Деятельность

И. — вершина академического стиля

русского балета. Лев Иванов-великий

лирик балетной сцены XIX века.

И. вводил новые пластические

характеристики, свободный рисунок рук,

медленный, как бы плывущий ход, размытость

контуров классической формы.

Старый балетный театр сосредоточил

действенное начало хореографического

спектакля лишь в его мимической стороне;

в танце же, в характере самих движений

оно проявлялось редко. Таким образом и

возникла вопиющая стилистическая

разноголосица мимической и танцевальной

сторон балета.

В прежние времена танец зачастую никак

не связывался с внутренним состоянием

героя. Герой мог отчаянно тосковать, но

в вариации делал все те же бравурные,

эффектные движения, вплоть до большого

пируэта, в котором нет и тени печали.

Таких вариаций в старых балетах было

множество. Но если у балетмейстера или

у балетоманов спрашивали: «С чего это

герой так веселится, когда у него такие

неприятности?» — они, как правило,

отвечали: «Как вы не понимаете, ведь

это же балет!» Выходило, что балету

иначе как нелепым, бессмысленным и быть

невозможно.

Характер героя и его внутреннее

состояние не часто проявлялись в самих

движениях. Даже маститый Петипа

далеко не всегда стремился к этому. Зато

Льву Иванову это было органически

свойственно. Потому его и следует считать

родоначальником современного русского

искусства балетмейстера, хотя и связанного

еще с французской и итальянской

постановочной традицией.

Несмотря на то что режиссерско-балетмейстерский

план «Щелкунчика» был разработан Петипа

и это, конечно же, сковывало творческие

возможности Иванова, он, тем не менее,

смог применить здесь и свои глубокие

музыкальные знания, и новые балетмейстерские

приемы, суть которых состояла в том,

чтобы средствами танца, гармонией

вполне определенных поз и движений

выразить основную мысль музыки, показать

развитие музыкальной драматургии.

Особенно удались балетмейстеру

характерные танцы последнего акта и

третья картина 1-го акта — «Снежинки»,

которую Иванов поставил самостоятельно,

без указаний Петипа.

Шедевром симфонического балета стало

«Лебединое озеро» где Иванов поставил

2-й н 4-й акты и репетировал 1-й и 3-й,

поставленные Петипа. Полное слияние

музыки и танца способствовало созданию

глубоких поэтических образов действующих

лиц спектакля — и главных, и кордебалета,

который по воле гениального композитора

и балетмейстера превратился в трепетную

лебединую стаю.

Премьера «Лебединого озера» 15 января

1895 года в Mapиинском театре показала, что

русский балет поднялся на новую ступень

в своем развитии. Программная

симфоническая музыка определяла развитие

балетного действия; музыкальные

характеристики образов заставляли

искать особые рисунки танца, который

стал танцем-действием. От исполнителей

требовалось проникновение в образ,

осмысление каждого своего движения —

в симфоническом балете не оставалось

места бездумному «танцеванию».

Белый лебедь П. И. Чайковского и Льва

Иванова стал эмблемой русского балета.

Художественные достижения Иванова

открывали новые пути развития перед

русской школой классического танца,

перед балетмейстерами будущего XX века.

«Азбука» классического танца

сформировалась во времена Петипа, но

приемы и способы «словосочетаний»,

формообразований на основе этой «азбуки»,

живые, подвижные и гибкие, продолжали

развиваться, отвечая требованиям жизни.

К концу XIX века танцевальная речь немало

изменилась и в практике самого Петипа,

который не без внутреннего сопротивления

влил в кантиленную пластику русской

школы стремительность виртуозных

итальянских приемов. Еще серьезнее и

значительнее были сдвиги в «Лебедином

озере» Л. И. Иванова. Продиктованные

задачей психологизации хореографического

образа, они вели к перестановке

акцентов в композиции узаконенных

движений; например, в поисках образности

раздвигались границы port de bras — то есть

изменялись движения рук, подчиненные

«лебяжьей» пластике танца солистки и

кордебалета.

Балетмейстер Лев Иванов, придумал «Танец

маленьких лебедей».

Лев Иванов — одна из виднейших фигур

в русском балетном искусстве. Танцовщик,

композитор, дирижер, он в конце концов

нашел себя как балетмейстер и к 1900-м гг.

стал одним из крупнейших реформаторов

русского — да и мирового — балета.

Ученик Петипа, он пошел дальше своего

учителя, переосмысливая, а порой нарушая

прежние каноны классического танца во

имя нового его содержания.

Важной побудительной причиной

сдвигов послужила музыка «Лебединого

озера».

Обращение Чайковского к балетной музыке

явилось новым этапом в истории русского

балетного театра. Музыка в балете стала

драматически содержательной, симфонически

развитой, тонко и мастерски инструментованной.

Из простого аккомпанемента танцам она

превратилась в их основу, давая

балетмейстерам богатейший творческий

импульс. Именно когда Петипа обратился

к творчеству Чайковского и Глазунова,

он сумел «симфонизировать» балет. Музыка

стимулировала новаторство форм танца

в постановке Льва Иванова. И если в

балетах Петипа утверждались высшие

достижения классического танца XIX века,

то «Лебединое озеро» Иванова предвещало

сложные и противоречивые судьбы этого

танца в XX веке. Хореограф, который до

тех пор диктовал свои условия композитору,

превращался в истолкователя музыки.

Здесь открывался и соблазнительный, но

в крайностях своих произвольный путь

обращения хореографов к музыке, не

предназначенной для балетного спектакля.

Лев Иванович Иванов (1834—1901) начинал

учиться танцу в Московской балетной

школе, потом был переведен в Петербургское

театральное училище. Классический танец

он изучал у лучших педагогов того

времени: А. И. Пименова, П. Фредерика, Э.

Гредлю, Ж. Петипа. Начало его деятельности

в петербургской труппе не было успешным,

хотя в свой дебют он удачно станцевал

Колена в «Тщетной предосторожности»

Обладая исключительными танцевальными

способностями и музыкальностью, Иванов

стремился достичь полного слияния

музыки и танца в балете — вот над чем

он работал долгие годы.

Протанцевав в петербургском театре,

под конец уже на положении первого

танцовщика, до начала 70-х годов, Л. Иванов

не ушел из театра, хотя и получил пенсию,

а остался в труппе педагогом-репетитором,

балетмейстером.

В 1882 году его назначают режиссером

балета, а в 1885 году — вторым балетмейстером.

Его первые самостоятельные постановки

— «Очарованный лес», «Шалости амура»,

«Гарлемский тюльпан». Все они были

сделаны хорошим профессионалом, но не

отличались оригинальностью хореографических

композиций, как не были интересны и по

своему содержанию. Однако Иванов

по-прежнему готовил себя к большой

работе, изучая симфоническую музыку,

теорию.

В 1890 году ему было поручено поставить

«Половецкие пляски» в опере Бородина

«Князь Игорь». Имея целью сделать

танцевальные сцены максимально

выразительными, Иванов смело сочетал

движения классического и народно-характерного

танцев. Эффект был необыкновенный.

Пластическое воплощение партитуры

Бородина шло у Иванова от музыки к

хореографическим формам. Для Иванова

музыка являлась основой. действенной

опорой спектакля. Это совпадало с

русскими танцевальными традициями.

Постановки «Половецких плясок» стала

заметным явлением и сразу же вошла в

фонд русской балетной классики.

Иванов многое сделал для развития

характерного народного танца и достиг

в этом совершенства: 11 октября 1900 года

в балете Ц. Пуни «Конек-Горбунок, или

Царь-девица» он впервые поставил

чардаш. Пластика народного танца

зримо воплотилась во Второй венгерской

рапсодии Ф. Листа, в ней ярко обозначены

черты симфонизированного характерного

танца. И Л.Иванов, для которого симфоническая

музыка была образной основой танца,

поставил рапсодию в рамках традиционной

театральности, передавая в танце характер

и дух венгерского народа.

Лев Иванов — многолетний соратник

и сотрудник Петипа, он был человеком

«тихой славы». На заре карьеры исполнял

главные мужские партии в ранних балетах

Петипа. Позже учил будущих артистов,

возобновлял и репетировал чужие

спектакли, обладал феноменальными

памятью и музыкальностью. Петипа

привлекал русского коллегу к постановочной

работе, когда по каким-то причинам желал

самоустраниться, либо если одному было

трудно справиться с масштабной работой.

Иванов всю жизнь находился в тени и

не роптал. Его звездный час наступил (и

миновал) в «Лебедином озере». Более

чуткий к образной сути музыки Чайковского,

Иванов создал истинный шедевр –

«лебединые сцены» – проникновенно-лирические

танцевальные сюиты, наполненные по-русски

распевными пластическими интонациями.

«Лебединые» сцены по праву считаются

непревзойденными по поэтичности,

музыкальности и красоте композиции.

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

The Nutcracker (Russian: Щелкунчик[a], tr. Shchelkunchik listen (help·info)) is an 1892 two-act «fairy ballet» (Russian: балет-феерия, balet-feyeriya) set on Christmas Eve at the foot of a Christmas tree in a child’s imagination. The music is by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, his Opus 71. The plot is an adaptation of E. T. A. Hoffmann’s 1816 short story The Nutcracker and the Mouse King. The ballet’s first choreographer was Marius Petipa, with whom Tchaikovsky had worked three years earlier on The Sleeping Beauty, assisted by Lev Ivanov. Although the complete and staged The Nutcracker ballet was not as successful as had been the 20-minute Nutcracker Suite that Tchaikovsky had premiered nine months earlier, The Nutcracker soon became popular.

Since the late 1960s, it has been danced by countless ballet companies, especially in North America.[1] Major American ballet companies generate around 40% of their annual ticket revenues from performances of The Nutcracker.[2][3] The ballet’s score has been used in several film adaptations of Hoffmann’s story.