Яйцо пасхальное — традиционный пасхальный символ и вместе с тем церковно-обрядовая пища, как правило, потребляемая в дни пасхальных торжеств. Дарить окрашенные в красный цвет яйца на Пасху — древний христианский обычай.

Как правильно дарить на Пасху яйца?

Традиционно яйца дарят при трехкратном пасхальном целовании и приветствии: Христос воскресе! — при этом принято, чтобы приветствуемый отвечал: Воистину Воскресе!

Что символизирует пасхальное яйцо?

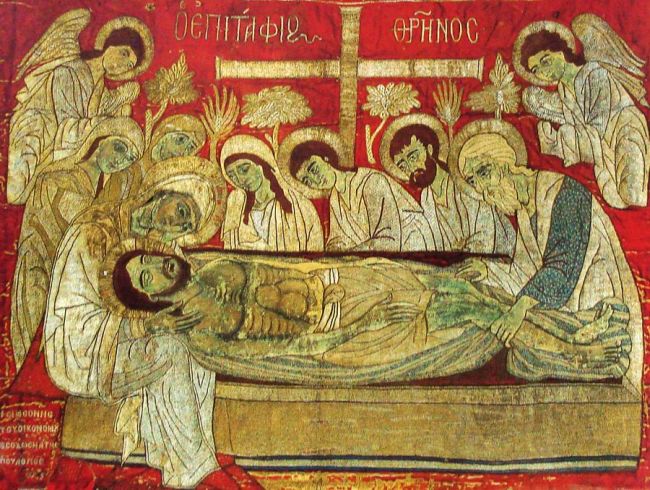

Яйцо служит символом гроба и вместе с тем — символом жизни. Окрашенное красной краской, оно знаменует Воскресение Христово и наше Искупление «драгоценною Кровию Христа, как непорочного и чистого Агнца» (1Пет.1:18-19), возрождение верующих во Христе. Помимо того, что красный цвет указывает на кровь Христову, пролитую на Кресте, он же знаменует царское достоинство Спасителя (на востоке в древности красный цвет считался царственным). Кроме того, красный цвет символизирует пасхальную радость и торжество. Таким образом, даря друг другу яйца и приветствуя один другого словами «Христос Воскресе!», православные исповедуют веру в Распятого и Воскресшего, в торжество Жизни над смертью, победу Правды над злом. Предполагается, что помимо названных причин первые христиане красили яйца в цвет крови не без намерения подражать ветхозаветному пасхальному обряду евреев, мазавших кровью жертвенных агнцев косяки и перекладины дверей своих домов (делая это по слову Божьему, во избежание поражения первенцев от Ангела-губителя) (Исх.12:7).

На Руси в древние времена пасхальному красному яйцу придавалось особое таинственное значение. Так, в одной русской рукописи XVI века скорлупа уподоблялась небу, внутренняя пленка («плева») — облакам, белок — во́дам, желток — земле, «сырость посреде́ яйца» (то есть, его жидкое состояние) — греху, а загустение яйца сопоставлялось с истреблением греха пролитием жертвенной крови Христа и Воскресением Христовым.

До христианства знало ли человечество обычай красить яйца?

Традиция окрашивания яиц появилась задолго до христианства, в далекой древности. В Африке найдены украшенные резьбой страусиные яйца, возрастом около 60 000 лет. Расписанные страусиные яйца, а также золотые и серебряные, часто встречаются в захоронениях древних шумеров и египтян, датируемых вплоть до начала III тысячелетия до Р. Х.

Когда, согласно преданию, в христианстве зародилась традиция красить яйца на Пасху?

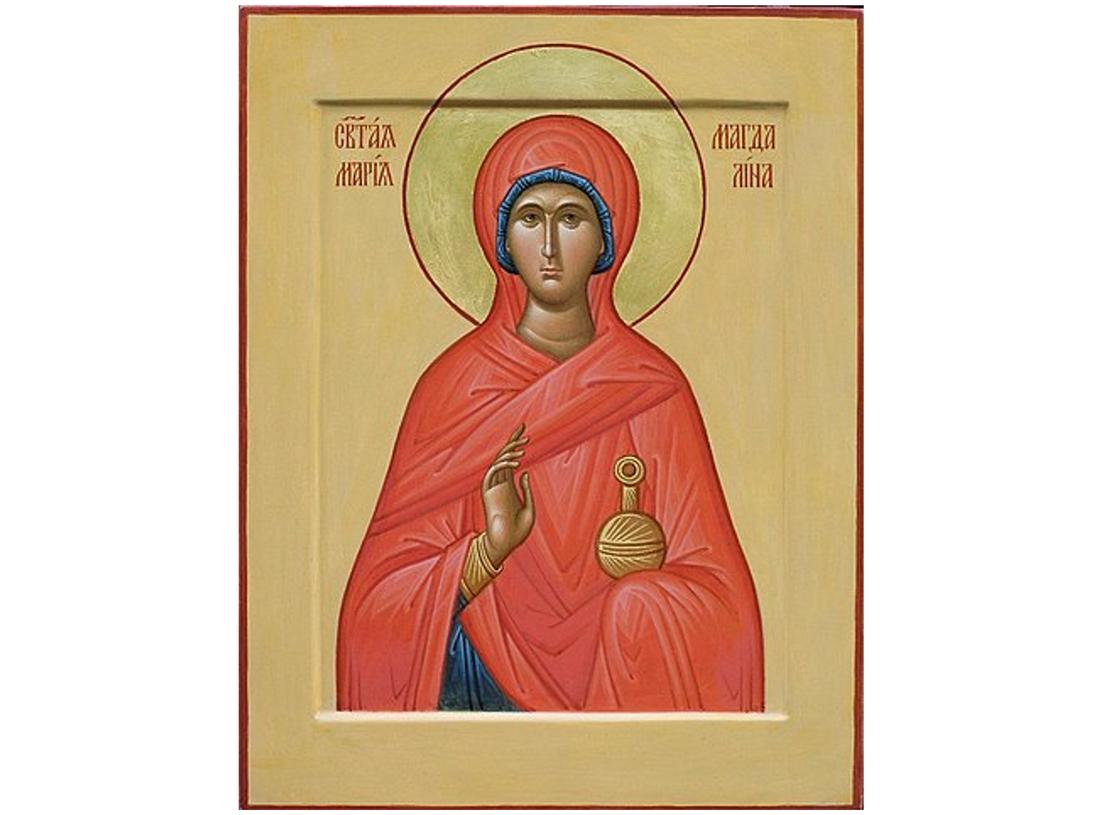

Христианская традиция красить яйца и дарить их друг другу на Пасху (при приветствии: Христос Воскресе!) восходит корнями к глубокой древности. Предание твердо связывает эту традицию с именем равноапостольной Марии Магдалины, которая, по Вознесении Господнем, отправилась в Рим, где встретилась с императором Тиверием, и проповедала ему Благовестие. Утверждается, что она начала свою проповедь словами «Христос Воскрес!» и подарила монарху красное яйцо.

Какие цвета кроме красного допустимы для пасхальных яиц?

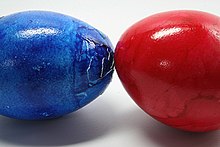

Со временем в практике окрашивания пасхальных яиц утвердились другие цвета, например, голубой (синий), напоминающий о Царстве Небесном, или зеленый, символизирующий возрождение к вечной блаженной жизни (духовную весну).

В наше время цвет для окрашивания яиц нередко выбирается не исходя из его символического значения, а на основе личных эстетических предпочтений, личной фантазии. Отсюда и столь большое количество цветов, вплоть до непредсказуемых.

Здесь важно помнить: цвет пасхальных яиц не должен быть траурным, мрачным (ведь Пасха — великий Праздник); кроме того, он не должен быть вызывающим, вычурным.

Можно ли расписывать пасхальные яйца?

Это не является грехом. Разные народы в разной мере сохранили древнюю традицию росписи пасхальных яиц. В старину даже существовала особая терминология для обозначения различий между крашеными и расписанными яйцами: крашенки — полностью окрашенные яйца; писанки — яйца, расписанные сюжетными и орнаментальными узорами. Яйца, снабженные узором в виде полосок, пятен и крапинок, именовались крапанками. При этом самым распространенным способом окрашивания яиц, пожалуй, был и остается способ с использованием луковой шелухи.

Можно ли украшать пасхальные яйца наклейками с иконами?

В настоящее время для украшения пасхальных яиц используются разнообразные виды наклеек, термопленка, зачастую снабженные изображениями Иисуса Христа, Богородицы, Ангелов, святых, храмов. Такая практика нередко подвергается критике в современной православной публицистике как профанация сакрального, поскольку через непродолжительное время указанным изображениям, скорее всего, предстоит стать частью бытового мусора. Необходимо учитывать: икона — не картинка; это — христианская святыня. И относиться к ней следует именно как к святыне.

Как правильно поступить со скорлупой от освященных яиц?

Некоторые, опасаясь прогневать Бога, стараются не выбрасывать в мусор скорлупу с освященных яиц: либо сжигают ее, либо закапывают в землю. Такая практика допустима, однако если яичная скорлупа не просто окрашена, а имеет нанесенные изображения Бога или Его святых, встает вопрос: насколько уместно сжигать или закапывать в землю лики святых; недалеко ли здесь до кощунства и святотатства.

Как самому освятить на Пасху яйца?

Существует традиция освящения пасхальных яиц (вместе с куличами и творожными пасхами). В Русской Православной Церкви освящение сопровождается «молитвой во еже благословити сыр и яйца» (то есть, на освящение сыра и яиц). Освятить яйца можно и самостоятельно, мирским чином. Для этого перед пасхальной трапезой (яйцами, куличом, пасхой) следует трижды пропеть тропарь Пасхи «Христо́с воскре́се из ме́ртвых, / сме́ртию смерть попра́в, / и су́щим во гробе́х живо́т дарова́в», затем окропить снеди освященной водой (если она есть) со словами: «Во имя Отца и Сына и Святаго Духа. Аминь».

Источники:

- Левашев П. Н. Обычай употребления красных яиц в праздник Пасхи / П. Левашев. — СПб.: тип. Катанского, 1895. — 8 с.

- Лебедев П. Я. Наука о богослужении православной церкви : В 2 ч. / Сост. преп. Моск. духов. семинарии Петр Лебедев. — 3‑е изд. — М.: кн. маг. В.В. Думнова, п/ф насл. бр. Салаевых, 1890. — 352 с.

- Пасха, христианский праздник // Энциклопедический словарь Брокгауза и Ефрона : в 86 т. (82 т. и 4 доп.). — СПб., 1890—1907.

- Коринфский А. А. Народная Русь: Круглый год сказаний, поверий, обычаев и пословиц рус. народа. — М.: М. В. Клюкин, 1901. — 724 с.

- Последование во Святую и Великую Неделю Пасхи и во всю Светлую седмицу. — М.: Издательство Московской Патриархии Русской Православной Церкви, 2012. — 176 с.

This article is about painted or chocolate eggs. For a secret message hidden in media, see Easter egg (media).

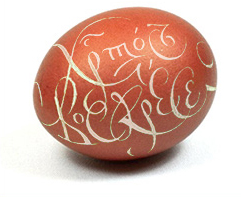

Easter egg of the Ukrainian variety with the Paschal greeting «Christ is Risen!»

Easter eggs, also called Paschal eggs,[1] are eggs that are decorated for the Christian feast of Easter, which celebrates the resurrection of Jesus. As such, Easter eggs are common during the season of Eastertide (Easter season). The oldest tradition, which continues to be used in Central and Eastern Europe, is to use dyed and painted chicken eggs.

Although eggs, in general, were a traditional symbol of fertility and rebirth,[2] in Christianity, for the celebration of Eastertide, Easter eggs symbolize the empty tomb of Jesus, from which Jesus was resurrected.[3][4][5] In addition, one ancient tradition was the staining of Easter eggs with the colour red «in memory of the blood of Christ, shed as at that time of his crucifixion.»[3][6]

This custom of the Easter egg, according to many sources, can be traced to early Christians of Mesopotamia, and from there it spread into Eastern Europe and Siberia through the Orthodox Churches, and later into Europe through the Catholic and Protestant Churches.[6][7][8][9] Mediaevalist scholars normally conclude that the custom of Easter eggs has its roots in the prohibition of eggs during Lent after which, on Easter, they have been blessed for the occasion.[10][11]

A modern custom in some places is to substitute chocolate eggs wrapped in coloured foil, hand-carved wooden eggs, or plastic eggs filled with confectionery such as chocolate.

History[edit]

The practice of decorating eggshells is quite ancient,[12] with decorated, engraved ostrich eggs found in Africa which are 60,000 years old.[13] In the pre-dynastic period of Egypt and the early cultures of Mesopotamia and Crete, eggs were associated with death and rebirth, as well as with kingship, with decorated ostrich eggs, and representations of ostrich eggs in gold and silver, were commonly placed in graves of the ancient Sumerians and Egyptians as early as 5,000 years ago.[14] These cultural relationships may have influenced early Christian and Islamic cultures in those areas, as well as through mercantile, religious, and political links from those areas around the Mediterranean.[15]

Red-coloured Easter egg with Christian cross, from the Saint Kosmas Aitolos Greek Orthodox Monastery

Eggs in Christianity carry a Trinitarian symbolism as shell, yolk, and albumen are three parts of one egg.[16] According to many sources, the Christian custom of Easter eggs was adopted from Persian tradition into the early Christians of Mesopotamia, who stained them with red colouring «in memory of the blood of Christ, shed at His crucifixion».[7][17][6][8][9] The Christian Church officially adopted the custom, regarding the eggs as a symbol of the resurrection of Jesus, with the Roman Ritual, the first edition of which was published in 1610 but which has texts of much older date, containing among the Easter Blessings of Food, one for eggs, along with those for lamb, bread, and new produce.[8][9]

Lord, let the grace of your blessing + come upon these eggs, that they be healthful food for your faithful who eat them in thanksgiving for the resurrection of our Lord Jesus Christ, who lives and reigns with you forever and ever.

Sociology professor Kenneth Thompson discusses the spread of the Easter egg throughout Christendom, writing that «use of eggs at Easter seems to have come from Persia into the Greek Christian Churches of Mesopotamia, thence to Russia and Siberia through the medium of Orthodox Christianity. From the Greek Church the custom was adopted by either the Roman Catholics or the Protestants and then spread through Europe.»[7] Both Thompson, as well as British orientalist Thomas Hyde state that in addition to dyeing the eggs red, the early Christians of Mesopotamia also stained Easter eggs green and yellow.[6][7]

Peter Gainsford maintains that the association between eggs and Easter most likely arose in western Europe during the Middle Ages as a result of the fact that Catholic Christians were prohibited from eating eggs during Lent, but were allowed to eat them when Easter arrived.[10][11]

Influential 19th century folklorist and philologist Jacob Grimm speculates, in the second volume of his Deutsche Mythologie, that the folk custom of Easter eggs among the continental Germanic peoples may have stemmed from springtime festivities of a Germanic goddess known in Old English as Ēostre (namesake of modern English Easter) and possibly known in Old High German as *Ostara (and thus namesake of Modern German Ostern ‘Easter’). However, despite Grimm’s speculation, there is no evidence to connect eggs with Ostara.[11] The use of eggs as favors or treats at Easter originated when they were prohibited during Lent.[10][11] A common practice in England in the medieval period was for children to go door-to-door begging for eggs on the Saturday before Lent began. People handed out eggs as special treats for children prior to their fast.[11]

Although one of the Christian traditions are to use dyed or painted chicken eggs, a modern custom is to substitute chocolate eggs, or plastic eggs filled with candy such as jelly beans; as many people give up sweets as their Lenten sacrifice, individuals enjoy them at Easter after having abstained from them during the preceding forty days of Lent.[18] These eggs can be hidden for children to find on Easter morning, which may be left by the Easter Bunny. They may also be put in a basket filled with real or artificial straw to resemble a bird’s nest.

Traditions and customs[edit]

Blessing of Easter foods in Poland

Lenten tradition[edit]

The Easter egg tradition may also have merged into the celebration of the end of the privations of Lent. Traditionally, eggs are among the foods forbidden fast days, including all of Lent, an observance which continues among the Eastern Christian Churches but has fallen into disuse in Western Christianity (although something similar has recently been instituted by a few as the “Daniel Fast»).

Historically, it has been traditional to use up all of the household’s eggs before Lent began.

This established the tradition of Pancake Day being celebrated on Shrove Tuesday. This day, the Tuesday before Ash Wednesday when Lent begins, is also known as Mardi Gras, a French phrase which translates as «Fat Tuesday» to mark the last consumption of eggs and dairy before Lent begins.

In the Orthodox Church, Great Lent begins on Clean Monday, rather than Wednesday, so the household’s dairy products would be used up in the preceding week, called Cheesefare Week.

During Lent, since chickens would not stop producing eggs during this time, a larger than usual store might be available at the end of the fast. This surplus, if any, had to be eaten quickly to prevent spoiling. Then, with the coming of Easter, the eating of eggs resumes. Some families cook a special meatloaf with eggs in it to be eaten with the Easter dinner.

One would have been forced to hard boil the eggs that the chickens produced so as not to waste food, and for this reason the Spanish dish hornazo (traditionally eaten on and around Easter) contains hard-boiled eggs as a primary ingredient.

In Hungary, eggs are used sliced in potato casseroles around the Easter period.

Symbolism and related customs[edit]

Some Christians symbolically link the cracking open of Easter eggs with the empty tomb of Jesus.[19]

In the Orthodox churches, Easter eggs are blessed by the priest at the end of the Paschal Vigil (which is equivalent to Holy Saturday), and distributed to the faithful. The egg is seen by followers of Christianity as a symbol of resurrection: while being dormant it contains a new life sealed within it.[3][4]

Similarly, in the Roman Catholic Church in Poland, the so-called święconka, i.e. blessing of decorative baskets with a sampling of Easter eggs and other symbolic foods, is one of the most enduring and beloved Polish traditions on Holy Saturday.

During Paschaltide, in some traditions the Pascal greeting with the Easter egg is even extended to the deceased. On either the second Monday or Tuesday of Pascha, after a memorial service people bring blessed eggs to the cemetery and bring the joyous paschal greeting, «Christ has risen», to their beloved departed (see Radonitza).

In Greece, women traditionally dye the eggs with onion skins and vinegar on Thursday (also the day of Communion). These ceremonial eggs are known as kokkina avga. They also bake tsoureki for the Easter Sunday feast.[20] Red Easter eggs are sometimes served along the centerline of tsoureki (braided loaf of bread).[21][22]

In Egypt, it is a tradition to decorate boiled eggs during Sham el-Nessim holiday, which falls every year after the Eastern Christian Easter.

Coincidentally, every Passover, Jews place a hard-boiled egg on the Passover ceremonial plate, and the celebrants also eat hard-boiled eggs dipped in salt water as part of the ceremony.

Colouring[edit]

Easter eggs before and after colouring

Heated wax paint used to decorate traditional Easter Eggs in the Czech Republic

The dyeing of Easter eggs in different colours is commonplace, with colour being achieved through boiling the egg in natural substances (such as, onion peel (brown colour), oak or alder bark or walnut nutshell (black), beet juice (pink) etc.), or using artificial colourings.

A greater variety of colour was often provided by tying on the onion skin with different coloured woollen yarn. In the North of England these are called pace-eggs or paste-eggs, from a dialectal form of Middle English pasche. King Edward I’s household accounts in 1290 list an item of ‘one shilling and sixpence for the decoration and distribution of 450 Pace-eggs!’,[23] which were to be coloured or gilded and given to members of the royal household.[24] Traditionally in England, eggs were wrapped in onion skins and boiled to make their shells look like mottled gold, or wrapped in flowers and leaves first in order to leave a pattern, which parallels a custom practised in traditional Scandinavian culture.[25] Eggs could also be drawn on with a wax candle before staining, often with a person’s name and date on the egg.[24] Pace Eggs were generally eaten for breakfast on Easter Sunday breakfast. Alternatively, they could be kept as decorations, used in egg-jarping (egg tapping) games, or given to Pace Eggers. In more recent centuries in England, eggs have been stained with coffee grains[24] or simply boiled and painted in their shells.[26]

In the Orthodox and Eastern Catholic Churches, Easter eggs are dyed red to represent the blood of Christ, with further symbolism being found in the hard shell of the egg symbolizing the sealed Tomb of Christ — the cracking of which symbolized his resurrection from the dead. The tradition of red easter eggs was used by the Russian Orthodox Church.[27] The tradition to dyeing the easter eggs in an Onion tone exists in the cultures of Armenia, Georgia, Belarus, Russia, Czechia, Romania, Slovenia, and Israel.[28] The colour is made by boiling onion peel in water.[29][30]

Patterning[edit]

When boiling them with onion skins, leaves can be attached prior to dyeing to create leaf patterns. The leaves are attached to the eggs before they are dyed with a transparent cloth to wrap the eggs with like inexpensive muslin or nylon stockings, leaving patterns once the leaves are removed after the dyeing process.[31][32] These eggs are part of Easter custom in many areas and often accompany other traditional Easter foods. Passover haminados are prepared with similar methods.

Pysanky[33] are Ukrainian Easter eggs, decorated using a wax-resist (batik) method. The word comes from the verb pysaty, «to write», as the designs are not painted on, but written with beeswax.

Decorating eggs for Easter using wax resistant batik is a popular method in some other eastern European countries.

Use of Easter eggs in decorations[edit]

In some Mediterranean countries, especially in Lebanon, chicken eggs are boiled and decorated by dye and/or painting and used as decoration[34] around the house. Then, on Easter Day, young kids would duel with them saying ‘Christ is resurrected, Indeed, He is’, breaking and eating them. This also happens in Georgia, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Greece, North Macedonia, Romania, Russia, Serbia and Ukraine. In Easter Sunday friends and family hit each other’s egg with their own. The one whose egg does not break is believed to be in for good luck in the future.

In Germany, eggs decorate trees and bushes as Easter egg trees, and in several areas public wells as Osterbrunnen.

There used to be a custom in Ukraine, during Easter celebrations to have krashanky on a table in a bowl with wheatgrass. The number of the krashanky equalled the number of departed family members.[35]

-

Ukrainian Easter eggs

-

Perforated egg from Germany, Sleeping Beauty

-

Norwegian Easter eggs

-

-

Perforated eggs

-

-

Pace eggs boiled with onion skins and leaf patterns.

-

Easter eggs decorated with straw

-

-

Easter egg games[edit]

Egg hunts[edit]

An egg hunt is a game in which decorated eggs, which may be hard-boiled chicken eggs, chocolate eggs, or artificial eggs containing candies, are hidden for children to find. The eggs often vary in size, and may be hidden both indoors and outdoors.[36] When the hunt is over, prizes may be given for the largest number of eggs collected, or for the largest or the smallest egg.[36]

Some central European nations (Czechs and Slovaks etc.) have a tradition of gathering eggs by gaining them from the females in return of whipping them with a pony-tail shaped whip made out of fresh willow branches and splashing them with water, by the Ruthenians called polivanja, which is supposed to give them health and beauty.

Cascarones, a Latin American tradition now shared by many US States with high Hispanic demographics, are emptied and dried chicken eggs stuffed with confetti and sealed with a piece of tissue paper. The eggs are hidden in a similar tradition to the American Easter egg hunt and when found the children (and adults) break them over each other’s heads.

In order to enable children to take part in egg hunts despite visual impairment, eggs have been created that emit various clicks, beeps, noises, or music so that visually impaired children can easily hunt for Easter eggs.[37]

Egg rolling[edit]

Egg rolling is also a traditional Easter egg game played with eggs at Easter. In the United Kingdom, Germany, and other countries children traditionally rolled eggs down hillsides at Easter.[38] This tradition was taken to the New World by European settlers,[38][39] and continues to this day each Easter with an Easter egg roll on the White House lawn. Rutherford B. Hayes started the tradition of the Easter Egg Roll at the White House.[40] The Easter Monday Egg Roll was normally held at the United States Capitol, however, by the mid-1870s, Congress passed a law forbidding the Capitol’s grounds to be used for the activity due to the toll it was taking on the landscape.[40] The law was enforced in 1877, but the rain that year canceled all outdoor activities.[40] In 1878, Hayes was approached by many young easter egg rollers who asked for the event to be held at the White House.[40] He invited any children who wanted to roll eggs to come to the White House in order to do so. The tradition still occurs every year on the South Lawn of the White House. Now, there are many other games and activities that take place such as “Egg Picking” and “Egg Ball.”[40] Different nations have different versions of the Easter Egg roll game.

Egg tapping[edit]

Eggs after an egg tapping competition (red wins)

In the North of England, during Eastertide, a traditional game is played where hard boiled pace eggs are distributed and each player hits the other player’s egg with their own. This is known as «egg tapping», «egg dumping», or «egg jarping». The winner is the holder of the last intact egg. The annual egg jarping world championship is held every year over Easter in Peterlee, Durham.[41]

It is also practiced in Italy (where it is called scuccetta), Bulgaria, Hungary, Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Lebanon, North Macedonia, Romania, Serbia, Slovenia (where it is called turčanje or trkanje), Ukraine, Russia, and other countries. In parts of Austria, Bavaria and German-speaking Switzerland it is called Ostereiertitschen or Eierpecken. In parts of Europe it is also called epper, presumably from the German name Opfer, meaning «offering» and in Greece it is known as tsougrisma. In South Louisiana, this practice is called pocking eggs[42][43] and is slightly different. The Louisiana Creoles hold that the winner eats the eggs of the losers in each round.

In the Greek Orthodox tradition, red eggs are also cracked together when people exchange Easter greetings.

Egg dance[edit]

Egg dance is a traditional Easter game in which eggs are laid on the ground or floor and the goal is to dance among them without damaging any eggs[44] which originated in Germany.

Pace egg plays[edit]

The Pace Egg plays are traditional village plays, with a rebirth theme. The drama takes the form of a combat between the hero and villain, in which the hero is killed and brought back to life. The plays take place in England during Easter.

In some countries like Sweden, Norway, Poland and Germany eggs are used as a table decoration hanging on a tree-branch

Variants[edit]

Chocolate[edit]

Chocolate eggs first appeared at the court of Louis XIV in Versailles and in 1725 the widow Giambone in Turin started producing chocolate eggs by filling empty chicken egg shells with molten chocolate.[45] In 1873 J.S. Fry & Sons of England introduced the first chocolate Easter egg in Britain. Manufacturing their first Easter egg in 1875, Cadbury created the modern chocolate Easter egg after developing a pure cocoa butter that could be moulded into smooth shapes.[46]

In Western cultures, the giving of chocolate eggs is now commonplace, with 80 million Easter eggs sold in the UK alone. Formerly, the containers Easter eggs were sold in contained large amounts of plastic, although in the United Kingdom this has gradually been replaced with recyclable paper and cardboard.[47]

-

Chocolate Easter egg bunny

-

Easter egg with candy.

Marzipan eggs[edit]

In the Indian state of Goa, the Goan Catholic version of marzipan is used to make easter eggs. In the Philippines, mazapán de pili (Spanish for «pili marzipan») is made from pili nuts.

-

Marzipan easter eggs

Artificial eggs[edit]

The jewelled Easter eggs made by the Fabergé firm for the two last Russian Tsars are regarded as masterpieces of decorative arts. Most of these creations themselves contained hidden surprises such as clock-work birds, or miniature ships.

In Bulgaria, Poland, Romania, Russia, Ukraine, and other Central European countries’ folk traditions, Easter eggs are carved from wood and hand-painted, and making artificial eggs out of porcelain for ladies is common.[48]: 45

Easter eggs are frequently depicted in sculpture, including a 8-metre (27 ft) sculpture of a pysanka standing in Vegreville, Alberta.

-

-

Easter egg sculpture in Gogolin, Poland

-

Giant easter egg in Suceava, Romania

[edit]

Christian traditions[edit]

While the origin of Easter eggs can be explained in the symbolic terms described above, among followers of Eastern Christianity the legend says that Mary Magdalene was bringing cooked eggs to share with the other women at the tomb of Jesus, and the eggs in her basket miraculously turned bright red when she saw the risen Christ.[49]

A different, but not necessarily conflicting legend concerns Mary Magdalene’s efforts to spread the Gospel. According to this tradition, after the Ascension of Jesus, Mary went to the Emperor of Rome and greeted him with «Christ has risen,» whereupon he pointed to an egg on his table and stated, «Christ has no more risen than that egg is red.» After making this statement it is said the egg immediately turned blood red.[50][51]

Red Easter eggs, known as kokkina avga (κόκκινα αυγά) in Greece and krashanki in Ukraine, are an Easter tradition and a distinct type of Easter egg prepared by various Orthodox Christian peoples.[52][53][54][55][56] The red eggs are part of Easter custom in many areas and often accompany other traditional Easter foods. Passover haminados are prepared with similar methods.

Dark red eggs are a tradition in Greece and represent the blood of Christ shed on the cross.[57] The practice dates to the early Christian church in Mesopotamia.[8][9]

In Greece, superstitions of the past included the custom of placing the first-dyed red egg at the home’s iconostasis (place where icons are displayed) to ward off evil. The heads and backs of small lambs were also marked with the red dye to protect them.

Parallels in other faiths[edit]

The egg is widely used as a symbol of the start of new life, just as new life emerges from an egg when the chick hatches out.[2]

Painted eggs are used at the Iranian spring holidays, the Nowruz that marks the first day of spring or Equinox, and the beginning of the year in the Persian calendar. It is celebrated on the day of the astronomical Northward equinox, which usually occurs on March 21 or the previous/following day depending on where it is observed. The painted eggs symbolize fertility and are displayed on the Nowruz table, called Haft-Seen together with various other symbolic objects. There are sometimes one egg for each member of the family. The ancient Zoroastrians painted eggs for Nowruz, their New Year celebration, which falls on the Spring equinox. The tradition continues among Persians of Islamic, Zoroastrian, and other faiths today.[58] The Nowruz tradition has existed for at least 2,500 years. The sculptures on the walls of Persepolis show people carrying eggs for Nowruz to the king.[citation needed]

The Neopagan holiday of Ostara occurs at roughly the same time as Easter. While it is often claimed that the use of painted eggs is an ancient, pre-Christian component of the celebration of Ostara, there are no historical accounts that ancient celebrations included this practice, apart from the Old High German lullaby which is believed by most to be a modern fabrication. Rather, the use of painted eggs has been adopted under the assumption that it might be a pre-Christian survival. In fact, modern scholarship has been unable to trace any association between eggs and a supposed goddess named Ostara before the 19th century, when early folklorists began to speculate about the possibility.[59]

There are good grounds for the association between hares (later termed Easter bunnies) and bird eggs, through folklore confusion between hares’ forms (where they raise their young) and plovers’ nests.[60]

In Judaism, a hard-boiled egg is an element of the Passover Seder, representing festival sacrifice. The children’s game of hunting for the afikomen (a half-piece of matzo) has similarities to the Easter egg hunt tradition, by which the child who finds the hidden matzah will be awarded a prize. In other homes, the children hide the afikoman and a parent must look for it; when the parents give up, the children demand a prize for revealing its location.

See also[edit]

- Balut

- Century egg

- Chinese red eggs

- Cascarón

- Easter Bilby

- Egg decorating in Slavic culture

- Festum Ovorum

- Kinder Surprise

- List of egg dishes

- List of foods with religious symbolism

- Resurrection of Jesus

- Salted duck egg

- Sham El Nessim

- Smoked egg

- Tea egg

- Vegreville egg

- Washi eggs

References[edit]

- ^ «The Legend of Paschal Eggs (Holy Cross Antiochian Orthodox Church)» (PDF).

- ^ a b David Leeming (2005). The Oxford Companion to World Mythology. Oxford University Press. p. 111. Retrieved 10 March 2013.

For many, Easter is synonymous with fertility symbols such as the Easter Rabbit, Easter Eggs, and the Easter lily.

- ^ a b c Anne Jordan (5 April 2000). Christianity. Nelson Thornes. ISBN 9780748753208. Retrieved 7 April 2012.

Easter eggs are used as a Christian symbol to represent the empty tomb. The outside of the egg looks dead but inside there is new life, which is going to break out. The Easter egg is a reminder that Jesus will rise from His tomb and bring new life. Orthodox Christians dye boiled eggs red to make red Easter eggs that represent the blood of Christ shed for the sins of the world.

- ^ a b The Guardian, Volume 29. H. Harbaugh. 1878. Retrieved 7 April 2012.

Just so, on that first Easter morning, Jesus came to life and walked out of the tomb, and left it, as it were, an empty shell. Just so, too, when the Christian dies, the body is left in the grave, an empty shell, but the soul takes wings and flies away to be with God. Thus you see that though an egg seems to be as dead as a stone, yet it really has life in it; and also it is like Christ’s dead body, which was raised to life again. This is the reason we use eggs on Easter. (In days past some used to color the eggs red, so as to show the kind of death by which Christ died,-a bloody death.)

- ^ Gordon Geddes, Jane Griffiths (22 January 2002). Christian belief and practice. Heinemann. ISBN 9780435306915. Retrieved 7 April 2012.

Red eggs are given to Orthodox Christians after the Easter Liturgy. They crack their eggs against each other’s. The cracking of the eggs symbolizes a wish to break away from the bonds of sin and misery and enter the new life issuing from Christ’s resurrection.

- ^ a b c d Henry Ellis (1877). Popular antiquities of Great Britain. p. 90. Retrieved 26 March 2016.

Hyde, in his Oriental Sports (1694), tells us one with eggs among the Christians of Mesopotamia on Easter Day and forty days afterwards, during which time their children buy themselves as many eggs as they can, stain them with a red colour in memory of the blood of Christ, shed as at that time of his crucifixion. Some tinge them with green and yellow.

- ^ a b c d Thompson, Kenneth (21 August 2013). Culture & Progress: Early Sociology of Culture, Volume 8. Routledge. p. 138. ISBN 9781136479403.

In Mesopotamia children secured during the 40-day period following Easter day as many eggs as possible and dyed them red, «in memory of the blood of Christ shed at that time of his Crucifixion»—a rationalization. Dyed eggs were sold in the market, green and yellow being favorite colors. The use of eggs at Easter seems to have come from Persia into the Greek Christian Churches of Mesopotamia, thence to Russia and Siberia through the medium of Orthodox Christianity. From the Greek Church the custom was adopted by either the Roman Catholics or the Protestants and then spread through Europe.

- ^ a b c d Donahoe’s Magazine, Volume 5. T.B. Noonan. 1881. Retrieved 7 April 2012.

The early Christians of Mesopotamia had the custom of dyeing and decorating eggs at Easter. They were stained red, in memory of the blood of Christ, shed at His crucifixion. The Church adopted the custom, and regarded the eggs as the emblem of the resurrection, as is evinced by the benediction of Pope Paul V., about 1610, which reads thus: «Bless, O Lord! we beseech thee, this thy creature of eggs, that it may become a wholesome sustenance to thy faithful servants, eating it in thankfulness to thee on account of the resurrection of the Lord.» Thus the custom has come down from ages lost in antiquity.)

- ^ a b c d Vicki K. Black (1 July 2004). Welcome to the Church Year: An Introduction to the Seasons of the Episcopal Church. Church Publishing, Inc. ISBN 9780819219664.

The Christians of this region in Mesopotamia were probably the first to connect the decorating of eggs with the feast of the resurrection of Christ, and by the Middle Ages this practice was so widespread that in some places Easter Day was called Egg Sunday. In parts of Europe, the eggs were dyed red and were then cracked together when people exchanged Easter greetings. Many congregations today continue to have Easter egg hunts for the children after services on Easter Day.

- ^ a b c Gainsford, Peter (26 March 2018). «Easter and paganism. Part 2». Kiwi Hellenist. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- ^ a b c d e D’Costa, Krystal. «Beyond Ishtar: The Tradition of Eggs at Easter». Scientific American. Archived from the original on 28 March 2018. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ^ Neil R. Grobman (1981). Wycinanki and pysanky: forms of religious and ethnic folk art from the Delaware Valley. University of Pittsburgh. Retrieved 18 April 2014.

During the spring cycle of festivals, ancient pre-Christian peoples used decorated eggs to welcome the sun and to help ensure the fertility of the fields, river …

- ^ «Egg Cetera #6: Hunting for the world’s oldest decorated eggs | University of Cambridge». Cam.ac.uk. 2012-04-10. Retrieved 2013-03-31.

- ^ Treasures from Royal Tombs of Ur By Richard L. Zettler, Lee Horne, Donald P. Hansen, Holly Pittman 1998 pgs 70-72

- ^ Green, Nile (2006). «Ostrich Eggs and Peacock feathers: Sacred Objects as Cultural Exchange between Christianity and Islam». Al-Masaq: Journal of the Medieval Mediterranean. 18 (1).

This article uses the wide dispersal of ostrich eggs and peacock feathers among the different cultural contexts of the Mediterranean – and beyond into the Indian Ocean world – to explore the nature and limits of cultural inheritance and exchange between Christianity and Islam. These avian materials previously possessed symbolic meaning and material value as early as the pre-dynastic period in Egypt, as well as amid the early cultures of Mesopotamia and Crete. The main early cultural associations of the eggs and feathers were with death/resurrection and kingship respectively, a symbolism that was passed on into early Christian and Muslim usage. Mercantile, religious and political links across the premodern Mediterranean meant that these items found parallel employment all around the Mediterranean littoral, and beyond it, in Arabia, South Asia and Africa.

- ^ Murray, Michael J.; Rea, Michael C. (20 March 2008). An Introduction to the Philosophy of Religion. Cambridge University Press. p. 68. ISBN 978-1-139-46965-4.

- ^ Williams, Victoria (21 November 2016). Celebrating Life Customs around the World. ABC-CLIO. p. 2. ISBN 9781440836596.

The history of the Easter egg can be traced back to the time of the advent of Christianity in Mesopotamia (around the first to the third century), when people use to stain eggs red as a reminder of the blood spilled by Christ during the Crucifixion. In time, the Christian church in general adopted this custom with the eggs considered to be a symbol of both Christ’s death and Resurrection. Moreover, in the earliest days of Christianity Easter eggs were considered symbolic of the tomb in which Jesus’s corpse was laid after the Crucifixion for eggs, as a near universal symbol of fertility and life, were like Jesus’s tomb, something from which new life came forth.

- ^ Shoda, Richard W. (2014). Saint Alphonsus: Capuchins, Closures, and Continuity (1956-2011). Dorrance Publishing. p. 128. ISBN 978-1-4349-2948-8.

- ^ Allen, Emily (25 December 2016). «When is Easter 2016? What are the dates for Good Friday, Easter Sunday and Easter Monday». The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 24 February 2016. Retrieved 26 February 2016.

Eggs illustrate new life, just as Jesus began his new life on East Sunday after the miracle of his resurrection. When eggs are cracked open they are said to symbolise an empty tomb.

- ^ Wagstaff, Natalie. «Kalo Paska — Happy Easter». Archived from the original on 2014-12-26. Retrieved 2014-12-10.

- ^ Walker, Judy. «Today’s Recipe from Our Files: Greek Easter bread, Tsoueki». NOLA.com. Retrieved 18 December 2022.

- ^ Red and Butter, Martha Stewart magazine

- ^ «Pace Egging». Historic UK. Retrieved 2021-02-16.

- ^ a b c «How did giving these become a Yorkshire tradition at Easter?». York Press. Retrieved 2021-02-16.

- ^ Hall, Stephanie (2017-04-06). «The Ancient Art of Decorating Eggs | Folklife Today». blogs.loc.gov. Retrieved 2021-02-16.

- ^ «Pace Egging: A Lancashire Tradition». www.timetravel-britain.com. Retrieved 2021-02-16.

- ^ «In Russia the Color Red Represents More Than You Know». TripSavvy. Retrieved 2019-03-19.

- ^ «How To Dye Easter Eggs with Onion Skins». Kitchn. Retrieved 2019-03-19.

- ^ Sorokina, Anna (2018-03-29). «How to paint Easter eggs with onion, coffee and beets (PHOTOS)». www.rbth.com. Retrieved 2019-03-19.

- ^ DONORSGrajewski, DONORS GOLDEN; rzej; Asia, Hołdys; Tomasz, Horbowski; Wojciech, Jakóbik; Kostek; rzej; Paweł, Lickiewicz; Filip, Lachert (2015-03-28). «The Easter Traditions in Belarus». Eastbook.eu. Archived from the original on 2019-03-29. Retrieved 2019-03-19.

- ^ «How to Dye Easter eggs naturally without a box onion skins beets cabbage». seriouseats.com.

- ^ «Natural Easter Eggs 3 Ways!/ with nylon stockings». natashaskitchen.com. 20 March 2013.

- ^ Culture – Pysanky, Ukrainian International Directory

- ^ «Osterdeko — fünf Ideen rund um das Osterei | Anton Doll Holzmanufaktur». www.antondoll.de. Retrieved 2020-08-18.

- ^ Yakovenko, Svitlana 2017, “The Magical Dyed Egg – Krashanka” in Traditional Velykden: Ukrainian Easter Recipes Archived 2017-03-26 at the Wayback Machine, Sova Books, Sydney

- ^ a b A. Munsey Pu Frank a. Munsey Publishers (March 2005). The Puritan April to September 1900. Kessinger Publishing. p. 119. ISBN 978-1-4191-7421-6.

- ^ Tillery, Carolyn (2008-03-15). «Annual Dallas Easter egg hunt for blind children scheduled for Thursday». The Dallas Morning News. Retrieved 2008-03-27.

- ^ a b «Easter Eggs — Egg Rolling». Inventors.about.com. 2012-04-09. Retrieved 2012-09-24.

- ^ «Easter Eggs: their origins, tradition and symbolism». Wyrdology.com. Archived from the original on 2008-05-17. Retrieved 2008-03-15.

- ^ a b c d e History of the White House Easter Egg Roll

- ^ Hutchinson, Pamela (8 April 2012). «Egg jarping: when hard-boiled eggs come to blows». The Guardian. Retrieved 14 June 2019.

- ^ «Pocking eggs or la toquette». Creolecajun.blogspot.com. 17 March 2008. Retrieved 2008-03-20.

- ^ «If Your Eggs Are Cracked, Please Step Down: Easter Egg Knocking in Marksville». Retrieved 2008-03-20.

- ^ Venetia Newall (1971). An egg at Easter: a folklore study. Routledge & K. Paul. p. 344. ISBN 978-0-7100-6845-3.

- ^ Caramia, G; Degl’Innocenti, D; Mozzon, M; Pacetti, D; Frega, NG (2012). «[The role of eggs in the diet: nutraceutical and epigenetic aspects]». La Pediatria Medica e Chirurgica: Medical and Surgical Pediatrics. 34 (2): 53–64. doi:10.4081/pmc.2012.1. PMID 22730629.

- ^ «Amazing archive images show how Cadbury cracked Easter egg market». Birmingham Mail. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

- ^ «The End of Egg-cessive Easter Waste??». Waste connect. Retrieved 15 April 2014.

- ^ Anderson, F.L.M., 1864, Seven Months’ Residence in Russian Poland in 1868, London:Macmillan and Co.

- ^ «Traditions of Great Lent and Holy Week». Melkite Greek Catholic Eparchy of Newton. Archived from the original on 2012-01-22. Retrieved 2012-09-24.

- ^ Terry Tempest Williams (September 18, 2001). Leap. Random House Digital, Inc. ISBN 9780679752578. Retrieved 7 April 2012.

After the Ascension, she travelled to Rome and was granted entrance to the court of Tiberius Caesar. At dinner, she told Caesar that Jesus had risen from the dead. He did not understand. To explain, Mary Magdalene picked up an egg from the table. Caesar responded by saying that a human being could no more rise from the dead than the egg in her hand turn red. The egg turned red.

- ^ Newall, Venetia (1971). An egg at Easter: a folklore study. p. 216. ISBN 9780710068453.

In Russian tradition an egg, which she held in her hand, turned red, as a proof of the Resurrection.

- ^ Red eggs at Pascha EasterArchived 2018-04-05 at the Wayback Machine he Most Useful KNOWLEDGE for the Orthodox Russian-American Young People,” compiled by the Very Rev’d Peter G. Kohanik, 1932-1934.

- ^ «Easter EGG». stdgocunion.org. Archived from the original on 21 December 2014. Retrieved 18 December 2022.

- ^ «Your Guide to the Food and Traditions of Greek Orthodox Easter».

- ^ «Red Easter Eggs — Questions & Answers». www.oca.org. Retrieved 18 December 2022.

- ^ Graham, Stephen (1905). With the Russian pilgrims to Jerusalem. T. Nelson. p. 245.

- ^ Red eggs About.com

- ^ «Photos: Painted eggs across Tehran». The other Iran. 2016-03-26. Retrieved 2018-04-02.

- ^ Winick, Stephen. Ostara and the Hare: Not Ancient, but Not As Modern As Some Skeptics Think. Folklife Today, 28 Apr 2016. Accessed 8 May 2019 at https://blogs.loc.gov/folklife/2016/04/ostara-and-the-hare/

- ^ «H2g2 — The Easter Bunny». BBC.com. Retrieved 2012-09-24.

External links[edit]

Media related to Easter eggs at Wikimedia Commons

This article is about painted or chocolate eggs. For a secret message hidden in media, see Easter egg (media).

Easter egg of the Ukrainian variety with the Paschal greeting «Christ is Risen!»

Easter eggs, also called Paschal eggs,[1] are eggs that are decorated for the Christian feast of Easter, which celebrates the resurrection of Jesus. As such, Easter eggs are common during the season of Eastertide (Easter season). The oldest tradition, which continues to be used in Central and Eastern Europe, is to use dyed and painted chicken eggs.

Although eggs, in general, were a traditional symbol of fertility and rebirth,[2] in Christianity, for the celebration of Eastertide, Easter eggs symbolize the empty tomb of Jesus, from which Jesus was resurrected.[3][4][5] In addition, one ancient tradition was the staining of Easter eggs with the colour red «in memory of the blood of Christ, shed as at that time of his crucifixion.»[3][6]

This custom of the Easter egg, according to many sources, can be traced to early Christians of Mesopotamia, and from there it spread into Eastern Europe and Siberia through the Orthodox Churches, and later into Europe through the Catholic and Protestant Churches.[6][7][8][9] Mediaevalist scholars normally conclude that the custom of Easter eggs has its roots in the prohibition of eggs during Lent after which, on Easter, they have been blessed for the occasion.[10][11]

A modern custom in some places is to substitute chocolate eggs wrapped in coloured foil, hand-carved wooden eggs, or plastic eggs filled with confectionery such as chocolate.

History[edit]

The practice of decorating eggshells is quite ancient,[12] with decorated, engraved ostrich eggs found in Africa which are 60,000 years old.[13] In the pre-dynastic period of Egypt and the early cultures of Mesopotamia and Crete, eggs were associated with death and rebirth, as well as with kingship, with decorated ostrich eggs, and representations of ostrich eggs in gold and silver, were commonly placed in graves of the ancient Sumerians and Egyptians as early as 5,000 years ago.[14] These cultural relationships may have influenced early Christian and Islamic cultures in those areas, as well as through mercantile, religious, and political links from those areas around the Mediterranean.[15]

Red-coloured Easter egg with Christian cross, from the Saint Kosmas Aitolos Greek Orthodox Monastery

Eggs in Christianity carry a Trinitarian symbolism as shell, yolk, and albumen are three parts of one egg.[16] According to many sources, the Christian custom of Easter eggs was adopted from Persian tradition into the early Christians of Mesopotamia, who stained them with red colouring «in memory of the blood of Christ, shed at His crucifixion».[7][17][6][8][9] The Christian Church officially adopted the custom, regarding the eggs as a symbol of the resurrection of Jesus, with the Roman Ritual, the first edition of which was published in 1610 but which has texts of much older date, containing among the Easter Blessings of Food, one for eggs, along with those for lamb, bread, and new produce.[8][9]

Lord, let the grace of your blessing + come upon these eggs, that they be healthful food for your faithful who eat them in thanksgiving for the resurrection of our Lord Jesus Christ, who lives and reigns with you forever and ever.

Sociology professor Kenneth Thompson discusses the spread of the Easter egg throughout Christendom, writing that «use of eggs at Easter seems to have come from Persia into the Greek Christian Churches of Mesopotamia, thence to Russia and Siberia through the medium of Orthodox Christianity. From the Greek Church the custom was adopted by either the Roman Catholics or the Protestants and then spread through Europe.»[7] Both Thompson, as well as British orientalist Thomas Hyde state that in addition to dyeing the eggs red, the early Christians of Mesopotamia also stained Easter eggs green and yellow.[6][7]

Peter Gainsford maintains that the association between eggs and Easter most likely arose in western Europe during the Middle Ages as a result of the fact that Catholic Christians were prohibited from eating eggs during Lent, but were allowed to eat them when Easter arrived.[10][11]

Influential 19th century folklorist and philologist Jacob Grimm speculates, in the second volume of his Deutsche Mythologie, that the folk custom of Easter eggs among the continental Germanic peoples may have stemmed from springtime festivities of a Germanic goddess known in Old English as Ēostre (namesake of modern English Easter) and possibly known in Old High German as *Ostara (and thus namesake of Modern German Ostern ‘Easter’). However, despite Grimm’s speculation, there is no evidence to connect eggs with Ostara.[11] The use of eggs as favors or treats at Easter originated when they were prohibited during Lent.[10][11] A common practice in England in the medieval period was for children to go door-to-door begging for eggs on the Saturday before Lent began. People handed out eggs as special treats for children prior to their fast.[11]

Although one of the Christian traditions are to use dyed or painted chicken eggs, a modern custom is to substitute chocolate eggs, or plastic eggs filled with candy such as jelly beans; as many people give up sweets as their Lenten sacrifice, individuals enjoy them at Easter after having abstained from them during the preceding forty days of Lent.[18] These eggs can be hidden for children to find on Easter morning, which may be left by the Easter Bunny. They may also be put in a basket filled with real or artificial straw to resemble a bird’s nest.

Traditions and customs[edit]

Blessing of Easter foods in Poland

Lenten tradition[edit]

The Easter egg tradition may also have merged into the celebration of the end of the privations of Lent. Traditionally, eggs are among the foods forbidden fast days, including all of Lent, an observance which continues among the Eastern Christian Churches but has fallen into disuse in Western Christianity (although something similar has recently been instituted by a few as the “Daniel Fast»).

Historically, it has been traditional to use up all of the household’s eggs before Lent began.

This established the tradition of Pancake Day being celebrated on Shrove Tuesday. This day, the Tuesday before Ash Wednesday when Lent begins, is also known as Mardi Gras, a French phrase which translates as «Fat Tuesday» to mark the last consumption of eggs and dairy before Lent begins.

In the Orthodox Church, Great Lent begins on Clean Monday, rather than Wednesday, so the household’s dairy products would be used up in the preceding week, called Cheesefare Week.

During Lent, since chickens would not stop producing eggs during this time, a larger than usual store might be available at the end of the fast. This surplus, if any, had to be eaten quickly to prevent spoiling. Then, with the coming of Easter, the eating of eggs resumes. Some families cook a special meatloaf with eggs in it to be eaten with the Easter dinner.

One would have been forced to hard boil the eggs that the chickens produced so as not to waste food, and for this reason the Spanish dish hornazo (traditionally eaten on and around Easter) contains hard-boiled eggs as a primary ingredient.

In Hungary, eggs are used sliced in potato casseroles around the Easter period.

Symbolism and related customs[edit]

Some Christians symbolically link the cracking open of Easter eggs with the empty tomb of Jesus.[19]

In the Orthodox churches, Easter eggs are blessed by the priest at the end of the Paschal Vigil (which is equivalent to Holy Saturday), and distributed to the faithful. The egg is seen by followers of Christianity as a symbol of resurrection: while being dormant it contains a new life sealed within it.[3][4]

Similarly, in the Roman Catholic Church in Poland, the so-called święconka, i.e. blessing of decorative baskets with a sampling of Easter eggs and other symbolic foods, is one of the most enduring and beloved Polish traditions on Holy Saturday.

During Paschaltide, in some traditions the Pascal greeting with the Easter egg is even extended to the deceased. On either the second Monday or Tuesday of Pascha, after a memorial service people bring blessed eggs to the cemetery and bring the joyous paschal greeting, «Christ has risen», to their beloved departed (see Radonitza).

In Greece, women traditionally dye the eggs with onion skins and vinegar on Thursday (also the day of Communion). These ceremonial eggs are known as kokkina avga. They also bake tsoureki for the Easter Sunday feast.[20] Red Easter eggs are sometimes served along the centerline of tsoureki (braided loaf of bread).[21][22]

In Egypt, it is a tradition to decorate boiled eggs during Sham el-Nessim holiday, which falls every year after the Eastern Christian Easter.

Coincidentally, every Passover, Jews place a hard-boiled egg on the Passover ceremonial plate, and the celebrants also eat hard-boiled eggs dipped in salt water as part of the ceremony.

Colouring[edit]

Easter eggs before and after colouring

Heated wax paint used to decorate traditional Easter Eggs in the Czech Republic

The dyeing of Easter eggs in different colours is commonplace, with colour being achieved through boiling the egg in natural substances (such as, onion peel (brown colour), oak or alder bark or walnut nutshell (black), beet juice (pink) etc.), or using artificial colourings.

A greater variety of colour was often provided by tying on the onion skin with different coloured woollen yarn. In the North of England these are called pace-eggs or paste-eggs, from a dialectal form of Middle English pasche. King Edward I’s household accounts in 1290 list an item of ‘one shilling and sixpence for the decoration and distribution of 450 Pace-eggs!’,[23] which were to be coloured or gilded and given to members of the royal household.[24] Traditionally in England, eggs were wrapped in onion skins and boiled to make their shells look like mottled gold, or wrapped in flowers and leaves first in order to leave a pattern, which parallels a custom practised in traditional Scandinavian culture.[25] Eggs could also be drawn on with a wax candle before staining, often with a person’s name and date on the egg.[24] Pace Eggs were generally eaten for breakfast on Easter Sunday breakfast. Alternatively, they could be kept as decorations, used in egg-jarping (egg tapping) games, or given to Pace Eggers. In more recent centuries in England, eggs have been stained with coffee grains[24] or simply boiled and painted in their shells.[26]

In the Orthodox and Eastern Catholic Churches, Easter eggs are dyed red to represent the blood of Christ, with further symbolism being found in the hard shell of the egg symbolizing the sealed Tomb of Christ — the cracking of which symbolized his resurrection from the dead. The tradition of red easter eggs was used by the Russian Orthodox Church.[27] The tradition to dyeing the easter eggs in an Onion tone exists in the cultures of Armenia, Georgia, Belarus, Russia, Czechia, Romania, Slovenia, and Israel.[28] The colour is made by boiling onion peel in water.[29][30]

Patterning[edit]

When boiling them with onion skins, leaves can be attached prior to dyeing to create leaf patterns. The leaves are attached to the eggs before they are dyed with a transparent cloth to wrap the eggs with like inexpensive muslin or nylon stockings, leaving patterns once the leaves are removed after the dyeing process.[31][32] These eggs are part of Easter custom in many areas and often accompany other traditional Easter foods. Passover haminados are prepared with similar methods.

Pysanky[33] are Ukrainian Easter eggs, decorated using a wax-resist (batik) method. The word comes from the verb pysaty, «to write», as the designs are not painted on, but written with beeswax.

Decorating eggs for Easter using wax resistant batik is a popular method in some other eastern European countries.

Use of Easter eggs in decorations[edit]

In some Mediterranean countries, especially in Lebanon, chicken eggs are boiled and decorated by dye and/or painting and used as decoration[34] around the house. Then, on Easter Day, young kids would duel with them saying ‘Christ is resurrected, Indeed, He is’, breaking and eating them. This also happens in Georgia, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Greece, North Macedonia, Romania, Russia, Serbia and Ukraine. In Easter Sunday friends and family hit each other’s egg with their own. The one whose egg does not break is believed to be in for good luck in the future.

In Germany, eggs decorate trees and bushes as Easter egg trees, and in several areas public wells as Osterbrunnen.

There used to be a custom in Ukraine, during Easter celebrations to have krashanky on a table in a bowl with wheatgrass. The number of the krashanky equalled the number of departed family members.[35]

-

Ukrainian Easter eggs

-

Perforated egg from Germany, Sleeping Beauty

-

Norwegian Easter eggs

-

-

Perforated eggs

-

-

Pace eggs boiled with onion skins and leaf patterns.

-

Easter eggs decorated with straw

-

-

Easter egg games[edit]

Egg hunts[edit]

An egg hunt is a game in which decorated eggs, which may be hard-boiled chicken eggs, chocolate eggs, or artificial eggs containing candies, are hidden for children to find. The eggs often vary in size, and may be hidden both indoors and outdoors.[36] When the hunt is over, prizes may be given for the largest number of eggs collected, or for the largest or the smallest egg.[36]

Some central European nations (Czechs and Slovaks etc.) have a tradition of gathering eggs by gaining them from the females in return of whipping them with a pony-tail shaped whip made out of fresh willow branches and splashing them with water, by the Ruthenians called polivanja, which is supposed to give them health and beauty.

Cascarones, a Latin American tradition now shared by many US States with high Hispanic demographics, are emptied and dried chicken eggs stuffed with confetti and sealed with a piece of tissue paper. The eggs are hidden in a similar tradition to the American Easter egg hunt and when found the children (and adults) break them over each other’s heads.

In order to enable children to take part in egg hunts despite visual impairment, eggs have been created that emit various clicks, beeps, noises, or music so that visually impaired children can easily hunt for Easter eggs.[37]

Egg rolling[edit]

Egg rolling is also a traditional Easter egg game played with eggs at Easter. In the United Kingdom, Germany, and other countries children traditionally rolled eggs down hillsides at Easter.[38] This tradition was taken to the New World by European settlers,[38][39] and continues to this day each Easter with an Easter egg roll on the White House lawn. Rutherford B. Hayes started the tradition of the Easter Egg Roll at the White House.[40] The Easter Monday Egg Roll was normally held at the United States Capitol, however, by the mid-1870s, Congress passed a law forbidding the Capitol’s grounds to be used for the activity due to the toll it was taking on the landscape.[40] The law was enforced in 1877, but the rain that year canceled all outdoor activities.[40] In 1878, Hayes was approached by many young easter egg rollers who asked for the event to be held at the White House.[40] He invited any children who wanted to roll eggs to come to the White House in order to do so. The tradition still occurs every year on the South Lawn of the White House. Now, there are many other games and activities that take place such as “Egg Picking” and “Egg Ball.”[40] Different nations have different versions of the Easter Egg roll game.

Egg tapping[edit]

Eggs after an egg tapping competition (red wins)

In the North of England, during Eastertide, a traditional game is played where hard boiled pace eggs are distributed and each player hits the other player’s egg with their own. This is known as «egg tapping», «egg dumping», or «egg jarping». The winner is the holder of the last intact egg. The annual egg jarping world championship is held every year over Easter in Peterlee, Durham.[41]

It is also practiced in Italy (where it is called scuccetta), Bulgaria, Hungary, Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Lebanon, North Macedonia, Romania, Serbia, Slovenia (where it is called turčanje or trkanje), Ukraine, Russia, and other countries. In parts of Austria, Bavaria and German-speaking Switzerland it is called Ostereiertitschen or Eierpecken. In parts of Europe it is also called epper, presumably from the German name Opfer, meaning «offering» and in Greece it is known as tsougrisma. In South Louisiana, this practice is called pocking eggs[42][43] and is slightly different. The Louisiana Creoles hold that the winner eats the eggs of the losers in each round.

In the Greek Orthodox tradition, red eggs are also cracked together when people exchange Easter greetings.

Egg dance[edit]

Egg dance is a traditional Easter game in which eggs are laid on the ground or floor and the goal is to dance among them without damaging any eggs[44] which originated in Germany.

Pace egg plays[edit]

The Pace Egg plays are traditional village plays, with a rebirth theme. The drama takes the form of a combat between the hero and villain, in which the hero is killed and brought back to life. The plays take place in England during Easter.

In some countries like Sweden, Norway, Poland and Germany eggs are used as a table decoration hanging on a tree-branch

Variants[edit]

Chocolate[edit]

Chocolate eggs first appeared at the court of Louis XIV in Versailles and in 1725 the widow Giambone in Turin started producing chocolate eggs by filling empty chicken egg shells with molten chocolate.[45] In 1873 J.S. Fry & Sons of England introduced the first chocolate Easter egg in Britain. Manufacturing their first Easter egg in 1875, Cadbury created the modern chocolate Easter egg after developing a pure cocoa butter that could be moulded into smooth shapes.[46]

In Western cultures, the giving of chocolate eggs is now commonplace, with 80 million Easter eggs sold in the UK alone. Formerly, the containers Easter eggs were sold in contained large amounts of plastic, although in the United Kingdom this has gradually been replaced with recyclable paper and cardboard.[47]

-

Chocolate Easter egg bunny

-

Easter egg with candy.

Marzipan eggs[edit]

In the Indian state of Goa, the Goan Catholic version of marzipan is used to make easter eggs. In the Philippines, mazapán de pili (Spanish for «pili marzipan») is made from pili nuts.

-

Marzipan easter eggs

Artificial eggs[edit]

The jewelled Easter eggs made by the Fabergé firm for the two last Russian Tsars are regarded as masterpieces of decorative arts. Most of these creations themselves contained hidden surprises such as clock-work birds, or miniature ships.

In Bulgaria, Poland, Romania, Russia, Ukraine, and other Central European countries’ folk traditions, Easter eggs are carved from wood and hand-painted, and making artificial eggs out of porcelain for ladies is common.[48]: 45

Easter eggs are frequently depicted in sculpture, including a 8-metre (27 ft) sculpture of a pysanka standing in Vegreville, Alberta.

-

-

Easter egg sculpture in Gogolin, Poland

-

Giant easter egg in Suceava, Romania

[edit]

Christian traditions[edit]

While the origin of Easter eggs can be explained in the symbolic terms described above, among followers of Eastern Christianity the legend says that Mary Magdalene was bringing cooked eggs to share with the other women at the tomb of Jesus, and the eggs in her basket miraculously turned bright red when she saw the risen Christ.[49]

A different, but not necessarily conflicting legend concerns Mary Magdalene’s efforts to spread the Gospel. According to this tradition, after the Ascension of Jesus, Mary went to the Emperor of Rome and greeted him with «Christ has risen,» whereupon he pointed to an egg on his table and stated, «Christ has no more risen than that egg is red.» After making this statement it is said the egg immediately turned blood red.[50][51]

Red Easter eggs, known as kokkina avga (κόκκινα αυγά) in Greece and krashanki in Ukraine, are an Easter tradition and a distinct type of Easter egg prepared by various Orthodox Christian peoples.[52][53][54][55][56] The red eggs are part of Easter custom in many areas and often accompany other traditional Easter foods. Passover haminados are prepared with similar methods.

Dark red eggs are a tradition in Greece and represent the blood of Christ shed on the cross.[57] The practice dates to the early Christian church in Mesopotamia.[8][9]

In Greece, superstitions of the past included the custom of placing the first-dyed red egg at the home’s iconostasis (place where icons are displayed) to ward off evil. The heads and backs of small lambs were also marked with the red dye to protect them.

Parallels in other faiths[edit]

The egg is widely used as a symbol of the start of new life, just as new life emerges from an egg when the chick hatches out.[2]

Painted eggs are used at the Iranian spring holidays, the Nowruz that marks the first day of spring or Equinox, and the beginning of the year in the Persian calendar. It is celebrated on the day of the astronomical Northward equinox, which usually occurs on March 21 or the previous/following day depending on where it is observed. The painted eggs symbolize fertility and are displayed on the Nowruz table, called Haft-Seen together with various other symbolic objects. There are sometimes one egg for each member of the family. The ancient Zoroastrians painted eggs for Nowruz, their New Year celebration, which falls on the Spring equinox. The tradition continues among Persians of Islamic, Zoroastrian, and other faiths today.[58] The Nowruz tradition has existed for at least 2,500 years. The sculptures on the walls of Persepolis show people carrying eggs for Nowruz to the king.[citation needed]

The Neopagan holiday of Ostara occurs at roughly the same time as Easter. While it is often claimed that the use of painted eggs is an ancient, pre-Christian component of the celebration of Ostara, there are no historical accounts that ancient celebrations included this practice, apart from the Old High German lullaby which is believed by most to be a modern fabrication. Rather, the use of painted eggs has been adopted under the assumption that it might be a pre-Christian survival. In fact, modern scholarship has been unable to trace any association between eggs and a supposed goddess named Ostara before the 19th century, when early folklorists began to speculate about the possibility.[59]

There are good grounds for the association between hares (later termed Easter bunnies) and bird eggs, through folklore confusion between hares’ forms (where they raise their young) and plovers’ nests.[60]

In Judaism, a hard-boiled egg is an element of the Passover Seder, representing festival sacrifice. The children’s game of hunting for the afikomen (a half-piece of matzo) has similarities to the Easter egg hunt tradition, by which the child who finds the hidden matzah will be awarded a prize. In other homes, the children hide the afikoman and a parent must look for it; when the parents give up, the children demand a prize for revealing its location.

See also[edit]

- Balut

- Century egg

- Chinese red eggs

- Cascarón

- Easter Bilby

- Egg decorating in Slavic culture

- Festum Ovorum

- Kinder Surprise

- List of egg dishes

- List of foods with religious symbolism

- Resurrection of Jesus

- Salted duck egg

- Sham El Nessim

- Smoked egg

- Tea egg

- Vegreville egg

- Washi eggs

References[edit]

- ^ «The Legend of Paschal Eggs (Holy Cross Antiochian Orthodox Church)» (PDF).

- ^ a b David Leeming (2005). The Oxford Companion to World Mythology. Oxford University Press. p. 111. Retrieved 10 March 2013.

For many, Easter is synonymous with fertility symbols such as the Easter Rabbit, Easter Eggs, and the Easter lily.

- ^ a b c Anne Jordan (5 April 2000). Christianity. Nelson Thornes. ISBN 9780748753208. Retrieved 7 April 2012.

Easter eggs are used as a Christian symbol to represent the empty tomb. The outside of the egg looks dead but inside there is new life, which is going to break out. The Easter egg is a reminder that Jesus will rise from His tomb and bring new life. Orthodox Christians dye boiled eggs red to make red Easter eggs that represent the blood of Christ shed for the sins of the world.

- ^ a b The Guardian, Volume 29. H. Harbaugh. 1878. Retrieved 7 April 2012.

Just so, on that first Easter morning, Jesus came to life and walked out of the tomb, and left it, as it were, an empty shell. Just so, too, when the Christian dies, the body is left in the grave, an empty shell, but the soul takes wings and flies away to be with God. Thus you see that though an egg seems to be as dead as a stone, yet it really has life in it; and also it is like Christ’s dead body, which was raised to life again. This is the reason we use eggs on Easter. (In days past some used to color the eggs red, so as to show the kind of death by which Christ died,-a bloody death.)

- ^ Gordon Geddes, Jane Griffiths (22 January 2002). Christian belief and practice. Heinemann. ISBN 9780435306915. Retrieved 7 April 2012.

Red eggs are given to Orthodox Christians after the Easter Liturgy. They crack their eggs against each other’s. The cracking of the eggs symbolizes a wish to break away from the bonds of sin and misery and enter the new life issuing from Christ’s resurrection.

- ^ a b c d Henry Ellis (1877). Popular antiquities of Great Britain. p. 90. Retrieved 26 March 2016.

Hyde, in his Oriental Sports (1694), tells us one with eggs among the Christians of Mesopotamia on Easter Day and forty days afterwards, during which time their children buy themselves as many eggs as they can, stain them with a red colour in memory of the blood of Christ, shed as at that time of his crucifixion. Some tinge them with green and yellow.

- ^ a b c d Thompson, Kenneth (21 August 2013). Culture & Progress: Early Sociology of Culture, Volume 8. Routledge. p. 138. ISBN 9781136479403.

In Mesopotamia children secured during the 40-day period following Easter day as many eggs as possible and dyed them red, «in memory of the blood of Christ shed at that time of his Crucifixion»—a rationalization. Dyed eggs were sold in the market, green and yellow being favorite colors. The use of eggs at Easter seems to have come from Persia into the Greek Christian Churches of Mesopotamia, thence to Russia and Siberia through the medium of Orthodox Christianity. From the Greek Church the custom was adopted by either the Roman Catholics or the Protestants and then spread through Europe.

- ^ a b c d Donahoe’s Magazine, Volume 5. T.B. Noonan. 1881. Retrieved 7 April 2012.

The early Christians of Mesopotamia had the custom of dyeing and decorating eggs at Easter. They were stained red, in memory of the blood of Christ, shed at His crucifixion. The Church adopted the custom, and regarded the eggs as the emblem of the resurrection, as is evinced by the benediction of Pope Paul V., about 1610, which reads thus: «Bless, O Lord! we beseech thee, this thy creature of eggs, that it may become a wholesome sustenance to thy faithful servants, eating it in thankfulness to thee on account of the resurrection of the Lord.» Thus the custom has come down from ages lost in antiquity.)

- ^ a b c d Vicki K. Black (1 July 2004). Welcome to the Church Year: An Introduction to the Seasons of the Episcopal Church. Church Publishing, Inc. ISBN 9780819219664.

The Christians of this region in Mesopotamia were probably the first to connect the decorating of eggs with the feast of the resurrection of Christ, and by the Middle Ages this practice was so widespread that in some places Easter Day was called Egg Sunday. In parts of Europe, the eggs were dyed red and were then cracked together when people exchanged Easter greetings. Many congregations today continue to have Easter egg hunts for the children after services on Easter Day.

- ^ a b c Gainsford, Peter (26 March 2018). «Easter and paganism. Part 2». Kiwi Hellenist. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- ^ a b c d e D’Costa, Krystal. «Beyond Ishtar: The Tradition of Eggs at Easter». Scientific American. Archived from the original on 28 March 2018. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ^ Neil R. Grobman (1981). Wycinanki and pysanky: forms of religious and ethnic folk art from the Delaware Valley. University of Pittsburgh. Retrieved 18 April 2014.

During the spring cycle of festivals, ancient pre-Christian peoples used decorated eggs to welcome the sun and to help ensure the fertility of the fields, river …

- ^ «Egg Cetera #6: Hunting for the world’s oldest decorated eggs | University of Cambridge». Cam.ac.uk. 2012-04-10. Retrieved 2013-03-31.

- ^ Treasures from Royal Tombs of Ur By Richard L. Zettler, Lee Horne, Donald P. Hansen, Holly Pittman 1998 pgs 70-72

- ^ Green, Nile (2006). «Ostrich Eggs and Peacock feathers: Sacred Objects as Cultural Exchange between Christianity and Islam». Al-Masaq: Journal of the Medieval Mediterranean. 18 (1).

This article uses the wide dispersal of ostrich eggs and peacock feathers among the different cultural contexts of the Mediterranean – and beyond into the Indian Ocean world – to explore the nature and limits of cultural inheritance and exchange between Christianity and Islam. These avian materials previously possessed symbolic meaning and material value as early as the pre-dynastic period in Egypt, as well as amid the early cultures of Mesopotamia and Crete. The main early cultural associations of the eggs and feathers were with death/resurrection and kingship respectively, a symbolism that was passed on into early Christian and Muslim usage. Mercantile, religious and political links across the premodern Mediterranean meant that these items found parallel employment all around the Mediterranean littoral, and beyond it, in Arabia, South Asia and Africa.

- ^ Murray, Michael J.; Rea, Michael C. (20 March 2008). An Introduction to the Philosophy of Religion. Cambridge University Press. p. 68. ISBN 978-1-139-46965-4.

- ^ Williams, Victoria (21 November 2016). Celebrating Life Customs around the World. ABC-CLIO. p. 2. ISBN 9781440836596.

The history of the Easter egg can be traced back to the time of the advent of Christianity in Mesopotamia (around the first to the third century), when people use to stain eggs red as a reminder of the blood spilled by Christ during the Crucifixion. In time, the Christian church in general adopted this custom with the eggs considered to be a symbol of both Christ’s death and Resurrection. Moreover, in the earliest days of Christianity Easter eggs were considered symbolic of the tomb in which Jesus’s corpse was laid after the Crucifixion for eggs, as a near universal symbol of fertility and life, were like Jesus’s tomb, something from which new life came forth.

- ^ Shoda, Richard W. (2014). Saint Alphonsus: Capuchins, Closures, and Continuity (1956-2011). Dorrance Publishing. p. 128. ISBN 978-1-4349-2948-8.

- ^ Allen, Emily (25 December 2016). «When is Easter 2016? What are the dates for Good Friday, Easter Sunday and Easter Monday». The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 24 February 2016. Retrieved 26 February 2016.

Eggs illustrate new life, just as Jesus began his new life on East Sunday after the miracle of his resurrection. When eggs are cracked open they are said to symbolise an empty tomb.

- ^ Wagstaff, Natalie. «Kalo Paska — Happy Easter». Archived from the original on 2014-12-26. Retrieved 2014-12-10.

- ^ Walker, Judy. «Today’s Recipe from Our Files: Greek Easter bread, Tsoueki». NOLA.com. Retrieved 18 December 2022.

- ^ Red and Butter, Martha Stewart magazine

- ^ «Pace Egging». Historic UK. Retrieved 2021-02-16.

- ^ a b c «How did giving these become a Yorkshire tradition at Easter?». York Press. Retrieved 2021-02-16.

- ^ Hall, Stephanie (2017-04-06). «The Ancient Art of Decorating Eggs | Folklife Today». blogs.loc.gov. Retrieved 2021-02-16.

- ^ «Pace Egging: A Lancashire Tradition». www.timetravel-britain.com. Retrieved 2021-02-16.

- ^ «In Russia the Color Red Represents More Than You Know». TripSavvy. Retrieved 2019-03-19.

- ^ «How To Dye Easter Eggs with Onion Skins». Kitchn. Retrieved 2019-03-19.

- ^ Sorokina, Anna (2018-03-29). «How to paint Easter eggs with onion, coffee and beets (PHOTOS)». www.rbth.com. Retrieved 2019-03-19.

- ^ DONORSGrajewski, DONORS GOLDEN; rzej; Asia, Hołdys; Tomasz, Horbowski; Wojciech, Jakóbik; Kostek; rzej; Paweł, Lickiewicz; Filip, Lachert (2015-03-28). «The Easter Traditions in Belarus». Eastbook.eu. Archived from the original on 2019-03-29. Retrieved 2019-03-19.

- ^ «How to Dye Easter eggs naturally without a box onion skins beets cabbage». seriouseats.com.

- ^ «Natural Easter Eggs 3 Ways!/ with nylon stockings». natashaskitchen.com. 20 March 2013.

- ^ Culture – Pysanky, Ukrainian International Directory

- ^ «Osterdeko — fünf Ideen rund um das Osterei | Anton Doll Holzmanufaktur». www.antondoll.de. Retrieved 2020-08-18.

- ^ Yakovenko, Svitlana 2017, “The Magical Dyed Egg – Krashanka” in Traditional Velykden: Ukrainian Easter Recipes Archived 2017-03-26 at the Wayback Machine, Sova Books, Sydney

- ^ a b A. Munsey Pu Frank a. Munsey Publishers (March 2005). The Puritan April to September 1900. Kessinger Publishing. p. 119. ISBN 978-1-4191-7421-6.

- ^ Tillery, Carolyn (2008-03-15). «Annual Dallas Easter egg hunt for blind children scheduled for Thursday». The Dallas Morning News. Retrieved 2008-03-27.

- ^ a b «Easter Eggs — Egg Rolling». Inventors.about.com. 2012-04-09. Retrieved 2012-09-24.

- ^ «Easter Eggs: their origins, tradition and symbolism». Wyrdology.com. Archived from the original on 2008-05-17. Retrieved 2008-03-15.

- ^ a b c d e History of the White House Easter Egg Roll

- ^ Hutchinson, Pamela (8 April 2012). «Egg jarping: when hard-boiled eggs come to blows». The Guardian. Retrieved 14 June 2019.

- ^ «Pocking eggs or la toquette». Creolecajun.blogspot.com. 17 March 2008. Retrieved 2008-03-20.

- ^ «If Your Eggs Are Cracked, Please Step Down: Easter Egg Knocking in Marksville». Retrieved 2008-03-20.