| Schindler’s List | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster |

|

| Directed by | Steven Spielberg |

| Screenplay by | Steven Zaillian |

| Based on | Schindler’s Ark by Thomas Keneally |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Janusz Kamiński |

| Edited by | Michael Kahn |

| Music by | John Williams |

|

Production |

|

| Distributed by | Universal Pictures |

|

Release dates |

|

|

Running time |

195 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $22 million[2] |

| Box office | $322.2 million[3] |

Schindler’s List is a 1993 American epic historical drama film directed and produced by Steven Spielberg and written by Steven Zaillian. It is based on the 1982 novel Schindler’s Ark by Australian novelist Thomas Keneally. The film follows Oskar Schindler, a German industrialist who saved more than a thousand mostly Polish-Jewish refugees from the Holocaust by employing them in his factories during World War II. It stars Liam Neeson as Schindler, Ralph Fiennes as SS officer Amon Göth, and Ben Kingsley as Schindler’s Jewish accountant Itzhak Stern.

Ideas for a film about the Schindlerjuden (Schindler Jews) were proposed as early as 1963. Poldek Pfefferberg, one of the Schindlerjuden, made it his life’s mission to tell Schindler’s story. Spielberg became interested when executive Sidney Sheinberg sent him a book review of Schindler’s Ark. Universal Pictures bought the rights to the novel, but Spielberg, unsure if he was ready to make a film about the Holocaust, tried to pass the project to several directors before deciding to direct it.

Principal photography took place in Kraków, Poland, over 72 days in 1993. Spielberg shot in black and white and approached the film as a documentary. Cinematographer Janusz Kamiński wanted to create a sense of timelessness. John Williams composed the score, and violinist Itzhak Perlman performed the main theme.

Schindler’s List premiered on November 30, 1993, in Washington, D.C. and was released on December 15, 1993, in the United States. Often listed among the greatest films ever made,[4][5][6][7] the film received universal acclaim for its tone, acting (particularly Neeson, Fiennes, and Kingsley), atmosphere, and Spielberg’s direction; it was also a box office success, earning $322 million worldwide on a $22 million budget. It was nominated for twelve Academy Awards, and won seven, including Best Picture, Best Director, Best Adapted Screenplay, and Best Original Score. The film won numerous other awards, including seven BAFTAs and three Golden Globe Awards. In 2007, the American Film Institute ranked Schindler’s List 8th on its list of the 100 best American films of all time. The film was designated as «culturally, historically or aesthetically significant» by the Library of Congress in 2004 and selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry.

Plot[edit]

In Kraków during World War II, the Nazis force local Polish Jews into the overcrowded Kraków Ghetto. Oskar Schindler, a German Nazi Party member from Czechoslovakia, arrives in the city, hoping to make his fortune. He bribes Wehrmacht (German armed forces) and SS officials, acquiring a factory to produce enamelware. Schindler hires Itzhak Stern, a Jewish official with contacts among black marketeers and the Jewish business community; he handles administration and helps Schindler arrange financing. Stern ensures that as many Jewish workers as possible are deemed essential to the German war effort to prevent them from being taken by the SS to concentration camps or killed. Meanwhile, Schindler maintains friendly relations with the Nazis and enjoys his new wealth and status as an industrialist.

SS-Untersturmführer (second lieutenant) Amon Göth arrives in Kraków to oversee construction of the Płaszów concentration camp. When the camp is ready, he orders the ghetto liquidated: two thousand Jews are transported to Płaszów, and two thousand others are killed in the streets by the SS. Schindler witnesses the massacre and is profoundly affected. He particularly notices a young girl in a red coat who hides from the Nazis and later sees her body on a wagonload of corpses. Schindler is careful to maintain his friendship with Göth and continues to enjoy SS support, mostly through bribery. Göth brutalizes his Jewish maid Helen Hirsch and randomly shoots people from the balcony of his villa; the prisoners are in constant fear for their lives. As time passes, Schindler’s focus shifts from making money to trying to save as many lives as possible. To better protect his workers, Schindler bribes Göth into allowing him to build a sub-camp at his factory.

As the Germans begin losing the war, Göth is ordered to ship the remaining Jews at Płaszów to Auschwitz concentration camp. Schindler asks Göth for permission to move his workers to a munitions factory he plans to build in Brünnlitz near his home town of Zwittau. Göth reluctantly agrees, but charges a huge bribe. Schindler and Stern prepare a list of people to be transferred to Brünnlitz instead of Auschwitz. The list eventually includes 1,100 names.

As the Jewish workers are transported by train to Brünnlitz, the women and girls are mistakenly redirected to Auschwitz-Birkenau; Schindler bribes Rudolf Höss, commandant of Auschwitz, for their release. At the new factory, Schindler forbids the SS guards from entering the production area without permission and encourages the Jews to observe the Sabbath. Over the next seven months, he spends his fortune bribing Nazi officials and buying shell casings from other companies. Due to Schindler’s machinations, the factory does not produce any usable armaments. He runs out of money in 1945, just as Germany surrenders.

As a Nazi Party member and war profiteer, Schindler must flee the advancing Red Army to avoid capture. The SS guards at the factory have been ordered to kill the Jewish workforce, but Schindler persuades them not to do so. Bidding farewell to his workers, he prepares to head west, hoping to surrender to the Americans. The workers give him a signed statement attesting to his role in saving Jewish lives and present him with a ring engraved with a Talmudic quotation: «Whoever saves one life saves the world entire». Schindler breaks down in tears, feeling he should have done more, and is comforted by the workers before he and his wife leave in their car. When the Schindlerjuden awaken the next morning, a Soviet soldier announces that they have been liberated. The Jews then walk to a nearby town.

An epilogue reveals that Göth was convicted of crimes against humanity and executed via hanging, while Schindler’s marriage and businesses failed following the war. In the present, many of the surviving Schindlerjuden and the actors portraying them visit Schindler’s grave and place stones on its marker (a traditional Jewish sign of respect for the dead), after which Liam Neeson lays two roses.

Cast[edit]

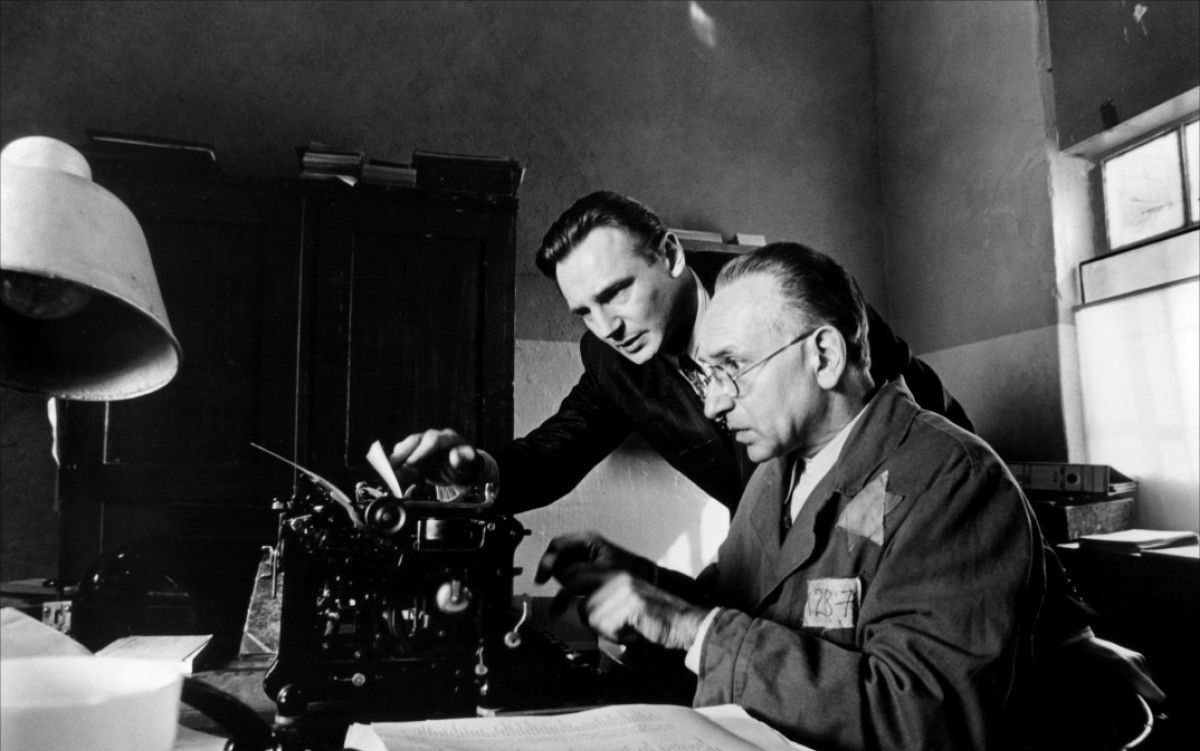

Liam Neeson plays Oskar Schindler in the film.

- Liam Neeson as Oskar Schindler

- Ben Kingsley as Itzhak Stern

- Ralph Fiennes as Amon Göth

- Caroline Goodall as Emilie Schindler

- Jonathan Sagall as Poldek Pfefferberg

- Embeth Davidtz as Helen Hirsch

- Małgorzata Gebel as Wiktoria Klonowska

- Mark Ivanir as Marcel Goldberg

- Beatrice Macola as Ingrid

- Andrzej Seweryn as Julian Scherner

- Friedrich von Thun as Rolf Czurda

- Jerzy Nowak as Investor

- Norbert Weisser as Albert Hujar

- Albert Misak as Mordecai Wulkan

- Michael Gordon as Mr. Nussbaum

- Aldona Grochal as Mrs. Nussbaum

- Uri Avrahami as Chaim Nowak

- Michael Schneider as Juda Dresner

- Miri Fabian as Chaja Dresner

- Anna Mucha as Danka Dresner

- Adi Nitzan as Mila Pfefferberg

- Jacek Wójcicki as Henry Rosner

- Beata Paluch as Manci Rosner

- Piotr Polk as Leo Rosner

- Bettina Kupfer as Regina Perlman

- Grzegorz Kwas as Mietek Pemper

- Kamil Krawiec as Olek Rosner

- Henryk Bista as Mr. Löwenstein

- Ezra Dagan as Rabbi Menasha Levartov

- Rami Heuberger as Joseph Bau

- Elina Löwensohn as Diana Reiter

- Krzysztof Luft as Herman Toffel

- Harry Nehring as Leo John

- Wojciech Klata as Lisiek

- Paweł Deląg as Dolek Horowitz

- Hans-Jörg Assmann as Julius Madritsch

- August Schmölzer as Dieter Reeder

- Hans-Michael Rehberg as Rudolf Höß

- Daniel Del Ponte as Josef Mengele

- Adam Siemion as Adam Levy

- Jochen Nickel as Wilhelm Kunde

- Ludger Pistor as Josef Leipold[a]

- Oliwia Dąbrowska as the Girl in Red

Production[edit]

Development[edit]

Poldek Pfefferberg, one of the Schindlerjuden, made it his life’s mission to tell the story of his savior. Pfefferberg attempted to produce a biopic of Oskar Schindler with MGM in 1963, with Howard Koch writing, but the deal fell through.[9][10] In 1982, Thomas Keneally published his historical novel Schindler’s Ark, which he wrote after a chance meeting with Pfefferberg in Los Angeles in 1980.[11] MCA president Sid Sheinberg sent director Steven Spielberg a New York Times review of the book. Spielberg, astounded by Schindler’s story, jokingly asked if it was true. «I was drawn to it because of the paradoxical nature of the character,» he said. «What would drive a man like this to suddenly take everything he had earned and put it all in the service of saving these lives?»[12] Spielberg expressed enough interest for Universal Pictures to buy the rights to the novel.[12] At their first meeting in spring 1983, he told Pfefferberg he would start filming in ten years.[13] In the end credits of the film, Pfefferberg is credited as a consultant under the name Leopold Page.[14]

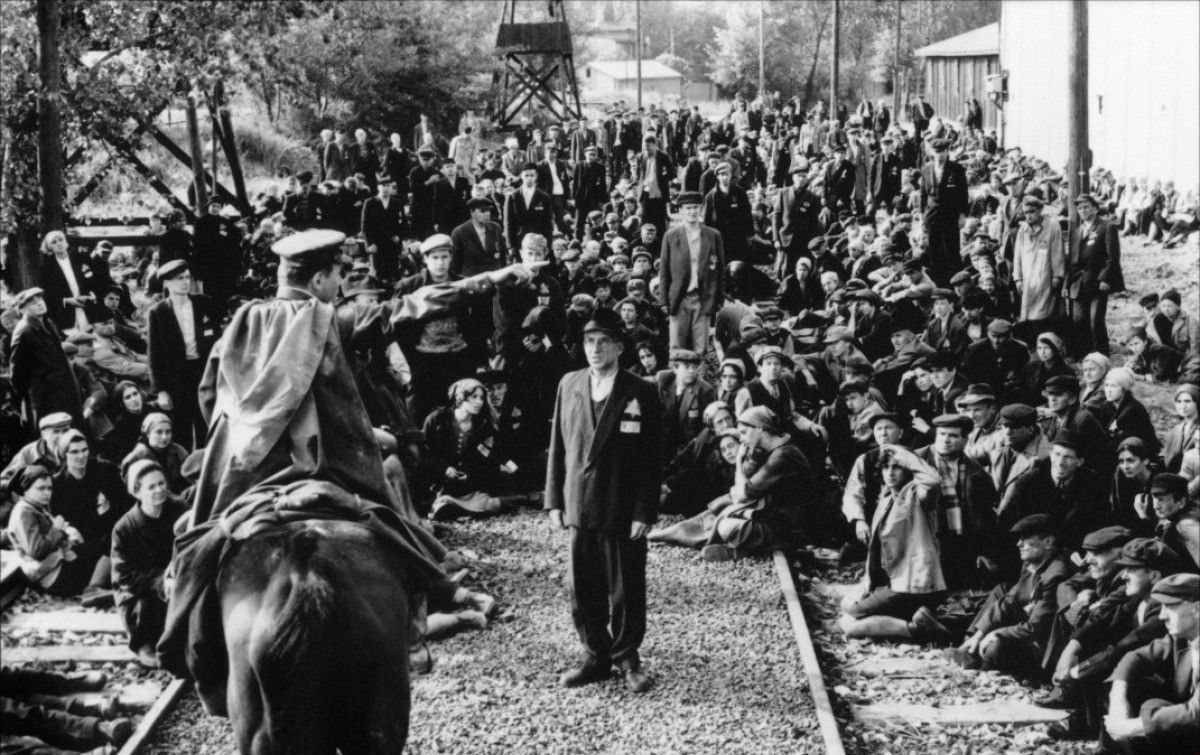

The liquidation of the Kraków Ghetto in March 1943 is the subject of a 15-minute segment of the film.

Spielberg was unsure if he was mature enough to make a film about the Holocaust, and the project remained «on [his] guilty conscience».[13] Spielberg tried to pass the project to director Roman Polanski, but he refused Spielberg’s offer. Polanski’s mother was killed at Auschwitz, and he had lived in and survived the Kraków Ghetto.[13] Polanski eventually directed his own Holocaust drama The Pianist (2002). Spielberg also offered the film to Sydney Pollack and Martin Scorsese, who was attached to direct Schindler’s List in 1988. However, Spielberg was unsure of letting Scorsese direct the film, as «I’d given away a chance to do something for my children and family about the Holocaust.»[15] Spielberg offered him the chance to direct the 1991 remake of Cape Fear instead.[16] Billy Wilder expressed an interest in directing the film as a memorial to his family, most of whom were murdered in the Holocaust.[17] Brian De Palma also refused an offer to direct.[18]

Spielberg finally decided to take on the project when he noticed that Holocaust deniers were being given serious consideration by the media. With the rise of neo-Nazism after the fall of the Berlin Wall, he worried that people were too accepting of intolerance, as they were in the 1930s.[17] Sid Sheinberg greenlit the film on condition that Spielberg made Jurassic Park first. Spielberg later said, «He knew that once I had directed Schindler I wouldn’t be able to do Jurassic Park.»[2] The picture was assigned a small budget of $22 million, as Holocaust films are not usually profitable.[19][2] Spielberg forwent a salary for the film, calling it «blood money»,[2] and believed it would fail.[2]

In 1983, Keneally was hired to adapt his book, and he turned in a 220-page script. His adaptation focused on Schindler’s numerous relationships, and Keneally admitted he did not compress the story enough. Spielberg hired Kurt Luedtke, who had adapted the screenplay of Out of Africa, to write the next draft. Luedtke gave up almost four years later, as he found Schindler’s change of heart too unbelievable.[15] During his time as director, Scorsese hired Steven Zaillian to write a script. When he was handed back the project, Spielberg found Zaillian’s 115-page draft too short, and asked him to extend it to 195 pages. Spielberg wanted more focus on the Jews in the story, and he wanted Schindler’s transition to be gradual and ambiguous instead of a sudden breakthrough or epiphany. He also extended the ghetto liquidation sequence, as he «felt very strongly that the sequence had to be almost unwatchable.»[15]

Casting[edit]

Neeson auditioned as Schindler early on in the movie’s development, He was cast in December 1992 after Spielberg saw him perform in Anna Christie on Broadway.[20] Warren Beatty participated in a script reading, but Spielberg was concerned that he could not disguise his accent and that he would bring «movie star baggage».[21] Kevin Costner and Mel Gibson expressed interest in portraying Schindler, but Spielberg preferred to cast the relatively unknown Neeson so that the actor’s star quality would not overpower the character.[22] Neeson felt Schindler enjoyed outsmarting the Nazis, who regarded him as somewhat naïve. «They don’t quite take him seriously, and he used that to full effect.»[23] To help him prepare for the role, Spielberg showed Neeson film clips of Time Warner CEO Steve Ross, who had a charisma that Spielberg compared to Schindler’s.[24] He also located a tape of Schindler speaking, which Neeson studied to learn the correct intonations and pitch.[25]

Fiennes was cast as Amon Göth after Spielberg viewed his performances in A Dangerous Man: Lawrence After Arabia and Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights. Spielberg said of Fiennes’ audition that «I saw sexual evil. It is all about subtlety: there were moments of kindness that would move across his eyes and then instantly run cold.»[26] Fiennes put on 28 pounds (13 kg) to play the role. He watched historic newsreels and talked to Holocaust survivors who knew Göth. In portraying him, Fiennes said «I got close to his pain. Inside him is a fractured, miserable human being. I feel split about him, sorry for him. He’s like some dirty, battered doll I was given and that I came to feel peculiarly attached to.»[26] Doctors Samuel J. Leistedt and Paul Linkowski of the Université libre de Bruxelles describe Göth’s character in the film as a classic psychopath.[27] Fiennes looked so much like Göth in costume that when Mila Pfefferberg met him, she trembled with fear.[26]

The character of Itzhak Stern (played by Ben Kingsley) is a composite of the accountant Stern, factory manager Abraham Bankier, and Göth’s personal secretary, Mietek Pemper.[28] The character serves as Schindler’s alter ego and conscience.[29] Dustin Hoffman was offered the role but he refused it.[30][31]

Overall, there are 126 speaking parts in the film. Thousands of extras were hired during filming.[15] Spielberg cast Israeli and Polish actors specially chosen for their Eastern European appearance.[32] Many of the German actors were reluctant to don the SS uniform, but some of them later thanked Spielberg for the cathartic experience of performing in the movie.[21] Halfway through the shoot, Spielberg conceived the epilogue, where 128 survivors pay their respects at Schindler’s grave in Jerusalem. The producers scrambled to find the Schindlerjuden and fly them in to film the scene.[15]

Filming[edit]

Principal photography began on March 1, 1993, in Kraków, Poland, with a planned schedule of 75 days.[33] The crew shot at or near the actual locations, though the Płaszów camp had to be reconstructed in a nearby abandoned quarry, as modern high rise apartments were visible from the site of the original camp.[34][35] Interior shots of the enamelware factory in Kraków were filmed at a similar facility in Olkusz, while exterior shots and the scenes on the factory stairs were filmed at the actual factory.[36] The production received permission from Polish authorities to film on the grounds of the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum, but objections to filming within the actual death camp were raised by the World Jewish Congress.[37] To avoid filming inside the actual death camp, the film crew constructed a replica of a portion of the camp just outside the entrance of Birkenau.[38]

There were some antisemitic incidents. A woman who encountered Fiennes in his Nazi uniform told him: «The Germans were charming people. They didn’t kill anybody who didn’t deserve it.»[26] Antisemitic symbols were scrawled on billboards near shooting locations,[15] while Kingsley nearly entered a brawl with an elderly German-speaking businessman who insulted the Israeli actor Michael Schneider.[39] Nonetheless, Spielberg said that, at Passover, «all the German actors showed up. They put on yarmulkes and opened up Haggadas, and the Israeli actors moved right next to them and began explaining it to them. And this family of actors sat around and race and culture were just left behind.»[39]

I was hit in the face with my personal life. My upbringing. My Jewishness. The stories my grandparents told me about the Shoah. And Jewish life came pouring back into my heart. I cried all the time.

— Spielberg on his emotional state during the shoot[40]

Shooting Schindler’s List was deeply emotional for Spielberg, as the subject matter forced him to confront elements of his childhood, such as the antisemitism he faced. He was surprised that he did not cry while visiting Auschwitz; instead, he found himself filled with outrage. He was one of many crew members who could not force themselves to watch during the shooting of the scene where aging Jews are forced to run naked while being selected by Nazi doctors to go to Auschwitz.[41] Spielberg commented that he felt more like a reporter than a film maker – he would set up scenes and then watch events unfold, almost as though he were witnessing them rather than creating a movie.[34] Several actresses broke down when filming the shower scene, including one who was born in a concentration camp.[21] Spielberg, his wife Kate Capshaw, and their five children rented a house in suburban Kraków for the duration of filming.[42] He later thanked his wife «for rescuing me ninety-two days in a row … when things just got too unbearable».[43] Robin Williams called Spielberg to cheer him up, given the profound lack of humor on the set.[43]

Spielberg spent several hours each evening editing Jurassic Park, which was scheduled to premiere in June 1993.[44]

Spielberg occasionally used German and Polish language dialogue to create a sense of realism. He initially considered making the film entirely in those languages, but decided «there’s too much safety in reading [subtitles]. It would have been an excuse [for the audience] to take their eyes off the screen and watch something else.»[21]

Cinematography[edit]

Influenced by the 1985 documentary film Shoah, Spielberg decided not to plan the film with storyboards, and to shoot it like a documentary. Forty percent of the film was shot with handheld cameras, and the modest budget meant the film was shot quickly over seventy-two days.[45] Spielberg felt that this gave the film «a spontaneity, an edge, and it also serves the subject.»[46] He filmed without using Steadicams, elevated shots, or zoom lenses, «everything that for me might be considered a safety net.»[46] This matured Spielberg, who felt that in the past he had always been paying tribute to directors such as Cecil B. DeMille or David Lean.[39]

Spielberg decided to use black and white to match the feel of documentary footage of the era. Cinematographer Janusz Kamiński compared the effect to German Expressionism and Italian neorealism.[46] Kamiński said that he wanted to give the impression of timelessness to the film, so the audience would «not have a sense of when it was made».[34] Universal chairman Tom Pollock asked him to shoot the film on a color negative, to allow color VHS copies of the film to later be sold, but Spielberg did not want to accidentally «beautify events».[46]

Music[edit]

John Williams, who frequently collaborates with Spielberg, composed the score for Schindler’s List. The composer was amazed by the film, and felt it would be too challenging. He said to Spielberg, «You need a better composer than I am for this film.» Spielberg responded, «I know. But they’re all dead!»[47] Itzhak Perlman performs the theme on the violin.[14]

In the scene where the ghetto is being liquidated by the Nazis, the folk song Oyfn Pripetshik (Yiddish: אויפֿן פּריפּעטשיק, ‘On the Cooking Stove’) is sung by a children’s choir. The song was often sung by Spielberg’s grandmother, Becky, to her grandchildren.[48] The clarinet solos heard in the film were recorded by Klezmer virtuoso Giora Feidman.[49] Williams won an Academy Award for Best Original Score for Schindler’s List, his fifth win.[50] Selections from the score were released on a soundtrack album.[51]

Themes and symbolism[edit]

The film explores the theme of good and evil, using as its main protagonist a «good German», a popular characterization in American cinema.[52][17] While Göth is characterized as an almost completely dark and evil person, Schindler gradually evolves from Nazi supporter to rescuer and hero.[53] Thus a second theme of redemption is introduced as Schindler, a disreputable schemer on the edges of respectability, becomes a father figure responsible for saving the lives of more than a thousand people.[54][55]

The girl in red[edit]

Schindler sees a girl in red during the liquidation of the Kraków ghetto. The red coat is one of the few instances of color used in this predominantly black and white film.

While the film is shot primarily in black and white, a red coat is used to distinguish a little girl in the scene depicting the liquidation of the Kraków ghetto. Later in the film, Schindler sees her exhumed dead body, recognizable only by the red coat she is still wearing. Spielberg said the scene was intended to symbolize how members of the highest levels of government in the United States knew the Holocaust was occurring, yet did nothing to stop it. He said: «It was as obvious as a little girl wearing a red coat, walking down the street, and yet nothing was done to bomb the German rail lines. Nothing was being done to slow down … the annihilation of European Jewry. So that was my message in letting that scene be in color.»[56] Andy Patrizio of IGN notes that the point at which Schindler sees the girl’s dead body is the point at which he changes, no longer seeing «the ash and soot of burning corpses piling up on his car as just an annoyance».[57] Professor André H. Caron of the Université de Montréal wonders if the red symbolizes «innocence, hope or the red blood of the Jewish people being sacrificed in the horror of the Holocaust».[58]

The girl was portrayed by Oliwia Dąbrowska, three years old at the time of filming. Spielberg asked Dąbrowska not to watch the film until she was eighteen, but she watched it when she was eleven, and says she was «horrified».[59] Upon seeing the film again as an adult, she was proud of the role she played.[59] Roma Ligocka, who says she was known in the Kraków Ghetto for her red coat, feels the character might have been based on her. Ligocka, unlike her fictional counterpart, survived the Holocaust. After the film was released, she wrote and published her own story, The Girl in the Red Coat: A Memoir (2002, in translation).[60] Alternatively, according to her relatives who were interviewed in 2014, the girl may have been inspired by Kraków resident Genya Gitel Chil.[61]

Candles[edit]

The opening scene features a family observing Shabbat. Spielberg said that «to start the film with the candles being lit … would be a rich bookend, to start the film with a normal Shabbat service before the juggernaut against the Jews begins».[15] When the color fades out in the film’s opening moments, it gives way to a world in which smoke comes to symbolize bodies being burnt at Auschwitz. Only at the end, when Schindler allows his workers to hold Shabbat services, do the images of candle fire regain their warmth through color. For Spielberg, they represent «just a glint of color, and a glimmer of hope.»[15] Sara Horowitz, director of the Koschitzky Centre for Jewish Studies at York University, sees the candles as a symbol for the Jews of Europe, killed and then burned in the crematoria. The two scenes bracket the Nazi era, marking its beginning and end.[62] She points out that normally, the woman of the house lights the Sabbath candles. In the film, it is men who perform this ritual, demonstrating not only the subservient role of women, but also the subservient position of Jewish men in relation to Aryan men, especially Göth and Schindler.[63]

Other symbolism[edit]

To Spielberg, the black and white presentation of the film came to represent the Holocaust itself: «The Holocaust was life without light. For me the symbol of life is color. That’s why a film about the Holocaust has to be in black-and-white.»[64] Robert Gellately notes the film in its entirety can be seen as a metaphor for the Holocaust, with early sporadic violence increasing into a crescendo of death and destruction. He also notes a parallel between the situation of the Jews in the film and the debate in Nazi Germany between making use of the Jews for slave labor or exterminating them outright.[65] Water is seen as giving deliverance by Alan Mintz, Holocaust Studies professor at the Jewish Theological Seminary of America in New York. He notes its presence in the scene where Schindler arranges for a Holocaust train loaded with victims awaiting transport to be hosed down, and the scene in Auschwitz, where the women are given an actual shower instead of receiving the expected gassing.[66]

Release[edit]

Schindler’s List opened in theatres on December 15, 1993, in the United States and December 25 in Canada. Its premiere in Germany was on March 1, 1994.[67] Its U.S. network television premiere was on NBC on February 23, 1997. Shown uncut and without commercials, it ranked No. 3 for the week with a 20.9/31 rating/share,[68] the highest Nielsen rating for any film since NBC’s broadcast of Jurassic Park in May 1995. The film aired on public television in Israel on Holocaust Memorial Day in 1998.[69]

The DVD was released on March 9, 2004, in widescreen and full screen editions, on a double-sided disc with the feature film beginning on side A and continuing on side B. Special features include a documentary introduced by Spielberg.[70] Also released for both formats was a limited edition gift set, which included the widescreen version of the film, Keneally’s novel, the film’s soundtrack on CD, a senitype, and a photo booklet titled Schindler’s List: Images of the Steven Spielberg Film, all housed in a plexiglass case.[71] The laserdisc gift set was a limited edition that included the soundtrack, the original novel, and an exclusive photo booklet.[72] As part of its 20th anniversary, the film was released on Blu-ray Disc on March 5, 2013.[73] The film was digitally remastered in 4K, Dolby Vision and Atmos and was reissued into theaters on December 7, 2018, for its 25th anniversary.[74] The film was released on Ultra HD Blu-ray on December 18, 2018.[75]

Following the success of the film, Spielberg founded the Survivors of the Shoah Visual History Foundation, a nonprofit organization with the goal of providing an archive for the filmed testimony of as many survivors of the Holocaust as possible, to save their stories. He continues to finance that work.[76] Spielberg used proceeds from the film to finance several related documentaries, including Anne Frank Remembered (1995), The Lost Children of Berlin (1996), and The Last Days (1998).[77]

Reception[edit]

Critical response[edit]

Schindler’s List received acclaim from both film critics and audiences, with Americans such as talk show host Oprah Winfrey and President Bill Clinton urging others to see it.[78][79] World leaders in many countries saw the film, and some met personally with Spielberg.[78][80] On Rotten Tomatoes, the film has received an approval rating of 98% based on 128 reviews, with an average rating of 9.20/10. The website’s critical consensus reads, «Schindler’s List blends the abject horror of the Holocaust with Steven Spielberg’s signature tender humanism to create the director’s dramatic masterpiece.»[81] Metacritic gave the film a weighted average score of 94 out of 100, based on 26 critics, indicating «universal acclaim».[82] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film a rare average grade of «A+» on an A+ to F scale.[83]

Stephen Schiff of The New Yorker called it the best historical drama about the Holocaust, a film that «will take its place in cultural history and remain there.»[84] Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times gave the film four stars out of four and described it as Spielberg’s best, «brilliantly acted, written, directed, and seen.»[85] Ebert named it one of his ten favorite films of 1993.[86] Terrence Rafferty, also with The New Yorker, admired the film’s «narrative boldness, visual audacity, and emotional directness.» He noted the performances of Neeson, Fiennes, Kingsley, and Davidtz as warranting special praise,[87] and calls the scene in the shower at Auschwitz «the most terrifying sequence ever filmed.»[88] In the 2013 edition of his Movie and Video Guide, Leonard Maltin awarded the picture a four-out-of-four-star rating; he described the movie as a «staggering adaptation of Thomas Keneally’s best-seller … with such frenzied pacing that it looks and feels like nothing Hollywood has ever made before … Spielberg’s most intense and personal film to date».[89] James Verniere of the Boston Herald noted the film’s restraint and lack of sensationalism, and called it a «major addition to the body of work about the Holocaust.»[90] In his review for The New York Review of Books, British critic John Gross said his misgivings that the story would be overly sentimentalized «were altogether misplaced. Spielberg shows a firm moral and emotional grasp of his material. The film is an outstanding achievement.»[91] Mintz notes that even the film’s harshest critics admire the «visual brilliance» of the fifteen-minute segment depicting the liquidation of the Kraków ghetto. He describes the sequence as «realistic» and «stunning».[92] He points out that the film has done much to increase Holocaust remembrance and awareness as the remaining survivors pass away, severing the last living links with the catastrophe.[93] The film’s release in Germany led to widespread discussion about why most Germans did not do more to help.[94]

Criticism of the film also appeared, mostly from academia rather than the popular press.[95] Sara Horowitz points out that much of the Jewish activity seen in the ghetto consists of financial transactions such as lending money, trading on the black market, or hiding wealth, thus perpetuating a stereotypical view of Jewish life.[96] Horowitz notes that while the depiction of women in the film accurately reflects Nazi ideology, the low status of women and the link between violence and sexuality is not explored further.[97] History professor Omer Bartov of Brown University notes that the physically large and strongly drawn characters of Schindler and Göth overshadow the Jewish victims, who are depicted as small, scurrying, and frightened – a mere backdrop to the struggle of good versus evil.[98]

Horowitz points out that the film’s dichotomy of absolute good versus absolute evil glosses over the fact that most Holocaust perpetrators were ordinary people; the movie does not explore how the average German rationalized their knowledge of or participation in the Holocaust.[99] Author Jason Epstein commented that the movie gives the false impression that if people were smart enough or lucky enough, they could survive the Holocaust.[100] Spielberg responded to criticism that Schindler’s breakdown as he says farewell is too maudlin and even out of character by pointing out that the scene is needed to drive home the sense of loss and to allow the viewer an opportunity to mourn alongside the characters on the screen.[101]

Bartov wrote that the «positively repulsive kitsch of the last two scenes seriously undermines much of the film’s previous merits». He describes the humanization of Schindler as «banal», and is critical of what he describes as the «Zionist closure» set to the song «Jerusalem of Gold».[102]

Assessment by other filmmakers[edit]

Schindler’s List was very well received by many of Spielberg’s peers. Filmmaker Billy Wilder wrote to Spielberg saying, «They couldn’t have gotten a better man. This movie is absolutely perfection.»[17] Polanski, who turned down the chance to direct the film, later commented, «I certainly wouldn’t have done as good a job as Spielberg because I couldn’t have been as objective as he was.»[103] He cited Schindler’s List as an influence on his 1994 film Death and the Maiden.[104] The success of Schindler’s List led filmmaker Stanley Kubrick to abandon his own Holocaust project, Aryan Papers, which would have been about a Jewish boy and his aunt who survive the war by sneaking through Poland while pretending to be Catholic.[105] According to scriptwriter Frederic Raphael, when he suggested to Kubrick that Schindler’s List was a good representation of the Holocaust, Kubrick commented, «Think that’s about the Holocaust? That was about success, wasn’t it? The Holocaust is about 6 million people who get killed. Schindler’s List is about 600 who don’t.»[105][b]

Filmmaker Jean-Luc Godard accused Spielberg of using the film to make a profit out of a tragedy while Schindler’s wife, Emilie Schindler, lived in poverty in Argentina.[107] Keneally disputed claims that she was never paid for her contributions, «not least because I had recently sent Emilie a check myself.»[108] He also confirmed with Spielberg’s office that payment had been sent from there.[108] Filmmaker Michael Haneke criticized the sequence in which Schindler’s women are accidentally sent off to Auschwitz and herded into showers: «There’s a scene in that film when we don’t know if there’s gas or water coming out in the showers in the camp. You can only do something like that with a naive audience like in the United States. It’s not an appropriate use of the form. Spielberg meant well – but it was dumb.»[109]

Claude Lanzmann, the director of the nine-hour Holocaust documentary Shoah (1985), called Schindler’s List a «kitschy melodrama» and a «deformation» of historical truth. «Fiction is a transgression, I am deeply convinced that there is a ban on depiction [of the Holocaust]», he said. Lanzmann also criticized Spielberg for viewing the Holocaust through the eyes of a German, saying «it is the world in reverse». He said: «I sincerely thought that there was a time before Shoah, and a time after Shoah, and that after Shoah certain things could no longer be done. Spielberg did them anyway.»[110]

[edit]

At a 1994 Village Voice symposium about the film, historian Annette Insdorf described how her mother, a survivor of three concentration camps, felt gratitude that the Holocaust story was finally being told in a major film that would be widely viewed.[111] Hungarian Jewish author Imre Kertész, a Holocaust survivor, feels it is impossible for life in a Nazi concentration camp to be accurately portrayed by anyone who did not experience it first-hand. While commending Spielberg for bringing the story to a wide audience, he found the film’s final scene at the graveyard neglected the terrible after-effects of the experience on the survivors and implied that they came through emotionally unscathed.[112] Rabbi Uri D. Herscher found the film an «appealing» and «uplifting» demonstration of humanitarianism.[113] Norbert Friedman noted that, like many Holocaust survivors, he reacted with a feeling of solidarity towards Spielberg of a sort normally reserved for other survivors.[114] Albert L. Lewis, Spielberg’s childhood rabbi and teacher, described the movie as «Steven’s gift to his mother, to his people, and in a sense to himself. Now he is a full human being.»[113]

Box office[edit]

The film grossed $96.1 million ($180 million in 2021 dollars)[115] in the United States and Canada and over $321.2 million worldwide.[116] In Germany, the film was viewed by over 100,000 people in its first week alone from 48 screens[117][118] and was eventually shown in 500 theaters (including 80 paid for by municipal authorities),[119] with a total of six million admissions and a gross of $38 million.[120][121][122] Its 25th anniversary showings grossed $551,000 in 1,029 theaters.[123]

Accolades[edit]

Spielberg won the Directors Guild of America Award for Outstanding Directing – Feature Film for his work,[124] and shared the Producers Guild of America Award for Best Theatrical Motion Picture with co-producers Branko Lustig and Gerald R. Molen.[125] Steven Zaillian won the Writers Guild of America Award for Best Adapted Screenplay.[126] The film also won the National Board of Review for Best Film, along with the National Society of Film Critics for Best Film, Best Director, Best Supporting Actor, and Best Cinematography. Awards from the New York Film Critics Circle were also won for Best Film, Best Supporting Actor, and Best Cinematographer. The Los Angeles Film Critics Association awarded the film for Best Film, Best Cinematography (tied with The Piano), and Best Production Design.[127][128][129] The film also won numerous other awards and nominations worldwide.[130]

Controversies[edit]

Commemorative plaque at Emalia, Schindler’s factory in Kraków

In Malaysia the film was initially banned, with the censors suggesting it seemed to be Jewish propaganda, informing the distributor that «the story reflects the privilege and virtues of a certain race only» and «It seems the illustration is propaganda with the purpose of asking for sympathy as well as to tarnish the other race.»[141] In the Philippines, chief censor Henrietta Mendez ordered cuts of three scenes depicting sexual intercourse and female nudity before the movie could be shown in cinemas. Spielberg refused, and pulled the film from screening in Philippine cinemas, which prompted the Senate to demand the abolition of the censorship board. President Fidel V. Ramos himself intervened, ruling that the movie could be shown uncut to anyone over the age of 15.[142]

According to Slovak filmmaker Juraj Herz, the scene in which a group of women confuse an actual shower with a gas chamber is taken directly, shot by shot, from his film Zastihla mě noc (The Night Overtakes Me, 1986). Herz wanted to sue, but was unable to fund the case.[143]

The song «Yerushalayim Shel Zahav« («Jerusalem of Gold») is featured in the film’s soundtrack and plays near the end of the film. This caused some controversy in Israel, as the song (which was written in 1967 by Naomi Shemer) is widely considered an informal anthem of the Israeli victory in the Six-Day War. In Israeli prints of the film, the song was replaced with «Halikha LeKesariya« («A Walk to Caesarea») by Hannah Szenes, a World War II resistance fighter.[144]

For the 1997 American television showing, the film was broadcast virtually unedited. The telecast was the first to receive a TV-M (now TV-MA) rating under the TV Parental Guidelines that had been established earlier that year.[145] Tom Coburn, then an Oklahoma congressman, said that in airing the film, NBC had brought television «to an all-time low, with full-frontal nudity, violence and profanity», adding that it was an insult to «decent-minded individuals everywhere».[146] Under fire from both Republicans and Democrats, Coburn apologized, saying, «My intentions were good, but I’ve obviously made an error in judgment in how I’ve gone about saying what I wanted to say.» He clarified his opinion, stating that the film ought to have been aired later at night when there would not be «large numbers of children watching without parental supervision».[147]

Controversy arose in Germany for the film’s television premiere on ProSieben. Protests among the Jewish community ensued when the station intended to televise it with two commercial breaks of 3–4 minutes each. Ignatz Bubis, head of the Central Council of Jews in Germany, said: «It is problematic to interrupt such a movie by commercials».[120] Jerzy Kanal, chairman of the Jewish Community of Berlin, added «It is obvious that the film could have a greater impact [on society] when broadcast unimpeded by commercials. The station has to do everything possible to broadcast the film without interruption.»[120] As a compromise, the broadcast included one break consisting of a short news update framed with commercials. ProSieben was also obliged to broadcast two accompanying documentaries to the film, showing «The daily lives of the Jews in Hebron and New York» prior to broadcast and «The survivors of the Holocaust» afterwards.[120]

Legacy[edit]

Schindler’s List featured on a number of «best of» lists, including the TIME magazine’s Top Hundred as selected by critics Richard Corliss and Richard Schickel,[4] Time Out magazine’s 100 Greatest Films Centenary Poll conducted in 1995,[148] and Leonard Maltin’s «100 Must See Movies of the Century».[5] The Vatican named Schindler’s List among the most important 45 films ever made.[149] A Channel 4 poll named Schindler’s List the ninth greatest film of all time,[6] and it ranked fourth in their 2005 war films poll.[150] The film was named the best of 1993 by critics such as James Berardinelli,[151] Roger Ebert,[86] and Gene Siskel.[152] Deeming the film «culturally, historically or aesthetically significant», the Library of Congress selected it for preservation in the National Film Registry in 2004.[153]

Due to the increased interest in Kraków created by the film, the city bought Oskar Schindler’s Enamel Factory in 2007 to create a permanent exhibition about the German occupation of the city from 1939 to 1945. The museum opened in June 2010.[154]

See also[edit]

- 1993 in film

- List of Holocaust films

Notes[edit]

- ^ The film incorrectly spells Leipold’s name as «Josef Liepold»[8]

- ^ Schindler is actually credited with saving more than 1,200 Jews.[106]

- ^ Williams also won a Grammy for the film’s musical score. Freer 2001, p. 234.

Citations[edit]

- ^ British Film Board.

- ^ a b c d e McBride 1997, p. 416.

- ^ «Schindler’s List (1993)». Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on April 16, 2021. Retrieved April 16, 2021.

- ^ a b Corliss & Schickel 2005.

- ^ a b Maltin 1999.

- ^ a b Channel 4 2008.

- ^ «AFI’s 100 Years … 100 Movies – 10th Anniversary Edition». American Film Institute. June 20, 2007. Archived from the original on May 19, 2019. Retrieved June 1, 2020.

- ^ Hughes, Katie (August 7, 2018). ««Schindler’s List» credits still». Flickr. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved August 7, 2018.

- ^ McBride 1997, p. 425.

- ^ Crowe 2004, p. 557.

- ^ Palowski 1998, p. 6.

- ^ a b McBride 1997, p. 424.

- ^ a b c McBride 1997, p. 426.

- ^ a b Freer 2001, p. 220.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Thompson 1994.

- ^ Crowe 2004, p. 603.

- ^ a b c d McBride 1997, p. 427.

- ^ Power 2018.

- ^ Palowski 1998, p. 27.

- ^ Palowski 1998, pp. 86–87.

- ^ a b c d Susan Royal interview.

- ^ Palowski 1998, p. 86.

- ^ Entertainment Weekly, January 21, 1994.

- ^ McBride 1997, p. 429.

- ^ Palowski 1998, p. 87.

- ^ a b c d Corliss 1994.

- ^ Leistedt & Linkowski 2014.

- ^ Crowe 2004, p. 102.

- ^ Freer 2001, p. 225.

- ^ «Dustin Hoffman: Facing down my demons». TheGuardian.com. December 14, 2012.

- ^ «Dustin Hoffman on ‘fear of success,’ why he turned down ‘Schindler’s List’«.

- ^ Mintz 2001, p. 128.

- ^ Palowski 1998, p. 48.

- ^ a b c McBride 1997, p. 431.

- ^ Palowski 1998, p. 14.

- ^ Palowski 1998, pp. 109, 111.

- ^ «Jews Try To Halt Auschwitz Filming». The New York Times. Reuters. January 17, 1993. Archived from the original on April 12, 2020. Retrieved April 12, 2020.

- ^ Palowski 1998, p. 62.

- ^ a b c Ansen & Kuflik 1993.

- ^ McBride 1997, p. 414.

- ^ McBride 1997, p. 433.

- ^ Palowski 1998, p. 44.

- ^ a b McBride 1997, p. 415.

- ^ Palowski 1998, p. 45.

- ^ McBride 1997, pp. 431–432, 434.

- ^ a b c d McBride 1997, p. 432.

- ^ Gangel 2005.

- ^ Rubin 2001, pp. 73–74.

- ^ Medien 2011.

- ^ a b 66th Academy Awards 1994.

- ^ AllMusic listing.

- ^ Loshitsky 1997, p. 5.

- ^ McBride 1997, p. 428.

- ^ Loshitsky 1997, p. 43.

- ^ McBride 1997, p. 436.

- ^ Schickel 2012, pp. 161–162.

- ^ Patrizio 2004.

- ^ Caron 2003.

- ^ a b Gilman 2013.

- ^ Ligocka 2002.

- ^ Rosner 2014.

- ^ Horowitz 1997, p. 124.

- ^ Horowitz 1997, pp. 126–127.

- ^ Palowski 1998, p. 112.

- ^ Gellately 1993.

- ^ Mintz 2001, p. 154.

- ^ Weissberg 1997, p. 171.

- ^ Broadcasting & Cable 1997.

- ^ Meyers, Zandberg & Neiger 2009, p. 456.

- ^ Amazon, DVD.

- ^ Amazon, Gift set.

- ^ Amazon, Laserdisc.

- ^ Amazon, Blu-ray.

- ^ Breznican, Anthony (August 29, 2018). «‘Schindler’s List’ will return to theaters for its 25th anniversary». Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on August 29, 2018. Retrieved August 29, 2018.

- ^ Schindler’s List 4K Blu-ray, archived from the original on November 8, 2018, retrieved November 8, 2018

- ^ Freer 2001, p. 235.

- ^ Freer 2001, pp. 235–236.

- ^ a b McBride 1997, p. 435.

- ^ Horowitz 1997, p. 119.

- ^ Mintz 2001, p. 126.

- ^ «Schindler‘s List (1993)». Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Archived from the original on February 27, 2021. Retrieved April 14, 2021.

- ^ «Schindler‘s List Reviews». Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on July 14, 2020. Retrieved January 22, 2020.

- ^ McClintock, Pamela (August 19, 2011). «Why CinemaScore Matters for Box Office». The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on April 26, 2014. Retrieved July 2, 2018.

- ^ Schiff 1994, p. 98.

- ^ Ebert 1993a.

- ^ a b Ebert 1993b.

- ^ Rafferty 1993.

- ^ Mintz 2001, p. 132.

- ^ Maltin 2013, p. 1216.

- ^ Verniere 1993.

- ^ Gross 1994.

- ^ Mintz 2001, p. 147.

- ^ Mintz 2001, p. 131.

- ^ Houston Post 1994.

- ^ Mintz 2001, p. 134.

- ^ Horowitz 1997, pp. 138–139.

- ^ Horowitz 1997, p. 130.

- ^ Bartov 1997, p. 49.

- ^ Horowitz 1997, p. 137.

- ^ Epstein 1994.

- ^ McBride 1997, p. 439.

- ^ Bartov 1997, p. 45.

- ^ Cronin 2005, p. 168.

- ^ Cronin 2005, p. 167.

- ^ a b Goldman 2005.

- ^ «Mietek Pemper: Obituary». The Daily Telegraph. June 15, 2011. Archived from the original on July 26, 2013. Retrieved March 16, 2016.

- ^ Ebert 2002.

- ^ a b Keneally 2007, p. 265.

- ^ Haneke 2009.

- ^ Lanzmann 2007.

- ^ Mintz 2001, pp. 136–137.

- ^ Kertész 2001.

- ^ a b McBride 1997, p. 440.

- ^ Mintz 2001, p. 136.

- ^ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. «Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–». Retrieved April 16, 2022.

- ^ Freer 2001, p. 233.

- ^ Loshitsky 1997, pp. 9, 14.

- ^ Harris, Mike (March 14, 1994). «‘Doubtfire’ sweeps up o’seas B.O.». Variety. p. 10.

- ^ Groves, Don (April 4, 1994). «‘Schindler’ dominates o’seas B.O.». Variety. p. 10.

- ^ a b c d Berliner Zeitung 1997.

- ^ Loshitsky 1997, pp. 11, 14.

- ^ Klady, Leonard (November 14, 1994). «Exceptions are the rule in foreign B.O.». Variety. p. 7.

- ^ Coyle, Jake (December 9, 2018). «‘Ralph’ tops box office again, ‘Aquaman’ is a hit in China». CTV News. Associated Press. Archived from the original on August 6, 2020. Retrieved June 1, 2020.

- ^ CBC 2013.

- ^ Producers Guild Awards.

- ^ Pond 2011.

- ^ Los Angeles Film Critics Association.

- ^ Maslin 1993.

- ^ National Society of Film Critics.

- ^ Loshitsky 1997, pp. 2, 21.

- ^ Giardina 2011.

- ^ BAFTA Awards 1994.

- ^ Chicago Film Critics Awards 1993.

- ^ Golden Globe Awards 1993.

- ^ American Film Institute 1998.

- ^ American Film Institute 2003.

- ^ American Film Institute 2005.

- ^ American Film Institute 2006.

- ^ American Film Institute 2007.

- ^ American Film Institute 2008.

- ^ Variety 1994.

- ^ Branigin 1994.

- ^ Kosulicova 2002.

- ^ Bresheeth 1997, p. 205.

- ^ Chuang 1997.

- ^ Chicago Tribune 1997.

- ^ CNN 1997.

- ^ Time Out Film Guide 1995.

- ^ Greydanus 1995.

- ^ Channel 4 2005.

- ^ Berardinelli 1993.

- ^ Johnson 2011.

- ^ Library of Congress 2004.

- ^ Pavo Travel 2014.

General sources[edit]

- «6th Annual Chicagos Film Critics Awards». Chicago Film Critics Association. 1993. Archived from the original on April 16, 2014. Retrieved July 2, 2018.

- «19th Annual Los Angeles Film Critics Awards». Los Angeles Film Critics Association. 2007. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved July 2, 2018.

- «The 66th Academy Awards (1994) Nominees and Winners». Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. March 21, 1994. Archived from the original on April 29, 2011. Retrieved July 2, 2018.

- «100 Greatest Films». Channel 4. April 8, 2008. Archived from the original on June 9, 2008. Retrieved July 2, 2018.

- «100 Greatest War Films». Channel 4. Archived from the original on May 18, 2005. Retrieved July 2, 2018.

- «AFI’s 100 Years … 100 Movies». American Film Institute. 1998. Archived from the original on May 29, 2015. Retrieved October 27, 2013.

- «AFI’s 100 Years … 100 Heroes and Villains» (PDF). American Film Institute. 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 4, 2019. Retrieved July 2, 2018.

- «AFI’s 100 Years … 100 Quotes» (PDF). American Film Institute. 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 13, 2011. Retrieved October 26, 2013.

- «AFI’s 100 Years … 100 Cheers». American Film Institute. May 31, 2006. Archived from the original on March 8, 2016. Retrieved October 26, 2013.

- «AFI’s 100 Years … 100 Movies – 10th Anniversary Edition». American Film Institute. June 20, 2007. Archived from the original on June 7, 2015. Retrieved October 26, 2013.

- «AFI’s 10 Top 10: Top 10 Epic». American Film Institute. 2008. Archived from the original on July 1, 2010. Retrieved October 26, 2013.

- Ansen, David; Kuflik, Abigail (December 19, 1993). «Spielberg’s obsession». Newsweek. Vol. 122, no. 25. pp. 112–116. Archived from the original on June 12, 2020. Retrieved March 7, 2020.

- «Bafta Awards: Schindler’s List». British Academy of Film and Television Arts. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 18, 2015.

- Bartov, Omer (1997). «Spielberg’s Oskar: Hollywood Tries Evil». In Loshitzky, Yosefa (ed.). Spielberg’s Holocaust: Critical Perspectives on Schindler’s List. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. pp. 41–60. ISBN 978-0-253-21098-2.

- Berardinelli, James (December 31, 1993). «Rewinding 1993 – The Best Films». reelviews.net. Archived from the original on February 1, 2017. Retrieved December 15, 2013.

- Branigin, William (March 9, 1994). «‘Schindler’s List’ Fuss in Philippines – Censors Object To Sex, Not The Nazi Horrors». The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on June 12, 2020. Retrieved June 1, 2020.

- Bresheeth, Haim (1997). «The Great Taboo Broken: Reflections on the Israeli Reception of Schindler’s List«. In Loshitzky, Yosefa (ed.). Spielberg’s Holocaust: Critical Perspectives on Schindler’s List. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. pp. 193–212. ISBN 978-0-253-21098-2.

- «Schindler’s List». British Board of Film Classification. Archived from the original on October 15, 2017. Retrieved October 14, 2017.

- Caron, André (July 25, 2003). «Spielberg’s Fiery Lights». The Question Spielberg: A Symposium Part Two: Films and Moments. Senses of Cinema. Archived from the original on October 23, 2014. Retrieved July 24, 2014.

- Chuang, Angie (February 25, 1997). «Television: ‘Schindler’s’ Showing». Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on June 12, 2020. Retrieved June 1, 2020.

- Corliss, Richard (February 21, 1994). «The Man Behind the Monster». Time. Archived from the original on November 9, 2014. Retrieved October 13, 2014.

- Corliss, Richard; Schickel, Richard (2005). «All-Time 100 Best Movies». Time. Archived from the original on August 18, 2013. Retrieved October 27, 2013.

- Cronin, Paul, ed. (2005). Roman Polanski: Interviews. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-57806-799-2.

- Crowe, David M. (2004). Oskar Schindler: The Untold Account of His Life, Wartime Activities, and the True Story Behind the List. Cambridge, MA: Westview Press. ISBN 978-0-465-00253-5.

- Ebert, Roger (December 15, 1993). «Schindler’s List». Roger Ebert’s Journal. Archived from the original on July 2, 2018. Retrieved July 2, 2018.

- Ebert, Roger (December 31, 1993). «The Best 10 Movies of 1993». Roger Ebert’s Journal. Archived from the original on November 13, 2020. Retrieved June 1, 2020.

- Ebert, Roger (October 18, 2002). «In Praise Of Love». Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on October 30, 2018. Retrieved July 2, 2018.

- Epstein, Jason (April 21, 1994). «A Dissent on ‘Schindler’s List’«. The New York Review of Books. New York. Archived from the original on August 4, 2020. Retrieved June 1, 2020.

- Freer, Ian (2001). The Complete Spielberg. Virgin Books. pp. 220–237. ISBN 978-0-7535-0556-4.

- Gangel, Jamie (May 6, 2005). «The man behind the music of ‘Star Wars’«. NBC. Archived from the original on July 2, 2018. Retrieved July 2, 2018.

- Gellately, Robert (1993). «Between Exploitation, Rescue, and Annihilation: Reviewing Schindler’s List». Central European History. 26 (4): 475–489. doi:10.1017/S0008938900009419. JSTOR 4546374. S2CID 146698805.

- Giardina, Carolyn (February 7, 2011). «Michael Kahn, Michael Brown to Receive ACE Lifetime Achievement Awards». The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on July 2, 2018. Retrieved July 2, 2018.

- Gilman, Greg (March 5, 2013). «Red coat girl traumatized by ‘Schindler’s List’«. Sarnia Observer. Sarnia, Ontario. Archived from the original on December 10, 2014. Retrieved October 20, 2013.

- Goldman, A. J. (August 25, 2005). «Stanley Kubrick’s Unrealized Vision». Jewish Journal. Archived from the original on October 17, 2013. Retrieved July 2, 2018.

- Greydanus, Steven D. (March 17, 1995). «The Vatican Film List». Decent Films. Archived from the original on October 18, 2013. Retrieved October 27, 2013.

- Gross, John (February 3, 1994). «Hollywood and the Holocaust». New York Review of Books. Vol. 16, no. 3. Archived from the original on July 2, 2018. Retrieved July 2, 2018.

- Haneke, Michael (November 14, 2009). «Michael Haneke discusses ‘The White Ribbon’«. Time Out London. Archived from the original on July 2, 2018. Retrieved June 1, 2020.

- Horowitz, Sara (1997). «But Is It Good for the Jews? Spielberg’s Schindler and the Aesthetics of Atrocity». In Loshitzky, Yosefa (ed.). Spielberg’s Holocaust: Critical Perspectives on Schindler’s List. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. pp. 119–139. ISBN 978-0-253-21098-2.

- Johnson, Eric C. (February 28, 2011). «Gene Siskel’s Top Ten Lists 1969–1998». Index of Critics. Archived from the original on November 27, 2015. Retrieved December 14, 2013.

- Keneally, Thomas (2007). Searching for Schindler: A Memoir. New York: Nan A. Talese. ISBN 978-0-385-52617-3.

- Kertész, Imre (Spring 2001). «Who Owns Auschwitz?» (PDF). Yale Journal of Criticism. 14 (1): 267–272. doi:10.1353/yale.2001.0010. S2CID 145532698. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 7, 2020.

- Kosulicova, Ivana (January 7, 2002). «Drowning the bad times: Juraj Herz interviewed». Kinoeye. Vol. 2, no. 1. Archived from the original on February 25, 2021. Retrieved October 28, 2013.

- Lanzmann, Claude (2007). «Schindler’s List is an impossible story». University College Utrecht. Archived from the original on March 26, 2018. Retrieved June 1, 2020.

- Leistedt, Samuel J.; Linkowski, Paul (January 2014). «Psychopathy and the Cinema: Fact or Fiction?». Journal of Forensic Sciences. 59 (1): 167–174. doi:10.1111/1556-4029.12359. PMID 24329037. S2CID 14413385.

- «Librarian of Congress Adds 25 Films to National Film Registry». Library of Congress. December 28, 2004. Archived from the original on April 7, 2020. Retrieved July 2, 2018.

- Ligocka, Roma (2002). The Girl in the Red Coat: A Memoir. New York: St Martin’s Press.

- Loshitsky, Yosefa (1997). «Introduction». In Loshitzky, Yosefa (ed.). Spielberg’s Holocaust: Critical Perspectives on Schindler’s List. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. pp. 1–17. ISBN 978-0-253-21098-2.

- Maltin, Leonard (1999). «100 Must-See Films of the 20th Century». Movie and Video Guide 2000. American Movie Classics Company. Archived from the original on May 30, 2020. Retrieved June 1, 2020.

- Maltin, Leonard (2013). Leonard Maltin’s 2013 Movie Guide: The Modern Era. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-451-23774-3.

- Maslin, Janet (December 16, 1993). «New York Critics Honor ‘Schindler’s List’«. The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 23, 2020. Retrieved December 15, 2013.

- McBride, Joseph (1997). Steven Spielberg: A Biography. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-684-81167-3.

- Medien, Nasiri (2011). «A Life Like A Song With Ever Changing Verses». giorafeidman-online.com. Archived from the original on October 29, 2013. Retrieved October 27, 2013.

- Meyers, Oren; Zandberg, Eyal; Neiger, Motti (September 2009). «Prime Time Commemoration: An Analysis of Television Broadcasts on Israel’s Memorial Day for the Holocaust and the Heroism» (PDF). Journal of Communication. 59 (3): 456–480. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2009.01424.x. ISSN 0021-9916. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 27, 2020. Retrieved June 1, 2020.

- Mintz, Alan (2001). Popular Culture and the Shaping of Holocaust Memory in America. The Samuel and Althea Stroum Lectures in Jewish Studies. Seattle; London: University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-98161-1.

- Palowski, Franciszek (1998) [1993]. The Making of Schindler’s List: Behind the Scenes of an Epic Film. Secaucus, NJ: Carol Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-55972-445-6.

- «Past Awards». National Society of Film Critics. 2013. Archived from the original on July 29, 2017. Retrieved July 2, 2018.

- Patrizio, Andy (March 10, 2004). «Schindler’s List: The DVD is good, too». IGN Entertainment. Archived from the original on June 12, 2020. Retrieved June 1, 2020.

- «PGA Award Winners 1990–2010». Producers Guild of America. Archived from the original on June 28, 2019. Retrieved July 2, 2018.

- Pond, Steve (January 19, 2011). «Steven Zaillian to Receive WGA Laurel Award». The Wrap News. Archived from the original on July 2, 2018. Retrieved July 2, 2018.

- Power, Ed (November 28, 2018). «Steven Spielberg’s year of living dangerously: How he reinvented cinema with Jurassic Park and Schindler’s List». The Independent. Archived from the original on March 16, 2020. Retrieved February 15, 2020.

- Rafferty, Terrence (1993). «The Film File: Schindler’s List». The New Yorker. Archived from the original on June 13, 2007. Retrieved July 2, 2018.

- Rosner, Orin (April 23, 2014). «לכל איש יש שם – גם לילדה עם המעיל האדום מ»רשימת שינדלר»» [Every person has a name – even the girl with the red coat in ‘Schindler’s List’] (in Hebrew). Ynet. Archived from the original on July 2, 2018. Retrieved July 2, 2018.

- Royal, Susan. «An Interview with Steven Spielberg». Inside Film Magazine Online. Archived from the original on October 24, 2008. Retrieved October 11, 2013.

- Rubin, Susan Goldman (2001). Steven Spielberg: Crazy for Movies. New York: Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 978-0-8109-4492-3.

- Schickel, Richard (2012). Steven Spielberg: A Retrospective. New York: Sterling. ISBN 978-1-4027-9650-0.

- Schiff, Stephen (March 21, 1994). «Seriously Spielberg». The New Yorker. pp. 96–109. Archived from the original on July 2, 2018. Retrieved July 2, 2018.

- «Schindler’s List». Hollywood Foreign Press Association. Archived from the original on October 29, 2013. Retrieved July 2, 2018.

- «Schindler’s List: Box Set Laserdisc Edition». Amazon. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved June 1, 2020.

- «Schindler’s List (Blu-ray + DVD + Digital Copy + UltraViolet) (1993)». Amazon. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved June 1, 2020.

- «Schindler’s List (Widescreen Edition) (1993)». Amazon. Archived from the original on March 15, 2021. Retrieved June 1, 2020.

- «Schindler’s List Collector’s Gift Set (1993)». Amazon. Archived from the original on November 4, 2013. Retrieved October 27, 2013.

- Staff (February 26, 1997). «After rebuke, congressman apologizes for ‘Schindler’s List’ remarks». CNN. Archived from the original on October 11, 2007. Retrieved July 2, 2018.

- Staff (February 28, 1994). «German «Schindler’s List» Debut Launches Debate, Soul-Searching». Houston Post. Reuters.

- Staff (February 26, 1997). «GOP Lawmaker Blasts NBC For Airing ‘Schindler’s List’«. Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on June 12, 2020. Retrieved June 1, 2020.

- Staff (December 5, 2014). «How did «Schindler’s List» change Krakow?». Pavo Travel. Archived from the original on February 11, 2015. Retrieved February 11, 2015.

- Staff (March 28, 1994). «Malaysian ‘Schindler’ ban may be reviewed». Variety. Reuters. p. 18. Archived from the original on May 16, 2021. Retrieved March 13, 2021.

- Staff (February 21, 1997). ««Mehr Wirkung ohne Werbung»: Gemischte Reaktionen jüdischer Gemeinden auf geplante Unterbrechung von «Schindlers Liste»«. Berliner Zeitung (in German). Berlin. Archived from the original on December 24, 2008. Retrieved July 2, 2018.

- Staff (January 21, 1994). «Oskar Winner: Liam Neeson joins the A-List after ‘Schindler’s List’«. Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on June 12, 2020. Retrieved June 1, 2020.

- Staff (March 3, 1997). «People’s Choice: Ratings according to Nielsen Feb. 17–23» (PDF). Broadcasting & Cable. p. 31. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 16, 2021. Retrieved July 2, 2018.

- Staff. «John Williams: Schindler’s List». All Media Network. Archived from the original on July 2, 2018. Retrieved July 2, 2018.

- Staff (January 8, 2013). «Spielberg earns 11th Directors Guild nomination». CBC News. Associated Press. Archived from the original on September 2, 2020. Retrieved June 1, 2020.

- Thompson, Anne (January 21, 1994). «Spielberg and ‘Schindler’s List’: How it came together». Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on May 28, 2020. Retrieved June 1, 2020.

- «Top 100 Films (Centenary) from Time Out». 1995. Archived from the original on August 7, 2020. Retrieved June 1, 2020.

- Verniere, James (December 15, 1993). «Holocaust Drama is a Spielberg Triumph». Boston Herald.

- Weissberg, Liliane (1997). «The Tale of a Good German: Reflections on the German Reception of Schindler’s List«. In Loshitzky, Yosefa (ed.). Spielberg’s Holocaust: Critical Perspectives on Schindler’s List. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. pp. 172–192. ISBN 978-0-253-21098-2.

External links[edit]

- Schindler’s List essay by Jay Carr at National Film Registry

- Schindler’s List at IMDb

- Schindler’s List at the American Film Institute Catalog

- Schindler’s List at the TCM Movie Database

- Schindler’s List at Box Office Mojo

- Schindler’s List at AllMovie

- Schindler’s List at Rotten Tomatoes

- Schindler’s List at Metacritic

- The Shoah Foundation, founded by Steven Spielberg, preserves the testimonies of Holocaust survivors and witnesses

- Through the Lens of History: Aerial Evidence for Schindler’s List at Yad Vashem

- Voices on Antisemitism Interview with Ralph Fiennes from the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

- Voices on Antisemitism interview with Sir Ben Kingsley from the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

- «Schindler’s List: Myth, movie, and memory» (PDF). The Village Voice. March 29, 1994. pp. 24–31.

| Schindler’s List | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster |

|

| Directed by | Steven Spielberg |

| Screenplay by | Steven Zaillian |

| Based on | Schindler’s Ark by Thomas Keneally |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Janusz Kamiński |

| Edited by | Michael Kahn |

| Music by | John Williams |

|

Production |

|

| Distributed by | Universal Pictures |

|

Release dates |

|

|

Running time |

195 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $22 million[2] |

| Box office | $322.2 million[3] |

Schindler’s List is a 1993 American epic historical drama film directed and produced by Steven Spielberg and written by Steven Zaillian. It is based on the 1982 novel Schindler’s Ark by Australian novelist Thomas Keneally. The film follows Oskar Schindler, a German industrialist who saved more than a thousand mostly Polish-Jewish refugees from the Holocaust by employing them in his factories during World War II. It stars Liam Neeson as Schindler, Ralph Fiennes as SS officer Amon Göth, and Ben Kingsley as Schindler’s Jewish accountant Itzhak Stern.

Ideas for a film about the Schindlerjuden (Schindler Jews) were proposed as early as 1963. Poldek Pfefferberg, one of the Schindlerjuden, made it his life’s mission to tell Schindler’s story. Spielberg became interested when executive Sidney Sheinberg sent him a book review of Schindler’s Ark. Universal Pictures bought the rights to the novel, but Spielberg, unsure if he was ready to make a film about the Holocaust, tried to pass the project to several directors before deciding to direct it.

Principal photography took place in Kraków, Poland, over 72 days in 1993. Spielberg shot in black and white and approached the film as a documentary. Cinematographer Janusz Kamiński wanted to create a sense of timelessness. John Williams composed the score, and violinist Itzhak Perlman performed the main theme.

Schindler’s List premiered on November 30, 1993, in Washington, D.C. and was released on December 15, 1993, in the United States. Often listed among the greatest films ever made,[4][5][6][7] the film received universal acclaim for its tone, acting (particularly Neeson, Fiennes, and Kingsley), atmosphere, and Spielberg’s direction; it was also a box office success, earning $322 million worldwide on a $22 million budget. It was nominated for twelve Academy Awards, and won seven, including Best Picture, Best Director, Best Adapted Screenplay, and Best Original Score. The film won numerous other awards, including seven BAFTAs and three Golden Globe Awards. In 2007, the American Film Institute ranked Schindler’s List 8th on its list of the 100 best American films of all time. The film was designated as «culturally, historically or aesthetically significant» by the Library of Congress in 2004 and selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry.

Plot[edit]

In Kraków during World War II, the Nazis force local Polish Jews into the overcrowded Kraków Ghetto. Oskar Schindler, a German Nazi Party member from Czechoslovakia, arrives in the city, hoping to make his fortune. He bribes Wehrmacht (German armed forces) and SS officials, acquiring a factory to produce enamelware. Schindler hires Itzhak Stern, a Jewish official with contacts among black marketeers and the Jewish business community; he handles administration and helps Schindler arrange financing. Stern ensures that as many Jewish workers as possible are deemed essential to the German war effort to prevent them from being taken by the SS to concentration camps or killed. Meanwhile, Schindler maintains friendly relations with the Nazis and enjoys his new wealth and status as an industrialist.

SS-Untersturmführer (second lieutenant) Amon Göth arrives in Kraków to oversee construction of the Płaszów concentration camp. When the camp is ready, he orders the ghetto liquidated: two thousand Jews are transported to Płaszów, and two thousand others are killed in the streets by the SS. Schindler witnesses the massacre and is profoundly affected. He particularly notices a young girl in a red coat who hides from the Nazis and later sees her body on a wagonload of corpses. Schindler is careful to maintain his friendship with Göth and continues to enjoy SS support, mostly through bribery. Göth brutalizes his Jewish maid Helen Hirsch and randomly shoots people from the balcony of his villa; the prisoners are in constant fear for their lives. As time passes, Schindler’s focus shifts from making money to trying to save as many lives as possible. To better protect his workers, Schindler bribes Göth into allowing him to build a sub-camp at his factory.

As the Germans begin losing the war, Göth is ordered to ship the remaining Jews at Płaszów to Auschwitz concentration camp. Schindler asks Göth for permission to move his workers to a munitions factory he plans to build in Brünnlitz near his home town of Zwittau. Göth reluctantly agrees, but charges a huge bribe. Schindler and Stern prepare a list of people to be transferred to Brünnlitz instead of Auschwitz. The list eventually includes 1,100 names.

As the Jewish workers are transported by train to Brünnlitz, the women and girls are mistakenly redirected to Auschwitz-Birkenau; Schindler bribes Rudolf Höss, commandant of Auschwitz, for their release. At the new factory, Schindler forbids the SS guards from entering the production area without permission and encourages the Jews to observe the Sabbath. Over the next seven months, he spends his fortune bribing Nazi officials and buying shell casings from other companies. Due to Schindler’s machinations, the factory does not produce any usable armaments. He runs out of money in 1945, just as Germany surrenders.

As a Nazi Party member and war profiteer, Schindler must flee the advancing Red Army to avoid capture. The SS guards at the factory have been ordered to kill the Jewish workforce, but Schindler persuades them not to do so. Bidding farewell to his workers, he prepares to head west, hoping to surrender to the Americans. The workers give him a signed statement attesting to his role in saving Jewish lives and present him with a ring engraved with a Talmudic quotation: «Whoever saves one life saves the world entire». Schindler breaks down in tears, feeling he should have done more, and is comforted by the workers before he and his wife leave in their car. When the Schindlerjuden awaken the next morning, a Soviet soldier announces that they have been liberated. The Jews then walk to a nearby town.

An epilogue reveals that Göth was convicted of crimes against humanity and executed via hanging, while Schindler’s marriage and businesses failed following the war. In the present, many of the surviving Schindlerjuden and the actors portraying them visit Schindler’s grave and place stones on its marker (a traditional Jewish sign of respect for the dead), after which Liam Neeson lays two roses.

Cast[edit]

Liam Neeson plays Oskar Schindler in the film.

- Liam Neeson as Oskar Schindler

- Ben Kingsley as Itzhak Stern

- Ralph Fiennes as Amon Göth

- Caroline Goodall as Emilie Schindler

- Jonathan Sagall as Poldek Pfefferberg

- Embeth Davidtz as Helen Hirsch

- Małgorzata Gebel as Wiktoria Klonowska

- Mark Ivanir as Marcel Goldberg

- Beatrice Macola as Ingrid

- Andrzej Seweryn as Julian Scherner

- Friedrich von Thun as Rolf Czurda

- Jerzy Nowak as Investor

- Norbert Weisser as Albert Hujar

- Albert Misak as Mordecai Wulkan

- Michael Gordon as Mr. Nussbaum

- Aldona Grochal as Mrs. Nussbaum

- Uri Avrahami as Chaim Nowak

- Michael Schneider as Juda Dresner

- Miri Fabian as Chaja Dresner

- Anna Mucha as Danka Dresner

- Adi Nitzan as Mila Pfefferberg

- Jacek Wójcicki as Henry Rosner

- Beata Paluch as Manci Rosner

- Piotr Polk as Leo Rosner

- Bettina Kupfer as Regina Perlman

- Grzegorz Kwas as Mietek Pemper

- Kamil Krawiec as Olek Rosner

- Henryk Bista as Mr. Löwenstein

- Ezra Dagan as Rabbi Menasha Levartov

- Rami Heuberger as Joseph Bau

- Elina Löwensohn as Diana Reiter

- Krzysztof Luft as Herman Toffel

- Harry Nehring as Leo John

- Wojciech Klata as Lisiek

- Paweł Deląg as Dolek Horowitz

- Hans-Jörg Assmann as Julius Madritsch

- August Schmölzer as Dieter Reeder

- Hans-Michael Rehberg as Rudolf Höß

- Daniel Del Ponte as Josef Mengele

- Adam Siemion as Adam Levy

- Jochen Nickel as Wilhelm Kunde

- Ludger Pistor as Josef Leipold[a]

- Oliwia Dąbrowska as the Girl in Red

Production[edit]

Development[edit]

Poldek Pfefferberg, one of the Schindlerjuden, made it his life’s mission to tell the story of his savior. Pfefferberg attempted to produce a biopic of Oskar Schindler with MGM in 1963, with Howard Koch writing, but the deal fell through.[9][10] In 1982, Thomas Keneally published his historical novel Schindler’s Ark, which he wrote after a chance meeting with Pfefferberg in Los Angeles in 1980.[11] MCA president Sid Sheinberg sent director Steven Spielberg a New York Times review of the book. Spielberg, astounded by Schindler’s story, jokingly asked if it was true. «I was drawn to it because of the paradoxical nature of the character,» he said. «What would drive a man like this to suddenly take everything he had earned and put it all in the service of saving these lives?»[12] Spielberg expressed enough interest for Universal Pictures to buy the rights to the novel.[12] At their first meeting in spring 1983, he told Pfefferberg he would start filming in ten years.[13] In the end credits of the film, Pfefferberg is credited as a consultant under the name Leopold Page.[14]

The liquidation of the Kraków Ghetto in March 1943 is the subject of a 15-minute segment of the film.

Spielberg was unsure if he was mature enough to make a film about the Holocaust, and the project remained «on [his] guilty conscience».[13] Spielberg tried to pass the project to director Roman Polanski, but he refused Spielberg’s offer. Polanski’s mother was killed at Auschwitz, and he had lived in and survived the Kraków Ghetto.[13] Polanski eventually directed his own Holocaust drama The Pianist (2002). Spielberg also offered the film to Sydney Pollack and Martin Scorsese, who was attached to direct Schindler’s List in 1988. However, Spielberg was unsure of letting Scorsese direct the film, as «I’d given away a chance to do something for my children and family about the Holocaust.»[15] Spielberg offered him the chance to direct the 1991 remake of Cape Fear instead.[16] Billy Wilder expressed an interest in directing the film as a memorial to his family, most of whom were murdered in the Holocaust.[17] Brian De Palma also refused an offer to direct.[18]

Spielberg finally decided to take on the project when he noticed that Holocaust deniers were being given serious consideration by the media. With the rise of neo-Nazism after the fall of the Berlin Wall, he worried that people were too accepting of intolerance, as they were in the 1930s.[17] Sid Sheinberg greenlit the film on condition that Spielberg made Jurassic Park first. Spielberg later said, «He knew that once I had directed Schindler I wouldn’t be able to do Jurassic Park.»[2] The picture was assigned a small budget of $22 million, as Holocaust films are not usually profitable.[19][2] Spielberg forwent a salary for the film, calling it «blood money»,[2] and believed it would fail.[2]

In 1983, Keneally was hired to adapt his book, and he turned in a 220-page script. His adaptation focused on Schindler’s numerous relationships, and Keneally admitted he did not compress the story enough. Spielberg hired Kurt Luedtke, who had adapted the screenplay of Out of Africa, to write the next draft. Luedtke gave up almost four years later, as he found Schindler’s change of heart too unbelievable.[15] During his time as director, Scorsese hired Steven Zaillian to write a script. When he was handed back the project, Spielberg found Zaillian’s 115-page draft too short, and asked him to extend it to 195 pages. Spielberg wanted more focus on the Jews in the story, and he wanted Schindler’s transition to be gradual and ambiguous instead of a sudden breakthrough or epiphany. He also extended the ghetto liquidation sequence, as he «felt very strongly that the sequence had to be almost unwatchable.»[15]

Casting[edit]

Neeson auditioned as Schindler early on in the movie’s development, He was cast in December 1992 after Spielberg saw him perform in Anna Christie on Broadway.[20] Warren Beatty participated in a script reading, but Spielberg was concerned that he could not disguise his accent and that he would bring «movie star baggage».[21] Kevin Costner and Mel Gibson expressed interest in portraying Schindler, but Spielberg preferred to cast the relatively unknown Neeson so that the actor’s star quality would not overpower the character.[22] Neeson felt Schindler enjoyed outsmarting the Nazis, who regarded him as somewhat naïve. «They don’t quite take him seriously, and he used that to full effect.»[23] To help him prepare for the role, Spielberg showed Neeson film clips of Time Warner CEO Steve Ross, who had a charisma that Spielberg compared to Schindler’s.[24] He also located a tape of Schindler speaking, which Neeson studied to learn the correct intonations and pitch.[25]